Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vaep20

Arts Education Policy Review

ISSN: 1063-2913 (Print) 1940-4395 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vaep20

Setting the stage for Social Emotional Learning

(SEL) policy and the arts

Scott N. Edgar & Maurice J. Elias

To cite this article: Scott N. Edgar & Maurice J. Elias (2020): Setting the stage for

Social Emotional Learning (SEL) policy and the arts, Arts Education Policy Review, DOI:

10.1080/10632913.2020.1777494

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2020.1777494

Published online: 13 Jun 2020.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Setting the stage for Social Emotional Learning (SEL) policy and the arts

Scott N. Edgar

a

and Maurice J. Elias

b

a

Music, Lake Forest College, Lake Forest, Illinois, USA;

b

Psychology, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA

ABSTRACT

Social Emotional Learning (SEL), like the arts, has accompanied human life throughout its

existence. SEL refers to our capacity to recognize emotions in ourselves and others and

manage them appropriately, be organized and set goals, solve problems and make deci-

sions effectively, establish positive and productive relationships with others, and handle

challenging situations capably. This issue is organized from broad, first addressing national

policy, to specialized, surveying practitioner local-level implementation. Instead of dividing

articles based upon arts content area (dance, media arts, music, theatre, dance), the articles

are organized by the level of policy, addressing each art content area within each level. This

issue should be read as a collective work highlighting the varied levels of explicit connec-

tion and the potential for a much more robust connection between arts education and

Social Emotional Learning.

KEYWORDS

Social Emotional Learning;

arts education; SEL

Social Emotional Learning (SEL), like the arts, has

accompanied human life throughout its existence. SEL

refers to our capacity to recognize emotions in our-

selves and others and manage them appropriately, be

organized and set goals, solve problems and make

decisions effectively, establish positive and productive

relationships with others, and handle challenging sit-

uations capably. Now referred to as the Collaborative

for Academic, Social Emotional Learning (CASEL) 5

skills, these competencies develop from birth, grow

and change with our experiences and development

(physical, cognitive, social, and emotional), and influ-

ence everything we do (Durlak et al., 2015; Elias

et al., 1997).

In recent years, SEL’s prominence in education has

grown significantly due to:

Proliferation of data showing the positive impact

of well-implemented, multiyear, systematic SEL

programs (Durlak et al., 2011, 2015).

Advances in the science of learning and develop-

ment showing the role of a positive school climate

and student engagement and voice in learning and

retention (Cantor et al., 2018).

The work of the National Commission on Social,

Emotional, and Academic Learning in defining

best practices and appropriate SEL policies (www.

nationathope.org).

CASEL’s Collaborating States Initiative, leading to

40 states (at the time of publication) working

actively on adopting standards or mandates for

SEL, character education, and/or positive school

culture and climate (https://casel.org/csi-resources/;

Dusenbury et al., 2015).

The Academy for SEL in Schools, which offers

online, hybrid certificate programs in Social

Emotional and Character Development Instruction

and School Leadership leading to membership in

an ongoing worldwide Virtual Professional

Learning Community (SELinSchools.org).

The creation of the Social Emotional Learning

Alliance for the United States, a national organiza-

tion of affiliated state organizations focused on

grass roots advocacy for SEL-related efforts in edu-

cation, as well as professional development and

implementation supports (www.SEL4US.org and

state affiliates, e.g., SEL4PA, SEL4CA, SEL4MA,

SEL4NJ, SEL4WA, SEL4TX).

The research has been compelling. Multiyear school

interventions related to SEL have reported significant

student gains in SEL, attitudes, positive social behav-

iors, and significant decreases in emotional and

behavioral problems, improved teacher satisfaction,

and 11% increases in academic performance (Durlak

et al., 2011; Sklad et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2017). The

CONTACT Scott N. Edgar [email protected] Music, Lake Forest College, Lake Forest, Illinois, USA.

ß 2020 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ARTS EDUCATION POLICY REVIEW

https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2020.1777494

explicit recognition that sense of purpose and other

positive virtues are part of SEL has been a relatively

recent development supporting the value of SEL

(Elias, 2014). While the research base is less robust for

children in low income, urban settings (Rowe &

Trickett, 2017), the data compiled over hundreds of

studies are equally compelling. This empirical consist-

ency has been aided by the codification of what it

means to implement SEL-related approaches

effectively.

SEL and the arts

In a series of interviews on SEL and the arts in 2009,

the Greater Good Science Center helped make a

strong case for convergence: “We need the arts

because they remind children that their emotions are

equally worthy of respect and expression. The arts

introduce children to connectivity, engagement, and

allow a sense of identification with, and responsibility

for, others” (Jessica Hoffman Davis). Artistic expres-

sion embodies the expression of emotion, aspiration,

relationships, regrets, values, imagination, and con-

cerns. Individuals create art in various media, but the

common denominator is that the arts come from peo-

ple and from the context of their experiences.

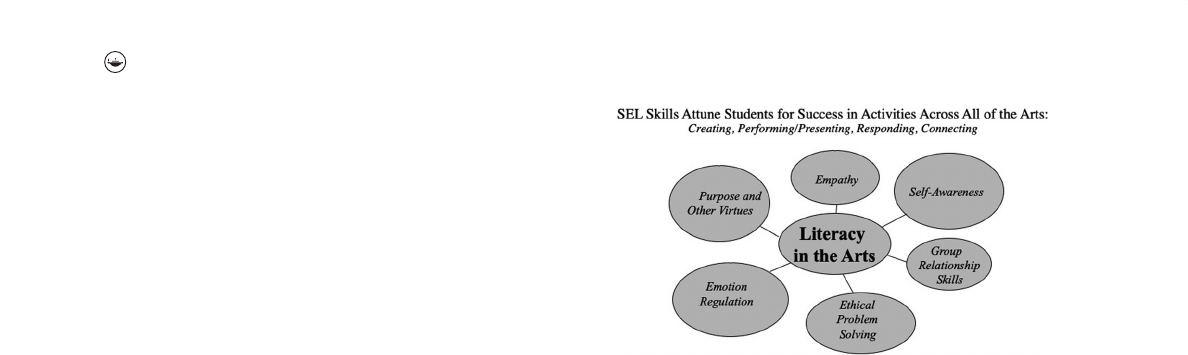

Consider the artistic processes defining the National

Core Arts Standards: Creating, Performing/Presenting/

Producing, Responding, and Connecting. Educators at

ArtsEd New Jersey have illustrated how SEL connects

to these processes: “The creative ideas, concepts, and

feelings that influence artists’ work emerge from a var-

iety of sources. One’s feelings, thoughts, personal traits,

strengths and limitations influence the creative process.”

One’s feelings vocabulary, one’s ability to discern

nuanced feelings in others, to understand situations, to

have a sense of the flow of history and co ntext, to man-

age one’s own emotions, to look realistically at one’s

strengths and limitations, to engage in and process a

variety of relationships, and to be able to focus one’s

energies for sustained problem solving and overcoming

setbacks all influence each and every one of the artis-

tic processes.

The pedagogy of SEL

For those engaging in arts instructio n, the instructional

strategies that have worked to build SEL skills in stu-

dents will also support the integration of SEL into the

four artistic processes. In the compilation below (Elias

& Kress, 2020), one can substitute “SEL skill” or

“artistic skill and process” for the word, “skill” as they

are synonymously effective. These skills represent the

intersections of SEL and arts education capitalizing on

well-established arts pedagogy strategies:

Naming: Establish terminology to serve as a short-

hand for the skill or set of skills.

Building motivation: Work with students to under-

stand why these skills could be helpful in their

everyday lives.

Modeling: Show students how to use the skill in

professional or personal life (to the extent

comfortable).

Prompting and Cueing Concepts and Skills

Learned Previously: Remind students to use skills

by creating visual and verbal signals; the more they

practice skills, the more they become internalized.

Pedagogy for Generalizing Skills:

Review: Review prior activities for the stu-

dents who were present, those who were

absent, and those who were present but not

fully attentive.

Repetit ion: Repetition helps students fin d out how

to flexibly apply the skill in many circumstances.

Anticipate Use: Highlight an upcoming

opportunity to use new skills, rem ind studen ts

in advance that it will help them to use

the skill.

Visual Reminders: Place (student-made) posters,

signs, and reminders of SEL themes and skills

in classrooms, guidance offices, group rooms,

the main office, on bulletin boards.

Testimonials: Create opportunities for students

to share examples of times they have used skills

(or could have used them to good advantage if

they would have remembered to do so).

Reinforcement: Students are especially attuned

to appreciation, both from adults and from

peers. When students “live” the SEL themes, let

them know they were noticed.

Figure 1. Literacy in the arts.

2 S. N. EDGAR AND M. J. ELIAS

Reflection: Opportunities for reflection via dis-

cussion, journaling, etc. build a habit of

thoughtfulness.

While arts educators cannot be solely responsible

for teaching SEL any more than they can for teaching

any other non-artistic skill, it is essential for arts edu-

cators to understand SEL and how to evoke it in the

context of artistic work. This process is illustrated in

Figure 1. If it is assumed that SEL attunes students to

success in activities across all artistic processes and

media, then making the appropriate connections to

SEL and related domains in arts instruction (and par-

ticularly the role and procedures of those individuals

who created the arts being studied) becomes integral

to arts education.

Policies, practices, and interpretations

One challenge the authors faced writing for this issue

was adapting an emerging social science construct for

an established humanist field. While all authors uti-

lized a common definition of SEL and approached

their work empirically, a broad range of methodolo-

gies, voices, and tone was embraced. Narratives, con-

tent analyses, and case studies were approaches these

authors have chosen to discover intersections between

SEL and the arts. Many arts teachers believe they are

already implementing a socially- and emotionally-rich

education. The touted benefits of arts education, such

as creativity, collaboration, and self-discovery are cer-

tainly congruent with SEL; however, without inten-

tionality, consistency, and sequence, relying on natural

occurrences in arts education is not enough to capital-

ize on the potential of artistic SEL. The critical,

empirical, and purposeful approach the authors in this

issue employed represents the rigor needed to advance

the intrinsic social and emotional benefits of the

arts classrooms.

While research, policy (school, district, state, and

national), and implementation of SEL is widespread,

the content-specific contextualization for the arts

remains disconnected. One of the primary challenges

of creating this issue was finding the researchers,

teachers, and artists implementing SEL in the arts. To

streamline the analysis and policy connections

between SEL and the arts, all authors have approached

their work utilizing CASEL’s definitions and the SEL

Learning Standards created for the state of Illinois

(www.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/PDF-7-

Illinois-SEL-Standards.pdf). Few formal connections

between SEL and the arts currently exist (a list of

some of these resources can be found below). This

issue was guided by a vision to comb existing arts and

educational policy for both explicit and implicit con-

gruences. Further, many authors chose to envision

what direct, explicit connections could be.

This issue is organized from broad, first addressing

national policy, to specialized, surveying practitioner

local-level implementation. Instead of dividing articles

based upon arts content area (dance, media arts,

music, theater, dance), the articles are organized by

the level of policy, addressing each art content area

within each level.

While there have been advances in SEL policy at

the state level, there is currently no national policy

in the United States for SEL. Lauren Kapalka

Richerme analyzed the 2015 Obama-administration

education policy, the Every Student Succeeds Act

(ESSA), for intersections with SEL. Kapalka

Richerme further evaluated this act and extrapo-

lated what federal SEL/arts policy could be.

As noted above, the activities involved in arts liter-

acy have a strong connection to SEL. In 2014, the

National Coalition for Core Arts Standards

released a set of standards for dance, media arts,

music, theater, and visual art. Matt Omasta led a

team (Stephanie Milling and Rebecca Lewis, dance;

Amy Petterson Jensen, media arts; Johanna Siebert,

music; Beth Murray, theater; and Mark Graham,

visual arts) of researchers on a content analysis of

the NCAS evaluating crossroads between the

standards and SEL.

Preparing arts teachers to incorporate SEL into

their classrooms begins with their own personal

experiences and in their undergraduate teacher

preparation programs. Daniel Hellman and

Stephanie Milling investigated the current imple-

mentation of SEL in arts teacher education stand-

ards and programs in two states, looking at

accreditation organization requirements, institution

documents, and course syllabi for how SEL is cur-

rently implemented in arts teacher education.

While widespread arts/SEL implementation is still

evolving, several models for assessment and meas-

urement have emerged. Erica Halverson and Yorel

Lashley present strategies for assessing SEL

artistically.

Local-level arts/SEL implementation has emerged

on different levels nationwide. Martha Eddy organ-

ized the narratives of some of these programs

through the lens of broad SEL core competencies

and movement. These implementations come from

ARTS EDUCATION POLICY REVIEW 3

a K-12 classroom (Adam Gohr); teacher prepar-

ation (Carolina Blatt-Gross); a professional per-

formance company (Kathryn Humphreys and

Louanne Smolin); and university collaborations

(Erica Halverson).

This issue concludes with a vision for what arts-

based SEL policy could look like and why this is

important for the future of arts education. The voi-

ces of Michael Blakeslee, National Association for

Music Education (NAfME) executive director and

Bob Morrison, Quadrant Research CEO, and Dale

Schmid, State Education Agency Directors of Arts

Education (SEADAE) president, are included.

Additionally, as this issue emerged during the

COVID-19 Pandemic, additional attention to con-

textualizing this issue amidst this trauma and uti-

lizing SEL as arts education advocacy is included.

While the articles do reflect a broad-to-narrow

scope of SEL and arts education policy, the articles do

interact and complement each other. For example, the

Hellman and Milling article on teacher preparation

intersects with the Omasta, et al. article on the

National Core Arts Standards. This issue should be

read as a collective work highlighting the varied levels

of explicit connection and the potential for a much

more robust connection between arts education and

Social Emotional Learning.

References

Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2018).

Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children

learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental

Science. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649

Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., &

Gullotta, T. P. (Eds.). (2015). Handbook for social and

emotional learning: Research and practice. Guilford Press.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor,

R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhanc-

ing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-ana-

lysis of school-based universal interventions . Child

Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.

1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Dusenbury, L. A., Zadrazil Newman, J., Weissberg, R. P.,

Goren, P., Domitrovich, C. E., & Mart, A. K. (2015). The

case for preschool through high school state learning

standards for SEL. In J. A. Durlak, C. E. Domitrovich,

R. P. Weissberg, & T. P. Gullotta (Eds.), Handbook for

social and emotional learning: Research and practice (pp.

532–548). Guilford Press.

Elias, M. J. (2014). The future of character education and

social-emotional learning: The need for whole school and

community-linked approaches. Journal of Research in

Character Education, 10(1), 37–42.

Elias, M. J., & Kress, J. E. (2020). Nurturing students’ char-

acter: Everyday teaching activities for social-emotional

learning. Routledge.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg , R. P., Frey, K. S.,

Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., Kessler, R., Schwab-

Stone, M. E., & Shriver, T. P. (1997). Promoting social and

emotional learning: Guidelines for educators. Association for

Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Rowe, H. L., & Trickett, E. J. (2017). Student diversity rep-

resentation and reporting in universal school-based social

and emotional learning programs: Implications for gener-

alizability. Educational Psychology Review,1–25. https://

doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9425-3

Sklad, M., Diekstra, R., Ritter, M. D., Ben, J., & Gravesteijn,

C. (2012). Effectiveness of school-based universal social,

emotional, and behavioral programs: Do they enhance

students’ development in the area of skill, behavior, and

adjustment? Psychology in the Schools, 49(9), 892–909.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21641

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P.

(2017). Promoting positive youth development through

School-Based Social and Emotional Learning

Interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child

Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. https://doi.org/10.1111/

cdev.12864

Resources for Arts-based SEL Instruction

Edgar, S. N. (2017). Music education and social emotional

learning: The heart of teaching music (and student work-

book). GIA Publications.

Farrington, C. A., Maurer, J., McBride, M. R. A., Nagaoka,

J., Puller, J. S., Shewfelt, S., Weiss, E. M., & Wright, L.

(2019). Arts education and social-emotional learning out-

comes among K–12 students: Developing a theory of

action. Ingenuity and the University of Chicago

Consortium on School Research.

New Jersey Arts Education Social Emotional Learning

Framework. www.selarts.org.

Pellitteri, J. S. (2006). The use of music in facilitating emo-

tional learning. In J. S. Pellitteri, R. Stern, C. Shelton, &

B. Muller-Ackerman (Eds.), Emotionally intelligent school

counseling (pp. 185–199). Erlbaum.

Pellitteri, J., Stern, R., & Nakhutina, L. (1999). Music: The

sounds of emotional intelligence. Voices from the Middle:

Social and Emotional Learning, 7(1), 25–29.

Simion, A. (2016, April). Strategies for inclusion of students

with ADHD through music and physical education in pri-

mary school. In The Future of Education Conference.

https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4432.1689

4 S. N. EDGAR AND M. J. ELIAS

Illinois Social Emotional Learning Standards

Goal 1-Self: Develop self-awareness and self-management

skills to achieve school and life success. Learning Standards:

Identify and manage one’s emotions and behavior.

Recognize personal qualities and external supports.

Demonstrate skills related to achieving personal and aca-

demic goals.

Goal 2-Others: Use social awareness and interpersonal

skills to establish and maintain positive relationships.

Learning Standards:

Recognize the feelings and perspectives of others.

Recognize individual and group similarities and differences.

Use communication and social skills to interact effect-

ively with others.

Demonstrate an ability to prevent, manage, and resolve

interpersonal conflicts in constructive ways.

Goal 3-Responsible Decisions: Demonstrate decision-

making skills and responsible behaviors in personal, school,

and community contexts. Learning Standards:

Consider ethical, safety, and societal factors in mak-

ing decisions.

Apply decision-making skills to deal responsibly with

daily academic and social situations.

Contribute to the well-being of one’s school

and community.

ARTS EDUCATION POLICY REVIEW 5