STIMULATING INVESTMENT

IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES

© IRENA 2020

Unlessotherwisestatedmaterialinthispublicationmaybefreelyusedsharedcopiedreproducedprintedandorstoredprovidedthatappropriate

acknowledgementisgiventoIRENAasthesourceandcopyrightholderMaterialinthispublicationthatisattributedtothirdpartiesmaybesubjectto

separatetermsofuseandrestrictionsandappropriatepermissionsfromthesethirdpartiesmayneedtobesecuredbeforeanyuseofsuchmaterial

ISBN----

CitationIRENACoalitionforAction()Stimulating investment in community energy: Broadening the ownership

of renewablesInternationalRenewableEnergyAgencyAbuDhabi

AbouttheCoalition

TheIRENACoalitionforActionbringstogetherleadingrenewableenergyplayersfromaround

theworldwiththecommongoalofadvancingtheuptakeofrenewableenergyTheCoalition

facilitatesglobaldialoguesbetweenpublicandprivatesectorstodevelopactionstoincrease

theshareofrenewablesintheglobalenergymixandacceleratetheglobalenergytransition

Aboutthispaper

ThiswhitepaperhasbeendevelopedjointlybymembersoftheCoalition’sWorkingGroupon

CommunityEnergyBuildingonseveralcasestudiesthepapershowcasespolicymeasures

and financing mechanisms that reflect best practices in community energy and oers

recommendationstogovernmentsandfinancialinstitutionsonhowtoacceleratecommunity

energydevelopment

Acknowledgements

ContributingauthorsHans-JosefFellandCharlotteHornung(EnergyWatchGroup)RohitSen(ICLEI–Local

Governments for Sustainability) Shota Furuya (Institute for Sustainable Energy Policies) Monica Oliphant

(InternationalSolarEnergySociety)AnnaSkowron(WorldFutureCouncil)StefanGsänger(WorldWindEnergy

Association)and StephanieWeckend EmmaÅberg Kelly Taiand AnindyaBhagirath under theguidanceof

RabiaFerroukhi(IRENA)

Furtheracknowledgements Malte Zieher (Bündnis Bürgerenergie) Erik Christiansen (EBO Consult) Johan

Hamels (Ecopower) Rainer Hinrichs-Rahlwes (European Renewable Energies Federation) Vasilios Anatolitis

andJanGeorge(FraunhoferInstituteforSystemsandInnovationResearch)MollyWalsh(FriendsoftheEarth

Europe)AnaAmazo(Guidehouse)EcoMatser(Hivos)JohnFarrell(InstituteforLocalSelf-Reliance)Namiz

Musafer(IntegratedDevelopmentAssociation)DavidRenné(InternationalSolarEnergySociety)Jan-Gerald

Andreas(KfWDevelopmentBank)OusmaneOuattaraandIbrahimTogola(Mali-FolkecenterNyetaa)Elizabeth

Doris (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) Leire Gorroño-Albizu (Nordic Folkecenter for Renewable

Energy)LeaRanalder(REN)HarryAndrews(Renew)JoshRobertsandDirkVansintjan(REScoopeu)Glen

Estill(SkyGenerationInc)LukeWilkinson(SustainabilityVictoria)PatrickDevine-Wright(UniversityofExeter)

PaulGipe(Wind-Works)AnnaLeidreiter(WorldFutureCouncil)TimoKarl(WorldWindEnergyAssociation)

SergioOceransky(YansaGroup)MelaniFurlanLinHerenčićandBorisPavlin(Zelenaenergetskazadruga)and

DialaHawilaEmanueleBiancoandCostanzaStrinati(IRENA)

StevenKennedyeditedandMyrtoPetroudesignedthereport

CoverphotographsarefromtheHokkaidoGreenFundChristopherHolzemBürgerwerkeandMali-Folkecenter

Nyetaa

Disclaimer

Thispublicationandthematerialhereinareprovided“asis”AllreasonableprecautionshavebeentakenbyIRENAandtheIRENACoalition

forActiontoverifythereliabilityofthematerialinthispublicationHoweverneitherIRENAtheIRENACoalitionforActionnoranyofits

ocialsagentsdataorotherthird-partycontentprovidersprovidesawarrantyofanykindeitherexpressedorimpliedandtheyacceptno

responsibilityorliabilityforanyconsequenceofuseofthepublicationormaterialherein

TheinformationcontainedhereindoesnotnecessarilyrepresenttheviewsofallMembersofIRENAorMembersoftheCoalitionMentionsof

specificcompaniesprojectsorproductsdonotimplyanyendorsementorrecommendationThedesignationsemployedandthepresentation

ofmaterialhereindonotimplytheexpressionofanyopiniononthepartofIRENAortheIRENACoalitionforActionconcerningthelegalstatus

ofanyregioncountryterritorycityorareaorofitsauthoritiesorconcerningthedelimitationoffrontiersorboundaries

FIGURES, TABLES AND BOXES .................................................................................................... 4

ABBREVIATIONS

........................................................................................................................ 5

1. COMMUNITY ENERGY: AN INVESTMENT WITH IMPACT

.......................................................... 7

2. THE BENEFITS OF COMMUNITY ENERGY AND BARRIERS TO ITS FINANCING

.......................... 9

2.1 Community energy supports an inclusive energy transition .............................................................................. 9

2.2 Barriers to mobilising investment still hinder community energy growth ..................................................... 11

3. ENABLING ENVIRONMENTS FOR COMMUNITY ENERGY INVESTMENT

.................................. 13

3.1 Supportive legislation and government policies are key to community energy growth .......................... 13

3.2 Policy design can be tailored to community energy ........................................................................................... 15

4. FINANCING COMMUNITY ENERGY PROJECTS

..................................................................... 18

4.1 Ownership and financing of community energy are interrelated ....................................................................18

4.2 Public sources of financing can be leveraged for community energy investment .....................................21

4.3 Private financing must step up .................................................................................................................................. 22

5. KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR GOVERNMENTS AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS

................................ 24

ANNEX I. CASE STUDIES: ENABLING ENVIRONMENTS FOR COMMUNITY ENERGY INVESTMENT..... 26

Victoria, Australia

.................................................................................................................................................................... 27

Denmark

..................................................................................................................................................................................... 28

Germany

..................................................................................................................................................................................... 29

Japan

........................................................................................................................................................................................... 30

Scotland, United Kingdom

................................................................................................................................................... 31

United States

............................................................................................................................................................................ 32

ANNEX II. CASE STUDIES: FINANCING COMMUNITY ENERGY PROJECTS

....................................... 33

Mindanao, Philippines

............................................................................................................................................................ 34

Guanacaste, Costa Rica

......................................................................................................................................................... 35

Department of Quiché, Guatemala

.................................................................................................................................... 36

REFERENCES

............................................................................................................................ 38

CONTENTS

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:4

FIGURES, TABLES

AND BOXES

Figure 1: Potential benefits of community energy .............................................................................................................. 10

Figure 2: Potential barriers to mobilising investment in community energy

................................................................ 11

Figure 3: External financing options for community energy projects

..........................................................................20

Table 1: Government measures, past and present, that can enable community energy investment

................... 16

Table 2: Legal forms of community ownership

..................................................................................................................... 19

Box 1 : Community energy in European Union Renewable Energy Directive and Electricity Directive

................14

Box 2: Impact investing

............................................................................................................................................................... 22

Box 3: Crowdfunding in sub-Saharan Africa

........................................................................................................................ 23

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 5

ASHDINQUI Asociación Hidroeléctrica de Desarrollo Integral Norte del Quiché

CARES

Community and Renewable Energy Scheme

CCA

Community choice aggregation

DFI

Development finance institution

FIT

feed-in tari

ICE

Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad

IRENA

International Renewable Energy Agency

KfW

Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau

kW

kilowatt

LLC

limited liability company

OLADE

Organización Latinoamericana de Energía

PAYG

pay-as-you-go

USD

United States dollar

VNM

virtual net energy metering

ABBREVIATIONS

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:6

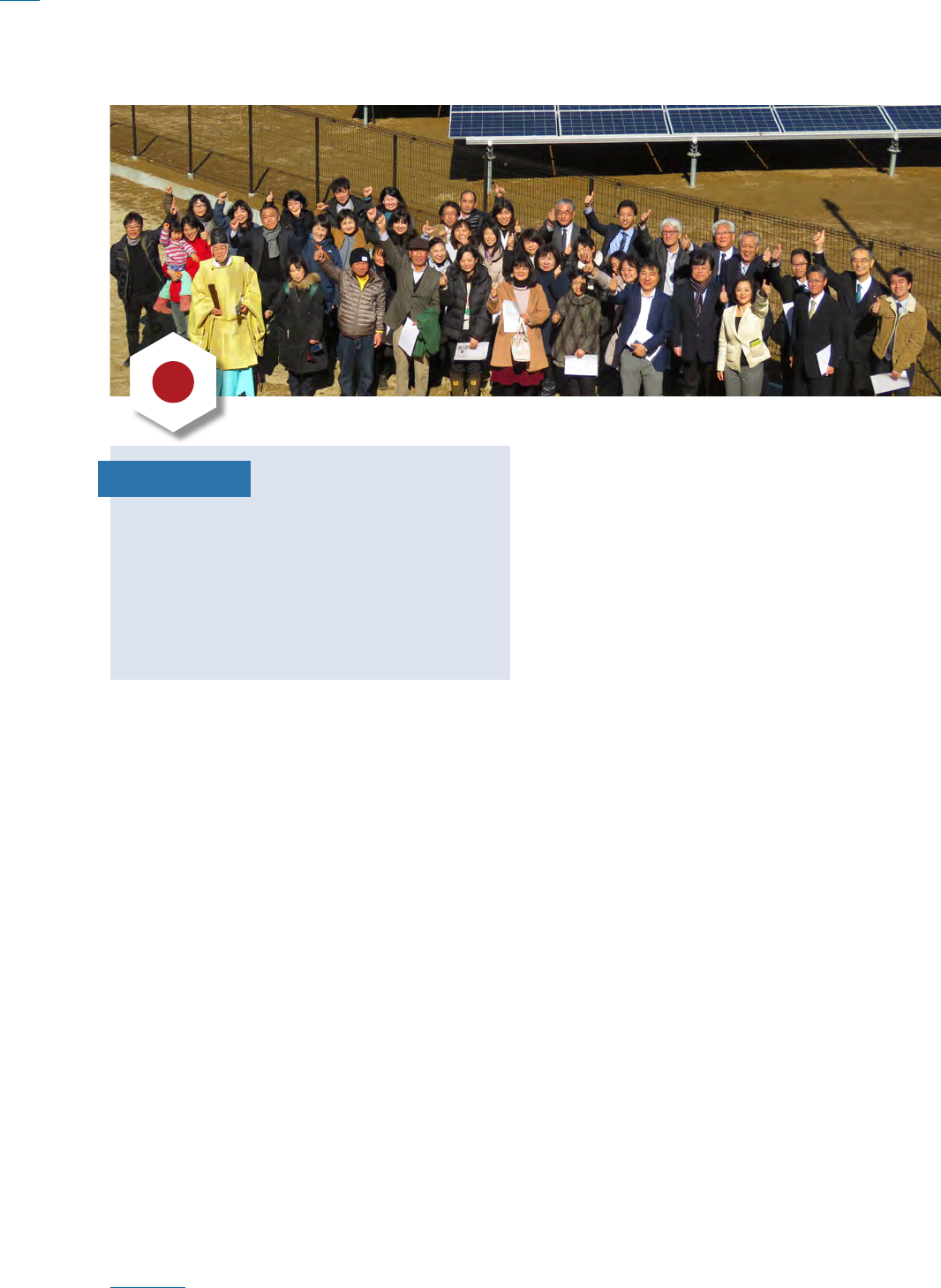

Photo: Hokkaido Green Fund

Launch ceremony for community wind project in Ishikari city, Japan

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 7

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred recovery

measures that have the potential to drive a

lasting shift in the global energy mix. While some

governments have announced more ambitious

climate commitments, many others have yet to

take decisive action to move towards a green

recovery. Renewable energy, with its inherent

adaptability and decentralised nature, is well

positioned to help build more equitable, inclusive

and resilient economies, while fostering increased

citizen participation in the energy transition

(IRENA, 2020b).

Citizen-driven renewable energy projects –

referred to here as “community energy” – can play

a considerable role in the post COVID recovery by

promoting local social and economic prosperity

while helping to meet climate and sustainability

objectives.

The International Renewable Energy Agency

(IRENA) Coalition for Action has defined

community energy as the “economic and

operational participation and ownership by citizens

or members of a defined community – be it at

the village, city or regional level – in a renewable

energy project, regardless of the size and scope of

the project”.

1

1 The IRENA Coalition for Action (2018) white paper “Community Energy: Broadening the Ownership of Renewables” defines

community energy as any combination of at least two of the following elements: (1) local stakeholders own the majority or

all of a renewable energy project; (2) voting control rests with a community-based organisation; (3) the majority of social and

economic benefits are distributed locally.

A diverse range of approaches to community

energy development is found around the world.

Successful approaches leverage the project’s

direct social and economic benefits (led by the

creation of revenues and jobs from renewable

energy generation) as well as its broader

contribution to local socio-economic development

(e.g. through the expansion of access to electricity).

While community energy projects can be found

across the electricity, heating and cooling, and

transport sectors, this white paper, developed by

the Coalition’s Community Energy Working Group,

reviews measures that stimulate and sustain

community energy initiatives in the electricity

sector. Although renewable energy investments

by citizens and communities have gained traction

in many countries, knowledge exchange on a

global level has been limited. This paper fills the

gap by showcasing policy measures and financing

mechanisms that reflect best practices and oering

recommendations to governments and financial

institutions on how to accelerate community

energy development and reap its benefits.

COMMUNITY ENERGY:

AN INVESTMENT WITH

IMPACT

01

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:8

A number of public and private investors are

increasingly prioritising environmental and social

performance in their practices. Nevertheless, the

lack of supportive policy frameworks and enabling

market environments remains a major barrier for

the mobilisation of investments in community

energy. Findings reported in this paper demonstrate

that public support and non-discriminatory access

to the electricity market and grid have key roles

to play in community energy development, even in

countries where communities already have access

to aordable and low-cost financing.

In addition to adopting specific policy targets

for community energy, policy makers can unlock

further investment by providing a stable,

predictable and non-discriminatory policy

environment. To raise private capital, innovative

alternative financing mechanisms such as

crowdfunding have emerged to meet the needs

of communities. If insucient private capital

is available, communities often rely on public

grants or other support schemes to get started.

The financial community can further support

investment by facilitating access to debt and equity

financing for small- and medium-scale renewable

energy projects and helping to create partnerships

among community energy investors.

The next chapter explores the substantial benefits

of community energy, as well as the barriers that

face communities seeking financing for their

projects. Chapter 3 surveys policy measures that

shape community energy development around

the world. Chapter 4 provides an overview of

how community energy projects are financed

and the role played by public and private actors.

Chapter 5 summarises key takeaways on enabling

community energy investments. Nine case studies

of community energy initiatives from around the

world make up the

Annex.

Photo: Nordic Folkecenter for Renewable Energy

Community solar thermal district heating project in Snested, Denmark

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 9

THE BENEFITS OF

COMMUNITY ENERGY

AND BARRIERS TO

ITS FINANCING

02

Community energy projects can bring substantial

benefits to the communities involved, as well

as broader benefits to society. Yet much more

investment is needed to realise community energy’s

full potential. By removing the regulatory, financial

and institutional barriers that continue to hinder

investments, more communities can contribute

to the energy transition (IRENA Coalition for

Action, 2018).

Community energy projects involve citizens and

communities as producers, distributors and sellers

of electricity – and as consumers. The projects

may benefit communities socially, economically,

environmentally and institutionally, with many of

the benefits filtering through to society at large

(see Figure 1). The extent to which communities

and society can benefit from community energy

may vary depending on local political frameworks,

ownership models and other factors.

Community energy adds local socio-economic

value through investment, job creation and

improved welfare. The transition to a renewables-

based energy system can play a key role in the

economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic

(IRENA, 2020b). Community-owned renewable

energy projects are of particular importance as

they are likely to employ local contractors and

re-invest in local enterprises, services and goods

and thus support local resilience (Gancheva et

al., 2018). Furthermore, successful community

energy projects often invest in capacity building

and skill development so that local populations

can maintain and operate installations, thereby

creating jobs along the entire renewable energy

value chain (Callaghan and Williams, 2014). In

some cases, the financial returns of projects can

be re-invested in public facilities such as hospitals,

used to retrofit buildings or channelled into other

renewable energy and energy eciency projects

(IZES, 2015). Finally, community energy projects

help generate welfare gains, such as health benefits

through reduced air, water and land pollution and

greenhouse gas emissions.

2.1 Community energy supports an inclusive energy transition

Photo: Mali-Folkecenter Nyetaa

Community solar project in Mali

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:10

Broadened participation

in the energy system

Accelerated access

to renewable energy

through citizen-driven

innovation

Increased energy

security through lower

energy costs and

greater price certainty

Socio-economic gain

through investment,

job creation and

improved welfare

Figure 1: Potential benets of community energy

Community energy improves energy security

through lower energy costs and greater price

certainty. Renewable generation, when locally

owned and managed, enables communities to

increase energy independence from external

energy suppliers often still reliant on fossil fuels,

reducing their exposure to fluctuating energy

prices and saving on costs. Community energy

projects may also be able to generate long-term

income through the sale of (excess) renewable

energy. Shareholders may elect to oer low-cost

power to people in disadvantaged areas, thereby

reducing energy poverty (Friends of the Earth

Europe and REScoop.eu, 2017), or otherwise share

savings across the community.

Community energy widens access to renewable

energy through citizen-driven innovation. In

developing countries, and in some developed ones,

many rural and remote communities continue to

struggle with access to aordable and reliable

energy. Community energy projects have spawned

innovative business models and technological

solutions that expand access, improve the

reliability of service, help build climate resilience,

increase possibilities for new productive activities

and improve livelihoods (IRENA, 2020c).

Such grassroots innovations can make significant

contributions to the broader energy transition

by expanding the development and uptake of

renewable energy and complementing existing

energy access initiatives (Callaghan and Williams,

2014; Ornetzeder and Rohracher, 2012; Rogers et

al., 2012).

Community energy broadens participation in

the energy system and expands awareness and

acceptance of renewable energy. Engaging

community members in shared decision-making

processes can lead to increased transparency

and inclusiveness in the planning, construction

and management of installations. By making

collective decisions about the use and distribution

of investments and generated income, as well as

exercising direct control over local financial and

energy resources, communities achieve greater

autonomy and self-governance. Citizen investment

in community energy projects can also foster

more positive attitudes towards renewable energy

development (Bauwens and Devine-Wright, 2018).

All of these forms of participation can increase

citizens’ sense of ownership and community unity,

as well as raise awareness, acceptance and active

support for the energy transition (IRENA, 2020c;

Renn, 2014).

Active citizens form the base of the successful energy transition in the Rhein-Hunsrück district

of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, as represented by the honorary municipal council of Horn

Photo: Energieagentur Rheinland-Pfalz

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 11

2.2 Barriers to mobilising investment still hinder community

energy growth

Community energy development continues to face

regulatory, financial and institutional barriers. The

nature and extent of the obstacles experienced

vary between projects and across countries, but

also depend on project size: Smaller projects and

organisations are more prone to encounter the

challenges listed.

Overall, community energy has unique

characteristics that distinguish them from the

structures and practices of other renewable energy

projects. These characteristics include, but are

not limited to, a strong reliance on decentralised

organisation, voluntary contributions from

community members with limited prior experience

in energy development and trust in collective

investments (see Figure 2). These dierences make

establishing financial viability and accessing third-

party financing particularly challenging, especially

for smaller projects.

Community energy and its benefits are not yet

widely understood and accepted. Attracting buy-

in from policy makers, financiers and citizens may

prove challenging owing to limited awareness,

understanding and support of community energy

and its associated benefits. Stakeholders may

question the reliability of renewables to cover

base load at all times or have reservations about

new technologies. For various reasons, they may

also mistrust or oppose the idea of collaborative

business models more generally (Brummer, 2018).

These underlying biases against community

energy projects may also increase distrust among

2 Community energy can take place on both large and small scales. For example, some co-operatives in Europe have invested

in gigawatt-scale renewable energy projects.

the general public, whose broad support is needed

to leverage investments and other resources from

local citizens and outside investors.

Policy frameworks for renewable energy are

structured around centralised, large-scale

projects. Traditional energy market structures

and regulatory frameworks are mostly designed

around centralised, large-scale energy generation

(IRENA, 2020e). Policy makers often do not have

community energy on their agendas, which

may lead to the implementation of policies

that (unintentionally) discriminate against

community energy. For example, small- and

medium-sized actors (such as communities) carry

disproportionate risks when participating in

auctions, discouraging diversity among auction

participants and leaving communities behind.

Communities are thus left to navigate an

unfavourable landscape that creates additional

investment uncertainties and subsequent planning

challenges (Brummer, 2018).

Community energy projects may have limited

access to capital and third-party finance. In many

countries, securing financing from traditional

sources still presents a challenge for community

energy projects, particularly those that require

early-stage support (Caramizaru and Uihlein,

2020; Haggett and Aitken, 2015). Community

energy projects below a certain size

2

may not

attract interest from commercial lenders since they

come with high bank transaction costs and oer a

limited return on investment.

Figure 2: Potential barriers to mobilising investment in community energy

Risk profiles of

individuals and

communities that dier

from those of private

sector companies

Limited access

to capital and

third-party

finance

Lack of knowledge

in and experience

with renewable

energy projects

Policy frameworks

structured around

centralised,

large-scale projects

Insucient awareness

and acceptance of

community energy

and its benefits

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:12

Moreover, debt and equity financing are typically

extended with a view to earning a profit. A

community energy project focused on creating

socio-economic and environmental value may not

generate sucient profits to attract debt financing

from local commercial financial institutions.

Communities that cannot meet collateral

requirements may also find it hard to secure loans

from commercial financial institutions (Ottinger

and Bowie, 2015).

The risk profiles of individuals and communities

are dierent from those of private sector

companies. In many countries, citizen-driven

investment in renewable energy has been absent,

as policy frameworks have typically not accounted

for the risks that communities face when investing

in individual projects. Coupled with the prospect

of facing direct personal risks and exposure

when investing, community members may be

reluctant to invest upfront in community energy

projects. Furthermore, many communities new to

renewable energy development develop stand-

alone projects. Unlike companies with several

projects in development, these communities

are unable to spread risks across a portfolio of

projects. Diculties in securing funding and

reliance on single projects means that these

communities also have more trouble covering costs

and expenditures incurred in the initial stages of

project development (Brummer, 2018). All of these

factors ultimately slow down the development of

community energy projects.

Community energy projects often rely on the

voluntary commitment and engagement of

citizens who may lack knowledge, capacity

and experience in setting up renewable

energy projects. Unlike established private or

commercial developers, who are experienced in

drafting project proposals and business plans

and have existing relationships with banks and

institutional investors, in many cases communities

have no track record in renewable energy

development (Haggett and Aitken, 2015) and

encounter diculties accessing related support

structures (Avelino et al., 2014). These factors

compound the challenges of securing both early-

stage and long-term financing for community

energy.

Participants of the 2nd World Community Power Conference in Bancoumana, Mali

Photo: Mali-Folkecenter Nyetaa

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 13

ENABLING

ENVIRONMENTS FOR

COMMUNITY ENERGY

INVESTMENT

03

Overcoming the barriers described in Chapter 2

requires a conducive enabling framework that

will allow community energy’s untapped potential

to benefit citizens and communities. To unlock

investments, policy frameworks should be non-

discriminatory and provide market access to all

types of investors, including communities.

Such frameworks include regulatory measures

that promote market entry for community energy

projects; financial measures that support their

funding; and administrative measures that help

communities acquire the skills and knowledge

needed to develop a renewable energy project.

Enabling frameworks proposed for a given

national or subnational jurisdiction should be

considered in the context of the jurisdiction’s

institutional environment and broader socio-

economic objectives.

3.1 Supportive legislation and government policies are

key to community energy growth

As is the case for all renewable energy projects,

stable, predictable and non-discriminatory policy

frameworks are key to enabling community

energy. Apart from mandating the establishment

of legal frameworks to promote and facilitate

the development of community energy, as in the

European Union (see Box 1), governments can

encourage community energy development by

implementing a range of individual measures or

making adjustments to existing policies.

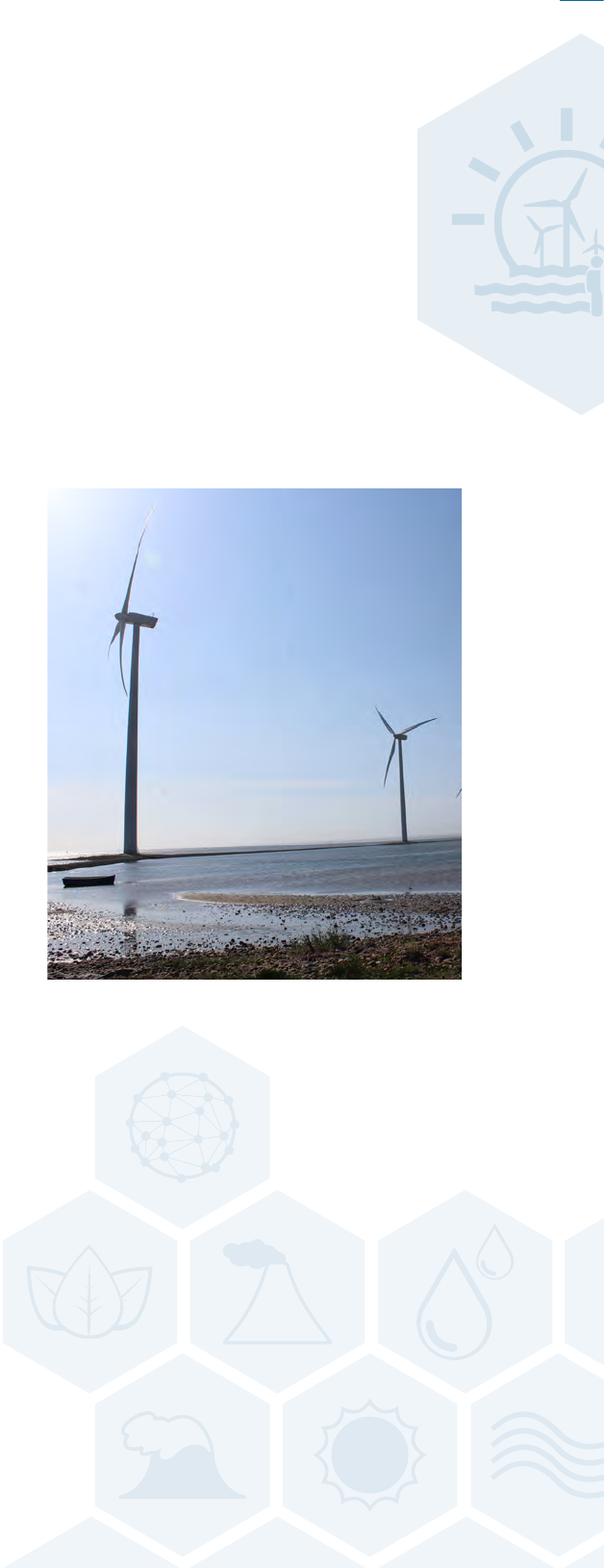

Community wind project owned by Thyborøn-

Harboøre Vindmøllelaug I/S af 2002, Denmark

Photo: Nordic Folkecenter for Renewable Energy

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:14

The development of community energy in the European Union (EU) has historically been driven by local and

national legislation. Community energy initiatives are now widespread in several countries in western and

northern Europe but remain comparatively rare in eastern, central, and southern Europe. As of 2020, there are

an estimated 1 750 energy communities (including renewable energy communities) in Germany, another 700

in Denmark, 500 in the Netherlands and several hundreds more throughout Europe (Caramizaru and Uihlein,

2020). Additionally, approximately 3 500 renewable energy co-operatives operate within the EU (RESCoop

MECISE, 2019).

The European Commission’s new Clean Energy Package (approved in 2019) mandates EU member states

to create an enabling legal framework to promote and facilitate the development of community energy.

“Energy communities” are recognised in two EU legislative documents under the formal definitions of “citizen

energy communities” (revised Internal Electricity Market Directive [EU] 2019/944) and “renewable energy

communities” (revised Renewable Energy Directive [EU] 2018/2001).*

The two directives set out specific criteria to ensure community energy projects can compete in the market

based on non-discriminatory and proportional terms. Member states are required to transpose both directives

into national frameworks and offset market and regulatory barriers in order to promote and facilitate the

advancement of community energy.

*

“Energy communities” are not only limited to renewable projects. They “may engage in generation, including from

renewable sources, distribution, supply, consumption, aggregation, energy storage, energy efficiency services or charging

services for electric vehicles or provide other energy services to its members or shareholders” (Electricity Market Directive

[EU] 2019/944).

Box 1 Community energy in European Union Renewable Energy Directive

and Electricity Directive

A multitude of renewable energy support

schemes exist and have been implemented in

dierent countries. As shown in Table 1, several

existing measures for renewable energy can be

tailored and designed to encourage community

energy development. First and foremost, a

policy environment generally conducive to

renewable energy is also beneficial for community

energy. More specific tools may include setting

sub-targets for community energy and creating

local ownership quotas for renewable energy

projects.

As per their non-discriminatory design,

administrative feed-in taris set by government

(FITs) have been very eective in supporting

renewable energy market growth, including

smaller community energy projects. Virtual net

energy metering schemes have also emerged

more recently to enable multiple customers to

share billing credits produced by o-site projects,

thus encouraging the growth of subscription-

based community energy projects (IRENA, 2019a).

The transition from FITs to auctions in countries

like Denmark, Germany and Japan has proven

challenging for community energy projects.

Some key features of auctions – such as bidding

procedures and prequalification requirements

that necessitate upfront investments without

being guaranteed a contract – disproportionately

increase financial risks for community actors (Fell,

2019; IRENA, 2019b; WWEA, 2019). Community

actors are consequently likely to limit their

participation to bidding processes where their

likelihood of being awarded a contract is high (e.g.

in auctions where the lowest bid is not the sole or

even the primary criterion for award).

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 15

Some countries have implemented auction design

elements aimed at favouring small and new players,

creating local jobs, contributing to subnational

development, and engaging communities (IRENA,

2019b). Policy design elements such as mandated

quotas and preferential rules for community

energy projects, legal limits on the involvement of

large private investors, and bonus payments for

community participation could contribute to the

growth of community energy projects. However,

the case study of Germany (see Annex) suggests

that auctions need to be carefully designed,

implemented and evaluated in order to avoid

unintended consequences and yield the intended

results. Engaging communities successfully in

auctions remains broadly challenging and further

adjustments to auction designs remain necessary

to promote community energy.

Legislation and government policies aimed

at community energy should be developed in

early and close consultation with citizens and

communities to ensure the desired outcome.

Streamlined administrative procedures and

capacity building opportunities are key for

community involvement and implementation of

projects. Governments can put in place a variety

of measures, such as one-stop shops, to break

down knowledge barriers by raising citizen

awareness of community energy, disseminating

best practices, assisting communities with the

project development process, and connecting

communities with funding sources. Governments

can also provide training opportunities to

communities to help them develop long-term

capacity in renewable energy.

Lastly, governments may opt to oer fiscal and

financial incentives to support the financing of

community energy projects: Options for direct

support include grants, loans, revolving funds,

and tax incentives. Public funding measures will

be further discussed in Chapter 4 on financing

community energy projects.

3.2 Policy design can be tailored to community energy

While many countries already have in place

ambitious targets and supporting policies for

renewable energy, there is ample scope to improve

community and citizen participation to ensure an

inclusive energy transition.

Through policy design, governments can tailor

renewable energy measures to provide better

support for community energy investment. As

Table 1 highlights, measures supporting community

energy can be implemented at various levels

of government, ranging from local to regional

to national. Many of these measures are already

being used to support grid connected community

energy projects in developed countries;

their application in other areas may require

modifications to accommodate local contexts.

Finally, governments must work in close co-

operation with financial institutions, the private

sector, communities that have developed projects

and other key stakeholders to design and

implement policy measures that remove barriers

to investment in community energy projects.

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:16

MEASURE

DESIGN OPTIONS ENABLING

COMMUNITY ENERGY

LIMITATIONS

REPRESENTATVE

JURISDICTIONS

IN WHICH

OPTION

HAS BEEN

IMPLEMENTED

SEE CASE STUDIES

IN

ANNEX

Renewable

energy

targets

Renewable energy targets that define specific

sub-targets for a broad range of types and sizes

of renewable energy projects, such as for community

energy, provide long-term signals to investors

about governments commitment and can therefore

increase investors’ confidence in community energy

investments (IRENA, 2015b).

Renewable energy targets are not

eective on their own and need

further policy measures to incentivise

implementation. They are highly

dependent on political commitment

(IRENA, IEA and REN21, 2018).

Scotland, UK

Local

ownership

quotas

By requiring project developers to oer a minimum

percentage of local ownership shares in a new

renewable energy project, governments can ensure

citizens have an opportunity to participate in and

benefit from projects (IEA-RETD, 2016a).

Quotas need to be well defined and

monitored to ensure they achieve

desired policy outcomes (IEA-RETD,

2016a).

Denmark

Virtual net

energy

metering

A variant of net energy metering, virtual net energy

metering enables multiple customers to share billing

credits produced by o-site projects and encourages

the growth of subscription-based community energy

projects (IRENA, 2019a).

As the penetration of distributed

renewable energy resources increases,

net metering may create cross-

subsidisation between prosumers

and those who do not self-consume

(IRENA, IEA and REN21, 2018).

United States

Feed-in

taris and

premiums

Feed-in taris or premiums can easily be designed

in a non-discriminatory manner and may also be

based on criteria such as project size and technology

to encourage certain types of projects, including

community energy (IRENA, 2015a).

Feed-in taris require active tari

setting and adjustment. In times of

rapidly decreasing costs and volatile

fossil fuel prices this may require

regular monitoring and adjustments

(IRENA, IEA and REN21, 2018).

Denmark

Germany

Japan

Scotland, UK

Auctions

While auctions have typically been designed to

procure electricity at lowest cost, a variety of design

elements may be implemented to achieve objectives

such as facilitating the inclusion of small and new

players and achieving a just and inclusive transition

(IRENA, 2019b).

Bidders have to fulfil certain

administrative, technical and financial

requirements in order to qualify

to bid in an auction. Since bidders

bear the risk of not being awarded

projects, auctions are likely to

pose disproportionate barriers for

community actors unless they are

specifically designed to encourage

participation from small and new

players (Fell, 2019; WWEA, 2019).

Denmark

Germany

Japan

Table 1: Government measures, past and present, that can enable community energy investment

Regulatory

TYPE

RegulatoryRegulatoryRegulatoryRegulatory

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 17

MEASURE

DESIGN OPTIONS ENABLING

COMMUNITY ENERGY

LIMITATIONS

REPRESENTATVE

JURISDICTIONS

IN WHICH

OPTION

HAS BEEN

IMPLEMENTED

SEE CASE STUDIES

IN

ANNEX

Grants

Grants can help de-risk community energy projects

by osetting expenses for early-stage community

energy project development as well as project costs

(IRENA, IEA and REN21, 2018).

Grants provided by foreign investors

do little to assist local capital markets

when local equity investment is small.

Grant financing in the form of

crowdfunding may be aected by

exchange rate fluctuations, unless it

is a donation (KfW Entwicklungsbank,

2005).

Victoria, Australia

Denmark

Department of

Quiché, Guatemala

Japan

Mindanao,

Philippines

Scotland, UK

Loans

Concessional loans with lower interest rates, longer

repayment periods or extended grace periods can

improve access to capital and reduce the costs of

borrowing for community energy projects (IRENA,

IEA and REN21, 2018),

The positive impacts of concessional

loans will extend beyond the projects

benefitting from the loans only if

supplemented by capacity building

for local lending institutions (IRENA,

2016).

Guanacaste,

Costa Rica

Revolving

funds

Revolving funds are a long-term source of credit for

community energy projects. The funds funnel all or

a portion of loan payments towards sustaining and

growing the funds for additional projects (Burke and

Stephens, 2017).

Management and monitoring play a

crucial role. Because the creditor bears

the credit risk, failed projects reduce

the amount of the revolving fund

(Setyawan, 2014).

Mindanao,

Philippines

Tax

incentives

Tax relief such as production tax credits, investment

tax credits and accelerated depreciation (IRENA,

IEA and REN21, 2018) can incentivise investments in

community energy projects by oering a higher rate

of return to prospective investors (Bauwens, Gotchev

and Holstenkamp, 2016).

Community energy projects

owned by non-taxable entities

(e.g. municipalities, non-profit

organisations) are unable to benefit

from such incentives (Farrell, 2016).

Scotland, UK

United States

One-stop

shops

One-stop shops dedicated to facilitating community

energy projects streamline the interface between

communities (or individuals) and government.

While their main aim is to reduce regulatory and

administrative burden, some one-stop shops also

provide information and advice including capacity-

building (OECD, 2020).

One-stop shops require political

commitment if they are to be eective.

Time and other resources must

be invested towards developing

sta capabilities to deliver services

eectively (OECD, 2020).

Victoria, Australia

Japan

Scotland, UK

FinancialFinancialFinancialFinancialAdministrative

TYPE

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:18

FINANCING

COMMUNITY ENERGY

PROJECTS

04

Key to scaling up investment in community

energy are contributions from community

members themselves and the availability of

external financing from public and private sources.

Since public resources are limited, the growth

of the community energy sector increasingly

depends on communities’ ability to access private

sources of financing. That they can do so under

the right circumstances has been borne out by

the experiences encapsulated in this section

and described more fully in the case studies

(see Annex).

4.1 Ownership and financing of community energy

are interlinked

The ownership structures and financing of

community energy are closely related. The optimal

mix of financing for a given project depends not

only on the characteristics of the project (e.g.

size, technology), but also, and especially, on the

ownership model and level of autonomy desired

by the community.

Table 2 provides an overview of common

ownership models through which community

actors collectively invest in and own energy

assets. While many community energy projects

strive for large shares of community ownership,

achieving this depends on the availability of local

knowledge and resources – services, labour, land

and financial capital. In some models such as co-

operatives, ownership comes with a direct level of

decision-making. In most co-operatives, individuals

are required to contribute to the common capital

by investing in membership shares as a condition of

membership (International Co-operative Alliance,

2017). In addition to individuals, other stakeholders

– such as conventional energy companies (e.g.

utilities, retailers etc.), non-profit organisations

and local authorities may also participate as

community members. In other models where

the community does not own the entire project,

these other stakeholders may serve as partners.

Partners can also contribute in a variety of ways

beyond owning a part of the project. For example,

municipalities can enter into agreements with

community actors to host community energy

projects on their infrastructure (e.g. public roofs)

(Roberts, Bodman and Rybski, 2014).

A rural community solar photovoltaic

micro-grid in Burkina Faso

Photo: Sahelia Solar

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 19

OWNERSHIP MODEL DESCRIPTION

Co-operative

Co-operatives are jointly owned by their members to achieve common economic,

social or cultural goals based on the democratic principle of “one member, one

vote”. A co-operative may be formed to provide services (consumer co-operatives)

or to pool investment capital (investment co-operatives). Maximising return on

capital is usually not a key objective.

Non-profit organisation

Non-profit organisations are formed by investments from members, who are

responsible for financing the organisation but do not take profits.

Association

Associations are private, non-profit organisations established around a common

cause. Decision-making power usually stems from the association’s statutes or by-

laws and rests with its members. A renewable energy association can take many

forms. Examples include enterprise associations and housing associations.

Community trust

Community trusts act as vehicles for broader community benefit, rather than

generating profits for investors. Returns from investments are used for specific

local purposes and are shared with people who are unable to invest.

Partnership

Partnerships are formed between individuals or legal persons to achieve a common

business purpose. A partnership can take the form of a general partnership (where

all partners can be held individually liable for the partnership’s debts) or a limited

partnership (where partners who do not participate in management activities have

limited liability for the partnership’s debts).

Corporation

Corporations are separate legal entities owned by their shareholders; as such,

shareholders benefit from limited liability for the corporation’s debts. Shareholders

holding more shares have greater voting power. The profits of a corporation are

paid out to shareholders as dividends.

Limited liability

company

LLCs combine the characteristics of a corporation with those of a partnership. Like

shareholders in a corporation, members of an LLC benefit from limited liability

for the company’s debts. Like partners in a partnership, the profits of an LLC are

passed through directly to its members.

Sources: Gancheva et al., 2018; IRENA, 2020d; Roberts, Bodman and Rybski, 2014

Table 2: Legal forms of community ownership

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:20

Most community ownership models will draw on

multiple financing options to cover the costs of

their energy projects, including contributions from

community members and financing from external

public and private sources. Figure 3 presents an

overview of external financing options available to

a community throughout the project development

and construction process. In many cases, smaller

projects may be financed entirely through direct

investments from community members. In others,

a combination of grants and debt financing (loans)

may be necessary. Larger projects are more likely

to rely on equity investments from external

parties. Debt-to-equity ratios for community

energy projects vary widely due to factors such

as the specific risk profile of a community and the

institutional environment within which it operates

(Dukan et al., 2019; IEA-RETD, 2016b).

To increase the number of available financing

options, multiple community projects can

be bundled to reduce transaction costs and

investment risk. Community energy projects are

often funded through project financing; however,

in situations where one community partners with

another entity the project may also be supported

through corporate or balance sheet financing.

Project financing implies that lenders are repaid

from the cash flow generated by the project or

the value of the project’s assets. Under corporate

financing, lenders have full recourse to all assets

and revenues of the funded entity in the event of

default. Financing is secured based on the balance

sheet of the entity (Yescombe, 2014).

Figure 3: External nancing options for community energy projects

Grant

Funds are awarded

and do not need to

be repaid by the

recipient.

• Governments and government agencies,

development finance institutions, climate

funds

• Private non-governmental organisations

and foundations

• Crowdfunding

Debt

Funds are borrowed

and repaid by the

recipient over time

with interest.

• Financial institutions (e.g. state and

commercial banks, non-banking financial

institutions, micro-finance institutions)

• Development finance institutions and

climate funds

• Crowdfunding

Equity

Funds are invested

in return for partial

ownership of assets.

• Public/private utilities

• Renewable energy project developers

• Private investors (e.g. angel investors,

venture capitalists, private equity firms)

• Crowdfunding

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 21

Public sources of financing for community energy

include governments, government agencies,

development finance institutions (DFIs), other

public banks and climate funds.

3

Public financing has the potential to accelerate

community energy, provided it is accompanied

by arrangements to involve communities in

participatory decision making, eorts to build the

technical and financial capacity of communities

and local partners, and opportunities for

communities to assume ownership should they

elect to do so.

DFIs and climate funds are governed by national

governments and have specific mandates to

support development outcomes; consequently,

they have a prominent role to play in directing

investments in community energy projects in

developing countries. DFIs are increasingly

deploying targeted measures to improve access

to debt and equity financing for small- and

medium-scale renewable energy projects. Such

measures include concessional loans at below-

market interest rates for renewable energy

projects and on-lent debt to local commercial

financial institutions. For example, the IRENA/

Abu Dhabi Fund for Development Project Facility

allocated USD 350 million in concessional loans

to 32 renewable energy projects with sustainable

development benefits, at a tenor of up to 20 years

and a five-year grace period (IRENA, 2020a).

While these public financing measures are partly

applicable to community energy projects, they

would need to be tailored further to fully unlock

the potential of community energy.

Given the challenges some communities still

face accessing capital and third-party financing,

in many countries grants remain an important

financial measure for directing targeted support

to community energy projects, bringing viable

projects to bankability and profitability. National

and regional governments in Australia, Guatemala,

3 For the purposes of this paper, DFIs include global and regional development banks, bilateral development agencies, and

national development banks.

Japan and Scotland (see Annex) as well as

DFIs have awarded grants to oset the costs of

early-stage project development activities as well

as project construction costs. An example is the

Pacific Renewable Energy Investment Facility, a

multi-donor fund providing loans and grants to

support renewable energy projects in smaller

Pacific island countries. From 2017 to 2019, eight

projects approved under the facility were allocated

over USD 141 million in financing, including over

USD 77 million in grant funding from the Asian

Development Bank (ADB, 2020).

Given the limited resources of public funding,

it is well recognised that public measures must

be used strategically to leverage debt and

equity financing (IRENA, 2016). Some countries

have put grants in place to further encourage

commercial lenders to finance community energy

projects by mitigating political, policy, credit and

currency risks. Governments and DFIs have also

implemented risk-mitigation measures aimed at

mobilising additional private investments in small-

and medium-scale renewable energy. Examples

include first-loss loans and first-loss guarantees

to address potential losses borne by commercial

lenders (IRENA, 2016).

Additional community energy investment can

also be supported through revolving funds. In

the Philippine province of Mindanao, the Asian

Development Bank has provided financing for

community energy projects and a revolving fund

to support local economic development. The fund

is replenished as loan recipients make repayments,

creating the opportunity to issue new loans

to other businesses that can make productive

use of renewable energy. Revolving funds can

therefore become a long-term source of credit for

community energy projects and local enterprises

(see

Annex).

4.2 Public sources of financing can be leveraged

for community energy investment

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:22

Private sources of financing for community energy

include renewable energy project developers

as well as financial institutions (e.g. commercial

banks, non-bank financial institutions, micro-

finance institutions) and private investors (e.g.

angel investors, venture capitalists, private equity

investors). In some countries where community

energy is a well-known and established form of

investment (e.g. Denmark, Germany), communities

have been able to raise financing through private

sources. However, communities in many countries

– particularly developing countries – still find it

dicult to gain access to private financing.

Although public finance has enabled private

finance to play a more prominent role in renewable

energy projects, direct investments in community

energy from the private sector continue to be

limited.

One option for communities is to make use of

joint-venture models to access financing. In a

model where a community energy project partners

with a private developer, the developer may raise

capital for its share of the project through equity

financing based on its track record and the income

projections of its portfolio. For example, in a joint

venture in the United Kingdom, Falck Renewables

and the Fintry Development Trust negotiated an

agreement in 2007 whereby Falck loaned capital

to the trust for “virtual ownership” of 1 of 15

turbines in a Scottish wind farm. The loan is to be

repaid over 15 years through the sale of electricity

generated by the turbine (Haggett et al., 2014).

Innovative financial and business models can also

help communities reduce their upfront investment

requirements, particularly equity. Under a pay-as-

you-go (PAYG) business model, a private partner

leverages its access to equity to finance the

community’s share of the project. The community

can then direct project revenues (or cost savings

realised from the project) to make regular

payments to the partner over a mutually agreed

time frame. Ownership transfers to the community

once it has repaid the partner (Muchunku et al.,

2017). PAYG schemes have been used to deploy

energy solutions to communities. For example,

with grant support from the United States African

Development Foundation, social enterprise Sosai

In addition to project financing (i.e. grants, debt

and equity), community energy may be indirectly

supported through investments in energy access

and local development programmes.

By linking energy access initiatives with community

energy, governments and DFIs can spur additional

local socio-economic development and strengthen

long-term community growth.

To support energy solutions for poor communities

in the “last mile”, a range of combinations of

public and private funding sources – within a

strong local ecosystem and with strengthened

local financial institutions – can play a critical role

(Rajagopal, 2019). For example, responsAbility

Investments launched a USD 200 million fund in

early 2020 in partnership with public and private

partners, including the European Investment Bank,

the International Finance Corporation, the UK

Department for International Development and the

government of Luxembourg, to support companies

providing energy access solutions in emerging

markets (responsAbility, 2020). Public programmes

for decentralised energy solution providers have

great potential to support community energy,

provided they are further tailored to create the

on-the-ground partnerships needed to give

communities access to energy.

Impact investing is an approach that intentionally

seeks to generate measurable social and

environmental impact alongside financial returns

(Global Impact Investing Network, 2020). It

comes in a variety of forms and vehicles. Some

approaches prioritise impact and generate

financial returns at below-market rates, while

others emphasise market-rate financial returns

for the investor alongside societal benefits.

Impact investments are becoming increasingly

widespread in both emerging and developed

markets, attracting a wide range of public and

private investors including individuals, non-

governmental organisations and foundations,

banks and development finance institutions.

Box 2 Impact investing

4.3 Private financing must step up

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 23

Renewable Energies successfully deployed solar

mini-grids in two villages in Kaduna State, Nigeria,

in 2017. The mini-grids provide electricity to over

800 individuals using a PAYG model (IRENA, 2018).

Alternative finance, developed outside the

traditional banking system (i.e. regulated banks

and capital markets), provides communities with

another potential source of funding. An example of

alternative finance is crowdfunding, which enables

a project or an organisation to raise capital from

a large number of individuals or entities (Mollick,

2014). By using predominantly online channels,

instruments and systems funding beneficiaries can

present proposals to the public and engage with

potential funders (see Box 3 on crowdfunding in

sub-Saharan Africa).

Crowdfunding models can be distinguished based

on the funders’ primary motivation for investing

and expected return. Non-investment-based

crowdfunding approaches (such as donation

and rewards-based crowdfunding) have been

leveraged to fund single and multiple community

energy projects in part or in full. For example,

Citizens Own Renewable Energy Network Australia

(corenafund.org.au) uses crowdfunded donations

to create a revolving fund for community energy

projects.

Other approaches replicate the traditional debt

and equity financing modalities. Examples include:

• Peer-to-peer lending platforms that provide

investors with a debt instrument. Abundance

Investments (www.abundanceinvestment.com)

oers debt-based investments in projects and

businesses in the renewable energy, energy

eciency and housing sectors.

• Equity platforms that allow investors to

acquire shares in projects. Windcentrale

(www.windcentrale.nl) is a Netherlands-

based organisation that has facilitated

co-operative wind turbine purchases

through its crowdfunding platform.

• Hybrid platforms oering a range of

investment options, including debt

instruments, shares and bonds. Triodos Bank

(www.triodoscrowdfunding.co.uk) operates

a crowdfunding platform through which it

connects investors with bond and equity

oerings from organisations focusing on

social and environmental impact.

Crowdfunding can thus facilitate individual

investors’ access to impact investment

opportunities in community energy, and even

help governments and other key actors to identify

– and direct investments towards – community

energy projects that have gained local community

support.

Crowdfunding has played a role in enhancing the

financing opportunities available to small and

medium-sized enterprises, including companies

deploying renewables-based solutions to widen

access to energy. Social enterprise Pawame

– a provider of pay-as-you-go solar home

systems to households across sub-Saharan

Africa – has successfully raised debt financing

through crowdfunding platforms such as TRINE

(trine.com) and Bettervest (bettervest.com).

In 2020, Pawame crowdfunded debt to finance

2 300 solar home systems for households (Solar-

Home-Systeme für Kenia – Pawame, 2020).

Box 3 Crowdfunding in sub-Saharan

Africa

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:24

KEY TAKEAWAYS

FOR GOVERNMENTS

AND FINANCIAL

INSTITUTIONS

05

When integrated into post-COVID recovery

measures, community energy oers vast untapped

potential to maximise socio-economic benefits

and local value creation, as well as to strengthen

the broader resilience of communities and beyond.

Drawing from the case studies in this paper (see

Annex), the following takeaways may serve

as guidance and inspiration for governments,

DFIs and other financial institutions on how to

design policies and mobilise finance to scale up

community energy investments.

Build awareness and develop a shared

understanding of community energy. There is a

need for broader awareness around the concept

of community energy and of the role communities

and citizens can play in the energy transition. A

common and widely recognised understanding

of community energy makes it easier for

governments and financial institutions to identify

best practices, design policies and mobilise funds

that reflect the specificities of community energy

actors. As the legal forms for community energy

may vary across jurisdictions, a strict definition of

community energy may be dicult to establish.

However, identifying a set of key characteristics

– such as minimum requirements for ownership,

decision making and profit sharing – may be used

to identify projects that qualify as community

energy and are thus eligible for support.

Adopt targets and policy designs that value

citizen participation and local socio-economic

development. While communities may not

always be able to compete on cost with large-

scale commercial renewable energy projects,

their participation in the energy transition is

widely recognised as an important way to

ensure inclusiveness and maximise local socio-

economic benefits. To fully realise the potential

of renewables to achieve broader development

goals, governments should establish community

energy targets and consult with community energy

representatives to ensure that supporting policies

(e.g. FITs, auctions, grants, tax incentives) are

designed to enable the participation of small and

new actors. Further policy frameworks addressing

sector coupling or energy eciency need to be

developed to strengthen positive eects on local

socio-economic development. More broadly,

governments should work towards establishing

non-discriminatory regulatory environments

which allow all investors – including communities

– to invest and access energy markets, including

clearly defined policies for access to the electricity

grid.

Establish dedicated agencies or one-stop shops

to support community energy. Community

energy projects are often initiated by committed

individuals who have limited expertise and

experience in setting up renewable energy

projects or navigating complex administrative

procedures. In addition to expanding awareness

of community energy, a dedicated entity (e.g.

public agency or non-governmental organisation)

can support communities and citizens by

helping streamline administrative procedures,

providing templates for project documentation,

oering other capacity-building activities and

even connecting communities with financing.

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 25

The Community and Renewable Energy Scheme

(CARES) in Scotland is an example of a one-stop

shop for communities and citizens interested in

investing in community energy.

Facilitate community access to capital through

targeted public finance. Access to debt and equity

financing can be particularly dicult for smaller

community energy projects, especially at the initial

stages of project development. Perceived or actual

risks throughout the project development process

result in less favourable lending terms at high

costs. Governments, DFIs and other public finance

institutions can oer support by establishing

grants, revolving funds and concessional loans at

below-market interest rates, and by on-lending

debt to local commercial financial institutions

for community energy projects. Public funds can

further be used to provide guarantees that de-

risk community energy projects, thereby enabling

access to commercial loans at a lower cost. Fiscal

and financial incentives can also reduce capital

costs. Financial instruments should be tailored to

the specificities of community energy projects,

as well as to national and local contexts, so as to

make renewable energy economically viable for

even the most vulnerable communities.

Support innovative financing mechanisms and

business models for community energy projects

and the most vulnerable. Given the limited

access to debt financing that many community

energy projects have, policy makers and financial

institutions can support innovative mechanisms

for raising equity financing that take into account

the unique characteristics of community energy

while preserving project ownership and control.

Community assets such as land rights and labour

can be converted into equity shares. Regulatory

environments that encourage financial institutions

to oer green investment options (e.g. debt

instruments, shares and bonds) can lower costs for

renewable energy projects, including community

energy. Additionally, innovative business models

and alternative financing mechanisms like

crowdfunding can support new partnerships

between community and private actors. Flexible

payment schemes such as PAYG can help to

distribute electricity across communities without

overlooking their most vulnerable members.

Other innovative finance mechanisms include

subscription-based models such as virtual net

energy metering (VNM) that allow citizens who

lack the means to invest in renewable energy to

take part in the energy transition. Such financing

mechanisms and business models should also

consider how communities will finance ongoing

operation and maintenance costs for their projects.

Encourage aggregation of and collaboration

between community energy projects. Partnerships

between communities through aggregation, or

project bundling, can enable smaller community

energy projects to gain access to financing schemes

typically available only to large-scale projects. The

aggregation of projects may reduce investment

risks by spreading them across several projects,

while also cutting transaction costs. To facilitate

the aggregation of community energy projects,

policy makers can create enabling frameworks for

communities to form partnerships, as showcased

by Community Choice Aggregation policies in the

United States. Aggregation also strengthens the

negotiating power of communities in purchasing

equipment and services from commercial

suppliers. For example, in Costa Rica, four regional

co operatives formed a consortium, Conelectricas,

to increase the profitability of their operations.

Integrate community energy in energy access

and local development programmes. Community

energy projects can play an important role in

providing access to aordable and reliable energy

for productive applications (e.g. agricultural

processing facilities, heat/cold storage facilities,

etc.) – particularly for vulnerable communities,

which are often located in remote or rural areas.

Combined with cross-sectoral policies (e.g.

concessional financing for productive equipment

and appliances), community energy projects

can also contribute to the broader development

of local economies. For example, a revolving

fund was established in Mindanao, Philippines to

support livelihood activities, leveraging electricity

produced by community energy projects.

Projected revenues from productive uses of

energy can be used to pay back investors and

reinvested in other community-led activities such

as energy eciency, infrastructure enhancements

or additional renewable energy projects.

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:26

ANNEX I. CASE STUDIES:

ENABLING ENVIRONMENTS

FOR COMMUNITY ENERGY

INVESTMENT

BROADENING THE OWNERSHIP OF RENEWABLES 27

A number of community energy policies have

emerged in Australia over the past decade, reflecting

interest in community energy at the state and

national levels (Parliament of Victoria Economic,

Education, Jobs and Skills Committee, 2017). As

of 2019, Australia had over 105 community energy

groups, approximately 50 of which were based in the

state of Victoria (Coalition for Community Energy,

2019).

Victoria’s state government implemented a range

of programmes to promote community energy

under its 2015 Renewable Energy Roadmap (State

of Victoria Department of Economic Development,

Jobs, Transport and Resources, 2015).

4

To support

community energy project development, the

Victorian government awards grants through

initiatives including its New Energy Jobs Fund,

Community Renewables Solar Grants Initiative and

Renewable Communities Program. The Renewable

Communities Programme has awarded over

USD 800 000 in funding to nine community energy

projects (Victoria State Government, n.d.).

4 The road map included a commitment to “encourage household and community development of renewable generation, products

and services”.

5 For example, see Citizens Own Renewable Energy Network Australia (corenafund.org.au) and the People’s Solar (thepeoplessolar.

pozible.com).

From 2017 to 2019, the Victorian government also

funded and supported a pilot programme to establish

three regional community power hubs. Each hub –

hosted by a local not-for-profit or social enterprise –

assists communities with testing project ideas, turning

viable ideas into bankable projects and connecting

them with capital (Community Power Hub, 2020). In

two years, the hubs have also helped in the financing

and commissioning of 15 community energy projects

with a combined capacity of over 1.3 MW. In the

process, they have generated local socio-economic

benefits valued at almost USD 8 million (Sustainability

Victoria, 2019).

The Victorian government continues to identify how

it can support communities’ eorts to tackle climate

change. Victoria’s 2017 renewable energy auction

scheme incorporated design elements requiring

proof of community engagement (IRENA, 2019b).

While community energy groups have welcomed

government support for business case development,

feasibility studies and project implementation, they

have described grant application processes as onerous

(Parliament of Victoria Economic, Education, Jobs

and Skills Committee, 2017). As a result, grassroots

organisations have emerged throughout Australia to

fill in financing gaps for community energy by raising

funding via donation-based crowdfunding.

5

In 2017,

the Australian government also lowered barriers

for small businesses seeking to raise capital by

establishing a legislative framework for investment

crowdfunding (Australian Securities & Investments

Commission, 2019).

• Government grants for community energy

have been administered through various

renewable energy programmes.

• Regional one-stop shops facilitate community

access to skills and knowledge, and connect

bankable projects with sources of capital.

Victoria, Australia

KEY FEATURES

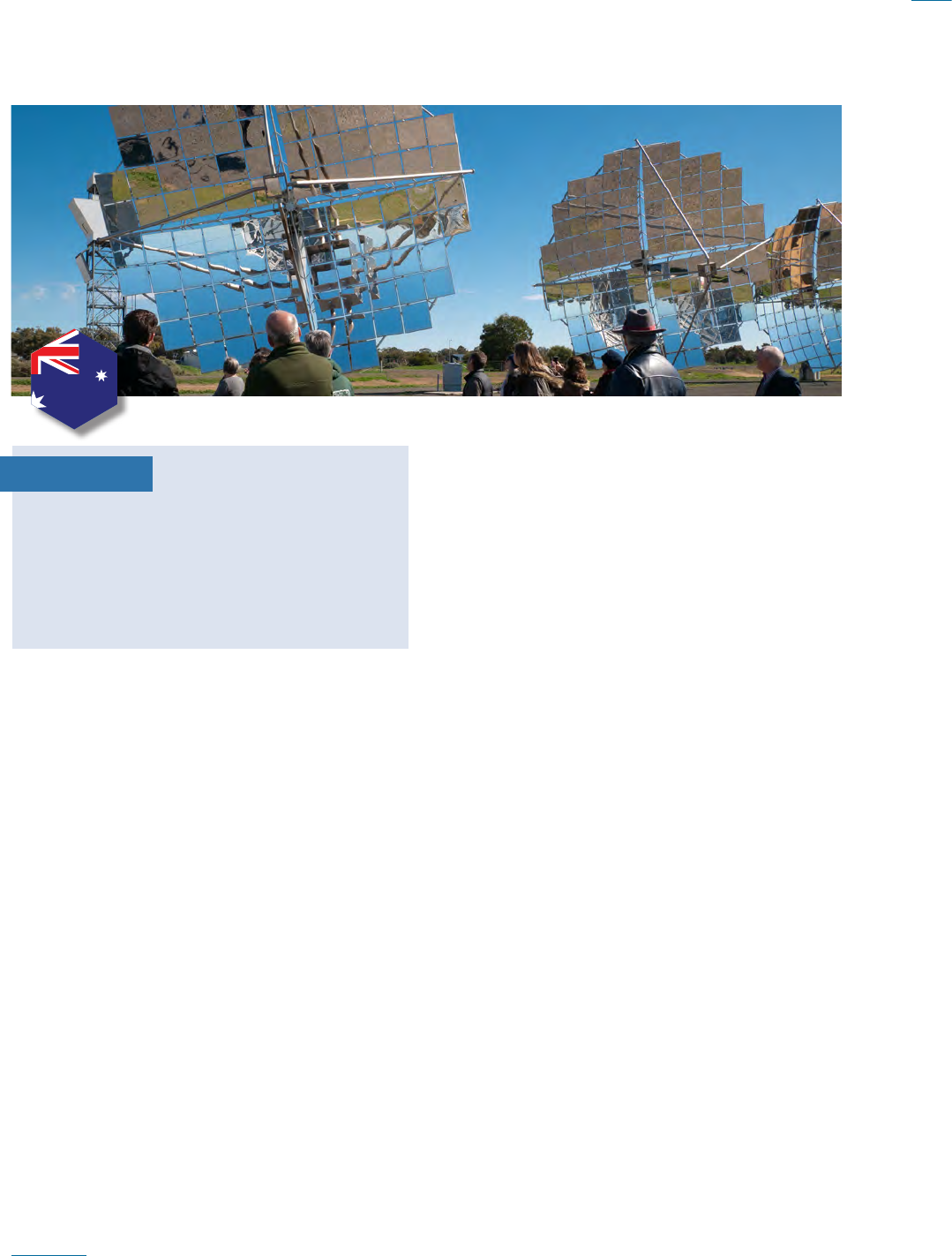

Photo: SSustainability Victoria/Esther Lloyd

Community Power Hub members attending a site demonstration of earlier prototype solar thermal

technology in Victoria, Australia

STIMULATING INVESTMENT IN COMMUNITY ENERGY:28

With regulations to support local renewable energy

in place as early as the 1970s, Denmark may be

considered the birthplace of modern community

energy. Denmark’s first phase of policy measures

included restricting the ownership of wind projects to

local actors within close proximity of the project and

limiting a single investor’s maximum ownership share

(Gorroño-Albizu, Sperling and Djørup, 2019), as well

as granting tax exemptions for income from wind

turbines and implementing fixed FITs (Gancheva et

al., 2018). Geographic eligibility for investment was

later expanded to the entire country, thereby allowing

external private ownership.

In the late 1990s, Denmark initiated a set of policy

reforms to liberalize its electricity market. Its FIT

scheme was initially phased out in favour of a

renewable portfolio standard (RPS), but a few years

later the government introduced a feed-in premium.

In part because premiums were set at levels too low

to attract projects and local ownership requirements

were changed, almost no new wind energy projects

– including community energy – were developed

between 2003 and 2008.

Consequently, wind power capacities flatlined almost

completely (IEA-RETD, 2016a). These developments

reduced local interest in wind power (WWEA, 2018b).

Because of the negative impacts of these reforms

on renewable energy deployment, Denmark began