A Fragmented Parallel Stream: The Bass Lines of Eddie Gomez in

the Bill Evans Trio

Gary Holgate

A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment

of requirements for the degree of

Master of Music (Performance)

Sydney Conservatorium of Music

University of Sydney

2009

1

I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted

to any other institution for the award of a degree.

Signed: ……………………………………………………………

Date: ……………………………………………………………………………….

2

Abstract

Eddie Gomez was the bassist in the Bill Evans Trio for eleven years. His contribution to

the group’s sound was considerable, but while there has been some recognition of his virtuoso

solos in the trio there has been little academic interest in his bass lines. This essay examines

bass lines from the album Since We Met, recorded in 1974 by Evans, Gomez and drummer

Marty Morell. Analysis of the bass accompaniments to the piano solos on “Since We Met”

and “Time Remembered” reveals that they form a fragmented two-feel. A traditional two-feel

employs two notes to emphasise the first and third beats in bar of 4/4 time. In Gomez’s bass

lines these two notes are frequently replaced with short rhythmic motifs. These motifs occur

in a variety of forms and at different metric displacements that alternately propel and retard

the forward motion of the music. Additionally, Gomez uses a wide range of register and

varied articulations to create a richly diverse bass line. The resulting effect has often been

interpreted as interactive or conversational with the soloist. However there is very little

interaction between the bass line and Evans’ solo. The bass line is a parallel stream to the solo

that energises and colours the music.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Mr Craig Scott, chair of the jazz unit at the Sydney Conservatorium of

Music, for his unfailing encouragement and support, and to Mr Phil Slater for his insightful

guidance.

3

Introduction

As a music student in the late 1970s I became fascinated by Eddie Gomez’s bass playing in

the Bill Evans Trio. There was a striking contrast between the flowing bass lines I was being

taught to construct and the fragmented bass lines that Gomez played. Yet despite the virtuosic

and disjointed nature of his bass lines, the trio sounded completely cohesive. My desire to

understand how this was achieved led to this essay.

The trio’s cohesive sound is particularly evident in the album Since We Met. It was one of

the last records made by Evans and Gomez with the drummer Marty Morell. Biographer Keith

Shadwick observes that the “most impressive aspect” of the recording is the “effortless

cohesion and unity of the trio” (Shadwick 160). This particular trio had been together for

nearly six years and recorded the album live at The Village Vanguard.

1

Morell usually played

a straight-ahead and quietly supportive role in the trio, and did so for this recording.

Consequently, I felt that I could focus on the piano and bass interaction on this album. Evans’

trios are often described as featuring ‘interplay’ between bass and piano, as in this quote from

the article on Evans in Grove Music Online. “This interplay ... re-emerged in his later

recordings with ... Eddie Gomez.” My research began with the assumption that the bass lines

were shaped by their interaction with the piano solo, and that an understanding of the lines

themselves would be best gained by examining the forms this interaction took. However, the

more I analysed the music, the clearer it became that there is little evidence of interplay

between bass and piano. Surprisingly, the independence of the bass line from the piano solo is

a much more significant feature.

Traditionally in jazz music the bass player takes a consonant role in the ensemble –

providing the foundations of harmony and time from which the soloist can launch

explorations of harmonic and metric tension and release (Pressing 202). The walking bass line

can fulfil this role extremely well, and its practice has been so widespread that it has become

one of the defining features of jazz music. Discussions of jazz bass development after the

1950s, as in Frank Tirro’s Jazz: A History, tend to focus on advances in bass soloing

4

1

The Village Vanguard is a small jazz club in New York City in which Evans performed

regularly throughout his career.

techniques while accepting that the walking bass lines are an important but relatively

uninteresting part of jazz music (392). Much of the success of Gomez’s long tenure in the Bill

Evans Trio was due to his subversion of this consonant foundation-laying role for the bass. He

rarely played walking bass lines. Instead, his bass accompaniment took the form of an

elaborately embellished two-feel. The resulting line was a fragmented independent voice.

Rather than just providing a foundation for the soloist, Gomez “consistently galvanized whole

sets” (Pettinger 190). He brought variety and contrast to Evans’ thoughtful and logically

developed solos, and in Evans’ words “was especially resourceful in not allowing the music to

become bland” (Pettinger 216).

There is a wealth of academic material available about Bill Evans. He was one of the most

influential jazz pianists of all time. His soloing style embraced order and thematic

development, which makes his recordings amenable to musicological analysis. Most of the

academic studies of Evans focus on his piano style and its effect on subsequent pianists.

Berardinelli, Smith and Widenhofer, for example, have produced excellent dissertations on

Evans’ style. However, there is little information on the relationship between the piano and

bass in his trios. His first trio (1959-61), with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian,

explored an egalitarian approach to group improvising that revolutionised the jazz piano trio

genre. LaFaro’s interactive role in that trio created an alternate style of bass playing to the

traditional walking line. Wilner has examined this influential first trio, but there is very little

material available on the later trio with Gomez. Literature devoted to Gomez himself is very

sparse, and what little is available focuses on his solos (for example, Hauff). His solos feature

long flowing melodic phrases and are totally different in style to his accompaniments. There

are practically no resources available for somebody who wants to understand Gomez’s

accompanying style.

5

About This Study

Usually it is impractical to treat a single note as the basic unit to study, for two reasons: a

single note has no meaning except in its relationships to other notes; and the task of analysing

a piece of music note by note would be prohibitively long (Agawi 16). However, analysing a

two-feel bass line in a jazz performance, such as in the subject of this analysis, is one case

where it is practical. In a traditional two-feel there are only two notes in each bar, on beats one

and three, and each note has a clear relationship to the harmony at that point. In Gomez’s two-

feel these two single notes are often replaced with short motifs. They consist of two, three,

four and sometimes five eighth-note triplets that are employed in a variety of rhythmic

displacements, each having different effects on the music. These rhythmic motifs are the focus

of this study.

With so many individual units to be examined, the length of the music studied has to be

limited. The piano solo on “Since We Met” is ideal for many reasons. It is a harmonically rich

original composition by Evans which is characteristic of the trio’s repertoire. Both the piano

solo and the accompanying bass line adhere closely to the harmonic structure of the tune.

Rhythmic diversity is consequently a major feature of the improvisation. It is something

Evans had consciously developed in his playing. In his interview with Marion McPartland,

released by Fantasy records, Evans said:

... the displacement of phrases and (you know) the way phrases follow one another and

their placement against the meter and so forth, is something that I’ve worked on rather

hard on and it’s something I believe in.

There is an extensive variety of rhythmic displacement in Gomez’s bass motifs during this

piano solo, and the examination of it occupies much of this essay.

As this is a written essay and not an aural presentation, the analysis needs to be of a visual

representation of the music. Transcription of the bass part cannot impart its full richness: the

array of vibratos that Gomez employs, the ghosted notes, percussive sounds, slurs, slides

between notes and other nuances of articulation do not translate easily onto the page. These

features individuate Gomez’s style and make his bass playing instantly recognizable to those

familiar with his sound. Nuances of note placement within the pulse, of playing slightly ahead

6

of or behind the beat, are not easy to notate either. An attempt to include all of these events

would result in

a heavily overloaded score requiring diacritics which are hard to read, and worse still,

make it impossible to distinguish the elements which are relevant from the ones which are

not (Arom 174).

Gomez frequently uses two devices in his bass lines that are particularly relevant to this study.

Percussive sounds made by plucking the string with the right hand, while gently holding the

string with the left hand to prevent it from vibrating at any particular pitch, make a vital

contribution to the rhythmic dynamism of the bass part and have been notated in the

transcriptions. Slurring, or sliding from one note to the next without re-plucking the second

note reduces the rhythmic propulsion of the bass line, and instances where the effect is most

striking have also been included in the transcription. The task of transcription was made much

easier by the rhythmic clarity of both Evans and Gomez’s lines. When the music is played

back at half speed, it still sounds accurately in time.

7

Background

Edgardo (Eddie) Gomez was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on 4th November 1944. His

family moved to New York when he was one year old, and that is where he spent his youth.

When he was twelve he took up the double bass, and at fourteen began studying with Orin

O’Brien - a student of the influential classical virtuoso, Fred Zimmerman - and eventually

studied bass with Zimmerman himself. However his first love was jazz music, and the warm

sound and individuality of Paul Chambers (bassist with Miles Davis) had an early impact

(Gilbert 14). One of his greatest subsequent influences was Scott LaFaro, his sound on the

bass and his prominent role in the Bill Evans Trio. Gomez attended New York’s High School

of Music and Art, and was a member of Marshall Brown’s Newport Festival Youth Band. On

graduating he continued his studies with Zimmerman at Juilliard. By the end of his third year

at Juilliard, Gomez was playing regularly around New York City. He was booked to work at

the Village Vanguard in March 1966 with saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, opposite the Bill

Evans Trio. On opening night Evans asked his manager, Helen Keane, to get “the bass

player’s name and number, I want to hire him” (Keane). In Gomez’s words,

Bill asked me to sit in that week, but he was one of my all-time heroes and I was in awe

of him, so I was kind of timid. I never did sit in with him that time (Johnston 37).

About a month after their meeting, a phone call came from Helen Keane, asking Gomez if he

would do a tour with Evans. About halfway through the tour

Bill sat down with me and said, “Listen - you’ve got the gig if you want to stay. I’d love

for you to be a regular member of this trio.” I was just flabbergasted... (Johnston 37).

Marty Morell joined the group two years later and that trio became the longest serving trio of

Evans’ career. The album Since We Met was recorded in 1974. The trio had been playing

together for six years.

William John (Bill) Evans (b Plainfield, New Jersey, 16 Aug 1929; d New York, 15 Sept

1980) was, according to Grove Music Online, “one of the most influential jazz musicians of

his generation” (Murray). By the time he asked Gomez to join his trio in 1966 Evans had won

a Grammy award for his album Conversations with Myself. He had for several years been

8

named “Best Jazz Pianist” in the Down Beat critics’ poll and readers’ poll, and by critics at the

influential British magazine, Melody Maker. He had a highly successful international career

as a jazz artist, and the position of bassist in his trio would have been one of the most sought

after in the world. An aim of this essay is through analysis of Gomez’s bass lines, to

appreciate why Evans asked him to join the trio, and why their collaboration was so

productive for so many years.

9

Glossary of Terms

Chorus:

The harmonic structure of the melody statement. In Evans’ music (and

most jazz music) the solos are based on successive repetitions of this

form.

Double Stops

Performed on the double bass by pressing two strings to the fingerboard

at the same time (stopping them), and plucking or bowing them

simultaneously.

Double Time

Feel

Playing so that the music sounds twice as fast, with written eighth notes

sounding like quarter notes, while the chords continue at the same speed

as before.

Downbeat

The first and third beats in each bar of 4/4 time.

Ghost Note

Performed on the double bass by muting the string with the left hand and

then plucking the string, creating a note of indeterminate pitch.

Notated on scores with a cross note-head - .

Half Time Feel

Playing so that the music sounds half the speed, with written half notes

sounding like quarter notes.

Offbeat

The second and fourth beats in each bar of 4/4 time.

Slur:

Performed on the double bass by sliding the left hand from one note to

the next without re-plucking the string. A portamento.

Two-Feel:

A style of bass line emphasizing the two downbeats in each bar in 4/4

time.

Voicing:

A series of notes played simultaneously on the piano to express a chord.

Walking bass:

A style of bass line featuring regular quarter notes moving mainly in

stepwise motion. It is the most common style of bass accompaniment in

jazz since the 1950s.

10

Analysis of “Since We Met”

The main chorus section of “Since We Met” is forty bars long and in a 4/4 swing feel with

tempo approximately 174 beats per minute. It is framed at the beginning and end by a twelve

bar section in 3/4 time. The band plays the introductory waltz together, and then the piano

introduces the melody chorus rubato. The piano continues to play alone for the next chorus,

soloing in tempo over the harmonic progression. The bass and drums join in for the last four

bars of this chorus, and accompany Evans for the next two choruses of his solo. Their entry is

approximately 2 minutes 40 seconds into the track, and marks the beginning of the following

analysis.

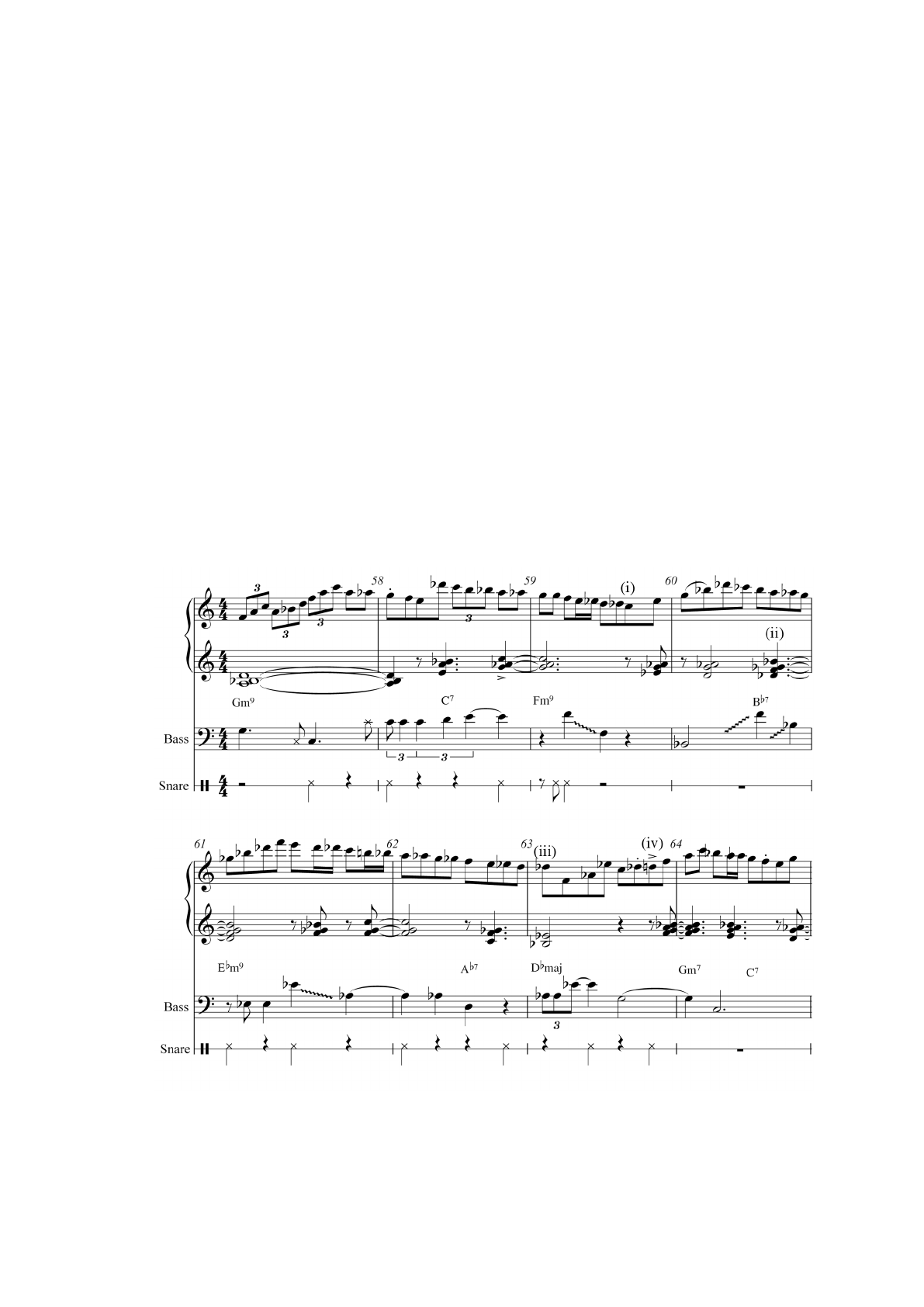

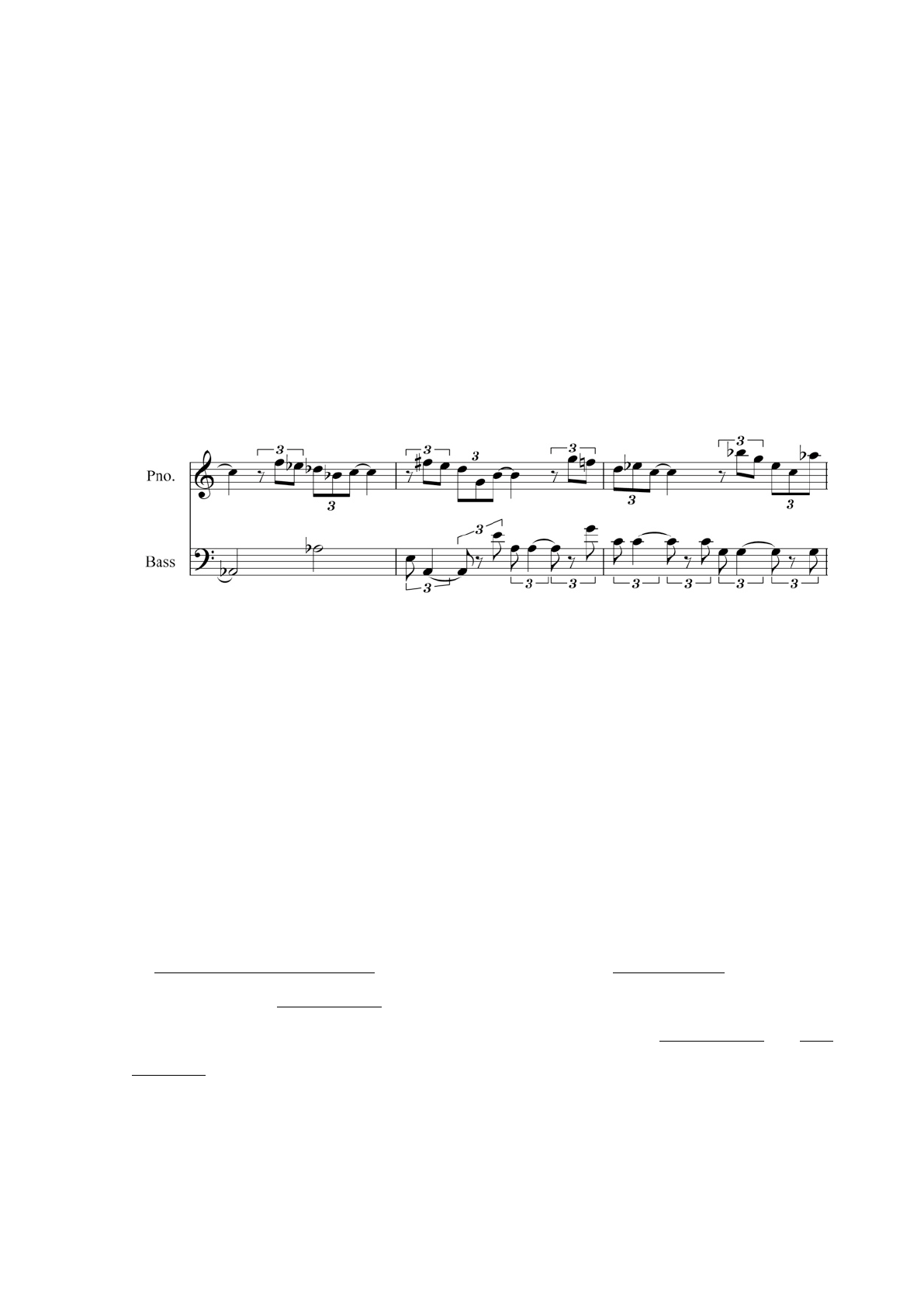

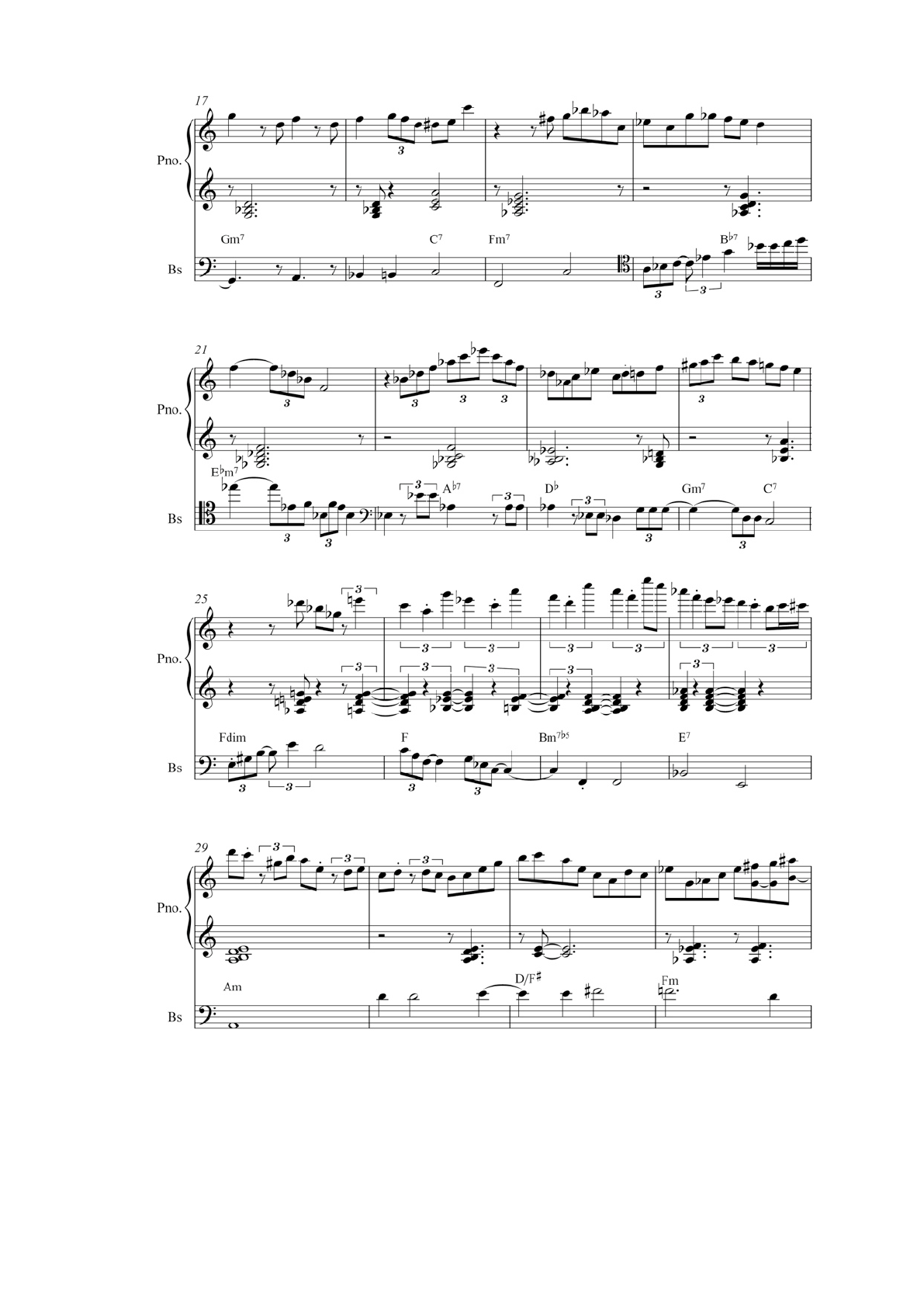

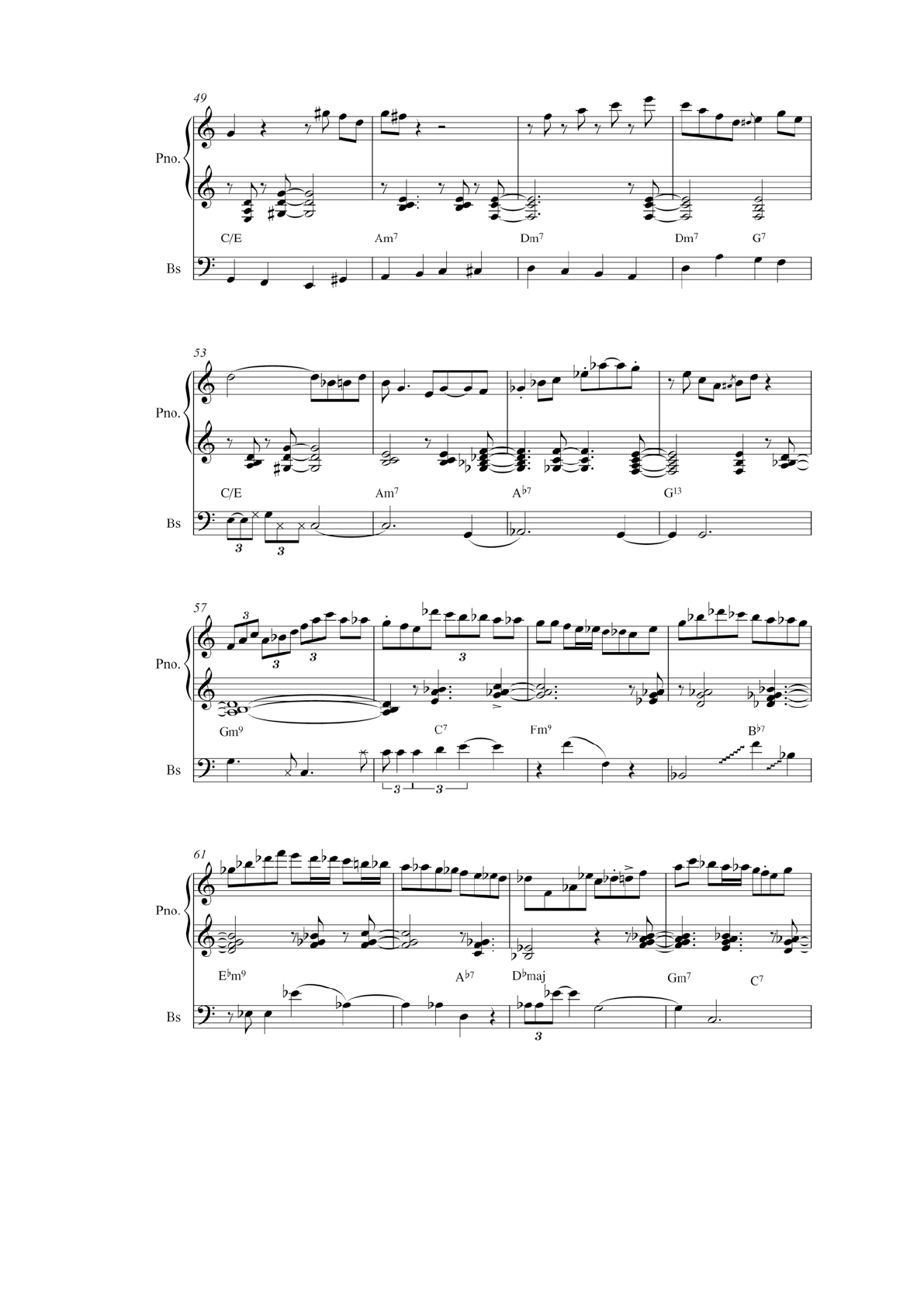

Figure 1. Piano from “Since We Met” showing piano solo construction.

11

The left hand part in Figure 1 displays the rootless voicings that many feel was Evans’

major contribution to jazz (Monson 129). A voicing is a series of notes played together to

express a chord. Before the 1950s pianists built these chords up from the root note of the

chord, expressing without ambiguity exactly what the chord was. Evans developed his own

system in which he chose which notes to include in his voicing, “and omitted the root notes

which tie down the chord and its sound. Without them a given chord can have several

identities” (Williams). Note in particular the ambiguous chordal clusters in bars six and seven,

and the three notes used to describe both the Am and D7 chords in bars nine, ten and eleven.

The voicing of Fm in bar twelve uses the same two notes as the voicing of E7 in bar eight.

Evans’ style of voicing allows great harmonic freedom to the bass player, as it allows many

appropriate note choices from the bass.

The solo line in the right hand exhibits Evans’ mastery and refinement of the bop language

and has been examined in Widenhoffer’s study on the pianist’s improvisational style

(Widenhoffer 44-51). The flowing eighth-note line in bars two to four leads smoothly into the

next chorus at bar five. The first eight bars of this chorus contain four two-bar phrases

balanced into two pairs. The first or antecedent phrase, labelled (a) in Figure 1, begins with a

descending triad with emphasis on the quarter notes. The second consequent phrase, labelled

(b), is built on an ascending diminished eighth-note figure. Typical of the bop style, this line

explores the altered extensions of the Bm

b5

and E7 chords. The next pair of phrases starts at

bar nine. The antecedent phrase, (c), begins like the first with descending quarter notes. Its

consequent phrase, (d), ascends like the first consequent phrase, but in a chromatic scale of

eighth-note triplets.

This excerpt is, like much of Evans’ work, a model of order and thematic development in

the bop idiom. Bill Evans is cited in Grove Music Online’s article on bop as an “important

American bop player” (Owens). The same article describes the bass as a time keeper that

states the pulse with a steady walking line. It would be reasonable to expect the bass line that

accompanies the solo from Figure 1 to be a walking bass line, or at least derived from a

walking bass line. However, Gomez’s bass line does not fit this description at all.

12

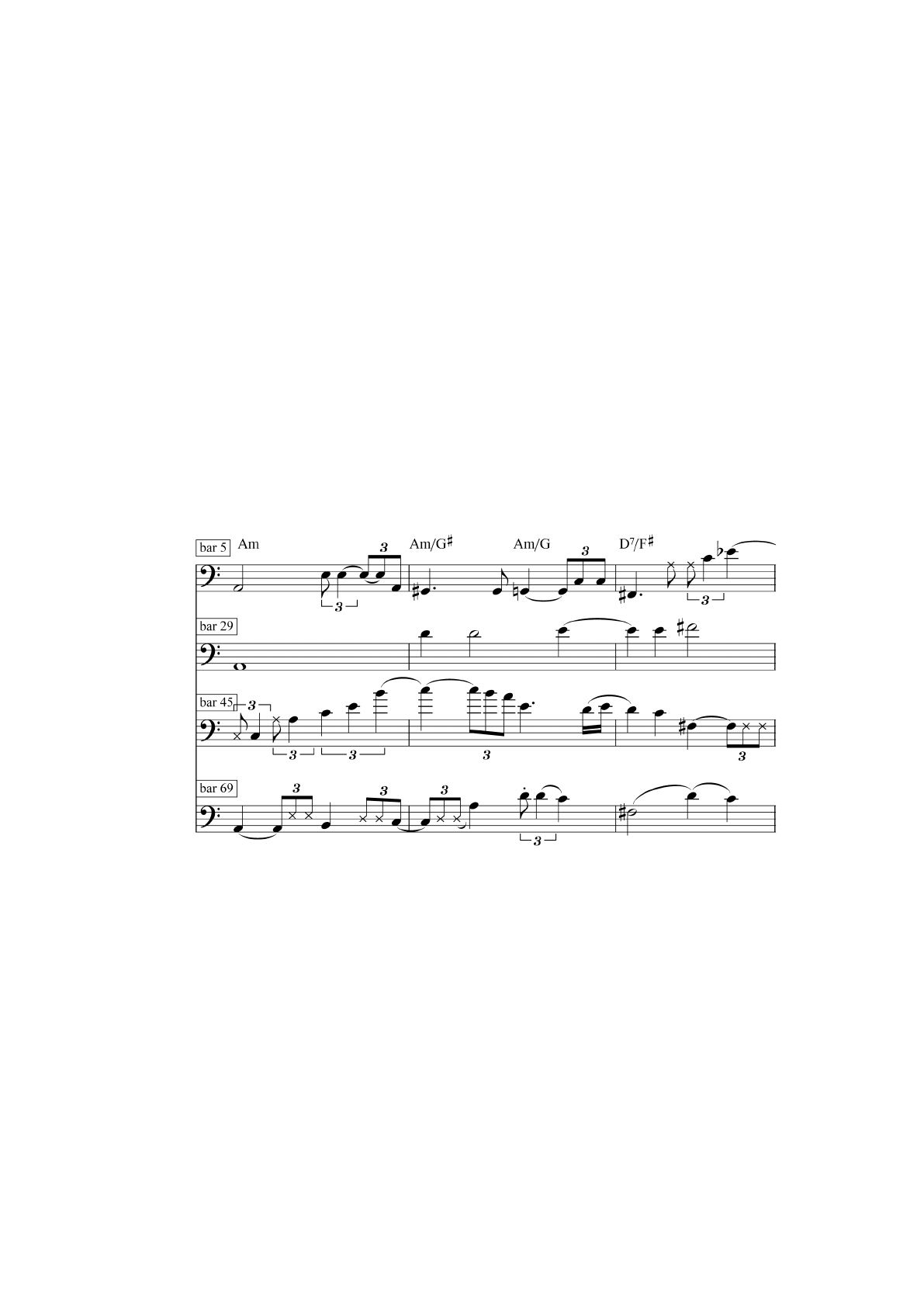

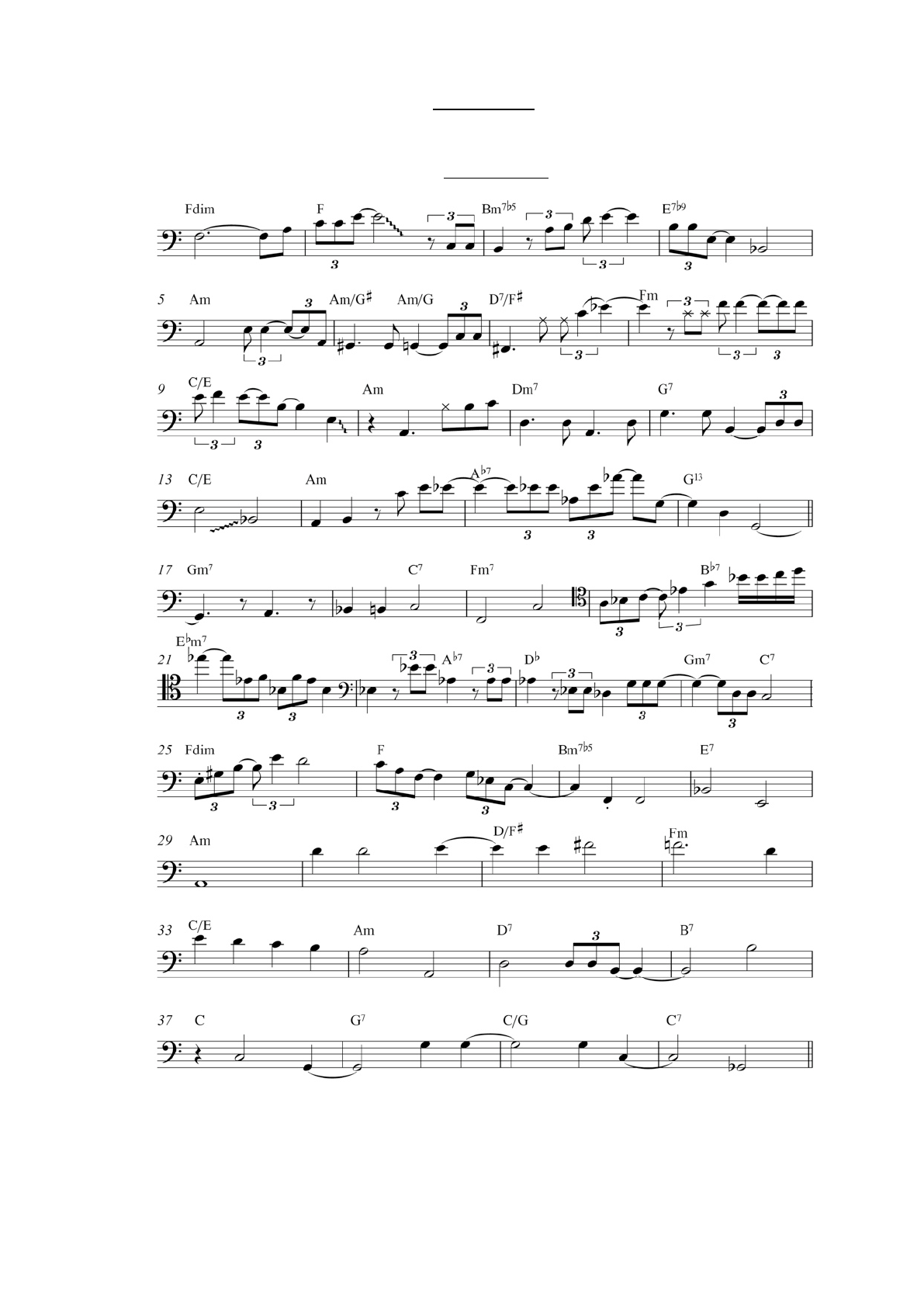

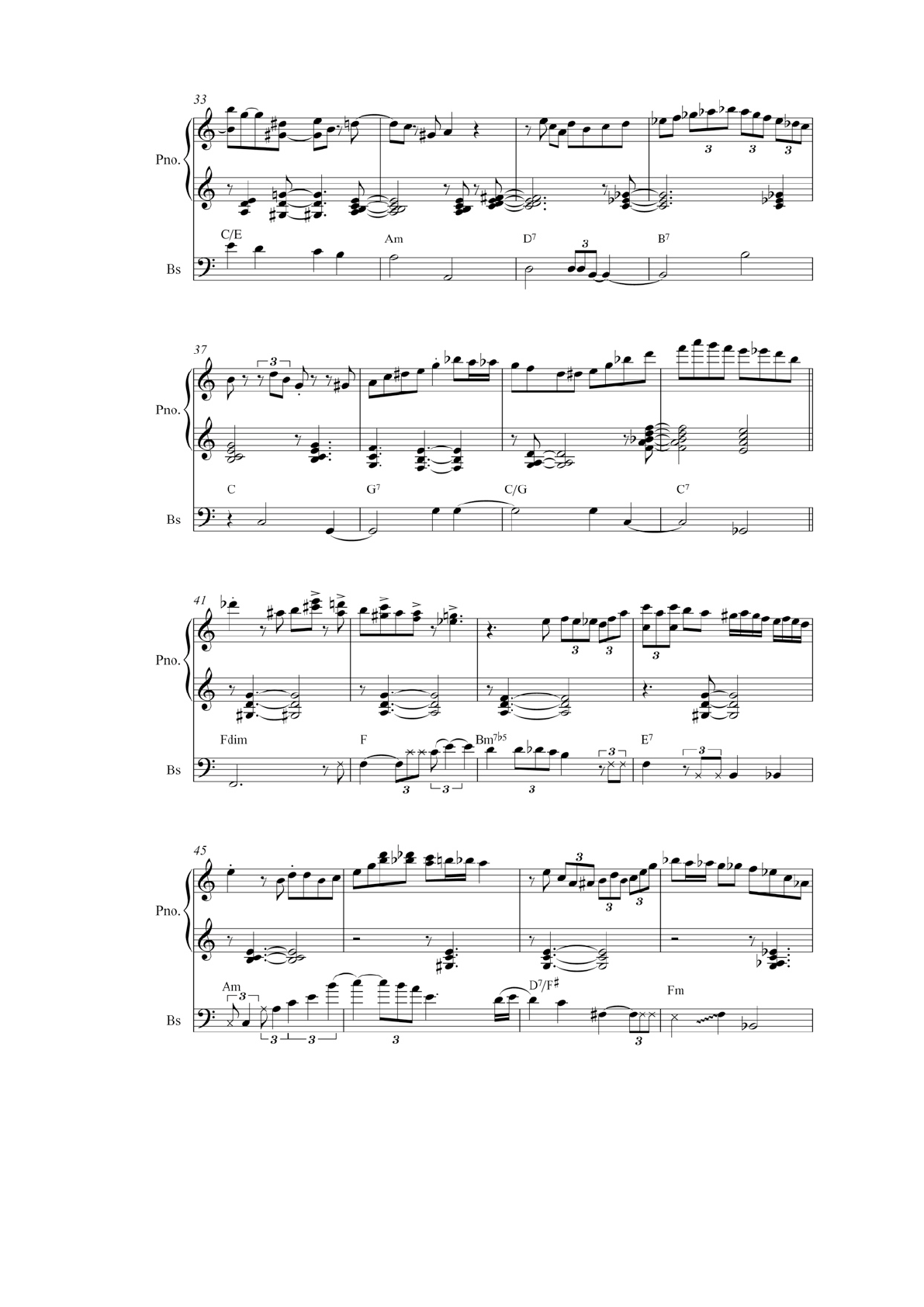

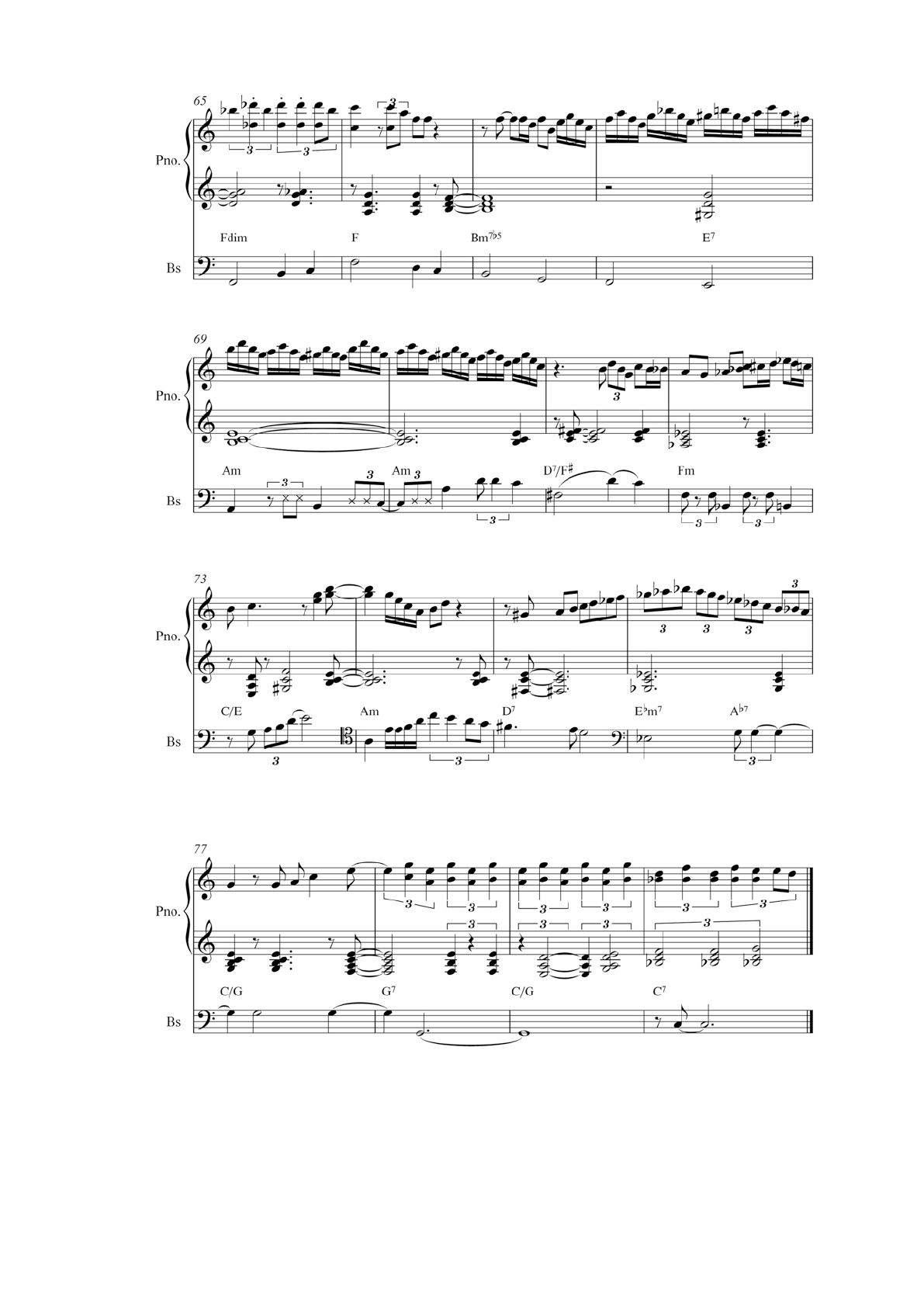

Figure 2. First twelve bars of bass from “Since We Met”.

The bass enters gently with long pedal G notes. The first note is played on the second

eighth note of the bar, which potentially could unsettle the music. An unambiguous down beat

would be a more customary choice for a bass entry after a chorus of solo piano. There are no

bass notes that fall on the first beat of any of the first four bars, and the third beat of the

second bar is the only downbeat that has a bass note in these four bars. The effect however, is

not to unsettle the rhythmic flow established during the solo chorus. Rather, the effect is

rhythmically neutral. The bass neither anchors the time feel with strong downbeats nor

propels the music with anticipated accents but instead continues the gently syncopated

accompaniment established by the left hand piano part during the previous chorus. The

rhythmic clarity of the music comes from the smoothly flowing bebop solo line.

The fifth bar of this excerpt is labelled (i) and marks the start of a new chorus. The new

chorus is strongly marked by the bass with a low F note on the first downbeat. The harmony

at this point is an F diminished chord which is resolved in the second bar to an F major. The

bass emphasizes the harmonic tension of the diminished chord by sustaining the low root note

throughout the first bar, and marks the resolution to the major chord in the second bar with a

motif comprising four eighth-note triplets. It culminates on the third eighth-note triplet after

the first beat and ascends through the third, fifth, and seventh tones of the F major chord. This

motif occurs not only at the point of resolution to F major, but also during a brief resting point

in the solo line, and provides impetus and an increase in forward motion at that point. The

bass continues to propel the music in the third bar of the chorus. A three note motif arrives at

13

the downbeat of the Bminor7

b5

, clearly marking the changing harmony. It is followed by

another four note motif that ascends through the seventh, eighth, tenth and eleventh degrees of

that chord, culminating on the eighth-note triplet after the second downbeat.

The motif at the beginning of bar four delays the arrival of the E7 chord by two eighth-

note triplets. The single B

b

on the downbeat at beat three matches seamlessly with the piano’s

two note voicing of E7. The G

#

and D which are the third and seventh degrees of the E7

become the seventh and third degrees of a B

b

7 chord. This tritone substitution is common

practice in jazz music and it is worth remembering here that Evans is credited with creating

the style of piano voicings that allows substitutions like this to emerge spontaneously and

effortlessly in the music. Bar five begins with a single unambiguous tonic from the bass on

the first downbeat, however the rhythmic variety manifest in the previous four bars continues

in the two note motif which starts on beat three. The two notes are eighth-note triplets with

the first on the downbeat at beat three and the second falling immediately after. This use of

the second eighth-note triplet in bass lines is highly unusual, and is a feature of Gomez’s bass

lines that individuates his accompanying style.

It has emerged already from examination of this very short musical excerpt that there is

significant rhythmic diversity in Gomez’s bass line, and that it functions as a two-feel. The

following examples are taken from the transcription at Appendix 1, and provide an

introduction to Gomez’s elaboration and decoration of the basic feel.

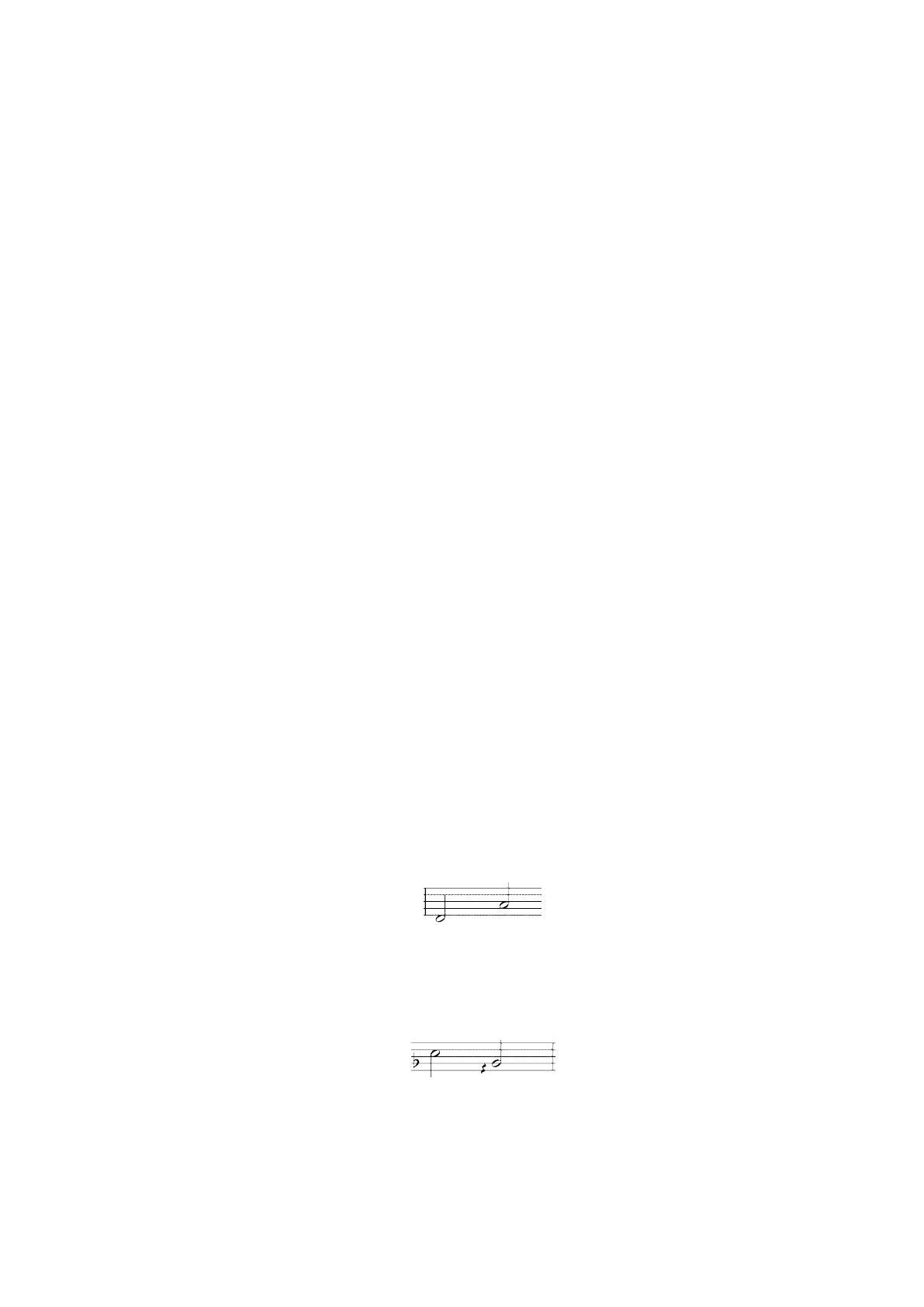

Figure 3. Bar 19. Two unadorned half notes, in this case the tonic and fifth of the chord, form

the basis of the two-feel.

Figure 4. Bar 13. In this bar the slur up to the B

b

reduces its rhythmic impetus compared to

the cleanly plucked string.

14

Figure 5. Bar 11. Adding an eighth note before each note in the two-feel increases the

rhythmic impetus of the bass line.

Figure 6. Bar 6. Anticipation and a slur.

In this example the first downbeat is arrived at by a slur, reducing its rhythmic impetus.

The next, at beat three, has a single anticipated eighth note as in Figure 5. The downbeat of

the next bar has the added impetus created by two anticipatory eighth-note triplets.

Figure 7. Bar 3. A three-note motif and a four-note motif.

The first downbeat here has two anticipatory eighth-note triplets combined with a slur. The

downbeat at beat three has two anticipatory eighth-note triplets, and one immediately after,

which has the effect of destabilising the pulse.

Figure 8. Bar 15. A five-note motif.

The first downbeat here is anticipated by a tied eighth-note. This device is commonly used

in walking bass lines to generate forward motion and add interest to the line. Gomez uses this

device less frequently than his others, only three times in the first chorus. The downbeat at

beat three is both preceded and followed by two eighth-note triplets. This five-note motif is

longer than he normally uses, and only occurs once in the first chorus.

15

Figure 9. Bars 16-17. A longer note.

An important feature of this bass line is the contrast between rhythmically dense eighth-

note triplet motifs and longer notes. In the first chorus there are two notes that are held for 4

beats, two for 3

1

/

2

beats, three for 2

1

/

2

beats, and sixteen that are 2 beats long.

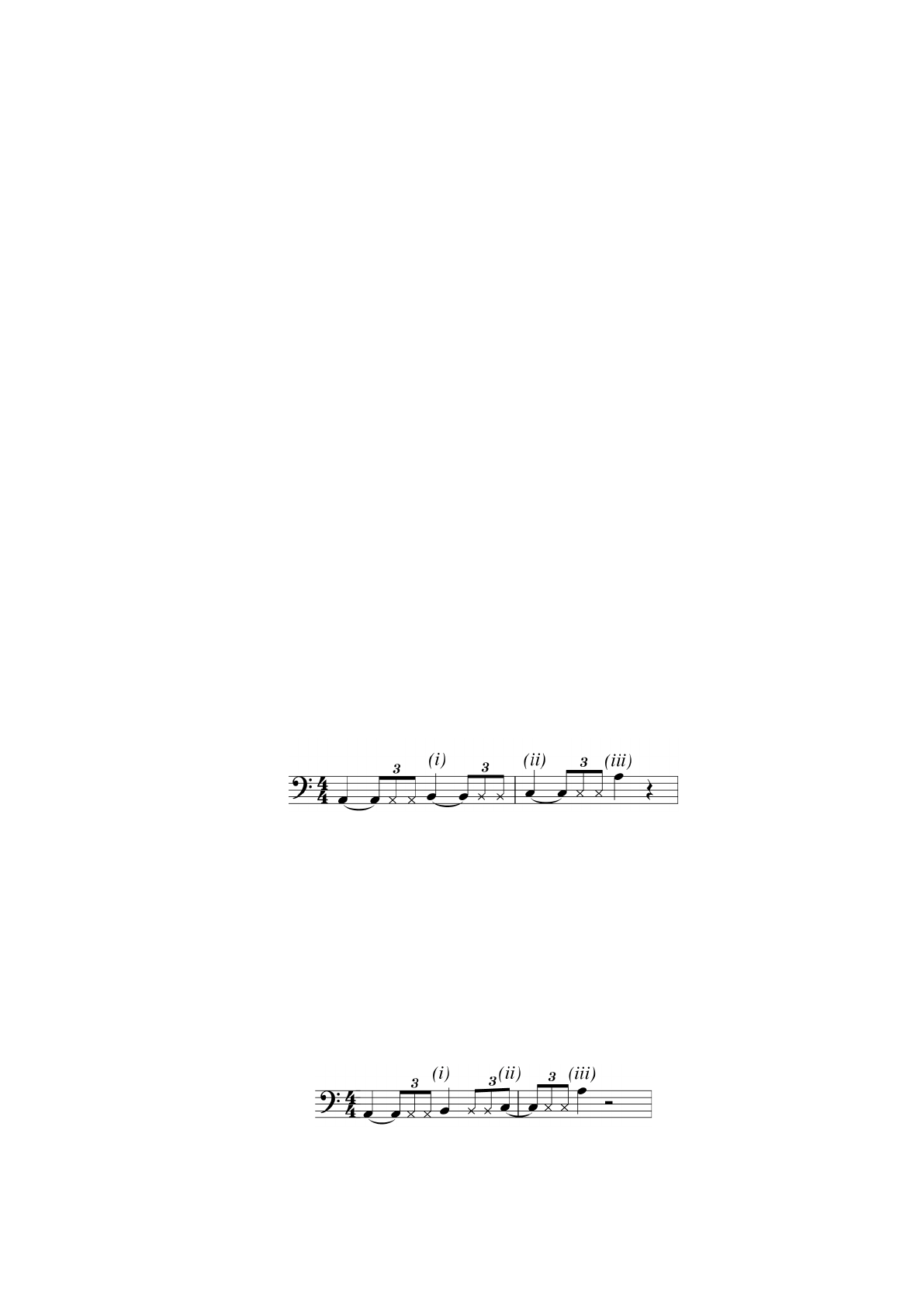

In a bar of 4/4 time there are twelve eighth-note triplets, and there are two downbeats per

bar. Therefore the maximum length for a motif would be five notes, as six would result in a

constant stream of notes between one downbeat and the next. There are four different places

that a motif can end: on the downbeat, on the eighth-note triplet immediately before or after

the downbeat, and two eighth-note triplets after the downbeat. (The other two places, on beats

two or four and on the eighth-note triplet after those beats, don’t sound like anticipated or

delayed downbeats. They sound like offbeats that push the music away from a two-feel and

into a four-feel or walking bass line.) Theoretically then, there are twenty possible rhythmic

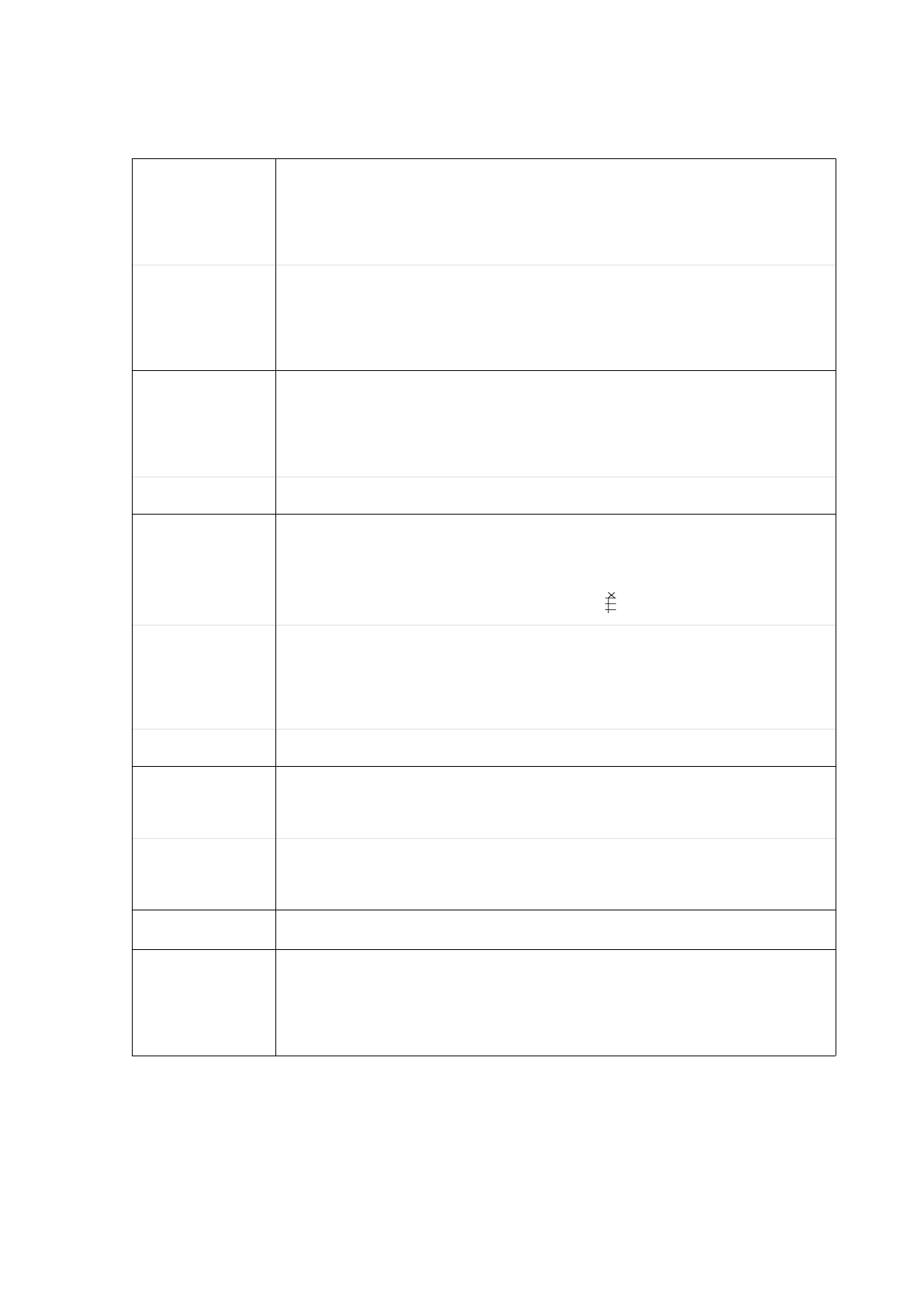

permutations for motifs, as set out in Figure 10, below.

16

A

Anticipating the

downbeat by an

eighth-note

triplet

B

Arriving on the

downbeat

C

Delayed arrival

by one eighth-

note triplet

D

Delayed arrival

by two eighth-

note triplets

One note

2x

20x

Two notes

6x

1x

Three notes

1x

7x

1x

4x

Four notes

2x

1x

Five notes

1x

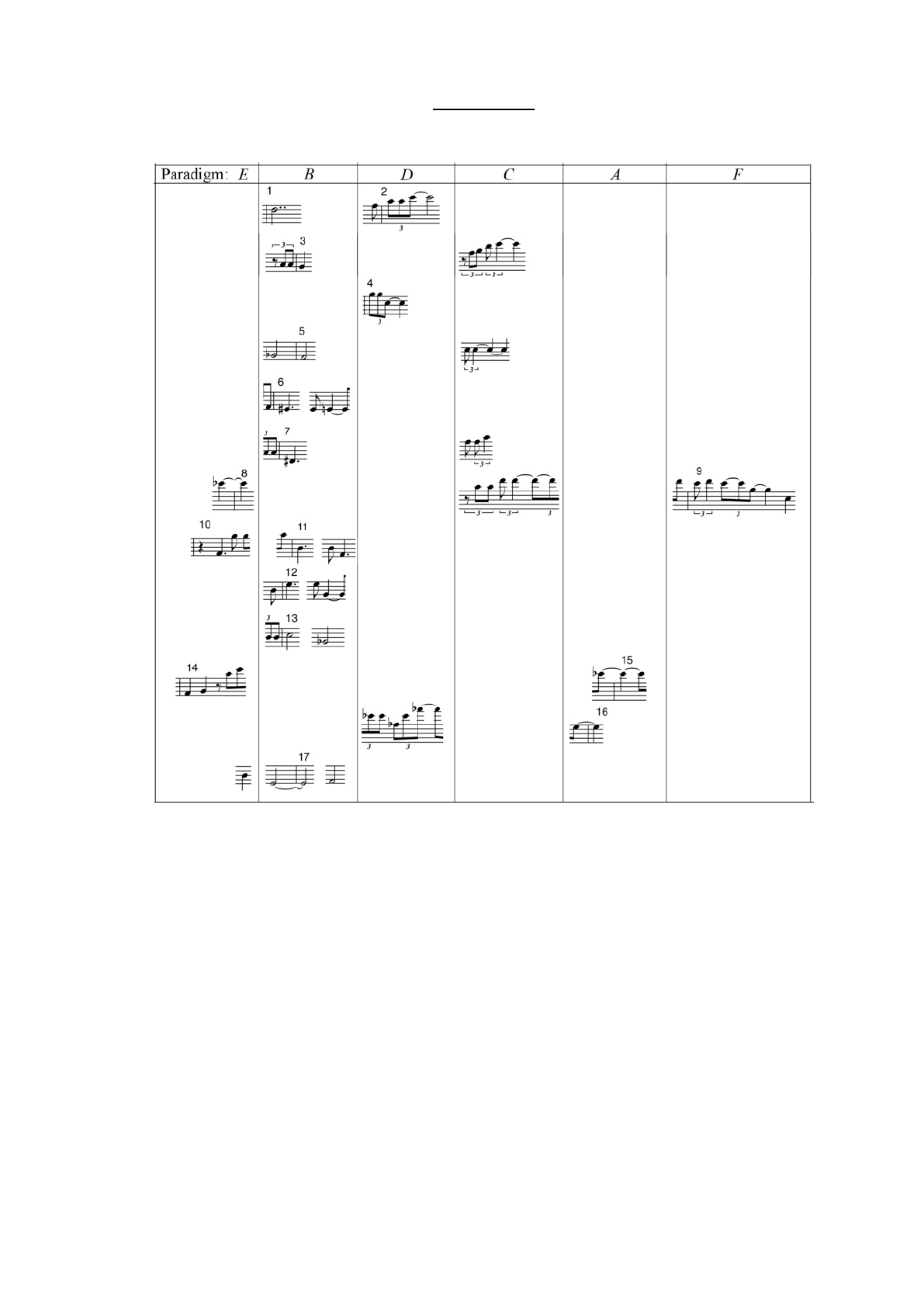

Figure 10. Paradigmatic chart of rhythmic motifs in one chorus of bass line to “Since We

Met”.

The chart above shows that motifs which arrive on the downbeat outnumber the others by

a considerable margin. Despite the dauntingly intricate look of the transcription at Appendix

1, the bass part consists largely of downbeats, and this is what generates the two-feel. There

are twenty unadorned downbeats in the first chorus that impart a clarity and feeling of space

to the music. The other motifs add complexity and interest, propelling and retarding the

rhythmic flow. Three-note motifs occur in all four paradigms and occur most frequently after

the single note.

The sequential arrangement of these motifs relative to each other and to the form of the

tune is of special interest. It is easy to examine this using a paradigmatic flow chart, with each

motif placed in a column according to its rhythmic displacement. Figure 11 uses the same

paradigms as Figure 10. The first six bars of the chorus are numbered and set out reading

from left to right across the chart. Viewing the music this way it becomes clear that the bass

17

line alternates the stabilising downbeats from column B with the destabilising motifs from

columns C and D. The extent to which Gomez is able to extract variety from the short motifs

is revealed by this short excerpt. Not only is there alternation between stabilising and

destabilising motifs, but also between the types of destabilising motifs. The motifs in bars two

and four that arrive two eight-note triplets after the downbeat (from column D) are alternated

with the motifs in bars three and five which arrive one eight-note triplet after the downbeat

(from column C).

Figure 11. Paradigmatic flow chart of first six bars of the chorus in the bass line to “Since We

Met”.

There is also alternation within each column. In column B the initial unadorned downbeat

at bar one is followed by the downbeat at bar three which has two anticipatory eighth-note

triplets. The two plain downbeats at bars four and five are followed by two downbeats in bar

six that are each anticipated by a single eighth-note triplet. In column D the initial ascending

four-note motif is followed by a descending three-note motif. In column C the initial four-note

motif contrasts with the subsequent two-note motif.

At this point it seems that a pattern is emerging, of clear downbeats at the start of each two

bars which correspond to the phrasing of the piano solo. The downbeats at the start of bars

one, three and five are all root notes, marking out the changing chords of the evolving chorus.

Between each of these clear signposts is a more ambiguous motif that allows the music a freer

floating feeling than a walking bass would allow. As the chorus unfolds however, the bass line

18

moves away from its initial alternation of contrasting motifs. Variety and unpredictability

emerge as the salient characteristics.

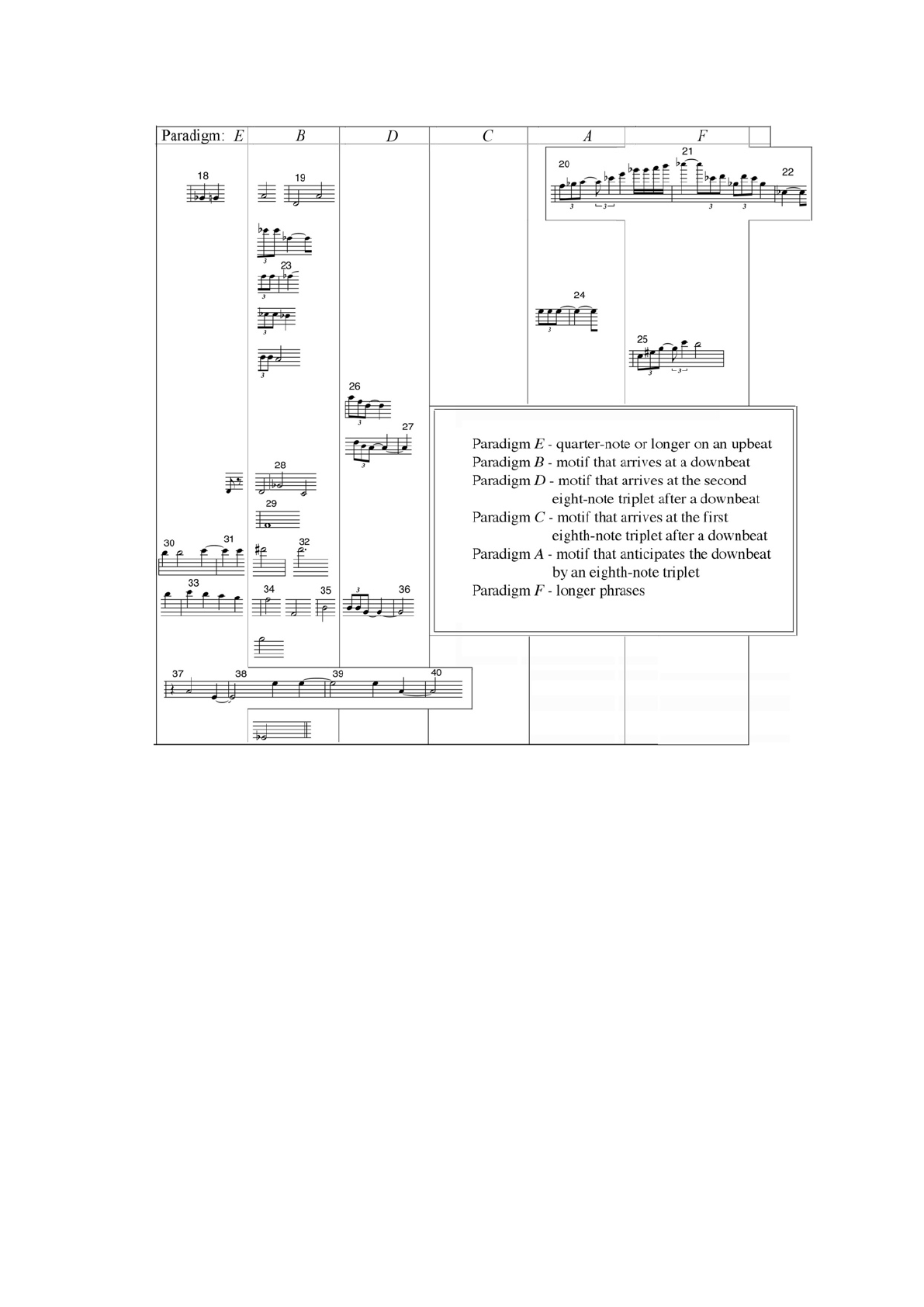

Appendix 2 is a paradigmatic flow chart of the entire first chorus of bass line, and shows

its variety on a number of different levels. Two columns have been added to the four that were

introduced at Figure 10. One, labelled E, contains upbeats which imply a four-feel or walking

bass line. The other column, labelled F, contains longer phrases which don’t fit in with any of

the motific paradigms.

Bar six and the first note in bar seven comprise three motifs which land on three successive

downbeats. They reinforce the chromatic descending bass line of the chorus at that point, and

provide a clear anchor for the music. As if to balance this excess of simple clarity, the bass

line floats freely for the next four bars, not playing a downbeat at all until bar eleven. This

four bar section, from bar seven to bar ten, contains the first three-note motif in column C, the

first use of an emphasised upbeat and the first longer phrase which occupies all of bar nine. It

is harmonically interesting at bars seven and eight too. Appendix 3 shows the bass and piano

parts with chord symbols to clarify the harmonic discussion in the following paragraphs.

Evans’ solo line in bars seven and eight is a chromatic scale in eighth-note triplets that

begins on the pickup to beat three, ascending through the third beat of bar eight before

descending to the next bar. The first note of each triplet grouping consequently forms a

diminished chord. At the same time that this line begins, the bass also ascends through a

diminished triad of a ghosted A, a C and an E

b

. The E

b

note is then held across the barline and

the changing chord. This E

b

is a highly unusual choice for a bass line to rest on, being the

flattened ninth of the D7 chord and becoming the flattened seventh of the subsequent F minor

chord. Rather than firmly anchoring the music, the bass here reinforces the harmonic

ambiguity of the chromatic solo line with both note choice and floating rhythmic feel. Often

in jazz music the bass supports the soloist with contrast, by providing clear foundations for

adventurous solo explorations, and by supplying syncopation and dissonant note choices to

add interest to more consonant solo passages. Gomez on the other hand often enhances the

contrasts within the piano solo. His bass line enhances the ambiguity of the solo in bars seven

19

and eight, and nine bars later he enhances a simple and clear piano line with an equally simple

and clear bass line.

Figure 12. Piano solo line and bass line in Bars 17 and 18 of “Since We Met”.

This is perhaps the simplest and most light hearted solo phrase in the entire chorus, and the

bass line matches the mood exactly for this brief period with a simple and uncluttered bass

line.

The listener’s ear is drawn to the bass line at bar nine. It is the first instance during this

chorus of a phrase that doesn’t fit into the motific paradigm chart. The bass plays a melodic

phrase in a space between phrases in the piano solo, and it attracts the listener’s attention.

Momentarily the music sounds more like a dialogue, with the ‘interplay’ between piano and

bass that some people claim is a feature of this trio. Immediately, however, the bass returns to

playing discreet bass notes, and the listener’s attention is drawn back to the melodic piano

solo line. The ear is drawn to order and melodic development in music. Gomez’s bass line is

irregular and its few short melodic phrases are not developed, which allows the focus to

remain on the evolving piano solo.

The bass’s next melodic phrase is a virtuosic line which almost slips by unnoticed, as it

occurs beneath a strongly developing solo passage in bars 19-21.

Figure 13. Bass line in bars 19-21 of “Since We Met”.

20

There are several aspects of this phrase that are of interest. It is technically difficult to move

quickly and accurately from the low F in bar 19 to the E

b

almost three octaves higher on the

first beat of bar 21. The rhythm is complex too, with eighth-note and quarter-note triplets as

well as sixteenth notes. Very few bassists could have executed this phrase in a way that

sounds so effortless. Also, its placement underneath a strongly developing solo line is in

marked contrast to the placement of the melodic bass phrase in bar nine which occurs during a

space between solo phrases. A search for ordered patterns and repetition in the bass line

reveals instead the high degree of variety contained in it. Melodic phrases occur in spaces

between piano phrases or simultaneously with piano phrases. The initial alternation between

rhythmically stabilising and destabilising motifs finishes after bar five to be replaced with

random groupings from the different paradigms. Ascending and descending motifs alternate

or appear in groups of the same type. Longer and shorter motifs are used in random

configurations. The upper and lower registers of the bass are employed without relation to the

pitches of the piano solo.

In bars 22-24, five consecutive three-note motifs follow and contrast with the virtuosic

phrase. Each is subtly different to the others. The first arrives at the downbeat on beat three

and is harmonically clear, with two tonics of the E

b

minor chord leading to the tonic of the

new A

b

dominant chord. The second motif has two ghosted notes followed by the fifth of the

new D

b

major chord, delaying the resolution until the third motif arrives at the tonic on the

downbeat at beat three. The fourth motif is metrically displaced and anticipates the next

downbeat by one eighth-note triplet. It has an unsettling effect on this passage, preventing it

from becoming too comfortable. The last motif is an unambiguous resolution to the dominant

chord on beat three, which leads back to the final sixteen bar section of the chorus.

Bar 25 marks the return to the initial A section of the chorus, and contains the third

melodic phrase in the bass line. In contrast to the start of the chorus when the bass anchored

the F diminished tonality with a tonic held through the whole bar, this time the bass plays a

melodic phrase through the first two beats and slurs to the high E which adds further timbral

interest. Evans marks the beginning of this new A section with a new melodic idea, a

descending triad motif which he repeats and develops over three bars before it evolves into a

four-note motif developed over the subsequent three bars. Gomez’s sensitivity to Evans’

21

melodic and rhythmic ideas and to the flow of the music is evident during these six bars. He

catches the second and third iteration of the piano’s descending triad with his own descending

triads. Where the piano’s consist of swung eighth-notes, almost quarter-note triplets, the

bass’s are in eighth-note triplets. After these two motifs the bass avoids further repetitions and

asserts its independence from the piano solo. It plays half notes and then a whole note which

allows space for the piano figures to evolve without interference or constraint from the bass.

Gomez’s different treatment of the beginning of these two A sections invites a comparison

between these two and the two in the following chorus. As can be seen in Figure 14, the bass

line is different for the start of each of these four A sections, demonstrating Gomez’s ability to

find diverse ways of treating the same chord progression.

Figure 14. Comparison between the first four bars of each A section in “Since We Met”.

The bass line at bar 41 is at the start of the second chorus and is similar to the first one. It

sustains an F-note through the first bar, underpinning the diminished chord as it did in bar

one. The four note motif in bar 42 is very similar to the motif in bar two, arriving at the major

seventh degree of the Fmajor via the fifth. However it is delayed by 1

2

/

3

of a beat which

means that it functions as the second downbeat of that bar. Like the first time, it arrives after

the downbeat and adds a floating feeling to the music.

The bass line for the second A section of the second chorus, bars 65-68, is different from

the other three. It is much simpler, containing only quarter and half notes. The root notes of

each chord appear on the first downbeat for the first three bars. The descending bass line in

22

bars 67 and 68 delays the arrival of the E7 chord by two beats. Evans also delays his arrival at

the E7 until the third beat of bar 68. His solo line revolves around an F note at the beginning

of the bar and there is no comping chord until an E7 chord is played on the third beat

simultaneous with the bass note. It is not possible to conclude from this that the pianist was

affected by the bass line or that Gomez was reacting to Evans’ solo line, but it is another

example of the empathy that existed between them, and a concrete illustration of why the

music sounds so cohesive.

In bars five, six and seven the bass clearly outlined the descending chromatic bass line of

the tune. The same chord sequence occurs in the second A section of the chorus and it is

interesting to compare the contrasting bass lines Gomez plays for this part of each A section in

both choruses.

Figure 15. Comparison of fifth to seventh bars of each A section in “Since We Met”.

The first occurrence, at bar five, is the only time that the descending bass line is spelled out by

the bass. At bar 29 the piano solo is developing a rhythmic motif, as described earlier, and the

bass stays rhythmically simple with only half and quarter notes. Melodically, however, the

bass line explores new areas. Its melodic contour is in complete contrast with the first

iteration. Instead of a chromatic descent, it ascends steeply. From the same starting point as in

bar five, a low A, it ascends to the F

#

two octaves higher than the F

#

in bar seven, totally

ignoring the written G

#

and G. Instead of the chromatic descending line, the bass plays a D

note through the first three beats, subtly reharmonising bar 30 to a D7

sus4

sound. Evans’ chord

23

voicing for this bar is typically ambiguous, allowing the bass the freedom to explore new

paths through the harmonic progression.

In the second chorus, at bar 45-47, Gomez’s ability to find fresh ways through the tune is

apparent. The three bar passage begins with two skipping motifs comprising a ghosted eighth-

note triplet on the beat followed by a quarter-note triplet. These are followed by a flowing

quarter-note triplet phrase that slurs into bar 46. The melodic contour again ignores the

descending original, flowing up and down again over a two octave range. The bass line in this

third A section contrasts with the other three both rhythmically and in contour. It follows the

harmony of the tune but is otherwise unrelated to the piano solo. The skips and slurs subtly

push and pull at the rhythmic momentum of the music, adding interest without compromising

the strength and clarity of the piano solo line.

In the fourth A section, at bars 69 and 70, the bass has a powerfully propulsive effect. After

the downbeat at bar 69 there are three three-note motifs. In each, the first two notes are

ghosted, and this alone adds to the rhythmic propulsion. If the final note in each motif were

held for the value of four eighth-note triplets then each motif would arrive at a downbeat, as

the three labelled (i), (ii) and (iii) do in Figure 16.

Figure 16. Regular placement of three-note motifs.

However, Gomez shortens the note at (i) by one eight-note triplet which means that the next

motif arrives an eighth-note triplet before the next down beat. He then shortens that note by

two eighth-note triplets which means that the subsequent motif arrives at (iii) a full beat

earlier. This is illustrated at Figure 17.

Figure 17. Metric contraction of three-note motifs. Bars 69 and 70 in “Since We Met”.

24

The effect of this metric contraction is to add a feeling of urgent anticipation to an otherwise

fairly decorative part of the piano solo.

The harmonic framework of the tune is adhered to closely by the piano and bass, with only

subtle anticipations and substitutions that effect the harmonic progression very little. This

allows for complex rhythmic explorations and metric displacements. Occasionally though,

Gomez plays an unexpected bass note which casts the piano voicing in a different light. The

most extreme example of this reharmonisation occurs in bars 35 and 36.

Figure 18. Bars 35 and 36 of “Since We Met”.

In the 36th bar of each melody choruses and in the second chorus of the piano solo Evans

plays E

b

minor7 and A

b

7 for two beats each. In his first solo chorus, shown at Figure 18, the

solo line outlines this E

b

minor7 to A

b

7 progression while an A

b

7 voicing is held through the

bar. The bass motif in bar 35 arrives at a B note which is held through the next bar. At first

examination of the transcription the note seems wrong, a mistake, and out of character with

the rest of the bass line. However, it is played assertively and sounds right. It is an effective

reharmonisation of the tune based on the diminished relationship between dominant chords.

The solo line and chord voicing are recontextualised by the bass and if the piano part is

rewritten enharmonically to reflect this, the reason that it sounds right becomes apparent.

25

Figure 19. Bars 35 and 36 of “Since We Met” transformed enharmonically.

Viewed this way, the piano’s A

b

7 voicing becomes a B7

b9

and the solo line a B Lydian mode.

This type of recontextualisation of the piano voicing and solo is used sparingly by Gomez and

only once during this piano solo.

Bars 49-52 are in striking contrast to the rest of the bass line. Not because they are

virtuosic or rhythmically complex, but because they contain a walking bass line. As one

listens to the music there seems no obvious reason why the bass should break into a walking

line at this time. Commonly in jazz, a bass would go from a two-feel to a walking line to raise

the intensity of the music. For example, Ron Carter in the Miles Davis Quintet of the 1960s

often played a two-feel during the first few choruses of medium tempo tunes, and by moving

into a walking line would mark a clear change in that piece’s intensity. In this case, however,

there is no such change. The four bars of walking are just another element of variety in a

constantly changing bass line, and have little effect on the overall dynamic of the tune. The

line is typical of common practice in walking bass line construction, with root notes of the

chords on the downbeats connected by lines featuring stepwise movement (hence the term

walking bass). A feature of this passage that makes it distinctively Gomez’s is the ghosted

notes. In other bands that Gomez works with (for example The Great Jazz Trio), he plays in a

more traditional way with long passages of walking bass lines. The ghosted notes that feature

in his walking lines help to individuate his sound.

The subsequent four bars provide contrast to the walking line, with long sustained notes.

At five beats long, the C note held over bars 53 and 54 is the longest note in the bass line. The

downbeat to bar 55 is held for three beats and is arrived at by a slur, reducing its rhythmic

impetus. The contrast to the previous four bars of walking bass provided by the longer notes is

26

further enhanced by the avoidance of downbeats altogether in bars 54 and 56. There is no

apparent feature in the piano solo or in the structure of the tune that provides a reason for the

abrupt change into a waking bass and then into sustained long notes. Again, variety and

contrast seem to be the defining characteristics of the bass line.

The piano solo reaches its peak in rhythmic intensity in an eight bar phrase starting on bar

57. The melodic contour of the line flows up and down five times in these eight bars.

Widenhoffer finds Evans “aggressive” in this phrase and notes that “the listener is kept off

balance by the fact that the apex of each contour never successively falls on the same portion

of the beat” (49). It is much more than an irregular contour that keeps the listener “off

balance”. This line is an example of the pianist’s deliberate “displacement of phrases against

the meter” (McPartland). Gomez’s bass line, rather than securely anchoring the time, adds to

the metric ambiguity.

Figure 20. Piano, bass and snare drum from bars 57-64 in “Since We Met”.

27

The drums play a subtle but important part in this section so the snare drum part has been

included in this transcription. Morell plays quietly with brushes throughout the piano solo and

generally maintain gentle offbeat accents on the snare drum. At bar 57 the snare beat isn’t

played on the offbeats, but on the downbeat at beat three, and then again on the first beat of

the next bar. The effect is of metric expansion, it sounds as if the drums are playing at half the

tempo. (Perhaps the impetus for this can be found in the longer duration notes and floating

time feel of the bass in the previous bars 53-56.) In bar 58 the bass plays a quarter-note triplet

figure starting on the second beat. On the fourth beat of that bar the piano plays an accented F

minor chord. The combined effect of the displaced snare beats and bass triplets in conjunction

with the phrasing of the solo line is that this F minor chord sounds like the downbeat of a new

bar. This is reinforced by the ascending arpeggio marked (i) that starts on the fourth beat of

bar 59. It too sounds like it begins on a downbeat. The E

b

minor chord marked (ii) intensifies

the displacement as it occurs 1

1

/

2

beats early. The drums adds to the effect with the next three

downbeats played on the snare. By now they sound disconcertingly like offbeats, adding to

the tension created by the piano’s consistent harmonic anticipation throughout the previous

three bars. The piano’s solo line in bar 62 is a descending chromatic line that doesn’t define

the meter either way. Not until the downbeat at bar 63 is the tension released with a D

b

major

arpeggio, marked (iii), that clearly defines the meter. The snare has returned to accents on the

offbeats and the listener is no longer, in Widenhoffer’s words, “off balance”. The meter is so

secure that the harmonic anticipation at (iv) doesn’t create the tension achieved in the

previous bars.

In the bass line, the frequent slurs between notes and the absence of eighth-note triplet

motifs during this passage allow maximum space for the interplay between snare and piano.

The bass remains metrically neutral during this passage, reinforcing neither the displaced time

feel nor the actual meter. In bars 59-62, the four bars that sound most disconcertingly

displaced, the bass balances evenly between offbeat and downbeat emphasis. The two F’s in

bar 59 are metrically ambiguous. The B

b

on the first beat of bar 60 defines it as a downbeat,

but the movement of descending fifths which arrives at the second beat of bar 61 strongly

suggests that it is the downbeat. While the piano has anticipated the harmonic movement to E

b

minor by one beat, the bass has clearly marked out the progression from Fminor7 to B

b

7 to E

b

minor, but all delayed by one beat. The bass slur from E

b

to A

b

in bar 61 increases the tension

28

created by the relentless anticipation from piano and drums, as it implies that beat four is a

new downbeat. The D on the third beat of bar 62 is a tritone substitution of the Ab7 chord and

meshes seamlessly with the piano’s left hand voicing and chromatic solo line. This clear

downbeat sets up the release of tension from the piano and drums which occurs on the

downbeat to bar 63.

The ambiguity of this section of bass line is juxtaposed with the simple clarity of the next

section, which starts at bar 65 and marks the return to the final A section. Widenhoffer notes

the reduction in intensity from this point to the end of the solo, and describes the

recapitulation of thematic material found earlier in the solo (50). The bass line in the first

eight bars of this section has been discussed earlier in the comparative analysis of all the A

sections. The final eight bars of the bass line start at bar 73 with a five note motif of eighth-

note triplets. A final burst of virtuosity takes the line into the upper register in bar 74. It

doesn’t fit into the motific paradigms that were the preoccupation of the earlier part of this

analysis, but is a melodic phrase consisting of four sixteenth notes, two quarter-note triplets,

two eighth-note triplets and a final dotted quarter-note. As with previous examples of melodic

phrases in this bass line, it is followed by simple and sparser motifs. A two note motif arrives

at the tonic D on the second downbeat of bar 75. A single half note provides the downbeat for

bar 76 and it is followed by a two note motif at the next downbeat. The chorus concludes with

pedal G notes, as did the previous chorus. This time however, the rhythmic momentum is

allowed to drop right down as the low G in bar 78 is sustained for nearly two full bars.

The analysis so far has examined the bass line bar by bar, exploring the multiple devices

that the bass employs in its accompaniment of the piano solo. It occurred to me that by

focussing at a micro level on the specific details of the bass line that I may have missed an

overarching or macrocosmic principal that governs its construction and connects it to the

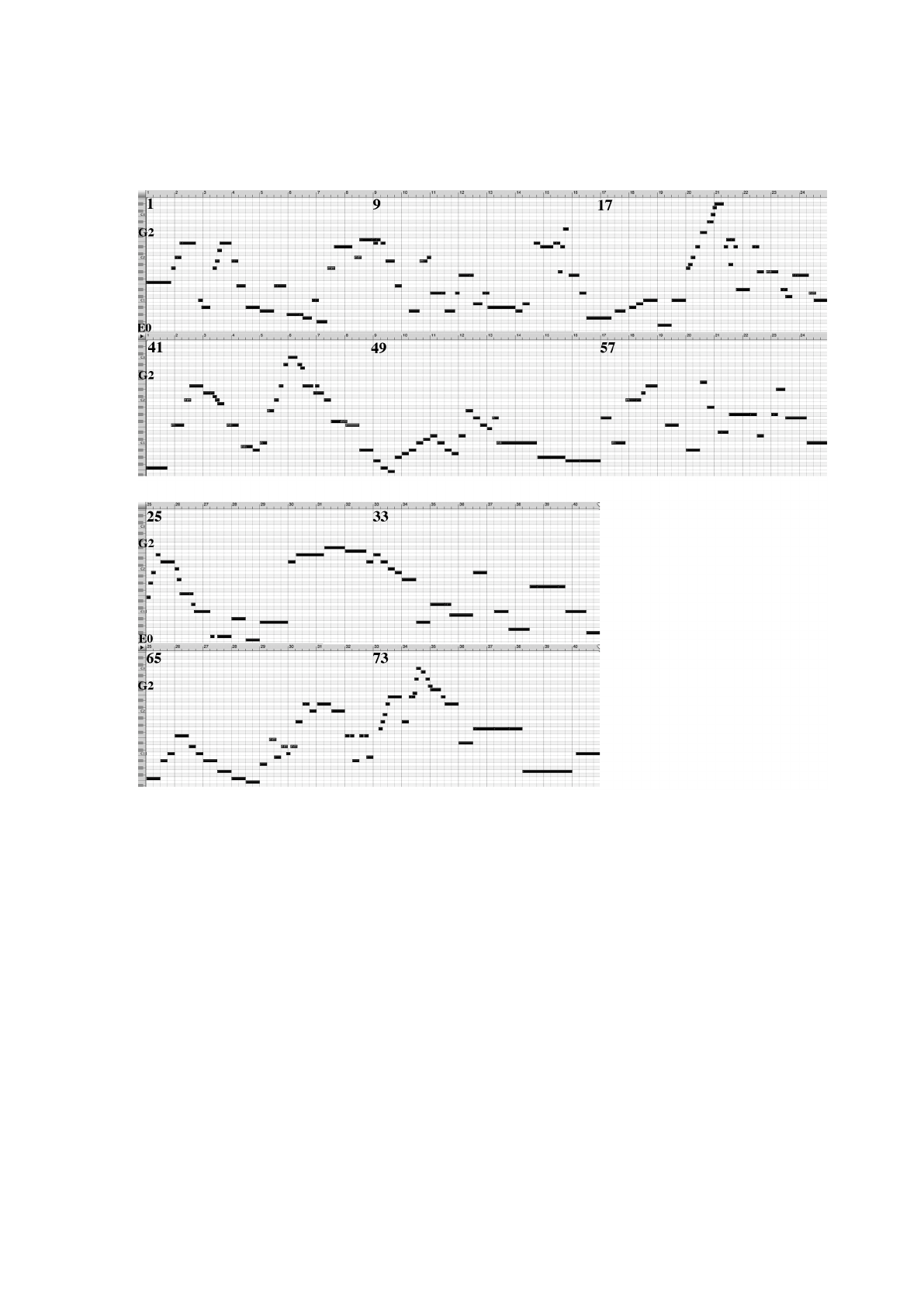

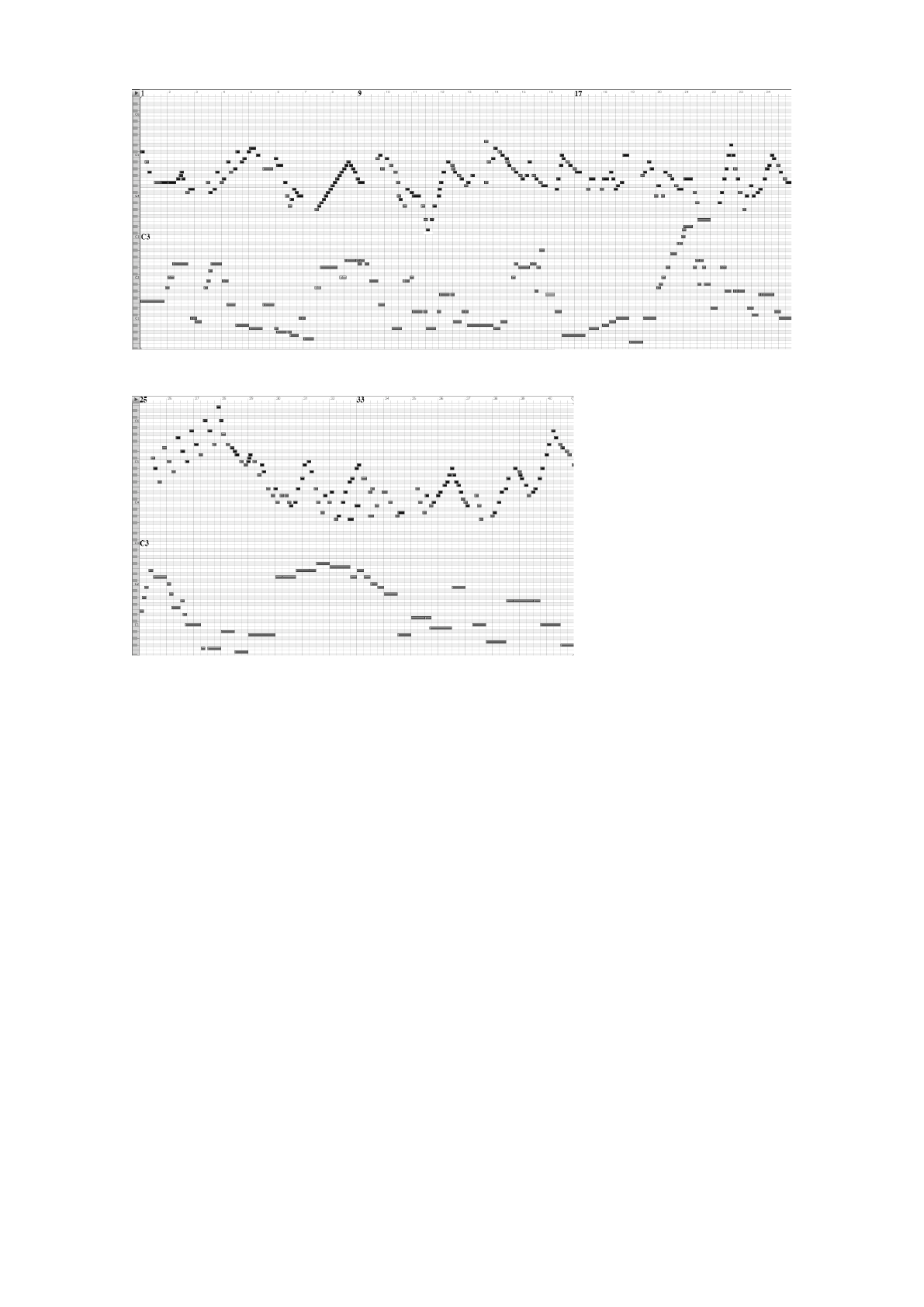

piano solo. To address this issue I prepared the graph which appears below at Figure 21. Many

of the features of the bass line described so far can be recognised in the graph. It has been

split in two to fit the page and is a graphical representation of the two choruses of bass line.

Bars 1-24 are numbered across the top of the first half, and the corresponding passage from

the second chorus is placed directly below with the bar numbers 41, 49 and 57 labelled in

bold. The second half of each chorus appears underneath, with the bar numbers 25, 33, 65 and

29

73 labelled in bold. To the left the pitches are labelled, with E0 (the lowest note on the bass)

and G2 (the first octave above the open G string) labelled in bold.

Figure 21. Graph of pitch and duration in the bass line for two choruses of “Since We Met”.

The first bass note of the chorus is 3

1

/

2

beats long and its pitch is F1. Consequently, it appears

on the graph as a long block that is midway between E0 and G2. The ascending and

descending movement of the first motifs is evident in the up and down movement of the

blocks, and the passages of longer and shorter notes are evident in the groups of longer and

shorter blocks. The melodic phrase from Figure 13 is visible on the graph as a steeply

ascending cluster of blocks at bar 20. The differences between the two choruses and the

variety inherent in the bass line is clearly visible in the variety of shapes made by the bass line

on this graph. There is a visible descent to bar 28 and to the corresponding bar in the second

chorus, bar 68. There is also an obvious similarity between the more static last four bars of

30

each chorus. However, the graph generally confirms that contrast and variety are the principal

characteristics of the bass line.

As mentioned earlier, some bass lines support the solo by providing contrast to the solo

line. Charlie Haden is one player who often anchors high pitched solo lines with low notes,

and fast flowing solo lines with long sustained notes. The graph at Figure 22 shows the pitch

and duration relationships between Gomez’s bass line and Evans’ solo line for the first chorus.

The graph is similar in construction to the one at Figure 21, but in this one the upper half of

each part, from D3 to C6, contains a graphical representation of the piano solo line. The lower

half, from E0 to E

b

3, contains the bass. Reading from left to right across the top half of the

first graph it is easy to recognise the piano’s descending first phrase, the consequent ascending

phrase, the descending third phrase and then the fourth ascending chromatic phrase which

appears as a straight line in bars seven and eight. The logically developing phrases of the

piano solo are visually apparent as the graph unfolds over the subsequent bars. The beautiful

wave shapes generated by the piano solo on this graph reflect the flowing lines of sound. As

can be seen from the graph there are no obvious visible relationships between the bass and

solo lines. The longer blocks in the bass section of the graph, representing longer duration

notes, occur independently of the flow of the piano solo. The bass line has its own up and

down pitch movement that is independent of the piano’s. Any correlation between the piano

and bass, such as the inverse pitch relationship that appears in bars four to seven and again in

bars 25-30, is contradicted elsewhere in the chorus.

31

Figure 22. Graph of pitch and duration in the piano solo line and bass line for the first chorus

of “Since We Met”.

The main characteristics of Gomez’s bass line are variety, fragmentation and

independence. It is largely a two-feel constructed with short motifs in the place of the more

traditional single notes. There is prodigious variety in the placement of these motifs relative to

the downbeat. Slurs and ghosted notes are mixed into the bass line which adds to the rhythmic

variety. The full range of the double bass is utilised, including the upper register which many

bass players reserve for their solos. These forays into the bass’s upper register occur

independently of the pitch of the piano solo. The bass line remains rhythmically independent

from the piano solo. Moments of space and simplicity in the piano solo are not necessarily

filled with more bass notes. Rhythmically dense parts of the solo are sometimes accompanied

by an equally dense bass line.

32

Analysis of “Time Remembered”

There are similarities between the arrangements of “Since We Met” and “Time

Remembered”. Both tunes are Evans compositions, and on both tracks the piano plays the

melody chorus alone and rubato before the bass and drums join. Both tunes are in 4/4 time but

“Time Remembered” is slower at 144 beats per minute and the chorus is shorter at 26 bars

long. It is an exploration of modal harmony, with all the chords being either major 7th with an

associated lydian mode, or minor 7th with a dorian mode (Danko 134). The piano solo is three

choruses long. The drums are more varied than on “Since We Met,” starting with brushes

implying a half tempo feel, and moving to sticks for the third chorus. This third chorus briefly

reaches a driving swing feel with walking bass line before finishing with an even eighth-notes

feel. Despite the differences between the compositions and the drum accompaniment the bass

lines in both performances share many similarities.

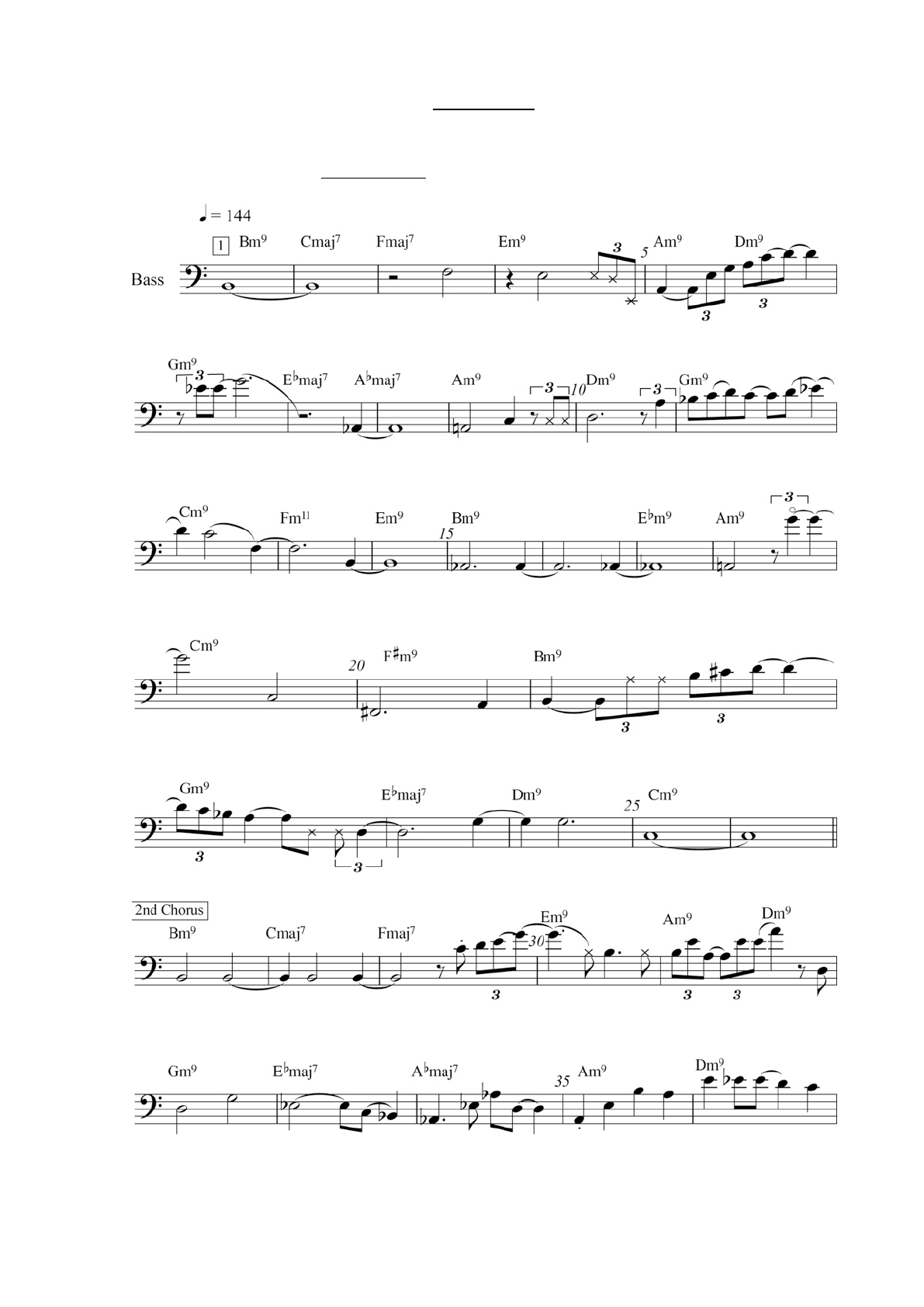

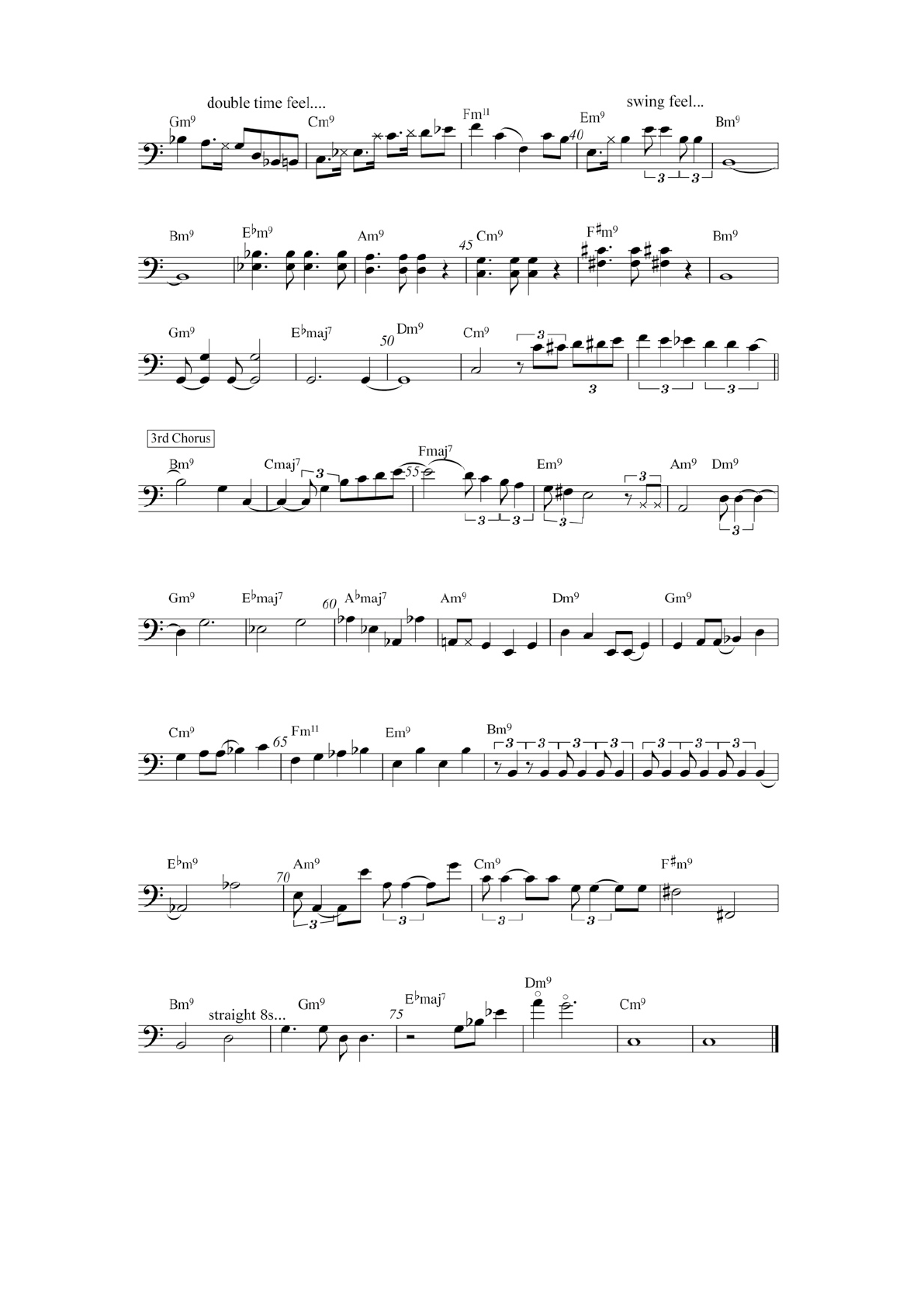

On “Time Remembered” the bass line incorporates great variety in pitch and rhythmic

density as can be readily seen in the graphical representation at Appendix 5. The line moves

constantly across the range of the double bass and alternates between flurries of short notes

and long sustained notes, as it does in “Since We Met”. The choruses have been aligned in the

graph so that the differences and similarities between each chorus are readily apparent. The

first two choruses begin with one pitch sustained across two bars. All three choruses sustain a

single pitch through bars 15 and 16, and the last two bars in the first and third chorus also

have only a single note. Apart from these similarities the choruses are varied within

themselves and different to each other.

Like the bass line in “Since We Met,” this bass line is for the most part an irregular two-

feel. As can be seen in the transcription at Appendix 4, the bass mostly plays the root note of

the chord on the downbeat, and alternates periods of simple clarity with periods of metric and

harmonic retardation and anticipation. A variety of short motifs are often used in the place of a

single note. The bass line is rich with slurs and ghost notes which add both timbral and

rhythmic interest. The ideas in the bass line remain undeveloped and fragmentary which

allows the listener’s attention to focus on the piano solo at it develops.

33

The range of contrasts within the bass line is even greater than on “Since We Met”. The

first note is a tonic B on the down beat, a consonant and unambiguous choice. It is allowed to

sustain through the entire next bar, becoming the major seventh of the C major chord, a

dissonant choice of bass note. The bass’s second note for the piece doesn’t occur until the

third beat of the third bar, and it is a tonic E. This rhythmic space, with only two notes in three

bars, is contrasted in the following few bars. The downbeat the fifth bar is preceded by three

ghosted eighth-note triplets. The second downbeat of that bar is delayed by two eighth-note

triplets which are part of a five-note motif. The next downbeat, in bar six, is delayed by a

whole beat and a long slur occupies the rest of that bar. The E

b

chord in bar seven is not

played by the bass at all, and the only bass note in that bar is an A

b

on beat four which

anticipates the next downbeat by a full beat. Three successive downbeats in bars nine and ten

are contrasted with a slurred phrase in bars eleven and twelve that retards and then anticipates

the harmonic movement.

The most unusual and dissonant notes in the three choruses of bass line occur in bars

fifteen and sixteen. The two low A

b

notes are a surprising choice for the B minor tonality of

the tune at that point. Evans’ chord voicing is recontextualised by these strong bass notes

which change it from a B minor9 to a dark sounding Ab minor

11b5b9

chord. It is particularly

dissonant in bar 15 because Gomez plays the first A

b

a little sharp, correcting the pitch by the

next A

b

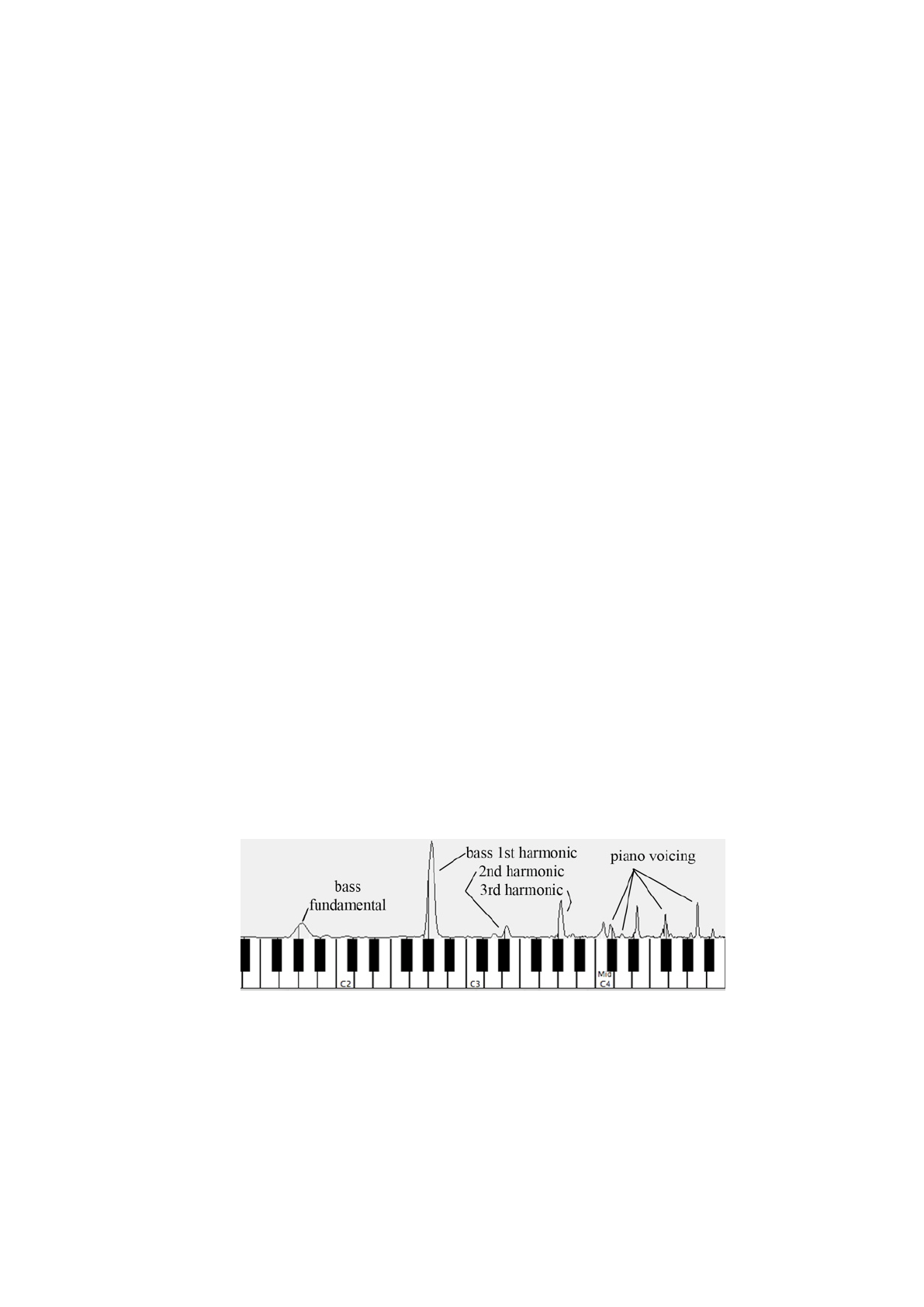

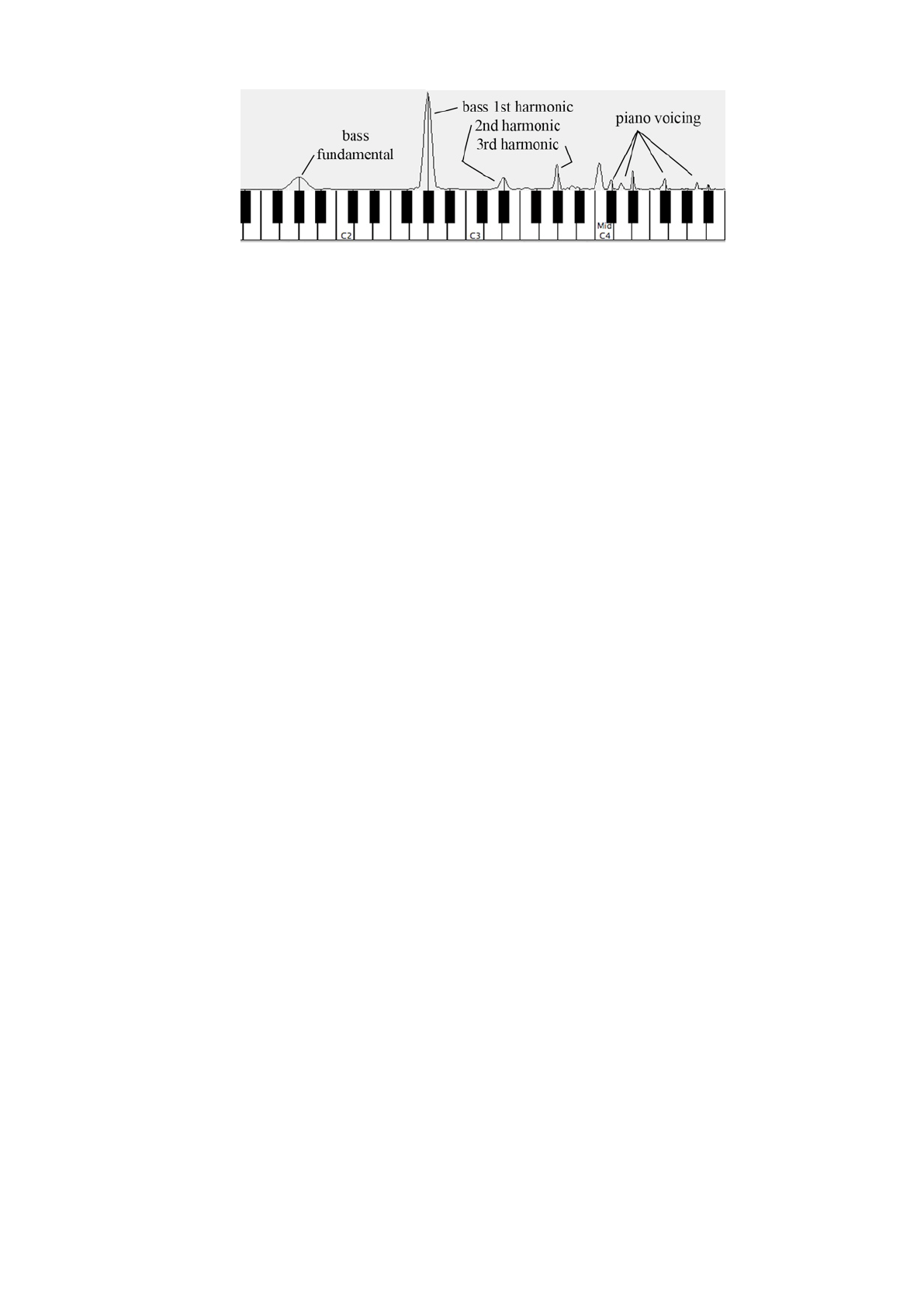

on the fourth beat. Figures 23 and 24 display the sound waves from bars 15 and 16

and show the effect that the two slightly different pitches have on the piano voicing.

Figure 23. Bar 15 in “Time Remembered”. A bass note that is sharp.

34

Figure 24. Bar 16 in “Time Remembered”. A bass note in tune.

In Figure 23 the fundamental of the bass’s Ab1 note is displaced to the right, showing that the

note is sharp. The harmonics of this note are consequently sharp too. The first, second and

third harmonics are labelled. C4 and E

b

4 are the fourth and fifth harmonics of the A

b

1, and

surround the two lower notes of the piano’s chord voicing. Because they are sharp they

interfere with the wave shapes of the piano notes distorting their visual appearance on the

graph. This is interpreted by the ear as a dissonant sound. When Gomez corrects the pitch,

shown in Figure 24, the wave forms are much clearer, and that is reflected aurally as a

decrease in dissonance. The initial A

b

in bar fifteen stands out more because it is out of tune

than because it is an inherently dissonant note choice. I have spent the time to examine it here

not because playing out of tune is a feature of Gomez’s bass lines, but because it is unusual to

hear such dissonance from him. His virtuosic and fragmentary bass lines only work so

seamlessly with the piano because they are so accurately in tune and in time.

A melodic bass line is used to connect the two chords in bars 21-22. The downbeat to bar

21 is a root note of the B minor chord. The bass line ascends the Dorian scale from B to the

minor third, D, which is held over the barline before descending the G Dorian scale. These

two bars are also another example of alternation between stabilising and destabilising. In

contrast with the stabilising root note on the downbeat of bar 21, there is no root note or

downbeat played in bar 22. The bass line avoids downbeats and root notes altogether until

settling the music with a root note downbeat to bar 25, which is held for two full bars.

The bass line generally follows the same principals as in “Since We Met” of alternation at

varying rates between stabilising and destabilising, simple and complex, rhythmically dense

and sparse. In “Time Remembered” an even broader range of timbral devices are used.

Harmonics, made by lightly touching the string with the left hand and plucking firmly with

35

the right, ring out strongly in bars 18 and 74. In both cases these high notes are juxtaposed

with low notes. Double stops occur in bars 43-46. In bars 43, 45 and 46 Gomez plays the root

and fifth of each chord in an insistent dotted quarter-note and eighth-note rhythm. Bar 44 he

uses the same rhythm but substitutes a D bass beneath the A minor chord, allowing the

double-stopped fifths to descend stepwise from bar 43 to 45. The rhythmic and timbral

density of these bars is situated between bars 42 and 46 which each contain only a single note.

Gomez plays two passages of walking bass line, in bars 35-40 and bars 60-66. In the middle

of the first walking passage he follows the piano solo into a double time feel briefly in bars

37-38. This is a rare example of an obvious ‘interaction’ between the piano and bass. The

walking line is brought to an abrupt halt in bar 40 with two destabilising rhythmic motifs on

beats three and four followed by a downbeat to bar 41 which is sustained for two full bars.

Figure 25. Bar 40 in “Time Remembered”. Two motifs that interrupts the rhythmic flow.

The two-note motifs in Figure 25 arrive at the second eighth-note triplet after the beat, and

their effect is to disrupt the rhythmic flow, almost like applying a brake to the forward

momentum. The longer passage of walking bass line in bars 60-66 is brought to an abrupt end

by a longer section employing the same motif, as shown in Figure 26. The first two iterations

of the motif are varied, with the first note of each motif omitted. These are followed by six

repeats of the two note motif. The piano solo line has been included in Figure 26 because it

provides another illustration of the piano and bass lines as parallel streams. In this example

the repetition of the bass motif and the three repetitions of the piano solo motif perfectly

enhance each other, creating an effective two bar interlude before the rest of the solo.

Figure 26. Bars 67-68 in “Time Remembered”. An extended example of an interruptive

motif.

36

The repeated motifs are contrasted with two simple half-note downbeats in bar 69.

However the piano keeps developing its motif through that bar, altering the pitches to match

the changing harmony but keeping the rhythm the same and repeating it on every third beat.

The bass complements this in the following two bars with a motif developed from its previous

two-note motif. Like that one, the new motif finishes on the second eighth-note triplet after

the beat, but this one is three notes long and recurs every two beats. Consequently, it doesn’t

coincide rhythmically with the piano’s motif but enhances it without interfering with its

development.

Figure 27. Bars 69-71 in “Time Remembered”. Development of a rhythmic motif.

The chords for the last four bars of each chorus are E

b

major7, D minor7 and two bars of

C minor. The bass doesn’t play a root note for the E

b

major7 or D minor7 in any of the three

choruses. Gomez ignores the E

b

totally in the first two chorus and plays a G through the

D minor7 bars, creating a G7sus4 sound which resolves to the C minor to conclude each

chorus. In the third chorus he plays a melodic phrase which includes a high E

b

without

emphasising it as a root note, and again plays a G through the D minor bar. Gomez’s

consistency in changing the written chord structure in this way led me to compare this

recording with others by the same trio of the same tune. In recordings of “Time Remembered”

on You’re Gonna Hear From Me made five years earlier, and on Live in Ottawa, recorded

seven months after Since We Met, Gomez plays the E

b

to D to C bass notes during the last

four bars of every chorus. A comparison between the performances on Since We Met and Live

In Ottawa is particularly revealing. The melody statements by Evans are almost identical. The

piano solos are the same length at three choruses. The drums move from brushes to sticks at

the same point, the start of the third chorus. The bass accompaniment is as varied and

fragmented, but from the second note all the particulars are different. The places in the chorus

37

where Gomez chooses to find alternatives to the root note are all different to those in the

version studied in this essay. He doesn’t use an A

b

bass note under any B minor chords. He

plays a walking line for much of the third chorus, and when he breaks away from it he does so

with a series of long metrically displaced slurs, not with the motif discussed in the previous

paragraph. After comparing the two versions it is easy to understand Evans’ assertion that in

all their years of playing together Gomez was “resourceful in not allowing the music to

become bland” (Pettinger 216).

Eddie Gomez’s bass lines in the Bill Evans Trio are a vital and unique contribution to the

group’s sound. Evans’ solos are so strong and clear that they don’t require a bass line which

simply keeps the time and outlines the harmonic progression. Evans “was economical in his

ideas and utilized melodic and rhythmic development as an integral part of his

improvisations” (Widenhoffer 73). In contrast, Gomez’s ideas “come pouring out” (Pettinger

177) in apparently random order. The lack of development within the bass line is a positive

attribute that allows the focus to remain on the solo. Single notes, short motifs and sometimes

walking lines alternately obscure or clarify the harmonic progression of the chorus while

frequently anticipating or delaying the meter. A variety of articulations and use of the full

range of the double bass add timbral interest to the music. Gomez demonstrates a keen

awareness of the pianist’s evolving ideas, but consistently avoids direct interaction with the

solo lines. The bass line is not interactive or conversational with the piano, but a richly varied

parallel stream that adds depth and vitality to our listening experience.

38

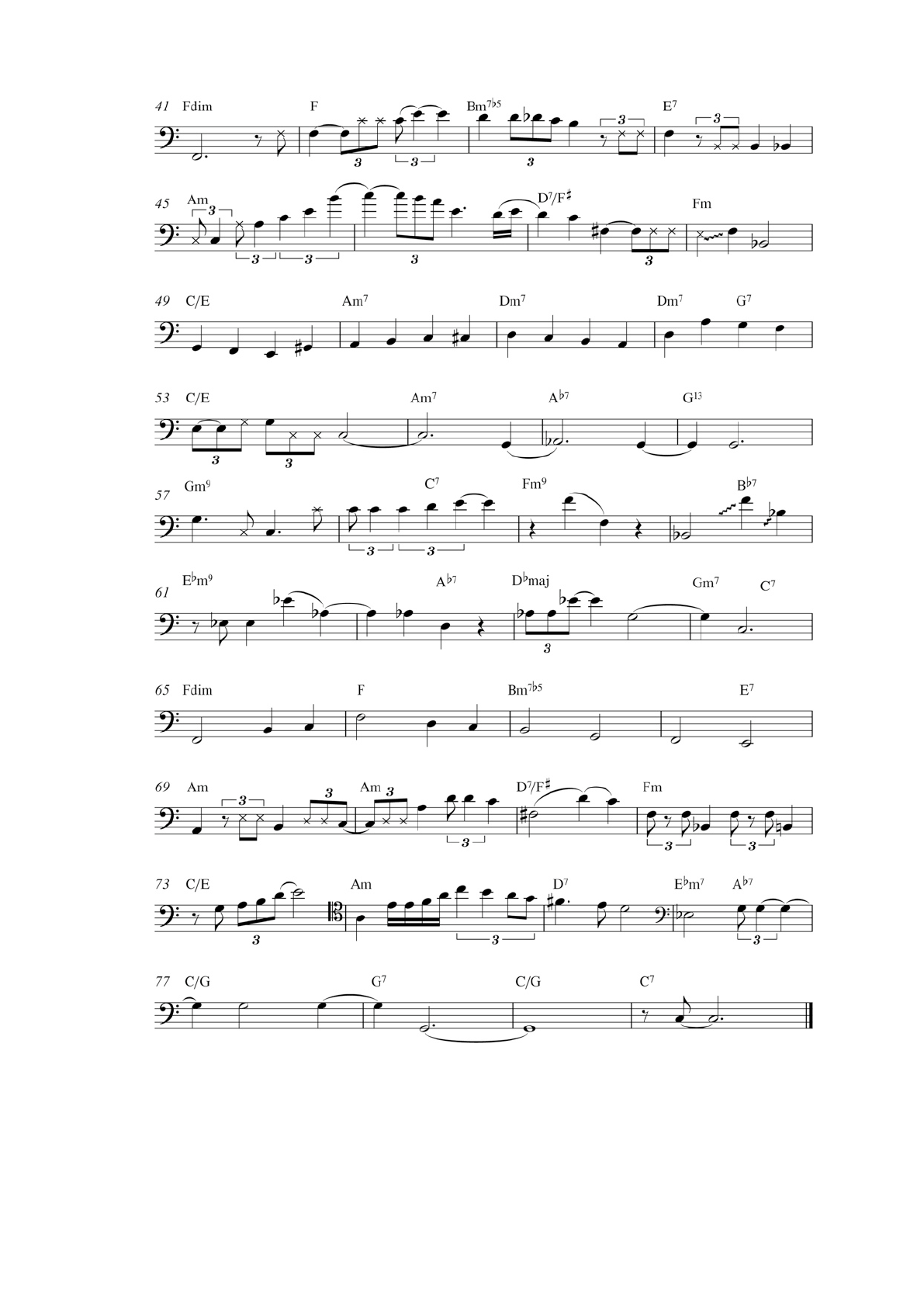

Appendix 1

Bass line during piano solo on “Since We Met,” starting at 2 minutes 40 seconds.

Transcribed from Bill Evans Trio. Since We Met. Fantasy OJCCD-622-2, 1974.

39

40

Appendix 2

Paradigmatic chart of first chorus of bass line on “Since We Met”.

41

42

Appendix 3

Piano solo and bass line on “Since We Met”.

Transcribed from Bill Evans Trio. Since We Met. Fantasy OJCCD-622-2, 1974.

43

44

45

46

47

Appendix 4

Bass line during piano solo on “Time Remembered”, starting at 44 seconds.

Transcribed from Since We Met. Bill Evans Trio. Fantasy OJCCD-622-2, 1974.

48

49

Appendix 5

Graphical representation of bass line during piano solo on “Time Remembered”.

50

List of Works Cited

Agawu, V. Kofi. Playing With Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation Of Classic Music. Princeton

University Press, 1991.

Arom, Simha. African Polyphony and Polyrhythm: Musical Structure and Methodology.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Berardinelli, Paula. Bill Evans: His Contributions as a Jazz Pianist and an Analysis of His

Musical Style. Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1992. In ProQuest Digital

Dissertations. available from www.proquest.com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/

(publication number AAT 9222946; accessed 27 March, 2007)

Bill Evans Trio. Since We Met. Fantasy OJCCD-622-2, 1974.

Bill Evans Trio. Live in Ottawa. Gambit Spain. 1974.

Bill Evans Trio. You’re Gonna Hear From Me. Milestone MCD 9164-2

Gilbert, Mark. “Eddie Gomez Talks to Mark Gilbert.” Jazz Journal International, 1993/3.

The Great Jazz Trio. Standards Collection. Denon Records, 1987.

Johnston, Richard. “Eddie Gomez”. Bass Player, Feb 1996.

Keane, Helen. The Complete Fantasy Sessions.

booklet accompanying The Complete Fantasy Recordings, Fantasy 9FCD-1012-2

Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz Interview, The Complete Fantasy Recordings, Disc 9.

Fantasy 9FCD-1012-2

51

Monson, Ingrid. “Jazz Improvisation.” The Cambridge Companion To Jazz, edited by Mervyn

Cooke and David Horn. 114-132. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Murray, Edward. "Evans, Bill (i)." Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 10 Sep. 2008

www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/09099>.

Owens, Thomas. "Bop." The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, 2nd ed. Ed. Barry Kernfeld.

Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. 5 Sep. 2008 www.oxfordmusiconline.com/

subscriber/article/grove/music/J052900>.

Pettinger, Peter. Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings. London: Yale University Press, 1998.

Pressing, Jeff. “Free Jazz and the avant-garde.” The Cambridge Companion To Jazz, edited by

Mervyn Cooke and David Horn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

202-216.

Shadwick, Keith. Bill Evans. Everything Happens To Me - A Musical Biography. London:

Backbeat Books, 2002.

Smith, Gregory Eugene. Homer, Gregory, and Bill Evans? The Theory of Formulaic

Composition in the Context of Jazz Piano Improvisation. Ph.D. diss., Harvard

University, 1983. ProQuest Digital Dissertations. available from

www.proquest.com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/ (publication number AAT 8322445;

accessed 27 March, 2007).

Tirro, Frank. Jazz: A History, 2

nd

ed. Yale University, New York: W.W.Norton & Company,

1993.

52

Widenhofer, Stephen Barth. Bill Evans: An analytical study of his improvisational style

through selected transcriptions. D.A. diss., University of Northern Colorado, 1988.

ProQuest Digital Dissertations available from

www.proquest.com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/ (publication number AAT 8909372;

accessed 27 March 2007)

Williams, Martin. Homage To Bill Evans. booklet accompanying The Complete Riverside

Recordings, Riverside RCD-018-2.

Wilner, Donald L. Interactive Jazz Improvisation in the Bill Evans Trio (1959-61): A Stylistic

Study For Advanced Double Bass Performance. Doctoral essay. University of Miami,

1995. In ProQuest Digital Dissertations available from

www.proquest.com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/ (UMI Number: 9611608; accessed 27

March, 2007)

53