This project was supported, in whole or in part, by cooperative agreement number 2019-CK-WX-K014

awarded to the National Police Foundation by the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community

Oriented Policing Services. The opinions contained herein are those of the author(s) or contributor(s) and

do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Refer

-

-

ences to specific individuals, agencies, companies, products, or services should not be considered an

endorsement by the author(s), the contributor(s), or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the refer

-

-

ences are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues.

The internet references cited in this publication were valid as of the date of publication. Given that URLs

and websites are in constant flux, neither the author(s), the contributor(s), nor the COPS Office can

vouch for their current validity.

This resource was developed under a federal award and may be subject to copyright. The U.S. Depart

-

-

ment of Justice reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable license to reproduce, publish, or

otherwise use and to authorize others to use this resource for Federal Government purposes. This

resource may be freely distributed and used for noncommercial and educational purposes only.

Recommended citation:

National Police Foundation. 2021.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database: 2021 Analysis Update

.

Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Published 2021

Contents

Letter from the Acting Director of the COPS Ofce ......................................................

..............................................

.............................................................................................

...........................................................................................

......................................................................................

....................................................................................

.................................................................................

....................................................................................

......................................................................................

..................................................................

................................................................................

iv

Letter from the President of the National Police Foundation v

Introduction 1

Data Analysis 3

Basic information 3

School information 3

Suspect information 13

Event information 20

Lessons Learned 29

About the National Police Foundation 32

About the COPS Ofce 33

A Preliminary Report on the Police

Foundation’s Averted School Violence Database

iii

Letter from the

Acting Director of

the COPS Ofce

Colleagues:

The COPS Office and the National Institute of Justice provided funding to the National Police

Foundation (NPF) to develop the Averted School Violence (ASV) database, which collects

information on school attacks—completed and averted—with the goal of mitigating and ulti-

mately preventing future injuries in educational institutions. In 2019, the COPS Office and the

NPF published a pair of reports examining data from the database: one a comparison of averted

attacks on schools with a similar number of attacks that were carried out, and the other an

analysis only of averted attacks.

Since the publication of those reports, the ASV database has continued to grow and now

contains more than three times as many cases of averted incidents of school violence as it did in

2019. This report compares the 120 new cases to the 51 cases in the original sample in an

ongoing effort to provide as much information as possible to schools, law enforcement, and

communities to enhance school security and protect our children.

Our schools must be safe and supportive learning environments. On behalf of the COPS Office,

we thank everyone who has submitted reports to the ASV database and who works every day

with students of all ages to make a difference in their communities. I urge everyone to continue to

use the ASV database to report incidents of school violence, both completed and averted, in the

hope that school shootings will soon be a thing of the past. I also thank the staff and leadership

of the National Police Foundation for their work on the ASV database and these publications on

averted school violence.

Sincerely,

Robert E. Chapman

Acting Director

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

iv

Letter from the

President of the National

Police Foundation

Dear colleagues,

Since the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, targeted school attacks—parti-

cularly those involving firearms—have increased in frequency and lethality, posing a vex-

ing challenge for policy makers, law enforcement officials, school administrators, mental and phys-

ical health practitioners, parents, students, and the communities in which the attacks

are perpetrated.

With funding support from the COPS Office, the National Police Foundation, in collaboration with

school safety subject matter experts and numerous national and state-level organizations, devel-

oped the Averted School Violence (ASV) database as a free resource to serve practitioners and

organizations involved in school safety. The ASV database is an online library of completed and

averted school violence narratives from across the country, containing incident-level information

and lessons learned.

The rationale behind developing the ASV database is that while there are numerous studies of

completed school attacks, fewer studies have been done on averted attacks, leaving a gap in

knowledge. Furthermore, practitioners suggest and open source research supports that averted

attacks happen with greater frequency than completed attacks and contain invaluable insights into

the strengths or potential weaknesses of school safety systems or practices, which if recognized

and addressed early can prevent or mitigate future attacks.

There are now more than 230 cases in the ASV database: more than 170 averted incidents and

more than 60 carried-out attacks. This report reflects a comprehensive analysis of 170 averted

attacks in the database. The vast majority of averted attacks occurred in suburban public high

schools with school populations ranging from 500–1,000 students. In the vast majority of attacks,

one suspect—typically a current student—planned to carry out the attack. A significant life chang-

ing or traumatic event occurred prior to the planned attack. Reasons for planning the attack were

most often tied to hating people, revenge seeking, and bullying. In almost all of the cases, peers

v

discovered the planned attack and reported it to some combination of parents, school officials,

and law enforcement. Firearms, specifically handguns, were the primary weapon to be used in

the

averted attacks.

The report concludes that positive school environments that provide violence prevention programs,

foster trust among students and staff, provide support to all students, and encourage early inter-

vention for students with behavioral challenges are key to averting school attacks. In many cases,

targeted school attacks can be prevented by persons who recognize the indicators of violence and

report their concerns to school and law enforcement officials directly or though anonymous report-

ing systems.

Multidisciplinary behavioral threat assessment teams are the foundation of early identifica-

tion and intervention. In addition, carefully selected, well trained, and properly equipped

school resource officers provide an important resource in the prevention and response to

school attacks.

In the end, efforts to prevent school attacks must be a “whole of community” effort in which school

administrators, teachers, and staff; school-based and community mental health providers; law

enforcement; and parents and students see something, say something, and do something to iden-

tify and extend resources to students in need of our help before they hurt themselves or others.

The National Police Foundation would like to thank the COPS Office for its support of the national

Averted School Violence database, a project that has undoubtedly saved the lives of our children,

teachers, staff, and school administrators.

Cordially,

Jim Burch

President

National Police Foundation

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

vi

Introduction

ALTHOUGH MASS VIOLENCE ATTACKS AT SCHOOLS ARE STATISTICALLY RARE,

their impact far exceeds their occurrences in the communities in which they occur and

across the nation. The U.S. Departments of Justice, Education, and Homeland Security

have dedicated considerable resources to enhancing school security and preventing these

attacks, as well as to studying and understanding mass casualty attacks and the perpetra-

tors who carry them out. There has also been a growing body of literature on completed

school-based mass violence attacks from multidisciplinary perspectives including child

development and psychology, sociology, and criminology. This combined literature has con-

tributed much to the overall understanding of perpetrators of school-based violence, the

types of schools at which attacks are more likely to occur, the social conditions surrounding

school attacks, and other variables that contribute to completed school attacks.

The number of completed attacks is far outnumbered by incidents in which an attack was

planned or was almost carried out but was averted thanks to the actions of persons in the

school or in the community. Individually, these incidents may be dismissed or only have a

short-term localized impact because they did not achieve their goal, because they did not

meet the requirements for a school to document the incident, or because of underreporting

in the media. While there have been a handful of studies conducted to identify common

ways in which planned attacks were discovered, who intervened to prevent a likely attack,

and the extent to which students reported potential planned attacks to authorities, there

remains a considerable gap in the school violence literature surrounding averted attacks

and what lessons can be learned from them regarding school safety and security.

To address this need, in 2014, two U.S. Department of Justice offices—the Office of Com-

munity Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office) and the National Institute of Justice (NIJ)—

provided funding to the National Police Foundation (NPF) to develop and maintain an

1

Averted School Violence (ASV) database.

1

The ASV

database collects, analyzes, and publishes averted

and completed acts of school violence that have

occurred since the April 20, 1999 attack on Colum-

bine High School in Littleton, Colorado. The data are

drawn from open source media articles as well as

from law enforcement, school officials, and others

entering reports directly into the ASV database.

The ASV database serves as a resource to law

enforcement, schools, mental health professionals,

and others involved in preventing school violence by

sharing lessons learned regarding the way planned

attacks were identified and prevented. In 2019, the

NPF conducted a preliminary analysis of 51 cases of

averted school violence in the ASV database to iden-

tify basic information about the schools involved, the

perpetrators and suspects, the weapons, and the

plots and incidents.

2

Also in 2019, the NPF con-

ducted a comparison of 51 averted and 51 com-

pleted school attacks from the ASV database to

identify important similarities and differences between

the types of incidents.

3

There are now more than 230 cases in the ASV data-

base: more than 170 averted attacks and more than

60 completed attacks. With more than three times

the number of averted cases as there were when the

2019 preliminary analysis was conducted, this report

leverages the data from the additional cases to con-

duct similar analyses; compare the findings from the

new cases to the initial 51 averted cases; and provide

overarching lessons learned and recommendations

that can be leveraged by school administrators, law

enforcement, and communities to enhance school

safety and security.

1. “Our Mission,” Averted School Violence, accessed February 11, 2021, https://www.avertedschoolviolence.org/.

2. Jeffrey A. Daniels,

A Preliminary Report on the Police Foundation’s Averted School Violence Database

(Washington, DC:

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2019), https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/ric.php?page=detail&id=COPS-W0871.

3. Peter Langman and Frank Straub,

A Comparison of Averted and Completed School Attacks from the Police Foundation’s

Averted School Violence Database

(Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2019),

https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/ric.php?page=detail&id=COPS-W0870.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

2

Data Analysis

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICAL ANALYSES WERE CONDUCTED ON THE 120 CASES

entered into the ASV database between February 2018 and August 2020. Analyses were

conducted using the same information as in the 2019 preliminary analysis: basic information

about each case, followed by descriptions of the schools in which the attacks were averted,

how the plots were discovered, what actions were taken to avert the potential incident, and

what weapons the perpetrators planned to use.

Basic information

The information used to develop 112 (93.3 percent) of the 120 additional reports on averted

incidents analyzed for this publication was identified by NPF staff and project subject matter

experts from open sources, school websites, and court records. The remaining eight reports

(6.7 percent) were entered by a law enforcement officer or school administrator directly

involved in the averted incident.

School information

As shown in figure 1 on page 4, averted school violence incidents analyzed for this publica-

tion occurred in 39 states throughout the United States. (The 51 incidents in the initial data-

set occurred in 27 states.) As is to be expected with a larger sample, there were more

states in the present dataset (22) than in the initial dataset (14) with more than one

averted incident. In the present dataset, California had 18 averted incidents, Florida 12,

New York 8, Pennsylvania 8, Michigan 5, North Carolina 5, Georgia 4, Kentucky 4, Ohio 4,

Oklahoma 4, Utah 4, Indiana 3, Maryland 3, Missouri 3, Vermont 3, Colorado 2, Illinois 2,

Nebraska 2, New Jersey 2, Oregon 2, Washington 2, and Wisconsin 2. Arizona, Arkansas,

Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Iowa, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Montana,

Nevada, New Mexico, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wyoming each had

one averted incident. Figure 1.1 on page 4 shows the distribution of incidents in the two

sample sets combined.

3

Figure 1. Distribution of new sample of ASV incidents (n=119)*

* There was one submission in which the state was unknown.

Figure 1.1. Distribution of combined samples of ASV incidents (n=170)

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

4

As shown in figure 2, of the 120 new averted school

incidents, 105 (87.5 percent) occurred in public

schools, eight (6.7 percent) in private schools, three

(2.5 percent) in charter schools, and three (2.5 per-

cent) in faith-based schools.

4

This is similar to the

finding in the preliminary analysis that the overwhelm-

ing majority (94.1 percent) of averted school attacks

occurred in public schools. Together, figure 2.1 shows

the types of schools where violent incidents were

most commonly averted.

Number of incidents

New sample

Figure 2. Types of schools where violent incidents were averted in both samples of ASV incidents

Public school

Private school

Faith-based

school

Charter school

Other afliation

105

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 95 100 105

48

0

0

0

2

1

8

3

3

105

Preliminary analysis

Figure 2.1. Types of schools where violent incidents were averted in combined samples of ASV incidents (n=170)

Public school

Private school

Faith-based

school

3

Charter school

Other afliation

8

153

5

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160

1

Number of incidents

4. There was one submission in which the school type was not listed.

Data Analysis 5

High school

Middle school/

Junior high school

College/University

Elementary

school

Preliminary analysis New sample

Furthermore (see figure 3), as in the preliminary anal-

ysis (see figure 3), attacks were most frequently

averted at high schools (63.3 percent, n=76) in the

new sample. However, whereas the preliminary anal-

ysis had only 11.8 percent of averted incidents (n=6)

at college or university campuses, in the new sample

colleges and universities accounted for 19.2 percent

(n=23) of the averted incidents. Meanwhile, middle

schools and junior high schools accounted for 15.7

percent of the averted incidents (n=8) in the prelimi-

nary analysis but 15.0 percent (n=18) of the averted

incidents in the new sample. Elementary schools

were the intended target of averted incidents in 3.9

percent of incidents (n=2) in the preliminary analysis

and 1.7 percent of incidents (n=2) in the additional

sample.

5

Together, figure 3.1 shows education levels

of schools where violent incidents were most com-

monly averted.

Figure 3. Education level of schools where violent incidents were averted in both samples of ASV incidents

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85

Number of incidents

35

8

6

2

2

76

18

23

Figure 3.1. Education level of schools where violent incidents were averted

in combined samples of ASV incidents (n=170)

High school

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160

Number of incidents

111

26

29

4

Middle school/

Junior high school

College/University

Elementary

school

5. There was one submission where the education level was missing.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

6

Preliminary analysis New sample

cont’d on pg. 8

Number of students,

Kindergarten–

12th grade

500 or less

501–1,000

1,001–2,000

2,001 or more

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Number of schools

16

5

33

18

27

15

11

7

Figure 4 (which continues on page 8) presents the

numbers and percentages for the size of the student

body at the schools where the violent incidents were

averted. Similar to the preliminary analysis, a plurality

of incidents from the new sample (27.5 percent,

n=33) were averted at K–12 schools with student

bodies of between 501 and 1,000 students, and

there was only one averted incident (0.8 percent) at a

college or university with a student body of 1,000 or

fewer.

6

Together, figure 4.1 on page 9 shows the

combined size of the student body at schools where

violent incidents were most commonly averted.

Figure 4. Size of student body at schools where violent incidents were

averted in both samples of ASV incidents

6. There were nine K–12 submissions in which the size of the student body was unknown and one K–12 submission in which this

information was not entered.

Data Analysis 7

Preliminary analysis New sample

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Number of schools

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

5

5

8

0

0

0

2

Figure 4. Size of student body at schools where violent incidents were

averted in both samples of ASV incidents cont’d from pg. 7

Number of students,

Colleges/University

1,000 or less

1,001–5,000

5,001–10,000

10,001–20,000

20,001–30,000

30,001–40,000

Above 40,000

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

8

Figure 4.1. Size of student body at schools where violent incidents were

averted in combined samples of ASV incidents (n=161)

Number of students,

Kindergarten–

12th grade

500 or less

501–1,000

1,001–2,000

2,001 or more

Number of students,

Colleges/University

1,000 or less

1,001–5,000

5,001–10,000

10,001–20,000

20,001–30,000

30,001–40,000

Above 40,000

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Number of schools

21

51

42

18

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Number of schools

2

3

2

7

6

9

0

Data Analysis 9

Figure 5 presents the community population clas-

sifications of the schools that were involved in the

new sample of averted violent incidents. Suburban

schools were still the most common intended

targets, but at a much lower rate (40.0 percent,

n=48, down from 68.6 percent in the initial sample).

In addition, while the percentage of rural schools

involved in averted incidents (25.8 percent, n=31)

stayed approximately the same as in the preliminary

analysis (25.5 percent), the percentage of urban

schools increased from 5.9 percent in the initial

sample to 33.3 percent (n=40) in the new sample of

averted school violence reports.

7

Together, figure 5.1

shows the combined population classifications of

communities where violent incidents were most com-

monly averted.

Together, figures 2 through 5.1 suggest that the

model averted school violence incident from the 120

additional cases is similar to the model from the pre-

liminary analysis: a public high school, with a student

body between 501 and 2,000 students, in a subur-

ban community. However, these figures—especially

when added to figure 1—also continue to demon-

strate that threats and planned violent attacks can

occur in any state, in any community, and at any

grade level.

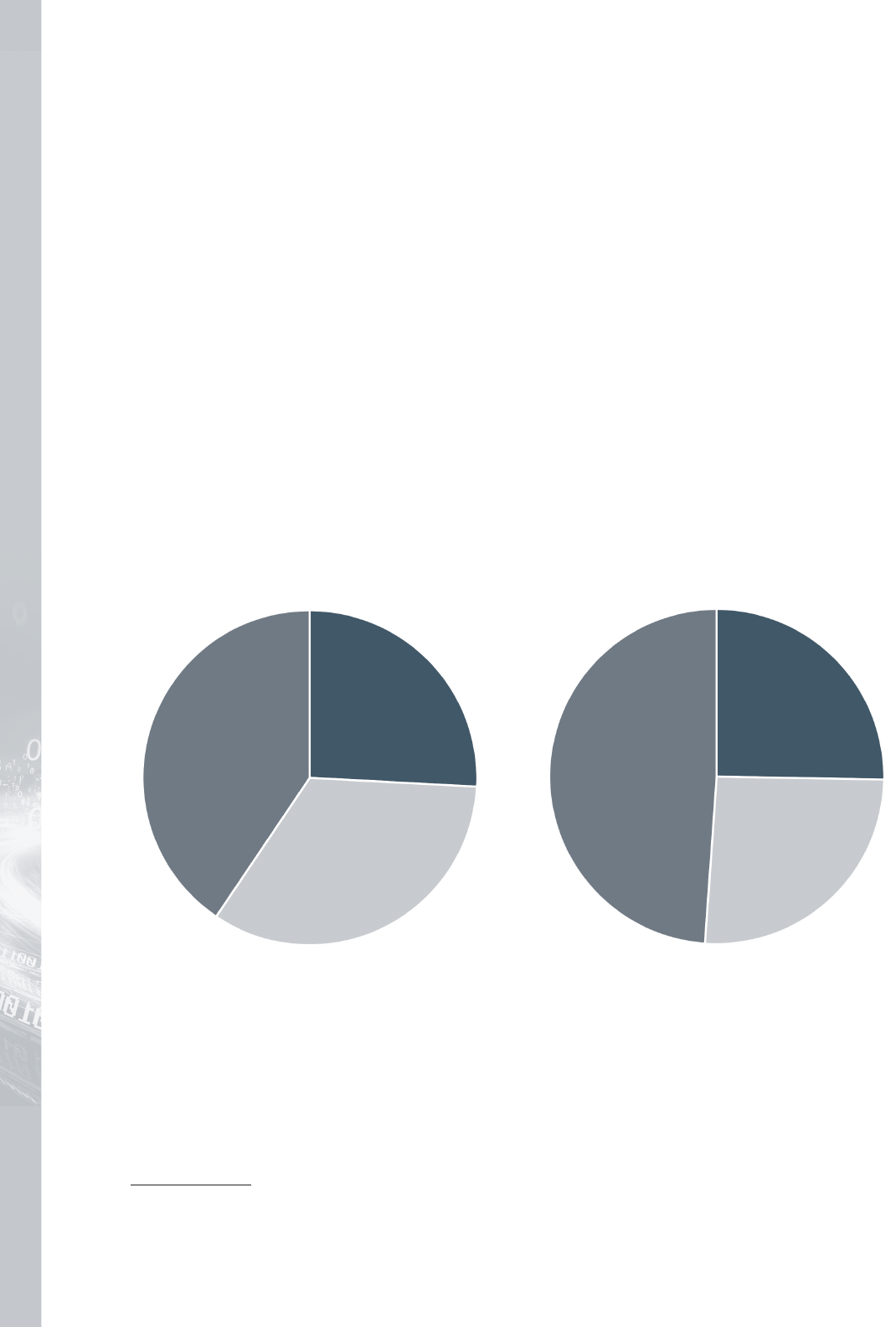

Figure 5. Population classication of communi-

ties where incidents of school violence were

averted in new sample of ASV incidents (n=119)

Rural

26.1%

Suburban

40.3%

Urban

33.6%

Figure 5.1. Population classication of commu-

nities where incidents of school violence were

averted in combined samples of ASV incidents

(n=170)

Urban

25.3%

Suburban

48.8%

Rural

25.9%

7. There was one submission where the population classification was missing.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

10

Counselors

The ASV case submission form asks about the pres-

ence of at least one counselor at the school. Most

schools did have at least one counselor at the time of

the averted incident. Of the 120 cases in the new

sample, 81.7 percent of the schools (n=98) had a

counselor at the time and it was unknown in 17.5

percent of cases (n=21). None of the cases indicated

that there were no school counselors at the time of

the averted incident.

8

Despite the overwhelming majority of schools having

at least one counselor during the time of the averted

incident, it is difficult to tell in many cases whether the

counselor(s) engaged with the suspect(s) in the inci-

dents. In only 9.2 percent (n=9) of the 120 averted

cases in the new sample was it noted that the coun-

selor(s) engaged with the suspect(s), while in 84.7

percent of cases (n=83) it was unknown. It was only

noted in 6.1 percent of the cases (n=6) that the school

did have at least one counselor but they did not

engage with the suspect(s).

Security systems

The ASV case submission form presents a number of

physical security measures and protocols that are

common at K–12 schools and college and university

campuses, and for each reported case there was no

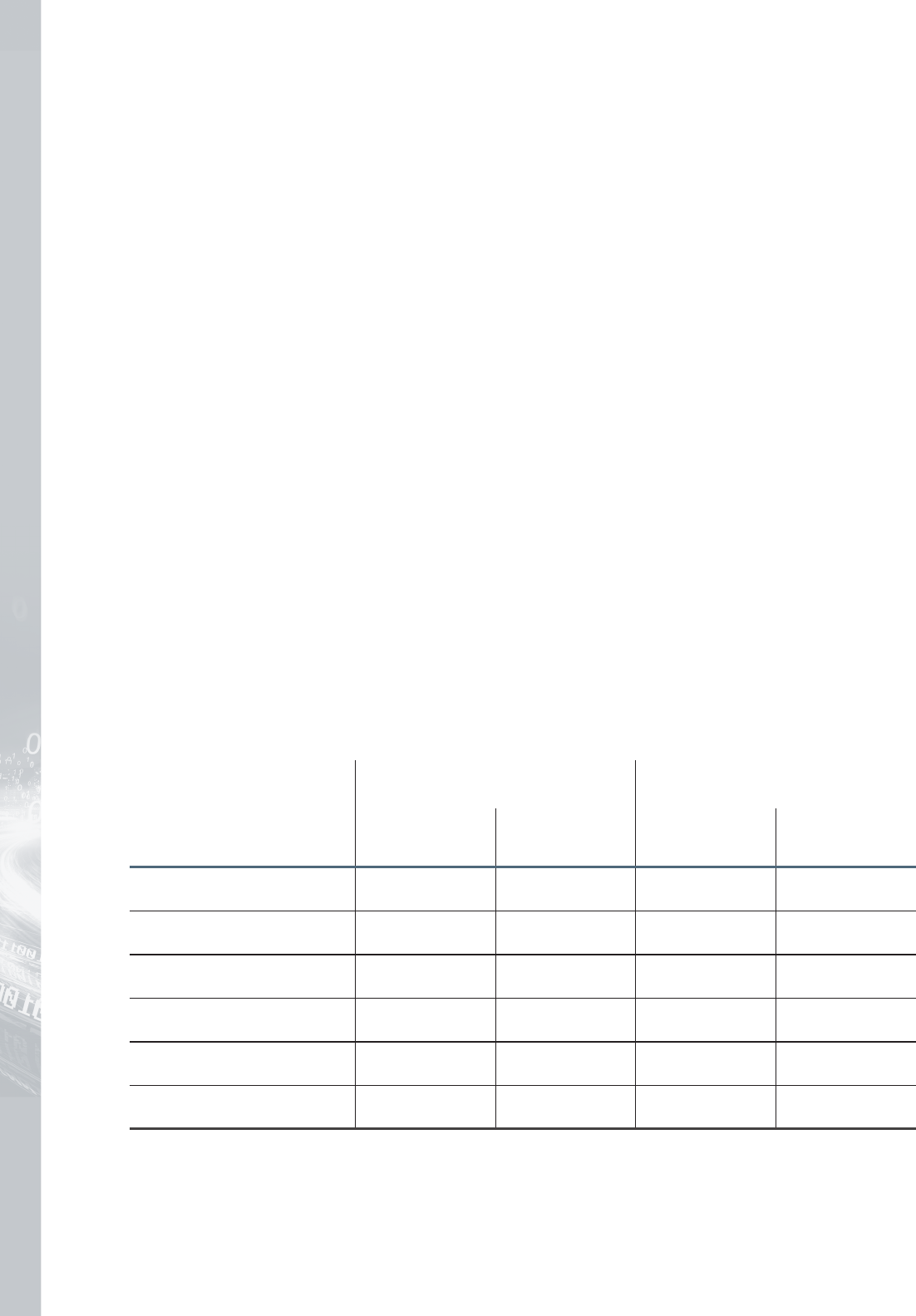

Table 1. Common security measures used by schools where potential attacks

were averted in both samples of ASV incidents

ASV schools where measure

was used (N)

ASV schools where measure

was used (%)

Security measure

Preliminary

analysis New sample

Preliminary

analysis New sample

Behavior threat assessment team 0 17 0.0 14.2

Blue Light security system 0 12 0.0 10.0

Controlled access to buildings during

school hours

9 29 17.6 24.2

Controlled access to grounds during

school hours

7 6 13.7 5.0

Locked entrance or exit doors 5 22 9.8 18.3

Locker checks 5 6 9.8 5.0

School police department 1 17 2.0 14.2

School staff monitoring hallways 6 8 11.8 6.7

Security cameras used to monitor the school 14 32 27.4 26.7

Security ofcers or police ofcers at/in school 30 55 58.8 45.8

Students required to go through

metal detectors

0 1 0.0 0.8

Teachers and staff required to wear badges/ID 2 9 3.9 7.5

Visitors must be escorted into building 1 3 2.0 2.5

Visitors required to sign in 8 15 15.7 12.5

Visitors required to wear badges/ID 7 13 13.7 10.8

Other 6 6 11.8 5.0

No security measures reported —* 39* —* 32.5*

* Among the schools included in the new sample, 39 did not appear to have any security measures in place. However, it is important

to note that the individuals reporting these cases may have been unable to obtain information on the schools’ security features through

open sources. Data are not available on the number of schools without security measures from the sample in the preliminary analysis.

8. There was one submission in which the indication of whether or not there was at least one counselor was missing.

Data Analysis 11

limit to the number of security measures that could

be selected. Whereas in the preliminary analysis more

than half of the schools involved had a security officer

or a police officer at the school as the primary secu-

rity measure, in the new sample there was no single

security measure that was in use by more than half of

the schools (however, security officers or police offi-

cers at the school were still the primary security mea-

sure). Interestingly, 5.0 percent of schools (n=6)

reported controlling access to school grounds during

school hours—less than in the preliminary analysis

(13.7 percent, n=7). Also, despite many security

experts continuing to recommend that students be

required to go through metal detectors, only one

school (0.8 percent) in the new sample —and none of

the schools in the preliminary analysis—had students

go through a metal detector.

When “Other” is selected, respondents are asked to

indicate what security measure(s) are not accounted

for in the provided checklist that were in place at the

school when the incident was averted. One person

noted that their school has a School Safety Commit-

tee that meets monthly to address safety issues con-

cerns, and one noted that their school has a

25-member Safety and Discipline Committee.

Another noted that not only teachers and staff but

also students are required to wear badges/ID. In

addition, one respondent noted that all students are

required to use clear backpacks, while another noted

that students are not allowed to carry backpacks at

all during the day and must store them in lockers.

One respondent noted that their school has a non-

sworn campus public safety agency and relies on the

local municipal police department for law enforce-

ment services.

Response training

The ASV case submission form also identifies five

response protocols or trainings that are increasingly

common at K–12 schools and college and university

campuses, and for each reported case there was no

limit to the number of protocols or trainings that could

be selected.

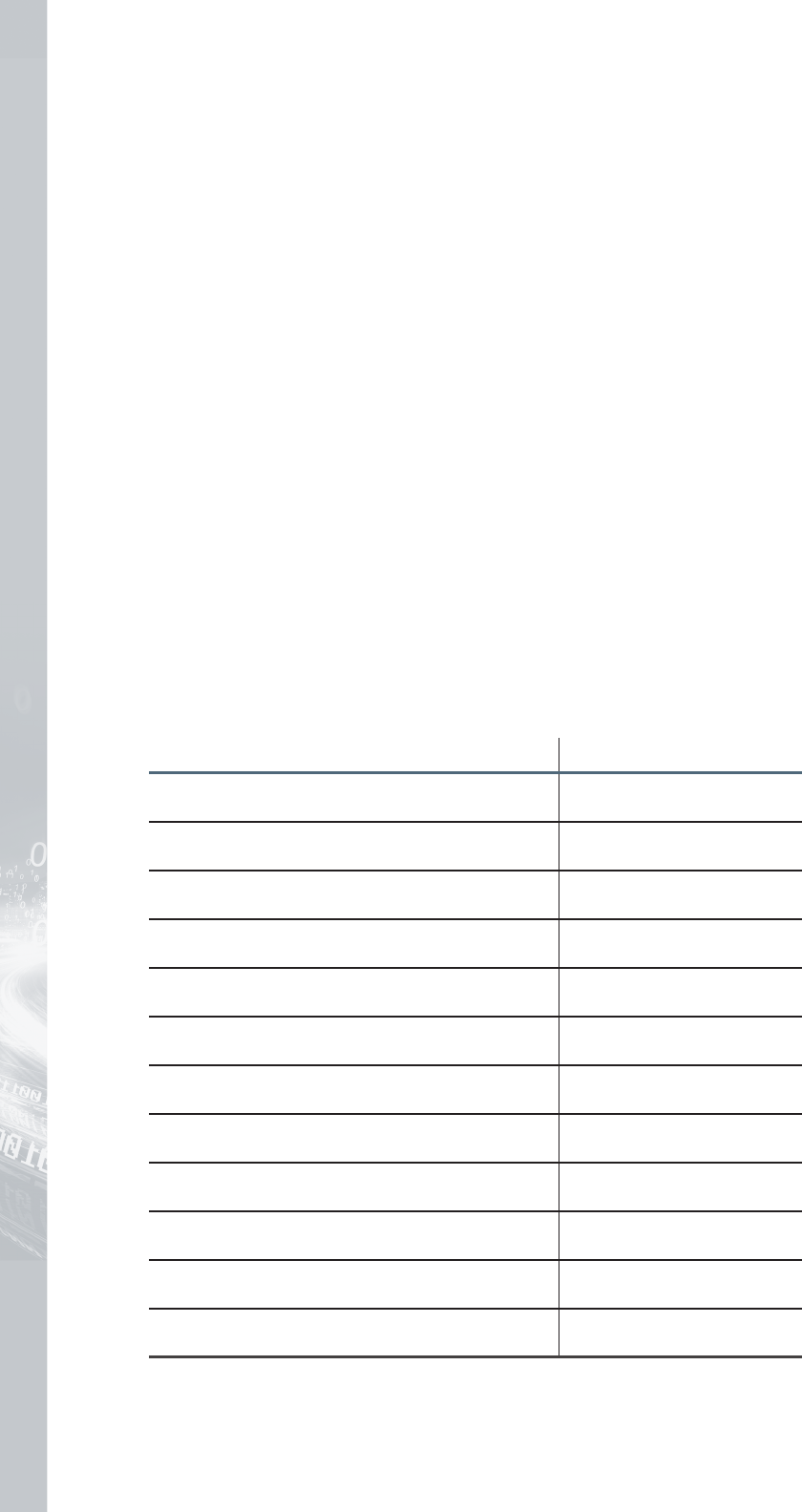

Table 2. Common protocols or trainings used by schools where potential attacks

were averted in both samples of ASV incidents

ASV response protocol

or training (N)

ASV response protocol

or training (%)

Response protocol

or training

Preliminary

analysis

Pr

eliminary

analysis New sample New sample

Active shooter trainings 4 19 7.8 15.8

All hazards drills 3 29 5.9 24.2

CIT trainings 0 2 0.0 1.7

Evacuation drills 2 12 3.9 10.0

Lockdown drills 5 20 9.8 16.7

Other 5 2 9.8 1.7

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

12

When “Other” is selected, respondents are asked to

indicate what response protocol(s) or training(s) are

not accounted for in the provided checklist that were

in place at the school when the incident was averted.

One respondent noted that their school had only fire

drills at the time of the averted incident and the other

respondent noted that the school had an emergency

action plan.

Suspect information

This section provides information about the alleged

suspects in the averted school violence incidents.

9

Information about the suspects involved in the new

sample of averted cases includes their age at the

time of the discovery of the plan, their gender, their

race or ethnicity, and their affiliation with the targeted

school. In addition, whether the suspects exhibited

any warning signs or behaviors—such as research-

ing, increasingly pathological preoccupation with a

cause or other acts of violence, an increase in the

frequency or variety of notable activities related to the

target, and communication to a third party of the

intent to do harm—was assessed, as well as addi-

tional warning signs and characteristics. The ASV

case submission form also collects information

regarding mental health and substance use,

life-changing or traumatic experiences, involvement

with the criminal justice system, engagement with

violent media or written materials, and admitted rea-

sons for planning the attack. Involvement in bully-

ing—as a bully, bullied target, or both—was also

assessed. It is also important to note that suspects

involved in planning school-based violent attacks are

not only current or former students, as will be sup-

ported by some of the information that follows.

As figure 6 on page 14 demonstrates, the over-

whelming majority (85.0 percent, n=102) of planned

but averted incidents of school-based violence

involved only one suspect. The next-largest percent-

age of cases (8.3 percent, n=10) involved a pair of

suspects, followed by cases involving three suspects

(4.2 percent, n=5). In the new sample, only 2.5 per-

cent (n=3) involved four or more suspects. Together,

figure 6.1 on page 14 shows the number of suspects

involved in planning school-based violence that were

ultimately averted.

9. The “Plotter information” section of the preliminary report only addressed information about lone or primary plotters, because of low

sample sizes and the presumption that the primary plotter was the “mastermind” of the plot. With more cases and the desire to

understand more about all suspects involved in planning school-based violence, this section treats all suspects as equal and includes

information about all of them. Therefore, some figures have combined information.

Data Analysis 13

Figure 6. Number of suspects involved in plotting attacks in new sample of ASV incidents (n=120)

Number of

suspects

One

Two

Three

Four or more

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110

Number of schools

102

10

5

3

Figure 6.1. Number of suspects involved in plotting averted attacks in

combined samples of ASV incidents (n=171)

Number of

suspects

One

Two

Three

Four or more

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140

Number of schools

132

22

8

9

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

14

Male

129; 93.5%

Younger

than 18

77; 61.6%

18 and older

48; 38.4%

White

53; 71.6%

Asian/Asian American

Figure 7. Demographics of suspects involved in plotting attacks in new sample of ASV incidents

SEX AGE RACE

Female

9; 6.5%

Middle Eastern

4; 5.4%

* Percentages may not add up exactly to 100 because of rounding.

Figure 7 shows the demographic information of the

suspects involved in the 120 cases in the new sam-

ple of averted attacks. The majority (93.25 percent,

n=129) of the suspects were male and nine (6.5 per-

cent) were female (of 138 total, as 11 of the 149 sus-

pects’ genders were unknown), which is consistent

with the preliminary report data (94.1 percent male

and 5.9 percent female). Ages of suspects—at the

time the incident was uncovered and averted—

ranged from 12 to 62, with the most common age

range being 14 to 18 years old (72.8 percent, n=91)

(of 125 total, as 24 of the 149 suspects’ ages were

unknown) and an average age of 18.6 years old.

Racial or ethnic identities are unknown or were not

provided in the cases of 75 of the 149 suspects. Of

the other 74 suspects, 53 were identified as White,

nine as Latinx, five as Asian or Asian American, four

as Middle Eastern, and three as Black or African

American.

10

Overall, the “typical” suspect is a lone

White male approximately 18 years of age.

5; 6.8%

Black/

African American

3; 4.0%

Latinx

9; 12.2%

Data Analysis 15

10. The ASV submission form allows for multiple selections, so it is possible that (for example) each of the three Black suspects was

also identified as Latinx, with an additional six of nine Latinx suspects being identified with another race or ethnicity (or not). The

total of Latinx, Asian, Middle Eastern, and Black suspects identified is 21, so even if each of those suspects was identified as partly

one of those races or ethnicities and partly White, there would be an additional 32 White suspects not identified with any other race

or ethnicity.

As shown in figure 8, a large majority of the averted

attacks were being planned by students who were

currently enrolled at the school they were plotting to

attack (75.9 percent, n=110) or former students (15.9

percent, n=23).

11

Current school officials accounted

for 2.1 percent of suspects (n=3) and former employ-

ees at the schools they targeted for 1.4 percent (n=2).

The remaining suspects (4.8 percent, n=7) had no

known prior affiliation with the targeted school.

The ASV case submission form collects information

about specific categories of warning signs each sus-

pect may have exhibited during their planning and

allows for multiple selections. Table 3 on page 17

provides each behavior and the number of times it

was selected in the new sample of cases. As is dis-

cussed in the Plot Discovery section, communicating

to a third party the intent to do harm through an

attack is one of the most common warning signs.

Figure 8. School afliation of suspects in new sample of ASV incidents (n=145)

Current student

Former student

Other

School ofcial

Former employee

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140

Number of suspects

2

3

23

110

7

11. There were four suspects whose prior affiliation or nonaffiliation with the school was unknown.

Therefore, the percentages are based on n=145.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

16

Table 3. Warning signs of suspects in new sample of ASV incidents

Behavior Suspects (n)

Directly communicated threat. The communication of a direct threat to a third party

beforehand. A threat is a written or oral communication that implicitly or explicitly states a

wish or intent to damage, injure, or kill the target or individuals symbolically or actually

associated with the target.

62

Energy burst. An increase in the frequency or variety of any noted activities related to the

target—even if the activities themselves are relatively innocuous—usually in the days or

weeks before the attack.

9

Fixation. Any behavior that indicates an increasingly pathological preoccupation with a

cause, other acts of violence, violent persons/subjects, their grievances, or their effects.

43

Identication. Any behavior that indicates a “warrior mentality,” is closely associated with

weapons or other military or law enforcement paraphernalia, identies with previous

attackers or assassins, or identies oneself as an agent to advance a particular cause or

belief system.

12

Last resort. Evidence of a “violent-action imperative” or “time imperative.” Increasing

desperation or distress through words or actions. The subject feels trapped, with no other

alternative than violence.

10

Leakage. The communication to a third party of an intent to do harm to a target through

an attack.

100

Novel aggression. An act of violence that appears unrelated to any targeted violence

pathway warning behavior committed for the rst time. Such behaviors may be engaged

to test the ability of the subject to actually do the violent act.

2

Pathway. Any behavior that is part of research, planning, preparation, or implementation

of an attack.

105

Data Analysis 17

The ASV case submission form also collects informa-

tion about specific characteristics each suspect may

have exhibited during their planning and allows for

multiple selections. Table 4 provides each character-

istic and the number of times it was selected in the

new sample of cases.

The ASV case submission form also collects informa-

tion related to whether each suspect was ever for-

mally treated for a mental illness or developmental

disorder and whether each suspect suffered from

addiction or substance use—whether formally diag-

nosed or not. The status of a formal diagnosis of

mental illness or developmental disorder was entered

for 20 of the suspects. Of those 20, there were 18

suspects who were formally treated for a mental

illness / developmental disorder and two who were

not. Of the 18 suspects identified as having had for-

mal diagnoses, there were eight about whom more

information was provided: (1) One had schizophrenia

and (2) one was evaluated for potentially having

schizophrenia after being arrested; (3) one was diag-

nosed with depression, anxiety, and a “real sense of

social awkwardness;” (4) one was diagnosed with

Antisocial Personality Disorder and Bipolar 1; (5) one

was diagnosed with depression and suicidal thoughts

or actions; (6) one was diagnosed with a learning dis-

ability; (7) one was diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol

Syndrome and Reactive Attachment Disorder; and

(8) one was diagnosed during the pre-trial but had

not been diagnosed before.

With respect to addiction and substance use, infor-

mation was entered with respect to 12 suspects: Five

suspects were reported to have suffered from addic-

tion or substance use and six were not. Of the five

suspects identified as having had addiction or sub-

stance use issues, more information was provided

Table 4. Characteristics of suspects in new sample of ASV incidents

Characteristic Suspects (n)

Impaired social or emoonal funconing

21

Depressed mood

21

Disregard for authority or rules

16

Social withdrawal or isolaon from peers

15

Easily enraged

14

Lacking empathy, guilt, remorse

14

Does not take responsibility for consequences

7

Hypersensivity (to cricism, failure, etc.)

7

Extreme narcissism

4

Other

7

None of the above

1

Unknown

67

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

18

about all of them: (1) One used methamphetamines,

(2) one used marijuana, (3) one used alcohol, (4) one

used alcohol and controlled substances, and (5) one

used cannabis and other unknown drugs.

Information about involvement in bullying was entered

for 25 suspects. Of those, 12 suspects had been bul-

lied before their planned attack was averted, and

eight had been involved in bullying—as a bully—in

addition to participating in planning an act of school-

based violence. Five of the 22 suspects were not

involved in bullying.

In the new sample of cases, information was entered

about life-changing or traumatic experiences with

respect to 18 suspects. There were 13 suspects who

had such experiences and five who had not. Of the

13 suspects who had experienced a life-changing

event or traumatic experience, two experienced loss

of a job or other financial issues; one experienced

loss of a job or other financial issues and was

harassed; one personally experienced a breakup,

separation, or divorce; one reported that things were

bad at home and they just wanted to end it all; one

had their biological father recently pass away; one

struggled with substance use and their father died by

suicide; one was homeless; and one had a partner

who was hospitalized.

In the new sample of averted cases, information was

entered about previous involvement with the crim-

inal justice system with respect to 48 suspects. Of

those, 26 were previously officially known to the

criminal justice system either as an offender or as a

victim, and 22 were not. For the suspects who had

previous offenses, some included threatening to

assault another person, burglary, previously having a

weapon on educational property, carrying a con-

cealed weapon and altering serial numbers on a fire-

arm, drug possession, stalking, vandalism, an

domestic violence.

One of the common perceptions of individuals who

commit school-based violence is that they frequently

engage with violent media, entertainment, and writ-

ten materials. In the new sample of averted cases,

information was entered with respect to 40 suspects

on this topic: 39 had engaged with violent media, and

Table 5. Suspects’ reasons for the planned attack in new sample of ASV incidents

Reason Averted School Violence Suspects (n)

Hates people

17

Grudge/Seeking revenge

17

Bullying

8

Resentment

5

Paranoid delusions / command hallucinaons

2

Rivalry

1

Envy

0

Did not provide a reason

44

Other

25

Data Analysis 19

one had not. Although multiple selections were

allowed, violent social media and websites were the

most common form of violent media engaged with by

suspects (n=19), followed by violent stories and jour-

nals (n=8) and video games (n=6).

The ASV case submission form also collects informa-

tion about specific reasons each suspect gave for

planning their attack and allows for multiple selec-

tions. Table 5 on page 21 provides each reason and

the number of times it was selected in the new sam-

ple of cases.

The final suspect information that the ASV case sub-

mission form collects is whether each suspect told or

threatened anyone directly and overtly about their

school violence plans—other than co-conspirators—

prior to the discovery of the plot itself. Information

about prior direct and overt threats was entered with

respect to 93 suspects, of whom 72 told or threat-

ened someone and 21 did not.

Event information

The ASV case submission form collects considerable

data about each incident of averted school violence,

including a summary of the incident, how it was

averted, who was involved in reporting the plan

before it could come to fruition, and the behaviors of

the individuals allegedly involved in planning the

attack. The ASV case submission form also collects

information on the weapon or weapons the suspect

or suspects intended to use in each of the alleged

incidents, as well as information about how they

obtained those weapons.

Time between plot discovery and aversion

In 115 of the 120 cases in the new sample, the report

included the number of days between when the plot

was discovered and when it was averted. Of those

115, in an overwhelming majority of the cases (73.0

percent, n=84), the date that the plot was discovered

and the date that it was averted were the same. In an

additional 21.7 percent of cases (n=25) cases, less

than seven days passed between when the plot was

discovered and when it was averted. In 3.5 percent of

cases (n=4), between eight days and two weeks

passed between discovery and aversion. In 0.9 per-

cent of cases (n=1) 18 days passed between discov-

ery and aversion, and in 0.9 percent of cases (n=1)

122 days passed between discovery and aversion.

Who discovered the plot

As demonstrated in figure 9 on page 21, plans of

school violence attacks are generally uncovered by

people in a small number of categories closely asso-

ciated with the school. While it is possible for multiple

people to discover a single plot (and the ASV submis-

sion form allows multiple selections), the majority of

potential school violence incidents were initially dis-

covered and reported by peers of the suspect(s).

School personnel—including an administrator (6 cases),

school resource officer (SRO) (5 cases), teacher (4

cases), counselor (2 cases), other faculty or staff

member (6 cases)—were also key personnel in dis-

covering plots in 23 of the cases in the new sample.

Other law enforcement—not including SROs—initially

discovered a potential incident of school violence in

10 cases. A parent or guardian of the suspect (5

cases) or parent or guardian of another student (4

cases) were also involved in discovering potential

plots of school violence. Other individuals—including

neighbors (2 cases), bystanders (2 cases), coworkers

and supervisors (2 cases), social media followers (6

cases), close relatives (6 cases), doctors and clini-

cians (3 cases), gun store employees (2 cases), or

other connections (8 cases)—were also responsible

for uncovering some of the potential plots in the new

sample. Together, figure 9.1 on page 21 shows the

people who most commonly initially discovered the

plot for averted incidents of school violence.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

20

10

14

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Number of schools

29

8

6

2

2

59

23

31

Peer

School personnel

(including SRO)

Other

Other law

enforcement

(not SRO)

Parent of

other student

Parent of suspect

Preliminary analysis New sample

Figure 9. Who discovered the plot in both samples of ASV incidents

Figure 9.1. Who initially discovered the plot in combined samples of ASV incidents

Peer

Other

School personnel

(including SRO)

Other law

enforcement

(not SRO)

Parent of suspect

Parent of

other student

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

Number of schools

88

37

31

Data Analysis 21

4

4

5

7

6

12

10

6

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Number of averted incidents of school violence

17

10

9

5

56

22

23

13

1

Suspect told

somebody

Suspect mentioned

plans on

social media

Other

Suspect was

overheard

Suspect wrote

about plans

Suspect seen

carrying a weapon

Unknown

Suspect began

shooting/setting off

explosives

Preliminary analysis New sample

Plot discovery

As displayed in figure 10, averted school violence

attacks were discovered in a handful of ways. While it

is possible for a single incident to be discovered mul-

tiple ways, of the cases in the new sample the largest

number of potential school violence plots (56 cases)

were initially discovered by at least one suspect tell-

ing another person—frequently a peer—of their plan,

who then reported it to a school administrator, SRO,

or other law enforcement. In 13 cases, at least one

suspect was overheard talking about their plans and

reported what they heard to a school administrator,

SRO, or other law enforcement. Closely related to

verbally telling someone, in 22 cases at least one

suspect posted about their plan on social media. An

additional 12 plots were discovered after at least one

suspect wrote about their plans and someone found

the note or saw them typing about it somewhere

other than social media. In 10 cases, the potential

attack was averted when the suspect was seen car-

rying a weapon, and in two cases the incident was

averted after the suspect began shooting or setting

off explosives. Together, figure 10.1 on page 23

shows the most common ways plots of averted inci-

dents of school violence were discovered.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

22

4

4

3

2

Figure 10. Method of plot discovery of averted incidents of school violence

Figure 10.1. Discovery of plots in combined samples of ASV incidents

Suspect told

somebody

Suspect mentioned

plans on

social media

Other

Suspect was

overheard

Suspect wrote

about plans

Suspect seen

carrying a weapon

Unknown

Suspect began

shooting/setting off

explosives

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Number of averted incidents of school violence

32

32

73

18

16

3

14

9

Data Analysis 23

How the incident of school

violence was averted

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Number of averted incidents of school violence

6

19

9

94

48

20

0

1

Arrested/tackled/

otherwise

physically retrained

Had conversation

about plans/violent

threats reported

Had social

media post/entry/

video reported

Other

Changed their

mind of their

own volition

Talked out

of committing

attack

Preliminary analysis New sample

The ASV case submission form collects data regard-

ing how the planned school violence incident was

ultimately averted in each case. As displayed in figure

11, the largest number of cases (94) in the new sam-

ple were averted with the arrest, tackle, or other

physical restraint of the alleged suspect or suspects

involved in the plot. In addition, in 48 cases, the

potential incident of school violence was averted

when the suspect had their conversation—most

commonly with a peer—reported. Closely related to

verbally telling someone, in 20 cases, the incident

was averted when at least one of the suspects had

their social media post, entry, or video reported.

Seven suspects changed their mind of their own voli-

tion and in one instance, the alleged suspect was

talked out of committing their attack. The “Other”

category was also selected for 13 cases. Together,

figure 11.1 on page 25 shows the most common

ways plots of potential incidents of school violence

were averted.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

24

15

13

7

5

Figure 11. How the incident of potential school violence was averted in both samples of ASV incidents

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110

Number of averted incidents of school violence

67

29

100

28

Arrested/tackled/

otherwise

physically retrained

Had conversation

about plans/violent

threats reported

Had social

media post/entry/

video reported

Other

Changed their

mind of their

own volition

Talked out

of committing

attack

Figure 11.1. How the incident of potential school violence was averted

in combined samples of ASV incidents

Data Analysis 25

7

6

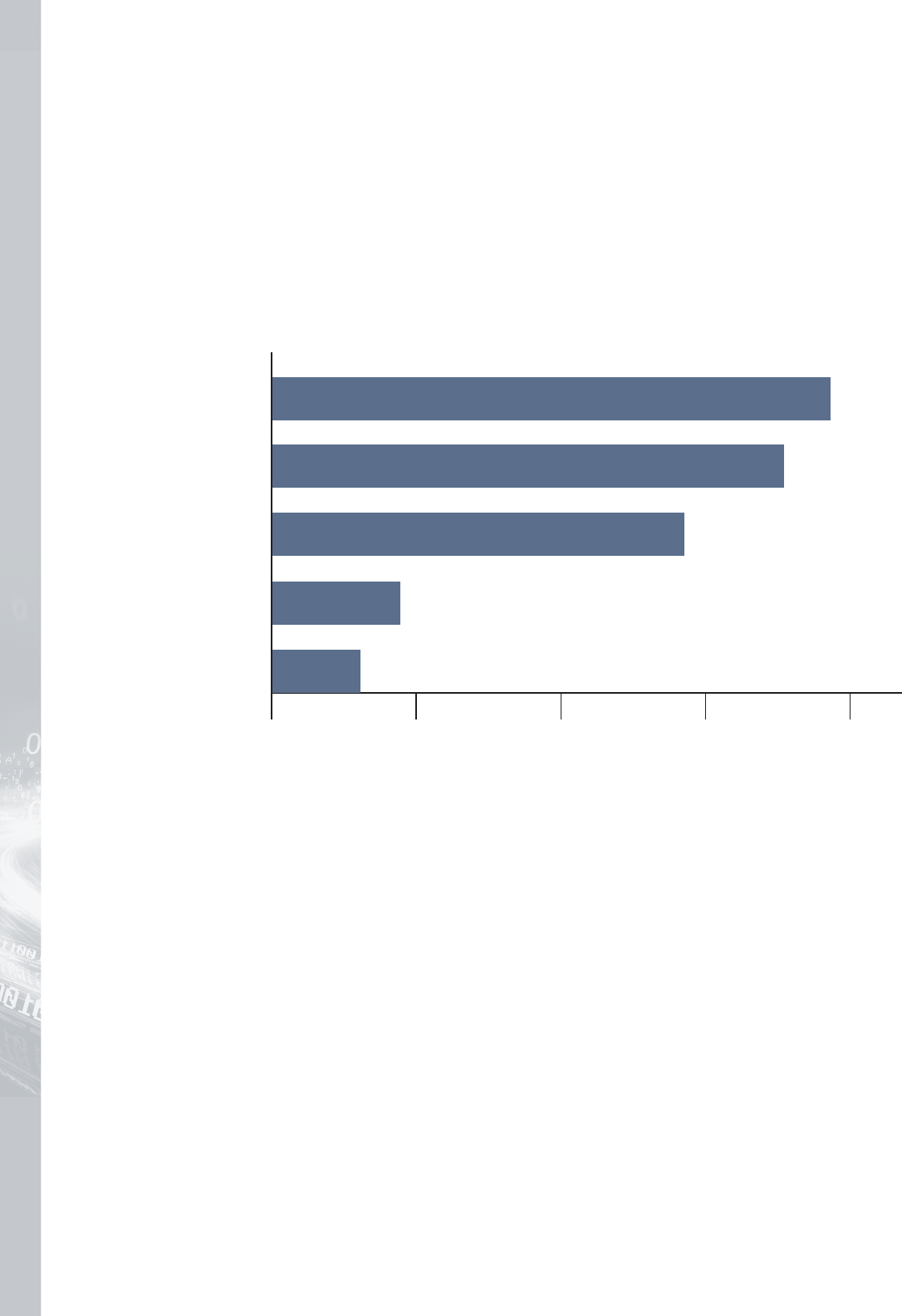

Weapons

The ASV case submission form collects data regard-

ing the types of weapons suspects in each case of

averted school violence intended to use. Of the 120

cases in the new sample, 113 identified what types of

weapons the suspects allegedly intended to use, but

in some of the cases, the suspect intended to use

more than one type of weapon (for example, they

intended to use a bomb or other explosive device as

a distraction for shooting). As displayed in figure 12,

the most common weapons included firearms,

knives, bombs and other explosive devices, and fire.

Firearms (94) were the most common intended

weapon. Suspects intended to use bombs and other

explosive devices in 29 cases and knives in 13 cases.

Three cases allegedly involved setting a fire or arson,

and one suspect allegedly intended to use a blunt

force object as a weapon. Together, figure 12.1 on

page 27 shows the most common weapons sus-

pects allegedly intended to use in potential incidents

of school violence.

Figure 12. Weapons intended for use in both samples of ASV incidents

Firearms

Bombs/other

explosives

Knives

Other

Fire/arson

Blunt force object

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Number of averted incidents of school violence

1

1

0

Preliminary analysis New sample

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

26

45

94

16

29

7

13

5

11

3

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140

Number of averted incidents of school violence

45

20

139

16

4

1

Firearms

Bombs/other

explosives

Knives

Other

Fire/arson

Blunt force object

Figure 12.1. Weapons intended for use in combined samples of ASV incidents

Data Analysis 27

Further analysis was conducted of the 94 cases in

the new sample where firearms were included in the

weapons suspects allegedly intended to use. Of

those 94 cases, the type of firearm was specified in

89 cases. A total of 116 firearms were identified,

meaning that in some of the cases the suspect or

suspects intended to use more than one type of fire-

arm. As displayed in figure 13, handguns or pistols

(38 cases) and rifles (35 cases) were the most com-

mon weapons.

Figure 13. Firearms intended for use in new sample of ASV incidents

Handgun/pistol

Rie

Unknown/missing

Shotgun

Other

0 10 20 30 40

35

9

38

28

6

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

28

Lessons Learned

IN ADDITION TO THE QUANTITATIVE FINDINGS from the 120 cases in the new sam-

ple—and the 171 total cases—of school violence attacks that were averted, there is a series

of important overarching lessons learned that emerged from the data.

Educate all members of the school community on indicators of potenal self-harm

and targeted violence and how to report concerning behavior.

As identified in the analysis, in many cases the suspects had an affiliation with the school

that was the intended target of their planned violent attack. Peers played a significant role in

initially discovering the potential school attacks (88 of the 171 total cases). In 31 cases,

school personnel—including administrators, faculty and staff, and SROs—were also identi-

fied as initially discovering the planned attack. In addition, parents of peers and parents of

alleged suspects were involved in identifying potential attacks.

The importance of educating the school community about how to report concerning behav-

ior is further emphasized by research conducted by the U.S. Secret Service on prior knowl-

edge of potential school-based violent attacks, which showed that at least one other person

was aware of the attacker’s plan in approximately 81 percent of incidents and more than

one person was aware in 59 percent of incidents.

12

In addition, research conducted by the

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on completed active shooter incidents in the United

States between 2000 and 2015 in prekindergarten through grade 12 (pre-K–12) school

settings, identified that the shooter was a student at the targeted school in 20 of the 30

cases (66.7 percent).

13

Together, these data suggest that it is extremely important to educate all members of the

school community—including administrators, faculty and staff, students, parents and

guardians—on the indicators of potential self-harm or violence directed at others as well as

12. William S. Pollack, William Modzeleski, and Georgeann Rooney,

Prior Knowledge of Potential School-

Based Violence: Information Students Learn May Prevent a Targeted Attack

(Washington, DC: U.S.

Secret Service, 2008), https://rems.ed.gov/docs/DOE_BystanderStudy.pdf.

13. J. Pete Blair and Katherine W. Schweit,

A Study of Active Shooter Incidents, 2000–2013

(Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2014), https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/

active-shooter-study-2000-2013-1.pdf/view; Katherine W. Schweit,

Active Shooter Incidents

in the United States in 2014 and 2015

(Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2016),

https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/activeshooterincidentsus_2014-2015.pdf/view.

29

how concerning behavior should be reported. Mem-

bers of the school community—particularly peers—

are likely to be attuned to and aware of suspicious

behaviors and comments made by classmates and

have demonstrated success in reporting suspicious

behaviors after being educated about them. For

example, anonymous reporting systems have been

shown to be effective in providing students—and

other members of the school community—to report

potential targeted violence and other concern-

ing behaviors.

14

14. School Safety Working Group,

Ten Essential Actions to Improve School Safety

(Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented

Policing Services, 2020), https://cops.usdoj.gov/RIC/ric.php?page=detail&id=COPS-W0891.

Averted School Violence (ASV) Database

2021 Analysis Update

30

Relaonships are crical to assessing

the viability of all threats and taking necessary

preventave acon.

Many of the potential incidents of school violence

were initially discovered by a member of the school

community. These cases were then averted after law

enforcement personnel were notified and the alleged

suspects were arrested. Relationships between

stakeholders in a positive and supportive school envi-

ronment can greatly impact the aversion of a violent

incident. In many cases, the time between when the

incident was discovered and when it was averted

was minimal.

Peers are the ones who initially discover plans of

school violence in many of the cases included in the

ASV database. Therefore, it is important for school

officials to ensure that every adult—administrator,

faculty, staff, or SRO—work to develop strong rela-

tionships with students so that students feel comfort-

able reporting concerns about possible threats.

While some school administrators may be concerned

about the restrictions of communicating with law

enforcement based on the federal Family Educational

Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), it is important to

note that sharing information about potential threats

or general concerns about school safety is not pro-

hibited by that law. Also, these relationships can help

establish protocols and processes for identifying,

addressing, and averting potential threats as well as

proactively communicating with staff, faculty mem-

bers, parents and guardians.

Behavioral threat assessment teams

are a crical tool.

Behavioral threat assessment teams are a critical tool

in quickly assessing threats and taking the actions

necessary to address them. Every report of a threat

or potential suspicious activity must be acted upon

as if it is a serious and credible threat, until it has been

investigated and determined to no longer be credible.

While there may be false negatives—cases in which

reports are deemed to not be credible—it is import-

ant to err on the side of caution, especially to ensure

that students continue to feel safe making reports.

It is also critical that there be a multidisciplinary team

in place to whom information can be referred and that

can conduct analysis and take appropriate actions to

connect persons to services well before an attack is

being planned. Behavioral threat assessment teams

staffed by school administrators, teachers, mental

health practitioners, and law enforcement provide an

opportunity to identify the appropriate resources and

interventions to assist students pre-crisis within the

school, family, and community environments.

Alleged suspects may be movated by a range

of things from seemingly insignicant incidents

to a desire to emulate previous mass aackers.

Alleged suspects of school violence are driven to the

precipice of committing a violent attack by a range of

motivations. In some cases, a change in their per-

sonal life (such as their parents getting divorced or a

breakup with a significant other) or academic life

(such as a disciplinary incident or significant change

in grades) can be the impetus for planning a mass

violence attack. In other cases, anniversaries of other

high-profile mass casualty attacks can have signifi-

cance and serve as motivation for those planning

school violence. Similarly, there is some research

pointing to a school shooting “contagion effect,” in

which the immediate aftermath of student suicides or

a completed school violence attack motivates others

to attempt to carry out an attack.

These data suggest, that there is no “profile” of a

school attacker but rather a complex set of personal

and environmental factors that influence a person’s

decision to commit an act of violence. It is clear

that additional research is necessary to identify not

only the factors that contribute to mass violence

attacks but also promising intervention strategies

and practices.

School resource ocers, security personnel, and

law enforcement play a crical role in prevenng

school aacks.

Amidst the national and local discussions regarding

the role of law enforcement in the communities they

serve and in educational environments, it is important

to recognize the role that public safety officers play in

providing mentorship, adult role models, and security

in schools. Carefully selected, well-trained school-

based public safety personnel provide an import-

ant resource in the prevention and response to

school attacks. K–12 schools as well as colleges and

universities should endeavor to engage school

administrators, teachers, staff, parents and students

regarding the role that law enforcement and security

personnel will play in creating safe and secure learn-

ing environments.

Information collected, analyzed, and reported via the

ASV database is critical to improve school safety.

Protecting students and school personnel is a com-

munity responsibility that can be maximized with

information sharing, transparency, and collaborative

communication. The ASV database mission is to

encourage individuals to share their stories and les-

sons learned from ASV incidents to prevent future

injuries and fatalities in educational institutions. The

lessons learned can be used to inform future school

policy and safety procedures. The lessons learned

will help to save lives through interventions before a

school violence event occurs.

Lessons Learned 31

About the National

Police Foundation

The National Police Foundation is a national,

nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to

advancing innovation and science in policing. As the

country’s oldest police research organization, the

National Police Foundation has learned that police

practices should be based on scientific evidence

about what works best, the paradigm of evidence-

based policing.

Established in 1970, the foundation has conducted

seminal research in police behavior, policy, and pro-

cedure and works to transfer to local agencies the

best new information about practices for dealing

effectively with a range of important police opera-

tional and administrative concerns. Motivating all of

the foundation’s efforts is the goal of efficient, humane

policing that operates within the framework of demo-

cratic principles and the highest ideals of the nation.

To learn more, visit the National Police Foundation

online at www.policefoundation.org.

32

About the COPS Ofce

The Office of Community Oriented Policing Ser-

vices (COPS Office) is the component of the U.S.

Department of Justice responsible for advancing the

practice of community policing by the nation’s state,

local, territorial, and tribal law enforcement agencies

through information and grant resources.

Community policing begins with a commitment to

building trust and mutual respect between police and

communities. It supports public safety by encourag-

ing all stakeholders to work together to address our

nation’s crime challenges. When police and commu-

nities collaborate, they more effectively address

underlying issues, change negative behavioral pat-

terns, and allocate resources.

Rather than simply responding to crime, community

policing focuses on preventing it through strategic

problem-solving approaches based on collaboration.

The COPS Office awards grants to hire community

policing officers and support the development and

testing of innovative policing strategies. COPS Office

funding also provides training and technical assis-

tance to community members and local government

leaders, as well as all levels of law enforcement.

Since 1994, the COPS Office has invested more

than $14 billion to add community policing officers to

the nation’s streets, enhance crime fighting technol-

ogy, support crime prevention initiatives, and provide

training and technical assistance to help advance

community policing. Other achievements include

the following:

To date, the COPS Office has funded the hiring of

approximately 130,000 additional officers by more

than 13,000 of the nation’s 18,000 law enforce-

ment agencies in both small and large jurisdictions.

Nearly 700,000 law enforcement personnel, com-

munity members, and government leaders have

been trained through COPS Office–funded training

organizations and the COPS Training Portal.

Almost 500 agencies have received customized

advice and peer-led technical assistance through

the COPS Office Collaborative Reform Initiative

Technical Assistance Center.

To date, the COPS Office has distributed more

than eight million topic-specific publications, train-

ing curricula, white papers, and resource CDs and

flash drives.

The COPS Office also sponsors conferences,

round tables, and other forums focused on issues

critical to law enforcement.

COPS Office information resources, covering a wide

range of community policing topics such as school

and campus safety, violent crime, and officer safety

and wellness, can be downloaded via the COPS

Office’s home page, https://cops.usdoj.gov.

33

-

-

-

The National Police Foundation, in collaboration with the COPS Office, implemented the Avert-

ed School Violence (ASV) database to provide a platform for sharing information about averted

incidents of violence in institutions of elementary, secondary, and higher education. The ASV

database defines an incident of averted school violence as a violent attack planned with

or without the use of a firearm that was prevented before any injury or loss of life occurred.

A preliminary report (Daniels 2019) analyzed 51 averted incidents of school violence to begin

to improve our understanding of averted school attacks. This report analyzes an additional

120 averted incidents of school violence, expanding the knowledge base and further develop-

ing lessons learned as our understanding grows of how school attacks are planned, discov-

ered, and thwarted.

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Community Oriented Policing Services 145

N Street NE

Washington, DC 20530

To obtain details on COPS Office programs, call the

COPS O

ffice Response Center at 800-421-6770.

Visit the COPS O

ffi

ce online at

cops.usdoj.gov

National Police Foundation

1201 Connecticut Ave NW

Suite 200

Washington, DC 20036

Visit the National Police Foundation online

at www.policefoundation.org

e022111977

Published 2021