the dominican study

Public Library Summer Reading Programs

Close

the Reading Gap

.

.

Susan Roman

Deborah T. Carran

Carole D. Fiore

June 2010

THE DOMINICAN STUDY:

PUBLIC LIBRARY

SUMMER READING

PROGRAMS CLOSE

THE READING GAP

The Institute of Museum and Library Services is the primary

source of federal support for the nation’s 123,000 libraries

and 17,500 museums. The Institute’s mission is to create

strong libraries and museums that connect people to

information and ideas.

This project was made possible by a grant from the U.S. Institute of Museum

and Library Services. National Leadership Grant LG-06-06-0102-06.

contents

Acknowledgements.................................................... i

Executive Summary ................................................... 1

Introduction and Background .................................... 7

Literature Search ..................................................... 13

The Dominican Study ............................................... 21

Summary of Results ................................................ 47

Conclusions and Lessons Learned ............................ 51

Call to Action: Close the Reading Gap ....................... 55

Appendixes............................................................. 59

.

acknowledgements

A research study such as this one has been on my personal research agenda for close to twenty

years, but it always fell to the bottom of the agenda for a variety of reasons. It rose to the top

when it became apparent that librarians needed to account for the amount of time, energy, and

expenses that are involved in public library summer reading programs. Even more important at

this time was accountability through hard data as to whether the public library reading programs

held over the summer made a difference in student achievement; i.e., did children who

participated in summer reading programs at the public library maintain or even gain in their

reading ability? The time had come to test this question through a national study using rigorous

research and to try to replicate findings from a study conducted in the 1970s.

Research projects such as this Dominican study involve the talents of many individuals and the

financial support of a funder. For the earliest discussions about the possibility of a study, we

thank Martha Crowley at the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) for guidance as

we prepared the grant proposal. She continued that support throughout the research when we

had questions until Rachel Frick assumed that guiding role after Ms. Crowley retired. We also

thank IMLS staff members Mary L. Chute, Joyce Ray, and Kevin Cherry for their interest and

help throughout the project. For granting us the funds to conduct the research, we thank the

reviewers and administration of IMLS.

Thanks go to the following for original discussions for partnering on the project: Ron Fairchild,

then director of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Summer Learning (now known as the

National Summer Learning Association, an independent organization since September 2009),

Carole D. Fiore, a consultant known for her publication on summer reading programs, Peggy

Rudd and Christine McNew of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission, and Eugene

Hainer and Patricia Froehlich of the Colorado State Library.

For the rigor of the research, we thank the Johns Hopkins University Center for Summer Learning

research team, which included Brenda McLaughlin, Deborah T. Carran, and Susanne Sparks. For

guidance on the refinement of the research methodology and other issues that arose during

the study, we gratefully extend our thanks to advisory board members Janice Del Negro, Tracie

Hall, Denise Davis, and Penny Markey.

I express sincere gratitude and thanks to my co-authors of this report, Carole Fiore and Deb

Carran. Their input was invaluable. My home institution’s President Donna M. Carroll and

Provost Cheryl Johnson-Odim have been supportive and encouraging from initial discussions

and throughout the study. Thank you.

Susan Roman

Dean and Professor

Graduate School of Library and Information Science

Dominican University

River Forest, IL

Project Administrator and Principal Investigator

.

i

the dominican study

Public Library Summer Reading Programs

Close

the Reading Gap

.

.

executive summary

.

“In fact, all people

today—youth and

adults—spend the

majority of their lives

learning outside the

walls of formal

classrooms.”

— “Museums, Libraries, and 21st Century Skills,”

IMLS, July 2009

executive summary

1

executive summary

The Graduate School of Library and Information Science at Dominican University received a

National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) for a three-

year research study to answer the question: do public library summer reading programs impact

student achievement? Conducted between 2006 and 2009, the study had its roots in programming

that began in the late 1800s.

For over a century, public librarians have designed summer reading programs to create and

sustain a love of reading in children and to prevent the loss of reading skills over the summer.

Recently, however, federal and private funding agencies, along with departments of education,

have challenged the effectiveness of public library summer reading programs, especially

considering the large amount of resources, both financial and human, that is invested in

developing and marketing summer reading programs. The concern is exacerbated, as well, by

the dismal reading scores of students on standardized tests in low-performing schools. This

then begged the question as to whether public library summer reading programs, in fact, reach

the stated goals and impact student achievement.

Dominican University, as the lead agency, contracted with the Johns Hopkins University Center for

Summer Learning to conduct the research and also partnered with the Colorado State Library and

the Texas State Library and Archives Commission to help identify possible sites. The study was

piloted at three public libraries. The full study was conducted at eleven sites across the United

States and was overseen by an Advisory Committee that helped shape and guide the research

parameters.

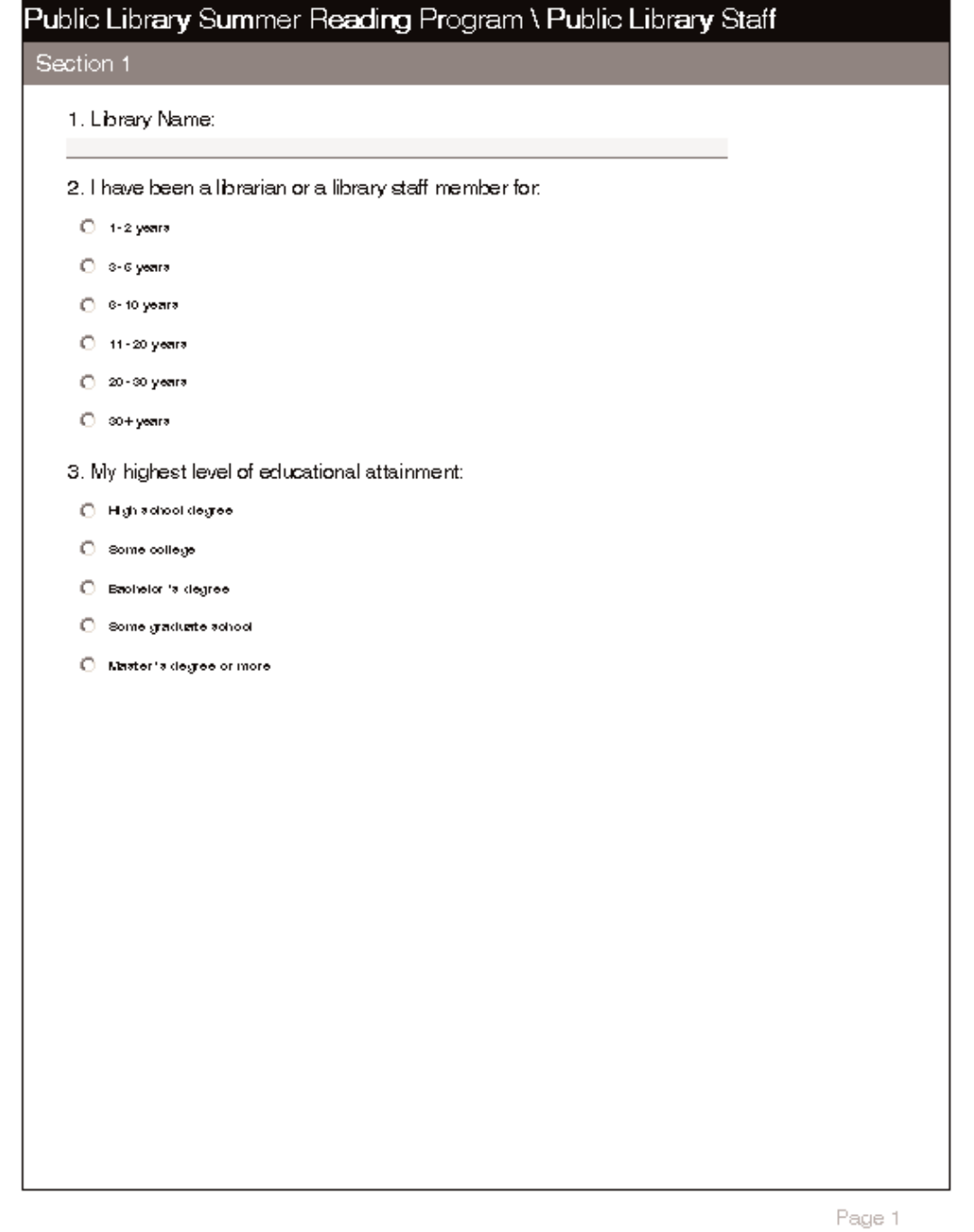

The Dominican study, as it has come to be known, involved the collection of data through

pretesting and posttesting of students at the end of third grade and at the beginning of their

fourth-grade year. Interviews and surveys of public librarians were conducted, as well as surveys

of students, their parents, their teachers, and school librarians.

The results of this Dominican study include the following:

I

Students who participated in the public library summer reading program scored higher

on reading achievement tests at the beginning of the next school year than those

students who did not participate and they gained in other ways as well.

I

While students who reported that they did not participate in the public library summer

reading program also improved reading scores, they did not reach the reading level of

the students who did participate.

I

Students who participated in the public library summer reading program had better

reading skills at the end of third grade and scored higher on the standards test than

the students who did not participate.

.

I

Students who participated in the public library summer reading program included more

females, more Caucasians, and were at a higher socioeconomic level than the group of

students who did not participate.

I

Families of students who participated in the public library summer reading program

had more books in their homes than those families of students not participating.

I

Students enrolled in the public library summer reading program reported that they like

to read books, like to go to the library, and picked their own books to read.

I

Parents of children enrolled in the public library summer reading program reported that

their children spent more time reading over the summer and read more books, were

well prepared for school in the fall, and read more confidently.

I

Parents of children enrolled in the public library summer reading program reported that

they would enroll their children in a summer reading program at the library again, made

more visits to the public library with their children, and read more books to/with their

children over the summer.

I

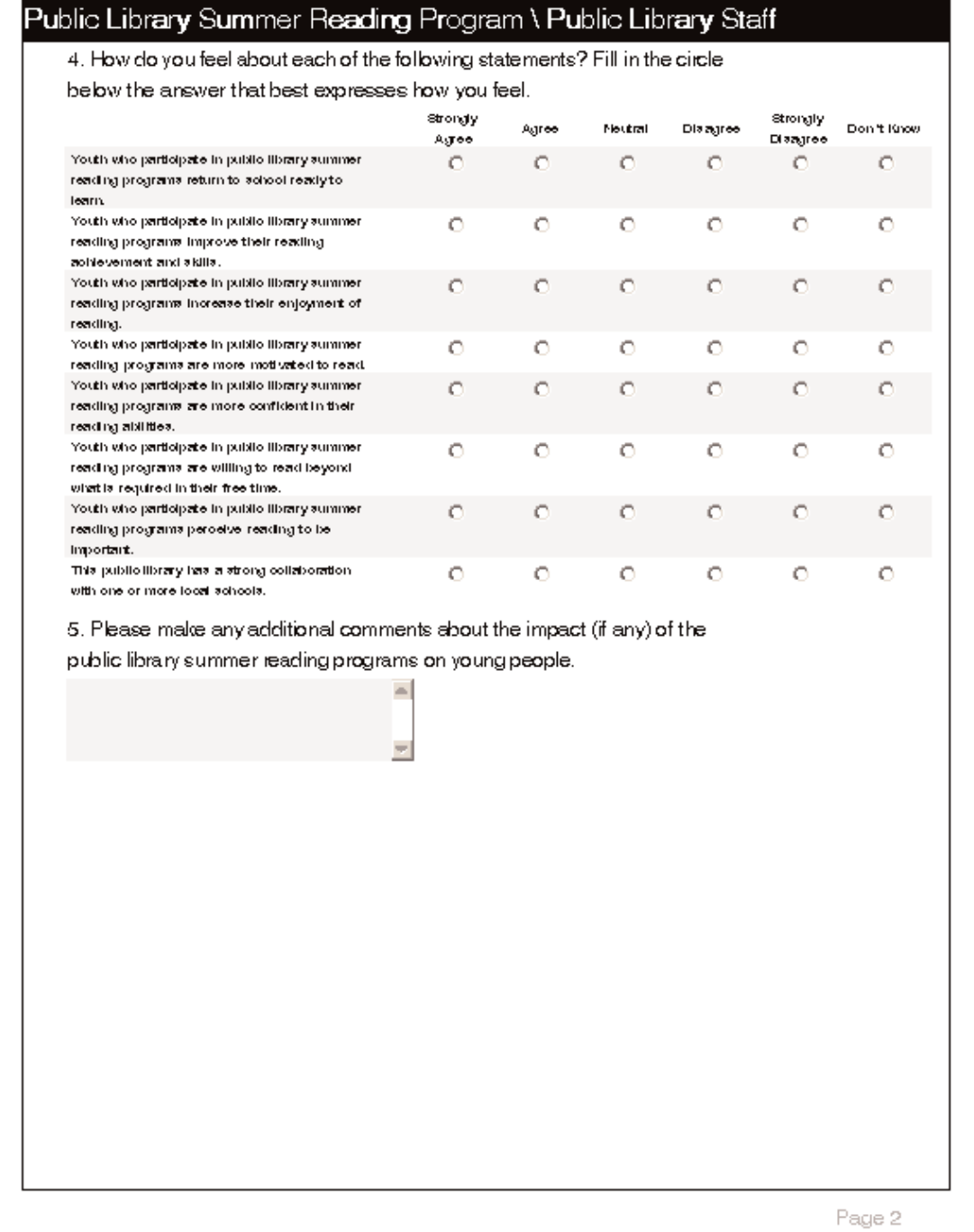

Teachers observed that students who participated in the public library summer reading

program returned to school ready to learn, improved their reading achievement and

skills, increased their enjoyment of reading, were more motivated to read, were more

confident in participating in classroom reading activities, read beyond what was

required in their free time, and perceived reading to be important.

I

School librarians observed that students who participated in the public library summer

reading program returned to school ready to learn, improved their reading achievement

and skills, increased their enjoyment of reading, were more motivated to read, were

more confident in their reading abilities, read beyond what was required in their free

time, and perceived reading to be important.

I

Public librarians observed/perceived that students who participated in the public

library summer reading program returned to school ready to learn, improved their

reading achievement and skills, increased their enjoyment of reading, were more

motivated to read, were more confident in their reading abilities, read beyond what

was required in their free time, perceived reading to be important, were enthusiastic

about reading and self-selecting books, and increased their fluency and

comprehension.

It is time to close the achievement gap in reading for our nation’s children. Based on

this study’s findings, we recommend:

1. Recognizing that public libraries play a significant role in helping to close the

achievement gap in school performance.

2. Promoting the powerful role that public libraries play in the education community

in helping children maintain and gain reading skills.

3. Engaging families in public library programs to promote early childhood literacy.

4. Investing more money in summer reading programs—especially in public libraries

that serve children and families in economically depressed areas.

5. Marketing to parents of school-age children so they understand the importance of

their children participating in summer reading programs and other out-of-school

library activities.

2 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

executive summary

3

6. Ensuring that librarians in public libraries work with teachers and school librarians

to identify non-readers and under-performing students and to reach out to those

students in order to engage them in library activities.

7. Reaching out to boys to get them involved in reading.

8. Expanding the definition of reading beyond books to include magazines, graphic

novels, etc.

9. Providing more books and reading material at the public library for children in economically

depressed neighborhoods since their more advantaged peers may have better access

to reading materials in their homes and in their local public libraries.

10. Helping children in lower-income areas build home libraries by partnering with

non-profit organizations such as First Book and Reading Is Fundamental.

11. Having librarians assume a role in influencing a child’s love of reading and lifelong

learning.

12

. Encouraging and supporting studies that continue research in this area and that offer

effective means for closing the reading achievement gap.

A complete report is available online at www.dom.edu/gslis.

the dominican study

Public Library Summer Reading Programs

Close

the Reading Gap

.

.

introduction and

background

.

“The 21st century

has changed how,

when, and where

we all learn.”

— “Museums, Libraries, and 21st Century Skills,”

IMLS, July 2009

introduction and background

7

introduction and background

THE “DOMINICAN STUDY”

Summer reading programs are offered by 95.2 percent of public libraries in the United States.

1

For years, public librarians have designed summer reading programs to create and sustain a

love of reading in children and to prevent the loss of reading skills, which research shows often

occurs during the summer months. Yet are summer reading programs actually accomplishing

the goals of the programs as hoped by the librarians? The study most often cited to support

librarian claims is over thirty years old. The Graduate School of Library and Information Science

at Dominican University with the Johns Hopkins University Center for Summer Learning, and in

partnership with the State Libraries of Texas and Colorado, prepared a National Leadership

Grant proposal for the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to investigate these

important questions: do public library summer reading programs have an impact on student

reading achievement; do public library summer reading programs spur a motivation to read

and enjoyment of reading; and what is the effect when schools and public libraries collaborate

to support summer reading programs? With grant monies from IMLS, the research project

began in 2006 and continued through 2009.

ESTABLISHING A MODEL FOR COMPREHENSIVE EVALUATION

In September 2005, IMLS brought representatives from eleven state libraries and their public

library partners to Washington, D.C., for a two-day workshop to develop outcome-based

evaluation logic models for evaluating summer reading programs. The goal of the workshop was

to assist public libraries in developing evaluation tools to gather data on the impact of summer

reading programs and to gather longitudinal data demonstrating the impact of public library

summer reading programs. Attendees were eager to develop a means of demonstrating the

value of summer reading programs to their funders, colleagues, and the community at large.

Many workshop participants concluded that while outcome-based evaluation of summer reading

programs is valuable, more rigorous research at the national level might provide stronger

evidence of the value of summer reading programs.

Public librarians are under pressure from their funders to prove that tax dollars spent on their

programs yield a valuable return on investment. In his article about current trends in budgeting,

“What is a Summer Worth,” workshop attendee Steve Brown wrote, “Last year, several public

libraries in the North Texas area suddenly found to their dismay that they were being asked to

explain the value of their summer reading activities.”

2

Mr. Brown stated that funders increasingly

1

F. William Summers, et al.,

Florida Libraries are Education: Report of a Statewide Study on the Educational Role of Public

Libraries

(Tallahassee, FL: School of Information Studies, Florida State University, 1999), iv.

2

Steve Brown, “What is a Summer Worth?”

Texas Library Journal

81, no. 2 (2005): 16–17.

.

regard survey data as insufficient evidence, instead preferring the rigor of quantitative research.

Certainly, outcome-based evaluation provides a convincing description of the impact of

programs; however, quantitative research is also needed to determine if there is a connection

between participation in public library summer reading programs and the prevention of

summer reading loss.

The methodology used by schools to study the impact of school-based intervention programs

on summer learning loss has included both quantitative and qualitative approaches, and

offered a model to study the impact of programs offered by public libraries. Student performance

on pretests at the end of a school year and posttest scores at the beginning of the following

school year had been compared to determine the impact of learning activities during the

intervening summer, and data on changes in motivation and enjoyment of reading had been

gathered through surveys. Yet due to the fiscal and logistical challenges of gathering pretest

and posttest data of summer reading program participants from their schools, this “dual”

methodology has rarely been utilized in studying summer reading programs sponsored by

public libraries. Heretofore, as well, studies were conducted in individual school districts or in

individual library systems—there had not been a research study conducted on a national scale.

This apparent division of labor and consequent assessment between schools and public libraries

begged the question: would research support that school and public library collaboration leads

to higher student reading achievement?

Certainly, both schools and public libraries have a stake in the nation’s children being successful

in school and beyond. National standards for school libraries, as outlined in Information Power:

Building Partnerships for Learning, as well as state standards, such as those found in School

Library Programs: Standards and Guidelines for Texas, recommend that school librarians

collaborate with teachers and public librarians to support higher student achievement.

3

Throughout the United States, school and public librarians are cooperating to support students,

and many of these collaborations are documented on the Association for Library Service to

Children (a division of the American Library Association) website.

4

While studies in more than a

dozen states demonstrate that student test scores are higher when school librarians collaborate

with teachers, we did not find research to demonstrate that collaboration between schools and

public libraries also supports student achievement.

5

8 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

3

Information Power: Building Partnerships for Learning

(Chicago: American Library Association, 1998). and

School Library

Programs: Standards and Guidelines for Texas

(Texas: Texas State Library and Archives Commission, May 2005).

4

www.ala.org/ala/alsc/alscresources/forlibrarians/SchPLCoopActivities.htm.

5

Library Research Service. School Library Impact Studies. (www.lrs.org/impact.asp)

introduction and background

9

An overview of existing research on summer reading programs in public libraries revealed that

the Barbara Heyns study, Summer Learning and the Effects of Schooling published in 1978, was

still being cited as the definitive study of the impact of summer reading programs on student

reading achievement. Subsequent quantitative research has primarily focused on the effect of

interventions by schools.

6

This Dominican University study provides a rigorous evaluation of the impact of public library

summer reading programs on summer reading loss through the examination of third-grade

students from large and small communities in rural, urban, and suburban areas, paying

particular attention to those students from low-income families. It also examines collaboration

between schools and public libraries.

The study focused on students at the end of third grade and followed them as they entered

fourth grade. This cohort was selected because less than one-third of U.S. fourth graders meet

the “proficient” standard on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). Fourth

graders in high-poverty schools score dramatically lower on NAEP reading tests than the

general population: over 85 percent fail to reach the proficient level. Fourth grade appears

to be a transitional year from learning to read to reading to learn. As researchers Jeanne S. Chall

and Vicki A. Jacobs stated: “One possible reason for the fourth-grade slump may stem from lack

of fluency and automaticity (that is, quick and accurate recognition of words and phrases). We

found this particularly among the poorest readers who read slowly and hesitatingly in grade 2

and beyond. Lack of fluency tends to result, ultimately, in children’s reading less and avoiding

more difficult materials.”

7

AN ASSESSMENT OF NEED FOR THE STUDY

Research indicates that children from families across the socioeconomic spectrum achieve

similar levels of reading improvement during the school year. However, while the reading skills

of more economically advantaged children remain stable or improve slightly during the

summer, the reading skills of children from low-income families decline. In fact, research shows

that a reading achievement gap of approximately three months develops between students

from lower- and higher-income families over the summer months. This loss accumulates each

summer and may become a gap of eighteen months by the end of sixth grade, and two or more

years by middle school.

8

Since the 1970s, studies have suggested that summer reading is an effective way to prevent

summer learning loss. In the aforementioned landmark study, Summer Learning and the Effects

6

Barbara Heyns,

Summer Learning and the Effects of Schooling

(New York: Academic Press, 1978).

7

Jeanne S. Chall and Vicki A. Jacobs, “Poor Childrenʼs Fourth-Grade Slump,

American Educator

(Spring 2003).

http://archive.aft.org/pubs-reports/american_educator/spring2003/chall.html

8

H. Cooper, B. Nye, K. Charlton, J. Lindsay and S. Greathouse, “The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores:

A narrative and meta-analytic review,”

Review of Educational Research

66 (1996): 227–268.

of Schooling, Barbara Heyns followed sixth and seventh graders in the Atlanta Public Schools

through two school years and the intervening summer and compared scores on reading

pretests and posttests. Heyns concluded that “The single summer activity that is most strongly

and consistently related to summer learning is reading.”

9

In her study, Heyns also stated that

“More than any other public institution, including the schools, the public library contributed to

the intellectual growth of children during the summer. Moreover, unlike summer school

programs, the library was used regularly by over half the sample and attracted children from

diverse backgrounds.”

10

For more than the last three decades, librarians have quoted this

study to justify summer reading programs.

A more recent study by Jimmy S. Kim concluded that summer achievement losses may be

prevented if elementary school students read four or five books during the summer. Kim

reported that regardless of race, socioeconomic level, or previous achievement, children who

read more books fared better on reading-comprehension tests in the fall than their peers who

had read one or no books over the summer.

11

A comprehensive bibliography of research on summer reading loss is available on the Alaska

State Library website at www.library.state.ak.us/pdf/checklist_161.pdf.

12

For this Dominican

study, an additional literature search was conducted. (See p. 13)

GRANT AWARDED

The Institute of Museum and Library Services awarded a multi-year National Leadership Grant

of $290,224 to Dominican University’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science to

conduct research from 2006 through 2009. The Cost Share Amount was $194,106 for a total

project cost of $484,330. Project Administrator and Principal Investigator, Susan Roman, dean

and professor of the Graduate School of Library and Information Science, contracted with the

Johns Hopkins University Center for Summer Learning to conduct the research, contracted with

Carole D. Fiore to manage the project, and worked with partners at the state library agencies in

Colorado and Texas to convene the Advisory Committee for the study. (Appendix A)

The charge to the advisory committee was to work with the administrative team to help refine

the research study plans, to help set objective parameters for the selection of sites for the

study, and to serve as guides and resources as the study progressed. The advisory committee and

the administrative team met for the first time during the Midwinter Meeting of the American

Library Association in January 2007. Following that meeting, a more comprehensive literature

search was conducted and the pilot sites for the study were selected.

10 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

9

Heyns, 161.

10

Heyns, 177.

11

Jimmy S. Kim, “Reading Books is Found to Ward Of ʻSummer Slump,ʼ ”

Education Week

(May 2004).

12

Alaska State Library, “Preventing Summer Reading Loss,”

Checklist

161 (April 2005).

the dominican study

Public Library Summer Reading Programs

Close

the Reading Gap

.

.

literature search

.

“For every one line

of print read by

low-income children,

middle-income

children read three.”

— Donna Celano and Susan B. Neuman in

“When Schools Close, the Knowledge

Gap Grows,” 2008.

literature search

13

literature search

For years, librarians and educators have stated that summer library programs are a key to

creating a nation of readers. And, as such, summer library programs are a key to creating a

nation of literate citizens. In the aggregate, summer library programs are an integral part of

public library services. “Virtually all public libraries (95.2 percent) provide summer reading

programs for children. More children participate in public library summer reading programs

than play Little League baseball. Moreover, these programs have been shown to play a definite

role in children improving reading skills over the summer.”

1

Recently, there have been numerous studies, most of them within the education field, that

explore the value of reading over the summer. However, the study most often cited is more than

thirty years old. Conducted in 1978, Summer Learning and the Effects of Schooling by Barbara

Heyns was the first thorough investigation of summer learning. In this landmark study, Heyns

followed sixth- and seventh-grade students in the Atlanta Public Schools through two academic

years and an intervening summer.

2

The most significant finding from the Heyns study is that “The single summer activity that is

most strongly and consistently related to summer learning is reading.”

3

Reading during the

summer, whether measured by number of books read, time spent reading, or even by the

regularity of library usage, systematically increases the vocabulary test scores of children.

“Although unstructured activities such as reading do not ordinarily lend themselves to policy

intervention,” Heyns writes, “I will argue that at least one institution, the public library, directly

influences children’s reading. Educational policies that increase access to books, perhaps

through increased library services, stand to have an important impact on achievement,

particularly for less advantaged children.”

4

Heyns makes several other statements based on her research regarding the effectiveness of the

public library on summer learning. Since libraries facilitate reading, they also promote reading

achievement. “More than any other public institution, including the schools, the public library

contributed to the intellectual growth of children during the summer. Moreover, unlike summer

school programs, the library was used regularly by over half of the sample and attracted

children from diverse backgrounds.”

5

Heyns reported that socioeconomic status had little impact on reading achievement over the

summer. While reading tends to be patterned by family situation, the increases in summer

1

F. William Summers, et al.,

Florida Libraries are Education: Report of a Statewide Study on the Educational Role of Public

Libraries

(Tallahassee, FL: School of Information Studies, Florida State University), iv.

2

Barbara Heyns,

Summer Learning and the Effects of Schooling

(New York: Academic Press, 1978).

3

Heyns, 161.

4

Heyns, 161.

5

Heyns, 177.

.

learning are largely independent of a child’s social class. She also reported in her study that

“each additional hour spent reading on a typical day, or every four books completed over the

summer, are worth an additional vocabulary word, irrespective of socioeconomic status, for

both black and white children.”

6

A conclusion from the Heyns study is that “the unique contribution of reading to summer

learning suggests that increasing access to books and encouraging reading may well have

substantial impact on achievement.”

7

Both the number of books read and participating in a

group in which reading and literacy activities are valued add significantly to improved reading

abilities, achievement, and attitudes. Therefore, attracting children to the library during the

summer and getting them involved in an organized reading program appears to be a significant

way that libraries can increase the summer learning of the young people in their service area.

In addition to Heyns’s study, other research that has been done prior to the Dominican study

has been summarized in Carole D. Fiore’s Summer Library Reading Program Handbook (Neal-

Schuman, 2005). A selection of recent studies not included in that publication is highlighted here.

In 2005, John Schacter and Booil Jo studied children in a reading summer day-camp and reported

that during summer vacation children who are economically disadvantaged experience declines

in reading achievement, while middle- and high-income children improve.

8

They also cite

previous research where the most widely implemented intervention—sending economically

disadvantaged students to summer school—did not lead to increases in reading achievement.

Another factor Schacter and Jo discussed in relationship to the findings in their research and

others they reviewed was an attrition rate. This was related to the mobility rate reported by the

elementary schools that were involved in the various studies.

Among the more recent and notable studies related to access to books and other literacy

materials are those by Susan Neuman. Neuman and her colleague Donna Celano report that the

achievement gap is not rooted in the classroom but in the learning that children do outside the

classroom, including time after school, weekends, holidays, and summer breaks. That gap was

found to be wider in poor neighborhoods that have little access to information. They found that

“book availability for middle-class children was about 12 books per child; in poor neighborhoods,

about 1 book was available for every 355 children.”

9

They also found that even when children

are given equal access to books, computers, and other information sources, children in low-

socioeconomic neighborhoods do not use materials the same way that children in more

affluent areas do. They contend that “the nation’s public libraries fill a tremendous need by

providing print, computers, and other materials to many underserved populations.”

10

14 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

6

Heyns, 168.

7

Heyns, 172.

8

John Schacter and Booil Jo, “Learning When School is Not in Session: A Reading Summer Day-Camp Intervention to Improve the

Achievement of Exiting First-Grade Students Who are Economically Disadvantaged,”

Journal of Research in Reading

28, no. 2

(May 2005): 158-169.

9

Donna Celano and Susan B. Neuman, “When Schools Close, the Knowledge Gap Grows,”

Phi Delta Kappan

(December 2009): 258.

10

Celano and Neuman, 258.

literature search

15

During their observations, Celano and Neuman found that “for every one line of print read by

low-income children, middle-income children read three.”

11

They also observed that while poor

and wealthier children can have equal access and spend equal time with information sources

such as books and computers while visiting public libraries during the summer, how they use

and interact with these materials differ greatly: “Poor children use books with less print and,

therefore, less information. They use the computer for more entertainment functions, rather

than information-gathering activities. In addition, as they use resources, they receive less

support from important mentors—parents, advisors, peers—who could scaffold and help them

absorb information.”

12

In addition, Neuman and Celano witnessed that the disparity between these socioeconomic

groups was greatest during the summer. They contend that public libraries are part of the

solution to solve this disparity. Part of the solution, according to Neuman and Celano, is to

“provide more opportunities for kids to be engaged during summers because, without these

opportunities, so much is lost.”

13

In 2008, Thomas G. White and James S. Kim designed and implemented a voluntary summer

reading program for third-, fourth-, and fifth-grade students. The study provided books and

encouraged silent and oral reading over the summer. White and Kim state: “Engagement with

text is the necessary first step if we want to improve reading skills when school is not in session

or prevent a decline in reading achievement that might otherwise occur.”

14

One of the experiments that White and Kim designed was comprised of groups of students in

grades three through five that received various levels of intervention (i.e. postcards or letters

to parents with suggestions for interaction with their child) and one control group that did

not receive any intervention. White and Kim documented that intervention had an impact on

students’ summer reading activity. Their results also imply that “merely giving students books

is not effective and that some form of scaffolding is necessary for voluntary summer reading to

have achievement benefits.”

15

White and Kim made the following recommendations for successful summer reading programs:

provide students with at least eight books closely matched to their reading level and interests;

send a postcard with each book to remind students of what they should be doing; send a letter

to parents asking them to listen and provide feedback on their child’s reading; and ask that the

postcards be returned so leaders can see if the program is being implemented as intended.

11

Celano and Neuman, 259.

12

Celano and Neuman, 259.

13

Susan Neuman, “Income Affects How Kids Use Technology and Access Knowledge,” Research in Brief, National Center for

Summer Learning (2009).

14

Thomas G. White and James S. Kim, “Teacher and Parent Scaffolding of Voluntary Summer Reading,”

Reading Teacher

(October 2008): 116.

15

White and Kim, 124.

Another pair of researchers who have added to the understanding of achievement by children

from high- and low-income families is Stephen Krashen and Fay Shin. They state that research

indicates there is surprisingly little difference in reading gains between children from high- and

low-income families during the school year. The difference is what happens in the summer.

They note that for children from low-income families, public libraries are the only obvious

source of books during the summer, and they report a strong relationship between the amount

of reading done over the summer and if the students had easy access to books at the library.

16

Krashen and Shin collaborated on a study that compared a traditional summer school reading

instruction program with one that featured voluntary free reading, also known as recreational

reading. The Krashen/Shin summer program lasted for six weeks, which is similar to the length

of time that many public libraries run their summer library programs. However, in the researchers’

program, students were in school for four hours per day. These hours were scheduled to allow

ample time for browsing and book selection; independent recreational reading; group-based

literature instruction; creation of related artistic projects; and participation in teacher-selected

group activities.

Findings and observations from the Shin/Krashen study include that students: who were in the

recreational reading group took out more books from the library over the course of the summer;

tended to select books that were at their grade level; who were once reluctant readers and

became enthusiastic readers confirmed the importance of access and conferences with teachers;

who were enthusiastic readers said that librarians and teachers encouraged them to read and

recommended specific books; having access to interesting reading and encouraging reading

year-round is important; and can improve in reading just by reading books they find interesting.

Overall, the results strongly confirm the importance of libraries. While not every community

would be able to set up a summer reading program as intensive as the one in the Shin/Krashen

study, the researchers recommended that communities should offer all children a plentiful

supply of reading material.

17

More recent studies from the public library side include the following two evaluations of

summer reading programs. The first is a final report on the evaluation of the “Books and

Beyond…Take Me to Your Reader!” summer reading program at the County of Los Angeles

Public Library, which was designed for children in kindergarten through grade three. The goals

of the program were to give these children the opportunity to improve and retain reading skills

to achieve greater success in school, and to encourage parents to participate and take an active

role in reading with their children. The findings were that the children who participated in the

program retained their skills, read more during the following school year, and had their parents

read more to them during the program.

18

16 The Dom inican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

16

Stephen Krashen and Fay Shin, “Summer Reading and the Potential Contribution of the Public Library in Improving Reading for

Children of Poverty,”

Public Library Quarterly

23 (3/4) (2004): 99–109.

17

Fay H. Shin and Stephen D. Krashen,

Summer Reading: Program and Evidence

(Boston: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2008).

18

“Evaluation of the Public Library Summer Reading Program: Books and Beyond…Take Me to Your Reader!” final report for The

Los Angeles County Public Library Foundation (December 2001).

literature search

17

The second report is an evaluation study of the 2007 “Guys Read” summer book club program,

designed by the Hennepin County Library in Minnesota for boys in grades four through six and

available to boys in the greater Minneapolis area. The program had goals to encourage boys to

read over the summer months and beyond; to foster boys’ positive attitudes/associations with

reading; and to promote positive relationships between boys and male book club facilitators.

Key findings from the study are that boys reported that they will read more, were more likely to

read, had a more positive perception about themselves as readers, were less likely to view girls

as being better readers, and were more likely to view reading as a positive, socially constructed

process.

19

As public librarians continue having to account for summer reading programs, it is anticipated

that more studies and evaluations of their programs, like the ones cited above, will be

forthcoming. In addition, independent studies such as the Dominican study will add to the

understanding of the great importance of reading and the beneficial role public libraries play

in closing the achievement gap in reading, not just for some but for all of the nation’s children.

Most importantly, however, is the contribution such research will have toward promoting

lifelong love of reading and learning.

19

Prepared by David OʼBrien, Deborah Dillon, and Cassandra Scharber, University of Minnesota. “Making a Difference: Guys

Read 2007,” An Evaluation Study completed in collaboration with the Guys Read Staff of Hennepin County Library, the Library

Foundation of Hennepin County Library and the College of Education + Human Development at the University of Minnesota.

the dominican study

Public Library Summer Reading Programs

Close

the Reading Gap

.

.

the dominican

study

.

“The public library is the

major source of reading

material for children of

poverty during the

summer.”

— Fay H. Shin and Stephen D. Krashen,

Summer Reading: Program and Evidence, 2008.

the dominican study

21

the dominican study

method

PARTICIPANTS

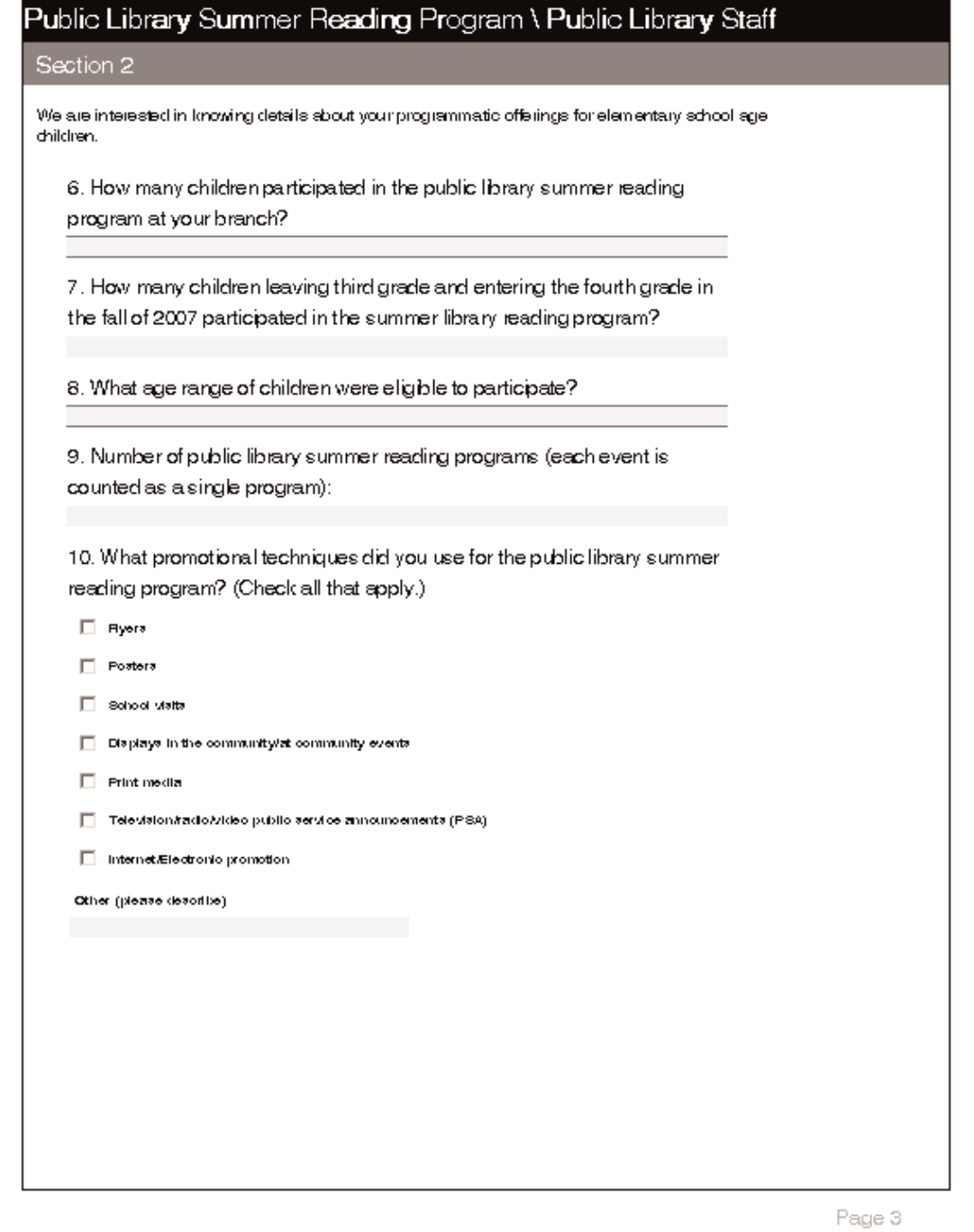

Students. A total of 367 students, attending 11 schools, returned signed parental consent forms

for program participation. All students attended one of the schools enrolled in the Dominican

study and were attending third grade during the Spring 2008 semester.

School Librarians. Nine (9) school librarians participated.

Fourth-Grade Teachers. Fifty-one (51) fourth-grade teachers participated.

Public Librarians. Eleven (11) public librarians who were partners with participating public schools

took part in the study. All librarians were working with or directing the public library summer

reading programs for elementary school-aged children.

Parents. Parents of student participants were encouraged to take part in the study. A total of

110 parents participated.

SETTINGS

Eleven schools and public library partners originally joined the study. Schools and public

library partners were located across the continental United States in the states of Oregon,

Colorado, Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky, Virginia, Mississippi, and Minnesota.

Schools. Eligible schools were required to meet the following inclusion criteria (a) the entire

school population had to have 50% or more students who qualified for free and reduced meals

(FARM), a common measure for children living in poverty, (b) at least 85% of the school population

were not limited English proficiency and were able to be assessed for reading using English-

language reading software, (c) they had to agree to distribute an Dominican study summer

library reading log to students, and (d) they had to sign a memorandum of understanding

(MOU) with a local public library. Schools that agreed to participate and met inclusion criteria

were given the incentive of a free software and site license for the computer-administered

Scholastic Reading Inventory (SRI) Enterprise Version.

Public Libraries. Partner libraries were required to meet the following inclusion criteria (a) offer

a free public library summer reading program with curriculum content of their choice, (b) agree

to send librarians to the partner school to promote the public library summer reading program

at the end of the 2008 school year, (c) encourage students to complete a Dominican study

summer reading logs, (d) provide a summer reading program for a minimum of four weeks, and

(e) sign a MOU with the local partner school. Unlike their school counterparts, partner libraries

were given no incentives for participation.

INSTRUMENTS

Scholastic Reading Inventory. The Scholastic Reading Inventory (SRI) was developed by Scholastic

Inc. and is reported to be an objective assessment of a student’s reading-comprehension level

(Scholastic, 2006). The instrument was initially developed in 1999 as a print-based assessment

tool, which was redesigned in an electronic application (Version 4.0/Enterprise Edition) and was

used in this study. Test-retest reliability has been estimated to be 0.89 for grades three through

ten over a four-month period. Studies supporting the SRI (Stenner, Burdick, Sanford, and Burdick,

2006) have reported reproducible measures of reader performance independently of item author,

source of text, and occasion of measurement. Content validity of reading passages was used

during instrument development and results indicated that the instrument items were authentic

and developmentally appropriate. Because the instrument spans developmental levels, criterion-

related validity analyses also indicated reading comprehension increased rapidly during

elementary school and maintained during middle school.

Student Survey. A 22-item paper version was group administered for students to self-report

their summer reading habits and activities. This survey was created by the evaluation team

and validated with a small group of professional educators for face validity. See Appendix B

for questionnaire.

Parent Survey. Parents completed a 20-item paper survey to report their child’s summer

reading activities, expectations of benefits from a public library summer reading program, and

parent satisfaction with the public library summer reading program if their child attended. This

survey was created by the evaluation team and validated with a small group of professional

educators for face validity. See Appendix C for questionnaire.

School Librarian Survey. School-based librarians in participating schools were asked to

complete an 11-item paper survey. Librarians reported their opinions on the benefit of public

library summer reading programs. This survey was created by the evaluation team and validated

with a small group of professional educators for face validity. See Appendix D for questionnaire.

Teacher Survey. Fourth-grade teachers in participating schools were asked to complete a

11-item paper survey asking for their opinions on the benefit of public library summer reading

programs. This survey was created by the evaluation team and validated with a small group of

professional educators for face validity. See Appendix E for questionnaire.

Public Librarian Interview. A scripted-interview schedule was created by the evaluation team

that consisted of 15 questions with recommended probes. Questions asked public librarians

about their resident libraries, feeder schools, a description of the 2008 summer reading

program for grades 2–4, and their opinions on outcomes for children who attended summer

reading programs. The interviews were conducted by a professional evaluator who was a

member of the study evaluation team. See Appendix F for interview questions.

22 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

the dominican study

23

Public Librarian Survey. Public librarians who agreed to be interviewed were asked to complete

a 20-item electronic survey posted on SurveyMonkey. Public librarians were asked to report

their opinions on the benefit of public library summer reading programs. This survey was

created by the study evaluation team and validated with a small group of professional

educators for face validity. See Appendix G for questionnaire and online survey.

Summer Reading Log. Students were asked to track their summer reading hours, number of books

read, times visited the library, and number of books checked out of the public library. This log was

created by the study evaluation team. See Appendix H for basic information sheet and log.

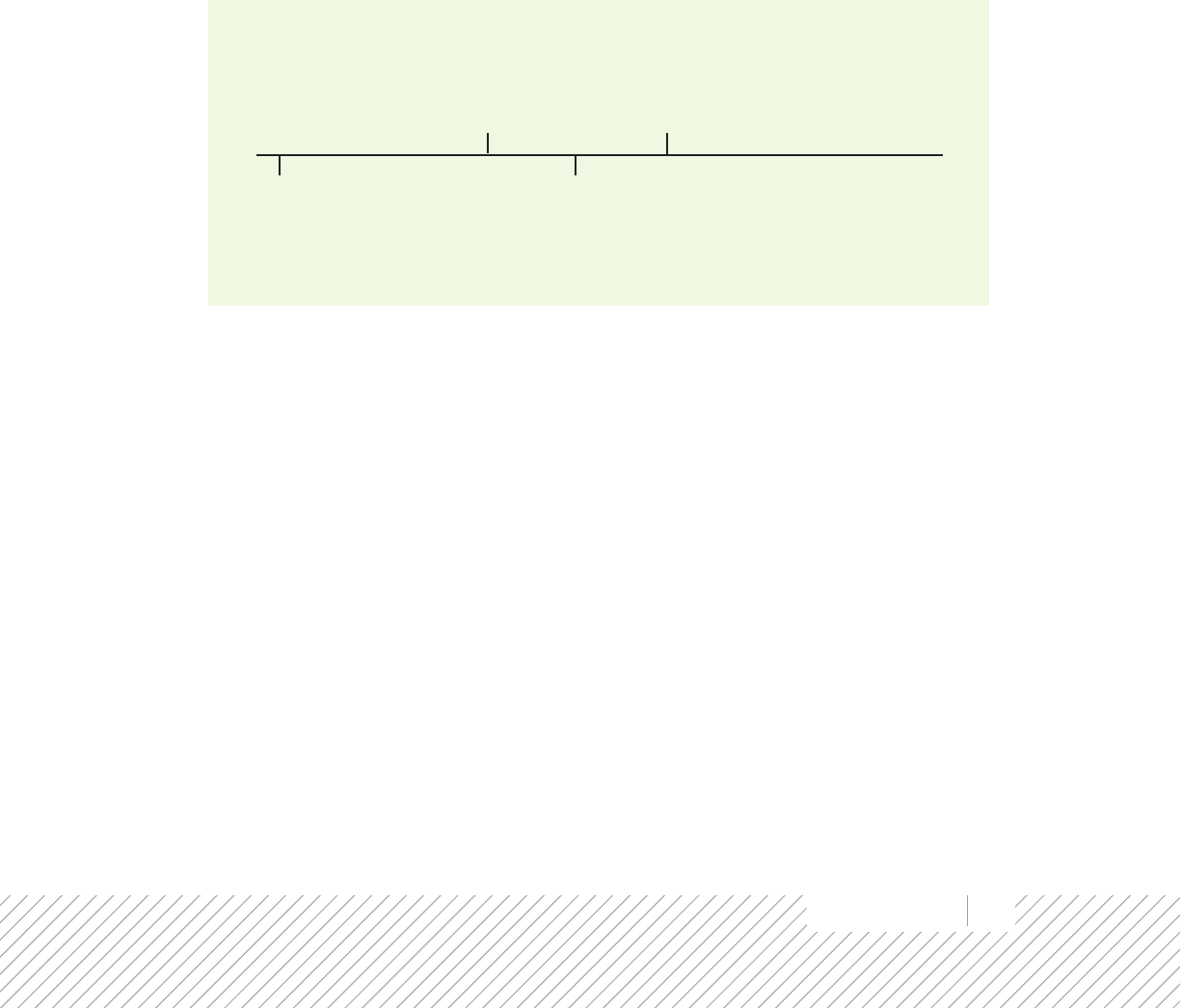

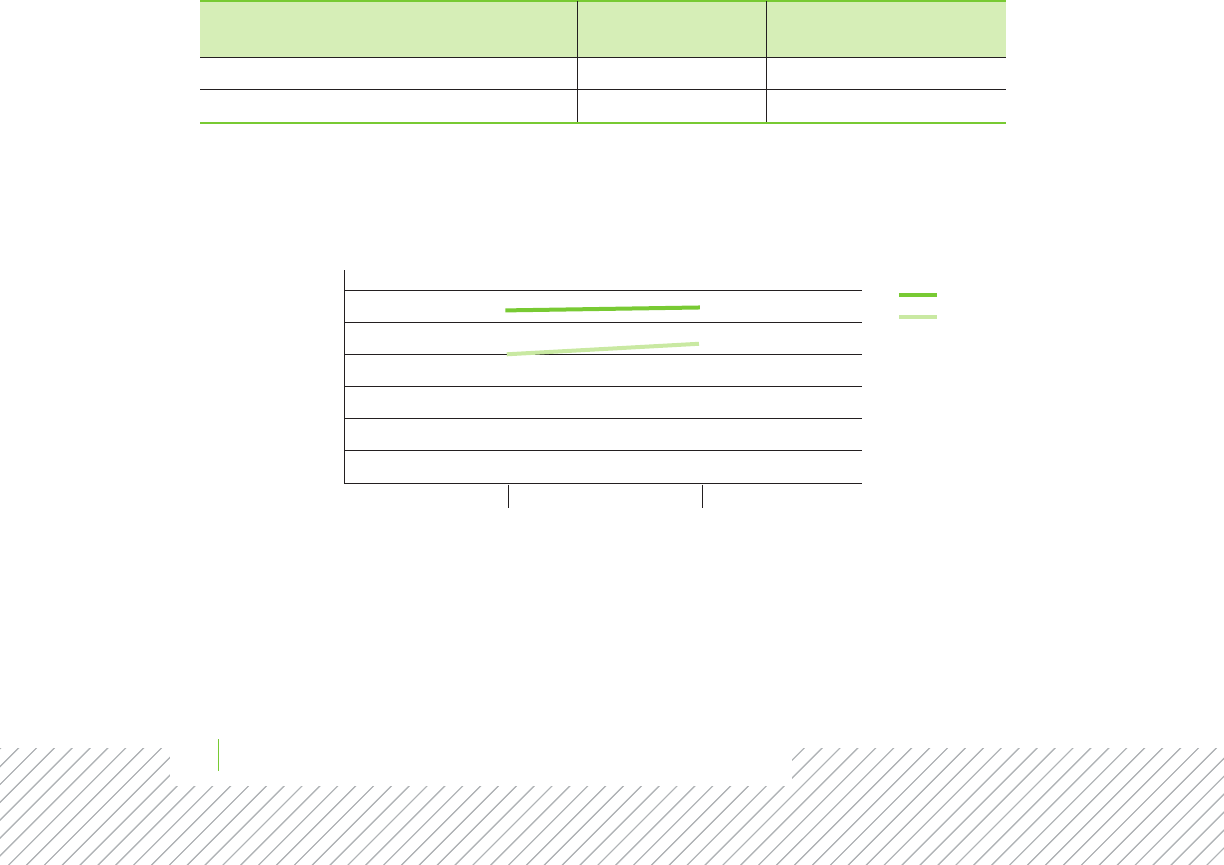

Figure 1. Dominican Study Procedure Timeline

PROCEDURE

This study occurred between Summer 2007 and Fall 2008, taking place in four time frames

(see Figure 1).

Summer/Fall 2007. During Summer 2007, the study evaluation team worked with the study’s

advisory committee on further developing evaluation questions and working through some of

the complicated issues of implementation. Several instruments were pilot-tested and several

local public library summer reading programs were consulted, including those from Palm Beach

County, Florida; El Paso, Texas; and Pueblo, Colorado. Helpful feedback from local public

libraries was incorporated into instruments and used to modify study procedures before

recruitment began.

Applications from public libraries and elementary schools were solicited during Fall 2007; public

libraries and schools across the United States were recruited to participate. See Appendix I for

school and public library application instructions. See Appendix J for school and public library

applications. Information about the program was posted on electronic professional

summer/fall 2007

I

Pilot

I

Recruitment

summer 2008

I

Public Librarian Interview

I

Public Librarian Survey

I

Summer Reading Log

spring 2008

I

Parent Consent

I

SRI Pretest

fall 2008

I

SRI Posttest

I

Student Survey

I

Parent Survey

I

Teacher Survey

I

School Librarian

Survey

announcement boards, sent to professional library and school organizations, and posted on a

study website. See Appendix K for recruitment flyers. The application deadline was October 31,

2007. A total of 26 schools and 34 libraries applied for the program, of which 18 were complete in

their required partnerships; 11 school and library partners were accepted into the study. See

Appendix L and M for the library and school privacy forms.

Spring 2008. Once library and school partners were identified, the process of parental permission

was initiated. See Appendix N for parental permission form cover letter. Participating schools were

sent packets of information to distribute to all third-grade student families. Materials consisted of

summary information about the study and a parental permission form that was required to be

signed and returned to the school; only students with signed parental consent forms were

included in the study. See Appendix O for parental permission form (in English and in Spanish.)

Contact information for study personnel, for the Johns Hopkins Homewood Institutional Review

Board, and for the Dominican University Institutional Review Board was also provided to parents

who might have had concerns or additional questions.

Schools were encouraged to initiate SRI testing in late Spring 2008 (pretest), prior to the end of

the school year. SRI scores were housed at the resident school sites. During this time, schools

were visited by the public librarians who called on the third-grade classrooms to promote the

public library summer reading program hosted by the public library. Students were encouraged

to participate in the library program and the summer reading logs were distributed to students.

Students exited third grade classrooms and their schools for summer.

Summer 2008. The public library summer reading programs were independently scheduled at

each host library and the library program curriculum selected by the host library. No constraints

were imposed on the libraries by the study in regard to content. The library programs were

authentic. Partner libraries programs were not given names of Dominican study student

participants due to issues of confidentiality. For this reason, libraries did not help track student

participants, nor did they record student attendance at summer reading programs. The student

self-report from the student surveys was used as the indicator of student summer reading

program attendance. Similarly, host libraries made decisions regarding custodial rights of the

summer reading logs: whether the library or the student retained the logs was at the discretion

of the host library. Public libraries that retained summer reading logs returned the logs to the

program office after the summer, and public libraries that did not retain the summer reading logs

told students to return logs to their fourth-grade teachers when school resumed in Fall 2008.

After the public library summer reading programs were concluded, public librarians were

contacted by the evaluation team for an interview, and they were also asked to fill out a survey

on SurveyMonkey.

24 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

the dominican study

25

Fall 2008. Students returned to school in Fall 2008 to fourth-grade classrooms. Schools were

encouraged to initiate SRI testing (posttest) within three weeks of the new school year. SRI

Spring 2008 and Fall 2008 scores were compiled at the resident school sites, along with student

demographic information, and sent to the program office. During this time, students completed

the student survey, parent surveys were distributed (sent home with students and returned), and

teachers and school librarians completed their respective surveys. All completed surveys and

program materials were returned to the program office by October 2008.

DESIGN

The design of this study was causal comparative, which is that student participants were not

randomly assigned or randomized between attending/not attending public library summer

reading programs but instead independently decided to participate or not participate. The

treatment condition of program attendance was not manipulated by the evaluation team. The

treatment condition of the study was the exposure of student participants to the public library

summer reading programs at the partner public libraries, as selected by participants’ families.

“In causal comparative research the groups are already formed and already differ in terms of

the independent variable. The difference was not brought about by the researcher” (Gay, Mills,

& Airasian, 2006, p. 218).

This naturalistic type of research did not randomly assign students to conditions nor did it

control for reading materials students accessed over the summer. This was not a quasi-

experimental study; students were not randomly assigned to groups and participation was

voluntary. We did not have a control group in this study: we chose not to assign children to a

“non-treatment” control group that would withhold participation in a public library summer

reading program. Instead we allowed participants to self-select, and the students who reported

not participating in a reading program were used as a comparison group. In this methodology,

there was no control over the quantity or quality of reading materials of students. There was no

control over what students did or read during the summer; the study allowed families to do

what they would naturally do over the summer.

results and analysis

Results will be presented for each instrument in the study, beginning with the surveys from

students, parents, teachers, and librarians. These will be followed by the librarian interviews

and conclude with the SRI results. First, we present a description of how students were

identified as public library summer reading program participants and a description of

student participants.

PUBLIC LIBRARY SUMMER READING PROGRAM PARTICIPATION

The determination of student enrollment and participation in their local public library summer

reading program was a challenge for the study. For reasons related to student confidentiality,

public libraries were not permitted to ask students enrolling in the summer reading program if

they were participating in the Dominican study. Further, student participant names could not be

released to the local public libraries for the purposes of the study to match student names on

enrollment. To identify students who did and did not participate in the summer reading

programs, the study relied on student self-report of attendance on the student survey. The

student survey was completed in school settings by 219 students and returned to the project

office. One item on this survey was used to differentiate between students who attended and

who did not attend public library summer reading programs during summer 2008. Students

were asked, “Did you join the summer reading program at the library last summer?” Yes or No.

A total of 206 students completed this item and were used to compare responses and scores for

the results.

26 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

the dominican study

27

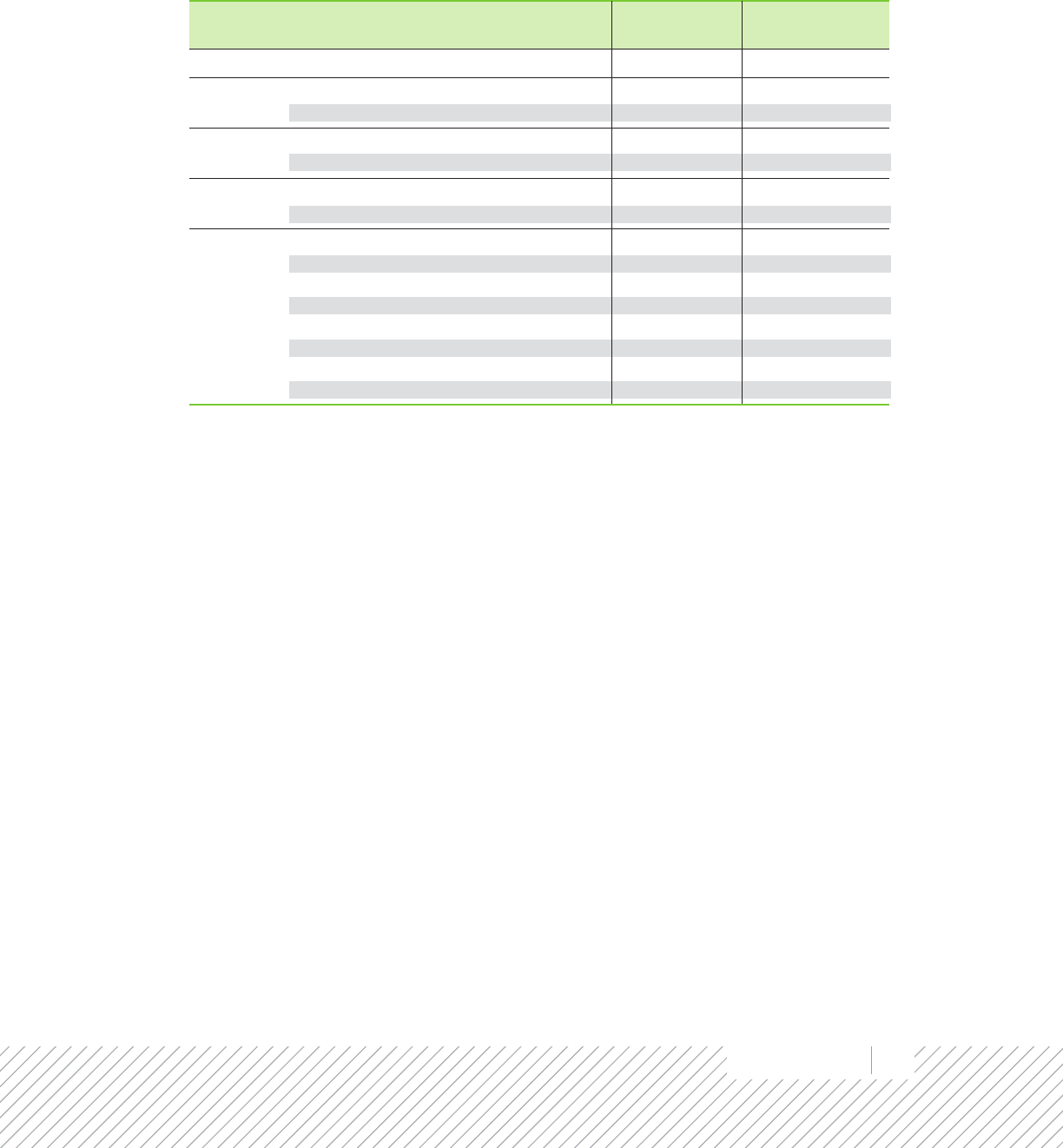

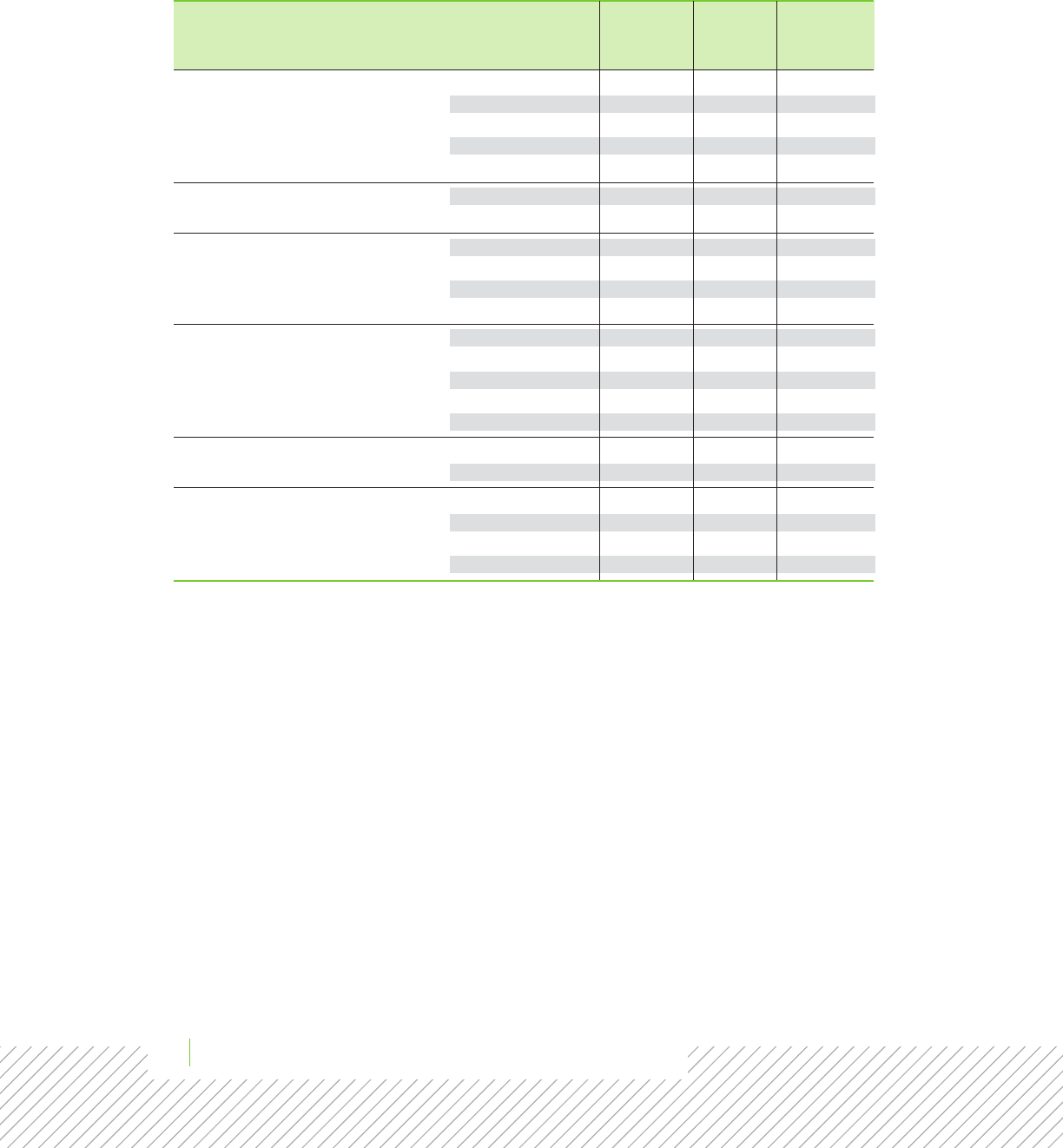

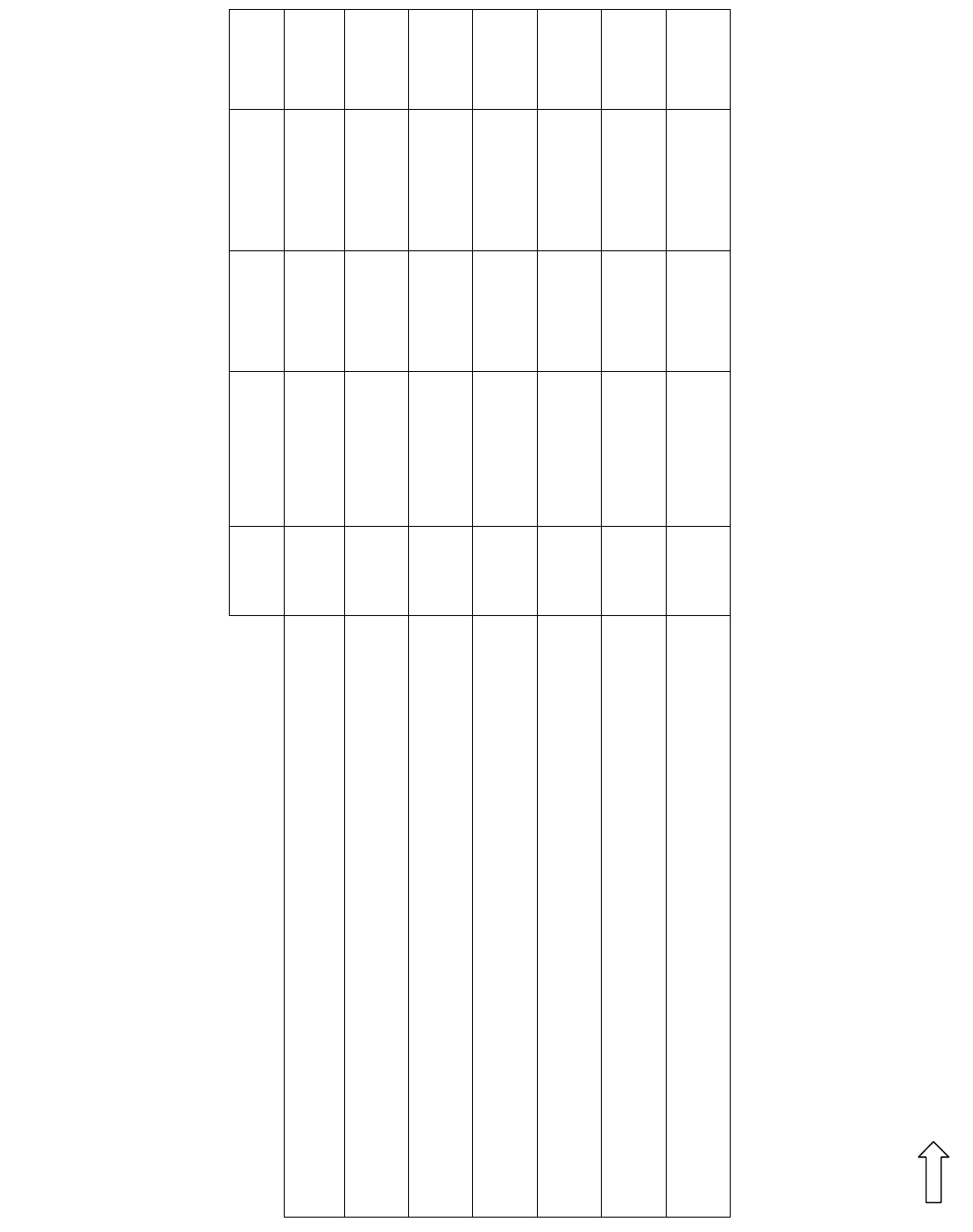

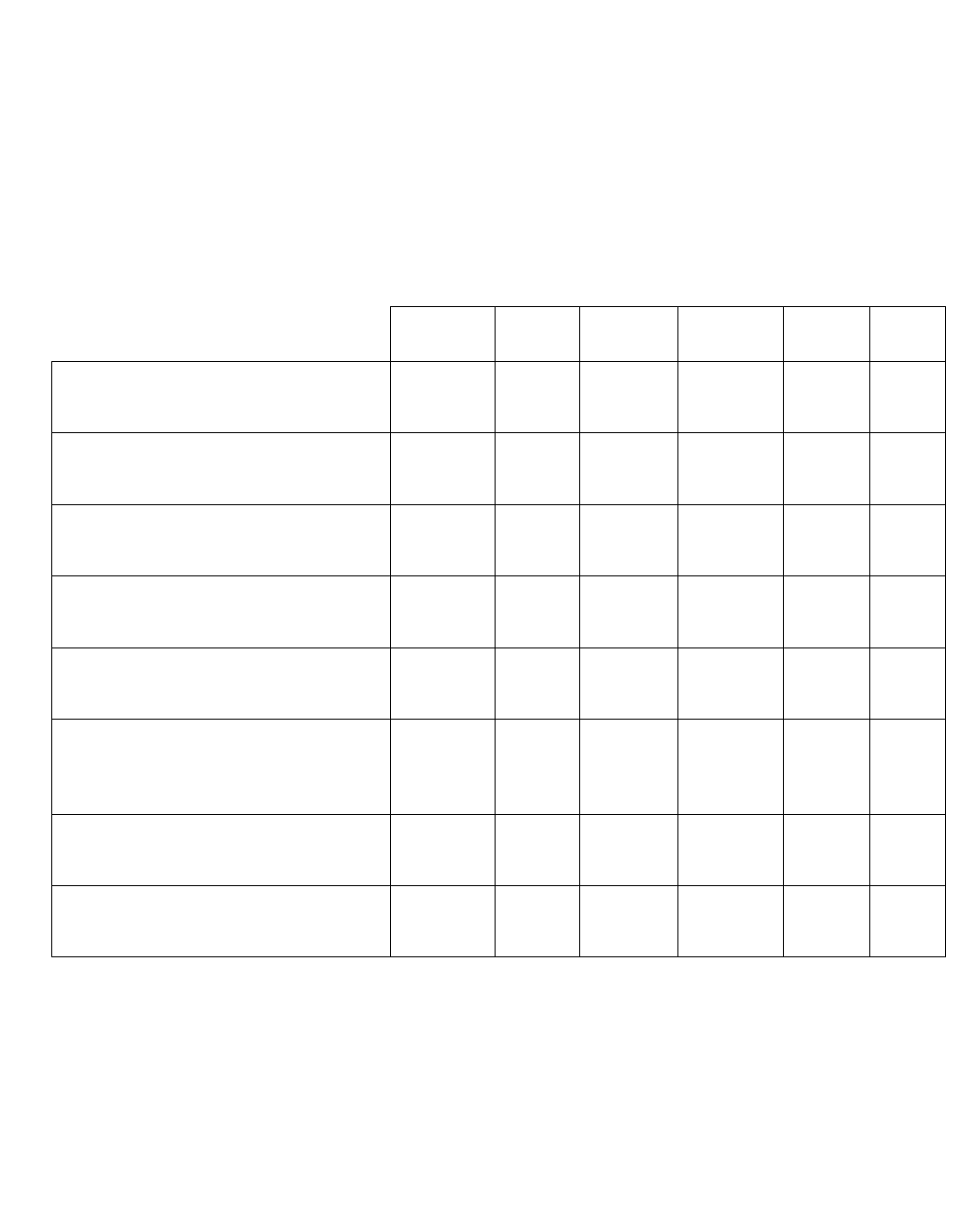

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of Total Pool of Students and Students Responding to

Survey Reported by Public Library Summer Reading Program Study Participants

Total Pool Yes: PLSRP No: PLSRP

N (%) N (%) N (%)

Participants 367 (100) 101 (100) 105 (100)

Gender Female 174 (51) 53 (54) 48 (47)

Male 166 (49) 45 (46) 54 (53)

IEP Yes 46 (14) 15 (15) 16 (16)

No 282 (86) 83 (85) 82 (84)

FARM Yes 202 (65) 51 (58) 58 (63)

No 110 (35) 37 (42) 34 (37)

Race American Indian/Alaska Native 2 (<1) 1 (1)

Asian 7 (2) 3 (3) 2 (2)

African American 116 (35) 27 (28) 35 (34)

Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander 4 (1) 0 3 (3)

Caucasian 162 (49) 61 (62) 51 (50)

Hispanic 28 (8) 2 (2) 5 (5)

Bi/Multi Racial 13 (4) 3 (3) 5 (5)

Other 4 (1) 1 (1) 1 (1)

Note: Yes: PLSRP = Yes, participated in public library summer reading program

No: PLSRP = No, did not participate in public library summer reading program

STUDENT DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics for the total pool of students who received

parental consent to participate in the study (N=367), and for the subsamples of students

(n=206) who reported participation in the pubic library summer reading program. The

demographic characteristics were provided by the schools. There were no significant

differences between students who did and did not attend the public library summer reading

programs in regard to gender, educational disabilities (IEP), socioeconomic status (free and

reduced meals—FARM), and race. Examination of Table 1 indicates that students who did not

enroll in public library summer reading programs (No: PLSRP) were more similar to the total

pool of participants. Students who did enroll in the public library summer reading programs

(Yes: PLSRP) were different from the total pool:

I

A slightly higher percentage of Yes: PLSRP students were female compared to

the total pool (54% v. 51%) with a slightly lower percentage of male (46% v. 49%)

I

A higher percentage of Yes: PLSRP students were not FARM compared to the

total pool (42% v. 35%)

I

A higher percentage of Yes: PLSRP students were Caucasian compared to the total

pool (62% v. 49%)

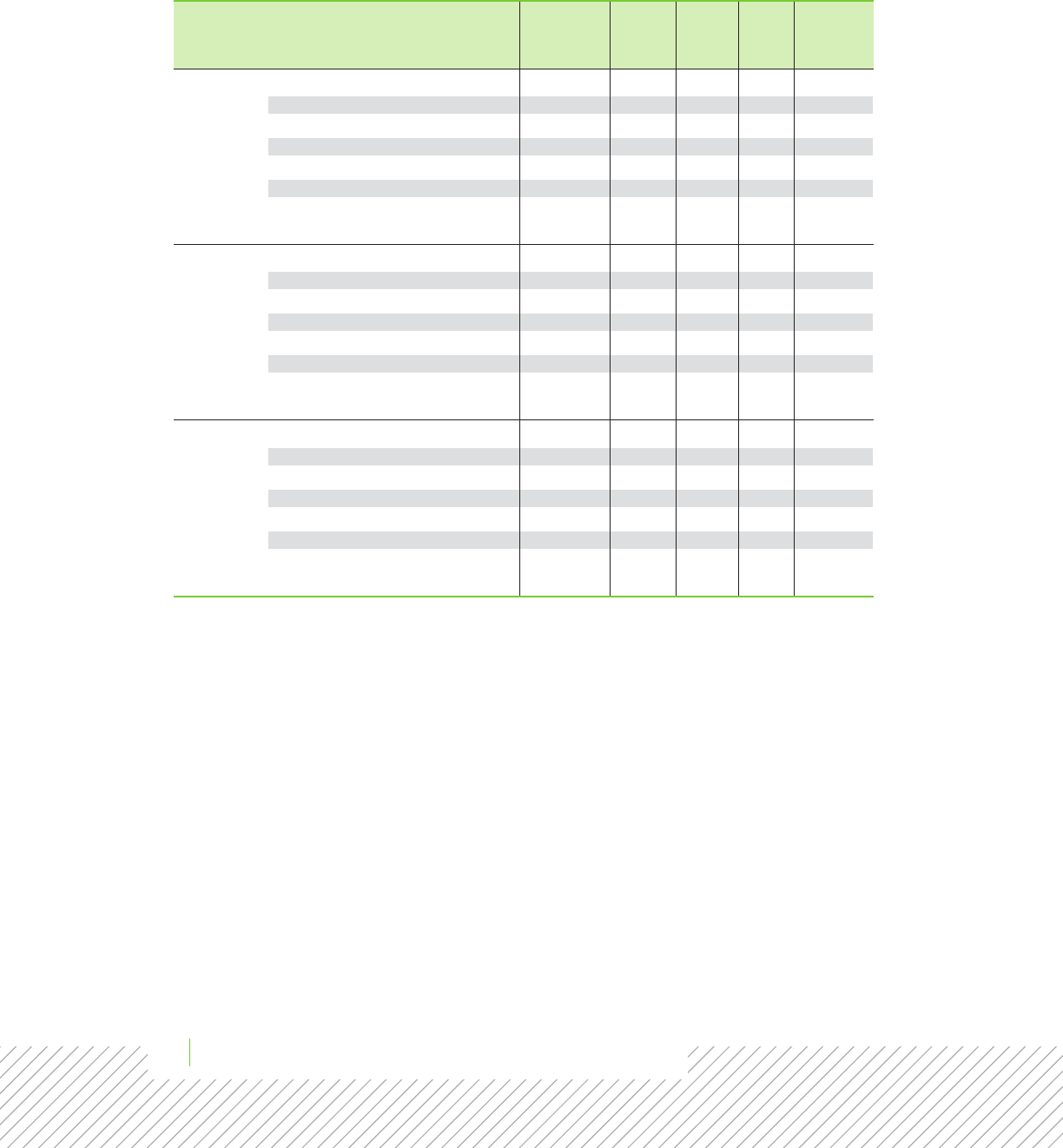

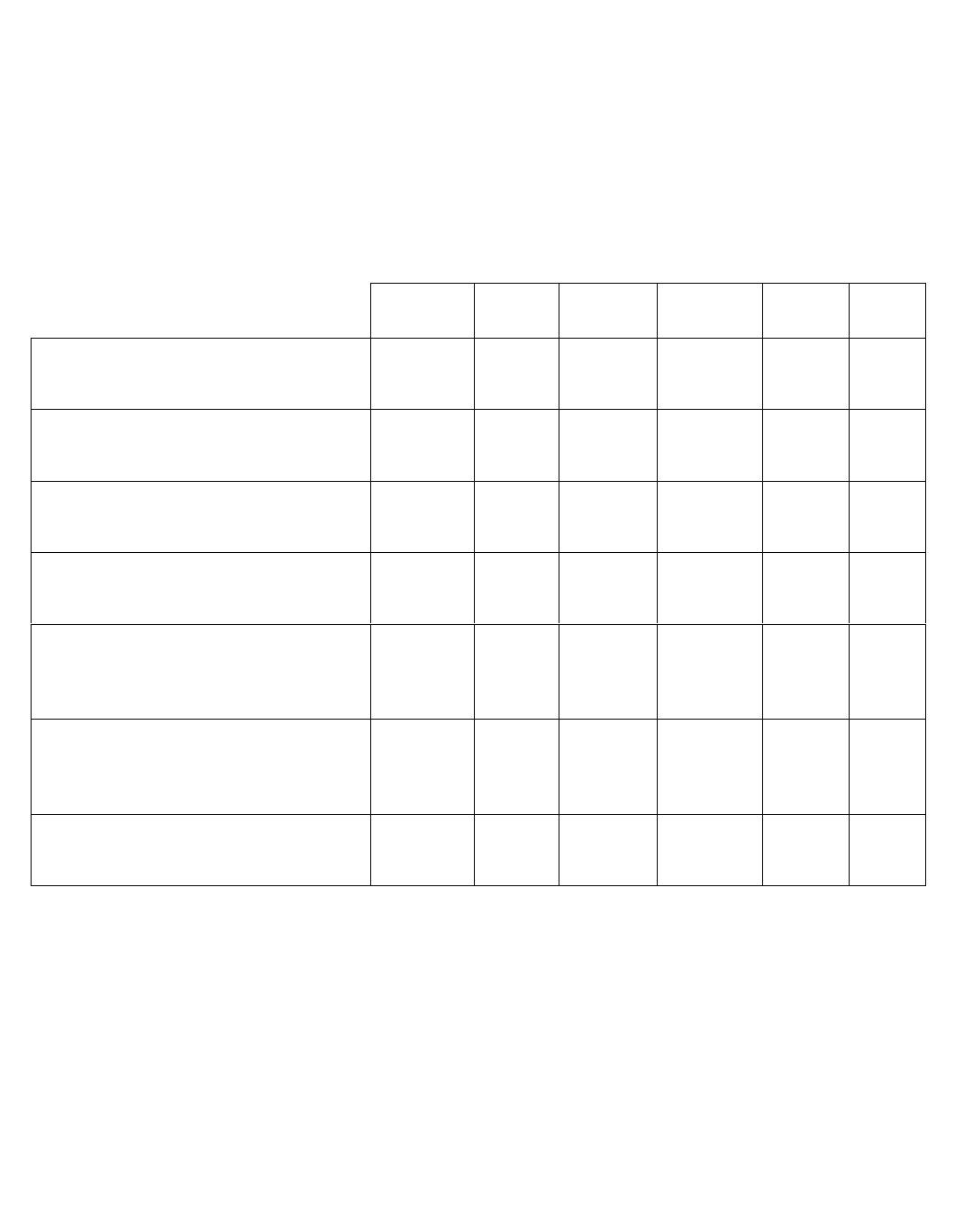

Table 2. Student Responses to Survey Items Related to Reading Habits,

Reported by Public Library Summer Reading Program Study Participants

Student Survey Item Yes Sometimes I Don’t Not No Total

Know Really

N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%)

All

I like to read books 111 (51) 93 (42) 1 (<1) 10 (5) 4 (2) 219 (100)

Respondents I like to go to the library 133 (62) 53 (25) 7 (3) 18 (8) 5 (2) 216 (100)

I remember what I read later 81 (36) 72 (34) 18 (8) 30 (14) 17 (8) 218 (100)

I know how to use the library 186 (86) 18 (8) 3 (1) 5 (3) 4 (2) 216 (100)

I pick my own books to read 158 (74) 54 (25) 0 2 (1) 0 214 (100)

I spend my free time reading 42 (20) 115 (55) 3 (1) 28 (13) 23 (11) 211 (100)

I read better now than at the 157 (72) 13 (6) 26 (12) 14 (6) 8 (4) 218 (100)

beginning of summer

Yes: PLSRP I like to read books 61 (60) 35 (35) 0 4 (4) 1 (1) 101 (100)

I like to go to the library 66 (65) 22 (22) 2 (2) 10 (10) 1 (1) 101 (100)

I remember what I read later 38 (38) 42 (41) 4 (4) 11 (11) 6 (6) 101 (100)

I know how to use the library 84 (84) 11 (11) 2 (2) 1 (1) 2 (2) 100 (100)

I pick my own books to read 77 (78) 22 (22) 00099 (100)

I spend my free time reading 22 (22) 57 (58) 1 (1) 11 (11) 8 (8) 99 (100)

I read better now than at the 75 (74) 5 (5) 14 (14) 6 (6) 1 (1) 101 (100)

beginning of summer

No: PLSRP I like to read books 42 (40) 52 (50) 1 (1) 6 (6) 3 (3) 104 (100)

I like to go to the library 59 (58) 28 (28) 5 (4) 6 (6) 4 (4) 102 (100)

I remember what I read later 35 (34) 28 (27) 12 (12) 19 (18) 9 (9) 103 (100)

I know how to use the library 90 (87) 6 (6) 1 (1) 4 (4) 2 (2) 103 (100)

I pick my own books to read 70 (69) 30 (30) 1 (1) 00101 (100)

I spend my free time reading 18 (18) 49 (49) 2 (2) 17 (17) 14 (14) 100 (100)

I read better now than at the 72 (69) 7 (7) 11 (10) 8 (8) 6 (6) 104 (100)

beginning of summer

28 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

the dominican study

29

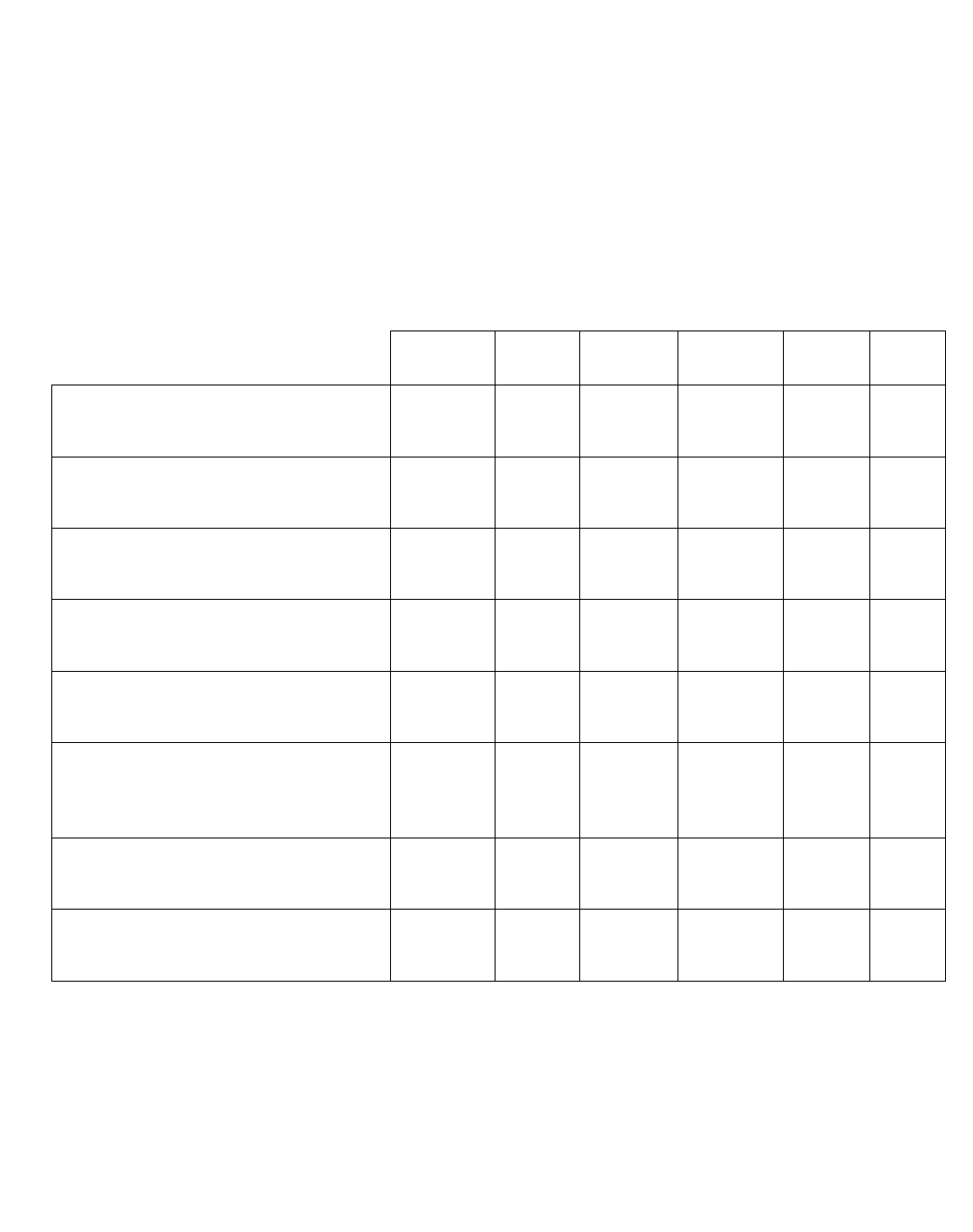

Table 3. Student Responses to Survey Items Related to Library Usage,

Reported by Public Library Summer Reading Program Study Participants

Respondents Student Survey Item Yes No Total

N (%) N (%) N (%)

All Respondents

Do you have a library card? 144 (67) 72 (33) 216 (100)

Did you join the PLSRP last summer? 73 (35) 133 (65) 206 (100)

Did you read books NOT from the library? 185 (91) 19 (9) 204 (100)

Did you read books from the library? 137 (66) 69 (33) 206 (100)

Yes: PLSRP Do you have a library card? 80 (80) 20 (20) 100 (100)

Did you join the PLSRP last summer? 51 (50) 50 (50) 101 (100)

Did you read books NOT from the library? 89 (90) 10 (10) 99 (100)

Did you read books from the library? 72 (73) 27 (27) 99 (100)

No: PLSRP Do you have a library card? 54 (53) 48 (47) 102 (100)

Did you join the PLSRP last summer? 20 (20) 80 (80) 100 (100)

Did you read books NOT from the library? 92 (92) 8 (8) 100 (100)

Did you read books from the library? 63 (62) 39 (38) 102 (100)

Table 4. Student Responses to Survey Items about Summer Reading Materials and

Activities, Reported by Summer Library Reading Program Study Participants

Yes: PLSRP No: PLSRP Total

N (%) N (%) N (%)

What else did you read this summer?

Magazines 46 (55) 38 (45) 84 (28)

Comic books 34 (45) 42 (55) 76 (25)

Newspapers 21 (57) 16 (43) 37 (12)

Websites 23 (48) 25 (52) 48 (16)

Other 23 (40) 35 (60) 58 (19)

What activities did you do this summer?

Family Trip 63 (52) 57 (48) 120 (27)

Video Games 49 (44) 63 (56) 112 (25)

Watch TV 60 (53) 54 (47) 114 (26)

Summer Camp 28 (54) 24 (46) 52 (12)

Museum 24 (52) 22 (48) 46 (10)

Note: Multiple Response Items, Total Based on Total Responses

STUDENT SURVEY

When students returned to school in Fall 2008 they were administered the student survey that

asked students to recall their summer reading habits and activities. A total of 219 surveys were

returned to the project (note: 206 students responded to the survey item differentiating summer

library participation). Summary results are presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Student reading habits are reported in Table 2. A higher percentage of students who

participated in the summer reading programs (Yes: PLSRP) reported they definitely liked to read

books, liked to go to the library, and picked their own books to read compared to students who

did not participate in the summer reading program. More students who participated in the

summer library program also reported they definitely or sometimes spent their free time

reading (80%) compared to the students who did not participate (No: PLSRP) (67%).

Student library usage is reported in Table 3. Compared to students who did not participate in

a summer reading program, a greater percentage of students who participated in a summer

reading program (Yes: PLSRP) had library cards, had joined a public library summer reading

program in past summers, and read books from the library.

Table 4 presents comparative results of student-reported summer reading materials and

activities. Students who attended a public library summer reading program (Yes: PLSRP)

reported reading more magazines and newspapers, watching TV, and attending summer camp;

students who did not attend a summer reading program (No: PLSRP) reported reading more

comic books and spending the summer playing video games.

PARENT SURVEY

When students returned to school in Fall 2008 the school sent home surveys for parents to

complete that asked parents to recall their child’s summer reading habits and activities. A total

of 110 surveys were returned to the project. Summary results are presented in Tables 5 and 6.

30 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

the dominican study

31

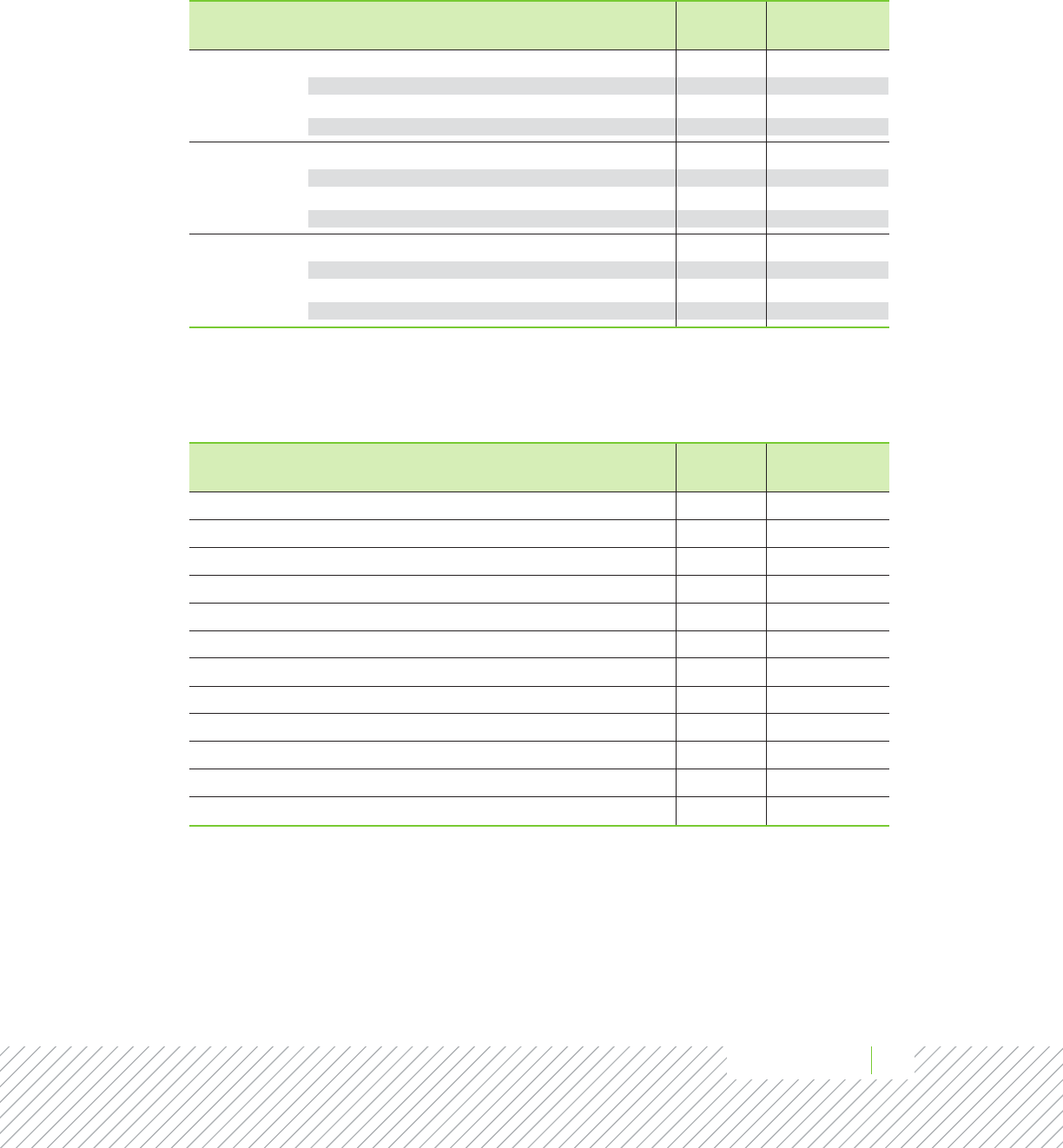

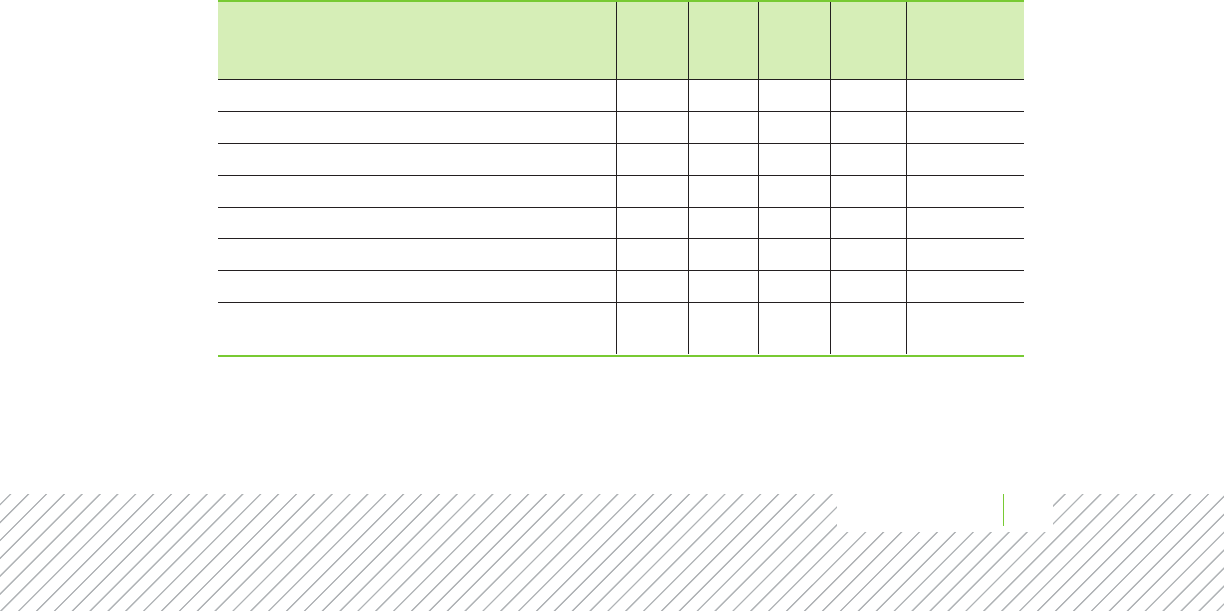

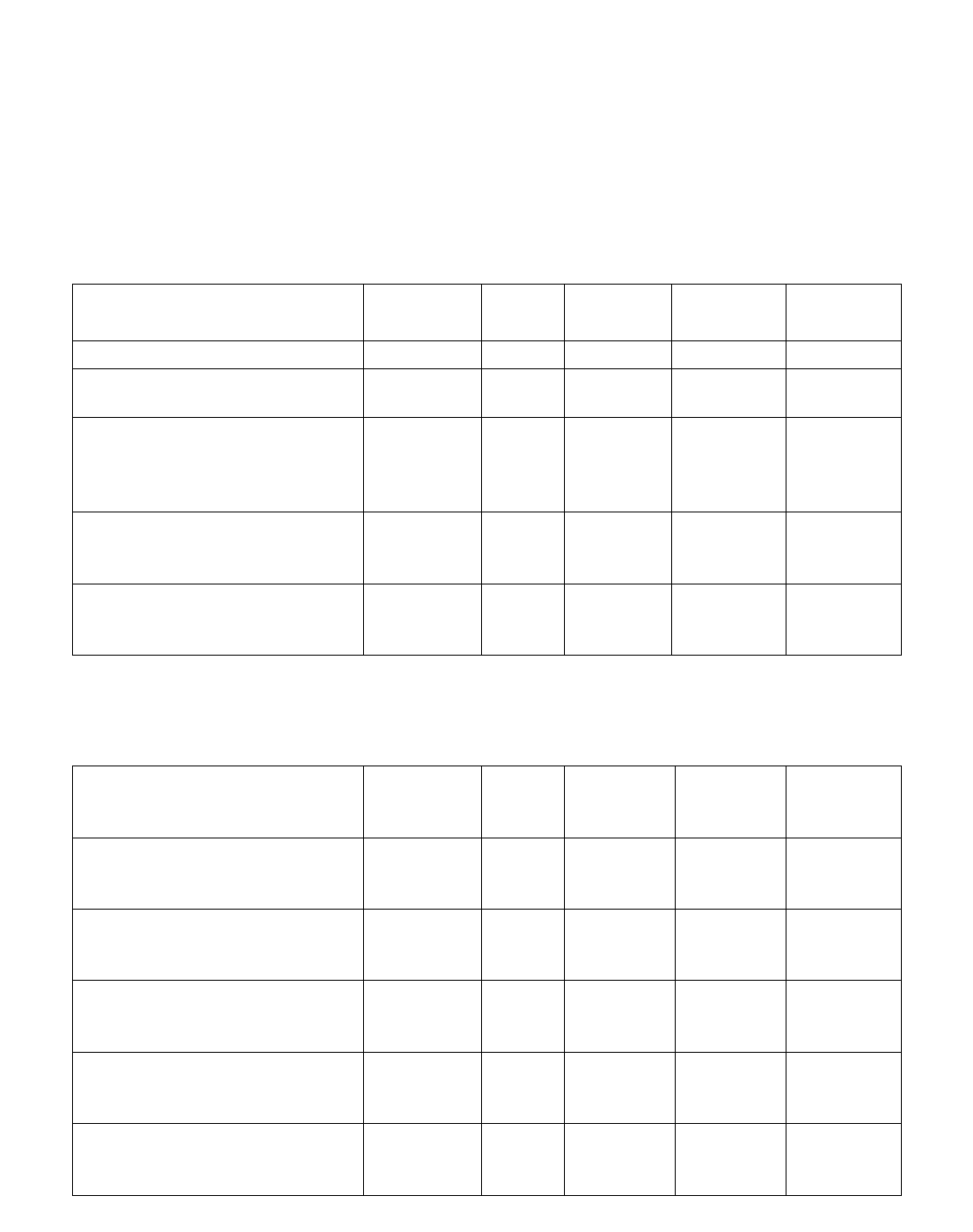

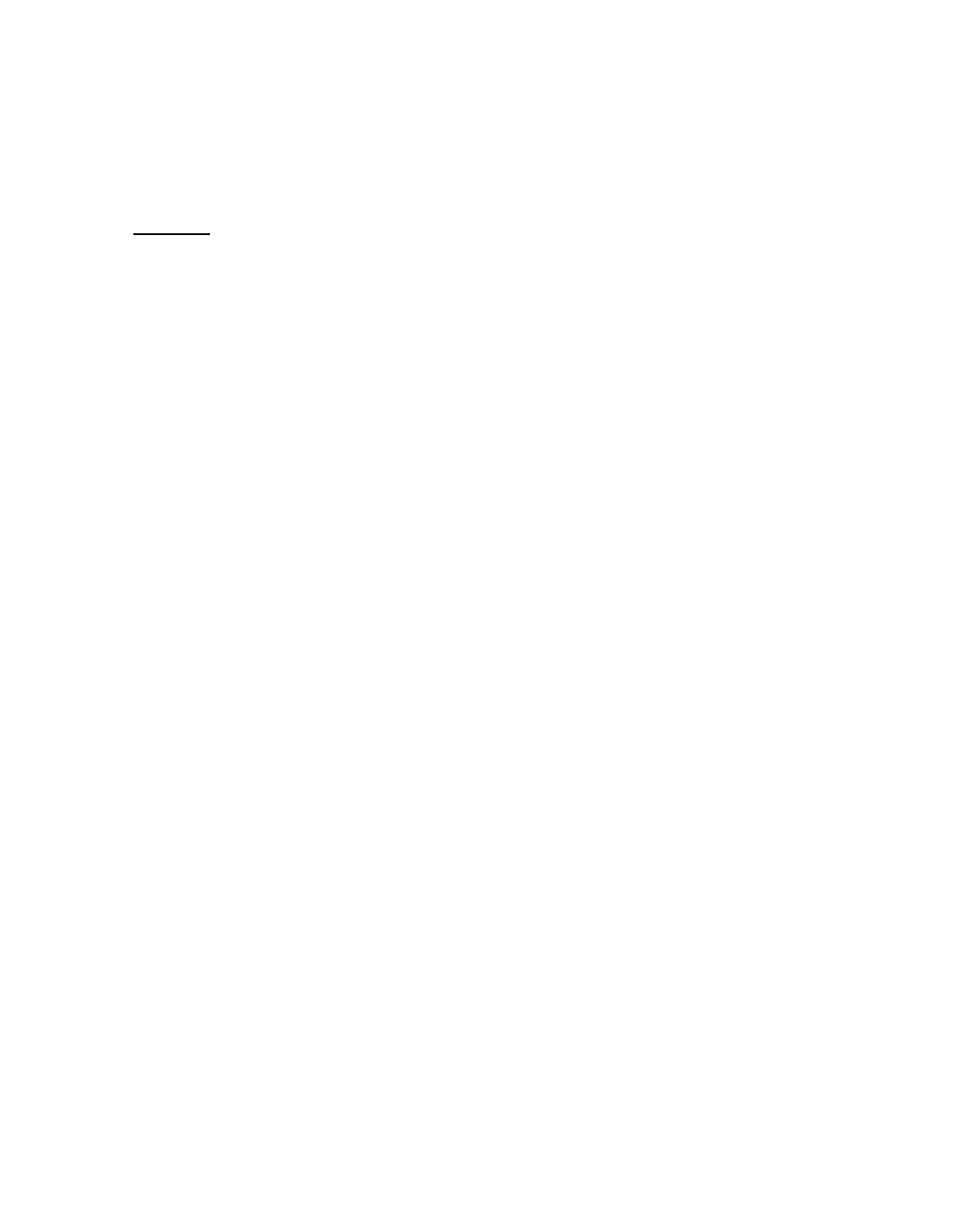

Table 5. Parent Responses to Survey Items about Child’s Reading Habits and the Public Library Summer

Reading Program Attended,* Reported by Public Library Summer Reading Program Study Participants

Parent Survey Item Strongly Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Total

Agree Disagree

N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%) N (%)

All

My child likes to read 47 (43) 34 (31) 16 (14) 7 (6) 6 (6) 110 (100)

Respondents My child spends free time reading 23 (21) 31 (28) 30 (27) 18 (16) 8 (7) 110 (100)

My child forgot over summer and 3 (3) 27 (25) 38 (35) 35 (32) 6 (6) 109 (100)

needed review

My child is well prepared for school 26 (24) 48 (44) 31 (28) 3 (3) 2 (2) 110 (100)

this fall

My child is better prepared this fall 16 (15) 31 (28) 48 (44) 13 (12) 1 (1) 109 (100)

No: PLSRP My child likes to read 13 (30) 19 (43) 7 (16) 3 (7) 2 (4) 44 (100)

My child spends free time reading 8 (18) 6 (14) 17 (39) 9 (20) 4 (9) 44 (100)

My child forgot over summer and 1 (2) 9 (20) 18 (41) 15 (34) 1 (2) 44 (100)

needed review

My child is well prepared for school 0 9 (20) 23 (52) 11 (25) 1 (2) 44 (100)

this fall

My child is better prepared this fall 8 (19) 15 (35) 15 (35) 5 (12) 0 43 (100)

Yes: PLSRP My child likes to read 28 (60) 8 (17) 7 (15) 3 (6) 1 (2) 47 (100)

My child spends free time reading 11 (23) 21 (45) 8 (17) 5 (11) 2 (4) 47 (100)

My child forgot over summer and 2 (4) 14 (30) 11 (24) 16 (35) 3 (6) 46 (100)

needed review

My child is well prepared for school 14 (30) 18 (38) 11 (23) 2 (4) 2 (4) 47 (100)

this fall

My child is better prepared this fall 7 (15) 9 (19) 24 (51) 6 (13) 1 (2) 47 (100)

My child read more books because 10 (27) 10 (27) 10 (27) 6 (16) 1 (3) 37 (100)

of the PLSRP*

My child read more often because 3 (8) 10 (27) 14 (38) 9 (24) 1 (3) 37 (100)

of the PLSRP*

The PLSRP helped my child be 5 (14) 13 (35) 14 (38) 4 (11) 1 (3) 37 (100)

more prepared*

The PLSRP helped my child read 4 (11) 14 (38) 15 (40) 3 (8) 1 (3) 37 (100)

more confidently*

We felt welcome at the PLSRP* 14 (38) 19 (51) 4 (11) 0037 (100)

I will enroll my child again in 22 (60) 11 (30) 4 (11) 0037 (100)

the PLSRP*

*Note: Only parents with a child attending a public library summer reading program responded to these items.

Table 6. Parent Responses to Survey Items about Home Literacy Indicators,

Reported by Public Library Summer Reading Program Study Participants

Parent Survey Item Response Total Yes: No:

PLSRP PLSRP

N (%) N (%) N (%)

N Library visits with child during summer None 18 (18) 3 (7) 10 (27)

1 or 2 10 (10) 3 (7) 5 (14)

2 or 3 14 (14) 4 (9) 7 (19)

3 or 4 11 (11) 4 (9) 5 (14)

more than 4 46 (46) 31 (68) 10 (27)

Read book to/with child over summer Yes 76 (78) 37 (84) 25 (69)

No 21 (22) 7 (16) 11 (31)

N times read to child per week 1 or 2 31 (40) 13 (36) 12 (46)

2 or 3 19 (25) 10 (28) 7 (27)

3 or 4 8 (10) 4 (11) 2 (8)

more than 4 19 (25) 9 (25) 5 (19)

N books at home less than 5 2 (2) 1 (2) 1 (3)

5 to 10 7 (7) 3 (6) 4 (11)

10 to 25 11 (11) 4 (9) 5 (14)

25 to 50 18 (18) 5 (11) 8 (22)

more than 50 62 (62) 33 (72) 19 (51)

Child has internet access at home Yes 71 (72) 32 (71) 27 (75)

No 27 (28) 13 (29) 9 (25)

Child's reading ability this year Exceptional 30 (30) 14 (30) 11 (31)

Above Grade 41 (41) 22 (48) 14 (39)

At Grade 23 (23) 9 (20) 8 (22)

Below Grade 5 (5) 1 (2) 3 (8)

Parent responses to questions on student reading habits are reported in Table 5. Parents of

students who participated in a summer reading program (Yes: PLSRP) reported their children

spent more time reading over the summer (65% agree or strongly agree) compared to parents

of students who did not participate in a summer reading program (32% agree or strongly

agree). Parents of students who participated in a summer reading program also had a different

view of their child’s readiness for school in the fall compared to the parents of students who did

not participate (No: PLSRP). Parents of students in a summer reading program felt their children

needed a review over the summer (34% agree or strongly agree v. 22% No: PLSRP) but also felt

that their child was well prepared for school in the fall (68% agree or strongly agree v. 20% No:

PLSRP); not one parent of a child who did not attend the public library summer reading

program strongly agreed that their child was well prepared for school in the fall. However, more

parents of children who did not attend public library summer reading programs agreed or

strongly agreed (54%) that their child was ‘better’ prepared for school in the fall compared to

parents whose children attended the public library summer reading programs (34%).

32 The Dominican Study: Public Library Summer Reading Programs Close the Reading Gap

the dominican study

33

Table 5 also presents parent responses to items targeting efficacy of the public library summer

reading programs. Nearly 50% of parents agreed or strongly agreed that because of the summer

reading programs their child read more books, was better prepared for school in the fall, and

read more confidently. There was no consensus from parents as to whether their child read more

often because of the public library summer reading program; responses were nearly evenly split

among agree, neutral, and disagree. Positive responses to the summer reading programs were

reported by parents, with nearly 90% of parents reporting that they felt welcome at the summer

reading programs and would enroll their child again.

Home literacy indicators are presented in Table 6. Parents of children who attended summer

reading programs reported more library visits made during the summer with their child (more

than 4 visits, 68%) compared to parents of students who did not attend summer reading

programs (27%). Parents of children who attended summer reading programs also reported

more often reading books to/with their child and more times during the week over the summer,

and they had more books in their home (more than 50 books, 72%) compared to parents of

children who did not attend summer reading programs (51%). While parents in both groups

similarly reported their children reading ability to be at grade, above grade, or exceptional,

more children in summer reading programs were reported to be above grade level.

TEACHER SURVEY

Fifty-one (51) teachers from 72.7% of participating schools completed the teacher survey in Fall

2008. All responses were submitted and entered into an Excel database for analysis. Seven

teachers (13.7%) reported teaching for 1–2 years, 11 teachers (21.6%) reported teaching for 3–5

years, five teachers (9.8%) reported 6–10 years of experience, 19 teachers (37.3%) reported

11–20 years of experience, eight teachers (15.7%) reported 20–30 years of experience, and one

teacher (2%) reported 30+ years of experience. Twelve teachers (23.5%) reported having a

bachelor’s degree, 15.7% (n=8) reported having completed some graduate school, and 56.9%

(n=29) reported having a master’s degree or higher.

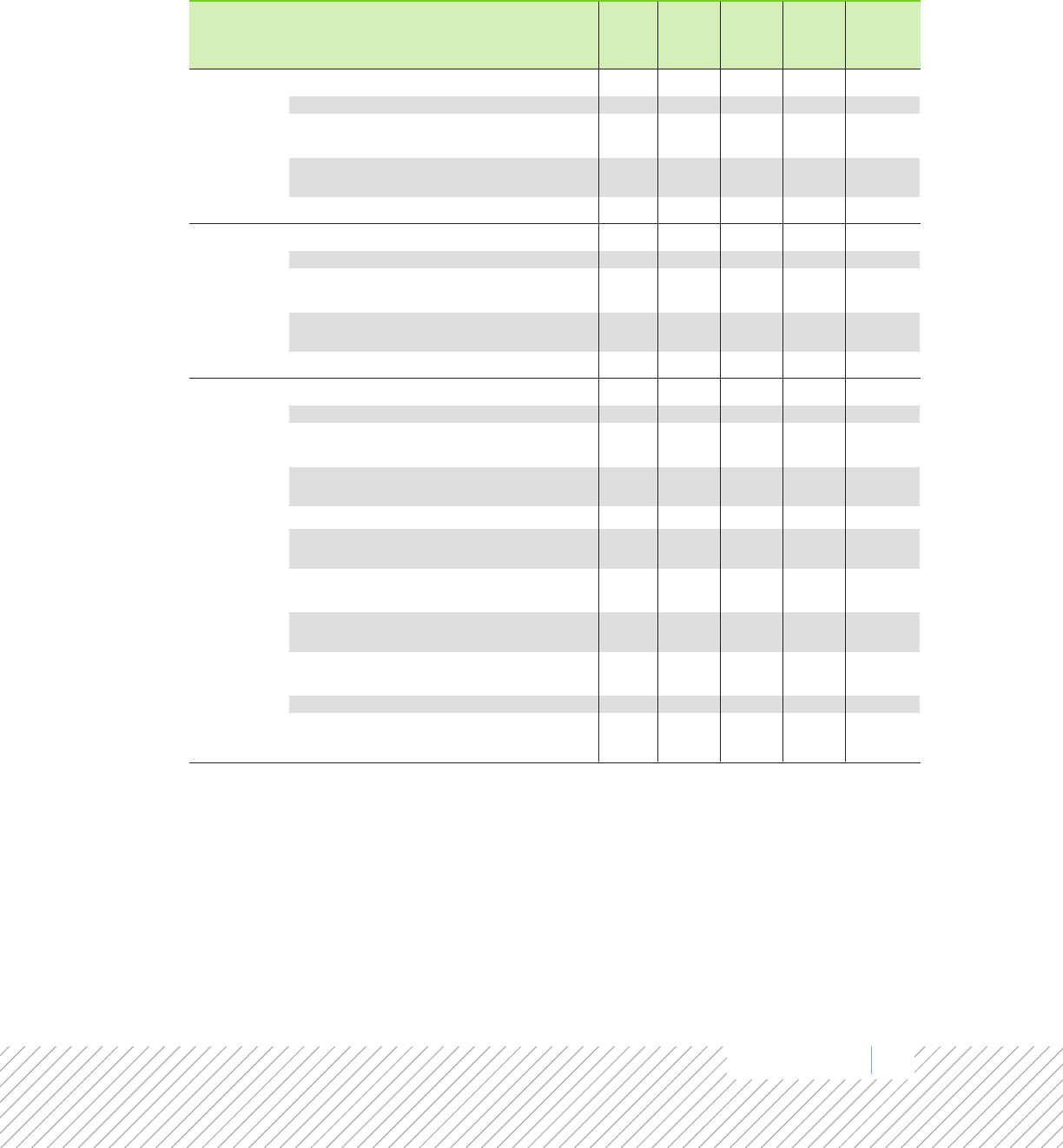

Table 7. Teacher Survey Responses to Items Related to Academic and

Reading Habits of Students who Attended Public Summer Library Reading Programs

Strongly Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Don’t

Agree Disagree Know

N(%) N(%) N(%) N(%) N(%) N(%)

Returned to school ready to learn 13(25.5) 28(54.9) 8(15.7) 002(3.9)

Improved reading achievement and skills 28(54.9) 18(35.3) 3(5.9) 002(3.9)

Increased reading enjoyment 26(51) 23(45.1) 2(3.9) 000

Were more motivated to read 26(51) 18(35.3) 7(13.7) 000

Were more confident in classroom 19(37.3) 17(33.3) 10(19.6) 1(2) 1(2) 2(3.9)

Read beyond required reading 18(35.3) 22(43.1) 9(17.6) 1(2) 00

Perceived reading as important 23(45.1) 26(51) 2(3.9) 000

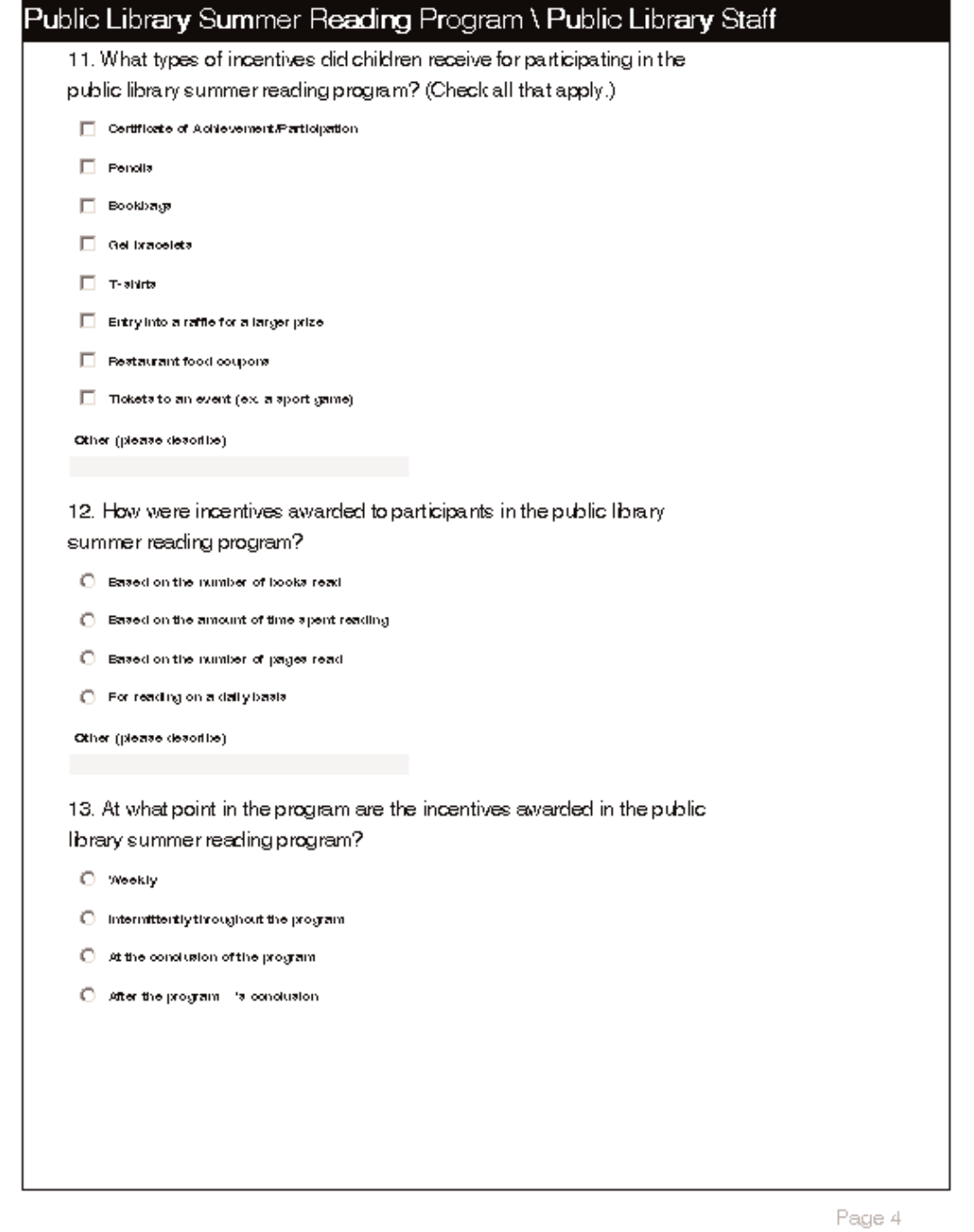

Teacher survey responses are presented in Table 7. Teachers mostly responded favorably to the

effect public library summer reading programs had on their students’ reading skills and habits.

Teachers strongly agreed, agreed, or were neutral when asked if students who participated in

public library summer reading programs were more motivated to read, had an increase in

reading enjoyment, and perceived reading as important. Eighty percent (80%) of teachers

agreed or strongly agreed that students who participated in public library summer reading

programs returned to school ready to learn and that these students read beyond what was

required in class. In addition, 90% agreed or strongly agreed that students who participated in

public library summer reading programs were more confident in classroom reading activities.

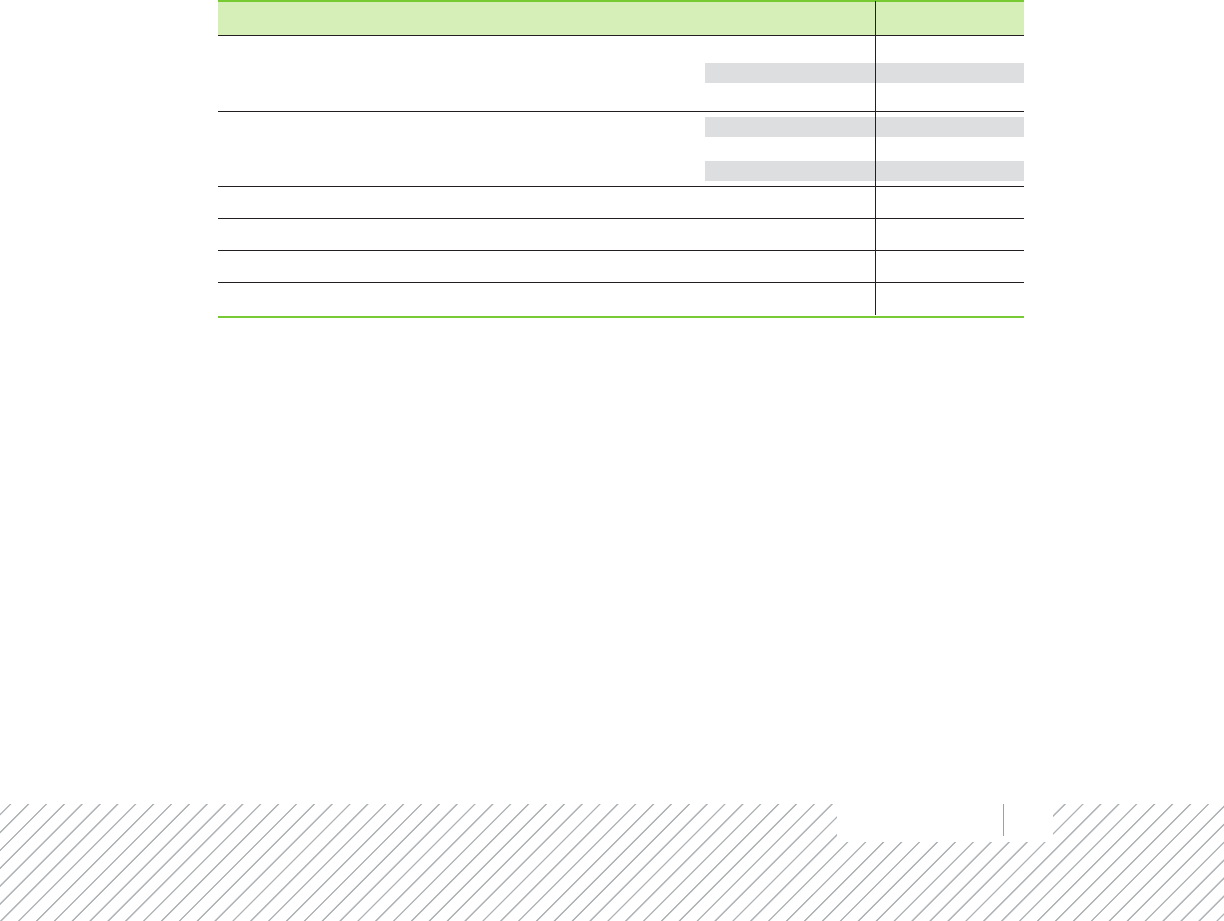

SCHOOL LIBRARIAN SURVEY

Five (5) school librarians completed the school librarian survey in Fall 2008, 45% of participating

schools. All responses were submitted to the project and entered into an Excel database for

analysis. One librarian (20%) reported being a librarian for 1–2 years, two librarians (40%)

reported 6–10 years of experience, and two librarians (40%) reported 20–30 years of experience.

One school librarian (20%) reported having a high-school degree and the rest (80%) reported

having a master’s degree or more.

School librarian survey responses are presented in Table 8 and were very favorable concerning

the impact of public library summer reading programs on student reading skills and habits.

Results indicate that all librarians agreed or strongly agreed that students who participated in a

public library summer reading program returned to school ready to learn with improved literacy

skills, were more motivated to read, and viewed reading as an important skill. Eighty percent

(80%) agreed/strongly agreed that students who participated in a public library summer reading

program also demonstrated more confidence in participating in classroom reading activities.

Table 8. School Librarian Survey Responses to Items Primarily Related to Academic and

Reading Habits of Students who Attended Public Library Summer Reading Programs

Strongly Agree Neutral Disagree Strongly Don’t

Agree Disagree Know

N(%) N(%) N(%) N(%) N(%) N(%)

Returned to school ready to learn 3 (60) 2 (40) 0000

Improved reading achievement and skills 4 (80) 1 (20) 0000

Increased reading enjoyment 4 (80) 1 (20) 0000

Were more motivated to read 3 (60) 2 (40) 0000

Were more confident in classroom 2 (40) 2 (40) 1 (20) 000

Read beyond required reading 2 (40) 2 (40) 0001 (20)

Perceived reading as important 3 (60) 2 (40) 0000