The University of Southern Mississippi The University of Southern Mississippi

The Aquila Digital Community The Aquila Digital Community

Honors Theses Honors College

Spring 5-2013

U.S. GAAP Versus IFRS: Reconciling Revenue Recognition U.S. GAAP Versus IFRS: Reconciling Revenue Recognition

Principles in the Software Industry Principles in the Software Industry

Jason T. Babington

University of Southern Mississippi

Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses

Part of the Accounting Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Babington, Jason T., "U.S. GAAP Versus IFRS: Reconciling Revenue Recognition Principles in the Software

Industry" (2013).

Honors Theses

. 182.

https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/182

This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital

Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila

Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected].

brought to you by COREView metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk

provided by Aquila Digital Community

The University of Southern Mississippi

U.S. GAAP Versus IFRS: Reconciling Revenue Recognition Principles in the Software

Industry

By

Jason T. Babington

A Thesis

Submitted to the Honors College of

The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Business Administration

in the School of Accountancy

November 2012

ii

iii

Approved by

_____________________

Michael Dugan

Horne Professor of Accountancy

____________________

Skip Hughes, Chair

School of Accountancy

_____________________

David Davies, Dean

Honors College

iv

Abstract

In the world of financial accounting, a demand for universal standards exists. The

two primary standard setting boards, The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)

and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), have made some strides in

developing universal standards, but they still are not fully reconciled in the area of

software revenue recognition. The main reason the two standards are not reconciled in

the area of software revenue recognition is that a difference exists in the critical event

between the standards. The critical event refers to the exact time a company recognizes

revenue on its books. The purpose of the study is to determine how close the two

standards are becoming to being fully reconciled in the area of software revenue

recognition and the two standards’ critical event.

v

Table of Contents

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………. 1

Literature Review…………………………………………............................................ 4

Conceptual Framework……………………………………………………5

FASB Concepts Statement No. 5 – Recognition and Measurement ……...6

Revenue Recognition – IASB and FASB…………………………………9

Software Revenue Recognition…………………………………………...12

Methodology…………………………………………………………………………….14

Research Design and Procedures…………………………………………14

Data Source……………………………………………………………….14

Participant(s)……………………………………………………………...15

Data Analysis……………………………………………………………..16

Further Limitations to Research…………………………………………..17

Discussion of Results……………………………………………………………………18

Sampling Procedures……………………………………………………..18

Statistical Methodology…………………………………………………..18

Analysis of Companies and Results from Paired T-test………………….19

1. Analysis for 2005………………………………………………..20

2. Analysis for 2006 and Comparison between years…...................27

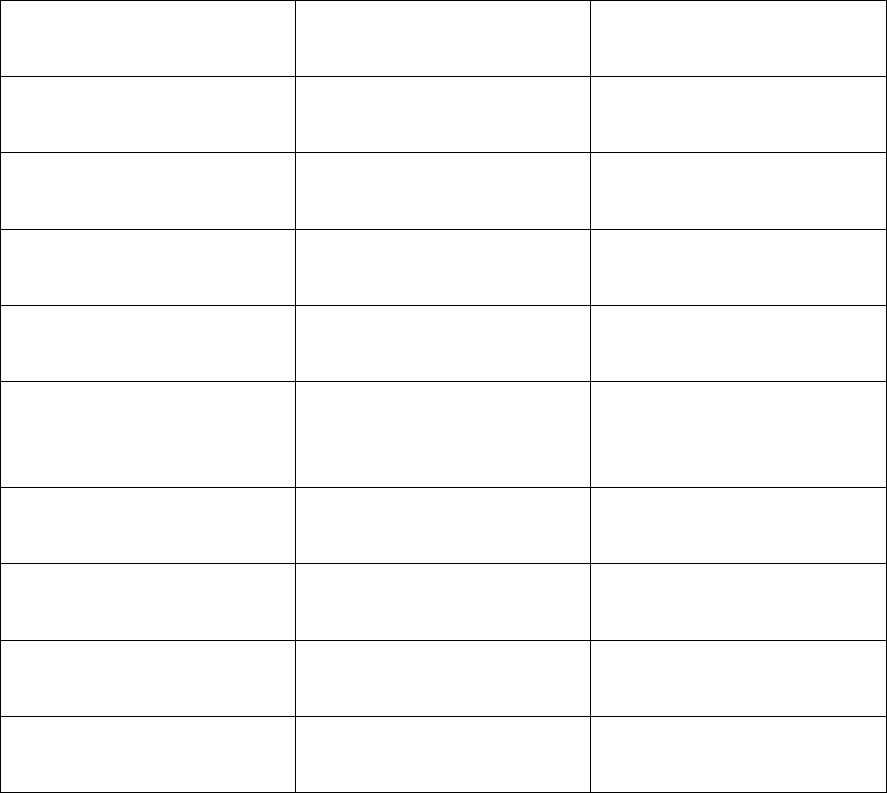

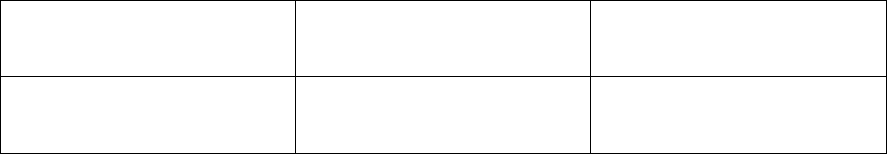

3. Analysis for Paired T-test 2005……………………….................34

4. Analysis for Paired T-test 2006 and Comparison between years..36

Possible Policy Implications……………………………………………...37

References……………………………………………………………………………

1

Introduction

In the discipline of financial accounting, a demand for universal standards exists.

The reasons for the existence of this demand range anywhere from the growth of cross-

border investing and capital flows to additional costs companies incur when preparing

their financial statements. In the world market today, two significant systems are used for

financial reporting - International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and United

States Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (U.S. GAAP). The Financial

Accounting Standards Board (FASB) sets U.S. GAAP, and the International Accounting

Standards Board sets IFRS. Because of the demand for uniform accounting standards,

U.S. GAAP and IFRS are very similar, but some differences exist. One of the major

differences between the two standards concerns the timing of recognition of revenue. The

specific industry in which these differences become most evident is the software industry.

Since the differences between revenue recognition principles between U.S. GAAP

and IFRS are well documented conceptually, my first focus on the problem is to evaluate

the historical perspective surrounding the recognition of revenue. The seminal article that

details the current standard setting stage in accounting is Stephen A. Zeff’s The Rise of

Economic Consequences. Zeff (1978) describes economic consequences as accounting

reports that have a significant impact on decision making to businesses, governments,

unions, investors, and creditors. Zeff also describes how the accounting reports have been

subject to increasing outside forces. These outside forces are individuals and groups who,

in the past, have not shown any interest in the setting of accounting standards, and they

invoke arguments contrary to what accountants have traditionally employed in setting

standards. An example of the traditional argument for accounting was to be as neutral as

possible as described by the FASB. Zeff argues that because of economic consequences,

these traditional assumptions are being severely questioned. Zeff concludes that the

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) must take these economic consequences

into consideration, mostly because of the possible adverse consequences possible

accounting standards could have on economic and social policies pursued by the

government (Zeff, 1978).

Zeff’s argument in a historical context is very relevant to accounting standard

setting today since it was written in the same era of standard setting for accounting. The

2

era is known as the decision usefulness era. The decision usefulness era began around the

time when Zeff wrote his piece on economic consequences. According to FASB

Concepts Statement No. 8 (2010), the purpose and objective of decision usefulness is to

provide financial information about the firm that is useful to present and potential

investors and other creditors. This will assist firms in making economic decisions about

providing resources to the firm (FASB, 2010). Zeff’s article sets the stage for the

potential consequences of standard setting from the concept of decision usefulness. The

financial statements in both U.S. GAAP and IFRS are specifically focused on the idea of

decision usefulness. For example, on the balance sheet in both standards, the company

lists its assets, liabilities, and stockholders’ equity. From that list, potential investors and

creditors can see the firm’s solvency and liquidity; thus, from this information they can

make the appropriate economic decisions about whether to invest in the firm. In terms of

revenue recognition, it is very important to understand the concept of decision usefulness,

since both U.S. GAAP and IFRS apply the concept to their own standard-setting

decisions. The possible consequences described in Zeff’s paper can explain much of the

reason behind why U.S. GAAP and IFRS still differ in this revenue recognition area. Zeff

describes one of the consequences is that accounting standards are becoming less neutral;

thus, this can allow for greater subjectivity when it comes to some areas. One possible

area that can possess some of the subjectivity Zeff was describing could be revenue

recognition.

While standard setting in accounting was transitioning to the idea of decision

usefulness, another important historical note was that a push was made for a conceptual

framework. A conceptual framework is essentially an attempt to establish a common set

of rules for all companies to follow when preparing their financial statements. Although

there was a push for a conceptual framework well before the decision usefulness era,

almost all of the statements published were during the decision usefulness era. The

conceptual framework adopted by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)

was based almost entirely on decision usefulness. In Stephen A. Zeff’s (1999) article The

Evolution of the Conceptual Framework for Business Enterprises in the United States, he

describes the evolving state of the conceptual framework, with the most crucial point

coming when the FASB decided to tackle the idea of a conceptual framework based on

the Trueblood Committee Report. The report embraced the idea of decision usefulness

(Zeff, 1999). The simultaneous historical development of the conceptual framework and

3

the decision usefulness approach helped spread the idea of decision usefulness to all

facets of the standard setting environment in financial accounting. Every rule and

statement in U.S. GAAP and later IFRS were based on the idea of decision usefulness.

From a historical perspective, it has become clear to me that revenue recognition

can have some subjectivity since the current standard setting environment of accounting

is in the decision usefulness era. In order to understand the central issue of why revenue

recognition is not completely reconciled yet under U.S. GAAP and IFRS, it is crucial for

businesses to understand the decision usefulness approach and the economic

consequences associated with it. The entire conceptual framework for standard setting in

accounting is rooted in the idea of decision usefulness.

With the historical perspective in mind and how revenue recognition has a

subjective past, I intend to evaluate how reconciled U.S. GAAP and IFRS are regarding

revenue recognition, specifically focusing on the software industry. Because of the

increased demand for universal standards, it becomes very important to show just how

close U.S. GAAP and IFRS are to having full reconciliation regarding revenue

recognition. By indicating how reconciled the two standards are becoming, it can be of

much use to software companies by helping them evaluate where they need to be in the

future when they start preparing their financial statements.

4

Literature Review

The scholarly literature concerning how U.S. GAAP and IFRS recognize revenue

mostly focuses on the conceptual differences in principles. Along with the actual FASB

and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) concepts and statements,

many scholars in accounting have tried to indicate the major fundamental differences in

how each recognizes revenue. Along with these articles that attempt to show the

fundamental, conceptual differences in revenue recognition principles, many articles also

evaluate the current situation regarding the efforts by the FASB and the IASB to

converge the two standards.

These articles that try to specifically describe the fundamental differences

between U.S. GAAP and IFRS are very important, but there also are many other

scholarly pieces regarding recognizing revenue from a historical perspective. The seminal

article that describes how companies should recognize revenue is John H. Myers’s The

Critical Event and Recognition of Net Profit. In his article, Myers (1952) describes profit

as being earned during an operating cycle. The cycle of buying inventory with cash to

eventually resell makes up the operating cycle. The problem that now faces the company

is for that company to decide at what point they recognize revenue. Should revenue be

recognized at a specific point in the cycle, or should it be spread over the cycle in some

manner? This specific point where a company decides to recognize revenue is what

Myers refers to as the critical event. Myers states for some companies it is easy to define

the critical event. For magazine publishers, they recognize revenue in the period the

magazines are distributed. The exchange is fairly simple: the sale occurs, and cash is

received at the time the subscription is booked (Myers, 1952). For software companies,

the critical event is not that simple to define. For example, because of bundling of

services and multiple-deliverable arrangements, it becomes more difficult to define the

critical event for software companies when they recognize revenue.

Along with these more historical articles, there are also some articles that describe

basic differences in U.S. GAAP and IFRS. The most important of these basic

differences is that U.S. GAAP tends to be more rules-based, while IFRS tends to be more

principles-based. All of these articles’ methodologies vary among comparative analyses,

case studies, and descriptive analyses.

5

In terms of my specific topic of revenue recognition differences in software

companies between U.S. GAAP and IFRS, it would be best to start with the historical

papers. These historical papers will address the conceptual framework of the FASB,

which is based on the very important approach of decision usefulness. The next step is

under the conceptual framework to evaluate FASB Concepts Statement No. 5 regarding

recognition and measurement concepts, including revenue recognition. Defining Myers’s

critical event will also be crucial in recognition and measurement, especially in terms of

software revenue recognition. Next, the literature will focus on contrasting revenue

recognition principles in general between the IASB and FASB, including how the two are

trying to converge. Finally, the literature will correlate all of these components to

recognizing software revenue for both U.S. GAAP and IFRS.

Conceptual Framework

The first important scholarly papers that evaluate the recognition of revenue

involve the institutional efforts to establish a conceptual framework in the field of

financial accounting. In The Evolution of the Conceptual Framework For Business

Enterprises in the United States, Stephen A. Zeff explains that the institutional efforts to

establish a conceptual framework in the United States first began with the Paton and

Littleton monograph in 1940 and later with the two Accounting Research Studies by

Moonitz and Sprouse in 1962-1963. In 1966, the American Accounting Association

issued a report that advocated the decision usefulness approach to the conceptual

framework. The report eventually laid the foundation for the conceptual framework of the

FASB, which published six concepts statements from 1978 to 1985 (Zeff, 1999).

Zeff’s article described the basic historical development of the conceptual

framework. Most importantly, the article described the simultaneous development of the

conceptual framework along with the approach of decision usefulness. The actual

concepts of the FASB conceptual framework are well presented in Paul A. Pacter’s

(1983) The Conceptual Framework: Make No Mystique About It. Pacter’s article

describes the FASB conceptual framework as not being a mystical image, but an

application of accounting concepts to real life scenarios. The first concept the FASB

published was called Concepts Statement No. 1. This statement concerned the objectives

of the financial statements. The statement defined the primary users of general purpose

financial statements to be investors, creditors, and other outsiders. The overriding

objective of financial reporting is to provide information useful in making investment,

6

credit and similar decisions. In other words, the statement basically established firmly the

approach of decision usefulness. Concepts Statement No. 2 identifies the qualitative

characteristics of accounting information. Relevance and reliability are the two primary

qualities that make accounting information useful in decision making. Concepts

Statement No. 3 defines the elements of financial statements of business enterprises. The

basic elements are: assets, liabilities, owners’ equity, revenues, expenses, gains, losses,

and comprehensive income. Concepts Statement No. 4 addresses financial reporting for

non-business organizations and finally, Concepts Statement No. 5 addresses the

complicated issue of recognition and measurement (Pacter, 1983). Revenue recognition

is discussed under Concepts Statement No. 5.

A further evaluation of the FASB conceptual framework reveals that the

conceptual framework has much subjectivity and also many imperfections and benefits.

These benefits and imperfections of the FASB conceptual framework are described very

well in David Solomons’s (1986) The FASB’s Conceptual Framework: An Evaluation.

One of the benefits Solomons describes is the FASB conceptual framework makes

economizing of effort possible. In other words, in Concepts Statement No. 3 the

definitions of the elements of the financial statements are already formulated; thus,

accounting problems should not be thought through again each time the board encounters

them. Another benefit in the FASB conceptual framework is there is more consistency

among the standards than if the standards were formulated independently of one another.

The FASB conceptual framework also aids in communication. For example, the FASB

conceptual framework defines words such as materiality, which in the past

did not always mean the same thing to all accountants. A final benefit the FASB

conceptual framework provides is the defense against politicization. The FASB is able to

claim that its standards were derived from a coherent body of concepts instead of from a

governmental agency (Solomons, 1986).

Despite the benefits, Solomons further describes that there also are many

imperfections concerning the FASB conceptual framework. For example, in Concepts

Statement No. 5 the FASB suggests that the ‘historical exchange price’ is more

descriptive of the amounts in the financial statements, while ‘transaction-based system’

would be a better description of the present accounting system. The question now

becomes whether the FASB conceptual framework needs a radical change or just a fine-

tuning. Solomons concludes that the FASB has not done enough changing in the

7

conceptual framework that is necessary, particularly involving Concepts Statement No. 5.

Solomons describes that the fundamental weakness of Concepts Statement No. 5 is in its

lack of discussion of the choice of attributes to be measured in financial statements, such

as historical cost, current cost, or net realizable value (Solomons, 1986). These apparent

imperfections in Concepts Statement No. 5 have led to even further complications. In an

article by Colleen Cunningham (2009) called FASB, IASB Plod Toward Convergence on

Revenue, there are more than 180 rules for revenue recognition, including some that

contradict others (Cunningham, 2009).

From the FASB conceptual framework, the foundation for revenue recognition is

apparent. The conceptual framework is rooted in the idea of decision usefulness; thus,

when the FASB was evaluating revenue recognition, it was approaching the area from the

standpoint of the external user. Another important revelation about the conceptual

framework in terms of revenue recognition is that ever since Concepts Statement No. 5

was published, there have been discrepancies concerning not only what attributes that are

applicable to recognition of revenue, but also when to recognize revenue; thus, that is

why the FASB now has over 180 rules for revenue recognition. In order to understand

what the FASB says about recognizing revenue, knowing what Concepts Statement No. 5

states

about recognition and measurement concepts in general, including revenue recognition,

is crucial to understand.

FASB Concepts Statement No. 5 – Recognition and Measurement

In order to better understand some of the discrepancies in Concepts Statement No.

5 discovered by some of the previous scholars in the field of financial accounting, an

examination at the FASB’s terminology is crucial. The first crucial definition is how the

FASB defines recognition. FASB Concepts Statement No. 5 (1984) states,

Recognition is the process of formally recording or incorporating an item into the

financial statements of an entity as an asset, liability, revenue, expense, or the

like. An item and information about it should meet four fundamental recognition

criteria to be recognized and should be recognized when the criteria are met. The

criteria are: Definitions- the items meet the definition of an element of the

financial statements, Measurability- it has a relevant attribute measurable with

sufficient reliability, Relevance- the information about it is capable of making a

8

difference in user decisions, and Reliability- the information is representationally

faithful, verifiable, and neutral (FASB, par. 6, 63).

The FASB’s definition of recognition seems pretty straightforward, but where it becomes

a little more complicated is when the FASB tries to define Measurability and its

attributes. Concepts Statement No. 5 further states,

The asset, liability, or change in equity must have a relevant attribute that can be

quantified in monetary units with sufficient reliability. Items currently reported in

financial statements are measured by different attributes, depending on the nature

of the item and the relevance and reliability of the attribute measured. Five

different attributes of assets (and liabilities) are used in present practice:

Historical cost, Current cost, Current market value, Net realizable Value, and

Present value of future cash flows. The different attributes often have the same

amounts, particularly at initial recognition. As a result, there may be agreement

about the amount but disagreement about the attribute being used. ‘Historical

exchange price’ is more descriptive of the quantity generally reflected in the

financial statements in present practice (and ‘transaction-based system would be a

better description of the accounting model than ‘historical cost system’) (FASB,

par. 65-69).

Obviously, by having all of these different attributes, some disagreement can exist when

it comes to the recognition criteria of Measurability; also, the FASB states an attribute as

being more indicative of the financial statements, but instead another attribute is more

indicative of our present accounting system. There are simply too many factors that

contribute to just one criterion for recognition. Inevitably, these many factors cause

revenue recognition to be very complex in nature. Before the FASB, there were scholars

in financial accounting who tried to identify the timing of recognition of revenue. One of

these scholars, John H. Myers, tried to identify the moment in time, or the critical event,

when companies should recognize revenue. For example, Myers (1952) in his article The

Critical Event and Recognition of Net Profit, suggests that profit is earned at the moment

of making the most critical decision or performing the most difficult task in the cycle of a

complete transaction. One example could be in the merchandising business when

merchandisers recognize revenue when they sell the item, because a transfer was made,

and there was objectivity. The critical event in the merchandising industry would be

when the merchandiser sells the item (Myers, 1952). The scenario is not always that

9

simple since in some cases, there may be a different ‘critical event.’ The FASB tries to

define the critical event in terms for every entity. When recognizing revenue Concepts

Statement No. 5 states,

Revenues and gains of an enterprise during a period are generally measured by

the exchange values of assets (goods and services) or liabilities involved, and

recognition involves consideration of two factors, (a) being realized or realizable

and (b) being earned, with sometimes one and sometimes the other being the more

important consideration. Revenues and gains generally are not recognized until

realized or realizable. Revenues and gains are realized when products,

merchandise, or other assets are exchanged for cash or claims to cash. Revenues

and gains are realizable when related assets received or held are readily

convertible to known amounts of cash or claims to cash. Revenues are not

recognized until earned. An entity’s revenue-earning activities involve delivering

or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute its

ongoing major or central operations, and revenues are considered to be earned

when the entity has substantially accomplished what it must do to be entitled to

the benefits represented by the revenues (FASB, par. 83-84).

According to the FASB, the critical event is whenever the revenue is realized or

realizable and earned. The type of entity will determine when revenue is recognized, or

that critical event. By reading what the FASB actually says, there are many factors to

consider. Many scholars in the field of financial accounting have all struggled in trying to

make sense of all of these factors. The factors described in the FASB have developed

much differently in the IASB. The specific differences in revenue recognition principles

between the FASB and the IASB are well documented by scholars in financial

accounting. Much of the focus of the literature today involving revenue recognition

involves these specific differences, and how the FASB and IASB are trying to reconcile

on revenue recognition principles.

Revenue Recognition – IASB and the FASB

There are many scholarly articles in the field of financial accounting that describe

the conceptual, fundamental differences in revenue recognition between U.S. GAAP and

IFRS. One article that conducts a comparative analysis of the two very effectively is

Hana Bohusova and Danuse Nerudova’s (2009) U.S. GAAP and IFRS Convergence in the

Area of Revenue Recognition. The background to the article is that in 2001, the IASB was

10

given a strong mandate to develop a single set of high-quality accounting standards. The

efforts of the mandate were to attempt to spread IFRS throughout the world through the

FASB – IASB Convergence Program. The areas of revenue recognition where the two

standards differ involve revenue recognition criteria, deferred payments, and long-term

contracts revenue recognition. Under U.S. GAAP, in order to recognize revenue, revenue

must be realized or realizable and must be earned. Under IFRS, if it is probable that

future economic benefits will flow to the enterprise, revenue can be measured reliably.

Under deferred payments, in U.S. GAAP discounting to present value is not required;

while under IFRS, value of revenues to be recognized is determined by discounting.

Finally, under long-term contracts U.S. GAAP allows a percentage of completion

method; while IFRS allows the percentage of completion method and the zero profit

method (Bohusova and Nerudova, 2009).

The Bohusova and Nerudova article evaluates the critical differences between

U.S. GAAP and IFRS very well. Many other articles evaluate how the two standards are

trying to converge. In terms of the continuing efforts to converge the two standards,

Frank E. Ryerson’s, (2010) article Major Changes Proposed to GAAP for Revenue

Recognition details that in September of 2002, FASB and the IASB jointly adopted the

Revenue Recognition Project. The goal of the project was to develop one revenue

recognition model that would be consistent for both U.S. GAAP and IFRS. Two possible

approaches were proposed that could possibly help converge the two standards. One

approach would be the asset and liability approach. The asset and liability model would

rely on the recognition and measurement of assets and liabilities, not recognize deferred

debit and deferred credits, and lead to a faithful and consistent depiction of transactions.

The other approach would be the earnings approach. The earnings model would lead to

recognition of deferred debit and deferred credits that do not meet the criteria of an asset

or liability and would account for revenue directly without consideration of how assets

and liabilities fluctuate during exchanges with customers. The earnings model was the

model that was eventually adopted by the FASB and the IASB (Ryerson, 2010).

In today’s current accounting standard-setting environment, there are still many

problems that face the convergence of U.S. GAAP and IFRS. In an article by Deborah L.

Lindberg and Deborah L. Seifert (2010) called A New Paradigm of Reporting, they

describe one of the main, fundamental differences between U.S. GAAP and IFRS is that

U.S. GAAP is more rule-based, while IFRS is more principles-based. The difference

11

implies that IFRS requires more judgment on the companies’ part. The differences in

approaches to financial reporting between U.S. GAAP and IFRS have still led to

differences in revenue recognition even after the adoption of the earnings model. The

major difference that still exists in revenue recognition is that U.S. GAAP requires

persuasive evidence of a sale arrangement, reasonable collectability of the revenue,

determinable prices, and occurrence of the delivery of goods and services rendered. IFRS

requires future economic benefits as well as revenues and costs that can be reliably

measured (Lindberg and Seifert, 2010). The two very different approaches of rules-based

versus principles-based financial reporting have currently led to a huge gap in revenue

recognition between the two standards.

Despite the huge gap between the two standards, there are still efforts being made

to try to reconcile the two standards. Steven M. Mintz in the article Proposed Changes in

Revenue Recognition Under U.S. GAAP and IFRS (2009) describes that in September

2002, the IASB and FASB announced plans to achieve full convergence in a document

known as the Norwalk Agreement. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

established a timeline for adoption of the Norwalk Agreement by 2014 for large

accelerated filers, and by 2016 for small, non-accelerated filers. If the Norwalk

Agreement is adopted, Mintz suggests many changes would take place. One change

would be to involve the use of contract-based revenue. The change would be that the

company would only recognize revenue during construction only if the customer controls

the item as it is constructed. Another change would involve the capitalization of costs.

The change that the contract origination costs causes is that the costs would be expensed

unless they qualify for capitalization under other standards (Mintz, 2009).

Since the SEC has still not taken action concerning the Norwalk Agreement, steps

are being made today. In Matthew G. Lamoreaux’s (2012) article A New System for

Recognizing Revenue, there are current revisions to the 2008 Proposed Accounting

Standards update regarding revenue recognition. The new proposal is expected to be

implemented no later than January 1, 2015. The steps being taken now to implement the

new proposal first involve identifying the contract with the customer. The next step is to

identify the separate performance obligations in the contract and then determine and

allocate the transaction price. Finally, the proposal will recognize revenue when a

performance obligation is satisfied (Lamoreaux, 2012).

12

The convergence of the FASB and the IASB regarding revenue recognition has

been a long and difficult process, and the scholarly literature of accounting standard

setting today reflects these complications. There are still major differences in revenue

recognition between the two standards, especially regarding software revenue

recognition.

Software Revenue Recognition

The actual standards for when to recognize software revenue vary greatly between

U.S. GAAP and IFRS. Bohusova and Nerudova in their article U.S. GAAP and IFRS

Converge in the Area of Revenue Recognition state,

The Accounting Standards Executive Committee (AcSEC) issued Statement of

Position – SOP 97-2, Software Revenue Recognition, to provide guidance on

when revenue on software arrangements should be recognized and in what

amounts. The SOP notes that the rights transferred under the software licenses are

substantially the same as those transferred in sales of other kinds of products and

that the legal distinction between a license and a sale should not cause revenue

recognition on software products to differ from other types of products. The same

underlying concept of delivery being the critical event for identifying when

revenue was earned was adopted. Because [sic] of the nature of software

arrangements, a need for persuasive evidence of arrangement was determined.

SOP 98-9 modified income recognition for arrangements with multiple elements.

The residual amount of the arrangement fee determined is allocated to the

deliverable elements. The portion of the fee allocated to an element should be

recognized as revenue when all criteria of SOP 97-2 are met with respect to the

element (Bohusova and Nerudova, pgs. 12-13).

Similar to software revenue, IFRS has standards regarding Construction Contracts in

International Accounting Standards (IAS) 18 and 11. Bohusova and Nerudova further

state,

In IAS 18 revenue is recorded at fair value. The revenue relating to long-time

contracts recording is the special area of revenue recording in IAS/IFRS. Revenue

and costs associated with construction contracts are determined in IAS 11

Construction Contracts. The nature of activities undertaken in construction

contracts is based on the [sic] situation when the date at which the contract

activity is entered into and the date when the activity is completed usually fall into

13

different accounting periods. There are two methods for revenue defining –

percentage of completion method and zero profit method. Under the completion

method [sic] contract revenue is matched with contract costs incurred in reaching

the stage of completion. The zero profit method is used when the outcome of

construction contract cannot be estimated reasonably. Revenue should be

recognized only to the extend [sic] of contract costs incurred that it is probable

will be recoverable and contract costs should be recognized as an expense in the

period in which they are incurred (Bohusova and Nerudova, pg. 14).

The critical event as described by Myers is different between the two standards. For U.S.

GAAP, SOP 97-2 notes that the time of delivery is the critical event. For multiple

elements, which exist in many software companies, the critical event becomes much

more complicated to define. Under U.S. GAAP, it would seem that the critical event for

multiple elements would be when all the criteria of SOP 97-2 are met and the

arrangement fee has been allocated to the elements. Under IFRS, the critical event is

much more subjective, which should come as no surprise since IFRS is more principles-

based than U.S. GAAP. The critical event under IFRS seems to be whenever a company

incurs the costs of completion, and if the costs cannot be reasonably estimated, then the

critical event would be whatever costs could be reasonably estimated. The

differences in the critical event for both U.S. GAAP and IFRS are reiterated in Christine

Miller’s (2009) article Tech Companies & IFRS. Miller identifies that if IFRS were

adopted for all software companies, it would require much more judgment on the

companies’ part because of the principles-based approach. Miller argues that a rules-

based approach for the software industry is better, because it provides better guidance

about recognition of revenue unlike a principles-based approach, which would require

weighing of different factors and more pressure on the company (Miller 2009).

The differences in the critical event for software recognition are the driving force

for my research. The scholarly literature of financial accounting well establishes what the

FASB conceptual framework says about recognition and measurement, and also how

U.S. GAAP and IFRS recognize revenue and how they are continuing to try to converge.

My research will add to the field of financial accounting a continuing exploration of what

the critical event for software revenue recognition is under U.S. GAAP and IFRS.

14

Methodology

The primary focus of my research is to evaluate the reconciliation of U.S. GAAP

and IFRS in the area of software revenue recognition. My primary research question

involves how close U.S. GAAP and IFRS are coming to being fully reconciled in the area

of software revenue recognition.

Research Design and Procedures

As mentioned in the scholarly literature of financial accounting, the primary

difference between U.S. GAAP and IFRS in the area of software revenue recognition

involves the timing of the recognition of revenue or the critical event. Most of the

research surrounding the critical event just describes the fundamental differences

between the two standards; in other words, there has not been much quantitative research

conducted about the critical event. My research is a quantitative study of the differences

between U.S. GAAP and IFRS involving the critical event.

My independent variable for the study is the type of standard being observed. The

two possible standards for observation are either U.S. GAAP or IFRS. My dependent

variable is the absolute value of the difference between revenues under U.S. GAAP and

revenues under IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets. I hypothesize that in order for

U.S. GAAP and IFRS to be considered reconciled, the absolute value of the difference

between revenues under U.S. GAAP and revenues under IFRS must not be significantly

different from zero. In order to retrieve the data, I searched the Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC) Edgar database. Once I retrieved the data for the revenues under U.S.

GAAP and IFRS and total assets, I manipulated the data into an Excel file by which I

could calculate the absolute value of the difference between revenues under U.S. GAAP

and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets. After I obtained the percentages I needed

in the Excel file, I used inferential statistics to evaluate how closely reconciled U.S.

GAAP and IFRS are.

Data Source

The primary source for my research design is the SEC Edgar database. The SEC

Edgar database contains all of the SEC filings that publicly traded companies

must disclose, including the 20-F form. The 20-F form contains a very important

schedule for my research known as a reconciliation schedule. The reconciliation schedule

reconciles net income under IFRS to net income under U.S. GAAP through a series of

15

adjustments. These adjustments are the dependent variables in my research, because they

are derived from the differences in the critical event for both U.S. GAAP and IFRS in the

area of software revenue recognition; thus, the computation for the absolute value of the

differences between revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is one way I incorporated the

critical event into my research. The total amount of the adjustments represents the

revenues for both U.S. GAAP and IFRS. The 20-F form also contains the differences in

balance sheet data both under U.S. GAAP and IFRS. The balance sheet contains total

assets, and that is where I obtained my data for total assets. The computation of total

assets is an average of year-end total assets under U.S. GAAP and year-end total assets

under IFRS.

As of January 2008, the SEC no longer requires foreign companies that have

adopted IFRS to disclose a reconciliation schedule. The SEC encouraged the initiative

mostly to make the process easier for U.S. companies to track foreign securities.

Although the reconciliation schedule is no longer required, the discrepancies in U.S.

GAAP and IFRS revenues would still exist today, because the two standards still differ

conceptually involving the critical event, as described in the scholarly literature of

financial accounting. Because of these circumstances, my data from the reconciliation

schedule are from the years ended 2005 to 2006. I observed the years 2005 to 2006 to

also see how reconciled or less reconciled U.S. GAAP and IFRS are in the area of

software revenue recognition during a course of two years.

Participant(s)

The participants in my research are fifteen software companies or companies that

provide services similar to software companies such as telecommunications, construction,

or computer programming. I specifically looked at their 20-F forms from the years ended

2005 to 2006. The process of random selection for the firms was simply by using the

search engine in the SEC Edgar database. In the search engine, I narrowed the search by

specifying companies that report using IFRS, and I also specified in the search engine

that the years must be 2006 or earlier. The reason why fifteen companies must be

observed is that fewer than 15 firms would result in an inadequate sample size for the

calculation of the t-statistic. All of the software companies are based in a country that has

adopted IFRS. The reason why I only looked at software companies that have adopted

IFRS is it shows a stark contrast between IFRS and U.S. GAAP, and they are the only

companies that have a reconciliation schedule.

16

Data Analysis

Once I obtained the information I needed from the fifteen software companies’

20-F forms and manipulated the data into an Excel file, I used inferential statistics in

order to answer my primary research question of how closely reconciled are U.S. GAAP

and IFRS in the area of software revenue recognition. The particular form of statistic I

used was a paired t-test. The absolute value of the differences between revenues under

U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets equals zero is my null

hypothesis, and the absolute value of the differences between revenues under U.S. GAAP

and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is greater than zero is my alternative

hypothesis. The lower the percentage, the more reconciled the two standards are. The

paired t-test will allow me to either reject the null hypothesis, which would mean the

absolute value of the differences between revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided

as a quantity by total assets is statistically significantly different from zero, and thus U.S.

GAAP and IFRS are not reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition; or fail to

reject the null hypothesis, which would mean the absolute value of the differences

between revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is not

statistically significantly different from zero, and provides empirical support that the U.S.

GAAP and IFRS are reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition. In other

words, if there is less difference, then there is a greater convergence between the critical

event under U.S. GAAP and the critical event under IFRS in the area of software revenue

recognition.

The main limitation to my research is that I have to use a software company; also

I have to use data from the years ended 2005 to 2006 since the reconciliation schedule is

no longer required as of 2008. The discrepancies still exist because the two standards

provide different definitions of the critical event. The main focus of my methodology is

to perform a quantitative study on the different standards’ definition of the critical event,

since not many scholars in the field of financial accounting have done quantitative studies

on the critical event. I hope to add to the scholarly literature of financial accounting a

quantitative perspective on the critical event, and in turn show how closely reconciled

U.S. GAAP and IFRS are in software revenue recognition quantitatively.

17

Further Limitations to Research

Besides the limitation imposed by the SEC regarding the reconciliation schedule,

there are also further limitations regarding data availability for the reconciliation

schedule. Most of the software companies on the SEC Edgar database report for only

two years, 2005 and 2006, which means that a trend is not possible to observe. Thus, the

research can only show a difference in two years regarding the reconciliation of the two

standards, but not a trend regarding the reconciliation of the two standards.

18

Discussion of Results

As mentioned in the methodology section, my primary focus for research is to

evaluate how closely reconciled U.S. GAAP and IFRS are in the area of software revenue

recognition. I hypothesize that in order for U.S. GAAP and IFRS to be fully reconciled,

the absolute value of the difference between revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS

divided as a quantity by total assets must be zero.

Sampling Procedures

The sample for research include fifteen software companies, or companies that

provide services similar to software such as telecommunications, construction, or

computer programming. The participating companies include: Alcatel-Lucent, Inmarsat

Holdings Ltd., Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, Global Crossing (UK) Finance Plc.,

Eircom Group Plc., Koninklijke Pn., National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, Open Joint

Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rostercam, Swisscom AG, TDC A/S,

Tele2 AB, Telecom Corp of New Zealand Ltd., Telefonica S A, and Telenor ASA. All of

the companies chosen have adopted IFRS; thus, each of the companies has a

reconciliation schedule for the years 2005 and 2006. The sample was collected from the

SEC Edgar database. The specific financial data observed from each company were their

reconciliation schedules. The reconciliation schedule includes the adjustments made to

IFRS net income to reconcile to U.S GAAP net income.

The qualifications for each of the companies to be considered for my research are

that each had to have adopted IFRS, which eliminated most U.S. companies; they had to

be software companies or services similar to software; and they had to have a

reconciliation schedule. In order to retrieve these specific data, I put the industry code for

software companies in the search engine on the SEC Edgar database. I further narrowed

the search by specifying only countries that have adopted IFRS. The SEC Edgar database

allows the researcher to only look at specific countries. After I narrowed the search down

to the specific countries, I randomly picked fifteen software companies that fit the

qualifications. Fifteen companies were chosen to have an adequate sample size in order to

calculate the t-statistic.

Statistical Methodology

In order to evaluate the reconciliation of U.S. GAAP and IFRS in the area of

software revenue recognition, inferential statistics were used. After the fifteen software

19

companies were chosen, all of the data from the reconciliation schedules were imported

to an Excel file. In the Excel file, I created a table for each of the years 2005 and 2006.

The first column included each of the company’s name, the second column and third

columns included revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS. The fourth and final column

included the absolute value of the difference between revenues under GAAP and IFRS

divided as a quantity by total assets. Excel allows the user to conduct a paired T-test, thus

through Excel I conducted a paired T-test. The areas of evaluation for the paired T-test

include: comparing the t-statistic to the t-Critical value for a two tailed, assessing the P-

value or alpha risk, and comparing the mean of the revenues for each of the two

standards.

The whole point of conducting the paired T-test is to provide a way to either

reject the null hypothesis, which is the difference in revenue between U.S. GAAP and

IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is zero, or fail to reject the null hypothesis. If I

reject the null hypothesis, that means the differences in revenue between U.S. GAAP and

IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets are statistically significant from zero, and the

two standards are not completely reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition.

If I fail to reject the null hypothesis, that means the differences in revenue between U.S.

GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets are not statistically significant from

zero, and the two standards are more reconciled in the area of software revenue

recognition.

Analysis of the Companies and Results from Paired T-test

Before I begin analyzing the individual companies and the paired T-test, an

outline for analysis would be appropriate. First, I will begin by analyzing the year 2005. I

will insert a table for 2005 with all of the data from the Excel file which will include:

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS for each company, the differences in revenue

between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets for each company,

and the mean of the differences in revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a

quantity by total assets. For each company, I will assess their differences in revenue

between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets by comparing it to

zero. The closer the differences are to zero compared to the other companies, the closer

reconciled that particular company is in the area of software revenue recognition. None of

the companies has a difference of zero, so this analysis is only for comparative purposes.

20

I will repeat the same process for the year 2006. After analyzing 2006, I will then

compare both years and see if 2006 is more reconciled than 2005.

After analyzing each of the individual companies, I will then conduct an overall

analysis by assessing the paired T-test. I will analyze the year 2005 first. For the year

2005, I will either reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis. I will do

the same for 2006, and I will then compare both years to once again see if 2006 is more

reconciled than 2005. This is the overall analysis of the companies, as opposed to before

where it was only comparing the companies to each other.

1. Analysis for 2005

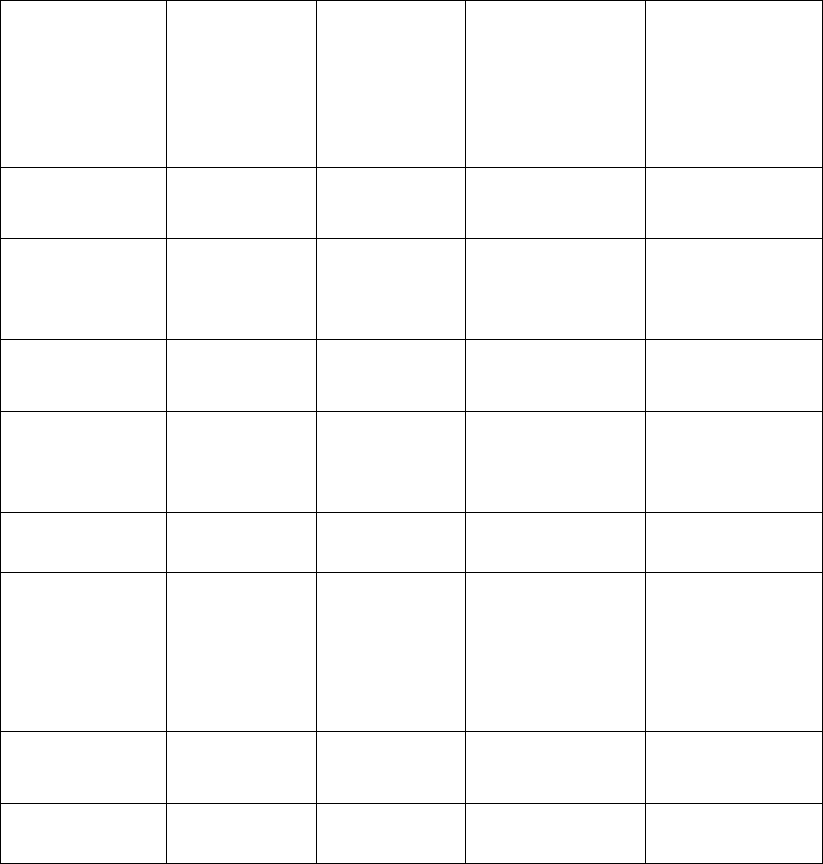

The following table refers to the year 2005. I have simply labeled the table: Table

1.

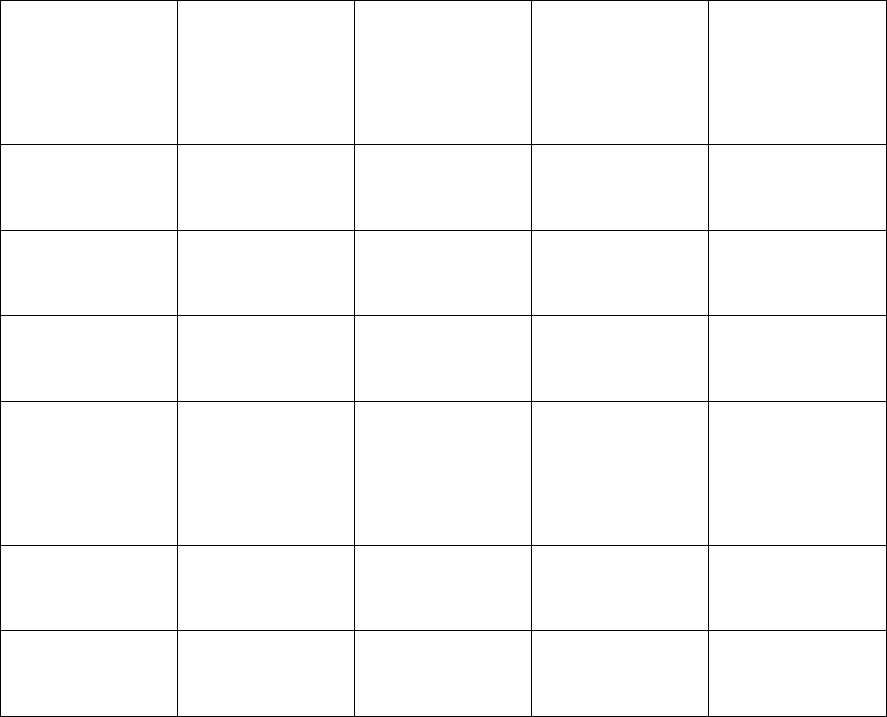

Differences in Revenue Table 2005

Table 1

Company

Rev for

GAAP

(in millions)

Rev for

IFRS

(in millions)

ABS (Rev

GAAP-Rev

IFRS/Total

Assets)

Mean of the

differences

Alcatel-Lucent

1,007

1,227

0.0074

0.0406

Inmarsat

Holdings Ltd.

98.3

64.3

0.0011

Telkom SA Ltd.

6,191

6,834

0.0215

France

Telecom

7,518

8,393

0.0293

Global

Crossing (UK)

11,558

26,781

.5093

Eircom Group

Plc.

33

99

.0022

Koninklijke Pn

1,393

1,437

0.0015

National

Telephone Co.

114

112

0.0001

21

The first company, Alcatel Lucent, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,007,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,227,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0074

or .74%. Compared to the mean of the differences for all companies, which is .0406 or

4.06%, Alcatel Lucent’s difference appears to be much lower. Their difference is slightly

higher to slightly lower when compared to some of the other companies. Compared to

Inmarsat Holdings Ltd., Eircom Group Plc., Koninklijke Pn, National Telephone Co. of

Venezuela, Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rosterdam, TDC

A/S, Tele2 AB, Telecom Corp of New Zealand, and Telenor ASA, Alcatel Lucent has a

slightly higher difference. Compared to Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, Global

Crossing (UK), Swisscom AG, and Telefonica S A, Alcatel Lucent has a slightly lower

difference. Although Alcatel Lucent has a slightly higher difference than most of the

of Venezuela

Open Joint

Stock Co. Long

Distance and

Internat

Comm.

Rosterdam

131

37

0.0031

Swisscom AG

2,901

2,519

0.0128

TDC A/S

1,575

1,574

0.00003

Tele2 AB

408

432

0.0008

Telecom Corp

of New

Zealand Ltd.

634

627

0.0002

Telefonica S A

3,071

3,577

0.0169

Telenor ASA

836

903

0.0022

22

companies sampled, their difference is much lower than the mean of the differences. The

reason for this occurrence is mostly that one of the companies had a difference of

50.93%, and thus the mean was slightly skewed. Overall, Alcatel Lucent is less

reconciled than most of the companies, and the only companies that are less reconciled

than Alcatel Lucent have a much higher difference than a majority of the companies. I

conclude that Alcatel Lucent is somewhat less reconciled when compared to the other

companies individually.

The second company, Inmarsat Holdings Ltd., has revenues under U.S. GAAP of

about 98,300,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 64,300,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0011

or .11%, which is much lower than Alcatel Lucent. Compared to the mean of the

differences for all companies, Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. difference appears to be much

lower. Their difference is much lower to just slightly higher when compared to other

companies. Compared to the National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, TDC A/S, Tele2 AB,

and Telecom Corp of New Zealand, Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. has a slightly higher

difference. Compared to Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, Global Crossing (UK),

Eircom Group Plc., Koninklijke, Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat

Comm. Rosterdam, Swisscom AG, Telefonica S A, and Telenor ASA, Inmarsat Holdings

Ltd. has a much lower difference. Obviously, Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. is much more

reconciled than Alcatel Lucent and many other companies. Thus, I conclude that Inmarsat

Holdings Ltd. is more reconciled when compared to the other companies individually.

The third company, Telkom SA Ltd., has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

6,191,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 6,834,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0215

or 2.15%, which is much higher than Alcatel Lucent, and much higher than Inmarsat

Holdings Ltd. Compared to the mean of the differences for all companies, their difference

is lower. Telkom SA Ltd. difference is much higher to slightly lower when compared to

some of the other companies. The only companies that have a slightly higher difference

than Telkom SA Ltd. are France Telecom and Global Crossing (UK). When compared to

all other companies, Telkom SA Ltd. difference is much higher. Although their

difference is lower than the mean, it is once again because the mean is slightly skewed.

Obviously, Telkom SA Ltd. is less reconciled than a majority of the companies. Thus, I

23

conclude that Telkom SA Ltd. is less reconciled when compared to other companies

individually.

The fourth company, France Telecom, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

7,518,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 8,393,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0293

or 2.93%, which is much higher than Alcatel Lucent, Inmarsat Holdings Ltd., and

Telkom SA Ltd. Compared to the mean of the differences for all companies, their

difference is lower. France Telecom’s difference is much higher than all of the companies

but one. The only company that France Telecom is more reconciled than is Global

Crossing (UK). Much like the scenario for Alcatel Lucent and Telkom SA Ltd., their

difference is only lower than the mean since the mean is skewed. Obviously, France

Telecom is less reconciled than a majority of the companies. Thus, I conclude that France

Telecom is less reconciled when compared to the other companies individually.

The fifth company, Global Crossing (UK), has revenues under U.S. GAAP of

about 11,558,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 26,781,000,000. Notice the

discrepancy in revenues for Global Crossing (UK) when compared to the other

companies. Their difference in revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a

quantity by total assets is .5093 or 50.93%. Global Crossing (UK) is by far the less

reconciled out of all the companies. They are the only company that has a difference

larger than the mean, which is why the mean is skewed. I can automatically conclude that

Global Crossing (UK) is less reconciled when compared to the other companies

individually.

The sixth company, Eircom Group Plc., has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

33,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 99,000,000. Their difference in revenues

under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0022 or .22%,

which is lower than Alcatel Lucent, Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, and Global

Crossing (UK), but higher than Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. Compared to the mean of the

differences, their difference is much lower. Compared to the other companies in the

industry, Eircom Group Plc. has a slightly higher to slightly lower difference. When

compared to Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rosterdam,

Swisscom AG and Telefonica S A, Eircom Group Plc. has a slightly lower difference.

When compared to Koninklijke Pn, National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, TDC A/S,

Tele2 AB, and Telecom Corp of New Zealand Ltd., Eircom Group Plc. has a slightly

24

higher difference. They have an equivalent difference with Telenor ASA. Eircom Group

has a lower difference with about the same amount of companies that have a higher

difference. Since Eircom Group Plc. has a difference well below the mean, I conclude

that Eircom Group Plc. is more reconciled when compared to the other companies

individually.

The seventh company, Koninklijke Pn, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,393,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,437,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0015

or .15%, which is lower than Alcatel Lucent, Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, Global

Crossing (UK), and Eircom Group Plc, but higher than Inmarsat Holdings. Compared to

the mean of the differences, their difference is much lower. Compared to the other

companies in the industry, Koninklijke Pn, has a slightly higher to slightly lower

difference. When compared to Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm.

Rosterdam, Swisscom AG, Telefonica S A, and Telenor ASA, Koninklijke Pn has a

slightly lower difference. When compared to National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, TDC

A/S, Tele2 AB, and Telecom Corp of New Zealand Ltd., Koninklijke Pn has a slightly

higher difference. Much like Eircom Group Plc., Koninklijke Pn has a slightly lower

difference with about the same amount of companies that have a higher difference. Since

Koninklijke Pn has a difference well below the mean, I conclude that Koninklijke Pn is

more reconciled when compared to the other companies individually.

The eighth company, National Telephone Company of Venezuela, has revenues

under U.S. GAAP of about 114,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 112,000,000.

Their difference in revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total

assets is about .0001 or .01%, which is obviously well below the mean of the differences.

The only company that has a lower difference is TDC A/S. Every other company has a

higher difference than the National Telephone Company of Venezuela. Obviously, I

conclude that the National Telephone Company of Venezuela is more reconciled when

compared to the other companies individually.

The ninth company, Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm.

Rosterdam, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about 131,000,000 and revenues under

IFRS of about 37,000,000. Their difference in revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS

divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0031 or .31%, which is higher than Inmarsat

Holdings Ltd., Eircom Group Plc, Koninklijke Pn, and the National Telephone Co. of

25

Venezuela, but lower than Alcatel Lucent, Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, and Global

Crossing (UK). Compared to the mean of the differences, their difference is much lower.

When compared to the other companies in the industry, like many of the other

companies, Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rosterdam has a

slightly higher to slightly lower difference. When compared to Swisscom AG and

Telefonica S A, they have a slightly lower difference. When compared to TDC A/S,

Tele2 AB, Telecom Corp of New Zealand Ltd., and Telenor ASA, they have a slightly

higher difference. Much like Eircom Group Plc and Koninklijke Pn, Open Joint Stock

Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rosterdam has a lower difference with about the

same amount of companies that have larger differences. Once again, because of the mean

being much higher, I conclude that Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat

Comm. Rosterdam is more reconciled when compared to the other companies

individually.

The tenth company, Swisscom AG, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

2,901,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 2,519,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0128

or 1.28%. Compared to the mean of the differences, it has a smaller difference. The only

companies that have a higher difference are Telkom SA Ltd, France Telecom, Global

Crossing (UK), and Telfonica S A. Every other company has a smaller difference.

Similar to some of the other companies, although Swisscom AG has a smaller difference

compared to the mean, they are still less reconciled when compared to the other

companies because of the mean being skewed. Thus, I conclude that Swisscom AG is less

reconciled when compared to the other companies individually.

The eleventh company, TDC A/S, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,575,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,574,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is virtually zero at about .00003 or .003%.

Obviously, TDC A/S has a lower difference than the mean and they are the most

reconciled out of all the companies. Thus, I conclude that TDC A/S is more reconciled

when compared to the other companies individually.

The twelfth company, Tele2 AB, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

408,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 432,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is about .0008 or .08%. Their difference is much

smaller than the mean of the differences. The only companies that have a smaller

26

difference are The National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, TDC A/S, and Telecom Corp

of New Zealand. All other companies have a larger difference. Thus, I can conclude that

Tele2 AB is more reconciled when compared to the other companies individually.

The thirteenth company, Telecom Corp of New Zealand, has revenues under U.S.

GAAP of about 634,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 627,000,000. Their

difference in revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is about .0002 or .02%, which is

much lower than the mean of the differences. The only companies that have a smaller

difference are the National Telephone Co. of Venezuela and TDC A/S. All other

companies have a larger difference. Thus, I can conclude that Telecom Corp of New

Zealand is more reconciled when compared to the other companies individually.

The fourteenth company, Telefonica S A, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of

about 3,071,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 3,577,000,000. Their difference

in revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.0169 or 1.69%, which is still lower than the mean. The only companies that have a

higher difference are Telkom SA Ltd. France Telecom, and Global Crossing (UK). Much

like Swisscom AG, Telefonica S A only has a smaller difference to mean because the

mean is skewed. Thus, I conclude that Telfonica S A is less reconciled when compared to

the other companies individually.

The fifteenth and final company, Telenor ASA, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of

about 836,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 903,000,000. Their difference in

revenues under U.S. GAAP and IFRS is about .0022 or .22%, which is identical to

Eircom Group Plc. difference. The analysis for Telenor ASA would be the same as the

analysis for Eircom Group Plc., thus I will not reiterate that analysis. As for Eircom

Group Plc., Telenor ASA is more reconciled when compared to the other companies

individually.

For the year 2005, six companies were considered less reconciled, while

nine companies were considered more reconciled in the area of software revenue

recognition. An important observation to the analysis was that out of the six companies

considered less reconciled, five had the highest revenue totals as compared to all

companies under both U.S. GAAP and IFRS. From that point, the higher amount of

revenue a company has in the software industry, the more likely there will be a larger

discrepancy in revenue totals between the two standards. Thus, the critical event seems

much harder to define when a company has much more revenue compared to the other

27

companies. Overall, there were more companies that were considered more reconciled in

the area of software revenue recognition; thus, for 2005 the two standards seem fairly

reconciled when the companies are compared against one another.

2. Analysis for 2006 and Comparison Between Years

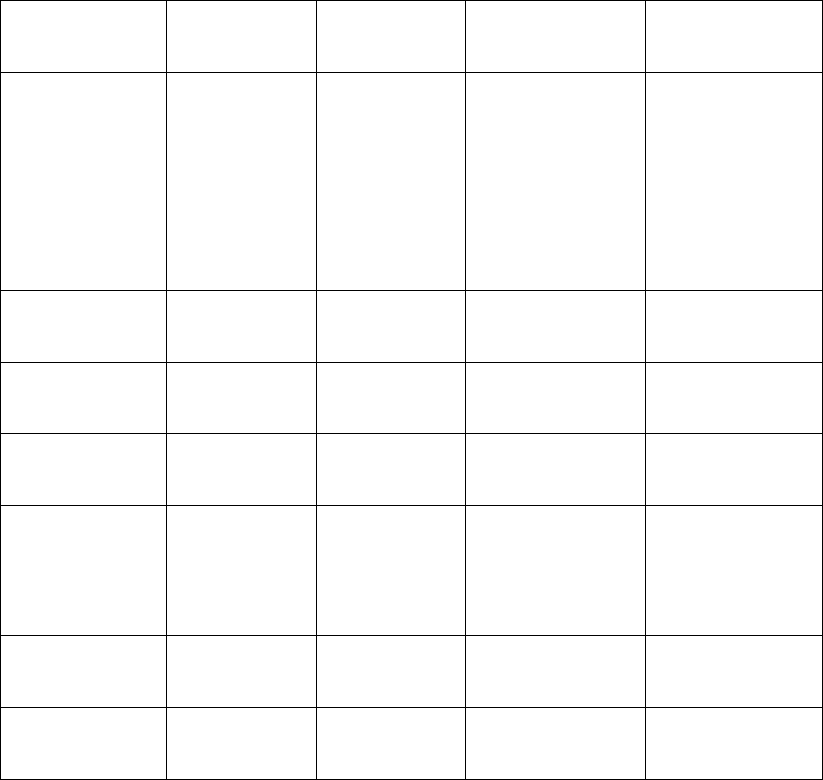

The following table is for the year 2006. I have simply labeled the table: Table 2.

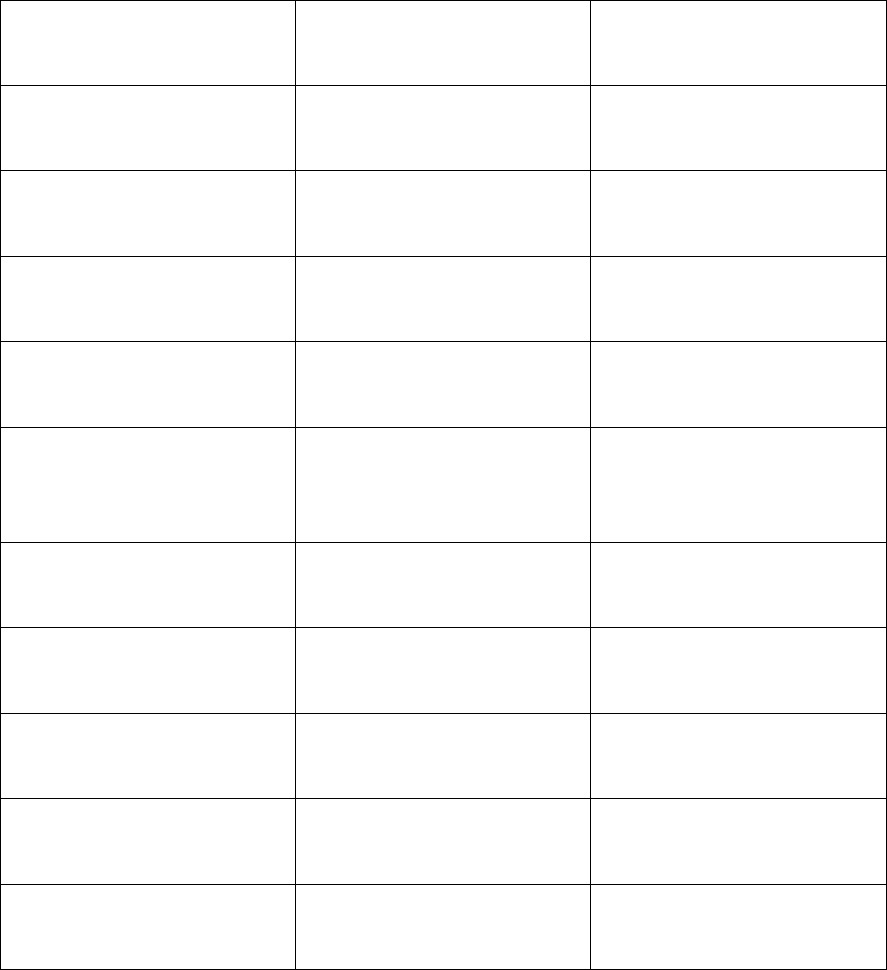

Differences in Revenue Table 2006

Table 2

Company

Rev. for

GAAP (in

millions)

Rev. for IFRS

(in millions)

ABS (Rev. for

GAAP – Rev.

for IFRS/Total

Assets)

Mean of the

Differences

Alcatel-Lucent

-780

-232

0.0095

0.03

Inmarsat

Holdings Ltd.

141.6

127.6

0.0002

Telkom SA Ltd.

1,442

1,516

0.0013

France Telecom

6,970

6,292

0.0118

Global Crossing

(UK)

-4,472

15,912

0.3550

Eircom Group

Plc.

106

103

0.0001

Koninklijke Pn.

1,569

1,583

0.0002

National

Telephone Co.

of Venezuela

588

589

0.00002

Open Joint

Stock Co. Long

10

55

0.0008

28

Distance and

Internat Comm.

Rostercom

Swisscom AG

1,979

1,992

0.0002

TDC A/S

1,148

1,187

0.0007

Tele2 AB

295

295

-

Telecom Corp

of New Zealand

Ltd.

-40

-282

0.0042

Telefonica S A

4,699

4,876

0.0031

Telenor ASA

1,101

1,134

0.0006

The first company, Alcatel Lucent, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

780,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 232,000,000. The difference in revenue

between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0095 or

.95%, which is lower than the mean of the differences or about .03 or 3%. When

compared to the other companies, Alcatel Lucent has a somewhat higher difference. The

only companies that have a higher difference are France Telecom and Global Crossing

(UK). All of the other companies have a lower difference. Similar to the case in 2005,

although Alcatel Lucent has a lower difference than the mean, the mean is slightly

skewed since one of the companies had a difference of .3550 or 35.5%. Thus, I can

conclude that Alcatel Lucent is less reconciled in the area of software revenue

recognition when compared to the other companies individually for 2006.

29

The second company, Inmarsat Holding Ltd., has revenues under U.S. GAAP of

about 141,600,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 127,600,000. The difference in

revenue divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0002 or .02%, which is much lower

than the mean of the differences. The only companies that have a lower difference are

Eircom Group Plc., National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, and Tele2 AB. Koninklijke Pn

and Swisscom AG have equivalent differences. All other companies have a higher

difference. Thus, I can conclude that Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. is more reconciled in the

area of software revenue recognition when compared to the other companies individually

for the year 2006.

The third company, Telkom SA Ltd., has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,442,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,516,000,000. The difference in

revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.0013 or .13%, which is lower than the mean. The only companies with a higher

difference are Alcatel Lucent, France Telecom, Global Crossing (UK), Telecom Corp of

New Zealand, and Telefonica S A. All other companies have a lower difference. Thus, I

conclude that Telkom SA Ltd. is less reconciled in the area of software revenue

recognition when compared to the other companies individually for the year 2006.

The fourth company, France Telecom, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

6,970,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 6,292,000,000. Their difference in

revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.0118 or 1.18%, which is lower than the mean of the differences. The only company with

a higher difference is Global Crossing (UK). All the other companies have a lower

difference. Thus, I conclude that France Telecom is less reconciled in the area of software

revenue recognition when compared to the other companies individually for the year

2006.

30

The fifth company, Global Crossing (UK) has revenues under U.S. GAAP of

about 4,472,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 15,912,000,000. Their difference

in revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.3550 or 35.5%. Obviously, their difference is well above the mean. Much like 2005,

Global Crossing (UK) is the only company with a difference larger than the mean, and is

the reason for the mean being skewed. Thus, Global Crossing (UK) is less reconciled in

the area of software revenue recognition when compared to the other companies

individually for the year 2006.

The sixth company, Eircom Group Plc., has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

106,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 103,000,000. Their difference in revenue

between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0001 or

.01%, which is much lower than the mean of the differences. The only companies with a

lower difference are National Telephone Co. of Venezuela and Tele2 AB. All the other

companies have a higher difference. Thus, I conclude that Eircom Group Plc. is more

reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition when compared to the other

companies individually for the year 2006.

The seventh company, Koninklijke Pn, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,569,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,583,000,000. Their difference in

revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.0002 or .02%, which is the same difference for Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. The same

analysis for Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. applies to Koninklijke Pn. Thus, Koninklijke Pn is

more reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition when compared to the other

companies individually for the year 2006.

The eighth company, National Telephone Co. of Venezuela, has revenues under

U.S. GAAP of about 588,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 589,000,000. Their

31

difference in revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets

is virtually zero at about .00002 or .002%. The only other company with a lower

difference is Tele2 AB, which is fully reconciled. Thus, National Telephone Co. of

Venezuela is more reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition when compared

to the other companies individually for the year 2006.

The ninth company, Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm.

Rostercom, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about 10,000,000 and revenues under

IFRS of about 55,000,000. Their difference in revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS

divided as a quantity by total assets is about .0008 or .08%, which is much lower than the

mean. Their difference is slightly lower to slightly higher than the other companies.

Alcatel Lucent, Telkom SA Ltd. France Telecom, Global Crossing (UK), Telecom Corp

of New Zealand, and Telfonica S A all have higher differences. The rest of the companies

have lower differences. There are almost as many companies with a higher difference

than a lower difference. Since their difference is much lower than the mean, I conclude

that Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rostercom is more

reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition when compared to the other

companies individually in the year 2006.

The tenth company, Swisscom AG, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,979,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,992,000,000. The difference in

revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.0002 or .02%, which is much lower than the mean of the differences. Their difference is

equivalent to Koninklijke Pn and Inmarsat Holdings Ltd. The same analysis for those

companies applies to Swisscom AG; thus, I conclude that Swisscom AG is more

reconciled in the area of software revenue recognition when compared to the other

companies individually for the year 2006.

32

The eleventh company, TDC A/S, has revenues under U.S. GAAP of about

1,148,000,000 and revenues under IFRS of about 1,187,000,000. Their difference in

revenue between U.S. GAAP and IFRS divided as a quantity by total assets is about

.0007 or .07%, which is much lower than the mean of the differences. The companies

with a higher difference are Alcatel Lucent, Telkom SA Ltd., France Telecom, Global

Crossing (UK), Open Joint Stock Co. Long Distance and Internat Comm. Rostercom,

Telecom Corp of New Zealnand Ltd., and Telefonica S A. All the other companies have a