A GUIDE TO THE SMALL BUSINESS

REORGANIZATION ACT OF 2019

Revised June 2022

Paul W. Bonapfel

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge, N.D. Ga.

This June 2022 compilation of A Guide to the Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019 merges

the July 2021 compilation of the Guide with material in the May-June 2022 Supplement and

incorporates revisions in a May 2022 compilation. The earlier compilations and this one update

the original version published at 93 Amer. Bankr. L. J. 571 (2019).

The May-June 2022 Supplement is in two parts. The first part supplements the July 2021

compilation with revisions and new material as of May 2022. The second part adds additional

revisions and materials as of June 2022. This June 2022 compilation includes all of the revisions

in both supplements.

The reader who is not familiar with the July 2021 compilation may consult only this June 2022

compilation, because it includes all the material in both of the supplements.

The reader who is familiar with the July 2021 compilation may consult only the May-June 2022

Supplement to review new material added to the July 2021 compilation. The reader who is also

familiar with the May 2022 Supplement may consult only the June part of the May-June 2022

Supplement to review new material.

This paper is not copyrighted. Permission is granted to reproduce it in whole or in part.

i

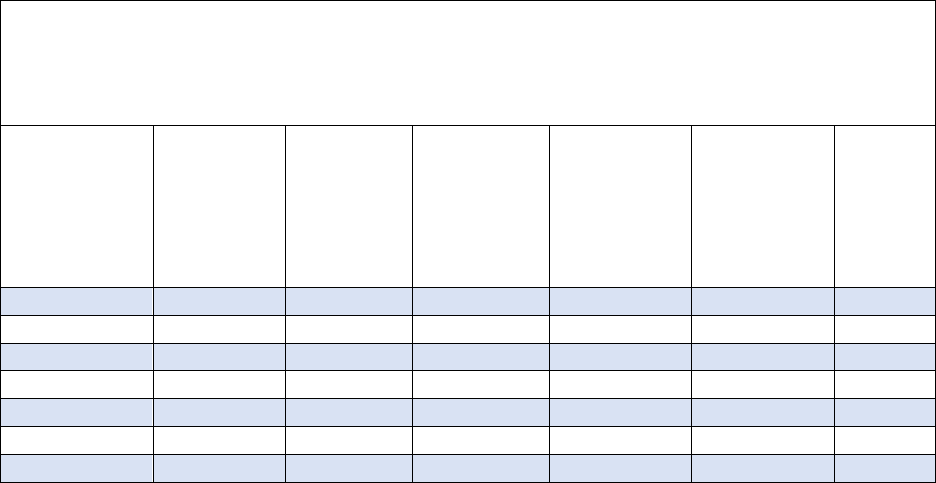

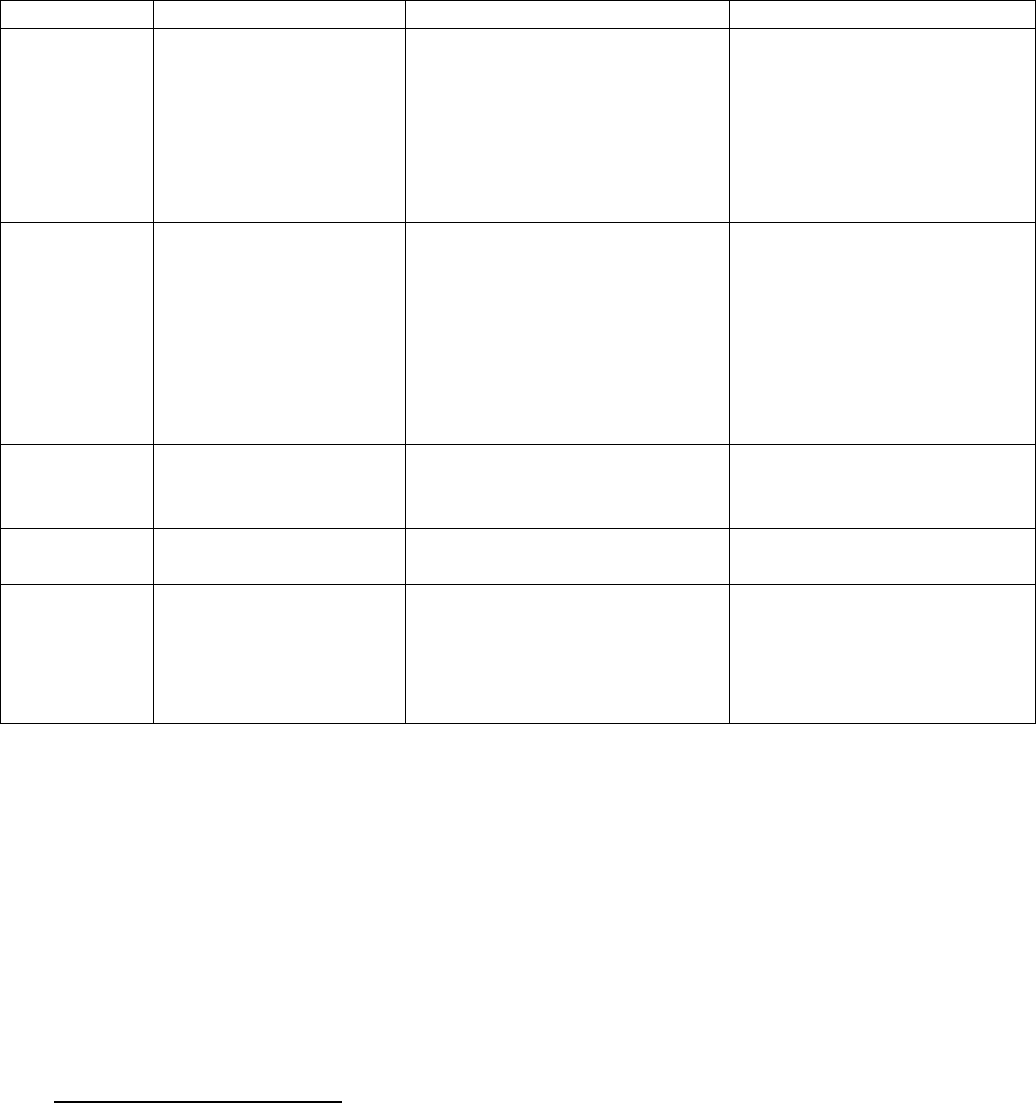

Table of Contents

I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1

II. Overview of Subchapter V ........................................................................................................ 7

A. Changes in Confirmation Requirements ................................................................................... 8

B. Subchapter V Trustee and the Debtor in Possession ................................................................. 9

C. Case Administration and Procedures ........................................................................................ 9

D. Discharge and Property of the Estate ...................................................................................... 10

1. Discharge – consensual plan ............................................................................................ 10

2. Discharge – cramdown plan............................................................................................. 10

3. Property of the estate ....................................................................................................... 11

III. Debtor’s Election of Subchapter V and Revised Definition of “Small Business Debtor” .... 11

A. Debtor’s Election of Subchapter V ......................................................................................... 11

B. Eligibility for Subchapter V; Revised Definitions of “Small Business Debtor” and “Small

Business Case” .............................................................................................................................. 17

1. Statutory provisions governing application of subchapter V and the debt limit .............. 17

2. Overview of eligibility for subchapter V ......................................................................... 19

3. Revisions to the definition of “small business debtor” and requirements for eligibility for

subchapter V in general ........................................................................................................ 21

C. Debtor Must Be “Engaged in Commercial or Business Activities”....................................... 24

1. Whether debtor must be engaged in commercial or business activities on the petition date

............................................................................................................................................... 25

2. What activities are sufficient to establish that the debtor is “engaged in commercial or

business activities” when the business is no longer operating .............................................. 28

D. What Debts Arise From Debtor’s Commercial or Business Activities .................................. 37

E. Whether Debts Must Arise From Current Commercial or Business Activities ...................... 44

F. What Debts Are Included in Determination of Debt Limit ..................................................... 46

G. Ineligibility of Corporation Subject to SEC Reporting Requirements and of Affiliate of Issuer

....................................................................................................................................................... 49

IV. The Subchapter V Trustee ..................................................................................................... 51

A. Appointment of Subchapter V Trustee ................................................................................... 51

B. Role and Duties of the Subchapter V Trustee ......................................................................... 53

1. Trustee’s duties to supervise and monitor the case and to facilitate confirmation of a

consensual plan ..................................................................................................................... 53

2. Other duties of the trustee ................................................................................................ 57

3. Trustee’s duties upon removal of debtor as debtor in possession .................................... 58

ii

C. Trustee’s Disbursement of Payments to Creditors .................................................................. 59

1. Disbursement of preconfirmation payments and funds received by the trustee .............. 59

2. Disbursement of plan payments by the trustee ................................................................ 61

D. Termination of Service of the Trustee and Reappointment .................................................... 62

1. Termination of service of the trustee ............................................................................... 62

2. Reappointment of trustee ................................................................................................. 63

E. Compensation of Subchapter V Trustee .................................................................................. 64

1. Compensation of standing subchapter V trustee .............................................................. 64

2. Compensation of non-standing subchapter V trustee ...................................................... 65

3. Deferral of non-standing subchapter V trustee’s compensation ...................................... 70

F. Trustee’s Employment of Attorneys and Other Professionals ................................................ 70

V. Debtor as Debtor in Possession and Duties of Debtor ............................................................ 76

A. Debtor as Debtor in Possession ............................................................................................... 76

B. Duties of Debtor in Possession................................................................................................ 77

C. Removal of Debtor in Possession............................................................................................ 81

VI. Administrative and Procedural Features of Subchapter V .................................................... 89

A. Elimination of Committee of Unsecured Creditors ................................................................ 90

B. Elimination of Requirement of Disclosure Statement ............................................................. 91

C. Required Status Conference and Debtor Report ..................................................................... 92

D. Time for Filing of Plan................................................................................................... 96

E. No U.S. Trustee Fees ............................................................................................................. 100

F. Modification of Disinterestedness Requirement for Debtor’s Professionals ........................ 100

G. Time For Secured Creditor to Make § 1111(b) Election ...................................................... 101

H. Times For Voting on Plan, Determination of Record Date for Holders of Equity Securities,

Hearing on Confirmation, Transmission of Plan, and Related Notices ...................................... 102

I. Filing of Proof of Claim; Bar Date ......................................................................................... 103

J. Extension of deadlines for status conference and debtor report and for filing of plan .......... 105

K. Debtor’s postpetition performance of obligations under lease of nonresidential real property--

§ 365(d) ....................................................................................................................................... 111

VII. Contents of Subchapter V Plan .......................................................................................... 113

A. Inapplicability of §§ 1123(a)(8) and 1123(c) ........................................................................ 113

B. Requirements of §1190 for Contents of Subchapter V Plan; Modification of Residential

Mortgage ..................................................................................................................................... 114

C. Payment of Administrative Expenses Under the Plan .......................................................... 119

VIII. Confirmation of the Plan ................................................................................................... 121

iii

A. Consensual and Cramdown Confirmation in General .......................................................... 121

1. Review of confirmation requirements in traditional chapter 11 cases and summary of

changes for subchapter V confirmation ............................................................................... 121

2. Differences in requirements for and consequences of consensual and cramdown

confirmation ........................................................................................................................ 124

3. Benefits to debtor of consensual or cramdown confirmation ......................................... 128

4. Whether balloting on plan is necessary .......................................................................... 133

5. Final decree and closing of case ..................................................................................... 135

B. Cramdown Confirmation Under §1191(b) ............................................................................ 137

1. Changes in the cramdown rules and the “fair and equitable” test ................................. 137

2. Cramdown requirements for secured claims.................................................................. 139

3. Components of the “fair and equitable” requirement in subchapter V cases; no absolute

priority rule ......................................................................................................................... 140

4. The projected disposable income (or “best efforts”) test ............................................... 141

i. Determination of projected disposable income......................................................... 143

ii. Determination of period for commitment of projected disposable income for more

than three years ............................................................................................................... 150

5. Requirements for feasibility and remedies for default ................................................... 156

6. Payment of administrative expenses under the plan ..................................................... 161

C. Postconfirmation Modification of Plan ................................................................................. 161

1. Postconfirmation modification of consensual plan confirmed under §1191(a) ............. 161

2. Postconfirmation modification of cramdown plan confirmed under §1191(b) ............. 164

D. § 1129(a) Confirmation Issues Arising in Subchapter V Cases ........................................... 165

1. Classification of claims; unfair discrimination .............................................................. 165

2. Acceptance by all classes and effect of failure to vote .................................................. 167

3. Classification and voting issues relating to priority tax claims ..................................... 168

4. Timely assumption of lease of nonresidential real estate .............................................. 169

5. The “best interests” or “liquidation” test of § 1129(a)(7) .............................................. 170

6. Voting by holder of disputed claim ............................................................................... 170

7. Individual must be current on postpetition domestic support obligations ..................... 171

8. Application of § 1129(a)(3) good faith requirement in context of consensual plan when

creditor objects because debtor is not paying enough disposable income .......................... 171

E. § 1129(b)(2)(A) Cramdown Confirmation and Related Issues Dealing With Secured Claims

Arising in Subchapter V Cases ................................................................................................... 176

1. The § 1111(b)(2) election .............................................................................................. 177

2. Realization of the “indubitable equivalent” of a secured claim -- § 1129(b)(2)(A)(iii) 187

iv

IX. Payments Under Confirmed Plan; Role of Trustee After Confirmation ............................. 190

A. Debtor Makes Plan Payments and Trustee’s Service Is Terminated Upon Substantial

Consummation When Confirmation of Consensual Plan Occurs Under §1191(a) .................... 190

B. Trustee Makes Plan Payments and Continues to Serve After Confirmation of Plan Confirmed

Under Cramdown Provisions of §1191(b) .................................................................................. 191

C. Unclaimed Funds................................................................................................................... 195

X. Discharge .............................................................................................................................. 197

A. Discharge Upon Confirmation of Consensual Plan Under §1191(a) .................................... 197

B. Discharge Upon Confirmation of a Cramdown Plan Under § 1191(b) ................................. 199

C. Exceptions to Discharge in Subchapter V Cases .................................................................. 200

1 Exceptions to discharge after consensual confirmation ................................................. 201

2. Exceptions to discharge after cramdown confirmation ................................................ 202

3. Procedure for determination of exceptions to discharge under § 523(a)(2), (4), or (6) 203

D. Whether § 523(a) Exceptions Apply to Cramdown Discharge of Entity ............................. 203

1. Statutory language and background .............................................................................. 203

2. Judicial debate over application of § 523(a) exceptions to cramdown discharge of an

entity .................................................................................................................................. 207

XI. Changes to Property of the Estate in Subchapter V Cases .................................................. 239

A. Property Acquired Postpetition and Earnings from Services Performed Postpetition as

Property of the Estate in Traditional Chapter 11 Cases .............................................................. 239

B. Postpetition Property and Earnings in Subchapter V Cases .................................................. 241

1. Property of the estate in subchapter V cases of an entity .............................................. 242

2. Property of the estate in subchapter V cases of an individual ....................................... 244

XII. Default and Remedies After Confirmation ........................................................................ 247

A. Remedies for Default in the Confirmed Plan ........................................................................ 247

B. Removal of Debtor in Possession for Default Under Confirmed Plan ................................. 249

C. Postconfirmation Dismissal or Conversion to Chapter 7 ...................................................... 251

1. Postconfirmation dismissal ............................................................................................ 251

2. Postconfirmation conversion ......................................................................................... 255

XIII. Effective Dates and Retroactive Application of Subchapter V ......................................... 257

APPENDIX A Lists of Sections of Bankruptcy Code and Title 28 Affected or

Amended By The Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019

(as amended by the Coronavirus, Aid, Relief, and Economic

Security Act)

v

APPENDIX B Summary of SBRA Interim Amendments to The Federal

Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure To Implement SBRA

APPENDIX C Summary Comparison of U.S. Bankruptcy Code Chapters

11, 12, & 13 (Prepared by Bankruptcy Judge Mary Jo Heston’s

Chambers)

APPENDIX D Key Events in the Timeline of Subchapter V Cases

(Prepared by Bankruptcy Judge Benjamin A. Kahn and

Law Clerk Samantha M. Ruben)

APPENDIX E Comparison of Subchapter V With Chapter 13 and Chapter 11

1

A Guide to the Small Business

Reorganization Act of 2019

Paul W. Bonapfel

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge, N.D. Ga.

I. Introduction

The Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019 (the “SBRA”)

1

enacted a new

subchapter V of chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code, codified as new 11 U.S.C. §§ 1181 – 1195,

and made conforming amendments to several sections of the Bankruptcy Code and statutes

dealing with appointment and compensation of trustees in title 28.

2

SBRA also revised the

definitions of “small business case” and “small business debtor” in § 101(51C) and § 101(51D),

respectively.

3

It took effect on February 19, 2020, 180 days after its enactment on August 23,

2019.

Subchapter V applies in cases in which a qualifying debtor elects its application. As

originally enacted, SBRA provided that a “small business debtor,” as defined in revised

§ 101(51D), could make the election. In the absence of the election, a small business debtor

would be in a “small business case,” which revised § 101(51C) defines as the case of a small

business debtor that does not elect subchapter V. SBRA did not change the pre-SBRA

1

Small Business Reorganization Act (SBRA) of 2019, Pub. L. No. 116-54, 133 Stat. 1079 (codified in 11 U.S.C.

§§ 1181-1195 and scattered sections of 11 U.S.C. and 28 U.S.C.).

2

Unless otherwise noted, references to sections are to sections of the Bankruptcy Code, title 11 of the United States

Code.

Section 3 of SBRA also enacts changes relating to prosecution of preference actions under 11 U.S.C. § 547

and to venue for certain proceedings brought by a trustee. These amendments apply in all bankruptcy cases.

SBRA § 3(a) amends § 547(b) to require that a trustee seeking to avoid a preferential transfer must exercise

“reasonable due diligence in the circumstances of the case” and must take into account a party’s “known or

reasonably knowable” affirmative defenses under § 547(c). SBRA § 3(a).

SBRA § 3(b) amends 28 U.S.C. § 1409(b) to provide that a trustee may sue to recover a debt of less than

$ 25,000 only in the district where the defendant resides. Prior to the amendment, the amount (as adjusted under 11

U.S.C. § 104 as of April 1, 2019) was $ 13,650. As of April 1, 2022, the adjusted amount under § 104 is $ 27,750.

3

SBRA § 4(1)(A)-(B).

2

provisions of chapter 11 that govern a small business case with one exception. SBRA amended

§ 1102(a)(3) to provide that no committee of unsecured creditors is appointed in a small business

case unless the court orders otherwise.

4

A debtor is a small business debtor under § 101(51D) only if, among other things, its

debts (with some exceptions) are within a specified debt limit. The debt limit at the time of

SBRA’s enactment was $ 2,725,625; on April 1, 2022, the debt limit was increased pursuant to

§ 104 to $ 3,024,725.

As Section III(B) discusses in detail, later legislation expanded the availability of

subchapter V on a temporary basis to debtors whose debts do not exceed $ 7.5 million if they

otherwise qualify as a small business debtor.

5

Under this legislation, § 1182(1) defines

eligibility for subchapter V, with the same language that defines a “small business debtor” in

§ 101(51D), except for the debt limit. On June 21, 2024, the provisions expire, and § 101(51D)

will again govern eligibility for subchapter V.

Appendix A is a chart that lists sections of the Bankruptcy Code that SBRA affected and

summarizes the changes, as affected by the later legislation.

The purpose of SBRA is “to streamline the process by which small business debtors

reorganize and rehabilitate their financial affairs.”

6

A sponsor of the legislation stated that it

4

SBRA, § 4(a)(11), 133 Stat. 1079, 1086.

5

Between March 27, 2022 and June 20, 2022, a debtor had to be a small business debtor as defined in § 101(51D),

and the debt limit was, therefore, $3,024,725. The change on June 21, 2022, was retroactive. See Section 3(B)(1);

Part XIII.

6

H.R. REP. NO. 116-171, at 1 (2019), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CRPT-

116hrpt171/pdf/CRPT-116hrpt171.pdf.

For a summary of small business reorganizations under the Bankruptcy Code, see Ralph Brubaker, The

Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019, 39 B

ANKRUPTCY LAW LETTER, no. 10, Oct. 2019, at 1-4.

Amendments to the Bankruptcy Code in 1994 permitted a qualifying small business debtor to elect small

business treatment. As amended, § 1121(e) provided that, in a small business case, only the debtor could file a plan

for 100 days after the order for relief and that all plans had to be filed within 160 days. In addition, amended

§ 1125(f) permitted parties to solicit acceptances or rejections of a plan based on a conditionally approved disclosure

3

allows small business debtors “to file bankruptcy in a timely, cost-effective manner, and

hopefully allows them to remain in business,” which “not only benefits the owners, but

employees, suppliers, customers, and others who rely on that business.”

7

Courts have taken the

legislative purpose of SBRA into account in their application of the new law.

8

SBRA has had a significant impact. A preliminary estimate was that approximately 40

percent of chapter 11 debtors in chapter 11 cases filed after October 1, 2007, would have

qualified as a subchapter V debtor and that about 25 percent of individuals in chapter 11 cases

statement and permitted a final hearing on the disclosure statement to be combined with the hearing on

confirmation.

The Bankruptcy Abuse Protection and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (“BAPCPA”) significantly

changed the small business provisions. Importantly, it eliminated the debtor’s option to choose small business

treatment. As such, a business that qualifies as a small business debtor became subject to all of the provisions

governing small business cases.

BAPCPA replaced both § 1121(e) and § 1125(f).

BAPCPA’s § 1121(e)(1) extended the exclusive time for the debtor to file a plan to 180 days and imposed a

new 300-day deadline for the filing of a plan. BAPCPA also added § 1129(c) to require confirmation of a plan in a

small business case within 45 days of its filing, unless the court extended the time.

BAPCPA’s § 1125(f) added a provision that permitted the court to determine that the plan provided

adequate information such that a separate disclosure statement was not required.

BAPCPA also added § 1116 to prescribe additional filing, reporting, disclosure, and operating duties

applicable only to small business debtors.

Although some of BAPCPA’s small business provisions facilitated chapter 11 reorganization for a small

business debtor, others appeared to reflect skepticism about the prospects for success of a small business debtor in a

chapter 11 case and specific, more intensive supervision of the administration of their cases. In practice, reporting

and confirmation requirements applicable to small business debtors remained burdensome or unworkable for many

small businesses. See, e.g., Amer. Bankr. Inst. Comm’n to Study the Reform of Chapter 11: 2012-14 Final Report &

Recommendations, 23 A

MER. BANKR. INST. L. REV. 1, 324 (2015) (For many small or medium-sized businesses,

“the common result of plan confirmation extinguishing pre-petition equity interests in their entirety [are]

unsatisfactory or completely unworkable.”).

Because SBRA did not repeal SBRA’s provisions relating to a “small business debtor,” a small business

debtor that does not elect subchapter V is in a small business case and subject to the provisions that BAPCPA added.

7

H.R. REP. NO. 116-171, at 4 (statement of Rep. Ben Cline). The court in In re Progressive Solutions, Inc., 615

B.R. 894, 896-98 (Bankr. C.D. Cal. 2020), reviewed the legislative progress of SBRA and included public

statements from several cosponsors of the law, including Senators Charles Grassley, Sheldon Whitehouse, Amy

Klobuchar, Joni Ernst, and Richard Blumenthal. See also Michael C. Blackmon, Revising the Debt Limit for “Small

Business Debtors”: The Legislative Half-Measure of the Small Business Reorganization Act, 14 B

ROOK. J. CORP.

FIN. & COM. L. 339, 344-45 (2020).

8

E.g., In re Ventura, 615 B.R. 1 , 6, 12-13 (Bankr. E.D.N.Y. 2020), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. Gregory

Funding v. Ventura (In re Ventura), 638 B.R. 499 (Bankr. E.D. N.Y. 2022); In re Progressive Solutions, Inc, 615

B.R. 894, 896-98 (Bankr. C.D. Cal. 2020).

4

would qualify.

9

Subchapter V thus changes the chapter 11 environment for both debtors and

creditors.

10

A study of 438 cases filed between subchapter V’s effective date of February 19,

2020 and December 31, 2020 indicates that it is working as intended.

11

Subchapter V resembles chapter 12

12

and chapter 13

13

in some respects. As in

subchapter V cases, both chapters 12 and 13 provide for a trustee in the case while leaving the

debtor in possession of assets and control of the business. The trustee in all of the cases has

9

Ralph Brubaker, The Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019, 39 Bankruptcy Law Letter, no. 10, Oct. 2019, at

5-6 (discussing Bob Lawless, How Many New Small Business Chapter 11s?, C

REDIT SLIPS (Sept. 14, 2019),

http://www.creditslips.org/creditslips/2019/09/how-many-new-small-business-chapter-11s.html. Professor Brubaker

points out that the percentage may ultimately be higher because pre-SBRA law provided incentives for a debtor to

avoid qualification as a small business debtor and because debtors who might not have filed under pre-SBRA law

because of its obstacles might now do so. The estimate does not take into account the increase in the debt limit that

the CARES Act temporarily made.

10

For a discussion of strategies for creditors in view of the enactment of subchapter V, see Christopher G. Bradley,

The New Small Business Bankruptcy Game: Strategies for Creditors Under the Small Business Reorganization Act,

28 A

MER. BANKR. INST. L. REV. 251 (2020).

11

Michelle M. Harner, Emily Lamasa, and Kinberly Goodwin-Maigetter, Subchapter V Cases By the Numbers, 40-

Oct Am. Bankr. Inst. J. 12 (Oct. 2021). Of the 438 cases filed in the period, 117 (27 percent) were individual cases,

of which 52 were jointly administered. As of June 30, 2021, confirmation had occurred in 221 cases, the debtor had

filed a plan that had not yet been confirmed in 105 cases, and the court had dismissed 82 cases. Id. at 59. Thus, the

debtor was able to confirm a plan in more than 62 percent of the cases not dismissed and in more than half of all of

the cases in the study.

Id.

In 130 of the 221 cases with confirmed plans, confirmation was consensual under § 1191(a) in 130 of them

(69 percent). In the 91 cases where cramdown confirmation occurred, 40 involved at least one class of creditors

voting against the plan and 51 had impaired classes that did not vote. Id.

The average number of days between filing of the case and confirmation was 184 days, and the median was

168. Id.

The authors concluded, id. at 60:

Overall, subchapter V appears to be working as intended. Small businesses are using the subchapter with

some regularity. The businesses also are, for the most part, confirming reorganization plans at a relatively

high rate in a relatively short period of time. Although more data is needed to fully understand the impact

of invoking the subchapter on both the short- and longer-term prospects of financially distressed small

businesses, the initial results are promising. Small businesses appear now to have a restructuring tool that is

both affordable and effective for addressing their financial needs.

12

As the court observed in In re Trepetin, 617 B.R. 841, 848, n. 14 (Bankr. D. Md. 2020):

Subchapter V and chapter 12 are not identical, and invoking chapter 12 standards may not be warranted in

every instance. Subchapter V starts with chapter 11 as its base and then draws on the structure of chapter

12, certain elements of chapter 13, and the recommendations of the American Bankruptcy Institute's

Commission to Study the Reform of Chapter 11 and the National Bankruptcy Conference.

13

See In re Louis, 2022 WL 2055290 at * *14 (Bankr. C.D. Ill. 2022) (The court noted that chapter 11 cases impose

fiduciary duties and administrative tasks such as preparing and filing operating reports and producing other financial

information that typically do not arise in chapter 13 cases and that representation requires understanding of

subchapter V provisions, including the advantages of consensual confirmation for an individual.).

5

oversight and monitoring duties and the right to be heard on certain matters. The subchapter V

trustee in some cases may make disbursements to creditors in a similar manner to disbursements

in chapter 12 and 13 cases.

14

But subchapter V differs from chapters 12 and 13 in significant ways. For example,

whereas confirmation standards requirements in chapter 12 (§ 1225) and chapter 13 (§ 1325) are

similar and do not contemplate voting by creditors, subchapter V confirmation requirements

incorporate most of the existing confirmation requirements in § 1129(a) and contemplate voting

by classes of creditors.

15

Unlike chapter 13, subchapter V does not provide for a codebtor stay.

Enactment of SBRA required revisions to the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure and

the Official Forms. The Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure of the Judicial

Conference of the United States (the “Rules Committee”) had authority to make changes in the

Official Forms to take effect on SBRA’s effective date. Changes to the Bankruptcy Rules,

however, take three years or more under procedures that the Rules Enabling Act, 28 U.S.C.

§§ 2071-77, require.

To take account of the new law, the Rules Committee made changes to the Official

Forms and promulgated interim rules (the “Interim Rules”) that amend the Federal Rules of

Bankruptcy Procedure.

16

The changes to the Official Forms became effective as of the effective

14

Part IX discusses disbursements in subchapter V cases.

15

Part VIII discusses confirmation requirements in subchapter V cases. For a discussion of debt limits in chapter 13

cases, see W. Homer Drake, Jr., Paul W. Bonapfel, & Adam M. Goodman, Chapter 13 Practice and Procedure §§

12:8 – 12:10.

16

On December 5, 2019, the Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules proposed Interim Amendments to the

Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (“Interim Rules”) to address provisions of SBRA for adoption in each

judicial district by local rule or general order and new Official Forms. The proposed Interim Rules and Official

Forms reflected changes in response to comments received. A

DVISORY COMMITTEE ON BANKRUPTCY RULES,

REPORT OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON BANKRUPTCY RULES (Dec. 5, 2019),

https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/december_5_2019_bankruptcy_rules_advisory_committee_report_0.pdf

On December 19, 2019, the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure approved the Interim Rules,

recommended their local adoption, and approved the new Official Forms. The Executive Committee of the Judicial

6

date of SBRA. The Rules Committee recommended that each judicial district adopt the Interim

Rules as local rules or by general order. Enactment of later legislation expanding the debt limit

required technical revisions in Interim Rule 1020 in and the Official Forms for voluntary

petitions.

17

Appendix B summarizes the changes that the Interim Rules made.

If a small business debtor does not elect subchapter V, the provisions that govern small

business cases apply.

18

The existence of two sets of provisions in chapter 11 for small business

debtors requires terminology to distinguish them. The Rules Committee refers to “small

business cases” and to “cases under subchapter V of chapter 11.”

This terminology is technically accurate. Under the SBRA amendments, a “small

business debtor” is not necessarily a debtor in a “small business case.” Rather, a “small business

case” is only a case under chapter 11 in which a small business debtor has not elected application

of subchapter V. In other words, a small business debtor that has elected application of

subchapter V is not in a small business case. Moreover, under the temporary extension of the

debt limits under later legislation, a debtor can be a subchapter V debtor, but not a small business

debtor, if its debts are less than $ 7.5 million but more than the limit for a small business debtor.

Conference, acting on an expedited basis on behalf of the Judicial Conference, approved the Interim Rules for

distribution to the courts.

The Interim Rules are located on the Current Rules of Practice & Procedure page of the U.S. Courts public

website (

USCOURTS.GOV). The new Official Forms are posted on the Forms page of the website, under the

Bankruptcy Forms table.

17

On April 6, 2020, the Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules proposed one-year technical amendments to

Interim Rule 1020 to take account of the revised definition of “debtor” under the CARES Act, which Section III(B)

discusses. The Advisory Committee also proposed conforming technical changes to official forms, including

Official Forms 101 and 202, which are the forms for the filing of a voluntary petition by an individual and a non-

individual, respectively.

On April 20, 2020, the Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure approved the amendments and

recommended their local adoption. It also approved the one-year technical change to the Official Forms.

18

For a summary of key features of a non-sub V small business case governed by the provisions for small business

cases, see supra note 6.

7

The distinction is important for at least one reason. Section 362(n) makes the automatic

stay inapplicable in certain circumstances when the debtor in the current case is or was a debtor

in a pending or previous small business case. Because a subchapter V debtor is not in a small

business case, § 362(n) will not apply in a later case of the subchapter V debtor.

19

Three types of cases are now possible under chapter 11: (1) a non-small business case

under traditional chapter 11 for a debtor who is not a small business debtor and either (a) has

debts in excess of the sub V debt limit or (b) has debts below the limit and is eligible for

subchapter V but does not elect it; (2) a small business case for a small business debtor that does

not elect subchapter V; and (3) a subchapter V case for a qualifying debtor who elects it. This

paper generally uses “traditional” to describe a chapter 11 case (including a small business case)

that is not a subchapter V case.

II. Overview of Subchapter V

For electing debtors who qualify, subchapter V: (1) modifies confirmation requirements;

(2) provides for the participation of a trustee (the “sub V trustee”) while the debtor remains in

possession of assets and operates the business as a debtor in possession; (3) changes several

19

In In re Abundant Life Worship Center of Hinesville, GA., Inc., 2020 WL 7635272 (Bankr. S.D. Ga. 2020), a

debtor whose earlier small business case had been dismissed seven months earlier filed a new chapter 11 case and

amended the petition to elect subchapter V. The debtor contended that § 362(n)(1) did not apply because, upon its

subchapter V election, it ceased being a debtor in a “small business case.” Id. at *8. The court ruled that the status

of the debtor in the current case made no difference: “The statute plainly requires only that the prior case was a

small business case, not the subsequent case.” Id. at * 18.

The debtor also contended that the exception in paragraph (n)(2) of § 362 to the operation of paragraph

(n)(1) applied. Section 362(n)(2)(B) provides that paragraph (n)(1) does not apply if the debtor establishes “that the

filing of the petition resulted from circumstances beyond the control of the debtor not foreseeable at the time the

case then pending was filed” (emphasis added) and that “it is more likely than not that the court will confirm a

feasible plan, but not a liquidating plan, within a reasonable time.”

The court rejected this argument, concluding that the language, “the case then pending” refers to a separate

case pending at the time of the filing of the second case. Because the debtor’s previous case was not a “case then

pending,” the court ruled, the exception did not apply. Id. at *11-12. The court thus followed Palmer v. Bank of the

West, 438 B.R. 167 (E.D. Wis. 2010).

8

administrative and procedural rules; and (4) alters the rules for the debtor’s discharge and the

definition of property of the estate with regard to property an individual debtor acquires

postpetition and postpetition earnings (which has implications for operation of the automatic stay

of § 362(a)). Only the sub V debtor may file a plan or a modification of it.

This Part provides an overview of these provisions. Later Parts discuss these and other

provisions in more detail. Appendix C is a chart that compares provisions of subchapter V with

those that govern traditional chapter 11, chapter 12, and chapter 13 cases.

A. Changes in Confirmation Requirements

The court may confirm a sub V plan even if all classes reject it. Moreover, the “fair and

equitable” requirement for “cramdown” confirmation does not include the absolute priority rule.

Instead, the plan must comply with a new projected disposable income requirement (applicable

in cases of entities as well as those of individuals). The cramdown requirements for a secured

claim are unchanged. (Part VIII).

A sub V plan may modify a claim secured only by a security interest in the debtor’s

principal residence if the new value received in connection with the granting of the security

interest was not used primarily to acquire the property and was used primarily in connection with

the small business of the debtor. Such modification is not permitted in traditional chapter 11

cases or in chapter12 or 13 cases. (Section VII(B)).

9

B. Subchapter V Trustee and the Debtor in Possession

Subchapter V provides for the debtor to remain in possession of assets and operate the

business with the rights and powers of a trustee unless the court removes the debtor as debtor in

possession. (Part V).

The United States Trustee appoints the sub V trustee. The role of the sub V trustee is to

oversee and monitor the case, to appear and be heard on specified matters, to facilitate a

consensual plan, and to make distributions under a nonconsensual plan confirmed under the

cramdown provisions. (Part IV).

C. Case Administration and Procedures

Subchapter V modifies the usual procedures in chapter 11 cases in several respects.

Appendix D summarizes the key events in a subchapter V case and the timeline for them.

No committee of unsecured creditors. A committee of unsecured creditors is not

appointed unless the court orders otherwise. (SBRA also makes this the rule in a non-sub V

small business case.) (Section VI(A)).

Required status conference and report from debtor. The court must hold a status

conference within 60 days of the filing “to further the expeditious and economical resolution” of

the case. Not later than 14 days before the status conference, the debtor must file a report that

details the efforts the debtor has undertaken and will undertake to achieve a consensual plan of

reorganization. (Section VI(C)).

Time for filing of plan. The debtor must file a plan within 90 days of the date of entry of

the order for relief, unless the court extends the time based on circumstances for which the

debtor should not justly be held accountable. The requirements in a non-sub V small business

case that a plan be filed within 300 days of the filing date (§ 1121(e)) and that confirmation

10

occur within 45 days of the filing of the plan (§ 1129(e)) do not apply in a sub V case. (Section

VI(D)).

No disclosure statement. Section 1125, which states the requirements for a disclosure

statement in connection with a plan and regulates the solicitation of acceptances of a plan, does

not apply in a sub V case, unless the court orders otherwise. Although no disclosure statement is

required, the plan must include: (1) a brief history of the business operations of the debtor; (2) a

liquidation analysis; and (3) projections with respect to the ability of the debtor to make

payments under the proposed plan. (Sections VI(B), VII(B)).

No U.S. Trustee fees. A sub V debtor does not pay U.S. Trustee fees. (Section VI(E)).

D. Discharge and Property of the Estate

1. Discharge – consensual plan

If the court confirms a consensual plan, a sub V debtor (including an individual debtor)

receives a discharge under § 1141(d)(1)(A) upon confirmation. The provision in § 1141(d)(5)

for delay of discharge in individual cases until completion of payments does not apply in a sub V

case. In the case of an individual, the § 1141(d)(1)(A) discharge does not discharge debts

excepted under § 523(a).

20

One effect of the grant of the discharge is that the automatic stay

terminates under § 362(c)(2)(C). (Section X(A)).

2. Discharge – cramdown plan

When cramdown confirmation occurs in a sub V case, § 1141(d) does not apply, and

confirmation does not result in a discharge. Instead, §1192 governs the discharge, which does

not occur until the debtor completes plan payments for a period of at least three years or such

longer time not to exceed five years as the court fixes. (Section X(B)).

20

§ 1141(d)(2).

11

Under §1192, the discharge in a cramdown case discharges the debtor from all debts

specified in § 1141(d)(1)(A) and all other debts allowed under § 503 (administrative expenses),

with the exception of: (1) debts on which the last payment is due after the first three years of the

plan or such other time not exceeding five years as the court fixes; and (2) debts excepted under

§ 523(a). (Section X(C)(2)). Under § 362(c)(2), the automatic stay remains in effect after

confirmation of a cramdown plan until the case is closed or dismissed, or the debtor receives a

discharge.

3. Property of the estate

Section 1115 provides that, in an individual chapter 11 case, property of the estate

includes assets that the debtor acquires postpetition and earnings from postpetition services.

Section 1115 does not apply in a subchapter V case.

21

If the court confirms a plan under the

cramdown provisions of §1191(b), however, property of the estate includes (in cases of both

individuals and entities) postpetition assets and earnings.

22

See Section XI(B).

III. Debtor’s Election of Subchapter V and Revised

Definition of “Small Business Debtor”

A. Debtor’s Election of Subchapter V

The provisions of subchapter V apply in cases in which an eligible debtor elects them.

23

If an eligible debtor does not make the election, the traditional provisions of Chapter 11 apply. If

21

§ 1181(a).

22

§ 1186(a).

23

One commentator has suggested that a creditor may want to attempt to limit the availability of subchapter V by

including in the credit agreement a commitment from the debtor not to make the election or to waive it, noting that

such a contractual provision may not be enforceable. Christopher G. Bradley, The New Small Business Bankruptcy

Game: Strategies for Creditors Under the Small Business Reorganization Act, 28 A

MER. BANKR. INST. L. REV. 251,

264 (2020). Professor Bradley suggests alternatively that a creditor could require a “springing” (sometimes referred

to as a “bad boy”) guarantee from a debtor’s insider that would arise if the debtor elected subchapter V. Id. at 264-

65.

12

the non-electing debtor is a small business debtor as defined in § 101(51D), the debtor is in a

“small business case” under § 101(51C), and the special provisions governing such cases apply.

As Section III(B) discusses, § 1182(1) defines eligibility for subchapter V until June 20,

2024. Thereafter, a debtor must be a small business debtor under § 101(51D) to be eligible for

subchapter V. Except for the debt limit ($ 3,024,725 under § 101(51D) and $ 7.5 million under

§ 1182(1)), eligibility for subchapter V is the same under both provisions.

An individual eligible for subchapter V will also be eligible for chapter 13 if the debtor

has regular income and debts that do not exceed the chapter 13 debt limits.

24

Effective June 21,

2022, the debt limit in a chapter 13 case was temporarily increased to $ 2,750,000 for both

secured and unsecured debts under the Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustment and Technical

Corrections Act (“BTATCA”).

25

On June 20, 2024, the debt limits return to $ 465,275 for

unsecured debts and $ 1,395,875 for secured debts.

26

Appendix E compares subchapter V cases with chapter 13 cases, small business cases,

and traditional chapter 11 cases.

The statute does not state when or how the debtor makes the election. Bankruptcy Rule

1020(a) requires a debtor to state in the petition whether it is a small business debtor.

27

In an

involuntary case, the Rule requires the debtor to file the statement within 14 days after the order

for relief. The case proceeds in accordance with the debtor’s statement unless and until the court

enters an order finding that the statement is incorrect.

24

§ 109(e) governs chapter 13 eligibility.

25

Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustments and Technical Corrections Act § 2(a), Pub. L. No. 117-151, 136 Stat. 1298

(June 21, 2022) (hereinafter “BTATCA”). The increased debt limits apply retroactively in any bankruptcy case

commenced on or after March 27, 2020 that is pending on the date of BTATCA’s enactment. Id. § 2(h)(2(A).

26

BTATCA § 2(i)(1)(A). The court may convert a chapter 11 case to chapter 13 if the debtor requests it. § 1112(c).

27

FED. R. BANK. P. 1020(a).

13

Interim Rule 1020(a) as originally promulgated added the requirement that the debtor

state in the petition whether the debtor elects application of subchapter V and provided that the

case proceed in accordance with the election unless the court determined that it is incorrect. In

an involuntary case, the Interim Rule required the debtor to state whether it is a small business

debtor and to make the election within 14 days after the order for relief.

28

In response to

temporary legislation that changed the debt limit for subchapter V eligibility to $7.5 million and

put the eligibility requirements in § 1182(1),

29

revised Interim Rule 1020 provides in both

instances for the debtor to state whether the debtor is a small business debtor or a debtor as

defined in § 1182(1) and, if the latter, whether the debtor elects application of subchapter V.

Revisions to the Official Forms for voluntary chapter 11 cases require the debtor to state

whether it is a small business debtor or a § 1182(1) debtor and whether it does or does not make

the election.

30

Revised Official Forms also provide for creditors to receive notice of the

debtor’s statement of its status and the election that it makes.

31

Parties in interest may object to a debtor’s statement of whether it is a small business

debtor or is eligible for subchapter V. Bankruptcy Rule 1020(b) requires an objection to a

debtor’s statement of its small business status within 30 days after the later of the conclusion of

the § 341(a) meeting or amendment of the statement. Interim Rule 1020(b) makes the same

28

INTERIM RULE 1020.

29

See Section III(B).

30

OFFICIAL FORM B101 ¶ 13 (Voluntary Petition for Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy); OFFICIAL FORM B102 ¶ 8

(Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy).

31

OFFICIAL FORM B309E2 is the form for individuals or joint debtors under subchapter V, and OFFICIAL FORM

B309F2 is the form for corporations or partnerships under subchapter V. Existing O

FFICIAL FORMS B309E

(individuals or joint debtors) and B309F (corporations or partnerships) were renumbered as B309E1 and B309F1.

Both new forms contain the same information as the existing notices but provide additional information applicable

in subchapter V cases.

The new forms require inclusion of the trustee and the trustee’s phone number and email address. The new

notices state that the debtor will generally remain in possession of property and may continue to operate the business

and advise that, in some cases, debts will not be discharged until all or a substantial portion of payments under the

plan are made.

14

requirement applicable to the statement regarding the debtor’s statement that it is an eligible

subchapter V debtor.

Most courts have determined that the burden is on the debtor to establish eligibility for

subchapter V if challenged.

32

A contrary view is that the objecting party as the moving party has

the burden of proving that the debtor is not eligible.

33

The issue may be academic in most cases

dealing with eligibility. For the most part, the outcomes do not appear to turn on the resolution

of factual disputes but on the legal conclusions to be drawn from the facts.

It is not clear whether a bankruptcy court’s order determining that a debtor is eligible is a

final order for purposes of appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 158(a)(1).

34

A district court or bankruptcy

32

NetJets Aviation, Inc. v. RS Air, LLC (In re RS Air, LLC), 2022 WL 1288608 at *8-9 (B.A.P. 9

th

Cir. 2022); In re

Blue, 630 B.R. 179, 187 (Bankr. M.D.N.C. 2021); National Loan Invs., L.P. v. Rickerson (In re Rickerson), 636

B.R. 416, 422 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 2021); Lyons v. Family Friendly Contracting LLC (In re Family Friendly

Contracting LLC), 2021 WL 5540887 at * 2 (Bankr. D. Md. 2021); In re Vertical Mac Construction, LLC, 2021

WL 3668037 at *2 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2021); In re Port Arthur Steam Energy, L.P., 629 B.R. 233, 235 (Bankr. S.D.

Tex. 2021); In re Offer Space, LLC, 629 B.R. 299, 304 (Bankr. D. Utah 2021); In re Ikalowych, 629 B.R. 261, 275

(Bankr. D. Colo. 2021); In re Johnson, 2021 WL 825156 at *4 (Bankr. N.D. Tex. 2021); In re Thurman, 625 B.R.

417, 419 n.4 (Bankr. W.D. Mo. 2020).

33

E.g., Hall L.A. WTS, LLC v. Serendipity Labs, Inc. (In re Serendipity Labs, Inc.), 620 B.R. 679, 680 n.3 (Bankr.

N.D. Ga. 2020); In re Body Transit, Inc., 613 B.R. 400, 409 n. 15 (Bankr. E.D. Pa. 2020) (“It is appropriate to place

the burden of proof on [the objecting party], as it is the de facto moving party.”).

34

In NetJets Aviation, Inc. v. RS Air, LLC (In re RS Air, LLC), 2022 WL 1288608 (B.A.P. 9

th

Cir. 2022), the court

reviewed the bankruptcy court’s eligibility order in connection with an appeal of the order confirming the

subchapter V plan. The court stated, “The interlocutory Subchapter V Order merged into the final Confirmation

Order.” Id. at *3 n. 3. The court cited United States v. Real Prop. Located at 475 Martin Lane, 545 F.3d 1134 ,

1141 (9

th

Cir. 2008) (under merger rule, interlocutory orders entered prior to the judgment merge into the judgment

and may be challenged on appeal).

In Gregory Funding v. Ventura (In re Ventura), 638 B.R. 499 (E.D. N.Y. 2022), however, the court in

reversing an order of the bankruptcy court determining that the debtor was eligible for subchapter V, without

discussing the finality issue, stated that district courts have appellate jurisdiction over final judgments, orders, and

decrees. Id. at *3.

The district court’s ruling in Guan v. Ellingsworth Residential Community Association, Inc. (In re

Ellingsworth Residential Community Association, Inc.), 2021 WL 3908525 (M.D. Fla. 2021), appeal dismissed,

2021 WL 6808445 (11

th

Cir. 2021) (unpublished), cert. denied, 2022 WL 1131391 (2022), indicates that an

eligibility determination is a final order. The creditor filed a notice of appeal after the bankruptcy court issued an

order scheduling a hearing on confirmation of the debtor’s subchapter V plan after a hearing at which it took the

eligibility objection under advisement. The creditor appealed the scheduling order, and the bankruptcy court denied

the creditor’s motion for a stay pending appeal. In a later order, the bankruptcy court determined that the debtor was

eligible. See In re Ellingsworth Residential Community Association, Inc., 619 B.R. 519 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2019).

The creditor did not seek leave to amend her notice of appeal to include the order denying a stay pending appeal or

the eligibility order.

15

appellate panel has jurisdiction to hear an appeal from an interlocutory order, with leave of the

court, under 28 U.S.C. § 158(a)(3) and § 158(b)(1), respectively.

35

Courts of appeals have

discretionary jurisdiction to hear an appeal of an interlocutory order (as well as a final one) of the

bankruptcy court under 28 U.S.C. § 158(d)(2) that a bankruptcy court, district court, or

bankruptcy appellate panel certifies on various grounds.

36

Bankruptcy Rule 1009(a) gives a debtor the right to amend a voluntary petition, list,

schedule, or statement “as a matter of course at any time before the case is closed.” A question

is whether a debtor may amend the small business designation or the subchapter V election that

the voluntary petition includes. Current Bankruptcy Rule 1020 does not address whether a

debtor can amend the small business designation, and Interim Rule 1020 likewise does not

address the issue of whether a delayed sub V election should be allowed and, if so, under what

circumstances.

37

The district court held that the scheduling order was interlocutory and that the order denying the eligibility

objections was not properly before the court. Guan v. Ellingsworth Residential Community Association, Inc. (In re

Ellingsworth Residential Community Association, Inc.), 2021 WL 3908525 at * 2 (M.D. Fla. 2021), appeal

dismissed, 2021 WL 6808445 (11

th

Cir. 2021) (unpublished), cert. denied, 2022 WL 1131391 (2022). The

implication is that the eligibility order was a final order because it finally resolved the objection to eligibility. The

district court nevertheless determined that, even if the creditor had properly raised the issue, the appeal would be

denied on the merits. Id.

The Eleventh Circuit dismissed the appeal sua sponte for lack of jurisdiction because the district court’s

order affirming the bankruptcy court’s interlocutory scheduling order was not a final order of the district court

within its appellate jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 158(d)(1). Guan v. Ellingsworth Residential Community

Association, Inc. (In re Ellingsworth Residential Community Association, Inc.), 2021 WL 6808445 (11

th

Cir. 2021)

(unpublished), cert. denied, 2022 WL 1131391 (2022).

35

In re Parkinson, 2021 WL 1554068 at * 2 (D. Idaho 2021). (“[R]eviewing and resolving any questions

concerning Subchapter V will not waste litigation resources, but will conserve them. In like manner, taking up

Appellants’ appeal at the current juncture will advance the ultimate termination of the underlying bankruptcy

litigation.”).

36

The lower court must certify either: (1) that the order involves a question of law as to which no controlling circuit

or Supreme Court authority exists or a matter of public importance; (2) that the order involves a question of law

requiring resolution of conflicting decisions; or (3) that an immediate appeal may materially advance the progress of

the case or proceeding in which the appeal is taken. 28 U.S.C. § 158(d)(2)(A)(i)-(iii).

37

The Advisory Committee Note to Interim Rule 1020 states, “The rule does not address whether the court, on a

case-by-case basis, may allow a debtor to make an election to proceed under subchapter V after the times specified

in subdivision (a) or, if it can, under what conditions.”

16

Part XIII discusses whether a debtor who does not make the subchapter V election in the

original petition may later amend the petition to elect application of Subchapter V. The issue

arose in cases filed before enactment of SBRA in which the debtor sought to proceed under

subchapter V when it became available. A similar issue may arise in a case filed by a debtor

between March 27 and June 20, 2022, if the debtor was not eligible for subchapter V at the time

of filing based on the amount of its debt but became eligible after enactment of the Bankruptcy

Technical Adjustments and Technical Correction Act on the latter date that increased the debt

limit, as Section III(B) discusses.

One problem with permitting a debtor to change the election is that deadlines for

conducting a status conference

38

and for filing a plan

39

run from the date of the order for relief.

The Advisory Committee in its Report observed, “Should a court exercise authority to allow a

delayed election, it is likely that one of the court’s prime considerations in ruling on a request to

make a delayed election would be the time restriction imposed by subchapter V. . . .”

40

Section

VI(J) and Part XIII discuss extension of the time limits and their effect on the ability of a debtor

to amend the petition to make an election after their expiration.

38

See Section VI(C).

39

See Section VI(D).

40

Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules, REPORT OF THE ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON BANKRUPTCY RULES (Dec.

5, 2019), at 3, available at

https://www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/december_5_2019_bankruptcy_rules_advisory_committee_report_0.pdf

17

B. Eligibility for Subchapter V; Revised Definitions of “Small Business Debtor” and

“Small Business Case”

1. Statutory provisions governing application of subchapter V and the debt limit

The operative statutory provision for application of subchapter V is § 103(i), which

SBRA added.

41

As amended by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (the

“CARES Act”)

42

in March 2020, it provides:

Subchapter V of chapter 11 of this title applies only in a case under chapter 11 in

which a debtor (as defined in section 1182) elects that subchapter V of title 11

shall apply.

As originally enacted by SBRA, § 1182(1) defined “debtor” as meaning a “small

business debtor,”

43

a term defined in § 101(51D). As Section III(B)(2) discusses below,

SBRA also revised the § 101(51D) definition of “small business debtor,” but did not

change the then-existing debt limit of $ 2,725,625 (now $ 3,024,725 as adjusted on April

1, 2022, under § 104).

The CARES Act increased the debt limit to $ 7.5 million through amendments to

§ 1182(a) and § 103(i). The CARES Act amended § 1182(1) so that its definition of

“debtor” is the same as the definition of “small business debtor” in revised §101(51D),

with a technical correction that it also made,

44

except that the debt limit in § 1182(1) is

$ 7.5 million.

45

It did not change the debt limit in revised § 101(51D). The CARES Act

changed § 103(i) to replace “small business debtor” with “debtor (as defined in section

41

SBRA inserted new subsection (i) in § 103 and renumbered existing subsections (i) through (k) as (j) through (l).

SBRA § 4(a)(2).

42

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act § 1113(a)(2), Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (Mar. 27,

2020). Before enactment of the CARES Act, § 103(i) provided:

Subchapter V of chapter 11 of this title applies only in a case under chapter 11 in which a small business

debtor elects that subchapter V of title 11 shall apply.

43

SBRA § 2(a).

44

The technical correction involved the exclusion of public companies. Later legislation changed the provision.

See Section III(G) and note 95 infra.

45

CARES Act § 1113(a)(1).

18

1182).” As thus amended, § 103(i) provides that subchapter V applies in the case of a

debtor as defined in § 1182 who elects is application.

The CARES Act provided for the increased debt limit to be effective for only one year

after its enactment on March 27, 2020.

46

The Covid-19 Bankruptcy Relief Extension Act of

2021

47

amended the CARES Act to extend the amended provisions for an additional year. On

March 27, 2022, §§ 1182(1) returned to its original language in the SBRA. At that time,

§ 1182(1) again defined “debtor” as “a small business debtor,” and § 103(i) therefore limited

application of subchapter V to a small business debtor who elected it.

The Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustment and Technical Corrections Act (“BTATCA”),

48

enacted on June 21, 2022, temporarily reinstated for two years the expired provisions of

§ 1182(a), with some changes relating to affiliated debtors. BTATCA made the same changes in

the definition of a small business debtor in § 101(51D).

49

The sunset provision of BTATCA

provides that, on June 21, 2024, § 1182(1) will define debtor as a “small business debtor.” At

that time, § 103(i) will make subchapter V applicable only if the debtor is a small business debtor

who elects it. The BTATCA changes to the definition of “small business debtor” do not

expire.

50

These temporary amendments in BTATCA became effective on the date of enactment.

51

They are retroactive to cases filed on or after March 27, 2020 that were pending on the date of its

46

CARES Act § 113(a)(5).

47

Covid-19 Bankruptcy Relief Extension Act of 2021§ 2(a)(1), Pub. L. No. 117-5, 135 Stat. 249 (Mar. 27, 2021).

48

Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustment and Technical Corrections Act, §§ 2(a), (d), Pub. L. No. 117-151, 136 Stat.

1298 (June 21, 2022) (hereinafter “BTATCA”).

49

See Sections III(F), (G).

It is somewhat amusing that, in the course of one week, three different debt limits governed eligibility for

subchapter V. On Sunday, March 27, 2022, the debt limit was $ 7.5 million. When that limit expired the next day,

it was $ 2,725,625, the debt limit under § 101(51D). On Friday, April 1, 2022, adjustments under § 104 made the

debt limit under § 101(51D) $ 3,024,725.

50

BTATCA § 2(i)(1)(B).

51

BTATCA § 2(h)(1).

19

enactment.

52

A debtor who filed a chapter 11 petition between March 27, 2022 and the effective

date of BTATCA but was not eligible for subchapter V because its debts exceeded the debt limit,

therefore, has the opportunity to seek to amend its petition to elect subchapter V.

Section XIII discusses the issues that arose when a debtor sought to amend its petition to

elect subchapter V in a case filed before the effective date of SBRA. That caselaw may provide

guidance in addressing retroactivity issues under the BTATCA amendments.

In summary, the effect of BTATCA is that until June 20, 2024, § 1182(1) states

the definition of a debtor eligible to be a sub V debtor. After that, a debtor must be a

small business debtor under the revised definition in § 101(51D). The only difference in

the language of the two statutes is the higher debt limit in the temporary version of

§ 1182(1). (Because none of this legislation changed the debt limit in the definition of

“small business debtor,” a debtor with debts in excess of the § 101(51D) limit but below

$ 7.5 million that does not elect subchapter V cannot be a small business debtor.)

BTATCA provides for an inflationary adjustment to the debt limit in § 1182(1)

under § 104.

53

Although this amendment does not expire, the next adjustment does not

take place until April 1, 2025, by which time § 1182(1) will no longer state the debt limit.

2. Overview of eligibility for subchapter V

In general, a debtor is eligible to elect subchapter V if the debtor: (1) is a “person;” (2) is

engaged in “commercial or business activities;” (3) does not have aggregate debts in excess of

the debt limit; and (4) at least 50 percent of the debts arise from the debtor’s commercial or

business activities,

54

subject to certain exceptions. (“Person” under § 101(41) includes an

52

BTATCA § 2(h)(2).

53

BTATCA § 2(b).

54

See generally, e.g., In re Blue, 630 B.R. 179, 191-93 (Bankr. M.D.N.C. 2021).

20

individual, corporation, or partnership but does not generally include a governmental unit. A

limited liability company is a “person.”

55

)

A debtor is ineligible for sub V if: (1) its primary activity is the business of owning single

asset real estate; (2) it is a member of a group of affiliated debtors that has aggregate debts in

excess of the debt limit; (3) it is a corporation subject to reporting requirements under the

Securities Exchange Act of 1934; or (4) it is an affiliate of a reporting corporation.

Although, as Section III(B)(1) explains, the statutory basis for determining a debtor’s

eligibility for subchapter V is § 1182(1) until June 20, 2024, the § 1182(1) definition contains the

same language as the definition of a small business debtor in § 101(51D), with the exception of

the amount of the debt limit ($ 7.5 million in § 1182(1), $ 3,024,725 in § 101(51D)). Because

the eligibility requirements in § 1182(1) are the same as those in § 101(51D) (and will return to

§ 101(51D) under BTATCA’s sunset provision), the next section discusses the definition of a

small business debtor, as SBRA and later legislation revised it.

Later sections discuss in detail: the requirement that the debtor be “engaged in

commercial or business activities” (Section III(C)); what debts “arose from” such activities

(Section III(D)); whether the commercial or business debts must be connected to the debtor’s

current commercial or business activities (Section III(E)); what debts are included in

determination of the debt limit (Section III(F)); and the exclusion of reporting companies and

affiliates of an issuer (Section III(G)).

55

E.g., In re QDN, LLC, 363 Fed. Appx. 873, 876 n. 4 (3d Cir. 2010); In re CWNevada, LLC, 602 B.R. 717 (Bankr.

D. Nev. 2019); In re 4 Whip, LLC, 332 B.R. 670, 672 (Bankr. D. Conn. 2005); In re ICLNDS Acquisition, LLC,

259 B.R. 289, 292-93 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio (2001); see In re Asociación de Titulares de Condominio Castillo, 581

B.R. 346, 358-60 (B.A.P. 1

st

Cir. 2018) (collecting cases).

21

3. Revisions to the definition of “small business debtor” and requirements for

eligibility for subchapter V in general

Under pre-SBRA law, paragraph (A) of § 101(51D) defined a “small business debtor” as

a person

56

(1) engaged in commercial or business activities, (2) excluding a debtor whose

principal activity is the business of owning or operating real property, (3) that has aggregate

noncontingent liquidated secured and unsecured debts

57

as of the date of the filing of the petition

or the date of the order for relief in an amount not more than $ 2,725,625 (adjusted on April 1,

2022 under § 104 to $ 3,024,725), (4) in a case in which the U.S. Trustee has not appointed a

committee of unsecured creditors or the court has determined that the committee is not

sufficiently active and representative to provide effective oversight of the debtor.

Paragraph (B) of former § 101(51D) excluded any member of a group of affiliated

debtors that had aggregate debts in excess of the debt limit (excluding debts to affiliates and

insiders).

SBRA amended the § 101(51D) definition of “small business debtor” and provided that a

small business debtor could elect application of subchapter V. As Section III(B)(1) explains,

later legislation temporarily put the eligibility requirements for subchapter V in § 1182(1),

increased the debt limit for subchapter V to $ 7.5 million, and made other revisions.

Except for the difference in the debt limits, the temporary language of § 1182(1) is

identical to the language of § 101(51D). Specifically, paragraphs (A) and (B) of § 1182(1) are

the same as paragraphs (A) and (B) of § 101(51D), as amended by both SBRA and later

legislation.

56

A trust is not a “person” unless it is a business trust. E.g., In re Quadruple D Trust, 639 B.R. 204 (Bankr. D. Col.

2022). The court’s opinion includes a comprehensive analysis of the standards for determining what is a business

trust, concluding that the debtor was not a business trust and that it was not eligible to file for bankruptcy protection.

57

§ 101(51D)(A). Debts owed to one or more affiliates or insiders are excluded from the debt limit. Id. See Section

III(F).

22

SBRA did not change the provision that a “small business debtor” does not include a

debtor that is “a member of a group of affiliated debtors” that has aggregate debts in excess of

the debt limit. § 101(51D)(B)(i). The Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustment and Technical

Corrections Act (“BTATCA”),

58

enacted on June 21, 2022, made a technical correction to this

language, which Section III(F) discusses. The same language is in § 1182(1).

SBRA also retained the requirement in § 101(51D) that the debtor be “engaged in

commercial or business activities.” SBRA revised paragraph (A), however, to add the

requirement that 50 percent or more of the debtor’s debt must arise from the debtor’s commercial

or business activities. The same requirements are temporarily in § 1182(1). Section III(C)

discusses eligibility issues that have arisen as to whether the debtor is “engaged in commercial or

business activities,” and Section III(D) considers what constitutes a debt arising from

commercial or business activity. Section III(E) addresses whether the debts arising from the

debtor’s commercial or business activities must arise from the debtor’s current commercial or

business activities.

SBRA made three other definitional changes in § 101(51D). Later legislation made a

technical correction to one of them. As amended, § 101(51D) and § 1182(1) contain identical

paragraphs (A) and (B).

First, amended paragraph (A) excludes a debtor engaged in owning or operating real

property from being a small business debtor only if the debtor owns or operates single asset real

58

Bankruptcy Threshold Adjustment and Technical Corrections Act, §§ 2(a)(1), Pub. L. No. 117-151, 136 Stat.

1298 (June 21, 2022) (hereinafter “BTATCA”).

.

23

estate.

59

Pre-SBRA § 101(51D) excluded a debtor whose principal activity was the business of

owning or operating real property.

Second, the requirement that no committee of unsecured creditors exist (or that it not

provide effective oversight) is eliminated. (Recall that SBRA provides that no committee will be

appointed in a non-sub V small business case unless the court orders otherwise.)

Finally, SBRA added subparagraphs (B)(ii) and (B)(iii) to exclude two additional types

of debtors to those that paragraph (B) excludes from being a small business debtor.

The first new exclusion, in (B)(ii), is for a corporation subject to reporting requirements

under § 13 or § 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.

60

As amended by later legislation,

the second new exclusion, in (B)(iii),

is for a debtor that is an affiliate of a corporation subject to

those reporting requirements.

Section III(G) discusses the exclusions for a public company and its affiliates.

An individual who does not have regular income may be a chapter 13 debtor in a joint

case with the individual’s spouse who does have regular income,

61

and an individual who is not a

family farmer or fisherman may be a chapter 12 debtor in a joint case with the individual’s

spouse who is engaged in a farming operation or a commercial fishing operation.

62

59

Section 101(51B) defines “single asset real estate” as “real property constituting a single property of project, other

than residential real property with fewer than 4 residential units, which generates substantially all of the gross

income of a debtor who is not a family farmer and on which no substantial business is being conducted by a debtor

other than the business of operating the real property and activities incidental thereto.” § 101(51B). For a

discussion of case law relating to the definition of “single asset real estate” in the sub V context, see In re NKOGS1,

LLC, 626 B.R. 860 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2021) (Debtor is qualified for subchapter V because the hotel that it owns and

operates is not a “single asset real estate” project.). See also In re Caribbean Motel Corp., 2022 WL 50401 (Bankr.

D. P.R. 2022) (motel renting rooms by the hour generating five to seven percent of income from providing food

service on request and selling goods such as prophylactics and aspirin is not a single asset real estate debtor).

60

§ 101(51D)(B)(ii).

61

11 U.S.C. § 109(e).

62

11 U.S.C. § 109(f) (only a family farmer or family fisherman may be a chapter 12 debtor); 11 U.S.C.

§ 101(18)(A) (definition of family farmer includes spouse); 11 U.S.C. § 101(19A) (definition of family fisherman

includes spouse).

24

Subchapter V has no such provision. Although an affiliate of an eligible subchapter V

debtor may be a subchapter V debtor even if the affiliate is not otherwise eligible, a spouse is not

an affiliate as defined in § 101(2).

63

SBRA amended the definition of “small business case” in § 101(51C) to exclude a

subchapter V debtor. Thus, a “small business case” is a case in which a small business debtor