DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

10 proposals to build

a safer world together

Strengthening the Global Architecture for Health

Emergency Preparedness, Response and Resilience

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

10 proposals to build

a safer world together

Strengthening the Global Architecture for Health

Emergency Preparedness, Response and Resilience

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

ii

10 proposals to build a safer world together – Strengthening the Global Architecture for Health Emergency Preparedness, Response and

Resilience

WHO/2022

© World Health Organization 2022

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence

(CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work

is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specic

organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license

your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add

the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization

(WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding

and authentic edition”.

Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the

World Intellectual Property Organization

(http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules/).

Suggested citation. 10 proposals to build a safer world together – Strengthening the Global Architecture for Health Emergency

Preparedness, Response and Resilience Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris .

Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders . To submit requests for commercial

use and queries on rights and licensing, see

http://www.who.int/about/licensing .

Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables, gures or

images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtain permission from the

copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of any third-party-owned component in the work rests solely

with the user.

General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the

expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or

of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent

approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.

The mention of specic companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or

recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the

names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published

material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and

use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall WHO be liable for damages arising from its use.

Cover photo: WHO is reaching the most vulnerable people in 15 African countries, including South Sudan, who are facing humanitarian situations such as drought,

natural disasters and displacement. © WHO

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

iii

Contents iii

Foreword from the Director-General iv

Executive summary v

Introduction 1

Purpose of the white paper 2

Proposals for strengthening global health emergency

preparedness, response and resilience 3

Governance 4

Systems 6

Financing 11

Equity, inclusivity and coherence 14

Next Steps 17

Annex 1: Strengthening HEPR systems capacities 18

Annex 2: Application of principles of equity,

inclusivity, and coherence 32

Contents

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

iv

Foreword from the Director-General

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed deep aws in the world’s defences

against health emergencies, exposed and exacerbated profound inequities

within and between countries, and eroded trust in governments and

institutions.

The world was, and remains, unprepared for large-scale health

emergencies. But this lesson is not a new one. For decades the emergence

of new epidemic-prone diseases, conicts, and other humanitarian

emergencies has caused global panic and alarm, followed by neglect and

underinvestment in health emergency preparedness, prevention and

response as public and political attention wanes.

Three interlinked priorities are key to the renewal and recovery of national

and global health systems that we need to break the cycle of panic and

neglect, improve population health, and make countries better prepared for

and more resilient against future health emergencies.

We must tackle the root causes of disease and ill-health; we must reorient

health systems towards primary health care and universal health coverage; and we must rapidly strengthen the global

architecture for health emergency preparedness and response. This white paper presents WHO’s proposals for how we can

achieve this third priority together.

In response to a request at our Executive Board, and in consultation with Member States and other stakeholders, we set

out ten proposals for a stronger global health security architecture, based on the principles of equity, inclusivity, and

coherence. The proposals build on the more than 300 recommendations from the various independent reviews of the

global response to COVID-19, and reports into previous outbreaks.

We call for stronger governance that is coherent, inclusive and accountable; stronger systems and tools to prevent,

detect and respond rapidly to health emergencies; stronger nancing, domestically and internationally; and a stronger,

empowered and sustainably nanced WHO at the centre of the global health security architecture.

Finally, to be able to implement these proposals eectively, we need a new international accord, which WHO’s Member

States are now negotiating. Since the Second World War, countries have entered into treaties on tobacco, nuclear, chemical

and biological weapons, climate change and many other threats to our shared security and well-being. It is common sense

now for countries to agree on a common approach to common threats, with common rules for a common response to

health emergencies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us all many painful lessons. The greatest tragedy would be not to learn them. Now is the

time to make the bold changes that must be made to keep future generations safer.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

WHO Director-General

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

v

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic continues to

highlight the need for a stronger, inclusive, equitable and

coherent health emergency preparedness, response, and

resilience (HEPR) architecture.

Building on the work of numerous reviews, panels, and

consultations, this White Paper outlines the Director-

General’s 10 proposals to strengthen HEPR under the aegis

of a new overarching Pandemic Accord that is currently

under negotiation. The recommendations are grouped

by the three main constituents of the global pandemic

architecture.

Governance

1 Establish a Global Health Emergency Council and

Committee on Health Emergencies for the World Health

Assembly

2 Make targeted amendments to the International Health

Regulations (2005)

3 Scale-up Universal Health and Preparedness Reviews

and strengthen independent monitoring

Systems

4 Strengthen global health emergency alert and

response teams that are trained to common standards,

interoperable, rapidly deployable, scalable and

equipped

5 Strengthen health emergency coordination through

standardized approaches to strategic planning,

nancing, operations and monitoring of health

emergency preparedness and response

6 Expand partnerships and strengthen networks for a

whole-of-society approach to collaborative surveillance,

community protection, clinical care, and access to

countermeasures

Financing

7 Establish a coordinating platform for nancing to

promote domestic investment and direct existing and

gap-lling international nancing to where it is needed

most

8 Establish a nancial intermediary fund for pandemic

preparedness and response to provide catalytic and gap-

lling funding

9 Expand the WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies to

ensure rapidly scalable nancing for response

10 Strengthen WHO at the centre of the global HEPR

architecture

The Director-General’s proposals are designed to support

and contribute to decision-making in the various fora

within and beyond WHO that will determine the future

global architecture of HEPR.

The Secretariat welcomes comments from Member

States and partners on these proposals through informal

consultations and feedback in writing.

Executive summary

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

1

This is the description of the plague of Athens in 430 BCE,

as told by the ancient Greek historian Thucydides in his

History of the Peloponnesian War. Almost two-and-a-

half millennia later, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

pandemic has demonstrated that although much has

changed, much has not.

At the time of writing, almost 6.3 million deaths have been

reported to WHO, but the true toll is much higher. Health

systems have been overwhelmed, and many health workers

have lost their lives or le their jobs because of burnout,

stress and anxiety. The global economy was plunged into its

deepest recession since the Second World War, forcing 135

million people into poverty. Widespread misinformation

and disinformation have caused confusion and distrust,

dividing families, communities and societies.

The pandemic has exposed divisions and inequities within

and between countries, and gaps in the world’s ability

to prepare for, prevent, detect and respond rapidly to

epidemics, pandemics and other health emergencies.

COVID-19 hit the poor and vulnerable hardest, while

reminding even the most privileged that infectious diseases

still have the power to upend not only health systems, but

also societies and economies.

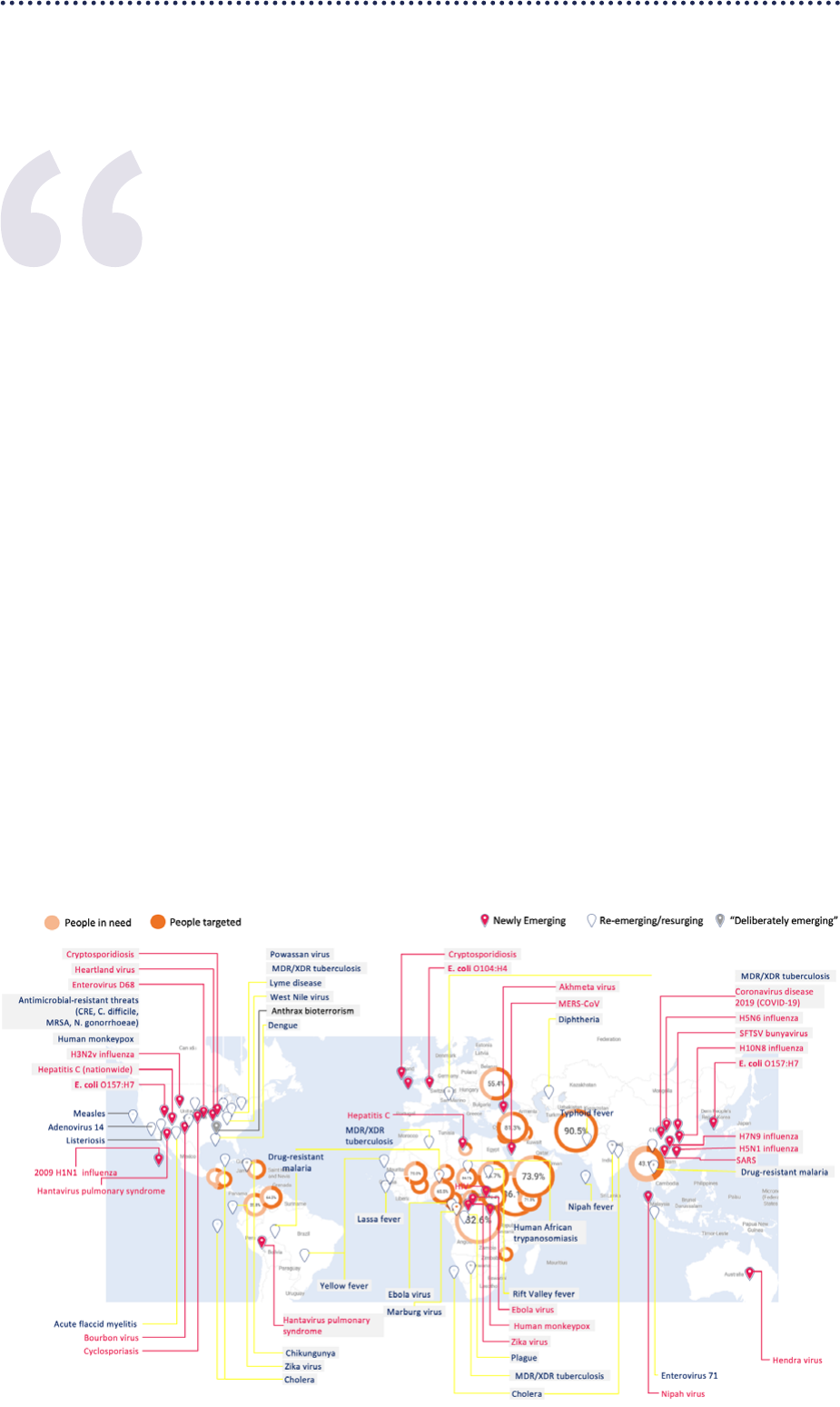

The risk of new health emergencies continues to increase,

driven by the escalating climate crisis, environmental

degradation, and increasing geo-political instability,

disproportionately impacting the poor and most vulnerable

(Figure 1). Humanitarian crises aected 300 million people

in 2022, putting them at an increased risk of the health

emergencies that inevitably follow.

The overall lesson is clear: the world is not prepared. This

lesson is not a new one. Just this century, epidemics of

SARS, H5N1, H1N1, MERS, Ebola and Zika have emerged,

only to be followed by a pattern of panic and neglect, in

which concern during emergencies gives way to apathy and

underinvestment in their aermath.

Thucydides wrote his account of the Plague of Athens

so that future generations might avoid the suering he

experienced. While COVID-19 has taken so much, it has

also given us the opportunity to learn the painful lessons

it has taught us, and use them to build a healthier, safer,

fairer world for the generations to come. We must seize that

opportunity before the world moves on to other priorities.

Introduction

The doctors were unable to cope, since they were treating the disease for the rst time and in ignorance:

indeed, the more they came into contact with suerers, the more liable they were to lose their own lives.

No other device of men was any help. Moreover, supplication at sanctuaries, resort to divination, and

the like were all unavailing. In the end, people were overwhelmed by the disaster and abandoned eorts

against it. … I shall give a statement of what it was like, which people can study in case it should ever

attack again, to equip themselves with foreknowledge so that they shall not fail to recognize it. I can give

this account because I both suered the disease myself and saw other victims of it.

Figure 1: Scale of health emergencies from all hazards (2021/2022)

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

2

There have been many expert reviews of the HEPR

architecture and the global response to the COVID-19

pandemic, yielding more than 300 recommendations

that have been analysed and discussed through

multiple international processes (Figure 2). The quality

of contributions to these reviews reects the depth of

thought, expertise and engagement of a broad spectrum

of stakeholders. Maintaining this engagement and

strengthening the links between stakeholders will be a

crucial determinant of the success of an agile, responsive

and exible HEPR architecture in the future.

Building on the work done to date, this white paper outlines

the Director-General’s 10 proposals to strengthen HEPR

under the aegis of a new overarching pandemic accord,

which is currently being developed by the Intergovernmental

Negotiating Body to dra and negotiate a WHO convention,

agreement or other international instrument on pandemic

prevention, preparedness and response.

The proposals focus on the architecture that will be needed

to ensure a signicantly more prepared world, and may need

to be adapted for specic threats and contexts. The proposals

do not attempt to assign roles and responsibilities within that

architecture. The capabilities and partnerships developed

during the response to COVID-19 will contribute to achieving

this ambitious agenda, and WHO will continue to engage with

others in determining wider roles and responsibilities.

Many of the proposals below are designed to build on,

complement and strengthen existing frameworks and

capacities established aer previous crises, strengthening

the bonds between global health partners. Other proposals

build on new and innovative mechanisms put in place

during the COVID-19 pandemic to ll critical gaps. In many

cases, these initiatives now need to be adapted and rened

according to the lessons of the pandemic in consultation

with Member States and partners. A small number of

proposals call for the establishment of new mechanisms

or structures that are currently being discussed in ongoing

Member State processes.

The proposals are grouped by the three main pillars of

the global HEPR architecture: governance, systems and

nancing, and are based on three key principles.

• They must promote equity, with no one le behind –

equity is both a principle and a goal, to protect the most

vulnerable.

• They should promote an HEPR architecture that is

inclusive, with the engagement and ownership of all

countries, communities and stakeholders from across

the One Health spectrum. Commitment to diversity,

equity and inclusivity is key to eective HEPR at all

levels, including equal participation in leadership and

decision-making, regardless of gender.

• They must promote coherence, reducing fragmentation,

competition and duplication; be aligned with existing

international instruments such as the International

Health Regulations (2005) and the Pandemic Inuenza

Preparedness Framework for the sharing of inuenza

viruses and access to vaccines and other benets; ensure

synergy between institutional capabilities for systems

strengthening and nancing; and promote the integration

of HEPR capacities into national health and social systems

based on universal health coverage and primary health care.

Purpose of the white paper

Figure 2. Reviews, reports and processes that have

informed this white paper

P

a

n

d

e

m

i

c

A

c

c

o

r

d

G

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

S

y

s

t

e

m

s

F

i

n

a

n

c

i

n

g

Equity

Inclusivity

Coherence

Independent Panel for Pandemic

Preparedness and Response report

GPMB and IOAC reports

Other reports

IHR Review Committee on the

Functioning of the International

Health Regulations (2005) during

the COVID-19 Response

Pan-European Commission on

Health and Sustainable Development

High Level Independent Panel on

Financing the Global Commons

for Pandemic Preparedness and

Response report

INB and WGPR processes

G20 and G7 processes

Other processes

GPMB: Global Preparedness Monitoring Board; Intergovernmental Negotiating Body to dra and negotiate a WHO convention, agreement or other international instrument on

pandemic prevention, preparedness and response; IOAC: Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee for the WHO Health Emergencies Programme; WGPR: Member States

Working Group on Strengthening WHO Preparedness and Response to Health Emergencies.

More than 300

recommendations

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

3

Health emergency preparedness, response and

resilience is multi-sectoral by nature

Dealing eectively with the multiplying complex and

multi-dimensional threats of the 21st century requires a

strengthened and agile approach to the way we prepare for

and respond to health emergencies. Where previously there

has been chronic neglect and underinvestment in national

capacities, we need to make smart, evidence-based

investments that deliver the best possible return in terms

of lives saved, sustainable development, global economic

stability and long-term growth. That means recognizing

that strengthening the global HEPR architecture must be

part of the broader eort towards the 2030 Sustainable

Development Goals.

Countries were already o track to meet their commitments

under the health-related Sustainable Development Goals

before COVID-19, and the pandemic has set back progress

even further. Achieving the health-related Goals will

therefore require a plan for recovery and renewal based

on rapidly accelerating progress in three interdependent

priority areas:

• Health promotion: preventing disease by addressing its

root causes;

• Primary health care: supporting a radical reorientation

of health systems towards primary health care, as the

foundation of universal health coverage; and

• Health security: urgently strengthening the global

architecture for HEPR at all levels.

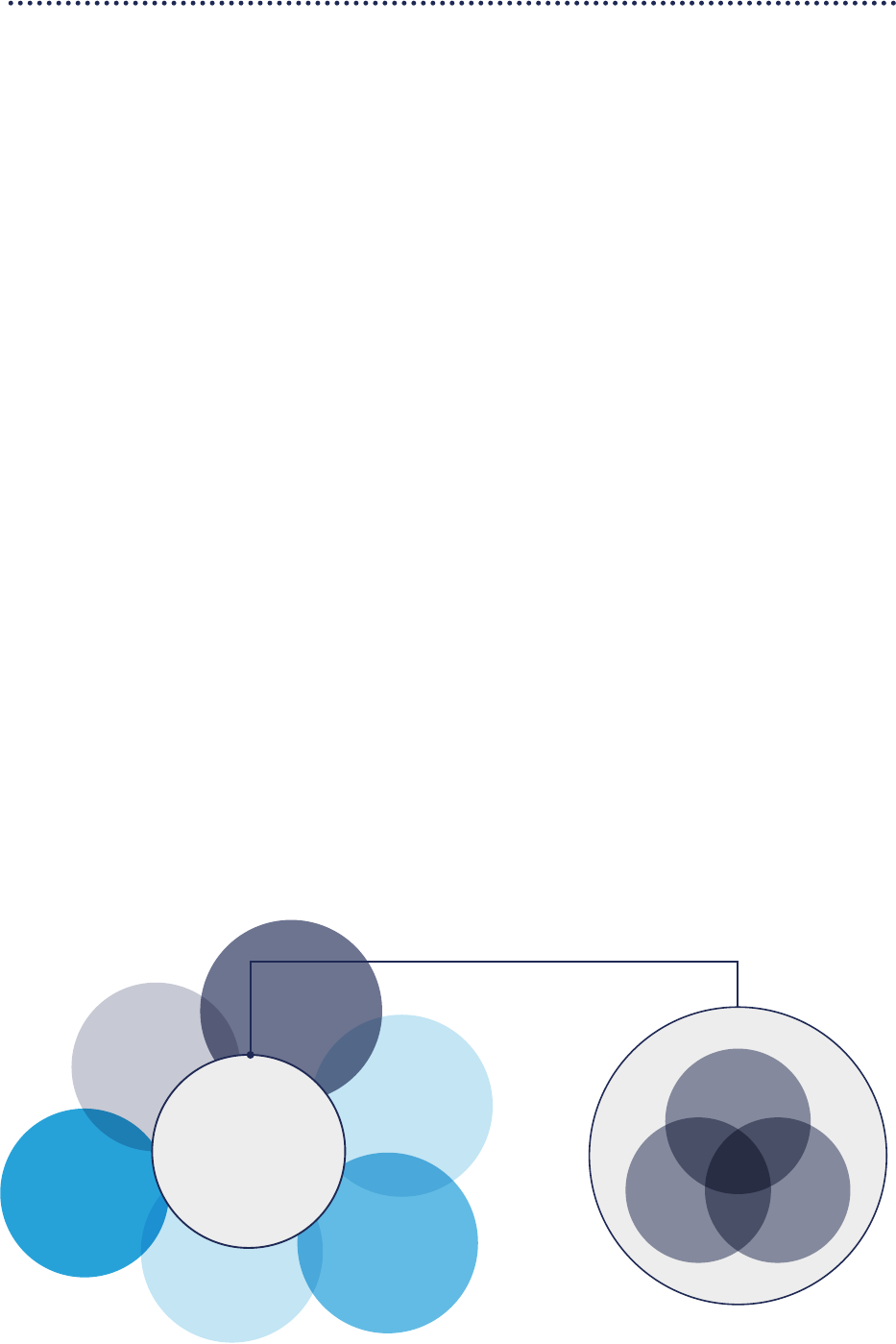

These priorities stem from the simple principle that there

is one health system, encompassing the common functions

and structures that are crucial for health security, for

primary health care, and for health promotion (Figure 3).

Targeting these common capacities for investment will

accelerate progress towards the health-related Sustainable

Development Goals at the same time as boosting national

and global health security. A renewed global architecture

for HEPR must be built on a foundation of strong national

health systems that are deeply connected with and

accountable to the communities they serve, and which

advance gender equity and human rights.

Many HEPR capacities straddle the boundary of the health

system and other governmental and societal sectors and

systems, such as education, nance, animal health and

agriculture, and the environment. Investments are also

needed to strengthen these links, and ensure greater

coherence in multi-sectoral planning, readiness and

response.

The need for greater coherence and coordination of

eort and investment extends to the global level. The

international community needs ways of working together

that deliver collaboration and coordinated, collective

action, and that address the fragmentation that impairs

the current global architecture for HEPR. That means

considering carefully the creation of new mechanisms, and

the addition of new organizations or institutes to what is

already a crowded landscape.

Figure 3. Investing in health security strengthens primary healthcare and health promotion, and vice versa,

within the broader health system

Animal health

and agriculture

Environment

Humanitarian and

disaster management

Economics and finance

Social welfare

and protection

Health system

Security

H

e

a

l

t

h

s

y

s

t

e

m

Primary

health care

Health

promotion

Health

security

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

4

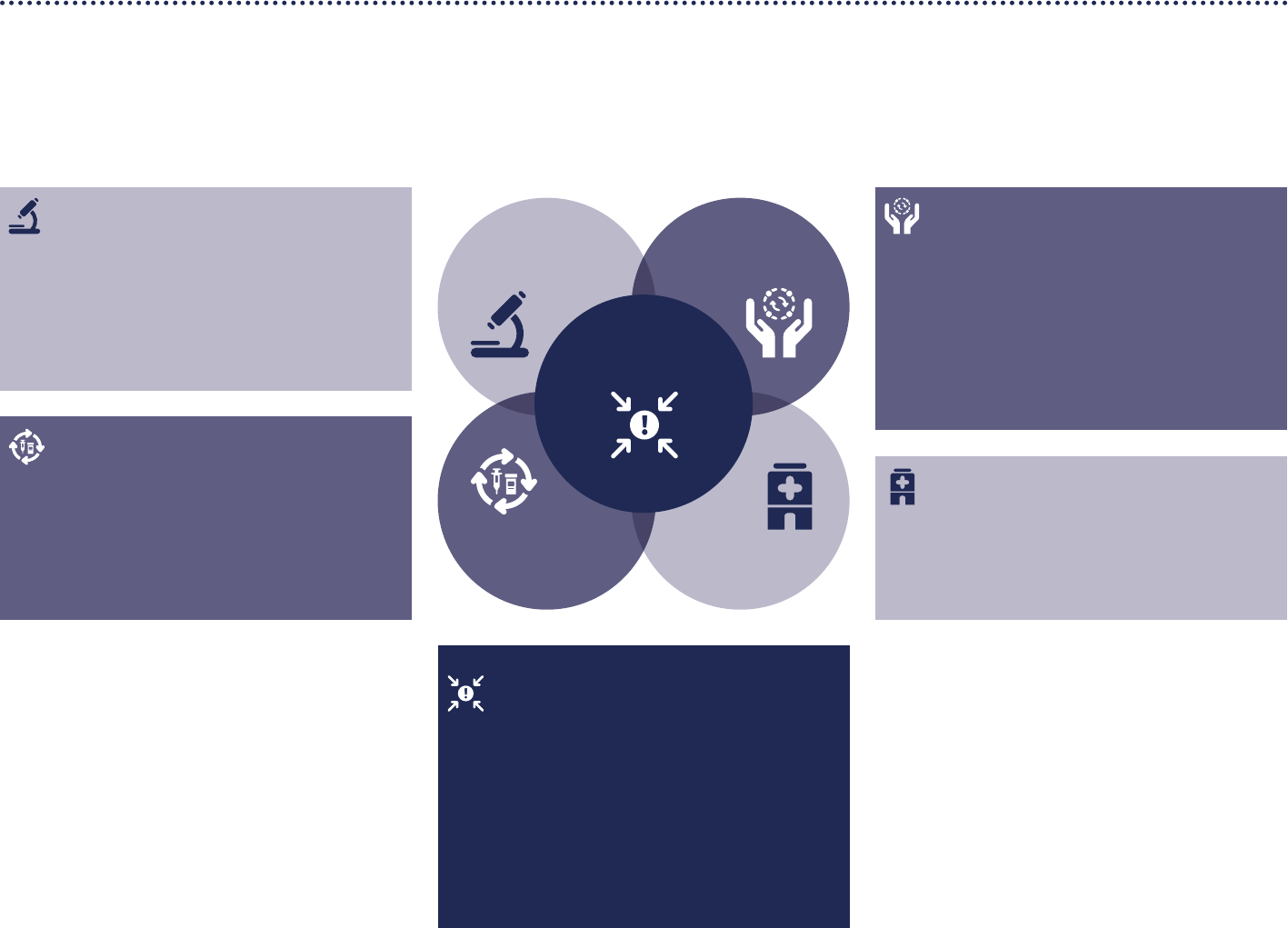

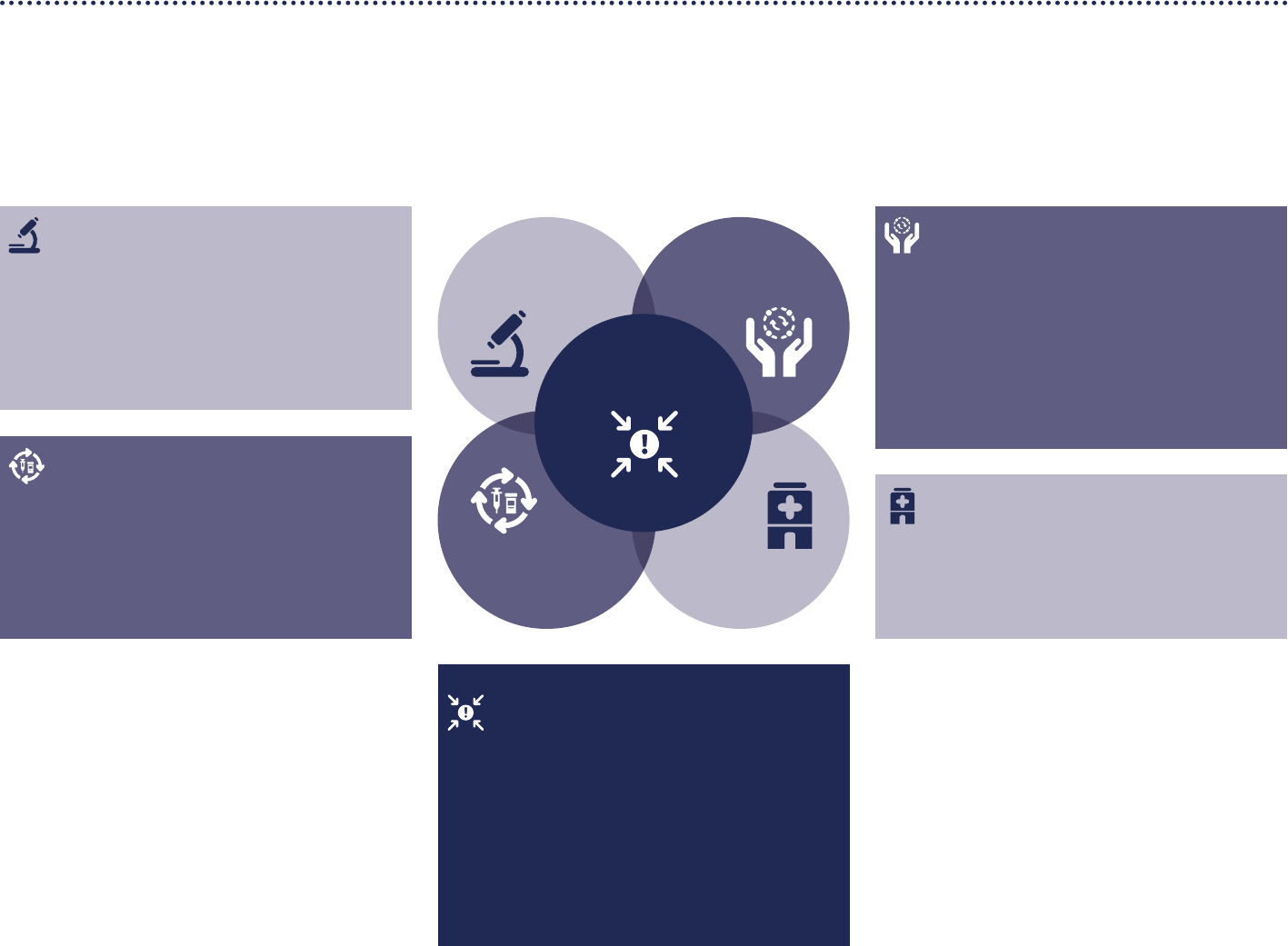

Figure 4. Summary of proposed solutions for the

strengthening of the global architecture for health

emergency preparedness, response and resilience

Within the broader context of recovery and renewal for

achieving the health-related Sustainable Development

Goals, and the need for greater coherence of the global

HEPR architecture under the aegis of a new Pandemic

Accord, 10 proposals for strengthening HEPR are outlined

below (Figure 4).

Governance

Eective governance is essential to bring greater equity,

inclusivity and coherence to the global architecture of

HEPR, enabling Member States and partners to work

collectively around a shared plan, galvanized by political

will, and with the resources to sustain positive changes.

Proposal 1. Establish a Global Health Emergency

Council and a Committee on Health Emergencies

of the World Health Assembly

HEPR must be elevated to the level of heads of state and

government to ensure sustained political commitment, and

break the cycle of panic and neglect that has characterized

the response to previous global health emergencies.

Several panels have proposed the establishment of a

high-level body on global health emergencies, comprising

heads of state and other international leaders. The

Director-General supports this concept, and proposes the

establishment of a Global Health Emergency Council, linked

to and aligned with the constitution and governance of

WHO, rather than creating a parallel structure, which could

lead to further fragmentation of the global architecture

of HEPR. Head of State participation, especially during

health emergencies, would further strengthen WHO’s

primary constitutional function to act as the directing

and coordinating authority on international health work

(WHO Constitution, Article 2(a)).

The Council would address health emergencies as well as

their broader context and social and economic impact. It

would have three primary responsibilities:

• Address obstacles to equitable and eective HEPR,

ensuring collective, whole-of-government and whole-

of-society action, aligned with global health emergency

goals, priorities and policies;

• Foster compliance with and adherence to global health

agreements, norms and policies; and

• Identify needs and gaps, swily mobilize resources, and

ensure eective deployment and stewardship of these

resources for HEPR.

The Council would be composed of heads of state and

government, attended by the United Nations Secretary

General and WHO Director-General, with heads of relevant

international organizations and other bodies as observers.

The Council would meet annually to review progress in

pandemic preparedness and response, and as required

in the event of a public health emergency of international

concern.

P

a

n

d

e

m

i

c

A

c

c

o

r

d

G

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

S

y

s

t

e

m

s

F

i

n

a

n

c

i

n

g

Equity

Inclusivity

Coherence

Systems

Capacity – strengthened health emergency alert

andresponse teams that are interoperable and

rapidly deployable

Coordination: standardized approaches for

coordinating strategy, nancing, operations

and monitoring of preparedness and response

Collaboration: expanded partnerships and

strengthened networks for collaborative surveillance,

community protection, clinical care and access to

countermeasures

Financing

Predictable nancing for preparedness –

coordinating platform for nancing with increased

domestic investment and more eective/innovative

international nancing

Rapidly scalable nancing for response – expanded

contingency fund for emergencies

Catalytic, gap-lling funding – expanded nancing

through a new nancial intermediary fund

Governance

Leadership – Global Health Emergency Council,

WHO Committee for Emergencies

Regulation – targeted amendments to the

International Health Regulations (2005)

Accountability – universal health and preparedness

review, independent monitoring mechanisms

Proposals for strengthening global health

emergency preparedness, response and resilience

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

5

The work of the Council would complement and be

linked with the work of a Standing Committee on Health

Emergencies, which the Executive Board established at its

151st session in May 2022.

To strengthen integrated governance, the Health

Assembly could also establish a new main committee on

emergencies, a Committee E. Such a new main committee

could be linked with both the Council and the Standing

Committee on Health Emergencies, and as an open-ended

committee of all WHO Member States, Committee E would

help to ensure global inclusivity. The Oicers of Committee

E and of the Standing Committee could be invited to attend

meetings of the Council to further promote coordination

among the three bodies.

Further, a Committee E could:

• Review the work of WHO in health emergency

preparedness, response and resilience;

• Act as a conference of State Parties to the International

Health Regulations (2005);

• Act as the peer review mechanism for the Universal

Health and Preparedness Review; and

• Consider any recommendation by the Executive Board

based on advice from the Standing Committee on Health

Emergencies.

Such an interlinked arrangement could strengthen WHO’s

constitutional role as the directing and coordinating

authority on international health work.

Proposal 2. Make targeted amendments

to the International Health Regulations (2005)

The International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) are the

international legally binding framework that denes the

rights and obligations of its 196 States Parties and of the

WHO Secretariat for handling public health emergencies

with potential to cross borders. The IHR remains an

essential legal instrument for public health emergencies

preparedness and response.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed some weaknesses in

the interpretation of, application of and compliance with

the IHR. The inherent tension between the aim to protect

health and the need to protect economies by avoiding

travel and trade restrictions has been noted by the IHR

Review Committee on the Functioning of the International

Health Regulations (2005) during the COVID-19 Response as

the most important factor limiting compliance with the IHR.

In addition, too many countries still do not have suicient

public health capacities to protect their own populations,

and to give timely warnings to WHO. The current reporting

mechanism on the implementation of plans of action to

ensure that the core capacities required by the IHR are

present and functioning lacks incentives for compliance.

The absence of a conference of the States Parties to the IHR

is an overarching limitation in their eective application

and compliance.

Further strengthening of IHR implementation compliance

will require some targeted amendments. Areas of focus

may include: improved accountability by establishing

the national responsible authority for the overall

implementation of the IHR, and a conference of State

Parties (see proposal 1 above); more specicity in relation

to notication, verication and information sharing;

capacity-building and technical support for surveillance,

laboratory capacity and public health rapid response; and

streamlining the process to bring IHR amendments into

force.

Ensuring that the IHR can be eiciently and eectively

strengthened to accommodate evolving global health

requirements is key to their continued relevance and

eectiveness as a global health legal instrument.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

6

Proposal 3. Scale up Universal Health and

Preparedness Reviews and strengthen

independent monitoring

In response to a proposal from several Member States, the

introduction of the Universal Health and Preparedness

Review (UHPR) was announced by the WHO Director-

General in November 2020, with the goal of building

solidarity, mutual trust and accountability for health,

through an innovative intergovernmental review process.

The UHPR is a Member State-led mechanism in which

countries agree to a voluntary, regular and transparent peer

review of their comprehensive national health emergency

preparedness capacities, incorporating lessons learned

from the COVID-19 pandemic on preparedness assessment.

It aims to:

• Enhance transparency and understanding of a country’s

comprehensive preparedness capacities among relevant

national stakeholders;

• Promote whole-of-government and whole-of-society

dialogue on preparedness in countries, including close

cooperation with governments, regional organizations

and civil society;

• Encourage compliance with commitments made under

the IHR and related Health Assembly resolutions in the

eld of emergency preparedness;

• Elevate considerations for preparedness beyond

the health sector and ensure the comprehensive

implementation of recommendations; and

• Promote national, regional and global solidarity,

dialogue and cooperation.

A pilot phase of the UHPR mechanism was completed in

2021. Based on lessons learned from the pilot phase, the

UHPR should now be scaled up to complement existing

assessment tools and processes, and a peer review

mechanism should be included as part of the UHPR

process.

Self-assessment and peer review of national capacities,

including through the UHPR, should be complemented

by independent monitoring at the international level. The

independent monitoring mechanism should be modelled

on best practice in independent monitoring of international

instruments, and should build on and strengthen existing

monitoring mechanisms, such as the Global Preparedness

Monitoring Board and the Independent Oversight and

Advisory Committee for the WHO Health Emergencies

Programme. The mechanism would be composed of an

independent body of leaders and experts, supported by a

transparent, evidence-based, expert-led data collection and

review process, to ensure objectivity and credibility. It would

have a broad scope, encompassing the global architecture

of HEPR systems, nancing and governance. It would report

its ndings and recommendations to the World Health

Assembly, the Global Health Emergency Council, and the

proposed coordination platform for nancing.

Together, these accountability tools for governments,

international organizations and other stakeholders across

all sectors will: identify the risks and determinants of health

emergencies; reveal gaps and weaknesses in the capacity

and performance of health emergency systems and

their nancing and governance; develop and implement

solutions to ensure equity, eectiveness and eiciency; and

promote compliance with obligations under international

law, including the IHR and the pandemic accord currently

under negotiation.

Systems

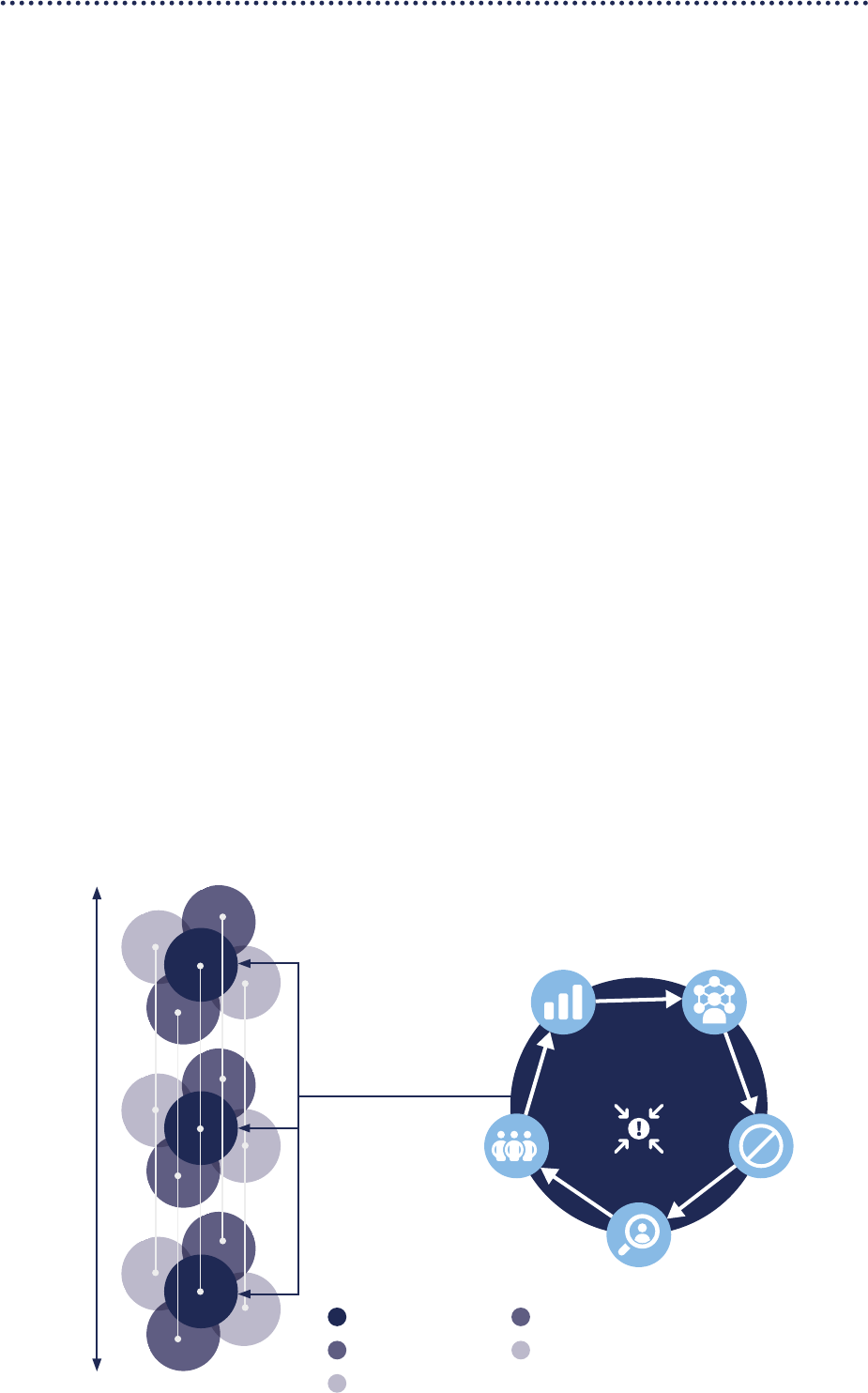

The ability to prepare for, prevent, detect and respond

eectively to health emergencies at national, regional and

global levels depends on the operational readiness and

capacities in ve core subsystems (Figure 5; expanded

on in Annex 1).

• Collaborative surveillance and public health intelligence

through strengthened multisectoral disease, threat

and vulnerability surveillance; increased laboratory

capacity for pathogen and genomic surveillance; and

collaborative approaches for risk assessment, event

detection and response monitoring.

• Community protection through two-way information

sharing to inform, educate and build trust; community

engagement to create public health and social measures

based on local contexts and customs; a multisectoral

approach to social welfare and livelihood protection to

support communities during health emergencies, and

mechanisms to ensure the protection of individuals from

sexual exploitation, abuse and harassment.

• Clinical care that is safe and scalable, with eective

infection prevention and control that protects, patients,

health workers and communities; and resilient health

systems that can maintain essential health services

during emergencies.

• Access to countermeasures through fast-track research

and development, with pre-negotiated benet sharing

agreements and appropriate nancing instruments; a

seamless link between research and development and

scalable manufacturing platforms and agreements for

technology transfer; coordinated procurement and

emergency supply chains; and strengthened population-

based services for immunization and other public health

measures.

• Emergency coordination with a trained health

emergency workforce that is interoperable, scalable

and ready to rapidly deploy; coherent national action

plans for health security to drive preparedness and

prevention; operational readiness through risk

assessment and reduction and prioritization of critical

functions; and rapid detection of and scalable response

to threats through the application of a standardized

emergency response framework.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

7

Access to

countermeasures

Emergency

coordination

Community

protection

Clinical care

Collaborative

surveillance

Emergency coordination

Strengthened health emergency alert and

response teams that are interoperable and

rapidly deployable

Coherent national action plans for

preparedness, prevention, risk reduction and

operational readiness

Scalable health emergency response

coordination through standardized and

commonly applied Emergency Response

Framework

Community protection

Proactive risk communication and infodemic

management to inform communities and build trust

Community engagement to co-create mass

population and environmental interventions

based on local contexts and customs

Multi-sectoral action to address community

concerns such as social welfare and livelihood

protection

Clinical care

Safe and scalable emergency care

Protecting health workers and patients

Health systems that can maintain essential

health services during emergencies

Collaborative surveillance

Strengthened national integrated disease, threat

and vulnerability surveillance

Increased laboratory capacity for pathogen and

genomic surveillance

Collaborative approaches for risk assessment,

event detection and response monitoring

Access to countermeasures

Fast track R&D with pre-negotiated benet

sharing agreements

Scalable manufacturing platforms and

agreements for technology transfer

Coordinated procurement and emergency

supply chains to ensure equitable access

Figure 5. Interconnected core subsystems for health emergency preparedness, response and resilience

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

8

These capacities must be embedded in strengthened

national health systems, and will require investment in

essential public health functions, primary health care and

health promotion. Strengthening integrated surveillance,

community engagement, health promotion, routine

immunization and other essential health services will reduce

the risk of health emergencies, and enable communities

to be ready for and more resilient to emergencies.

Strong primary health and public health systems enable

communities to better assess context-specic threats

and vulnerabilities to reduce risk through prevention and

readiness. The link between communities and national

health emergency systems is critical to rapidly communicate

risk and scale up support once an event has been detected.

Given these interdependencies and the breadth of actors

involved, it is critical that the ve core subsystems are

well integrated within countries, and have strong links to

structures for support, coordination and collaboration at

regional and global levels across all phases of the health

emergency cycle of prepare, prevent, detect, respond and

recover (Figure 6).

Proposals for strengthening both the subsystems and the

linkages between them are outlined below.

Proposal 4. Strengthen global health emergency

alert and response teams that are trained to

common standards, interoperable, rapidly

deployable, scalable and equipped

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to expose national-level

decits in the core capacities required for eective HEPR.

National capacities are the fundamental building blocks

of global health security; therefore, these decits confer

profound systemic risks.

Mitigating these risks will require substantial investments

in many countries to build and strengthen professionalized

multidisciplinary health emergency teams, fully integrated

into national resilient health systems and other relevant

sectors under the One Health approach. The scale and

nature of workforce needs depend on national context, but

the most substantial and widespread gaps highlighted by

COVID-19 are in the areas of epidemiology and surveillance,

including laboratories; the health system workforce required

to rapidly scale up safe emergency clinical care and maintain

essential services during an emergency; the non-clinical

aspects of protection, such as working conditions and

fair remuneration; and the community engagement and

infodemic management resources needed to strengthen

trust in health authorities and build community resilience to

health emergencies.

Figure 6. Interlinkages between ve core subsystems for health emergency preparedness, response and resilience across

the emergency cycle

National

Regional

Global

Recover Prepare

Respond

Detect

Prevent

Emergency

coordination

Emergency coordination Community protection

Clinical care

Access to countermeasures Collaborative surveillance

Global

National

Regional

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

9

Smart investments in strengthening national capacities

will enable the development of globally deployable health

emergency alert and response teams to strengthen regional

and global preparedness, detection and response. Combined

with mechanisms for emergency coordination (see Proposal

5) to support training, accreditation and deployment,

strengthened national alert and response teams can give rise

to a country-owned yet internationally deployable global

health emergency workforce.

Proposal 5. Strengthen health emergency

coordination through standardized approaches

to strategic planning, nancing, operations and

monitoring of health emergency preparedness

and response

Health emergency subsystems are dependent on each other

for operational eectiveness. At national level, COVID-19

demonstrated that overall health emergency preparedness

and response management systems were oen fragmented.

At regional and global levels, the pandemic highlighted

a lack of consistency in national approaches, a lack of

eective mechanisms to coordinate and communicate

action between countries, and challenges in eiciently

channelling international support to where it was most

needed.

Remedying this fragmentation will require further

investment in ensuring greater consistency and

standardization in emergency coordination at national

level, including through a commonly applied emergency

response framework. Application of this framework must

be enabled by strengthened infrastructure, workforce and

leadership that is resourced and empowered to: strengthen

operational readiness through assessment of risks and

vulnerabilities, and prioritization of critical functions across

all core subsystems; develop context-specic strategies

and plans for preparedness, prevention, readiness and

response; mobilize the necessary resources; and monitor

and evaluate actions. Health emergency management

should be embedded in broader whole-of-government

national disaster management systems.

A strengthened and redesigned network of public health

emergency operations centres can connect international

and regional technical, nancial and operational support to

national emergency management systems, and at the same

time can improve coordination between countries and

international partners across the health emergency cycle.

Box 1.

Detecting and preventing

spillovers: a planetary perspective

to health emergency preparedness,

response and resilience

What do the past four public health emergencies of

international concern (PHEIC) have in common? Ebola

virus disease in Western Africa in 2014; the 2015–16

Zika virus epidemic; the 2018–20 Kivu Ebola epidemic;

and the COVID-19 pandemic: all were the result of

zoonotic “spillover” events, in which a pathogen jumps

the species barrier from another animal into a human

population. In each of the above cases, viral pathogens

were able to spread in human populations before

being detected.

Foreshortening the time between a spillover event and

its initial detection is a major focus of the One Health

movement, and a crucial component of strengthening

the global HEPR architecture. The intrinsic links

between health and disease in humans, domestic

animals and wildlife means that an early warning

system linked to surveillance and risk analysis at and

beyond the three-way interface of humans, animals, and

the environment is essential if we are to detect spillover

events while containment is still a feasible option.

The rapid introduction of new technologies for

surveillance, such as genomic sequencing, that has

followed in the wake of COVID-19 in many countries

has brought us an increment closer to realising the

vision set out by the tripartite of WHO, FAO and OIE in

their landmark 2004 report that relaunched the One

Health concept. Fully implementing the tripartite’s

2004 recommendations will be a key consideration as

consultations on reforms to the governance, nancing,

and systems of global HEPR continue.

Ultimately, our collective approach to spillovers

must move beyond detection to embrace prevention.

Global deforestation, the trade in wildlife and wildlife

products, and over-intensive animal rearing are

not only disastrous for ecosystems and the global

environment, they also drastically amplify the risk

of spillover events. And as the rate of environmental

degradation and ecosystem loss increases, so to does

the risk of spillovers with epidemic and pandemic

potential. Investments in HEPR only make sense in

the context of a broader concerted and coordinated

international eort to protect the health of the planet

itself. Detecting and containing spillovers as close to

when and where they rst occur is the key to stopping

outbreaks from becoming epidemics and pandemics,

but addressing the root causes of spillovers is the key

to preventing those outbreaks in the rst place.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

10

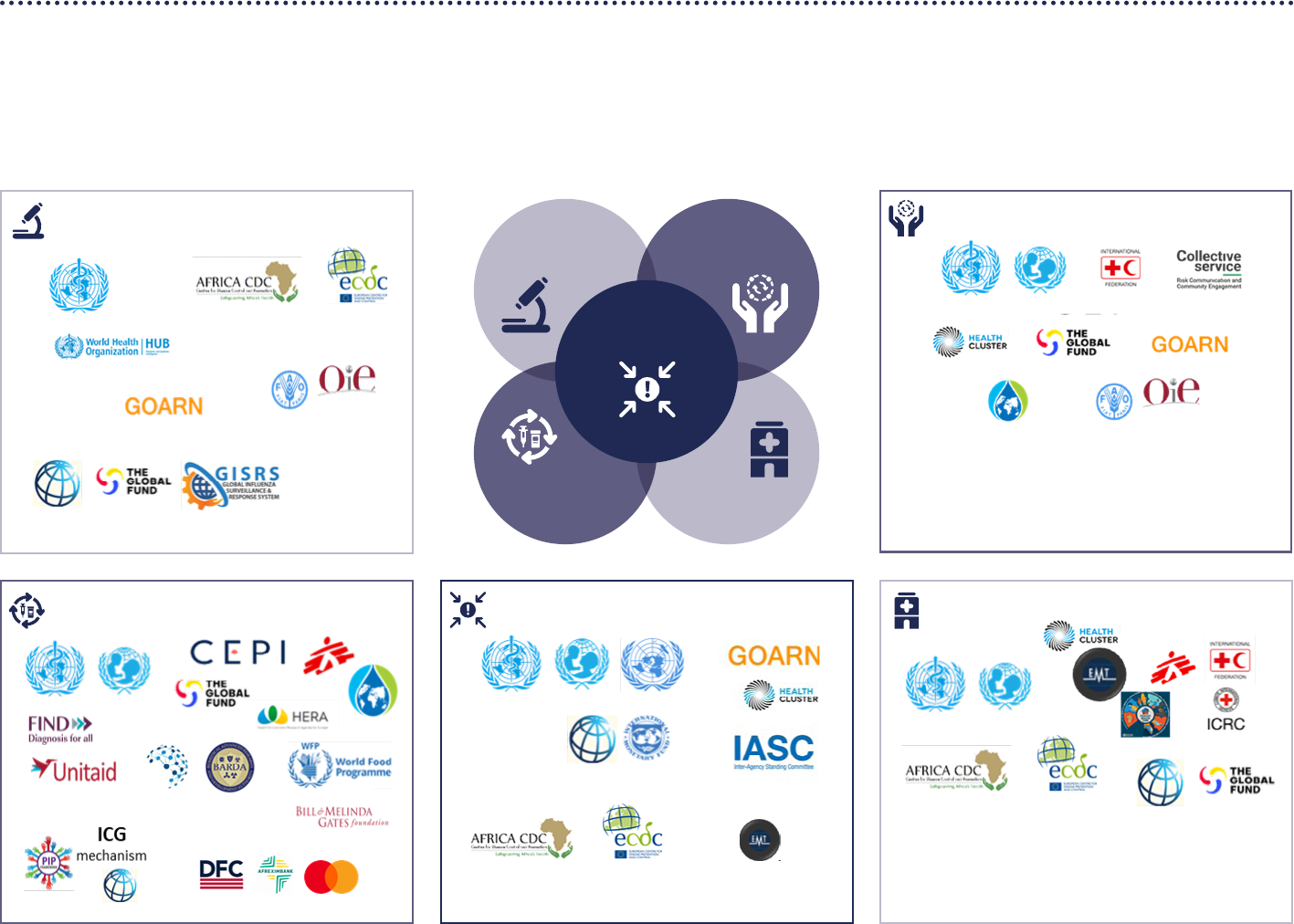

Proposal 6. Expand partnerships and strengthen

networks for a whole-of-society approach to

collaborative surveillance, community protection,

clinical care, and access to countermeasures

COVID-19 has shown that resilience to health emergencies

can be strengthened in key areas by broader and closer

collaboration between organizations and institutions at

national, regional and global levels before health emergencies

hit. This will require the strengthening and, where required,

the establishment of whole-of-society, interdisciplinary,

multi-partner networks for collaborative surveillance, clinical

care, community protection and access to countermeasures.

This will enable the extensive ecosystem of HEPR partners

at the global, regional and national levels to fully participate

according to their strengths and capabilities to co-create

innovative and timely solutions in an agile and collaborative

way (see Figure 7 for a non-exhaustive illustration of the

ecosystem of international partners for COVID-19).

Ad hoc and time-limited regional and global collaborations

between national authorities, multilateral institutes and

the private sector, such as the Access to COVID-19 Tools

Accelerator (including COVAX) and the African Union Vaccine

Acquisition Trust, played a crucial role in accelerating

the development of COVID-19 medical countermeasures.

Consolidating and building on these COVID-19 successes,

while ensuring that collaborative arrangements are in place

and build on existing networks between various global

health agencies, industry and the scientic community to

ensure fair access and scalable manufacturing, will help

to protect the world from both known and theoretical

pandemic threats.

At the same time, forecasting pandemic risks and

detecting infectious threats can be transformed by closer

interdisciplinary collaboration nationally, regionally

and globally. The WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic

Intelligence is a new initiative that will play a leading role in

strengthening collaborative surveillance. The WHO Hub will

also drive further development of initiatives such as Epidemic

Intelligence from Open Sources and the International

Pathogen Surveillance Network. Established global

surveillance systems for specic pathogens, such as the Global

Inuenza Surveillance and Response System, also provide a

strong foundation upon which to build.

COVID-19 has also highlighted the role that collaborative

eorts play in building the resilience of communities to health

emergencies. The need to invest in collaborative arrangements

that bring communities of practice and communities of

circumstance together to design response and resilience

measures has been highlighted aer every major health

emergency of the past two decades: COVID-19 makes these

calls impossible to ignore.

The ecosystem of international partners for COVID-19 can

be used as the basis for expanding the network of relevant

partners, strengthening the links between them, and

developing collaboration hubs for each of the ve core

subsystems to further strengthen the global architecture for

HEPR.

Box 2.

Strengthening every link

in the countermeasure chain

The unprecedented global eort to develop vaccines

and diagnostics for COVID-19 is oen portrayed as an

overnight success. But, as with many such successes,

it was built on many years of diligent work before the

pandemic.

In 2016, in the wake of the world’s deadliest recorded

outbreak of Ebola virus disease, the WHO R&D

Blueprint was launched to bring together a broad cast

of researchers from academia and industry, regulators,

governmental and non-governmental organizations,

and multilateral institutes to prioritize action against

a list of potential pandemic threats. Stemming from

these eorts the Coalition for Emerging disease

Preparedness Innovations, which was also launched

in 2016, funded several of the ambitious vaccine-

development programmes that ultimately yielded

three of the vaccines that have received WHO

Emergency Use Listing for use against COVID-19.

Getting these vaccines to where they are needed has

proven more challenging. Despite the eorts and some

notable successes of COVAX – the vaccines pillar of the

Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) – vaccine

access remains highly inequitable more than two

years into the pandemic. Many of the world’s most

vulnerable populations remain unprotected, which has

prolonged the acute phase of the pandemic.

Learning the lessons of COVID-19 will mean building

on the strengths and successes of the organizations

and initiatives that existed before the pandemic,

consolidating and institutionalizing what worked

during time-limited collaborations such as ACT-A, and

addressing the shortfalls that have resulted not only

in inequitable access to countermeasures, but also

in disparities in the speed, quantity and eiciency

with which dierent categories of countermeasures –

vaccine, therapeutics, and diagnostics – have been

developed, tested, approved, and distributed to where

they are needed most.

Much of this work will need to be done at the global

and regional level to bring together partners from

the length and breadth of the value chain through

formal and informal mechanisms that span dierent

pathogens and categories of countermeasures. These

mechanisms, or mechanism, will need to provide the

necessary incentives – with appropriate tolerances

for risk – and benet-sharing agreements to ensure

that future countermeasures are delivered equitably,

rapidly, and at scale.

Continued on next page …

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

11

Box 2. (continued)

The Pandemic Inuenza Preparedness Framework,

which celebrated its 10th anniversary last year,

provides a case study in how to guarantee the access of

developing countries to vaccines and other pandemic-

related supplies. However, as COVID-19 has shown,

the nal step in the value chain can oen be the most

diicult step to take. The vaccine and immunization

programmes of countries, along with the capacity of

countries to rapidly adopt and adapt to new vaccines,

diagnostics and therapeutics, have been implicated

in every public health emergency of international

concern to date. Building these capacities, which lie at

the heart of resilient national health systems, will be

crucial to prevent and respond to future epidemics and

pandemics.

Key features of an agile, equitable, and risk-

tolerant global system to ensure the development,

manufacture, and distribution of medical

countermeasures for pandemic threats

• End-to-end partnerships, built on the pre-existing

trust that exists between core partners such as CEPI,

Gavi, Global Fund, UNICEF and WHO, and which

provides a forum for new stakeholders

• Inclusive governance, with a strong voice for low-

income countries, lower middle-income countries,

and civil society organizations

• Rapid decision making, based on the “no regrets”

principle of emergency response

• Streamlined and coordinated regulatory processes

across high-income, middle-income and low-

income countries, balancing the need for speed and

safety

• A multi-country platform for clinical trials to obtain

statistically signicant results more quickly from

broad and representative populations

• Links to resilient emergency supply chains

• Pre-agreed, rapidly accessible funding for

global procurement, and appropriate, risk-

tolerant mechanisms to fund development and

manufacturing

• Seamless linkage of the development process to

distributed manufacturing capacity, with rapid

transfer of knowhow from innovator companies

• Support to strengthen the science–policy interface

and decision making in countries, and to strengthen

the readiness of health systems to rapidly access

and deploy countermeasures

Financing

Financing an eective health emergency preparedness

and response architecture will require approximately an

additional US$ 10 billion per year, according to WHO–World

Bank analyses presented in 2022 to the G20. However,

eective nancing depends not only on more funds, but

also on strengthened and innovative mechanisms to ensure

that funds are accessed and delivered in ways that are agile

and risk tolerant, to ensure the best possible return on

investment and the most eective and timely allocation of

resources to ll critical gaps.

Proposal 7. Establish a coordinating platform

for nancing to promote domestic investment

and direct existing and gap-lling international

nancing to where it is needed most

Every country should step up domestic investments to

prepare for health emergencies, but low-income countries

and some lower middle-income countries need urgent

international support to strengthen HEPR.

International nancial support can come from many

dierent actors, both public and private, with oen

overlapping and competing priorities. Greater coordination

and simplication is needed across this funding landscape

to ensure that existing funding ows are coordinated

and targeted to the most critical gaps in the global HEPR

architecture, such as national-level preparedness gaps,

funding for regional and global institutions that support

HEPR, investments in upstream and emergency research

and development and downstream manufacturing and

procurement, and rapidly accessible funding to initiate

and scale emergency response operations. Where existing

funding ows are insuicient to ll critical gaps in core

national and global HEPR capacities, these ows should be

augmented by additional catalytic and gap-lling funding

through a nancial intermediary fund (see below).

To bring coherence and eiciency across domestic

and international investments, including additional

investments through a proposed nancial intermediary

fund, a new coordination platform is required that unites

the technical work of WHO and other HEPR partners

as needed, with the nancial investments of the World

Bank and other international nancial institutions. This

coordinating platform for nance and health would monitor

the performance of HEPR funding ows, improve eective

allocation to critical priorities, and help to mobilize and

direct catalytic and gap-lling nancial support. This new

mechanism should strive for worldwide representation,

building on the work of the G20’s Joint Finance and Health

Task Force.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

12

Community protection

Access to

countermeasures

Emergency

coordination

Community

protection

Clinical care

Collaborative

surveillance

and other One Health

stakeholders

Other major contributors include nongovernmental

organizations, civil society organizations and the

private sector

Collaborative surveillance

and other One Health

stakeholders

and other donors

and other regional centres

for disease control

Emergency coordination

and other regional centres

for disease control

and other donors

Access to countermeasures

and other donors

Clinical care

and other donors

and other regional centres

for disease control

Other major contributors include nongovernmental

organizations, civil society organizations and the

private sector

Figure 7. Illustrative ecosystem of international partners for COVID-19 (non-exhaustive)

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

13

Proposal 8. Establish a nancial intermediary

fund for pandemic preparedness and response to

provide catalytic and gap-lling funding

Existing funding ows do not cover gaps in the HEPR

architecture. A new pooled fund has been proposed by

several reviews and organizations as a potential solution

for international nancing to better support national

preparedness and response, and global public goods.

Most recently, WHO and the World Bank recommended

to the G20’s Joint Finance and Health Task Force the

establishment of a Financial Intermediary Fund (FIF),

to be hosted by the World Bank.

The FIF should avoid duplication and ensure

complementarity with existing HEPR nancing eorts

and institutions. Critical design elements for a FIF should

include:

• A central role for WHO to enable direct linkage between

national and global HEPR assessment and planning

processes and the investments proposed by the FIF;

• Governance mechanisms that include a coalition of

participating donors, and that are informed by objective

assessments of HEPR needs and the perspectives of

beneciary country governments;

• Work with existing multilateral development banks

and implementing partners, who should be eligible for

nancing; and

• Funding proposals would be based on national action

plans for health security and related nancing plans,

lling gaps identied through the IHR monitoring

framework and UHPR (see above).

Proposal 9. Expand the WHO contingency fund for

emergencies to ensure rapidly scalable nancing

for response

At present, funding mechanisms for emergency response

are fragmented and unpredictable. The WHO contingency

fund for emergencies (CFE) is able to disburse relatively

modest amounts rapidly for early response, but it is not

designed to directly nance elements of national response,

nor the eorts of key partners, oen leading to operational

gaps when implementing multi-disciplinary and multi-

sectoral response plans. In addition, in the event that

initial containment eorts fail, WHO’s CFE is not designed

to support the scale-up and adaptation of response, nor

sustain a response over durations longer than the initial

few months. In the absence of pre-negotiated draw-down

mechanisms to enable access to larger tranches of exible

funding triggered by the escalation of health emergencies,

critical windows for scale-up are oen missed due to a

reliance on unpredictable, oen inexible, and frequently

insuicient funding from ad hoc appeals.

Addressing the problems above will require two

innovations. First, the CFE should be expanded in size

and scope to enable the direct nancing of national and

international partners in the rst stages of the response,

including deployments through the health emergency

workforce and emergency supply chain. This will ensure

that multisectoral health emergency response plans can be

fully and rapidly implemented. Second, in the event that

initial response eorts are unable to contain an infectious

threat or suiciently mitigate the eects of a non-infectious

hazard, an additional substantial draw-down facility should

be triggered to ensure that the multisectoral response

can be scaled up to cover additional geographical areas

and populations for an extended duration. The triggers

for activation of this draw-down facility should be pre-

negotiated, transparent and based on the “no regrets”

precautionary principle.

An expanded CFE could satisfy both needs, with

contingency funds accessed via two transparent

mechanisms: a rapid response facility and a sustained

scale-up facility, both of which would be linked to a

standardized and commonly applied emergency response

framework for alert, verication, risk assessment and jointly

developed strategic plans and resource requirements for

rapid and scalable response.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

14

Equity, inclusivity and coherence

IEquity, inclusivity, and coherence are key principles

reected in the WHO Constitution, and central to the

“happiness, harmonious relations and security of all

people”.

In all countries, the burden of risks of and vulnerabilities

to health emergencies inevitably fall disproportionately

on the most socially and economically disadvantaged

and marginalized. As the ongoing experience of COVID-19

shows, the failure of the HEPR architecture to adequately

address equity, particularly equitable access to medical

countermeasures, has magnied and prolonged the

acute phase of the pandemic. As Member States have

emphasized, equity is not limited to access to medical

countermeasures, but includes universal health coverage

and national health systems strengthening.

An eective, equitable, inclusive, trusted and accountable

HEPR architecture must meet the needs of all countries

and communities, including the most marginalized and

those in fragile, vulnerable and conict-aected contexts.

It is therefore essential that all countries be involved, and

all communities be represented, in the translation of the

proposals set out here into context-specic solutions, and

in the allocation of investments for HEPR, with an equal

role for low-income and middle-income countries in the

leadership and accountability mechanisms of a new HEPR

architecture.

Member States have also highlighted the importance of

coherence, acknowledging ‘the central role of WHO in the

global health architecture, with its normative and standard-

setting functions, and provision of technical assistance

and support, as well as its convening power at the global,

regional and national levels.’ Broadening inclusion in global

HEPR must go hand in hand with strengthening the links

between current stakeholders to: empower coordination;

reduce fragmentation, competition and duplication; and

accelerate investment in HEPR within the broader context

of the drive towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

Only in applying these principles of equity, inclusivity

and coherence consistently and rigorously in the design

and operations of the HEPR architecture at all levels, and

monitoring their application, can we achieve the outcomes

we seek. They apply across the three pillars of Governance,

Systems and Financing, and are, in eect, a pillar in their

own right, as they are at the heart of strengthening WHO

in fullling its constitutional functions at the heart of the

global architecture of HEPR.

This requires a shared understanding of how equity,

inclusivity and coherence will be applied in practice,

and how they will be monitored, based on measurable,

objective metrics, to ensure action and accountability.

Annex 2 provides details of how these principles will be

applied and monitored in each of the 10 proposals.

.

Figure 8. Equity, inclusivity and coherence at the heart of

the global architecture for health emergency preparedness,

response and resilience

E

q

u

i

t

y

I

n

c

l

u

s

i

v

i

t

y

C

o

h

e

r

e

n

c

e

Trust

P

a

n

d

e

m

i

c

A

c

c

o

r

d

Inclusivity

• All 194 Member States with an equal voice

• Whole of government & whole of society approach

• Collaborative networks of multi-sectoral & multi-

disciplinary partners

Coherence

• Science, evidence and expertise to set the norms,

standards and regulations

• Trusted, impartial and authoritative information to

communicate risk

• Coordinated assessment, strategy, nancing,

operations & monitoring

Equity

• Highest level of health for all

• Equitable access to countermeasures and other

essential resources

• First responder and last resort to protect the most

vulnerable

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

15

Proposal 10. Strengthen WHO at the centre of the

global HEPR architecture

Sustained commitment to equity, inclusivity and coherence

(Annex 2) will be best served by the strengthening of and

sustained investment in the only multilateral organization

with a mandate that encompasses the systems, nance

and governance of HEPR: WHO. To achieve this, the world

needs a strengthened WHO, with the authority, nancing

and accountability to eectively full its unique mandate

as the directing and coordinating authority on international

health work.

The Organization has essential responsibilities: for setting

international norms and standards; for promoting and

conducting research in the eld of health; for providing

data and information; for developing evidence-based

policy and guidance; for investigating and responding to

health emergencies as a rst responder and as a provider

of last resort, including in the most vulnerable and

fragile contexts; and for maintaining strong relationships

within the global health ecosystem. Discharging these

responsibilities requires adequate and sustainable

nancing. A pandemic accord, adopted by WHO Member

States, would reinforce the legitimacy and authority of WHO

and complement steps that Member States are already

taking to ensure sustainable nancing of the Organization.

The accord would also ensure that the technical expertise

of WHO, its oices and its various scientic, normative,

operational and monitoring bodies and networks, are

utilized most eectively and eiciently within an equitable,

inclusive and coherent architecture for health emergency

preparedness and response.

Strengthening WHO at the core of the global HEPR

architecture will continue to build and sustain trust in

its mission, contributing to a safer world built on equity,

inclusivity and coherence. A world with fewer health

emergencies, with rapid detection and response when

they do occur, with equitable access, with reduced health,

social and economic impacts, and with rapid and equitable

recovery (Figure 8).

Box 3.

Context is key to eective health

emergency preparedness, response

and resilience in fragile, conict-

aected and vulnerable settings

As COVID-19 has shown, health emergencies can have

markedly dierent impacts even among countries and

communities with seemingly similar capacities, risks,

and vulnerabilities. One size of response does not

t all, and nowhere is this more true than in fragile,

conict-aected and vulnerable settings (FCVs). In

these settings, the causes of and responses to health

emergencies can interact with and oen amplify

pre-existing risks and vulnerabilities in unpredictable

ways. In these contexts, operational readiness for

preparedness and response must account for a

number of key challenges, including:

• Shis in resources required for critical measures

for prevention, control and mitigation of infectious

outbreaks may further compromise the already

limited capacity to deliver essential health services

• Limitations on testing capacity may impact

surveillance capabilities, requiring additional

approaches to obtain a correct picture of the situation

• Capacity to scale up treatment and readiness to

utilize new diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines is

oen limited locally due to existing health systems

challenges

• Social and public health measures, as applied

in higher resource settings, may be harmful and

threaten the livelihoods and social cohesion of

communities in the absence of adequate measures

to support communities

• In areas with armed conict, violence and

insecurity, preparedness, prevention and response

measures must be carefully negotiated and

designed with communities to avoid amplifying

conict and any existing mistrust in authorities

• Communities in fragile, conict-aected and

vulnerable settings may oen be in geographically

and socio-economically isolated areas, and pose

unique logistical and security challenges

Strong community engagement is needed to build

trust and protection, as well as ensure eective

implementation of HEPR measures. Eective disease

control in FCVs must be based on a pragmatic and

contextualised adaptation of global guidance and

goals that accounts for other public health threats

and social economic realities. Done in this way, HEPR

measures can reinforce the key role of health as a

driver of peace and sustainable development.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

16

Box 4.

Understanding the disproportionate eects of the COVID-19 response on

women and children can strengthen health emergency preparedness,

response and resilience in the future

The past two years have seen increasing evidence of the

unique impact that COVID-19 and the public health and

social measures of the response have had on women,

children, and men.

Although men generally have higher mortality rates

from COVID-19 than women, women and girls are

disproportionately aected by the social and economic

consequences of the pandemic. For example, women

comprise around 70% of health and social care workers

globally and 90% of the nursing and midwifery workforce

and yet they hold only 25% of leadership roles in health.

Women are typically clustered into lower-status, lower

paid jobs in health and social care. Investing in equal pay

– which includes recognizing unpaid health care work – is

fair and urgent.

As in other health emergencies, the COVID-19 pandemic

has intensied pre-existing gender inequalities, as

reected by:

• Increased burden of unpaid care work, which falls

mainly on women and girls, due to the impacts of

COVID-19 on the caregiving infrastructure

• Increased burden of paid health and social work

during the pandemic falls disproportionately on

women, who represent the largest share of health and

social care workers globally

• Increased risk of domestic and gender-based violence

due to the combined eect of enforced home-

based connement, restrictions on movement, and

disruptions to health and social services

• Increased risk of unintended pregnancies and

maternal deaths from disruptions to sexual and

reproductive health services

• Higher probability of loss of job and/or income

for women

• Exacerbation of existing barriers to services, driving

inequitable coverage, such as inability to leave

children unattended

Children of all ages and in all countries have been

aected various ways by the socio-economic impacts

of the COVID-19 pandemic and response measures,

including through:

• Disruptions in essential nutrition and health services

and increased food insecurity, mainly due to

decreased purchasing power of families

• Disruptions in education and learning caused by

school closures, which has also aected access to

school meals and signicantly increased rates of

stress, anxiety and other mental health issues. It is

estimated that 24 million children may never return to

school, due to the economic impact of the pandemic

• An increased likelihood that children experience and

observe physical, psychological and sexual abuse at

home

• Increased threat of child labour, child marriage and

child traicking as a result of increased economic

vulnerability

As with other health emergencies, COVID-19 has hit the

most vulnerable hardest at the same time as increasing

the number of vulnerable people. It is crucial to learn

from and recognize how and why COVID-19 has had a

disproportionate impact on women and children, and

ensure that our collective priorities for strengthening the

health emergency preparedness, response and resilience

architecture are anchored in the principles of equity,

inclusivity and coherence.

DRAFT FOR CONSULTATION

JUNE 2022

17

Next Steps

The HEPR systems, nance and governance proposals

described in this white paper represent a coherent

approach to developing a t-for-purpose HEPR

architecture. Operationalizing that architecture will require

an additional level of detail, followed by implementation

by both WHO and our partners. Change will not be easy, but

time is of the essence – health emergencies can strike at any

time and the COVID-19 pandemic is not over. WHO stands

ready to build from the work done during the pandemic to

develop the new capabilities required of it and to engage

closely in ongoing processes, including the development of

a Pandemic Accord.

The Director-General’s proposals are designed to support

and contribute to decision-making in the various fora within

and beyond WHO that will determine the future global

architecture of HEPR. History tells us that the world has a

small window of opportunity to endorse and implement the

proposals in this white paper before global attention shis

and we begin another cycle of panic and neglect.

The Secretariat welcomes comments and feedback on

the proposals contained in the white paper. Consultations

will continue to take place over the coming months with

Member States, UN partners, other international and