Vet Times

The website for the veterinary profession

https://www.vettimes.co.uk

RSPCA PROSECUTIONS: QUESTION OF HUMAN AND

ANIMAL WELFARE?

Author :

Mhairi Cameron

Categories :

Vets

Date :

April 6, 2009

Mhairi Cameron

explains why, in the wake of a controversial RSPCA prosecution, she believes

animal neglect and abuse are not black-and-white issues

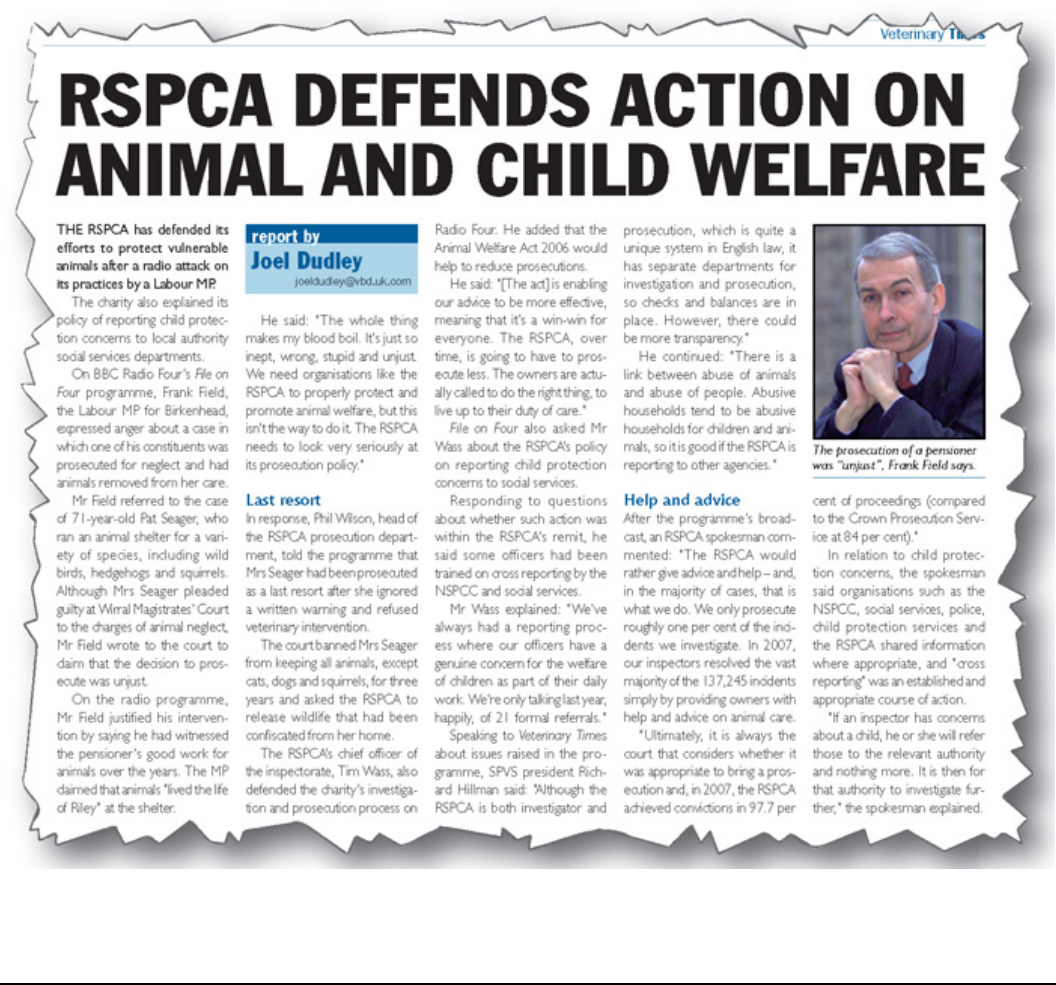

LAST year, Veterinary Times reported on a BBC Radio Four interview with Frank Field,

Labour MP for Birkenhead, and Tim Wass, chief officer of the RSPCA’s inspectorate.

The interview centred around two issues: that of Pat Seager, a 71-year-old from Mr Field’s

constituency who was prosecuted by the RSPCA for neglect last year; and the RSPCA’s policy on

reporting child protection concerns to social services and the NSPCC.

Mr Field was very disappointed in Mrs Seager’s prosecution for animal neglect, and he felt that

this was typical of inappropriate prosecutions by the charity for neglect. Prior to the prosecution,

Mrs Seager was reportedly well known in the local area for her efforts on behalf of animal welfare.

As well as caring for injured wildlife, she was often said to find unwanted pets abandoned on her

doorstep, and the local police frequently brought her animals in need of care that had been left

behind after drug raids.

I was stimulated to discover more about this case, because I feel strongly that, just as animal and

child abuse may be linked, animal neglect and abuse is often the symptom of an underlying

problem or difficulty for the owner involved. Regarding animal neglect (which can cover a huge

spectrum of inadequacy in animal care), it is so often the case that mental illness, personal

difficulties or an inability to cope is the root cause.

1 / 9

In the case of abuse, a much more severe, and perhaps, dangerous psychological illness can be

involved. I imagine that to have schemes in place to deal with such conditions would be a massive

drain on resources and, as is often the case in our society, we may be very limited in the help we

can provide to the individuals involved (prosecution may be the simplest option).

However, especially in the case of neglect, I think we are fundamentally ignoring the issue of

“human welfare” by the way such situations are dealt with. I also don’t believe that simply

preventing people from keeping animals, in many cases, is ultimately the most beneficial course of

action for animal welfare.

I appreciate that Mrs Seager had refused the “help and advice” that had been offered by the

RSPCA and local vets, but this help and advice is not enforceable without a prosecution.

Struggling to cope

Often, people may require more sophisticated or experienced interpersonal communication and

help before they are able to accept advice from an outside agent. I believe 99 per cent of us do our

imperfect best to deal with the situations presented to us. I think it is true to say that we all struggle,

to a greater or lesser degree at some point in our lives, and we all require humane support,

understanding and compassion to successfully overcome hurdles.

To be berated and criticised for mistakes we have made, rather than receiving muchneeded

understanding, is liable to lead to anger, frustration and isolation. Indeed, the people who may be in

greatest need of help are often those who are most difficult to help in any practical way. Breaking

through human defences such as pride and denial can be a painful and difficult process.

According to local press reports and interviews, RSPCA inspectors, together with a local vet and

council member, attended Mrs Seager’s home in October 2006 and removed 11 birds and four

hedgehogs. She was then banned from keeping any animals apart from dogs, cats and squirrels at

Wirral Magistrates’ Court in September 2008 and was handed a 12-month conditional discharge

(see breakout panel). She had pleaded guilty to eight offences of failing to meet the needs of

animals in her care. It seems that the welfare issues centred around the conditions in which the

wild animals were kept at Mrs Seager’s home. It is reported that she was unable to provide a

suitable environment to maintain the welfare of these animals.

I have been unable to find any description of the condition of the animals that were removed,

though the complainants viewed them to be in a bad enough state to contact the RSPCA in the first

place. Mrs Seager appeared to be very distraught when the animals were removed.

Wildlife treatment

As an interesting aside, I presume she was allowed to keep the squirrels because otherwise they

2 / 9

would have had to be destroyed (it is illegal to release grey squirrels into the wild). However, I am

unsure why the conditions she kept the squirrels in were deemed to be appropriate for the

animals’ welfare (and thus they didn’ t need to be destroyed for their own good), whereas the

conditions she kept the hedgehogs and birds under were not – and thus the latter had to be

removed to a more appropriate setting on welfare grounds.

I can remember treating one “wild” hedgehog that had been “rescued”. It remained domesticated

with the family that brought it in – despite attempts to rerelease it into the wild – and the animal

appeared to be very happy. They are gaining significant popularity as domesticated pets

nowadays, and I wonder if the stress effects on a hedgehog that has been “rescued” from the wild

and kept in captivity are any worse than those on a squirrel? I would be interested to hear more

from readers about this subject.

When we are dealing with wildlife, any option for admin istering treatment is far from ideal, even in

specialist centres. Wherever possible, we should send any casualties to wildlife hospitals but, in my

experience, they are few and far between, and often limited by funding and capacity.

Usually, a choice exists between either trying to treat and possibly semi-domesticate a wild animal

(at least on a temporary basis) or euthanising it. Very few members of the public (or the profession,

for that matter) would be willing or able to devote the time, money and effort that many animal

carers do. In my area, certainly, the problem is much greater than the resources we have available.

Surely, people like Mrs Seager should be encouraged and supported by local animal charities? As

vets, we simply aren’ t always in a position to provide wildlife with optimum care. We aren’t even

in a position to provide the humans in our country with the optimum level of care. Therefore, with

regard to wildlife, as with people, we must simply do our best.

We have a character in my area who seems to be not unlike Mrs Seager, and I am very grateful for

the help she gives these animals. She has a number of “disabled” but very happy birds and

mammals under her care, and she often knows more about their individual species requirements

than we do as vets. We simply cannot keep up a supremely high level of wildlife skills on top of our

usual commitments, especially when the treatment we do provide for wild animals is often

free – and this is where we step into the realm of ethics. If the only choices for an animal are

euthanasia or living under less-than-perfect conditions – but with appropriate food, water and

shelter – who are we to say that the animal is better off euthanised?

We cannot make all these decisions as vets, certainly not while trying to run a business. In my

area, it is often the case that the RSPCA is unable to attend to a wild animal in need within good

time for geographical reasons – which is when our local carer will step in and help.

Difficulties

As is the case for most people trying to make a difference where they have identified a need, it can

3 / 9

be very difficult, at times, not to become overinvolved emotionally.

The scale of the problem can often be overwhelming, which is when people need help and support

(it is well recognised that human carers need help and support, which is what charities such as

Crossroads – www.crossroads.org.uk – provide, and animal carers can be no different). Not

everyone has a personality that allows him or her to deal with these matters in a cool, professional

manner. Through disengaging from such situations emotionally, we can make decisions – such as

how funds are best applied, which animals to treat and which to euthanise. For some people, it can

take a trusted outside party to help people make the correct decisions.

However, just because some people may care “too much”, it does not mean that they do not have

a significant contribution to make towards animal welfare.

Our society has evolved to the point where we recognise the need to protect our weaker members

(such as children, animals, the elderly and ill). But we still seem to have a harsh attitude when

dealing with each other as adults.

It seems that we apportion blame readily, and we are quite unforgiving of typical human error and

reactions to stress, insecurity and tiredness. We often do not appreciate or even see a person’s

qualities and potential, as we are blinded by one another’s inadequacies.

After adolescence, we are suddenly bereft of the support mechanisms, second chances and

encouragement of our childhood, and we often respond defensively with frequent and open

criticism of our fellow man, which is much easier to give than our understanding, forgiveness and

help.

As a profession, we are gifted to have such schemes as the Vet Surgeons’ Health Support

Programme, because we have recognised a specific need within the profession for this type of

support. I hope that both the RSPCA and our profession, as custodians of animal welfare, can

extend this compassion to those whose best in looking after a much-loved animal may be far from

good enough, because they themselves are in need of help and support.

Many animal lovers can play a very vital part in caring for unwanted animals and wildlife in need,

and the therapeutic and life-enhancing value for individuals helping in this way cannot be

underestimated. Of course, the primary role of the RSPCA must always be animal protection, but I

feel that welfare charities should be more in touch with the needs and mental health of owners and

keepers, even in the most horrific cases, and be able to provide even more of a specialised,

supportive role (or, in the least, to refer this responsibility appropriately) to people who may

themselves be vunerable and sometimes desperately in need of help. In these cases, I feel that

prosecution alone may be inappropriate or inadequate to deal with the situation.

• To view or download Veterinary Times articles, visit www.vetsonline.com

4 / 9

The RSPCA’s viewpoint

AT the time of Pat Seager’s trial, the RSPCA issued the following statement.

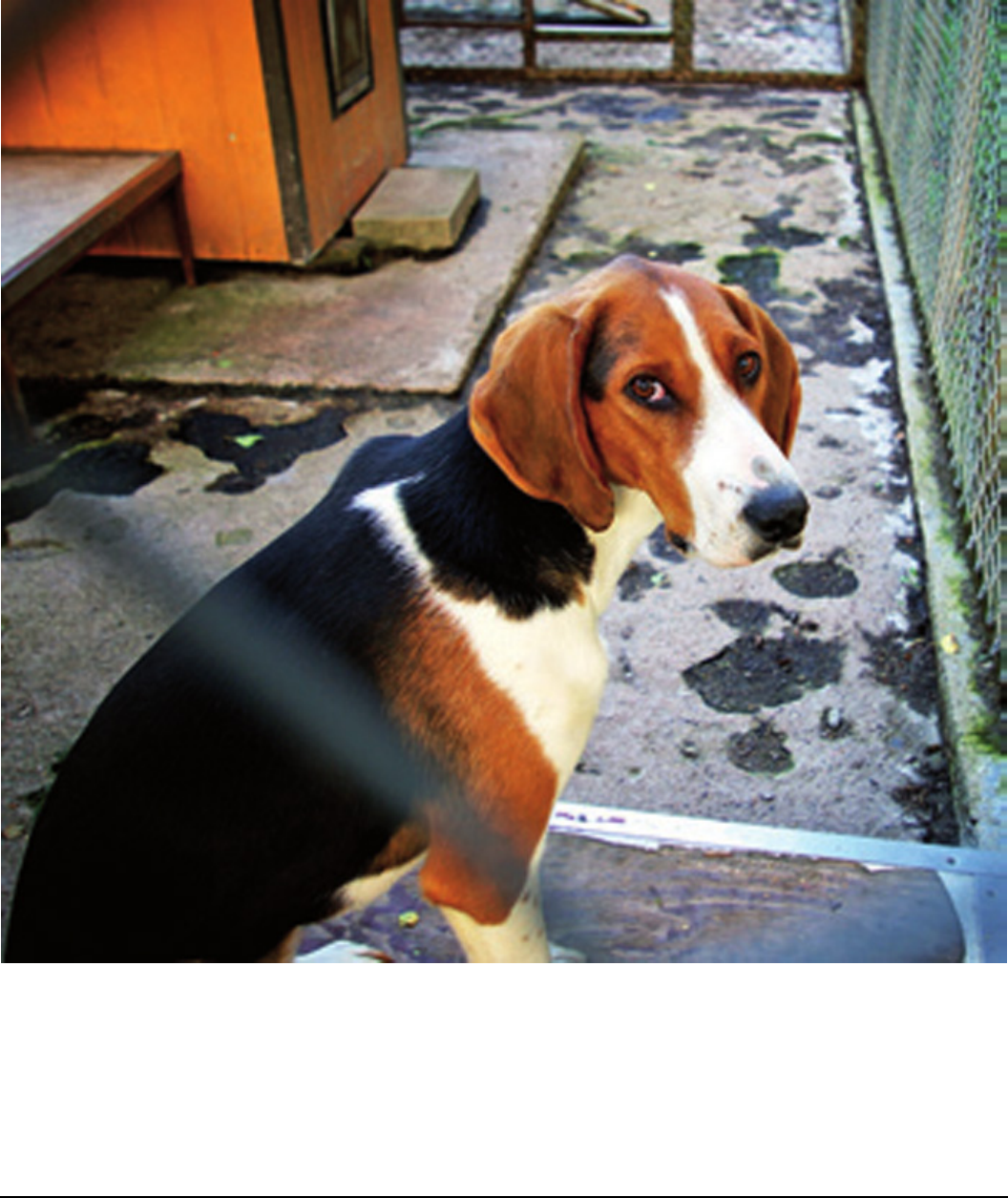

“RSPCA inspectors first visited Ms Seager’s home in October 2006 following concerns raised by

members of the public about the conditions that a large number of animals and birds were being

kept in at the property. Inspectors discovered a number of animals and wild birds (including

hedgehogs, crows, pigeons and magpies) living in cramped, dirty conditions, and offered Ms

Seager help and advice on how the situation could be remedied.

“The RSPCA made a number of followup visits to Ms Seager in January 2007, and again in

February and August, to monitor the animals and birds, but were unable to gain entry to the

property.

“On August 21, 2007, an RSPCA inspector, a veterinary surgeon and a local authorityappointed

inspector successfully revisited Ms Seager’ s home and found a number of animals and wild birds

still living in small, dirty cages and in need of immediate veterinary treatment. Eleven birds and four

hedgehogs were removed by the local authority inspector and taken to the RSPCA Stapeley

Grange Wildlife Centre and Cattery in Cheshire. Ms Seager was advised on how to improve

conditions for the remaining animals and birds. Offers to move other animals to a more suitable

establishment were rejected, as was free veterinary treatment.

“RSPCA inspectors returned to Ms Seager’s home in September 2007 and found no improvement

in the living conditions. A variety of animals, including cats, dogs, hedgehogs, and wild birds, were

removed by the RSPCA and taken for veterinary examination. The majority of the animals and

birds removed on both occasions were successfully treated and released back in to the wild. A

small number were euthanised on veterinary advice due to the severity of their condition. Ms

Seager accepted adult written cautions for failing to meet the needs of her dogs and cats, and it

has been agreed that those animals will be returned to her.”

In the statement, RSPCA prosecution case manager Phil Wilson was quoted as saying: “Anyone

who purports to provide sanctuary for wildlife has a duty of care to ensure the needs of those

animals are met. Anyone operating such an establishment must ensure that he or she acts in the

best interest of the animals at all times, something that I believe Ms Seager lost sight of. The

decision to instigate criminal proceedings was very much a last resort, and the end of a long road

of advice, offers and written warnings that, for the most part, were ignored. It was with some

sadness that the RSPCA was placed in this position, but the intransigence of Ms Seager and her

refusal to take advice left us with no choice.”

5 / 9