TExES

English as a Second

Language (ESL)

Supplemental #154

Preparation Manual

Texas Education Agency Austin, Texas

September 2019

i

TExES English as a Second Language (ESL) Supplemental #154

Preparation Manual

© 2019 by the Texas Education Agency

Copyright © Notice.

The Materials are copyrighted © and trademarked ™ as the property of

the Texas Education Agency (TEA) and may not be reproduced without

the express written permission of TEA, except under the following

conditions:

1. Texas public school districts, charter schools, and Education Service

Centers may reproduce and use copies of the Materials and Related

Materials for the districts’ and schools’ educational use without obtaining

permission from TEA.

2. Residents of the state of Texas may reproduce and use copies of the

Materials and Related Materials for individual personal use only, without

obtaining written permission of TEA.

3. Any portion reproduced must be reproduced in its entirety and remain

unedited, unaltered and unchanged in any way.

4. No monetary charge can be made for the reproduced materials or any

document containing them; however, a reasonable charge to cover only

the cost of reproduction and distribution may be charged.

Private entities or persons located in Texas that are not Texas public

school districts, Texas Education Service Centers, or Texas charter

schools or any entity, whether public or private, educational or non-

educational, located outside the state of Texas MUST obtain written

approval from TEA and will be required to enter into a license agreement

that may involve the payment of a licensing fee or a royalty.

For information contact: Office of Copyrights, Trademarks, License

Agreements, and Royalties, Texas Education Agency, 1701 N. Congress

Ave., Austin, TX 78701-1494; phone 512-463-7004; email:

ii

Dedication

This manual is dedicated to Texas educators who are seeking appropriate English as a

second language (ESL) certification necessary for instructing in an ESL program.

Specifically, this resource equips Texas educators who desire to increase capacity in

their districts and to enhance their existing ESL programs beyond minimum compliance

standard.

For questions regarding this manual or the implementation of ESL programs, contact

the TEA English Leaner Support Division at [email protected].

To register for the TExES ESL Supplemental #154 exam and for other preparation

resources, go to www.tx.nesinc.com.

iii

This page intentionally left blank.

iv

TExES English as a Second Language (ESL) Supplemental #154 Preparation Manual i

Dedication ............................................................................................................................................. ii

Foreword ............................................................................................................................................... v

Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................ vi

Preface ................................................................................................................................................ vii

Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................. ix

Domain III ..................................................................................................................... 1

Competency 8: The ESL teacher understands the foundations of ESL education and types of ESL

programs. .............................................................................................................................................. 1

Competency 9: The ESL teacher understands factors that affect ESL students’ learning and

implements strategies for creating a multicultural and multilingual learning environment. .................. 21

Competency 10: The ESL teacher knows how to serve as an advocate for ESL students and facilitate

family and community involvement in their education. ........................................................................ 43

Domain I ..................................................................................................................... 52

Competency 1: The ESL teacher understands fundamental language concepts and knows the

structure and conventions of the English language. ............................................................................ 52

Competency 2: The ESL teacher understands the process of first language (L1) and second

language (L2) acquisition and the interrelatedness of L1 and L2 development. ................................. 71

Domain II .................................................................................................................... 95

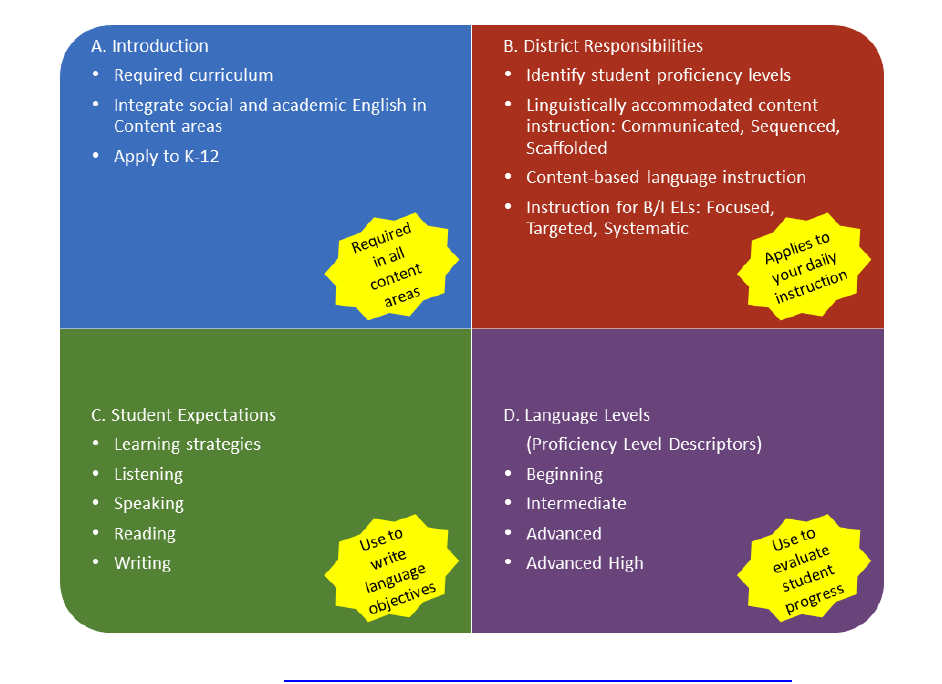

Competency 3 – 6 Combined Components ........................................................................................ 96

Competency 3: The ESL teacher understands ESL teaching methods and uses this knowledge to

plan and implement effective, developmentally appropriate instruction. ........................................... 142

Competency 4: The ESL teacher understands how to promote students’ communicative language

development in English. .................................................................................................................... 146

Competency 5: The ESL teacher understands how to promote students’ literacy development in

English. ............................................................................................................................................. 152

Competency 6: The ESL teacher understands how to promote students’ content- area learning,

academic-language development and achievement across the curriculum. ..................................... 159

Competency 7: The ESL teacher understands formal and informal assessment procedures and

instruments used in ESL programs and uses assessment results to plan and adapt instruction. ..... 162

References ............................................................................................................... 190

Appendix ................................................................................................................... 214

List of Tables and Figures ......................................................................................... 218

v

Foreword

The purpose of this guide is to provide supplemental information on Domains I, II

and III of the TExES English as a Second Language (ESL) Supplemental #154 exam.

The guide will explain in context the significance of ESL education in public schools in

Texas, as well as the historical background across the United States, and specifically

define terminology within each competency’s descriptive statements or components.

The sequencing of the domains and competencies will provide foundational

information on ESL education (Domain III) prior to reviewing language

concepts/language acquisition (Domain I) and ESL instruction/assessment (Domain II)

as demonstrated below:

*Standards described on p.5 of TExES™ Program Preparation Manual linked in title above.

In order to understand ESL education, it is vital to understand the historical

context of its development, recognize the transitions of ESL programming over the past

century, and acknowledge the legislative impact on ESL education during the 21st

century. Additionally, the guide will familiarize examinees with the competencies to be

tested, exam question formats, and appropriate study resources.

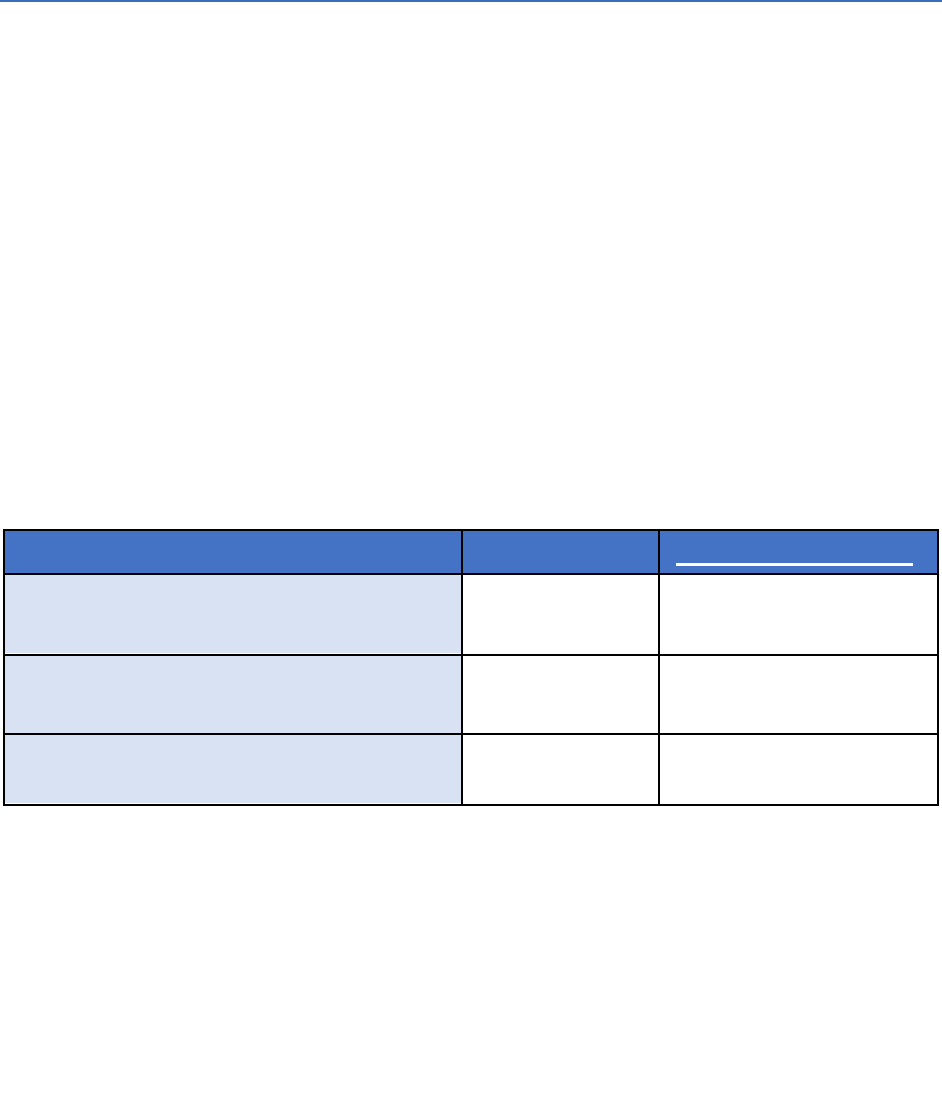

Domain

Competencies

Standards Assessed*

III. Foundations of ESL Education, Cultural

Awareness, and Community Involvement

8, 9, & 10

English as a Second

Language II, VII

I. Language Concepts and Language

Acquisition

1 & 2

English as a Second

Language I, III

II. ESL Instruction and Assessment

3, 4, 5, 6, & 7

English as a Second

Language I, III-VI

vi

Acknowledgments

The TEA English Learner Support Division has worked in partnership with

Region 10 Education Service Center (ESC) to develop this preparation manual. The

dedication of Region 10 ESC to ensure quality of research-based information and their

tireless efforts to the organization of this valuable resource is greatly appreciated.

vii

Preface

Who are English Learners (ELs)?

An English learner is any student who has a primary language or home language

other than English and who is in the process of acquiring English language proficiency.

This includes students at different stages of English language development that need

varying levels of linguistic accommodations that are communicated, sequenced, and

scaffolded to effectively access content in English instruction as they acquire the

English language according to Title 19 of the Texas Administrative Code (TAC),

Chapter 74, Subchapter A, Section §74.4(b)(2).

Why ESL Education?

Texas currently has 1,055,172 identified English learners enrolled as of Spring

2019, making up 20% of the total student population or 1 in 5 students in Texas. Of

those students, 464,888 (44%) are participating in a bilingual program, while 545,597

(52%) are participating in an ESL Program. Over 130 languages are represented in

Texas schools. Nearly 89% of the identified English learners in Texas have a primary

language of Spanish. The next nine prominent language backgrounds of English

learners in Texas are: Vietnamese (1.6%), Arabic (1.2%), Urdu (0.5%), Mandarin

(0.5%), and Burmese (0.3%) Telugu (0.3%), Korean (0.3%), French (0.3%), and Swahili

(0.3%) (TEA, personal communication, May 2, 2019). There has been an increase of

39,880 identified English learners from 2018 to 2019 (TEA, personal communication,

May 2, 2019). This increase includes students who are entering Texas schools in early

education years to begin schooling as well as students transferring from other states or

viii

countries. In Texas, over 78% of English learners are born in the United States

(Sugarman & Geary, 2018).

The state of Texas strives to serve the state’s growing and diverse English

learner population by requiring Local Education Agencies (LEAs) to provide all students

identified as English learners the full opportunity to participate in effective bilingual

education or ESL programs (TAC, §89.1201(a)), in accordance with the Texas

Education Code (TEC), Chapter 29, Subchapter B. Participation in effective ESL and

bilingual programs will help to ensure English learners attain English proficiency,

develop high levels of academic attainment in English, and meet the same academic

achievement standards expected of all students (United States Department of

Education [USDE], 2012).

ix

Acronyms

ARD: Admission, Review, and Dismissal

BICS: Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills

CALLA: Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach

CALP: Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency

EL: English Learner

ELPS: English Language Proficiency Standards

ESL: English as a Second Language

ESOL: English for Speakers of Other Languages

ESSA: Every Student Succeeds Act

GLAD - Guided Language Acquisition Design

IEP: Individualized Education Program

HLS: Home Language Survey

LAS Links: Language Assessment System

LEA*: Local Education Agencies

*Note: The term LEA and ‘districts’ are used interchangeably throughout this manual.

L1: Primary or native language

L2: Second language

LEP: Limited English Proficient (as used in PEIMS*, see EL*)

LPAC: Language Proficiency Assessment Committee

OCR: Office of Civil Rights

OLPT: Oral Language Proficiency Test

PEIMS: Public Education Information Management System

x

PLDs: Proficiency Level Descriptors

QTEL: Quality Teaching for English Learners

SE: Student Expectation

SDAIE: Specially Designed Academic Instruction in English

SPED: Special Education

STAAR: State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness

SIOP: Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol

TAC: Texas Administrative Code

TEC: Texas Education Code

TEA: Texas Education Agency

TELPAS: Texas English Language Proficiency Assessment System

1

Domain III

Foundations of ESL Education, Cultural Awareness, and Community and Family

Involvement

Learning about the foundations of ESL Education provides critical background

knowledge for everything else involving the education of English learners. Basic cultural

awareness of students' different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, their families, their

communities, and any prior living conditions experienced by English learners, such as

refugee students, will result in a richer understanding of the heterogeneity of the English

learner population. As a result, ESL teachers will be better prepared to help coordinate

appropriate services and match each unique English learner with the correct

programming.

Competency 8: The ESL teacher understands the foundations of ESL education

and types of ESL programs.

8.A: The ESL teacher knows the historical, theoretical, and policy foundations of

ESL education and uses this knowledge to plan, implement, and advocate for

effective ESL programs.

Historical Context and Resulting Foundations in Policy

English as a Second Language (ESL) education dates back as far as the late

17

th

and early 18

th

century colonialism in North America when a variety of people from

diverse cultural and language backgrounds were steadily arriving in the New World

(Crawford, 1987). The author found this original wave of mass immigration resulted in

about eighteen different European languages, including English (commonly spoken

throughout the territories that today make up the United States), in addition to multiple

Native American languages. According to this research, first generation families wanted

to preserve their customs and languages. Although the most prevalent language was

2

English, other languages such as German, Dutch, French, Swedish, and Polish were

also very common, and resulted in strong support for bilingual education in many

schools.

The shift in attitudes towards bilingualism and multiculturalism began in the late

19

th

century and after World War I, with a patriotic call to unify Americans under one

common language (Crawford, 1987). As noted by Crawford (1987), between the 1920’s

to 1960’s, English learners in public school systems had to assimilate into English-

speaking environments, leaving many who were unable to do so behind. In response to

the needs of the English learner population, advocates for ESL and bilingual education

have since brought forth court cases. Such cases resulted in several important

legislative changes in policy and law that ensured the protection of English learners’

rights to an equitable education (Wright, 2010).

Many of the significant court rulings discussed in this section are based on the

due process and equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment to the U.S.

Constitution:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or

immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

U.S. Const. amend. XIV, §1

Key Court Cases

1896 - Plessy v. Ferguson

3

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its now infamous decision in Plessy v.

Ferguson. This decision maintained that "separate but equal" public facilities, including

school systems, are constitutional. Although the decision related to the segregation of

African American students, in many parts of the country Native American, Asian, and

Hispanic students also faced routine segregation (Plessy v. Ferguson, 1896).

1923 - Meyer v. Nebraska

Nebraska passed a law which prohibited schools from teaching children any

language other than English. A Lutheran school teacher, Meyer, who taught his

students in German, was convicted under this law. The U.S. Supreme Court declared

the law unconstitutional. This case is significant in that it upholds the 14th Amendment

as providing legal protection for language minorities (Meyer v. Nebraska, 1923).

1954 - Brown v. Board of Education

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed Plessy v. Ferguson after 58 years in

Brown v. Board of Education. Again, even though the case related to African American

students, the ruling emphasized the responsibility of states to create equal educational

opportunities for all, effectively paving the way for future policy on ESL and bilingual

education (Brown v. Board of Education, 1954).

1974 - Lau v. Nichols

When this case came before the Supreme Court, San Francisco public schools

offered no programs for second language learners. In 1971, the San Francisco,

California school system was integrated as a result of a federal court decree.

Approximately 2,800 Chinese ancestry students in the school system did not speak

4

English. Of these students, 1,000 received supplemental courses in English language,

and 1,800 did not receive such instruction (Lau v. Nichols, 1974).

The non-English-speaking Chinese students who did not receive additional

instruction brought forth a class action suit against officials responsible for the operation

of the San Francisco Unified School District. The students alleged that the school

district did not provide equal educational opportunities and, therefore, was denying their

Fourteenth Amendment rights. The District Court denied relief, and the Court of Appeals

affirmed the decision. The plaintiff filed a petition for certiorari (ordering a lower court to

deliver its record in a case so that the higher court may review it), and the United States

Supreme Court granted the petition due to public importance of the issue.

The Supreme Court found that the California Education Code:

required that the English language was the basic language of instruction in all

schools;

required compulsory, full-time education for children between the ages of six

and sixteen; and

required that students who had not met the standards of proficiency in English

would be allowed to graduate in twelfth grade and receive a diploma (Lau v.

Nichols, 1974).

The Supreme Court ruled that these state-imposed standards “did not provide for

equality of treatment simply because all students were provided with equal facilities,

books, teachers, and curriculum” (Lau v. Nichols, 1974). The San Francisco Unified

School District received substantial federal financial assistance, and based on

guidelines imposed upon recipients of such funding, “school systems must assure that

5

students of a particular race, color, or national origin are not denied the same

opportunities to obtain an education generally obtained by other students in the same

school system” (Lau v. Nichols, 1974).

Implications of Lau v. Nichols

With Lau vs. Nichols, the U.S. Supreme Court guaranteed children an

opportunity to a meaningful education regardless of their language

background. Although the court did not specifically mandate bilingual

education, it did mandate that schools take effective measures to overcome

the educational challenges faced by non-English speakers.

The Office of Civil Rights (OCR) interpreted the court’s decision as effectively

requiring bilingual education unless a school district could prove that another

approach would be equally or more effective (Pottinger, 1970).

1981 - Castañeda v. Pickard

The case of Castañeda v. Pickard (1981) was tried in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Texas in 1978. This case was filed against the

Raymondville Independent School District (RISD) in Texas by Roy Castañeda, the

father of two Mexican American children.

Mr. Castañeda claimed that the RISD was discriminating against his children

because of their ethnicity. He argued that the classroom his children were being taught

in was segregated, using a grouping system for classrooms based on criteria that were

both ethnically and racially discriminating (Castañeda v. Pickard, 1981).

The Castañeda v. Pickard (1981) case was tried, and on August 17, 1978, the court

system ultimately ruled in favor of the Raymondville Independent School District, stating

6

they had not violated any of the Castañeda children's constitutional or statutory rights.

As a result of the District Court ruling, Castañeda filed for an appeal, arguing that the

District Court made a mistake in its ruling.

In 1981, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in favor of the

Castañeda, and as a result, the court decision established a three-part assessment for

determining how programs for English learners would be held responsible for meeting

the requirements of the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 (EEOA).

The criteria are listed below:

The program for English learners must be “based on sound educational

theory.”

The program must be “implemented effectively with resources for personnel,

instructional materials, and space.”

After a trial period, the program must be proven effective in overcoming

language barriers (EEOA, H.R.40, 92

nd

Cong. 1974).

1982 - Plyler v. Doe

Under revisions, Texas education laws in 1975 allowed the state to withhold

funds from local school districts for educating children of undocumented immigrants.

The U.S. Supreme Court reasoned that undocumented immigrants and their children

are afforded Fourteenth Amendment protections (Plyler v. Doe, 1982).

Federal Regulations

1964 - Civil Rights Act

In 1964, the Civil Rights Act established that public schools, which receive federal

funds, could not discriminate against English learners:

7

No person in the United States shall, on the grounds of race, color, or national

origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of or be subjected

to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial

assistance (Pub. L. 88–352, title VI, § 601, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 252).

The mandate was detailed more specifically for English learners in the May 25th,

1970 Memorandum:

Where inability to speak and understand the English language excludes national

origin-minority group children from effective participation in the educational program

offered by a school district, the district must take affirmative steps to rectify the

language deficiency in order to open its instructional program to these students

(U.S. Department of Education, 2018, p. 1).

1968 - Bilingual Education Act

The Bilingual Education Act (BEA) of 1968 was created under Title VII as a part

of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 and was the first

comprehensive federal intervention that helped to shape education policy of language

minority students (de Jong, 2011). It was originally introduced by the Texas Senator

Ralph Yarborough, who explained that Spanish-speaking students completed four years

less schooling than their Anglo peers on average across the state (de Jong, 2011).

According to de Jong (2011), the BEA received much support due to similar

experiences nationwide with English learner populations and passed in 1968 in an effort

to secure more resources, trained personnel and special programs to meet the needs of

this population. Through the BEA, Yarborough proposed bilingual education to address

the perceived English proficiency problem (de Jong, 2011).

8

2002 - No Child Left Behind

A reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of

1965, No Child Left Behind (NCLB, 2002) was the primary law for K–12 general

education in the United States from 2002–2015. NCLB (2002) impacted every public

school in the United States. Its goal was to level the playing field for all students

including:

students in poverty,

minorities,

students receiving special education services, and

those who speak and understand limited or no English.

Other NCLB (2002) components:

NCLB gave more flexibility to states in how they spent federal funding, as

long as schools were improving;

NCLB required that all teachers must be “highly qualified” in the subject they

teach;

NCLB required special education teachers to be certified and to demonstrate

knowledge in every subject they teach; and

NCLB said that schools must use science and research-based instruction and

teaching methods.

2015 - Every Student Succeeds Act

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) is an amendment and reauthorization

of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 that replaced NCLB. It

9

recognized the unique needs of English learners, including the recognition of subgroups

of English learners such as:

English learners with disabilities,

recently arrived English learners (newcomers), and

long-term English learners.

It moved several provisions relevant to English learners (e.g., accountability for

performance on the English language proficiency assessment) from Title III, Part A to

Title I, Part A of the ESEA. The ESSA amendments to Title I and Title III took effect on

July 1, 2017 (ESSA, 2017).

Effective ESL Programming Theories

Historically, theories on effective ESL programs have focused on the difference

between bilingual and English-only approaches (de Jong, 2002). The contrast often

further emphasized when summative program evaluations only determined whether

bilingual education is more effective than an English-only approach rather than on the

quality implementation of the program itself (de Jong, 2002) and its impact on student

achievement.

According to recent comprehensive research by Collier and Thomas (2009),

content-based ESL programs that embed language support across all disciplines within

an inclusionary model have been shown to have a greater impact on English learner

achievement over ESL programs with models that isolate English learners from other

peers and only offer supplemental English language support. In order to more fully close

the achievement gap, ensure long-term success in the English language, accelerate

English learner growth, effective enrichment models (instead of isolated models focused

10

on remediation) are needed (Collier and Thomas, 2009). The state of Texas requires

that every student who has a primary language other than English and who is identified

as an English learner be provided the opportunity to participate in a bilingual education

or ESL program (TEC §29.051).

Planning, Implementing, and Advocating for Effective ESL programs

The United States Department of Education (USDE, 2018) recognizes the

heterogeneity of English learners by providing policy makers with comprehensive

guidelines for planning ESL programming. Key elements such as program

implementation, performance, and analysis, are considered to effectively support school

improvement efforts for English learners. Based on these guidelines, the state of Texas

permits districts to choose from two state-approved ESL program models: ESL content-

based and ESL pull-out; and four state-approved bilingual models: transitional bilingual-

early exit, transitional bilingual-late exit, dual language immersion one-way, or dual

language immersion two-way (TAC, §89.1210(c)). All program models are required to

provide English learners with targeted language instruction in English that is both

culturally and linguistically responsive in addition to ensuring that instruction addresses

the affective, linguistic, and cognitive needs of English learners in accordance to TEC,

§29.055(b) and TAC, §89.1210(b). In the next section 8.C, ESL and bilingual program

models are described in detail. The section titled Placement in section 7.A explains

when a district is required to provide an ESL program and when a district is required to

provide a bilingual education program.

Advocacy may hold a variety of meanings in various circumstances, but for the

purposes for ESL education, it ultimately involves taking action when facing the

11

inequities in our educational system experienced by English learners. The National

Education Agency (NEA, 2015) notes that both individuals and institutions have a role in

advocacy at both micro and macro levels, and that ultimately efforts should culminate in

the spirit of collaboration in order to have the most impact. For teachers seeking ESL

certification, increasing their knowledge about the English learner populations they will

serve can be a first step. The resulting changes from advocacy have long lasting

impacts on English learner populations and our public-school system as a whole (NEA,

2015).

8.B: The ESL teacher knows types of ESL programs (e.g., self-contained, pull-out,

newcomer centers, dual language immersion) their characteristics, their goals,

and research findings on their effectiveness.

Defining Characteristics of Programs for English Learners

In an effort to meet the needs of English learners, school districts around the

country have implemented a variety of programs to provide instruction in English as a

second language (ESL). Texas requires bilingual education and ESL programs to be

integral parts of the general program and guides local education agencies (LEAs) to

seek appropriately certified teaching personnel, thereby ensuring a full opportunity for

English learners to master the essential knowledge and skills required by the state

(TAC, §89.1210(b)). Ensuring equitable participation for English learners, developing

proficiency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing in the English language, and

developing literacy and academic language skills are common goals in both ESL and

bilingual programs (TAC, §§ 89.1201(b)-(c)).

12

Texas ESL Program Models

Figure 1. State Approved Program Models for English Learners.

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210,” by Texas Education Agency, 2019, and “TEC, §29.066.” Copyright 2019 by

Texas Education Agency.

Texas has two state-approved ESL program models as outlined in TAC,

§89.1210(d): 1) ESL Content-Based, 2) ESL Pull-Out.

ESL Content-Based Program

Table 1 details characteristics of ESL content-based programming.

Table 1. ESL Content Based Program Model TAC, §89.1210(d)(1)

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(d)(1),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education

Agency.

Components

Description

General

Description

An English acquisition program that serves students identified as English learners

through English instruction

Certifications

By a teacher certified in ESL under TEC, §29.061(c) through English language

arts and reading, mathematics, science and social studies.

Goal

The goal of content-based ESL is for English learners to attain full proficiency in

English in order to participate equitably in school.

Instructional

Approach

This model targets English language development through academic content

instruction that is linguistically and culturally responsive in English language arts

and reading, mathematics, science, and social studies.

13

ESL Pull-Out Program

Table 2 details characteristics of ESL Pull-Out programming.

Table 2. ESL Pull-Out Program Model TAC, §89.1210(d)(2)

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(d)(2),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education

Agency.

ESL-related Terminology

ESL-related programming may frequently include the use of the following terms:

Self-contained - a class in which one teacher teaches all or most subjects to one class

of students.

Newcomer Centers - an entry point for English learners who have recently enrolled in

U.S. schools and typically used in districts with large numbers of newcomers. Students

enroll in these programs for usually about one year until they are prepared to transition

to a mainstream school in the district (U.S. Department of Education, 2017). In Texas,

English learners “…shall not remain enrolled in newcomer centers for longer than two

years” (TAC, §89.1235).

Components

Description

General Description

An English acquisition program that serves students identified as English

learners through English instruction

Certifications

By a teacher certified in ESL under TEC, §29.061(c) through English

language arts and reading.

Goal

The goal of ESL / pull-out is for English learners to attain full proficiency in

English in order to participate equitably in school.

Instructional

Approach

The model targets English language development through academic content

instruction that is linguistically and culturally responsive in English Language

arts and reading. Instruction shall be provided by the ESL teacher in a pull-

out or inclusionary delivery model.

14

Texas Bilingual Program Models

In Texas, there are four (4) state-approved bilingual education program models: 1)

Transitional Bilingual/Early Exit, 2) Transitional Bilingual/Late Exit, 3) Dual Language

Immersion/Two-Way, 4) Dual Language Immersion/One-Way (TAC, §89.1210(c)).

Transitional Bilingual/Early Exit

Table 3 delineates characteristics of the Transitional Bilingual/Early Exit Program.

Table 3. Transitional Bilingual/Early Exit TAC §89.1210(c)(1)

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(c)(1),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education Agency.

Transitional Bilingual/Late Exit

Table 4 provides a detailed description of the Transitional Bilingual/Late Exit

program.

Table 4. Transitional Bilingual/Late Exit TAC, §89.1210(c)(2)

Note: Adapted from “TAC, § 89.1210(c)(2),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education Agency.

Components

Description

General

Description

A bilingual program model in which students identified as English learners are served in both

English and another language and are prepared to meet reclassification criteria to be

successful in English-only instruction not earlier than two or later than five years after the

student enrolls in school.

Certifications

Instruction in this program is delivered by a teacher appropriately certified in bilingual education

under TEC, §29.061(b)(1) for the assigned grade level and content area.

Goal

The goal of early-exit transitional bilingual education is for program participants to utilize their

primary language as a resource while acquiring full proficiency in English.

Instructional

Approach

This model provides instruction in literacy and academic content through the medium of the

students’ primary language, along with instruction in English that targets second language

development through academic content.

Components

Description

General

Description

A bilingual program model in which students identified as English learners are served in both

English and another language and are prepared to meet reclassification criteria to be

successful in English-only instruction not earlier than six or later than seven years after the

student enrolls in school.

Certifications

Instruction in this program is delivered by a teacher appropriately certified in bilingual education

under TEC, §29.061(b)(1) for the assigned grade level and content area.

Goal

The goal of late-exit transitional bilingual education is for program participants to utilize their

primary language as a resource while acquiring full proficiency in English.

Instructional

Approach

This model provides instruction in literacy and academic content through the medium of the

students’ primary language, along with instruction in English that targets second language

development through academic content.

15

Bilingual Dual Language Immersion/One way

Table 5 describes the bilingual dual language immersion/one-way program

model.

Table 5. Dual Language Immersion/One-Way TAC, §89.1210(c)(3)

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(c)(3),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education Agency.

Bilingual Dual Language Immersion/Two Way

Table 6 describes the bilingual dual language immersion/two-way program

model.

Table 6. Dual Language Immersion/Two-Way TAC, §89.1210(c)(4)

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(c)(4),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education Agency.

Components

Description

General

Description

A bilingual/biliteracy program model in which students identified as English learners are served in

both English and another language and are prepared to meet reclassification criteria in order to

be successful in English-only instruction not earlier than six or later than seven years after the

student enrolls in school.

Certifications

Instruction provided in a language other than English in this program model is delivered by a

teacher appropriately certified in bilingual education under TEC, §29.061. Instruction provided in

English in this program model may be delivered either by a teacher appropriately certified in

bilingual education or by a teacher certified in ESL in accordance with TEC §29.061.

Goal

The goal of one-way dual language immersion is for program participants to attain full proficiency

in another language as well as English.

Instructional

Approach

This model provides ongoing instruction in literacy and academic content in the students’ primary

language as well as English, with at least half of the instruction delivered in the students’ primary

language for the duration of the program.

Components

Description

General

Description

A bilingual/biliteracy program model in which students identified as English learners are

integrated with students proficient in English and are served in both English and another

language and are prepared to meet reclassification criteria in order to be successful in English-

only instruction not earlier than six or later than seven years after the student enrolls in school.

Certifications

Instruction provided in a language other than English in this program model is delivered by a

teacher appropriately certified in bilingual education under TEC, §29.061. Instruction provided in

English in this program model may be delivered either by a teacher appropriately certified in

bilingual education or by a teacher certified in ESL in accordance with TEC §29.061.

Goal

The goal of two-way dual language immersion is for program participants to attain full proficiency

in another language as well as English.

Instructional

Approach

This model provides ongoing instruction in literacy and academic content in the students’ primary

language as well as English, with at least half of the instruction delivered in the students’ primary

language for the duration of the program.

16

Departmentalization vs. Paired Teaching Bilingual Programs

Table 7 clarifies teacher certification requirements when using

departmentalization or the paired teaching approach within a transitional bilingual

program model compared to a dual language immersion program model in elementary

school.

Table 7. Departmentalization vs. Paired Teaching in Bilingual Programs

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(c)(1),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education Agency.

Summary: Goals and Instructional Design of ESL Programs and Bilingual Programs

Table 8. Summary: ESL Program Model Goals and Instructional Design

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(d)(2),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas Education Agency.

Program Model

Departmentalization

Paired Teaching

Transitional Bilingual

Education Program Models

Early-exit

Late-exit

Local decision to use more

than one content-area

teacher to deliver core

content instruction

All teachers must be

certified in bilingual

education

Local decision to use two content-area teachers to deliver core

content instruction

Both teachers must be certified in bilingual education

Dual Language Program

Models

One-way

Two-way

Local decision to use more

than one content-area

teacher to deliver core

content instruction

All teachers must be

certified in bilingual

education

Local decision to use two content-area teachers to deliver core

content instruction

The teacher delivering the partner language component of

instruction must be certified in bilingual education

The teacher delivering the English component of instruction

must be certified in either bilingual education or English as a

Second Language (ESL)

Program Model

Goal

Instructional Approach

Content-Based ESL

English learners will attain

full proficiency in English in

order to participate

equitably in school.

English learners receive all content area instruction (English

language arts and reading, mathematics, science, and social

studies) by teacher(s) certified in ESL and the appropriate grade

level and content area.

Pull-Out ESL

English learners will attain

full proficiency in English in

order to participate

equitably in school.

English learners receive instruction in English language arts and

reading (ELAR) by an ESL certified teacher.

A pull-out model can be implemented

by an ELAR and ESL certified teacher within the ELAR

classroom

through co-teaching of an ESL certified teacher and ELAR

certified teacher

through an additional ESL/ELAR course provided by an ESL

and ELAR certified teacher

17

Table 9. Summary: Bilingual Program Model Goals and Instructional Design

Note: Adapted from “TAC, §89.1210(c)(1)-(4),” by Texas Education Agency, 2019. Copyright 2019 by Texas

Education Agency.

Research Findings on Effectiveness of ESL and Bilingual Program Types

Based on the available research, there is a positive correlation between

inclusionary content-based ESL program models that embed language support across

all content areas and English learner growth. Success is evident when compared to

ESL programs that take English learners out of mainstream classes and away from their

peers in order to offer only supplemental English language support (Collier & Thomas,

2009).

Thomas and Collier (2002) examined the effect that different program types had

on English learners’ long-term academic achievement and found that overall ESL taught

through academic content is more effective than ESL pull-out. When comparing

transitional bilingual program models, students in 6th grade who participated in late exit

programming, were nearing their native language peers’ English proficiency 50th

percentile while students who participated in early exit programming were nearing their

Program Model Type

Goal

Instruction

Transitional bilingual/early

exit

Transitional bilingual/late

exit

Primary language used

as a resource

Full proficiency in English

is acquired to participate

equitably in school

Literacy and academic content in

primary language and English

Teacher(s) certified in grade

level/content area and in bilingual

education

Primary language instruction decreases

as English is acquired

Dual language

immersion/one way

Dual language

immersion/two way

Full proficiency in primary

language is attained

Full proficiency in English

is attained to participate

equitably in school

Full proficiency includes

grade-level literacy skills

in both languages

Literacy and academic content in

primary language and English

Teacher(s) certified in grade

level/content area and in bilingual

education (or paired with an ESL

certified teacher)

At least half of instruction delivered in

the students’ primary language for the

duration of the program

18

native language peers’ English proficiency 30th percentile (Felber-Smith, 2009). It was

also determined that the biggest predictor in academic success in English was the

amount of formal schooling that a child receives in his or her native/primary language.

The programs that assisted students to fully reach their English-speaking peers in both

the students’ primary language (L1) and second language (L2) in all subjects,

maintained that level of high achievement through the end of schooling, and had fewest

dropouts were bilingual dual language immersion programs. In fact, the study found

bilingual students outperformed comparable monolingual students in academic

achievement in all subjects, after 4-7 years of dual language schooling (Thomas &

Collier, 2002).

8.C: The ESL teacher applies knowledge of the various types of ESL programs to

make appropriate instructional and management decisions.

Informing Instructional Design

In all ESL and bilingual programs, LEAs are required to accommodate the

instruction, pacing, and materials so that English learners participating in an ESL or

bilingual program have the opportunity to master the Texas Essential Knowledge and

Skills (TEKS) and the English Language Proficiency Standards (ELPS) as required

curriculum in all content areas (TAC, §89.1210(a)).

If English learners are enrolled in a bilingual education program, the instruction

should likewise be designed to support mastery for each content area in either their

primary language or in English (TAC, §89.1201(a)). Both the bilingual education

program and ESL program are intended to be integral parts of the general educational

program required under Chapter 74, Subchapter A (relating to Curriculum

19

Requirements) and include all foundation and enrichment areas, ELPS, and college and

career readiness standards (TAC, §89.1203(6)).

Incorporating the ELPS involves ensuring English learners have the opportunity

to develop both social language proficiency in English needed for daily social

interactions and the academic language proficiency needed to “…think critically,

understand and learn new concepts, process complex academic material, and interact

and communicate in English academic settings” (TAC, §74.4(a)(2)). Effective

instructional design should therefore include second language acquisition strategies that

provide English learners the opportunity “…to listen, speak, read, and write at their

current levels of English development while gradually increasing the linguistic

complexity of the English they read and hear, and are expected to speak and write”

(TAC, §74.4(a)(4)).

Informing Management Decisions

Decisions involving the management of ESL and bilingual education programs

within an LEA essentially begin with the process for identifying students who qualify for

entry into a program. Component 7.D explains the English learner identification and

placement process for the Language Proficiency Assessment Committee (LPAC). ESL

and/or bilingual programs should be in place based on the needs of the student

population, as well as appropriate staffing of certified teachers. Monitoring program

effectiveness based on student data and making decisions in the best interest of

English learners becomes a collaborative effort between, teachers, campus leaders,

and parents within the LPAC at each campus (TAC, §89.1265(a)). The LPAC committee

must make informed management decisions about English learners within the programs

20

regarding placement, instructional practices, assessment, and any other special

programs that impact the student. Certified ESL teachers should understand their role in

supporting the ongoing coordination between the ESL program and the general

educational program, while ensuring that the ESL program in place is addressing the

affective, linguistic, and cognitive needs of their English learners (TAC, §89.1210(b)).

8.D: The ESL teacher applies knowledge of research findings related to ESL

education, including research on instructional and management practices in ESL

programs, to assist in planning and implementing effective ESL programs.

Assisting in Planning for Effective ESL Programs

In order to ensure the effectiveness of an ESL program, choosing the right

program for each individual English learner will be an essential starting point. Various

factors including what the individual district and school can offer and the number of

other English learners and their backgrounds can have an impact on developing and

executing a plan. The role of the ESL teacher is to assist the LPAC in evaluating

student data once an English learner is identified in order to recommend the best

instructional program for each student, serve as an advocate for the English learner,

and initiate a plan of action (TAC, §89.1220(b)).

Monitoring Implementation of Effective ESL Programs

An effective ESL program must monitor the implementation process to include:

the academic progress in the language or languages of instruction for English

learners;

the extent to which English learners are becoming proficient in English;

the number of students who have met reclassification as English proficient;

and

21

the number of teachers and aides trained and the frequency, scope, and

results of the professional development in approaches and strategies that

support second language acquisition (TAC, §89.1265(b)).

Competency 9: The ESL teacher understands factors that affect ESL students’

learning and implements strategies for creating a multicultural and multilingual

learning environment.

9.A: The ESL teacher understands cultural and linguistic diversity in the ESL

classroom and other factors that may affect students’ learning of academic

content, language, and culture (e.g., age developmental characteristics, academic

strengths and needs, preferred learning styles, personality, sociocultural factors,

home environment, attitude, exceptionalities).

Cultural and Linguistic Diversity

This component of the competency focuses on understanding the cultural and

linguistic diversity of English learners. Teachers understand how culture, as well as

other related factors, may affect students’ learning of academic content, language, and

the school environment. According to the National Council of Teachers of English

(NCTE, 2019), culturally supportive practices are necessary for reducing the

achievement gap in schools. Phillips, McNaughton, and MacDonald (2004) found

conclusive evidence that achievement gaps can be significantly reduced, and in some

cases, completely eliminated, when culturally supportive practices are implemented to

address cultural and linguistic diversity early on. The Texas Education Research Center

(Wilkinson et al., 2011) recommends professional development that supports educators

in advancing their understanding of English learners from both sociocultural and

sociolinguistic perspectives as well as adopting curriculum that addresses the language

diversity in the state.

22

In Texas, the different aspects of targeted language support and cultural

considerations are an integral part of ESL and bilingual program content and methods

of instruction, in accordance with TEC, §29.055(b). TAC, §89.1210(b) further describes

how these aspects are integral components of ESL and bilingual programs and

prominently introduces the concept of culturally and linguistically responsive teaching,

as it plays a central role in informing the work of the TEA English Learner Support

Division. TEA (personal communication, May 10, 2019) offers the following definition for

the concept of culturally and linguistically responsive teaching.

Teachers of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Students

Teachers should:

value the funds of linguistic and cultural knowledge, prior experiences, and

interests of their students;

view students’ cultural and linguistic resources as foundations rather than

barriers to learning;

capitalize on students' cultural and linguistic resources as a basis for

intentional instructional connections;

understand that teaching and learning are culturally situated and vary among

cultural and linguistic groups;

recognize the language demands necessary for academic content curriculum

development;

understand that the development and preservation of cultural and linguistic

identity influences academic achievement; and

23

employ differentiated methods to ensure equitable access to language and

content (Gay, 2010; Nieto, Bode, Kang, and Raible, 2008; Ladson-Billings,

2009; Au, 2009, as cited in TEA, personal communication May 10, 2019).

Learning Academic Content

When considering the challenges English learners face when learning academic

content in English, it is important to realize how much more work is involved when

processing new content while also learning a new language (Kong, 2009).

Several studies, including Butler & Castellon-Wellington (2000/2005), Francis &

Rivera (2007), Parker, Louie, & O’Dwyer (2009), Stevens, Butler, & Castellon-

Wellington (2000), as cited in Kong (2009), have determined that English language

proficiency scores can undoubtedly predict academic reading test scores in some

populations of English learners K-12, if and when the content alignment between the

academic assessment is in alignment with the English learner population’s

characteristics. For example, scores from recently arrived students as compared to

students who were nearing reclassification as English proficient should be analyzed

separately. Clearly, learning academic content is inextricably linked to learning

language in relation to the English learner’s language acquisition level.

Language

For English learners, learning a language is a complex yet natural process

requiring comprehensible input of information in context (Krashen, 1982). Myhill (2004)

further argues that language acquisition occurs in a cultural context, which is

conditioned by society as a whole, and students rely on prior “culturally determined

experiences” as their background knowledge for developing literacy. Through

24

interactions with students, teachers build linguistic bridges between their own discourse

and that of their English learners in order to develop the new academic register in

English, the students’ second language (L2) or other additional language (Gibbons,

2012).

Culture

Researchers have long known that an English learner’s cultural background

knowledge is critical for reading comprehension, thereby making text from one’s own

culture easier to comprehend (Steffensen, Joag‐dev, and Anderson, 1979) even when

the native culture texts are more linguistically complex, (Johnson, 1981) as cited in

Floyd and Carrell (1987). Consequently, instructional content that an English learner

can connect to his or her existing cultural understanding will result in better

comprehension (Floyd & Carrell, 1987).

So, what is culture, exactly? Culture, according to Garcia (1993, as cited in

Trumbull & Pacheco, n.d., p. 3) is the system of “values, beliefs, notions about

acceptable and unacceptable behavior, and other socially constructed ideas that

members of the society are taught.” Every person has a culture that shapes his or her

habits and behaviors both personally and professionally. However, people are often

unaware that this invisible web of understanding is how they make sense of the world

around them (Geertz, 1973; Greenfield, Raeff, & Quiroz, 1996; Philips, 1983 as cited in

Trumbull & Pacheco, n.d.). Because of this, Trumbull & Pacheco (n.d) note that people

will not notice their own culture until they encounter someone whose behaviors and

customs are different from their own. Additionally, culture is not something permanent,

25

genetic, or acquired by a person’s ethnicity or race, but rather a dynamic aspect to a

person’s identity that can adapt and grow with the individual (Trumbull & Pacheco, n.d.).

Culture manifests itself at different levels. Hall (1976) compared culture to an

iceberg as illustrated in Figure 2, noting that certain aspects are visible to the naked

eye, as in surface culture, while the majority of cultural differences require a deeper

understanding.

Figure 2. Hall’s Iceberg Model Analogous to the Different Levels of Culture

Note. Adapted from Beyond Culture, by E. T. Hall, 1976, Garden City, NY: Anchor Press/Doubleday. Copyright 1976

by Edward T. Hall.

Hammond (2015) elaborates on this understanding and offers the metaphor of a

tree, tying in how the emotional response from the brain affects each level of culture

more deeply as shown in Figure 3.

26

Figure 3. Hammond’s Tree Analogy Representing Surface, Shallow, and Deep Culture

Adapted from Culturally Responsive Teaching & The Brain (p. 24), by Z. Hammond, 2015, Thousand Oaks, CA:

Corwin. Copyright 2015 by Corwin.

Surface culture includes all the visible and tangible aspects of culture, such

as food, dress, celebrations, and traditional art, which have a low emotional

charge and are the types of changes that do not create much anxiety.

Shallow culture focuses on the behavior resulting from implicit norms around

casual every day social interactions, including such common differences as

rules regarding eye contact, manners, courtesy, the concept of time, or

personal space. The deeper cultural values are driving the overt behavior.

Because of the strong emotional charge inherent in this type of

communication, people from a different cultural background may misinterpret

different behaviors as rude, disrespectful, or offensive, resulting in distrust

and a fractured relationship.

27

Deep culture requires an understanding of the subconscious assumptions

that ultimately guide a person’s view of the world, and include the ethical

reasoning, spiritual beliefs, values, and theories that drive the behavior

observed at the shallow cultural level. The intense emotional charge behind

this deep cultural level is at the heart of how people learn new information

because the mental models created here help the brain interpret the threats

and rewards in an environment. When a person experiences a challenge to

deep cultural values, this can trigger the fight or flight response, resulting in

culture shock (Hammond, 2015).

A teacher’s cultural perspective at the deeper level influences what and how one

teaches (Myhill, 2004). Because cultural habits come so naturally, teachers frequently

reinforce skills and behaviors common in their own culture without realizing their

students’ own cultural perspectives may be very different (Myhill, 2004). The resulting

cultural dissonance, or uncomfortable sense of disharmony, often causes behavioral

misunderstandings in the classroom (Black, 2006). So deeply embedded are the

dominant culture’s values and concepts of learning that many teachers and school

officials are unaware of the impact it may have on English learners with potentially

different cultural understandings (Myhill, 2004). Consequently, the behavioral

misunderstandings English learners often experience may stand in the way of socio-

cultural adaptation.

In order to address the cultural dissonance, Black (2006) found that effective

classroom instruction for English learners should involve:

28

recognizing ethnocentrism;

knowing and understanding some background of the student's cultural

heritage;

understanding social, economic, and political issues and values in different

cultures;

adopting a growth-oriented, asset-based attitude that all students can learn;

and

creating classroom environments where all students feel cared for,

appreciated, and accepted.

Phases of Acculturation

English learners, especially newcomers and refugee students, must often go through

the process of adjusting to a new culture, known as acculturation. Further

understanding the phases of acculturation is critical to supporting students as they learn

to navigate a new culture:

Honeymoon Phase: Students may convey a notable sense of excitement at

the novelty of life in a new culture during this phase.

Hostility Phase: After the initial excitement wears off, students may

experience cultural dissonance as their own mannerisms are misunderstood

or they encounter behaviors from members of the new culture that they find

offensive. Students going through this phase may experience impatience,

anxiety, or even frustration and anger. Teachers who cultivate a supportive,

respectful, and caring classroom environment can help their students mitigate

these emotions and to lower their affective filter (providing a safe and

29

comfortable learning environment in which students are free to take linguistic

risks). The affective filter is further explained in 2.A.

Humor Phase: Through rich, culturally inviting experiences, students can

redefine their cultural identity as they gain new understanding and begin to

feel a part of their new culture.

Home Phase: Students arriving at this phase finally feel at ease, have

learned to value their own unique bilingual and bicultural identity (Herrera &

Murry, 2011).

Understanding the influence one’s own culture has on instruction, how different

levels of cultural depth can help shed new light on behavior, and how a student’s

affective filter can impact learning during the process of acculturation will help ESL

teachers reach English learners from a diverse range of cultures.

Other Factors

Beyond cultural and linguistic differences, a number of other factors influence a

student’s learning of language, culture, and academic content leading to each individual

English learner learning a new language at a different pace and with varying efficiency

(Lightbrown and Spada, 2013). ESL teachers must understand how all factors often

interact and play a significant ongoing role in a student’s growth and academic

achievement.

Age & Developmental Characteristics

The English learner’s age and coinciding developmental characteristics influence

second language acquisition. Additionally, students with well-developed literacy skills in

their primary language (L1) are in a much better position to acquire a second language

30

more readily (Lightbrown and Spada 2013). Motivation plays a key role in older learners’

language acquisition success, with pronunciation and intonation being their biggest

challenge (Macaro, 2010). For all ages of English learners, understanding that the

interaction between developmental sequences in English (L2) and the influence of their

primary language (L1) requires explicit instruction that helps students to analyze

differences in both languages in order to progress beyond the more obvious patterns in

which both languages are similar (Spada and Lightbrown, 2002).

Academic Strengths and Needs

With English learners, their academic needs often take center stage due to the

inherent cultural challenges and the hurdles they face throughout the language

acquisition process. In fact, Escamilla (2012) notes that perceptions of emergent

bilinguals often focus on their English language deficiencies instead of viewing their

progress through a holistic bilingual lens, as cited in Texas Essential Knowledge and

Skills for Spanish Language Arts and Reading and English as a Second Language

(2017). Understanding that each individual English learner will have unique strengths

and needs is an important consideration when creating a plan to help them succeed.

Preferred Learning Styles, Personalities, Home Environment, Attitudes and Other

Sociocultural Factors

The concept of different learning styles in the context of learning a second language

coincides with the idea that a combination of sociocultural factors and an English

learner’s unique strengths can influence the way he/she approaches learning and is

ultimately better able to absorb, process, and retain information (Kinsella, 1995 as cited

in Reid, 2002). When English learners are already literate in their primary languages, an

31

additional challenge in English language acquisition could involve the way they have

grown accustomed to learning in their primary language and through that unique

culture’s approach to instruction (Haynes, 2017). Additionally, their primary language

development and level of competency positively impacts their readiness for English

language acquisition (Cummins, 1986 as cited in Robinson, Keough, and Kusuma-

Powell, 2004). Therefore, it is important to recognize the value and importance in the

quality of English learners’ primary language in their home environments and time that

they have spent acquiring their primary language (Robinson, Keough, and Kusuma-

Powell, 2004). Beyond cultural and environmental factors, differences in personality

from student to student can also influence learning styles and learning preferences

(Connor, 2004). Robinson, Keogh and Kusuma-Powell (2004) organize these

interrelated factors into three basic categories:

Learner characteristics or personal traits (Izzo, 1981; Kusuma-Powell, 1992;

Ramirez, 1995; Sears, 1998);

Situational or environmental factors (Ramirez, 1995; Sears, 1998); and

Prior language development and competence (Cummins, 1979; Adamson,

1993).

Consequently, an ESL teacher must know how to differentiate instruction in order

to appeal to the learning styles, personalities, and sociocultural factors influencing

diverse learners.

Exceptionalities

The term exceptionalities refers to a student’s learning disabilities and/or

giftedness. In the context of ESL programs, it is important to distinguish between

32

learning disabilities and the language acquisition process. English learners may have

exceptionalities, but their status as English learners is not in itself a disability. In fact,

Klingner, Vaughn, & Boardman (as cited in Klingner & Eppolito, 2014) note,

we should regard students who begin school already knowing another language

besides English as having a head start over their peers. If we nurture their

bilingualism and capitalize on their linguistic, cultural, and experiential

strengths—helping them to feel ‘smart’ rather than ‘at risk’ —then we will enrich

their school experiences as well as our own (p. 1).

When serving English learners with exceptionalities, the factors that impact academic

learning are due to not only language barriers but also learning differences, and so

require different kinds of support (Hamayan, Marler, Sanchez-Lopez, and Damico,

2013).

For this reason, proper identification of English learners with learning disabilities

is extremely important since interventions that may work to help address processing,

linguistic, or cognitive disabilities often do not help children acquire second language

proficiency (Hamayan, Marler, Sanchez-Lopez, and Damico, 2013). Misidentification of

English learners as having a learning disability, as Hamayan, Marler, Sanchez-Lopez, &

Damico (2013) explain, can also undermine efforts to challenge students academically

and hold them to higher standards. In fact, English learners accurately identified with a

disability can benefit from a strengths-based instructional approach that builds resilience

by targeting the whole learner and addressing their socio-emotional need to feel

capable as they garner a sense of accomplishment from their effort (Osher, n.d. as cited

in deBros, 2016).

33

According to the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), English

learners offer unique challenges when identifying giftedness due to their inherent

diversity in aspects such as primary language, socio-economic status, personal and

parental prior educational opportunities, and cultural perspective on the concept of

giftedness (Langley, 2016). Since oral English language proficiency itself may take from

three to five years for basic development and five to seven years to develop

academically, gifted students may go unidentified by an English language assessment

(Hakuta, Butler, & Witt, 2000, as cited in Langley, 2016). English learners with

exceptionalities can be identified sooner by balancing quantitative assessment with

qualitative measures that include ability, achievement, and creativity in non-verbal,

culture-free formats based on teacher or parental observations. Once identified, English

learners with exceptionalities need thoughtful, responsive, and inclusive programming

that focuses on developing latent abilities through a strengths-based approach.

9.B: The ESL teacher knows how to create an effective multicultural and

multilingual learning environment that addresses the affective, linguistic, and

cognitive needs of ESL students and facilitates students’ learning and language

acquisition.

Creating an Effective Multicultural Environment

Creating an effective multicultural environment involves recognizing, embracing,

and finding ways to thrive on the cultural differences among both students and the

teacher. A multicultural environment can serve as the foundation for growth and

development, offering multiple unique opportunities for collaborative work, conflict

resolution, and new understandings (Gorski, 2006). Through experiential, self-directed

learning, students draw on their prior intercultural experiences and personal attitudes to

34

drive new learning (Krajewski, 2011). Expanding beyond understanding of cultural and

linguistic diversity, the ESL teacher must know how to leverage multiculturalism and

multilingualism in order to address the affective, linguistic, and cognitive needs of

English learners while facilitating both content learning and language acquisition in

accordance with TAC, §89.1210(b).

Affective Needs

According to TAC §89.1210(b), in order to address the affective needs of English

learners, both bilingual and ESL programs must “instill confidence, self-assurance, and

a positive identity with their cultural heritages.” These programs should also be

“designed to consider the students' learning experiences” and “incorporate the cultural

aspects of the students' backgrounds” (b).

Collier and Thomas (1997) assert, “sociocultural processes are the emotional

heart of experiences in school,” and since these processes “can strongly influence

students' access to cognitive, academic, and language development in both positive

and negative ways, educators need to provide a sociocultural supportive school

environment” (p.42). Their prism model, as illustrated in Figure 4, serves as a

foundation for the critical elements that must be present in a school environment for

English learners to succeed (Collier & Thomas, 1997).

35

Figure 4. The Prism Models and the Critical Elements of the

School Environment of English Learners.

Note. Adapted from “School Effectiveness for Language Minority Students,” by V. P. Collier, & W. P. Thomas, W.,

1997, National Clearing House for Bilingual Education, p. 42. Copyright 1997 by Wayne P. Thomas & Virginia P.

Collier. Retrieved from http://www.thomasandcollier.com/assets/1997_thomas-collier97-1.pdf

The importance of meeting students’ socio-emotional or affective needs in a

holistic approach to learning is rooted in the development of humanistic psychology

(Rossiter, 2003). Maslow (1943), emphasized that human physiological needs such as

safety, security, a sense of belonging, and self-esteem must be met first in order for the

individual to reach one’s full potential and achieve any cognitive goals (as cited in

Rossiter, 2003). Krashen (1982) further expands on this concept as it applies to

language learning in his affective filter hypothesis, which holds that affective variables,

such as motivation, self-confidence, and anxiety, facilitate second language acquisition.

The five hypotheses of Krashen’s theory on second language acquisition are described

fully in 2.A.

36

Linguistic Needs

TAC, §89.1210(b) also calls for addressing the linguistic needs of English

learners and requires both bilingual and ESL programs to provide intensive instruction

in listening, speaking, reading, and writing in English through the ELPS. In bilingual

programs these skills and content instruction must be taught in both the students’

primary language and in English (TAC, §89.1210(b)). Both bilingual and ESL programs

also require instruction to be “... structured to ensure that the students master the

required essential knowledge and skills and higher-order thinking skills in all subjects”

(TAC, §89.1210(b)(2)(A)-(B)).

Addressing the linguistic needs of students is another critical component of an

effective program achieved through ensuring comprehensible input as proposed in

Krashen’s (1982) comprehensible input hypothesis. In order for students to comprehend

the content presented, it must be delivered in such a way as to be understandable to

each individual learner and just one level above the English learner’s listening ability so

that, although they may understand the essence of what is communicated, they must

still deduce or infer further meaning (Krashen, 1982).

Cognitive Needs

As the third requirement to both bilingual and ESL programs, English learners

are to be provided with “instruction in language arts, mathematics, science, and social

studies using second language acquisition methods” (TAC, §89.1210(b)(3)(A)-(B)). In

bilingual programs, the instruction must be “both in their (the English learners’) primary

language and in English” with second language acquisition strategies “in either their

primary language, in English, or in both, depending on the specific program model(s)

37

implemented by the district” (TAC, §89.1210(b)(3)(A)). The content area instruction in

both bilingual and ESL programs must also be “structured to ensure that the students

master the required essential knowledge and skills and higher-order thinking skills,” and

for bilingual programs, “in both languages” and “all subjects” (TAC, §89.1210(b)(3)(A)).

English learners have unique cognitive needs as they learn essential knowledge

and develop higher order thinking skills. Research has found that implementing

cognitive strategies, such as concrete prompts and scaffolds, facilitate the learner’s

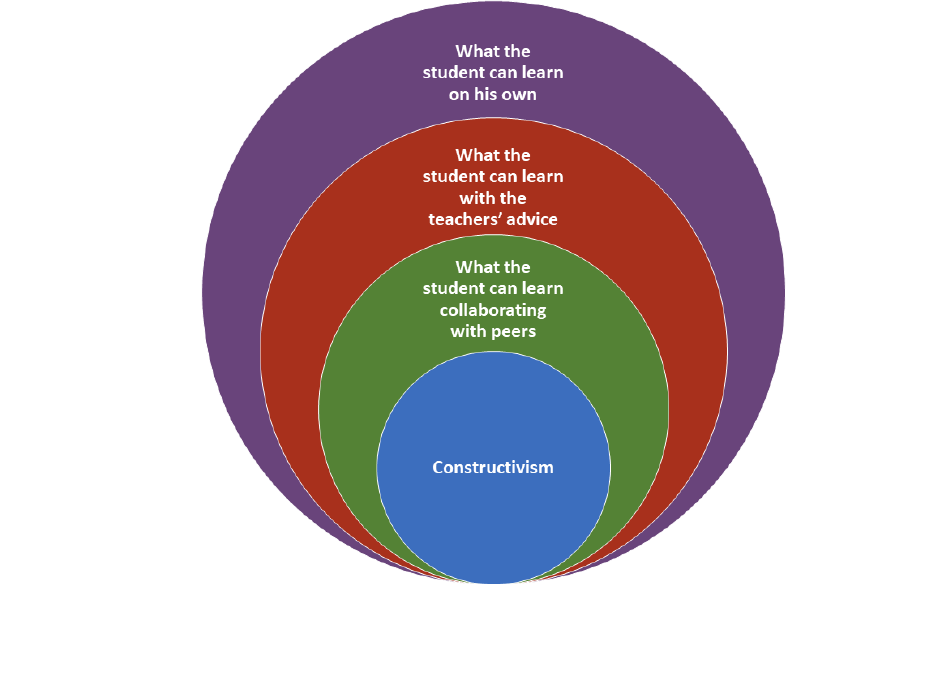

approach to different levels of cognitively demanding tasks, including memory recall and