Praise for The Invention of the White Race

“A powerful and polemic study.” Times Literary

Supplement

“A monumental study of the birth of racism in the

American South which makes truly new and convincing

points about one of the most critical problems in U.S.

history … a highly original and seminal work.” David

Roediger, author of The Wages of Whiteness

“A must read for all social justice activists, teachers, and

scholars.” Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, author of Red Dirt:

Growing Up Okie

“Allen transforms the reader’s understanding of race and

racial oppression from what mainstream history often

portrays as an unfortunate sideshow in U.S. history, to a

central feature in the construction of U.S. (and indeed

global) capitalism. Allen destroys any notion that ‘race’ is

a biological category but instead locates it in the realm of

a construction aimed at oppression and social control.

This is more than a look at history; it is a foundation for a

path toward social justice.” Bill Fletcher Jr., coauthor of

Solidarity Divided

“Decades before people made careers ‘undoing racism,’

Ted Allen was working on this trailblazing study, which

has become required reading.” Noel Ignatiev, coeditor of

Race Traitor, author of How the Irish Became White

“A real tour de force, a welcome return to empiricism in

the subfield of race studies, and a timely reintroduction of

class into the discourse on American exceptionalism.”

Times Higher Education Supplement

“As magisterial and comprehensive as the day it was first

published, Theodore Allen’s The Invention of the White

Race continues to set the intellectual, analytical and

rhetorical standard when it comes to understanding the

real roots of white supremacy, its intrinsic connection to

the class system, and the way in which persons committed

to justice and equity might move society to a different

reality.” Tim Wise, author of White Like Me: Reflections

on Race from a Privileged Son

“One of the most important books of U.S. history ever

written. It illuminates the origins of the largest single

obstacle to progressive change and working-class power

in the U.S.: racism and white supremacy.” Joe Berry,

author of Reclaiming the Ivory Tower

“As organizers of workers, we cannot effectively counter

the depth of white racism in the U.S. if we don’t

understand its origin and mechanisms. Ted has figured

something out that can guide our work – it’s

groundbreaking and it’s eye-opening.” Gene Bruskin, U.S.

Labor Against the War

“An intriguing book that will be cited in all future

discussions about the origins of racism and slavery in

America.” Labor Studies Journal

“A must read for educators, scholars and social change

activists – now more than ever! Ted Allen’s writings

illuminate the centrality of how white supremacy continues

to work in maintaining a powerless American working

class.” Tami Gold, director of RFK in the Land of

Apartheid and My Country Occupied

“If one wants to understand the current, often

contradictory, system of racial oppression in the United

States – and its historical origins – there is only one place

to start: Theodore Allen’s brilliant, illuminating, The

Invention of the White Race.” Michael Goldfield, author

o f The Color of Politics: Race and the Mainspring of

American Politics

“An outstanding, insightful original work with profound

implications.” Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, author of Social

Control in Slave Plantation Societies

“Few books are capable of carrying the profound weight

of being deemed to be a classic – this is surely one.

Indeed, if one has to read one book to provide a

foundation for understanding the contemporary U.S. – read

this one.” Gerald Horne, author of Negro Comrades of the

Crown

“A richly researched and highly suggestive

analysis … Indispensable for readers interested in the

disposition of power in Ireland, in the genesis of racial

oppression in the U.S., or in the fluidity of ‘race’ and the

historic vicissitudes of ‘whiteness.’ ” Choice

“The Invention of the White Race’s contributions to the

debates on notions of a ‘white race’ are unquestionable

and its relevance not simply for scholars of American

history but for those interested in notions of race and class

in any historical and geographical setting is beyond

doubt.” Labour History Review

“Theodore W. Allen has enlisted me as a devoted reader.”

Metro Times Literary Quarterly

“The most important book on the origin of racism in what

was to become the United States – and more important

now perhaps than when it was first released in the mid

nineties.” Gregory Meyerson, coeditor of Cultural Logic

“This ‘modern classic’ presents an essential

reconstruction of concepts necessary to any understanding

of the Western heritage in the context of World history.”

Wilson J. Moses, author of The Golden Age of Black

Nationalism

“Truly original, and worthy of renewed engagement.”

Bruce Nelson, author of Irish Nationalists and the

Making of the Irish Race

“The Invention of the White Race is an important work

for its meticulously researched materials and its insights

into colonial history. Its themes and perspectives should

be made available to all scholars … A classic without

which no future American history will be written.” Audrey

Smedley, author of Race in North America: Origin and

Evolution of a Worldview

“The most comprehensive and meticulously documented

presentation of the historical, or as he calls it,

‘sociogenic’ theory of racial oppression.” Freedom Road

Magazine

This edition published by Verso 2012

First published by Verso 1997

© Theodore W. Allen 1997

Introduction to the second edition and appendices G and H

© Jeffrey B. Perry 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84467-844-0

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84467-770-2

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

“There is a sacred veil to be drawn over the

beginnings of all government.” (Edmund Burke, 16

February 1788, on the impeachment trial of Warren

Hastings for maladministration of British rule in

India)

“The origin of states gets lost in a myth, in which one

may believe, but which one may not discuss.” (Karl

Marx, The Civil War in France, 1848–1850)

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Lists of Figures and Tables and a Note on Dates

Introduction to the Second Edition

PART ONE Labor Problems of the European Colonizing

Powers

1 The Labor Supply Problem: England a Special Case

2 English Background, with Anglo-American

Variations Noted

3 Euro-Indian Relations and the Problem of Social

Control

PART TWO The Plantation of Bondage

4 The Fateful Addiction to “Present Profit”

5 The Massacre of the Tenantry

6 Bricks without Straw: Bondage, but No Intermediate

Stratum

PART THREE Road to Rebellion

7 Bond-labor: Enduring …

8 … and Resisting

9 The Insubstantiality of the Intermediate Stratum

10 The Status of African-Americans

PART FOUR Rebellion and Reaction

11 Rebellion – and Its Aftermath

12 The Abortion of the “White Race” Social Control

System in the Anglo-Caribbean

13 The Invention of the White Race – and the Ordeal of

America

Appendices

Notes

Index

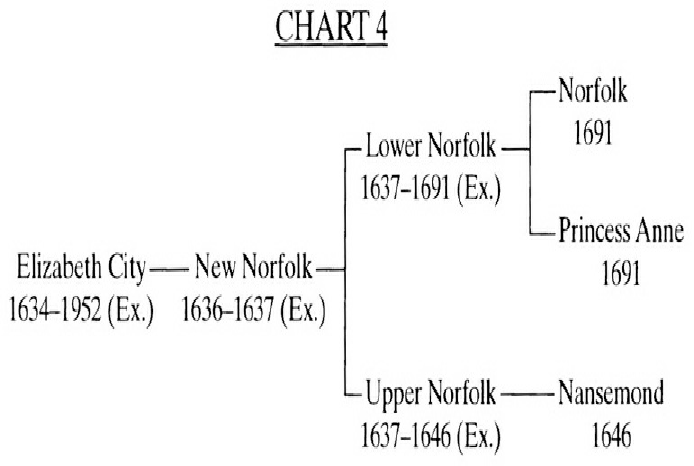

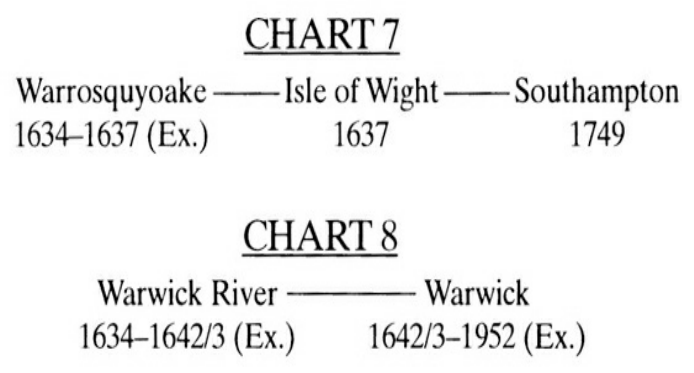

List of Figures

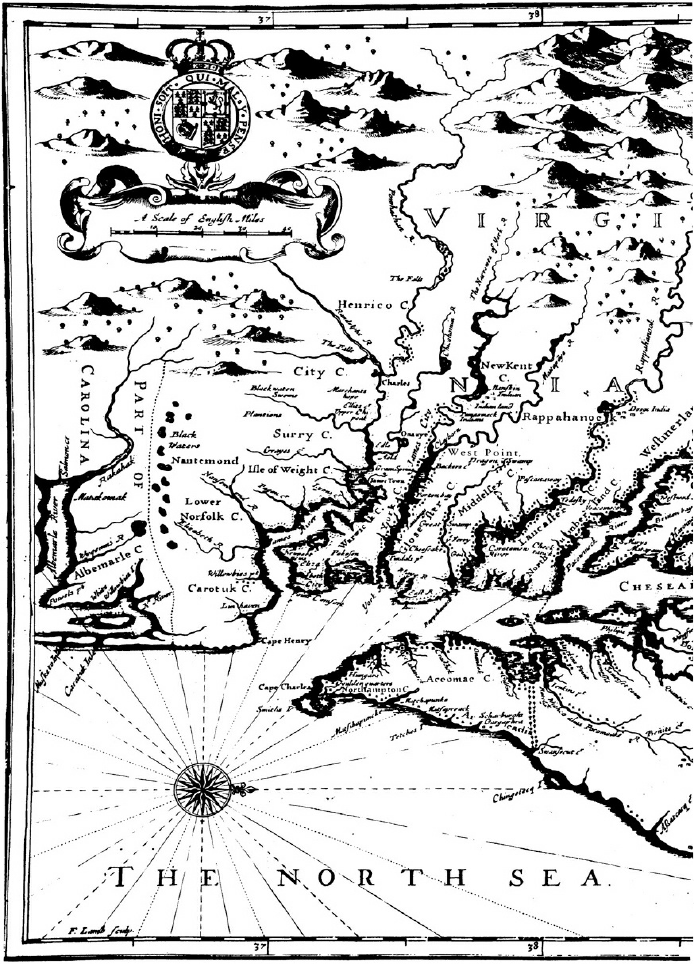

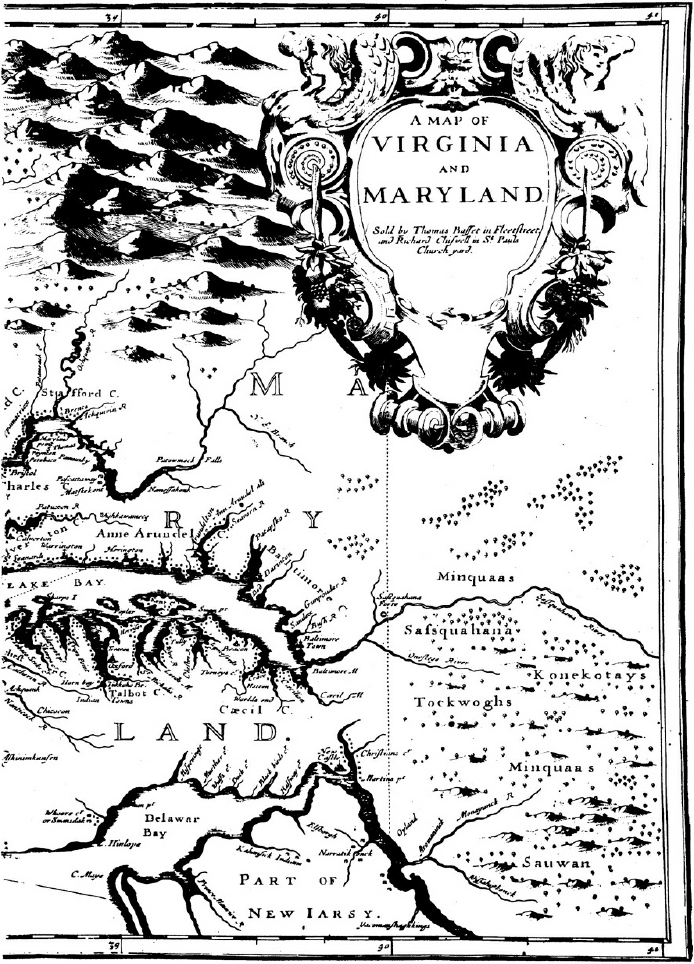

1 Map of the Chesapeake region, circa 1700

2 List of governors of Colonial Virginia

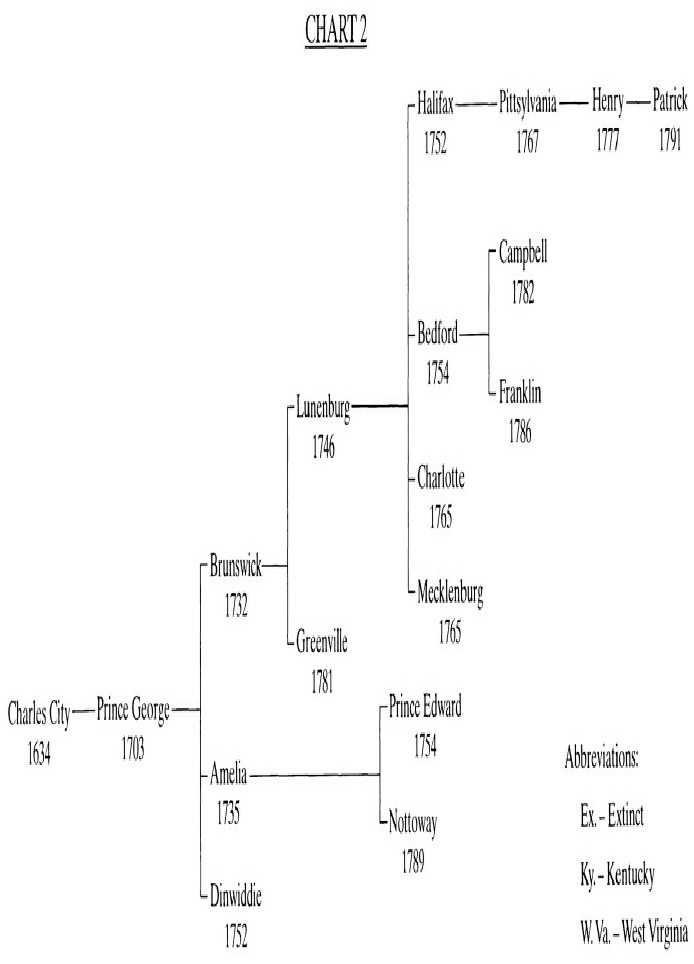

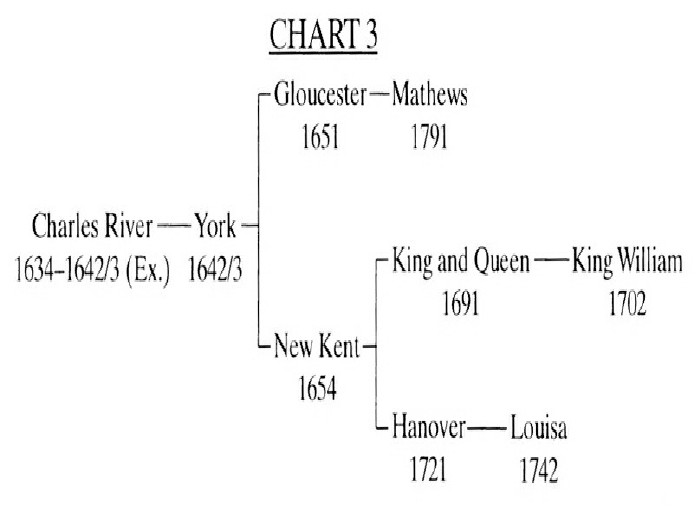

3 Virginia counties, and dates of their formation

List of Tables

4.1 Shipments of persons to Virginia by the Virginia

Company and by separate planters, 1619–21

4.2 Comparative day wages in Virginia, January 1622,

and in Rutland County, England, in 1610–34

5.1 Approximate number of English emigrants to

Virginia and the death rate among them in the

Company period 76

9.1 Increase in concentration of landholdings in Virginia,

1626–1704 167

10.1 African-American and European-American

landholding in the entire state of Virginia in 1860

and in Northampton County in 1666 185

A Note on Dates

Prior to 1750, the legal year began on 25 March.

Therefore, dates from 1 January through 24 March are

often rendered with a double-year notation. For example,

24 March 1749 would be written as 24 March 1748/9, but

the next day would be given as 25 March 1749. But a year

later the dates for those March days would be, in the

normal modern way, 24 March 1750 and 25 March 1750.

Where one year only is indicated, it is to be understood to

accord with the modern calendar.

Introduction to the Second Edition

“When the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there

were no ‘white’ people there; nor, according to the

colonial records, would there be for another sixty years.”

That arresting statement, printed on the back cover of the

first volume of The Invention of the White Race by

Theodore W. Allen, first published in 1994, reflected the

fact that, after twenty-plus years of studying Virginia’s

colonial records, he found no instance of the official use

of the word “white” as a symbol of social status prior to

its appearance in a 1691 law. As he explained, “Others

living in the colony at that time were English; they had

been English when they left England, and naturally they

and their Virginia-born children were English, they were

not ‘white.’ ” White identity had to be taught, and it would

be another six decades until the word “would appear as a

synonym for European-American.”

In this second volume of The Invention of the White

Race, Allen elaborates on his findings in order to develop

the groundbreaking thesis that the ruling class invented the

“white race” as a social-control mechanism in response to

the labor solidarity manifested in the later, civil-war

stages of Bacon’s Rebellion (1676–77). To this he adds

two important corollaries: 1) the ruling elite deliberately

instituted a system of racial privileges in order to define

and establish the “white race”; and 2) the consequences

were not only ruinous to the interests of African-

Americans, they were also “disastrous” for European-

American workers, whose class interests differed

fundamentally from those of the ruling elite.

In Volume I, subtitled Racial Oppression and Social

Control, Allen prepared the conceptual groundwork for

Volume II to be free of what he calls the “White

Blindspot.” He offered a critical examination of the two

main historiographical positions on the slavery and racism

debate: the psycho-cultural approach, which he strongly

criticized, and the socioeconomic approach, which he

sought to free from certain theoretical weaknesses. He

then proceeded, using the mirror of Irish history, to

develop a definition of racial oppression in terms of

social control, a definition free of the absurdities of

“phenotype,” or classification by complexion. The volume

offered compelling analogies between the oppression of

the Irish in Ireland (under Anglo-Norman rule and under

“Protestant Ascendancy”) and white supremacist

oppression of African-Americans and Indians. Allen

showed the relativity of race by examining how Irish

opponents of racial oppression in Ireland were

transformed into “white American” defenders of racial

oppression. He also examined the difference between

national and racial oppression through a comparison of

“Catholic Emancipation” outside of Ulster and “Negro

Emancipation” in America.

In this volume, The Origin of Racial Oppression in

Anglo-America, Allen tells the story of the invention of the

“white race” in the late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-

century Anglo-American plantation colonies. His primary

focus lies with the pattern-setting Virginia colony, and he

pays special attention to how the majority-English labor

force was reduced from tenants and wage-laborers to

chattel bond-servants in the 1620s. In this qualitative

break from long-established English labor laws, Allen

finds an essential precondition for the emergence of the

lifetime hereditary chattel bond-servitude imposed upon

African-American laborers under the system of white

supremacy and racial slavery. He also documents many

significant instances of labor solidarity and unrest,

especially during the 1660s and 1670s, most spectacularly

during the civil-war stage of Bacon’s Rebellion, when

“foure hundred English and Negroes in Arms” fought

together to secure freedom from bondage.

It was in the period after Bacon’s Rebellion that the

“white race” was invented as a ruling-class social-control

formation. Allen describes systematic ruling-class

policies that conferred privileges on European-American

laborers and bond-servants while blocking normal class

mobility and imposing or extending harsh disabilities on

African-Americans. Eventually, these policies culminated

in a system of racial slavery, a form of racial oppression

that also imposed severe proscriptions on free African-

Americans. Allen emphasizes that, in 1735, when African-

Americans in Virginia were deprived of their long-held

right to vote – with the aim, in the words of Governor

William Gooch, “to fix a perpetual Brand upon Free

Negros & Mulattos” – it was not an “unthinking decision.”

Rather, it was a deliberate step in the process of

establishing a system of racial oppression by the

plantation bourgeoisie, even though it entailed repealing a

law that had existed in Virginia for more than a century.

The key to understanding racial oppression, Allen

argues, can be found in the formation of the intermediate

social-control buffer stratum, which serves the interests of

the ruling class. In the case of racial oppression in

Virginia, any persons of discernible non-European

ancestry after Bacon’s Rebellion were denied a role in the

social-control buffer group, the bulk of which was made

up of laboring-class “whites.” In the Anglo-Caribbean, by

contrast, under a similar Anglo ruling elite, “mulattos”

were included in the social-control group and often

promoted to middle-class status. For Allen, this was the

key to understanding the difference between Virginia’s

ruling-class policy of fixing “a perpetual Brand” on

African-Americans and the West Indian planters’ policy of

formally recognizing the middle-class status of “colored”

descendants who earned special merit through their

service to the regime. Here, the difference between racial

oppression and national oppression can be explained by

the fact that in the West Indies there were “too few” poor

and laboring-class Europeans to create an adequate petit

bourgeoisie, while in the continental colonies there were

“too many” laborers to extend social mobility to all of

them.

The references to an “unthinking decision” and “too

few” poor and laboring class Europeans are consistent

with Allen’s repeated efforts to challenge what he

considered to be the two main arguments that undermine

and disarm the struggle against white supremacy in the

working class: 1) white supremacism is innate, and it is

therefore useless to challenge it, and 2) European-

American workers benefit from “white race” privileges.

These two arguments, opposed by Allen, are related to

two master historical narratives rooted in writings on the

colonial period. The first argument is associated with the

“unthinking decision” explanation for the development of

racial slavery offered by historian Winthrop D. Jordan in

his influential work White Over Black. The second

argument is associated with historian Edmund S. Morgan’s

similarly influential American Slavery, American

Freedom, which maintains that, as racial slavery

developed, “there were too few free poor [European-

Americans] on hand to matter.” Allen’s work directly

challenges both Jordan’s theory of the “unthinking

decision” and Morgan’s theory of “too few free poor.”

Allen convincingly argues that the racial privileges

conferred by the ruling class upon European-American

workers not only work against the interests of the direct

victims of white supremacy, they also work against the

workers’ interests. He further argues that these “white-

skin privileges” are “the incubus that for three centuries

has paralyzed” the will of European-Americans “in

defense of their class interests vis-à-vis those of the ruling

class.”

With its meticulous primary research, its equalitarian

motif, its emphasis on the dimension of class struggle in

history, and its groundbreaking analysis, Allen’s The

Invention of the White Race is now widely recognized as

a scholarly classic. It has profound implications for

American history, African-American history, labor

history, American studies, and “whiteness” studies, as

well as important insights in the areas of Caribbean

history, Irish history, and African Diaspora studies. Its

influence will only continue to grow in the twenty-first

century.

In an effort to assist readers and encourage meaningful

engagement with Allen’s work, this new edition of

Volume II of The Invention of the White Race: The

Origin of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America includes a

few minor corrections, many based on Allen’s notes.

There are also two new appendices, “A Guide to The

Invention of the White Race, Volume II” (drawn in part

from Allen’s unpublished “Synoptic Table of Contents”)

and a select bibliography. In addition, you will find a new,

expanded index at the end of this volume.

Jeffrey B. Perry

PART ONE

Labor Problems of the European

Colonizing Powers

1

The Labor Supply Problem: England

a Special Case

In 1497, within half a decade of Columbus’s first return to

Spain from America, the Anglo-Italian Giovanni Caboto,

o r John Cabot as he was known in his adopted country,

made a discovery of North America, and claimed it for

King Henry VII, the first Tudor monarch of England. The

English westering impulse, after then lying dormant for

half a century, gradually revived in a variety of projects,

schemes and false starts. By the first decade of the

seventeenth century, an interval of peace with Spain

having arrived with the accession of James I to the throne,

English colonization was an idea whose time had come.

1

In 1607 the first permanent English settlement in America

was founded at Jamestown, Virginia. By the end of the

first third of the century four more permanent Anglo-

American colonies had been established: Somers Islands

(the Bermudas), 1612; Plymouth (Massachusetts), 1620;

Barbados, 1627; and Maryland, 1634.

2

The English were confronted with the common twofold

problem crucial to success in the Americas: (1) how to

secure an adequate supply of labor; and (2) how to

establish and maintain the degree of social control

necessary to assure the rapid and continuous expansion of

their capital by the exploitation of that labor. In each of

these respects, however, the English case differed from

those of other European colonizing powers in the

Americas, in ways that have a decisive bearing on the

origin of the “peculiar institution” – white racial

oppression, most particularly racial slavery – in

continental Anglo-America.

European Continental Powers and the

Colonial Labor Supply

The continental European colonizing powers, for

economic, military and political reasons, and in some

cases because of access to external sources, did not

employ Europeans as basic plantation laborers.

Spain and Portugal

The accession in 1516 of Francis I of France and in 1517

of Charles I of Spain, and the installation of the latter as

Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, in 1519,

set off a round of warring that would involve almost every

country in Europe, from Sweden to Portugal, from the Low

Countries to Hungary, for a century and a quarter. The

Spanish-headed Holy Roman Empire was at the same time

heavily engaged in war with the Ottoman Turks until after

the defeat of the latter in the Mediterranean naval battle of

Lepanto in 1571. Portugal, with a population of fewer than

1.4 million,

3

was involved in protecting its world-circling

empire against opposition from both Christian and

Moslem rivals. France was Spain’s main adversary in the

struggle over Italy, the Netherlands and smaller European

principalities.

These wars imposed great manpower demands on every

one of the continental governments seeking at the same

time to establish colonial ventures. Belligerents who

could afford them sought to hire soldiers from other

countries. The bulk of Spain’s armies, for example, were

made up of foreign mercenaries.

4

Portugal, however,

lacking Spain’s access to American silver and gold to

maintain armies of foreign mercenaries, had to rely on its

own resources.

5

So critical was the resulting manpower

situation in 1648 that Antonio Vieira, the chief adviser to

King John IV, felt obliged to advocate the temporary

surrender of Brazil to Protestant Holland as the best way

out of the sea of troubles besetting the Portuguese interest

in Africa, Asia, America, and, indeed, vis-à-vis Portugal’s

Iberian neighbor. Portugal was so depleted of men for

defense, he said, that “every alarm” took “laborers from

the plough.”

6

Even if, despite this circumstance, a

ploughman did manage to get to Brazil, he was not to be

expected to do any manual labor there: “the Portuguese

who emigrated to Brazil, even if they were peasants from

the tail of the plough, had no intention of doing any manual

work.”

7

Bartolomé de Las Casas, concerned with the genocidal

exploitation of the native population by the Christian

colonizers in the West Indies, suggested that, “If

necessary, white and black slaves be brought from Castile

[Spain] to keep herds, build sugar mills, wash gold,” and

otherwise be of service to the colonists. In 1518, Las

Casas briefly secured favorable consideration from King

Carlos for a detailed proposal designed to recruit “quiet

peasants” in Spain for emigration to the West Indies. The

emigrants were to be transported free of charge from their

Spanish homes to the colonies. Once there, they were to be

“provided with land, animals, and farming tools, and also

granted a year’s supply of food from the royal granaries.”

But, again, these emigrant peasants were not expected to

do much labor. Rather they were to be provided with

slaves from Spain. It was specified that any emigrant who

offered to build a sugar mill in the Indies was to be

licensed to take twenty Negro slaves with him. With his

assistants, Las Casas toured Spain on behalf of the plan

and received a favorable response from the peasants he

wanted to recruit for the project. But as a result mainly of

the opposition of great landowners who feared the loss of

their tenants in such a venture, the plan was quickly

defeated.

8

Thus was defined official emigration policy; it

assured that Spaniards going to the American colonies

were not to be laborers, but such as lawyers and clerks,

and men (women emigrants were extremely few) of the

nobility or knighthood, who were “forbidden by force of

custom even to think of industry or commerce.”

9

A few

Spanish and Portuguese convicts, presumably of

satisfactory Christian ancestry, were transported to the

colonies early on, but they were not intended and

themselves did not intend to serve in the basic colonial

labor force.

10

The single instance in which basic plantation labor

needs were supplied from the Iberian population occurred

in 1493. In that year, two thousand Jewish children, eight

years old and younger, were taken from their parents,

baptized as Christians, and shipped to the newly founded

Portuguese island sugar colony of São Tomé, where fewer

than one-third were to be counted thirteen years later.

11

In Spain, seven years of plague and famine from 1596 to

1602, followed by the expulsion of 275,000 Christianized

Moors in a six-year period beginning in 1602,

12

reduced

the population by 600,000 or 700,000, one-tenth of all the

inhabitants.

13

Thus began a course of absolute population

decline that lasted throughout the seventeenth century.

14

As

it had been with the Jews before, the expelled moriscos

were officially ineligible for emigration to the Americas,

since émigrés were required to prove several generations

of Catholic ancestry.

15

Holland

For the better part of a century up to the 1660s, Holland, in

the process of winning her independence from Spain in the

Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648), was the leading

commercial and trading country of Europe. Holland’s

10,000 ships exceeded the total number held by the rest of

northern Europe combined.

16

On this basis the new Dutch

Republic developed a thriving and expanding internal

economy. Large areas were diked and drained to increase

the amount of cultivable land.

17

Up until 1622, Dutch

cities grew, some at a phenomenal rate; in that year, half

of Holland’s population lived in cities of more than

10,000 inhabitants.

18

The population of Amsterdam alone

had grown to 105,000, three and a half times its size in

1585.

19

These cities were expanding not from an influx of

displaced Dutch peasants, but because urban needs were

growing faster than those of rural areas,

20

and because

Holland’s “obvious prosperity … acted as a lodestar to

the unemployed and the underemployed of neighboring

countries.”

21

Although the casual laborer in Holland was frequently

out of work, “unemployment … was never sufficiently

severe to induce industrial and agricultural workers to

emigrate on an adequate scale to the overseas possessions

of the Dutch East and West India Companies.”

22

Those

who did decide to emigrate to find work “preferred to

seek their fortune in countries nearer home.”

23

Plans for

enlisting Dutch peasant families for colonizing purposes

came to little, outside of the small settlement at the Cape

of Good Hope, which in the seventeenth century was

mainly a way station for ships passing to and from the

Dutch East Indies.

24

As far as the East Indies were

concerned, it was never contemplated “that the European

peasant should cultivate the soil himself.” Rather, he

would supervise the labor of others.

25

France

In seventeenth-century France the great majority of the

peasants were holders of small plots scarcely large

enough to provide the minimum essentials for survival.

The almost interminable religious wars that culminated in

the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) had ravaged much of the

country, and epidemic disease had greatly reduced the

population.

26

But while French poor peasants groaned

under the burden of feudal exactions, they were still bound

by feudal ties to the land;

27

they had not been “surplussed”

by sheep, as many peasants had been in Spain and

England.

The first successful French colonization efforts were

undertaken on the Bay of Fundy (1604) and at Quebec

(1608). The laborers for the colony’s upbuilding and

development were to be wage workers, transported at the

expense of the French government or other sponsoring

entity, and employed under three to five year contracts.

But New France was not destined to become a plantation

colony, indeed not even a primarily agricultural colony.

28

A century after these first Canadian settlements were

established, their population was only ten thousand,

including a few persons representing a soon-abandoned

notion of supplying the labor needs of Canadian colonies

from African sources.

29

Some time before the end of the

seventeenth century, the French government turned to the

idea of Christianizing and Gallicizing the Indians as a

means of peopling New France and developing a labor

force for it; that plan also failed, however, because the

Indians did not perceive sufficient advantage in such a

change in their way of living,

30

and they had the resources

and abilities to be able to fend off French pressure on the

tribal order. Indeed, until the establishment of the

Louisiana colony early in the eighteenth century, the entire

question of supplying labor for French agricultural

undertakings became irrelevant for North America.

French participation in the development of plantation

colonies was to occur in the West Indies and, as

mentioned, in Louisiana. Having begun with Martinique

and Guadeloupe in 1635, in 1697 the French capped a

series of Caribbean acquisitions by taking control from

Spain of the previously French-invested western half of

Hispaniola under the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick.

31

In

the beginning, wage laborers called engagés, hired under

three-year contracts at rates four or five times those

prevailing in France, were shipped to serve the labor

needs of these colonies.

32

The supply of labor in this form

seems to have reached its peak, however, well before

1697. Although the total number of engagés is not known,

some 5,200 were shipped from La Rochelle, the chief

embarkation point, in the period 1660–1710, a rate of

around one hundred per year.

33

This was numerically

miniscule compared to the total number of imported

laborers, which was running at a rate of 25,000 to 30,000

per year in the latter half of this period.

The reasons for the relegation of engagé labor to

economic insignificance were both economic and

political.

34

The mortality rate among plantation laborers

on St Domingue, whatever their nativity, was such that

most did not survive three years.

35

However, the

obligation to pay relatively high wages to the engagés, be

their numbers large or small, coupled with the fact that the

French colonies had ready access to African labor

supplies, first through the Dutch and later from French

businessmen, made engagé labor relatively less

profitable, provided that the costs of social control of the

laboring population drawn from African sources could be

kept satisfactorily low.

36

Moreover, the need to recruit large French armies for

the wars first with Spain and then with England, and the

drain on revenues entailed in their support, rendered

politically inappropriate the export of engagés to the

French West Indies. Louis XIV finally forbade even the

forcible transportation of indigent persons to the American

colonies. His chief minister from 1661 to 1683, Jean

Baptiste Colbert, declared that he had no intention of

depopulating France in order to populate the colonies.

37

Other sources of labor

The Spanish and the Portuguese first looked to the native

populations to solve their colonial labor problem. The

Spanish did so with such spirit that, in the course of a

century and a half from 1503 to 1660, they tripled

Europe’s silver resources and added one-fifth to Europe’s

supply of gold.

38

In the process, the fire-armed and steel-

bladed Conquistadors almost completely destroyed the

indigenous population by introducing exotic diseases, and

by the merciless imposition of forced labor in gold mining

and in the fields. The native population of Hispaniola was

thus reduced from 1 million in 1492 to around twenty-six

thousand in 1514, and to virtual extinction by the end of

the sixteenth century.

39

The same genocidal labor regime

in mines and fields simultaneously destroyed the native

population of Cuba at a comparable rate.

40

Epidemic European diseases – smallpox, measles, and

typhus – and forced labor under a system of encomienda

a nd repartimiento

41

reduced the population of central

Mexico from 13.9 million in 1492 to 1.1 million in

1605.

42

The impact of disease and of the mita,

43

the

equivalent of the Mexican repartimiento, was equally

devastating to the Indian population of Peru, which was

reduced from 9 million to 670,000 in 1620.

44

In Brazil, the Portuguese (and the Dutch as well, during

the life of the New Holland colony, 1630–54) also sought

to recruit their labor force from the native population.

However, they found that, while the people “were

prepared to work intermittently for such tools and trinkets

as they fancied,” they were unwilling to work for them as

long-term agricultural laborers, or as bound-servants.

45

In

the test of wills that lasted until late in the seventeenth

century, the indigenous population was largely successful

in avoiding reduction to slavery.

46

Thus for two opposite reasons – the accessibility of a

native labor force that eventually led to its destruction,

and the inaccessibility due to resistance by the native

population ensconced in dense continental forests – the

Iberians turned to Africa as a source of labor for colonial

America. This was a labor reserve with which they, as

part of medieval Europe and as colonizers of Atlantic

islands, were already somewhat familiar.

47

Medieval

Europe secured its slaves by trade with southern Russia,

Turkey, the Levant and the eastern coast of the Adriatic

Sea (the ethnic name Slav is the root of the various

Western European variations of the word “slave”), as

well as by purchasing Negroes supplied by North African

Arab merchants.

48

Spain enslaved Moslem “Moors” in

border regions during the “reconquista” wars against the

Arab regime on the Iberian peninsula.

49

In the middle of

the fifteenth century, the Portuguese established direct

access to African labor sources by successfully executing

a maritime end run around the North African Arabs.

50

By

the end of that century Portuguese enterprise, with papal

blessing,

51

had supplied twenty-five thousand Africans as

unpaid laborers to Europe, plus one thousand to São

Tomé, and seven and a half thousand to islands in the

Atlantic.

52

In the sixteenth century the African proportion

of the slave population increased in Portugal and Spain. In

Lisbon, a city of 100,000 people in 1551, there were

9,950 slaves, most of them Africans. In Seville (1565),

Cadiz (1616), and Madrid (up to about 1660), the slave

population included Turks and Moors, but the largest

number were Africans.

53

During the very early days of

American colonization, a number of American Indians

were shipped to be sold at a profit in Spain.

54

In 1518, King Charles I of Spain, acting with papal

sanction, authorized the supply to Spanish America of four

thousand Africans as bond-laborers, for which project he

awarded the contract to a favorite of his.

55

This was the

origin of the infamous Asiento de negros (or simply

Asiento, as it came generally to be called), a license

giving the holder the exclusive right to supply African

laborers to Spanish colonies in the Americas (and to

Portuguese Brazil as well during the sixty years, 1580–

1640, when Portugal was united with Spain in a single

kingdom). At various times it was directly awarded by the

Spanish crown to individuals or to governments by state

treaty. The Asiento was the object of fierce competition

among European powers, especially in the last half of the

seventeenth century. Allowing for brief periods of

suspension, it was held successively by Portugal, Holland,

and France, and passed finally to Britain as a part of the

spoils of the War of Spanish Succession (1702–14).

56

The

Asiento was finally ransomed from Britain for £100,000

in 1750.

57

Scholars’ estimates of the total number of Africans

shipped for bond-servitude in the Americas under the

Asiento and otherwise range from 11 to 15 million.

58

Of

the 2,966,000 who disembarked in Anglo-America,

2,443,000 went to the British West Indies and 523,000 to

continental Anglo-America (including the United States).

59

Two other aspects of the matter seem to have been

slighted in previous scholarship: first, the significance of

this movement of labor in the “peopling” of the Americas;

and, second, the implications to be found in the story of

this massive transplantation of laborers for the history of

class struggle and social control in general in the

Americas.

I am not qualified to treat these subjects in any

comprehensive way, but I venture to comment briefly,

prompted by an observation made by James A. Rawley,

whose work I have cited a number of times:

The Atlantic slave trade was a great migration long ignored by historians.

Euro-centered, historians have lavished attention upon the transplanting of

Europeans. Every European ethnic group has had an abundance of

historians investigating its roots and manner of migration. The transplanting

of Africans is another matter … [that] belongs to the future.

60

As to the first of the questions – the African migration and

the “peopling” of the Americas – it is to be hoped that

among subjects that belong to the future historiography

invoked by Rawley, emphasis may be given to the degree

to which the migration (forced though it was) of 10 or 11

million Africans shaped the demographics of the Americas

as a whole. It is certain that more Africans than Europeans

came to the Americas between 1500 and 1800.

61

It would

seem that such a demographic assessment might add

strength to arguments that place the African-American and

the “Indian” in the center of the economic history of the

hemisphere, and in so doing sustain and promote the cause

of the dignity of labor in general. Such a demographic

assessment might be of service in responding to the cry for

justice for the Indians from Chiapas (from Las Casas to

Subcómmandante Marcos), or to an African-American

demand for reparations for unpaid bond-servitude; or in

assessing the claim of the “Unknown Proletarian,” in a

possibly wider sense than even he intended:

We have fed you all for a thousand years –

For that was our doom you know,

From the days when you chained us in your fields

To the strike of a week ago

You have taken our lives, and our babies and wives,

And we’re told it’s your legal share;

But if blood be the price of your lawful wealth,

Good God! We have bought it fair.

62

Second, with regard to the class struggle and social

control in general in the Americas, attention will need to

be given to the resistance and rebellion practiced by the

African bond-laborers and their descendants, from the

moment of embarkation from the shores of Africa

63

to the

years of maroon defiance in the mountains and forests of

America;

64

from the quarry’s first start of alarm

65

to the

merger of the emancipation struggle with movements for

national independence and democracy four hundred years

later.

66

Historically most significant of all was the Haitian

Revolution – an abolition and a national liberation rolled

into one: it was the destruction of French rule in Haiti that

convinced Emperor Napoleon to see and cede the

Louisiana territory (encompassing roughly all the territory

between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains)

to the United States, without which there would have been

no United States west of the Mississippi. By defeating

Napoleon’s plan to keep St Domingue in sugar plantation

slavery, the Haitian Revolution ushered in an era of

emancipation that in eighty-five years broke forever the

chains of chattel bondage in the Western Hemisphere –

from the British West Indies (1833–48), to the United

States (1865), to Cuba (1868–78), to Brazil (1871–78). It

was in Haiti that the Great Liberator, Simon Bolivar,

twice found refuge and assistance when he had been

driven from Venezuela. Pledging to the Haitian president,

Pétion, that he would fight to abolish slavery, Bolivar

sailed from Haiti at the end of 1816 to break the colonial

rule of Spain in Latin America.

67

England and the Colonial Labor Supply

English colonialists were to share the motives and

aspirations felt by their counterparts looking westward

from the European continent: the search for uncontested

access to the fabled treasures of the East; the hope of

finding rich gold and silver mines; an eagerness to find

alternate sources of more mundane products such as hides,

timber, fish and salt; and the furtherance of strategic

interests vis-à-vis rival military and commercial powers

in the development of this new field of activity.

68

Much

would be said and proposed also in the name of the

defense of one Christian faith (of the Protestant variety in

the English case of course). But all endeavors, holy and

profane, were to be held in orbit by the gravitational field

of capital accumulation.

69

In regard to the problem of a colonial labor supply,

however, the situation of the English bourgeoisie was

unique; this was as a result of developments that are so

familiar to students of English history that a brief summary

will suffice in the present context. With the end of the

Wars of the Roses (1450–85), a convergence of

circumstances – some old, some new – launched the cloth-

making industry into its historic role as the transformer of

English economic life to the capitalist basis.

70

Principal

among these circumstances were: (1) the emergence of a

strong monarchy; (2) England’s relative isolation,

compared to the countries of continental Europe;

71

(3)

improved means of navigation, especially benefiting the

coastal shipping so well suited to the needs of an island

nation; (4) improved and extended use of water power for

cloth-fulling mills, and for other industrial purposes; and

(5) the rural setting of the cloth industry, outside the range

of the regulations of the urban-centred guilds.

The price of wool rose faster than the price of grain,

and the rent on pasture rose to several times the rent on

crop land.

72

The owners increased the proportion of

pasture at the expense of arable land. One shepherd and

flock occupied as much land as a dozen or score of

peasants could cultivate with the plough. Ploughmen were

therefore replaced by sheep and hired shepherds; peasants

were deprived of their copyhold and common-land rights,

while laborers on the lords’ demesne lands found their

services in reduced demand. Rack-rents and

impoverishing leasehold entry fees were imposed with

increasing severity on laboring peasants competing with

sheep for land. At the beginning of the sixteenth century,

somewhere between one sixth and one third of all the land

in England belonged to abbeys, monasteries, nunneries and

other church enterprises. In the process of the dissolution

of the monasteries, most of the estimated 44,000 religious

and lay persons attached to these institutions were cast

adrift among the growing unemployed, homeless

population.

73

As these lands were expropriated, under

Henry VIII the process of conversion to pasture was

promoted more vigorously than it had been by their former

owners.

74

Henry VIII’s return of 48,000 English soldiers

in 1546 from a two-year turn in Boulogne tended further to

the creation of a surplus proletariat.

75

The effect was only

partially offset by the participation of regular and

volunteer English soldiers in the Dutch war for the

independence of Holland from Spain later in the century,

and by the Tyrone War in Ireland.

76

Generally speaking,

the sixteenth century was relatively free of war and

plague.

77

The population of England is estimated to have

grown by 1.3 million in the last six decades of the

sixteenth century, to 4.1 million, but by only another 0.9

million in the entire seventeenth century.

78

Occurring at a

time when employment in cultivation was being reduced

more rapidly than it was being increased in sheep raising

and industry, this demographic factor added substantially

to the swelling surplus of the semi-proletarian and vagrant

population.

79

During the early decades of the seventeenth

century, the oppressive effects of this catastrophic general

tendency to increasing unemployment and vagrancy were

exacerbated by purely political and cyclical factors, and

by market disruptions occasioned by continental wars. In

1614–17, James I – enticed by Alderman Cockayne’s

scheme whereby the Crown coffers were to be enriched

by five shillings on each of 36,000 pieces of finished and

dyed cloth to be exported annually – imposed extremely

strict limitations on the export of unfinished cloth.

80

The

effect was a serious dislocation of trade, and mass

unemployment in the cloth industry. English cloth exports

fell until in 1620 they were only half the pre-1614 level.

81

The man who had been serving for some time as

treasurer and chief officer of the Virginia Company,

Edwin Sandys, urged the colony’s cause by pointing out

that in Britain, “Looms are laid down. Every loom

maintains forty persons. The farmer is not able to pay his

rent. The fairs and markets stand still …”

82

Recovery was

slow. In 1624, an investigating committee of the House of

Commons reported that there were still twelve thousand

unemployed cloth workers.

83

A modern scholar has

concluded that the next decade did not mark much

improvement, noting that the proportion of the people

receiving poor relief was greater in the 1631–40 period

than at any other time before or since.

84

East Anglia, the

native region of most of the emigrants to Anglo-America

in those years, was at that time especially hard hit by a

depression in the cloth trade.

85

The English case for colonization came thus to be

distinguished from those of Spain, Portugal, France, and

Holland in its advocacy of colonization as a means of

“venting” the nation’s surplus of “necessitous people” into

New World plantations.

86

Francis Bacon (1561–1626)

favored colonization as a way to “disburthen the land of

such inhabitants as may well be spared.” Just who those

were who could be spared had been identified some time

before by the premier advocate of overseas exploration

and settlement, Richard Hakluyt (1552?-1616): it was the

surplus proletarians who should be sent. Contrasting

England with the continental countries interminably

devouring their manpower in wars and their train of

disease and pestilence, Hakluyt pointed out that “[t]hrough

our long peace and seldom sickness wee are growen more

populous … (and) there are of every arte and science so

many, that they can hardly lyve by one another.” Richard

Johnson, in his promotional pamphlet Nova Britannia,

noted that England abounded “with swarmes of idle

persons … having no meanes of labour to releeve their

misery.” He went on to prescribe that there be provided

“some waies for their forreine employment” as English

colonists in America.

87

Commenting on the peasant

uprising in the English Midlands in 1607, the House of

Lords expressed the belief that unless war or colonization

“vent” the daily increase of the population, “there must

break out yearly tumours and impostures as did of late.”

88

The English Variation and the “Peculiar

Institution”

The conjunction of the matured colonizing impulse, the

momentarily favorable geopolitical constellation of

powers, the English surplus of unemployed and

underemployed labor, coupled with the particular native

demographic and social factors as the English found them

in Virginia, and the lack of direct English access to

African labor sources, produced that most portentous and

distinctive factor of English colonialism: of all the

European colonizing powers in the Americas, only

England used European workers as basic plantation

workers. This truly “unthinking decision,”

89

or, more

properly, historical accident, was of incidental importance

in the ultimate deliberate Anglo-American ruling class

option for racial oppression. Except for this peculiarity,

racial slavery as it was finally and fully established in

continental America, with all of its tragic historical

consequences, would never have been brought into being.

Essential as this variation in the English plantation

labor supply proved to be for the emergence of the Anglo-

American system of racial slavery, however, it was not

the cause of racial oppression in Anglo-America. The

peculiarity of the “peculiar institution” did not derive from

the fact that the labor needs of Anglo-American plantation

colonies came to the colonies in the chattel-labor form.

Nor did it inhere in the fact that the supply of lifetime,

hereditary bond-laborers was made up of non-Europeans

exclusively. These were common characteristics

throughout the plantation Americas.

The peculiarity of the “peculiar institution” derived,

rather, from the control aspect; yet not merely in its

reliance upon the support of the free non-owners of bond-

labor, as buffer and enforcer against the unfree proletariat;

for that again was a general characteristic of plantation

societies in America.

The peculiarity of the system of social control which

came to be established in continental Anglo-America lay

in the following two characteristics: (1) all persons of any

degree of non-European ancestry were excluded from the

buffer social control stratum; and (2) a major,

indispensable, and decisive factor of the buffer social

control stratum maintained against the unfree proletarians

was that it was itself made up of free proletarians and

semi-proletarians.

How did this monstrous social mutation begin, evolve,

survive and finally prevail in continental Anglo-America?

That is the question to be examined in the chapters that

follow.

2

English Background, with Anglo-

American Variations Noted

The same economic, social, and technological

developments in sixteenth-century England that supplied

the material means for the final overthrow of Celtic

Ireland in the Tyrone War (1594–1603) provided the

impetus that launched England on its career as a world

colonial power. The capitalist overthrow of the English

peasantry in the first half of the sixteenth century was the

forerunner of the destruction of the Celtic tribal system in

the seventeenth. The expropriated and uprooted sixteenth-

century English copyholders had their counterparts in the

“kin-wrecked” remnants of broken Irish tribes reduced to

tenantry-at-will and made aliens in their own country.

But while the adventitious factor of the English

Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century was a

decisive condition for the seventeenth-century English

option for racial oppression in Ireland, it was not the force

that shaped the events that culminated in the establishment

of racial oppression in continental Anglo-America.

1

Rather, the system of class relations and social control

that emerged in the colonies in the seventeenth century

rested on the rejection in fundamental respects of the

pattern established in England in the sixteenth century.

With few exceptions, historians of the origin of racial

slavery have generally ignored, or inferentially denied, the

significance of this oceanic disjunction in social patterns.

2

The “social control” approach which the present work

takes to the origin and nature of “the peculiar institution”

makes it necessary to revisit the epoch of English history

that produced the founders of Jamestown.

On the Matter of “Transitions”

Many economic historians, taking the long view, have

agreed with Adam Smith that the transition to capitalist

agriculture in England in the sixteenth century was “a

revolution of the greatest importance to public

happiness.”

3

At the threshold of the sixteenth century,

however, the English copyholder, plowing the same land

that his grandfather had plowed with the same plow,

4

had

little feeling for “transitions.” If it had been given to him

to speak in such terms, he might well have made his case

on historical grounds. It was the laboring people – the

copyholders, freeholders, serfs, artisans and wage earners

– and not the bourgeoisie, who had swept away the feudal

system. Out of the workings of the general fall in

agricultural prices in the period between the third quarters

of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as a result of

which landlords preferred to get cash rents rather than

rents in produce; out of the shortage of labor induced by

the worst-ever onset of plague in England, which, within a

space of sixteen months in 1349–50 carried off from one-

fifth to one-half of the population;

5

out of the constant

round of bloody and treacherous baronial wars for state

hegemony (ended only with the Wars of the Roses, 1450–

85), and the desultory Hundred Years’ War with France,

1336–1453; and, above all, out of the Peasant Revolt of

1381, Wat Tyler’s Rebellion,

6

which drew a line in the

ancient soil beyond which feudal claims would never be

reasserted – thus had been wrought the end of the feudal

order in England. And so occurred the English peasant’s

Golden Age,

7

wherein the self-employed laboring peasant,

as freeholder, leaseholder, or copyholder, held

ascendancy in English agriculture.

8

Our copyholder might then go on to say that now the

bourgeoisie, burgesses, landlords, merchants and such

were apparently attempting to destroy the peasantry; and if

that was what was meant by transition to capitalism, the

price was too high.

9

And he would conclude with a

reminder and a warning: he – his kith and kin – had fought

once, and would fight again, to maintain their place on the

land and in it.

10

Fight they did. Between 1500 and 1650, “hardly a

generation … elapsed without a peasant uprising.” In local

fence-destroying escapades, in large riots, and in

rebellions of armed forces of thousands which “at

intervals between 1530 and 1560 set half the counties of

England in a blaze,”

11

the English “commons” fought. In

some cases they were allies of the anti-Reformation,

sensing the connection between the Reformation and the

agrarian changes that threatened the majority of the

peasantry. Even then, the peasants still forwarded their

own demands regarding land ownership and use,

enclosures, rack-rents, etc. Years that their revolts have

made memorable include 1536, 1549, 1554, 1569 and

1607.

In these struggles the peasants made clear their sense of

the great heart of the matter; in the words of Tawney:

Reduced to its elements their complaint is a very simple one, very ancient

and very modern. It is that … their property is being taken away from

them … [and] to them it seems that all the trouble arises because the rich

have been stealing the property of the poor.

12

For this they fought in the northern rebellion of 1536,

known as the Pilgrimage of Grace.

13

This revolt, set off by

Henry VIII’s suppression of monasteries, confronted that

king with the greatest crisis of his reign.

14

Although

ecclesiastical issues united the movement, “the first

demands of the peasants were social and not religious”;

for them it was a class struggle “of the poor against the

rich,” and their demands “against raised rents and

enclosures” were included in the program of the

movement.

15

The peasants fought again in 1549, climaxing a three-

year period of “the greatest popular outcry against

enclosing.”

16

In that year, peasant revolts spread to more

than half the counties of England. Led by Robert Ket,

himself a landowner, a rebel army of sixteen thousand

peasants captured Norwich, England’s second-largest city.

They set up their “court” on Mousehold Heath outside the

city, where they maintained their cause for six weeks.

17

They demanded that “lords, knights, esquires, and

gentlemen” be stopped from commercial stock-raising,

and rent-gouging, and from privatizing common lands. We

can agree with Bindoff that this was “a radical

programme, indeed, which would have clipped the wings

of rural capitalism.”

18

The peasants fought also in 1607, the very year of the

founding of Jamestown. These were the peasants of the

Midland counties. Thousands, armed with bows and

arrows, with pikes and bills, and with stones, sought

justice by their own direct action. The later use of the term

“Levellers,” though more figurative, still was socially

congruent with the literal sense in which these Midland

rebels applied it to themselves as “levellers” of fences

and hedges set up by the landlords to bar peasants from

their ancient rights of common land. To the royal demand

that they disperse, they defiantly replied that they would

do so only if the king “wolde promis to reforme those

abuses.”

19

The peasants fought, but in the end they could not stop

the “rich … stealing the property of the poor.” Small

landholders constituted the majority of the laboring

population in English agriculture at the end of the fifteenth

century,

20

but by the end of the seventeenth century more

than four-fifths of the land was held by capitalist

employers of wage-labor.

21

Well before that time, the

majority of the English people were no longer self-

employed peasants but laborers dependent upon wages.

22

Not only were they to be dependent upon wages, making

crops and cloth that they would never own, but at wages

lower than they had ever been. In the course of the

sixteenth century the real wages of English laborers fell

into an abyss from which they would not emerge until the

end of the nineteenth century.

23

As a typical peasant, “Day

labourer was now [his or her] full description … and the

poor cottager[s] could expect only seasonal employment at

a wage fixed by the justice of the peace.”

24

One-fourth of

the people of England in the 1640s were but “housed

beggars,” the term used by Francis Bacon to distinguish

them from wandering roadside mendicants.

25

“Why No Upheaval?”

“Why did it not cause an upheaval?” That is a logically

compelling question which some historians have posed in

light of their findings regarding the general deterioration

wrought upon the lives of the laboring population during

the “long” sixteenth century, 1500–1640.

26

The same

question, but in a form more particularly suited to this

present study, is, “How did the English bourgeoisie

maintain social control?”

In establishing its dominance over the pillaged and

outraged peasantry, the English bourgeoisie did, of course,

meet rebellion with armed repression (generally after

deceitful “negotiations” designed to divide the opposition

and to buy time for the mobilization of government

military forces). Having traditionally no standing army, the

government employed German and Italian mercenaries on

some occasions, along with men recruited from the

personal retinues of the nobility. But foreign mercenaries,

however important they might have been in certain critical

moments, for fiscal and political reasons could not supply

the basic control functions on a regular basis. And the very

economic transformation that brought the laboring masses

of the countryside to revolt was simultaneously reducing

the ranks of the retainers whom the nobility might

profitably maintain for such ongoing repressive services.

Saving a portion of the yeomanry

The solution was found by deliberately fostering a lower-

middle-class stratum. It was in the nature of the capitalist

Agrarian Revolution that non-aristocrats rose out of the

ranks of the bourgeoisie into the highest councils and

organs of power, to serve side by side with the

increasingly bourgeoisified old-line aristocrats. Likewise,

lower and local functions at the shire level were filled by

men from the ranks of the lesser bourgeois country

gentlemen and exceptionally upwardly mobile peasants

turned capitalist farmers, who might buy into a knighthood.

But yet another layer was needed, which would be of

sufficient number to stand steadfast between the gentry and

the peasants and laborers.

But the juggernaut of the Agrarian Revolution threatened

the land titles of the laboring peasants of all categories,

from those with hereditary freeholds through all the

gradations of tenants to the “customary” tenant-at-will.

27

The state therefore made a political decision to preserve a

sufficient proportion of peasants – preference going

naturally, but not exclusively, to hereditary freehold

tenants – as a petit bourgeois yeomanry (typified by the

classic “forty-shilling freeholder”

28

) to serve in militia

and police functions.

29

The case has not been better understood or stated than it

was by Francis Bacon, looking back at close range in

1625 to write his History of the Reign of King Henry VII

(1485–1509):

Another statute was made for the … soldiery and militar[y] forces of the

realm.… That all houses of husbandry, that were used with twenty acres of

ground and upwards, should be maintained and kept up for ever; together

with a competent proportion of land to be used and occupied by them; and in

no wise severed from them (as by another statute in his successor’s [Henry

VIII’s] time was more fully declared).… This did wonderfully concern the

might and mannerhood of the kingdom, to have farms of a standard,

sufficient to maintain an able body out of penury, and did in effect amortise

a great part of the lands of the kingdom unto the hold and occupation of the

yeomanry or middle people, of a condition between gentlemen and cottagers

or peasants.… For to make good infantry, it requireth men bred not in a

servile or indigent fashion, but in some free and plentiful manner. Therefore

if a state run most to noblemen and gentlemen, and that the husbandmen and

ploughmen be but as their work folks and labourers, or else mere cottagers

(which are but housed beggars), you may have a good cavalry, but never

good stable bands of foot [soldiers].… Thus did the King secretly sow

Hydra’s teeth whereupon (according to the poet’s fiction) should rise up

armed men for the service of this kingdom.

30

Bacon likened the process of expropriation of the peasants

to the necessary thinning of a stand of timber, whereby all

but a few trees are cleared away to allow sound growth of

the rest for future needs. By this policy, he said, England

would escape certain ills besetting the governments of

other countries such as France and Italy

[w]here in effect all is noblesse or peasantry (I speak of people out of

towns), and therefore no middle people; and therefore no good forces of

foot; in so much as they are enforced to employ mercenary bands of

Switzers and the like for their foot [soldiers].

31

Here was the recognition of the curbs that policy must

sometimes impose on blind economic forces, restraining

“the invisible hand” in order to avoid promoting “an end

which was no part of [the] intention” of the ruling class.

32

It was in the nature of the transformation powered by the

capitalist Agrarian Revolution that the non-aristocratic

bourgeois gentry should move increasingly into the control

of affairs. On the other hand, the deliberate preservation of

a portion of economically independent self-employed and

laboring small property-owners was not an economic

necessity but rather a first derivative of the economic

necessities, a political necessity for the maintenance of

bourgeois social control, upon which the conduct of the

normal process of capitalist accumulation depended.

(Even so, it was not a total loss economically, since the

yeoman was a self-provider and a principal source of tax

revenue.)

33

The inner conflicts of the bourgeoisie, the conflicts with

self in its own various parts – now the governors of a

strife-torn nation among striving nations; and, again, as

land-grabbing, rack-renting landlords, gentry, merchants,

squires, and occasional interloping peasant upstarts, “like

tame hawks for their master, and like wild hawks for

themselves,” as Bacon put it

34

– caused this basic policy

to evolve by vicissitudes. But the center held: the same

guiding principle obtained when Bacon wrote his history

of Henry VII’s reign that been in force more than a century

before.

The successful day-to-day operation of the social order

of the newly ascendant bourgeoisie depended upon the

supervisory and enforcement functions performed at the

parish level by yeoman constables, church wardens,

Overseers of the Poor, jailers, directors of houses of

correction, etc.

35

They were charged with serving legal

orders and enforcing warrants issued by magistrates or

higher courts. They arrested vagrants, administered the

prescribed whippings on these vagrants’ naked backs, and

conveyed them to the boundary of the next parish,

enforcing their return to their home parishes. As Overseers

of the Poor, they ordered unemployed men and women to

the workhouses and apprenticed poor children without

their parents’ leave. Trial juries were generally composed

of yeomen, and they largely constituted the foot soldiery of

the militia, the so-called “trained bands.” They discharged

most of these unpaid obligations unenthusiastically, but

with a sense of duty appropriate to their social station.

36

Nevertheless, prior to the Great Rebellion and Civil War

of the mid-seventeenth century, yeomen militiamen

showed themselves less than reliable for major armed

clashes with peasants. In Ket’s Rebellion they were left

behind when the final assault was made by the king’s

forces of cavalry and one thousand foreign mercenaries.

37

And, on account of the “great backwardness in the trained

bands,” the king’s commanders were constrained to rely

exclusively on the gentlemen cavalry and their own

personal employees in the battle against one thousand

peasant rebels at Newton in the Midlands in 1607.

38

Yeomen did enjoy certain special privileges. For one,

they were entitled to vote for their shire’s member of

Parliament. Of far more substantial importance was their

right to apprentice their sons to lucrative trades and

commerce, and to send their sons to schools and

universities.

39

But like the civic duties to which they were

assigned, these privileges were theirs because, and only

because, of their property status. It never occurred to the

ruling classes of England that they could enlist such a

cheap yet effective social control force from the ranks of

the propertyless classes, the housed beggars, laborers and

cottagers, or the vagabonds. That notion would await the

coming of the Anglo-American continental colonies.

The “Labor Question”: Conflict and

Resolution

The ruling class effected the same balance of class policy

and the blind instinctual drive for maximum immediate

profits by its individual parts in regard to the costs of

employment of propertyless laborers.

40

In the century and a half, 1350–1500, following the

great plague, it had been seen that no amount of legislation

could keep down labor costs where labor was in short

supply. Laws designed to prevent laborers from moving

about in search of higher wages, and laws fixing penalties

for paying or receiving wages in excess of statutory

maximums, were equally ineffective in restraining wages.

Half a dozen such laws were passed in that period,

41

but

by its end the laborer’s real wage was nearly thrice what

it had been at its beginning.

42

The objective might have

been accomplished if it had been possible to reimpose

serfdom, but the landlord class no longer had the power to

do so.

43

But the emergence of a massive labor surplus in the

early decades of the sixteenth century presented the

employing classes with an opportunity which they were

quick to exploit for regulating labor costs. At a certain

point it occurred to the government to redress the

imbalance by instituting slave labor. Parliament

accordingly in 1547 enacted a law, 1 Edw. VI 3, which

would have had the effect of creating a marginal, yet

substantial, body of unpaid bond-labor, to serve as an

anchor on the costs of paid labor. Refusing to recognize

the legitimacy of the offspring of their own agrarian

revolution, the ruling class presumed that every

unemployed person was merely another “vagabond,”

willfully refusing to work and thus frustrating the proper

establishment of fair wages. The 1547 law sought remedy

along the following lines:

who so ever … man or woman [being able-bodied and not provided with the

prescribed property income exemption] shall either like a serving man

wanting [lacking] a maister or lyke a Begger or after anny other such sorte

be lurking in anny howse or howses or loytringe or Idelye wander[ing] by

the high waies syde or in stretes, not applying them self to soem honnest and

allowed art, Scyence, service or Labour, and so do contynew by the space

of three dayes or more to gither and offer them self to Labour with anny

that will take them according to their facultie, And yf no man otherwise will

take them, doe not offer themself to work for meate and drynk … shall be

taken for a Vagabonde …

44

Any person found to be transgressing the provisions of the

law, upon information provided to a magistrate by any

man, was upon conviction to be formally declared a

“vagabond,” branded with a V, and made a slave for a

period of two years to the informant. The slave was to be

fed only bread and water and, at the owner’s discretion,

such scraps as the owner might choose to throw to the

slave. The law specified that the slave was to be driven to

work by beating, and held to the task by chaining, no

matter how vile the work assignment might be. Such a

two-year slave who failed in a runaway attempt was to be

branded with an S and made a slave for life to the same

owner from whom he or she had tried to escape. A second

unsuccessful attempt to escape was to be punished by

death.

This was not just one of the many anti-vagabond laws

enacted by the English Parliament in the sixteenth

century;

45

it was distinguished from others by three

features: (1) the definition of “vagrancy” was extended to

cover any unemployed worker refusing to work for mere

board; (2) the beneficiary of the penalty was not the state

in any of its parts, but private individual owners of those

who were enslaved; (3) the enslaved persons were

reduced to chattels of the owners, like cattle or sheep, and

as such they could be bought, sold, rented, given away,

and inherited (“as any other movable goodes or

Catelles”).

46

With this 1547 law, the quest for wage

control had passed its limits in a double sense, by going to

zero wages, and by exceeding the limits of practicability.

In 1550, Parliament repealed the law, citing as a reason

the fact that “the good and wholesome laws of the realm

have not been put in execution because of the extremity of

some of them.”

47

Many contemporary observers perceived the causal

connection of the officially deplored depopulating

enclosures of arable land and the growth of vagrancy, and

they viewed the case of the displaced peasants and

laborers with sympathy. “Whither shall they go?” asked

one anguished commentary. “Forth from shire to shire, and

to be scattered thus abroad … and for lack of masters, by

compulsion driven, some of them to beg and to steal.”

48

During the life of the slave law, bold, honest preacher

Bernard Gilpin made the point in a sermon in the presence

of Edward VI himself: “Thousands in England beg now

from door to door who have kept honest houses.”

49

There were those who considered such facts a

justification for slavery as a means of saving these victims

of expropriation from running further risks to their very

souls, by the sin of idleness. But a widespread reluctance