A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO

PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

4

th

Revised Edition - 2019

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 2

This guide is intended to provide a brief introduction to basic topics in pediatric rheumatology.

Each topic is accompanied by at least one up-to-date reference that will allow you to explore the

topic in greater depth.

In addition, a list of several excellent textbooks and other resources for you to use to expand

your knowledge is found in the Appendix.

We are interested in your feedback on the guide! If you have comments or questions, please

feel free to contact us via email at pedrheumguide@gmail.com.

Supervising Editors:

Dr. Ronald M. Laxer, SickKids Hospital, University of Toronto

Dr. Tania Cellucci, McMaster Children’s Hospital, McMaster University

Dr. Evelyn Rozenblyum, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto

Section Editors:

Dr. Michelle Batthish, McMaster Children’s Hospital, McMaster University

Dr. Roberta Berard, Children’s Hospital – London Health Sciences Centre, Western

University

Dr. Liane Heale, McMaster Children’s Hospital, McMaster University

Dr. Clare Hutchinson, North York General Hospital, University of Toronto

Dr. Mehul Jariwala, Royal University Hospital, University of Saskatchewan

Dr. Lillian Lim, Stollery Children’s Hospital, University of Alberta

Dr. Nadia Luca, Alberta Children’s Hospital, University of Calgary

Dr. Dax Rumsey, Stollery Children’s Hospital, University of Alberta

Dr. Gordon Soon, North York General Hospital and SickKids Hospital Northern Clinic in

Sudbury, University of Toronto

Dr. Rebeka Stevenson, Alberta Children’s Hospital, University of Calgary

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 3

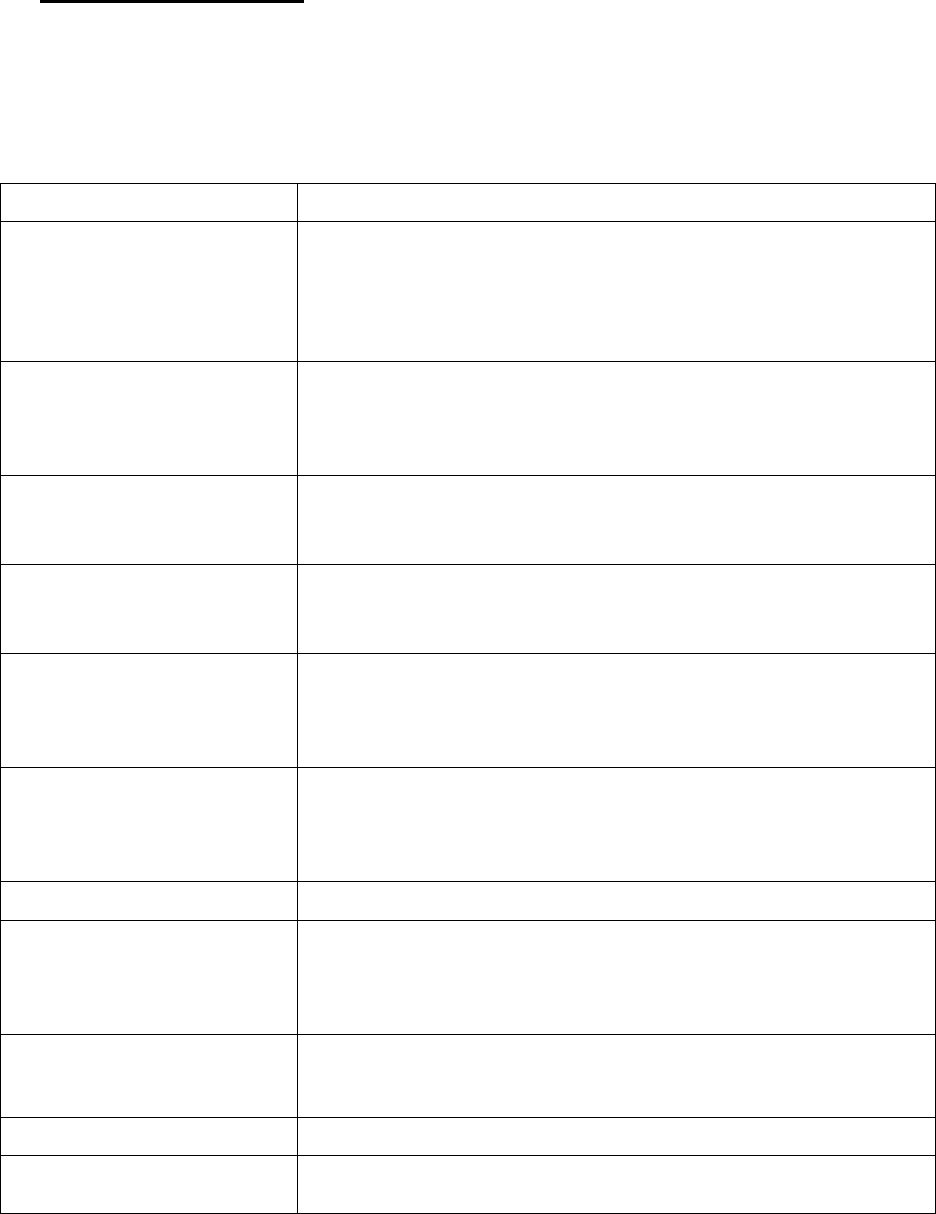

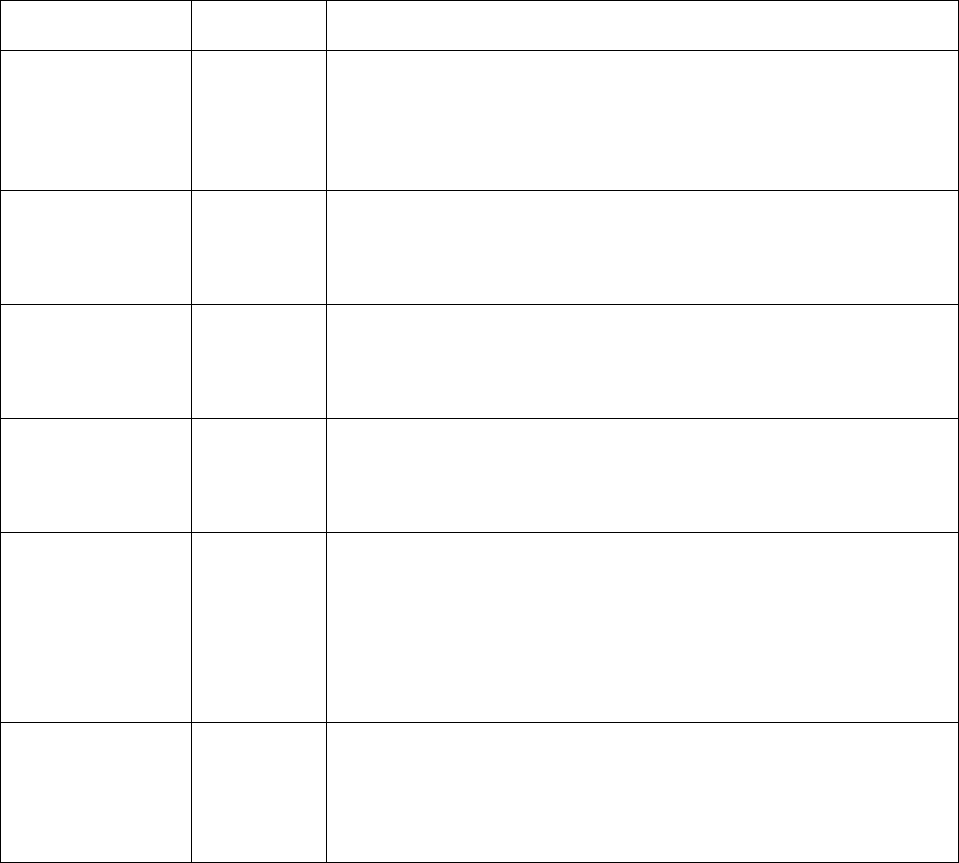

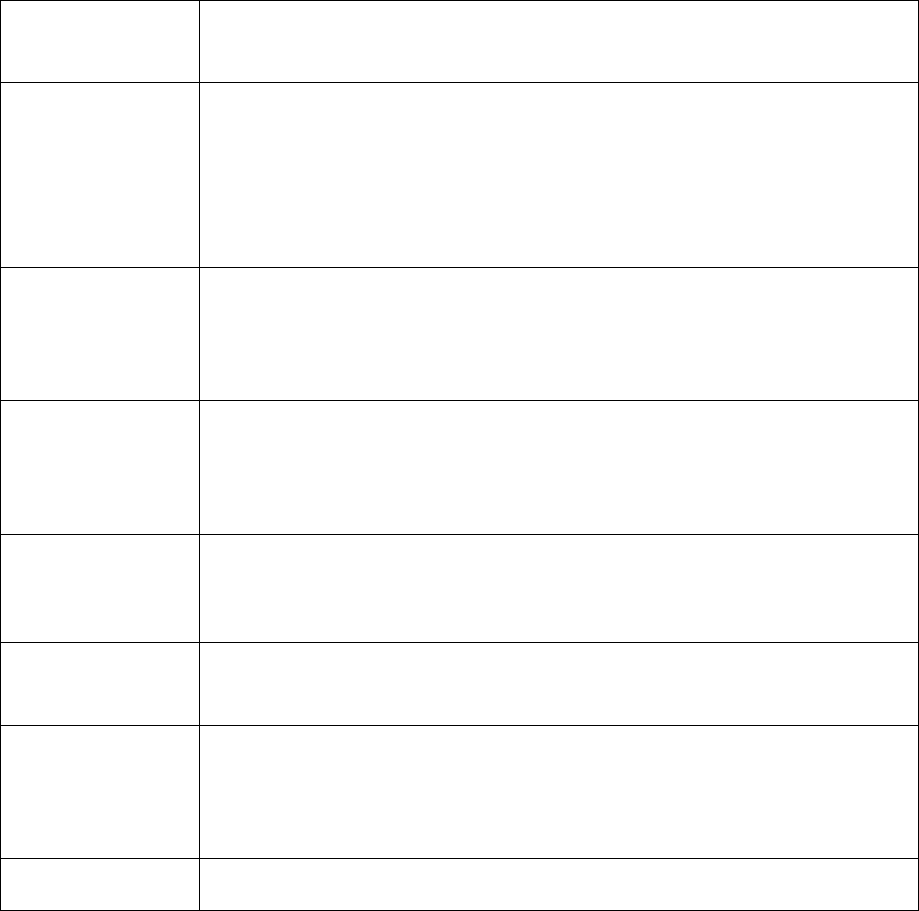

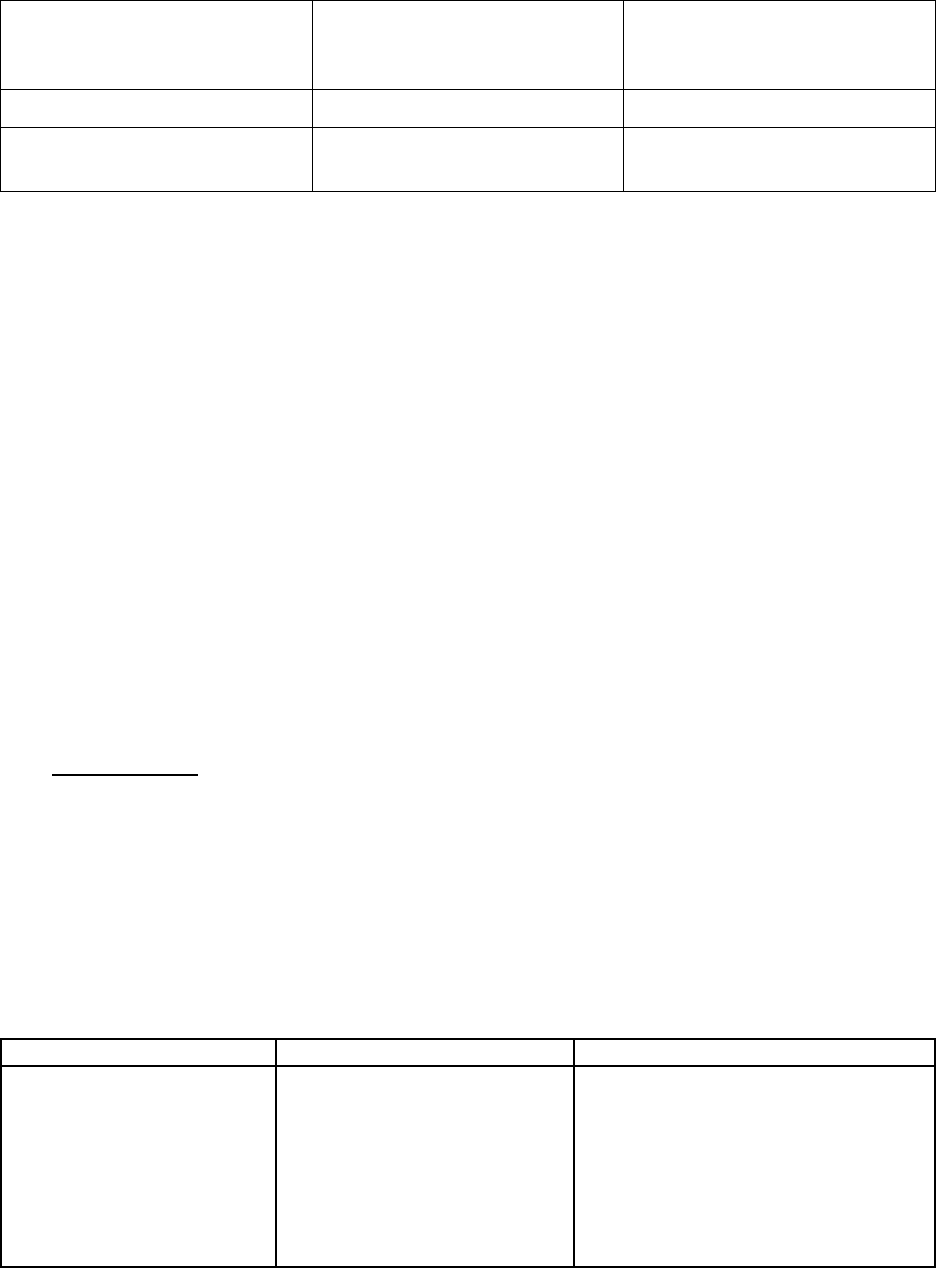

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Section

Topic

Page #

1

Pediatric Rheumatology Clinical Assessment

4

2

Approaches and Differential Diagnoses for Common

Complaints Referred to Pediatric Rheumatology

14

3

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

25

4

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Related Conditions

35

5

Systemic Vasculitis

42

6

Idiopathic Inflammatory Myopathies

56

7

Scleroderma and Related Syndromes

60

8

Autoinflammatory Diseases

67

9

Uveitis

76

10

Inflammatory Brain Diseases

79

11

Infection and Infection-Related Conditions

85

12

Pain Syndromes

92

13

Pediatric Rheumatology Emergencies

96

14

Medications

107

Appendix

Helpful Resources in Pediatric Rheumatology

115

Notes:

Please consider that all treatment regimens discussed in the guide are

suggestions based on evidence-based guidelines and/or common practices by

the pediatric rheumatologists who are Section Editors of the Guide. Alternative

treatment approaches may be used in other centres.

More detailed information on medications (class, action, dose, side effects, monitoring)

may be found in the Medications section.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 4

SECTION 1 – PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

1A. Pediatric Rheumatologic History

An appropriate rheumatologic history for a new patient should cover the following areas:

History of presenting complaint

Onset, duration, pattern

Potential triggers, such as trauma, infection or immunizations

Severity and impact on function, including school and activities of daily living

Associated symptoms

Factors that improve or worsen symptoms

Previous investigations

Previous treatment, including effectiveness and adverse reactions

Past medical history

Chronic medical conditions

Admissions to hospital, surgeries

Eye examinations

Development

Brief review of all domains - gross motor, fine motor, speech, language, hearing, social

Immunizations

All childhood vaccinations

Varicella – Infection or vaccination?

Medications

Prescribed medications – dose, route, frequency, adherence

Over-the-counter medications, vitamins, herbal supplements

Allergies

Travel history (especially risk factors for tuberculosis or Lyme infections)

Family history

Ethnicity and consanguinuity

Rheumatologic diseases: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS)

Premature osteoarthritis

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Psoriasis

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Vasculitis

Autoinflammatory diseases, including early hearing loss and early

renal failure

Other autoimmune diseases: Diabetes mellitus type I, Celiac disease, Thyroid disease

Social history

Parents marital status, occupations, care providers, drug coverage, adolescent psychosocial

assessment (e.g. HEEADSSS)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 5

Review of systems

General: Energy level, fatigue, poor sleep, non-restful sleep

Anorexia, weight loss

Fevers → frequency, duration, pattern, associated symptoms

Functioning → home, social, school, extra-curricular activities, work

HEENT: Photophobia, blurred vision, redness, pain

Sicca symptoms (dry eyes, dry mouth)

Nasal and/or oral ulcers (painful or painless)

Epistaxis

Dysphagia

Otalgia, hearing difficulties

CVS: Chest pain, orthopnea, syncope

Peripheral acrocyanosis

Raynaud phenomenon

Respiratory: Difficulty breathing, shortness of breath

Pleuritic chest pain

Prolonged cough, productive cough, hemoptysis

GI: Recurrent abdominal pain, “heartburn”

Diarrhea, constipation, bloody stools, melena

Nausea, vomiting

Skin: Any type of skin rash on face, scalp, trunk, limbs

Petechiae, purpura

Nodules

Ulcers (includes genital/perineal)

Photosensitivity

Alopecia, hair changes

Nail changes (pits, onycholysis) and nail fold changes

Joints: Pain (day and/or night), swelling, redness, heat, decreased range of motion

Loss of function, reduced activities, pain waking from sleep

Inflammatory → morning stiffness or gelling, improves with activity or exercise

Mechanical → improves with rest, “locking”, “giving away”

Muscles: Pain

Muscle weakness (proximal vs. distal)

Loss of function, reduced activities

CNS: Headaches

Psychosis, visual distortions

Cognitive dysfunction, drop in school grades

Seizures

PNS: Motor or sensory neuropathy

GU: Dysuria, change in urine volume or colour

Irregular, missed or prolonged menstrual periods, heavy menses

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 6

1B. Pediatric Rheumatologic Examination

Vital signs (including blood pressure percentiles)

Height, weight, BMI (percentiles, recent changes)

General appearance

HEENT: Conjunctival injection or hemorrhage, pupils (shape and reaction)

Complete ophthalmoscope examination from cornea to fundus

Nasal mucosa, nasal discharge, sinus tenderness

Oropharyngeal mucosa, tongue, tonsils

Thyroid

CVS: Heart sounds, murmurs, rubs, precordial examination

Vascular bruits (if indicated)

Peripheral pulses, peripheral perfusion, capillary refill

Lungs: Respiratory excursion, percussion, breath sounds, adventitious sounds

Abdomen: Tenderness, peritoneal signs, masses, bowel sounds, bruits (if indicated)

Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly

LN: Assess all accessible lymph node groups

Skin: Any type of skin rash, including petechiae, purpura, nodules, and ulcers

Alopecia, hair abnormalities

Nails: Nail pits, clubbing, onychonychia

Nail fold capillaries – thickening, branching, drop-out, hemorrhages

Digital ulcers, splinter hemorrhages, loss of digital pulp

CNS: Mental status

Cranial nerves

Motor: muscle bulk, tone, power/strength, tenderness, deep tendon reflexes

Cerebellar

Gait (walking, running, heels, toes, and tandem)

Sensory (if indicated), allodynia borders (if indicated)

Joints: Begin with a screening exam, such as the Pediatric Gait Arms Legs Spine

(pGALS)

Assess all joints for heat, swelling, tenderness, stress pain, active and passive

range of motion, deformity

Enthesitis sites

Localized bony/joint tenderness

Leg length (functional and/or actual)

Thigh, calf circumference difference (if indicated)

Back: Range of motion, tenderness, stress pain from repetitive motion

Scoliosis

Modified Schober test (if indicated)

Other: Fibromyalgia tender points (if indicated)

References:

1. Foster HE, Jandial S. pGALS – paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine: a simple

examination of the musculoskeletal system. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2013; 11(1):44.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 7

1C. Laboratory Testing in Pediatric Rheumatology

General Principles

Interpret all laboratory results in context of specific patient

Consider the clinical rationale and potential impact of all laboratory tests that are ordered,

especially for autoantibody testing

Review all laboratory test results to guide interpretation of abnormalities

Trends in laboratory values may be more important than isolated abnormalities

Complete blood cell count and differential

Hemoglobin, red blood cell count and mean corpuscular volume

o Normocytic or microcytic anemia in chronic inflammatory disease

o Autoimmune hemolytic anemia in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

o Non-immune hemolytic anemia in macrophage activation syndrome (MAS)

o Iron deficiency anemia if chronic blood loss (e.g. due to NSAIDs, inflammatory bowel

disease)

White blood cell count and differential

o High white blood cell counts may be due to infection, systemic inflammation, or side-

effect of corticosteroids

o Leukopenia with lymphopenia and/or neutropenia may be due to systemic inflammation

or medications

Platelet count

o Active inflammation may lead to increased platelet counts (e.g. subacute phase of

Kawasaki disease, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), or Takayasu arteritis)

o Active disease may also lead to reduced platelet counts (e.g. SLE)

Acute phase response to systemic inflammation

Acute phase reactants are plasma proteins produced by the liver that change production

during acute phase of inflammation

Acute phase response mediated by cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF (which are the

target of many biologic agents used in childhood rheumatic diseases)

Substantial acute phase response may be seen in infection, trauma, burns, tissue infarction,

advanced cancer and immune-mediated disease

Mild elevation may be seen in conditions such as obesity, pregnancy, and strenuous

exercise

Overall effect of acute phase response is to protect host from damage

Excessive or prolonged acute phase response may be deleterious itself (e.g. septic shock,

MAS, malignancy)

C-reactive protein (CRP)

Direct measure of inflammation (sensitive but not specific)

Level rises rapidly in response to inflammation and falls quickly with appropriate treatment

May reflect severe disease more closely than other acute phase reactants, although this

may be patient-specific and/or disease-dependent (e.g. CRP typically rises in patients with

SLE when there is infection, serositis or MAS, but may be normal with active disease)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 8

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

Indirect measure of acute phase reaction

Changes more slowly than CRP

Measure rate at which red blood cells settle in a tube of anticoagulated blood in one hour

Depends on fibrinogen, gamma globulins

Ferritin

Protein central to iron homeostasis

Serum ferritin levels increase in setting of inflammation

Very high levels suggestive of macrophage activation syndrome

May not function as a reliable measure of iron status in setting of inflammatory disease

Summary of laboratory changes in acute phase response to systemic inflammation:

Increase in acute phase response

Decrease in acute phase response

CRP, ESR

Complement proteins

Fibrinogen, coagulation proteins

Ferritin

Ceruloplasmin

Haptoglobin

G-CSF

IL-1 receptor antagonist

Serum amyloid A

Albumin

Transferrin

IGF-1

Complement

Increased levels of complement components frequently seen in inflammation

Low complement levels present in SLE, acute post-infectious glomerulonephritis,

membrano-proliferative glomerulonephritis, or liver disease

Congenital complement deficiencies predispose either to recurrent infections (mainly

encapsulated organisms) or to unusual autoimmune disease (“lupus-like” disease)

In SLE, serial measurements of C3 and C4 are useful to monitor disease activity

o Complement levels tend to fall during a flare and return to normal concentration after

appropriate therapy

o Persistently low C3 associated with lupus nephritis

Autoantibodies

Antinuclear antibodies (ANA)

Autoantibodies directed against nuclear, nucleolar or perinuclear antigens

ANA should not be used as a screening tool

o Low titres of ANA (e.g. ANA ≤ 1:80) may be present in up to 30% of normal healthy

population and may revert to negative over time

o ANA may also be present in non-rheumatologic diseases (e.g. infection, malignancy,

medications)

No need to repeat ANA regularly once positive titre established (from Choosing Wisely:

Pediatric Rheumatology Top 5 by American College of Rheumatology)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 9

Low titres of non-specific ANA may be seen in JIA patients, but positive ANA titres ≥ 1:160

in JIA patients are associated with younger age at onset, higher risk of uveitis, asymmetric

arthritis and lower number of affected joints over time

Persistent higher titres of ANA > 1:160 suggest connective tissue diseases, such as SLE

o Negative ANA makes diagnosis of SLE unlikely

Specific antibodies (e.g. anti-double stranded DNA) should only be requested if ANA is

positive and there is evidence of rheumatic disease (highlighted in Choosing Wisely:

Pediatric Rheumatology Top 5 by American College of Rheumatology)

Anti-double stranded DNA (Anti-dsDNA)

Anti-dsDNA autoantibody targets DNA in nucleus of cell

Highly specific for SLE

Titres are affected by disease activity and may be used to monitor disease progression and

response to therapy

Autoantibodies to extractable nuclear antigen (ENA)

Specific ENA antibodies

Characteristic disease associations

Anti-Ro/SSA

SLE, Neonatal lupus erythematosus, Sjögren

Anti-La/SSB

SLE, Neonatal lupus erythematosus, Sjögren

Anti-Sm (Anti-Smith)

SLE

Anti-RNP

Mixed connective tissue disease, SLE, Systemic sclerosis

Anti-histone

Drug-induced lupus, SLE

Anti-Scl 70

Diffuse systemic sclerosis

Anti-centromere

Limited systemic sclerosis (CREST)

Anti-Jo1

Polymyositis with interstitial lung disease, juvenile

dermatomyositis (JDM)

Anti-SRP

Anti-Mi-2

JDM with profound myositis & cardiac disease

JDM with good prognosis

Rheumatoid factor (RF)

IgM autoantibody that reacts to Fc portion of IgG

Present in 85% of adults with rheumatoid arthritis

Present in only 5-10% of children with JIA

o Helpful in classification and prognosis of JIA, but should not be used as a screening test

since arthritis is a clinical diagnosis

o Children with RF-positive polyarthritis are at higher risk of aggressive joint disease with

erosions and functional disability

RF may also be detected in chronic immune-complex mediated diseases, such as SLE,

systemic sclerosis, Sjögren, mixed connective tissue disease, cryoglobulinemia and chronic

infection (subacute bacterial endocarditis, hepatitis B and C, TB)

Anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACCP)

Antibodies to citrullinated peptides found in inflamed synovium

Highly specific for rheumatoid arthritis, but often positive in older children with polyarticular

Rheumatoid factor positive JIA

Indicates increased risk of aggressive disease and progressive joint damage

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 10

Antiphospholipid antibodies

Heterogeneous group of antibodies directed against cell membrane phospholipids

Include lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, anti-β

2

-glycoprotein I

Associated with increased risk of arterial or venous thrombosis (but lupus anticoagulant

paradoxically prolongs laboratory PTT)

May be produced due to primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) or secondary to

SLE, other autoimmune diseases, malignancy, infection or drugs

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA)

Antibodies target antigens in cytoplasmic granules of neutrophils

May be pathogenic by activating neutrophils, leading to perpetuation of chronic inflammation

High sensitivity and specificity for primary small vessel systemic vasculitides

ANCA

Immunofluorescence

pattern

Antigen specificity

(ELISA)

Disease associations

c-ANCA

Cytoplasmic

Proteinase-3 (PR3)

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

p-ANCA

Perinuclear

Myeloperoxidase

(MPO)

Microscopic polyangiitis

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with

polyangiitis

Ulcerative colitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

SLE

Anti-Glomerular Basement Membrange (Anti-GBM) antibodies

Antibodies target alpha-3 chain of type IV collagen, which is normally present in glomerular

and alveolar basement membranes

Antibody binding to basement membranes in lungs and kidneys activates classical

complement pathway and neutrophil-dependent inflammation, leading to small vessel

vasculitis with immune complex formation

Production of antibodies may be triggered by environmental factors (e.g. infection, cigarette

smoking)

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) Genetics

Many genes of the major histocompatibility complex (especially HLA class I and II genes)

have been associated with rheumatic disorders

HLA-B27

HLA class I gene that is present in only 7-10% of the general population (may be higher in

some First Nations groups)

Found in 90-95% of Caucasians with ankylosing spondylitis and many patients with JIA

(particularly enthesitis related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis), inflammatory bowel disease,

isolated acute anterior uveitis, and reactive arthritis

HLA-B27 may play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory disease

HLA-B51

May be associated with Behçet disease

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 11

Additional tests:

Urinalysis

Routinely used to assess for proteinuria and hematuria associated with renal involvement in

autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases

Fecal calprotectin

May be measured as an indicator of underlying gastrointestinal inflammation

Genetic testing

Often ordered to confirm diagnosis of genetic fever syndromes and other autoinflammatory

disorders

Cytokine profiling

May be used in research contexts to qualify the inflammatory response and guide therapy

May become more widely available in upcoming years

References:

1. Mehta J. Laboratory testing in pediatric rheumatology. Pediatr Clin N Am 2012; 59:263-

84.

2. Pilania RK, Singh S. Rheumatology panel in pediatric practice. Indian J Pediatr 2019;

56(5):407-14.

1D. Diagnostic Imaging in Pediatric Rheumatology

General Principles

Interpret all imaging results in context of specific patient

Consider the clinical rationale and potential impact of all imaging that is ordered, including

risks of sedation, radiation and contrast administration

Imaging alone is not sufficient to confirm any rheumatic disease

Repeat imaging may be helpful to assess response to therapy, disease progression and

development of damage or to screen for specific organ involvement in systemic conditions

Review of questionable or unexpected imaging findings with a pediatric radiologist who has

specific expertise (e.g. musculoskeletal or neuroradiology training) is recommended

X-ray

Bone and joint X-rays

o Often ordered as initial testing for pain and deformity

o May be used to rule out bony abnormalities or injuries, such as fracture, that may

explain symptoms

o Helpful to image both affected and non-affected sides to assess for subtle changes

o May be normal at disease onset

o Most likely to be ordered in assessment of patients with possible JIA or other

inflammatory arthritis, non-bacterial osteomyelitis, or systemic sclerosis

o Findings in JIA may include effusion, soft tissue swelling, periarticular osteopenia,

joint space narrowing, erosions, subchondral cysts, osteophytes, bone deformity,

fusion, or accelerated bone development in young children

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 12

Chest X-rays

o May be used to assess for heart and lung involvement in systemic autoimmune or

autoinflammatory diseases

Ultrasound

May be used to assess for effusions and other findings of synovitis or to facilitate joint

injections

May also be used with Doppler to assess vasculature for obstruction of blood flow, which

may be due to thrombosis or vasculitis in rheumatic diseases

Highly operator dependent and requires specific skill and experience, especially with

pediatric patients

Many rheumatologists are currently performing point-of-care ultrasonography to aid clinical

assessment of disease activity and joint injection

Computed tomography (CT)

Chest CT may be useful to identify findings of interstial lung disease and pulmonary

hemorrhage in connective tissue diseases

CT angiograms may be used to assess for findings of vasculitis when magnetic resonance

or conventional angiograms are not easily accessible

While CT may identify findings for a number of rheumatic diseases, it is often not the first

imaging of choice because of the associated radiation.

If CT is deemed necessary, radiation may be reduced with high resolution techniques

Magnetic resonance imaging

Ideal imaging modality for synovitis in specific joints (e.g. temporomandibular, sacroiliac and

cervical spine) and may identify early signs of disease and/or damage in JIA

Whole body MRI protocols have been developed to assess for enthesitis and chronic non-

bacterial osteomyelitis

Specialized protocols have been developed to identify findings in inflammatory myositis

Ideal imaging modality to identify findings of brain inflammation (especially if 3T or higher

strength magnet available) and may also be used to assess for inflammation in aorta, blood

vessels and other organs (e.g. gastrointestinal tract); MR angiography should be requested

for more accurate imaging of blood vessels

Limitations are that MRI is expensive and less accessible and longer scan times often

require sedation for younger children

Echocardiography

Typically used to assess for coronary artery aneurysms in Kawasaki disease and for carditis

or other cardiopulmonary involvement in systemic autoimmune or autoinflammatory

diseases

Antenatal use of echocardiography is important in babies at risk of neonatal lupus

erythematosus to assess for myocarditis and endocardial fibroelastosis

Some centres may require consultation with cardiologist in conjunction with imaging

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 13

Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan

Measures bone mineral density

Used most often in patients on chronic steroid therapy at baseline and at regular intervals to

monitor for development of osteopenia/osteoporosis

References

1. Pilania RK, Singh S. Rheumatology panel in pediatric practice. Indian J Pediatr 2019;

56(5):407-14.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 14

SECTION 2 – APPROACHES TO AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES FOR COMMON

COMPLAINTS REFERRED TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

2A. Approach to Childhood Joint Pain

Differential diagnosis for pain involving a single joint:

Traumatic

Fracture

Soft tissue injury (e.g. strains, sprains)

Foreign body synovitis

Infection-related

Septic arthritis

Osteomyelitis

Chronic infections, such as tuberculosis or Lyme disease

Reactive arthritis including post-Streptococcal reactive arthritis

Acute rheumatic fever

Inflammatory

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

Chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Genetic autoinflammatory syndromes (e.g. familial Mediterranean fever,

pyogenic arthritis pyoderma gangrenosum and acne)

Behçet disease

Neoplastic

Musculoskeletal tumors (e.g. osteoid osteoma, osteosarcoma)

Hematologic malignancy

Hemarthrotic

Traumatic

Coagulopathy (e.g. hemophilia)

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

Arteriovenous malformation

Hematologic

Sickle cell disease (e.g. pain crisis, dactylitis)

Mechanical

Overuse or repetitive strain injury

Tendon/ligament/meniscal injury

Apophysitis

Joint damage (e.g. prior trauma, infection, congenital anomaly)

Orthopedic

Avascular necrosis (AVN)

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

Osteochonditis dissecans

Pain syndrome

Complex regional pain syndromes (CRPS)

Potential investigations for pain involving a single joint:

X-rays

Joint aspiration and synovial fluid analysis and/or culture

Blood work: CBC and differential, ESR, CRP

Consider, if indicated:

o Further infectious testing (e.g. blood culture, Lyme serology, TB skin test)

o Further imaging (e.g. ultrasound, MRI)

o Autoimmune serology (e.g. ANA, HLA B27)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 15

Differential diagnosis for pain involving multiple joints:

Inflammatory

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Juvenile dermatomyositis

Scleroderma/mixed connective tissue disease/overlap syndromes

Systemic vasculitis (e.g. Henoch-Schönlein purpura / IgA vasculitis)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Genetic autoinflammatory syndromes

Sarcoidosis

Chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis / chronic recurrent multifocal

osteomyelitis

Serum sickness

Infection-related

Acute infections (e.g. parvovirus B19, EBV, Neisseria gonorrheae)

Chronic infections (e.g. tuberculosis (Poncet arthritis), Lyme disease)

Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE)

Reactive arthritis, including acute rheumatic fever (ARF)

Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis may rarely present with multifocal

involvement

Immunological

Immunodeficiency associated with arthritis (e.g. Wiskott-Aldrich)

Neoplastic

Leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, cancers with systemic

involvement

Mechanical

Overuse injuries, repetitive strain injuries

Apophysitis

Hypermobility – benign or due to connective tissue disease (e.g. Ehlers-

Danlos)

Skeletal dysplasias

Metabolic

Rickets

Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy)

Glycogen storage disease, mucopolysaccharidoses

Pain syndrome

Fibromyalgia

Potential investigations for pain involving multiple joints:

Blood work: CBC and differential, blood film, ESR, CRP

Infectious testing (e.g. Parvovirus B19 serology, EBV serology, throat culture, ASOT)

Consider, if indicated:

o Autoimmune serology (e.g. ANA, Rheumatoid factor, HLA B27)

o Imaging (e.g. X-rays, ultrasound, MRI)

o Urinalysis

o Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 16

What do clinical features associated with joint pain tell you about underlying diagnosis?

Signs/symptoms

Associated conditions

Severe joint pain

Infection-related, malignancy, trauma, AVN, pain syndrome

Pinpoint tenderness

Osteomyelitis, trauma, AVN, malignancy, enthesitis, chronic non-

bacterial osteomyelitis

Night pain

Malignancy, osteoid osteoma, benign nocturnal limb pain

Redness

Septic arthritis, acute rheumatic fever, reactive arthritis

Migratory joint pain

Leukemia, acute rheumatic fever

Non weight bearing

Infection, malignancy, discitis, myositis, pain syndrome

Hip pain

Infection-related, AVN, SCFE, malignancy, chondrolysis, transient

synovitis, JIA (particularly enthesitis related arthritis)

Back pain

Usually benign, but consider bone or spinal cord tumour, discitis,

spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, JIA (enthesitis related arthritis),

myositis, osteoporosis, CNO, pain syndrome

Periarticular pain

Malignancy, hypermobility, pain syndrome, CNO

Dactylitis

JIA (particularly enthesitis related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis),

sickle cell, trauma

Clubbing

Cystic fibrosis, IBD, malignancy (especially lung), familial,

hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

Weight loss

Malignancy, systemic autoimmune rheumatologic diseases, IBD

Muscle weakness

Myositis, overlap syndromes, malignancy, pain-related weakness

Rash

Systemic autoimmune rheumatologic diseases, vasculitis, JIA

(particularly systemic arthritis and psoriatic arthritis), acute

rheumatic fever, Lyme disease, serum sickness, autoinflammatory

syndromes

Oral ulcers

Vasculitis, Behçet disease, SLE, IBD, autoinflammatory

syndromes

Eye pain and redness

Reactive arthritis, enthesitis related arthritis. IBD, Behçet disease

Nail or nail fold changes

Systemic autoimmune rheumatologic diseases, psoriasis,

subacute bacterial endocarditis

Raynaud phenomenon

Systemic autoimmune rheumatologic diseases

School withdrawal

Pain syndrome, chronic fatigue

Travel

Infection-related (e.g. tuberculosis, Lyme disease, viral)

Consanguinity

Genetic or metabolic diseases (e.g. autoinflammatory diseases)

References:

1. Nannery R, Heinz P. Approach to joint pain in children. Paediatr and Child Health 2018;

28(2):43-49.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 17

2. Tse SM, Laxer RM. Approach to acute limb pain in childhood. Pediatr Rev 2006; 27:170-

80.

3. Sen ES, et al. The child with joint pain in primary care. Best Pract & Res Clin Rheumatol

2014; 28:888-906.

2B. Approach to Childhood Back Pain

Differential diagnosis for back pain in children

Inflammatory

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis, chronic recurrent multifocal

osteomyelitis

Transverse myelitis (e.g. SLE)

Infection-related

Acute infections (e.g. osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, discitis, epidural

abscess)

Chronic infections (e.g. tuberculosis (Pott disease))

Reactive arthritis

Neoplastic

Musculoskeletal tumors (e.g. osteoblastoma, osteosarcoma, spinal cord

tumors, metastases)

Leukemia, lymphoma

Mechanical

Spondylolysis, spondylolisthesis

Scoliosis

Scheuermann disease

Disc prolapse

Degenerative disc disease

Trauma

Fracture

Hematologic

Sickle cell pain crisis

Pain syndrome

Other

Fibromyalgia

Neurofibromatosis

Potential investigations for back pain in children:

Investigations may not be needed and depend on clinical assessment

Consider, if indicated:

o Imaging (e.g. X-rays, MRI)

o Autoimmune serology (e.g. ANA, Rheumatoid factor, HLA B27)

o Blood work (e.g. CBC and differential, ESR, CRP)

References:

1. Altaf F, et al. Back pain in children and adolescents. Bone Joint J 2014; 96B:717-23.

2. Nigrovic PA. Evaluation of the child with back pain. UpToDate. Updated December

2018. URL: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-the-child-with-back-pain.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 18

2C. Approach to Fevers

Definition of fever of unknown origin:

Temperature > 38 degrees Celsius lasting ≥ 8 days with no clear source of fever

Differential diagnosis for fever of unknown origin in children

Infectious

Bacterial (e.g. abscess, mastoiditis, osteomyelitis, pyelonephritis,

sinusitis, typhoid fever, tuberculosis)

Viral (e.g. Adenovirus, CMV, EBV, Enterovirus, HIV)

Other infections including parasitic and fungal (e.g. malaria, Lyme

disease, Toxoplasma, Blastomycosis)

Inflammatory

Serum sickness

Systemic vasculitis (e.g. Kawasaki disease)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Juvenile dermatomyositis

Systemic arthritis/JIA

Behçet disease

Inflammatory bowel disease

Genetic autoinflammatory syndromes

Castleman syndrome

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (primary or secondary HLH/MAS)

Sarcoidosis

Drug-induced

Drug fevers or intoxication

Neoplastic

Leukemia, lymphoma

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Neuroblastoma

Endocrinologic

Hyperthyroidism

Thyroiditis

Diabetes insipidus

Other

Pancreatitis

Factitious fevers

Potential investigations for fever of unknown origin in children:

Investigations will depend on clinical assessment and serial re-examination

Initial blood work: CBC and differential, blood film, electrolytes, urea, creatinine, glucose,

ESR, CRP, ferritin, liver enzymes, albumin, LDH

Urinalysis

Initial infectious work-up: blood culture, urine culture, nasopharyngeal swab for viruses

Consider, if indicated:

o Imaging (e.g. X-rays, abdominal ultrasound)

o Further infectious testing (e.g. ASOT, Monospot, cerebrospinal fluid testing)

o Testing for immunodeficiency (e.g. complement and immunoglobulin levels)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 19

Definition of recurrent fevers:

≥ 3 episodes of unexplained fever within 6 months separated by ≥ 7 days of good health

Differential diagnosis for recurrent fevers

Infectious

Repeated viral or bacterial infections

Viral (e.g. CMV, EBV, Parvovirus, hepatitis viruses, HIV)

Bacterial (e.g. Typhoid fever, occult dental abscess, endocarditis,

Mycobacteria)

Parasitic or fungal (e.g. malaria, Borrelia, Brucellosis, Yersinia)

Inflammatory

Genetic autoinflammatory syndromes

Periodic fever with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis (PFAPA)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic arthritis/JIA

Inflammatory bowel disease

Behçet disease

Polyarteritis nodosa

Sarcoidosis

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (primary or secondary HLH/MAS)

IgG4 disease

Hematologic

Cyclic neutropenia

Neoplastic

Leukemia, lymphoma

Immunologic

Drug-induced

DiGeorge syndrome

Chediak-Higashi

Combined immunodeficiency syndrome

Drug fevers or intoxication

Other

CNS abnormality (e.g. hypothalamic dysfunction)

Castleman disease

Factitious fevers

Potential investigations for recurrent fevers:

Clinical assessment during episode of fever and when well

Fever diary including pattern of fever and associated symptoms

Blood work during episode and when well: CBC and differential, ESR, CRP, ferritin, liver

enzymes, albumin, LDH, immunoglobulins (including IgD)

Urinalysis

Consider, if indicated:

o Infectious testing (e.g. blood culture, viral serology)

o Autoimmune serology (e.g. ANA)

o Genetic testing

References:

1. Antoon JW, et al. Pediatric fever of unknown origin. Pediatr Rev 2015; 36(9):380-91.

2. Soon GS, Laxer RM. Approach to recurrent fever in childhood. Can Fam Physician

2017; 63(10):756-62.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 20

2D. Approach to Recurrent Oral Ulcers

Differential diagnosis for recurrent oral ulcers in children

Inflammatory

Inflammatory bowel disease

Celiac disease

Behçet disease

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome (HIDS)

Periodic fever with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis (PFAPA)

A20 haploinsufficiency (HA20)

Sarcoidosis

Infectious

Viral (e.g. Herpes simplex, Coxsackie)

Reactive arthritis

Hematologic

Cyclic neutropenia

Drugs

Azathioprine, Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine

Other

Aphthous stomatitis

What are the characteristics of oral ulcers in different inflammatory conditions?

SLE

Painless shallow oral ulcers, typically located on roof of mouth

where hard and soft palate meet

Inflammatory bowel

disease

Painful aphthous ulcers anywhere in oropharynx, sometimes

associated with cheilitis

Behçet disease

Painful aphthous ulcers or punched-out ulcers on tongue, lips,

gingiva and/or buccal mucosa

Celiac disease

Painful recurrent aphthous ulcers

PFAPA

Painful aphthous ulcers with discrete margins, typically on

buccal mucosa, associated with febrile episodes

HIDS

Painful aphthous ulcers with discrete margins, typically on

buccal mucosa, associated with febrile episodes

Sarcoidosis

Painless well-circumscribed brownish red or violaceous lesions

(sometimes nodular), erythematous gingival enlargement,

submucosal swelling of palate

References:

1. Siu A, et al. Differential diagnosis and management of oral ulcers. Semin Cutan Med

Surg 2015; 34(4):171-7.

2. Le Doare K, et al. Fifteen-minute consultation: a structured approach to the management

of recurrent oral ulceration. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2014; 99(3):82-6.

3. Stoopler ET, Al Zamel G. How to manage a pediatric patient with oral ulcers. J Can Dent

Assoc 2014; 80:e9.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 21

2E. Additional differential diagnoses

Differential diagnosis for lymphadenopathy in children

Inflammatory

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic arthritis/JIA

Kawasaki disease

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (primary or secondary HLH)

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease

Castleman disease

Rosai-Dorfman disease

Monogenic autoinflammatory diseases

Periodic fever with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis (PFAPA)

Serum sickness

Sarcoidosis

Infectious

Viral (e.g. EBV, CMV, HIV)

Bacterial (e.g. Bartonella, tuberculosis)

Bacterial spirochete/tick bourne (e.g. Lyme disease)

Neoplastic

Lymphoma, leukemia

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Neuroblastoma

Other

Drug-induced

Differential diagnosis for erythema nodosum in children

Infectious

Viral (e.g. EBV, CMV, HIV)

Bacterial (e.g. Group A Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, Bartonella, Yersinia,

tuberculosis)

Inflammatory

Inflammatory bowel disease

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Behçet disease

Systemic vasculitis (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with

polyangiitis)

Sarcoidosis

Neoplastic

Lymphoma, leukemia

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma

Drug-related

Oral contraceptives

Antibiotics (e.g. sulpha drugs, penicillins, macrolides)

Other

Idiopathic

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 22

Differential diagnosis for recurrent parotitis

Infectious

Viral: HIV (diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis), Influenza B, mumps, EBV,

CMV, Parvovirus, Paramyxovirus, Adenonvirus

Bacterial: Streptococcal infections, Staphylococcus aureus, Bartonella,

Haemophilus

Tuberculosis

Inflammatory

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Sjögren syndrome

IgG4 related disease

Neoplastic

Parotid tumours

Lymphoma

Other

Sialolithiasis

Juvenile recurrent parotitis

Pneumoparotid

Differential diagnosis for muscle weakness

Inflammatory

Juvenile dermatomyositis

Juvenile polymyositis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Mixed connective tissue disease

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Systemic sclerosis

Overlap myositis

Inclusion-body myositis

Focal myositis

Orbital myositis

Granulomatous myositis

Eosinophilic myositis

Inflammatory bowel disease

Autoinflammatory diseases (e.g. TNF-receptor associated periodic

syndrome, Chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy

and elevated temperature, Familial Mediterranean fever)

Infectious

Viral (e.g. Enterovirus, Influenza, Coxsackievirus, Echovirus, Parvovirus,

Hepatitis B, HTLV)

Bacterial/Spirochetal (e.g. Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Borrelia)

Parasitic (e.g. Toxoplasmosis, Trichinosis)

Genetic

Muscular dystrophy (e.g. Duchenne, Becker)

Congenital myopathies (e.g. Spinal muscular atrophy)

Metabolic

Metabolic diseases (e.g. mitochondrial, glycogen storage)

Other

Endocrinopathies (e.g. thyroid-associated myopathies)

Trauma

Toxins

Neuromuscular transmission disorders (e.g. myasthenia gravis)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 23

Differential diagnosis for chorea and abnormal movements in children

Inflammatory

Autoimmune encephalitis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Behçet disease

Hashimoto encephalitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Sjögren syndrome

Celiac disease

Sarcoidosis

Infectious

Acute rheumatic fever

Lyme disease

Malaria

Neurosyphilis

Tuberculosis

Creutzfeld-Jacob disease

Neurologic

Benign hereditary chorea

Huntington disease

Idiopathic basal ganglia calcification

Ataxia telengiectasia

Tic disorder

Neoplastic

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Tumors with basal ganglia involvement

Drug-related

Dopaminergic and other drugs

Other

Porphyria

Wilson disease

Liver failure

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 24

Differential diagnosis for stroke-like presentations in children

Inflammatory

CNS vasculitis (primary angiography-positive or secondary vasculitis)

Systemic vasculitis (e.g. polyarteritis nodosa)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Structural

Arterial dissection

Fibromuscular dysplasia

Moyamoya disease

Hematologic

Thromboembolic disease (e.g. prothrombotic condition, atherosclerosis)

Hemoglobinopathies (e.g. sickle cell disease)

Vasospastic

Reversible vasoconstrictive syndromes

Drug-induced (e.g. cocaine)

Genetic

Deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2)

Channelopathies

Connective tissue disorders (e.g. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan

syndrome)

Neurofibromatosis

Metabolic

CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical

infarcts and leukoencephalopathy), MELAS (mitochondrial

encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke-like episodes)

References:

1. Hambleton L, et al. Lymphadenopathy in children and young people. Paediatr and Child

Health 2016; 26(2):63-7.

2. Penn E, Goudy S. Pediatric inflammatory adenopathy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2015;

48(1):137-51.

3. Leung AKC, et al. Erythema nodosum. World J Pediatr 2018; 14(6):548-54.

4. Baszis K, et al. Recurrent parotitis as a presentation of primary pediatric Sjögren

syndrome. Pediatrics 2012; 129:179-82.

5. Huber AM. Juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Pediatr Clin North Am 2018;

65(4):739-56.

6. Gilbert DL. Acute and chronic chorea in childhood. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2009; 16(2):71-

6.

7. Tsze DS, Valente JH. Pediatric stroke: a review. Emerg Med Int 2011; 734506.

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 25

SECTION 3 – JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS

3A. Introduction to Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA)

Arthritis is diagnosed in the presence of joint effusion OR two or more of the following:

limited range of movement with joint line tenderness or painful range of movement

Currently, the most widely-used classification criteria for JIA is by the International League of

Associations for Rheumatology (ILAR) from the late 1990’s

o Definition: JIA is arthritis of unknown etiology that begins before the 16th birthday

and persists for at least 6 weeks and in which other causes of arthritis are excluded

o Classification: Recognizes 7 distinct subtypes of JIA, based on their presentation

within the first 6 months

1. Oligoarthritis

2. Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor Negative)

3. Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor Positive)

4. Systemic arthritis

5. Enthesitis-related arthritis

6. Psoriatic arthritis

7. Undifferentiated arthritis

A recent re-classification of JIA was proposed by Pediatric Rheumatology International

Trials Organization (PRINTO) in 2019, but has not been validated

o Most prominent changes proposed in the new PRINTO criteria are that JIA is

considered a group of distinct clinical phenotypes (rather than a single disease) that

begin before the 18

th

birthday and are not classified by the number of joints involved

Oligoarthritis

ILAR Classification Criteria for Oligoarthritis *

Definition: Arthritis affecting 1 to 4 joints during the first 6 months of disease

Subcategories:

1. Persistent oligoarthritis: Affects not more than 4 joints throughout disease course

2. Extended oligoarthritis: Affects more than 4 joints after the first 6 months of disease

Exclusions:

o Psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in the patient or first degree relative

o Arthritis in an HLA-B27 positive male beginning after 6

th

birthday

o Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, or acute anterior uveitis,

or history of one of these disorders in 1

st

degree relative

o Presence of IgM Rheumatoid Factor on at least 2 occasions at least 3 months apart

o Presence of systemic JIA

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

Oligoarthritis is the most common subtype of JIA

Typical patient is a young girl with positive ANA who presents with a small number of swollen

joints

Most frequent joints to be involved are knees, ankles, wrists, or elbows

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 26

Hip involvement is distinctly uncommon, especially early in disease, unless the disease

develops into extended oligoarthritis or is really part of enthesitis-related arthritis

ANA is positive in 60-80% of patients (antigenic specificity is unknown for ANA in JIA)

Oligoarticular JIA with positive ANA is associated with a higher risk of asymptomatic uveitis

(see Section 9)

Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor Negative)

ILAR Classification Criteria for Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor Negative) *

Definition:

Arthritis affecting 5 or more joints during first 6 months of disease

Negative testing for RF

Exclusions:

o Psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in the patient or first degree relative

o Arthritis in an HLA-B27 positive male beginning after 6

th

birthday

o Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, or acute anterior uveitis,

or history of one of these disorders in 1

st

degree relative

o Presence of IgM Rheumatoid Factor on at least 2 occasions at least 3 months apart

o Presence of systemic JIA

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

Children with RF negative polyarthritis are frequently younger and have a better prognosis

than those with RF positive disease

ANA is positive in about 25% of patients

Joint involvement is frequently symmetrical, affecting large and small joints alike

Less than 50% of patients go into spontaneous remission, and long-term sequelae are

frequent, especially with hip and shoulder involvement

Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor Positive)

ILAR Classification Criteria for Polyarthritis (Rheumatoid Factor Positive) *

Definition:

Arthritis affecting 5 or more joints during first 6 months of disease

2 or more positive tests for RF at least 3 months apart during first 6 months of disease

Exclusions:

o Psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in the patient or first degree relative

o Arthritis in an HLA-B27 positive male beginning after 6

th

birthday

o Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, or acute anterior uveitis,

or history of one of these disorders in 1

st

degree relative

o Presence of systemic JIA

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

All patients are RF positive, many are positive for anti-CCP antibodies, and ANA is positive in

40-50%

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 27

RF positive polyarthritis mostly affects adolescent girls

Patients with RF positive polyarthritis share many characteristics with adults with rheumatoid

arthritis, including symmetrical polyarthritis especially involving the PIP joints and MCP joints

Children may develop rheumatoid nodules and similar complications to adult disease,

including joint erosions and Felty syndrome (neutropenia and splenomegaly)

RF positive polyarthritis is associated with more joint erosion and damage and with worse

radiographic outcome

Remission rates (off medications) are lowest among RF positive patients

Systemic Arthritis

ILAR Classification Criteria for Systemic Arthritis *

Definition:

Arthritis affecting 1 or more joints

Associated with or preceded by fever of at least 2 weeks duration that is documented to be

daily, or “quotidian” for at least 3 days

Accompanied by 1 or more of:

Evanescent (non-fixed) erythematous rash

Generalized lymph node enlargement

Hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly

Serositis

Exclusions:

o Psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in the patient or first degree relative

o Arthritis in an HLA B27 positive male beginning after 6

th

birthday

o Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, or acute anterior uveitis,

or history of one of these disorders in 1

st

degree relative

o Presence of IgM Rheumatoid Factor on at least 2 occasions at least 3 months apart

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

Typical symptoms of systemic arthritis include:

o Once or twice daily fever spikes to >38.5°C, which then return to baseline or below

o Salmon-coloured, evanescent rash accompanying the fever, occasionally pruritic, and

lesions may be elicited by scratching the skin (Koebner phenomenon)

o Lymphadenopathy (common), splenomegaly (10%) and hepatomegaly (less common)

o Arthritis may develop later (usually within first year of fever) and is usually polyarticular,

affecting knees, wrists and ankles, but cervical spine and hip involvement also occurs

An infectious work-up should be done and bone marrow aspirate to exclude malignancy

strongly considered before starting corticosteroid treatment

Systemic JIA is associated with macrophage activation syndrome, a potentially life

threatening inflammatory complication (see Section 13)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 28

Enthesitis Related Arthritis (ERA)

ILAR Classification Criteria for Enthesitis Related Arthritis *

Definition:

Arthritis and enthesitis

Or, arthritis or enthesitis with at least 2 of the following:

Presence or history of sacroiliac joint tenderness or inflammatory back pain

Presence of HLA-B27 antigen

Onset of arthritis in a male over 6 years of age

Acute (symptomatic) anterior uveitis

History of ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis related arthritis, sacroiliitis with

inflammatory bowel disease, or acute anterior uveitis in a first-degree relative

Exclusions:

o Psoriasis or a history of psoriasis in the patient or first degree relative

o Presence of IgM Rheumatoid Factor on at least 2 occasions at least 3 months apart

o Presence of systemic JIA

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

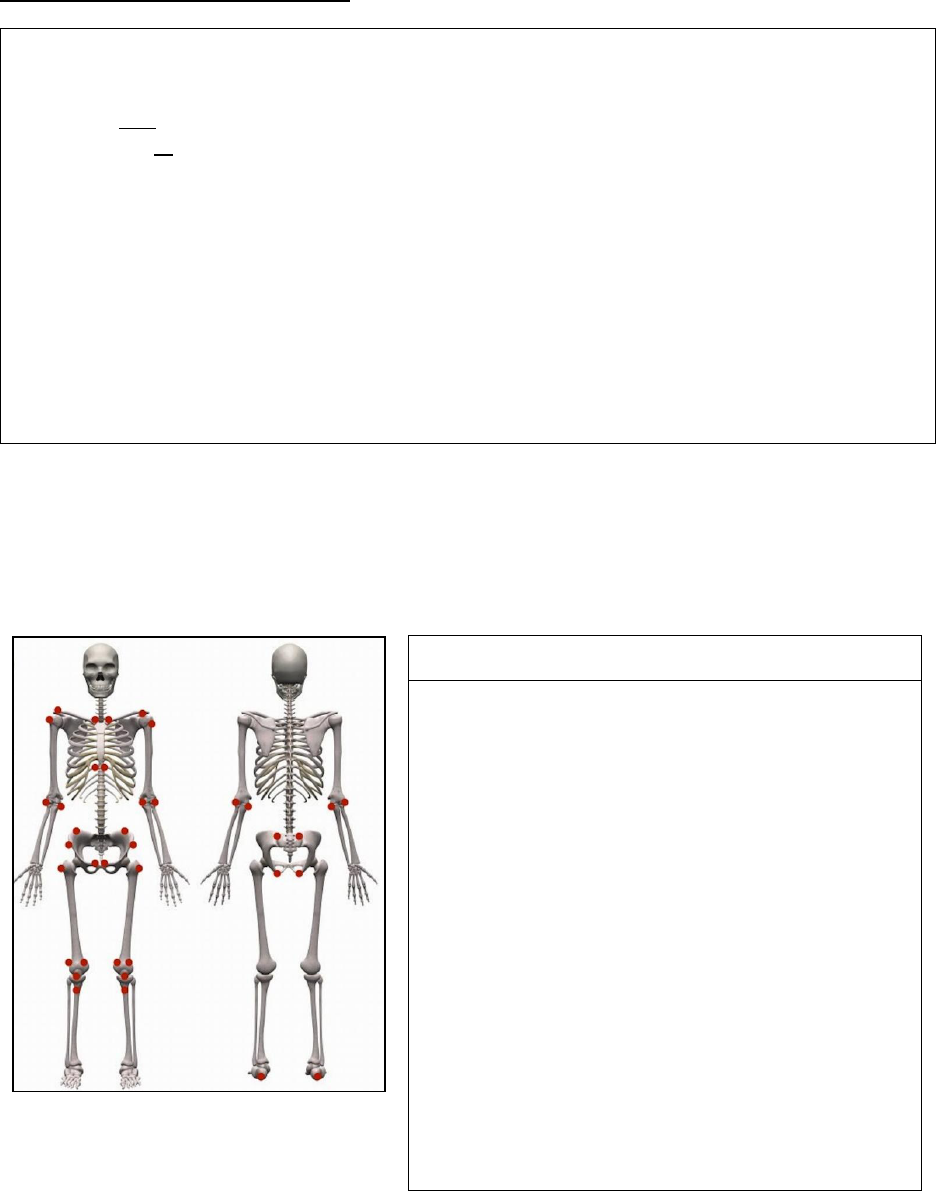

Hallmark of ERA is enthesitis (inflammation of the insertion sites of tendons, ligaments and

fascia) and asymmetrical oligoarthritis, predominantly affecting the lower extremities

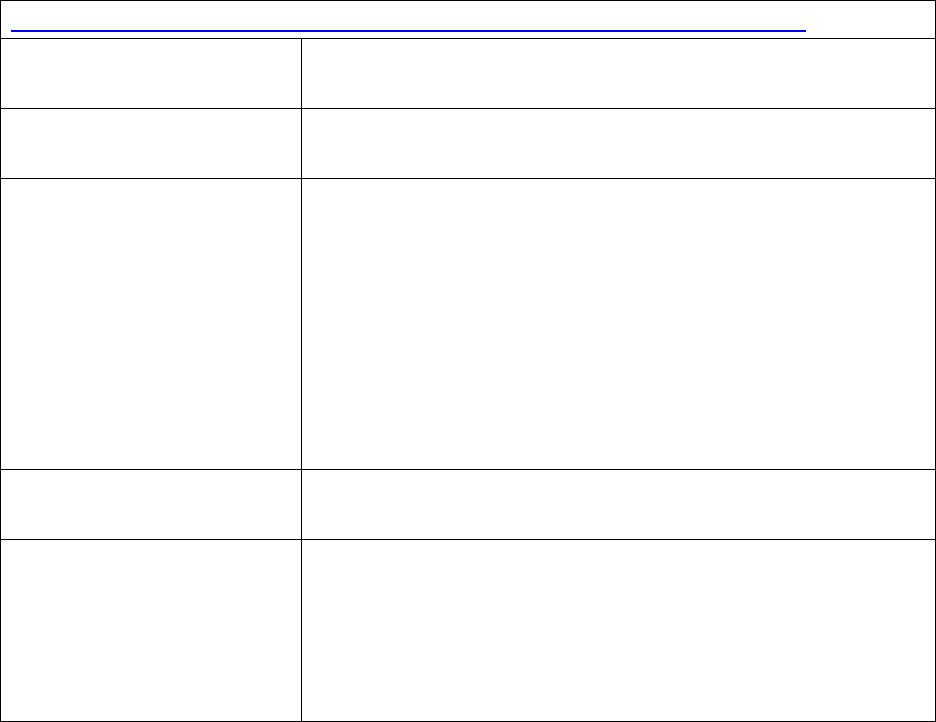

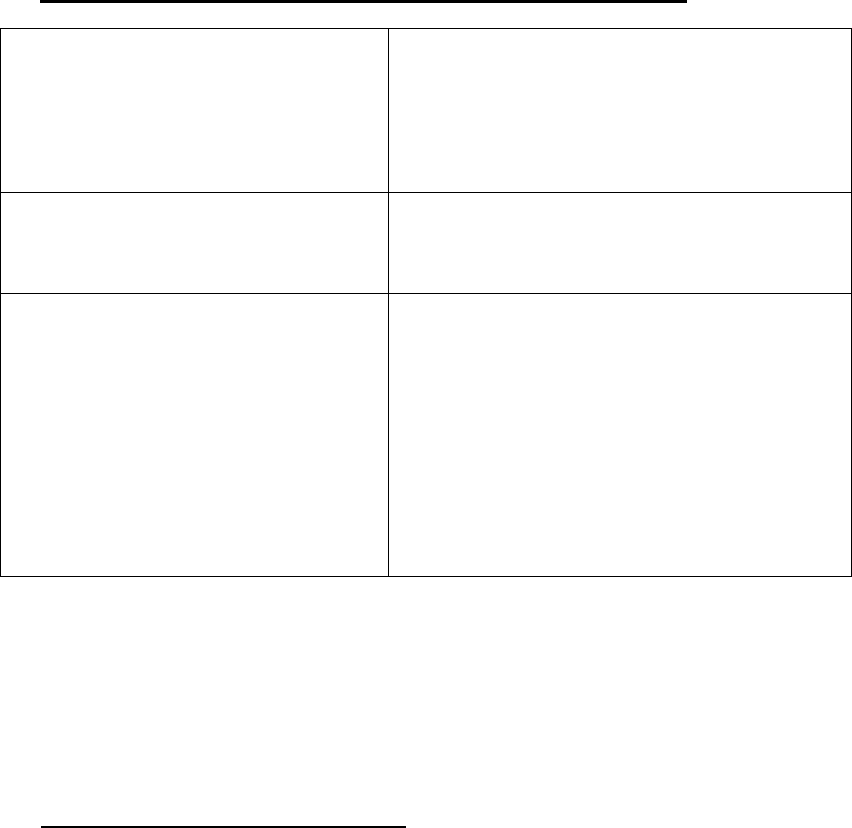

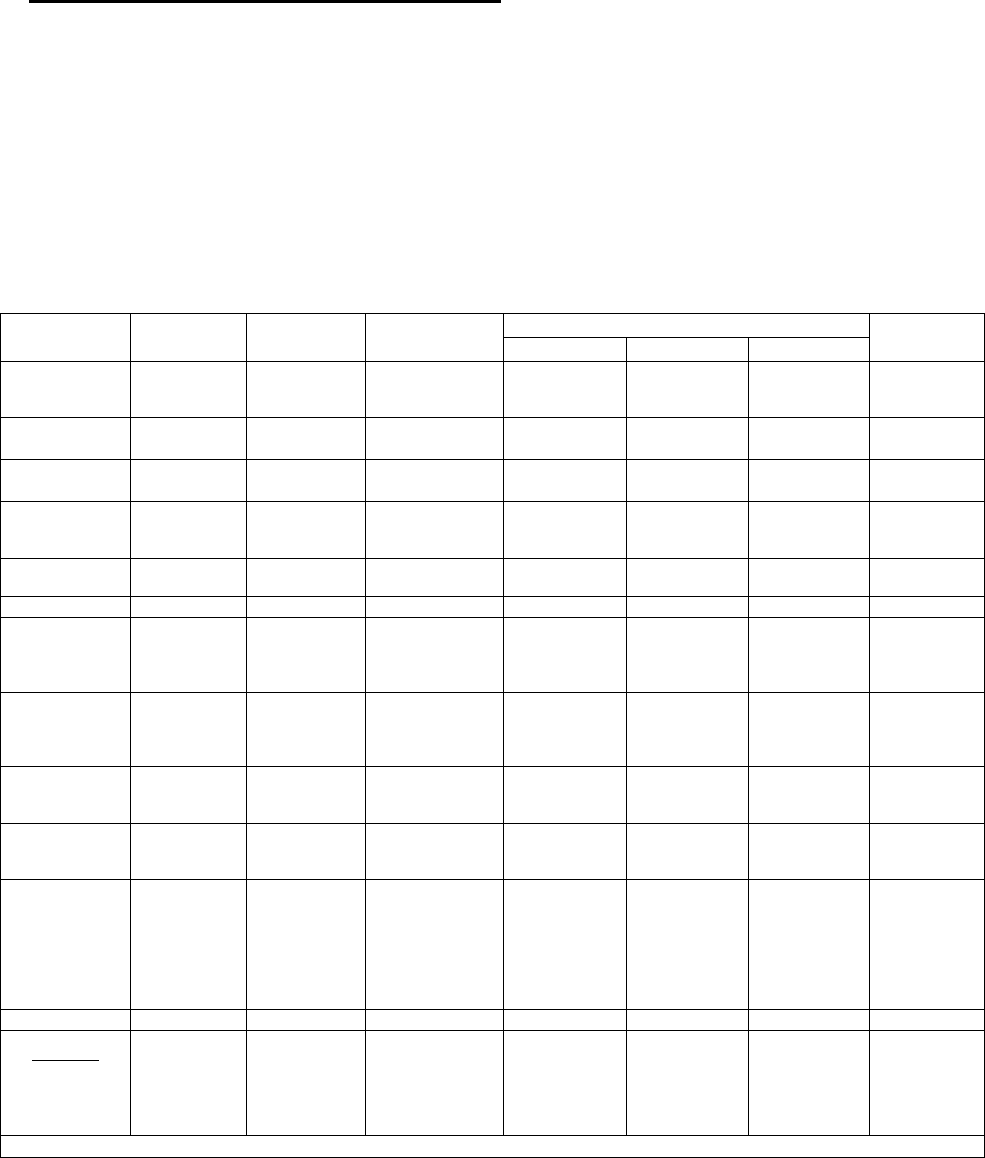

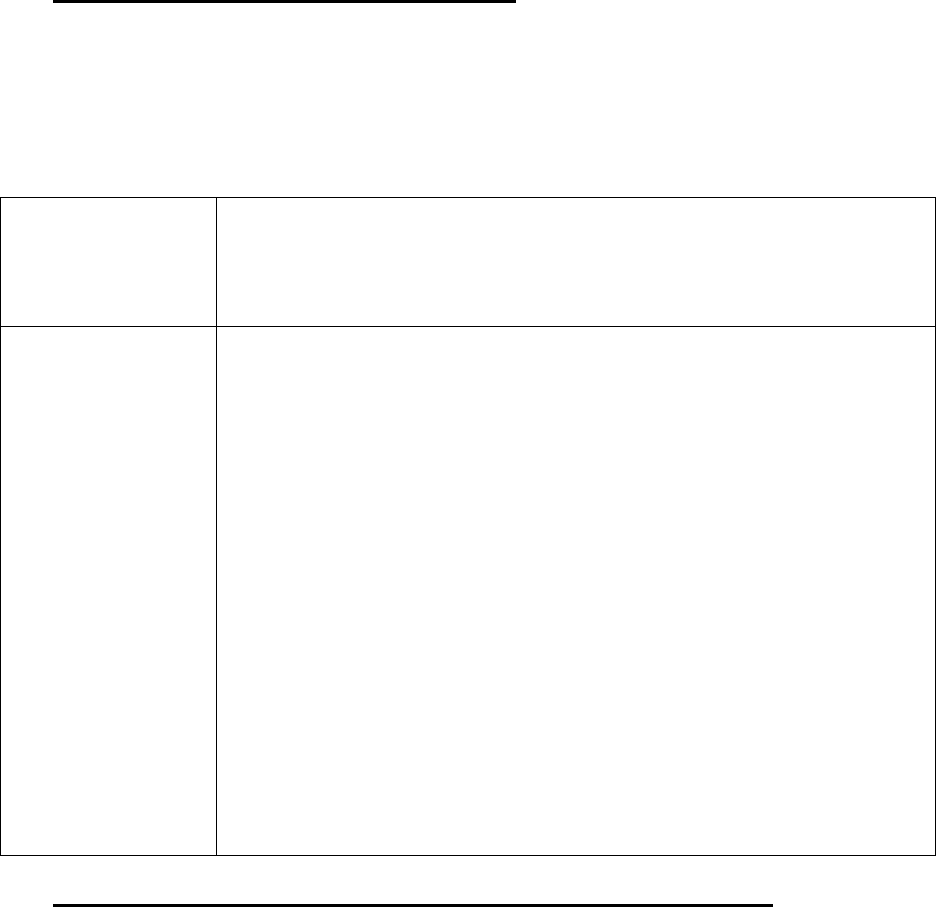

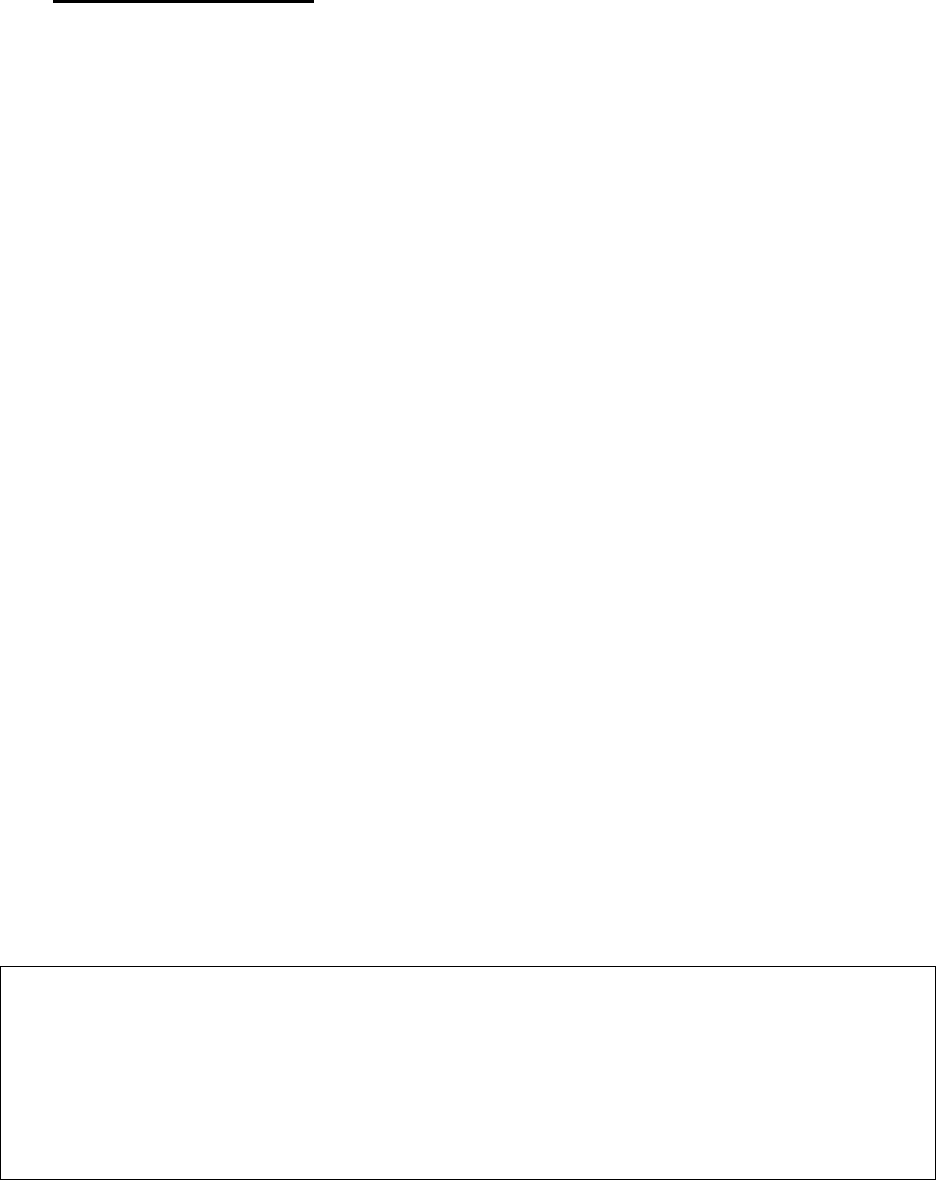

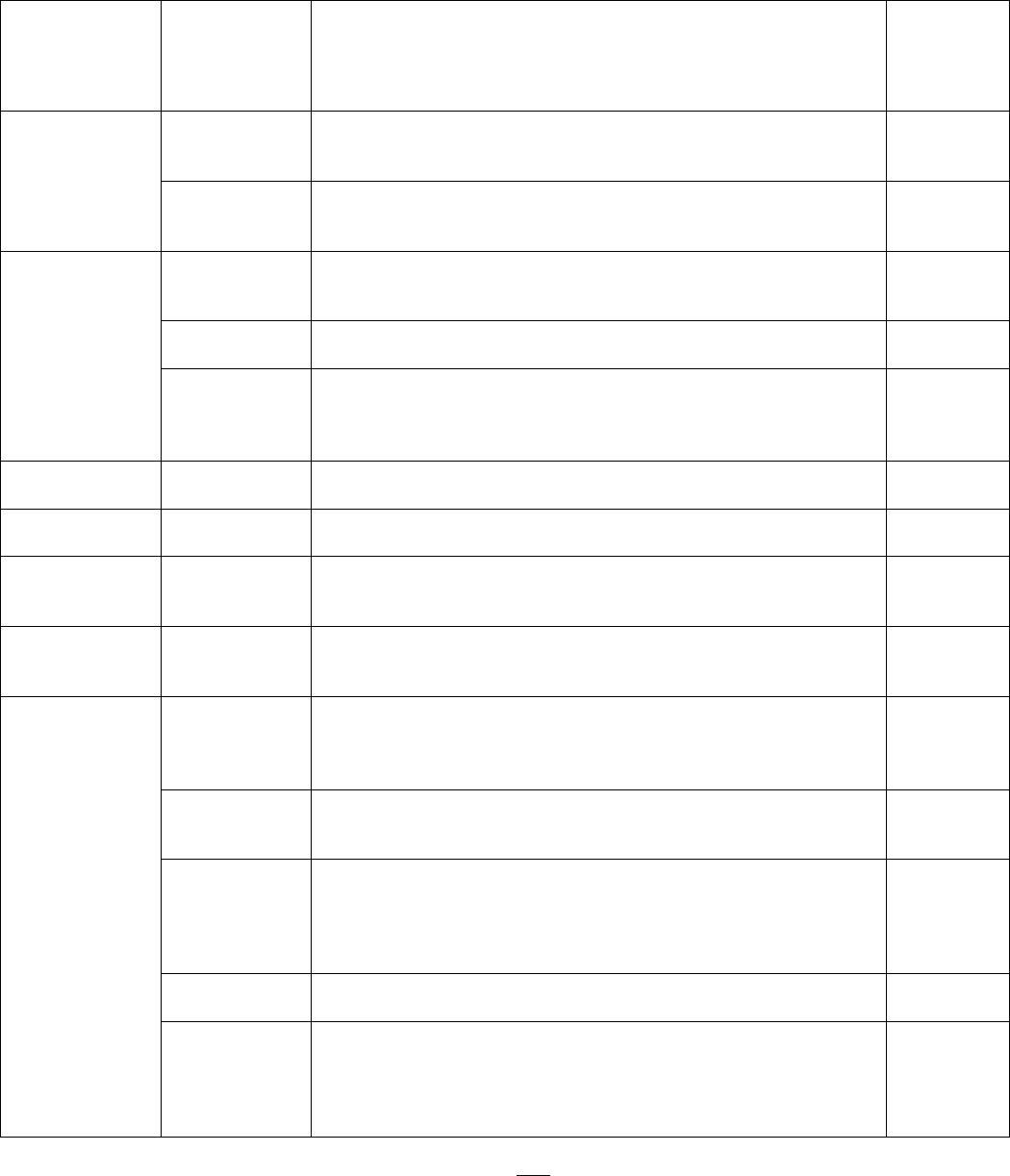

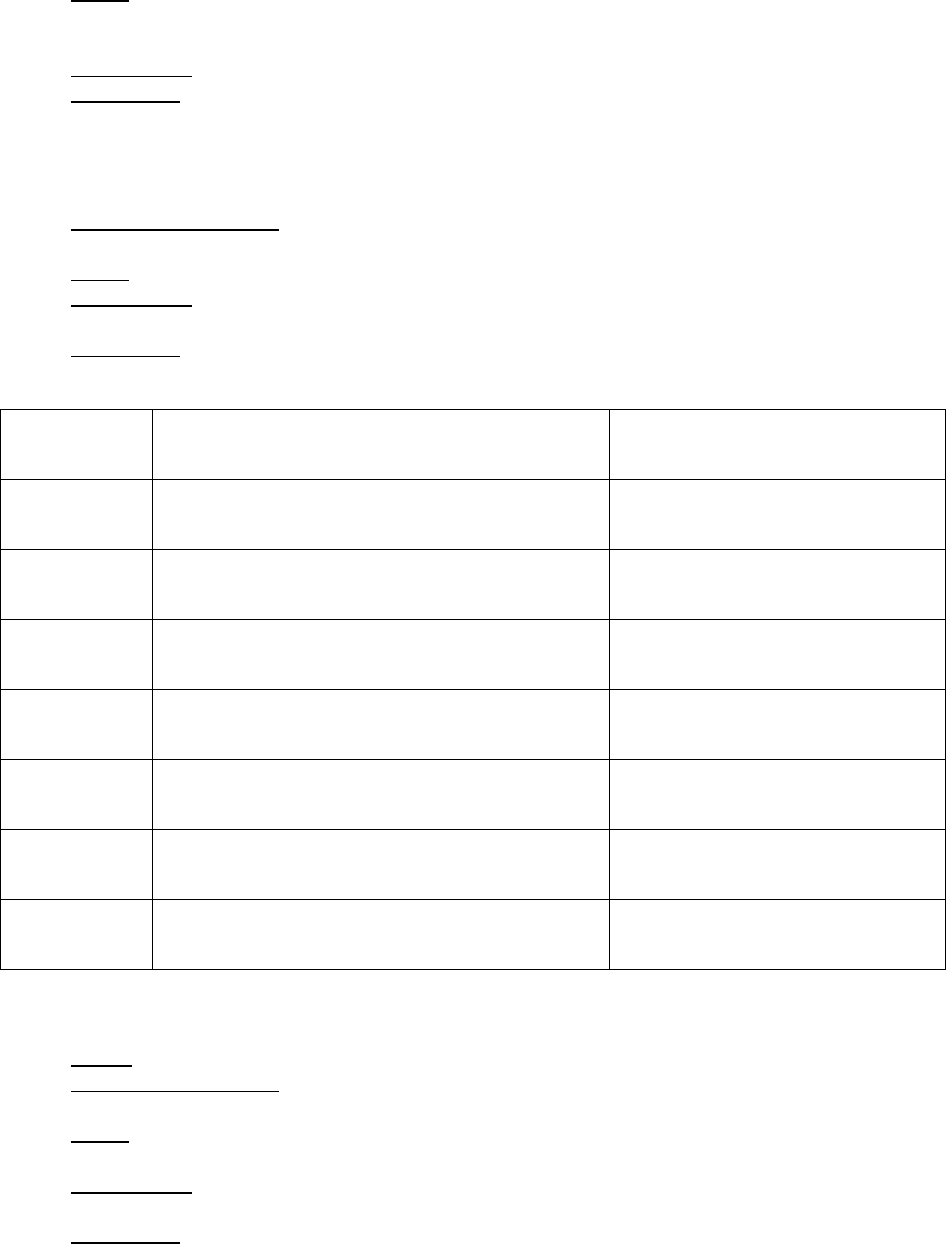

Entheses by anatomic region

Region

Enthesitis exam

Chest

Costernal junctions (1

st

and 7

th

)

Shoulder

Acromioclavicular junction

Supraspinatus insertion into greater tubercle of

humerus

Elbow

Common flexor insertion into medial epicondyle

of humerus

Common extensor insertion into lateral

epicondyle of humerus

Pelvis

Abdominal muscle insertions into iliac crest

Sartorius insertion into anterior superior iliac

spine

Posterior superior iliac spine

Gracilis and adductor insertion into pubis

symphysis

Hamstring insertion into ischial tuberosity

Hip extensor insertion into greater trochanter of

femur

Knee

Quadriceps tendon insertion to patella

Infrapatellar ligament insertion to patella and

tibial tuberosity

Ankle

Achilles tendon insertion into calcaneus

Foot

Plantar fascia insertion into calcaneus,

metatarsal heads and base of 5

th

metatarsal

Image adapted with permission from: Jariwala M, Burgos-Vargas R, “Juvenile Spondyloarthropathies” in Pediatric

Rheumatology: A Clinical Viewpoint, 2017, Pages 229-46, Copyright Springer Singapore (2017).

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 29

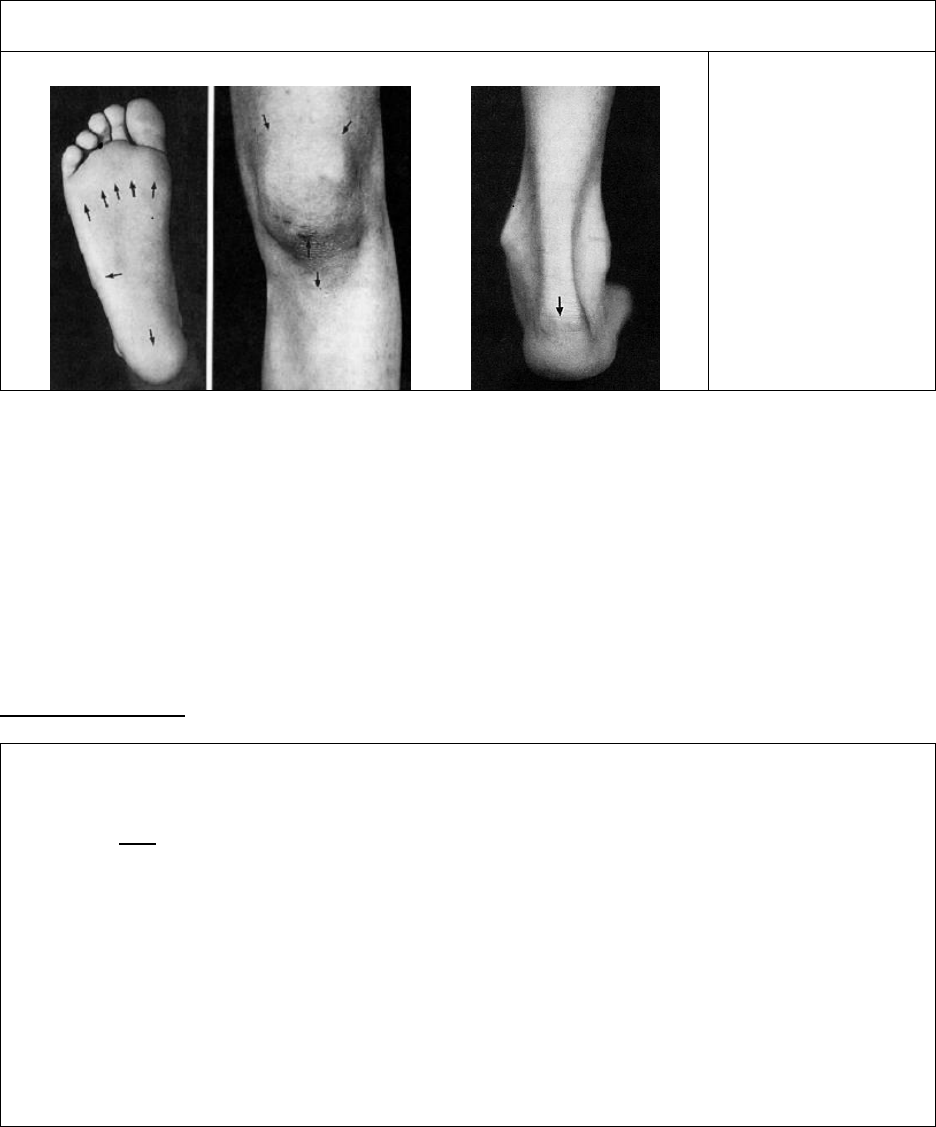

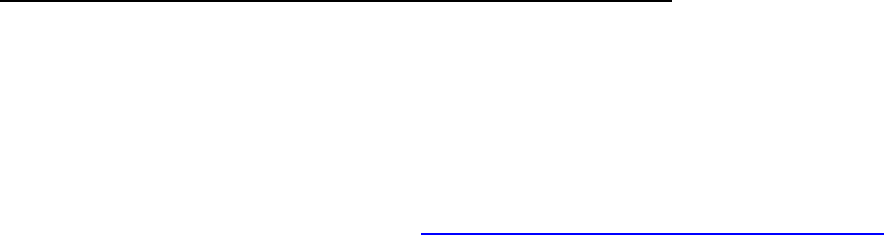

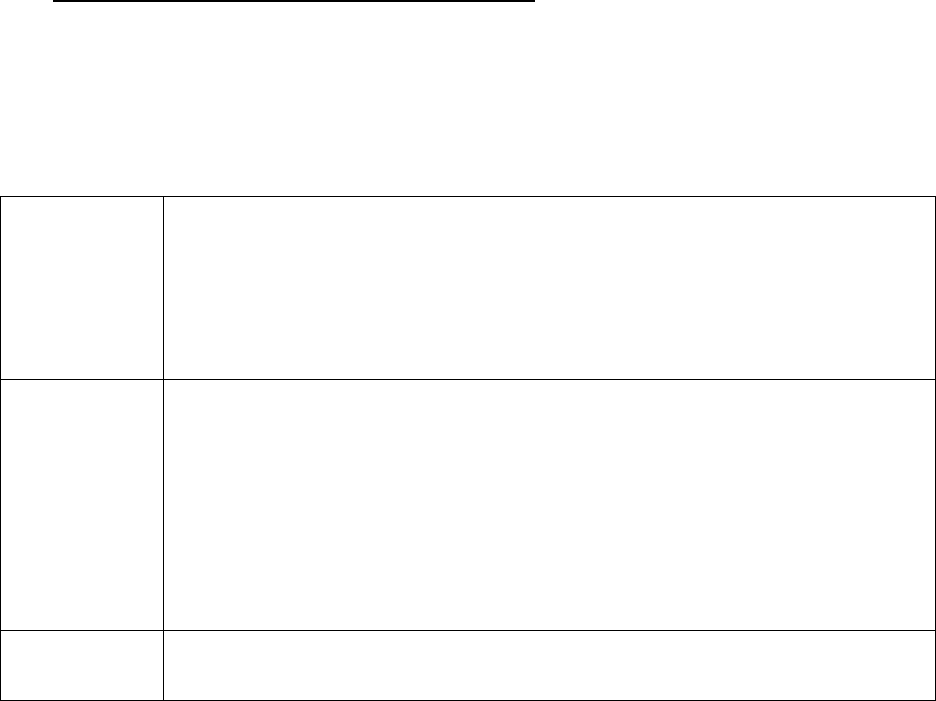

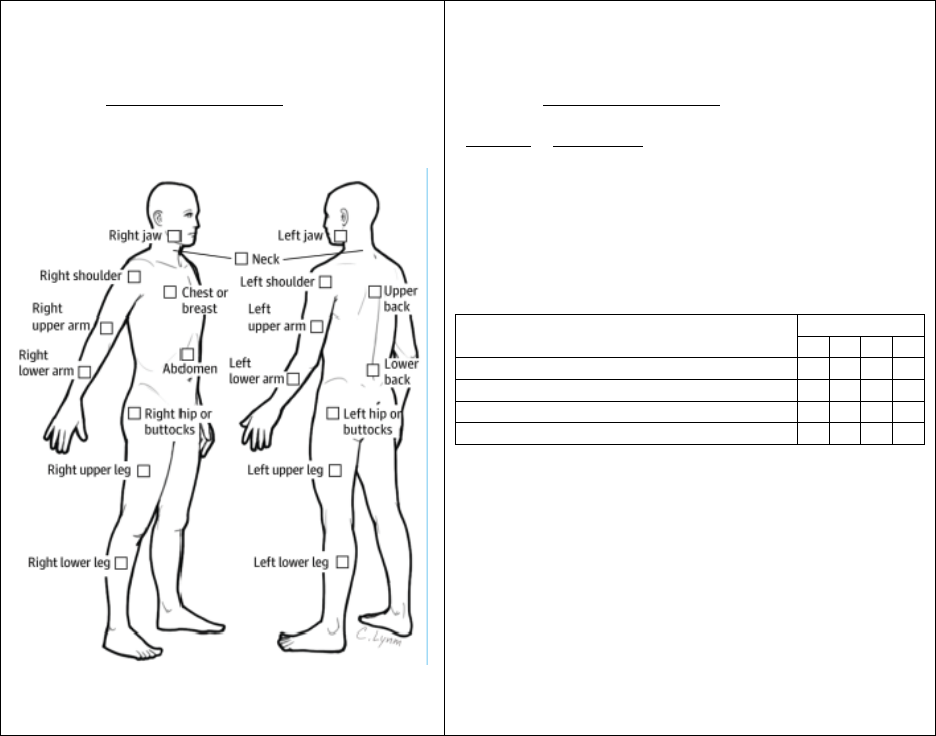

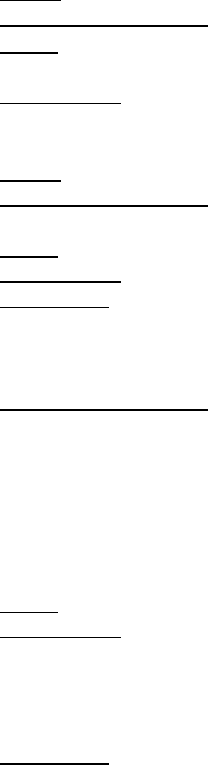

Common sites of enthesitis in the lower body

A B C

A. Insertions of

plantar fascia

B. Insertions of

quadriceps and

patellar tendons

C. Insertion of

Achilles tendon

Images were published in “Spondyloarthropathies of childhood” in Pediatrics Clinics of North America, 1995,

Volume 42, Pages 1051-1070, Copyright Elsevier (1995).

ERA typically occurs in boys, usually over 6 years of age with familial predilection

Axial involvement (involvement of the sacroiliac joints and/or spine) typically develops later

Other manifestations include tarsitis (diffuse inflammation of tarsal joints and surrounding

tendon sheaths) and dactylitis (sausage-shaped swelling of entire digit)

Symptomatic anterior uveitis may develop in children with ERA and this usually presents

with significant eye pain and redness, which may be unilateral

Gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia) should be

carefully evaluated for possible inflammatory bowel disease

Psoriatic Arthritis

ILAR Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis *

Definition:

Arthritis and psoriasis

Or, arthritis and at least 2 of the following:

Dactylitis

Nail-pitting or onycholysis

Psoriasis in a first-degree relative

Exclusions:

o Arthritis in an HLA B27 positive male beginning after 6

th

birthday

o Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis related arthritis, sacroiliitis with IBD, or acute anterior uveitis,

or history of one of these disorders in 1

st

degree relative

o Presence of IgM Rheumatoid Factor on at least 2 occasions at least 3 months apart

o Presence of systemic JIA

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

Psoriasis may develop after arthritis and may lead to reclassification of JIA type as psoriatic

Typically asymmetric, and involves both large and small joints

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 30

Clinical hallmark is dactylitis, which is caused by simultaneous inflammation of the flexor

tendon and synovium, leading to the typical “sausage digit” appearance

Undifferentiated Arthritis

ILAR Classification Criteria for Undifferentiated Arthritis *

Definition: Arthritis that fulfils criteria in no category or in 2 or more of above categories

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

References:

1. Crayne CB, Beukelman T. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Oligoarthritis and polyarthritis.

Ped Clin North Am 2018; 65(4):657-74.

2. Weiss PF, Colbert RA. Juvenile spondyloarthritis: A distinct form of juvenile arthritis. Ped

Clin North Am 2018; 65(4):675-90.

3. Lee JJY, Schneider R. Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Ped Clin North Am 2018;

65(4):691-709.

4. Petty RE, et al. ILAR classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Second revision,

Edmonton 2001. J Rheumatol 2004; 31(2):390-2.

5. Martini A, et al. Toward new classification critieria for juvenile idiopathic arthritis: First

steps, Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization International

Consensus. J Rheumatol 2019; 46(2):190-7.

3B. Approach to Management of JIA

Goals of therapy

1. Eliminate inflammation with goal to achieve clinical remission

2. Prevent joint damage

3. Promote normal growth and development

4. Maintain normal function and optimize quality of life

5. Minimize medication toxicity

Timing of assessments:

o Children with suspected JIA should be reviewed by a pediatric rheumatologist in 4-6

weeks and those with possible systemic JIA within 7 days

o Follow-up is recommended at intervals of 3-4 months in patients with controlled

disease and more often in those with uncontrolled disease

Disease monitoring:

o Assessments of disease activity by a pediatric rheumatologist and multidisciplinary

team are essential for disease monitoring

o Laboratory monitoring is often an essential part of management, especially during

disease flares and medication changes (escalation and weaning)

o Surveillance joint X-rays should not be ordered routinely to monitor disease activity,

but may be used as needed to assess for joint damage (highlighted in Choosing

Wisely: Pediatric Rheumatology Top 5 by American College of Rheumatology)

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 31

o Ultrasound and/or MRI could be considered to detect early or subclinical disease

activity or damage and MRI is usually indicated for monitoring of temporomandibular,

sacroiliac, hip, and subtalar joints

o Careful monitoring by an eye care provider is essential to assess for chronic anterior

uveitis, especially in patients with oligoarthritis and positive ANA

o Screening for asymptomatic uveitis should take place within 4 weeks of diagnosis

Multidisciplinary approach:

o Multidisciplinary team is part of comprehensive JIA management

o Occupational and physical therapists play an important role in treating JIA

o Psychosocial aspects of disease must be recognized and addressed

Treat-to-Target Strategy for JIA:

o Target of treatment is complete remission, which means absence of signs and

symptoms of inflammatory disease activity, including extra-articular manifestations

(e.g. uveitis)

o Minimal or low disease activity may be an alternative target, particularly in patients

with longstanding or difficult-to-treat disease

o Setting the target and therapeutic decisions should be based on individual patient

characteristics and agreed on with the patient/parents

o Rapid escalation and changes in therapy may be required until target is achieved

o In all patients, at least a 50% improvement in disease activity should be reached

within 3 months and the target within 6 months; however, patients with systemic JIA

should be fever-free within 1 week

Medications:

o Initial therapy with an NSAID may be started by a patient’s primary care physician;

however, further therapy should be directed by a pediatric rheumatologist

o Intra-articular corticosteroids and methotrexate remain key medications for JIA

o Potential algorithms for treatment of oligoarthritis, polyarthritis and systemic JIA are

included in the following pages

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 32

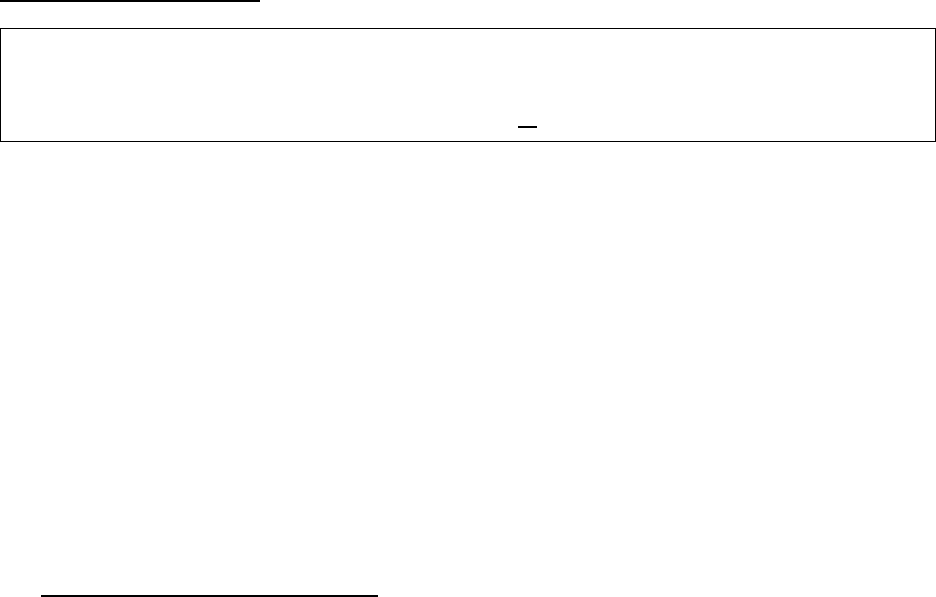

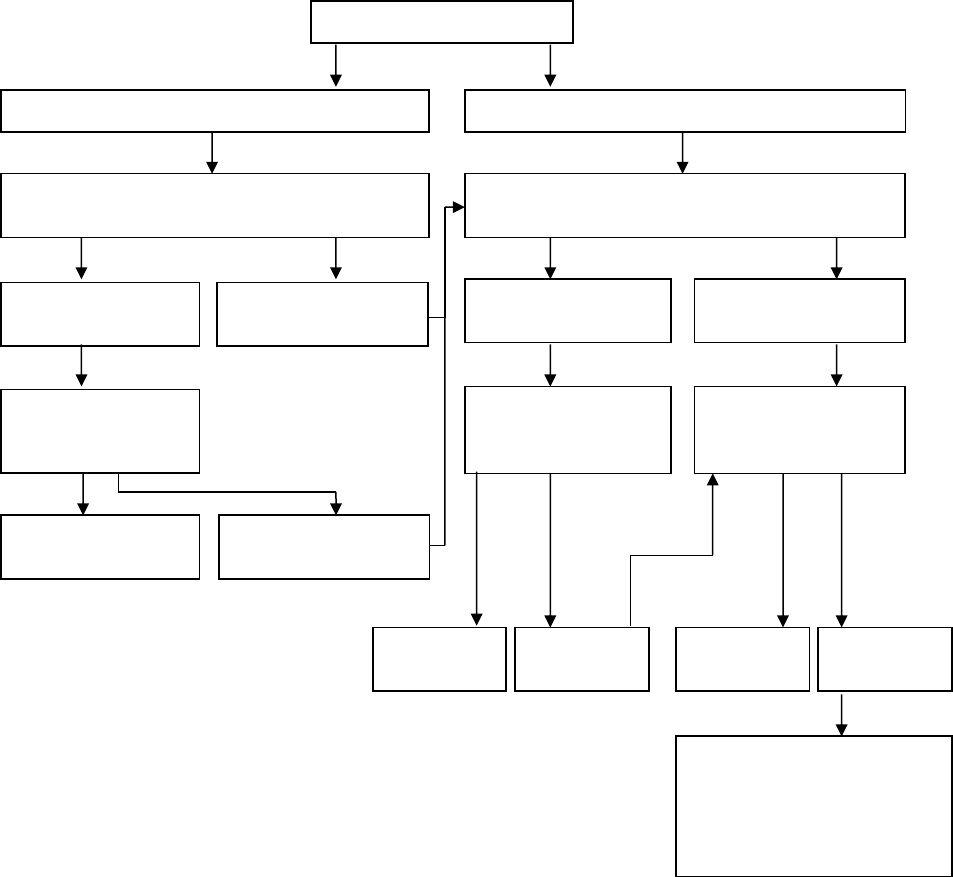

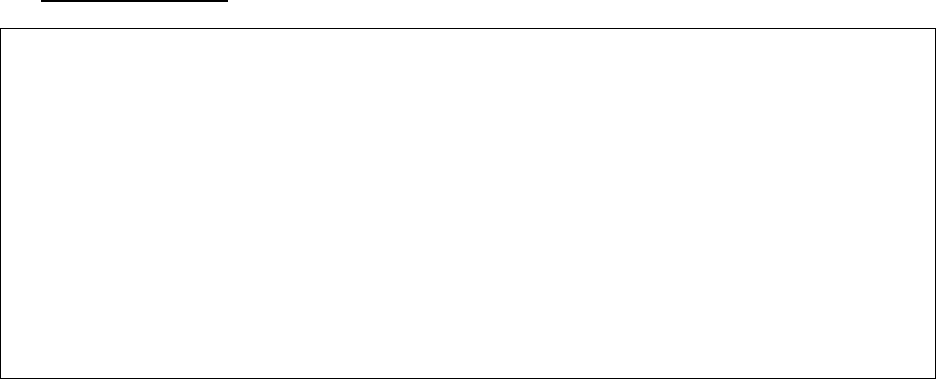

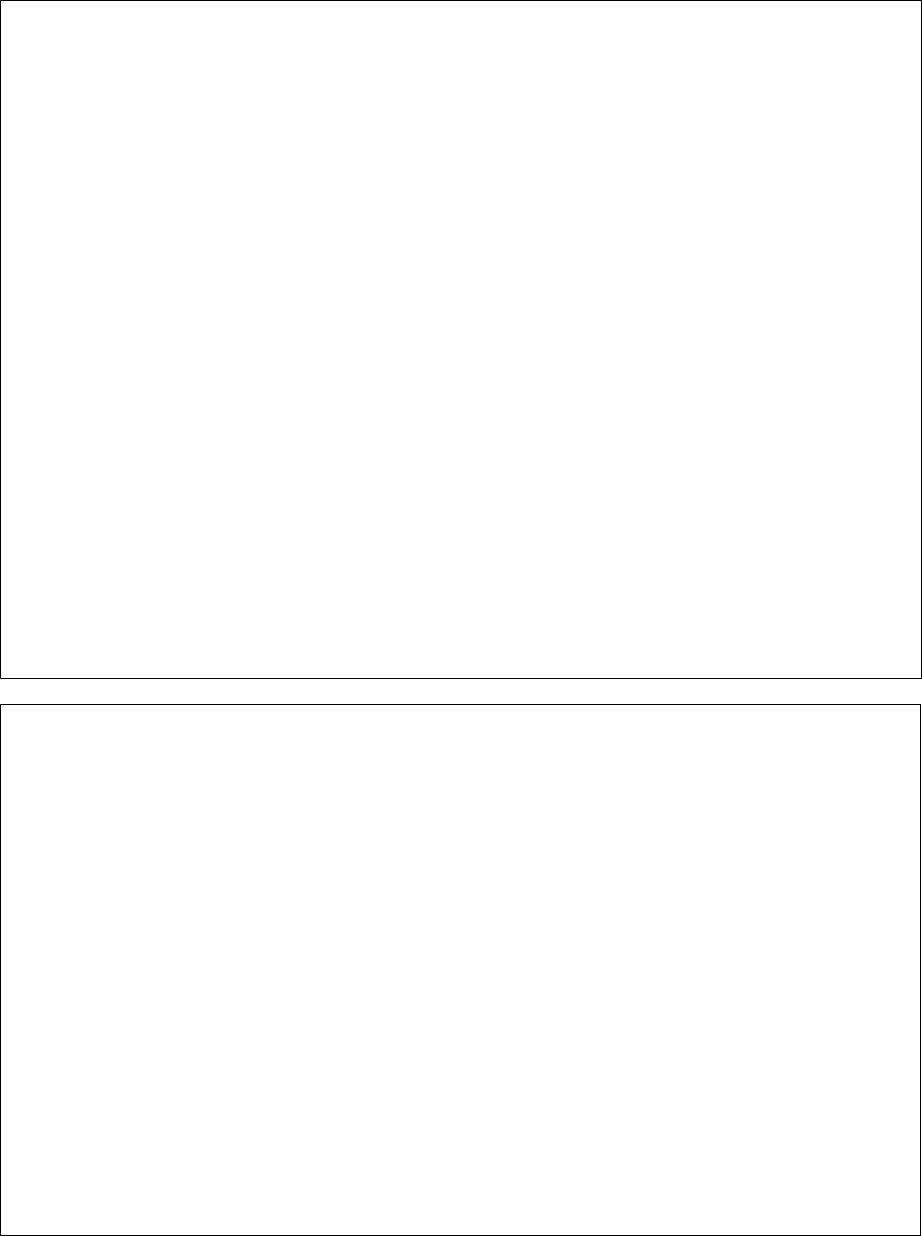

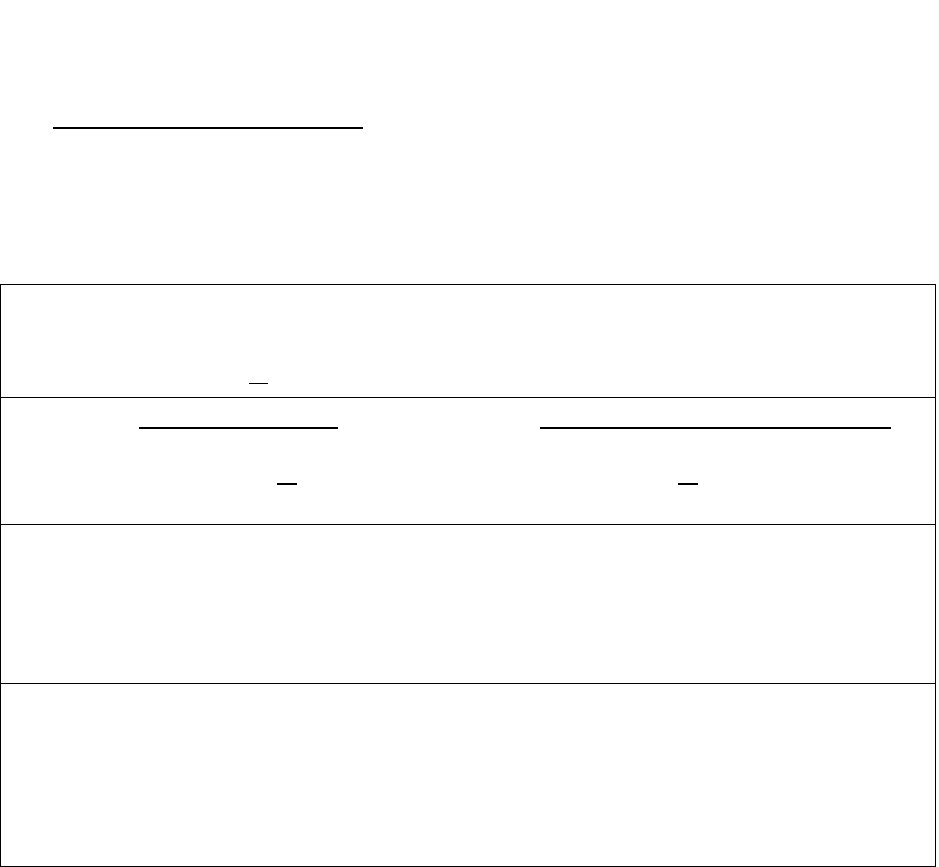

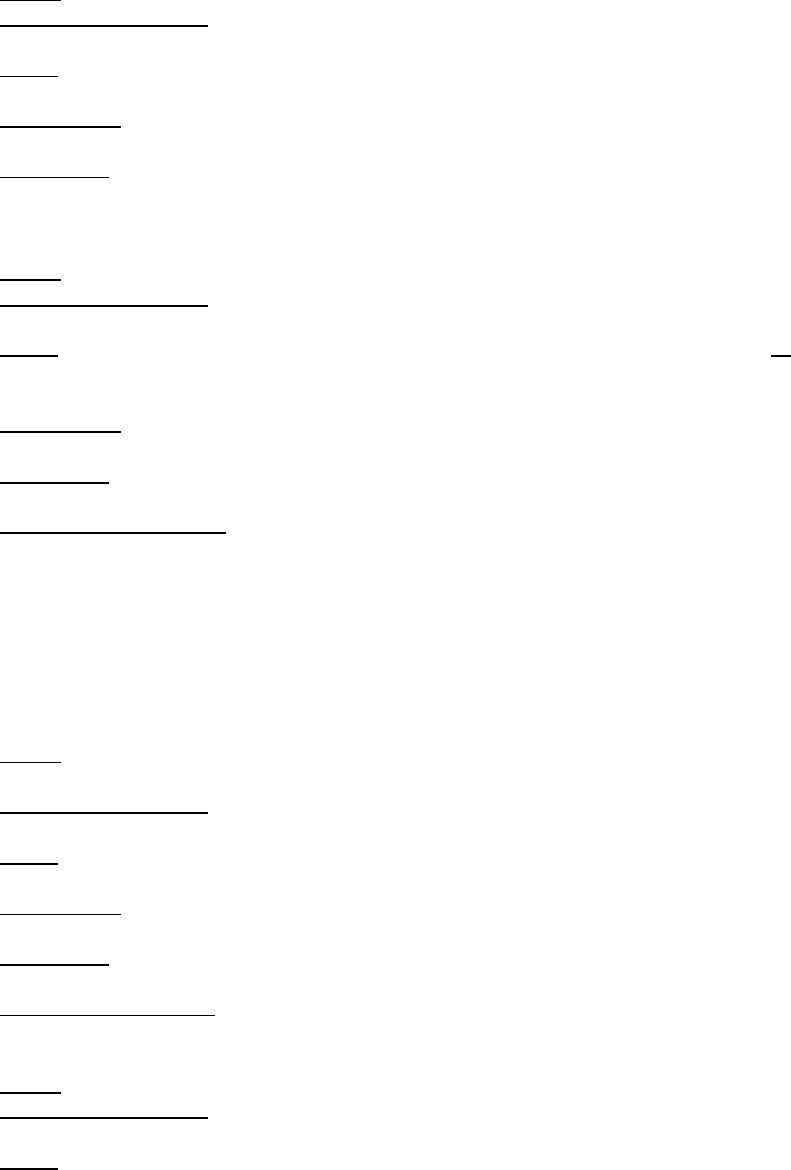

An Algorithm for Treatment of Oligoarthritis

Persistent oligoarticular

arthritis

Inadequate response

Oligoarticular arthritis

NSAID or Intra-Articular Corticosteroid injection (IAC) withTriamcinolone hexacetonide

Improvement

Inadequate response

Follow and, if no IAC, continue NSAID

Recurrence

Remission

Evolves into polyarticular

arthritis

Intermittent IAC, or

consider adding disease-

modifying drug

Management same as

polyarticular JIA

(see next algorithm)

Inadequate response

Remission

Consider biologic agent

Repeat or first IAC

Remission

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 33

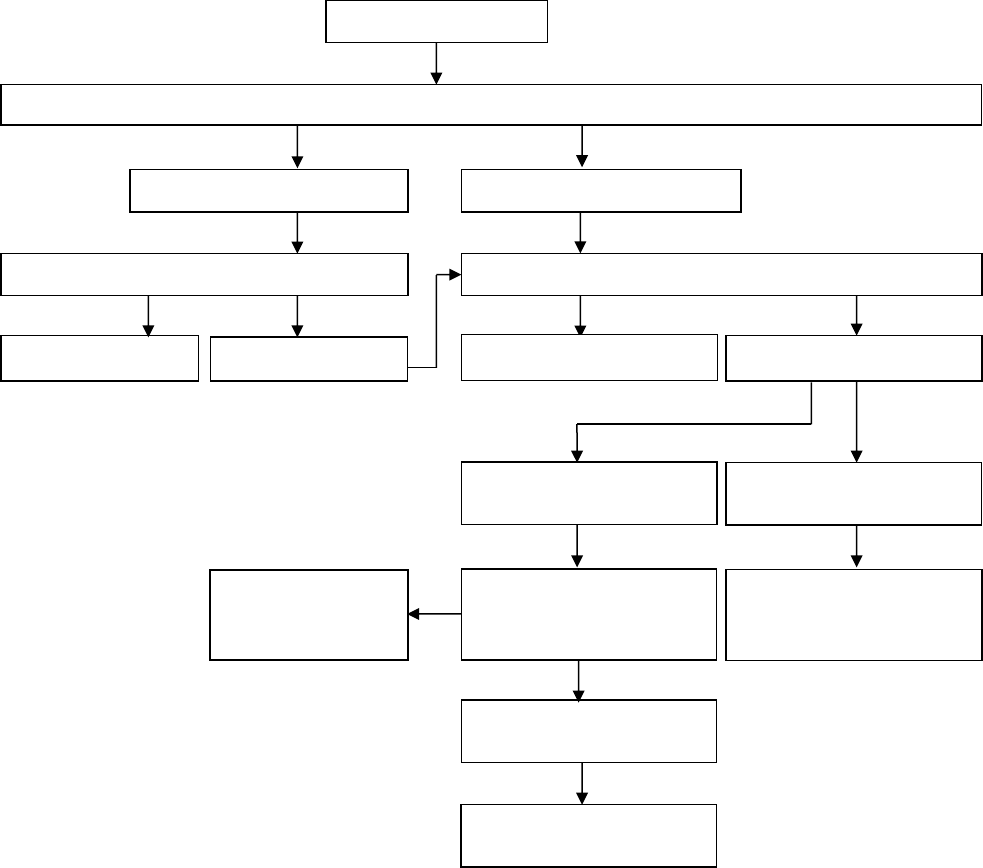

An Algorithm for Treatment of Polyarthritis

Inadequate

response

If inadequate

response, consider

switch to different

anti-TNF agent or

other biologic agent

(e.g. abatacept,

tocilizumab)

Consider adding

anti-TNF therapy

Continue therapy

and follow

Remission

Recurrence

Optimise disease-modifying drug

Consider IAC or low dose oral

corticosteroids as bridging therapy

Continue therapy and follow

Polyarthritis

NSAID with or without Intra-Articular Corticosteroid injections (IAC)

Consider using disease-modifying drug, such as methotrexate, as part of initial

therapy for moderate to severe polyarthritis

Improvement

Inadequate response

Add disease-modifying drug, such as

methotrexate or leflunomide

Continue NSAID and follow

Recurrence

Remission

Improvement

Recurrence

Remission

Improvement

Inadequate

response

N.B. A limited course of Corticosteroids

(< 3 months) during initiation or

escalation of therapy may be added in

patients with high-moderate disease

activity

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 34

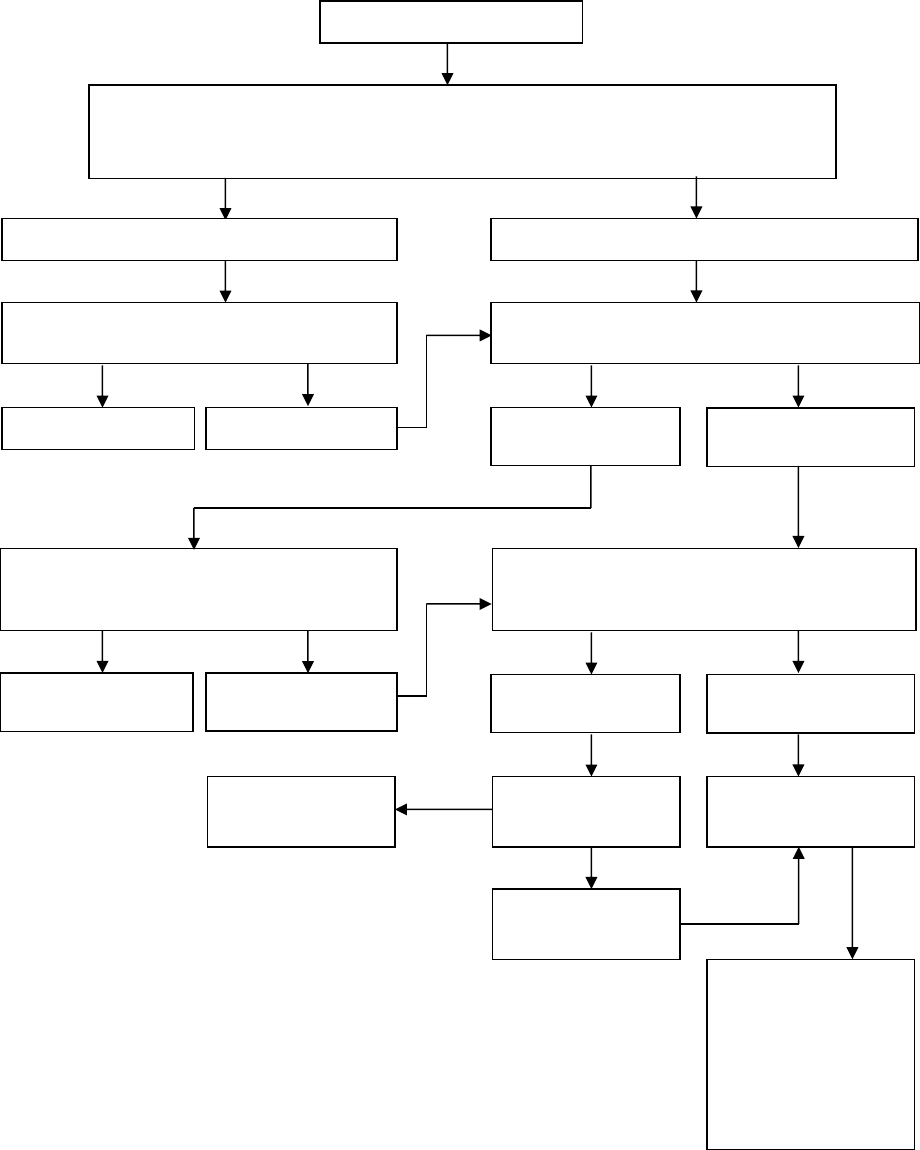

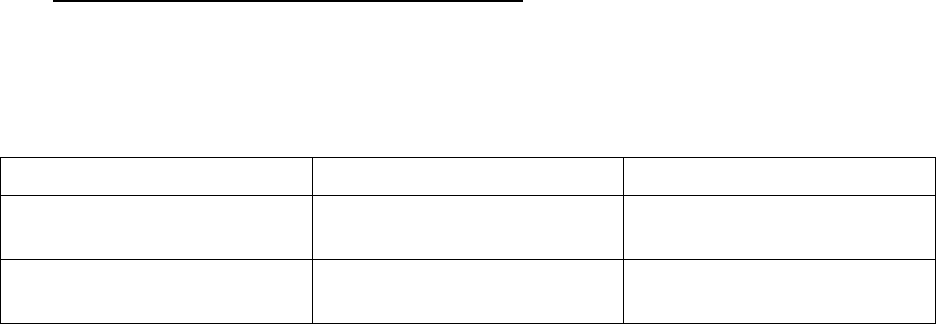

An Algorithm for Treatment of Systemic JIA

References

1. Giancane G, et al. Recent therapeutic advances in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Best Pract

Res Clin Rheumatol 2017; 31(4):476-87.

2. Ravelli A, et al. Treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis to target: recommendations of an

international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(6): 819-28.

3. Beukelman T, et al. 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the

treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis... Arthritis Care Res 2011; 63(4):465-82.

4. Ringold S, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline

fot the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Therapeutic Approaches for Non-

Systemic Polyarthritis, Sacroilitis, and Enthesitis. Arthritis Care Res 2019; 71(6):717-34.

5. Cellucci T, et al. Management of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis 2015: A Position Statement

from the Pediatric Committee of the Canadian Rheumatology Association. J Rheumatol

2016; 43(10):1773-6.

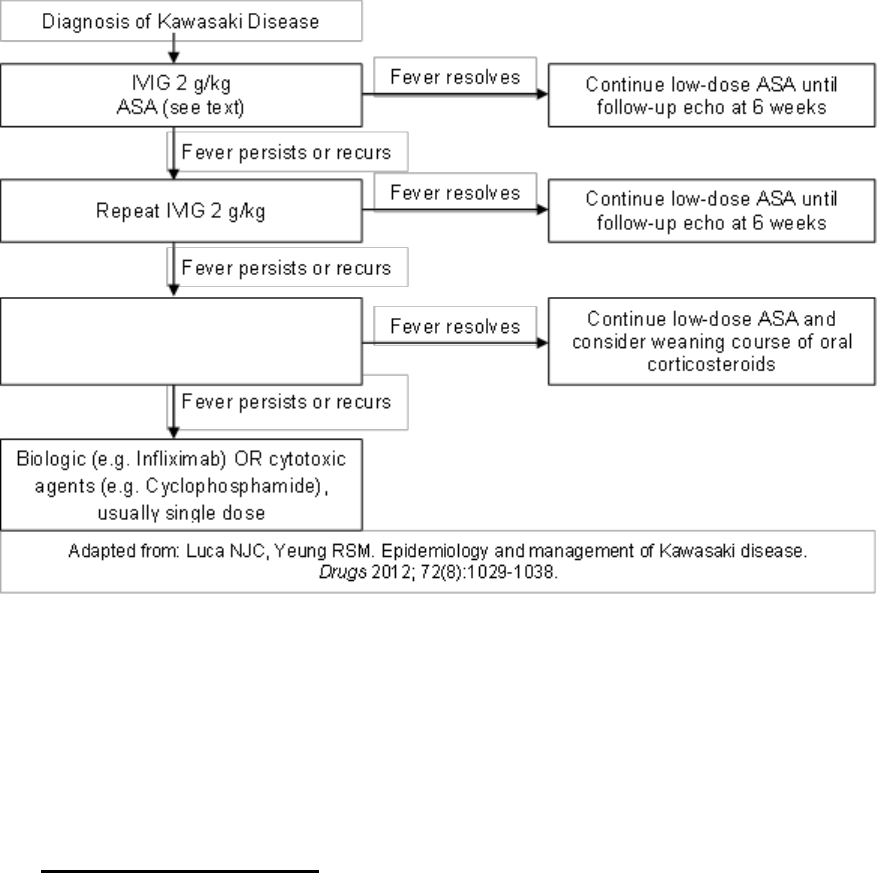

Systemic arthritis

Mild to moderate disease

Moderate to severe disease

NSAID and/or Corticosteroidsand/or

Anakinra

Corticosteroids and/or biologic agent,

such as anti-IL-1 or anti-IL-6 therapy

Improvement

Inadequate

response

Improvement

Inadequate

response

Continue therapy

and follow

Continue therapy

and follow

Add or change

biologic anti-IL-1 or

anti-IL-6 agent

Remission Recurrence

Recurrence

Remission

Recurrence

Remission

Change biologic therapy or

consider methotrexate,

leflunomide, or anti-TNF

agent, or abatacept if

prominent arthritis

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 35

SECTION 4. SYSTEMIC LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS & RELATED CONDITIONS

4A. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

Multi-system inflammatory disease characterized by autoantibody and immune-complex

mediated inflammation of blood vessels and connective tissues

Pediatric-onset SLE accounts for 10-20% of all cases of SLE

Female predominance, especially in adolescence and adulthood

Ethnic predilection in Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians

Positive family history of SLE in 10%

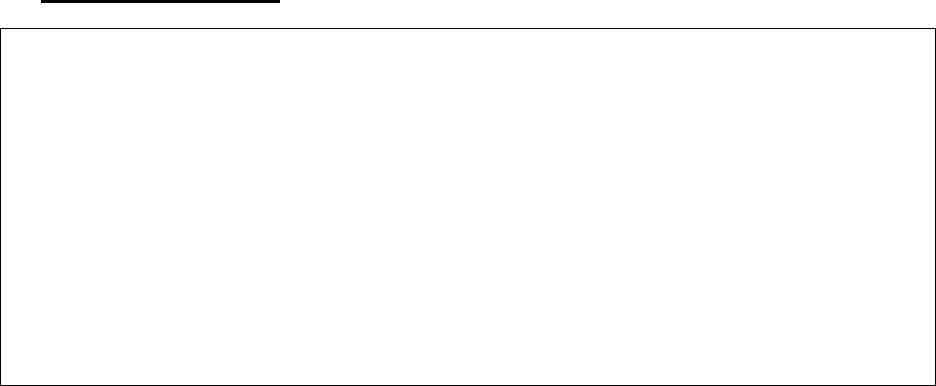

1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Classification Criteria for SLE *

Patients are classified as having SLE if they have ≥ 4/11 of following criteria:

Malar rash (butterfly rash sparing nasolabial folds)

Discoid lupus rash **

Photosensitivity

Oral or nasal mucocutaneous ulcerations (typically painless)

Non-erosive arthritis involving two or more peripheral joints

Nephritis (characterized by proteinuria and/or cellular casts)

CNS involvement (characterized by seizures and/or psychosis)

Serositis (pleuritis or pericarditis)

Cytopenia (thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, leukopenia, hemolytic anemia with

reticulocytosis)

Positive ANA

Positive immunoserology (anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm (anti-Smith), antiphospholipid antibodies)

* Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research studies

and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

** Uncommon in children

1997 ACR classification criteria are not diagnostic criteria and were designed to identify a

homogeneous population of SLE patients for research studies; however, the presence of ≥ 4

criteria is specific for SLE (>93%) and so the criteria have been widely used for diagnosis

In 2012, newer Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics (SLICC) classification

criteria for SLE were developed that incorporated more immunologic criteria and were more

sensitive (>95%) but less specific (83%) than the 1997 ACR criteria

New EULAR/ACR classification criteria for SLE have been developed in 2019 and may be

adopted in the future since they are both sensitive (>95%) and specific (>93%) for SLE

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 36

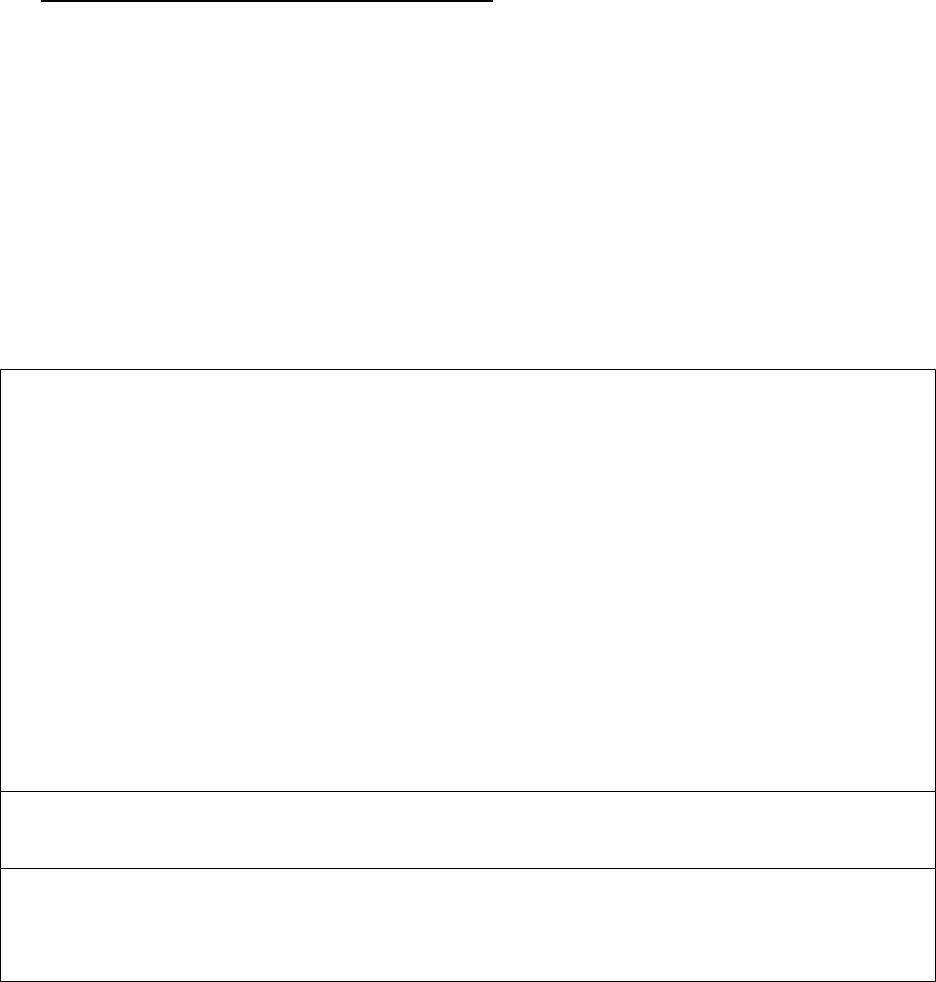

2019 Proposed European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and American College

of Rheumatology (ACR) Classification Criteria for SLE *

Clinical domains

Points**

Constitutional domain

Fever

2

Cutaneous domain

Non-scarring alopecia

Oral ulcers

Subacute cutaneous or discoid lupus

Acute cutaneous lupus

2

2

4

6

Arthritis domain

Synovitis or tenderness in at least 2 joints

6

Neurologic domain

Delirium

Psychosis

Seizure

2

3

5

Serositis domain

Pleural or pericardial effusion

Acute pericarditis

5

6

Hematologic domain

Leukopenia

Thrombocytopenia

Autoimmune hemolysis

3

4

4

Renal domain

Proteinuria >0.5 g/24 hours

Class II or V lupus nephritis

Class III or IV lupus nephritis

4

8

10

Immunological domains

Points**

Antiphospholipid antibody domain

Anti-cardiolipin IgG >40 GPL

Or anti-β

2

-glycoprotein I IgG >40 units

Or lupus anticoagulant

2

Complement proteins domain

Low C3 or low C4

Low C3 and low C4

3

4

Highly specific antibodies domain

Anti-dsDNA antibody

Anti-Sm (Anti-Smith) antibody

6

6

* In order to be classified as having SLE, patients must have all of the following: (a) ANA

≥1:80 (entry criterion); (b) ≥10 points in total; and (c) at least one clinical criterion

N.B. Classification criteria are designed to identify a homogeneous population for research

studies and are not diagnostic criteria, although they are often used for diagnosis in practice

** Only the highest criterion in a given domain is counted toward total number of points

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 37

Other clinical features of SLE not included in any of the above classification criteria:

o Additional constitutional symptoms (i.e. fatigue, weight loss, anorexia)

o Other rashes (e.g. annular erythema, maculopapular or linear (nonspecific) rash, bullous

lupus (rare), palmar/plantar/periungual erythema, livedo reticularis, or vasculitic rash)

o Myalgia, and/ or myositis

o Raynaud phenomenon (see Section 7E)

o Lymphadenopathy

o Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly

o Decreased concentration and cognitive dysfunction, stroke, mood disorder, headache

o Pneumonitis, pulmonary hemorrhage

o Myocarditis, Libman-Sacks endocarditis

Other common laboratory features of SLE:

o Elevated ESR with normal CRP (except high CRP in infection and/or serositis)

o Elevated IgG levels

o Other autoantibodies: anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-RNP, Rheumatoid factor

May be accompanied by macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) at onset or anytime during

course

Treatment

o Use minimum required treatment to maintain clinical and laboratory quiescence

o More aggressive treatment used for more severe organ involvement

o Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil™)

Considered standard therapy for SLE

Proven efficacy in decreasing frequency and severity of disease flares

Improves serum lipid profile

May be helpful in lowering antiphospholipid antibody titres and preventing thrombotic

recurrences in patients with SLE

o Corticosteroids

Often used in initial therapy for SLE with dose depending on severity and organ

involvement

Pulse (very high dose) therapy is used for severe lupus nephritis, hematologic crisis,

CNS disease or other life or organ-threatening manifestations

o Azathioprine

Typically used for hematologic and renal manifestations

o Mycophenolate mofetil

Used for hematologic, renal and CNS manifestations

o Cyclophosphamide

Used for severe renal and CNS manifestations

o Rituximab

Used for resistant thrombocytopenia and in other specific scenarios, such as when a

patient is unresponse to other therapies

o Belimumab

Adjunctive therapy for mild/moderate SLE (trials excluded those with severe CNS

and renal involvement)

Course and Outcomes

o Relapsing and remitting course of disease

o 10-year survival >90%

o Most deaths related to infection, renal, CNS, cardiac, and pulmonary disease

A RESIDENT’S GUIDE TO PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

© Copyright of The Hospital For Sick Children Page 38

o Additional morbidity related to disease and/or treatment:

Early-onset coronary artery disease

Bone disease → osteopenia, osteoporosis, avascular necrosis

Malignancy

Infection

Childhood-onset SLE vs. adult-onset SLE

Children have more active disease at presentation and over time

Children more likely to have active renal disease (~70% vs. 30-60% in adults)

Children receive more intensive drug therapy and sustain more long-term damage

References:

1. Harry O, et al. Childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update. J

Pediatr 2018; 196:22-30.

2. Tarvin SE, O’Neil KM. Systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, and mixed

connective tissue disease in children and adolescents. Ped Clin North Am 2018;

65(4):711-37.

3. Weiss JE. Pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: More than a positive antinuclear

antibody. Pediatr Rev 2012; 33(2):62-73.

4. Tedeschi SK, et al. Multicriteria decision analysis process to develop new classification

criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019; 78(5):634-40.

4B. Neonatal Lupus Erythematosus (NLE)

Disease of developing fetus and newborn characterized by transplacental passage of

maternal autoantibodies

Pathogenesis linked to maternal anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies

Presence of autoantibodies is necessary but not sufficient to cause NLE since many

mothers with autoantibodies deliver healthy, unaffected infants

Mothers of infants with NLE may have SLE, Sjögren syndrome, or another autoimmune

disease; however, many mothers are healthy with no known autoimmune disease

Incidence of NLE is 1-2% in children of mothers with anti-Ro and/or anti-La antibodies

Higher risk for subsequent children once one child has been affected (e.g. 16% of

subsequent siblings of child with congenital heart block)

Clinical features

o Cardiac

Most important and severe manifestation is complete congenital atrioventricular (AV)

heart block

Complete heart block is associated with significant morbidity and mortality

(congestive heart failure, fetal hydrops, intrauterine death)

Other manifestations include less severe conduction abnormalities, carditis and risk

of endocardial fibroelastosis

o Skin

Classic NLE rash is annular, erythematous papulosquamous rash with fine scale and