2018

Colorado

Local Government

Handbook

Research Publication No. 719

The following Legislative Council Staff members

contributed to this report:

Chris Creighton, Fiscal Analyst

Anna Gerstle, Fiscal Analyst

Vanessa Reilly, Research Analyst

Libby Taylor, Constituent Services Analyst

This page intentionally left blank.

Introduction

This handbook is intended to serve as a resource guide on the role and responsibilities of local

governments, including counties, municipalities, special districts, and school districts. It is divided

into the following nine sections:

Section 1 provides an overview of the Colorado Department of Local Affairs;

Sections 2 through 4 describe county governments, municipal governments, and city and county

governments;

Section 5 provides an overview of local government land use and planning powers;

Sections 6 and 7 describe special districts and public schools;

Section 8 discusses the initiative and referendum process for local governments; and

Section 9 describes the laws concerning term limits and recall of local elected officials.

This page intentionally left blank.

Table of Contents

Section I: Overview of Colorado Department of Local Affairs ............................................................................. 1

Section II. County Governments .............................................................................................................................. 3

Organization and Structure .................................................................................................................................... 3

County Elected Officials ......................................................................................................................................... 3

Salaries of County Officials ................................................................................................................................... 6

House Rule Counties ............................................................................................................................................. 9

County Powers and Responsibilities .................................................................................................................... 9

County Revenue Sources .................................................................................................................................... 10

Revenues and Expenditures ............................................................................................................................... 11

Section III: Municipal Governments ...................................................................................................................... 15

Statutory Towns and Cities .................................................................................................................................. 15

Home Rule Municipalities .................................................................................................................................... 17

Annexation ............................................................................................................................................................. 19

Discontinuance of Incorporation ......................................................................................................................... 21

Abandoned Municipalities .................................................................................................................................... 21

Financial Powers of Municipalities ..................................................................................................................... 22

Revenues and Expenditures ............................................................................................................................... 23

Section IV: City and County Governments............................................................................................................ 25

Revenues and Expenditures ............................................................................................................................... 25

Section V: Local Government Use and Planning Powers ................................................................................... 29

General Land Use and Planning Laws for Local Governments ..................................................................... 29

Municipal Land Use and Planning Powers ........................................................................................................ 29

County Land Use and Planning Powers ............................................................................................................ 30

Local Governments and the Power of Eminent Domain ................................................................................. 30

Section VI: Special Districts .................................................................................................................................... 33

Types of Special Districts .................................................................................................................................... 33

Organization and Oversight of Special Districts ............................................................................................... 35

Dissolution of Special Districts ............................................................................................................................ 37

Reporting Requirements ...................................................................................................................................... 38

Section VII: Public Schools...................................................................................................................................... 41

School Districts ...................................................................................................................................................... 41

Types of Public Schools ....................................................................................................................................... 43

Section VIII: Initiative and Referendum Process for Local Governments......................................................... 45

Section IX: Term Limits and Recall of Local Elected Officials............................................................................ 47

Term Limits ............................................................................................................................................................ 47

Recall ...................................................................................................................................................................... 47

Appendix A: Colorado Municipalities ..................................................................................................................... 49

Appendix B: Colorado School Districts .................................................................................................................. 53

This page intentionally left blank.

Local Government Handbook 1

Section I: Overview of Colorado Department of Local Affairs

The Department of Local Affairs (DOLA) is responsible for supporting Colorado's local communities

and building local government capacity through training, technical, and financial assistance.

The divisions of the department serve several purposes for local entities, including: disaster

recovery; provision of affordable housing; property tax assessment and collection; training for local

government officials; and distribution of state and federal aid for community projects. In

FY 2018-19, the department was comprised of five sections: the Executive Director’s Office, the

Division of Property Taxation, the Division of Housing, and the Division of Local Government. As

shown below in Table 1, funding for this department consists of 11.7 percent General Fund,

58.9 percent cash funds, 3.8 percent reappropriated funds, and 25.6 percent federal funds.

Table 1

Department of Local Affairs FY 2018-19 Appropriation

(millions)

General

Fund

Cash

Funds

Reappropriated

Funds

Federal

Funds

Total

Appropriation

$37.1

$186.1

$12.1

$80.8

$316.1

11.7%

58.9%

3.8%

25.6%

100.0%

Source: Joint Budget Committee Staff.

Cash funds are separate funds received from taxes, fees, and fines that are earmarked for specific

programs and typically related to the identified revenue source. For example, some of the largest

cash funds in the department's budget come from the Local Government Severance Tax Fund

($52 million), lottery proceeds credited to the Conservation Trust Fund ($50 million), Local

Government Mineral Impact Fund ($48.0 million), Marijuana Tax Cash Fund ($21.6 million), and the

Local Government Limited Gaming Impact Fund ($5.1 million). The following section describes the

functions of each division, and Table 2 on page 2 shows the FY 2018-19 appropriations to the

department's divisions.

Division of Property Taxation. The Division of Property Taxation has three primary

responsibilities. First, the division oversees the administration of property tax laws, including

issuing appraisal standards and training county assessors. Second, the division grants tax

exemptions for charities, religious organizations, and other eligible entities. Lastly, the division sets

valuations for public utility and rail transportation companies. The division is managed by the

property tax administrator, who is appointed by the State Board of Equalization. The division also

provides funding for the State Board of Equalization, which supervises the administration of

property tax laws by local county assessors. The division accounted for $3.7 million, or 1.2 percent,

of DOLA's total appropriation for FY 2018-19.

Division of Local Government. Currently, there are 3,842 local governments in Colorado. The

Division of Local Government provides information and training for local governments in budget

development, purchasing, demographics, land use planning, community development, water and

wastewater management, and regulatory issues. Lastly, the division distributes state and federal

moneys to assist local governments in capital construction and community services, including:

2 Local Government Handbook

Community Services Block Grants;

Community Development Block Grants;

Local Government Mineral and Energy Impact Grants;

Local Government Severance Tax Fund distributions;

Limited Gaming Impact Grants; and

Conservation Trust Fund distributions.

The division accounted for $195.7 million, or 61.9 percent, of DOLA's total appropriation for

FY 2018-19.

Board of Assessment Appeals. The Board of Assessment Appeals (BAA) is a quasi-judicial body in

DOLA that hears individual taxpayer requests for property tax abatements, and property tax

exemptions. The three-member board hears appeals concerning the valuation of real and personal

property, property tax abatements, and property tax exemptions. The three-member board is

appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate.

Table 2

Divisions within the Department of Local Affairs

FY 2018-19 Appropriation (millions)

Division

General

Fund

Cash Fund

Reappropriated

Funds

Federal

Funds

Total

Appropriation

Director’s

Office

$1.8

$1.5

$4.1

$1.4

$8.8

2.8%

Property

Taxation

$2.3

$1.2

$0.2

$0.0

$3.8

1.2%

Housing

$17.9

$21.3

$1.1

$67.5

$107.8

34.1%

Local

Government

$15.2

$162.0

$6.6

$11.9

$195.7

61.9%

Total

Appropriation

$37.1

$186.1

$12.1

$80.8

$316.1

100.0%

Source: Joint Budget Committee Staff

Local Government Handbook 3

Section II. County Governments

Organization and Structure

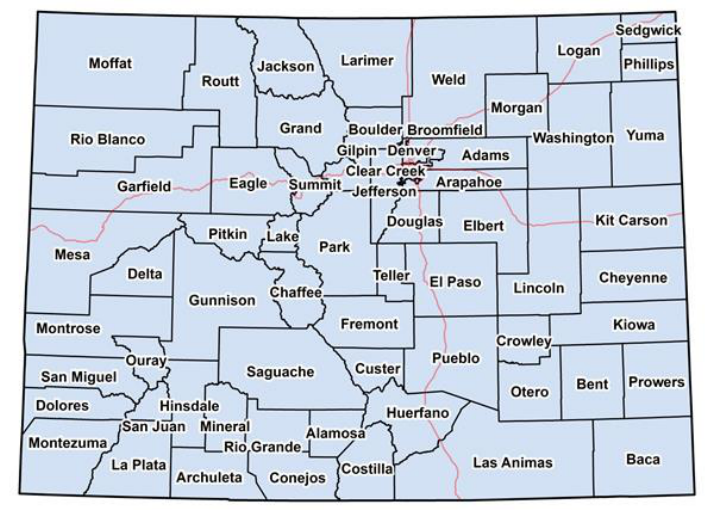

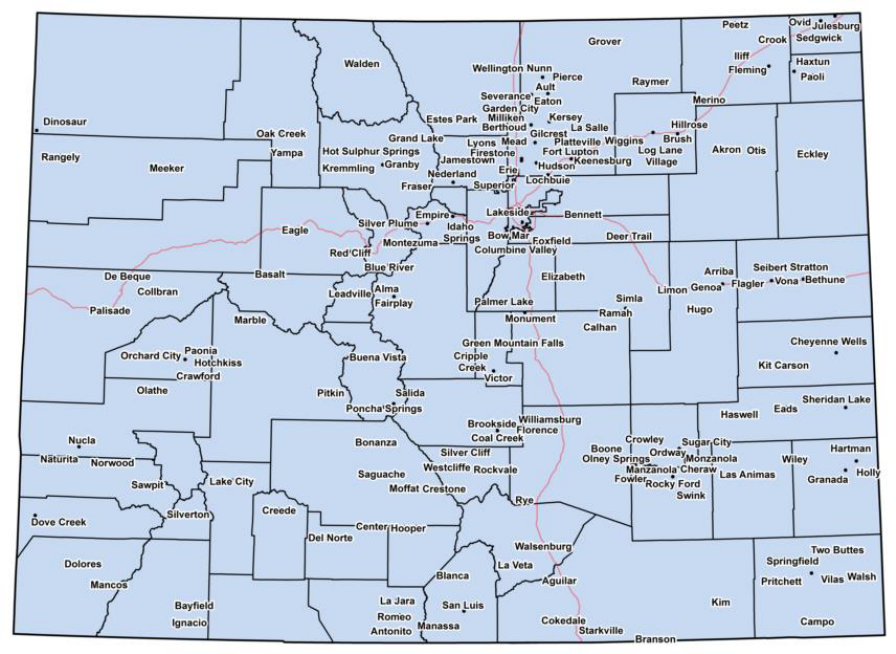

Colorado is divided into 64 counties. Counties are political subdivisions of state government, and

may only exercise those powers specifically provided in state law. Generally, counties are

responsible for law enforcement; the provision of social services on behalf of the state; the

construction, maintenance, and repair of roads and bridges; and general control of land use in

unincorporated areas. County boundaries are established in statute.

The Colorado Constitution establishes the following county officers: commissioners, treasurer,

assessor, coroner, clerk and recorder, surveyor, and sheriff, with duties provided under state law.

All counties in Colorado are assigned to one of six categories based on population and other factors

for the purposes of setting the salaries of elected county officials. Counties are also assigned a

different "class” in state law for the purpose of fixing fees collected by the county and “categories”

for the purpose of setting county elected official salaries.

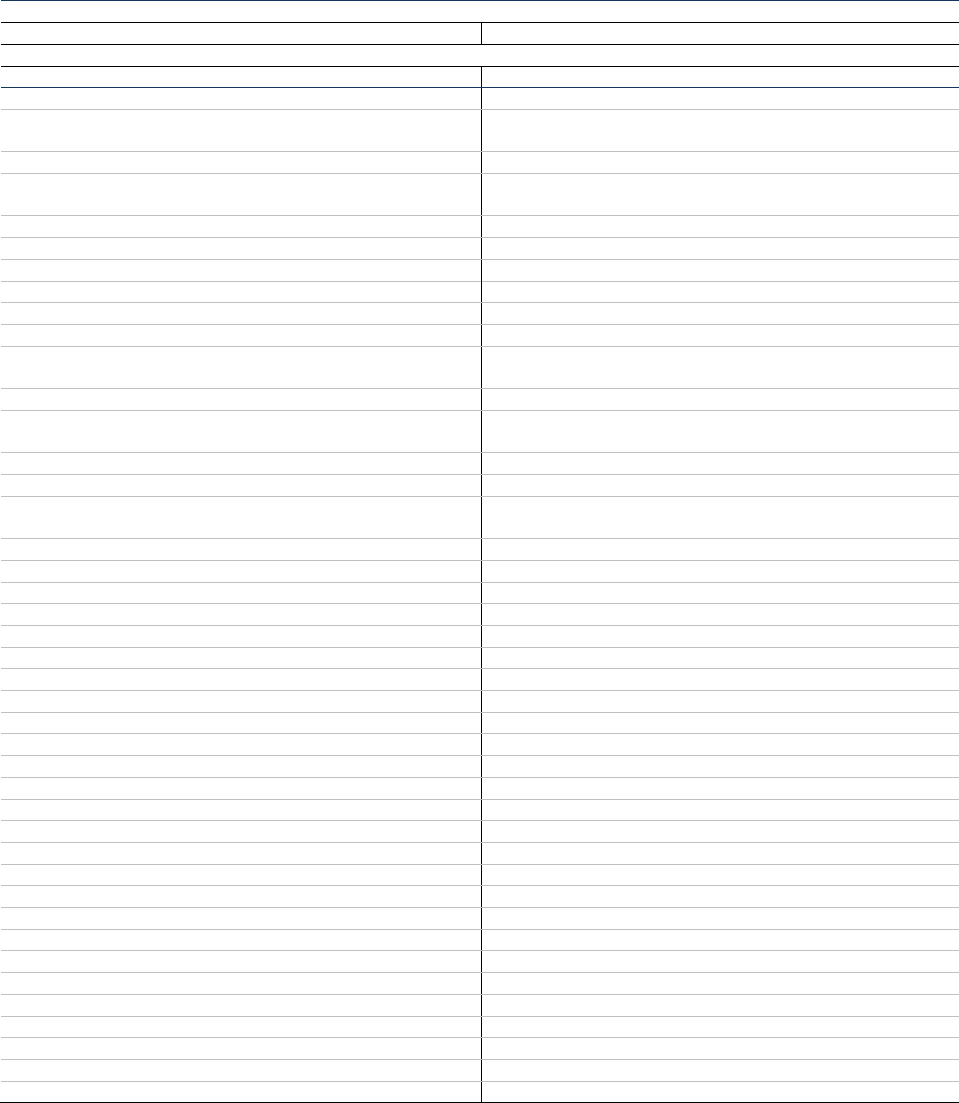

Map 1

Colorado Counties

County Elected Officials

County commissioners. The board of county commissioners is the primary policy-making body for

the county and is responsible for the county’s administrative and budgetary functions. Most

counties have three commissioners who represent separate districts, but are elected by the voters of

the entire county. Any county with a population over 70,000 may expand its board from three to

five commissioners by a vote of county electors.

4 Local Government Handbook

The other county elected officers are the county clerk and recorder, county assessor, county

treasurer, county sheriff, county coroner, and the county surveyor, who are elected to four-year

terms under the state constitution. These elected officials have specific powers and duties that are

prescribed by law, and they function independently from each other and from the board of county

commissioners. However, the county commissioners approve the budgets for all county

departments. County officers must be qualified electors and have resided in the county for at least

one year preceding election. The constitution also provides for a county attorney who, by statute, is

appointed by and reports to the county commissioners.

County clerk and recorder. As the primary administrative officer of the county, the county clerk and

recorder records deeds in the county and serves as the clerk to the board of county commissioners.

The clerk is also an agent of the state Department of Revenue and is charged with the administration

of certain state laws relating to motor vehicles, certification of automobile titles, and motor vehicle

registrations. The clerk administers all primary, general, and special elections held in the county,

oversees voter registration, publishes notices of elections, appoints election judges, and ensures the

printing and distribution of ballots. The board of county commissioners has a duty to supervise the

conduct of general and special elections, and is expected to consult and coordinate with the clerk

and recorder on rendering decisions and interpreting state election codes. The clerk and recorder

also issues marriage licenses, maintains records and books for the board of commissioners, collects

license fees and charges required by the state, maintains property ownership records, and provides

deed abstracts upon request.

County treasurer. The county treasurer is responsible for the receipt, custody, and disbursement of

county funds. The treasurer collects some state taxes and all property taxes in the county, including

those for other units of local government such as cities and school districts, minus a statutory

collection fee. The treasurer also conducts sales of property for delinquent taxes.

County assessor. The county assessor is responsible for discovering, listing, classifying, and valuing

all property in the county in accordance with state laws. It is the assessor's duty to determine the

actual and taxable value of property. Most real property, such as residential and commercial

property, is reassessed every odd-numbered year, and personal property is reassessed every year.

The assessor is required to send out a notice of valuation each year to property owners, which

reflects the owner's property value and the amount of property taxes due to the county treasurer.

Qualifications for county assessors are addressed by the Real Estate Appraiser's Act. The act

requires, among other things, that real estate appraisers meet state licensing requirements and that

county assessors comply with the licensing requirements within two years after taking office.

County sheriff. Counties are responsible for law enforcement, which includes supporting the court

system and the district attorney function, as well as providing jail facilities through the sheriff. The

county sheriff is the chief law enforcement officer of the unincorporated areas of a county and is

responsible for maintaining the peace and enforcing the criminal laws of the state. The sheriff

supports the county court system and is required to serve and execute processes, subpoenas, writs,

and orders as directed by the court. The sheriff oversees the operation of the county jail, and must

maintain and feed prisoners. The sheriff is also the fire warden for prairie or forest fires in the

county and is responsible for county search and rescue functions. County sheriffs can also provide

Local Government Handbook 5

law enforcement for, or share jurisdiction with, a municipality through a contract for services or an

intergovernmental agreement (IGA). State law specifies that any candidate for county sheriff must:

be a citizen of the United States;

be a resident of the state of Colorado;

be a resident of the county in which the person will hold the office;

have a high school diploma or a college degree;

complete a criminal history record check; and

provide a complete set of fingerprints to a qualified law enforcement agency.

Any person who has been convicted of any federal or state felony charge is ineligible for the office of

sheriff unless the person has been pardoned.

County coroner. The county coroner is responsible for investigating the cause and manner of

deaths, issuing death certificates, and requesting autopsies. The coroner is the only county official

empowered to arrest the county sheriff, or to fill the position of interim county sheriff in the event of

a vacancy. Similar to the requirements for county sheriff, state law specifies that any candidate for

county coroner must:

be a citizen of the United States;

be a resident of the state of Colorado;

be a resident of the county in which the person will hold the office;

have a high school diploma or a college degree;

complete a criminal history record check;

provide a complete set of fingerprints to a qualified law enforcement agency according to state

law; and

possess knowledge and experience concerning the medical-legal investigation of death.

Additionally, any person who has been convicted of any federal or state felony charge is ineligible

for the office of county coroner unless he or she has been pardoned.

A constitutional amendment, passed in 2002, authorizes the General Assembly to require that

coroners receive minimum training upon election to office. State law requires that a person who is

elected or appointed to the office of coroner for the first time to attend a training course for at least

40 hours using the curriculum developed by the Colorado Coroners Standards and Training (CCST)

board, which is overseen by the Department of Public Health and Environment. Within one year of

taking office, any person who is elected or appointed to the office of coroner for the first time must

obtain certification in basic medical-legal death investigation from the Colorado Coroners

Association or another training provider approved by the CCST board. State law also requires each

coroner to complete a minimum of 16 hours of in-service training provided by the Colorado

Coroners Association or by another training provider approved by the CCST board during each year

of the coroner's term. The CCST board has the authority to grant an extension of up to one year to

obtain certification or determine that a combination of education, experience, and training satisfies

the requirement to complete 16 hours of in-service training annually.

6 Local Government Handbook

County surveyor. The county surveyor is responsible for any surveying duties pertaining to the

county and for settling boundary disputes when directed by a court or when requested by interested

parties. The county surveyor establishes the boundaries of county property, including road

rights-of-way, and supervises construction surveys that impact the county. County surveyors also

create survey markers and monuments, and conduct surveys relating to toll roads and reservoirs.

State law requires that county surveyors meet the requirements to qualify as a professional land

surveyor and requires surveyors to file an official bond of $1,000 with the county clerk and recorder.

Salaries of County Officials

The Colorado Constitution requires the General Assembly to set the salary levels for county

commissioners, sheriffs, treasurers, assessors, clerk and recorders, and coroners. The General

Assembly is required to consider specific factors when fixing the compensation of county officers

and must set a level of compensation that reflects variations in the workloads and responsibilities of

each county officer.

The state constitution also provides that county officers cannot have their compensation changed

during their terms of office. Further, any change in compensation may occur only when the

compensation of all county officers within the same county is adjusted, or when the compensation

for the same county office in all of the counties of the state is increased or decreased.

County categorization. All Colorado counties are assigned a category — I through VI — for the

purpose of setting the salaries of elected county officials. In general, the counties in categories I

through III are larger counties that are required to pay higher salaries than counties in categories IV

through VI. The category assignments are based on factors including population, the number of

persons residing in the unincorporated areas of the county, assessed valuation of properties in the

county, motor vehicle registration, building permits, and other factors reflecting the workloads and

responsibilities of county officers. These categories are subject to change, based on factors like

population growth or property valuation. The salary schedule does not affect the city and county

governments of Broomfield and Denver, or the home rule counties (Pitkin and Weld) that are

authorized to set their own compensation rates.

In 2015, the General Assembly changed the categorization of counties for the purpose of setting

salaries. Specifically, four subcategories were added to each classification, for a total of

24 categories. All changes to county salaries were effective starting January 1, 2016, for all terms of

office beginning after this date. As a result, a county will be responsible for administering salaries

based on both categorizations until all terms that began prior to January 1, 2016, have expired.

County elected officials' salary commission. In 2015, an independent commission was required to

make recommendations to the General Assembly on the equitable and proper salaries to be paid to

county elected officials. The County Elected Officials' Salary Commission was repealed by the 2015

General Assembly, effective January 1, 2016.

Local Government Handbook 7

Terms beginning prior to January 1, 2016. The salaries of elected county officials for terms of office

that began prior to January 1, 2016, are summarized in Table 3. The counties that fall into each

category are shown in Table 4.

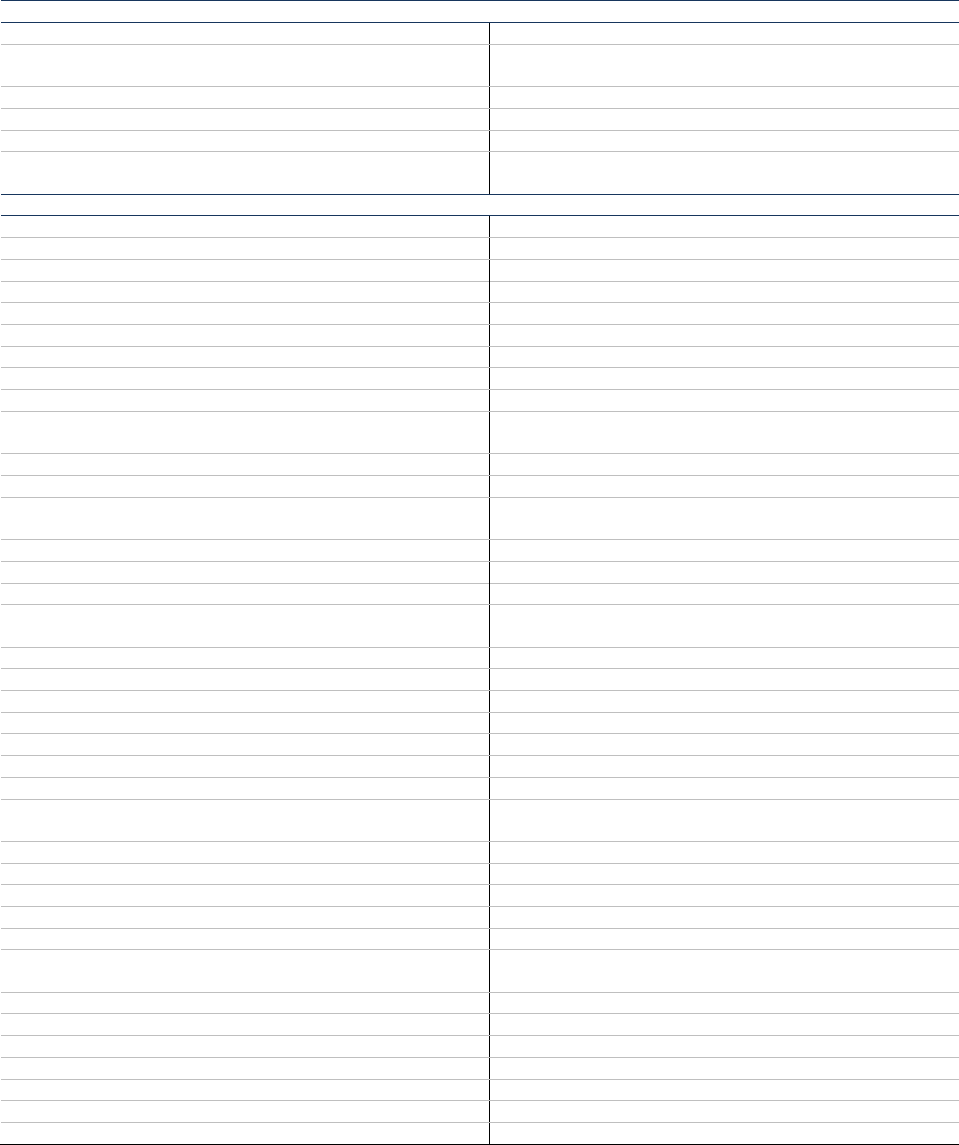

Table 3

Salaries of County Officials Whose Terms of Office Began Prior to January 1, 2016

County

Category

County

Commissioners

County

Sheriffs

County Treasurers,

Assessors, and Clerks

County

Coroners

County

Surveyors

I

$87,300

$111,100

$87,300

$87,300

$5,500

II

$72,500

$87,700

$72,500

$44,200

$4,400

III

$58,500

$76,000

$58,500

$33,100

$3,300

IV

$49,700

$66,600

$49,700

$22,100

$2,200

V

$43,800

$49,100

$43,800

$9,900

$1,100

VI

$39,700

$46,500

$39,700

$9,000

$1,000

Source: Section 30-2-102 (2.2), C.R.S.

Table 4

Categories of Counties to Set Salaries of County Officials Whose Terms Began Prior to

January 1, 2016

County

Category

Counties

I

Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Douglas, El Paso, Jefferson, Larimer, Pueblo, and Weld*

II

Eagle, Fremont, Garfield, La Plata, Mesa, Pitkin*, Routt, and Summit

III

Alamosa, Archuleta, Chaffee, Clear Creek, Delta, Gilpin, Grand, Gunnison, Las Animas,

Logan, Moffat, Montezuma, Montrose, Morgan, Otero, Park, Rio Blanco, San Miguel, and

Teller

IV

Custer, Elbert, Huerfano, Kit Carson, Lake, Ouray, Prowers, Rio Grande, Washington,

and Yuma

V

Baca, Bent, Cheyenne, Conejos, Costilla, Crowley, Dolores, Hinsdale, Lincoln, Mineral,

Phillips, Saguache, and San Juan

VI

Jackson, Kiowa, and Sedgwick

Source: Section 30-2-102 (1), C. R. S.

*Home rule counties are authorized to set their own compensation rate.

Terms beginning on or after January 1, 2016. Senate Bill 15-288 established 24 categories — I-A

through VI-D — for the purposes of establishing the salaries of county officers whose terms begin on

or after January 1, 2016.

The General Assembly may move a county to another category after considering a county’s

population, persons residing in unincorporated areas, the assessed valuation of property in the

county, and motor vehicle registrations, building permits, military installations, and other factors

that may reflect the variations in workloads and responsibilities of county officers and the tax

resources of the counties. Prior to January 1 and every two years thereafter, the director of research

of Legislative Council is required to adjust the salaries of elected county officials for inflation and

post such adjusted salary amounts on the General Assembly's website.

8 Local Government Handbook

Government officials may not increase their salary for a current term. As a result, county officers

will not receive an increase in their salary, based on the categories in Table 5 and Table 6, until a new

term begins.

Table 5 shows the 2018 salaries of elected county officials for terms of office that began on or after

January 1, 2016.

Table 5

Salaries of County Officials Whose Terms of Office Began On or After January 1, 2016

County

Category

County

Commissioners

County

Sheriffs

County

Treasurers,

Assessors,

and Clerks

County

Coroners

County

Surveyors

I-A

$120,485

$153,332

$120,485

$120,485

$7,591

I-B

$111,217

$141,537

$111,217

$111,217

$7,007

I-C

$101,949

$129,742

$101,949

$101,949

$6,423

I-D

$92,681

$117,947

$92,681

$92,681

$5,839

II-A

$100,059

$121,037

$100,059

$61,001

$6,073

II-B

$92,362

$111,726

$92,362

$56,309

$5,605

II-C

$84,665

$102,416

$84,665

$51,617

$5,138

II-D

$76,968

$93,105

$76,968

$46,924

$4,671

III-A

$80,737

$104,889

$80,737

$45,682

$4,554

III-B

$74,527

$96,821

$74,527

$42,168

$4,204

III-C

$68,316

$88,753

$68,316

$38,654

$3,854

III-D

62,106

80,684

62,106

$35,140

$3,503

IV-A

$68,592

$91,916

$68,592

$30,501

$3,036

IV-B

$63,316

$84,846

$63,316

$28,155

$2,803

IV-C

$58,039

$77,775

$58,039

$25,808

$2,569

IV-D

$52,763

$70,705

$52,763

$23,462

$2,336

V-A

$60,449

$67,764

$60,449

$13,663

$1,518

V-B

$55,799

$62,551

$55,799

$12,612

$1,401

V-C

$51,149

$57,339

$51,149

$11,561

$1,285

V-D

$46,500

$52,126

$46,500

$10,510

$1,168

VI-A

$54,791

$64,176

$54,791

$12,421

$1,380

VI-B

$50,576

$59,239

$50,576

$11,466

$1,274

VI-C

$46,362

$54,303

$46,362

$10,510

$1,168

VI-D

$42,147

$49,366

$42,147

$9,555

$1,062

Source: Section 30-2-102, C.R.S.

Recent legislation. House Bill 16-1367 recategorized counties in regard to setting salaries for county

officials. HB 18-1242 modified the categories of four counties, which increased the salaries for each

county. Table 6 summarizes the categorization of counties under both bills. Several of these

categories are not currently applied to any counties and are therefore not included in Table 6;

however, a county could be moved to another category with future legislation.

Local Government Handbook 9

Table 6

Categories of Counties to Set Salaries of

County Officials Whose Terms Began On or After January 1, 2016

County

Category

Counties

I-A

Adams, Arapahoe, Boulder, Douglas, El Paso, Jefferson, Larimer, Pueblo, and Weld*

I-D

Mesa

II-A

Eagle, Garfield, La Plata, Routt, and Summit

II-C

Fremont and Pitkin*

III-A

Alamosa, Chaffee, Clear Creek, Gunnison, Moffat, Montrose, Morgan, Park, Rio Blanco,

San Miguel, and Teller

III-B

Archuleta, Delta, Gilpin, Grand, and Logan

III-C

Otero

III-D

Las Animas and Montezuma

IV-A

Custer, Elbert, Ouray, and Prowers

IV-B

Kit Carson, Lake, Washington, and Yuma

IV-C

Huerfano and Rio Grande

V-A

Baca, Conejos, Costilla, Lincoln, Mineral, Phillips, and San Juan

V-B

Crowley, Hinsdale, and Saguache

V-C

Bent and Dolores

V-D

Cheyenne

VI-C

Jackson and Sedgwick

VI-D

Kiowa

Source: Section 30-2-102 (1.5)(a), C. R. S.

* Home rule counties are authorized to set their own compensation rate (Pitkin and Weld Counties).

House Rule Counties

The Colorado Constitution enables the voters of a county to adopt a home rule charter providing for

the organization and structure of their county. A county charter may establish, either at the outset

or by subsequent amendment, its own structure of county government. This includes the number,

terms, qualification, duties, compensation, and method of selection of county officials and

employees. A county home rule charter does not provide the “functional” home rule powers found

in municipal charters, and, as subdivisions of the state, a home rule county must continue to provide

the county services required by law. Thus, state statute determines the functions, services, and

facilities provided by home rule counties. Currently, there are two home rule counties in Colorado:

Pitkin and Weld. Broomfield and Denver are also “home rule,” but have unique dual city/county

status and specific constitutional provisions. City and county governments are discussed further in

Section IV.

County Powers and Responsibilities

Mandatory services. Counties have the powers, duties, and authorities that are explicitly conferred

upon them by state law. Specific statutory responsibilities include the provision of jails, weed

10 Local Government Handbook

control, and establishment of a county or district public health agency to provide, at minimum,

health and human services mandated by the state.

Discretionary powers. Counties also have several discretionary powers to provide certain services

or control certain activities. Listed below are other commonly used powers or services that a board

of county commissioners is authorized to implement. Under state law, counties have the authority

to:

provide veteran services;

operate emergency telephone services;

provide ambulance services;

conduct law enforcement;

operate mass transit systems;

build and maintain roads and bridges;

construct and maintain airports;

lease or sell county-owned mineral and oil and gas rights;

provide water and sewer services;

control wildfire planning and response;

promote agriculture research and protect agricultural operations;

administer pest control; and

operate districts for irrigation, cemeteries, libraries, recreation, solid waste and disposal, and

various types of improvement districts.

Under state law, a board of county commissioners is also authorized to control specific activities

through police powers or through licensing requirements. Some of the most common county

powers are used to regulate activities such as marijuana, trash removal, animal control, disturbances

and riots, and the discharge of firearms in unincorporated areas of urban counties. In other areas,

such as liquor licenses, landfills, and pest control, counties and the state share authority.

County Revenue Sources

Counties have the power to collect property and sales and use taxes, as well as to incur debt, enter

into contracts, and receive grants and gifts. While property taxes are the main source of county

revenue, counties may also collect other sources of revenue at the local level and receive state and

federal dollars.

County property taxes. Under Colorado law, property taxes, also called ad valorem taxes, may only

be assessed for local government services. Property taxes are paid on a proportion of a property’s

value. This assessed value of a property is determined by multiplying the actual value by the

assessment rate, and the property tax is determined by multiplying a property's assessed value by a

mill levy. A mill is one-tenth of a cent; or $1 of taxes for each $1,000 of assessed value. County

property tax levies are restricted by the 5.5 percent limit on annual growth of revenue in state law,

and the mill levy rate limit and the property tax revenue limit under the Taxpayer's Bill of Rights

(TABOR). According to the Department of Local Affairs' Division of Property Taxation, the largest

share of property tax revenue (50.1 percent) goes to support the state's public schools. County

Local Government Handbook 11

governments claim the next largest share (19.6 percent), followed by local and special districts

(18.9 percent), municipal governments (4.9 percent), and junior colleges (1.1 percent).

Debt. Counties can incur either revenue debt, based solely upon a specified revenue stream, or

general obligation debt, which constitutes a general obligation of the local government to repay the

debt. Counties may also enter into lease-purchase arrangements (as an alternative to debt financing)

to build major facilities such as justice centers.

Sales taxes. Sales taxes are levied in most counties. The tax is collected at no charge by the state

Department of Revenue and remitted monthly to the county.

Use taxes. Counties may also collect a use tax. A use

tax is levied on the retail price of certain tangible

personal property purchased outside a taxing

jurisdiction, but stored, used, or consumed within that

jurisdiction. Counties are limited to collecting a use

tax on construction and building materials and motor

vehicles. The purpose of a use tax is to equalize

competition between in-county and out-of-county vendors making wholesale purchases. If a county

has a use tax on construction and building materials, for example, a vendor is required to pay use

tax on the building materials purchased outside of the county and used within the county. When

this circumstance occurs, the county sales tax is not collected.

Revenues and Expenditures

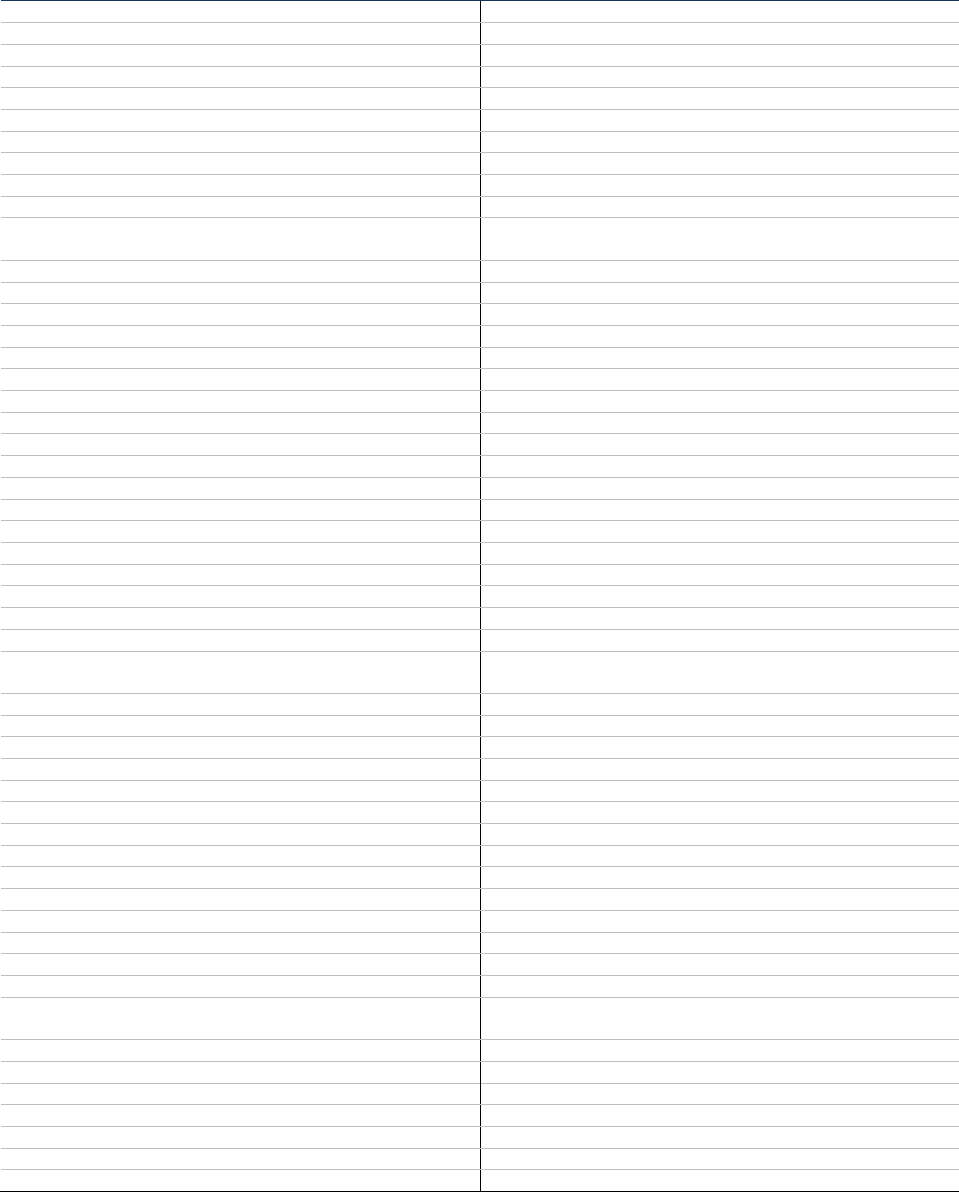

Table 7 shows the total amounts of revenue received by Colorado counties in 2015, of which

36.4 percent is from property tax revenue, 15.3 percent is from sales and use taxes, and 12.7 is

percent from state and federal sources for social services. Table 8 shows the total amount of

expenditures spent by Colorado counties in 2015, including 20.1 percent on public safety,

17.0 percent on social services, 13.0 percent on public works, and 9.6 percent on capital outlay. 2015

is the most recent available data due to lag time between the end of the fiscal year and time it takes

to complete yearend auditing and additional time needed for DOLA to verify revenue and

expenditure actuals submitted by counties.

A use tax is levied on the retail price of

certain tangible personal property

purchased outside a taxing jurisdiction,

but stored, used, or consumed within that

jurisdiction.

12 Local Government Handbook

Table 7

2015 Revenue Totals for Colorado County Governments

Revenue Sources

Amount

% of Total

Local Tax Revenue

General Property

$1,378,122,753

36.4%

General Sales and Use

$579,751,418

15.3%

Specific Ownership

$116,684,511

3.1%

Other

$7,043,374

0.2%

Total Local Revenue

$2,081,602,056

55.0%

Intergovernmental Revenue

Social Services

$481,198,082

12.7%

Highway Users Tax

$199,414,920

5.3%

Conservation Trust Fund

$10,359,205

0.3%

Vehicle Registration Fees

$7,748,430

0.2%

Other Intergovernmental

Sources

$457,068,630

12.1%

Total Intergovernmental

Revenue

$1,155,789,267

30.5%

Other Tax Revenue

Service Charges

$360,852,826

9.5%

Licenses, Permits, and

Capital Fees

$63,799,547

1.7%

Fines and Forfeits

$7,886,571

0.2%

Enterprise Transfers

$2,447,770

0.1%

Miscellaneous

$111,320,026

2.9%

Total Other Tax Revenue

$546,306,740

14.4%

Total Revenue

$3,783,698,063

100.0%

Source: Department of Local Affairs.

Local Government Handbook 13

Table 8

2015 Expenditure Totals for Colorado County Governments

Local Expenditures

Amount

% of Total

Operating Expenditures

Public Safety

$768,207,517

20.1%

Social Services

$649,124,862

17.0%

General Government

$674,186,522

17.7%

Public Works

$497,380,191

13.0%

Health

$172,831,128

4.5%

Culture and Recreation

$165,213,659

4.3%

Judicial

$96,333,530

2.5%

Miscellaneous

$96,828,246

2.5%

Total Operating Expenditures

$3,120,105,655

81.7%

Other Expenditures

Capital Outlay

$365,023,720

9.6%

Transfer to Enterprises and

Outside Entities

$195,331,262

5.1%

Debt Service

$138,942,536

3.6%

Total Other Expenditures

$699,297,518

18.3%

Total Expenditures

$3,819,403,173

100.0%

Source: Department of Local Affairs.

This page intentionally left blank.

Local Government Handbook 15

Section III: Municipal Governments

Overview. There are 272 municipalities in Colorado, including 97 home rule municipalities, 172

statutory municipalities, 2 consolidated city and county governments, and 1 territorial charter

municipality. A brief description of each type of government follows.

Statutory Towns and Cities

Formation. Residents of unincorporated areas may form a municipal corporation under the

authority of state statutes. Municipalities formed under these laws, called statutory cities and

towns, are limited to exercising powers specifically granted to them by state law. In general,

ordinances of statutory towns and cities that conflict with state laws are invalid. Residents in areas

with 2,000 or fewer persons may form a statutory town, and residents in areas with more than 2,000

persons may form a statutory city. There are 12 statutory cities and 160 statutory towns in Colorado.

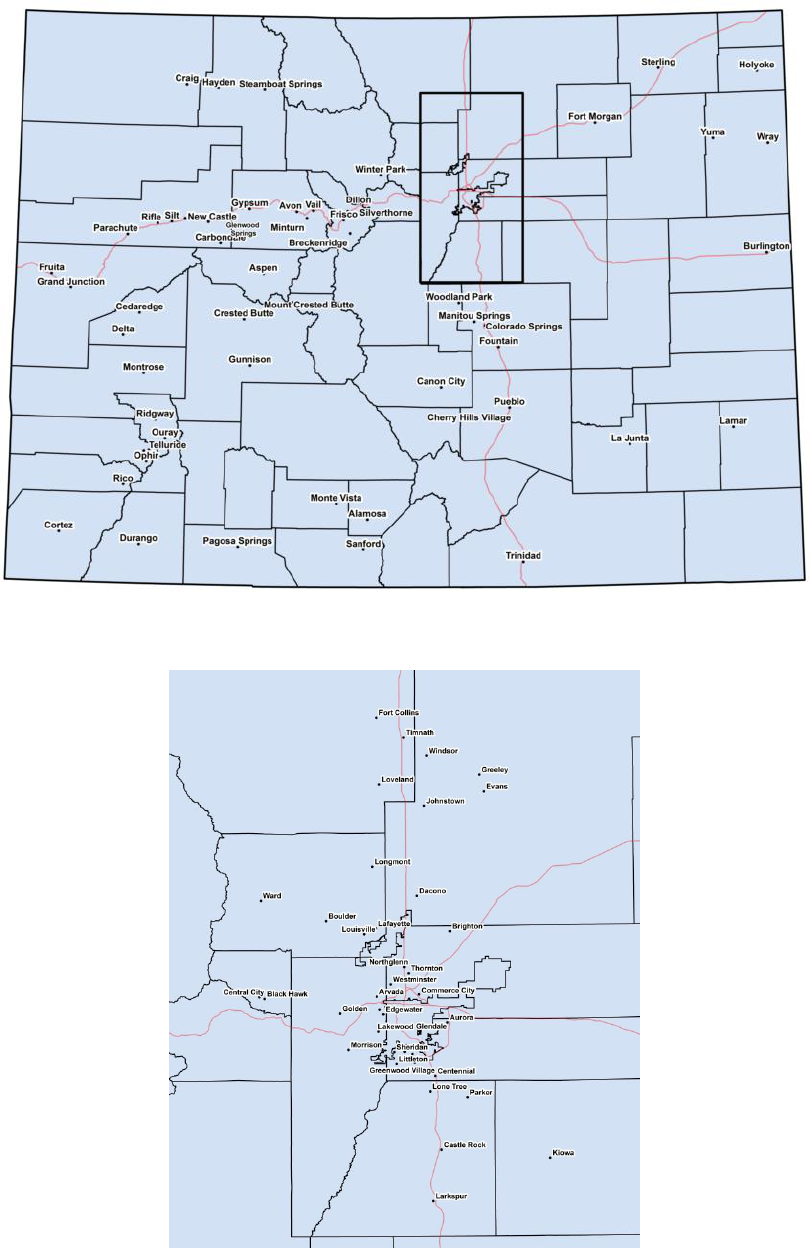

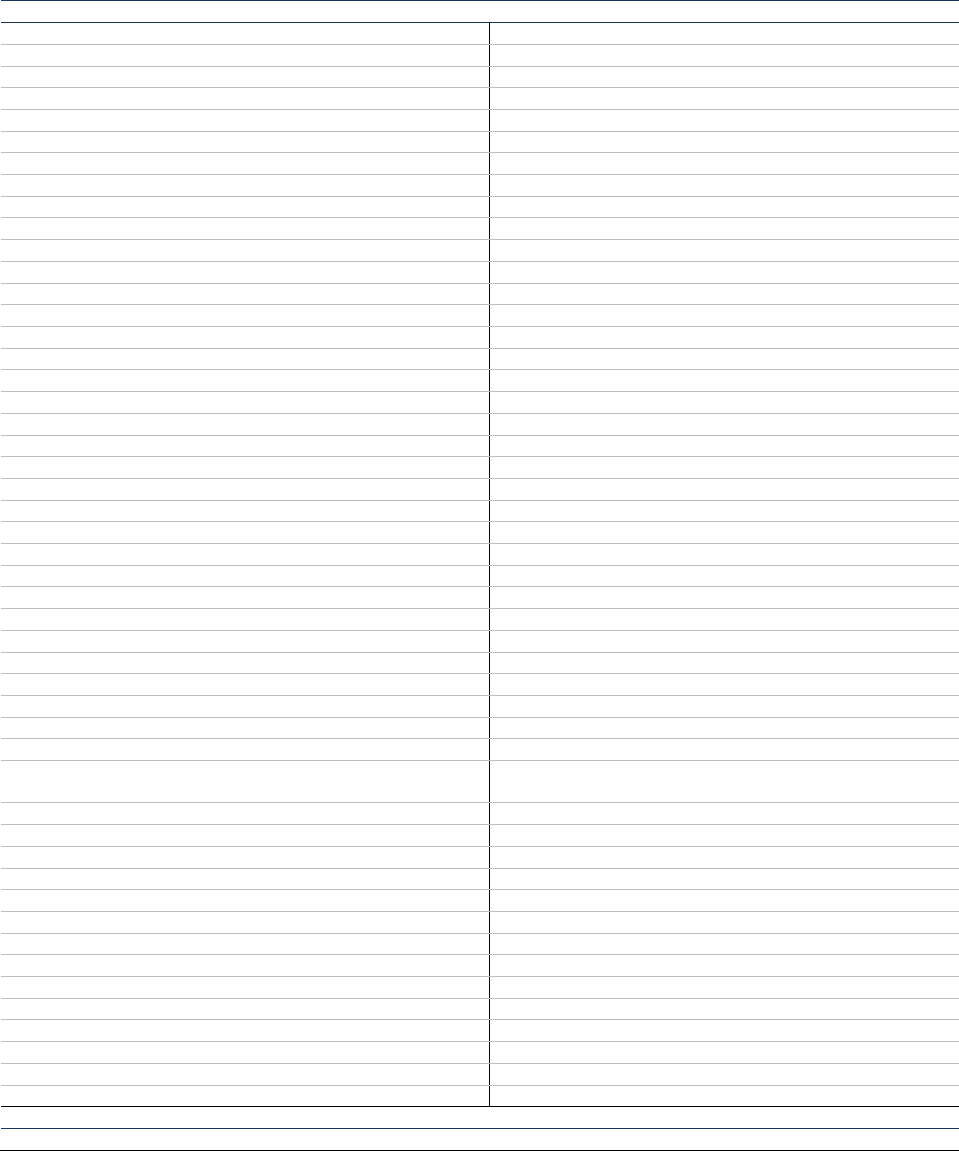

These statutory cities and towns are shown in the map below and a list can be found in Appendix A.

The small number of statutory cities reflects the preference of city residents for constitutional home

rule authority over statutory powers.

Map 2

Colorado Statutory Cities

16 Local Government Handbook

The process for forming a statutory town or city is similar. Residents must first file a petition for

incorporation with the district court of the county in which the municipality is to be located. The

petition must be signed by at least 150 registered electors who are landowners and residents of the

area to be incorporated. However, if the area is located in a county with a population of fewer than

25,000, 40 signatures are required. The court reviews the petition to determine whether the

proposed municipality satisfies statutory requirements. For example, the law prohibits an

incorporation election if the proposed area includes, on average, fewer than 50 persons per square

mile. The court will order an incorporation election after it determines that the proposed area for

incorporation satisfies statutory requirements. Incorporation occurs if a majority of the registered

electors vote to approve the incorporation.

If the area of proposed incorporation includes fewer than 500 registered electors, the board of county

commissioners may refuse to permit an incorporation election if it determines the proposal fails to

satisfy certain statutory requirements. For example, the board may refuse to permit an

incorporation election if the proposed incorporation is inconsistent with a county or regional

comprehensive plan.

Municipal powers. State law provides statutory cities and

towns a broad range of powers to address the needs of

their denser populations through self-government,

including administrative, police, and financial powers.

Administrative powers enable municipalities to fill

vacancies in municipal offices, appoint a board of health,

and provide ambulance, hospital, and other services.

Police powers enable municipalities to enforce local laws,

as well as enact measures to preserve and protect the

safety, health, and welfare of the community. These

powers enable municipalities to prohibit offensive or

unwholesome businesses within municipal limits or to compel such businesses to abate their

impacts. For example, Amendment 64, approved by the voters in 2012, allows towns and cities to

either regulate or prohibit the sale of recreational marijuana within their boundaries. Statutes

provide municipalities additional powers to finance municipal activities. Municipalities are also

granted significant authority to manage land use and growth.

Town governments. The legislative and corporate authority of statutory towns is vested in a board

of trustees that consists of a mayor and up to six trustees. The mayor and members of the board of

trustees are elected from the town at large. The mayor presides over board of trustees meetings and

has the same voting powers as other board members. However, a town may adopt an ordinance

that limits mayors to voting only when there is a tie vote of the board, provided the ordinance also

authorizes the mayor to veto spending ordinances. This limit also provides that the veto may be

overruled by a two-thirds vote of the board. The board of trustees is required to appoint a clerk,

treasurer, and town attorney, or adopt an ordinance that provides for the election of these offices.

The clerk is the custodian of municipal records. The board may also appoint a town administrator

to oversee staff and the daily operations of the town. Terms of the mayor and trustees are two years,

unless an ordinance is adopted to extend the terms to four years. Because they lack specific

Administrative powers enable

municipalities to fill vacancies in

municipal offices, appoint a board

of health, and provide ambulance,

hospital, and other services. Police

powers enable municipalities to

enforce local laws, as well as enact

measures to preserve and protect

the safety, health, and welfare of the

community.

Local Government Handbook 17

authority, statutory towns may not adopt a city council-city manager form of municipal

government.

City governments. The legislative and corporate authority of statutory cities is vested in an elected

mayor and city council. The mayor presides over city council meetings and has the same voting

powers as other board members. The mayor is responsible for supervising the conduct of municipal

officers and investigating complaints against them. As with statutory towns, cities may adopt an

ordinance that limits mayors to voting only when there is a tie vote of the board. The ordinance

must also authorize the mayor to veto spending ordinances that may be overruled by a two-thirds

vote of the board. Mayors are elected from the city at large. Members of the council are elected to

represent a specific ward. The city clerk and treasurer are elected from the city at large. However,

the city council may submit a proposal to the registered electors to change the city clerk and

treasurer to appointive offices. If approved by the voters, the appointment of the city clerk and

treasurer would be made by the city council. The city council may also submit a proposal to the

registered electors to return these offices to elective offices.

City council-city manager governments. Most Colorado municipalities with over 5,000 residents are

organized as city council-city manager municipalities. Under this form of government, the mayor

and the council primarily address policy matters, and a professional manager implements and

administers the council's policies. At least 5 percent of a city's registered electors must sign a

petition to cause an election to adopt a city council-city manager form of municipal government.

This petition specifies whether the mayor will be elected from among the members of the city

council or will be elected from the city at large. If the voters approve reorganizing as a city

council-city manager form of municipal government, the council appoints a city manager to

supervise the administration of the city and to ensure that city ordinances are enforced. The council

must choose a manager based on his or her executive and administrative qualifications. The city

manager does not need be a resident of the city or state at the time of appointment, but may be

required, by ordinance, to reside in the city after appointment. The council may not appoint a sitting

council member as city manager. The manager has the power to appoint and remove all officers and

employees in the administrative service of the city. The council is prohibited from directing the

hiring or removal of administrative officers and employees.

Home Rule Municipalities

Overview. The Colorado Constitution allows cities and towns to adopt a home rule charter. Home

rule charters have been adopted by 97 municipalities in Colorado. Home rule municipalities can be

seen in the map below and are listed in Appendix A. A home rule charter provides a city or town

with greater authority to regulate local and municipal matters than is available to statutory

municipalities. Most home rule municipalities have adopted the city council-city manager form of

municipal government.

18 Local Government Handbook

Map 3

Colorado Home Rule Municipalities

Map 4

Colorado Home Rule Municipalities Front Range Zoom

Local Government Handbook 19

Formation. The process for adopting, amending, and repealing home rule charters is specified in

state statute. Under state law, at least 5 percent of the registered electors of a municipality may

petition the municipality's governing body to hold a charter commission election. Alternatively, the

governing body may adopt an ordinance to cause a charter commission election. If approved by the

voters, the charter commission has 120 days to draft a home rule charter. The charter identifies the

municipality's powers, governing structure, terms of elected offices, budget and election procedures,

procedures for initiative and referendum of measures, and the process for the recall of officers.

Once approved by the commission, a charter must be submitted to the voters for their approval. If

rejected by the voters, the commission may draft another charter for consideration at a future

election. Rejection of the second charter by the voters results in the dissolution of the charter

commission. Home rule charters may be amended or repealed through similar procedures as the

creation of a charter. State law also provides a process for voters to adopt a home rule charter at the

time of incorporation.

Powers. A home rule charter provides a city or town with the greatest authority to regulate local

and municipal matters. In general, a home rule city's ordinances pertaining to local matters

supersede conflicting state laws. For example, the courts have determined that zoning is primarily a

matter of local concern. Consequently, a home rule municipality may adopt its own procedures to

rezone an area instead of following the statutory requirement pertaining to rezoning. State statute

also grants home rule municipalities additional powers. For example, the Local Government Land

Use Control Enabling Act allows home rule cities and towns to regulate activities that impact a

community or surrounding area, to provide planned and orderly use of land, and to protect the

environment.

Matters of local, state, and mixed concerns. State laws

may take precedence over conflicting home rule

ordinances when such issues are a matter of statewide

concern. For example, the Colorado Supreme Court

determined that a city ordinance imposing a total ban on

oil and gas development within the City of Greeley was illegal because it conflicted with "the

interest of the state in promoting the efficient and fair development, production, and utilization of

oil and gas resources in the state." According to a recent Colorado Supreme Court decision, a

standard test is not available for determining whether a matter is a local, state, or mixed concern.

Rather, the court has made such a determination on an ad hoc basis, "considering the totality of

circumstances.” For example, the court has identified several factors to be considered, including the

need for statewide uniformity and the extraterritorial impacts of municipal legislation. The court

may also consider whether the subject matter is traditionally governed by state or local government

and any state constitutional provisions that specifically address the issue.

Annexation

Annexation is the process whereby land that is adjacent to a municipality is incorporated into the

municipal boundaries. The Bill of Rights in the Colorado Constitution limits the authority of

State laws may take precedence over

conflicting home rule ordinances

when such issues are a matter of

statewide concern.

20 Local Government Handbook

municipalities to annex lands. Annexation of an unincorporated area may not occur unless one of

the following conditions is met:

annexation has been approved by the majority vote of the landowners and the registered electors

in the area proposed to be annexed;

the annexing municipality has received a petition for annexation signed by more than 50 percent

of landowners who own more than 50 percent of the area that is proposed to be annexed; or

the area is entirely surrounded by, or is solely owned by, the annexing municipality.

The constitution allows the General Assembly to

establish annexation procedures under specific

conditions. It has used this authority to create three

annexation procedures: annexation initiative by petition

of landowners; annexation by election; and annexation

by ordinance. A brief description of these procedures

follows.

Requirements of land to be annexed. State statutes limit the type of land that may be annexed. Such

lands must be one-sixth contiguous with the existing municipal boundary. The land must also share

a community of interest with the annexing municipality; be urban or likely to become urban; and be

capable of being integrated with the annexing municipality. Consent of a land owner is required if

his or her land will be divided by annexation. A school district may be required to approve the

annexation if the annexation divides the district. Additionally, an annexation may not occur if it will

extend a municipal boundary more than three miles in any one year. The law also establishes a

process for annexing a parcel of land that is sought by different municipalities.

Petition for annexation by landowners. Individuals comprising more than 50 percent of the

landowners and owning more than 50 percent of an area of land may petition the governing body of

a municipality to annex their land. The municipality's governing body must then determine if the

proposed annexation satisfies statutory requirements. If the petition is found to be in compliance,

the governing body establishes a date for a public hearing on the annexation. At least 25 days prior

to that hearing, the municipality must prepare an impact report that includes maps, plans to finance

the annexation, plans to extend municipal services to the area, and the effects of the annexation on

local public school systems. After the public hearing, if the governing body determines that all

statutory requirements have been met, it may annex the territory without an election.

Petition for annexation election. Annexation may also occur by election in the area proposed for

annexation. Either 75 qualified electors or 10 percent of the qualified electors of an area, whichever

is less, may petition the governing body of a municipality to hold an annexation election. The

petition, maps, and statements regarding the area to be annexed must be filed with the municipal

clerk. The petition is reviewed by the governing body to determine if it complies with state law. If

the petition complies with all requirements, a public hearing is set and an impact report is created by

the municipality. The governing body may then call the annexation election. Three commissioners

are appointed by the district court to oversee the annexation election. Notice of the election must be

published at designated polling places and once a week for four weeks in a newspaper of general

The General Assembly has used this

constitutional authority to create

three annexation procedures:

annexation initiative by petition of

landowners; annexation by election;

and annexation by ordinance.

Local Government Handbook 21

circulation. All landowners, including corporate landowners, who are registered electors in the area

proposed to be annexed may vote in the annexation election.

Annexation by ordinance. State law creates a

streamlined process for annexing enclaves and lands that

are owned by the municipality. An enclave is an

unincorporated area entirely contained within the

boundaries of a municipality. Once an enclave has

existed for three years, it may be annexed by a municipal

ordinance. Annexation may only occur after notice of

the annexation is published in a newspaper of general

circulation in the area proposed to be annexed once a week for four weeks, with the first notice

published at least 30 days prior to the adoption of the ordinance. A municipality must satisfy

additional requirements to annex an enclave with a population over 100 people and more than

50 acres. To annex such areas, the municipality must form a nine-member annexation transition

committee to facilitate communication among the annexing municipality, affected counties, and

residents, business owners, and property owners within the enclave. The committee must include

two representatives of the annexing municipality, two representatives from the county or counties

where the enclave is situated, and five members who live, own a business, or own real property

within the enclave.

Discontinuance of Incorporation

Unless otherwise provided for in a home rule city's charter, state law outlines the process for how a

home rule or statutory city may discontinue its incorporation. The proceedings for discontinuance

of incorporation begin when a petition for discontinuance is filed with the district court of the

county where the municipality exists. The petition must be signed by at least 25 percent of the

registered electors of the municipality. Upon verification of the petition, the court will notify the

electors of the municipality of a vote at the next regular election on whether or not to discontinue the

incorporation of the municipality.

At least two-thirds of the electorate must vote to discontinue incorporation. After an affirmative

vote of the electorate, the governing body of the municipality is to make sure that all of the debts of

the municipality are paid and deposit any municipal documents or records with the county clerk

and recorder for safekeeping. The county clerk and recorder must then certify the discontinuance of

incorporation with the Secretary of State and provide notice within the county of the discontinuance.

Abandoned Municipalities

If a municipality has failed to hold elections or have any government activity for a period of five

years, the county attorney may ask the Secretary of State to determine the municipality abandoned

and discontinue its incorporation. If the Secretary of State determines that the municipality is

abandoned, the county clerk and recorder of the county in which the abandoned municipality is

An enclave is an unincorporated

area entirely contained within the

boundaries of a municipality. Once

an enclave has existed for three

years, it may be annexed by a

municipal ordinance.

22 Local Government Handbook

located must provide notice of its discontinuance within the county and maintain any of the

municipality's documents for safekeeping.

Financial Powers of Municipalities

Overview. State law provides municipalities with a variety of revenue-raising mechanisms to pay

for municipal expenses and infrastructure improvements. Municipal revenue sources primarily

include sales and use taxes and property taxes. Municipalities also may employ debt financing tools

authorized in state law.

Sales and use taxes. Sales and use taxes are the primary revenue sources for Colorado

municipalities. A sales tax is a tax levied on the sale of goods and services. A use tax is levied on

the retail purchase price of certain tangible personal property outside a taxing jurisdiction but

stored, used, or consumed within that jurisdiction. State law allows municipalities to collect a sales

or use tax if approved by their residents at an election. Most municipalities that collect a sales tax

also collect a use tax.

Property taxes. Most Colorado municipalities assess a

property tax. According to the Department of Local

Affairs' Division of Property Taxation, municipal

governments collect 4.9 percent of the property tax

collected in the state. A property tax is determined by

multiplying a property's assessed value by a mill levy.

A mill is one-tenth of a cent; or $1 of taxes for each

$1,000 of assessed value. County assessors determine property values, and municipalities set the

mill levies.

General obligation and revenue bonds. Municipalities may issue general obligation and revenue

bonds to finance buildings, recreational facilities, and other public infrastructure improvements.

General obligation bonds are secured by the municipality's authority to levy property taxes. In the

event of default, holders of general obligation bonds may compel a tax levy to satisfy the issuer’s

obligation on the defaulted bonds. Revenue bonds are used to pay for projects that generate income,

such as a water infrastructure improvements. Revenue bonds are repaid using the income

generated by the project. Municipalities may also issue sales and use tax revenue bonds. These

bonds are special, limited obligations that are payable solely from the revenue derived from a

municipality's sales and use tax. General obligation securities are considered more secure than

revenue bonds because of the municipality's obligation to repay the debt. Interest received from

municipal bonds is exempt from federal and Colorado income tax.

Certificates of participation. Certificates of participation (COPs) may also be used by municipalities

to pay for infrastructure improvements. COPs are a type of municipal debt which can be contracted

by cities without voter approval. Courts have ruled that, because of their structure, COPs do not

constitute long-term obligations of the issuing authority, and are therefore exempt from state and

local laws that require voter approval of long-term debt. COPs are leases divided or “certificated”

into shares. These shares are the certificates of participation that are sold to investors and represent

General obligation bonds are

secured by the municipality's

authority to levy property taxes…

Revenue bonds are repaid using the

income generated by the project.

Local Government Handbook 23

a proportionate interest in the right to receive revenues paid by the lessee (a municipality) to the

lessor/vendor. COPs, compared to other lease-purchases, are for a larger dollar amount, with a

longer term, and are usually rated by bond rating agencies.

Revenues and Expenditures

Table 9 shows the total amounts of revenue received by Colorado municipalities in 2015, including

52.4 percent from sales and use taxes, 9.6 percent from service charges, and 7.5 percent from

property tax revenue. Table 10 shows the total amounts of expenditures spent by Colorado

municipalities in 2015, including 28.5 percent on public safety, 17.9 percent on capital outlay, and

13.3 percent on culture and recreation. 2015 is the most recent available data due to lag time

between the end of the fiscal year and time it takes to complete yearend auditing and additional

time needed for DOLA to verify revenue and expenditure actuals submitted by municipalities

governments.

Table 9

2015 Revenue Totals for Colorado Municipalities

Revenue Sources

Amount

% of Total

Local Tax Revenue

General Sales and Use

$2,257,668,615

52.4%

General Property

$322,461,871

7.5%

Franchise

$127,682,408

3.0%

Specific Ownership

$26,750,487

0.6%

Employment Occupation

$13,760,323

0.3%

Other

$136,694,761

3.2%

Total Local Revenue

$2,885,018,465

66.9%

Intergovernmental Revenue

Highway Users Tax

$106,408,002

2.5%

Conservation Trust Fund

$28,556,900

0.7%

Vehicle Registration Fees

$11,046,035

0.3%

Cigarette Tax

$8,120,783

0.2%

Other Intergovernmental Sources

$388,755,086

9.0%

Total Intergovernmental Revenue

$542,886,806

12.6%

Other Tax Revenue

Service Charges

$413,500,536

9.6%

Licenses, Permits, and Capital Fees

$187,252,654

4.3%

Enterprise Transfers

$79,907,616

1.9%

Fines and Forfeits

$64,494,200

1.5%

Miscellaneous

$139,371,489

3.2%

Total Other Tax Revenue

$884,526,495

20.5%

Total Revenue

$4,312,431,766

100.0%

Source: Department of Local Affairs.

24 Local Government Handbook

Table 10

2015 Expenditure Totals for Colorado Municipalities

Local Expenditures

Amount

% of Total

Operating Expenditures

Public Safety

$1,181,921,072

28.5%

General Government

$688,696,119

16.6%

Culture and Recreation

$550,341,873

13.3%

Public Works

$481,182,657

11.6%

Judicial

$38,353,365

0.9%

Health

$33,769,942

0.8%

Miscellaneous

$137,336,504

3.3%

Total Operating Expenditures

$3,111,601,532

75.0%

Other Expenditures

Capital Outlay

$742,283,668

17.9%

Debt Service

$173,076,857

4.2%

Transfers to Enterprises and Outside

Entities

$122,339,075

2.9%

Total Other Expenditures

$1,037,699,600

25.0%

Total Expenditures

$4,149,301,132

100.0%

Source: Department of Local Affairs.

Local Government Handbook 25

Section IV: City and County Governments

A city and county is a distinct entity established under Article XX of the state constitution that

operates under a home rule charter and exercises the powers of municipal and county government.

These entities have powers similar to home rule municipalities to regulate local and municipal

matters. City and county governments are also responsible for providing the services required of

counties and county officers. Currently, Denver and Broomfield are the only city and county

governments in Colorado.

Establishment. The establishment of a city and county

occurs by a constitutional amendment. The General

Assembly may refer a constitutional amendment to the

voters by passing a concurrent resolution, or citizens may

place a measure on a statewide ballot through the

initiative process. For example, state voters approved a referendum to form the City and County of

Broomfield in 1998, which consolidated areas previously located in four counties: Adams, Boulder,

Jefferson, and Weld.

Revenues and Expenditures

Table 11 shows the total amounts of revenue received by city and county governments in 2015,

including 35.0 percent from sales and use taxes, 18.8 percent from general property taxes, and

13.1 percent from service charges. Table 12 shows the total amounts of expenditures spent by these

governments in 2015, including 31.4 percent on public safety, 10.6 percent on capital outlay, and

10.4 percent on culture and recreation.

Currently, Denver and Broomfield

are the only city and county

governments in Colorado.

26 Local Government Handbook

Table 11

2015 Revenue Totals for Colorado

City and County Governments

Revenue Sources

Amount

% of Total

Local Tax Revenue

General Sales and Use

$704,315,167

35.0%

General Property

$379,470,687

18.8%

Franchise

$49,181,930

2.4%

Specific Ownership

$28,586,104

1.4%

Employment Occupation

$48,293,000

2.4%

Other

$95,555,780

4.7%

Total Local Revenue

$1,305,402,668

64.8%

Intergovernmental Revenue

Social Services

$82,204,029

4.1%

Highway Users Tax

$20,995,949

1.0%

Conservation Trust Fund

$6,686,014

0.3%

Other Intergovernmental Sources

$123,012,952

6.1%

Total Intergovernmental Revenue

$232,898,944

11.6%

Other Tax Revenue

Service Charges

$264,489,652

13.1%

Licenses, Permits, and Capital Fees

$65,761,610

3.3%

Enterprise Transfers

$3,031,026

0.2%

Fines and Forfeits

$54,461,292

2.7%

Miscellaneous

$88,954,079

4.4%

Total Other Tax Revenue

$476,697,659

23.7%

Total Revenue

$2,014,999,271

100.0%

Source: Department of Local Affairs.

Local Government Handbook 27

Table 12

2015 Expenditure Totals for Colorado

City and County Governments

Local Expenditures

Amount

% of Total

Operating Expenditures

Public Safety

$584,323,849

31.4%

General Government

$340,637,082

18.3%

Culture and Recreation

$194,367,920

10.4%

Social Services

$134,906,426

7.3%

Public Works

$60,591,383

3.3%

Judicial

$45,735,331

2.5%

Health

$24,573,302

1.3%

Miscellaneous

$48,002,143

2.6%

Total Operating Expenditures

$1,433,137,436

77.0%

Other Expenditures

Debt Service

$177,518,725

9.5%

Capital Outlay

$197,886,271

10.6%

Transfers to Enterprises and Outside

Entities

$51,585,346

2.8%

Total Other Expenditures

$426,990,342

23.0%

Total Expenditures

$1,860,127,778

100.0%

Source: Department of Local Affairs.

This page intentionally left blank.

Local Government Handbook 29

Section V: Local Government Use and Planning Powers

Overview. In general, home rule governments have greater authority over land use and other types

of local matters than statutory local governments. However, state statutes grant land use and

planning powers to both home rule and statutory municipal and county governments. For example,

state law grants both municipal and county governments the authority to regulate impacts of new

developments that affect state interests, such as large water projects and natural hazards, including

flood plains and avalanche paths.

General Land Use and Planning Laws for Local Governments

Local Government Land Use Control Enabling Act. This act allows counties and municipalities to

regulate activities that impact a community or surrounding area to provide for the planned and

orderly use of land, and to protect the environment. The law also allows a local government to

provide for the phased development of services and regulate the location of activities and

development that may cause significant changes in population density.

House Bill 1041 powers. In 1974, the General Assembly

enacted House Bill 1041, the Areas and Activities of State

Interest Act, to ensure that the impacts of new

developments that affect state interests are considered

and mitigated. Areas of state interest include natural

hazards and significant historical, natural, or

archeological resources. Activities of state interest

include the construction of major new domestic water

and sewage treatment systems, waste disposal sites, and

highways. The act authorizes local governments,

specifically statutory and home rule municipalities and counties, to determine whether a

development impacts an area or activity of state interest and to regulate the development of such

projects according to legislatively defined criteria.

Municipal Land Use and Planning Powers

Statutory municipalities. Statutory municipalities are granted zoning and planning powers that are

similar to those granted to counties. For example, a municipal government may divide the city into

districts and regulate the location and use of buildings, structures, and land for trade, industry, and

other purposes.

Home rule municipalities. The state constitution provides the authority for a home rule

municipality to regulate local and municipal matters. State law further provides that a home rule

city's ordinances pertaining to local matters supersede conflicting state laws, and the courts have

determined that zoning is primarily a matter of local concern. Consequently, a home rule

municipality may adopt its own procedures for zoning. In general, a home rule city's ordinances

…state law grants both municipal

and county governments the

authority to regulate impacts of new

developments that affect state

interests, such as large water

projects and natural hazards,

including flood plains and

avalanche paths.

30 Local Government Handbook

that conflict with matters of state interest may be invalid. For example, the courts have determined

that the efficient production of oil and gas is a state interest, and local government land use policies

that interfere with this objective may be invalid.

County Land Use and Planning Powers

Zoning. A board of county commissioners may establish

zoning for all or part of the unincorporated area of a

county by dividing and classifying land according to its

intended use (e.g., residential, commercial, or

agricultural). This is accomplished by having the county

planning commission recommend a zoning plan for

consideration by the board. Once a zoning plan is approved, the board can amend any provision of

the county zoning regulations after submitting changes to the planning commission for review and

suggestions.

State law authorizes a county planning commission to enact a zoning plan for all or any part of the

unincorporated territory within the county. County zoning regulations promulgated under the

county planning code may include the classification of land uses and the distribution of land

development. Zoning plans typically identify the type and density of use that is appropriate for a

specific area. For example, a county may zone an area for agricultural activities. Other activities,

such as a commercial development, would be required to obtain a special use permit to be

constructed in that area. Counties are prohibited from adopting an ordinance that is in conflict with

any state statute; however, a county ordinance and statute may coexist as long as they do not

contain express or implied conditions that are in conflict with each other. If a conflict does exist, the

ordinance is preempted by state law.

County comprehensive plans. A county comprehensive plan or “master plan” is a planning

document intended to guide the growth and long-term development of the unincorporated areas of

a county. County comprehensive plans are advisory documents only and cannot bind decisions

made by a county planning commission or the board of county commissioners. State law requires

counties to adopt master plans if the county has a population of 100,000 or more, or a population

over 10,000 and a 10 percent growth rate in a five-year period. The advisory nature of a

comprehensive plan does not prohibit a county from denying a specific development application

based on noncompliance with the comprehensive plan, provided the plan is adopted legislatively by

the board and the plan is sufficiently specific to ensure consistent application. Additionally, a

county comprehensive plan can be a binding document if the board authorizes a comprehensive

plan, or any part of the plan through zoning, regulations, or land use codes.

Local Governments and the Power of Eminent Domain