1

REPORTABLE

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA

CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION

Civil Appeal Nos 10866-10867 of 2010

M Siddiq (D) Thr Lrs …Appellants

Versus

Mahant Suresh Das & Ors …Respondents

WITH

Civil Appeal Nos 4768-4771/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 2636/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 821/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 4739/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal Nos 4905-4908/2011

Digitally signed by

CHETAN KUMAR

Date: 2019.11.09

11:47:46 IST

Reason:

Signature Not Verified

2

WITH

Civil Appeal No 2215/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 4740/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 2894/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 6965/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 4192/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 5498/2011

WITH

Civil Appeal No 7226/2011

AND WITH

Civil Appeal No 8096/2011

3

J U D G M E N T

INDEX

A. Introduction

B. An overview of the suits

C.

D. The aftermath of 1856-7

D.1 Response to the wall

D.2 Period between 1934-1949

E. Proceedings under Section 145

F. Points for determination

G. The three inscriptions

H. Judicial review and characteristics of a mosque in Islamic law

I. Places of Worship Act

J. Juristic personality

J.1 Development of the law

J.2 Idols and juristic personality

J.3 Juristic personality of the first plaintiff

J.4 Juristic personality of the second plaintiff

K. Analysis of the suits

L. Suit 1: Gopal Singh Visharad

L.1 Pleadings

L.2 Issues and findings of the High Court

L.3 Analysis

M. Suit 3: Nirmohi Akhara

M.1 Pleadings

4

M.2 Conflict between Suit 3 and Suit 5

M.3 Issues and findings of the High Court

M.4 Limitation in Suit 3

M.5 Oral testimony of the Nirmohi witnesses

M.6

Documentary evidence in regard to the mosque (1934-1949)

N. Suit 5: The deities

N.1 Array of parties

N.2 No contest by the State of Uttar Pradesh

N.3 Pleadings

N.4 Written statements

N.5 Issues and findings of the High Court

N.6 Shebaits: an exclusive right to sue?

A suit by a worshipper or a person interested

Nirmohi Akhara and shebaiti rights

N.7 Limitation in Suit 5

The argument of perpetual minority

N.8 The Suit of 1885 and Res Judicata

N.9 Archaeological report

N.10 Nature and use of the disputed structure: oral evidence

N.11 Photographs of the disputed structure

N.12 Vishnu Hari inscriptions

N.13 The polestar of faith and belief

Travelogues, gazetteers and books

Evidentiary value of travelogues, gazetteers and books

N.14 report

O. Suit 4: Sunni Central Waqf Board

O.1 Analysis of the plaint

O.2 Written statements

5

O.3 Issues and findings of the High Court

O.4 Limitation in Suit 4

O.5 Applicable legal regime and Justice, Equity and Good Conscience

O.6 Grants and recognition

O.7 Disputes and cases affirming possession

Impact of Suit of 1885

Incidents between 1934 and 1950

O.8 Proof of namaz

O.9 Placing of idols in 1949

O.10 Nazul land

O.11 Waqf by user

O.12 Possession and adverse possession

O.13 Doctrine of the lost grant

O.14 The smokescreen of the disputed premises the wall of 1858

O.15 Analysis of evidence in Suit 4

O.16 The Muslim claim to possessory title

P. Analysis on title

P.1 Marshalling the evidence in Suit 4 and Suit 5

P.2 Conclusion on title

Q. Reliefs and directions

PART A

6

A. Introduction

1. These first appeals centre around a dispute between two religious

communities both of whom claim ownership over a piece of land admeasuring

1500 square yards in the town of Ayodhya. The disputed property is of immense

significance to Hindus and Muslims. The Hindu community claims it as the birth-

place of Lord Ram, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. The Muslim community claims

it as the site of the historic Babri Masjid built by the first Mughal Emperor, Babur.

The lands of our country have witnessed invasions and dissensions. Yet they

have assimilated into the idea of India everyone who sought their providence,

whether they came as merchants, travellers or as conquerors. The history and

culture of this country have been home to quests for truth, through the material,

the political, and the spiritual. This Court is called upon to fulfil its adjudicatory

function where it is claimed that two quests for the truth impinge on the freedoms

of the other or violate the rule of law.

2. This Court is tasked with the resolution of a dispute whose origins are as

old as the idea of India itself. The events associated with the dispute have

spanned the Mughal empire, colonial rule and the present constitutional regime.

Constitutional values form the cornerstone of this nation and have facilitated the

lawful resolution of the present title dispute through forty-one days of hearings

before this Court. The dispute in these appeals arises out of four regular suits

which were instituted between 1950 and 1989. Before the Allahabad High Court,

voluminous evidence, both oral and documentary was led, resulting in three

judgements running the course of 4304 pages. This judgement is placed in

PART A

7

challenge in the appeals.

3. The disputed land forms part of the village of Kot Rama Chandra or, as it is

otherwise called, Ramkot at Ayodhya, in Pargana Haveli Avadh, of Tehsil Sadar

in the District of Faizabad. An old structure of a mosque existed at the site until 6

December 1992. The site has religious significance for the devotees of Lord

Ram, who believe that Lord Ram was born at the disputed site. For this reason,

the Hindus refer to the disputed site as Ram Janmabhumi or Ram Janmasthan

(i.e. birth-place of Lord Ram). The Hindus assert that there existed at the

disputed site an ancient temple dedicated to Lord Ram, which was demolished

upon the conquest of the Indian sub-continent by Mughal Emperor Babur. On the

other hand, the Muslims contended that the mosque was built by or at the behest

of Babur on vacant land. Though the significance of the site for the Hindus is not

denied, it is the case of the Muslims that there exists no proprietary claim of the

Hindus over the disputed property.

4. A suit was instituted in 1950 before the Civil Judge at Faizabad by a Hindu

worshipper, Gopal Singh Visharad seeking a declaration that according to his

religion and custom, he is entitled to offer prayers at the main Janmabhumi

temple near the idols.

5. The Nirmohi Akhara represents a religious sect amongst the Hindus,

known as the Ramanandi Bairagis. The Nirmohis claim that they were, at all

material times, in charge and management of the structure at the disputed site

9 December 1949, on which date

an attachment was ordered under Section 145 of the Code of Criminal Procedure

PART A

8

1898. In effect, they claim as shebaits in service of the deity, managing its affairs

and receiving offerings from devotees. Theirs is a Suit of 1959 for the

6. The Uttar Pradesh Sunni Central Board of W Sunni Central Waqf

Board

declaration of their title to the disputed site. According to them, the old structure

was a mosque which was built on the instructions of Emperor Babur by Mir Baqi

who was the Commander of his forces, following the conquest of the sub-

continent by the Mughal Emperor in the third decade of the sixteenth century.

The Muslims deny that the mosque was constructed on the site of a destroyed

temple. According to them, prayers were uninterruptedly offered in the mosque

until 23 December 1949 when a group of Hindus desecrated it by placing idols

within the precincts of its three-domed structure with the intent to destroy,

damage and defile the Islamic religious structure. The Sunni Central Waqf Board

claims a declaration of title and, if found necessary, a decree for possession.

7. A suit was instituted in 1989 by a next friend on behalf of the deity

Bhagwan Shri Ram Virajman-Asthan Shri

Ram Janmabhumi

both the idol and the birth-place as juridical entities. The claim is that the place of

birth is sanctified as an object of worship, personifying the divine spirit of Lord

Ram. Hence, like the idol (which the law recognises as a juridical entity), the

place of birth of the deity is claimed to be a legal person, or as it is described in

legal parlance, to possess a juridical status. A declaration of title to the disputed

PART A

9

site coupled with injunctive relief has been sought.

8. These suits, together with a separate suit by Hindu worshippers were

transferred by the Allahabad High Court to itself for trial from the civil court at

Faizabad. The High Court rendered a judgment in original proceedings arising

out of the four suits and these appeals arise out of the decision of a Full Bench

dated 30 September 2010. The High Court held that the suits filed by the Sunni

Central Waqf Board and by Nirmohi Akhara were barred by limitation. Despite

having held that those two suits were barred by time, the High Court held in a

split 2:1 verdict that the Hindu and Muslim parties were joint holders of the

disputed premises. Each of them was held entitled to one third of the disputed

property. The Nirmohi Akhara was granted the remaining one third. A preliminary

decree to that effect was passed in the suit brought by the idol and the birth-place

of Lord Ram through the next friend.

9. Before deciding the appeals, it is necessary to set out the significant

events which have taken place in the chequered history of this litigation, which

spans nearly seven decades.

10. The disputed site has been a flash point of continued conflagration over

decades. In 1856-57, riots broke out between Hindus and Muslims in the vicinity

of the structure. The colonial government attempted to raise a buffer between the

two communities to maintain law and order by set ting up a grill-brick wall having

a height of six or seven feet. This would divide the premises into two parts: the

inner portion which would be used by the Muslim community and the outer

portion or courtyard, which would be used by the Hindu community. The outer

PART A

10

courtyard has several structures of religious significance for the Hindus, such as

the Sita Rasoi and a platform called the Ramchabutra. In 1877, another door was

opened on the northern side of the outer courtyard by the colonial government,

which was given to the Hindus to control and manage. The bifurcation, as the

record shows, did not resolve the conflict and there were numerous attempts by

one or other of the parties to exclude the other.

11. In January 1885, Mahant Raghubar Das, claiming to be the Mahant of

Ram Janmasthan instituted a suit

1

Suit of 1885 -Judge,

Faizabad. The relief which he sought was permission to build a temple on the

Ramchabutra situated in the outer courtyard, measuring seventeen feet by

twenty-one feet. A sketch map was filed with the plaint. On 24 December 1885,

the trial judge dismissed the suit, `noting that there was a possibility of riots

breaking out between the two communities due to the proposed construction of a

temple. The trial judge, however, observed that there could be no question or

doubt regarding the possession and ownership of the Hindus over the Chabutra.

On 18 March 1886, the District Judge dismissed the appeal against the judgment

of the Trial Court

2

but struck off the observations relating to the ownership of

Hindus of the Chabutra contained in the judgment of the Trial Court. On 1

November 1886, the Judicial Commissioner of Oudh dismissed the second

appeal

3

, noting that the Mahant had failed to present evidence of title to establish

ownership of the Chabutra. In 1934, there was yet another conflagration between

the two communities. The domed structure of the mosque was damaged during

1

(OS No. 61/280 of 1885)

2

Civil Appeal No. 27/1885

3

No 27 of 1886

PART A

11

the incident and was subsequently repaired at the cost of the colonial

government.

12. The controversy entered a new phase on the night intervening 22 and 23

December 1949, when the mosque was desecrated by a group of about fifty or

sixty people who broke open its locks and placed idols of Lord Ram under the

FIRistered in relation to the

incident. On 29 December 1949, the Additional City Magistrate, Faizabad-cum-

Ayodhya issued a preliminary order under Section 145 of the Code of Criminal

Procedure 1898

4

CrPC 1898

nature. Simultaneously, an attachment order was issued and Priya Datt Ram, the

Chairman of the Municipal Board of Faizabad was appointed as the receiver of

the inner courtyard. On 5 January 1950, the receiver took charge of the inner

courtyard and prepared an inventory of the attached properties. The Magistrate

passed a preliminary order upon recording a satisfaction that the dispute between

the two communities over their claims to worship and proprietorship over the

structure would likely lead to a breach of peace. The stakeholders were allowed

pujaris were permitted to go inside the place where the idols were kept, to

perform religious ceremonies like bhog and puja. Members of the general public

were restricted from entering and were only allowed darshan from beyond the

grill-brick wall.

4

(1) Whenever a District Magistrate, or an Executive Magistrate specially empowered by the Government in this

behalf is satisfied from a police-report or other information that a dispute likely to cause a breach of the peace

exists concerning any land or water of the boundaries thereof, within the local limits of his jurisdiction, he shall

make an order in writing, stating the grounds of his being so satisfied, and requiring the parties concerned in such

dispute to attend his Court in person or by pleader, within a time to be fixed by such Magistrate, and to put in

PART A

12

The institution of the suits

13. On 16 January 1950, a suit was instituted by a Hindu devotee, Gopal

Singh Visharad

5

Suit 1 Civil Judge at Faizabad, alleging that he

was being prevented by officials of the government from entering the inner

courtyard of the disputed site to offer worship. A declaration was sought to allow

the plaintiff to offer prayers in accordance with the rites and tenets of his religion

Sanatan Dharm ma

courtyard, without hindrance. On the same date, an ad-interim injunction was

issued in the suit. On 19 January 1950, the injunction was modified to prevent the

idols from being removed from the disputed site and from causing interference in

the performance of puja. On 3 March 1951, the Trial Court confirmed the ad-

interim order, as modified. On 26 May 1955, the appeal

6

against the interim order

was dismissed by the High Court of Allahabad.

14. On 5 December 1950, another suit was instituted by Paramhans

Ramchandra Das

7

Suit 2

similar to those in Suit 1. Suit 2 was subsequently withdrawn on 18 September

1990.

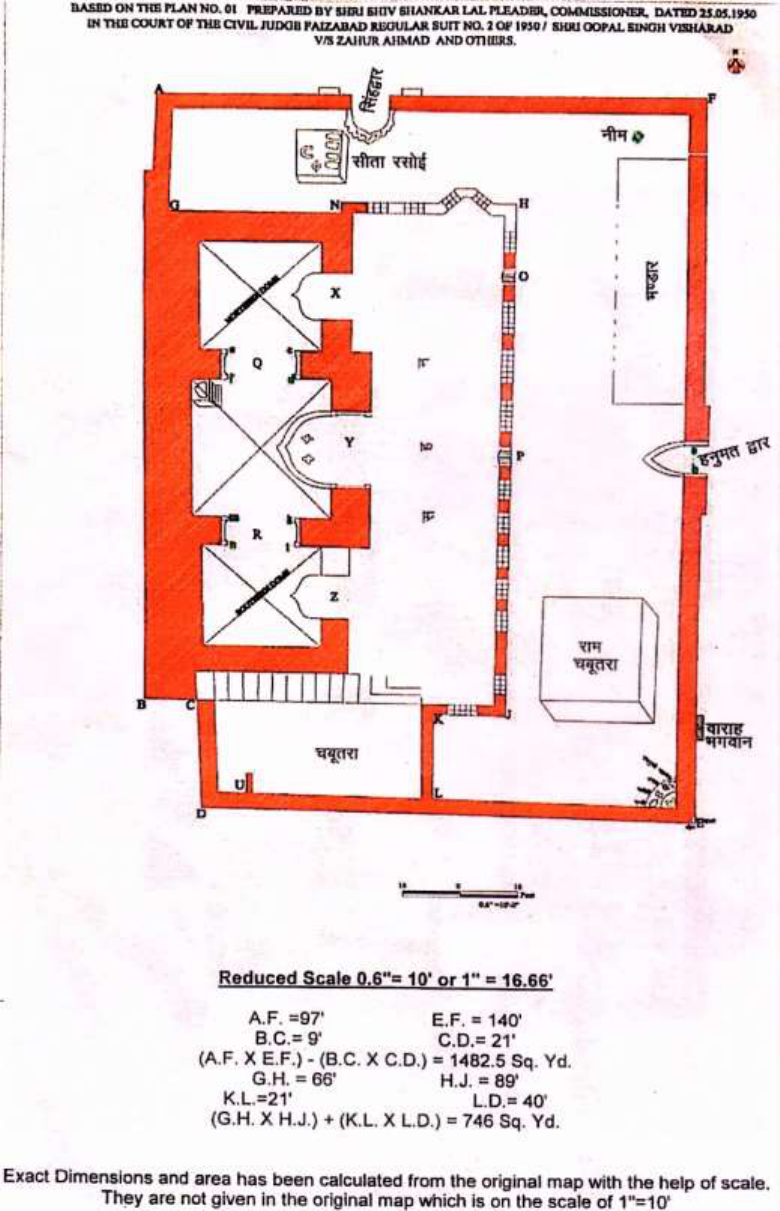

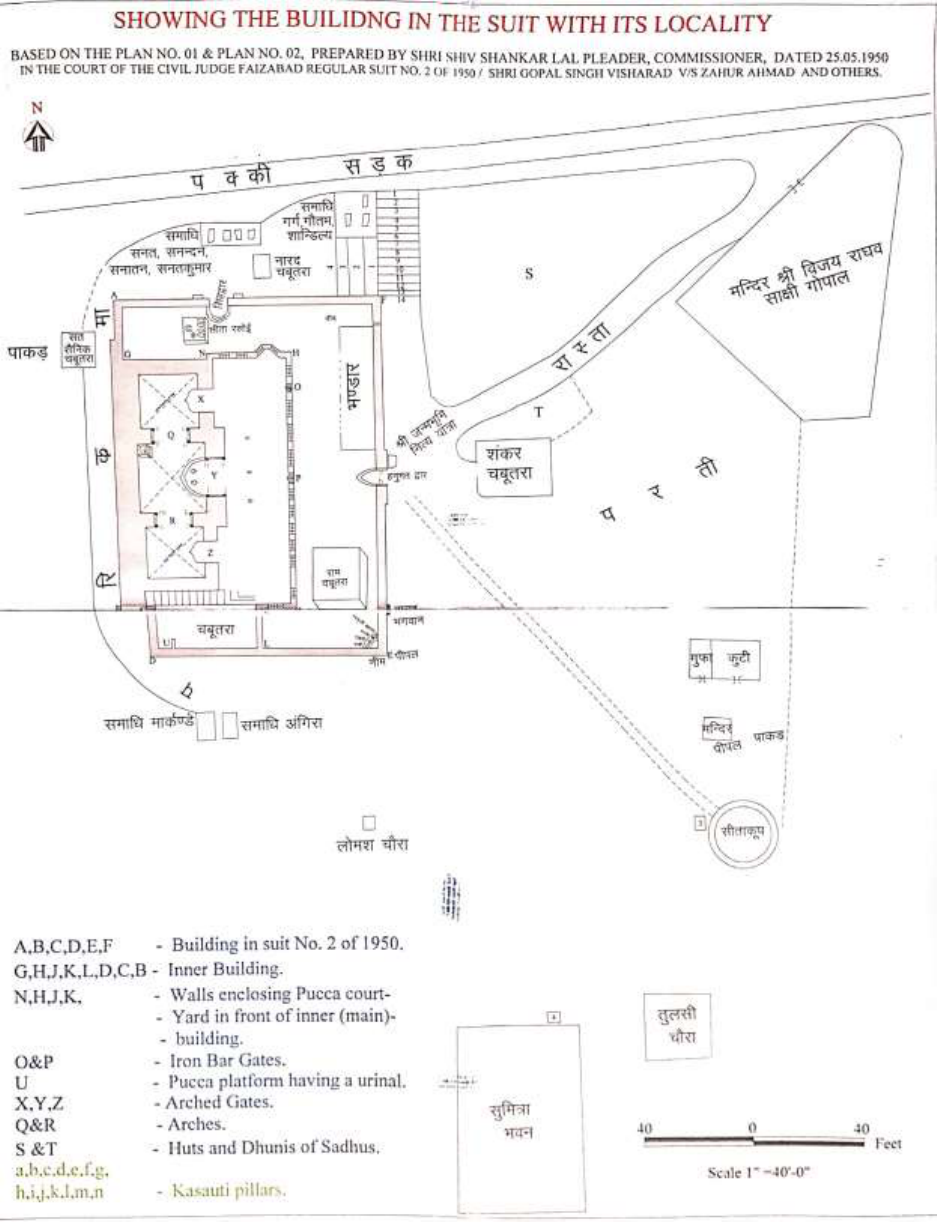

15. On 1 April 1950, a Court Commissioner was appointed in Suit 1 to prepare

a map of the disputed premises. On 25 June 1950, the Commissioner submitted

a report, together with two site plans of the disputed premises which were

numbered as Plan nos 1 and 2 to the Trial Court. Both the report and maps

5

Regular Suit No 2 of 1950. Subsequently renumbered as Other Original Suit (OOS) No 1 of 1989.

6

FAFO No 154 of 1951

7

Regular Suit no 25 of 1950 (subsequently renumbered as Other Original Suit (OOS) No 2 of 1989)

PART A

13

indicate the position at the site and are reproduced below:

Report of the Commissioner

REPORT

Sir,

I was appointed a commissioner in the above case

to prepare a site plan of the locality and building in suit on

scale. Accordingly, in compliance with the order of the

court, I visited the locality on 16.4.50 and again on

30.4.50 after giving due notice to the counsel of the

parties, and made necessary measurements on the spot.

On the first day of my visit none of the parties were

present, but on the second day defendant no. 1 was

present with Shri Azimullah Khan and Shri Habib Ahmad

Khan counsel. At about noon defendant no. 1 presented

an application, attached herewith, when the measurement

work had already finished.

Plan No. I represents the building in suit shown by

the figure ABCDEF on a larger scale than Plan no.II,

which represents the building with its locality.

A perusal of Plan No.I would show that the

building has got two gates, one on the east and the other

gate to the building. At this gate there is a stone slab fixed

to the g -Shri Janma

Hanumanji is placed at the top of the gate. The arch of

a and b,

thereon. To the south of this gate on the outer wall there

has got at its top images of Garura in the middle and two

lions one on each side.

On entering the main gate there is pucca floor on the

eastern and northern side of the inner building, marked by

letters GHJKL DGB on the north of the eastern floor there

is a neem tree, and to the south of it there is the bhandara

(kitchen). Further south there is a raised pucca platform,

stands a small temple having idols of Ram and Janki

installed therein. At the south-eastern corner E there is a

PART A

14

joint neem-pipal tree, surrounded by a semi-circular pucca

platform, on which are installed marble idols of

Panchmukhi Mahadev, Parbati, Ganesh and Nandi.

On this platform there is a pucca

chulha with chauka and belna, made of marble, affixed by

its side. To the east of the chulha there are four pairs of

marble foot prints of Ram, Lakshman, Bharat &

Shatrunghna.

The pucca courtyard in front of the inner (main) building is

enclosed by walls NHJK intercepted by iron bars with two

iron bar gates at O and P as shown in the Plan no.I. At the

southern end of this Courtyard there are 14 stairs leading

to the roof of the building, and to the south of the stairs

the

marked U at its south-west corner. There are three arched

gates, X,Y and Z leading to the main building, which is

divided into three portions, having arches at Q and R.

There is a chhajja (projected roof) above the arch Y. 31.

The three arches, Y, Q and R are supported on 12 black

n in Plan no. I. The pillars e to m have carvings of kamal

flowers thereon. The pillar contains the image of Shankar

Bhagwan in Tandava nritya form and another disfigured

image engraved thereon. The pillar J contained the

carved image of Hanumanji. The pillar N has got the

image of Lord Krishna engraved thereon other pillars have

also got carvings of images which are effaced.

In the central portion of the building at the north-western

corner, there is a pucca platform with two stairs, on which

is installed the idol of Bal Ram (infant Ram).

At the top of the three portions of the building there are

three round domes, as shown separately in Plan no.I,

each on an octagonal base. There are no towers, nor is

there any ghusalkhana or well in the building.

Around the building there is a pucca path known as

parikrama, as shown in yellow in Plan Nos.I & II. On the

west of t

Other structures found on the locality have been shown in

Plan no.II at their proper places.

The land shown by letters S and T is covered by huts and

dhunis of sadhus. Adjacent to and south of the land

PART A

15

shown by letter T, there is a raised platform, bounded by

over it, and a stone slab is fixed close to it with the

- - west of this well

there is another stone slab fixed into the ground with the

-

Sumitra Bhawan there is a stone slab fixed to the ground,

marked, carved with the image of Shesh nag.

The names of the various samadhis and other structures

as noted in Plan No. II were given by sadhus and others

present on the spot.

Plans nos.I and II, which form part of this report, two

notices given to parties counsel and the application

presented by defendant no.1 are attached herewith.

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

Shiva Shankar Lal,

Faizabad.

Pleader

25.5.50

PART A

16

Site map (Plan I)

PART A

17

Site map (Plan II)

PART A

18

16. On 17 December 1959, Nirmohi Akhara instituted a suit

8

through its

Suit 3

affairs of the Janmasthan and the temple had been

receiver under Section 145. A decree was sought to hand over the management

and charge of the temple to the plaintiff in Suit 3.

17. On 18 December 1961, the Sunni Central Waqf Board and nine Muslim

residents of Ayodhya filed a suit

9

Suit 4

seeking a declaration that the entire disputed site of the Babri Masjid was a public

mosque and for the delivery of possession upon removal of the idols.

18. On 6 January 1964, the trial of Suits 1, 3 and 4 was consolidated and Suit

4 was made the leading case.

19. On 25 January 1986, an application was filed by one Umesh Chandra

before the Trial Court for breaking open the locks placed on the grill-brick wall

and for allowing the public to perform darshan within the inner courtyard. On 1

February 1986, the District Judge issued directions to open the locks and to

provide access to devotees for darshan inside the structure. In a Writ Petition

10

filed before the High Court challenging the above order, an interim order was

passed on 3 February 1986 directing that until further orders, the nature of the

property as it existed shall not be altered.

8

Regular Suit No 26 of 1959 (subsequently renumbered as OOS No. 3 of 1989)

9

Regular Suit No. 12 of 1961 (subsequently renumbered as OOS No. 4 of 1989)

10

Civil Misc. Writ No. 746 of 1986

PART A

19

20. On 1 July 1989, a Suit

11

Suit 5

Bhagwan Shri Ram Virajman -place

Asthan Shri Ram Janam Bhumi, Ayodhya a next friend for a

declaration of title to the disputed premises and to restrain the defendants from

interfering with or raising any objection to the construction of a temple. Suit 5 was

tried with the other suits.

21. On 10 July 1989, all suits were transferred to the High Court of Judicature

at Allahabad. On 21 July 1989, a three judge Bench was constituted by the Chief

Justice of the High Court for the trial of the suits. On an application by the State

of Uttar Pradesh, the High Court passed an interim order on 14 August 1989,

directing the parties to maintain status quo with respect to the property in dispute.

22. During the pendency of the proceedings, the State of Uttar Pradesh

acquired an area of 2.77 acres comprising of the disputed premises and certain

adjoining areas. This was effected by notifications dated 7 October 1991 and 10

October 1991 under Sections 4(1), 6 and 17(4) of the Land Acquisition Act 1894

Land Acquisition Act

amenities to pilg

challenging the acquisition. By a judgment and order dated 11 December 1992,

the acquisition was set aside.

23. A substantial change took place in the position at the site on 6 December

1992. A large crowd destroyed the mosque, boundary wall, and Ramchabutra. A

makeshift structure of a temple was constructed at the place under the erstwhile

11

Regular Suit No. 236 of 1989 (subsequently renumbered as OOS No. 5 of 1989)

PART A

20

central dome. The idols were placed there.

e

24. The Central Government acquired an area of about 68 acres, including the

premises in dispute, by a legislation called the Acquisition of Certain Area at

Ayodhya Acquisition Act 1993

envisaged the abatement of all suits which were pending before the High Court.

Simultaneously, the President of India made a reference to this Court under

(w)hether a Hindu temple

or any Hindu religious structure existed prior to the construction of the Ram

Janam Bhoomi and Babari Masjid (including the premises of the inner and outer

.

25. Writ petitions were filed before the High Court of Allahabad and this Court

challenging the validity of the Act of 1993. All the petitions and the reference by

the President were heard together and decided by a judgment dated 24 October

1994. The decision of a Constitution Bench of this Court, titled Dr M Ismail

Faruqui v Union of India

12

held Section 4(3), which provided for the abatement

of all pending suits as unconstitutional. The rest of the Act of 1993 was held to be

valid. The Constitution Bench declined to answer the Presidential reference and,

as a result, all pending suits and proceedings in relation to the disputed premises

stood revived. The Central Government was appointed as a statutory receiver for

the maintenance of status quo and to hand over the disputed area in terms of the

12

(1994) 6 SCC 360

PART A

21

adjudication to be made in the suits. The conclusions arrived at by the

Constitution Bench are extracted below:

-section (3) of Section 4 of the Act abates all

pending suits and legal proceedings without providing for an

alternative dispute resolution mechanism for resolution of the

disputes between the parties thereto. This is an extinction of

the judicial remedy for resolution of the dispute amounting to

negation of rule of law. Sub-section (3) of Section 4 of the Act

is, therefore, unconstitutional and invalid.

(1)(b) The remaining provisions of the Act do not suffer from

any invalidity on the construction made thereof by us. Sub-

section (3) of Section 4 of the Act is severable from the

remaining Act. Accordingly, the challenge to the constitutional

validity of the remaining Act, except for sub-section (3) of

Sec. 4, is rejected.

(2) Irrespective of the status of a mosque under the Muslim

law applicable in the Islamic countries, the status of a mosque

under the Mahomedan Law applicable in secular India is the

same and equal to that of any other place of worship of any

religion; and it does not enjoy any greater immunity from

acquisition in exercise of the sovereign or prerogative power

of the State, than that of the places of worship of the other

religions.

(3) The pending suits and other proceedings relating to the

disputed area within which the structure (including the

premises of the inner and outer courtyards of such structure),

commonly known as the Ram Janma Bhumi - Babri Masjid,

stood, stand revived for adjudication of the dispute therein,

together with the interim orders made, except to the extent

the interim orders stand modified by the provisions of Section

7 of the Act.

(4) The vesting of the said disputed area in the Central

Government by virtue of Section 3 of the Act is limited, as a

statutory receiver with the duty for its management and

administration according to Section 7 requiring maintenance

of status quo therein under sub-section (2) of Section 7 of the

Act. The duty of the Central Government as the statutory

receiver is to handover the disputed area in accordance with

Section 6 of the Act, in terms of the adjudication made in the

suits for implementation of the final decision therein. This is

the purpose for which the disputed area has been so

acquired.

PART A

22

(5) The power of the courts in making further interim orders in

the suits is limited to, and circumscribed by, the area outside

the ambit of Section 7 of the Act.

(6) The vesting of the adjacent area, other than the disputed

area, acquired by the Act in the Central Government by virtue

of Section 3 of the Act is absolute with the power of

management and administration thereof in accordance with

sub-section (1) of Section 7 of the Act, till its further vesting in

any authority or other body or trustees of any trust in

accordance with Section 6 of the Act. The further vesting of

the adjacent area, other than the disputed area, in

accordance with Sec. 6 of the Act has to be made at the time

and in the manner indicated, in view of the purpose of its

acquisition.

(7) The meaning of the word "vest" in Section 3 and Section 6

of the Act has to be so understood in the different contexts.

(8) Section 8 of the Act is meant for payment of compensation

to owners of the property vesting absolutely in the Central

Government, the title to which is not in dispute being in

excess of the disputed area which alone is the subject matter

of the revived suits. It does not apply to the disputed area,

title to which has to be adjudicated in the suits and in respect

of which the Central Government is merely the statutory

receiver as indicated, with the duty to restore it to the owner

in terms of the adjudication made in the suits.

(9) The challenge to acquisition of any part of the adjacent

area on the ground that it is unnecessary for achieving the

professed objective of settling the long standing dispute

cannot be examined at this stage. However, the area found to

be superfluous on the exact area needed for the purpose

being determined on adjudication of the dispute, must be

restored to the undisputed owners.

(10) Rejection of the challenge by the undisputed owners to

acquisition of some religious properties in the vicinity of the

disputed area, at this stage is with the liberty granted to them

to renew their challenge, if necessary at a later appropriate

stage, in cases of continued retention by Central Government

of their property in excess of the exact area determined to be

needed on adjudication of the dispute.

(11) Consequently, the Special Reference No. 1 of 1993

made by the President of India under Art. 143(1) of the

Constitution of India is superfluous and unnecessary and

does not require to be answered. For this reason, we very

respectfully decline to answer it and return the same.

PART A

23

(12) The questions relating to the constitutional validity of the

said Act and maintainability of the Special Reference are

The proceedings before the High Court

26. The recording of oral evidence before the High Court commenced on 24

July 1996. During the course of the hearings, the High Court issued directions on

ASI

scientific investigation and have the disputed site surveyed by Ground

Penetrating Technology or Geo- GPR

and flooring extending over a large portion of the disputed site. In order to

facilitate a further analysis, the High Court directed the ASI on 5 March 2003 to

undertake the excavation of the disputed site. A fourteen-member team was

constituted, and a site plan was prepared indicating the number of trenches to be

laid out and excavated. On 22 August 2003, the ASI submitted its final report.

The High Court heard objections to the report.

27. Evidence, both oral and documentary, was recorded before the High

Court. As one of the judges, Justice Sudhir Agarwal noted, the High Court had

before it 533 exhibits and depositions of 87 witnesses traversing 13,990 pages.

Besides this, counsel relied on over a thousand reference books in Sanskrit,

Hindi, Urdu, Persian, Turkish, French and English, ranging from subjects as

diverse as history, culture, archaeology and religion. The High Court ensured that

PART A

24

the innumerable archaeological artefacts were kept in the record room. It

received dozens of CDs and other records which the three judges of the High

Court have marshalled.

The decision of the High Court

28. On 30 September 2010, the Full Bench of the High Court comprising of

Justice S U Khan, Justice Sudhir Agarwal and Justice D V Sharma delivered the

judgment, which is in appeal. Justice S U Khan and Justice Sudhir Agarwal held

Muslims, Hindus and Nirmohi Akhara - as joint

holders of the disputed premises and allotted a one third share to each of them in

a preliminary decree. Justice S U Khan held thus:

and Nirmohi Akhara are declared joint title holders of the

property/ premises in dispute as described by letters A B C D

E F in the map Plan-I prepared by Sri Shiv Shanker Lal,

Pleader/ Commissioner appointed by Court in Suit No.1 to the

extent of one third share each for using and managing the

same for worshipping. A preliminary decree to this effect is

passed.

However, it is further declared that the portion below the

central dome where at present the idol is kept in makeshift

temple will be allotted to Hindus in final decree.

It is further directed that Nirmohi Akhara will be allotted share

including that part which is shown by the words Ram

Chabutra and Sita Rasoi in the said map.

It is further clarified that even though all the three parties are

declared to have one third share each, however if while

allotting exact portions some minor adjustment in the share is

to be made then the same will be made and the adversely

affected party may be compensated by allotting some portion

of the adjoining land which has been acquired by the Central

Government.

The parties are at liberty to file their suggestions for actual

partition by metes and bounds within three months.

PART A

25

List immediately after filing of any suggestion/ application for

preparation of final decree after obtaining necessary

instructions from Hon'ble the Chief Justice.

Status quo as prevailing till date pursuant to Supreme Court

judgment of Ismail Farooqui (1994(6) Sec 360) in all its

minutest details shall be maintained for a period of three

months unless thi

Justice Sudhir Agarwal partly decreed Suits 1 and 5. Suits 3 and 4 were

dismissed as being barred by limitation. The learned judge concluded with the

following directions:

(i) It is declared that the area covered by the central dome of

the three domed structure, i.e., the disputed structure being

the deity of Bhagwan Ram Janamsthan and place of birth of

Lord Rama as per faith and belief of the Hindus, belong to

plaintiffs (Suit-5) and shall not be obstructed or interfered in

any manner by the defendants. This area is shown by letters

AA BB CC DD in Appendix 7 to this judgment.

(ii) The area within the inner courtyard denoted by letters B C

D L K J H G in Appendix 7 (excluding (i) above) belong to

members of both the communities, i.e., Hindus (here

plaintiffs, Suit-5) and Muslims since it was being used by both

since decades and centuries. It is, however, made clear that

for the purpose of share of plaintiffs, Suit-5 under this

direction the area which is covered by (i) above shall also be

included.

(iii) The area covered by the structures, namely, Ram

Chabutra, (EE FF GG HH in Appendix 7) Sita Rasoi (MM NN

OO PP in Appendix 7) and Bhandar (II JJ KK LL in Appendix

7) in the outer courtyard is declared in the share of Nirmohi

Akhara (defendant no. 3) and they shall be entitled to

possession thereof in the absence of any person with better

title.

(iv) The open area within the outer courtyard (A G H J K L E F

in Appendix 7) (except that covered by (iii) above) shall be

shared by Nirmohi Akhara (defendant no. 3) and plaintiffs

(Suit-5) since it has been generally used by the Hindu people

for worship at both places.

PART A

26

(iv-a) It is however made clear that the share of muslim

parties shall not be less than one third (1/3) of the total area

of the premises and if necessary it may be given some area

of outer courtyard. It is also made clear that while making

partition by metes and bounds, if some minor adjustments are

to be made with respect to the share of different parties, the

affected party may be compensated by allotting the requisite

land from the area which is under acquisition of the

Government of India.

(v) The land which is available with the Government of India

acquired under Ayodhya Act 1993 for providing it to the

parties who are successful in the suit for better enjoyment of

the property shall be made available to the above concerned

parties in such manner so that all the three parties may utilise

the area to which they are entitled to, by having separate

entry for egress and ingress of the people without disturbing

each others rights. For this purpose the concerned parties

may approach the Government of India who shall act in

accordance with the above directions and also as contained

in the judgement of Apex Court in Dr. Ismail Farooqi (Supra).

(vi) A decree, partly preliminary and partly final, to the effect

as said above (i to v) is passed. Suit-5 is decreed in part to

the above extent. The parties are at liberty to file their

suggestions for actual partition of the property in dispute in

the manner as directed above by metes and bounds by

submitting an application to this effect to the Officer on

Special Duty, Ayodhya Bench at Lucknow or the Registrar,

Lucknow Bench, Lucknow, as the case may be.

(vii) For a period of three months or unless directed

otherwise, whichever is earlier, the parties shall maintain

Justice D V Sharma decreed Suit 5 in its entirety. Suits 3 and 4 were dismissed

as being barred by limitation. Justice D V Sharma concluded:

declared that the entire premises of Sri Ram Janm Bhumi at

Ayodhya as described and delineated in annexure Nos. 1 and

2 of the plaint belong to the plaintiff Nos. 1 and 2, the deities.

The defendants are permanently restrained from interfering

with, or raising any objection to, or placing any obstruction in

the construction of the temple at Ram Janm Bhumi Ayodhya

PART A

27

The parties preferred multiple Civil Appeals and Special Leave Petitions before

this Court against the judgment of the High Court.

Proceedings before this Court

29. On 9 May 2011, a two judge Bench of this Court admitted several appeals

and stayed the operation of the judgment and decree of the Allahabad High

Court. During the pendency of the appeals, parties were directed to maintain

status quo with respect to the disputed premises in accordance with the

directions issued in Ismail Faruqui. The Registry of this Court was directed to

provide parties electronic copies of the digitised records.

30. On 10 September 2013, 24 February 2014, 31 October 2015 and 11

August 2017, this Court issued directions for summoning the digital record of the

evidence and pleadings from the Allahabad High Court and for furnishing

translated copies to the parties. On 10 August 2015, a three judge Bench of this

Court allowed the Commissioner, Faizabad Division to replace the old and worn

out tarpaulin sheets over the makeshift structure under which the idols were

placed with new sheets of the same size and quality.

31. On 5 December 2017, a three judge Bench of this Court rejected the plea

that the appeals against the impugned judgement be referred to a larger Bench in

view of certain observations of the Constitution Bench in Ismail Faruqui. On 14

March 2018, a three judge Bench heard arguments on whether the judgment in

Ismail Faruqui required reconsideration. On 27 September 2018, the three judge

Bench of this Court by a majority of 2:1 declined to refer the judgment in Ismail

PART A

28

Faruqui for reconsideration and listed the appeals against the impugned

judgement for hearing.

32. By an administrative order dated 8 January 2019 made pursuant to the

provisions of Order VI Rule 1 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, the Chief

Justice of India constituted a five judge Bench to hear the appeals. On 10

January 2019, the Registry was directed to inspect the records and if required,

engage official translators. On 26 February 2019, this Court referred the parties

to a Court appointed and monitored mediation to explore the possibility of

bringing about a permanent solution to the issues raised in the appeals. On 8

March 2019, a panel of mediators comprising of (i) Justice Fakkir Mohamed

Ibrahim Kalifulla, a former Judge of this Court; (ii) Sri Sri Ravi Shankar; and (iii)

Mr Sriram Panchu, Senior Advocate was constituted. Time granted to the

mediators to complete the mediation proceedings was extended on 10 May 2019.

Since no settlement had been reached, on 2 August 2019, the hearing of the

appeals was directed to commence from 6 August 2019. During the course of

hearing, a report was submitted by the panel of mediators that some of the

parties desired to settle the dispute. This Court by its order dated 18 September

2019 observed that while the hearings will proceed, if any parties desired to settle

the dispute, it was open for them to move the mediators and place a settlement, if

it was arrived at, before this Court. Final arguments were concluded in the batch

of appeals on 16 October 2019. On the same day, the mediation panel submitted

arrived at by some of the parties to the present dispute. The settlement was

PART B

29

signed by Mr Zufar Ahmad Faruqi, Chairman of the Sunni Central Waqf Board.

Though under the settlement, the Sunni Central Waqf Board agreed to relinquish

all its rights, interests and claims over the disputed land, this was subject to the

fulfilment of certain conditions stipulated. The settlement agreement received by

this Court from the mediation panel has not been agreed to or signed by all the

parties to the present dispute. Moreover, it is only conditional on certain

stipulations being fulfilled. Hence, the settlement cannot be treated to be a

binding or concluded agreement between the parties to the dispute. We,

however, record our appreciation of the earnest efforts made by the members of

the mediation panel in embarking on the task entrusted by this Court. In bringing

together the disputants on a common platform for a free and frank dialogue, the

mediators have performed a function which needs to be commended. We also

express our appreciation of the parties who earnestly made an effort to pursue

the mediation proceedings.

B. An overview of the suits

33. Before examining the various contentions of the parties before this Court,

we first record the procedural history, substantive claims and reliefs prayed for in

the pleadings of the three Suits before this Court.

Suit 1 - OOS No 1 of 1989 (Regular Suit 2 of 1950)

34. The suit was instituted on 13 January 1950 by Gopal Singh Visharad, a

Sanatan Dharm

PART B

30

(i) A declaration of his entitlement to worship and seek the darshan of Lord

Ram, according to religion and custom at the Janmabhumi temple

without hindrance; and

(ii) A permanent and perpetual injunction restraining defendant nos 1 to 10

from removing the idols of the deity and other idols from the place where

they were installed; from closing the way leading to the idols; or interfering

in worship and darshan.

Defendant nos 1 to 5 are Muslim residents of Ayodhya; defendant no 6 is the

State of Uttar Pradesh; defendant no 7 is the Deputy Commissioner of Faizabad;

defendant no 8 is the Additional City Magistrate, Faizabad; defendant no 9 is the

Superintendent of Police, Faizabad; defendant no 10 is the Sunni Central Waqf

Board and defendant no 11 is the Nirmohi Akhara.

The case of the plaintiff in Suit 1 is that, as a resident of Ayodhya, he was

worshipping the idol of Lord Ram and Charan Paduka

plaint are as follows:

East: Store and Chabutra of Ram Janam Bhumi

West: Parti

North: Sita Rasoi

The cause of action for Suit 1 is stated to have arisen on 14 January 1950, when

the employees of the government are alleged to have unlawfully prevented the

as

PART B

31

represented by defendant nos 1 to 5, as a result of which the Hindus were stated

that the idols, including the idol of Lord Ram, would be removed. These actions

35. Denying the allegations contained in the plaint, defendant nos 1 to 5 stated

in their written statements that:

(i) The property in respect of which the case has been instituted is not

Janmabhumi but a mosque constructed by Emperor Babur. The mosque

was built in 1528 on the instructions of Emperor Babur by Mir Baqi, who

-

continent by the Mughal emperor;

(ii) The mosque was dedicated as a waqf for Muslims, who have a right to

worship there. Emperor Babur laid out annual grants for the maintenance

and expenditure of the mosque, which were continued and enhanced by

the Nawab of Awadh and the British Government;

(iii) The Suit of 1885 was a suit for declaration of ownership by Mahant

Raghubar Das only in respect of the Ramchabutra and hence the claim

that the entire building represented the Janmasthan was baseless. As a

consequence of the dismissal of the Suit on 24 December 1885,

(iv) The Chief Commissioner Waqf appointed under the U.P. Muslim Waqf Act

1936 had held the mosque to be a Sunni Waqf;

PART B

32

(v) Muslims have always been in possession of the mosque. This position

possession of that p

(vi) Namaz had been offered at Babri Masjid until 16 December 1949 at which

point there were no idols under the central dome. If any person had placed

any idol inside the mosque with a mala fide intent, ion of the

(vii) Any attempt of the plaintiff or any other person to enter the mosque to offer

worship or for darshan would violate the law. Proceedings under Section

145 of the CrPC 1898 had been initiated; and

(viii) The present suit claiming Babri Masjid as the place of the Janmasthan is

without basis as there exists, for quite long, another temple with idols of

Lord Ram and others, which is the actual place of the Janmasthan of Lord

Ram.

A written statement was filed by the defendant no 6, the State, submitting that:

(i) The property in suit known as Babri Masjid has been used as a mosque for

the purpose of worship by Muslims for a long period and has not been

used as a temple of Lord Ram;

(ii) On the night of 22 December 1949, the idols of Lord Ram were

surreptitiously placed inside the mosque imperilling public peace and

tranquillity. On 23 December 1949, the City Magistrate passed an order

under Section 144 of CrPC 1898 which was followed by an order of the

same date passed by the Additional City Magistrate under Section 145

PART B

33

attaching the disputed property. These orders were passed to maintain

public peace; and

(iii) The City Magistrate appointed Shri Priya Datt Ram, Chairman, Municipal

Board, Faizabad-cum-Ayodhya as a receiver of the property.

Similar written statements were filed by defendant no 8, the Additional City

Magistrate and defendant no 9, the Superintendent of Police.

Defendant no 10, the Sunni Central Waqf Board filed its written statement stating:

(i) The building in dispute is not the Janmasthan of Lord Ram and no idols

were ever installed in it;

(ii) The property in the suit was a mosque known as the Babri mosque

constructed during the regime of Emperor Babur who had laid out annual

grants for its maintenance and expenditure and they were continued and

enhanced by the Nawab of Awadh and the British Government;

(iii) On the night of 22-23 December 1949, the idols were surreptitiously

brought into the mosque;

(iv) The Muslims alone had remained in possession of the mosque from 1528

up to the date of the attachment of the mosque under Section 145 on 29

December 1949. They had regularly offered prayers up to 21 December

1949 and Friday prayers up to 16 December 1949;

(v) The mosque had the character of a waqf and its ownership vested in God;

(vi) The plaintiff was estopped from claiming the mosque as the Janmabhumi

of Lord Ram as the claim in the Suit of 1885 instituted by Mahant

Raghubar Das (described to be the edecessor) had been

PART B

34

confined only to the Ramchabutra measuring seventeen by twenty-one

feet outside the mosque; and

(vii) There already existed a Ram Janmasthan Mandir, a short distance away

from Babri Masjid.

In the ment of defendant nos 1 to 5, it was

averred that the disputed site has never been used as a mosque since 1934. It

continuous possession by virtue of which the claim of the defendants has ceased.

Suit 3 - OOS no 3 of 1989 (Regular Suit no 26 of 1959)

36. The suit was instituted on 17 December 1959 by Nirmohi Akhara through

Mahant Jagat Das seeking a decree for the removal of the receiver from the

management and charge of the Janmabhumi temple and for delivering it to the

plaintiff.

Defendant no 1 in Suit 3 is the receiver; defendant no 2 is the State of Uttar

Pradesh; defendant no 3 is the Deputy Commissioner, Faizabad; defendant no 4

is the City Magistrate, Faizabad; defendant no 5 is the Superintendent of Police,

Faizabad; defendant nos 6 to 8 are Muslim residents of Ayodhya; defendant no 9

is the Sunni Central Waqf Board and defendant no 10 is Umesh Chandra

Pandey.

The cause of action is stated to have arisen on 5 January 1950 when the

management and charge of the Janmabhumi temple was taken away by the City

Magistrate and entrusted to the receiver. Nirmohi Akhara pleaded that:

PART B

35

(i) There exists in Ayodhya since the days of yore an ancient Math or

Akhara of Ramanandi Bairagis called the Nirmohis. This is a religious

establishment of a public character;

(ii) The Janmasthan, commonly known as Janmabhumi, is the birth-place of

Lord Ram and belongs to and has always been managed by Nirmohi

Akhara;

(iii) The Janmasthan is of ancient antiquity lying within the boundaries shown

by the letters A B C D in the sketch map appended to the plaint within

which stands the

E. The building denoted by the letters E F G H I J K L E is the main

Janmabhumi temple, where the idols of Lord Ram with Lakshman,

Hanuman and Saligram have been installed. The temple building has been

in the possession of Nirmohi Akhara and only Hindus have been allowed to

enter the temple and make offerings such as money, sweets, flowers and

fruits. Nirmohi Akhara has been receiving these offerings through its

pujaris;

(iv) Nirmohi Akhara is a Panchayati Math of the Ramanandi sect of Bairagis

which is a religious denomination. The customs of Nirmohi Akhara have

been reduced to writing by a registered deed dated 19 March 1949;

(v) Nirmohi Akhara owns and manages several temples;

(vi) No Mohammedan has been allowed to enter the temple building since

1934; and

(vii) Acting under the provisions of Section 145 of the CrPC 1898, the City

Magistrate placed the main temple and all the articles in it under the

PART B

36

charge of the first defendant as receiver on 5 January 1950. As a

consequence, the plaintiffs have been wrongfully deprived of the

management and charge of the temple.

37. In the written statement filed on behalf of defendant nos 6 to 8, Muslim

residents of Ayodhya, it was stated that Babri Masjid was constructed by

Emperor Babur in 1528 and has been constituted as a waqf, entitling Muslims to

offer prayers. Moreover, it was submitted that:

(i) The Suit of 1885 by Raghubar Mahant Das was confined to Ramchabutra

and has been dismissed by the Sub-Judge, Faizabad;

(ii) The property of the mosque was constituted as a waqf under the U.P.

Muslim Waqf Act 1936;

(iii) Muslims have been in continuous possession of the mosque since 1528 as

a consequence of which all the rights of the plaintiffs have been

extinguished;

(iv) On the eastern and northern sides of the mosque, there are Muslim

graves;

(v) Namaz was continuously offered in the property until 16 December 1949

and the character of the mosque will not stand altered if an idol has been

installed surreptitiously; and

(vi) There is another temple at Ayodhya which is known as the Janmasthan

temple of Lord Ram which has been in existence for a long time.

PART B

37

The plaint was amended to incorporate the averment that on 6 December 1992

In the replication filed by Nirmohi Akhara to the joint written statement of

defendant nos 6 to 8, the existence of a separate Janmasthan temple was

denied. It was stated that the Janmasthan temple is situated to the North of the

Janmabhumi temple.

A written statement was filed in the suit by Defendant no 9, the Sunni Central

Waqf Board denying the allegations.

In the written statement filed by defendant no 10, Umesh Chandra Pandey, it was

submitted:

(i) The Janmasthan is a holy place of worship and belongs to the deity of

Shri Ram Lalla Virajman for a long period of time. The temple is possessed

and owned by the deity. Lord Ram is the principal deity of Ram

Janmabhumi;

(ii) Nirmohi Akhara has never managed the Janmasthan;

(iii) In 1857, the British Government attempted to divide the building by

creating an inner enclosure and describing the boundary within it as a

mosque but no true Muslim could have offered prayers there;

(iv) The presence of Kasauti pillars and the carvings of Gods and Goddess on

the pillars indicated that the place could not be used by a true Muslim for

offering prayers;

PART B

38

(v) The place was virtually landlocked by a Hindu temple in which worship of

the deity took place;

(vi) The Suit of the Nirmohi Akhara was barred by limitation having been

instituted in 1959, though the cause of action arose on 5 January 1950;

and

(vii) Nirmohi Akhara did not join the proceedings under Section 145 nor did

they file a revision against the order passed by the Additional City

Magistrate.

In the replication filed by Nirmohi Akhara to the written statement of defendant no

10, there was a detailed account of the founding of the denomination. Following

the tradition of Shankaracharya since the seventh century CE, the practice of

setting up Maths was followed by Ramanujacharya and later, by Ramanand.

Ramanand founded a s

Ram. The spiritual preceptors of the Ramanandi sect of Bairagis established

These Akharas are Panchayati Maths. Nirmohi Akhara owns the Ram

Janmasthan temple which is associated with the birth-place of Lord Ram. The

outer enclosure was owned and managed by Nirmohi Akhara until the

proceedings under Section 145 were instituted.

Suit 4 - OOS 4 of 1989 (Regular Suit no 12 of 1961)

38. Suit 4 was instituted on 18 December 1961 by the Sunni Central Waqf

Board and nine Muslim residents of Ayodhya. It has been averred that the suit

has been instituted on behalf of the entire Muslim community together with an

PART B

39

application under Order I Rule 8 of the CPC. As amended, the following reliefs

have been sought in the plaint:

A declaration to the effect that the property indicated

by letters A B C D in the sketch map attached to the plaint is

the land adjoining the mosque shown in the sketch map by

letters E F G H is a public Muslim graveyard as specified in

para 2 of the plaint may be decreed.

(b) That in case in the opinion of the Court delivery of

possession is deemed to be the proper remedy, a decree for

delivery of possession of the mosque and graveyard in suit by

removal of the idols and other articles which the Hindus may

have placed in the mosque as objects of their worship be

nts.

(bb) That the statutory Receiver be commanded to hand over

[Note : Prayer (bb) was inserted by an amendment to the plaint pursuant to the

order of the High Court dated 25 May 1995].

Defendant no 1 in Suit 4 is Gopal Singh Visharad; defendant no 2 is Ram

Chander Dass Param Hans; defendant no 3 is Nirmohi Akhara; defendant no 4 is

Mahant Raghunath Das; defendant no 5 is the State of U.P.; defendant no 6 is

the Collector, Faizabad; defendant no 7 is the City Magistrate, Faizabad;

defendant no 8 is the Superintendent of Police of Faizabad; defendant no 9 is

Priyadutt Ram; defendant no 10 is the President, Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha;

defendant no 13 is Dharam Das; defendant no 17 is Ramesh Chandra Tripathi;

and defendant no 20 is Madan Mohan Gupta.

The suit is based on the averment that in Ayodhya, there is an ancient historic

mosque known commonly as Babri Masjid which was constructed by Babur more

PART B

40

than 433 years ago following his conquest of India and the occupation of its

territories. It has been averred that the mosque was built for the use of the

Muslims in general as a place of worship and for the performance of religious

ceremonies. The main construction of the mosque is depicted by the letters A B

C D on the plan annexed to the plaint. Adjoining the land is a graveyard.

According to the plaintiffs, both the mosque and the graveyard vest in the

Almighty and since the construction of the mosque, it has been used by the

Muslims for offering prayers while the graveyard has been used for burial. The

plaint alleged that outside the main building of the mosque, Hindu worship was

being conducted at a Chabutra admeasuring 17x21 feet on which there was a

small wooden structure in the form of a tent.

The plaint contains a recital of the Suit of 1885 by Mahant Raghubhar Das for

permission to construct a temple on the Chabutra which was dismissed. The

plaintiffs in Suit 4 contend that the Mahant sued on behalf of himself, the

Janmasthan and all persons interested in it, and the decision operates as res

judicata as the matter directly and substantially in issue was the existence of the

Babri Masjid, and the rights of the Hindus to construct a temple on the land

adjoining the mosque.

According to the plaintiffs, assuming without admitting that there existed a Hindu

temple as alleged by the defendants on the site of which the mosque was built

433 years ago by Emperor Babur, the Muslims by virtue of their long exclusive

and continuous possession commencing from the construction of the mosque

and ensuing until its desecration perfected their title by adverse possession. The

PART B

41

plaint then proceeds to make a reference to the proceedings under Section 145

of CrPC 1898. As a result of the order of injunction in Suit 2 of 1950, Hindus have

been permitted to perform puja of the idols placed within the mosque but Muslims

have been prevented from entering.

According to the plaintiffs, the cause of action for the suit arose on 23 December

1949 when the Hindus are alleged to have wrongfully entered the mosque and

desecrated it by placing idols inside the mosque. The injuries are claimed to be

continuing in nature. As against the state, the cause of action is alleged to have

arisen on 29 December 1949 when the property was attached by the City

Magistrate who handed over possession to the receiver. The receiver assumed

charge on 5 January 1950.

The reliefs which have been claimed in the suit are based on the above

averments. Essentially, the case of the plaintiffs proceeds on the plea that

(i) The mosque was constructed by Babur 433 years prior to the suit as a

place of public worship and has been continuously used by Muslims for

offering prayers; and

(ii) Even assuming that there was an underlying temple which was

demolished to give way for the construction of the mosque, the Muslims

have perfected their title by adverse possession. On this foundation, the

plaintiffs claim a declaration of title and, in the event that such a prayer is

required, a decree for possession.

PART B

42

39. In the written statement filed by Gopal Singh Visharad, the first defendant

(who is also the plaintiff in Suit 1), it has been stated that if the Muslims were in

possession of the mosque, it ceased in 1934. The Hindus claim to be in

possession after 1934 and their possession is stated to have ripened into

adverse possession. According to the written statement, no prayers were offered

in the mosque since 1934. Moreover, no individual Hindu or Mahant can be said

to represent the entire Hindu community. Hindu puja is stated to be continuing

inside the structure, which is described as a temple since 1934 and admittedly

since January 1950, following the order of the City Magistrate. In an additional

written statement, a plea has been taken that the UP Muslim Waqf Act 1936 is

ultra vires. It has been averred that any determination under the Act cannot

operate to decide a question of title against non-Muslims. In a subsequent written

statement, it has been stated that Hindus have worshipped the site of the

Janmabhumi since time immemorial; the Muslims were never in possession of

the Janmabhumi temple and, if they were in possession, it ceased in 1934. The

suit is alleged to be barred by limitation.

As regards the Suit of 1885, it has been submitted that the plaintiff was not suing

in a representative capacity and was only pursuing his personal interest.

The written statement of Nirmohi Akhara denies the existence of a mosque.

Nirmohi Akhara states that it was unaware of any suit filed by Mahant Raghubar

Das. According to it, a mosque never existed at the site and hence there was no

occasion for the Muslim community to offer prayers till 23 December 1949. It is

urged that what the property described as Babri mosque is and has always been

PART B

43

a temple of Janmabhumi with idols of Hindu Gods installed within. According to

the written statement, the temple on Ramchabutra had been judicially recognised

in the Suit of 1885. It was urged that the Janmabhumi temple was always in the

possession of Nirmohi Akhara and none else but the Hindus were allowed to

enter and offer worship. The offerings are stated to have been received by the

representative of Nirmohi Akhara. After the attachment, only the pujaris of

Nirmohi Akhara are claimed to have been offering puja to the idols in the temple.

The written statement contains a denial of Muslim worship in the structure at least

since 1934 and it is urged that Suit 4 is barred by limitation. In the additional

written statement, Nirmohi Akhara has denied that the findings in the Suit of 1885

operate as res judicata. There is a denial of the allegation that the Muslims have

perfected their title by adverse possession.

The State of Uttar Pradesh filed its written statement to the effect that the

government is not interested in the property in dispute and does not propose to

contest the suit.

In the written statement filed on behalf of the tenth defendant, Akhil Bhartiya

Hindu Mahasabha, it has been averred that upon India regaining independence,

there is a revival of the original Hindu law as a result of which the plaintiffs cannot

claim any legal or constitutional right. In an additional written statement, the tenth

defendant denies the incident of 22 December 1949 and claims that the idols

were in existence at the place in question from time immemorial. According to the

written statement, the site is the birth-place of Lord Ram and no mosque could

have been constructed at the birth-place.

PART B

44

The written statement by Abhiram Das and by Dharam Das, who claims to be his

chela, questions the validity of the construction of a mosque at the site of Ram

Janmabhumi. According to the written statement, the site is landlocked and

surrounded by places of Hindu worship and hence such a building cannot be a

valid mosque in Muslim law. The written statement contains a denial of a valid

waqf on the ground that a waqf cannot be based on adverse possession.

According to the written statement, at Ram Janmabhumi there was an ancient

temple tracing back to the rule of Vikramaditya which was demolished by Mir

Baqi. It has been averred that Ram Janmabhumi is indestructible as the deity is

divine and immortal. In spite of the construction of the mosque, it has been

submitted, the area has continued to be in the possession of the deities and no

one could enter the three domed structure except after passing through Hindu

places of worship. The written statements filed by the other Hindu defendants

broadly follow similar lines. Replications were filed to the written statements of

the Hindu parties.

Suit 5 – OOS no 5 of 1989 (Regular Suit no 236 of 1989)

40. The suit was instituted on 1 July 1989 claiming the following reliefs:

Bhumi at Ayodhya, as described and delineated in Annexure

I, II and III belongs to the plaintiff Deities.

(B) A perpetual injunction against the Defendants prohibiting

them from interfering with, or raising any objection to, or

placing any obstruction in the construction of the new Temple

building at Sri Rama Janma Bhumi, Ayodhya, after

demolishing and removing the existing buildings and

structures etc., situate thereat, in so far as it may be

PART B

45

This

Ram Janmabhumi, Ayodhya also called Bhagwan Sri Ram L

Deoki Nandan Agrawala, a former judge of the Allahabad High Court as next

friend. The next friend of the first and second plaintiffs is impleaded as the third

plaintiff.

The defendants to the suit include:

(i) Nirmohi Akhara which is the Plaintiff in Suit 3;

(ii) Sunni Central Waqf Board, the Plaintiff in Suit 4;

(iii) Hindu and Muslim residents of Ayodhya; and

(iv) The State of Uttar Pradesh, the Collector and Senior Superintendent of

Police.

Several other Hindu entities including the All India Hindu Mahasabha and a Trust

described as the Sri Ram Janmabhumi Trust, are parties to the Suit as is the

Shia Central Board of Waqfs.

The principal averments in Suit 5 are that:

(i) The first and second plaintiffs are juridical persons: Lord Ram is the

presiding deity of the place and the place is itself a symbol of worship;

(ii) The identification of Ram Janmabhumi, for the purpose of the plaint is

based on the site plans of the building, premises and adjacent area

prepared by Sri Shiv Shankar Lal, who was appointed as Commissioner by

the Civil Judge at Faizabad in Suit 1 of 1950;

PART B

46

(iii) The plaint contains a reference to the earlier suits instituted before the Civil

Court and that the religious ceremonies for attending to the deities have

been looked after by the receiver appointed in the proceedings under

Section 145. Although seva and puja of the deity have been conducted,

darshan for the devotees is allowed only from behind a barrier;

(iv) Alleging that offerings to the deity have been misappropriated, it has been

stated that the devotees

removiDeed of

Trust was constituted on 18 December 1985 for the purpose of managing

the estate and affairs of the Janmabhumi;

(v) Though both the presiding deity of Lord Ram and Ram Janmabhumi are

claimed to be juridical persons with a distinct personality, neither of them

was impleaded as a party to the earlier suits. As a consequence, the

decrees passed in those suits will not bind the deities;

(vi) Public records establish that Lord Ram was born and manifested himself in

human form as an incarnation of Vishnu at the premises in dispute;

(vii) The place itself Ram Janmasthan - is an object of worship since it

personifies the divine spirit worshipped in the form of Lord Ram. Both the

deity and the place of birth thus possess a juridical character. Hindus

worship the spirit of the divine and not its material form in the shape of an

idol. This spirit which is worshipped is indestructible. Representing this

spirit, Ram Janmabhumi as a place is worshipped as a deity and is hence

a juridical person;

PART B

47

(viii)

its devotees is not essential for its existence since the deity represented by

the land is indestructible;

(ix) There was an ancient temple during the reign of Vikramaditya at Ram

Janmabhumi. The temple was partly destroyed and an attempt was made

to raise a mosque by Mir Baqi, a Commander of Emperor Babur. Most of

the material utilised to construct the mosque was obtained from the temple

including its Kasauti pillars with Hindu Gods and Goddesses carved on

them;

(x) The 1928 edition of the Faizabad Gazetteer records that during the course

of his conquest in 1528, Babur destroyed the ancient temple and on its site

a mosque was built. In 1855, there was a dispute between Hindus and

Muslims. The gazetteer records that after the dispute, an outer enclosure

was placed in front of the mosque as a consequence of which access to

the inner courtyard was prohibited to the Hindus. As a result, they made

their offerings on a platform in the outer courtyard;

(xi) The place belongs to the deities and no valid waqf was ever created or

could have been created;

(xii) The structure which was raised upon the destruction of the ancient temple,

utilising the material of the temple does not constitute a mosque. Despite

the construction of the mosque, Ram Janmabhumi did not cease to be in

possession of the deity which has continued to be worshipped by devotees

through various symbols;

PART B

48

(xiii) The building of the mosque could be accessed only by passing through the

adjoining places of Hindu worship. Hence, at Ram Janmabhumi, the

worship of the deities has continued through the ages;

(xiv) No prayers have been offered in the mosque after 1934. During the night

intervening 22-23 December 1949, idols of Lord Ram were installed with

due ceremony under the central dome. At that stage, acting on an FIR,

proceedings were initiated by the Additional City Magistrate under Section

145 of the CrPC and a preliminary order was passed on 29 December

1949. A receiver was appointed, in spite of which the possession of the

plaintiff deities was not disturbed;

(xv) The plaintiffs, were not a party to any prior litigation and are hence not

bound by the outcome of the previous proceedings; and

(xvi) The Ram Janmabhumi at Ayodhya which contains, besides the presiding

deity, other idols and deities along with its appertaining properties

constitutes one integral complex with a single identity. The claim of the

Muslims is confined to the area enclosed within the inner boundary wall,

erected after the annexation of Oudh by the British.

The plaint contains a description of the demolition of the structure of the mosque

on 6 December 1992 and the developments which have taken place thereafter

including the promulgation of an Ordinance and subsequently, a law enacted by

the Parliament for acquisition of the land.

PART B

49

41. In the written statement filed by Nirmohi Akhara, it has been stated that:

(i) The idol of Lord Ram has been installed not at Ram Janmabhumi but in

the Ram Janmabhumi temple. Nirmohi Akhara has instituted a suit

seeking charge and management of Ram Janmabhumi temple;

(ii) While the birth-place of Lord Ram is not in dispute, it is the Ram

Janmabhumi temple which is in dispute. The Muslims claim it to be a

mosque while Nirmohi Akhara claims it to be a temple under its charge

-place of Lord Ram), Mohalla Ram Kot at

Ayodhya;

(iii) Nirmohi Akhara is the Shebait of the idol of Lord Ram installed in the

temple in dispute and has the exclusive right to repair and reconstruct the

temple, if necessary; and

(iv) person. The plaintiffs of suit 5

have no real title to sue. The entire premises belong to Nirmohi Akhara,

the answering defendant. Hence, according to the written statement the

plaintiffs have no right to seek a declaration.

According to the written statement of the Sunni Central Waqf Board:

(i) Neither the first nor the second plaintiffs are juridical persons;

(ii) There is no presiding deity of Lord Ram at the place in dispute;

(iii) The idols were surreptitiously placed inside the mosque on the night of 22-

23 December 1949. There is neither any presiding deity nor a Janmasthan;

(iv) The Suit of 1885 was instituted by Mahant Raghubar Das in his capacity

as Mahant of the Janmasthan of Ayodhya seeking permission to establish

PART B

50

a temple over a platform or Chabutra. The mosque was depicted in the site

plan on the western side of the Chabutra. The suit was instituted on behalf

of other Mahants and Hindus of Ayodhya and Faizabad. The suit was

dismissed. The first and second appeals were also rejected. Since the

claim in the earlier suit was confined only to the Chabutra admeasuring

seventeen by twenty-one feet outside the mosque, the claim in the present

suit is barred;

(v) There exists another temple known as the Janmasthan temple situated at

a distance of less than one hundred yards from Babri Masjid;

(vi) The mosque was not constructed on the site of an existing temple or upon

its destruction;

(vii) During the regime of Emperor Babur the land belonged to the State and

the mosque was constructed on vacant land which did not belong to any

person;

(viii) The structure has always been used as a mosque ever since its

construction during the regime of Emperor Babur, who was a Sunni

Muslim;

(ix) The possession of Muslims was uninterrupted and continuous since the

construction of the mosque, until 22 December 1949. Therefore, any

alleged right to the contrary is deemed to have been extinguished by

adverse possession;

(x) Prayers were offered in the mosque five times every day, regularly until 22

December 1949 and Friday prayers were offered until 16 December 1949;

PART B

51

(xi) On 22-23 December 1949, some Bairagis forcibly entered into the mosque

and placed an idol below the central dome. This came to the knowledge of

Muslims who attended the mosque for prayers on 23 December 1949 after

which proceedings were initiated under Section 145 of the CrPC 1898. The

possession of the building has remained with the receiver from 5 January

1950;

(xii) The third plaintiff in Suit 5 could have got himself impleaded as a party to

the suit instituted by the Sunni Central Waqf Board. Having failed to do so

the third plaintiff cannot maintain Suit 5 as the next friend of the deities;

(xiii) The third plaintiff has never been associated with the management and

puja of the idols and cannot claim himself to be the next friend of Lord

Ram;

(xiv) There is no presiding deity as represented by the first plaintiff and it is

incorrect to say that the footsteps (charan and other structures constitute

one integral complex with a single identity;

(xv) The concept of a mosque envisages that the entire area below as well as

above the land remains dedicated to God. Hence, it is not merely the