High. Learn. Res. Commun. Volume 5, Num. 4 | December 2015

*Corresponding author ([email protected])

Suggested citation: Ryan, P. (2015). Quality assurance in higher education: A review of literature. Higher Learning

Research Communications, 5(4). http://dx.doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i4.257

Quality Assurance in Higher Education: A Review of Literature

Patricia Ryan

Academic Quality and Accreditation, Laureate Education, Inc.

Submitted: August 24, 2015 | Peer-reviewed: November 29, 2015 | Editor-reviewed: December 26, 2015

Accepted: December 28, 2015 | Published: December 31, 2015

Abstract: The aim of this paper is to present a general view and a brief literature review of the

main aspects related to quality assurance in global higher education. It provides an overview of

accreditation as a mechanism to ensure quality in higher education, examines models of QA, and

explores the concept of quality. In addition, this paper provides a review of research on the

effectiveness of quality assurance practices, with a particular focus on student involvement with

quality assurance. In reviewing the concept of quality assurance itself, the author noted there is

a need for a common framework for a quality assurance model; however, there is no agreement

as to a QA definition or a QA model. Furthermore, although quality is the utmost significant

concern for accrediting bodies, accreditation structures are decentralized and complex at both

the regional and international level. Another challenge identified revolves around the concerns of

faculty members and other stakeholders, such as students, about the QA process. Given that

students are at the center of higher education, and invest time and money in the system, the

author concludes involving them could improve QA processes.

Keywords: Quality assurance, higher education, accreditation, accountability, continuous

improvement, involving students in quality assurance

Introduction

“What is important in knowledge is not quantity, but quality. It is important to know what is

significant, what is less so, and what is trivial. –Leo Tolstoy

By 2025, the projected global demand for higher education could reach 263 million

students, which is an increase from a little less than 100 million students in 2000 (Karaim, 2011,

p. 551). This could represent an increase of 163 million students in 25 years (Karaim, 2011). As

the demand for quality education increases, there is a growing demand for quality assurance (QA)

for international universities where there is increased mobility of students, faculty, programs, and

higher education institutions in global networks (Hou, 2012; Varonism, 2014). Quality assurance

can be a driver for institutions to achieve excellence in higher education. However, ensuring that

the quality of educational programs meets local and international standards simultaneously has

become a great challenge in many countries (OECD & World Bank, 2007). Hence, a need

emerges for cooperation of quality assurance agencies and acceptance of quality assurance

review decisions.

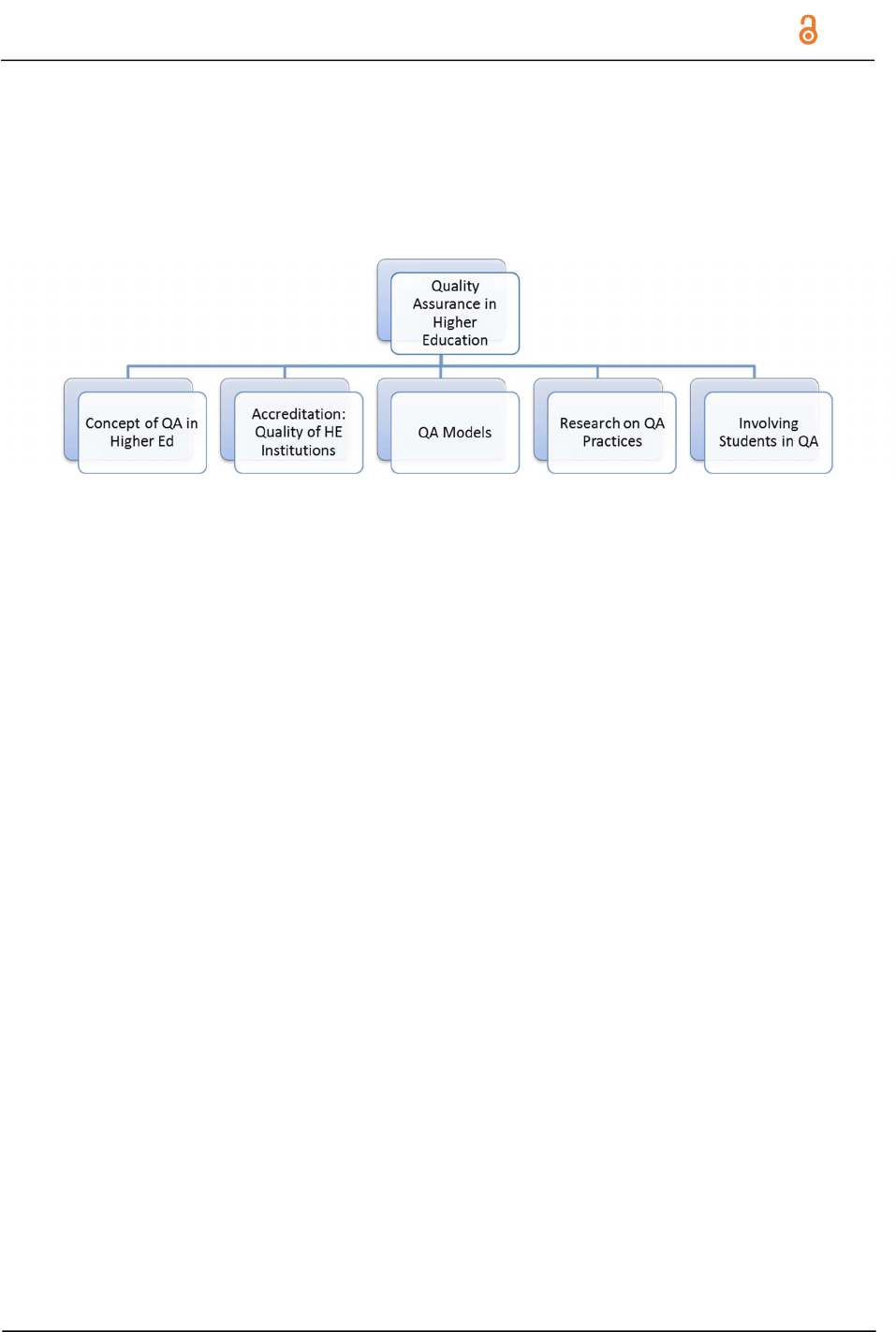

In order to address this emerging need, a common framework for a quality assurance

model would provide consistent assessment of learning design, content, and pedagogy

(Puzziferro & Shelton, 2008). As shown in Figure 1, a conceptual model of quality assurance (QA)

www.hlrcjournal.com Open Access

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

in higher education comprises several areas. As such, the aim of this paper is to examine the

literature surrounding quality assurance in global higher education. It provides an overview of

accreditation as a mechanism to ensure quality in higher education, examines models of QA, and

explores the concept of quality. In addition, this paper provides a review of research on the

effectiveness of quality assurance practices, with a particular focus on student involvement with

quality assurance.

Figure 1. Quality assurance in higher education conceptual model.

The Concept of Quality Assurance in Higher Education

Internationalization in higher education has resulted in “a growing demand for

accountability and transparency . . . [which has] in turn led to a need to develop a quality culture,

while addressing the challenges of globalized higher education” (Smidt, 2015, p. 626). In a

practical sense, quality assurance reviews provide external, third party, independent, objective

insights. Such reviews offer observations about partner institutions, products, programs, services,

and processes, and they provide recommendations for improvement. Nonetheless, “the

perception of quality assurance is very multi-dimensional and contextual and a gap exists in the

view between professionals in quality assurance and academic staff and students” (Smidt, 2015,

p. 626). Several key dimensions of quality in higher education include excellence, value,

consistency, and meeting needs and expectations; yet no one quality assurance framework can

address all aspects of quality, so choices are made about what kinds of quality are assessed

(Harvey, 2014; Wilger, 1997).

A common framework for a quality assurance model would provide consistent assessment

of learning design, content, and pedagogy (Puzziferro & Shelton, 2008). However, there are many

disparate ways to characterize quality in education. According to Barnett (1992), there are two

conceptions of quality in higher education. The first is tacit conceptions of value and intellectual

property in academia. It is the character and quality of the contributions of higher education's

members that are at issue rather than any outcomes. The other conception of quality is the

performance conception, in which higher education is seen as a product with inputs and outputs.

In this view, the quality of higher education is measured in terms of performance as captured in

performance indicators. Another conception of quality in higher education is of faculty-student

interaction (Lundberg & Schreiner, 2004; Vincent, 1987).

The literature contains many different definitions of quality assurance in higher education.

In examining definitions of quality, Schindler, Puls-Elvidge, Welzant, and Crawford (2015) noted

two main strategies for formulating definitions in the literature (p. 4-5). Some authors “construct a

broad definition that targets one central goal or outcome” (Schindler et al, 2015; referencing

Bogue, 1998; Harvey & Green, 1993). On the other hand, other definitions “identify specific

indicators that reflect desired inputs (e.g., responsive faculty and staff) and outputs (e.g.,

High. Learn. Res. Commun. Volume 5, Num. 3 | September 2015

P. Ryan

employment of graduates)” (Schindler et al., 2015; referencing Barker, 2002; Cheng & Tam, 1997;

Lagrosen, Seyyed-Hashemi, & Leitner, 2004; Oldfield & Baron, 2000; Scott, 2008; Tam, 2010;

Vlăsceanu et al., 2007).

Although Schindler et al. (2015) identified four broad conceptualizations of quality in higher

education (quality as purposeful, transformative, exceptional, and accountable), there is no

agreement on a definition of quality (p. 8). Probably, the main obstacle in developing a common

framework is how different regions address the matter, since “accreditation and quality assurance

are no longer purely national undertakings” (Green, Marmolejo, & Egron-Polak, 2012, p. 452),

and different jurisdictions take different approaches to quality assurance and program

accreditation. For instance, while some accrediting bodies in different jurisdictions establish

mutual recognition of their standards through private agreements, there are other instances where

such recognition depends on a governmental or nongovernmental body or agency that provides

standing to the accrediting agencies in their respective jurisdictions (2012, p. 451-452).

Accreditation: Quality Assurance of Higher Education Institutions

According to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA, 2007), three factors

influence the quality assurance trends in international higher education. First, quality assurance

is more competitive and rigorous than ever before. Second, quality assurance is becoming

recognized regionally. Third, there is a need for an international quality assurance framework with

acknowledgement and reciprocity across countries. Program offerings across international

boundaries require students to enroll in multiple jurisdictions as part of their degree programs.

These innovative approaches to higher education demand greater awareness of the attributes

and requirements of quality assurance organizations worldwide. Wong (2012) expressed the

importance for institutions to demonstrate value and performance and states that higher

education organizations apply principles for private industry to assess quality initiatives.

“Accreditation is a review of the quality of higher education institutions and programs”

(CHEA, 2014, para.1). An institution or program is granted accreditation for meeting minimum

standards of quality. One common accreditation theme is quality assurance assessment and

continuous improvement. Accrediting agencies have developed standards and procedures to

guide institutions in the process of voluntary commitment to continuous improvement, by way of

application for accreditation. These standards are used by review committees as the basis for

judgment and to make recommendations and decisions.

Regional accreditation is comprehensive and indicates that an institution has achieved

quality standards in areas such as faculty, administration, curriculum, student services, and

overall financial well-being (Eaton, 2011). Regional accreditors require compliance with quality

standards and criteria. In the United States, regional accreditation is conducted and granted by

seven accrediting bodies in six regions. The accrediting bodies are Western Association of

Schools and Colleges (WASC) Accrediting Commission for Senior Colleges and Universities,

Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) Commission on Colleges (COC), Middle

States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE), New England Association of Schools and

Colleges (NEASC), the Higher Learning Commission (HLC), and the Northwest Commission on

Colleges and Universities (NWCCU).

Quality is the utmost significant concern for all regional accrediting agencies in the United

States. Evidence of the significant emphasis on quality is found in every U.S. regional accrediting

agency’s goals statement.

www.hlrcjournal.com Open Access

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

The WASC Senior Colleges and Universities Commission (WSCUC) is a regional

accrediting agency. Two of WSCUC’s strategic goals emphasize quality. One goal states WSCUC

will “ensure the efficiency and effectiveness of peer review as the foundation of quality

assurance.” Another goal states WSCUC will “create internal research capacity that supports

institutional and Commission efforts and provides information to the public related to the quality

of higher education in the region” (WSCUC, 2014, 2014–15 Strategic Priorities, paras. 1.a. and

1.c.).

Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges’ (SACS COC)

mission statement focuses on quality: “The mission of the Southern Association of Colleges and

Schools Commission on Colleges is to assure the educational quality and improve the

effectiveness of its member institution” (SACS COC, 2014, Mission Statement, para.1).

The Mid-Atlantic Region Commission on Higher Education (2014) states in its mission,

“the Middle States Commission on Higher Education is a voluntary, non-governmental,

membership association that is dedicated to quality assurance and improvement through

accreditation via peer evaluation” (para.1). NEASC Commission on Institutions of Higher

Education’s (CIHE) mission endorses quality in education: “through its process of assessment,

the Commission encourages and assists in the improvement, effectiveness and excellence of

affiliated educational institutions” (CIHE, 2014, p.1).

HLC has issued the following statement: “The federal government has a distinct interest

in the role of accreditation in assuring quality in higher education for the students who benefit from

federal financial aid programs. As a recognized gatekeeper agency by the U.S. Department of

Education (USDE), HLC, ‘the Commission’ agrees to fulfill specific federally defined

responsibilities within the accreditation processes” (HLC, 2014, para. 2).

The Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU; 2014) is an

“independent, non-profit membership organization recognized by the U.S. Department of

Education as the regional authority on educational quality and institutional effectiveness of higher

education institutions in the seven-state Northwest region.” (para.2).

Regardless of how central quality assurance is among these accrediting bodies, “the U.S.

accreditation structure is decentralized and complex, mirroring the decentralization and

complexity of American higher education (Eaton, 2012). Recognizing international study

programs and programs “offered by nondomestic institutions or providers involves a new level of

complexity (Knight, 2005). Indeed, "quality assurance has become an international endeavor and

a key component of higher education policies in nearly every country, especially given that

students and scholars move across national and regional boundaries at unprecedented rates

(Blanco-Ramirez, 2014; citing Altbach et al., 2010; Harvey, 2004).

Models of Quality Assurance

The applications of quality assurance processes in higher education are discussed in the

literature, yet skepticism prevails on the effectiveness of any one QA model (Asif, Raouf, &

Searcy, 2012). One of the reasons for this skepticism could be attributed to the fact that the types

of services and the quality frameworks the agencies use vary from one QA organization to

another. For example, the Baldrige Program is an affiliate of the National Institute of Standards

and Technology (NIST) and it is dedicated to performance excellence. Baldrige administers the

Malcom Baldrige National Quality Award. Award recipients must demonstrate achievements and

improvements that meet seven categories of the criteria for performance excellence. There are

High. Learn. Res. Commun. Volume 5, Num. 3 | September 2015

P. Ryan

three versions of the criteria: (1) business/nonprofit, (2) education, (3) health care organizations.

Baldrige aims to strengthen U.S. competitiveness and serve as a model for national excellence

and award programs around the world (Asif et al., 2012; Baldrige 2014a; Baldrige, 2014b). The

Baldrige education criteria for performance excellence are a powerful mechanism to assess

performance excellence, but the criteria lack a theoretical foundation (Asif et al., 2012, p. 3109).

Furthermore, the Baldrige criteria for performance excellence are too vague and do not address

the requirements from an academic standpoint (Asif et al., 2012, p. 3110).

The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA), in collaboration with the

higher education sector, developed and maintains the UK Quality Code for Higher Education to

assure quality standards for higher education institutions in the United Kingdom (QAA, 2014).

Quality Matters (QM) is a leader in quality assurance for online education and has received

national recognition for its peer-based approach and continuous improvement in online education

and student learning. QM subscribers include community and technical colleges, colleges and

universities, K–12 schools and systems, and other academic institutions (Varonism, 2014).

Quality Matters is also a leading provider of tools and processes used to evaluate quality

in course design (Quality Matters, 2014a). The Quality Matters Rubric is a widely used set of

standards for the design of online and blended courses at the college level (Quality Matters, 2014;

Varonism, 2014). More than 700 colleges and universities subscribe to the nonprofit QM program

(Quality Matters, 2014a). The QM process for continuous improvement is the framework for

quality assurance efforts in online learning and provides effective professional development for

faculty making the transition into distance education. The Quality Matters Rubric is a set of eight

general standards and 41 specific standards used to evaluate the design of online and blended

courses. The QM Rubric is complete with annotations that explain the application of the standards

and the relationships among them. A scoring system and set of online tools facilitate the

evaluation by a team of peer reviewers (Pollacia & Terrie, 2009; Quality Matters, 2014b;

Varonism, 2014). As online programs proliferate in international higher education, many

constituents have concerns about quality. Quality assurance is becoming more significant. While

the QM program offers a systematic quality assurance process for the design of online programs,

it lacks criteria to determine the quality of delivery and instructor and faculty engagement.

Therefore, QM is not a total solution (Pollacia & Terrie, 2009; Quality Matters, 2014b).

Aside from the differences in types of services and quality frameworks developed and

used by different agencies, another difficulty identified in the literature is a lack of cultural

sensitivity (Gift, Leo-Rhynie, & Moniquette, 2006; Hodson & Thomas, 2010; Smith, 2010).

Furthermore, Stella and Woodhouse (2011) argued higher education institutions in developing

countries could be at a disadvantage in transnational education and the establishment of a set of

minimum standards because of their capacity “to participate effectively in the global trading

system” (p. 12).

Research on Effectiveness of QA Practices

Higher education gleaned the concept of quality from commercial settings and private

industry (Newton, 2002). Methods of quality assurance were introduced in England in the 1980s

as part of the Teaching Quality Assessment (TQA). TQA provided a third party review and

assessment at the institutional level and peer reviewers conducted the TQA review (Cheng,

2010). Then, TQA was replaced with subject reviews during the period of 1995–2001. Subject

review was replaced by the institutional audit by the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) for higher

education in England (Cheng, 2010).

www.hlrcjournal.com Open Access

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

Cheng (2010) conducted a study using theoretical sampling to select academics from

seven institutions in England. The study examined how quality and audit affect the work of

academics through capturing their perceptions and experiences of quality audits. The study

examined eight criteria for quality assurance mechanisms. Four were internally devised and

implemented (peer observation, student course evaluation, annual program review, and the

approval system for new and revised programs and units). The other four mechanisms were

externally developed: England’s QAA institutional audit, two external examining systems, and

regulatory bodies. Cheng analyzed the perceived effects of the eight mechanisms on the following

aspects of academic work: teaching practices, curriculum development, power relations between

faculty and students, and faculty workload (Cheng, 2010). The results of Cheng’s study showed

that quality audits remain a source of controversy. Two thirds of the respondents felt the quality

audit was futile and bureaucratic because their work focuses on research and teaching. This

finding, Cheng said, indicated that academics want to maintain autonomy. The academics

exhibited resistance to the quality audit which produced “game-playing” attitudes to quality

assurance mechanisms (Cheng, 2010, p. 269). Issues of power and control surfaced and suggest

a relationship exists between the university and the QAA because of a need to have a quality

assurance mechanism in place to meet the requirements of the QAA. Academics viewed the

university’s relationship with QAA as distant from their own work and did not feel “ownership of

and responsibility for” the quality audit process (Cheng, 2010, p. 269).

Grifoll, et al. (2012) presented a collection of characteristics of good practice in external

quality assurance and highlight connections between the QA practices and the potential benefits

for institutions of higher education. According to the authors’ survey research, 43% of respondents

follow processes that link QA reviews with qualifications frameworks in Europe, but only seven

agencies reported they are successful in doing so (Grifoll et al., 2012). The paper identified

practices that quality assurance agencies are expected to implement, as well as areas where

progress was needed, thus proposing a vision for the future of quality assurance reviews. The

article reported the following examples of good QA practices:

Practices regarding external QA procedures

Practices which enhance stakeholders’ involvement in QA of higher education

Practices aiming at improving the infrastructure and resources of agencies

However, there is a limitation to this survey research. The survey does not provide

adequate information on how different agencies include quality of online education in their QA

strategic plan for program or institutional QA review (Grifoll et al., 2012, p. 25).

Since 1992, the Online Learning Consortium (OLC, formerly Sloan-C) has served as a

clearinghouse for research with the aim to help institutions create high-quality educational

experiences in the U.S. and international field of online education. The OLC Quality Scorecard,

first developed in 2010 (and launched in 2011), was the result of a research study conducted in

2009. The research study used the Delphi methodology. The Delphi method gains consensus

from subject matter experts on a given topic because “it replaces direct confrontation and debate

by a carefully planned, anonymous, orderly program of sequential individual interrogations usually

conducted by questionnaires” (Brown, Cochran, & Dalkey, 1969, p. 1). The release of the new

OLC Quality Scorecard is the result of three years of research involving user study and feedback.

In addition to serving as an evaluation instrument, the Quality Scorecard can be used as an

instructive tool for developing quality online learning programs (OLC, 2014).

High. Learn. Res. Commun. Volume 5, Num. 3 | September 2015

P. Ryan

Success and Challenges in QA Review Practices

In the past 10 years, heightened interest has been directed toward quality assurance in

international higher education (OECD & World Bank, 2007). Historically, quality assurance

agencies have not focused their attention on assessing imported or exported academic programs,

with some exceptions. Now, however, an increase in cross-border education has introduced a

new challenge in the field of quality assurance. The QA models mentioned in this paper (QM,

Baldrige, OLC) are examples of QA systems, but the higher education sector has mixed views on

the appropriateness of quality standards (OECD & World Bank, 2007). For example, there is a

range of opinions about the value of international criteria for quality assurance of higher education

because such standardization may jeopardize the integrity of the countries’ higher education

systems and may not necessarily improve the quality of the academic programs (OECD & World

Bank, 2007, p. 38–39).

One challenge of quality assurance reviews is faculty members and other stakeholders’

concerns about the QA process. Altman, Schwegler, and Bunkowski (2014) investigated faculty

beliefs and their plans to participate in the peer quality assurance reviews using the Quality

Matters Rubric. The researchers use a qualitative approach to examine faculty members’

perceptions of completing the QA peer review. Although faculty were skeptical before participating

in the QA process, the results indicate that many of the concerns and criticisms of the peer review

process did not validate earlier assumptions. The study examined faculty beliefs, instead of

rumors, to identify specific faculty concerns that could be directly addressed. The results, though

limited due to small sample size, stated online course quality is an important goal, and, with plans

for expansion, an established standard (such as the QM rubric) requires scientific inquiry for

appropriate and improved application of the standard (Altman, Schwegler, & Bunkowski, 2014).

This research can be used to guide changes in QA processes and to increase participation in QA

reviews with the goal of improving the online course design quality with a greater number of

institutions (Altman, Schwegler, & Bunkowski, 2014, p. 109).

Concerns about the QA process reflect another challenge in itself: creating a quality

culture. All stakeholders within an institution need to share a vision as to what quality is and

choose a management model to improve overall quality and maintain continuous improvement

(Lomas, 2003).

Certainly, another major challenge in quality assurance revolves around digital learning

and the integration of technology. According to Stella and Gnanam (2004), with the increasing

amount of digital educational offerings, consumers “expect the quality assurance agencies to

provide more information about the quality of those educational services to make intelligent

choices (p. 148). In turn, “this raises issues of quality assurance controls by the exporting and

importing countries and whether quality assurance should discriminate between in-country

providers and the transnational providers” (2004, p. 148).

Involving Students in QA Processes

Involving students in QA processes is an important topic and educational leaders are

considering how best to include students in their QA systems. Student involvement in evaluating

and enhancing the quality of their higher education institution is carried out though specific

activities, such as responding to focus group interviews and questionnaires, participating in QA‐

related working groups, and involving themselves in QA processes (Elassy, 2013, p. 166).

www.hlrcjournal.com Open Access

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

The quality of educational services provided by a university is a crucial aspect of strategic

plans in the student-centered education context. Students’ evaluation of the academic programs

is a significant assessment instrument used for stimulating quality enhancement in a university

(Stukalina, 2014). Carmichael, Palermo, Reeve & Vallence (2001) argue that the perspective of

the individual learner should be placed at the core of quality in all areas of education, and,

consequently, learners are an essential component of quality assurance programs and

processes.

Introducing students to quality assurance processes and allowing them to participate in

external evaluation panels provide good experiences for students. In the role of student

representative, the student has the ability to see the situation from the learner’s perspective, which

others may not be able to take into account. Furthermore, the students are stakeholders in higher

education, with time and money investments in the system. As such, they have a special interest

in the quality of the academic program (Alaniska et al., 2006). Yet, according to the European

Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA), some agencies face challenges

in finding qualified students to participate in QA processes (2006). For instance, students who do

not participate in faculty or institutional boards may lack the necessary tacit competencies to

participate in quality assurance evaluations. In addition, language and cultural issues present

challenges to the involvement of students in QA initiatives (Alaniska et al., 2006).

Irrespective of the challenges, the benefits for involving students in QA processes can be

grouped into two categories: benefit to the student and benefit to the QA process. Benefits for the

student include development of communication, analytical reasoning, and leadership skills

(Elassy, 2013). The Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) in the United Kingdom reports that student

participation is “an opportunity for students to develop their ability to analyse the quality of their

programmes, creating a sense of ownership of these programs” (QAA, 2009, p. 2).

Students have a multifaceted understanding of quality in higher education. Another benefit

of involving students in quality assurance initiatives is transparency, meaning all participants see

the outcomes and subsequent changes. Student participation in QA activities influences the

quality of higher education (Palomares, 2014). Including students is key in the QA process

because they provide an important lens for quality assurance in higher education.

Conclusion

This paper has presented an overview and a brief literature review of the main aspects

related to quality assurance in higher education. In reviewing the concept of quality assurance

itself, it can be said there is a need for a common framework for a quality assurance model;

however, there is no agreement as to a QA definition or a QA model. Furthermore, although

quality is the utmost significant concern for accrediting bodies, accreditation structures are

decentralized and complex at both the regional and international level. The difficulties and

skepticism in choosing one QA model or another can be seen in the various types of services and

the quality frameworks the agencies use, which vary from one QA organization to another, and

from one jurisdiction to another. Another challenge revolves around the concerns of faculty

members and other stakeholders, such as students, about the QA process. Given that students

are at the center of higher education, and invest time and money in the system, involving them

could improve QA processes.

High. Learn. Res. Commun. Volume 5, Num. 3 | September 2015

P. Ryan

References

Alaniska, H., Codina, E. A., Bohrer, J., Dearlove, R., Eriksson, S., Helle, E. M, & Wiberg, L. K. (2006).

Student involvement in the processes of quality assurance agencies. Retrieved from

http://www.enqa.eu/pubs.lasso

Altman, B. W., Schwegler, A. F., & Bunkowski, L. M. (2014). Beliefs regarding faculty participation in peer

reviews of online courses. Internet Learning, 3(1).

Asif, M. & Raouf, A. (2012). Setting the course for quality assurance in higher education. Quality & Quantity,

1–16.

Asif, M., Raouf, A., & Searcy, C. (2012). Developing measures for performance excellence: Is the Baldrige

criteria sufficient for performance excellence in higher education? Quality & Quantity, 47(6), 3095–

3111. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11135-012-9706-3

Baldrige Foundation. (2014a). Baldrige performance excellence. Retrieved from http://www.baldrigepe.org/

Baldrige Foundation. (2014b). 2013–2014 Baldrige education criteria for performance excellence: Category

and item commentary. Retrieved from http://www.nist.gov/baldrige/

Barnett, R. (1992). Improving higher education: Total quality care. Bristol, PA: SRHE and Open University

Press.

Blanco-Ramirez, G. (2014). International accreditation as global position taking: An empirical exploration of

U.S. accreditation in Mexico. Higher Education, 69(3), 361-374. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10734-

014-9780-7

Brown, B., Cochran, S., & Dalkey, N. (1969). The Delphi method, II: Structure of experiments. Santa

Monica, CA: RAND Corp. Retrieved from http://www.rand.org

Carmichael, R., Palermo, J., Reeve, L., & Vallence, K. (2001). Student learning: 'The heart of quality' in

education and training. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 26(5), 449–463.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930120082023

Cheng, M. (2010). Audit cultures and quality assurance mechanisms in England: A study of their perceived

impact on the work of academics. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(3) 259–271.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562511003740817

Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA). (2014). Information about accreditation. [Para. 1].

Retrieved from http://www.chea.org/

Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA). (2007). What presidents need to know about

international accreditation and quality assurance. Presidential Guidelines Series, 6. Retrieved from

http://www.chea.org/

Karaim, R. (2011). Expanding higher education. CQ Global Researcher, 5(22), 525–572. Retrieved from

http://www.sagepub.com/

Eaton, J. S. (2011). U.S. accreditation: Meeting the challenges of accountability and student achievement.

Education in Higher Education, 5(1). Retrieved from

Eaton, J. S. (2012). An overview of U.S. accreditation. Washington, DC: CHEA. (ERIC Document

Reproduction Service No. ED544355)

www.hlrcjournal.com Open Access

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

Elassy, N. (2013). A model of student involvement in the quality assurance system at institutional level.

Quality Assurance in Education, 21(2), 162–198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684881311310692

Gift, S., Leo-Rhynie, E., & Moniquette, J. (2006). Quality assurance of transnational education in the

English-speaking Caribbean. Quality in Higher Education, 12(2), 125-133.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13538320600916692

Green, M. F., Marmolejo, F., & Egron-Polak, E. (2012). The internationalization of higher education: Future

prospects. In D. K. Deardorff, H. de Wit, J. D. Heyl, & T. Adams (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of

international higher education (pp. 439-457). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452218397.n24

Grifoll, J., Hopbach, A., Kekalainen, H., Lugano, N., Rozsnyai, C., & Shopov, T. (2012). Quality procedures

in the European higher education area and beyond – visions for the future: Third ENQUA survey.

Harvey, L. (2014). Quality. In Analytic quality glossary. Retrieved from

http://www.qualityresearchinternational.com/glossary/quality.htm

Higher Learning Commission (HLC). (2014). Relationship with the federal government and other

organizations. [Para. 2]. Retrieved from https://www.ncahlc.org/About-the-Commission/about-

hlc.html

Hodson, P. J., & Thomas, H. G. (2010). Higher education as an international commodity: Ensuring quality

in partnerships. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 26(2), 101-112.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602930020018944

Hou, A. (2012). Mutual recognition of quality assurance decisions on higher education institutions in three

regions: A lesson for Asia. Higher Education, 64(6), 911–926. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-

012-9536-1

Laureate International Universities, Academic Quality and Accreditation, Quality Assurance (LIU, AQA,

QA). (2014). Quality assurance process [White paper submitted as partial requirement for patent

application to U.S. Patent Office]. Patent Pub. No. 2014/0188575 A1. Washington, DC: US Patent

and Trademark Office.

Lomas, L. (2003, September). Embedding quality: The challenges for higher education. Paper presented

at the European Conference on Educational Research, University of Hamburg.

Lundberg, C. A. & Schreiner, L. A. (2004). Quality and frequency of faculty-student interaction as predictors

of learning: An analysis by student race/ethnicity. Journal of College Student Development, 45(5).

549–565. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/csd.2004.0061

Knight, J. (2005). International race for accreditation stars in cross-border education. International Higher

Education, 40, 2-3.

Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE). (2014). Mission. Retrieved from

http://www.msche.org/?Nav1=ABOUT&Nav2=MISSION

New England Association of Schools and Colleges (NEASC), Commission on Institutions of Higher

Education (CIHE). (2014). CIHE Mission. Retrieved from https://cihe.neasc.org/about-us/cihe-

mission

Newton, J. (2002). Views from below: Academics coping with quality. Quality in Higher Education, 8 (1),

39–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13538320220127434

High. Learn. Res. Commun. Volume 5, Num. 3 | September 2015

P. Ryan

Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU). (2014). [Para. 2]. Retrieved from

http://www.nwccu.org/

OECD & World Bank. (2007). Cross-border tertiary education: A way towards capacity development.

Online Learning Consortium (OLC). (2014). Retrieved from http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/

Palomares, F. M. G. (2014, February 14). Involving students in quality assurance. University World News.

Pollacia, L., & Terrie, M. (2009). Using web 2.0 technologies to meet Quality Matters (QM) requirements.

Journal of Information Systems Education, 20(2), 155–164.

Online Learning Consortium. (2014, September 23). The online learning consortium unveils new release of

its quality scorecard for online programs. [Press Release]. Retrieved from

http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/

Puzziferro, M. & Shelton, K. (2008). A model for developing high-quality online courses: Integrating a

systems approach with learning theory. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3–4).

Newbury, MA: Online Learning Consortium.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). (2009). Integrated quality and enhancement review:

Student engagement. [Information bulletin 2010]. The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher

Education: Gloucester.

Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). (2014). UK quality code for higher education.

Gloucester, UK: The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. Retrieved from

http://www.qaa.ac.uk/

Quality Matters (QM). (2014a). Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/

Quality Matters (QM). (2014b). Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/rubric

Schindler, L., Puls-Elvidge, S., Welzant, H., & Crawford, L. (2015). Definitions of quality in higher education:

A synthesis of the literature. Higher Learning Research Communications, 5(3), 3-13.

http://dx.doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

Shelton, K. (2014). Quality scorecard 2014: Criteria for performance excellence in the administration of

online programs. Session presented at the Online Learning Consortium International Conference,

Orlando, FL.

Smidt, H. (2015). European quality assurance—A European higher education area success story [overview

paper]. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, & P. Scott (Eds.), The European higher education

area: Between critical reflections and future policies (pp. 625-637). London, UK: Springer Open.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_40

Smith, K. (2010). Assuring quality in transnational higher education: A matter of collaboration or control?

Studies in Higher Education, 35(7), 793-806. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070903340559

Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACS COC). (2014). Mission

statement. Retrieved from http://www.sacscoc.org/

Stella, A., & Gnanam, A. (2004). Quality assurance in distance education: The challenges to be addressed.

Higher Education, 47, 143-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:HIGH.0000016420.17251.5c

www.hlrcjournal.com Open Access

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

Stella, A., & Woodhouse, D. (2011). Evolving dimensions of transnational education. In A. Stella & S.

Bhushan (Eds.), Quality assurance of transnational higher education: The experiences of Australia

and India. New Dehli, India: AUQA/NUEPA.

Stukalina, Y. (2014). Identifying predictors of student satisfaction and student motivation in the framework

of assuring quality in the delivery of higher education services. Business, Management &

Education, 12(1), 127–137. http://dx.doi.org/10.3846/bme.2014.09

Varonism, E. M. (2014). Most courses are not born digital: An overview of the Quality Matters peer review

process for online course design. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 31(4), 217–229.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/CWIS-09-2013-0053

Vincent, T. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

WASC Senior College and University Commission (WSCUC). (2014). Retrieved from

http://www.wascsenior.org/about

Wilger, A. (1997). Quality assurance in higher education: A literature review. Stanford, CA: National Center

for Postsecondary Improvement.

Wong, V.Y-Y. (2012). An alternative view of quality assurance and enhancement. Management in

Education, 26(1), 38–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0892020611424608