IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 2

Table of Contents

Part I: Introduction to the IHI Open School and Curriculum Integration 3

About this Guide 3

A Brief History and Overview 3

A Closer Look at the IHI Open School Courses 4

Introduction to Curriculum Integration 6

Part II: Planning for Success 9

Curricular Structure 9

Curricular Design 10

Part III: Securing Buy-in and Sustaining Your Efforts 15

Engaging Key Stakeholders 15

Sustaining Local Integration 18

Part IV: Appendix and Additional Resources 20

IHI Open School Course List 20

How to Appropriately Credit the IHI Open School 21

Resources to Support Curriculum Integration and Curriculum Design Efforts 22

Authors:

Wendy Madigosky, MD, MSPH, Director, Foundations of Doctoring Curriculum and

Interprofessional Education and Development, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Center;

Faculty Network Advisor, IHI Open School

Gina Deitz, Community Manager, IHI Open School

Laura Fink, Senior Managing Editor, IHI

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to the members of our faculty network for their contributions

and feedback through individual survey responses and interviews with our team.

Access this guide online at any time at:

http://www.ihi.org/education/IHIOpenSchool/Courses/Pages/OSInTheCurriculum.aspx

.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 3

Part I: Introduction to the IHI Open School

and Curriculum Integration

About this Guide

Before we begin, here’s a quick overview of how we hope this guide will help you:

Who is this guide for?

This guide is for educators in health care who would like to take advantage of content from the IHI

Open School to help teach quality improvement and patient safety. We created the guide with the

hope that anyone interested in using the Open School as a teaching tool would find it valuable.

University faculty, leaders of residency programs and other graduate or post-licensure programs,

and trainers in hospitals and health care organizations should find plenty of relevant and

actionable advice.

Why have a guide to curriculum integration?

More than 1,000 universities and hospitals have used Open School courses in some capacity. Over

the years, the Open School has heard from many educators who are interested in teaching quality

and safety or are inspired by the Open School, but who aren’t always sure how to integrate the

courses into their teaching. In other cases, educators who are already teaching with the Open

School have asked how to improve or sustain their teaching of this material.

What does this guide cover?

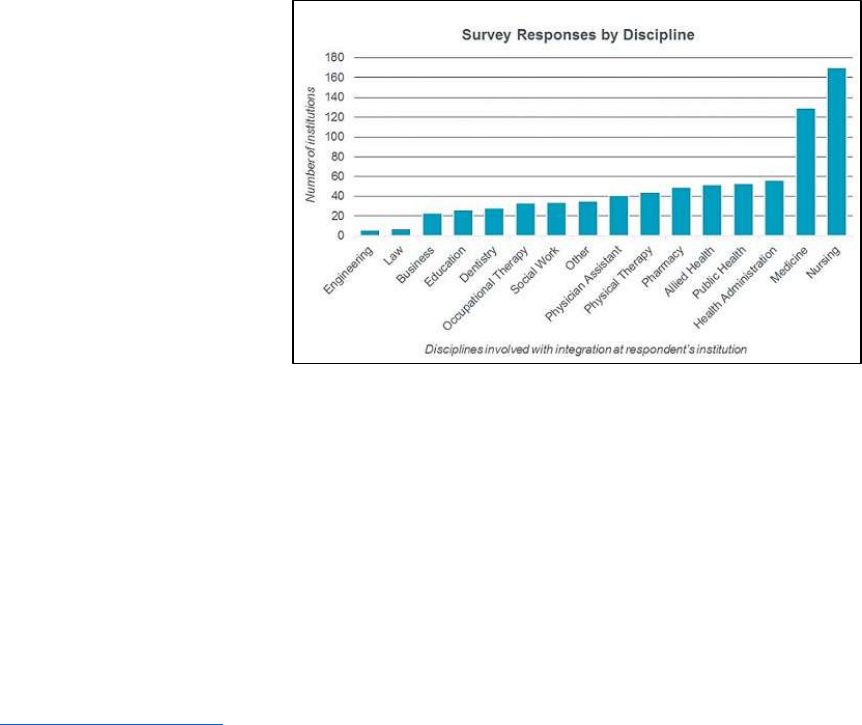

In 2016, the Open School

surveyed hundreds of faculty

who use the Open School

courses in their teaching.

These educators represented a

diverse set of health

professional programs from 16

countries, and this guide

brings together their collective

expertise and experiences.

This guide touches upon the

following aspects of teaching

with the Open School: typical

approaches to integration,

strategies for supplementing the courses with other learning tools, tips for securing approval from

critical stakeholders, and advice on sustaining changes over time once an effective program is in

place. Whether you are associated with a university, post-licensure or graduate training program,

or a professional organization, this guide will help you use the Open School to pursue your unique

educational goals.

A Brief History and Overview

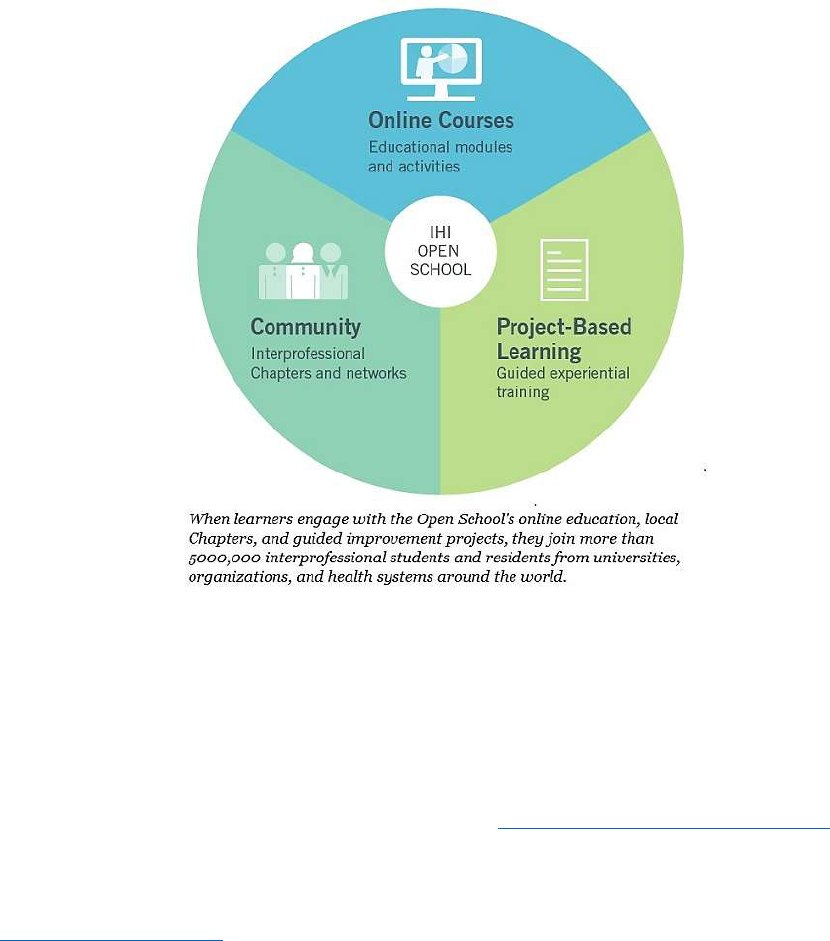

The IHI Open School began as a handful of online courses, first published in September 2008,

designed to provide a basic education in quality and safety for all health professions students.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 4

Since then, the online course catalog has grown to include more than 30 courses, including

courses designed for Graduate Medical Education (GME) faculty and professionals.

Meanwhile, the scope of the Open School has also evolved to include a large and vibrant

interprofessional Chapter Network, which is comprised of more than 830 local Chapter groups

that meet face-to-face at university campuses and organizations around the world. Chapter

activities include learning together about the principles of quality improvement, teaching others

on campus or at a health system about quality improvement, and working on quality

improvement projects.

Today, there is also a third arm of the Open School, which helps learners gain practical experience

with improvement in their local settings. Through project-based learning opportunities, the Open

School provides expert guidance and coaching to help learners achieve real results in improving

health and health care.

The tireless efforts of university faculty and other educators around the world have been

instrumental to the Open School’s success in each of these three areas. These individuals have

been vital in bringing the skills of improvement, safety, system design, and leadership to the next

generation of health care professionals.

A Closer Look at the IHI Open School Courses

For educators who are unfamiliar with the Open School courses, here is a brief overview of what

they include and how you might use them.

The Open School offers more than 30 online courses in quality, safety, leadership, the Triple Aim,

and patient-centered care. Thirteen of the introductory level courses (QI 101–Q105, PS 101–105,

TA 101, PFC 101, and L 101) comprise the Open School’s Basic Certificate in Quality and Safety.

(When you enter the catalog, look for the courses indicated with an asterisk.)

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 5

Beyond the Basic Certificate, there are other 100-level courses that teach introductory concepts

for all health professions. There are also 200-level courses, which teach intermediate concepts

and specialized topic areas, and there is a 300-level course — a project-based learning module,

which we will discuss later.

The courses incorporate mixed media, including video and interactive discussion, to engage

learners and cater to different learning styles. Courses are grouped into catalogs and broken down

into lessons, which take 15–45 minutes to complete. As you are thinking through what to assign to

learners in your program, keep these different options for “chunking” material in mind.

Educators are often surprised to learn the Open School courses are free for students, residents,

and faculty to access. We provide open access to these audiences because we are committed to

making quality and safety education available to future health professionals. Please note that

when learners or faculty make use of Open School materials, we ask that they credit us

appropriately, including throughout course materials such as assessments or syllabi. (For

guidance on the preferred language to acknowledge the Open School, see page 21 in the

Appendix.)

To provide free access to health professionals in training, IHI offers individual and group

subscriptions to professionals, who can earn continuing education credits. Academic and

professional groups can purchase subscriptions that provide access to the Team Tracking Tool.

These tools help educators teach the content and monitor learners’ progress.

Open School courses can help faculty and organizations achieve several goals:

Introducing learners to the fundamental concepts and importance of quality improvement

and patient safety worldwide.

Meeting structural or accreditation standards.

Creating a shared understanding of improvement and a common language within an

organization or a class.

Helping prepare students or staff members to be leaders in their careers.

We’ll share many strategies to help accomplish these goals throughout this guide.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 6

Introduction to Curriculum Integration

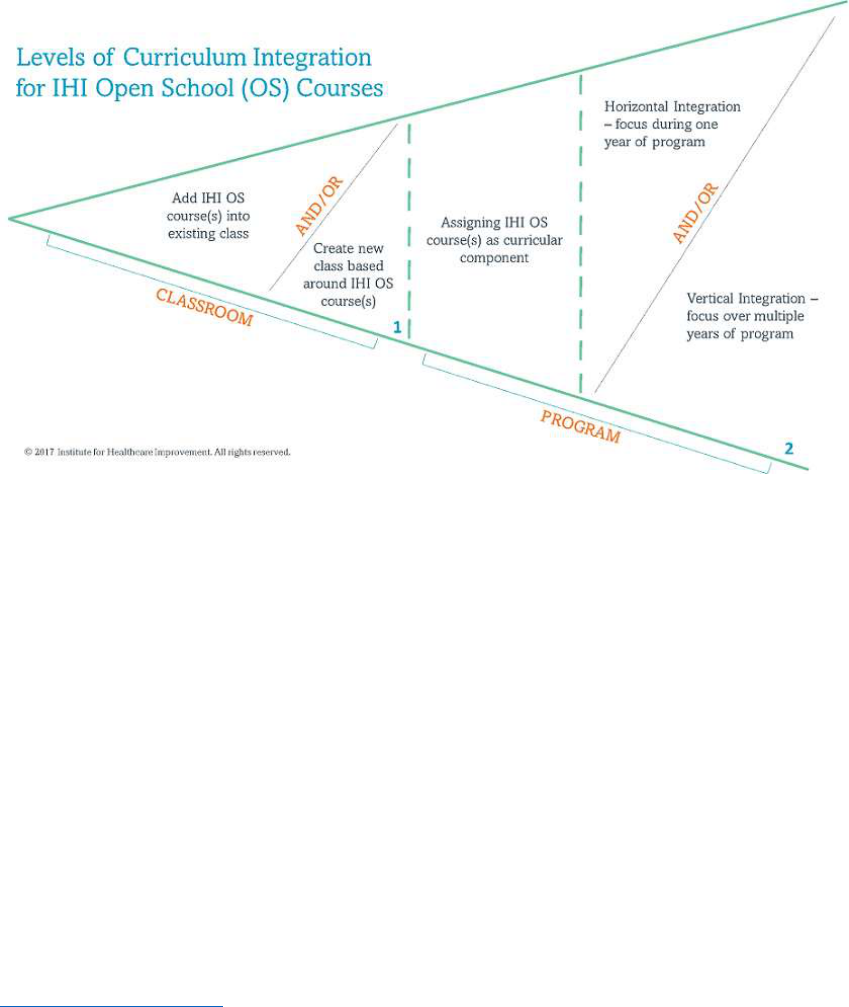

When we talk about “curriculum integration,” we are referring to the intentional inclusion of one

or more Open School courses within a broader educational experience. As far as what a

“curriculum” entails, that is up to you, the educator, to define. The Open School courses may be

included by one professor in the curriculum for a single class; or, they may be a central curricular

component of a multi-year clinical program. For example, an institutional committee may assert

that Open School courses should be covered incrementally, at multiple points throughout a

student’s training.

For simplicity, we will describe two levels of integration, which we will call “classroom

integration” and “program integration.” Although this depiction should not limit you (on the

contrary, we welcome you to go outside the lines), we hope that understanding common

approaches, and some of their benefits and challenges, will give you a place to start as you think

about integrating the courses in your own way.

As you begin to envision how you will integrate the Open School courses into your curriculum,

consider two key questions:

How deep will the learning experience be?

Experts have defined five levels of competency in quality improvement: novice, advanced

beginner, competent, proficient, and expert (see the article “Designing Education to Improve

Care” on page 22 in the Appendix). On the simpler side, the goal may be basic exposure to a few

key concepts — perhaps the Model for Improvement or the fundamentals of patient safety. On the

more ambitious side, some educators choose to weave the Open School courses with other forms

of content and applied learning opportunities. Consider: What level of proficiency do you want

learners to achieve?

How broad will the integration be?

Integrating the Open School courses may begin and end with one faculty member and a single

course. Or, the integration may span a year of training or more, as an integral component of

For this guide,

“curriculum

integration” is the

intentional

inclusion of one or

more Open School

courses within a

broader

educational

experience.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 7

program-level requirements. Consider: To what extent will the education be a coordinated effort,

taking place across different classes, semesters, or years of training?

As previously mentioned, there are two main levels of integrating the Open School courses into

the curriculum: the classroom level and the program level. This section of the Guide will provide

some description of each of these levels — including where they will naturally overlap — and

successful models within them.

Level 1: Classroom integration

Adding Open School courses to the curriculum of an individual class can be a simple way to bring

quality and safety training to a select group of learners, especially in situations that require little

or no involvement from administration or more than one faculty member. Depending upon the

existing infrastructure, here are two common forms of classroom-level integration.

A. Embed IHI Open School courses into existing teaching material.

Understanding quality and safety can enhance health professionals’ effectiveness in virtually

every area of work, so opportunities to weave the courses into existing teaching material

should be easy to find. At the classroom level, “integration” in its simplest form is the step of

adding a few Open School courses (or even part of one course, perhaps a lesson) to the

syllabus, teaching material, or homework for an existing class.

With this approach, look for ways to anchor the content to existing material. As part of a class

on maternal health, for example, you might include one or more Open School courses on

person- and family-centered care, and relate the learning back to the clinical topic area. If you

already teach quality improvement concepts, classroom integration can be as intuitive as

adding Open School courses to the relevant discussion.

B. Create a new class inspired by the IHI Open School courses.

With more than 30 online courses (comprising more than 80 more narrowly focused lessons),

the Open School can easily serve as the foundation for learning about quality and safety; the

courses provide excellent building blocks for educators who want to design from the ground

up. The courses could be the primary source of learning about quality and safety concepts or

could play a key supportive role.

Although tied to a specific classroom, this form of curriculum integration requires

coordination at the program level. For example, programmatic leadership will likely want to

establish how a new class will factor into overall learning goals and requirements. This model

of classroom integration therefore overlaps with our next discussion, which focuses on

program-level integration. (Note: For advice on making the case for inclusion of a new class

in a competitive curricular environment, see pages 15–18.)

Level 2: Program integration

Integration at the program level means the Open School courses are a central component of

program-wide curricular goals. The education may still be tied to the classroom setting or may be

entirely independent of classroom learning. For example, Graduate Medical Education programs

often rely on the courses to introduce quality and safety concepts to residents, which faculty then

reinforce in the clinical setting. Compared to classroom-level integration, the educational design

may be more or less complicated; however, more people will likely need to be involved in

approving, coordinating, and perhaps teaching the material. This need for coordination can create

a challenge at the outset, but the collaborative effort helps ensure the Open School integration will

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 8

last. As with classroom-level integration, there are different ways to approach integration at the

program level.

A. Assign IHI Open School courses as a stand-alone requirement.

The Open School online courses can offer a stand-alone introduction to key topic areas, and

many organizations rely on them as a way to provide this training independent of classroom

learning or everyday work responsibilities. For example, many programs ask trainees or staff

to complete the Basic Certificate in Quality and Safety (the Open School’s pre-packaged

curriculum of 13 foundational courses) outside of their clinical duties, and learners submit

their certificates of completion as proof of their work. Other programs assign a hand-picked

selection of courses and subscribe to the Open School’s Team Tracking Tool to monitor

learners’ progress.

Although this option does not provide the depth of learning of the approaches we’ll describe

next, assigning Open School courses as independent learning is effective for programs that

wish to introduce some fundamental concepts without significant changes to the existing

structures. It’s a good place to start for hospitals who want to create a common language in

patient safety and quality improvement across the organization. It’s also a good place to start

for academic programs that aren’t yet able to invest significant time or resources into teaching

quality and safety.

B. Assign IHI Open School courses as part of a broader effort to teach quality and

safety.

Including the Open School courses as part of a centralized curriculum to teach quality and

safety requires significant coordination among educators and program leadership, but the

result can be worth the effort. Teaching Open School content in multiple encounters across

classes or program years can help learners understand its ongoing connection to their

primary studies. Two ways institutions can structure a coordinated, multi-faceted Open

School integration effort include:

○ Horizontal program integration:

Horizontal integration refers to teaching Open School content over multiple time frames

within a program year. It is a coordinated effort among faculty so that learners are taking

courses each semester or across planned didactic sessions that build upon each other over

the training year.

As with individual classroom integration, if the institution already has quality and safety

programming in place, integrating the Open School courses can be as simple as making

appropriate connections to existing subject matter.

○ Vertical program integration:

Vertical integration takes the use of the Open School courses a step further, spanning

across multiple program years. In this approach, quality and safety may become a focus

throughout the full health professional program or associated training. It is a highly

coordinated effort, in which faculty and learners understand the education to be a core

competency.

Achieving this extensive level of integration requires bringing together a group of

educators that represent each stage of training. This group, which may be

interprofessional, must design a synchronized plan for presenting different aspects of

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 9

safety and quality over time. The potential payoff is a cooperative group of faculty and

learners who share a common commitment to patient safety and quality improvement.

For more examples and models of curriculum integration, including the Six-Step Approach for

Curriculum Development in Medical Education, see page 22 in the Appendix.

Part II: Planning for Success

Curricular Structure

The most common question educators have when they begin to think about teaching with the

Open School is: “Where do I start?”

Faculty around the world who have already integrated the courses respond with the same advice:

Don’t wait for a state of readiness — just dive in. And as you do, follow the same general advice

you would give to others at the outset of an improvement project: Set an aim, establishing what

you are trying to accomplish, for whom, and by when; create a list of the key measures you’ll

track; and start with a small test of change. Starting small — with one course, topic area, or small

group of students (e.g., learners in one discipline) — can help secure buy-in across the institution

and keep things manageable for individual faculty.

As with any improvement effort, you’ll want to stay focused on outcomes, with the needs of your

learners at the center. Planning will be a critical step that can make all the difference in your

success. Be sure to answer the following questions at the outset of your integration effort.

How will I choose what to teach?

There is no need to assign all the Open School courses right away or at once. Instead, start small,

and start with yourself. If you are a university faculty member, the courses are all free. Personally

reviewing as many Open School courses as you can will allow you to note the most relevant topics

or the ones you feel are most important to teach first. We also recommend two resources to help

you and your colleagues identify the material you’d like to teach:

The course catalog offers a high-level view of the entire curriculum.

For greater detail, course summaries include lesson-by-lesson outlines of key learning

content.

Taking time to get acquainted with the breadth of content available should help you envision your

ideal curriculum. In your vision, be sure to keep overall program-level objectives in mind.

When you feel comfortable with the content, you may want to start by assigning the courses in

one topic area (e.g., patient safety, quality improvement, or population health). Or start with just

one introductory course, such as PFC 101: Introduction to Patient-Centered Care. After some

early success (defined by positive feedback from students, for example), you can gradually expand

to other content areas or more advanced coursework.

Will the content be required or optional?

There are many programs that require Open School courses for class credit, graduation, or

certification. There are also many programs that offer the courses as a voluntary opportunity for

Visit the “How to

improve” section

on IHI.org for

resources and

general advice on

leading

improvement

projects using the

Model for

Improvement as

your guide.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 10

intrinsically motivated students or staff. Both of these are great options, but one may work better

for your context.

If you are planning to require the courses, consider using the Open School’s Team Tracking Tool

to understand your learners’ progress. Available by subscription, this tool captures overall course

completions, names of participants, post-lesson assessment scores, and other useful data for

faculty.

How will I ensure learners have time to complete the content?

As you envision your assignments, keep the time requirements in mind. Every course and course

lesson include an estimated completion time, usually between 15–45 minutes per lesson, on the

first page. If you are adding courses to an already packed curriculum or syllabus, try to think of

what you can shorten or remove. In the professional setting, think of how you can help create

time for staff to participate.

How will the Open School fit into the broader quality and safety curriculum, if

applicable?

The Open School courses provide strong foundational knowledge in the areas of quality

improvement, patient safety, and several other health care improvement topics. However,

supporting the course learning with additional resources, group discussion, activities, and

projects can raise learners’ confidence and proficiency. Think of how you can connect the courses

to classwork and these other types of learning opportunities — starting with some of the ideas

below.

Curricular Design

Weaving different content types and teaching formats together can reinforce concepts and bring

them to life. When it comes to selecting additional subject matter to pair with the Open School

courses — whether for assignments, lectures, or group activities — consider supplemental content

from within the Open School and beyond. The Open School offers many free educational activities

on its website, outside of the courses.

You should also look beyond the Open School to find compelling content that’s relevant to your

group — perhaps in relation to the discipline of study, local current events, or a particular topic of

interest. Here are a few formats you may want to include in your teaching and some ideas to get

you started:

Reading materials

Many faculty assign academic papers and books, such as specific sections of The Improvement

Guide, to dive more deeply into specific topics of interest. Check the “Additional Resources” pages

within the Open School courses, usually included at the end of each lesson (prior to the post-

lesson assessment). These resource pages list helpful books, articles, and other opportunities to

further explore the topic area. We’ve listed a few reading recommendations in the Appendix as

well.

To keep the content fresh and relevant to your particular setting, consider adding news articles

into the mix. Current events can contextualize concepts and add urgency to the learning —

especially if learners see a chance to make a difference.

Access this guide

online at any time

at

http://www.ihi.or

g/education/IHIOp

enSchool/Courses/

Pages/OSInTheCur

riculum.aspx.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 11

Classroom activities or didactic sessions

Group activities — especially with instructor support — are important for learners’ long-term

retention of concepts. Just like with clinical skills, improvement methodology takes practice and

requires mentorship. To give learners the opportunity to discuss new ideas and to practice new

skills right away, consider these examples for classroom or group learning sessions:

Flipped classroom

Instead of waiting for learners to come together to introduce them to a new concept, ask them to

do independent learning first. If you assign a course as pre-work, the group will have a head start

when they meet. This can allow more time for richer discussion.

Example: At the University of Colorado School of Medicine, students review PS 105:

Responding to Adverse Events in preparation for a panel discussion about error

disclosure. The panel presentation, which includes patients, providers, and hospital

representatives who have been involved in adverse events, is followed by small group

discussion and a role-play activity. Faculty lead Dr. Wendy Madigosky says using the

Open School course as pre-work elevates the students’ level of reflection and engagement

during the discussion.

Learner-led presentations

As educators know, one of the best ways to master a topic is to teach it. With this in mind, some

faculty use the teach-back method with the Open School courses. It’s an effective way to both

assess the presenter’s learning and re-engage the audience in the topic (or introduce them to it,

depending how the content is divvied up).

Examples: At Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman in Malaysia, faculty Nem-Yun Boo

requires learners to take courses independently and then create their own presentations

based on the material, in which they explain what they’ve learned. The presentations

provide faculty with a face-to-face opportunity to identify and clarify important points

learners may have missed.

All residents at Boston Medical Center complete a selection of Open School courses as

part of the core curriculum of their intern year. In their second year, internal medicine

residents participate in a quality or safety initiative. Residents looking for additional

learning complete the Open School’s Basic Certificate and spend three weeks on rotation

at the VA Boston Healthcare System. The VA provides opportunities for residents to join

institutional improvement initiatives and present their work, learnings, and experience to

their peers and the leadership team.

Games

Games are a fun way to break up didactic content and expand upon that learning. Look for games

and exercises on the Open School website, including the following games that reinforce important

improvement concepts and include instructional videos, learning objectives, and discussion

questions for facilitators:

○ Measurement — How Do You Measure the Banana?

○ Systems Design — The Paper Airplane Game

○ Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Cycles — The Coin Spinning Game

○ Variation — Candy Counting Activity

○ Leadership and Management — The Red Bead Experiment

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 12

Case studies

Also available through the Open School, case studies help learners understand how concepts

relate to real-life situations. Case studies can put a human face on ideas in the abstract, engaging

learners on a more personal level — and perhaps inspiring them to take action. The Open School’s

case studies include facilitator guides with learning objectives and discussion questions. (See page

23 in the Appendix for a list of the Open School’s most popular case studies.) Faculty also use and

discuss real-life examples and cases, which may be drawn from learners’ own experiences, to

create meaningful teaching moments.

Examples: At Texas Woman’s University School of Nursing, Master’s students in the

Nursing Health Systems Management track have to find a completed improvement project

at their place of work (clinical or not) and describe how they’d sustain or continue to

improve the results of that project.

As part of the patient safety curriculum at Vanderbilt University’s School of Medicine in

Tennessee, students complete a reflection exercise about adverse events and near misses.

They reflect on personal experiences as well as those of team members who are not

physicians.

Simulated project work

Project-based work is necessary to master the skills and understand the idiosyncrasies of quality

improvement. Learners with busy schedules may feel intimidated by the idea of finding time for

larger projects, especially those that require teamwork. It can help to provide class time or

protected time from clinical training for learners to create and work on team-based projects,

whether real or simulated, especially when faculty and mentors make themselves available for

coaching.

Examples: At the University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing, students work in teams

to plan a quality improvement project to tackle a theoretical problem, including writing a

project charter, creating aims, and developing measurement plans. Assistant Professor

Terry Jones, RN, PhD, says it’s valuable to provide class time to practice this critical

planning phase.

During their rotation at the VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston Medical Center

residents are expected to lead an interdisciplinary one-hour lunch session on a specific

case, facilitating small groups to run rapid root cause analyses and propose potential

interventions. Drs. Lakshman Swamy and Christopher Worsham, Chief Residents who

supervise these sessions, bring the proposals to decision makers who often use them to

effect real change.

Observation

Observing how quality and safety principles relate to the real world of health care (or even other

high-risk industries) can contextualize and enhance learners’ understanding.

Examples: At the University of Colorado School of Medicine, students review PS 104:

Teamwork and Communication in a Culture of Safety and attend a lecture reinforcing

the importance of teamwork. Then, they shadow local hospital teams to see best practices

in action.

At East Carolina University in North Carolina, PFC 201: A Guide to Shadowing: Seeing

Care through the Eyes of Patients and Families is pre-work before a half-day patient

shadowing event. Students follow patients and families through their health care journey

to better understand the care experience from patients’ points of view.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 13

Learning assessments

Generally, you will want to include some type of learning evaluation in your curriculum. Almost

every Open School course includes a short assessment, usually consisting of five or six multiple

choice questions, at the end of each lesson. (Learners must score 75 percent or higher to complete

a course.) However, you may want to create additional assessments to track collective learning

over time or evaluate specific outcomes that are important to you. Many GME faculty use the

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)’s Clinical Learning Environment

Review (CLER) program to measure learning outcomes, for example. Other faculty create their

own written assessments, and others opt for a face-to-face format, which allows instructors to

identify and clarify misunderstandings in real-time. Improvement projects, which we’ll discuss

next, provide a more rigorous (and potentially even more valuable) opportunity to assess learners’

ability to apply concepts and improve patient care. (For tools to assess training program

outcomes, see page 22 in the Appendix).

Example: At the University of Texas at Austin, educator Terry Jones, RN, PhD,

administers a self-assessment at the beginning of her class to check students’ knowledge of

quality and safety (e.g., conducting root cause analysis, writing project charters, etc.).

When the class is concluding, she asks them the same questions again, to see how far

they’ve come.

Project-based learning

Reading, case studies, group activities, and observation can go a long way toward bringing

concepts to life, but there is no replacement for the actual experience of setting up and leading a

quality improvement project in the real world. Quality and safety experts and experienced faculty

strongly recommend pairing didactic content with applied learning, such as project work or

practical experience. These types of opportunities can take some work to set up, but the learning

will be meaningful. Here are a few tips to get started:

Find projects that are institutionally supported

Your institution may already have improvement projects in progress that learners can join. Try

starting there. If you are looking to design a new project, make sure it aligns with leadership-level

goals. Keep in mind that Open School Chapters around the world are working on local

improvement projects every day, so check for a Chapter in your area; they may be able to help you

find a project or involve your learners in their efforts.

Examples: The Duke University Chapter in North Carolina has developed a strong

partnership with the Duke Health System. Alongside faculty, the Chapter helped build the

Quality and Innovation Scholars Program (QISP). Now moving into its third year, QISP

matches students from multiple professions with physicians and health system leaders,

who immerse them in interdisciplinary, systems-level quality improvement and

innovation. Learn more, including how students and faculty got the program off the

ground, from the Open School Blog.

The internal medicine residency program at Boston Medical Center follows a case-based

model to teach quality improvement. During rotation at the VA Boston Healthcare

System, residents have protected time to focus on quality improvement and patient

safety. They review patient safety incidents and screen them for improvement

opportunities, with the chance to begin a project or join an existing project during the

rotation.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 14

Build partnerships with service organizations or local hospitals

Look for local hospitals and organizations that are willing to accept help from students. Some

potential partners may meet you with skepticism, but ask faculty and administrative colleagues for

contacts who might be willing to build a relationship. Some schools have established student-run

free health clinics, which create a perfect avenue for incorporating quality improvement in the

clinic’s standard work and processes. Forming a long-term relationship with a partner organization

can create enduring opportunities for many learners to come.

Examples: The University of Dundee in Scotland invites small groups of medical students

to work with clinical teams and learn how to gather information about patient

experiences and feed it back to the clinical teams. These encounters begin in year one of

the curriculum, and the students have the option for more in-depth work related to

improvement and human factors science. Dr. Peter Davey, a lead faculty for the program,

says it’s a chance for the participants to establish meaningful relationships with patients

and other providers. They learn about the people — instead of just the tasks — of

medicine, and they can begin to incorporate a person-centered mindset into their

improvement work.

The University of Cincinnati Open School Chapter in Ohio established an interprofessional

student-run clinic that operates in partnership with St. Vincent de Paul, a local charitable

organization. This collaboration helped establish numerous health services for patients

and clients, as well as opportunities for students to meaningfully practice quality

improvement.

Use the IHI Open School’s project-based learning opportunities

Through two project-based learning opportunities, the Open School provides expert guidance and

coaching to help learners achieve real results in improving health and health care. Refer to QI

301: Guide to the IHI Open School Quality Improvement Practicum (for learners) and GME 207:

Faculty Advisor Guide to the IHI Open School Quality Improvement Practicum (for faculty

advisors) in the main Open School course catalog. Also look for offerings of the semi-synchronous

course Leadership and Organizing for Change.

Examples: At Pennsylvania State University School of Nursing, students who had

completed Open School courses on leadership, quality, and patient safety in their

leadership class suggested incorporating Leadership and Organizing for Change into the

program’s leadership practicum the following semester. Associate Professor Karen Wolf,

PhD, was pleasantly surprised that her students were so enthusiastic to continue to

advance their learning and leadership.

After learning the basics of quality and safety through other Open School courses,

students of Frontier Nursing University take the Open School’s Practicum to support

them through their first improvement projects at local hospitals and rural health clinics.

Lead faculty Diana Jolles, MSN, PhD, has seen her students develop greater mastery of

the content, and many partner organizations have praised the level of skills her students

bring to the work with their local teams.

Similarly, faculty at the University of Stirling in Scotland have integrated the Basic

Certificate in Quality and Safety and the Open School Practicum into the nursing

curriculum, and more than 600 students have completed improvement projects as a

result. Teaching fellow Brian James reiterated how important it was for students to

participate in projects outside the comfort of the classroom, to gain first-hand experience

Opportunities for

students to learn

about people –

instead of just the

tasks – of

medicine help

them incorporate

a person-centered

mindset into their

improvement

work.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 15

with the challenges of leading improvement. He said although some students were

deterred by initial setbacks, they often shared overwhelmingly positive feedback at the

conclusion of projects — having observed the meaningful changes they helped create.

For three specific models for facilitating experiential learning at the point of care, see pages 23–

28 in the Appendix or review GME 205: A Roadmap for Facilitating Experiential Learning in

Quality Improvement.

Part III: Securing Buy-in and Sustaining Your

Efforts

Engaging Key Stakeholders

In addition to the tasks described in Section II, focused on structuring and designing your

curriculum, you’ll need to think about building support for your efforts. Adding Open School

materials into educational programming may require approval from fellow faculty and leadership,

depending upon what you are planning. In some cases, securing buy-in can be the biggest

challenge you’ll face, especially when you’re starting a new class or planning program integration.

However, the same advice for any improvement effort continues to apply: Start small and expand

your efforts with each incremental success.

As you progress further into integrating Open School courses into the curriculum, it’s unlikely all

your learners and colleagues will readily agree on exactly how the courses should be incorporated.

(Frankly, some will feel they should not be added to a jam-packed curriculum in any form.)

Faculty, students, administrators, and/or professional colleagues may not understand the

importance of quality and safety training. And, very likely, they may feel overcommitted in their

current responsibilities. All this can inhibit those around you from appreciating and supporting

your vision.

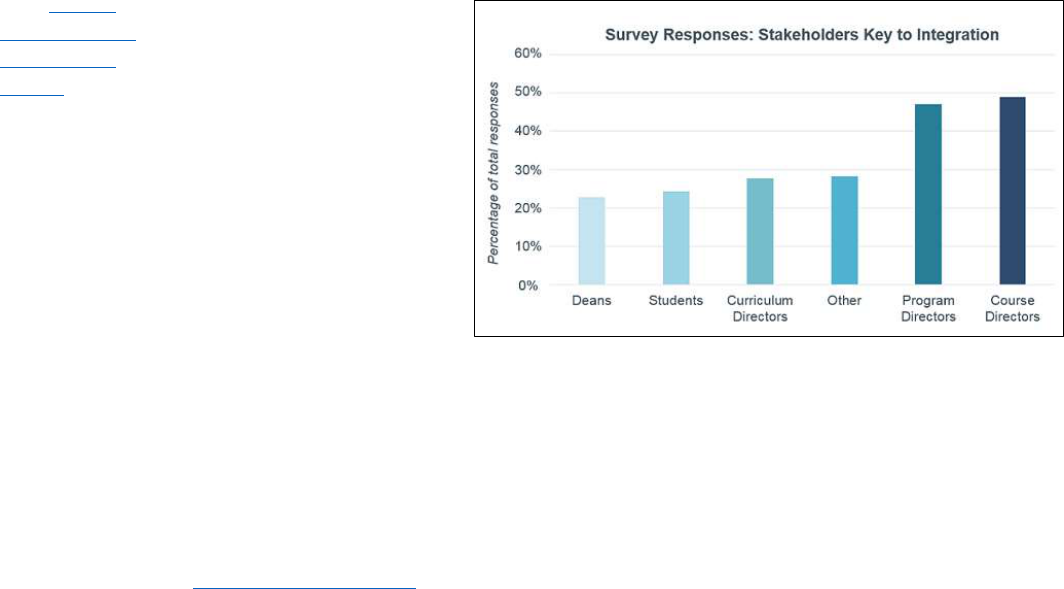

How do you overcome these

hurdles? Time and again,

faculty and other leaders of

Open School integration

efforts have underscored the

importance of gathering

support from across their

institutions: students,

curriculum and program

directors, faculty, and deans

are all groups you can and

should engage. You never

know who will become your

biggest champions, and,

ideally, you should strive to develop a multi-tiered network of ongoing support.

Students and Learners

Learners who have taken an Open School course or two can speak to the importance of quality

improvement and patient safety as part of their learning experience. Ideally, find learners within

Familiarize

yourself with our

goals, mission,

and work to

inform your

conversations

with

stakeholders.

Take OS 101:

Introduction to

the IHI Open

School.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 16

your organization who can provide testimonials to help bring other faculty, administration, or

students on board. Student champions can describe the relevance of the courses to their

education, increasing peers’ willingness to accept the courses as meaningful work. Here are a few

tips to begin building your cohort of student champions:

Connect with the IHI Open School Chapter at your institution

Look for the Open School Chapter nearest to you. With luck, there may be one at your institution

— in which case, be sure to involve them in your efforts to integrate the courses into the

curriculum. You can also start your own Chapter.

Examples: At the University of British Columbia, Chapter Leaders were instrumental in

leading multiple efforts to integrate quality improvement into programming. With the

support of Chapter Faculty Advisors, they led efforts to design a Quality Improvement

Practicum Program that connects students with local improvement projects. They also

spurred a successful initiative to add the Basic Certificate in Quality and Safety as an

elective credit.

At University of South Carolina School of Medicine, students are required to go to at least

one Open School Chapter meeting as part of their training.

Be clear about how the courses will grow students’ skills and provide long-term

benefits

At all costs, avoid suggesting the courses are one more hurdle to jump or box to check for busy

students and staff. Instead, explain that the science of improvement will help learners be better

health care professionals and that it will contribute to greater success and satisfaction in their

careers. For example, remind students they can add the Basic Certificate to their resumes and that

the Open School offers chances to both learn about and practice health care leadership.

Understanding patient safety concepts will help them prevent adverse events, and improvement

methodology will help them be more efficient in their work.

Provide clear instructions to make taking the courses as easy as possible

Before you assign Open School courses to students, provide clear instructions to ensure they will

have no trouble finding the online content. For example, institutional subscribers should

distribute the log-in information they receive with their subscription. Making things as easy as

possible for your learners will help reduce fears that assignments will be confusing or time

consuming.

Align the course work with project work

As previously mentioned, there is nothing as motivating as seeing real results, especially those

that benefit patients or colleagues. Working on local improvement projects can elicit buy-in as

you help learners gain a deeper appreciation of quality improvement as a method to lead

meaningful change.

Show that you value feedback

Don’t be shy about asking for feedback. Soliciting feedback from learners helps them feel valued

and personally invested, and improving your own curriculum shows that you practice what you

preach.

Faculty

Oftentimes, a lack of trained faculty makes it difficult for programs to teach quality and safety and

becomes a limiting factor for integrating the topics within a curriculum. If possible, help create

opportunities for faculty to study quality and safety. The more they know, the better luck you will

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 17

have in building a network of educators who can promote and spread the Open School. Here are a

few tips to grow a network of devoted faculty:

Develop your own background in quality improvement

Others will gain trust in you if you can point to your own quality and safety expertise or successful

improvement efforts. Beyond that, you may find you can apply quality improvement to your

course integration initiative. If you don’t have the necessary experience to inspire others, join

forces with someone who does. Adding an expert’s voice will add legitimacy and can be

persuasive.

Develop faculty awareness of the principles of quality and safety

If possible, bring together a group of educators, perhaps representing different disciplines or

learning stages, to work together to develop capacity for teaching quality and safety across your

institution. As a place to begin, the Open School offers seven courses for Graduate Medical

Education faculty, listed in the Appendix of this guide, to support efforts to train residents in

quality and safety and develop didactic curriculum on these topics.

Examples: East Carolina University has not only integrated Open School courses into

training for students and medical residents, but it has made the Open School’s Basic

Certificate a requirement for a year-long interprofessional fellowship program for faculty,

called “Teachers of Quality Academy.” As part of that program, faculty complete a quality

improvement project, which they present at an annual quality symposium. According to

Dr. Elizabeth Baxley, faculty development became a clear goal for her institution when

they recognized a significant return on investment.

Introduce faculty to the IHI Open School and the benefits of using the courses

In addition to this guide, there are many Open School resources that explain its mission and value

to educators. Refer colleagues to the Open School Overview, or, better yet, direct them to specific

materials from the Overview that you think will be persuasive. For example, you can share an

introductory course, OS 101: Introduction to the IHI Open School: Join the Movement to

Improve Health & Health Care. We’ve mentioned the value of local testimonials. As you get

started with your campaign, you can also point to user ratings on the course overview pages.

Examples: During a faculty meeting, Connie Boerst, President and CEO of Bellin College

in Wisconsin, proved to colleagues that the Open School was more than “busy work”: She

took the room through an Open School course, page by page. The demonstration opened

their eyes to the high-quality, interactive learning experience the courses provide.

Administration and Organizational Leaders

Integrating the Open School courses, especially at the program level, requires program,

curriculum, and administrative directors to carve out time for students, trainees, or other learners

to complete the work. The support of leadership over time is crucial for long-term success of Open

School course integration. Here are some ideas to get leaders interested in your work:

Show how the IHI Open School can fill an educational gap

Identify and highlight ways in which the Open School courses can help fill gaps in the curriculum,

especially in meeting outside requirements from overseeing bodies, such as accreditation

committees. Look to standard nursing requirements and to the ACGME’s Clinical Learning

Environment Review program, for example. Compare requirements to the course summaries,

which you can also print and distribute.

Example: Many organizations and schools identify interprofessional learning as a

priority, but struggle to find ways to bring health care disciplines together. The Open

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 18

School courses and Chapter Network can help fill this gap. Advocates of the Open School

have often emphasized the potential for quality and safety learning events and activities

to build common ground and establish shared goals across health professions.

Partner early in the curriculum development process

Want to make sure administrators feel invested? Involve key partners in the development of the

curriculum early on. Consider including deans, course and program directors, and other experts

in quality and safety (at hospitals, this may include your quality improvement team staff or other

clinical leaders).

Highlight your support network of student and faculty champions

Although support from leadership is critical, the reality is that it may come only after a critical

mass of other stakeholders are onboard. As you identify and develop “early adopters,” raise those

people up, and help increase the volume of their voices.

These tips should help you begin using Open School courses in the curriculum. In addition to the

integration examples throughout this guide, you can find other resources in the Appendix,

including John Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model on page 22.

Sustaining Local Integration

Once you’ve successfully integrated the courses into your curriculum — whatever that means to

you, based on the definitions and aims you’ve set forth — be sure to celebrate! However, keep in

mind that a crucial step remains: Developing a sustainability plan. Planning for how you will

sustain the work in the future will help ensure many cycles of learners will continue to benefit

from the Open School.

The sooner you can start thinking about long-term plans, the better. Here are few

recommendations:

○ Continue to look for opportunities to link Open School content to institutional priorities

and/or program requirements and competencies.

○ Keep reminding administrators of the value of the Open School for students, staff, and

customers, and point to positive results (the more concrete, the better, so look for

opportunities for long-term assessment and evaluation).

○ Continue to grow dedication to improvement science from faculty and educators — if you

leave your role, there should be others who will pick up where you left off.

○ Join forces with your local Open School Chapter or start one. A local Chapter provides a

ready-made cohort of learners eager to support the use of the Open School.

○ Lastly, always practice what you preach! Use improvement science in the integration

process every step of the way: Even after you have a successful curriculum, continue to

gather feedback from students and other faculty, and run PDSA (plan-do-study-act)

cycles to improve.

Ongoing Inspiration and Support

Remember, you are not alone in this work. Please look to the Open School for support, as well as

to hundreds of faculty, students, and other leaders who are driving efforts to integrate the Open

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 19

School into institutions and organizations around the world. Here are a few key ways to stay

connected:

Join improvement communities online

Online support networks give you access to a wide group of educators who are doing similar work

all over the world. The Open School’s Faculty Network, for example, is a place to connect and

share ideas, experiences, and learning. You can also join the Open School Faculty Advisor listserv

by emailing openschool@ihi.org.

Connect with the improvement community at conferences or events throughout

the year

Nothing proves you’re not alone like a large-scale event of like-minded people. IHI’s annual

world-class conferences, including the National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care,

offer opportunities to learn the latest improvement ideas and best practices for generating change

in your organization. Be sure to inquire about faculty scholarships, which are often available for

conferences.

Keep in touch with the IHI Open School

The Open School regularly updates its courses and other content and is constantly adding new

material. For example, changes in 2016 included redesigning the Basic Certificate, releasing a new

suite of improvement games, and developing this guide. Provide a valid email address when you

register on ihi.org to ensure you’re aware of changes that can affect you and your learners.

Consider, also, subscribing to the Open School newsletter for updates, coming events, and new

content.

Join or start an IHI Open School Chapter at your institution

We cannot emphasize enough: Having an organized group of learners who are interested in

quality improvement and patient safety — and are passionate about spreading the learning —

offers a terrific advantage for sustaining and expanding course integration efforts. Learn more

about the Chapter Network, including how to get a new Chapter started or become a Faculty

Advisor.

And as always, please feel free to reach out to our team at openschool@ihi.org any time. We hope

to hear from you, and we wish you the best of luck!

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 20

Part IV: Appendix and Additional Resources

IHI Open School Course List

Improvement Capability

○ QI 101*: Introduction to Health Care Improvement

○ QI 102*: How to Improve with the Model for Improvement

○ QI 103*: Testing and Measuring Changes with PDSA Cycles

○ QI 104*: Interpreting Data: Run Charts, Control Charts, and other Measurement Tools

○ QI 105*: Leading Quality Improvement

○ QI 201: Planning for Spread: From Local Improvement to System-Wide Change

○ QI 301: Guide to the IHI Open School Quality Improvement Practicum

Patient Safety

○ PS 101*: Introduction to Patient Safety

○ PS 102*: From Error to Harm

○ PS 103*: Human Factors and Safety

○ PS 104*: Teamwork and Communication in a Culture of Safety

○ PS 105*: Responding to Adverse Events

○ PS 201: Root Cause and Systems Analysis

○ PS 202: Building a Culture of Safety

○ PS 203: Partnering to Heal: Teaming Up Against Healthcare-Associated Infections

○ PS 204: Preventing Pressure Ulcers

Person- and Family-Centered Care

○ PFC 101*: Introduction to PFCC

○ PFC 102: Dignity and Respect

○ PFC 201: Seeing Care Through the Eyes of Patients and Families

○ PFC 202: Basic Skills for Conversations about End-of-Life Care

Triple Aim for Populations

○ TA 101*: Introduction to the Triple Aim for Populations

○ TA 102: Improving Health Equity

Leadership

○ L 101*: Introduction to Health Care Leadership

*To complete the Basic Certificate in Quality & Safety, one must complete this course.

Project-Based Learning

○ QI 301: Guide to the IHI Open School Quality Improvement Practicum

○ Leadership and Organizing for Change

Take one of our

sample courses to

familiarize

yourself with our

design and

approach.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 21

Graduate Medical Education

○ GME 201: Why Engage Trainees in Quality and Safety?

○ GME 202: A Guide to the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) Program

○ GME 203: The Faculty Role: Understanding & Modeling Fundamentals of Quality &

Safety

○ GME 204: The Role of Didactic Learning in Quality Improvement

○ GME 205: A Roadmap for Facilitating Experiential Learning in Quality Improvement

○ GME 206: Aligning Graduate Medical Education with Organizational Quality & Safety

Goals

○ GME 207: Faculty Advisor Guide to the IHI Open School Quality Improvement Practicum

How to Appropriately Credit the IHI Open School

When Open School courses, lessons, videos, figures, text, assessment questions, or other

materials are used for classroom or program integration, they must be appropriately referenced

by learners and educators. Here is the format IHI requests:

For an IHI Open School Online Course:

Author(s). Lesson Title. In: Course Title [IHI Open School online course]. Boston,

Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; year published:page number.

www.ihi.org/onlinecourses. Updated date of last update. Accessed date.

Example: Lloyd R, Murray S, Provost L. Lesson 1: An overview of the Model for

Improvement. In: QI 102: The Model for Improvement: Your Engine for Change [IHI

Open School online course]. Boston, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare

Improvement; 2009:3. www.ihi.org/onlinecourses. Updated August 19, 2015. Accessed

October 15, 2015.

For an IHI Open School Activity:

Author(s). Activity title. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Open School website. url. date

accessed.

Example: Hilliard R. An extended stay. Institute for Healthcare Improvement Open

School website.

http://www.ihi.org/education/ihiopenschool/resources/Pages/Activities/CaseStudyAnE

xtendedStay.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2015

If referring to content that is referenced within Open School resources, please include both Open

School information as well as the original reference. If you’re unsure how to reference content,

please don’t hesitate to email openschool@ihi.org.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 22

Resources to Support Curriculum Integration and Curriculum

Design Efforts

The following is just a sampling of the resources that faculty are using to supplement the courses

and design quality and safety training programs. The Open School is beginning to develop a more

comprehensive list of resources to assist educators, which will be available later this year.

Models to Support Program Development

○ Armstrong G, Headrick L, Madigosky W, Ogrinc G. Designing education to improve

care. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2012;38(1):5-

14. https://ipecollaborative.org/uploads/S2-JQPS-0212_Armstrong.pdf. Accessed

January, 24 2017.

○ Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum Development for Medical

Education: A Six-Step Approach. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins

University Press; 2009.

○ Kotter, JP. Leading Change. 2nd ed. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School

Press; 2012.

Assessment Tools

There are a number of ways in which faculty measure program or class outcomes in addition to the

Open School assessment questions at the end of each lesson. Here are a few assessment tools

faculty shared with us:

All disciplines

Quality improvement curricular assessments used across disciplines include the Quality

Improvement Knowledge Application Tool (QIKAT) and the Systems Quality

Improvement Training and Assessment Tool (SQITAT).

Graduate Medical Education

Most GME faculty consider ACGME CLER guidelines in their program design. You can revisit the

CLER goals and approach for strengthening clinical training for medical residents in GME 202: A

Guide to the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) Program.

Commonly Required Readings

○ Langley GJ, Moen RD, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP. The Improvement

Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. Hoboken, New

Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. 2009.

○ Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. (Committee on Quality of Health Care in

America, Institute of Medicine). To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

○ Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st

Century. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2001.

○ Galt KA, Paschal KA. Foundations in Patient Safety for Health Professionals. Sudbury,

Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC; 2011.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 23

IHI Open School Content

Top Case Studies:

○ Code Blue — Where To (AHRQ)

○ The Unfortunate Admission

○ A Downward Spiral: A Case Study in Homelessness

Most Watched Videos:

○ What Happened to Josie?

○ How Do You Use a Driver Diagram?

○ How Can We Define ‘Quality’ in Health Care?

Learning from Other Curriculum Integration Efforts

Through conversations with faculty in compiling this guide, the Open School gathered a multitude

of examples of how organizations, faculty, and students are using our courses. Of course, we

couldn’t fit all of these stories here. For additional case studies and examples, we encourage you

to visit our website, where you can find continued inspiration and ideas.

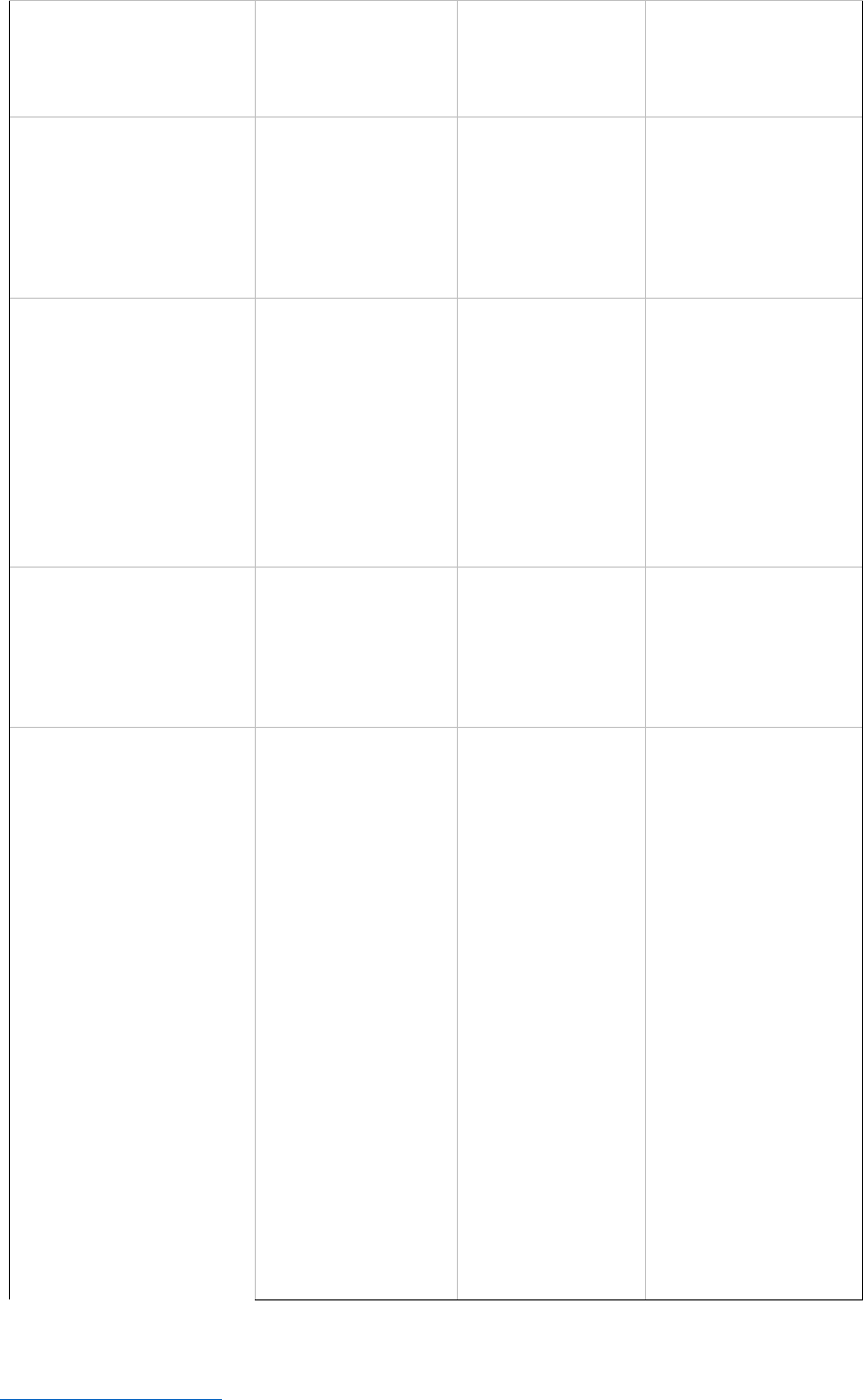

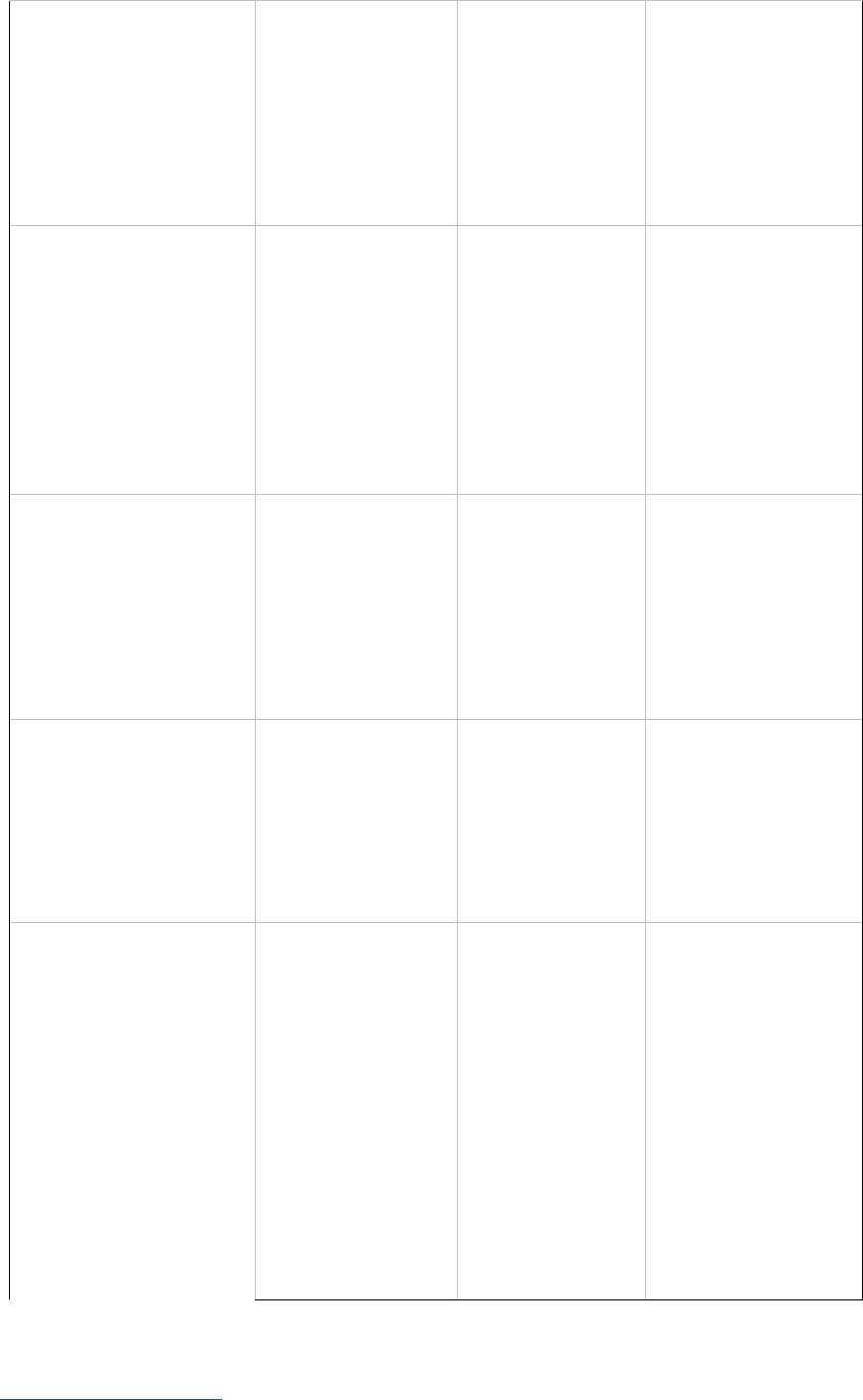

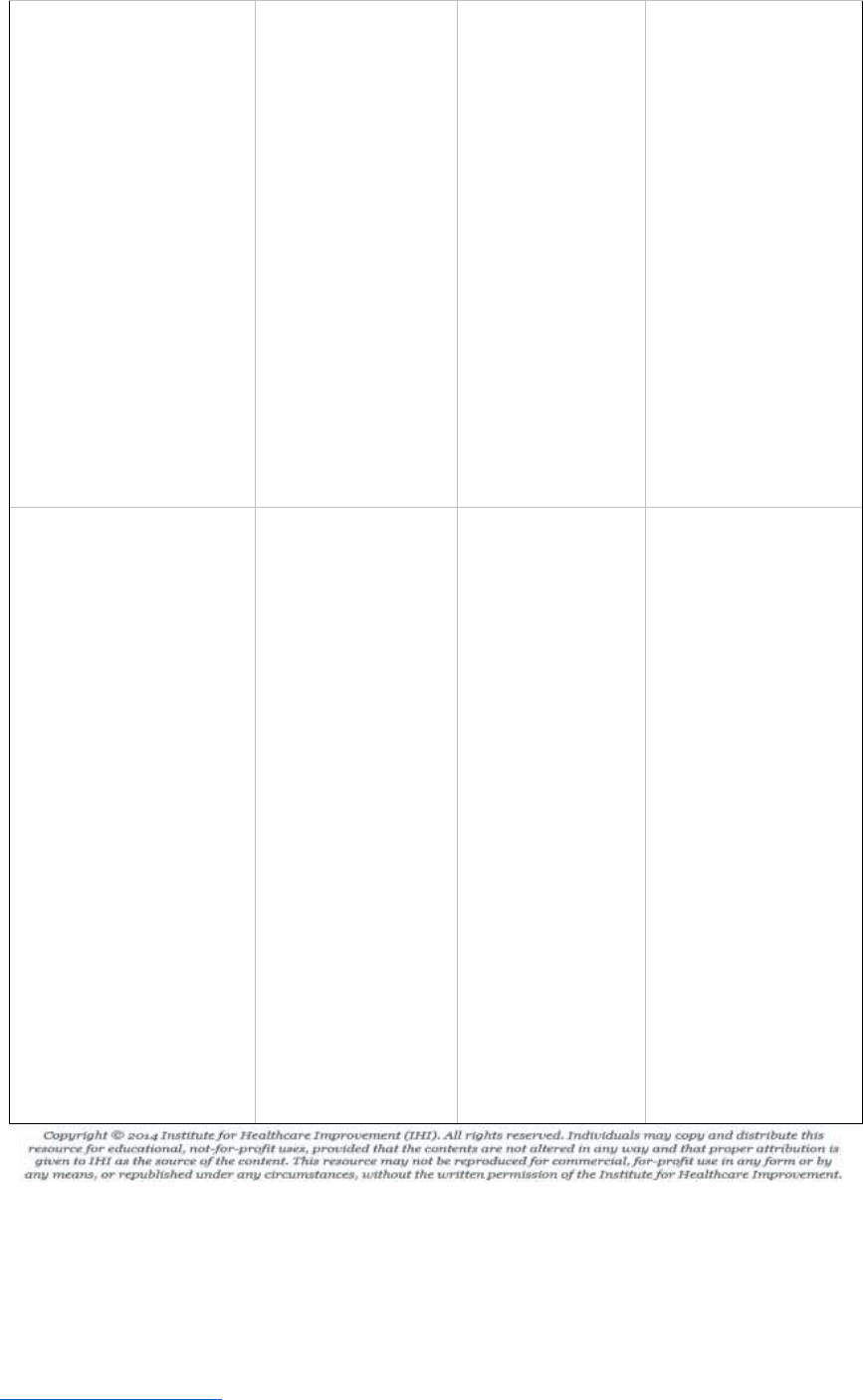

Facilitating Experiential Learning in Quality Improvement

The table below introduces IHI’s adaptable three-model framework for supporting project-based

learning. The guide for implementing this three-model framework with trainees at the point of

care is available in GME 205: A Roadmap for Facilitating Experiential Learning in Quality

Improvement.

Team-Based

Model

Unit-Based

Model

Systems-Based

Model

Definition

Focused on behavior

change and limited

process change to

improve a workflow that

is within the control of

the interdisciplinary

medical team

Focused on a

workflow in a

particular unit or

clinic with aims that

are tied to

institutional priorities

Focused on a workflow

that crosses multiple

units/clinics with an aim

to improve systems at the

departmental or

institutional level

Scenario

An inpatient team

composed of an

attending physician, two

residents, medical

students, nurses a

pharmacist, and a social

worker will spend the

next two weeks together

on service, integrating

quality and safety into

their daily routine of

bedside

interdisciplinary rounds

(if in an ambulatory

A group of four to six

trainees will be

rotating at one-month

intervals through an

inpatient unit,

working clinically with

various attending

physicians but

assigned to a QI

project with a single

advisor

A group of six to eight

trainees will be rotating

through many units within

a hospital during the

period but conducting a

QI project in a selected

unit with a single advisor

and a small team of

involved attending

physicians

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 24

setting, the

interdisciplinary team

may have a slightly

different composition)

Improvement

objective

Discover a new practice

or innovation relating to

team

behavior/workflow, or

solve a problem that

pertains to routine

patient care

To develop a new

practice or innovation

that serves the unit or

clinic as a whole

To make system-level

change that helps achieve

institutional objectives

around quality and safety

Educational

objective

To motivate trainees to

incorporate

improvement principles

and systems-based

thinking into their daily

clinical routines, and to

move toward

integrating QI/PS into

clinical care rather than

thinking of it as a

separate activity

To demonstrate to the

trainee that even with

a limited amount of

time in a unit, she or

he can and should

play a vital role in

accelerating the

progress of that unit’s

improvement

initiatives

To integrate trainees into

the larger institutional

objectives for quality and

safety; to make robust

direct connections

between clinical care

trainees are providing at

the bedside and the larger

quality and safety aims of

the institution in which

they train

“Owned” by

The rounding team in

an inpatient unit, or a

clinical team in an

ambulatory setting

The nursing leader

and clinical director of

the unit/clinic

The quality

director/leader and a

nursing director who

oversee one or more

units/clinics or the

department as a whole

Required faculty

leadership

Led by faculty members

while they are working

to clinically supervise

trainees (for example, as

attending physicians on

an inpatient service or

as preceptors in a clinic

or emergency

department); faculty

should consider

themselves “competent

to proficient” in QI/PS,

with basic knowledge in

QI/PS and a clear

understanding of the

workflow and behaviors

of the team/unit/clinic/

department

Led by faculty

members who are

“unit owners” (have

QI/PS as a key aspect

of their job

description and are

responsible for the

quality output of their

area); may be a

clinical director of a

unit, or the unit-

specific quality leader;

are proficient in

QI/PS knowledge and

skills; have a deep

understanding of the

unit’s workflow and

priorities; are in a

position to influence

changes in workflows

and systems beyond

the behaviors of a

particular team of

physicians; have the

ability to influence the

Led by faculty members

who are directors of

quality or quality officers

for a department, or

clinical leaders such as

Vice Chair for Clinical

Services, with quality

playing a central role in

their job description; are

in a position of leadership

that allows them to

influence multiple clinical

leaders across units of

their department; have a

deep understanding of

departmental priorities

and functioning; are

“proficient to expert” in

their understanding of

QI/PS

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 25

culture of the

attending physicians

they oversee, and have

strong links to

interprofessional

clinical leaders

(nursing, pharmacy,

social work, and case

management)

Scope of

improvement(s)

Scope should be

appropriate to the team

structure/workflow and

the available timeframe

based on trainees’

rotation schedule; the

problem that becomes

the focus for the

improvement effort

must be a “felt need” of

the team

Scope of

improvements or

changes is appropriate

for the unit/clinic

setting; efforts focus

on systems

improvements that

are mainly contained

within the unit/clinic

Can involve systems and

processes that cut across

multiple units or clinics;

larger systems are

restructured

Duration

Can be as short as two

weeks, or as long as a

month or two

Flexible, but typically

will last two to six

months (or even up to

a year, depending on

local capability and

whether the clinical

experience is

rotational or

longitudinal)

Can last anywhere from

several months to a year

or more, depending on the

time required for buy-in

and the duration of each

PDSA cycle

Interprofessionalism

Does not require

significant

modifications to the

workflow of providers

who are not on the

improvement team

Interprofessional

collaboration required

among a group of care

providers and staff in

one particular unit or

clinic (nurses,

pharmacists, medical

assistants, etc.)

Interprofessional

collaboration is critical to

success; requires buy-in

from multiple

stakeholders

Defining the

problem to be

addressed

The problem should be

limited to something

that the team can

address; the problem

should be a “felt need”

of the team (not

necessarily a unit or

institutional priority);

finally, the

improvement efforts

should target a problem

of inconsistency in

team’s operations or

processes or in its care

delivery.

The problem should

be a unit priority that

is relatively focused

and very achievable

within the constraints

of two to six months.

You will likely

determine your

problem of focus

based on your unit’s

particular weaknesses

with respect to the

overall organization’s

quality and safety

strategy.

Due to the longitudinal

nature of this project, the

problem could be a sub-

project of one of the stated

hospital-wide aims. (For

example, it could be

related to reducing length

of stay, hospital-acquired

infections, mortality,

readmissions, etc.) The

aim is tied to a specific

outcome measure.

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 26

Encouraging buy-in

Since the projects will

have such rapid

turnover, it is important

to ensure that the

clinical staff who are

involved in each “new”

project be supportive of

the structure of rapid

turnover of

improvement teams and

projects, which is why

the team must

determine the focus of

the project and why the

project must be based

on an actual “felt need”

of the team.

The team could use

multidisciplinary

rounds with nursing,

social work,

respiratory therapy,

etc., as a venue to

discuss quality and

safety issues and

suggest areas for

improvement that

could become a

medium-term QI

project.

Buy-in from the unit

leadership will help

facilitate buy-in from the

clinicians and caretakers

on the front lines.

Designing metrics

Metrics will be specific

to the project and the

timeframe. In such a

short-term project, you

should record

measurements daily.

Metrics will be

specific to the project

and the timeframe. In

unit-based projects,

you should record

measurements on a

weekly basis.

Metrics will be specific to

the project and the

timeframe. In medium- to

longer-term projects like

these, the measurement

system is likely to be more

complex. You can review

process measures every

couple of weeks and

outcome measures on a

monthly basis.

Institutional resources

might be available to

capture these

measurements and report

them.

Baseline data

collection

You should collect

baseline data (i.e.,

assess the current state

of the problem) within

the first 48 hours of the

clinical team’s

assembling, selecting a

topic, and starting their

on-service time

together.

You can collect

baseline data over a

week or two,

depending on the

scope of the project

and the sample size of

patients that will serve

as the baseline

population.

You can collect baseline

data over whatever time

frame you deem optimal

to collect sufficient data.

Institutional resources

may be mobilized to help

with data collection,

analysis, and reporting.

Improvement cycles

Conduct tests of change

on a daily basis over a

span of two or three

weeks, and evaluate the

results of each test the

following day or shortly

thereafter.

PDSA cycles will vary

from a few days to a

few weeks each.

PDSA cycles require more

planning to move forward

than in the other models,

and will vary from a few

weeks to a month each.

Tracking changes

As part of the daily

routine, perhaps at the

beginning or end of

Track weekly

summary statistics

This model lends itself to

summary statistics every

two to four weeks with a

IHI Open School Faculty Guide: Best Practices for Curriculum Integration

Return to the Table of Contents Institute for Healthcare Improvement • ihi.org 27

bedside rounds, the

team can huddle to

discuss progress since

the prior day on their

improvement initiative.

with a continuously

updated run chart.

continuously updated run

chart, with monthly to

quarterly aggregated

statistics and bigger-

picture run charts to

demonstrate perturbation

of the system. (Updates

may occur more often

toward the beginning of

the initiative, and less

frequently over time.)

Pros

The rapid cycling

inherent in this

approach requires that

the improvement work

be completely

integrated into clinical

care rather than

separate/superimposed.

The ability to work on a

problem that the team

feels is important will

achieve more buy-in.

The goal here is not

necessarily to transform

the system, but to allow

trainees to participate

meaningfully in an