External author:

Wolf Heinrich REUTER

Benefits and

drawbacks of an

“expenditure rule”, as

well as of a "golden

rule", in the EU fiscal

framework

Euro Area Scrutiny

STUDY

Requested by the ECON committee

EN

Economic Governance Support Unit (EGOV)

Directorate-General for Internal Policies

PE 645.732- September 2020

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

2 PE 645.732

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 3

Abstract

Focusing the EU fiscal framework on an expenditure rule could

help to increase transparency, compliance and ownership. In

various other respects, like estimation errors or counter-

cyclicality of prescribed fiscal policy, an expenditure rule is similar

to a structural balance rule.

If the EU decides to go beyond the current focus on fiscal

aggregates, a two-rule system aimed at safeguarding specific

expenditures could be placed at the centre of the EU fiscal

framework. The key challenge is to define and measure the

protected expenditures.

Benefits and

drawbacks of an

“expenditure rule”, as

well as of a "golden

rule", in the EU fiscal

framework

Euro Area Scrutiny

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

4 PE 645.732

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Economic and Monetary

Affairs.

AUTHORS

Wolf Heinrich REUTER

Staff of the German Council of Economic Experts*

* This paper reflects the personal views of the author and not necessarily those of the German Council of

Economic Experts. The author would like to thank Patricia Bucher and Paul Mannschreck for their research

assistance as well as Mustafa Yeter for the very helpful detailed comments on drafts of the paper.

ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE

Jost ANGERER

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Donella BOLDI

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

The Economic Governance Support Unit provides inhouse and external expertise to support EP

committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny

over EU internal policies.

To contact the Economic Governance Support Unit or to subscribe to its newsletter please write to:

Economic Governance Support Unit

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

Email: egov@ep.europa.eu

Manuscript completed in August 2020

© European Union, 2020

This document and other supporting analyses are available on the internet at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author- and do not necessarily

represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 5

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 6

LIST OF FIGURES 7

LIST OF TABLES 7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8

1. INTRODUCTION 9

2. TYPES OF FISCAL RU LES 9

2.1. Budget Balance, Structural Balance and Expenditure Rules 9

2.1.1. Cyclically-Adjusted Expenditures and Revenues 9

2.1.2. Budget Balance or Deficit Rules 10

2.1.3. Cyclically-Adjusted or Structural Balance Rules 10

2.1.4. Expenditure Rules 11

2.2. Golden Rules and Exceptions 12

2.2.1. Expenditure Categories Worth Protecting 12

2.2.2. Relationship with Fiscal Rules 13

3. EXPERIENCE WITH THE CURRENT EU FISCAL FRAMEWORK 14

3.1. Current Fiscal Rules at the European Level 14

3.2. Forecast and Real-Time Errors 15

3.2.1. Mean Absolute Errors 17

3.2.2. Mean Errors 18

3.2.3. Other Forecast and Estimation Errors 19

3.3. Exceptions and Compliance 19

3.4. Composition of Public Expenditures 21

3.5. Pro-Cyclicality of the Current Framework 22

4. FOCUSING THE EU FRAMEWORK ON AN EXPENDITURE RULE 23

4.1. Proposals for Expenditure Rules 23

4.2. Assessment of Rule Performance Based on Past Data 25

4.3. Calibration 26

5. CONVERTING AN EU FISCAL RULE INTO A GOLDEN RU LE 27

5.1. Proposals for Safeguarding Specific Expenditure Categories 27

5.2. Limits Set by Golden Rules 30

6. CONCLUSIONS 31

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

6 PE 645.732

REFERENCES 32

ANNEX 36

6.1. Formal Description of Cyclically-Adjusted Balance and Expenditure Rules 36

6.2. Additional Details on Composition of Public Expenditures in the EU 36

6.2.1. Development of Specific Expenditure Categories 36

6.2.2. Specific Expenditure Categories during Fiscal Consolidations 40

6.3. Forecast Errors based on AMECO Vintages 41

6.4. Calculation of past growth rates of cyclically-adjusted revenue, potential GDP and

expenditures 42

6.5. Additional results regarding forecast and real-time estimation errors 46

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AMECO

European Commission’s annual macro-economic database

EDP

Excessive deficit procedure

EU

European Union

EU15

15 Member States of the EU (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany,

Greece, Italy, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, United

Kingdom)

GDP

Gross domestic product

IMF

International Monetary Fund

MTO

Medium-term objective

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OG

Output gap

R&D

Research and development

SGP

Stability and Growth Pact

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 7

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Main variables necessary for evaluating compliance with EU fiscal rules 16

Figure 2: Mean (absolute) errors of forecasts and real-time estimates (EU15, 2005-2015) 17

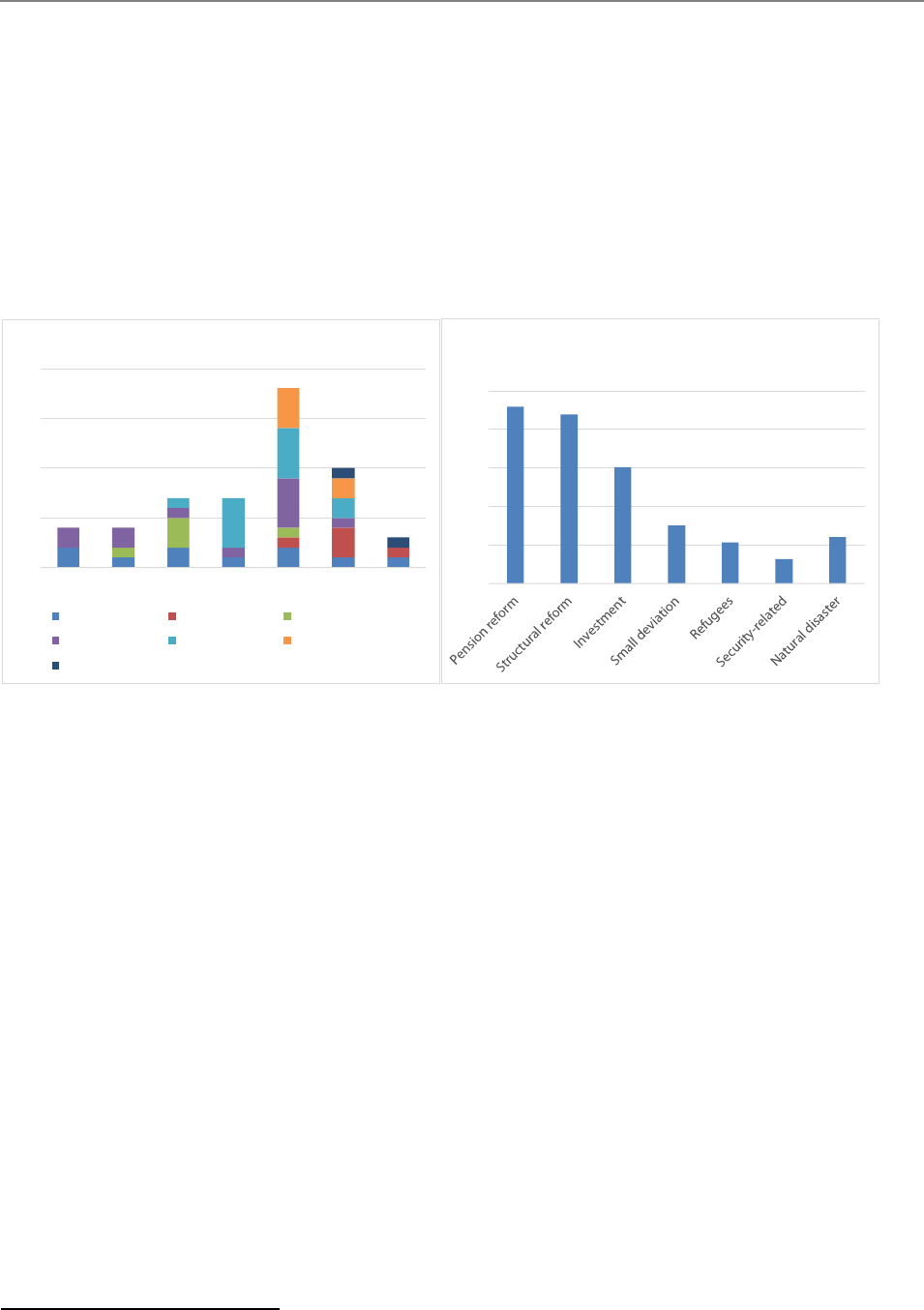

Figure 3: Number and average size of exceptions granted between 2012 and 2018 20

Figure 4: Public investment and education expenditures in the EU15 from 1995 to 2019 21

Figure 5: Comparison of limits set for expenditure growth with observed fiscal policy (EU15) 25

Figure 6: Public investment expenditures in the EU15 from 1995 to 2019 37

Figure 7: Public investment expenditures in EU27 from 1995 to 2019 37

Figure 8: Public education expenditures in EU15 from 1995 to 2018 38

Figure 9: Public education expenditures in EU27 from 1995 to 2018 38

Figure 10: Public basic research and R&D expenditures in the EU15 from 2001 to 2018 39

Figure 11: Public basic research and R&D expenditures in EU25 from 2001 to 2018 39

Figure 12: Comparison of measures of potential GDP growth (forecast, real-time, ex-post) 44

Figure 13: Comparison of growth rates of different measures of public expenditure 45

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Differences between types of fiscal rules 12

Table 2: Comparison of expenditure rule proposals 24

Table 3: Comparison of proposals related to a ‘Golden Rule’ in the context of the EU fiscal framework29

Table 4: Fiscal consolidations and specific public expenditure categories 41

Table 5: Mean absolute errors and mean errors of forecasts and real-time estimates 46

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

8 PE 645.732

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This paper discusses two possible avenues for reforming the EU fiscal framework: focusing the framework

on an expenditure rule to reduce complexity, and introducing a Golden Rule to safeguard specific public

expenditures. An overarching challenge when reforming the EU fiscal framework is to increase

compliance with its fiscal rules. The best-designed rules are no good if they are not complied with or if

the leeway granted by these rules is not used where it would be advisable. A more transparent, more

predictable and less complex fiscal framework could make a significant contribution to enhancing

compliance and the role of fiscal rules. The most important lever is to increase national governments’

ownership as well as the visibility of rules for politicians, the general public and the media.

Expenditure Rule

The benefits of expenditure rules are often discussed in comparison to observed fiscal policy, but not in

relation to other possible rules or rule designs. Because fiscal policy is often chosen not purely in line with

the limits set by fiscal rules, however, analysing observed fiscal policy to evaluate the current fiscal

framework might be misleading. For example, expenditure and structural balance rules per se would have

both prescribed a more counter-cyclical fiscal policy in the EU over the past few decades. Under the

current framework it appears to be not the rule design itself but, rather, political decisions outside the

scope of the fiscal rules, non-compliance with these rules, and accompanying regulations like the use of

exceptions that tended to foster pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

Expenditure rules are also similar to structural balance rules in various other respects. Like structural

balance rules, expenditure rules are associated with significant challenges when forecasting and

estimating the variables necessary for their operationalisation. These errors are substantial and biased in

the case of variables required to operationalise structural balance rules. They are smaller, although still

significant, and less biased, in the case of expenditures. However, the operationalisation of expenditure

rules also requires other variables, such as discretionary revenue measures, which involve cumbersome

estimates and are associated with a high degree of uncertainty.

The main advantages of expenditure rules are that the constrained variable is more directly controlled by

governments, it is more transparent and the ceiling set by the rule for fiscal policy is less volatile.

Golden Rule

This paper discusses options for converting a fiscal rule under the EU fiscal framework into a Golden Rule,

which would allow debt issuance to finance specific expenditure categories. There is a concern that needs

to be adressed first, which is that such a rule would go beyond the current focus of the EU fiscal framework

on fiscal aggregates and distinguishes between different expenditures in Member States.

The main challenge when introducing a Golden Rule is to clearly and narrowly define the deductible

expenditures. Ideally, each spending decision involves a cost-benefit analysis and a subsequent decision

to engage irrespective of the category it belongs to. One proposed workaround is to identify expenditure

categories which on average exhibit certain growth effects or future benefits. This identification, however,

can be very difficult in practice. Furthermore, governments need to be prevented from using ‘creative

accounting’ to shift other expenditures into the defined deductible categories.

Addressing the bias of politicians towards too low investment expenditures does not remove the bias

towards excessively high deficits in general. Furthermore, long-term fiscal sustainability still implies that

there is a limit to the amount of annual debt issuance, which, however, might be higher with a Golden

Rule. This suggests that a cap should be set on the amount of expenditures that is deductible, which

would result in a system of two rules: one setting a limit on total expenditures (deductible and non-

deductible) and a second one setting a lower limit on the non-deductible portion of expenditures.

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 9

1. INTRODUCTION

Ever since the European (Monetary) Union was launched, a framework for the surveillance and

coordination of its Member States’ fiscal policies has been in place. The aim behind the various types of

fiscal rules set under this framework is to ensure sustainable public finances of the Member States. This

framework has been reformed and amended in various stages over the years. Among academics,

policymakers and the general public, there has been an ongoing debate about the need for further

reforms to reduce complexity, enhance transparency, increase compliance with the rules, ensure

sustainable public finances, while supporting economic growth and stabilisation, and improve the quality

of public finances. The EU’s economic governance and fiscal framework have been under official review

since the beginning of this year.

Fiscal rules are introduced to counteract the deficit bias of politicians and governments. Empirical and

theoretical studies have shown that various politico-economic incentives tend to encourage

governments to run deficits which are higher than would be optimal (literature surveys e.g. in Feld, 2018;

Wyplosz, 2012). These incentives relate, among other things, to various interest groups’ access to a

common budgetary resource (‘common pools´), political budget cycles and asymmetric information.

Spillover effects of high debt ratios also play a role in a monetary union. It has empirically been shown

that, in general, fiscal rules can curb the deficit bias and reduce deficits (e.g. Badinger and Reuter, 2015,

2017; Eyraud et al., 2018b; Heinemann et al., 2018; Caselli and Reynaud, 2020).

Despite having fiscal rules in place, however, fiscal policy in the EU has been pro-cyclical and debt levels

have not sharply decreased across Member States. Furthermore, (net) public investment ratios have not

increased considerably and fiscal rules are not complied with in many years. At the same time the fiscal

framework has become more comprehensive and complex. Against this background, this paper analyses

two prominently discussed reforms. First, the refocusing of the EU fiscal framework on one rule – namely

an expenditure rule. Broadly, this rule would set a limit for expenditure growth which is related to

medium-term potential GDP growth. And, second, the conversion of an existing or reformed fiscal rule,

like an expenditure or structural balance rule, into a Golden Rule, which would allow debt issuance

specifically to finance particular expenditures that benefit current and, especially, future generations,

such as investment expenditures or expenditures to mitigate climate change.

Section 2 discusses the differences between various types of fiscal rules and the design of Golden Rules.

The current EU fiscal framework is presented in Section 3, which also investigates the implementation

and challenges associated with it, based on past data. Section 4 compares various proposals for a new

expenditure rule and Section 5 the proposals for Golden Rules. Section 6 concludes, and the Annexes

provide further details on calculations and methodology as well as additional figures and estimates.

2. TYPES OF FISCAL RULES

2.1. Budget Balance, Structural Balance and Expenditure Rules

2.1.1. Cyclically-Adjusted Expenditures and Revenues

To investigate the relationship between different types of fiscal rules, a distinction based on their

properties between different components of public revenues and expenditures is useful. Some sub-

components of public expenditures are directly linked to the position in the economic cycle. For example,

expenditures related to unemployment tend to be higher if the economy is in a downturn, as there are

more people unemployed, and they tend to be lower if the economy is in an upswing. While in some

countries other expenditure categories, such as old-age or other social security expenditures, are also

sensitive to the economic cycle (Christofzik et al., 2018), unemployment-related expenditures (EU28

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

10 PE 645.732

average: 3.1 per cent of total expenditures) are the main cyclical component of public expenditures

(European Commission, 2019a). Thus, the European Commission estimates cyclically-adjusted

expenditures as total public expenditures net of cyclical unemployment-related expenditures, where the

latter would be observed if the output gap were fully closed or, more intuitively, that would on average

materialise over the medium term, i.e. across the economic cycle.

Public revenues can also be split into sub-components which are sensitive to the economic cycle and

those which are not. In comparison with expenditures, a much larger portion of public revenues is

sensitive in this way, as tax revenues depend strongly on the level of activity by firms and households.

Thus, when estimating cyclically-adjusted revenues, the European Commission assumes only non-tax

revenues (EU28 average: 11.4 per cent of total revenues) to be independent of the economic cycle

(European Commission, 2019a). Again, cyclically-adjusted revenues correspond to the level of revenues

that would be observed if the output gap were fully closed, i.e. when GDP is at its potential.

2.1.2. Budget Balance or Deficit Rules

One of the most common types of fiscal rules worldwide is a budget balance or deficit rule. It sets a limit

on the gross budget balance, i.e. the difference between public revenues and public expenditures. Many

of the rules introduced at a fairly early stage, e.g. shortly after World War II, were such rules (Eyraud et al.,

2018b), with the 3 per cent deficit rule in the Maastricht Treaty being a prominent example. The

advantage of such a budget balance rule is that it is very simple and the variable constrained by the rule

– the budget balance – is directly observable. No adjustments or estimates are necessary. This is also why

forecasting the variables and compliance with the rule is typically easier for budget balance rules than for

other types of rule. Apart from the effects of the economic cycle on the cyclical components, governments

usually have fairly direct control over revenue and expenditure aggregates.

The main problem with this type of rule, however, is its pro-cyclicality. Governments often do not apply

the limit set by a budget balance rule as an upper bound, but rather as some kind of target (Reuter, 2015;

Caselli and Wingender, 2018). Rules are not complied with in a significant proportion of years.

Consequently, the constrained budget balance is often right at its limit in many years – even those in

which economic conditions are benign. This allows no buffers or fiscal headroom for economically

challenging times. Applied in this way, budget balance rules can lead to pro-cyclical fiscal policy.

Downturns are usually accompanied by a cyclical reduction in revenues and a cyclical increase in

unemployment-related expenditures. To comply with such a rule, the government would therefore need

to pro-cyclically increase revenues or cut expenditures during downturns. During upturns, on the other

hand, the limit set by the rule is complied with more easily because revenues and budget balances tend

to increase in such cases. Governments, especially if they perceive rules as targets, are tempted to pro-

cyclically loosen fiscal policy at a time when they could build up fiscal buffers.

2.1.3. Cyclically-Adjusted or Structural Balance Rules

To address the pro-cyclicality, newer ‘second-generation’ fiscal rules set a limit for the cyclically-adjusted

budget balance or structural balance (Eyraud et al., 2018b). The former represents the difference between

cyclically-adjusted revenues and cyclically-adjusted expenditures. It is the budget balance that would

theoretically be observed if the output gap were fully closed. The structural balance is the cyclically-

adjusted balance net of temporary one-off measures (European Commission, 2019a).

The advantage here is that – compared with budget balance rules – such a rule automatically permits

larger deficits in downturns and restricts fiscal policy more strongly during upturns. The portions of

revenues and expenditures that automatically change together with the economic cycle (‘automatic

stabilisers’) are not constrained by the rule and are thus not restricted in supporting the stabilisation of

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 11

the economy. The rule only aims to place constraints on government policy with respect to discretionary

decisions on revenues and expenditures.

The main problem with such a rule is that the cyclically-adjusted budget balance is not directly observable

but, rather, has to be estimated. In addition to the variables necessary to forecast and calculate the budget

balance, the output gap and (semi-)elasticities of various revenue and expenditure categories are needed

for such estimates (plus one-off measures for the structural balance). The errors in forecast and real-time

estimates of the output gap and potential GDP can be quite large (see Section 3.2). As a result, evaluation

of rule compliance is very complex and the rule might prescribe different policy stances at different points

in time, e.g. in real-time compared with ex-post reassessments. Consequently, this causes difficulties in

fiscal planning and the real-time implementation of fiscal policy. In addition, this adversely affects

transparent communication with the general public and policymakers.

2.1.4. Expenditure Rules

Reforms focusing on expenditure rules are proposed (see Section 4.1) in an attempt to address the

challenges posed by the implementation of cyclically-adjusted budget balance rules. Expenditure rules

are in force in different forms across the world, including the EU’s current Stability and Growth Pact (SGP).

However, the most commonly proposed expenditure rule restricts the growth rate in public expenditures

to some limit related to potential GDP growth, net of some cyclical expenditure components and net of

discretionary changes in revenues. The latter are subtracted so that countries can choose the size of

government in terms of the ratio of expenditures to GDP according to the political preferences of the

electorate. This allows governments to permanently increase (cut) expenditures as a share of GDP if the

change is offset by permanent tax increases (cuts).

The properties of such an expenditure rule are similar to a rule constraining the cyclically-adjusted budget

balance (also discussed e.g. in Cottarelli, 2018). With the latter, aside from the initial starting position,

cyclically-adjusted expenditures are allowed to increase as much as cyclically-adjusted revenues to

comply with the rule. Growth in cyclically-adjusted expenditures is approximately equal to the growth in

expenditures net of (cyclical) unemployment-related expenditures. Because – without any discretionary

changes (e.g. in the tax code) – revenues are closely aligned with GDP, cyclically-adjusted revenues are

closely related to potential GDP. Thus, growth in cyclically-adjusted revenues net of discretionary revenue

changes is approximately equal to growth in potential GDP. Taken together, aside from the initial st arting

position, both rule types restrict the growth in expenditures net of cyclical unemployment-related

expenditures and discretionary revenue measures to potential GDP growth. The EU fiscal framework also

recognises the similarity between the two rules, as expenditure rules are used to operationalise

adjustment of the structural balance (see Section 3.1).

As far as pro-cyclicality is concerned, expenditure rules work similarly to structural balance rules because

cyclical revenue shortfalls do not have to be compensated for by expenditure cuts. With structural

balance rules, this is due to the cyclical adjustment of revenues, while in the case of expenditure rules it

is because the constrained variable is only affected by discretionary changes in revenues. A difference

arises where revenues cyclically rise (fall) more sharply than what is mechanically calculated based on

output increases (declines) and elasticities. In that case, a cyclically-adjusted balance rule would restrict

fiscal policy too much in a downturn and an expenditure rule would restrict it too little in an upswing.

Despite the similarities, one reason why expenditure rules are currently preferred in the literature is that

expenditures net of some expenditure items and their growth rate are directly observable and are mostly

directly controlled by the government. Furthermore, the greater part of the constrained variable is easy

to communicate and forecast errors for expenditures tend to be smaller. For expenditure rules as well,

however, some components need to be estimated and they involve complexity and uncertainty: i) growth

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

12 PE 645.732

rate of potential GDP; ii) effects and size of discretionary revenue measures; iii) (for some rule proposals)

cyclical adjustment of (unemployment-related) expenditures.

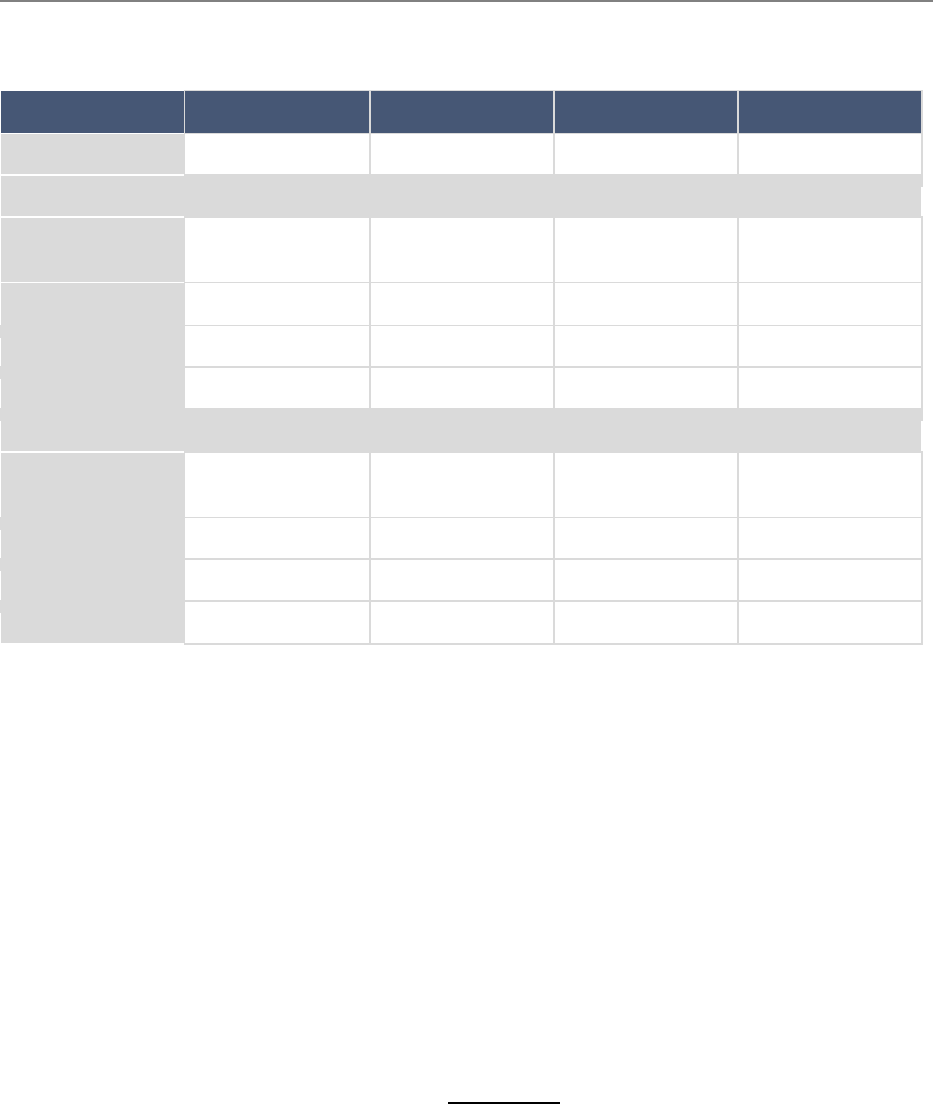

Table 1: Differences between types of fiscal rules

Budget balance

Cyclically-adjusted (or

structural) balance

Expenditure growth

Problem

Pro-cyclicality

Measurement/ estimation

Measurement/ estimation

Dealing with

the economic

cycle

None

Cyclical adjustment of

expenditures and

revenues based on the

output gap

Cyclical revenue changes

not part of rule, (possible)

cyclical adjustment of

expenditures

Variables

necessary to

assess rule

compliance

Revenues, expenditures

Revenues, expenditures,

elasticities, output gap,

potential GDP, (one-off

measures)

Expenditure growth,

discretionary revenue

measures, potential GDP

growth

Source: own illustration

2.2. Golden Rules and Exceptions

2.2.1. Expenditure Categories Worth Protecting

Within the context of reforming fiscal frameworks there is also a debate about the quality of public

finances and how the framework can contribute to improving it. Higher quality is typically associated with

a larger share of expenditures that are more beneficial to economic growth, development and future

generations than others. The European Commission identifies expenditures with growth and value added

for the future in its proposals for a multiannual financial framework and its country-specific

recommendations for the Member States. Among these are expenditures for infrastructure investment

(especially digital infrastructure), public research, research and development (R&D), climate-related

investment, regional policy, investment in education and training, and public employment agencies.

Romp and De Haan (2007) and Bom and Ligthart (2014) survey the extensive literature on the effects of

public investment on output (growth). Although not all studies find a positive effect, there seems to be a

consensus that an increase in public capital increases economic growth in the short run and the effect is

stronger in the long run. However, there is a high degree of uncertainty about the estimated size of this

impact. It is heterogeneous across countries, regions, sectors and types of investment, and it depends on

the level and quality of the public capital stock in place (Romp and De Haan, 2007). Besides the long-term

effects, investment expenditures also seem to have a greater impact on demand than other expenditure

categories (Auerbach and Gorodnichenko, 2012; Gechert and Will, 2012). Increasing or reducing the

former rather than the latter therefore also has an effect on output in the short-term.

Investment expenditures as defined in the national accounts (‘gross fixed capital formation by the

government’) focus on physical capital such as infrastructure, housing and machinery. They als o include

spending on defence and intangible non-financial assets such as software. However, they do not include

maintenance spending or investment by state-owned enterprises (Barbiero and Darvas, 2014).

Furthermore, they do not include expenditure categories for example related to mitigating climate

change, education, or the accumulation of human capital. However, similar to investment expenditures,

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 13

these categories also incur costs today, and their benefits – such as reduced future losses due to climate

change and educational benefits – also accrue to future generations.

While studies seem to confirm the generally positive impact of some expenditure categories, it appears

that the main challenge is to clearly and narrowly define which expenditure categories are identified as

beneficial or worth protecting and which expenditures belong to each category. Furthermore, not every

project or expenditure within an identified category has a positive effect. And not every expenditure

category that is not listed above does not contain expenditures with positive longer-term effects. Ideally,

each spending decision involves a cost-benefit analysis and a subsequent decision to engage irrespective

of the expenditure category it belongs to. In addition, there are most probably strong interdependencies.

As an example, expenditures on the implementation of the rule of law do not form part of the categories

above, but they enable the other categories to have a positive effect. It is not always possible to

differentiate between productive and unproductive expenditures as, in many cases, both will be needed.

A proposed workaround is to identify expenditure categories which on average exhibit certain growth

effects or future benefits and accept the inaccuracy when it comes to each single expenditure item. In

general, however, it can be very difficult to identify the growth effects or future benefits of specific

categories over time and across countries, especially if politicians reallocate expenditures. Furthermore,

the identification of specific expenditures is usually made non-specifically and without reference to the

level of expenditures already implemented in that particular category. Consequently, the underlying

assumption is that spending in the respective category will always be associated with positive growth

contributions of equal size, irrespective of how and for what specific purpose the relevant expenditures

are made. However, this is not necessarily the case.

Even after categories have been identified, the issue of measurement is challenging. In many cases data

on the stock of public capital is not available and needs to be constructed based on historical series of

flow figures (Eurostat and OECD, 2014; Christofzik et al., 2019). While the latter are currently available for

physical capital, they might be more difficult to obtain for other categories, like mitigation of climate

change or human capital. In addition, replacement investment does not automatically increase the assets

available. Usage and time depreciate capital. Only if investment expenditure is higher than the

depreciation of existing assets are additional assets created for future generations. Depreciation has to

be estimated in order to obtain net investment figures, which is even more difficult than measuring gross

investment (Barbiero and Darvas, 2014). International comparisons of net investment figures are

especially difficult as various necessary assumptions differ across countries, such as the institutional

division of labour, frameworks and assumed usage periods (Christofzik et al., 2019). In the absence of any

double accounting systems for governments, reliable workarounds would need to be found.

2.2.2. Relationship with Fiscal Rules

The question is whether fiscal rules cause policymakers to put less emphasis on the expenditures

discussed above than would be optimal. The reasons given can broadly be grouped into two categories.

First, some of the expenditures identified above might be easier to cut than others. Thus, if compliance

with fiscal rules requires some expenditures to be reduced, these categories are cut not because they are

the lowest priority but because it is easier timewise and politically to do so. While it may be easy to

postpone the start of a new investment project today, for example, it might be hard to reduce public-

sector employment and wages or social benefits, which tend to be fixed for years ahead. Given the various

effects on demand, moreover, a reduction based on investment expenditure would tend to have a

stronger negative impact on economic growth than a similar reduction based on other expenditures.

Second, expenditures in the categories above either partially or mainly benefit future generations. This

means that, in one sense, they should also bear a share of the costs. This can be achieved by financing

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

14 PE 645.732

them through debt issuance. If they are not financed by debt, all of the costs are borne by the current

generation, which has to pay for them in the form of higher taxes or lower spending in other areas. This

can lead to less investment than would be ideal. A low-interest-rate environment makes it cheaper to shift

costs into the future. On the other hand, however, future generations are not able to fully participate in

the current political process. Thus although they cannot choose which investments are implemented,

their fiscal headroom is reduced. For example, while the current generation might choose to build roads,

which count as investment, future generations might want to reduce the scope for individual mobility.

Furthermore, policymakers might attach less importance to the future side-effects of higher debt and

might therefore opt for a higher level of debt than is ideal in order to gain some of the short-term benefits.

Some would argue that specific expenditures should be safeguarded through the design of fiscal rules.

This could be achieved by setting different limits to different expenditure aggregates. The most

prominent example would be a Golden Rule, which sets a limit to expenditures excluding investment

expenditures and allows borrowing to finance the latter. More generally, it sets a limit on a fiscal

aggregate net of a measure of deductible expenditures. Golden Rules have been implemented in various

countries and can come in different forms with respect to the rule type and the expenditures excluded. A

Golden Rule can essentially be designed based on any rule type, which means that there could be a

Golden expenditure rule or a Golden structural balance rule. Another option for safeguarding

expenditures is to add exceptions to fiscal rules, which either temporarily or permanently allow

exceptional and limited breaches of the fiscal rules and permit specific expenditures. The current EU rules

have exceptions added to them (see Section 3.3). Any rule containing an exception that permanently

allows non-compliance with the fiscal rule to the extent of specific expenditures would be equivalent to

a Golden Rule as described above.

One of the most serious challenges in implementing Golden Rules is associated with adverse incentives

for governments to engage in ‘creative accounting’. In cases where an exception in the form of a Golden

Rule is granted too casually, this could provide incentives to relabel public expenditures or to use

accounting tricks in order to (over-) exploit the leeway provided by the rule (Milesi-Ferretti, 2004). Burret

and Feld (2018) show how Swiss cantons, where a debt brake is in force, shift expenditures from

constrained parts of the budget to unconstrained parts for investment expenditure purposes. Von Hagen

and Wolff (2006) and Buti et al. (2006) provide empirical evidence that stock-flow adjustments have been

used in the EU to hide deficits from the SGP rules. Koen and Noord (2005) show for the EU Member States

that budgetary gimmickry is more likely the more binding fiscal rules become. Governments somehow

need to be prevented from shifting expenditures into the defined deductible categories. In addition,

categories need to be defined so as to minimise the incentives to increase one type of expenditure

benefiting future generations in favour of other expenditures that also benefit future generations. If, for

example, investment in physical capital is deductible but education expenditures are not, governments

might opt to invest a higher proportion of the total in physical capital rather than investing in human

capital.

3. EXPERIENCE WITH THE CURRENT EU FISCAL FRAMEWORK

3.1. Current Fiscal Rules at the European Level

Fiscal rules have been part of the European governance framework since the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992.

However, the framework has gradually evolved as a result of major reforms and has been augmented

considerably over time. These changes introduced ‘second-generation fiscal rules’, increased the

flexibility of the framework and amended institutional monitoring and governance. Whereas the

framework started out with just two simple fiscal rules – the 3 per cent deficit rule and the 60 per cent

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 15

debt-to-GDP rule – it has evolved into a complex web of rules and regulations today. Various rules coexist

with a multitude of exceptions and escape clauses as well as comprehensive provisions for assessing

compliance with the rules. In addition to the EU fiscal framework, policymakers also face fiscal rules at the

national and subnational levels when taking fiscal policy decisions.

In 2005, a rule restricting the structural balance and, in 2011, a rule on expenditure growth were

introduced in the preventive arm of the SGP. The former rule states that the structural balance should be

larger than or equal to a medium-term objective (MTO), which each country sets in its Stability or

Convergence Programme (European Commission, 2019b). The MTO for countries which signed the Fiscal

Compact must be larger than -0.5 per cent of GDP, unless their debt ratio is significantly below 60 per

cent of GDP and their sustainability risks are low, in which case the MTO needs to be larger than -1 per

cent of GDP. Furthermore, the European Commission calculates a minimum MTO for each country.

The two rules in the EU framework are connected, as the expenditure rule basically implements the path

towards the MTO set by the structural balance rule: i) In the case of a country which complies with the

latter rule, i.e. for which the structural balance is higher than or equal to their MTO, the expenditure rule

states that the growth in net expenditures should be less than or equal to the medium-term growth rate

of potential GDP (European Commission, 2019b). As described in Section 2.1.4, this is equivalent to a rule

which states that the structural balance should be improving or remaining constant. ii) If the country does

not comply, net expenditure growth should be less than the medium-term growth in potential GDP by a

‘convergence margin’, which means that the structural balance should improve by a specific margin.

The expenditure rule in the EU fiscal framework defines net expenditures as total expenditures net of the

following items: i) discretionary revenue measures, ii) interest expenditures, iii) expenditures on EU

programmes matched by EU funds and iv) cyclical unemployment-related expenditures. By excluding

some investment expenditures, the expenditure rule in its current form already resembles a very limited

form of Golden Rule. Investment expenditures not matched by EU funds are smoothed over a four-year

period. The medium-term growth rate of potential GDP, which serves as the limit on expenditure growth,

is calculated for each country as the average of potential GDP over the past five years, the current year

and the forecasts for the next four years.

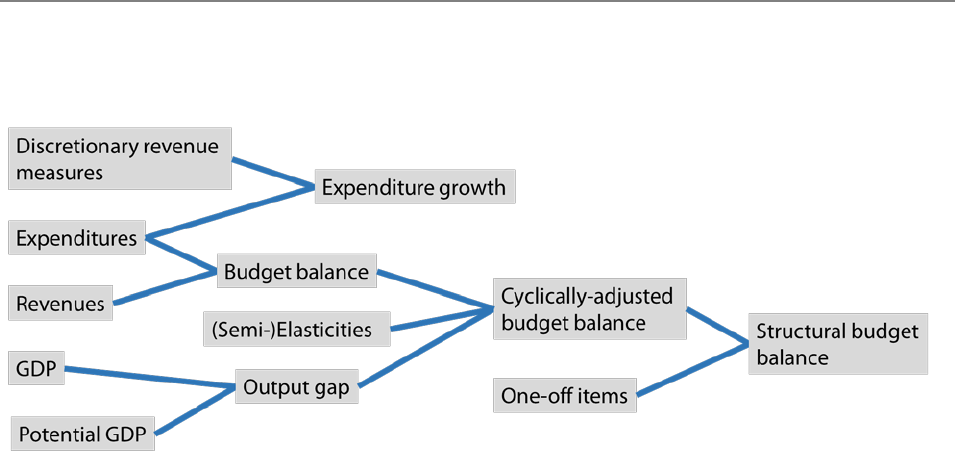

3.2. Forecast and Real-Time Errors

A series of variables are necessary to evaluate compliance with EU fiscal rules. When deciding on fiscal

policy ex-ante or in real-time, policymakers need to rely on forecasts and estimates of those variables.

Forecast errors can lead to incorrect policy prescriptions which were not originally intended by the fiscal

rules. Furthermore, most variables are also revised considerably ex-post such that any assessment of

compliance – even without changes in policy – can change over time. Figure 1 depicts the main variables

needed in the EU fiscal framework and their relationships. The latter are still underrepresented though,

as, e.g., a forecast of GDP is also necessary to forecast the cyclical parts of expenditures or revenues.

When interpreting the results below it is also important to note that errors in the estimation of variables

used to operationalise fiscal rules might also be influencing the ex-post observations of certain variables.

For example, an erroneous reduction in potential GDP during a downturn could – as a result of overly

restrictive fiscal rules – lead to procyclical policies such as expenditure cuts, which in turn reduce GDP.

This could make the error self-fullfilling in the sense that lower GDP also lowers potential GDP estimates

(Fatás, 2019). In this case, therefore, the errors calculated from the difference between values published

for potential GDP in forecasts and ex-post might seem lower than they actually were.

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

16 PE 645.732

Figure 1: Main variables necessary for evaluating compliance with EU fiscal rules

Source: own illustration

In the following, the European Commission’s macro-economic database (AMECO) is used to calculate the

forecast and real-time errors for some of the main variables. The figures compare the forecast of a variable

for a specific year (t) from two years ahead (t-2), one year ahead (t-1) and in real-time (t) with the variable

value which was published four years after the specific year (t+4). The mean error is defined as the mean

difference between the two points in time across years and countries. As this difference can be positive

or negative, however, some of the errors might cancel each other out when a simple mean is taken. Mean

absolute errors are therefore also calculated, which take the mean of the absolute values of the

differences across countries and years. Annex 6.1 provides a more detailed methodological background.

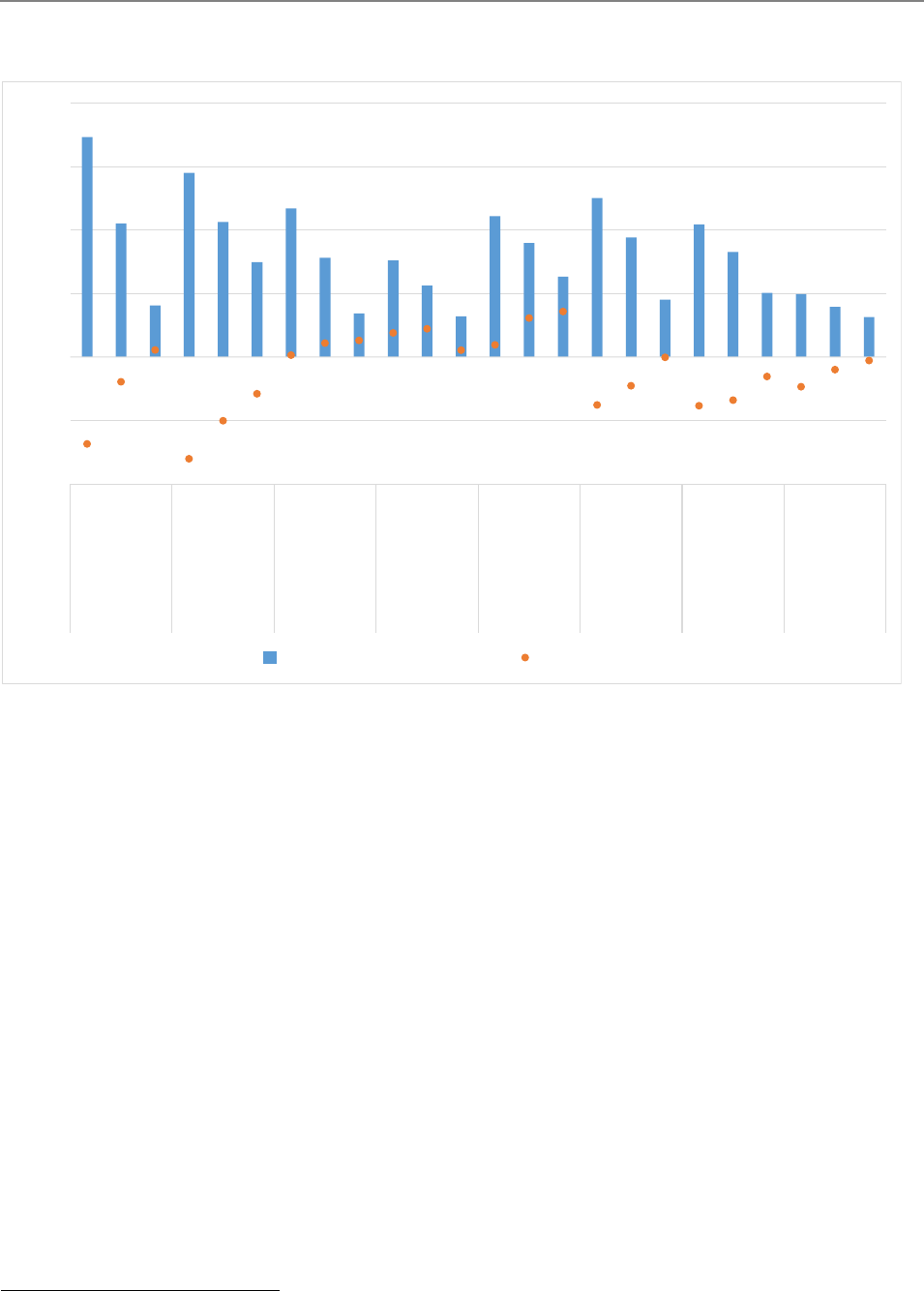

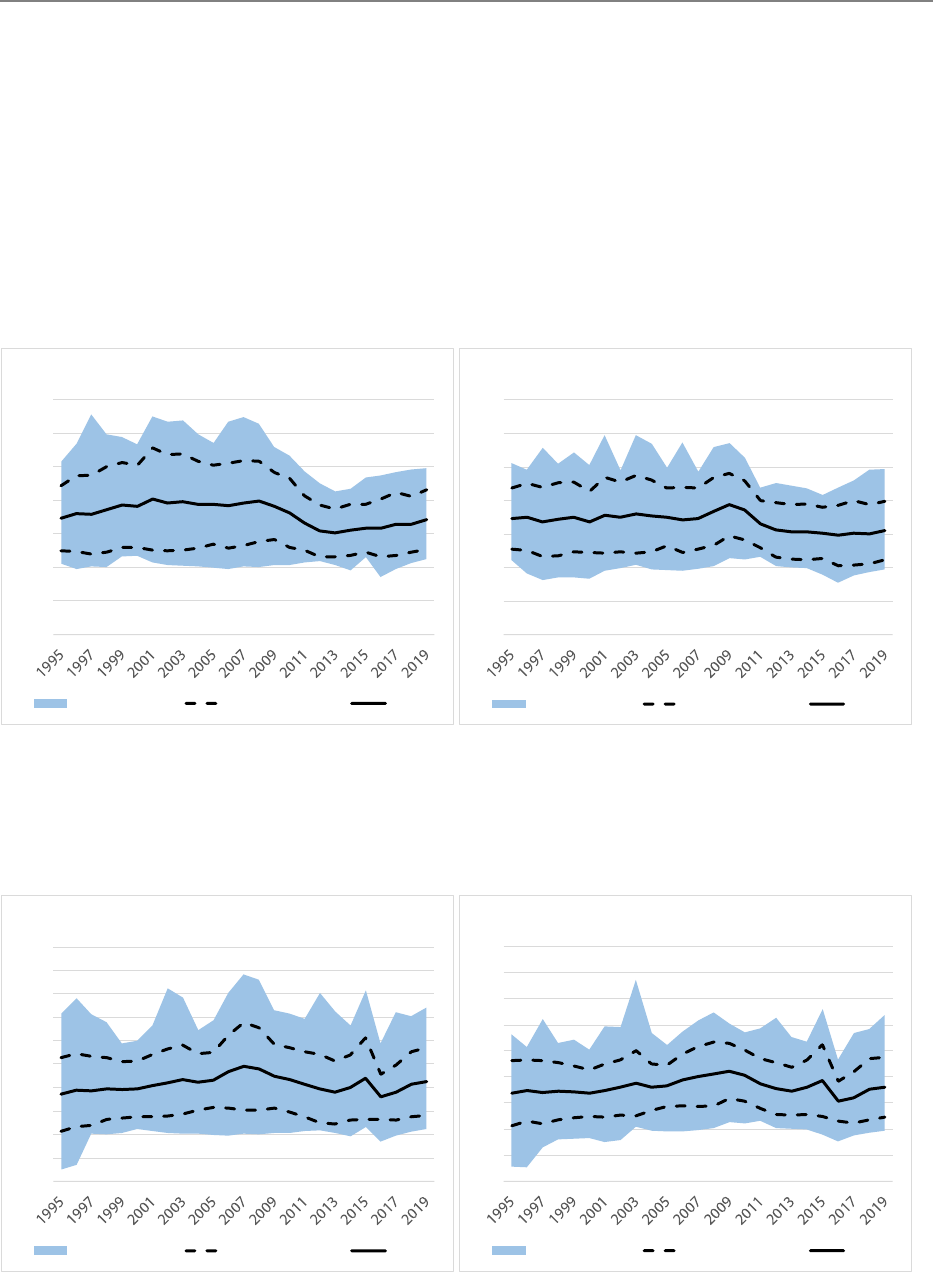

Figure 2 presents the two measures of errors for the EU15 from 2005 to 2015. The timeframe is chosen to

have a consistent dataset which only compares data which is availabe for all countries and years across

all variables in forecast and ex-post data. However, Table 5 in Annex 6.5 presents the results for other

country and time samples (e.g. for the EU27 or excluding the years of the financial crisis), as well as for the

structural balance (for which data is only available for a shorter time period). For the years where data

overlaps, errors for the structural and the cyclically-adjusted balance are very similar.

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 17

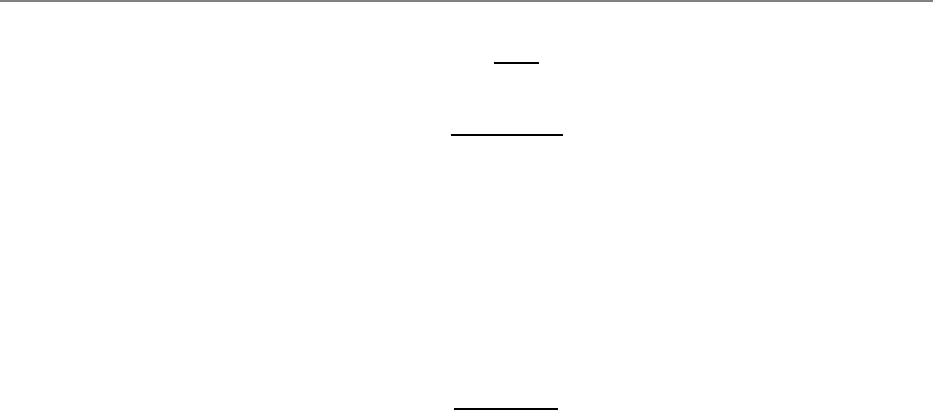

Figure 2: Mean (absolute) errors of forecasts and real-time estimates (EU15, 2005-2015)

Notes: Calculations are based on 164 observations (no data for Luxembourg in 2002). Mean errors are calculated as mean across

countries and time of the difference between values for year t values in autumn vintage of year t+4 and in autumn vintage of

year t-2, t-1 and t. Mean absolute errors are the mean of the absolute value of the differences. To make results comparable only

years and vintages are included which are available for all variables in all years and countries. More details on calculations can be

found in Annex 6.1. Budget balance: net lending or borrowing. pp.: differences in percentage points.

Sources: European Commission’s AMECO database, Firstrun project, own calculations

3.2.1. Mean Absolute Errors

Figure 2 shows that, comparable to findings in other studies

1

, mean absolute errors are substantial,

especially in the case of forecasts for two years ahead. For real GDP this amounts to about 3.5 per cent of

GDP. Even for the variable which shows the lowest mean absolute error, i.e. expenditures, the two-year

ahead forecasts are associated with mean absolute errors of 1.5 per cent of GDP. Mean absolute errors in

real-time are substantially smaller than in forecasts, but are still quite significant. Whereas in the cases of

real GDP, revenues, expenditures and the budget balance the mean absolute errors for real-time

estimates are below 1 per cent of GDP, they are still larger than 1 per cent for all measures that involve

estimates of potential GDP. The mean absolute errors for the growth rate of potential GDP are only about

half the size of the errors for the level of potential GDP. The reason seems to be that errors for potential

1

Merola and Pérez (2013) calculate a mean absolute error for real GDP of around 1.3 per cent of GDP for the one-year ahead forecast and

between 0.7 per cent and 1.2 per cent for real-time estimates for 15 European countries (1999 - 2007). De Deus and de Mendonça (2015)

find very similar errors in real-time based on data from the IMF, the OECD and the European Commission (1998 - 2011).

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

t-2 t-1 t t-2 t-1

t t-2 t-1 t t-2 t-1 t t-2 t-1

t t-2 t-1 t t-2 t-1 t t-2 t-1 t

Real GDP

(% of GDP)

Potential GDP

(% of GDP)

Revenues

(% of GDP)

Expenditures

(% of GDP)

Output Gap

(pp.)

Budget

balance

(pp.)

Cyclically-

adjusted

budget

balance

(pp.)

Growth of

potential GDP

(pp.)

Mean Absolute Error Mean Error

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

18 PE 645.732

GDP are correlated over time

2

, i.e. if the value is revised for one year the previous year is very likely to also

be revised in the same direction.

The smallest mean absolute errors for forecasts and real-time estimates can be observed for expenditures.

Especially in forecasts the mean absolute errors for expenditures are substantially smaller (1.5 per cent for

two-year ahead and 1.1 per cent for one-year ahead forecasts) than, for example, the ones for real GDP.

In real-time, the mean absolute error for expenditures was equal to 0.6 per cent of GDP. However, when

interpreting these numbers one needs to bear in mind that expenditures are only a fraction of GDP. As a

percentage of expenditures, therefore, the mean absolute errors for the same sample would be much

higher (3.1 per cent in two-year ahead forecasts and 1.3 per cent in real-time).

3

As a percentage of the

variable itself, the errors are comparable to the errors for real GDP. Nevertheless, the errors expressed as

a percentage of GDP might be more relevant in terms of policy prescriptions.

3.2.2. Mean Errors

Besides the large size of the mean absolute errors, a bias in the errors can be observed for some of the

variables as well. The mean errors for real and potential GDP are strongly negative. This means that GDP

forecasts were too optimistic during the time period considered here. While for real GDP, however, the

bias vanishes from forecasts to estimates in real-time and the mean error in real-time is close to zero, there

remains a bias of -0.6 per cent of GDP for the real-time estimates of potential GDP. So while real GDP in

real-time was on average neither too optimistic nor too pessimistic, potential GDP estimates remained

too optimistic. This translates into a bias in the estimates of the output gap, which in real-time was on

average 0.7 percentage points of GDP too low compared with the estimates of four years later. Put

differently, the cyclical position in real-time was on average estimated to be worse than it turned out to

be ex-post. This confirms findings in other studies for different countries and time periods.

4

This pessimistic error in output gap estimates translates into errors in the estimation of the cyclically-

adjusted measures of the budget balance, which are based on output gaps. While the real-time mean

error for revenues, expenditures and the budget balance is close to zero, it is -0.3 percentage points for

the cyclically-adjusted budget balance, and it is -0.8 percentage points in the two-year-ahead forecasts.

Thus, the cyclically-adjusted fiscal position looked better in real-time than it did ex-post, and it looked

even better in forecasts. This means that cyclically-adjusted or structural balance rules in the time period

considered here were on average too lax in forecasts and real-time compared with ex-post estimates.

5

The estimation of potential GDP is often based on filtering techniques (such as the methods currently

used by the European Commission). These are prone to revisions especially because of end-of-sample

problems, i.e. they are sensitive to the latest available forecasts or observations of actual GDP (GCEE,

2019). A series of improvements to the currently used methods are discussed, such as using other

indicators, different models and estimation methods. However, ultimately, any revision of GDP is likely to

be composed of cyclical and structural factors, such that potential GDP also needs to be revised when

actual GDP is, although the exact extent of this will remain uncertain. Recognising the uncertain nature

2

The correlation of the value for a specific year () and the year before ( 1) for the two-year ahead forecasts is 0.69.

3

The same applies to revenues, for which Buettner and Kauder (2010), for example, calculate a mean absolute error of 4.5 per cent of

revenues in forecasts. This is comparable to the results presented for revenues in this section (error of 2.3 per cent of GDP).

4

Some of the studies are surveyed in Navarini and Zoppè (2020). Eyraud and Wu (2015) find a similar mean error for real-time output gap

estimates of 1.2 percentage points of GDP for the Eurozone countries between 2003 and 2013 and Kempkes (2012) finds a mean error of

1.0 to 1.3 percentage points for the EU15 between 1996 and 2011.

5

Eyraud and Wu (2015) and Claeys et al. (2016) show similar results for the structural balance (-0.5 per cent of GDP for Eurozone countries

between 2003 and 2013, and -0.7 per cent of GDP for core EU15 countries from 2003 to 2014 respectively). Frankel and Schreger (2013) also

document over-optimism on the part of European countries when forecasting fiscal balances between 1999 and 2011.

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 19

of potential GDP estimates, the EU has added a (constrained) judgement component to the

implementation of the rules and is trying to mitigate the implications of uncertainty (Buti et al., 2019).

3.2.3. Other Forecast and Estimation Errors

An additional source of uncertainty on top of those discussed in the previous sections is hidden in the

estimation of (semi-)elasticities and weights used to translate the cyclical position of GDP measured by

the output gap into cyclically-adjusted budget balance figures. Elasticities are revised every nine years

and weights are revised every six years (European Commission, 2019a). The currently used elasticities are

estimated based on data from 1990 to 2013 (Mourre et al., 2014). Between 2005 and 2014 changes in

budgetary semi-elasticities for the EU27 ranged between -0.02 and 0.15, with an average change of 0.05

(Girouard and André, 2005; Price et al., 2014). Given that the average budgetary semi-elasticity is 0.50,

these changes have quite significant effects on cyclically-adjusted variables.

To evaluate compliance with an expenditure rule, discretionary revenue measures – and their impact in a

specific year, but also in subsequent years – have to be estimated. Estimates of discretionary revenue

measures have only very recently been published in the AMECO dataset, starting with the vintages of

2014. It is therefore not yet possible to conduct a comparable analysis to the one above of forecast or real-

time errors. However, it appears that they can potentially become quite substantial.

6

A series of

assumptions and projections are necessary to estimate e.g. the impact of a change in the tax code (e.g.

changes in tax rates or the tax base) on current and future revenues. This involves, among others things,

estimating the microeconomic behavioural reactions to tax changes, e.g. changes in labour supply in

response to changes in labour taxation. Although the European Commission relies on national estimates

of discretionary revenue measures, it defines a procedure and common methodology as to how Member

States should assess the budgetary effects (European Commission, 2019b). This bottom-up approach is

used to evaluate compliance with the EU expenditure rule. This could be problematic as there is an

information asymmetry between Member States and the European Commission, estimations depend on

national budgeting practices and there is an incentive for Member States to present biased estimates.

Furthermore, as also discussed by Deutsche Bundesbank (2019), it would be desirable to conduct an in-

depth and independent ex-post examination of the quality and errors inherent in estimates of

discretionary revenue measures, e.g. at the European level.

3.3. Exceptions and Compliance

Many fiscal rules have exceptions and escape clauses added to them. The European rules allow larger

deficits or expenditures in the context of an escape clause for unusual events and severe economic

downturns (EC Regulations 1466/1997 and 1467/1997). Furthermore, there are exceptions, for exa mple,

for public investment, major structural or pension reforms (EC Regulation 1055/2005; EU COM (2015) 12

final) and small and temporary deviations. The activation of such an escape clause or exception allows, to

a certain extent, a deviation from limits set by the rules. This does not mean that the rules are not complied

with, because the exceptions and escape clauses are essential parts of the rules’ design and deviations

from the limits in such cases are intended. One of the most important goals of fiscal rules is precisely to

build up fiscal buffers so as to be able to spend more than what the rules would allow in extraordinary

times for events such as natural disasters and severe economic crises. Nevertheless, poorly designed or

excessive numbers of exceptions could undermine the goals of fiscal rules.

6

The mean absolute change in the estimate of discretionary revenue measures from one vintage to the next for the years between 2014 and

2019 across the EU15 was 0.09 percentage points of GDP. This number is quite large when one considers that the other errors presented in

this section were calculated across several vintages and that the mean absolute value of discretionary revenue measures in the same

sample is only 0.33 percentage points of GDP.

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

20 PE 645.732

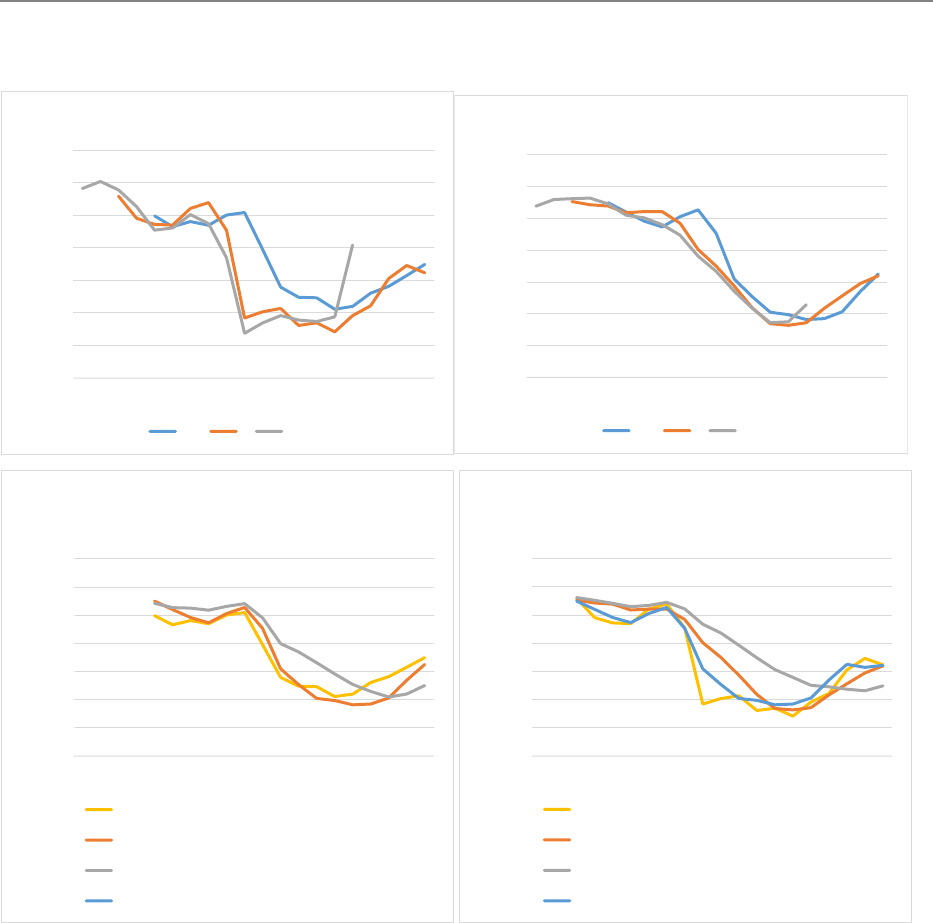

The EU’s escape clause for severe economic downturns had never been activated until the COVID-19

pandemic (Council of the EU, 2020). As shown in Figure 3, however, the escape clause for unusual events

and other exceptions have been used quite extensively in recent years. A total of 18 exceptions were

granted in 2016. Nonetheless, the investment clause has only been used five times since 2012 (Bulgaria

in 2013 and 2014, Romania and Slovakia in 2014, and Italy in 2016). These exceptions can be quite

substantial and have meant that, on average, some countries have been allowed to run deficits in excess

of the limits of the rules by 0.46 per cent of GDP due to pension reforms, 0.44 per cent due to structural

reforms and 0.30 per cent due to exceptions for investment expenditures between 2012 and 2018.

7

Figure 3: Number and average size of exceptions granted between 2012 and 2018

Notes: Numbers are based on figures reported in Assessments of the Stability Programmes by the EU Commission. Preliminary

numbers for 2018. Exceptions for refugees, security-related measures and natural disasters constitute exceptions for unusual

events. No size figures are reported for exceptions for small deviations.

Sources: Christofzik et al. (2018), EU Commisson assessments of stability programmes of Member States, own compilation

The use of escape clauses and exceptions is intended by the fiscal rules, and exceeding the limit to the

extent approved is still in compliance with the rules. In addition to this, however, countries seem to often

not comply with the rules, at least in terms of economic not legal compliance. According to calculations

by the European Fiscal Board (2019), average economic compliance with EU fiscal rules was only 57 per

cent between 1998 and 2018. Studies on fiscal rules at the national level (Reuter, 2019) and worldwide

(Lledó and Reuter, 2018) find similar compliance rates of around 50 per cent. Examining the types of fiscal

rules, Cordes et al. (2015) and Reuter (2019) find that expenditure rules at the national level tend to be

complied with more often than budget or structural balance rules. According to the European Fis cal

Board (2019), this seems not to be the case for the EU fiscal rules. Contrary to the general intention behind

fiscal rules, countries do not seem to treat rules as ceilings, but rather as targets which are aimed at over

the medium term (Reuter, 2015). If rules were designed to be targets from the outset, however, their

design and, especially, their calibration would be different. Furthermore, the low level of compliance has

to be taken into account when analysing the effects of fiscal rules on observed fiscal policy, e.g. within

the context of the pro-cylicallity of fiscal policy.

7

These numbers are close to the maximum amount which can be granted for structural reforms and investment per adjustment period,

which is 0.5 per cent of GDP (there is no such cap for the pension reform exception).

0

5

10

15

20

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018*

Number of granted exceptions

Pension reform

Structural reform Investment

Small deviation Refugees Security-related

Natural disaster

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

Average size of granted exceptions

(2012-2018, % of GDP)

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 21

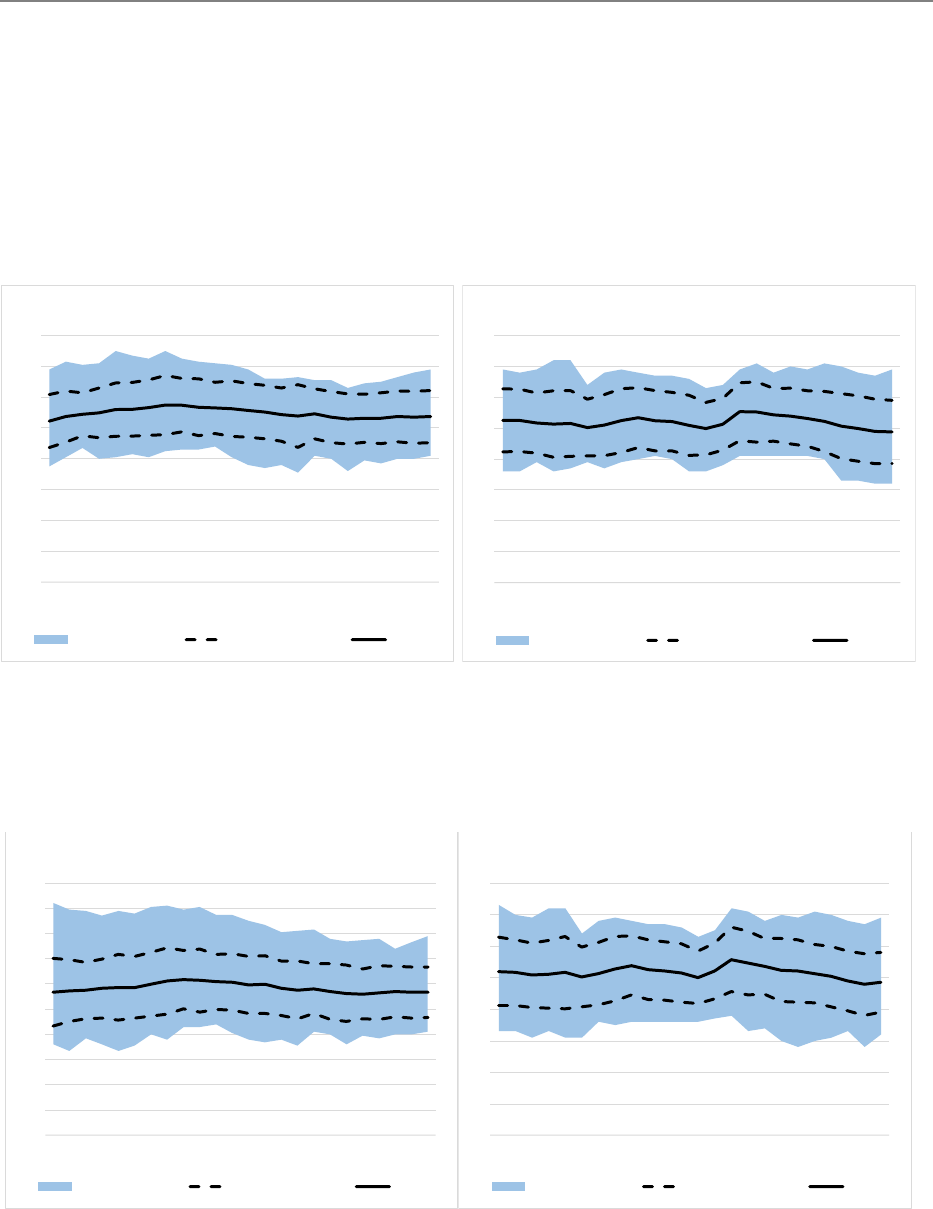

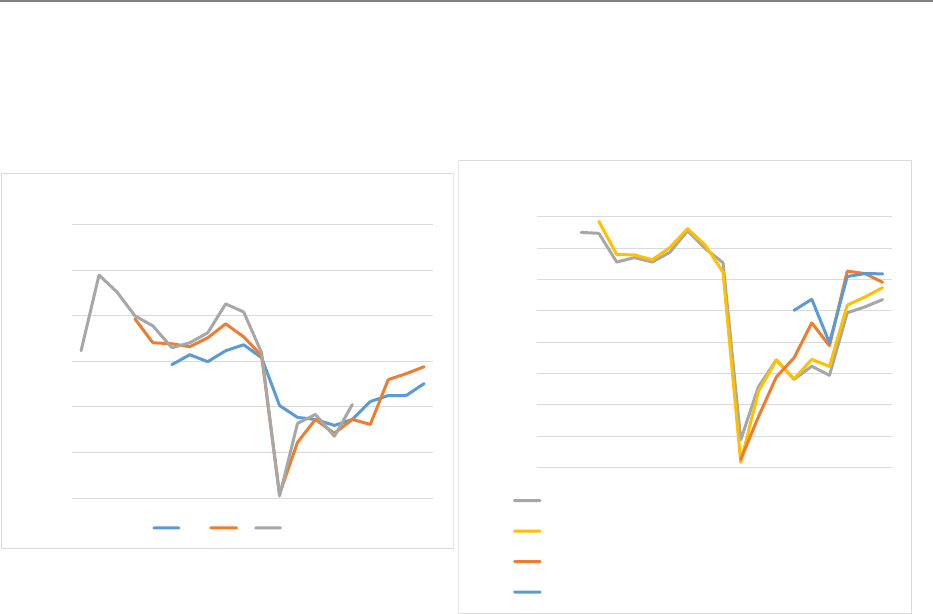

3.4. Composition of Public Expenditures

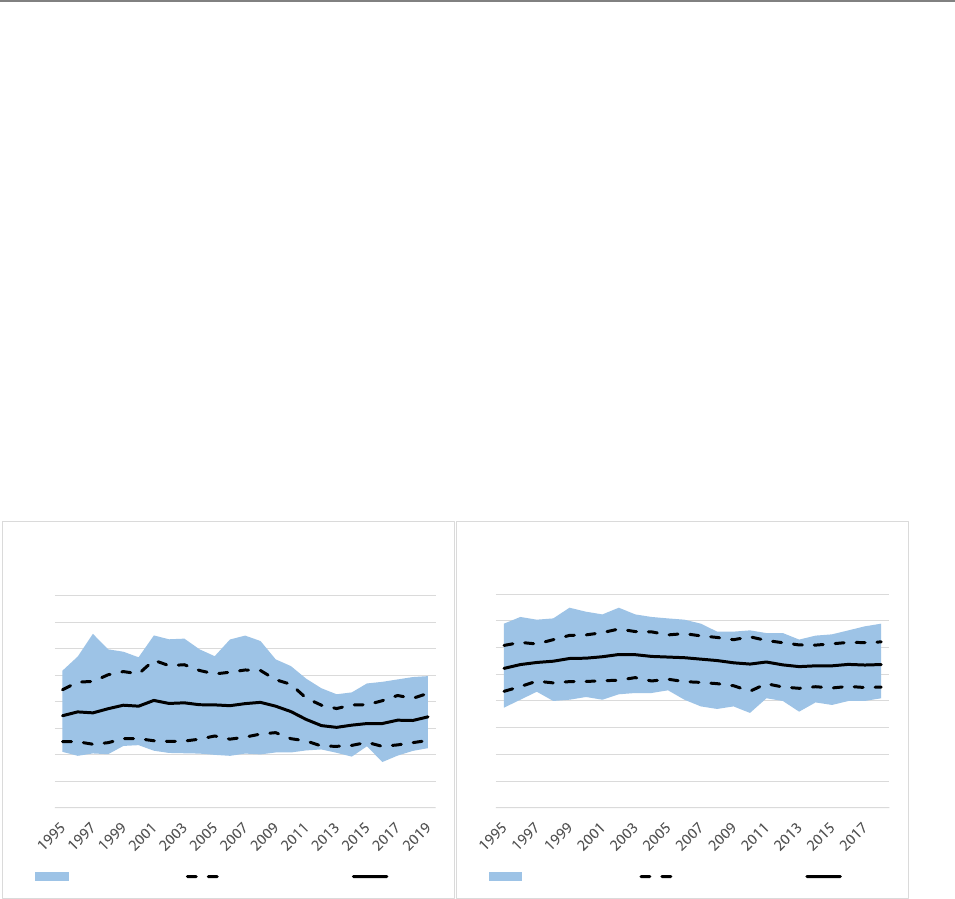

Overall the share of public investment (here represented by ‘gross fixed capital formation by the

government’) and public education expenditures in total expenditures in the EU15 are on average at

around the same level in 2019 as in 1995 (Figure 4). The shares increased up until the mid of the 2000s,

decreased around the financial crisis and caught up some of the loss since then. Spending on basic

research and R&D increased as a percentage of total expenditures between 2001 and 2018 (Figure 10).

Annex 6.2 discusses the development of the shares also as a percentage of GDP in more detail. The

development was quite heterogenous across countries. For example, the sharpest drops in the share of

investment expenditures between 2008 and 2013 were observed in Member States that had financial

assistance programmes. Furthermore, many countries in an excessive deficit procedure (EDP) seemed to

have reduced their investment shares (European Fiscal Board, 2019). However, any comparison of

investment figures across countries – even between the group of EU Member States – is problematic

(Christofzik et al., 2019). For example, the reliance on outsourced public services is quite heterogenous

across Member States and across time.

Figure 4: Public investment and education expenditures in the EU15 from 1995 to 2019

Notes: Investment expenditures are represented by gross fixed capital formation by the government. Education expenditures by

the government according to COFOG classification. Blue areas represent the range between the maximum and minimum values

in each year. Lines represent the mean and mean plus and minus one standard deviation across Member States.

Sources: European Commission’s AMECO database, Eurostat, own calculations

To what extent the EU fiscal rules played a role in the reduction of these investment shares is an open

question. So far the rules, especially if they are cyclically-adjusted, do not directly interfere in the

composition of public expenditures. Initial studies which try to identify the possible effects of fiscal rules

on public investment have not come up with clear-cut findings across the studies (Turrini, 2004; Perée

and Välilä, 2005; Bacchiocchi et al., 2011; Dahan and Strawczynski, 2013; Hauptmeier et al., 2015).

However, specific expenditures like investment and the ones discussed in the previous section might be

reduced (relative to others) first and most sharply during fiscal consolidations. Annex 6.2 discusses the

empirical relationship across the past 23 years in detail. Overall, the results suggest that expenditures on

investment and, to a smaller extent, on education as well as basic research and R&D are reduced as a

percentage of GDP during periods of fiscal consolidation. However, expenditures on education as well as

basic research and R&D are affected less than other expenditure categories, which means that their share

of total expenditures increases. Overall, the share in total expenditures accounted for by investment

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

16%

General government gross fixed capital

formation (% of Total Expenditure)

Max-Min-Range Mean +/- Std.Dev. Mean

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Public Education

(% of Total Expenditure)

Max-Min-Range Mean +/- Std.Dev. Mean

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

22 PE 645.732

expenditures does not seem to be systematically related to periods of fiscal consolidation or expansion

over the past 23 years.

3.5. Pro-Cyclicality of the Current Framework

Section 2.1.1 introduced a distinction between cyclical and structural parts of public finances. Any change

in the cyclical part has, by definition, a counter-cyclical effect. In a downturn this automatically r esults in

a larger deficit, lower revenues and higher expenditures. Fiscal rules which exclude cyclical components

from the variables constrained by the rule – such as cyclically-adjusted or structural budget balance rules

as well as expenditure rules which exclude (cyclical) unemployment-related expenditures – theoretically

do not prevent these counter-cyclical effects from happening. However, this counter-cyclical effect can

be weakened or even reversed if discretionary fiscal measures counteract the automatic stabilisation of

the cyclical component. Indeed, Fatas (2019), for example, shows that discretionary policy in the euro area

eliminated the benefits of automatic stabilisers between 2010 and 2014 and turned fiscal policy pro-

cyclical.

Within the context of fiscal rules, one or several of the following reasons could lead discretionary fiscal

policy to counteract the automatic stabilisers and thus turn fiscal policy pro-cyclical:

1. A bias in forecasts of the cyclical part of public finances might force discretionary fiscal policy to

take countermeasures to comply with fiscal rules. As seen in Section 3.2, assessments of the

position in the economic cycle both in forecasts and real-time have shown a bias and have been

too pessimistic over the past few years. Consequently, rules limiting cyclically-adjusted measures

have been too loose both in forecasts and real-time relative to ex-post assessments. In this

respect, therefore, rules seem to have on average not forced discretionary fiscal policy to

counteract automatic stabilisers owing to a bias in forecasts. On the contrary, these rules would

have actually made it possible to strengthen cyclical components by pursuing discretionary

policy in a downturn. Although the rules have not been restrictive enough during upturns,

discretionary policy has not needed to use all of the additional leeway granted by the rules.

2. The limits of fiscal rules might be changed pro-cyclically such that discretionary fiscal policy needs

to adjust. There appears to be no sign of any systematic changes in line with the economic cycle

to the limits of the EU fiscal rules, e.g. the minimum MTOs which are set for Member States. The

six-pack and two-pack reforms under the European fiscal framework tend to provide more fiscal

headroom to Member States for economic stabilisation purposes.

3. Exceptions and escape clauses might be applied pro-cyclically. Under the EU fiscal framework the

average change in the output gap during the years when the 64 exceptions were granted

between 2012 and 2018 (see Section 3.3) was a positive 0.49 percentage points. The average level

of the output gap was close to zero (0.08 per cent). 70 per cent of the years in which exceptions

were granted to countries saw a positive change in the output gap. It seems that exceptions were

granted especially for years in which there was an economic upturn (positive change in the

output gap). This would enable policymakers to expand discretionary fiscal policy pro-cyclically.

However, exceptions have only very recently been used extensively, which means that this

observation is severely limited because it is based on a very short time period.

4. Non-compliance with fiscal rules might be pro-cyclical. The European Fiscal Board (2019) points

out that compliance with cyclically-adjusted rules under the EU framework was relatively low

before 2008 and in recent years, which are both periods with fairly benign economic conditions.

By not complying with the rules, discretionary policy fostered a pro-cyclical fiscal stance, which

the rules would not have prescribed. Larch et al. (2020) look at the role of compliance with fiscal

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 23

rules as part of a more systematic approach. They find that compliance with fiscal rules would

have been associated with a more counter-cyclical fiscal stance, i.e. that non-compliance with the

cyclically-adjusted rules increases the likelihood of running pro-cyclical fiscal policies.

5. Aside from fiscal rules, policymakers face a variety of challenges which can lead them to pursue

pro-cyclical discretionary policies. Potential reasons could be high debt levels which mean that,

even in a downturn and although the rules would allow it, discretionary fiscal policy is used not

counter-cyclically but pro-cyclically. The European Fiscal Board (2019) points to the possibility

that concerns about fiscal sustainability may have pushed governments to consolidate more than

the fiscal rules would prescribe. The failure to build up buffers in the EU by running a pro-cyclically

expansionary discretionary fiscal policy in fairly good economic times before the financial crisis

was followed by pro-cyclical restrictive discretionary fiscal policy to try to rein in debt increases in

2012 and 2013. In both periods the fiscal rules per se did not force policymakers to act pro-

cyclically: on the contrary they would have allowed policy to be counter-cyclical.

In summary: It seems that political decisions outside the scope of the fiscal rules, non-compliance with

the rules and the use of exceptions – rather than rule design or forecast errors – tended to foster pro-

cyclical fiscal policy in the EU.

4. FOCUSING THE EU FRAMEWORK ON AN EXPENDITURE RULE

4.1. Proposals for Expenditure Rules

Many authors and institutions have suggested reforming the EU fiscal framework by focusing it on an

expenditure rule (Ayuso-i-Casals, 2012; Carnot, 2014; Andrle et al., 2015; Christofzik et al., 2018; Cottarelli,

2018; Darvas et al., 2018; Eyraud et al., 2018b; Kopits, 2018). Table 2 presents some of the proposals for

which a more detailed description of the proposed rule is available and compares their features with the

existing expenditure rule under the EU fiscal framework.

The proposed rules all set a limit on the growth rate of a derivative of gross expenditures, which in most

cases is net of interest expenditures, some measure of unemployment-related expenditures and an

estimate of discretionary revenue measures. The limit set by the rule is in most cases directly or indirectly

related to the growth rate of potential GDP. Furthermore, all proposals combine the expenditure rule with

some mechanism related to the debt ratio or debt reduction targets.

Differences between the proposals are only visible in the details, which suggests that there already seems

to be a consensus on the broad design of an expenditure rule on which the EU fiscal framework could be

focused. The proposals differ, e.g., in the details of how limits are set and in the extent of debt correction,

either driven by formulas or by a process involving national governments, fiscal councils or the European

Commission. Another dimension in which the proposals differ is the design and usage of an adjustment

account, which in some proposals captures deviations between planned and actual expenditures and in

others also includes estimation errors or deviations from medium-term targets.

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

24 PE 645.732

Table 2: Comparison of expenditure rule proposals

Limit Excluded items Debt correction Adjustment account Special features

I

U

R

Other

Current EU rule

Medium-term potential GDP

growth

√ √ √

EU-funded investment

Implicit by relation to

MTOs

National investment

averaged over four

years

European Fiscal Board

(2018, 2019)

Trend rate of potential GDP

growth (limit fixed for a three-

year period)

√ √ √

EU-funded investment

Debt ratio within

range of long-run

objective within

maximum number of

years

Deviations of planned

expenditure growth;

subject to maximum;

decumulates in case of

windfall gain

Member States with

debt ratio below 60%

of GDP not subject to

net expenditure

ceiling

Christofzik et al. (2018)

Medium-term potential GDP

growth

√ √ √

Relative to difference

between present debt

levels and long-term

limit

Non-compliance

margin with structural

balance rule;

estimation errors;

small deviations in

budgetary process

Claeys et al. (2016)

Medium-term potential GDP

growth

√

√

All labour-market-re lated

expenditure; one-off

expenditure

0.02 times difference

between debt level in

previous year and 60 %

debt criterion

Difference between

actual expenditure

growth and the

expenditure growth

limit

Public investment

smoothed over

several years and

accounted for similarly

to corporate

investment

Darvas et al. (2018)

(very similar to

Bénassy-Quéré et al.,

2018)

Medium-term debt reduction

target set by national

government

(based on

potential GDP growth)

√

√

All unemployment

spending (except when

due to discretionary

changes)

Limit directly takes

care of debt correction

Limited deviations

between actual and

budgeted spending

I interest payments; U cyclical unemployment-related expenditures; R discretionary revenue measures:

Sources: Studies as indicated in first column of table, own compilation

Benefits and drawbacks of an “expenditure rule”, as well as of a "golden rule", in the EU fiscal framework

PE 645.732 25

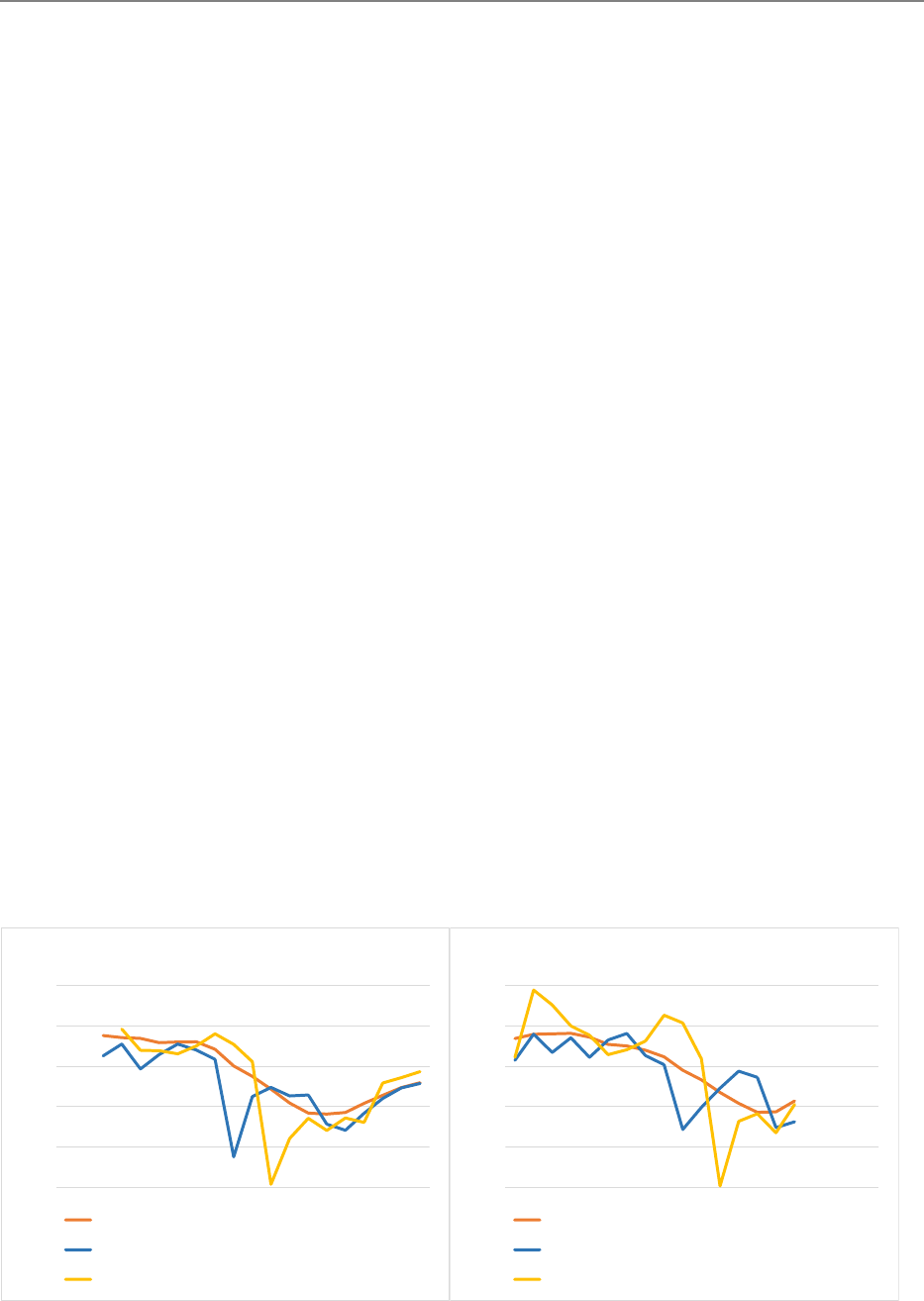

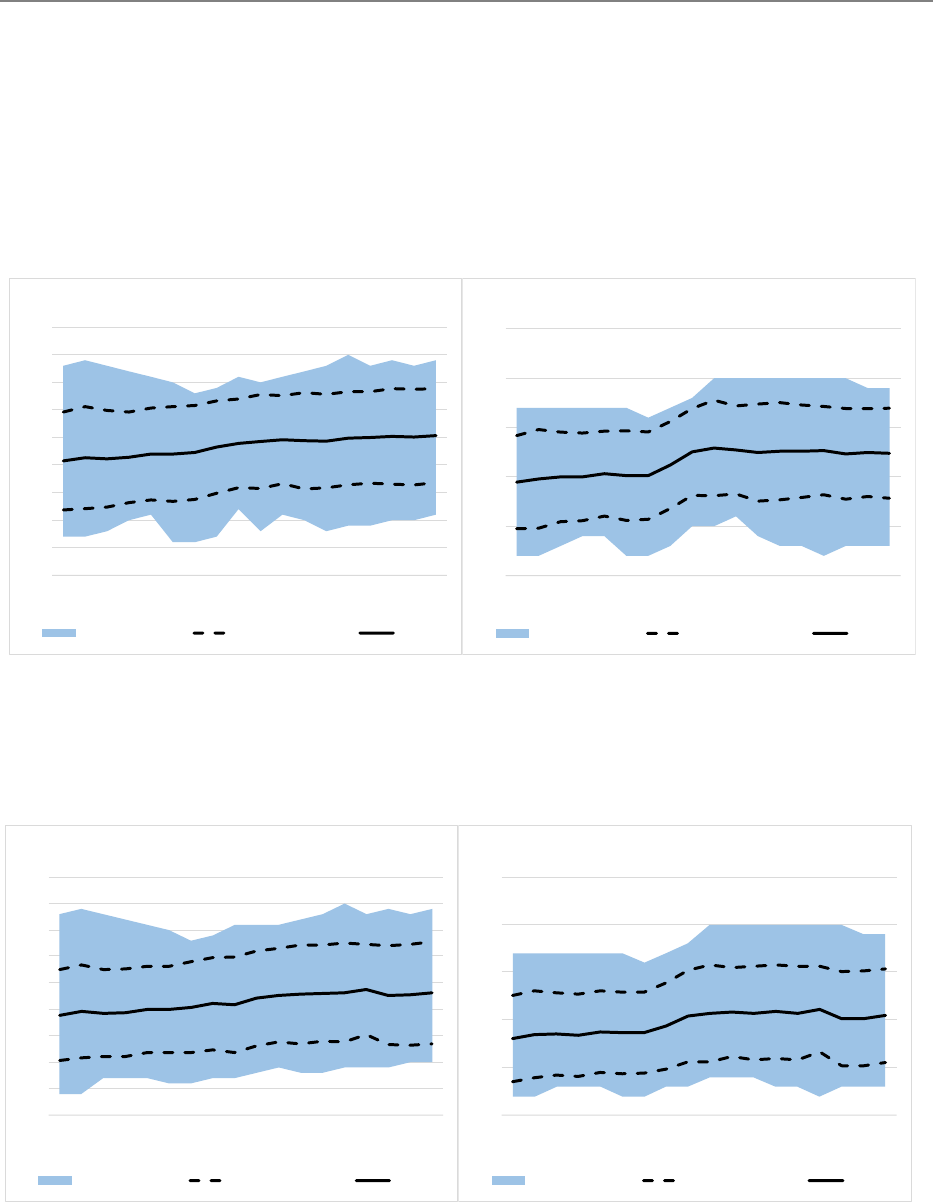

4.2. Assessment of Rule Performance Based on Past Data

A starting point for investigating the possible performance of the proposed expenditure rules is to

compare limits that would have been set by different rule types with actual expenditure growth based

on past data. To isolate the effect of the rule type from the exact numerical calibration, both rules

considered in this exercise set a limit which would keep the cyclically-adjusted budget balance

constant over the medium-term. Policymakers can decide to calibrate the rules such that, for exa mple,

they improve the cyclically-adjusted budget balance (e.g. in relation to the debt ratio) or constantly

allow some borrowing. However, this is independent of the rule type and is discussed in Section 4.3.

Figure 5 presents the following three variables as published in real-time, i.e. data for year from the

autumn vintage in year , and ex-post, i.e. data from the autumn vintage in year + 4:

1. Growth rate of primary expenditures, which represents observed fiscal policy. Expenditures net

of cyclical unemployment-related expenditures and discretionary revenue measures would be

needed for an exact representation of most proposed expenditure rules. However, the latter

two variables are only available for a very short time period. Annex 6.2 discusses the differences

for the years in which data overlaps. When interpreting the following results it is important to

bear in mind the sizeable differences between different expenditure measures.

2. Five-year moving average of potential GDP growth, which represents the limit set by an

expenditure rule. The five-year average is just one possible way of calculating the limit in

relation to potential GDP. Annex 6.2 discusses other averages proposed for expenditure rules

in comparison with annual potential GDP estimates.

3. Growth rate of the sum of cyclically-adjusted revenues and the cyclical component of

expenditures, which represents the limit on expenditure growth to keep the cyclically-adjusted

balance constant in a specific year. A detailed discussion of this calculation can be found in

Annex 6.2. It is important to remember that this measure does not capture the actual limit set

by a cyclically-adjusted balanced budget rule. This measure shows by how much expenditures

could have grown without the cyclically-adjusted balance deteriorating.

Figure 5: Comparison of limits set for expenditure growth with observed fiscal policy (EU15)

Notes: Average potential GDP refers to backward-looking five-year moving average; calculation details in Annex 6.2.

Sources: European Commission’s AMECO database, Firstrun project, own calculations

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Real-Time

Average potential GDP growth

Constant cyclically-adjusted balance

Observed primary expenditure growth

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018

Ex-Post

Average potential GDP growth

Constant cyclically-adjusted balance

Observed primary expenditure growth

IPOL | Economic Governance Support Unit

26 PE 645.732

The values depicted in Figure 5 represent averages across the EU15. Although a country-by-country

analysis would be too comprehensive for this paper, it could reveal interesting country-specific

insights, which are ignored in the following discussion. Furthermore, the discussion below is based on