6HVVLRQ

7+(3526$1'&2162)),6&$/58/(6

(08),6&$/58/(6$1(:$16:(572$12/'48(67,21"

)DEUL]LR%DODVVRQHDQG'DQLHOH)UDQFR

,QWURGXFWLRQ

Fiscal sustainability is a central tenet of European Monetary Union

(EMU); it is a precondition for financial and monetary stability. Budgetary

flexibility is needed for stabilisation policy; it has become more important

in EMU as member states can no longer rely on a monetary policy tailored

on national needs nor on exchange rate adjustments. EMU fiscal rules have

been designed with the goal to ensure that national policies keep a sound

fiscal stance while allowing sufficient margins for budgetary flexibility in

bad times

1

.

The Stability and Growth Pact commits EMU member states to a

medium term objective of budgetary position close to balance or in surplus.

The main rationale for such a target is that its attainment will allow

member states to deal with normal cyclical fluctuations while keeping the

government deficit within the value of 3% of GDP set in the Treaty of

Maastricht

2

. Compliance with this threshold, and with the 60 per cent

ceiling for the debt to GDP ratio, will prevent the public finances of EMU

member states from taking unsustainable paths.

In this paper we try to assess to what extent the issue facing the

founders of EMU was a new one in the field of public finance and to what

extent the solution chosen can be regarded as innovative. To this end, we

review the literature on budgetary rules from its very beginning to the years

immediately before the Treaty of Maastricht (section 2). The review is

largely based on quotations drawn from economists and policy makers. On

the basis of this review, in section 3 we argue that the bulk of EMU fiscal

__________

*

Research Department, Banca d’Italia. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors

and do not commit the Banca d’Italia. The authors wish to thank Prof. Sergio Steve for his

comments and suggestions.

1

The economic policy framework of EMU is extensively examined in Buti and Sapir (1998) and in

Buti, Brunila and Franco (2001). The theory of fiscal sustainability and its links with EMU fiscal

rules are reviewed in Balassone and Franco (2000a); see also the papers in Banca d’Italia (2000).

On the flexibility allowed by EMU fiscal rules see Buti

. (1997) and Balassone and Monacelli

(2000).

2

The actual definition of this medium term objective requires several factors to be taken into

account; see section 3.1.

regulation does not qualify as innovative; however, the interaction between

the multinational nature of EMU and the lack of a federal political

authority (a truly innovative feature) shaped the solution chosen. The

highly decentralised setting of fiscal policy in EMU gave prominence to

moral hazard issues and EMU fiscal rules, while drawing heavily on ideas

that are central to the long lasting debate on fiscal rules, are innovative in

the way in which different approaches are blended and complemented by

innovative and pragmatic choices.

7KHEDODQFHGEXGJHWUXOHDQGLWVDPHQGPHQWV

Mankind has always displayed a certain degree of awareness of the

potential negative effects of excessive borrowing. Exhortation to sound

fiscal behaviour can be found as early as in the Bible: “And thou shalt lend

unto many nations, but thou shalt not borrow” (Deuteronomy 15:6).

Several centuries later, as Hansen (1941) reminds us: “Scholastic

theologicians, like Thomas Aquinas, were bitterly opposed to loans…

Political philosophers of the early modern period continued to regard the

prior accumulation of treasures as superior to borrowing… [For] Jean

Bodin … emergencies should be met by accumulated hoards, and only war

provided justification for extraordinary levies or loans. Thomas Hobbes

was more realistic … [allowing] the monarch [to resort] occasionally even

to the public credit… [but] Adam Smith reverted to the older tradition …

Hume likewise wrote … [that] to mortgage the public revenues … [is] a

practice that appears ruinous” (p. 110).

Burkhead (1954) notes that there is a common body of doctrine that

may be characterised as the classical view of debt and deficits that goes

from Smith to Mill. These writers recognised that there are productive uses

to which borrowed resources may be put; however, they feared that

unproductive use was more likely and strongly opposed deficit finance

when giving policy advice. They noted that interest payments would pose a

burden on future taxpayers, but their main concern was the loss of wealth

borne when the deficit was incurred in the first place.

Smith opposed unbalanced budget on the ground that government

borrowing would deprive society of resources which could be invested

more productively. He also noted that beyond a certain threshold debt

inevitably leads to national bankruptcy.

Say argued that the possibility of borrowing allows governments “…

to conceive gigantic projects that lead sometimes to disgrace, sometimes to

glory, but always to a state of financial exhaustion; to make war

themselves and stir up others to do the like; to subsidize every mercenary

agent and deal in the blood and the consciences of mankind; making capital

which should be the fruit of industry and virtue, the prize of ambition,

pride, and wickedness

3

”.

Ricardo refers to the debt as “… one of the most terrible scourges

which was ever invented to afflict a nation

4

”, as “… a system which tends

to make us less thrifty, to blind us to our real situation”. He feared that the

citizen initially “deludes himself with the belief, that he is as rich as

before” and then, faced with the taxes levied to pay for the debt, is tempted

“… to remove himself and his capital to another country, where he will be

exempted from such burthens

5

”.

In short, for a long time the only budgetary rule was that of a

balanced budget. This rule was probably based on an analogy between

government and family finance drawn when the budget of the State was the

budget of a monarch and it was separate from the finances of his subjects.

The precept was therefore to avoid living beyond one’s means. “As Adam

Smith put it, ‘what is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can

scarcely be folly in that of a great kingdom’”

6

or, following Dickens’ Mr.

Micawber: “… if a man had twenty pounds a year for his income, and

spent nineteen pound nineteen shillings and sixpence, he would be happy,

but … if he spent twenty pounds one he would be miserable

7

”.

In the second part of the XIX century, the precept of a balanced

budget still found a widespread endorsement. Ursula Hicks notes that

“Gladstonian budgeting is inextricably bound up with the theory of the

ever-balanced (or even over-balanced) budget” (1953, p. 25) and quotes the

following statement by Lowe, a disciple of Gladstone, “I would define a

Chancellor of the Exchequer as an animal who ought to have a surplus; if

__________

3

Say (1853), p. 483.

4

The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, P. Sraffa, ed., (1952-73), vol. IV, p. 197.

5

The Works and Correspondence of David Ricardo, P. Sraffa, ed., (1952-73), vol. IV, p. 247-8.

6

Premchand (1983), p.4.

7

Charles Dickens, .

under extraordinary conditions he has not a surplus he fails to fulfil the

very end and object of his being” (p. 25)

8

.

Deficit and debt drew less attention from economists. For instance,

as Burkhead (1954) notes, Marshall’s 3ULQFLSOHV devote no attention to

these issues. Noticeably, Puviani (1903) devotes most of its analysis of

fiscal illusion to public expenditure and revenue. While he notes that

politicians may prefer borrowing to extraordinary levies because citizens

underestimate future interest burdens, this argument remains relatively

unimportant in his analysis of the methods employed by governments to

influence citizens’ perception of fiscal policy.

The consensus on the balanced budget is witnessed by Pigou’s 1929

writing: “in normal times the main part of a government’s revenue is

required to meet regular expenditure that recurs year after year. There can

be no question that in a well-ordered State all such expenditure will be

provided for out of taxation, and not by borrowing. To meet it by

borrowing … would involve an ever-growing government debt and a

corresponding ever-growing obligation of interest. … The national credit

would suffer heavy damage; ... This thesis is universally accepted” (1929,

p. 233).

Even after the keynesian revolution the virtue of a balanced budget

kept being praised. Truman’s 1951 (FRQRPLF 5HSRUW RI WKH 3UHVLGHQW

stated that “… we should make it the first principle of economic and fiscal

policy in these times to maintain a balanced budget, and to finance the cost

of national defence on a ‘pay-as-we-go’ basis”.

As Schumacher noted in 1946, the precepts of sound public finance

were grounded in the opinion that the economy is self-equilibrating

9

. “The

logical corollary of orthodox economics is orthodox finance. If it is

believed that all factors of production are normally and inevitably utilised

by private business, it follows that the State can obtain the use of such

factors only by preventing private business from using them. … From this

it follows that the first principle of ‘sound’ public finance is that the budget

should be balanced” (p. 86).

__________

8

U. Hicks relates this view to the objective of reducing the debt and taxation, to the prevailing

favourable economic conditions and also to some difficulties in managing the budget. She notes the

growth of administrative expertise in budgeting contributed to the development of a different

approach in the 1930s.

9

Schumacher, while reporting these views, did not share them.

Almost seventy years later than Pigou, Buchanan echoes his words:

“the first century and one-half of our national political history did, indeed,

embody a norm of budget balance. This rule was not written in the

constitution document, as such, but rather it was part of an accepted set of

attitudes about how government should, and must, carry on its fiscal

affairs” (1997, p. 119).

However, even in family finance borrowing is not necessarily evil.

Even classical advocates of the balanced budget were aware of the

necessity of allowing borrowing in certain circumstances and of its

usefulness in others. Therefore economists have had a hard job in trying to

specify under what circumstances exception to the balanced budget rule

were to be allowed, caught between the Scylla of missed opportunities as a

consequence of the constraint and the Charybdis of waste and instability

caused by its removal.

The need for exceptions as well as the need for tight rules to deal

with them was clearly recognised by Pigou (1929). He deemed it to be

plain that when “non-remunerative government expenditures RQ D ZKROO\

DEQRUPDOVFDOH have to be undertaken, as in combating the consequences

of an earthquake or to meet an imminent threat of war … to collect what is

required, and required at a very short notice in these conditions, through

the machinery of taxation is politically and administratively impracticable”

(p. 39; italics ours). He also argued that concerning “government

expenditure devoted to producing capital equipment … WKHIUXLWVRIZKLFK

ZLOOVXEVHTXHQWO\ EH VROGWR SXUFKDVHUVIRU IHHV … it is generally agreed

that the required funds ought to be raised by loans. …Upon this matter …

there is no room for controversy” (p. 36; italics ours). Finally, he notes that

“…since changes in taxation always involve disturbance, to keep the rates

of taxation as nearly as possible constant from year to year … it may be

desirable … to arrange a budget so that good and bad years make up for

one another, DGHILFLWLQRQHEDODQFLQJDVXUSOXVLQDQRWKHU" (p. 35; italics

ours).

2UGLQDU\YVH[WUDRUGLQDU\ILQDQFH

One first exception was thus found in the distinction between

ordinary and extraordinary finance: the former dealt with recurrent

expenditures, to be financed by recurrent revenues so as to avoid the

depletion of non-renewable assets; the latter dealt with one-off outlays to

be backed also by borrowed funds. Also the rationale for this exception

was found by way of analogy to family finance. De Viti de Marco (1953)

points out that “…if an individual has to face an expense which he reckons

to exceed his annual income … he will either have to sell his assets or raise

a loan” (p. 390, our translation) and applies the same line of reasoning to

public finances

10

.

De Viti de Marco is very much aware of classification problems as

the extraordinariness of an outlay is a matter for subjective assessment both

at the individual and at the collective level: “this subjective element does

not allow to define a rigorous and objective rule that draws the line …

between ordinary and extraordinary finance” (p. 390, our translation).

Margins for moral hazard and opportunistic behaviour arise as “the

distinction between ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’ receipts and expenditure

is admittedly not clear-cut, depending ultimately on the judgement of the

classifying authority as to whether the receipts and expenditure in question

are to continue indefinitely in the future” (United Nations, 1951, p. 61).

While extreme cases were easily identified (on the one hand, interest

outlays and salaries; on the other, the cost of a war), in some cases it is not

straightforward to see what is ordinary and what is not. “It is impossible to

define ex ante what is an extraordinary outlay. Building a school may be an

extraordinary effort for a small town, an ordinary one for a big city”

(Einaudi, 1948, p. 318; our translation). Ultimately, “there is no great

technical difficulty in producing for a series of years budgets which are

balanced at the end of the year to the nearest penny … Perhaps half a

dozen financial writers in the country would understand from the published

accounts what was happening, but I doubt if any one of the half dozen is

capable of making the position clear to the public

11

”.

National experiences did not differ much. “In the case of France, the

extraordinary budget was proverbially the dumping place for all

expenditures which could not be balanced by tax receipts” (Hansen, 1941,

p. 199). In 1945 Keynes notes that in the United Kingdom “the present

criterion leads to meaningless anomalies. A new G.P.O. is charged

‘below’, a new Somerset House ‘above’. A Capital contribution to school

buildings is ‘above’ in the Exchequer Accounts and is paid for out of

Revenues, and is ‘below’ in the Local Authority Accounts and is paid for

__________

10

De Viti de Marco goes on to justify deficit finance as a less painful alternative to extraordinary

taxation which may penalise liquidity constrained taxpayers.

11

Sir F. Phillips, writing in 1936, quoted in Middleton (1985), p. 82.

out of loans. The cost of a road is ‘above’, of a railway ‘below’. And so

on

12

”. “In Canada, although not always realised even by Canadians, a

budgetary distinction between ordinary and capital expenditures has been

made ever since the confederation in 1867. The official reports show

surpluses in fifty of the sixty-six years following 1867; but if the

accounting were made on the United States basis, surpluses would appear

in only fifteen of the sixty-six years” (Hansen, 1941, p. 199)

13

.

7KHGRXEOHEXGJHW

The double budget is a refinement of the ordinary/extraordinary

distinction which reduces the degree of arbitrariness of the decision

concerning which expenditures can be deficit-financed. The budget is split

into a current and a capital account. While the former must be balanced or

in surplus, the latter can run a deficit (the so-called JROGHQUXOH) and thus

allows to spread the cost of durables over all the financial years in which

they will be in use rather than charging it entirely on one year. It can be a

powerful instrument in overcoming liquidity constraints and fostering

economic development structurally.

Arguments along these lines can be found earlier than the dual

budget debate per se. The productive character of a large part of public

outlays was noted by German scholars in the second part of the XIX

century. They also argued that government can borrow to finance

undertakings that are expected to improve the income of future generations

(Cohn, 1895). Bastable (1927) argues that “non-economic (i.e. non-

remunerative) expenditure is primarily to be met out of income, and, unless

it can be so dealt with, ought not to be incurred…[and] … that borrowing

__________

12

Memorandum by Keynes for the National Debt Enquiry, 21 June 1945, in D. Moggridge and A.

Robinson, eds., (1971-89), vol. XXVII, pp. 406-7. On the UK experience, Clarke (1998) also notes

that “in the best Gladstonian tradition …. On the expenditure side, what mattered was expenditure

above the famous ‘line’ in the Exchequer accounts, dating from the Sinking Fund Act of 1875,

broadly … distinguishing a revenue account from a capital account – but by no means

unambiguously … Only an old Treasury hand could be expected to know the difference within this

hybrid accounting framework …. therefore, the simple moral imperative of balancing the budget

was in practice wrapped in the esoteric conventions of the public accounts” (p. 64).

13

In Italy, in the late 19

th

Century and the early 20

th

Century revenues and expenditures related to the

construction of railways were included in a special balance sheet and separated from other ordinary

and extra-ordinary items. Revenues were represented by the proceeds of the sale of bonds,

expenditures by the outlays for investment projects (see Nitti, 1903). De facto, an item specific

golden rule was implemented.

should hardly ever be adopted except for strictly economic expenditure,

and then only when the extension of the State domain is clearly advisable”

(pp. 670-1).

The usefulness of a dual budget has been long debated

14

. It is still an

unsettled issue, which has been tackled in different ways in different

countries and at different times. Sweden, introduced the dual budget in

1937 and suppressed it in 1980.

First of all, the distinction between current and capital items retains a

certain degree of ambiguity which can be used opportunistically. “The

classification procedures which are to be followed in separating “current”

and “capital” transactions are among the most controversial and difficult

questions in budgetary procedure, especially in view of the frequent abuses

of so-called “capital budgets” in hiding deficits which otherwise would

have become apparent” (United Nations, 1951, p. 11).

According to Lindbeck (1968), this distinction “facilitated tactical

political manoeuvres and hampered the fiscal policy debate for many years

[in Sweden] by focusing it on complicated bookkeeping issues understood

by very few and of very little economic relevance” (p. 34).

In principle, one can distinguish between durable goods producing a

direct revenue, durable goods producing an indirect revenue as,

respectively, investments by publicly owned enterprises and public

infrastructures that reduce the costs borne by private producers and/or

consumers and durable goods with pure consumption functions. It may be

argued that the latter should be excluded from the capital account as they

do not affect growth and thus do not imply a future financial benefit for the

public sector; therefore they worsen the sector’s net worth.

In practice, however, the divide between the second and the third

category is very unclear. In the case of infrastructures, for example, there is

the issue of the treatment of expenditures determined by the attempt to

reduce the impact on the environment. If the overall costs increase should

these expenditures be considered as producing an indirect revenue or as

pure consumption? If for this reason we include in the capital account all

durables, we end up creating a distortion in allocation only based on

duration, rather than on contribution to growth, thus "the analogy with

__________

14

See the accounts in Premchand (1983) and Poterba (1995). For a recent discussion in the context of

EMU, see Balassone and Franco (2000b).

private accounting may be conductive to an irrational preference for capital

expenditures over current expenditures" (Goode and Birnbaum, 1955,

p. 1)

15

.

Clearly there are current expenditures, such as those increasing

human capital, that can give a relevant contribution to growth as "indirect

revenue need not come through a durable good" (Steve, 1972, p. 164; our

translation). If one is not careful about the expenditures to be included in

the capital section, the dual budget may result “...in a preference for

expenditures on physical assets rather than greater spending for intangibles

such as health or education” (Colm and Wagner, 1963, p. 125). Thus, "the

need for a return, either in the limited financial sense or in the broader

context of the social return, is a view that needs to be applied over a wider

spectrum of public expenditures and not confined to capital budget only"

(Premchand, 1983, p. 296).

However, the inclusion in the capital account (which can be financed

through debt) of all expenditures contributing to human capital would

imply high levels of deficits and pose serious problems of classification

16

.

One should also take into account that a part of expenditures replaces

existing capital.

Furthermore, the possibility to borrow, without strict limits, in order

to finance investments can lower the attention paid when evaluating the

costs and benefits of each project. In a way with the double budget the

analogy between government and private finance moves from the

household to the business sector where the distinction between current and

capital budget is customary. But the analogy between public sector

accounts and those of private enterprises overlooks the absence of

mechanisms that would penalise the public body investing in low revenue

projects.

__________

15

For a discussion along these lines see also Steve (1972; pp. 163-5). Steve also notes that drawing

the line between durable goods with direct and indirect revenue would pose similar problems.

16

Bastable (1927) already acknowledged the usefulness of non-remunerative expenditures such as

those on education, improved housing and the like, however he also pointed out that there is a “…

difficulty of application. The results of expenditure of the kind are hard to trace or measure, and

any of statement respecting them must rest in a great degree of conjecture”. (pp. 621-2).

6WDELOLVDWLRQSROLF\

Another attempt at justifying deviations from the balanced budget

rule came from Keynesian theory where the budget plays a crucial role in

cushioning the effects of cyclical downswings in the economy

compensating for insufficient private demand. Therefore a balanced budget

was no longer to be achieved in each financial year but to be attained over

the whole length of the economic cycle.

On April the 5

th

of 1933 Keynes wrote on The Times: “The next

budget should be divided into two parts, one of which shall include those

items of expenditure which it would be proper to treat as loan-expenditure

in the present circumstances”. Later he sharpens the distinction between

the government’s own current expenditure and a capital budget to provide

for sufficient national investment. In 1942 he writes: “I should aim at

having a surplus on the ordinary budget, which would be transferred to the

Capital Budget, thus gradually replacing dead-weight debt by productive or

semi-productive debt… I should not aim at attempting to compensate

cyclical fluctuations by means of the ordinary budget, I should leave this

duty to the capital budget

17

”.

Fiscal policy in Sweden and in the USA moved along these lines

18

.

In 1937 Sweden reformed its budget rules and abandoned the annual

balancing. In Lindbeck’s account, the Swedish reform was based on the

idea that “in normal times the capital budget should be financed by loans

whereas the current budget should be financed by taxes. In boom periods

the current budget should, however, be overbalanced, hence part of the

capital budget would be financed by taxes; in recession the current budget

should be underbalanced, hence partly financed by loans” (1968, p. 33).

Hansen explains how in the USA, “President Roosevelt … divided

federal expenditures into ‘ordinary’ and ‘extraordinary’. The former relate

to the ‘operating expenditure for the normal and continuing functions of

government’ … [and] … should be met out of current revenues’… He

expressed the hope that in times of prosperity current revenues would so

__________

17

‘Budgetary Policy’, 15 May 1942, in D. Moggridge and A. Robinson, eds., (1971-89), vol. XXVII,

pp. 277-8.

18

These developments reflected common problems but were to a large extent unrelated. On the

relationship between Swedish fiscal policy and Keynesian theories see Lundberg (1996). He recalls

that in 1929 Lindhal considered the use of fiscal policies to affect the level and composition of

demand and that Myrdal was asked to write an appendix to the government budget proposal of

January 1933 on the issue of the feasibility of active fiscal policies.

far exceed ordinary expenditures as to produce ‘a surplus that can be

applied against the public debt’… The extraordinary expenditures, which

are concerned with loans, capital expenditure and relief of need, he deemed

to be sufficiently flexible in character as to permit their contraction and

expansion as a ‘partial offset for the rise and fall in the national income”

(1941, p. 219).

However, the idea of balancing the government accounts over the

course of the business cycle had an exceptionally brief life span. Blinder

and Solow (1974) point out that while it “… had considerable appeal… in

the immediate post-Keynesian years, when the balanced budget was [still]

influential, it is almost never discussed nowadays” (p. 37). It was the turn

of functional finance to take the lead.

“Functional finance rejects completely the traditional doctrines of

‘sound finance’ and the principle of trying to balance the budget over the

solar year or any other arbitrary period … government fiscal policy …

shall all be undertaken with an eye only to the results of these actions on

the economy” (Lerner, 1943, p. 41).

Hansen noted that “if one adopts wholeheartedly the principle that

government financial operations should be regarded exclusively as

instruments of economic and public policy, the concept of a balanced

budget, however defined, can play no role in the determination of that

policy” (1941, p. 188).

The way in which these ideas were first met is exemplified in the

following passage by Chamberlain in 1933

19

: “If I were to pretend I could

lay out a programme under which what I borrowed this year would be met

by a surplus at the end of three years, everyone would soon perceive that I

was only resorting to the rather transparent device of making an

unbalanced budget look respectable

20

”.

__________

19

Middleton (1985) reviews the debate about budgetary policy in the United Kingdom in the 1930s.

In 1933 the Treasury stressed the risks related to unbalanced budgets: “Would not the ordinary

taxpayer and the business man very soon begin to have a feeling of uneasiness and apprehension?

After all people will realise that the bill must be paid if not this year next year or the year after.

Uncertainty and apprehension about the future would very quickly cancel out any immediate

psychological benefit which the reduction of taxation by unbalancing the Budget would promote”

(1985, p. 88).

20

Neville Chamberlain (Chancellor of the Exchequer), quoted in Sabine (1970, p. 15).

It was also pointed out that “the requirement of a balanced budget

was and still is the simplest and clearest rule to impose ‘fiscal discipline’

and to hold government functions and expenditure to a minimum… Even

an avowedly counter cyclical policy is believed to give rise to an upward

trend in expenditures that might not otherwise occur. The expenditures

undertaken to counteract a depression are unlikely to be discounted in the

succeeding boom. If the boom is countered at all, the measures taken will

be credit restriction or increased taxation” (Smithies, 1960).

The obstacles posed by politics to a symmetric and timely reaction

of the budget to cyclical developments were stressed. Agreement over the

appropriate budgetary items to use may take too long; it may prove

difficult to reduce expenditures once they have been increased. Drees

(1955) and Steve (1972) provide early discussions of the relevance of the

balance of powers between the Parliament and the Government and of the

relationship between the Government and its Parliamentary majority:

budgetary rules cannot be evaluated per se but need to be set in the overall

institutional context.

Among the remedies suggested to the political problem described, an

enhanced reliance on automatic stabilisers and the so-called formula

flexibility were suggested. The latter consisted in the introduction of a

predetermined relationship between tax rates (or benefits levels) and the

level of economic activity

21

.

But support in favour of functional finance was strong. “Even if

stability in the budget has something to recommend it, stability in the

economy is surely better… Who makes the rule? Who decides when to

abide to it and when to countermand it? Furthermore, within the framework

of a political democracy, the case for taking stabilisation policy out of the

hands of politicians is an uneasy one: into whose hands shall it be

placed?… No budgetary rule can be provided with a solid intellectual

foundation. This will hardly be new to economists. The best that can be

said for rules is that some of them may be better than incompetently

__________

21

Biehl, in summarising several papers on fiscal policy issues, notes that “It is strange to see that,

e.g., the old-fashioned concept of the simple budget balance rule is still widely used in many

countries and that …. the full employment budget concept, the structural margin of fiscal impact

concept, and the concept of the cyclically adjusted neutral budget … are only known to a small

circle of specialists.” (1973, p. 6).

managed discretionary policy…” (Blinder and Solow, 1974, pp. 43 and

45). This view was broadly accepted in some public finance textbooks

22

.

Along the same lines, though less aggressively, Steve (1972) notes

that “budgetary policy cannot be reduced to simple rules, it should take

into account the overall effects of the budget on private demand

components and national income” (p. 170; our translation)

23

.

The stagflation in the 70s; the difficulties concerning the estimate of

the actual impact of budget changes on the economy; the risks of fine

tuning given the lags between the decision to change the budget and its

implementation; the development of theoretical models questioning the

possibility for the Government to influence the level of government

activity all contributed to a decline of interest in the theory of functional

finance.

Advocates of the balanced budget regained the fore. “The balanced-

budget principle played a crucial role in holding the pre-keynesian fiscal

constitution together, and constraining the otherwise inherent biases of that

system to over-expenditure and deficit finance. Once the balanced-budget

had been bowled over by the Keynesian revolution, those biases were

unleashed” (Buchanan, Wagner and Burton, 1978, p. 47)

24

.

Politicians praised again the virtues of balanced budgets: “At one

time, it was regarded as the hallmark of good government to maintain a

balanced-budget; to ensure that, in time of peace, Government spending

was fully financed by revenues from taxation, with no need for

Government borrowing. Over the years, this simple and beneficent rule

was increasingly disregarded … And I have balanced the budget” (Nigel

Lawson, Budget Statement, 1988).

__________

22

See, for instance, Johansen (1965), in which the use of budgetary items for stabilisation policy is

unquestioned, the focus of the analysis being on the choice of the most appropriate instruments.

23

Steve stresses that the budget balance cannot be considered in isolation: the level and composition

of public revenue and expenditure are extremely important.

24

Keynes’ own views about active fiscal policy were rather prudent. He stressed the need to control

inflation and retain appropriate market incentives. In evaluating the UK budget in 1940, he noted

“The importance of a war budget is not because it will ‘finance’ the war. The goods ordered by the

supply department will be financed anyway. Its importance is

: to prevent the social evils of

inflation now and later; to do this in a way which satisfies the popular sense of social justice; whilst

maintaining adequate incentives to work and economy”. (‘Notes on the Budget’, 21 September

1940, in Moggridge and Robinson, eds., 1971-89, vol. XXII, p. 218).

The recent policy debate has largely recognised that in normal

circumstances automatic stabilisers ought to be allowed to operate freely

25

.

On the contrary, discretionary fiscal action is generally considered

problematic in view of irreversibility and timing problems and of the

uncertainty about its effects

26

.

(08ILVFDOUXOHVDQHZDQVZHUWRDQROGTXHVWLRQ"

European Monetary Union represents a new historical development.

For the first time a number of sovereign countries adopt a common

currency while retaining independent fiscal policies. The need for fiscal

rules complementing monetary union has been at the core of the debate on

EMU since the early nineties

27

.

Some arguments were put forward against the introduction of fiscal

rules at the European level. It was noted that fiscal rules may have costs in

terms of stabilisation policies and may hamper the achievement of

allocative and distributive objectives. It was also noted that excessively

stringent rules may be counter-productive. If the Pact leads to an unduly

tight fiscal stance in one or more countries, pressure may mount on the

ECB to deliver a monetary offsetting

28

. Otherwise, the credibility of the

Pact may be endangered

29

.

However, the prevailing view in the policy debate was clearly in

favour of the introduction of formal rules. It was argued that procedural or

fiscal rules are necessary because the factors that in recent decades have

__________

25

The issue is extensively discussed in OECD (1999). OECD notes that “in the future governments

should guard against the asymmetric use of automatic stabilisers, although this obviously does not

preclude all discretionary action, particularly for structural reasons.” (p. 145).

26

See European Commission (2001), Kilpatrick (2001), Taylor (2000) and Wren-Lewis (2000).

27

For a review of the justifications put forward for the Pact and for an analysis of its potential

macroeconomic implications see European Commission (1997), Artis and Winkler (1997) and

Eichengreen and Wyplosz (1998).

28

Canzoneri and Diba (2001).

29

It was also noted that the multiplicity of fiscal authorities does not provide strong arguments in

favour of permanent constraints on the deficit as it may actually dilute the pressure on the central

bank. According to Canzoneri and Diba (2001), a more relevant reason to have fiscal rules is to

underpin the ‘functional’, as opposed to the ‘legal’, independence of the central bank. Without a

credible deficit criterion ensuring government fiscal solvency, the central bank would not be able

to keep control of the price level.

determined fiscal profligacy in several countries have not disappeared.

Moreover, the multinational dimension of EMU is likely to increase the

need for such rules.

Stark (2001) describes the genesis and the rationale of the Stability

and Growth Pact

30

; he stresses how in Europe, up to the early nineties, lax

fiscal policy “… occurred although it is indisputable that unsound fiscal

policy practices have adverse effects on price stability, growth and

employment: large deficits and large public debt place constraints on the

ability of a country … to act during different stages of the business

cycle…; the State’s absorption of resources which would otherwise have

found their way into private investments results in higher long term interest

rates …; … a stifling government debt ratio impair(s) the overall efficiency

of an economy and create(s) risks to price stability…; these problems are

especially pronounced in monetary union since … the policy of a single

country might have adverse consequences for all the other participating

countries”. These arguments combine the two main strands of opinion

about the budgetary balance: the one stressing the importance of

stabilisation policies and budgetary flexibility and the other maintaining

that unbalanced budgets imply distortions in the allocation of resources

31

.

It was also pointed out that, without strong rules, the legal

independence of the European Central Bank (ECB) may turn out to be an

empty shell because of pressure by high-debt countries for ex ante bail-out

(refraining from raising interest rates in conditions of inflationary tensions)

or ex post bail-out (debt relief through unanticipated inflation).

EMU can

induce unilateral fiscal expansions since governments may feel less

inclined to preserve fiscal rectitude, as they individually face a less steep

interest rate schedule in a monetary union than under flexible exchange

rates.

The debate on fiscal rules in EMU was grounded on the wider

debate that took place in the nineties about the role of fiscal institutions and

procedures in shaping budgetary outcomes

32

. While certain political

configurations, such as weak coalition governments, have been recognised

as conducive to budgetary misbehaviour or to hampering attempts to

__________

30

See also Costello (2001).

31

See Buti (1998).

32

See Kopits and Symansky (1998).

redress the budgetary situation

33

, inadequate budgetary institutions and

procedures may also contribute to a lack of fiscal discipline

34

.

In this context, institutional reforms in the fiscal domain have been

discussed and introduced in several countries. As noted by Beetsma (2001),

these reforms come in two main categories: (a) the introduction of

procedural rules conducive to a responsible fiscal behaviour and (b) the

introduction of a fiscal rule, i.e. a permanent constraint on domestic fiscal

policy in terms of an indicator of the overall fiscal performance (budget

balance, borrowing, debt, reserves) of central and/or local government.

In national experiences, both types of measures have proved to be

effective tools in containing political biases in fiscal policy-making and in

achieving and sustaining fiscal discipline. In a multinational context, the

adoption of harmonised tight budgetary procedures may lead to

fundamental problems from the point of view of national sovereignty

(Beetsma, 2001). Moreover, institutional reforms are more difficult to

monitor centrally, compared to numerical targets. The latter are also

simpler to evaluate and easier to grasp by public opinion and policy-

makers. In the end a clear consensus emerged about the introduction of

common numerical rules and an elaborated multilateral surveillance

mechanism

35

.

The fiscal framework of EMU was developed gradually. The Treaty

of Maastricht in 1992 set the fiscal criteria to be met for joining Monetary

Union. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), adopted by the European

Council in Amsterdam in June 1997, developed these criteria with a view

to permanently restraining deficit and debt levels while allowing room for

fiscal stabilisation. The Pact also strengthened the monitoring procedures

complementing the quantitative rules.

__________

33

See, e.g., Roubini and Sachs (1989), Alesina and Drazen (1991), Alt and Lowry (1994), Alesina

and Perotti (1995) and Balassone and Giordano (2001).

34

See, e.g., von Hagen and Harden (1994) and the essays in Strauch and von Hagen (2000).

35

See Buti and Sapir (1998) and Stark (2001).

$GHVFULSWLRQ

36

As we have anticipated in the introduction, EMU fiscal rules have

been designed with the goal to ensure that national policies keep a sound

fiscal stance while allowing sufficient margins for budgetary flexibility in

bad times.

The Treaty of Maastricht stated that budget deficits cannot be larger

than 3 per cent of GDP unless (a) under exceptional circumstances, such as

deep recessions, (b) they remain close to 3 per cent, (c) the excess only

lasts for a limited period of time

37

. If the deficit exceeds the 3 per cent limit

when the above three conditions are not met, the deficit is deemed

“excessive” and it sets off a procedure intended to force corrective

measures by the deviating country. If such measures are not taken the

Treaty foresees monetary sanctions which increase as situations of

excessive deficit persist

38

.

The Stability and Growth Pact specified what is meant by

“exceptional” and “limited period” in the clauses allowing a deficit greater

than 3 per cent of GDP not to be considered “excessive”. A recession is

considered exceptional if real GDP diminishes by 2 per cent. Milder

recession (where the reduction in real GDP is of at least 0.75 per cent) may

also be considered exceptional if, for example, they are abrupt. The excess

above 3 per cent must be reabsorbed as soon as the “exceptional

circumstances” allowing it are over.

The Pact also specified that each country should aim for a medium

term objective of a budgetary position “close to balance or in surplus”.

According to the guidelines provided by the European Council

39

, the choice

of the medium term target should take into account both the budgetary

risks of recessions and those linked to fluctuations of other economic

factors (e.g. interest rates). Countries with debt ratios above 60 per cent of

GDP should also take into account the need to decrease such ratio, at a

satisfactory pace, towards the threshold. Moreover, an increase in the debt

__________

36

A more detailed description of the rules is provided in Buti and Sapir (1997) and in Cabral (2001).

37

The three conditions make the 3 per cent threshold extremely binding (see Buti ., 1997).

38

See Cabral (2001) for a description.

39

Council Resolution on the Stabilty and Growth Pact, 17 June, 1997; Council Regulation

n. 1466/97, 7 July 1997; Council Declaration, 1 May 1998; Opinion of the Monetary Committee,

12 October 1998 as approved by the Council.

ratio during recessions should be avoided

40

. Finally, other risk factors, such

as the effects of demographic trends, ought to be taken into account

41

.

According to the European Council, compliance with the Pact

should be assessed considering the cyclical position of the economy. In

practice, EMU fiscal rules require that each member state choose a

budgetary target in cyclically adjusted terms and let automatic stabilisers or

discretionary action operate symmetrically around it. The lower this budget

balance with respect to the 3 per cent threshold, the wider the margins for

counter cyclical policy without running the risk of an excessive deficit.

Each member state must submit its budgetary targets officially in

multi-year budgetary documents (Stability Programmes); these documents

are updated annually and are subject to a review by the European

Commission aimed at assessing their consistency with EMU fiscal rules.

Overall, the approach taken by the EU can be characterised as less

flexible than the solutions adopted in some federally structured countries

42

:

a) the rules are defined on the basis of established numerical parameters;

b) H[ SRVW compliance with the parameters is required each year;

overshoots must be rapidly dealt with;

c) margins of flexibility are envisaged only in connection with exceptional

cyclical events (established H[DQWH as a decline in GDP) or in any case

events beyond the governments’ control;

d) no special provision is made for investment expenditure

43

;

e) monitoring procedures are envisaged, whereby peer pressure is

strengthened by the European Council’s power to make formal

representations to governments of the need to adopt corrective measures

during the year and by the application of pre-established monetary

sanctions.

__________

40

Art. 104C of the Treaty says that when the ratio is above 60 per cent of GDP it must “diminish

sufficiently” and approach 60 per cent “at a satisfactory pace”. If the ratio increases, the excessive

deficit procedure begins. It should be noted that, while the Treaty allows exceptions to the 3 per

cent deficit criterion, it does not for the criterion concerning the debt ratio See Balassone and

Monacelli (2000).

41

The choice of the medium term fiscal target is examined in Artis and Buti (2001, Dalgaard and de

Serres (2001) and Barrel and Dury (2001).

42

See Balassone and Franco (1999).

43

No distinction is made in the Treaty between current and capital expenditure for the purposes of

determining the deficit. The volume of capital expenditure is included only among the relevant

factors to be borne in mind when deciding whether there is excessive debt.

$QHZDQVZHUWRDQROGTXHVWLRQ"

With European Monetary Union for the first time the need for fiscal

rules arises in a multinational context. The review in the previous section

shows how the arrangements adopted are deeply embedded in the long-

lasting debate on budgetary rules. The novel features of EMU guided the

choice between alternative solutions and required the introduction of some

innovations.

The need to reconcile fiscal soundness and budgetary flexibility led

to combine different approaches:

a) setting a predetermined upper bound for the deficit is a new pragmatic

solution

44

;

b) balancing the budget over the cycle is a precept derived from the

keynesian approach. In 1951 a report by the United Nations,

commenting the 1937 Swedish reform, points out that “while counter –

cyclical budgeting introduced an element of flexibility in the fiscal

policy of Government, the concept of ‘financial soundness’ has been

retained” (p. 69);

c) prudence when fixing the average target to be achieved over the cycle

(“close to balance or in surplus”) has a classical flavour. In 1927

Bastable argued that “the safest rule for practice is that which lays down

the expedience of estimating for a moderate surplus, by which the

possibility of a deficit will be reduced to a minimum” (p. 611).

The stress on fiscal soundness motivates the rejection of a dual

budget approach and of any distinction between ordinary and extraordinary

finance. However, pragmatism called for the allowance of margins for

exceptional circumstances, this rests on the idea that “in some

circumstances, indeed, a balanced budget is a pedantic luxury, which a

community, hard pressed by sudden and exceptional misfortune, can ill

afford” Dalton (1934, p. 12).

A broadly balanced budget, like that required by the SGP, may

negatively affect the public investment level; this effect can be especially

relevant during the transition to the low debt levels consistent with the

chosen structural balance. The double burden determined by this transition

__________

44

The deficit ceiling, although arbitrary, is reminiscent of the results obtained by Domar (1944) in

the analysis of fiscal sustainability assuming a constant deficit. Perhaps conscious of the partial

equilibrium nature of Domar’s results, the introduction of a debt ceiling as well avoids

convergence at high levels of debt. See Balassone and Franco (2000a).

can be assimilated to that arising from the transition from a pay-as-you-go

to a funded pension system. However, besides the criticism to the double

budget system examined in the previous sections, in the context of EMU

the golden rule would be an obstacle to deficit and debt reduction. In

particular, given the ratio of public investment as a percentage of GDP, the

long-run equilibrium level of government debt could be very high,

especially in an environment of low inflation. This could imply that the

debt ratio would rise in low-debt countries, while in high-debt countries

there would be a very slow pace of debt re-absorption. The golden rule

would also meet with practical difficulties, such as the evaluation of

amortisation, and would make the multilateral surveillance process more

complex, by providing leeway for opportunistic behaviour. Governments

would have an incentive to classify current expenditure as capital

spending

45

.

The asymmetry in EMU between the monetary regime, with the

single currency and a single monetary authority, and the political

landscape, lacking an authority of federal rank, gave prominence to moral

hazard issues. It is probably at the roots of the rejection of both the dual

budget and the distinction between ordinary and extra-ordinary finance. It

motivated the adoption of a detailed multilateral surveillance procedure

and the introduction of a predetermined limit for the annual deficit in a

framework that envisages the targeting of a balanced budget over the

cycle

46

.

EMU may be termed a “radical federation”, where in the absence of

fiscal rules member states enjoy absolute autonomy in matters of public

expenditure and taxation and recourse to debt. In this context, the stability

of monetary and financial conditions represents a public good to which all

local governments contribute by maintaining sustainable budget positions.

There is an incentive for each local government to exploit the benefits

accruing from the discipline of others without itself complying with the

rules. This creates a double cost for the other entities: the free-rider’s

__________

45

See Balassone and Franco (2000b).

46

EMU fiscal rules are targeted at national governments while many EMU member states have a

federal or highly decentralised structure. A free riding problem can re-emerge at national level.

This problem is analysed in Balassone and Franco (1999).

excessive indebtedness can put pressure on interest rates to rise; it can also

result in bankruptcies requiring bail-outs

47

.

The need for monitoring was felt also in earlier days. For instance,

Durrell (1917) argues that: “the public and the Parliament should be

satisfied that … there is some authority which … will give timely warning

if that expenditure or those obligations are either outrunning

the revenue

provided for the year or engaging the nation too deeply in the future”

(p. 242). However the monitoring procedure adopted for EMU is novel

with respect to its scale, complexity and tightness.

Until now the chosen mix of approaches has been successful in

securing a reduction in budget deficits and debt across EMU member

states. It remains to be seen whether it will also be successful in

maintaining fiscal discipline once at regime. Unfavourable economic

developments will put to test EMU’s fiscal constitution and the issue of

legitimacy of rules in a democracy pointed out by Blinder and Solow may

come to the fore again.

Fiscal rules can be successfully implemented over a long period of

time only if public opinion considers them a valuable contribution to policy

making. In the words of Bastable (1927): “it but remains to again lay

emphasis on the fact that good finance cannot be attained without

intelligent care on the part of the citizens. The rules of budgetary

legislation are serviceable in keeping administration within limits; but

prudent expenditure, productive and equitable taxation, and due

equilibrium between income and outlay will only be found where

responsibility is enforced by the public opinion of an active and

enlightened community (p. 761).

__________

47

The risks clearly increase if member states are asymmetric in some relevant respect (e.g.

accumulated public debt). These considerations are likely to have motivated the inclusion of a

“rule” concerning not only deficits but also debt.

5()(5(1&(6

Alesina, A. and A. Drazen (1991), “Why are Stabilizations delayed?”,

$PHULFDQ(FRQRPLF5HYLHZ, vol. 82, pp. 1170-88.

Alesina, A. and R. Perotti (1995), “The Political economy of budget

Deficits”, ,0)6WDII3DSHUV, vol. 42, pp. 1-31.

Alt, J.E. and R.C. Lowry (1994), “Divided Government and Budget

Deficits: Evidence from the States”, $PHULFDQ 3ROLWLFDO 6FLHQFH

5HYLHZ, vol. 88, pp. 811-28.

Artis, M.J., and M. Buti (2001), “Setting Medium-Term Fiscal Targets in

EMU”, in A. Brunila, M. Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Artis, M.J., and B. Winkler (1997), “The Stability Pact: safeguarding the

credibility of the European Central Bank”, CEPR Discussion Paper,

No. 1688, August.

Balassone, F. and D. Franco (1999), “Fiscal Federalism and the Stability

and Growth Pact: a Difficult Union”, -RXUQDORI3XEOLF)LQDQFHDQG

3XEOLF&KRLFH, vol. XVII, n. 2-3, pp. 137-66.

_______________________________ (2000a), “Assessing Fiscal

Sustainability: a Review of Methods with a view to EMU”, Banca

d’Italia.

_______________________________ (2000b), “Public Investment, the

Stability Pact and the Golden Rule”, )LVFDO 6WXGLHV, vol. 21, n. 2,

pp. 207-29.

Balassone, F. and R. Giordano (2001), “Budget Deficits and Coalition

Governments”, 3XEOLF&KRLFHvol. 106, pp. 327-49.

Balassone, F. and D. Monacelli (2000), “EMU Fiscal Rules: is there a

Gap?”, Temi di discussione, n. 375, Banca d’Italia.

Banca d’Italia (2000), )LVFDO 6XVWDLQDELOLW\, Proceedings of the Banca

d’Italia workshop on Public Finance held in Perugia, 20-22 January

2000, Rome.

Barrel, R. and K. Dury (2001), “Will the SGP Ever Be Breached?”, in A.

Brunila, M. Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Bastable, C.F. (1927), 3XEOLF)LQDQFH, Macmillan, London.

Beetsma, R. (2001), “Does EMU Need a Stability Pact?”, in A. Brunila, M.

Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Biehl, D. (1973), “Introduction of Round Table Discussion”, in H. Giersch,

)LVFDO3ROLF\DQG'HPDQG0DQDJHPHQW, J.C.B. Mohr, Tubingen.

Blinder, A. and R. M. Solow (1974), 7KH (FRQRPLFV RI 3XEOLF )LQDQFH,

The Brookings Institution, Washington.

Brunila, A., M. Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001), 7KH6WDELOLW\DQG*URZWK

3DFW±7KH)LVFDO$UFKLWHFWXUHRI(08, Palgrave, forthcoming.

Buchanan, J.M. (1997), “The balanced budget amendment: Clarifying the

arguments”, 3XEOLF&KRLFH, 90, pp. 117-38.

Buchanan, J.M., R.E. Wagner and J. Burton (1978), “The consequences of

Mr. Keynes”, Hobart Paper 78, Institute of Economic Affairs,

London.

Burkhead, J. (1954), “The balanced Budget”, 4XDUWHUO\ -RXUQDO RI

(FRQRPLFV, LXVIII, May, pp. 191-216.

Buti, M., D. Franco and H. Ongena (1997), “Budgetary Policies During

Recessions – Retrospective Application of the Stability and Growth

Pact to the Post-War Period”, 5HFKHUFKHV(FRQRPLTXHVGH/RXYDLQ,

Vol. 63, No. 4, pp. 321-66.

_________________________________ (1998), “Fiscal discipline and

flexibility in EMU: the implementation of the Stability and Growth

Pact”, 2[IRUGUHYLHZRI(FRQRPLF3ROLF\, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 81-97.

Brunila, A., M. Buti and D. Franco (eds.) (2001),7KH6WDELOLW\DQG*URZWK

3DFW±7KH)LVFDO$UFKLWHFWXUHRI(08, Palgrave, Basingstoke.

Buti, M. and A. Sapir (1998), (FRQRPLF3ROLF\LQ(08±$6WXG\E\WKH

(XURSHDQ&RPPLVVLRQ6HUYLFHV, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Cabral, A.J. (2001), Main Aspects of the Working of the Stability and

Growth Pact, in A. Brunila, M. Buti and D. Franco (eds.)

(2001).Canzoneri, M.B. and B.T. Diba (2001), “The Stability and

Growth Pact: a Delicate Balance or an Albatross?”, in A. Brunila, M.

Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Clarke, P. (1998), “Keynes, Buchanan and the Balanced Budget doctrine”,

in J. Maloney (1998), 'HEWDQG'HILFLWV, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

Cohn, G. (1895), 7KHVFLHQFHRI)LQDQFH, Chicago, University of Chicago

Press.

Colm, G. and P. Wagner (1963), “Some observation on the budget

concept”, 5HYLHZRI(FRQRPLF6WXGLHV, Vol. 45, pp. 122-6.

Costello, D. (2001), “The SGP: How Did We Get There?”, in A. Brunila,

M. Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Dalsgaard, T. and A. de Serres (2001), “Estimating Prudent Budgetary

Margins”, in A. Brunila, M. Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Dalton, H., T. Brinley, J.N. Reednam, T.J. Hughes and W.J. Leaning

(1934), 8QEDODQFHG %XGJHWV ± $ 6WXG\ RI WKH )LQDQFLDO &ULVLV LQ

)LIWHHQ&RXQWULHV, London, George Routledge & Sons.

De Viti de Marco, A. (1953), 3ULQFLSL GL HFRQRPLD ILQDQ]LDULD, Torino,

Einaudi.

Drees, W.Jr. (1955), 2Q WKH OHYHO RI *RYHUQPHQW H[SHQGLWXUH LQ WKH

1HWKHUODQGVDIWHUWKH:DU, Leiden.

Durrel, A.J.V. (1917), 7KHSULQFLSOHDQGSUDFWLFHRIWKHV\VWHPRIFRQWURO

RYHU3DUOLDPHQWDU\JUDQWV, London, Gieves Publishing House.

Einaudi, L. (1948), 3ULQFuSLGLVFLHQ]DGHOODILQDQ]D, Torino, Boringhieri.

Eichengreen, B. and C. Wyplosz (1998), “Stability Pact: more than a minor

nuisance?”, (FRQRPLF3ROLF\, April, pp. 67-104.

European Commission (2001), 3XEOLF)LQDQFHVLQ(08±, Brussels.

Goode, R. and E.A. Birnbaum (1955), *RYHUQPHQW &DSLWDO %XGJHWV,

Washington D.C., International Monetary Fund.

Hansen, A.A. (1941), )LVFDO 3ROLF\ DQG %XVLQHVV &\FOHV, New York,

Northon & C.

Hicks, U. K. (1953), “The Budget as an Instrument of Policy, 1837-1953”,

7KH7KUHH%DQNV5HYLHZ, pp. 16-34.

Johansen, L. (1965), 3XEOLFHFRQRPLFV, Amsterdam, North-Holland.

Keynes, J. M. (1971-1989), 7KH &ROOHFWHG :ULWLQJV RI -RKQ 0D\QDUG

.H\QHV, Macmillan, London.

Kilpatrick, A. (2001), “Transparent Frameworks, Fiscal Rules and Policy-

making under Uncertainty”, paper included in this volume.

Kopits, G. and S. Symansky (1998), “Fiscal Policy Rules”, IMF

Occasional Paper, No. 162.

Lerner, A.P. (1943), “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt”, 6RFLDO

5HVHDUFK, 10, pp. 38-51.

Lindbeck, A. (1968), “Theories and Problems in Swedish Economic Policy

in the Post-War Period”, $PHULFDQ (FRQRPLF 5HYLHZ, June

Supplement, pp. 1-80.

Lundberg, E. F. (1996), 7KH 'HYHORSPHQW RI 6ZHGLVK DQG .H\QHVLDQ

0DFURHFRQRPLF 7KHRU\ DQG LWV ,PSDFW RQ (FRQRPLF 3ROLF\,

Raffaele Mattioli Foundation, Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Maloney, J. (1998), 'HEWDQG'HILFLWV, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar.

Middleton, R. (1985), 7RZDUGV WKH 0DQDJHG (FRQRP\ .H\QHV WKH

7UHDVXU\DQGWKHILVFDOSROLF\GHEDWHRIWKHV, London,

Methuen,

Moggridge, D. and A. Robinson (eds.) (1971-89), 7KH&ROOHFWHG:ULWLQJV

RI-RKQ0D\QDUG.H\QHV, London, Royal Economic Society.

Nitti, F. S. (1903), 3ULQFLSLGL6FLHQ]DGHOOH)LQDQ]H, Napoli, Luigi Pierro.

OECD (1999), (FRQRPLF2XWORRN, No. 66, Paris.

Pigou, A.C. (1929), $ 6WXG\ LQ 3XEOLF )LQDQFH, 2

nd

revised edition,

London, Macmillan.

Poterba, J.M. (1995), “Capital budgets, borrowing rules and state capital

spending”, -RXUQDORI3XEOLF(FRQRPLFV, Vol. 56, pp. 165-87.

Premchand, A. (1983), *RYHUQPHQW EXGJHWLQJ DQG H[SHQGLWXUH FRQWUROV

WKHRU\DQGSUDFWLFH, Washington, IMF.

Puviani, A. (1903), Teoria dell’illusione fiscale, reprinted by F. Volpi,

Milano, ISEDI, 1973.

Roubini, N. and J.D. Sachs (1989), “Political and Economic Determinants

of Budget Deficits in the Industrial Democracies”, (XURSHDQ

(FRQRPLF5HYLHZ, Vol. 33, pp. 903-38.

Sabine, B.E.V. (1970), %ULWLVK %XGJHWV LQ 3HDFH DQG :DU ,

London, Allen and Unwin.

Say J.B. (1853), $7UHDWLVHRQ3ROLWLFDO(FRQRP\, translation from the 4

th

French edition, Philadelphia, Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

Schumacher, E. F. (1944), “Public Finance – Its Relation to Full

Employment”, in F.A. Burchardt (ed.), 7KH (FRQRPLFV RI )XOO

(PSOR\PHQW, Basil Blackwell, Oxford.

Sraffa, P. (ed.) (1952-73), 7KH :RUNV DQG &RUUHVSRQGHQFH RI 'DYLG

5LFDUGR, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Stark, J. (2001), “Where did the Pact come from? Genesis of a Pact”, in A.

Brunila, M. Buti e D. Franco (eds.) (2001).

Steve, S. (1972), /H]LRQLGLVFLHQ]DGHOOHILQDQ]H, Padova, Cedam.

Strauch, R. and J. von Hagen (eds.) (2000), ,QVWLWXWLRQV3ROLWLFVDQG)LVFDO

3ROLF\, Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Taylor, J. B. (2000), “Reassessing Discretionary Fiscal Policy”, -RXUQDORI

(FRQRPLF3HUVSHFWLYHV, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 21-36.

United Nations (1951), %XGJHWDU\ 6WUXFWXUH DQG &ODVVLILFDWLRQ RI

*RYHUQPHQW$FFRXQWV, New York.

von Hagen, J. and I. Harden (1994), National Budget Processes and Fiscal

Performance, (XURSHDQ (FRQRP\ 5HSRUWV DQG 6WXGLHV, No. 3,

pp. 311-418.

Wren-Lewis, S. (2000), “The Limits to Discretionary Fiscal Stabilisation

Policy”, 2[IRUG 5HYLHZ RI (FRQRPLF 3ROLF\, Vol. 16, No. 4,

pp. 92-105.

),6&$/58/(686()8/32/,&<)5$0(:25.

25811(&(66$5<251$0(17"

*HRUJH.RSLWV

7KHEXGJHWVKRXOGEHEDODQFHG

WKHWUHDVXU\VKRXOGEHUHILOOHG

SXEOLFGHEWVKRXOGEHUHGXFHG«

M. T. CICERO (63 B.C.)

,QWURGXFWLRQ

Rules-based macroeconomic policies are in fashion. In the monetary

area, since the early nineties, an increasing number of countries have

adopted inflation targeting. The latter has displaced the targeting of

monetary aggregates, or of the exchange rate, as the rule of choice in

advanced economies. In the fiscal area, a parallel trend is under way, as

rules to eliminate or to contain budget deficits and to reduce the public debt

are gaining considerable popularity in various parts of the world

1

.

All these rules share at least one feature in common: they seek to

confer credibility to the conduct of macroeconomic policies by removing

discretionary intervention. Their goal is to achieve trust by guaranteeing

that fundamentals will remain predictable and robust regardless of the

government in charge. There are, however, obvious differences; for one

thing, credibility is not built at a uniform speed. Whereas an exchange rate

rule may provide immediate credibility following its introduction—and

equally, may be vulnerable to a sharp and sudden loss in credibility in the

event of an erosion in competitiveness or perception of misaligned

fundamentals—inflation targeting may take longer to establish credibility,

and balanced-budget rules usually become credible only after an extended

track record.

__________

* International Monetary Fund. Robert Hagemann, Geert Langenus, Ludger Schuknecht, and other

workshop participants provided useful comments. The author alone is responsible for the views

expressed, which do not necessarily reflect those of the International Monetary Fund.

1

Following the definition in Kopits and Symansky (1998), a fiscal policy rule is a permanent

constraint on fiscal policy, expressed in terms of a summary indicator of fiscal performance, such

as the government budget deficit, borrowing, debt, or a major component thereof.

Perhaps partly because of the long gestation period and partly

because of the particular experience of some countries, occasionally fiscal

rules are characterized as a fig leaf. According to this view, governments

either do not need rules since they apply discipline on a discretionary basis

anyway, or alternatively, if they adopt rules, they are not likely to follow

them seriously.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the merits of these

arguments, though without attempting to refute the truism that some

governments do in fact follow prudent countercyclical fiscal policy on a

discretionary basis, in a manner that is observationally-equivalent to a

well-designed set of fiscal rules. This point applies equally to prudent

discretionary monetary policy that obviates reliance on inflation targeting.

Specifically, an attempt is made here to find support for a rules-based fiscal

policy framework. As part of this endeavour, much of the paper is

devoted—drawing on international experience—to a discussion of the

attributes that such a framework must have in order to maximize its

usefulness.

In weighing the pros and cons of fiscal policy rules, the paper

ventures beyond the mainly Eurocentric focus of this workshop and takes a

broader view, since much of the recent popularity of fiscal rules can be

found in emerging market economies, as they seek to establish credibility

in financial markets. Also, wherever relevant, the discussion is cast in the

broader setting of rules-based macroeconomic policies, that is, including

references to monetary rules as well.

(YROXWLRQRIILVFDOSROLF\UXOHV

The virtue of fiscal discipline has been heralded for a long time—

during at least two millennia, as attested by the opening citation. However,

occasionally, departures from discipline have been justified politically and

conferred analytical respectability—most notably, in the aftermath of the

Great Depression. In many advanced economies, discretionary demand

management, instead of remaining broadly neutral or of offsetting the

effect of the cycle, has led to a nearly continuous increase in government

spending that outpaced revenue capacity. In other words, fiscal policy

exhibited a procyclical stance and a deficit bias

2

. A similar process can be

detected in some less developed countries, where the deficit bias emerged

with the pursuit of developmental objectives, against the background of

swings in capital flows and primary commodity prices

3

. Starting in

the 1980s, recognition of this bias and its contribution to public

indebtedness, as well as of its potential adverse repercussions on private

investment, prompted some governments to introduce medium-term fiscal

consolidation programs to restore macroeconomic stability and fiscal

sustainability. More recently, this was increasingly followed by a shift to

fiscal policy rules.

Formal attempts at casting the virtue of fiscal discipline into

permanent rules, through constitutional or legal provisions, at various

levels of government, span over a century and a half. During this period,

we can identify three fairly distinct waves. In the first wave, subnational

governments in some federal systems adopted autonomously the golden

rule. Under this rule, most states in the U.S. since the mid-19

th

century and

several cantons in Switzerland since the 1920s assumed an obligation to

maintain current budget balance. In essence, their goal was to gain access

to market-based financing of capital expenditure, absent a precedent of

bailouts by the national government.

In the second wave, after World War II, several industrial countries

(Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands) introduced balanced-budget rules that

underpinned their stabilization programs, following monetary reform. Most

of these were of the golden rule type. Other rules, limiting or prohibiting

the financing of budget deficits from specified domestic sources (mainly

central banks), were assumed in the 1960s, including in some developing

countries (Indonesia, CFA franc zone). Under all these rules, considerable

scope remained for creative accounting and other nontransparent practices

that could undermine compliance.

The current wave, starting with New Zealand’s Fiscal Responsibility

Act of 1994—shortly after the pioneering introduction of inflation

targeting in that country—has seen an increasing number of industrial and

emerging market economies introduce fiscal rules (Table 1). These rules

__________

2

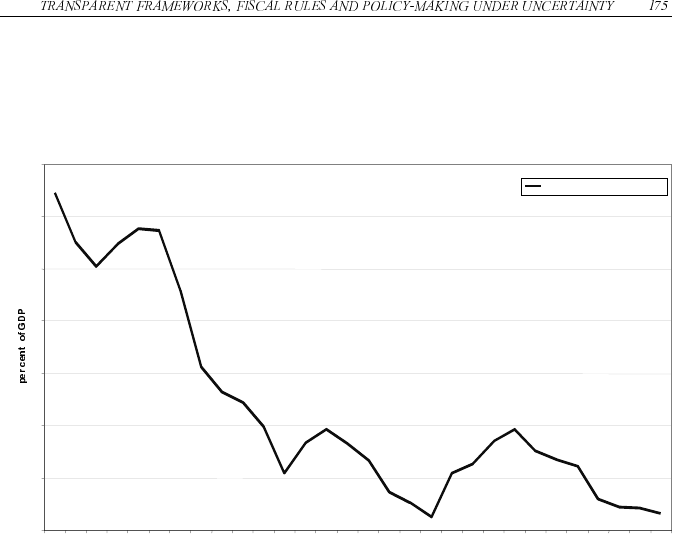

For evidence of a procyclical fiscal stance since the 1970s in the euro area, see European

Commission (2000). Similarly, Taylor (2000) found that during much of the last four decades the

U.S. has followed a procyclical (or at best ineffective) discretionary fiscal policy.

3

Procyclical fiscal policy has been documented for Latin America in 1970-95, in Gavin and others

(1996).

encompass a range of balanced-budget obligations, debt limits, and

expenditure limits, at various levels of government. In contrast to the

previous waves, a common denominator of the recent rules is that they are

supported by more or less strict transparency standards consisting of

generally accepted accounting conventions, timely and regular reporting

requirements, and a medium-term macro-budgetary framework. Generally,

all these elements are enshrined in broad legislation or international treaty,

with carefully spelled out accountability obligations. By analogy, inflation

targeting is usually set in an institutional context characterized by

transparency, central bank independence, and accountability.

Present fiscal policy rules are fairly diverse in both design and

implementation. Whereas Anglo-Saxon countries place primary emphasis

on transparency (Australia, Canadian provinces, New Zealand, United

Kingdom), in continental Europe (EMU Stability and Growth Pact,

Switzerland’s proposal) and emerging market economies (Argentina,

Brazil, Colombia, Peru, India’s proposal) rely far more on a set of

numerical reference values (targets, limits) on performance indicators. In

federal systems with strong subnational autonomy, the rules are assumed

only by the central government (Argentina, India’s proposal); in other

federal systems with concern about potential bailouts and external

spillovers of fiscal misbehaviour across jurisdictions, the rules are imposed

on each government level in a coordinated fashion (Brazil, EMU).

Most rules allow for escape clauses in the event of unforeseen

exogenous shocks. Objectively determined escape clauses may take

various forms: simply a medium-term target balance or surplus, without

explicit margins around it (New Zealand); explicit margins around a target

balanced-budget or surplus requirement, calibrated on cyclical deviations

in output growth (EMU, Swiss proposal); or alternatively, operation of a

contingency fund (Argentina, Peru). In other cases, the escape clause is to

be invoked in a discretionary manner, in the event of an international crisis,

a national calamity, or other loosely defined shocks (Brazil, India’s

proposal, U.S. proposal).

An independent arbitration authority is clearly defined in some

countries (Brazil, EMU), while at most a monitoring agency has been

appointed in others (Argentina). In some instances, the government is

subject to financial or judicial sanctions for noncompliance with the rules

(Brazil, Canadian provinces, EMU, CFA franc zone). For the most part, the

authorities are exposed to loss of reputation upon noncompliance.

8QQHFHVVDU\RUQDPHQW"

Skepticism about the usefulness or effectiveness of fiscal rules is

grounded on several arguments, ranging from theoretical to practical ones.

From a theoretical perspective, neither traditional macroeconomic analysis,

nor any principles of public finance are predicated on a rules-based fiscal

policy. Indeed, a discretionary approach has been widely viewed as

instrumental for the achievement of conventional fiscal goals or

functions—namely, stabilization, distributional fairness, and allocative

efficiency. Likewise, monetary rules were not deemed to be superior to

discretionary monetary policy. In all, the main virtue of discretionary

demand management was that it afforded short-run flexibility to offset

large exogenous disturbances, especially those that could lead to a

prolonged and significant unemployment. In the postwar period very few

authors (Friedman, 1948) questioned this conventional wisdom

4

.

Another source of skepticism (or at least agnosticism) about rules is

that a government can commit credibly to fiscal discipline without any

permanent rules. This observation finds support in a few practical

illustrations. In this regard, U.S. fiscal and monetary discipline in recent

years has been viewed as an example of prudent discretionary

policymaking. Since the mid-1990s, high growth and low inflation,

accompanied by budget surpluses, can be taken as evidence of the

redundance of formal balanced-budget requirements and inflation

targeting

5

. In a similar vein, it has been argued that rules do not really

matter in the conduct of fiscal policy, and further, that policy credibility is

formed regardless of actual adherence to rules. The example of Germany

suggests that public confidence (at home or abroad) in policy management

has not been altered by the authorities’ more than occasional failure to

meet, since the 1970s, the golden rule or the M3 target. Likewise, in Japan,

suspension of the rule since 1975 has had no effect in this regard. An

alternative interpretation of these examples is that a reputation of prudent

macroeconomic management acquired through a prolonged period of good

__________

4

In a departure from the mainstream, Friedman (1948) recommended a cyclically-adjusted

balanced-budget rule as a long-run policy guideline, with the purpose of eliminating the

uncertainty and undesirable political implications of discretionary action, including a procyclical

fiscal stance. However, he qualified the proposal with the caveat that such a rule may be

insufficient to offset stubborn and strong cyclical fluctuations, which would warrant discretionary

intervention.

5