The E¤ect of Foreign Investors on Local Housing Markets:

Evidence from the UK

y

Filipa Sá

June 30, 2017

Abstract

I use newly-released administrative data on properties owned by overseas companies to study

the e¤ect of foreign investment on the housing market in England and Wales. To estimate the

causal e¤ect, I construct an instrument for foreign investment based on economic shocks abroad.

Foreign investment is found to have a positive e¤ect on house price growth. This e¤ect is present

at di¤erent percentiles of the distribution of house prices and is stronger in local authorities

where housing supply is less e lastic. Foreign investment is also found to reduce the rate of home

ownership. There is no evidence of an e¤ect on the housing stock or the share of vacant homes.

Key words: foreign investors, house prices

JEL Classi…cation: R 21, F21

Filipa Sá, School of Management & Business, King’s College London, Franklin-Wilkins Building, 150 Stamford

Street, London SE1 9NH, UK. Email: …lipa.sa@kcl.ac.uk.

y

I would like to thank Beatrice Faleri and Xinyu Li for excellent research assistance. I am very grateful to Philippe

Bracke and Alan Manning for their insightful comments and sug gestions and to Stuart Gray at the Land Registry

for help with the data . I have also received useful comments from seminar participants at the European M eeting of

the Urban Economics Association in C openh agen and the Bank of England.

1

1 Introduction

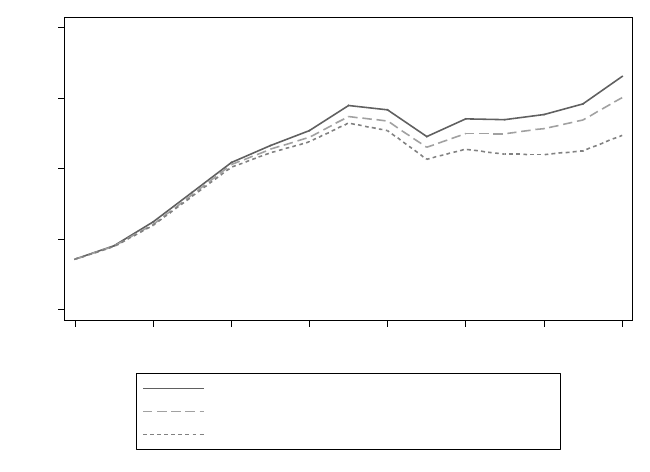

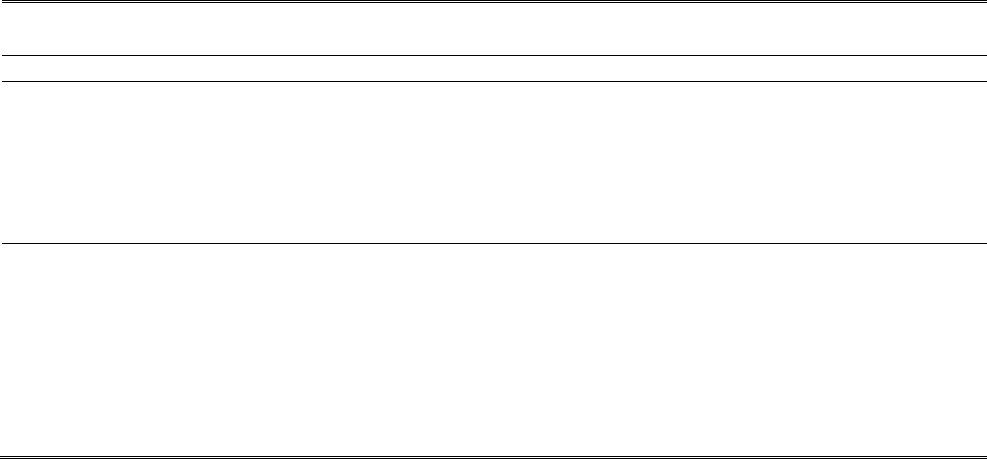

House prices in the UK have increased signi…cantly since the late 1990s. Figure 1 reports average

house prices in England and Wales using data from the Land Registry house price index database.

Average house prices almost tripled during the period shown, from just over £ 70,000 in 1999 to

about £ 215,000 in 2014. Apart from a reduction in 2009, at the height of the global …nancial crisis,

house prices increased every year during this period. What factors may be behind this upward

trend in house prices?

On the supply side, lack of available land for construction and regulatory constraints — such as

planning delays and restrictions — may be contributing to house price appreciation. In 2004, the

UK government commissioned a review on housing supply (Barker 2004). This review concluded

that a much higher rate of house building would be necessary to reduce the trend rate of house

price growth to a level comparable with the EU average. A related review on land use planning

(Barker 2006) argued for a need to make the planning application process more e¢ cient and to

incentivise the use of vacant previously developed land. A recent study by Hilber and Vermeulen

(2015) looks at how supply constraints a¤ect the transmission of income shocks to house prices.

They …nd that an increase in earnings raises house prices by more in areas with tighter regulatory

constraints (measured by the refusal rate of major residential projects).

On the demand side, Sá (2015) uses an IV approach to examine the causal e¤ect of immigration

on house prices. The …ndings suggest that an in‡ow of immigrants into a local area generates native

outmigration and has a negative e¤ect on local house prices. Badarinza and Ramadorai (2016) look

at the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices in London. They construct a proxy for foreign

investment based on two ideas: …rst, foreign investors are more likely to invest in the UK property

market when their home countries face negative economic con ditions; second, foreign investors

exhibit "home bias abroad", i.e., they tend to choose areas in the UK where people from their home

country live. The focus of their paper is di¤erent from Sá (2015) because foreign buyers are not

necessarily residents in the UK, but may be purchasing properties purely for investment purposes.

The authors …nd a signi…cant "safe haven" e ¤ect, with increases in foreign risk bein g associated

with higher house prices in parts of London with a high share of foreign-origin residents. A related

strand of literature uses macro data to examine the e¤ect of foreign capital in‡ows on the housing

2

market. Aizenman and Jinjarak (2009) use panel regressions to study the association between the

current account and real estate prices across countries. They conclude that there is a positive

association between current account de…cits and appreciation of real estate prices. Sá, Towbin and

Wieladek (2014) estimate a panel VAR for OECD countries and look at the e¤ect of capital-in‡ow

shocks on the housing market. They …nd that capital-in‡ow shocks have a signi…cant and positive

e¤ect on real house prices, real credit to the private sector, and real residential investment.

In this paper, I look at the e¤ect of foreign investment on the housing market in England and

Wales. Unlike Badarinza and Ramadorai (2016), I do not use economic shocks abroad as a proxy

for foreign investment, but measure foreign investment directly using a new dataset released by

the Land Re gistry. This dataset contains information on all property transactions in England and

Wales registered to overseas companies. My sample is broader than the one in Badarinza and

Ramadorai (2016) and includes all local authorities in England and Wales and not just in London.

Also, while Badarinza and Ramadorai (2016) focus on the average e¤ect on hous e prices, I also

look at heterogeneous e¤ects across the distribution of house prices and across local authorities

with di¤erent levels of supply constraints. In addition, I look at other outcome variables, such as

the housing stock, vacant homes and home ownership.

The newly-released Land Registry dataset is used to calculate the share of total residential

transactions registered to overseas companies in each year and local authority for the period from

1999 to 2014. This share is calculated in volume and in value (using information on transaction

prices). To see how these shares correlate with house prices, Figure 1 plots the evolution of house

prices and foreign transactions calculated as averages across all local authorities in England and

Wales. All three series display an upward trend. The value share is more volatile than the volume

share, probably due to measurement error in reported transaction prices. This issue is discussed in

more detail in the data section.

Behind these averages, there is signi…cant regional variation, as illustrated in Figures 2 and 3

and in Table 1. Average house prices in the S outh East, particularly in London, are signi…cantly

higher than in other regions, reaching a value of almost £ 1.3 million in Kensington and Chelsea

in 2014. Foreign investment also tends to be concentrated in the South East — Westminster

and Kensington and Chelsea have by far the largest shares of transactions registered to overseas

companies. Some of the major cities in the North — such as Liverpool, Leeds and Manchester —

3

also attract large shares of foreign investment. Interestingly, the city of Salford (part of Greater

Manchester) had a signi…cant share of foreign investment in 2014. After looking at the addresses

of properties in Salford sold to overseas investors in that year, it appears that many of them are in

an apartment block partly funded by Chinese investors

1

.

This paper makes use of this regional variation and identi…es the e¤ect of foreign investment

on house prices from spatial correlations between the share of foreign transactions and changes

in house prices across local authorities. A potential problem in interpreting these correlations as

causal e¤ects is that the direction of causality between foreign investment and hou se prices is not

clear, because foreign investors are not randomly allocated across geographic areas. To overcome

this issue, I borrow from Badarinza and Ramadorai (2016) and use measures of economic shocks

abroad and the idea of "home bias" to construct an instrument for foreign investment.

To preview the results, I …nd that foreign investment has a positive and signi…cant e¤ect on

house prices. An increase of one percentage point in the volume share of residential transactions

registered to overseas companies leads to an increase of about 2:1 percent in house prices. To have a

better idea of the magnitude of this e¤ect, I use the model to construct the counterfactual evolution

of house prices when the share of foreign investment is set to zero. I …nd that average house prices in

England and Wales in 2014 would have been about 19% lower in the absence of foreign investment

(at approximately $174; 000, compared with an actual average of about $215; 000). Looking at

the e¤ect at di¤erent points of the distribution of house prices, I …nd that foreign investment

does not just raise prices of expensive homes, but has a positive e¤ect at di¤erent percentiles of the

distribution. To examine how supply restrictions a¤ect the propagation of foreign investment shocks

to house prices, I use the data in Hilber and Vermeulen (2015) to calculate the house price-earnings

elasticity for each local authority in England. I then divide local authorities into di¤erent quartiles

of this elasticity and estimate the model separately for each quartile. As expected, I …nd that

foreign investment increases prices by more in local authorities with a larger house price-earnings

elasticity, which are the ones with a less elastic housing supply.

I also examine th e e¤ect of foreign investment on other outcome variables. Looking at the

e¤ect on the housing stock, I do not …nd evidence that an increase in foreign investment leads

1

A report by the BBC on Chinese investment in major cities in the North, particularly Salford, can be found at:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/new s/business-36086 012

4

to an increase in housing construction, contrary to the suggestions of some estate agents in prime

London areas

2

. I also do not …nd evidence in favour of "buy-to-leave " — the hypothesis that foreign

buyers purchase properties purely for capital appreciation and do not occupy them or rent them

out. However, I do …nd evidence that foreign inve stment reduces home ownership rates, suggesting

that some residents may be priced out of the market in areas where foreign investors are more

active and have to rent rather than own their homes.

The …ndings in this paper are useful to inform the policy debate on the impact of foreign invest-

ment on the housing market. This topic has attracted the attention of the Mayor of London (Sadiq

Kahn), who has recently launched an inquiry into the consequences of foreign property ownership

in the capital. Other countries have also been debating this issue and have introduced policies to

control foreign investment in the housing market in an attempt to reduce house price appreciation.

For example, Australia has a legislative framework which encourages foreign investment in new

residential projects, but imposes tighter controls on the purchase of existing dwellings (Gauder,

Houssard and Orsmond (2014)); Switzerland has quotas on the number of residential properties

that can be s old to foreigners; and the Canadian city of Vancouver h as recently introduced a 15%

property tax on foreign home buyers.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. The next section describes the key data sources,

particularly the new Land Registry Overseas Companies Dataset (OCD). Section 3 discusses the

empirical methodology use d to estimate the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices and presents

the results. Section 4 discusses some robustness checks. Section 5 looks at the e¤ec t of foreign

investment on the h ousing stock, vacant homes and home ownership. Section 6 concludes.

2 Data

2.1 Investment by overseas companies

Data on all land, commercial and residential properties in England and Wales registered to overseas

companies are obtained from the Land Registry Overseas Companies Dataset (OCD), published in

March 2016. The dataset contains around 100,000 title records and collects information on tenure

2

Fo r examp le, research by Savills (2014) suggests that foreign investors play a major role in sti mulating the supply

of new housi ng in L ondon.

5

(freehold or leasehold), address, price paid (where available), name and country of incorporation

of the legal owner and date of registration. While the data go as far back as the mid-1960s,

the majority of records were registered from 1999 onwards. The public version of the datase t

contains data up to October 2015. The dataset includes overseas companies only and does not

cover properties owned by private individuals, UK companies or charities.

Prior to the release of this dataset, similar d ata were published on the website of the Private

Eye magazine, together with an informative map showing all land and properties in England and

Wales registered to overseas companies

3

. The Private Eye obtained these data from the Land

Registry under a Freedom of Information request. Their dataset covers the period from 1999 to

2014 and contains more complete information on price paid than the Land Registry dataset. I use

this dataset to …ll in missing information on prices in the Land Registry OCD. Therefore, the data

used for the empirical analysis cover the period from 1999 to 2014.

To assess the relative importance of foreign investment in a given local authority and year, it

is important to scale foreign transactions by the total number of transactions. To do this, I use

information on all property sales in En gland and Wales from the Land Registry Price Paid Data

(PPD). This dataset only covers residential properties sold at full market value. Until October

2013, only sales to private individuals were included. Since then, the dataset also includes buy-

to-let sales and sales to companies. To ensure consistency across time, I focus on transfers of

residential property to private individuals for all years.

I use two measu res of foreign investment by local authority and year. The …rst measure is

the volume share of foreign transactions and is calculated by dividing the number of reside ntial

properties registered to overseas companies (from the Land Registry OCD) by the total number of

residential transfers to private individuals (from the Land Registry PPD). The second measure is

the value share of foreign transactions and is obtained by dividing the total value of all residential

properties registered to overseas companies by the total value of all residential properties bought

by private individuals. The append ix contains more details on the construction of the volume and

value shares.

There are some potential measurement problems with these shares of foreign investment. On e

problem is that the Land Registry OCD only includes purchases by overseas companies, but not

3

http://www.private-eye.co.u k/registry

6

by non-resident private individuals. This implies th at the shares of foreign transactions may un-

derestimate the true importance of foreign investment in the local housing market. In practice,

however, most foreign investment is likely to be directed through a company, because tax rates on

rental income are generally lower for non-resident companies than for individuals

4

.

Another issue is that the Land Registry OCD only contains information on the country of

incorporation, bu t does not reveal the country of ultimate ownership of the companies that invest

in UK property. Table 2 lists the countries of incorporation with the largest shares of investment

in UK property in 2014 (in volume). About 34% of p urchases of property in England and Wales by

overseas companies in 2014 were done by companies incorporated in the British Virgin Islands. The

channel islands of Guernsey and Jersey also had large shares, as well as the Isle of Man. All these

territories have low tax rates. It is possible that some UK investors may register a company overseas

in order to pay less taxes. If this is the case, the volume and value shares would overestimate the

true importance of foreign investment in the local h ousin g market because the numerator would

include some properties bought by UK investors via a company registered overseas. To get a sense of

the extent of this problem, the robustness section reports results excluding properties registered to

companies incorporated in Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of M an. Given their geographic proximity,

these are the most likely countries of incorporation of UK companies seeking to reduce their tax

liabilities.

An additional issue with the calculation of the foreign shares is that the transaction prices

reported in the Private Eye dataset are likely to su¤e r from measurement error. Some of the

information on prices is reported by visitors to the Private Eye website, who can click on a link on

the map to report additional information about a record. Occasionally, price paid …gures contain

errors and may not refer to an individual property, but to all properties registered to the same

company. Because of this issue with the price data, it is useful to consider the results for the value

share alongside those for the volume share, which is calculated solely from administrative data and

does not su¤er from measureme nt problems. In the empirical analysis, I use an IV approach to

deal with endogeneity in the shares of foreign investment, which should help address measurement

error in the value share.

4

Fo reign companies pay corporation tax on rental income at 20%, whereas tax rates for non-resident and resident

individuals vary between 20% and 45%, depending on i ncome.

7

2.2 House prices and other controls

Data on house prices are obtained from the Land Registry house price index dataset. The index is

based on repeated sales and measured at monthly frequency (it is converted to annual by taking

averages). Using repeated sales to measure house price changes has the advantage of holding

constant the quality of the housing stock.

In the regression analysis, I control for local economic conditions by including lags of the unem-

ployment rate and the bene…ts rate (the proportion of the population receiving any state bene…ts).

All data sources and de…nitions are listed in Table A1 in the appendix. Table 3 reports descriptive

statistics for the key variables.

3 Foreign buyers and house prices

3.1 Speci…cation

The following model is used to estimate the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices:

ln(P

it

) =

F T

it

T T

it

+ X

it1

+

t

+

i

+ "

it

(1)

where ln(P

it

) is the change in the log of the house price index in local authority i between

years t 1 and t. The main independent variable is the share of foreign transactions to total

transactions (

F T

it

T T

it

). As described in the data section, this is obtained by dividing the volume or

value of residential properties registered to overseas companies by the total volume or value of

residential transfers to private individuals. The coe¢ cient can be interpreted as the percentage

change in hou se prices corresponding to an annual increase of one percentage point in the share of

foreign transactions.

X

it1

is a set of controls and includes a lagged dependent variable and one year lags of the

local unemployment rate and the share of the local population claiming state bene…ts. The un-

employment rate and the bene…ts rate capture local macroeconomic conditions, which may a¤ect

housing demand. The model includes a lagged dependent variable to allow for inertia in house price

growth. Case and Shiller (1989) …nd evidence that an increase in house prices in one year tends

8

to be followed by an increase in the subsequent year. Other studies examining the determinants

of house price growth — for example, Favara and Imbs (2015) and Jordà, Schularick and Taylor

(2015) — also include a lagged dependent variable in the model.

Year dum mies (

t

) capture national trends in in‡ation and other economic variables. Since the

model is written in …rst-di¤erences, time-invariant factors that are speci…c to each local authority

and that a¤ect the level of house prices have been di¤erenced out. However, local authority …xed

e¤ects (

i

) are still included to capture di¤erent trends in house prices at the local level. The

model is es timated in …rst di¤erences to account for heterogeneous trends across local authorities

and because house prices are measured as an index, whose level has no economic interpretation.

Following the recommendation in Bertrand, Du‡o and Mullainathan (2004) and Angrist and Pischke

(2009), standard errors are heteroskedasticity-robust and are clustered by local authority to account

for correlation within groups.

The e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices is identi…ed from spatial correlations between

the share of foreign transactions and changes in house prices across local authorities. Identi…cation

relies on variation in the s hare of foreign buyers across local authorities and time.

There are two potential problems in interpreting these correlations as causal e¤ects. First,

foreign investment and hous e prices may b e spatially correlated because of common …xed in‡uences,

for example, the climate or local amenities. This would lead to a correlation between the two

variables, even in the absence of any genuine e¤e cts of foreign investment. The second problem

is that the direction of causality between foreign investment and house prices is not clear because

foreign investors are not randomly allo cated across geographic areas.

To address the …rst problem, the model is estimated with the dependent variable in …rst-

di¤erences. This eliminates time-invariant, area-speci…c factors that a¤ect foreign investment and

house prices. To address the second problem, I construct an instrument for the value and volume

shares of foreign investment. The instrument is based on the analysis in Badarinza and Ramadorai

(2016), who look at the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices in London. The authors do not

look directly at measures of foreign investment, since this information was not available until the

recent release of the Land Registry OCD. Instead, they construct a proxy for foreign investment

based on two ideas: …rst, foreign investors are more likely to invest in the UK property market when

their home countries face negative economic conditions; second, foreign investors exhibit "home bias

9

abroad", i.e., they tend to choose areas in the UK where people from their home country live.

"Home bias abroad" may arise if foreign investors …nd it easier to rent property to residents from

their home country, because there are no language or cultural barriers. Also, in areas where some

nationalities are more highly represented, local estate agents specialise in dealing with investors

from those countries, reducing transaction costs for foreign investors who buy property in those

areas

5

. The notion of "home bias abroad" is closely related to an instrument that is typically used

in the literature on immigration, which relies on the historical settlement pattern of immigrants by

country of origin to predict the current geographic distribution of the immigrant population — see,

for example, Cortes (2008) and Sá (2015). This instrument is based on the notion that immigrant

networks are an important determinant of the locational choices of new immigrants, because they

facilitate the job search process and assimilation into a new culture (Munshi 2003).

I follow Badarinza and Ramadorai (2016) and construct the following instrument for the share

of foreign investment in local authority i in year t:

P

c

f

c

i

z

c

t1

where f

c

i

is the share of residents in local authority i that were born in foreign country c from the

2001 Census and z

c

t1

is a measure of economic conditions in country c in year t 1, speci…cally the

economic risk index from the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). The index is constructed

by awarding risk points for 5 components: GDP per capita, real annual GDP growth, annual

in‡ation rate, budget balance as a percentage of GDP and current account as a percentage of GDP.

Countries with lower risk are awarded a higher value for the index. The index is available for 140

countries for the period 1984 to 2015. Because population data from the Census is available for

only 60 countries and regions, it is necessary to c ombine the economic risk indices to match the

regions in the Census. I do this by calculating weighted indices us ing population shares from the

IMF World Economic Outlook as weights. In the robustness section, I estimate the model using

an alternative measure of economic conditions abroad to construct the instrument.

The validity of this instrument relies on two identi…cation assumptions. First, I assume that the

geographic distribution of the foreign-born population in 2001 is uncorrelated with recent changes

5

In prime central London locations, there are seve ral property consultancy …rms that specialise in helping Russian

and Chinese investors buy property in those areas.

10

in the economic performance of di¤erent UK local authorities. In that case, f

c

i

is correlated with

changes in house prices on ly through its relation with current foreign investment in those areas.

The second identifying assumption is the exogeneity of economic con ditions abroad to economic

conditions of UK local authorities. This is a plausible assumption because economic conditions

abroad should be largely determine d by country-speci…c political and institutional factors and year

…xed e¤ects should capture global macroeconomic shocks.

3.2 Results

Table 4 reports the results of estimating model (1) by OLS and IV. The OLS results suggest a

positive correlation between the share of foreign investment in volume and in value and house price

growth. The coe¢ cients are very similar with and without controlling for changes in the local

unemployment rate and the bene…ts rate.

The IV coe¢ cients are signi…cantly larger, pointing to considerable attenuation bias in the OLS

estimates, likely due to measu rement error in the shares of foreign investment. The IV results imply

that, on impact, house prices increase by about 2% when the volume share of total transactions

registered to overseas companies increases by one percentage point. For the value share, the increase

in house prices is about 1:4%. The instrument is highly signi…cant in the …rst stage an d has the

expected sign: when economic conditions abroad improve — corresponding to an increase in the

index of economic conditions abroad (weighted by local foreign population) — foreign buyers invest

less in the UK housing market. The F-statistic on the excluded instruments is around 8. This is

below the benchmark value of 10 suggested by Stock, Wright and Yogo (2002), but is above the

20% maximal bias threshold (6:66) in Stock and Yogo (2005). The table also reports the Anderson-

Rubin Wald test of the signi…cance of the foreign shares in the structural equation, which is robust

to the presence of weak instruments. The test indicates that the foreign shares have a signi…cant

e¤ect on house price growth.

To better un derstand the magnitude of these results, I use the IV coe¢ cients to predict the

evolution of average hou se prices when the volume share of overseas transactions is set to zero.

Figure 4 reports the evolution of actual average house prices across local authorities in England

and Wales (solid line), as well as the evolution of average house prices predicted by the model

with the volume share of overseas transactions observed in the data (long dashed line) and with a

11

volume share of overseas transactions equal to zero (short dashed line). Predicted house prices are

close to observed house prices, indicating that the model does well in explaining the evolution of

house prices. Without any foreign investment in the housing market, average house prices would

be lower. For e xample, in 2014, average house prices without foreign investment would be about

19% lower (at approximately $174; 000, compared with an actual average of about $215; 000).

To get a sense for how the response of house prices changes over time, I follow the method

introduced in Jordà (2005) and estimate impulse responses at di¤erent points in time using local

projections. This method estimates impulse responses directly, without the need to specify the

unknown multivariate dynamic process, as would be the case with a vector autoregression (VAR).

Local projections are obtaine d by estimating sequential regressions of the endogenous variable

shifted forward:

ln(P

it+h

) ln(P

it+h1

) =

h

F T

it

T T

it

+ X

it1

+

t

+

i

+ "

it

(2)

The vector of estimates f

h

g

h=0;1;:::

measures the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices at

horizon h. To acc ount for endogeneity in the share of foreign investment, I estimate the regressions

using the ins trument based on economic shocks abroad. This approach is described in Jordà,

Schularick and Taylor (2015) as local projection instrumental variables (LP-IV) and has also been

used in Favara and Imbs (2015) to study the e¤ect of sho cks to credit supply on house price growth.

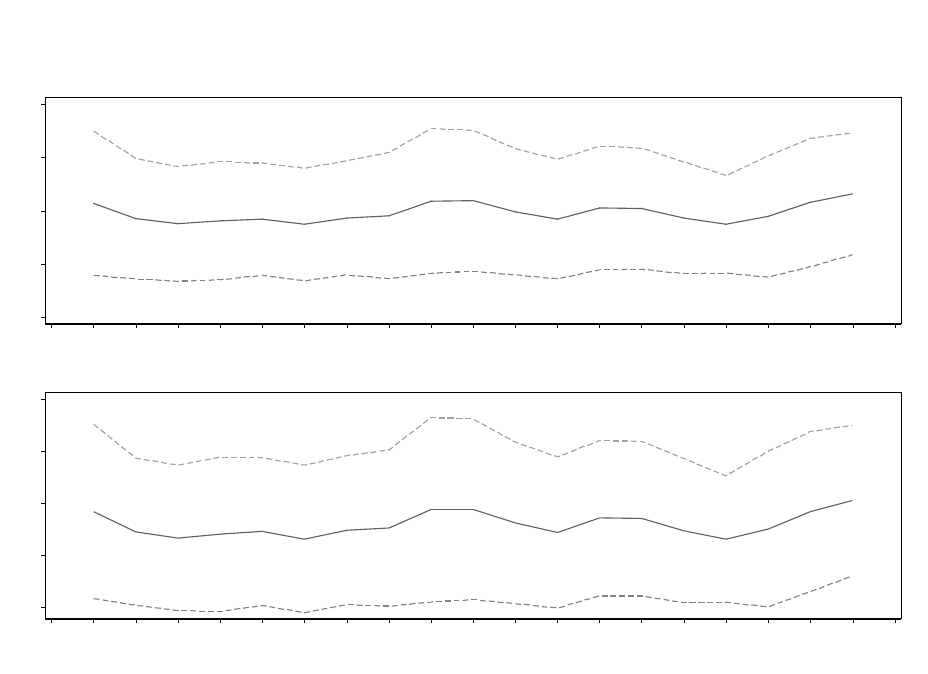

Figure 5 reports the impulse responses over a period of four years. The e¤ect of an inc rease in

foreign investment on house price growth is quite persistent and only becomes insigni…cant four

years after the shock.

3.3 E¤ect along the distribution of house prices

Foreign buyers are more active at the top end of the housing market. For example, in 2012, 13%

of all residential property transactions in England and Wales above £ 1 million were registered to

overseas companies, compared with only 2% of properties under £ 1 million. Therefore, it is possible

that most of the impact of foreign investment on house prices is felt at the top end of the market.

To test this hypothesis, I estimate the following model to study the e¤ect of foreign investment

at di¤erent percentiles of the distribution of house prices:

12

ln(P

pit

) =

p

F T

it

T T

it

+

p

X

it1

+

pt

+

pi

+ "

pit

(3)

The d ependent variable is the log of the p th percentile of house prices in local authority i

in year t. As before, the vector X

it1

includes a lagged dependent variable and two controls for

local macroeconomic conditions — one-year lags of the local unemployment rate and of the share

of the local population claiming state bene…ts. The coe ¢ cient

p

captures the e¤ect of overseas

investment on each percentile of the distribution of house prices. This model is similar to the one

adopted in Dustmann, Frattini and Preston (2013) to study the e¤ect of immigration along the

distribution of wages.

Table 5 reports the results of estimating the model for selected percentiles of the distribution

of house prices with the share of foreign transactions measured in volume and in value. Panel A

reports OLS results and panel B rep orts IV results using the instrument based on economic shocks

abroad. Results are reported with and without controlling for the lagged unemployment rate and

bene…ts rate. The OLS coe¢ cients suggest a slightly larger e¤ect of foreign investment at the top

end of the distribution of house prices. However, the IV coe¢ cients point to a similar positive e¤ect

of foreign investment on house prices at all points of th e distribution. For example, an increase in

the volume share of residential properties registered to overseas companies of one percentage point

increases house prices at the 95th percentile by about 2:3% and increase s house prices at the 5th

percentile by about 2:1%.

To obtain a more detailed picture, I estimate the model using a …ner grid of house price per-

centiles. Figure 6 reports the IV coe¢ cients in percentile intervals of …ve percentage points. These

coe¢ cients correspond to the results in columns (2) and (4) of Table 5. The …gure suggests that

foreign investment does not increase prices only for expensive homes, but has a positive e¤ect at

all points of the house price distribution.

3.4 Supply constraints and the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices

The response of house prices to foreign investment should depend on supply conditions. In local

authorities where housing supply is more constrained by regulation or geography, house prices

should increase by more in response to an increase in f oreign investment. To test this hypothesis, I

13

use the estimates of the house price-earnings elasticity for lo cal authorities in England constructed

by Hilber an d Vermeulen (2015). The h ouse price-earnings elasticity is a proxy for the elasticity of

housing supply — in areas where supply is less elastic, a positive shock to demand (for example,

an increase in earnings) would lead to a larger increase in house prices. Therefore, a higher house

price-earnings elasticity re‡ects a less elastic supply of housing.

Hilber and Vermeulen (2015) estimate the house price-earnings elasticity by running a regression

of the log of house prices on earnings and interactions of earnings with the share of planning

applications for major residential projects that are refused permission, the share of land already

developed and the elevation range. The refusal rate measures regulatory constraints to house

building, while the share of land already developed and the elevation range measure land scarcity.

To address endogeneity in the refusal rate, the authors use the share of votes for the Labour Party

in the 1983 general election as an instrument. This is motivated by the fact that Labour voters

tend to be less protective of housing value s than Conservative voters. As an additional instrument,

they use the change in the delay rate of major planning applications after a reform introduced by

the Labour government in 2002, which set a target to speed up the planning process. To address

endogeneity in the share of land already developed, the authors instrument it with population

density in 1911. The model is estimated using annual data for the period from 1974 to 2008.

I use the estimated coe¢ cients in Hilber and Vermeulen (2015) and their data to construct

estimates of the house price-earnings elasticity for each local authority in England

6

. Figure 7

reports these elasticities and shows that local authorities in the South East are considerably more

elastic, especially in Greater London. Local authorities in the North and East of England have

much lower house price-earnings elasticities, re‡ecting lower regulatory restrictions and more space

available for construction. I then separate local authorities in England into four quartiles, according

to the house price-earnings elasticity, and estimate model (1) separately for each of these quartiles.

The results, reported in Table 6, suggest that foreign investment only has a positive e¤ect on house

prices for local authorities with a higher hous e price-earnings elasticity (i.e., a lower elasticity of

housing supply). The e¤ect of foreign investment is insigni…cant for local authorities in the bottom

two quartiles.

This analysis is related to some recent studies using US data which look at how the elasticity

6

More details on the constructi on of the elasti citie s c an be found in the append ix.

14

of housing supply a¤ects the propagation of shocks to house prices. These studies make use of

the elasticities of housing supply by metropolitan area constructed by Saiz (2010), which take into

account geographic and regulatory constraints to house building. Favara and Imbs (2015) analyse

whether branching deregulations across US s tates have a di¤erential e¤ect in counties with di¤erent

elasticities of housing supply. They …nd that the response of house prices is more muted in counties

where supply is more elastic, whereas the response of the housing stock is more muted in counties

where supply is less elastic. Adelino, Schoar and Severino (2012) look at a di¤erent sh ock to credit

supply — changes to the conforming loan limit, which determines the maximum size of a mortgage

that can be purchased or securitised by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. They …nd that cheaper credit

increases house prices by more in regions where housing supply is less elastic. Mian and Su… (2009)

compare house price growth between 1997 and 2007 in US metropolitan areas with high and low

supply elasticities. They …nd a strong increase in house price growth in inelastic areas until 2005,

followed by a large collapse in 2006 and beyond. By contrast, house price growth in elastic areas

remains low and ‡at during this period. All these …ndings are consistent with the results in Table

6.

4 Extensions and Robustness Checks

4.1 Alternative Samples

Many local authorities with large shares of foreign investment are located in London, as shown in

Figure 3 and Table 1. To test whether the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices is di¤erent

in London and other parts of England and Wales, I estimate model (1) for the 32 London local

authorities. The results, reported in the …rst two columns of Table 7, suggest that foreign investment

has a positive e¤ect on house prices in London. However, the e¤ect is smaller than the average

e¤ect across all local authorities reported in Table 4. An increase of one percentage point in the

volume share of foreign investment increases house prices in London by 0:6%, compared with 2:1%

across all local authorities in England and Wales. For the value share, the e¤ect in London is 0:5%,

compared with 1:4% across all local authorities.

Another fact illustrated by Figure 3 is that many local authorities have a very small share of

foreign investment. To test how this a¤ects the results, I estimate model (1) for local authorities

15

with a volume share of foreign transactions above 0:5%. This leaves only 26 out of 172 local

authorities. The results, reported in the last two columns of Table 7, point again to a positive e¤ect

of foreign investment on house price growth. Comparing with the results for all local authorities in

Table 4, the IV coe¢ cients are somewhat smaller for local authorities with a high share of foreign

transactions.

A possible limitation with the de…nition of foreign transactions used in this paper is that the

Land Registry OCD includes all properties bought by overseas companies, but does not provide

information on the country of ultimate ownership. It is possible that some UK investors register

companies overseas to bene…t from lower taxes and use those companies to invest in property at

home. To assess how this may a¤ect the results, I recalculate the foreign shares excluding properties

registered to companies incorporated in Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man. Because of their

geographic proximity, these are the most likely countries of incorporation of UK companies seeking

to reduce their tax liabilities. Table 8 reports the results of estimating model (1) f or this sample.

The coe¢ cients are similar to the ones reported in Table 4, suggesting that the results are not

being driven by transactions registered to companies in these territories.

4.2 Alternative Instrument

The IV results rep orted so far are based on an instrument that captures economic conditions

abroad, measured by the ec onomic risk index of the ICRG. To check robustness of the results to

the choice of instrument, I construct an alternative instrument based on the index of economic

policy uncertainty of Baker, Bloom and Davis (2016). The index is constructed by searching key

words in newspaper articles and is available for 15 countries (in addition to the UK). High values

of the index denote a higher degree of economic policy uncertainty. Using these data, I construct

the following instrument f or the volume and value shares of foreign investment in local authority i

in year t:

P

c

f

c

i

z

c

t1

where f

c

i

is the share of residents from foreign country c living in local authority i in the 2001

Census (as before) and z

c

t1

is the one-year lagged value of the index of economic policy uncertainty

16

for country c from Baker, Bloom and Davis (2016).

The IV estimates of the coe¢ cients in model (1) with this alternative instrument are reported

in Table 9. Compared with the results in Table 4, the coe¢ cients with this alternative instrument

are smaller. For the model with the full set of controls, the coe¢ cients imply that, on impact, house

prices increase by about 1:4% when the volume share of total transactions registered to overseas

companies increases by one percentage point. For the value share, the increase in house prices

is about 0:7%, which is half the size of the e¤ect reported in Table 4. The instrument is highly

signi…cant in the …rst stage and has the expected sign: an increase in economic policy uncertainty

abroad increases foreign investment in the UK housing market. The F-statistic on the excluded

instruments is somewhat lower for the volume share than the one reported in Table 4. However,

for the value share, the new instrument is stronger, with an F-statistic above the benchmark value

of 10 suggested by Stock, Wright and Yogo (2002). The Anderson-Rubin test con…rms that foreign

investment has a signi…cant e¤ect on house price growth.

5 Foreign buyers and other housing market outcomes

5.1 Housing stock

To test whether foreign investment encourages the construction of new housing, I estimate model (1)

with the change in the log stock of dwellings as the dependent variable (instead of the change in the

log of the house price index). Annual data on the dwelling stock are obtained from the Department

for Communities and Local Government (DCLG). Data are only available for local authorities in

England from 2001. The results of estimating the model by OLS and IV are reported in Table 10

and suggest there is no signi…cant e¤ect of foreign investment on the change in the housing stock.

It appears that foreign investment does not signi…cantly increase housing construction, resulting

instead in a signi…cant increase in prices. I have also estimated the model separately for local

authorities with a high and low house price-earnings elasticity (split at the median). I …nd that

this insigni…cant e¤ect is present in both groups of local authorities (the results are rep orted in

Table A2 in the Appendix).

17

5.2 Vacant Homes

One of the concerns expressed by commentators and policy makers when discussing the e¤ect of

foreign investment on the housing market is that homes bought by foreign investors are likely

to be left empty, with a negative e¤ect on local communities. This is sometimes described as

"buy-to-leave" (Financial Times (2016)).

Annual data on vacant dwellings are available from the DCLG for English local authorities from

2004 onwards. These data are obtained f rom council tax returns. Dwellings reported to the local

authority as vacant may be eligible for a council tax exemption or discount. Vacant dwellings are

classi…ed into long-term or short-term vacant, depending on whether they have been unoccupied or

substantially unfurnished for more or less than six months. To study the e¤ect of foreign investment

on vacant dwellings, I use thes e data to estimate model (1) with the change in the log number of

short-term and long-term vacant dwellings as the dependent variable. The results — reported

in Table A3 in the Appendix — point to an insigni…cant e¤ect of foreign investment on vacant

dwellings. The OLS coe¢ cients point to a positive correlation between the volume share of foreign

transactions and the number of short-term vacant dwellings, but this relation becomes insigni…cant

in the IV regress ions.

Council tax data on vacant dwellings have two potential limitations. First, local authorities have

discretion over the level of council tax discount th ey apply to vacant dwellings and m ay decide not

to apply any discount. In local authorities that do not award any discount, there is less incentive

for home owners to report their properties as vacant, which could lead to underreporting of vacant

homes. Another issue is that foreign investors may not be aware that they are eligible for a council

tax exemption or may view the exemption as too small to warrant reporting the home as vacant,

which may be particularly true at the high-end of the market.

To overcome these limitations, I use an alternative source of data on vacant homes. The 2011

Census reports the number of household spaces with no us ual residents. These are hous ehold

spaces that are vacant or used as second addresses, but may still be used by short-term residents

and visitors. Table 11 lists the 10 local authorities in England and Wales with the largest share of

household spaces with no usual residents. Many of these local authorities (for example, in Wales,

Cornwall and the Isle of Wight) are holiday destinations. However, the large share of homes with

18

no usual residents in the City of London, Westminster and Kensington and Chelsea is probably a

result of foreign investors buying in prime areas for long-term capital appreciation.

To examine the e¤ec t of foreign investment on vacant homes using this alternative data source,

I regress the share of household space s with no usual residents in each local authority on the share

of foreign transactions (in volume and in value):

vacant

i

=

F T

i

T T

i

+ "

it

(4)

The model is estimated by OLS and IV (using the alternative instrument based on econ omic

policy uncertainty abroad) for the cross-section of local authorities in England and Wales

7

. The

results are reported in the …rst two columns of Table 12. The OLS results sugge st a positive and

signi…cant correlation between foreign investment and vacant homes. However, the IV coe¢ cients

are insigni…cant. These results, together with the …ndings based on data from the DCLG, indicate

that there is no clear evidence that foreign investment in the housing market increases the number

of vacant homes.

5.3 Home Ownership

The results on the e¤ect of foreign investment on house prices suggest that an increase in foreign

investment leads to a signi…cant increase in prices at all points of the house price distribution. A

potential consequence of this is that residents may not b e able to a¤ord to buy a home in areas

where foreign investors are more active and may be forced to rent th eir homes instead.

To test this hypothesis, I collect data from the 2011 Census on the share of households in

owner-occupied accommodation for local authorities in England and Wales. I then estimate model

(4) with this share as the dependent variable. The results, reported in the last two columns of

Table 12, suggest that an increase in foreign investment in the hou sing market leads to a reduction

in the share of households who own their homes. The IV coe¢ cients imply that an increase of

one percentage point in the volume share of foreign transactions redu ce s the share of households

who own their homes by 5:6 percentage points. For the value share, the e¤ect is also negative and

signi…cant at 3 percentage points. There is evidence that residents are priced out of the market in

7

The usual instrument (based on t he economic risk index) produces weak …rst-s tage results for this c ross-sect ional

sample.

19

areas where foreign investors are more active.

6 Conclusions

This paper identi…es the causal e¤ect of foreign investment on the housing market in England

and Wales. It u ses a dataset recently released by the Land Registry on property transactions

registered to overseas companies. The paper uncovers a number of interesting results. Foreign

investment is found to have a positive e¤ect on house prices at di¤erent percentiles of the house

price distribution. This suggests that foreign investment in the housing market does not only drive

up prices of expensive homes, but has a "trickle down" e¤ect to less expensive properties. I also

highlight an important interaction between housing demand shocks and housing supply — increases

in foreign investment only appear to drive up prices in areas wh ere housing supply is particularly

constrained, either because there is less land available for construction or because of regulatory

constraints.

Looking beyond the impact on prices, I …nd no evidence that foreign investment has encouraged

construction of new housing. I also do not …nd evidence that more homes are left vacant in local

areas where foreign buyers are more active. Howe ver, I do …nd evidence that the rate of home

ownership declines as a result of foreign investment. These results should help inform the debate

on the impact of foreign investment on the housing market.

King’s College London, IZA, CEPR and Centre for Macroeconomics

20

References

[1] Adelino, M, Schoar, A., and Severino, F. (2012). ‘Credit Supply and House Prices: Evidence

from Mortgage Market Segmentation’, NBER Working Paper No. 17832.

[2] Aizenman, J. and Jinjarak, Y. (2009). ‘Current Account Patterns and National Real Estate

Markets’, Journal of Urban Economics, vol. 66, pp. 75–89.

[3] Angrist, J. D. and Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s

Companion, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[4] Badarinza. C. and Ramadorai, T. (2016). ‘Home Away from Home? Foreign Demand and

London House Prices’, Journal of Financial Economics, forthcoming, available at SSRN:

http://ssrn.com/abstract=2353124

[5] Baker, S. R., Bloom, N. and Davis, S. J. (2016). ‘Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty’,

The Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

[6] Barker, K. (2004). ‘Review of Housing Supply: Final Report — Recommendations’, London:

HMSO.

[7] Barker, K. (2006). ‘Barker Review of Land Use Planning: Final Report –Recommendations’,

London: HMSO.

[8] Bertrand, M., Du‡o, E. and Mullainathan, S. (2004). ‘How Much Should We Trust Di¤erence-

in-Di¤erences Estimates?’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 119(1), pp. 249-275.

[9] Case, K. E. and Shiller, R. J. (1989). ‘The E¢ ciency of the Market for Single-Family Homes’,

The American Economic Review, vol. 79(1), pp. 125-137.

[10] Cortes, P. (2008). ‘The E¤ect of Low-Skilled Immigration on U.S. Prices: Evidence from CPI

Data’, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 116(3), pp. 381-422.

[11] Dustmann, C., Frattini. T. and Preston, I. P. (2013). ‘The E¤ect of Immigration along the

Distribution of Wages’, Review of Economic Studies, vol. 80(1), pp. 145-173.

21

[12] Favara, G. and Imbs, J. (2015). ‘Credit Supply and the Price of Housing’, The American

Economic Review, vol. 105(3), pp. 958-992.

[13] Financial Times (2016). ‘The impact of ‘buy to leave’ on prime London’s housing market’,

February 12, 2016.

[14] Gauder, M., Houssard, C. and Orsmond, D. (2014). ‘Foreign Investment in Residential Real

Estate’, Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, June quarter.

[15] Hilber, C. A. L. and Vermeulen, W. (2015). ‘The Impact of Supply Constraints on House

Prices in England’, The Economic Journal, vol. 126(591), pp. 358–405.

[16] Jordà, O. (2005). ‘Estimation and Inference of Impulse Responses by Local Projections’, The

American Economic Review, vol. 95 (1), pp. 161–82.

[17] Jordà, O., Schularick, M. an d Taylor, A. M. (2015). ‘Betting the House’, Journal of Interna-

tional Economics, vol. 96(S1), pp. S1-S140.

[18] Mian, A. and Su…, A. (2009). ‘The Consequences of Mortgage Credit Expansion: Evidence

from the U.S. Mortgage Default Crisis’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 124(4), pp.

1449-1496.

[19] Munshi, K. (2003). ‘Networks in the Mod ern Economy: Mexican Migrants in the US Labor

Market’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 118(2), pp. 549–599.

[20] Sá, F., Towbin, P. and Wieladek, T. (2014). ‘Capital In‡ows, Financial Structure and Housing

Booms’, Journal of the European Economic Association, vol. 12(2), pp. 522–546.

[21] Sá, F. (2015). ‘Immigration and House Prices in the UK’, The Economic Journal, vol. 125, pp.

1393–1424.

[22] Saiz, A. (2010). ‘The Geographic Determinants of Housing Supply’, The Quarterly Journal of

Economics, vol.125(3), pp. 1253-1296.

[23] Savills (2014). ‘The World in London: Dynamics of a Global City — Overseas investors help

fund housing for the cosmopolitan city’, July 2014.

22

[24] Stock, J. H., Wright, J. and Yogo, M. (2002). ‘A Survey of Weak Instruments and Weak

Identi…cation in Generalised Method of Moments’, Journal of Business & Economic Statistics,

vol. 20, pp. 518-529.

[25] Stock, J. H., and Yogo, M. (2005). ‘Testing for Weak Instruments in Linear IV Regression’, in

Identi…cation and Inference for Econometric Models: Essays in Honor of Thomas Rothenberg,

D. W. K. Andrews and J. H. Stock, eds., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

23

A Appendix. Construction of foreign shares

To construct the shares of foreign investment, I divide the number (or value) of residential properties

registered to overseas companies (from the Land Registry OCD) by the total number (or value)

of residential transfers to private individuals (from the Land Registry PPD) in a given year and

local authority. Because the Land Registry PPD only contains residential properties, I classify

transactions in the Land Registry OCD into residential and commercial and retain only transactions

of residential properties.

This classi…cation is done in three stages. First, I use certain key words in the address …eld

to classify properties. For example, if the address …eld contains the words "‡at" or "apartment",

the property is classi…ed as residential; if the address …eld contains the words "land", "garage",

"industrial estate", "store", "farm", etc., the property is classi…e d as non-residential. In a second

stage, I merge properties that remain unclassi…ed after the …rst stage with data from the Ordnance

Survey AddressBase dataset, which contains information on whether an address is commercial or

residential. The merge is done by property number or name, street and postcode. Finally, any

remaining unclassi…ed properties are searched manually in the Royal Mail Address Finder software

or on Google maps and classi…ed as residential or commercial. At the end of this process, 98; 271

records were classi…ed out of a total of 99; 345 transactions in the Land Registry OCD. About 50%

of the classi…ed records are residential properties.

B Appendix. Calculation of house price-earnings elasticities

The calculation of house price-earnings elasticities is based on equation (8) in Hilber and Vermeulen

(2015):

log(house price

j;t

) =

0

+

1

log(earnings

j;t

) +

2

log(earnings

j;t

) refusal rate

j

+

3

log(earnings

j;t

) %developed

j

+

4

log(earnings

j;t

)

elevation

j

+

34

P

i=1

4+i

D

t

+

352

P

i=1

38+i

D

j

+ "

j;t

where j denotes local planning authority (LPA) and t denotes year. The dependent variable

24

is the log of the mix-adjusted house price index and the main regressor is the log of male weekly

earnings. The model is estimated on 34 years of data (1974-2008). Regulatory constraints are

captured by the refusal rate of planning applications for major projects (consisting of 10 or more

dwellings), averaged over the period from 1979 to 2008. Land scarcity is captured by the share of

land already developed in 1990 and the elevation range. The model includes year …xed e¤ects (D

t

)

and LPA …xed e¤ects (D

j

). The refusal rate is instrumented with the share of votes for the Labour

Party in the 1983 general election and the change in the delay rate of major planning applications

following a reform introduced by the Labour government in 2002, which set a target to speed up

the planning process. The share of land already developed is instrumented with population density

in 1911.

The authors standardise the three measures of supply constraints by subtracting the mean and

dividing by the standard deviation. With this standardisation, the coe¢ cient

1

can be interpreted

as the house price-earnings elasticity for an LPA with average levels of the supply constraints.

I use the coe¢ cients and data in Hilber and Vermeulen (2015) to calculate the house-price

earnings elasticity in each LPA as follows:

\

elasticity

j

=

b

1

+

b

2

refusal rate

j

+

b

3

%developed

j

+

b

4

elevation

j

The local authorities in my sample do not exactly match the LPAs in Hilber and Vermeulen

(2015), because the Land Registry house price index is available at a lower level of disaggregation

than the mix-adjusted house price index used in their p aper. In cases where there is no match, I take

the average of the house price-earnings elasticities for all LPAs in a given local authority. Because

the measures of supply constraints are standardised, it is possible to obtain negative elasticities for

some local authorities, as shown in Figure 7.

25

Figure 1. Evolution of average house prices and share of foreign transactions

Source: Land Registry house price index, Land Registry Overseas Companies Dataset and Private Eye

offshore companies dataset (for values).

Figure 2. Average house prices in England and Wales, 2014

Source: Land Registry house price index.

0 .5 1

1.5 2

%

50000 100000

150000 200000 250000

£

1999

2002

2005

2008 2011

2014

year

average house prices (£)

foreign transactions - volume (%)

foreign transactions - value (%)

Figure 3. Average share of residential transactions in England and Wales registered to a foreign-owned

company, 2014

Volume

Value

Source: Land Registry Overseas Companies Dataset and Private Eye offshore companies dataset (for

values).

Table 1. Local authorities with the largest share of foreign transactions, 2014

Local authority

Foreign

transactions -

volume (%)

House prices (£)

Local authority

Foreign

transactions -

value (%)

House prices (£)

Westminster

13.1

922,702

Westminster

27.2

922,702

Kensington and Chelsea

12.1

1,288,406

Kensington and Chelsea

23.5

1,288,406

Salford

3.9

116,588

Greenwich

14.4

298,352

Camden

3.6

756,487

Salford

13.1

116,588

Liverpool

2.6

111,859

Bournemouth

7.6

198,537

Hammersmith

2.6

721,100

Manchester

6.4

130,355

Tower Hamlets

2.4

382,242

Camden

6.1

756,487

Lambeth

1.8

433,625

Bexley

5.7

244,459

Leeds

1.7

146,745

Kingston Upon Thames

5.2

406,106

Barnet

1.4

430,363

Leicester

4.7

129,463

Source: Land Registry house price index, Land Registry Overseas Companies Dataset and Private Eye offshore

companies dataset (for values).

Table 2. Countries of incorporation with the largest shares of investment, 2014

Country

Share of overseas investment in 2014

(in volume)

British Virgin Islands

33.5

Guernsey

19.4

Jersey

11.5

Isle of Man

10.1

Seychelles

2.9

Hong Kong

2.4

Luxembourg

2.1

Cyprus

1.7

Singapore

1.4

Panama

1.4

Source: Land Registry Overseas Companies Dataset.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics (1999 – 2014)

Variable

Observations

Mean

SD

Min

Max

Δ log house price index

2,580

0.069

0.091

-0.180

0.406

Δ total dwellings

1,963

0.007

0.010

-0.221

0.334

Share dwellings with no usual residents

(a)

173

0.045

0.024

0.019

0.207

Share households in owner-occupied

173

0.621

0.112

0.238

0.797

accommodation

(a)

Share foreign transactions - volume

2,752

0.003

0.011

0.000

0.214

Share foreign transactions - value

2,752

0.007

0.028

0.000

0.499

Unemployment rate

2,386

0.069

0.028

0.011

0.180

Benefits rate

2,752

0.149

0.049

0.044

0.331

House price - earnings elasticity

(b)

2,411

0.175

0.347

-0.492

1.151

(a) Cross-section from the 2011 Census.

(b) Author’s calculations, based on coefficients and data in Hilber and Vermeulen (2015).

Table 4. House prices and foreign transactions

Δ log house prices

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Panel A. OLS

Share foreign transactions - volume

0.647***

0.659***

(0.123)

(0.132)

Share foreign transactions - value

0.161***

0.160**

(0.060)

(0.066)

Lagged Δ log house price

0.510***

0.446***

0.520***

0.460***

(0.011)

(0.017)

(0.011)

(0.017)

Lagged Δ unemployment rate

-0.085*

-0.101**

(0.048)

(0.049)

Lagged Δ benefits rate

-1.139***

-1.071***

(0.289)

(0.291)

R

2

within

0.858

0.862

0.857

0.860

Panel B. IV

Share foreign transactions - volume

2.166***

2.116***

(0.828)

(0.787)

Share foreign transactions - value

1.394***

1.427***

(0.535)

(0.537)

Lagged Δ log house price

0.467***

0.388***

0.456***

0.361***

(0.014)

(0.022)

(0.019)

(0.028)

Lagged Δ unemployment rate

-0.050

-0.099

(0.048)

(0.067)

Lagged Δ benefits rate

-1.493***

-1.795***

(0.294)

(0.343)

First-stage coefficients

-0.018***

-0.017***

-0.028***

-0.025***

(0.006)

(0.006)

(0.010)

(0.008)

Kleinbergen-Paap Wald rk F-statistic

7.797

8.065

8.364

8.695

Anderson-Rubin Wald test

49.826***

48.912***

49.826***

48.912***

Observations

2,408

2,005

2,408

2,005

Number of clusters

172

172

172

172

Notes: Panel A reports OLS coefficients from regressions of the log change in house prices on the share of

residential transactions registered to foreign-owned companies in volume (columns 1 and 2) and in value

(columns 3 and 4). Panel B reports coefficients of an IV specification in which the share of foreign transactions

is instrumented with a variable based on economic shocks abroad (see text for details on the construction of

the instrument). All variables are defined in appendix Table A1. The sample includes 172 local authorities in

England and Wales for the period 1999-2014. Regressions include local authority and year fixed effects and a

lagged dependent variable. Standard errors are clustered by local authority.

Stock-Yogo weak identification critical values: 16.38 (10%), 8.96 (15%), 6.66 (20%) and 5.53 (25%).

***Significant at the 1 percent level; ** significant at the 5 percent level; * significant at the 10 percent level.

Figure 4. Counterfactual analysis

Notes: The figure reports the evolution of average house prices for 172 local authorities in England and

Wales (solid line), the evolution of average house prices predicted by the model with the actual observed

value share of foreign transactions (dashed line) and the evolution of average house prices predicted by

the model when the value share of foreign transactions is set to zero in all local authorities (short dashed

line). The coefficients used in the predictions are from an IV regression of the log change in house prices

on the share of foreign transactions in volume. The share of foreign transactions is instrumented with a

variable based on economic shocks abroad (see text for details on the construction of the instrument).

The sample includes 172 local authorities in England and Wales for the period 1999-2014. The regression

includes local authority and year fixed effects and a lagged dependent variable.

50000 100000 150000 200000 250000

£

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

year

average house prices

predicted house prices

predicted house prices with no foreign buyers

Notes: The figure reports estimated coefficients and 90 percent confidence interval from local projection

instrumental variables (LP-IV) equations, which look at the effect of an increase in the share of foreign

investment (in volume and in value) on house price growth for four years after the shock. The share of

foreign transactions is instrumented with a variable based on economic shocks abroad (see text for

details on the construction of the instrument). The sample includes 172 local authorities in England and

Wales for the period 1999-2014. The regression includes local authority and year fixed effects, a lagged

dependent variable and lagged changes in the unemployment rate and in the benefits rate.

0 2 4 6 8

0 1 2

3 4

Years

Panel A. House price response to instrumented volume share of foreign transactions

0 2

4 6 8 10

0 1 2

3 4

Years

Panel B. House price response to instrumented value share of foreign transactions

(dashed lines are 90 percent confidence bands)

Figure 5. House prices: impulse responses to instrumented shock to share of foreign transactions

Table 5. House prices and foreign transactions – impact on different percentiles of the distribution of

house prices

Share foreign transactions

volume

value

Dependent variable – percentile of

distribution of house prices

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Panel A. OLS

5

th

percentile

0.814***

0.784***

0.175**

0.185**

(0.198)

(0.163)

(0.078)

(0.084)

10

th

percentile

0.837***

0.834***

0.202**

0.210**

(0.192)

(0.184)

(0.094)

(0.104)

25

th

percentile

0.772***

0.808***

0.160*

0.167*

(0.164)

(0.189)

(0.082)

(0.093)

50

th

percentile

0.818***

0.864***

0.200***

0.211***

(0.165)

(0.164)

(0.064)

(0.073)

75

th

percentile

1.020***

1.064***

0.254***

0.264***

(0.147)

(0.155)

(0.078)

(0.088)

90

th

percentile

1.279***

1.270***

0.328***

0.317***

(0.196)

(0.195)

(0.108)

(0.117)

95

th

percentile

1.597***

1.556***

0.401***

0.378***

(0.223)

(0.199)

(0.128)

(0.137)

Panel B. IV

5

th

percentile

2.053**

2.139***

1.314***

1.423***

(0.817)

(0.822)

(0.491)

(0.508)

10

th

percentile

1.712***

1.852***

1.092***

1.229***

(0.662)

(0.688)

(0.400)

(0.429)

25

th

percentile

1.669***

1.840***

1.069***

1.230***

(0.606)

(0.639)

(0.388)

(0.432)

50

th

percentile

2.087***

2.186***

1.331***

1.444***

(0.776)

(0.803)

(0.492)

(0.527)

75

th

percentile

1.945***

1.867***

1.246***

1.239***

(0.687)

(0.638)

(0.432)

(0.420)

90

th

percentile

2.465***

2.156***

1.572***

1.422***

(0.850)

(0.733)

(0.524)

(0.467)

95

th

percentile

2.754***

2.316***

1.757***

1.527***

(0.865)

(0.695)

(0.529)

(0.439)

Controls

No

Yes

No

Yes

Observations

2,408

2,005

2,408

2,005

Number of clusters

172

172

172

172

Notes: Panel A reports OLS coefficients from regressions of the log change of different percentiles of the

distribution of house prices on the share of residential transactions registered to foreign-owned companies

in volume (columns 1 and 2) and in value (columns 3 and 4). Panel B reports coefficients of an IV

specification in which the share of foreign transactions is instrumented with a variable based on economic

shocks abroad (see text for details on the construction of the instrument). The sample includes 172 local

authorities in England and Wales for the period 1999-2014. Regressions include local authority and year

fixed effects and a lagged dependent variable. Controls include lagged changes in the unemployment rate

and in the benefits rate. Standard errors are clustered by local authority.

***Significant at the 1 percent level; ** significant at the 5 percent level; * significant at the 10 percent

level.

Notes: The figures report the estimated IV regression coefficients and 90 percent confidence interval

from a regression of the log change in different percentile of the distribution of house prices on the share

of foreign transactions in volume and in value. The share of foreign transactions is instrumented with a

variable based on economic shocks abroad (see text for details on the construction of the instrument).

The sample includes 172 local authorities in England and Wales for the period 1999-2014. Regressions

include local authority and year fixed effects, lagged changes in the unemployment rate and in the

benefits rate and a lagged dependent variable.

0 1 2 3 4

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

100

Year of observation

Panel A. Impact of volume share of foreign transactions

.5 1 1.5 2 2.5

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

100

Year of observation

Panel B. Impact of value share of foreign transactions

(dashed lines are 90 percent confidence bands)

Figure 6. Effect of foreign transactions across the distribution of house prices

Figure 7. House price-earnings elasticity

Source: Author’s calculations, based on coefficients and data in Hilber and Vermeulen (2015). See the

appendix for more details on the calculation of the elasticities. Local authorities in England only.

Table 6. House prices and foreign transactions – effect across different quartiles of the distribution of

house price-earnings elasticity

Δ log house prices

volume share

value share

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Panel A. OLS

Quartile 1

-0.405

-0.166

-0.035

-0.025

(0.626)

(0.705)

(0.022)

(0.030)

Quartile 2

-0.171

-0.136

-0.017

-0.007

(0.162)

(0.135)

(0.032)

(0.031)

Quartile 3

1.033*

1.150**

0.380**

0.411**

(0.602)

(0.559)

(0.164)

(0.159)

Quartile 4

0.298***

0.299***

0.156***

0.155***

(0.078)

(0.098)

(0.034)

(0.038)

Panel B. IV

Quartile 1

49.926

118.252

0.718

0.642

(103.028)

(489.064)

(0.912)

(0.728)

Quartile 2

-5.942

-0.210

-0.500

-0.018

(11.022)

(8.408)

(0.913)

(0.737)

Quartile 3

5.940***

6.370***

4.073***

3.812***

(2.052)

(2.060)

(1.443)

(1.064)

Quartile 4

0.712**

0.652**

0.496**

0.483*

(0.325)

(0.330)

(0.251)

(0.263)

Controls

No

Yes

No

Yes

Notes: Panel A reports OLS coefficients from regressions of the log change in house prices on the share of

residential transactions registered to foreign-owned companies in volume (columns 1 and 2) and in value

(columns 3 and 4). Panel B reports second-stage coefficients of an IV specification in which the share of

foreign transactions is instrumented with a variable based on economic shocks abroad (see text for

details on the construction of the instrument). All variables are defined in appendix Table A1. Local

authorities are classified into four groups, corresponding to each quartile of the distribution of the house

price-earnings elasticity. Regressions are run separately for each of these four groups of local authorities.

The sample includes 150 local authorities in England for the period 1999-2014. Regressions include local

authority and year fixed effects and a lagged dependent variable. Controls include lagged changes in the

unemployment rate and in the benefits rate. Standard errors are clustered by local authority.

***Significant at the 1 percent level; ** significant at the 5 percent level; * significant at the 10 percent

level.

Table 7. House prices and foreign transactions – alternative samples

Δ log house prices

London LAs

High transaction LAs

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

Panel A. OLS

Share foreign transactions - volume

0.281***

0.387***

(0.087)

(0.122)

Share foreign transactions - value

0.160***

0.199***

(0.035)

(0.045)

Lagged Δ log house price

0.321***

0.314***

0.413***

0.408***

(0.075)

(0.072)

(0.036)

(0.034)

Lagged Δ unemployment rate

-0.026

-0.037

-0.060

-0.084

(0.065)

(0.064)

(0.141)

(0.144)

Lagged Δ benefits rate

-0.755

-0.801

-1.832**

-1.817**

(0.501)

(0.501)

(0.850)

(0.835)

R

2

within

0.896

0.897