Walden University Walden University

ScholarWorks ScholarWorks

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection

2019

Nursing Knowledge on Pressure Injury Prevention in the Intensive Nursing Knowledge on Pressure Injury Prevention in the Intensive

Care Unit Care Unit

Yanick Jacob

Walden University

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

Part of the Nursing Commons

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an

authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected].

Walden University

College of Health Sciences

This is to certify that the doctoral study by

Yanick Jacob

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Carolyn Sipes, Committee Chairperson, Nursing Faculty

Dr. Patricia Senk, Committee Member, Nursing Faculty

Dr. Joanne Minnick, University Reviewer, Nursing Faculty

Chief Academic Officer and Provost

Sue Subocz, Ph.D.

Walden University

2019

Abstract

Nursing Knowledge of Pressure Injury Prevention in the Intensive Care Unit

by

Yanick Jacob

MS, Walden University, 2019

BS, Long Island University College, 1985

Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Nursing Practice

Walden University

November 2019

Abstract

Over 60,000 hospital patients die each year from complications associated with hospital-

acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs). Pressure-injury rates have increased by 2% within the

past decade as life expectancy has also increased due to high cost in Medicare. Evidence

shows that the incidence of pressure injuries (PIs) in healthcare facilities is increasing,

with high rates of occurrence in intensive care units (ICUs). At the clinical site for which

this project was developed, multiple in-services had been provided to staff regarding PIs,

but uncertainty persisted about how knowledgeable the nurses were. This project, using

the Academic Center for Evidence Star Model of Knowledge Transformation improved

the nurses’ knowledge and their practice related to PI prevention in the ICU, as well as to

translate evidence into nursing practice. A literature review was conducted on PI

prevention to inform the project. The project provided an educational program for

intensive care nurses on PI prevention and determined, based on participants’ pre- and

posttest responses, that nurses’ knowledge improved as a result of participation. This

project, involving 55 nurses, includes information on the Pieper-Zulkowski Pressure

Ulcer Knowledge Test (PZ-PUKT) measuring pressure knowledge which resulted in an

85% improvement on injury prevention, 76% in wound description, as well as, 62% in

the Braden Scale. Improvements in knowledge and practice resulting from nurses’

participation in an evidence-based education session on PI prevention may bring positive

social change to the organization at which this project was conducted.

Nursing Knowledge of Pressure Injury Prevention in the Intensive Care Unit

by

Yanick Jacob

MS, Walden University, 2019

BS, Long Island University, 1985

Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Nursing Practice

Walden University

November 2019

Dedication

I would like to dedicate my Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) final project to

God, who gave me the strength to pursue my dreams. To my family, especially Claudel,

my husband, who was always there for me, staying up me while I was working on my

project. Without his help, this dream could not have been a success. I wanted to thank my

kids, Vanessa and Tamara, for understanding and cooperating with me. Many times, I

wanted to quit, but they kept me going and said they believed in me. To all family

members (with special thanks to my sister Gladys), friends, and coworkers, who have

helped and supported me along this process, this is for you.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the team of faculty—Dr. Carolyn Sipes, Dr. Patricia

Senk, Dr. Joanne Minnick, and Dr. Nancy Moss—who helped me achieve this journey;

their mentorship enabled me to get to this point. I would like to thank all my family and

friends who have supported me reach this goal.

i

Table of Contents

List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... iv

Section 1: Nature of the Project ...........................................................................................1

Introduction ....................................................................................................................1

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................2

Purpose ...........................................................................................................................3

Addressing the Gap in Practice ......................................................................................4

Practice-Focused Question.............................................................................................5

Nature of the Doctoral Project .......................................................................................6

Approach Used...............................................................................................................6

Significance of the DNP Doctoral Project .....................................................................7

Stakeholder Analysis .....................................................................................................8

Contributions to Nursing Practice ..................................................................................8

Transferability of Knowledge ........................................................................................8

Implications for Positive Social Change ........................................................................9

Summary ........................................................................................................................9

Section 2: Background and Context ..................................................................................11

Introduction ..................................................................................................................11

Concepts, Models, and Theories ..................................................................................11

Literature Review.........................................................................................................13

Search Strategy ............................................................................................................15

Local Background and Context ...................................................................................16

ii

Relevance to Nursing Practice .....................................................................................17

Role of the DNP Student..............................................................................................18

Professional Role in the Project ............................................................................ 19

Motivation for Completing the Project ................................................................. 19

Potential Biases ..................................................................................................... 20

Expert Panel .......................................................................................................... 20

Summary ......................................................................................................................21

Section 3: Collection and Analysis of Evidence ................................................................23

Introduction ..................................................................................................................23

Practice-Focused Question...........................................................................................23

Sources of Evidence .....................................................................................................23

Setting and Sample Population ....................................................................................24

Participants ...................................................................................................................24

Procedures ....................................................................................................................25

Instrumentation and Materials .....................................................................................26

Protection of Participants .............................................................................................27

Project Ethics and Institutional Review Board (IRB) ..................................................27

Data Analysis and Synthesis ........................................................................................27

Summary ......................................................................................................................28

Section 4: Findings and Recommendations .......................................................................29

Findings and Implications ............................................................................................30

Recommendations ........................................................................................................36

iii

Strengths and Limitations ..................................................................................... 37

Future Directions .................................................................................................. 39

Section 5: Dissemination Plan ...........................................................................................40

Plan for Dissemination .................................................................................................40

Analysis of Self ............................................................................................................42

As Scholar ............................................................................................................. 42

Project Manager .................................................................................................... 43

Summary ......................................................................................................................44

References ..........................................................................................................................45

Appendix A: Power Point Presentation for Expert Panel ..................................................54

Appendix B: Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Pretest ....................................................59

Appendix C: Pieper Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Posttest ..................................................61

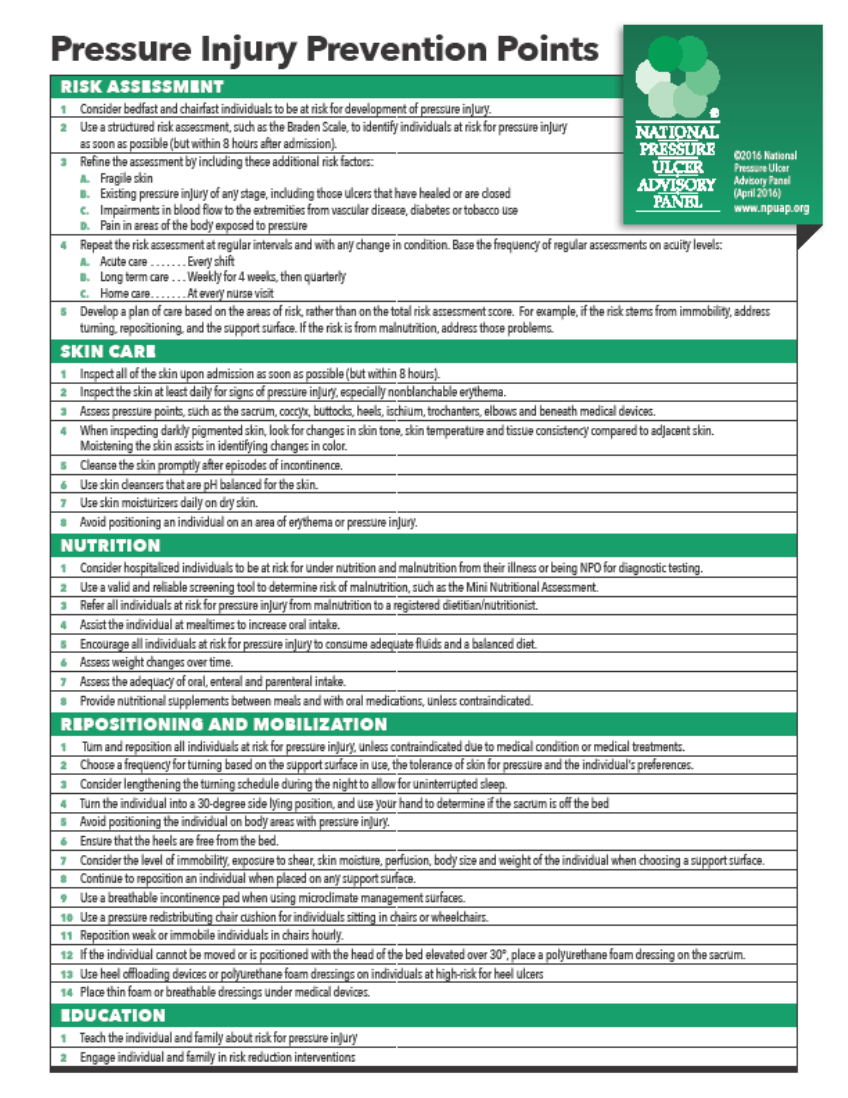

Appendix D: Education Packet ..........................................................................................63

Appendix E: Best Practice Checklist/Pressure Injury Prevention Bundle .........................65

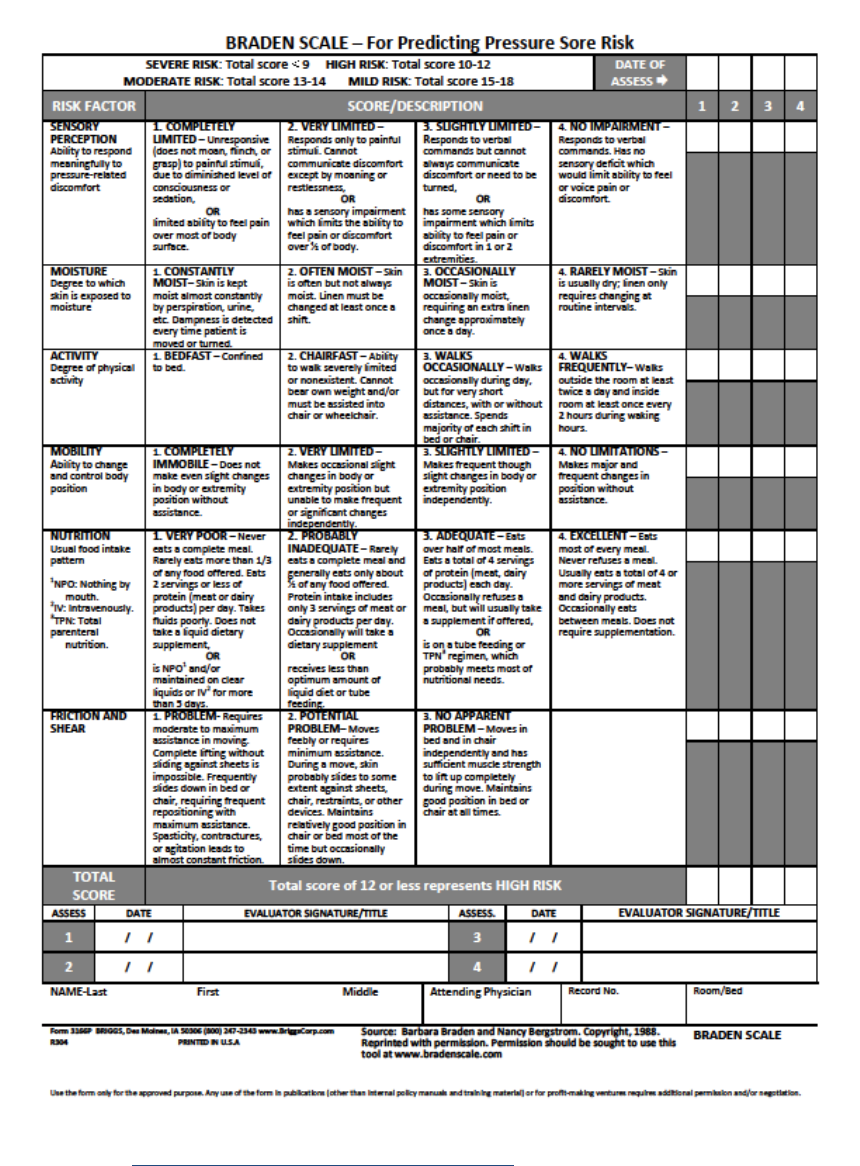

Appendix F: Braden Scale Risk Assessment Tool ............................................................66

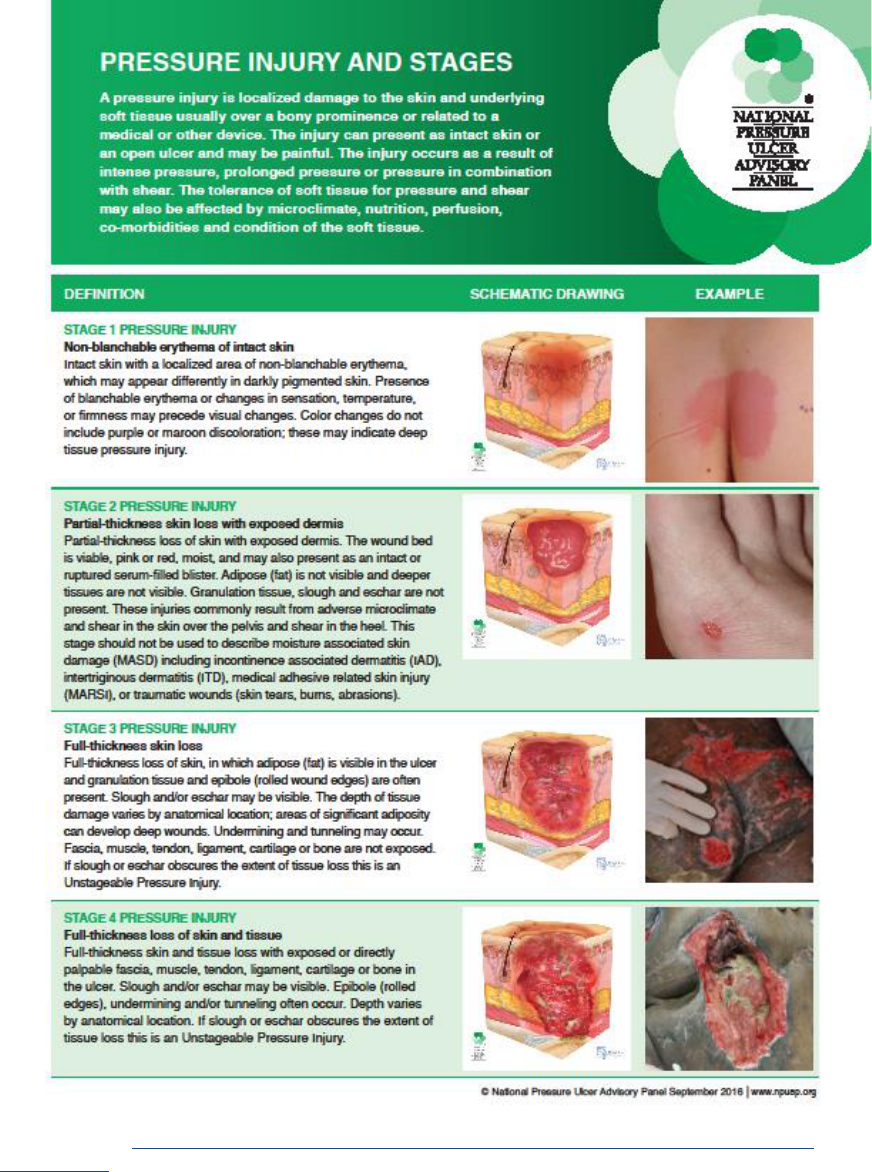

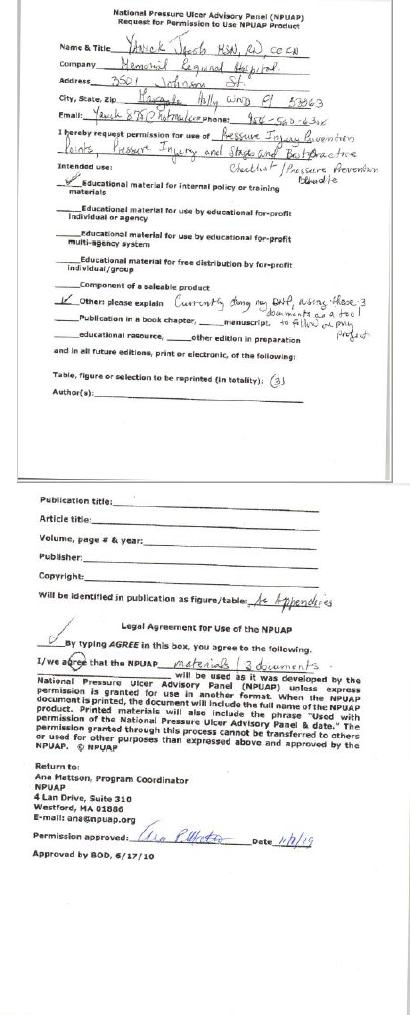

Appendix G: Permission for NPUAP Product ...................................................................67

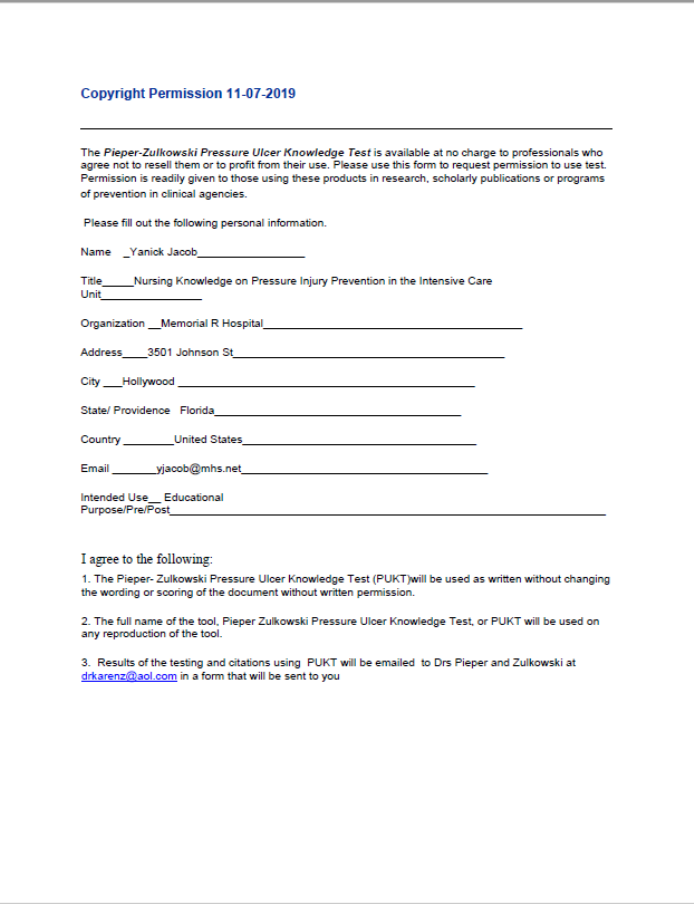

Appendix H: Permission for Pieper-Zulkowski Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test .............68

iv

List of Tables

Table 1. Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Pressure Injury Prevention ..................326

Table 2. Comparison of Nurses' Knowledge on Staging ...................................................37

Table 3. Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Braden Scale .........................................38

Table 4. Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Education Program ................................39

1

Section 1: Nature of the Project

Introduction

The quality of care provided by acute-care facilities is being scrutinized by many

government agencies, such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

The Institute of Medicine and the Institute of Healthcare Improvement have voluntarily

joined organizations such as the Leapfrog Group and Hospital Quality Initiative (HQI) to

ensure healthcare quality for the public by identifying when nursing may influence

negative outcomes in hospitals (Leapfrog Group, 2011). Quality indicators include

hospital-related conditions such as catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs)

and hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs). Pressure injuries (PIs), formerly known

as pressure ulcers, continue to be a problem in the hospital setting. As defined by the

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP, 2016), a PI is “a localized injury to the

skin and/or underlying tissue over a bony prominence, as a result of pressure, or pressure

in combination of shear.”

In the United States, it is estimated that 2.5 million patients per year are affected

with PIs (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2014). In the intensive

care unit (ICU), pressure injuries are associated with an increased risk of death, longer

length of stay, and discomfort (Apostolopoulou et al., 2014). In addition, the

development of PIs has been used as a measure of the quality of care that is provided to

patients (Meddings et al., 2015).

The goal of this project was to provide education to critical-care nurses on PI

prevention and to assess participants’ knowledge and practice improvement after

2

completion of the education. A staff education project was developed to meet the need

for an evidence-based educational program to support nursing knowledge about PI

prevention and assessment. The target population consisted of critical-care registered

nurses in a medical ICU. In this 30-bed ICU in a tertiary-care facility in the southeastern

United States, PIs remain at 0.3% to 1% per month, as compared to the national incidence

rate of 2.5% (Padula, 2017).

Problem Statement

The practice problem for this DNP project was the high occurrence of PIs

developing in the ICU. Patients in the ICU are critically ill, with many experiencing

multiorgan failure, so prevention of PI is essential. PI affects the comfort of the patient

and extends the patient’s duration of stay in the hospital. On average, the organization

admits several patients with life-threatening disease, infection, and PIs. The facility

provides numerous opportunities for nurses to learn about PIs, including skills fair and a

routine in-service on PI prevention, but PI has always seemed to be an issue. The facility

also has new staff members whose knowledge base on prevention is unknown. The

problem is significant because nurses frequently do not use the preventive measures

available to them. To help nurses gain a better understanding of how best to prevent PIs,

this project was developed to provide evidence-based information to the nurses in the

ICU. I sought to assess nurses’ knowledge and practice related to PI prevention in order

to identify any supports that might be needed for an improvement or change in practice.

Currently, HAPIs represent a national concern due to increased patient morbidity, the

high cost of treatment, and medical expenses (Zaratkiewicz et al., 2011). The

3

development of pressure injuries is linked to poor patient outcomes, but most HAPIs can

be prevented if hospitals improve the quality of their care. However, since July 2015, due

to higher incidents of HAPIs, PI has increased by 2% as life expectancy has also

increased (Cano, Anglade, Stamp, & Young, 2015).

Currently, there is evidence that the incidence of PIs in healthcare facilities is

increasing. Over 60,000 hospital patients die each year from complications associated

with HAPIs. HAPI rates vary depending on the clinical setting, ranging from 2.2% to

23.9% in long-term care to 0% to 17% in home care (Health Research & Educational

Trust, 2017). According to NPUAP (2015), PI care in the United States costs around $11

billion annually. Costs for an individual PI can vary from $500 to $70,000. According to

the Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN, 2017), PI is a complex

problem due to multiorgan failure and comorbidities. Recognizing that PIs cannot be

completely eliminated, the WOCN (2017) issued a position statement on avoidable

versus unavoidable PIs. Policies and campaigns have been implemented to encourage

hospitals to improve the quality of care in an effort to reduce unnecessary and

preventable costs. Medical devices related to PI have come to be more than 30% of the

overall hospital-acquired pressure ulcer injury (HAPU/I) rate therefore to treat PIs

quickly, to reduce the cost and improve quality interventions must be implemented

(Health Research & Educational Trust, 2017).

Purpose

The purpose of this staff education project was to provide an educational program

to intensive care nurses on PI prevention and to determine whether nursing knowledge

4

improved when measured by pre- and posttest responses. Nurses perform and inspect all

pressure points on admission, on transfers, at the beginning of each shift, for each end-of-

shift report, and at discharge, but PI remains a concern in the project agency.

Addressing the Gap in Practice

A better understanding of the gap between theory and practice may encourage

healthcare providers to pay more attention to evidence-based practice (EBP)

recommendations in order to reduce PI incidence in healthcare settings. In this case, there

is a gap in nursing education and application of knowledge regarding PI prevention.

The staff education project was developed to address the gap in practice regarding

EBP for PI prevention by improving nurses’ knowledge of PIs. In order to ensure

superior prevention of PIs, it is necessary to assess nurses’ knowledge and practice (Joint

Commission Resources, 2012). The Pieper-Zulkowski Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test

(PZ-PUKT) was used to measure PI knowledge in addition to factors attributed to

development of pressure injuries (Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014). It has been reported that

many nurses have inadequate knowledge concerning PIs and the staging of wounds

(Delmore et al., 2018) and need to be educated on PI prevention.

Waugh (2014) conducted a systematic review using seven studies to examine

nursing knowledge and PI prevention and found that there was no relation to the

application of adequate PI prevention. Furthermore, nurses with higher levels of

education have scored higher in knowledge in some studies, whereas other studies have

shown no difference in knowledge associated with nurses’ education (Waugh, 2014).

5

The WOCN (2017) recommended further research to identify the development of

risk factors for PI and interventions for clinical practice. The WOCN has noted the need

for a fuller understanding of the conditions and risk factors associated with avoidable and

unavoidable PIs.

Practice-Focused Question

The practice-focused question for this project helped to identify the clinical

problem relating to PI prevention (Fineout-Overholt, Melynk, Stillwell, & Williamson,

2010). The question was as follows: To what extent will the nurses’ knowledge on

pressure injuries improve after attending a structural education program?

Due to a lack of documentation on PI prevention, it appeared that the nursing staff

did not understand the importance of adequate preventative measures for PIs. For

example, the Braden Scale is highly predictive of PI development, although it is utilized

inefficiently. In 2014, wound experts with NPUAP affirmed that not all PIs can be

prevented in the ICU, suggesting that the development of PI may be unavoidable in

critically ill patients (Cox, Roche, & Murphy, 2018). In the facility, the Braden Scale is

used as an assessment tool for patients at risk of PI. Understanding the scale and its

scoring assist in determining the level of risk. A score of 15-18 identifies a patient at risk,

a score of 13-14 identifies moderate risk, a score of 10-12 indicates high risk, and a score

below 9 identifies greater risk (Cox et al., 2018). However, Bergstrom and Braden (2002)

recommended that low subscale scores are to be used for prevention protocols, as these

are now required by CMS (Cox et al., 2018). In addition, there may be a lack of research

6

evidence on the effectiveness of some interventions that are available (Gray, Grove &

Sutherland, 2017).

Nature of the Doctoral Project

The evidence that was used to meet the purpose of this doctoral project included

information obtained from various literatures. In identifying the research problem, I used

research from Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Medline,

Joanna Briggs Institute, and Cochrane. The population involved in this project included

wound care nurses, the wound care champion RN of the unit, dieticians, and a physical

therapist. A questionnaire tool was provided to all nurses in the critical care units in the

medical ICU to measure knowledge and practice on PIs. The doctoral project was

conducted to assess nursing knowledge of an EBP for PI prevention in intensive care

nurses after providing an educational program. I used a validated questionnaire tool to

assess nurses’ knowledge of PI prevention and practice. The staff education project

involved pretest-posttest administration of a questionnaire to determine the effect of

education on nursing knowledge on PI. ICU nurses involved in delivering regular care to

any patient at risk of PI were included.

Approach Used

The approach that was used for this doctoral project included a comprehensive

literature review on PI prevention and practice in the ICU. The project was directed by

the Academic Center for Evidence (ACE) Star Model of Knowledge Transformation to

translate evidence into nursing practice, which has been used as a guide to increase

understanding of the use of EBP in nursing practice and its relevance in clinical decision

7

making (Stevens, 2013). The development of nursing knowledge is relevant.

Furthermore, it will be evaluated to appropriately answer the research question. The ACE

model was used to assist in nursing education, PI prevention, practice, skin assessment,

and the Braden Scale.

Significance of the DNP Doctoral Project

The NPUAP has developed many educational materials regarding PI. The

persistence of PIs as a problem in the hospital setting can be attributed to the inadequacy

of efforts to disseminate the knowledge required to prevent these injuries (NPUAP,

European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, & Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance, 2014).

I discussed the need for this project with the nurse manager and how it might be

beneficial to assess nursing knowledge and practice. In 2011, the Center for Medical

Surveillance began reporting HAPI rates for hospitals on its Hospital Compare website,

and in 2014, the Affordable Care Act began reducing reimbursement to hospitals that

were in the highest quartile for incidence of hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) for

Medicare patients (Meddings et al., 2015). PI is considered as a localized injury to the

skin or underlying body tissue that occurs over bony prominences (NPUAP, 2016).

Working in ICU exposes staff to the rigors of PI prevention in immobile patients, and

despite the many protocols that are available to deal with the issue, it keeps occurring.

Efforts to assess nursing knowledge and practice can be useful if problems can be

identified and improvements in the quality of patient care can be achieved. Such efforts

to support PI prevention are important because the incidence of HAPIs has increased

nationally in medical ICUs (Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, 2012).

8

Stakeholder Analysis

Stakeholders in this project were the hospital administrators, the nurse manager

for the unit, and the wound care specialists. These experts were informed of the project

and were asked to offer guidance. The stakeholders may be impacted by the results of the

pretest/posttest questionnaires, and could further impact the rate of PI incidence in the

facility.

Contributions to Nursing Practice

PIs can contribute to increased length of hospital stay, increased chance of death,

missed employment days, social isolation, pain, suffering, and financial burden

(Strazzieri-Pulido, Gonazalez, Nogueria, Padilha, & Santos, 2019). Hospital mortality

rates have increased to 11.2% with patients who developed HAPIs and the rate of

mortality with readmission within 30 days after discharge was 15.3% (Lyder et al., 2012).

This project assessed nurses’ knowledge of PI prevention and practice with the

implementation of an evidence-based education program. Nursing knowledge of

prevention and assessment of PIs is essential to lowering PI rates.

Transferability of Knowledge

Through this DNP project, critical-care nurses gained knowledge and experience

on PI prevention in nursing practice. An additional goal of this project is to support

positive change by sharing the findings with others in similar practice areas with similar

issues such as PIs. Dealing with PI is a major concern in hospitals because CMS will no

longer reimburse for PIs caused while patients are hospitalized (Cooper, 2013).

9

Implications for Positive Social Change

There have been a number of suggestions to increase nursing knowledge over the

years. Some of the most effective involve providing standard operating protocols in the

practice setting, providing summaries of information at conferences and workshops, and

recognizing continuous educational achievements through certifications and honors.

Assessing critical-care nurses’ knowledge and practice through an evidence-based

educational program on PI prevention may bring positive social change to the

organization at which this project was conducted. Educational program can bring

knowledge closer to nurses, alleviate the strain of nurses’ workload, and give nurses

motivation to receive continuing education. In efforts to transfer knowledge, professional

bodies require that all nurses complete a required continuing education regimen over a

period of time. Several resolutions in assisting continuing education have been proposed,

such as making required reading material available in summary form as well as having

the material available for staff through electronic means. However, these methods have

not been taken up effectively (Clark et al., 2015; Coventry, Maslin-Prothero, & Smith,

2015).

Summary

In the field of acute care, critically ill patients are at a high risk for developing

PIs. Preventing PIs is a healthcare concern in the hospital where I implemented this DNP

project, and this project was an effort to mitigate PIs by determining the level of nurses’

knowledge of PI prevention and practice in the ICU through an educational program. In

Section 2, I present the background and context of project, which are supported by a

10

comprehensive literature review on PI prevention and practice.

11

Section 2: Background and Context

Introduction

In the hospital- and home-care settings, there are an increasing number of

patients who are immobilized by illness. This situation has led to an increase in the

incidence of PIs. PIs represent a significant concern in the hospital-care setting. The

focus question for this project was the following: To what extent will the nurses’

knowledge on pressure injuries improve after attending a structural education program?

This project assessed the impact of an evidence-based education program on nurses’

knowledge of PI prevention and assessment.

The DNP project focused on assessing the information that was possessed by

nurses and disseminating information in regard to PI prevention. It encompassed a

literature review on the prevention of PIs. Using a pre- and posttest questionnaire as the

chief study design, I obtained information from nurses on their knowledge of current

practice guidelines. In this section, I present the theoretical models for the project, a

literature review, and the project’s relevance to nursing practice.

Concepts, Models, and Theories

Theoretical frameworks create a reference for interpretation or generalization of

the literature. The theoretical framework suggested that evidence-based practice (EBP) is

valid; therefore, confirming the need to understand research findings. Furthermore,

evidence-based nursing practice is the identification of theories on human health and

human experiences to direct modalities of care. Using EBP to make changes in current

practices have proven effective and demonstrate positive outcomes. Failure to apply EBP

12

to guide nursing care increases the risk of poor effects (Chrisman, Jordan, Davis, &

Williams, 2014). With this in mind, I used the evaluation criteria proposed Chrisman, et,

al, 2014) to guide the direction of this project.

Nurses have developed numerous EBP models to help in understanding evidence

in the context of nursing practice. The ACE model assists in examining and applying

EBP in a manner that is useful for nursing. (Academic Center for Evidence-Based

Practices [ACEBP], 2012).

Using the ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation, one can discover

barriers when moving evidence into practice and implementing solutions grounded in

EBP. The ACE model includes competencies for essential skills of knowledge

management, accountability for the scientific basis of nursing practice, organizational and

policy changes, and the development of scientific foundations for EBP. This model was

developed for clinical and educational use to assess nurses’ willingness to practice

evidence-based care and to measure the impact of related professional development. The

model, represented by a five-pointed star, defines knowledge and integrates best research

evidence with clinical expertise to achieve EBP. Point 1 of the star represents primary

research studies; Point 2 represents evidence summary; Point 3 refers to evidence-based

clinical practice guidelines; Point 4 represents evidence in action; and Point 5 represents

evaluation of the impact of the EBP on satisfaction, efficacy, patient health outcomes,

and health policy (Correa-de-Araujo, 2015).

Another model that can be considered is the health benefit model (HBM), which

was developed as a way to understand the perceived benefits and consequences of

13

decision-making behaviors (Roden, 2004). Garrett-Wright (2011) applied the HBM to

perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention from the theory of planned

behavior.

Literature Review

Bradshaw (2010) acknowledged that an important feature that distinguishes the

nursing profession is taking accountability for practice and examining the best way to

deliver care; this statement fully reflects the essence of EBP related to PI treatment.

However, the main problem in PI treatment lies in the fact that there is a gap between

theory and practice. To prove the validity of this assumption, PI treatment should be

considered in terms of risk assessment strategies. Consistency in nursing assessment,

documentation, and relevance to the interventions planned will improve PI prevention

and decrease the risk of PI development. Identification of extrinsic and intrinsic risk

factors for PI development is necessary.

However, a retrospective observational study conducted using the U.S. Premier

Healthcare Database (PHD) showed the importance of identifying risk factors for HAPIs

and improving best practice for PI prevention (Dreyfus, Gayle, Trueman, Delhougne, &

Siddiqui, 2018). Patients who may receive a mixture of treatments for other pathologies

may not be receiving proper nutrition as income constraints may dictate diet. In addition,

literature indicates that unmodifiable factors associated with patients with disease

processes and comorbidities have a great effect on PI development and patients’ ability to

adhere to preventive measures (NPUAP, 2017; WOCN Society, 2017).

14

PIs are responsible for over 60,000 annual cases of hospital death in the United

States due to complications (ICSI, 2012). Meanwhile, difficulty in obtaining

reimbursement for ulcer treatment raises operating costs in healthcare institutions. The

cost of treatment has been set at a figure of around $11 billion every year, which

underscores the need to reduce the incidence of PI at a local and national scale (Bauer,

Rock, Nazzal, Jones, & Qu, 2016).

Several comprehensive reviews addressing PI prevention and nursing knowledge

were identified. The NPUAP provides information on identifying and staging PI along

with current treatment and served as a resource for project. Waugh (2014) discovered that

there was no significant nursing knowledge with PI prevention when nursing knowledge

was effectively identified. However, the lack of knowledge to nursing practice scored

higher with higher application of PI prevention. Furthermore, although nurses who scored

high were highly educated, there was no major difference in knowledge scores for nurses

with higher levels of education (Waugh, 2014).

Moore and Cowman (2014) compared PI incidence between patients assessed

with the Braden risk assessment tool (n = 74) and patients examined through unstructured

risk evaluation (n = 76), concluding that there was no statistical difference between the

groups. They further compared PI assessment using the Waterlow risk assessment tool (N

= 420), the Ramstadius risk screening tool (N = 420), and no formal risk assessment (N =

420). The findings they obtained gave Moore and Cowman reason to assert that there was

no statistical difference in PI incidence across the three patient groups.

15

In the facility studied, wound care prevention is essential, and the Braden Scale

has been used as the most complete process for validation (Garcia-Fernandez, Pancorbo-

Hildago, & Agreda, 2014). Depending on the score, the nurse assessing the patient may

initiate preventive measures. The Braden score system consists of six subscales—sensory

perception, moisture, activity, mobility, nutrition, and friction/shear—for identifying

patients at risk for pressure injury (AHRQ, 2016).

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature review was conducted using CINAHL, Medline,

Cochrane, and the Walden library database. Boolean operators were used for key words

such as pressure injury, knowledge, prevention, critical care, skin assessment, education,

staging, and Braden Scale. With high occurrence of PI’s in mind, there have been broad

attempts to develop methods for reducing the incidence of PI in high-risk patients. To this

end, there have been several proposed methods that have taken into account the type of

care setting and the patient group. Some of the methods proposed are inspecting the skin

frequently, relieving pressure on risk areas, reducing moisture by applying creams,

preventing friction and forces of shear when moving the patient, making sure that the

patient receives proper nutrition, and paying special attention to patients at risk during

rounding (Tayyib, Coyer, & Lewis, 2015).

The knowledge and skills required for preventing PIs consist of patient-risk

assessment, practice protocols for prevention of ulceration, assessment of ulcers, and

management of PIs. The accumulation of such knowledge is the essence of this DNP

project. I sought to implement an evidence-based PI prevention program that was

16

dedicated to increasing the knowledge of nurses. The logical premise underlying the

project was that with sufficient knowledge, a nurse should be able to handle and prevent

PIs.

Local Background and Context

The clinical site where this staff education project was piloted was a 30-bed

medical ICU in a tertiary-care facility in a hospital in the southeastern United States.

Patients in a ICU setting such as the project site may be unconscious and

immunocompromised. They may also be receiving medications that increase the risk of

developing PI. Hospitalized patients being treated for a variety of illnesses require

constant monitoring by nurses to ensure that the risk of PI is minimal. Many of these

patients have multiorgan failure. It is essential to note that immobilization is one of the

chief contributors to the PI problem (Cox et al., 2018).

Under new CMS guidelines, Stage 2-4 or unstageable PIs that were not present on

admission were considered injuries. Suspected deep-tissue injury was replaced by deep-

tissue injury (CMS, 2018). Evidence-based guidelines provide essential vision to

clinicians and stakeholders related to patients who received interventions and offered to

support HAPI that was unavoidable due to critically ill patients. With the implementation

of a quality-improvement initiative 67% reduction in HAPIs were reflected avoidable

(Jacobson, Thompson, Halvorson, & Zeitler, 2016).

The implementation of continuing education programs in PI prevention seems to

be eliminating the incidences of the injury. It is a reference point from which the need to

17

develop other novel solutions or to intensify the use of the existing ones can be

supported.

DNP-prepared nurses must take roles of leadership and advocate for changes that

better serve the patient. They are also required to take part in the generation of nursing

wisdom and the dissemination of information to others. This role of dissemination was

integral to this project. The aim was to ensure that the delivery methods were effective.

Being in the ICU makes one realize that despite the bulletin boards and booklets

available in the area and the nurses’ lounge advocating PI prevention, a large part of the

nurses’ day is spent tending to already-developed PIs. With an increasing number of

geriatric ICU patients, there is need to consider all approaches that could prevent this

susceptible group of patients from developing PIs. This calls into question the validity of

the methodologies suggested for prevention. However, scrutiny of these methods yields

evidence that the recommendations are valid in practice (Mallah, Nassar, & Badr, 2015).

The question of how much of the available knowledge is actually disseminated and

internalized successfully therefore arises. This seems to be the logical progression to

finding a solution to the practice problem.

Relevance to Nursing Practice

PI continues to represent a financial problem for the healthcare system and a

challenge to patients’ quality of life (Parnham, 2015). Although the NPUAP has provided

many protocols, guidelines, and educational materials related to PIs to all organizations,

PIs remain a problem in the hospital setting, which can be attributed to the inadequacy of

efforts to disseminate the knowledge required to prevent these injuries (NPUAP et al.,

18

2014). Nuru, Zewdu, Amsalu, and Mehretie (2015) found PI knowledge to be good in

over half of the nurses in an institutional study, but they found practice essentials to be

good in less than half of the nurses. In the study, many reasons were given for the

development of this problem, including inadequate resources and equipment and a staff

shortage, which may have affected work performance and caused fatigue (Nuru et al.,

2015).

In another study by Gunningberg et al. (2015), the thematic description of this PI

knowledge was found to be weak. Using a PI knowledge tool, the researchers were able

to test for the themes of nutrition, classification and observation, risk assessment, and

etiology and causes. From their findings, they recommended an extensive educational

campaign. This is why the knowledge base of nurses was an important factor to consider

in the current project.

Role of the DNP Student

My role as the DNP student in this project was to assess nurses’ knowledge and

practice related to PI prevention in the ICU. To achieve this, I used pre- and posttest

questionnaires.

My primary objectives as a DNP-prepared nurse are to serve as a role model and

to engage in EBP research, identifying gaps that exist and undertaking to structure and

implement projects to fill those gaps. The DNP-prepared nurse should provide incentive

for nurses to undertake interventions and research. My role in this project also involved

evaluating the success of the project in terms of the set of objectives, which involved

19

determining whether nurses’ knowledge of PI prevention and practice improved after an

educational session.

Professional Role in the Project

The professional obligation of registered nurses is to ensure that all of the

knowledge that their colleagues acquire through education and experience is passed on.

In order for information to be raised the levels of knowledge and wisdom, it must be

tested in the crucible of evidence. The interventions have already been tested. Therefore,

I sought in this DNP project to establish whether the dissemination of this knowledge was

complete and the effect it had on the incidence and management of PIs.

Motivation for Completing the Project

I was a key figure in an interprofessional practice team, serving as a conduit for

information, a conflict arbitrator, a leader, and a project director. While working in the

ICU and seeing many protocols for PI prevention, documentation, and skin assessment, I

noted that PIs continued to occur. During past practicum experiences, I had noticed that

there seemed to be a gap concerning PI prevention related to knowledge. My role was to

educate the nursing staff on the importance of skin assessment for patients in the ICU and

to assess nurses’ knowledge on PI prevention before and after education was provided.

My motivation for this doctoral project derived from my interest in determining

what research was currently available that would support and identify the need to

implement a PI prevention program and its impact on nurse knowledge. I had no bias for

this project.

20

Potential Biases

During the project, one potential challenge that I identified was staff cooperation,

which could have affected the accuracy of questionnaire results. Although EBP is used

for guiding advanced nursing practice, there are some barriers involved when

implementing interventions. The educational intervention in this project was based on

quality improvement models that can be applied in the healthcare setting.

Expert Panel

I conducted a staff education project using the staff education plan. A PowerPoint

(PPT) presentation was presented to the participants (Appendix A). I explained the

pretest, which was a 47-item questionnaire administered to the nursing staff prior to staff

education in order to determine participants’ current knowledge and understanding of PI

prevention (Appendix B), as well as the posttest, which was a 47-item questionnaire that

was administered to the nursing staff after the completion of the education program to

determine new knowledge and understanding of PI prevention (Appendix C).

I will present the education packet (Appendix D) which I will have reviewed with

the expert panel of: nurse manager, two clinical managers, and RNs on that unit. The

education packet will include current evidence on Pressure Injury Prevention from the

NPAUP including: wound description and staging information and risks factors. I will

also include a Best Practice check list, which will provide information on Pressure Injury

Prevention and what should be applied for each patient (Appendix E), and finally, I

include the Braden Scale, concerning risk assessment on pressure injury and level of

intervention to follow (Appendix F). I will explain the conduction of the pre-

21

test, develop the intervention with feedback from your expert panel, revise the education

packet present the information then conduct the post-test and evaluate it then work with

the expert panel and make recommendations.

The overall goal is to educate staff on Pressure Injury prevention as studies have

shown that educating staff will lead to improvement in clinical outcomes (Kavanagh et

al., 2012). The DNP project is an integral part of developing the skills to research and

develop evidence-based nursing knowledge. The DNP project proposed seeks to mitigate

this by first assessing the degree of knowledge the nurses have on Pressure Injury

prevention and then charting a course for their continuous education.

The DNP prepared nurse must take the role of leadership and advocate for

changes that better serve the patient. They are also required to take part in the generation

of nursing wisdom and in disseminating this knowledge to others. This role of

dissemination is the key part of this project. The aim is to ensure that the delivery

methods are effective.

Summary

The role of the DNP nurse as a leader and advocate is best exemplified by the

DNP project. In the same breath, the DNP nurse is able to sharpen their research skills

while contributing to the body of nursing wisdom. A practicum stint in the ICU revealed

that despite the large amount of information available on PIs, there are still many cases of

ICU-related pressure injuries. In light of this, a new strategy must be adopted.

The project proposes to couple an evaluation of the degree of knowledge with a

subsequent educational initiative for nurses in the ICU. The results of this project are

22

aimed at improving the patient outcome, quality care, and the management of hospital

and patient resources as well as adding to the body of nursing knowledge. Through

evidence-based practice research modalities, we are able to understand the problem and

generate the most viable solutions for the good of the entire healthcare system. Section 3

details the collection and analysis of evidence on nursing knowledge on pressure injury

prevention and practice.

23

Section 3: Collection and Analysis of Evidence

Introduction

HAPIs remain a national concern due to patient morbidity, the high cost of

treatment, and reimbursement cases (Zaratkiewicz et al., 2011). The aim of this staff

education project was to provide education to critical-care nurses on PI prevention and to

assess staff knowledge after completion of the education. In this section, I describe the

collection and analysis of evidence, addressing the following topics: (a) practice-focused

question, (b) setting/population sample, (c) participants, (d) procedures, (e)

instrumentation materials, (f) data analysis, (g) protection of participants, and (h) project

ethics and Institutional Review Board (IRB), concluding with a summary. The project

plan was to obtain data and analyze evidence through the use of a questionnaire on PI

prevention. The questionnaires were distributed, collected, and analyzed to ensure that

the research questions had been answered as predicted.

Practice-Focused Question

According to Stillwell, Fineout-Overholt et al. (2010), a practice-focused question

identifies a clinical problem for staff to recognize and understand. The focus question for

this staff education project was the following: To what extent will the nurses’ knowledge

of PIs improve after attending a structural education program?

Sources of Evidence

The sources of evidence that were used for this doctoral project were obtained

from numerous articles in the literature. All articles were reviewed and organized into

sections related to PIs, prevention, skin bundle, knowledge, staging, wounds, and best

24

practice. Sources of evidence were gathered from CINAHL, Joanna Briggs Institute,

Medline, and Cochrane. Recommendations and further research related to knowledge and

practice of PI prevention were considered in order to address the practice-focused

question. My aim was for the staff education project to address a gap in the knowledge of

critical-care nurses and provide the necessary evidence to improve nurses’ practice and

maintain PI prevention. The staff education project site was an acute-care tertiary Level 1

trauma unit consisting of 763 beds.

Setting and Sample Population

The selected setting was a 30-bed ICU in a medical ICU located in the

southeastern region of the United States Working in the ICU exposes staff to the rigors of

PI due to patient immobility and hemodynamic instability. The sample population

consisted of 20 RNs working in the ICU. As the DNP student directing this project, I had

the stakeholders assist in the selection of the healthcare individuals. The stakeholders

who assisted in the process were the wound care nurse, the wound care RN of the unit,

and the clinical specialist of the unit. In this organization, nurses are expected to

formulate and communicate changes to practice and management in the healthcare

setting.

Participants

All participants for this staff education project were registered nurses working in

intensive care with direct patient care responsibilities. The age range for participants was

23-65 years. Participants were informed of this staff educational project and informed

25

that all data, questionnaires, and surveys would be kept confidential and anonymous in a

locked cabinet in the ICU charge office.

Procedures

The staff education project took 2 weeks. A PPT presentation was shown to the

participants and took approximately 60 minutes (Appendix A). I explained the pretest,

which was a 47-item questionnaire administered to the nursing staff prior to the staff

education in order to determine their current knowledge and understanding of PI

prevention (Appendix B), as well as the posttest, a 47-item questionnaire administered to

the nursing staff after the completion of the education program to determine new

knowledge and understanding of PI prevention (Appendix C). I presented the education

packet (Appendix D), which I had reviewed with an expert panel consisting of the nurse

manager, two clinical managers, and RNs on that unit. The education packet included

current evidence on PI prevention from the NPAUP, including wound description,

staging information, and risk factors. I also included a best practice checklist, which

provided information on PI prevention and what should be applied for each patient

(Appendix E). Finally, I included the Braden Scale concerning risk assessment for PIs

and levels of intervention to follow (Appendix F). The duration of each test was

approximately 20-30 minutes. The posttest questionnaire consisted of 47 questions used

by Pieper and Zulkowski (2014) utilizing a Likert scale. The Likert scale was used to

evaluate the self-reported knowledge before the pre-test and after the posttest. A

nonparametric t -test result was used to identify the trends between ordered groups and to

examine the frequency and knowledge with respect to PI prevention test completion

26

(Terry, 2015). The findings from the pre- and posttest were analyzed to determine change

in practice.

Instrumentation and Materials

Due to its high reliability, the Pressure Ulcer Knowledge Test (the Pieper test)

was used to assess nurses’ knowledge of PI prevention, referring to the research question.

This test has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.8 and shows good validity for PI prevention and

skin assessment and staging (Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014).

Through this staff educational project, I sought to address the PI concern by

getting an overall perspective on information dynamics as they related to PI prevention.

The quantity and quality of information that is available to the nursing staff were

assessed. The data collection method consisted of performing a skin assessment on all

patients who met the inclusion criteria, at the beginning of the shift and at the end-of-shift

report. Skin assessment was the driver for a nursing intervention to identify early skin

damage and to prevent skin damage (Tume, Siner, Scott, & Lane, 2014). Other data

collection involved documenting the Braden Scale for each patient. The Braden score

system consists of six subscales: sensory perception, moisture, activity, mobility,

nutrition, and friction/shear (Tayyib et al., 2015). The first subscale uses a scale of 1 to 3,

and the remaining five subscales use a scale of 1 to 4. The lower the score, the higher the

patient’s risk of developing sores or injuries is. Depending on the score, the nurse

assessing the patient then initiates preventive measures.

27

Protection of Participants

All participants for this project were registered nurses working in intensive care

with direct patient care. Upon conducting a project, it is crucial to ensure the protection

of human subjects in terms of autonomy, confidentiality, nonmaleficence, and

beneficence (Gray et al., 2017). All participants were protected, as all data,

questionnaires, and surveys were kept confidential in a locked cabinet in the ICU charge

office.

Project Ethics and Institutional Review Board (IRB)

As per protocol regarding rules and ethical and federal regulations, I submitted

the DNP project to the Walden University IRB for approval.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The need to evaluate the incidence of PIs in critically ill patients in the ICU was

closely related to the clinical question. The pre- and posttest questionnaire helped to

closely represent the clinical question when exploring the outcomes of nurse-driven

behaviors to decrease PIs. After the education session, posttest questionnaires were given

to the participating nurses in anonymously labeled packets. Responses from these

questionnaires were evaluated and analyzed. DNP projects are crucial in evaluating

practice guidelines and settings to ensure that the quality of care continuously increases.

This particular staff education project was conducted to ensure that the body of

knowledge that was available to the nurses reached its target audience efficiently and

therefore enabled them to meet the needs of their immobilized and sometimes

unconscious patients.

28

Summary

In summary, the need to assess nurses’ knowledge and practice related to PI

prevention in the ICU continues to be a concern. Although PIs may remain an issue,

having ongoing education, training, assessment, and a guidelines tool on PI prevention to

improve nurses’ knowledge and practice related to PI is essential to preventing further

injuries. In order to raise information to the levels of knowledge and wisdom, it must be

tested in the crucible of evidence. In Section 4, I present the findings and

recommendations.

29

Section 4: Findings and Recommendations

The local problem serving as inspiration for this DNP project was the high

occurrence of PIs developing in the ICU. In Section 3, I addressed the gap in practice

concerning PI and explored how to mitigate risks by assessing nurses’ knowledge. In the

following section, I evaluate current practice pertaining to PIs and conduct pre- and

posttest evaluations. The findings from this PI study may support the need for

improvement or change in practice. Better understanding of the gap between theory and

practice may encourage healthcare providers to pay more attention to EBP

recommendations in order to reduce PI incidence in healthcare settings. As a reminder,

the guiding practice-focused question for this project was the following: To what extent

will the nurses’ knowledge on pressure injuries improve after attending a structural

education program? The purpose of this educational project was to provide further

education on PI prevention and to identify whether nurses’ knowledge improved based on

the training. The focus of the training was assessment and understanding of better

methods of PI prevention.

The aim of this educational project was to identify whether nurses’ knowledge

improved after an educational session. PIs in the ICU are inevitable; however, assessing

and analyzing new evidence and strategies for PI prevention could reduce the incidence

of PIs in the hospital. This study was based on multiple sources of evidence to support the

conclusion. The sources of evidence used for the staff education included literature

obtained from CINAHL Plus with Full-Text, Joanna Briggs Institute, Medline, Cochrane,

and ProQuest. Development of the process included a pretest and posttest on nursing

30

knowledge of PI prevention that were administered to the nursing staff. Results of the

pretest and posttest were compared to identify outcomes. The comparison between the

pretest and posttest responses determined that nurses’ understanding had increased after

the intervention. Section 4 contains a discussion of the findings, implications, strengths,

and limitations of the study, as well as my analysis of myself.

Findings and Implications

The project objective was to assess nurses’ knowledge of PI prevention in the

ICU after attending a structured educational program. The aim of conducting this study of

a staff education project was achieved by using the Pieper Knowledge Test. The Pieper

Knowledge Test was used to measure five categories: (a) PI prevention, (b) staging, (c)

wound description, (d) the Braden Scale and (e) program education. Permission to

conduct the project was pursued, reviewed, and obtained from the project agency’s

Institutional Review Board (IRB), which issued project approval on June 21, 2019,

(Reference # 005544). A PPT was presented to the participants (Appendix A). This

project required the distribution of a pretest questionnaire on current knowledge and

understanding of PI prevention (Appendix B) and was administered to the nurses. In

order to understand the change in nurse’s knowledge to determine the presence of new

knowledge and understanding of PI prevention, a posttest questionnaire was administered

to the nursing staff by the expert panel after the completion of the educational program

(Appendix C). An educational packet on PI prevention was presented to the nurses

(Appendix D). Using the NPAUP guidelines, the education packet included current

evidence on PI prevention, including wound description and staging information and risk

31

factors. The packet included a best practice checklist, which provided information on PI

prevention (Appendix E), and the Braden Scale: risk assessment on PI and interventions

Appendix F). The results from the pre- and posttest assessment of the participants’

practice and knowledge of PI prevention were analyzed. Among the 47 questionnaires

from the Pieper Knowledge Test, I selected 14 of the questions related to prevention,

staging, knowledge, the Braden Scale, and education to determine knowledge deficits and

any needs for improvements in knowledge.

There were 75 nurses in the ICU. Seventy-five (100%) nurses were administered

the pretest and provided with the education packet on PI prevention in the ICU. Seventy-

five participants completed a color-coded pretest. Following the completion of the

pretest, 75 participants were administered the education presentation and packet.

Participants were allowed to ask questions throughout presentation, which lasted 30

minutes. After the education presentation, the participants were given the color-coded

posttests, which they were allowed 2 weeks to complete. Upon return, each participant’s

pretest and posttest were matched. Of the 75 initial participants, only 55 (73%) nurses

completed both the pretest and the posttest. Therefore, 55 total participants were included

in the complete data set to determine any change in knowledge.

The following results reflect responses to two general questions on nurses’

knowledge on PI prevention and show strong improvement in nurses’ knowledge on PI

prevention (see Table 1). Prior to education, only 30 nurses (54%) demonstrated

knowledge concerning patient assessment for PI development on admission to the

hospital, compared to 45 nurses (81%) on the posttest; thus, there was an increase of

32

27%. The second question concerning care given to prevent or to treat PI and to treat PI

documentation demonstrated that 34 (61%) of participants indicated that this idea was

important on the pretest, compared to 43 (78%) of participants on the posttest,

demonstrating 16% improvement in understanding. In both cases, participants’

knowledge increased.

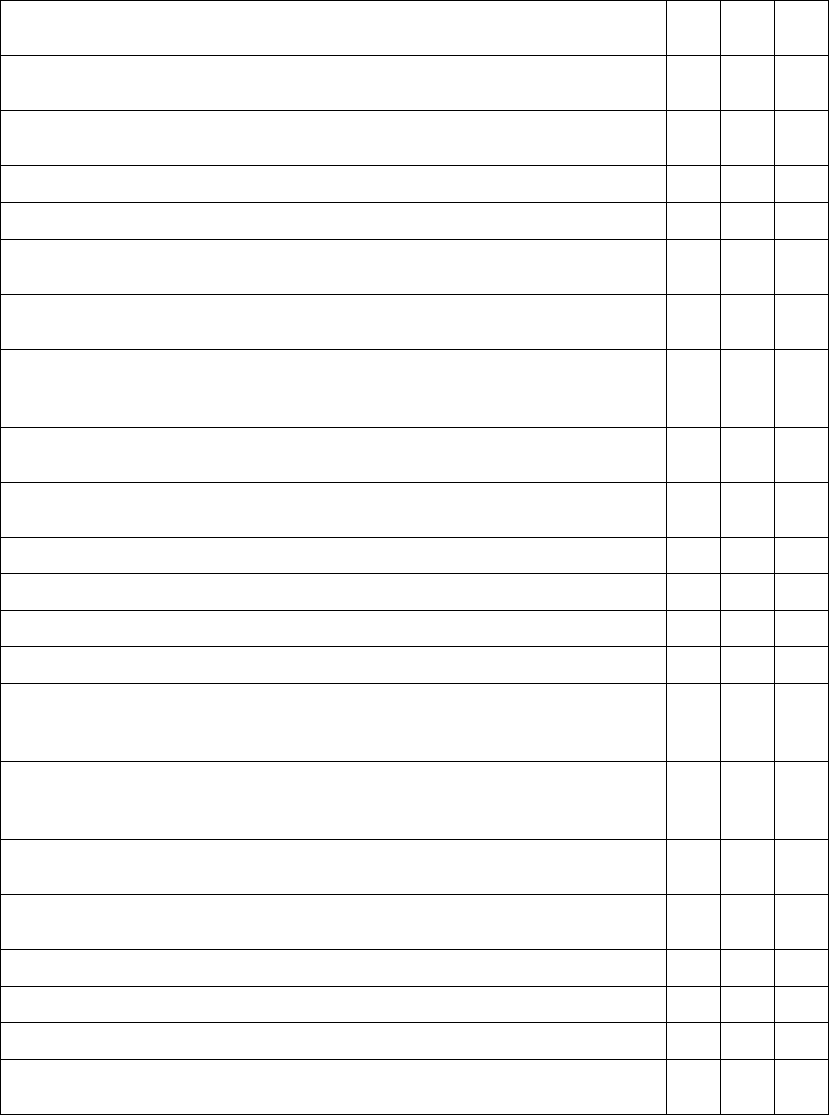

Table 1

Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Pressure Injury Prevention

Question item

Pre-test

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Posttest

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Percent

change

All individuals should be

assessed on admission to a

hospital for risk of pressure

injury development

30 (54%)

45 (81%)

27%

All care given to prevent or

treat pressure injuries must

be documented

34 (61%)

43 (78%)

17%

The next four questions focused on the staging of wounds, differentiating Stage I

and Stage II (see Table 2). The first question asked participants about the definition of

Stage I and the description of a lightly pigmented person. Prior to education, 33 (60%) of

the nurses were able to define Stage I in a lightly pigmented person. Post education, there

was an increase so that 42 (76%) nurses were able to define Stage I in a lightly pigmented

person. The results indicated that after education, there was increased knowledge for

Question 1. The second question asked participants about the description of Stage II and

how to identify full thickness skin loss. On the pretest, 22 (40%) participants indicated

that full thickness of the skin loss is described as Stage II. On the posteducation

33

assessment, 20 (36%) participants demonstrated knowledge on full thickness skin loss in

Stage II. As noted below, there was a decrease by 4% on the posttest for Question 2.

Although there was a decrease of 4% on the Stage II description, results demonstrated

improvement of knowledge on staging. Question 3 asked participants to identify whether

Eschar is healthy. The results for the third question indicated that prior to education, 25

(45%) of the participants described healthy tissue as Eschar. After education, 7 (13%) of

the nurses indicated that Eschar is not considered healthy tissue. The fourth question

asked each participant to describe slough; 32 (58%) participants identified slough as

“yellow cream necrotic tissue” on the pretest, and 40 (73%) did so education. The results

for Question 4 on slough indicate that there was an increase in knowledge.

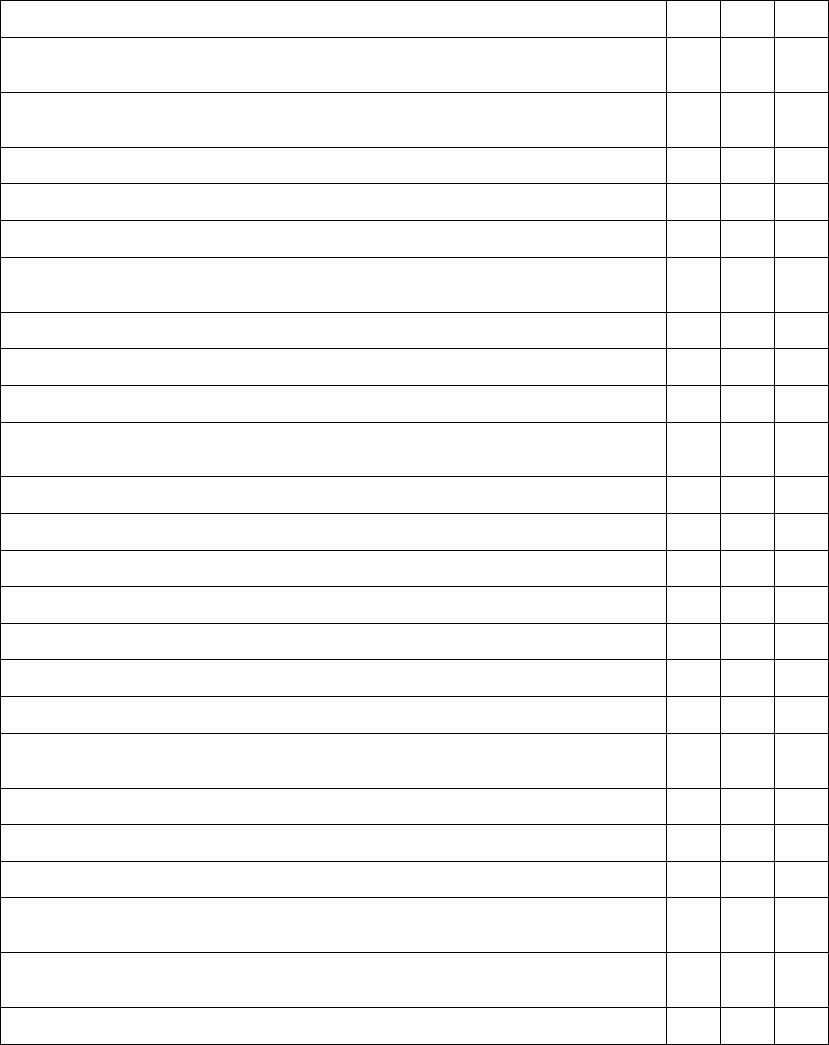

Table 2

Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Staging

Question item

Pre-test

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Posttest

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Percent

change

Stage I pressure injuries are

defined as intact with non-

blanche erythema in lightly

pigmented persons

Stage II pressure injuries are

full thickness skin loss

33 (60%)

22 (40%)

42 (76%)

20 (36%)

16%

4%

Eschar is healthy tissue

Slough is yellow or cream

necrotic tissue on a wound

bed

25 (45%)

32 (58%)

7 (13%)

40 (73%)

32%

15%

The next two questions related to the nurses’ knowledge on the Braden Scale (see

Table 3). The first question showed that 24 (44%) of the participants indicated an

34

understanding about risk factors for the development of PIs such as immobility,

incontinence, impaired nutrition, and altered level of consciousness. On the posttest, 43

(78%) of the participants were able to identify the risk factors for patients concerning PIs.

This result indicates that the overall knowledge of risk factors improved significantly for

the participants. For the second question, 22 (40%) participants agreed that a low Braden

score is associated with a higher risk of PI. In the posttest results, 28 (50%) of the nurses

agreed that the increase of PI is contributed to a low Braden score. Results for Question 2

showed a 10% change in knowledge after education.

Table 3

Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Braden Scale

Question item

Pre-test

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Posttest

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Percent

change

Risk factors for

development of pressure

injuries are immobility,

incontinence, impaired

nutrition, and altered level

of consciousness

24(44%)

43(78%)

34%

A low Braden score is

associated with increased

pressure injury risk

22(40%)

28 (50%)

10%

In the next two questions, participants were asked about the values of education as

a direct impact on nurses’ knowledge (see Table 4). The first question involved the issue

of whether the incidence of PIs can be decreased after an education session; 34 (62%) of

the participants agreed on the pretest, and 50 (90%) of the participants agreed on the

posttest, indicating 28% improvement. Question 2 asks about participants knowledge of

35

government intervention regarding risk, prevention, and treatment, 32 (58%) of the

nurses agreed. Following education, 42 (76%) of the participants acknowledged that PIs

were increasing tremendously. Results showed 18% improvement. After education, in

responding to both questions, participants showed improved knowledge.

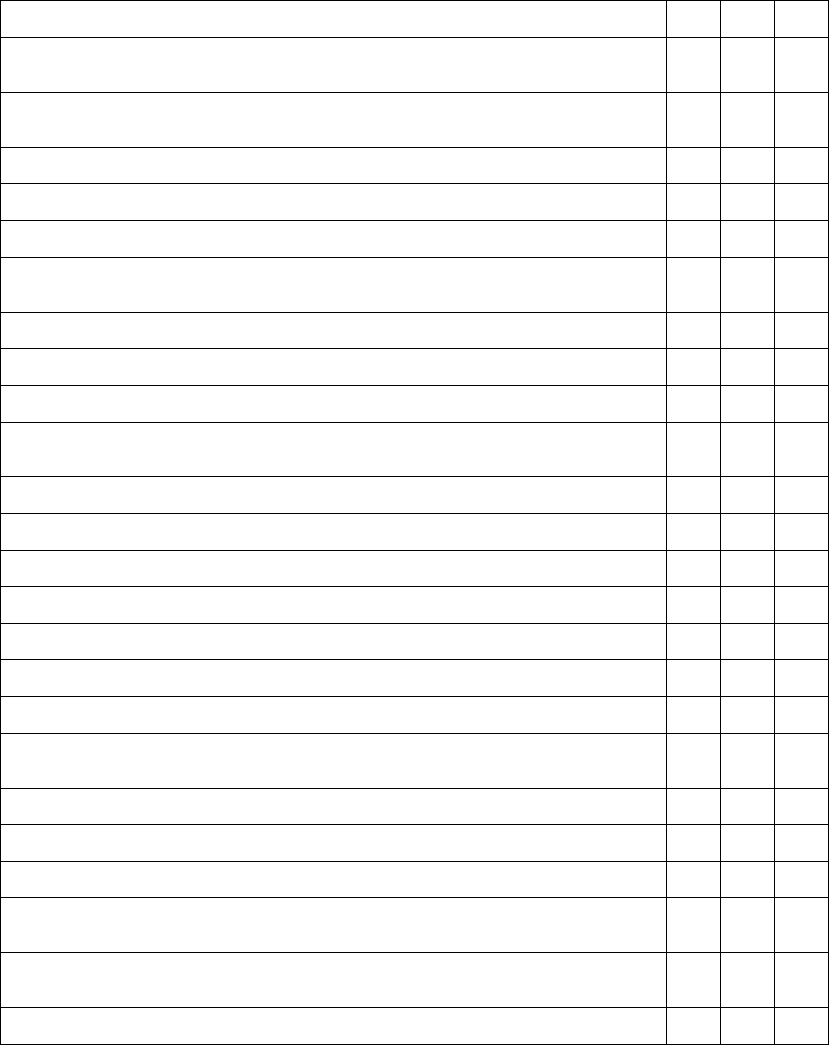

Table 4

Comparison of Nurses’ Knowledge on Education Program

Question item

Pre-test

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Posttest

Strongly agree

N = 55 (%)

Percent

change

Educational programs may

reduce the incidence of

pressure injuries

34 (62%)

50 (90%)

28%

The incidence of pressure

injury is so high that the

government has appointed a

panel to study risk,

prevention, and treatment

32 (58%)

42 (76%)

18%

The implications noted show an improvement in nursing knowledge and a

decrease in nurses’ knowledge on staging. The improvements seen were in nurses’

knowledge on PI prevention, wound description, the Braden Scale, and the education

program. The results indicate that with education, nurses’ scope of knowledge can be

expanded. As a result, from a practical standpoint, patient care can be improved. If nurses

can successfully understand PI, can correctly identify wound description, can understand

the metric of the Braden Scale, and can see the value in an education program, patients

can continue to reap the benefit of more informed nurses. From a reverse viewpoint,

being able to understand where nurses have fallen short in understanding can yield better

36

opportunities for implementing education during follow-up. The need to understand the

implication on decreased staging knowledge could provide an opportunity to develop

better programs that can help nurses understand the implications of full thickness skin

loss. As a result, future nurses may be able to identify staging better and make

adjustments in practice more quickly.

Recommendations

This doctoral project was conducted to assess nurses’ knowledge on PI prevention

and to understand whether nurses’ knowledge decreased or increased following an

educational program in the ICU. There are significant issues facing nurses in relation to

their knowledge on PIs. The findings from the posttest strongly indicate that the

educational program may decrease the incidence of PI, resulting in better patient care.

The overall goal is to educate staff on PI prevention, as studies have shown that educating

staff leads to improvement in clinical outcomes. According to Henry and Foronda (2017),

improving nurses’ knowledge of PI prevention results in preventing HAPI incidents. The

results from this project indicated positive outcomes in two areas:

1. Increased education on PI prevention: When nursing staff are given education

about a topic, they can apply that knowledge for better outcomes. This project

clearly demonstrated that when the nursing staff was educated, their knowledge

about PIs increased. The results may translate into better patient care and

earlier identification of the start of PI. Henry and Foronda (2017) reviewed and

discussed the nurse education programs for the prevention and identification of

HAPI and concluded that education programs increased nurses’ knowledge of

37

HAPIs. In addition, creating a culture of success education can promote high-

quality care and safety for patients (Henry & Foronda, 2017).

a. Development of useable tools pertaining to PI and skin condition and

placement of these tools in accessible areas: This educational program

demonstrated different models of what is considered healthy skin and what is

considered a PI. Hospitals and institutions might consider adding visual

guidelines for nurses to reference (see Appendix E) provided by WOCN

(2017). They also might consider placing guidelines in high-traffic or high-

visibility areas as a reminder for nurses between educational programs. Henry

and Foronda (2017) suggested including a number of PI and wound pictures

for each stage to help solidify nurses’ education. Furthermore, Ebi, Hirko, and

Mijena (2019) did a cross-sectional study design on nurses’ knowledge of

pressure ulcers and certified the use of an educational program on PIs to keep

nurses well-informed regarding current knowledge. In addition, reviewing PI

prevention guidelines on a regular basis is useful in increasing nurses’

knowledge on PI prevention (Ebi et al., 2019).

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the doctoral project are the use of a reliable and valid tool to

assess the nurses’ knowledge on pressure injury prevention and documentation. This has

not been previously attempted in this ICU. The results were startling, with far fewer

nurses than expected having a robust knowledge of pressure injury prevention and

documentation. The positive post-test results clearly demonstrate the impact of an

38

educational program on increasing knowledge of pressure injury prevention. In the

future, such programs should be presented regularly to all existing and new staff to

ensure that all staff is competent and knowledgeable regarding pressure injury prevention

and documentation.

Study limitations include the fairly large attrition number in participation. There

are 75 nurses on the Intensive Care Unit but only 55 (73%) nurses participate in the

educational periods. Although participants were informed of the anonymity of their

participation, only 55 (73%) participated in the complete pre-test and post-test. The

significance of this attrition is not known, but it may be concluded that there is a lack of

commitment to pressure injury prevention. Other interpretations of this limitation might

be because of the demanding nature of the profession and other education programs

occurring simultaneously. Lastly, part of the limitation on the study may have been the

design in that completing questionnaires may not be desirable to participants may affect

results (Ebi et al., 2019). Other limitations of this project were the limited participant

pool-specifically one facility, one ICU and to distribute only to nurses. Also, the small

sample size of this group prevents generalizability to a larger audience. Although, new

evidence-based practice suggested that the Pieper Pressure Ulcer knowledge test has

proven to be a safe practice for adult learners to self-identify, self -learn and self-correct

knowledge (Delmore, et al., 2018).

The Pieper Knowledge Test has been tested before to determine the strengths and

limitation in clinical practice to measure the staff knowledge. Negativity on PI prevention

can lead to lack of knowledge on preventive measures and may influence the nurses’

39

performance. Research suggests pressure injury prevention can result from a lack of

knowledge on pressure injury prevention, and may contribute to lack of adequate

validation therefore the results cannot be generalized (Dalvand, Ebadi & Geshiagh,

2018).

Future Directions

The future directions for researchers interested in pressure injury prevention could

include routine educational programs on pressure injury prevention, and assessing nurses’

knowledge on staging, on wound description and Braden Scale. Having accurate, up–to-

date and ongoing knowledge regarding pressure injury, prevention, risk, staging, and

treatment is one way to prevent pressure injuries (Pieper & Zulkowski, 2014). Providing

a structured staff educational project is important to closing the gap and can be effective

in changing the culture in the intensive care unit with the development of guidelines and

protocols.

40

Section 5: Dissemination Plan

The purpose of this project was to determine whether nursing knowledge

improved when comparing intensive-care nurses’ responses to a pre- and posttest

questionnaire after an educational program on PI prevention. My plan is to disseminate

the project’s findings and share the results with clinicians within the organization. Nurses

are the primary audience with which I intend to share the project’s outcomes. The

following paragraphs outline the plan for dissemination and describe the rationale for the

audience of nurses as the primary recipients.

Plan for Dissemination

The dissemination of a project is a crucial procedure to transfer findings to

stakeholders. Presenting the findings to the organization’s leadership provided a valuable

opportunity for the organization leader to stimulate change. The promotion of new

strategies to develop advanced levels of clinical judgment, systems thinking, delivering,

and evaluating evidence-based care practices will be undertaken with the intention of

improving patient outcomes (Association of Critical Care Nurses [AACN], 2015). The

most tremendous impact has been to provide the findings. I plan to disseminate the

findings in three tiers: internally within the organization, externally as a publication, and

in an ongoing fashion at a selection of local and national conferences. The rationale for

choosing these stakeholders stems from the idea that the results generated from the DNP

project can be contributed in multiple outlets. First, from the perspective of internal

dissemination, I plan to share the results in my facility through ongoing education in the

ICU. The project demonstrated the effectiveness of staff response to an educational

41