The United Nations Convention against Corruption

National

Anti-Corruption

Strategies

A Practical Guide for

Development and

Implementation

UNITED NATIONS

New York, 2015

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME

Vienna

The United Nations

Convention against Corruption

National Anti-Corruption

Strategies:

A Practical Guide for Development

and Implementation

© United Nations, September 2015. All rights reserved, worldwide.

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not

imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the

United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of

its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

This publication has not been formally edited.

Publishing production: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Ofce

at Vienna.

iii

Acknowledgements

This Guide is a product of the Corruption and Economic Crime Branch of the United

Nations Ofce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and has been developed in line with the

thematic programme entitled “Action against corruption, economic fraud and identity-

related crimes (2012-2015)” and pursuant to resolution 5/4 of the Conference of the

States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption.

UNODC wishes to thank its consultants Richard Messick and Matthew Stephenson for

their substantive contributions to the drafting of this Guide.

UNODC also acknowledges with profound gratitude those who have contributed their

expertise and experience at various stages of the development of this Guide and the

experts who participated in the international expert group meeting held in Vienna from

6 to 8 May 2015: Roberta Solis Ribeiro, Chief, International Affairs Advisory, Ofce

of the Comptroller-General, Brazil; Levan Kakava, Head, Investigation Service, Ministry

of Finance, Georgia; Levan Shanava, Specialist, Investigation Service, Ministry of

Finance, Georgia; Daviti Simonia, Investigator of Especially Important Cases, Anti-

Corruption Agency, Georgia; Orsolya I-Valde, Legal Adviser, National Protective

Service, Hungary; Kaushik Goburdhun, Chief Legal Adviser, Independent Commission

Against Corruption, Mauritius; Theunis Keulder, Chair, Namibia Institute for Democracy;

Lise Stensrud, Policy Director, Norad, Norway; José das Neves, Deputy Commissioner

for Education, Campaigns and Research, Anti-Corruption Commission, Timor-Leste;

Zelia Trindade, Deputy Prosecutor-General, Timor-Leste; Phil Mason, Senior Anti-

Corruption Adviser, Financial Accountability and Anti-Corruption Team, Department for

International Development, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland;

Jennifer Widner, Professor of Politics and International Affairs, Princeton University,

United States of America; James Wasserstrom, Strategy Adviser, Special Inspector-

General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Washington, D.C., United States; Gillian Dell,

Transparency International; Anga Timilsina, Programme Manager, Global Anti- corruption

Initiative, United Nations Development Programme; and Jonathan Agar, Associate Legal

Ofcer, Ofce of Legal Affairs of the Secretariat.

UNODC wishes to acknowledge the contributions of UNODC staff members Ronan

O’Laoire and Constantine Palicarsky, who were responsible for the development of the

Guide, and also acknowledges the expertise and comments provided by the following

staff members: Dimitri Vlassis, Candice Welsch, Oliver Stolpe, Robert Timothy Steele,

Jason Reichelt, Samuel De Jaegere, Zorana Markovic, Virginia de Abajo-Marqués,

Annika Wythes, Troels Vester, Claudia Sayago, Shervin Majlessi, Jennifer Sarvary

Bradford and Akharakit Keeratithanachaiyos.

UNODC wishes to express its gratitude to the Government of Australia for its generosity

in providing funding for the development of this Guide.

v

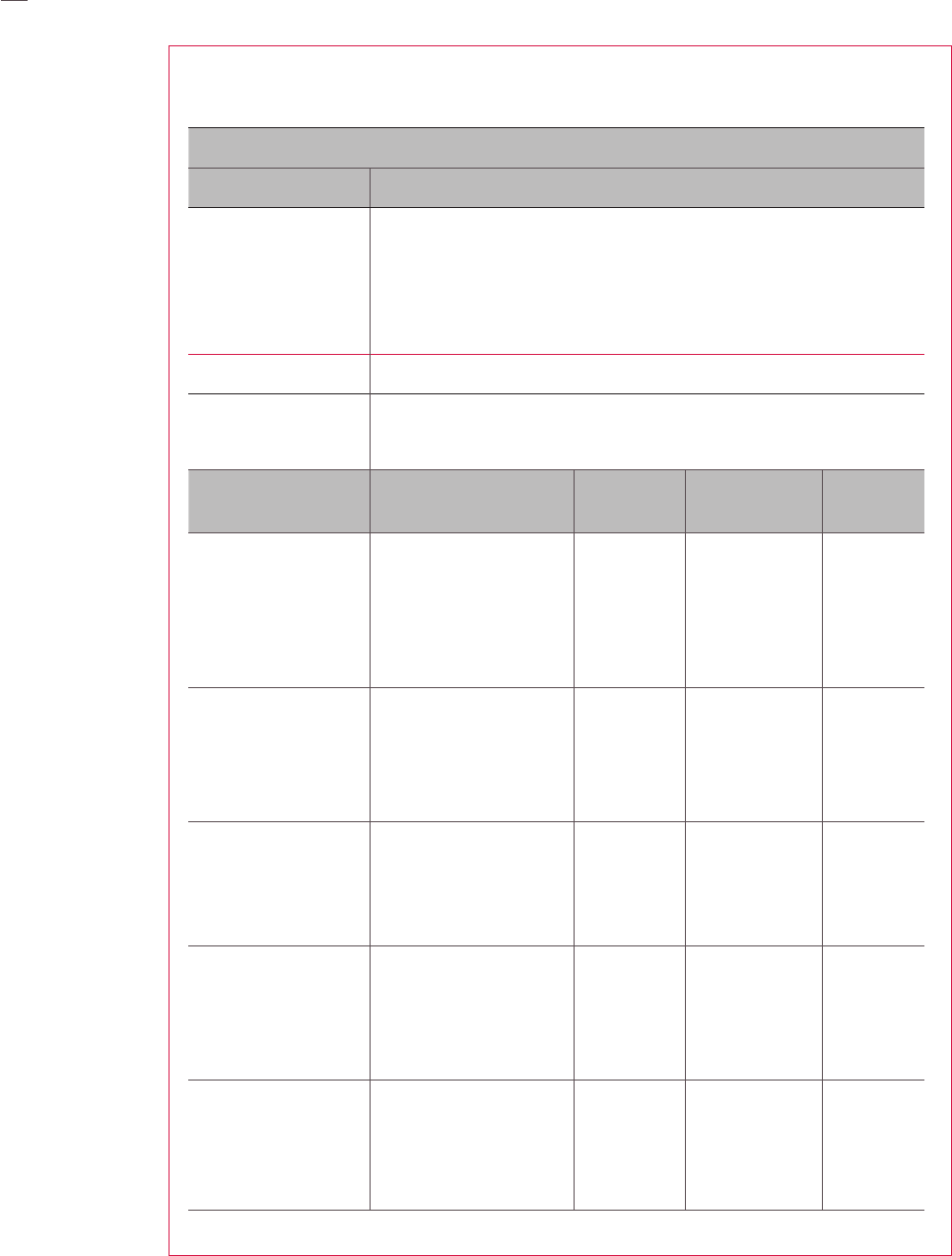

Contents

Introduction ............................................................... 1

I. Drafting process ........................................................ 5

A. Assign responsibility for drafting the strategy to a small,

semi-autonomous group .............................................. 5

B. Ensure the continued support and involvement of senior political leaders ..... 6

C. Consult regularly with all government agencies that will be affected by

the strategy ......................................................... 7

D. Solicit the views of the political opposition whenever possible ............... 8

E. Engage all sectors of society in the drafting process ....................... 8

F. Emphasize communication, transparency and outreach throughout

the drafting process .................................................. 10

G. Allocate sufficient time and resources to drafting the strategy ............... 10

H. Take advantage of other countries’ experience and expertise ................ 11

II. Preliminary diagnosis and situation analysis ................................. 13

A. Conduct a preliminary diagnosis of corruption challenges .................. 13

1. Self-assessments, peer reviews and other assessments ................ 15

2. Cross-country comparisons of corruption or governance ................ 16

3. Country-specific surveys of corruption perceptions .................... 17

4. Surveys of actual experience with corruption. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

5. Internet platforms and social media ................................. 19

6. Information collected by government agencies ........................ 20

7. Comparisons of different data sources ............................... 21

8. Vulnerability assessments ......................................... 22

9. Proxy measurements ............................................. 23

B. Assess obstacles to effective reform .................................... 23

1. Evaluate resource constraints ...................................... 23

2. Address potential opposition and support ............................ 24

III. Formulating anti-corruption measures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

A. Tailor the strategy to the diagnosis, taking account of constraints ............ 27

B. Be ambitious but realistic ............................................. 27

C. Identify concrete, specific measures to be taken .......................... 28

vivi

D. Describe the objective of each reform element ............................ 29

E. Consider the costs, benefits, burdens, opposition and support

for each element. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

F. Pay attention to prioritization and sequencing ............................ 30

G. Specify implementation times for different reforms ........................ 31

IV. Ensuring effective implementation ........................................ 33

A. Put a single, high-level entity in charge of coordination and implementation ... 34

B. Provide the coordination and implementation body with sufficient authority .... 35

C. Foster cooperation between the coordination body and the implementing

agencies ........................................................... 36

D. Harness the power of reputation ....................................... 36

E. Have each agency agree to an implementation, monitoring and

evaluation schedule .................................................. 37

F. Do not underestimate the challenges of coordinating implementation ........ 38

V. Monitoring, evaluating and reporting ....................................... 39

A. Monitoring and evaluating implementation ............................... 40

1. Disaggregate policy reforms into discrete steps ....................... 41

2. Select one or more indicators of progress ............................ 41

3. Choose a baseline for each indicator ................................ 43

4. Establish realistic targets for each implementation indicator ............ 43

5. Watch for indicator manipulation ................................... 44

6. Be cautious when using agency self-evaluations ...................... 44

7. Utilize evaluations to adjust implementation targets and strategy goals ... 44

8. Allocate sufficient time and adequate resources for evaluation ........... 45

B. Monitoring and evaluating impact ....................................... 45

1. Do not use year-to-year changes in corruption index scores to measure

strategic impact ................................................. 46

2. Select impact indicators that can be compared over time ............... 47

3. Isolate the impact of the policies implemented pursuant to the strategy ... 47

4. Be sensitive to the cost and time required ............................ 49

5. Involve civil society organizations, scholars, research organizations

and citizens ..................................................... 50

6. Provide methods for ongoing revision to the strategy ................... 50

C. Public reporting of results of monitoring and evaluation .................... 50

1. Internal reporting as part of coordination mechanisms, ensuring the

accountability of the implementation process ......................... 50

2. Reporting to higher authorities in the executive or parliament ........... 50

3. Public reporting ensures transparency in the implementation of

the national strategy .............................................. 50

Annex. Kuala Lumpur statement on anti-corruption strategies ................... 53

1

Introduction

The United Nations Convention against Corruption is a comprehensive international

instrument intended to combat the scourge of corruption around the world. As observed

in the preamble to the Convention, corruption not only threatens the stability and security

of societies, the institutions and values of democracy, ethical values and justice, sustain-

able development and the rule of law, but is also a transnational phenomenon that affects

all societies and economies, making international cooperation to prevent and control it

essential. With ratication by 176 States parties (as at 24 July 2015), the Convention

has established opposition to corruption as a global norm and made the elimination of

corruption a global aspiration.

States parties to the Convention must undertake effective measures to prevent corruption

(chapter II, articles 7 to 14), criminalize corrupt acts and ensure effective law enforce-

ment (chapter III, articles 15 to 42), cooperate with other States parties in enforcing

anti-corruption laws (chapter IV, articles 43 to 50) and assist one another in the return

of assets obtained through corruption (chapter V, articles 51 to 59). Moreover, in addition

to calling for effective action in each of these specic areas, article 5 imposes the more

general requirements that each State party: (a) develop and implement or maintain effec-

tive, coordinated anti-corruption policies; (b) establish and promote effective practices

aimed at the prevention of corruption; and (c) periodically evaluate relevant legal instru-

ments and administrative measures with a view to determining their adequacy to prevent

and ght corruption (see box 1). Furthermore, under article 6, each State party is required

to ensure the existence of a body or bodies, as appropriate, that prevent corruption by

implementing the policies referred to in article 5 and, where appropriate, overseeing and

coordinating the implementation of those policies. Thus, one of the most important

obligations of States parties under the Convention, and to which they are to be held

accountable under the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation of the Convention

established under article 63,

1

is ensuring that their anti-corruption policies are effective,

coordinated and regularly assessed.

1

See Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption resolutions 3/1 and 4/1

(contained in documents CAC/COSP/2009/15 and CAC/COSP/2011/14).

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

2

Box 1. Article 5 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (Preventive

anti-corruption policies and practices)

1. Each State Party shall, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its legal

system, develop and implement or maintain effective, coordinated anti-corruption

policies that promote the participation of society and reflect the principles of the rule

of law, proper management of public affairs and public property, integrity, transparency

and accountability.

2. Each State Party shall endeavour to establish and promote effective practices

aimed at the prevention of corruption.

3. Each State Party shall endeavour to periodically evaluate relevant legal instruments

and administrative measures with a view to determining their adequacy to prevent and

fight corruption.

4. States Parties shall, as appropriate and in accordance with the fundamental prin-

ciples of their legal system, collaborate with each other and with relevant international

and regional organizations in promoting and developing the measures referred to in

this article. That collaboration may include participation in international programmes

and projects aimed at the prevention of corruption.

For many countries, achieving the objective of article 5 of the Convention against

Corruption may entail the drafting, publication and implementation of a national anti-

corruption strategy; in other words a blueprint for a realistic, comprehensive and inte-

grated plan for reducing corruption in that country. A formal, written strategy is by no

means required for compliance with articles 5 and 6; States parties can maintain effective,

coordinated anti-corruption policies without promulgating a strategy document. But, as

referred to in the Kuala Lumpur statement on anti-corruption strategies (see annex),

publishing a national anti-corruption strategy can be an effective way for States parties

to ensure they meet their obligations under article 5. In the statement, which the

Conference of the States Parties took note of in its resolution 5/4, entitled “Follow-up

to the Marrakech declaration on the prevention of corruption”, it is also recognized that

anti- corruption strategies could provide a comprehensive policy framework for actions

to be taken by States in combating and preventing corruption and could be a useful tool

for mobilizing and coordinating the efforts and resources of Governments and other

stakeholders, for policy development and implementation and for ensuring the monitoring

of policy implementation. Indeed, to date, UNODC has identied over 70 countries that

have issued either a single national anti-corruption strategy or a set of documents that

together constitute a comprehensive, coordinated anti-corruption framework of the kind

foreseen in the Kuala Lumpur statement.

Existing national anti-corruption strategy documents vary widely in length, detail, scope

and emphasis. This is both expected and desirable. There is no “one-size-ts-all” approach

to producing an effective strategy, particularly given that different countries have very

different legal, cultural and political traditions and face very different challenges, oppor-

tunities and constraints. But there has also been considerable variation, and often con-

siderable disappointment, in how effective different countries’ strategy documents have

been in achieving the goals outlined in the Kuala Lumpur statement. For example, in a

2014 report to the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament, the

European Commission found that although in some cases, work on national anti-

corruption strategies was a catalyst for genuine progress, in some others, impressive

strategies had little or no impact on the situation on the ground.

2

Other assessments of

2

European Commission, “Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament: EU anti-corruption

report”, document COM(2014) 38.

3

Introduction

the experience with national strategies have likewise found considerable variation in their

quality and impact.

3

Moreover, even though there is no single correct approach to devel-

oping a national anti-corruption strategy, there are common challenges and difculties

as well as lessons to be learned from past successes and failures.

Responding to a request by the Conference of the States Parties to the Convention in

its resolution 5/4 to identify and disseminate good practices among States parties regard-

ing the development of national anti-corruption strategies, and consistent with the respon-

sibility of the United Nations Ofce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to provide technical

assistance to States parties to help them meet their obligations under the Convention,

4

this Guide offers recommendations for countries considering drafting or revising a

national anti-corruption strategy. Although the focus of the present Guide is on recom-

mendations for the development of formal national anti-corruption strategy documents,

many of the recommendations may also be relevant to countries that plan to meet their

obligations under article 5 without adopting a formal strategy.

The analysis is broken down into the following ve key aspects of an effective national

anti-corruption strategy document:

1. The drafting process for the strategy should be overseen by a body that has

sufcient autonomy, expertise and political backing, and should involve substantive

input from key stakeholders from both inside and outside the Government;

2. The strategy should contain a preliminary evaluation and diagnosis of the main

corruption challenges that the country faces, including the obstacles to the imple-

mentation of an effective anti-corruption policy. The preliminary diagnosis should

also identify gaps or limitations in current knowledge or understanding of those

issues;

3. Based on the preliminary evaluation and diagnosis, the strategy should contain

an anti-corruption policy that lays out ambitious but realistic objectives, identies

top priorities in both the near term and longer term and establishes the appropriate

sequencing of reforms;

4. The strategy should include an implementation plan in which responsibility for

overseeing its execution is assigned to a coordination unit and mechanisms to ensure

the various agencies carrying out different aspects cooperate with one another are

provided for;

5. The strategy should contain a plan for monitoring and evaluating the plan’s

implementation and impact to ensure that the elements of the policy plan are properly

executed, that they are having the desired impact and that they can be revised as

necessary.

Two preliminary observations are in order before proceeding. First, a national anti-

corruption strategy is not merely a technocratic document whose implementation depends

on whether national leaders are sufciently determined to do so. One purpose of devel-

oping and promulgating a national anti-corruption strategy is to help generate and

3

See United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Department for International Development, Why Cor-

ruption Matters: Understanding Causes, Effects and How to Address Them. Evidence Paper on Corruption (London,

January 2015); Southeast Europe Leadership for Development and Integrity, Anti-Corruption Reloaded: Assessment of

Southeast Europe, rev. ed. (Soa, Center for the Study of Democracy, 2014); United Nations Development Programme,

Anti-Corruption Strategies: Understanding What Works, What Doesn’t and Why? Lessons Learned from the Asia-Pacic

Region (Bangkok, 2014); Maíra Martini, “Examples of national anti-corruption strategies”, Anti-Corruption Helpdesk

Answer (Berlin, Transparency International, 2013); Karen Hussmann, ed. Anti-Corruption Policy Making in Practice:

What can be Learned for Implementing Article 5 of UNCAC? Report of Six Country Case Studies: Georgia, Indonesia,

Nicaragua, Pakistan, Tanzania and Zambia (Bergen, Norway, U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, 2007).

4

See CAC/COSP/2009/15, sect. I.A, resolution 3/4, entitled “Technical assistance to implement the United Nations

Convention against Corruption”.

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

4

maintain the leadership, citizen demand and broad support necessary to act effectively

against corruption. A strategy document that simply identies a series of sound, sensible

policies will not advance these objectives. The document, as well as the processes for

drafting it and for ensuring post-promulgation implementation and revision, should create

a sense of ownership and commitment among those both inside and outside the

Government, and should establish targets and benchmarks that enable both domestic and

foreign audiences to hold the Government accountable to the goals it has set for itself.

Second, an overarching theme of this Guide is that strategy drafters must strike a balance

between ambition and realism. A strategy that is too cautious and limited—one that

proposes only easy-to-achieve policy changes—may not address a country’s most press-

ing corruption concerns and will thus not generate the excitement, focus and pressure

needed to make signicant progress in preventing and combating corruption. On the

other hand, an overly ambitious strategy, with grand objectives that are not feasible given

the country’s resources and capacity, will be ignored or dismissed as impractical, and

might further contribute to a sense of frustration and resignation among the citizenry.

The balance between ambition and realism is not an easy one to strike, and the right

approach will vary by country, but those responsible for developing the national anti-

corruption strategy must be mindful of it at every stage of the process.

5

Drafting process

The rst step in formulating an effective national anti-corruption strategy is designing

the process for drafting the document. Decisions regarding process are crucial, as they

affect both the content of the document and the likelihood of its successful implemen-

tation. The particular institutions and individuals who will take responsibility for drafting

the strategy will vary from country to country, and political considerations, resource

constraints and other factors will dictate at least certain aspects of the process. None-

theless, there are some general principles that may be worth following, or at least

following as closely as possible, when setting up a process for drafting a national anti-

corruption strategy. The eight principles listed below are worth emphasizing in

particular.

A. Assign responsibility for drafting the strategy

to a small, semi-autonomous group

Designing the drafting process is critical and great care should be taken at this crucial

rst stage. A relatively small committee or organization should have primary responsi-

bility for drafting the strategy document and should have a reasonable degree of auton-

omy in developing the draft. A clear directive from a senior political leader, preferably

the Head of the Government, setting out the drafting unit’s mandate and responsibilities,

can be useful for clarifying responsibilities and avoiding “turf battles” among different

agencies.

5

Ideally, the drafting body should be chaired by an individual with sufcient stature,

legitimacy and political inuence to act as an effective “champion” for the drafting body,

and ultimately for the strategy itself. The chair should serve both as an effective liaison

with other senior political leaders and as the public face of the national anti-corruption

strategy-drafting process. He or she need not necessarily be involved in the details or

technical aspects of the drafting process, but should have an overall leadership and

managerial role.

5

In the United Kingdom, the Prime Minister issued a directive putting the Home Ofce and the Cabinet Ofce in

charge of drafting the national strategy. See John Bray, “UK national anti-corruption plan: coming soon”, Integrity Matters,

No. 13 (London, Control Risks, 2014).

I.

6

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

A balance must be struck when selecting the members of the drafting body because—as

will be emphasized below—getting broad-based participation and support from a range

of stakeholders is essential to producing an appropriate and effective strategy. At the

same time, however, a national anti-corruption strategy is not likely to be effective if it

is a long “wish list” or a haphazard collection of disconnected, unorganized ideas and

suggestions. It is almost always advisable to identify a small number of primary drafters

responsible for the language of the document. Such individuals must be carefully selected

because they need to be able to consult broadly with a range of stakeholders and experts,

but not have an attachment to any preconceived agenda. At the same time, the primary

drafters also need to construct a strategy that has a coherent vision. They should have

sufcient stature to be respected and sufcient technical expertise to be able to produce

a rigorous, high-quality document. They should also be open to input from different

sources and should represent a diverse group of people so that they are trusted by a

wide range of stakeholders. These qualities are not always found in the same person, so

it may be important to assign the primary drafting responsibilities to a diverse

committee of individuals with different but complementary skill sets, who can work

together effectively.

One approach that a number of countries have followed is to establish a high-level

drafting committee supported by a small group of technical experts responsible for

actually writing the strategy. In Cameroon, a six-person drafting team reported to an

eight-member national commission representing relevant ministries, the legislature, the

supreme court, civil society and the business community. In Pakistan, a small project

team drawn from the anti-corruption bureau and key agencies worked under a steering

committee chaired by a high-ranking government ofcial and composed of senior gures

from across State institutions, civil society, the media and the private sector.

6

B. Ensure the continued support and involvement

of senior political leaders

It is vital that the national anti-corruption strategy has high-level political support, and

that such support is maintained throughout the process. Ideally, senior political leaders,

preferably the Head of State, should openly and publicly endorse the strategy-drafting

process at the outset. During the drafting process, support from senior leaders can be

demonstrated in a variety of ways, including speeches on the importance of having a

comprehensive national anti-corruption strategy and public statements urging citizens to

provide input to the committee. In addition to public endorsements at the beginning and

end of the process, it is also helpful if senior political leaders are kept informed and

involved throughout the development of the strategy, perhaps sometimes attending meet-

ings of the drafting committee.

Once the drafting process is complete, a formal, legal endorsement of the nal document

strategy may be required. The form of this endorsement will depend on the nation’s

legal and political traditions. Some countries may require the strategy to be submitted

to parliament for approval by way of a resolution or even legislation; in others, an

executive decree may sufce. Even where formal endorsement is not necessary, it can

be a useful way of cementing support for the strategy. For many countries, a legislative

vote of approval will be the best means of doing so.

6

Unless otherwise noted, information about a State’s strategy is taken from the text of its national anti-corruption

strategy.

7

Chapter I. Drafting process

Admittedly, senior political leaders may sometimes have different views about the causes

of corruption or the priorities for ghting it, and there are legitimate concerns that if

such leaders are involved in the drafting process, they might use their inuence in ways

that many anti-corruption advocates (perhaps including some members of the drafting

body) might view as weakening the strategy. But a national anti-corruption strategy is,

by its nature, a “top-down” mechanism that relies on the efforts of a range of government

ministries, agencies and institutions for its success. Without high-level political support

and without the sense throughout every level of government that the senior leadership

backs the strategy and its drafters, a national anti-corruption strategy is unlikely to be

effective, no matter what it says on paper. If the senior leadership will not support a

robust anti-corruption strategy, a better course may to be to focus on the development

of a broad-based consensus on problems and solutions, and defer drafting a strategy

until some future date.

C. Consult regularly with all government agencies

that will be affected by the strategy

The national anti-corruption strategy-drafting process should ensure the appropriate

participation of representatives of any government agency responsible for carrying out

any part of the anti-corruption strategy. This will include executive branch agencies such

as the ministries of justice and interior, the specialized anti-corruption agency, the

ombudsman, the police, nancial intelligence units, agencies responsible for public

procurement and the civil service commission or other entities in charge of recruiting,

promoting and disciplining public employees. Where the strategy will affect or require

action by agencies outside the direct control of the executive—the judiciary, the legis-

lature, independent entities such as the national audit agency, independent regulatory

commissions and regional or local governments—they too must be part of the process.

In Ghana, for example, strategy drafters sought input from parliamentarians and the

judiciary, while in Estonia consultations were held with a number of entities independent

of the Government, including the public prosecutor and the competition law agency. In

Peru, special workshops were organized to hear the views of members of the judiciary

and the supreme audit agency, and input from the ombudsman (defensor del pueblo)

was sought throughout the drafting process.

The inclusion of various agencies in the strategy-drafting process is important for numer-

ous reasons. Most obviously, representatives of different agencies have different kinds of

expertise that may improve the quality of the strategy, for example by identifying problems

and challenges that the lead drafters may have missed (or misunderstood) and by sug-

gesting creative solutions. It is also vital that at least some participants in the drafting

process can provide accurate nancial and budgetary information, as these considerations

will be critical to effective implementation. But perhaps even more importantly, different

agencies will typically have responsibilities when it comes to implementing the strategy,

and their acceptance and active support is critical if the strategy is to succeed. Participation

in the drafting process will give them more of a sense of “ownership” of the strategy.

There is always a risk that representatives of government agencies will be overly resistant

to reforms (a common, though not always justied, complaint about bureaucrats every-

where). The views of government agencies should be respected but not considered dis-

positive. On balance, it is better to involve representatives of all relevant government

departments in the process early, and to have a chance to address their concerns, rather

than to present them with a strategy that they were not involved in developing and thus

may resist. Partly for that reason, the consultations should extend not only to the political

8

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

leadership of the various implementing agencies, but also to the technical staff or career

civil servants who will play a key role in implementing the strategy’s recommendations.

Another advantage of involving multiple agencies in the strategy-drafting process is that

it can improve these agencies’ ability to coordinate and cooperate on anti-corruption

issues; their interaction in the drafting process may facilitate cooperation on implemen-

tation, monitoring and evaluation—all of which are critical to the strategy’s success.

D. Solicit the views of the political opposition

whenever possible

Perhaps more controversially, it may be advisable during the strategy-drafting process

to involve not only members of the current Government, but also members of the political

opposition (the parliamentary opposition, or possibly leaders of regional or local gov-

ernments from opposition parties). Their involvement can be useful for many reasons.

First, input from the opposition is a gesture of good faith by the Government—an

endorsement of the idea that ghting corruption is not a partisan issue—and it may

reduce the degree to which the national anti-corruption strategy is viewed as a political

tool of the current administration. Second, opposition parties are often well-positioned

to raise and represent the views of constituencies that might otherwise be marginalized

in the drafting process; the opposition can also raise concerns if the strategy-drafting

process is ignoring issues or concerns relating to certain communities. Third, Govern-

ments change—yesterday’s opposition can become tomorrow’s ruling party—and the

long-term sustainability of a national anti-corruption strategy often depends on whether

it continues to enjoy support following a change in Government.

The inclusion of opposition representatives in the drafting process is, however, not with-

out risk. The presence of opposition representatives in drafting discussions may chill the

free exchange of ideas, and in some cases opposition parties may exploit their role to

advance their political interests or even to sabotage the process to deny the Government

a politically popular achievement. Even when those fears are overblown, the Government

may nonetheless be reluctant to include the opposition in the drafting process. Where

direct participation by opposition representatives is not feasible or desirable, it would

still be appropriate for the strategy’s drafters to consult with leading opposition gures

as part of a more general consultation with a range of experts.

E. Engage all sectors of society in

the drafting process

The strategy drafters should nd appropriate ways to engage broadly with those outside

of the Government: civil society organizations, the business community, the media,

academics, the general public and other stakeholders. The reasons are straightforward:

rst, such stakeholders may have valuable information and useful recommendations for

crafting a more effective strategy that is better tailored to the country’s particular needs

and circumstances; second, inclusion of a broad range of voices in the drafting process

may help build a common vision and increase the legitimacy of the strategy, and hence

political support for it, in the wider society. Those who feel that their voices were heard

in the creation of a policy are more likely to be allies in pushing the strategy forward

and ensuring its effective implementation.

7

7

Elinor Ostrom, “Beyond markets and States: polycentric governance of complex economic systems”, American

Economic Review, vol. 100, No. 3 (2010), pp. 641-672.

9

Chapter I. Drafting process

Broad-based consultations are not without their risks, and although steps can be taken

to minimize them and ensure a productive dialogue (see box 2), strategy drafters need

to bear these risks in mind. Too much emphasis on achieving consensus or trying to

reect the input of all stakeholders can result in a watered-down strategy, one full of

generalities and aspirations but short on concrete choices among competing priorities

and approaches. It is also possible that including outside stakeholders in the drafting

process might backre: if participating stakeholders feel that their views were ignored,

or that the consultations were a sham, they may feel alienated by the strategy-drafting

process, and thus be less likely to become strong allies in its implementation. The strat-

egy drafters must do their best to ensure that the various stakeholders feel that their

views are taken seriously and that they have an impact on the drafting process. At the

same time, drafters must be clear that, ultimately, the draft will integrate a range of

views and perspectives into a coherent document, meaning that the nal national anti-

corruption strategy will not always do or say exactly what every stakeholder would like.

Box 2. Ensuring a productive dialogue with stakeholders

To improve policy implementation, the Government of Australia issued a guidance note

to ministries that included a chapter on stakeholder consultation. It recommends that

before engaging stakeholders, the following questions be addressed:

• Is the purpose and benefit of stakeholder engagement during the implemen-

tation clear?

• Have the right stakeholders been identified?

• Has the cost-effectiveness of different communication channels been

considered?

• Is a wide consultation process using social media beneficial?

• Has sufficient consideration been given to how stakeholder interactions will be

managed during the implementation phase?

• Is there clear accountability for stakeholder engagement, including managing

expectations?

• When is the best time for stakeholders to be engaged?

• How will the information obtained through stakeholder engagement be acted on?

• Is there a communication strategy for consulting with stakeholders?

• If government advertising is proposed, have relevant guidelines been consid-

ered and applied?

• Have staff been provided with guidance on identifying potential conflicts of inter-

est? In particular, are there satisfactory arrangements to manage perceptions

or instances of conflict of interest that may arise from consulting with

stakeholders?

Source: Australia, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Australian National Audit Office,

Better Practice Guide: Successful Implementation of Policy Initiatives (Canberra, 2014), p. 36.

These considerations have important implications for the timing of consultations with

stakeholders as well. A key question is whether to wait until a rough draft of the strategy

document is ready before engaging with stakeholders, or whether consultations should

begin earlier in the process. Both alternatives carry risks. If drafters wait until they have

a text, they might be accused of using the consultations not as a genuine effort to solicit

outside input, but simply as a way to win support and legitimacy for what they wanted

to do anyway. On the other hand, open-ended consultations can produce long, unfocused

lists of suggestions. Not only can this be inefcient, but it also risks alienating those

whose suggestions are not ultimately included in the nal draft. One way to navigate

10

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

between these pitfalls might be to structure consultations in stages, rst soliciting general

input about the country’s corruption challenges, then producing a preliminary draft or

outline and then seeking more focused input. Another, complementary approach might

be to structure early consultations around recent ndings concerning the country’s cor-

ruption problems. For instance, if there is a current survey reporting citizens’ experiences

with bribery in different government agencies, the strategy drafters could seek input from

stakeholders on their perspective on these ndings, and what might be done about them.

F. Emphasize communication, transparency and

outreach throughout the drafting process

In addition to (and perhaps in conjunction with) the consultations with stakeholders, the

drafters of the national anti-corruption strategy should endeavour to be transparent about

the process to the extent feasible (though of course sometimes condentiality might be

required, for example in the case of consultations with other government departments

on sensitive internal matters). Besides maintaining transparency, the Government should

have a plan to publicize the work of the national anti-corruption strategy-drafting body,

so that the general public and interested stakeholders know that their input is welcome

and to explain why ghting corruption, and having a national anti-corruption strategy,

are considered priorities. An effective media and communications strategy serves many

functions: encouraging more, and more diverse, input into the process; increasing the

legitimacy of the strategy-drafting process; sending the signal that the Government is

committed to ghting corruption; and sustaining interest and attention to the strategy-

drafting process, particularly given that the process is likely to take time.

G. Allocate sufficient time and resources

to drafting the strategy

The strategy-drafting process needs adequate time and resources. It is simply not realistic

to suppose that within the space of a few weeks the drafting committee will be able to

consult widely with a broad range of stakeholders inside and outside of Government,

assemble and review the relevant data and evidence, gather new data where there are

critical gaps in the knowledge base required to produce a sound national anti-corruption

strategy and develop a set of well-reasoned, coordinated policy proposals. Providing

adequate time and resources is therefore critical.

How long it will take to draft the strategy will depend on several factors: does the

strategy follow on from an earlier one? How much background research has already

been done? How easy will it be to obtain information from different agencies about their

activities? Another important consideration will be the time required to consult with

different stakeholders. How difcult will it be to hold meetings across the country? How

long will it take to schedule them?

Even with a good deal of background information at hand, drafters in Cameroon found

it a major challenge to prepare a rst draft in the three months allotted for that task.

8

Drafters in Pakistan were able to produce a draft in a little over 10 months, but much

of the research they needed had already been done, and signicant support from the

donor community helped them accelerate the process. A 2014 survey by the United

8

Cameroon, Commission Nationale Anti-Corruption, Stratégie nationale de lutte contre la corruption 2010-2015

(Yaoundé, 2010), p. 13.

11

Chapter I. Drafting process

Nations Development Programme (UNDP) of strategies in the Asia-Pacic region found

that drafting a strategy usually takes between one and two years.

9

The point about the time and resources required for drafting a good strategy is worth

emphasizing because the development of a national anti-corruption strategy is often

prompted by a scandal, putting leaders under pressure to act quickly and decisively. In

other cases, a newly elected Government may want to put an anti-corruption strategy in

place quickly to demonstrate its commitment to a campaign pledge to ght corruption.

Proponents of a national anti-corruption strategy may need to take advantage of these

windows of political opportunity. In some cases, it might be necessary to accelerate the

process of drafting a strategy for other reasons, such as completing the process within

the current budget cycle. In contrast, when an election is pending, it may be unrealistic

to expect signicant progress on drafting a national anti-corruption strategy until after

the election is concluded. Whatever the circumstances, all too often, countries allocate

too little time and too few resources to producing a high-quality strategy document, and

as a result the strategy has little impact in the long run.

H. Take advantage of other countries’

experience and expertise

Strategy drafters should make productive but judicious use of experts from other nations

with experience of drafting, advising on or implementing national anti-corruption strat-

egies. Many States parties to the Convention, particularly developing countries and coun-

tries in transition, may have signicant technical capacity limitations, but all countries

are likely to benet from the expertise and differing views that outside experts can bring

to the drafting process. Such knowledge exchanges are encouraged under article 60 of

the Convention, in which States parties are called upon to consider affording one another

the widest measure of technical assistance in their respective plans and programmes to

combat corruption, including the mutual exchange of relevant experience and specialized

knowledge. Foreign consultants can add signicant value, both through the additional

technical capacity they can bring to bear and their ability to draw from the experiences

of other jurisdictions.

At the same time, however, it is vital that each country retains full ownership of its

national anti-corruption strategy, and that the strategy is appropriately tailored to the

specic needs and circumstances of that country. The drafting of a national anti- corruption

strategy should not be “outsourced” to foreign experts. This is not only because foreign

experts may not always fully understand the unique challenges and circumstances of a

particular country, but also because a national anti-corruption strategy is likely to be

effective only if there is a strong sense of domestic ownership and commitment. Too

often, countries hire foreign consultants to draft their national anti-corruption strategy

documents and there is only minimal input from the domestic ofcials who are entrusted

with implementing the strategy and the citizens who the strategy is supposed to benet.

In these cases, when the foreign experts depart, the strategy is unlikely to be implemented

effectively, and in many cases may languish in obscurity.

A related, and important, point concerns the role of donor support for the national

anti-corruption strategy-drafting process. If taken seriously and done right, producing a

national anti-corruption strategy will, as explained above, be resource- and time- intensive.

For less afuent countries, therefore, international donor support can be essential.

9

Anti-Corruption Strategies: Understanding What Works, What Doesn’t and Why?, p. 14.

12

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

Further more, international donors, and the increasing attention that the donor community

pays to issues of corruption and good governance, may—along with the pressure arising

from the Government’s obligation to comply with the provisions of the Convention against

Corruption—provide countries with the impetus to move forward with a serious, substan-

tive national anti-corruption strategy. At the same time, however, donors may not always

have a clear understanding of a particular country’s circumstances, and may sometimes

push in directions that are not appropriate for that country. Moreover, a national anti-

corruption strategy that is produced mainly to please international donors is unlikely to

have the sort of genuine domestic support and legitimacy that are prerequisites for long-

term, lasting results. Thus, it is important to consider carefully the appropriate relationship

between international donors and recipient countries, so that donor support can be used

most productively in the development of an effective anti-corruption strategy.

13

Preliminary diagnosis and situation analysis

An effective national anti-corruption strategy must be based on an accurate assessment

of the problems and challenges that the particular country faces in combating corruption.

This preliminary diagnosis, sometimes termed a “situation analysis”, consists of two

main elements: an assessment of the nature, extent and impact of the country’s corruption

problems and an assessment of the obstacles that may hinder the implementation of

effective anti-corruption reform. These two elements are described in more detail below.

A. Conduct a preliminary diagnosis of

corruption challenges

Although corruption is a universal phenomenon, countries face very different types of

corruption problems and challenges. It is impossible to combat a problem that is not

understood. Therefore, as stressed in the Technical Guide to the United Nations Con-

vention against Corruption, the rst step in drafting an effective national anti-corruption

strategy is the collection and analysis of information about the extent and nature of the

nation’s corruption problem.

10

How severe is it? Who is affected the most by it? What

kinds of harm is it causing? What forms does it take? What sectors of the economy are

most affected? In what government agencies is it most prevalent? The more information

the strategy drafters have about the answers to these questions, the greater their ability

to set priorities, allocate resources and align the strategy’s objectives with the problems

that confront the country.

Although a preliminary diagnosis of the country’s corruption problem is a critical input

into a strategy, few strategies devote sufcient attention to this essential rst step. A

content analysis done for this Guide of 53 national strategies found that only 13 con-

tained a detailed discussion of the state of corruption in the country.

11

The remaining

40 contained little diagnosis, merely referencing a few statistics or noting that certain

sectors were more corrupt than others; some simply stated that corruption was a major

10

UNODC and United Nations Interregional Crime and Research Institute (Vienna, 2009), p. 6.

11

Examples of good preliminary diagnoses include the 2009 strategy for Armenia, the strategy for the former Yugoslav

Republic of Macedonia for the period 2011-2015 and two strategies for Estonia, one for the period 2008-2012 and the

other for the period 2013-2020.

II.

14

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

14

problem. The lack of an adequate preliminary analysis in these strategies is consistent

with the results of a 2007 review of national anti-corruption strategies by the U4 Anti-

Corruption Resource Centre,

12

and a 2014 review by UNDP of anti-corruption strategies

in the Asia-Pacic region.

13

Both of these reviews also found that the great majority of

anti- corruption strategies contained little, if any, analysis of the corruption problems the

country faced.

One reason policymakers may be tempted to skip an initial diagnosis and situation

analysis is that they think corruption problems are obvious.

14

Obvious corruption prob-

lems, however, may not be the most severe or most damaging, but simply those that are

most visible or salient. Focusing on such problems is often a misleading basis for design-

ing public policy;

15

the most harmful problems may be hardly noticeable, or even invis-

ible. Even when an obvious problem merits priority attention, an initial diagnosis is still

crucial, because it can help policymakers understand the reasons for the problem and to

craft a more effective response. More importantly, a key part of an initial assessment is

estimating how severe different corruption problems are. This leads to the creation of a

baseline against which the impact of the strategy can later be evaluated, another critical

element in a national strategy discussed in chapter V, section A, subsection 3, below.

Moreover, the preliminary diagnosis of a country’s corruption challenges is not simply

an assessment of the scope or extent of corruption in the country. It must also include

at least a preliminary attempt to evaluate the country’s current experience in combating

corruption. Are there important gaps in the laws? Are the laws enforced effectively? Do

the agencies responsible for investigating and prosecuting corruption have sufcient

resources and technical skills? Which agencies have responsibility for combating

corruption or addressing associated issues? Are their roles and responsibilities clear, or

are there gaps or redundancies? What other aspects of the country’s laws and institutions

may be contributing to the corruption problem? These and other questions should be

taken into account when evaluating the challenges a country faces.

Assessing the nature and extent of a country’s corruption problem, however, is challeng-

ing. Many of the available techniques are time- and resource-intensive, perhaps prohib-

itively so for some countries. As a rst step in the process of developing a national

anti-corruption strategy, the drafters will need to formulate a realistic plan for gathering

information from a range of sources. All information sources have their strengths and

weaknesses, and the drafters need to keep this in mind and use a diverse range of mate-

rials to develop at least a preliminary assessment of the main corruption problems. The

eight sources of information listed below may prove useful in conducting this preliminary

assessment, although, as noted, each has its own limitations and drawbacks.

12

See Hussmann, ed., Anti-Corruption Policy Making in Practice: What can be Learned for Implementing Article 5 of

UNCAC?.

13

Anti-Corruption Strategies: Understanding What Works, What Doesn’t and Why?.

14

That is the reason Georgian ofcials gave for issuing an anti-corruption plan in 2000 without doing an evaluation

rst. See Jessica Schultz and Archil Abashidze, “Anti-corruption policy making in practice: Georgia—a country case

study”, in Anti-Corruption Policy Making in Practice: What can be Learned for Implementing Article 5 of UNCAC?,

Hussmann, ed., p. 69.

15

Daniel Kahneman, “Maps of bounded rationality: psychology for behavioral economics”, American Economic Review,

vol. 93, No. 5, pp. 1449-1475.

1515

Chapter II. Preliminary diagnosis and situation analysis

1. Self-assessments, peer reviews and other assessments

The corruption assessments and reviews done by international organizations and non-

governmental organizations can be a valuable and easily accessible source of information.

All parties to the Convention against Corruption have completed or are in the process

of completing the rst cycle of the Implementation Review Mechanism, during which

compliance with chapter III (Criminalization and law enforcement) and chapter IV (Inter-

national cooperation) was reviewed.

Each implementation review begins with the State party under review submitting a

self-assessment in which it identies the steps taken to comply with the Convention,

including legal provisions, national policies and proof of implementation of these through

case summaries and statistics, as well as an outline of how the institutions forming part

of the national anti-corruption framework operate, at both the domestic and international

levels. Two States parties then act as peer reviewers and, working on the basis of con-

sensus, make observations on gaps that have been identied and recommendations on

how these can be addressed in order to strengthen the national anti-corruption framework.

They also identify good practices. The State under review may also identify technical

assistance needs. In many cases, one of the needs for technical assistance identied is

the need to develop a national anti-corruption strategy or action plan in order to imple-

ment the recommendations and to strengthen anti-corruption reform (examples from the

Convention review process appear in box 3). During the sixth session of the Implemen-

tation Review Group, a large number of countries reported on the national implementa-

tion efforts that had been triggered by the country reviews. Most frequently, these actions

related to the development of national strategies in line with the Convention; legislative

reforms, including in respect of transnational bribery, money-laundering and illicit enrich-

ment; strengthening investigative, prosecutorial and judicial capacity; enhancing inter-

agency coordination; and establishing measures to protect witnesses, experts and reporting

persons.

Box 3. Linkages between the findings of country reviews and the development of

national anti-corruption strategies

• Tunisia is in the process of adopting a national plan of action that will be a

cornerstone of the national anti-corruption strategy that is also being devel-

oped, and incorporates the recommendations arising from the review of imple-

mentation of the Convention.

• The Philippines has used the momentum generated by the implementation

review process to establish a presidential inter-agency committee in order to

formulate and develop plans, policies and response strategies to enhance com-

pliance with the Convention.

• In Kenya, the State President has repeatedly affirmed his commitment to imple-

menting the recommendations emanating from the review. This creates the

political conditions to strengthen the existing national anti- corruption

strategy.

In addition, the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Ofcials in Inter-

national Business Transactions of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Devel-

opment (OECD), the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption, the African Union

Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, and the Criminal Law Convention

on Corruption and the Civil Law Convention on Corruption of the Council of Europe

also require parties to undergo a review process to assess compliance. These reviews,

which are also compulsory and include an element of peer review, often highlight areas

16

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

16

where the examined State is not in full compliance with its obligations under the relevant

convention and include recommendations for further actions to address such areas.

In addition to these formal peer review reports, UNDP, the World Bank, the regional

development banks and a number of non-governmental entities—domestic and interna-

tional civil society organizations, universities and research centres—conduct country

reviews that focus on or at least include assessments of corruption, integrity and gover-

nance. Prominent examples include Transparency International’s National Integrity Sys-

tem assessments, Global Integrity’s reports and the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre’s

country evaluations. Other relevant information may be gathered through assessments

and evaluations on combating money-laundering and countering the nancing of terror-

ism, such as the mutual evaluations carried out by the Financial Action Task Force, as

well as the informal national risk assessments carried out by the World Bank.

All of these reports and reviews are particularly helpful because they not only provide

information about the extent and nature of corruption, but they often contain essential

information about gaps or weaknesses in a country’s anti-corruption laws, policies and

institutions. Many States have used the process of evaluation and assessment as a starting

point for reform. Of course, the fact that these reviews are qualitative rather than quan-

titative also introduces an element of subjectivity. Nonetheless, when such reviews exist,

they should be carefully considered by the strategy drafters when conducting the pre-

liminary diagnosis of the country’s main challenges in ghting corruption.

2. Cross-country comparisons of corruption or governance

To get a general sense of the extent of a country’s corruption problem, strategy drafters

often consult international indexes that purport to compare the level of corruption or the

quality of governance among different countries in a region or across the world. Strategy

drafters (and others) may be particularly interested in how their country ranks in relation

to other countries in the same region or with a comparable level of economic develop-

ment. These international indexes are typically based on the opinions or perceptions of

country experts, though some incorporate other data as well.

Two of the most commonly used indexes are Transparency International’s Corruption

Perceptions Index and the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators.

16

The U4

Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, the World Bank, the Vera Institute of Justice and

Transparency International’s Gateway Project have catalogued a wide range of additional

measures. The U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre has compiled a guide to 14 of the

most well-known comparative corruption indicators with a summary of what each

purports to measure.

17

The World Bank has identied 39 cross-national corruption or

integrity indicators

18

and the Vera Institute has compiled 53 different sources that compare

governance performance across nations.

19

The Gateway Project’s search engine examines

over 500 different data sources not only for cross-country indicators but for country-

specic studies as well.

20

16

Both the Corruption Perceptions Index and the Worldwide Governance Indicators are composite measures. That is,

they take data from other sources, standardize them and aggregate them to create a single number summarizing the

underlying sources. They are both, in a sense, a “poll of polls”. See Transparency International, “Corruption Perceptions

Index 2014: full source description” (Berlin, 2014); Laura Langbein and Stephen Knack, “The worldwide governance

indicators: six, one, or none?”, Journal of Development Studies, vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 350-370.

17

Soa Wickberg, “How-to guide for corruption assessment tools”, Expert Answer No. 365 (Bergen, Norway, U4

Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, 2013).

18

World Bank, AGI Data Portal, Links to Governance Indicators. Available at www.agidata.org.

19

Vera Institute of Justice, Rule of Law Indicator Instruments: A Literature Review. A Report to the Steering Committee

of the United Nations Rule of Law Indicators Project (New York, 2008).

20

Transparency International, Gateway: Corruption Assessment Toolbox. Available at http://gateway.transparency.org.

1717

Chapter II. Preliminary diagnosis and situation analysis

While a country’s ranking on these various indicators can provide a rst estimate of

how severe the corruption problem is, care is required when interpreting these measures.

The index scores are derived from different kinds of data, each with strengths and

weaknesses that the strategy drafters must bear in mind if they decide to use these index

scores when developing the initial corruption assessment. For example, the index scores

based on subjective evaluations by experts can be distorted because experts read one

another’s writings and talk among themselves, and their perceptions may reect a

“conventional wisdom” rather than their independent judgement.

21

Moreover, while infor-

mation on the perceived overall level of corruption in the country can be useful for

mobilizing the public behind the strategy—for example, by demonstrating that corruption

is viewed as a serious problem—this sort of aggregated national-level data are of little

value in formulating the content of the strategy. To develop an appropriately tailored

strategy to combat corruption, it is not enough to know how corrupt a country is per-

ceived to be relative to other countries. What is required is precise, detailed information

on the nature and source of corruption, and the leading cross-national indicators do not

provide such information.

3. Country-specific surveys of corruption perceptions

Strategy drafters may also be able to draw on (or commission) in-depth surveys of the

nation’s citizens or businesses. These country-specic surveys are usually more detailed

than cross-country surveys, with questions about the extent and nature of corruption, its

seriousness and whether it has lessened or worsened over time, as well as questions

about specic types of corruption or about corruption in particular sectors or government

agencies. In addition to the general public, country-specic surveys may target investors,

business executives, members of the news media or other experts in particular areas.

Their views can be especially useful in areas such as bid-rigging and the purchase of

defence equipment in which ordinary citizens are unlikely to have the specialized knowl-

edge required on which to base their perceptions.

22

The principal problem with perception surveys is that there can be a signicant gap

between perceptions of corruption and the actual extent of it.

23

The reasons for the

divergence are several and may include the reluctance of respondents to truthfully answer

questions about corruption,

24

the inuence of respondents’ characteristics (e.g., education,

income and ethnic afliation),

25

media coverage

26

and different views among respondents

21

See Stephen Knack, “Measuring corruption: a critique of indicators in Eastern Europe and Central Asia”, Journal of

Public Policy, vol. 27, No. 3 (2007), pp. 255- 291; Daniel Treisman, “What have we learned about the causes of

corruption from ten years of cross-national empirical research?”, Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 10 (2007),

pp. 211-244.

22

These expert perception surveys are distinct from and serve a different function to the expert consultations, which

are discussed in the preceding chapter and should be part of the strategy-drafting process. In some cases, the two may

be linked.

23

See Benjamin A. Olken, “Corruption perceptions vs. corruption reality”, Journal of Public Economics, vol. 93, Nos.7

and 8 (2009), pp. 950-964; Bonvin Blaise, “Corruption: between perception and victimization: policy implications for

national authorities and the development community”, in Challenging Assumptions on Corruption and Democratization:

Key Recommendations and Guiding Principles (Bern, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, 2008); Knack,

“Measuring corruption”; Treisman, “What have we learned about the causes of corruption from ten years of cross-national

empirical research?”; Michael Johnston, “Measuring the new corruption rankings: implications for analysis and reform”,

in Arnold J. Heidenheimer and Michael Johnston, eds., Political Corruption: Concepts and Contexts, 3rd ed. (New

Brunswick, New Jersey, Transaction Publishers, 2002), part XIII, chap. 44, pp. 865-884.

24

See Jan Sonnenschein and Julie Ray, “Government corruption viewed as pervasive worldwide: majorities in 108 out

of 120 countries see widespread problem”, Gallup, 18 October 2013; Aart Kraay and Peter Murrell, “Misunderestimating

corruption”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 6488 (Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2013).

25

See Diylan Donchev and Gergely Ujhelyi, “What do corruption indexes measure?”, Economics and Politics, vol. 26,

No. 2 (2014), pp. 309-331; Olken, “Corruption perceptions vs. corruption reality”.

26

Richard Rose and William Mishler, “Explaining the gap between the experience and perception of corruption”, Studies

in Public Policy, No. 432 (Glasgow, Centre for the Study of Public Policy, 2007).

18

National Anti-Corruption Strategies: A Practical Guide for Development and Implementation

18

about what constitutes corruption in the rst place.

27

Perceptions of corruption can be

important to understand in their own right and, at least in some cases, they may reect

an underlying reality, particularly when perception data are corroborated by other sources.

Nonetheless, perception-based data should always be treated with caution and should

never be the exclusive source for diagnosing a country’s corruption challenges.

4. Surveys of actual experience with corruption

Those responsible for developing the national anti-corruption strategy can also use or

commission surveys that ask about respondents’ actual experiences with corruption, in

addition to, or instead of, asking them about their perceptions of corruption. Such expe-

rience surveys may, for example, ask citizens or businesses

28

about how often they have

paid a bribe in the past year, and can also include questions on the agency to which the

bribe was paid, how much was paid and the purpose of the payment. Some of the most

detailed methodologies in this area were developed and tested by UNODC in its cor-

ruption research in Afghanistan, Iraq and the western Balkans. The UNODC household

and business sector surveys

29

focus on the experience of those surveyed as victims of

corruption, allowing for both a detailed identication and analysis of specic corruption

scenarios and for pinpointing the most vulnerable sectors, agencies and groups. This

kind of survey also provides data that may serve as a baseline for future monitoring and

evaluation purposes. Experience surveys are an attractive source of information about

corruption because they can offer a more objective, quantitative measure of at least some

forms of corruption.

Because of the nature of this kind of survey, it is mostly suitable for detecting the typical

cases of petty, administrative corruption. For obvious reasons, the majority of the

population may have no direct experience with “grand corruption” involving political

and business elites, trading in inuence or procurement fraud. To address the inherent

weaknesses of household surveys, experience-based surveys have also been carried out

with the business sector, focusing on business practices, dealings with governmental

authorities and participation in public procurement. In addition to the UNODC surveys,

examples of such business surveys include the international crime against businesses

survey by the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute, the

UNODC crime and corruption business surveys, the Global Competitiveness Survey by

the World Economic Forum, the World Business Environment Survey by the World Bank

and the World Competitiveness Yearbook of the International Institute for Management

Development.

There are other limitations that should be considered in relation to experience-based sur-

veys. There is evidence that in some countries, respondents may be unwilling to admit

that they have personally engaged in corrupt transactions, even when they are the victims

in those exchanges.

30

In addition, differences in respondents’ willingness to participate in

a survey or to answer questions honestly may introduce biases into the results; this issue

is too often neglected, but it can be a serious problem, especially when non-

response rates are very high and very likely not to be random. In countries where large

27

Sandra Sequeira, “Advances in measuring corruption in the eld” in New Advances in Experimental Research on

Corruption, Danila Serra and Leonard Wantchekon, eds. (Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, United Kingdom, 2012),

pp. 145-176.

28

The World Bank regularly surveys rms in its client countries, asking detailed questions about whether they had to

pay a bribe to obtain power, water or phone service or a construction or import licence and other matters associated with

starting or operating a business. See World Bank, “World Bank’s enterprise survey: understanding the questionnaire”

(Washington, D.C., January 2011).

29

See conference room paper entitled “Quantitative approaches to assess and describe corruption and the role of

UNODC in supporting countries in performing such assessments” (CAC/COSP/2009/CRP.2).

30

Kraay and Murrell, “Misunderestimating corruption”.

1919

Chapter II. Preliminary diagnosis and situation analysis

segments of the population may not have a telephone or may be hard to reach in person,

biases of this kind have been detected.

31

Collecting original survey data can be expensive

and time-consuming and may require specialized skills, which may pose challenges, par-

ticularly in poorer countries where the required infrastructure is lacking. Nonetheless, when

used properly, survey data can be a valuable source of information on corruption.

The costs of these surveys on corruption can be reduced in several ways. A preliminary

assessment using other sources can be conducted, and the survey could be limited to

those areas where it would be most productive. In some cases, questions about corruption

can be added to a survey already planned by the Government, an international organi-

zation or a private entity. This will be far less expensive than commissioning an entirely

new survey.

A number of countries and organizations have now chosen to combine experience and

perceptions questions into a single survey to help offset the weaknesses of each. The

most extensive cross-national experience and perception survey to date is Transparency

International’s 2013 Global Corruption Barometer, during which 114,000 citizens in

107countries were asked not only about their perception of corruption in their country,

but also if anyone in their household had had to pay a bribe to obtain a public service

within the previous two years. UNODC has also conducted a number of mixed perception

and experience surveys and can provide model questionnaires. The Government of

Zambia made good use of a combined perception and experience survey in drafting its

2007 national anti-corruption strategy: 1,500 households, 1,000 public servants and man-

agers of 500 businesses were asked about both their direct experience with corruption

and their perceptions. The Government then used the responses to focus prevention efforts

on departments where the results showed corruption to be especially pronounced.

32

5. Internet platforms and social media

Although the traditional method for gathering information about citizens’ personal expe-

rience with corruption has been through surveys, a recent innovation for gathering such