June 30, 2012

Accuracy of Coding in the Hospital-

Acquired Conditions–Present on

Admission Program

Final Report

Prepared for

Susannah G. Cafardi

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Rapid Cycle Evaluation Group

Division of Research on Traditional Medicare

Mail Stop WB-06-05

7500 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, MD 21244-1850

Prepared by

Catherine L. Snow, MPH

Linda Holtzman, MHA

Hugh Waters, PhD

Nancy T. McCall, ScD

Michael Halpern, MD

Lisa Newman, MSPH

John Langer, PhD

Terry Eng, MS

Carolyn Reyes Guzman, MPH

RTI International

3040 Cornwallis Road

Research Triangle Park, NC 27709

RTI Project Number 0209853.230.001.085

_________________________________

RTI International is a trade name of Research Triangle Institute.

Accuracy of Coding in the Hospital-Acquired Conditions—Present on Admission Program

Final Report

by Catherine L. Snow, MPH; Linda Holtzman, MHA; Hugh Waters, PhD;

Nancy T. McCall, ScD; Michael Halpern, MD; Lisa Newman, MSPH;

John Langer, PhD; Terry Eng, MS; Carolyn Reyes Guzman, MPH

Federal Project Officer: Susannah G. Cafardi

RTI International

CMS Contract No. HHSM-500-2005-00029I

June 30, 2012

This project was funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services under contract no.

HHSM-500-2005-00029I. The statements contained in this report are solely those of the authors

and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services. RTI assumes responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the information

contained in this report.

iii

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................1

ES.1 Methods..........................................................................................................................1

ES.2 Data ...............................................................................................................................2

ES.3 Results ............................................................................................................................3

SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ON ACCURACY OF CODING ...........7

1.1 Objectives ......................................................................................................................7

1.2 Selected Phase II Conditions for Medical Record Validation .......................................7

1.3 Conceptual, Operational, and Clinical Definitions of Accuracy of Coding ..................8

1.3.1 Conceptual Definition of Accuracy of Coding .....................................................8

1.3.2 Operational Definitions of Accuracy of Coding ...................................................9

1.3.3 RTI Physician Review for Accuracy of Coding .................................................10

SECTION 2 SAMPLING DESIGN...............................................................................................11

2.1 Sampling Plan ..............................................................................................................11

2.1.1 Measures of Interest ............................................................................................11

2.1.2 Estimated Magnitude of the Parameters .............................................................11

2.1.3 Margin of Error and Confidence Intervals ..........................................................12

2.1.4 Sample Size Requirements for Medical Record Abstraction .............................12

2.2 Sampling Frame ...........................................................................................................13

2.3 Medical Record Sampling Plan ...................................................................................13

2.3.1 Linking CERT Medical Records to MedPAR Data ............................................13

2.3.2 Sampling Plan for Assessing Accuracy of POA Coding ....................................14

2.3.3 Sampling Plan for Assessing Accuracy of HAC Coding....................................14

SECTION 3 MEDICAL RECORD VALIDATION PLAN ..........................................................17

3.1 Medical Record Validation Flow Diagrams ................................................................17

3.2 Medical Record Abstraction Tools ..............................................................................19

3.2.1 Type of Review ...................................................................................................20

3.2.2 Preliminary Evidence ..........................................................................................20

3.2.3 Part I—Should the Listed Condition Be Coded? ................................................20

3.2.4 Part II—Was the Listed Condition Present on Admission? ...............................21

3.2.5 Disposition ..........................................................................................................21

3.3 Medical Record Validation Process .............................................................................21

3.4 RTI Institutional Review Board ...................................................................................22

iv

SECTION 4 DATA ANALYSIS ...................................................................................................23

4.1 Unreported HAC Observations ....................................................................................23

4.2 Over-Reported POA Observations ..............................................................................25

4.3 Strength of Evidence for POA .....................................................................................27

4.4 Abstraction Observations .............................................................................................28

4.4.1 Physician Queries Related to Potential HACs ..................................................28

4.4.2 Pressure Ulcer Coding ......................................................................................30

SECTION 5 DISCUSSION ...........................................................................................................31

REFERENCES ..............................................................................................................................35

APPENDIX A: ASSESSMENT OF THE REPRESENTATIVENESS OF THE CERT

RECORDS ..........................................................................................................36

APPENDIX B: APPENDIX OF TOOLS .....................................................................................45

APPENDIX C: CLINICAL CODING GUIDELINES .................................................................63

LIST OF FIGURES

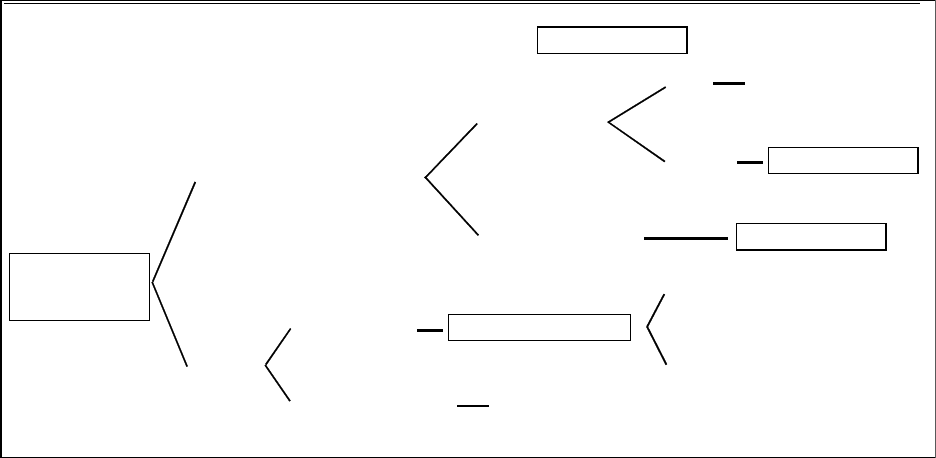

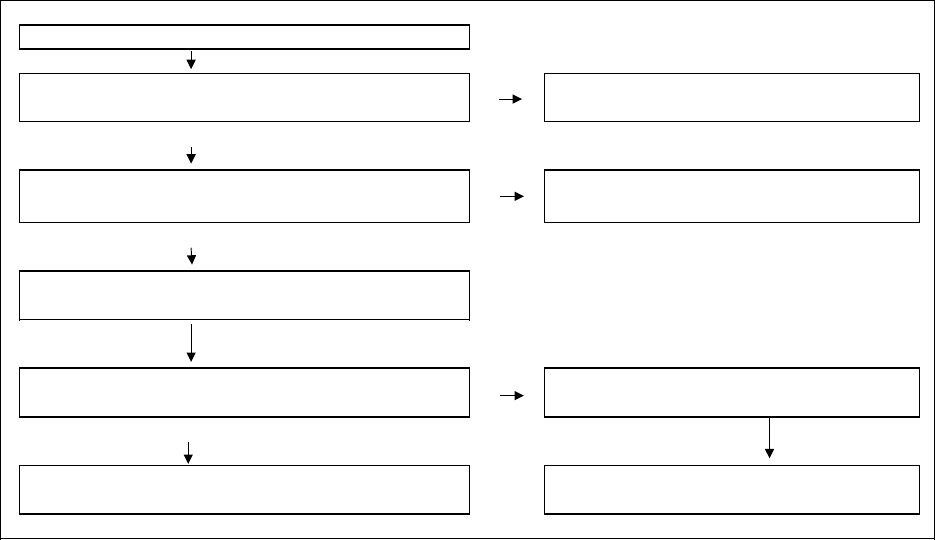

Figure 1-1 Conceptual definition of the accuracy of coding ....................................................... 8

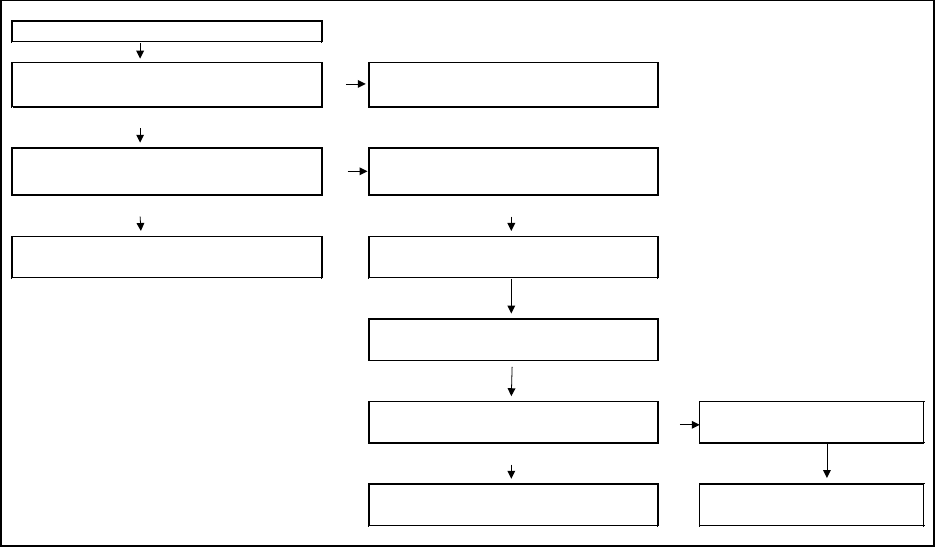

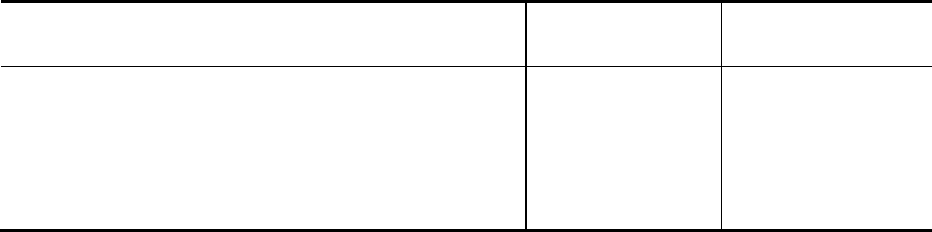

Figure 3-1 Unreported HACs: Medical record validation flow diagram .................................. 18

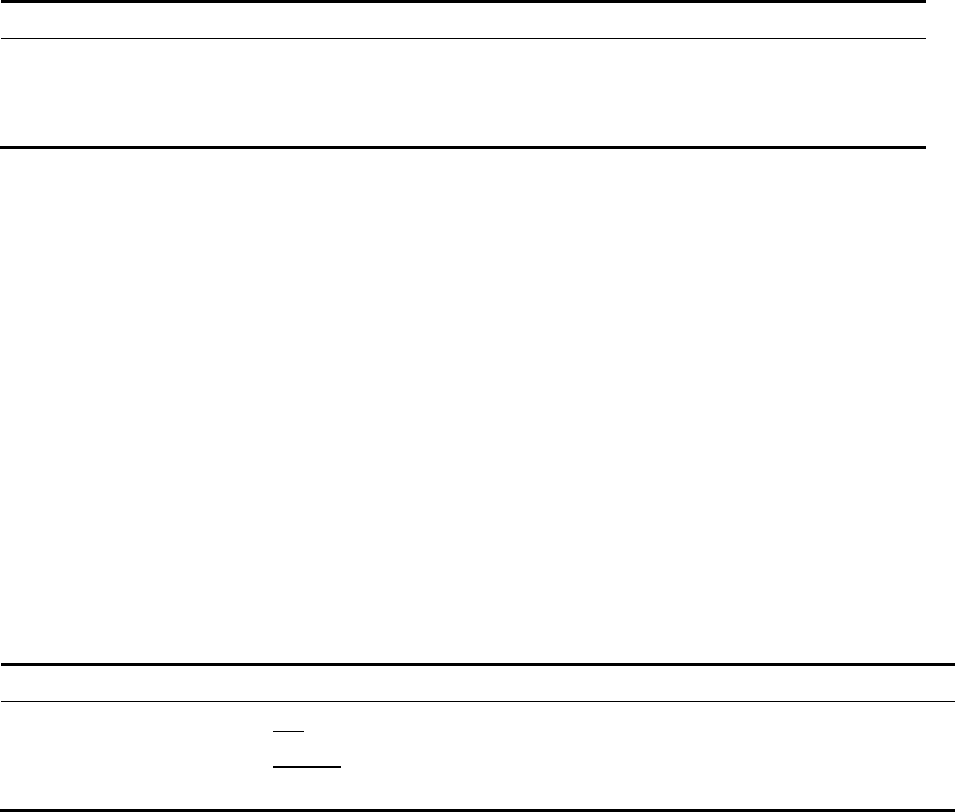

Figure 3-2 Over-reported POA: Medical record validation flow diagram ................................ 19

LIST OF TABLES

Table ES-1 Summary of HAC coding accuracy: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE ................................. 3

Table ES-2 Summary of POA coding accuracy: All five POA conditions combined .................. 4

Table 2-1 Sample sizes for each condition ............................................................................... 12

Table 4-1 Summary of HAC coding accuracy: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE ............................... 23

Table 4-2 Number of unreported HAC cases determined to be present on admission for

three clinical conditions: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE ................................................. 24

Table 4-3 Number of cases where condition was present and how it affected patient care

or three clinical conditions: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE ............................................. 24

Table 4-4 Number of cases stratified by level of evidence that the unreported HAC cases

were present for three clinical conditions: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE ...................... 25

Table 4-5 Summary of POA coding accuracy: All five POA conditions combined ................ 25

Table 4-6 Over-reported POA: number of cases where the condition was present, but not

on admission, or was not present at all .................................................................... 26

Table 4-7 Over-reported POA: POA summary of evidence .................................................... 27

Table 4-8 Over-reported POA: POA pressure ulcer evidence ................................................. 28

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Under the Hospital-Acquired Conditions—Present on Admission (HAC-POA) program,

accurate coding of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) and present on admission (POA)

conditions is critical for correct payment. The purpose of the HAC-POA program, funded by the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), is to evaluate the HAC-POA payment policy

related to preventable HACs. The principal objective of the Accuracy of Coding component,

which is the subject of this report, is to determine the level of accuracy of coding for HACs and

for POA conditions. This study was conducted jointly by RTI International and Clarity Coding.

For payment purposes, for each condition there are two questions that are key to

assessing the accuracy of coding:

1. Is there documented clinical evidence that a condition was present during the

hospitalization? We identified unreported cases, where a HAC-associated

condition existed but was not reported by the hospital.

2. If yes, was the condition POA?

We identified over-reported POA cases, where a HAC-associated secondary

diagnosis code was reported as POA when it was not in fact POA.

After considering a wide range of data sources and discussing priorities with the projects’

funders, we focused on three types of POA s for examining under-reporting:

1. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI),

2. Vascular catheter-associated infections (VCAI),

3. Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolisms (DVT/PE); and

five types of HACs for examining POA over-reporting:

1. CAUTI ,

2. VCAI,

3. Falls and trauma,

4. Stage III and IV pressure ulcers, and

5. Extreme manifestations of poor glycemic control.

ES.1 Methods

Clarity Coding, under subcontract to RTI, abstracted medical records to confirm if cases

were correctly coded for both HAC and POA status. Our operational definition for accuracy of

coding is based on diagnostic and procedural information about the patient as coded and reported

2

by the hospital on the claim form, matched against the documentation in the patient’s medical

record, while factoring in relevant coding guidelines from definitive sources.

We selected claims included in the Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 and FY 2010 Medicare

Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file that had one or more of the five HAC-associated

diagnoses coded as POA. We also included records of patients that did not have a HAC coded,

but were at risk of developing the condition (e.g., had an indwelling urinary catheter, central

catheter, or certain orthopedic procedures). We merged these MedPAR data with medical

records—obtained by CMS through its Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program.

To assess accuracy of HAC and POA coding, a coding expert reviewed the full medical

record for each case. The Clarity Coding coder would make a technical coding change without

physician review if the medical record clearly stated that the condition presented during the

hospitalization but the wrong diagnosis code was used by the hospital. If the coders were unable

to make a decision due to clinical ambiguity, they referred the case to an RTI physician for

review and decision. Linda Holtzman, MHA, was the Clarity Coding Project Director for this

activity, supervising a team of four coders.

ES.2 Data

Through a combination of training, monitoring, and inspection, RTI and Clarity Coding

provided a high level of data protection and quality control. CMS staff provided us with the FY

2009 and FY 2010 medical records received by the CERT program, including the information

necessary to link these medical records to Medicare claims data. After excluding those hospitals

not subject to the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS)—and therefore not

subject to the HAC-POA policy—our sampling frame was 10,465 unique CERT medical

records. Using beneficiary and hospital identification information in the medical records, we

linked the records to the MedPAR claims data for FY 2009 and FY 2010. This step allowed us

to create an electronic database linking claims data to the medical records, and populating the

database with information from the MedPAR claims, including diagnosis codes, procedure

codes, and other data elements that might be useful for our analyses.

To ensure that the CERT records were representative of all Medicare IPPS discharges,

we compared characteristics of the CERT medical records to the characteristics of all discharges

from IPPS hospitals in the FY 2009 and FY 2010 MedPAR database. We verified that the

distributional properties of the CERT records are consistently similar to the MedPAR records for

patient and hospital characteristics such as patient age, gender, race, principal diagnoses, and

hospital size and location. (For a more detailed analysis of the representativeness of the CERT

records, please refer to Appendix A.)

We sought to have 264 CERT records for assessing accuracy of reporting HACs for each

of the three selected conditions. To identify VCAI records for validation, we screened MedPAR

records with a central line or venous catheterization coded as having been inserted during the

hospitalization—excluding records where VCAI was coded as hospital acquired (POA = N or U)

or present on admission (POA = Y or W). This yielded 881 CERT records; a random sample of

264 was selected.

3

CERT medical records for DVT/PE validation were selected by identifying MedPAR

records with corresponding claims that did not have DVT/PE coded as hospital acquired or POA,

but did have certain orthopedic procedures with a high risk for developing DVT/PE (hip

resurfacing, hip replacement, and knee replacement)—for a total of 222 CERT records. While

this was less than the 264 desired for coding review, there were no additional discharges in

which the patient had undergone one of these orthopedic procedures.

For CAUTI cases, we first identified MedPAR records that linked to CERT records and

had the presence of an indwelling urinary catheter coded, excluding any MedPAR cases where

CAUTI was coded as hospital acquired (POA = N or U) or present on admission (POA = Y or

W). This produced 90 CERT records for review. Next, MedPAR records were linked with their

corresponding physician claims to identify cases where a physician billed for insertion of

indwelling urinary catheter during the inpatient stay. This yielded an additional 35 CERT

records for review. And, third, RTI staff manually screened the CERT records for the presence

of an indwelling urinary catheter. Of 308 cases screened, 139 had evidence that the beneficiary

had an indwelling catheter inserted at some time during the hospital admission. Of these, one

record could not be read, leaving a total of 263 CERT records.

To test for POA status, we selected all CERT records that had one of the 12 HACs coded

as POA on its linked MedPAR claim. This process yielded a total sample of 318 cases across

five conditions: CAUTI (13), VCAI (5), Stage III or IV pressure ulcers (105), falls and trauma

(181), and extreme manifestations of poor glycemic control (14).

ES.3 Results

We did not find patterns of widespread under-reporting of HACs or over-reporting of

POA status. In just 23 out of a total of 749 HAC cases (3%), the condition was determined to be

present but not reported. Of the disagreements that were observed, the most frequent were for

CAUTI cases, 6% of which were inaccurately coded (i.e., the condition was present but not

coded by the hospital). The least frequent disagreement was for DVT/PE cases, with no

inaccurately coded HACs (Table ES-1). For 17 of 23 HAC cases, the condition was POA. This

leaves just 6 of the 749 cases that were both hospital acquired and inaccurately coded.

Table ES-1

Summary of HAC coding accuracy: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE

Disposition

CAUTI

n

CAUTI

%

VCAI

n

VCAI

%

DVT/PE

n

DVT/PE

%

Hospital coded/reported accurately

247

94%

257

97%

222

100%

Hospital did not code/report

accurately

16 6% 7 3% 0 0%

Total 263 100% 264 100% 222 100%

NOTE: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; DVT/PE, deep vein

thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HAC, hospital-acquired condition; VCAI, vascular catheter-

associated infections.

4

The results for over-reported POA cases are similar in magnitude. Of all the cases coded

POA, 91% were coded accurately (Table ES-2). However, the level of uncertainty around this

estimate is large, given the small number of CERT medical records available for abstraction. Of

the 28 POA cases coded inaccurately, the highest percentages are attributable to Stage III and IV

pressure ulcers, with 9% (9 out of 105 cases) being incorrectly reported as POA; and falls and

trauma, with 8% (14 out of 181 cases) incorrectly reported as POA.

Table ES-2

Summary of POA coding accuracy: All five POA conditions combined

Disposition N %

Hospital coded/reported accurately 290 91%

Hospital did not code/report accurately 28 8%

Total

318

100%

NOTE: POA, present on admission.

When evaluating medical records coded by the hospital as the condition being POA, the

coders looked for two things: (1) whether the condition existed during the stay, and (2) whether

the condition was POA. This approach allowed for two ways in which the Clarity Coding coder

could disagree with the hospital coder. From the cases reviewed in this study, the former seemed

to be the main reason for coder disagreement; 23 out of 28 inaccurately coded POA cases were

inaccurate because the condition was not present at the time of admission or at any time during

the hospitalization.

Clarity Coding was asked to provide RTI with their observations from the detailed

medical record reviews they performed. They noted that two specific types of cases were

particularly challenging: unreported CAUTI and over-reported POA pressure ulcers. They

provided specific cases illustrating that two coding issues identified may affect interpretation of

the validation results: a lack of physician queries in the medical records, and the requirement to

code progression of pressure ulcers to Stage III or IV during the hospitalization as POA. The

coders found numerous instances in which the hospital coding was in accordance with coding

guidelines, but the conditions might have been perceived as hospital acquired by clinicians

unfamiliar with coding practices. Using exclusively clinical validation criteria not requiring

conformance with official coding guidelines, more instances of under-reporting of HACs or

over-reporting of POA may have been found. However, from a coding perspective the

conditions could not be determined to be hospital acquired. Coding is fundamental to

administration of the HAC-POA program, and its requisites must be observed.

With respect to progression of pressure ulcers to Stage III or IV during the

hospitalization, coding guidelines direct that the Stage III or IV pressure ulcer be confirmed as

POA if a lower stage ulcer was recognized on admission and progressed to a higher stage ulcer

during the admission. CMS may wish to discuss the unintended consequences of coding

guidelines on the HAC-POA payment policy with the other Cooperating Parties.

5

The inconsistency in how hospitals store queries creates issues with accessing them. This

can impede any type of external coding review and inadvertently skew its findings. If possible,

hospitals should be urged to uniformly include all queries and their responses as part of the

permanent medical record. This would ensure that a complete clinical picture is available to

reviewers and can be reflected in their findings.

6

[This page left intentionally blank]

7

SECTION 1

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ON ACCURACY OF CODING

1.1 Objectives

The purpose of this project, funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

(CMS), is to evaluate the Hospital-Acquired Conditions–Present on Admission (HAC-POA)

payment policy related to preventable hospital-acquired conditions (HACs). This policy is one

of several recent CMS value-based purchasing initiatives designed to improve the structure of

payment incentives aimed at improving health care performance. Accurate coding of HACs is

essential for these payment incentives to be effective—as is correctly identifying whether HAC-

associated conditions are present on admission (POA) rather than acquired in the health care

setting.

The principal objective of the Accuracy of Coding component of the HAC-POA Project

is to determine the level of coding accuracy for HACs and for POA conditions. Through

medical record abstraction, we have evaluated the degree to which independent coders validated

hospitals’ coding of conditions that are hospital acquired and those that are POA. This study was

conducted jointly by RTI and Clarity Coding.

1.2 Selected Phase II Conditions for Medical Record Validation

RTI worked with the project’s funders to identify the Phase II conditions for the study.

The funders provided key inputs for this process, including information and recommendations

regarding the selection of HACs, examples of algorithms for assessing the accuracy of coding,

feasibility of case identification, relevant literature, and, when physician reviews were necessary,

which data elements to consider including in these reviews. For Phase II, we focused on

assessing the accuracy of coding of three types of HACs: (1) catheter-associated urinary tract

infections (CAUTI); (2) vascular catheter-associated infections (VCAI), also described as central

line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI); and (3) deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary

embolisms (DVT/PE). CAUTI was identified by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) as a

priority condition in terms of incorrect coding and reporting. The CDC suggested VCAI for

consideration—and provided a computer algorithm to use as a template in developing our

abstraction tool (Trick et al., 2004). DVT/PE was selected as a clinical condition for the study

because of strong, objective confirmatory diagnostic testing readily available for patients

presenting with symptoms of either DVT or a PE.

As discussed in more detail below, we identified 10,465 medical records—obtained by

CMS from its Comprehensive Error Rate Testing (CERT) program. However, when we merged

these CERT records with the Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 and FY 2010 Medicare Provider Analysis

and Review (MedPAR) records that had one or more of the HAC-associated diagnoses coded as

POA, we obtained only 318 matches. The project’s funders therefore determined that all CERT

records that matched a MedPAR record with a relevant POA code would be abstracted. The

following five conditions had matching CERT records and so are the subject of our assessment

of accuracy of POA coding: (1) CAUTI, (2) VCAI, (3) falls and trauma, (4) Stage III and IV

pressure ulcers, and (5) extreme manifestations of poor glycemic control.

8

1.3 Conceptual, Operational, and Clinical Definitions of Accuracy of Coding

1.3.1 Conceptual Definition of Accuracy of Coding

Under CMS’s HAC-POA program, hospitals have financial incentives to record clinical

conditions as POA—for example, a history of a DVT following a prior orthopedic procedure.

Hospitals also potentially have incentives to mischaracterize or under-report clinical conditions

that are acquired during the hospitalization. For example, a hospital could label a Stage III

pressure ulcer as a Stage II instead if the ulcer was acquired during the hospitalization, or label a

pressure ulcer as Stage III rather than Stage II if it is POA.

Accurately coding HACs and POA conditions is critical for correct payment under the

HAC-POA program. For payment purposes, for each condition, two questions are key to

assessing the accuracy of coding:

1. Is there documented clinical evidence that the condition was present during the

hospitalization?

2. If yes, was the condition POA?

This task looks at how accurately hospital coders reported the answers to these two

questions on claims submissions. Figure 1-1, below, provides a conceptual framework.

Figure 1-1

Conceptual definition of the accuracy of coding

POA

Accurately Coded

Condition Existed

Not POA

Coded

Coded as POA

Condition did not Exist

POA

Condition Existed

Not Coded

Not POA

Condition did not Exist

Accurately Coded

HAC

-

Diagnosis Code

POA

Inaccurately Coded

Inaccurately Coded

Inaccurately Coded

Associated

For each condition, the first question is whether a HAC-associated diagnosis was coded

on the claim, as shown in the far left box of Figure1-1. Following the path in the lower section

9

of the figure, a “Not Coded” leads to the possibility of either incorrect coding (coded that the

condition did exist) or correct coding (coded that the condition did not exist). This study focuses

on whether a condition not coded by the hospital did exist, resulting in an inaccurately coded

case as illustrated in the diagram. To further understand what this kind of inaccurate coding

represents, we looked at these cases to determine if they were POA or hospital acquired. We

first identified the total number of cases for which the coding was inaccurate—in other words,

evidence that the condition existed during the hospitalization but was not coded. Secondly, we

identified which of these unreported cases should have been coded POA.

At the top of Figure1-1, the HAC-associated diagnosis is correctly coded, and the

concern is the accuracy of POA coding. POA can be over-reported in two ways. The first is

when the condition is coded as POA, but was in fact hospital acquired. The second type of over-

reporting occurs when the condition is coded and reported as POA, but the condition itself did

not actually exist during the stay. Both conditions are presented in the top half of Figure 1-1, and

we analyze both when we assess the accuracy of POA coding.

To summarize, this study focuses on two types of coding inaccuracies:

• HAC-associated secondary diagnosis code is not coded but the condition existed

during the hospital stay; and

• HAC-associated secondary diagnosis code is coded and reported as POA when it was

not POA.

1.3.2 Operational Definitions of Accuracy of Coding

RTI explored several alternatives for defining and measuring accuracy of coding in Phase

I, including literature reviews, discussions with the project funders, and conversations with

coding and other experts. Our operational definition of accuracy of coding is based on

diagnostic and procedural information about the patient as coded and reported by the hospital on

the claim form, matched against the documentation in the patient’s medical record, while

factoring in relevant coding guidelines from definitive sources.

We abstracted medical records to confirm if cases were correctly coded—based on

clinical information documented by the responsible physicians and other qualified health care

providers. Cases were referred for review by an RTI physician whenever medical judgment was

needed. If the Clarity Coding coder did not agree with the diagnosis code based on clinical

documentation and coding guidelines and felt confident that a diagnosis change was appropriate,

the coder reported the case as coded incorrectly by the hospital. For example, if the physician

narrative description states, “UTI due to indwelling catheter,” yet the diagnosis code reported by

the hospital was for a simple UTI, the Clarity Coding coder would make a technical coding

change without physician review.

If the coders were unable to make a decision due to clinical ambiguity, they referred the

case to an RTI physician for review and comment. These referral cases included clinical or

diagnostic uncertainty as well as unclear or incomplete documentation. This type of HAC under-

reporting was identified by the 2010 report from the Inspector General of Health and Human

10

Services on the topic of adverse events in hospitals—for cases in which “… physician reviews

determined that the beneficiary experienced a ‘catheter-associated urinary tract infection,’ yet the

billing data included a more general diagnosis code for ‘urinary tract infections, not otherwise

specified’” (Levinson, 2010).

To assess accuracy of HAC and POA coding, the full medical records for these cases

were reviewed by a coder. While validating the coding, the coders also abstracted information

from the medical record, allowing us to develop categories of explanations, where possible, for

over-reporting of POA cases and under-reporting of HAC cases.

There may be instances of “false disagreement” between the hospital and the Clarity

Coding coder that arose due to incompleteness of the medical record. The medical records

obtained through the CERT program did not always include the physician query forms. These

forms allow the physician to augment or clarify ambiguous documentation in the medical record.

Although physician query forms are the approved means for clarifying documentation, these

forms are not consistently included in the formal medical record. Depending on the hospital, and

sometimes on the physician, queries may be made in a nonpermanent form—for example, with a

sticky note—and responses may be documented in a query database and not included in the

medical record. As a result, we may not have had complete physician query information

consistently available as part of the medical record requested by the CERT program.

Linda Holtzman, MHA, was the Clarity Coding Project Director for this activity; she

supervised a team of four coders. Ms. Holtzman and each of the coders are credentialed as

Certified Coding Specialists (CCS), Registered Health Information Technicians (RHIT), or

Registered Health Information Administrators (RHIA). Ms. Holtzman is a CCS-P (specialized in

physician coding) and Certified Professional Coder specialized in hospital coding (CPC-H), as

well as an RHIA. She personally conducted validation coding and provided guidance on the

development of the final validation tools and insights into validation findings.

1.3.3 RTI Physician Review for Accuracy of Coding

Two kinds of physician assistance were made available to the Clarity Coding coders to

help determine the accuracy of a given case. If only minimal clinical clarification on a case was

needed, the Clarity Coding coder was able to query an RTI physician directly by phone. If more

formal physician review was needed, the coder was able to submit the case to the RTI physician

in writing, including a brief reason for the review request. RTI physicians made a diagnostic

assessment concerning the potential presence of an identified condition and made the final

determination on coding accuracy of the record on all formally reviewed cases.

11

SECTION 2

SAMPLING DESIGN

2.1 Sampling Plan

There were several key components of the sampling plan for this study:

1. Assumptions about the rates of coding accuracy (error) to be estimated through

medical record abstraction and review;

2. Descriptions of the parameters to be estimated;

3. Desired margins of error of the parameter estimates;

4. The sample sizes required to achieve the objective of estimating the coding

accuracy rates; and

5. The medical record sampling plan.

As described below, we discussed these components of the sampling plan with the

funders, and drew upon evidence from the literature and other sources to develop our sample size

estimates.

2.1.1 Measures of Interest

As described above in Section 1.3, the statistical measure of interest for HACs is the rate

at which a condition is not coded by the hospital as a HAC, but where our validation process

determines the condition was hospital acquired. Similarly, the statistical measure of interest for

POA coding is the rate at which a condition is reported by the hospital as POA, but our

validation process determined the condition was not POA.

2.1.2 Estimated Magnitude of the Parameters

For the reasons described below in Sections 2.3.2 and 2.3.3, we employed a single-stage

sampling process to identify medical records for POA validation, and a multistage process to

identify medical records for HAC validation. This necessitated drawing two independent

samples for the HAC under-reporting sample and the POA over-reporting sample.

To calculate the sample size for this study, we assumed a 20% error rate in reporting

HACs. There is little empirical evidence as to the likely error rate in coding HACs, so the results

of a small study that reviewed medical records for 80 patients at a single academic medical

center were used as a guide. That study found that 35% of patients with a secondary diagnosis of

a urinary tract infection (UTI) actually had a CAUTI (Meddings et al., 2009). Given that RTI is

using a broader sample of patients, and not just those with a secondary diagnosis of a UTI, we

used a 20% error rate.

We assumed a 12.5% error rate for reporting HACs as POA. Studies in California

involving pneumonia and lung cancer cases indicated that POA coding agreed with two widely

used comorbidity algorithms—the Deyo/Charlson and the Elixhauser algorithms, respectively

12

(Southern, Quan, and Ghali, 2004)—86% to 95% of the time, respectively (Stukenborg et al.,

2007). Therefore, as the starting point for our sample size calculation, we took the midpoint of

the 86–95% range (90.5%) and subtracted from 100% to obtain 9.5%. Because most other states

have not had as much experience with POA coding as California has, we increased the estimate

of the error rate by 3 percentage points to 12.5%.

2.1.3 Margin of Error and Confidence Intervals

For quality improvement studies and reporting, many of the Healthcare Effectiveness

Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure samples developed by the National Committee for

Quality Assurance (NCQA) are designed to yield a probability of Type I error not greater than

±5%. Type I error is equivalent to an unreported HAC—the failure to identify a true null

hypothesis that a condition exists. For this task, we agreed upon a ±5% margin of error for the

HAC under-reporting sample, and ±3% margin of error for the POA over-reporting sample.

2.1.4 Sample Size Requirements for Medical Record Abstraction

Based on the above assumptions, the base sample size calculated for under-reporting for

each HAC was 264 records, and the sample size for estimating POA over-reporting was 499

records. As the project progressed, it became clear not enough records would be eligible for the

POA accuracy of coding review. Table 2-1, below, shows the actual number of records eligible

for review by condition. For CAUTI and VCAI under-reporting, 264 records were selected. For

DVT/PE, only 222 cases were identified as eligible for review. We selected all CERT records

that matched MedPAR records containing one of the orthopedic procedure codes that define the

denominator for the DVT/PE HAC measure.

The sample size issue was more acute for the POA cases, rendering RTI unable to

conduct POA coding accuracy by individual condition. We therefore developed abstraction tools

for all conditions coded as POA that had five or more eligible medical records, and conducted

medical record abstraction for all such cases. We conducted our analyses across the full set of

cases.

Table 2-1

Sample sizes for each condition

Hospital-acquired condition

HAC unreported

sample

POA over-

reported sample

Vascular catheter-associated infection 264 13

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection

264

5

Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism

222

—

Pressure ulcers — 105

Falls and trauma — 181

Manifestations of poor glycemic control — 14

NOTE: HAC, hospital-acquired condition; POA, present on admission.

13

2.2 Sampling Frame

A sampling frame represents the population from which the sample is to be drawn. To

comply with the Improper Payments Information Act (IPIA) of 2002 and support Medicare Fee

for Service (FFS) contractors in targeting review and education, CMS runs the CERT program

(CMS, 2012). This initiative selects a sample of Medicare claims and reviews them for accuracy

of payment, including the medical necessity of the hospitalization. Each year, the CERT

program samples discharges for all clinical conditions from Medicare claims. The component of

the CERT process relevant to this task is discharges from acute care hospitals subject to the

Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS). There were approximately 20 million

such discharges in FY 2009 and FY 2010. Note that the IPPS excludes many types of hospitals

and other providers, such as comprehensive cancer centers, psychiatric hospitals, and

rehabilitation facilities.

CMS staff provided us with the FY 2009 and FY 2010 medical records received by the

CERT program for use in this task, including the information necessary to link the medical

records to Medicare claims data. After excluding those hospitals not subject to the IPPS (and

therefore not subject to the HAC-POA policy), our sampling frame was 10,465 unique CERT

medical records. Using beneficiary and hospital identification information in the medical

records, we linked the records to the MedPAR claims data for FY 2009 and FY 2010.

The CERT program uses random sampling to choose records for review; however, the

randomization process is not publicly available. It should be noted that RTI was not provided

with complete information about the degree of randomness used in the chart selection process.

To ensure that the CERT records were representative of all Medicare IPPS discharges, we

compared characteristics of the CERT medical records to the characteristics of all discharges

from IPPS hospitals in the FY 2009 and FY 2010 MedPAR database. The distributional

properties of the CERT records are consistently similar to the MedPAR records across patient

and hospital characteristics such as patient age, gender, race, principal diagnoses, and hospital

size and location. Given the large sample sizes of approximately 20 million MedPAR records

and 11,000 CERT records, further analysis of this question should not be necessary. The CERT

records are broadly representative of the MedPAR records and therefore are representative of the

population of IPPS-eligible Medicare discharges. For our analysis, it should therefore not be

necessary to apply weighting to the CERT records when conducting analysis applicable to claims

data from the entire IPPS-eligible Medicare population. For a more detailed analysis of the

representativeness of the CERT records, please refer to Appendix A.

2.3 Medical Record Sampling Plan

The key issues encountered in the medical record sampling included linking the CERT

medical records to MedPAR claims, and identifying medical records for coding validation.

2.3.1 Linking CERT Medical Records to MedPAR Data

The CERT program’s medical records are electronic images that are linkable to the FY

2009 and FY 2010 MedPAR claims data. We linked 10,465 unique CERT medical records to

their respective IPPS-eligible MedPAR claims, using beneficiary and hospital identification

information in the medical record. This step allowed us to create an electronic database linking

14

claims data to the medical records, and populating the database with information from the

MedPAR claims—including diagnosis code(s), procedure code(s), and other data elements that

might be useful in our analyses. This database enabled us to identify which of the linked medical

records were eligible for inclusion in the validation samples.

2.3.2 Sampling Plan for Assessing Accuracy of POA Coding

Identification of medical records for validating POA coding was straightforward. Using

the linked MedPAR–medical record database, claims with at least one of the 10 HAC-associated

diagnosis codes reported as POA for coding validation were selected. The following five

conditions were selected for medical record abstraction, with the number of CERT records in

parentheses: CAUTI (13); VCAI (5); Stage III or IV pressure ulcers (105); falls and trauma

(181); and extreme manifestations of poor glycemic control (14). This process yielded a total

sample of 318 cases across all five conditions. This was in contrast to the desired 499 records

per condition. We developed abstraction tools for these five conditions.

2.3.3 Sampling Plan for Assessing Accuracy of HAC Coding

A multistage process was used to identify medical records for validation of appropriate

reporting for CAUTI. DVT/PE and VCAI record identification was more straightforward. The

sampling plans for each of these conditions are outlined below.

2.3.3.1 Sampling Plan for CAUTI

To identify CAUTI cases for review, we first identified MedPAR records that linked to

CERT records and had the presence of an indwelling urinary catheter coded on the MedPAR

record (ICD-9 code 57.94 or 57.95), excluding any cases where CAUTI was coded as hospital

acquired or POA. This produced 90 CERT records for review.

To produce more cases, MedPAR records were linked with their corresponding physician

claims (Medicare Part B claims) to identify cases where a urology consult was provided

(identified using CMS specialty code 34) or a physician billed for insertion of indwelling urinary

catheter during the inpatient stay (CPT code 51702 or 51703). This yielded an additional 35

CERT records for review.

We then explored the use of proxies to identify MedPAR records that showed a high

likelihood of the patient having had an indwelling catheter inserted. Of the MedPAR records

with an indwelling urinary catheter coded, 35% had a general infection reported and 37% had

stays in an intensive care unit (ICU) or critical care unit (CCU). To obtain more CAUTI cases

for review, we identified 5,236 cases that did not have an indwelling urinary catheter coded, but

did have an ICU or CCU stay, as well as one of the following infections coded as a secondary

diagnosis:

112.2 Candidiasis of other urogenital sites

590.10 Acute pyelonephritis without lesion of renal medullary necrosis.

590.11 Acute pyelonephritis with lesion of renal medullary necrosis

15

590.2 Renal and perinephric abscess

590.3 Pyeloureteritis cystica

590.8 Pyelonephritis unspecified-inflammation of the kidney and its pelvis due to

infection

590.81 Pyelitis or pyelonephritis in diseases classified elsewhere

595.0 Acute cystitis

597.0 Urethral abscess

599.0 Urinary tract infection site not specified

RTI’s staff screened these CERT records for the presence of an indwelling urinary

catheter. Of the 308 such cases screened, 139 had evidence that the beneficiary had an

indwelling catheter inserted at some time during the hospital admission. These cases, in addition

to the 125 cases previously identified, provided the cases needed to obtain a sample of 264

CERT medical records.

2.3.3.2 Sampling Plan for VCAI

To identify VCAI records for validation, we screened MedPAR records with a central

line or venous catheterization coded as having been inserted during the hospitalization, excluding

records where VCAI was coded as hospital acquired or POA. This yielded 881 CERT records; a

random sample of 264 was selected.

2.3.3.3 Sampling Plan for DVT/PE

CERT medical records for DVT/PE validation were selected by identifying MedPAR

records with corresponding claims that did not have DVT/PE coded as hospital acquired or POA,

but did have one of the following orthopedic procedures coded:

00.85—00.87 Hip resurfacing, total or partial

81.51—81.52 Hip replacement, total or partial (not revision)

81.54 Knee replacement, total or partial

This yielded a total of 222 CERT records. While this was less than the 264 desired for

the coding review, there were no additional discharges available in which the patient had

undergone one of these orthopedic procedures.

16

[This page left intentionally blank]

17

SECTION 3

MEDICAL RECORD VALIDATION PLAN

To facilitate the HAC and POA coding validation, we developed criteria for each

condition based on materials provided by the funding partners, the published literature, and other

key informant sources. We incorporated these criteria into an abstraction tool for each condition.

Clarity Coding used the abstraction tool to gather information from the medical records

concerning the characteristics of the cases where there was disagreement between the coders and

the hospital coding.

While there are common elements among the conditions being examined, each

abstraction tool is tailored for the validation needs of the specific condition. Since the general

flow of coding validation is the same across the conditions, in this section we describe the

general process for validating unreported HAC cases and over-reported POA cases. A general

description of the abstraction tool follows. A copy of each abstraction tool, with condition-

specific criteria, is available in Appendix B.

3.1 Medical Record Validation Flow Diagrams

Figures 3-1 and 3-2, below, show the medical record validation flow diagrams. The

process starts with the linking of the FY 2009 or FY 2010 MedPAR data to the CERT program

medical records, and ends with the outputs of the data analysis. Figure 3-1 displays the medical

record validation flow diagram for assessing under-reporting of hospital-acquired CAUTI,

VCAI, and DVT/PE. CERT records without a corresponding MedPAR record were excluded

from the study. Of those CERT records that did have a corresponding MedPAR file, those with

a CAUTI, VCAI, or DVT/PE diagnosis were excluded—since they by definition do not represent

an unreported HAC case.

The linked MedPAR and CERT data were then screened for the presence of clinical

proxies and procedures that might indicate the presence of an unreported HAC. For those

records that did show one or more of these proxies and procedures, a sample was generated if

there were more than enough cases of that HAC type (see Section 2.1.4—Sample Size

Requirements for Medical Record Abstraction). The record was then sent for coding validation,

as shown in Figure 3-1. Records containing complexities or ambiguities that required additional

physician review were set aside by the coders and sent to one of the study physicians. Once

coded, all the records were reassembled for data entry.

18

Figure 3-1

Unreported HACs: Medical record validation flow diagram

Yes

Yes Yes

Yes

Excluded from Under Reporting Study

Record Sent for Coding Validation

Corresponding CERT Record

Linked to Claims Data

No

FY2009 & FY2010 CERT Records

CAUTI, VCAI, or DVT/PE Coded on claim as

Hospital Acquired or Present on Admission?

Excluded from Under Reporting Study

No

Output for Data Analysis

Output for Data Analysis

Presence of Proxy or Procedure?

Sample Generated (if applicable)

Abstraction Tool Completed by Coder?

No

Reviewed by RTI Physican

Figure 3-2, below, displays the medical record validation flow diagram for assessing

over-reported POA coding. As with the potential HAC cases, for each case it was essential to

have a CERT record that corresponded with the MedPAR claim(s) available for validation

purposes. If this condition was not met, the record in question was excluded.

In cases where a CERT record was sent for validation, the Clarity Coding coder

abstracted the information required to complete the validation tool. If the Clarity Coding coder

agreed with the hospital coder or made a technical coding change, the record was then sent to be

entered into the analytic database. If the Clarity Coding coder believed that medical judgment

was necessary, the coder referred the case to an RTI physician reviewer. Prior to doing so, the

coder populated the validation tool with information from the record—including specific

comments as to why the case was ambiguous. A similar flow occurred for the validation of POA

coding.

19

Figure 3-2

Over-reported POA: Medical record validation flow diagram

Yes

Yes

Yes

FY2009 & FY2010 CERT Records

Corresponding CERT Record Linked to Claims Data

CAUTI, VCAI, Stage II or IV Pressure Ulcer, Fall/Trama,

or Poor Glycemic Control Coded as Present on Admission?

Chart Sent for Coding Validation

Abstraction Tool Completed by Coder?

Output for Data Analysis

Excluded from Over-Reported Study

Excluded from Over-Reported Study

Output for Data Analysis

No

Reviewed by RTI Physican

No

No

If one of the potentially over-reported conditions—CAUTI, VCAI, Stage III or IV

pressure ulcers, falls and trauma, or poor glycemic control—was not coded as POA, then the

record was excluded. If one or more of these conditions was included, then the record was sent

for review by a coder, who completed the appropriate abstraction tool based on the type of

suspected over-reported condition (see Section 3.2, below). If coders had difficulties interpreting

the record or noted ambiguities, then the record was sent for review by an RTI physician.

Finally, the completed abstraction records were collected and entered into a database.

3.2 Medical Record Abstraction Tools

RTI developed abstraction tools for each condition of interest. These tools contain a list

of data elements for coders to collect from the medical record when conducting the validation.

The tools document evidence abstracted by the coders that supports their agreement or lack of

agreement with the hospital’s coding. The abstraction tools also provide the means by which

coders submitted cases for formal physician review. For CAUTI and VCAI—the only

conditions evaluated for both under-reporting and over-reporting—a single tool was developed

that could be used for either kind of review. The following sections describe the five main

components of the tools: Type of Review, Preliminary Evidence, Part I—Should the Listed

Condition be Coded?, Part II—Was the Listed Condition Present on Admission?, and

Disposition. Copies of the abstraction tools, including details of their clinical content, are

included in Appendix B.

20

3.2.1 Type of Review

Each tool has a similar format. At the top of each page is a box with checkboxes to

identify the type of record being abstracted. There are two record types: (1) over-reported, when

the listed condition is coded and indicated as POA; and (2) unreported, when the listed condition

was not coded. The applicable review type is designated in this section for each record.

Additional record-specific information is also displayed here. This includes the CERT record

identification number (CID#), admission date, discharge date, principal diagnosis code,

secondary diagnosis code(s), and procedure code(s). All of this information was prepopulated by

RTI from the linked MedPAR/CERT database. There are also fields for the coder abstracting the

record to self-identify and document the date of the abstraction. These are the only two fields in

this section that must be entered directly by the abstractor.

3.2.2 Preliminary Evidence

The conditions being reviewed for an unreported HAC have a “Preliminary” section in

the beginning of the abstraction tool. This section confirms that the condition exists, using

appropriate criteria such as presence of an indwelling urinary catheter. On each abstraction tool,

either Y or N is circled to indicate yes or no in response to the principal questions. More specific

information is entered as appropriate—for example, the date of insertion of an indwelling urinary

catheter.

3.2.3 Part I—Should the Listed Condition Be Coded?

Part I—Should the Condition be Coded—establishes whether the condition was

genuinely present during the stay and actually affected patient care. The response to the title

question is Yes, No, or Refer to Physician Advisor (PA). The response marked here is

dependent on the Yes or No responses to the questions in subparts A and B, described below.

Part I is separated into two subparts: (A) Did the Listed Condition Exist during the

Stay?, and (B) Did the Listed Condition Affect Patient Care? In cases where the listed condition

is being reviewed for an unreported HAC, subpart A asks if there is physician documentation of

the diagnosis. It also asks whether the listed condition was listed in the discharge diagnoses, and

if so, which position in the list it occupied. This is necessary because the discharge forms do not

identify specific conditions beyond the eighth secondary diagnosis.

Subpart A continues with two levels of evidence that vary in terms of how strongly the

clinical information supports the presence of a condition. Both levels include one or more yes-

or-no questions. These responses must be supported by documented findings in the medical

record. Level I evidence is sufficient to conclusively determine a condition was hospital

acquired. Further abstraction in this subpart, including looking for Level II evidence, was not

necessary after Level I evidence was identified.

All of the abstraction tools include Subpart A, but conditions reviewed exclusively for

POA do not have the initial questions about relevant physician documentation and discharge

diagnoses and are not divided into the Levels of Evidence. In other respects, Subpart A is the

same in all abstraction tools regardless of review type.

21

Subpart B is also the same on all of the tools regardless of review type. This component

assesses if the condition, once it is confirmed as present, affected patient care. This was assessed

by responses to a series of yes-or-no questions related to the treatments received and their impact

on patient care. The responses to these questions must be supported by evidence from the

medical record by checking box(es) from the provided list of appropriate evidence.

If the answer to either “should the listed condition be coded” or “did the listed condition

affect patient care” differed from the medical record, then the coder used his or her judgment to

make a yes-or-no determination. If the coder could not confidently make a decision, or if

medical judgment was necessary (or both), then the coder referred the case to a physician.

3.2.4 Part II—Was the Listed Condition Present on Admission?

The Part II title question was answered by checking one of the following options: (1)

Yes, present on admission; (2) No, developed after admission; or (3) Refer to physician. A

subsequent question asks for medical record documentation. As above, if the coder had any

doubts regarding the answers and believed that medical judgment was necessary, Refer to

physician was the response chosen.

3.2.5 Disposition

Each abstraction tool concluded with a disposition box. Each review type has a

corresponding series of options that are checked as appropriate. For the over-reported POA

review type, the hospital either correctly coded the condition as POA (the condition was

correctly coded as both existing and being POA) or did not correctly code the condition.

Incorrect coding includes records that were coded as POA when the condition was in fact

hospital acquired, or a condition that was coded as existing when it did not exist or did not affect

patient care.

In the unreported HAC review type, the hospital either correctly coded the absence of

condition or did not correctly code a condition that was in fact present. If it was determined that

the hospital is not correct—the condition should have been coded but was not—then the coder

proceeded to determine if the unreported condition was POA or hospital acquired.

3.3 Medical Record Validation Process

For a task designed to estimate accuracy of coding, uncompromising quality in data

collection, transmission, storage, and analysis is essential. Through a combination of training,

monitoring, and inspection, RTI has provided a high level of quality control, based on a quality

assurance plan developed collaboratively with Clarity Coding.

RTI obtained a selected group of acute care medical records from the CERT program for

FY 2009 and FY 2010. For tracking purposes, these medical records were delivered to RTI via

overnight courier by the CERT program contractor. The records were kept on an encrypted hard

drive, and a confidential process was used for obtaining, analyzing, and storing the medical

records. At the outset of this task, RTI also created an electronic data management system.

After documenting the receipt of incoming records, RTI entered the information into a dataset

22

containing the key data elements—including those needed to link the CERT records to the

MedPAR claims.

RTI worked with Clarity Coding to develop a data exchange protocol that ensured a

secure exchange of the medical records, similar to the data exchange with the CERT program

contractor. An encrypted hard drive containing the medical records was sent by courier to

Clarity Coding, with a signature receipt required. RTI also tracked the transmission of all of the

abstraction forms sent to and received from Clarity Coding—again using signed receipts for

confirmation.

To identify errors in screening or data collection early on, RTI reviewed the abstraction

tools with the abstraction task leader, Linda Holtzman, on multiple occasions to ensure that these

tools were clear and consistent. Ms. Holtzman also abstracted an initial batch of cases to confirm

that they had been appropriately identified for abstraction. The coders received an abstraction

training manual detailing the abstraction process, the use of each abstraction tool, and the key

procedures relative to the abstraction.

Each completed abstraction form was keyed into a form-based data entry tool that RTI

created and programmed for MS Excel, using VBA code for greater functionality. Checkboxes

and yes-or-no answers allowed only valid responses to be entered, while any free text sections of

the form allowed free form data entry so data could be keyed exactly as it appeared on the form.

All keying was completed by RTI staff, with independent rekeying by a different staff member.

Any differences were reconciled and recorded by the task leader.

3.4 RTI Institutional Review Board

In December 2010, the project received an exemption from the RTI Institutional Review

Board (IRB). We completed and submitted the request for exemption to the IRB, describing the

study procedures, participant population, risks to participants, methods of receipt and storage of

the medical records, and the measures taken to protect patient confidentiality. The medical

record validation activities began only after receiving written IRB approval. After IRB approval,

we modified our Data Use Agreement (DUA) with CMS to include the analysis of the CERT

program’s medical records. All individuals with direct access to the records—including the

coders at Clarity Coding, the RTI physicians, and all other RTI staff with access to the data—

were added to the DUA.

23

SECTION 4

DATA ANALYSIS

In this section, we describe the analyses carried out to assess the accuracy of coding and

the level of agreement or disagreement between the hospital-coded MedPAR records and the

RTI/Clarity Coding assessment of the same medical records. The initial strategy for this study

included analyses using the Kappa statistic and the Prevalence-Adjusted Bias-Adjusted Kappa

(PABAK) statistic. However, given the small sample sizes for assessing accuracy of POA

coding and the lack of discordant results (see discussion below), we concluded that summarizing

the level of agreement between hospital and Clarity Coding coders using the Kappa statistic and

the PABAK, which is used to interpret the Kappa, would not have yielded meaningful results

(Cunningham, 2009).

4.1 Unreported HAC Observations

When evaluating medical records for unreported HACs, the initial question is whether the

condition—CAUTI, VCAI, or DVT/PE—existed and should have been coded. If the condition

did indeed exist, the second question then is whether it was hospital acquired or POA. Table 4-1

shows that in 23 out of 749 total HAC cases, the condition was present but not reported.

In aggregate, we found an unreported HAC in just 3% (23 of 749) of the medical records

with final dispositions that we evaluated for under-reporting of CAUTI, VCAI, and DVT/PE. Of

the disagreements that were observed, the most frequent were for CAUTI cases, of which 6% (16

of 263) were inaccurately coded (i.e. the condition was present but not coded by the hospital).

The least frequent disagreement was for DVT/PE cases, with zero unreported HACs.

Table 4-1

Summary of HAC coding accuracy: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE

Disposition

CAUTI

n

CAUTI

%

VCAI

n

VCAI

%

DVT/PE

n

DVT/PE

%

Hospital coded/reported

accurately

247

94%

257

97%

222

100%

Hospital did not code/report

accurately

16 6% 7 3% 0 0%

Total 263* 100% 264 100% 222 100%

NOTE: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; DVT/PE, deep vein

thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HAC, hospital-acquired condition; VCAI, vascular catheter-

associated infection.

* There were originally 264 CAUTI cases, but one record was damaged and could not be opened

to be read.

However, in 17 of these 23 cases, the condition was POA. This leaves just 6 of the 749

cases as unreported HACs that were not POA (Table 4-2).

24

Table 4-2

Number of unreported HAC cases determined to be present on admission for three clinical

conditions: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE

Disposition CAUTI VCAI DVT/PE

Unreported HAC was present on admission

10

7

0

Unreported HAC was not present on admission 6 0 0

Total 16 7 0

NOTE: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; DVT/PE, deep vein

thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HAC, hospital-acquired condition; VCAI, vascular catheter-

associated infection.

For a coder to mark a condition as an unreported HAC, it must have both existed during

the hospital stay and affected patient care. Further information on this particular guideline,

which has consistently defined “other diagnoses” for more than 20 years, can be found in

Appendix C. For detailed information on how patient care could be affected by each condition,

please refer to Part I.B within each of the abstraction tools, in Appendix B. Table 4-3

summarizes how these distinctions influenced medical record validation. Overall, the coding

guideline requiring that the condition affect patient care appears to have had very little influence

on the final outcome of the cases, as evidenced by the fact that in only one case a present

condition was judged to have not affected patient care. That is the only case where a condition

was identified but not considered to be an unreported HAC.

Table 4-3

Number of cases where condition was present and how it affected patient care for three

clinical conditions: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE

Disposition CAUTI VCAI DVT/PE

Condition was present and did affect patient care 16 7 0

Condition was present and did not affect patient care 1 0 0

Total

1

7

7 0

NOTE: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; DVT/PE, deep vein

thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; VCAI, vascular catheter-associated infection.

The strength of evidence supporting unreported classifications varies considerably. Each

of the unreported HAC abstraction tools includes two levels of evidence. Level I is clear and

objective evidence that the condition was present, such as specific laboratory results. Level II

evidence, while sufficient to confirm that a HAC was present, is more subjective. General signs

of infection counted as Level II for some conditions. Condition-specific details for both levels of

evidence are available in the abstraction tools, in Appendix B.

As evidenced in Table 4-4, the majority of the cases where the Clarity Coding coders

determined that the condition existed did in fact include Level I evidence. There are only two

cases where only Level II evidence was present and one case where both Level I evidence and

25

Level II evidence are present. This is partly due to the fact that the Clarity coders were

instructed to not continue abstracting for Level II evidence once Level I evidence was confirmed,

since Level I was sufficient to determine the existence of the condition. The small number of

cases with both levels of evidence does not mean that there might not be more such cases.

Table 4-4

Number of cases stratified by level of evidence that the unreported HAC cases were present

for three clinical conditions: CAUTI, VCAI, DVT/PE

Level of evidence

CAUTI

VCAI

DVT/PE

Level I evidence present 15 5 0

Level II evidence present

0

2

0

Level I & Level II evidence present

1

0

0

Total 16 7 0

NOTE: Coders may not have looked for Level II evidence after identifying Level I evidence,

acting consistently with the abstraction instructions provided to them. CAUTI, catheter-

associated urinary tract infection; DVT/PE, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism; HAC,

hospital-acquired condition; VCAI, vascular catheter-associated infection.

4.2 Over-Reported POA Observations

The results for over-reported POA cases are similar in magnitude. As shown in

Table 4-5, 91% of all cases coded POA were coded accurately. However, the level of

uncertainty around this estimate is large, given the small number of CERT medical records

available for abstraction. Of the 28 POA cases coded inaccurately, the highest percentages are

attributable to Stage III and IV pressure ulcers, with 10% (10 out of 105 cases), and falls and

trauma, with 8% (14 out of 181 cases) being incorrectly reported as POA, respectively. VCAI

and poor glycemic control each had only one inaccurately coded CERT record, while CAUTI

had two inaccurately coded CERT records.

Table 4-5

Summary of POA coding accuracy: All five POA conditions combined

Disposition N %

Hospital coded/reported accurately

290

91%

Hospital did not code/report accurately 28 9%

Total 318 100%

NOTE: POA, present on admission.

When evaluating medical records coded by the hospital with the condition being POA,

the coders looked for two things: (1) whether the condition existed during the stay, and (2)

whether the condition was POA. This approach allowed for two ways in which the Clarity

Coding coder could disagree with the hospital coder. From the cases reviewed in this study, the

former seemed to be the main reason for coder disagreement; 23 out of 28 inaccurately coded

26

POA cases were inaccurate because the condition did not exist at the time of admission or at any

time during the hospitalization (Table 4-6).

Table 4-6

Over-reported POA: number of cases where the condition was present, but not on

admission, or was not present at all

Disposition N

Condition was present but not on admission 5

Condition was not present at all 23

Total 28

NOTE: POA, present on admission.

Of the 23 cases incorrectly coded with respect to the presence of the condition, falls and

trauma accounted for 13 cases and Stage III and IV pressure ulcers accounted for 8 cases.

A single case each was attributable to CAUTI and poor glycemic control. VCAI did not account

for any such cases. Clarity Coding provided us with two concrete examples of records they

abstracted where this was true. The first is a pressure ulcer case, summarized as follows:

73-year-old nursing facility resident was admitted through the emergency

department with change in mental status, uncontrolled diabetes, and dehydration

on April 19 (discharged on May 2). The emergency department nurse

documented a pressure ulcer present on admission and formally notified the

emergency department physician. A wound care consult was ordered on

admission. Multiple wound care notes documented the skin breakdown variously

as “denuded areas,” “partial to full thickness skin loss,” and “partial thickness

skin loss.” However, the wound care notes did not use the term “decubitus” or

“pressure ulcer” and never documented the stage. Nurse’s notes variously

documented Stage I and II pressure ulcers and excoriations. Unfortunately, all

physician progress notes were too faint to read and the Discharge Summary,

while documenting decubitus ulcer of the buttocks, did not document the stage.

The hospital coded 707.23 for stage III pressure ulcer of the buttocks, present on

admission. The Clarity Coding coder disallowed Stage III because the stage

could not be confirmed with the existing documentation.

Here is another example of how this concept applied to a CAUTI case:

An 82-year-old male was admitted on March 15 (discharged on March 16) for

right lower quadrant pain ascribed to an incarcerated inguinal hernia with

partial bowel obstruction. The patient had a chronic indwelling Foley catheter

with a history of recurrent urinary tract infections with MRSA. Urinalysis in the

emergency department was positive for more than 50 WBCs and the patient was

put on Vancomycin. A urology consultation documented the impression as

“chronically colonized bladder due to catheter dependent status” and stated that

27

“regardless of what the culture shows, the patient does not appear to be overtly

septic.” The urologist recommended stopping antibiotics “unless overt infection

apparent.” The urine culture showed a colony count >100,000 for MRSA and

>100,000 for Corynebacterium. Vancomycin was continued through the stay and

the patient was sent home on Bactrim. The Discharge Summary gave the

diagnosis as “recurrent urinary tract infection versus bacterial colonization with

chronic indwelling Foley catheter.”

The hospital coded 996.64 and 599.0 for CAUTI, present on admission. In the

absence of coding guidelines on chronic bacterial colonization associated with

indwelling urinary catheters, and after discussion with an RTI physician reviewer

centering on continuation of antibiotics, the Clarity Coding coder ultimately

allowed this.

4.3 Strength of Evidence for POA

The type of evidence supporting a condition as being POA varies. The first main

category is documentation that the condition was either established or evolving upon admission,

as evidenced by one of the following being documented upon admission: (1) a diagnosis of the

condition, with documentation by a physician that the condition existed or that it cannot be

clinically determined, or (2) the possibility or suspicion that the condition is present on

admission..

The other main category is documentation of definitive treatment for the condition upon

admission; this documentation is by definition condition-specific. The specific types of evidence

cited to support a condition as being POA for each case are presented in Table 4-7, below. The

summary of the evidence presented in the table shows that in nearly all cases there was

documentation of the condition having been established or evolving at admission. In more than

half of the correctly coded cases, both types of evidence were present to support the hospital’s

coding.

Table 4-7

Over-reported POA: POA summary of evidence

Level of evidence

CAUTI

VCAI

Poor

glycemic

control

Falls

&

trauma

Pressure

ulcer

Condition was established or evolving

upon admission

9 3 6 73 36

Definitive treatment was ordered upon

admission

0 0 0 0 3

Both types of evidence were present

2

1

7

94

56

Total

11

4

13

167

95

NOTE: CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; POA, present on admission; VCAI,

vascular catheter-associated infection.

28

Stage III and IV pressure ulcers have some unique criteria to support the condition being

POA. Pressure ulcers also had the highest degree of coder disagreement among the POA

conditions. Table 4-8, below, presents evidence for a POA determination, specifically for the

pressure ulcer cases. Only 32 of the 95 correctly coded cases had a single piece of evidence in

support of the POA coding; 58 of the cases had two pieces of evidence, and 5 cases had three.

Documentation of a current or healing pressure ulcer was cited in 83% of the cases, followed by

treatment of other measures ordered within 24 hours of admission, which was cited 62% of the

time. A pressure ulcer was never documented as a possible, suspected, or differential diagnosis

in our review. While cited only four times, cases where a Stage I or II pressure ulcer POA

progressed to a Stage III or IV during the stay are of particular interest. A specific case that

exemplifies this issue is discussed in detail in Section 4.4.2.

Table 4-8

Over-reported POA: POA pressure ulcer evidence

Level of evidence N %

Documentation of current or healing pressure ulcer upon admit 79 83%

Pressure ulcer possible, suspected, or differential diagnosis within 24

hours of admission

0 0%

Localized skin or underlying tissue injury, sore, ulcer, or wound over

bony prominence documented on admission at site later diagnosed

with pressure ulcer

7 7%

Treatment or other measures, including consultation, ordered within

24 hours of admission

59 62%

Stage I or II pressure ulcer present on admission that progressed to

Stage III or IV during the stay

4 4%

Primary source physician documentation of present on admission, or

inability to clinically determine

14 15%

NOTE: POA, present on admission.

4.4 Abstraction Observations

Clarity Coding was asked to provide RTI with their observations from the detailed

medical record reviews they performed that may have implications for interpreting the findings.