A NEW MEXICO

HOMEOWNER’S

GUIDE TO

SOLAR

Leases, Loans,

and Power

Purchase

Agreements

Leases, Loans, and PPAs

By Nate Hausman, Clean Energy States Alliance

with Anne Jakle, Mark Gaiser, Ken Hughes, and Jeremy Lewis

New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department

July 2015

acknowledgements

Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA) prepared this guide through the New England Solar Cost-Reduction

Partnership, a project under the U.S. Department of Energy SunShot Initiative Rooftop Solar Challenge II.

The U.S. Department of Energy SunShot Initiative is a collaborative national effort that aggressively drives

innovation to make solar energy fully cost-competitive with traditional energy sources before the end of the

decade. Through SunShot, the Energy Department supports efforts by private companies, universities, and

national laboratories to drive down the cost of solar electricity to $0.06 per kilowatt-hour. Learn more at energy.

gov/sunshot.

The Energy Conservation and Management Division (ECMD) of the New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural

Resources Department develops and implements effective clean energy programs — renewable energy, energy

efciency, alternative fuels, and safe transportation of radioactive waste — to promote economic growth,

environmental sustainability, and wise stewardship of New Mexico’s natural resources while protecting public

health and safety for New Mexico and its citizens. For more information, visit http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/

ECMD/.

Special thanks to Lise Dondy for her help conceptualizing, preparing, and reviewing this guide. Thanks to

the following individuals for their review of the guide: Maria Blais Costello (Clean Energy States Alliance),

Bryan Garcia (Connecticut Green Bank), Janet Joseph (New York State Energy Research and Development

Authority), Elizabeth Kennedy (Massachusetts Clean Energy Center), Emma Krause (Massachusetts

Department of Energy Resources), Suzanne Korosec (California Energy Commission), Warren Leon (Clean

Energy States Alliance), Jeremy Lewis (New Mexico Energy, Minerals & Natural Resources Department),

Le-Quyen Nguyen (California Energy Commission), Anthony Vargo (Clean Energy States Alliance), Marta Tomic

(Maryland Energy Administration), Selya Price (Connecticut Green Bank), and David Sandbank (New York

State Energy Research and Development Authority).

Disclaimers

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under Award Number DE-EE0006305.

This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United

States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any

legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process

1 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Introduction

pg2

Financing for the

Residential Solar

Marketplace

pg3

What You Need

to Know about

Leases, PPAs, and

Loans

pg5

Common Terms in

Solar Financing

pg8

Weighing the

Benets of Direct

Ownership

versus Third-Party

Financing

pg13

Questions to Ask

pg17

Solar Financing

Resources for

Homeowners

pg21

contents

2 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

introduction

Are you thinking about installing a solar photovoltaic (PV) system on your house and are trying to gure out

how to pay for it? Perhaps you are debating whether to purchase the system outright or take advantage of

a nancing option. Perhaps you do not yet know which nancing options are available to you.

If you are thinking about going solar, there is good news: The price of a solar PV system has come down

dramatically in recent years, and there are more ways to pay for it. But with so many solar nancing

options now available, the marketplace for these products has become increasingly complex. It can be

hard to choose among the different packages and vendors. The differences between them may not be

readily apparent. Some contracts are lled with confusing technical jargon, and key terms can be buried

in the ne print of a customer contract.

This guide is designed to help homeowners make

informed decisions about nancing solar.

This guide is designed to help you make informed decisions and select the best option for your needs

and nances. It describes three popular residential solar nancing choices—leases, power purchase

agreements (PPAs), and loans—and explains the advantages and disadvantages of each, as well as how

they compare to a direct cash purchase. It attempts to clarify key solar nancing terms and provides a

list of questions you might consider before deciding if and how to proceed with installing a solar system.

Finally, it provides a list of other resources to help you learn more about nancing a solar PV system. The

guide does not cover technical considerations related to PV system siting, installation, and interconnection

with the electricity grid,

1

nor does it cover all of the particular local market considerations that may impact

nancing a PV system.

3 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

financing

Options for Homeowners

The size of a residential solar PV installation can vary dramatically, but in New Mexico, it is

generally between 3 and 8 kilowatts (kW) depending on a variety of factors, including the available

roof space (or ground space if it is a ground-mounted system), site conditions such as roof aspect

and shading, the electricity usage of the home, and available nancing.

2

To put these system sizes

into context, a 4 kW system in New Mexico produces slightly more electricity than the average New

Mexican household uses in a year.

3

A system’s size is unsurprisingly a key determinant of its cost.

4

While the price of systems varies

considerably, a residential solar PV system in New Mexico usually costs between $13,000

and $30,000, roughly the same as a new car.

5

Just as buying a car outright can be nancially

burdensome for many automobile customers, so too can paying the entire cost upfront for a

solar PV system.

6

That’s where solar nancing comes into play.

Financing innovations have helped fuel the exponential

growth of the solar market in the United States.

Financing innovations have helped fuel the exponential growth of the solar market in the United

States and fall into two broad categories based on ownership of the solar PV system: third-party

ownership and homeowner ownership via a loan. A later section of this report explicitly compares

the types of nancing.

Some solar companies will arrange for the installation of a solar system and also provide nancing

for the system. These companies are often called full-service solar developers. In other cases, the

installer is a different entity than the nancial lender. A solar nancing lender might be a bank, a

solar company, a credit union, a public-private partnership, a green bank, or a utility.

4 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Third-party ownership of residential solar systems allows homeowners to avoid high, upfront

system costs and instead spread out their payments over time. It also often puts some or all of the

responsibility for system operation and maintenance on the third-party owner. Currently, more than

60 percent of homeowners nationally who install solar take advantage of third-party ownership. The

two most common third-party ownership arrangements are solar leases and PPAs.

Under a solar lease arrangement, a homeowner enters into a service contract to pay scheduled,

pre-determined payments to a solar leasing company, which installs and owns the solar system on

the homeowner’s property. The homeowner consumes whatever electricity the leased solar system

produces. If the system provides excess electricity to the grid, the homeowner may get credit for

that generation from the electrical utility. As with all types of solar nancing options, under a solar

lease arrangement the homeowner pays the regular utility rate for any electricity consumed beyond

what the solar system generates.

With a residential solar PPA, a homeowner contracts with a project developer that installs, owns,

and operates a solar system on the homeowner’s site and agrees to provide all of the electricity

produced by the system to the homeowner at a xed per-kilowatt-hour rate, typically competitive

with the homeowner’s electric utility rate.

Loan nancing is becoming another popular to way for homeowners to pay for solar. Similar to

leases and PPAs, solar loans allow customers to spread the system’s cost over time, but unlike

leases or PPAs they enable customers to retain ownership of the system. Solar loans have the

same basic structure as other kinds of loans and are being offered by an increasing number of

lending institutions—from banks and credit unions to utilities, solar manufacturers, state green

banks and nancing programs, housing investment funds, and utilities. Unlike third-party solar

ownership, because a solar loan arrangement enables a customer to own a solar system outright,

the homeowner can benet directly from state and federal incentives. However, the customer also

incurs any liabilities associated with ownership.

Third-party ownership of

residential solar systems

allows homeowners

to avoid high, upfront

system costs and

instead spread out their

payments over time.

5 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

What you

need to know

about Leases, PPAs, and Loans

Solar Leases

A solar lease involves a scheduled payment, usually monthly. With a solar lease, a developer installs

and owns the solar system on the home. In return, the homeowner pays a series of scheduled lease

payments to the developer. A typical lease term in New Mexico is 25 years.

Because a lease agreement can deal with system maintenance in a variety of ways, it is important to

clarify who is responsible for maintenance costs as a solar PV system may require maintenance or

replacement of parts during the lease contract term. Most solar leases cover maintenance, but may not

cover the cost of replacing equipment, such as the inverter.

7

One common option for the homeowner is

to make a single payment toward operations and maintenance upfront. That approach could reduce the

third-party owner’s incentive to provide good maintenance service. This risk can be reduced if the solar

lease contains a minimum performance guarantee or the contract clearly states that operations and

maintenance are covered by the third party. Such guarantees help ensure that the third-party owner

properly maintains the system.

Solar leases can be attractive to homeowners because

of their relative simplicity compared to PPAs.

The benets of a solar lease include elimination of most or all of the upfront cost of a system and,

if indicated in the contract, transferring operations and maintenance responsibilities to a qualied

third-party owner. Homeowners who enter into a lease pay a set price for the equipment (and

sometimes maintenance). Because they do not know for sure how much electricity the solar panels

will produce, they cannot know exactly how much money they will save on their electric bills.

6 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Ideally, monthly electric bill savings will be greater than the lease payments, making for a cash-

positive transaction. Many solar leases come with an escalating (meaning increasing) payment

schedule, described in more detail below. Homeowners should thoroughly scrutinize escalating

payment schedules when assessing the desirability of a particular lease.

The Solar Access to Public Capital (SAPC) working group, convened by the National Renewable

Energy Laboratory, has developed a standardized solar lease template (https://nancere.nrel.

gov/nance/solar_securitization_public_capital_nance). This template can be modied to include

different terms and has not been adopted by all solar developers, so you should closely examine a

solar lease contract before executing it.

Solar Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs)

Under a residential solar PPA, a solar nance company buys, installs, and maintains a solar system

on a homeowner’s property. The homeowner purchases the energy generated by the system on

a per-kilowatt-hour basis through a long-term contract at rates competitive with the local retail

electricity rate. This allows the homeowner to use solar energy at a prescribed per-kilowatt-hour

rate while avoiding the upfront cost of the solar system and steering clear of system operations

and maintenance responsibilities. Because the homeowner knows how much the solar electricity

will cost for the entire term of the PPA, the homeowner is insulated from possible increases in utility

electricity rates.

8

Ideally, a homeowner’s PPA per-kilowatt-hour payments will be less than the retail electricity rate,

making the transaction cash-ow positive from day one. If you consider this option, you should look

carefully at your electricity bill to see how your current rate compares with the rate proposed by

the company offering the PPA. You can ask your contractor to calculate the projected per-kilowatt-

hour rate and annual savings. For PPAs with an escalating rate, you should consider whether local

electricity rates are likely to increase in the future. As with a solar lease, because you would not

own the system, any applicable tax credits go to the third-party system owner.

The SAPC working group standardized PPA contract can be found at https://nancere.nrel.gov/

nance/solar_securitization_public_capital_nance. As with all solar nancing contracts, you

should closely scrutinize a PPA contract before executing it because terms vary.

Ideally, a homeowner’s

PPA per-kilowatt-hour

payments will be less

than the retail electricity

rate, making the

transaction cash-ow

positive from day one.

7 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Solar Loans

Solar loans allow customers to borrow money from a lender or solar developer for the installation

of a solar PV system. With this approach, the homeowner owns the installed system. A wide

variety of loan offerings are available with different monthly payment amounts, interest rates,

lengths, credit requirements, and security mechanisms.

9

Some solar loan products offer bundling

of energy efciency improvements along with the solar PV installation or allow for inclusion of

roof replacement or energy-related improvements, which could reduce the number of solar

panels needed.

Some loans require an asset to serve as collateral to secure the loan. When the lender takes a

security interest in the solar customer’s home, it is called a home equity loan. Other loans do not

require an asset to collateralize the loan other than perhaps the solar system itself. These are

called unsecured loans.

With many solar loans, the solar PV system can start saving the homeowner money right away

by structuring the repayment terms so that the monthly loan payments are less than the resulting

reduction in the amount on your electricity bill. Alternatively, paying off the loan sooner and over

a shorter duration may delay immediate positive cash ow, but will reduce the amount of interest

paid and shorten the time needed to enter the post-loan period when monthly savings will be

much greater.

Lenders for solar loans can be banks, credit unions, state programs, utilities, solar developers, or

other private solar nancing companies. Private loans that cover solar are likely available in your

jurisdiction; solar companies in your area will likely be able to put you in touch with a variety of

lenders experienced in solar loans and may have their own nancing options available.

Lenders for solar

loans can be banks,

credit unions, state

programs, utilities,

solar developers, or

other private solar

nancing companies.

8 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

common terms

in Solar Financing

It is important to scrutinize the contractual elements in a solar lease, PPA, or loan. Here are some

common contract terms to look for.

Buyout Options: Many third-party nancing contracts allow the homeowner to buy out or pay

off the remainder of your payments in one lump sum at any time after a designated period of

time. Some contracts provide for an option to buy out at the fair market value of the system.

Look to see if there is a buyout option in the contract, under what circumstances a customer

can buy out of a contract, and how the buyout price is calculated. Contracts may differ in how

they approach this issue, and methods of calculating buyout prices can vary. If a clear buyout

option is not included in the offer, the customer can always try to request one.

Contract Term: Contract term, duration, and payback period all refer to the period of time under

which a customer’s solar nancing agreement is operative. Most residential nancing contracts

last for between 5 and 25 years, and some last even longer. By way of comparison, solar panels

typically come with a 20-25 year warranty and their productive lifespan can exceed that. Inverters

have separate warranties, which are typically 5-10 years, though some are longer. At the end of

a solar lease or PPA term, the homeowner may have several options: 1) renew the contract and

continue the monthly payments, 2) purchase the system at a designated price or the fair market

value of the system, which may or may not be negligible after the term of a contract, or 3) have

the third-party lender arrange for system removal. In the case of a solar loan, the homeowner will

continue to own the system after the loan is fully paid off.

Credit Requirement: As a prerequisite to entering into most third-party nancing contracts,

third-party lenders require a credit (or “FICO”) score. Many third-party nancing arrangements

are only available to customers who have a credit score of 650 or higher. Some nancing

arrangements may be available to customers with sub-650 credit scores, but they may come

9 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

with higher interest rates. Knowing a credit score at the outset can be a useful way to determine

eligibility for third-party nancing. Some special loan programs in New Mexico, such as

Homewise, are targeted at lower income or lower FICO score customers.

Down Payment: Many third-party lenders offer options for initial customer down payments.

Generally, initial down payments range from $0 to $3,000. By putting some money down upfront

toward the cost of a solar system, the homeowner will likely receive a lower monthly payment,

a shorter duration of contract term (in the case of a solar lease or loan), or get a lower per-

kilowatt-hour rate (in the case of a PPA). With a down payment, some third-party lenders will

waive or reduce escalators.

Escalation Clause: Many third-party nancing options contain a clause that increases a

customer’s monthly payment on an annual basis to account for ination and projected annual

increases in electricity rates. This is often referred to as an annual “escalation clause,”

“escalator clause,” or simply an “escalator.” In many solar lease and PPA contracts, payments

escalate at an annual rate between 1 and 3 percent. Escalation clauses are not problematic per

se—keep in mind that the average annual increase in U.S. residential electricity rates over the

past decades was over 3 percent

10

and the average annual rate of ination was 2.4 percent

11

—but they should be understood and closely examined for reasonableness. The escalator

is a compounding rate, meaning that it applies not just to the initial payment rate but to the

increases added after each year due to the escalation charges. For example, if the payment

rate for a PPA is 12 cents per kilowatt hour in the rst year, with an annual escalator of 3

percent, the customer will be paying 18.2 cents per kilowatt hour in year 15. But if the escalator

is only 1 percent, the customer will be paying only 13.8 cents in year 15. It is good to calculate

or ask for a table of what each year’s payment rate will be.

Home Ownership Transfer Provisions: It is important to look for contract terms that clarify

the allocation of obligations in the case of a transfer of home ownership. Under a third-party

ownership model, the homeowner can usually transfer the solar lease or PPA to the next

homeowner for the remainder of the contract term, provided the new owner is approved (usually

a credit score qualifying a person for a mortgage also meets the criteria to take over the third-

party lending agreement obligations). A homeowner can also move the leased solar system

to a new home, but must pay all costs associated with relocating the system.

Look for contract

terms that clarify

the allocation of

obligations in

the transfer of

home ownership.

10 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Solar panels can add value to a home,

12

but third-party solar ownership can also be a

complicating factor during the sale of a home. Some buyers may be wary of buying a house

with a solar system. With a relatively scant history of solar home sales data, it can be difcult

to calculate the value of a residential solar system during the home sales process, especially

when a system is third-party owned and the buyer would like to assume the remaining lease

or PPA payments. Examine the provisions of a contract that relate to ownership transfer to

determine what the options would be if the home is sold before the end of the contract term,

and have a clear understanding of those conditions with the installer.

Late Payment Charges: Solar nancing contracts may allow for additional fees or penalties to

be charged by the nancing company in the event a homeowner is late on making a payment.

Look at the terms of the solar nancing contract closely before signing it to gauge the fairness

of the allowable penalties associated with late payments.

Minimum Production Guarantees: Many lease and PPA arrangements offer solar production

or output guarantees, usually in terms of a certain number of kilowatt hours of electricity

produced per year. With such a guarantee, if an installed system fails to meet the minimum level

of production output guaranteed, the third-party owner will compensate the homeowner on a

per-kilowatt-hour basis for the electricity production shortfall. Prospective solar lease or PPA

customers should check to see if a minimum production guarantee is included in the terms of their

contact and what accommodations are provided in the case of a production shortfall, including

whether compensation is based on a wholesale or retail per-kilowatt-hour price. When a customer

directly owns a solar system, production shortfall risks are incurred by the owner. In this case, no

production guarantees are provided unless offered by a panel manufacturer or installer.

Net Metering: Net metering, sometimes referred to as “net energy metering,” enables solar system

owners to use their solar electricity generation to offset their electricity consumption. Simply put, the

customer’s meter runs backwards for the amount of solar electricity produced by the solar system and

added to the grid. In New Mexico, customers can receive a payment or bill credit from their utility for

the excess electricity they produce and add to the grid over the course of a certain billing period. It

is important to note that a residential, grid-tied PV system will not function in the case of an electricity

outage unless the home has an accompanying electricity storage system and the ability to “island”

(disconnect from the grid). The reason is that stand-alone PV systems are designed to shut down

when the grid goes down, to prevent the system from feeding power back into the grid and causing

injury to utility employees working on the power lines.

11 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Operations and Maintenance: If the homeowner chooses a lease or PPA model, the third-party

owner owns the solar system and will likely cover operations and maintenance over the course

of the contract term. It is important to check your contract, because some lease contracts may

divvy up responsibilities differently. Under most third-party ownership arrangements, the third-

party owner also incurs accidental risks associated with panel ownership, including unforeseen

destructive events or panel malfunction. Under the solar loan model, the solar customer owns

the system directly and therefore incurs the liabilities associated with such ownership. A

homeowner who owns a solar system outright or nances through a loan may be responsible for

insuring the solar PV system, which could be added to homeowner’s insurance or an existing

property policy. Because large, third-party nancing entities have established relationships with

insurance companies, they often receive more favorable rates than do residential customers

looking for solar property insurance. In some cases, solar leases or PPAs may require

homeowners to increase their homeowner’s insurance to cover risks associated with the system.

Another way to mitigate risk is to purchase an extended warranty. Solar panels may come with

a manufacturer’s warranty guaranteeing at least 80 percent system performance for 20-25

years, but homeowners who direct purchase or nance their system through a loan may want

to seek additional protection. While panel manufacturers usually offer extended performance

guarantees, other system components such as disconnects, inverters, racking, and wires may

come with relatively short warranties or no warranties at all. Homeowners may want to purchase

an extended warranty to cover replacement or repair of these components, system installation

workmanship defects, or the risk that a panel manufacturer will have undergone bankruptcy by

the time a homeowner pursues a manufacturer’s warranty claim.

Pre-Payment: A pre-payment option can be similar to a buyout option and allows homeowners

to pay some or all of the payments for a PV system before the payments become due. Pre-

payment can range from zero to full pre-payment. Full, upfront pre-payment can allow a

homeowner to reap some of the benets of third-party ownership, such as maintenance

coverage, while avoiding ongoing interest payments.

One way to mitigate

risk is to purchase an

extended warranty.

12 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Production Estimates: Residential solar systems usually come with electricity production or

output estimates. System underperformance of a production estimate can be costly for a solar

homeowner. Under the lease model, system underperformance can be particularly problematic

because a homeowner owes the solar developer a xed payment regardless of the amount of

electricity produced by the leased system. On the other hand, the homeowner gains if the leased

solar system overproduces. Under a PPA model, the homeowner only pays for the amount of

electricity actually produced by the system. Thus, when actual system output falls below the

production estimate, homeowners leasing their solar system may do worse than PPA customers.

Solar Incentives: The federal government provides a 30 percent federal investment tax credit

(ITC) for the purchase of residential solar systems. However, it is scheduled to expire at the

end of 2016 and may not be renewed by Congress. New Mexico, too, offers a Solar Market

Development Tax Credit for residential solar systems that covers 10 percent of purchase an

installation costs up to $9,000, which can be carried forward for 10 years. The New Mexico state

credit is also set to expire at the end of 2016.

13

In addition, New Mexico investor-owned utilities

will purchase Solar Renewable Energy Certicates (SRECs) from residential solar system owners

to help meet the state-mandated Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS). SRECs are tradable

commodities representing the green attributes associated with solar energy generation.

14

It is important to note that the 30 percent ITC, 10 percent New Mexico residential solar incentive,

and SRECs are only available to the owners or purchasers of a solar system. In other words, if

the homeowner agreed to a solar lease or PPA with a third-party system owner, the homeowner

will be unable to take advantage of these incentives. Instead, the third-party owner will realize

the federal tax incentive and SREC benets, while the New Mexico solar tax credit will go

unrealized. Under a loan arrangement where a solar customer owns the solar system, the solar

customer will be able to take direct advantage of incentives. Solar installers should be able to

provide an estimate of the payback period for a direct purchase, taking into account all of the

available incentives. Make sure they explain all of the payback calculation assumptions. Interest

paid on solar loans that are secured through a home equity loan may also be tax deductible. It

is important to consider the impact of the available incentives on the economic benets based

on the homeowner’s tax bracket before deciding whether third-party ownership (such as a

solar lease or PPA) or direct ownership (either through a loan arrangement or through outright

purchasing) makes more sense.

The federal government

provides a 30 percent

federal investment

tax credit (ITC) for the

purchase of residential

solar systems.

13 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Weighing the

benefits

of Direct Ownership versus Third-Party Financing

A direct, upfront, cash purchase of a residential solar system is typically the least expensive

option in terms of total dollars spent, because no interest costs or nance fees are incurred. In

many cases, however, a homeowner will not have the cash available to pay for a system outright.

And, even when a homeowner does have enough cash to pay for a solar system, it may still be

nancially advantageous to nance the solar system and invest the cash elsewhere.

A homeowner nancing solar through a lease or PPA

generally will have fewer concerns about maintenance

and operation of the system.

It is important to note that with a lease, PPA, or loan, homeowners will have an additional monthly

bill to pay beyond their regular monthly electric utility bill. However, the utility electric bill should

be greatly reduced. A homeowner nancing solar through a lease or PPA generally will have fewer

concerns about maintenance and operation of the system. Maintenance, monitoring, insurance,

and warranties are usually provided through a solar lease or PPA arrangement. For example, the

replacement of most system parts in order to maintain a solar system’s production performance

will be covered by the third-party developer over the term of the contract under a lease or PPA

arrangement. Some homeowners may feel more comfortable knowing that they do not bear these

maintenance and operation responsibilities. Others may prefer to control and manage a system

sited on their property.

Solar systems generally require no maintenance. They should be inspected periodically and

may need to be cleaned for optimized performance. If a homeowner lives in an area where snow

buildup occurs, the panels may need to be cleared of snow from time to time. Other maintenance

issues which can occur over the lifetime of a system may include loose wiring connections, loss of

inverter function, or breaking or cracking of the panels themselves.

14 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

When a homeowner directly owns the solar PV system, either through upfront cash purchase or

a solar loan, and the system is not covered under any other insurance policy or covered under

a warranty, the homeowner will bear the risk of system malfunctions, accidents, or any other

unforeseen circumstances that result in the loss or curtailment of the solar system’s output.

Under a solar lease or PPA arrangement, these risks are borne by the third-party owner rather

than the homeowner.

On the other hand, when a homeowner nances his or her solar purchase through a lease or PPA,

the nancing contract often limits the homeowner’s ability to alter the property if doing so would

negatively impact solar access or solar system performance. For example, construction of a

chimney could pose a problem if it would cast a shadow on the solar system. When homeowners

directly own their solar system, they are not bound by a third-party owner’s restrictions.

As noted above, with a third-party ownership arrangement (lease or PPA), a homeowner will not

be able to take advantage of federal incentives such as the ITC and state incentives such as New

Mexico’s Solar Market Development Tax Credit and SRECs. However, the fact that the third-party

company will receive some of these incentives (excluding the state Solar Market Development Tax

Credit) should allow it to offer more favorable nancing arrangements to the homeowner than would

otherwise be the case. Under the direct-ownership model, whether a system is nanced through a

loan or purchased outright, the homeowner will be able to realize these incentives directly.

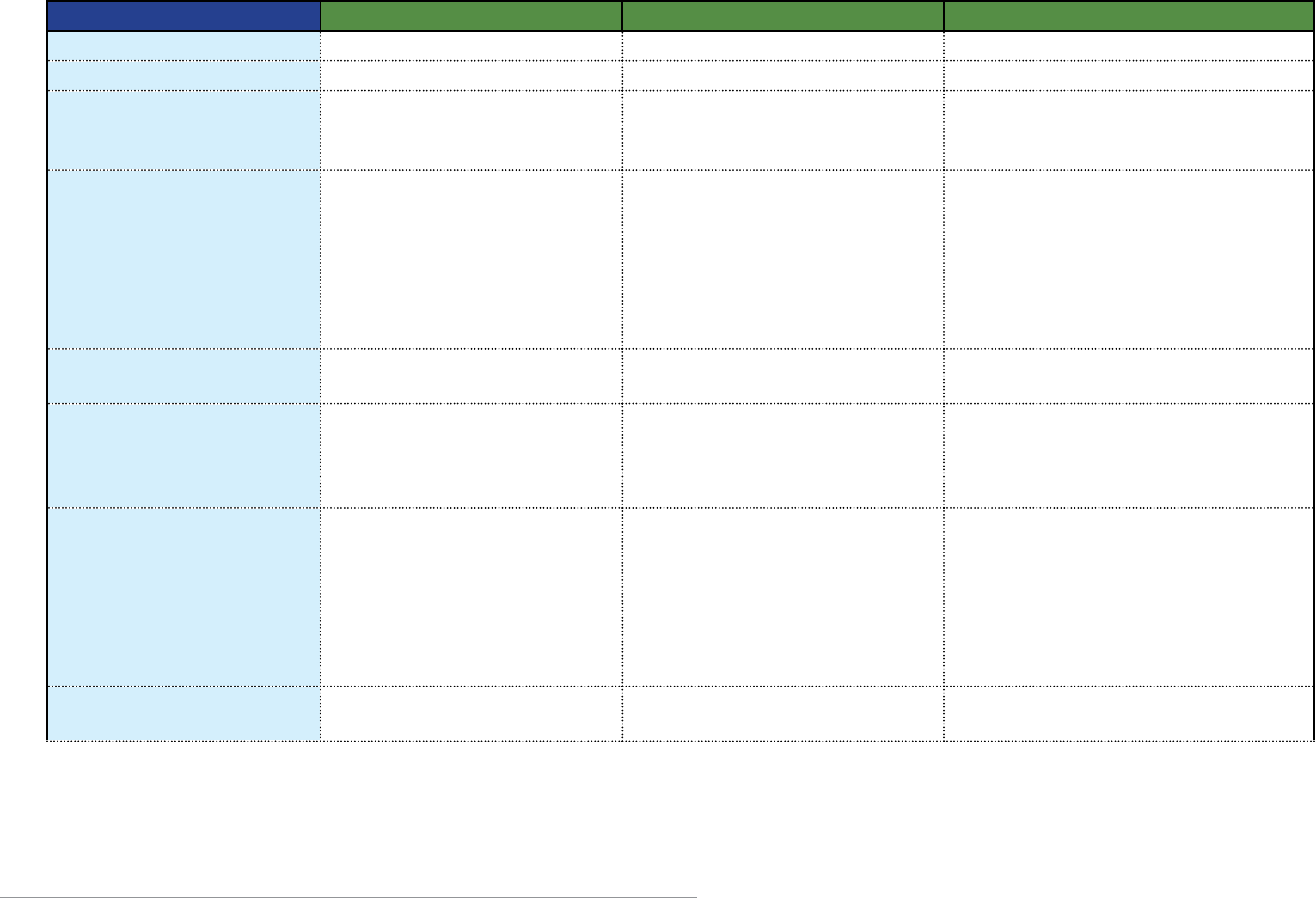

The following table summarizes the similarities and differences among the different arrangements.

With a third-party

ownership arrangement,

a homeowner will

not be able to take

advantage of federal

and state incentives.

15 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Solar Leases Residential Solar PPAs Solar Loans/Direct Purchase

Who buys the system? Third-party developer Third-party developer Homeowner

Who owns the system? Third-party developer Third-party developer Homeowner

Who takes advantage of the

federal and state incentives

available for solar?

Third-party developer, excluding

the New Mexico Solar Market

Development Tax Credit

Third-party developer, exclud-

ing the New Mexico Solar Market

Development Tax Credit

Homeowner

Who is responsible for

operations and maintenance

of the solar system?

Usually the third-party developer Third-party developer Homeowner, though for homeowners

to receive the New Mexico Solar Market

Development Tax Credit installers are

required to provide them with a two-

year warranty on parts, equipment and

labor, reducing the risk of immediate

issues related to improper installation

Who incurs the risk of

damage or destruction

Third-party developer Third-party developer Homeowner

What happens if the

homeowner sells the home

where the solar system is

located?

Depends on the contract Depends on the contract If the homeowner finances the system

through a loan, the homeowner remains

responsible for loan payments after the

transfer unless negotiated with the buyer

Are financing payments

fixed?

Yes – payments are pre-set but

may include an annual escalator,

increasing payments each year

No – payments to the third-party

developer/owner are on a per

kilowatt-hour basis based on

electricity generated by the solar

array; per kilowatt-hour payments

may include an annual escalator

If the homeowner finances the system

through a loan, the loan payments will

be fixed; if the homeowner decides

to purchase a system outright, a

contractor may sometimes offer several

payment installments instead of one

lump sum

What contract duration

terms are available?

Terms can vary, but in New

Mexico tend to be 25 years

Terms can vary, but are often in

the range of ~20–25 years

If the homeowner finances the system

through a loan, the loan terms can vary

Table 1. Comparing Residential Solar PPAs, Solar Leases, & Solar Loans/Direct Purchases

16 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Solar Leases Residential Solar PPAs Solar Loans/Direct Purchase

Does this type of financing

arrangement require a down

payment?

Not necessarily; down payment

requirements vary

Not necessarily; down payment

requirements vary

If the homeowner finances the system

through a loan, down payment

requirements can vary

Is this type of financing ar-

rangement widely available?

Somewhat – solar leasing is

available in New Mexico, but

through a limited number of

companies

Somewhat – residential solar PPAs

are available in New Mexico, but

through a limited number of com-

panies

Yes – solar and energy improvement

loans are increasingly available; a

homeowner can always directly cash-

purchase a solar system

Do contracts provide

minimum production

guarantees?

Yes, usually – solar lease provid-

ers commonly provide minimum

production guarantees

Yes, usually – PPA providers com-

monly provide minimum produc-

tion guarantees

A loan contract does not include

production guarantees; however, a

solar panel manufacturer or developer/

installer may provide a production

guarantee

Are there escalator clauses

in the contracts?

Usually; check the contract for

specific terms

Usually; check the contract for

specific terms

If the homeowner finances the system

through a loan, interest rates may

increase over time depending upon the

specific terms of the loan

Is insurance coverage

provided?

Yes Yes No – homeowners who directly own

their solar system and want to be

covered will need to find coverage

either through an insurance policy

or through the purchase of a new or

expanded policy; homeowners may

decide to forgo insurance coverage

altogether and bear the risks of solar

system ownership; for homeowners to

receive the New Mexico Solar Market

Development Tax Credit installers are

required to provide them with a two-

year warranty on parts, equipment

and labor, thereby reducing the risk of

immediate issues related to improper

installation

Table 1. Comparing Residential Solar PPAs, Solar Leases, & Solar Loans/Direct Purchases (continued)

17 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

questions to ask

As you go through the process of deciding whether to purchase or nance solar panels, below are

some questions to ask yourself and the companies you are interviewing.

Questions Related to Making the Decision to Go Solar

Have you received quotes from at least three solar installation companies?

Will the solar developer install the system directly or will that be done by a

sub-contracted installer?

How long has the solar developer and/or installer been in business? What

is the solar developer/installer’s reputation and nancial standing? Do you

know anyone who has used this solar developer/installer before? Have you

received references?

Does the solar installer have the proper state certications and licenses, if

required?

Will an on-site visit be performed to assess whether your house is a viable site

for a solar system?

Will you be able to monitor the electrical production of your solar system once

it is installed?

Will the electricity produced by your system cover all of your electrical needs at

home? On average, will your system produce excess electricity? How much will

you be compensated by your utility for excess electricity production?

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

notes

18 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Questions Related to Financing

Have you asked the solar developer to calculate the payback and walk you

through the contract and any assumptions?

Given your personal tax situation, does it make more sense to own (through

a loan or direct purchase) your solar system to take advantage of all the

federal and state tax incentives? With the New Mexico Solar Market

Development Tax Credit, consider that this credit is dependent upon

having a tax liability and for some New Mexico residents this credit may

not be usable.

What is the interest rate and duration (in years) of the nancing

agreement? Have you shopped around to compare other nancing packages?

Will you have to make a down payment? Do you have the option to make a

down payment to reduce monthly xed payments (lease) or kilowatt-hour

rate (PPA)?

Will your monthly loan payments be equal to or less than the savings on

your electric bill? You’ll want to factor in how much of your electricity needs

will be met by your solar PV system as that will impact the reduction of

your electric bill. If the system doesn’t cover a signicant portion of your

electricity needs, then your savings may not be substantial enough to justify

the payments for your PV system.

Is there an escalation clause included in the nancing agreement? If so,

what is the annual escalation rate?

If you are nancing through a PPA, is the electricity rate you are being

offered lower than what you are currently paying?

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

notes

19 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Questions Related to Financing (continued)

If you are nancing through a lease or PPA, is there a pre-payment option

under which you can pay some or all of your lease or PPA payments before

they become due?

If you are nancing your system through a lease or PPA, what happens

at the end of the contract term? Does the contract require you to buy

the system at the end of your term? If so, how is the buyout amount

determined?

Can you buy out your nancing contract? Under what circumstances?

At what rate? At what point? How is that rate calculated?

What happens if you sell your home before the end of your solar contract

term? For instance, what happens if the buyer does not qualify to assume

your solar lease or PPA? What if the buyer does not want the solar system

included in the property sale?

If you are nancing your system through a lease or PPA, what happens

if you need to replace the roof during the contract term?

Could the system be removed or repossessed if the lender goes out of

business or gets into nancial trouble?

Can the lender sell the contract to a new entity? Will you be notied if

that happens?

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

notes

20 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Questions Related to the Operations of the Solar PV System

Who will perform operations and maintenance on the system? If the third-

party owner performs operation and maintenance, whom specically would

you contact if there is a problem? Are you obligated to notify someone within

a certain timeframe if there is a problem? How quickly will that person

respond to your request for help? Will there be any charges for parts and

labor? What services does the operations and maintenance contract cover?

Does the contract contain minimum production guarantees? If so, what

accommodations are provided in the case of a production shortfall? Will

shortfall compensation be based on a wholesale or retail per-kilowatt-hour

price?

What are the insurance requirements? Who insures the system? Do you

have to pay for any damage? Are there damage reporting requirements? Is

there a minimum insurance coverage requirement for the house in order to

install a solar system on it? What will your current home insurance policy

cover with respect to your solar system?

Who is responsible for warrantying the system? If there is a warranty,

is it with you or the solar company? Will you receive a copy of the

warranty agreement?

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

yes no notes

notes

21 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

Solar Financing

resources

for Homeowners

Financing Your Solar System, EnergySage: www.energysage.com/solar/nancing

EnergySage, an online marketplace that provides price quotes from multiple PV installers, has a

webpage dedicated to solar nancing. This webpage provides information for homeowners to

navigate their solar nancing options.

Homeowners Guide to Financing a Grid-Connected Solar Electric System, U.S. Department of

Energy: www1.eere.energy.gov/solar/pdfs/48969.pdf

DOE’s Homeowners Guide to Financing a Grid-Connected Solar Electric System provides an

overview of the nancing options that may be available to homeowners who are considering

installing a solar electric system on their house. It explains the benets of a solar PV system, key

terms, and various options for homeowners nancing a solar PV system.

Introduction to Solar Project Finance, Solar Outreach Partnership Solar Training Video:

see www.youtube.com/watch?v=fojwEO3zpH8

Under the U.S. Department of Energy’s SunShot Solar Outreach Partnership, the International City/

County Management Association and Meister Consultants Group produced a video series for

local government ofcials covering many aspects of installing solar. One of the videos covers the

basics of solar project nancing, which may be useful for homeowners interested in nancing a

residential solar system.

Solar Leasing for Residential Photovoltaic Systems, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL):

www.nrel.gov/docs/fy09osti/43572.pdf

NREL’s Solar Leasing for Residential Photovoltaic Systems guide examines the solar lease option for

residential PV systems. It also describes two lease programs: the Connecticut Solar Lease Program

and SolarCity’s program.

22 | A NEW MEXICO HOMEOWNER’S GUIDE TO SOLAR FINANCING

endnotes

1

Homeowners who want to generate their own electricity through a solar PV system and hook up to the larger electrical distribution grid must go through

an interconnection process. Each state establishes interconnection standards regulating the process by which an electricity generator can connect to a

distribution grid. Information on New Mexico’s interconnection standards can be accessed via http://programs.dsireusa.org/system/program/detail/3038.

2

See http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/ECMD/RenewableEnergy/documents/RooftopSolarEconomicsFeb2015.pdf.

3

See http://www.eia.gov/electricity/state/newmexico. Note that state incentive programs and utility interconnection rules may inuence system sizes because

utility incentives may vary for different certain system sizes, and interconnection complexity and fees may increase for larger systems.

4

Among other things, the full cost of an installation may vary depending on system size, PV module and inverter type and brand, equipment options (for

example, solar tracker panels, microinverters), geographic location, the age and quality of the existing roof or the need to install a ground or pole-mounted

system, available incentives, labor costs, permitting fees, participation in a group purchasing program, etc.

5

Solar PV system costs are often reported as per watt (W) or per kilowatt (kW) to allow for cost-comparison across different system sizes. For more information

about solar PV pricing trends in New Mexico, see http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/ECMD/RenewableEnergy/documents/RooftopSolarEconomicsFeb2015.pdf;

for pricing trends nationally over time, see http://emp.lbl.gov/sites/all/les/lbnl-6858e.pdf.

6

Although solar costs in the United States have been dropping, there is some indication that this trend may not continue depending in part on importation

tariffs placed on foreign-made solar panels. In addition, some states have begun to reduce their solar rebates and other incentives as solar PV has become

more cost competitive.

7

An inverter converts the electricity generated from solar PV panels in the form of direct current (DC) into alternating current (AC), a form which can more

readily be used for electrical consumption in the U.S. and can ow into a larger electrical grid.

8

The average rate of increase in U.S. residential electricity rates over the past ten years was over 3%. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory has compiled

a database of average electricity rates for each utility in the country. It is searchable by ZIP code. http://en.openei.org/datasets/dataset/u-s-electric-utility-

companies-and-rates-look-up-by-zipcode-feb-2011.

9

A security mechanism for a solar loan could be a legal interest in property, which may allow the lender to repossess the property in the case of a default.

10

EIA Short Term Energy Outlook: http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/report/electricity.cfm.

11

You can learn more about U.S. ination at http://www.usinationcalculator.com/ination/current-ination-rates/.

12

See, for example, http://emp.lbl.gov/sites/all/les/lbnl-6484e.pdf.

13

For more information on the New Mexico residential solar credit, see http://www.emnrd.state.nm.us/ECMD/CleanEnergyTaxIncentives/SolarTaxCredit.html.

14

In early 2015, for systems less than 10 kW (most residential systems), Public Service Company of New Mexico (PNM) was offering 2.5 cents per kWh for SRECs for

a term of 8 years, El Paso Electric (EPE) was offering 2 cents per kWh for 8 years, and Southwestern Public Service Company (SPS) was offering 8 cents per kWh

for 12 years.

Photo Credits

Cover: L-R: Photos courtesy of Energy Trust of Oregon and NREL

Page 4 – Photo courtesy of New Mexico EMNRD

Page 6 – Photo courtesy of New Mexico EMNRD

Page 8 – Photo courtesy of Rhode Island Commerce Corporation

Page 10 – Photo courtesy of Energy Trust of Oregon

Page 11 – Photo courtesy of New Mexico EMNRD

Page 12 – Photo courtesy of New Mexico EMNRD

Page 13 – Photo courtesy of greenhomesforsale.com

Page 14 – Photo courtesy of New Mexico EMNRD

Clean Energy States Alliance (CESA) is a national, nonprot coalition of

public agencies and organizations working together to advance clean

energy. CESA members—mostly state agencies—include many of the

most innovative, successful, and inuential public funders of clean energy

initiatives in the country.

CESA works with state leaders, federal agencies, industry representatives,

and other stakeholders to develop and promote clean energy technologies

and markets. It supports effective state and local policies, programs, and

innovation in the clean energy sector, with an emphasis on renewable

energy, nancing strategies, and economic development. CESA facilitates

information sharing, provides technical assistance, coordinates multi-state

collaborative projects, and communicates the views and achievements

of its members.

Clean Energy States Alliance

50 State Street, Suite 1

Montpelier, VT 05602

802.223.2554

www.cesa.org

Copyright 2015