College of William & Mary Law School

William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository

Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans

2019

Right on Time: First Possession in Property and

Intellectual Property

Dotan Oliar

James Y. Stern

William & Mary Law School, jyst[email protected]

Copyright c 2019 by the authors. 3is article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository.

h4ps://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs

Repository Citation

Oliar, Dotan and Stern, James Y., "Right on Time: First Possession in Property and Intellectual Property" (2019). Faculty Publications.

1906.

h4ps://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1906

395

RIGHT ON TIME: FIRST POSSESSION IN PROPERTY AND

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

DOTAN OLIAR & JAMES Y. STERN

A

BSTRACT

How should we allocate property rights in unowned tangible and intangible

resources? This Article develops a model of original acquisition that draws

together common law doctrines of first possession with original acquisition

doctrines in patent, copyright, and trademark law. The common denominator is

time: in each context, doctrine involves a trade-off between assigning

entitlements to resources earlier or later in the process of their development and

use. Early awards risk granting exclusivity to parties who may not be capable

of putting resources to their best use. Late awards prolong contests for

ownership, which may generate waste or discourage acquisition efforts in the

first place. While the doctrinal resolution of these timing questions varies in

different resource contexts, the determination depends upon a recurring and

discrete set of functional considerations. This Article applies its theory to assess

a host of doctrinal features in our patent, copyright, and trademark laws, to

analyze recent intellectual property law developments, and to suggest directions

for reform.

Professor of Law, University of Virginia School of Law and Associate Professor of Law,

William & Mary Law School, respectively. We thank Avi Bell, Hanoch Dagan, John Duffy,

Peter Menell, Gideon Parchomovsky, Ariel Porat, Betsy Rosenblatt, George Rutherglen, and

Paul Stephan, as well as participants at the 2017 meeting of the American Law & Economics

Association, the Intellectual Property Scholars Conference, the Property Works-In-Progress

Conference, and the UCLA Faculty Workshop for useful comments and suggestions. © 2019

Dotan Oliar & James Y. Stern.

396 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

CONTENTS

I

NTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 397

I. FIRST POSSESSION: FORMS AND FUNCTIONS ............................................. 404

II. ORIGINAL ACQUISITION IN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY .............................. 417

A. Patent ........................................................................................... 420

B. Trademark ................................................................................... 428

C. Copyright ..................................................................................... 435

III. GRASPING POSSESSION ............................................................................ 440

A. Doctrinal Implications ................................................................. 440

1. Patent Trolls: Of Abstract Ideas and IPRs ............................. 440

2. The Hunt for Secondary Meaning ......................................... 444

B. Institutional Implications ............................................................. 446

1. Possession, Information, and Intellectual Property ............... 446

2. Intellectual Property as Property: Flexibility and

Standardization ...................................................................... 451

C. Theoretical Implications .............................................................. 453

1. On Defining IP Goods ........................................................... 453

2. Divided Possession Rules ...................................................... 456

CONCLUSION ................................................................................................... 457

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 397

INTRODUCTION

Time is central to intellectual property (“IP”) law. Congress, courts, and

scholars rightfully give considerable attention to questions about when IP rights

should end,

1

but there is comparatively little analysis of when they should begin.

While ownership of IP rights might be expected to start at original acquisition

through creation

2

or use,

3

matters are not quite so simple.

The foundation of ownership is first possession. Though some treat this as a

normative or philosophical proposition,

4

this Article means it in a positive,

practical sense. Ordinarily, someone comes to own something by acquiring title

from someone else who owned it, who acquired title from someone else who

owned it before that, and so on, until one gets back to the very first owner and

the so-called “root” of title.

5

But how did the first owner come to own it? How,

in other words, do things come to be owned?

6

The basic answer property law

gives is first possession: ownership of an unowned resource goes to whomever

does something referred to as “possessing” it before anyone else.

7

1

See U.S. CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 8 (empowering Congress to secure IP rights that last for

“limited [t]imes”); 15 U.S.C. § 1127 (2012) (defining “abandoned” trademark as among other

things, when mark becomes a generic name for goods it designates); 17 U.S.C. § 302(a)

(2012) (stating that copyrights of individual authors generally expire seventy years after

author’s death); 35 U.S.C. § 154(2) (2012) (stating that patents generally expire twenty years

after they are applied for); Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 189 (2003) (upholding

constitutionality of copyright term after it was extended by twenty years against arguable

violation of “limited [t]imes” clause); W

ILLIAM D. NORDHAUS, INVENTION, GROWTH, AND

WELFARE: A THEORETICAL TREATMENT OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE 76-80 (1969) (providing

canonical theoretical framework for setting optimal patent term).

2

See 17 U.S.C. § 102 (stating that copyrights are generally granted to whoever fixes

original work of authorship in physical object); 35 U.S.C. § 101 (stating that patents are

generally granted to whoever invents any new and useful invention).

3

Trademarks have long been awarded to whoever was the first to merely adopt and use a

mark in commerce. See Hydro-Dynamics, Inc. v. George Putnam & Co., 811 F.2d 1470, 1473

(Fed. Cir. 1987) (“The requirements of both adoption and use devolve from the common law;

trademark rights in the United States are acquired by such adoption and use . . . .”); see also

15 U.S.C. § 1127 (defining “use in commerce” as “bona fide use of a mark in the ordinary

course of trade”).

4

See, e.g., JOHN LOCKE, TWO TREATISES OF GOVERNMENT 306 (Peter Laslett ed.,

Cambridge Univ. Press 1960) (1690) (“He that is nourished by the Acorns he pickt up under

an Oak, or the Apples he gathered from the Trees in the Wood, has certainly appropriated

them to himself. . . . I ask then, When did they begin to be his? . . . And ‘tis plain, if the first

gathering made them not his, nothing else could.”).

5

See Carol M. Rose, Possession as the Origin of Property, 52 U. CHI. L. REV. 73, 73

(1985).

6

See id. (theorizing why certain actions, namely possession, allow one to obtain ownership

of things).

7

See 2 WILLIAM BLACKSTONE, COMMENTARIES *3 (noting that “whoever was in

occupation of any determinate spot of [ground] . . . acquired for the time a sort of ownership”);

398 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

Modern readers may be tempted to dismiss first possession as an essentially

antiquarian topic, given that so much of the tangible substance of the planet is

already owned, but the temptation should be resisted.

8

There are a number of

reasons why an understanding of first possession remains valuable, and this

Article concentrates on one of particular significance: first possession is the

principal device used to award exclusive rights to the products of human

imagination and ingenuity—that is, in the field of intellectual property.

9

This is

no small matter. In recent years, more than one million new IP rights have been

registered with the U.S. government annually, reflecting claims to everything

from pharmaceutical drugs to pop songs and from product logos to computer

code,

10

and many more have been created but not registered.

11

Information is the

most valuable resource of our age and the yet-to-be-owned expanses of human

creativity are seemingly endless. Attention to the rules allocating IP rights

remains critical.

Are we doing a good job propertizing creations of the mind? Do existing laws

and doctrines tend to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” the

constitutional aim of U.S. patent and copyright laws?

12

Or can these rules be

Dean Lueck, First Possession, in 2 NEW PALGRAVE DICTIONARY OF ECONOMICS AND THE LAW

132, 133-36 (Peter Newman ed., 1998) (describing first possession as rule which “grants an

ownership claim to the party that gains control before other potential claimants”).

8

The 1890 Census declared that the frontier region of the United States no longer existed.

See FREDERICK JACKSON TURNER, THE FRONTIER IN AMERICAN HISTORY 1 (1920) (“[A]t

present the unsettled area has been broken into by isolate bodies of settlement that there can

hardly be said to be a frontier line.”); Thomas W. Merrill, Accession and Original Ownership,

1

J. LEGAL ANALYSIS 459, 460 (2009) (suggesting principles of accession are primary

mechanism by which original title to property is established).

9

Cf. JOHN F. KENNEDY, “LET THE WORD GO FORTH”: THE SPEECHES, STATEMENTS, AND

WRITING OF JOHN F. KENNEDY 101 (Theodore C. Sorensen ed., 1988) (declaring “New

Frontier” beyond which “are the uncharted areas of science and space”).

10

For example, more than three hundred thousand patents were issued, and three hundred

thousand trademarks and four hundred thousand copyrights were registered in 2016, the last

year for which all statistics are available. See U.S.

COPYRIGHT OFFICE, FISCAL 2016 ANNUAL

REPORT 16 (2016), https://www.copyright.gov/reports/annual/2016/ar2016.pdf [https://perma

.cc/4XUA-C5YC] (stating that 414,269 copyrights were registered in 2016); U.S. P

ATENT &

TRADEMARK OFFICE, PERFORMANCE AND ACCOUNTABILITY REPORT 178, 193 (2016),

https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/USPTOFY16PAR.pdf [https://perma.cc

/GF8M-A77D] (stating that 334,107 patents were issued in 2016 and that 309,188 trademarks

were registered).

11

Copyrights and trademarks do not require registration as a prerequisite for their validity,

which depends only on fixation of an original work in a physical object or on the use of a

distinctive mark in commerce, respectively. See, e.g., 17 U.S.C. § 102(a) (2012); 15 U.S.C.

§ 1052(f) (2012).

12

U.S. CONST. art. I, § 8, cl. 8; Dotan Oliar, Making Sense of the Intellectual Property

Clause: Promotion of Progress as a Limitation on Congress’s Intellectual Property Power,

94 GEO. L.J. 1771, 1845 (2006) (arguing that promotion of progress is not merely preambular

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 399

improved to better advance knowledge and human welfare? As the major

frontiers left for the human race to conquer increasingly become intangible, a

thorough understanding of the principles of first possession can help us perfect

our management of this legal frontier by implementing the lessons from the

common law’s long experience with the award of rights in physical resources.

This is particularly so in light of the special challenges that intangible resources

present. However difficult the concept of possession may sometimes be to apply

to physical goods,

13

it is immensely more complicated for “things” that exist

only in the mind’s eye. Custom and intuition provide less reliable safety nets,

making a good theoretical grip on the concept of possession particularly

valuable.

What, then, counts as first possession under traditional legal principles? For

centuries, the common law wrestled with the concept of possession and the

problem of defining those actions sufficient to confer rights in things that are

unowned.

14

The rule of first possession was applied across a broad swath of

resources, and the specific conduct qualifying as possession varied with the

nature of the resource.

15

Behavior as diverse as the snaring or killing of a wild

animal,

16

diverting a stream of water to farmland,

17

digging above a mineral

statement of purpose, but rather constitutional limitation subject to deferential standard of

review).

13

See, e.g., Popov v. Hayashi, No. 400545, 2002 WL 31833731, at *1, *2 (Cal. Super. Ct.

Dec. 18, 2002) (determining owner of historic home run ball when one individual had actual

possession, while another made substantial steps towards possession before being illegally

interfered with by a third party in his attempt).

14

See Rose, supra note 5, at 73 (“The law tells us what steps we must follow to obtain

ownership of things, but we need a theory that tells us why these steps should do the job.”).

15

John F. Duffy, Rethinking the Prospect Theory of Patents, 71 U. CHI. L. REV. 439, 447

(2004) (noting that although “rule-of-capture” is applied to both mining and patent claims,

application of rule varies with each subject).

16

See Pierson v. Post, 3 Cai. 175, 175 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1805) (holding that possession of

wild animal required capturing or mortally wounding it, rather than simply giving chase);

D

ALE D. GOBLE & ERIC T. FREYFOGLE, WILDLIFE LAW: CASES AND MATERIALS 98-100 (2002)

(describing early notions of property rights in hunting and capturing “beasts of the forest”).

17

See, e.g., Eddy v. Simpson, 3 Cal. 249, 251-52 (1853) (holding first possession of water

not to be possession of fluid itself, but rather its use).

400 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

deposit,

18

and viewing a sunken ship at the bottom of the ocean with a

submersible camera

19

have been treated as acts of possession.

20

As varied and idiosyncratic as these different actions may seem, patterns can

nevertheless be discerned. One of the clearest ways to make sense of the seeming

hodgepodge of possessory rules is to think about them in terms of a common

metric: time. Each of these possessory practices can usefully be placed on a

chronology starting with the first preliminary steps necessary to appropriate the

resource at issue and ending when the resource is consumed, commercialized,

or otherwise put to use.

21

The common law has tended to embrace either of two

approaches to first possession within the context of this chronology. One

recognizes an exclusive claim upon a resource when a claimant has undertaken

substantial investments and remains in hot pursuit—what this Article calls a

first-committed-searcher rule.

22

The other approach withholds any protection

until a claimant has somehow changed the resource in such a way that the

claimant is able to control and use it—what this Article calls a rule of capture.

23

This distinction between first possession rules in physical resources is key to

understanding original acquisition rules in IP law.

We begin by exploring the relative advantages and disadvantages of these

approaches in their application to tangible goods, setting out a framework to

analyze first possession questions. Prior scholarship noted many of the issues

18

See Union Oil Co. v. Smith, 249 U.S. 337, 346-48 (1919) (holding that while one

permissibly explores public lands for minerals, one has substantial interest in any minerals as

long as one puts forth persistent and diligent effort in ones prospecting).

19

See Columbus-America Discovery Grp. v. Atl. Mut. Ins., 974 F.2d 450, 465 (4th Cir.

1992) (holding that viewing sunken ship with submersible camera was sufficient to create

possessory interest in ship).

20

See Richard A. Epstein, The Allocation of the Commons: Parking on Public Roads, 31

J. LEGAL STUD. 515, 515 (2002) (analyzing how different systems of allocation in parking,

including possession of spaces, metered parking, and parking permits, effect formation and

transformation of property rights in parking spaces); Gregg W. Kettles, Formal Versus

Informal Allocation of Land in a Commons: The Case of the Macarthur Park Sidewalk

Vendors, 16 S.

CAL. INTERDISC. L.J. 49, 72-73 (2006) (discussing practices allocating

sidewalk spots to street vendors in Los Angeles).

21

See Arun S. Subramanian, Assessing the Rights of IRU Holders in Uncertain Times, 103

COLUM. L. REV. 2094, 2102-04 (2003) (asserting that most modern commentators view rights

of use, possession, and disposition as essential to establishing property rights); see also 26

U.S.C. § 7701(e)(1)(B) (2012) (identifying transfer of control as indicative of lease transfer);

Property, B

LACK’S LAW DICTIONARY (10th ed. 2014) (defining property as right to possess,

use, and enjoy). Property has been defined as requiring “control over [an] item and an intent

to control it or to exclude others from it.” R

OGER BERNHARDT & ANN M. BURKHART, REAL

PROPERTY IN A NUTSHELL 4 (7th ed. 2016).

22

See WILLIAM M. LANDES & RICHARD A. POSNER, THE ECONOMIC STRUCTURE OF

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW 17 (2003).

23

See Lueck, supra note 7, at 135 (describing actual capture as “capturing or ‘reducing to

possession’ a flow from the asset”).

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 401

that first possession rules present, but does so in a fragmented and often

unidirectional manner, with some commentators stressing the problems we

attribute to later awards and others stressing the problems we associate with

earlier ones.

24

What is missing is a comprehensive overview of the

considerations at play and an understanding of how these concerns relate to one

another and to the structure of first possession.

The essential tradeoff this Article identifies is as follows. On the one hand,

when exclusive rights vest early in the process of ultimate appropriation and use,

there is a risk those rights will be awarded to a party who will ultimately fail to

capture and use the resource.

25

On the other hand, when exclusive rights vest

late in the process, there is the danger either of a longer period of potentially

wasteful investment by parties competing to own the resource

26

or of potential

capturers opting to stay home because of the risk of losing investments prior to

capture—especially to free-riders profiting from the work they have done.

27

At

its core, first possession presents an ever-present tension between two recurring

sets of opposing concerns, one of which counsels in favor of earlier awards and

the other in favor of later ones. That tension does not necessarily result in a

stalemate, however, and its proper resolution in one context does not entail a

single solution to problems in all others. In different areas, the optimal timing of

an award of property rights is a function of the relative strength of these

countervailing concerns.

Elaborating on this tradeoff, this Article develops a framework to analyze and

evaluate the rules that govern the award of IP rights. In different areas within

our patent, copyright, and trademark systems, legal doctrine uses variants of the

two conceptions of the first possession rule to determine when exclusive rights

24

See supra notes 17-23 and accompanying text (discussing articles and cases that dealt

with some of respective problems with late and early rewards of possession).

25

See Columbia Motor Car Co. v. C. A. Duerr & Co., 184 F. 893, 904-11 (2d Cir. 1911)

(discussing controversial Selden patent, where Selden was awarded automobile patent before

Henry Ford, but court held that Ford did not infringe on patent due to Selden’s inferior

combination of automobile components and alleged lack of advancement of automobile

industry); U.S. Patent No. 549,160 (filed May 8, 1879). Other potential drawbacks of early

awards include the creation of incentives to carry out actions that are not ultimately necessary

to the ultimate deployment of the resource.

26

Yoram Barzel, Optimal Timing of Innovations, 50 REV. ECON. & STAT. 348, 348-49

(1968) (recognizing that “competition between potential innovators to obtain priority

rights . . . from innovations can result in premature applications of discoveries”).

27

Cf. Edmund W. Kitch, The Nature and Function of the Patent System, 20 J.L. & ECON.

265, 266 (1977) (viewing system which follows prospect theory of patents as set of

opportunities to pursue technological advances with associated set of probabilistic costs and

returns). Other potential costs include overinvestment in other aspects of the claiming process,

such as by inefficiently accelerating the process of development, as well as what might be

called anticompetitive behavior like secrecy and sabotage. See infra Part I (discussing first

possession rule).

402 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

are established and who among competing claimants should receive them. One

of the lessons that emerges from the study of IP doctrine is the dual function that

first possession rules play. Most obviously, first possession serves to resolve

disputes among rival contenders for exclusive rights in the same resource. But

first possession also sets the conditions for the acquisition of exclusive rights as

such, establishing what a person must do for exclusive rights to vest, whether in

tangible property or intellectual property.

28

The picture that emerges is complex, but modeling the rules governing the

award of IP rights in terms of first possession helps us understand those rules

and their implications more clearly. For example, many of the reforms

undertaken in response to what are thought to be abuses by so-called “patent

trolls” reflect an attempt to push the award of patent rights later in time.

29

This

suggests, on the one hand, that the patent troll problem is connected with early

awards of patent rights, and on the other hand, that policymakers should be

vigilant to ensure that the benefits of delaying the award of rights are compared

against the full range of the costs associated with later awards cataloged in the

discussion that follows.

Analogizing intellectual property to property is not free from difficulty,

30

and

the limits of our approach should be understood. The conceptual structure

borrowed from traditional property law can illuminate principles at work in IP

law. At the same time, however, the notion of intellectal property is an analogy,

not necessarily an identity. What this Article wishes to highlight here are

fundamental similarities with respect to the theory and doctrines of original

acquisition. This does not deny substantial theoretical and doctrinal differences

between property and intellectual property.

Modeling intellectual property with a possessory framework must be done

with sensitivity to differences in context. In the IP arena, concerns over notice

and information are much more pronounced than they are with respect to

tangible resources. Often, such concerns can be substantially mitigated through

the creation of registries and other notice mechanisms, and once in place, such

institutional devices may facilitate a more flexible approach to original

acquisition than might otherwise be feasible. The rules can more closely track

the idealized trade-off that shapes first possession doctrine, but they are also

more fluid because the nature of the claimable resources themselves is more up-

for-grabs. Not surprisingly, IP doctrine entails greater variation in the rules that

28

See infra notes 39-49 and accompanying text (reviewing criteria under which one may

gain exclusive rights through first possession).

29

See infra Part III.A.1.

30

Compare Mark A. Lemley, Property, Intellectual Property, and Free Riding, 83 TEX.

L. R

EV. 1031, 1032 (2005) (resisting notion that property law provides proper conceptual

framework for directing our thinking about IP law), with Frank H. Easterbrook, Intellectual

Property Is Still Property, 13 H

ARV. J.L. PUB. POL’Y 108, 118 (1990) (suggesting there is no

conceptual difference between tangible and intellectual property).

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 403

set the time of a right’s award than does common-law property.

31

There are also

many instances in which IP doctrine changed the specific time at which

exclusive rights can be acquired. Sometimes, doctrinal change pushed that time

of acquisition earlier, such as in the case of intent to use applications in

trademark law, but other times later in time, such as in the case of the America

Invents Act. This variation, this Article suggests, has to do with the more

frequent changes in the relative costs and benefits of awarding rights earlier and

later in time, and of providing notice and administering exclusive rights in

information, in the dynamic market settings in which IP rights operate.

This Article is not the first academic work to explore the practical effects of

first possession rules,

32

but it is the first to develop a comprehensive account of

the major considerations that shape the doctrinal form of first possession and to

describe the design of first possession rules in terms of a consistent set of policy

tradeoffs between early and late awards of rights. Neither is this Article the first

to suggest parallels between IP doctrines and first possession

33

or to raise

questions about the timing of the award of IP rights.

34

It is, however, the first to

31

E.g., Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, Pub. L. 112-29, 125 Stat. 284, 329 (2011)

(codified as amended in scattered sections of 35 U.S.C.) (amending time in which patents

expire).

32

The leading article is Dean Lueck, The Rule of First Possession and the Design of the

Law, 38 J.L. & ECON. 393, 430-31 (1995) (observing effects of first possession rules on variety

of legal fields).

33

See Abraham Drassinower, Capturing Ideas: Copyright and the Law of First

Possession, 54 CLEV. ST. L. REV. 191, 191 (2006) (analogizing originality requirement in

copyright law to first possession requirement in property); Timothy R. Holbrook, Equivalency

and Patent Law’s Possession Paradox, 23 HARV. J.L. & TECH. 1, 4 (2009) (discussing

similarities and differences between patent and property law in applying principles of actual

and constructive possession); Timothy R. Holbrook, Patent Anticipation and Obviousness as

Possession, 65 E

MORY L.J. 987, 1035 (2016) (drawing parallel between enablement in patent

law and possession in property); Timothy R. Holbrook, Possession in Patent Law, 59 SMU

L. REV. 123, 175 (2006) (arguing that enablement is best means to demonstrate property-like

possession in patent law); Lisa Larrimore Oullette, Pierson, Peer Review, and Patent Law, 69

V

AND. L. REV. 1825, 1826 (2016) (comparing grant of possession in Pierson to more causal

standard applied in patent law which favors early chasers who put in little effort); Alfred C.

Yen, Restoring the Natural Law: Copyright as Labor and Possession, 51 OHIO ST. L.J. 517,

531 (1990) (outlining “basic copyright doctrines of originality and the idea/expression

dichotomy and then comparing them to the natural law of property through labor and

possession”).

34

See, e.g., Christopher A. Cotropia, The Folly of Early Filing in Patent Law, 61 HASTINGS

L.J. 65, 70 (2009) (criticizing legal incentives to file for patents early); Paul R. Gugliuzza,

Early Filing and Functional Claiming, 96 B.U.

L. REV. 1223, 1227 (2016) (noting

complexities and variables in determining optimal timing of patent issuance); Kitch, supra

note 27, at 285 (considering how awarding patents based on priority induces inefficiency in

early invention); Mark A. Lemley, Ready for Patenting, 96 B.U.

L. REV. 1171, 1186 (2016)

(noting problems with early filing on patent issuance).

404 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

undertake a systematic examination of first possession in IP law and to explicate

the similarities, and differences, in the functional considerations that underlie

first possession doctrines in physical property and across the three major areas

of IP law: patent, copyright, and trademark.

This Article proceeds in three stages. Part I outlines the role of first possession

doctrines in property law, pointing out differences in the way first possession is

approached in different contexts and discussing reasons for these differences. It

advances a general framework of original acquisition to guide inquiries into the

timing of property awards built around the characteristic tradeoffs that early and

late awards entail. Part II turns to intellectual property. It examines patent,

trademark, and copyright law to show how a variety of doctrines work together

in each of these fields to establish what is in effect a system based on original

acquisition. It points out ways in which the same core concerns first possession

rules present in the realm of tangible property illuminate the approach to the

award of IP rights. Part III steps back to engage in a more critical analysis, noting

ways in which existing doctrine gets things right and others in which it does not.

This Article concludes by considering the major themes that emerge from

considering the original acquisition concept as it plays out in the domain of

intellectual property, identifying lessons for both property and IP law.

I. F

IRST POSSESSION: FORMS AND FUNCTIONS

First possession is a bedrock principle of property law. Property regimes have

developed possessory claiming rules for the allocation of rights in all manner of

resources, ranging quite literally from diamonds

35

to dung.

36

Yet despite a

seemingly unitary doctrinal construct, important differences remain in the way

possession rules operate in different contexts. The key variable is time. Imagine

a chronology that begins with the first actions a person may take having any

relationship to a resource, like simply becoming aware of its existence or

forming an intent to use it. The timeline then proceeds through the various

actions necessary for a person to derive a benefit from the resource: preparations

for its pursuit; pursuit itself; the successful completion of pursuit by bringing the

resource within one’s control; cultivation and improvement to enable beneficial

use; and finally actual use, enjoyment, consumption of the resource, or its

transfer to another.

In theory, property law could have picked any point along this temporal

continuum as the one at which property rights vest. In practice, property law

essentially limited its choices to two. In some contexts, property law has deemed

“possession” to be satisfied at a comparatively early point in time. Under this

approach, possession occurs when a person has undertaken significant steps

toward the resource’s appropriation and use, even though actual control has not

yet been achieved. This Articles calls this variant of first possession a “first-

35

See Armory v. Delamirie (1722) 93 Eng. Rep. 664, 664 (KB).

36

Haslem v. Lockwood, 37 Conn. 500, 500 (1871).

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 405

committed-searcher rule.”

37

Alternatively, and more commonly, property law

has deemed possession to be satisfied at a later point in time. Under this

approach, possession occurs only after a person has obtained control over the

resource. This Articles calls this variant of first possession a “rule of capture.”

38

These are very much ideal types, but they roughly represent two notional points

around which property law’s first possession doctrines tend to coalesce.

The property canon offers clear illustrations of each approach. Consider

Pierson v. Post,

39

a staple of first-year American property law curricula. The

case involved a hunter, Post, who chased a wild fox for some period of time,

only to lose the animal to a farmer, Pierson, who suddenly appeared on the scene

and quickly killed it.

40

The hunter sued the farmer to recover the value of the

animal’s pelt, but the court sided with the farmer.

41

The dissent argued that it

was enough to claim a wild animal if “the pursuer be within reach, or have a

reasonable prospect . . . of taking” it.

42

In our terms, it advocated awarding the

fox to the first committed searcher. The majority, however, rejected this course,

holding that “pursuit alone vests no property or right in the huntsman.”

43

In the

majority’s view, possession of wild animals required either “actual bodily

seizure” or having otherwise “wounded, circumvented or ensnared them, so as

to deprive them of their natural liberty, and subject them to the control of their

pursuer.”

44

The majority, in other words, held that first possession of foxes

would be satisfied only by the rule of capture.

A similar distinction can also be seen in the practices described in Professor

Robert Ellickson’s seminal study of nineteenth century whalers.

45

The usual rule

among whalers was analogous to the rule of capture adopted in Pierson v. Post:

A whaler establishes possession only after successfully lancing a whale with a

harpoon tethered and secured to the whaler’s boat.

46

The whale, in other words,

had to be brought under submission. This norm, known as the “fast-fish-loose-

37

See LANDES & POSNER, supra note 22, at 17 (stating that property law gives “first

committed searcher the exclusive right to conduct the search operation”).

38

See GOBLE & FREYFOGLE, supra note 16, at 98-99 (describing rule of capture based on

historical development through allocation of rights over wildlife).

39

3 Cai. 175 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1805).

40

Id. at 175.

41

Id. at 177-80.

42

Id. at 182 (Livingston, J., dissenting).

43

Id. at 177 (majority opinion).

44

Id. at 177-79.

45

See Robert C. Ellickson, A Hypothesis of Wealth-Maximizing Norms: Evidence from the

Whaling Industry, 5 J.L. ECON. & ORG. 83, 88-94 (1989) (discussing different property regime

norms in whaling industry).

46

See id. at 89-90 (“[The] rule was in practice likely to reward the first harpooner, who

had performed the hardest part of the hunt, as opposed to free riders waiting in the wings.”);

see also HERMAN MELVILLE, MOBY-DICK 305-06 (First Avenue 2014) (1851).

406 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

fish” rule, reflects a rule of capture approach to first possession of whales. But

some fisheries followed a first-committed-searcher approach. In waters

inhabited by the more aggressive sperm whale, custom granted an exclusive

claim to the first to lance a whale and mark its body with a harpoon, regardless

of whether the harpoon remained connected to the whaler’s vessel, so long as

the whaler remained in active pursuit.

47

In other words, a whaler could acquire

a claim to a whale at a stage prior to actual capture by making substantial

progress toward capture and demonstrating a commitment to following

through.

48

This norm, known as the “iron-holds-the-whale” rule, reflects a first-

committed-searcher approach to the first possession of whales.

49

The cases dealing with first possession suggest a recurring set of competing

practical considerations, some of which push for early awards of property rights

and some which push for late awards. Ideally, property doctrine would take

account of the relative strength of these considerations, which dictate the point

in time—or equivalently, the standard of performance—that should count as

satisfying the possession requirement with respect to a particular resource.

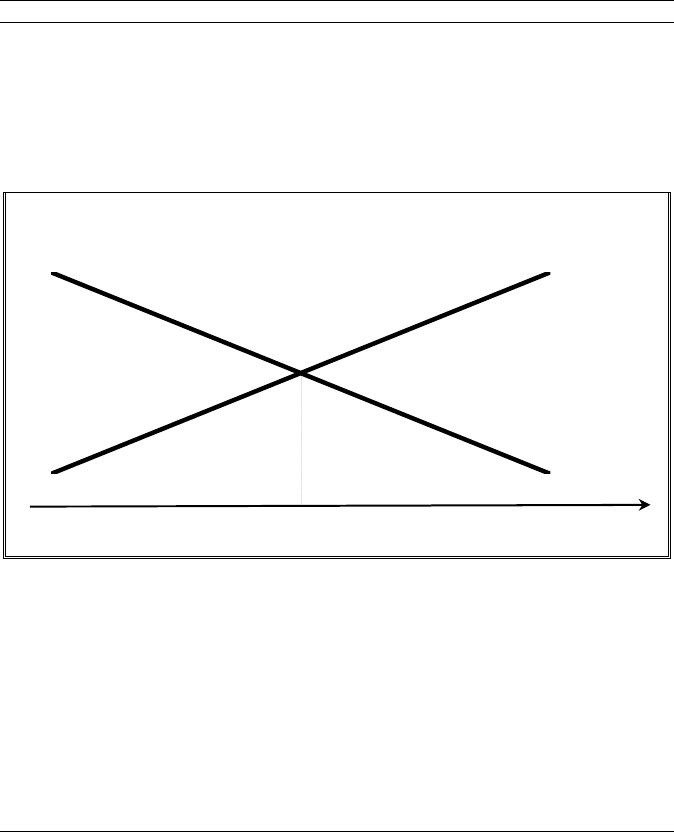

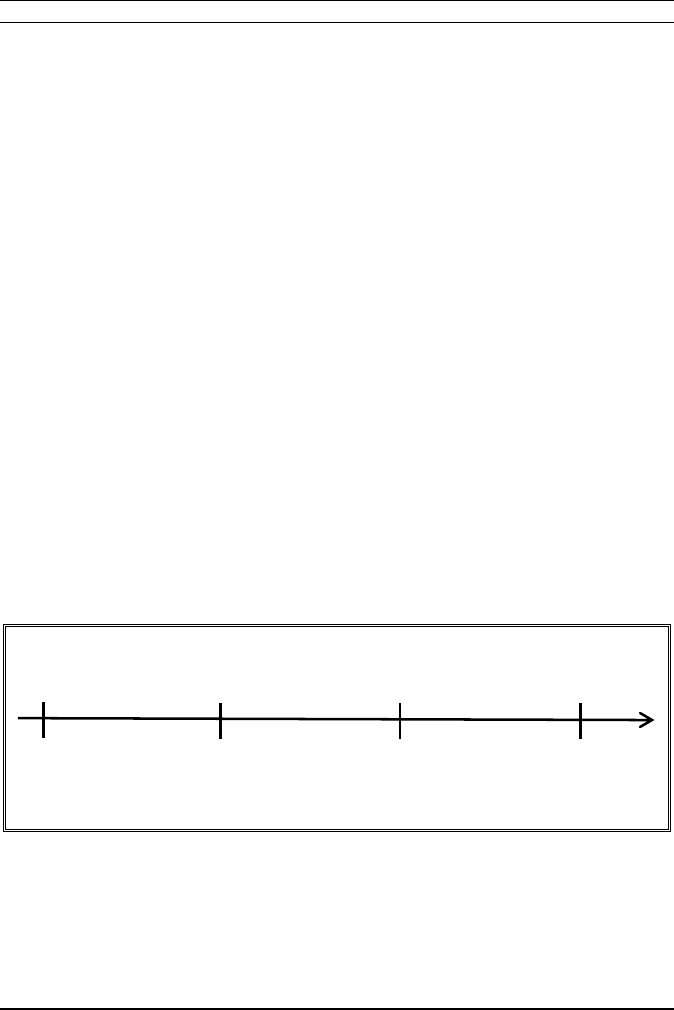

Figure 1 below illustrates the marginal benefits and costs of pushing back the

moment that is deemed to satisfy the possession requirement. Formally, the

optimal time to deem possession as having been established is the point where

the marginal benefit and marginal cost are equal. Differences in the way property

law approaches first possession can be understood as reflecting how the balance

between the relative pros and cons of early and late awards changes for different

resources along the course of their acquisition.

47

See Ellickson, supra note 45, at 90-92 (discussing “iron-holds-the-whale” property

norm, which required affixment of harpoon to whale coupled with fresh pursuit).

48

See Swift v. Gifford, 23 F. Cas. 558, 560 (D. Mass. 1872) (“[H]e who first strikes [the

whale] so effectually that the iron remains fast should have the better right, the pursuit still

continuing, it is reasonable, though merely conventional, and ought to be upheld.”).

49

See Ellickson, supra note 45, at 90-92. First-committed-searcher rules are frequently

coupled with a requirement that the claimant eventually complete capture before a durable

property right will be awarded. The primary role of the first-committed-searcher rule in these

situations is to provide the priority rule used to resolve disputes between two otherwise valid

claims, establishing the point in time used to resolve the contest between them.

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 407

Figure 1. Optimal Timing of Possession.

50

Marginal Benefit

(increased likelihood

of completion)

Marginal Cost

(discouragement &

competition waste)

t*

Time

Understanding this balance and the shift in equilibrium from one resource

context to another depends on an analysis of the competing forces that push in

favor of early and late awards. The magnitude of these concerns varies with

changes in factors such as the characteristics of the resources at issue, the ways

people desire to use them, the manner in which they are likely to be pursued,

and the technologies available to the legal system.

51

But the core concerns that

underlie this tradeoff are strikingly stable across the landscape of property law.

52

The principal danger of awarding rights too early in the development process

is the risk that they will go to someone who will fail to complete the proverbial

50

The curves are drawn schematically and need not be straight lines. While in many cases

it is reasonable to assume that the marginal benefit curve is downward sloping and that the

marginal cost curve is upward sloping, other depictions can fit equally well without any

significant change in the analysis. For example, the marginal cost curve may be flat. The only

essential assumption for the argument about a reasonably administrable optimal timing for

possession is that the marginal benefit curve initially lies above the marginal cost curve, and

that they intersect just once. When these assumptions are violated, first possession may not

be a suitable candidate for allocating property rights over previously unowned resources,

which is consistent with alternative social mechanisms for resource management, such as

common property or auctions. The discussion of such mechanisms is beyond the scope of this

Article.

51

Cf. Elinor Ostrom, Private and Common Property Rights, in 2 ENCYCLOPEDIA OF LAW

AND

ECONOMICS: CIVIL LAW AND ECONOMICS 332, 338 (Boudewijn Bouckaert & Gerrit De

Geest eds., 2000) (arguing that optimal strategy is to manage common property changes based

on given resource’s purpose of use, quantity, related technology, and other factors).

52

See infra note 69 and accompanying text (noting importance of property right timing to

optimize variety of resources).

408 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

chase, leaving the resource underused.

53

In such cases, it would have been better

to allow the ownership race to continue. The problem is essentially one of

misallocation. Awarding exclusive rights to a resource at an early stage when

considerable work must still be done to put the resource to use involves the

possibility that the resource will be awarded to someone who is not very good

at—and possibly incapable of—carrying out the tasks that still remain.

54

Late

awards can therefore be seen as a mechanism to identify the more capable, cost-

effective searchers.

When a party receives an early award but fails to follow through, the right can

sometimes be reallocated to a more capable party through voluntary exchange

or, perhaps, via abandonment and a new contest for possession.

55

Such

reallocations, however, will often be associated with transaction costs, which

may be prohibitive or otherwise entail significant waste, such as delay in the use

of the resource and search and negotiation costs associated with the reallocation

process itself.

56

Further, early awards may incentivize those who are incapable

of completing the chase but are able to take an early lead (deemed sufficient to

obtain a property right) to nevertheless join the race and do so.

57

But their hope

of profiting from such early lead may disincentivize more capable pursuers from

joining in. Paying to get the entitlement from the less capable yet early pursuer

would reduce their incentive to successfully complete the series of actions

necessary to bring the resource into its ultimate use.

On the other side of the ledger, a system in which rights are awarded later—

as under a rule of capture—presents two chief social costs. One is excessive and

wasteful investment in resource search and pursuit.

58

Efforts expended by those

53

See supra note 21 and accompanying text (discussing importance of timing when

conferring property interests); see also Eric R. Claeys, Exclusion and Exclusivity in Gridlock,

53 ARIZ. L. REV. 9, 10 (2011) (“[W]hen too many individuals have the rights to exclude in

relation to a resource, the resources may be underused.”).

54

See Lueck, supra note 32, at 394 (discussing critics who claim that early property awards

granted in homesteading, oil and gas extraction, and patent process encourage suboptimal

resource use and overexploitation).

55

See, e.g., Gary D. Libecap, Assigning Property Rights in the Common Pool:

Implications of the Prevalence of First-Possession Rules for ITQs in Fisheries, 22

MARINE

RESOURCES ECON. 407, 413 (2009) (noting that while first possession “rewards exploration

and risk taking,” later trade can “reallocate the resource to higher-valued users” and more

efficient uses).

56

See id. at 409.

57

Terry L. Anderson & Peter J. Hill, The Race for Property Rights, 33 J.L. & ECON. 177,

183-84 (1990) (discussing this phenomenon in context of squatters and speculators in land-

based property regimes).

58

See Lueck, supra note 32, at 402 (“[L]aws that rely on first possession tend to define

possession and grant ownership quite early to thwart wasteful investment.”); see also Barzel,

supra note 26, at 352 n.11 (suggesting that earlier grants of rights will prevent resources from

being wasted in course of competition); Duffy, supra note 15, at 443-44 (noting preference

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 409

who set out to capture a resource but are beaten by someone else are often

deadweight social loss, and to the extent later awards result in claimants having

to do more work to receive rights, later awards will mean that ownership races

may last longer and involve a greater number of participants and greater levels

of wasteful duplication of effort.

59

The other, and related, problem with late

awards concerns their incentive effects. Because those who unsuccessfully

compete for a resource get nothing for their troubles, would-be competitors may

be discouraged from entering the competition in the first place.

60

The greater

their troubles—i.e., the larger the investment in time, labor, and money they

must make to obtain the resource—the greater the discouragement.

61

Given the wasteful duplication problem, this could be a good thing, up to a

point: fear of losing might reduce the number of competitors and therefore the

amount of wasted investment.

62

But it would be the rare case that these two

factors would be perfectly offsetting.

In many cases, late awards will not have these two offsetting effects on entry

simultaneously, as the two often arise in different settings. Excessive entry that

leads to wasteful, duplicative effort and rent dissipation is likely to arise in

settings where participants are reasonably assured that the per-participant

expected value of joining the race are greater than or equal to the cost of

participating.

63

Good examples are the fishery,

64

a grazing commons, and

for granting property rights early can avoid wasteful duplications of effort); Aditya Bamzai,

Comment, The Wasteful Duplication Thesis in Natural Monopoly Regulation, 71 U.

CHI. L.

REV. 1525, 1525 (2004).

59

Peter S. Menell & Suzanne Scotchmer, Intellectual Property Law, in 2 HANDBOOK OF

LAW AND ECONOMICS 1475, 1489 (A.M. Polinsky & S. Shavell eds., 2007).

60

Steve P. Calandrillo, An Economic Analysis of Property Rights in Information:

Justifications and Problems of Exclusive Rights, Incentives to Generate Information, and the

Alternative of a Government-Run Reward System, 9 FORDHAM INTELL. PROP. MEDIA & ENT.

L.J. 301, 307 n.17 (1998) (“However, we must not lose sight of the wasted effort put forth by

the loser of the race, which is a social loss that is usually unrecoverable. The reward system

would not solve this dilemma, but the existence of the problem militates towards a scheme in

which the beneficiary of the reward should be recognized early on . . . .”).

61

This concern extends more broadly than the concern about wasteful duplication of effort.

If a competitor is able to capitalize on a would-be claimant’s contributions, there is no social

waste as such, but there is a private loss when the claimant is unable to recoup her costs. The

disincentive to participation this creates can thus result in what is ultimately a social loss.

62

Cf. Lueck, supra note 32, at 399-400 (suggesting heterogeneity among claimants may

reduce wasteful competition by discouraging entry).

63

Richard S. Higgins, William F. Shughart II & Robert G. Tollison, Free Entry and

Efficient Rent Seeking: Efficient Rents 2, 46 P

UB. CHOICE 247, 255 (1985) (“[W]hen there are

no restrictions on the number of individuals who may vie for the right to capture . . . entry

will occur, and resources will be spent up to the point where the expected net value of the

transfer is zero.”).

64

For a classical treatment of one such case, see H. Scott Gordon, The Economic Theory

of Common-Property Resource: The Fishery, 62 J.

POL. ECON. 124, 130-31 (1954)

410 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

multiple-party drilling into a common oil reservoir. To illustrate, imagine an

open fishery governed by the rule of capture. Assume that the per-day costs and

benefits, as a function of the number of fishermen, are as follows:

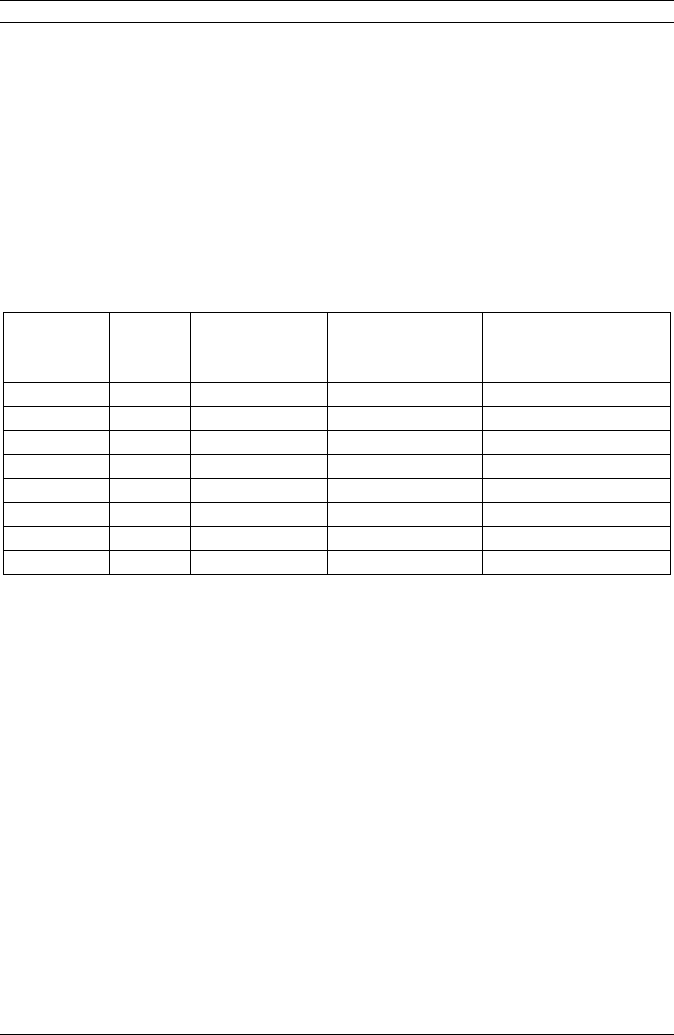

Table 1. The Fishery: Public and Private Costs and Yield as a Function of the

Number of Fishermen (in Dollars).

Fishermen Total

Cost

Total

Expected

Yield

Net Expected

Social Value

Net Expected Profit

per Fisherman

0 0 0 0 0

1 10 16 6 6

2 20 29 9 4.5

3 30 40 10 3.33

4 40 49 9 2.25

5 50 56 6 1.2

6 60 61 1 0.16

7 70 64 (-6) (-0.85)

The first column in Table 1 simply designates different numbers of fishermen

that may operate on the fishery. The second column reflects the assumption that

operating a boat on the fishery costs ten dollars, such that the total social cost of

fishing is ten times the number of fishermen. The third column reflects an

assumption of diminishing marginal returns per unit of effort, a general

phenomenon observed in the world. Here, this assumption can be motivated by

the realization that fishery congestion reduces the fishery’s yield.

65

The fourth

column is simply the difference between the third and the second columns. The

last column divides the fourth column by the first to obtain the per fisherman net

expected return.

As Table 1 suggests, it would be socially optimal that only three fishermen

operate on the fishery, which would maximize the fourth column, “Net Expected

Social Value.” However, since all are free to join the fishing race, as many as

six fishermen would enter, because the expected private return to entry would

still be positive (see the last column). Though such entry would be privately

beneficial, it is excessive from a social point of view because it decreases the net

social value of the fishery. Each of the fourth, fifth, and sixth entrants increases

(suggesting that, on common properties with free entry, number of entrants would be

excessive, tending to dissipate value of the resource). A similar scenario applies for an oil

field that lies beneath land parcels owned by many owners, from which each could drill and

extract oil.

65

The diminishing returns assumption can be motivated easily respecting the fishery.

Doubling the number of boats on the fishery from one to two, say, will not likely result in

double yield because of friction between the two fishermen: sometimes one would catch a

fish that the other would have caught had it been alone on the fishery, or because they would

get in each other’s way occasionally and slow down.

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 411

social costs by ten dollars, but increases social value by an amount lesser than

ten. In essence, each fisherman joining the fishery disregards the negative

externality it imposes on others. For our purposes, an implicit assumption

supports the conclusion of excessive entry, which is that fish are many, that a

fishing day involves the fishing of many fish, and that all fishermen are similarly

situated and can observe the number of fishermen on the fishery. In such cases,

each fishermen knows, virtually with certainty, that she will cover her costs and

will not operate at a loss.

Things are different in a scenario where race participants are not assured of

recouping their participation costs with reasonable certainty. Such is

characteristically the case when there is one prize, allocated to one winner at the

end of a relatively costly and prolonged pursuit. Take, for instance, a potential

company pursuing a pharmaceutical patent where the expected revenue—if the

chase is successful—is $1.5 billion, but where research and development

(“R&D”) is expected to last five years and cost $1 billion. Patents are awarded

under a rule of capture to the first to complete R&D. Firms cannot know how

many others are participating in the R&D race. If firms believe that there’s a

significant chance that a rival might get the patent before they do, the firms may

be reluctant to begin R&D, fearing a worst case scenario where they may invest

nearly the full one billion dollars only to discover that a rival filed for a patent

before they did. In contrast to the first scenario, a participant in this race cannot

be assured to cover costs (i.e., there is a greater risk involved), and does not

know exactly how many others are already in the race (so she might join a race

with a negative expected value).

Later awards may further deter entry in cases where a claimant can free-ride

on the investments of others who have accomplished earlier steps that enable

capture.

66

While free-riding avoids duplication of effort, it can lead to especially

sharp disincentive effects to the extent it weakens the correspondence between

the size of investment and the likelihood of winning the competition.

67

If

ownership is assigned to someone who merely delivers the coup de grâce, others

will be reluctant to undertake costlier or more difficult parts of the hunt that

make the ultimate kill possible.

The downward sloping curve in Figure 1 represents the marginal benefit of

delaying the moment that the law regards as possession in the chronology of a

resource’s pursuit. The curve is positive, indicating that there is always some

benefit to delaying the award of rights. The further along in the chronology of

the chase the pursuer is, the greater the probability that she will complete it

66

See, e.g., Lemley, supra note 30, at 1039-40 (“The professed fear is that property owners

won’t invest sufficient resources in their property if others can free ride on that investment.”).

67

Jerome H. Reichman, How Trade Secrecy Law Generates a Natural Semicommons of

Innovative Know-How, in T

HE LAW AND THEORY OF TRADE SECRECY: A HANDBOOK OF

CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH 185, 196 (Rochell C. Dreyfuss, Katherine J. Strandburg & Edward

Elgar eds., 2011) (noting that free riding by competitors creates disincentives to invest in

innovation in the first place).

412 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

successfully. Gains represented by increases in the probability of success often

accrue at a decreasing rate, however.

To illustrate, imagine a hunter chasing a fox in a dense forest. Assume that

the hunter is moving at twenty feet per second and the fox at ten feet per second,

and that the probability that the hunter will catch the fox is a decreasing linear

function of the area that the hunter needs to scout in search of the fox. If the

hunter spots the fox from one hundred feet away, by the time she reaches the

place she saw it, the fox could be hiding anywhere in a circle with an area of

roughly 2,500ߨ square feet (ߨ*50

2

), because the fox could have traveled fifty

feet in any direction during that time. By the same logic, if the sighting were

from eighty feet away, the fox would have to be searched for in an area of 1,600ߨ

square feet, and if it were seen from sixty feet away, the search area would be

900ߨ square feet. The first twenty foot movement reduced the search area by

900ߨ square feet (from 2,500ߨ to 1,600ߨ), the next twenty foot movement

toward the fox reduced that area by only 700ߨ square feet (from 1,600ߨ to

900ߨ). So while the benefits of progressing in the race toward the fox remain

positive, they accrue at a decreasing rate.

The upward sloping curve in Figure 1, meanwhile, represents the marginal

cost of delaying the moment defined as possession. Again, this curve is positive

because there is a cost to prolonging the race—racers will incur duplicative and

wasteful costs throughout the relevant timeframe. It is drawn as upward sloping

because longer races may be more costly per unit of time: longer hunting races,

for example, generally require the participants to carry more equipment and

provisions. Moreover, races that last longer may allow more parties to join. The

likelihood of either wasteful duplication of effort or depressed participation

resulting in underdevelopment can therefore be expected to increase with time.

68

A few further comments about the relationship between time and resource

waste are in order. The literature on possession has given considerable attention

to issues of wasteful competition associated with possession-based regimes,

with a special emphasis on timing issues.

69

Any rule for claiming resources has

68

While Figure 1 depicts what we believe are the most likely shapes of the marginal cost

and benefit curves associated with ownership races, these shapes are not essential. For

example, our analysis applies equally well to races characterized by a fixed marginal cost. In

that case, the marginal cost curve would be flat, and nothing in the analysis would change

materially. The optimal time of possession would still be determined by the intersection of

the two curves, and a relatively high fixed marginal cost would suggest that possession should

be awarded earlier in time during the race compared to an alternative of a lower fixed marginal

cost. See supra note 50.

69

See, e.g., Anderson & Hill, supra note 57, at 177 (“Economics literature on the evolution

of property rights has increasingly emphasized the optimal timing for establishing those

rights.”); Richard A. Epstein, Past and Future: The Temporal Dimension of the Law of

Property, 64 W

ASH. U. L.Q. 667, 670 (1986) (“Time offers a unique measuring rod, sufficient

in principle to resolve two or two thousand competing claims for priority.”); David D.

Haddock, First Possession Versus Optimal Timing: Limiting the Dissipation of Economic

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 413

the potential to distort people’s behavior because in theory, a rational claimant

should be willing to spend up to the expected value of a given resource itself in

order to obtain it.

70

Unless there is social value in the actions that the law requires

a person to take to establish a claim to a resource that is at least equal to the

value of the resource to a claimant, the rule will lead to excessive claiming and

deadweight loss (including the value of establishing ownership). It might not be

the end of the world to have to queue up the night before to get tickets to a rock

concert, for example, but on the whole, the queuing process itself wastes

people’s time and is justifiable only if there is no better way to distribute tickets.

In this last case, an auction rather than a first possession based queue might be

the better allocation mechanism.

71

Early awards under a first-committed-searcher rule present a special problem

in this regard. The genius of anchoring the award of rights in possession is that

they can avoid the sort of waste that a claiming protocol might otherwise

generate because they require claimants to perform a task that is itself necessary

for the resource to be used. A rule awarding ownership of a parcel of farmland

to the best dressed person at City Hall next Tuesday creates incentives to engage

in otherwise pointless behavior—showing up at City Hall in fancy clothes on

Tuesday. By contrast, a rule awarding ownership of the land to the person who

begins the process of cultivating it only encourages a claimant to do something

she would have done anyway to enjoy the property. It is effectively costless.

72

This singular advantage of reliance on possession is less likely to hold true,

however, to the extent possession rules adhere to a first-committed-searcher

model. Since first-committed searcher-rules identify steps that are more

preliminary in the overall process of putting a resource to use, there is a greater

risk that those steps are not actually optimal, or even necessary, to the resource’s

ultimate development.

73

So, for example, one problem with awarding possession

Value, 64 WASH. U. L.Q. 775, 783 (1986) (“Timing is also a concern when modeling

innovation and the sometimes valuable patents and copyrights that follow.”); Lueck, supra

note 32, at 398 (“Maximizing resource value is, in effect, a problem of optimally timing the

establishment of rights . . . .”); Ronen Perry & Tal Z. Zarsky, Queues in Law, 99 I

OWA L. REV.

1595, 1629 (2014) (suggesting that allocation of “specific assets at a relatively early stage,

when claimant heterogeneity is still large” can partly resolve issue of wasteful races and

duplicative investments).

70

The value of the resource would be discounted by the probability of being unsuccessful

in claiming it.

71

See supra note 50.

72

There may be costs and distortions, however, to the extent the action constituting

possession does not facilitate a particular use, or worse, is actually incompatible with that use.

Animal conservation, for instance, is at odds with a rule requiring mortal wounding, and an

interest in confidentiality of an expressive work would conflict with a rule requiring

publication.

73

See Claeys, supra note 53, at 10 (noting that early award of property rights can lead to

underutilization of resources).

414 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

of the fox in Pierson v. Post to the first person to saddle up and mount a horse

is that it might not actually be necessary to use a horse to catch the fox—as

farmer Pierson showed.

Even when possession rules are perfectly designed, there is still the potential

for distortion, however, insofar as they center on first possession and therefore

reward not just the ability to take possession but to do so faster than anyone else.

Awarding a pot of gold to the first person across the finish line creates identical

incentives to invest in training, whether the race itself is a one-hundred-meter

sprint or a marathon. The sprinter will train just as hard as the marathoner to win

the race, even though the amount of energy needed to move a human body 26.2

miles is much greater than the amount needed to move it one hundred meters.

And unlike possession itself, faster possession is not necessarily essential to the

optimal use of the resource.

74

For this reason, first-committed-searcher rules

may have some value to the extent they do not require as much work to be

completed before ownership is awarded. How much this is true is uncertain,

however. If instead of doing more to develop a resource, claimants direct their

energies to qualify as first-committed searchers faster, early awards may face

the same problem of inefficient racing for resources.

75

In addition, faster

claiming and faster resource development may often be valuable in and of itself

and also generate positive external benefits—particularly for intellectual

property.

76

Concerns about wasteful racing may therefore be less pressing than

they are sometimes made out to be.

77

It should also be noted that, apart from

investments in speed, competition can generate social waste by encouraging

behavior intended to tilt the competitive field—theft and fencing, espionage and

secrecy, sabotage and conflict.

78

To the extent later awards translate to more

protracted competition, they present a greater danger of social cost through such

anti-competitive conduct.

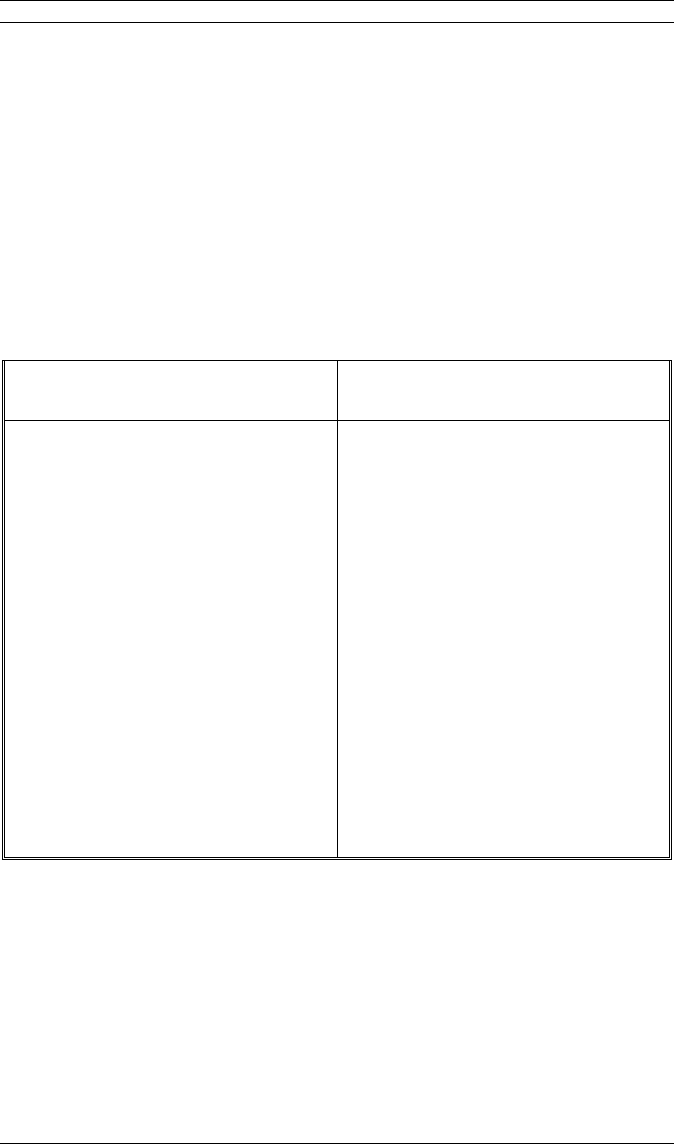

Figure 2 sets out the central concerns in the design of rules for awarding

property rights. The costs identified are relative: in most cases, the drawbacks

that are listed can occur at some level with either late or early awards, but they

74

See Lueck, supra note 32, at 399 (noting that “rush” of competitors can lead to early

grant of possession that is neither socially optimal nor valuable).

75

See Donald G. McFetridge & Douglas A. Smith, Patents, Prospects, and Economic

Surplus: A Comment, 23 J.L. & ECON. 197, 201 (1980) (noting negative effects when

possession rights go to “first rather than the best” claimant).

76

See Douglas W. Allen, Homesteading and Property Rights; or, “How the West Was

Really Won,” 34 J.L.

& ECON. 1, 1-6 (1991) (arguing that incentives for faster settlement

created by 19th century homesteading policies reduced enforcement costs and helped secure

U.S. government claims to western land).

77

See Duffy, supra note 15, at 467-68 (noting that inefficiencies of racing in intellectual

property are not significant).

78

See ROBERT D. ATKINSON & STEPHEN J. EZELL, INNOVATION ECONOMICS: THE RACE FOR

GLOBAL ADVANTAGE 190 (2012) (“[T]he race for global innovation advantage creates both

global opportunities and threats, because countries can implement their innovation policies in

ways that are either ‘good,’ ‘bad,’ or ‘ugly.’”).

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 415

are thought to be comparatively more serious with one model than with the other.

At least within the context of intellectual property, failure to follow through is

generally the most significant danger associated with early awards—especially

where early awards result in rights that are broader than anything the claimant

could possibly develop—while disincentives to compete and wasteful

duplication are generally the most significant drawback of late ones.

Figure 2. Early vs. Late Awards.

Costs of Early Awards

(First Committed Searcher)

Costs of Late Awards

(Actual Capture)

Deadweight loss from misallocation to

less capable/incapable claimants

▫ Resource underuse/non-use

▫ Transaction and reassignment costs

Wasteful claiming conduct

▫ Inefficient racing to begin search

▫ Unnecessary search behavior

Slower capture/completion

(when faster development desired)

Greater uncertainty as to resource

boundaries and characteristics

Often an ambiguous standard that

requires discretion in application (e.g.,

as to what “committed” means)

Disincentives to compete from risk of

lost investment, especially with free-

riding

Wasteful duplication of effort

Wasteful claiming conduct

▫ Inefficient racing to capture

▫ Inefficient capture rates

(e.g., endangered species)

Where rights are time-limited, longer

effective exclusivity period

Other competitive waste

▫ Self-help, fencing, secrecy

▫ Theft and espionage

▫ Interfering capture activities

▫ Sabotage, conflict, violence

The basic trade-off discussed above and depicted in Figures 1 and 2 has been

idealized and simplified in our discussion so far. In practice, administrability

concerns are a third variable that is often critical.

79

In Figure 1, the proper point

in time to award property rights would in theory be time t*—the exact point in

the possession continuum where the marginal benefit of delay just equals its

cost. For a number of reasons, however, the meaning of possession in various

contexts will also be shaped by practical demands like the need for clear rules,

intuitive concepts, and notice to race participants. To avoid wasteful duplication

of effort and lost investments, for instance, it is important for would-be

79

Michael W. Carroll, One Size Does Not Fit All: A Framework for Tailoring Intellectual

Property Rights, 70

OHIO ST. L.J. 1363, 1424-30 (2009) (discussing importance of

administrability when creating effective IP regime).

416 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

competitors to be able to observe and understand what counts as possession

fairly easily so that, e.g., they know not to continue expending efforts to win a

race that has already ended.

80

It does not do much good to end the race early

(i.e., declare a winner and stop the simultaneous search effort) if the other

participants do not know it is over. A clear test for possession also helps forestall

conflict among would-be competitors, encourages investment and facilitates

exchange by providing security of holdings, and reduces the costs of

administering and policing a property system.

81

While the need for clear and

intuitive tests for possession does not intrinsically align with either early or late

awards, in practice it tended to skew in favor of later awards at common law

because actual capture is often, though not always, more unambiguous than a

committed search.

The technology of the hunt determines what points in its chronology can even

be considered as viable candidates for possession from the perspective of

providing notice. In the context of hunting foxes, for example, it seems that such

informational considerations push for the rule of capture. What earlier stage in

the hunt could be set as the standard for a first-committed searcher? A certain

distance from the fox? A wound? If so, what type of wound confers property

rights (a scratch or mortal wounds)? What are the chances that other hunters

would be able to see both the hunter and the fox and determine the distance

between them in a dense forest? In the context of whaling, by contrast, the act

of sinking a harpoon into the body of the whale in the open sea by a party in hot

pursuit is a clear—or at least much clearer—informational marker to third

parties, and makes the first-committed-searcher rule a much more viable

candidate. The administrability concern adds to those discussed previously, and

can push the timing of grants of exclusive rights to either earlier or later points

in time.

To return to the example of Ellickson’s whalers cited earlier,

82

the trade-offs

embodied in the choice between first-committed-searcher and actual capture

models are evident in both the features that were universal among whaling norms

across all whaling fisheries and the ways in which those norms differed. As

Ellickson notes, no group of whalers adopted a rule awarding exclusive rights in

a whale to the first crew to lower a boat in pursuit.

83

That would be too soon.

Why? It would create too great a risk of awarding the prize to someone less

80

Cf. Kitch, supra note 27, at 278 (arguing that patents act as signaling devices to

competing firms to reduce amount of duplicative investment in innovation).

81

Joseph William Singer, The Rule of Reason in Property Law, 46 U.C. DAVIS L. REV.

1369, 1376 (2013) (noting that clear property regime “allows actors to invest in reliance on

clear rules of the game, avoids unfair surprise, controls the arbitrary discretion of judges, and

promotes equality before the law by treating like cases alike”).

82

See supra notes 45-49 and accompanying text (discussing Robert Ellickson’s seminal

study of nineteenth century whalers).

83

See Ellickson, supra note 45, at 88 n.14, 95 (noting that certain norms, including “first

boat in the water” were not observed in whaling industry).

2019] RIGHT ON TIME 417

capable of completing the task of capture, it would create incentives to get boats

in the water earlier than would be optimal, and it would not send a clear signal

as to which whale the whaler intended to pursue. At the other end of the

spectrum, neither did any of the whaling communities wait until a whale was

actually killed to assign claims to the animal. Among other difficulties, such a

rule would risk rewarding free-riders seeking to benefit from the significant

efforts others had already made to subdue a whale. Rather, both rules—iron-

holds-the-whale (first-committed searcher) and fast-fish-loose-fish (rule of

capture)—pick points that are in between.

The same concerns also help account for the way norms among whalers

differed in different contexts. Sperm whales tend to be relatively fast swimmers

and vigorous fighters,

84

prone to diving when harpooned, which often made it

necessary for the fishermen to cut the line lest their ship sink. Their hunt

involved costly and prolonged chases—over days—during which the whale

would be tired out. Waiting until a sperm whale had been brought under actual

control before giving a whaler a claim to the animal risked failing to reward

those whose early efforts made later capture possible—the free-riding problem.

The iron-holds-the-whale rule therefore seems to have been adapted to

conditions presented in sperm whale fisheries.

85

The right whales predominant

elsewhere, by contrast, were comparatively slow swimmers with docile

temperaments.

86

There was little need to award possession sooner, and waiting

until the whale had been brought under actual control ensured that the whale

went to the person who had “performed the hardest part of the hunt.”

87

To summarize: the primary problem with early awards is the risk that a

claimant will fail to proceed successfully with development of a resource after

being awarded it. The primary problems with late awards are the potential for

prolonging costly multiparty races and disincentivizing race participation when

participation is time-consuming and costly. Determining the moment of

possession should be made in light of the ability to convey clear notice to race

participants as to the moment in which a resource is taken into possession. Those

considerations play out differently for different resources.

II. O

RIGINAL ACQUISITION IN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

The concept of possession might not seem like it has much to do with

intellectual property. Possession has a certain physical flavor,

88

and the

resources IP law governs are intangible by definition. A human being cannot

84

See id. at 425 (discussing nature of sperm whales).

85

See id.

86

Id.

87

Id. at 89.

88

See OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES, JR., THE COMMON LAW 216 (Little, Brown & Co. 1945)

(1881) (“To gain possession, then, a man must stand in a certain physical relation to the object

and to the rest of the world . . . .”).

418 BOSTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 99:395

literally reach out and grab an idea, much less skewer it with a harpoon. As one

venerable eighteenth-century jurist put it, “But how is possession to be taken, or

any act of occupancy to be asserted, on mere intellectual ideas? . . . All writers

agree that no act of occupancy can be asserted on a bare idea of the mind.”

89

Yet the concept of possession can be extended to apply to intellectual

creations without conceptual or linguistic violence. We certainly speak of

possessing intangibles, like a sense of humor

90

or a secret.

91

Indeed, IP doctrines

occasionally invoke the concept of possession explicitly, most obviously in the

case of patent law’s “written description” requirement.

92

Just like “property”

serves as an imperfect analogy to “intellectual property,” so does “first

possession” to “original acquisition of intellectual property.”

The concept of possession, as property law has traditionally conceived it, is