Working poor in Europe

Wyattville Road, Loughlinstown, Dublin 18, Ireland. - Tel: (+353 1) 204 31 00 - Fax: 282 42 09 / 282 64 56

email: [email protected] - website: www.eurofound.europa.eu

1

Being in work greatly reduces the risk of poverty. Nevertheless, in the European Union, 8% of the employed population

fell into the category of ‘working poor’ in 2007, in the sense of having an income below 60% of the national average.

The proportion varies markedly across countries and social groups. In most countries, the issue of working poor is not

a policy priority of either the government or the social partners, although it can be included in general policies to

combat poverty and social exclusion. Although there is little evidence to prove it to date, the working poor are likely to

have been particularly affected by the current economic recession.

Introduction

The objective of combating social exclusion and poverty was a prominent feature of the Lisbon Strategy in 2000, which

presented the vision of a socially cohesive as well as an economically prosperous and competitive European Union.

Employment is often claimed to be the best protection against poverty. However, available data at EU level indicate that

as many as 6% of employees and 18% of self-employed people are classified as poor. The ‘working poor’ are a section

of the population that is difficult to identify not only due to the lack of specific data but also because the concept

combines two levels of analysis: the working status of individuals (individual level) and the income status of the

household in which they live, which is below the poverty threshold (collective level).

This comparative study is based mainly on contributions from national correspondents in the 27 EU Member States

(EU27) together with Norway, comprising the network of the European Working Conditions Observatory (EWCO). Its

aim is fourfold:

to obtain an insight into the extent of in-work poverty in the individual European countries and the characteristics of

those affected;

to examine policies in place to tackle the problem of people in work on low levels of income and any assessments that

have been carried out into the effectiveness of such policies;

to consider the views of social partners towards the working poor;

to investigate the effect of the current economic recession on the scale of in-work poverty.

For the purpose of this comparative study, the working poor are defined in the same way as the indicator used by the

European Commission to assess and monitor in-work poverty. Therefore, the working poor are those who are employed

and whose disposable income puts them at risk of poverty. ‘Employed’ is defined here as being in work for over half of

the year and ‘risk of poverty’ is defined as having an income below 60% of the national median (see box for definitions

of wages, earnings and income). Income is measured in relation to the household in which a person lives and covers the

income of all household members, which is shared among them after being adjusted for household size and composition.

This means, for example, that a man and a woman living in the same household are assumed to have the same

equivalised income irrespective of their individual earnings.

The study covers people on low wages, or low earnings in the case of self-employed persons. Low wages, defined in an

analogous way as low income – that is, below 60% of the median earnings of those in full-time employment – potentially

put individuals at risk of poverty.

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

2

If persons are at risk of poverty, this may not be simply because of low wages but because their wages are insufficient

to maintain the income of the household in which they live at a certain level. Equally, a person can earn a wage well

below the poverty threshold but not be at risk of poverty because the income of other household members is sufficient

to raise the overall household income above the poverty threshold. Such a person is, therefore, not counted as being

working poor as defined here. A person can have earnings well above the poverty threshold but, because they share a

household with people who are not working, they can be counted as being working poor.

Nature and extent of in-work poverty

The data in this section stem from the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) for 2007, which are

the latest available and relate to the situation in 2006 (for details see Annex 3). Detailed data for Bulgaria and Romania

are not available in the EU-SILC 2007; therefore, information on these two countries was taken, if available, from the

respective national contributions. For the total number of working poor, the EU27 and Norway are covered.

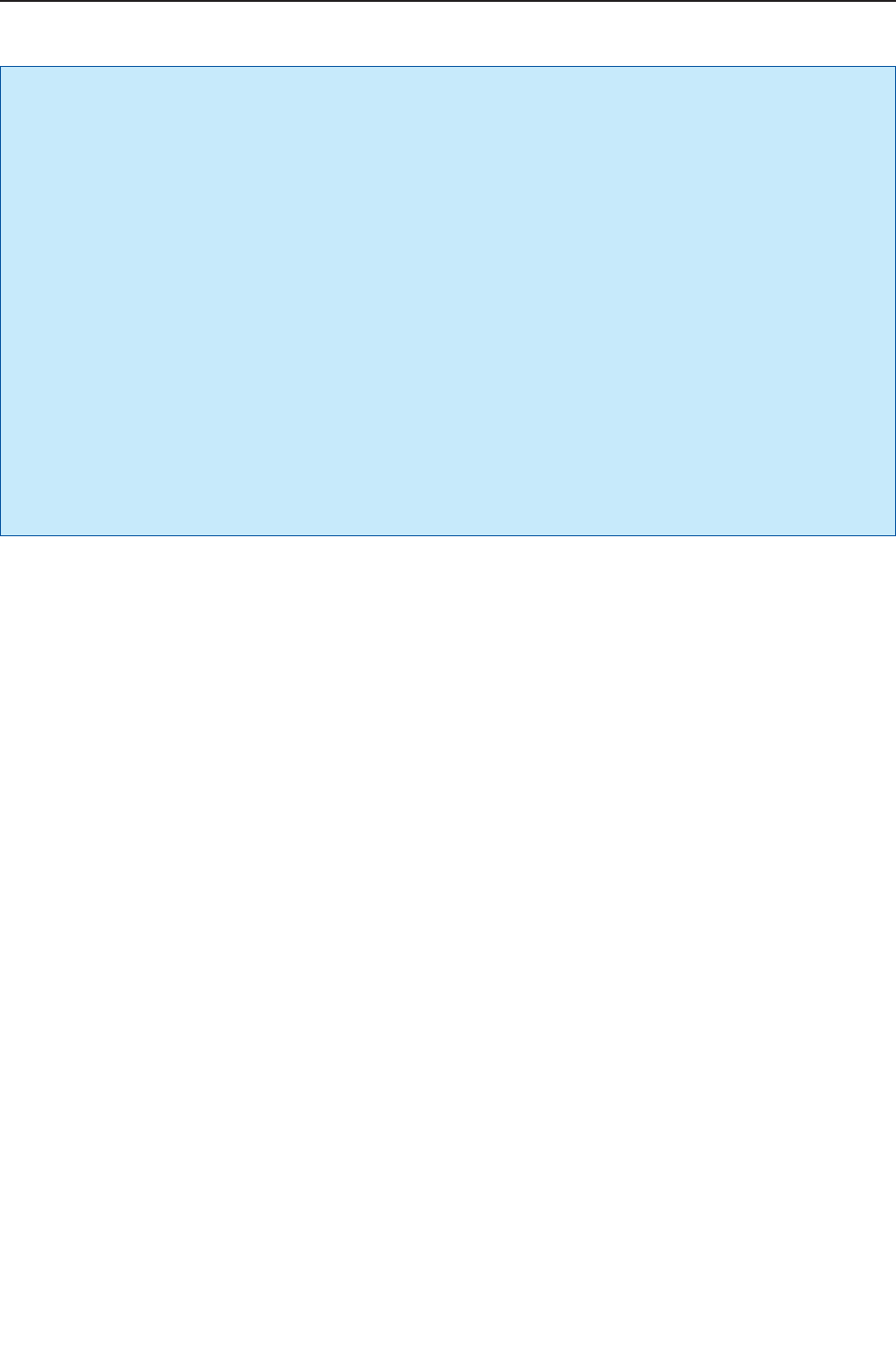

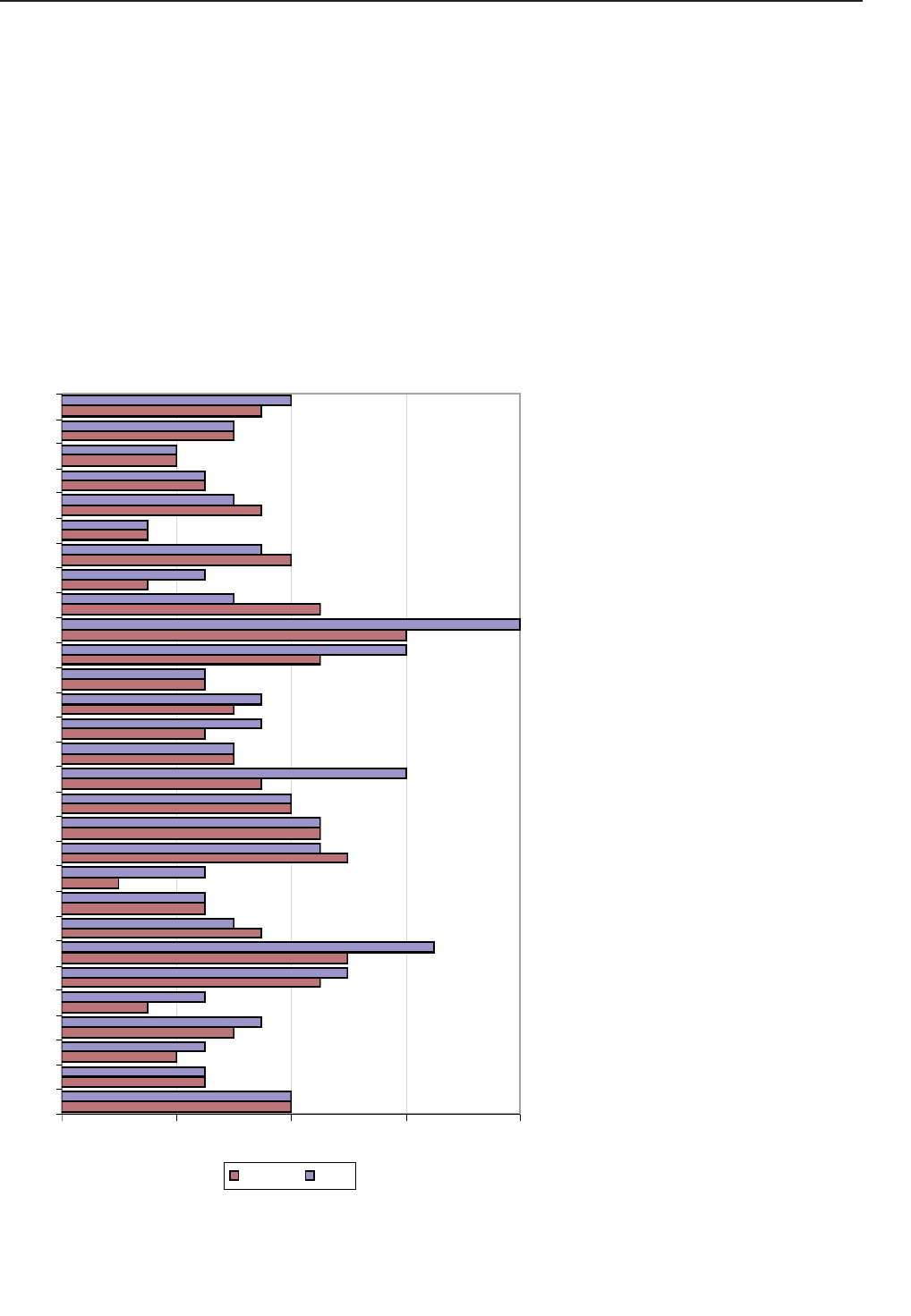

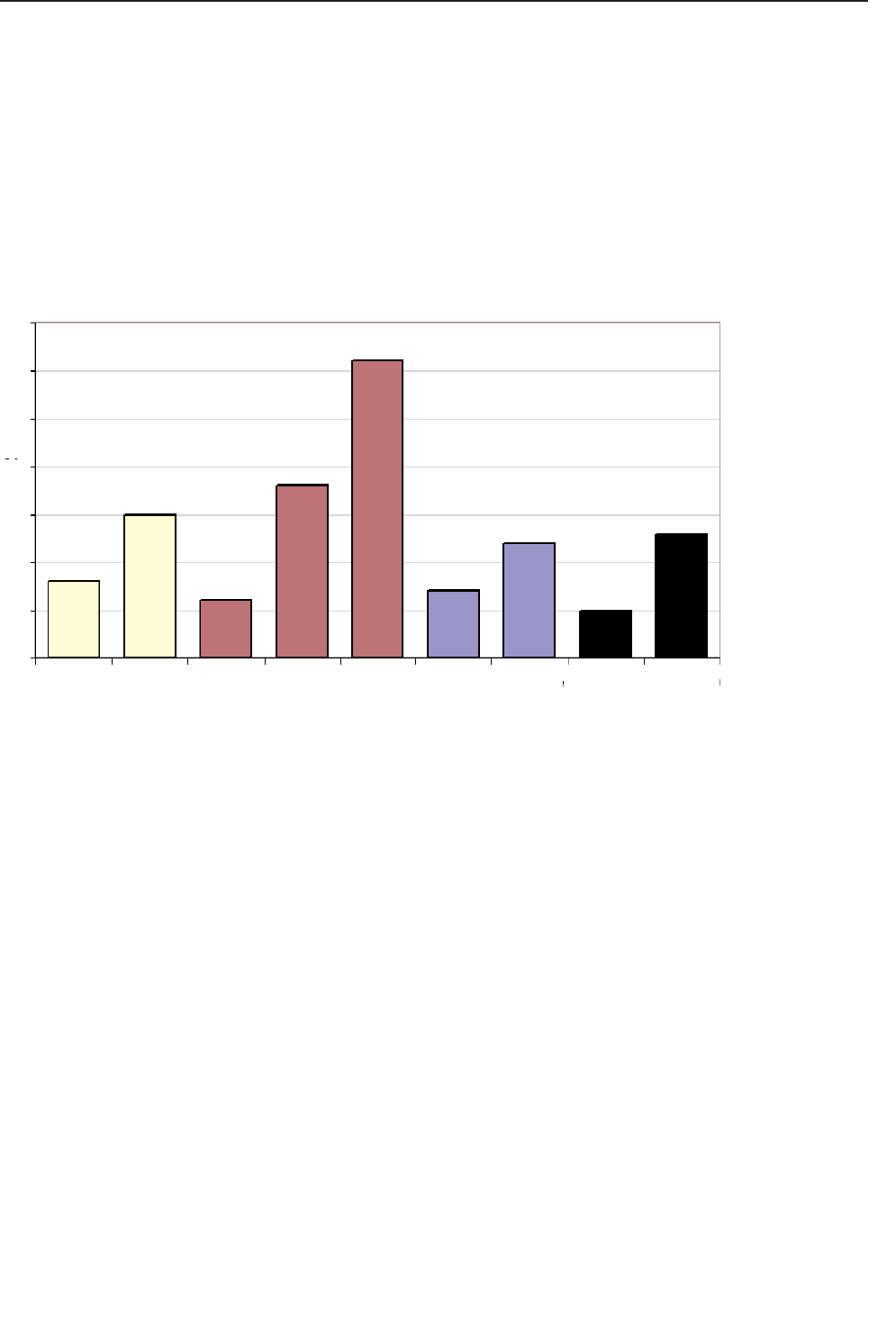

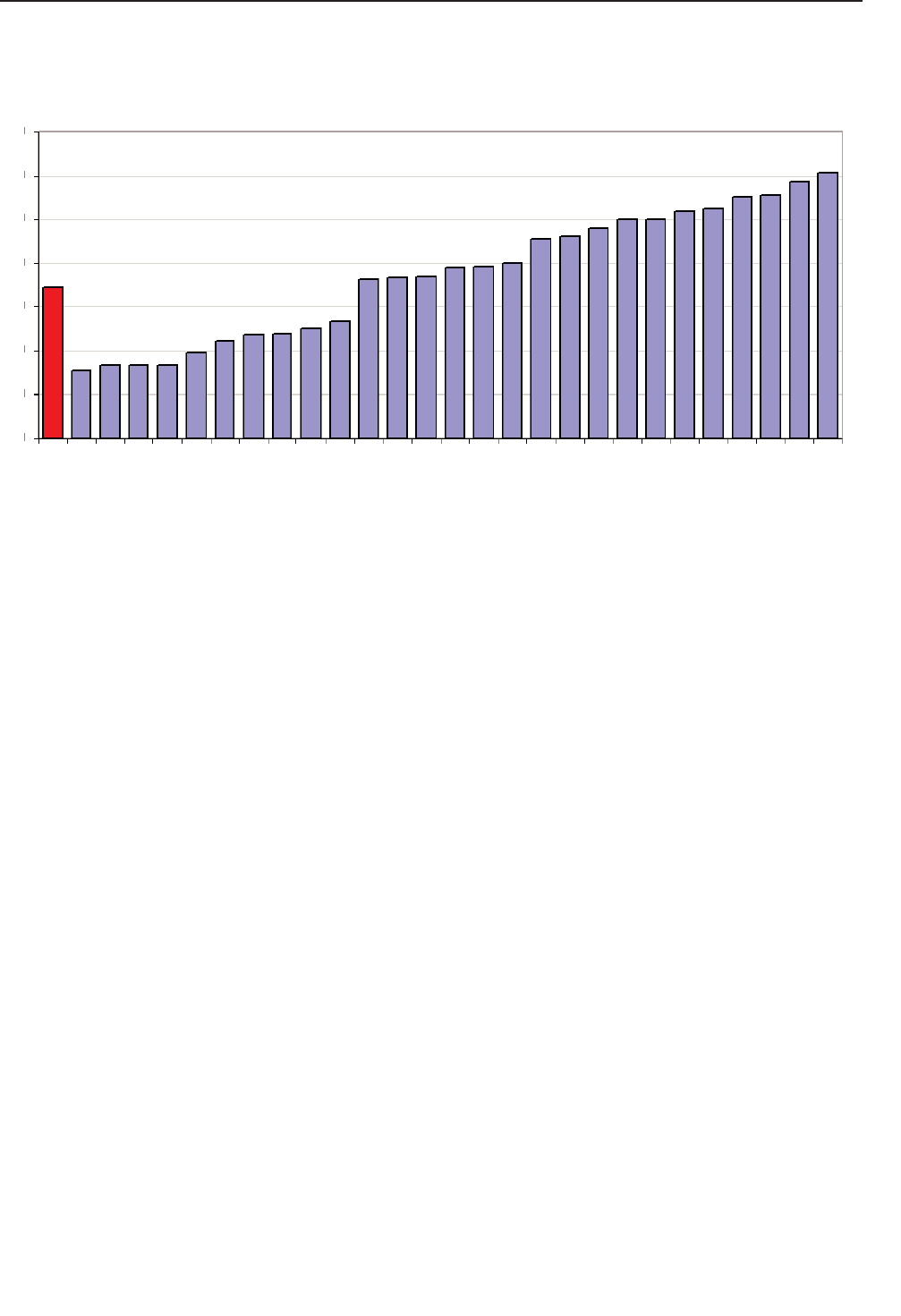

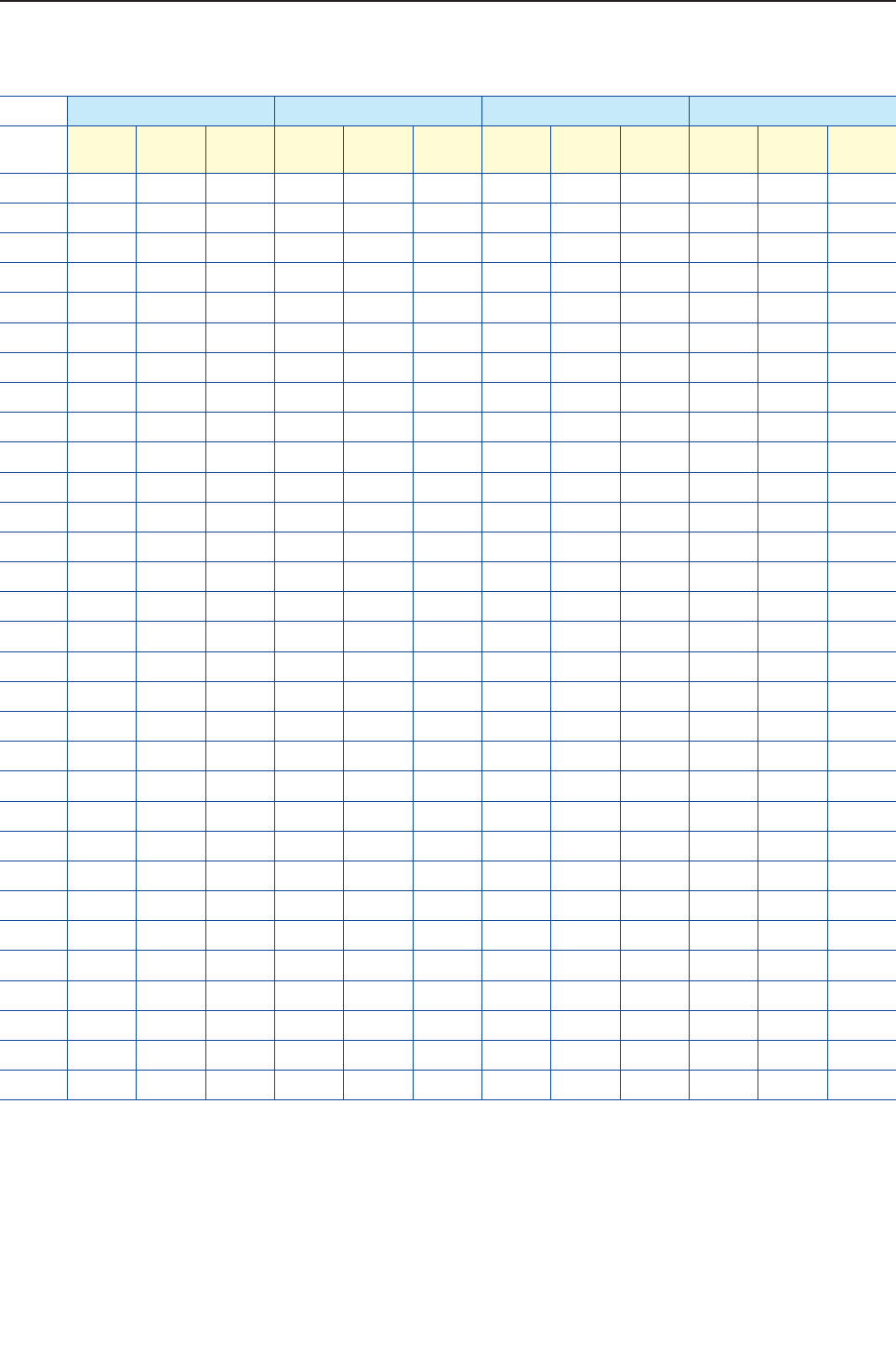

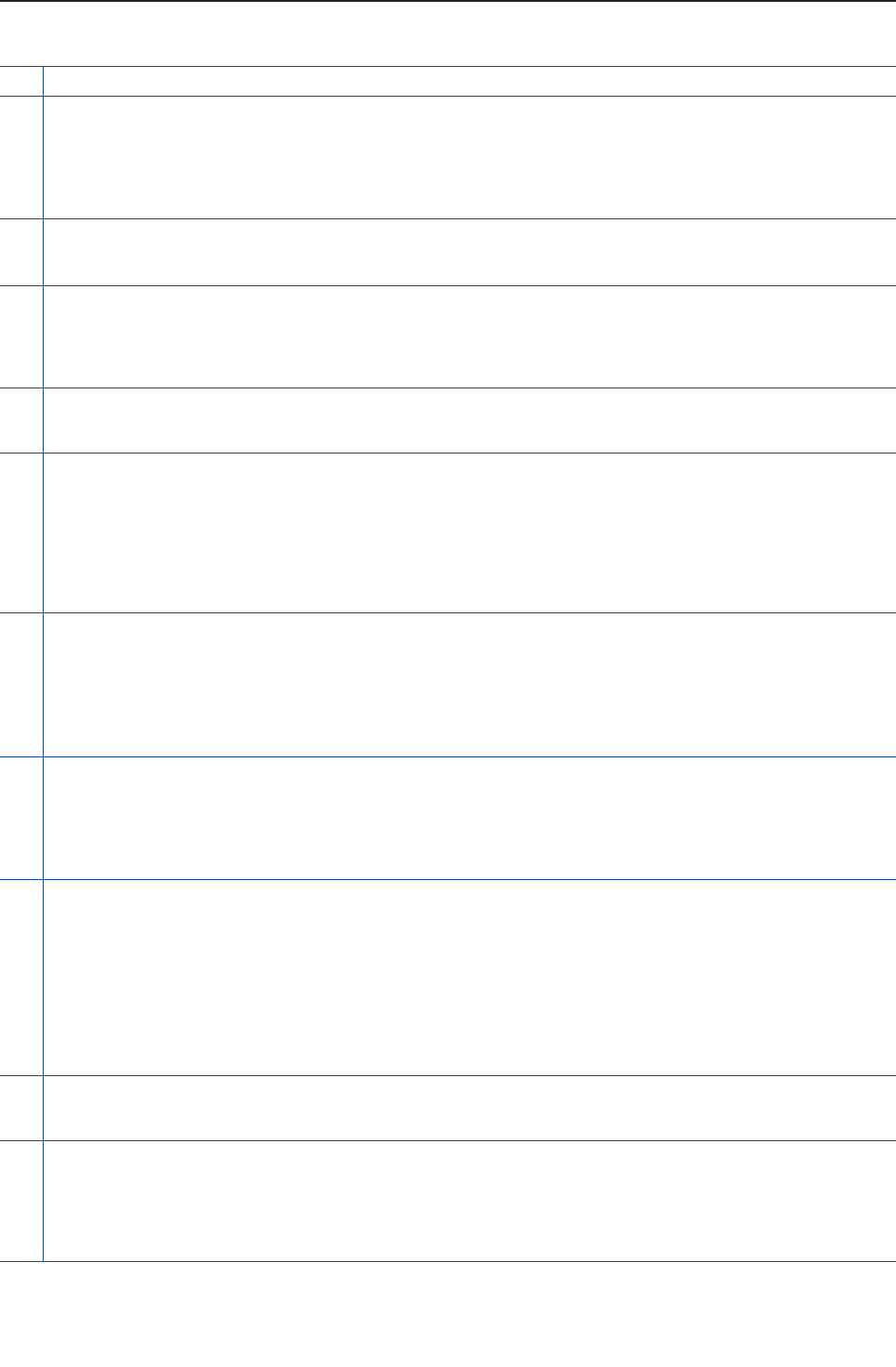

In 2007, in the EU27, about 8% of persons in employment were considered as working poor, meaning that 8% of the

working age population (18 years and over) was working and nevertheless living under the poverty threshold (Figure 1).

However, significant differences arise among the individual Member States: Greece (14%), Poland (12%), Spain (11%)

as well as Italy, Latvia and Portugal (10% each) show the highest in-work poverty rates. The Member States with the

lowest in-work poverty rates are the Czech Republic (3%), Belgium, Denmark and Malta (4% each). In Romania, the at

risk of poverty rate for employees was 4%, while the risk for self-employed people, including in the agricultural sector,

was about 37% in 2006. More recent data raise the total in-work poverty rate to 18%, which may be a result of the use

of new data to measure this (European Commission, 2009b).

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

Definitions of wages, earnings and income

Wages: corresponds to the compensation received by workers in exchange for their work.

Earnings: relates to the wages and salaries of employees or the net profits of self-employed people from their business

activities.

Income: refers to the total revenue of individuals or households received over a given period of time – here over a year

– that is, the sum of wages and salaries, social transfers, capital receipts and other items, net of any taxes or social

security contributions paid on the various sources of income.

Note: Household income is defined to include all income received by individuals living in a household. This is

converted into an average amount per individual to allow for the economies which result from individuals sharing a

household – that is, from the fact that the cost of durable goods, such as furniture or a television, or the cost of the

accommodation can be shared between the household members. Therefore, those living in a household are weighted as

follows: the first adult (a person aged 18 years or over) is assigned a weight of one, the second and subsequent adults

are assigned a weight of 0.5 and children up to the age of 14 years are assigned a weight of 0.3. Household income is

then divided by the weighted number of people living there and the resulting ‘equivalised’ income is attributed equally

to all of the members concerned.

3

Working poor in Europe

Figure 1: In-work poverty risk in the EU, 2007 (%)

Note: Romania is not shown because of problems with national data. See Annex 4 for list of country codes.

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

Being a relative indicator, the in-work poverty rate makes it possible to compare countries where the poverty threshold is

very different. For example, in 2007, the absolute at risk of poverty threshold amounts to €1,494 in Luxembourg, but to €74

in Bulgaria. Luxembourg has an above average working poor rate (9%) while Bulgaria has a below average rate (5%).

Effect of employment status

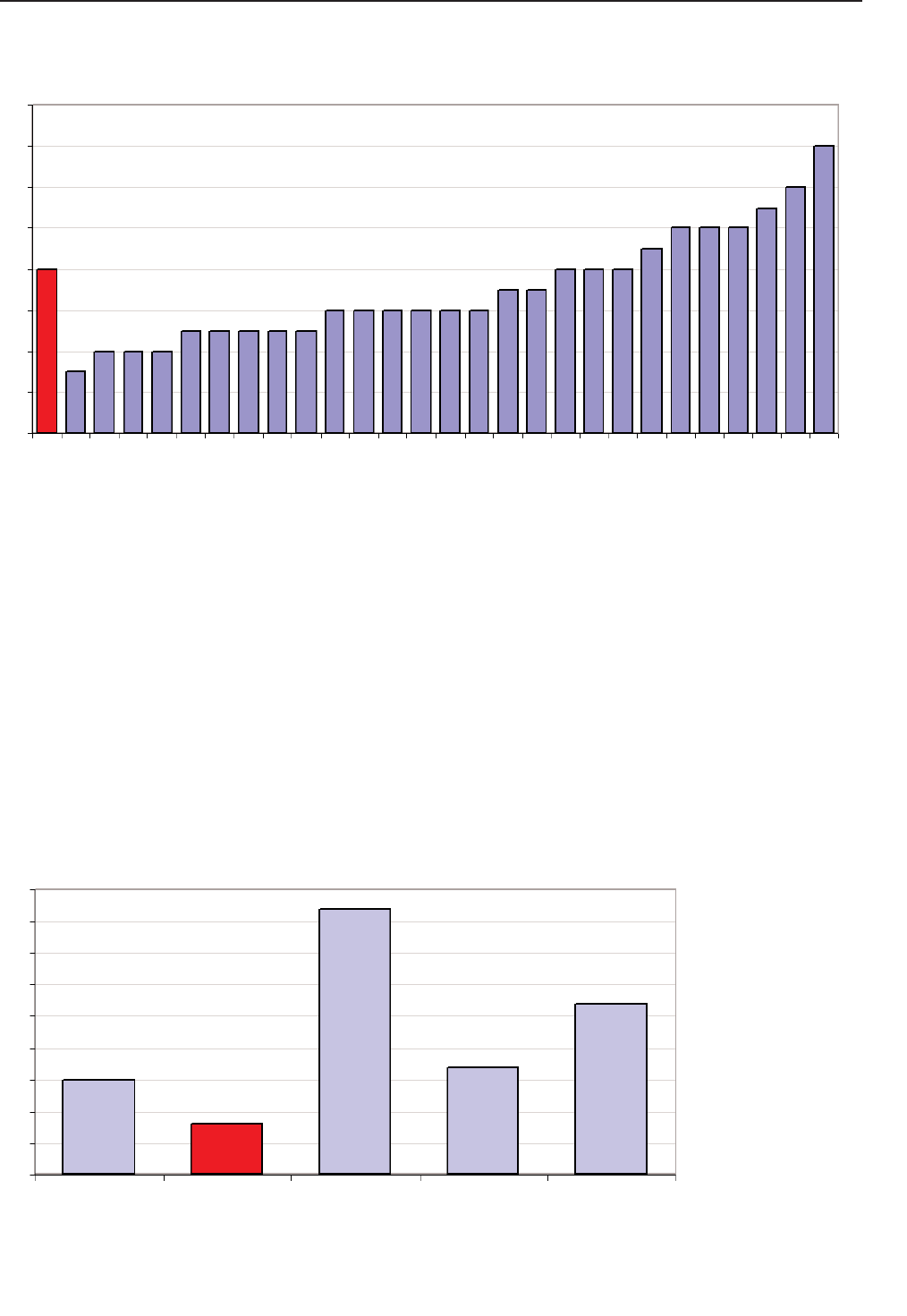

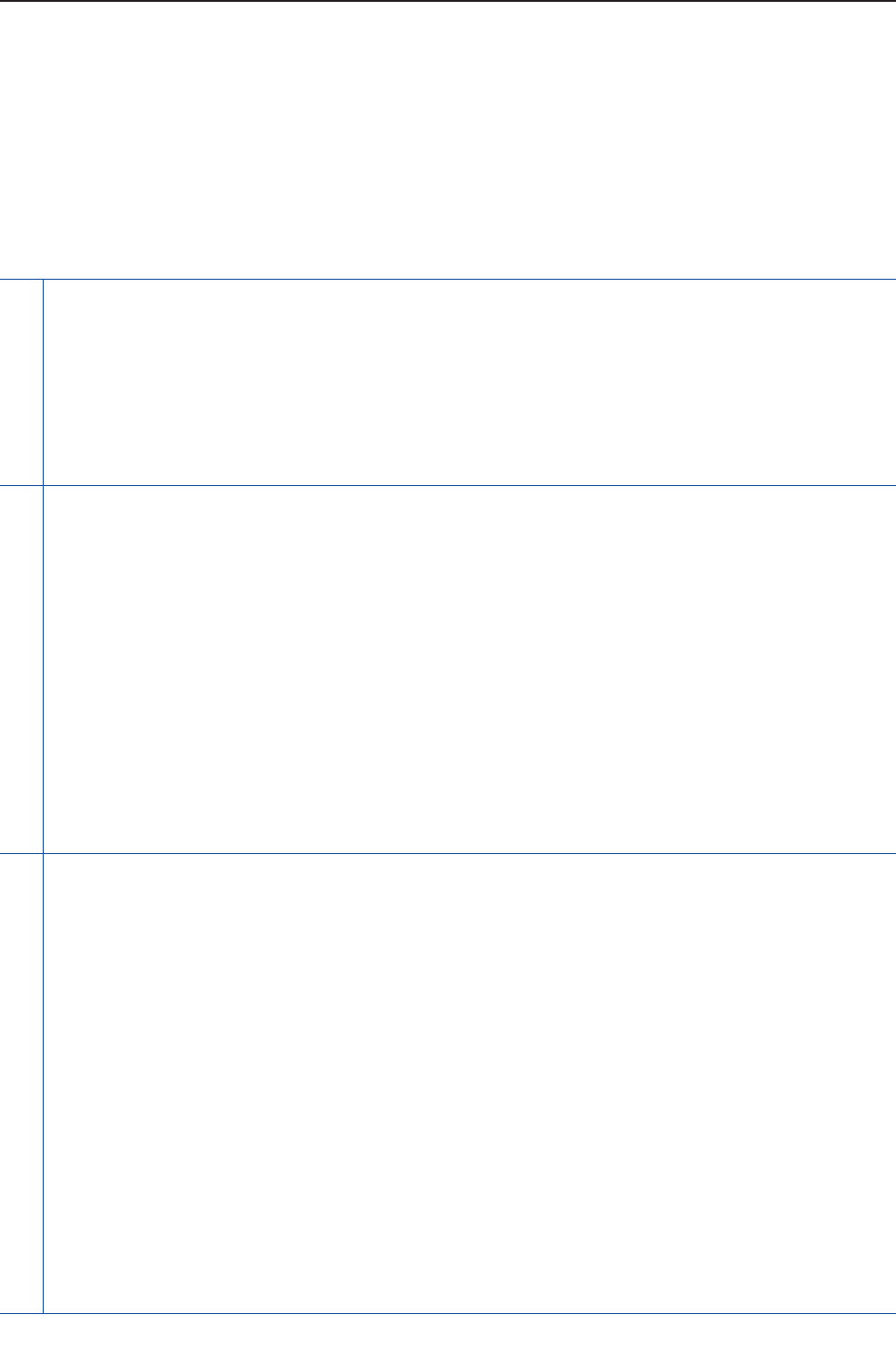

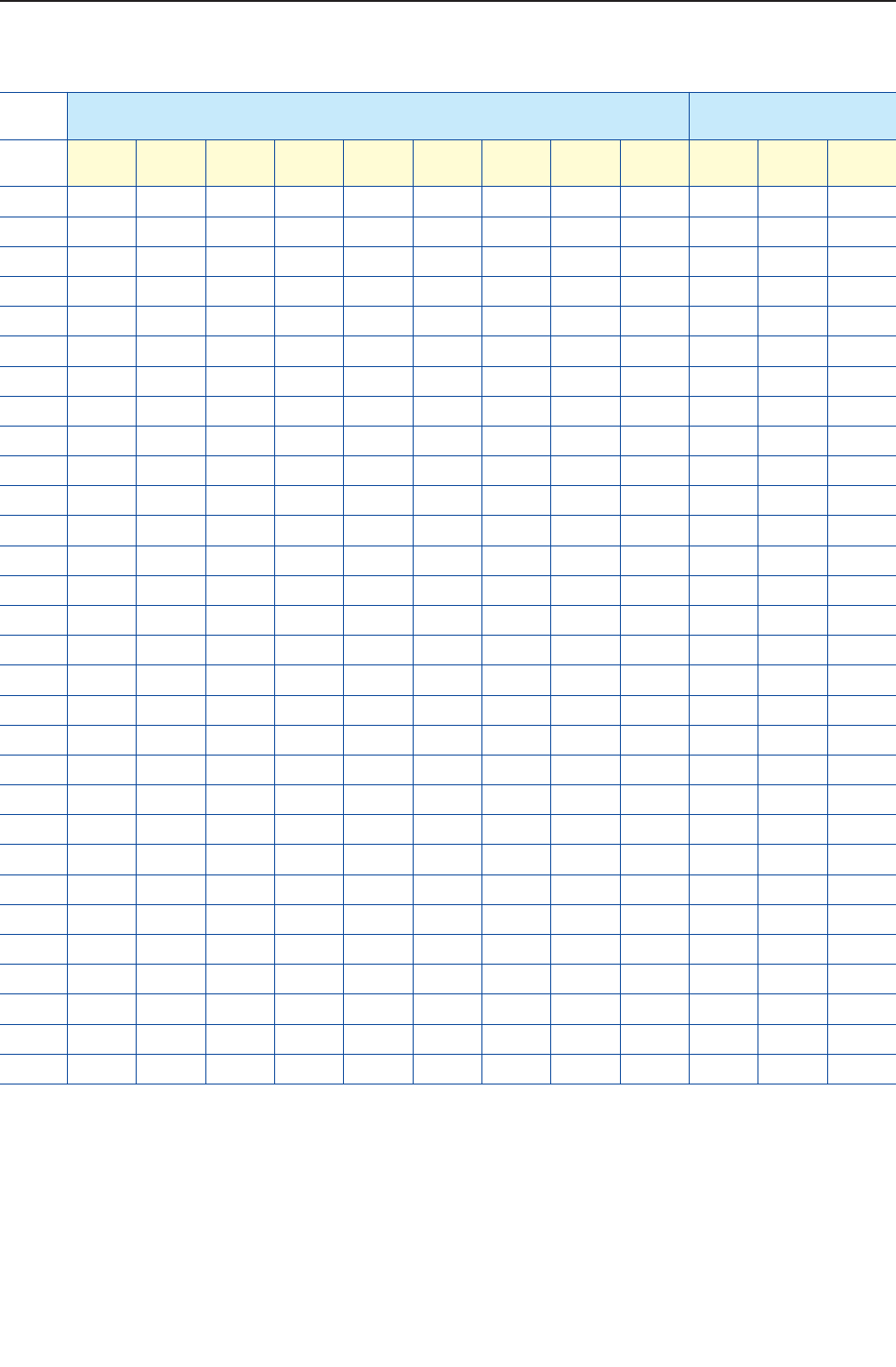

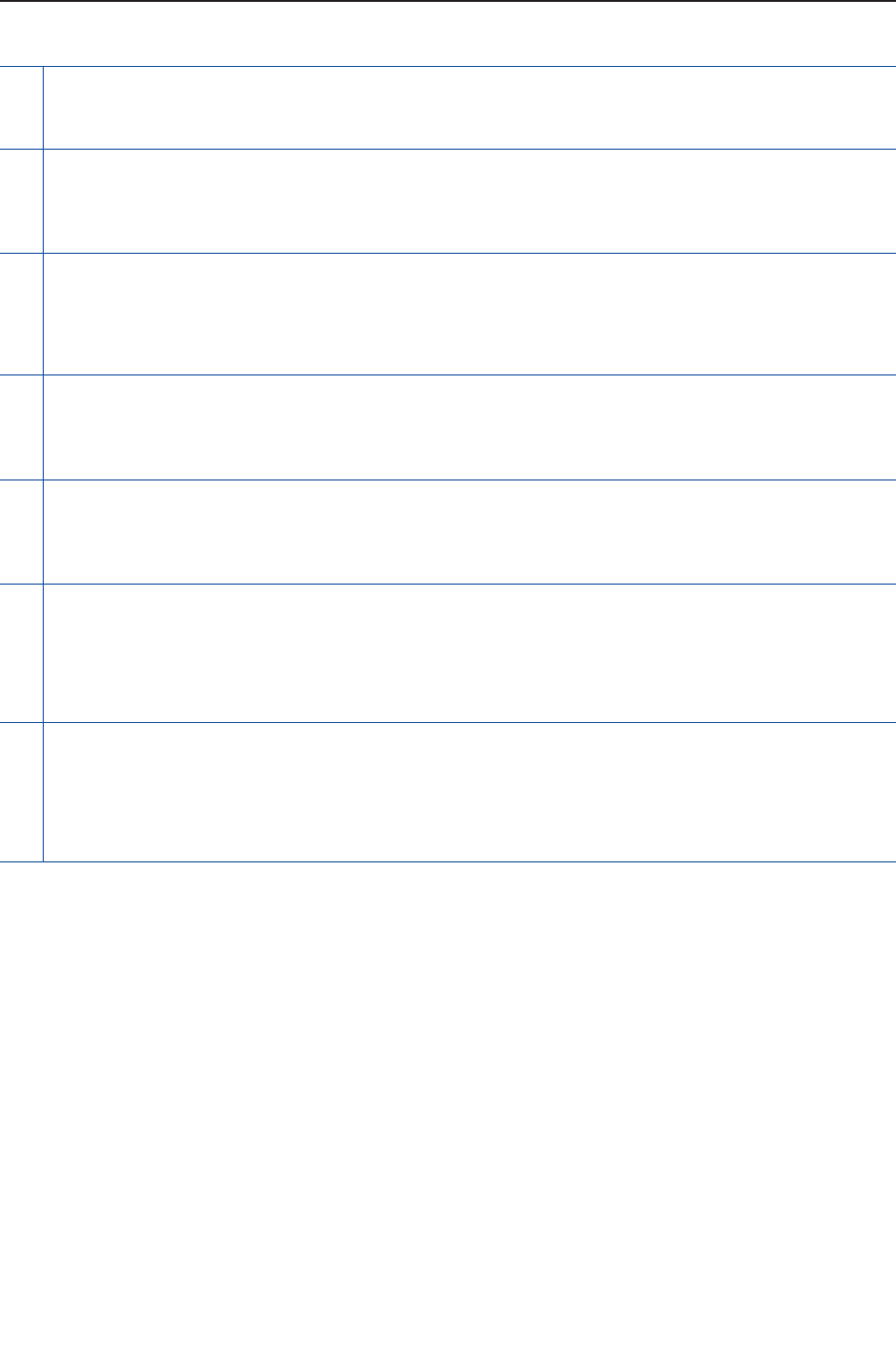

Clearly, being employed greatly reduces the risk of poverty and social exclusion (Figure 2). In general, unemployed

people face the greatest risk of poverty, with a rate of 42% in 2006, followed by others not in work who are recorded as

being economically inactive (27%) and retired people (17%). Overall, the risk of poverty amounted to 15% in 2006 in

the then 25 EU Member States (EU25) for the whole population. However, even if people in employment are less

exposed to the risk of poverty than other groups, they represent a large proportion of those at risk of poverty, since a

large part of the population of working age (15–64 years) is in work: 65% in the EU27 (Eurostat, 2009).

Figure 2: Incidence of poverty risk, by most frequent economic activity status, EU25, 2007 (%)

Note: No data available for Bulgaria and Romania.

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

16

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

0

8

6 6 6 6

5555

5

444

3

66

101010

9

888

77

14

12

11

CZEU27 SKSINLBGMTDKBE FI FRIE UKLTEESEDENOATHUCY ITLU PLESPTLV EL

45

15

Total

20

25

30

35

40

5

10

15

0

42

8

17

27

Employed Unemployed Other inactiveRetired

4

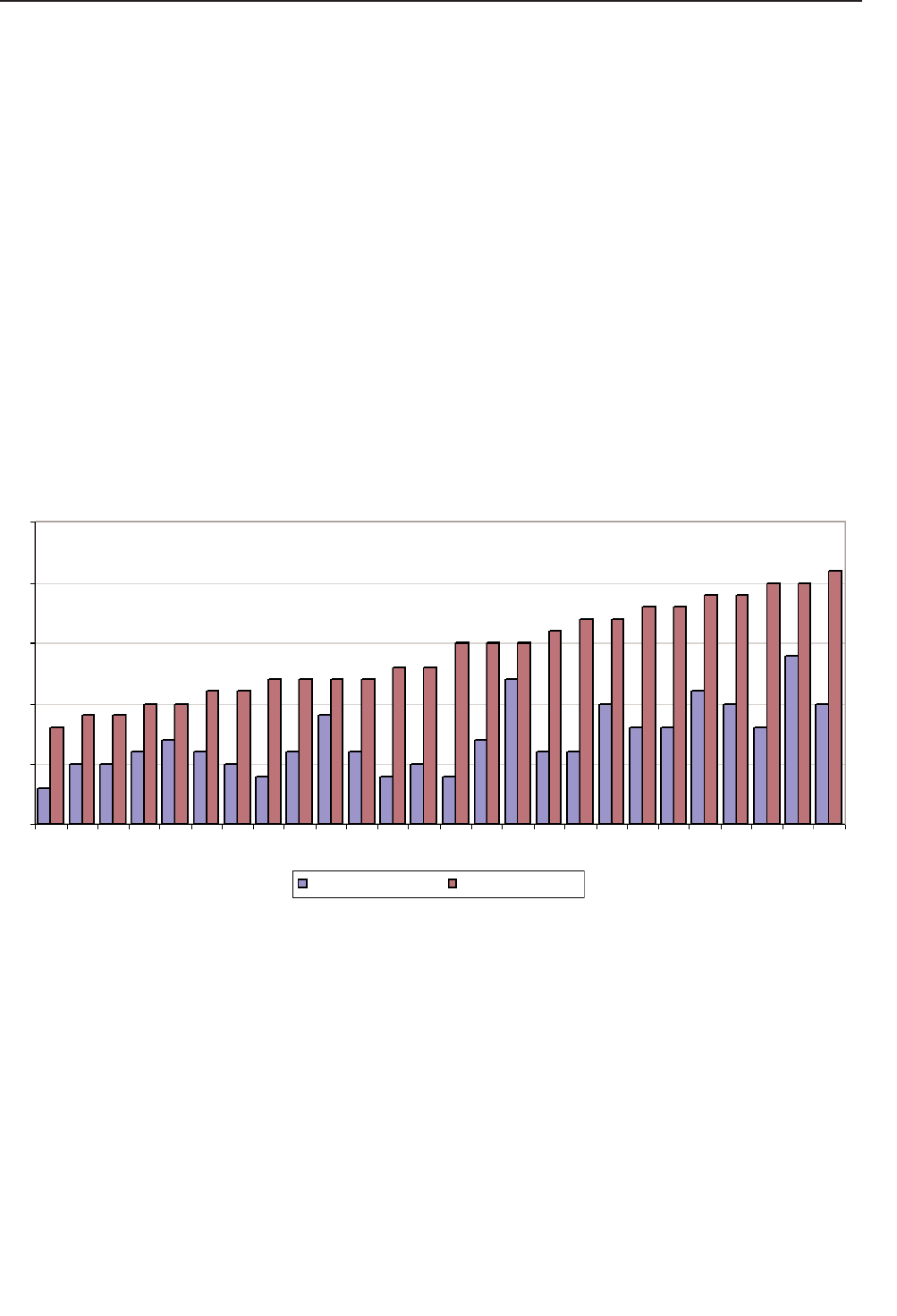

The in-work poverty risk tends to vary with the overall risk of poverty. The southern EU countries of Greece, Italy and

Spain and the Baltic states of Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania have a high risk for both employed people and the total

population, while the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Hungary and Sweden have a low risk for both

employed persons and the total population (Figure 3). However, a large variability arises between the two ratios, which

can be explained by a mix of factors, such as the incidence of poverty risk in each economic activity status group of the

population and their proportion of the total population. Above all, it depends on the extent to which people in

employment with low earnings share households with others in work, who might earn more and therefore effectively

share their income as well – as opposed to living alone. Hence, the working poor have more weight in total poverty in

countries such as Luxembourg, Poland and Sweden, where the difference between the two ratios is three percentage

points only, compared with the Baltic states and Belgium, Cyprus, Ireland and the United Kingdom (UK), where the

ratios differ by about 10–12 percentage points. In the latter group of countries, therefore, a smaller proportion of people

on low earnings – many of whom are women – tend to live alone or in households with no else in work, while at the

same time, persons not in work tend to represent a large proportion of those at risk of poverty. This is especially the case

for older persons aged 65 years or more in Cyprus; this group is also particularly at risk, albeit to a lesser extent, in the

other countries. In this group of countries, therefore, a larger proportion of those at risk of poverty live in ‘workless’

households.

Figure 3: At risk of poverty rate and in-work poverty, EU25, 2007 (%)

Note: No data available for Bulgaria and Romania.

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

Some people are more or less likely to be among the working poor; thus, their specific characteristics are also important

and will be examined in more detail. These characteristics include personal (gender, age and education), household

(single person, households with dependent children or without) and occupational factors (months worked in year,

professional status, full-time or part-time work, type of employment contract).

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

25

3

CZ SK SINL

In-work poverty risk

MTDK BEFIFR IE UKLT EESE DENOATHU CY ITLU PL ESPT LVEL

20

5

0

10

15

Total poverty rate

6

9

5

9

5

8

6

10

7

10

4

1111

5

4

5

13

13

4

12

6

12

9

12

6

12

8

17

10

17

6

6

16

15

12

7

1515

14

20

8

10

11

8

1919

1818

21

10

20

5

Working poor in Europe

Personal characteristics

Gender effects

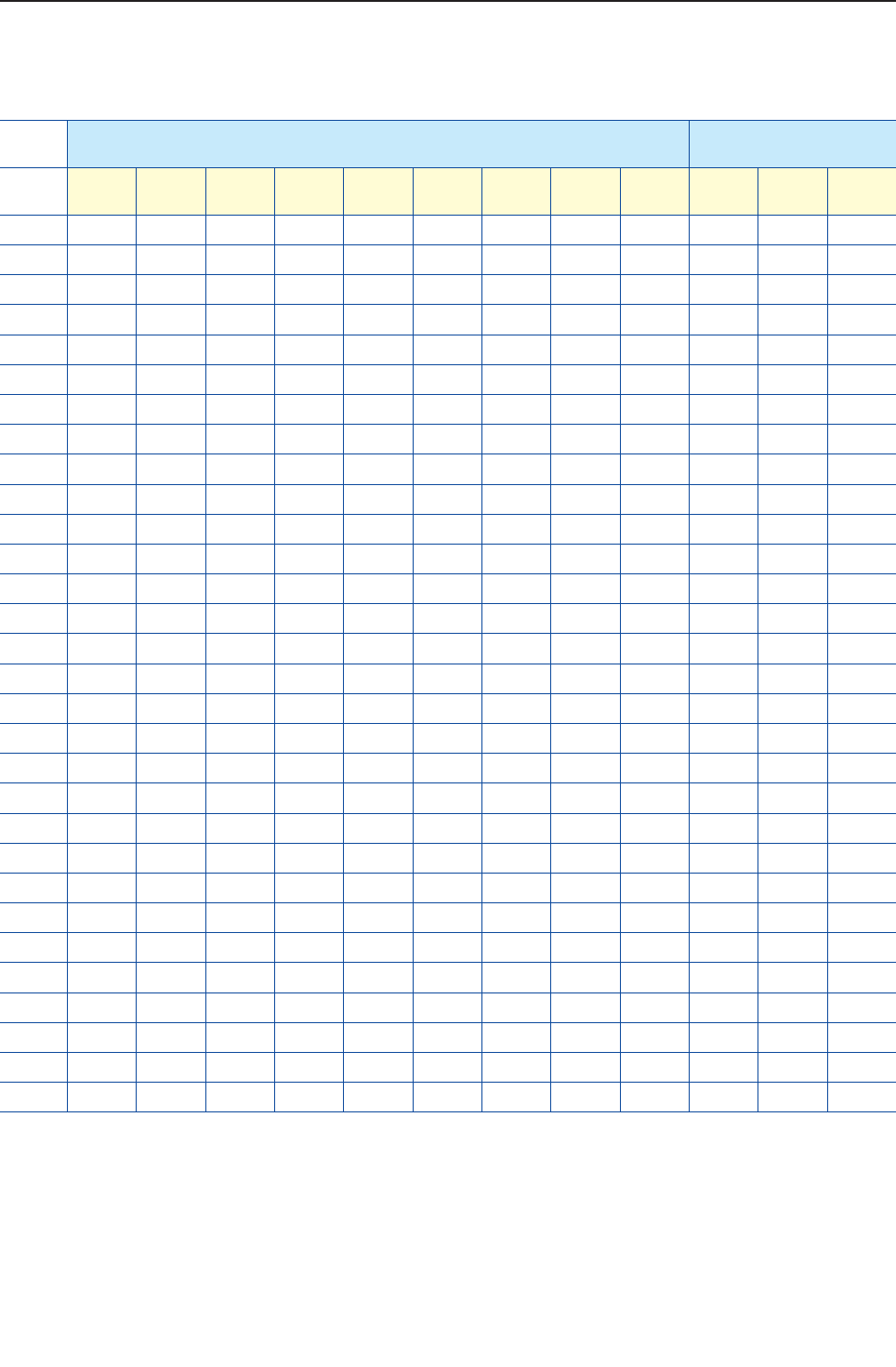

Although women face a higher poverty risk, statistics show that, if they are in work, they are on average across the EU

less likely than men to live in households with a poverty-level of income. Indeed, the in-work poverty risk is lower for

women (7%) than for men (8%) in the EU27 average. In 12 countries (Denmark, France, Greece, Hungary

, Italy, Malta,

Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden) men are more affected, while in 11 countries (Austria,

Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Ireland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia and the

UK) no gender differences are observed (Figure 4). The in-work poverty risk is higher for women than for men only in

Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Latvia and Norway. The in-work poverty risk for women ranges from 2% in Malta and 3%

in the Czech Republic and Denmark to 10% in Latvia and Poland and 12% in Greece.

Figure 4: In-work poverty risk, by gender, EU27, 2007 (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

EU25

0

Women

161284

Men

AT

HU

FR

FI

ES

EL

EE

DK

DE

CZ

CY

BG

BE

NO

NL

MT

LV

LU

LT

IT

IE

SK

SI

SE

RO

PT

PL

UK

6

Nevertheless, as stated in one of the country reports, the above figures do not reflect the actual situation of women in

the labour market, since women in work tend to be in a more vulnerable situation than their male counterparts. Women

are more likely than men to be employed in low-paid jobs, working part time or in temporary employment, and they are

also more likely than men to be single parents, so being at particular risk of poverty. This is offset, however, in many

countries by the fact that single women without children – including those living alone and those sharing a household

with others – are, on average, less likely to have an income below the poverty line than single men, who perhaps are

more likely to live alone. It should be borne in mind that women living as part of a couple with a man have the same

risk of poverty by definition, since household income is assumed to be divided equally between all of the people living

in the household.

Age effects

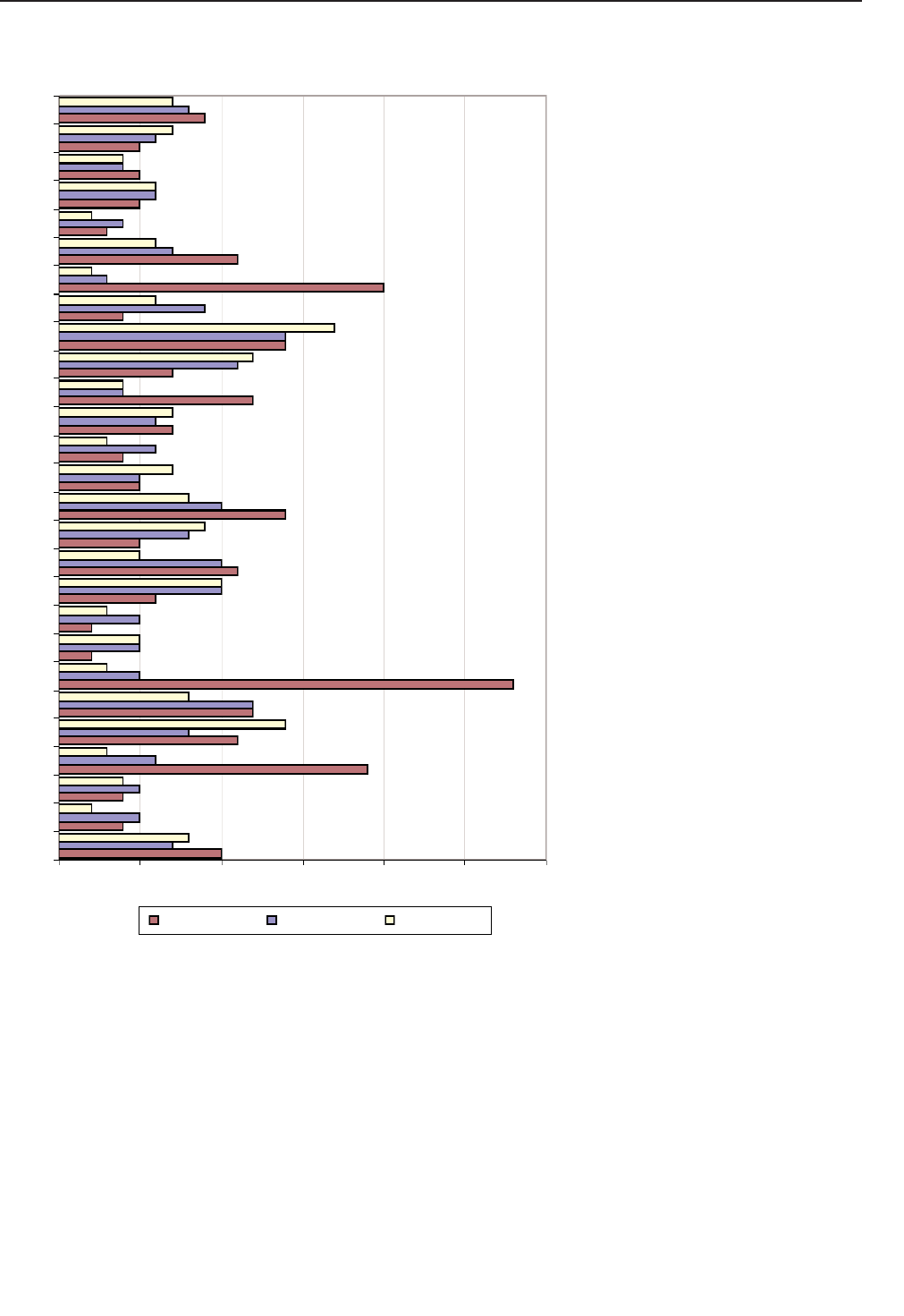

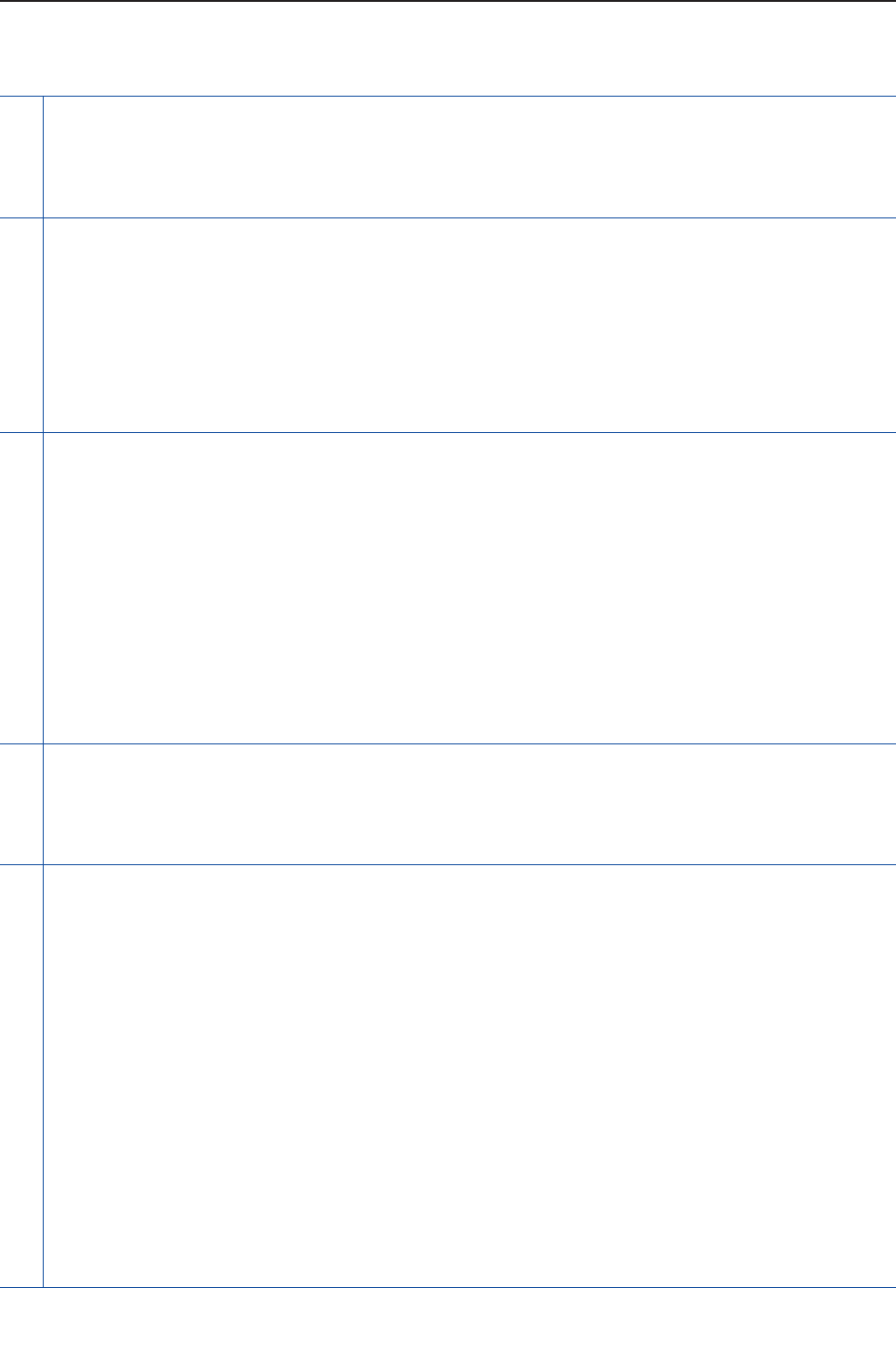

According to data for the EU25, it seems that in-work poverty risk decreases with the age of workers: Figure 5 shows

that younger workers face the highest risk of in-work poverty (9%), followed by workers aged 25–54 years (8%) and

older workers (7%). This can be explained by the fact that young people often start their careers with low-paid jobs.

However, substantial differences arise among the Member States. The EU pattern of young workers facing the highest

risk of in-work poverty is evident in nine countries: Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Norway,

Sweden and the UK. Young workers are most seriously affected in the northern countries, where the in-work poverty

risk reaches 19% in Sweden, 20% in Denmark and 28% in Norway.

On the other hand, in as many as six Member States – Austria, Greece, Ireland, Lithuania, Portugal and Spain – older

workers face a higher in-work poverty risk than young workers. It seems that, in the southern EU countries, younger

persons leave their home later; for example, in Spain they only leave home on average in their early 30s. Meanwhile, in

the northern countries, young people establish their own households earlier, such as in Finland. Accordingly, while in

the southern countries, young people have some income support from other members of the household, this is less the

case in northern EU Member States, where a larger proportion of young people live alone.

A third pattern is apparent in six of the 10 new Member States (NMS) joining in 2004 (the Czech Republic, Estonia,

Hungary, Malta, Slovakia and Slovenia): in these countries, workers aged 25 to 54 years show the highest in-work

poverty risk among all age groups within their country. In Poland, the youngest and middle age groups are most affected,

while in Cyprus, Latvia and the Netherlands the greatest risk is among the middle age group and older workers.

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

7

Working poor in Europe

Figure 5: In-work poverty risk, by age, EU25, 2007 (%)

Note: No data available for Bulgaria and Romania.

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

Concerning the young working poor, the risk is higher for women (10%) than for men (9%) in the EU25 average, which

may be due to the existing gender segregation of the labour market (Table A2 in Annex 1). In general, young women are

encouraged to choose training programmes or apprenticeships in relatively low-wage occupations in the services sector.

According to the German contribution, an explanation is that men tend to more often choose apprenticeships or

occupations in the manufacturing or construction sectors, which are characterised by higher than average apprenticeship

and entry wages. Among the working poor aged 25 to 54 years, men (9%) face a higher risk than women (7%); likewise,

among older workers, men (8%) are more affected than women (7%).

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

EU25

0

18–24 years

2015105

AT

HU

FR

FI

ES

EL

EE

DK

DE

CZ

CY

BE

NO

NL

MT

LV

LU

LT

IT

IE

SK

SI

SE

PT

PL

UK

3025

25–54 years 55–64 years

8

Educational effects

When looking at the educational level of workers in the EU25, the in-work poverty risk decreases with the level of

education: Figure 6 shows that low education is typically associated with a higher in work poverty risk (14%) than a

medium (8%) or high education (3%). Low education is defined as ISCED 0–2, according to the International Standard

Classification of Education (ISCED), meaning no education beyond compulsory schooling. Medium education is

defined as ISCED 3–4, meaning at least three years of education or training successfully completed after compulsory

schooling. High education is defined as ISCED 5–6, meaning a third-level qualification.

For low-educated workers, the in-work poverty risk ranges between 5% in Denmark and 28% in Poland (Table A3 in

Annex 1). According to the Polish country report, however, a survey on The working poor in Poland – conducted by the

Centre for Public Opinion Research (Centrum Badań Opinii Społecznej, CBOS) – finds that most working poor have

either vocational (45.3%) or secondary education (28.2%). A smaller proportion has only primary (17.8%) or higher

education (8.7%). Thus, although in-work poverty affects mainly workers with low education, it also affects higher

educated workers.

For medium-educated workers, the in-work poverty risk is between 2% in Malta and 13% in Poland, while for highly

educated workers, the risk is between 0% in Portugal and 6% in Sweden. Only four countries diverge from this trend: in

Estonia, Finland and the Netherlands, the risk for being among the working poor is the same for low and medium-

educated workers. In Sweden, the in work poverty risk is similar for all of the groups (between 6% and 7%), reflecting

perhaps the relatively high level of social transfers in that country. Their redistribution effect tends to reduce the risk of

poverty across households, making differences in educational levels less relevant from this perspective.

Figure 6: In-work poverty risk, by personal characteristics, EU25, 2007 (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

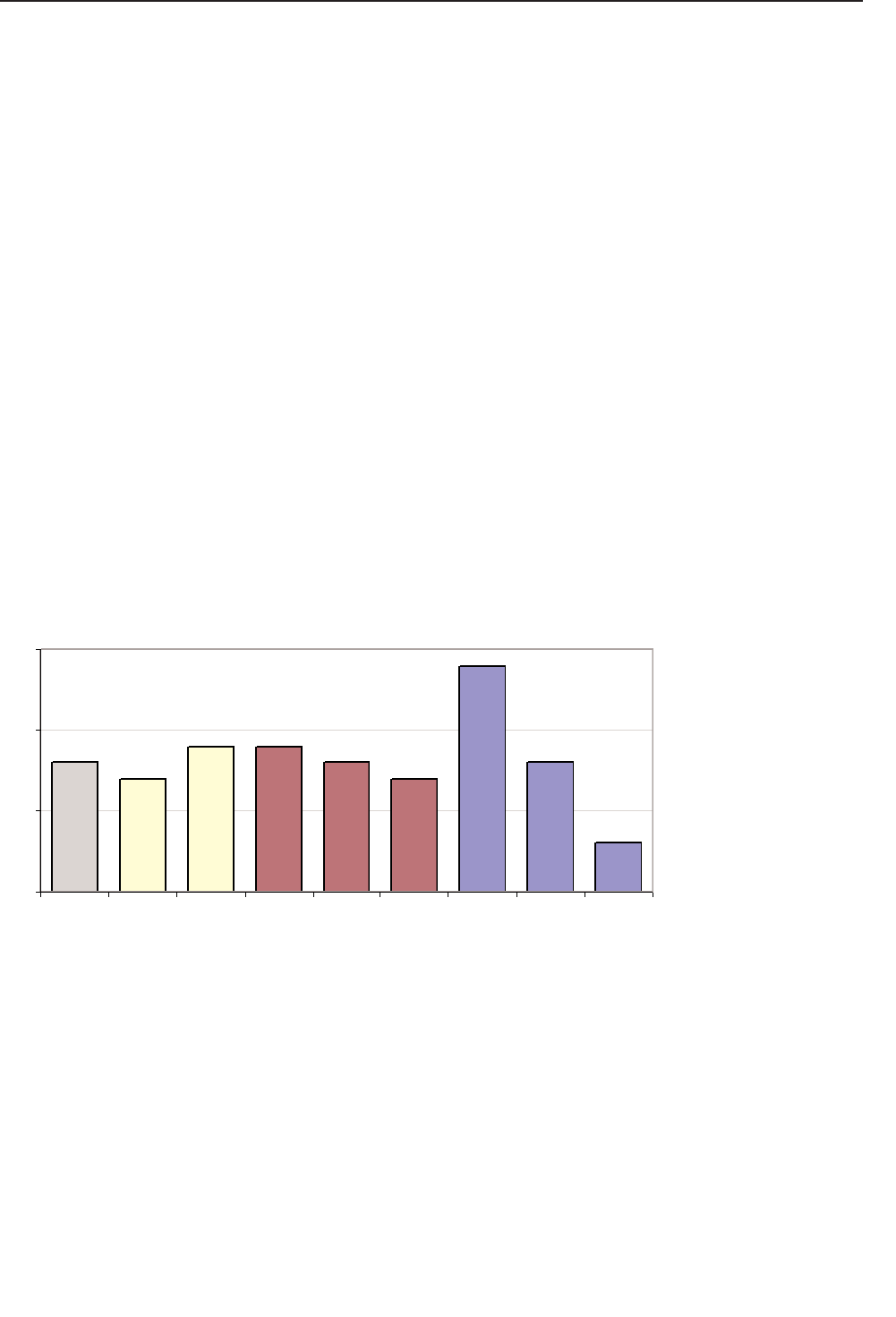

Household characteristics

Beyond individual characteristics, the incidence of in-work poverty is connected to household characteristics (Figure 7).

Single parents with dependent children face the highest risk, at 18% for the EU25 average; this proportion is even higher

in the Baltic and southern EU countries – 27% in Estonia, 24% in Lithuania, 23% in Latvia and Spain, and 22% in

Cyprus and Greece (Table A3 in Annex 1). The in-work poverty risk for single parents ranges between 8% in Denmark

and 39% in Luxembourg. Single persons as well as households with dependent children show an in-work poverty risk

of 10% in the EU25, ranging between 3% in Malta and 14% in Norway and Sweden for the former category and between

4% in Denmark and 18% in Greece for the latter. In Finland, a specific concern about single parents at risk of in-work

poverty was recorded in the beginning of the 2000s due to the increase in the proportion of that group, while the Spanish

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

8

Total

5

10

15

0

8

3

8

14

7

9

9

7

18–24

years

MenWomen 25–54

years

55–64

years

Low

education

High

education

Medium

education

9

Working poor in Europe

report emphasises changes in family structures along with a weakening of the protective nature of families. In general,

households without children have a lower risk of in-work poverty (6%), except for single people without children, who

have a higher risk than those living in households composed of two adults or more without children (10% compared with

5%).

Figure 7: In-work poverty risk, by household characteristics, EU25, 2007 (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

Occupational factors

Some specific features of the labour market such as low pay, precarious employment and inability to find full-time work

seem to be linked with in-work poverty

. According to the data, having a job for less than a full year, being part-time

employed or having a temporary employment contract strongly raises the risk of in-work poverty. A temporary contract

of employment is fixed in terms of its duration, which in many cases is one year or less.

Figure 8 reveals that working less than a full year is associated with an almost double rate of poverty risk (15% for the

EU25) compared with working a full year (8%). Working part time (12%) also nearly doubles the risk compared with

full-time work (7%). Having a temporary employment contract (13%) increases the poverty risk almost three times

compared with having a permanent contract (5%).

In the EU25, the in-work poverty risk for those working less than a full year lies between 4% in the Netherlands and

26% in Greece (Table A4 in Annex 1). The risk for part-time workers is lowest in the Czech Republic and the

Netherlands (both 4%) and highest in Lithuania and Portugal (both 28%). Meanwhile, the risk of being working poor

when holding a temporary employment contract varies between 5% in the Netherlands and 20% in Norway and Sweden.

Part-time workers are more likely to be working poor in the NMS, especially the Baltic countries, Hungary and Poland.

Self-employed persons in the EU25 have a three times higher risk of being working poor than employees: 18% compared

with only 6%. However, data regarding self-employed people are less reliable due to underreporting and income

fluctuations from one year to another. The in-work poverty risk for self-employed individuals ranges from 5% in Cyprus

and 6% in the Czech Republic to 26% in Poland, 27% in Estonia and 30% in Spain.

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

10

Single person

5

10

15

0

20

6

10

18

9

5

Two or more

adults without

dependent

children

Households

without

dependent

children

Single parent

with

dependent

children

Two or more

adults with

dependent

children

Households

with

dependent

children

10

For family workers, data on the working poor also seem to be less reliable, which may be due to the small size of this

group – for example, in Denmark, Finland or Sweden – or to underreporting problems. Family workers are people who

help to run a family farm or business without receiving a wage or salary. Overall, however, the number of working poor

among unpaid family workers is large and reaches 31% in the EU25. This proportion rises to 39% for the NMS. In the

Baltic countries and in Poland, but also in the southern EU Member States, family workers are heavily affected by in-

work poverty. A specific feature of the Romanian economy is that more than two million people work in subsistence

agriculture – mostly self-employed or unpaid family workers – many of whom can be defined as working poor because

they receive no earnings.

Figure 8: In-work poverty, by job characteristics, EU25 (%)

Source: Eurostat, EU-SILC 2007

Table A5 in Annex 1 shows the proportion of full-time employees and self-employed people with earnings lower than

60% of the median earnings. This proportion is particularly high for Latvia (22%), Lithuania (21%) and Germany (20%),

and relatively low in Belgium (6%), Finland (7%) and France (9%). Interestingly, the share for women is higher than for

men in all countries, pointing to their relatively lower pay. Table A6 in Annex 1 shows the overlap between working poor

and low pay, defined as the proportion of full-time employees and self-employed people at risk of poverty (that is, with

an income lower than 60% of median income) in relation to full-time employees and self-employed persons with

earnings lower than 60% of median earnings. In this case, the share for women is smaller than for men, with the

exceptions of Cyprus and Germany.

Migrants seem to be particularly vulnerable to in-work poverty, since they tend to combine various adverse

characteristics, such as being in low-skilled jobs with low rates of pay and living in single-earner households. However,

information on migrants has been scarce in the national contributions to this report. The situation described above seems

to be confirmed in Austria, Denmark, Malta and Norway to some degree. In Norway, non-western immigrants form the

most important group of ‘low-income individuals’ (27% in 2004–2006 compared with 12% in 1996–1998). Furthermore,

in Malta, the majority of immigrants arriving by boat from Africa tend to work in the informal economy, with low pay

and poor working conditions. In Austria, the in-work poverty rate among people with a migration background (11%) is

twice as high as for Austrian workers (5%). In Denmark, in-work poverty exists among migrant workers to some degree;

however, Polish workers seem to have no problems providing for themselves (see Danish national report). In Bulgaria,

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

8

Full year

5

10

15

0

20

35

30

25

13

5

12

7

31

18

6

15

Temporary

contract

Permanent

contract

Part-timeFull-timeFamily

worker

Self-

employed

EmployeeLess than

full year

11

Working poor in Europe

contrary to the assumption that migrants are among the poor population in the country, their standard of living is about

or above average and they tend to create jobs.

According to some national contributions, people in the informal economy are more likely to be among the working poor

because it constitutes an employment situation which usually implies poor working conditions and low pay. In Bulgaria,

where the irregular economy represents about 35% of gross domestic product (GDP), the risk of being poor is much

higher for people engaged in undeclared work (25% in 2003 and 11% in 2007) than in the formal economy (8% in 2003

and 3% in 2007) (World Bank, 2008). However, data relating to the illegal economy are only estimates and should be

treated with caution. In the case of Malta and Spain, the informal economy is also mentioned as a particular source of

in-work poverty. In Malta, the majority of migrants – especially those arriving by boat from Africa – tend to work in the

irregular economy. Trade unions and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) report that such workers are often paid

low wages with poor working conditions. In Spain, employment precariousness – which seems to be linked with in-work

poverty (see above) – is strongly associated with informal work. In Hungary, the scale of undeclared work is also

substantial, where the informal economy is estimated at 15%–18% of GDP. It is most widespread in the construction and

agricultural sectors but its relation with the group of working poor is still unknown.

Main trends and research studies

Looking at the development trends in the number of working poor between 2000 and 2007, the tendencies observed

should be considered with caution: in many instances, the reports do not provide any data (or for different time periods)

and often only estimations are provided. It seems that, in several EU Member States, the number of working poor has

declined (Estonia, Ireland, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden), while in 10 countries it has increased (Austria,

Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Spain and the UK). In some countries – Belgium, Bulgaria,

the Czech Republic, Denmark and Norway – the risk has remained stable. No uniform pattern emerges either regarding

the persons more or less affected during this period. An increase in the working poor was mentioned in three NMS in

relation to self-employed people: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and particularly Romania, where the poverty risk

increased from 30% in 2000 to 37% in 2006. On the other hand, in Estonia the situation of self-employed people

improved moderately. In some Member States – Estonia, Finland, Latvia and Spain – single parents with dependent

children have become more affected. In Norway, non-western immigrants have become the most important group of low-

income individuals. In the Netherlands, migrants seem to have benefited least from the economic upswing in 2000–2007.

Overall, national research on the working poor is limited: just eight countries have performed studies specifically

addressing this subject. In many other countries, the group of working poor was mentioned or examined in the

framework of more general studies on poverty, employment, inequality or social exclusion. In the case of Bulgaria and

Romania, studies conducted together with the World Bank looked at poverty but also provided interesting insights into

the situation of the working poor. Overall, the studies confirm the picture of the working poor already given above.

Personal characteristics (especially educational level), job characteristics (temporary employment, type of employment

contract, part-time work, self-employment) and the household context (especially single parenthood) determine the

extent of the population affected by in-work poverty (Table 1).

Selected factors include:

the dominance of the working poor in certain sectors of the economy (in Bulgaria, in the textiles, clothing, leather and

footwear industries; in Spain, in agriculture and fishery, as well as in hotels and restaurants and the cleaning industry;

in Ireland, in the wholesale and retail trade sector and in personal service activities; in Romania, in subsistence

agriculture);

being employed in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Spain);

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

12

being employed through temporary work agencies (Ireland);

living in particular regions (mainly referring to the poverty levels in certain regions in Latvia or in the capital city of

Norway);

living in multi-generational households (for example, in Poland, a large proportion of working poor lives in

households with more than two generations – parents, dependent children and others).

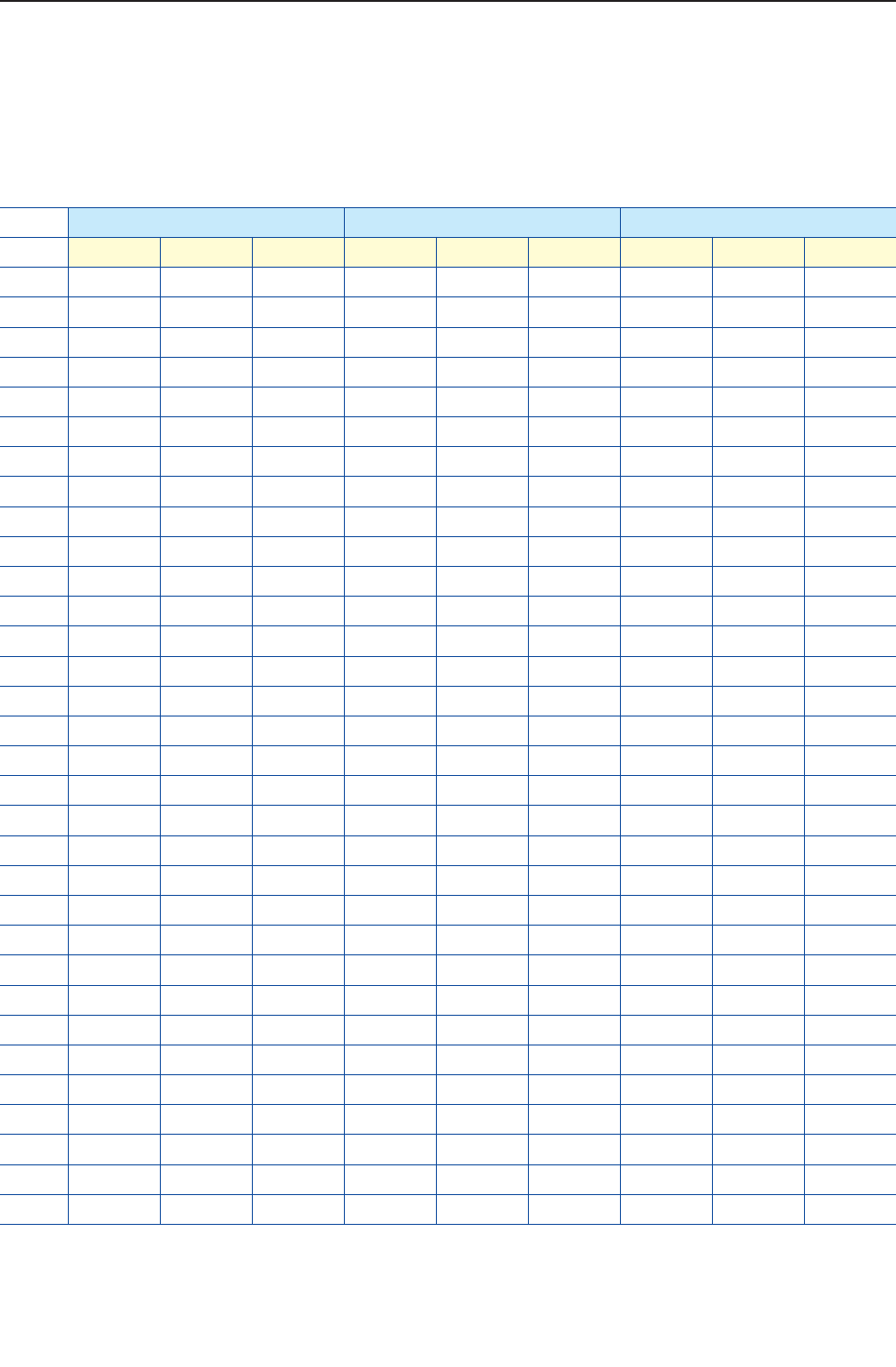

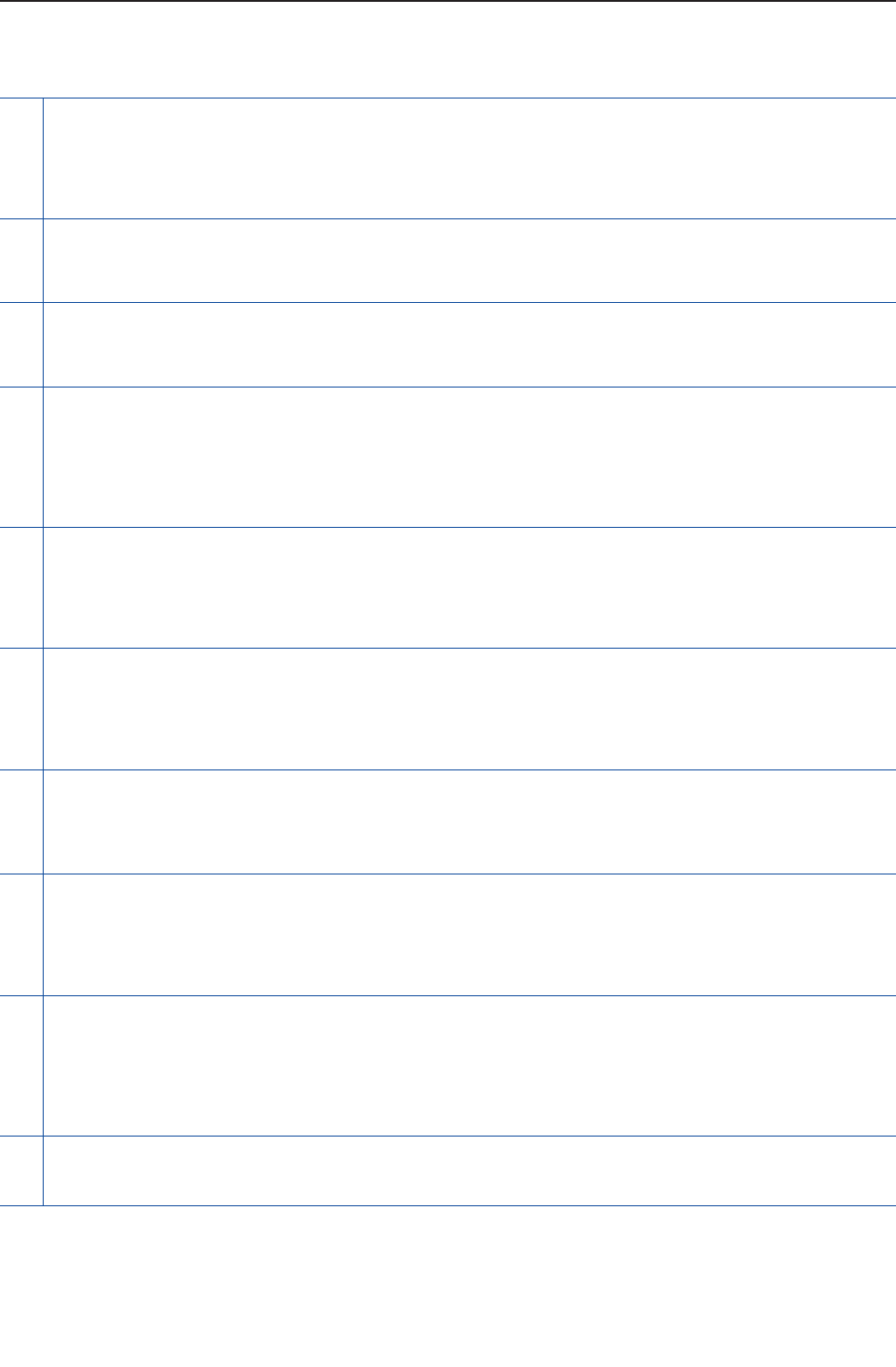

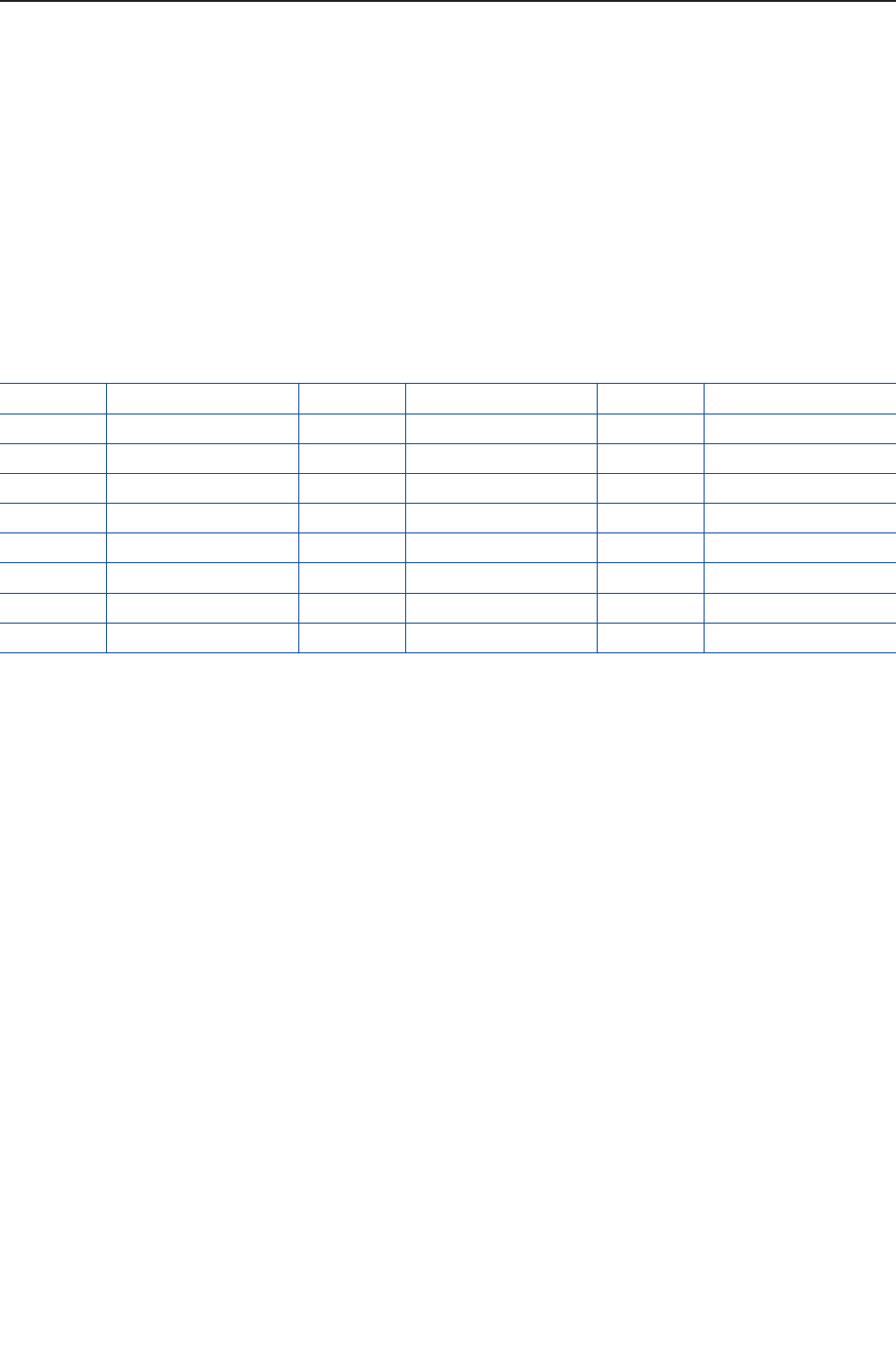

Table 1: Main findings of studies on working poor in selected countries

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

BE An analysis by Marx and Verbist (2008) on the nature and causes of in-work poverty in Belgium revealed the following.

Belgium has a relatively compressed wage structure, including a fairly low incidence of low pay.

Poverty rates among workers are comparatively low, but the working poor constitute a significant proportion of the

working age population that lives in relative poverty.

In-work poverty is mainly a problem of single-parent households and single earner couples with children.

The best protection against poverty that a household can have is two working adults; thus, policies supporting dual

earnership are of crucial importance.

EL A study carried out by the Institute of Social Policy of the National Centre for Social Research (Εθνικό Κέντρο Κοινωνικών

Ερευνών, EKKE), examining the relationship between employment and poverty in Greece, came to the following

conclusions (GR0706039I).

Working men are at a 1.25 times greater risk of becoming poor than working women.

The risk of poverty for people aged 55 years and older is 1.62 times greater than for those aged 25–54 years, and 1.28

times greater than for young people aged 16–24 years. A large number of older workers are self-employed in the

agricultural sector and/or have a low level of education.

Employed people with low educational levels face an over two times greater risk of poverty than employed people in

general.

Self-employed people show a risk of poverty 3.7 times higher than that of employees and 1.6 times higher than that of

workers as a whole. The greatest risk of poverty according to employment status is faced by assistants in family

businesses. However, the data on the employment of self-employed people must be treated with caution due to the

incidence of tax evasion.

People employed on a part-time basis are at a 2.4 times greater risk of poverty than those employed in full-time jobs. The

poverty rate in this group also appears to be greater than that of retired and non-active individuals.

ES The study Working poor and low salaries in Spain, prepared by the University of Oviedo in northern Spain, found that a

number of variables have an influence on the working poor.

Existence of dependent relatives – wage earners who live in households under the poverty line can be found in greater

measure in families with dependent children (14%), especially in single-parent ones (23%), or when the wage earner lives

in a household where there are more than two adults with one or more children (14%).

Household’s work intensity, as defined in the EU-SILC (the number of months of the year worked by members of the

household of working age relative to the total number of months if each of them worked throughout the year) – the

probability that a wage earner lives in a poor household decreases as the work intensity increases: 10% of full-time

workers can be defined as working poor, compared with 14% of part-time workers.

Type of occupation – manual workers, especially skilled workers in agriculture, unskilled workers and workers in the

services sector have a higher probability of becoming working poor.

Educational attainment – workers with low levels of education are more likely to be working poor (16% of them can be

defined as working poor) in comparison to workers with a medium and high educational level (11% and 5% respectively).

Sector of economic activity – a high proportion of poor households and low earnings are associated with the agriculture

and fishing sectors. High proportions are also found in the hotels and restaurants sector and in domestic and cleaning

services, which are characterised by temporary work and job rotation.

Other variables – the association between poor households and low wages and small-sized companies is strong. In

addition, low-income and temporary jobs are other variables affecting poverty distribution: for example, only 5% of

Spanish workers with permanent employment contracts can be considered as working poor, whereas 12% of all

temporary workers are in this situation.

13

Working poor in Europe

Table 1: Main findings of studies on working poor in selected countries (cont’d)

Note: See references for full details of national studies on the working poor.

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

LU Frederic Berger in his study ‘Work is not always enough to keep people from poverty’ (2007) showed the following.

The incidence of the working poor is especially high among blue-collar workers, 22% of whom fall into this category,

compared with 3% of private sector white-collar employees, 12% of self-employed workers and less than 1% of national

and international public sector employees (LU0801019Q). Workers with fixed-term employment contracts were more

exposed to poverty than those with open-ended contracts: 20% compared with 8%.

PL A survey study on The working poor in Poland by CBOS underlines the importance of household characteristics for in-

work poverty analysis.

Working poor households are composed of 4.2 persons on average.

A significant proportion lives in multi-generational households.

The working poor have lower expectations towards income.

In addition, more than half (55.1%) of the Polish working poor are 40 years old and over. Some 35.6% of working poor

are between 40 and 49 years old; 20–29 years olds comprise 22.3% of the working poor population. Although in-work

poverty is spread among different age groups, it is more common among middle-aged Poles than younger workers.

SE A study by Halleröd and Larsson (2008) covering characteristics on the working poor in Sweden and the reasons for their

poverty found the following.

In-work poverty is a growing but relatively uncommon problem in Sweden. There is a clear connection between blue-

collar service workers and in-work poverty, which seems to be increasing over time.

Women with temporary work contracts have a greater risk of in-work poverty.

The highest rate of in-work poverty risk is found among self-employed people. These figures should however be

interpreted carefully since there is a risk of measurement problems due to the tax system. Swedish self-employed persons

might gain other resources from their business than that measured as income in the statistics.

In-work poverty in Sweden is mainly a problem for single households with no children.

It is predominantly the younger segment of the labour force that is affected by in-work poverty.

The majority of working poor in Sweden are poor because they have been partly out of work during the year of

observation. The challenge of working poor is hence a problem of unemployment rather than one of low wages.

SI Reasons for and extent of the working poor (Vzroki in obseg pojava zaposlenih revnih), a study conducted by the

University of Ljubljana (2008), concluded the following.

The working poor issue has not received particular attention in Slovenia. According to the study’s focus groups, factors

that influence the risk of poverty rates include: type of activity, type of employment contract, length of service,

educational level, low pay, self-employment, region and age.

UK A 2008 study conducted by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) showed the following.

UK families with children were twice as likely to face in-work poverty as those without children, and lone parents were

twice as likely to face in-work poverty as families with a couple heading the family.

Some 35% of working households headed by someone aged 18–21 years were poor; a quarter of all working poor

households have at least one disabled adult; and ethnic minority headed households face about twice the risk of working

poverty as households headed by a white person.

A number of shifts occurred in the incidence of in-work poverty over the previous decade and in-work poverty has

increased in the UK: 57% of poor households had someone in work in 2008, whereas the equivalent figure was 47% in

1998. From 1998 to 2008, the number of working poor households in the UK rose from two million to two and a half

million. The proportion of working households that were poor also increased in the same period.

A study published by the government Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) reviewing the problem of in-work poverty

in the UK found the following.

Despite the fact that the number of children in poverty had decreased in the previous 10 years, the number of poor

children living in working households had remained constant at 1.4 million in the same period.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation also published a 2008 report on the relationship between in-work poverty and child

poverty

, concluding the following.

In-work poverty had increased steadily in the UK in the previous 10 years.

14

Policy responses

In most countries, policies addressing the working poor cannot be clearly separated from policies aiming to combat

poverty and social exclusion, including those related to the respective social welfare systems. Nevertheless, in the form

of various transfer payments and social benefits, certain policies tackle in-work poverty. These comprise fiscal measures,

such as in-work benefits or tax credits paid to those with earnings below a certain level; labour market policies, such as

minimum wages, wage policies in general, unemployment benefits, unemployment assistance and start-up benefits;

family policies; or a combination of all of these measures. In most EU countries, combating unemployment and/or

increasing employment has become a policy priority, since unemployment is considered to be a key driver of poverty.

Exceptions to this rule are Cyprus and Ireland, as well as the UK – where the issue has been addressed with specific

policies over the past five to 10 years – and Norway, where it has been addressed since the end of the 1990s. Bulgaria

and Germany started to pay more attention to the problem of in-work poverty from 2005 onwards. In Bulgaria, the

working poor became a policy priority of the government in 2005, when the issue was included in planning, strategy and

other documents related to poverty, social inclusion and the labour market. In Germany, the Second report on poverty

and wealth of the federal government (2. Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht der Bundesregierung (1.9Mb PDF)),

published in 2005, identified the high unemployment rate as the most serious problem and the real challenge for policies

aiming to combat poverty. Moreover, unemployment had concentrated in specific groups, such as low-skilled and older

workers, and a large proportion of unemployed people experienced long spells of unemployment. Therefore, the

government pursued a proactive approach intended to improve the (re)integration of non-active or unemployed persons

into the labour market. The core piece of this approach was the reform of the unemployment benefit system (Viertes

Gesetz für moderne Dienstleistungen am Arbeitsmarkt), which was approved in 2003 and came into force on 1 January

2005 (DE0401205F). Formulating its aims in the Second report on poverty and wealth, the government announced that

this reform would, in particular, help to avoid the so-called ‘careers in poverty’ (Armutskarrieren) – referring to people

trapped in long-term poverty.

In most countries, policies directly or indirectly addressing the working poor have not changed in recent years.

In France, the issue emerged in the early 2000s; however, the policies implemented focused on the problems of

unemployment and integration rather than on in-work poverty. In Austria, a ‘needs-oriented basic cover’

(Mindestsicherung) amounting to a €733 monthly net income is expected to be introduced on 1 September 2010. In

Belgium, despite the incidence of (in-work) poverty being very low, the federal government approved an ambitious

action plan in 2008 including 59 measures to combat poverty. While the plan acknowledges the working poor problem,

it focuses on measures to prevent unemployment traps and fiscal strategies to make work pay more. In Italy, the debate

focuses on family poverty. More recently, however – as in other countries, such as Slovakia – the issues of in-work

poverty and social inclusion and exclusion have become more pressing within the context of the current economic and

financial crisis; for details on the impact of and measures to fight global recession, see the section on ‘Impact of

economic crisis’.

For most of the countries, the national reports did not detect any notable conflicts between reducing the number of

working poor and increasing the number of people in work. In recent years, the governments’ main concern has been to

encourage employment and combat unemployment rather than to improve the conditions of the working poor.

Policymakers in the Netherlands concentrated primarily on solving the labour shortage problem.

Greece, Ireland, Slovenia and the UK are the only countries to have acknowledged a conflict of interests between

reducing the number of working poor and increasing the number of employed people. In Greece, the trade unions and

the Economic and Social Council of Greece (Οικονομική και Κοινωνική Επιτροπή της Ελλάδας, OKE) have criticised

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

15

Working poor in Europe

the implementation of active labour market programmes such as subsidised training and work experience programmes,

arguing that these tools reduce the official unemployment rate at the expense of job quality, create in work poverty and

have a ‘social dumping’ effect. In Ireland, the priority of employers and the government has been focused on increasing

the number of people in work. Trade unions and social interest groups have also agreed that it is important to increase

the number of people in work, but have argued that Ireland’s model of national-level social partnership could go further

in terms of achieving social and redistributive goals like reducing the number of working poor. Overall, it is evident that

the Irish model of social partnership – which has been largely based on a wage moderation and tax reduction trade-off

– has been primarily geared towards economic growth and employment creation rather than any redistributive function.

In Slovenia, one indicator of the conflict of policy interests is the high number of temporary employment contracts: the

Employment Service of Slovenia (Zavod Republike Slovenije za zaposlovanje, ZRSZ) counted 12,283 available posts

in August 2009, 10,075 of which were on a temporary basis. With regard to the UK, attitudes differ according to political

affiliation: left-wing economists and the trade union movement consider that policies to boost the income levels of poor

households will have a positive effect on the economy and employment rates, as well as improving social justice. By

way of contrast, more economically liberal sources have argued that many policies designed to tackle in-work poverty

are likely to have an adverse effect on employment rates.

In at least 10 countries – Belgium, Estonia, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Norway, Spain, Poland and the UK – policies

are targeted either exclusively or at least partly at families. In some countries, vulnerable groups or groups at risk of

poverty are generally addressed by policy measures. More specifically, Bulgarian policies focus on members of ethnic

groups and retired persons, while Hungary supports lifelong learning, particularly of low-skilled and disabled people. In

Ireland, Malta, Norway and the UK, policies are directed – apart from families – at individual workers. Policies in

Portugal concentrate among other things on the integration of immigrants. Slovakia focuses on children and youth,

elderly people, disabled persons, unemployed people and its Roma population.

For further details, see Annex 2. The information provided, however, is only tentative and may not be exhaustive.

Minimum wages

Minimum wages and their impact on reducing poverty give rise to conflicting views. While their supporters – trade

unions, in particular – consider minimum wages as an important means of improving workers’ standard of living and

reducing poverty, their opponents argue that minimum wages increase the unemployment of low-skilled workers. Their

effect in both regards, it should be noted, depends on the level at which the minimum wages are set and whether they

lead to a change in wage differentials. If they are set at a low level, they are likely to have little negative impact on job

creation and the employment of low-skilled workers; however, they will also then have little positive effect on reducing

the number of working poor. If minimum wages are set at a higher level, they will have a greater impact in both respects.

Moreover, their overall effect as regards both in-work poverty and job creation will also depend on whether wage

differentials – the rates of pay for higher wage jobs relative to those paying the minimum wage – remain the same or are

squeezed. In other words, raising wages at the bottom end of the wage hierarchy can lead either to other wages being

increased in proportion and wage differentials being maintained or to other wages remaining the same and thus

differentials being squeezed. Since the minimum wage tends to be set well below the poverty threshold, the effect of

minimum wages on in-work poverty depends to an important extent on whether wage differentials are maintained and

other wages increase consequently or whether differentials are squeezed.

Minimum wage systems exist in most of the countries covered here, although they differ considerably in nature and

level. In the EU and Norway, it is possible to distinguish broadly between two groups of countries. The first, comprising

20 out of the 27 EU Member States (Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland,

Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and the

UK), has a national statutory minimum wage set by the government, in many cases after consultation with or a

recommendation of the social partners. Cyprus has a statutory minimum wage for a few specific occupations only (Funk

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

16

and Lesch, 2005). The remaining Member States (Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy and Sweden) do not have

a national minimum wage; instead, sectoral collective agreements regulate minimum pay rates.

Large differences arise in minimum wages according to workers’ age and qualifications or by sector of economic

activity. A number of countries apply lower rates to younger, low-qualified or less experienced workers. The group of

countries with differences based on age includes Belgium, the Czech Republic, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Malta, the

Netherlands and the UK. Differences based on qualifications or occupations exist in Belgium, Greece, Hungary, Ireland,

Luxembourg, Malta and Romania. In Austria, almost the entire private sector has been covered by minimum wage

standards of €1,000 a month since 1 January 2009 (AT0902039I). In some branches of the economy, this has been agreed

retrospectively. However, in a few branches, no evidence of the actual implementation of this regulation could be

provided. In Germany, statutory minimum wages apply to selected industries only and vary substantially. Minimum

wage legislation in the UK distinguishes between three groups of workers: lower rates apply to younger workers; the

national minimum wage is not applicable to self-employed workers; and workers in the agricultural sector have a

statutory sectoral level of minimum pay awarded by the Agricultural Wages Board. In other countries such as Estonia,

Latvia and Slovakia, the minimum wage regulations apply to all employees.

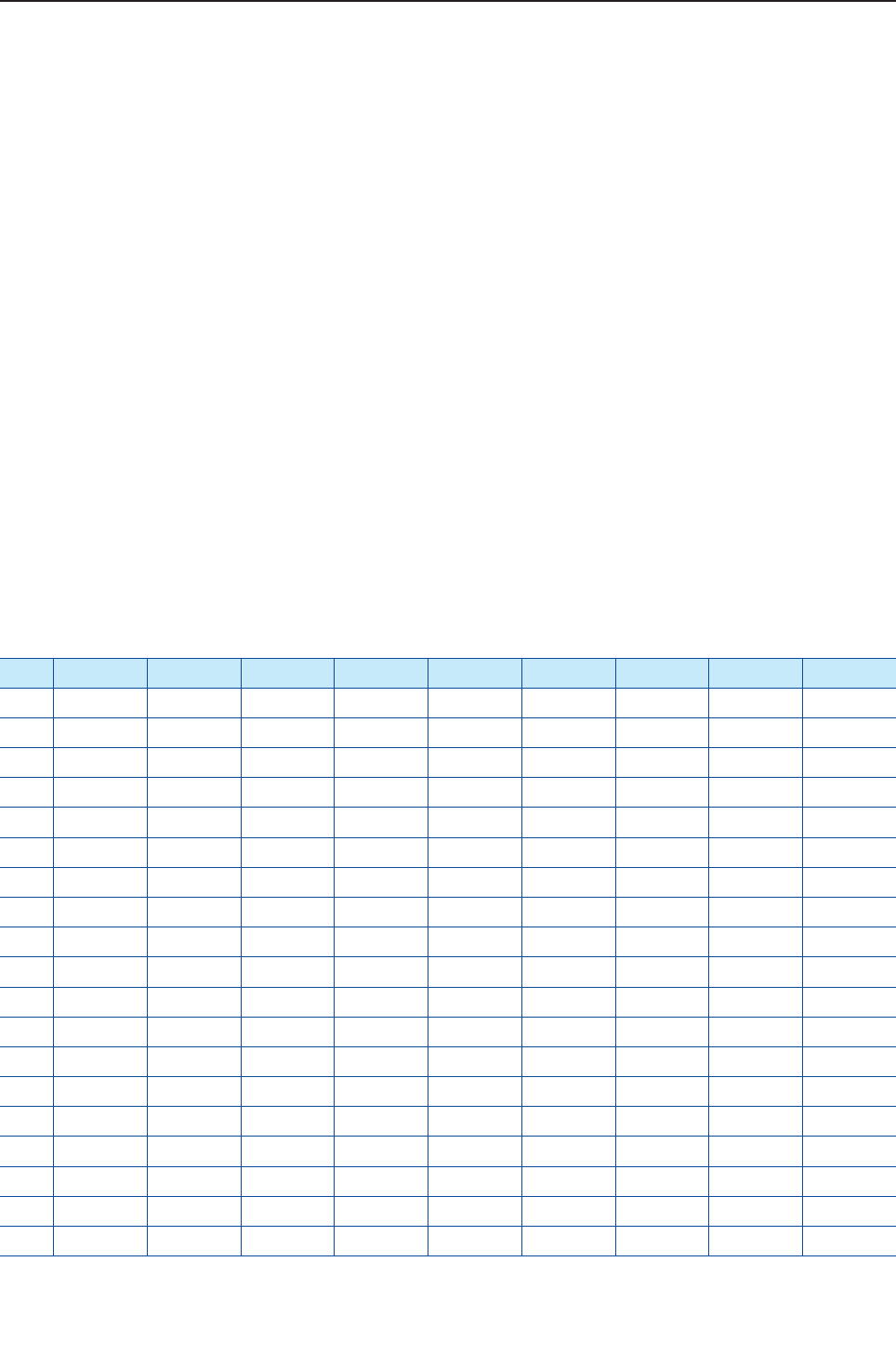

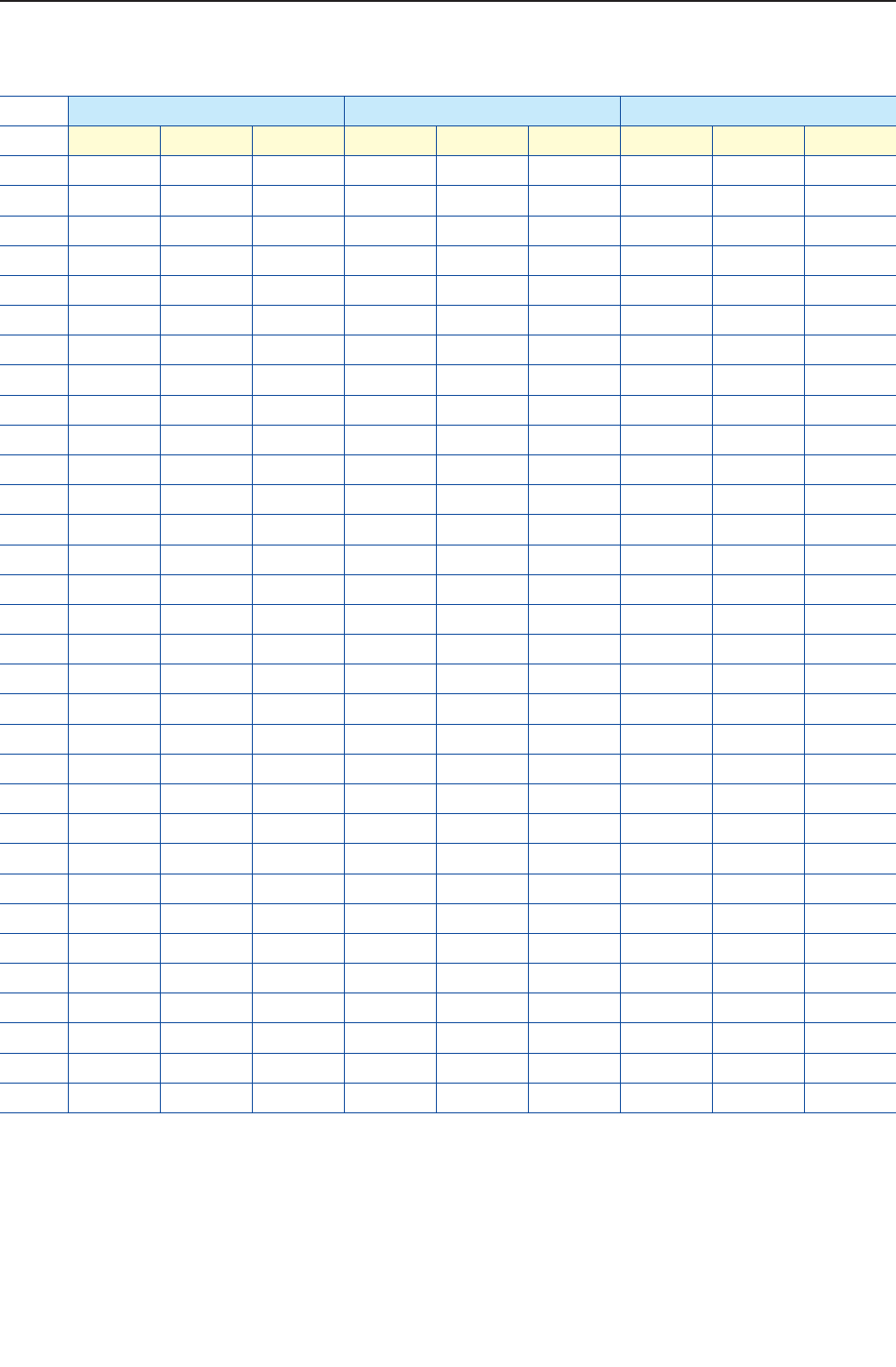

In all EU Member States for which data are available (Table 2), the level of minimum wages tends to be set well below

the poverty line and even declined in a number of countries during recent years when measured as a proportion of

average monthly earnings in services and industry. This was particularly the case in Ireland and seven of the NMS:

Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania and Slovenia. Elsewhere, the proportion slightly

increased (Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Spain) or remained unchanged (Luxembourg and the UK).

Table 2: Minimum monthly wage as proportion of average monthly earnings in industry and services (%)

Source: Eurostat

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008

BE - - 46.4 - - - - - -

BG - - 39.7 41.4 42.6 49.6 45.6 42.1 42.2

CZ 31.0 34.2 36.9 38.1 38.4 39.1 39.7 38.1 35.0

EE - - 30.5 32.4 34.6 33.2 30.5 - -

ES - - 36.2 35.6 37.7 40.4 41.4 42.1 43.1

FR - - - - - - - 48.1 -

HU - - 42.1 38.6 40.7 38.2 39.6 36.5 35.4

IE - - 50.0 47.7 50.0 52.0 51.0 43.0 42.0

LT - - 36.9 36.2 38.5 38.3 36.1 33.5 35.2

LU - - 50.4 50.4 49.6 50.7 50.4 50.5 50.2

LV - - 35.2 37.3 39.1 33.6 30.6 31.5 34.7

MT - - 53.9 51.6 49.0 50.6 50.6 49.2 52.0

NL - - 49.3 47.7 46.1 45.5 - - -

PL - - 33.0 33.9 35.1 33.7 36.1 32.4 -

PT - - 43.0 40.7 40.0 40.5 40.7 41.6 40.0

RO - - 31.3 37.3 34.4 32.6 35.7 29.1 -

SI - - 45.3 46.3 44.1 45.6 46.6 43.9 43.6

SK - - 32.4 34.0 34.1 34.4 34.8 46.6 -

UK - - 34.4 34.4 37.9 37.0 36.9 38.2 38.0

17

Working poor in Europe

National contributors’ assessments on the role of minimum wages in reducing in-work poverty differ by country:

minimum wages are considered very important in lowering the proportion of working poor in Austria, where the number

of full-time employees earning less than the proposed minimum wage declined significantly. The importance of

minimum wages in this respect is also recognised in Belgium, Bulgaria (with a strong increase in the minimum wage

over recent years), the Czech Republic, Denmark, France and the UK. With regard to the UK, the majority of experts

have deemed that the national minimum wage has effectively regulated the problem of low pay while also not having an

adverse effect on employment rates. The national minimum wage enjoys support from the Confederation of British

Industry (CBI) and the Conservative Party, as well as from trade unions and the Labour Party. In Cyprus, raising the

minimum wage to 50% of the national average wage has brought relief to very low-paid people. However, trade unions

emphasise the need to improve current regulations by setting rates of increase higher than the average overall increases

to prevent the minimum wage level from being below the poverty level.

A 2003 survey by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) on the impact of the minimum wage in Ireland

found that the proportion of workers on the minimum wage rate decreased substantially from 21% in 1999 to 4.5% in

2002. By contrast, an earlier comprehensive study concluded that only 5% of employees had their pay increased as a

direct result of the introduction of the minimum wage. According to the authors, tight labour market conditions and

labour shortages were a more significant factor behind wage increases and reducing the incidence of working poor in

many low paying sectors of economic activity, as unemployment decreased sharply from the late 1990s. The study found

that as many as 81% of employers claimed that they would have increased wages to attract or retain labour, regardless

of the minimum wage. The impact of the national minimum wage in reducing the numbers of working poor is mainly

limited to specific sectors. It was highest in traditionally low paying sectors such as wholesale and retail trade, hotels

and restaurants and bars, and textiles manufacturing.

The Hungarian correspondent, by contrast, underlines the negative aspects of the significant increase in the minimum

wage. This increase led to a decline in employment in almost all cases. Furthermore, considering poverty as a whole,

most poor people do not benefit from the minimum wage increases, given that they are unemployed or economically

inactive.

In Malta, the impact that minimum wage legislation had on the working poor is limited since only a small fraction of

workers is receiving a minimum wage.

Swedish experts are undecided about whether the minimum wage plays a role in reducing in-work poverty. While some

regard it as the reason for the low number of working poor in Sweden today, others do not think that a raised minimum

wage would mean fewer working poor since so many other factors affect the situation – such as the income of the spouse

and frequency of temporary employment. The Greek study also emphasises the need for other measures in addition to

minimum wages to support low-income groups.

Minimum wages and their impact on employment and the risk of poverty are being widely debated in Germany between

the trade unions and employer organisations (see below).

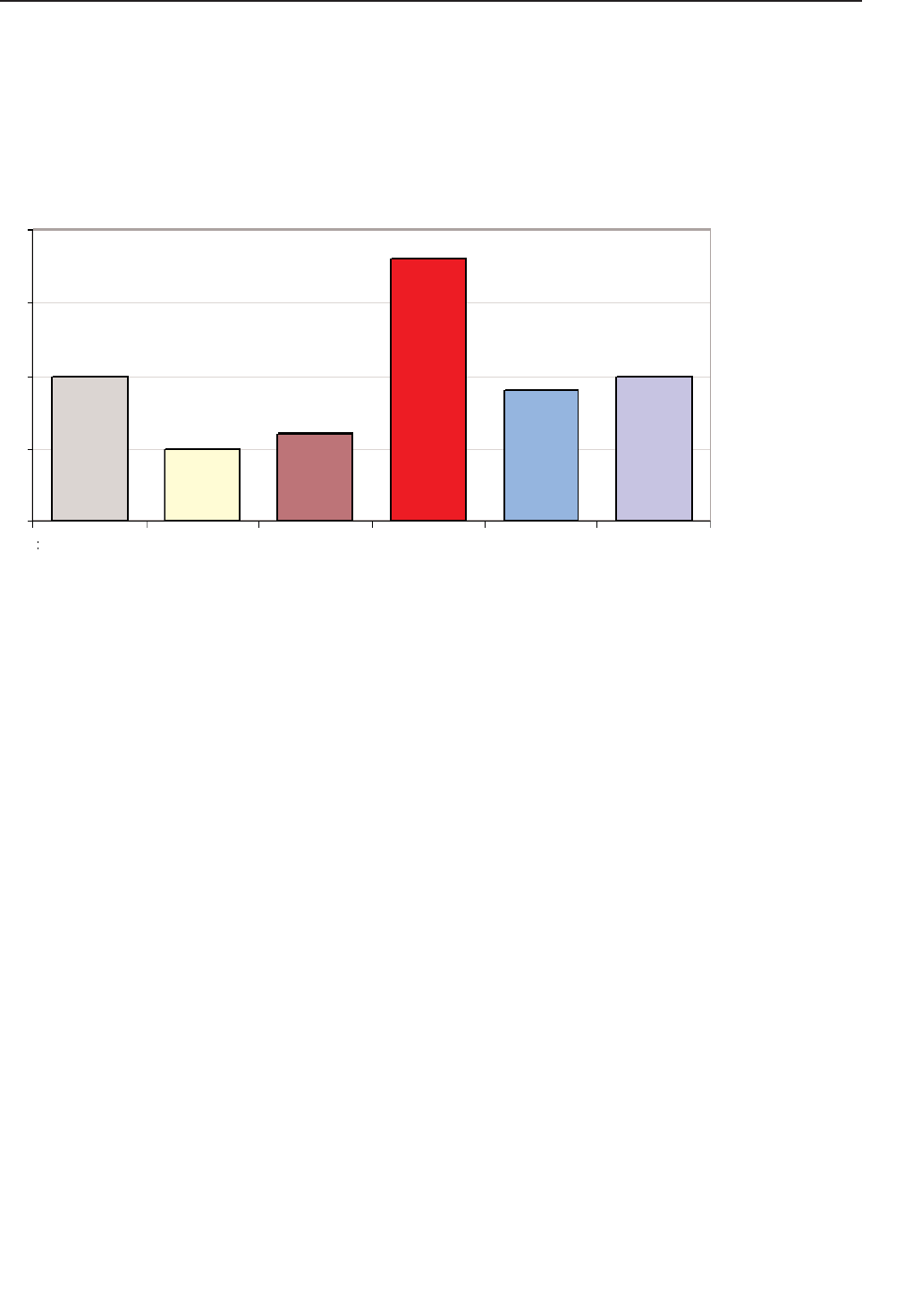

Effectiveness of policies

Assessing the effectiveness of policies towards the working poor is particularly complex. As already mentioned, the

strategies and policies so far developed in most countries do not tend to directly target the working poor, but poor people

at large. Thus, analyses on the effectiveness of those policies primarily consider poverty alleviation in general. It is

generally stated that social transfers, excluding pensions, effectively reduce the risk of poverty albeit to a varying degree

from country to country, ranging from a poverty reduction effect of 60.7% in Sweden to 15.4% in Bulgaria (Figure 9).

This also reflects differences in the size of social transfer expenditure, which varies between 12% of GDP in Latvia and

15% in Bulgaria and 30% in Sweden.

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

18

Figure 9: Impact of social transfers, excluding pensions, on at-risk-of-poverty rate for total population, 2007 (percentage

reduction)

Source: European Commission, 2009a, Growth, jobs and social progress in the EU, based on EU-SILC 2007

More specifically, the French report refers to assessments of transfers to single-parent families (mainly women with

children); these help to reduce the proportion of such families living below the poverty line from 46% to 27%. However,

the social welfare system is more efficient for categories less affected by the risk of poverty. For couples with children,

the poverty rate declines from 22% before transfers to 12% after transfers.

In Norway, although poverty reduction funding has been steadily increasing, the percentage of low-income individuals

has not changed significantly in the last decade. Policies to reduce the proportion of the working poor have evidently

been insufficient. However, the composition of the group has changed, making immigrants the new main target group

for effective political measures to reduce the number of working poor.

In Belgium, measures such as the minimum wage and credit systems for low-wage workers are considered to have

contributed to preventing in-work poverty. Nevertheless, Marx et al (2009) do not regard the further development of

these measures as crucial, because the major group of poor people who are working does not belong to the group of low-

paid workers. The key problem of the working poor is having a single income, combined with an inexistent or

insufficient social benefit to help carry the financial burden of a household (partner and/or children). Thus, future efforts

to combat in-work poverty should focus even more strongly on boosting dual earnership by improving work-life balance

and general employment policies. Moreover, the authors emphasise that significant categories of the working poor –

specifically single persons and single parents – require targeted cash transfers by tax credit and/or social benefit in order

to remain shielded from poverty.

Views of the social partners

According to the information provided by the national contributions, in most countries social partners express differing

perspectives regarding the group of working poor. One exception can be found in Finland, where trade unions and

employer organisations share the common goal of continuously raising the number and quality of jobs. These efforts may

have had an important impact on the increasing educational level of the population through the provision of further

education to employees at their workplaces – more so than in other European countries.

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

0

35

CZEU27 SK SI NLBG MT DKBE FIFRIEUKLTEE SEDERO AT HUCYIT LUPLES PTLVEL

50

60

70

40

30

20

10

27

25

2424

22

19

1717

17

15

52

5050

48

46

46

40

3939

3737

36

61

59

56

55

52

19

Working poor in Europe

Similarly, in Ireland, the quality and quantity of jobs are significant priorities for the trade unions while, at the same time,

employers emphasise the importance of attracting high-quality high value-added jobs. Nevertheless, on balance, the

priority of employers would tend to lean more towards maximising the quantity of jobs. In Slovakia, by contrast, the

issue of in-work poverty and its reduction as well as issues of working conditions and quality have become less important

than increasing the number of jobs.

Trade unions

Information available for a number of EU Member States and Norway indicates that the problems related to the working

poor are primarily addressed by trade unions. In most countries, however, trade unions do not explicitly discuss the issue

of working poor but rather other related issues such as the different forms of non-standard employment and their social

implications. In terms of pay, trade unions focus on the level of minimum wages and collective bargaining. As various

countries reported – Belgium, Cyprus, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Malta, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden – trade

unions consider minimum wage policies explicitly as an important instrument of social protection.

Trade unions in Austria, Finland and Germany specifically address the issue of non-standard forms of employment. In-

work poverty appears to be significant among workers hired under these forms of employment. In Slovenia, the social

partners give a high priority to the problem of the working poor. Actions undertaken by the trade unions towards the

reduction of in-work poverty include ensuring proper wages for employed people and proper social protection for those

out of the labour market.

In a few countries – Germany, Slovenia and the UK – debates take place on the conflicting goals of quality and quantity

in job creation. Trade unions in the UK emphasise that there is no contradiction between the quality of jobs and levels

of employment; they argue that measures to boost the living standards of individuals and families experiencing in-work

poverty are likely to have a beneficial effect on levels of consumption and demand – and subsequently on growth and

employment. However, employer representatives do not acknowledge the existence of such a link. They generally argue

that excessive public expenditure, the imposition of further regulations on companies and rising wage levels are likely

to impact adversely on employment levels in the UK. The economic recession has not altered the substance of this

debate.

In Bulgaria, Ireland, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal and Romania, trade unions have provided explicit proposals on how

to reduce the number of working poor and/or low-paid workers.

In Bulgaria, negotiations on social programmes at company level along with the development of a voucher system

offer new opportunities to reduce the number of working poor. Currently, about 250,000–300,000 workers are eligible

to participate in the food voucher scheme. Some branches and sectors of economic activity had already established

mutual aid funds, which offer credit under favourable conditions.

In Ireland, trade unions consider the national minimum wage as important for helping the working poor. In addition,

they advocate the following measures: reforming in-work social welfare entitlements, keeping minimum wage earners

out of the tax net, enhancing workers’ skills and training, and organising workers collectively into unions to prevent

the downgrading of wages.

The Luxembourg Chamber of Employees (Chambre des salaries Luxembourg, CSL) has emphasised that – apart from

the regular adjustment of the minimum guaranteed income (revenu minimum garanti, RMG) and the minimum social

wage – tax credits for employees should not be considered as a substitute for a consistent pay policy. Moreover, child

bonuses (like all family allowances) should be regularly adjusted for inflation. In addition, transfers should be better

targeted and people’s qualifications should be enhanced. The Economic and Social Council (Conseil économique et

social, CES) is calling for a more targeted family allowance system, the conversion of the single parent reimbursement

into a single parent bonus and a regular adjustment of the taxation scale.

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

20

The Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (Landsorganisasjonen i Norge, LO) suggests strengthened public

control of the labour market and emphasises the importance of full-time employment, thereby opposing policies which

imply a more extensive use of part-time work. In addition, the trade unions have proposed other specific measures to

secure jobs and sufficient salaries for vulnerable groups such as young, older and immigrant workers. At the same

time, the level of social security benefits should be increased in order to keep pace with the general level of salaries

and to help raise the effective income of workers in these groups.

The General Confederation of Portuguese Workers (Confederação Geral dos Trabalhadores Portugueses, CGTP)

considers that the problem of in-work poverty should be explicitly mentioned as a priority in the 2008–2011 National

Action Plan for Inclusion (Plano Nacional para a Inclusão, PNAI). In CGTP-IN’s ‘Ten strategic themes to change

policy’, some measures to reduce the number of working poor include raising the national minimum wage and

supervising non-standard types of employment.

In Romania, the priority of trade unions has been to maintain the number of jobs and to negotiate the highest minimum

wages possible.

Trade unions in the other countries are less specific and concentrate their debate on improving the social welfare systems,

reducing income inequalities and raising minimum wages as a useful tool to help reduce poverty at large. In Poland, low

unionisation levels and loose regulatory regimes weaken the position of trade unions in demanding higher wages for

low-paid jobs – for example, in supermarkets, fast food outlets and security services – particularly in times of economic

crisis.

In Germany, trade unions demand the introduction of statutory minimum wages; in Spain, they call for the introduction

of sectoral minimum wages; and in Greece, they seek the introduction of national industry-wide minimum wages. Lower

taxes or tax exemptions for low-paid or minimum wage earners are part of trade union demands in Estonia, Ireland and

the UK. In France, the French Christian Workers’ Confederation (Confédération Française des Travailleurs Chrétiens,

CFTC) argues that the quality of employment should not be traded for the quantitative objective of reducing

unemployment.

Therefore, CFTC proposes to implement a job quality index based on important indicators such as

qualifications, lifelong learning, gender equality, health and safety in the workplace and work–life balance so that it can

monitor developments in this trade-off.

According to the country reports, trade unions seem to have a decisive role only in Belgium and Ireland, where they are

usually successful in implementing and managing such schemes. In Belgium, where the in-work poverty rate is very low,

trade unions try to avoid major attacks on the social welfare system in general and defend collective wage formation by

automatic indexation as well as minimum wages. Furthermore, they oppose flexible ‘mini-jobs’ – that is, small,

temporary jobs. As noted, trade unions in Ireland consider the national minimum wage as being important for helping

the working poor.

In Cyprus, where – apart from declining wages and increasing dismissals – illegal and undeclared work is on the rise,

trade unions are concentrating their activities on identifying cases of violation of collective agreements, preventing

unjustified dismissals and demanding the implementation of collective agreements.

Employer organisations

Employer organisations usually do not state or propose direct measures to reduce in-work poverty. Positions regarding

the minimum wage are diverse: from strong opposition to acceptance. To explain their reservations, employers advance

economic theory linking minimum wage increases with a higher cost of labour and therefore negative impacts on

employment and competitiveness. In a number of countries, they accept minimum wage regulations, such as in Austria,

Belgium, Cyprus to some extent, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania and Sweden.

Working poor in Europe

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

21

Working poor in Europe

However, employer organisations frequently oppose increases in minimum wage rates, such as in Bulgaria, Hungary,

Luxembourg, Slovakia, Slovenia and the UK. In Ireland, where employers generally support measures aiming to reduce

the extent of in-work poverty, important differences arise between associations representing small and large companies.

Representatives of the Small Firms Association (SFA) have voiced strong opposition to the minimum wage. Meanwhile,

the majority of affiliates of Ireland’s largest employer organisation, the Irish Business and Employers Confederation

(IBEC), which originally opposed the concept of the minimum wage, pay above the rate and are generally in support of

measures to reduce the number of working poor.

In Germany, where minimum wages exist only for selected industries, the Confederation of German Employers’

Associations (Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Arbeitgeberverbände, BDA) strongly opposes the introduction of a

national statutory minimum wage. BDA argues that it would be a barrier preventing low-skilled workers and long-term

unemployed people from being (re-)integrated into the labour market. The employer body considers the reform of the

unemployment benefit system in 2005 as, in principle, an appropriate approach to preventing poverty. BDA also

emphasises that many households can raise their income level by working in low-wage jobs.

In other countries, employer organisations propose measures to help to reduce the number of low-paid workers. These

measures include: the improvement of employability, for example, through education and training (Bulgaria, Estonia,

Greece); increased use of part-time and temporary jobs, and temporary agency work (Finland); tax measures to improve

the income situation of low-paid persons (Hungary); and supporting the private sector (Norway). In France, the

Movement of French Employers (Mouvement des Employeurs de France, MEDEF) fully supports the aims of the Active

Solidarity Income (Revenu de Solidarité Active, RSA), which was introduced on 1 June 2009 to replace the Minimum

Integration Income (Revenu Minimum d’Insertion, RMI). The purpose is to combine the reduction of poverty with a

better integration into employment and to avoid the threshold effect observed with the social income system. Under that

system, when an unemployed person accepted a job, as they were earning more, some social incomes were cut or

reduced, and their final income was actually lower than before. Thus, the RSA system is designed to ensure that every

additional hour worked results in a better total income for workers.

The reports on Bulgaria, Cyprus and Malta explicitly address the role of the informal economy with respect to the

working poor. In Bulgaria and Malta, employers accept the minimum wage regulations for people working in the formal

economy, but workers employed in the informal economy – in Malta, illegal migrants in particular – are often paid very

low wages under poor working conditions. Trade unions in Malta oppose these practices and are calling on the

government to curtail this abuse on the part of some employers, especially in the construction sector. Seasonal and

homeworkers are also more prone to have inferior terms and conditions of employment when they work in the informal

economy.

Impact of economic crisis

One of the aims of this report was to look for evidence of the first signs of the impact of the economic crisis on the

working poor. Nevertheless, as the crisis starting point is not the same in each country, varied situations arise in this

respect and, on the whole, the effects are largely unclear so far.

Out of the 28 countries, including Norway, three national correspondents delivered reports containing data (Bulgaria and

Portugal) or a clear answer (Ireland) showing that the number of working poor has increased as a result of the economic

crisis. In Portugal, the in-work poverty risk rose from 10% in 2007 to 12% in 2008, with a two percentage point increase

for both men and women. In Bulgaria, the in-work poverty risk of self-employed people reached a record level of 10%

in 2008. According to the Irish contribution, the recession hit Ireland particularly hard and had a very negative impact

on the working poor: those who did not lose their jobs in many cases had their pay reduced and/or saw increases in taxes

and social security contributions.

© European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, 2010

22

Furthermore, many reports state that the proportion of in-work poverty has probably increased during the recession, or

they expect that the situation of the working poor will deteriorate. However, no evidence of an increase is seen in

Germany, the Netherlands and Norway. The German report states that the number of recipients of ‘unemployment

benefit II’ (Arbeitslosengeld II) – the lower rate of unemployment benefit, which serves as an income supplement

(Aufstocker) for employed and unemployed people – actually decreased between September 2008 and February 2009.

According to the Dutch contribution, there have been no wage cuts in the Netherlands and the reduction in working time

in some companies has been compensated. According to the Norwegian contribution, the recession has had a smaller

impact on Norway and the working poor in comparison to many other countries.