Report of the Garda

Síochána Inspectorate

Review of Entry Routes

to the Garda Síochána

Advice by the Garda Síochána Inspectorate

May 2018

1

The objective of the Garda Síochána Inspectorate is:

‘To ensure that the resources available to the Garda

Síochána are used so as to achieve and maintain the

highest levels of eciency and eectiveness in its

operation and administration, as measured by reference

to the best standards of comparable police services.’

(s. 117 of the Garda Síochána Act 2005)

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

1

Table of contents

Glossary 2

1. Introduction 3

2. Diversity 9

3. Entry at Garda Rank 17

4. Entry at Sergeant and Inspector Rank (Mid-Level Leaders) 33

5. Entry at the Senior Leadership Level 47

6. Entry at Assistant Commissioner (Executive Leaders) 57

7. Summary of Proposals 61

Appendices 66

References 73

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

2 3

Glossary

AGSI Association of Garda Sergeants and Inspectors

BA Bachelor of Arts

BAME Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic

DPER Department of Public Expenditure and Reform

ECTS European Credit Transfer System

EEA European Economic Area

EU European Union

GRA Garda Representative Association

HMICFRS Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services

HR Human Resources

IPLDP Initial Police Learning and Development Programme

LGBT Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender

NCA National Crime Agency

NPPF National Police Promotion Framework

OSPRE Objective Structured Performance Related Examination

PAS Public Appointments Service

POST Peace Ocer Standards and Training

PRSA Personal Retirement Savings Accounts

PRSB Police Registration and Services Board

PSEU Public Service Executive Union

PSNI Police Service of Northern Ireland

RCMP Royal Canadian Mounted Police

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

2 3

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

4 5

1.1 The Remit

In October 2016, the Minister for Justice

and Equality requested the Garda Síochána

Inspectorate under section 117(2) of the Garda

Síochána Act 2005 ‘to examine entry routes to An

Garda Síochána for police ocers from other police

services and the opening up of promotion opportunities

for Garda members to persons outside An Garda

Síochána’.

At present, entry to the sworn ranks of the Garda

Síochána is almost exclusively at the garda

rank as a trainee garda. The exceptions are the

arrangements whereby members of certain ranks

of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI)

can compete for posts at superintendent, chief

superintendent and assistant commissioner levels

and the open public competitions for appointment

to deputy commissioner and commissioner.

Part 1 of the terms of reference requests the

Inspectorate to examine entry routes into the

Garda Síochána for police officers from other

police services at the garda rank.

The Inspectorate was asked to examine:

Options for a fast track entry process (having

regard to the practice/experience of other

police services) including modied eligibility

requirements and a modied training

programme;

How the recruitment process might operate;

The potential benets (including

consideration of likely take-up rate) to be

gained from creating a more attractive entry

route for serving/former police ocers

from other police services versus the cost of

recruitment/training etc.; and

Any other relevant issues.

Part 2 of the terms of reference is about the

opening up of appointment opportunities at the

mid to higher ranks for persons outside the Garda

Síochána. At present, promotion opportunities to

the ranks of sergeant and inspector are closed

to persons outside the Garda Síochána. On

the other hand, the appointment competitions

to superintendent, chief superintendent and

assistant commissioner are open to equivalent

members of the PSNI.

The Inspectorate was asked to:

Assess international best practice in relation

to recruitment to the mid to higher ranks in

comparable police services;

Assess the arrangements that allow PSNI

members to participate in Garda Síochána

promotion competitions and identify factors

inuencing their limited impact to date;

Identify appropriate options for opening up

opportunities for entry to some or all of these

ranks to experienced police professionals or

other persons with the required skill set;

Consider how the recruitment processes

might operate;

Consider induction/training requirements;

and

Consider any other relevant issues.

The Inspectorate was also asked to take account

of the Garda Síochána’s dual remit as a policing

and security service and the importance of

maintaining its operational capacity.

1.2 Background to the Remit

– Changing Policing in

Ireland (2015) Report

The Minister indicated to the Inspectorate that the

background to the request was recommendation

4.8 of the Inspectorate’s report Changing Policing in

Ireland (2015) which recommended that ‘the Garda

Síochána considers establishing an entry and training

scheme for ocers from other police services, garda sta

and reserves as full-time garda members’.

To achieve this recommendation, the report said

that it would be necessary to assess the benets

of appointing Irish nationals and other European

Union (EU) Member State nationals serving in

other police services that have standards similar

to those of the Garda Síochána and to develop

a suitable, abridged training course to take into

account the skills of successful candidates.

The report also discussed the need for the Garda

Síochána to implement recruitment policies and

strategies to attract a more diverse applicant pool

in terms of ethnicity, experience, thought and

skills and to target highly skilled individuals to

work in the organisation.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

4 5

It pointed to opportunities to provide transfer

opportunities at the highest ranks of the Garda

Síochána. In most of the police services that the

Inspectorate had engaged with, it was found that

there was a much greater diversity, mix of skills

and experience in senior management teams.

This had advantages in terms of experience and

learning compared with the situation in the Garda

Síochána where all sworn members in the senior

management team had joined as trainee gardaí.

The Minister said that ‘there would be value in a

broader examination of the possibilities for opening

up entry routes to the Garda Síochána at all levels

including fast track entry for policing professionals

from other jurisdictions at the lower ranks and the

targeted intake of experienced and skilled police ocers

at the senior ranks.’

The Inspectorate has consulted with the Garda

associations and understands that the topic of

new entry routes is a sensitive one for serving

Garda Síochána members of all ranks who will be

concerned about any eect on career progression

opportunities. Engagement with the associations

will be essential in order to help create an

environment that is conducive to supporting

any new entry routes that are created following

consideration of this report. The proposals

that are outlined seek to provide the basis for a

balanced approach and, if accepted, would form

part of a holistic strategy relating to recruitment,

talent management and appointments in the

organisation. These are issues also referred to in

Changing Policing in Ireland.

1.3 Creating New Entry Routes

There are a number of arguments supporting

the creation of new entry routes into the Garda

Síochána.

Expansion of the Garda Síochána

In the summer of 2016, the Government approved

a Five Year Reform and High Level Workforce Plan

for the Garda Síochána to support implementation

of the recommendations for reform made in

Changing Policing in Ireland (2015). This plan is

based on increasing the strength of the service

from a total of 16,000 to 21,000 by 2021. This will

comprise 15,000 sworn members, 4,000 civilian

sta and 2,000 Reserve members. It is planned

that 800 gardaí will be recruited annually from

2017. The permitted number of sergeants and

inspectors will increase on a pro-rata basis over

the same period.

This expansion of the Garda Síochána will create

an opportunity to develop new approaches to

recruitment and will happen at the same time as

considerable numbers of members across all ranks

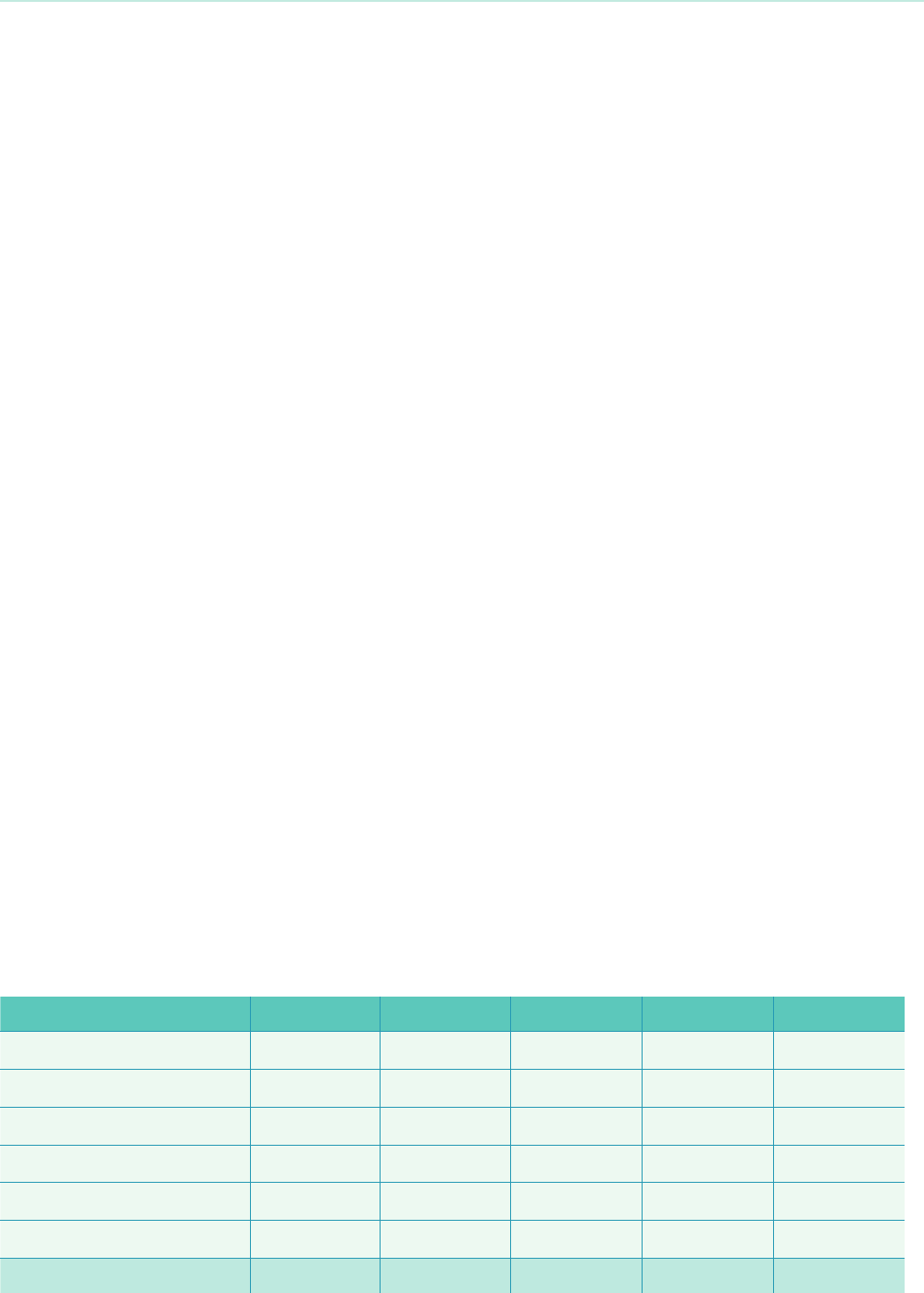

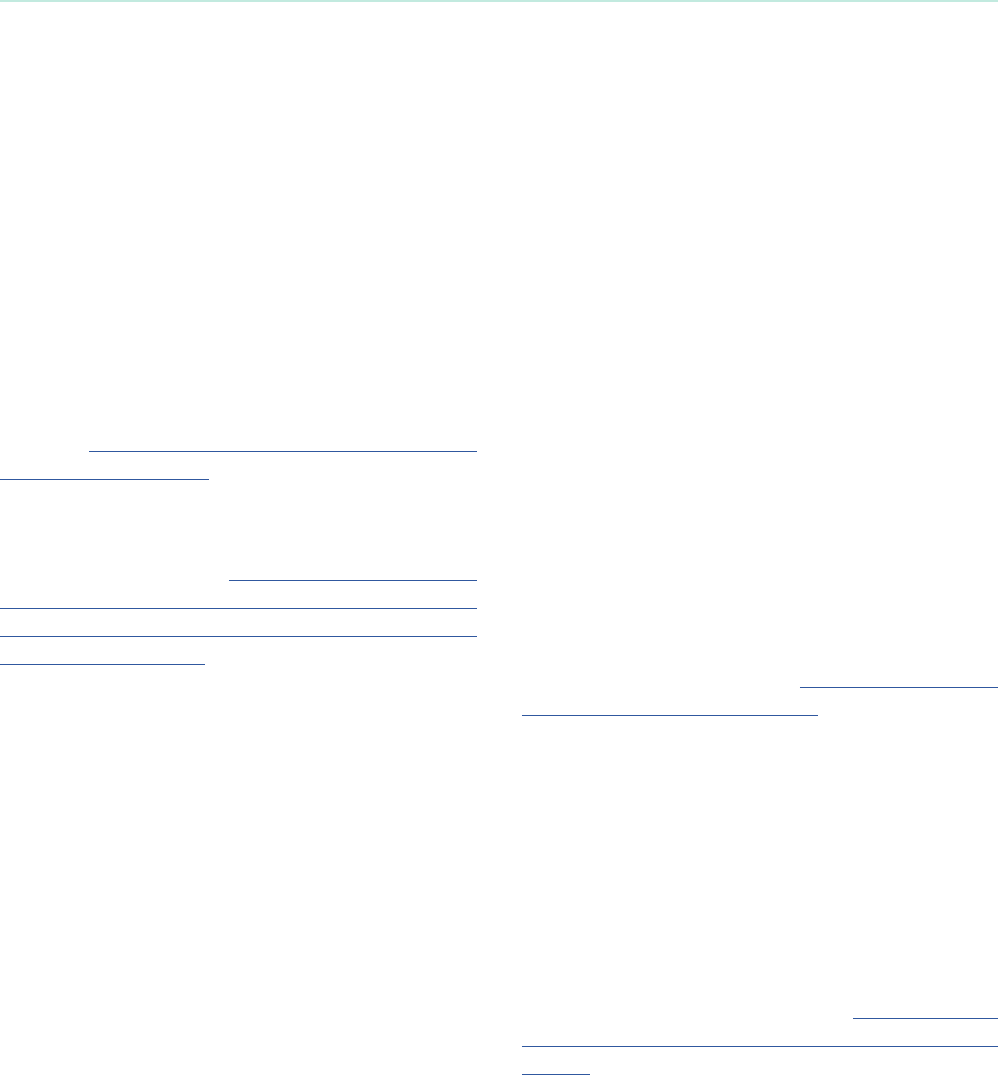

will retire. Figure 1 shows details of compulsory

retirements from the Garda Síochána in the period

up to the end of 2021.

Figure 1 - Compulsory retirements from the Garda Síochána in the period up to the end of 2021

Rank 31/12/2017 31/12/2018 31/12/2019 31/12/2020 31/12/2021

Assistant Commissioner 2 0 1 1 1

Chief Superintendent 3 4 5 4 4

Superintendent 6 14 9 16 14

Inspector 6 11 5 13 9

Sergeant 18 27 37 51 59

Garda 26 47 60 90 80

Total 61 103 117 175 167

Source: Garda Síochána, 30 April 2017

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

6 7

The resulting loss of policing experience at the

various levels will pose a challenge. Workforce

planning, succession planning and talent

management will be essential to address it, as

previously recommended in Changing Policing in

Ireland (2015).

1

In this context, the Inspectorate considers that

having the capacity to recruit already trained and

experienced police ocers from other jurisdictions

at various levels could be an important contributor

to the maintenance of operational capacity and

capability. It would help to diversify and open

up the organisation and expedite cultural change

by introducing new inuences and experiences.

Shorter induction training and the resulting

ability to ll operational roles more quickly could

be a significant benefit to meeting expansion

targets. The Inspectorate includes re-entry of

suitable former gardaí in this category, enabling

the organisation to benet from additional skills

and experience which they may have acquired.

Civilianisation in the Garda Síochána

In approving the expansion of the organisation,

the Government decided on the principle of

“civilian by default”, according to which Garda

sta are to be employed in all roles that do not

expressly need sworn garda powers. Accelerating

the pace of civilianisation towards a goal of 20%

of the total strength is a key reform objective and

contributor to operational capability.

In previous reports, the Inspectorate has

emphasised the need to maximise the utilisation

of appropriately qualied Garda sta in specialist

roles that do not need sworn garda powers.

Such roles need to be properly designed. While

this review is concerned with entry routes to

sworn roles, the Inspectorate emphasises that

cultural acceptance by the Garda Síochána of the

multitude of specialist skills that civilians can

bring to modern policing and the range of tasks

that they can perform needs to be advanced as

part of the organisation’s HR strategy.

1 Recommendations 3.11 and 4.3

2 NowcalledHerMajesty’sInspectorateofConstabularyandFireandRescueServices(HMICFRS).

3 DeloitteUniversityPress(2017)DeloitteGlobalHumanCapitalTrends.Thelengthoftheaveragecareerisincreasingbuttheaverage

tenureatajobis4-5years.Creatinganenvironmentthatallowsforlearning,developmentandrotationalassignmentsand“multi-

trackedcareerpathing”willbeimportantinthefuture.

The Inspectorate believes that all posts that do not

require the use of sworn powers should be lled

by Garda sta.

Governance, Performance and Culture

Previous reports by the Inspectorate, public

scrutiny of the Garda Síochána and the associated

media reporting have highlighted significant

concerns about governance, performance and

culture in the Garda Síochána and point to an

organisation in urgent need of transformational

change. The independent Culture Audit of the

Garda Síochána, published in May 2018, is an

important step towards understanding and

changing the culture of the organisation (Garda

Síochána, 2018).

The modernisation agenda and organisational

growth provide opportunities to expand the

skills base and reshape the leadership prole of

the Garda Síochána. The creation of new entry

routes, including for police ocers from other

jurisdictions could enhance and diversify the

skills and experience prole within the Garda

Síochána in a constructive way.

The Policing Authority in its submission noted

that recruitment, along with training, external

challenge, exposure to other ideas, diversity of a

workforce and transparency are among the tools

which may be used to change and renew cultures.

In its 2016 report, Her Majesty’s Inspector of

Constabulary pointed to the correlation between

the best performing police services in England and

Wales and openness of recruitment processes.

2

Changing Employment Trends

The Inspectorate is mindful of changes in

employment trends generally in wider society.

International research suggests that nowadays

people may no longer necessarily aspire to staying

with one employer throughout their careers.

3

This

trend may present opportunities for the Garda

Síochána to attract officers from other police

services at various levels.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

6 7

1.4 Methodology

After reviewing the Minister’s request, the

Inspectorate agreed with the Department of

Justice and Equality (hereafter referred to as the

Department) that the best way forward was to

provide advice to the Minister under section 117(2)

(c) of the Garda Síochána Act 2005. This view was

taken as the request made to the Inspectorate did

not involve carrying out an inspection or review

of an existing Garda Síochána practice.

Having examined the terms of reference, the

Inspectorate informed the Department that

the consideration of entry routes to the Garda

Síochána provided an opportunity to address

the implications for policing arising from the

changing composition of society. It was agreed,

therefore, that the question of enhancing diversity

in the Garda workforce would be examined by the

Inspectorate even though this is not specically

included in the terms of reference. This topic is

examined in Chapter 2 while the need to increase

the diversity of experience at all levels of the

organisation is a theme running throughout the

report.

In undertaking its work, the Inspectorate

consulted with the Department, as well as

the Department of Public Expenditure and

Reform, the Public Appointments Service, the

Garda Síochána, the Policing Authority, staff

associations and unions. Some of those made

written submissions. The views they presented

have been taken into account and are summarised

where appropriate in the report. The Inspectorate

considers the views of stakeholders on the terms

of reference as important to the development of

options for new entry routes.

Desktop research was undertaken in regard

to police recruitment and transfer practices at

all levels internationally. This included police

services in Europe, the UK and other common

law jurisdictions, such as Canada, Australia, New

Zealand and the USA. The Inspectorate met with

the UK College of Policing and Her Majesty’s

Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue

Services (HMICFRS). Teleconferences were held

with Police Scotland, the PSNI and Victoria Police

(Australia). The Netherlands Police was consulted

by email. The Inspectorate is grateful to all those

who provided assistance.

1.5 Structure of the Report

Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 6 review the issues raised by

the terms of reference at the various Garda levels

– each chapter considers bands of ranks that have

largely similar functions. These are:

Garda;

Sergeant and inspector (mid-level leaders);

Superintendent and chief superintendent

(senior-level leaders); and

Assistant commissioner (executive-level

leaders).

The rationale for this breakdown is that at

each of these levels, there are different risks,

opportunities and inhibitors to opening up

appointments beyond currently serving Garda

Síochána members. In each chapter we look at

existing policy for appointment within the Garda

Síochána, compare that against international

practice, consider the views of stakeholders,

analyse the identified options and outline

proposals for further consideration.

Supplementary information regarding recruitment

and appointment practices internationally is set

out in Appendices 1, 2 and 3 and relevant pensions

information is outlined in Appendix 4.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

8 9

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

8 9

2

Chapter 2

Diversity

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

10 11

2.1 What Does Diversity

Mean?

The concept of diversity embraces and values all

aspects of dierence. The word is often used in

the context of dierence, for example, in gender,

ethnicity and social background. This has been

the case in policing, with many international

police services being challenged to increase the

representativeness of women and members

of black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME)

communities at all ranks.

2.2 Why is it Important?

Representativeness in police services goes to

the heart of the historic principle of policing

by consent. The public must have confidence

in the police service if their consent is to be

sustained. Creating a police service that reects

the composition of the communities it serves

and that displays cultural competence in terms

of awareness of diverse cultures is important to

maintain and enhance its legitimacy. The fostering

of a more inclusive and diverse service will bring

benets for the organisation in terms of cultural

diversity and language skills, which in turn

would yield benets for service users and victims

of crime.

The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission

Act 2014 now sets out a positive duty on public

bodies, including the Garda Síochána, to have

regard, in the performance of their functions, to

the need to eliminate discrimination, promote

equality and protect the human rights of sta and

the persons to whom services are provided.

The Policing Authority’s submission said

that it is important that the Garda Síochána is

representative of the communities it serves, noting

that the existing “single front door” recruitment

is unlikely to provide a diverse mix of recruits

for a very long time. The Policing Authority

recommends the development of a programme

of positive action to actively encourage a more

diverse applicant pool including, for example,

more candidates from ethnic minorities, under-

represented socio-economic groups and women.

Such a programme would include targeted

marketing, visiting schools and communities and

auditing existing recruitment tools to ensure that

there are no unintended or inappropriate barriers

to entry. It could also include targeted “pre-

joining” training or education opportunities for

under-represented communities.

The Garda Representative Association (GRA) in

its submission recognised the policing and societal

benets associated with improving diversity in the

service and envisaged greater recruitment from

non-Irish nationals who have made Ireland their

home and from members of the LGBT (lesbian,

gay, bisexual and transgender) community

and traveller groups. The Association of Garda

Sergeants and Inspectors (AGSI) suggested greater

proactivity and outreach to diverse communities

to raise awareness about recruitment.

2.3 Policing and Diversity

Ireland is becoming increasingly diverse, yet its

police service does not reect this diversity. In

recent years, the percentage of female members

has grown and currently stands at 26.5% of the

total sworn strength. As part of this review, the

Garda Síochána was asked to provide information

on the level of ethnic diversity currently in the

organisation, but was unable to do so. The

Inspectorate was informed that the organisation

does not record this information, as asking such

questions may be viewed as discriminatory.

The 2016 census shows that the largest ethnic

grouping in the population was ‘White Irish’

with 3,854,226 (82.2% of usual residents) and that

835,695 persons (17.8%) indicated that they had

an ethnicity other than ‘White Irish background’.

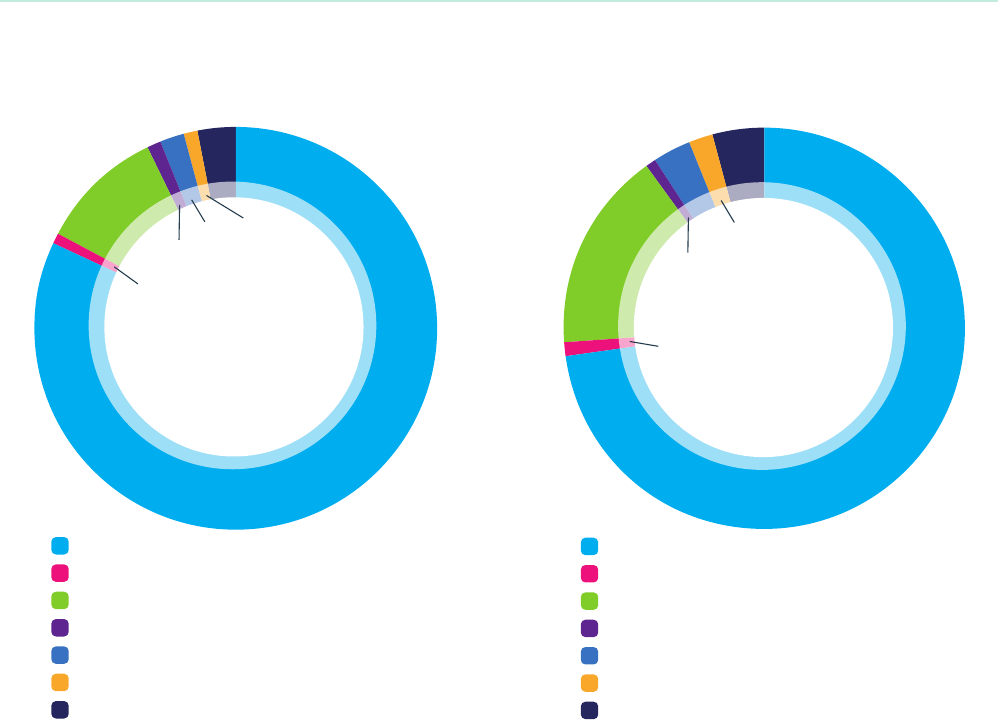

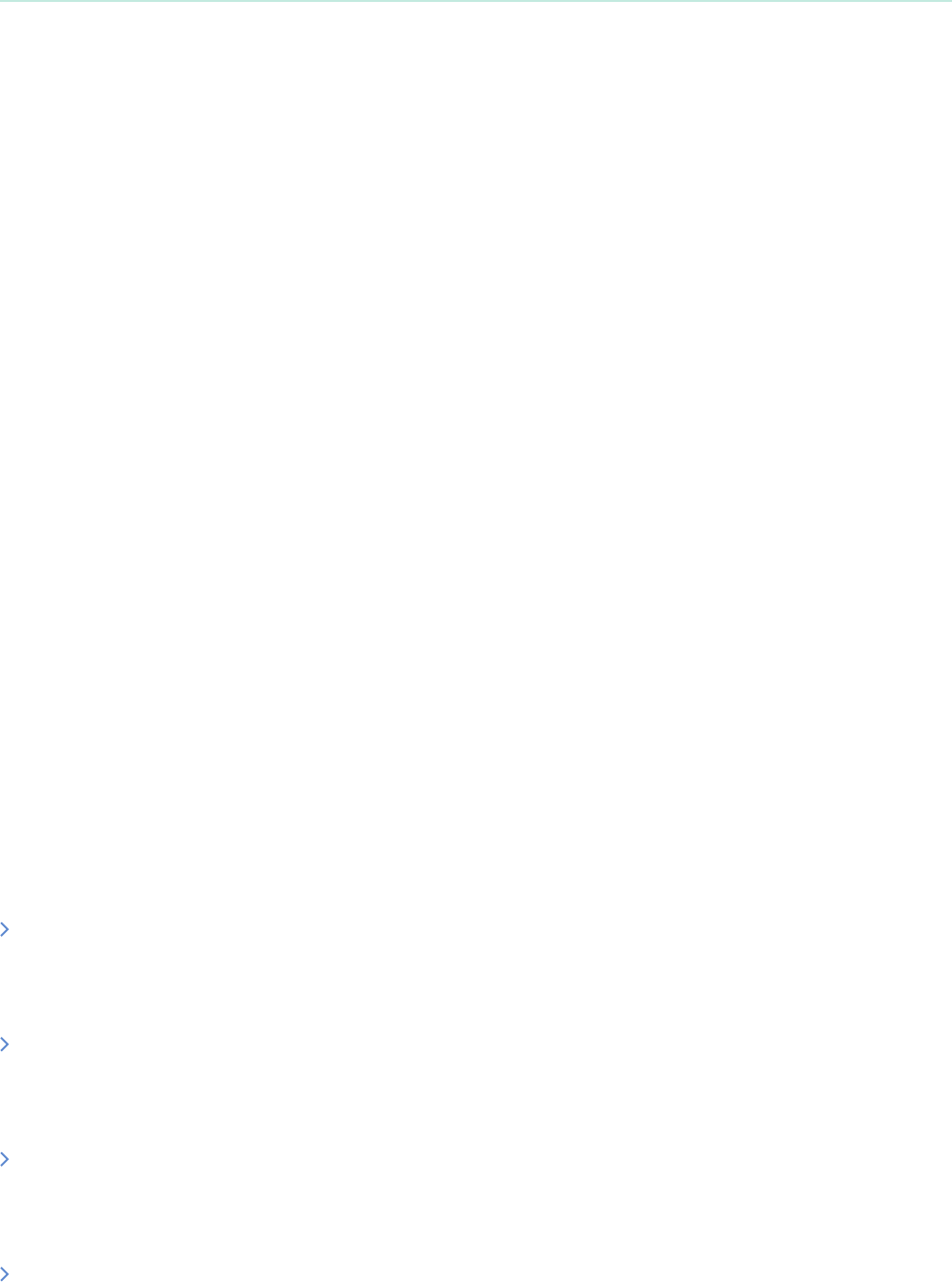

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of

different ethnicities in the ‘usually resident’

population category on Census Night.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

10 11

Figure 2 - Ethnicity of Usually Resident

Population -Census 2016

82%

10%

3%

1%

1%

White Irish

White Irish Traveller

2%

1%

Any other white background

Black or black Irish

Asian or Asian Irish

Other - including mixed

Not Stated

Source: Census data 2016

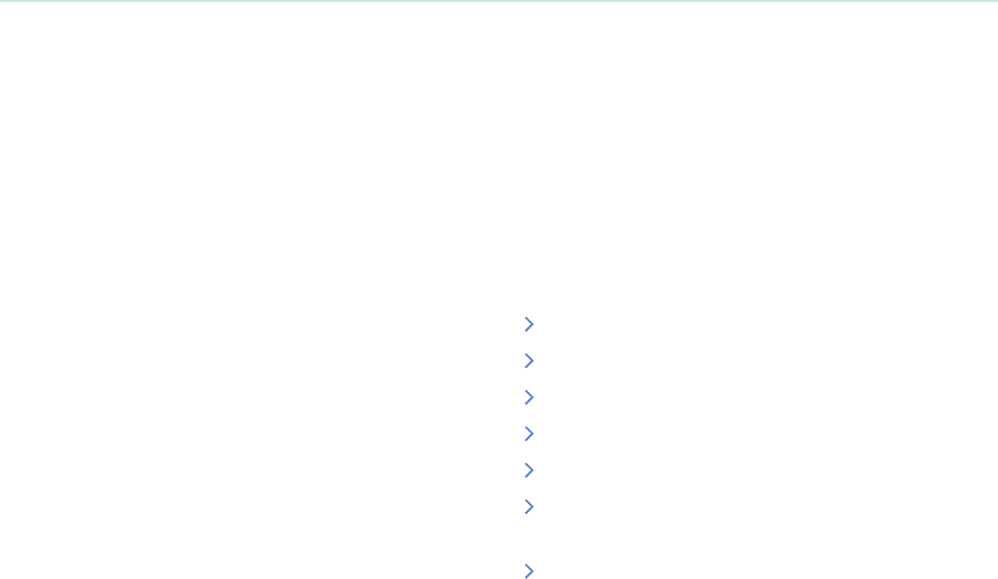

Figure 3 illustrates that there is greater ethnic

diversity in the age ranges from which members

of the Garda Síochána are recruited. In Census

2016, there were 909,980 persons in the 20 to 34

age category. Of this gure, 666,935 (73%) dened

themselves as ‘White Irish’, while 209,927 (23%)

were of other ethnic backgrounds and 33,118 (4%)

did not state their ethnicity.

Figure 3 - Ethnicity amongst 20-34 year olds in

Census 2016

73%

16%

3%

4%

1%

White Irish

White Irish Traveller

2%

1%

Any other white background

Black or black Irish

Asian or Asian Irish

Other - including mixed

Not Stated

Source: Census data 2016

The eligibility requirements to join the Garda

Síochána are outlined in Chapter 3, with one

of the main criteria being EU or European

Economic Area (EEA) nationality. It is not possible

to determine from census data exactly what

proportion of the ethnic minority population

would be eligible to apply to join the Garda

Síochána. However, sizeable proportions of all

ethnic groups are either Irish or EU citizens,

indicating that there is potential to proactively

seek to increase recruitment from these groups.

Policing such a diverse population requires an

equally diverse police service and therefore

attention needs to be focused on increasing gender

and BAME diversity in all ranks and grades. In the

Modernisation and Renewal Programme 2016–

2021, the Garda Síochána recognised that ‘a diverse

and inclusive workforce provides the potential to better

understand and serve our community’. It noted the

importance of creating a working environment

that is open, inclusive and non-discriminatory.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

12 13

It referred to the development that was underway

of:

A Diversity and Inclusion Strategy;

Diversity networks in areas such as LGBT,

gender and ethnicity to allow members

and sta with common experiences and

perspectives to share them and to provide

feedback; and

A Workplace Equality, Diversity and

Inclusion proong tool to ensure policies and

practices comply with legislation.

The commitment by the Garda Síochána in its 2018

Policing Plan to develop a positive action plan to

attract and recruit applicants from minority and

diverse groups, including reviewing barriers or

disincentives to entry, is welcome. So too is the

commitment to further develop partnerships

with minority and diverse groups to promote

engagement.

In order to facilitate analysis of trends in the levels

of diversity, the Inspectorate proposes that Garda

members and sta should be asked to provide self-

identied data on ethnic origin, having regard to

data protection requirements. This would be done

with a view to measuring trends in recruitment,

appointment and retention of members and sta

from under-represented groups. This is common

practice in other police services.

2.4 Migrant Integration

Strategy

In response to the challenge of promoting

integration, especially in the context of a rapid

change in the composition of the population, the

Government published the Migrant Integration

Strategy (Department of Justice and Equality,

2017). The strategy’s vision is that ‘migrants are

facilitated to play a full role in Irish society, that

integration is a core feature of Irish life and that Irish

society and Irish institutions work together to promote

integration’. The strategy is based on the principle

that successful integration is the responsibility of

society as a whole. It seeks to encourage action

by government, public bodies, service providers,

business, non-governmental organisations and

local communities.

The Public Service Reform Plan – Our Public

Service 2020 (Department of Public Expenditure

and Reform, 2017) – indicates that consideration

will be given as to how the public service can

support this strategy.

Action 44 of the Migrant Integration Strategy

states that ‘proactive outreach and support measures

[should] be undertaken by all public sector employers

to increase the number of persons from an immigrant

background working at all levels in the civil service

and the wider public service. There will be a

particular focus on increasing the numbers of people

from immigrant backgrounds working in front-line

services. This work will have regard to public service

employment principles of merit and transparency, and

to restrictions regarding non-EEA nationals working

in the Irish Public Service’.

The Inspectorate notes that Action 45 of the

strategy commits the Civil Service to putting

in place ‘arrangements to identify the number of

civil servants from ethnic minorities with the aim of

having 1% of the workforce from ethnic minorities’.

It commits to ‘broaden outreach in schools and ethnic

communities to raise awareness of career opportunities’

and there is an undertaking ‘to review the composition

of the applicant pool to understand where applicants

to the civil service come from and develop targeted

measures to encourage those areas of society that are

not applying’.

2.5 Promoting Diversity

In order to tackle the challenge of establishing a

more representative workforce, the Inspectorate

believes that current efforts to improve

diversity, as reected in the 2018 Policing Plan,

need to continue and increase to show that the

organisation values diversity and inclusion and

that recruits from traditionally under-represented

groups will be welcome. Eorts to engage with

ethnic minority communities to build trust and

relationships with them also need to continue,

including the promotion of the Garda Síochána

as a potential career.

Research by the College of Policing in England

indicates that the success of targeted recruitment

appears to depend on an organisation conveying

to prospective applicants from under-represented

groups that it values diversity.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

12 13

The College identified a number of activities

that may convey that diversity is valued. These

include employing a female minority recruiter,

publicising sponsorship of minority and women’s

causes, presenting inclusiveness policy statements

and creating highly diverse advertisements.

In addition to using the usual channels for

advertising positions in the Garda Síochána,

consideration should be given to utilising

a wider array of mechanisms and places,

including community centres, ethnic and

community newsletters and social media sites,

as well as through contact with associations and

organisations that serve ethnic communities.

The Garda website could publish promotional

information illustrating diversity in the

organisation. For example, the Inspectorate has

seen innovative recruitment videos developed

by other police services which seek to present

policing as a career that is attractive to people

from all communities and genders.

The Inspectorate notes the work being done by the

Garda National Diversity Bureau (formerly the

Garda Racial Intercultural and Diversity Oce),

along with outreach work being conducted in

divisions throughout the country to establish

links with new and diverse communities.

Structured community engagement by Garda

members who understand the demographics of

their areas and engage regularly with community

groups, community representatives, faith

leaders, schools and colleges, forms the basis

upon which to promote the Garda Síochána as a

viable place to work and an employer of choice.

This is particularly important as some potential

applicants may have come from countries where

there is a level of mistrust or fear of police services.

Running or attending recruitment fairs would

also create opportunities to showcase the career

opportunities available in the Garda Síochána,

with invitations being actively extended to

under-represented groups. The Inspectorate is

aware that Community Policing Units in some

divisions already do this. Taster sessions which

create opportunities to expose potential applicants

to the breadth and the realities of policing are run

by some police services.

Police Scotland informed the Inspectorate that

it has a Positive Action Recruitment Team,

which aims to increase the number of BAME

officers employed in the organisation. Using

their existing connections in the community,

they encourage members of under-represented

communities to attend a four-day Introduction

to Policing programme. The programme includes

information on tness, vetting, the application

process and a visit to the Scottish Police College.

A recent programme resulted in 45 applications to

join Police Scotland, of which 18 were successful.

They provide workshops in places of worship and

other venues in diverse communities and also

provide brieng campaigns across the country

with information about applying to join Police

Scotland.

2.6 Structured Recruitment

Strategies to Improve

Representativeness

Targeted Recruitment

In England and Wales, a national programme –

Police Now – has been established as a graduate

leadership programme with the aim of bringing

talented graduates into policing directly from

university. It is not a fast track promotion

programme. Once participants are confirmed

in rank at the two-year point, they may choose

to apply for promotion in the normal way. The

programme is more fully described in Appendix 1.

The Police Now programme has a particular focus

on developing the constable’s leadership role in

disadvantaged communities to tackle local crime

problems in partnership with communities and

other agencies. It has become a national brand

and uses proactive and targeted approaches in

universities and through social media to attract

applicants.

As a result of proactive targeting, Police Now

attracts a more diverse and representative pool

of applicants than police recruitment generally

and uses a rigorous selection process. In the 2015

pilot in the London Metropolitan Police Service,

67 recruits were successful from 1,248 applicants.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

14 15

The scheme was expanded to six other services in

2016, when there was an intake of 112 graduates

from 2,423 applicants. In 2017, the scheme was

extended to 19 participating police services with

a recruitment target of 250. Of the 2016 cohort,

54% are female and 20% are from black and ethnic

minority backgrounds. The percentage of BAME

applications increased by 34% over the rst year.

A scheme such as Police Now, using targeted

recruitment methods, has the potential to attract

high calibre and diverse candidates who might

not otherwise consider a career in policing.

The methods used are innovative and the

Inspectorate suggests that consideration be given

to incorporating the targeted advertising and

branding aspects of the Police Now programme

into the Garda Síochána recruitment model with

the aim of seeking to attract a broader and more

diverse cohort of applicants to the organisation.

Targeted recruitment and other strategies to

improve representativeness will need to be

accompanied by appropriate human resources

and retention and progression policies, diversity

awareness and management training. Ongoing

evaluation of progress will be necessary.

Volunteer Scheme and Cadets Schemes for

Young People

Many police services in the UK offer young

volunteer schemes or work experience for senior

students to provide an insight into careers

in policing, including front-line and support

roles. These typically provide opportunities

for young people to join the policing family

and gain an insight into community policing.

Programmes are designed to develop key life

skills and help to prepare young people for

their future careers, whether this is within

the police service or another profession. At

the end of the programme, participants may

continue volunteering within the policing

family. Although the schemes are not a recruitment

tool, they do oer insights into policing that may

spark interest in policing as a career.

The development of volunteer initiatives such

as a cadet scheme in the Garda Síochána was

recommended in the Changing Policing in Ireland

(2015) report. Another possible approach would

be an apprenticeship which could be linked

with existing unemployment and back-to-work

schemes.

The Garda Reserve

Information provided by the Garda Síochána

shows that there is a range of dierent nationalities

represented within the Garda Reserve. In the

Inspectorate’s view, the Reserve provides

signicant opportunities for increasing diversity

in the organisation.

Firstly, the Garda Reserve provides an opportunity

for people from all backgrounds, including

minority or under-represented communities, to

become involved in policing their community

on a part-time voluntary basis. This exposure

to policing, without sacrificing employment

or education activities, enables people to

gain experience of policing and contribute to

society. Both the Garda Síochána and the wider

community benet from the skills, experiences

and cultural awareness of these members.

The Inspectorate, therefore, proposes that the

recruitment campaigns for reserves include

proactive marketing to under-represented groups.

Consideration could also be given to developing

roles for people with specialist skills to provide

niche support in areas such as cyber security. This

is an approach recently taken by the UK’s National

Crime Agency (NCA), which has created NCA

Specials who are industry professionals that assist

with serious and organised crime. Recently, a City

of London Police investigation into a £1.5Bn. fraud

was assisted by the work of a special constable

who was employed in the banking sector and who

became one of the people leading the prosecution.

The service is now actively seeking to enhance the

recruitment of specials with skills that can assist

policing.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

14 15

Secondly, there is an opportunity to develop the

Garda Reserve as a route into the regular service.

Garda data shows that 6%

4

of the Reserve are from

31 other countries. Developing this route could

contribute to increasing representativeness.

Currently Reserve members qualifying as trainee

gardaí are required to complete the full 32-week

foundation training even though they are already

trained in many areas.

The Garda College told the Inspectorate that

it would not be possible to grant a recruit from

the Reserve pathway any exemption to regular

training as reserves do a very short training

programme and perform a limited range of duties.

It is anticipated that the range of Reserve duties

will be addressed in the strategic review of the

Reserve currently underway. This could result

in reserves performing a greater range of duties.

Consideration could be given to taking their

training and experience into account in abridged

training if they are appointed to the regular

service. As part of the review, consideration could

also be given to marketing the Garda Reserve

to under-represented groups to develop it as a

pathway to policing.

2.7 Conclusion

The Inspectorate has outlined a number of

approaches that the Garda Síochána could

develop to increase diversity and to further

enhance work already underway in this regard.

Diversity brings benets for police organisations

as well as for communities and service users. It

gives access to a wider talent pool and is likely

to lead to greater cultural awareness and assist

with community engagement and community

cohesion. More generally, diverse teams are

stronger and more successful when they accept

and encourage diering perspectives.

In developing actions and processes to attract

and retain people from diverse backgrounds with

diverse skills and experiences, the Garda Síochána

needs to ask for and listen to the views of the

communities it wishes to attract into policing.

4 38outoftotalReservestrengthof603asat31October2017

The experiences of serving members, reserves and

sta from minority groups will be invaluable in

designing recruitment tactics that are successful

in attracting high quality applicants from under-

represented groups.

Recruiting a more diverse workforce is only the

rst step; having an inclusive mindset, where

dierence is valued and people feel able to express

their views and opinions, will help to ensure the

Garda Síochána not only attracts and appoints,

but also retains, a more representative workforce.

Proposal 1

That the Garda Síochána continue to

advance its development of a comprehensive

Diversity and Inclusion Strategy.

To achieve this, the Garda Síochána should

consider:

Collecting self-identied data on

the ethnic origin of its members and

sta, having regard to data protection

requirements, with a view to measuring

trends in recruitment, appointment and

retention of members and sta from

under-represented groups;

Assessing the impact of HR and related

actions already underway to develop

cultural competency in the organisation

and promote the values of diversity and

inclusion; and

Continuing to develop a working

environment that is open, inclusive and

non-discriminatory.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

16 17

Proposal 2

That recruitment approaches are developed

that will encourage applications from

minority and diverse groups.

To achieve this, the Garda Síochána should

consider:

Utilising targeted approaches to market

the Garda Síochána as a career, such

as those used in the advertising and

branding of Police Now;

Using recruitment fairs, taster sessions

and volunteer schemes to attract

applications from under-represented

groups; and

Proactively marketing the Garda Reserve

to under-represented groups to develop it

as a pathway to policing.

Proposal 3

That the Garda Síochána, as part of the review

of the Reserve, consider the development of

a strategy that would enable people with

high level skills to contribute to policing in

specialist areas such as cyber security and

the development of targeted approaches to

attract them into the Reserve.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

16 17

3

Chapter 3

Entry at

Garda Rank

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

18 19

3.1 Introduction

The Inspectorate has been asked to examine

options for a fast track entry process at the garda

rank for police ocers from other police services

including modied eligibility requirements and a

modied training programme.

In approaching this, the Inspectorate understands

the term “fast track entry process” to entail:

A recruitment process that is as ecient as

possible, and

A training process that has regard to previous

policing experience and is geared towards

imparting the skills and knowledge needed

so that an experienced police ocer from

another jurisdiction can operate competently

in the Garda Síochána.

Recruitment of experienced ocers from other

police services is often referred to as “lateral

entry”. In the Report of the Independent

Commission on Policing for Northern Ireland (the

Patten Commission), it was recommended that

‘lateral entry of experienced police ocers from other

police services…should be actively encouraged’. In the

USA, lateral entry generally has a specic meaning

and refers to the recruitment of police ocers (but

not ranking ocers) who are currently employed

as a police ocer in another US police service. For

the purposes of clarity and to avoid confusion,

this report uses the term “experienced police

ocer entry” instead of “lateral entry”.

3.2 Current Entry Process

– New Members

The eligibility criteria for admission as a

trainee garda are set out in the Garda Síochána

(Admissions and Appointments) Regulations

2013. In summary, these specify that an applicant:

Be aged between 18 and 35 years;

Be of good character;

Pass a physical competency test;

5 Recommendation4.7

Be a national of an EU Member State, of an

EEA State or the Swiss Confederation, or be a

refugee under the Refugee Act, 1996;

Has had a period of one year’s continuous

residence in the State at application and

during the eight years immediately preceding

that period has had a total residence in the

State amounting to four years; and

Has passed the Leaving Certicate or

equivalent and is procient in two languages,

one of which must be Irish or English.

The recruitment process is managed by the Public

Appointments Service (PAS). It consists of a series

of assessments, competitive interview, physical

and medical tests and security checks. The initial

stages of the selection process are conducted by

PAS. Candidates who qualify through this process

are sent forward to the Garda Commissioner

for consideration in regard to medical, physical

competency and security aspects. In Changing

Policing in Ireland (2015), the Inspectorate

identied a number of issues around recruitment

practices and the promotion of policing as a

career. It included a recommendation to develop

a strategic plan to ensure eective and ecient

recruitment practices to attract a diverse range of

high quality candidates.

5

Successful candidates are oered a non-salaried

training contract of 32 weeks with a training

allowance (€184 per week). This covers the rst

phase of the trainee garda/probationer training

programme (introduced in September 2014).

The Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree in Applied

Policing is the foundation programme for garda

trainees. It has three phases. The programme runs

over 104 weeks and consists of:

Phase I – a 32-week residential training

course at the Garda College, followed by two

weeks’ leave;

Phase II – a 34-week programme in an

operational unit working alongside a tutor

garda; and

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

18 19

Phase III – a 36-week programme in which

the trainee garda is on independent patrol,

essentially performing regular unit duties in a

division.

Trainee gardaí are attested at the end of Phase I

training. The attested garda is placed on the Garda

pay scale and the two-year probation period starts

at that time. Any who do not reach the standard

required for progression into the next phase must

repeat all or part of the training. Trainees who

fail to meet the standard for progression, having

been afforded the opportunity to repeat once

during any of the modules/phases, are deemed

unsuitable for a career in the Garda Síochána.

Successful completion of the programme results

in the award of a BA (Level 7) in Applied

Policing, which is accredited by the University

of Limerick. In Changing Policing in Ireland

(2015), the Inspectorate recommended that the

Garda Síochána conducts a review of Phase I

training with a view to reducing the duration of

the foundation programme.

6

This would reduce

the residential portion of the training, allowing

trainees to get out on patrol sooner.

Under these arrangements, a qualified and

experienced police officer from another

jurisdiction applying to become a garda member

must apply like every other candidate and satisfy

all requirements. This includes completing the

initial 32-week residential course before being

placed on the minimum of the pay scale and then

completing the two-year probation period.

3.3 International Practice

Relating to Recruitment

The Inspectorate has examined international

practices regarding recruitment, in particular as

it relates to experienced police ocers. To best

outline the ndings, the UK experience and that

outside the UK are set out separately.

6 Recommendation4.17

UK Practice – General Recruitment

There are 43 police services in England and

Wales, each of which operates its own recruitment

procedures, subject to national standards. Recruits

are trained under the Initial Police Learning

and Development Programme (IPLDP) which

provides a standard across England and Wales,

with some variations to take account of local

police service needs.

The College of Policing, the regulatory body for

policing standards, has been working with police

services and higher education partners to develop

new entry routes into policing and some police

services will begin oering them from September

2018.This will involve phasing out the current

IPLDP over a number of years. The new routes

are:

Police Constable Degree Apprenticeship,

which is a professional degree-level

apprenticeship. This enables new recruits to

join the police service as an apprentice police

constable and earn while they learn. During

the three-year programme the apprentice will

complete a degree in professional policing

practice and will be assessed against national

assessment criteria as an integral part of their

degree apprenticeship;

Degree Holder Entry Programme, which

is aimed at degree holders in any subject

area. This will be a two-year (minimum)

practice-based programme enabling

candidates to perform the role of a police

constable. Successful completion results in

the achievement of a graduate diploma in

professional policing practice; and

A Pre-join Degree in Policing, which

involves completion of a three-year

knowledge-based degree in professional

policing prior to joining the police service.

Becoming a special constable may be

included as part of the programme.

Candidates who are subsequently recruited

will undertake practice-based training to

develop specic skills and will be assessed

against national assessment criteria in order

to demonstrate operational competence.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

20 21

The development of these entry routes is linked

with the development of the Policing Education

Qualications Framework, referred to later in this

chapter.

UK Practice – Experienced Ocer

Recruitment

While there are variations between police

services in terms of size, policing challenges

and distribution across urban and rural areas,

the common standards and legislation facilitates

mobility between police services. These are

referred to as transfers. No UK police service

operates an experienced ocer entry process for

ocers serving outside the UK.

The College of Policing and individual police

services regularly advertise details of policing

vacancies and opportunities for transferees on

their website. These include various opportunities

for police constables and detective constables,

posts in specialist roles, for example, in Child

and Adult Protection Teams, and posts up to chief

superintendent level. The College’s Leadership

Review – Recommendations for delivering

leadership at all levels (2015) also pointed to

how entry routes and talent programmes can

support the development of a critical mass in

police leadership with a diversity of backgrounds,

experience, thinking and perspectives which

together can have a major impact on positive

cultural change.

To be eligible to transfer to another England and

Wales police service as a constable, applicants

must be serving within a Home Office police

service or have so served within the last five

years and have a satisfactory record generally.

7

However, the London Metropolitan Police Service

now accepts transfer applications from ocers in

non-Home Oce services (e.g. the PSNI, Police

Scotland).

Successful applicants are given generic induction

and familiarisation training. This varies and in

the case of Lincolnshire Police, for example, lasts

seven days.

7 AHomeOfcepoliceserviceisanyoneofthe43policeservicesinEnglandandWales.

8 AsdeterminedinareviewofthepolicewebsitesofthepoliceservicesinFrance,Germany,Austria,Belgium,Netherlands,Spain,

Sweden,Norway,Denmark,andFinland.

Police Scotland recruits officers who want to

transfer to Scotland from other parts of the UK.

The process is not specically advertised and is

always open. Applicants must have ve years’

service, meet all necessary standards and pass an

interview. The application form seeks evidence of

transferrable skills. Because there are signicant

differences in laws, processes and procedures

compared with other parts of the UK, successful

applicants undertake a three-week conversion

course. The training is generic as the selection

process screens for recruits who are qualified

for appointment. No probation period applies to

such transfers. Between 30 and 40 ocers transfer

to Police Scotland each year through this route.

These include a small number of ranking ocers

(sergeant or inspector). There are two intakes per

year, in March and September. Specialist police

training recognised under national policing

qualications, such as public order and rearms

training, can be carried forward into Police

Scotland.

In Northern Ireland, transfers into the PSNI from

other UK police services have been facilitated

through a formal transferee process but there

is no recruitment at present. The last process

was in 2013 when 27 appointments were made

following 58 applications. Applications were

open to constables, detective constables, sergeants

and detective sergeants but appointment was

to the rank of constable. Candidates had to be

substantive in rank, attached to a Home Oce

police service, have a satisfactory sickness record,

pass a medical assessment, a substance misuse test

and an interview. Training, which for new recruits

is over a two-year period, was condensed to eight

weeks and there was no probationary period.

Practice in Other Jurisdictions

European police services reviewed by the

Inspectorate do not run experienced police ocer

entry programmes into their police services from

other jurisdictions.

8

All of these countries have

strict language requirements and some restrict

police posts to nationals of the particular country.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

20 21

In the USA, Canada and Australia, which have

multiple police services, a multitude of policies

apply (see Appendix 2 for full details). However,

an important theme is that intra-jurisdictional

transfers/recruitment are more frequent than

inter- jurisdictional ones. The former draw

heavily on common standards and training from

accredited services and abridged training is

common.

Accredited experience often can allow for entry

at a pay level comparable to an ocer’s previous

posting. The Inspectorate found that the USA

makes use of state approved selection and training

standards and that Australia is the best example

of inter-jurisdictional recruitment of experienced

officers with policing experience in Australia,

New Zealand or the UK recognised.

In Australia, there is no country-wide experienced

police ocer entry process and police ocers

wishing to join another police service must apply

to that police service and have prior policing

experience assessed. Victoria Police, for example,

in its Prior Policing Programme, recognises

prior policing service only in the case of those

who have served as an operational police ocer

in Australia, New Zealand or the UK. Each

application is assessed individually. Applicants

may be required to undertake a skills gap analysis

to assess how much their knowledge deviates

from current Victorian law and Victoria Police

policy and operational procedures. The skills

gap analysis takes into consideration educational

qualications, the amount and quality of policing

service and how up to date it is. The Inspectorate

was told that between 10 and 20% of applicants

are successful.

Suitable recruits undertake an individualised

abridged training programme, consisting of only

their identied mandatory training sessions and

they are then fast tracked by attending sessions

with more senior training groups. The length

of this training depends on the assessment and

performance in training but will be between

eight weeks and 24 weeks, compared with the

normal recruit training of 31 weeks. There is no

generic abridged training programme as Victoria

Police has moved away from a “one size ts all”

abridged programme to individualised training

programmes.

However, recruits undertake all foundation

training assessments, which ensures that they

leave training holding all competency expectations

of a general duties constable who has completed

the full training programme. The Inspectorate

was informed that many of these recruits achieve

acting sergeant positions relatively quickly after

recruitment.

Western Australia Police has run international

recruitment campaigns for “transitional police

ocers”, the most recent in 2012. It is the only

policing service in Australia to explicitly recognise

policing experience from Ireland as “compatible”.

Successful applicants were nominated by Western

Australia Police for a permanent residency visa.

This is no longer done but applicants from the UK

and Ireland can still apply at any time if they are

Australian or New Zealand citizens or permanent

residents of Australia. Previous policing service

was recognised for pay purposes. A tax oset was

available for relocation expenses

Applicants to Western Australia Police must have

three years “compatible policing experience” and

have nished probation. Previous service must

have occurred within the previous 18 months for it

to be recognised. The three-year minimum service

requirement was a condition of the agreement

with the immigration authorities, but in practice,

the police service sought officers with more

experience who would be ready for operational

roles. Applicants for transitional police ocer

are tested over a ve- day period. If their prior

learning and experience is considered appropriate,

shortened training of 13 weeks, compared with

the normal 28 weeks, is offered. This covers

police systems, policies and equipment and

familiarisation with legislation.

The Inspectorate is aware that a significant

number of former gardaí joined Western Australia

Police in the last decade, along with colleagues

from the PSNI and other UK police services, and

some have achieved promotion. One such ocer

told the Inspectorate that in recognising the skill

sets of officers from all UK services, Ireland,

New Zealand and South Africa, this service has

become more diverse and this has been key to its

modernisation in an environment where fresh

ideas on policing are openly encouraged.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

22 23

New Zealand Police last recruited from abroad in

2008. It provided an eight-week course instead of

the usual 16 weeks. Under its current recruitment

processes, overseas police ocers must be New

Zealand or Australian citizens or hold New

Zealand residency. They must pass the normal

recruiting process and undergo full training.

3.4 Stakeholder Engagement

Views of the Policing Authority

In its submission to the Inspectorate, the Policing

Authority said that the current arrangements for

recruitment of gardaí are inappropriate for the

needs of the modern Garda Síochána organisation

and are not suitable for attracting the widest

possible range of experience and talent. It noted

that, in common with other policing services, the

traditional entry route at trainee garda level and

the traditional internal career path will continue

to be appropriate for a large proportion of sworn

members. However, for a number of reasons

including culture change, openness to a broad

range of skills and experience, diversity and

agility, the Policing Authority was of the view

that there is signicant merit in broadening the

range of entry routes to the garda ranks. In this

regard, the Policing Authority emphasised that

reform of entry routes to the garda ranks was not

an end in itself. It recommended that a number

of dierent options be examined, implemented

and evaluated, emphasising that this should

complement the Government policy of “civilian

by default” referred to earlier.

Views of Garda Associations

The GRA indicated that it saw some merit in

providing a condensed training course for entry

to garda rank. It pointed to those who have served

in police services that fully subscribe to “Peelian

Principles”

9

of policing and Commissioner

Michael Staines’ declaration that ‘the Garda

Síochána will succeed not by force of arms or numbers,

but on their moral authority as servants of the

people’. It also emphasised that there could be no

automatic right to “leapfrog” other candidates.

9 PeelianprinciplessummarisetheideasthatSirRobertPeeldevelopedaroundethicalpolicingandpolicingbyconsentofthepeople.

The AGSI indicated that there is a high interest

in taking up garda trainee positions from across

all social, geographic and demographic groups.

Additionally, AGSI does not see a skills decit in

the front-line operational units or in specialist or

investigation units/sections. It therefore does not

believe that the Garda Síochána needs to seek to

recruit experienced police ocers from abroad.

If it becomes policy to recruit in this manner,

AGSI said that recruits with previous policing

experience should complete the normal recruit

training and probationary periods and should

not be considered for specialist duties for which

they may be qualified until completing three

years of regular policing duties. Additionally,

it emphasised that, if ocers from abroad who

have specialist skills are assigned, there must

be a process for skills transfer to existing Garda

Síochána personnel.

Both the GRA and AGSI expressed concerns

about the impact of alternative entry routes on

their membership, in particular opportunities for

development or specialist posts. They suggested

reciprocal arrangements with any other service

from which the Garda Síochána would draw

applicants and this was also referred to by the

Association of Garda Superintendents in their

submission.

3.5 Case for Experienced

Police Ocers

The Inspectorate has found limited but germane

examples internationally of the recruitment

of experienced police officers from other

jurisdictions.

As discussed earlier, police services in Australia

recruit officers with prior policing experience

from other Australian States and New Zealand

and give abridged training. They also generally

recognise policing experience from the UK,

subject to citizenship and residency conditions.

Shortened courses have also been provided by

Police Scotland and the PSNI to officers from

other UK police services.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

22 23

This demonstrates that the generic skills of police

ocers can be transferable, subject to supports

in respect of knowledge, policies and practices.

In this context, many common law jurisdictions

have broadly similar standards in many policing

functions.

The potential benets of opening up recruitment

to garda rank to experienced ocers are:

They would come from a diversity of police

backgrounds which would introduce fresh

thinking, perspectives, ideas, policing

knowledge and approaches into the

organisation. This would assist the opening

up of the organisation’s culture;

They would not need to undertake the full

garda training programme. This would speed

up the intake of new members and reduce

training time, thereby improving agility of

recruitment and assisting the Garda Síochána

to meet the recruitment targets set by

Government in the period to 2021;

They may have specialist policing skills

which are increasingly in demand in a

modern police service (e.g. public order,

rearms, drugs investigation, child

protection, cyber crime); and

It is inecient that applicants to the Garda

Síochána who are already qualied and

experienced police ocers, with track records

and skills that would be of benet to the

organisation, are required to complete the full

training programme on the same basis as a

recruit with no prior experience.

There are many Irish nationals serving in other

police services who emigrated in the last ten

years or so. Enabling them to be eligible to

join the Garda Síochána with modified entry

arrangements and a shorter, tailored training

programme would be of benet, not just to the

Garda Síochána organisation and policing, but

also to the community in general. For example,

the Inspectorate met an ocer working in another

police service with family ties in the jurisdiction

who has transferrable skills that would be in

demand in the Garda Síochána.

As he is over the age limit for traditional entry, he

cannot apply in the normal way and, even then, it

makes no sense that he should have to undertake

the 32-week residential training, the full 72- week

on-the-job training and the probationary period.

3.6 Eligibility Issues

Relating to Recruitment

of Experienced Ocers

from Other Jurisdictions

For an experienced ocer recruitment scheme

to be eective, ecient and viable, a number of

issues relating to eligibility need to be considered

to maximise the potential of the scheme to

attract high quality candidates, and ensure those

selected enhance Garda Síochána capability upon

appointment. These are:

Nationality and Residence

To attract as diverse a pool of candidates

as possible, the Inspectorate considers that

experienced police officers, irrespective of

nationality, who meet Garda standards, should

be eligible to apply to the Garda Síochána.

Such individuals should be viewed as skilled

professionals who can add to the capability and

capacity of Irish policing.

At present, applicants for admission as a trainee

garda must be nationals of an EU Member

State, an EEA Member State, Switzerland or

alternatively be legally resident in the State for

a specied period. The Inspectorate considers

that experienced officers working in policing

organisations outside of the EEA, in, for example,

the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand

could be suitable applicants.

For the Garda Síochána to get the most benet

from this kind of recruitment, it would be

important that as few limitations as possible are

placed on nationality and residence so that all

such potential candidates who could contribute

relevant experience would have access. Rather

than nationality, the key issue should be the quality

of the candidates’ policing knowledge, experience

and skills as assessed against Garda requirements.

How the application and recruitment process

could be designed is discussed below.

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

24 25

In proposing recruitment of experienced police

ocers from other jurisdictions including from

outside the EEA, the Inspectorate understands that

this would require amendment of the statutory

work permit scheme, which currently only allows

for a permit to be granted if the applicant can

provide a service or skill not available in the State.

The Inspectorate considers that this is justied on

the grounds of the experience prole required.

Age and Experience

The Inspectorate considers that officers of the

calibre and experience that the Garda Síochána

would be seeking to attract are likely to be close

to or exceed the age of 35 years which is the

current maximum age for recruitment at garda

rank. However, in order to attract experienced

candidates, the upper age limit of 35 years would

need to be modied to take account of the number

of years of conrmed service in another policing

organisation. It is suggested that such ocers

should be required to pass a fitness test. This

approach would be essential to enhance take-up

rate of a scheme.

The Inspectorate considers that experienced

ocers should have a minimum of three years’

conrmed service following training in order for

the Garda Síochána to realise sucient benet in

terms of knowledge and experience transfer.

While the general question of age limits is outside

the terms of reference, it is considered that there

may be merit in reviewing the current maximum

age limit of 35 years for normal entry into the

Garda Síochána in order to maximise recruitment

opportunities and diversity. A revision of the age

limit could also encourage people with a variety

of backgrounds and managerial and leadership

experience to consider a career change to policing.

The Requirement to Study Irish and

Language Requirements Generally

The Garda College pointed out that Irish is taught

as part of the foundation training course to enable

gardaí to conduct business in Irish and that this

might present a practical challenge for transfer

entry.

10 AnGardaSíochánaOfcialLanguagesAct2003LanguageScheme2016–2019

While it is a constitutional right for citizens to

conduct their business in Irish, the Garda Síochána

Irish language scheme

10

makes provision for the

manner in which this service is to be delivered.

In particular, it is to be provided through ‘a panel

of procient speakers in each Garda Division’. The

Garda Síochána Act 2005 (section 33(2)) also

provides that the Garda Commissioner shall ‘to the

extent practicable, ensure that members of the Garda

Síochána in a district that includes a Gaeltacht area are

suciently competent in the Irish language to enable

them to use it with facility in carrying out their duties’.

The Inspectorate considers that an experienced

officer entry scheme from other jurisdictions

would not compromise the operation of these

panels as the numbers of gardaí involved are

small compared to the overall member cohort.

Experienced ocers who are recruited should be

exempted from the requirement to learn Irish to

lessen recruitment barriers. It is understood that

such a waiver is already in place for members

who join from the PSNI under the promotion

arrangements referred to later. Sections 9 and 10

of the Garda Síochána Act 2005, which set out

the parameters for appointment of the Garda

Commissioner and Deputy Commissioner, also

make no reference to a requirement in relation to

the Irish language.

In order to attract the most diverse pool of

candidates, the Inspectorate considers that the

language requirement for experienced police

officers from other police services should be

modied to require prociency in English only.

Knowledge of other languages would, of course,

be an advantage.

Assessing Knowledge/Understanding of

Current Irish Policing-Related Law and

Practice

The Inspectorate considers that the single biggest

practical challenge in devising an entry scheme

for experienced police officers will be around

the dierences in law, policies and practices as

they relate to policing in dierent jurisdictions.

However, while Irish law and procedures are

dierent to those in neighbouring jurisdictions

REVIEW OF ENTRY ROUTES TO THE GARDA SÍOCHÁNA

24 25

and other common law countries, police ocers

who have worked in both the Garda Síochána and

other common law police services have conrmed

the Inspectorate’s view that there is a lot of

commonality. The vital learning for new recruits

will be to understand the key dierences and

to know how and when to apply the provisions

that exist in Irish law. They will also, of course,

have to gain an understanding of life in Ireland,

in general.

The Inspectorate considers that the material on

law, policies and practices in relation to the Garda

Síochána, which is currently delivered to recruits

in the College, could be developed, quickly and

at little cost, into a “pre-read” which could be

made available to experienced ocers applying

for entry. A broadly similar approach is taken by

Police Now, the graduate entry programme in

England and Wales (referred to in Chapter 2 and

Appendix 1), which tests recruits on the pre-read

material on the rst day of training. The PSNI also

gave transferees pre-read material to study before

attending its transferee training programme.

The Inspectorate proposes that a test – which

could be called the Experienced Police Ocers

Knowledge Test – could be developed. A Qualied

Lawyers Transfer Test is administered by the Law

Society and is a conversion test that assesses the

tness of lawyers who are qualied overseas to

practise as solicitors in this jurisdiction. The Law

Society website provides direction to required

knowledge, showing past exams and gives a

reading list.

Through a police knowledge test, a police ocer

from another jurisdiction would be assessed on

their knowledge of Irish policing law, practice

and application at the end of training and before

appointment is confirmed. Information and

references could be posted on the Garda Síochána

website as a guide to interested applicants.

3.7 The Recruitment Process

The Inspectorate envisages a recruitment process

led by the PAS in active partnership with the

Garda Síochána. Overall, it would need to be as

attractive and as easy to navigate as possible to

encourage people to consider it.

Proactive recruitment strategies and human

resource information and support would need

to be put in place to encourage applications from

experienced ocers in other jurisdictions and

assist them in the joining and induction process,

if appointed.

The Inspectorate considers that a special stream

for experienced police ocers recruitment could

be created as part of the general Garda Síochána

recruitment process.

A relatively speedy process to validate prior

experience and to carry out an initial evaluation

of skills and competencies would be key to the

success of attracting experienced police ocers

from abroad. Candidates should be required

to set out details and evidence of performance

in another police service, evidence of police

training and conrmation that they are clear of

any disciplinary issues that may impact on their

appointment. A process could broadly consist of:

A competency-based application form

enabling candidates to outline details of

their experience and skills, with examples

of where they have demonstrated policing

competencies as well as evidence of

experience, training and discipline record;

Shortlisting of candidates, evaluation of

competencies and values;

An interview (video-conference could

be utilised) and any related assessments

necessary; and