8101_05/19

Appendix C

Washington State

Social Emotional Learning

Implementation Guide

Contents

Page

Using This Implementation Guide ................................................................................................... ii

Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1

SEL Is a Shared Responsibility ..................................................................................................... 2

What Is Washington’s SEL Implementation Guide? ................................................................... 4

Why Is Social Emotional Learning Important? ............................................................................ 9

Why Does SEL Matter for Washington’s Students? ................................................................... 9

How Can We Implement SEL in Our School and Community? ................................................. 10

Where to Start? School and Community Readiness to Implement .......................................... 11

Research and Evidence Base ..................................................................................................... 11

Guiding Principles ......................................................................................................................... 15

Equity ...................................................................................................................................... 155

Cultural Responsiveness ......................................................................................................... 166

Universal Design ..................................................................................................................... 188

Trauma-Informed Practice ........................................................................................................ 20

Essential Elements of the Washington SEL Implementation Guide ........................................... 265

Building Adult Capacity ........................................................................................................... 277

Creating Conditions to Support Students’ SEL ........................................................................ 377

Collaborate With Families and Communities ......................................................................... 477

Conclusions ................................................................................................................................. 533

References .................................................................................................................................. 544

SEL Implementation Guide: Resource List .................................................................................... 62

Glossary ......................................................................................................................................... 63

Acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 677

Glossary References .................................................................................................................... 699

i

Figures

Page

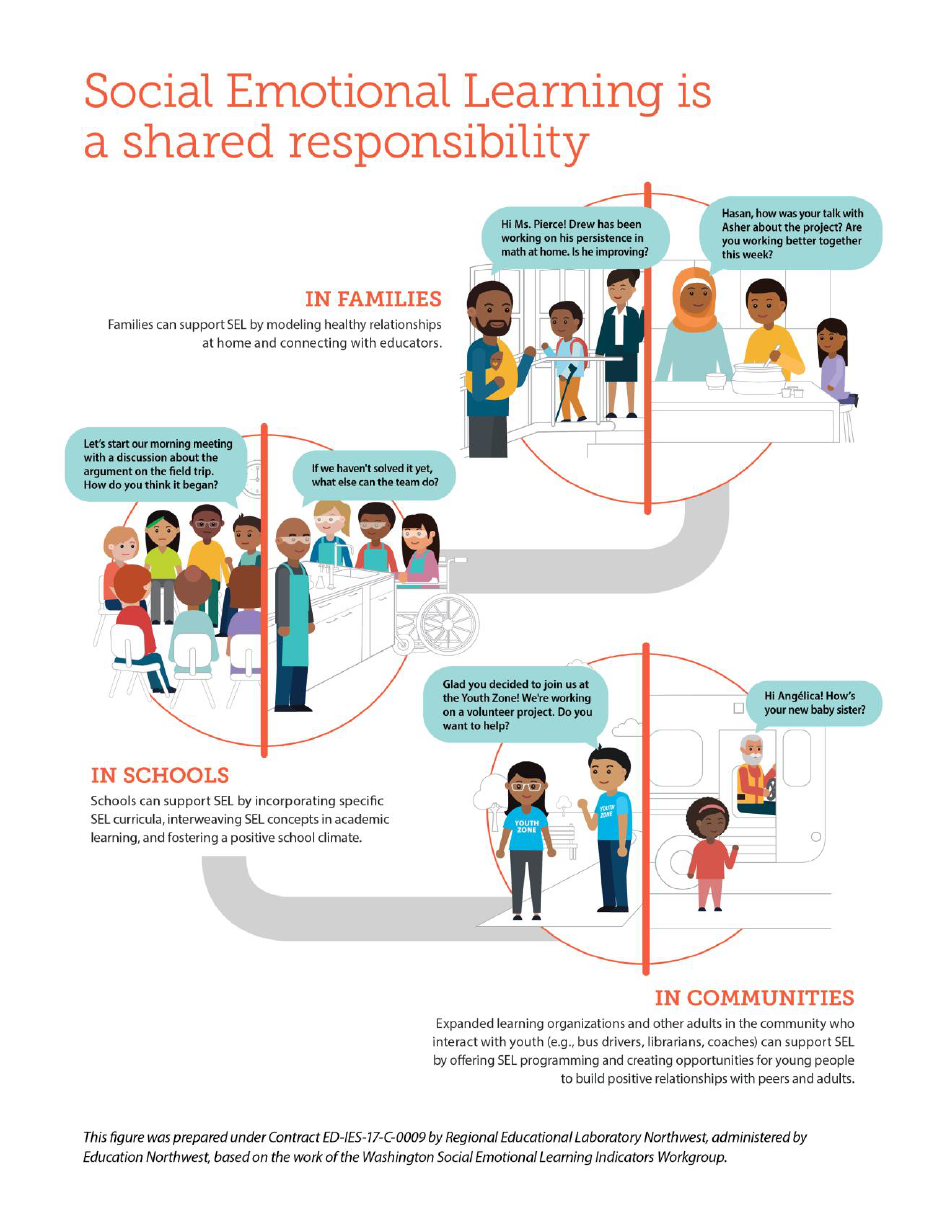

Figure 1. Social Emotional Learning Is a Shared Responsibility ...................................................... 3

Figure 2. Framework for the Washington SEL Implementation Guide .......................................... 5

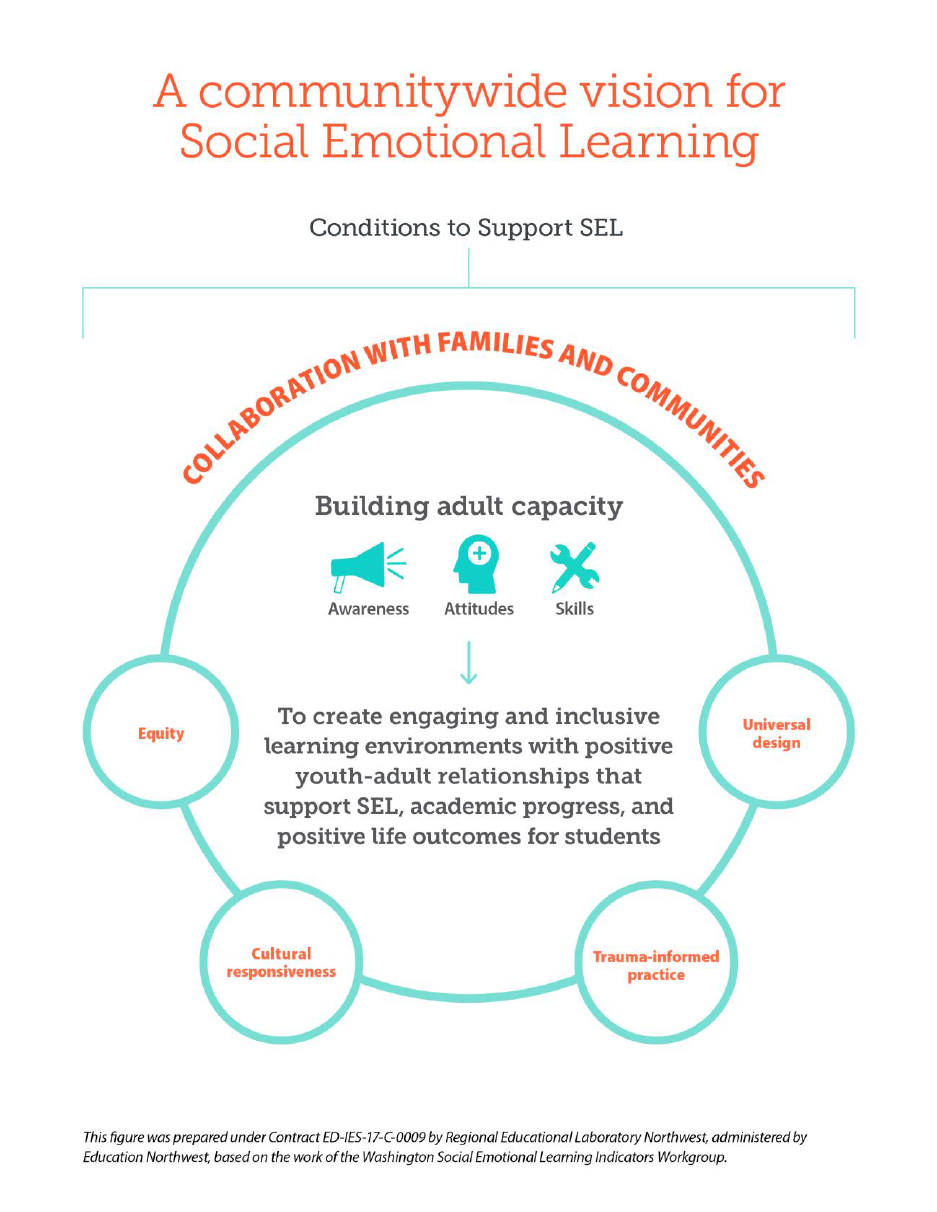

Figure 3. A Community-Wide Vision for Social Emotional Learning ............................................... 7

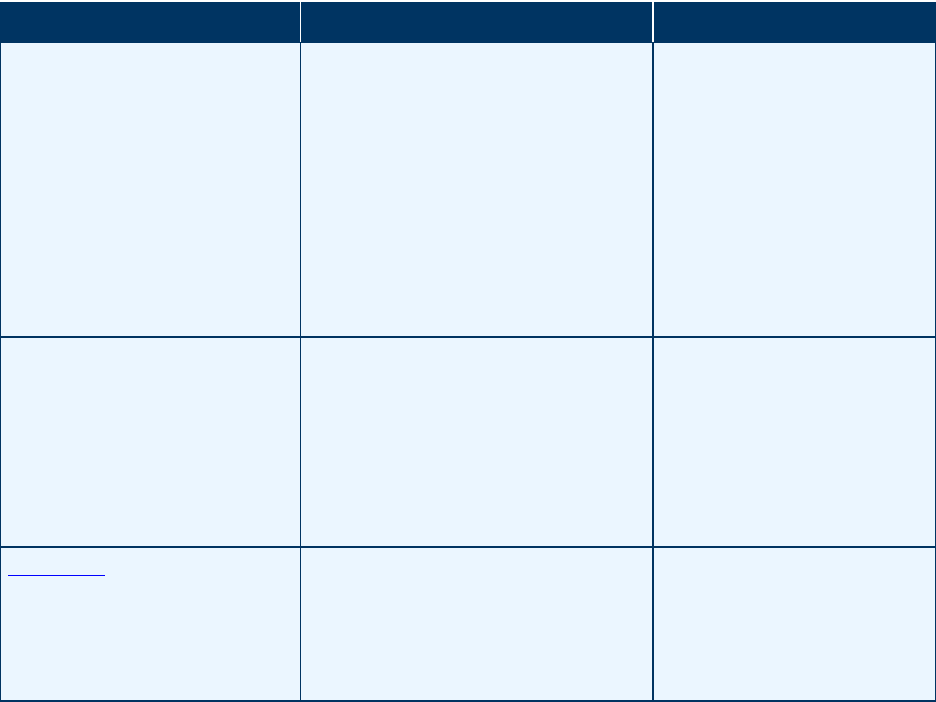

Figure 4. Resources of Washington State’s SEL Indicators Implementation Plan .......................... 8

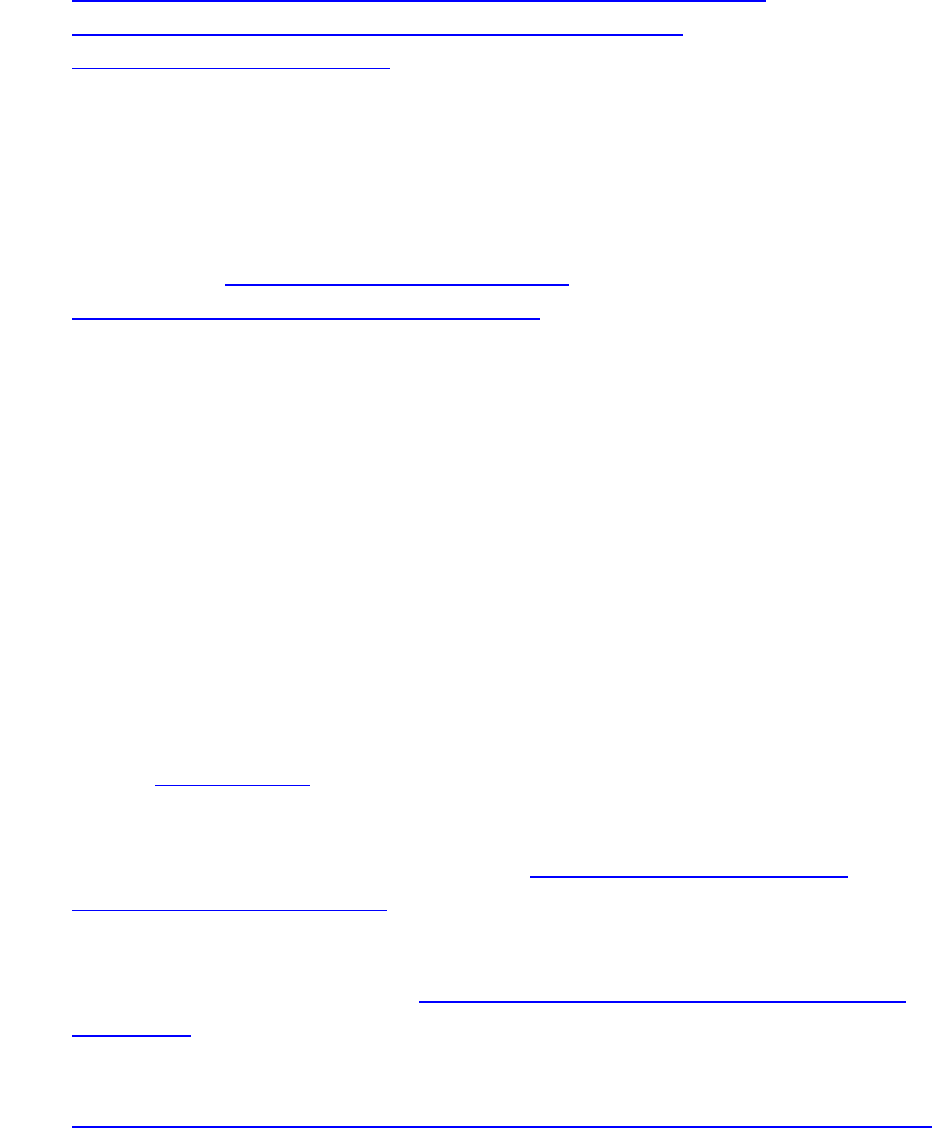

Figure 5. Universal Design for Learning Principles ..................................................................... 199

Figure 6. Essential Elements of the SEL Implementation Guide ................................................. 266

Using This Implementation Guide

This Implementation Guide is designed to be used with other documents that make up

Washingtons SEl Resource Package and by anyone who works with children and youth and is

concerned with their social emotional well-being. It includes perspectives for school leaders,

educators, youth serving organizations, and parents/families and provides overarching

concepts that are centered around the principles that are foundational for the development of

SEL in Washington State: Equity, Cultural Responsiveness, Universal Design and Trauma-

Informed Practices.

This Guide aligns with other SEL resources in Washington State such as the Washington SEL

Standards/Benchmarks/Indicators, SEL Briefs, and the SEL Module, which are all part of

Washington State’s SEL Resource Package, and are intended to be a collective of tools that are

mutually supportive toward SEL implementation.

This Guide is designed to be used systemically where schools, communities, and families work

together to understand and grow their respective roles in bolstering their students’ SEL

development in a mutually supportive manner.

The developers of this Guide recommend that anyone planning to implement SEL read the

Guide in its entirety before beginning implementation. Prior reading can be beneficial to those

individuals facilitating conversations with collaborators as they plan and coordinate efforts to

set the stage for a successful and sustained application.

ii

—C-1—

Introduction

Social and emotional learning (SEL) is a process through which individuals build awareness and

skills in managing emotions, setting goals, establishing relationships, and making responsible

decisions that support success in school and in life. Educators, families, business leaders,

students, and administrators in Washington State and nationally agree that SEL is essential for

students to succeed in school,

careers, and life, and should

be part of teaching and

learning in schools. Many

schools and communities

need guidance about how to

effectively implement SEL

practices across the whole

day.

This Washington SEL

Indicators (SELI) Workgroup

created this Implementation

Guide as part of their

collective of products and

resources grounded by a set

of guiding principles for

education (equity, cultural

responsiveness, universal

design, and trauma-informed

practices) and serving as the

foundation of social

emotional teaching and

learning specific to

Washington State. SELI

Workgroup members agreed

that all adults engaged in SEL

implementation need to build

the necessary awareness,

attitudes, and skills to support and teach SEL. Then, they will be better informed and more

effective in fostering learning for every student that includes an intentional focus on individual

SEL Is Happening in Pockets Across Washington State, but

More Guidance and Support Are Needed

A statewide landscape scan of SEL in K–12 education identified

a need for a common language and framework for SEL

implementation and for guidance on how to integrate SEL with

academics and other school initiatives related to equity, climate,

MTSS, and trauma-informed practices (Petrokubi, Bates, &

Denton, 2019).

A statewide survey of districts conducted as part of this scan

revealed a need for the following:

• Funding for SEL resources

• Additional time and support for adult skill and knowledge

development, including understanding of child and

adolescent development

• Simple, high-impact strategies to integrate SEL into all

aspects of districts’ work and build specific SEL skills

• Family and community partnerships

• Strategies for promoting inclusive and culturally responsive

learning environments

Stakeholder engagement sessions with families, educators,

community-based organizations, and Tribal representatives

across the state (See Stakeholder Feedback and Community

Outreach Summary) and in an online survey conducted by OSPI

revealed that SEL should be connected to and adapted to the

community. By collaborating closely with students, families,

community-based organizations, and tribes; schools can design,

plan, and implement SEL approaches that fit the local culture

and context.

—C-2—

student's social emotional development. Washington State has an opportunity now to commit

to implementing SEL in a truly collaborative fashion—bringing together educators, families,

school counselors, youth development workers, district administrators, youth, and the many

others who impact students’ social emotional learning—by implementing plans that are

responsive to and embedded in the cultures and communities present. Washington State’s SEL

Module has a segement devoted to “What is SEL” and provides an overview of the important

elements of SEL in meeting the needs of all students.

SEL Is a Shared Responsibility

School is a social place where diverse individuals come together to learn how to learn together.

They communicate their thoughts and values, get along with others, navigate differences, and

resolve conflicts. What happens before and after school can be as important as what happens

during the school day. Young people develop and practice SEL every day in their families,

schools, and communities. The school’s role in supporting students’ social emotional

development is an enhancement, not a substitute, for the learning and development of those

skills that take place at home and in the community; it is a necessary complement to that

learning. It takes schools, families, and community partners, such as expanded learning

opportunity (ELO) programs, to build full-day learning environments and approaches to SEL

instruction that support children and youth in building SEL competencies. The more that

families, schools, and communities collaborate, the more support young people experience for

their social emotional development. As demonstrated in Figure 1, everyone has a shared role

and a shared responsibility.

For more information about how schools, families, and communities can support SEL

implementation, see the following briefs that have been developed by the SELI Workgroup as

part of Washington State's SEL Resource Package:

• Education Leaders

• Educators

• Parents and Families

• Community and Youth Development Organizations

• Culturally Responsive Practices

—C-3—

Figure 1. Social Emotional Learning Is a Shared Responsibility

—C-4—

What Is Washington’s SEL Implementation Guide?

The SELI Workgroup developed the Washington SEL Implementation Guide to provide a

comprehensive and school/community-specific plan to improve SEL outcomes for all the

children and youth they serve. Different localities will implement evidence-based, equity-

focused SEL in ways that meet the specific needs of their own students. However, without

attention to each of the components addressed in this Implementation Guide, districts and

schools cannot reasonably expect to meet the needs of all students.

The SELI Workgroup interacted with and learned from many stakeholders: families, students,

community professionals, youth development professionals, teachers, principals, school board

members, school counselors, social workers, psychologists, superintendents, and others. The

Workgroup used this feedback to inform their development of an SEL Resource Package with a

framework consisting of three essential elements and four guiding principles. The Workgroup

determined that the essential elements are the key implementation practices that, when

grounded in the guiding principles, lead to successful SEL implementation and sustainability.

They also determined that the guiding principles form the foundation that grounds the SEL

work and connects and aligns it with other educational efforts.

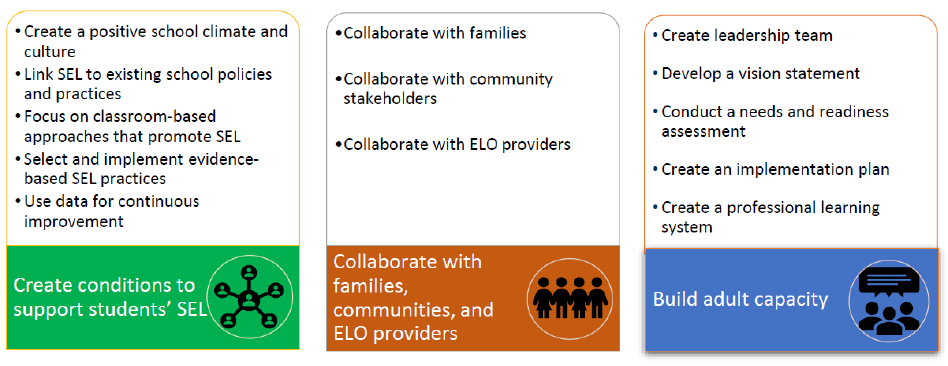

The following three essential elements are critical to ensuring that SEL efforts in schools stay

true to Washington State’s commitment to every child:

1. We must create the conditions to support student SEL – maintain a positive school climate

and culture and infuse SEL into school policies and practices inside and outside of the

classroom.

2. We must do this work in collaboration – with the full school community involved from the

outset of planning, through implementation and review. That includes families, students,

youth-serving organizations, educators, and professionals who play critical roles in the life

of a school (e.g., school counselors, social workers, and psychologists).

3. We must build adult capacity – readiness to engage our own social emotional skills to

support and relate with all students, to identify and counter bias, and to create learning

environments in which students feels safe enough to stretch their learning.

This work must be firmly grounded in the four guiding principles of equity, cultural

responsiveness, universal design, and trauma-informed practices. Figure 2 describes the

essential elements and guiding principles that make up the framework. “The goal of

Washington’s public education system is to prepare every student who walks through our

school doors for post-secondary aspirations, careers, and life. To do so, we must embrace an

approach to education that encompasses the whole child” (Reykdal, 2017, p. 1). To meet this

—C-5—

goal, we must support and challenge each other to consistently revisit the guiding principles at

each stage: planning; implementation, review, revision; and sustainability.

Figure 2. Framework for the Washington SEL Implementation Guide

Framework for the Washington Social Emotional Learning Implementation Guide

The framework commits to four guiding principles:

• Equity. Each child receives what he or she needs to develop to his or her full academic and social

potential.

• Cultural Responsiveness. Draws upon students’ unique strengths and experiences while orienting

learning in relation to individuals’ cultural context.

• Universal Design. Provides a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all

people by removing barriers in the curriculum.

• Trauma-Informed Practices. Recognizes the unique strengths and challenges of children and

youth in light of the adversities they face.

The framework has the following three essential elements:

• Create conditions to support students’ SEL by creating a positive school climate and culture,

linking SEL to existing school policies and practices, focusing on classroom-based approaches

that promote SEL, selecting and implementing evidence-based SEL practices, and using data for

continuous improvement.

• Collaborate with families, communities, and ELO providers in the design, implementation, and

review of local plans to integrate SEL in schools and communities.

• Build adult capacity in terms of awareness, attitudes, and skills that support SEL for all students

by creating a leadership team, developing a vision statement, conducting a needs and readiness

assessment, creating an implementation plan, and creating a professional learning system.

Each element of the framework for the Washington SEL Implementation Guide connects to the

others. Collaboration between families, schools, and communities will build programs, policies,

and practices that are responsive to the diverse cultures of each school community. To support

capacity building, schools must successfully integrate trauma-informed approaches and

universal design into SEL instructional practices or strategies. Engaging diverse perspectives in

the design, implementation, and review of SEL efforts can help identify signs of, and solutions

to, inequitable practices or outcomes.

A Community-Wide Vision for SEL

A community-wide vision for SEL that is connected and adapted to the community is essential.

As illustrated in Figure 3, schools create the conditions to support students’ SEL, collaborate

—C-6—

with families and communities, and build adult capacity to create engaging and inclusive

learning environments with positive youth–adult relationships that support SEL, academic

progress, and positive life outcomes for students. To develop the framework for the

Implementation Guide, the SELI Workgroup conducted community outreach sessions and

gathered input from diverse stakeholders. The process drew on the principles of codesign,

facilitated conversation, feedback on draft documents, public comment, and surveys. See the

Stakeholder Feedback and Community Outreach Summary for stakeholder feedback, the

community outreach process, and a copy of the

interview protocol.

The Washington SEL Implementation Guide:

• Supports local community needs and assets

• Is shaped by a commitment to equity, cultural

responsiveness, universal design, and trauma-

informed practices

• Approaches the social emotional development of

children as a shared responsibility among families,

educators, youth development professionals, and

other youth- and family-serving agencies and

organizations

Stakeholder Feedback Takeaway:

Families participating in feedback

sessions were supportive of SEL in

schools but did not want to see their

diverse cultural experiences and values

negated by implementation of

standards that do not value diversity.

Families want the opportunity to

understand in advance what the school

aims to teach their children; this lets

them explore the ideas along with the

students.

—C-7—

Figure 3. A Community-Wide Vision for Social Emotional Learning

—C-8—

Implementation Resources

The Washington SELI Workgroup developed implementation resources to support education

stakeholders as they implement SEL in schools. Figure 4 describes the implementation

resources.

Figure 4. Washington State’s SEL Indicators Implementation Plan Resources

Washington SEL Resource

Description

Use

Washington State SEL

Implementation Guide

Statewide implementation guide for

schools with three focus areas: creating

the conditions to support SEL, capacity

building, and engagement of local

communities in a collaborative process.

This guide helps Washington State’s

schools develop a comprehensive and

school/community-specific plan to

improve SEL outcomes for all of the

students they serve.

Help educators, administrators,

staff, parents and families and

community members

understand the need to develop

a coherent SEL plan to

implement at the school level.

(see SEL briefs included in this

resource package)

Standards, Benchmarks, and

Indicators (SBI)

A scaffolded tool to help answer the

question, “What are the ‘look fors’ when

assessing a student’s social emotional

learning competence?”

Help educators plan

opportunities for students to

learn, practice, and demonstrate

understanding of their emotions

and behaviors. (see SEL

Standards Benchmarks and

Indicators)

SEL Module

The online module is composed of five

segments that support systemic SEL

within schools and communities and

provide a structure as educators

implement the SBI.

Help educators, administrators,

school staff, other professionals,

parents and families who

interact with youth to build their

understanding of SEL.

The Washington State SELI has been careful to ensure that the Washington State Standards,

Benchmarks, and Indicators (SBI) and the Washington SEL Implementation Guide take the

following essential considerations into account as part of the design:

• Washington State’s student body is increasingly culturally and linguistically diverse.

• SEL is not a uniform system of experiences or values. Any SEL implementation must be

careful not to standardize a dominant culture’s set of values as universal.

• Bias, historical oppression, exposure to trauma, and inequitable access to resources

influence students’ social emotional skill development and adults’ perceptions of students’

skills.

—C-9—

Why Is Social Emotional Learning Important?

SEL competencies are necessary for success in academic learning and are associated with

increased academic achievement, higher income, better health, and social engagement (Durlak,

Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011; Farrington et al., 2012; Greenberg,

Domitrovich, Weissberg, & Durlak, 2017; Taylor, Oberle, Durlak, & Weissberg, 2017). Students

who have positive teacher relationships and a

sense of belonging engage more consistently in

learning, attend school more regularly, and

achieve at higher levels. SEL benefits all

students. All students benefit from being in

developmentally rich and safe environments and

having supportive adults who care about them

and take interest in their lives. But, SEL especially benefits students who face additional stress

due to trauma and adversity and lack of access to quality housing, food, health care, and safety

(The National Commission of Social, Emotional, & Academic Development. ). SEL also provides

an important and necessary foundation for approaches to discipline that are student centered

and restorative in nature (Osher et al., 2008; Osher, Bear, Sprague, & Doyle, 2010).

SEL Is a Whole-School Effort

Providing high-quality learning opportunities for SEL involves more than just choosing a

curriculum or adding circle time into a classroom routine. Although SEL implementation can

start with these types of practices, to achieve the best outcomes for students, SEL should be

intentionally integrated throughout the day. Schools need to build a positive school climate and

culture, explicitly teach social emotional skills, infuse SEL into academic instruction, partner

with families and communities, and teach all adults practices that can be used to promote SEL

(Jones & Kahn, 2017; Oberle, Domitrovich, Meyers, & Weissberg, 2016; Weissberg, Durlak,

Domitrovich, & Gullotta, 2015). SEL is most effective when it promotes cultural responsiveness,

equity, and youth voice. Ensuring student voice can ensure that SEL efforts do not overlook

student needs and insights.

Why Does SEL Matter for Washington’s Students?

Our public schools are doing well by many measures, but our state’s promise is to provide

ample support for the basic education of all children however, we see the results in data and in

individual stories of students who do not make it to graduation. Further, we know that we need

to prepare all students to be college and career ready. Often, employers say that the

Washington State's

Proposed SEL Standards

Self-Awareness

Social Awareness

Self-Management

Social Management

Self-Efficacy

Social Engagement

—C-10—

candidates who come to them do not have the necessary social emotional skills to be successful

in the workforce.

Intentional SEL Implementation Can Be an Opportunity to Advance Equity

Our state constitution promises a basic education to all children. Although our public schools

provide positive learning opportunities for many students, we cannot ignore the fact that we

continue to produce poor outcomes for disproportionate numbers of particular groups of

students. Racial and ethnic disparities compound for students with disabilities, who also, as a

group, face disproportionate discipline, higher rates of chronic absenteeism, and lower

graduation rates (Losen & Gillespie, 2012).

SEL can support a transformative approach to education through building skills and

competencies—founded on strong, respectful relationships, and focused on the appreciation of

similarities and differences—to develop collaborative solutions for community and social

problems (Jagers, Rivas-Drake, & Borowski, 2018).

If we rush to implement SEL without simultaneously addressing issues related to equity and

inclusion, we run the risk of reinforcing inequities in our schools and in our communities. By

developing SEL plans starting with equity in mind, Washington State can fulfill on its promise to

help all students do better in school and lead more successful and fulfilling lives. The

Washington SEL Implementation Guide allows for continuous adaptation at the individual,

school, and district levels to ensure SEL is equitable for students of all cultures, languages,

histories, identities, and abilities.

How Can We Implement SEL in Our School and Community?

Every district, school, and community across Washington State is unique, and there is no one-

size-fits-all approach to implementing schoolwide and community-wide SEL (see report: K–12

Social and Emotional Learning Across Washington). However, research on SEL implementation

points to some best practices to promote consistent and powerful outcomes for schools and

youth-serving organizations. Action steps and additional resources are provided in the Essential

Elements (p. 26) section of this guide. Using these elements as an outline to support schools

and communities in implementing SEL will ensure that they are using best practices from a

strong evidence base.

The Washington SELI Workgroup developed this guide specifically for Washington State schools

and communities. They identified guiding principles to support an integrated approach to SEL

and reflect leading research in the field. They also created SEL Implementation Guide:

Additional Resources (page 61) with other high-quality SEL implementation guides and supports

—C-11—

that are recommended to be used as additional resources during SEL implementation processes

(see SEL Annotated BibliographiesImplementation Guide: Resource List).

Where to Start? School and Community Readiness to Implement

Each school, district, and community has unique needs, resources, and readiness to implement

SEL. In a recent survey about SEL administered to Washington State district staff members, 91

percent of responding districts reported that SEL is reflected in their mission, goals, or strategic

plans, and 93 percent of districts reported having at least one school working to address SEL

(Petrokubi, Bates, & Denton, 2019). Only 14 percent of the 168 districts that responded

reported having adopted SEL-specific policies or procedures.

School administrators who have implemented SEL see considerable benefit in preparing their

staff for that journey. Implementing SEL is often met with mixed reactions. Many staff have

intense workloads, and SEL is often seen as “one more thing” for them to take on, rather than a

strategy that will ultimately benefit both their students and themselves. In an SEL-influenced

environment, students learn to manage their own behavior and to regulate their emotions,

leading to better-managed classrooms and fewer disciplinary issues. However, some staff might

experience a level of emotional vulnerability when they embark on teaching SEL to their

students. School leaders can help their school realize the potential benefits of an SEL-influenced

learning environment and alleviate feelings of vulnerability by providing professional

development on SEL for adults. Some schools that have not yet implemented SEL have spent up

to a year before regular professional development just to plan, acclimate, and prepare for

school implementation. It can be equally useful to include key community members and

families in the development.

No matter where a school is in its process of SEL implementation, we hope that this guide and

embedded resources can help serve the school and community in improving social emotional

and academic outcomes for youth.

Research and Evidence Base

In past years, SEL was sometimes treated as “just one more thing” to add to educators’ already

busy days and significant responsibilities. Research shows that implementing purposeful,

evidence-based SEL programs and practices improves students’ academic outcomes, attitudes,

and social emotional skills; improves students’ and educators’ sense of well-being and safety;

and reduces disciplinary incidents, emotional distress, and drug use (Durlak et al., 2011; Taylor

et al., 2017).

—C-12—

Research shows that we should expect to see the following benefits from successful SEL

implementation:

• Increased social emotional competencies in adults and children, which are essential for

navigating diverse communities (Darling-Hammond & Cook-Harvey, 2018)

• More positive relationships between and among children and adults, and between and

among the various adults who support children (Berg, Nolan, Yoder, Osher, & Mart, 2019;

Jones, Brush, et al., 2017)

• More positive environments that support children’s learning, in and out of school (Durlak,

Weissberg, & Pachan, 2010; Durlak & Weissberg, 2013; Jones, Brush, et al., 2017)

As these positive relationships and social emotional competencies increase, we expect to see

results in various indicators of school health and student success, including:

• An increase in regular student attendance and academic achievement (Durlak et al., 2011;

Taylor et al., 2017)

• A decrease in overall behavior referrals in schools (Sklad, Diekstra, De Ritter, Ben, &

Gravesteijn, 2012)

• An increase in student resilience (Cantor, Osher, Berg, Steyer, & Rose, 2018; Thompson,

2014)

• An increase in teacher/educator well-being and job satisfaction (Greenberg, Brown &

Abenavoli, 2016)

• An increase in family, school, and community connections and collaboration (Garbacz,

Swanger-Gagné, & Sheridan, 2015; Osher, Moroney, & Williamson, 2018)

• Improved public health (Greenberg, Domitrovich, Weissberg, & Durlak, 2017; Jones et al.,

2015; Jones et al., 2017)

• An increase in the number of students attaining a high school diploma, a college degree,

and a full-time job (Jones, Greenberg, & Crowley, 2015)

• A workforce that meets the needs of employers (National Network of Business and Industry

Associations, 2014; National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2016)

—C-13—

Reflection Question for Readers: What are some ways your school or district supports SEL

implementation?

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

—C-14—

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

—C-15—

Guiding Principles

Washington State has the opportunity to take a leading role in developing an intentional

approach to SEL that engages the full school community (families, educators, students, youth-

serving agencies, and community members) and is grounded in the principles of equity, cultural

responsiveness, universal design, and trauma-informed practices. These principles were

outlined in the first report from the Social Emotional Learning Benchmarks (SELB) Workgroup,

Addressing Social Emotional Learning in Washington’s K–12 Public Schools, and are further

refined in the current Washington SEL Implementation Guide based on new research on SEL.

Equity

According to the National Equity Project, “educational equity means that each child receives

what he or she needs to develop to his or her full academic and social potential” (National

Equity Project, 2019). This guide focuses specifically on issues of education equity as they relate

to race, gender, disability, sexual orientation, and economic status.

Equity does not happen by accident. It requires deliberate and continuous effort to understand

the likelihoodand actual impacts of programs, policies, and practices. It takes courage to face

up to inequitable outcomes and work to change when we have invested energy and resources

into developing processes or practices thought to be effective. The need for a purposeful and

reflective approach holds true for SEL implementation.

Research demonstrates that SEL can help reduce opportunity gaps with its focus on positive,

respectful relationships between students and educators as a foundation for learning. Equity

will not magically follow implementation of SEL programs without intentional and explicit effort

to plan, monitor, and revise for equitable outcomes.

1

Planning for equity includes deciding how

“success” of SEL efforts will be measured and what outcomes will be tracked and why. Moving

forward with implementation of SEL practices and strategies without attending to issues of

equity risks exacerbating existing inequities rather than reducing them.

Schools must move beyond planning and set concrete action steps for improvement. Each

school community will need to build inclusive working groups that will be able to look at

1

According to Marsh et al. (2018, p. 8), research “suggests that SEL support could foster greater equity for

traditionally underserved groups … research has also provided evidence of disparities in SEL support for African

American and Latinx students in comparison to their White peers. Scholars have observed gaps by race/ethnicity in

both perceptions of school culture/climate and in reported social emotional learning, echoing extensive literature

on racial inequities in educational resources (e.g., Baker, Green, 2005; Hough et al., 2017) and in academic

outcomes (e.g., CEPA, n.d.).”

—C-16—

current policies and practices and carefully assess the likely impacts of proposed SEL

approaches for equity. Racism in schools limits the beneficial effects of SEL through threats to

students’ identity development, stereotype threat, micro-aggressions, and reduced student

access to high-quality supports (Petrokubi, Bates, & Malinis, 2019). Approaching SEL with a

commitment to equity “requires addressing barriers at the systemic (poverty) institutional

(exclusionary discipline) and individual (implicit bias and burnout of staff) levels. This includes

efforts to recruit and retain a more diverse workforce that reflects the student population,

equity policies, professional development for educators, anti-bias trainings for educators, and

school-family-community partnership” (Petrokubi, Bates & Malinis, 2019, p. 6; see also

Simmons, Bracket, & Adler, 2018).

Considerations for Implementation

To implement an equity-focused SEL effort, consider the following questions:

• To what extent have you considered the historical, socio-political, and racialized context of

education in the United States when developing your SEL implementation plans?

• To what extent is creating equitable and accessible learning environments and outcomes an

explicit part of your SEL work?

• What opportunities do you have for adults to develop their own self-awareness, social

emotional intelligence, and cultural competence and to surface and confront the ways in

which they contribute to racial vulnerability of students?

• Are your practices and policies grounded in the understanding that all learning is social and

emotional and that all students are oriented to opportunity and belonging in our

communities and schools?

• To what extent do you use SEL practices to facilitate healing from the effects of systemic

oppression, build cross-race alliances, and create joyful, liberatory learning environments?

• Do your policies and practices build new opportunity structures and pathways to existing

opportunities, rather than reproduce racial inequity?

For more information, see the National Equity Project, which proposes practices for advancing

education equity through SEL.

Cultural Responsiveness

Culture is a complex concept. At times culture is defined by race or ethnicity. It may be

tempting to attempt to distill different cultures into a set of rules in which a person can become

competent (and thereby avoid offending those who come from those cultures). However, this

—C-17—

rule-setting attempt to better connect with individuals who come from different cultures is

inappropriate. Culture is fluid and dynamic, with variations within cultural groups based on

race, ethnicity, age, gender identity, sexual identity, immigration experience, and community

type (e.g., rural, urban) (Petrokubi, Bates, & Malinis, 2019). Although many broad behaviors

and SEL competencies (e.g., self-awareness or social awareness) are found across cultures, the

way they are defined, expressed, and achieved is socially and culturally influenced (Petrokubi,

Bates, & Malinis, 2019; Simmons, Brackett, & Adler, 2018).

Culturally responsive approaches draw upon students’ unique strengths and experiences while

orienting learning in relation to individuals’ cultural context (Gay, 2013). Cultural

responsiveness addresses existing issues of power and privilege and can empower all students

in ways that respect and honor their intersecting cultural influences. Social emotional

competencies such as self-awareness and social awareness are necessary to recognize the

influence of one’s own

culture and to interact with

others in a culturally

responsive way.

Delivering a culturally

responsive education

requires ongoing attention

to attitudes, environments,

curricula, teaching

strategies, and

family/community

involvement efforts. To be

culturally responsive, we

must use culturally

competent and responsive

approaches: fully engage

with the students, families,

and staff who comprise our

school communities;

support educators in

recognizing their own

cultural perspectives; and

identify SEL approaches that are culturally responsive (see the Culturally Responsive Practices

Brief).

Example of a Washington Standards Benchmarks and Indicators

That Consider Cultural Responsiveness (see Standards, Benchmarks and

Indicators in the SEL Resource Pacakge for a complete list)

STANDARD 4

SOCIAL AWARENESS – Individuals have the ability to

take the perspective of and empathize with others from

diverse backgrounds and cultures..

BENCHMARK

4B

Demonstrates an awareness and respect for similarities

and differences among community, cultural, and social

groups.

Early

Elementary

Late Elementary

Middle School

High

School/Adult

With adult

assistance, I

can identify

ways that

people and

groups are

similar and

different.

I can identify how

backgrounds can

be similar and

different and can

demonstrate

acceptance of

differing social

beliefs and

perspectives.

I can practice and

adapt clear

strategies for

accepting,

respecting, and

supporting

similarities and

differences

between myself

and others.

I can identify

how

perspectives and

biases affect

interactions with

others and how

advocacy for the

rights of others

contributes to

the common

good.

—C-18—

Considerations for Implementation

To implement a culturally responsive SEL effort, consider the following questions:

• What supports do you have in place to allow adults in your school to critically examine their

own socio-cultural identities and biases?

• What professional learning opportunitieson the importance of respecting cultural

differences are available to adults in your school?

• What types of curricular and instructional materials related to the cultures of your students

do you have available to teachers?

• In what ways does the school provide support for adults in the school to get to know

individual students’ past experiences?

• To what extent do teachers take an interest in, and use in their teaching, students’ past

experiences, home and community culture, and world in and out of school?

• To what extent does your school build inclusive classroom environments?

For more information, see the Equity Assistance Center at Education Northwest’s Culturally

Responsive Teaching Guide.

Universal Design

Learners vary in how they perceive, engage with, and execute a task (CAST, 2018). Schools and

educators must expect variability among learners and plan in advance for ways to ensure access

to SEL instruction and opportunities to practice SEL skills for all learners.

We know our schools include diverse learners with various abilities and disabilities. Designing

learning environments that take into account this variability reduces barriers and recognizes

the strengths of learners. The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), a leading

organization in the field of education design and implementation, explains that universal design

for learning “aims to change the design of the environment rather than to change the learner.

When environments are intentionally designed to reduce barriers, all learners can engage in

rigorous, meaningful learning” (CAST, n. d.)

The concept of universal design originates in designing physical environments that are inclusive.

If a district were planning to build a new middle school in 2020, it would not consider breaking

ground with a design that left out a ramp for wheelchair users, or a fire alarm system with both

visual and audio signals. Similarly, we should not be comfortable “breaking ground” on a new

—C-19—

SEL program without planning in advance how it will incorporate accessibility and flexibility for

different learners.

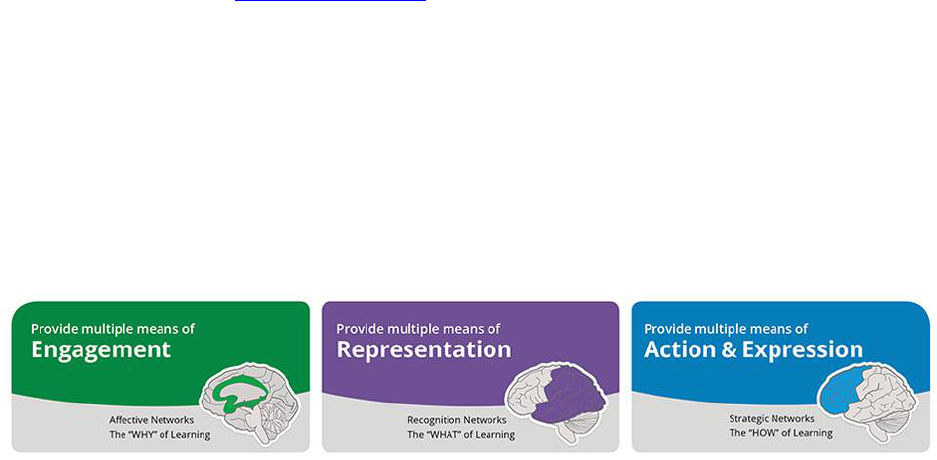

UDL is a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on

cognitive neuroscience. The UDL Guidelines provide educators with specific, concrete

suggestions, applicable to any discipline or domain of learning to ensure broad access for all

learners. The guidelines cover strategies for offering multiple means for representing

knowledge or understanding and for presenting new material. The UDL Guidelines are

organized according to three principles of UDL as illustrated in Figure 5: Engagement,

Representation, and Action and Expression. Each principle is broken down into guidelines, and

each guideline has “checkpoints” with more detailed suggestions.

Figure 5. Universal Design for Learning Principles

Source: UDL Guidelines. http://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/about-graphic-organizer

The Washington SEL Implementation Guide provides an opportunity to engage universal design

principles from the planning stages through implementation and review. When schools and

educational institutions implementing SEL commit to the concepts outlined in the

Implementation Guide, they will create an alliance of educators, families, and community

professionals who can collaborate and share best practices for universal design in SEL.

—C-20—

Considerations for Implementation

To implement an SEL effort that incorporates principles of universal design, consider the

following questions:

• How are you considering variability in students’ reading, listening comprehension,

communication, and other skills when you select and design SEL curricula and lesson

plans?

• How do you consider variability in students’ social emotional and academic development

when teaching and integrating social emotional skills?

• What universal design approach do you use to maximize “desirable challenges” (such as

the challenge to meet high standards) and minimize “undesirable” ones (such as

frustration and boredom), and identify how SEL can better equip students to react to

both?

• How are you intentional in the student-level data you collect, analyze, and use to

determine students’ SEL needs, and are the data available to the right people at the right

time to influence learning conditions for students?

• In what ways are classroom teachers provided ongoing professional learning

opportunities to support the provision of a safe and supportive learning environment,

conditions for collaboration and community, and opportunities to practice social

emotional skills for all students?

• How are appropriate professionals/teachers empowered to conduct small group and/or

more targeted social emotional learning interventions for students who need extra

support?

• Which systems are in place to recognize the need for and provide individualized social

emotional intervention and goal setting when needed?

For more information, see Ohio’s UDL and UDL and SEL webpage, which provides materials

that highlight how UDL can be incorporated into SEL.

Trauma-Informed Practices

Trauma is broadly defined as “any experience in which a person’s internal resources are not

adequate to cope with external stressors” (Davidson, 2017, p. 4). It can be provoked by one-time

experiences (such as divorce or the death of a family member) or ongoing experiences (such as

abuse and neglect). Trauma may also be a collective experience, such as the historical trauma

—C-21—

Native American and Alaska Native communities have suffered. Historical trauma is “cumulative,

collective emotional and psychological injury over the lifespan and across generations resulting

from a history of group trauma experiences” (Petrokubi, Bates, & Malinis, 2019, p. 5).

Washington State’s SEL Module has a segment devoted to this subject of common approaches

to selecting and adapting evidence-based programs to meet the needs of all students.

The potential effects of trauma on children and youth who have had adverse childhood

experiences

2

must be considered when striving for an equitable approach to learning, including

SEL (DeCandia & Guarino, 2015; Thompson, 2014). A trauma-sensitive approach recognizes the

unique strengths and challenges of children and youth in light of the adversities they have

faced. Exposure to trauma can have neurological effects that impede the learning process as

well as students’ ability to cope with stress (Cantor et al., 2018). Because of this, teachers must

be aware of the need to adapt practices to better serve students experiencing the effects of

trauma and adjust their thinking about trauma-triggered behaviors (Walkley & Cox, 2013).

Adults who experience secondary effects of working with students who are affected by trauma

also need support themselves (Davidson, 2017; Petrokubi, Bates, & Malinis, 2019). It is also

important to note that children in under-resourced living environments are at greater risk for

chronic traumatic exposure and its effects (Blair & Raver 2016).

Fortunately, educators can play a powerful role in helping students to build resilience through

supportive relationships and trauma-informed teaching practices. Trauma-informed practices

are grounded in the following (DeCandia & Guarino, 2015):

• Understanding of adverse childhood experiences and their prevalence

• Recognition of the signs and symptoms of trauma

• Understanding of the effects of trauma on the developing brain

• Recognition of the survival strategies employed by students who have experienced trauma

• Responses that ensure a physically and emotionally safe learning environment

• Commitment to fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and

practices

2

The common definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) involves stressful or traumatic events

experienced before age 18 that fall into three broad domains: abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction (e.g.,

Burke Harris & Renschler, 2015). ACEs can include experiences such as abuse, parental separation or divorce,

parental substance abuse, and parental mental illness. ACEs can also include personal victimization, hunger,

disturbances in family functioning, loss of a parent, challenging peer relationships, and poor health), and ecological

risk factors, including community violence, economic hardship, racial and other forms of discrimination, and

stressful experiences within the school (e.g., Cantor et al., 2018; Wade, Shea, Rubin, & Wood, 2014).

—C-22—

• Active measures to resist re-traumatization

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (2008) provides guidance on how school

personnel can help a student with traumatic grief. Trauma-informed practices can include

informing school administrations and school counselors/psychologists about concerns about a

student and making yourself available to talk about experiences of trauma. Teachers can be

flexible in balancing daily school expectations with sensitivity to students’ experiences of

difficulty and use strategies to encourage self-regulation skills.

SEL can be an empowering tool for youth who have experienced trauma, as it can afford

students greater self-awareness and management skills to cope, social awareness and skills to

interact appropriately with others despite the effects of trauma, and decision-making skills to

navigate life circumstances from a foundation of social emotional competency (Darling-

Hammond, Flook, Cook-Harvey, Barron, & Osher, 2019; Weissberg, Durlak, Domitrovich, &

Gullotta, 2015). SEL also helps to create a climate in which all youth, including youth who have

experienced trauma, feel respected and supported. A focus on SEL gives educators an

opportunity to focus on building positive relationships with students, to partner with their

families, and to collaborate with other youth-serving organizations in their school communities.

These relationships and partnerships provide a foundation both for trauma-informed responses

and for supporting social emotional learning. In this way, trauma-informed practices can be

thought of as “healing-centered” practices.

States are beginning to connect SEL and trauma-informed practices at all levels of the school

system. For example, Tennessee calls the integration of social and personal competencies

schoolwide and in classrooms a “buffer to the effects of trauma” (p. 8) and calls for a trauma-

informed approach to SEL implementation. New York does the same (giving special attention to

the need for educator support regarding the implementation of trauma-informed practices),

and points to external resources. In addition, Michigan recently developed an online module

connecting SEL and trauma. Delaware and Wisconsin connect trauma-informed practices to

their SEL work. (for futher information see National Environmental Scan in the Resource

Pacakage supporting documents).

Considerations for Implementation

To implement a trauma-informed SEL effort, consider the following questions:

• To what extent are adults in your school provided ongoing professional learning

opportunities on the effects of adverse childhood experiences and resulting trauma on

learning and behavior?

—C-23—

• To what extent are adults in your school supported in the implementation of both (1)

universal strategies that are trauma-informed and (2) customizable strategies in working

with students experiencing the effects of trauma?

• To what extent do adults take a strength-based approach in working with students?

• To what extent does your school employ policies and practices such as restorative justice,

Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS), wraparound mental health services,

and trauma-sensitivity training—practices that move away from punitive and exclusionary

discipline practices, and build a “healing” culture and climate?

• To what extent does your school encourage and sustain open and regular communication

for everyone in the school community?

• To what extent does your school use data to identify vulnerable students and determine

outcomes and strategies for continuous quality improvement?

• What tiers of support and flexible accommodations does your school provide to address

different students’ needs?

• To what extent does your school provide access, voice, and ownership to staff, students,

and community?

• To what extent does your school support adult awareness of one’s own history or ongoing

experience of trauma; how it may affect interactions with students, families, and

colleagues; and strategies to recognize and cope with the secondary trauma that can result

from working with students of varied backgrounds?

For more information, OSPI provides 10 Principles of a Compassionate School; also see The

National Child Traumatic Stress Network Child Trauma Toolkit for Educators.

—C-24—

Question: How would your school use the four guiding principles (equity, cultural

responsiveness, universal design, and trauma-informed practices) to approach SEL

implementation?

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________________

—C-25—

ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF THE

WASHINGTON SEL

IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE

—C-26—

Essential Elements of the Washington SEL Implementation

Guide

In this section, we discuss each of the essential elements of the SEL Implementation Guide in

more detail. Each element is composed of multiple components, and for each component,

there are potential action steps for successful implementation and linked resources for further

information about how to implement the component in your school. The steps listed here are

not a comprehensive list of activities, but suggested work that schools and districts may pursue.

Figure 6. Essential Elements of the SEL Implementation Guide

Build Adult Capacity —C-27—

Build Adult Capacity

Educators play an essential role in creating safe and supportive learning environments;

therefore, building the capacity of the adults in the school setting is critical to shaping the

culture of the school and setting the stage for positive outcomes for children (Jones & Kahn,

2017). Building adult capacity starts with creating a strong leadership team that can begin to

implement SEL. Adult capacity is strengthened through the creation of a vision statement, a

needs and resource assessment, and a comprehensive implementation plan. SEL involves adult

learning and unlearning; it is important for adults to reflect on their own social emotional

awareness and to identify factors or situations that either trigger distress or expand their ability

to connect, learn, and grow as adults (Greenberg, Brown, & Abenavoli, 2016). Effective SEL

requires adults to shift their mindsets, skills, and behaviors to model SEL and promote equity

and inclusion for all students. Building the space and time for self-reflection involves creating a

professional learning system that will support SEL efforts. Washington State’s SEL Module has a

focus on the importance of sdult SEL to meet the needs of all students.

Create a Leadership Team

An important early step in SEL implementation is the formation of a leadership team. Research

has shown that engagement and active support from school leaders is the biggest predictor of

whether whole-school implementation takes hold and has a positive impact on students'

growth (Devaney, O’Brien, Resnik, Keister, & Weissberg, 2006).

The leadership team’s responsibilities should include developing a shared vision for SEL, setting

realistic goals, overseeing the process of implementation, facilitating clear communication, and

monitoring outcomes. When assembling a team, school leaders need to consider the skills and

resources that team members bring to the table (such as existing knowledge of SEL, enthusiasm

for the vision of schoolwide SEL, knowledge of school culture and operations, knowledge of

data collection and feedback processes, communication and collaboration skills, and time to

commit to the work of implementation).

School leaders need to look beyond the school building for leadership team members. Families

and community professionals can bring valuable knowledge, perspectives, and resources of

their own. The family is the central place where specific skills and competencies (as well as

broader attitudes and values) are formed (National Commission on Social, Emotional, &

Academic Development, 2018). It is valuable to include families in SEL planning efforts, to

proactively seek their input, and to maintain ongoing communication. Family members can

offer insight into the diverse cultural strengths students bring to the classroom. Community

partners working with youth see another side of our students’ lives and have perspectives that

Build Adult Capacity —C-28—

can enrich the process of implementing SEL at school. Building relationships with families and

community members and involving them in every stage of the implementation process builds

trust and enables the leadership team to be more understanding of, and responsive to, the

needs and values of the communities to which they belong.

Action Steps

Schools can do the following to create a strong leadership team:

• A leadership team should include a school leader (e.g., administrator, lead teacher, or

support staff), representation from various positions within the school (e.g., administrators,

teachers, student support staff), and partners representing the broader community.

• Key partners (teachers, students, families, building staff, community partners) representing

diverse perspectives and backgrounds should be engaged right away for input into every

stage of planning to ensure cultural sensitivity throughout the process. When selecting key

partners, consider who will be most involved in or affected by SEL implementation.

• Ensure that there is Tribal consultation and collaboration and that this representation

meets all federal requirements. Include the Tribal designee from a local Tribal government

as part of the leadership team to ensure that implementation of SEL is a collaborative,

trustful, and respectful process that recognizes the sovereignty of Native communities and

Native students.

Once the leadership team is created, it needs to:

• Learn background information about SEL and what’s happening at the state and district

level and engage in SEL professional development to more deeply understand and model

SEL best practices.

• Communicate with the state and district, within the leadership team, and with a broader

community of stakeholders and coordinate competing initiatives.

• Plan implementation, oversee professional training and development, guide

implementation to ensure plans are being implemented as written, and set reasonable

goals and expectations.

• Assess and collect data on the success of implementation and use the information to

continuously improve practices accordingly.

Build Adult Capacity —C-29—

Resources

CASEL SEL School Implementation Guide: Create a Team. This section of the schoolwide

Implementation Guide outlines the process for recruiting, forming, and sustaining an SEL

leadership team to manage the SEL planning and implementation process for the school.

School Climate Resource Package. This package is full of tips and resources for improving school

climate, including effective strategies for developing a school leadership team. The guide was

developed by the National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments (NCSSLE) at

American Institutes for Research (AIR), contracted by the U.S. Department of Education.

NIEA Consultation Guides. The National Indian Education Association provides three guides to

Building Relationships With Tribes: A Native Process of ESSA Consultation. This resource is

meant to provide states and districts the high-level strategies necessary to build trusting,

reciprocal, and long-lasting relationships with the Tribal nations.

Create a Vision

An early task of the leadership team is to craft a vision statement that expresses the community’s

aspirations with regard to social emotional learning. At a team meeting, members might be

asked to reflect together on some of the following questions: What are our core values, and

who are we striving to become? What skills, understanding, and relationships do we want

members of our community to develop? What kind of culture are we intending to build?

A vision statement can impart a powerful, shared sense of the importance of SEL

implementation. Team members work together to craft a draft of the vision statement that

conveys their hopes and expectations for SEL. By seeking feedback on the draft vision

statement from key stakeholders, the leadership team invites the community to participate in a

dialogue about the culture we seek to build together to nurture the social emotional and

academic lives of young people. After feedback has been collected, the leadership team creates

a final vision statement that can bring together and motivate the community and that reminds

them of the goals that the work of implementation will serve. The vision statement should also

be used to drive the school’s SEL efforts and will provide structure and coordination to

effectively implement that vision.

Why? A vision statement with clear goals can serve as a rallying cry to generate commitment to

SEL throughout the system and to provide a focal point for an aligned and integrated

approach—it ensures that everyone is on the same page in terms of purpose, goals, and

methods of SEL implementation.

Build Adult Capacity —C-30—

Who participates? The leadership team crafts the vision with input from key stakeholders to

ensure broad understanding and acceptance and cultural responsiveness.

What? An SEL plan should include a framework for supporting children in developing SEL skills.

Action Steps

To create a vision statement, consider the following:

• Consider including language that reflects the overarching values and ensures broad

understanding, acceptance, and cultural responsiveness.

• Brainstorm innovative ideas with established and new partners.

• Ask stakeholders to engage in the vision development process.

• Once you have developed your vision statement, consider developing talking points or a

communication guide (or both) for communicating your vision, plan, and why SEL is

important (both internally and externally).

Resources

CASEL School SEL Implementation Guide: Developing a Shared Vision. This resource outlines the

what, where, when, why, and who of a schoolwide vision and plan for SEL implementation. The

document includes a rubric for assessing the development of a shared vision and goals for SEL,

a step-by-step process for how to engage in the work, vision statement examples, and a

conversation guide for vision conversations with your team.

Assess Needs and Resources

Many schools are already implementing practices that may or may not fit within the

Washington SEL Implementation Guide. These practices may need to be identified and aligned

to the Implementation Guide. To help with this process, schools and districts can conduct

resource and needs assessments to support their SEL efforts. A needs assessment is a systemic

process designed to assess the strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement within an

organization (Corbett & Redding, 2017). It is important to consider multiple kinds of data when

conducting the assessment (e.g., policy and procedural data, demographic data, student

performance data, and perception data) to capture a robust picture of all factors affecting and

affected by SEL in the school. Needs assessments give the leadership team an opportunity to

understand the needs of students and staff; resource assessments help leadership teams

understand the available materials to support the effort, including understanding the various

efforts underway that already support SEL.

Build Adult Capacity —C-31—

Action Steps

Before conducting a needs assessment, develop a comprehensive plan. The completed

assessment plan should yield the what, when, who, how, and why of the SEL program (Wrabel,

Hamilton, Whitaker, & Grant, 2018). Additional steps in developing a needs assessment include

the following:

• Assess available resources, priorities, and systems to support SEL—at the district, school,

classroom, and individual role levels (including support staff, cafeteria workers,

maintenance personnel, community partners, etc.).

• Identify data sources that can inform a needs assessment for SEL. Sources can include

administrative data, surveys and observations of school/classroom environments,

professional development offerings and participation, information about existing SEL

curricula in school and during out-of-school time, district and school SEL priorities and goals,

local conditions (neighborhood conditions, family poverty levels, adverse childhood

experiences), and youth SEL competency assessments.

• Needs assessments should be used to identify potential sources of inequity; once identified,

plans should be developed to address them.

• The leadership team (with family- and community-partnership feedback) can ask guiding

questions to structure the work: What are our existing resources that will help us in this

work? What existing programs can we build upon? Who can help us in the work?

• Consider also assessing the degree to which individuals within an organization are

motivated and have the capacity to take on SEL implementation.

Resources

CASEL Schoolwide SEL Implementation Rubric. This resource includes a rubric to guide schools

through a review of their current level of SEL implementation. The rubric helps schools identify

needs and resources, set goals, and develop concrete action steps for SEL. It can also be used as

a tool by school teams as part of an internal information gathering or a quality improvement

process.

Using Needs Assessments for School and District Improvement. This guide, from the Center on

School Turnaround, is designed to help state and local education agencies and schools design

needs assessments that are aligned with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

Investing in Evidence-Based Social and Emotional Learning: Companion Guide to Social

Emotional Learning Interventions Under the Every Student Succeeds Act: Evidence Review. This

Build Adult Capacity —C-32—

RAND Corporation report provides guidance for schools on using federal ESSA funds to select

and implement a high-quality SEL program.

Create an Implementation Plan

Develop an implementation plan based on the needs and resource assessments and align this

plan to your vision.

A schoolwide or community-wide plan for SEL serves a number of roles:

• Creates a roadmap to ensure successful, high-quality SEL implementation,

• Communicates to the community that the school is committed to the work,

• Guides and keeps the school on track to achieve the vision and mission,

• Articulates information about professional learning and curricula and the process of

implementation, communication, and evaluation,

• Includes tasks, timelines, milestones, division of responsibilities, and resources, and

• Aligns with district and state guidelines.

Implementation is an iterative process and involves all district stakeholders in continuous cycles

of improvement. The implementation process is purposeful and is described in enough detail

that an independent observer can identify the specific set of activities being carried out and

measure their strength (National Implementation Research Network, 2019). According to the

National Implementation Research Network, a strong implementation plan defines what

effective interventions need to be carried out, how they will be carried out, who will carry them

out, and where they will be carried out. Good implementation is the bedrock of an SEL

program’s success and largely depends on thoughtful guidance by school and district leaders

who are strategic, invested, and supportive.

Improving the SEL skills, culture, and climate of your school is more than just choosing and

implementing curricula that explicitly teach SEL skills (although this should be a part of it). Your

plan should include professional learning, communication, and assessment. Your plan should

also embed SEL into the ecosystem of your school and should be integrated into policies,

procedures, academic curricula, staff practices, and existing frameworks (such as multi-tiered

systems of support [MTSS], PBIS, wellness programs, and trauma-informed practices).

Build Adult Capacity —C-33—

Action Steps

Your school can take the following steps for successful SEL implementation:

• Identify the who, what, how, and where of your implementation plan.

• As in the planning process, keep key stakeholders engaged to ensure broad perspectives

and generate wide understanding and acceptance.

• Develop a communication plan for how you’ll explain SEL to parents, teachers, community

partners, and others. Incorporate inclusive and varied ways for communicating to all

stakeholders.

• Articulate long-term and short-term outcome goals for your plan as well as how your school

will measure success.

• Plan the rollout of the SEL effort, including ways in which SEL will be embedded throughout

multiple initiatives, how it will be explicitly taught to students, and how it will become

integrated as a way of doing things in the school.

Resources

The National Implementation Research Network’s Active Implementation Hub. This resource

provides a set of online materials, tools, and guides to promote the knowledge and practice of

implementation science.

CASEL Guide for Schoolwide SEL: Communication Planning. This online resource provides

support for schools as they work on developing communication strategies to keep stakeholders

engaged and excited about SEL implementation. The guide’s section on Foundational Learning

also has some helpful resources for communicating the “big ideas” behind SEL, including a

sample introductory presentation and a list of supporting research.

SEL: Feedback and Communication Insights from the Field (The Wallace Foundation). This

document explores the language around SEL and defines the many different terms that are

used around the country to define both social emotional competencies and skills. The

document also discusses the research it draws on and which terms were the most motivating

and understandable.

Create Professional Learning for SEL

Meaningful, intensive, and ongoing professional learning opportunities for educators are vital

for strengthening and sustaining SEL efforts (Reyes, Brackett, Rivers, Elbertson, & Salovey,

Build Adult Capacity —C-34—

2012). A cohesive professional system shows educators the relevance of professional learning

to their daily work:

If teachers sense a disconnect between what they are urged to do in a professional

development activity and what they are required to do according to local curriculum

guidelines, texts, assessment practices, and so on—that is, if they cannot easily

implement the strategies they learn, and the new practices are not supported or

reinforced—then the professional development tends to have little impact (Darling-

Hammond, Wei, Andree, Richardson, & Orphanos, 2009, p. 10).

Teachers often understand the importance of SEL, but they do not feel that they have the time

or resources to implement SEL in their classrooms (Yoder & Gurke, 2017). Schools and districts

need to ensure that staff receive pre-service training and ongoing, job-embedded professional

learning related to SEL (including coaching and professional learning communities); adequate

time to plan, teach, and integrate SEL; and time to collaborate across roles (e.g., counselors and

teachers) to better support students. To support teachers in their efforts to implement SEL-

related practices, coaches and administrators can observe teacher practice and provide

feedback (Yoder & Gurke, 2017). Key training topics include culturally responsive SEL,

developmentally appropriate SEL, and family engagement in SEL.

Consider reviewing Washington State’s SEL Module, learning segment 3: Creating a Professional

Culture on SEL. It is a starting point for identifying the importance of adults’ social emotional

competencies—for their work with students and their own well-being. The module also

provides strategies and action steps for building a culture focused on SEL.

Action Steps

Schools can create a professional learning system by taking the following steps:

• Develop professional learning for ongoing activities, implementation, and action planning

based on the needs and resource assessment.

• Embed multiple forms of professional learning on SEL, including workshops, virtual learning

experiences, book studies, professional learning communities, coaching and ongoing

support.

• Embed SEL activities within all professional development activities, such as welcoming

rituals and optimistic closures, so that adults can see the benefits of SEL for themselves.

• Create time during the school day for adults to meet with students with an agenda for

relationship building and non-academicly based conversation.

Build Adult Capacity —C-35—

• Provide opportunities and spaces for adults to reflect on their own social emotional

competencies and attune to their own emotional well-being.

• Connect professional development opportunities with existing curriculum guidelines,

assessment practices, teacher effectiveness frameworks, and initiatives so that educators

can easily implement the strategies they learn.

• Recognize and support all adult staff within the school—as well as families and

communities—as important implementers of SEL. Provide learning opportunities for all

adults who interact with students, equipping them to model social emotional competencies

consistently throughout the school day.

• Consider partnering with ELOs, community-based organizations, and parents/families in

offering professional development opportunities that promote SEL.

• Incorporate anti-bias professional development and personal reflection tools that support

adults in being receptive to diverse perspectives of students, families, and community

members (see https://gtlcenter.org/sites/default/files/SelfAssessmentSEL.pdf).

Resources

Sample documents that focus on educator professional learning related to SEL include the

following:

Social and Emotional Learning Guiding Principles (p. 3). California’s third SEL principle—build

capacity—emphasizes the need to provide pre-service SEL training and ongoing professional

development for educators.

Educator Effectiveness Guidebook for Inclusive Practice. Created by Massachusetts educators,

this guidebook includes SEL implementation and learning tools for districts, schools, and

educators that are aligned to the MA Educator Evaluation Framework and that promote

evidence-based best practices for inclusion.

Guidelines on Implementing Social and Emotional Learning Curricula (pp. 7–8). This document

contains guidelines for Massachusetts schools and districts on how to effectively implement

social and emotional learning curricula for students in Grades K–12.

Connecting Social and Emotional Learning to Michigan's School Improvement Framework (pp.