The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S.

Department of Justice and prepared the following final report:

Document Title: Data and Research on Human Trafficking:

Bibliography of Research-Based Literature

Author: Elżbieta M. Goździak ; Micah N. Bump

Document No.: 224392

Date Received: October 2008

Award Number: 2007-VT-BX-K002

This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally-

funded grant final report available electronically in addition to

traditional paper copies.

Opinions or points of view expressed are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the official position or policies of the U.S.

Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking:

Bibliography of Research-Based Literature

ELŻBIETA M. GOŹDZIAK, PH.D.

AND

MICAH N. BUMP, M.A.

Institute for the Study of International Migration,

Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University

October 2008

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking:

Bibliography of Research-Based Literature

FINAL REPORT

September 2008

AUTHORS:

ELŻBIETA M. GOŹDZIAK, PH.D.

PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR

AND

MICAH N. BUMP, M.A.

RESEARCH ASSOCIATE

INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION

Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service

Georgetown University

Washington DC

Prepared for

Karen J. Bachar, Ph.D.

Social Science Analyst

Violence and Victimization Research Division

Office of Research and Evaluation

National Institute of Justice

U.S. Department of Justice

NIJ GRANT-2007-VT-BX-K002

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgements............................................................................................................. 3

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 4

Abstract............................................................................................................................. 12

Introduction...................................................................................................................... 13

Compiling the Bibliography............................................................................................. 15

Sources and Databases Searched........................................................................................... 15

Search Terms Used ................................................................................................................. 17

Results of the Search Process.......................................................................................... 18

Manual Purging and Initial Analysis of Results................................................................... 18

Development of the Taxonomy........................................................................................ 21

Journal Articles................................................................................................................26

Empirical Nature..................................................................................................................... 26

Disciplinary Focus................................................................................................................... 28

Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 29

Sampling .................................................................................................................................. 30

Trafficking Type ..................................................................................................................... 31

Trafficked Populations ........................................................................................................... 33

Reports.............................................................................................................................. 35

Authoring Organization ......................................................................................................... 35

Empirical Nature..................................................................................................................... 36

Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 37

Discipline and Methodology................................................................................................... 37

Discipline and Sampling .........................................................................................................38

Empirical Nature, Peer Review and Trafficking Type........................................................ 38

Discipline and Trafficking Type ............................................................................................ 39

Trafficked Populations ........................................................................................................... 40

Books ................................................................................................................................ 41

Research Gaps.................................................................................................................. 43

Scope......................................................................................................................................... 43

Theory ...................................................................................................................................... 43

1

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 44

Neglected Issues and Topics ................................................................................................... 45

References ........................................................................................................................ 48

2

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It would not have been possible to complete this research project without the assistance

of several individuals.

At the National Institute for Justice (NIJ), we wish to convey our gratitude to our Project

Officer Dr. Karen J. Bachar, Social Science Analyst in Violence and Victimization

Research Division in Office of Research and Evaluation, for her guidance, support, and

patience at every step of this endeavor. This project would have been exceedingly more

difficult without her intellectual input and cheerful disposition. We are also very grateful

to Dr. Cindy J. Smith, Chief of the International Center at NIJ, for her support throughout

this research and invitation to present preliminary findings from this project to the Senior

Policy Operating Group on Human Trafficking.

At Georgetown University, we are thankful to our graduate research assistants Raluca

Georgiana Golumbeanu and Jitka Jerabkova who worked tirelessly in preparing the

EndNote database. We wish to thank Dr. Bill Olsen, the Principal Social Sciences

Bibliographer at the Lauinger Memorial Library, for his assistance in identifying

appropriate bibliographic databases and training our research assistants.

We thank the two anonymous peer-reviewers who provided many helpful comments that

substantially improved this report. We are particularly pleased to hear that “the depth and

extensiveness of the literature review on human trafficking is unprecedented” and that

that “the development of the taxonomy will be of great assistance to future research

efforts.”

While we received assistance from many individuals, the content of this report (including

any errors there may be) is the sole responsibility of the authors of this report. Our

interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are our own and do not necessarily

reflect the official position of the National Institute for Justice (NIJ).

3

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The subject of human trafficking, or the use of force, fraud or coercion to transport

persons across international borders or within countries to exploit them for labor or sex,

has received renewed attention within the last two decades. In the United States, human

trafficking became a focus of activities in the late 1990s and culminated in the passage of

the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) signed into law on October 16, 2000.

With the enactment of the TVPA, the United States took a lead in combating human

trafficking, prosecuting traffickers, and protecting victims. Subsequent reauthorization

legislations, the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Acts of 2003 and 2005,

further strengthened the US anti-trafficking initiatives.

While the majority of experts on human trafficking assert that the greatest number of

victims of trafficking are women and children, there is little systematic and reliable data

on the scale of the phenomenon; limited understanding of the characteristics of victims

(including the ability to differentiate between the special needs of adult and child victims,

girls and boys, women and men), their life experiences, and their trafficking trajectories;

poor understanding of the modus operandi of traffickers and their networks; and lack of

evaluation research on the effectiveness of governmental anti-trafficking policies and the

efficacy of rescue and restore programs, among other gaps in the current state of

knowledge about human trafficking.

Such information is vital to helping decision-makers craft effective policies, service

providers develop culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate and efficacious

programs, and law enforcement enhance their ability to identify and protect victims and

prosecute traffickers. Further, those responsible for addressing trafficking in persons and

related issues must be able to differentiate between the often sensational publications

intended to raise awareness about the issue and the more serious literature, based on

systematic, methodologically rigorous, and peer-reviewed empirical research

(qualitative, quantitative, legal, policy analysis, etc.).

With these assumptions and needs in mind, the Institute for the Study of International

Migration (ISIM) at Georgetown University embarked on a project, supported by a grant

from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), to:

● Compile a comprehensive bibliography of English language research-

based literature on human trafficking using EndNote, an

electronic bibliographic management program;

● Develop a taxonomy to categorize the identified references according to

a set of criteria devised in consultation with the National Institute of

Justice; and

● Analyze the compiled bibliography to assess the state of the English

language research literature on trafficking in persons.

4

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

This report provides a detailed description of the processes involved in identifying

English language research-based literature on human trafficking; the databases searched

and the keywords used to identify pertinent references; discussion of the development of

the taxonomy used to categorize identified research-based journal articles, reports, and

books; and the results of the categorization of the research according to the taxonomy.

The report ends with a discussion of research gaps.

The Bibliography

The research team used EndNote to organize and build a comprehensive bibliography of

English language research-based literature on trafficking in persons, including trafficking

for sexual and labor exploitation as well as trafficking to obtain human organs. The final

product includes 741 citations distributed among reports, journal articles, and books.

Reports, at 429, account for 58 percent of all publications. Journal articles constitute the

second largest category at 218 citations or 29 percent and are followed by books at 94

citations or 13 percent. A free-standing hard copy of the developed bibliography

accompanies this report. The EndNote database will be available for downloading from

the National Institute of Justice for those users who have access to Endnote.

Traffickin

g

Biblio

g

raph

y

- Final Citations b

y

T

y

pe of Publication - N

= 741

Reports, n=429, 58%

Books, n=94, 13%

Journal Articless,

n=218, 29%

5

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

The Taxonomy

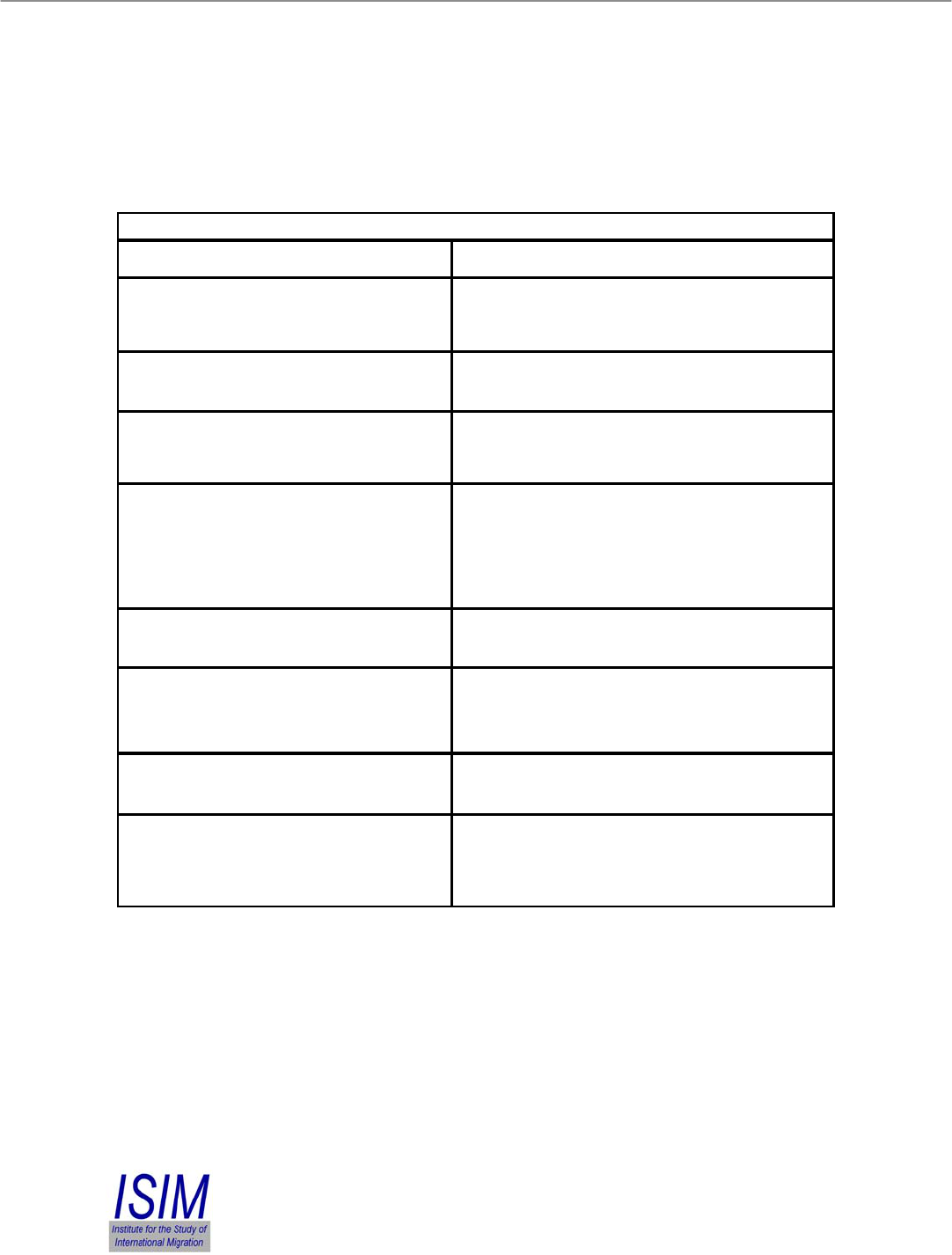

The research team, in consultation with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), has

devised taxonomy to categorize identified research-based literature on human trafficking;

see table below.

Taxonomy

1. Types of publications

a. Reports b. Journal articles c. Books

2. Type of research and type of review

a. Empirical Research – Peer Reviewe

d

b

. Empirical Research – Not Peer Reviewed

c. Non-Empirical – Peer Reviewed

d. Non-Empirical – Not Peer Reviewed

3. Disciplinary framework

a. Social Sciences b. Law/Criminal Justice

c. Medicine and Epidemiology

4. Methodological issues (Sample)

a. Population b. Random c. Convenience d. Unknown

5. Methodological issues (Research Methods)

a. Qualitative research

i. Case study ii. Ethnography

iii. Evaluation iv. Comparative

b. Quantitative

i. Evaluation ii. Comparative iii. Statistical

6. Type of trafficking

a. Sex trafficking b. Labor trafficking

c. Domestic servitude d. Organ trafficking

7. Trafficked populations

a. Children

i. Girls ii. Boys

b

. Adults

i. Women ii. Men

8. Stage/Phase

a. Recruitment b. Captivity c. Rescue

d. Return/Reintegration

9. Geographical focus*

a. The Americas

b

. Europe

c. Africa

d. Asia

e. Australia and the Pacific

* For the sake of space, we only included regional distinctions here. The final classification includes both

continents and individual countries.

Major Findings

Journal Articles

The analysis of publications on human trafficking yielded 218 journal articles. Of the 218

research-based articles, 39 were based on empirical research, while 179 articles were

based on non-empirical research.

6

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

At 96 articles or 46 percent, the largest classification consisted of articles that were non-

empirical, but published in peer-reviewed journals. This challenged traditional notions of

the type of research published in peer-reviewed journals, which hold that the peer review

process tends to eliminate non-empirical research. At 83 articles or 37 percent, non-

empirical articles published in journals that do not use the peer-review process constitute

the second largest group. At 68 citations or 31 percent, articles published in law journals

constitute the bulk of journal articles in this category.

Articles based on empirical research are far less numerous. Thirty nine journal articles are

based on empirical research; 36 of these articles were published in peer-reviewed

journals, while three were not peer-reviewed. The majority of empirical research focuses

on trafficking for sexual exploitation; only three out of the 39 journal articles deal with

trafficking for labor exploitation and one focuses on domestic servitude. The remaining

35 analyze various aspects of trafficking for sexual exploitation. Of the 39 empirical

journal articles, 30 discuss trafficked women, seven discuss trafficked children, and two

include discussion of trafficked men. With one exception, all empirical articles used

qualitative methodologies. The majority of empirical articles, 27 or 66 percent, used

convenience samples; seven or 17 percent used population samples (mostly clients in a

particular program), and two articles utilized random sampling for their data collections.

All samples were quite small, ranging from case studies of one to couple hundred of

victims.

Fifty three percent (115 articles) of the journal articles fall into the social sciences

category, while 51 percent (110 articles) fall into the law/criminal justice category. Three

of the reviewed articles are classified as medical paper and additional three as unknown.

The analysis of methodological approaches shows the predominance of qualitative

methodologies in all four categories of articles. Quantitative methodologies are

noticeably scarce; only seven articles are based on quantitative methodologies. The

scarcity of quantitative studies stems from both the unavailability of datasets on

trafficking in persons and difficulty in gaining access to the existing databases. The

significant reliance on qualitative methodologies affects trafficking researchers across all

disciplines. The vast majority of journal articles are based on unknown samples.

A great deal of research has focused on trafficking for sexual exploitation, to the

detriment of investigating trafficking for bonded labor and domestic servitude. The

uneven focus on sex trafficking and the sizeable percentage of journal articles that offer

no clear indication of the type of trafficking analyzed appears to be a constant across

disciplines. The vast majority of studies focus on women. Very little is known about

trafficking of men and boys, either for sexual exploitation or bonded labor. Only 14

journal articles include discussion of male victims of trafficking and one discusses the

plight of male children. Thirty two articles discuss child victims, but make no obvious

distinction between male and female children.

7

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Reports

In contrast to journal articles, the vast majority of reports are based on empirical research.

Sixty eight percent (or 292 reports) of all reports (n=429) are based on empirical

research. The remaining 32 percent (or 137 reports) are based on non-empirical research.

The largest number of reports based on empirical research fall into the social science

category. Reports classified as falling within the law/criminal justice domain are more

evenly distributed between those based on empirical and those not based on empirical

research; 46 and 56 reports, respectively. Similarly to journal articles, there are very few

reports which can be classified as medical and/or epidemiological; only four reports.

The analysis of methodological approaches indicates the predominance of qualitative

methodologies in all four categories. The reports follow the same pattern as journal

articles in terms of their methodological approaches and data collection methods with the

preponderance of qualitative methodologies. However, the pattern is different in terms of

quantitative approaches. Reports based, at least in part, on quantitative methodologies

are much more numerous then articles based on quantitative research; 95 versus seven,

respectively.

Convenience sampling is the most prevalent sampling method; the majority of social

science and law/criminal justice reports use convenience samples. Somewhat

surprisingly, four medical/epidemiological reports rely on convenience sampling as well.

Random sampling was used in 23 or 5.3 percent of the analyzed reports. Interestingly,

200 reports (or 46.6 percent) are based on unknown samples.

Similarly to journal articles, the highest concentration of reports in every category

focuses on trafficking for sexual exploitation; 383 reports or 89 percent discuss sex

trafficking, while 238 or 55 percent analyze trafficking for labor exploitation. As the

numbers suggest, some reports deal with both types of trafficking in persons. There are

also 12 reports in the “unknown” category as the authors use a generic descriptor “human

trafficking” to depict the phenomenon under discussion.

The majority of reports discuss women (296 reports or 34 percent) and girls (243 reports

or 28 percent). Far fewer reports focus on men (89 reports or 10 percent); slightly higher

number of reports include discussion of boys (175 reports or 20 percent). Sixty one

reports include discussion of children without differentiating between boys and girls.

Books

The analysis of publications on human trafficking yielded 94 books. Books did not lend

themselves to an easy categorization according to the four-domain taxonomy used to

classify journal articles. We were unable to determine which book was peer-reviewed

and which was not as there are no formal review standards for trade and university

presses, and often no standards at all for popular presses.

8

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

With very few exceptions, all books in this bibliography are based on research or a

systematic inquiry or examination and collection of information about a particular

subject. However, very few books are based solely or in large part on empirical research

and empirical data collected by the author/s. The vast majority of the 94 books are based

on non-empirical research. Similarly to journal articles, these books include policy

analyses; compilations of information from secondary sources on a particular facet of

human trafficking; critiques of trafficking frameworks; or authors’ views on the human

trafficking debate.

Research Gaps

The analysis of the compiled bibliography on trafficking in persons suggests that the

dominant anti-trafficking discourse is not evidence-based but grounded in the

construction of particular mythology of trafficking (Sanghera 2005: 4). Despite the

increased interest in human trafficking, relatively little systematic, empirically grounded,

and based on solid theoretical underpinnings research has been done on this issue.

‘In no area of the social sciences has ideology contaminated knowledge more

pervasively than in writings on the sex industry,’ asserts Ronald Weitzer, a sociologist at

the George Washington University. This claim certainly extends to trafficking for sexual

exploitation, an area ‘where cannons of scientific inquiry are suspended and research

deliberately skewed to serve a particular political and moral agenda (Weitzer 2005: 934;

see also Weitzer 2007; Rubin 1984 and 1993; Goode 1997). Much of the research on

human trafficking for sexual exploitation has been conducted by activists involved in

anti-prostitution campaigns (e.g. Raymond 1998, 2004; Hughes 2004, 2005). These

activists adopt an extreme (i.e., absolutists, doctrinaire, and unscientific) version of

radical feminist theory, which does not distinguish between trafficking for forced

prostitution and voluntary migration (legal or irregular) for sex work. Few of the radical

feminist claims about sex trafficking are amenable to verification or falsification (Weitzer

2005: 936).

Research on human trafficking for labor exploitation is disconnected from theory as well.

There are few attempts to analyze issues of cross-border trafficking for labor exploitation

within existing international migration theories. There is also no attempt to develop a new

theoretical framework in which to comprehensively analyze the phenomenon. Poverty

and the aspiration for a better way of life are by far the most discussed ‘push factors’ and

principal reasons for explaining why women and, in particular, children are at risk for

trafficking (Williams and Masika 2002: 5).

Similarly to theoretical approaches, development of innovative methodologies to study

human trafficking is also in its infancy. Reliance on unrepresentative samples is

widespread. Most studies relay on interviews with ‘key stakeholders.’ Studies that do

include interviews with victims are limited to very small samples. There is a need to

emphasize the limitations of small samples for generalizations and extrapolations, while

9

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

at the same time stressing the value of ethnographic investigations for formulating

hypotheses for further studies, including preparation of survey questionnaires.

Predominant methodologies include qualitative data collection techniques, mainly

interviews. Victims’ and stakeholders’ narratives are important but need to be

augmented by participant observation. Participant observation is needed, but difficult.

The main obstacle to conducting empirical qualitative research on human trafficking is

related to gaining access to trafficked persons. There is a need to facilitate researchers’

access to victims while protecting victims who are willing to participate in research

projects.

In order to acquire the broadest possible picture of the trafficking phenomenon, several

different data collection methods, including quantitative and qualitative methods, need to

be tested. Estimation methods that have been gaining currency in studies of hidden

populations include rapid assessment, capture-recapture methodology and Respondent-

Driven Sampling (RDS). These methods have been successfully used to study the

homeless (Williams and Cheal 2002), street children (Gurgel et al. 2004), and women in

street prostitution (Brunovskis and Tyldum 2004). Researchers in Norway, for example,

were quite successful in employing telephone surveys of sex workers operating through

individual advertisements (Tyldum and Brunovskis 2004).

There is a need for both quantitative and qualitative research that would provide both

macro-and micro-level understanding of the trafficking phenomenon. Rigorous

ethnographic and sociological studies based on in-depth interviews with trafficking

survivors would provide baseline data on trafficking victims and their characteristics. Too

often victims of trafficking remain one-dimensional figures whose stories are condensed

and simplified, which does not bode well for the development of culturally appropriate

services. In order to develop appropriate assistance and treatment programs for

trafficking survivors, increased attention needs to be paid to the expertise and practical

knowledge of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and their experience in working

with different groups of trafficking survivors, including women, men, and children.

Given the fact that services to trafficked persons are in their infancy, monitoring and

evaluation studies should be an integral part of every assistance program, public and

private. Well-designed monitoring and evaluation studies, particularly external

evaluations, can identify effective policies and ‘best practice’ approaches as well as

assess the success of different programs. Particularly important are longitudinal studies of

the effects of rehabilitation programs on the ability of survivors to integrate into the new

society or re-integrate into their native one.

There is also a need for effective cooperation and coordination of research within and

among different regions of the world. In addition, there is a need to establish a forum

where research results can be exchanged between different scholars as well as shared

with policy makers and service providers; such a forum can take a form of a specialized

publication or an international task force. This forum should be free of moral and

10

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

political influences and devoted solely to scholarly pursuits. The need to fill in the gaps in

our knowledge and share research results is urgent. As Liz Kelly observed, ‘Lack of

research-based knowledge may inadvertently deepen, rather than loosen the factors that

make trafficking both so profitable and difficult to address. (Kelly, 2002: 60).

11

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

ABSTRACT

The subject of human trafficking, or the use of force, fraud or coercion to transport

persons across international borders or within countries to exploit them for labor or sex,

has received renewed attention within the last two decades. While the majority of experts

on human trafficking assert that the greatest number of victims of trafficking are women

and children, there is little systematic and reliable data on the scale of the phenomenon;

limited understanding of the characteristics of victims (including the ability to

differentiate between the special needs of adult and child victims, women, girls, men, and

boys), their life experiences, and their trafficking trajectories; poor understanding of the

modus operandi of traffickers and their networks; and lack of evaluation research on the

effectiveness of governmental anti-trafficking policies and the efficacy of rescue and

restore programs, among other gaps in the current state of knowledge about human

trafficking. Such information is vital to helping decision-makers craft effective policies;

service providers develop culturally sensitive and linguistically appropriate and

efficacious programs, and law enforcement enhance their ability to identify and protect

victims and prosecute traffickers.

This report presents findings from a 12-month project undertaken by the Institute for the

Study of International Migration (ISIM) at Georgetown University to:

• Compile a comprehensive bibliography of English language research-based

literature on human trafficking using EndNote, an electronic bibliographic

management program;

• Develop a taxonomy to categorize the identified references according to a set of

criteria devised in consultation with the National Institute of Justice; and

• Analyze the compiled bibliography to assess the state of the English language

research literature on trafficking in persons.

The report provides a detailed description of the processes involved in identifying

English language research-based literature on human trafficking; the database searched

and the keywords used to identify pertinent references; discussion of the development of

the taxonomy used to categorize identified research-based journal articles, reports, and

books; and the results of the categorization of the research according to the taxonomy.

The report ends with a discussion of research gaps.

12

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

INTRODUCTION

The subject of human trafficking, or the use of force, fraud or coercion to transport

persons across international borders or within countries to exploit them for labor or sex,

has received renewed attention within the last two decades. Trafficking for forced labor

or sexual exploitation is believed to be one of the fastest growing areas of criminal

activity. A study by the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that the

criminal profits of human trafficking could exceed $31 billion dollars, which would make

it the second largest source of illegal income worldwide after drug trafficking (Belser

2005). Combating trafficking has become an increasingly important priority for many

governments around the world (Laczko 2005).

In the United States, human trafficking became a focus of activities in the late 1990s and

culminated in the passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) signed into

law on October 16, 2000. With the enactment of the TVPA, the United States took a lead

in combating human trafficking, prosecuting traffickers, and protecting victims.

Subsequent reauthorization legislations, the Trafficking Victims Protection

Reauthorization Acts of 2003 and 2005, further strengthened the US anti-trafficking

initiatives. However, despite tremendous efforts by the federal as well as local

governments, non-governmental organizations, and the research community working

together to fight human trafficking, solutions remain elusive.

While the majority of experts on human trafficking assert that the greatest number of

victims of trafficking are women and children, there is little systematic and reliable data

on the scale of the phenomenon; limited understanding of the characteristics of victims

(including the ability to differentiate between the special needs of adult and child victims,

girls and boys, women and men), their life experiences, and their trafficking trajectories;

poor understanding of the modus operandi of traffickers and their networks; and lack of

evaluation research on the effectiveness of governmental anti-trafficking policies and the

efficacy of rescue and restore programs, among other gaps in the current state of

knowledge about human trafficking. Such information is vital to helping decision-

makers craft effective policies, service providers develop culturally sensitive and

linguistically appropriate and efficacious programs, and law enforcement enhance their

ability to identify and protect victims and prosecute traffickers.

Further, those responsible for addressing trafficking in persons and related issues must be

able to differentiate between the often sensational publications

intended to raise

awareness about the issue and the more serious literature, based on systematic,

methodologically rigorous, and peer-reviewed empirical research (qualitative,

quantitative, legal, policy analysis, etc.), intended to help explain the root causes of

human trafficking; provide estimates of the number of trafficked victims; map and

analyze trafficking trends and routes; examine the different types of exploitation;

understand the resiliency and the suffering of trafficked victims; and assess the

appropriateness of treatment modalities and psycho-social programs aimed at

13

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

rehabilitating victims; as well as other dimensions of this extremely complex

phenomenon.

With these assumptions and needs in mind, the Institute for the Study of International

Migration (ISIM) at Georgetown University embarked on a project, supported by a grant

from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ), to:

● Compile a comprehensive bibliography of English language research-based

literature on human trafficking using EndNote, an electronic bibliographic

management program;

● Develop a taxonomy to categorized the identified references according to

a set of criteria devised in consultation with the National Institute of

Justice; and

● Analyze the compiled bibliography to assess the state of the English

language research literature on trafficking in persons.

The subsequent sections of the report provide a detailed description of the processes

involved in identifying English language research-based literature on human trafficking;

the database searched and the keywords used to identify pertinent references; discussion

of the development of the taxonomy used to categorize identified research-based journal

articles, reports, and books; and the results of the categorization of the research-based

literature according to the taxonomy. The report ends with a discussion of existing

research gaps.

14

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

COMPILING THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

As indicated in the introduction, the first task of this project was to compile a

comprehensive bibliography of English language research-based literature on trafficking

in persons, including trafficking for sexual and labor exploitation as well as trafficking to

obtain human organs. Media reports, opinion pieces, essays, and journal articles not

based on research were excluded from the final bibliography. This section of the report

discusses the sources and databases as well as the process used to identify pertinent

references.

The research team used EndNote to organize and build the bibliography. EndNote is a

software package that facilitates bibliographic management by allowing users to search

and import references from online bibliographic databases, organize references by

grouping, tagging, and sorting as well as creating custom fields. Users can easily export

custom-made reference lists to quickly create specialized bibliographies or conduct

further analysis in statistical programs. By organizing the research and the analysis in

EndNote, the research team has created a dynamic document that will benefit researchers,

students, and policymakers. All future users of the document will be able to use the file as

a point of departure for their own research and analysis and can easily add new references

or modify exiting entries by categorizing them according to their own taxonomies, built

using those created by the research team, or by devising totally new categorizations.

EndNote allows users to create up to seven custom fields to categorize documents.

Furthermore, users have the option to re-title unused fields according to their individual

research needs. EndNote also allows users to create bibliographies in different styles

(e.g.; APA, American Anthropologist, annotated, etc.) or by types of work (e.g., journal

articles, books, reports, etc.).

The bibliography on human trafficking developed in the course of this project includes

journal articles, books, and dissertations from the catalogues and online databases of

several major US universities. It also contains reports and conference papers issued by

international organizations, governmental institutions, think-tanks, universities, and

international and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The list below

indicates where we searched to compile the bibliography. A free-standing hard copy of

the developed bibliography accompanies this report. The EndNote database will be

available for downloading from the National Institute of Justice.

Sources and Databases Searched

Journal Articles

In order to identify journal articles, the research team searched the following databases:

Social Science Databases

- EBSCO Academic Search Premiere

- JSTOR

15

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

- PAIS

- ProQuest Social Science

- Social Science Index

- Sociological Abstracts

Medical Databases

- Medline

- PubMed

Government/Law/Politics Databases

- Government and Politics

- HeinOnline

- International Political Science Abstracts

- Legal Trac

- LexisNexis

- LexisNexis Academic

- PolicyFile

- Westlaw

- Worldwide Political Science Abstracts

Reports and Papers

In order to identify reports, white papers, and other publications not appearing in

academic journals, the research team searched the following sources:

International organizations

- ILO

- IOM

- UNICEF Innocenti Research Center

- UNICRI

- UNIFEM

- UNESCO

- UNODC

- www.ungift.org

NGOs/think-tanks/ programs

- Alliances against Human Trafficking

- Amnesty International

- Anti-Slavery International

- childtrafficking.com

- Human Rights Watch

- The National Criminal Justice Reference Service

- Polaris Project

- Protection Project (The Johns Hopkins University)

-

RAND Corporation

16

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

- Save the Children

- Terre des hommes

- Vital Voices Global

- Women’s Studies Program (University of Rhode Island )

Books and Dissertations

Library Catalogues

- American University

- Columbia University

- Georgetown University

- George Washington University

- Harvard University

- Johns Hopkins University

- Princeton University

- Stanford University

- University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)

- Yale University

Online Bookstores

- Amazon.com

- Powells Bookstore

- Alibris

Bibliographies

- The research team also cross-checked the compiled bibliography against the

bibliography published in the 2005 International Migration Special Issue on Data

and Research on Human Trafficking (Laczko and Goździak 2005).

- Selected bibliographies of certain books and journal articles were also consulted

to cross-check and supplement the results of the electronic databases searches.

Search Terms Used

When searching electronic databases the research team used variations of the truncation

search mechanism for the term “traffic*” in order to capture all relevant literature on

human trafficking. Therefore, we applied this mechanism using the following terms:

“human traffic*,” “child traffic*,” “labor traffic*,” “sex traffic*,” and “youth traffic*.”

We also used the following keywords: “human trafficking,” “labor trafficking,” “sex

trafficking,” “youth trafficking,” as well as all related combinations resulting from our

primary search such as “human trafficking and law enforcement,” “human trafficking and

prostitution,” “human trafficking and child abuse and neglect,” or “human trafficking and

crime,” to illustrate just a few possible combinations.

17

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

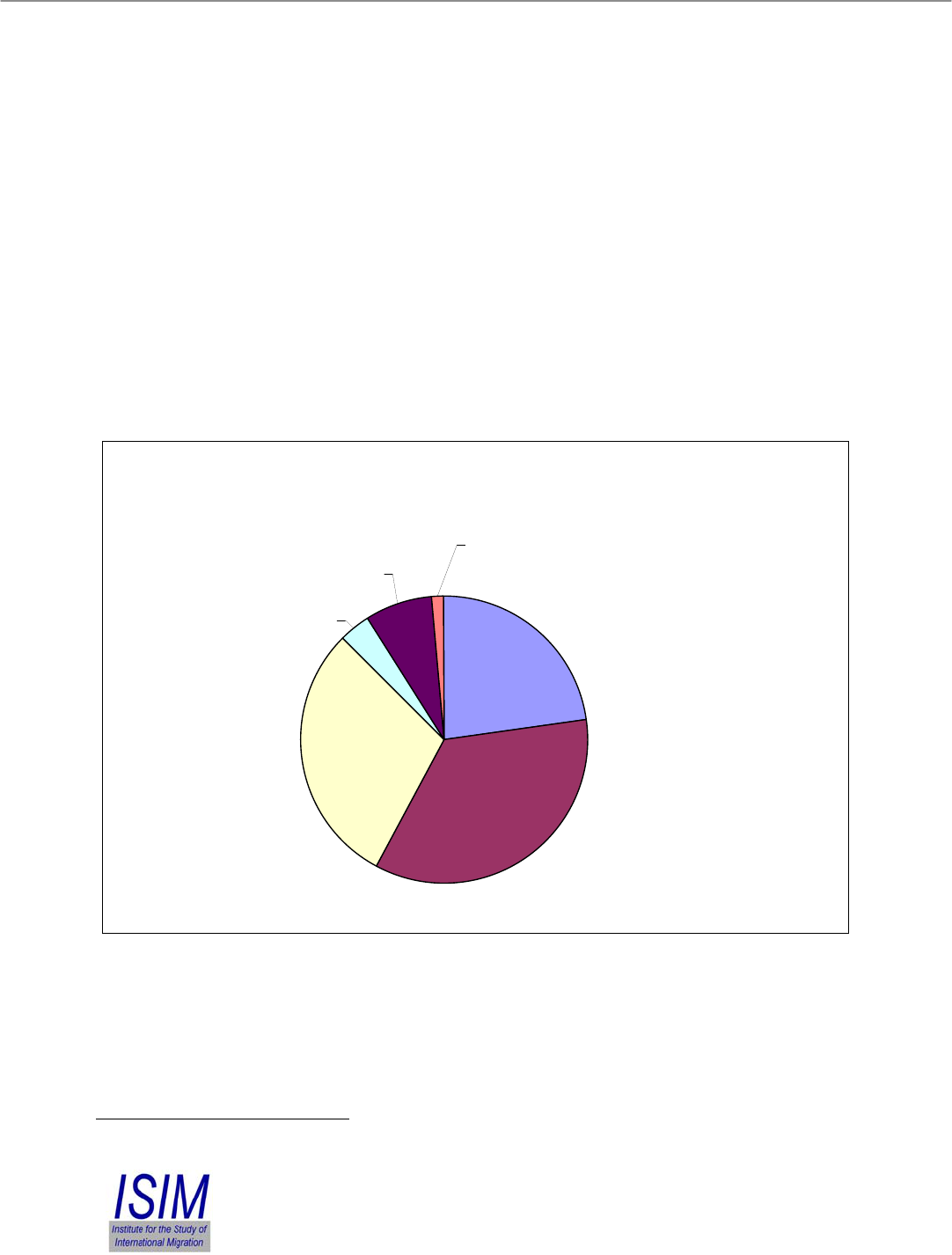

Results of the Search Process

The search process described above produced 6,374 raw citations that were imported into

EndNote. The list of raw citations was immediately reduced to 2,388 citations through

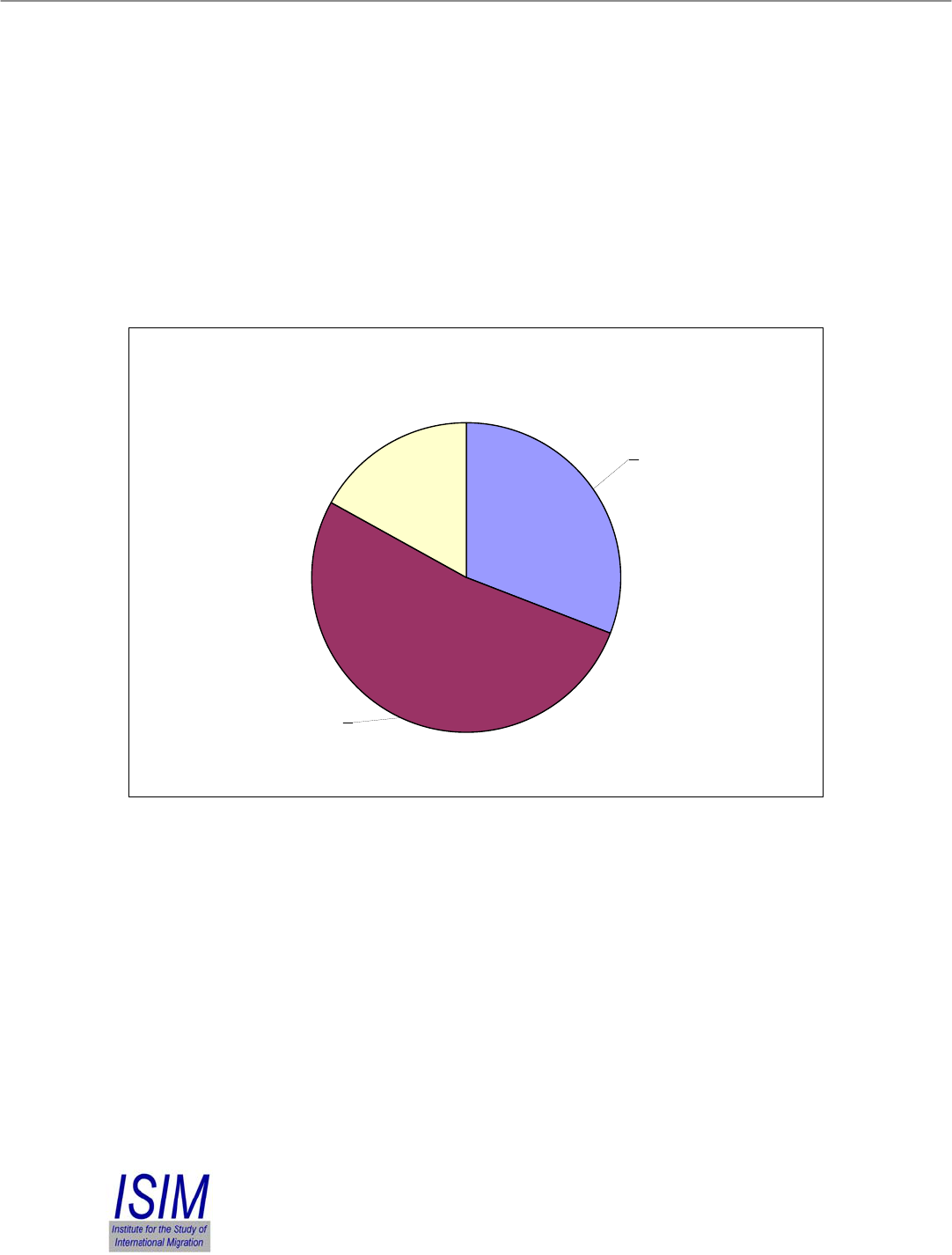

the use of EndNote’s “delete duplicates” filter. Figure 1 presents the breakdown, by type

of publication of the 2,388 citations. Figure 1 shows that reports constitute the largest

group of publications and account for 52 percent of all publications found through the

preliminary search process. Journal articles are the second largest category and account

for 31 percent of all initially identified publications, while books account for 17 percent.

Figure 1: Trafficking Bibliography - Initial Citations by Type of

Publication - N= 2388

Books, 403, 17%

Reports, n=1249,

52%

Journal Article,

n=736, 31%

Manual Purging and Initial Analysis of Results

The manual purging and initial analysis of the preliminary results consisted of three

steps:

1. Purging duplicates not caught by EndNote;

2. Purging citations not related to trafficking; and

3. Separating non-research based publications from research-based literature.

This phase of the research has been carried out for 1,249 reports, 736 journal articles, and

403 books. Reports and journals were the main focus of our analysis because they are the

most numerous of the three categories.

18

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Purging duplicates not filtered by Endnote

We compiled most of the initial 2,388 citations by importing search results from the

sources listed above into EndNote. Many of these initial entries were duplicates. While

EndNotes’ duplicate filter eliminated the majority of redundant references, it only

captured duplicates with perfectly matched information in all fields. For instance, if one

database used a first or middle initial of a particular author while a different database

used the full first name for the same author or if different keywords were used by

different databases for the same reference, the citation will not be considered a duplicate

by Endnote. Additionally, some databases listed reports by the organization which

commissioned them while other databases listed reports by the authors who actually

wrote them; thus, some reports were listed twice. Given these differences in listing

references, all entries had to be manually double checked for further duplicates not

caught by the EndNote filter. This was a very time-consuming but necessary effort.

Purging citations not related to trafficking

In addition to manually filtering duplicates, the research team removed citations not

related to human trafficking. Many citations tangentially related to the topic of human

trafficking--such as child abuse, violence against women, commercial sexual exploitation

of children, child labor, child fostering, and HIV/AIDS--were automatically included in

the search results imported into Endnote. This automatic inclusion might have resulted

from the fact that the phrase ‘human trafficking’ was used in the abstract and/or as a

keyword. These references were eliminated from the preliminary search results unless the

research and the resulting publication indicated, for example, a correlation or a causal

relationship between child labor and child trafficking or discussed child fostering as a

risk factor for child trafficking. If there was no substantial discussion of any dimension of

human trafficking, the reference was removed.

Separating documents not based on research

The preliminary results of the literature search indicated that there is a plethora of

published works dealing with the topic of human trafficking, but many of these

publications are not research-based. Therefore, the research team had to separate out

references based on research from non-research based writings such as opinion pieces,

essays, manuals and guides for identifying trafficking victims, accounts of anti-

trafficking activities undertaken by various entities, and descriptions of task forces, to

name a few examples.

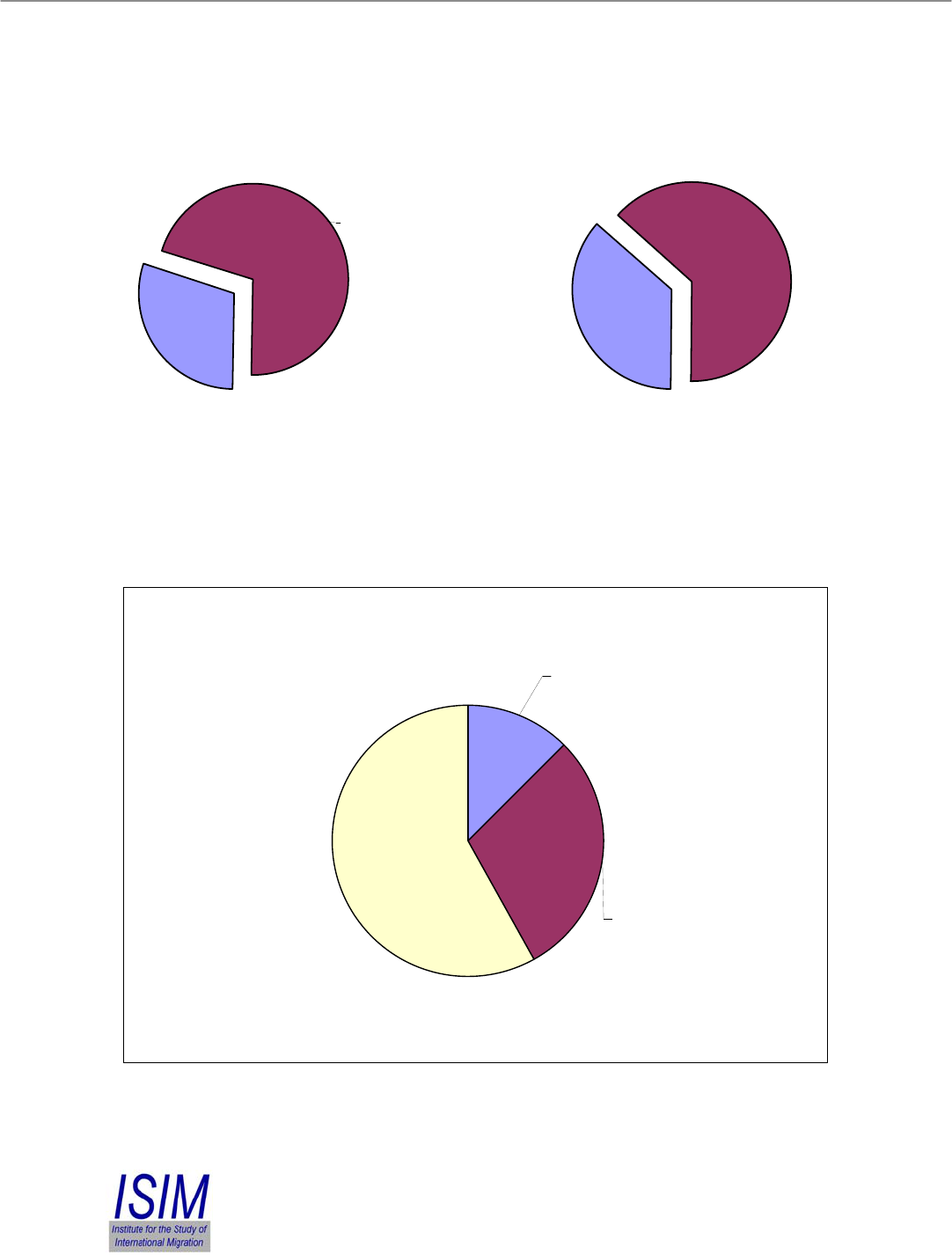

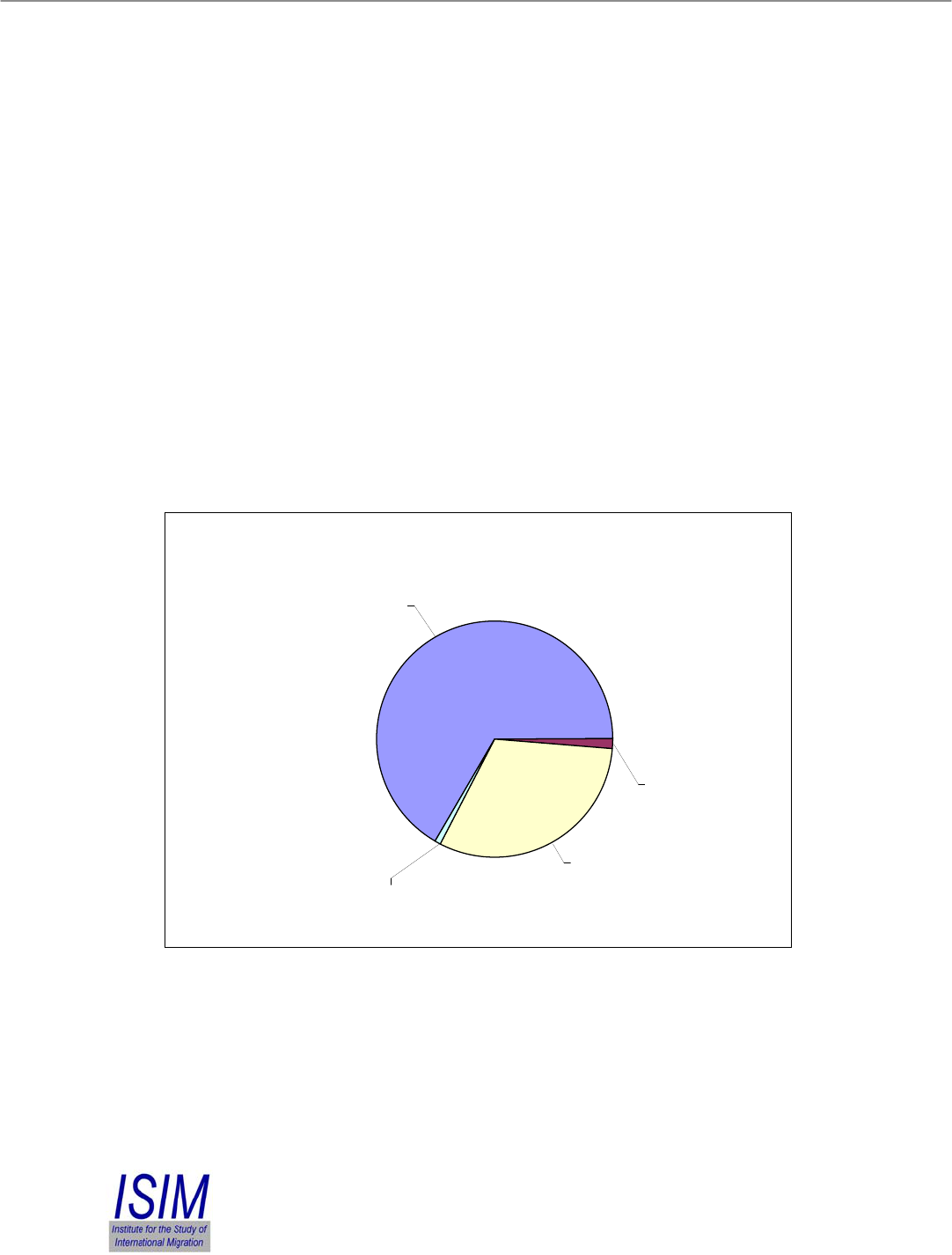

Figure 2 demonstrates the results of the first three stages of the manual purging process

for reports and journal articles. Seventy percent of the 736 citations categorized as

“journal articles” in the preliminary search results were eliminated because they were

either duplicates, not based on research, or not related to human trafficking. More than 63

percent of “reports” were purged for the same reason.

19

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Figure 2: Trafficking Bibliography – Journal Articles and Reports Eliminated because of

Redundancy, Lack of Relevance to Trafficking, and Not Being Research Based

Journal Articles

Reports

Pu rg ed

Purged

Journal

Articles, 518,

Rep orts , 746,

63.4%

70.4%

Remain ing

Re ma ining

Reports , 429,

36.6%

Journal

Articles, 218,

29.6%

Figure 3 depicts the final distribution of the literature after completing the manual

purging process. In total, there are 741 citations distributed among reports, journal

articles, and books. Reports, at 429, accounted for 58 percent of all publications. Journal

articles constitute the second largest category at 218 citations or 29 percent and are

followed by books at 94 citations or 13 percent.

Figure 3: Trafficking Bibliography - Final Citations by Type of

Publication - N = 741

Reports, n=429, 58%

Books, n=94, 13%

Journal Articless,

n=218, 29%

20

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

DEVELOPMENT OF THE TAXONOMY

Agencies, disciplines, and professions concerned with human trafficking are very diverse

and so is the growing number of publications on this issue. As a result both a novice

scholar of human trafficking and an expert on the topic have increasingly more difficulty

embracing the scope of this field. Therefore, there is a need for a schema or a

classification of existing literature that would provide decision-makers, service providers,

and scholars with an access to research results on trafficking in persons most appropriate

for their goals and objectives: be it legislative pursuits aimed to introduce a new policy

or amend an existing one; practical pursuits aimed at evaluating program outcomes; or

research endeavors aimed at identifying research gaps and designing new studies.

“Over the last two centuries systematics or taxonomies have proven to be of great value

[…] to disciplines as diverse as chemistry via Dimitri Mendeleev’s Periodic Table of

chemical elements circa 1889, genetics as a consequence of Gregor Mendel’s 19

th

century

study of pea, which in turn led to the human genome project” (Reisman, forthcoming).

Anthropologists have observed that taxonomies are generally embedded in local cultural

and social systems, and serve various social functions.

In this project, the research team, in consultation with representatives of the National

Institute of Justice (NIJ), has devised a taxonomy sufficiently robust to categorize

identified research-based literature on human trafficking and flexible enough to expand

existing categories to accommodate new research-based publications. The taxonomy is

also simple enough to be user-friendly.

This taxonomy is not meant to be a ranking system of research-based publications in the

English language; rather it is conceived as a mechanism that allows for tailored

assessment of available research by an individual user. For example, policy-makers

trying to decide what kind of anti-trafficking activities to fund might give the highest

marks to publications based on evaluation research. Furthermore, those tasked with

assessing cost-effectiveness of projects they fund might value quantitative evaluations

over qualitative research. Since most law journals are not peer-reviewed, legal scholars

might never use the ‘peer-reviewed’ category to assess the quality of legal research.

Instead, they might want to cross-reference legal studies with the titles of the most

prestigious law journals to evaluate existing legal scholarship on human trafficking.

Conversely, an academe-based anthropologist might cross-reference empirical, peer-

reviewed publications with a particular type of qualitative methodology—ethnography, or

case study—to arrive at publications most valuable to their work.

The table below presents the taxonomy used to categorize English language publications

included in the final bibliography of research-based literature on human trafficking.

21

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Taxonomy

1. Types of publications

a. Reports b. Journal articles c. Books

2. Type of research and type of review

a. Empirical Research – Peer Reviewe

d

b

. Empirical Research – Not Peer Reviewed

c. Non-Empirical – Peer Reviewed

d. Non-Empirical – Not Peer Reviewed

3. Disciplinary framework

a. Social Sciences b. Law/Criminal Justice

c. Medicine and Epidemiology

4. Methodological issues (Sample)

a. Population b. Random c. Convenience d. Unknown

5. Methodological issues (Research Methods)

a. Qualitative research

i. Case study ii. Ethnography

iii. Evaluation iv. Comparative

b. Quantitative

i. Evaluation ii. Comparative iii. Statistical

6. Type of trafficking

a. Sex trafficking b. Labor trafficking

c. Domestic servitude d. Organ trafficking

7. Trafficked populations

a. Children

i. Girls ii. Boys

b

. Adults

i. Women ii. Men

8. Stage/Phase

a. Recruitment b. Captivity c. Rescue

d. Return/Reintegration

9. Geographical focus*

a. The Americas

b

. Europe

c. Africa

d. Asia

e. Australia and the Pacific

* For the sake of space, we only included regional distinctions here. The final classification includes both

continents and individual countries.

As can be seen from the table above, the first task the research team had undertaken in

classifying the identified publications was to sort them by type of publication; i.e. report,

journal article or book. Secondly, we classified each publication according to a type of

research—empirical or non-empirical—and according to whether the publication was

peer-reviewed or not.

We read each publication to ascertain the methodology used and assess whether the

publication was based on empirical research. We emphasized empiricism because the

existing knowledge base on human trafficking is limited and largely not based on

empirical research. A 2005 analysis of trafficking research indicated that the field had not

moved beyond estimating the scale of the problem; mapping routes and relationships

between countries of origin, transit, and destinations; and reviewing legal frameworks

and policy responses (Goździak and Collett 2005). The situation is not much different in

2008; there is still no reliable data on the number of trafficking cases and the

22

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

characteristics of the victims and perpetrators. The methodologies used to produce

estimates of the scope of trafficking, especially in North America, are not very

transparent; therefore it is hard to evaluate the validity and reliability of the data.

One element contributing to this limited knowledge is the fact that development of

research methods on human trafficking remains in its infancy. Many studies rely on

overviews, commentaries, and anecdotal information. By focusing on the empirical

nature of the articles we aimed to examine the extent to which the field has moved

beyond stating that there is a problem to a more systematic and rigorous collection of

empirical data and analysis of a wide range of human trafficking issues. Empirical

research encompasses studies that base their findings on direct or indirect observations to

analyze a problem or test a hypothesis and reach a conclusion. We have conducted our

analysis of the empirical nature of the studies in this bibliography with an understanding

of the complexity of scientific research and the fact that the various disciplines involved

in trafficking research operate in very different ways.

In addition to focusing on the empirical nature of the publications, we investigated

whether or not a particular publication was peer-reviewed. Peer review is the process of

subjecting a work to the critical eye of experts in the same field and has the important

function of promoting high standards and preventing poorly researched or unwarranted

claims. For this reason, studies that are not subject to peer review are often considered to

lack scientific rigor and to be of lesser quality. Scholars and editors deem peer review

necessary because it allows for mistakes and oversights to be caught and provides an

opportunity to improve the analysis or presentation of research results. While some have

critiqued the peer review system as “biased, incomplete, and unaccountable,” it is one of

the standard benchmarks of academic rigor and quality, and thus we have taken it into

account (Horton 2000). It is important to note that many university-based law journals in

the United States do not rely on the peer review process. In addition, legal scholarship is

mostly non-empirical. Social science research, on the other hand, tends to be both

empirical and non-empirical, but published in peer-reviewed publications. Medical

research is almost exclusively empirical and published in peer-reviewed journals.

The peer-review determination for journal articles was made using two approaches:

1. Visiting the journal’s website, which usually describes the peer review

process if it exists; and/or

2. Cross-checking the journal’s title with Ulrich's International Periodicals

Directory, which is a source of bibliographic and publisher information,

including peer-review information, on more than 300,000 periodicals of

all types.

We did not determine reports or books to be peer reviewed unless the authors specifically

stated that the report had been subject to such scrutiny and explained the process.

23

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Taking into account our focus on the empirical nature of the research and peer review, we

categorize the reports and journal articles under one of the following categories:

• Empirical Research and Peer Reviewed

• Empirical Research and Not Peer Reviewed

• Non-Empirical and Peer Reviewed

• Non-Empirical and Not Peer Reviewed

In order to better understand the academic disciplines engaged in trafficking research as

well as the methodologies they employ, we analyzed each reference for its disciplinary

focus and methodological approach. The three broad categories used for discipline were:

• Social Sciences

• Law/Criminal Justice

• Medicine/Epidemiology

While it is possible to further subcategorize each of these disciplines, many articles and

reports did not mention the exact disciplinary approach, thus necessitating the usage of

broader categories. Where evident, we noted the specific discipline of the study. In some

instances, the articles were inter-disciplinary and thus required dual categorization. The

process of dual categorization was carried out for all the different elements of the

taxonomy.

In terms of the methodologies employed in trafficking research, we assessed the type of

sample used by the investigators and the nature of the methodology. We divided the

sample types into three categories: population, random, and convenience. Whether or not

the research was qualitative or quantitative was also determined. If the authors indicated

the exact nature of the qualitative or quantitative research we were able to further

categorize and indicate whether a particular article or report were based on case studies;

stakeholder and/or victim interviews; evaluation; comparative research; rapid assessment;

survey; or statistical analysis.

We also analyzed each article according to several elements of human trafficking, which

included: the type of trafficking; the trafficked population; and the stage of the trafficking

situation. One of the early criticisms of the worldwide political response to trafficking has

been that it is too focused on trafficking for sexual exploitation to the detriment of

trafficking for labor exploitation, domestic servitude, and organ trafficking. In order to

see how the research reflected these issues, we categorized each article based on the type

of trafficking studied. This category included sex, labor, domestic servitude, and organ

trafficking. We made note of studies that addressed more than one category.

Observers have also voiced concern about lack of clarity with regard to the type of

populations studied in trafficking research. This is particularly true in regard to the

distinction between “women” and “girls.” Often times a research abstract and title will

24

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

indicate that the study focuses on women and girls, but then fails to adequately

distinguish the two groups. Lack of research on trafficked men and boys is another area

of concern. Thus, the categorization of the trafficked population according to the age and

sex of the population studied is an important part of the taxonomy.

The fact that trafficking is an ongoing process with several different stages underscores

the need for researchers to define what phase or aspect of trafficking they investigate.

This could include recruitment mechanisms; treatment while in captivity; escape or

rescue from the hands of the traffickers; and return and reintegration of the survivor into

society. Given these different elements of the trafficking process, we categorized the

research according to which aspect (or aspects) the researchers focused on.

Lastly, we categorized the research according to the geographical focus of the study. This

analysis included a regional and country level categorization. As with the other elements

of the taxonomy, many studies included more than one categorization.

25

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

JOURNAL ARTICLES

The analysis of publications on human trafficking yielded 218 journal articles. As

indicated above, only research-based articles in English were included. Media articles,

essays, and opinion pieces were excluded. Of the 218 research-based articles, 39 were

based on empirical research, while 179 articles were based on non-empirical research.

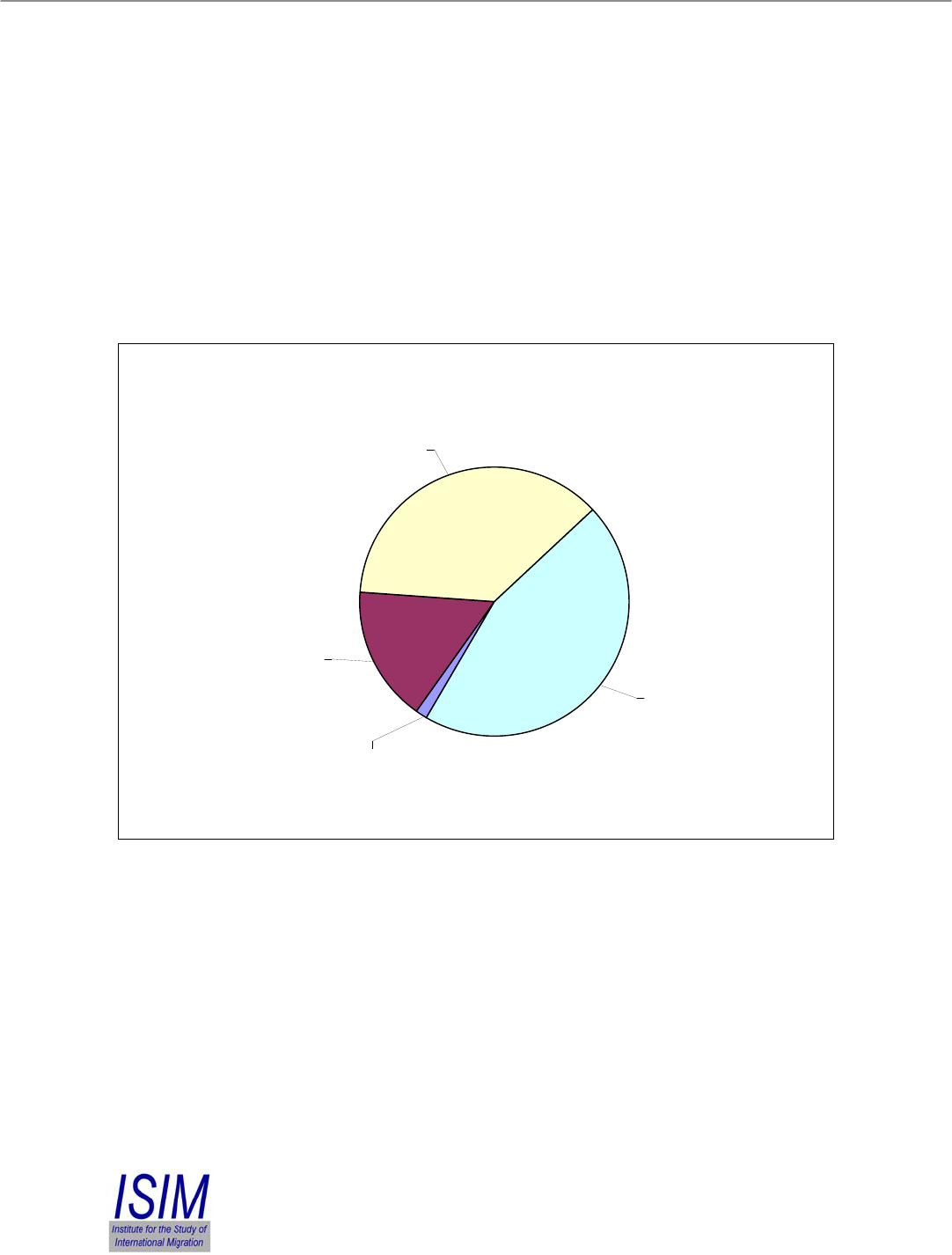

Figure 4 presents the results of the classification of the 218 journal articles included in

this bibliography.

Figure 4: Categorization of Journal Articles, n = 218

N

on-Empirical/Not

Peer Reviewed,

n=83, 37%

N

on-Empirical/Peer

Reviewed, n=96,

46%

Empirical

Research/Peer

Reviewed, n=36,

16%

Empirical

Research/Not Peer

Reviewed , n=3, 1%

Empirical Nature

Non-empirical articles published in peer-reviewed journals

At 96 articles or 46 percent, the largest classification consisted of articles that were non-

empirical, but published in peer-reviewed journals. This challenged traditional notions of

the type of research published in peer-reviewed journals, which hold that the peer review

process tends to eliminate non-empirical research. It seems that peer-reviewed journals

have published non-empirical research on trafficking in persons because of the dynamic

created by the sudden and intense political and academic interest in human trafficking

following the debate and passage of the Palermo Protocol and the Trafficking Victims

Protection Act of 2000.

26

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Additionally, the difficulty of conducting empirical research on human trafficking,

including impeded access to trafficked victims, law enforcement representatives, and

prosecutors, as well as the length of time it takes to conduct empirical research have also

contributed to the predominance of non-empirical research on trafficking in persons.

Editors realized that their readership desired more information on trafficking, but little

empirical research was being done, thus, non-empirical studies, mostly in the form of

literature and data reviews (e.g.; Adepoju 2005; Andrees 2005; Goździak 2005; Schauer

2006) or description and analysis of anti-trafficking policies (e.g.; Obuah 2006; Raymond

2004), have been published. Our analysis demonstrates that the peer-review element,

which is used as a measure of quality in academia, is not a good indicator of whether

trafficking research is empirical in nature.

Non-empirical articles published in non-peer-reviewed journals

At 83 articles or 37 percent, non-empirical articles published in journals that do not use

the peer-review process constitute the second largest group. At 68 citations or 31 percent,

articles published in law journals constitute the bulk of journal articles in this category.

In the United States, legal research is leading the way among the still scarce academic

research on human trafficking. Legal scholarship encompasses a wide range of journal

articles, including articles published before the adoption of the UN Protocol on

Trafficking or shortly after the passage of the TVPA of 2000. Most of these articles focus

on the legal analysis of the scope and practical efficacy of the proposed legal protections

applicable to victims of trafficking (e.g.; Chuang 1998) or on the analysis of the

provisions of the TVPA of 2000 (e.g.; Ryf 2002; Chapkis 2003).

Empirical journal articles

Articles based on empirical research are far less numerous. We identified 39 journal

articles based on empirical research; 36 of these articles were published in peer-reviewed

journals, while three were not peer-reviewed (Allred 2006; Petros 2005; Spear 2004).

Empirical research is most prevalent in social sciences (e.g.; Aghatise 2004; Bastia 2005;

Coonan 2005; Erokhina 2007; Goździak 2007; Silverman 2007). The majority of

empirical research focuses on trafficking for sexual exploitation; only three out of the 39

journal articles deal with trafficking for labor exploitation (Goździak 2007; Lange 2007;

Shigekane 2007) and one focuses on domestic servitude (Constable 1996). The

remaining 35 analyze various aspects of trafficking for sexual exploitation. Of the 39

empirical journal articles, 30 discuss trafficked women, seven discuss trafficked children,

and one includes a discussion of trafficked men (Augustin 2005; Wilson 2006).

1

With

one exception (Aghatise 2004), all empirical articles used qualitative methodologies. The

majority of empirical articles, 27 or 66 percent, used convenience samples; seven or 17

percent used population samples (mostly clients in a particular program), and two articles

utilized random sampling (Erokhina 2007; Okonoufa 2004) for their data collections. All

samples were quite small, ranging from case studies of one to couple hundred of victims.

1

Some are double counted because they include discussion of more than one population.

27

http://isim.georgetown.edu

This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not

been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s)

and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data and Research on Human Trafficking Goździak & Bump

Disciplinary Focus

As shown in Table 1, 115 articles or 53 percent of the journal articles fall into the social

sciences category, while 110 or 51 percent fall into the law/criminal justice category.

Three of the reviewed articles are classified as medical paper and additional three as

unknown.

The distribution shown in Table 1 indicates that the non-empirical nature of trafficking

research is prevalent across academic disciplines.

Table 1: Cate

g

orization of Journal Articles b

y

Em

p

irical Nature/Peer Review and

Disci

p

line

Discipline

Criminal Justice/Law Medicine

Social

Sciences

Unknown

Total

Empirical Research -

Not Peer Reviewed

1 0 2 0

3

Empirical Research - Peer

Reviewed

7 7 30 0

44

Not Empirical Research -

Not Peer Reviewed

74 0 11 2

87

Not Empirical Research -

Peer Reviewed

28 1 72 1

102

Total 110 8 115 3 236

*Totals presented in this table exceed the actual number of journal articles due to multiple