Ready, Set, Go, Review:

Screening for Behavioral Health

Risk in Schools

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

(SAMHSA) under contract number HHSS2832017000751/HHSS28342001T with SAMHSA, U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in consultation with John Kelley, Ph.D. Nadine Benton

served as Contracting Officer Representative.

Disclaimer

The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily

reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA or HHS. Nothing in this document constitutes a direct

or indirect endorsement by SAMHSA or HHS of any non-federal entity’s products, services, or policies,

and any reference to non-federal entity’s products, services, or policies should not be construed as such.

Public Domain Notice

All material appearing in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied

without permission from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this publication may

not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of the

Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS.

Electronic Access

This publication may be downloaded at https://www.samhsa.gov/ebp-resource-center

.

Recommended Citation

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Ready, Set, Go, Review: Screening for

Behavioral Health Risk in Schools. Rockville, MD: Office of the Chief Medical Officer, Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

Originating Office

Office of the Chief Medical Officer, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 5600

Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20857. Published 2019.

Nondiscrimination Notice

SAMHSA complies with applicable Federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate on the basis of

race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex. SAMHSA cumple con las leyes federales de derechos

civiles aplicables y no discrimina por motivos de raza, color, nacionalidad, edad, discapacidad o sexo

iii

Forward

“In 2003, the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health concluded that

America’s mental health service delivery system was in shambles. The Commission’s

final report stated that “for too many Americans with mental illnesses, the mental health

services and supports they need remain fragmented, disconnected and often inadequate,

frustrating the opportunity for recovery.” A number of the recommendations of the

President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health were not implemented or have

only been partially realized. Since then, quality of life has not fundamentally changed for

adults with serious mental illnesses (SMI) and children and youth with serious emotional

disturbances (SED) and their families in the United States.”

-The Way Forward (2017)

Students are routinely screened for physical health issues (e.g., vision, hearing). However,

emotional or behavioral health issues are generally detected after they have already emerged. It

is time for that to change.

The Ready, Set, Go, Review: Screening for Behavioral Health Risk in Schools toolkit is designed

to guide schools through the process of developing comprehensive screening procedures, as well

as provide readily available resources to facilitate the implementation of effective behavioral

health screening in schools.

iv

Introduction

Fairhaven School District is a mid-sized suburban district. Students in Fairhaven are

generally high achieving, but they are not immune to typical challenges faced by many

students within their state and across the nation. The superintendent of schools, Dr.

May, is concerned with “educating the whole child” and recognizes the importance of

addressing educational factors which impact upon students’ success in school beyond the

traditional curriculum and academic influences. She wants to build upon students’

strengths and help them develop social and emotional “life skills,” while also identifying

students who present “risk factors” associated with adjustment difficulties that may be

related to behavioral or psychological problems. Dr. May recognizes that both these

factors (social and emotional skills and behavioral health risk factors) influence a

student’s performance in the classroom. While Fairhaven is like other school districts

which have limited fiscal and staff resources, Dr. May has prioritized these issues as part

of the District’s strategic plan. She has worked with families in the district to make this a

priority and has even used student “focus groups” to gain their perspective. However,

she is unsure of where to start or how to prepare the development of a comprehensive

plan that will help the district accomplish these goals.

Screening is a Component of a Comprehensive Systems Framework

School administrators like Dr. May often recognize the importance of addressing social and

emotional needs of students. In fact, a recent internal survey conducted by the School

Superintendents Association indicated that “students’ behavioral health needs” were the top

concern of superintendents across the country (K. Jackson, personal communication, June 25,

2018). Research conducted by The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning

1

(CASEL) identified “social and emotional factors” as the most powerful influence over students’

achievement in school (CASEL, 2003). Students come to school each day with more than their

lunch and backpack. They bring life factors that shape their learning and development. These

influences range from family issues, health concerns, and culture of origin to behavior, learning

profiles, and abilities. Virtually all have the potential to impact the mental health of students.

Although historically mental health has been viewed through the lens of mental illness (e.g.,

depression, anxiety, etc.), society has come to recognize that good mental health is not simply

the absence of illness, but also the possession of skills necessary to cope with life’s challenges.

As education professionals, school staff need to understand the role mental health plays in the

school context because it is so central to our students’ social, emotional, and academic success.

Research estimates that one in five students will experience a significant mental health problem

during their school years. These issues vary in severity, but approximately 70% of those who

need treatment will not receive appropriate mental health services (Perou, et al., 2013). Failure to

address students’ mental health needs is linked to poor academic performance, behavior

problems, school violence, dropping out, substance abuse, special education referral, suicide, and

criminal activity (Darney, Reinke, Herman, Stormont, & Ialongo, 2013; Hawton, Saunders, &

O’Connor, 2012). These issues may seem foreign to elementary school, but mental health

concerns can develop as early as infancy, and, like other aspects of child development, the earlier

schools address them, the better.

Family is the first source of support for a child’s mental health. However, the increased stress

and demands of life today make it imperative that schools partner with families to help students

thrive. Indeed, schools are excellent places to promote good mental health. Students spend a

significant amount of time in school and educators can observe and address their needs. Doing so

2

effectively requires developing the capacity both to reinforce students’ natural mental health

strengths and to respond to students suffering from the more acute mental health disorders that

are on the rise today. However, school leaders often lack the information needed to implement

effective comprehensive school-wide behavioral health services.

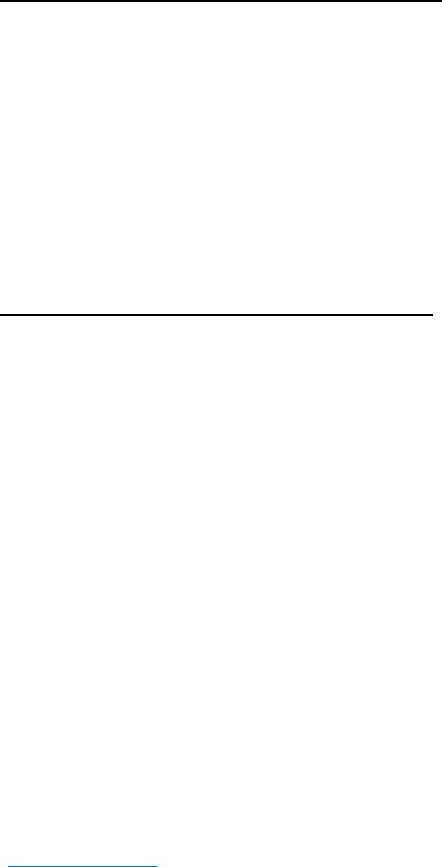

Despite the lack of information for these comprehensive services, many school districts have

elements of a tiered system of support in place as part of their overall student support programs

(e.g., building level support teams, data-based decision making, school-wide bullying prevention

and interventions, positive behavioral interventions, counseling services, etc.). These elements

can serve as the basis for the development of a comprehensive Multi-Tiered Systems of Support

(MTSS) to address behavioral health needs of students. MTSS can serve as the framework to

provide universal programs to help all students develop critical social and emotional skills, as

well as provide school-wide approaches to teach appropriate behavioral skills and manage

problem behaviors. MTSS also includes the provision of “targeted” services for students

displaying the emergence of problematic behaviors and emotions, as well as “intensive” services

for students with chronic psychological issues or maladaptive behaviors. Effective elements of

MTSS include the use of student data to screen for “risk” or the potential development of social,

emotional, and behavioral problems. Data are also used to help make decisions on when students

may need additional supports beyond the universal interventions provided to all students, to

monitor the effectiveness of certain programs, as well as measure the progress of individual

students. To collect varying types of data, many schools are incorporating the use of “screening”

tools to gain access to information not apparent in typical behavioral data (e.g., office referrals,

attendance records, etc.).

3

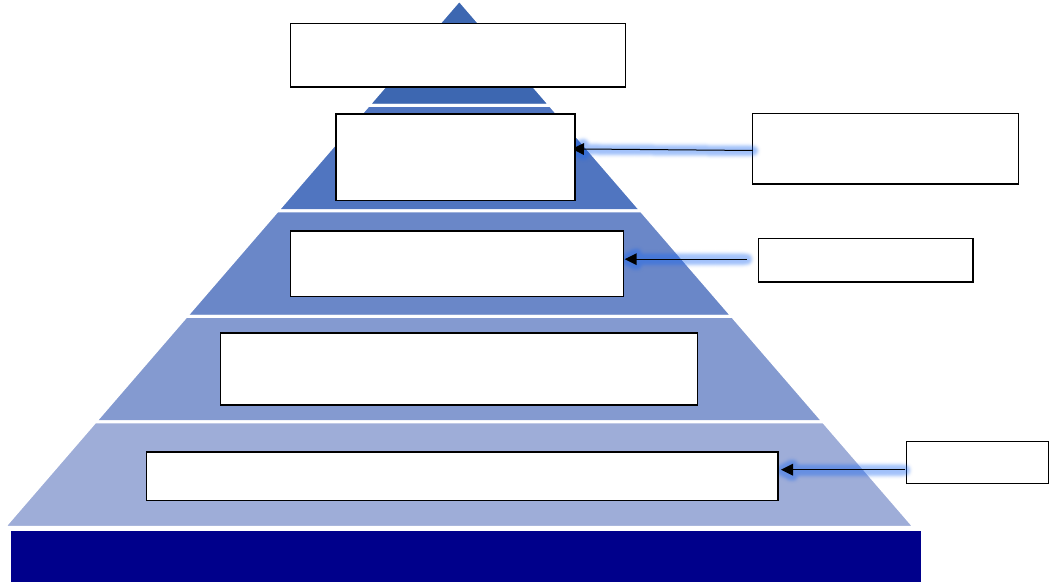

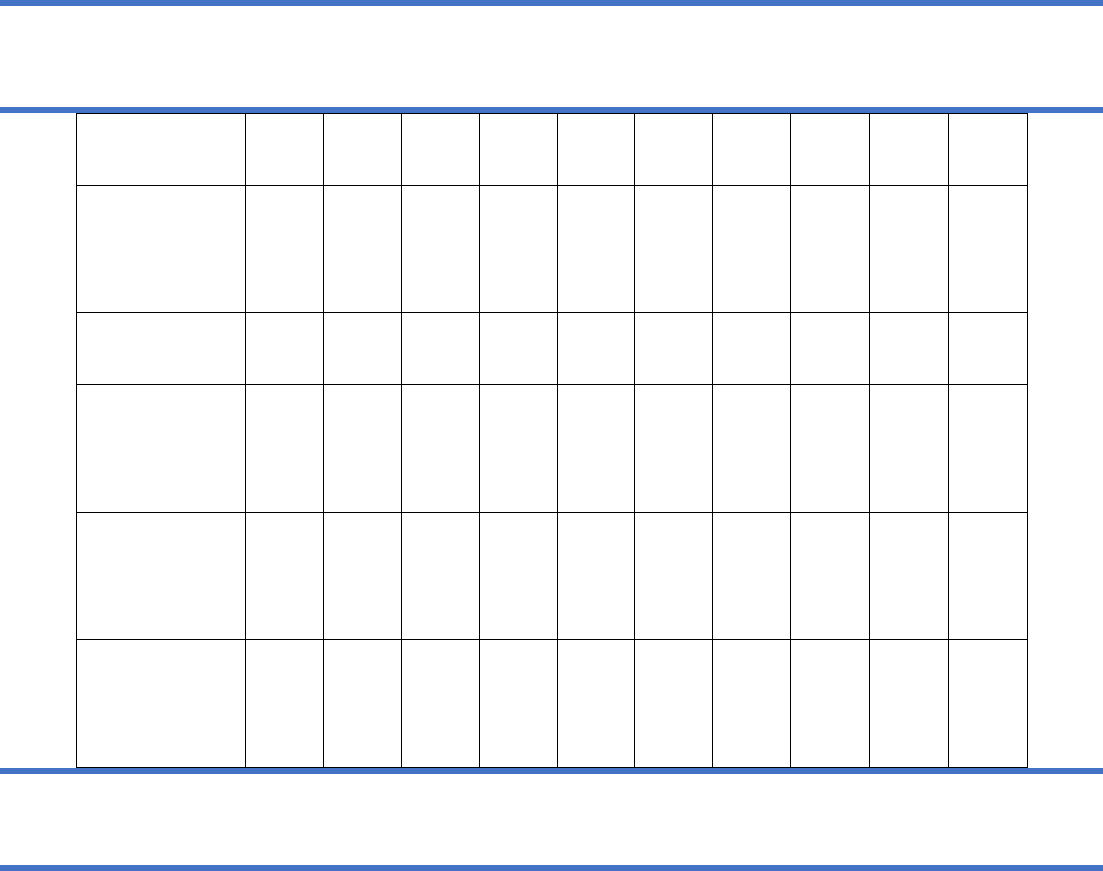

School Support

Intensive School

Interventions With

Community Support

Targeted School Interventions

With Community Support

Early Identification of Students With

Mental Health and Behavioral Health

Concerns

School Based Prevention & Universal Interventions

-

Students with

Severe/Chronic Problems

At-Risk Students

All Students

Targeted School Interventions

with Community Support

Early Identification of Students with Mental

Health and Behavioral Health Concerns

School-Based Prevention & Universal Interventions

Intensive School

Interventions with

Community Support

Intensive Community

Interventions w/ School Support

The Continuum of School Mental Health Services

Adapted from “Communication Planning and Message Development: Promoting School-Based Mental Health

Services” in Communique, Vol. 35, No.1. National Association of School Psychologists, 2006.

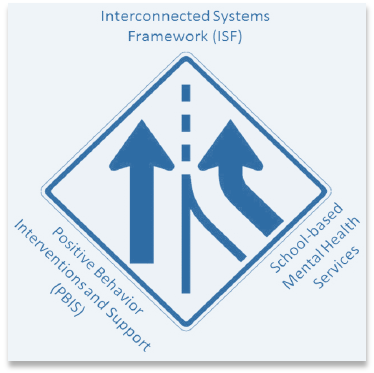

The provision of these services does not occur in isolation. Many schools are using an

Interconnected Systems Framework (ISF) to integrate the supports and services provided in

multiple systems (e.g., positive behavioral supports, school mental health services, community

supports, etc.). An ISF strategically aligns the goals and processes of school initiatives. The

Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) in

collaboration with other partners produced Advancing Education Effectiveness: Interconnecting

School Mental Health and School-Wide Positive Behavior Support (Barrett, Eber, & Weist,

2013), which describes the “proposed mechanism that can effectively link School Mental Health

(SMH) and PBIS in order to leverage the individual strengths of each of these processes and

produce enhanced teaching and learning environments through their strategic linkage” (p. V).

4

This monograph (https://www.pbis.org/common/cms/files/Current%20Topics/Final-

Monograph.pdf) is an excellent guide and resources for school districts interested in developing a

comprehensive behavioral health support system for students.

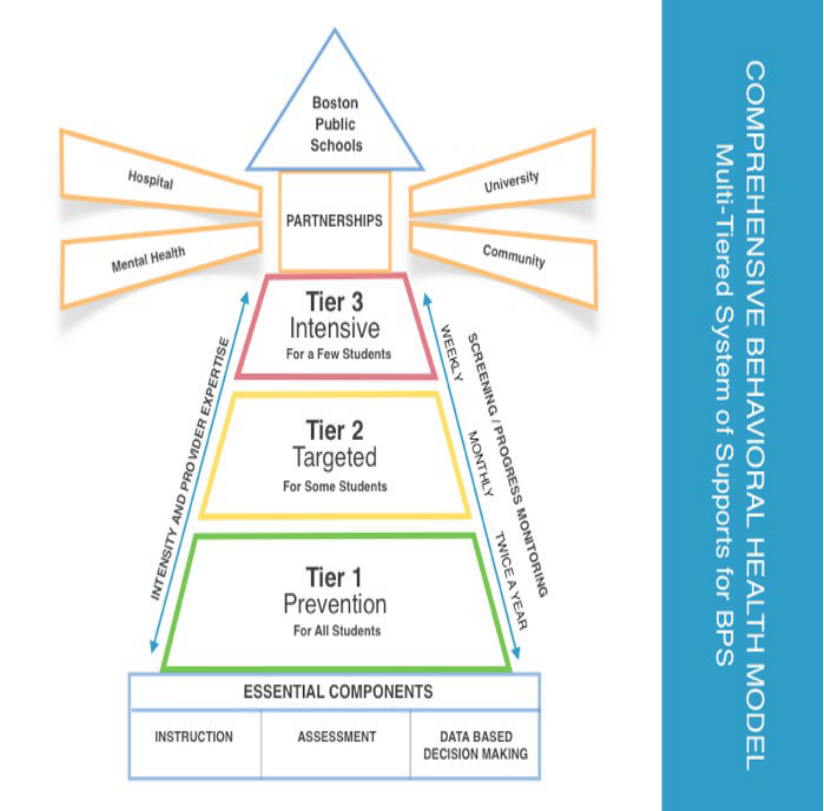

Screening in Schools is an Expanding Practice

School-wide universal screening for mental health issues is a practice that has become more

prevalent and is now recommended by The National Association of School Psychologists

(NASP, 2009), as well as the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine, who built

upon criteria established by the World Health Organization (O’Connell, Boat, & Warner, 2009).

Universal screening for behavioral and mental health issues can help with early identification of

students who are at-risk or in need of intervention related to these concerns, as research suggests

that significantly more students require mental health or behavioral services than currently

receive them (NASP, 2009). Universal screening for these concerns, particularly when

implemented within a multi-tiered model of behavioral support, may help these students receive

earlier services than they otherwise would and may prevent the need for more intensive special

education or therapeutic services.

Definition of Screening

While schools engage in various types of “assessment,” screening students for possible

behavioral health adjustment difficulties is different than other types of testing conducted in

school. According to the University of Maryland Center for School Mental Health, “mental

health screening is the assessment of students to determine whether they may be at risk for a

mental health concern. Screening can be conducted using a systematic tool or process with an

5

entire population, such as a school’s student body, or a group of

students, such as a classroom or grade level(s)” (CSMH, 2018).

This type of assessment differs from other activities such as

psycho-educational evaluations for special education eligibility

determination, diagnostic assessment for identifying specific

psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, etc.), or risk for

violence assessment (e.g., threat assessment). All these

assessments have their value in schools, but screening tends to be

broad-based in nature by evaluating groups of students and is

designed to identify “risk factors” for adjustment difficulties.

The purpose of screening includes (CSMH, 2018):

• Identify students at risk for poor outcomes

• Identify students who may need monitoring or intervention

(e.g., targeted supports for emerging adjustment problems,

intensive supports for chronic behavioral issues)

• Inform decisions about needed services

• Identify personal strengths/wellness as well as risk factors/emotional distress

• Assess effectiveness of universal social/emotional/behavioral curriculum

Identification Is Not

Diagnosis

The goal in identifying students with

possible mental health or substance

use problems is to provide the

option for further assessment. Such

identification does not involve

reaching a diagnosis of a condition.

Only mental health or medical

professionals (as determined by

each state’s licensing laws) are

qualified to make a diagnosis.

Neither action signs nor screening

tools provide sufficient information

to reach a diagnosis.

Research-based Practices in Screening

The use of universal screening instruments to get information about student academic, emotional,

behavioral, or social needs is a valuable practice within school-wide multi-tiered systems of

support (Bruhn, Woods-Groves, Huddle, 2014; Eklund, Kilgus, von der Embse, Broadmore, &

6

Tanner, 2017; Oakes, Lane, & Ennis, 2016). Universal screening allows for the early

identification of students who may need additional behavior support, including those exhibiting

both externalizing and internalizing patterns of problem behavior (Eklund et al., 2017; Kilgus &

Eklund, 2016; Oakes et al., 2016). Rather than relying only on teacher nomination or

examination of existing school data (e.g., attendance, grades), which are both a reaction to

existing problem behavior and more likely to identify students with externalizing problem

behavior, systematic universal screening is a proactive practice, decreasing the likelihood that

schools will overlook a student in need of support or intervention (Bruhn et al., 2014). Universal

screening shifts the focus from a reactive, wait-to-fail model to a proactive system in which

needs are identified early and interventions are delivered efficiently to the level of need

demonstrated by the student (Dowdy et al., 2015).

Why Intervene Early?

The good news is that that schools can help mitigate the effects of mental illness and allow

individuals to live fulfilling, productive lives. Research demonstrates that students with good

mental health are more successful in school. Longitudinal studies provide strong evidence that

interventions that strengthen students’ social, emotional, and decision-making skills also

positively affect their academic achievement in terms of higher standardized test scores and

better grades (Fleming et al., 2005; Durlack, et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2017). Half of those who

will develop mental health disorders show symptoms by age 14 (Kessler, et al., 2005). Therefore,

early identification of risk factors or signs of adjustment difficulties provide an opportunity to

intervene before problems develop into more significant and costly impairments. Unfortunately,

signs are often ignored and not met with supports for the child. When schools, families, or the

community do not act early to support students, consequences such as suicide, incarceration,

7

homelessness, and school drop-out can be the outcome (Darney, et al., 2013; Hawton, et al.,

2012).

Involving Families and Students in Developing a Screening Process

When schools make students’ behavioral health a priority and engage in screening as part of their

multi-tiered systems of support, it is vital to involve families and students from the initial

planning phases. Parents/guardians are partners in the education process and have primary

responsibility for the health and well-

being of their child. They can serve as

strong advocates from the community to

support this type of program. Families

“W

E NEED TO KNOW WHAT IT

’

S

FOR,

WHO WILL SEE IT,

AND WHAT

DIFFERENCE IT WILL MAKE

.”

Student Voice

are key to promoting a youth’s healthy

development. As with physical health

decisions, parents/guardians are the decision makers regarding their child’s care for any

identified mental health problems. They have valuable information about their child’s normal

feelings and behavior. Encouraging the involvement of parents/guardians before asking consent

to conduct a screening is a valuable approach. The positive involvement of parents/guardians

may include engaging them in the process of setting goals for an identification initiative and in

the selection of methods for identifying mental health problems.

Students will be the subjects of the screening process and can provide important feedback to

facilitate the effective implementation of screening tools and supportive interventions. Critical to

this work will be the process of relationship building between young people and adult partners.

Schools need to emphasize the importance of creating space for students to advise and support

decision making through the stages of development, implementation, and evaluation of screening

8

activities. Involving students in decisions that impact on them can benefit their emotional health

and wellbeing by helping them to feel part of the school and wider community and to have some

control over their lives. At an individual level, benefits include helping students to gain belief in

their own capabilities, including building their knowledge and skills to make healthy choices and

developing their independence. Collectively, students benefit through having opportunities to

influence decisions, to express their views and to develop strong social networks.

Steps to engaging parents/guardians and students will be discussed in later sections of this

toolkit.

9

Ready: Preparing Infrastructure for Screening in Schools

Dr. May recognizes that she needs to engage in preparation to “lay the groundwork” for

the Fairhaven Schools to develop a comprehensive behavioral health program, which

includes screening of students for mental health and substance use risk factors. While her

intentions are good, Dr. May realizes that an effective program will involve various

stakeholder groups in the district. She decides that she will start with her annual

strategic planning review, where she evaluates the progress on goals and develops new

goals based upon the needs of the district. Dr. May always involves other administrators,

teachers and other school staff, as well as parents/guardians and students in this process.

She determines that this will be a good opportunity to discuss her desire to develop a

comprehensive behavioral health program, with mental health screening as part of this

program.

Strategic Planning for Comprehensive Behavioral Health Supports

Strategic planning is the process of setting goals, deciding on actions to achieve those goals and

mobilizing the resources needed to take those actions. A strategic plan describes how goals will

be achieved using all available resources. School districts of all sizes use strategic planning to

achieve the broad goals of improving student outcomes and responding to changing

demographics while staying within the funding that they are provided or able to secure. Planning

for engaging in “screening” should be embedded within the districts’ strategic plan.

Unfortunately, many school districts engage in the development of this type of plan in an

inefficient, ineffective manner. They tend to engage in the “tell, then sell” method by developing

a plan, then trying to “sell” it to the community. Instead, many school districts have proactively

shifted their strategic planning process to genuinely include and involve parents/guardians and

10

other constituents. At the school district level, strategic planning requires community

engagement and support. Collaborative leaders in education know that without community

support and the insight that comes with community engagement their strategic plans are likely to

fail. It is important to gain insights and gauge community preferences as early as possible.

School districts that engage

early in the planning process

have a much greater chance of

building a successful and

community supported plan.

Prioritizing students’ mental

health, which includes the

promotion of emotional

wellness and support for

emotional challenges, needs to

be a critical component of a

district’s strategic plan.

“Screening” under IDEA

While similar in concept, universal behavioral health

screening presented in this toolkit is different than

“screening” under the Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act (IDEA).

Universal screening under IDEA is a method by which school

personnel determine which students are “at risk” for not

meeting grade level standards. Universal screening can be

accomplished by reviewing a student’s recent performance

on state or district tests or by administering an academic

screening to all students. The screening of a student by a

teacher or specialist to determine appropriate instructional

strategies for curriculum implementation is not considered to

be an evaluation for eligibility for special education and

related services.

IDEA also permits the screening of children under the age of

three who have been referred to programs to determine

whether they are suspected of having a disability.

The Sacramento City Unified

School District (SCUSD)

developed a document entitled

“Strategic Recommendations:

Creating Capacity for Mental Health Services for SCUSD Students”

(http://www.scusd.edu/sites/main/files/file-attachments/final_report_-

_creating_capacity_for_mh.pdf). This document serves as a model for community and

11

stakeholder engagement and the development of an actionable

strategic plan to address the mental and substance use needs of

students. The value of having an effective strategic plan is that it

guides the allocation of resources and decision making is

measured against actions/strategies that will address the goals

outlined in the plan. Communication and decisions regarding

mental health screening are guided by the plan.

Clarifying Screening Needs

Many schools currently collect data on students. These range

from office discipline referrals (ODRs), attendance data, and

grades/GPA to health visits to the school nurse and family

economic indicators. Analysis of the data can help to identify

“risk factors” or students may be demonstrating adjustment

difficulties or other challenges. Developing and employing an

Early Warning System (EWS) that identifies at-risk students

through the analysis of readily available and highly predictive

student academic and engagement data is critical. Utilizing data

systematically to identify at-risk students as early as possible will

allow for the application of more effective prevention and early

intervention services. Utilization of various data tools assist

schools in identifying at-risk students. The Early Warning System

(EWS) High School Tool

(http://www.earlywarningsystems.org/resources/early-warning-

Screening for

Emotional

Wellbeing

Some schools choose to engage in

“strength-based” screening or

screening for emotional well-being.

It is widely recognized that a

student’s emotional health and

well-being influences their cognitive

development and learning, as well

as their physical and social health

and their mental wellbeing in

adulthood. Mental well-being is not

simply the absence of mental illness

but is a broader indicator of social,

emotional and physical wellness.

There are three key purposes for

which schools and colleges might

wish to measure mental wellbeing:

• to provide a survey

snapshot of student mental

wellbeing to inform

planning

• to identify individual

students who might benefit

from early support

• to consider the impact of

early support and targeted

interventions

12

system-high-school-tool/) was developed by the National High School Center at the American

Institutes for Research to allow users to identify students showing early warning signs of risk for

dropping out of high school. The tool calculates research-based early warning indicators that are

predictive of whether students graduate or drop out of high school. A middle school version

(http://www.earlywarningsystems.org/resources/early-warning-system-middle-grades-tool/) is

also available. These tools are in the public domain and are free to use.

It is important for schools to analyze existing data before making the determination to engage in

additional screening of students. This prevents a duplication of data, expenditure of additional

resources and staff time, as well as unnecessary demands placed upon the student population.

However, despite their predictive validity, ODRs do not detect a full range of emotional and

behavioral problems. ODRs are more highly correlated with externalizing behavior problems

(e.g., disruptive behavior, attention problems) than with other behavioral and mental health

problems (e.g., concentration problems, depression, anxiety, adaptive skills; Walker, Cheney,

Stage, Blum, & Horner, 2005). The reliance on ODRs to identify at-risk students places the focus

primarily on students with externalizing behavior problems, passing over students at risk of

internalizing behavior concerns (Walker et al., 2005). Additional data points are often needed to

conduct more thorough school-wide identification of students in need.

The decision to engage in additional screening is often based upon the needs of the school. The

Behavioral Health Team (see section below on school based teams) can make this determination

based upon several factors. To determine the areas in need of screening, multiple methods can

be used, including stakeholder interviews, focus groups and/or reviews of existing data sources.

The initial data can be used to determine the areas of greatest need, and the subsequent screening

data can be used to clarify this need and eventually inform creation of a plan for intervention.

13

Developing the Screening Process and Procedures

As indicated in the Introduction, “screening” is part of a larger comprehensive behavioral health

supports with a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) Interconnected Systems Framework

(ISF). However, the process of “screening” is far more than simply choosing a tool to use and

administering the assessment to students. Careful planning and preparation is required. Issues

related to the following factors must be addressed;

• Obtaining district, staff and family buy-in

• Allocating resources (fiscal and staffing) to support the screening process

• Defining roles and responsibilities of all staff involved in the screening process

• Addressing ethical and legal/liability considerations (e.g., parental consent and student

assent; communication; confidentiality)

• Selection of the right standardized screener(s) for your school/district (contextual fit)

• Training and professional development regarding screening (administration, data

analyses, decision-making, intervention selection, and decision-rules)

• Developing/expanding your data systems

• Identifying and coordinating resources necessary to support students in need of additional

intervention

The Ohio Positive Behavioral and Interventions Support (PBIS) Network has produced “School-

Wide Universal Screening for Behavioral and Mental Health Issues: Implementation Guidance.”

14

This is an excellent guide for school districts which are developing a screening process. This

document is available in Appendix I.

School-based Behavioral Health Teams

As schools and districts plan for the incorporation of universal screening as part of their

comprehensive behavioral health support plan, it is important for teams to understand how to

plan for and make decisions from the data collected through the screening process. If a school

team whose purpose is to address student behavior or school climate issues does not already

exist, establishing or repurposing a leadership team is the first step in the process of

implementing school-wide screening for behavioral and mental health issues. It is recommended

that this team consist of leaders who will help plan, implement and evaluate the screening

process through collaboration and feedback with other school professionals, parents/guardians,

and any other indicated groups. This representative team should meet regularly to ensure that

screening efforts are planned for, implemented and monitored effectively.

Different schools may have different names for this team and may already have a team of this

nature in place that can subsume screening under its purview. If another team (e.g., Instructional

Support Team, Child Study Team, PBIS Team, etc.) adds this process to its agenda, it is

important that all members are aware of the importance of implementing this school-wide

screening before moving forward. The Center for School Mental Health (CSMH) at the

University of Maryland has developed the “School Mental Health Teaming Playbook: Best

Practices and Tips from the Field” (2018). The Playbook defines a behavioral health or “mental

health team” as “a group of school and community stakeholders that meet regularly and use data-

based decision making to support student mental health, including improving school climate,

15

promoting student and staff well-being, and addressing individual student strengths and needs”

(p.2).

Many schools have teams that meet to discuss and strategize about student mental health issues.

Schools may have one team devoted to the full continuum of mental health supports or multiple

teams that address different parts of the continuum. The CSMH Teaming Playbook

(http://csmh.umaryland.edu/media/SOM/Microsites/CSMH/docs/Reports/School-Mental-Health-

Teaming-Playbook.pdf) is an excellent resource for guiding schools on team development.

Selection of a Screening Tool

Selection of a screening tool should be based upon the areas of identified need of the individual

school or district. A wide variety of evidence-based screening instruments have been developed

and are available for use in the schools. Many of the tools are available at no cost to the school

district. However, while cost is a significant consideration, the primary considerations should be

whether the evidence-based instrument provide the appropriate information that the school

desires and whether the instrument is a good “contextual fit” for the school. The Ohio PBIS

Network (2016) has identified the following considerations to help schools select an appropriate

screening tool.

Population

• A screening instrument should always be chosen based on its relevance to the

school’s demographics and characteristics.

• Screeners must always be age- and developmentally appropriate.

• Ideally, a screener should have been validated or normed on a sample similar to

the population being evaluated.

16

• Many student and contextual factors (e.g., gender,

ethnicity, socioeconomic status, home language,

parent involvement) have been shown to affect cut

scores and overall prediction of risk status.

Feasibility and usability

• It must be practical to universally administer the

screener within the desired context, including clear

instructions and examples of any difficult concepts.

• The cost of the screener should not outweigh the

benefits obtained as a result of the process.

• Involved stakeholders (e.g., students,

parents/guardians, teachers and administrators)

should consider the screener to be acceptable and

useful.

What Is a

Screening Tool?

A screening tool is a brief list of

questions relating to a students’

behavior, thoughts, and feelings. It

usually takes only 5–15 minutes to

answer. A specific method is used

to score the answers to the

questions, and the score suggests

the degree to which the student

may have a problem. As with

medical tests, the language used

to refer to the results of screening

may be confusing. When a score

indicates a likely problem, it is

called a positive finding; when the

score indicates that a problem is

not likely, it is called a negative

finding. Like other medical tests,

sometimes screening tools might

miss problems or suggest a

problem when one may not exist.

Time

• Consider the amount of time to collect, score, enter,

manage and analyze screener data, in addition to administration time.

• Personnel time to train staff in the administration and completing the screening

process is an additional consideration that may be more important than the

physical cost of materials.

17

Psychometric evidence

• Reliability: the degree that the chosen screener results in similar scores each time

it is used.

• Validity: the degree that the chosen screener measures what it is supposed to

measure.

• Screeners should have valid cut scores, which help reduce false positives and

negatives and assure that students are receiving the services they need.

• False positives may be more desirable than false negatives with regard to

screening (e.g., it is better to catch too many students than too few).

Several compendiums of evidenced-based screening tools have been compiled by various

organizations. See Appendix III for a listing of these compendiums.

A number of jurisdictions have developed useful resources. For example, the Florida Project

Aware site developed a number of useful guiding questions for selecting a screening instrument.

18

Guiding Questions for Social-Emotional Screener Selection (Florida Project AWARE)

Goals and Objectives:

• What is the purpose of the social‐emotional screening process?

• What valued outcomes will be achieved?

• How will social‐emotional screening supplement existing Tier 1/screening data to inform decision making?

• How will a social‐emotional screener improve student access to a continuum of supports?

Technical Adequacy

1

:

• Norms: What type of sample was used to research the screener/develop norms?

• Reliability: Does the screener produce consistent results?

• Validity: Does the screener assess what it is intended to?

• How well does the screener predict future outcomes (problems and strengths)?

• Sensitivity/Specificity: Does the screener adequately capture true positives and true negatives?

• How many students does the screener misclassify (e.g., students truly at risk but identified as not being at risk [missed],

students truly not at risk but identified as being at risk [misidentify])?

Social Validity and Treatment Utility:

• Do students and family support the implementation of the screener?

• What valued outcome is the screener intended to inform?

• What questions about student mental health problems/risks and well‐being/protective factors can be addressed with the

screener?

• Does the screener align with preventive interventions/Tier 1 supports (e.g., inform intervention)?

• Does the screener predict future risk (e.g., identify students who may benefit from additional interventions)?

Usability and Practicality:

• Does the district/school have the necessary infrastructure to implement the screener?

• How much does the screener cost ‐‐ per manual, per student, per use?

• Manual or web‐based administration, scoring, reporting?

• Are multiple translations (e.g., English, Spanish) needed/available?

• Are there fiscal resources available to purchase and support the screener use over time?

• How many items does the screener contain and how long does it take to administer?

• Where and how will the data be securely stored ‐‐ via Excel sheets, district‐based data systems, or separate online

databases?

• How will data be used for decision‐making?

• What are the training and coaching needs to support effective implementation of the screening procedure?

19

1. Professionals with training in statistics, quantitative methods, and measurement (e.g., psychologists) can provide valuable guidance on

the appropriate screening tool selection and its use for the intended student population and purpose.

Cultural and Linguistic Considerations

The Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has developed

guidance on identifying mental health and substance use problems in students. Contained within

this guide are the following cultural and linguistic considerations when engaged in a screening

process (SAMHSA, 2011).

Are culturally and linguistically diverse populations being served?

Use of tools developed and tested primarily on an English-speaking population from the

mainstream culture introduces many important considerations related to the linguistic and

cultural appropriateness of the tool and interpretation of results. Schools should be aware that the

predictive effectiveness of available tools and their accuracy in screening cross-cultural

populations may not have been fully researched. Lack of research on the cultural appropriateness

of the tools requires special attention regarding how to make these tools meaningful for people of

different cultures and for those who speak diverse languages. Such attention is especially

important because of the significant variation across cultural beliefs and practices in what is

considered normal development and developmentally appropriate parenting. Variation may be

most significant for preschool and younger students.

What degree of literacy and fluency in English do the respondents have?

Some tools have translations, and some have been tested for a range of literacy levels. However,

even when translations are available, schools may need to determine if a tool effectively

communicates concepts to the specific population being served. Therefore, it is necessary to

determine whether the available translation is easily understood by the participating students,

parents/guardians, families, and other informants.

20

What are the cultural beliefs and values of the service population regarding normal

development, mental health, and substance use?

Cultural differences in child-raising customs and in what is considered normal development may

show up as problems if the screening tool has not been normed for or informed by such

variations. The tool may be consistently misunderstood by the population being served, or it may

fail to distinguish the students with problems from those who are developing normally. Different

cultural groups should be consulted and asked to identify areas where misunderstandings may

occur. If necessary, another tool may be selected, or the existing tool may be modified by

rewording a question or weighting certain responses differently than prescribed.

Because changes to the screening tool or the interpretation of the results may affect the tool’s

validity, it is advisable to consult with the tool’s developers before making final changes. Tool

developers may have worked with other organizations on tool modifications, or they may have

recent research results that have not been published. At the very least, the developers can provide

insight into how the proposed changes may affect the screening results.

What are the limitations of using a screening tool that has not been fully tested with a particular

cultural group?

If a tool’s predictive effectiveness has not been fully researched for a school’s target population,

the school should keep in mind that the findings may not be as reliable or valid as the findings

for students from populations on which it has been normed and studied. Even when language is

not a concern, the school should select a tool that is seen to be acceptable, useful, and in

accordance with a specific community’s values and expectations regarding child raising or

mental health.

21

Few screening tools are designed for and tested on a variety of groups that differ culturally and

linguistically from the majority of the population. As a result, feedback from members of such

groups is needed to help assess whether proposed screening tools will be clearly understood and

to identify any screening items that will not be able to predict targeted problems in that culture.

The knowledge and understanding of cultural values acquired during this process must inform

the interpretation of screening results. The person administering the screens must be aware that

cultural differences in child rearing may result in very different interpretations of a student’s

behavior. Items that may be misinterpreted or that can carry a different meaning in a specific

culture should be given less weight, and the overall score should be considered less accurate.

Ideally, a school will work with its cross-cultural staff and representatives from the different

cultural groups it serves to identify such issues, select tools that minimize those issues, and help

other staff understand the nature of the cultural differences. Training to help staff members who

administer the screens to discuss potential cultural issues with the family also would be of value.

The following resources are available for a more detailed discussion of culturally and

linguistically appropriate screening tools that have been studied.

Communicating with Stakeholders Before Screening

Involvement of stakeholder groups prior to initiating screening is important to maximize the

effectiveness of the process. Schools may want to consider communicating with the following

groups to provide valuable information, as well as seek feedback and answer questions regarding

the screening.

22

Parents/Guardians and Students

Encouraging the involvement of parents/guardians before asking consent to conduct a screening

is a valuable approach. The positive involvement of parents/guardians may include engaging

them in the process of setting goals for a screening initiative and in the selection of methods for

identifying mental health problems. Explaining the purpose and intended use of screening tools

to students, in language they can understand, is also important.

What schools can do:

• Prepare the school and the broader community by providing information about mental

health, screening, and treatment. This approach may include educating residents about the

mental health problems that exist in the community and the resources that are needed to

address those problems.

• Address parental/guardian concerns regarding the impact of “screening” students (e.g.,

labeling and identifying students, stigma associated with risk factors).

• Involve families and community stakeholders in the planning of an early identification

initiative so their concerns are identified and addressed (e.g., conduct focus groups,

ensure that the planning team has parent/guardian and student members).

• Make special efforts to solicit the input and involvement of students and their families as

well as the input of different cultural groups in the local community to learn about their

beliefs and attitudes about mental health.

Screening tools generally focus on indications of problems. However, it is imperative that

schools use such tools thoughtfully in a strengths-based context. Partnering with a family

advocacy or youth advocacy organization can help in planning and implementing a family-

23

friendly or youth-friendly approach. Introducing the screening initiative can present an

opportunity to provide information about mental health problems and the value and nature of

intervention and treatment, which helps frame the discussion in a strengths-based context.

Involving students in decisions that impact them can benefit their emotional health and wellbeing

by helping them to feel part of the school and wider community and to have some control over

their lives. At an individual level, benefits include helping students to gain belief in their own

capabilities, including building their knowledge and skills to make healthy choices and

developing their independence. Collectively, students benefit from having opportunities to

influence decisions, to express their views and to develop strong social networks.

School Staff

Involving school staff in the development of a screening process and communicating the intent

and outcomes will facilitate “buy in” and cooperation. Teachers and other staff members often

provide critical input. Sharing information and communicating with staff in the following ways

may be helpful:

• Communicate screening process and procedures

• Provide professional development around implementation and data-based decision

making

• Share data and information:

o Graphs presented at staff meetings

o Progress of students and effectiveness of systems

o Screening procedures reviewed prior to each implementation

o Connecting outcome data to interventions for students

24

Community Organizations/Agencies

Community providers augment the work of school staff and ensure access to the full continuum

of programs and services for all students. Partnering with community agencies allow schools to

maximize resources and options available to students and families.

Considerations for communicating with community partners include:

• Develop a memorandum of understanding/agreement of clearly defined roles and

responsibilities

• Provide professional development around implementation of screening process

• Share data and information regarding outcomes (upon parental consent)

• Communicate legal/ethical guidelines

Ethical and legal considerations

Before implementing any form of systematic screening, it is important to review any relevant

federal, state, local and district guidelines that may help determine the legality, ethics, and

typical policy of conducting universal screenings in schools. It is important to emphasize that the

screening described in this toolkit does not fulfill the legal requirements under IDEA. Schools

should reference IDEA regulations regarding “child find” requirements and permissible

“screening.” However, there is general guidance provided on many issues related to behavioral

health screening.

FERPA and HIPAA

The relationship between the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and the

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, often

25

creates confusion on the part of school administrators, health care professionals, and others as to

how these two laws apply to records maintained on students. When schools engage in mental

health screening, knowing which laws apply and how they will impact the use and

communication of screening results is critical. The U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services and the U.S. Department of Education issued “Joint Guidance on the Application of the

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) And the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) To Student Health Records”

(https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/doc/ferpa-hipaa-guidance.pdf). This document seeks

to answer many questions that school officials and others have had about the intersection of these

federal laws.

In addition, SAMHSA funds the Center of Excellence for Protected Health Information which

develops and disseminates training, technical assistance, and educational resources for healthcare

practitioners, families, individuals, states, and communities on various privacy laws and

regulations as they relate to information about mental and substance use disorders. These include

the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and 42 CFR Part 2. The

intersection of these laws and regulations with other privacy laws such as the Family Education

Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) are also addressed.

https://www.caiglobal.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1149&Itemid=195

Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment

Schools also need to consider rights afforded under the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment

(PPRA). PPRA affords parents/guardians of elementary and secondary students certain rights

26

3

regarding the conduct of surveys, collection and use of information for marketing purposes, and

certain physical exams. These include, but are not limited to, the right to:

• Consent before students are required to submit to a survey that concerns one or more of

the following protected areas (“protected information survey”) if the survey is funded in

whole or in part by a program of the U.S. Department of Education (ED)

1. Political affiliations or beliefs of the student or student’s parent;

2. Mental or psychological problems of the student or student’s family;

3. Sex behavior or attitudes;

4. Illegal, anti-social, self-incriminating, or demeaning behavior;

5. Critical appraisals of others with whom respondents have close family relationships;

6. Legally recognized privileged relationships, such as with lawyers, doctors, or

ministers;

7. Religious practices, affiliations, or beliefs of the student or student’s parent; or

8. Income, other than as required by law to determine program eligibility.

• Receive notice and an opportunity to opt a student out of -

1. Any other protected information survey, regardless of funding;

2. Any non-emergency, invasive physical exam or screening required as a condition of

attendance, administered by the school or its agent, and not necessary to protect the

immediate health and safety of a student, except for hearing, vision, or scoliosis

27

screenings, or any physical exam or screening permitted or required under State law;

and

3. Activities involving collection, disclosure, or use of personal information collected

from students for marketing or to sell or otherwise distribute the information to

others. (This does not apply to the collection, disclosure, or use of personal

information collected from students for the exclusive purpose of developing,

evaluating, or providing educational products or services for, or to, students or

educational institutions.)

• Inspect, upon request and before administration or use -

1. Protected information surveys of students and surveys created by a third party;

2. Instruments used to collect personal information from students for any of the above

marketing, sales, or other distribution purposes; and

3. Instructional material used as part of the educational curriculum.

These rights transfer from the parents/guardians to a student who is 18 years old or an

emancipated minor under State law. A template for PPRA notification to parents/guardians is in

Appendix I.

Obtaining Informed Parental Consent

A school must have in place clearly written procedures that comply with a state’s legal

requirements for requesting consent and notifying legal guardians or students of the results of

screening activities. These procedures should identify specific circumstances in which the

28

information will be shared with other service providers. Schools should consider the following

factors when implementing key steps of the screening process:

If the legal guardian is to be the informant, getting parental consent is straightforward.

The school needs to:

• Explain that the tool can help identify if the student has a social or emotional challenge;

• Inform the legal guardians that if such a challenge is identified, they will be assisted in

following up on the information;

• Explain confidentiality;

• Let parents/guardians know that they and their students are not required to complete the

tool or answer any question they find objectionable; and

• Encourage legal guardians to ask questions and express concerns about their student’s

social and emotional development.

If the legal guardian will not be present when the screening tool is administered, the school

needs to obtain written, informed consent from the legal guardian. Passive consent from

parents/guardians may be obtained, if there is a provision for the parent and/or student to “opt

out” of the screening. The following steps have been found to be helpful in answering legal

guardians’ questions and addressing their concerns:

• Provide information about the tool, the process, and follow-up assistance;

• Provide a contact name for someone who can answer questions; and

• Make a copy of the screening tool available to the legal guardians.

29

It is recommended that organizations require active consent, which means that a student is not

screened unless the legal guardian has signed a consent form and returned it to the school.

However, properly executed passive consent procedures are appropriate. The Wisconsin

Department of Public Instruction has developed a “question and answer” document

(https://dpi.wi.gov/sites/default/files/imce/sped/pdf/rti-consent.pdf) that provides guidance on

obtaining consent for screening

Obtaining the Assent of Students

Although most minors cannot provide legal consent, schools should seek informed assent from a

student who is asked to complete a screen. Assent is the willing agreement to participate in an

activity for which the purpose and process has been explained and any alternatives have been

discussed. In addition to being the right thing to do, assent is a practical necessity when the

informant’s willingness to participate openly is critical to obtaining useful results. In many cases,

it may be advisable to document a student’s informed assent with a signed assent form. A student

who has communicated unwillingness to participate can refuse to participate even when his or

her legal guardians have given formal consent. Some schools find it useful to develop guiding

principles, such as those developed by the Early Identification Workgroup of the

Federal/National Partnership (FNP) for Transforming Child and Family Mental Health and

Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment.

30

Principles Guiding Screening for Early Identification of Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents

Developed by the Early Identification Workgroup of the Federal/National Partnership (FNP) for Transforming Child

and Family Mental Health and Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment, December 18, 2006.

1. First, do no harm.

2. Obtain informed consent.

• Screening should be a voluntary process—except in emergency situations, which preclude obtaining consent

prior to screening. In these circumstances, consent should be obtained as soon as possible during or after

screening.

• Informed consent for screening a student should be obtained from parents, guardians, or the entity with legal

custody of the student. Informed assent from students should be obtained. Clear, written procedures for

requesting consent and notifying parents/guardians and students of the results of early identification activities

should be available.

3. Use a scientifically sound screening process.

• All screening instruments should be shown to be valid and reliable in identifying students in need of further

assessment.

• Screening must be developmentally, age, gender, and racially/ethnically/culturally appropriate for the student

to the greatest degree possible and use of results should be informed by potential limits to validity as indicated.

• Early identification procedures and approaches should respect and take into consideration the norms,

languages, and cultures of communities and families.

• Any person conducting screening and involved with the screening process should be qualified and

appropriately trained.

4. Safeguard the screening information and ensure its appropriate use.

• Screening identifies only the possibility of a problem and should never be used to make a diagnosis or to label

the student.

• Confidentiality must be appropriately ensured and limits to confidentiality must be clearly shared within the

scope of obtaining informed consent/assent (e.g., when immediate steps must be taken to protect life in an

emergency situation).

5. Link to assessment and treatment services.

• If problems are detected, screening must be followed by notifying parents, students, guardians, or the entity

with legal custody; explaining the results; and offering referral for an appropriate, in-depth assessment

conducted by trained personnel with linkages to appropriate services and supports.

31

Options for Funding Behavioral Health Screening

Funding of screening programs are often incorporated within the larger comprehensive

behavioral health program within the school. Following are general best practices suggestions for

financing school-based behavioral health programs (National Center for School Mental Health,

2018):

• Create multiple and diverse funding and resources at each tier to support a full

continuum of services

• Maximize leveraging and sharing of funding and resources to attract an array of funding

partners

• Increase reliance on more permanent versus short-term funding

• Use best practice strategies to retain staff

• Use economies of scale to maximize efficiencies

• Utilize third party reimbursement mechanisms (e.g., Medicaid, CHIP, private insurance)

to support services

• Utilize evidence-based practices and programs (cost effectiveness; return on

investment)

• Evaluate and document outcomes, including the impact on academic and classroom

functioning

• Use outcome findings to inform school district, community partner (e.g. collaborating

systems) contributions, and state-level policy impacting funding and resource allocation.

Many schools support behavioral health and screening programs through the general operating

funds of the district. However, following are some suggestions for funding alternatives.

32

1. Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment

There is no service category in Medicaid entitled “school based services”, however, the

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit provides

comprehensive and preventive health care services for children under age 21 who are

enrolled in Medicaid. EPSDT is key to ensuring that children and adolescents receive

appropriate preventive, dental, mental health, and developmental, and specialty services.

Periodic developmental and behavioral screening dur ing early childhood is essential to

identify possible delays in growth and development, when steps to address deficits can be

most effective. These screenings are required for children enrolled in Medicaid and are

also covered for children enrolled in CHIP. In order to bill Medicaid for EPSDT services,

the service must be coverable in the state plan, the child or adolescent must be a

Medicaid recipient and the service must be provided by a qualified provider who meets

provider screening requirements. For more information about EPSDT, go to

https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/epsdt/index.html.

2. Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Title IV Part A: Student Support and Academic

Enhancement Grants (SSAEC)

SSAEC are flexible block grants and are allocated to states using the Title I finding

formula. Funds will be allocated to states using the Title I funding formula. States will

allocate funds to LEAs using the same formula. Specialized instructional support

personnel must be involved in the development of district plans and applications for these

funds.

33

Districts must use at least 20% of these funds on efforts to improve student mental and

behavioral health, school climate, or school safety, which could include:

• comprehensive school mental and behavioral health service delivery systems,

• trauma informed policies and practices,

• bullying and harassment prevention,

• social–emotional learning,

• improving school safety and school climate,

• mental health first aid training, and

• professional development activities

3. ESSA Full Service Community Schools

ESSA authorizes a competitive grant program to support school community partnerships

to address the academic, health, mental health, and other needs of the school and

community at large. Any district wishing to receive a full-service community schools

grant must specify how specialized instructional support personnel will be involved in the

partnership and service delivery model.

4. ESSA Project School Emergency Response to Violence (Project SERV)

Funds are available to strengthen violence prevention activities as part of the activities

designed to restore the equilibrium of a learning environment that was disrupted by a

violent or traumatic crisis at a school.

5. SAMHSA Project AWARE-SEA Grants

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for

Mental Health Services (CMHS) accepts applications on an annual basis for Project

AWARE (Advancing Wellness and Resilience in Education) - State Education Agency

34

(SEA) grants (AWARE-SEA). The purpose of this program is to build or expand the

capacity of State Educational Agencies, in partnership with State Mental Health Agencies

(SMHAs) overseeing school-aged students and local education agencies (LEAS), to: (1)

increase awareness of mental health issues among school-aged students; (2) provide

training for school personnel and other adults who interact with school-aged students to

detect and respond to mental health issues; and (3) connect school-aged students, who

may have behavioral health issues (including serious emotional disturbance [SED] or

serious mental illness [SMI]), and their families to needed services.

The AWARE-SEA program supports the development and implementation of a

comprehensive plan of activities, services, and strategies to decrease youth violence and

support the healthy development of school-aged students.

35

Set: Screening Implementation Planning

Dr. May has established the foundations for her comprehensive behavioral health

program. Through her involvement with various stakeholder groups, she has prioritized

students’ mental health supports within the district’s strategic plan and has established

an initial goal of “screening” specific grade levels to pilot the process. Dr. May has

established a Behavioral Health Team (BHT) which facilitates the overall behavioral

health supports for the district and will guide the implementation of the screening

process. Realizing that it will take time to “scale up” the screening process, the BHT has

recommended screening of students for mental health risk factors during the transition

years of grade 6 and grade 9. While the team has selected an evidenced-based screening

tool, several additional steps need to be established prior to engaging in screening.

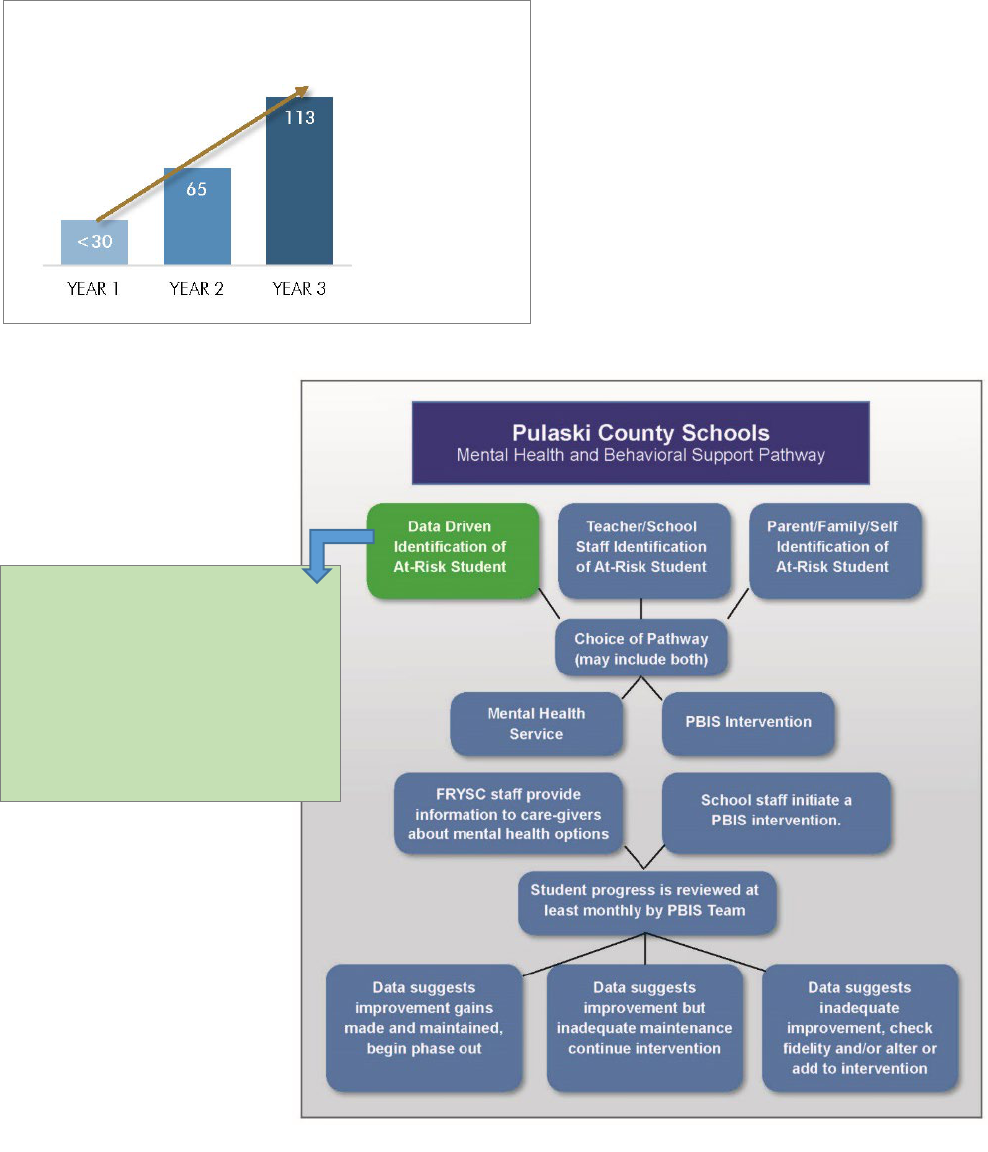

Starting Slow and Small

As schools and districts plan for the incorporation of universal screening as part of their multi-

tiered system of support, it is important for teams to understand how to plan for and make

decisions from the data collected through the screening instrument. For districts and schools

considering adding a universal screening process to their system of support, starting “slow” or

“small” is often a prudent initial approach. This allows the school to test out procedures and gain

valuable feedback. Starting small provides opportunities to make critical changes to the

screening process before scaling up the program.

Examples of “starting slow” may include:

• Screening students during important “transition” grade levels (e.g., grade 6 and 9)

• Targeting specific classes across grade levels that already present risk factors

36

• Teacher referral for student screening

• Pilot screening with select teachers

• Program/Intervention Evaluation

Staff Preparation

Ideally, individuals involved with both the screening process

and outcomes should be included in the planning stage.

Schools should consider including the building leadership

team (principal, assistant principal, etc.), families, education

and mental health professionals, primary care providers,

representatives of community agencies and any other relevant

individuals (Weist et al., 2007). Planning should include who

will complete the screening tool (e.g., student,

parent/guardian, or teacher) in addition to when and where

the screening will occur, and consideration of issues related to consent, confidentiality, and “buy

in” from staff, parents/guardians, and students. It is important to consider the plan for sharing the

screening information with parents/guardians, as well as connecting the student to further

assessment and/or treatment.

Utilizing Existing

Opportunities to

Screen

Schools engage in “screening” of

students at different points in the

school year. Consider using one of

the following opportunities to infuse

behavioral health screening.

• Physical/vision/dental

screening

• Academic screening

• School climate survey

• Youth Risk Behavior survey

It is important for staff to access training to increase their knowledge of emotional wellbeing and

indicators of emotional adjustment problems to help them identify mental health difficulties in

their students. This includes being able to refer them to relevant support, either within the school

or services in the community. This type of professional development is universally important.

However, in the context of behavioral health screening, it is vital for staff to recognize and

understand the signs and symptoms of both internalizing and externalizing emotional problems.

37

As part of the behavioral health screening process, the behavioral health team (e.g., the school-

based team leading the screening process) needs to establish a data interpretation process,

training of school implementation teams on this process, as well as building capacity, expertise,

and fluency in the use of data to inform decision making (see Data-based Decision Making

section in the “Go” chapter).

Resource Mapping

For districts and schools considering adding a universal screening process to their system of

support, Missouri School-wide Positive Behavior Support has a planning tool available for teams

to use as a guide (MO SW-PBS Tier II, 2017).

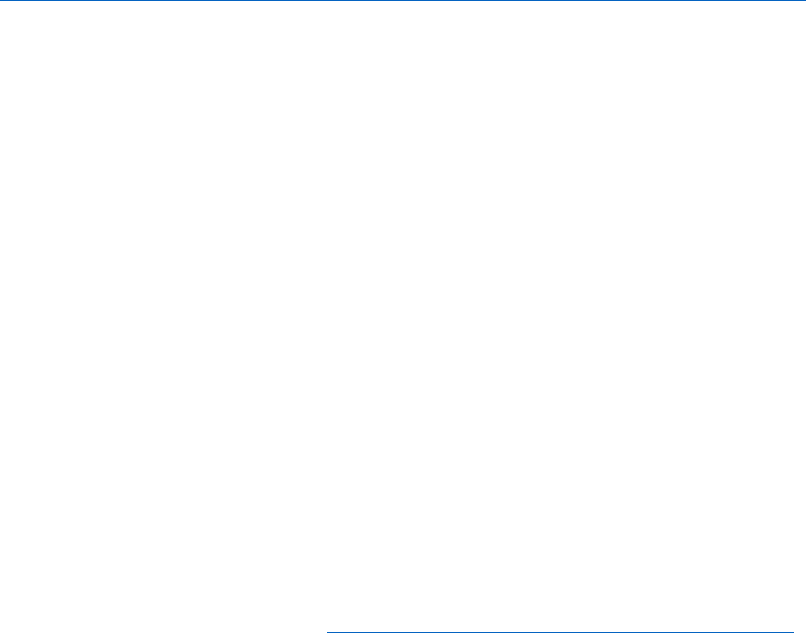

As part of the process of assessing the school’s ability to respond to the screening data with the

adequate level of support, schools can estimate their projected capacity for intervention by

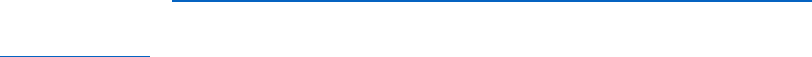

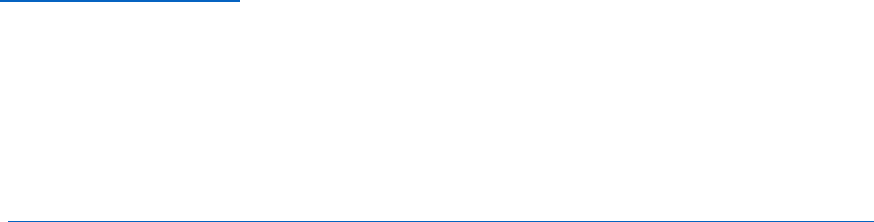

Total Student

Our Numbers

Our Numbers

Enrollment

80%

____________

10%

15%

1%

5%

At _____(School Name)______, the student population is ___________ students. Based on the expected

percentages in tiered intervention, ____________ students, or 80%, will use expected behaviors when the

school implements Tier I Universal practices with fidelity. Approximately _________ – _________ students, or

10-15%, may need additional support, or Tier II Intervention, to reliably perform expected behaviors. Finally, it

is possible that ________ –________ students, or 1-5%, may need the most intensive level of support, a Tier III

Behavior Intervention Plan, over the course of the school year.

(MO SW-PBS Tier II/Tier III workbook, 2017)

38

completing a simple projection table (MO SW-PBS, 2017). The goal is to have effective

universal supports in place to sufficiently support approximately 80% of the students and provide

the environment to support the success of students who require targeted or intensive support as

they learn and practice new skills.

It is important to have a complete understanding of available school and community resources.

Mapping services and resources that are available in the school and in the surrounding

community to address the mental health needs of students and families is part of the screening

process. A key goal of resource mapping is to ensure that all staff is aware of what resources are

available within the school and community. There is a need for clear systems of who can make

referrals, how referrals will be made, and a plan to follow-up to determine the success of the

referral. Resource mapping identifies school and community assets, providing more specific

details about the resources/services that are available within the school, neighborhoods, larger

community, and State. When resource mapping is done well, there is a systematic process that

can match available resources with student and family needs (Lever, et. al., 2014).

The University of Maryland Center for School Mental Health has published the “Resource

Mapping in Schools and School Districts: A Resource Guide”

(http://csmh.umaryland.edu/media/SOM/Microsites/CSMH/docs/Resources/Briefs/Resource-

Mapping-in-Schools-and-School-Districts10.14.14_2.pdf). This provides excellent guidance on

engaging in a resource mapping process for schools.

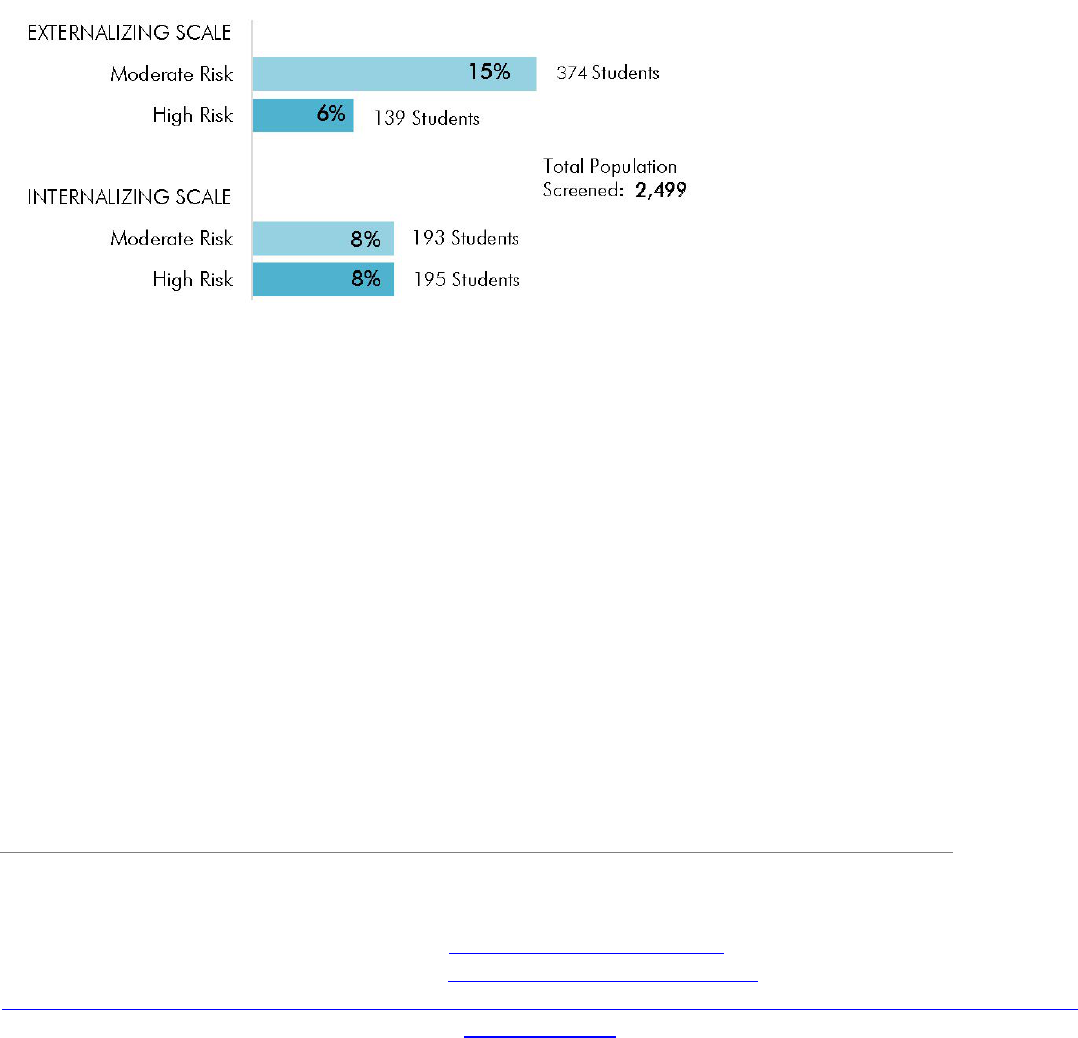

Referral Pathways

Schools frequently use school-employed mental health professionals (e.g., school psychologists,

social workers) or partner with mental health and substance abuse providers to ensure that

39

identified students have access to assessment and treatment. Sometimes these mental health

partners are integrated in the school setting through school-based mental health clinics or are in

the community setting. Organizations that serve students may be reluctant to screen for students

with mental health or substance use problems if they believe that appropriate assessment and

treatment are not available. When organizations anticipate an access-to-care problem, they

should explore the willingness of the local mental health and substance abuse treatment

community to support a planned identification initiative. Treatment providers are likely to

experience busy times of the year; as a result, providers may be more willing and able to

accommodate referrals from a screening program if the program is scheduled for a less busy time

of year.

The School Mental Health Referral Pathways (SMHRP) Toolkit

(https://knowledge.samhsa.gov/resources/school-mental-health-referral-pathways-toolkit) was

funded by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to

help state and local education agencies and their partners develop effective systems to refer

youth to mental health service providers and related supports. The SMHRP Toolkit provides

best-practice guidance and practical tools and strategies to improve coordination and

collaboration, both within schools and between schools and other youth-serving agencies. The

SMHRP Toolkit supports the cultivation of systems that improve the well-being of young people

by providing targeted mental health supports at the earliest sign that a need is present. The

SMHRP Toolkit delves deeply into the topic of referral pathways, which are defined as the

series of actions or steps taken after identifying a student with a potential mental and/or

substance use issue. Referral pathways vary from community to community based on cultural

and linguistic considerations and the resources available, including the public and private

40

organizations providing services to school-aged students. School and community-based mental

and substance use providers must understand their local community to ensure the seamless

provision of supports to students and their families. While referral pathways may involve

different partners, depending on the community, all effective referral pathways share similar

characteristics:

• They define the roles and responsibilities of all partners in a system.

• They have clearly articulated procedures for managing referrals within and between

partners.

• They share information efficiently across partners.

• They monitor the effectiveness of the evidence-based interventions provided by all

partners within a system.

• They make intervention decisions collaboratively based on what is best for young people

and their families.

The SMHRP Toolkit provides sample memorandums of understanding (MOUs) between school

districts and community providers.

The School-based Mental Health Model adopted by the Arkansas Department of Education

(http://www.arkansased.gov/public/userfiles/Learning_Services/School_Health_Services/SBMH

_Manual_June2012.pdf) is based on a strong foundation of collaboration and cooperation

between mental health providers and school districts. Partners share information readily and

easily, having established mechanisms to support this prior to implementation of the program

through an interagency agreement and/or business associate agreement.

Potential clinical partners include:

41

1. Private practitioners

Health professionals who are willing to support the early identification process and accept

referrals to assess students with positive screens.