Parental leave policies in graduate medical education: A systematic

review

Laura S. Humphries, Sarah Lyon, Rebecca Garza, Daniel R. Butz, Benjamin Lemelman,

Julie E. Park

*

Section of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

article info

Article history:

Received 10 February 2017

Received in revised form

1 June 2017

Accepted 20 June 2017

Keywords:

GME

Leave of absence

Maternity leave

Paternity leave

Parental leave

abstract

BACKGROUND: A thorough understanding of attitudes toward and program policies for parenthood in

graduate medical education (GME) is essential for establishing fair and achievable parental leave policies

and fostering a culture of support for trainees during GME.

METHODS: A systematic review of the literature was completed. Non-cohort studies, studies completed

or published outside of the United States, and studies not published in English were excluded. Studies

that addressed the existence of parental leave policies in GME were identified and were the focus of this

study.

RESULTS: Twenty-eight studies addressed the topic of the existence of formal parental leave policies in

GME, which was found to vary across time and ranged between 22 and 90%. Support for such policies

persisted across time.

CONCLUSIONS: Attention to formal leave policies in GME has traditionally been lacking, but may be

increasing. Negative attitudes towards parenthood in GME persist. Active awareness of the challenges

faced by parent-trainees combined with formal parental leave policy implementation is important in

supporting parenthood in GME.

© 2017 Published by Elsevier Inc.

1. Introduction

Parenthood during graduate medical education (GME) has been

a topic of interest since the late 1970s. With increasing percentages

of women in medicine, this subject has resurfaced recently as part

of a broader conversation within government and industry about

gender in the American workplace.

1

Women physicians face

particular challenges because their training programs, which can

span nearly a decade, coincide with traditional childbearing years.

Although these challenges are well known, formal and informal

support for parenthood in GME remains variable and poorly defined.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)

does not have a single, defined parental leave policy that all GME

programs must follow.

2

While the ACGME mandates that GME

programs must have leave policies in place, the ACGME does not

provide specific recommendations or guidelines for their

development. Instead, individual GME programs are left to create

their own leave policies that are consistent with applicable laws

(Table 1) and that satisfy the relevant certifying board

requirements.

2

The goal of this study is to provide a systematic review of

parental leave policies in graduate medical education. Specifically,

we aim to identify the number of studies available in the literature

addressing the existence of parental leave policies in GME.

2. Methods

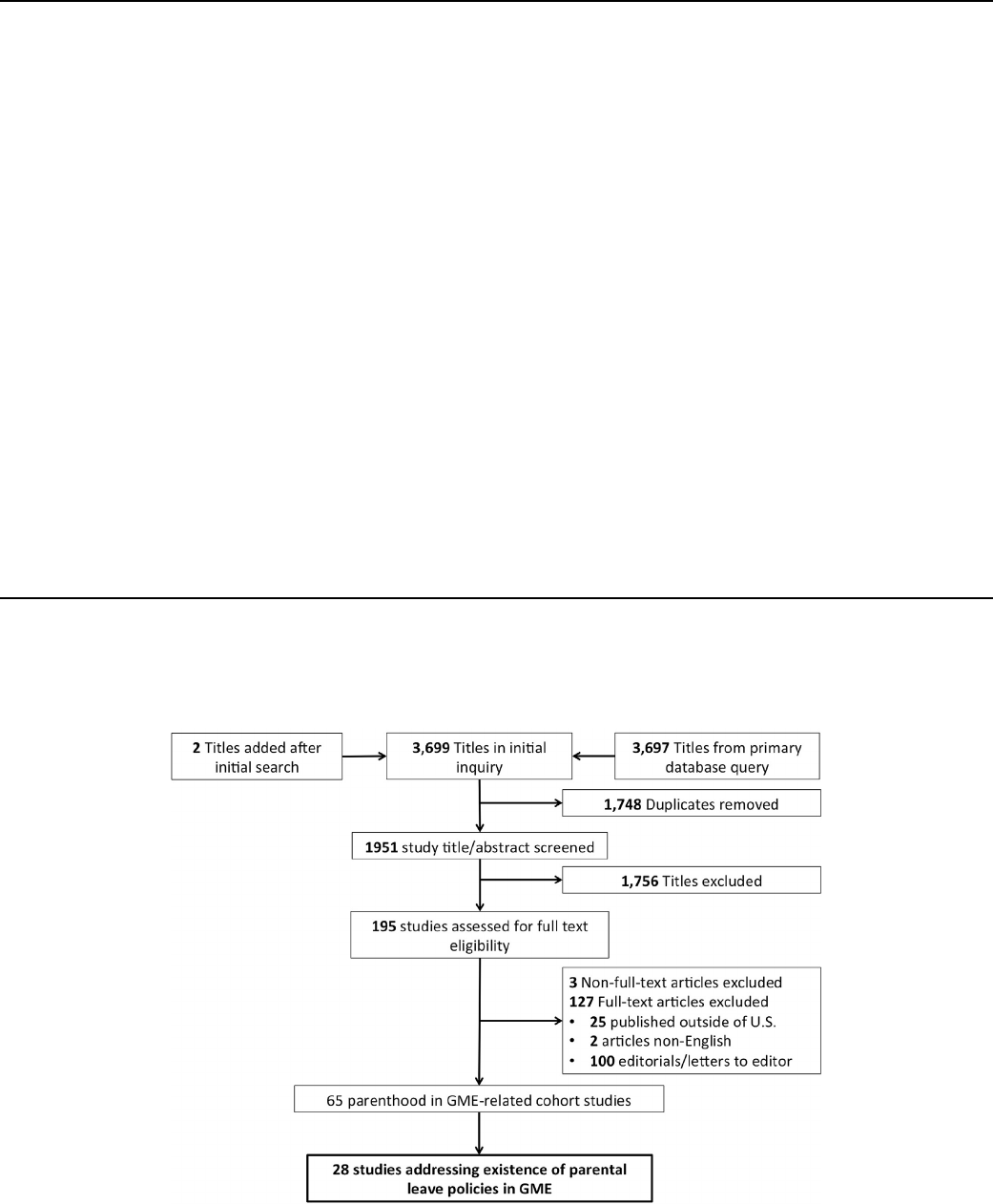

An electronic search of the PubMed, Medline, Scopus, and Psy-

chInfo databases was completed using multiple search terms

(Fig.1), including internship, residency, leave and pregnancy (Table 2).

Search criteria incorporated relevant articles from January 1,1960 to

December 13, 2015. Studies that pertained to family planning or

leave (including pregnancy/childbearing, paternity/maternity/

parental leave, breastfeeding and childcare issues) during GME in

the United States (including studies addressing these issues in res-

idency, fellowship, or across multiple training time periods) were

included in the initial pool of studies reviewed. Non-cohort studies

* Corresponding author. The University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sci-

ences, 5841 S. Maryland Avenue, MC 6035, Chicago, IL 60637, United States.

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

The American Journal of Surgery

journal homepage: www.americanjournalofsurgery.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.023

0002-9610/© 2017 Published by Elsevier Inc.

The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 634e639

Table 1

Parental leave policies: United States government laws and Graduate Medical Education regulations.

United States Government Laws

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII

3

Prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) (1978)

4

Amendment to Title VII of Civil Rights Act of 1964. Prohibits discrimination in employment against women

affected by pregnancy or related conditions.

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (1990)

5

Prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in employment, public services, public accommodations

and in telecommunications.

Employers must treat women who are temporarily unable to perform their jobs due to medical condition related

to pregnancy or childbirth similar to any other temporarily disabled employee

Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) (1993)

6

Entitles eligible employees of covered employers to take unpaid, job-protected leave for speci fied family and

medical reasons.

12 workweeks leave in a 12-month period.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)

(2010)

7

Amendment to Section 7 of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

Employers required to provide “reasonable break time for an employee to express breast milk for her nursing

child for 1 year after the child's birth each time such employee has need to express the milk.”

Employers required to provide “a place, other than a bathroom, that is shielded from view and free from

intrusion from coworkers and the public, which may be used by an employee to express breast milk”

Graduate Medical Education Regulations

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical

Education (ACGME)

2

IV.A.3. An applicant invited to interview for a resident/fellow position must be informed in writing or by

electronic means of the terms, conditions and benefits of appointment to the ACGME-accredited program, either

in effect at the time of the interview or that will be in effect at the time of his or her eventual appointment

A) Information that is provided must include: financial support; vacations; parental, sick, and other leaves of

absence; and professional liability, hospitalization, health, disability, and other insurance accessible to residents/

fellows and their eligible dependents.

IV.B.2. The contract/agreement of appointment must directly contain or provide a reference to the following

items:

h) disability insurance for residents/fellows;

i) vacation, parental, sick, and other leave(s) for residents/fellows, compliant with applicable laws

j) timely notice of the effect of leaves on the ability of residents/fellows to satisfy requirements for program

completion

IV.G Vacation and Leaves of Absence

IV.G.I. The sponsoring institution must have a policy for vacation and other leaves of absence, consistent with

applicable laws.

IV. G.2. This policy must ensure that each of its ACGME-accredited programs provides its residents/fellows with

accurate information regarding the impact of extended leave of absence upon the criteria for satisfactory

completion of the program and upon a resident's/fellows' eligibility to participate in examinations by the

relevant certifying board(s).

Fig. 1. Article selection process.

L.S. Humphries et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 634e639 635

(e.g. editorials, letters to the editor), studies completed or published

outside of the United States and studies not published in English

were excluded. Studies that addressed the existence of parental

leave policies in GME were identified and were the focus of this

study. Two of the investigators independently completed study

selection, and a third investigator resolved discrepancies. Data

extraction was completed by one individual (LSH).

This study adhered to standardized methodological principles of

PRISMA for reporting systematic reviews.

8

Due to the heterogeneity

of the data reporting amongst articles, a qualitative analysis was

performed for each results category. Themes included existence of

formal leave policies, amount of leave time allowed, impact of

parental leave on training and support for parenthood in residency.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic review results

In the first inquiry of the systematic review, 3,699 papers were

identified. After duplicates were removed, 165 articles

9e73

met

initial inclusion criteria. Editorials that otherwise met initial in-

clusion criteria (n ¼ 100) were removed to compile the final list of

65 articles. All were cross-sectional studies: 62 survey, 1 database

58

and 2 interview studies.

21,57

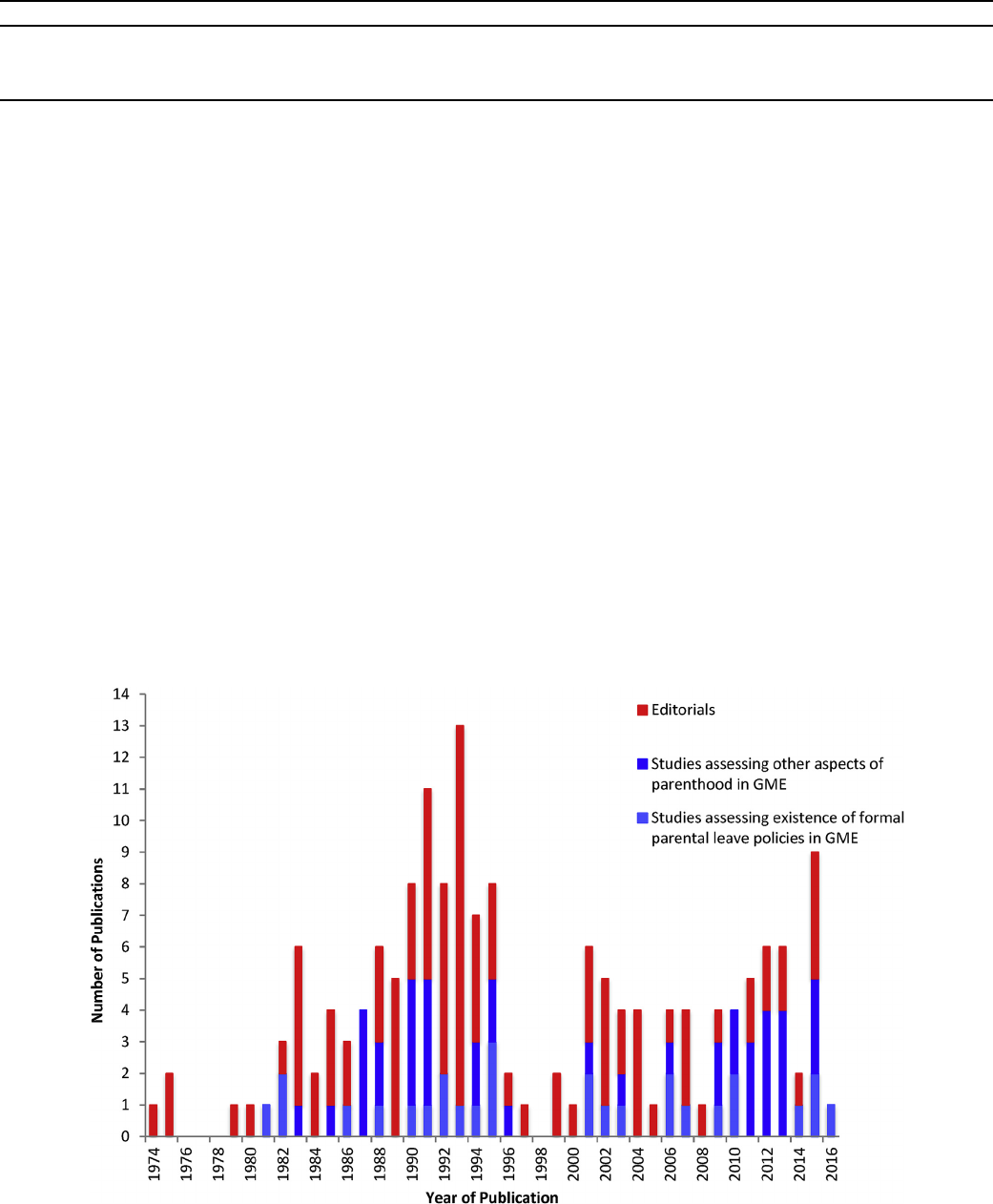

Publications on parenthood in GME

were clustered in two time periods d the late 1980s-early 1990s

and the 2000s (Fig. 2). Of these, 28 articles specifically addressed

the existence of parental leave policies (Fig. 2).

3.2. Subjects

Twenty-one studies focused on parental leave policies during

residency and/or fellowship, and 7 articles focused on this topic

across multiple professional periods. Surveyed individuals varied,

including female residents, male residents, partners of male

residents, fellows, program directors, department chairs, female

faculty, and male faculty. No studies included partners of female

residents. Various medical and surgical specialties were

represented.

3.3. Existence of parental leave policies

Twenty-eight studies addressed the topic of the existence of

formal parental leave policies in graduate medical educa-

tion.

12,1 4e16,18,21,22,24,27e29,33,34,42e45,49,52e54,58e 63,66

Six of the

included 28 studies were from surgical specialties including gen-

eral surgery,

18,44,59

otolaryngology,

21

urology

42

and thoracic

surgery.

49

The existence of formal family leave policies varied across time.

Of the studies published between 1986 and 1992, two studies re-

ported existence of maternity leave policies with 22e66% of sur-

veyed programs having formal policies.

52,60

None in this time

period mentioned paternity leave. Of the studies published be-

tween 1995 and 2016, nine described maternity or family leave

policies.

12,21,22,43e45,54,59

In a 1991 survey of program directors of

Boston-area hospitals, 82% (9/11) of responding hospitals indicated

Table 2

Systematic review search terms used for article search.

Search engine Number of articles Search terms

PubMed 1483 ((residency, leave) OR ((residency, pregnancy))

Medline 808 residency, leave OR residency, pregnancy

Scopus 1539 (((internship OR residency) AND leave) OR ((internship OR residency) AND pregnancy))

PsychInfo 135 (residency and leave) OR (residency and pregnancy)

Fig. 2. Published editorials and studies on parenthood in graduate medical education (GME) across time. (Color version of figure available online.)

L.S. Humphries et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 634e639636

they had a specific written maternity leave policy, and 75% of

programs reported implementation of the policy.

52

Six studies

described having formal paternity leave policies, all after the year

1995.

12,22,28,34,43,45,59

The existence of formal family leave policies varied across spe-

cialty. Surveys of pediatric and radiology residency program di-

rectors indicated high rates of formal maternity leave policies: 90%

and 88%, respectively.

43,45

Within surgery, individual institutions

have demonstrated success with following a set of general guide-

lines for management of maternity in residency.

18,21

Female urol-

ogists reported a 42% formal maternity leave policy at their

institutions,

42

and a recent general surgery study indicated that

67% of programs have a formal maternity leave policy.

59

As to paternity leave, obstetrics-gynecology (OB-GYN) programs

had the highest proportion of such policies at 69%.

22

Forty-eight

percent of surveyed general surgery programs had formal pater-

nity leave policies in 2016, with larger programs more likely to have

these policies (72% of programs with >6 residents vs. 40% of pro-

grams with <6 residents).

59

3.4. Parental leave time and impact on length of training

In the absence of formal parental leave time allotment,

leave time for family purposes was taken from vacation

time,

16,18,29,33,43,53,60

sick leave

29,43,52,53

or disability.

16,52

Two

studies reported that female residents took unpaid leave.

33,53

In a

survey of female residents and partners of male residents, 50% of

female residents were covered by formal maternity leave policies

compared to 70% of working partners of male residents.

33

One

study investigated the impact of parental leave on extending resi-

dency training and the timing of entrance into the specialty board

certification.

58

There were maximum limits of absence from

training for 21 of 26 specialties. The impact of a six-week parental

leave in training could result in no delay in board entry or could

result in delay of up to one year, depending on the rules of different

specialty boards. In this study, most boards did not have specific

policies related to parental leave.

3.5. Parental leave support

High support for the development of standardized policies for

parental leave across specialties was observed, even in the earlier

studies from the 1990s.

12,14,27

Eighty-seven percent of surveyed

residents at a single institution favored maternity/paternity leave in

1994.

27

Seventy-five percent of radiology program directors sup-

ported the development of standardized residency program

guidelines for pregnant residents.

14

Over 50% of pediatric female

residents with children felt that existence of maternity leave,

length of leave and time needed to make up absence were impor-

tant in selecting a residency program, while more than 33% of male

residents felt paternity leave policies were important in choosing a

residency program.

12

A survey study within one general surgery

program demonstrated that resident maternity could be managed

safely and fairly to the satisfaction of both residents and faculty.

18

A few studies, however, found lack of support for parental is-

sues. One study within thoracic surgery indicated that while 76%

(67/88) of surveyed women expressed need for a reproductive

health wellness policy to allow extended time for reproductive

planning, pregnancy and family care issues, only 32% (8/25) of men

expressed this need.

49

4. Discussion

The topic of parenthood in medicine broadly, and in GME spe-

cifically, has been discussed since the late 1970s. Both published and

informal conversations among governing bodies within medical

and surgical specialties have reemerged in recent years, including

among the American College of Surgeons in the last year.

74

This

conversation is timely, as there has been a noticeable shift within

industry (e.g. Google, Facebook,

75

Amazon

76

and Netflix

77

) and the

U.S. military

78

toward more family-friendly employment policies.

Our review shows a number of issues surrounding the topic of

parenthood in GME, specifically in regard to the existence of formal

parental leave policies. The complex nature of these topics and

wide variation between studies preclude performance of quanti-

tative meta-analysis, thus making way for qualitative discussion.

The ACGME does not have a formal parental leave policy that

GME programs must follow. Instead, the ACGME mandates that

GME programs must create leave policies that are consistent with

applicable laws ( Table 1) and that satisfy the relevant certifying

board requirements.

2

As such, there is great variability across

specialties and individual GME programs as to how parental leave is

approached and handled. This inconsistency is reflected in the re-

sults of this study.

The existence of formal parental leave policies varied across

institutions and specialties and has seemed to increase over time.

Maternity leave was the main focus of early studies. The existence

and study of paternity leave and parental leave policies appeared in

more recent years, mostly after 1995. In addition, issues of

parenthood outside of traditional male-female relationships (e.g.

same-sex partnerships, non-married unions), including adoption,

were considered in more recent publications but were still scarce.

In the absence of formal parental leave policies, leave time desig-

nated for other reasons was often used for situations of family leave

(e.g. sick leave, disability, vacation). Female residents were less

likely to be covered by formal maternity leave policies than part-

ners of male residents.

The lack of uniformity in parental leave policy and guidelines

perpetuates the lack of parity for having children during GME

across programs. The attitudes of GME programs toward parent-

hood may range from hostile, to indifferent, to supportive.

Combining a family and medical career is stressful,

37,60,61,65

more so

for females than males.

49,61,71,72

Pregnancy and childbirth altered

trainee choice of GME program, date of completion, career plans

and/or pursuit of additional degrees more often for women than for

men.

13

The perception of negative impact on one's career may

result in delay in childbearing for many female residents across

specialties.

34

The performance of a pregnant or parent female

resident is likely to be perceived negatively both by the resident

herself

34,35

and her colleagues,

16,26

as well as by the program di-

rector or department chair.

26,60

Perhaps one of the most impactful findings of negative

perception of parenthood in residency was from a 2016 survey of

general surgery program directors.

59

Sixty-one percent of program

directors reported that becoming a parent negatively affected fe-

male trainees' work, including increased burden on fellow resi-

dents (33%), fewer scholarly activities (9%), fewer clinical activities

(8%), less dedication to patient care (6%) and decreased timeliness

(5%).

59

In addition, general surgery program directors were less

likely to report that becoming a parent negatively affects a male

resident's than a female resident's work (34% vs. 61%) and reported

that children decrease female resident well-being more often than

that of male residents (32% vs. 9%). Fifteen percent of general sur-

gery program directors said they would advise against having

children during residency.

This perception of negative impact of parenthood on clinical

performance and academic productivity, especially for women,

persists despite data that indicate the opposite. For example, the

number of clinical cases completed by pregnant OB-GYN residents

has not been shown to be significantly different than peers, and

L.S. Humphries et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 634e639 637

academic productivity does not seem to differ based on a parent

trainee's gender.

21,40

In a retrospective review of general surgery

residents, factors such as age, sex and incidence of childrearing

during training were not associated with increased risk of attri-

tion.

79

In addition, general surgery residents with children during

training did not have significantly different total case numbers, in-

service scores or written/oral board pass rates than those without

children.

79

In a different study, perceived impact of childbearing on

general surgery resident training had no effect on a resident's de-

cision to have a child during residency for most trainees who had

children in residency.

67

The majority of female surgeons without

children reported that family had no effect on their career, whereas

women with children reported that their family affected their

career a moderate amount. Only 15% of 128 female surgeons with

children felt that having children markedly slowed their career.

32

Furthermore, there remains high career and personal satisfac-

tion among residents and physicians who have children. Career

satisfaction was not significantly different between female physi-

cians with and without children. Ninety-one percent of women

surveyed were “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their careers.

66

High overall rates of career satisfaction were also reported among

female orthopedic and thoracic surgeons.

32,49

Thus, in the midst of

prevalent negative attitudes toward trainee parents and females in

particular, a culture change toward an environment of support for

trainee parents is imperative to identify means to aid in their

success.

In the face of diverse approaches to parenthood in GME, training

programs have managed to graduate competent physicians and

surgeons, indicating that combining parenthood and residency

training is possible. The environment of support for parenthood in

GME would best be reinforced by formal parental leave policies.

Currently, parental leave policies created by specific GME programs

are often limited by the requirements of their governing specialty

boards.

58

Most specialty boards have a “time spent” requirement

that must be fulfilled in order for graduating residents to be eligible

for their board examinations. For example, the American Board of

Surgery (ABS) requires 48 weeks per year of full-time clinical ac-

tivity over a 5-year residency, allowing an additional 4 weeks of

non-clinical time for “documented medical conditions.” Other ar-

rangements beyond the standard medical leave must be approved

by the ABS. In contrast, the American Board of Plastic Surgery

(ABPS) recently allowed the 48-week/year of clinical training to be

averaged across the 6-year training period to accommodate for

extended leaves of absence; the remaining 4 weeks in the year

could be dedicated to vacation, meeting attendance, medical leave

or other reasons as determined by the institution or program.

80

In

addition, in the final 2 years of training, plastic surgery residents

may have 1 week leave for medical reasons. In contrast, vacation

time allotment is determined by the GME in many institutions as

the residents are considered hospital employees; thus, in these

cases, program directors have less leeway in allocating additional

parental leave time.

The amount of “time spent” engaged in clinical activity in

training may eventually give way to quality of “time spent” with the

introduction of competency-based milestones.

81,82

This transition

in the way trainees are evaluated could impact the actual length of

time required to complete residency, and thus, provide more flex-

ibility for parental leave. Making the process of having children

during training fair for all trainees will require a shift in attitude

toward greater support, and this culture change must be reinforced

with adoption of formal parental leave policies.

5. Conclusion

Although more parental leave policies in training programs have

emerged over time, negative attitudes towards childbearing and

childrearing in training continue to impact residents and fellows.

Issues around paternity leave and adoption have entered the con-

versation only in recent years. Despite persistent challenges,

parenthood in GME seems to have a neutral or positive overall

impact on trainee performance and productivity. A culture shift

toward support and increased awareness of the challenges faced by

parent-trainees, coupled with formal parental leave policies from

medical governing bodies, is needed.

Clinical trial registration

Not applicable.

Funding source

No external funding was secured for this study.

Commercial associations/financial disclosures

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the prod-

ucts, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

References

1. Bass BL, Napolitano LM. Gender and diversity considerations in surgical

training. Surg Clin N. Am. 2004;84(6):1537e1555. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.suc.2004.06.008.

2. Education ACFGM. ACGME Institutional Requirements. Institutional Organization;

2010. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/ab_ACGMEPoliciesProcedures.pdf.

3. Civil Rights Act of 1964. Public Law 88-352, 78 Stat. 241. 1964.

4. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978. Public Law 95-555, 92 Stat. 2076.

1978.

5. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Public Law 101-336, 104 Stat. 327. 1990.

6. Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993. Public Law 103-3, 107 Stat. 6. 1993.

7. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111-148, 124 Stat. 119.

2010.

8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grouppara TP. Preferred reporting items

for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. JClinEpidemiol.

2009;62(10):1006e1012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

9. Abbett SK, Hevelone ND, Breen EM, et al. Interest in and perceived barriers to

flexible-track residencies in general surgery: a national survey of residents and

program directors. JSURG. 2011;68(5):365e371. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.jsurg.2011.04.007.

10. Balk SJ, Christoffel KK, Bijur PE. Pediatricians' attitudes concerning motherhood

during residency. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144(7):770e777.

11. Bergman AS, Adler R. Support services for pediatric trainees. A survey of

training program directors. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145(9):1002e1005.

12. Berkowitz CD, Frintner MP, Cull WL. Pediatric resident perceptions of family-

friendly benefits. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):360e366. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.013.

13. Blair JE, Mayer AP, Caubet SL, Norby SM, O'Connor MI, Hayes SN. Pregnancy and

parental leave during graduate medical education. Acad Med. November

2015;1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001006.

14. Blake ME, Oates ME, Applegate K, Kuligowska E. Proposed program guidelines

for pregnant radiology residents. Acad Radiol. 2006;13(3):391e401. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2005.10.007.

15.

Bongiovi ME, Freedman J. Maternity leave experiences of resident physicians.

J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1993;48(6), 185e188e193.

16. Braun DL, Susman VL. Pregnancy during psychiatry residency : a study of at-

titudes. Acad Psychiatry. 1992;16(4):178 e 185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/

BF03341390.

17. Brogdon BG, Herbert DE. Pregnancy in radiology residents. Investig Radiol.

1991;26(1):102e103.

18. Carty SE, Colson YL, Garvey LS, et al. Maternity policy and practice during

surgery residency: how we do it. Surgery. 2002;132(4):682e688. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1067/msy.2002.127685.

19. Chen MM, Yeo HL, Roman SA, Bell Jr RH, Sosa JA. Life events during surgical

residency have different effects on women and men over time. Surgery.

2013;154(2):162e170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2013.03.014.

20. Cochran A, Belder WE, Crandall M, Brasel K, Hauschild T, Neumayer L. Barriers to

advancement in academic surgery: views of senior residents and early career fac-

ulty. AJS. 2013;206(5):661e666. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.07.003.

21. Cole S, Arnold M, Sanderson A, Cupp C. Pregnancy during otolaryngology

residency: experience and recommendations. Am Surg. 2009;75(5):411e415.

22. Davis JL, Baillie S, Hodgson CS, Vontver L, Platt LD. Maternity leave: existing

policies in obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstet Gynecol.

L.S. Humphries et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 634e639638

2001;98(6):1093e1098.

23. Dixit A, Feldman-Winter L, Szucs KA. Frustrated,”“depressed,” and “devas-

tated” pediatric trainees: US academic medical centers fail to provide adequate

workplace breastfeeding support. J Hum Lactation. 2015;31(2):240e248. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1177/0890334414568119.

24. Dixit A, Feldman-Winter L, Szucs KA. Parental leave policies and pediatric

trainees in the United States. J Hum Lactation. 2015;31(3):434e439. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1177/0890334415585309.

25. Eskenazi L, Weston J. The pregnant plastic surgical resident: results of a survey

of women plastic surgeons and plastic surgery residency directors. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(2):330e335.

26. Franco K, Evans CL, Best AP, Zrull JP, Pizza GA. Conflicts associated with phy-

sicians' pregnancies. Am J Psychiatry . 1983;140(7):902e904. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1176/ajp.140.7.902.

27. Franco K, Tamburrino M, Campbell N, Evans C, Jurs S. Conflict with physician

pregnancy revisited. Acad Psychiatry. 1994;18(3):146e153. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1007/BF03341869.

28. Gabbe SG, Morgan MA, Power ML, Schulkin J, Williams SB. Duty hours and

pregnancy outcome among residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet

Gynecol. 2003;102(5 Pt 1):948e951.

29. Gjerdingen DK, Chaloner KM, Vanderscoff JA. Family practice residents' ma-

ternity leave experiences and benefits. Fam Med. 1995;27(8):512e518.

30. Grunebaum A, Minkoff H, Blake D. Pregnancy among obstetricians: a com-

parison of births before, during, and after residency. Am J Obstet. Gynecol.

1987;157(1):79e83.

31. Halperin TJ, Werler MM, Mulliken JB. Gender differences in the professional

and private lives of plastic surgeons. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(6):775e779.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181b02292.

32. Hamilton AR, Tyson MD, Braga JA, Lerner LB. Childbearing and pregnancy

characteristics of female orthopaedic surgeons. J Bone Jt Surg Am

. 2012;94(11):

1e9. http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.K.00707.

33. Harris DL, Osborn LM, Schuman KL, Reading JC, Prather MB, Politzer RM. Im-

plications of pregnancy for residents and their training programs. J Am Med

Womens Assoc. 1990;45(4), 127 e8e131.

34. Holliday EB, Ahmed AA, Jagsi R, et al. Pregnancy and parenthood in radiation

oncology, views and experiences survey (PROVES): results of a blinded pro-

spective trainee parenting and career development assessment. Radiat Oncol

Biol. 2015;92(3):516e524. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.02.024.

35. Hutchinson AM, Anderson NS, Gochnour GL, Stewart C. Pregnancy and child-

birth during family medicine residency training. Fam Med. 2011;43(3):

160e165.

36. Kacmar JE, Taylor JS, Nothnagle M, Stumpff J. Breastfeeding practices of resi-

dent physicians in Rhode Island. Med Health R I. 2006;89(7):230e231.

37. Klebanoff MA, Shiono PH, Rhoads GG. Outcomes of pregnancy in a national

sample of resident physicians. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(15):1040e1045. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199010113231506.

38. Klebanoff MA, Shiono PH, Rhoads GG. Spontaneous and induced abortion

among resident physicians. JAMA. 1991;265(21):2821e 2825.

39. Klevan JL, Weiss JC, Dabrow SM. Pregnancy during pediatric residency. Atti-

tudes and complications. Am J Dis Child. 1990;144(7):767e769.

40. Lashbrook DL, Frazier LM, Horbelt DV, Stembridge TW, Rall MJ. Pregnancy

during obstetrics and gynecology residency: effect on surgical experience. Am J

Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189(3):662e665. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/S0002-

9378(03)00877-9.

41. Lerner LB, Stolzmann KL, Gulla VD. Birth trends and pregnancy complications

among women urologists. J Am Coll Surg . 2009;208(2):293e297. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.012.

42. Lerner LB, Baltrushes RJ, Stolzmann KL, Garshick E. Outcomes/epidemiology/

socio economics satisfaction of women urologists with maternity leave and

childbirth timing. JURO. 2010;183(1):282e286. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

j.juro.2009.08.113.

43. Manaster BJ, Hulen R. Pregnancy and maternity policies in radiology resi-

dencies: the 1993 survey of the American Association for Women Radiologists.

Acad Radiol

. 1995;2(9):804e806.

44. Mayer KL, Ho HS, Goodnight JE. Childbearing and child care in surgery. Arch

Surg. 2001;136(6):649e655.

45. McPhillips HA, Burke AE, Sheppard K, Pallant A, Stapleton FB, Stanton B. To-

ward creating family-friendly work environments in pediatrics: baseline data

from pediatric department chairs and pediatric program directors. PEDIATRICS.

2007;119(3):e596ee602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2397.

46. Miller NH, Miller DJ, Chism M. Breastfeeding practices among resident physi-

cians. PEDIATRICS. 1996;98(3 Pt 1):434e437.

47. Orth TA, Drachman D, Habak P. Breastfeeding in obstetrics residency: exploring

maternal and colleague resident perspectives. Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(4):

394e400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2012.0153.

48. Osborn LM, Harris DL, Reading JC, Prather MB. Outcome of pregnancies expe-

rienced during residency. J Fam Pract. 1990;31(6):618e622.

49. Pham DT, Stephens EH, Antonoff MB, et al. Birth trends and factors affecting

childbearing among thoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(3):890e895.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.041.

50. Phelan ST. Pregnancy during residency: I. The decision “to be or not to be”.

Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(3 Pt 1):425e431.

51. Phelan ST. Pregnancy during residency: II. Obstetric complications. Obstet

Gynecol. 1988;72(3 Pt 1):431e436.

52. Phelan EA. A survey of maternity leave policies in Boston area hospitals. JAm

Med Womens Assoc. 1991;46(2):55e58.

53. Phelan ST. Sources of stress and support for the pregnant resident. Acad Med.

1992;67(6):408e410.

54. Philibert I, Bickel J. Maternity and parental leave policies at COTH hospitals: an

update. Council of Teaching Hospitals. Acad Med. 1995;70(11):1056e1058.

55. Pincus S. Women in academic dermatology. Results of survey from the pro-

fessors of dermatology.

Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(9):1131e1135.

56. Riggins C, Rosenman MB, Szucs KA. Breastfeeding experiences among physi-

cians. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(3):151e154. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/

bfm.2011.0045.

57. Rodgers C, Kunkel ES, Field HL. Impact of pregnancy during training on a

psychiatric resident cohort. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1994;49(2):49e52.

58. Rose SH, Burkle CM, Elliott BA, Koenig LF. The impact of parental leave on

extending training and entering the board certification examination process: a

specialty-based comparison. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(11):1449e1453. http://

dx.doi.org/10.4065/81.11.1449.

59. Sandler BJ, Tackett JJ, Longo WE, Yoo PS. Pregnancy and parenthood among

surgery residents: results of the first nationwide survey of general surgery

residency program directors. J Am Coll Surg. January 2016:1e7. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.004.

60. Sayres M, Wyshak G, Denterlein G, Apfel R, Shore E, Federman D. Pregnancy

during residency. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(7):418e423. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1056/NEJM198602133140705.

61. Shapiro J. Children during residency: it“s easier if you”re a man. J Am Med

Womens Assoc. 1981;36(7):227e231.

62. Shapiro J. Pregnancy during residency: attitudes and policies. J Am Med

Womens Assoc. 1982;37(4), 96e7e101e3.

63. Shapiro J. Attitudes of physician faculty members and residents toward the

pregnant medical resident. J Med Educ. 1982;57(6):483e486.

64. Shaw PM, Vouyouka A, Reed A. Time for radiation safety program guidelines

for pregnant trainees and vascular surgeons. YMVA. 2012;55(3):862e868.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2011.11.045. e862.

65. Sheth S, Freedman MT, Arak G. Policies and attitudes toward the pregnant

radiology resident. Investig Radiol. 1985;20(4):413e

415.

66. Sinal S, Weavil P, Camp MG. Survey of women physicians on issues relating to

pregnancy during a medical career. J Med Educ. 1988;63(7):531e538.

67. Smith C, Galante JM, Pierce JL, Scherer LA. The surgical residency baby boom:

changing patterns of childbearing during residency over a 30-year span.

J Graduate Med Educ. 2013;5(4):625e629. http://dx.doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-

12-00334.1.

68. Tucker JB, Margo KL. Profile of women family practice residents. Fam Med.

1987;19(4):269e271.

69. Turner PL, Lumpkins K, Gabre J, Lin MJ, Liu X, Terrin M. Pregnancy among

women surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147(5). http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/

archsurg.2011.1693.

70. Verheyden CN, McGrath MH, Simpson P, Havens L. Social problems in plastic

surgery residents. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(4):772ee778e. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001098.

71. Willett LL, Wellons MF, Hartig JR, et al. Do women residents delay childbearing

due to perceived career threats? Acad Med. 2010;85(4):640e646. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2cb5b.

72. Wilson MD, Carpenter RO, Radius SM, Oski FA. Attitudes and factors affecting

the decisions of men and women pediatrics residents toward having children

during their residencies. Acad Med. 1991;66(12):770e772.

73. Windsor AM, Julian TM. Sexuality, reproduction, and contraception among

residents in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(5 Pt 1):

787e792.

74. Statement on the importance of parental leave. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2016;101(4):

35e36.

75. Cohen D. Facebook Offers All Employees 4 Months' Parental Leave. Published.

AdWeek; December 1, 2015. http://www.adweek.com/digital/four-months-

parental-leave/. Accessed 8 February 2017.

76. Tepper T. Amazon's parental leave: the new free Soda? Money. Published

http://time.com/money/4098026/amazon-paid-parental-leave-benefits/;

November 3, 2015. Accessed 8 February 2017.

77. Tepper T. The pros and cons of Netflix's new parental leave plan. http://time.

com/money/3985632/netflix-unlimited-parental-leave/; August 2015.

78. Ferdinando L. Carter Announces 12 Weeks Paid Military Maternity Leave, Other

Benefits. U.S. Department of Defense. Published; January 28, 2016. https://www.

defense.gov/News/Article/Article/645958/carter-announces-12-weeks-paid-

military-maternity-leave-other-benefits. Accessed 8 February 2017.

79. Brown EG, Galante JM, Keller BA, Braxton J, Farmer DL. Pregnancy-related

attrition in general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(9):893. http://dx.doi.org/

10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1227.

80. The American Board of Plastic Surgery, Inc. May 2016:1e 92.

81. Bluth M. The General Surgery Milestone Project. July 2015:1e19.

82. McGrath MH. The plastic surgery milestone project. J Graduate Med Educ.

2014;6(1s1):222e224. http://dx.doi.org/10.4300/JGME-06-01s1-25.

L.S. Humphries et al. / The American Journal of Surgery 214 (2017) 634e639 639