&>)9;0579-744-/-&>)9;0579-744-/-

(793:(793:

$:@+0747/@)+<4;@(793: $:@+0747/@

%-:141-6+-,<+);176%-:141-6+-,<+);176

)6-1440)5

&>)9;0579-744-/-

2/1440):>)9;0579--,<

%"*-6)=741

&"9<6>)::-9

"!16316:

%-1=1+0

&--6-?;8)/-.79),,1;176)4)<;079:

7447>;01:)6,),,1;176)4>793:);0;;8:>793::>)9;0579--,<.)+8:@+0747/@

$)9;7.;0-$:@+0747/@75576:

!-;<:367>07>)++-::;7;0-:->793:*-6-B;:@7<

%-+755-6,-,1;);176%-+755-6,-,1;);176

)6-1440)5%"*-6)=741&"9<6>)::-9"!16316: %-1=1+0)6,"$&-41/5)6

%-:141-6+-,<+);176

#?.79,)6,*773#.)8816-::

#7?.79,0*

0;;8:>793::>)9;0579--,<.)+8:@+0747/@

'01:>7931:*97</0;;7@7<.79.9--*@&>)9;0579-744-/-!1*9)91-:(793:;0):*--6)++-8;-,.7916+4<:17616

$:@+0747/@)+<4;@(793:*@)6)<;0791A-,),5161:;9);797.(793:79579-16.795);17684-):-+76;)+;

5@>793::>)9;0579--,<

Resilience Education

Page 1 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Print Publication Date: Jan 2013 Subject: Psychology, Social Psychology, Clinical Psychology

Online Publication Date: Aug 2013 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557257.013.0046

Resilience Education

Jane E. Gillham, Rachel M. Abenavoli, Steven M. Brunwasser, Mark Linkins,

Karen J. Reivich, and Martin E. P. Seligman

Oxford Handbook of Happiness

Edited by Ilona Boniwell, Susan A. David, and Amanda Conley Ayers

Abstract and Keywords

As a primary learning and social environment for most children, schools have tremendous

potential to, and responsibility for, promoting resilience and well-being in children. This

chapter reviews the rationale for focusing on resilience in education and illustrates some

of the ways that schools can promote resilience in young people. Although resilience edu

cation can also encompass academic or educational resilience, the authors focus primari

ly on the power of schools to promote students’ social and emotional well-being and pro

vide examples from their team’s work on school-based resilience and positive psychology

interventions. As they hope to show, resilience education holds great promise in promot

ing the well-being of all students.

Keywords: resilience, positive youth development, prevention, well-being, positive education, positive psychology,

children, adolescents, youth, schools, education

The aim of education should always transcend the development of academic com

petence. Schools have the added responsibility of preparing fully-functioning and

resilient individuals capable of fulfilling their hopes and their aspirations. To do

so, they must be armed with optimism, confidence, self-regard, and regard for oth

ers, and they must be shielded from unwarranted doubts about their potentialities

and capacity for growth.

Pajares (2009, p. 158)

Introduction

ONE of the most striking findings in developmental and clinical research is that children

who have been exposed to trauma, poverty, community violence, and other serious risk

factors often reach, and sometime surpass, normal developmental milestones. Research

has identified many qualities in individuals and their social environments that promote re

silience, and many of these qualities are malleable. That is, individuals can learn specific

Resilience Education

Page 2 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

skills that contribute to resilience, and social environments can be structured in ways

that promote resilience.

As a primary learning and social environment for most children, schools have tremendous

potential to—and responsibility for—promoting resilience and well-being in children. This

chapter reviews the rationale for focusing on resilience in education and illustrates some

of the ways that schools can promote resilience in young people. Although resilience edu

cation can also encompass academic or educational resilience, we focus primarily on

(p. 610)

the power of schools to promote students’ social and emotional well-being and

provide examples from our team's work on school-based resilience and positive psycholo

gy interventions. As we hope to show, resilience education holds great promise in promot

ing the well-being of all students.

Resilience

Many children who are exposed to harmful experiences and environments are remarkably

resilient (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten, 2001). These children do not suffer

the negative consequences that are expected for them. They adapt. Many of them thrive.

Such resilience does not imply that risk factors such as poverty, violence, and trauma are

benign or should be accepted. The phenomenon of resilience does imply, however, that

psychologists’ understanding of children's development has been deficient. For many

decades, clinical and developmental research focused on how children are damaged by

adversity and ignored the capacity for positive development and growth even in the worst

circumstances.

Resilience has been defined as a “dynamic process of positive adaptation or development

in the context of significant adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 543). Youth who show re

silience display “good outcomes in spite of serious threats to adaptation or

development” (Masten, 2001, p. 228). As researchers have expanded their focus from pre

dicting negative outcomes to also predicting positive outcomes and adaptation, they have

discovered many qualities within people, families, and communities that can promote re

silience. Although some qualities are especially important for children in high risk con

texts, many promote children's social and emotional well-being in general (Collaborative

for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), 2003; Goleman, 1995; Luthar,

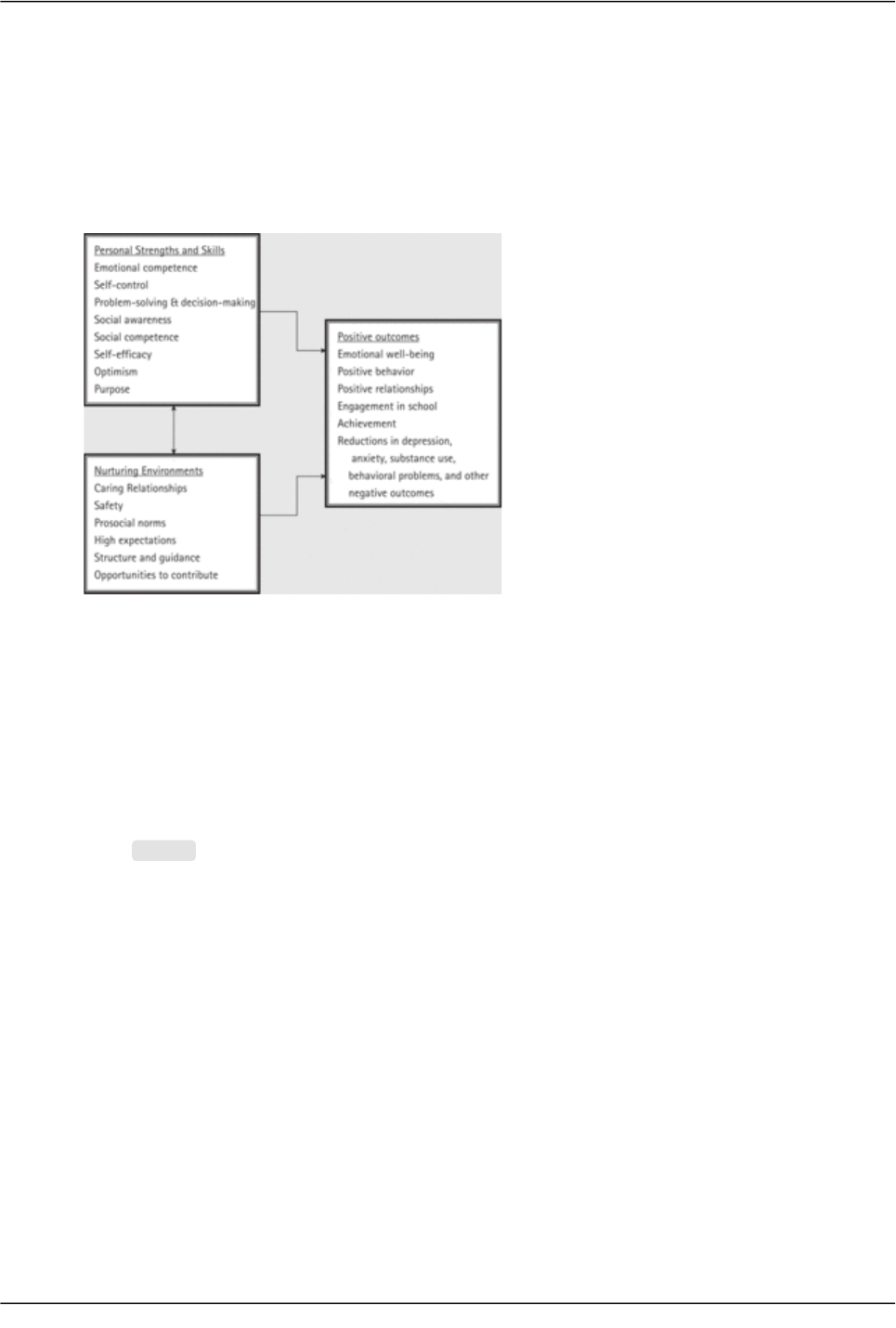

2006; Zins, Bloodworth, Weissberg, & Walberg, 2004). Fig. 46.1 lists many of these pro

motive qualities.

Some of the personal strengths and skills that are frequently mentioned across the re

silience literature include: emotional competence (emotion awareness and regulation),

self-regulation (impulse control, goal setting, self-discipline, perseverance), problem-solv

ing and decision-making (being able to think creatively, flexibly, and realistically about the

problems one encounters), social awareness (perspective taking, empathy, respect for

others), social competence (communication, social engagement, teamwork, conflict man

agement, giving and receiving help), self-efficacy, optimism, and a sense of purpose or

Resilience Education

Page 3 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Fig. 46.1 Personal and social qualities that promote

resilience.

meaning (for reviews, see Benard, 2004; CASEL, 2003; Goleman, 1995; Luthar, 2006;

Reivich & Shatté, 2002; Zins et al., 2004). For example, personal skills and strengths such

as self-control, problem-solving, and optimism are linked to higher academic achieve

ment, to more positive relationships, and to greater emotional well-being (Duckworth &

Seligman, 2005; Fincham & Bradbury, 1993; Seligman, 1991). These personal qualities in

clude many of the character strengths identified in recent research in positive psychology

(Park & Peterson, 2006; Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Family, school, and community environments also promote resilience. Some of the envi

ronmental factors that foster resilience include caring relationships, safety, prosocial

norms, high expectations, structure and guidance, and opportunities to contribute or to

matter (Benard, 2004; Benninga, Berkowitz, Kuehn, & Smith, 2006; CASEL, 2003; Eccles,

Flanagan, Lord, Midgley, Roeser, & Yee, 1996; Luthar, 2006; Reivich & Shatté, 2002;

Wang, 2009;

(p. 611)

Zins et al., 2004). Students with strong connections to school and to

family are less likely than their peers to develop depression and to engage in substance

use, violence, and other risky behaviors (Benard, 2004; Resnick et al., 1997; Rutter,

Maughan, Mortimore, & Ouston, 1982; Wang, 2009). These connections may be especially

important to children who are growing up in communities plagued by poverty and vio

lence (Rutter et al., 1982; Wang, Haertel, & Walberg, 1994).

Positive environments and adaptive personal characteristics can be mutually reinforcing.

Nurturing environments encourage the development of children's strengths. For example,

teachers who convey high expectations and who help students to reach their potential

promote optimism, self-efficacy, and persistence in their students. Children's strengths al

so shape their environments. Students who can control impulses help to create a safe

school environment. Students who are kind help to create a nurturing and supportive en

vironment. Over time, these different personal and environmental qualities interact and

work together to promote resilience. Some qualities are linked to specific outcomes or

Resilience Education

Page 4 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

are especially important in particular contexts. Thus, Fig. 46.1 presents a simplified mod

el.

Research suggests that the characteristics of children's social environments are stronger

predictors of resilience than children's personal qualities. In her review of the last 50

years of resilience research, Luthar (2006) concludes:

The first major take-home message is this: Resilience rests, fundamentally, on re

lationships. The desire to belong is a basic human need and positive connections

with others lie at the

(p. 612)

very core of psychological development; strong, sup

portive relationships are critical for achieving and sustaining resilient adaptation.

(p. 42)

This calls to mind Peterson's three-word summary of positive psychology research: “Other

people matter” (Peterson, 2006, p. 249). Peterson also reminds us that “we are all the oth

er people who can matter so much” (Peterson, 2008, np).

Resilience Education

The role of schools

Next to family, school is the most important social environment for most children. In the

USA, more than 94,000 public schools provide education to more than 47 million students

(Snyder & Hoffman, 2003). An additional 28,000 private schools provide education to

more than 5 million children (Snyder, Tan, & Hoffman, 2006). Children and teens spend,

on average, more than 30 hours a week at school (Juster, Ono, & Stafford, 2004). Because

of its central role in children's development, formal education has enormous potential to

promote resilience. Rutter and colleagues (1982) emphasize this potential in the opening

to their ground breaking study of schools in the UK:

For almost a dozen years during a formative period of their development, children

spend almost as much of their waking life at school as at home. Altogether, this

works out to some 15,000 hours (from the age of five until school leaving) during

which schools and teachers may have an impact on the development of children in

their care. (p. 1)

Schools can promote resilience by providing nurturing environments and by cultivating

students’ personal skills and strengths. Schools that provide children with safe and car

ing learning environments make a profound difference in children's lives, especially when

these qualities are lacking or inconsistent in children's communities or families (Rutter et

al., 1982; Wang et al., 1994). Schools are an ideal place for children to learn self-regula

tion and social skills such as empathy and teamwork that are essential for positive rela

tionships and achievement. And because interpersonal and academic challenges are a

regular part of life for most students at one time or another, there is ample opportunity to

teach coping and problem solving skills in schools. Ultimately, education that focuses on

Resilience Education

Page 5 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

resilience has the potential to promote students’ growth and well-being both in and out of

school, and long after students’ participation in formal education has ended.

Overlap with other educational initiatives

Resilience education (education that aims to foster students’ resilience) overlaps with ed

ucational initiatives that promote good character (Berkowitz & Bier, 2004; Elias, Wang,

Weissberg, Zins, & Walberg, 2002) and social and emotional learning (CASEL, 2003,

2007), as well as psychosocial interventions that aim to prevent psychopathology, sub

stance use, and other negative outcomes (National Research Council and Institute of

Medicine, 2009; Weissberg, Kumpfer, & Seligman, 2003). For example, CASEL defines so

cial and emotional learning as “the process of acquiring the skills to recognize and man

age emotions, set and achieve positive goals, appreciate the perspectives of others, estab

lish and maintain positive

(p. 613)

relationships, make responsible decisions, and handle

interpersonal situations effectively” (CASEL, 2007, p. 1). Similarly, Elias and colleagues

define social emotional learning as “the process through which we learn to recognize and

manage emotions, care about others, make good decisions, behave ethically and responsi

bly, develop positive relationships, and avoid negative behaviors” (Elias et al., 1997, as

cited in Zins et al., 2004, p. 4). These behaviors and skills are central to resilience as well

as to social and emotional well-being more generally. Resilience education is a component

of “positive education” (Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich, & Linkins, 2009) and of posi

tive youth development (Catalano, Berglund, Ryan, Lonczak, & Hawkins, 2004).

The need for resilience education

Many psychologists and educators have argued that resilience skills are more important

for children today than ever before (e.g., Greenberg et al., 2003). The number of children

exposed to major adversity is staggering. In the USA, close to 50% of youth are exposed

to violence each year, including 19% who witness a violent act within their community

(Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, Hamby, & Kracke, 2009). Nearly 10% of youth witness vio

lence between family members each year and nearly 10% of children are victims of physi

cal or emotional abuse or neglect (Finkelhor et al., 2009). About 20% of children under 18

live in poverty (US Census Bureau, 2009). Children who live in poverty are more likely to

experience other family and community risk factors such as violence, parental depres

sion, parental conflict, abuse, and neglect (Evans, 2004). They are more likely than chil

dren from middle class or affluent communities to attend struggling schools and to be ex

posed to pollution and other environment risk factors (Evans, 2004). Thus, multiple risk

factors converge in the lives of many children.

Psychological and behavioral difficulties are also very common among children. In a given

year, about 20% of children will have diagnosable psychological disorders, such as de

pression or anxiety, that create at least mild impairment in functioning (US Department of

Health and Human Services, 1999). Each year, about 5–9% of children are classified as

having a “serious emotional disturbance” (US Department of Health and Human Services,

1999). Many adolescents experience elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and other

Resilience Education

Page 6 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

psychological difficulties that do not reach the threshold for clinical diagnoses (Nolen-

Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, 1986). In a recent Centers for Disease Control and Pre

vention study, 28.5% of youth reported feeling so sad or hopeless that they stopped their

normal activities at some point in the past year, and 11.3% had made a plan to commit

suicide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008).

There is some evidence that rates of psychological problems have increased during the

last century. For example, research by Twenge and colleagues indicates that narcissistic

and antisocial personality traits, depression, and anxiety have increased substantially

over the last 50–70 years (Twenge, 2000; Twenge & Foster, 2010; Twenge et al., 2010).

These findings are controversial; other research suggests that the rates of depression and

other disorders have not increased substantially (Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006). Nev

ertheless, mental health and public health experts agree that psychological and behav

ioral difficulties are extremely prevalent among school-age youth, especially during ado

lescence. Adolescents who develop depression and substance dependence are at high risk

for future episodes and the associated difficulties throughout adulthood (Harrington,

Fudge, Rutter, Pickles, & Hill,

(p. 614)

1990; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003). Thus, programs that

promote resilience during adolescence could have an enormous impact across a life time.

Teaching resilience broadly

Relevant to all students

Recent studies suggest that prevention programs that target youth at high risk are partic

ularly beneficial (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2007; Horowitz & Gar

ber, 2006; Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, 2009), but educational initiatives that aim

to reach all children are also important. Many risk factors are common and many children

(even those believed to be at “low risk”) will experience significant stressors or distress

at some point during their school years. In addition, our knowledge of risk factors is in

complete. Significant risk factors may exist and even be common in environments that

have traditionally been viewed as “low risk.” For example, recent research suggests that

many youth from backgrounds that are traditionally considered to be privileged are at

high risk for anxiety, substance use, and other problems, perhaps because of the intense

pressures to achieve and limited time with parents (Luthar & Latendresse, 2005).

Applicable to a range of challenges

When people think about resilience, major adversities typically come to mind, for exam

ple, the child who performs well in school and who develops close connections to others

despite enduring years of abuse and neglect. While such outcomes clearly signify re

silience, our research team conceptualizes resilience more broadly. The process of re

silience is also reflected in positive adaptation in response to everyday stressors (e.g.,

conflicts with peers, low marks in school) and common life transitions (e.g., the birth of a

sibling, the break-up of relationship during adolescence). This broader definition appears

justified given the evidence that both major life events and daily stressors contribute to

depression and other difficulties (Bockting, Spinhoven, Koeter, Wouters, & Schene, 2006;

Resilience Education

Page 7 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Kwon & Laurencaeu, 2002; Libby & Glenwick, 2010; Sund, Larsson, & Wichstrom, 2003;

Thompson et al., 2007). Over time, responses to everyday events can develop into habits

that either promote or detract from well-being, relationships, and ability to reach one's

goals.

Consistent with comprehensive education

Resilience education is consistent with a broad view of the purpose of education, as

preparing youth to become lifelong learners who are productive, caring, and responsible

members of the community (Cohen, 2006; Elias et al., 2002; Seligman et al., 2009). This

broader view of education is supported by many parents and educators. For example, re

cent surveys indicate that two-thirds of adults in the USA believe that schools should be

responsible for dealing with the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of their students

(Rose & Gallup, 2007). About 85% want schools to focus more on the prevention of drug

and alcohol abuse (Rose & Gallop, 2000). Respondents also gave high ratings to educa

tional goals such as preparing youth to become responsible citizens, improving social con

ditions, enhancing happiness,

(p. 615)

and enriching people's lives (Rose & Gallup, 2000).

More than 70% of respondents wanted schools to focus more on promoting racial and

ethnic understanding and tolerance (Rose & Gallup, 2000). Creating the conditions neces

sary to meet these expectations should be a focus of our educational system.

Approaches and findings

Two general approaches to enhancing resilience are through: (1) teaching skills and culti

vating strengths and (2) promoting a nurturing school climate or culture. Initiatives that

focus on teaching resilience skills and cultivating strengths often use curricula and for

mal instruction, explicit modeling, and/or coaching. Initiatives that focus on school cli

mate may focus on instructional practices; school rules, policies, goals, and aspirations;

support networks such as counseling and advisory; and increased collaborations with

families and with individuals and organizations in the community that serve youth (Be

nard, 2004; Cohen, McCabe, Michelli, & Pickeral, 2009). Several approaches may be com

bined to weave resilience education into the fabric of the school.

Research findings

There is considerable evidence for benefits from curricula and other school-based inter

ventions that are designed to promote resilience in youth. For example, the Coping with

Stress Course, which teaches coping and problem solving to adolescents with elevated

symptoms of depression, prevents the onset of depressive disorders (Clarke et al., 1995).

The Social Decision Making and Social Problem Solving Program, a curriculum that

teaches self-control, social awareness, problem-solving, and decision-making, increases

prosocial behavior and reduces behavioral problems in students (Elias, 2004). The Pro

moting Alternative THinking Strategies (or PATHS) program, which teaches emotional

awareness, social competence, and problem-solving, improves social skills and prevents

behavior problems and symptoms of anxiety and depression (Greenberg, Kusché, & Rig

gs, 2004). The Seattle Social Development program, a program for 1st through 6th

Resilience Education

Page 8 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

graders that promotes a positive classroom environment and teaches social competence

and problem-solving skills, prevents aggression, violence, substance use, and other high-

risk behavior through adolescence (Hawkins, Smith, & Catalano, 2004).

Programs that teach resilience and promote students’ social and emotional development

have a wide range of positive effects. CASEL recently reviewed the relevant research lit

eratures for: (1) universal programs (often delivered to whole classrooms), designed for

implementation with all students, (2) indicated programs (typically small group interven

tions), designed for students who are showing early signs of behavioral or emotional

problems, and (3) after-school programs (Payton et al., 2008). Together these reviews in

cluded more than 300 studies with about 300,000 students. On average, these programs

significantly improved students’ emotional well-being, social skills, classroom behavior,

attitudes about school, and achievement. All three types of programs (universal, indicat

ed, after-school) were beneficial relative to control. These findings are consistent with

those of other recent reviews of school and community programs designed to promote so

cial and emotional development and prevent psychological and behavioral problems (e.g.,

Catalano et al., 2004; Greenberg et al., 2003; Zins et al., 2004).

(p. 616)

The CASEL review also found that children from different geographic, socioeco

nomic, and racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds benefited from school-based pro

grams. Findings from CASEL's reviews of universal and indicated programs suggest that

these programs are effective when delivered by school staff, and not just by external re

search teams that may take the lead in developing and evaluating them. This is a promis

ing finding that suggests that programs that promote social and emotional skills can be

effectively incorporated into regular educational practice.

Benefits for learning and achievement

Despite the common concern that devoting resources to students’ social and emotional

well-being may detract from efforts to promote student achievement, recent reviews con

firm what many teachers and resilience researchers have long argued: the personal and

environmental qualities that promote social and emotional resilience also promote stu

dents’ learning and engagement in school. For example, self-regulation and optimism pre

dict success at school, even when controlling for past achievement or scores on intelli

gence tests (Duckworth & Seligman, 2005; Schulman, 1995). Students who feel more con

nected to school have better attendance and higher achievement (Christenson & Havsy,

2004; Goodenow, 1993; Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 1989). Indeed, these personal and en

vironmental factors may be at least as important to achievement as intellectual capacity

alone (Lopes & Salovey, 2004). For example, Duckworth and Seligman (2005) found that

self-discipline was a stronger predictor than IQ of adolescents’ grades. Sternberg and col

leagues (2001) estimate that IQ accounts for less than 30% of grades, job performance,

and other real-world outcomes, meaning that other individual and environmental factors

play a crucial role in achievement.

Resilience Education

Page 9 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Attending to social and emotional well-being may also prevent disengagement from

school, which is common in adolescence. Children's enjoyment of school often declines

during middle school and high school (Eccles et al., 1996). In the USA, more than 10% of

students leave school without obtaining a high school diploma or its equivalent. Only

about 74% of students graduate from high school on time (Snyder & Tan, 2005). Some

students are pulled away from school by work, family, and other pressures. Research sug

gests, however, that factors that push students away (such as difficulties getting along

with teachers and peers) are even more important (Christenson & Havsy, 2004; Jordan,

McPartland, & Lara, 1999).

This disengagement coincides with changes in school environment that make it difficult

to maintain a positive school culture. For example, as children make the transition from

elementary school to middle school, they encounter larger schools, larger classes, more

distant relationships with teachers and peers, and feedback systems that focus on perfor

mance relative to others rather than effort and self-improvement (Eccles et al., 1996). It is

not surprising that students’ perceptions of school become more negative during this

time. In a recent survey of youth in California, 61% of 5th graders reported their schools

provided caring relationships and 62% reported that their schools provided high expecta

tions. By 11th grade, these numbers had dropped to 29% and 35%, respectively. Few stu

dents across all grades reported meaningful opportunities to participate (Benard & Slade,

2009). Thus, the social qualities that promote resilience appear to be lacking in many

high schools. Programs that promote positive connections to school can enhance engage

ment in learning. For example, the Check & Connect program, which provides caring

mentors from within the school

(p. 617)

community to students at risk for school failure,

reduces students’ behavioral problems and suspensions, and increases attendance and

achievement (Christenson & Havsy, 2004). Programs that promote students’ social and

emotional skills can also enhance their academic achievement (CASEL, 2007; Elias et al.,

2002; Greenberg et al., 2003; Seligman et al., 2009; Zins et al., 2004). For example, sever

al substance use and violence prevention programs that promote problem-solving, cop

ing, and social competence also improve grades, graduation rates, standardized test

scores, as well as specific reading, math, writing, and cognitive skills (Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009; Wilson, Gottfredson, & Najaka, 2001).

The CASEL reviews found significant benefits on achievement for universal, indicated,

and after-school programs (Payton et al., 2008).

Two Programs for Children and Adolescents

For the past 15 years, our research team has been developing, evaluating, and (more re

cently) disseminating school-based interventions designed to promote resilience and well-

being in children and adolescents. Much of this work has focused on two types of inter

ventions: programs designed to promote resilience by teaching problem solving and cop

ing skills, and programs intended to increase students’ positive emotions, personal

Resilience Education

Page 10 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

strengths, and sense of meaning and fulfillment. Here we briefly review two of our pro

grams for school-age youth.

The Penn Resiliency Program

The Penn Resiliency Program (PRP; Gillham, Reivich, & Jaycox, 2008) is a school-based,

group program for late elementary through middle-school age students (approximately

10–14 years old). PRP grew out of cognitive behavioral theories and interventions used to

treat psychological disorders, especially depression (Beck, 1976; Beck, Rush, Shaw, &

Emery, 1979; Ellis, 1962; Seligman, 1991).

PRP is delivered in a small group format by teachers and counselors. The program uses a

variety of teaching methods. Group leaders introduce concepts and skills through skits,

discussions, and didactic instruction. Students then practice these skills through role

plays and other hands-on activities, first using hypothetical scenarios. Group leaders then

help students apply the skills to their own experiences. Each lesson ends with assign

ments that encourage students to use the skills in real life situations. For a detailed de

scription of PRP see Gillham, Brunwasser, and Freres (2008).

PRP fosters several personal strengths and skills that are related to resilience (Reivich &

Gillham, 2010; Reivich & Shatté, 2002):

• Emotional competence—being able to identify, label, and express emotions, and con

trol emotions when appropriate.

• Self-control—being able to identify and resist impulses that are counterproductive

for a given situation or for reaching long-term goals.

(p. 618)

• Problem-solving and decision-making—especially the skills of flexibility (being able to

consider a range of possible interpretations, to see situations from multiple perspec

tives, and to generate a variety of solutions to problems) and judgment (being able to

make informed decisions based on evidence).

• Social awareness—being able to consider others’ perspectives and empathize with

others.

• Social competence—being able to work through challenges in important relation

ships.

• Self-efficacy and realistic optimism—confidence in one's abilities to reach goals and

to identify and implement coping and problem-solving skills that are suited to a situa

tion.

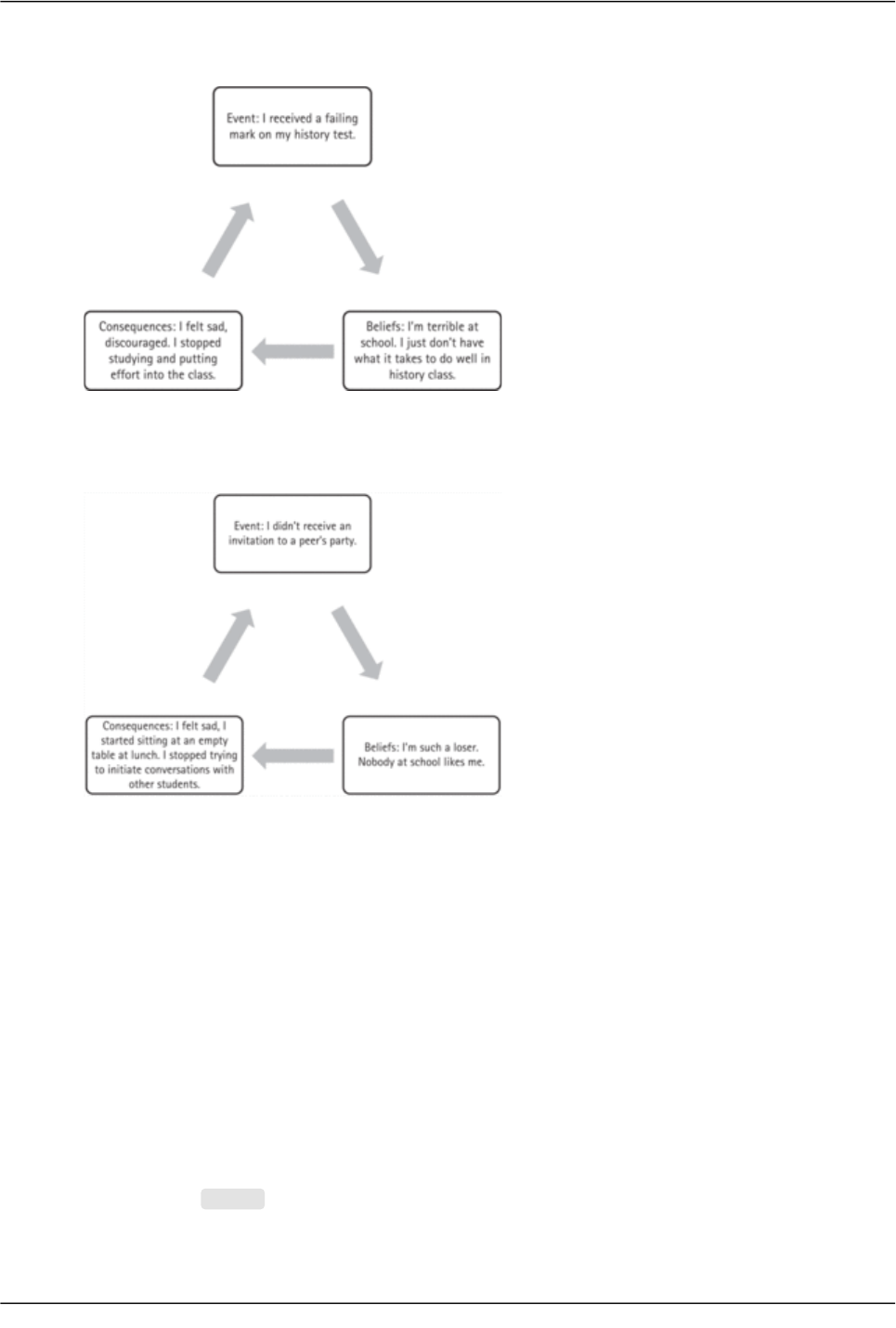

PRP includes two major components: cognitive skills and problem-solving. The cognitive

component teaches a variety of skills that help students to become more aware of their

emotions and to think more flexibly and accurately about problems. Ellis's ABC model is

central to this component: when Activating events (or adversities) occur, our Beliefs or in

terpretations largely determine the event's emotional and behavioral Consequences.

Resilience Education

Page 11 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Fig. 46.2 A negative self-fulfilling prophecy in an

achievement context.

Fig. 46.3 A negative self-fulfilling prophecy in a so

cial context.

Thus, in the same situations, different sets of beliefs may lead people to respond in very

different ways.

In PRP, students learn to identify their emotional experiences, to monitor their interpreta

tions (or “self-talk”), and to identify habitual patterns in their thinking (e.g., pessimism)

that may be inaccurate or maladaptive. A major goal of the cognitive component is to in

terrupt self-defeating thought-behavior patterns. Pessimistic beliefs (e.g., “I'm stupid”) of

ten lead to maladaptive behaviors (e.g., not studying), which then increase the likelihood

of negative outcomes (e.g., poor grades). The negative outcomes then reinforce the

person's initial pessimistic belief, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. These downward spi

rals are often visible in achievement contexts but play an important role in social interac

tions as well (see Figs 46.2 and 46.3). Once they are able to identify self-talk, students

learn to challenge negative or maladaptive interpretations by evaluating the accuracy of

their beliefs and by

(p. 619)

considering alternative interpretations. These twin skills, ac

curacy and flexibility, are at the heart of PRP.

Resilience Education

Page 12 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Our goal is not simply to swap a pessimistic thinking style with an optimistic one. Rather,

we want to help students detect patterns in their self-talk, feelings, and behaviors that

may be counterproductive. Often, the skills of flexibility and accuracy lead to greater opti

mism. But sometimes they can lead students to recognize that they are at least partly re

sponsible for a problem. By learning to interpret problems more accurately, students can

begin to solve them. The cognitive component can also promote social awareness as stu

dents apply their knowledge of emotions and self-talk to understand the perspectives of

others.

The second component of PRP teaches a variety of problem-solving skills. Students learn

to set realistic goals and subgoals and to develop plans for reaching them. Assertiveness

training helps students to express their needs respectfully without escalating conflicts.

The negotiation skill incorporates assertiveness as well as active listening and creative

brainstorming to find solutions that work for both parties. PRP teaches a five-step ap

proach to problem-solving that is based on Dodge's and Crick's (1990) social information

processing model and incorporates many of the other PRP skills. When problems arise,

students are encouraged to: (1) stop and think, especially about their goals, (2) evaluate

the situation (look for clues, consider others’ perspectives), (3) brainstorm about solu

tions creatively (generate a list of possible solutions), (4) decide what to do (consider the

pros and cons of different options and how they affect short- and long-term goals), and (5)

go for the goal (enact the solution and evaluate the outcome; if the solution didn't work

try the process again). The creative brainstorming and decision-making steps apply the

cognitive skills (e.g., flexibility, accuracy, and critical thinking) learned in previous lessons

to one's outward behavior.

Finally, PRP also teaches skills for managing difficult emotions and for coping with nega

tive events that are beyond one's control. Students share their personal methods of cop

ing

(p. 620)

with intense emotions and also learn new skills, like deep breathing and re

laxation techniques. PRP emphasizes the importance of seeking help and support from

friends and family. Although the second component focuses on behavioral skills (or what

students can do when problems happen), students continue to apply the cognitive skills

throughout the program. For example, they examine and challenge beliefs that can inter

fere with effective problem-solving, that fuel procrastination, or that lead to aggression or

passivity and interfere with assertiveness. The problem-solving and coping skills target

behaviors that often contribute to downward spirals (see Figs 46.2 and 46.3).

In addition to teaching specific cognitive, coping, problem solving, and social skills, PRP's

group format also provides opportunities for students to receive support from teachers

and for students to support and help each other. Thus, although PRP primarily develops

personal skills and strengths, it may also help to create a nurturing social environment.

Research findings

PRP has been evaluated extensively. Recent meta-analytic reviews identified 19 con

trolled studies of PRP, including 17 that evaluated PRP's effects on depression and 15 that

evaluated PRP's effects on hopelessness, pessimism, and other cognitive styles linked to

Resilience Education

Page 13 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

depression (Brunwasser & Gillham, 2008; Brunwasser, Gillham, & Kim, 2009). Together,

these studies evaluated PRP with more than 2000 children from a wide variety of geo

graphic, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Findings from these reviews indicate

that PRP significantly improves thinking styles. Students who participated in PRP were

more optimistic than controls and these effects endured for at least 1 year (the last as

sessment examined in the meta-analysis). Similarly, PRP significantly reduced and pre

vented depressive symptoms and these effects also endured for at least 1 year. Although

fewer studies have examined PRP's long-term effects, findings from some of these studies

are promising. For example, the first study of PRP found that the benefits on depression

lasted for 2 years and the benefits on optimism lasted for at least 3 years (Gillham &

Reivich, 1999; Gillham, Reivich, Jaycox, & Seligman, 1995). A few recent studies have

found positive effects on anxiety symptoms and behavioral problems (for a review, see

Gillham, Brunwasser, & Freres, 2008). Research on PRP's effects on academic achieve

ment is underway. A similar resilience program developed by our team for older adoles

cents and young adults has also been found to improve optimism and reduce and prevent

symptoms of anxiety and depression (Seligman, Schulman, DeRubeis, & Hollon, 1999;

Seligman, Schulman, & Tryon, 2007).

The high school positive psychology program

Like many programs designed to promote resilience and positive youth development, PRP

focuses extensively on students’ responses to setbacks and challenges. Our team's high

school positive psychology curriculum (Reivich et al., 2007) is based on recent work in

positive psychology (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2002) which offers an alterna

tive, complementary approach to resilience. Positive psychology highlights the impor

tance of enhancing well-being more broadly, and not simply in response to stressors.

Schools can also promote resilience by helping students to develop close relationships, to

identify and use their strengths, to experience positive emotions, and to engage in activi

ties that are meaningful to them. Interventions that target these outcomes improve life

satisfaction and

(p. 621)

reduce depression (Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006; Seligman,

Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Ultimately, we believe that edu

cational initiatives that integrate both perspectives will be most helpful.

The high school positive psychology curriculum is based largely on Seligman's (2002)

three pathways to happiness. The program includes three units: The Pleasant Life, the

Engaged Life, and The Meaningful Life. Many of the program's skills and activities have

been used and tested in other positive psychology interventions (e.g., Seligman et al.,

2005, 2006). The Pleasant Life unit focuses on increasing positive emotion. Lessons focus

on savoring, gratitude, and optimism. For example, a gratitude lesson encourages stu

dents to think about people who have helped them but whom they have not yet thanked.

Students write a letter expressing gratitude and are encouraged to share it in person. A

lesson on “counting our blessings” encourages students to think about the good things

that happen each day and to log them in a journal each evening. These activities can

counter negative thinking styles that are targeted in PRP and so they are likely to reduce

Resilience Education

Page 14 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

negative emotions. But they go far beyond this. They actively promote positive emotions

like contentment and joy, and may deepen interpersonal relationships.

The Engaged Life unit is the largest. It promotes strengths (e.g., kindness, creativity, per

severance, integrity) that are valued across time and throughout history (Dahlsgaard, Pe

terson, & Seligman, 2005; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The program encourages stu

dents to identify their personal (or signature) strengths and to use them more in their

everyday lives. Students identify their strengths through several activities including com

pleting the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths for Youth (Park & Peterson, 2006), and

by reflecting on past experiences when they were “at their best.” They develop action

plans for using signature strengths and for developing other strengths that are important

to them. The family tree of strengths activity encourages students to interview family

members and find out about strengths that run through their family tree.

During the Meaningful Life unit, students reflect on life purpose and meaning. Rather

than focus on meaning in the abstract sense (i.e., What is the meaning of life?), teachers

encourage students to think about what makes life meaningful for them. Teachers engage

students in discussions about meaning, and students read relevant passages from litera

ture and from the personal reflections of others. We've used excerpts from The Meaning

of Life (Friend & the Editors of Life, 1991), which contains short essays by philosophers,

writers, artists, politicians, spiritual leaders, sports figures, comedians, and others. Stu

dents reflect on how these different perspectives fit with their own views on life meaning.

Students and their parents then complete a back-and-forth meaning journal in which they

dialogue about the meaning of life. In our experience, students’ discussions of meaning

typically center on the importance of connections to others, institutions, and values that

are larger than the self.

The positive psychology curriculum is designed to be delivered by teachers in a small- or

large-class format. The program uses a variety of teaching methods. Teachers introduce

concepts and skills through in-class activities and discussions. Most lessons end with as

signments that encourage students to apply the positive psychology concepts and strate

gies in their everyday lives. Students write reflections about their experiences when us

ing the positive psychology strategies. Lessons typically begin with a discussion of stu

dents’ experiences and reflections.

We developed our positive psychology program to target well-being broadly, rather than

resilience specifically. But we now believe that these concepts and skills are as essential

to

(p. 622)

resilience as the skills covered in PRP. By promoting students’ capacity for pos

itive emotions, to use strengths such as kindness, teamwork, humor, and creativity, and to

experience strong connections with other people and with purposes outside the self, posi

tive psychology provides a strong foundation that can help youth cope with adversity. Re

search indicates that positive emotions enhance problem-solving (Fredrickson, 2001). Al

so, many studies over many decades document the power of close relationships to protect

against depression and other psychological and physical health problems (Leavy, 1983;

Uchino, Cacioppo, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 1996). The positive psychology program aims to pro

Resilience Education

Page 15 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

mote upward spirals; it promotes flourishing by helping students to build upon what they

do well.

Research

We have nearly completed our first scientific evaluation of the high school positive psy

chology program. In that study, 347 9th grade students were randomly assigned to regu

lar grade Language Arts classes or to Language Arts classes that included the positive

psychology curriculum. We followed students for 4 years, until graduation from high

school. Preliminary analyses examining effects through students’ 11th grade year suggest

two major areas of benefit (Gillham, Linkins, & Reivich, 2009; Seligman et al., 2009). The

positive psychology program improved students’ social skills (e.g., empathy, cooperation,

assertiveness, and self-control) according to both teachers’ and mothers’ reports. It also

improved students’ engagement in school, according to teacher reports. The findings on

teachers’ report measures are especially encouraging. Teachers who completed question

naires did not deliver the curriculum and were not informed about students’ condition as

signments. Thus, they are unlikely to be biased by an awareness of students’ participation

in the positive psychology program. There was no overall effect on students’ achieve

ment, but follow-up analyses indicated that the positive psychology program significantly

improved Language Arts achievement among students with average and low (but not

high) levels of achievement at baseline. Contrary to our expectations, we found no effects

on students’ symptoms of depression or anxiety although other positive psychology inter

ventions have been successful at reducing depressive symptoms (Seligman et al., 2006;

Sin & Lyobomirsky, 2009).

School community and culture

Curricula like PRP and our high school positive psychology program appear to promote

well-being in students. Such programs are likely to be most effective when delivered as

part of a school's comprehensive focus on social and emotional well-being and resilience.

Reviews of research on positive youth development, social and emotional learning, pre

vention, and character education converge on the conclusion that isolated curricula are

not as helpful as approaches that are embedded into school culture and delivered over

many years in a child's life (e.g., CASEL, 2003; Gottfredson, 2000). This finding is consis

tent with research documenting the importance of social contextual factors in promoting

resilience in youth (Luthar, 2006).

Recently, our team's work has increasingly focused on promoting resilience through the

classroom, school, and other contexts where children live. In our trainings for teachers

and counselors who deliver our programs, we first encourage teachers to apply the con

cepts and skills to their own lives so that they can experience first-hand the benefits of

the resilience

(p. 623)

and positive psychology skills. We hope that our approach to train

ing teachers leads to a strong personal connection with the concepts and skills, increas

ing the likelihood that they will be effective models for students both in and out of the

classroom. In some of our school collaborations, we are consulting with teachers, coun

selors, and other staff to develop curricula for all ages and to infuse resilience education

Resilience Education

Page 16 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

into everyday interactions and instruction across disciplines. Integrating resilience and

positive psychology skills explicitly through formal instruction also helps to create com

mon language and practices among educators and students that contribute to a culture of

resilience education.

Given the daily stress and challenges they face, teachers who are resilient and use their

strengths are likely to be more effective (Stanford, 2001). Even in the absence of formal

resilience curricula for students, supportive work environments and professional develop

ment for teachers can go a long way in the promotion of resilience and learning in the

students that they teach. When schools support teachers in their own social and emotion

al development, for example, those teachers can more effectively model social and emo

tional skills for students (Elias et al., 1997). A teacher's optimism can motivate a child to

persist through a challenging assignment; a teacher's own flexible thinking about prob

lems can encourage students to think through conflicts from multiple perspectives. In ad

dition, teachers who can regulate their own impulses and emotions may be skilled in

classroom management and creating environments conducive to student learning and

well-being. Indeed, teachers who approach classroom management with respect for stu

dents’ perspectives and appreciate the importance of group cohesion ultimately have

more time for academic subjects throughout the school year (Elias et al., 1997).

Both life satisfaction and grit, or perseverance toward long-term goals, determine teacher

effectiveness as measured by student learning (Duckworth, Quinn, & Seligman, 2009).

The hard work of gritty teachers pays off in terms of student learning and achievement.

Duckworth and colleagues also suggest that “teachers higher in life satisfaction may be

more adept at engaging their pupils, and their zest and enthusiasm may spread to their

students” (p. 545). More broadly, a positive school culture that cultivates strengths en

ables teachers to bring the best of themselves to their professions. As a result, increased

teacher engagement can promote students’ learning in the classroom as well as foster the

meaningful teacher-student relationships that nurture positive development in students.

Recent reviews of social and emotional learning programs highlight the importance of

strengthening ties between home and school, as well as between school and the larger

community. We have developed a resilience program for parents that teaches them the

core PRP skills so they can apply them in their own lives and support their children's use

of these skills. Several activities in the positive psychology curriculum (e.g., family tree of

strengths, meaning journals) create opportunities for students and parents to work to

gether, and for parents to provide guidance as students identify their personal strengths

and what makes life most meaningful. Many parents appreciate the opportunity to share

their values so openly with their children. Students’ reflections suggest that they are

grateful for the deeper connection to parents and the life lessons learned.

Other activities help to strengthen connections to the larger community. For example, in

the paragons of strengths activity, students interview members of the larger community

who exemplify different strengths. Community service projects help youth put many of

their strengths to use. These projects can provide youth with meaningful opportunities to

Resilience Education

Page 17 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

connect with others and make a positive difference in the world. Community service may

(p. 624)

also lead to long-term benefits in well-being (Bowman, Brandenberger, Hill, Laps

ley, & Quaranto, 2010).

Conclusions

Positive psychology and resilience research have identified many qualities of individuals

and social contexts that enable people to adapt and to thrive in their everyday lives and

when confronted with adversity. Given their central role in students’ lives, schools have

enormous potential (and, many argue, responsibility) to promote social and emotional

well-being and resilience in youth both within and outside of school settings.

Many educators are understandably skeptical of curricula that purportedly foster well-be

ing in students, as many isolated programs—even some that have been implemented

widely—either have not been evaluated rigorously or have not shown positive effects. Re

cent reviews, however, suggest that comprehensive and well-integrated programs do, in

fact, contribute to well-being in children and adolescents, and research has identified sev

eral programs that can significantly reduce emotional or behavioral problems and dra

matically cultivate social skills, strengths, positive relationships, and achievement.

As we have shown, integrating resilience into education through explicit instruction can

equip students with the skills needed to rise above and grow from major challenges and

daily struggles. Simultaneously, embedding principles of resilience and positive psycholo

gy into educational practices can help to create a school climate that contributes to stu

dent learning and positive development in non-academic domains. Perhaps now more

than ever before, resilience education has the power to help students successfully navi

gate the academic and non-academic demands they juggle, as well as grow and thrive in

the face of adversity and the challenges of childhood and adolescence.

Disclosures

The University of Pennsylvania has licensed the Penn Resiliency Program to Adaptiv

Learning Systems. Drs. Reivich and Seligman own Adaptiv stock and could profit from the

sale of this program. None of the other authors has a financial relationship with Adaptiv.

References

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: Interna

tional Universities Press.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression.

New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Benard, B. (2004). Resiliency: What we have learned. San Francisco, CA: WestEd.

Resilience Education

Page 18 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Benard, B., & Slade, S. (2009). Listening to students: Moving from resilience research to

youth development practice and school connectedness. In R. Gilman, E. S. Huebner, & M.

J. Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 353–369). New York,

NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Benninga, J. S., Berkowitz, M. W., Kuehn, P., & Smith, K. (2006). Character and acade

mics: What good schools do. Phi Delta Kappan, 87, 448–452.

(p. 625)

Berkowitz, M. W., & Bier, M. C. (2004). Research-based character education. An

nals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591, 72–85.

Bockting, C. L. H., Spinhoven, P., Koeter, M. W., Wouters, L. F., & Schene, A. H. (2006).

Prediction of recurrence in recurrent depression and the influence of consecutive

episodes on vulnerability for depression: A 2-year prospective study. Journal of Clinical

Psychiatry, 67, 747–755.

Bowman, N. A., Brandenberger, J. W., Hill, P. L., Lapsley, D. K., & Quaranto, J. C. (2010).

Serving in college, flourishing in adulthood: Does community engagement during the col

lege years predict adult well-being? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2, 14–34.

Brunwasser, S. M. & Gillham, J. E. (2008, May). A meta-analytic review of the Penn Re

siliency Program. Paper presented at the Society for Prevention Research, San Francisco,

CA.

Brunwasser, S. M., Gillham, J. E., & Kim, E. S. (2009). A meta-analytic review of the Penn

Resiliency Program's effects on depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical

Psychology, 77, 1042–1054.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A. M., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004).

Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of pos

itive youth development programs. Annals of the American Academy of Political and So

cial Science, 591, 98–124.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2008). Youth risk behavior surveillance:

United States, 2007 (MMWR Publication No. SS-4). Atlanta, GA: Coordinating Center for

Health Information and Service.

Christenson, S. L., & Havsy, L. H. (2004). Family-school-peer relationships: Significance

for social, emotional, and academic learning. In J. E. Zins, R. P. Weissberg, M. C. Wang, &

H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What

does the research say? (pp. 59–75). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Clarke, G. N., Hawkins, W., Murphy, M., Sheeber, L. B., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Seeley, J. R.

(1995). Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high

school adolescents: A randomized trial of group cognitive intervention. Journal of the

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 34, 312–321.

Resilience Education

Page 19 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Cohen, J. (2006). Social, emotional, ethical, and academic education: Creating a climate

for learning, participation in democracy, and well-being. Harvard Educational Review, 76,

201–237.

Cohen, J., McCabe, L., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research,

policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111, 180–213.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2003). Safe and

sound: An educational leader's guide to social and emotional learning programs. Chicago,

IL: Author. Retrieved from http://casel.org/publications/safe-and-sound-an-educa

tional-leaders-guide-to-evidence-based-sel-programs/

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2007). The bene

fits of school-based social and emotional learning programs: Highlights from a forthcom

ing CASEL report. Chicago, IL: Author. Retrieved from http://

www.melissainstitute.org/documents/weissberg-3.pdf

Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (2007). Fast track randomized controlled

trial to prevent externalizing psychiatric disorders: Findings from grades 3 to 9. Journal

of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 1250–1262.

Costello, E. J., Erkanli, A., & Angold, A. (2006). Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent

depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1263–1271.

(p. 626)

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Shared virtue: The con

vergence of valued human strengths across culture and history. Review of General Psy

chology, 9, 203–213.

Dodge, K. A., & Crick, N. R. (1990). Social information-processing bases of aggressive be

havior in children. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 8–22.

Duckworth, A. L., Quinn, P. D., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Positive predictors of teacher

effectiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 540–547.

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting

academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science, 16, 939–944.

Eccles, J. S., Flanagan, C., Lord, S., Midgley, C., Roeser, R., & Yee, D. (1996). Schools,

families, and early adolescents: What are we doing wrong and what can we do instead?

Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 17, 267–276.

Elias, M. J. (2004). Strategies to infuse social and emotional learning into academics. In J.

E. Zins, R. P. Weissberg, M. C. Wang, & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Building academic success

on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? (pp. 113–134). New York,

NY: Teachers College Press.

Resilience Education

Page 20 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Elias, M. J., Wang, M. C., Weissberg, R. P., Zins, J. E., & Walberg, H. J. (2002). The other

side of the report card: Student success depends on more than test scores. American

School Board Journal, 189, 28–30.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., …

Shriver, D. P. (1997). Promoting social and emotional learning: Guidelines for educators.

Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Lyle Stuart.

Evans, G. W. (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59,

77–92.

Fincham, F. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (1993). Marital satisfaction, depression, and attribu

tions: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 442–452.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S., & Kracke, K. (2009). Children's exposure

to violence: A comprehensive national survey. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice,

Office of Justice Programs.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broad

en-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

Friend, D., & the Editors of Life. (1991). The meaning of life: Reflections in words and pic

tures on why were are here. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

Gillham, J. E., Brunwasser, S. M., & Freres, D. R. (2008). Preventing depression in early

adolescence: The Penn Resiliency Program. In J. R. Z. Abela & B. L. Hankin (Eds.), Hand

book of depression in children and adolescents (pp. 309–332). New York, NY: Guilford

Press.

Gillham, J. E., Linkins, M., & Reivich, K. J. (2009, June). Teaching positive psychology to

9th graders: Results through 11th grade. Paper presented at the first World Congress of

the International Positive Psychology Association, Philadelphia, PA.

Gillham, J. E., & Reivich, K. J. (1999). Prevention of depressive symptoms in school chil

dren: A research update. Psychological Science, 10, 461–462.

Gillham, J. E., Reivich, K. J., & Jaycox, L. H. (2008). The Penn Resiliency Program (also

known as The Penn Depression Prevention Program and The Penn Optimism Program).

Unpublished manuscript, University of Pennsylvania.

Gillham, J. E., Reivich, K. J., Jaycox, L. H., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1995). Prevention of de

pressive symptoms in schoolchildren: Two-year follow-up. Psychological Science, 6, 343–

351.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Resilience Education

Page 21 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

(p. 627)

Goodenow, C. (1993). Classroom belonging among early adolescent students: Re

lationships to motivation and achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 13, 21–43.

Gottfredson, D. G. (2000). School climate, population characteristics, and program

quality. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquen

cy Prevention. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED446312).

Gottfredson, G. D., & Gottfredson, D. C. (1989). School climate, academic performance,

attendance, and dropout. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improve

ment. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED308225).

Greenberg, M. T., Kusché, C. A., & Riggs, N. (2004). The PATHS curriculum: Theory and

research on neurocognitive development and school success. In J. E. Zins, R. P. Weiss

berg, M. C. Wang, & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Building academic success on social and emo

tional learning: What does the research say? (pp. 170–188). New York, NY: Teachers Col

lege Press.

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., O’Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., &

Elias, M. J. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through

coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58, 466–

474.

Harrington, R., Fudge, H., Rutter, M., Pickles, A., & Hill, J. (1990). Adult outcomes of

childhood and adolescent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47, 465–473.

Hawkins, J. D., Smith, B. H., & Catalano, R. F. (2004). Social development and social and

emotional learning. In J. E. Zins, R. P. Weissberg, M. C. Wang, & H. J. Walberg (Eds.),

Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say?

(pp. 135–150). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Horowitz, J. L., & Garber, J. (2006). The prevention of depressive symptoms in children

and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

74, 401–415.

Jordan, W. J., McPartland, J., & Lara, J. (1999). Rethinking the causes of high school

dropout. The Prevention Researcher, 6, 1–3.

Juster, F. T., Ono, H., & Stafford, F. P. (2004). Changing times of American youth: 1981–

2003. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Retrieved from

http://www.ns.umich.edu/Releases/2004/Nov04/teen_time_report.pdf

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., & Poulter, R. (2003).

Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a

prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 709–717.

Kwon, P., & Laurenceau, J. (2002). A longitudinal study of the hopelessness theory of de

pression: Testing the diathesis-stress model within a differential reactivity and exposure

framework. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 1305–1321.

Resilience Education

Page 22 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Leavy, R. L. (1983). Social support and psychological disorder: A review. Journal of Com

munity Psychology, 11, 3–21.

Libby, C. J., & Glenwick, D. S. (2010). Protective and exacerbating factors in children and

adolescents with fibromyalgia. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55, 151–158.

Lopes, P. N., & Salovey, P. (2004). Toward a broader education: Social, emotional and

practical skills. In J. E. Zins, R. P. Weissberg, M. C. Wang, & H. J. Walberg (Eds.), Building

academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? (pp. 76–

93). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Luthar, S. S. (2006). Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five

decades. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3.

Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 739–795). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

(p. 628)

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A crit

ical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543–562.

Luthar, S. S., & Latendresse, S. J. (2005). Children of the affluent: Challenges to well-be

ing. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 49–53.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American

Psychologist, 56, 227–238.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotion

al, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Washington,

DC: The National Academies Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Girgus, J. S., & Seligman M. E. P. (1986). Learned helplessness in

children: A longitudinal study of depression, achievement, and explanatory style. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 435–442.

Pajares, F. (2009). Toward a positive psychology of academic motivation: The role of self-

efficacy beliefs. In R. Gilman, E. S. Huebner, & M. J. Furlong (Eds.), Handbook of positive

psychology in schools (pp. 149–160). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2006). Moral competence and character strengths among ado

lescents: The development and validation of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths

for Youth. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 891–909.

Payton, J., Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., Schellinger, K. B.,

& Pachan, M. (2008). The positive impact of social and emotional learning for kinder

garten to eighth-grade students: Findings from three scientific reviews. Chicago, IL: Col

laborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL).

Peterson, C. (2006). A primer in positive psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University

Press.

Resilience Education

Page 23 of 26

PRINTED FROM OXFORD HANDBOOKS ONLINE (www.oxfordhandbooks.com).©Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights

Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a title in

Oxford Handbooks Online for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

Subscriber: Swarthmore College; date: 11 July 2019

Peterson, C. (2008). Other people matter: Two examples. Psychology Today. Retrieved

from http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-good-life/200806/other-people-

matter-two-examples

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook of