Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

1

Department of Rehabilitation Services

Physical Therapy

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Inpatient Physical Therapy management of the patient following total hip arthroplasty,

hemiarthroplasty, hip resurfacing, or revision total hip arthroplasty.

ICD 9 Codes:

Choose the primary diagnosis for the first ICD9 when entering charges. Use secondary

supporting ICD9 codes depending upon impairments per individual patient.

Table 1: ICD 10 Codes: may include, but are not limited to:

M16.9 Hip Osteoarthritis

M08.059 Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

affecting the hip

M08.059 Rheumatoid Arthritis with

Rheumatoid factor affecting the hip

M08.859 Rheumatoid Arthritis without

Rheumatoid Factor affecting the hip

M87.059 Osteonecrosis affecting the hip

M16.300A Hip Osteoarthritis secondary to hip

dysplasia

S72.009A Femoral Neck Fracture

M84.453A Pathological femoral neck fracture

M93.259 Osteochondritis Dissecans affecting

the hip

S73.006A Hip Dislocation

Case Type / Diagnosis:

This standard of care applies to patients following hip hemiarthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty

(THA), and hip resurfacing as a result of disorders that include, but are not limited to:

• Osteoarthritis (OA)

• Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

• Avascular necrosis (AVN)

• Congenital hip dysplasia

• Tumors/Osteosarcoma

• Traumatic joint injuries

• Rotrusio Acetabuli

• Arthritis associated with Paget's

Disease

• Ankylosing Spondylitis

• Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

This standard of care serves as a guide for clinical decision-making for physical therapy (PT)

management of this patient population at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) acute care PT

services.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

2

The purpose of hip hemiarthroplasty, THA, and hip resurfacing is to reduce pain, restore

function and correct deformity by improving the biomechanics of the hip joint. This is done by

replacing the damaged joint with a prosthetic implant, realigning the soft tissues, and eliminating

structural and functional deficits. The Center of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports

that each year in the United States 332,000 total hip replacements are performed

1

. In 2013

approximately 500 total hip replacements were performed at BWH

2

. The demand for primary

total hip arthroplasties is estimated to grow by 174% by the year 2030, with the demand for

revision procedures to grow by 137% within the same time frame

3

.

Surgical Techniques:

Total Hip Arthroplasty

If both the acetabulum and the femoral head are damaged then a THA may be indicated. A THA

consists of a femoral and acetabular component. During a THA the hip is dislocated exposing the

joint cavity and femoral head. The deteriorated femoral head is removed. The acetabulum is

prepared by cleaning and enlarging it with circular reamers of gradually increasing size

1

. The

new acetabular shell is implanted securely within the prepared hemispherical socket. The

acetabular socket can be made of metal, ultra-high molecular-weight polyethylene, or a

combination of polyethylene backed by metal. The plastic inner portion of the implant is placed

within the metal shell and fixed into place. Next, the femur is prepared to receive the stem. The

stem portions of most hip implants are made of titanium- or cobalt/chromium-based alloys. They

come in different shapes and some have porous surfaces to allow for bone in growth. A femoral

neck osteotomy is performed, and the hollow center portion of the bone is cleaned and enlarged,

creating a cavity that matches the shape of the implant stem. The top end of the femur is

smoothed allowing the stem to be inserted flush with the bone surface. If the ball is a separate

piece, the proper size is selected and attached. Cobalt/chromium-based alloys or ceramic

materials (aluminum oxide or zirconium oxide) are used in making the ball portions, which are

polished smooth to allow easy rotation within the prosthetic socket. The ball is seated within the

cup allowing proper alignment of the joint.

Hip replacements may be cemented, cementless, or hybrid (a combination of cemented and

cementless components), depending on the type of fixation used to hold the implant in place.

Cemented THA are more commonly recommended for older patients, for patients with

conditions such as RA, and for younger patients with compromised health or poor bone quality

and density. These patients are less likely to put stresses on the cement that could lead to fatigue

fractures

4

.

Figure 1: Total Hip Arthroplasty

http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00377

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

3

Hip Hemiarthroplasty

If only one part of the joint is damaged or diseased, a partial hip replacement, or hip

hemiarthroplasty, may be recommended. In most instances, the acetabulum is left intact and the

head of the femur is replaced, using components similar to those used in a total hip replacement.

A hip hemiarthroplasty can be either a unipolar or bipolar prosthesis. The most common form of

partial hip replacement is unipolar

1

. In a unipolar prosthesis the head is fixed to the stem. In a

bipolar prosthesis there is an additional polyethylene bearing between the stem and the

endoprosthetic head component

5

.

Hip Resurfacing

Hip resurfacing is a technique for hip arthroplasty that has recently emerged. BWH is one of the

few New England Hospitals that offers hip resurfacing. The acetabular component is replaced

similar to a total hip replacement, however the head of the femur is covered or "resurfaced" with

a hemispherical component. This fits over the head of the femur and spares the bone of the

femoral head and the femoral neck. It is fixed to the femur with cement around the femoral head

and has a short stem that passes into the femoral neck

1

. Hip resurfacing conserves bone, restores

the proximal femoral anatomy, and has lower wear rates. A meta-analysis found that patients

following hip resurfacing have better functional outcomes on the Western Ontario and the

McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) and Harris hip score (HHS) than those

following THA

6

. Indications for hip resurfacing can include osteoarthritis, developmental

dysplasia of the hip and avascular necrosis

7

. Hip resurfacing is an option for younger patients

with more demanding lifestyles that would put them at higher risk for earlier failure of a THA.

Certain patients, however, are at greater risk for requiring revision of resurfacing, including those

with smaller femoral head size, older patients, and patients with developmental dysplasia

7

.

Figure 2: THA vs. Hip Resurfacing

http://www.methodistorthopedics.com/hip-resurfacing-arthroplasty

Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty:

Primary total hip arthroplasties have a 95% survivorship at 10 years or greater. With life

expectancy growing and younger patients with higher activity levels undergoing THA, revision

total hip arthroplasties are an unfortunate necessity

8

. The incidence of revision THA in a

fourteen month span of October 2005 to December 2006 was 51,345 patients in the United

States

9

. The reasoning for revision varies and can be due to complications following THA along

with other causes. These reasons for hip revision can be separated into three main categories:

implant-related factors, patient related factors, and failures related to surgical technique. The

most common indications may include the following:

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

4

Table 3: Reasons for Hip Revisions

Implant-related factors:

Surgical technique factors:

Periprosthetic fracture

Recurrent dislocation/instability*

Delamination of the porous coating

Infection*

Osteolysis

Malpositioning of components

Aseptic loosening*

*= leading factors requiring revision

Certain risk factors put patients at jeopardy for adverse events requiring revision THA. Patients

with RA have a higher baseline risk for infectious disease compared to the general population.

Patients with RA were found to have higher risk of prosthetic joint infections compared to

patients with OA, resulting in a need for revision

10

. Sickle cell anemia, poor bone density,

obesity, the male gender, and younger age are also risk factors that result in complications

requiring revision total hip replacement

8

.

Surgical Approach:

There are different approaches that can be used in order to perform a THA. The approach that is

chosen is based on the surgeon’s experience and patient factors. Knowing which approach was

used in addition to the specifics of the patient’s operating room report will help guide the

therapist in postoperative rehabilitation management. Each approach has a specific location for

the incision that is defined by its relation to the gluteus medius.

Posterior Approach:

The posterior (Moore) approach accesses the hip by splitting the gluteus maximus posterior to

the gluteus medius. The posterior capsule and external rotators are divided. The femur is then

flexed and internally rotated to complete exposure of the hip joint

11

.This approach gives

excellent access to the acetabulum and preserves the hip abductors. The external rotators and the

posterior capsule are repaired at the end of the procedure.

Figure 3: Posterior Approach

http://www.jaaos.org/content/15/12/707/F1.expansion

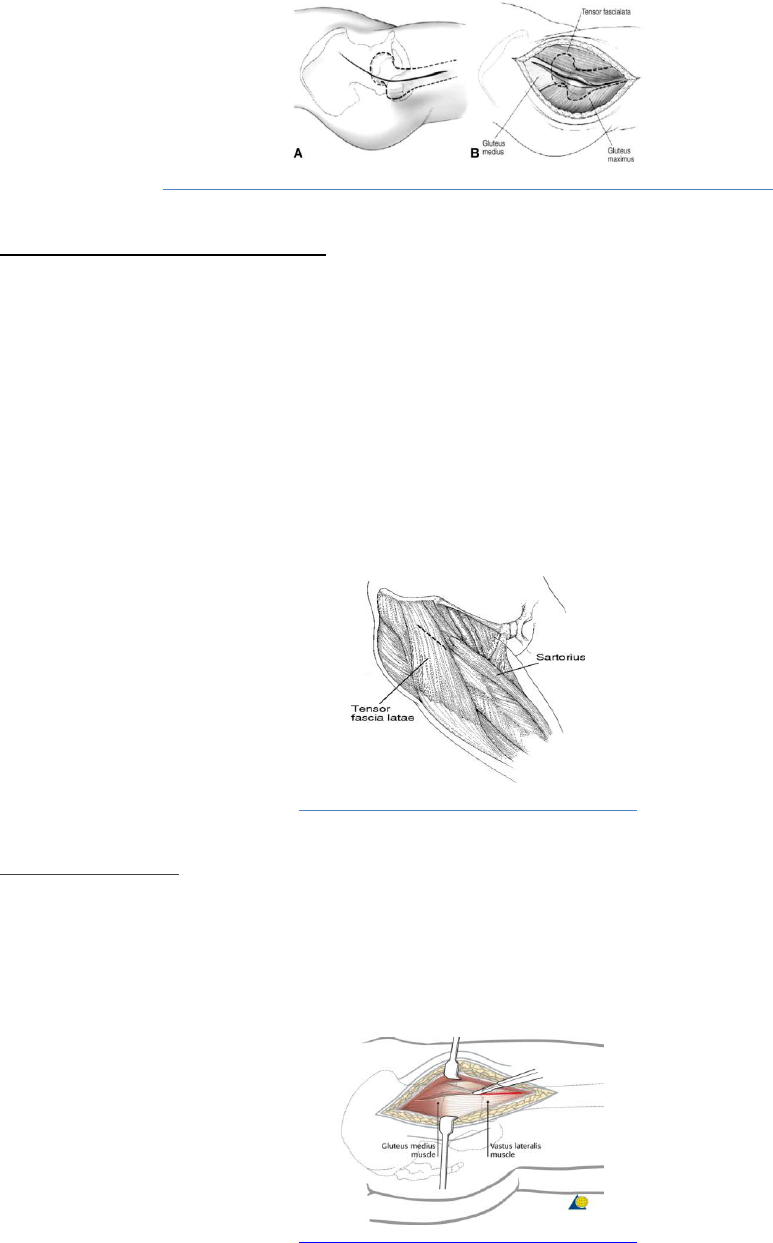

Anterior Lateral Approach:

The anterolateral (Watson-Jones) approach accesses the hip joint through the interval between

the tensor fasciae latae and the gluteus medius. The hip is dislocated anteriorly and a femoral

neck osteotomy is performed or the neck osteotomy is made in situ. The anterior fibers of

gluteus medius are often reflected from the greater trochanter and repaired at the conclusion of

the surgery

12

.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

5

Figure 4: Anterior Lateral Approach

http://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.5371/jkhs.2011.23.2.95&vmode=PUBREADER

Direct Anterior Approach (DAA):

The direct anterior (Heuter) approach is a modification of the Smith-Peterson (Anterior)

approach. The incision is made lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine and is carried down

through the skin and subcutaneous tissues to the fascia. The fascia over the tensor fascia lata

muscle is then split. An interval is made between the tensor fascia lata and rectus femoris

muscles. The leg is then externally rotated and the rectus femoris muscle is detached from the

anterior capsule and the femoral neck is divided. The capsule is then released. Traction is applied

to the femur to expose the acetabulum, the femoral head is removed, and the acetabular

component is placed. The femur is exposed by external rotation, extension and abduction in

order for the femoral stem to be placed. The subcutaneous tissue and fascia are sutured and the

skin is closed at the end of the procedure

13

.

Figure 5: Direct Anterior Approach

http://www.jaaos.org/content/15/12/707/F4.large.jpg

Lateral Approach:

The lateral (Bauer’s) approach requires elevation of the hip abductors (gluteus medius and

gluteus minimus) in order to access the joint. The abductors may be lifted up by osteotomy of the

greater trochanter and reapplied afterwards using wires. The hip abductors could also be divided

at their tendinous portion or through the functional tendon and repaired using sutures.

Figure 6: Lateral Approach

http://www.jaaos.org/content/15/12/707/F4.large.jpg

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

6

Trochanteric Osteotomy:

This may be an additional aspect of the surgery for any of the above procedures. This allows for

additional exposure of the hip joint by lifting the hip abductors off the greater trochanter with an

osteotomy.

Peri-Operative Medical Management:

Anticoagulation Therapy

Patients undergoing THA are often started on anticoagulants such as warfarin, heparin, low

molecular weight heparin (Lovenox), or aspirin the night before surgery to decrease risk for

blood clots. This dose is adjusted after surgery depending on the patient’s international ratio

(INR) hematology values. At the time of discharge, patients who are at a high risk for deep vein

thrombosis (DVT) will remain on anticoagulation therapy for approximately 3weeks. High-risk

patients include those who have undergone bilateral THA, have a history of prior DVT, are on

estrogen therapy, have a recent history of cancer, or have undergone THA secondary to hip

fracture

14

.

Pain Management

There are different modes of analgesia used during and after a THA. Either general or spinal

anesthesia is used during surgery. A local anesthetic pericapsular injection is also commonly

used, however not all the time, for additional pain control. General anesthesia is a combination of

intravenous (IV) drugs and inhaled gasses to produce unconsciousness and an inability to feel

pain during surgery. Spinal anesthesia is a spinal block that forms regional anesthesia. An

injection of local anesthetic is placed into the subarachnoid space typically at the level of T8.

Patients that receive spinal anesthesia are under conscious sedation during their surgery. The

pericapsular injection most commonly consists of Clonidine®, Toradol®, Epinephrine®, and

Ropivacaine® used for pain control. Clonidine® is an antihypertensive that decreases blood

pressure. Toradol® is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that treats pain and

inflammation. Epinephrine® is sympathomimetic agent that relaxes muscles and tightens blood

vessels. Ropivacaine® is a local anesthetic that blocks pain by causing decreased sensation and

numbness. A study of 325 patients found that a pericapsular injection is effective in decreasing

post-operative pain and allows for early mobilization with resulting earlier discharge

15,16

. After

surgery, the patient is brought to the post anesthesia care unit (PACU) where anesthesiologists

and nurses assist with pain control. Patient’s pain is treated with IV narcotics, most often

Dilaudid® and/or Morphine®. IV pain management is often discontinued on post-operative day

1 (POD#1) and the patient is then transitioned to oral (PO) pain medication consisting of short

and long acting narcotics. Short-acting narcotics such as Oxycodone® or oral Dilaudid® are

used as needed for breakthrough pain control. If necessary, IV infusions of Morphine® or

Dilaudid® are also provided to the patient for additional breakthrough pain relief. Long-acting

narcotics such as Oxycontin® are slow release and are used to treat pain around-the-clock.

Pain management is necessary to allow patient comfort and to facilitate mobility following THA.

At BWH PT is coordinated with the nursing staff to allow for patients to receive pain medication

approximately 30-45 minutes prior to mobility. This allows for the medication to be effective

during treatment sessions. While pain management plays an important role in assisting with

mobility, there are negative side effects that narcotics can have limiting PT treatment. Nausea,

vomiting, dizziness, and drowsiness as a result of narcotics can restrict PT intervention in the

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

7

acute care setting

15

. These side effects should be assessed by the physical therapists during their

examination of the patient and should be communicated with the nurse and responding clinician.

Indications for Treatment:

The typical length of stay at BWH for patients following THA is two to three days excluding the

day of surgery. Due to the short length of stay following THA, the focus of PT management

begins on POD#1 with initial evaluation and an afternoon treatment session. Patients are then

seen by PT once a day for a treatment session on POD#2 and POD#3. The PT evaluation

includes patient education, mobility, and functional training as well as increasing ROM and

motor control of the articular and peri-articular structures of the hip joint. It is important to keep

in mind that ROM, along with proper soft tissue balance, is required to ensure proper

biomechanics in the hip joint. Therefore, PT must address both impairments in order to ensure

good outcomes.

The World Health Organization developed the International Classification of Functioning

Disability and Health (ICF) as a framework to define the spectrum of problems that patients face

with different diagnoses, including OA. Osteoarthritis causes musculoskeletal pain and is one of

the primary reasons why patients elect for THA. One study found that the ICF core set for OA

allows there to be focus on aspects of patient’s everyday life that may not have been taken into

account otherwise in their treatment when following up at three weeks, three months and six

months post THA

17

. A study of 64 patients looked at their desired functional improvements

before and after THA. The study found that a majority of the patients were concerned with

activities and partition such as walking, moving around, and recreation/leisure activities.

However at three months post THA majority of their concern was regarding dressing

18

.

Therefore PT treatment should focus on the full picture of the patient’s health, using the ICF

model as guide when tailoring treatments for patients following THA. The following are lists of

potential body structures, body functions, activities and participation limitations that may

indicate treatment in patients following THA.

Table 4: ICF: Total Hip Arthroplasty

19

Body Structure/Function(s):

Activity Limitations:

Participation Restrictions:

• Range of motion (ROM)

• Muscle performance

(including strength, power,

and endurance)

• Motor control

• Balance

• Gait

• Tissue integrity

• Pain

• Sensation

• Knowledge deficit

• Aerobic capacity/endurance

• Ventilation/gas exchange

• Bed mobility

• Transfers

• Ambulation

• Stair climbing

• Functional activities

• Basic/instrumental

activities of daily

living (B/IADLs)

• Quality of life

• Community

Mobility

• Driving

• Working

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

8

Contraindications / Precautions for Treatment:

The following post-operative activity recommendations are often included in the PT consults for

patients following THA in the acute care setting. Specific orders regarding precautions and the

approach used, however is not always included in the PT consult. It is important to review the

operative note along with the patients chart to ensure the proper activity restrictions and

precautions are followed. It may be necessary to contact the responding clinician to clarify orders

if the operative note or chart are not clear. Orders and precautions can include but are not limited

to the following:

• Weight bearing Status:

o Weight bearing as tolerated (WBAT) to full weight bearing (FWB)

o WBAT with bilateral upper extremity support

o Partial weight bearing (PWB)

• Hip Dislocation Precautions: based on the surgical approach used:

o Posterior Precautions: No hip flexion greater than ninety degrees, no hip adduction or

internal rotation beyond neutral, and none of the above motions combined.

o Limited Posterior Precautions: No combination of hip flexion greater than ninety

degrees, no hip adduction or internal rotation beyond neutral.

o Anterior Precautions: No lying flat, no prone lying, no bridging and no hip external

rotation.

o Modified Anterior Precautions: No prone lying, no bridging and no hip external

rotation.

o Direct Anterior Precautions: no bridging

o Lateral Precautions: The patient will likely have hip abduction restrictions.

o Global Precautions: most often ordered for a patient following a hip resurfacing

surgery or a revision hip surgery following multiple dislocations. This set of

precautions are a combination of both posterior and anterior dislocation precautions.

This is due to the large incision into both the posterior and anterior hip capsule to

expose the femoral head.

• Trochanteric osteotomy: If a trochanteric osteotomy is performed the orders may include

restrictions for hip abduction. It may be stated as, “passive abduction only” or “functional

abduction only.” This is to allow for bone healing and to prevent a non-union

20

.

• Positioning of the operative extremity: Positioning recommendations may include:

o Positioning the operative extremity in neutral rotation with a towel roll proximal to

the knee to prevent external rotation

o Locking the foot control of the bed in extension to prevent the operative knee from

resting in a flexed position

o Use of a hip abduction pillow or folded pillow between the patient’s lower

extremities to prevent the operative extremity from adducting

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

9

Early Post-Operative Complications:

It is important to recognize signs and symptoms of early post-operative complications and

consult with other health care providers as appropriate. The common acute care complications

following THA are:

• Blood loss requiring transfusion

15

o Decreased blood pressure, pallor appearance, fatigue, shortness of breath,

dizziness

21

• Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

22

o calf pain or tenderness, swelling with pitting edema, increased skin temperature,

cyanosis

21

• Pulmonary embolism

22

o Chest pain, chest wall tenderness, back pain, upper abdominal pain, syncope,

shoulder pain, shortness of breathing, hemoptysis, new onset of wheezing, painful

respiration, new cardiac arrhythmia

21

• Excessive joint bleeding

o Excessive swelling, discoloration, pain

21

• Hematoma

23

o Excessive swelling, discoloration, pain

21

• Joint infection

8

o Swelling, warmth, fatigue, temperature, wound drainage, erythema

21, 24

• Joint dislocation

23, 25

o Pain, limb shortening and internal rotation, decreased hip ROM

21

• Sciatic nerve injury

24, 26

If a patient presents during the first few days post-operatively with increased pain not consistent

with surgical pain, excessive swelling, decreased muscle strength or sensation along a motor

and/or sensory nerve distribution, sudden shortness of breath and decreased oxygen saturation

along with increased resting heart rate, PT interventions must be stopped, and the medical team

consulted.

Late-Onset Post-Operative Complications:

• Skin necrosis:

o Devitalized tissue that consists of necrotic cells called eschar. Eschar is dry,

leathery and rigid. This requires drainage and potentially surgery to correct the

defect

24

.

• Persistent joint drainage in the weeks following THA:

o This complication is often treated with joint aspiration, antibiotics, and at times

debridement and joint lavage. A wound vacuum may be placed.

• Large hematoma formation:

o Patients are often advised by the surgeon to rest the hip joint, use ice to help

decrease the size of the hematoma, and stop taking anticoagulants. If the

hematoma does not resolve, patients may need surgical evacuation

21

.

• Wound healing complications in the first few weeks after surgery:

o This typically occurs in patients who are on chronic steroids or chemotherapy,

have RA, obesity, diabetes, or are active smokers. The signs and symptoms

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

10

include increased joint swelling, pain, and redness in the joint or at the site of the

incision

21

.

• Dislocation:

o A systematic literature review found that rates of hip dislocation vary depending

on the surgical approach: anterior lateral 0.70%, lateral 0.43%, and posterior

lateral with soft tissue repair 1.01%

27

. Reported dislocation rates following the

direct anterior approach were found to be 0.96% in 1037 procedures, 0.61% in

437 procedures, 1.3% in 2132 procedures and 1.5% in 1374 procedures

23

.

• Heterotrophic ossification:

o Abnormal bone growth in the muscle or other connective tissue that causes

swelling, warmth near the hip joint, and erythema along with elevated serum

alkaline phosphatase levels. Heterotrophic ossification can lead to decreased

ROM and stiffness

24

.

Evaluation:

Medical History: A patient’s past medical history should be reviewed detailing both pre-

existing medical conditions and past surgical interventions. It should be noted if

additional consults were requested prior to surgery for medical clearance. Some co-

morbid conditions that can affect outcomes are:

o Diabetes

22

o asthma

o medication-controlled hypertension

o coronary artery disease or prior myocardial infarction

o stroke with residual neurological deficits

o cancer

o renal disease requiring dialysis

o peripheral vascular disease with claudication

o Parkinson’s disease

o Rheumatoid arthritis

22

o systemic disorders

o obesity

28

History of Present Illness: Attention to pre-operative ROM, hip muscle strength, and

functional mobility are among the most important data for the physical therapist during

the medical history review. It is also imperative to review relevant diagnostic imaging

and other tests that lead to the current diagnosis and decision to pursue surgical

management. Inquire about presenting signs and symptoms, including: duration/severity,

impact on function, and any prior management of symptoms via PT, medication, or other

conservative means.

Hospital Course: Read the operative report and note positioning, approach used, if the

surgeon needed to perform a trochanteric osteotomy, or additional fixation was required.

Record the surgeon, date of surgery, type of anesthesia used and note any complications

or additional procedures intra-operatively in the initial evaluation.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

11

When reviewing the chart and orders, note any consults that were placed, post-operative

complications, and the trend of lab values, along with post-operative precautions based

on approach. Post-operative laboratory workup, especially hematocrit and INR level,

need to be monitored when evaluating a patient following THA in the acute care setting.

INR levels should not exceed 3.0 or higher and appropriateness of treatment must be

discussed with the medical team. Please refer to the General Surgery Standard of care for

further details on hematocrit and INR parameters.

Social History: Include general demographics of age, sex, and primary language. This

also consists of a review of the patient’s home environment, family/caregiver support,

occupation, patient’s goals, use of assistive devices, possession of durable medical

equipment (DME) and prior level of function considering self-care and home

management activities. For patients following THA this may also include previous

exercise routines or programs, activity levels, history of falls and participation in PT.

Medications: Review current pharmacological management of existing medical

conditions. Common pain medications used in the acute management of patients

following THA are:

o Dilaudid

o Hydromorphone

o Oxycodone

o Oxycontin

Take note of the route of administration for medications (i.e. via IV, PO, etc), as this will

help guide the examination. Record the type of pain medication the patient is receiving

and when it was last administered in the initial evaluation. Patients are also often on the

anticoagulant medication, such as Warfarin, to prevent DVT.

Examination:

Observation: Upon observation note the patient position, appearance, and

lines/drains/tubes. Foley catheters are typically discharged by 6am on POD#1 prior to the

patient being seen by PT. The following is a list of common lines/drains/tubes and

positioning devices that may be seen with patients following THA:

• Nasal Cannula for oxygen therapy

• Pneumatic (compression) boots for DVT prophylaxis

• Telemetry/cardiac depending on if there is specific co-morbid conditions

• Continuous oxygen saturation monitors

• Towel roll next to the distal thigh to prevent lower extremity external rotation

• Hemovac or Jackson Pratt (JP) drain to extract excess fluid from the operated hip

joint

• Hip abduction pillow placed between the patient’s lower extremities

o This may be removed POD #1. See posture under Musculoskeletal

examination for more details.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

12

Communication, Affect, Mental Status/Cognition, Language, and Learning Style:

The patient’s level of arousal/alertness, orientation, ability to follow commands,

communicate/make needs known, primary language and learning preferences is taken

into account and documented in the examination.

Pain:

Intensity of pain is documented at every inpatient encounter using the visual analogue

scale (VAS) or verbal report scale (VRS) if possible. Plan of action such as pre-

medication or cryotherapy is also included in the systems review. Other qualitative

details of pain that are important to obtain include the frequency, alleviating/aggravating

factors, and descriptors of pain. Pain assessment should be made pre, during and post

PT.

Musculoskeletal:

• Anthropometrics: Body Mass Index (BMI) and/or height and weight of the patient

should be included in the systems review to assist with guiding your examination and

proper fit of necessary assistive devices.

• Range of Motion: Observation or goniometric measurement of ROM of all lower

extremity (LE) joints and gross assessment of ROM of the upper extremity (UE)

joints are to be documented in the systems review. Active and passive ROM of the

operative hip is measured in supine, seated and standing. Hip flexion, extension and

abduction are measured in the supine position, flexion in the seated position, and

extension in the standing position. Limitations in ROM are also documented to

further describe the end-feel of the joint (i.e. firm, bony, empty/painful).

• Strength: Manual muscle test (MMT) or gross measurement of the LE and UE

muscles is assessed and documented. Special attention is given to assess quadriceps,

hip abductor and hip flexor strength, and the quality of an isometric quad contraction

of the quadriceps, and gluteals (i.e. trace, poor, fair, and good) via palpation and

observation. Even though joint surgery is successful at eliminating many joint related

factors, reduced muscle mass, muscle length, and weakness are not addressed by

surgical interventions. Therefore, attention to these impairments is important in

developing an appropriate treatment plan and achieving good outcomes.

• Posture: Assessment and documentation of posture and positioning in supine, sitting,

or standing are included in a systems review. Special attention should be paid to the

degree of hip rotation of the lower extremities to maintain hip precautions according

the patients specific surgical approach. If the patient has posterior precautions they

may have a hip abduction pillow between their legs that can be removed on POD #1

and a folded pillow can be placed between the patient’s lower extremities while in

supine to assist in preventing the patient from adducting their operative leg.

• Leg length: Patients will often have a shortened extremity pre-operatively secondary

to degenerative changes. Equal leg length is difficult to achieve after THA and the

surgeon will perform systematic and reproducible perioperative steps to minimize

major leg length discrepancy. Post-operatively, if the operative extremity was

lengthened, the patient may experience hip flexor tightness and pain. If a leg length

discrepancy is found after THA it can result in limping, neurological damage, patient

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

13

dissatisfaction, lumbar pain and the need for contralateral shoe lifts. A study of

twenty patients found that a leg length inequality from 1-20 mm at follow up of 16

months post-operatively does not impair the symmetry of hip kinematics and kinetics

during gait and stair climbing

29

. The patient may perceive a leg length discrepancy in

the early post-operative phase secondary to soft tissue tightness. This may take time

to resolve.

• Gait: Qualitative gait assessment is detailed with comments on the type, pattern, and

biomechanics of gait, as well as the type of assistive device used and amount of

assistance provided. Changes in stride and step length, as well as cadence should be

documented in patients with hip OA both before and after THA.

Neuromuscular:

• Sensation: Sensation testing along peripheral nerve distributions in bilateral LE for

light touch is assessed on POD#1-2 to ensure that there is no nerve damage.

Peripheral nerve palsy after primary THA ranges from 0.09% to 3.7% and in revision

THA from 0% to 7.6%. In addition to sensation changes patients may present with

other symptoms if nerve damage did occur during surgery. The following is a list of

possible nerves that may be damaged and associated symptoms

26

:

o Sciatic Nerve: the incidence of sciatic nerve palsy related to THA ranges from

0.05% to 1.9%. Patients may present with foot drop if the sciatic nerve is

injured during surgery and further neurological evaluation may be warranted

to asses both divisions of the sciatic nerve

26

. The sciatic nerve is most often

injured with use of a posterior approach for THA

30

.

▪ Peroneal Nerve: the incidence of peroneal nerve injury is 0.3% to

2.1%

26

.

o Femoral Nerve: the incidence of femoral neuropathy related to THA is 0.01%

to 2.3%. Patients will present with thigh pain, quadriceps weakness, and

anteromedial and medial paresthesias of the leg

26

. The femoral nerve can be

damaged when the direct anterior approach or anterolateral approach is used

for THA

23, 30

.

o Obturator Nerve: the incidence of obturator nerve injury is 0.01%. Injury to

the obturator nerve can present as hip adductor weakness, and groin or thigh

pain

26

. Injury to the obturator nerve with use of the lateral approach for

THA

30

.

o Superior Gluteal Nerve: There is no reported cases of injury to the superior

gluteal nerve following THA, however it is important to note that

postoperative pain and weakness of the abductors of the hip may mask injury

to this nerve

26

. Use of the lateral approach for THA puts the superior gluteal

nerve at risk for injury

30

.

• Proprioception: Hip joint proprioceptive testing may be indicated depending on where

the patient is in their post-operative course, as this may impact balance, gait, strength

and functional mobility.

• Balance: Following THA qualitative observations should be documented:

o Static and dynamic sitting balance. This may include with and without UE

support.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

14

o Static and dynamic standing balance. This may include use of an assistive

device, wide and narrow base of support, and level and uneven surfaces as

appropriate.

Particularly in the acute post-operative phase, sitting and standing balance may be

impaired, thereby impacting the overall plan of care. In the sub-acute period, patients

after THA should be examined in their ability to perform static and dynamic standing

without assistive devices, as well as unilateral standing as appropriate.

Cardiovascular/Pulmonary:

• Vital Signs: Blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and peripheral oxygen

saturation should be assessed and documented as appropriate during PT

evaluation/treatments based on the patient’s symptomatology, particularly in the early

post-operative days. As previously referenced, anemia and concomitant orthostatic

hypotension are common complications immediately after THA. They can cause

clinical symptoms such as shortness of breath, lightheadedness or dizziness, blurred

vision, and nausea. The clinical signs include drop in blood pressure with positional

changes, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and vomiting. Attention to these signs and

symptoms including appropriate documentation is important during the patient

examination following THA, in addition to communication with the clinical team

21, 24

.

• Pulmonary Status: Assess and document auscultation of breath sounds, breathing

pattern, cough quality and cough production

24

• Endurance: Examination of activity tolerance by utilizing the rate of perceived

exertion (RPE) scale or a gross subjective and objective assessment of fatigue level

should be documented in patients following THA. This should detail the amount of

functional activities the patient was able to tolerate during the exam

24

.

Integumentary:

• Dressing/Incision: The surgical incision is closed with either staples or dermabond

and covered with a clean sterile dressing of gauze held in place with tegaderm while

the patient is in the operating room. This dressings remains in place for 3-5 days to

decrease risk of infection. After 3-5 days the dressing is removed, if the incision is

draining then the gauze is replaced until it becomes clean and dry. Once the incision

is clean and dry then it will be left open to air. If the sterile dressing that placed in

operating room becomes saturated, then the dressing will be changed by the medical

team while the patient is admitted to BWH.

• Skin: Skin assessment is noted, including observation of presence/absence of

dressing, surgical incision location, discoloration/erythema, drainage, or ecchymosis.

Any pressure points due to immobility or bracing should also be assessed.

• Edema: Soft tissue edema commonly occurs immediately after THA, as well as in the

sub-acute phase. Therefore, the amount of LE edema is documented by gross

qualitative assessment, or via circumferential measurements as appropriate.

Functional Tests and Outcome Measures:

The following functional tests and measures may be used in the acute care setting and

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

15

during the home or outpatient phase of rehabilitation to assess locomotor and functional

capacity of patients status post THA:

• Timed Get Up and Go (TUG)

31

o To assess balance, fall risk, and walking ability

• Six Minute Walk Test (6MWT)

31, 32

o To assess aerobic capacity/endurance

• Hip and Knee Satisfaction Scale

33

o To assess patient satisfaction following hip/knee replacement

• Harris Hip Score (HHS)

6, 18, 32

o To assess patient satisfaction following hip/knee replacement

• Oxford Hip Score

31

o To assess patient satisfaction following hip/knee replacement

• The Hip Dysfunction and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS)

18, 34

o To assess patient satisfaction following hip/knee replacement

• Western Ontario and the McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)

6,

17, 31, 32, 34, 35

o To assess pain, physical function and stiffness in patients with hip/knee

OA

• Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS)

36

o To assess impairment and set functional goals

• Short-Form-36 (SF-36)

17, 31

o To assess quality of life

Assessment:

PT Diagnosis:

Based on the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice

19

, patients following THA are classified

into the following practice pattern:

• 4H: Impaired Joint Mobility, Motor Function, Muscle Performance, and Range of

Motion Associated with Joint Athroplasty

19

.

Problem List:

In the first days following THA patients impairments will result in decreased independence

with bed mobility, transfers, ambulation, functional activities, basic/instrumental activities of

daily living and quality of life. Please refer to Rehabilitation Management under Indications

for Treatment for further details.

Figure 7: ICF Model

http://www.canchild.ca/en/canchildresources/internationalclassificationoffunctioning.asp

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

16

Table 4: ICF: Total Hip Arthroplasty

19

Body Structure/Function(s):

Potential impairments in body

structure may include but are

not limited to:

Activity Limitations:

Potential functional

limitations may include but

are not limited to:

Participation Restrictions:

Potential participation

restrictions may include but

are not limited to:

• Range of motion

(ROM)

• Muscle performance

(including strength,

power, and endurance)

• Motor control

• Balance

• Gait

• Tissue integrity

• Pain

• Sensation

• Knowledge deficit

• Aerobic

capacity/endurance

• Ventilation/gas

exchange

• Bed mobility

• Transfers

• Ambulation

• Stair climbing

• Functional activities

• Basic/instrumental

activities of daily

living (B/IADLs)

• Quality of life

• Community Mobility

• Driving

• Working

Prognosis:

Most patients are expected to ambulate without assistive devices within three to six weeks

after their surgery. Patients should exhibit operative hip strength >/=4+/5 MMT within 3

months following THA. The overall long-term goal for the patient is to at least return to their

pre-operative level of function with less pain; however most tend to see an overall

improvement when compared to their pre-operative function.

The degree to which patients reach these projected goals depends in part on the reason for the

THA, prior functional level, co-morbidities and post-op complications. Patients with lower

pre-operative

function may require more intensive PT intervention. This may extend recovery

times

because the patient is less likely to achieve functional outcomes

similar to those of

patients who have less pre-operative dysfunction

37

. A review of publications on the recovery

of physical functioning after THA showed improvements in: perceived physical functioning,

functional capacity such as walking and rising from a chair, and actual daily activity as

measured by WOMAC-PF, SF-36-PF and walking speed with gait analysis, 6-8 months post-

surgery

31

. A study of 437 patients found that the largest improvements for physical

impairment, activity limitations, and social participation restrictions occurs within 3 months

post-surgery. There is a rapid improvement in physical impairment seen within the first two

weeks post-surgery. Participation restrictions worsen early after THA and then quickly

improve over the next 3 months post THA. Patients that are male, non-obese, that do not

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

17

have low back pain, and that are of younger age were found to have statistically significant

better outcomes over time post THA. This study also found that although the greatest

improvements occurs by 3 months post-operatively, a 28% of total improvements in ICF

constructs occurs between 3 and 12 months post THA

34

.

Goals: Typical goals following THA are as follows and should be tailored/individualized

based on the unique characteristics of each individual patient:

Short Term Goals: The short term goals for this patient population during their hospital

course are:

Within 2-3 days:

1. The patient will be independent and able to demonstrate knowledge of safety and

compliance with hip precautions and positioning with all mobility.

2. The patient will perform all bed mobility and transfers with least amount of assistance

and devices.

3. The patient will ambulate household distances (50-100 feet) and negotiate stairs with

a step-to or step-through pattern, with least amount of assistance and devices.

4. The patient will demonstrate a fair to good isometric quad contraction and MMT of

>/= 3-/5 to increase independence with bed mobility, transfers, and ambulation.

5. The patient will be independent with home exercise program and activity precautions.

*These short term goals will vary depending on the patient’s prior level of function, as

well as the patient’s own personal goals.

Long Term Goals: The long term goals for this patient population are:

Within 2-4 weeks:

1. Independent gait with unilateral upper extremity support of a crutch/cane for

greater than or equal to three hundred feet.

2. Initiation of standing and balance therapeutic exercise program.

3. Initiation of use of stationary bicycle within precautions if one is available.

Within 4-6 weeks:

1. Ambulate greater than or equal to five hundred feet with least restrictive device.

2. Progression to use of no assistive device by home/outpatient PT.

3. Initiation of outpatient PT program.

Within 8-10 weeks:

1. Return to work as applicable.

2. Ambulate community distances with no assistive device.

Treatment Planning / Interventions

Established Pathway ___ Yes, see attached. _X_ No

Established Protocol _X__ Yes, see attached. __ No

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

18

Interventions most commonly used for this case type/diagnosis:

A study of 57 patients following primary THA randomly assigned twice daily PT and

showed earlier achievement of functional milestones than those of the control group who

received PT only once-daily

38

. At BWH patients receive PT twice on POD#1 and are

educated on independent therapeutic exercise program and encouraged to complete the

program 3-5 times a day. Their independent therapeutic exercise program typically

consists of exercise that target muscles of the hip, knee and ankle and are focused on

increasing strength and ROM. Treatments that may be initiated in a patient following

THA as deemed appropriate by the evaluating PT are as follows:

• Flexion, extension, abduction (if indicated), and adduction Active/Active

Assisted/Passive ROM of operative hip

32, 39

.

• Therapeutic exercise/strength training with focus on isometric and functional hip

flexor and quadriceps control, hamstrings, as well as hip abductors, adductors,

and gluteal muscles

32, 39

.

• Respiratory and circulatory exercises starting POD#1, to include deep breathing,

coughing, and ankle pumps. A systematic review that looked at a study of 14

patients found that a progressive arm-interval exercise program with an arm

ergometer improved patient’s distances with the 6-minute-walk test following

THA

32

.

• Seated closed chain exercises progressing to standing closed chain exercises when

the patient demonstrates good pain control, muscle strength, and balance

32, 40

.

• Resistive Exercises for the quadriceps and hamstrings are generally not used in

the acute phase of rehabilitation. However a study of 36 patients found that a

progressive resistive training program for the first 12 weeks post operatively

improved maximal dynamic muscle strength by 30% and improved stair climbing

power by 35% when compared to use of electrical stimulation and standard

rehabilitation

32, 41

.

• Gait training on even surfaces, stair training and uneven terrain as indicated

• Balance and coordination activities

• Body mechanics and postural exercises

Functional Training in Self-Care and Home Management:

Starting on POD#1 bed mobility and transfer and basic/instrumental activities of daily

living training is started in order to promote the patient’s independence. Patients are

educated on the use of proper assistive devices and equipment as indicated. This can

include use of a bedrail, or transfer devices. The goal is to gradually progress patient’s

mobility without assistive equipment by POD#2-3 to allow them to function safety and

independently in their home environment. Vehicle transfers are also introduced and

reviewed with the patient prior to discharge home.

Prescription and Application of Appropriate Assistive Devices/Durable Medical

Equipment:

Patients are measured, fit, and trained with the most appropriate assistive device to

increase safety and independence during ambulation and transfers. The most common

ambulatory devices used in patients immediately following THA are walkers (standard or

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

19

rolling), axillary crutches, and in some cases, only a straight cane or a single crutch. As

patients mobility improves and as safety allows they will be progressed to the least

restrictive assistive devices. Other durable medical equipment (DME) generally used or

recommended to facilitate safe and independent transfers include commodes, raised toilet

seats, ADL equipment, and tub/shower seats.

Frequency & Duration:

Patients are generally in the hospital for 2-3 days post-operatively. Patients are followed

at a frequency of five to seven times per week and are reassessed every 7-10 days if they

remain in BWH. Most patients do not stay in the acute care hospital greater than 3 days

unless there are post-operative complications. The expected number of visits per episode

of care ranges from 12 to 60. The various episodes of care following THA consist of

inpatient acute care PT, short-term rehabilitation or home PT, and outpatient PT (when

indicated). Based on the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, it is anticipated that 80%

of patients will achieve their anticipated goals and expected outcomes during this time

frame of visits

19

.

During the acute care stay, THA patients are typically seen once daily,

except on POD#1 when they are seen for their initial evaluation and an afternoon

treatment session. The focus of treatment during this time is on improving hip joint

ROM, muscle control and balance, and functional independence. If outpatient care is

required, ROM, strength, proprioception, gait, balance, and swelling impairments should

be assessed and treatment should be progressed as appropriate in order to maximize

functional outcomes.

Patient / family education:

Education for patients undergoing a THA is an integral component of the clinical

pathway for these patients. Pre-operative joint class is available for patients to prepare

them for their surgery and recovery. Most orthopedic surgeons at BWH refer and highly

recommend that their patients attend joint class to obtain knowledge in preoperative

preparation, hospital stay, surgical procedure, expectations following surgery and

rehabilitation. Interdisciplinary handouts and educational videos are offered as part of

BHW’s pre-operative education and are available on the orthopedic website. Pre-

operative education can reduce a patient’s hospital stay by twenty four hours by

promoting early functional recovery and improving functional outcomes

15

. Pre-operative

exercise programs are also beneficial for patient outcomes after surgery. A systematic

review of randomized control studies found that exercise-based intervention prior to a

total hip replacement reduces pain and improves physical function

35

.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

20

Education for patients and their families/caregivers is continued throughout their stay at

the hospital. On POD #1 they are educated on:

• Correct positioning of the operative LE

• Hip dislocation precautions

• Importance of initiating early mobility

• Safety with mobility and use of appropriate assistive devices

• Weight bearing precautions (if indicated)

• PT plan of care: including independent exercises, and the expected discharge

goals and outcomes.

Patients are provided with education handouts that outlines the above information for

future reference and for use at home after discharge. The white boards located in each

patient room can also be utilized to write down goals and recommendations for nursing

staff.

Recommendations and referrals to other providers:

• Occupational Therapy (OT): Patients who are in need of assistance for B/IADL

are referred to occupational therapy for training with appropriate adaptive

equipment. OT is generally consulted immediately post-operatively in

conjunction with PT. Occupational therapy will assess a patient if the patient’s

plan is to discharge home, or if a patient may potentially have specific OT needs

secondary to pre-existing co-morbidities. Occupational therapy is consulted to

assess a patient’s ability to comply with dislocation precautions during activities

such as toileting, dressing, and ADL’s. OT generally evaluates a patient on

POD#2 to maximize participation and independence with B/IADL’s. OT can

provide a patient with special equipment to optimize a patient’s independence

with ADL’s. Equipment could include: sock donner, long handled sponge, shoe

horn, grabber, elastic shoe laces, leg lifter etc. If the patient’s plan is to discharge

to a rehab facility generally OT is deferred while in the inpatient setting to the

rehab setting to optimize ability to participate.

• Ortho Tech: Ortho techs are consulted on a case by case basis to place a bed

frame and trapeze on the beds of patients following a THR to allow the patient to

perform bed mobility and weight shifting as appropriate. Ortho techs will also be

consulted if a hip abduction brace is indicated. A hip abduction brace is used if a

patient has had pervious hip surgery with multiple dislocations, or during the

surgery the surgeon assessed that the patient was going to require external support

to prevent dislocation. Fitting a hip abduction brace can be performed the day

that the order is placed and the physical therapist should accompany the ortho

tech for the initial fitting. It is the physical therapists role to clarify ROM orders

for the brace and a wearing schedule, as well as progress the patient’s bed and

transfer mobility. Please see the hip abduction procedure guide on the T drive for

additional information.

• Social Work: Social workers may be consulted in complicated situations where

patients may have difficulty coping with recovery and have limited social

supports.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

21

• Care Coordination: An appointment is made for most patients prior to their THA

with a Care Coordinator at the Preoperative Clinic. A Care Coordinator is a

registered nurse that specializes in discharge planning. Since the length of stay

following a THA is short it is important to initiate discharge planning prior to

surgery. A Care Coordinator will screen patients based on their living situation,

social supports, prior level of function, and home environment to help create safe

discharge plans based on each patient’s individual needs. They will meet with

patients following THA on POD#1 and facilitate all discharges both to home and

rehabilitation facilities, provide clinical updates to insurance companies, and

arrange transportation to another facilities as needed.

Re-evaluation

The average inpatient length of stay following THA is 3 days. Patients are re-evaluated on a

daily basis with respect to their ROM, quality of movement, muscle contraction, pain intensity,

gait quality, and functional independence. If the patient’s hospital course is prolonged due to

complications, a formal re-evaluation will be performed every 7-10 days to re-assess progression

towards the previously outlined goals and outcomes. In the outpatient setting, the patient is to be

formally re-evaluated every 30 days; however impairments such as ROM should be monitored

each visit. A re-evaluation is also indicated if there has been a significant change in signs and

symptoms.

Discharge Planning

Commonly expected outcomes at discharge:

It is expected that most patients following THA will be discharged home after the

inpatient acute care phase. Several factors including age, co-morbidities, living situation

and support at home all may contribute to a patients discharge to short term rehabilitation

versus home. Commonly expected outcomes for discharge home are the ability to

comply with hip dislocation precautions with all mobility, the ability to perform bed

mobility and functional transfers independently, safely ambulate household distances of

50-100ft on even and uneven surfaces with an assistive device, and improve hip ROM

and strength as identified in the goals.

Transfer of Care:

Discharge planning is often started at the patient’s pre-operative visit with Care

Coordination. During the initial PT evaluation discharge recommendations are

established from a PT perspective. Communication with care coordination and patient’s

multidisciplinary team will help to ensure successful transition of care and should be

docummented in the patient’s medical record. Discharge recommendations should be

documented in the initial physical therapy evaluation and any other encounter notes as

appropriate. The selection of a discharge destination takes planning and careful

consideration of multiple factors such as patient’s social supports, living environment,

and their functional mobility progress with skilled PT while at BWH. Proper

documentation and communication of discharge recommendations will facilitate in the

patients transfer of care to either home with services or to an extended care facility.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

22

Patient’s discharge instructions:

• Review with the patient and family/caregivers dislocation precautions, safety,

assist needed at home, use of proper assistive devices and equipment, proper gait

and stair climbing techniques, positioning and home therapeutic exercise.

• Provide patients and their family/caregivers with education handouts that outline

importance information that has been reviewed throughout PT sessions while at

BWH.

Authors: Reviewed by:

Jessica Lesage, PT Brendan Connor, PT

December, 2015 Carolyn Beagan, PT

PUT ON ELLUCID AWAITING LINDA”S FINAL APPROVAL

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

23

REFERENCES:

1. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Orthopedic Hip Replacement. Available

at:http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Hip_Replacement/default.asp Retrieved

October 24, 20014.

2. Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Hip Replacement. Available at:

http://www.brighamandwomens.org/Departments_and_Services/orthopedics/resources/hi

p-replacement.aspx Retrieved October 24,2014

3. Kurtz, S., Ong, K., Lau, E., Mowat, F., & Halpern, M. (2007). Projections of primary and

revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states from 2005 to 2030. The Journal of

Bone and Joint Surgery.American Volume, 89(4), 780-785.

4. Joint Replacement Institute. Types of Hip Replacement and Methods of Fixation.

Available at: http://www.jri-docs.com/hip-resurfacing-replacement/hip-

replacement/resources/types-of-hip-replacement-and-methods-of-fixation Retrieved

February 23, 2015.

5. Bhattacharyya, T., & Koval, K. J. (2009). Unipolar versus bipolar hemiarthroplasty for

femoral neck fractures: Is there a difference? Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma, 23(6),

426-427.

6. Smith, T. O., Nichols, R., Donell, S. T., & Hing, C. B. (2010). The clinical and

radiological outcomes of hip resurfacing versus total hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis

and systematic review. Acta Orthopaedica, 81(6), 684-695.

7. Prosser, G. H., Yates, P. J., Wood, D. J., Graves, S. E., de Steiger, R. N., & Miller, L. N.

(2010). Outcome of primary resurfacing hip replacement: Evaluation of risk factors for

early revision. Acta Orthopaedica, 81(1), 66-71.

8. Ulrich, S. D., Seyler, T. M., Bennett, D., Delanois, R. E., Saleh, K. J., Thongtrangan, I.,

et al. (2008). Total hip arthroplasties: What are the reasons for revision? International

Orthopaedics, 32(5), 597-604.

9. Bozic, K. J., Kurtz, S. M., Lau, E., Ong, K., Vail, T. P., & Berry, D. J. (2009). The

epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the united states. The Journal of Bone

and Joint Surgery.American Volume, 91(1), 128-133.

10. Bongartz, T., Halligan, C. S., Osmon, D. R., Reinalda, M. S., Bamlet, W. R., Crowson, C.

S., et al. (2008). Incidence and risk factors of prosthetic joint infection after total hip or

knee replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 59(12),

1713-1720.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

24

11. Suh, K. T., Park, B. G., & Choi, Y. J. (2004). A posterior approach to primary total hip

arthroplasty with soft tissue repair. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research,

(418)(418), 162-167.

12. Masonis, J. L., & Bourne, R. B. (2002). Surgical approach, abductor function, and total

hip arthroplasty dislocation. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, (405)(405),

46-53.

13. Lovell, T. P. (2008). Single-incision direct anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty

using a standard operating table. The Journal of Arthroplasty, 23(7 Suppl), 64-68.

14. Beksac, B., Gonzalez Della Valle, A., & Salvati, E. A. (2006). Thromboembolic disease

after total hip arthroplasty: Who is at risk? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research,

453, 211-224.

15. Ibrahim, M. S., Khan, M. A., Nizam, I., & Haddad, F. S. (2013). Peri-operative

interventions producing better functional outcomes and enhanced recovery following

total hip and knee arthroplasty: An evidence-based review. BMC Medicine, 11, 37-7015-

11-37.

16. Kerr, D. R., & Kohan, L. (2008). Local infiltration analgesia: A technique for the control

of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: A case study of 325 patients.

Acta Orthopaedica, 79(2), 174-183.

17. Pisoni, C., Giardini, A., Majani, G., & Maini, M. (2008). International classification of

functioning, disability and health (ICF) core sets for osteoarthritis. A useful tool in the

follow-up of patients after joint arthroplasty. European Journal of Physical and

Rehabilitation Medicine, 44(4), 377-385.

18. Heiberg, K. E., Ekeland, A., & Mengshoel, A. M. (2013). Functional improvements

desired by patients before and in the first year after total hip arthroplasty. BMC

Musculoskeletal Disorders, 14, 243-2474-14-243.

19. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice; 2nd Edition, APTA. Phys Ther 2001; 81: 9-744.

20. Lakstein, D., Backstein, D. J., Safir, O., Kosashvili, Y., & Gross, A. E. (2010). Modified

trochanteric slide for complex hip arthroplasty: Clinical outcomes and complication rates.

The Journal of Arthroplasty, 25(3), 363-368.

21. Dutton, M. (2008). Orthopaedic examination, evaluation, and intervention (2nd ed.). New

York: McGraw-Hill Medical.

22. Soohoo, N. F., Farng, E., Lieberman, J. R., Chambers, L., & Zingmond, D. S. (2010).

Factors that predict short-term complication rates after total hip arthroplasty. Clinical

Orthopaedics and Related Research, 468(9), 2363-2371.

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

25

23. Barton, C., & Kim, P. R. (2009). Complications of the direct anterior approach for total

hip arthroplasty. The Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 40(3), 371-375.

24. Sullivan, S. (2007). Physical rehabilitation (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis.

25. Kotwal, R. S., Ganapathi, M., John, A., Maheson, M., & Jones, S. A. (2009). Outcome of

treatment for dislocation after primary total hip replacement. The Journal of Bone and

Joint Surgery.British Volume, 91(3), 321-326.

26. Brown, G. D., Swanson, E. A., & Nercessian, O. A. (2008). Neurologic injuries after total

hip arthroplasty. American Journal of Orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.), 37(4), 191-197.

27. Kwon, M. S., Kuskowski, M., Mulhall, K. J., Macaulay, W., Brown, T. E., & Saleh, K. J.

(2006). Does surgical approach affect total hip arthroplasty dislocation rates? Clinical

Orthopaedics and Related Research, 447, 34-38.

28. Huddleston, J. I., Wang, Y., Uquillas, C., Herndon, J. H., & Maloney, W. J. (2012). Age

and obesity are risk factors for adverse events after total hip arthroplasty. Clinical

Orthopaedics and Related Research, 470(2), 490-496.

29. Benedetti, M. G., Catani, F., Benedetti, E., Berti, L., Di Gioia, A., & Giannini, S. (2010).

To what extent does leg length discrepancy impair motor activity in patients after total

hip arthroplasty? International Orthopaedics, 34(8), 1115-1121.

30. Uskova, A. A., Plakseychuk, A., & Chelly, J. E. (2010). The role of surgery in

postoperative nerve injuries following total hip replacement. Journal of Clinical

Anesthesia, 22(4), 285-293.

31. Vissers, M. M., Bussmann, J. B., Verhaar, J. A., Arends, L. R., Furlan, A. D., & Reijman,

M. (2011). Recovery of physical functioning after total hip arthroplasty: Systematic

review and meta-analysis of the literature. Physical Therapy, 91(5), 615-629.

32. Di Monaco, M., Vallero, F., Tappero, R., & Cavanna, A. (2009). Rehabilitation after total

hip arthroplasty: A systematic review of controlled trials on physical exercise programs.

European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 45(3), 303-317.

33. Mahomed, N., Gandhi, R., Daltroy, L., & Katz, J. N. (2011). The self-administered

patient satisfaction scale for primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Arthritis, 2011, 591253.

34. Davis, A. M., Perruccio, A. V., Ibrahim, S., Hogg-Johnson, S., Wong, R., Streiner, D. L.,

et al. (2011). The trajectory of recovery and the inter-relationships of symptoms, activity

and participation in the first year following total hip and knee replacement. Osteoarthritis

and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society, 19(12), 1413-1421.

35. Gill, S. D., & McBurney, H. (2013). Does exercise reduce pain and improve physical

function before hip or knee replacement surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis

Standard of Care: Total Hip Replacement

Copyright © 2015 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved

26

of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 94(1),

164-176.

36. Yeung, T. S., Wessel, J., Stratford, P., & Macdermid, J. (2009). Reliability, validity, and

responsiveness of the lower extremity functional scale for inpatients of an orthopaedic

rehabilitation ward. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 39(6), 468-

477.

37. Petersen, M. K., Andersen, N. T., & Soballe, K. (2008). Self-reported functional outcome

after primary total hip replacement treated with two different periopera-tive regimes: A

follow-up study involving 61 patients. Acta Orthopaedica, 79(2), 160-167.

38. Stockton, K. A., & Mengersen, K. A. (2009). Effect of multiple physiotherapy sessions

on functional outcomes in the initial postoperative period after primary total hip

replacement: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and

Rehabilitation, 90(10), 1652-1657.

39. Jesudason, C., & Stiller, K. (2002). Are bed exercises necessary following hip

arthroplasty? The Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, 48(2), 73-81.

40. Trudelle-Jackson, E., & Smith, S. S. (2004). Effects of a late-phase exercise program

after total hip arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine

and Rehabilitation, 85(7), 1056-1062.

41. Suetta, C., Andersen, J. L., Dalgas, U., Berget, J., Koskinen, S., Aagaard, P., et al. (2008).

Resistance training induces qualitative changes in muscle morphology, muscle

architecture, and muscle function in elderly postoperative patients. Journal of Applied

Physiology (Bethesda, Md.: 1985), 105(1), 180-186.