NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—1

st

Quarter 2017

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

640-1

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

Table of Contents

Section 1. Purpose

Section 2. Scope

Section 3. Short Title

Section 4. Definitions

Section 5. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction—Group Long-Term Care Insurance

Section 6. Disclosure and Performance Standards for Long-Term Care Insurance

Section 7. Incontestability Period

Section 8. Nonforfeiture Benefits

Section 9. Producer Training Requirements

Section 10. Authority to Promulgate Regulations

Section 11. Administrative Procedures

Section 12. Severability

Section 13. Penalties

Section 14. Effective Date

Section 1. Purpose

The purpose of this Act is to promote the public interest, to promote the availability of long-term care insurance policies, to

protect applicants for long-term care insurance, as defined, from unfair or deceptive sales or enrollment practices, to establish

standards for long-term care insurance, to facilitate public understanding and comparison of long-term care insurance

policies, and to facilitate flexibility and innovation in the development of long-term care insurance coverage.

Drafting Note: The purpose clause evidences legislative intent to protect the public while recognizing the need to permit flexibility and innovation with

respect to long-term care insurance coverage.

Drafting Note: The Task Force recognizes the viability of a long-term care product funded through a life insurance vehicle, and this Act is not intended to

prohibit approval of this product. Section 4 now specifically addresses this product. However, states must examine their existing statutes to determine

whether amendments to other code sections such as the definition of life insurance and accident and health reserve standards and further revisions are

necessary to authorize approval of the product.

Section 2. Scope

The requirements of this Act shall apply to policies delivered or issued for delivery in this state on or after the effective date

of this Act. This Act is not intended to supersede the obligations of entities subject to this Act to comply with the substance

of other applicable insurance laws insofar as they do not conflict with this Act, except that laws and regulations designed and

intended to apply to Medicare supplement insurance policies shall not be applied to long-term care insurance.

Drafting Note: See Section 6J.

Drafting Note: This section makes clear that entities subject to the Act must continue to comply with other applicable insurance legislation not in conflict

with this Act.

Section 3. Short Title

This Act may be known and cited as the “Long-Term Care Insurance Act.”

Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act

640-2

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

Section 4. Definitions

Unless the context requires otherwise, the definitions in this section apply throughout this Act.

A. “Long-term care insurance” means any insurance policy or rider advertised, marketed, offered or designed

to provide coverage for not less than twelve (12) consecutive months for each covered person on an

expense incurred, indemnity, prepaid or other basis; for one or more necessary or medically necessary

diagnostic, preventive, therapeutic, rehabilitative, maintenance or personal care services, provided in a

setting other than an acute care unit of a hospital. The term includes group and individual annuities and life

insurance policies or riders that provide directly or supplement long-term care insurance. The term also

includes a policy or rider that provides for payment of benefits based upon cognitive impairment or the loss

of functional capacity. The term shall also include qualified long-term care insurance contracts. Long-term

care insurance may be issued by insurers; fraternal benefit societies; nonprofit health, hospital, and medical

service corporations; prepaid health plans; health maintenance organizations or any similar organization to

the extent they are otherwise authorized to issue life or health insurance. Long-term care insurance shall not

include any insurance policy that is offered primarily to provide basic Medicare supplement coverage, basic

hospital expense coverage, basic medical-surgical expense coverage, hospital confinement indemnity

coverage, major medical expense coverage, disability income or related asset-protection coverage, accident

only coverage, specified disease or specified accident coverage, or limited benefit health coverage. With

regard to life insurance, this term does not include life insurance policies that accelerate the death benefit

specifically for one or more of the qualifying events of terminal illness, medical conditions requiring

extraordinary medical intervention or permanent institutional confinement, and that provide the option of a

lump-sum payment for those benefits and where neither the benefits nor the eligibility for the benefits is

conditioned upon the receipt of long-term care. Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, any

product advertised, marketed or offered as long-term care insurance shall be subject to the provisions of

this Act.

B. “Applicant” means:

(1) In the case of an individual long-term care insurance policy, the person who seeks to contract for

benefits; and

(2) In the case of a group long-term care insurance policy, the proposed certificate holder.

C. “Certificate” means, for the purposes of this Act, any certificate issued under a group long-term care

insurance policy, which policy has been delivered or issued for delivery in this state.

D. “Commissioner” means the Insurance Commissioner of this state.

Drafting Note: Where the word “commissioner” appears in this Act, the appropriate designation for the chief insurance supervisory official of the state

should be substituted.

E. “Group long-term care insurance” means a long-term care insurance policy that is delivered or issued for

delivery in this state and issued to:

(1) One or more employers or labor organizations, or to a trust or to the trustees of a fund established

by one or more employers or labor organizations, or a combination thereof, for employees or

former employees or a combination thereof or for members or former members or a combination

thereof, of the labor organizations; or

(2) Any professional, trade or occupational association for its members or former or retired members,

or combination thereof, if the association:

(a) Is composed of individuals all of whom are or were actively engaged in the same

profession, trade or occupation; and

(b) Has been maintained in good faith for purposes other than obtaining insurance; or

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—1

st

Quarter 2017

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

640-3

(3) An association or a trust or the trustees of a fund established, created or maintained for the benefit

of members of one or more associations. Prior to advertising, marketing or offering the policy

within this state, the association or associations, or the insurer of the association or associations,

shall file evidence with the commissioner that the association or associations have at the outset a

minimum of 100 persons and have been organized and maintained in good faith for purposes other

than that of obtaining insurance; have been in active existence for at least one year; and have a

constitution and bylaws that provide that:

(a) The association or associations hold regular meetings not less than annually to further

purposes of the members;

(b) Except for credit unions, the association or associations collect dues or solicit

contributions from members; and

(c) The members have voting privileges and representation on the governing board and

committees.

Thirty (30) days after the filing the association or associations will be deemed to satisfy the

organizational requirements, unless the commissioner makes a finding that the association or

associations do not satisfy those organizational requirements.

(4) A group other than as described in Subsections E(1), E(2) and E(3), subject to a finding by the

commissioner that:

(a) The issuance of the group policy is not contrary to the best interest of the public;

(b) The issuance of the group policy would result in economies of acquisition or

administration; and

(c) The benefits are reasonable in relation to the premiums charged.

F. “Policy” means, for the purposes of this Act, any policy, contract, subscriber agreement, rider or

endorsement delivered or issued for delivery in this state by an insurer; fraternal benefit society; nonprofit

health, hospital, or medical service corporation; prepaid health plan; health maintenance organization or

any similar organization.

Drafting Note: This Act is intended to apply to the specified group and individual policies, contracts, and certificates whether issued by insurers; fraternal

benefit societies; nonprofit health, hospital, and medical service corporations; prepaid health plans; health maintenance organizations or any similar

organization. In order to include such organizations, each state should identify them in accordance with its statutory terminology or by specific statutory

citation. Depending upon state law, insurance department jurisdiction and other factors, separate legislation may be required. In any event, the legislation

should provide that the particular terminology used by these plans and organizations may be substituted for, or added to, the corresponding terms used in this

Act. The term “regulations” should be replaced by the terms “rules and regulations” or “rules” as may be appropriate under state law.

The definition of “long-term care insurance” under this Act is designed to allow maximum flexibility in benefit scope, intensity and level, while assuring that

the purchaser’s reasonable expectations for a long-term care insurance policy are met. The Act is intended to permit long-term care insurance policies to

cover either diagnostic, preventive, therapeutic, rehabilitative, maintenance or personal care services, or any combination thereof, and not to mandate

coverage for each of these types of services. Pursuant to the definition, long-term care insurance may be either a group or individual insurance policy or a

rider to such a policy, e.g., life or accident and sickness. The language in the definition concerning “other than an acute care unit of a hospital” is intended to

allow payment of benefits when a portion of a hospital has been designated for, and duly licensed or certified as a long-term care provider or swing bed.

G. (1) “Qualified long-term care insurance contract” or “federally tax-qualified long-term care insurance

contract” means an individual or group insurance contract that meets the requirements of Section

7702B(b) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, as follows:

(a) The only insurance protection provided under the contract is coverage of qualified long-

term care services. A contract shall not fail to satisfy the requirements of this

subparagraph by reason of payments being made on a per diem or other periodic basis

without regard to the expenses incurred during the period to which the payments relate;

Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act

640-4

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

(b) The contract does not pay or reimburse expenses incurred for services or items to the

extent that the expenses are reimbursable under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, as

amended, or would be so reimbursable but for the application of a deductible or

coinsurance amount. The requirements of this subparagraph do not apply to expenses that

are reimbursable under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act only as a secondary payor.

A contract shall not fail to satisfy the requirements of this subparagraph by reason of

payments being made on a per diem or other periodic basis without regard to the

expenses incurred during the period to which the payments relate;

(c) The contract is guaranteed renewable, within the meaning of section 7702B(b)(1)(C) of

the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended;

(d) The contract does not provide for a cash surrender value or other money that can be paid,

assigned, pledged as collateral for a loan, or borrowed except as provided in [insert

reference to state law equivalent to Section 4G(1)(e) of the Long-Term Care Insurance

Model Act];

(e) All refunds of premiums, and all policyholder dividends or similar amounts, under the

contract are to be applied as a reduction in future premiums or to increase future benefits,

except that a refund on the event of death of the insured or a complete surrender or

cancellation of the contract cannot exceed the aggregate premiums paid under the

contract; and

(f) The contract meets the consumer protection provisions set forth in Section 7702B(g) of

the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended.

(2) “Qualified long-term care insurance contract” or “federally tax-qualified long term care insurance

contract” also means the portion of a life insurance contract that provides long-term care insurance

coverage by rider or as part of the contract and that satisfies the requirements of Sections

7702B(b) and (e) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended.

Drafting Note: The definition of “qualified long-term care insurance contract” has been added to assist states in regulating long-term care insurance policies

that are federally tax-qualified. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and Section 7702B of the Internal Revenue Code,

as amended, provide a definition of this term and clarify federal income tax treatment of premiums and benefits. Treasury Regulations 1.7702B-1 and

1.7702B-2, and Notice 97-31 issued by the Internal Revenue Service, further address these issues.

Section 5. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction—Group Long-Term Care Insurance

No group long-term care insurance coverage may be offered to a resident of this state under a group policy issued in another

state to a group described in Section 4E(4), unless this state or another state having statutory and regulatory long-term care

insurance requirements substantially similar to those adopted in this state has made a determination that such requirements

have been met.

Drafting Note: By limiting extraterritorial jurisdiction to “discretionary groups,” it is not the drafters’ intention that jurisdiction over other health policies

should be limited in this manner.

Section 6. Disclosure and Performance Standards for Long-Term Care Insurance

A. The commissioner may adopt regulations that include standards for full and fair disclosure setting forth the

manner, content and required disclosures for the sale of long-term care insurance policies, terms of

renewability, initial and subsequent conditions of eligibility, non-duplication of coverage provisions,

coverage of dependents, preexisting conditions, termination of insurance, continuation or conversion,

probationary periods, limitations, exceptions, reductions, elimination periods, requirements for

replacement, recurrent conditions and definitions of terms.

Drafting Note: This subsection permits the adoption of regulations establishing disclosure standards, renewability and eligibility terms and conditions, and

other performance requirements for long-term care insurance. Regulations under this subsection should recognize the developing and unique nature of long-

term care insurance and the distinction between group and individual long-term care insurance policies.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—1

st

Quarter 2017

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

640-5

B. No long-term care insurance policy may:

(1) Be cancelled, non-renewed or otherwise terminated on the grounds of the age, gender or the

deterioration of the mental or physical health of the insured individual or certificate holder;

(2) Contain a provision establishing a new waiting period in the event existing coverage is converted

to or replaced by a new or other form within the same company, except with respect to an increase

in benefits voluntarily selected by the insured individual or group policyholder; or

(3) Provide coverage for skilled nursing care only or provide significantly more coverage for skilled

care in a facility than coverage for lower levels of care.

C. Preexisting condition.

(1) No long-term care insurance policy or certificate other than a policy or certificate thereunder

issued to a group as defined in Section 4E(1) shall use a definition of “preexisting condition” that

is more restrictive than the following: Preexisting condition means a condition for which medical

advice or treatment was recommended by, or received from a provider of health care services,

within six (6) months preceding the effective date of coverage of an insured person.

(2) No long-term care insurance policy or certificate other than a policy or certificate thereunder

issued to a group as defined in Section 4E(1) may exclude coverage for a loss or confinement that

is the result of a preexisting condition unless the loss or confinement begins within six (6) months

following the effective date of coverage of an insured person.

(3) The commissioner may extend the limitation periods set forth in Sections 6C(1) and (2) above as

to specific age group categories in specific policy forms upon findings that the extension is in the

best interest of the public.

(4) The definition of “preexisting condition” does not prohibit an insurer from using an application

form designed to elicit the complete health history of an applicant, and, on the basis of the answers

on that application, from underwriting in accordance with that insurer’s established underwriting

standards. Unless otherwise provided in the policy or certificate, a preexisting condition,

regardless of whether it is disclosed on the application, need not be covered until the waiting

period described in Section 6C(2) expires. No long-term care insurance policy or certificate may

exclude or use waivers or riders of any kind to exclude, limit or reduce coverage or benefits for

specifically named or described preexisting diseases or physical conditions beyond the waiting

period described in Section 6C(2).

D. Prior hospitalization/institutionalization.

(1) No long-term care insurance policy may be delivered or issued for delivery in this state if the

policy:

(a) Conditions eligibility for any benefits on a prior hospitalization requirement;

(b) Conditions eligibility for benefits provided in an institutional care setting on the receipt

of a higher level of institutional care; or

(c) Conditions eligibility for any benefits other than waiver of premium, post-confinement,

post-acute care or recuperative benefits on a prior institutionalization requirement.

(2) A long-term care insurance policy or rider shall not condition eligibility for non-institutional

benefits on the prior or continuing receipt of skilled care services.

Drafting Note: The amendment to the section is primarily intended to require immediate and clear disclosure where a long-term care insurance policy or

rider conditions eligibility for non-institutional benefits on prior receipt of institutional care.

Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act

640-6

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

(3) No long-term care insurance policy or rider that provides benefits only following

institutionalization shall condition such benefits upon admission to a facility for the same or

related conditions within a period of less than thirty (30) days after discharge from the institution.

Drafting Note: Section 6D(3) is language from the original model act which did not prohibit prior institutionalization. The drafters intended that Section

6D(3) would be eliminated after adoption of the amendments to this section which prohibit prior institutionalization. States should examine their Section 6

carefully during the process of adoption or amendment of this Act.

E. The commissioner may adopt regulations establishing loss ratio standards for long-term care insurance

policies provided that a specific reference to long-term care insurance policies is contained in the

regulation.

F. (1) Long-term care insurance applicants shall have the right to return the policy, certificate or rider to

the company or an agent/insurance producer of the company within thirty (30) days of its receipt

and to have the premium refunded if, after examination of the policy, certificate or rider, the

applicant is not satisfied for any reason.

(2) Long-term care insurance policies, certificates and riders shall have a notice prominently printed

on the first page or attached thereto including specific instructions to accomplish a return. This

requirement shall not apply to certificates issued pursuant to a policy issued to a group defined in

Section 4E(1) of this Act. The following free look statement or language substantially similar shall

be included:

“You have 30 days from the day you receive this policy, certificate or rider to review it and return

it to the company if you decide not to keep it. You do not have to tell the company why you are

returning it. If you decide not to keep it, simply return it to the company at its administrative

office. Or you may return it to the agent/insurance producer that you bought it from. You must

return it within 30 days of the day you first received it. The company will refund the full amount

of any premium paid within 30 days after it receives the returned policy, certificate or rider. The

premium refund will be sent directly to the person who paid it. The policy, certificate or rider will

be void as if it had never been issued.”

G. (1) An outline of coverage shall be delivered to a prospective applicant for long-term care insurance at

the time of initial solicitation through means that prominently direct the attention of the recipient

to the document and its purpose.

(a) The commissioner shall prescribe a standard format, including style, arrangement and

overall appearance, and the content of an outline of coverage.

(b) In the case of agent solicitations, an agent shall deliver the outline of coverage prior to

the presentation of an application or enrollment form.

(c) In the case of direct response solicitations, the outline of coverage shall be presented in

conjunction with any application or enrollment form.

(d) In the case of a policy issued to a group defined in Section 4E(1) of this Act, an outline of

coverage shall not be required to be delivered, provided that the information described in

Section 6G(2)(a) through (h) is contained in other materials relating to enrollment. Upon

request, these other materials shall be made available to the commissioner.

Drafting Note: States may wish to review specific filing requirements as they pertain to the outline of coverage and these other materials.

(2) The outline of coverage shall include:

(a) A description of the principal benefits and coverage provided in the policy;

(b) A description of the eligibility triggers for benefits and how those triggers are met;

(c) A statement of the principal exclusions, reductions and limitations contained in the

policy;

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—1

st

Quarter 2017

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

640-7

(d) A statement of the terms under which the policy or certificate, or both, may be continued

in force or discontinued, including any reservation in the policy of a right to change

premium. Continuation or conversion provisions of group coverage shall be specifically

described;

(e) A statement that the outline of coverage is a summary only, not a contract of insurance,

and that the policy or group master policy contains governing contractual provisions;

(f) A description of the terms under which the policy or certificate may be returned and

premium refunded;

(g) A brief description of the relationship of cost of care and benefits; and

(h) A statement that discloses to the policyholder or certificateholder whether the policy is

intended to be a federally tax-qualified long-term care insurance contract under 7702B(b)

of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended.

H. A certificate issued pursuant to a group long-term care insurance policy that policy is delivered or issued

for delivery in this state shall include:

(1) A description of the principal benefits and coverage provided in the policy;

(2) A statement of the principal exclusions, reductions and limitations contained in the policy; and

(3) A statement that the group master policy determines governing contractual provisions.

Drafting Note: The above provisions are deemed appropriate due to the particular nature of long-term care insurance, and are consistent with group

insurance laws. Specific standards would be contained in regulations implementing this Act.

I. If an application for a long-term care insurance contract or certificate is approved, the issuer shall deliver

the contract or certificate of insurance to the applicant no later than thirty (30) days after the date of

approval.

J. At the time of policy delivery, a policy summary shall be delivered for an individual life insurance or

annuity policy that provides long-term care benefits within the policy or by rider. In the case of direct

response solicitations, the insurer shall deliver the policy summary upon the applicant’s request, but

regardless of request shall make delivery no later than at the time of policy delivery. In addition to

complying with all applicable requirements, the summary shall also include:

(1) An explanation of how the long-term care benefit interacts with other components of the policy;

(2) An illustration of the amount of benefits, the length of benefit, and the guaranteed lifetime benefits

if any, for each covered person;

(3) Any exclusions, reductions and limitations on benefits of long-term care benefits;

(4) A statement that any long-term care inflation protection option required by [cite to state’s inflation

protection option requirement comparable to Section 11 of the Long-Term Care Insurance Model

Regulation] is not available under this policy. If inflation protection was not required to be

offered, or if inflation protection was required to be offered but was rejected, a statement that

inflation protection is not available under the policy that provides long-term care benefits, and an

explanation of other options available under the policy, if any, to increase the funds available to

pay for the long-term care benefits;

Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act

640-8

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

(5) If applicable to the policy type, the summary shall also include:

(a) A disclosure of the effects of exercising other rights under the policy;

(b) A disclosure of guarantees, fees or other costs related to long-term care costs of insurance

charges in the base policy and any riders; and

(c) Current and projected periodic and maximum lifetime benefits; and

(6) The provisions of the policy summary listed above may be incorporated into a basic illustration

required to be delivered in accordance with [cite to state’s basic illustration requirement

comparable to Sections 6 and 7 of the Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation] or into the

life insurance policy summary which is required to be delivered in accordance with [cite to state’s

life insurance policy summary requirement comparable to Section 5 of the Life Insurance

Disclosure Model Regulation].

K. Any time a long-term care benefit, funded through a life insurance vehicle by the acceleration of the death

benefit, is in benefit payment status, a monthly report shall be provided to the policyholder. The report shall

include:

(1) Any long-term care benefits paid out during the month;

(2) Any costs or changes that apply or will apply to the policy or any riders;

(3) An explanation of any changes in the policy, e.g. death benefits or cash values, due to long-term

care benefits being paid out; and

(4) The amount of long-term care benefits existing or remaining.

L. If a claim under a long-term care insurance contract is denied, the issuer shall, within sixty (60) days of the

date of a written request by the policyholder or certificateholder, or a representative thereof:

(1) Provide a written explanation of the reasons for the denial; and

(2) Make available all information directly related to the denial.

M. Any policy, certificate or rider advertised, marketed or offered as long-term care or nursing home

insurance, as defined in Section 4A of the NAIC Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act, shall comply with

the provisions of this Act.

Section 7. Incontestability Period

A. For a policy or certificate that has been in force for less than six (6) months an insurer may rescind a long-

term care insurance policy or certificate or deny an otherwise valid long-term care insurance claim upon a

showing of misrepresentation that is material to the acceptance for coverage.

B. For a policy or certificate that has been in force for at least six (6) months but less than two (2) years an

insurer may rescind a long-term care insurance policy or certificate or deny an otherwise valid long-term

care insurance claim upon a showing of misrepresentation that is both material to the acceptance for

coverage and which pertains to the condition for which benefits are sought.

C. After a policy or certificate has been in force for two (2) years it is not contestable upon the grounds of

misrepresentation alone; such policy or certificate may be contested only upon a showing that the insured

knowingly and intentionally misrepresented relevant facts relating to the insured’s health.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—1

st

Quarter 2017

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

640-9

D. (1) A long-term care insurance policy or certificate may be field issued if the compensation to the

field issuer is not based on the number of policies or certificates issued.

(2) For purposes of this section, “field issued” means a policy or certificate issued by a producer or a

third-party administrator pursuant to the underwriting authority granted to the producer or third

party administrator by an insurer and using the insurer’s underwriting guidelines.

E. If an insurer has paid benefits under the long-term care insurance policy or certificate, the benefit payments

may not be recovered by the insurer in the event that the policy or certificate is rescinded.

F. In the event of the death of the insured, this section shall not apply to the remaining death benefit of a life

insurance policy that accelerates benefits for long-term care. In this situation, the remaining death benefits

under these policies shall be governed by [cite to state’s life insurance incontestability clause]. In all other

situations, this section shall apply to life insurance policies that accelerate benefits for long-term care.

Section 8. Nonforfeiture Benefits

A. Except as provided in Subsection B, a long-term care insurance policy may not be delivered or issued for

delivery in this state unless the policyholder or certificateholder has been offered the option of purchasing a

policy or certificate including a nonforfeiture benefit. The offer of a nonforfeiture benefit may be in the

form of a rider that is attached to the policy. In the event the policyholder or certificateholder declines the

nonforfeiture benefit, the insurer shall provide a contingent benefit upon lapse that shall be available for a

specified period of time following a substantial increase in premium rates.

B. When a group long-term care insurance policy is issued, the offer required in Subsection A shall be made to

the group policyholder. However, if the policy is issued as group long-term care insurance as defined in

Section 4E(4), other than to a continuing care retirement community or other similar entity, the offering

shall be made to each proposed certificateholder.

C. The commissioner shall promulgate regulations specifying the type or types of nonforfeiture benefits to be

offered as part of long-term care insurance policies and certificates, the standards for nonforfeiture benefits,

and the rules regarding contingent benefit upon lapse, including a determination of the specified period of

time during which a contingent benefit upon lapse will be available and the substantial premium rate

increase that triggers a contingent benefit upon lapse as described in Subsection A.

Section 9. Producer Training Requirements

A. (1) An individual may not sell, solicit or negotiate long-term care insurance unless the individual is

licensed as an insurance producer for accident and health or sickness or life [include other lines of

authority as applicable] and has completed a one-time training course. The training shall meet the

requirements set forth in Subsection B.

(2) An individual already licensed and selling, soliciting or negotiating long-term care insurance on

the effective date of this Act may not continue to sell, solicit or negotiate long term care insurance

unless the individual has completed a one-time training course as set forth in Subsection B, within

one year from [insert effective date of this legislation].

(3) In addition to the one-time training course required in Paragraphs (1) and (2) above, an individual

who sells, solicits or negotiates long-term care insurance shall complete ongoing training as set

forth in Subsection B.

(4) The training requirements of Subsection B may be approved as continuing education courses

under [insert reference to applicable state law or regulation].

B. (1) The one-time training required by this Section shall be no less than eight (8) hours and the

ongoing training required by this Section shall be no less than four (4) hours every 24 months.

Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act

640-10

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

(2) The training required under Paragraph (1) shall consist of topics related to long-term care

insurance, long-term care services and, if applicable, qualified state long-term care insurance

Partnership programs, including, but not limited to:

(a) State and federal regulations and requirements and the relationship between qualified

state long-term care insurance Partnership programs and other public and private

coverage of long-term care services, including Medicaid;

(b) Available long-term services and providers;

(c) Changes or improvements in long-term care services or providers;

(d) Alternatives to the purchase of private long-term care insurance;

(e) The effect of inflation on benefits and the importance of inflation protection; and

(f) Consumer suitability standards and guidelines.

(3) The training required by this Section shall not include training that is insurer or company product

specific or that includes any sales or marketing information, materials, or training, other than those

required by state or federal law.

C. (1) Insurers subject to this Act shall obtain verification that a producer receives training required by

Subsection A before a producer is permitted to sell, solicit or negotiate the insurer’s long-term care

insurance products, maintain records subject to the state’s record retention requirements, and make

that verification available to the commissioner upon request.

(2) Insurers subject to this Act shall maintain records with respect to the training of its producers

concerning the distribution of its Partnership policies that will allow the state insurance

department to provide assurance to the state Medicaid agency that producers have received the

training contained in Subsection B(2)(a) as required by Subsection A and that producers have

demonstrated an understanding of the Partnership policies and their relationship to public and

private coverage of long-term care, including Medicaid, in this state. These records shall be

maintained in accordance with the state’s record retention requirements and shall be made

available to the commissioner upon request.

D. The satisfaction of these training requirements in any state shall be deemed to satisfy the training

requirements in this state.

Drafting Note: Guidance on the implementation of the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA), Pub. L. 109-171, provided by the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services in the July 27, 2006 State Medicaid Director Letter (SMDL #06-019) states that “[t]he State insurance department must provide assurance

to the State Medicaid agency that anyone who sells a policy under the Partnership receives training and demonstrates an understanding of Partnership

policies and their relationship to public and private coverage of [long term care].” There is no guidance as to how the State insurance department is to

accomplish this requirement. This drafting note provides information to the State insurance departments with respect to achieving the aforementioned

requirements.

Section 9C of the NAIC Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act requires insurers to obtain and maintain records verifying that producers who sell, solicit or

negotiate long-term care insurance products on their behalf have received the training required in this Section and to make such records available to the State

insurance department. In addition, Section 9C(2) requires insurers to obtain and maintain records concerning the training of their agents for Partnership

policies. Insurers are to maintain records that verify its producers have received the training required for Partnership policies and that they demonstrate an

understanding of the policies and their relationship to public and private long-term care coverage.

State insurance departments, in order to meet the standards contained in the DRA concerning producer training should consider developing a process to

communicate with the State Medicaid agency on how the DRA requirements will be met. They should develop a process to verify insurance company

compliance with these requirements including, as an audit step, the verification of compliance with the above requirements as part of a market conduct

examination. In addition, State insurance departments should consider performing annual, random verifications of insurance company compliance. Finally,

consideration may be given to deeming thos training programs, specifically approved by the State for Partnership policy training that qualify for Continuing

Education, as meeting the requirements contained in Section 9C(2).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—1

st

Quarter 2017

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

640-11

Section 10. Authority to Promulgate Regulations

The commissioner shall issue reasonable regulations to promote premium adequacy and to protect the policyholder in the

event of substantial rate increases, and to establish minimum standards for producer education, marketing practices, producer

compensation, producer testing, independent review of benefit determinations, penalties and reporting practices for long-term

care insurance.

Drafting Note: Each state should examine its statutory authority to promulgate regulations and revise this section accordingly so that sufficient rulemaking

authority is present and that unnecessary duplication of unfair practice provisions does not occur.

Section 11. Administrative Procedures

Regulations adopted pursuant to this Act shall be in accordance with the provisions of [cite section of state insurance code

relating to the adoption and promulgation of rules and regulations or cite the state’s administrative procedures act, if

applicable].

Section 12. Severability

If any provision of this Act or the application thereof to any person or circumstance is for any reason held to be invalid, the

remainder of the Act and the application of such provision to other persons or circumstances shall not be affected thereby.

Section 13. Penalties

In addition to any other penalties provided by the laws of this state, any insurer and any producer found to have violated any

requirement of this state relating to the regulation of long-term care insurance or the marketing of such insurance shall be

subject to a fine of up to three (3) times the amount of any commissions paid for each policy involved in the violation or up

to $10,000, whichever is greater.

Drafting Note: The intention of this section is to authorize separate fines for both the insurer and the producer in the amounts suggested above.

Section 14. Effective Date

This Act shall be effective [insert date].

______________________________

Chronological Summary of Actions (all references are to the Proceedings of the NAIC).

1987 Proc. I 11, 19, 655, 677-680, 700 (adopted).

1987 Proc. II 15, 23, 632-633, 727, 730-734 (amended and reprinted).

1988 Proc. I 9, 20-21, 629-630, 652, 661-665 (amended and reprinted).

1989 Proc. I 9, 24-25, 703, 754-755, 789-793 (amended).

1989 Proc. II 13, 23-24, 468, 476-477, 479-484 (amended and reprinted).

1990 Proc. I 6, 27-28, 477, 541-542, 556-561 (amended and reprinted).

1991 Proc. I 9, 17, 609-610, 662, 666-671 (amended and reprinted).

1993 Proc. I 8, 136, 819, 844, 845(amended).

1993 Proc. 1

st

Quarter 3, 34, 267, 275, 276 (amended).

1994 Proc. 1

st

Quarter 4, 39, 446-447, 458 (amended).

1996 Proc. 2

nd

Quarter 10, 33, 731, 812, 823-824 (amended).

1997 Proc. 1

st

Quarter 54, 55, 56, 57, 700, 701-704 (amended).

1998 Proc. 1

st

Quarter 16, 17, 769, 801-804, 894 (amended).

1999 Proc. 4

th

Quarter 18, 929, 969, 972-978 (amended).

2006 Proc. 4

th

Quarter 44, 48-60 (amended, reprinted).

2007 Proc. 3

rd

Quarter 42-44 (amended).

2009 Proc. 3

rd

Quarter Vol. I 95-102, 114-119, 205-210, 312-315 (amended).

2016 Proc. 3

rd

Quarter (amended).

Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act

640-12

© 2017 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

This page is intentionally left blank

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners ST-640-1

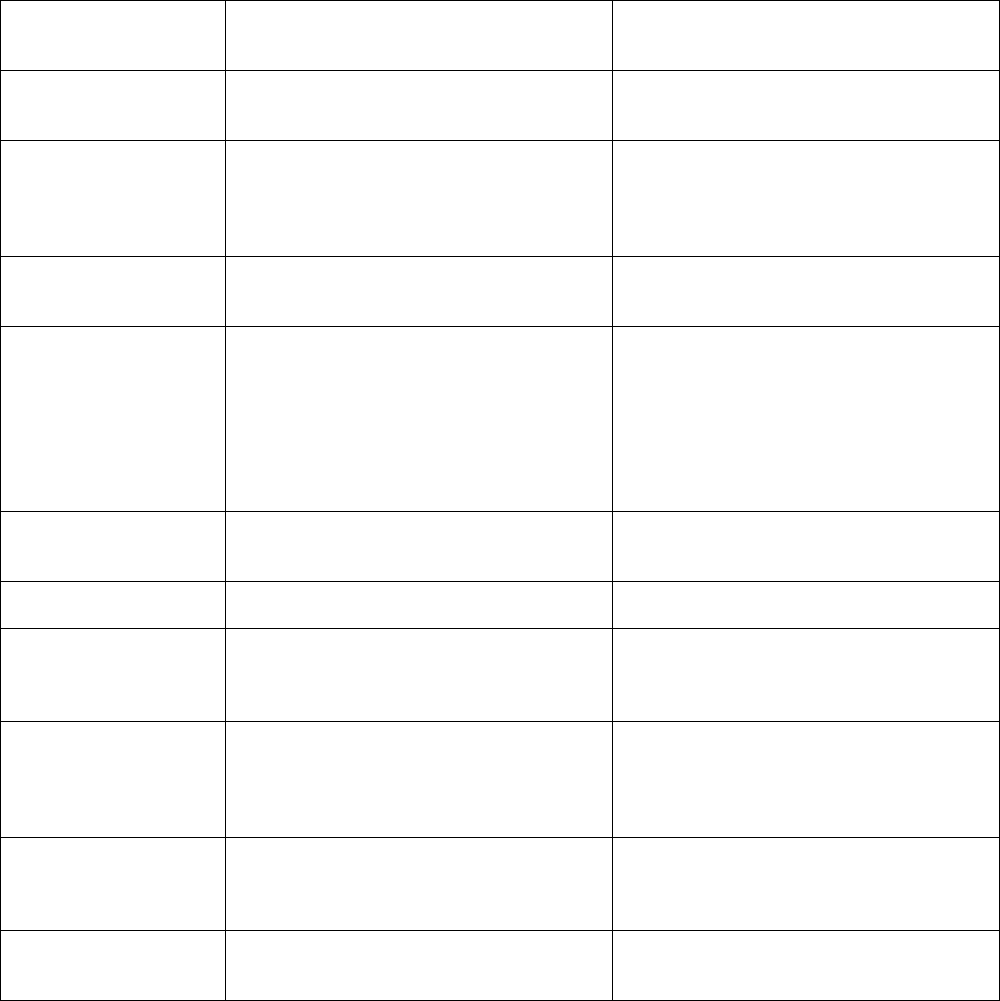

This chart is intended to provide readers with additional information to more easily access state statutes, regulations,

bulletins or administrative rulings related to the NAIC model. Such guidance provides readers with a starting point

from which they may review how each state has addressed the model and the topic being covered. The NAIC Legal

Division has reviewed each state’s activity in this area and has determined whether the citation most appropriately

fits in the Model Adoption column or Related State Activity column based on the definitions listed below. The NAIC’s

interpretation may or may not be shared by the individual states or by interested readers.

This chart does not constitute a formal legal opinion by the NAIC staff on the provisions of state law and should not

be relied upon as such. Nor does this state page reflect a determination as to whether a state meets any applicable

accreditation standards. Every effort has been made to provide correct and accurate summaries to assist readers in

locating useful information. Readers should consult state law for further details and for the most current information.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

ST-640-2

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

This page is intentionally left blank

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners ST-640-3

KEY:

MODEL ADOPTION: States that have citations identified in this column adopted the most recent version of the NAIC

model in a substantially similar manner. This requires states to adopt the model in its entirety but does allow for variations

in style and format. States that have adopted portions of the current NAIC model will be included in this column with an

explanatory note.

RELATED STATE ACTIVITY: Examples of Related State Activity include but are not limited to: older versions of the

NAIC model, statutes or regulations addressing the same subject matter, or other administrative guidance such as bulletins

and notices. States that have citations identified in this column only (and nothing listed in the Model Adoption column) have

not adopted the most recent version of the NAIC model in a substantially similar manner.

NO CURRENT ACTIVITY: No state activity on the topic as of the date of the most recent update. This includes states that

have repealed legislation as well as states that have never adopted legislation.

NAIC MEMBER

MODEL ADOPTION RELATED STATE ACTIVITY

Alabama

A

LA

.

C

ODE

§§ 27-19-100 to 27-19-110

(2003) (previous version of model).

Alaska

A

LASKA

S

TAT

.

§§ 21.53.010 to 21.53.200

(1990/2011) (portions of previous version of

model).

American Samoa

NO CURRENT ACTIVITY

Arizona

A

RIZ

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

§§ 20-1691 to

20-1691.12 (1987/2008) (portions of

previous version of model).

Arkansas

A

RK

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§ 23-97-301 to 23-97-321

(2005) (previous version of model).

California

C

AL

.

I

NS

.

C

ODE

§§ 10231 to 10237.6

(1989/2018).

Colorado

C

OLO

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

. §§ 10-19-101 to

10-19-115 (1990/2018) (portions of previous

version of model);

3 COLO. CODE REGS.

§ 702-4:4-4-1 (1997/2011); 702-4:4-4-4

(2010/2013) (partnerships);

B

ULLETIN B-1-20 (2007);

B

ULLETIN B-4.30 (2012).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

ST-640-4

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NAIC MEMBER

MODEL ADOPTION RELATED STATE ACTIVITY

Connecticut

C

ONN

.

G

EN

.

S

TAT

.

§ 38a-501 (1991/2017)

(commissioner shall develop regulations).

Delaware

D

EL

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

tit. 18, §§ 7101 to 7109

(1989/2010) (previous version of model);

D

OMESTIC FOREIGN INSURERS BULLETIN 23

(2006).

District of Columbia

D.C.

C

ODE

§§ 31-3601 to 31-3612

(2000/2005) (previous version of model).

Florida

F

LA

.

STAT

. §§ 627.9401 to 627.9408

(1988/2015); FLA. ADMIN. CODE ANN. r.

69O-157.001 to 69O-157.023 (1989/2008);

MEMORANDUM 2003-002 (2003);

M

EMORANDUM 2006-16 (2006);

MEMORANDUM 2007-011 (2007);

MEMORANDUM 2008-002 (2008).

Georgia

G

A

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§ 33-42-1 to 33-42-6

(1988/2019) (previous version of model).

Guam

NO CURRENT ACTIVITY

Hawaii

H

AW

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

431:10H-101 to

431:10H-117 (1999/2017) (previous version

of model).

Idaho

I

DAHO

C

ODE

§§ 41-4601 to 41-4611

(1988/1999) (previous version of model);

B

ULLETIN 2007-8 (2007); BULLETIN 2016-2

(2016).

Illinois

215

I

LL

.

C

OMP

.

S

TATS

. 5/351A-1 to

5/351A-11 (1989/2001) (previous version of

model).

Indiana

I

ND

.

C

ODE

§§ 27-8-12-1 to 27-8-12-19

(1987/2003).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners ST-640-5

NAIC MEMBER

MODEL ADOPTION RELATED STATE ACTIVITY

Iowa

I

OWA

C

ODE

§§

514G.101

to 514G.113

(2008/2015) (previous version of model);

B

ULLETIN 2008-17 (2008); BULLETIN 2009-7

(2009); B

ULLETIN 2009-7 (REVISED) (2009);

BULLETIN 2014-1 (2014).

Kansas

K

AN

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

§§ 40-2225 to 40-2228

(1987/2002) (portions of previous version of

model); K

AN. STAT. ANN. § 40-2136

(2008/2012).

Kentucky

K

Y

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

§§ 304.14-600 to 304.14-625

(1992/2010) (portions of previous version of

model); K

Y. REV. STAT. § 304.14-630

(2010); K

Y. REV. STAT. § 304.14-560

(1990/2010) (Consumer’s Guide); B

ULLETIN

91-1 (1991); BULLETIN 92-2 (1992);

BULLETIN 93-1 (1993); BULLETIN 94-1

(1994); BULLETIN 96-4 (1996); BULLETIN 8-4

(2004).

Louisiana

L

A

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

§§ 22:1181 to 22:1191

(1989/2012) (previous version of model);

B

ULLETIN 9-5-2006 #1 and #2 (2006);

B

ULLETIN 12-28-2009 (2009).

Maine

M

E

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

tit. 24-A, §§ 5071 to

5084 (2000/2019) (previous version of

model); M

E. REV. STAT. ANN. tit. 36, § 2525

(1989) (tax credit);

BULLETIN 347 (2007);

B

ULLETIN 362 (2009); BULLETIN 363 (2009);

B

ULLETIN 417 2017); BULLETIN 418 (2017);

BULLETIN 419 (2017).

Maryland

M

D

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

I

NS

.

§§ 18-101 to 18-120

(2008/2014); MD. CODE ANN. INS. § 16-214

(1996) (life insurance riders);

BULLETIN 13-2009 (2009);

B

ULLETIN 2010-33 (2010).

Massachusetts

M

ASS

.

G

EN

.

L

AWS

ch. 176U, §§ 1 to 9

(2013/2019) (previous version of model);

211 M

ASS. CODE REGS. §§ 65:01 to 65:102

(1989/2005) (portions of previous version of

act and regulation); B

ULLETIN 2013-11

(2013).

Michigan

M

ICH

.

C

OMP

.

L

AWS

§§ 500.3901 to 500.3955

(1992/2006) (previous version of act and

regulation); M

EMORANDUM 1-27-2016

(2016); BULLETIN 2016-01-INS (2016).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

ST-640-6

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NAIC MEMBER

MODEL ADOPTION RELATED STATE ACTIVITY

Minnesota

M

INN

.

S

TAT

.

§§ 62S.01 to 62S.34

(1997/2019) (qualified policies);

MINN. STAT. §§ 62A.46 to 62A.56

(1986/2003) (non-qualified policies);

B

ULLETIN 2007-4 (2007); BULLETIN 2007-4

(A

DDENDUM) (2007); BULLETIN 2007-5

(2007); B

ULLETIN 2007-10 (2007);

M

INN. R. §§ 2745.0010 to 2745.0050 (1992)

(non-qualified plans).

Mississippi

M

ISS

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§

43-13-601

to

43-13-607 (2014) (partnership program).

Missouri

M

O

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

§§ 376.1100 to 376.1130

(1990/2002) (previous version of model);

B

ULLETIN 2008-04 (2008);

BULLETIN 2008-09 (2008).

Montana

M

ONT

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§ 33-20-127 to

33-20-128 (1991/2007); MONT. CODE ANN.

§§ 33-22-1101 to 33-22-1129 (1989/2007)

(previous version of model);

MEMORANDUM 9-7-2007 (2007);

M

EMORANDUM 2-23-2010 (2010).

Nebraska

N

EB

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

. §§ 44-4501 to 44-4521

(1987/2018) (portions of previous version of

model); B

ULLETIN CB-113 (2007); BULLETIN

CB-114 (2007); B

ULLETIN CB-133 (#2)

(2015).

Nevada

N

EV

.

A

DMIN

.

C

ODE

§§ 687B.005 to

687B.140 (1988/2016).

New Hampshire

N.H.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

§§ 415-D:1 to

415-D:13 (1990/2003) (previous version of

model); B

ULLETIN 2010-020-AB (2010).

New Jersey

N.J.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

§§ 17B:27E-1 to

17B:27E-12 (2004) (previous version of

model); N.J.

ADMIN. CODE §§ 11:4-34.1 to

11:4-34.32 (1989/2010) (portions of previous

version of model law and regulation).

New Mexico

N.M.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

§§ 59A-23A-1 to

59A-23A-13 (1989/2013) (portions of

previous version of model).

New York

N.Y.

I

NS

.

L

AW

§ 1117 (1986/2016).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners ST-640-7

NAIC MEMBER

MODEL ADOPTION RELATED STATE ACTIVITY

North Carolina

N.C.

G

EN

.

S

TAT

.

§§ 58-55-1 to 58-55-50

(1987/2019) (previous version of model);

N.C.

GEN. STAT. § 108A-70.4 (2010)

(partnerships); BULLETIN 2011-B-6 (2011).

North Dakota

N.D.

C

ENT

.

C

ODE

§§ 26.1-45-01 to

26.1-45-14 (1987/2019) (previous version of

model); B

ULLETIN 2007-4 (2007); BULLETIN

2007-3 (2007); B

ULLETIN 2012-2 (2012);

BULLETIN 2013-1 (2013); BULLETIN 2014-1

(2014).

Northern Marianas

NO CURRENT ACTIVITY

Ohio

O

HIO

R

EV

.

A

NN

.

§§ 3923.41 to 3923.50

(1988/2013); BULLETIN 2008-2 (2008).

Oklahoma

O

KLA

.

S

TAT

.

tit. 36, §§ 4421 to 4430

(1987/2018); BULLETIN 6-23-2008 #1 and #2

(2008).

Oregon

O

R

.

R

EV

.

S

TAT

.

§§ 743.650 to 743.665

(1989/2016) (previous version of model);

B

ULLETIN 2014-3 (2014).

Pennsylvania

40 P

A

.

C

ONS

.

S

TAT

. §§ 991.1101 to 991.1115

(1921/2010); 31 PA. CODE §§ 89a.101 to

89a.129 (2002) (portions of previous version

of model); N

OTICE 7-30-2016 (2016).

Puerto Rico

P.R.

L

AWS

A

NN

.

tit.

26,

§§

10251

to 10261

(2011) (previous version of model).

Rhode Island

R.I.

G

EN

.

L

AW

§§ 27-34.2-1 to 27-34.2-22

(1988/2013); BULLETIN 2011-2 (2011);

B

ULLETIN 2018-16 (2018).

South Carolina

S.C.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§ 38-72-10 to 38-72-100

(1988/2019); BULLETIN 4-2009 (2009).

South Dakota

S.D.

C

ODIFIED

L

AWS

A

NN

.

§§ 58-17B-1 to

58-17B-16 (1989/2007) (previous version of

model);

BULLETIN 89-3 (1989);

BULLETIN 95-2 (1995); BULLETIN 2007-4

(2007); BULLETIN 2007-7 (2007).

Tennessee

T

ENN

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§ 56-42-101 to

56-42-111 (1988/2016) (previous version of

model); B

ULLETIN 9-22-2008 (2008)

(partnership); MEMORANDUM 9-29-2015

(2015) (partnerships).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—Spring 2020

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

ST-640-8

© 2020 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

NAIC MEMBER

MODEL ADOPTION RELATED STATE ACTIVITY

Texas

T

EX

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§ 1201.105 (2005);

TEX. CODE ANN. §§ 1651.001 to 1651.107

(2005/2017); 28

TEX. ADMIN. CODE

§§ 3.3801 to 3.3874 (1990/2009) (portions of

previous version of model);

B

ULLETIN B-0018-15 (2015);

B

ULLETIN B-0010-18 (2018).

Utah

U

TAH

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§§ 31A-22-1401 to

31A-22-1414 (1991/2019) (previous version

of model); B

ULLETIN 2014-7 (2014).

Vermont

V

T

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

tit. 8, §§ 8081 to 8099

(2005/2011) (portions of previous version of

model); B

ULLETIN HCA-130 (2010).

Virgin Islands

NO CURRENT ACTIVITY

Virginia

V.A.

C

ODE

§§ 38.2-5200 to 38.2-5210

(1987/2002); ADMIN. LETTER 1990-23

(1990) (NAIC Shopper’s Guide); A

DMIN.

LETTER 2007-3 (2007).

Washington

W

ASH

.

R

EV

.

C

ODE

A

NN

. §§ 48.84.010 to

48.84.910 (1986/2008); WASH. REV. CODE

ANN. §§ 48.85.010 to 48.85.900 (1993/2012)

(partnership).

West Virginia

W.

V

A

.

C

ODE

A

NN

.

§

33-12-8a (2009)

(producer training); W.VA. CODE ANN.

§§ 33-15A-1 to 33-15A-11 (1989/2004)

(previous version of model);

I

NFORMATIONAL LETTER 182 (2012).

Wisconsin

W

IS

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

.

§ 146.91 (1987/2007);

§ 632.84 (1987/1989); § 600.03 (1977/2013);

§ 625.16 (1981/1990); W

IS. ADMIN. CODE

§ I

NS. 3.46 (1991/2014) (previous version of

model); § 3.455 (1991/2008);

B

ULLETIN 7-23-2001 (2001);

B

ULLETIN 11-19-2008 (2008);

B

ULLETIN 11-21-2008 (2008).

Wyoming

W

YO

.

S

TAT

.

A

NN

. §§ 26-38-101 to

26-38-111 (1988/1999);

M

EMORANDUM 01-2009 (2009)

(partnerships).

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—April 2011

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

Proceeding Citations

Cited to the Proceedings of the NAIC

© 2011 National Association of Insurance Commissioners PC-640-1

Section 1. Purpose

The first reported interest in developing a regulatory climate for the private financing of long-term care was in 1985, when

conferences among regulators, legislators and industry representatives were held. Members of Congress were also interested

in the area of nursing home insurance. 1986 Proc. I 681-682.

The advisory committee appointed in 1986 reported a great deal of interest within the insurance industry in entering the long-

term care market. They recommended that in order to develop private insurance as a viable financing mechanism for long-

term care, the issue be considered as a whole. Piecemeal implementation would lessen the potential role of the insurance

industry. 1986 Proc. II 707-709.

The advisory committee’s Long-Term Care Report suggested lack of consumer demand was the primary reason insurers had

not developed long-term care insurance products. Many people remain unaware of the financial risks associated with nursing

home care and erroneously believe Medicare and Medicare supplement insurance will address their long-term care needs.

1986 Proc. II 709.

The Long-Term Care Report suggested that in order for the development of long-term care insurance to reach its fullest

potential, the regulatory climate must be positive. Existing barriers to the growth and diversification of the marketplace must

be addressed. 1986 Proc. II 711.

Legislation was introduced in Congress during the 1989-90 session to regulate long-term care insurance at the federal level.

One bill drew heavily on the NAIC Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act. Another bill afforded favorable tax treatment for

the purchase of long-term care insurance. 1989 Proc. I 774.

In testimony on a congressional bill, the NAIC indicated that more than two-thirds of the states have adopted the NAIC model

act and/or regulation. States ware urged to adopt the amendments also. The NAIC would withdraw its opposition to federal

regulation if the states have not adopted the model act or regulation within two years. 1989 Proc. II 500.

The industry advisory committee presented a report indicating the approach of adding long-term care benefit riders to life

policies to a very valuable one and requested assistance from the NAIC in nurturing its development. It was the consensus of

the working group that it was acceptable for a life product to contain a rider covering long-term care benefits. The reserving

standards would need to be considered, so it was recommended that the Life Insurance (A) Committee and Life and Health

Actuarial Technical Task Force become involved in this task. 1989 Proc. I 776.

The working group recommended addition of a drafting note to the model act recognizing the viability of life insurance

products offering long-term care insurance benefits. 1989 Proc. I 703. An assignment for the future was to develop a

regulatory scheme for non-illusionary benefits. 1989 Proc. I 765.

The definition of long-term care was revised in 1989 to include riders, and the footnote modified. 1989 Proc. II 479-480.

Section 2. Scope

By mid-1988 the long-term care working group had begun to consider the applicability of the Long-Term Care Insurance

Model Act to home health care benefits and continuing care retirement communities. 1988 Proc. II 629.

Recommendations from the subgroup on how to deal with the issue of continuing care retirement communities included

developing a separate model act and regulation, developing a consumer’s guide, monitoring federal proposals on retirement

communities and/or nursing home requirements, and soliciting input from associations and consumers. 1989 Proc. I 765-766.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—April 2011

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

Proceeding Citations

Cited to the Proceedings of the NAIC

PC-640-2 © 2011 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

Section 2 (cont.)

A continuing care retirement community is a residential facility which provides residential, personal care and health care

services (including long-term care) to people of retirement age. The central idea is that people live independently as long as

their health permits, and, if necessary, transfer to a nursing home, usually located on the premises. 1989 Proc. I 770.

The subgroup compiled information on CCRCs and found about half of the states had some sort of regulation. More than half

of those require departments other than the insurance department to regulate CCRCs. Individual state regulation varies

widely, with earlier legislation focused more on consumer protection, and more recent statutes regulating the financial aspects

of CCRCs. 1989 Proc. I 771.

In late 1995 an industry trade association contacted the NAIC because it was concerned about the regulatory oversight of life

insurance used to fund long-term care. The association said some provisions in the Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act and

Regulation should not apply to life/long-term care insurance. The Senior Issues Task Force agreed to consider the issue. 1996

Proc. 1

st

Quarter 712.

Amendments adopted in 1997 were recommended by the life insurance industry because the models as constructed were not

an exact fit for life insurance products with long-term care riders. 1997 Proc. 1

st

Quarter 699.

Section 3. Title

Section 4. Definitions

A. Long-term care refers to the broad spectrum of medical and support services provided to persons who have lost some

or all capacity to function on their own due to a chronic illness or condition and are expected to need such services over a

prolonged period of time. 1986 Proc. II 709.

The working group considered requiring that a policy marketed as long-term care insurance cover two years of benefits. The

concern raised was that the regulatory process would not cover products offering benefits covering less than a two-year

period. A move toward the two-year requirement would create a loophole for substandard products. This loophole currently

exists at the one-year level. If the model act is to apply to all products, the definition should be changed entirely. The working

group did not reach a consensus on this issue and tabled the discussion. 1989 Proc. I 765.

The drafters considered extensively the pros and cons of changing the definition from 12 to 24 months. There is definitely a

need for products which offer coverage for less than two years, but perhaps they should not be referred to as “long-term.”

The concern was raised that the model does not really mandate coverage for any specific length of time because of the

terminology used. Upon further discussion it was decided that by mandating that any product marketed as long-term care

insurance can’t be called anything else, the affect is to mandate coverage for 12 months in the current model. 1989 Proc. II

514.

The definition was changed to include supplemental riders for life insurance and annuities. 1989 Proc. II 476.

A definitional change was made in December 1989 to include policies or riders which provide for payment of benefits based

on cognitive impairment or the loss functional capacity. 1990 Proc. I 542.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—April 2011

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

Proceeding Citations

Cited to the Proceedings of the NAIC

© 2011 National Association of Insurance Commissioners PC-640-3

Section 4A (cont.)

A special joint committee was appointed to study the issue of accelerated benefits of life insurance policies used for long-term

care. The committee’s task was to determine where these products would be regulated. The definition of long-term care was

modified to make clear when products would have to meet the requirements of the Long-Term Care Act. Accelerated benefits

products not authorized under the Accelerated Benefits Regulation, which otherwise fit the definition of long-term care,

would be regulated under the Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act and Regulation. Life insurance products which accelerate

to provide monthly nursing home benefits only as long as the insured remains confined would be subject to the Long-Term

Care Insurance Model Act. Benefits not conditioned on the receipt of long-term care are excluded from the Long-Term Care

Insurance Model Act. 1991 Proc. IB 687.

G. In 1998 the Senior Issues Task Force was charged with the task of reviewing the Long-Term Care Insurance Model

Act and Regulation for compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). 1998

Proc. 2

nd

Quarter II 882.

HIPAA created tax-qualified plans so the task force needed to determine how the NAIC models needed to be adjusted to

clearly accommodate such plans. 1998 Proc. 2

nd

Quarter II 882.

The chair of the working group asked interested parties how many companies still wrote a substantial percent of policies that

were not tax-qualified. An association representative responded that her association had recently compiled results of a survey

showing 80-90% of long-term care insurance business was in policies qualifying for favorable tax treatment under HIPAA.

1998 Proc. 4

th

Quarter II 765.

Regulators discussed whether they should refer to “qualified” plans or “tax-qualified” plans. The working group agreed to use

“tax-qualified” in the parts of the model that set standards for what to disclose to consumers. An interested party commented

that some states have tax benefits and suggested use of the term “federally tax-qualified.” A regulator suggested that the

model clarify that the terms are synonymous. 1999 Proc. 1

st

Quarter 612.

Subsection G contained a definition of a qualified long-term care insurance contract. Paragraph (2) applied to life riders. 1998

Proc. 3

rd

Quarter 719.

Section 5. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction—Group Long-Term Care Insurance

The advisory committee expressed the opinion that the provision authorizing the Commissioner to extend extra-territorial

jurisdiction over all long-term care insurance issued to residents of the state went significantly further than other existing

model laws. The advisory group spoke against allowing each state to extend jurisdiction over the certificates because it would

cause an employee benefit plan to be structured differently according to the regulation of each state where the employer was

located. The task force chose to retain the provision in the final draft. 1987 Proc. I 705-706.

The title of this section was changed to its present form when a footnote was added in December of 1987 to clarify the intent

of the drafters that this provision regarding discretionary groups not limit jurisdiction over other health policies. 1988 Proc. I

663.

Section 6. Disclosure and Performance Standards for Long-Term Care Insurance

A. In June of 1987, the model was amended to grant the commissioner the authority to make regulations on continuation

and conversion. This had not been included in the initial model. 1987 Proc. II 729, 732.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—April 2011

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

Proceeding Citations

Cited to the Proceedings of the NAIC

PC-640-4 © 2011 National Association of Insurance Commissioners

Section 6A (cont.)

It was suggested when the regulation was being amended in 1989, to include the words “inflation protection” to authorize the

states to promulgate regulations, because without this some states might have difficulty implementing the section on inflation

protection in their regulation. The committee chair expressed concern that the suggestion implies that states do not have

jurisdiction to promulgate this type of benefit enhancement without an act by the legislature. Inflation protection is a part of

the minimum standards and is consistent with the actions directed in the Long-Term Care Insurance Model Act. The task

force rejected the proposal. 1990 Proc. I 542.

B. The task force subgroup recommended that long-term care insurance products must be guaranteed renewable and

non-cancellable. The advisory committee said this would give the insurer no option to cancel an entire block of business if it

didn’t meet necessary business expectations, and would preclude the spirit of innovation and flexibility. The language adopted

provides the policy could not be terminated due to the deterioration of health or increased age of the insured individual. 1987

Proc. I 706.

An amendment to the model added a prohibition against issuing coverage for skilled nursing care only or coverage that

provides significantly more skilled care in a facility than coverage for lower levels of care. The intention of this section is to

prohibit a type of policy which would offer a benefit which is illusory to the long-term care risk. 1987 Proc. II 729, 732.

After adoption of a clarifying amendment in December of 1987, the model now reads “significantly more coverage for skilled

care.” 1988 Proc. I 663.

C. As adopted in December of 1986, the model contained a preexisting condition limitation period of six months for

coverage of a person age 65 or older and a 24-month limitation for an insured person under the age of 65. The rationale for

this decision was the concern that, as long-term care products become available, they would attract high-risk segments of the

insurable population. The preexisting condition limitation recognized the untested nature of long-term care coverage, and

would serve to help control policy costs by avoiding adverse selection. 1987 Proc. I 707.

In June of 1987, the NAIC voted to make several modifications to the preexisting condition portion of the model. Preexisting

condition restrictions were removed for insurance sold as group employment benefit policies. Another amendment changed

the limitation period to a uniform six months, with no distinction based on age. Finally, the definition of preexisting condition

was changed. The model initially defined the term as “preexisting condition means the existence of symptoms which would

cause an ordinarily prudent person to seek diagnosis, care or treatment for a condition for which medical advice or treatment

was recommended by, or received from a provider of health care services.” The underlined portion of the definition was

deleted. 1987 Proc. II 730, 732. Clarifying changes were made to this amendment in December of 1987 to change the

wording from “employer’s group policy” to “policy issued to a group.” 1988 Proc. I 664.

The subgroup was urged by the advisory committee to reinstate the provisions with regard to preexisting conditions and return

to the earlier definition, but the group decided against such changes. Both provisions as they now exist in the model closely

parallel the similar provisions in Medicare policies. 1988 Proc. I 710.

The subgroup considered deleting Subsection C(3) but at the urging of the advisory committee allowed it to remain part of the

model. The major purpose of this provision was to allow maximum flexibility in the product so as to encourage variation,

thereby meeting the needs of the greater number of insurance consumers. With long-term care products on the drawing boards

of many health insurers, a crystal ball would be necessary to foresee all the variations in product design that will emerge. 1987

Proc. I 707.

The advisory committee suggested language for Subsection C(4) which would have allowed an insurer the right to exclude

from coverage named diseases or physical conditions of the applicant. The purpose of that section was to encourage insurers

to accept these persons who would otherwise be denied insurance because of certain chronic preexisting conditions and

thereby make available limited coverage to such persons. 1987 Proc. I 707-708.

NAIC Model Laws, Regulations, Guidelines and Other Resources—April 2011

LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE MODEL ACT

Proceeding Citations

Cited to the Proceedings of the NAIC

© 2011 National Association of Insurance Commissioners PC-640-5

Section 6C (cont.)

The subgroup rejected the suggestion in favor of a broader coverage, which was adopted in June of 1987 as an amendment to

Subsection C(4). 1987 Proc. II 730, 733.

D. As adopted in 1986, the model permitted policies which conditioned benefits on admission to a facility for the same

or related condition within a period of less than 30 days after discharge from an institution. The advisory committee suggested