Monetary Policy

Report

October 2017

Canada’s Inflation-Control Strategy

1

Inflation targeting and the economy

The Bank’s mandate is to conduct monetary policy to promote

the economic and nancial well-being of Canadians.

Canada’s experience with ination targeting since 1991 has

shown that the best way to foster condence in the value

of money and to contribute to sustained economic growth,

employment gains and improved living standards is by keeping

ination low, stable and predictable.

In 2016, the Government and the Bank of Canada renewed

Canada’s ination-control target for a further ve-year period,

ending December 31, 2021. The target, as measured by the

consumer price index (CPI), remains at the 2 per cent midpoint

of the control range of 1 to 3 per cent.

The monetary policy instrument

The Bank carries out monetary policy through changes in the

target for the overnight rate of interest.

2

These changes are

transmitted to the economy through their inuence on market

interest rates, domestic asset prices and the exchange rate,

which affect total demand for Canadian goods and services.

The balance between this demand and the economy’s

production capacity is, over time, the primary determinant of

ination pressures in the economy.

Monetary policy actions take time—usually from six to eight

quarters—to work their way through the economy and have

their full effect on ination. For this reason, monetary policy

must be forward-looking.

Consistent with its commitment to clear, transparent com-

munications, the Bank regularly reports its perspective on

the forces at work on the economy and their implications for

ination. The Monetary Policy Report is a key element of this

approach. Policy decisions are typically announced on eight

pre-set days during the year, and full updates of the Bank’s

outlook, including risks to the projection, are published four

times per year in the Monetary Policy Report.

Inflation targeting is symmetric and flexible

Canada’s ination-targeting approach is symmetric, which

means that the Bank is equally concerned about ination rising

above or falling below the 2 per cent target.

Canada’s ination-targeting framework is exible. Typically,

the Bank seeks to return ination to target over a horizon of six

to eight quarters. However, the most appropriate horizon for

returning ination to target will vary depending on the nature

and persistence of the shocks buffeting the economy.

Monitoring inflation

In the short run, the prices of certain CPI components can be

particularly volatile. These components, as well as changes in

indirect taxes such as GST, can cause sizable uctuations in

CPI.

In setting monetary policy, the Bank seeks to look through

such transitory movements in CPI ination and focuses on a

set of “core” ination measures that better reect the under-

lying trend of ination. In this sense, these measures act as an

operational guide to help the Bank achieve the CPI ination

target. They are not a replacement for CPI ination.

The Bank’s three preferred measures of core ination are CPI-

trim, which excludes CPI components whose rates of change

in a given month are the most extreme; CPI-median, which

corresponds to the price change located at the 50th percentile

(in terms of basket weight) of the distribution of price changes;

and CPI-common, which uses a statistical procedure to track

common price changes across categories in the CPI basket.

1 See Joint Statement of the Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada on the Renewal of the Ination-Control Target (October 24, 2016) and Renewal of the

Ination-Control Target: Background Information—October 2016, which are both available on the Bank’s website.

2 When interest rates are at very low levels, the Bank has at its disposal a suite of extraordinary policy measures that could be used to provide additional monetary

stimulus and/or improve credit market conditions. The Framework for Conducting Monetary Policy at Low Interest Rates, available on the Bank’s website,

describes these measures and the principles guiding their use.

The Monetary Policy Report is available on the Bank of Canada’s website at bankofcanada.ca.

For further information, contact:

Public Information

Communications Department

Bank of Canada

234 Wellington Street

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G9

Telephone: 613-782-8111;

1-800-303-1282 (toll-free in North America)

Email: info@bankofcanada.ca; Website: bankofcanada.ca

ISSN 1201-8783 (Print)

ISSN 1490-1234 (Online)

© Bank of Canada 2017

Monetary Policy Report

October 2017

This is a report of the Governing Council of the Bank of Canada:

Stephen S. Poloz, Carolyn A. Wilkins, Timothy Lane, Lawrence Schembri, Lynn Patterson and Sylvain Leduc.

Contents

Global Economy ............................................................ 1

Global financial conditions ...............................................2

United States ............................................................2

Other advanced economies..............................................3

Inflation ..................................................................4

Emerging-market economies ............................................5

Commodity prices .......................................................5

Canadian Economy.........................................................7

Box 1: Canadian Inflation: The Role of Globalization and Digitalization ...8

Box 2: Key Inputs to the Base-Case Projection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Recent developments ...................................................10

Economic slack .........................................................12

Box 3: Wage Dynamics and Inflationary Pressures......................13

Inflation .................................................................14

Monetary and financial conditions......................................15

Economic outlook.......................................................16

Business investment ....................................................18

Exports .................................................................19

Household spending . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .20

Inflation outlook ........................................................21

Summary of key projection issues ......................................22

Appendix: Recent changes to ToTEM ...................................24

Risks to the Inflation Outlook ............................................27

Global Economy

The global economic expansion continues to strengthen and broaden

across countries (Chart 1a). Growth in the United States rebounded in the

second quarter, and the expansion in the euro area appears to have rmed

(Chart 1b). Economic activity is also showing signs of improvement in

some oil-exporting countries and emerging-market economies (EMEs) that

were previously in recession. Global growth is projected to average around

3

1

/

2

per cent over the 2017–19 period, in line with the projections in the July

Monetary Policy Report (Table 1).

Ination has remained below target across most advanced economies,

reecting past excess capacity, still-weak wage growth and, in some cases,

temporary factors. Ination in wages and prices is expected to rise gradually

as existing slack is absorbed.

The global outlook remains subject to substantial uncertainty, notably

around US trade policy as well as geopolitical developments. The Bank’s

base-case projection continues to include some judgment that acknow-

ledges the potential adverse effects of uncertainty on investment.

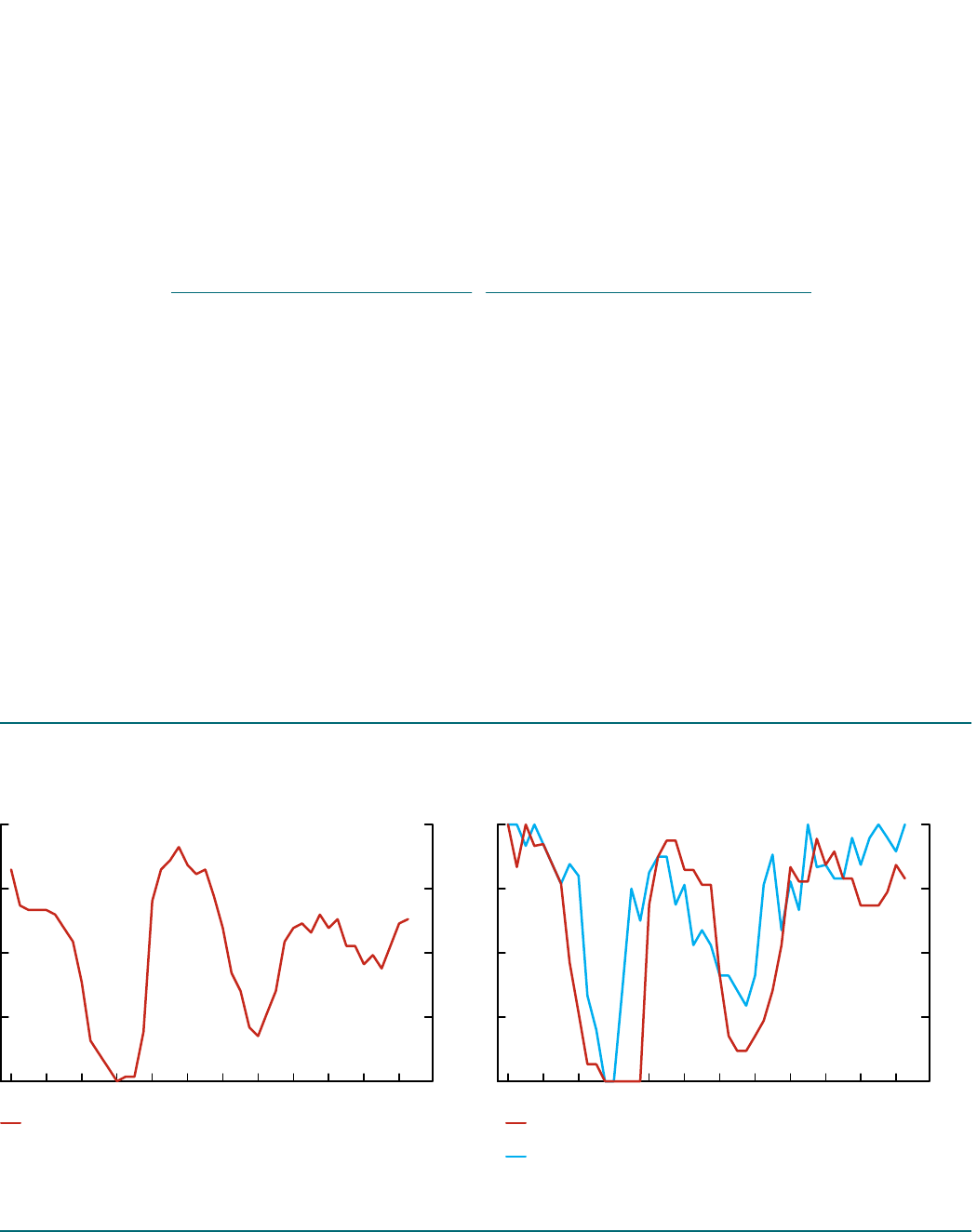

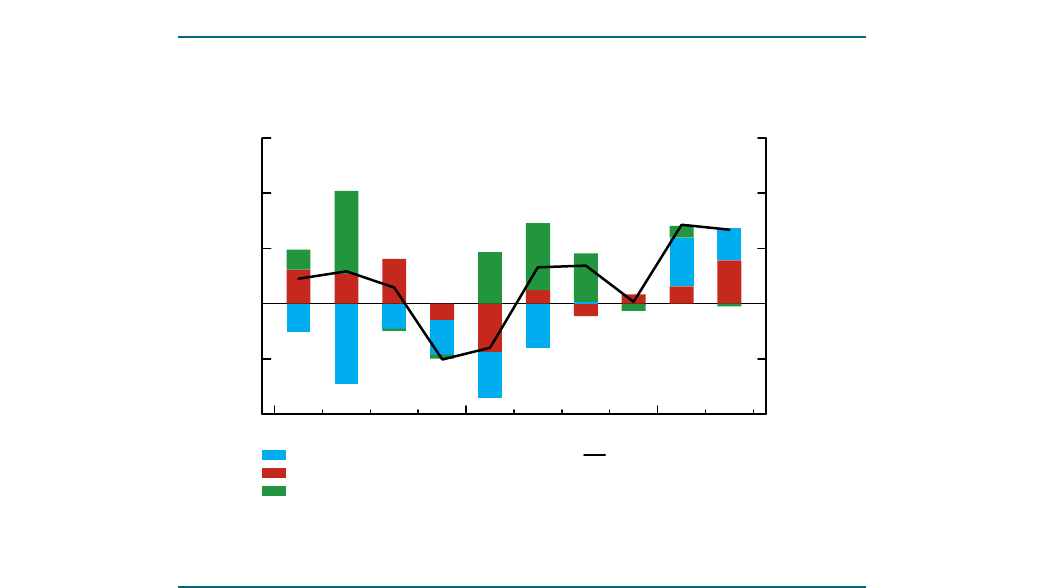

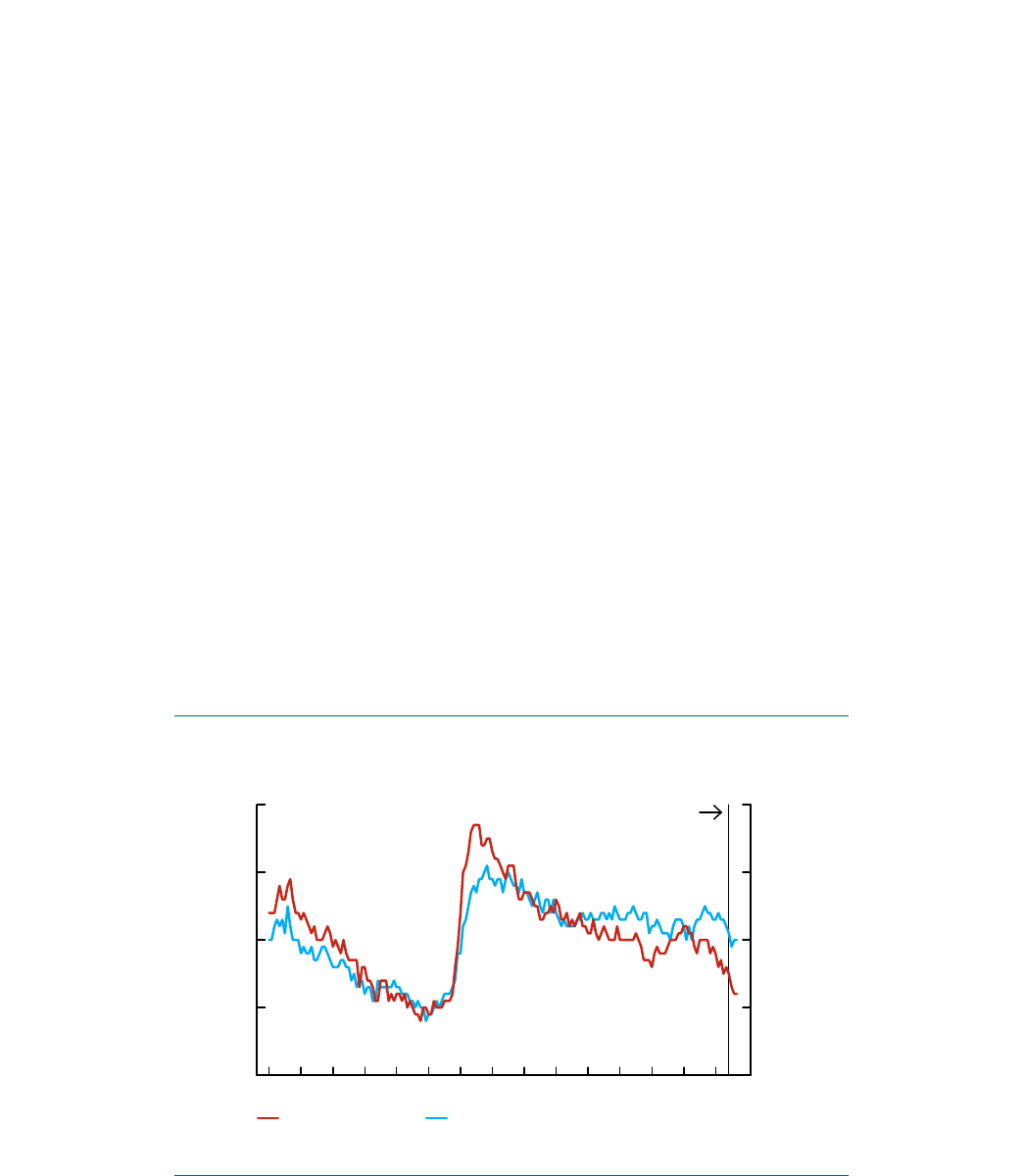

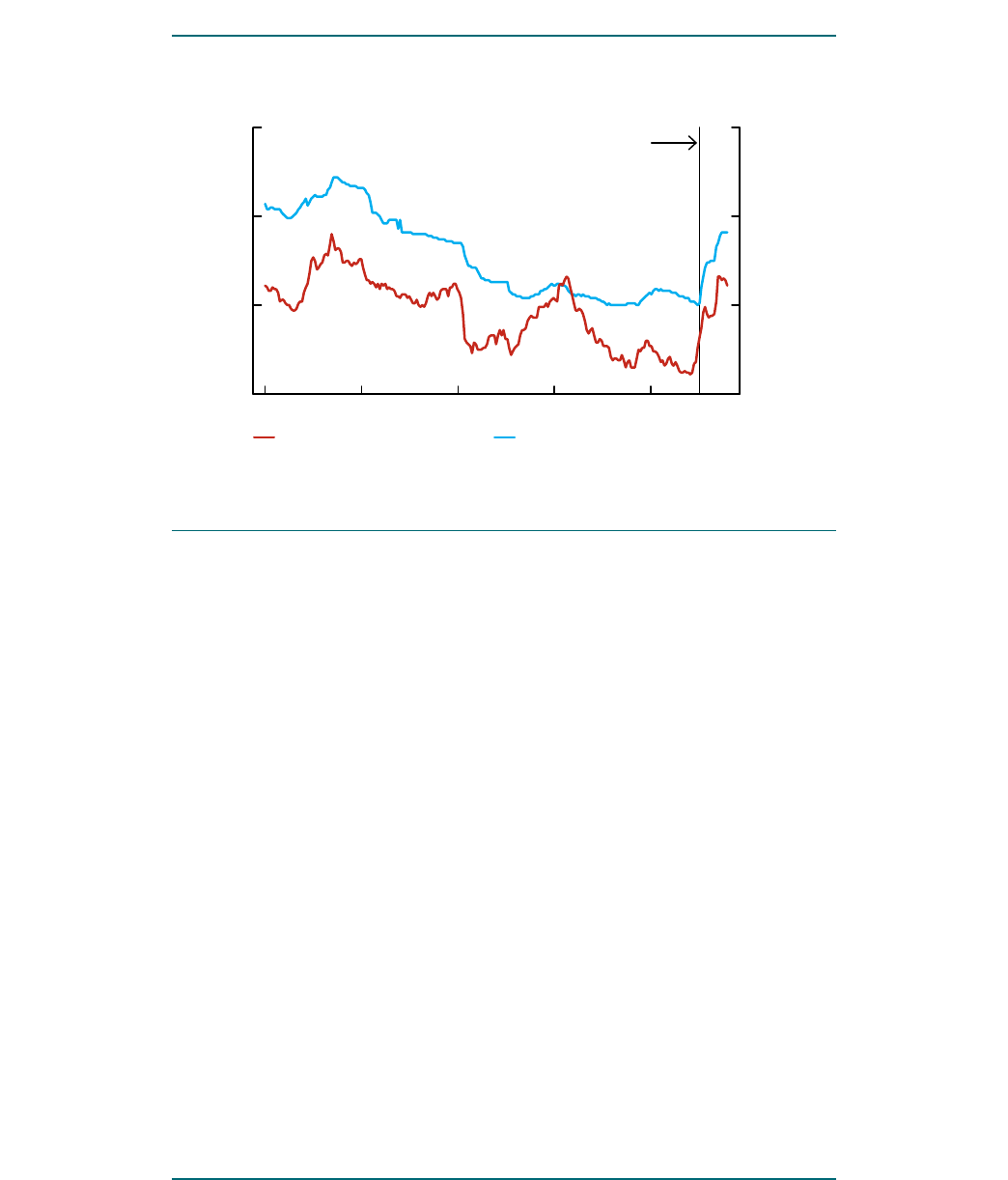

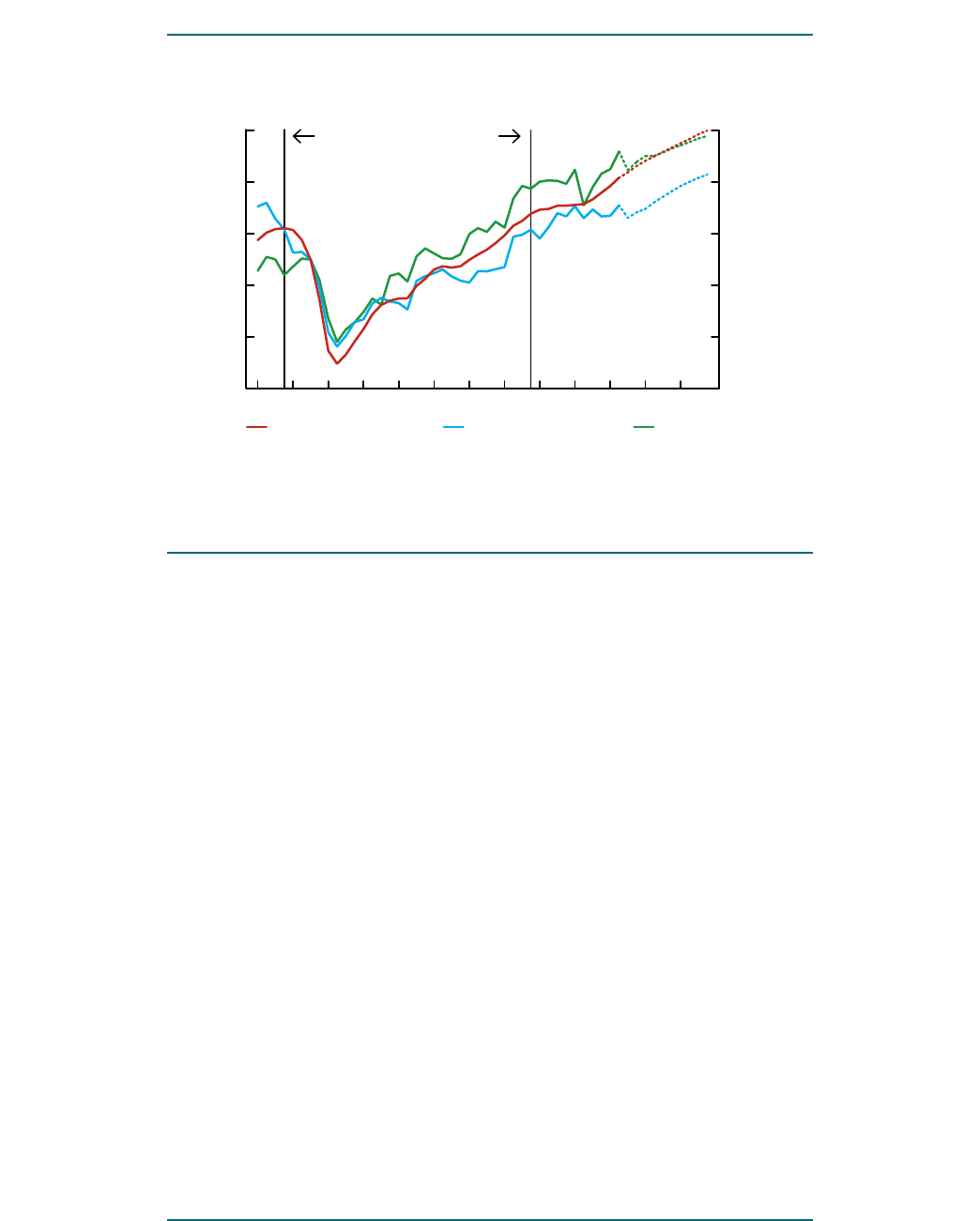

Chart 1:

Growth is becoming more synchronous across countries globally and within the euro area

a. Real GDP growth in selected countries,

a

quarterly data b. Real GDP growth in euro area countries, quarterly data

Share of countries with year-over-year growth exceeding the previous

3-year average

Share of countries with year-over-year growth exceeding the previous

3-year average

Share of countries with positive quarter-over-quarter growth

a.

The share of countries is based on 57 advanced and emerging-market economies accounting for 87 per cent of global GDP in purchasing power parity.

Sources: National sources and Eurostat via Haver Analytics and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: 2017Q2

0

25

50

75

100

2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

%

0

25

50

75

100

2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

%

GLOBAL ECONOMY

1

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Accommodative global financial conditions are

supporting growth

Global nancial conditions remain accommodative. Yields on long-term

sovereign bonds have changed little on average since July; in particular,

in the United States, Germany and Japan, yields have uctuated within a

narrow range. Stock market indexes in advanced economies have con-

tinued to climb amid improving economic sentiment and conditions. The

US Federal Reserve’s process of normalizing its balance sheet that began

in October is expected to contribute to a modest and gradual steepening

of the US yield curve. However, the announcement of these plans in

September had a minimal impact on yields.

Partly reecting increased uncertainty over US trade and scal policy, as

well as softer ination prospects, the US dollar had been weakening in

2017against a basket of currencies, although it has regained some strength

recently.

The US economy is projected to expand at a moderate pace

Economic growth in the United States rebounded in the second quarter, as

anticipated in the July Report. Consumption growth improved after a weak

rst quarter. Business investment growth remained robust, supported by,

but not limited to, the ongoing recovery in energy investment (Chart 2). In

contrast, residential investment contracted following two quarters of strong

growth, as spending on renovations and commissions on sales of existing

homes declined.

The outlook for economic growth for the second half of 2017 is roughly

unchanged from July. The recent hurricanes had a devastating impact on

affected communities, with signicant albeit transitory aggregate economic

effects. Consumption, housing and business investment are likely to be

negatively affected, resulting in a lower outlook for growth in gross domestic

product (GDP) in the third quarter. Recovery and reconstruction efforts are

expected to provide a modest boost to economic activity starting in the

fourth quarter.

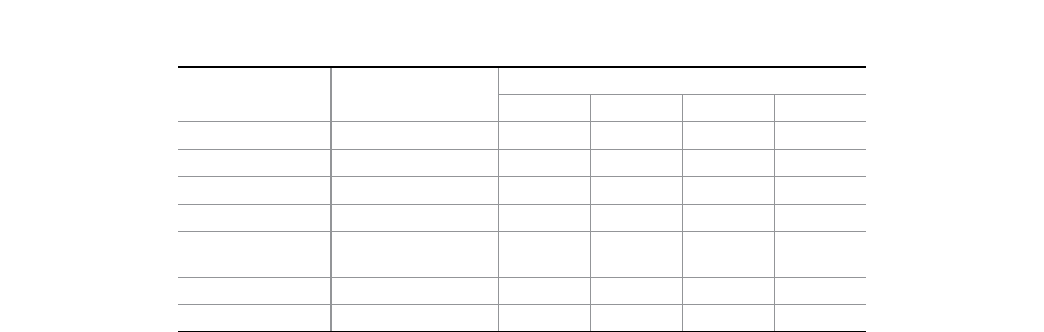

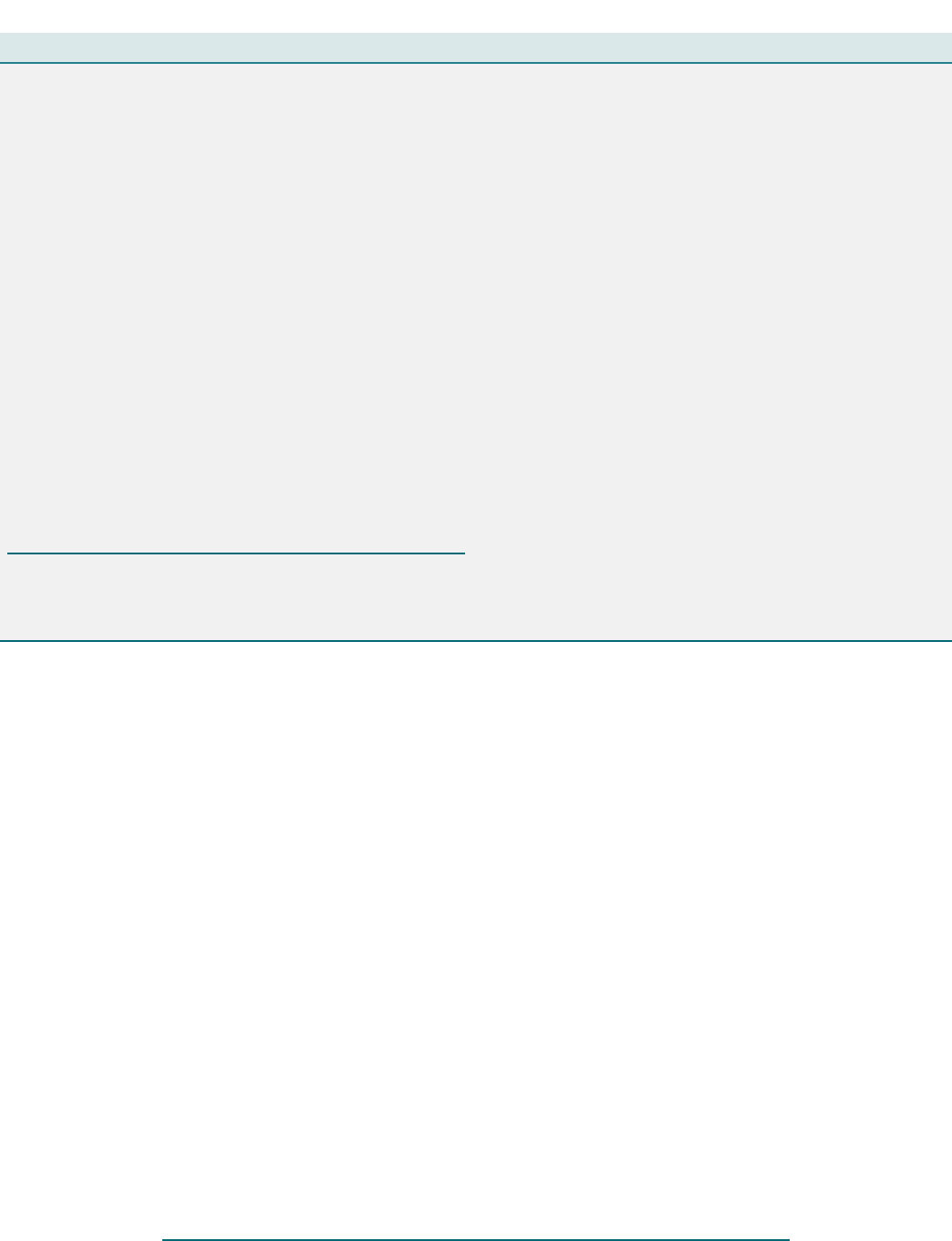

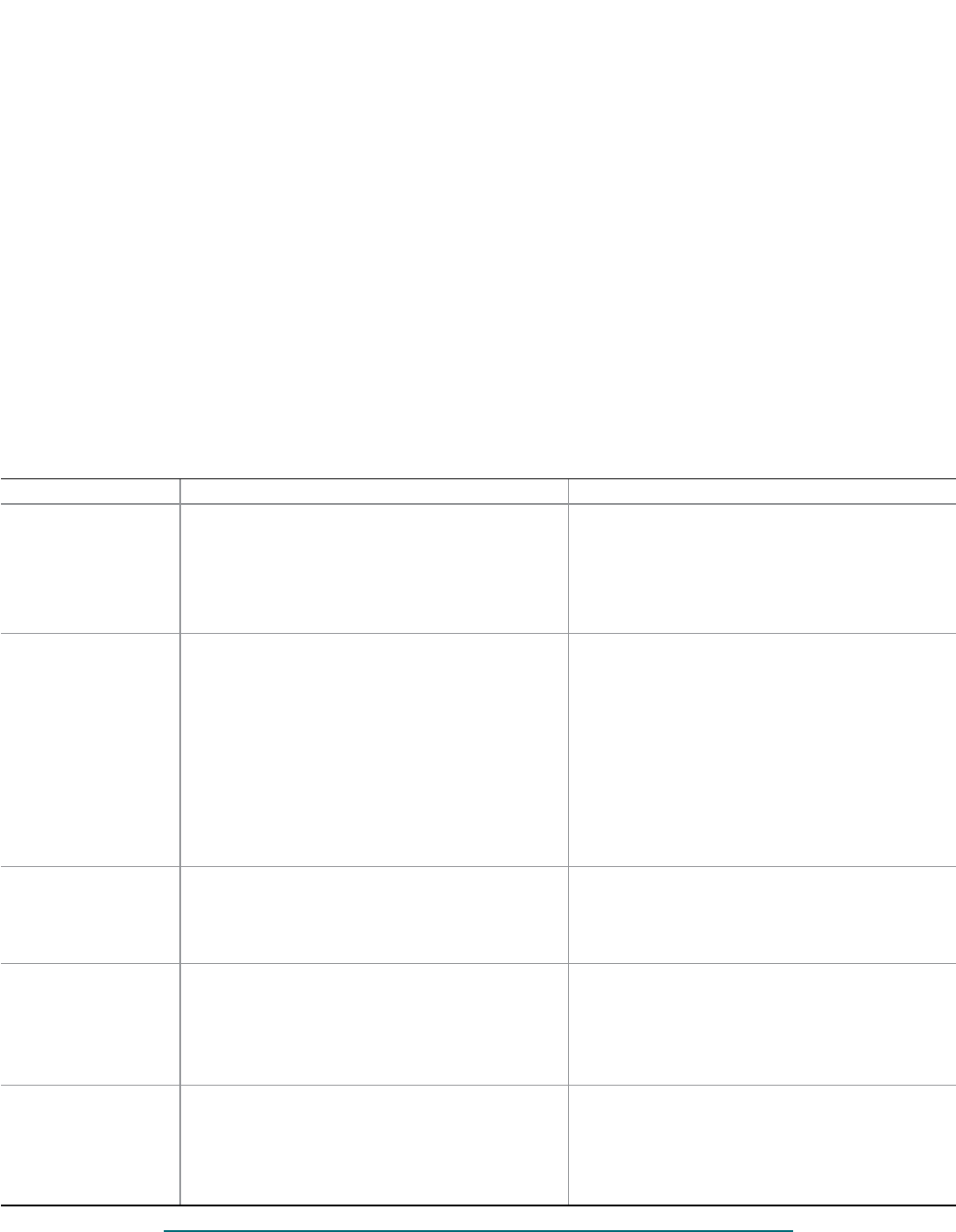

Table 1: Projection for global economic growth

Share of real global

GDP

a

(per cent)

Projected growth

b

(per cent)

2016 2017 2018 2019

United States 15 1.5 (1.6) 2.2 (2.2) 2.2 (2.1) 2.0 (1.8)

Euro area 12 1.8 (1.7) 2.3 (1.9) 1.8 (1.7) 1.6 (1.5)

Japan 4 1.0 (1.0) 1.5 (1.1) 0.9 (0.8) 0.8 (0.8)

China 18 6.7 (6.7) 6.8 (6.6) 6.4 (6.3) 6.3 (6.3)

Oil-importing

EMEs

c

33 3.6 (3.6) 4.0 (4.0) 4.0 (4.0) 4.2 (4.2)

Rest of the world

d

18 1.0 (1.0) 1.4 (1.7) 2.2 (2.5) 2.8 (2.7)

World 100 3.0 (3.0) 3.4 (3.4) 3.4 (3.4) 3.5 (3.4)

a.

GDP shares are based on International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates of the purchasing-power-parity

valuation of country GDPs for 2016 from the IMF’s October 2017 World Economic Outlook.

b.

Numbers in parentheses are projections used in the previous Report.

c.

The oil-importing emerging-market economies (EMEs) grouping excludes China. It is composed of large

emerging markets from Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa (such as India, Brazil and South

Africa) as well as newly industrialized economies (such as South Korea).

d. “Rest of the world” is a grouping of all other economies not included in the rst ve regions. It is composed

of oil-exporting emerging markets (such as Russia, Nigeria and Saudi Arabia) and other advanced

economies (such as Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia).

Source: Bank of Canada

2

GLOBAL ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Overall, economic fundamentals remain consistent with projected GDP

growth of about 2per cent on average over 2017–19. Business investment is

expected to expand at a solid pace. Consumption growth is anticipated to

stay rm, supported by strong labour market conditions. Net exports, how-

ever, will likely continue to be a drag on growth.

As in July, the Bank’s base-case projection does not incorporate any new

scal or trade measures. While sizable tax cuts are under active considera-

tion, material uncertainty remains about whether agreement will be reached

on such a package and, if so, its size, timing and design. If stimulative scal

measures were enacted, growth could be higher than projected. Likewise,

growth could be lower if protectionist trade policies led to a generalized

decline in cross-border co-operation.

The euro area economy has gained momentum

Second-quarter growth in the euro area was stronger than expected and

remained broad-based across member countries. Data since the July

Report also point to more momentum in economic activity than previ-

ously anticipated. As a result, the growth outlook for 2017 is now above

2 per cent. Growth should moderate gradually in 2018, reaching about

1

1

/

2

per cent in 2019, roughly in line with the pace of expansion of potential

output.

In Japan, economic activity in the second quarter strengthened signicantly

more than expected, resulting in an improved economic outlook for 2017.

Growth was driven by a boost to public investment and a pickup in con-

sumption. Overall, growth should slow to around 1per cent over 2018–19,

reecting demographics and other structural factors, and a sluggish pace of

nominal wage increases.

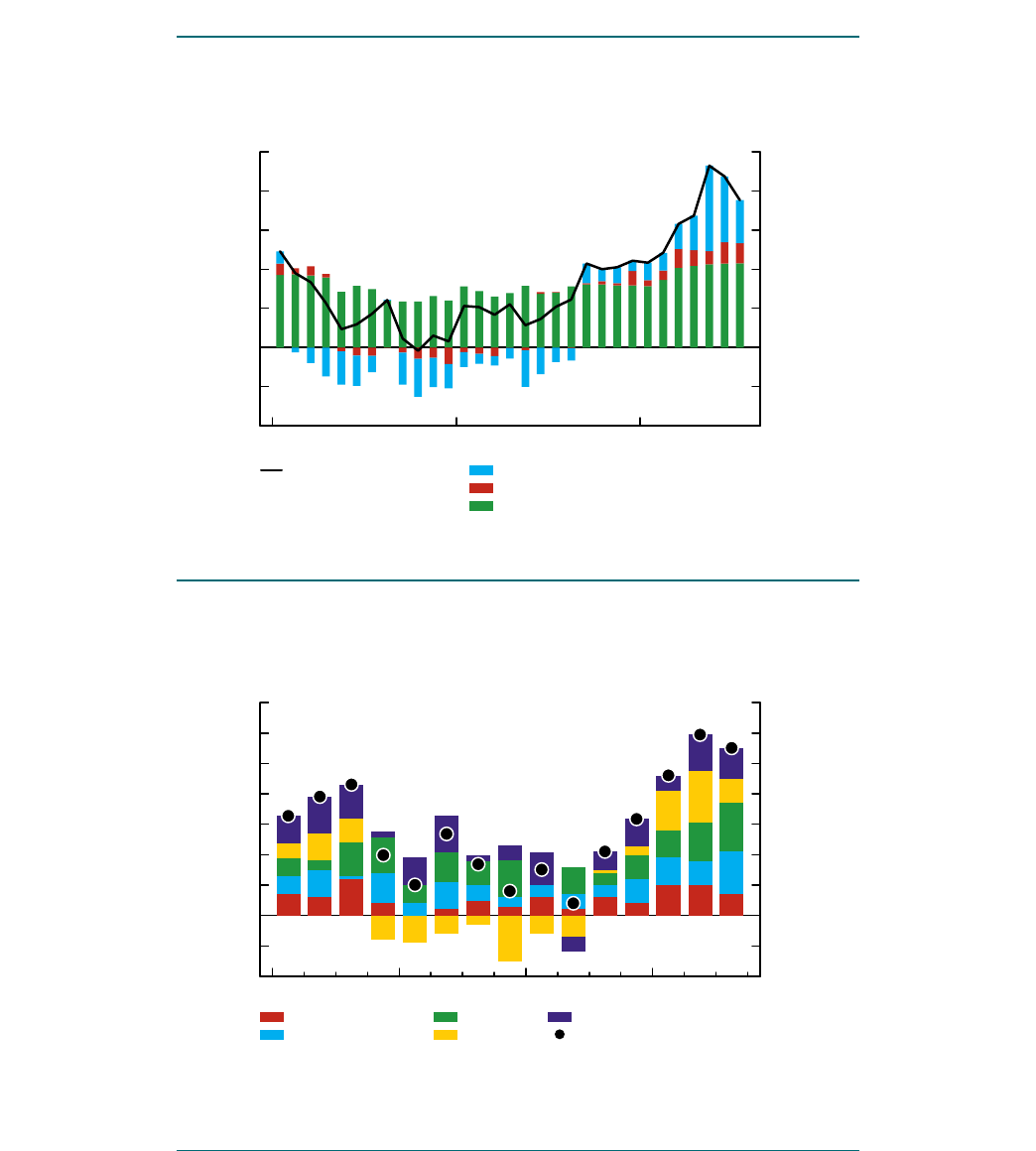

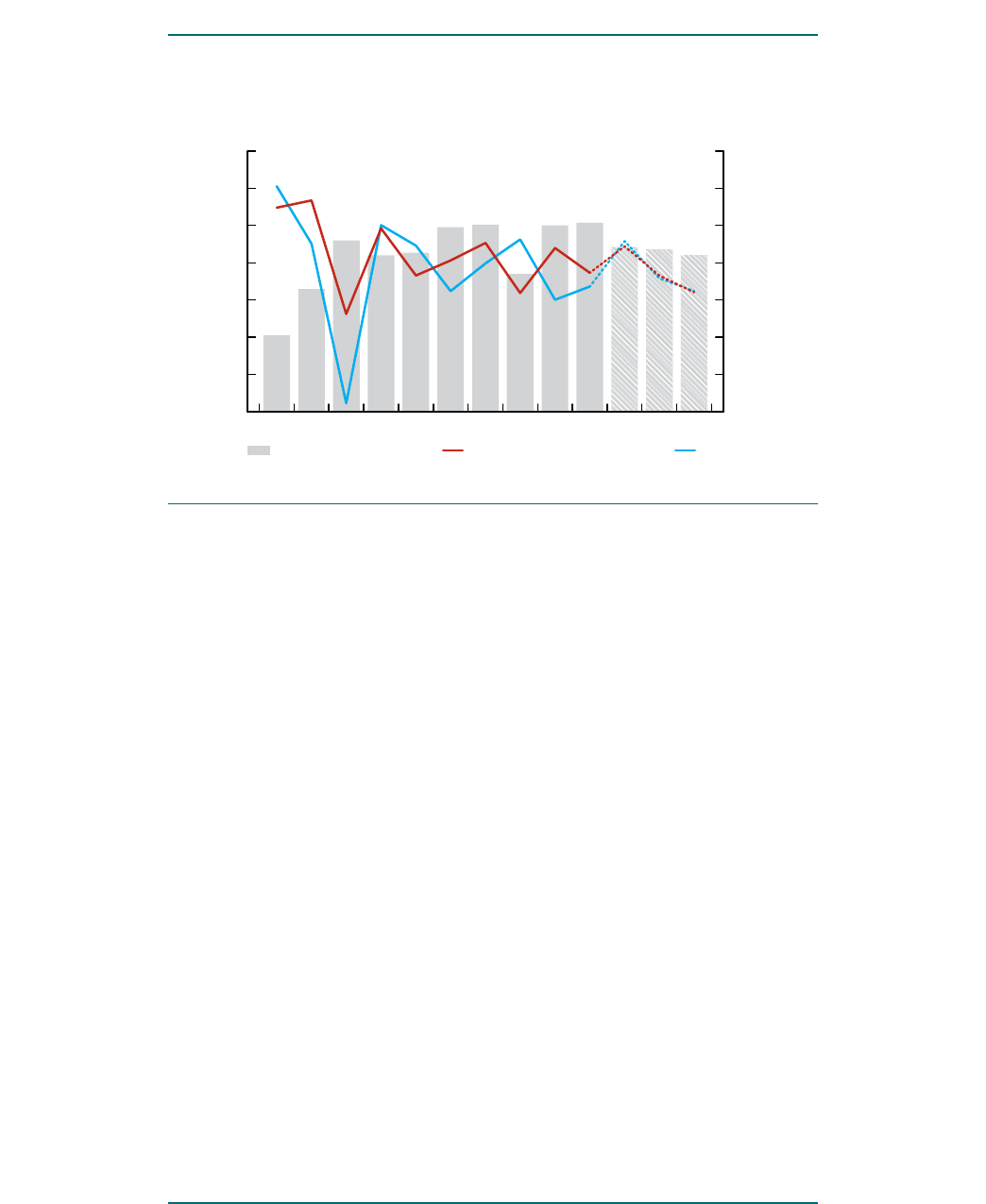

Chart 2:

US business investment growth remained robust

Contributions to quarter-over-quarter annualized business investment growth, quarterly data

Mining and oil- eld investment (left scale)

Non-oil equipment investment (left scale)

Other investment components

a

(left scale)

Total business investment

(right scale)

a.

Other investment components include non-oil structures and intellectual property products.

Sources: US Bureau of Economic Analysis

via Haver Analytics and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: 2017Q2

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

2015 2016 2017

%

Percentage points

GLOBAL ECONOMY

3

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Inflation continues to track below target in advanced

economies

Ination has remained soft and generally below target in several advanced

economies (Chart 3). Given the lag between economic activity and ination,

the ongoing strength in growth can be expected to contribute to improve-

ments in labour market conditions and, therefore, a gradual rming in wage

and price ination.

The softness in core ination in advanced economies has mainly been

due to past excess capacity. However, in contrast to the United States,

the decline in many countries that started in 2016 was likely associated

with prior appreciation of their currencies and with falling prices of goods

imported from emerging markets, notably China.

1

The effects of these fac-

tors appear to have largely dissipated, as suggested by the uptick in ina-

tion in the euro area and Japan in recent months.

In the United States, core ination started declining in 2017 despite the

depreciation of the US dollar. A large part of this slowdown can be attributed

to lower prices for services, such as telecommunications. Looking ahead,

core ination in the United States is expected to reach 2 per cent by 2019 as

a tight labour market exerts upward pressure on wage ination.

While the Bank assesses ination dynamics through the lens of economic

slack and ination expectations, the continuing softness in ination across

a number of advanced economies calls for further analysis. One possible

explanation is that the behaviour of ination in advanced economies has

changed, and ination is now less responsive to changes in economic slack

1 For background information, see S. Bhatnagar, A.-K. Cormier, K. Hess, P. de Leon-Manlagnit,

E.Martin, V. Rai, R. St-Cyr and S. Sarker, “Low Ination in Advanced Economies: Facts and Drivers,”

Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2017-16 (October 2017).

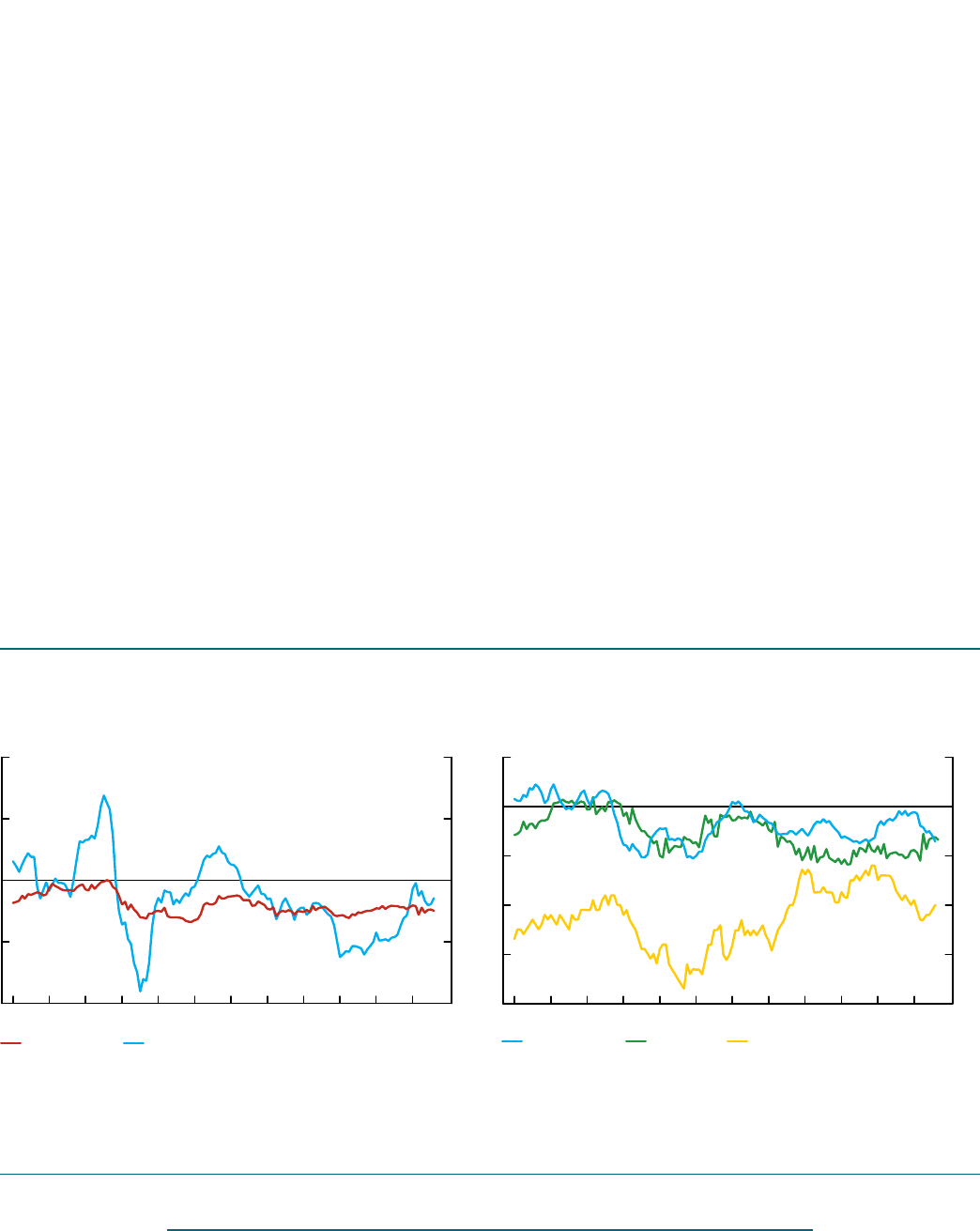

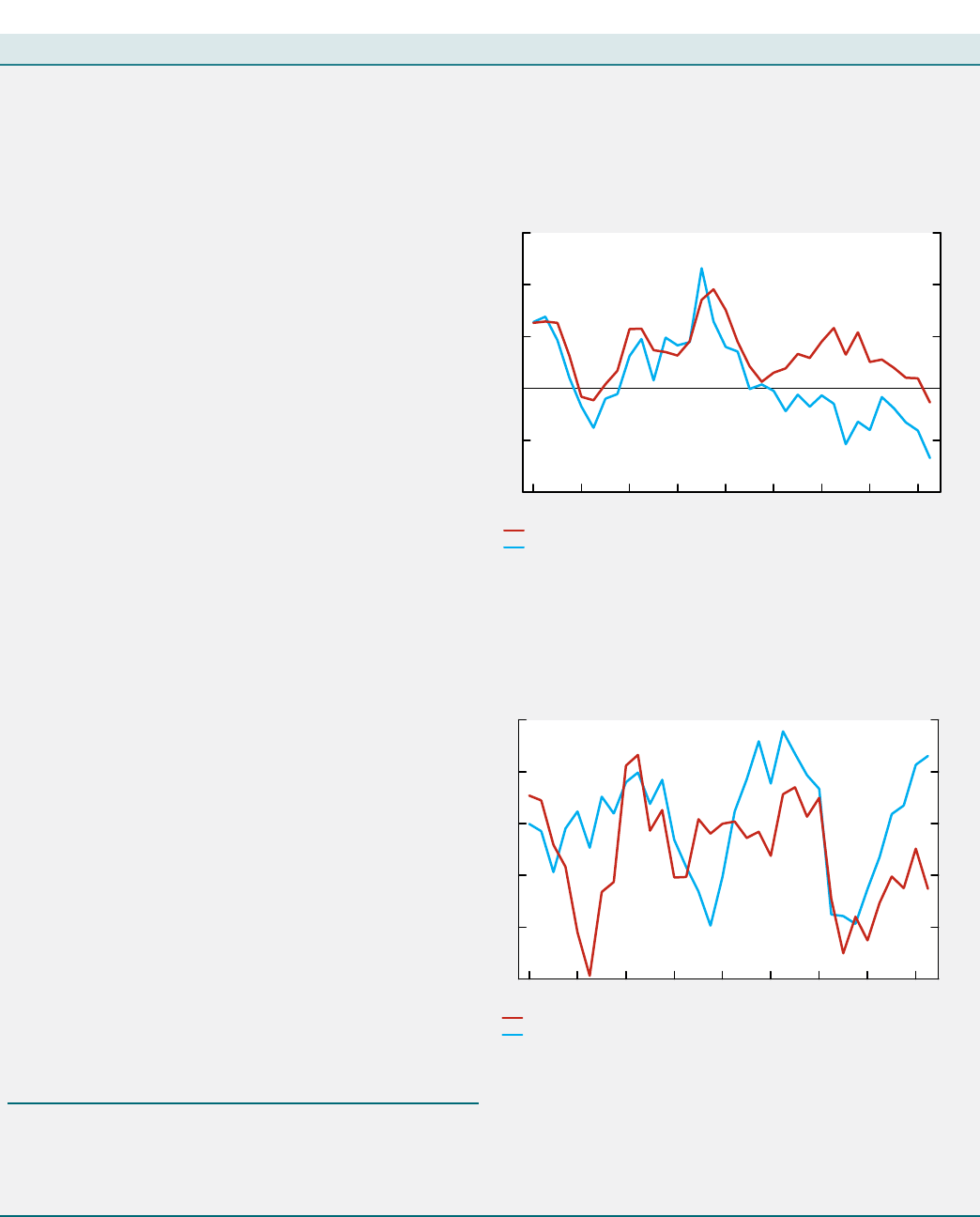

Chart 3:

In ation remains below target in advanced economies

a. Aggregate deviation of year-over-year in ation measures from central

bank total in ation targets,

a

monthly data

Core in ation T o t a l i n a t i o n

b. Deviation of year-over-year core in ation rates from central bank total

in ation targets, monthly data

United States Euro area Japan

a.

The aggregate deviation from total in ation targets is a weighted average for 11 advanced economies representing around 40 per cent of global GDP. The

weighted average is calculated using GDP shares based on International Monetary Fund estimates of the purchasing-power-parity valuations of GDP. In ation

targets are xed using 2017 targets.

Sources: National sources via Haver Analytics, International Monetary Fund and

Bank of Canada calculations

Last observations: All series except euro area, August 2017;

euro area, September 2017

2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

-3.0

-1.5

0.0

1.5

3.0

Percentage points

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016

Percentage points

4

GLOBAL ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

than in the past.

2

Another possibility is that technological advances, such

as the rise of e-commerce and the digital economy, may be playing a role.

So far, available evidence suggests that the overall effects of these techno-

logical factors on ination are small, but the Bank will continue to examine

the potential role of these and other factors (Box 1, page 8).

Emerging markets continue to drive global growth

Economic activity in China has been somewhat stronger than anticipated,

with GDP expanding robustly in the third quarter. Nevertheless, growth is

expected to soften in the coming quarters, mainly as a result of earlier policy

measures targeting the housing and nancial sectors and a smaller contri-

bution from scal policy. Despite some progress on nancial sector delever-

aging, nancial stability risks remain elevated as total credit continues to

expand at a strong pace. Looking ahead, economic growth is expected to

moderate from 6.8 per cent in 2017 to 6.3 per cent in 2019 as it continues to

shift toward a more sustainable pace and composition.

For oil-importing EMEs, the economic environment has remained gener-

ally favourable, with narrow credit spreads and sustained capital inows.

GDP growth should average about 4per cent over 2017–19, supported by

ongoing recoveries in countries previously in recession and progress on

growth-enhancing reforms. In India, economic growth has been dragged

down by the lingering adverse effects of the currency exchange initiative

launched in late 2016 as well as by the transitory costs associated with the

introduction of the national goods and services tax in July. Notwithstanding

the effects on near-term growth, these and other major reforms are

expected to support medium-term growth in India.

Growth in the “rest of the world” grouping is expected to increase from

about 1

1

/

2

per cent in 2017 to around 2

3

/

4

per cent in 2019. The economic

adjustment in oil-exporting countries is progressing as the impact from past

declines in oil prices eases.

Prices of oil and industrial commodities have risen

By convention, oil prices are assumed to remain close to their recent

average of about US$55 per barrel (Brent), roughly US$5 higher than

assumed in July (Box 2, page 9). Prices have been supported by stronger-

than-expected demand over the summer, with US demand for gasoline

reaching a ve-year high. Declines in US crude oil inventories over the last

six months and a recent stabilization in the number of active US oil rigs sug-

gest that the oil market is rebalancing (Chart 4).

Over the near term, risks to the oil price assumption are tilted to the down-

side. Prices could be lower if excess supply results from a pickup in shale

drilling activity in the United States or from a deterioration in compliance

with agreed production cuts by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting

Countries and some other oil producers.

Prices of some non-energy commodities have also increased since July.

Spot prices for base metals have risen by about 12 per cent in response to a

combination of stronger global demand and commodity-specic supply fac-

tors. Strong steel production in China over the summer supported the rise

2 For example, the IMF’s April 2013 World Economic Outlook nds evidence that the responsiveness of

ination to unemployment has been declining gradually since the mid-1970s. This attening of the Phillips

curve was found to hold throughout a sample of more than 20 advanced economies. These ndings

suggest that the ination consequences of changes in economic slack are much smaller than in the past.

GLOBAL ECONOMY

5

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

in prices of certain base metals, such as iron, nickel and zinc. In addition,

higher aluminum prices have been supported by cuts to capacity in China,

while concerns over further disruptions to mining activity in the Philippines

have boosted nickel prices. Lumber prices have increased, driven mainly

by wildres in British Columbia and the western United States and poten-

tial supply disruptions caused by the hurricanes in the United States and

the Caribbean. In contrast, agricultural prices have declined following a

seasonal drop in livestock prices and expectations of stronger global crop

yields.

Agricultural prices are expected to stay near current lows, while some

modest growth in prices of base metals, excluding iron, should be sup-

ported by strong demand and ongoing declines in inventories. The Bank

of Canada’s non-energy commodity price index is therefore expected to

remain roughly at over the projection horizon, given these contrasting

underlying outlooks.

Chart 4:

Falling crude oil inventories and a stabilizing rig count in the United States have driven up oil prices since July

a. US crude oil inventories and rig count, monthly data

US crude oil inventories, excluding

Strategic Petroleum Reserve (left scale)

US shale oil rigs

a

(right scale)

b. Crude oil prices, monthly data

Western Canada Select West Texas Intermediate Brent

a.

As an indicator for shale oil rigs, we use the number of horizontal rigs in the United States, which can also include shale gas and some conventional rigs.

Sources: US Energy Information Administration, oil prices from exchange sources

via Haver Analytics and Bloomberg L.P., Baker Hughes and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: September 2017

2014 2015 2016 2017

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

200

300

400

500

600

Number of rigs

Millions of barrels

0

25

50

75

100

125

2014 2015 2016 2017

US$ per barrel

6

GLOBAL ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Canadian Economy

Economic activity continued to grow rapidly in the second quarter of 2017,

exceeding expectations at the time of the July Report. Growth continued to

be broadly based across regions and industries and has become more bal-

anced across components of aggregate demand (Chart 5). In the rst half of

the year, growth was very strong. Consumption and residential investment

were robust, and growth in exports and business investment picked up. In

this context, excess capacity has declined more rapidly than expected, and

the Bank now estimates the output gap to be between -0.5 and 0.5 per cent

in the third quarter.

Looking ahead, the level of economic activity will be supported by rising foreign

demand and the recent rming of commodity prices, still-accommodative

monetary and nancial conditions, and public infrastructure spending. The

economy is expected to progress on a more sustainable path: the total

contribution to growth from consumption and residential investment is

projected todecline, in part because of recent interest rate increases, while

the contribution from exports is expected to improve andthat from business

investment to remain steady.

The Bank’s projection incorporates the effects of three important develop-

ments since July, namely, the policy rate increases in July and September,

the appreciation of the Canadian dollar and the increase in commodity

prices. It also reects the Bank’s current assessment of the following key

issues: the level and future growth rates of potential output; the evolution of

Chart 5:

Growth continues to be broadly based across industries

GDP at basic prices, percentage of 22 major industries growing on a month-over-month basis,

6-month moving average, monthly data

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: July 2017

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2007 2009 2011 2013 20152008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2017

%

CANADIAN ECONOMY

7

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Box 1

Canadian Infl ation: The Role of Globalization and Digitalization

The role of globalization and digitalization has received

increasing attention among policy-makers as a potential

explanation for soft infl ation across a number of advanced

economies. In this context, the Bank has investigated

whether such global factors might shed light on unexplained

softness in Canadian infl ation in recent years.

1, 2

Globalization is likely not a signifi cant contributor

to infl ation softness

Given that Canada is a small open economy, there is con-

siderable scope for globalization to aff ect Canadian infl ation.

For example, increased imports of goods from China in the

2000s were estimated to have reduced infl ation in Canada.

3

Globalization may infl uence infl ation through several

channels. New analysis examining the recent unexplained

softness in infl ation considered the impact coming through

import prices, including the implications of global slack.

It also explored the eff ect of the integration of Canada in

global value chains on domestic wages and price setting.

This analysis did not detect a signifi cant link between these

factors and the unexplained softness, although over time

the factors could become more relevant.

The eff ect of digitalization on Canadian infl ation

appears to be small, but this could change

As noted in the July Report and in Poloz (2017), structural

changes related to technological advances and digitalization

could also be aff ecting consumer price index (CPI) infl ation

globally.

4

Bank staff have reviewed the literature on the

implications of digitalization for infl ation and reported on

consultations with fi rms on the digital transformation in

some service industries.

5

This analysis reviews three key channels through which

digital technologies may aff ect infl ation:

1 See D. Brouillette and L. Savoie-Chabot, “Global Factors and Infl ation in Canada,”

Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2017-17 (October 2017).

2 The Bank bases its analysis on a Phillips curve framework, where infl ation

dynamics are explained by a measure of economic slack, infl ation expectations,

movements in commodity prices and movements in the exchange rate.

3 See L. Morel, “The Direct Eff ect of China on Canadian Consumer Prices: An

Empirical Assessment,” Bank of Canada Staff Discussion Paper No. 2007-10

(September 2007).

4 S. S. Poloz, “The Meaning of ‘Data Dependence’: An Economic Progress Report”

(speech to the St. John’s Board of Trade, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador,

September 27, 2017).

5 See W. Dong, J. Fudurich and L. Suchanek, “Digital Transformation in the Service

Sector—Insights from Consultations with Firms in Wholesale, Retail and Logistics,”

Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note (forthcoming); and K. Charbonneau,

A. Evans, S. Sarker and L. Suchanek, “Digitalization and Infl ation: A Review of the

Literature,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note (forthcoming).

• Falling prices of goods and services related to informa-

tion and communications technology (ICT) can aff ect

the CPI. The prices of some ICT products have rapidly

decreased since the 1990s as a result of technological

improvements. However, the trend in Canada appears to

be somewhat diff erent, refl ecting in part limited compe-

tition in the Canadian telecommunications sector, which

has off set some of the downward pressure on prices

relative to other countries.

6

• Digital technologies can change market structure.

Digital technologies can allow certain “superstar” fi rms

to become dominant, but they can also increase com-

petition, especially through e-commerce, which may

infl uence how retailers set prices. Evidence for Canada

suggests the latter impact is likely limited so far because

of the very small share of online retail sales held by

Canadian fi rms and the similarity between the behaviour

of online and offl ine prices.

7

To the extent that technol-

ogies are substitutes for labour, they may reduce the

bargaining power of workers and weigh on wage growth.

• Cost-effi cient technologies lead to increases in produc-

tivity. Digital innovation can create disinfl ationary pres-

sure through a reduction in production costs. However,

productivity eff ects from digitalization are diffi cult to

identify in offi cial statistics.

8

Results from the Bank’s

consultations suggest that, on balance, fi rms have seen

some reduction in operational costs, but effi ciencies are

yet to be realized for many.

There is some evidence that digitalization has had a damp-

ening eff ect on infl ation in advanced economies.

9

However,

its eff ect on Canadian infl ation appears to be small. The

relatively low adoption rate of e-commerce and other digital

technologies in Canada compared with other advanced econ-

omies could be one explanation for smaller eff ects in Canada.

The Bank will continue to explore the evolving role of global

factors, particularly digitalization.

6 See, for example, Sveriges Riksbank, “Digitalization and Infl ation,” Monetary Policy

Report (February 2015): 55–59.

7 See, for example, A. Cavallo, “Are Online and Offl ine Prices Similar? Evidence

from Large Multi-Channel Retailers,” American Economic Review 107, no. 1 (2017):

283–303; and Y. Gorodnichenko and O. Talavera, “Price Setting in Online Markets:

Basic Facts, International Comparisons, and Cross-Border Integration,” American

Economic Review 107, no. 1 (2017): 249–282.

8 E. Brynjolfsson and A. McAfee, “Race Against the Machine: How the Digital

Revolution Is Accelerating Innovation, Driving Productivity, and Irreversibly

Transforming Employment and the Economy,” The MIT Center for Digital Business

Research Brief (January 2012).

9 See, for example, Sveriges Riksbank (2015); M. Ciccarelli and C. Osbat, “Low

Infl ation in the Euro Area: Causes and Consequences,” European Central Bank

Occasional Paper Series No. 181 (January 2017); and ECB, Economic Bulletin,

Issue 2 (2015).

8

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

wages and ination, together with the potential implications of globalization

and technology (Box 1); and the sensitivity of the economy to interest rates

given elevated household indebtedness.

3

Over time, the Bank will update its

judgment as appropriate with additional data.

Largely as a result of the robust pace of growth in the rst half of the year,

real GDP is forecast to grow at 3.1 per cent in 2017. Relative to the July

projection, growth for the year is revised up, mainly because of unexpected

strength in household consumption and business investment in the second

quarter. After moderating in the second half of 2017, GDP is expected to

grow by 2.1 per cent in 2018 and 1.5 per cent in 2019 (Table 2 and Box 2).

As such, economic activity is forecast to remain close to full capacity and

at times possibly modestly above, depending on how the supply side of the

economy evolves.

Consumer price index (CPI) ination has recently picked up from low levels,

reecting higher gasoline prices, dissipating drag from food ination, and

improving economic conditions. Ination is expected to continue to rise

toward 2 per cent as the temporary effects of past uctuations in food

and electricity prices fade. Compared with the July ination projection, the

stronger Canadian dollar is expected to have a dampening impact in 2018,

while the more rapid absorption of economic slack is expected to have

an opposite, albeit smaller, effect. In this context, ination is projected to

increase to close to 2 per cent over the course of 2018 and to remain around

2 per cent until the end of 2019.

3 S. S. Poloz, “The Meaning of ‘Data Dependence’: An Economic Progress Report” (speech to the

St.John’s Board of Trade, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, September 27, 2017).

Box 2

Key Inputs to the Base-Case Projection

The Bank’s projection is always conditional on several key

assumptions, and changes to them will aff ect the outlook

for the global and Canadian economies. The Bank regularly

reviews these assumptions and assesses the sensitivity of

the economic projection to them.

• Oil prices are assumed to remain near recent average

levels. The per-barrel prices in US dollars for Brent, West

Texas Intermediate and Western Canada Select are

about $55, $50 and $40, respectively, about $5 higher

than assumed in the July Report.

• By convention, the Bank does not attempt to forecast

the exchange rate in the base-case projection. Over the

projection horizon, the Canadian dollar is assumed to

remain close to its recent average of 81 cents, compared

with the 76 cents assumed in July.

• The Bank estimates that the output gap is in a range of -0.5

to 0.5 per cent in the third quarter. For the projection, the

output gap is assumed to be at the midpoint of this range.

1

1 The level of potential output is estimated to be about 0.1 per cent higher in the

second quarter than projected in the July Report, while the level of GDP is higher

by 0.3 per cent.

This compares with the July assumption that the output

gap was -0.5 per cent, the midpoint of a -1 to 0 range, in

the second quarter of 2017.

• Business investment in the second quarter of 2017

was more robust than expected, and this increased

strength is expected to persist over the projection

horizon. Thus, the annual growth of potential output is

now assumed to be 1.5 per cent over 2018–19, which

is slightly above the assumption since April 2017

(Table 2). Further details on the Bank’s assessment

of potential output are provided in the Appendix to

the April 2017 Report, and a full reassessment will be

presented in April 2018.

• The neutral nominal policy rate is defi ned as the real

rate that is consistent with output at its potential level

and with infl ation equal to target after the eff ects of

all cyclical shocks have dissipated, plus 2 per cent

for the infl ation target. For Canada, the neutral rate

is estimated to be between 2.5 and 3.5 per cent. The

economic projection is based on the midpoint of this

range, which remains unchanged.

CANADIAN ECONOMY

9

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Growth is still expected to moderate in the second half

of 2017

The economy grew at a rapid pace in the rst half of 2017, averaging just

over 4 per cent growth at an annual rate (Table 3, Chart 6). This exceptional

strength reected robust growth in consumer spending, underpinned by

favourable nancial conditions and rising household employment and

income. Consumption growth has become more widespread across

regions, since the rebound in incomes in energy-producing provinces is now

more entrenched. A broad-based expansion in business investment and a

surge in energy exports were also contributors to growth. However, after a

strong rst quarter, housing activity pulled back in the second quarter. The

housing decline was driven by a contraction of resale activity in the Toronto

market, which was partly in response to the measures introduced by the

Ontario government in April (Chart 7). Overall, real GDP growth in the rst

half of the year was widespread, with more than two-thirds of industries and

most major demand components contributing to the expansion.

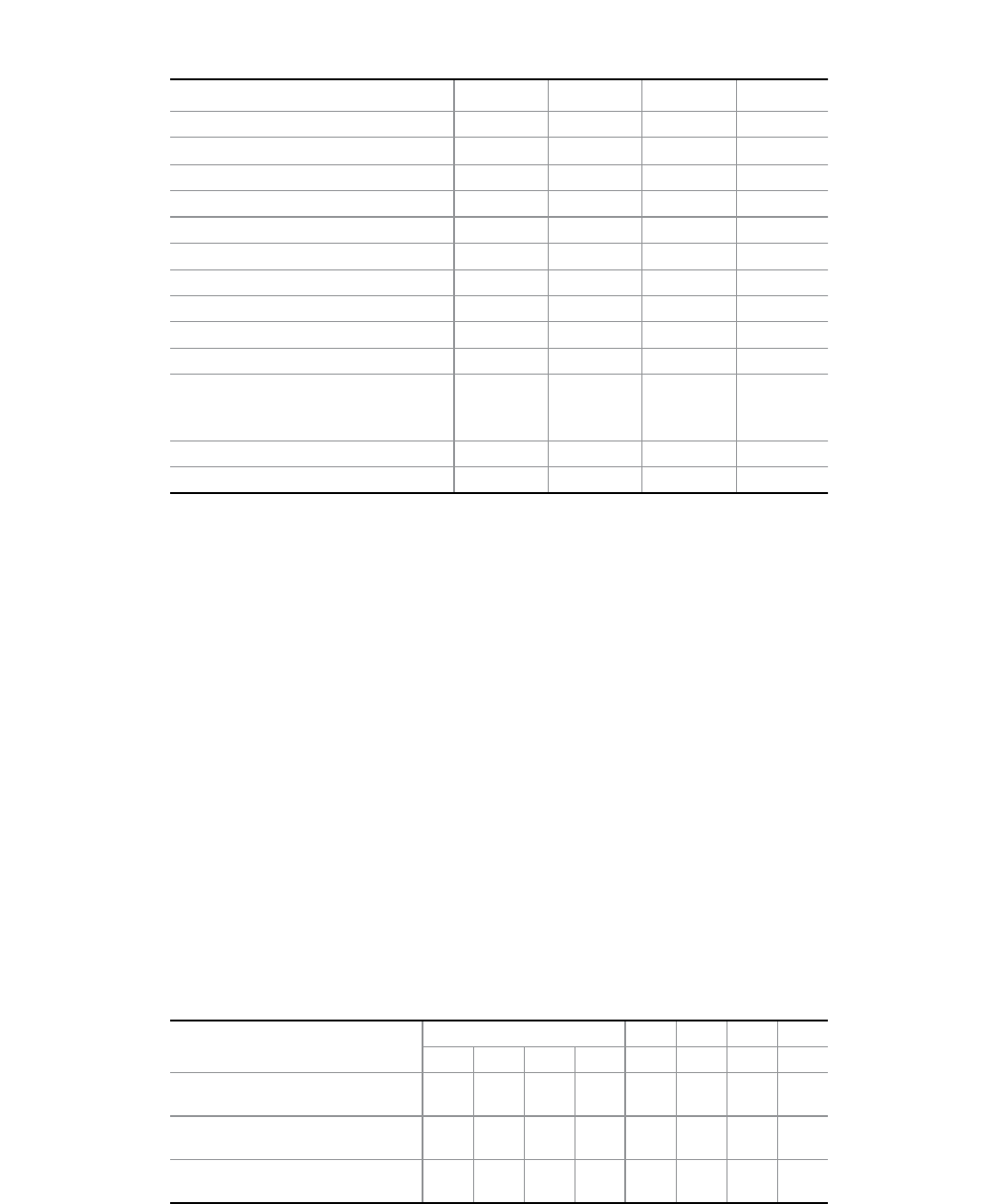

Table2: Contributions to average annual real GDP growth

Percentage points

a, b

2016 2017 2018 2019

Consumption 1.4 (1.4) 2.1 (1.9) 1.3 (1.3) 1.0 (1.0)

Housing 0.2 (0.2) 0.2 (0.3) 0.0 (0.0) -0.2 (-0.1)

Government 0.5 (0.5) 0.4 (0.5) 0.4 (0.3) 0.2 (0.0)

Business xed investment -1.0 (-1.0) 0.2 (-0.1) 0.4 (0.3) 0.3 (0.4)

Subtotal: Final domestic demand 1.1 (1.1) 2.9 (2.6) 2.1 (1.9) 1.3 (1.3)

Exports 0.4 (0.4) 0.5 (0.5) 0.6 (0.7) 0.8 (0.8)

Imports 0.2 (0.2) -1.0 (-0.9) -0.5 (-0.6) -0.6 (-0.5)

Subtotal: Net exports 0.6 (0.6) -0.5 (-0.4) 0.1 (0.1) 0.2 (0.3)

Inventories -0.3 (-0.3) 0.7 (0.6) -0.1 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

GDP 1.5 (1.5) 3.1 (2.8) 2.1 (2.0) 1.5 (1.6)

Memo items (percentage change):

Range for

potential output

1.1–1.5

(1.1–1.5)

1.0–1.6

(1.0–1.6)

1.1–1.7

(1.1–1.7)

1.1–1.9

(1.1–1.9)

Real gross domestic income (GDI) 0.8 (0.8) 4.0 (4.0) 2.3 (1.5) 1.6 (1.5)

CPI in ation 1.4 (1.4) 1.5 (1.6) 1.7 (1.8) 2.1 (2.1)

a.

Numbers in parentheses are from the projection in the previous Report.

b.

Numbers may not add to total because of rounding.

Table 3: Summary of the projection for Canada

Year-over-year percentage change

a

2017 2016 2017 2018 2019

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4 Q4

CPI in ation

1.9

(1.9)

1.3

(1.4)

1.4

(1.3)

1.4 1.4

(1.4)

1.4

(1.6)

2.1

(2.0)

2.1

(2.1)

Real GDP

2.3

(2.3)

3.7

(3.4)

3.1

(2.8)

3.1 2.0

(2.0)

3.1

(2.7)

1.7

(1.8)

1.5

(1.5)

Quarter-over-quarter percentage

change at annual rates

b

3.7

(3.7)

4.5

(3.0)

1.8

(2.0)

2.5

a.

Numbers in parentheses are from the projection in the previous Report. Details on the key inputs into the

base-case projection are provided in Box 2.

b.

Over the projection horizon, 2017Q3 and 2017Q4 are the only quarters for which some information about

real GDP growth was available at the time the projection was conducted. This is why quarter-over-quarter

percentage changes are not presented past that horizon. For longer horizons, fourth-quarter-over-fourth-

quarter percentage changes are presented.

10

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Real GDP growth is expected to moderate to a still-solid pace close to

2 per cent at an annual rate over the second half of the year as growth in

consumption and investment slows and exports temporarily decline in the

third quarter. Still, consumption growth is expected to remain solid, sup-

ported by ongoing growth in employment and income and elevated con-

sumer condence. The Canada child benet introduced in 2016 will continue

to support the level of consumption, although the effects on growth have

dissipated. Recent data show a decline in drilling rig activity and weakness

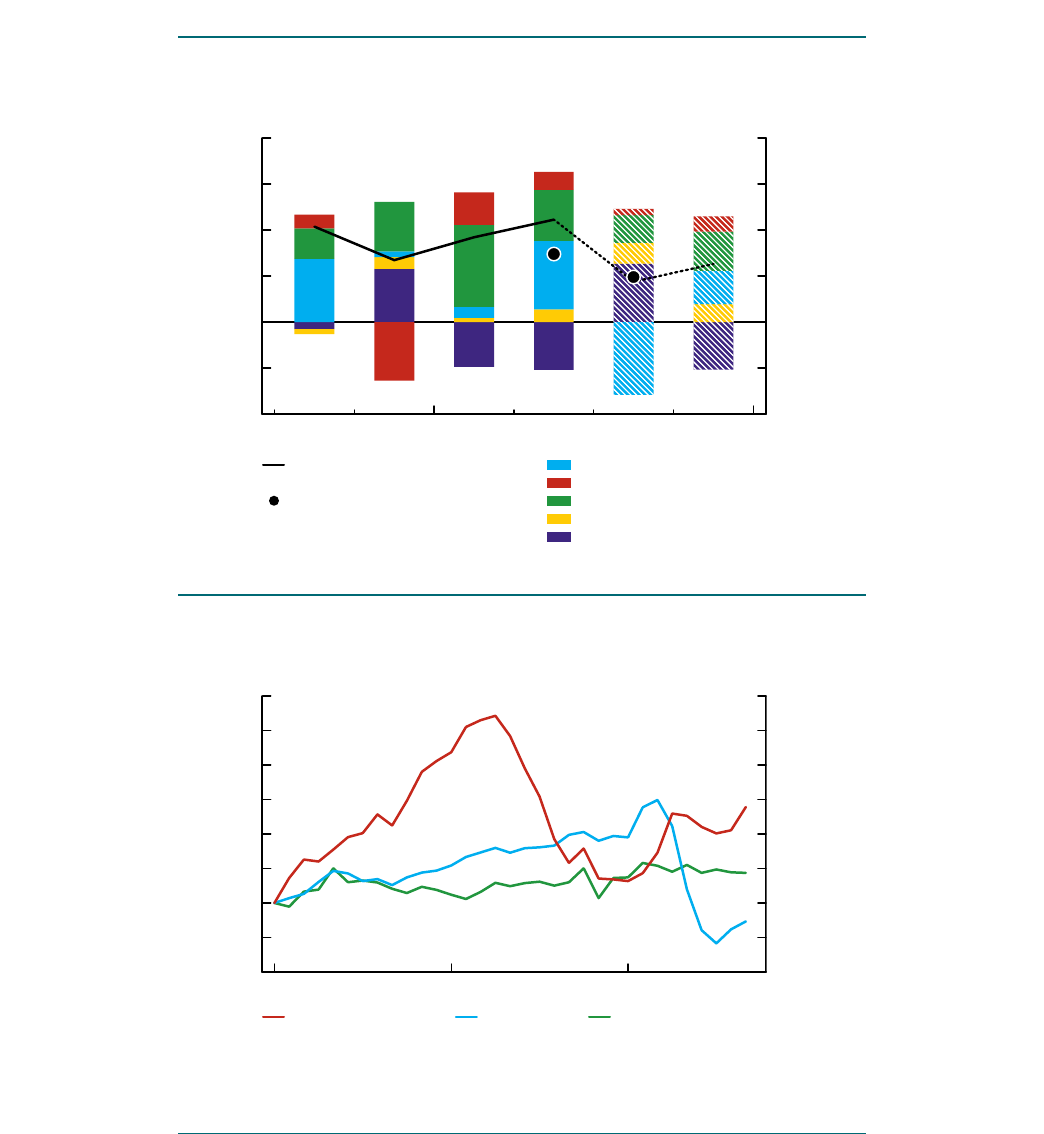

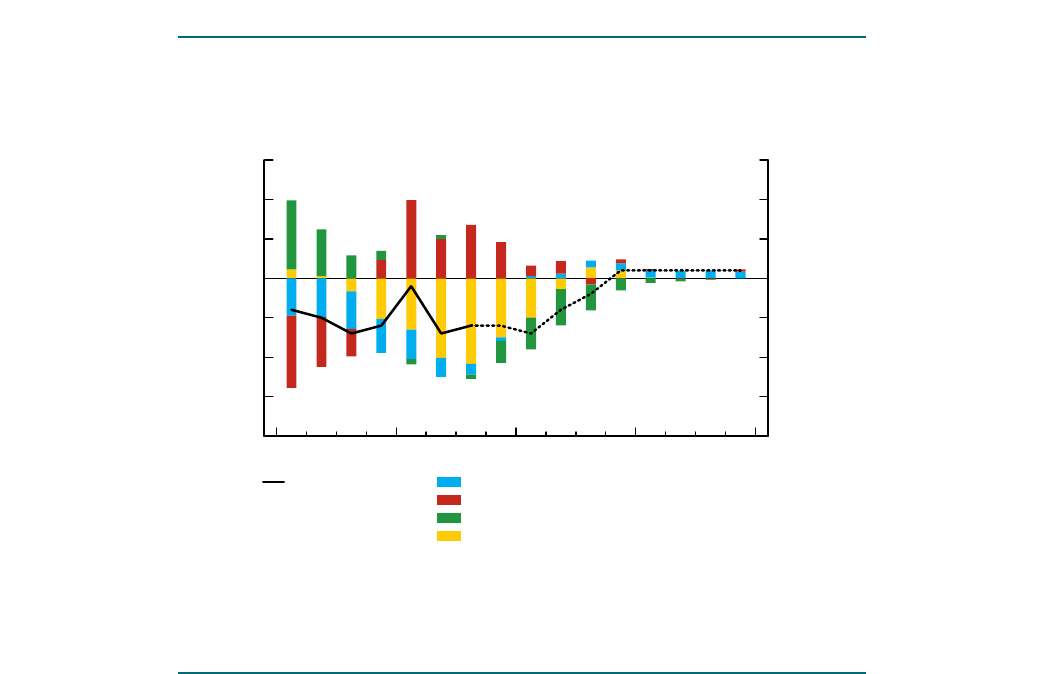

Chart 6:

The recent strong growth is expected to moderate

Contribution to real GDP growth, quarterly data

GDP growth, quarterly, at annual

rates (left scale)

GDP growth estimate in July Report,

quarterly, at annual rates (left scale)

Exports (right scale)

Business xed investment (right scale)

Consumption and housing (right scale)

Government (right scale)

Others (inventories and imports, right scale)

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada estimates and calculations Last data plotted: 2017Q4

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

%

2016 2017

Percentage points

Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4

Chart 7:

Dynamics of housing activity vary across regions

Multiple Listing Service residential sales, index: January 2015 = 100, monthly data

British Columbia (19%) Ontario (44%) Rest of Canada (36%)

Note: Numbers in parentheses represent the latest 12-month moving average of the share of total MLS

residential sales. Shares do not add to 100% because of rounding.

Sources: Canadian Real Estate Association

and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: September 2017

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

150

160

2015 2016 2017

Index

CANADIAN ECONOMY

11

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

in imports of machinery and equipment. Nonetheless, business investment

growth is expected to pick up later in the year, buoyed in part by the launch

of some large projects.

4

The temporary decline in exports in the third quarter is largely due to sched-

uled reductions in motor vehicle production and the unwinding of temporary

factors that boosted growth in the spring.

5

However, with the reversal of

these temporary effects, export growth is anticipated to rebound in the

fourth quarter, in line with foreign demand. Housing activity is estimated to

have declined further in the third quarter, dampened by the slowdown in

Ontario, but is expected to increase in the fourth quarter, as resales have

recently started to pick up.

The economy is operating close to capacity

Robust growth over recent quarters has contributed to a rapid narrowing of

the output gap, and the Bank estimates that the Canadian economy is now

operating close to capacity (Box 2).

6

This estimate incorporates an assess-

ment of the impact of strong recent investment on potential output growth.

The robust growth of demand, combined with declining excess capacity,

is providing an important incentive for businesses to invest and hire more

workers. New rms could also be created, and workers could increase their

hours worked or participation in the labour force.

7

Growth in employment has remained strong at the national level and has

been broad-based across sectors and regions. The unemployment rate has

continued to fall, but its decline likely overstates the degree of improvement

in the labour market (Chart 8). In particular, the Bank’s labour market indi-

cator, a composite indicator, is still relatively high. Its current level reects

4 Several large multi-year projects began around mid-2017, including Husky’s West White Rose project

in Newfoundland and Labrador, and Enbridge’s Line 3 in Alberta and Saskatchewan and gas pipeline

expansion in British Columbia.

5 Changes in the production mandates of multinational automobile assemblers are coming into effect in

the second half of 2017.

6 Responses to the Bank’s autumn Business Outlook Survey also suggest that, although the degree of

slack differs across regions, capacity pressures have increased over the past 12 months.

7 The endogenous response of labour market participation and hours worked to strong demand growth

contributes 0.3 per cent to the level of potential by the end of 2019. This response was originally

incorporated into the Bank’s projection in the April 2016 Report.

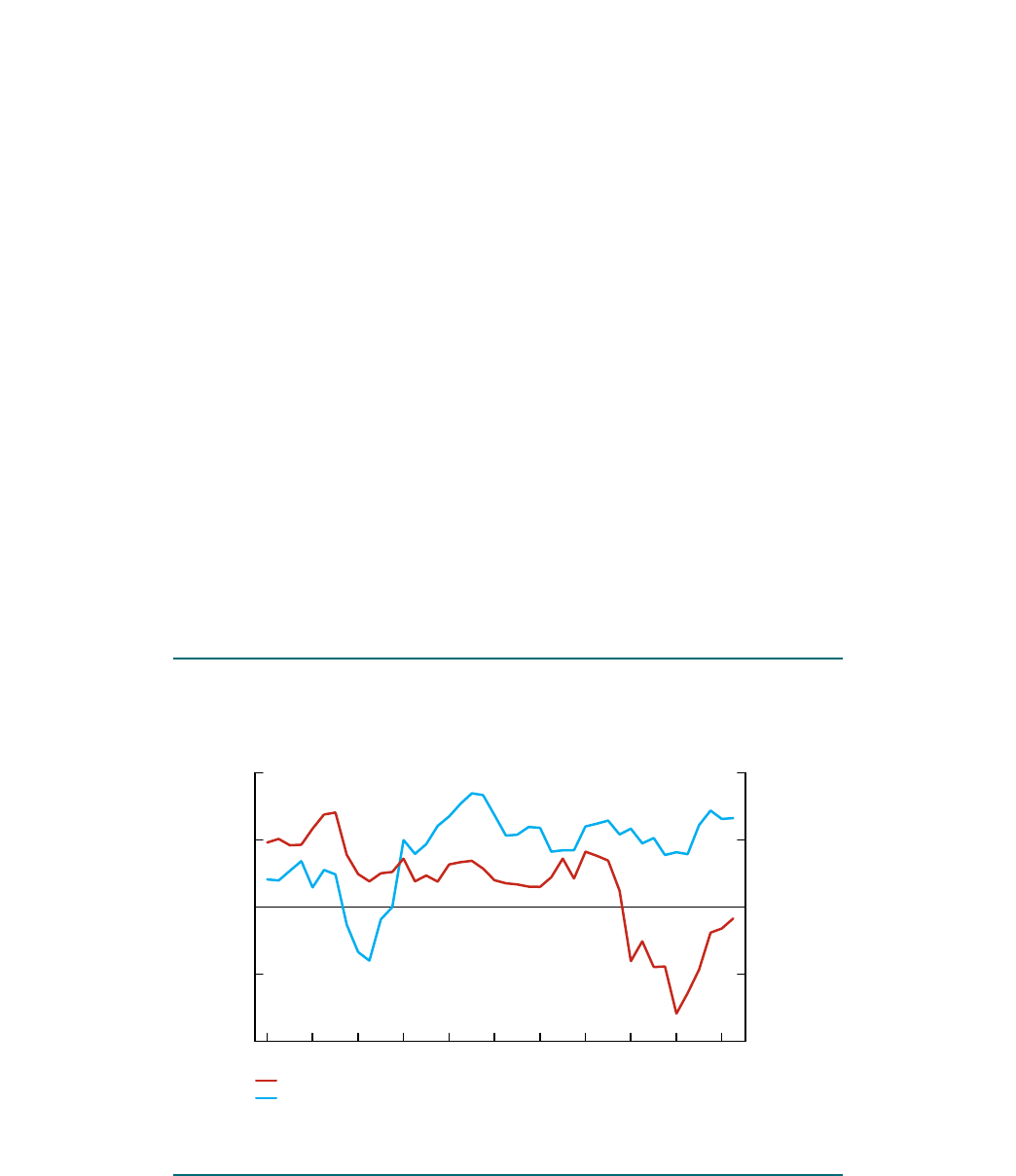

Chart 8:

The Bank’s labour market indicator is still relatively high

Monthly data

Unemployment rate Labour market indicator

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: September 2017

5

6

7

8

9

2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017

%

July Report

12

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Box 3

Wage Dynamics and Infl ationary Pressures

Infl ationary pressures coming from wages are muted

The Canadian economy has benefi ted from impressive

employment gains over the past year. Nonetheless, there

is evidence of slack remaining in the labour market; for

example, average hours worked, although improving, are

still below trend.

1

Other evidence of labour market slack

comes from the Bank of Canada labour market indicator,

which remains high relative to its level before the Great

Recession, and from the labour force participation rate of

youth, which remains low.

The growth of compensation per hour worked and various

measures of wage growth also remain below their histor-

ical averages. For example, unit labour costs for both the

total economy and the resource sector have been declining

since 2016 (Chart 3-A). Unit labour cost (ULC)—defi ned

as labour compensation per hour worked divided by labour

productivity—is viewed as a useful way to measure infl a-

tionary pressure coming from the labour market. ULC has

declined recently because labour productivity has grown

faster than hourly compensation (Chart 3-B). Overall, labour

cost pressur es are growing at a moderate pace and are

below what would be expected at this stage of the cycle.

Consequently, infl ationary pressures from wages remain

muted.

Another factor that could explain the absence of wage pres-

sures is globalization.

2

The possibility of relocating produc-

tion activities to low-wage countries may have reduced the

bargaining power of workers in advanced economies and

lowered their wage expectations. In turn, more-integrated

global activity and openness to trade could also increase

competition in domestic markets, which could further

restrain the growth of domestic wages.

Labour market slack is weighing on wage growth

Based on estimates from a wage-equation regression

model, past labour market slack appears to be the key factor

weighing on wage growth since 2011, with the peak impact

of labour market slack on wage infl ation being felt after

1 See D. Brouillette, K. Gribbin, J.-D. Guénette, J. Ketcheson, O. Kostyshyna,

J.Lachaine and C.Scarff e, “A Canada–US Comparison of Labour Market

Conditions,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note No. 2017-4 (April 2017).

2 The impact of globalization on infl ation is discussed in Box 1.

(continued…)

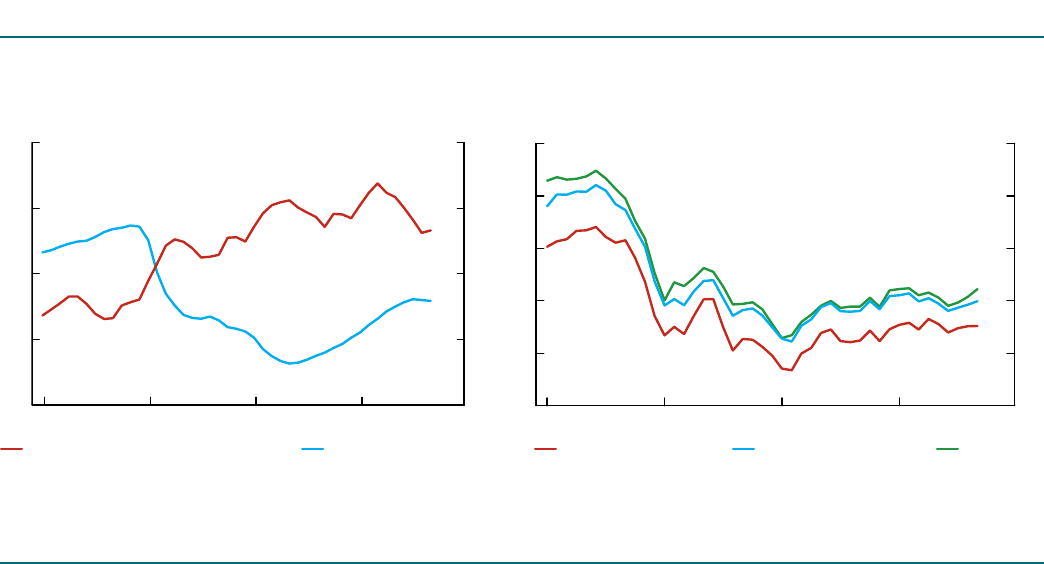

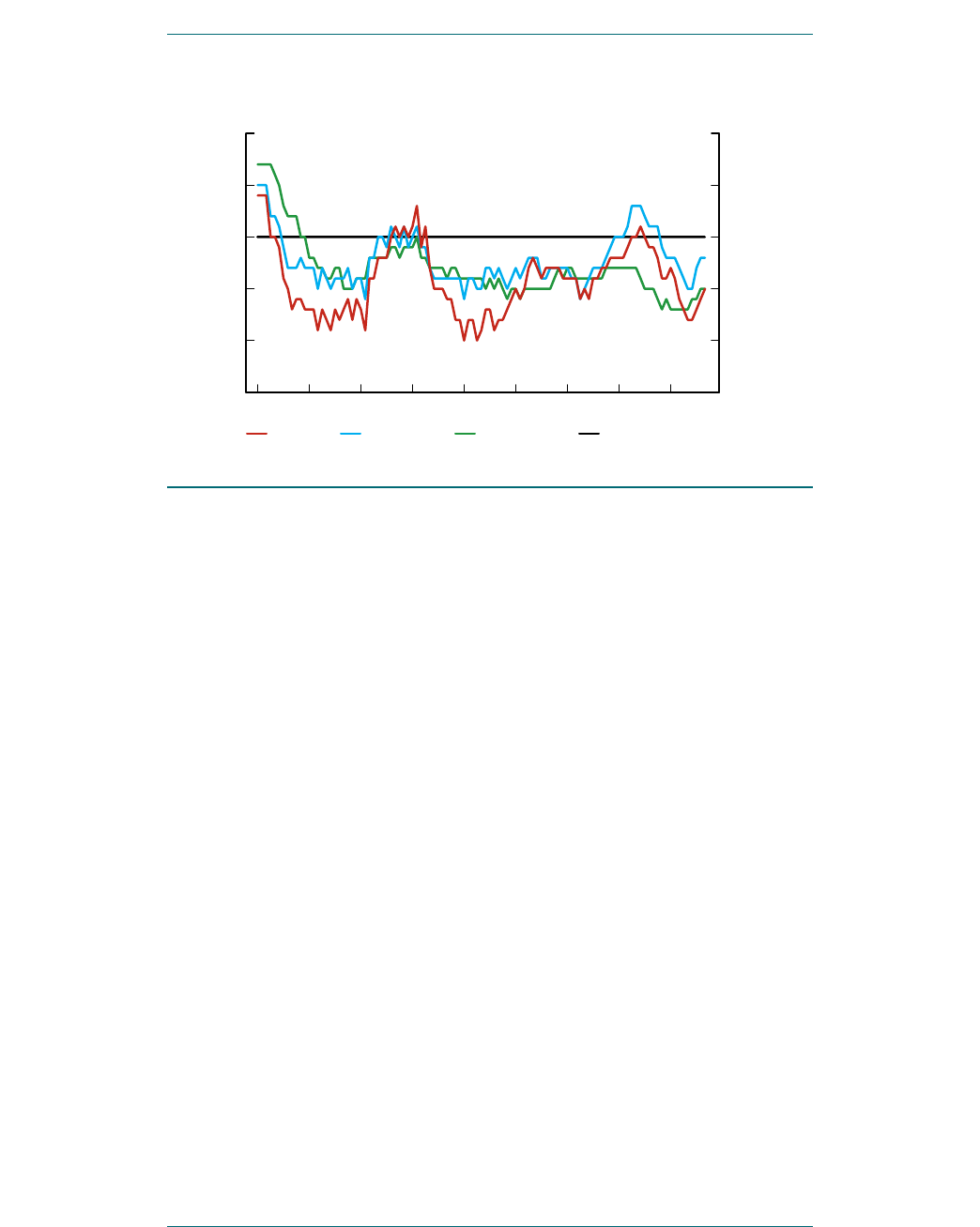

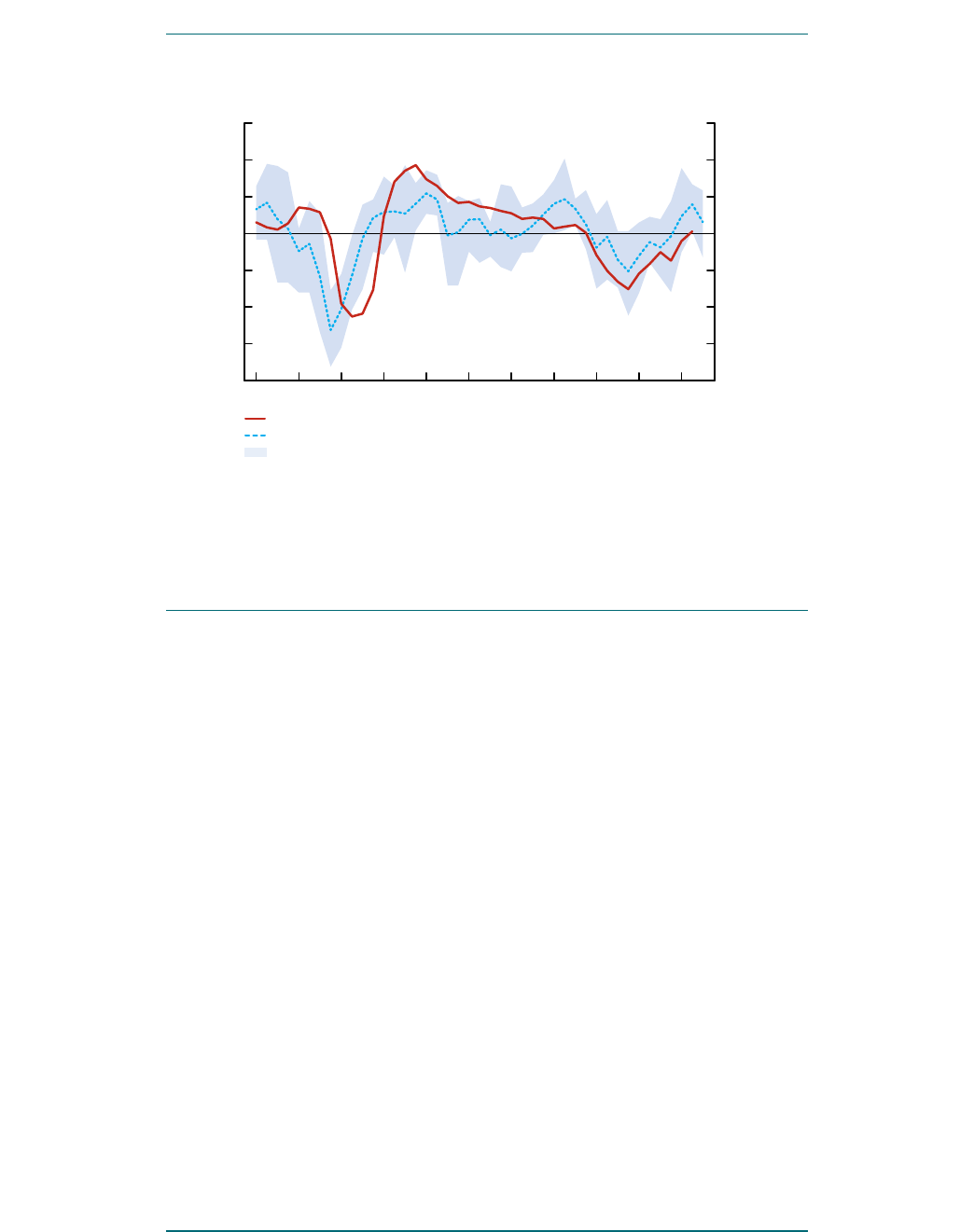

Growth in unit labour costs has been subdued

recently

Year-over-year percentage change, quarterly data

Unit labour cost, total economy (left scale)

Unit labour cost, resource sector (right scale)

Sources: Statistics Canada

and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: 2017Q2

Chart 3-A:

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

%%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

Unit labour costs decrease when compensation

grows less quickly than labour productivity

Year-over-year percentage change, quarterly data

Compensation per hour worked (left scale)

Labour productivity (right scale)

Sources: Statistics Canada

and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: 2017Q2

Chart 3-B:

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

0

1

2

3

4

5

%%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

CANADIAN ECONOMY

13

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

the fact that the long-term unemployment rate remains elevated, average

hours worked remain low and wage growth continues to be modest (for

details on wage growth dynamics, see Box 3). With recent productivity

gains exceeding wage increases, labour cost pressures have been relatively

low. Moreover, according to the autumn Business Outlook Survey, there

is clear evidence of ongoing slack in energy-producing regions. As well,

binding labour shortages appear to be prevalent only in British Columbia

and in specic sectors.

Taken together, these developments indicate that labour markets are not yet

a source of inationary pressures and that opportunities for further expan-

sions of employment remain.

Inflation has increased as expected and remains below

2 per cent

CPI ination has increased in recent months, largely as expected. CPI ination

rose from a trough of 1 per cent in June to 1.6 per cent in September, mostly

reecting dynamics in gasoline prices. Hurricane Harvey’s disruption of rening

capacity temporarily boosted gasoline prices and, thus, ination by 0.2 per-

centage points in September. Additional contributors to the recent rise in CPI

ination were the fading effects of factors such as weak ination in food prices

and dissipating economic slack. However, these two factors, together with the

electricity rebates in Ontario, still contribute to keeping CPI ination below the

2 per cent target. Moreover, the recent appreciation of the Canadian dollar is

estimated to reduce projected ination. Several other factors, including digital-

ization, may be having some dampening impact on ination (Box 1).

Ination in the second half of 2017 is expected to be similar on average

to that forecast in July. The impact of the change in the exchange rate is

slightly greater, while that from economic slack is slightly less.

Box 3 (continued)

roughly one year.

3

The drag from weak labour produc-

tivity in 2015 has now dissipated, owing to the rebound

of labour productivity over the fi rst half of 2017. But other

factors could also be at play. For example, workers formerly

employed in the relatively high-paying oil and gas sector

may have moved to lower-paid jobs in other sectors. Bank

staff estimate that the decline in commodity prices may

have reduced wage growth by about 0.5 percentage points

by mid-2016. However, these reallocation eff ects, and other

factors holding down wage growth, appear to be fading.

3 See D. Brouillette, J. Ketcheson, O. Kostyshyna and J. Lachaine, “Wage Growth in

Canada and the United States: Factors Behind Recent Weakness,” Bank of Canada

Staff Analytical Note No. 2017-8 (July 2017). Labour market slack is measured

by the labour gap—the percentage diff erence between actual total hours worked

and trend total hours worked, based on the integrated framework approach

to estimating potential output and the output gap. See L. Pichette, P.St-Amant,

B.Tomlin and K.Anoma, “Measuring Potential Output at the Bank of Canada: The

Extended Multivariate Filter and the Integrated Framework,” Bank of Canada Staff

Discussion Paper No. 2015-1 (January 2015).

Wage growth is expected to pick up as labour market

slack dissipates

Wage growth is projected to increase as the eff ects of past

labour market slack continue to dissipate in coming quar-

ters. Moreover, if productivity growth remains strong, it

could lead to higher wages, especially as the labour market

tightens. Wage growth could potentially accelerate if labour

shortages were to become more pervasive since, historically,

strong wage growth has been associated with signifi cant

excess demand in the labour market.

The recently announced increases to the minimum wage in

Ontario and Alberta could have disproportionately higher

eff ects on the wages of younger workers. However, they are

expected to have only a small positive impact on aggregate

national wages.

Looking ahead, stronger wage growth should contribute to

the expected gradual increase in infl ation over the projec-

tion horizon.

14

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Core ination measures also started to drift upward in recent months,

consistent with declining slack in the past and the diminishing drag from

weak food ination. The range of core measures was 1.5 to 1.8 per cent in

September (Chart 9). These levels are roughly consistent with estimates of

the evolution of excess capacity over previous quarters.

Monetary and financial conditions are somewhat less

stimulative

Financial conditions for both households and businesses remain broadly

stimulative but have become less so since the middle of this year (Chart 10).

Market interest rates have risen, partly reecting improvements in economic

conditions in Canada and related increases in the Bank’s policy rate in July

and September.

The rise in bank funding costs prompted nancial institutions to raise

mortgage and consumer credit rates. For example, ve-year xed mortgage

rates have increased by about 50 basis points since the July Report. The

estimated effective rate for businesses has increased by about 50 basis

points since early June, in line with business prime rates. In that context,

the Bank’s Business Outlook Survey and Senior Loan Ofcer Survey both

report that, aside from the overall increase in interest rates, business lending

conditions were broadly unchanged during the third quarter of 2017.

8

The

surveys noted that recent healthy rm performance and competition among

lenders helped ease non-price borrowing conditions for businesses, while

some rms in commodity and related industries saw a modest rise in bor-

rowing costs.

The Canadian dollar has appreciated against the US dollar, reecting higher

commodity prices, narrower US–Canada interest rate spreads and the

weaker US dollar. The US dollar remains somewhat lower than it was in July,

despite rming in recent weeks.

8 Both surveys dene the cost of credit as spreads over base rates rather than as the level of rates.

Chart 9:

The Bank’s three measures of core in ation drifted up, consistent

with decreasing economic slack

Year-over-year percentage change, monthly data

CPI-trim CPI-median CPI-common Target

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada Last observation: September 2017

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

%

CANADIAN ECONOMY

15

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

GDP growth is expected to moderate to a more

sustainable pace

The Bank projects that economic growth will slow and quarterly growth

rates will average close to potential growth over 2018–19 (Table 3). The

composition of GDP growth is anticipated to remain relatively balanced.

Solid growth of foreign demand is expected to support export growth and

promote business investment. Consumption and residential investment

are projected to moderate as households respond to less-accommodative

nancial conditions and as macroprudential and other housing policy

measures continue to weigh on activity in the housing market. Government

spending is expected to boost growth over the coming quarters, reecting

previously announced scal measures.

9

Economic growth is expected to remain broad-based across sectors. The

solid expansion of the service sector is projected to continue, and the recent

strength in goods-producing industries is now more entrenched (Chart 11).

Results from the Business Outlook Survey also suggest that strong indica-

tors of future sales remain widespread across regions and sectors (Chart 12).

9 The Bank’s scenario also incorporates measures announced since the July 2017 Report, including the

new spending measures contained in the British Columbia budget update. Moreover, the persistently

weaker-than-expected data for government infrastructure spending suggest a more modest pickup in

the current year and, therefore, a smaller payback thereafter than was projected in July.

Chart 10:

Borrowing rates have increased recently

Weekly data

Effective business interest rate Effective household interest rate

Note: For more information on the series, see

Statistics > Credit Conditions > Financial Indicators

ontheBank of Canada’s website.

Source: Bank of Canada Last observation: October 20, 2017

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

%

July Report

16

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Chart 11:

The expansion of the service sector continues, while the strength in

goods-producing industries is more entrenched

Contribution to growth in real GDP at basic prices, seasonally adjusted, monthly data

Growth in real GDP at

basic prices (year-over-

year percentage change,

leftscale)

Goods, commodity-related industries (right scale)

Goods, non-commodity-related industries (right scale)

Se rvices (right scale)

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: July 2017

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

2015 2016 2017

Percentage points%

Chart 12:

Indicators of future sales continue to suggest healthy sales

prospects across all regions

Contribution to balance of opinion,

a

quarterly data

Atlantic provinces

British Columbia

Ontario

Prairies

Quebec

Total balance of opinion

a.

Percentage of rms in the Business Outlook Survey reporting that recent indicators (order books,

advance bookings, sales inquiries, etc.) have improved compared with 12 months ago minus the

percentage of rms reporting that indicators have deteriorated

Source: Bank of Canada Last observation: 2017Q3

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

2014 2015 2016 2017

%%

CANADIAN ECONOMY

17

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

The recovery in business investment is becoming more

entrenched

After rebounding in the rst part of 2017, business investment is expected to

grow at a more moderate, but steady, pace over the projection period. With

the economy operating close to capacity, ongoing increases in household

and foreign demand, solid prot margins and robust business condence

are expected to support growth in business investment (Chart 13 and

Chart 14). Results from the autumn Business Outlook Survey indicate that

while intentions to increase investment spending have come down from

recent high levels, they remain widespread across sectors and regions.

10

Data on business investment may not fully capture rm expenditures to

increase capacity and productivity. For example, spending on cloud com-

puting or other information technology infrastructure services is often treated

as an operating expense rather than as an investment per se. Yet, such

innovation may lead to stronger productivity and potential output for a given

level of investment spending. The results of both the Business Outlook Survey

and consultations conducted by the Bank indicate that businesses expect to

continue to focus on digital technologies to grow their productive capacity.

11

The rming of global commodity prices and the improvement in the bal-

ance sheets of oil and gas companies will support a gradual expansion of

commodity-related investment, but growth prospects are limited, given the

assumed outlook for oil prices (Box 2). Non-commodity business investment

is expected to expand with the growth of demand in Canada’s major trading

partners. Nevertheless, uncertainty about US trade policy and structural

10 The survey was conducted from August 24 to September 19, before the US Department of Commerce

issued a preliminary ruling recommending the levy of countervailing and anti-dumping duties on some

Canadian aircraft exports.

11 See, for example, OECD, “Key Issues for Digital Transformation in the G20” (January 12, 2017);

B.vanArk, C. Corrado, A. Erumban and G. Levanon, “Navigating the New Digital Economy,”

Conference Board of Canada (2016); and W. Dong, J. Fudurich and L. Suchanek, “Digital

Transformation in the Service Sector—Insights from Consultations with Firms in Wholesale, Retail and

Logistics,” Bank of Canada Staff Analytical Note (forthcoming).

Chart 13:

Pro t margins for oil and gas industries are recovering strongly,

while in other industries they remain close to historical highs

Operational pro t margin, quarterly data

Oil and gas extraction and support activities (left scale)

Non- nancial industries, excluding oil and gas extraction and support activities

(right scale)

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations Last observation: 2017Q2

4

5

6

7

8

-30

-15

0

15

30

%%

2007 2009 2011 2013 20152008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2017

18

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

challenges, including expected low trend labour force and productivity

growth in Canada relative to history, are expected to continue to restrain

investment growth.

12

Exports are anticipated to grow in line with foreign demand

As expected in July, Canadian export growth has shown temporary

weakness in recent months, partly due to the expected retrenchment in

automobile production in the third quarter. Over the projection, exports

are anticipated to grow roughly in line with strengthening foreign demand

(Char t 15). The growth of imports is expected to slow with decelerating

domestic demand. However, the contribution of net exports to GDP growth

over 2018 and 2019 is slightly weaker than anticipated in the July Report

following the recent appreciation of the Canadian dollar.

Over the past year, the growth of exports of services, driven by transporta-

tion and travel services, has been solid and should continue at a similar

pace. Non-commodity goods exports have also picked up recently, and

several goods components, including industrial machinery and equip-

ment, plastics and rubber products, and food and beverage products, are

expected to benet from global growth.

As a result of several ongoing challenges, the growth of non-commodity

goods exports is expected to remain moderate. Deteriorating competitive-

ness and the relocation of production outside Canada by some multinational

rms have contributed to a loss of productive capacity and a reduction

in the global market share of Canadian goods exporters. An important

12 The effect of this uncertainty is projected to reduce investment growth by about 0.7 percentage points

and subtract about 0.2 percentage points from Canadian export growth in both 2017 and 2018.

Chart 14:

Indicators of business sentiment have improved inrecent quarters

Quarterly data

Business investment (year-over-year percentage change, left scale)

Historical average of surveys

a

(right scale)

Range of selected business surveys

a

(right scale)

a. Deviations from their historical average and scaled by their standard deviations

Sources: Statistics Canada, The Conference Board

of Canada, The Gandalf Group, Canadian Federation

of Independent Business, IHS Markit, Chartered

Professional Accountants of Canada, Export

Development Canada, Bank of Canada and Bank of

Canada calculations

Last observations:

Business investment, 2017Q2;

range and historical average

of selected surveys, 2017Q3

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

-4

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

-40

-30

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

%%

CANADIAN ECONOMY

19

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

example is recent developments in the auto industry. Uncertainty about pro-

posed trade measures and the status of trade agreements is also assumed

to be hindering Canada’s ability to benet from an improving global outlook.

Growth of commodity exports is expected to be modest over the next two

years, since production and exports have been restrained by limited invest-

ment in new capacity in the sector in recent years. Over the longer term,

these exports could grow more strongly if commodity prices increased

further and investment and productive capacity expand.

Household spending is expected to slow

Consumption growth is projected to moderate and residential investment is

expected to contract modestly over 2018–19. Several factors are expected

to weigh on household spending, notably, an anticipated slowdown in the

growth of disposable income (Chart 16). Moreover, while nancial condi-

tions remain broadly stimulative, higher interest rates have increased

the cost of new borrowing and of servicing outstanding debt. The higher

borrowing costs are likely to dampen household spending, particularly on

durable goods and housing. Given higher overall debt levels, such spending

is expected to be more sensitive to interest rate changes than in previous

cycles (see the Appendix for a description of recent changes to the model-

ling of household consumption and debt). While higher interest rates on con-

sumer credit, home equity lines of credit and variable-rate mortgages affect

borrowers immediately, the impact of the recent rate increases on holders

of xed-rate mortgages will be gradual. Mortgages with xed rates of three

to ve years represent a large share of the total debt of households, and

income gains should help xed-rate mortgage holders to continue servicing

their debt at renewal.

13

13 In particular, at current interest rates, households with ve-year xed-rate mortgages can renegotiate

at a lower rate than at origination, and most of those renewing over the projection horizon are likely to

experience a lower debt-service ratio, mostly because of cumulative income gains. These mortgage-

holders are thus well positioned to adapt to higher mortgage rates.

Chart 15:

Exports are projected to increase with foreign demand

Chained 2007 dollars, index: 2008Q3 = 100, quarterly data

Foreign demand,

non-commodity exports

a

Non-commodity exports Commodity exports

a.

Foreign demand for Canadian non-commodity exports is based on GRACE (2007 = 100). For details,

seeA. Binette, T. Chernis and D. de Munnik, “Global Real Activity for Canadian Exports: GRACE,”

Bankof Canada Staff Discussion Paper No. 2017-2 (January 2017).

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations and projections

75

85

95

105

115

125

2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

Index

Start of

nancial

crisis

Start of

oil price

shock

20

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Other factors are also expected to weigh on housing activity. The level of

housing starts is projected to decrease in the coming years, in line with

an anticipated gradual slowing of population growth. Moreover, macro-

prudential and other housing policy measures, while contributing to more

sustainable debt proles going forward, are also expected to weigh on

housing demand. In particular, the Ofce of the Superintendent of Financial

Institutions (OSFI) recently announced new guidelines aimed at reinforcing

residential mortgage underwriting practices. These guidelines are expected

to subtract about 0.2 per cent from the level of GDP by the end of 2019.

14

Taken together, recent interest rate increases and macroprudential policy

changes are likely to have a moderating inuence on residential investment

as some prospective homebuyers respond by taking on smaller mortgages

while others delay purchases.

CPI inflation is expected to increase to around 2 per cent

CPI ination is anticipated to average 1.4 per cent in the fourth quarter and

to move up to around 2 per cent in the second half of 2018, staying close to

the target thereafter (Table 3 and Char t 17).

In the base-case projection, the gradual increase in projected ination

primarily reects the unwinding of temporary factors. Downward pressures

from below-average growth in food prices should completely dissipate by

the beginning of 2018, while those from the electricity rebates in Ontario

should last until the middle of the year. After subtracting an estimated

0.2percentage points from ination in the second half of 2017, pass-through

effects of the stronger Canadian dollar are expected to become stronger,

with a peak impact on ination of -0.5 percentage points in the second

quarter of 2018, before fading by the end of 2018.

14 OSFI published its review of Guideline B20, Residential Mortgage Underwriting Practices and

Procedures, on October 17. The new guidelines take effect January 1, 2018. The Bank’s estimate of the

effects of these guidelines incorporates model simulations and historical experience following changes

to housing regulations. There is considerable uncertainty around the overall impact of these measures

on the economy because it is difcult to forecast the change in behaviour of borrowers and lenders.

Chart 16:

Consumption growth is projected to moderate, in line with

disposable income

Nominal percentage change, annual data

Savings rate (in per cent)

Household disposable income Consumption

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada calculations and projections

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019

%

CANADIAN ECONOMY

21

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

This projection is consistent with medium- and long-term ination expecta-

tions remaining well anchored. The September 2017 Consensus Economics

forecast for CPI ination is 1.6per cent in 2017 and 1.9 per cent in 2018. A

quarterly question on long-term ination expectations shows an average of

2 per cent through 2027.

Based on the past dispersion of private sector forecasts, a reasonable range

around the base-case projection for CPI ination is ±0.3 percentage points.

This range is intended to convey a sense of forecast uncertainty. A comple-

mentary perspective is provided using statistical analysis of the Bank’s fore-

cast errors, which suggests that a 50 per cent condence interval around

the base-case projection widens from ±0.3 percentage points in the fourth

quarter of 2017 to ±0.6 percentage points by the end of 2019. Over the same

period, a90 per cent condence band widens from ±0.6 to ±1.5percentage

points.

Summary of key projection issues

The Canadian economy is operating close to capacity, and ination is

expected to increase to close to 2 per cent over the next several quarters. In

this context, the Bank is focusing on assessing the importance of four key

issues.

The Bank is assessing the extent to which potential growth increases with

strong demand, given that the economy is close to capacity. The base-

case projection incorporates some effect of strong demand growth on

potential.

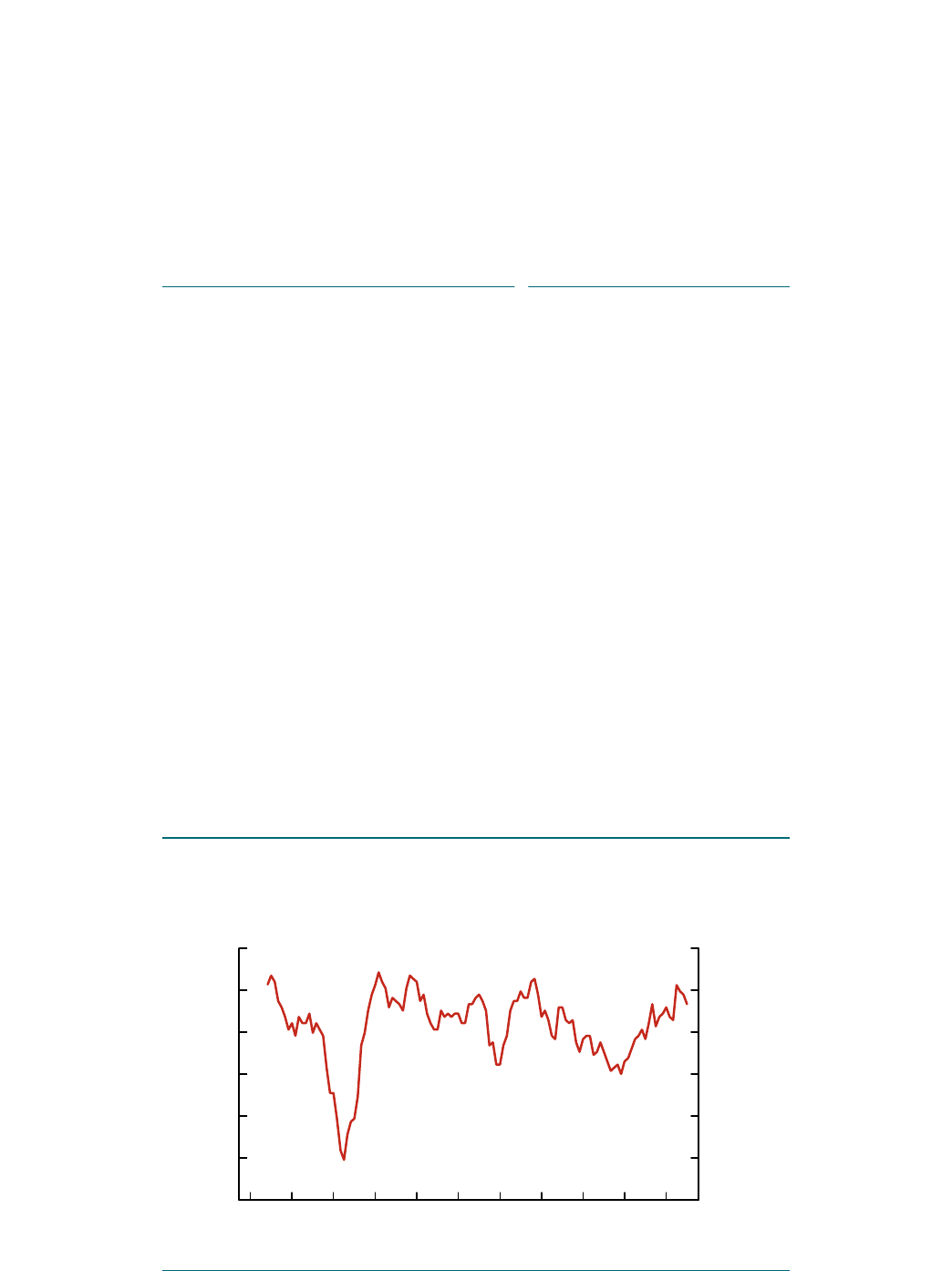

Chart 17:

CPI in ation is expected to increase and remain close to 2 per cent

over the projection horizon

Contribution to the deviation of in ation from 2 per cent, quarterly data

CPI in ation

(year-over-year

percentage change,

left scale)

Output gap (right scale)

Commodity prices, excluding pass-through

a

(right scale)

Exchange rate pass-through (right scale)

Other factors

b

(right scale)

Total in ation proj

a.

This also includes the effect on in ation of the divergence from the typical relationship between gasoline

and crude oil prices, the introduction of the cap-and-trade plan in Ontario and the Alberta carbon levy.

b. From mid-2016 until early 2018, on net, other factors mostly represent the expected impact of below-average

in ation in food products and the estimated impact on electricity prices of Ontario’s Fair Hydro Plan.

Sources: Statistics Canada and Bank of Canada estimates, calculations and projections

2016 2017 2018 2019

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Percentage points

%

22

CANADIAN ECONOMY

BANK OF CANADA • MONETARY POLICY REPORT • OCTOBER 2017

Global and technological factors have lowered ination in advanced

economies in recent years. Their impact on Canadian ination to date

does not appear to be signicant, but work in this area continues. In the

Bank’s projection, the dynamics of ination in Canada reect the tem-

porary effects of sector-specic factors, exchange rate pass-through and

the evolution of economic slack.

Despite recent labour market improvements, wage gains remain subdued

and are likely to increase only gradually. The projection builds in scope

for greater labour market participation and hours worked before wage

increases would add meaningful upward pressure on ination.

Finally, household spending is being inuenced by high levels of house-

hold debt and various macroprudential and other measures targeting the

housing market. The Bank’s main policy model has been revised to reect

that households are more responsive to interest rates when they are

carrying elevated debt loads. The projection also incorporates estimates

of the effects of the new housing measures.

The Bank will continue to monitor all of these issues, given their signicance

for the ination outlook.

CANADIAN ECONOMY