ACF

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Administration on Children, Youth and Families

Administration

for Children

and Families

1. Log No: ACYF-CB-IM-21-01 2. Issuance Date: January 5, 2021

3.

Originating Office: Children’s Bureau

4.

Key Words: Title IV-B, Title IV-E, Court Improvement Program

TO: State, Tribal and Territorial Agencies Administering or Supervising the Administration of

Titles IV-E and IV-B of the Social Security Act, and State and Tribal Court Improvement

Programs.

SUBJECT: Achieving Permanency for the Well-being of Children and Youth

LEGAL AND RELATED REFERENCES: Titles IV-B and IV-E of the Social Security Act

(the Act).

PURPOSE: To provide information on best practices, resources, and recommendations for

achieving permanency for children and youth in a way that prioritizes the child’s or youth’s well-

being. Using an analysis of child welfare data, this Information Memorandum (IM) also outlines

typical patterns in exit outcomes for children and youth in foster care. This IM reviews the

permanency goals of reunification, adoption, and guardianship and emphasizes the importance of

state and tribal child welfare agencies and courts focusing on each child’s unique needs,

attachments, and connections when making permanency decisions.

This IM is organized as follows:

I. Background

II. Key Data Observations Regarding Permanency

III. Best Practice Guidance for Achieving Permanency and Well-Being across

Permanency Goals – Reunification, Guardianship, Adoption

IV. Conclusion

I. BACKGROUND

In previous IMs, the Children’s Bureau (CB) provided recommendations for implementing

primary prevention networks aimed at strengthening families (ACYF-CB-IM-18-05)

1

, ensuring

appropriate family time during foster care placement (ACYF-CB-IM-20-02)

2

, and utilizing

foster care as a support for families (ACYF-CB-IM-20-06)

3

. This IM builds on those best

1

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/im1805.pdf

2

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/im2002.pdf

3

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/im2006.pdf

2

practices and key principles with a continued focus on the importance of preserving family

connections for children as a fundamental child welfare practice. CB believes that efforts to

achieve permanency for children and youth must include safe and deliberate preservation of

familial connections in order to successfully ensure positive child well-being outcomes. This

focus on family connections is imperative in the work done by agencies and courts because it can

mitigate the effects of trauma that children and youth in foster care have already experienced and

can also reduce further trauma.

Children have inherent attachments and connections with their families of origin that should be

protected and preserved whenever safely possible. This is what fuels CB’s commitment to two

overarching goals: (1) strengthening families through primary prevention to reduce child

maltreatment and the need for families to make contact with the formal child welfare system; and

(2) dramatically improving the foster care experience for children, youth, and their parents when

a child’s removal from the home and placement in foster care is necessary. While focused on

achievement of permanency, this IM outlines best practices which also influence each of these

goals. Emphasizing a child’s attachments and connections while ensuring safety, rather than

solely prioritizing timeframes in efforts to achieve permanency will serve to strengthen and

preserve families; prevent future maltreatment from occurring after permanency is achieved; and

significantly improve a child’s foster care experience.

We believe there is much to learn from the patterns we see in the data available to CB from the

Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS), as well practice trends in

the qualitative data gathered through the Child and Family Services Reviews (CFSR). Since

reunification is the primary goal for nearly all children entering foster care, we are particularly

concerned about what the data reveal regarding the likelihood of achieving reunification. An

analysis of AFCARS data on exits for children and youth entering foster care, shows us that

while over 85 percent of children and youth will eventually achieve permanency through

reunification, guardianship or adoption (after four to five years), less than 50 percent will return

to their families of origin through reunification

4

. Additionally, data gathered through round

three of the CFSR

5

indicate that agencies and courts made concerted efforts to achieve

reunification in a timely manner in 49 percent of the applicable cases.

Federal law and regulation clearly emphasize the importance of working to preserve families and

for agencies to make reasonable efforts to prevent removal and finalize permanency goals.

6

The

law also emphasizes preserving family and community connections for children and youth in

foster care. CFSR findings

7

related to these requirements indicate that states need to make

improvements in these areas. In order to improve permanency outcomes and preserve

4

This analysis can be found the “Context Data” that are provided to supplement the Statewide Data Indicators that

are distributed semi-annually.

5

See https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cfsr_aggregate_report_2020.pdf

6

“Reasonable efforts” are a title IV-E agency requirement to obtain a judicial determination that the child welfare

agency has made efforts: (1) to maintain the family unit and prevent the unnecessary removal of a child from the

home, as long as the child’s safety is ensured, and (2) to make and finalize a permanency plan in a timely manner

(sections 471(a)(15) and 472(a)(2)(A) of the Act).

7

See https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cfsr_aggregate_report_2020.pdf

3

connections for children, it is critical that courts provide active judicial oversight over agency

efforts to:

• Thoroughly explore existing familial relationships and maternal and paternal relatives as

possible placements (section 471(a)(29) of the Act);

• Safely place children with relatives or fictive kin and people who they know, when

determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all

relevant State child protection standards (section 421 and 471(a)(19) of the Act);

• Make all reasonable efforts to keep siblings together unless such a joint placement would

be contrary to the safety or well-being of any of the siblings (section 471(a)(31) of the

Act);

• Keep children in their communities, including in their schools, and connected to

classmates and teachers, if remaining in such school is in their best interests, (section

471(a)(30) and 475(1)(G) of the Act);

• Thoroughly review the status of each child during periodic reviews and permanency

hearings, specifically assessing: 1) the safety of the child and the continuing necessity for

the child’s placement in foster care; 2) progress made toward alleviating or mitigating the

causes necessitating placement in foster care; and 3) the extent of compliance with the

case plan (including the agency’s provision of appropriate services for the child and

parents to improve the condition of the parent’s home) (sections 475(1)(B), and (5)(B)

and (C) of the Act); and

• Apply the exceptions for filing a petition for termination of parental rights when, at the

option of the state, the child is placed with a relative/fictive kin, when there is a

documented compelling reason not to file based on the best interest of the child (which

would include consideration of a child’s key attachments), or when the state has not

provided such services to the family as the state deems necessary for the safe return of the

child to the child’s home (section 475(5)(E) of the Act).

These requirements are intended to preserve a child’s family connections and support meaningful

efforts toward reunification. Data analysis presented later in this IM reveals that children whose

parents’ parental rights have been terminated may have longer durations in care that may not

result in a finalized adoption. Therefore, we must carefully consider on an individual basis for

each child and family, whether terminating parental rights is truly in the best interest of the child.

This IM seeks to emphasize the importance of safely guarding and protecting family

relationships while pursuing permanency for children and youth. Agencies and courts must be

certain that termination of parental rights is necessary to achieve what is best for the long-term

well-being of children and youth.

As CB continues to advance national efforts to transform the child welfare system into one that

promotes primary prevention, family well-being, and healing, we must pause and consider the

trajectory we have been on, the outcomes that children and youth are experiencing, and where

4

course correction may be needed. While we are mindful of the length of time children spend in

foster care, and do not want to unnecessarily prolong that, timeliness should not be the primary

driver when considering how to best achieve permanency for children and youth. We believe

that we will see reunification achieved more often, and with more expedience, by improving

efforts to place children with relatives/fictive kin at the onset of foster care placement, nurturing

children’s relationships with their parent(s) during foster care placement, and making concerted

efforts to provide parents with the services and supports they need to achieve reunification. We

believe that this will result in improvements in outcomes related to both permanency and child

and family well-being. When reunification cannot be achieved safely, focusing on family

connections can improve the likelihood that children exit foster care to guardianship or adoption

with relatives/fictive kin. When a child’s experience in foster care is marked by safety,

meaningful family time, preserved and nurtured connections, and high quality, family-centered,

trauma-informed service provision, children and youth have a better chance of achieving

meaningful permanency in a way that enhances their well-being.

II. Key Data Observations Related to Permanency

Using AFCARS data, CB conducted three separate analyses which are referenced in this IM. All

three analyses are based on an entry cohort approach in which all children who enter care within

a fiscal year are selected to establish a cohort, and multiple unique entry cohorts are established

by identifying entries from multiple fiscal years.

The first set of analyses selected entry cohorts for each year from FY 2013 to FY 2018 (six entry

cohorts in total) and follows children in the cohorts from their entry date to their date of

discharge, or September 30, 2019 (the end of FY 2019), whichever comes first.

8

Children are

not observed beyond FY 2019 because FY 2019 is the most recent year for which we have

complete data. The purpose of this analysis is to describe the exit outcomes of children when

maximal time is allowed to observe exits, and to observe how these exit outcomes vary.

The second set of analyses selected entry cohorts for FY 2015 to FY 2017 (three entry cohorts in

total) and followed each child for exactly two years from their date of entry. In contrast to the

first set of analyses that allowed maximal time to observe exits, this approach uses a standard

amount of time (two years) so that each entry cohort, and each child in each cohort, is followed

for the same amount of time. The purpose of this analysis is to describe the exit outcomes

children experience within two years of entry, rather than eventual exit outcomes with maximal

time to observe exits.

The third set of analyses selected entry cohorts for FY 2013 to FY 2015 (three entry cohorts in

total) and follows children to September 30, 2019, or their date of discharge, whichever comes

first. In that respect, it is identical to the first set of analyses. The primary difference in the third

set of analyses is that children are distinguished based on whether their parents’ parental rights

8

Each subsequent entry cohort is followed by one fewer full years than the preceding entry cohort because each

entry cohort has the same endpoint (September 30, 2019), but the entry cohorts are separated by a year. For

example, the 2013 entry cohort is followed for up to seven years, the 2014 entry cohort is followed for up to six

years, and so on.

5

were terminated or not. The purpose of this analysis is to describe the population of children

who become legally free and to characterize what their eventual exit outcomes are.

Taken together, the three sets of analyses allow us to make objective statements about the most

frequent, or typical, exit outcomes for children who enter foster care when a maximum amount

of time is allowed to observe outcomes (the first and third analyses), or when a fixed,

abbreviated amount of time is allowed to observe outcomes (the second analysis). These

analyses allow us to identify patterns that have been typical for children who have entered foster

care in recent years, and to use those patterns to project what we might expect for children who

newly enter care. These patterns then provide critical context for the best practice considerations

outlined in the next section.

We refer to the first two sets of analyses to establish what exit outcomes have been typical. We

focus first on answering the following questions based on allowing for maximal time to observe

exits:

• What exit outcomes are most likely for children and youth entering care?

• What differences are observed when the data are disaggregated by age at entry?

Secondly, to examine the typical outcomes within two years of entry, we answer the following

question:

• What exit outcomes can be observed within two years or less of entry into care?

What exit outcomes are most likely for children and youth entering care?

• Typically, just under 50 percent of children and youth who enter care are reunified.

• Typically, just under 25 percent of children and youth who enter care are adopted.

• Typically, about ten percent of children and youth who enter care exit to guardianship.

• Typically, about six percent of children and youth exit to live permanently with relatives

other than the ones from whom the child was removed. (These exits could also include

guardianship by a relative).

• Typically, about eight percent of all children and youth who enter care are emancipated.

6

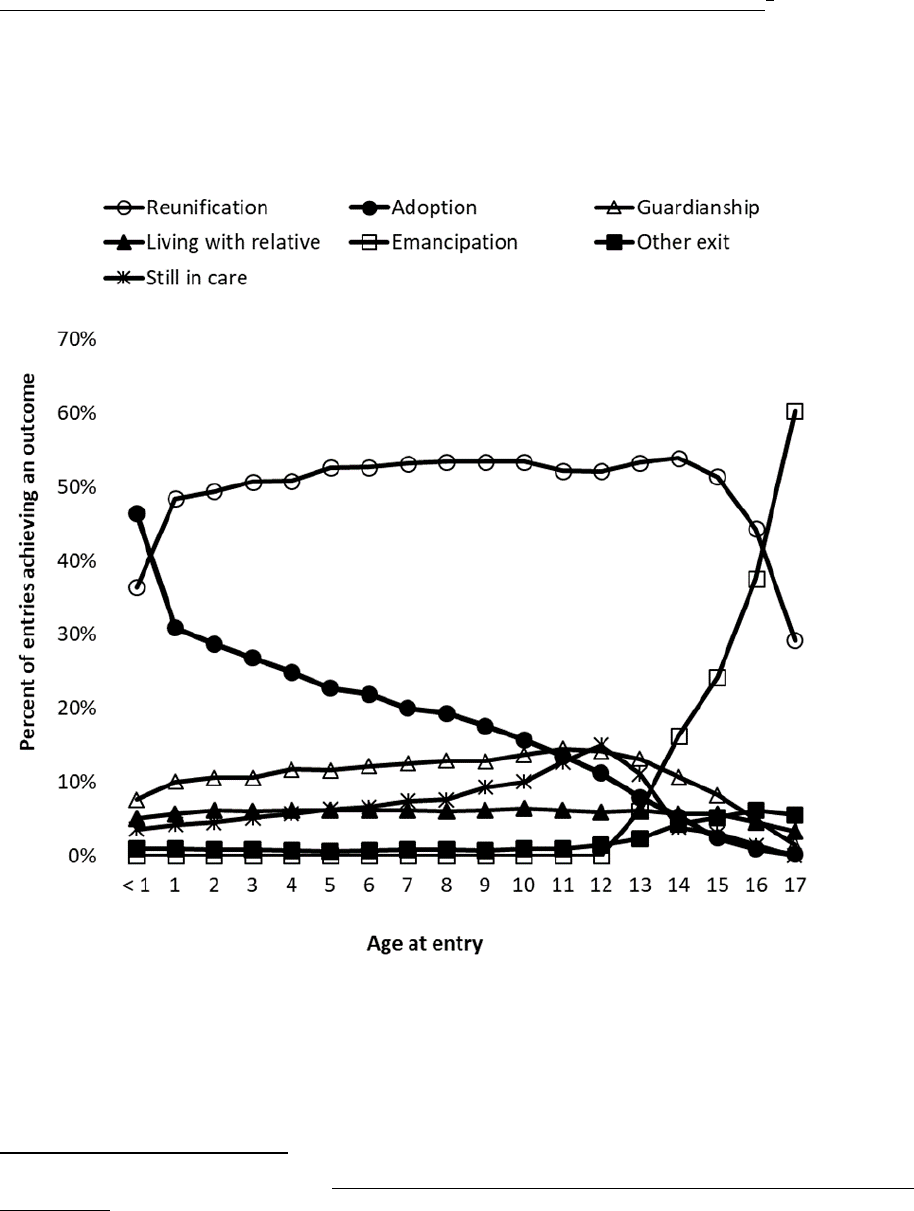

What differences are observed when the data are disaggregated by age at entry?

9

The graph below displays the outcomes typically experienced by children and youth who entered

care in FY 2015 and were followed for up to five years following their entry, displayed by their

age at entry.

Figure 1: Exit Patterns for Children/Youth Entering Care in FY 2015, by Age at Entry

Based on what typically happens to children who enter care, we can extrapolate to what is likely

to happen to children who enter care. The following observations of likely outcomes are derived

from the graph above:

9

An earlier version of this graph appeared in Beyond Common Sense: Child Welfare, Child Well-Being, and the Evidence for

Policy Reform, F. Wulczyn, R.P. Barth, Y.T. Yuan, B.J. Harden, and J. Landsverk, 2005, in which the authors make the case that

child welfare outcomes should be understood from a developmental perspective, and child welfare policies should reflect that

perspective.

7

• Generally, reunification is the most likely outcome for children and youth who enter care

between the ages of 1 and 16 years.

• Children less than age 1 who enter care are the only group for whom adoption is the most

likely outcome. The likelihood of exiting to adoption decreases the older the child is

when they enter care.

• The likelihood of exiting to guardianship increases the older the child or youth is when

they enter care, until approximately age 13.

• Children and youth most likely to still be in care after four years are those who enter care

between the ages of 9 and 13 years.

• For youth who enter foster care between the ages of 13 and 17 years, the likelihood of

exiting to emancipation significantly increases the older the youth is when they enter

care.

(“Other exit” noted in the graph includes discharges to run away, death of child, and transfer to

another agency. These are mostly observed at older ages except for death of child, which can

occur at any age.)

Turning to the second analysis, which looks to see how many children/youth achieve

permanency within two years of their entry, we asked the following question:

What exit outcomes can be observed within two years or less of entry into care?

• Sixty-five percent of children and youth entering care will achieve permanency of some

kind within two years.

• Forty-four percent of children and youth who enter care exit to reunification within two

years.

• Nine percent of children and youth who enter care exit to adoption within two years.

• Eight percent of children and youth who enter care exit to guardianship within two years.

• Five percent of children and youth who enter care exit to live permanently with relatives

within two years.

• Except for adoption, most exits to permanency are achieved within the first 12 to 18

months of entry into care.

8

Taken together, the first two sets of analysis reveal the following patterns:

• Although permanency was the most frequent outcome, it can take some time. Within two

years of entry, 65 percent achieved permanency and 88 percent of entrants achieve

permanency within seven years.

• Most reunifications occur within the first two years of entry, after which reunifications

became less likely.

• Children who entered foster care between the ages of 9 and 13 who do not reunify within

the first two years may stay in foster care longer – either waiting to be adopted or aging

out.

• For youth entering at age 16 or older, emancipation is the most likely outcome.

Additionally, those who are not reunified within the first year are much less likely to be

reunified in subsequent years when compared to younger children who enter care and do

not reunify in the first year.

We refer to the third set of analyses to describe the experiences of children whose parents’

parental rights were terminated after the child entered care. We answer the following questions

based on allowing for maximal time to observe exits.

• How frequently do children and youth who enter foster care have their parents’ parental

rights terminated and what differences are observed by age at entry?

• What exit outcomes are observed for children and youth who have had their parents’

parental rights terminated and what differences are observed by age at entry?

• After entry, how long does it take for children and youth to have their parents’ parental

rights terminated and what differences are observed by age at entry?

How frequently do children and youth have their parents’ parental rights terminated and what

differences area observed by age at entry?

• About a quarter of children and youth who enter care have their parents’ parental rights

terminated.

• Over half of the newborns (0 to 3 months at entry) who enter care have their parents’

parental rights terminated.

• Just under a quarter of children who enter between the ages of 6 and 10 have their

parents’ parental rights terminated.

• Just over 10 percent of the children who enter between the ages of 11 and 16 have their

parents’ parental rights terminated.

9

What exit outcomes are observed for children and youth who have had their parents’ parental

rights terminated and what differences are observed by age at entry?

• Children who enter care and have their parents’ parental rights terminated more

frequently fail to discharge and stay in care longer than children whose parent’s parental

rights are not terminated. As the age at entry increases, the likelihood of these children

staying in care also increases.

• Typically, 95 percent or more of the infants (under age 1) who have their parents’

parental rights terminated are adopted.

• Typically, 90 percent of children who enter care between the ages of 1 and 5, and have

their parents’ parental rights terminated, are adopted.

• Typically, 85 percent of children who enter care between the ages of 6 and 10 and have

their parents’ parental rights terminated, are adopted. Those in this age group who are

not adopted are most likely to stay in care when compared to younger children or

children of the same age whose parents’ parental rights are not terminated.

• Typically, 55 percent of children who enter care between the ages of 11 and 16, and have

their parents’ parental rights terminated, are adopted. And 28 percent of the children and

youth in this age group who are not adopted age out of care.

How long does it take for children and youth to have their parents’ parental rights terminated and

what differences are observed by age at entry?

• Most children and youth who have had their parents’ parental rights terminated

experienced that within two years of entry.

• Of children who enter care under age 1 and have their parents’ parental rights terminated,

32 percent have parental rights terminated within one year. In contrast, of those children

who are between the ages of 1 and 5 years at entry, and have their parents’ parental rights

terminated, 21 percent have parental rights terminated within one year. This pattern

continues as age at entry increases.

Placement of Siblings

It is important to note that children may enter foster care as sibling sets, but we are unable to

ascertain whether exits to permanency occur in the same way (same goal, same timeframe) for

siblings based on current AFCARS data. Placing siblings together is a critical aspect of securing

permanency for children and must be prioritized. Data from round 3 of the CFSR

10

indicates

that children were placed with their sibling in only 46 percent of the 1,547 applicable cases.

While it was determined that a valid reason for separation existed in 65 percent of cases, we urge

agencies and courts to consider the lifelong implications of separating siblings and make every

10

See https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cfsr_aggregate_report_2020.pdf

10

effort to reunite siblings, especially in their permanent homes. Permanency plans that result in

severing sibling attachments do not support the lifelong connections and relationships associated

with permanency and well-being for children and youth. It is a grievous consequence of foster

care that we must prevent at all cost.

III. Best Practice Guidance for Achieving Permanency and Well-Being across

Permanency Goals – Reunification, Guardianship, Adoption

The term “permanency” is used to define one of three outcomes we aim to achieve for children

in foster care. All three interconnected outcomes (safety, permanency and well-being) allow a

child to truly thrive; therefore it is important that our efforts to achieve permanency do not

sacrifice safety or well-being. For children in foster care, experiencing permanency and well-

being should be one and the same. The statute is clear that the best interest of the child is

paramount in permanency planning and is a compelling reason not to terminate parental rights in

certain circumstances. CB strongly urges agencies and courts to remain mindful of child

development needs, and the unique needs of an individual child, and ensure that those needs are

not eclipsed by haste to comply with timelines and process. Such haste may be contrary to the

best interest of children.

We do not want children to stay in foster care longer than is absolutely necessary to keep them

safe, and we also do not believe that it is in a child’s best interest to sever parental attachments

and familial connections in an effort to achieve “timely permanency.” Timeliness is but one of a

host of considerations when meeting the needs of children and should not be the lone or primary

driver for determining what is best for children. Placing timeliness above the substance of

thorough execution of case plans and reasonable or active efforts to achieve them runs the risk of

placing process over substance and promoting shortcuts in practice that can be harmful to

children and families.

By focusing on preserving a child’s connections and nurturing parental attachment while a child

is in foster care, we can steward a child’s time in foster care in such a way that true healing can

occur, and families can be reunited safely. In situations where guardianship or adoption is

determined to be the most appropriate goal for a child’s long-term well-being, agencies should

consider how they can safely preserve the child’s original family attachments through adoption

or guardianship with relatives/fictive kin.

Children in foster care should not have to choose between families. We should offer them the

opportunity to expand family relationships, not sever or replace them. We recognize that

reunification is not always possible

11

; however, CB believes that the vast majority of children in

foster care have relative or fictive kin relationships that are of great value to them. When we

nurture and protect relationships with siblings, family, and fictive kin, we increase the chances

for youth to achieve permanency. When these relationships are prioritized, protective factors are

increased, which promotes current and future well-being. The most critical factors for

11

Note that in instances where aggravated circumstances and severe physical/sexual harm exists it may not be appropriate for

parental or family involvement to continue as described in this IM. There are also instances of children who are abandoned.

Statistically these situations make up a very small percentage of the foster care population.

11

consideration in permanency planning should be the safety of the family home and a child’s key

attachments and family connections. These factors, rather than the number of months spent in

foster care, or even a child’s new attachment to resource parents, should drive permanency

decisions. By keeping the focus on what really matters for positive child outcomes, we believe

agencies, tribes and courts can dramatically improve the likelihood of reunification and

permanency with relatives for the vast majority of children and youth in foster care, reduce the

duration of time children and youth spend in foster care and improve the well-being of children

and youth during and after foster care.

There are critical aspects of practice that serve to protect and preserve a child’s core identity and

sense of belonging. These include things like crafting meaningful plans for family time (with

siblings and parents) at the onset of placement, conducting exhaustive and ongoing kin searches,

doing the difficult work of supporting resource parents to co-parent rather than replace a parent,

and making placement decisions that carefully consider a child’s connections to their

community. When agencies and courts don’t invest time and effort in these practices, we

prevent children from experiencing true permanency and well-being. Research also indicates

that kinship placement, early stability, and intact sibling placement are predictors of permanency

achievement.

12

Agencies and courts cannot afford to settle for available placements that separate

siblings, or make case plan decisions that take children and youth away from all that they know

and love and unnecessarily terminate parent-child relationships.

While children who have had their parents’ parental rights terminated no longer have legal

parents, they most often still have living parents, other relatives that they are connected to, and

fictive kin with whom they have existing relationships. Children and youth in foster care have

stories and memories that make up who they are, and they deserve to have all of those things

safely preserved for them while they endure the trauma of being removed and displaced from all

that they know. This is why Permanency Outcome 2 (and the five items that comprise it) in the

CFSR aims to ensure the preservation of connections and continuity of family relationships. It is

a child welfare outcome for states to achieve for all children in foster care because of how

critically important each practice (shared below) in that outcome is:

• Place siblings together in foster care (CFSR, Item 7);

• Ensure frequent and meaningful family time experiences for children with their parents

and with siblings who are placed separately (CFSR, Item 8);

• Preserve key connections such as a child’s school, neighborhood, community, faith,

extended family, Tribe, and friends (CFSR, Item 9);

• Place children with relatives (CFSR, Item 10); and

12

Becci A. Akin, Predictors of foster care exits to permanency: A competing risks analysis of reunification, guardianship, and

adoption, Children and Youth Services Review, Volume 33, Issue 6, 2011, Pages 999-1011, ISSN 0190-7409,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.01.008.

12

• Make efforts to promote, support, and/or maintain a positive relationship between

children and their parents through activities that go beyond visitation (CFSR, Item 11),

such as:

o Encouraging parents to participate in school activities, extracurricular activities,

and health appointments (and providing transportation for parents to be able to

participate).

o Providing therapeutic opportunities to help parents strengthen their relationship

with their child.

o Encouraging resource parents to mentor or serve as support role models for

parents.

o Facilitating contact with a parent unable to participate in family time due to

distance or other barriers.

These permanency practices are the key to ensuring that children have positive, healthy, and

nurturing attachments and relationships with their parents, siblings, and others. These healthy

relationships become the foundation for lifelong thriving — we must ensure that all children and

youth exit care with this foundation. Over the past four years, through multiple roundtable

discussions and meetings, CB leadership has met routinely with young people around the

country, to include the recent completion of 12 regional roundtables with young leaders across

the United States.

13

We heard directly from young people who described their experience in

foster care as missing these critical attachments and relationships. Youth recounted experiences

of being separated from siblings, some losing contact altogether. Still others aged out of care

only to find that they had relatives and kin living in close proximity to them, yet no efforts were

made to preserve those connections. These youth often reference ‘relational permanency’ as

something they need to thrive. Legal permanence alone doesn’t guarantee secure attachments

and lifelong relationships. The relational aspects of permanency are critically important and

fundamental to overall well-being.

We must work to safely preserve children’s key attachments and support them as they build new

attachments with resource parents and new permanent caregivers. Children do not need to have

previous attachments severed in order to form new ones

14

. In fact, they will be better positioned

to develop new relationships if we work to preserve their original connections, sparing them

from additional grief and loss.

What ultimately matters for permanency are relationships and connections, so we must ensure

that our efforts to achieve permanency reflect this understanding. We must work to ensure that

the expectations outlined in CFSR Permanency Outcome 2 are put into practice (preserved

connections should be routinely assessed in case planning meetings, court hearings and reviews

because of the influence they have on achieving permanency and well-being). These practices

must not be thought of as ‘extra’ things that are only applicable for children with a goal of

reunification, but they should be viewed as some of the most important things children need to

thrive long-term with any permanency goal.

13

See CB Letter summarizing roundtables.

14

Centre for Parenting & Research Research, Funding & Business Analysis Division. (2006). The importance of attachment in

the lives of foster children. https://earlytraumagrief.anu.edu.au/files/research_attachment.pdf

13

CB has been promoting system transformation with the priority of keeping families safely

together. This value of preserving families must be present at every stage of the work in our

child welfare systems if we want to improve outcomes for children and families. It must be the

compass that guides our path to achieving the permanency goals of reunification, adoption, and

guardianship so that the well-being of every child is also achieved.

Achieving Reunification

The analysis in section II of this IM indicated that children and youth who enter foster care have

a less than 50 percent chance of being reunified. This pattern reveals that our efforts to

strengthen and preserve families have been profoundly inadequate. Outside of situations of

egregious abuse and neglect to children by their parents, a finding of aggravated circumstances,

or abandonment, the goal for a child placed in foster care is most often reunification. Federal

law

15

requires title IV-B/IV-E agencies to provide reasonable efforts to make it possible for

children to reunify with their parents safely. The qualitative data we gather through the CFSR,

which considers the circumstances for the child, and the nature of the efforts made by the agency

and courts, also confirms that significant improvement is needed. Round three results

16

of the

CFSR found that agencies made concerted efforts to achieve reunification within 12 months of

the child’s entry into foster care in 49 percent of foster care cases.

As we consider the best practices that are required to achieve reunification, we must start with

assessing the parent-child relationship, including attachment, and prioritizing that in services.

Some parents working toward reunification may need the support of a trauma-informed

counselor or therapist who can help them learn to work through their own past trauma, along

with the trauma their children have experienced from abuse or neglect and removal, as they seek

to repair and restore parent-child attachments and relationships. Parents love their children

deeply, but may not have experienced healthy parent-child attachment for various reasons.

Assessing and supporting the parent-child relationship is critical to enable safe and timely

reunification, but is often missing from the array of services offered to parents. Round three

CFSR

17

results related to service array noted that trauma-informed services, transportation, and

visitation services were often insufficiently available.

The analysis in section II of this IM noted that infants have the least opportunity to be reunified

as termination of parental rights and adoption are pursued quickly for that population in

particular. While we recognize that infants are the most vulnerable to abuse and neglect, we also

want to ensure that parents are given every opportunity to reunify with their infant children. For

parents struggling with substance abuse in particular, treatment opportunities that allow them to

have their children live with them offer the kind of support that parents need to overcome

addiction while safely developing and demonstrating their parenting skills. It is critical that

parents of infants be given ample opportunities to safely bond with their children and develop

attachments that are critical for those children to thrive.

15

Section 471(a)(15)(B)(ii) of the Act

16

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cfsr_aggregate_report_2020.pdf

17

Ibid

14

The results of our analyses that are descripted in section II suggest that another population that

may benefit from focused attention is children and youth who entered care between the ages of 9

and 13 years. This age group is most likely to still be in care after four years, so agencies and

courts should ensure that adequate efforts are being made to work toward reunification and

ensure connections are being preserved in a meaningful way to support their well-being while

they are in care.

This work of repairing and supporting attachment and relationships during foster care takes time,

particularly when parents may also be dealing with other issues such as poverty, housing

instability, substance use disorders, or domestic violence. But this is the distinctive and

challenging work of child welfare. Agencies must emphasize the importance of these efforts at

all times and frontline staff must see it as a critical responsibility. Agency culture, policy and

practice must be designed and implemented to provide parents the time and resources they need

to effectively work through all that is necessary to bring healing to their families. If agencies

have done the work to improve the child’s experience in foster care, by preserving their

connections, implementing meaningful family time, and utilizing foster care as a support for

families, then the length of time the child stays in foster care will facilitate healing.

In addition to practices focused on supporting the parent-child relationships, preserving

connections. and utilizing foster care as a support for families, there are a few other critical

practice areas and systemic processes assessed in the CFSR

18

outcomes and systemic factors that

influence concerted efforts to achieve reunification:

• Agencies conducted a comprehensive assessment of parents’ needs and provided

appropriate services to address needs of parents in 42 percent of foster care cases (Well-

Being Outcome 1, Item 12B).

• Children and parents were adequately engaged in case planning in 55 percent of foster

care cases (Well-Being Outcome 1, Item 13).

• Agencies conducted frequent, quality caseworker visits with parents in 41 percent of

foster care cases (Well-Being Outcome 1, Item 15).

• Two states achieved substantial conformity with the Case Review systemic factor.

o 37 states received a strength rating for ensuring timely periodic reviews and

permanency hearings; however, concerns noted with agency efforts in working

with children and parents in Permanency Outcomes 1 and 2 and Well-Being

Outcome 1 signal opportunities for courts to improve the quality of reviews and

hearings to assess these efforts as required.

States must ensure that parents receive adequate comprehensive assessments of their needs in

order to properly inform service planning. Successful engagement of parents is critical for

obtaining the information needed to inform a proper assessment of a parent’s needs.

18

Ibid

15

Engagement must be nurtured through frequent, meaningful worker contact. The very act of

assessment also serves to reinforce engagement – as parents are asked to share their stories and

workers demonstrate empathy and care in response, trust is built. This trust builds rapport and

provides the best foundation for effective ongoing case planning.

Stakeholders interviewed through the CFSR report that some agencies contract out an assessment

of parents and, as a result parents, may go months before having any of their needs, their history

or their relationships assessed. Many parents have experienced their own trauma, have been in

foster care themselves as children, or have compounding needs that leave them feeling

overwhelmed. Additionally, CB leadership has met regularly with parents across the country

who have lived experience and expertise to share related to having a child involved with the

child welfare system. These meetings have reinforced the need for robust parental supports and

services to help support parental resiliency, protective capacities, and healing. It is vital that the

child welfare workforce be trained, supported, resourced, and equipped to do the work of

engaging parents and assessing their needs, even if additional outside assessments are needed.

This aspect of case practice is so critical because of its implications for developing a trusting

relationship. Outsourcing assessments completely can prevent effective parental engagement

from occurring which can negatively impact outcomes.

The initial opening of a case is the most critical time for engaging parents. Agencies should

convey to parents that the goal of the agency and court is to keep families safely together, clearly

explain what makes their family home unsafe for their child, and share the steps for how they can

address those safety threats. Agencies should demonstrate in written case plans and through

verbal explanations to parents: 1) why placement is necessary for safety; 2) how foster care will

be used as a support for their family; 3) how the agency and court will ensure that they have

everything that they need to achieve reunification; 4) how changes in the safety of the home will

be assessed; and 5) how family time will be arranged to offer them as much time with their

children as safely possible. That approach of clear communication, focused on what matters

most, indicates to parents that the agency and court are invested in preserving and supporting

their relationship with their child. That can help buffer the grief parents experience due to

separation, which often is displayed as anger toward the child welfare agency. Many parents

have expressed to CB that when agencies approached them as people who love their children, but

are in need of help, rather than treating them punitively and assuming they don’t care about their

children, they were much more receptive to being engaged.

Ensuring high quality legal representation for parents and children is critical to preventing

unnecessary parent child separation, promoting the well-being of children and parents, ensuring

that reasonable efforts

19

and active efforts are made, and achieving all forms of permanency

when a child or youth becomes known or involved with the child welfare system.

20

Research

19

“Reasonable efforts” are a title IV-E agency requirement to obtain a judicial determination that the child welfare agency has

made efforts (1) to maintain the family unit and prevent the unnecessary removal of a child from the home, as long as the child’s

safety is ensured, and (2) to make and finalize a permanency plan in a timely manner (sections 471(a)(15) and 472(a)(2)(A) of the

Act).

20

The CB issued Informational Memorandum ACYF-CB-IM-17-02 that provides details on representation concepts, benefits,

and resources that are helpful for developing or strengthening legal representation programs. See also,Technical Bulletin on

Frequently Asked Questions: Independent Legal Representation for more information.

16

makes clear that high quality legal representation, particularly multi-disciplinary legal

representation,

21

is impactful in helping to achieve and expedite reunification.

22

Reinstatement of Parental Rights

A review of exits from foster care over the past three years reveals that 15 percent of youth who

aged out of care

23

had their parents’ parental rights terminated prior to their exit from foster care.

The analysis shared in section II on children and youth who have had their parents’ parental

rights terminated showed that that group is more likely to still be in care than children and youth

who have not had parental rights terminated (over 25 percent will go on to age out of care). In

many instances, this results in children staying in foster care for long periods of time, often

without the important connections to familial support that are necessary for their well-being.

Together these data points demonstrate that there are groups of children or youth who will enter

care, have their parents’ parental rights terminated, and then will have longer stays in care that

will end without permanency. As of current AFCARS reporting for 3/31/2020, there are 73,200

children and youth in foster care who have had their parents’ parental rights terminated but have

still not achieved permanency. For some of these children and youth who are still in foster care,

there may be just cause to reconsider reunification with one or both parents. That is, we should

consider the possibility that reunification may be a viable option for these children and youth.

Currently, 22 states have laws that allow for reinstatement of parental rights.

24

These statutes are

most often grounded in the best interest of the child legal standard and are grounded in the

understanding that life circumstances can and do often change for the positive for parents. A

parent or parents who may not have been able to safely or adequately care for a child in the past

may become a safe and appropriate option in the future.

25

Numerous state statutes also speak to

the age and maturity level of children and youth, length of time in care, and failure of agencies to

achieve stated permanency goals despite making reasonable efforts.

26

Inherent in these laws is

the recognition that the nature of the safety issues that may have existed at the time of

termination for a young child may no longer pose the same threats to safety for an older child or

youth, or that concerns that existed at the time of termination may no longer exist due to

successful parental recovery or other forms of sustained progress. Reinstatement of parental

rights and reunification with a parent or parents may be particularly appropriate for older youth

in foster care as they are better able to express their preferences and concerns and have better

developed protective capacities than younger children.

21

See https://familyjusticeinitiative.org/advocacy/high-quality-representation/

22

An important study conducted in New York City in 2019 provides especially compelling evidence of the

effectiveness of the multi-disciplinary approach in achieving reunification. A companion, qualitative study released

in 2020 lends further support to the model. See, ACYF-CB-IM-17-02 for a summary of additional research

demonstrating the connection between legal representation and reunification.

23

There are differences across states based on whether children who transition to extended foster care are considered to “age out”

when they turn 18, or when they discharge from extended foster care. This figure includes all emancipations, regardless of

whether the child was over 18. Of these emancipations, 16 percent were over 18 at the time of emancipation.

24

See https://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/reinstatement-of-parental-rights-state-statute-sum.aspx

25

Id.

26

Id.

17

In light of the fact that permanency is focused on relationships and connections, and recognizing

that many parents may not have received adequate supports to achieve reunification before

termination, while others may have experienced significant positive changes in their life since

the time of termination, reinstatement of parental rights and reestablishment of the legal

connection is an important addition to the permanency continuum that can promote well-being.

CB encourages states that have such statutes to exercise the option actively when appropriate.

CB further strongly encourages states that do not currently have reinstatement of parental rights

statutes in place to give thoughtful consideration to crafting and enacting legislation to provide

this important permanency option for children and youth.

Achieving Guardianship

Guardianship is an appropriate permanency goal. This is particularly true in cases where parental

rights should not be terminated but the best plan for the child based on case circumstance is that

he or she not be reunified. This permanency goal legally preserves parental rights while ensuring

another caregiver bears the responsibility for direct care and custody of the child. The following

parental rights are transferred to the legal guardian per section 475(7) of the Act: protection,

education, care and control of the person, custody of the person, and decision making. There are

a number of circumstances where parents themselves may decide that guardianship with a

relative is best for their child, or a relative caregiver may indicate a desire to pursue this

permanency option. For youth who do not want their parents’ parental rights terminated, but

desire to have another legal caregiver, guardianship may offer just what they need. If safety

concerns exist with maintaining parental rights, adoption would be the more appropriate

permanency goal to pursue.

Guardianship can be achieved with a relative or non-relative and may include a subsidy

27

. All of

these benefits should be discussed with families to determine what would contribute to the best

long-term outcome for the child. Whether guardianship occurs with relatives or non-relatives, all

guardians should have access to post-guardianship services to ensure that they can meet the

needs of the children in their care. Unfortunately, children can still experience instability after

guardianship, so concerted efforts must be made to prepare families for this permanency option

and offer a range of supportive services that families can access even after guardianship is

legalized. Families must be educated about all of the services older youth are eligible for,

including eligibility for the John H. Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to

Adulthood and Educational Training Vouchers (section 477 of the Act).

For children with a permanency plan of guardianship, federal law (section 475(1)(E) and (F) of

the Act) requires agencies to document, in the child’s case plan, the steps the agency is taking to

place the child with a legal guardian, and to legalize the guardianship. At a minimum, the law

requires that the documentation must include: information about the child-specific recruitment

efforts that have been conducted; steps that the agency took to determine that it is not appropriate

for the child to be reunified or adopted; reasons why guardianship is in the child’s best interests;

reasons for any separation of siblings during placement; the child’s eligibility for title IV-E

27

Section 473(d) of the Act

18

kinship guardianship assistance; efforts made to discuss adoption by relative as a more

permanent alternative to guardianship; and efforts made by to discuss with the child's parents the

guardianship arrangement. An assessment of these required efforts should occur during periodic

reviews and permanency hearings to ensure appropriate progress is being made in achieving the

goal.

To ensure successful guardianships, efforts must be made to help potential guardians understand

the child’s needs, particularly as it relates to the impact of trauma, issues of attachment, and the

losses associated with foster care placement (removal, any loss of connections, inability to

reunify, etc.) that may impact children differently due to age and circumstances. CB funded the

National Adoption Competency Mental Health Training Initiative (NTI)

28

to provide

comprehensive training on these issues to child welfare workers, supervisors and mental health

practitioners in order to improve outcomes for children being cared for by resource families,

adoptive families, and guardianship families. By training the workforce who supports those

pursuing guardianship, potential guardians can be better prepared to know how to understand and

address behaviors that are likely linked to trauma, attachment or loss.

As with any permanency goal, intentional efforts to preserve a child’s key connections can

strengthen and support the positive outcomes that can be achieved through guardianship.

Visitation with parents, as appropriate, and frequent time with siblings, should be included as

part of final guardianship orders to ensure that those connections continue. Post-permanency

services and community-based supports are critical to the long-term success of guardianship.

Access to those services should also be noted in final orders to ensure that agencies and courts

have thoroughly considered and provided all that the family needs.

Achieving Adoption

Adoption is a critically important permanency option for children in foster care who are unable

to be reunified with their parents. While child welfare agencies and courts should strive to

ensure that children are safely preserved with their own families whenever possible, we

acknowledge that there will be circumstances where a child must be permanently removed from

harmful family dynamics and unsafe relationships. Adoption provides the permanent security of

a new forever home for children who need that.

For children with a permanency plan of adoption, federal law (section 475(1)(E) of the Act)

requires agencies to document, in the child’s case plan, the steps the agency is taking to place the

child with an adoptive family and finalize the adoption. At a minimum, the law requires that the

documentation must include information about child-specific recruitment efforts that have been

conducted. An assessment of these required efforts should occur during periodic reviews and

permanency hearings to ensure appropriate progress is being made in achieving the goal.

Adoption may occur with a child’s relatives or with unrelated resource parents. In either case,

adoption should be viewed as an opportunity to expand a child’s experience of family rather than

replace their previous family. Unless safety concerns prevent connections from being preserved,

28

https://adoptionsupport.org/nti/

19

adoptive families should acknowledge the child’s previous family connections and relationships

and work to sustain those. Many state laws (currently 29 states and the District of Columbia)

29

allow for continuing to support relationships with parents through open adoption and post

adoption contact agreements and this can include siblings and extended family.

Federal law (section 471(a)(31) of the Act) requires that every effort should be made to have

siblings adopted by the same family. When that cannot occur, there should be a clear plan in

place for how sibling relationships will be preserved through consistent and quality contact.

Ongoing sibling relationships, regardless of the age of the child, should always be preserved for

children. Relationships with parents and other extended family may also be preserved when

ongoing connection does not pose a threat to safety and preserving those relationships is best for

the child. In situations where children had been having regular contact with parents prior to

termination, that contact should continue with support from a counselor to help the parents and

child adapt to new roles.

Pre-adoptive families who wish to sever the child’s family connections for any reason other than

safety should receive training and supportive counseling to understand the impact that will have

on the child. Decisions for adoption finalization should be contingent upon whether the family

will in fact support what is best for the child in preserving connections. Agencies and courts

should insist on protecting a child’s key connections even if it means losing a potential adoptive

family. Agencies must proactively prepare potential adoptive families to understand the

importance of connections and the impact that has on child well-being.

Adoptive families have the unique privilege of stewarding a child’s past in a way that can

promote healing and positive outcomes for their future. By committing to love and nurture a

child forever, adoptive families accept all that a child is, including their family history.

Honoring that history will look different for each child, depending on case circumstances and the

child’s needs, but it must be carefully considered.

Similar to guardianship, there are risks to stability in adoption as well. Researchers estimate that

between five and 20 percent of children and youth who exit to guardianship or adoption

experience some form of instability.

30

To ensure successful adoptions, efforts must be made to

help adoptive parents understand the child’s needs, particularly as it relates to the impact of

trauma, issues of attachment, and the losses associated with foster care placement (removal, any

loss of connections, inability to reunify, etc.) that may impact children differently due to age and

circumstances. There may be a tendency for adoptive parents to assume that offering to adopt a

child and give them a new family will significantly or automatically change a child’s sense of

connection with their birth families. They must be prepared to understand how attachment and

connection works for children so they can have appropriate expectations and know how to best

support their child through the transition.

29

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/cooperative.pdf

30

White, K. R., Rolock, N., Testa, M., Ringeisen, H., Childs, S., Johnson, S., & Diamant-Wilson, R. (2018). Understanding

post adoption and guardianship instability for children and youth who enter foster care. Washington, DC: Office of Planning,

Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

20

The National Adoption Competency Mental Health Training Initiative

31

is a tremendous

resource for working with adoptive families. All adoptive families should be referred to an

adoption competent therapist who can be an ongoing resource as their child experiences

developmental changes so they can be prepared to understand and address behaviors that are

likely linked to trauma, attachment or loss. Parents who adopt infants and younger children may

not see the impact of trauma and attachment issues in behaviors until the child gets older but it’s

important that they begin to implement parenting techniques that take into account the child’s

history of trauma and can help form and support healthy attachment.

As the research and related resources for trauma and attachment have continued to grow in

recent years, there is growing understanding in the field that many families who adopted children

from foster care years ago may not have been provided adequate training and support related to

these issues. As a result, CB has heard of situations where parents were left unprepared to handle

the significant behaviors that their children experienced. Many of these families have been in

crisis with nowhere to turn. Young people from the ACF Youth Engagement Team,

32

in

addition to other youth CB has spoken to, have echoed the importance of providing trauma-

informed services to adoptive families. It is critical that agencies and courts ensure that families

are adequately connected to an array of post-adoption services so that they have access to what

they need at any time. These services could include support groups, adoption-competent

therapeutic supports, and attachment specialists.

Reinvigorating and Reinvesting in Efforts to Achieve Permanency for Older Youth

To achieve the legal requirements around permanency and well-being, CB urges states to

evaluate and invest in their continuum of permanency services. The continuum of services

should be centered on supporting and strengthening family and kinship bonds, as well as include

services to develop new supportive relationships when needed. The continuum should include

services that can be delivered as system prevention services and services that can help maintain

permanency following an exit from the system. Given the large numbers of older youth who

continue to leave the system without permanency, 20,000 annually

33

, and the increasing

likelihood, shown in the AFCARS analysis, that youth who enter care at age 15 or older will

emancipate, it is crucial that states evaluate their continuum of permanency practices and

services to ensure that they are effective for older youth and their families.

All children and youth need the benefit and foundation of family to experience healthy child and

adolescent development. All the research available, as well as the voices of young people,

demonstrate that permanency is crucial to a successful and secure transition to

adulthood. Agencies should evaluate their permanency continuum to ensure that services to

support reunification, adoption, and guardianship are tailored to adolescents and young adults,

including their families and support networks. This means, first and foremost, listening to young

31

https://adoptionsupport.org/nti/

32

The ACF Youth Engagement Team was developed in 2020 in order to gather expertise from former foster youth in identifying

key recommendations for the ALL‐IN Foster Adoption Challenge and state and federal efforts toward achieving permanency for

all waiting children and youth.

33

The AFCARS Report https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport27.pdf

21

people as a group of experts that can guide agencies in improving practice and as individuals in

their own cases. Federal law requires that youth 14 and older be consulted about their case plans

and have a case planning team (section 475(1)(B) if the Act). The law also requires youth age 14

and older be consulted title about IV-E guardianship (section 473(d)(3)(A)(iv) of the Act).

Young people overwhelmingly say that they want permanency, but they want their voices to be

heard about who they care about and who is important to them. Young people want to work

towards permanency with skilled professionals who they can build trust with and who will show

them respect. Valuing and listening to the voices of young people allows agencies to increase

the odds that both legal and relational permanency can be achieved for older youth. As states

and agencies evaluate and build their continuum of permanency services, we encourage states to

consider the following:

1. Integrate practices that uphold the expectation that permanency must be achieved for

older youth and is central to a successful transition to adulthood (communicated across

the agency, including by those in leadership positions).

2. Establish processes that provide youth-centered and youth-led permanency and transition

planning and that actively engage the community and family the youth identifies.

3. Train caseworkers on how to engage young people in the permanency planning process

and the work necessary to achieve permanency. This should at least include: training in

insights from adolescent brain development, the impact of trauma on permanency and

relationship building; practical strategies for engaging youth in the discussion of

permanency; and steps for repairing and building trust and relationships. Agencies should

have mechanisms in place to determine if meaningful engagement is occurring, such as

surveys, data collection, and youth advisory councils. Youth should be members of

leadership committees and workgroups to ensure that engagement is occurring system

wide.

4. Provide a wide array of permanency services to young people, including, but not limited

to: reunification and family preservation services; family finding and engagement; child

specific recruitment that focuses on family; kin and non-kin; grief and loss counseling;

family counseling; and post-permanency services.

5. Establish processes, such as case reviews, team meetings and executive approval, to

ensure the continued pursuit and finalization of permanency efforts, including

reunification, adoption, and guardianship.

6. Establish processes to ensure that the option of having youth reside with a parent or

guardian as an allowable supervised independent setting, is being exercised, when that

would be the most appropriate option for a young person.

34

7. Ensure that practices and services are in place to increase the odds that joint placement

can occur for siblings, that regular visitation occurs when joint placement is not possible

due to safety issues, and that therapeutic supports are provided to nurture sibling

relationships when needed.

35

34

See CWPM section 8.3A.3 Question/Answer #3

35

See also sections 473(d)(3)(B) and (e)(3) related to siblings and the title Iv-E adoption assistance and guardianship

programs.

22

8. Schedule ongoing agency-wide planning opportunities for where young people lead and

help to develop innovative and effective ways to provide legal and relational permanency

to older youth. This planning should build upon existing discussions and work in the

field being led by alumni groups. Child welfare agencies and courts are encouraged to

take action to make the existing permanency plans (reunification, adoption, and

guardianship) more responsive to the needs of adolescents and young adults and to be

open to new and creative ways that allow young people to establish and maintain multiple

strong, long-lasting, and nurturing relationships that provide them the love, support and

family identity they need as they age.

Timeliness

All permanency planning and practices require thoughtful attention to timeliness. The statutory

requirements for timelines, most notably, the termination of parental rights timelines

36

(TPR),

were established in part to prevent children and youth from remaining in foster care longer than

necessary. However, the statute also contains specific provisions allowing for: exceptions to the

timelines in the form of aggravated circumstances that allow for expedition in certain

circumstances; and documentation of compelling reasons why terminating parental rights is not

in the best interest of the child (section 475(5)(E)(ii) of the Act). These options were included in

the law in recognition that all families are unique and that there must be flexibility in the law to

make prudent decisions based on the individual circumstances of each family and child. While

timeliness is essential, and it is critical not to cause undue delay in the lives of children and

families, CB cautions agencies not to place timeliness before the substance of what best supports

familial relationships and the best interest of the child.

On June 23, 2020, CB issued a letter strongly encouraging all child welfare agencies to

thoughtfully consider decisions of whether to file for termination of parental rights in instances

where services and supports have been interrupted, are not available to meet specific needs,

where family time has been inadequate, or where court operations are unable to offer hearings of

needed due to COVID-19.

37

The letter emphasized that such decisions should always be made

on the individual child and family’s unique circumstances. Although the letter was issued to

provide guidance during the COVID-19 pandemic and public health emergency, the legal

requirements it highlights are equally important during times of normalcy and times of natural

disasters or public health crises. A child welfare agency may choose not to file a petition for

termination of parental rights if the agency documents compelling reasons for determining it is

not in the best interest of the individual child, including instances where a child is living with a

relative (section 475(5)(E)(ii) and (iii) of the Act) or when guardianship would be an appropriate

permanency goal. The consistency and availability of services, supports, and family time, and

how such availabilities impact parents, children and their relationship, are important factors in

decision making.

36

Sec 475(5)(E) of the Act. These timelines were first added to statute by Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) Public Law

105-89. Timeliness is also reflected in the requirement that a permanency plan be established within 60 days (see 45 CFR

1356.21(g)).

37

CB Letter issued June 23, 2020: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/parental_rights_adoption_assistance.pdf

23

IV. Conclusion

Child welfare systems have a high duty and legal responsibility to achieve and support improved

permanency outcomes for children and youth in foster care. The first step toward improvement

requires that stakeholders agree that family relationships and connections are key to child well-

being, family relationships and connections directly influence a child’s sense of permanency, and

that more meaningful efforts toward reunification should be an urgent priority. Child welfare

systems must center all work on preserving and creating such relationships as a critical

component of child and family well-being. We strongly encourage all title IV-B/IV-E agencies

to commit to the practices that ensure the preservation and continuity of family relationships and

connections for all children and youth in foster care. Prioritizing those efforts will ensure that

we achieve permanency for children in a way that strengthens their connections, healthy

attachments, and sense of belonging to support lifelong thriving. To implement this approach

successfully, agency and court leaders must mobilize service providers, attorneys, and resource

families in every community to promote this view of permanency. We must make every effort to

protect and preserve connections for all children and youth in foster care.

Inquiries: CB Regional Program Managers

/s/

Elizabeth Darling

Commissioner

Administration on Children, Youth and Families

Disclaimer: IMs provide information or recommendations to States, Tribes, grantees, and others

on a variety of child welfare issues. IMs do not establish requirements or supersede existing laws

or official guidance.

Resources

Partnering with relatives to promote reunification. Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2020).

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/factsheets_families_partner_relatives.pdf

Partnering with Parents to Promote Reunification. Child Welfare Information Gateway (2019).

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/factsheets_families_partnerships.pdf

Strategy Brief: What are some effective strategies for achieving permanency? Casey Family

Programs (2018)

https://caseyfamilypro-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/media/SF_Effective-strategies-for-achieving-

permanency.pdf

24

Guardianship Assistance Policy and Implementation, A National Analysis of Federal and State

Policies and Programs. Casey Family Programs (2018)

https://caseyfamilypro-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/media/Guardianship-Assistance-Policy-and-

Implementation_Technical-Report.pdf

Information Packet: How have states implemented parental rights restoration and reinstatement?

Casey Family Programs (2018)

https://caseyfamilypro-wpengine.netdna-

ssl.com/media/SF_Parental_Rights_Restoration_Reinstatement.pdf

Working with Kinship Caregivers. Child Welfare Information Gateway (2018).

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/kinship.pdf

The Quality Improvement Center for Adoption and Guardianship Support and Preservations

https://www.qic-ag.org/

Child and Youth Connections: Results from CFSR Round 3 (2015-2018) .Report found at

https://www.cfsrportal.acf.hhs.gov/resources/cfsr-findings