Asset Recovery Handbook

A Guide for Practitioners

Jean-Pierre Brun

Larissa Gray

Clive Scott

Kevin M. Stephenson

Asset Recovery Handbook

Asset Recovery Handbook

A Guide for Practitioners

Jean-Pierre Brun

Larissa Gray

Clive Scott

Kevin M. Stephenson

© 2011 e International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / e World Bank

1818 H Street NW

Washington DC 20433

Telephone: 202-473-1000

Internet: www.worldbank.org

E-mail: feedback@worldbank.org

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10

is volume is a product of the sta of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / e

World Bank. e ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily

re ect the views of the Executive Directors of e World Bank or the governments they represent. e

World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work.

e maps in this book were produced by the Map Design Unit of e World Bank. e boundaries, colors,

denominations, and any other information shown on these maps do not imply, on the part of e World

Bank Group, any judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or acceptance of such

boundaries.

Rights and Permissions

e material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work

without permission may be a violation of applicable law. e International Bank for Reconstruction and

Development / e World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission

to reproduce portions of the work promptly.

For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete informa-

tion to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone:

978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com.

All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the O ce of

the Publisher, e World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2422;

e-mail: pubrights@worldbank.org.

ISBN: 978-0-8213-8634-7

eISBN: 978-0-8213-8635-4

DOI: 10.1596/978-0-8213-8634-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brun, Jean-Pierre, 1962-

Asset recovery handbook : a guide for practitioners / Jean-Pierre Brun and Larissa Gray.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8213-8634-7 — ISBN 978-0-8213-8635-4 (electronic)

1. Forfeiture—Criminal provisions. 2. Searches and seizures. I. Gray, Larissa. II. Title.

K5107.B788 2011

345’.0773—dc22

2010048779

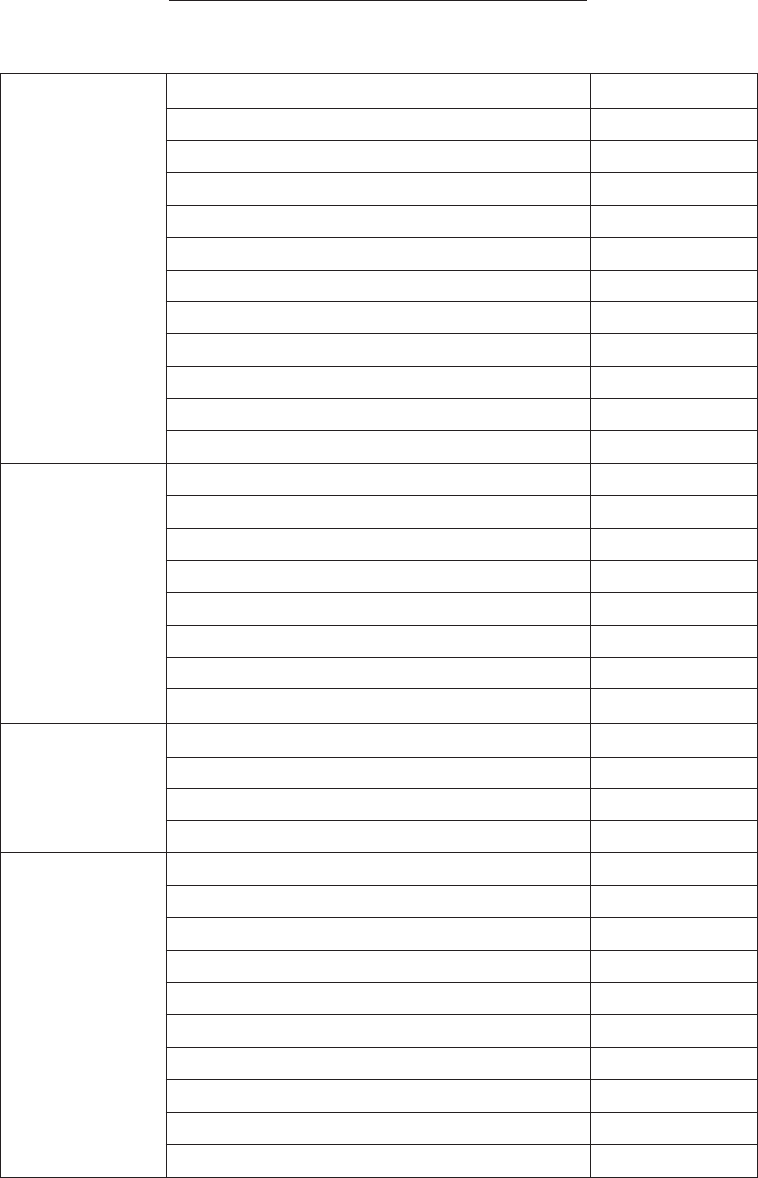

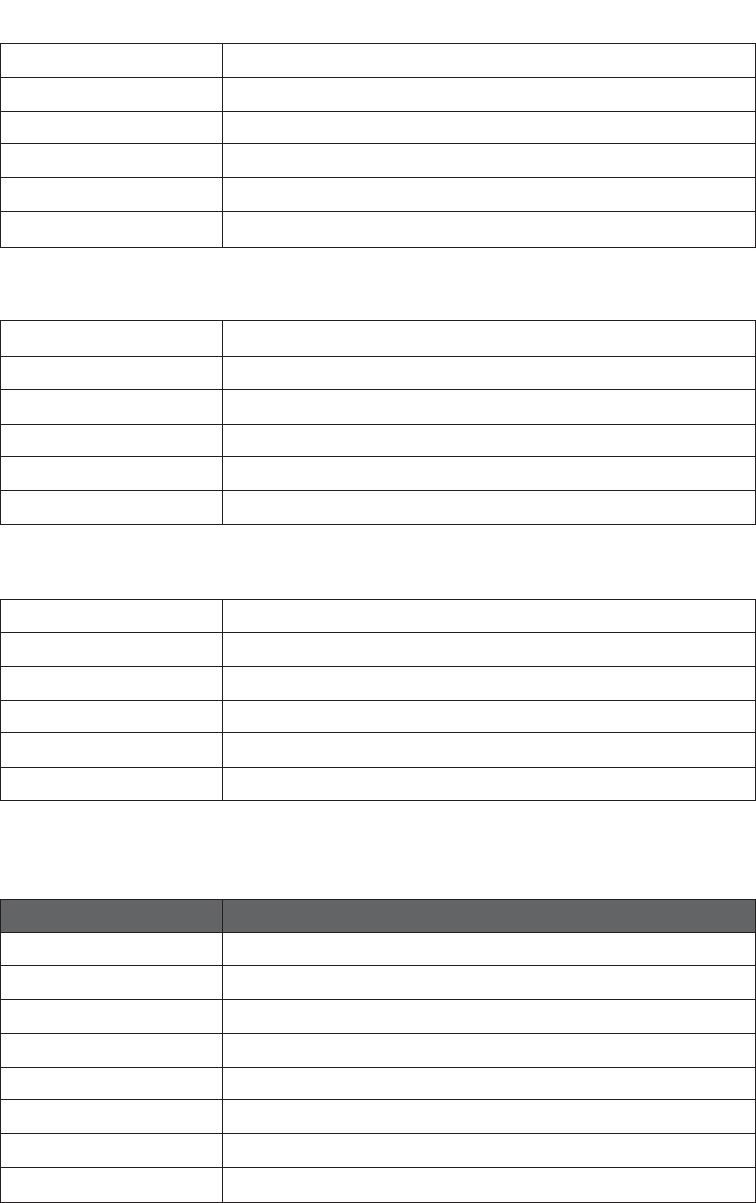

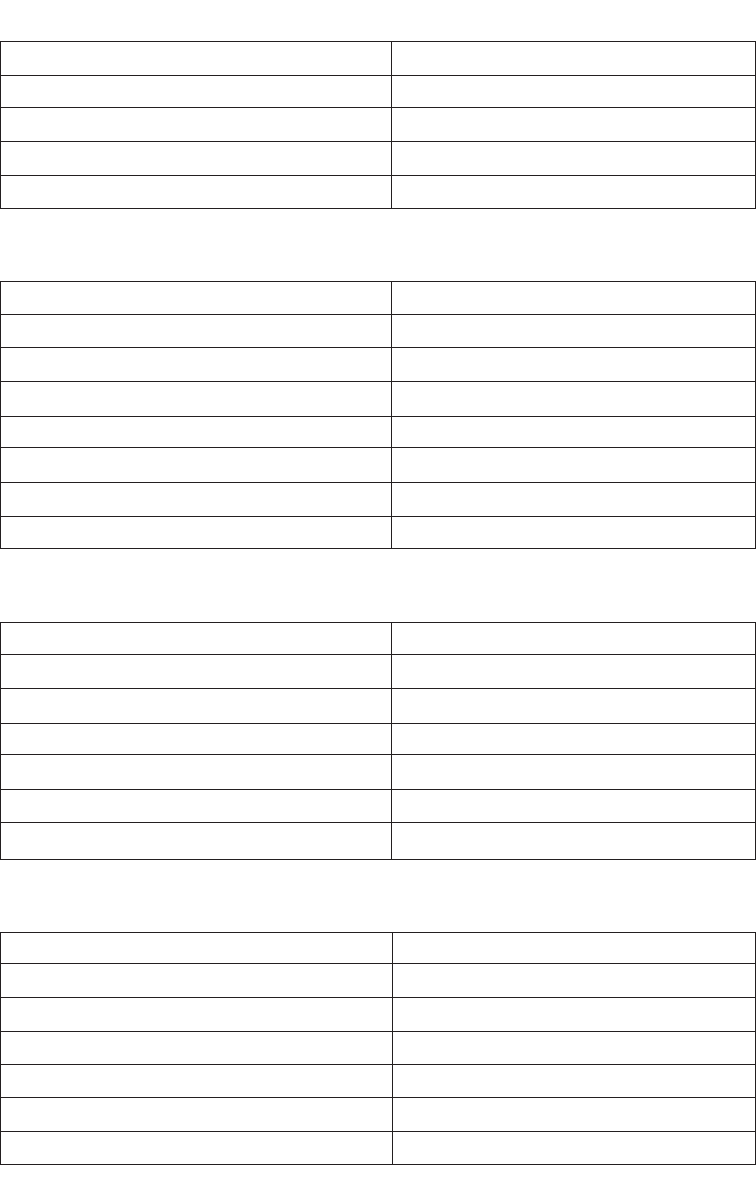

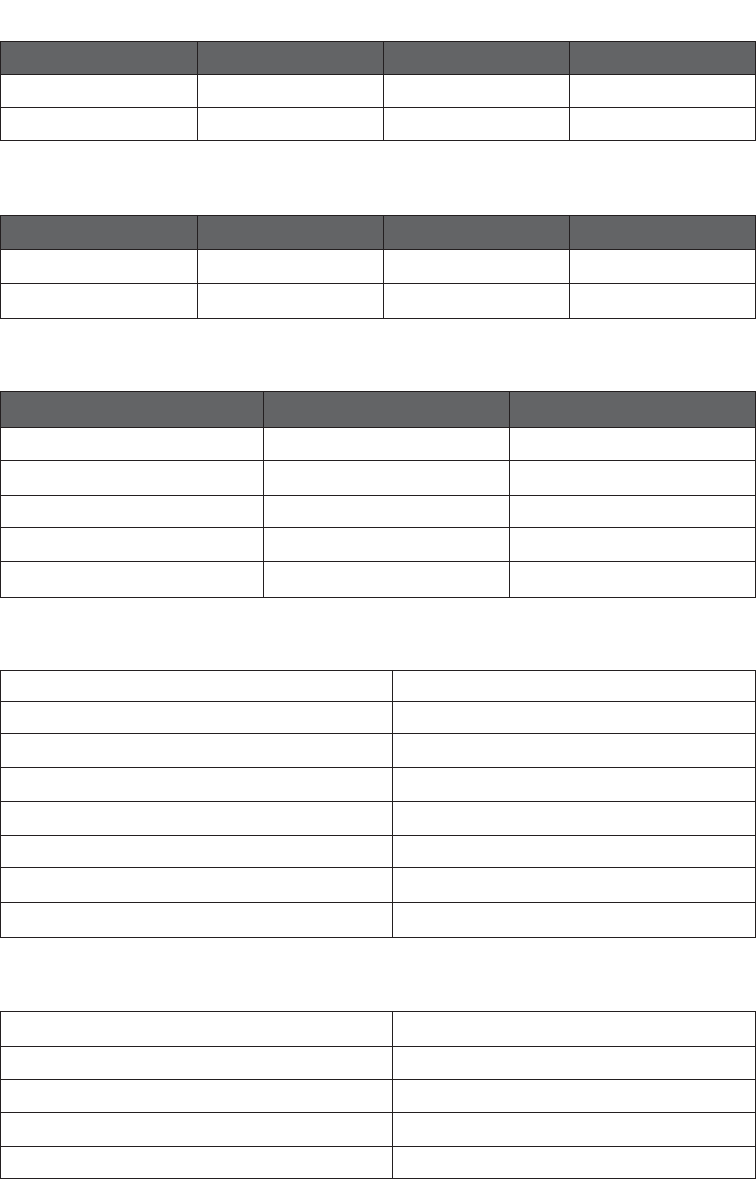

Contents

Preface xi

Acknowledgments xiii

Acronyms and Abbreviations xv

Introduction 1

Methodology 2

How the Handbook Can Be Used 3

1. Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and

Avenues for Recovering Assets 5

1.1 General Process for Asset Recovery 5

1.2 Legal Avenues for Achieving Asset Recovery 9

1.3 Use of Asset Recovery Avenues in Practice: Three Case Examples 14

2. Strategic Considerations for Developing and Managing a Case 19

2.1 Gathering Facts: Initial Sources of Information 19

2.2 Assembling a Team or Unit, Task Forces, and Joint Investigations with

Foreign Authorities 22

2.3 Establishing Contact with Foreign Counterparts and Assessing

Ability to Obtain International Cooperation 25

2.4 Securing Support and Adequate Resources 27

2.5 Assessing Legislation and Considering Legal Reforms 28

2.6 Addressing Legal Issues and Obstacles 29

2.7 Identifying All Liable Parties 34

2.8 Specific Considerations in Criminal Cases 34

2.9 Implementing a Case Management System 38

3. Securing Evidence and Tracing Assets 41

3.1 Introducing a Plan and Important Considerations 41

3.2 Creating a Subject Profile 43

3.3 Obtaining Financial Data and Other Evidence 43

3.4 Identifying Relevant Data: Examples from Commonly

Sourced Documents 61

3.5 Organizing Data: Creating a Financial Profile 71

3.6 Analyzing Data: Comparing the Flows with the Financial Profile 72

3.7 Garnering International Cooperation 74

vi I Contents

4. Securing the Assets 75

4.1 Terminology: Seizure and Restraint 75

4.2 Provisional Order Requirements 76

4.3 Pre-restraint or Pre-seizure Planning 79

4.4 Timing of Provisional Measures 85

4.5 Exceptions to Restraint Orders for Payment of Expenses 86

4.6 Ancillary Orders 87

4.7 Third-Party Interests 87

4.8 Alternatives to Provisional Measures 89

5. Managing Assets Subject to Confiscation 91

5.1 Key Players in Asset Management 92

5.2 Powers of the Asset Manager 93

5.3 Recording Inventory and Reporting 94

5.4 Common Types of Assets and Associated Problems 95

5.5 Ongoing Management Issues 99

5.6 Consultations 101

5.7 Liquidation (Sale) of Assets 101

5.8 Fees Payable to Asset Managers 101

5.9 Funding Asset Management 102

6. Mechanisms for Confiscation 103

6.1 Confiscation Systems 105

6.2 How Confiscation Works 107

6.3 Confiscation Enhancements 114

6.4 Third-Party Interests 118

6.5 Confiscation of Assets Located in Foreign Jurisdictions 119

6.6 Recovery through Confiscation for the Victims of Crime 119

6.7 Disposal of Confiscated Assets 120

7. International Cooperation in Asset Recovery 121

7.1 Key Principles 122

7.2 Comparative Overview of Informal Assistance

and MLA Requests 127

7.3 Informal Assistance 131

7.4 MLA Requests 138

7.5 Cooperation in Cases of Confiscation without a Conviction 156

7.6 Cooperation in Civil Recovery (Private Law) Cases 157

7.7 Asset Return 158

8. Civil Proceedings 159

8.1 Potential Claims and Remedies 160

8.2 Bringing a Civil Action to Recover Assets 169

8.3 Final Dispositions 173

8.4 Formal Insolvency Processes 174

Contents I vii

9. Domestic Confiscation Proceedings Undertaken

in Foreign Jurisdictions 177

9.1 Jurisdiction 177

9.2 Procedure for Beginning an Action 178

9.3 Role of the Jurisdiction Harmed by Corruption Offenses in

Foreign Investigation and Prosecution 179

9.4 Ensuring Recovery of Assets from the Foreign Jurisdiction 183

Appendix A. Offenses to Consider in Criminal Prosecution 187

Appendix B. Explanation of Selected Corporate Vehicles

and Business Terms 193

Appendix C. Sample Financial Intelligence Unit Report 199

Appendix D. Planning the Execution of a Search and

Seizure Warrant 201

Appendix E. Sample Document Production Order for

Financial Institutions 203

Appendix F. Serial and Cover Payment Methods in Electronic

Funds Transfers 209

Appendix G. Sample Financial Profile Form 213

Appendix H. Possible Discussion Points with

Contacts—Informal Assistance Stage 235

Appendix I. Mutual Legal Assistance Template and

Drafting Tips 237

Appendix J. Web Site Resources 241

Glossary 249

Index 253

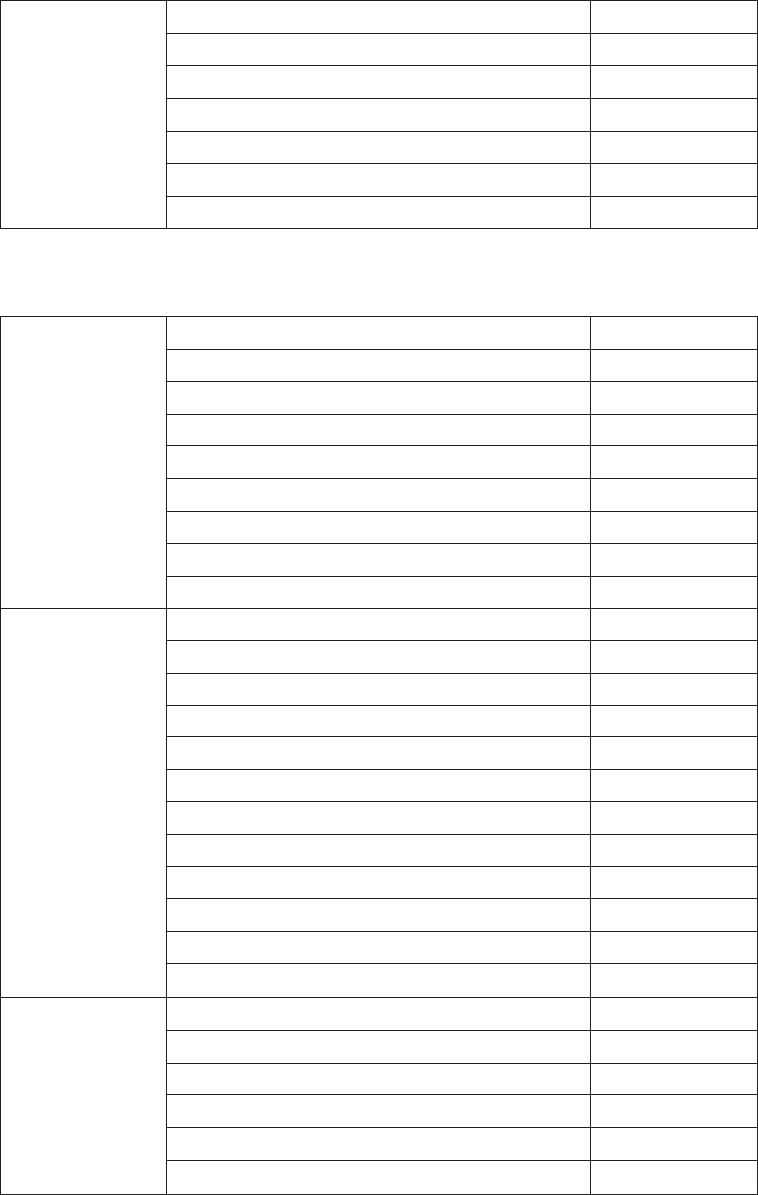

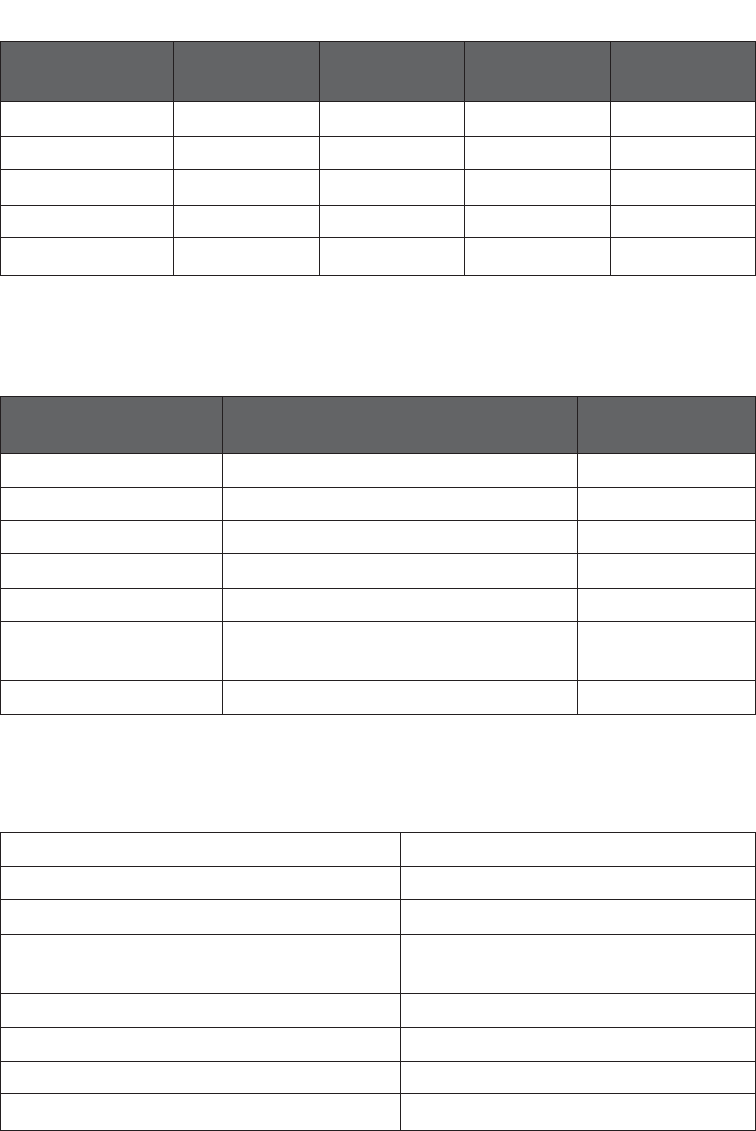

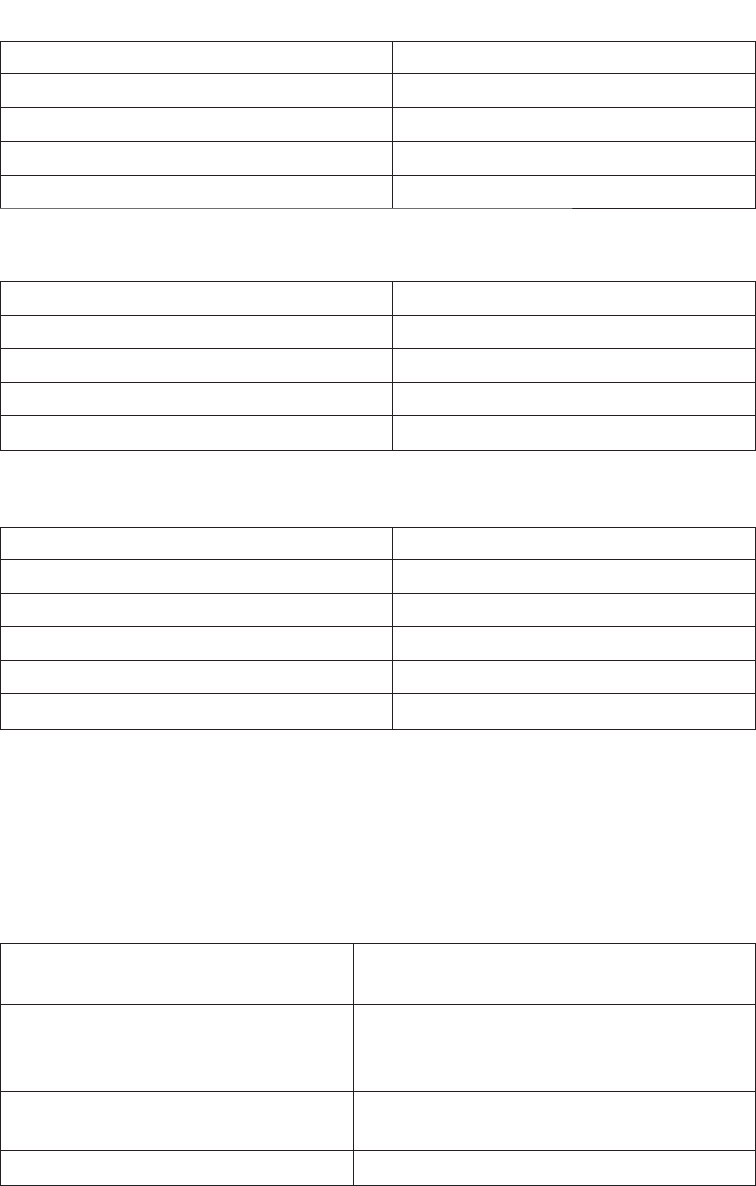

Boxes

1.1 Legal Framework for Asset Recovery 10

1.2 Alternative Means of Recovering Assets 15

2.1 Role and Contribution of FIUs in Asset Recovery Cases 21

2.2 Obstacles to International Cooperation 26

2.3 Strategic Decisions in Peru—Legislation Allowing

Plea Agreements 28

2.4 Prosecution of Accounting, Records, and Internal Control

Provisions in the United Kingdom and the United States 36

2.5 Examples of Challenges in Establishing the Elements of the Offense 37

3.1 Checklist for Collection of Basic Information 44

3.2 Tracing and Recovering Assets—Efforts in the United Kingdom 46

3.3 Elaborating Sufficient Grounds for a Search Warrant 55

3.4 Important Items to Seize 56

3.5 Documentation to Be Requested from Financial Institutions 58

viii I Contents

3.6 Retention Orders 59

3.7 Forms and Documents Related to the Wire Transfer Process 65

3.8 Red Flags in Contracts, Payment Documentation, Payment Records,

and Payment Mechanisms 69

4.1 Drafting Affidavits 78

4.2 An Example of Pre-restraint Planning Decisions in Practice 83

6.1 Historical Background and Recent Developments in Confiscation 104

6.2 Issues Encountered in Determining the Proceeds of

Crime—A Case Example 110

6.3 Using “Related Activities” to Capture the Full Benefit 118

7.1 Connecting With People—A Case Example from Peru 124

7.2 Contact Points for International Cooperation 125

7.3 Disclosure Obligations—A Barrier to MLA Requests 127

7.4 Investigative Jurisdiction in France, Switzerland, the

United Kingdom, and the United States 133

7.5 Facilitating Informal Assistance 134

7.6 Spontaneous Disclosures from Switzerland 137

7.7 Selecting a Legal Basis to Include in an MLA Request 139

7.8 Overcoming Dual Criminality—Illicit Enrichment and Corruption

of Foreign Public Officials 142

7.9 Bank Secrecy and Fiscal Offenses—A Ground for Refusing MLA? 146

7.10 Avoiding Rejections of MLA Requests That Are Overly Broad 149

7.11 Worldwide Orders in the United Kingdom 153

7.12 Requirements for Direct Enforcement of MLA Requests for

Confiscation in the United Kingdom and the United States 154

7.13 Asset Recovery Pursuant to an MLA Request in France 158

8.1 Case Examples of Proprietary (Ownership) Claims 160

8.2 The U.S. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations

(RICO) Statute 163

8.3 Compensation for Damages Where Assets Are Misappropriated 164

8.4 Fyffes v. Templeman and Others (2000) 166

8.5 World Duty Free Company Limited v. The Republic of Kenya (2006) 167

8.6 Disgorgement of Profits—Practice in the United States 168

8.7 Circumstantial Evidence Considered in Federal Republic

of Nigeria v. Santolina Investment Corp., Solomon & Peters,

and Diepreye Alamieyeseigha (2007)

170

8.8 Requirements for Restraint Orders in France, Panama, and the

United Kingdom 171

8.9 The Ao Man Long Case 173

8.10 Enforcement of Judgments When the Defendant Is

Absent from the Proceeding 174

9.1 Establishing Jurisdiction Where Limited Acts Have Occurred

in the Territory 179

9.2 Establishing Jurisdiction over Nationals in the United Kingdom

and the United States 180

Contents I ix

9.3 Jurisdiction to Prosecute Money Laundering Offenses in France,

the United Kingdom, and the United States 181

9.4 Confiscation Proceedings Initiated by Foreign Authorities 182

9.5 Important Role of the Jurisdiction Harmed by Corruption—

A Case Example from Haiti 183

9.6 Direct Recovery in Practice 185

9.7 Asset Return Options Available in Switzerland 186

A.1 Illicit Enrichment Provisions in France 190

F.1 Hiding Originating Customer Information 211

F.2 Monitoring Records from Financial Institutions 211

I.1 MLA Drafting and Execution Tips 240

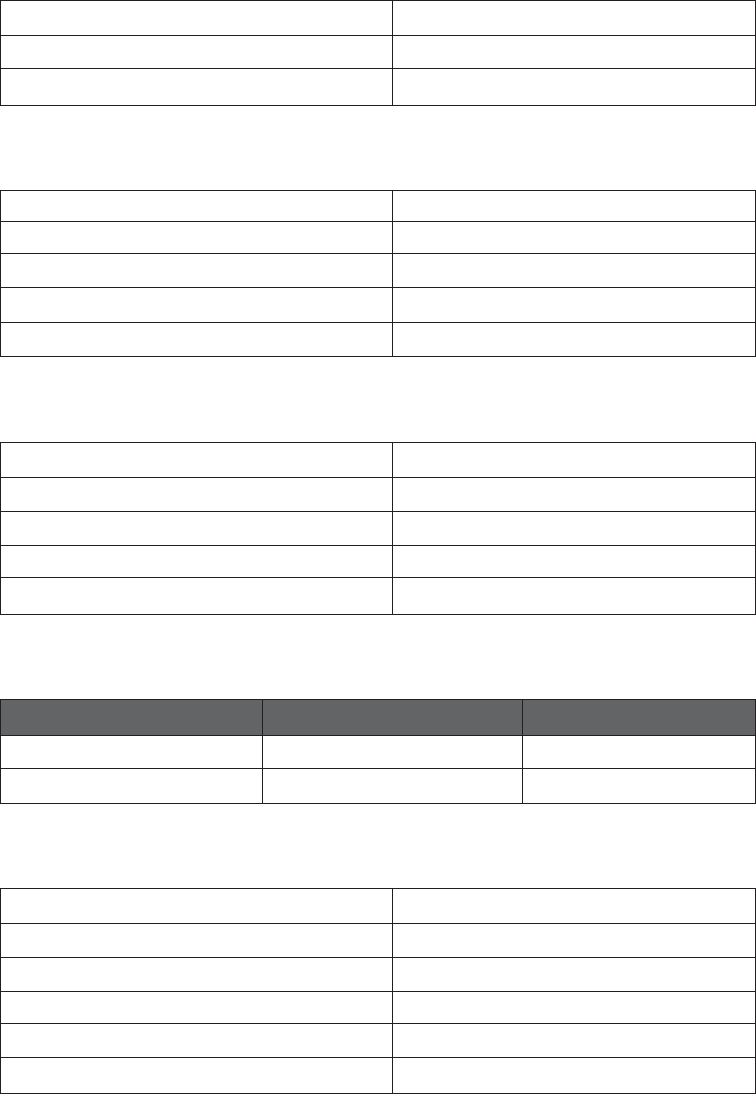

Figures

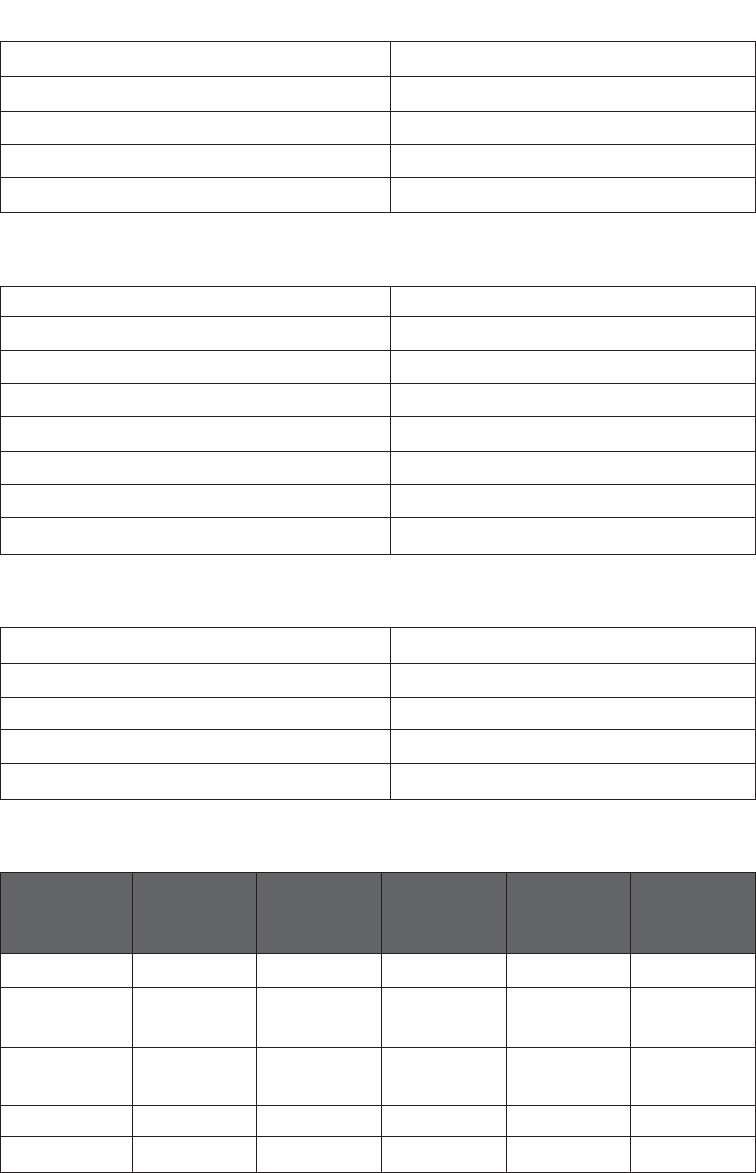

1.1 Process for Recovery of Stolen Assets 6

2.1 Standards of Proof 33

2.2 Criminal Charges to Consider 35

3.1 Five Effective Questions to Use in an Investigation 48

3.2 Preliminary Information Available from Other Government Agencies 49

3.3 Basic Cross-Border Wire Transfer Process 63

3.4 Sample SWIFT Message Format and Code Interpretation 68

3.5 Sample Flow Chart 72

3.6 Sample Chart of Relationships and Assets 73

5.1 Seized Motor Vehicles Left Outdoors 97

6.1 Confiscation of an Asset in a Foreign Jurisdiction 120

7.1 Phases of Asset Recovery and Integrating International Cooperation 122

7.2 Flow Chart of International Cooperation 130

7.3 Informal Assistance and Formal MLA Requests—

What Can Be Requested? 131

7.4 Flow of an MLA Request in the Presence of a Treaty or

Domestic Legislation 155

A.1 Criminal Charges to Consider 187

F.1 Serial/Sequential and Cover Payment Methods 210

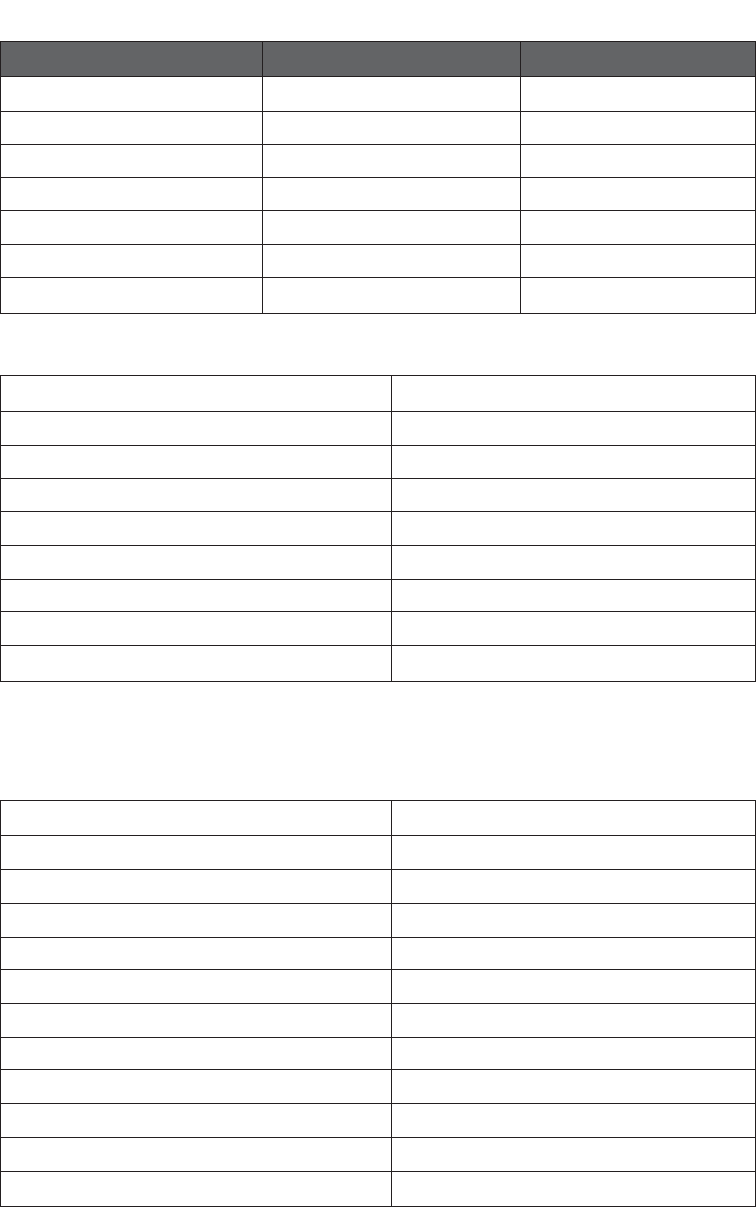

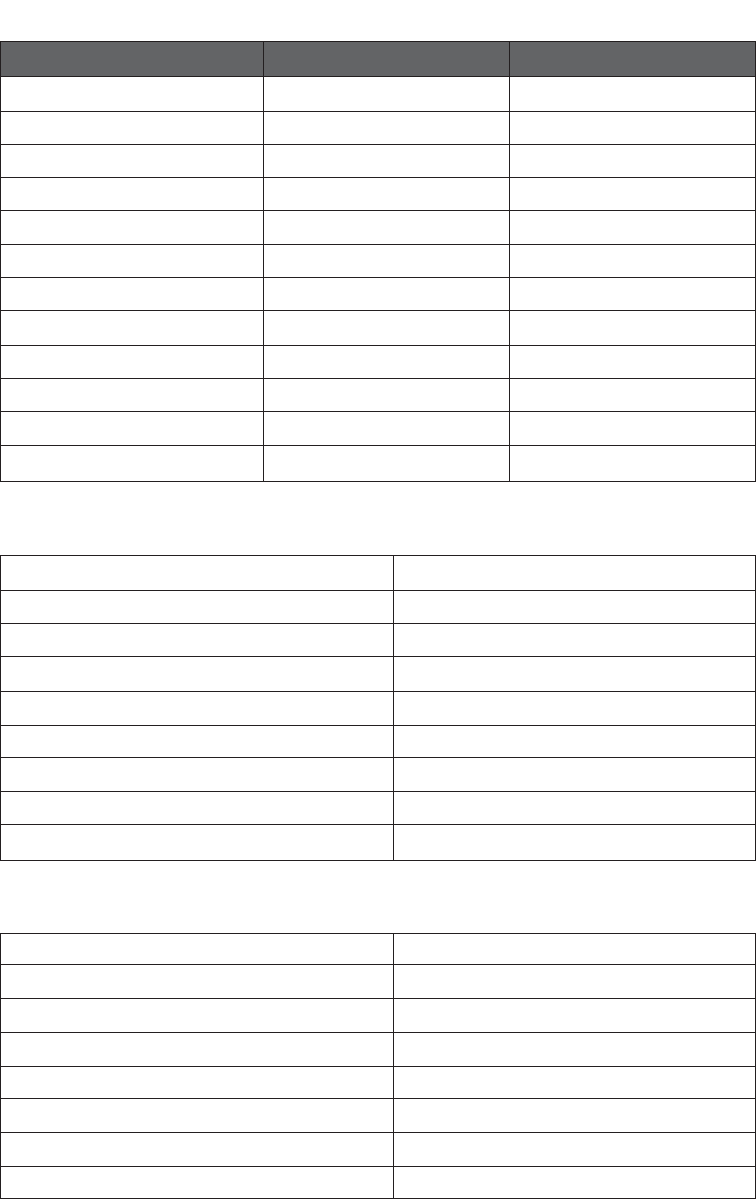

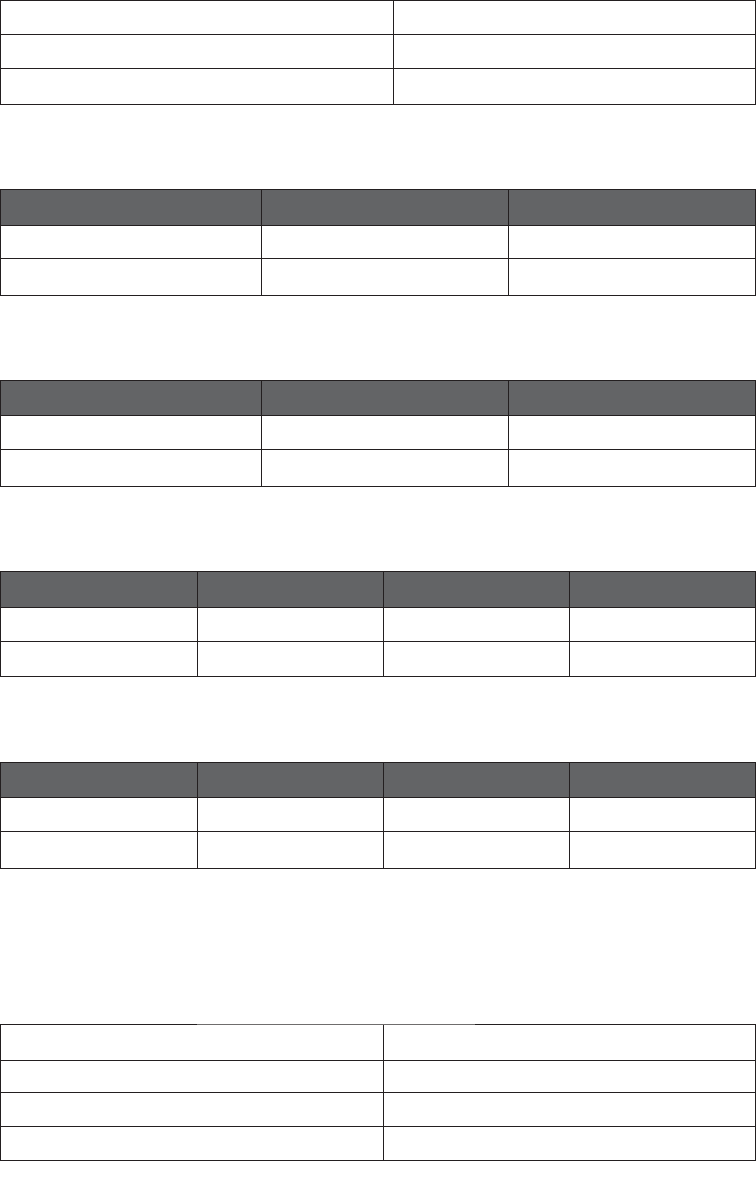

Tables

4.1 Considerations in Partial Control or Limited Restraint 84

7.1 Differences between Informal Assistance and MLA Requests 129

Preface

Developing countries lose between US$20 to US$40 billion each year through bribery,

misappropriation of funds, and other corrupt practices. Much of the proceeds of cor-

ruption nd “safe haven” in the world’s nancial centers. ese criminal ows are a

drain on social services and economic development programs, contributing to the fur-

ther impoverishment of the world’s poorest countries. e victims include children in

need of education, patients in need of treatment, and all members of society who con-

tribute their fair share and deserve assurance that public funds are being used to improve

their lives. But corruption a ects us all by undermining con dence in governments,

banks, and companies in both developed and developing economies.

e international community has responded to the challenge and, in principles and

through international agreements, is now moving forward. e G20 has put the ght

against corruption at the forefront of its e orts to improve global integrity and account-

ability. e Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative was launched in September 2007 by

the World Bank and the United Nations O ce on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to pro-

mote the rati cation and implementation of the United Nations Convention against

Corruption (UNCAC), and speci cally its chapter 5, which provides the rst compre-

hensive and innovative framework for asset recovery.

Many developing countries have already sought to recover stolen assets. A number of

successful high-pro le cases with creative international cooperation have demonstrated

that asset recovery is possible. However, to date, only US$5 billion in stolen assets have

been recovered. What we need now is more visible, tangible progress in forcefully pros-

ecuting bribery cases, and systematic recovery of proceeds of corruption.

However, recovering proceeds of corruption is complex. e process can be over-

whelming for even the most experienced of practitioners. It is exceptionally di cult

for those working in the context of failed states, widespread corruption, or with lim-

ited resources. We must support their e orts as they grapple with the strategic, orga-

nizational, investigative, and legal challenges of recovering stolen assets, whether

through criminal con scation, nonconviction based con scation, civil actions, or

other alternatives.

We hope that the guide will prove useful for law enforcement o cers, prosecutors,

investigating judges, lawyers, and other experts. We also expect that it will be helpful to

xii I Preface

those making policy decisions regarding legislation and management of resources

devoted to ghting corruption, and we look forward to using the handbook to provide

technical assistance and promote capacity building in countries interested in the StAR

Initiative.

Ngozi N. Okonjo-Iweala Yury Fedotov

Managing Director, e World Bank Executive Director, UNODC

Acknowledgments

is handbook is the result of special collaborative e orts from colleagues around the

world. eir time and expertise were invaluable in developing a practical tool to assist

practitioners in recovering the proceeds and instrumentalities of corruption.

is publication was written by Jean-Pierre Brun (team leader, Financial Market Integ-

rity Unit, World Bank), Larissa Gray (Financial Market Integrity Unit), Kevin

Stephenson (Financial Market Integrity Unit), and Clive Scott (United Nations O ce

on Drugs and Crime [UNODC]), with the participation of Nina Gidwaney (Financial

Market Integrity Unit).

e authors are especially grateful to Jean Pesme (manager, Financial Market Integrity

Unit, Financial and Private Sector Development Network) and Adrian Fozzard (Stolen

Asset Recovery [StAR] Initiative coordinator) for their ongoing support and guidance

on this project.

e team bene ted from many insightful comments during the peer review process,

which was co-chaired by Jean Pesme and Tim Steele (senior governance specialist, StAR

Secretariat). e peer reviewers were Raymond Baker (director, Global Financial Integ-

rity), Yara Esquivel (Integrity Vice Presidency, World Bank), Frank Fariello (Legal

Department, World Bank), Agustin Flah (Legal Department, World Bank), Jeanne

Hauch (Integrity Vice Presidency, World Bank), Lindy Muzila (UNODC), and Mutembo

Nchito (prosecutor, Zambia).

As part of the dra ing and consultation process, practitioners’ workshops were held in

Vienna, Austria (May 2009) and Marseille, France (May 2010). Practitioners brought

experience conducting criminal con scation, non-conviction based con scation, civil

actions, investigations, asset tracing, international cooperation and asset management—

from both civil and common law jurisdictions, and from both developed and develop-

ing countries. e people participating (from both public and private sectors) were Yves

Aeschlimann (Financial Market Integrity Unit), Jean-Marc Cathelin (France), France

Chain (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD]), Hamza

Chraiti (Switzerland), Anne Conestabile (OECD), Margaret Cotter (International Mon-

etary Fund), William Cowden (United States), Maxence Delorme (France), Nick deVil-

liers (South Africa), Adrian Fajardo (Mexico), Frank Filippeli (United States), Clara

Garrido (Colombia), John Gilkes (United States), Dorothee A. Gottwald (UNODC),

xiv I Acknowledgments

Guillermo Jorge (Argentina), Vitaliy Kasko (Ukraine), William Loo (OECD), Marko

Magdic (Chile), Olaf Meyer (Germany), Holly Morton (United Kingdom), Elnur

Musayev (Azerbaijan), Shane Nainappan (United Kingdom), Nchima Nchito (Zambia),

Jean Fils Kleber Ntamack (Cameroon), Pedro Pereira (International Centre for Asset

Recovery), Stephen Platt (Jersey), Frederic Ra ray (Guernsey), Linda Samuel (United

States), Jean-Bernard Schmid (Switzerland), Salim Succar (Haiti), Jose Ugaz (Peru),

Gary Walters (United Kingdom), Jean Weld (United States), Simon Williams (Canada),

and Annika Wythes (UNODC).

e handbook also bene ted from the contributions of eodore S. Greenberg

(Financial Market Integrity Unit), David M. Mizrachi (Panama), and Felicity Toube

(United Kingdom).

A special thanks also to elma Ayamel for arranging the logistics of the workshops in

Vienna and Marseille; and to Maria Orellano and Miguel Nicolas de la Riva for their

administrative support.

Jean-Pierre Brun

Task Team Leader

Financial Market Integrity Unit

World Bank

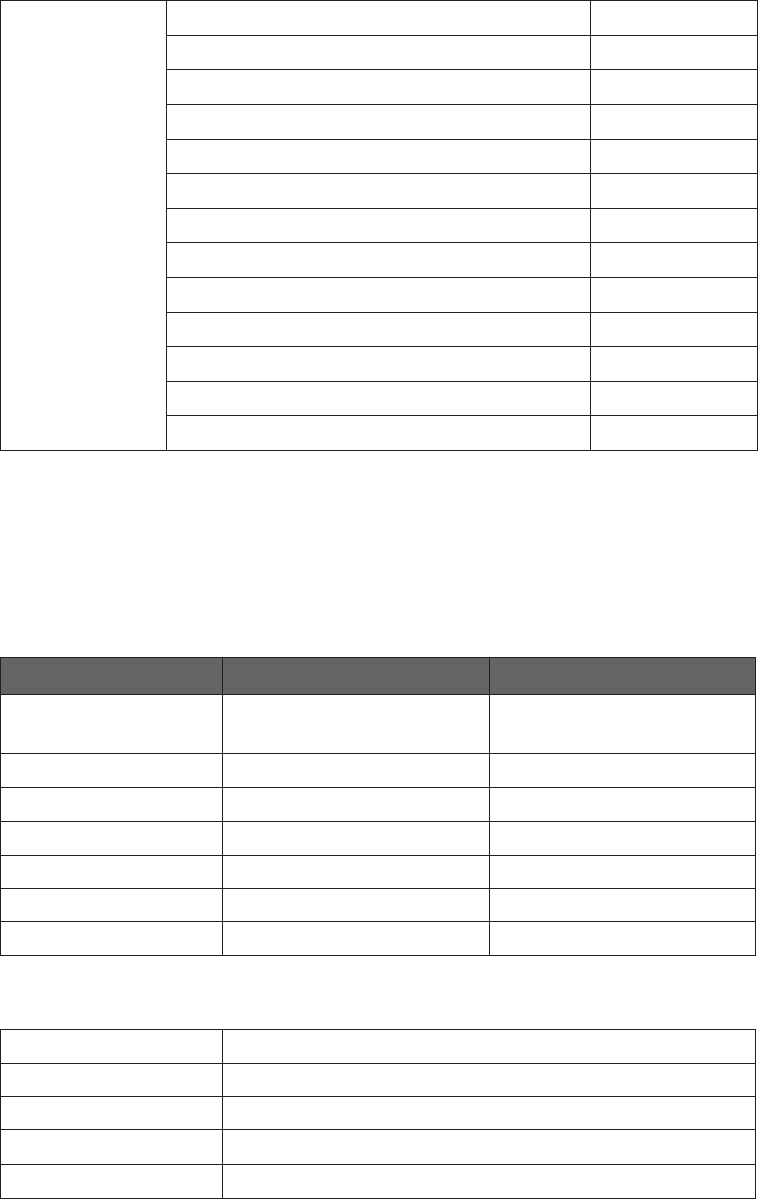

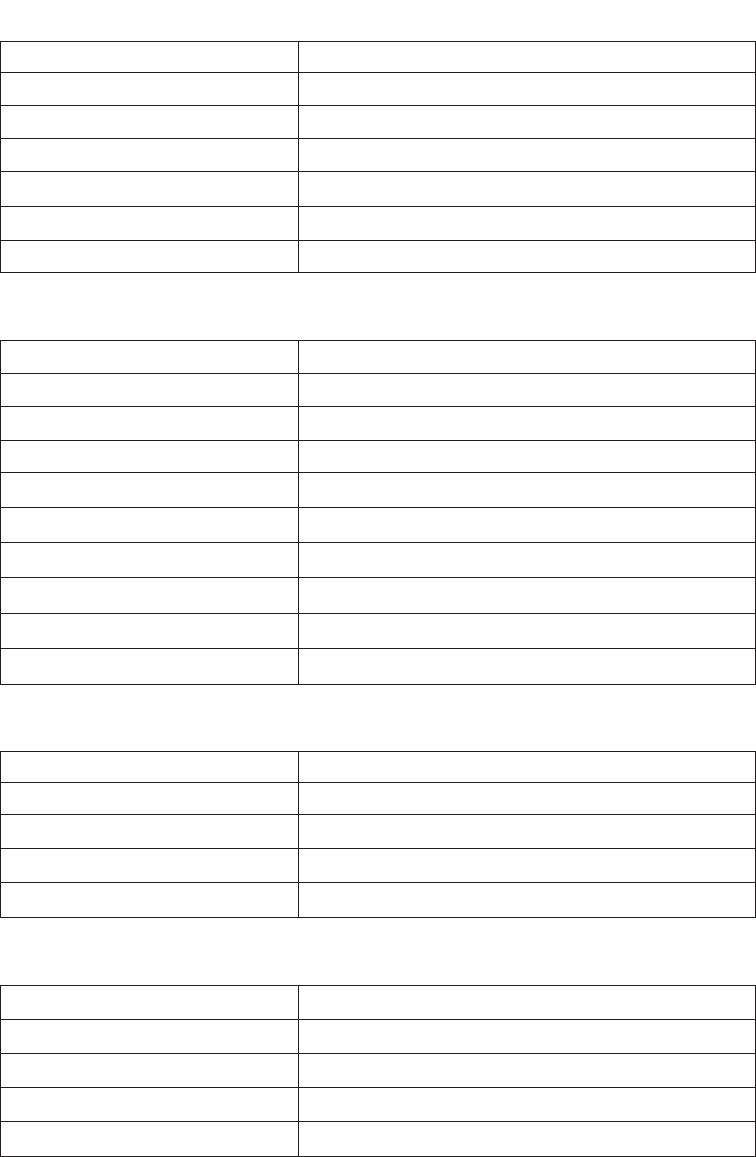

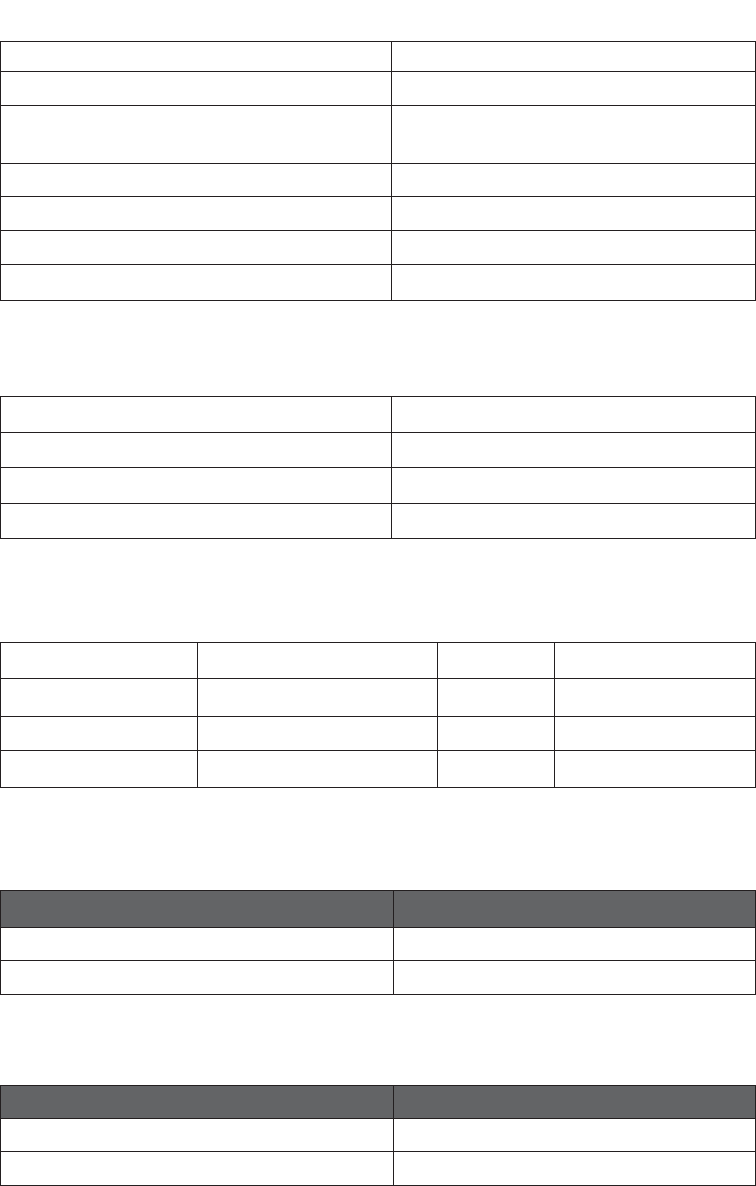

Acronyms and Abbreviations

BIC Bank identi er code

CARIN Camden Assets Recovery Inter-Agency Network

CHAPS Clearing House Automated Payments System

CHIPS Clearing House Interbank Payments System

CTR Currency transaction report

ECHR European Court of Human Rights

EWHC (Ch.) England and Wales High Court (Chancery Division)

FATF Financial Action Task Force

FCPA Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

Fedwire Fedwire Funds Service

FIU Financial intelligence unit

GDP Gross domestic product

IBC International business corporation

ICSID International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes

LLC Limited Liability Company

MLA Mutual legal assistance

NCB Non-conviction based

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PEP Politically exposed person

PTC Private trust company

RICO Racketeer In uenced and Corrupt Organizations

StAR Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative

STR Suspicious transaction report; Suspicious activity report

SWIFT Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications

UAE United Arab Emirates

UNCAC United Nations Convention against Corruption

UNODC United Nations O ce on Drugs and Crime

UNTOC United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime

WDF World Duty Free Company Limited

Introduction

e the of public assets from developing countries is an immense development problem.

e amount of money stolen from developing and transition jurisdictions and hidden in

foreign jurisdictions each year is approximately $20–$40 billion—a gure equivalent to

20–40 percent of ows of o cial development assistance.

1

e societal costs of corruption

far exceed the value of assets stolen by public leaders. Corruption weakens con dence in

public institutions, damages the private investment climate, and ruins delivery mechan-

isms for such poverty alleviation programs as public health and education.

2

Recognizing the serious problem of corruption and the need for improved mechanisms

to combat its devastating impact and facilitate the recovery of corruption proceeds, the

international community introduced a new framework in the United Nations Conven-

tion against Corruption (UNCAC). Chapter V of the convention provides this framework

for the return of stolen assets, requiring states parties to take measures to restrain, seize,

con scate, and return the proceeds of corruption. To do so, they may use various mecha-

nisms, such as:

direct enforcement of freezing or con scation orders made by the court of another •

state party;

3

non-conviction based asset con scation, particularly in cases of death, ight, or •

absence of the o ender or in other cases;

4

civil actions initiated by another state party, allowing that party to recover the •

proceeds as plainti ;

5

con scation of property of a foreign origin by adjudication of an o ense of money •

laundering or other o enses;

6

court orders of compensation or damages to another state party and recognition •

by courts of another state party’s claim as a legitimate owner of assets acquired

through corruption;

7

spontaneous disclosure of information to another state party without prior •

request;

8

and

international cooperation and asset return.•

9

1. World Bank, Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative: Challenges, Opportunities, and Action Plan (Washington,

DC, 2007), 9.

2. Ibid.

3. United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), art. 54(1)(a) and 54(2)(a).

4. UNCAC, art. 54(1)(c).

5. UNCAC, art. 53.

6. UNCAC, art. 54(1)(b) and 54(2)(b).

7. UNCAC, art. 53(b) and (c).

8. UNCAC, art. 56.

9. UNCAC, art. 55 and 57.

2 I Asset Recovery Handbook

Even with this framework, the practice of recovering stolen assets remains complex. It

involves coordination and collaboration with domestic agencies and ministries in mul-

tiple jurisdictions with di erent legal systems and procedures. It requires special inves-

tigative techniques and skills to “follow the money” beyond national borders and the

ability to act quickly to avoid dissipation of the assets. To ensure e ectiveness, the com-

petent authority (“the authority”) must have the capacity to launch and conduct legal

proceedings in domestic and foreign courts or to provide the authorities in another

jurisdiction with evidence or intelligence for investigations (or both). All legal options—

whether criminal con scation, non-conviction based con scation, civil actions, or

other alternatives—must be considered. is process may be overwhelming for even

the most experienced practitioners. It is exceptionally di cult for those working in the

context of failed states, widespread corruption, or limited resources.

e complexity of the process highlights the need for a practical tool to help practitio-

ners navigate the process. With this in mind, the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative, a joint

initiative of the United Nations O ce of Drugs and Crime and the World Bank focused

on encouraging and facilitating more systematic and timely return of stolen assets, has

developed this Asset Recovery Handbook: A Guide for Practitioners. Designed as a how-

to manual, the handbook guides practitioners as they grapple with the strategic, organi-

zational, investigative, and legal challenges of recovering assets that have been stolen by

corrupt leaders and hidden abroad. It provides common approaches to recovering stolen

assets located in foreign jurisdictions, identi es the challenges that practitioners are

likely to encounter, and introduces good practices. By consolidating into a single frame-

work the information dispersed across various professional backgrounds, the handbook

will enhance the e ectiveness of practitioners working in a team environment.

Methodology

To develop the Asset Recovery Handbook as a practical tool to help practitioners navi-

gating the issues, laws, and theory, the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative drew on those

people who have practical day-to-day experience in one or more of the core areas of

asset recovery. Participants included law enforcement, nancial investigators, investi-

gating magistrates, prosecutors, lawyers in private practice, and asset managers. ey

brought experience—from developed and developing jurisdictions and from civil and

common law systems—in conducting criminal con scation, non-conviction based

asset con scation, civil actions, investigations, asset tracing, international cooperation,

and asset management. ey have worked with other national agencies as well as with

foreign counterparts. Being familiar with some of the challenges in this regard, they

have developed their own methods and ideas for overcoming those challenges.

e overall format of the handbook and key topics for consideration were agreed on by

a group of practitioners at a workshop held in Vienna, Austria, in May 2009.

10

ese

10. Participating practitioners in the May 2009 Vienna workshop brought experience from practice in

Argentina, Azerbaijan, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, France, Guernsey, Jersey, Peru, South Africa,

Switzerland, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, and Zambia.

Introduction I 3

were developed by the authors into a dra version, and then presented and discussed at

a second practitioners’ workshop held one year later in Marseille, France.

11

e second

workshop was followed by additional contributions and consultations, and the nal

version was agreed to by the expanded group.

How the Handbook Can Be Used

e Asset Recovery Handbook is designed as a quick-reference, how-to manual for

practitioners—law enforcement o cials, investigating magistrates, and prosecutors—

as well as for asset managers and those involved in making policy decisions in both civil

and common law jurisdictions. Given diverse audiences and legal systems, it is impor-

tant that readers keep in mind that a practice or strategy that has worked in one jurisdic-

tion may not work in another. Likewise, an investigative technique that is permitted in

one jurisdiction may not be permitted—or may have di erent procedural requirements—

in another. In addition, jurisdictions may use di erent terminology to describe the same

legal concept (for example, some jurisdictions use “con scation” and others use “forfei-

ture”) or procedure (some jurisdictions’ assets may be “seized,” whereas others’ may be

“restrained,” “blocked,” or “frozen”).

12

Or di erent jurisdictions may assign di erent

roles and responsibilities to those people who are involved in asset recovery: in some

jurisdictions, investigations are conducted by an investigating magistrate; in others, by

law enforcement authorities or prosecutors.

e handbook attempts to point out these di erences where they exist, and it high-

lights how di erent concepts or practices may o er similar solutions to the same chal-

lenges. However, the handbook is not designed to be a detailed compendium of law and

practices. Each practitioner therefore should read the handbook in the context of his or

her speci c jurisdiction’s legal system, law enforcement structures, resources, legisla-

tion, and procedures—without being restrained by the terminology or the concepts

used to illustrate the challenges and tools for successful recovery of assets. e practi-

tioner should also consider the context of the legal system, law enforcement structures,

resources, legislation, and procedures of the speci c jurisdiction where the asset recov-

ery procedures will be sought.

e primary purpose of this handbook is to facilitate asset recovery in the context of grand

corruption, particularly as outlined in chapter V of UNCAC. Nonetheless, asset con sca-

tion and recovery can and should be applied to a wider range of o enses—particularly,

11. Practitioners participating in the May 2010 Marseille workshop brought experience from Argentina,

Azerbaijan, Brazil, Cameroon, Chile, Colombia, France, Germany, Guernsey, Haiti, Peru, South Africa,

Switzerland, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States, and Zambia.

12. For example, in South Africa’s Prevention of Organised Crime Act, 1998, “con scation” is de ned as

value-based orders made pursuant to chapter V of the act. In other jurisdictions, these orders are described

as “pecuniary penalty orders” (for example, in federal and many state con scation laws in Australia). In

Mexico, the term “forfeiture” is preferred because this refers to the proceeds and instrumentalities of crime;

“con scation,” on the other hand, refers to the assets of an individual. In Jersey, “forfeiture” is used with the

instrumentalities of crime, and “con scation” relates to the proceeds of crime.

4 I Asset Recovery Handbook

the asset con scation provisions set out in the United Nations Convention against

Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Vienna) and the United Nations Con-

vention against Transnational Organized Crime.

e handbook is organized into nine chapters, a glossary, and 10 appendixes of addi-

tional resources. Chapter 1 provides a general overview of the asset recovery process

and legal avenues for recovery, along with practical case examples. Chapter 2 presents a

host of strategic considerations for developing and managing an asset recovery case,

including gathering initial sources of facts and information, assembling a team, and

establishing a relationship with foreign counterparts for international cooperation.

Chapter 3 introduces the techniques that practitioners may use to trace assets and ana-

lyze nancial data, as well as to secure reliable and admissible evidence for asset con s-

cation cases. e provisional measures and planning necessary to secure the assets prior

to con scation are discussed in chapter 4; and chapter 5 introduces some of the man-

agement issues that practitioners will need to consider during this phase. Con scation

systems are the focus of chapter 6, including a review of the di erent systems and how

they operate and the procedural enhancements that are available in some jurisdictions.

On the issue of international cooperation, chapter 7 reviews the various methods avail-

able, including informal assistance and mutual legal assistance requests; and guides

practitioners through the entire process. Finally, chapters 8 and 9 discuss two addi-

tional avenues for asset recovery—respectively, civil proceedings and domestic con s-

cation proceedings undertaken in foreign jurisdictions.

e glossary de nes many of the specialized terms used within the handbook. Because

jurisdictions o en use di erent terminology to describe the same legal concept or pro-

cedure, the glossary provides examples of alternative terms that may be used.

e appendixes contain additional reference tools and practical resources to assist prac-

titioners. Appendix A provides an outline of o enses where criminal prosecution is

concerned. Appendix B presents a detailed list and descriptions of commonly used

corporate vehicle terms. For those reviewing suspicious transaction reports, appendix

C provides a sample nancial intelligence unit report. Appendix D o ers a checklist of

some additional considerations for planning the execution of a search and seizure war-

rant. Appendixes E and G, respectively, provide a sample production order for nancial

institutions and a sample nancial pro le form. Appendix F outlines the serial and

cover payment methods used by correspondent banks in relation to electronic fund

transfers, and it discusses the new cover payment standards that became e ective in

November 2009. Appendix H o ers discussion points that practitioners may use to

begin communications with their foreign counterparts. With respect to mutual legal

assistance requests, Appendix I provides an outline for a letter of request, with key

dra ing and execution tips. Finally, Appendix J provides a broad range of international

and country-speci c Web site resources.

One of the rst considerations in an asset recovery case is the development of an e ec-

tive strategy for both obtaining a criminal conviction (if possible) and recovering the

proceeds and instrumentalities of corruption. Practitioners must be aware of the vari-

ous legal avenues available for recovering assets, as well as some of the factors or obsta-

cles that may lead to the selection of one avenue over another. is chapter introduces

the general process for asset recovery and the various recovery avenues (most of which

are discussed in greater detail in subsequent chapters).

1.1 General Process for Asset Recovery

Whether pursuing assets through criminal or non-conviction based (NCB) con sca-

tion or through proceedings in a foreign jurisdiction or through a private civil action,

the objectives and fundamental process for recovery of assets are generally the same.

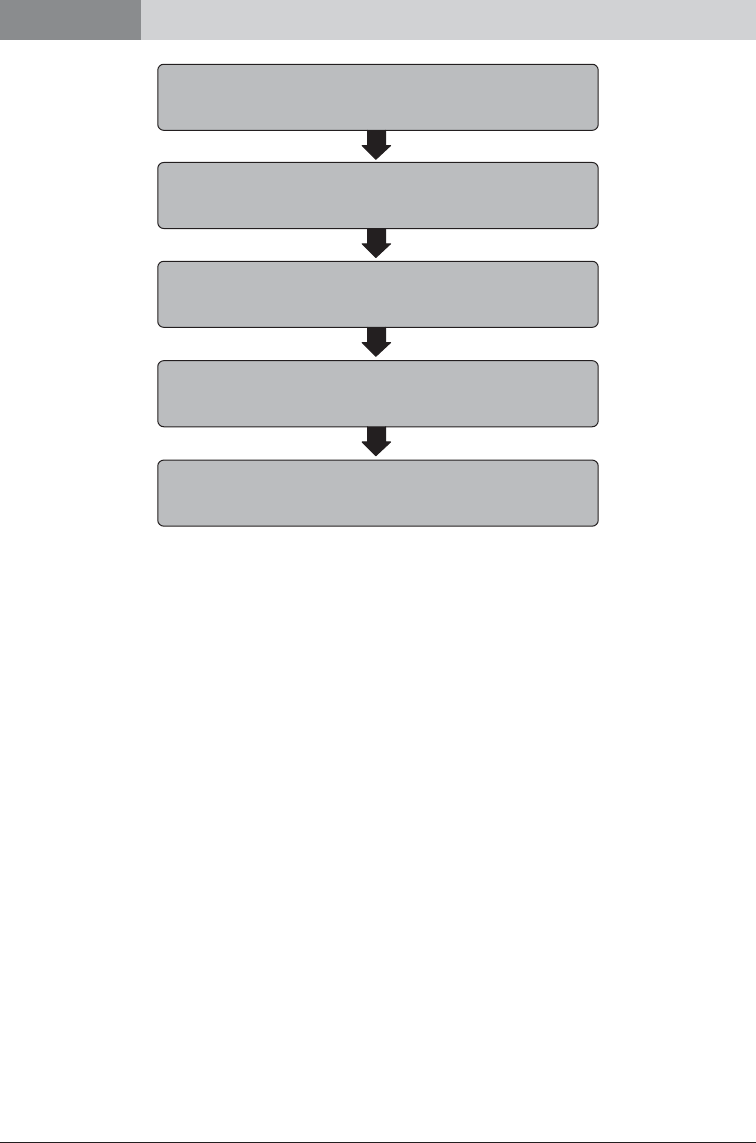

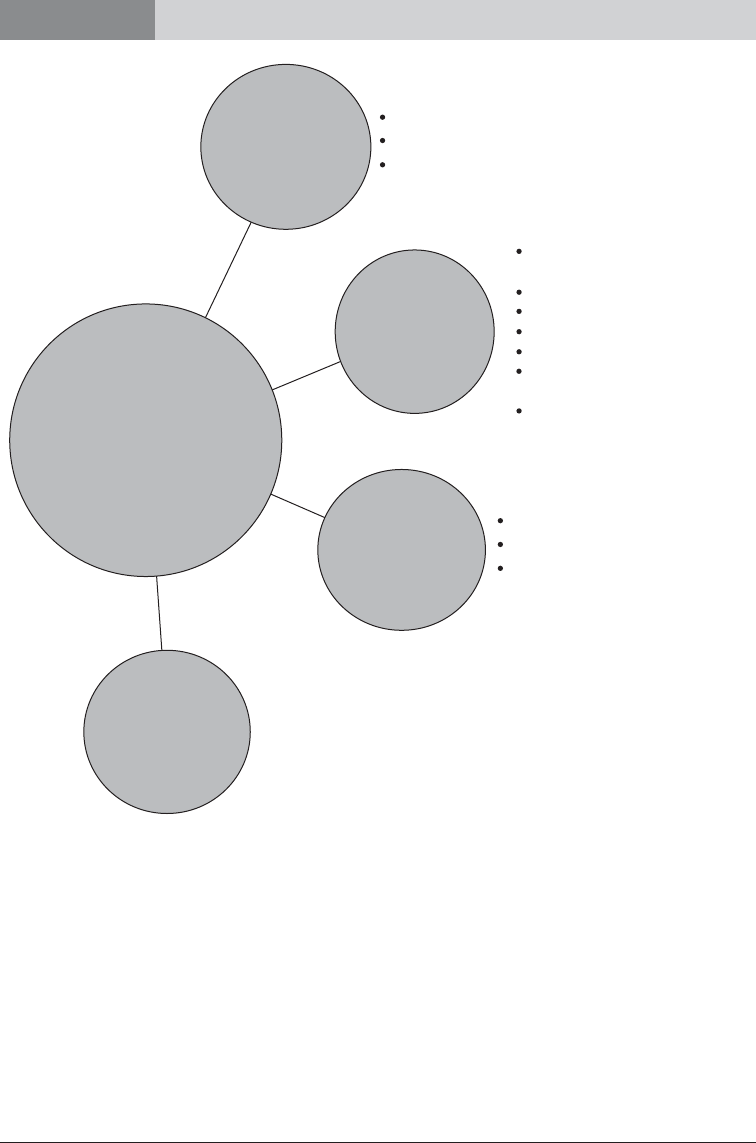

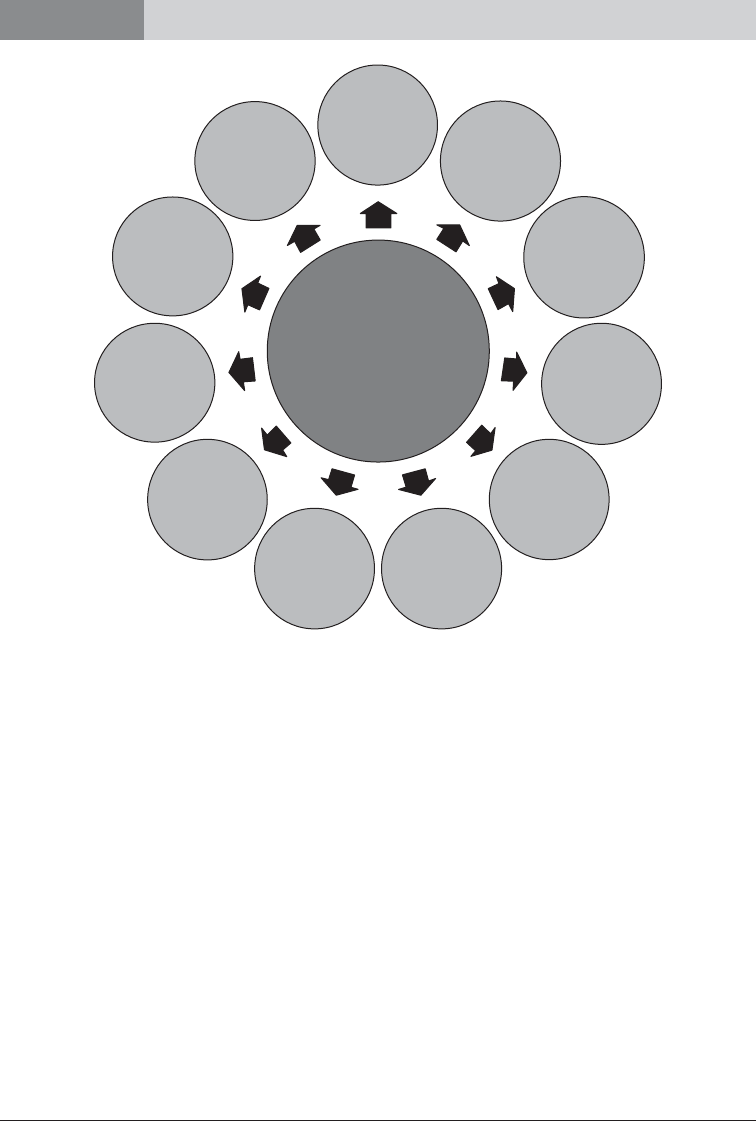

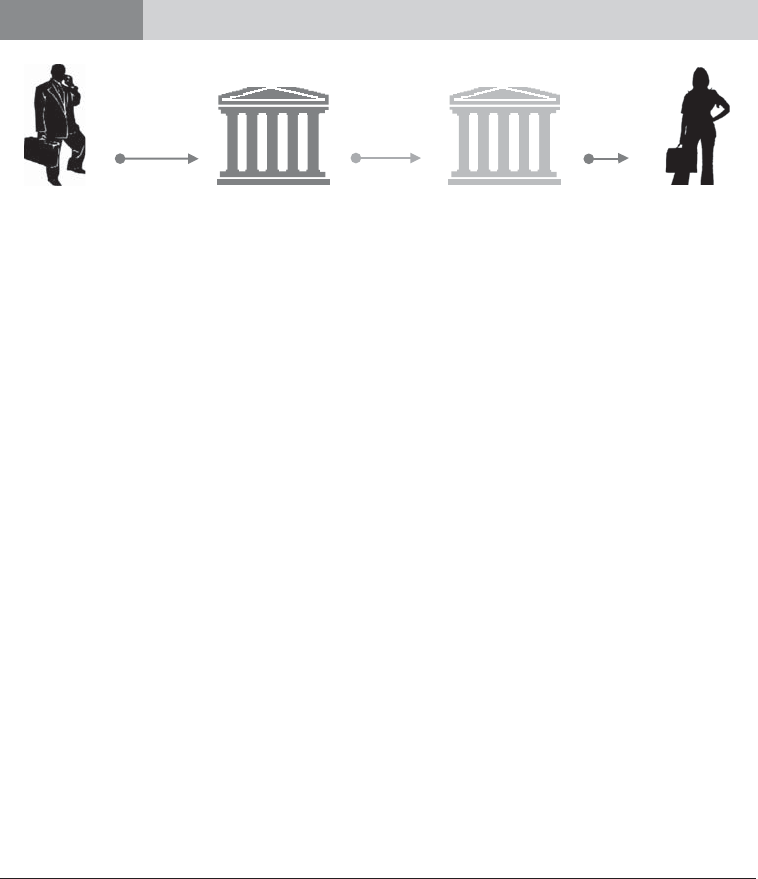

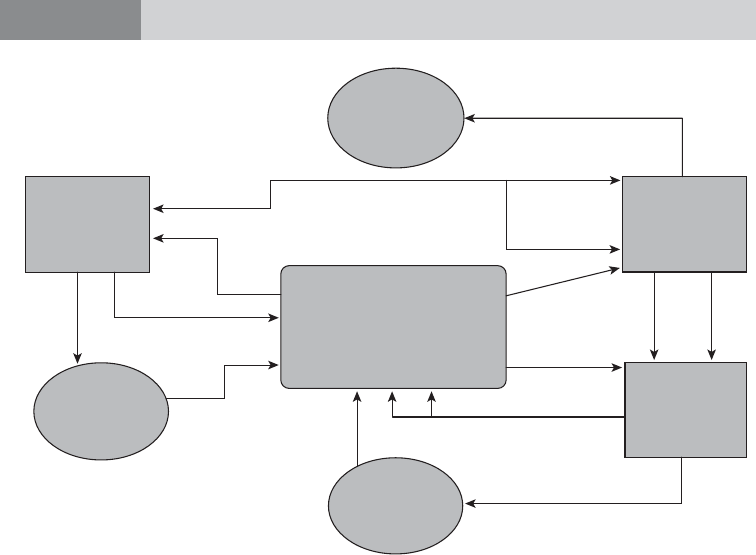

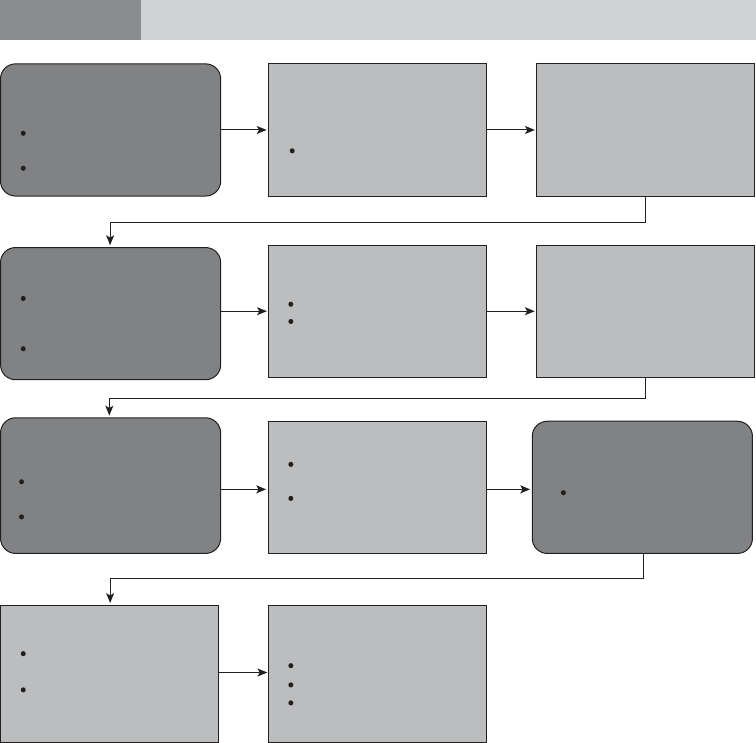

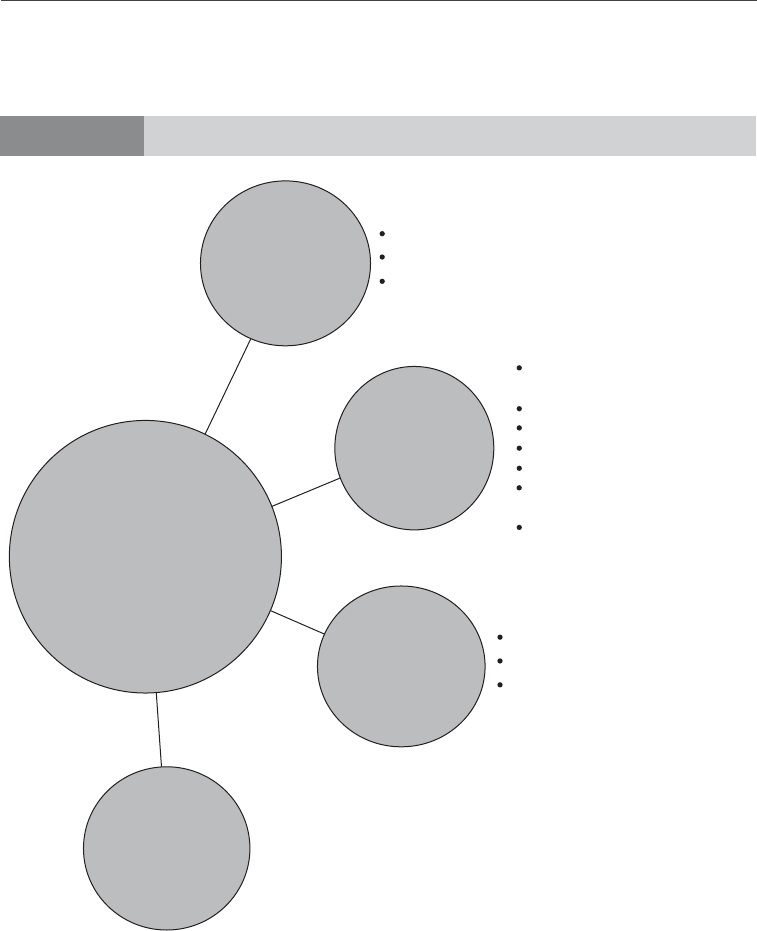

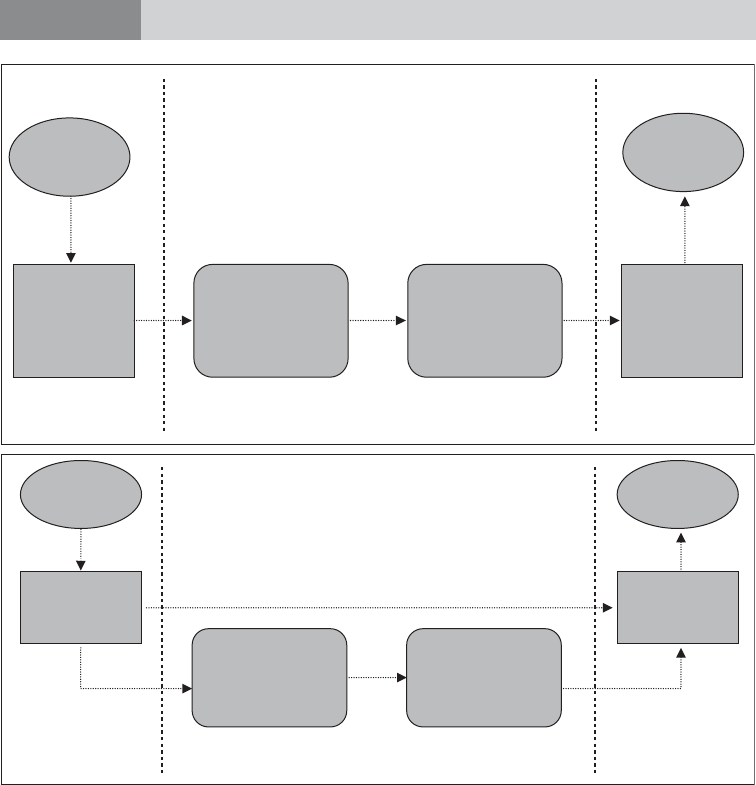

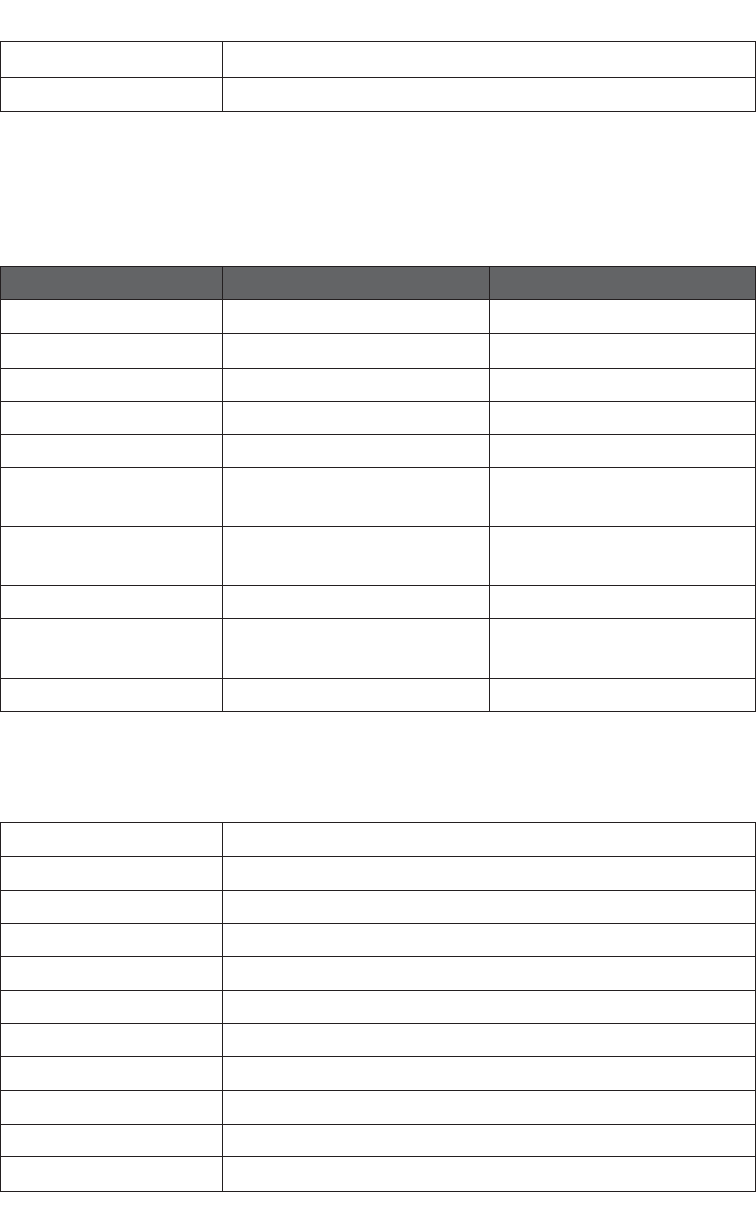

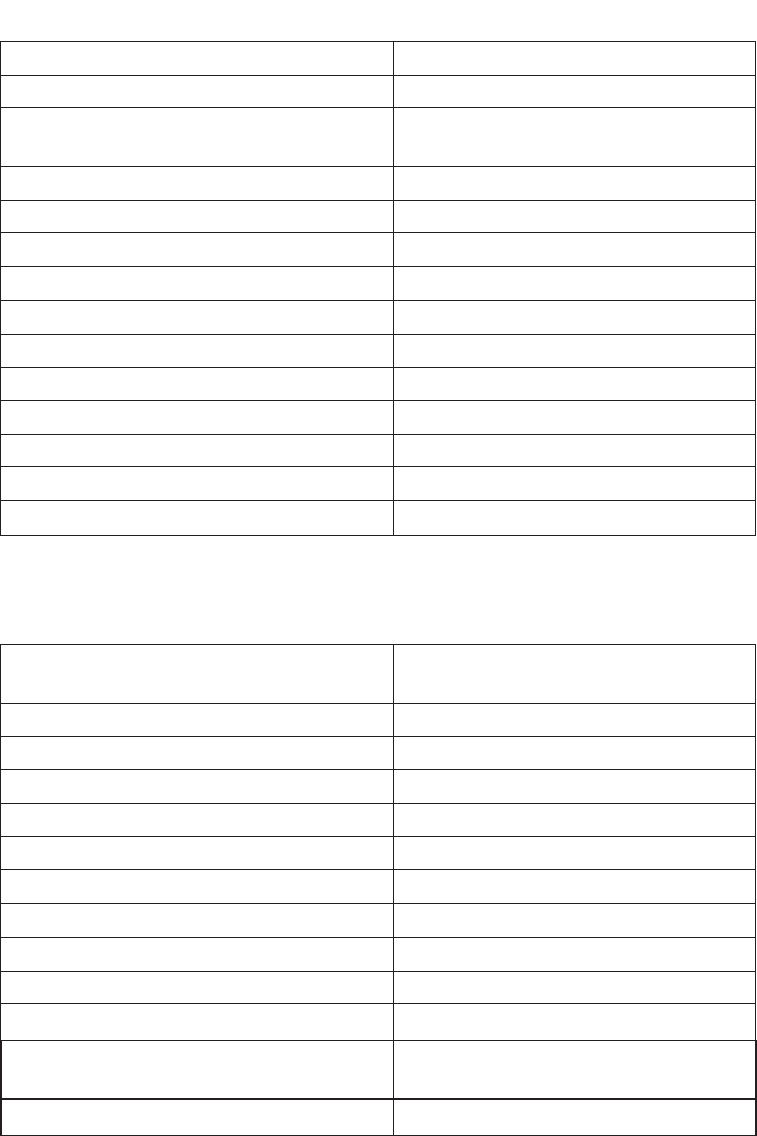

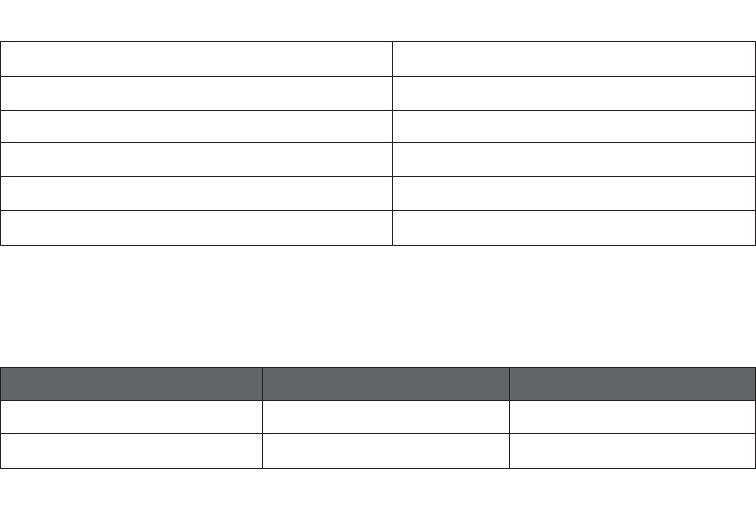

Figure 1.1 illustrates this process.

1.1.1 Collection of Intelligence and Evidence and Tracing Assets

Evidence is gathered and assets are traced by law enforcement o cers under the super-

vision of or in close cooperation with prosecutors or investigating magistrates, or by

private investigators or other interested parties in private civil actions. In addition to

gathering publicly available information and intelligence from law enforcement or

other government agency databases, law enforcement can employ special investigative

techniques. Some techniques may require authorization by a prosecutor or judge (for

example, electronic surveillance, search and seizure orders, production orders, or

account monitoring orders), but others may not (for example, physical surveillance,

information from public sources, and witness interviews). Private investigators do not

have the powers granted to law enforcement; however; they will be able to use publicly

available sources and apply to the court for some civil orders (such as production orders,

on-site review of records, pre ling testimony, or expert reports). Criminal investigative

techniques and tracing are discussed in detail in chapter 3, and investigative techniques

in civil actions are discussed in chapter 8.

1. Overview of the Asset Recovery

Process and Avenues for

Recovering Assets

6 I Asset Recovery Handbook

1.1.2 Securing the Assets

During the investigation process, proceeds and instrumentalities subject to con sca-

tion must be secured to avoid dissipation, movement, or destruction. In certain civil

law jurisdictions, the power to order the restraint or seizure of assets subject to con s-

cation may be granted to prosecutors, investigating magistrates, or law enforcement

agencies. In other civil law jurisdictions, judicial authorization is required. In common

law jurisdictions, an order to restrain or seize assets generally requires judicial authori-

zation, with some exceptions in seizure cases. Asset restraint and seizure is discussed in

detail in chapter 4; restraint in private civil actions is discussed in chapter 8. Systems to

manage assets will also need to be in place (see chapter 5).

1.1.3 International Cooperation

International cooperation is essential for the successful recovery of assets that have been

transferred to or hidden in foreign jurisdictions. It will be required for the gathering of

evidence, the implementation of provisional measures, and the eventual con scation of

the proceeds and instrumentalities of corruption. And when the assets are con scated,

cooperation is critical for their return. International cooperation includes “informal

assistance,” mutual legal assistance (MLA) requests, and extradition.

13

Informal assistance

13. For the purposes of this handbook, “informal assistance” is used to include any type of assistance that

does not require a formal MLA request. Legislation permitting this informal, practitioner-to-practitioner

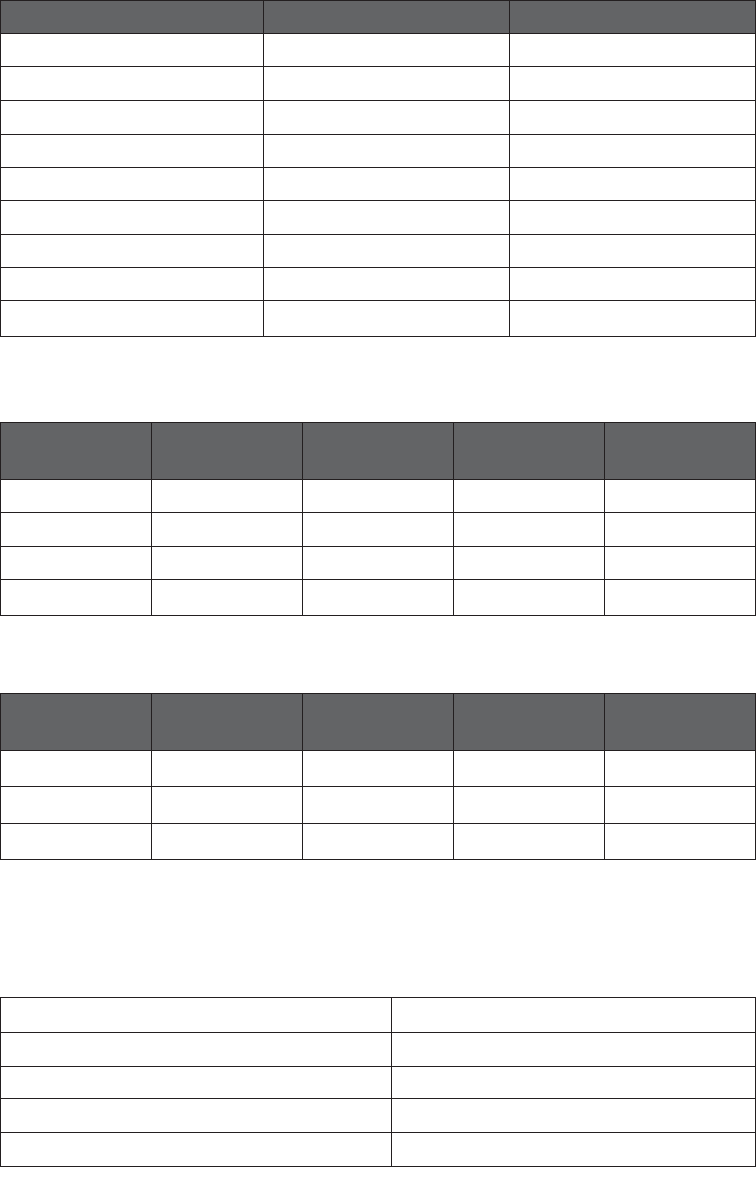

FIGURE 1.1

Process for Recovery of Stolen Assets

Collecting Intelligence and Evidence and

Asset Tracing

(Domestically and in foreign jurisdictions using MLA)

Securing the Assets

(Domestically and in foreign jurisdictions using MLA)

Court Process

(To obtain conviction [if possible], confiscation, fines,

damages, and/or compensation)

Enforcing Orders

(Domestically and in foreign jurisdictions using MLA)

Return of Assets

Source: Authors’ illustration.

Note: MLA = mutual legal assistance.

Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and Avenues I 7

is o en used among counterpart agencies to gather information and intelligence to assist

in the investigation and to align strategies and forthcoming procedures for recovery of

assets. An MLA request is normally a written request used to gather evidence (involving

coercive measures that include investigative techniques), obtain provisional measures,

and seek enforcement of domestic orders in a foreign jurisdiction. International coopera-

tion is addressed in chapter 7.

1.1.4 Court Proceedings

Court proceedings may involve criminal or NCB con scation or private civil actions

(each described below and in subsequent chapters); and will achieve the recovery of

assets through orders of con scation, compensation, damages, or nes. Con scation

may be property based or value based. Property-based systems (also referred to as

“tainted property” systems) allow the con scation of assets found to be the proceeds or

instrumentalities of crime—requiring a link between the asset and the o ense (a require-

ment that is frequently di cult to prove when assets have been laundered, converted, or

transferred to conceal or disguise their illegal origin). Value-based systems (also referred

to as “bene t” systems) allow the determination of the value of the bene ts derived from

crime and the con scation of an equivalent value of assets that may be untainted. Some

jurisdictions use enhanced con scation techniques, such as substitute asset provisions

or legislative presumptions to assist in meeting the standard of proof. Chapter 6 describes

these and other con scation issues; chapter 8 describes private civil actions.

1.1.5 Enforcement of Orders

When a court has ordered the restraint, seizure, or con scation of assets, steps must be

taken to enforce the order. If assets are located in a foreign jurisdiction, an MLA request

must be submitted. e order may then be enforced by authorities in the foreign jurisdic-

tion through either (1) directly registering and enforcing the order of the requesting juris-

diction in a domestic court (direct enforcement) or (2) obtaining a domestic order based

on the facts (or order) provided by the requesting jurisdiction (indirect enforcement).

14

is will be accomplished through the mutual legal assistance process (described above

and in chapter 7). Similarly, private civil judgments for damages or compensation will

need to be enforced using the same procedures as for other civil judgments.

1.1.6 Asset Return

e enforcement of the con scation order in the requested jurisdiction o en results in

the con scated assets being transferred to the general treasury or con scation fund of

assistance may be outlined in MLA legislation and may involve “formal” authorities, agencies, or adminis-

trations. For a description of this type of assistance and comparison with the MLA request process, see

section 7.2 of chapter 7.

14. See United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), art. 54 and 55; United Nations Conven-

tion against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), art. 13; United Nations Convention against Nar-

cotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, art. 5; and the Terrorist Financing Convention, art. 8. For

restraint or seizure, see UNCAC, art. 54(2).

8 I Asset Recovery Handbook

the requested jurisdiction (not directly returned to the requesting jurisdiction).

15

As a

result, another mechanism will be needed to arrange for the return of the assets. If

UNCAC is applicable, the requested party will be obliged under article 57 to return the

con scated assets to the requesting party in cases of embezzlement of public funds or

laundering of such funds, or when the requesting party reasonably establishes prior

ownership. If UNCAC is not applicable, the return or sharing of con scated assets will

depend on domestic legislation, other international conventions, MLA treaties, or spe-

cial agreements (for example, asset sharing agreements). In all cases, total recovery may

be reduced to compensate the requested jurisdiction for its expenses in restraining,

maintaining, and disposing of the con scated assets and the legal and living expenses

of the claimant.

Assets may also be returned directly to victims, including a foreign jurisdiction,

through the order of a court (referred to as “direct recovery”).

16

A court may order

compensation or damages directly to a foreign jurisdiction in a private civil action.

A court may also order compensation or restitution directly to a foreign jurisdiction

in a criminal or NCB case. Finally, when deciding on con scation, some courts have

the authority to recognize a foreign jurisdiction’s claim as the legitimate owner of

the assets.

If the perpetrator of the criminal action is bankrupt (or companies used by the perpe-

trator are insolvent), formal insolvency procedures may assist in the recovery process.

All of these mechanisms are explained further in chapters 7, 8, and 9.

A number of policy issues are likely to arise during any e orts to recover assets in

corruption cases. Requested jurisdictions may be concerned that the funds will be

siphoned o again through continued or renewed corruption in the requesting

jurisdictions, especially if the corrupt o cial is still in power or holds signi cant

in uence. Moreover, requesting jurisdictions may object to a requested country’s

attempts to impose conditions and other views on how the con scated assets should

be used. In some cases, international organizations such as the World Bank and civil

society organizations have been used to facilitate the return and monitoring of

recovered funds.

17

15. Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) Initiative Secretariat, “Management of Con scated Assets” (Washington,

DC, 2009), http://www.worldbank.org/star.

16. UNCAC, art. 53 requires that states parties take measures to permit direct recovery of property.

17. In 2007, the U.S. Department of Justice led a civil con scation action against a U.S. citizen indicted in

2003 for allegedly paying bribes to Kazakh o cials for oil and gas deals. e action was for approximately

$84 million in proceeds. e American citizen agreed to transfer those proceeds to a World Bank trust fund

for use on projects in Kazakhstan. See “U.S. Attorney for S.D.N.Y, Government Files Civil Forfeiture Action

Against $84 Million Allegedly Traceable to Illegal Payments and Agrees to Conditional Release of Funds to

Foundation to Bene t Poor Children in Kazakhstan,” news release no. 07-108, May 30, 2007, http://www.

usdoj.gov/usao/nys/pressreleases/May07/pictetforfeiturecomplaintpr.pdf; World Bank, “Kazakhstan BOTA

Foundation Established,” news release no. 2008/07/KZ, June 4, 2008, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/

INTKAZAKHSTAN/News%20and%20Events/21790077/Bota_Establishment_June08_eng.pdf.

Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and Avenues I 9

1.2 Legal Avenues for Achieving Asset Recovery

e legal actions for pursuing asset recovery are diverse. ey include the following

mechanisms:

domestic criminal prosecution and con scation, followed by an MLA request to •

enforce orders in foreign jurisdictions;

NCB con scation, followed by an MLA request or other forms of international •

cooperation to enforce orders in foreign jurisdictions;

private civil actions, including formal insolvency process;•

criminal prosecution and con scation or NCB con scation initiated by a foreign •

jurisdiction (requires jurisdiction over an o ense and cooperation from the juris-

diction harmed by the corruption o enses); and

administrative con scation.•

e availability of these avenues, either domestically or in a foreign jurisdiction, will

depend on the laws and regulations in the jurisdictions involved in the investigation,

as well as international or bilateral conventions and treaties. Box 1.1 outlines the vari-

ous laws relevant to practitioners pursuing these avenues. In addition, there are other

legal, practical, or operational realities that will in uence the avenue selected. Some of

these strategic considerations, obstacles, and case management issues are discussed in

chapter 2.

1.2.1 Criminal Prosecution and Confi scation

When authorities seeking to recover stolen assets decide to pursue a criminal case,

criminal con scation is a possible means of redress. Practitioners must gather evidence,

trace and secure assets, conduct a prosecution against an individual or legal entity, and

obtain a conviction. A er obtaining a conviction, con scation can be ordered by the

court. In some jurisdictions, particularly common law jurisdictions, the standard of

proof for con scation will be lower than the standard required for obtaining the con-

viction. For example, “balance of probabilities” will be needed for con scation, whereas

“beyond a reasonable doubt” will be required for a conviction. Other jurisdictions apply

the same standard to both conviction and con scation. See gure 2.1 in section 2.6.5

for an explanation of the standards of proof. Generally, unless enhanced con scation

provisions apply, con scation legislation will provide for con scation of proceeds and

instrumentalities that are directly or indirectly traceable to the crime.

18

18. e form and operation of “enhanced con scation provisions” are discussed in more detail in chap-

ter 6. Enhancements include substitute asset provisions that permit con scation of assets not con-

nected with a crime if the original proceeds have been lost or dissipated, presumptions about the

unlawful use or derivation of assets in certain circumstances, presumptions about the extent of unlaw-

ful bene ts owing from certain o enses, and the reversal of the onus and burden of proof in certain

circumstances.

10 I Asset Recovery Handbook

BOX 1.1 Legal Framework for Asset Recovery

Legislation and procedures (domestic and foreign jurisdictions):

Confi scation provisions (criminal, NCB, administrative);•

MLA;•

Criminal law provisions and codes of procedures (corruption, money laun-•

dering);

Private (civil) law provisions and codes of procedure; and•

Asset sharing laws.•

International conventions and treaties

a

UNCAC;•

United Nations Convention against the Illicit Traffi c in Narcotic Drugs and •

Psychotropic Substances;

UNTOC;•

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Convention on •

Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Offi cials in International Business

Transactions;

Southeast Asian Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Treaty;•

Inter-American Convention against Corruption;•

Council of Europe Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confi s-•

cation of the Proceeds of Crime (1990) and the revised Council of Europe

Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confi scation of the Pro-

ceeds of Crime and on the Financing of Terrorism (2005);

Council of the European Union Framework Decision 2003/577/JHA on the •

Execution in the European Union of Orders Freezing Property or Evidence;

Council of the European Union Framework Decision 2006/783/JHA on the •

Application of the Principle of Mutual Recognition to Confi scation Orders;

Southern African Development Community Protocol against Corruption •

(2001);

African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption and •

Related Offenses (2003);

Commonwealth of Independent States Conventions on Legal Assistance •

and Legal Relationship in Civil, Family and Criminal Matters;

Scheme Relating to Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters within the •

Commonwealth (the Harare Scheme);

Mercosur Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Treaty (Dec. No. •

12/01); and

Bilateral MLA treaties.•

a. See appendix J for available Web site resources.

Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and Avenues I 11

International cooperation, including informal assistance and requests for MLA, will be

used throughout the process to trace and secure assets in foreign jurisdictions, as well

as to enforce the nal order of con scation.

19

A bene t of criminal prosecution and con scation is the societal recognition of the

criminal nature of corruption and the accountability of the perpetrator. Further,

penalties of imprisonment, nes, and con scation serve to deter future o enders. In

addition, criminal investigators generally have the most aggressive means of gather-

ing information and intelligence, including access to data from law enforcement

agencies and nancial intelligence units (FIUs), use of provisional measures and

coercive investigative techniques (such as searches, electronic surveillance, exami-

nation of nancial records or access to documents held by third parties), as well as

grand juries or other means of compelling testimony or evidence. And, in most

jurisdictions, MLA is provided only in the context of criminal investigations. How-

ever, signi cant barriers may exist to obtaining a criminal conviction and con sca-

tion: insu cient evidence; lack of capacity or political will; or the death, ight, or

immunity of the perpetrator. Furthermore, the conduct giving rise to the request

may not be a crime in the jurisdiction where the relief is being sought. ese and

other barriers are discussed in chapter 2.

1.2.2 Non-Conviction Based Confi scation

Another type of con scation gaining traction throughout the world is con scation with-

out a conviction, referred to as “NCB con scation.”

20

NCB con scation shares at least

one common objective with criminal con scation—namely, the recovery and return of

the proceeds and instrumentalities of crime. Likewise, deterrence and depriving corrupt

o cials of their ill-gotten gains are other societal equities realized by NCB con scation.

NCB con scation di ers from criminal con scation in the procedure used to con scate

the assets. A criminal con scation requires a criminal trial and conviction, followed by

the con scation proceedings; NCB con scation does not require a trial or conviction,

but only the con scation proceedings. In many jurisdictions, NCB con scation can be

established on a lower standard of proof (for example, the “balance of probabilities” or

“preponderance of the evidence” standard), and this helps ease the burden on the

authorities. Other (mainly civil law) jurisdictions require a higher standard of proof—

speci cally, the same standard required to obtain a criminal conviction.

19. UNCAC, art. 54(1)(a); UNTOC, art. 13(1)(a); and United Nations Convention against Narcotic Drugs

and Psychotropic Substances, art. 5(4)(a) require states parties to take measures to give e ect to foreign

orders.

20. Jurisdictions include Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, some of the provinces of Canada

(Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan), Colombia, Costa Rica, Fiji, Guernsey,

Honduras, Ireland, Isle of Man, Israel, Jersey, Liechtenstein, New Zealand, the Philippines, Slovenia, South

Africa, Switzerland, ailand, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Zambia. International conven-

tions and multilateral agreements also have introduced NCB con scation. See UNCAC, art. 53(1)(c) and

recommendation 3 of the Financial Action Task Force 40+9 Recommendations.

12 I Asset Recovery Handbook

However, because NCB con scation is not available in all jurisdictions, practitioners

may have di culty obtaining MLA to assist with investigations and to enforce NCB

con scation orders. NCB con scation is discussed in greater detail in chapter 6.

1.2.3 Private Civil Action

Authorities seeking to recover stolen assets have the option of initiating proceedings in

domestic or foreign civil courts to secure and recover the assets and to seek damages

based on torts, breach of contract, or illicit enrichment.

21

e courts of the foreign

jurisdiction may be competent if a defendant is a person (individual or business entity)

living or incorporated in the jurisdiction (personal jurisdiction), if the assets are within

or have transited the jurisdiction (subject matter jurisdiction), or if an act of corruption

or money laundering was committed within the jurisdiction. As a private litigant, the

authorities seeking redress can hire lawyers to explore the potential claims and reme-

dies (ownership of misappropriated assets, tort, disgorgement of illicit pro ts, contrac-

tual breaches). e civil action will entail collecting evidence of misappropriation or of

liabilities based on contractual or tort damages. Frequently, it is possible to use evi-

dence gathered in the course of a criminal proceeding in a civil litigation. It is also pos-

sible to seek evidence with the assistance of a court prior to ling an action.

e plainti usually has the option to petition the court for a variety of orders, includ-

ing the following:

Freezing, embargo, sequestration, or restraining orders (potentially with world-•

wide e ect) secure assets suspected to be the proceeds of crime, pending the

resolution of a lawsuit laying claim to those assets. In some jurisdictions, interim

restraining orders may be issued pending the outcome of a lawsuit even before

the lawsuit has been led, without notice and with extraterritorial e ect. ese

orders usually require the posting of a bond, guarantee, or other undertaking by

the petitioner.

Orders against defendants oblige them to provide information about the source •

of their assets and transactions involving them.

Orders against third parties for disclosure of relevant documents are useful in •

obtaining evidence from banks, nancial advisers, or solicitors, among others.

“No-say” (gag) orders prevent banks and other parties from informing the defen-•

dants of a restraint injunction or disclosure order.

Generic protective or conservation orders preserve the status quo and prevent •

the deterioration of the petitioner’s assets, legal interests, or both. Such orders

usually require showing the likelihood of success on the merits and an imminent

risk in delaying a decision.

e principal disadvantages of litigating in a foreign jurisdiction are the cost of tracing

assets and the legal fees entailed in obtaining relevant court orders. However, the litigant

21. UNCAC art. 53(a) calls on states parties to permit another state party to initiate a civil action in domes-

tic courts.

Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and Avenues I 13

has more control in pursuing civil proceedings and assets in the hands of third parties

and may have the advantage of a lower standard of proof. For example, civil cases in

common law jurisdictions usually are decided on a “balance of probabilities” or “pre-

ponderance of the evidence” standard.

Similarly, arbitration proceedings related to international contracts obtained through

bribes or illicit advantages awarded to corrupt o cials may open promising avenues,

including the cancellation of contracts, and potential claims for torts or damages. ese

avenues are discussed in greater detail in chapter 8.

1.2.4 Actions Initiated by Foreign Jurisdictions

Authorities seeking to recover stolen assets may choose to support a criminal or NCB

con scation proceeding that has been initiated in another jurisdiction against the cor-

rupt o cial, associates, or identi ed assets. At the conclusion of the proceedings, the

state or government may be able to obtain a portion of the recovered assets through

orders of the foreign courts or pursuant to legislation or agreements.

22

is will require

that the foreign authority has jurisdiction; the capacity to prosecute and con scate;

and, most important, the willingness to share the proceeds. e initiation of an action

by a foreign authority may take place in one of two ways:

Authorities in the jurisdiction harmed by corruption may ask the foreign author-1.

ities to open their own case. is may be accomplished by ling a complaint or,

even more simply, by sharing incriminating evidence and a case le with author-

ities of the foreign jurisdiction. In all cases, the foreign authorities ultimately have

the discretion to pursue or ignore the case. If authorities pursue it, the jurisdic-

tion harmed by the o enses will need to cooperate with the foreign authorities to

ensure they have the necessary evidence.

Foreign authorities may open a case independent of request from the jurisdiction 2.

harmed by corruption. Foreign authorities may receive information linking a

corrupt o cial to their jurisdiction—whether through a newspaper article, a sus-

picious transaction report (STR), or a request for informal assistance or MLA—

and decide to investigate money laundering or foreign bribery activities under-

taken within their national territory.

e involvement of the victim—including a state or government that has been harmed

by corruption o enses—in the proceedings is generally encouraged in most jurisdic-

tions; however, it generally is limited to discussions with practitioners and does not

extend to actual standing in the proceedings. In some civil law jurisdictions, however, it

may also be possible for the victim to participate in foreign proceedings as a private

prosecutor or as a civil party to the proceedings. In both civil and common law jurisdic-

tions, it may be possible to recover assets from these proceedings through court-ordered

compensation, restitution, or damages as a party harmed by corruption o enses or as a

legitimate owner in con scation proceedings.

22. UNCAC art. 53(b) and 53(c) require states parties to take measures to permit direct recovery.

14 I Asset Recovery Handbook

is avenue is an interesting option if the jurisdiction seeking redress does not have

the legal basis, capacity, or evidence to pursue an international investigation on its

own. Moreover, if the limitation period rules out the prosecution of the initial corrup-

tion charges, it may be possible to investigate o enses of money laundering or posses-

sion of stolen assets in other jurisdictions. On the other hand, the jurisdiction that has

been harmed by corruption o enses has no control over the proceedings, and success

largely depends on the foreign authorities’ priorities. In addition, unless the return of

the assets is ordered by the court, it will be dependent on asset sharing agreements or

the authorities’ ability to return the assets on a discretionary basis (see section 9.4 in

chapter 9).

1.2.5 Administrative Confi scation

Unlike criminal or NCB con scation, which requires court action, administrative con-

scation generally involves a non-judicial mechanism for con scating assets used or

involved in the commission of the o ense. It may occur by operation of statute, pursu-

ant to procedures set out in regulations, and is typically used to address uncontested

con scation cases. e con scation is carried out by an authorized agency (such as a

police unit or a designated law enforcement agency), and o en follows a process similar

to that traditionally used in customs smuggling cases. e procedures usually require

notice to persons with a legal interest in the asset and publication to the public at large.

Generally, administrative con scation is restricted to low-value assets or certain classes

of assets. For example, legislation may permit the con scation of any amount of

cash, but prohibit the con scation of real property. Another variation on this type of

con scation, called “abandonment” by some jurisdictions, employs a similar proce-

dure. Another non-judicial means to recover assets is through taxation of the illicit

pro ts (see box 1.2).

1.3 Use of Asset Recovery Avenues in Practice: Three Case Examples

Outlined below are three short case examples that demonstrate how the various avenues

discussed throughout this chapter have been used to recover assets in practice. Each

case involved several jurisdictions and incorporated a number of di erent strategic

approaches, depending on the circumstances of the case, the avenues available in the

domestic and foreign jurisdictions, or repatriation arrangements.

1.3.1 Case of Vladimiro Montesinos and His Associates

Following televised videos that showed Vladimiro Montesinos (personal adviser to

Peru’s president Alberto Fujimori and de facto chief of Peru’s intelligence service) brib-

ing an elected opposition congressman in September 2000, funds were traced to several

jurisdictions, including the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and the United

States. Ultimately, more than $250 million was recovered from Switzerland and the

United States and from local banks in Peru.

Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and Avenues I 15

For the $48 million of assets in Switzerland, two options were discussed with the Swiss

investigating magistrate: e Peruvian authorities could prosecute the o enders domes-

tically for corruption and then seek recovery of the assets through MLA requests and

signed waivers. Or Switzerland could pursue drug tra cking and related money laun-

dering o enses that were involved in the case. With the second option, recovery would

be reduced because Peru would have to share a percentage of the assets with Switzerland.

Peru decided to pursue the rst option. To lay the groundwork, Peruvian authorities

introduced legislation permitting guilty pleas (plea agreements) and other forms of

cooperation.

23

In return for a reduced criminal sentence or dismissal of proceedings,

defendants provided useful information regarding known or unidenti ed crimes and

unknown evidence, access to the proceeds of crime, or testimony against key gures. In

addition, defendants signed waivers authorizing the foreign banks that held their money

to transfer it to the Peruvian government accounts. Several million dollars were recov-

ered through the use of these waivers.

23. Referred to as the “E cient Collaboration Act” (Law 27.378).

BOX 1.2 Alternative Means of Recovering Assets

Taxation of Illicit Profi ts

A public offi cial or an executive from a state-owned company who receives

bribes, misappropriated funds, or stolen assets may be liable for income taxes on

this illicit income. In such a case, authorities do not have to prove the illicit origin

of assets. It is suffi cient to prove that they represent undisclosed revenue. The

authorities simply prove that the taxpayer has made a taxable gain or received

taxable income and that he or she is liable for the appropriate amount of taxes,

including interest and penalties if the tax was not paid on time. Therefore, the

evidentiary burden is less than in a civil recovery case. Given the fact that this

approach generally does not involve court proceedings, this mechanism is poten-

tially cheaper and faster than civil recovery or criminal proceedings.

Fines and Compensation Orders in Criminal Trials

In criminal cases, the court may order the defendant to pay fi nes, compensation

to the victim, or both. Such orders may accompany confi scation orders, or may

be ordered in lieu of confi scation orders. Although fi nes or compensation orders

may be easier to achieve than a separate proceeding for confi scation, the enforce-

ment of such orders is likely to be more diffi cult. Enforcement of fi nes and com-

pensation orders may proceed through civil courts, whereas confi scation orders

will be enforced against assets that have been previously restrained. In addition,

the amount of the fi ne may be limited by statute and therefore insuffi cient on its

own to meet the recovery being sought.

16 I Asset Recovery Handbook

For the assets allegedly in the Cayman Islands, Peru hired local lawyers to assist with

pursuit of $33 million transferred through a Peruvian bank. Peruvian authorities also

met with the FIU to seek its assistance. A er several months of nancial analysis, Peru

discovered that the money had never been sent to the Cayman Islands, but had remained

in the Peruvian bank. A back-to-back loan scheme had been used to simulate the

“transfer” to the Cayman bank and the “return” to the Peruvian bank. When this was

discovered, the funds in the Peruvian bank were seized.

In the United States, Victor Venero Garrido, an associate of Montesinos, was arrested in

coordination with the Peruvian authorities; his apartment was seized; and $20 million

was frozen. Another $30 million of Montesinos’ funds held in the name of a front man

were also frozen. NCB con scation proceedings in California and Florida were used to

recover the funds, and the entire amount was repatriated to Peru. e repatriation agree-

ment with the United States was conditioned on the investment of the money in human

rights and anticorruption e orts.

In Peru, more than $60 million was recovered by Peruvian authorities seizing and con-

scating properties, vehicles, boats, and other assets through approximately 180 crimi-

nal proceedings involving more than 1,200 defendants.

1.3.2 Case of Frederick Chiluba and His Associates

In 2002, a task force was established in Zambia to investigate corruption allegations

against the former president Frederick Chiluba and his associates during the period

1991–2001, to assess whether criminal proceedings could be brought, and to determine

the best options for recovering assets. In 2004, the attorney general of Zambia initiated

a civil suit in the United Kingdom to recover funds transferred to London and across

Europe between 1995 and 2001 to fund the former president’s expensive lifestyle—

including a residence valued at more than 40 times his annual salary.

24

ese proceed-

ings were launched in addition to ongoing criminal proceedings in Zambia.

ree factors informed the decision to launch the civil action in addition to the criminal

proceedings: First, most of the defendants were located in Europe, making domestic

criminal prosecution and con scation impossible in a number of cases.

25

Second, most

of the evidence and assets were located in Europe, which made a European venue a more

favorable option. And, third, speci cally with respect to the cases whereas domestic

criminal prosecution and con scation was possible, successful international coopera-

tion through an MLA request was unlikely. Zambia lacked the bilateral or multilateral

agreements, procedural safeguards, capacity, and experience necessary to collect evi-

dence and enforce con scation orders across Europe. Instead, court orders obtained in

a European jurisdiction would be easier to enforce in jurisdictions that were parties to

the Brussels Convention on recognition of foreign court decisions in Europe.

24. Attorney General of Zambia v. Meer Care & Desai & Others, [2007] EWHC 952 (Ch.) (U.K.).

25. Zambia did not have NCB con scation legislation at that time; however, it was adopted subsequently.

Overview of the Asset Recovery Process and Avenues I 17

London was chosen as the European venue because most of the funds diverted from

Zambia had passed through two law rms and bank accounts in the United Kingdom,

and the attorney general of Zambia was able to establish jurisdiction over defendants in

jurisdictions that were parties to the Brussels Convention. Finally, it was anticipated

that decisions obtained from courts in the United Kingdom would also be enforceable

in Zambia when they were registered before the courts.

e High Court of London found su cient evidence of a conspiracy to transfer approx-

imately $52 million from Zambia to a bank account operated outside ordinary govern-

ment business—the “Zamtrop account”—and held at the Zambia National Commercial

Bank in London. Forensic experts traced the monies received in the Zamtrop account

back to the ministry of nance. ey also substantially traced the funds leaving the

Zamtrop account, and they revealed that $25 million was misappropriated or misused.

In addition, the High Court found no legitimate basis for payments of about $21 million

made by Zambia pursuant to an alleged arms deal with Bulgaria and paid into accounts

in Belgium and Switzerland.

e Court held that the defendants conspired to misappropriate $25 million from the

Zamtrop account and $21 million from the arms deal payments. e Court also held

that the defendants had broken the duciary duties they owed to the Zambian Republic

or dishonestly assisted in such breaches. As a result, the defendants were held liable for

the amounts and assets corresponding to misappropriated funds.

1.3.3 Case of Diepreye Alamieyeseigha

In the case involving Diepreye Peter Solomon Alamieyeseigha, former governor of

Bayelsa State, Nigeria, this jurisdiction was able to recover $17.7 million through domes-

tic proceedings and through cooperation with authorities in South Africa and the

United Kingdom.

In September 2005, Alamieyeseigha was rst arrested at Heathrow Airport by the

London Metropolitan Police on suspicion of money laundering. An investigation

revealed that Alamieyeseigha had $2.7 million stashed in bank accounts and in his

home in London, as well as London real estate worth an estimated $15 million.

Alamieyeseigha was released on bail and subsequently le the jurisdiction in November

2005, returning to Nigeria.

In Nigeria, he claimed immunity from prosecution. He was subsequently removed

from o ce by Bayelsa State’s lawmakers, and thereby lost his immunity. Later in

November 2005, Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission charged him

with 40 counts of money laundering and corruption, and it secured a court order

restraining assets held in Nigeria.

For assets in the United Kingdom, close cooperation between the Commission and the

London Metropolitan Police’s Proceeds of Corruption Unit was crucial. e $1.5 million

in cash seized from Alamieyeseigha’s London home was con scated under the Proceeds

18 I Asset Recovery Handbook

of Crime Act on the basis of a court order that the assets represented proceeds of crime.

In May 2006, the court ordered the funds repaid to Nigeria, and the transfer was made a

few weeks later. For the bank accounts, the process was more challenging because assets

and evidence were located in the Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands, the Seychelles,

South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Nigerian authorities recognized that requesting

assistance from these jurisdictions could take considerable time and that orders from

Nigerian courts would not necessarily be executed. In addition, the pursuit of legal pro-

ceedings in each of these jurisdictions was a daunting prospect because the Nigerian

authorities had little evidence linking Alamieyeseigha to these assets and linking the

assets to acts of corruption.

As a result, Nigerian authorities decided to bring civil proceedings in the United Kingdom

and simultaneously pursue criminal proceedings in Nigeria. To secure evidence, the Nige-

rian authorities obtained a disclosure order for the evidence compiled by the Metropoli-

tan Police in the course of its investigation.

26

Nigeria was able to use this evidence together

with Alamieyeseigha’s income and asset declaration

27

to obtain a worldwide restraint

order covering all assets owned directly or indirectly by Alamieyeseigha and a disclosure

order for documents held at banks and by Alamieyeseigha’s associates.

In parallel with those proceedings, the South African Asset Forfeiture Unit initiated

NCB con scation proceedings against Alamieyeseigha’s luxury penthouse. Funds were

returned to Nigeria following the sale of the property in January 2007.

Before a Nigerian high court in July 2007, Alamieyeseigha pleaded guilty to six charges

of making false declaration of assets and caused his companies to plead guilty to 23

charges of money laundering. He was sentenced to two years in prison, and the court

ordered the con scation of assets in Nigeria. Alamieyeseigha’s guilty pleas e ectively

voided his defense in the civil proceedings in the London High Court; and, in December

2007, the Court issued a summary judgment con scating property and a bank account

in the United Kingdom. A judgment in July 2008 led to the con scation of the remain-

ing assets in Cyprus, Denmark, and the United Kingdom.

26. e Nigerian application for disclosure was not contested by the Metropolitan Police. is departed

from the usual practice: the police usually do not concede to providing evidence gathered through criminal

investigations to assist private parties pursuing civil claims.

27. e declaration was led in 1999 when Alamieyeseigha was rst elected state governor. It indicated that

he had assets amounting to just over half a million dollars and an annual income of $12,000.

2. Strategic Considerations for

Developing and Managing a Case

Successful asset recovery requires a comprehensive plan of action that incorporates a

number of important steps and considerations. Practitioners will need to gather and

assess the facts to understand the case; assemble a team; identify key allies; communicate

with foreign practitioners; grapple with the legal, practical, and operational challenges

28

;

and ensure e ective case management. Each facet will help practitioners select the most

appropriate legal avenue for recovering assets—whether criminal or non-conviction

based (NCB) con scation followed by a mutual legal assistance (MLA) request for

enforcement, private civil action, or a request that authorities in another jurisdiction pur-

sue criminal or NCB con scation. Experience has demonstrated that whereas a criminal

conviction is always important to combat and deter corruption, criminal con scation may

not be the best option for asset recovery. Some authorities will use a combination of the

avenues to pursue con scation.

29

Alternatively, the presence of obstacles may warrant

consideration of another legal avenue. In cases involving multiple jurisdictions, a number

of di erent avenues may be pursued—for example, domestic con scation followed by an

MLA request for enforcement in one jurisdiction and private civil recovery in another.