Ontario Works

Chapter 3

Section

3.11

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

494

Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

1.0 Summary

Many Ontarians who are either unemployed or

underemployed need help to pay for their basic

living expenses including food, shelter and cloth-

ing. In 2017/18, more than 450,000 individuals

(that includes recipients and their dependents)

received assistance from the Ministry of Children,

Community and Social Services’ (Ministry) Ontario

Works program.

Ontario Works is designed to provide temporary

nancial assistance and employment supports to

help recipients obtain employment and to become

self-reliant. To be eligible for assistance, applicants

must demonstrate that they live in Ontario and

that their income and assets are below specied

amounts. Applicants are also required to participate

in activities to help them obtain employment,

unless specic circumstances are temporarily pre-

venting them from doing so, such as being a sole

parent with pre-school-aged children.

The Ministry contracts with 47 service man-

agers (large municipalities or groups of smaller

municipalities) and 101 First Nations to deliver the

Ontario Works program. In 2017/18, the Ministry

provided almost $3 billion in transfer payments to

these service managers to deliver the program.

Since our last audit in 2009, the average

monthly number of Ontario Works cases increased

by almost 25% from 202,000 to 250,000 in

2017/18. Although Ontario Works is intended

to be a temporary assistance program, we found

that since 2008/09, the average length of time

people depend on the program has nearly doubled,

increasing from an average of 19 months to almost

three years in 2017/18. Service managers have

identied that 36% of recipients have barriers

affecting their employability, such as homelessness

and mental health concerns, that they need help to

resolve. We also found that in each of the last ve

years, the Ontario Works program has helped only

10% to 13% of recipient cases to successfully nd

employment and leave the program.

The cost of the Ontario Works program to the

Province has also increased more than 55% since

our audit in 2009, from $1.9 billion to almost

$3 billion in 2017/18. In addition, beginning in

January 2018 the Province funds 100% of the cost

of nancial assistance payments to recipients,

whereas in 2009 service managers funded 20% of

this cost.

Overall, we found that the Ministry’s oversight

of the program and the service managers that

deliver it is ineffective. The Ministry has not col-

lected sufcient information to understand the

signicant increase in time recipients spend on

assistance, nor has it adequately assessed or held

service managers accountable for their efforts to

help Ontario Works recipients to overcome signi-

cant barriers and to nd employment to become

self-reliant.

495Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

Our audit also found that many of the same

issues we identied in our 2009 Annual Report are

still present today. We found that in many cases,

service managers do not take the necessary steps on

a timely basis to help recipients obtain employment

or ensure that only eligible applicants are accepted

in the program. For example, we found required

checks to verify applicant information, such as

income and assets, were frequently not completed.

As well, we found that the Ministry still does not

monitor and ensure that service managers complete

nancial reassessments of recipients on a timely

basis, nor whether they investigate fraud tips to

conrm that recipients are still eligible for Ontario

Works. Completing these processes also reduces

the risk of overpayments by service managers to

ineligible recipients.

Furthermore, due to the implementation of the

Ministry’s IT system, Social Assistance Management

System (SAMS), for a period of over two years,

from November 2014 to March 2017, the Ministry

suspended its Eligibility Verication Process that

requires service managers to review recipients

who have a high risk of ineligibility. The Ministry

re-introduced this process in April 2017, and the

reviews completed during the rst year identied

almost $11 million in overpayments and the need

to terminate about 4,200 Ontario Works cases,

equivalent to 2% of the entire caseload. Although

these reviews identied many ineligible recipients,

we found that service managers did not complete

more than 40% of the eligibility verication cases

assigned to them during 2017/18. The Ministry has

also not conducted an analysis of service managers’

employment results to take action to improve the

overall effectiveness of the Ontario Works program.

The following are some of our specic concerns

about the Ministry’s administration of the

Ontario Works program:

•

Few recipients nd employment and the

Ministry does not take action to improve

results. We found signicant differences in

recipient employment outcomes between

service managers that should be followed up

by the Ministry to identify best practices and

instances that require corrective action. For

example, in 2017/18, we noted that while

the percentage of recipient cases exiting to

employment across all service managers was

10%, this ranged from as low as 2% of all

cases at one service manager, to as high as

29% at another.

•

Ministry contracts with service managers

lack meaningful targets for recipient

employment and mechanisms to hold

them accountable for program delivery.

We found that service managers’ contracts

do not specify the program requirements that

service managers are expected to comply

with. In addition, although these contracts

allow for the Ministry to recover funds

where service managers do not achieve their

recipient employment and earnings targets,

the Ministry advised us that it has never

recovered funding for failing to achieve tar-

gets. More signicantly, we found that almost

half the current contracts lack meaningful

targets for employment and earnings as

service managers had already achieved their

targets halfway into their two-year contracts.

•

The Ministry lacks measures to assess

whether service managers are effective

in helping 36% of recipients identied as

having barriers to employment to over-

come them. We identied that caseworkers

had assessed 36% of Ontario Works recipients

as having barriers that affect their ability

to prepare for or nd employment because

they needed to stabilize their life. Service

managers across Ontario told us that these

barriers include mental health conditions,

addictions and homelessness. Although the

Ministry expects service managers to help

recipients overcome these barriers, it does not

analyze and assess whether service managers

are effective in assisting recipients to over-

come their employment barriers. If service

managers do not make progress assisting

496

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

these individuals, it is possible that they will

not leave Ontario Works for employment for

many years.

•

The Ministry does not measure whether

recipients nd stable employment to

become self-reliant. A one-time Ministry

study that examined recipient exits to

employment in 2013 found that 35% of these

individuals returned to Ontario Works within

about a year-and-a-half of their exit. However,

the Ministry’s current performance measures

do not measure whether individuals leaving

the program retain employment over time or

later return to Ontario Works.

•

The Ministry does not know whether

service managers are meeting its staff-

to-recipient guidelines. We found that the

Ministry does not collect information from

service managers on the number of casework-

ers they employ and their recipient caseload

(recipient-to-caseworker ratio). It also does

not compare service manager caseloads to its

caseload guidelines to assess whether service

managers are staffed to effectively deliver

the Ontario Works program. We compared

the recipient caseloads of the service man-

agers we visited and found that one of the

service managers signicantly exceeded the

Ministry’s guidelines for a typical recipient

caseload in each of the last ve years. On

average, in 2017/18, caseworkers at this ser-

vice manager had a caseload of 158 recipients

compared with the Ministry’s guidelines of

between 90 and 120 recipients per case-

worker. In addition, all four of the service

managers we visited exceeded the Ministry’s

caseload guidelines for recipients with signi-

cant barriers to employment, which Ministry

guidance suggests may need to be as low as

45 recipients to each caseworker.

•

The Ministry’s IT system is inadequate for

caseworkers to manage recipient cases.

We found that the Ministry’s IT system, Social

Assistance Management System (SAMS),

does not have the functionality to allow case-

workers to record recipient skills, barriers to

employment, or referrals to training or com-

munity services in a way that would enable

service managers to gather and analyze such

factors for their entire caseload. Without this

information, service managers face challenges

to understanding the prole of recipients on

their caseload, tracking recipients’ progress

toward obtaining employment, and designing

suitable training and employment programs

for the individuals on their caseload.

•

The underlying cause of overpayments to

recipients is not tracked, limiting the abil-

ity of service managers to prevent them.

We found that service managers do not have

the ability to record the reason that overpay-

ments occur in their information system

(SAMS). Without consolidated data to under-

stand the most common systemic causes of

overpayments, service managers are unable

to identify which of their processes they need

to improve to prevent or reduce the number

of overpayments in the future.

•

Ministry efforts to prevent fraudulent spe-

cial diet applications are insufcient. The

Ministry is aware that the special diet allow-

ance is not always administered as intended,

and that some recipients are using it to

supplement their monthly income rather than

to pay for extra dietary costs associated with a

particular medical condition. However, it has

not taken any action to address this issue.

•

Immigration status affecting recipient

eligibility is not consistently veried with

the federal government. The Ministry has

an agreement with the federal government

to obtain information on the immigration

status of Ontario Works recipients. However,

it does not use this agreement to check that

all recipients (who cannot demonstrate their

legal status in Canada) are still eligible, or

should be terminated from Ontario Works

because they are no longer legally permitted

497Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

to remain in Canada or have already been

removed from the country. We reviewed

Ontario Works recipient data and identied

over 500 individuals where there is a risk that

they may no longer be eligible for Ontario

Works. We asked the Ministry to request that

the federal government check the status of a

sample of these 500 individuals. However, the

Ministry informed us that the federal govern-

ment would not release the full results of any

completed checks to the Ministry because they

had been requested for the purposes of our

audit. As a result, the information the Ministry

obtained was limited to summary results on

the immigration status of these individuals.

These summary results identied eligibility

concerns for one-quarter of these individuals

for which the Ministry requires additional

information from the federal government to

conrm their eligibility. Therefore, we were

unable to complete our work in this area.

The following are some of our specic concerns

about the delivery of the Ontario Works program

by service managers:

•

Critical information is overlooked by

caseworkers, increasing the risk of errors

in determining applicant eligibility. At the

four service managers we visited, we found

that caseworkers did not always investigate

red ags in applicant information or obtain

or review required documentation relevant

to assessing eligibility for Ontario Works,

including in as many as 60% of the les we

reviewed at one of the service managers. In

one case, for example, a caseworker failed to

identify that people in Canada on work per-

mits are considered temporary residents and

are not eligible for Ontario Works. As a result,

overpayments totalling more than $9,200

were made to this ineligible recipient.

•

Overpayments can occur because all ser-

vice managers do not reassess recipients

when required. At two of the four service

managers we visited, we found that in 20% to

35% of the recipient les we reviewed, case-

workers did not meet with recipients at least

once every two years as required to review

their nancial information and status to

conrm that they remain eligible for Ontario

Works and the amount of nancial assistance

they are receiving. If service managers do not

perform these reassessments on time, there

is a risk that overpayments may be made for

several months or years to recipients who are

no longer eligible for assistance or eligible for

a lower amount of assistance.

•

Caseworkers do not consistently work with

recipients to help them progress toward

obtaining employment. At the four service

managers we visited, caseworkers did not

always meet with recipients on a timely basis

to review their progress in activities designed

to help them nd employment, including in

50% of the les we examined at two service

managers. Caseworkers are required to meet

recipients at least once every three, four or six

months, yet in several of the les we exam-

ined, periods between reviews were longer

than one year, or twice the maximum allow-

able time. In one case, a recipient’s progress

had not been reviewed for approximately

three years.

•

Decisions to waive recipient employment

participation requirements are question-

able when not supported with evidence.

At the four service managers we visited, we

found that caseworkers did not always obtain

sufcient evidence to conrm that recipients

are unable to participate in activities designed

to help them obtain employment. At one of

the service managers, we found that in as

many as 40% of the les we reviewed recipi-

ents’ were allowed not to participate without

evidence to explain the reason for this. This

included, for example, a recipient deferred

due to medical reasons for a period of one

year without supporting medical documenta-

tion as required.

498

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

This report contains 19 recommendations, with

45 action items, to address our audit ndings.

OVERALL MINISTRY RESPONSE

The Ministry of Children, Community and Social

Services (Ministry) welcomes the advice of the

Auditor General with respect to the delivery and

oversight of the Ontario Works program. This

program provides a vital service to the people

of Ontario to help those in need nd sustainable

employment and achieve self-reliance. The Min-

istry is committed to working with service man-

agers to implement an accountability model that

focuses on the achievement of outcomes and

the recommendations of the Auditor General

will be important as the Ministry moves forward

to improve the effectiveness and integrity of

the program.

OVERALL RESPONSE FROM

SERVICE MANAGERS

The four audited service managers welcome

the advice of the Ofce of the Auditor General

of Ontario and are committed to addressing the

Auditor General’s recommendations in order

to better serve the needs of all Ontario Works

recipients.

We will continue to review our existing

processes and take the additional steps that

are required to ensure that we comply with the

Ministry of Children, Community and Social

Services’ (Ministry) requirements. Through

our partnership with the Ministry, we will also

work to explore opportunities to increase the

efciency of existing processes to ensure that

our resources are used effectively.

We welcome the opportunity to reect on

how we can improve the delivery of Ontario

Works to help vulnerable Ontarians in nancial

need, and on how to best assist them to work

toward obtaining employment, and becoming

self-sufcient.

•

Service managers across Ontario are

approximately one year behind investi-

gating approximately 6,000 fraud tips

to ensure only eligible recipients are

receiving assistance. We noted that service

managers investigated about 17,000 fraud

tips in the last three years. More than 25% of

the investigations identied an overpayment,

and 10% resulted in terminating the recipient

from Ontario Works. Timely reviews of these

fraud tips are critical to identifying and mini-

mizing overpayments.

Overall Conclusion

Our audit concluded that the Ministry of Children,

Community and Social Services, together with

service managers, does not have effective systems

and procedures in place to ensure that only eligible

recipients receive nancial assistance and that

recipients receive the employment supports they

require to obtain employment and become self-

reliant. We found that service managers were not

taking sufcient steps to ensure that all recipients

are eligible for the program, and that all recipients

are participating as required in employment assist-

ance activities aimed at obtaining employment. As

well, changes to the Ministry’s Social Assistance

Management System are required in order for the

Ministry and service managers to improve their

administration of the program.

Our audit also concluded that the Ministry

does not have effective systems and processes to

measure, evaluate and publicly report on the effect-

iveness of the Ontario Works program. While the

Ministry does collect some relevant performance-

related information from service managers, other

critical information about recipients is not system-

atically collected or not used to measure and evalu-

ate the effectiveness of the Ontario Works program.

This includes information on recipient barriers to

obtaining employment and employment sustain-

ability. In addition, the Ministry does not report the

information it does collect on recipient employment

outcomes to the public.

499Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

2.0 Background

In Ontario, social assistance is provided by the Min-

istry of Children, Community and Social Services

(Ministry) under two programs:

•

Ontario Works—for unemployed or under-

employed people in temporary nancial need;

and

•

Ontario Disability Support Program—

intended to help people with eligible disabil-

ities live as independently as possible and to

reduce or eliminate disability-related barriers

to employment.

In 2017/18, these two programs provided social

assistance to approximately 610,000 individuals

as well as to their qualifying family members for

a total of 950,000 people a month, on average.

Approximately 60% of these individuals received

assistance through the Ontario Disability Sup-

port Program and 40% received assistance from

Ontario Works. Total provincial transfer payments

for these two programs totalled $8.1 billion in

2017/18, which accounted for 5.3% of total prov-

incial expenditures. Transfer payments for Ontario

Works, the subject of this audit, were almost $3 bil-

lion in 2017/18.

2.1 Overview of Ontario Works

The Ministry’s Ontario Works program is a social

assistance program that provides nancial and

employment assistance to unemployed or under-

employed Ontarians who are in temporary nancial

need. Ontario Works provides nancial assist-

ance to help eligible applicants with basic living

expenses such as food, clothing, and shelter. It also

provides various employment assistance activities

for eligible applicants intended to increase their

employability and to help them obtain employment

and become self-reliant.

To be eligible for assistance, applicants must

demonstrate nancial need by providing evidence

that their income and asset levels are below speci-

ed amounts. In addition, applicants are also

required to sign an agreement to participate in

activities designed to gain skills to progress toward

obtaining sustainable employment, unless granted

a deferral. Applicants who can be granted a deferral

include applicants who are sole-support parents

with pre-school-aged children, applicants with

caregiver responsibilities, or applicants experien-

cing exceptional circumstances such as illness.

The Ontario Works Act, 1997 (Act) and its regu-

lations govern the delivery of the Ontario Works

program. The Act gives the Ministry the authority

to designate delivery agents to administer the pro-

gram. The Ministry has designated 47 Consolidated

Municipal Service Managers and District Social

Services Administration Boards as well as 101 First

Nations—referred to in this report as service man-

agers—to deliver the program. A service manager

is typically either a large municipality or a grouping

of smaller ones. In 2017/18, the Ministry provided

almost $3 billion in transfer payments to service

managers to deliver the Ontario Works program;

service managers provided Ontario Works assist-

ance to approximately 250,000 cases and 454,000

beneciaries (individuals plus their dependents) a

month, on average.

2.1.1 Role of Ministry and Service

Managers in Delivery of Ontario Works

Service managers are responsible for delivering the

Ontario Works program to eligible individuals who

live in their geographic area in accordance with the

Act and its regulations, as well as program direc-

tives and policies issued by the Ministry. Service

managers operate local Ontario Works ofces that

residents use to access services. Appendix 1 lists

service managers, their respective number of local

ofces, Ministry funding, and caseloads for the

2017/18 scal year.

Service managers’ primary responsibilities

include:

500

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

•

determining applicants’ initial and ongoing

eligibility for the program;

•

providing recipients with nancial assistance

and supports to help them to work toward

obtaining employment; and

•

establishing processes to prevent and detect

fraud, recover overpayments and prevent the

misuse of assistance.

The Ministry is responsible for administering the

Ontario Works program, including setting overall

program requirements and standards for program

delivery that service managers must follow.

Figure 1 shows the governance structure for the

Ontario Works program as of May 2018. The Min-

istry enters into contracts with service managers

to deliver Ontario Works and provides funding to

service managers to cover the costs of delivering

the program. Funding provided to service managers

includes reimbursement for the nancial assistance

payments made to Ontario Works recipients, and

funding to cover service managers’ program deliv-

ery costs which includes providing employment

supports to Ontario Works recipients, and admin-

istration costs. The Ministry is also responsible

for monitoring service managers’ delivery of the

program within the context of the Act, regulations,

directives and policies it has developed.

2.1.2 Number of Ontarians Receiving

Ontario Works Assistance

Since our last audit of the program in 2009, the

average number of Ontario Works cases increased

by almost 25% from 202,000 to 250,000 in

2017/18. Over this same period, the population

in Ontario increased by approximately 10%. The

majority of the increase in the Ontario Works case-

load occurred in 2009/10 following the downturn

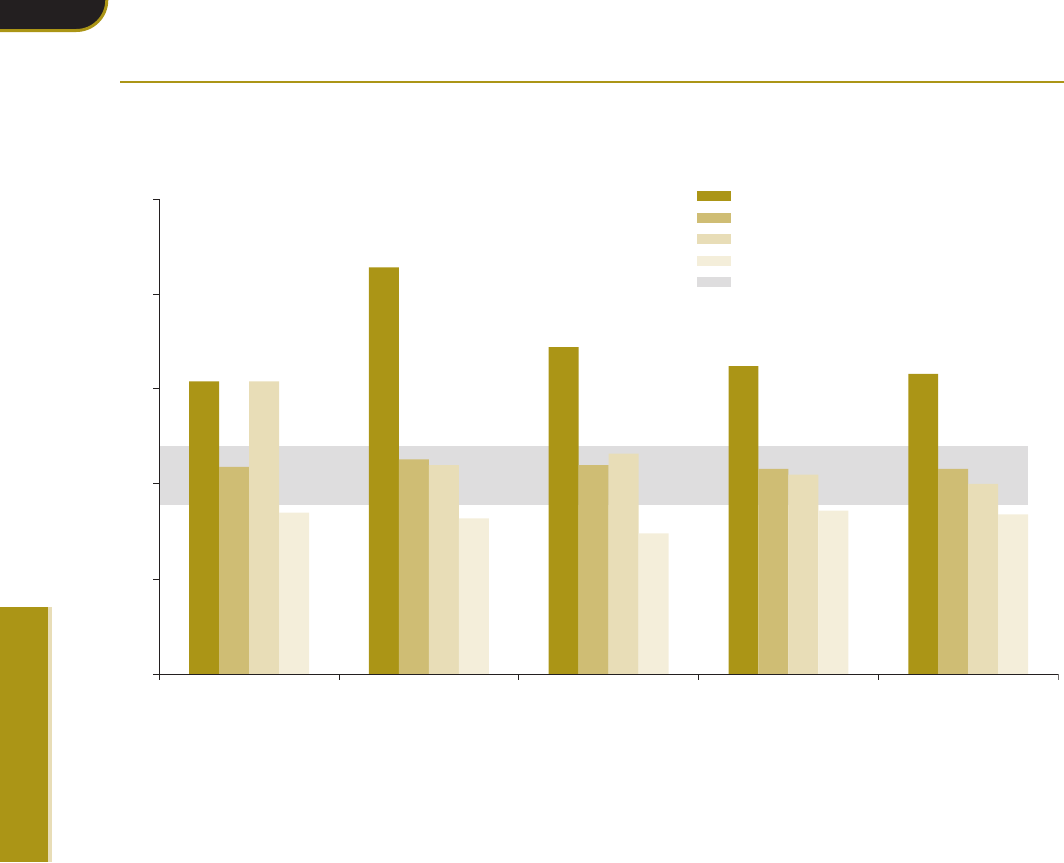

in the economy that began in late 2008. Figure 2

illustrates the average monthly number of cases

and beneciaries each scal year between 2003/04

and 2017/18.

Although the number of Ontario Works cases

has remained stable over the past ve years,

the Ministry told us that it is still higher than its

pre-recession levels. In contrast, the unemploy-

ment rate was 5.8% in 2017/18, down from 6.3%

in 2007/08. The Ministry explained that policy

changes since 2008 have increased the number of

people eligible for the Ontario Works program. For

example, the amount of assets a person is permitted

to have has risen, which has allowed more people

to qualify. In addition, the Ministry said that once

on Ontario Works, individuals and families may

have circumstances that hinder their exit from the

program such as a low level of education, or loss of

jobs in their industry such as manufacturing.

The average length of time individuals are

accessing Ontario Works has also increased, from

19 consecutive months in 2008/09 to 35 con-

secutive months in 2017/18. Figure 3 shows the

increase in number of consecutive months spent on

Ontario Works between 2008/09 and 2017/18.

2.1.3 Provincial Cost of Ontario Works

Total Ministry funding provided to service man-

agers for the Ontario Works program has increased

by approximately 60% from $1.9 billion in 2008/09

when we last audited the program to nearly

$3.0 billion in 2017/18 as illustrated in Figure 4.

Key reasons for the increase include:

•

an increase of 19% in the average number of

Ontario Works recipients and beneciaries

from 380,000 in 2008/09 to 454,000 in

2017/18 as shown in Figure 2;

•

nancial assistance rate increases since 2009

ranging from 1% to 2% each year, and as high

as 4.8% in 2014 for single recipients;

•

changes to applicant asset and income exemp-

tions, and other policy changes;

•

the Ministry’s estimated annual costs associ-

ated with key changes in the last ve years,

and projected costs of key changes for the

next three years (Appendix 2);

•

a change in February 2017 to end the deduc-

tion of child support income from social

assistance payments (at the time that it

501Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

Figure 1: Ontario Works Governance Structure, May 2018

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

* Ontario Works Administrators are employees of the 47 Consolidated Municipal Service Managers and District Social Services Administration Boards referred to in this report as service managers. Ontario Works Administrators

are individuals appointed by service managers, with the approval of the Ministry, to oversee the delivery of the program in accordance with the

Ontario Works Act

. Administrators report to senior management within their

municipalities, and are accountable to the Ministry through the Regional Program Ofce in their geographical area.

• Business Services

• Program Integrity

• Ontario Works Support Unit

• Operational Improvement

• Business Support Services

• Accountability and Oversight

• Business Operations and

Support Services

• Business Technology Solutions

• Services Initiatives Unit

• Social Assistance Modernization

• Policy Operations and Program Design

• Policy Design and Implementation

Deputy Minister

Director

Social Assistance and Municipal Operations Branch

Director

Social Assistance Service Delivery Branch

5 Ministry Regional

Program Offices

Ontario Works Administrators*

Program Delivery – Municipal Responsibility

Municipal Service Managers

Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

5 Units 4 Units 3 Units

Director

Ontario Works Branch

Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM)

Social Assistance Operations Division

Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM)

Social Policy Development Division

502

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

implemented this change, the Ministry esti-

mated that it would increase Ontario Works

nancial assistance expenditures by approxi-

mately $48 million each year from now on);

and

•

a gradual increase in the percentage of total

nancial assistance and employment assist-

ance expenditures that the Province reim-

burses to municipalities.

Historically, the provincial and municipal gov-

ernments have shared the costs of Ontario’s social

assistance programs. However, in 2008 as part of

the Provincial-Municipal Service Delivery Review

and Agreement, the Province and municipalities

Figure 2: Average Monthly Ontario Works Caseload and Beneciaries, 2003/04–2017/18

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Cases

Beneficiaries

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

350,000

400,000

450,000

500,000

2003/04

2004/05

2005/06

2006/07

2007/08

2008/09

2009/10

2010/11

2011/12

2012/13

2013/14

2014/15

2015/16

2016/17

2017/18

Figure 3: Average Number of Consecutive Months Recipients Are on Ontario Works, 2008/09–2017/18

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

19

18

19

20

22

24

27

32

34

35

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/152015/162016/172017/18

503Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

reached a consensus that the Province would fully

fund the cost of nancial assistance and employ-

ment assistance expenditures to reduce uncertainty

and volatility in municipal expenditures. To

implement this change, the Province increased the

proportion of expenditures that it funded over a

nine-year period beginning in 2010. Because of this

agreement, the provincial share of Ontario Works

nancial assistance and employment assistance

expenditures has increased from 80% at the time of

our last audit to 100% beginning in 2018. Figure 5

illustrates the annual changes to provincial-munici-

pal cost-sharing arrangements.

The Ministry also pays up to 50% of service

managers’ administration costs. This has not

changed since our 2009 audit. However, since

2011/12 the Ministry has provided service man-

agers with the exibility to use program delivery

funding (for administration and employment costs)

interchangeably according to their local needs.

Therefore, the Ministry may reimburse service

managers for more than 50% of their administra-

tion costs.

2.2 Eligibility for Ontario Works

Service managers are responsible for determining

an applicant’s eligibility for Ontario Works. To be

eligible for assistance, applicants must meet the

eligibility criteria set out in the Ontario Works Act,

1997 and its regulations. Applicants must live in

Ontario and be legally entitled to reside in Canada

permanently. An exception is refugee claimants

who are eligible even though they have yet to be

granted the right to stay in Canada permanently.

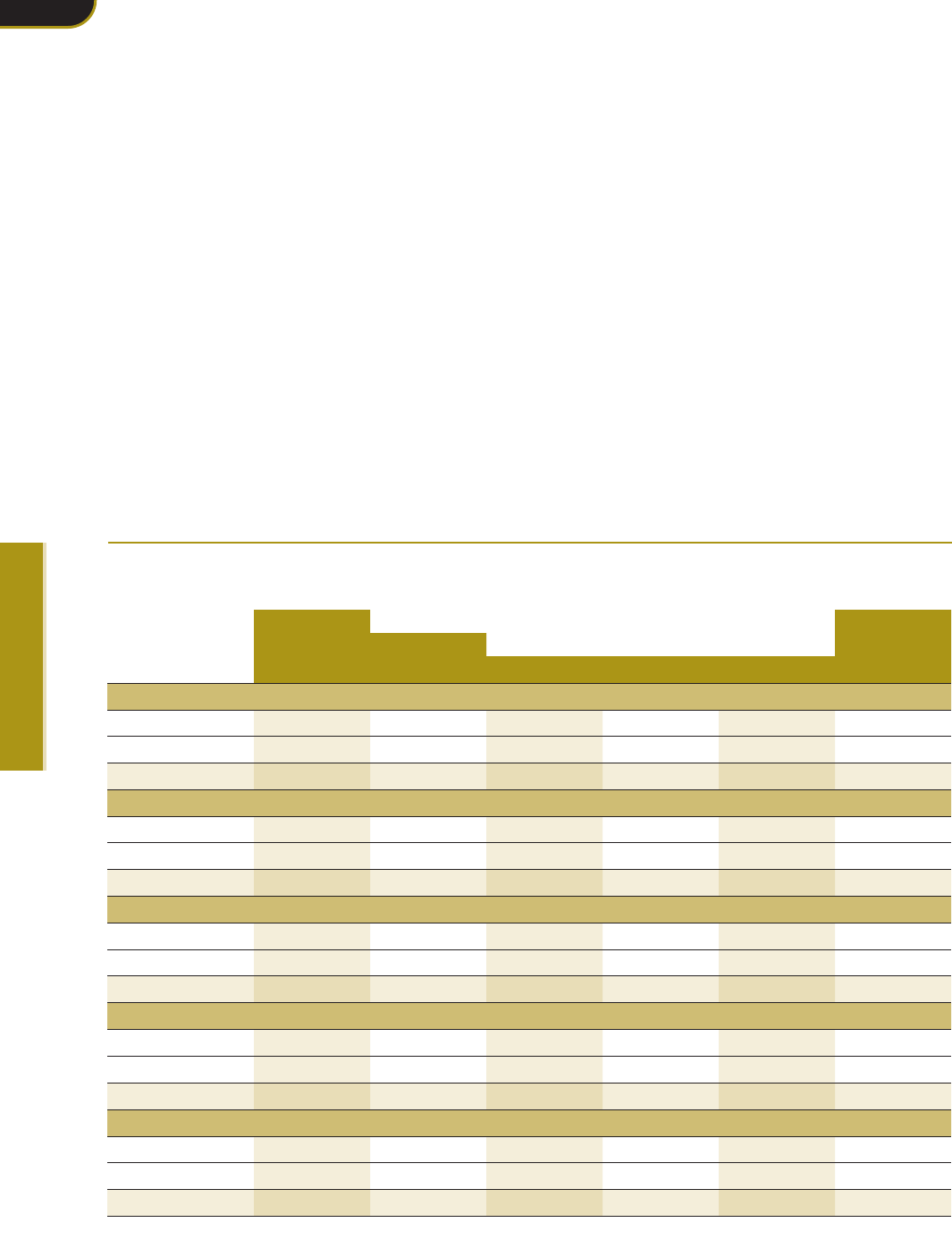

Figure 4: Provincial Transfer Payments to Service Managers and Average Monthly Caseload, 2008/09–2017/18

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Program Delivery

Financial Employment

Average Monthly Assistance Assistance Administration Total

Caseload # ($ million) ($ million) ($ million) ($ million)

2017/18 250,292 2,399 210 366

2,975

2016/17 252,247 2,279 204 375

2,858

2015/16 250,640 2,174 196 353

2,723

2014/15 246,903 2,013 189 365

2,567

2013/14 252,767 1,888 184 362

2,434

2012/13 259,819 2,031 177 328

2,536

2011/12 260,766 1,998 173 332

2,503

2010/11 251,280 1,924 189 318

2,431

2009/10 237,634 1,803 193 205

2,201

2008/09 202,181 1,534 171 194

1,899

Figure 5: Ontario Works Provincial-Municipal Cost Sharing 2009–2018

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Financial Assistance and Employment Assistance Cost Share %

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Ongoing

Provincial Share 80.0 80.6 81.2 82.8 85.8 88.6 91.4 94.2 97. 2 100.0 100.0

Municipal Share 20.0 19.4 18.8 17. 2 14.2 11.4 8.6 5.8 2.8 0.0 0.0

504

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

Applicants must be willing to make efforts to

nd, prepare for and keep a job. They also must

demonstrate nancial need by providing evidence

that their income and asset levels are below speci-

ed amounts. Unless specically exempt, all of an

applicant’s assets are included in the determination

of eligibility. Exemptions include an applicant’s

house and vehicle. To be eligible, as of September

2017, a person’s net assets must be worth less than

$10,000 if the person is single and $15,000 if the

person has a spouse. Prior to September 2017, the

asset limits were $2,500 for a single person and

$5,000 for a person with a spouse.

2.2.1 Role of Caseworkers in Determining

Eligibility for Ontario Works

People seeking help from Ontario Works can apply

online, in person at a service manager’s Ontario

Works ofce, or by telephone. The Ontario Works

caseworker’s responsibilities begin when an

applicant makes contact to schedule an in-person

meeting. At that meeting, the caseworker begins

the process of determining if the applicant quali-

es for assistance. Caseworkers are responsible for

verifying information provided by the applicants to

prove their eligibility and carrying out applicable

third-party checks, such as with Equifax Canada

Inc. and the Canada Revenue Agency. Service

managers carry out third-party checks using the

information-sharing agreements that the Ministry

has entered into.

If an applicant qualies for Ontario Works and

becomes a recipient, the caseworker will create a

formal plan, referred to as a participation agree-

ment. The participation agreement is a plan that

sets out the employment activities, including their

duration, that the recipient will undertake. The

recipient must sign this agreement and carry out

the agreed activities as a condition of receiving

assistance. The activities in the agreement are

intended to help the recipient gain skills and prog-

ress toward sustainable employment.

All recipients must participate in employment

activities unless the caseworker waives their

requirement to participate. The Ontario Works

regulations set out the circumstances under which

service managers may defer an applicant’s require-

ment to participate. These circumstances include:

•

if the participant is a sole parent with pre-

school-aged children;

•

if the participant is a caregiver for a family

member;

•

if, in limited cases, the participant is over 65

years of age and does not qualify for the full

Old Age Security pension or the Guaranteed

Income Supplement; or

•

if exceptional circumstances apply to the

participant.

Following the initial appointment, caseworkers

are typically required to meet with Ontario Works

recipients every three months to adjust the participa-

tion agreement as the recipient progresses or their

circumstances change, and to discuss other pro-

grams and supports that can help the recipient. Min-

istry policy also requires caseworkers to meet with

recipients at least once every two years to review

recipients’ nancial status and information to ensure

that they remain eligible for Ontario Works.

2.2.2 Demographics of Ontario Works

Recipients

As of March 2018, more than 60% of Ontario Works

cases were single recipients without children. Over

60% of Ontario Works recipients were born in Can-

ada, and the primary recipients of Ontario Works

were between the ages of 25 and 34 years. As well, as

of March 2018, 44% of all Ontario Works recipients

lived in the Greater Toronto Area. These demograph-

ics have remained relatively stable since our last

audit, not changing more than 5% in each of these

categories when compared with March 2018. Fig-

ures 6 to 9 illustrate the demographics of Ontario

Works cases by family structure; residency status in

Canada; age of applicant; and geographical location.

505Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

2.3. Financial Assistance for

Ontario Works Recipients

Eligible Ontario Works applicants receive nancial

assistance for basic needs and shelter, and may

qualify for other allowances such a special diet

allowance, pregnancy nutritional allowance or

remote communities’ allowance. The amount of

nancial assistance and allowances available are set

by the Province and are based on family size. Fig-

ure 10 shows the rates for basic needs and shelter

at the end of the 2017/18 scal year and at the time

of our last audit in 2008/09.

Figure 6: Ontario Works Cases by Family Structure,

March 2018

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Couples wit

hout

children (2%)

Singles wit

hout

children (6

1%)

Couples with children (8%)

Singles wit

h

children (29%)

Figure 8: Ontario Works Cases by Residency Status in Canada, March 2018

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

1. Refugee Claimants are individuals who have made a claim for refugee status, but have not yet had their status determined. Refugee claimants are eligible for

Ontario Works effective the date they formally make a claim for refugee protection.

2. Convention Refugees relate to asylum seekers approved by the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada and granted convention refugee status. They are

eligible to apply for Permanent Residence, but in these cases have not yet done so and retain the status of convention refugees.

Born in

Canada (63%)

Born outside

Canada (37%)

Canadian

Citizen (43%)

Permanent

Resident (32%)

Convention

Refugee

2

(5%)

Refugee

Claimant

1

(20%)

Figure 7: Percentage of Ontario Works Cases by

Geographical Location, March 2018

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

City of

Ottawa (8%)

City of

Toronto (30%)

Rest of Ontario (48%)

Rest of Greater

Toronto Area (14%)

506

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

In addition, eligible applicants receive assist-

ance for health and non-health-related expenses,

referred to as mandatory and discretionary bene-

ts. Mandatory health-related benets include drug

coverage; discretionary health-related benets

include dental care for adults. See Appendix 3 for a

list of mandatory and discretionary benets.

The Ministry does not prescribe the rates for dis-

cretionary benets; therefore, service managers have

the authority to set rates they deem appropriate.

Service managers also have the authority to provide

any health or non-health-related benet they feel

is appropriate where failure to provide this benet

would harm the health of the recipient. Service man-

agers can set the rate for the discretionary benets

they provide, but the Ministry provides maximum

funding of $10 per Ontario Works case per month.

Figure 11 shows the type of nancial assistance

and associated costs provided by service managers

Figure 9: Ontario Works Cases by Age of Head of Family,* March 2018

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

* The Head of Family is the applicant.

1,591

16,494

21,009

77,074

57,225

44,219

29,024

1,365

0 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 60,000 70,000 80,000

Under 18

18–21

22–24

25–34

35–44

45–54

55–64

Over 64

Age

Figure 10: Maximum Monthly Ontario Works Basic Needs and Shelter Rates in 2008/09 and 2017/18 ($)

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Single Person with Couple with

Single Person One Child Couple Two Children

2008/09 2017/18 2008/09 2017/18 2008/09 2017/18 2008/09 2017/18

Basic needs 216 337 360 354 429 486 429 486

Shelter allowance 356 384 560 632 560 632 660 744

Total Maximum

Allowance

572 721 920 986 989 1,118 1,089 1,230

Figure 11: Breakdown of Financial Assistance

Payments to Ontario Works Recipients, 2017/18

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

* Other benets and allowances include mandatory and discretionary

benets described in Appendix 3.

Other Benefits and Allowances*

$168 million (7.0%)

Shelter

$1,159 million

(48.3%)

Basic Needs

$996 million (41.5%)

Special Diet

Allowance

$77 million (3.2%)

507Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

to Ontario Works recipients in the 2017/18 scal

year. Basic needs and shelter assistance made up

90% of the total amount of nancial assistance pay-

ments. Mandatory and discretionary benets and

other allowances comprised 7% of payments, and

special diet allowances accounted for 3% of pay-

ments to Ontario Works recipients.

The special diet allowance is available to recipi-

ents and their families who require a special diet

due to one or more approved medical conditions

from a list of more than 40. In order to be eligible

for the special diet allowance, applicants must sub-

mit an application form completed by a health-care

professional such as a doctor, nurse or dietitian.

Service managers use a special diet payment

schedule issued by the Ministry to determine the

amount of the allowance depending on the medical

condition. The monthly amounts vary from $30

to $59 (depending on age) for lactose intolerance,

$32 to $63 (depending on age) for a milk allergy,

$97 for an allergy to wheat, and up to $191 for an

individual with cystic brosis. An individual may

have multiple special requirements; however, the

total allowance for any one member of a family may

not exceed $250 per month.

2.4 Ontario Works Employment

Assistance

As noted in Section 2.2.1, Ontario Works recipi-

ents are required to participate in employment

assistance activities as a condition of eligibility for

receiving basic nancial assistance. These activities

include unpaid community service activities, or

employment support activities such as job search,

participation in basic education or job-specic

training and development of employment-related

skills. The Ministry requires service managers to

submit a service plan every two years. The plan

sets out how the service manager will invest in

employment-related strategies that best reect

their caseload, local conditions and priorities, and

offers the best results to their participants. Each

service manager is required to provide and make

available to recipients each of the programs listed

in Figure 12.

For Ontario Works recipients who are not yet

able to benet from one or more of these employ-

ment assistance activities due to personal circum-

stances—such as homelessness, transience, or lack

of available child-care—the Ministry requires ser-

vice managers to help these participants to resolve

these obstacles as a rst step toward participating

in employment assistance activities.

Figure 12: Ministry-Mandated Employment Activities

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

Community Placements The program can help arrange placements in a community agency so that participants can

gain work experience. Participants will be able to practice skills, improve their condence

and get up-to-date job references and contacts.

Education Programs Education programs are available to help participants nish high school, improve language

skills or upgrade reading, writing or math skills.

Employment Placements The program can connect participants who are ready for a job with employers who are

hiring. The program can also help participants prepare for an interview and help with

training for a job, if required.

Job-Specic Skills Training If participants need special training or skills for a job, the program can assist with nding

help to develop those skills.

Learning, Earning and Parenting

(LEAP)

If participants are young parents between the ages of 16 to 25, LEAP provides supports to

nish high school, improve parenting skills, prepare for and nd work.

Literacy Screening and Training The program can help participants access help to improve reading, writing and math skills.

508

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

2.5 Oversight and Performance

Measurement

As described in Section 2.1.1, the Ministry enters

into contracts with service managers for the

delivery of Ontario Works. The Ministry’s primary

means of monitoring service managers’ delivery of

Ontario Works is through its team of approximately

30 regional program supervisors and program man-

agers who are responsible for the nancial monitor-

ing and oversight of individual or clusters of service

managers. These staff review service managers’

reimbursement claims for payments made to

Ontario Works recipients. They also negotiate con-

tracts with service managers and are expected to

review service managers’ progress reports related

to these contracts. These contracts are two years

in duration and require service managers to set

annual targets and report results for indicators that

include recipient employment earnings and the

percentage of recipients who nd employment. Fig-

ure 13 illustrates the performance indicators that

service managers were required to report on in the

calendar years following our 2009 audit.

The Ministry also requires service managers to

participate in its Eligibility Verication Process.

In this review process, the Ministry identies a

sample of Ontario Works cases as having a high

likelihood of missing or incorrect information. Such

information may affect a recipient’s eligibility or

the amount of assistance the recipient receives. The

Ministry identies the cases for eligibility verica-

tion by comparing a recipient’s income or expense

information to tax data. Equifax Canada then com-

bines this information with other consumer credit

information to provide the Ministry with the high-

est risk cases. The Ministry then assigns high-risk

cases for service managers to review to determine

whether the recipient still meets eligibility require-

ments and whether the amount of assistance should

be changed.

3.0 Audit Objective and Scope

Our audit objective was to assess whether the

Ministry of Children, Community and Social Ser-

vices (Ministry) with municipal service managers

have effective systems and processes in place to:

•

ensure only eligible recipients receive nan-

cial and employment support that is com-

mensurate to their needs, in accordance with

legislative and policy requirements; and

•

measure, evaluate, and publicly report on the

effectiveness of the Ontario Works program

in helping people in temporary nancial need

to nd employment.

In planning for our work, we identied the audit

criteria (see Appendix 4) we would use to address

our audit objective. These criteria were established

based on a review of applicable legislation, direc-

tives, policies and procedures, and internal and

external studies. Senior management at the Min-

istry and the service managers we visited reviewed

and agreed with the suitability of our objective and

related criteria.

We focused on the Ministry’s and service

managers’ activities in the ve-year period ending

March 2018. We conducted our audit between

Figure 13: Ontario Works Performance Indicators

Reported by Service Managers

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

2010–2015

Average monthly employment earnings per case

Average amount of monthly earnings at exit from Ontario Works

% of caseload with monthly employment income

% of caseload exiting to employment

Job retention rate since exiting to employment (in months)

Job retention rate % among those exiting to employment

Average length of time to exit assistance due to employment

2016–2018*

Average monthly employment earnings per case

% of caseload with employment earnings

% of caseload exiting to employment

% of total exits from assistance due to employment

* Service managers were required to select and report on only two of the

four employment outcome indicators between 2016 and 2018.

509Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

January 2018 and September 2018. We obtained

written representation from Ministry management

and the four service managers we visited that,

effective November 8, 2018, they have provided

us with all the information they are aware of that

could signicantly affect the ndings or the conclu-

sion of this report.

Our audit work was conducted at the Min-

istry and four of the 47 service managers across

Ontario: City of Toronto, City of Windsor, District

of Thunder Bay Social Services Administration

Board, and Regional Municipality of Peel. Collect-

ively, the four service managers we visited repre-

sented approximately 42% of the total Ontario

Works caseload in 2017/18. We also sent a survey

to all 47 service managers and received a response

from each of them to gain a better understanding

of how they deliver the Ontario Works program

across the province.

Our audit work included an analysis of poli-

cies and procedures, and relevant documents and

reports, as well as detailed discussions with staff

at the Ministry’s corporate ofce involved in the

design, funding, oversight and performance meas-

urement of the Ontario Works program.

We also met with the Ministry’s regional pro-

gram managers and supervisors responsible for

overseeing the nancial and operational perform-

ance of the four service managers we visited.

Our audit work at service managers included

interviews with key personnel responsible for

delivering the Ontario Works program in accord-

ance with legislative and policy requirements, as

well as interviews with caseworkers responsible for

providing services to Ontario Works recipients. We

also performed data analysis and reviewed Ontario

Works recipients’ les to determine whether service

managers comply with Ontario Works program

requirements, and to identify trends related to ser-

vice managers’ efciency, effectiveness, and compli-

ance with program requirements. We also obtained

information from service managers about the out-

comes of Ontario Works recipients that used their

employment services. However, we did not evaluate

service managers’ administration of contracts with

external parties that provide employment supports

to recipients.

In addition, to gain an understanding of Ontario

Works recipients’ experience in the program, we

spoke to senior staff at the Income Security Advo-

cacy Centre. The Centre is a community legal clinic

funded by Legal Aid Ontario that advocates on

behalf of low-income Ontarians and has provided

advice to the government on improving the Ontario

Works program.

We also reviewed the relevant audit reports

issued by the Ontario Province’s Internal Audit

Division in determining the scope and extent of

our audit work. We last audited the Ontario Works

program in 2009.

We conducted our work and reported on the

results of our examination in accordance with

the applicable Canadian Standards on Assurance

Engagements—Direct Engagements issued by the

Auditing and Assurance Standards Board of the

Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada. This

included obtaining a reasonable level of assurance.

The Ofce of the Auditor General of Ontario

applies the Canadian Standards of Quality Control

and, as a result, maintains a comprehensive quality

control system that includes documented policies

and procedures with respect to compliance with

rules of professional conduct, professional standards

and applicable legal and regulatory requirements.

We have complied with the independence

and other ethical requirements of the Code of

Professional Conduct of the Canadian Professional

Accountants of Ontario, which are founded on

fundamental principles of integrity, objectivity, pro-

fessional competence and due care, condentiality

and professional behaviour.

510

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

4.0 Detailed Audit

Observations: Ministry of

Children, Community and

Social Services

4.1 Cost of Ontario Works

Increasing but Ministry Does Not

Effectively Oversee or Hold Service

Managers Accountable

4.1.1 Service Managers Do Not Always

Comply with Ministry Requirements

The Ministry contracts with service managers

to deliver Ontario Works but it is the Ministry’s

responsibility to ensure that the service managers

comply with legislation and Ministry policies

designed to ensure that the program is effective.

However, we found that the Ministry does not

conduct inspections of service managers to conrm

their compliance despite the fact that the provincial

share of Ontario Works nancial assistance and

employment assistance expenditures increased

from 80% at the time of our last audit in 2009

to 100% in 2018. When service managers do not

complete requirements that affect, for example,

eligibility, or do not do so on a timely basis, ineli-

gible recipients may remain undetected for longer,

resulting in larger overpayments that service man-

agers must later recover (discussed in Section 4.4).

Our audit identied several areas where the

Ministry needs to take steps to improve service man-

agers’ compliance to ensure that only those who are

eligible for the program receive assistance and that

individuals progress toward obtaining employment.

These issues are discussed in Section 5, which

details our observations about service managers.

Specically, in relation to eligibility, we found:

•

third-party checks of nancial informa-

tion were not performed in many cases

(Section 5.1.1);

•

critical information relating to establish-

ing eligibility was not always obtained or

reviewed (Section 5.1.2);

•

individuals’ ongoing eligibility was not always

reassessed every two years as required by

Ministry policy (Section 5.1.3);

•

targeted eligibility reviews of recipients with

a high risk of ineligibility were not always

completed (Section 5.1.4); and

•

fraud tips and incarceration alerts were

not always reviewed or investigated within

the timeframes required by the Ministry

(Section 5.1.5).

Relating to ensuring that individuals progress

toward obtaining employment to become self-

reliant, employment results varied from a low of 2%

of recipients nding employment during 2017/18 at

one service manager visited to 15% at another ser-

vice manager visited. Regarding compliance with

Ministry requirements, we identied that:

•

not all the decisions to exempt recipients from

employment activities were supported with

the required evidence (Section 5.2); and

•

not all recipients had met with their case-

worker as regularly as required by Ministry

policy to ensure that they were participating

in employment activities (Section 5.3.1).

4.1.2 Ministry Cancelled its Process to

Review Service Manager Compliance and

Seven Years Later It Has Yet To Replace It

The Ministry stopped completing reviews that

assess service managers’ compliance with Ontario

Works requirements in 2011 with the intent of

replacing them with a new risk-based program to

monitor service managers. However, as of 2018,

seven years after it stopped completing compliance

reviews, it has yet to implement a process to replace

these reviews.

At the time of our 2009 audit, and up until 2011,

the Ministry’s staff conducted compliance reviews

of service managers. Compliance reviews consisted

of examining a sample of Ontario Works recipient

511Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

case les to assess whether the service manager

complied with program requirements and stan-

dards. These reviews covered areas such as recipi-

ent eligibility and nancial assistance, the provision

of discretionary benets, overpayment collection,

and the completion, appropriateness, and effective-

ness of recipient participation agreements.

In our 2009 Annual Report, we noted that these

compliance reviews identied many of the same

issues and concerns that we raised during our audit

at that time.

RECOMMENDATION 1

We recommend that the Ministry of Children,

Community and Social Services (Ministry)

re-institute its reviews of service managers’

compliance with Ontario Works requirements,

or implement a suitable process, to reinforce

to service managers the need to comply with

requirements designed to ensure:

•

nancial assistance is provided in the correct

amount and only to eligible individuals; and

•

recipients progress toward obtaining

employment to become self-sufcient.

MINISTRY RESPONSE

The Ministry agrees with the recommendation

and acknowledges that strengthened oversight

processes and tools are required to achieve

greater accountability in meeting Ministry

requirements designed to ensure service man-

agers provide nancial assistance in the correct

amount to eligible individuals and that recipi-

ents progress toward obtaining employment to

become self-sufcient.

The Ministry will establish a multifaceted

outcomes-based approach with required tools

and processes to ensure service managers effect-

ively and efciently achieve program objectives

and client outcomes.

This outcomes-based approach to account-

ability, supported by appropriate data analysis

and reporting, will place the onus on service

managers to have the appropriate strategies and

controls in place to meet Ministry requirements

including the achievement of positive outcomes

for recipients. This approach emphasizes clearly

dened expectations while providing service

managers with exibility to meet the needs of

their communities.

By April 2020, the Ministry will:

•

dene and clearly communicate expecta-

tions, requirements, standards and targets

which will include program oversight, and

eligibility verications;

•

develop a strong agreement based on the

Ontario Government’s Transfer Payment

Accountability best practices, with specic

expectations, reporting requirements,

corrective actions, and risk management

requirements;

•

implement a series of new mechanisms to

proactively identify and prevent perform-

ance and eligibility issues;

•

establish a process to actively monitor a

range of performance indicators covering

service delivery and management against

targets; and

•

benchmark performance results as means for

continuous improvement of operations.

This approach will be further strengthened

by the end of 2020/21 with:

•

a Risk-Based Certicate of Assurance process

to be completed by service managers;

•

targeted Quality Assurance reviews by the

Ministry to validate the accuracy and con-

sistency of service manager reported nd-

ings; and

•

third-party reviews for targeted situations

when signicant concerns or opportunities

are identied.

512

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

service managers, and found that almost 30% of

service managers did not have any targets in their

contracts for the number of recipients expected to

leave the program for employment. These service

managers had only chosen and set targets for the

Ministry’s two performance indicators related to

measuring employment earnings for recipients of

Ontario Works.

Furthermore, we found that service managers

are required to assign a points weighting to achiev-

ing each of the targets set and are considered

to have achieved the outcomes built into their

contracts if they exceed a certain threshold of

points. The Ministry advised us that 23 out of 47

service managers in Ontario had already achieved

enough points at the end of 2017, the rst year of

the current contracts, to meet their two-year con-

tractual obligation. This suggests that the targets

established in these contracts are of little value in

encouraging service managers to improve their

performance to help recipients to nd employment

and become self-sufcient.

RECOMMENDATION 2

To hold service managers accountable for

delivering the Ontario Works program in com-

pliance with the program’s requirements, and

to improve program outcomes, we recommend

that the Ministry of Children, Community and

Social Services (Ministry) update its contracts

with service managers to include:

•

requirements to comply with Ontario Works

legislation, Ministry directives and polices;

•

additional performance indicators and

meaningful targets to measure service man-

agers’ progress in assisting Ontario Works

recipients nd employment and become

self-sufcient;

•

targets for service delivery, including

reducing and preventing overpayments; and

•

mechanisms to hold service managers

accountable for meeting the terms of the

agreements.

4.1.3 Ministry Contracts with Service

Managers Lack Mechanisms to Hold

Service Managers Accountable

Contracts Do Not Specify Program Requirements

or Service Delivery Targets that Service Managers

Must Meet

We found that the contracts with service managers

for the delivery of Ontario Works do not include a

requirement for service managers to comply with

Ontario Works legislation, Ministry program direc-

tives or key Ministry policies. For example, one of

the Ministry’s key policies is the requirement for

service managers to participate in its Eligibility

Verication Process described in Section 2.5; how-

ever, the contracts do not include a requirement for

service managers to complete these reviews.

In addition, the contracts also do not include

measures and targets for service delivery (based on

the standards dened in the Ontario Works legisla-

tion and Ministry directives) such as reducing

overpayments, improved overpayment collection

and timely investigation of fraud referrals.

Service Managers’ Administration and

Employment Assistance Funding Is Not Linked to

Their Performance

The current contracts with service managers

(described in Section 2.5) include a requirement to

achieve annual performance targets for indicators

relating to recipient employment earnings and the

percentage of recipients who nd employment. The

contracts also allow the Ministry to recover funds

when service managers do not achieve these targets.

However, the Ministry advised us that it has never

exercised its ability to recover funding from service

managers for failing to achieve these targets.

In addition, for the performance indicators that

the service managers currently report on, service

managers are only required to pick and set targets

for two of the Ministry’s four indicators (as noted in

Figure 13). We reviewed the indicators chosen by

service managers for 2017, the rst year of the cur-

rent two-year contracts between the Ministry and

513Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

MINISTRY RESPONSE

The Ministry agrees with the recommendation

and will implement, for April 2020, a compre-

hensive service contract with service managers

for the delivery of Ontario Works, reecting

principles and requirements of the Ontario

Government’s Transfer Payment Accountability

Directive. This contract will act as one of the

primary mechanism for governing the account-

ability relationships and interactions between

the Ministry and service managers.

The service contract will include specic

expectations including complying with program

requirements, reporting requirements, correct-

ive actions and risk management requirements.

The Ministry, in consultation with service man-

agers, will establish key performance indicators

as well as appropriate targets related to service

delivery and those that demonstrate recipients’

progress toward nding employment and

becoming self-sufcient.

The Ministry is also exploring further enhan-

cing the service contract by the end of 2020/21

with provisions for Certicate of Assurance,

Quality Assurance Reviews and third-party aud-

its where warranted to hold service managers

accountable for meeting the terms of these

agreements.

4.2 Ministry Lacks Targets

and Performance Indicators to

Improve the Effectiveness of

Ontario Works

4.2.1 Only 10% of Recipients Find

Employment and the Ministry Has Not

Taken Action to Improve Results

We found that the Ministry has not set provincial

targets for the number of Ontario Works recipients

it expects to nd employment. It also does not

combine the employment results it collects from

individual service managers to monitor and evalu-

ate the overall effectiveness of the Ontario Works

program in getting recipients into the workforce.

To understand how many recipients typically

nd work and leave the program annually, we

combined the monthly data collected by the Min-

istry from service managers for the percentage of

recipients who leave the program for employment.

We found that province-wide, only 10% to 13% of

Ontario Works recipient cases left the program for

employment in the last ve years, including just

10% in 2017/18. Figure 14 shows the province-

wide results over the last ve years for exits to

employment, as well as the results we calculated

for the Ministry’s performance indicators related to

recipient employment earnings.

Ministry Does Not Compare Service Manager

Employment Results to Identify Best Practices

and to Take Corrective Action

We found that the Ministry does not compare the

employment results it collects from service man-

agers to identify best practices and instances that

require corrective action. We analyzed these results

and found signicant differences between service

managers’ employment results that the Ministry

should follow up. For example, in 2017/18, at

one-third of all service managers, the percentage

of recipient cases exiting to employment was more

than 20%, but at one-fth of service managers, it

was less than 10%. Figure 15 shows the service

managers with the highest and lowest percentage

of exits to employment compared with the provin-

cial average.

As described in Section 5.4, we found that the

employment supports for Ontario Works recipients

offered by the four service managers we visited

varied. Therefore, it is important for the Ministry

to investigate the links between service manager

employment supports and recipient employment

outcomes to take action to improve results.

514

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

Ministry Does Not Publicly Report on Recipient

Employment Outcomes

The Ministry reports various statistics about the

Ontario Works program publicly on its website

including the number of recipients on assistance;

recipient demographics; the length of time recipi-

ents spend on assistance; and the percentage of

recipients with earnings. However, the Ministry

does not publicly report on the number and

proportion of Ontario Works recipients who nd

employment each year. Reporting these results

would provide Ontarians with information on the

effectiveness of the program in helping individuals

to get a job.

4.2.2 Ministry Does Not Have Targets to

Reduce Rapidly Increasing Time Recipients

Are on its Temporary Assistance Program

The intent of the Ontario Works program is to

provide temporary nancial assistance to those in

need to help them nd employment and become

self-sufcient. However, we found that similar to

our observations when we last audited this pro-

gram in 2009, the Ministry has not dened what it

considers to be a temporary period. In addition, as

shown in Figure 3, we found that recipient time on

assistance has almost doubled, from an average of

19 consecutive months in 2008/09 to nearly three

years in 2017/18.

Despite this trend, we found that the Ministry

has not established province-wide or service man-

ager specic targets and performance indicators

for recipient time on assistance. It also does not

currently have targets and performance indicators

in place that measure the length of time it takes

Ontario Works recipients to nd employment. We

noted that until 2015, the Ministry did have an

indicator that measured how long it took recipients

that left Ontario Works for employment to do so.

However, the Ministry stopped tracking data and

measuring outcomes for this indicator in 2015 in

order to implement its Information Technology

system, and it has yet to replace the indicator with

a new one.

In other jurisdictions, we found that some Can-

adian provincial social assistance programs measure

and report on an individual’s time on assistance.

For example, British Columbia’s Income Assistance

program reports the median time on assistance

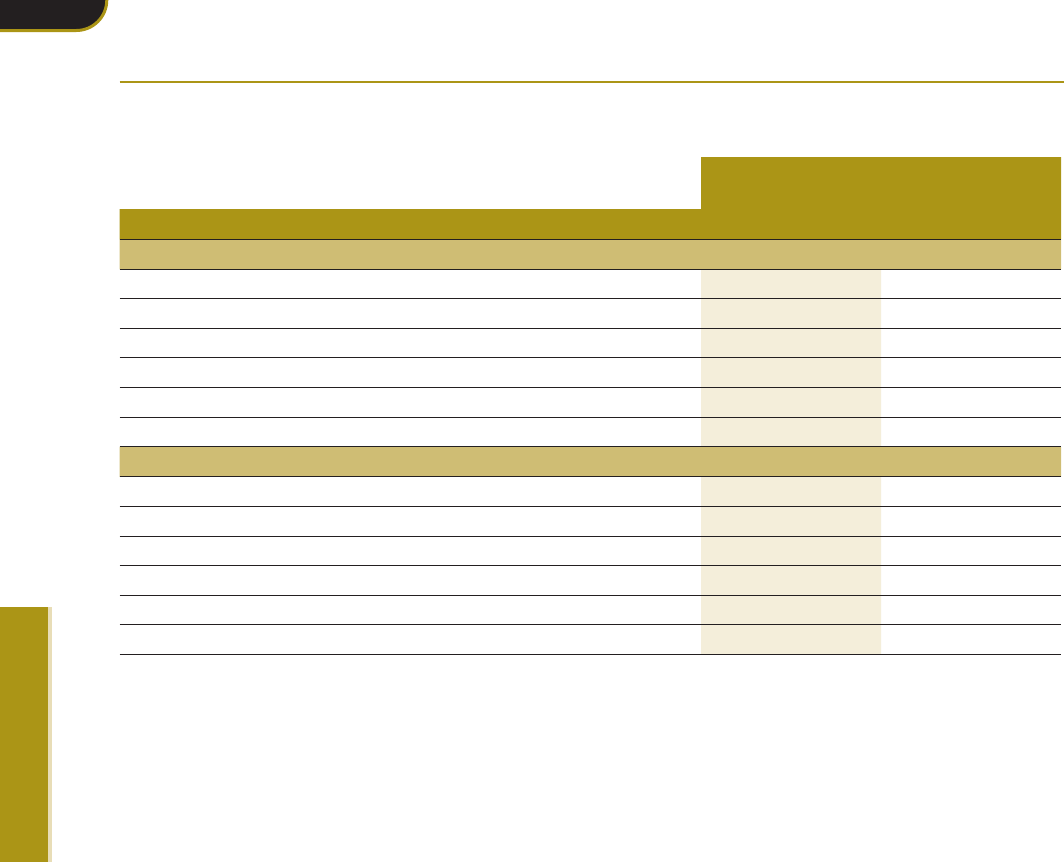

Figure 14: Ontario Works Performance Indicator Results, 2013/14–2017/18

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18

% of caseload exiting to employment 13 12 9 10 10

% of caseload with employment earnings 10 10 11 12 12

Average monthly employment earnings per case* ($) 732 778 810 778 815

* A case refers to a single individual or a family unit on social assistance (for example, a family on social assistance is counted as one case).

Figure 15: Service Managers’ Performance Indicator Results, 2017/18

Source of data: Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services

% of % of Average Monthly

Caseload Exiting Caseload with Employment Earnings

to Employment Employment Earnings per Case ($)

Province 10 12 815

Service Manager High 29 22 966

Service Manager Low 2 9 698

515Ontario Works

Chapter 3 • VFM Section 3.11

for those it considers employable. In addition, the

Saskatchewan Assistance Program reports on the

percentage of individuals it deems employable who

leave the program within six months.

Ministry Lacks Information to Explain Increasing

Time on Assistance

We noted that the Ministry has data for the length

of time on assistance province-wide and by service

manager, but it does not regularly analyze and com-

pare time on assistance to labour market conditions

or to the demographics of recipients. Such compari-

son could improve its understanding of the reasons

for the growing duration of time on assistance. In

addition, the Ministry does not compare differences

in time on assistance between service managers to

determine whether these differences are reasonable

and to take corrective action where they are not.

According to our analysis of Ministry data for

2017/18, the average length of time an individual

spent on Ontario Works at one service manager

could be more than twice as long as the average

at another, depending on where in Ontario an

individual lived. Figure 16 shows the differences in

the average length of time on assistance between

service managers in Ontario.

Ministry Employment Indicators Do Not Measure

Whether Recipients Find Stable Employment

The Ministry’s current performance indicators

relating to whether an individual has found

employment do not measure whether recipients

nd stable employment. This is because these indi-

cators do not make the distinction between those

who temporarily leave Ontario Works—such as for

seasonal work or a temporary contract—and those

who have found long-term employment. Individ-

uals who are on and off Ontario Works for tempor-

ary work count as an exit to employment every time

they leave the program. We noted that until 2015,

the Ministry did have indicators that measured how

long individuals who left the program for employ-