United States’ Teen Dating Violence Policies: Summary of Policy

Element Variation

Hannah I. Rochford

1,*

, Corinne Peek-Asa

1

, Anne Abbott

2

, Ann Estin

3

, Karisa Harland

4

1

Injury Prevention Research Center, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

2

National Resource Center for Family-Centered Practice, Coralville, Iowa, USA

3

College of Law, 290 Boyd Law Building, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

4

Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins

Drive, 1008 Roy Carver Pavilion, Iowa City, IA 52242

Abstract

As Teen Dating Violence (TDV) has gained attention as a public health concern across the United

States (US), many efforts to mitigate TDV appear as policies in the 50 states in the form of

for programming in K-12 schools. A keyword search identified 61 state-level school-based TDV

policies. We developed an abstraction form to conduct a content analysis of these policies and

generated descriptive statistics and graphic summaries. Thirty of the policies were original and 31

were additions or revisions of policies enacted by 17 of the 30 states previously. Of a possible

score of 63, the minimum, mean, median, and maximum scores of currently active policies were

3.0, 17.7, 18.3 and 33.8, respectively. Results revealed considerable state-to-state variation in

presence and composition of school-based TDV policies. Opportunity for improving policies was

universal, even among those with most favorably scores.

Keywords

teen dating violence; adolescent dating violence; public health law; K-12 programming

Introduction

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a prevalent and preventable public health challenge. While

this type of harm impacts many societies, and many prevention strategies foreseeably

transcend social, cultural and political contexts, this work offers a summary of the U.S.

policies enacted in an effort to mitigate TDV. The United States Center for Disease Control

and Prevention defines TDV as: “verbal, physical, emotional, psychological, or sexual abuse

in a dating relationship, including stalking and perpetration via electronic media” [1] when

“one or both partners is between thirteen and twenty years of age” [2]. TDV can cause acute

physical injuries and mental health concerns and influence long- term health outcomes,

*

Corresponding author: MPH, Department of Health Management and Policy, College of Public Health, University of Iowa, 145 N.

Riverside Drive, Room N271, Iowa City, 52242-2007, United States. hannah-rochford@uiowa.edu.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material contains Appendices A, B, and C.

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Published in final edited form as:

J Public Health Policy

. 2022 December ; 43(4): 503–514. doi:10.1057/s41271-022-00365-7.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

including an increased risk for pregnancy, risky sexual behavior, eating disorders, substance

abuse, suicide or suicidal ideation [3], victimization in adult relationships [4], depression,

smoking, and binge drinking [5].

The public health burden of TDV disproportionately falls on teenage girls and teens who

are Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual [6]. National figures from the US 2015 Youth Risk Behavior

Surveillance System (YRBSS) indicate that among students who dated, the prevalence of

physical TDV victimization was 40% higher among girls than boys (11.7% vs 7.4%), and

sexual TDV rates were 2.6-times higher in girls than boys (14.0% vs 5.4%). State-based

rates of TDV varied widely, with physical TDV highest in Arkansas (15.6%) and lowest

in Massachusetts (6.7%) [7]. Prior research suggests approximately one out of five teens

engage in an abusive relationship, and 10% of reported intentional injuries to adolescent

girls are the result of dating violence by male partners [3].

Efforts to prevent and mitigate the consequences of TDV have largely taken the form of state

policies that attempt to reduce teen dating violence through programming in kindergarten

(K)-12 schools [8, 9]. K-12 schools are a common setting for health-related programming

and supportive services to children and youth, including awareness building and prevention

education around TDV [8]. These programs offer opportune access points for introducing

awareness, prevention, and recognition strategies and opportunities for delivering support

resources to the population at risk for TDV, and to the school staff with whom these teens

engage. Schools are also sites of TDV incidents, and personnel often work with students

who have expressed violent behavior toward someone in or out of school. Recent research,

however, provides reason to suspect many US schools are not adequately prepared to address

TDV for lack of awareness and understanding [4]. In a national survey of high school

guidance counselors, a group often engaged in responding to TDV, 58% had not received

TDV education, 81% were unaware of a school protocol for responding to TDV incidents,

and 90% had not been trained to assist students victimized by TDV [10].

Violence prevention theoretical frameworks like the socioecological model suggest a need

to implement interventions beyond the individual level [10], and studies of TDV laws

and policies support this. Recent work has affirmed that improving TDV perpetration and

responses to TDV behaviors require effective interventions to facilitate re-shaping social

norms and culture around TDV [11]. Some states have enacted legislative action only

recently, since 1992. The oldest TDV policy that has not been updated since its enactment

in 2002. Thus, our figures display 2002 as the oldest year of enactment for a currently

active policy, although the first state to enact a law did so in 1992, then updated it.) Policies

meant to address public health concerns vary widely in terms of their written quality,

implementation integrity ( the extent to which a policy’s implemented form aligns with what

a policy’s authors intended to occur), and overall capacity to help implementers achieve

the intended impact on health outcomes. A community-based participatory research effort

conducted by Gulliot-Wright et al. [12] on Texas-specific TDV legislation and school-based

curriculum found gaps in uptake of school-based prevention programming. They identified

legislation that addressed individual- and system-level causes for violence as an important

opportunity for prevention. Jackson et al. [13] also examined Texas-specific TDV policies

Rochford et al.

Page 2

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

from an implementation perspective and found most districts had developed basic policies

and were making progress in implementation.

Nationally, Black, Hoefer, & Ricard [14] scored TDV policies using the advocacy group

Break the Cycle’s

A – F grading system. This system focuses on ability youth (those under

age 18) to make use of civil protective orders and modeled their relationship with other

system-level factors (state political and economic conditions) to TDV prevalence. They

found an inverse association between the caliber of a TDV policy and TDV outcomes.

Cascardi, et al. [15] examined TDV policies in the context of policies against ‘bullying’(a

pattern of unwanted, aggressive behaviors involving a perceived power imbalance, and

occurring between youths who are not family members or dating partners) based on the

binary inclusion or exclusion of a purpose statement and discussion of prohibited behaviors

and harmful effects, enumeration of school jurisdiction, discussion of protected groups,

local or district policy development and implementation, designation of a specialist within

schools, reporting or investigation procedures, and sanctions recommended.

To our knowledge, although TDV state policies have been studied and scored, a gold

standard for assessing the elements in state laws does not yet exist. The goal of this

work was to synthesize current approaches to TDV legislation and position future research

efforts to elucidate what drives policy variation, and how TDV policy variation shapes

TDV outcomes. Thus, we systematically abstracted and described states’ TDV law content

and distinguished among those with presence, partial presence, or absence of 34 policy

components.

Methods

Law students identified school-based state TDV policies from keywords searches in

Westlaw

®

. Westlaw Codified Law Index terms for the search are reported elsewhere.

[16] The study period was defined by the enactment dates of all policies identified in

2019: related policies were enacted as early as 1992 and as recently as 2018. The project

leader (KH) organized the legal language by state and by effective periods in MonQcle

(a software system developed by the Temple University Center for Public Health Law

Research to support policy surveillance and scientific legal research projects) in preparation

for component scoring.

School-based TDV Policy Abstraction Form Development

To understand states’ approaches to school-based TDV policy, the authors (HR, CP, AA, AE,

KH) developed and applied an abstraction form to measure TDV policy components based

on our literature search of peer-reviewed health sciences, social sciences, education, and law

publications available as of 2019. As no one has yet established best practices to guide TDV

legislative evaluation, our study team developed a scoring system to identify components

of a comprehensive law and allowed for components to be designated as present, partially

present, or absent. Four sources guided our scoring system for components: US Department

of Education (DOE) recommendations on best practices for anti-bullying laws and policies

[17], policy elements in existing laws [18], S

tart Strong

’s TDV model school policy [19]

and best practices for public health law evaluation [20]. The team (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH)

Rochford et al.

Page 3

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

that developed the scoring system was multidisciplinary with broad expertise: a legal expert

on family law pertaining to intimate partner violence, an epidemiologist with experience

in domestic violence research, two injury epidemiologists with experience conducting

violence research and policy evaluations, and a biostatistician with experience conducting

longitudinal, hierarchical modeling analysis.

Select authors (HR, AA, KH)revised our original abstraction form using an iterative process

during a pilot period. Three individuals (HR, AA,KH) with graduate training in public health

and experience working with sexual and intimate partner violence policies piloted use of the

abstraction form with policies from two states that the same select authors (HR, AA, KH)

perceived to present low risk for error in coding (Michigan and Pennsylvania), from two

states perceived to present moderate risk for error in coding (Delaware and Massachusetts),

and from two states perceived to present high risk for error in coding (California and

Connecticut). In coding, the project leader (KH) assessed initial abstraction results of two

authors (HR, AA) for areas of frequent (recurrent in piloted policies) or severe discrepancy

(scores by one party indicating full presence of a component and another party indicating

absence), or both. The authors (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH) clarified intent and criteria for coding

each abstraction item of concern. The authors (HR, CP, AA, AE, KH) retained in the final

version all the originally proposed sections of the instrument. Full abstraction occurred after

the pilot process was complete.

Policy Element Abstraction & Analysis

Abstraction Process—We included 34-items in the abstraction form, organized into 7

sections. The full abstraction form is available in Appendix A. We scored each item in

each Section from 0 – 2 scale where 0 indicated the element was not present, 1 that it was

partially present or encouraged, and, 2 that it was fully present or required. We standardized

the item on the minimum number of years of TDV prevention education for students to a

0-12 scale (of years of schooling) from a 0-13 scale (thus some scores involve decimals).

Two graduate students (HR, AA) with training in public health, public policy, and violence

research (neither of whom participated in the piloting of the instrument) completed formal

abstraction using MonQcle

®

; the project leader (KH) adjudicated discrepancies. During the

abstraction process, we first coded the original policies of the 30 states that had any policy,

then coded any subsequent updates. Each student carried out abstraction independently, prior

to the generation of the Krippendorff’s alpha for inter-rater reliability to correct for change

agreement, handle multiple coders, and measure intercoder agreement for nominal, ordinal,

and interval data. [21] The inter-rater reliability score generated using Krippendorf’s alpha

was 0.88.

Analysis of Abstracted Data—We separated states according to the presence or absence

of school-based TDV policies, and assigned a scored of 0 for those with no laws. We

isolated scores of states with school-based TDV policies to derive their distribution and a

series of descriptive statistics. We generated descriptive statistics for each of the 7 policy

component sections.

Rochford et al.

Page 4

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Several states had more than one score because they updated their school-based policy

between the start and end of the analysis period (1992 – 2018). In these instances, we used

the overall score and Section-specific scores of the current policy. To determine the presence

of a temporal trend we assessed changes in state policy scores, in each state, over time, using

a Pearson correlation test for policy score and year of enactment.

Results

Thirty states had enacted at least one related policy by 2019, scoring between 3 and 33.77

out of a possible 68. Our TDV policy search yielded 61 policies from 30 states. Of these,

30 policies were original, and 31 were additions or revisions enacted by 17 of the 30

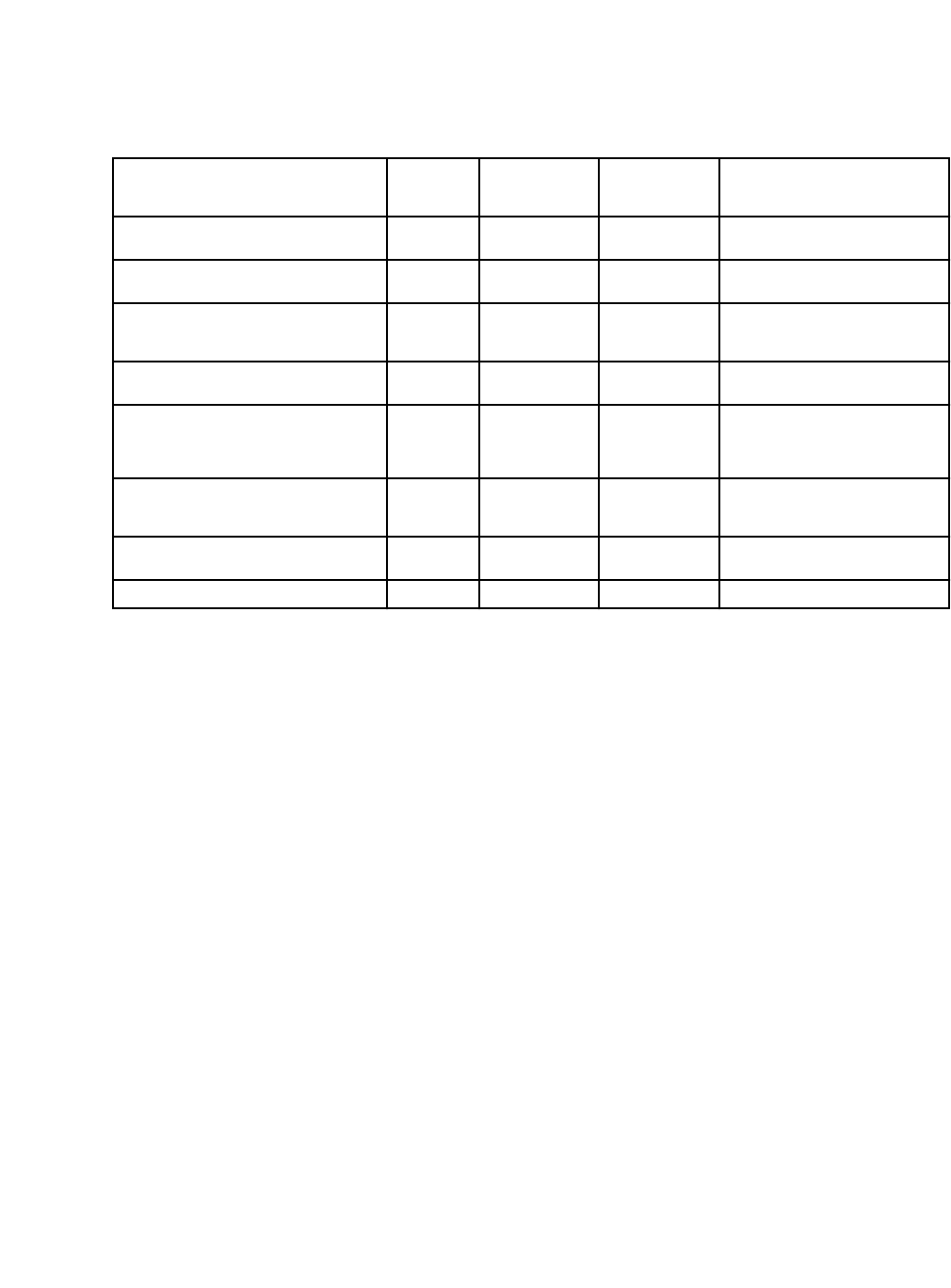

states. Table 1 displays states with policies, scores for currently active policies, and the

year the state enacted its latest policy. Twenty-one states enacted no TDV policy between

1992 and 2018. States enacted policies with the lowest scores in 2005, 2015, and 2017, and

with the highest scores in 2011, 2017, and 2018. The highest component score was Ohio’s

at 33.77, and the lowest component score observed was 3, held by both Maryland and

Washington. California, Connecticut, Tennessee, Ohio, and Virginia implemented or revised

TDV policies most recently. Maine Michigan and Washington maintained policies for the

longest duration. The association between the date of enactment and the component score is

not significant (correlation of 0.501). For policies active in 2018 or earlier, the mean year of

enactment was 2012. California had the largest number of policy updates (5 revisions since

1994).

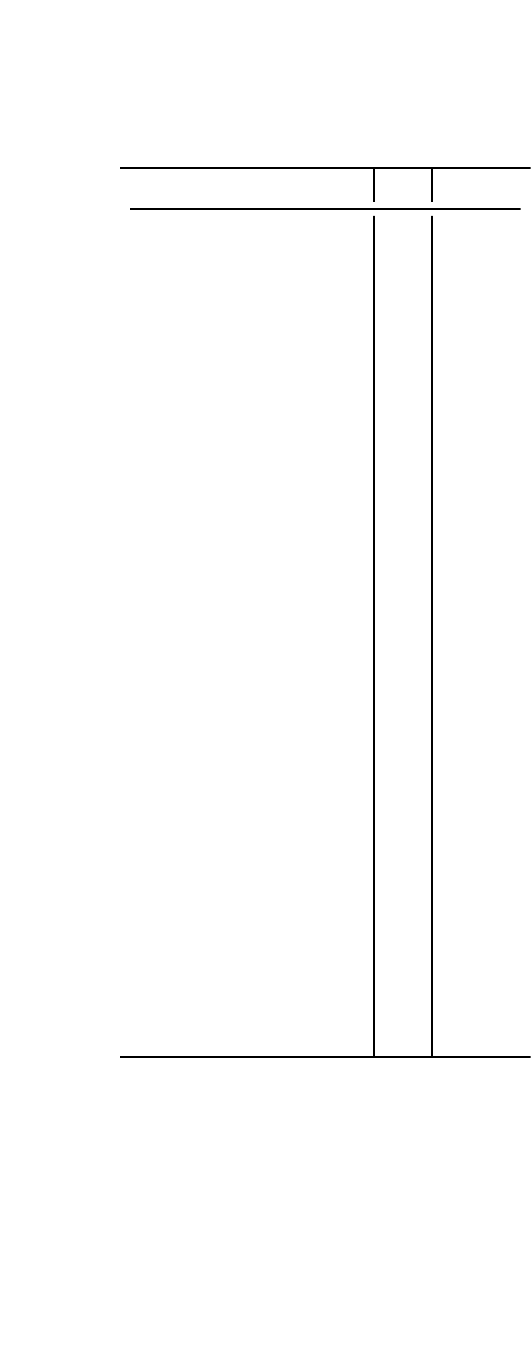

Table 2 summarizes policy component scores, identifying the state with the lowest and

highest for each. The abstract form version used to score school-based TDV polices is

available in Supplemental Material Appendix C). States’ more recent policies generally had

the highest component score, except for revisions in Maryland and New Jersey. Maryland’s

updated policy lowered the total score from 5 in 2010 to 3 in 2012, reflecting a reduction of

the policy’s Section 5 score from 4 to 2 after that allowing students’ parents to opt them out

of the TDV-related curriculum. New Jersey’s score change over time was the most dramatic,

increasing from 6.0 in 2003 to 20.92 in 2011. New Jersey’s updated policy lowered the total

score from 20.92 in 2011 to 19.85 in 2014, after Section 4 score decreased from 5 to 4 after

removal of the term ‘comprehensive’ (see Supplemental Material Appendix B for full detail

on within-state policy score changes).

All states received the same component score for the types of schools covered, with no

states covering non-public schools (although states do have jurisdiction over educational

content required in all types of schools). Section 2 components most prevalent across

policies included inclusion of: a purpose and prohibition statements, a definition consistent

with the CDC definition of TDV, and specification of policy scope. Fewer policies included

electronic communication (text messaging, social media messaging and posts) components

within their TDV definitions, offered TDV definitions that enumerated groups, or discussed

harms associated with TDV. New Jersey ranked highest in the definition section, (score of

6 of 14). Delaware ranked highest in the district policy section (5 of 6) for having required

districts to adopt policies by a specified date and for having provisions for reviewing district

policies and reports of TDV incidents to the DOE. Some states called for districts to

Rochford et al.

Page 5

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

adopt policies but failed to specify a date or need for policy review and incident reporting

provisions in them. District policy scores in Section 4 were highest for Ohio (11 of 20), then

Delaware (9 of 20). Most leading states had fewer than half of district policy elements of an

ideal policy.

With respect to dating violence education for students, Arkansas led with a score of 9.85 of

14. All states with TDV policies at least encouraged dating violence prevention education

for students, but most did not include the remaining policy components of Section 5.

Maryland, with a score of 2, ranked lowest here. Policies of many states included no dating

violence prevention education for school staff-related (13 of all 30 states with a school-based

TDV policy scored 0 in this section). Alaska, Connecticut, and Louisiana scored highest; 8

of 10, due to including 4 of the 5 major provisions. The final section contained only one

element – availability to victims of school-based alternatives to protective orders or school

transfer options, or both. Except for Pennsylvania and Texas, state TDV policies included

neither of these.

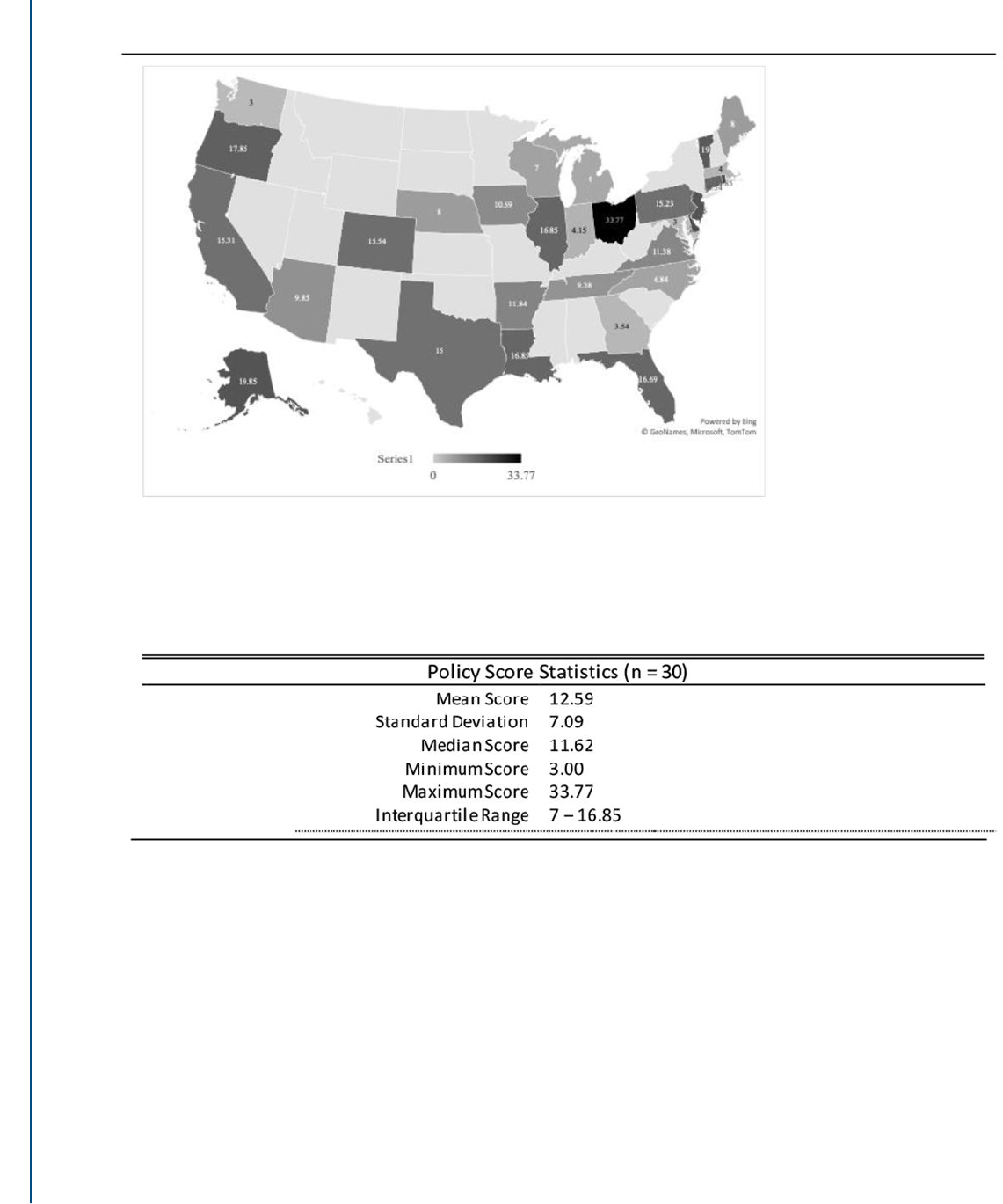

Figure 1 displays a map of scores for 2019 together with the summary statistics for TDV

school policies active as of 2019.

Discussion

This policy content analysis revealed considerable variation in presence and composition

of school-based TDV policies from state-to-state. It also revealed universal opportunity

for policy improvement: even the states with the most comprehensive policies scored

about halfway toward an ideal policy with all components (33.77 / 68.0). Important

opportunities for improvement include: explicitly expanding the scope of school-based

TDV policies to encompass both public and private schools; incorporating broader TDV

training; establishing provisions for in-school protective orders; supporting victims with

protective orders and transfer options; and, eliminating parental ability to opt their student

out of healthy relationship programming. While scores generally improved as states revised

policies over time, no strong relationship appeared between the year of enactment and a

policy score across states.

Acting on these opportunities could advance the health and safety for those at risk because

TDV victims face challenges finding resources to support them outside of school. Judicial

authorities and police hold misconceptions about potential severity of TDV, assuming

damage to be mild and short term [13]. Their views compound barriers TDV survivors

encounter if they seek legal protections available to adult survivors. Thus, state policies

that call for schools to prepare and address TDV are critical to effective prevention and

intervention.

Beyond K-12 educational settings (one dimension of the socioecological model’s societal

and community layer) research has identified other factors that indicate probability of

violence within teen dating partnerships: prosocial beliefs (the view that positive, healthy

interactions will be helpful to an individual, and negative, unhealthy interactions will

be detrimental to an individual), emotional competencies, alcohol consumption patterns,

Rochford et al.

Page 6

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

exposure to violent family conflict, parental monitoring and parental discipline practices,

social connectedness in one’s school, and exposure to violent neighborhood settings [22–

24]. Other policies may offer levers to mitigate risk factors / support protective factors for

TDV that are active in societal, community, and relational contexts.

Limitations and next steps

Although we conducted a comprehensive search of state TDV laws that impact schools,

the search process may not have captured every school-based policy relevant to TDV.

We did not examine policies that impact other types of school violence or sexual health

programming, except for that of states which placed their teen dating violence provisions

within sexual health policies. Future research should elucidate additional risk and protective

factors for TDV and model the impact of specific K-12 TDV programming provisions on

TDV outcomes; examine what promotes the uptake of robust K-12 TDV programming and

identify and evaluate strategies beyond school-based interventions for preventing TDV and

mitigating its consequences.

Examining sexual health and wellness education policies at the state and district level may

also shed insight on opportunities for preventing harm in teen dating relationships. Even

so, our detailed data can assist other researchers to explain what factors may be driving the

policy variation and how variation shapes TDV outcomes.

Conclusion

TDV is a preventable harm that compromises population health across societies. The policy

variation measured in this work revealed that all U.S. states have the opportunity to revise

their policies to be more comprehensive. This work also creates a foundation for quasi-

experimental studies to identify which policy components are most protective against TDV

in the U.S.. It similarly offers a foundation for policies of other nations to be abstracted and

analyzed against TDV outcomes of other societies. Related findings can and should inform

policy decisions aiming to reduce TDV within US and international contexts.

Supplementary Material

Refer to Web version on PubMed Central for supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Maria Doering Critchlow, Paden Hanson, and Erick Orantes for performing the keyword searches

that identified the policies included in this work’s content analysis.

Funding Sources

This work was funded through the CDC/NCIPC-funded University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center

(CDC/NCIPC R49CE002108).

About the authors:

Hannah I. Rochford, MPH is a PhD student at the Injury Prevention Research Center, 2190

Westlawn, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Rochford et al.

Page 7

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Corinne Peek-Asa, PhD is the Director at the Injury Prevention Research Center, 2190

Westlawn, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

Anne Abbott, MPP is a PhD Student and Program Director at the National Resource Center

for Family-Centered Practice, University of Iowa, Coralville, Iowa, USA.

Ann Estin, JD, is professor of family law at the College of Law, University of Iowa, Iowa

City, Iowa, USA.

Karisa Harland, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Emergency Medicine,

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen Dating Violence Fact Sheet. 2014. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/tdv-factsheet.pdf Accessed January 6, 2016.

2. Carlson CN. Invisible victims: Holding the educational system liable for teen dating violence at

school. Harv. Women’s LJ. 2003;26:351.

3. Silverman JG, Raj A, Mucci LA, Hathaway JE. Dating violence against adolescent girls and

associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality.

jama. 2001 Aug 1;286(5):572–9. [PubMed: 11476659]

4. Levy B, Giggans PO. What parents need to know about dating violence. Seal Press; 1995.

5. Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating

violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2013 Jan 1;131(1):71–8. [PubMed:

23230075]

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth online: High school YRBS - United States 2019

Results | DASH | CDC. Retrieved from https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Results.aspx?

OUT=&SID=HS&QID=&LID=XX&YID=&LID2=&COL=&ROW1=&ROW2=&FR=&FG=&FS

L=&FGL=&PV=&TST=&C1=&C2=&QP=&SYID= . Accessed June 6, 2022

7. Zaza S, Kann L, Barrios LC. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents: Population estimate and

prevalence of health behaviors. Jama. 2016 Dec 13;316(22):2355–6. [PubMed: 27532437]

8. De La Rue L, Polanin JR, Espelage DL, Pigott TD. A meta-analysis of school-based interventions

aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research.

2017 Feb;87(1):7–34.

9. Break the Cycle. 2010 State Law Report Cards: A National Survey of Teen Dating Violence Laws.

Los Angeles, CA 2010.

10. Khubchandani J, Price JH, Thompson A, Dake JA, Wiblishauser M, Telljohann SK. Adolescent

dating violence: A national assessment of school counselors’ perceptions and practices. Pediatrics.

2012 Aug 1;130(2):202–10. [PubMed: 22778298]

11. Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence: a global public health problem. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva.

2006;11:1163–78.

12. Guillot-Wright S, Lu Y, Torres ED, Macdonald A, Temple JR. Teen Dating Violence Policy: An

Analysis of Teen Dating Violence Prevention Policy and Programming.

13. Jackson RD, Bouffard LA, Fox KA. Putting policy into practice: Examining school districts’

implementation of teen dating violence legislation. Criminal Justice Policy Review. 2014

Jul;25(4):503–24.

14. Hoefer R, Black B, Ricard M. The impact of state policy on teen dating violence prevalence.

Journal of Adolescence. 2015 Oct 1;44:88–96. [PubMed: 26255246]

15. Cascardi M, King CM, Rector D, DelPozzo J. School-based bullying and teen dating

violence prevention laws: overlapping or distinct?. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2018

Nov;33(21):3267–97. [PubMed: 30253722]

Rochford et al.

Page 8

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

16. Harland KK, Vakkalanka JP, Peek-Asa C, Saftlas AF. State-level teen dating violence education

laws and teen dating violence victimisation in the USA: a cross-sectional analysis of 36 states.

Injury prevention. 2021 Jun 1;27(3):257–63.

17. Stuart-Cassel V, Bell A, Springer JF. Analysis of State Bullying Laws and Policies. Office of

Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, US Department of Education. 2011 Dec.

18. National Conference of State Legislatures. Teen Dating Violence. 2015. Retrieved from http://

www.ncsl.org/research/health/teen-dating-violence.aspx. Accessed December 5, 2015.

19. Schaeffer S, Lee D, Gallopin C, Rosewater A, Vollandt L, Rosenbluth B, Ball B, Miller

K, Alex C. School and District Policies to Increase Student Safety and Improve School

Climate: Promoting Health Relationships and Preventing Teen Dating Violence. Futures Without

Violence. 2012. Retrieved from https://startstrong.futureswithoutviolence.org/wp-content/uploads/

school-and-districtpolicies-and-appendix.pdf Accessed January 6, 2016.

20. Hall MA. Coding case law for public health law evaluation: A methods monograph for the Public

Health Law Research Program (PHLR) Temple University Beasley School of Law. Public Health

Law Research, November. 2011 Nov 26.

21. Kang N, Kara A, Laskey HA, Seaton FB. A SAS MACRO for calculating intercoder agreement in

content analysis. Journal of Advertising. 1993 Jun 1;22(2):17–28.

22. Foshee V, Reyes L, Tharp A, Chang L, Ennett S, Simon T, Latzman N, Suchindran C. Shared

longitudinal predictors of physical peer and dating violence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015

Jan 1; 56(1):106–12.

23. Foshee V, McNaughton Reyes H, Chen M, Ennett S, Basile K, DeGue S, Vivolo-Kantor A,

Moracco K, Bowling J. Shared risk factors for the perpetration of physical dating violence,

bullying, and sexual harassment among adolescents exposed to domestic violence. Journal of

youth and adolescence. 2016 Apr;45(4):672–86. [PubMed: 26746242]

24. Flaspohler P, Elfstrom J, Vanderzee K, Sink H, Birchmeier Z. Stand by me: The effects of peer and

teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools.

2009 Aug;46(7):636–49.

Rochford et al. Page 9

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Key messages:

•

Teen dating violence (TDV) is a prevalent and preventable public health

challenge across societies.

•

Policies enacted by U.S. states to prevent and respond to TDV often make use

of K-12 programming, and vary widely in terms of their presence and written

caliber.

•

All TDV policies active in U.S. states as of 2019 have the opportunity to

improve their comprehensiveness, with the most robust policy (enacted in

Ohio in 2018) scoring only 33.77 out of a possible 68.

Rochford et al. Page 10

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Figure 1.

2019 TDV Policy Score Heat Map by State

Rochford et al. Page 11

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Rochford et al. Page 12

Table 1.

States with currently active TDV school policies and their scores at a scored year

30 States With TDV School Policies

*

Score Scored Year

Maryland 3.00 2017

Washington 3.00 2005

Georgia 3.54 2015

Massachusetts 4.00 2010

Indiana 4.15 2010

Michigan 6.00 2004

North Carolina 6.84 2009

Wisconsin 7.00 2012

Nebraska 8.00 2009

Maine 8.00 2002

Tennessee 9.38 2018

Arizona 9.85 2010

Iowa 10.69 2007

Virginia 11.38 2018

Arkansas 11.84 2015

Texas 15.00 2015

Pennsylvania 15.23 2011

California 15.31 2018

Colorado 15.54 2016

Connecticut 16.54 2018

Florida 16.69 2014

Louisiana 16.85 2014

Illinois 16.85 2013

Oregon 17.85 2016

Vermont 19.00 2011

New Jersey 19.85 2014

Alaska 19.85 2017

Rhode Island 21.85 2011

Delaware 22.00 2017

Ohio 33.77 2018

*

Note: The 21 States without TDV school policies as of 2019 are Alabama, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri,

Montana, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia,

Wyoming.

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

Rochford et al. Page 13

Table 2.

TDV School Policy Score Elements for States with a Policy

Policy Abstraction Form Elements

Range of

Possible

Scores

Mean

(Standard

Deviation)

State(s) with the

Highest Scoring

Policy

State(s) with the Lowest Scoring

Policy

Section 1

-- Types of schools Covered

(1 2-point item)

0-2 0.93 (0.25)

All other states

scored 1.

VA & WA (0)

Section 2

– Definitions

(6 2-point items)

0-14 1.43 (1.74) NJ (6)

AR, GA, IN, IA, ME, MD, MA, MI,

NE, NC, TN, VT, VA, WA (0)

Section 3

– District Policy

(3 2-point items)

0-6 0.6 (1.19) DE (5)

AZ, AR, CA, CO, GA, IN, IA, LA,

ME, ME, MA, MI, NE, NC, PA,

TN, VT, VA, WA, WI (0)

Section 4

– District Policy Components

(10 2-point items)

0-20 1.7 (2.64) OH (11)

CT, GA, IA, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI,

NE, NC, VT, VA, WA, WI (1)

Section 5

– Dating Violence Prevention

Education for Students

(7 2-point items; items 5c and 5d required

standardization to fit a 2-point scale)

0-14 6.23 (2.24) AR (9.85) MD (2)

Section 6

– Dating Violence Prevention

Education for School Staff

(5 2-point items)

0-10 2.23 (2.78) AK, CT, LA (8)

AZ, AR, GA, IN, IA, MD, MA, MI,

NE, NJ, NC, WA, WI (0)

Section 7

– Protections and Legal Rights

(1 2-point item)

0-2 0.06 (0.25) PA, TX (1) All other states scored 0.

Total Scores 0-68 12.59 (7.09) OH (33.77) MD, WA (3)

J Public Health Policy

. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2023 February 07.