Northern Illinois University Northern Illinois University

Huskie Commons Huskie Commons

Honors Capstones Undergraduate Research & Artistry

Spring 5-8-2022

Code-Switching: Patterns and Motivations for Thai American Code-Switching: Patterns and Motivations for Thai American

Bilingual Speakers Bilingual Speakers

Holly Young

Northern Illinois University

Follow this and additional works at: https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/studentengagement-

honorscapstones

Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Young, Holly, "Code-Switching: Patterns and Motivations for Thai American Bilingual Speakers" (2022).

Honors Capstones

. 1425.

https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/studentengagement-honorscapstones/1425

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research & Artistry at Huskie

Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Capstones by an authorized administrator of Huskie

Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected].

NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY

Code-Switching: Patterns & Motivations for

Thai American Bilingual Speakers

A Capstone Submitted to the

University Honors Program

In Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements of the Baccalaureate Degree

With Honors

Department of Anthropology

By

Holly Young

DeKalb, Illinois

May 14, 2022

University Honors Program

Capstone Faculty Approval Page

Capstone Title: “Code-Switching: Patterns & Motivations for Thai American Bilingual

Speakers”

Student Name: Holly Young

Faculty Supervisor: Kanjana Thepboriruk

Faculty Approval Signature:

Department of World Languages & Cultures

Date of Approval: 05/08/2022

Date and Venue of Presentation:

• 04/08/2022 – Society for Linguistic Anthropology (SLA) Annual Meeting

• 04/09/2022 – Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) Student Conference

• 05/19/2022 – Southeast Asian Linguistics Society (SEALS) Annual Meeting

Check if any of the following apply, and please tell us where and how it was published:

󠆷 Capstone has been published (Journal/Outlet):

________________________________________________________________

󠆷 Capstone has been submitted for publication (Journal/Outlet):

________________________________________________________________

Completed Honors Capstone projects may be used for student reference purposes, both

electronically and in the Honors Capstone Library (CLB 110).

If you would like to opt out and not have this student’s completed capstone used for reference

purposes, please initial here: _______ (Faculty Supervisor)

Young 1

Abstract

This study examines the structural patterns and social motivations behind Code-Switching (CS)

as it is used by English-dominant, bilingual Thai Americans. CS is defined here as an umbrella

term that encompasses both intersentential and intrasentential language mixing. For the purpose

of this study, bilingual speakers are considered those who use Thai and English in some aspect of

their everyday lives, whether talking with friends, family, etc.; native-like fluency in both

languages is not necessary. A total of fourteen participants were selected throughout the US

using a preliminary biodata survey. Participants were paired based on their language use, age,

and place of residence. Each pair then met via Zoom for approximately 1-2 hours to engage in

peer-to-peer conversation. The conversations involved two sessions: 1) brief introductions, 2)

informal interviews. For the second session, participants were individually sent one question at a

time via the chatbox and were asked to “interview” their conversational partner and also answer

the question themselves. The questions centered on participants’ own experiences growing up

and living as Thai Americans, as well as their opinions on Thai and American culture, in order to

elicit potential connections between their styles and motivations for CS and their Thai American

identities. Following data collection, methods of analysis consisted of transcribing the

conversation recordings and identifying salient structural patterns of CS. This paper focuses on

only one pair of participants, Mac and Pearl, as they were found to use the most Thai during their

conversation.

Keywords: Code-Switching, Bilingualism, Thai American, Identity

Young 2

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to examine the structural patterns and social motivations

behind Code-Switching as it is used by English-dominant, bilingual Thai Americans. Drawing

closely on the work of Heller (1988), Myers-Scotton (1993), and Grosjean (2001, 145), Code-

Switching (hereafter, CS) is defined here as a type of language contact phenomena that involves

the alternate use of two or more languages in an utterance or conversation. This study uses a broad

definition of CS that includes both intersentential and intrasentential (i.e., Code-Mixing) language

mixing. Though CS can occur between different registers, dialects, languages, and so on, the

definition of CS used in this study focuses specifically on bilingual CS between Thai and English.

Data from the 2019 American Community Survey estimates that there are currently

342,917 people living in the United States who identify as either Thai alone (i.e., single race;

73.3%) or Thai in combination with other race(s) (26.7%). 24% of the Thai population living in

the US are US-born, and 76% are foreign born (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). Of the 318,176 Thai

people who are at least five years old, 42% speak English only at home, and the remaining 58%

speaking a language other than English (presumably Thai) at home. The highest concentration of

Thai people in the US is in Los Angeles, CA with an estimate of 33,000 Thai people (counting

people who identify as a single race only). Other cities with high Thai populations are New York

City, NY (11,000), Washington, D.C. (10,000), Chicago, IL (8,000), and Dallas, TX (7,000)

(Budiman, 2021).

The current scope of research on Thai-English CS is very limited. Previous studies have

focused on CS by Thai-dominant speakers in written language in social media (Jitpaisarnwattana,

2014; Chalaemwareel and Rodrigo, 2020) and educational settings (Bennui, 2008; Boonsuk and

Ambele, 2019) and scripted spoken language in Thai music (Likhitphongsathorn and Sappapan,

2013; Chairat, 2014) and television shows (Kannaovakun and Gunther, 2003; Papijit, 2013).

Existing studies on Thai-English CS in spoken language all focus on scripted language, rather than

spontaneous natural language. This study aims to fill the current gap in Thai-English CS research

by investigating spontaneous natural language used by English-dominant bilingual speakers.

The definition of bilingualism used in this study follows Grosjean’s (2010) definition,

which emphasizes language use over fluency. Bilingual speakers are defined here as people who

speak at least two languages and use each language in at least one domain of their everyday lives.

For instance, a bilingual speaker could be someone who uses Thai at home with family members

and English everywhere else. The definition of bilingualism used here emphasizes listening and

speaking and does not require proficiency in reading and writing both of a speaker’s languages.

The following pages are structured as follows. First, the background and methodology for

this study are described in detail. Focusing on just one pair of participants, the results section

presents overall trends and particular examples for analysis. Analysis draws largely on three main

concepts: 1) Wei and Milroy’s (1995) categorization of three Levels of CS, 2) Gumperz’s (1982,

cited in Woolard 2006) we- vs. they-code dichotomy, and 3) Myers-Scotton’s (1993) Matrix

Language Hypothesis. In the examples provided below, the transliteration of all Thai words is

provided in italics and followed by the English translation in SMALL CAPS in parentheses. The

original Thai text is included in the footnotes below. Thai words are transcribed using the Royal

Thai General System of Transcription (Thai Royal Institute, 1999). All translations were

completed by me with the aid of my faculty mentor Dr. Kanjana Thepboriruk.

Young 3

Background

Thai is a Tai-Kra-Dai language in mainland Southeast Asia and Southern China (Gutman

and Avanzati 2013; Diller, Edmondson, and Luo 2008). Thai is the official language of the

Kingdom of Thailand and is the first language of more than 38.8 million people around the world

(Diller and Reynolds 2002; “Thai - Worldwide Distribution”). Both Thai and English use Subject,

Verb, Object (SVO) word order. However, unlike English, Thai noun phrases are head-initial,

meaning that adjectives are placed after the head nouns. Furthermore, Thai adjectives can be used

as the predicate in a sentence. When this occurs, the adjectives are considered intransitive verbs

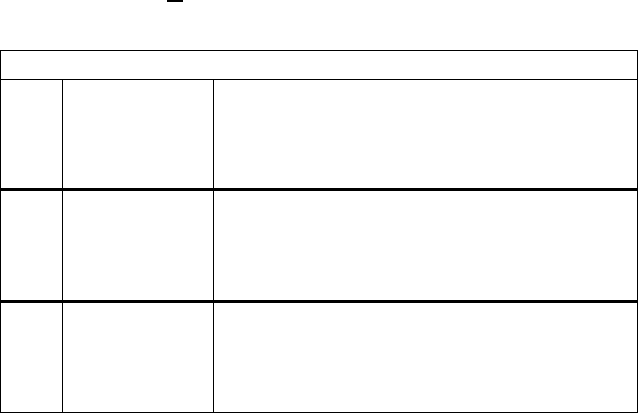

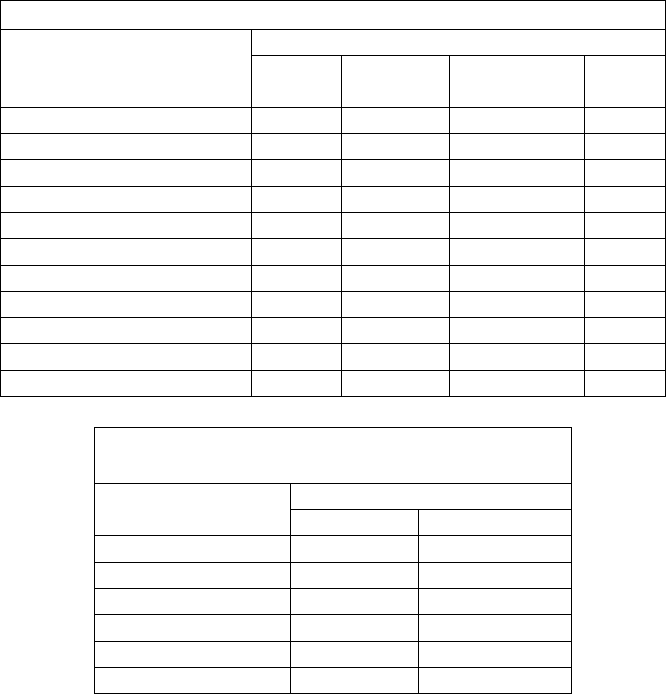

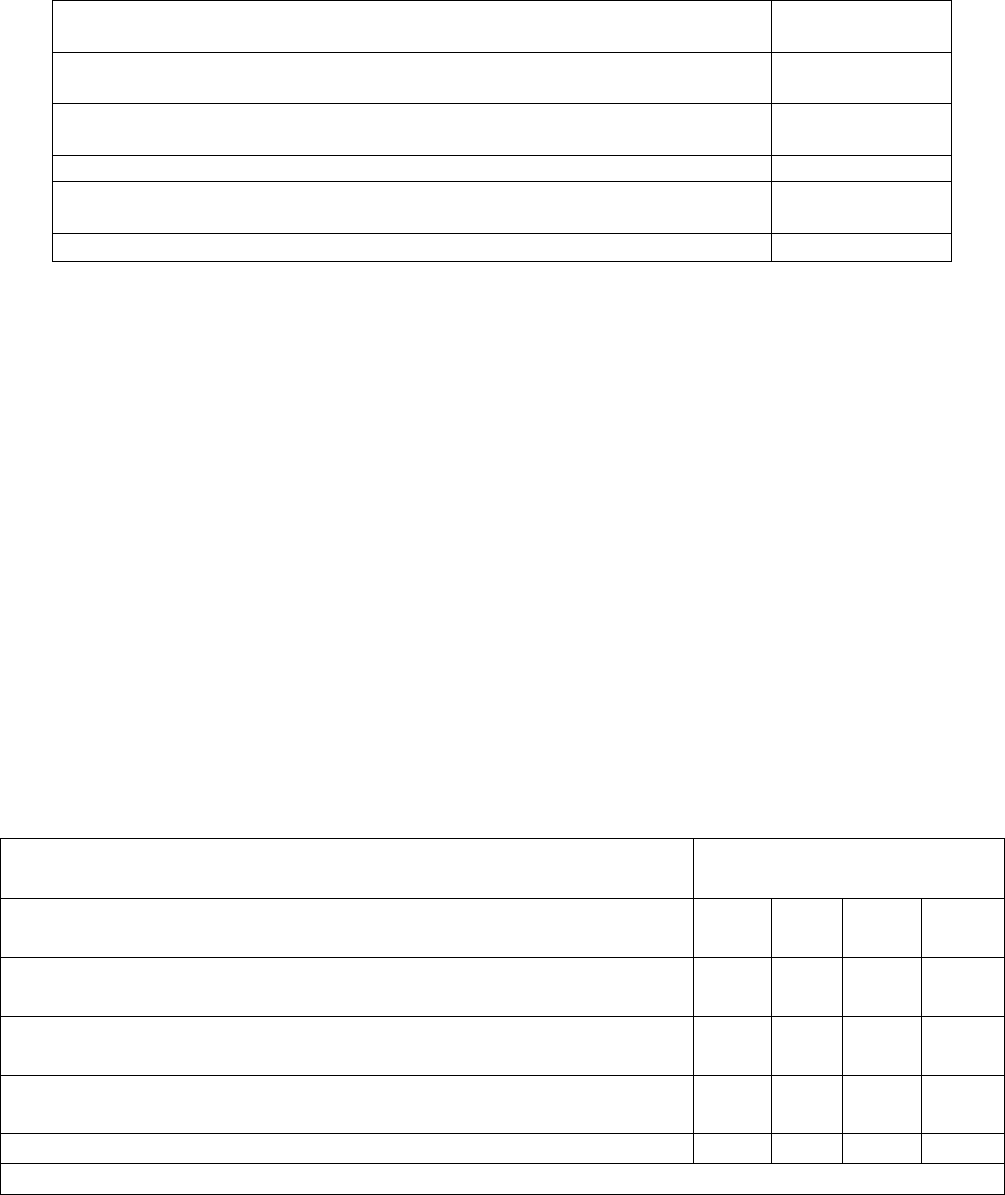

and do not require a copula (Iwasaki and Ingkaphirom 2009, 91). Table 1 below shows two

examples of Thai adjectives used as intransitive verbs. Note how neither of these examples

includes a separate copula, as it is already included in the adjectives “lazy” and “spicy”. Notice

also how these examples contrast with English adjectives, which must be accompanied by a form

of the copula “to be” (e.g., “She is smart.”). The third example in Table 1 shows an incorrect use

of a Thai copula.

Table 1. Thai Adjectives as Intransitive Verbs

1

Thai

Transliteration

khon

amerikan

khikiat

Gloss

person

American

lazy

Translation

“American people are lazy”

2

Thai

Transliteration

ahan

thai

phet

Gloss

food

Thai

spicy

Translation

“Thai food is spicy.”

3

Thai

*

Transliteration

ahan

thai

pen

phet

Gloss

food

Thai

is

spicy

Translation

“Thai food is spicy.”

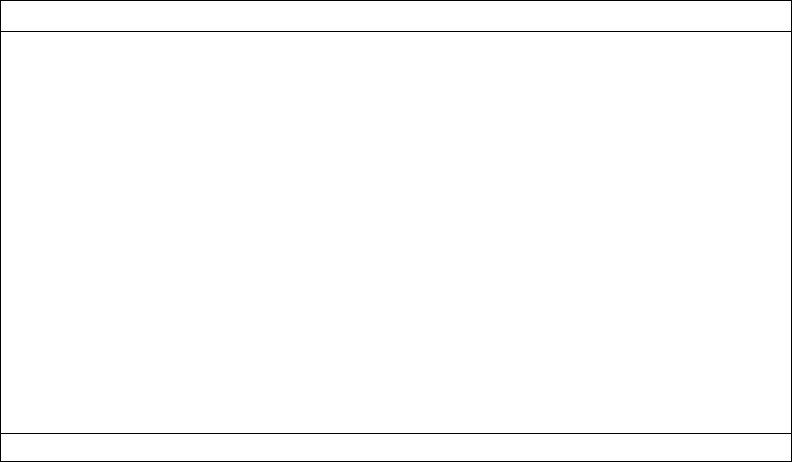

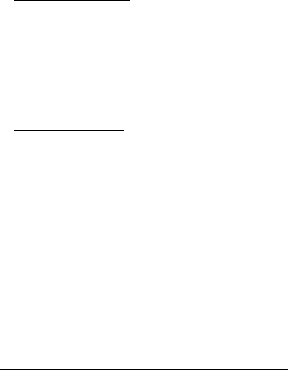

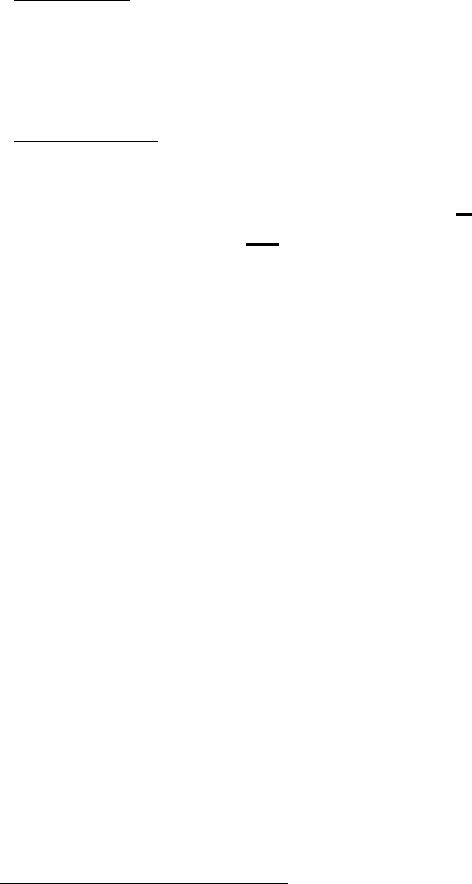

CS is a communicative strategy for conveying linguistic and social information and

achieving interactional goals. Commonly cited reasons for CS are listed below in Table 2. A

speaker may switch to another language to fill a linguistic need, convey a particular meaning

associated with a language or its vocabulary, or discuss a particular topic in the language they are

more proficient in or in which it is more appropriate to discuss that topic. CS may also be used to

amplify or emphasize a speaker’s message, convey strong emotion such as anger, or maintain

continuity between speakers’ turns by continuing the last language used. Additionally, when

quoting another person, a speaker may switch to the language the original speaker used.

CS may also be used to achieve interactional goals, including specifying the addressee(s)

or excluding someone from the conversation. In some instances, switching to another language

may signal a speaker’s personal involvement or detachment from the topic of discussion. At other

times, CS is used when giving commands or trying to end an argument, with the use of a particular

language amplifying or emphasizing a speaker’s statement (Grosjean 1982, 154). Further

interactional goals for CS include raising a speaker’s status, showing expertise or authority, and

asserting or negotiating a particular identity. For example, in language communities where English

Young 4

is not the dominant language, speakers may switch to English in order raise their own status or

assert a modern identity (Lee 2006).

Table 2. Common Reasons for Code-Switching

• Fill a linguistic need (e.g., a lexical item)

• Convey a particular connotation or meaning

• Discuss a particular topic

• Specify speaker involvement or express detachment from topic

• Amplify or emphasize message (to give commands or end an argument)

• Convey strong emotion (e.g., anger, excitement)

• Continue the last language used (continuity)

• Quote someone

• Specify addressee

• Exclude someone from conversation

• Change role of speaker: raise status, show expertise or authority

• Negotiate identity (e.g., present a modern identity)

• Mark and emphasize group identity, signal solidarity

• Establish contrast and signal upcoming change (contextualization cues)

Adapted from Grosjean (1982, 152); Hoffman (1991, 115-116); Gumperz (1976, 1982)

CS may also be used to emphasize group identity and signal solidarity. This is closely

related to Gumperz’s (1982, cited in Woolard 2006) we- vs. they-code dichotomy. In situations of

bilingual CS by ethnic minority groups, Gumperz states that one language is the “we-code” and

the other is the “they-code”. The we-code (or in-group code) is the language that is associated with

solidarity and familiarity. According to Gumperz, this is typically the minority language. The

majority language, on the other hand, is typically the they-code (or out-group code), which is

associated with more formality and less intimate, personal relations (Gumperz 1982; in Woolard

2006, 76-78). Woolard notes that linguists should avoid making “a priori assumptions about which

code is the we-code, as it can change across generations, lifespans, and contexts” (Woolard 2006,

78). Indeed, one would expect that Thai—the minority language in the context of the United

States—would be the we-code for the participants of this study and that Thai would therefore be

used to emphasize group identity and build solidarity between participants. However, as the results

later reveal, there are instances in which speakers use Thai as the they-code and English as the we-

code.

Another important concept proposed by Gumperz (1976, cited in Auer and Di Luzio 1992)

is that of contextualization cues. Contextualization cues are signaling mechanisms used by

speakers to establish a context in which the meaning of their utterance(s) can be interpreted (Auer

and Di Luzio 1992, 25). Contextualization cues may be nonverbal (e.g., posture, gaze) or verbal.

Linguistic variation, including CS, is one major type of verbal contextualization cue. Many

contextualization cues are used to establish contrast and signal an upcoming change, such as a

change in speaker role. Code-Switching is a meaningful contextualization cue because of both the

contrast established through switching languages and the concomitant indexing of the attitudes

and values associated with the language being switched to (Auer and Di Luzio 1992, 32-33).

Young 5

Myer’s Scotton’s (1993) Matrix Language Hypothesis describes the structural constraints

that are imposed by one language onto another in instances of bilingual CS. The hypothesis posits

the existence of a Matrix language and an Embedded language during instances of CS. The Matrix

language is the language that provides more morphemes (i.e., that is used more), and it is typically,

though not always, a speaker’s first language. The Embedded language, then, provides fewer

morphemes (i.e., is used less) and is usually not a speaker’s first language. Myers-Scotton states

that the Matrix language (hereafter, ML) “projects the morphosyntactic frame for the utterance in

question” (1993, 486). In other words, the structure of the ML conditions the way the Embedded

language (hereafter, EL) is inserted into the ML. As the participants in this study were all English-

dominant bilingual speakers, one would expect English to be the ML and Thai to be the EL during

participants’ conversations. Moreover, one would expect all instances of Thai-English CS by these

English-dominant speakers to follow Myers-Scotton’s (1993) Matrix Language Hypothesis, with

Thai insertions being conditioned by the English language’s structure.

Methodology

Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited via social media (Facebook, Instagram, and Discord) and were

not informed about the study’s focus on CS. Instead, they were told that the study was designed to

learn about their experiences as Thai Americans and their opinions on Thai and American culture

(Appendix A). The original age group intended for the study was 18-30 years old but was too

limiting, so it was extended to anyone over 18 years old. Participants were asked to complete a

brief biodata survey via Qualtrics (Qualtrics 2005) (Appendix B) to obtain basic demographic

information (e.g., age, place of birth, place of residence) and information about their linguistic

background. For linguistic background, participants listed which language(s) they regularly used

in a number of domains (e.g., at work, stores, home) and quantified the number of hours of media

consumed across various modes (i.e., reading, watching, and listening) in Thai and English per

week. They also quantified how many hours they spent speaking and writing Thai and English per

week.

In total, fifteen people responded to the survey. One respondent did not report using any

Thai at all and was not included in the sample group. The fourteen remaining respondents were

grouped into seven pairs based on their language use, age, and place of residence. Language use

was considered the most important factor when pairing participants together. Participants who had

similar language use were paired together so that they would feel comfortable speaking Thai and

English as they normally do (i.e., to the same extent). Second, participants’ ages were considered

when determining pairs. Age-based social hierarchy is very salient in Thai language and culture

(Iwasaki and Horie 2000), so participants with similar ages were paired together in order to

stimulate peer-to-peer conversation and make participants feel more comfortable during the

conversation. The seven pairs had an average age gap of 5.7 years. Finally, participants’ places of

residence were considered during the pairing process. Efforts were made to pair participants living

in the same time zones together for their scheduling convenience. Ultimately, language use and

age remained the two most significant factors for determining pairs, and these factors were used

to optimize instances of CS during data collection.

Young 6

Participants

The fourteen participants had an average age of 29 years old. The youngest participant was

21 years old, and the oldest was 48 years old. The seven pairs had an average age gap of 5.7 years,

with the smallest gap being one year and the largest gap being eleven years.

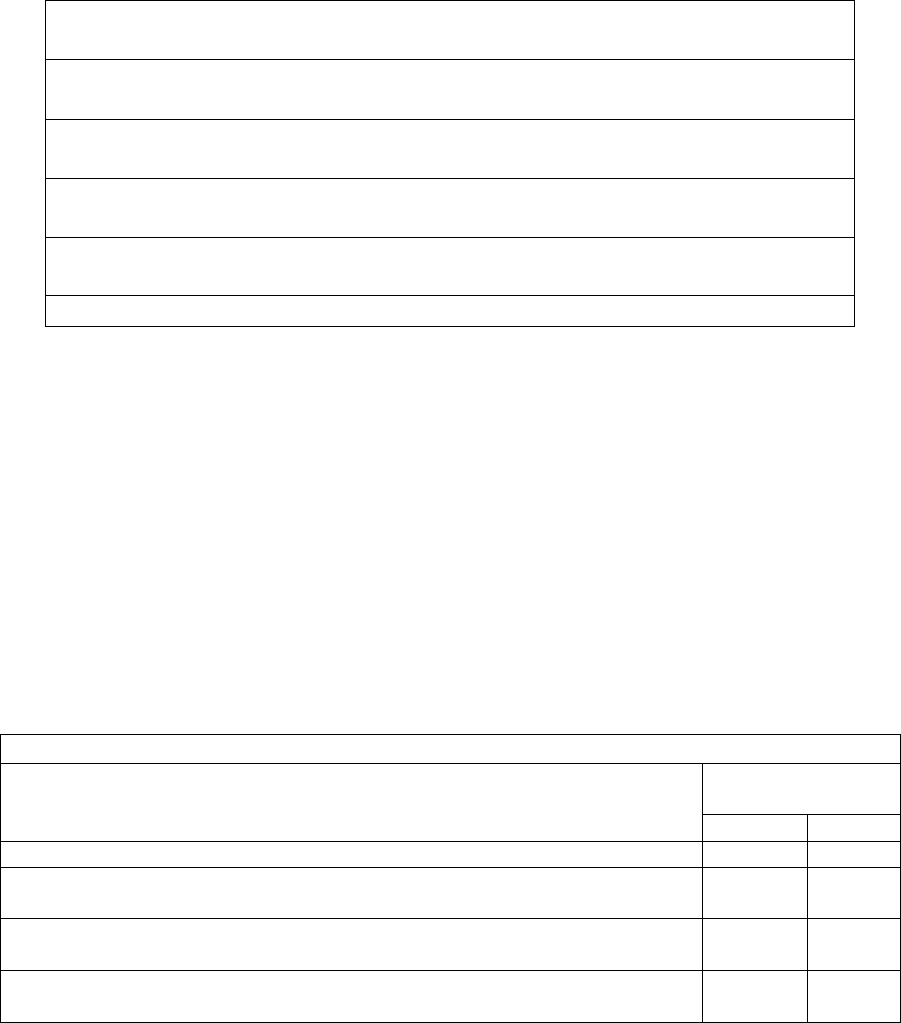

In the biodata survey (Appendix B), participants were asked which language(s) they used

in a variety of domains, in addition to their first language and the language they felt most

comfortable using. Choices included Thai, English, Other, and Not Applicable (NA), and

participants could choose more than one language for each domain. None of the participants chose

only Other for any of the domains. Other was always chosen in combination with English or both

Thai and English. Thus, for the purpose of this paper, responses of English and Other are combined

with responses of only English in Table 3 below. Responses of Thai, English, and Other are

combined with responses of both Thai and English. Table 3 presents the number of participants

who chose only Thai, only English, both Thai and English, and NA during the survey questions

about their linguistic background. Table 4 presents the average amount of time (in hours)

participants reported spending watching, reading, writing, listening to, and speaking Thai and

English per week.

Table 3. Participants’ Language(s) and Domains of Use

Number of Participants who Responded…

Only

Thai

Only

English

Both Thai

and English

NA

First language

7

4

3

0

Most comfortable using

0

7

7

0

At work

0

12

2

0

In the community

0

7

7

0

At stores

0

12

2

0

With friends

0

10

4

0

With sibling(s)

2

6

4

2

With parent(s)

7

0

7

0

At home

2

4

8

0

With children

0

1

1

12

With spouse/partner

0

9

2

3

Table 4. Average Amount of Time Spent

Using Thai and English per Week

Activity

Time (in Hours)

Thai

English

Watching

1.07

11.27

Reading

0.25

15.13

Writing

0.50

8.67

Listening

1.10

10.33

Speaking

6.13

45.47

Total

9.05

90.87

Tables 3 and 4 above show the clear English-dominance of the fourteen participants. When

asked about their first language, half of the participants reported Thai as their first language and

Young 7

the other half reported either only English (4) or both Thai and English (3) as their first languages.

However, when asked about the language(s) they felt most comfortable using, all of the

participants chose English (7) or both Thai and English (7). In all of the domains except speaking

with parent(s), the majority of participants responded that they used only English or both Thai and

English. Table 4 reveals that participants spent, on average, 10 times more hours using English per

week than they did Thai.

This paper focuses on one pair of participants, Mac and Pearl (nicknames chosen by the

participants), as they exhibited the most CS during their conversation. Mac is a 48-year-old 1.5

generation Thai American whose first language is Thai but who is most comfortable using English.

1.5 generation Americans are people who were born abroad, immigrated to the U.S. when they

were between 5 and 18 years old, and grew up in the U.S. (Kim 1999, 29, cited in Suppatkul 2012).

Mac reported spending 5 hours speaking Thai and 25 hours speaking English per week. He

reported that he typically uses Thai in the community, at home, and with his parents; he uses

English at work, in the community, at stores, and with friends. Pearl is 37-year-old second

generation Thai American whose first language is Thai and who is most comfortable using Thai

and English. Pearl reported spending 5 hours speaking Thai and 50 hours speaking English per

week. She reported that she typically uses Thai at home and with her siblings, parents, and

children; she uses English or both Thai and English for everything but talking to her parents. She

talks to her parents in Thai only.

Data Collection

I met with each pair online via Zoom (Yuan 2011) for approximately 1-2 hours to collect

interview data. I started by introducing myself using a bilingual introduction script to prime the

participants and show them that they could feel comfortable using Thai throughout the interview

(Appendix C). The rest of the interview was split into two parts. First, participants were asked to

briefly introduce themselves and to rate their Thai speaking ability on a scale of one to five.

Participants were asked to rate their Thai speaking ability to help stimulate CS during their

conversation, for bilingual speakers usually do not CS unless they are familiar with their

conversational partner’s linguistic background and attitudes (Gumperz 1977, 8). Both Mac and

Pearl rated their Thai speaking ability at 4.5 out of 5.

Second, each participant was sent questions one at a time via the chatbox, alternating

between Thai and American content. There were two sets of nearly identical questions, one asking

about Thai culture and the other asking about American culture. The questions were designed

using the General Ethnicity Questionnaire previously created by Tsai, Ying, and Lee (2000). Pairs

of matching Thai and American questions were asked consecutively. For example, the question

“Do you celebrate any Thai holidays? If so, how and with whom do you celebrate them?” was

followed by “Do you celebrate any American holidays? If so, how and with whom do you celebrate

them?” After these two questions, the next question would be a question about American content,

followed by one about Thai content. The entire interview followed this pattern. The questions were

ordered in this manner so that both participants asked questions about both Thai and American

content, rather than splitting the questions so that one participant asked only Thai-focused

questions and the other asked only American-focused questions. As the interview progressed, the

questions progressed from more surface level content (e.g., holidays, food, travel experience) to

Young 8

deeper content (e.g., what makes someone Thai/American, how participants self-identify)

(Appendix D).

Participants were asked to read aloud the question they were sent in the chatbox (i.e., to

ask their partner the question). This was done in order to transform the interview into an informal,

conversation-like interview between the two participants, rather than a standard interview in which

the researcher asks the participants the questions. All questions were written in English, as the

study focuses only on oral bilinguals and participants were told that the ability to read Thai was

not a prerequisite for participation in the study. Questions that participants already answered before

being asked, either in their self-introduction or in response to a different question, were not

repeated. For example, many participants talked about where they grew up and their experience

(if any) living in Thailand during their self-introduction, so they were not sent the questions about

those topics. Participants were also encouraged to ask follow-up questions and to ask for

clarification on questions when needed.

Data Analysis

In total, 9 hours and 51 minutes of conversation were recorded from the seven pairs. This

paper focuses only on Mac and Pearl’s conversation, which lasted one hour and 52 minutes, or

1.866 hours. The interviews were transcribed using the automatic transcription option on Happy

Scribe (Assens and Bastié 2017). The initial transcripts generated by Happy Scribe were then

manually checked for accuracy, and all instances of Thai were added into the transcript because

Happy Scribe only generates monolingual transcripts. The audio recordings were uploaded to Praat

(Boersma and Weenink 2022), where each instance of Thai was segmented and labelled with the

speaker and topic (i.e., question). Responses to questions about Thai content, such as Thai holidays

and food, were considered “Thai” topics; responses to questions about American holidays, food,

etc. were considered “American” topics. Total quantities of Thai per speaker and topic were

calculated manually. For the purpose of this study, some instances of Thai are not considered CS.

These include the proper names of Thai foods, holidays, or places (e.g., temples, restaurants), as

well as lakhon (Thai dramas), in isolation. Consider the two examples below.

Pearl (35:51)

(Talking about American holidays) The caveat was we celebrated it, but it was always Thai food. So you

had somtam (PAPAYA SALAD) lap (DICED MEAT SALAD) khao niao (STICKY RICE) mu ping (GRILLED

PORK) kai ping(GRILLED CHICKEN)

1

It was never American food. Even Thanksgiving.

Mac (45:04)

(Talking about Thai desserts) The ones you mentioned, lotchong (RICE NOODLES IN COCONUT MILK)

thapthimkrop (WATER CHESTNUTS IN COCONUT MILK) arai phuak nia (AND STUFF LIKE THAT),

2

I really

like those, but I also really like…

In the first example, Pearl lists off a number of Thai foods. The only Thai she uses is the names of

these foods. In contrast, in the second example, Mac lists two Thai foods but then ends in Thai

with arai phuak nia, which translates to AND STUFF LIKE THAT. In the analysis, only the latter phrase

is considered to be CS, and not the food names.

1

2

Young 9

In addition to quantifying the amount of CS per speaker and topic, each instance of CS was

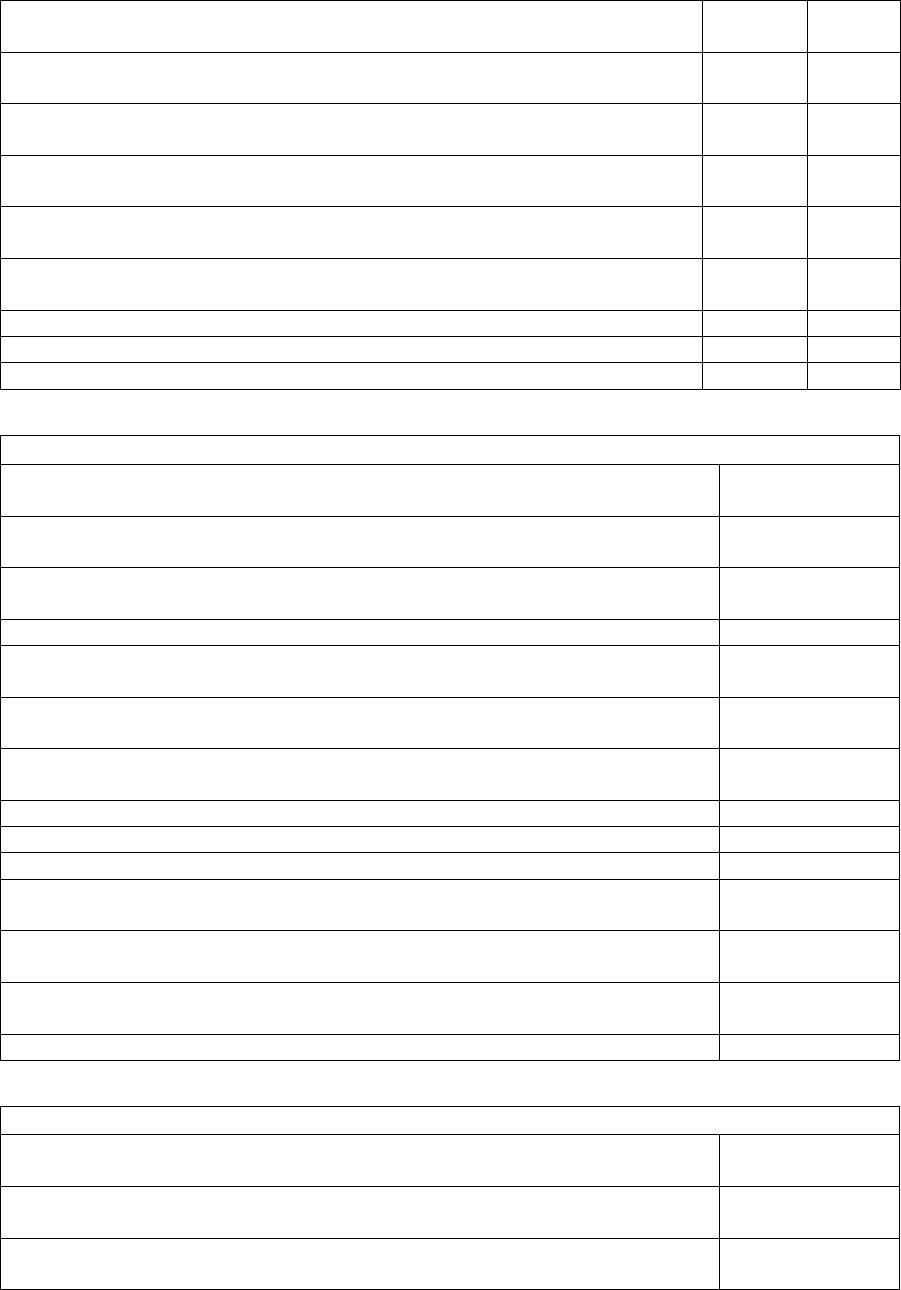

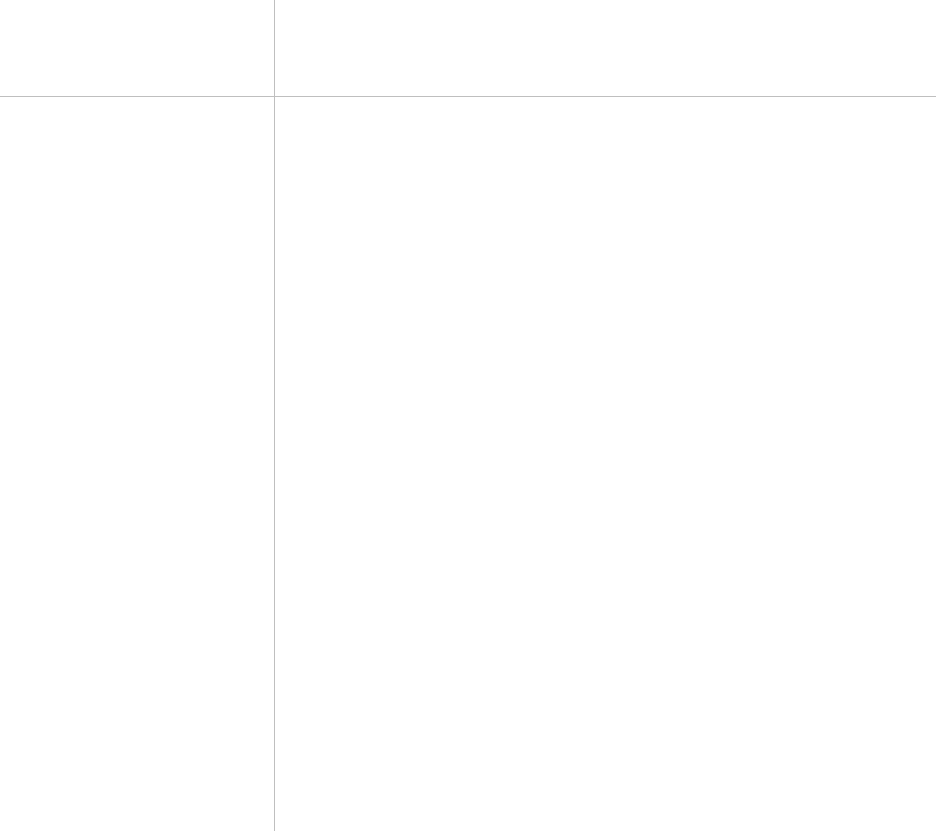

categorized into one of three levels. This study’s analysis draws on that of Wei and Milroy (1995),

which identifies three levels of codeswitching: A, B, and C. Table 5 below shows each of these

levels. Level A involves a switch between different speakers’ turns. Level B involves an

intersentential switch within a single speaker’s turn. And Level C, or Code-Mixing, involves an

intrasententional switch within a single speaker’s turn. After categorizing each instance of CS as

Level A, B, or C, the total number of instances of each level of CS per speaker were calculated.

Table 5. Levels of Code-Switching

Level of CS

SPEAKER 1

Language A

SPEAKER 2

Language A

No CS

SPEAKER 1

Language A

SPEAKER 2

Language B

Level A CS

SPEAKER 1

Sentence 1

Language B

Sentence 2

Language A

Level B CS

Sentence 3

Constituent 1

Language A

Constituent 2

Language B

Level C CS

Adapted from Wei and Milroy (1995)

Results

This analysis focuses on only one pair of participants, Mac and Pearl, as they were found

to use the most Thai during their conversation. Their conversation lasted 111.970 minutes, or 1.866

hours. The total amount of time during which Thai was used throughout the conversation was

399.588 seconds, or 6.66 minutes. Pearl spoke considerably more Thai during the conversation

than Mac did. She spoke Thai for 322.503 seconds, or 5.375 minutes, while Mac spoke Thai for

77.085 seconds, or 1.285 minutes. Thus, Pearl spoke more than four times as much Thai as Mac

did. Table 6 below illustrates the amount (in seconds) of Thai each speaker used throughout the

conversation. Table 6 presents the questions in the order that they were discussed during the

conversation. Only the questions for which at least one of the speakers code-switched are included

in the table. Tables 7.1 and 7.2 present the questions ranked from the highest to lowest amount of

Thai used. Table 7.1 shows the data for Pearl, and Table 7.2 shows the data for Mac.

Table 6. Amount of Thai used per Speaker per Question

Question

Amount of Thai

(in seconds)

Pearl

Mac

1

Self-introduction

11.155

0

2

On a scale of 1 to 5 (5 = native-like), how well do you speak Thai?

Why do you give yourself that rating?

23.995

38.375

3

Have you ever lived in Thailand? If so, what was your experience

like?

50.097

2.704

4

How much (and what kinds of) Thai culture were you exposed to

growing up?

10.987

0

Young 10

5

Do you celebrate any Thai holidays? If so, how and with whom do you

celebrate them?

22.250

2.073

6

Do you celebrate any American holidays? If so, how and with whom

do you celebrate them?

10.701

3.791

7

What do you think of American food and eating culture? Do you have

any favorite American foods?

52.688

6.305

8

What do you think of Thai food and eating culture? Do you have any

favorite Thai foods?

48.123

16.167

9

Are there any aspects of Thailand or Thai culture that you really like

or dislike?

59.383

7.670

10

Are there any aspects of the US or American culture that you really

like or dislike?

6.034

0

11

Do you feel proud and/or patriotic when you think about Thailand?

14.265

0

12

What do you think makes someone Thai?

12.825

0

Total

322.503

77.085

Table 7.1. Questions with the Most CS for Pearl

Question

Amount of Thai

(in seconds)

1

Are there any aspects of Thailand or Thai culture that you really like or

dislike?

59.383

2

What do you think of American food and eating culture? Do you have any

favorite American foods?

52.688

3

Have you ever lived in Thailand? If so, what was your experience like?

50.097

4

What do you think of Thai food and eating culture? Do you have any

favorite Thai foods?

48.123

5

On a scale of 1 to 5 (5 = native-like), how well do you speak Thai? Why

do you give yourself that rating?

23.995

6

Do you celebrate any Thai holidays? If so, how and with whom do you

celebrate them?

22.250

7

Do you feel proud and/or patriotic when you think about Thailand?

14.265

8

What do you think makes someone Thai?

12.825

9

Self-introduction

11.155

10

How much (and what kinds of) Thai culture were you exposed to growing

up?

10.987

11

Do you celebrate any American holidays? If so, how and with whom do

you celebrate them?

10.701

12

Are there any aspects of the US or American culture that you really like

or dislike?

6.034

Total

322.503

Table 7.2. Questions with the Most CS for Mac

Question

Amount of Thai

(in seconds)

1

On a scale of 1 to 5 (5 = native-like), how well do you speak Thai? Why

do you give yourself that rating?

38.375

2

What do you think of Thai food and eating culture? Do you have any

favorite Thai foods?

16.167

Young 11

3

Are there any aspects of Thailand or Thai culture that you really like or

dislike?

7.670

4

What do you think of American food and eating culture? Do you have any

favorite American foods?

6.305

5

Do you celebrate any American holidays? If so, how and with whom do

you celebrate them?

3.791

6

Have you ever lived in Thailand? If so, what was your experience like?

2.704

7

Do you celebrate any Thai holidays? If so, how and with whom do you

celebrate them?

2.073

Total

77.085

For both Mac and Pearl, questions about food, their likes and dislikes of Thai culture, and

their own proficiency in speaking Thai rank among the top questions for which they used Thai.

While Pearl used Thai when introducing herself and talking about how much Thai culture she was

exposed to growing up, her likes and dislikes of American culture, her feelings (or lack thereof) of

pride and/or patriotism for Thailand, and what she thinks “makes someone Thai”, Mac did not use

Thai for any of these topics. Additionally, there were no topics that only Mac used Thai to talk

about. One would expect that participants would use more Thai when answering questions that

focused on Thai culture (e.g., food, holidays). The data generally supports this hypothesis, as eight

out of the twelve questions for which Pearl used Thai and five out of the seven questions for which

Mac used Thai asked about Thailand or the Thai language or culture. Therefore, the majority of

CS occurred when discussing Thai content.

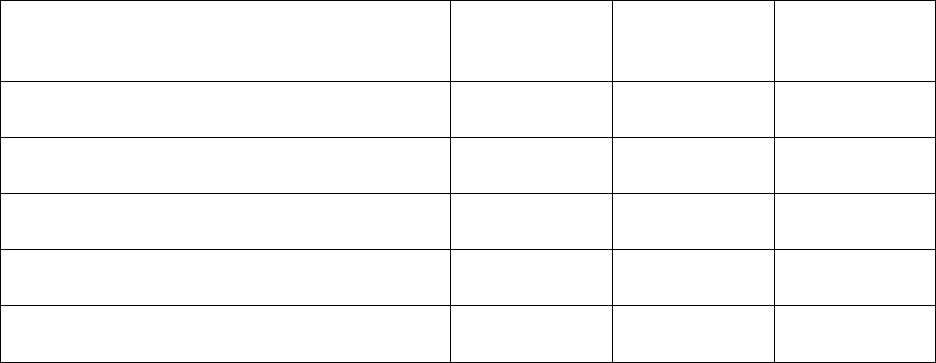

In total, there were 79 instances of CS during Mac and Pearl’s conversation. Returning to

Wei and Milroy’s (1995) three levels of CS, Mac and Pearl together had the most CS at Level C,

with approximately 62 instances of Level C CS. There were 14 instances of Level B CS and only

3 instances of Level A CS. Individually, Mac and Pearl each code-switched the most at Level C,

followed by Level B and then Level A. Whereas Pearl had significantly more instances of Level

C CS than Level B CS, Mac had comparable amounts of Levels B and C CS. These results are

presented below in Table 8.

Table 8. Instances of Code-Switching per Level per Speaker

Instances of CS

Level of CS

SPEAKER 1

Language A

Total

SPEAKER 2

Language A

No CS

Pearl

Mac

Total

%

SPEAKER 1

Language A

SPEAKER 2

Language B

Level A CS

2

1

3

3.80

SPEAKER 1

Sentence 1

Language B

Sentence 2

Language A

Level B CS

6

8

14

17.72

Sentence 3

Constituent 1

Language A

Constituent 2

Language B

Level C CS

51

11

62

78.48

Total

59

20

79

100

Adapted from Wei and Milroy (1995)

Example 1 below includes all three levels of CS. This excerpt comes from the first half of

the interview, when Mac and Pearl were asked to rate their own proficiency in speaking Thai.

Young 12

Example 1

Mac (06:31)

I can get around Bangkok and talk to people in sort of regular everyday language without them knowing.

phut phasa thai dai kap khon thi krungthep ni khao cha mai ru wa wa phom pen khon thi ni tae tha phut

rue arai a rueang arai thi man man baep man man yak noi nia khao at cha ru (WHEN I SPEAK THAI WITH

THAI PEOPLE IN BANGKOK, THEY WON'T KNOW THAT I'M FROM HERE [THE US]. BUT IF I TALK OR WHAT-

ABOUT SOMETHING THAT'S, LIKE, A LITTLE DIFFICULT, THEY MIGHT KNOW).

3

If they're paying attention,

they'll be able to tell because eventually I get stuck.

Pearl (07:05)

phuak sap luek luek a (ALL THE DEEP VOCAB),

4

yeah

Mac (07:08)

khrap luek luek ni yak chai lae doichpho rao mai dai mai dai chai thi ni a khue wa wela wela klap klap

pai mueang thai nia man cha khlong khuen reo mak na wela wela ma thi ni nia man cha khoi khoi baep

(YEAH, THE DEEP [STUFF] IS DIFFICULT, YEAH, AND ESPECIALLY [WHEN] WE DON'T HAVE A CHANCE TO

USE IT HERE. SO WHEN BACK IN THAILAND, IT'LL BECOME MORE FLUENT VERY QUICKLY. WHEN HERE,

IT'LL LITTLE BY LITTLE)

5

erode, right? It just erodes slowly.

First, Level A CS occurs when Pearl starts her turn in Thai after Mac ends his turn in English. In

Mac’s next turn, he then continues speaking Thai (continuity, see Table 1). Level B CS occurs in

Mac’s first turn when he switches from English to Thai after his first sentence. Here, Mac switches

to Thai to repeat his statement about his ability to “get around” Bangkok using Thai without people

knowing he’s from the U.S. Finally, Level C CS occurs in Mac’s second turn when he switches

back to English with the word “erode”. Mac’s switch here likely served to fill a lexical need, which

attests to his earlier statement about the DEEP Thai vocabulary that is difficult for him. Though he

could have continued his sentence in Thai, he needed to switch to English in order to fill a linguistic

need. This is a common reason for CS (Grosjean 1982; see Table 1).

Example 2 below shows one instance where a switch to Thai is made (by Pearl) to convey

a particular connotation or meaning. When talking about how they have to behave when in

Thailand, Mac and Pearl agree on the importance of khwamriaproi (ORDERLINESS,

POLITENESS). In Examples 3 and 4, Pearl switches to Thai when describing her reaction to eating

beef for the first time (3) and eating “American stuff” (i.e., food) (4). In both of these examples,

Thai is used to express a particular emotion: disgust. In Example 2, Pearl uses Level C CS, and

Mac uses Level B CS. Examples 3 and 4 both show Level C CS.

Example 2

Mac (16:08)

I get that sense. But you just naturally do it right. You just know not to be, like, demonstrative and loud

when you're there, sort of…

Pearl (16:19)

3

4

5

Young 13

[overlapping] and the level of riaproi

(ORDERLY/POLITE)

6

Mac (16:20)

chai tong mi khwamriaproi chai (YEAH, YOU HAVE TO BE ORDERLY/POLITE, YEAH).

7

Yeah, I definitely

feel the same way.

Example 3

Pearl (46:05)

And the first couple of times I tried the beef, I'm like, oh my God, cha uak (I’M GOING TO THROW UP).

8

Example 4

Pearl (51:57)

If I eat this American stuff, I'm like uan fri (AUTOMATICALLY FAT).

9

I'm like, here you go. ao hai ao hai

(GIVE TO)

10

someone else. I'm like mai kin mai aroi (I DON’T EAT. IT’S NOT DELICIOUS),

11

yeah.

Another common use of CS by participants was quoting other people (Table 1). This

occurred primarily as Level C CS. Example 5 below shows one instance where Pearl switches to

Thai to quote her cousins. This excerpt comes from a discussion Mac and Pearl had on Thai food

and eating culture. After joking about the small serving sizes of food in Thailand compared to in

the United States, Pearl says the following:

Example 5

Pearl (50:21)

I didn’t care. My cousins crack on me all the time, like, cha kin mot ro (ARE YOU GOING TO EAT IT ALL?).

12

I'm like, watch me.

In this example, Pearl uses Thai when quoting her cousins who live in Thailand and not when

quoting her own response (“watch me”). Here, Pearl uses Thai as a tool for distancing or

disaligning herself from her Thai cousins. Thai is used as a contextual cue to establish contrast

between Pearl, a Thai American who states that she loves food (38:57), and her Thai cousins who

“crack” on her “all the time” for eating IT ALL when she visits Thailand.

Here, Pearl uses CS to negotiate her identity as a Thai American—someone who is neither

fully Thai nor fully American—and disaligns herself with the Thainess and Thai people in

Thailand. While Gumperz’s (1982) we- vs. they-code posits that the minority language (in this

case, Thai) is typically the we-code and the majority language (in this case, English) is typically

the they-code, in this example, the opposite is true. There are other examples, such as Example 1

6

เรียบร้อย

7

ใช่ ต้องมีความเรียบร้อย ใช่

8

จะอ้วก.

9

อ้วนฟรี

10

เอาให้ เอาให้

11

ไม่กิน ไม่อร่อย

12

Young 14

above, in which Mac and Pearl use Thai to discuss their similarities and build companionship

between one another, between themselves as fellow Thai Americans. However, Example 5 above

illustrates that there are also instances in which Thai is used as a distancing tool and a means for

negotiating a Thai American identity that is different from a Thai identity.

In contrast to Example 5, Example 6 below illustrates one instance of Thai being used as a

way for speakers to align themselves with other Thai people. In this example, Pearl expresses her

frustration at being charged admission when she visits historical parks and heritage sites in

Thailand. To provide some more context, in Thailand, Thai people are not charged admission to

certain historical parks or heritage sites, while foreigners are. In this quote, Pearl describes how

the employees at these sites always try to charge her admission because “SHE DOESN’T HAVE A

THAI FACE”. This excerpt is drawn from a longer quote in which Pearl is describing her past

experiences travelling to Thailand.

Example 6

Pearl (15:59)

Pearl pai thiao thi nai khao ko cha phayayam kep tang chai mai (WHEREVER I TRAVEL, THEY WILL TRY

TO CHARGE ADMISSION, RIGHT?)

13

you know, and Pearl ko baep han pai baep arai wa cha kep thammai

rao pen khon thai suan yai khon thai eng khao ko cha baep mong rao baep oe ai ni man na mai chai thai

tae man phut phasa thai samniang oke kep di mai di (I LIKE, TURN TO THEM, AND I’M LIKE WHAT THE

HELL? WHY WOULD YOU CHARGE ME? I'M THAI. FOR THE MOST PART, THAI PEOPLE WILL LIKE LOOK AT

ME, AND THEY'RE LIKE, “SHE DOESN'T HAVE A THAI FACE, BUT SHE CAN SPEAK THAI WITH AN OKAY

ACCENT. SHOULD WE CHARGE OR NOT CHARGE HER?”)

14

and then I, you know, I typically just walk past

and they're like okay.

In this example, Pearl again uses Thai to quote Thai people. It’s also important to note that, when

quoting the Thai people who are debating whether or not to charge her (AND THEY’RE LIKE, “SHE

DOESN’T HAVE A THAI FACE, BUT SHE CAN SPEAK THAI WITH AN OKAY ACCENT. SHOULD WE CHARGE

OR SHOULDN’T CHARGE HER?”), Pearl uses the second person pronoun man.

15

man translates to “it”

and is used when referring to animals or inanimate objects, so referring to a person as man can be

perceived as derogatory. At the same time, man can also be used endearingly with people with

whom one is close to or older than. In this instance, Pearl uses man when quoting how other people

refer to her when she is in Thailand. The people she quotes are unnamed and presumably strangers.

Therefore, it is more likely that Pearl intends to use man derogatorily here, rather than endearingly,

to convey her frustration and anger at not being perceived as Thai while in Thailand.

Interestingly, when Pearl describes her own response in this quote (AND I’M LIKE WHAT

THE HELL? WHY WOULD YOU CHARGE ME? I’M THAI.), she uses Thai, whereas in Example 5 above,

she uses English (“I’m like, watch me.”). In Example 6, Pearl aligns herself with Thai people in

Thailand, contending that, akin to the people who attempt to charge her admission, “I’M THAI” too.

When aligning herself with the other Thais here, she uses Thai to quote herself, but when

contrasting herself with her cousins in Example 5 above, she uses English to quote herself. In

Example 5, Thai is the they-code, which Pearl uses to distance herself from other Thai people.

13

14

15

Young 15

Example 6 instead shows Thai as the we-code, with Pearl using Thai to align herself with other

Thai people.

The next two examples, Examples 7 and 8, show instances of Level C CS in which Thai

adjectives are lexically inserted into English sentences. Both examples were spoken by Pearl, yet

they illustrate different ways of inserting Thai adjectives into English. In Example 7, Pearl

compares the flavors of Thai and Filipino food when answering a question about American

holidays. In Example 8, Pearl discusses what she likes and dislikes about American culture, noting

that Americans that she has “come across” are LAZY.

Example 7

Pearl (37:27)

At least at the Thai parties, you know, you have all the different umami flavors. phet (SPICY) priao (SOUR)

khem (SALTY) wan (SWEET)

16

versus where Filipino food is just lian (GREASY).

17

Example 8

Pearl (01:20:09)

From my own experience, you know, Americans that I've come across [are] khikiat (LAZY).

18

In Example 7, Pearl states that “Filipino food is just GREASY”, while in Example 8, she simply

states that “Americans…[are] LAZY”, leaving out the copula verb. Recall that, in the Thai language,

adjectives that are used as the predicate in a sentence—as in Examples 7 and 8—are considered

intransitive verbs and do not require a copula like in English (Iwasaki and Ingkaphirom 2009, 91).

Thus, we get the structure seen in the first two examples in Table 1 above.

Following Myers-Scotton’s (1993) Matrix Language Hypothesis, the data show that

English was the ML and Thai was the EL throughout Mac and Pearl’s conversation. Therefore,

according to Myers-Scotton, the structure of the English language should condition how Thai is

inserted into the English sentences. In Example 7 above, Pearl includes the English copula “is”

even though the Thai adjective GREASY does not require it. Thus, the English language conditions

the way the Thai adjective is used by Pearl. In Example 8, however, the English copula verb “are”

is absent. Though the ML (English) should condition how words from the EL (e.g., Thai

adjectives) are inserted, in this instance, the Thai structure takes precedence over the English

structure. This example therefore does not follow Myers-Scotton’s Matrix Language Hypothesis.

Discussion

Very little research has been conducted on Thai-English CS, and the work that has been

done has focused on Thai-dominant speakers, whereas this study focuses on English-dominant

speakers. For this reason, there is no data on English-dominant Thai-English bilingual speakers to

which the findings from this study can be compared. In previous research (Young 2021) conducted

last year on Thai celebrities Vuthithorn “Woody” Milintachinda and Lalisa “Lisa” Manoban, as

well as earlier studies on scripted CS, including those conducted by Likhitphongsathorn and

16

17

18

Young 16

Sappapan (2013) and Chalaemwareel and Rodrigo (2020), Thai-English CS primarily takes the

form of lexical insertion of English words or other linguistic items into Thai sentences. In other

words, data from previous studies, which have all focused on Thai-dominant speakers, show a

clear preference for Level C CS. For example, Woody and Lisa’s styles of CS were characterized

by lexical insertion of English verbs (e.g., “pretend”, “focus”) and exclamations (e.g., “Oh my

god!”) (Young 2021). The preference for Level C CS also holds true for scripted language. In their

study of Thai-English CS in Thai pop songs, Likhitphongsathorn and Sappapan (2013) found that

68.39% of CS instances across 146 songs were Level C CS. The remaining 31.61% of CS instances

were Level B CS (p. 498).

The motivations for using CS discussed in the examples with Mac and Pearl above—

continuing the last language used, filling a linguistic need, expressing emotion, conveying a

particular meaning, quoting someone, asserting or negotiating a particular identity, expressing

group identity and solidarity—have been identified by other scholars studying Thai-English CS.

In Woody and Lisa’s conversation, for example, Lisa was the first to use English, and Woody then

continued in English during his next turn (continuity, see Table 1) (Young 2021). In

Chalaemwareel and Rodrigo’s (2020) study of Thai Twitter users written Thai-English CS,

13.33% of survey participants stated that they used English vocabulary because they did not know

the Thai meaning or equivalent (i.e., filling a linguistic need) (p. 94). Participants also cited using

English to better express emotion (20.00%) and convey a particular meaning (38.18%). Asserting

or negotiating a particular identity and expressing group identity and solidarity were present in

Woody and Lisa’s conversation. As celebrities, Woody and Lisa used English to assert a modern

identity. This finding is also supported by Lee (2006) in her study of the association of English

with modernity in Korean television commercials. At the same time, Woody and Lisa’s use of

English served as a means of building solidarity and expressing their shared identity as bilingual

Thai celebrities who have lived abroad for extensive periods of time (Young 2021).

Unlike Woody and Lisa, the participants in this study did not use English to index a modern

identity. None of the participants were famous celebrities, as Woody and Lisa are. Additionally,

the participants were all English-dominant, so their conversation was also English-dominant. Akin

to Woody and Lisa, the participants in this study used CS to build solidarity and express their

shared identity—in this case, a Thai American identity that is neither fully Thai nor fully American.

For instance, in Example 1 above, Mac and Pearl emphasize their shared Thai American identity

and build solidarity through expressing their shared struggle with DEEP VOCAB.

Despite the significant contribution the present study makes in filling the current gap in the

literature on Thai-English CS, this study is not without its limitations. One limitation of this study

is the small sample size. The sample size of fourteen participants is certainly not large enough to

be able to make generalizations about demographic-based patterns (e.g., based on age or gender).

Another possible limitation is the variability in age differences across pairs. One pair had an age

difference of only one year, while another (Mac and Pearl) had an 11-year age difference. Though

the likelihood of these varying age gaps contributing to differences in the seven pairs’ patterns and

motivations for CS is small, it is certainly worth considering, especially given the salience of age-

based social hierarchy in the Thai language and culture (Iwasaki and Horie 2000).

The first step for the continuation of this study is to investigate Myers-Scotton’s (1993)

Matrix Language Hypothesis in more detail, focusing especially on the data from the remaining

Young 17

six pairs. Further analysis of identity performance and negotiation as it is achieved through

participants’ Thai-English CS is also necessary to elucidate the connection(s) between language

and identity. In analyzing identity, special attention should be paid to the variable use of Thai as

the we- vs. they-code. Another interesting direction for this research in the future is a comparative

analysis of the different styles (and perhaps motivations) of CS for first, 1.5, and second generation

Thai Americans. The current study focused on two speakers: 1) Mac, a 1.5 generation Thai

American, and 2) Pearl, a second generation Thai American. Interestingly, Pearl used significantly

more Thai during her conversation with Mac, even though she and Mac both rated their Thai

speaking abilities at 4.5 out of 5. Finally, comparing the findings presented here with comparable

data on Thai-dominant speakers would be illuminating for the study of Thai-English CS; however,

as previously mentioned, the current lack of research prevents such a comparison.

Conclusion

This study has examined Thai-English Code-Switching as it is used by English-dominant

Thai American bilingual speakers. In particular, this study focused on one pair of participants, Mac

and Pearl, who used the most Thai throughout their conversation. During their 111.97 minute long

conversation, Mac and Pearl used Thai for a total of 6.66 minutes. Following Wei and Milroy’s

(1995) classification of three Levels of CS, both Mac and Pearl showed a clear preference for

Level C CS (i.e., Code-Mixing), with 78.48% of their 79 instances of CS being Level C CS. Levels

B and A CS occurred much less frequently, comprising 17.72% and 3.80% of the total instances

of CS, respectively.

Common reasons that the participants in this study code-switched include continuing the

last language used (Example 1), filling a linguistic need (Example 1), conveying strong emotion

(Examples 3 and 4), expressing a particular meaning associated with Thai vocabulary (Example

2), quoting someone (Examples 5 and 6), asserting or negotiating a particular identity (Examples

1, 5, and 6), and expressing group identity and solidarity (Example 1). Mac and Pearl used Thai to

assert their shared Thai American identity and to build solidarity based on their shared experiences.

Analyzing the data using Gumperz’s (1982, cited in Woolard 2006) we-/they-code dichotomy,

though Thai was expected to be the we-code during the conversation, Pearl used Thai as both the

we- and they-codes. She used Thai to both distance herself from (Example 5) and align herself

with (Example 6) other Thai people.

Examining the structure of the CS itself, English was the dominant language of the

conversation, so one would expect instances of Thai to adhere to the English language’s structure,

according to Myers-Scotton’s (1993) Matrix Language Hypothesis. However, Pearl varied in her

adherence to (Example 7) and challenging of (Example 8) this hypothesis. With Thai adjectives

specifically, there were instances in which Pearl’s lexical insertion of Thai adjectives into English

did not follow the English language structure as one would expect.

In conclusion, the findings from this study illustrate the flexibility of both Gumperz’s

(1982) we-/they-codes and Myers-Scotton’s (1993) Matrix Language Hypothesis. Throughout

Mac and Pearl’s conversation, Pearl used Thai variably in ways that challenged the seemingly

fixed nature of these two concepts. This study presents an initial examination of the structural

patterns and social and linguistic motivations for Thai-English Code-Switching in spontaneous

Young 18

natural language. Given the current lack of research on Thai-English CS—and CS by English-

dominant speakers specifically—there is still much room for future explorations of the subject.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the completion of this Honors Capstone project and for conference travel was

provided by the Enhance Your Education (EYE) Grant from the NIU Honors Program and the

Research, Engagement and Academic Diversity (READ) Grant from the NIU Office of Student

Engagement and Experiential Learning (OSEEL). Additionally, the completion of this project

would not have been possible without the continued support and education funding from the NIU

Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS). Finally, I would like to thank my faculty mentor Dr.

Kanjana Thepboriruk in the Department of World Languages and Cultures for guiding and

supporting me throughout both my undergraduate career and this research project.

Young 19

Appendix A: Participant Recruitment Script

Sawatdii kha, my name is Holly Young, and I am an undergraduate student studying

anthropology and linguistics at Northern Illinois University. For my senior research project this

year, I am conducting research focusing on Thai-American identities and the Thai-American

experience. I am seeking Thai-American bilinguals between 18 and 30 years old who use both

Thai and English in some aspect of their everyday lives to participate in my study. You do not

need native-like proficiency in Thai, nor do you need to be equally fluent in Thai and English to

participate. Ability to read and write Thai is also not necessary. Even if you only use Thai with

certain people or some of the time, such as talking with family or friends, I encourage you to

participate in this study.

After completing a preliminary survey (linked below), you will be paired with another

participant and asked to discuss 2-3 preselected topics. The topics will center on your personal

experiences, as this study is ultimately about hearing and learning from your experiences. If you

volunteer to participate, your conversation will be recorded both visually and audibly. However,

the recordings will not be shared with anyone, and your information will remain strictly

confidential. Participation in the study will take approximately 60-90 minutes in total via Zoom,

but the length of time may vary depending on how long participants choose to spend on each topic.

No prior knowledge or preparation is necessary for participation in this study. If you or anyone

you know is interested in participating, please fill out the survey below. Feel free to contact me

with any questions or concerns via email: [email protected]. Thank you!

Young 20

Appendix B: Biodata Survey

1. Name

_______________________________________________________________

2. Age

________________________________________________________________

3. Place of residence

▼ Alabama (1) ... Wyoming (52)

4. Place of birth

/

o USA (1)

o Thailand (2)

o Other (Please specify ) (3)

________________________________________________

5. Please select your first language(s)

( 1 )

▢ English (1)

▢ Thai (2)

▢ Other (Please specify ) (3)

________________________________________________

6. Please list any other language(s) you use

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

Young 21

7. Please check all that apply

Thai

English

Other

Language(s)

Not applicable

/

Language(s) you’re most

comfortable using

is/are......

▢

▢

▢

▢

At work you

use......

▢

▢

▢

▢

In the community you use...

...

▢

▢

▢

▢

At the store(s) you use...

...

▢

▢

▢

▢

With your friends you use...

...

▢

▢

▢

▢

With your sibling(s) you

use... ...

▢

▢

▢

▢

With your parent(s) you

use... ...

▢

▢

▢

▢

At home you use...

...

▢

▢

▢

▢

With your child(ren) you

use... ...

▢

▢

▢

▢

With your spouse/partner

you use... /...

▢

▢

▢

▢

Young 22

8. Please specify the number of hours per week that you...

...

Thai

English

Other

Language(s)

Watch TV show/movies/lakhon/videoclip

///

Read documents/news/books/newspapers

///

Write messages/chat/email/LINE

///

Listen to music/radio/podcasts/news

///

Speak

Young 23

Appendix C : Bilingual Introduction Script

sawatdikha khun ___[name]___ kap khun ___[name]___ khop khun mak na kha (HELLO, [NAME]

AND [NAME]. THANK YOU SO MUCH)

19

for participating in my project. chan chue holli kha lae pi

ni (MY NAME IS HOLLY, AND THIS YEAR),

20

I am a senior studying at Northern Illinois University

na kha

21

Your conversation today will be a part of my undergraduate senior thesis project. wanni

(TODAY)

22

the conversation cha baeng pen song suan (WILL BE DIVIDED INTO TWO PARTS).

23

It

will be divided into two parts na kha nueng cha naenam tua eng tham khwam ruchak kan kon

(FIRST, YOU’LL INTRODUCE YOURSELVES, GET TO KNOW EACH OTHER).

24

Introduce yourselves, get

to know each other first laeo suan thi song ko cha khuy kan (AND FOR THE SECOND PART, YOU’LL

CHAT)

25

about your experiences as Thai Americans and your opinions on Thai and American

culture na kha chan cha song khamtham nai (I WILL SEND QUESTIONS IN)

26

chatbox thi la khon thi

la khamtham (ONE PERSON AT A TIME, ONE QUESTION AT A TIME).

27

I will send you each one

question at a time in the chatbox, and please feel free to ask follow-up questions. pho phrom laeo

(ONCE YOU ARE READY),

28

you can signal for the next question, using one of the Zoom reactions.

chai phasa nai ko dai kha thai ko dai angkrit ko dai (YOU CAN USE WHATEVER LANGUAGE, THAI

OR ENGLISH).

29

Feel free to use whatever language you want. mi khamtham mai kha (DO YOU

HAVE ANY QUESTIONS?)

30

Do you have any questions before we begin?

What name should I use to refer to you in the study? chue arai ko dai chuelen ko dai chueplom

ko dai (ANY NAME IS FINE, A NICKNAME OR PSEUDONYM).

31

You can use whatever name you’d

like.

So now I’m going to start recording, and then I will ask for your full legal name and your

permission to record. Please keep your camera on during the conversation for the sake of your

conversational partner. I am going to turn my camera off, but I will be here if you have any

questions. The recording will not be shared with anyone else, and I will only be using the audio

for analysis. phrom mai kha (ARE YOU READY?)

32

Are you ready for me to start the recording?

19

___[name]___ ___[name]___

20

21

(this is a polite ending particle used by female speakers)

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Young 24

Appendix D: Interview Questions

33

Part 1

1. Please introduce yourself.

2. On a scale of 1 to 5 (5 = native-like), how well do you speak Thai? Why do you give

yourself that rating?

3. Did you grow up in Thailand or the US? What was your experience growing up like?

4. Have you ever lived in Thailand? If so, what was your experience like?

5. Is there anything else that you want to talk about or ask your partner or me before moving

on to the second part?

Part 2

1. How much (and what kinds of) Thai culture were you exposed to growing up?

2. Do you celebrate any Thai holidays? If so, how and with whom do you celebrate them?

3. Do you celebrate any American holidays? If so, how and with whom do you celebrate

them?

4. What do you think of American food and eating culture? Do you have any favorite

American foods?

5. What do you think of Thai food and eating culture? Do you have any favorite Thai

foods?

6. Are there any aspects of Thailand or Thai culture that you really like or dislike?

7. Are there any aspects of the US or American culture that you really like or dislike?

8. Do you feel proud and/or patriotic when you think about the US?

9. Do you feel proud and/or patriotic when you think about Thailand?

10. What do you think makes someone Thai?

11. What do you think makes someone American?

12. How do you identify? Do you identify more closely with Thai culture or American

culture?

13. Is there anything else that you want to talk about or ask your partner or me?

33

Questions were generally sent in this order. Questions were excluded if participants already answered them in the

natural flow of the conversation.

Young 25

References

Assens, Marc, and André Bastié. "Happy Scribe." 2017.

Auer, Peter, and Aldo Di Luzio. Chap. 1 in The Contextualization of Language, 1-37. Amsterdam: J.

Benjamins, 1992.

Bennui, Pairote. "A study of L1 interference in the writing of Thai EFL students." Malaysian Journal of

ELT Research, no. 4 (2008): 72-102.

Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. "Praat: doing phonetics by computer." 2022.

Boonsuk, Yusop, and Eric A. Ambele. "Refusal as a Social Speech Act among Thai EFL University

Students." Arab World English Journal, no. 10 (2019): 213-224.

Budiman, Abby. Thai in the U.S. Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center. June 16, 2021.

https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/asian-americans-thai-in-the-u-s/ (accessed

April 27, 2022).

Chairat, Patrapee. "English Code-Mixing and Code-Switching in Thai Songs." NIDA Journal of

Language and Communication 19, no. 22 (2014): 1-29.

Chalaemwareel, Kawin, and Russell Rodrigo. "Thai-English Code-Mixing on Twitter in Thailand:

Motivations and Impact on English Language Development."

5. 2020. 87-103.

Diller, Anthony, Jerry Edmondson, and Yongxian Luo. The Tai-Kadai Languages. London: Routledge,

2008.

Grosjean, Francois. Bilingual: Life and reality. Harvard University Press, 2010.

—. Life with Two Languages: An Introduction to Bilingualism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard

University Press, 1982.

Gumperz, John J. Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Gumperz, John J. "The Sociolinguistic Significance of Conversational Code-Switching." RELC Journal

8, no. 2 (1977): 1-34.

Gutman, Alejandro, and Beatriz Avanzati. Tai-Kadai Languages. 2013.

http://www.languagesgulper.com/end/Taikadai.html (accessed April 27, 2022).

Heller, Monica. "Introduction." In Codeswitching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic Perspectives, by

Monica Heller, 1-24. De Gruyter, Inc., 1988.

Hoffmann, Charlotte. An Introduction to Bilingualism. New York: Longman Inc., 1991.

Iwasaki, Shoichi, and Preeya Ingkaphirom. A Reference Grammar of Thai. New York, New York:

Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Iwasaki, Shoichi, and Preeya Ingkaphirom Horie. "Creating speech register in Thai conversation."

Language in Society 29, no. 4 (2000): 519-554.

Young 26

Jitpaisarnwattana, Napat. "Language Choice and Code-Switching Practices among Thai Students: A Case

Study." Proceeding of International Conference on Language and Communication. 2014. 229-

253.

Kannaovakun, Prathana, and Albert C. Gunther. "The Mixing of English and Thai in Thai Television

Programs." MANUSYA 6, no. 2 (2003): 66-80.

Lee, Jamie S. "Linguistic Constructions of Modernity: English Mixing in Korean Television

Commercials." Language in Society 35 (2006): 59-91.

Likhitphongsathorn, Teeratorn, and Pattama Sappapan. "Study of English Code-mixing and Code-

switching in Thai Pop Songs." n.d.: 494-505.

Myers-Scotton, Carol. "Common and Uncommon Ground: Social and Structural Factors in

Codeswitching." Language in Society 22, no. 4 (1993): 475-503.

Papijit, Whralak. "Thai-English code-mixing in Hormone The Series." 2013.

Qualtrics. "Qualtrics." Provo, Utah, 2005.

Suppatkul, Panu. "Thai-American Identity: Second-Generation, 1.5-Generation, and Parachut Children in

the U.S." 31, no. 2 (July-December 2012): 79-108.

Thai - Worldwide Distribution. n.d. https://www.worlddata.info/languages/thai.php (accessed April 27,

2022).

Thai Royal Institute. "." January 11, 1999.

Tsai, Jeanne L., Yu-Wen Ying, and Peter A. Lee. "The Meaning of ‘Being Chinese’ and ‘Being

American’: Variation among Chinese American Young Adults." Journal of Cross-Cultural

Psychology 31, no. 3 (May 2000): 302-32.

U.S. Census Bureau. "2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates Selected Population Profiles,

Table S0201." 2019.

Wei, Li, and Lesley Milroy. "Conversational Code-Switching in a Chinese Community in Britain: A

Sequential Analysis." Journal of Pragmatics 23, no. 3 (1995): 281-299.

Woolard, Kathryn A. "Codeswitching." In A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology, 73-94. Oxford:

Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2006.

Young, Holly. "Thai-English Code-Mixing & Code-Switching on The Woody Show: 'Your Thai is

Getting Better!'." 2021.

Yuan, Eric. "Zoom." 2011.