1

REPORT

Evaluation of Postdoctoral NRSA T32 Institutional Training Grant Program

National Institute of General Medical

S

c

i

ence

Panel Roster

Chair

Schwinn, Debra A., M.D.

Professor of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology, Biochemistry

Associate Vice President for Medical Affairs

Carver College of Medicine

University of Iowa

Members

Beaudet, Arthur L., M.D.

Professor

Department of Molecular and Human Genetics

Baylor College 0f Medicine

Coopersmith, Craig M., M.D.

Professor of Surgery

Emory University School of Medicine

Gutierrez-Hartmann, Arthur, M.D.,

Professor Departments of Medicine and of Biochemistry & Molecular Genetics

University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus

Mayeux, Philip R., Ph.D.

Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology

University of Arkansas For Medical Sciences

Nakamoto, Robert K., Ph.D.

Professor, Department of Mol. Physiology & Biophysics

University of Virginia

Whittington, Robert A, M.D.

Professor, Dept of Anesthesiology

Columbia University-

John G Younger, M.D.

Chief Technology Officer and Director

Akadeum Life Sciences, Inc

2

Executive Summary

NIGMS’s postdoctoral National Research Service Award (NRSA) T32 Institutional Training Grants

seek to increase physician involvement in research in 4 areas of biomedicine that fall within

NIGMS’s purview due to broad, systemic mechanisms of disease/treatment. These areas include

Medical Genetics; Clinical Pharmacology; Burn, Trauma, and Perioperative Injury; and

Anesthesiology. In May 2018, the NIGMS convened an external panel of experts as a working group

of the NIGMS Advisory Council to examine whether these institutional clinical postdoctoral research

training (CPRT) T32 programs are achieving their goal.

Overall, the panel noted that postdoctoral institutional T32 grants are a common NIH-wide pathway

for developing physician scientists through mentored research during later years of training (e.g.,

residency, fellowship, transition to faculty). This makes them distinct from predoctoral programs

such as the NIGMS Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP leading to the MD-PhD degree).

U.S. MD-PhDs practice in surgical disciplines, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, or critical care

medicine only 13% of the time, whereas 21% of all U.S. physicians are in these fields. This means

fewer medical scientists trained at the predoctoral stage are active in these focus areas. Given this,

the panel found that the NIGMS CPRT T32 program supports physician scientist research training

opportunities in these research areas that are not supported by other categorical NIH Institutes.

While the panel was able to make a meaningful assessment of NIGMS postdoctoral T32 program

outcomes with the considerable amount of data provided by the NIGMS Office of Program Planning,

Analysis and Evaluation (OPAE), it should be noted that outcome parameters may have been

underestimated as some data were not accessible (e.g., research funding by industry or other

national federal/non-federal entities, details of faculty appointment, etc.). Overall, NIGMS

postdoctoral T32 programs demonstrate similar outcomes in terms of grant applications/awards,

publications, and faculty status, compared with other postdoctoral T32s across the NIH.

Achievement of senior faculty status (%) also compares favorably with MSTP graduates. Of note,

in terms of diversity (higher % under-represented minorities and women), NIGMS CPRT T32s

compare favorably with other postdoctoral T32 and MSTP programs, and significantly better than

K08/K23 programs. Approximately 34% of all NIGMS postdoctoral T32 trainees ultimately apply for

investigator-initiated NIH research grants, with 54% of those applicants receiving subsequent NIH

funding (≈20% overall). Those with at least one funded grant averaged 3.1 to 4.4 grants per funded

trainee depending upon their CPRT focus area. This proportion of trainees receiving NIH grant

funding is approximately half that achieved by individual K08 awardees. However, panel members

cited the need for trainees to generate data (often within the context of a postdoctoral T32 training

program) to compete successfully for K08/K23 or R01 funding. Panel members also noted that the

impact of institutional T32 training grants goes beyond supporting individuals, to positively

influencing programs and institutions in developing physician scientists.

Given these findings, the panel recommends that NIGMS maintain its support for the CPRT

postdoctoral NRSA programs and that the focus be assessed with regards to changes in clinical

research and practice, as well as changes in financial obstacles to training of clinician scientists

that have occurred since the inception of the programs. The issues for each research focus are

unique and need to be considered individually. Finally, the panel notes that NIGMS (and ideally,

3

the NIH more broadly) should delineate clear goals for all training programs and develop metrics

that will allow continuous assessment of program success individually and nationally.

Introduction

Institutional Postdoctoral T32s are part of the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award

(NRSA)s established in 1974 by the National Research Service Award Act; this award mechanism

has been in continuous operation since that time. Within NIGMS, postdoctoral institutional T32s

support researchers in 4 specified shortage areas: 1) Medical Genetics; 2) Clinical Pharmacology;

3) Burn, Trauma, and Perioperative Injury; and 4) Anesthesiology. These clinical research programs

are located in NIGMS because they address broad, systemic mechanisms of disease/treatment

and therefore do not fit into the missions of the disease- or organ systems-based categorical NIH

Institutes. NIGMS’s NRSA program has been a primary means of supporting clinical postdoctoral

research training programs relevant to the NIH mission for the last 40 years. Physicians interested

in research often do not have the protected time necessary to begin or continue scientific

training/work through their residency, fellowship, and early career years. Programs developed with

these institutional training grants provide protected and mentored research time for physicians to

develop skills and identities as scientists, and to train in basic or clinical/translational areas. These

institutional grants aim to prepare trainees for careers that have a significant impact on the health-

related research needs of the Nation.

Institutions receiving these awards are expected to include training opportunities in the fundamental

concepts of multidisciplinary research, as well as research techniques critical to trainee areas of

focus. Additional program activities have included attendance at local and national scientific

meetings and workshops, training in specific methods or analytic techniques (sometimes including

working toward a MS or MPH degree), and training designed to enhance research independence

and scientific capability. This clinical postdoctoral research training (CPRT) program aims to

enhance and develop research training for physicians interested in research careers relevant to the

NIH mission. Specific program goals focus on increasing the number of clinicians trained in

research methodology and the number of physicians involved in research throughout the course of

their careers.

Overview of NIGMS Postdoctoral T32 Program (1990-2016)

History: Program began in 1974; data examined by the evaluation panel covered years 1990-

2016.

Goal: Develop physician scientists through mentored research during later years of clinical training.

Why Train Physician/Clinician Scientists? Clinician scientists are uniquely trained to bridge the

gap between scientific discoveries and clinical medicine. This small cadre of physicians, trained in

both clinical medicine and science (basic, translational, clinical) identify challenging clinical

problems and bring them to the laboratory, as well as translate new laboratory discoveries to the

clinic. As reported in the NIH Physician-Scientist Workforce Working Group Report in 2014,

1

physician scientists are considered an endangered species in the medical workforce, making

dedicated training pathways imperative.

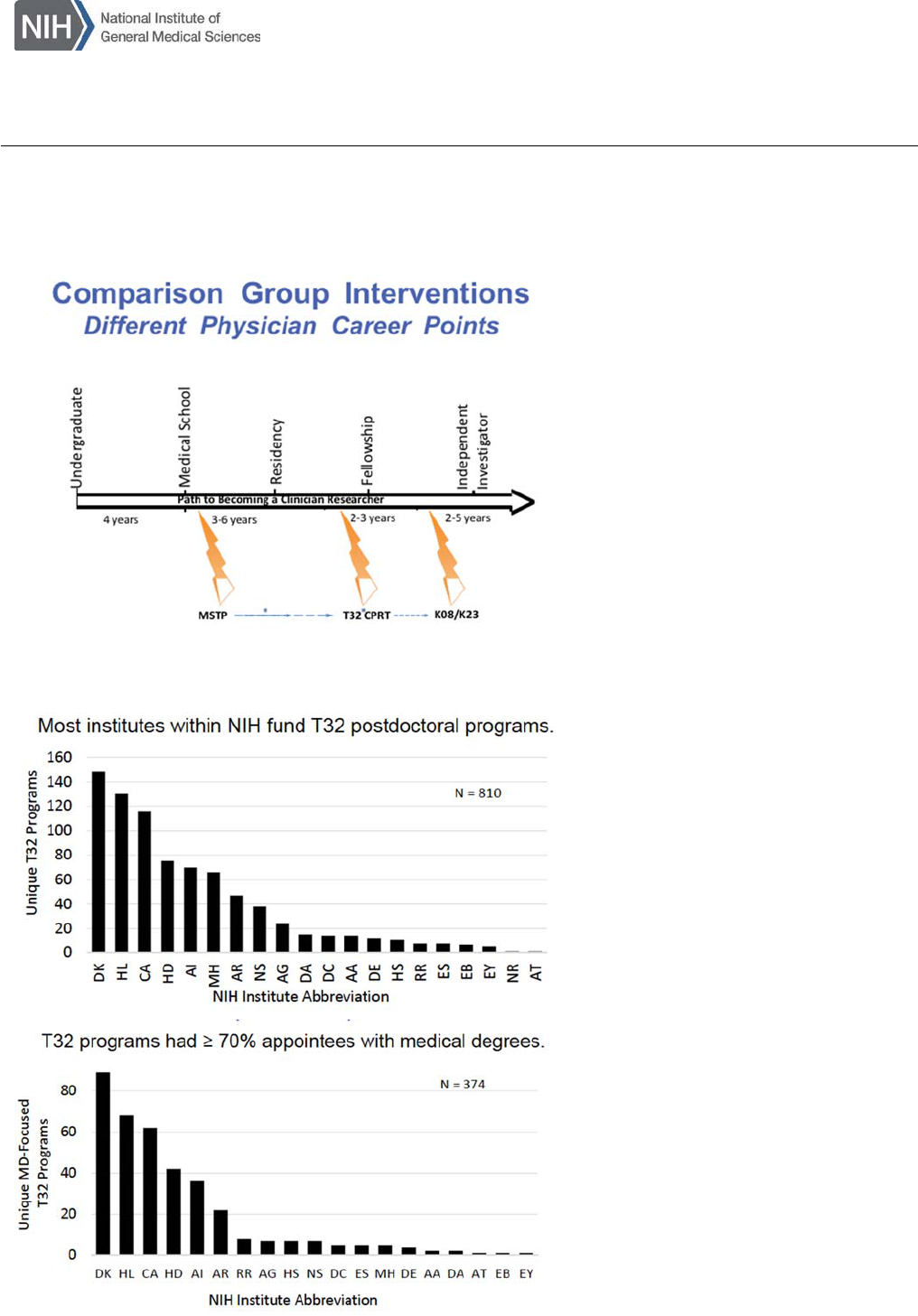

Postdoctoral T32 Intervention Timing: Postdoctoral research training occurs during post-

medical school residency, fellowship, or transition to faculty years (Figure 1).

4

NIH Institutes Participating in Postdoctoral T32 Research Training: Virtually all NIH Institutes

participate in postdoctoral T32 training programs. Specifically, 20 NIH Institutes besides NIGMS

sponsor primarily clinical postdoctoral T32 programs. Between 1999 and 2003 there were 810

unique postdoctoral programs funded by these 20 institutes (defined as programs with >90%

postdoctoral trainees) and of these, 374 have ≥70% trainees with medical degrees (Figure 2).

Years of CPRT T32 Training: At least 2 years of training are expected (80% overall research

effort).

Location of Current NIGMS CPRT T32 Awardees: In 2016, NIGMS supported 45 T32 programs

at 35 institutions in 21 states across the U.S.

Total number of NIGMS CPRT program participants (1990-2016): 2119

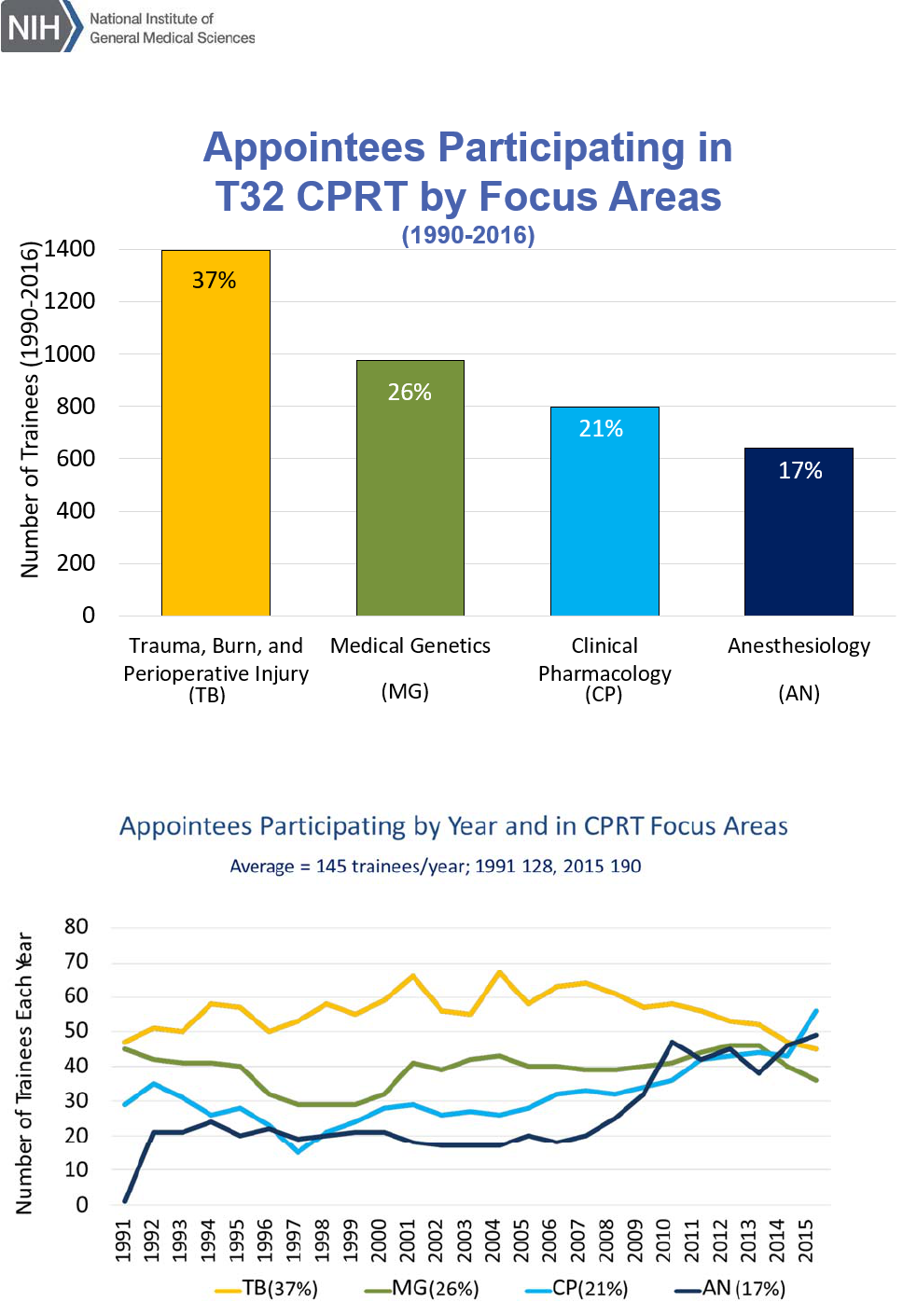

Four Current NIGMS CPRT (T32) Programs / Focus Areas (Figures 3 and 4):

Medical Genetics (26%)

Clinical Pharmacology (21%)

Burn, Trauma, and Perioperative Injury (37%)

Anesthesiology (17%)

Number of CPRT T32 Awards Per Year: From 1992-2015, the number of CPRT T32 trainees

grew from 120 to 190/year, averaging 145/year over that time period. Given 190 trainees in 45 T32

programs in the U.S. in 2015/2016, this averages 4.2 trainees per program (including all training

years).

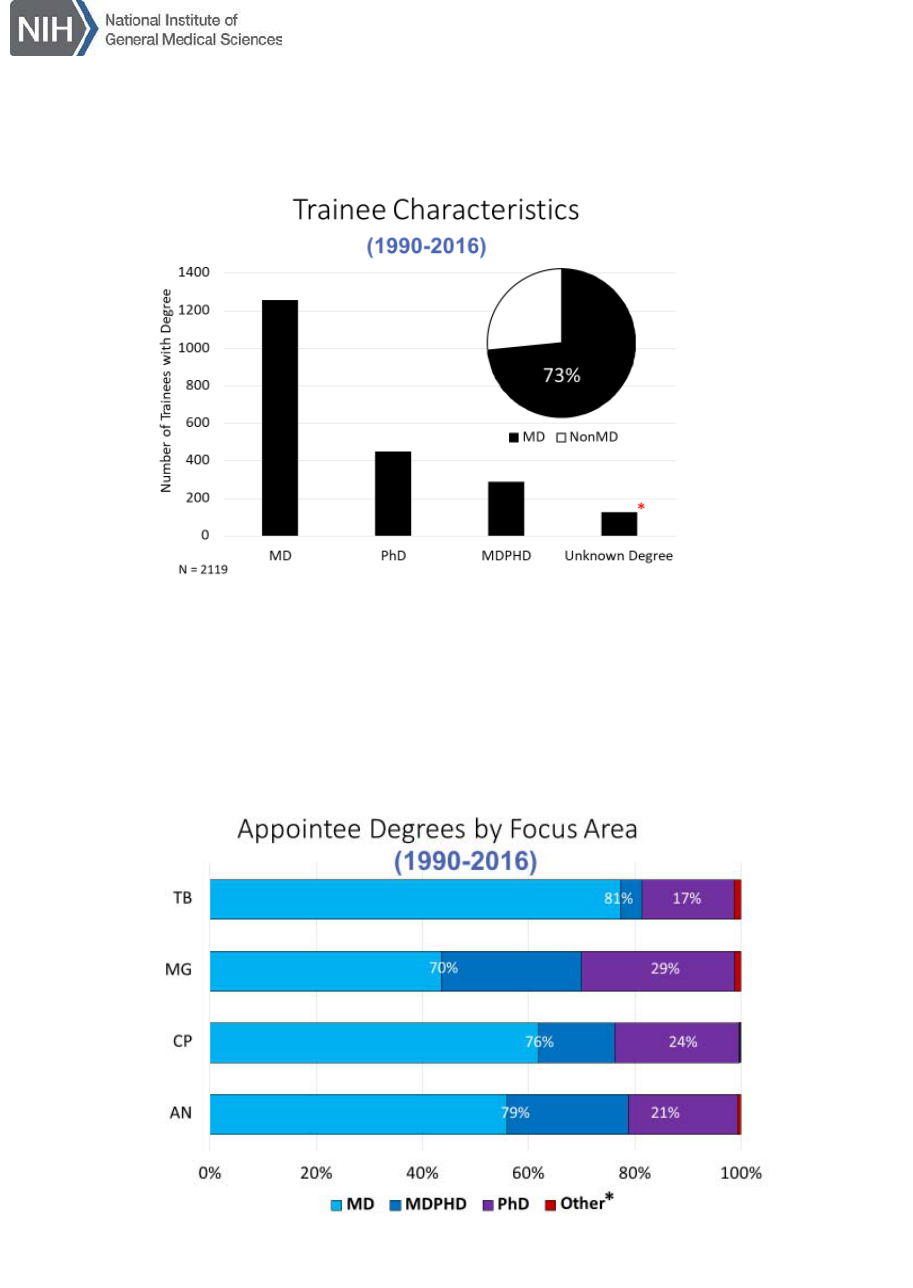

Trainee Characteristics: On average 73% of the 2119 program trainees are physicians (MD 60%,

MD-PhD 13%) (Figure 5). The percentage of MD versus PhD trainees for each T32 program is

shown in Figure 6.

Percent NIGMS CPRT T32 Trainees Who Completed the MSTP Program: 4% of NIGMS T32

trainees were former NIGMS MSTP trainees.

Comparison Groups

The panel determined that the best comparator group for NIGMS postdoctoral CPRT T32 programs

is similar postdoctoral T32 programs supported by other NIH Institutes. However, data available for

this comparison was limited to application and success data for NIH awards. Since MSTP programs

train MD-PhD students and the training is longer, occurs during medical school in generally a much

wider array of research areas, the committee felt MSTP programs were not a good comparison for

the CPRT programs. Similarly, the K mechanisms support trainees at later career stages and differ

in the type of mentorship and in their selection criteria. Thus, although not good comparators for

this assessment, the latter groups proved useful in providing some insights into the broader issues

and nature of training and support of physician scientists.

Caveats

NIGMS Postdoctoral CPRT T32 Programs in Context: In assessing the CRPT programs it is

critical to recognize broader issues in the overall national effort to train and develop a highly skilled

workforce of physician scientists.

1

Since these programs are targeted to a specific stage in the

training path (Figure 1) and highly focused on 4 specific areas relevant to NIGMS, assessment of

5

the data must be made in this context.

Data Limitations: The panel recognized that data collection for these programs over time is

challenging and the efforts of OPAE staff were commendable and extensive (in several cases this

required integrating several internal/external databases, which required individual validation before

being presented to the review group). In spite of these efforts, some data were not available (e.g.,

research career outcomes in government and industrial settings, grants obtained by trainees from

non-NIH government sources [NSF, DOD, PCORI] or national foundations, details of faculty status,

additional degrees obtained [MS, MPH], co-investigator status on grants, some publications not

associated with a NIH grant, or even data complicated by name changes). As a result, there is

likely under-reporting in all groups, but particularly with this group of physician scientists who are

commonly funded via a combination of NIH and non-NIH sources over their careers. Despite these

limitations, the panel was able to make a reasonable assessment of the program.

Evolution of Scientific Fields: A final key factor is that these 4 programs have been in existence

for many years and the nature of medical research and research training in each specialty have

evolved over time. These factors are not captured in the data collected, and are therefore outside

the scope of this evaluation, but they are critical to future planning by NIGMS. Some of these issues

include the establishment of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), which funds

basic science aspects of human genome science and which might be able to partner in some clinical

genetics/genomics training; introduction of pharmacogenetics as an important discipline within

clinical pharmacology; integration of pain medicine more closely with anesthesiology; and blurring

of boundaries between burn, trauma, and perioperative injury and resuscitation science and surgical

critical care outcomes.

Evaluation of Program Effectiveness

Evaluation of the NIGMS CPRT T32 programs by the review committee started with answering the

4 questions listed below.

QUESTION 1: Has the T32 Clinical Postdoctoral Research program been successful in

increasing clinician’s participation in the research community?

Overall the panel consensus was YES, NIGMS CPRT T32 programs have had a positive impact in

increasing clinician participation in research. This is because rigorous research training can occur

at various points throughout a physician’s education (pre-medical school, medical school,

residency, fellowship, beginning faculty years; Figure 1). Acceptance into most MD-PhD and MSTP

programs occurs during application to medical school or in year 1, yet some medical students

discover an interest in science later. Reviewers noted that the concept of “multiple on-ramps” to a

scientific career better reflects optimal physician scientist training opportunities than the classic

“pipeline” description. Thus, the ability to train physician scientists in the 4 NIGMS CPRT programs

later in their careers is important. Each specialty has some unique variations in training needs and

field-specific challenges (e.g., financial issues and/or clinical time commitments) that influence the

path and length of time to a successful research career, yet all share key similarities that aid in

increasing clinician participation in research.

NIGMS CPRT programs target MD and MD-PhD degree holders; the pool for this training are MDs

who develop a strong interest in these areas of research most often during residency. Overall 73%

6

of all NIGMS T32 trainees have MD degrees and the most of the rest have PhD degrees (Figure

5). In the very clinically-focused programs, 80% of the trainees had MD degrees and in Medical

Genetics programs 70% of the trainees had MD degrees (Figure 6).

T32 programs provide trainees with financial support for protected research time coupled with

programmatic activities and mentored research instruction aimed at preparing them for pursuit of

research careers. While the 2014 NIH Physician-Scientist Workforce Working Group suggested

shifting somewhat from T32 toward individual investigator-initiated training awards (e.g., NIH K or

F series),

1

the panel noted that for this group of investigators, 18-24 months of T32 research is often

needed to obtain preliminary data facilitating successful individual K08/K23 applications. As has

been reviewed elsewhere, such investigator-initiated training awards are an important step toward

successful K99 and R01 awards, and ultimately long-term research careers as physician scientists.

The panel noted that within an institution CPRT T32 programs facilitate development of a research-

oriented environment and a more discipline-diverse research training community of mentors,

collaborators, and non-T32-supported fellows. One panel member described this as providing more

research “oxygen” within departments. Another member pointed out that MSTP program directors

generally advise medical students interested in surgical/trauma/anesthesiology specialties to apply

specifically to residency programs that have T32 grants since this is viewed as a marker of serious

scientific commitment by a division, department, or program.

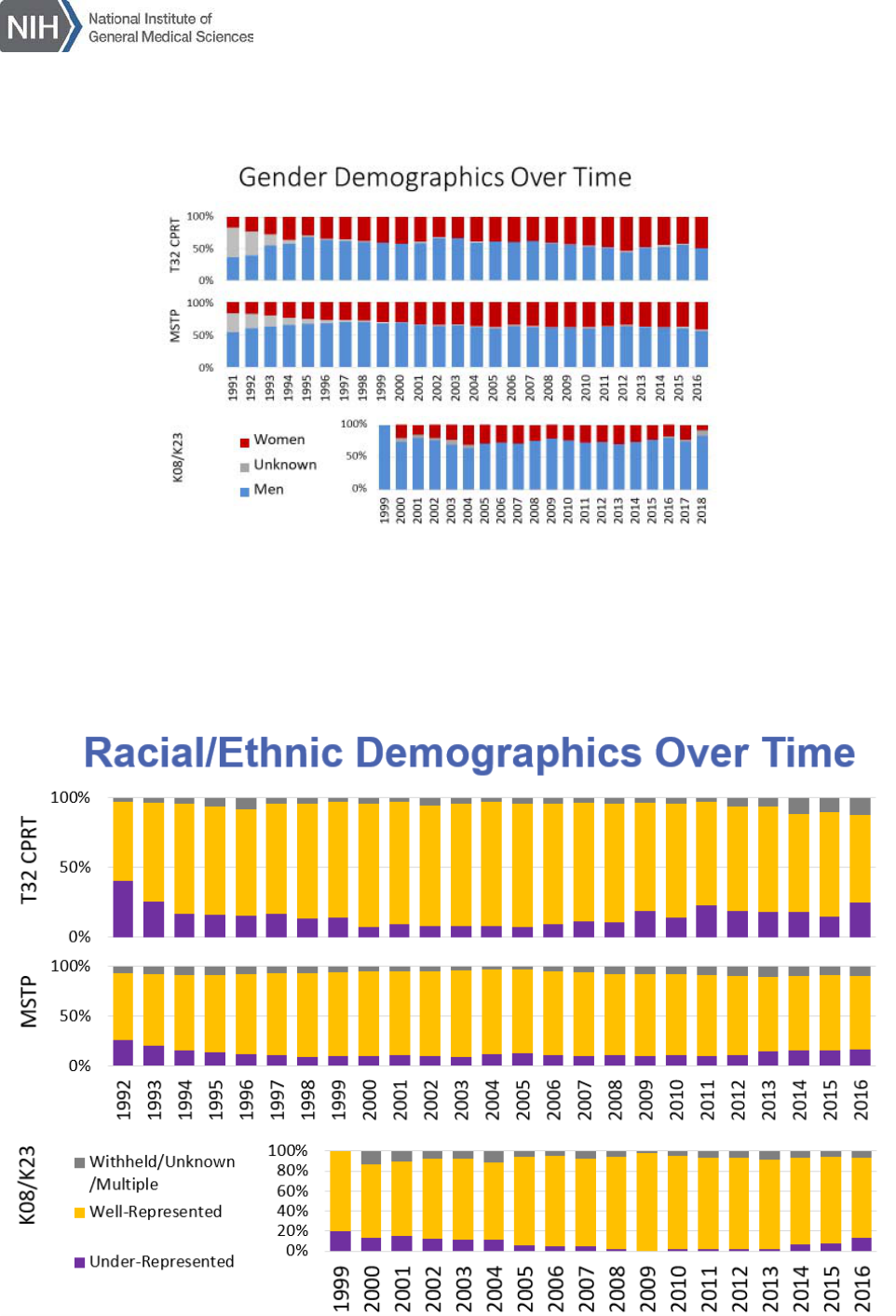

The review panel noted that NIGMS CPRT T32 programs have contributed significantly to

development of a more diverse clinical research workforce. Figure 7 shows gender demographics

for NIGMS programs over time. In terms of training women physician scientists, the CPRT T32

program compares favorably with MSTP and K08/K23 programs. Figure 8 shows racial/ethnic

demographics over the same period. Again, institutional T32s racial/ethnic inclusion compare

favorably with both MSTP and K08/K23 programs.

In terms of program outcomes, the proportion of CPRT T32 graduates who seek and garner

research support, and ultimately have independent research programs, is comparable to trainees

from other postdoctoral training programs across the NIH that seeking to involve MDs in research.

These outcomes are considered in detail in answering the next three questions.

QUESTION 2: Do T32 appointee career trajectories continue towards research and scientific

enterprise?

It is important to note that surgery, anesthesiology, and clinical genetics have long clinical residency

and fellowship training periods. Depending on when research training occurs, many years may

pass before faculty status is possible. Therefore, the review panel focused on intermediate and

long-term outcomes following completion of the CPRT T32 program, since grants and publications

may be shifted several years later compared to other programs. Ultimately, attainment of a senior

level academic career position is a marker for overall long-term research/academic success.

For question 2, the review panel examined whether CPRT T32 program graduates stay in academic

medicine. Physician scientists have many pathways beyond academic medicine by which they may

stay involved in science. These include working for government agencies, pharmaceutical or

biotechnology companies, non-profit organizations, and in science policy leadership positions.

Unfortunately, the panel could not evaluate these career pathways since currently such data are

7

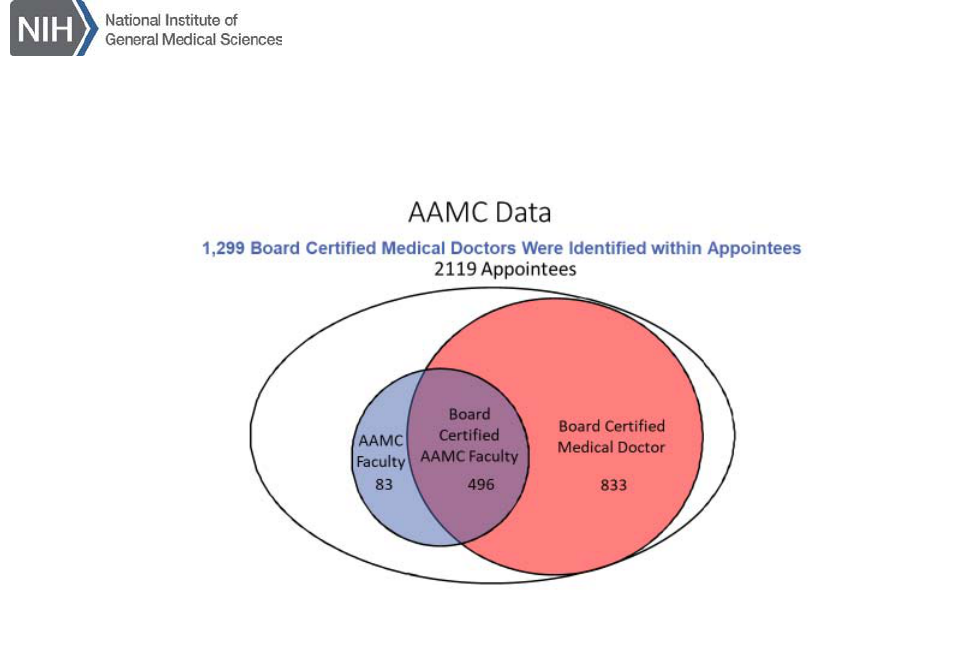

not captured in a consistent manner. In terms of faculty status, Figure 9 shows a merging of AAMC

faculty data with national data on board certification. These data suggest that of the 2119 CPRT

T32 trainees from 1990-2016, 1299 (61%) have clinical board certification and 579 (27%) are

current members of the faculty at an academic medical center (AMC). The panel noted that board

certification numbers appear internally consistent. Given that ≈70% of T32 trainees are MDs, recent

MD T32 trainees (e.g., surgery disciplines) may not have completed their residency, and for many

specialties board certification can take up to 1-5 years post-residency to accomplish, trainees from

the last 5 years might not yet be board certified or been able to join the faculty.

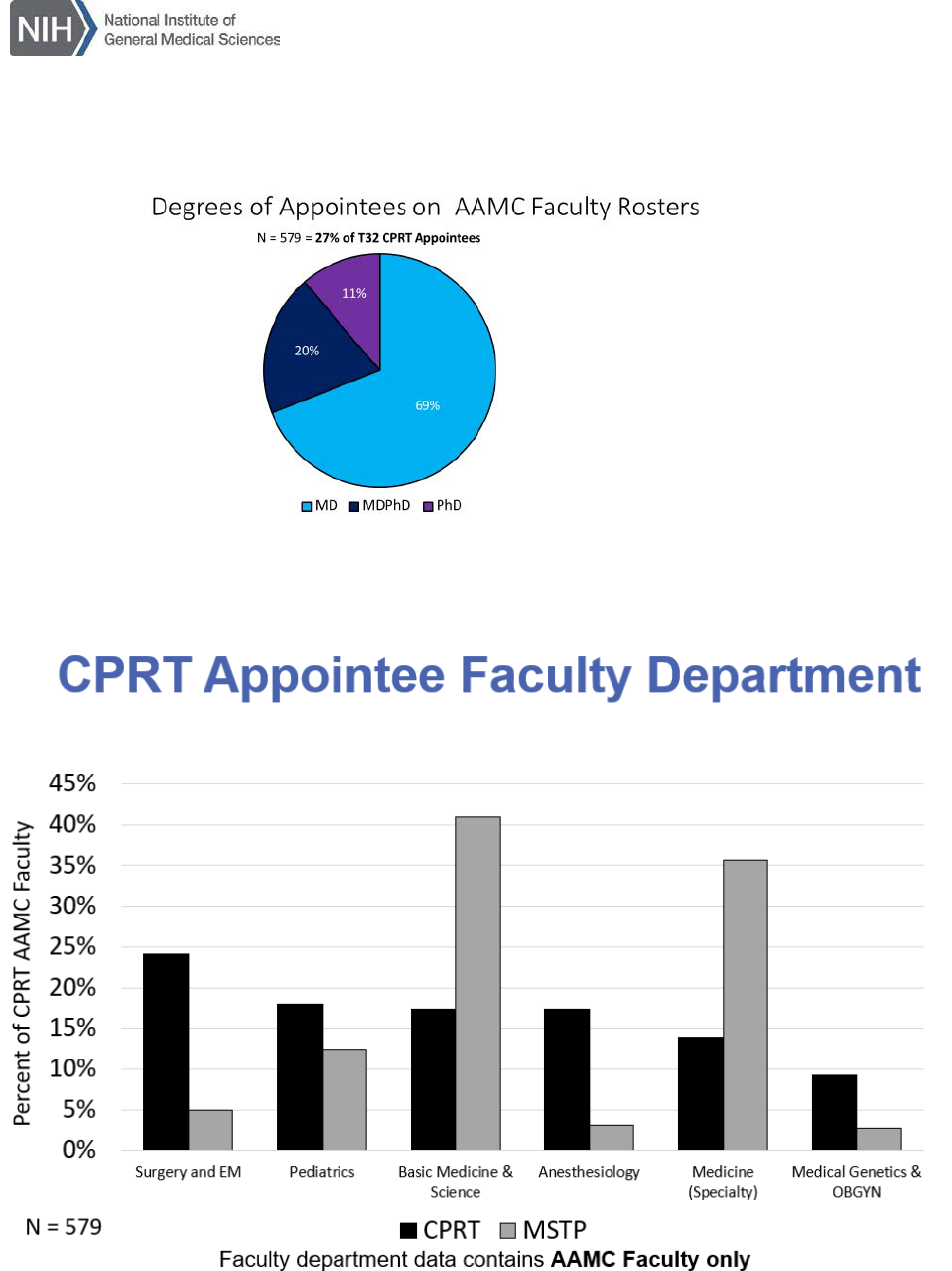

For those CPRT T32 trainees with faculty appointments, 89% have an MD degree. Figure 11 shows

which department CPRT T32 and MSTP graduates join. Overall, T32 graduates join surgery,

anesthesia, basic science, medicine and pediatrics departments, all areas relevant to the 4 NIGMS

focus areas, at higher rates relative to MSTP trainees. Figure 12 compares CPRT T32 and MSTP

faculty at their highest AAMC rank; in this comparison, CPRT T32 graduates compare favorably in

terms of the percent of graduates who ultimately reach Associate Professor and Full Professor rank.

Taken together, CPRT T32 trainees appear to join the faculty and to be promoted to more senior

levels at approximately similar rates to other relevant NIH-funded physician scientist trainees.

However, more nuanced analysis is not possible. The review panel noted that data for comparison

of faculty promotion track were not available, and even if available might be complicated by

inconsistent definitions across universities. In general, tenure track and clinician scientist promotion

tracks at academic medical centers reflect more research-intensive careers compared with more

clinically-oriented clinical educator or clinician promotion tracks. As such, capturing promotion track

information might provide a marker for guiding evaluation of effectiveness of individual physician

scientist training pathways going forward. However, it is important to remember that mentoring is

an important aspect of being a faculty member. Research training provides a unique vantage point

from which to mentor the next generation of physician scientists, no matter what the faculty

member’s career track.

Question 3: What outcomes are correlated with completion of T32 training programs?

Key indicators of a successful research career are research funding and publications. The review

panel therefore examined research grant applications, grant awards, and scientific publications for

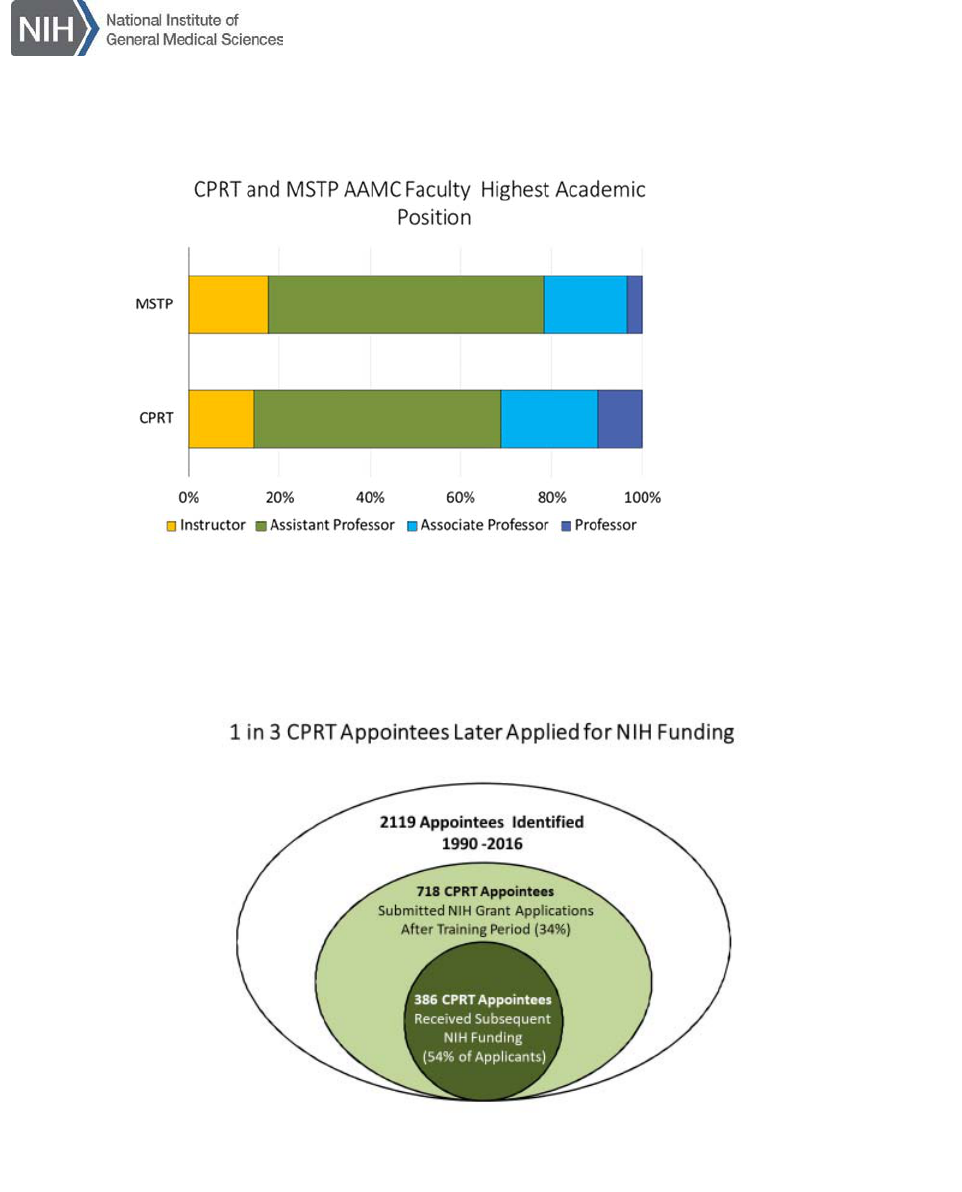

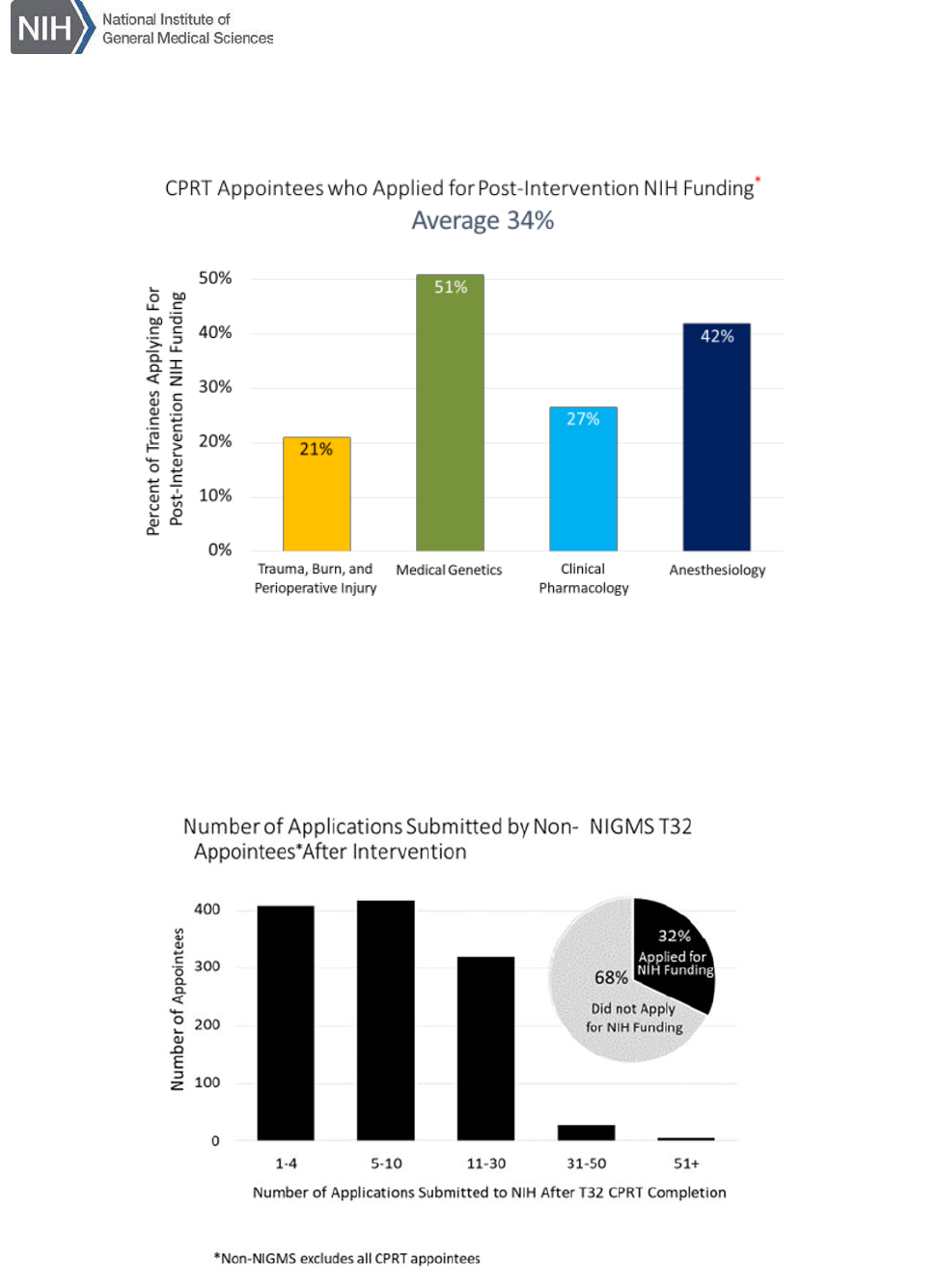

CPRT T32 trainees. Of the 2119 CPRT trainees identified from 1990-2016, 718 (34%) submitted

NIH grant applications after the training period (Figure 13). Figure 14 shows distribution of these

application by individual focus program, with alumni of the medical genetics and anesthesiology

programs having the highest percentage of NIH applications (51% and 42%, respectively). The

overall 34% NIGMS T32 NIH grant submission rate is comparable with 32% seen with non-NIGMS

T32 programs across the NIH (Figure 15). Figure 13 shows that 386 (54% of the NIH grant

applicants) received NIH funding (≈20% of all CPRT trainees), with the highest percent securing

NIH grants from medical genetics and anesthesiology focus areas (Figure 16). However, taking

into account the success rate (success rate = number of applications submitted / total applications

by focus), the overall success rate is similar in all 4 focus areas at ≈23% (burn/trauma 19%, medical

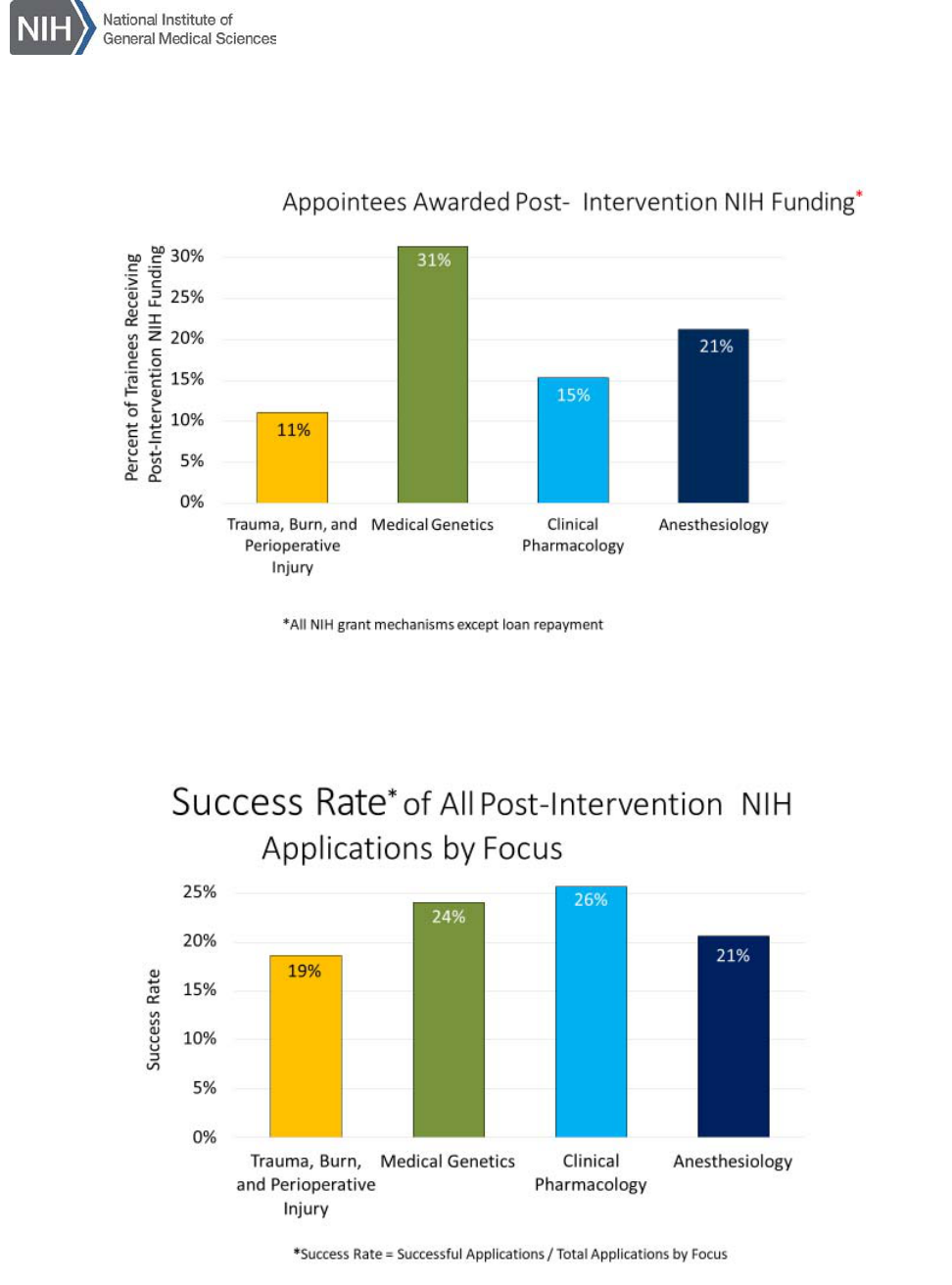

genetics 24%, clinical pharmacology 26%, anesthesiology 21%; Figure 17).

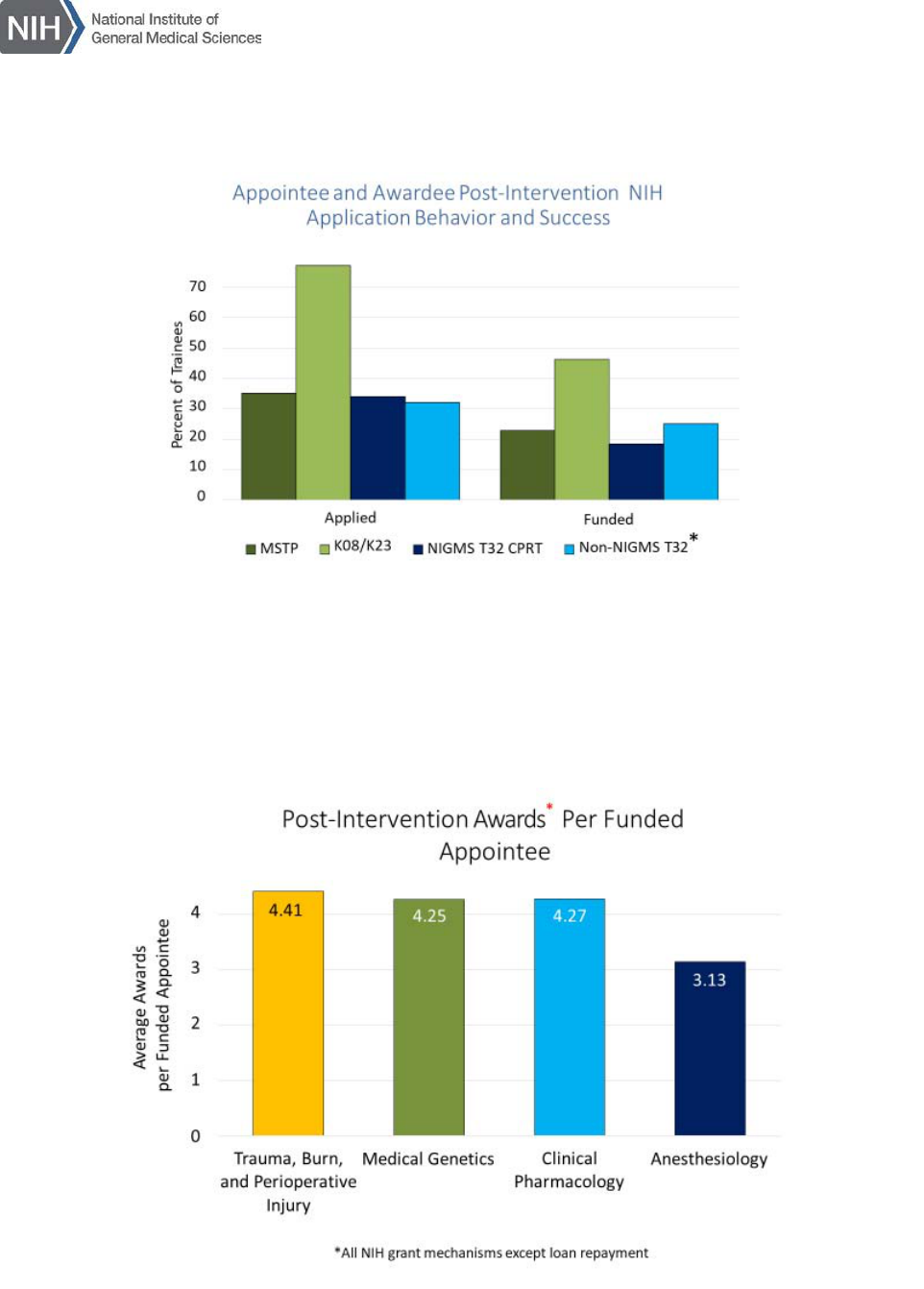

Figure 18 compares NIGMS T32 CPRT trainees with other training pathways within the NIH.

NIGMS CPRT T32 graduates apply for NIH funding at similar rates as non-NIGMS T32 and MSTP

8

graduates, although CPRT trainees have slightly fewer funded NIH grants. Both MSTP and all T32

trainees apply for, and receive, NIH grants at approximately half the rate of K08/K23 awardees.

K08/K23 graduates most often have had prior research experience (e.g., T32 or MSTP training)

since successful applications for these awards tend to require preliminary data. The CPRT T32 or

MSTP graduates who are successful in receiving a K08/K23 awards are captured in the K-series

outcomes, as well as in their original training mechanism.

Another potentially strong indicator of continued research career success is receipt of multiple NIH

grants, which was seen for 5-6% for CPRT T32 graduates. Figure 19 shows that for this subset of

CPRT T32 graduates, the total number of NIH grants ranges from 3.1 to 4.4 per funded appointee,

depending on focus area.

Since it is known that K awardees are twice as likely to apply for, and receive, NIH research support

than other trainees, application for K awards provides a good indicator of movement toward a

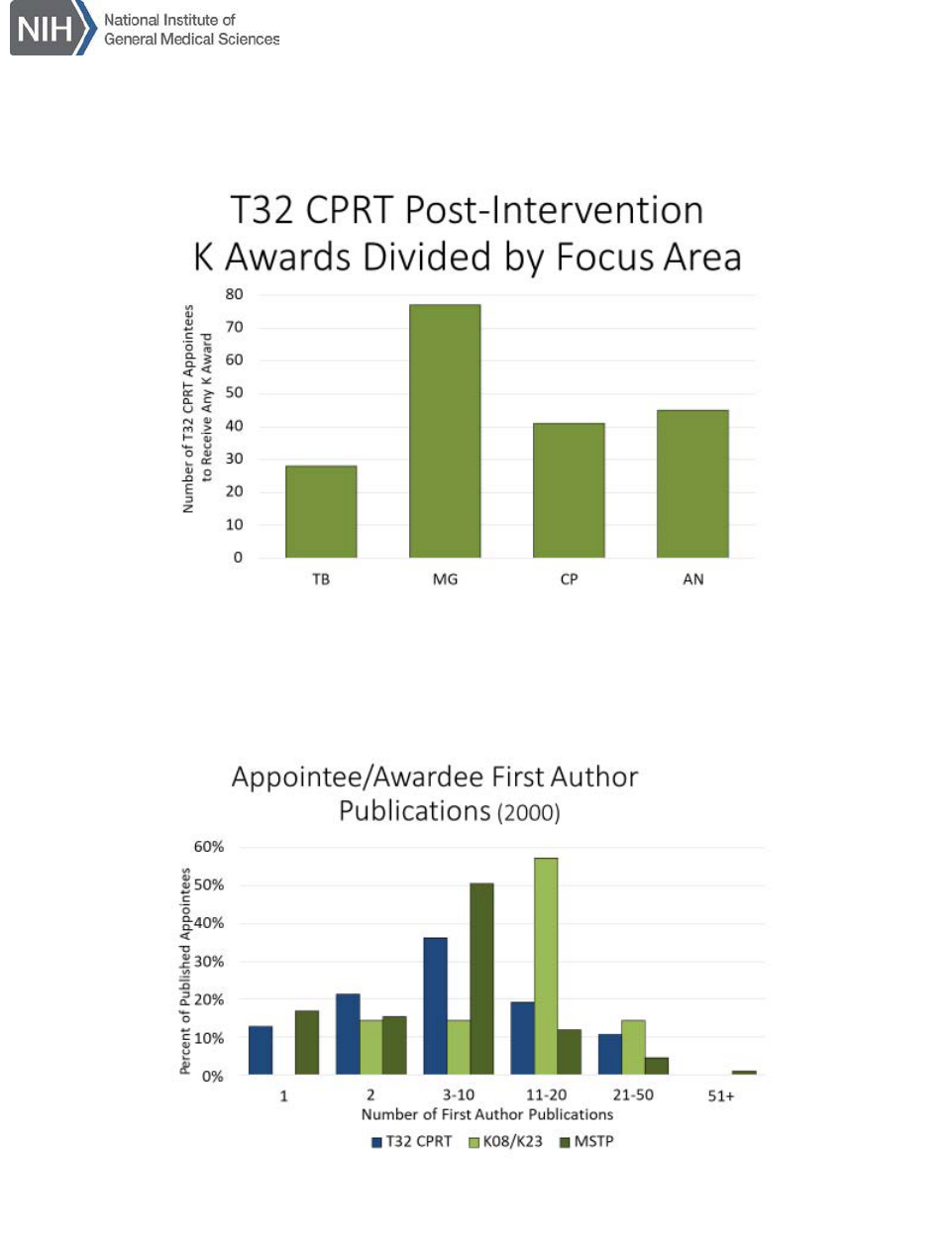

research career. For the period examined, 185 K awards were obtained by CPRT graduates from

any NIH institute (roughly 9% of the graduates): 28 burn/trauma, 75 medical genetics, 40

pharmacology, 42 anesthesia (Figure 20). It should be noted that NIGMS K awards are made only

in the areas of anesthesiology, clinical pharmacology and trauma/burn injury, and not in medical

genetics. Indeed, it is not uncommon for CPRT T32 trainees to apply for K awards from other NIH

institutes, since once a research project is defined, it may ultimately fit better within specific mission

of other NIH institutes. The panel viewed any NIH K award, no matter the institute of origin, a

success metric for NIGMS CPRT T32 graduates.

Scientific publications offer another measure of a successful research trajectory. About 11-14% of

the CPRT trainees cited an NIH grant in their publications after completion of the program. First

author publications for the subset of CPRT T32 trainees appointed in 2000 are shown in Figure 21

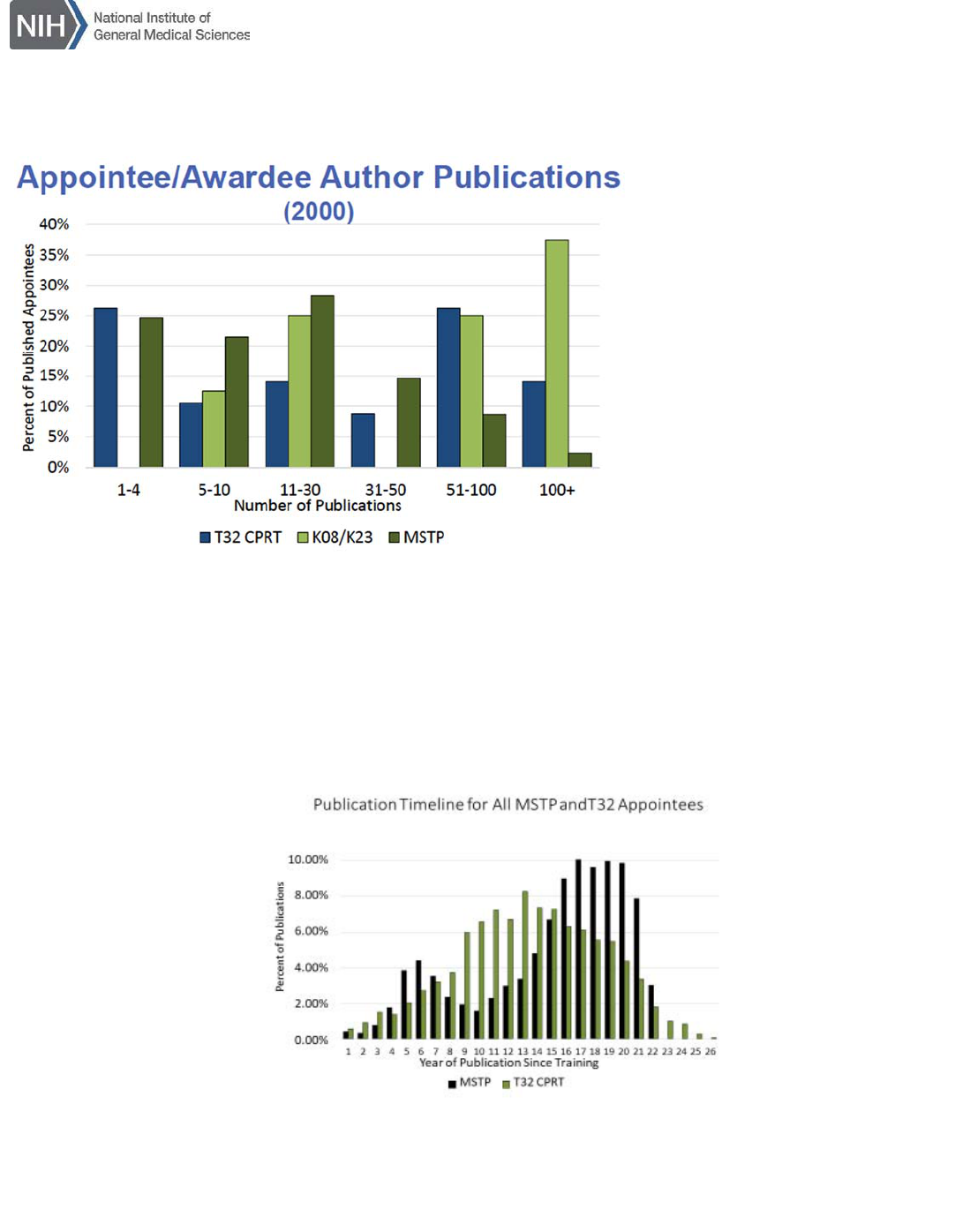

and total publications in Figure 22. Compared with K08/K23 and MSTP graduates, CPRT T32

trainees who publish have remarkably similar publication rates; this is surprising given their

significantly shorter training time (2 versus 4-5 years). These data also suggest K08/K23 grantees

have a somewhat higher number of publications compared with CPRT T32 and MSTP trainees.

Figure 23 shows publication time lines for both CPRT T32 and MSTP trainees. It should be

remembered that MSTP (MD-PhD) training occurs for 3-4 years during medical school and followed

by a hiatus where MSTP graduates complete clinical portions of medical school, residency and

sometimes fellowship; the bi-modal distribution of publications for MSTP graduates in Figure 23

shows this clearly. In contrast, T32 training usually comes at the end of residency or fellowship and

is most often 2 years in duration.

Question 4: Do trainees remain clinically in their area of research focus after research

training is completed?

YES. AAMC Faculty department membership in surgical disciplines, anesthesiology, emergency

medicine, medical genetics, and critical care medicine, indicate that CPRT T32 trainees are

overrepresented in the focus areas of this training program compared with MSTP trainees. Since

CPRT T32 research occurs during either residency, fellowship, or transition to faculty, clinical

aspects of trainee careers are generally set by the time they begin their T32 research experience.

What can change is the precise focus of research within those disciplines as a subset of trainees

move from mentored to independent investigators. The panel viewed this as healthy since science

9

changes continually and cutting-edge scientific approaches are then integrated into these clinical

disciplines.

Summary

Overall, NIGMS CPRT T32 programs demonstrate similar outcomes, in terms of grant

applications/awards, publications, and faculty status, as other postdoctoral T32s across the NIH.

Achievement of senior faculty status (%) also compares favorably with that of MSTP graduates.

Approximately 34% of all NIGMS postdoctoral T32 trainees ultimately apply for investigator-initiated

NIH research grants, with 54% of those applicants receiving subsequent NIH funding (≈20%

overall); those with at least one grant averaged 3.1 to 4.4 per trainee. This is approximately half

that achieved by individual K08 awardees. However, panel members cited the need for trainees to

generate data (often within the context of a postdoctoral T32 training program) to compete

successfully for K08/K23 or R01 funding. Panel members also noted that the impact of institutional

T32 training grants goes beyond supporting individuals, to positively influencing programs and

institutions in developing physician scientists. Given these data, the panel felt NIGMS T32

programs fulfill a critical niche in physician scientist research training not supported by other

categorical NIH Institutes.

Panel Recommendations

1. The panel recommends that NIGMS continue its support of the postdoctoral NRSA CPRT T32

programs and re-assess the emphasis of the programs in regard to changes in clinical research

and practice, as well as changes in financial obstacles to training of clinician scientists that have

occurred since the inception of the programs (e.g., income differential compared to clinical

pursuits). The issues for each research area have unique characteristics that need to be

considered individually.

2. NIGMS should define clear goals for its clinically focused research training programs (CPRT

T32, MSTP, K08/K23) and develop metrics than can be routinely collected by each CPRT

program and collectively by NIGMS for all CPRT programs. Such data could provide a basis for

measuring success and continuing enhancement for each program and for CPRT programs

overall. The committee felt that, if required, support for such data collection would be beneficial

for all institutional and individual training grant mechanisms.

3. Medicine and clinical research have evolved over the last 30 years; research technology, clinical

pressures and research areas have changed, and NIGMS should reexamine the focus areas of

these programs to ensure they are best serving the clinical research workforce needs.

Some suggestions:

Medical Genetics training has undergone significant changes including the establishment of

NHGRI, success of human genome study, introduction of genomic technology into the clinic,

and board certification. The Institute should explore with NHGRI areas of commonality with

the possibility of co-funding or the transfer of medical genetics training to NHGRI.

Broaden Trauma, Burn, and Injury to include emergency and critical care medicine (e.g.,

Trauma, Burn, Injury and Critical Care research)

10

Examine clinical pharmacology to see what it encompasses today (for example,

pharmacogenetics, systems biology, mathematical models, big data), current workforce

needs, and how this fits within the NIH. It is recommended that input be sought from

experts credentialed in this field.

Consider incorporating pain medicine more clearly within the Anesthesiology focus area.

4. Examine the feasibility of expanding loan repayment eligibility for this group of clinical

investigators in the 4 NIGMS focus areas, once updated. This is important since these trainees

fulfill critical niche in medical research not supported by other categorical NIH Institutes.

11

References

1. Physician-Scientist Workforce Working Group Report. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD,

June 2014 (https://acd.od.nih.gov/documents/reports/PSW_Report_ACD_06042014.pdf).

2. 2016 Physician Specialty Data Report. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC),

Washington, D.C., 2016 (see Table 1.1. Active Physicians in the Largest Specialties, 2015,

http://www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/458480/1-1-chart.html)

3. National MD-PhD Program Outcomes Study. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC),

Washington, D.C., April 2018 (https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/AAMC-National-MDPhD-

Program-Outcomes-Study-2018.pdf). See Figure 12 and Table 4 for data cited.

12

APPENDIX: Supporting Material

Figure 1: Timing of Postdoctoral T32 (CPRT) Programs Compared with Other Physician Research

Training Grants

Figure 2: Non-NIGMS T32 Postdoctoral Programs (1999-2003)

13

Figure 3: Trainees Participating in NIGMS T32 CPRT by Focus Area

Figure 4: Trainees Participating in NIGMS T32 CPRT by Year and Focus Area Over Time

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 5: Majority of NIGMS CPRT Postdoctoral T32 Trainees Are Physicians (73%)

Figure 6: Percent MD or MD-PhD versus PhD Trainees for Each Focus Area

[73% of T32 CPRT Trainees held a medical degree (MD)]

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 7: NIGMS CPRT T32 Programs Recruitment of Women to Science Training

Figure 8: NIGMS CPRT T32 Programs Recruitment of Under Represented Minorities to Science

Training

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 9: Board Certification and Faculty Status of CPRT T32 Trainees (1990-2016)

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 10: Degrees Of CPRT T32 Trainees Who Joined Academic Medical Faculty

Figure 11: Departments Joined As Faculty By CPRT T32 versus MSTP Trainees

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 12: Highest Academic Position for CPRT T32 versus MSTP

Figure 13: Schematic of NIGMS CPRT T32 Trainees Who Later Applied for NIH Funding

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 14: Distribution of NIGMS CPRT T32 Trainees Who Applied For NIH Funding By Focus

Area

Figure 15: Non-NIGMS T32 Program Trainees Who Submitted NIH Grants

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 16: Distribution of NIGMS CPRT T32 Trainees Who Received NIH Funding By Focus Area

Figure 17: Success Rate (Successful Applications / Total Applications by Focus) For NIGMS

CPRT T32 Trainees Who Received NIH Funding

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 18: Comparison of NIGMS CPRT T32 Trainees With Other NIH Training Pathways In

Terms of NIH Grant Applications and Funded Grants

Figure 19: Average NIH Awards For 5-6% of CPRT T32 Trainees Who Received Multiple NIH

Grants Over Their Career, By Focus Area

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 20: Number of T32 CPRT Trainees Who Received Any K Award, By Focus Area

Figure 21: First Author Publications Per Appointee By Training Mechanism (Year 2000)

T32ClinicalPostdoctoralResearchTraining(CPRT)Progra

m

EvaluationRepor

t

Figure 22: Total Publications Per Appointee By Training Mechanism (Year 2000)

Figure 23: Publication Timeline For All MSTP and T32 Trainees