MAY 2024 | FACT SHEET

1350 I STREET NW SUITE 700 WASHINGTON, DC 20005

Women and Families Struggle

with Child Care Following the

Federal Funding Cliff, But Fare

Better in States with Additional

State Funding for Child Care

Shengwei Sun

Under a crisis long in the making and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, child care remains

inaccessible and unaordable for many families with young children in the United States. Chronic

underinvestment in the child care system has resulted in child care costs being transferred to families in

the form of unaordable care and to early educators who subsidize the system with low wages.

To stabilize the child care sector during the pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), passed

by Congress and signed into law by President Biden in March 2021, included $24 billion in child care

stabilization grants and $15 billion in supplemental child care discretionary funds to states. The ARPA child

care stabilization funds provided critical support to child care programs, early educators, and families with

young children. However, the $24 billion Child Care Stabilization funds expired on September 30, 2023,

removing an essential support from early educators and families with young children. Another funding cli

is approaching in September of 2024, with $15 billion for the Child Care and Development Block Grant set

to expire, adding pressure to an already stretched industry.

Meanwhile, at least 11 states and the District of Columbia have dedicated signiicant new state funding

to grants to child care providers, programs to support their child care workforces, or other solutions

that directly support providers over the past two years. Recent data suggests that these state-level

investments provided critical relief for both early childhood educators and families with young children

following the expiration of the Child Care Stabilization grants.

1350 I STREET NW SUITE 700 WASHINGTON, DC 20005

2

A new National Women’s Law Center (NWLC) analysis of Census Household Pulse Survey data inds that the share of

respondents with children under 12 years old in their household who lacked child care increased by more than 5 percentage

points (from 17.8 percent to 23.1 percent) between fall 2023 and spring 2024 in states without signiicant additional state

funding to support the child care sector.

Additionally, in the 11 states and DC where signiicant additional state investments in child care programs and providers

have been made, the share of women respondents with children under age 12 who wanted to work but reported not

working for pay because they were caring for a child not in school or child care decreased from 45.3% to 31.9%.

This data reinforces the indings of a survey of more than 10,000 early childhood educators from all states and settings

conducted by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) in January 2024. In that survey, early

childhood educators reported challenges following the loss of federal funding last September, such as increased levels

of burnout among educators, sta shortages, rising operating costs for programs, and closures of child care programs

outnumbering openings in their communities. The NAEYC survey further found that in the 11 states and DC, where

additional investments have been made, early childhood educators signiicantly less often reported raising tuition or that

their program waitlist had grown in the previous six months.

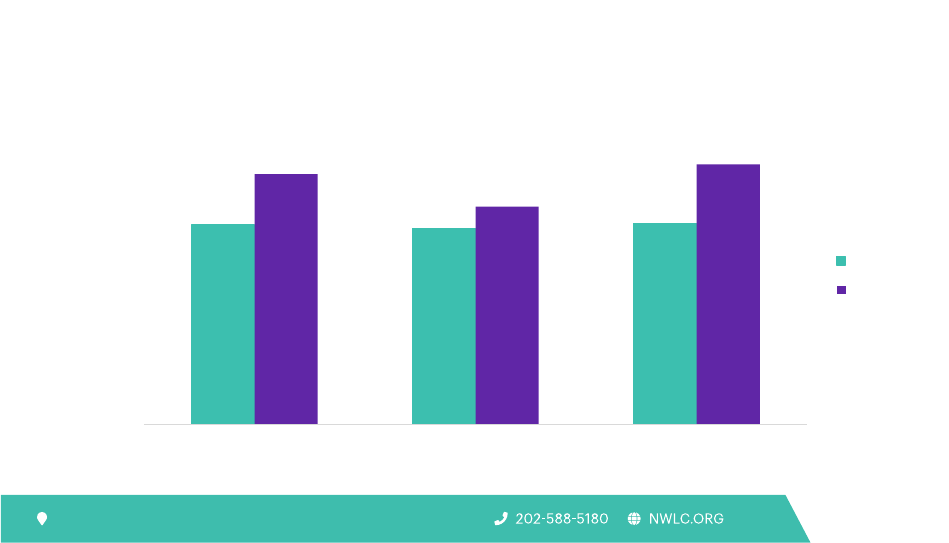

The Share of Parents Who Lacked Child Care in the Past Four Weeks Increased

after the Child Care Funding Cli in States Without Additional State Funding to

Support the Child Care Sector.

NWLC analysis of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey shows that among those with children under 12 years old

in the household, there was a signiicant increase in children not being able to attend child care. Speciically, the share of

respondents who reported that, at some point in the past four weeks, children in their household were unable to attend

child care as a result of child care being closed, unavailable, unaordable, or because they were concerned about their

child’s safety in care, increased nationwide from 17.7% in August-October 2023 to 22.2% in January-April 2024. Both women

and men experienced this increase.

Our analysis further shows that the increase in the share of parents with children under age 12 who reported not having

child care at some point in the past four weeks is concentrated in the states without signiicant additional state funding for

child care, increasing from 17.8% to 23.1%. In comparison, the change in the share of parents reporting not having child care

in the past four weeks in the 11 states and DC with additional state funding for child care programs and providers is smaller

in magnitude and is not statistically signiicant.

17.7%

17.4%

17.8%

22.2%*

19.3%

23.1%*

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

Overal l In states providing significant

additional funding for child care

In states not providing significant

additional funding for child care

Share with children under age 12 who reported not having child

care in the past 4 weeks

Aug-Oct 2023

Jan-Apr 2024

1350 I STREET NW SUITE 700 WASHINGTON, DC 20005

3

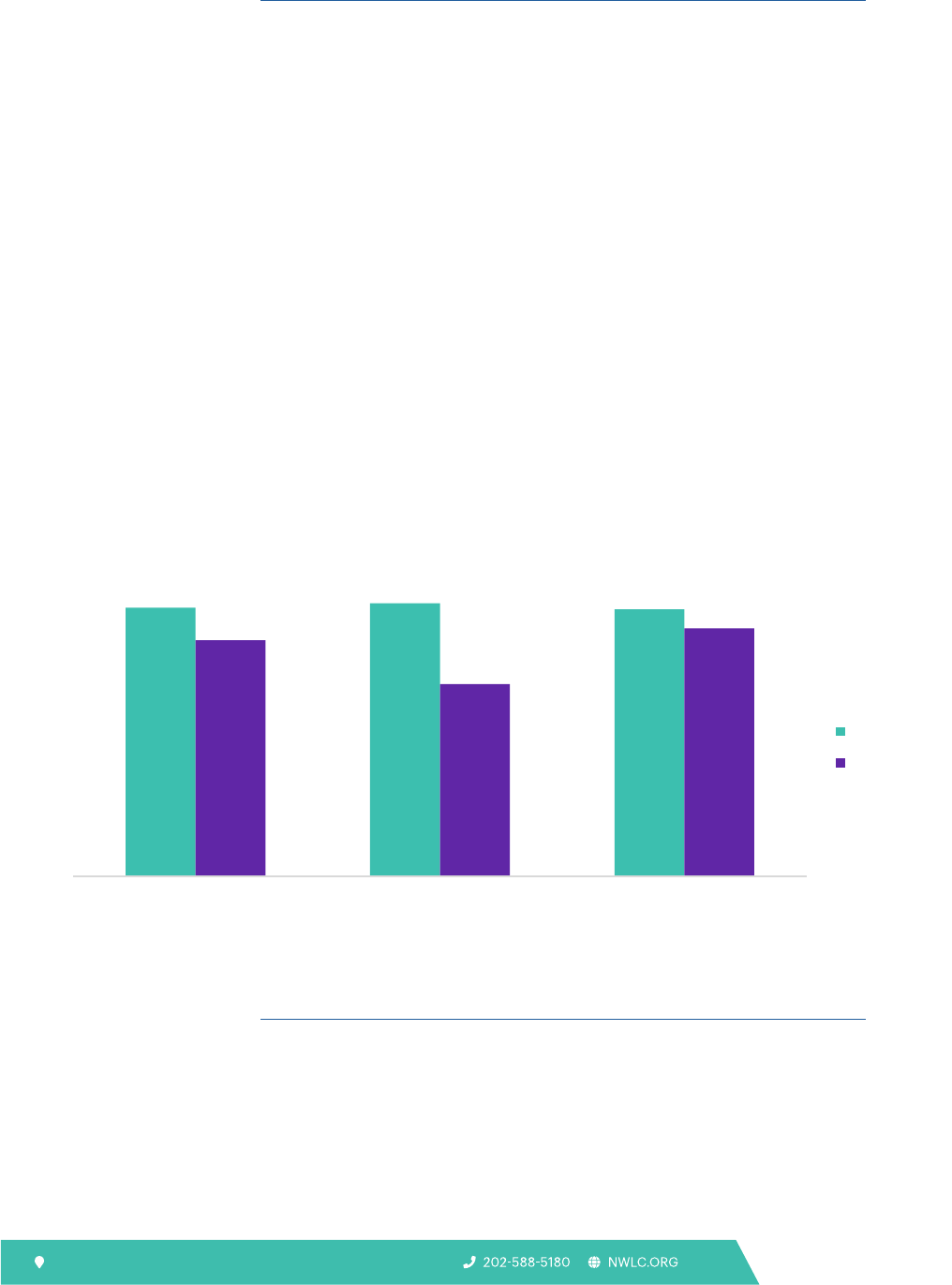

The Share of Women Who Wanted to Work but Reported Not Working for Pay Due

to Child Care Decreased in States That Dedicated Additional State Funding to

Support the Child Care Sector.

Having child care support is critical for parents’ ability to earn an income and for families’ economic security, especially for

women who shoulder disproportionate caregiving responsibilities.

About two in ive (44.6% in fall 2023 and 39.1% in spring 2024; the dierence is not statistically signiicant) women

respondents with children under 12 years old who wanted to work for pay reported not working for pay in the past seven

days because they were caring for a child not in school or child care. However, in the 11 states and DC with signiicant

additional state funding for the child care sector, the share of women respondents who reported so signiicantly decreased

between fall 2023 and spring 2024, from 45.3% to 31.9%.

Source: NWLC calculations based on August 23—October 30, 2023 (Phase 3.10) and January 9—April 1, 2024 (Phase 4.0) of the U.S. Census

Bureau Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau, “Measuring Household Experiences During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic,

2020-2024 Household Pulse Survey,” https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html, accessed April

18, 2024. The analytic sample is restricted to women with children under 12 years old in their household who did not work for pay in the last

7 days but wanted to work. Those who retired or did not want to be employed were excluded from the sample. Calculations for men are not

included due to insuicient sample sizes.

*Statistically signiicant dierence between August-October 2023 and January-April 2024 (p < 0.01).

44.6%

45.3%

44.3%

39.1%

31.9%*

41.1%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

Overal l In states providing significant

additional funding for child care

In states not providing significant

additional funding for child care

Share of Women Who Wanted to Work But Reported Not Working for

Pay in the Last 7 Days Because They Were Caring for a Child Not in

School or Child Care

Aug-Oct 2023

Jan-Apr 2024

Source: NWLC calculations based on August 23—October 30, 2023 (Phase 3.10) and January 9—April 1, 2024 (Phase 4.0) of the U.S. Census

Bureau Household Pulse Survey. U.S. Census Bureau, “Measuring Household Experiences During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic,

2020-2024 Household Pulse Survey,” https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html, accessed April

18, 2024. The analytic sample is restricted to respondents with children under 12 years old in their household.

*Statistically signiicant dierence between August-October 2023 and January-April 2024 (p < 0.01).

1350 I STREET NW SUITE 700 WASHINGTON, DC 20005

4

The author would like to thank Melissa Boteach, Karen Schulman,

Whitney Pesek, Sarah Javaid, Kathryn Domina, Jasmine Tucker,

Sydney Petersen, Eun Kim, Delaney Wallace, and Sarah Yergeau

for their review, design, and dissemination of this fact sheet.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

****

1 American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 31, 207 (2021).

2 The White House Council of Economic Advisers Working Paper, “Did Stabilization Funds Help Mothers Get Back to Work After the COVID-19 Recession?” (November 7, 2023), https://www.whitehouse.

gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Child-Care-Stabilization.pdf.

3 In addition to the District of Columbia, these 11 states include Alaska, California, Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Vermont, Washington, and New Mexico. See Julie

Kashen and Laura Valle-Gutierrez, “With Arrival of Child Care Cli, Some States Have Stepped in to Save the Sector” (The Century Foundation, January 2024), https://tcf.org/content/report/with-arrival-

of-child-care-cli-some-states-have-stepped-in-to-save-the-sector/.

4 Unless otherwise noted, all numbers appeared in this fact sheet are from NWLC analyses of U.S. Census Bureau, “Measuring Household Experiences During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic,

Household Pulse Survey,” Census.gov, https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-dataproducts/household-pulse-survey.html. As a Census Bureau’s experimental data product, the Household

Pulse Survey was designed to quickly and eiciently collect data regarding household’s experiences during the pandemic. The survey was conducted virtually, and the overall response rates are

signiicantly lower than most federally sponsored surveys, raising concerns about nonresponse bias (For more on nonresponse bias for the 2020 Household Pulse Survey, see https://www2.census.

gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_NR_Bias_Report-inal.pdf). Other potential sources of error of the Household Pulse Survey data include measurement, coverage,

processing, and item nonresponse. All results in this analysis should therefore be interpreted with caution.

5 All comparative statements in this factsheet have undergone statistical testing and are statistically signiicant at the 90 percent conidence level.

6 The Census Household Pulse Survey uses the term “daycare” whereas NWLC uses “child care.”

7 National Association for the Education of Young Children, “‘We Are NOT OK’: Early Childhood Educators and Families Face Rising Challenges as Relief Funds Expire” (February 2024), https://www.

naeyc.org/sites/default/iles/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/feb_2024_brief_wearenotok_inal_1.pdf.

CONCLUSION

The data underscores that the child care crisis is a policy choice and that public funding works. However, access to child

care shouldn’t depend on a family’s zip code and state funding alone is not enough. The federal government must secure

robust funding to ensure that every family across the country can access aordable child care.

As the nation faces another federal child care funding cli in September 2024, it is more important than ever that

policymakers inally make the long overdue investments in child care that families and early educators need and deserve—

and that is essential to our economy. In the long run, sustained and robust federal public investment is critical for

transforming the child care system so that all families have access to child care that meets their needs and early educators

are fairly compensated and supported.