1

Implementing a Fair

Workweek Law in Illinois

Protecting Frontline Workers

from Unpredictable Schedules

February 14, 2022

Grace Dunn

Frank Manzo IV, MPP

Larissa Petrucci, PhD

Robert Bruno, PhD

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

i

Executive Summary

Fair workweek laws, also called predictive scheduling laws, have been implemented in Oregon and seven

municipalities—including the City of Chicago—to protect workers from unstable scheduling practices.

Implemented in June 2020, Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance covers workers at large employers in

seven essential and face-to-face industries: building services, health care, hotels, manufacturing,

restaurants, retail trade, and warehouse services industries. This report investigates the potential impact

of expanding this ordinance to become a statewide policy in Illinois.

Research has found that erratic scheduling practices negatively affect workers’ well-being and

disproportionately afflict Hispanic and Black workers.

• Job satisfaction, worker health, and overall well-being are lower among workers who work

irregular, unpredictable shifts.

• 44 percent of Hispanic workers have less than 15 days of advance notice of their work schedules

and 37 percent of Black workers have less than 15 days advance notice of their work schedules.

• Fair workweek laws typically include “Advance Notice” standards to ensure that employers

provide employees their schedules a set number of days before the workweek begins as well as

“Predictability Pay” when employers make last-minute adjustments to employees’ schedules.

After Oregon implemented its Fair Workweek Act to expand protections to 172,000 workers in the

retail, food service, and accommodations industries, worker outcomes improved.

• Workers reported improvements in rest times between shifts and advance notice of schedules.

• The weekly earnings of affected workers increased by 5 percent and underemployment decreased

by 1 percent, relative to the rest of the United States.

• Directly affected employers with 500 or more employees have seen worker turnover decrease

and stable employment increase, relative to national average.

Implementing a statewide fair workweek law that extends the Chicago Fair Workweek to large

businesses would protect up to 1.6 million essential and frontline workers in Illinois.

• A fair workweek law would disproportionately benefit women (54 percent), Hispanic workers (30

percent), and Black workers (12 percent).

• Of those workers who would be directly affected, 69 percent do not have college degrees and 44

percent earn less than $15 per hour.

• While jobs for high-wage Illinois workers have increased by 4 percent since January 2020, jobs for

low-wage Illinois workers are still 18 percent below their pre-pandemic levels.

• Many workers who would be protected by the law—especially those in accommodation and food

services—have been unable to work for extended periods of time due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

• The law could help make jobs in essential and face-to-face industries more attractive and improve

worker retention by promoting workforce stability, which reduces turnover costs for employers.

The implementation of a fair workweek law would protect more than one million Illinois workers from

unstable scheduling practices. These workers are disproportionately women and people of color.

Implementing a fair workweek law would increase job satisfaction and overall well-being, improve rest

between shifts and advance notice of work schedules, and produce higher wages and less

underemployment—helping to address labor shortages for directly affected businesses in Illinois’

essential and face-to-face industries.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

ii

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

i

Table of Contents

ii

About the Authors

ii

Introduction

1

Background Research on Fair Workweek Laws

2

Early Economic Impacts of Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act

4

A Fair Workweek Law Would Protect More than One Million Workers in Illinois

7

Conclusion and Recommendations

12

Sources

13

Cover Photo Credits

14

About the Authors

Grace Dunn is a Research Associate at the Illinois Economic Policy Institute. She earned a Bachelor of Arts

in Public Policy from the University of Michigan Ford School of Public Policy and a Minor in Writing. She

can be contacted at gdunn@illinoisepi.org.

Frank Manzo IV, M.P.P. is the Executive Director of the Illinois Economic Policy Institute. He earned a

Master of Public Policy from the University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy and a Bachelor of Arts

in Economics and Political Science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He can be

contacted at fmanz[email protected]rg.

Larissa Petrucci, Ph.D. is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Project for Middle Class Renewal at the

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She earned a Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology from the

University of Oregon, a Master of Arts in Sociology from the University of Oregon, and a Bachelor of Arts

in Sociology from San Francisco State University. She can be contacted at [email protected].

Robert Bruno, Ph.D. is a Professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Labor and

Employment Relations and is the Director of the Project for Middle Class Renewal. He earned a Doctor of

Philosophy in Political Theory from New York University, a Master of Arts from Bowling Green State

University, and a Bachelor of Arts from Ohio University. He can be contacted at [email protected].

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

1

Introduction

Unpredictable schedules and unstable hours are major issues for many workers in the United States,

especially those in low-wage sectors (Golden, 2015). In general, unpredictable scheduling practices

hamper employees’ abilities to pursue supplemental work and education, to budget, and to schedule

routine necessities like childcare or doctor’s appointments while causing psychological distress for

families (Henly & Lambert, 2014; Schneider & Harknett, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic compounded

economic inequities for workers in essential and face-to-face industries who earn lower wages and

experience high job volatility. Furthermore, the national labor shortage in sectors like leisure and

hospitality has reaffirmed the need to review and update work schedule standards (Manzo & Bruno, 2020;

Bivens & Shierholz, 2021).

In 1938, Congress created the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) to create universal workplace standards

and define employers’ obligations to their employees (FLSA, 2011). As the arrangements in the modern

workplace have changed, so has the need to update labor standards to reflect today’s economy. In 2014,

San Francisco became the first city in the United States to pass ordinances regulating unpredictable

schedules for hourly workers (Taylor, 2021). Since then, multiple states and municipalities have enacted

or begun to enact fair workweek laws—also known as predictive scheduling laws—to extend FLSA

protections and prevent the negative workforce and family outcomes that researchers have linked with

erratic scheduling.

Predictive scheduling laws have been implemented in one state, Oregon, as well as at least seven

municipalities: New York City, San Jose, Seattle, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Emeryville (California), and

Chicago (NWLC, 2019). At the federal level, U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren and U.S. Representative Rosa

DeLauro have introduced predictive scheduling legislation with their Schedules That Work Act to provide

fair work hour stipulations nationally (The Office of Senator Elizabeth Warren, 2019).

Most fair workweek legislation covers hourly workers in the retail trade, food service, or hospitality

industries. The smallest businesses are generally not included due to minimum employee size provisions.

However, Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance, implemented in July 2020, is one of the most expansive

ordinances to date covering seven different industries: building services, health care, hotels,

manufacturing, restaurants, retail trade, and warehouse services (BACP, 2021a). Workers employed in

covered industries are protected if they work for an employer that has 100 or more employees, or for a

nonprofit organization that has 250 or more employees. Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance not only

covers more industries than most predictive scheduling laws, but it also applies to hourly employees who

earn less than $26 per hour or salaried employees who earn less than $50,000 per year. “Temp workers”

on assignment for 420 hours within an 18-month period are also covered (BACP, 2021a).

This study, conducted by the Illinois Economic Policy Institute and the Project for Middle Class Renewal at

the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, investigates the effects of the nation’s lone statewide

predictive scheduling law and the potential impact of expanding Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance to

become a statewide policy in Illinois.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

2

Background Research on Fair Workweek Laws

According to a research study published in the American Sociological Review, routine instability leads to

psychological distress, poor sleep quality, and unhappiness—and the association is stronger with routine

instability than it is with low wages (Schneider & Harknett, 2019). Predictive scheduling laws aim to reduce

these outcomes by implementing a series of protections to prevent unpredictable scheduling practices.

These include Advance Notice, Access to Hours, Predictability Pay, Right to Request, and Right to Rest.

Advance Notice standards ensure that employers provide employees their schedules a set number of days

before the workweek begins. Employees who are provided more advance notice of their work schedules

report lower levels of income volatility (Schneider & Harknett, 2017). According to the 2017-2018

American Time Use Survey, the average number of days of advance notice for workers varies greatly by

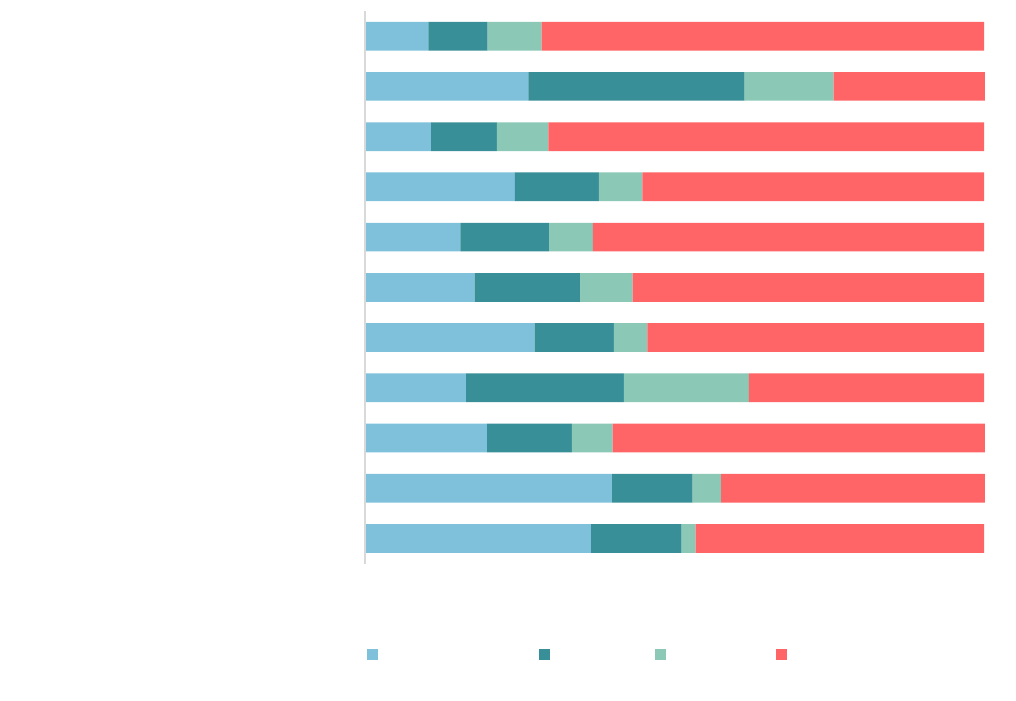

racial or ethnic background. On average, 44 percent of all workers of Hispanic or Latinx ethnicity in the

United States had less than 15 days of advance notice of their work schedules (Figure 1). This number was

slightly lower for Black or African American workers at 37 percent (Figure 1).

Figure 1: How Far in Advance Workers Knew Their Work Schedules by Race, 2017-2018 Averages

Source(s): Author’s analysis of the 2017-2018 American Time Use Survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2019).

The lack of advanced notice is even more problematic when looking at specific industries. In the United

States, routine uncertainty of work schedules is more pronounced for workers in the leisure and

hospitality industry and in wholesale and retail trade. On average, 61 percent of workers in the leisure

and hospitality industry and 42 percent of workers in the wholesale and retail trade industry had less than

15 days of advance notice of their work schedules (Figure 2). Both industries are typically targeted in

predictive scheduling laws. In construction, 53 percent of workers have less than 15 days of advance

notice of their work schedules, but this industry is usually not included in predictive scheduling laws.

Fair workweek laws also protect weekly hours worked for employees in covered industries. Access to

Hours provisions ensure that employers first offer additional hours of work to their qualified existing

employees before hiring additional employees. This is designed to help curb underemployment (NWLC,

2019). Workers experience “underemployment” when they want and are available to work full-time but

are instead working part time for economic reasons such as their hours being cut back or when they are

13.8

18.6

17.8

23

20.8

19

16.1

15.4

21.2

16.6

14.5

9.4

10.2

7.3

9.3

52.8

55.9

56.6

48.5

53.3

0 20 40 60 80 100

Asian

White

Non-Hispanic or Latino

Hispanic or Latino ethnicity

Black or African American

Percent of Workers Who Knew Their Work Schedules in Advance

Less than 1 week 1-2 weeks 2-4 weeks 4 or more

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

3

employed in occupations that do not efficiently utilize their skills, level of educational attainment, or

experience. Underemployment disproportionately afflicts Black and Latinx workers, women, and part-

time workers (Golden & Kim, 2020). When employers make last-minute adjustments to employees’

schedules, such as reduced hours or changes to work shifts, Predictability Pay provisions require

employees be compensated for changes. In the Chicago Fair Workweek Ordinance, 1 hour of Predictability

Pay is required for any shift change within 10 days (BACP, 2021a). Right to Request provisions protect

employees who want to request schedule changes without fear of retaliation from their employers.

Vermont and New Hampshire have enacted right to request provisions statewide.

Figure 2: How Far in Advance Workers Knew Their Work Schedules by Industry, 2017-2018 Averages

Source(s): Author’s analysis of the 2017-2018 American Time Use Survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2019).

Finally, Right to Rest standards guarantee that employers will provide a minimum amount of time

between shifts. This protects employees from being overworked and from working “clopening” shifts—

which are when employees work the closing shift followed by the opening shift just a few hours later.

Employees who consent to work without the minimum rest time are paid at a higher rate when Right to

Rest standards are in place. This provision often includes a “good faith” estimate of what expected hours

are when an employee first starts a job (NWLC, 2019). Oregon is the only state to have implemented all

five of these work scheduling standards statewide.

36.5

39.9

19.7

16.3

27.4

17.7

15.4

24.2

10.7

26.4

10.2

14.6

13.0

13.7

25.5

12.8

17.0

14.3

13.6

10.6

34.9

9.6

2.3

4.6

6.6

20.2

5.4

8.5

7.1

7

8.3

14.4

8.7

46.6

42.6

60.1

38.0

54.4

56.8

63.2

55.2

70.4

24.4

71.5

0 20 40 60 80 100

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting

Construction

Manufacturing

Wholesale and Retail Trade

Transportation and Utilities

Information

Financial Activities

Professional and Business Services

Education and Health Services

Leisure and Hospitality

Public Administration

Percent of Workers Who Knew Their Work Schedules in Advance

Less than 1 week 1-2 weeks 2-4 weeks 4 or more

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

4

Early Economic Impacts of Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act

The Oregon Fair Workweek Act is the only predictive scheduling law to be implemented statewide.

Oregon’s law applies to employees in the retail, hospitality, or food service industries. It covers employees

in the private sector and does not include salaried individuals. Employers must employ 500 or more

employees worldwide for the law to apply (BOLI, 2021). Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act is estimated to cover

approximately 172,000 workers (Wolf et al., 2018).

Tenets of Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act require employers to provide a “good faith estimate” of work

schedules upon hiring. This good faith estimate includes the median number of hours an employee can

work in a month. Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act also includes voluntary standby lists. Voluntary standby

lists allow employees to be placed on “standby” for on-call scheduling to show they would like additional

hours without compensation for last-minute schedule changes through Predictability Pay.

The Oregon Fair Workweek Act was progressively implemented over two years. The first part of the law

went into effect on July 1, 2018 and required qualifying employers to provide good faith estimates of the

work schedule, voluntary standby lists, 7 days of advance notice of work schedule, rest between work

shifts, input into work schedule, and compensation for schedule changes. The second part of the law, the

creation of a right of enforcement filing a lawsuit with Oregon’s Bureau of Labor and Industries (BOLI),

went into effect on January 1, 2019. As of July 1, 2020, the final element of Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act

was implemented. Employees must now receive 14 days of advance notice of work schedules instead of

the previous 7 days’ notice (BOLI, 2021).

A study by researchers at the University of Oregon assessed the efficacy of Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act

by conducting in-depth interviews with 75 workers and 23 managers and schedulers in businesses across

the state. The researchers found that there were some improvements in scheduling due to the law.

Workers mainly reported experiencing Right to Rest between shifts, the Right to Request, and Advanced

Notice of work schedules. However, while the study found that Advance Notice standards did result in

more frequent advance notices of schedules, workers were still experiencing last-minute scheduling

changes as a result of understaffing (Loustaunau et al., 2020).

Managers were also encouraged to find ways to avoid Predictability Pay, made possible by provisions in

the law that gave workers the option to waive their right to Predictability Pay (Loustaunau et al., 2020).

Allowed under the law, employers created voluntary standby lists and one-off waivers to avoid

compensating their workers with Predictability Pay. Employers have also relied on their own

interpretations of the law to force workers to “volunteer” for schedule changes in order to avoid

Predictability Pay. Nevertheless, despite language in the law that facilitated these policy circumventions,

workers did note an improvement in scheduling.

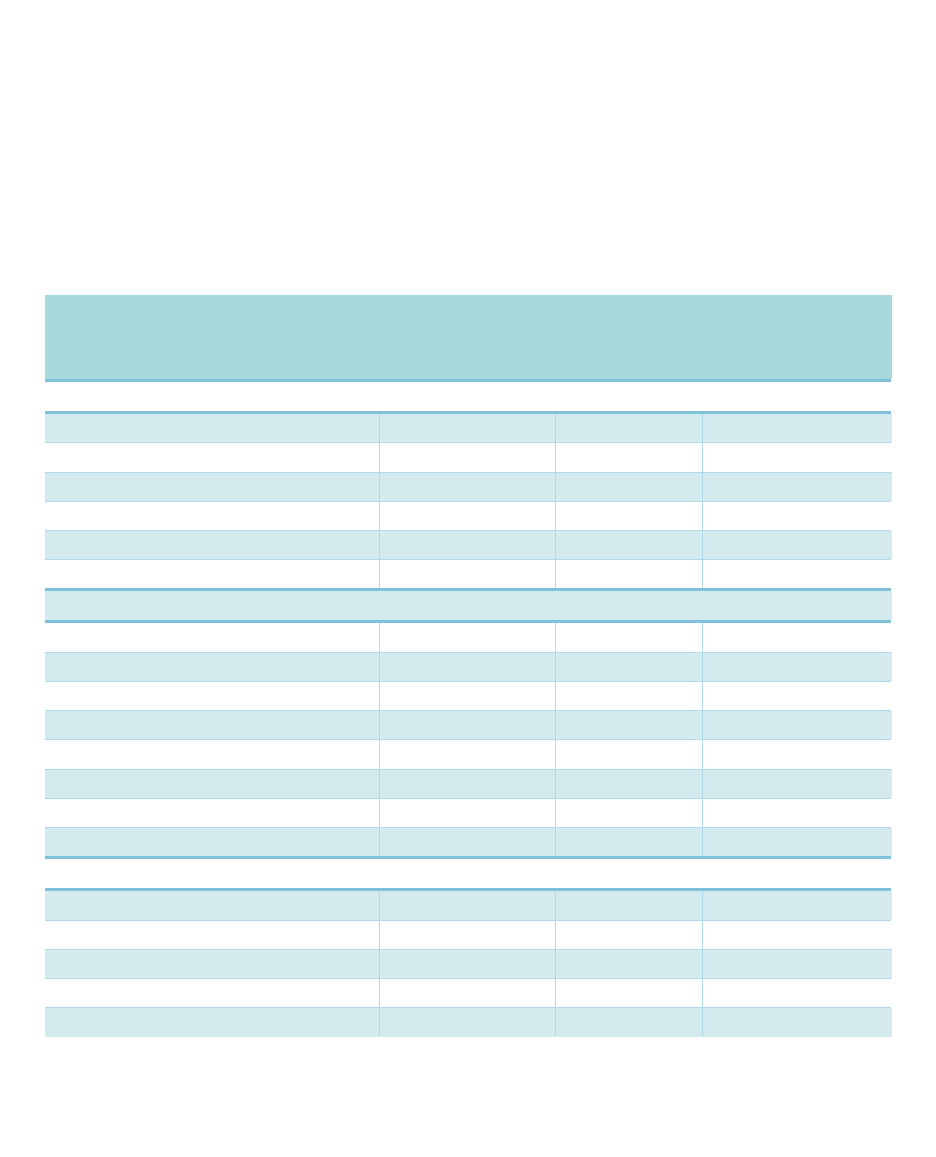

Figure 3 assesses the labor market outcomes of Oregon workers who are paid by the hour and employed

in either the retail trade industry or the accommodation and food services industry against their

counterparts in all other U.S. states. The data come from the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation

Groups (CPS-ORG), a monthly survey conducted jointly by the U.S. Department of Labor and U.S. Census

Bureau that is used to measure various economic outcomes, from state unemployment rates to annual

union membership rates (EPI, 2021). A total of 30 months of data from January 2016 through June 2018

is compared with 30 months of data from July 2018 through December 2020 to assess outcomes before

and after Oregon implemented its Fair Workweek Act.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

5

The data reveal positive impacts for retail workers and accommodation and food services workers who

are paid by the hour in Oregon since enactment of the Fair Workweek Act (Figure 3). On average, these

hourly workers experienced an increase in their hourly earnings from about $16 per hour to $19 per hour,

a gain of 18 percent. By comparison, their counterparts in the rest of the United States saw their wages

rise by just 12 percent, a difference of 6 percent. Similarly, the median worker saw his or her hourly

earnings rise by 19 percent to $15 per hour in Oregon after the law compared to just a 15 percent increase

to $14 per hour in the rest of the United States, a difference of 4 percent. Hours worked by employees

were generally unchanged in both areas but were about 2 percent lower for hourly workers in Oregon’s

retail trade and accommodation and food services industries relative to their peers in all other states.

Despite this hours differential, the workers covered by Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act experienced a 17

percent income boost per week ($98) on average compared with just 12 percent ($75) for their

counterparts in the rest of the United States, a 5 percent difference. These data suggest that Oregon’s

Fair Workweek Act helped close the gap in wages between Oregon’s retail trade and food services workers

and their counterparts in the rest of the United States.

1

Furthermore, the share of hourly workers in these

covered industries who were underemployed—or involuntarily employed part-time for economic

reasons—fell further in Oregon than in the rest of the United States, indicating that the policy may have

contributed to a 0.6 percent drop in underemployment in Oregon (Figure 3).

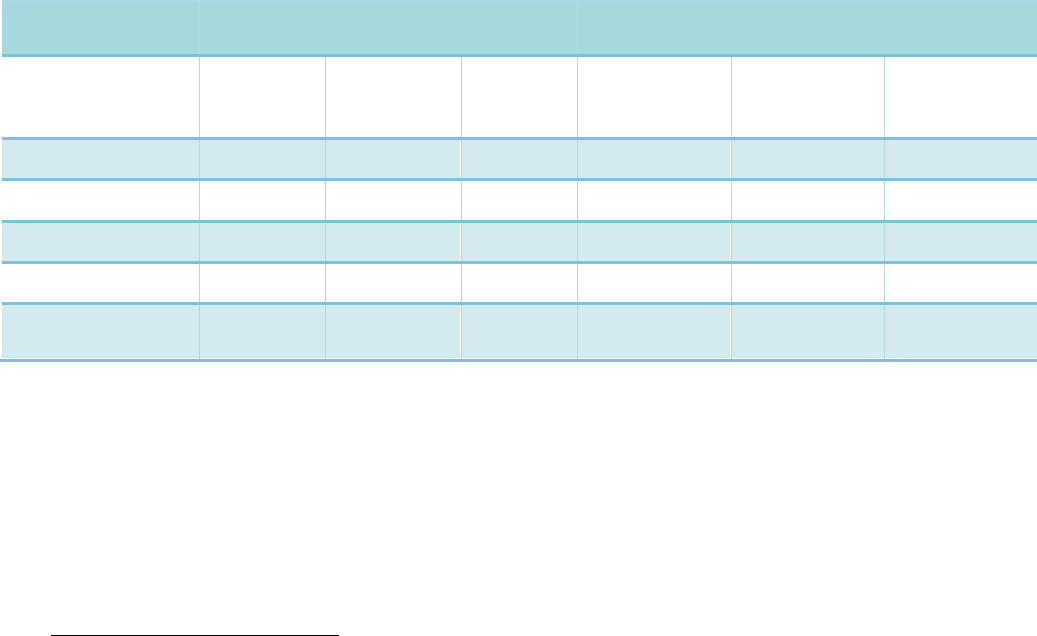

Figure 3: Labor Market Outcomes in Covered Industries Before and After Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act

Hourly

Workers

Oregon: Retail Trade, Accommodation,

and Food Services Paid by the Hour

All Other States: Retail Trade, Accommodation,

and Food Services Paid by the Hour

Labor Market

Outcome

30-Month

Average

Pre-Policy

30-Month

Average

Post-Policy

Difference

30-Month

Average

Pre-Policy

30-Month

Average

Post-Policy

Difference

Average Wage

$16.21

$19.14

+18.1%

$17.13

$19.13

+11.7%

Median Wage

$12.59

$15.00

+19.2%

$12.50

$14.40

+15.2%

Hours Worked

35.8

35.5

-1.0%

35.8

36.0

+0.6%

Weekly Wages

$580.86

$679.02

+16.9%

$613.53

$688.97

+12.3%

Underemployed

Workers

8.4%

7.4%

-1.1%

7.1%

6.6%

-0.5%

Source(s): Author’s analysis of 2016-2020 Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Groups (CPS-ORG) data from the U.S.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (EPI, 2021).

Figure 4 further explores labor market changes for affected Oregon workers in the retail trade industry

and the accommodation and food services industry. The data come from Quarterly Workforce Indicators

collected and released by the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD)

program (LEHD, 2021). While the dataset includes all workers employed in these industries and is not

limited to just hourly employees, it does allow researchers to evaluate changes by the size of business

establishments, including those with 500 or more employees who are directly covered by Oregon’s policy.

1

Though not shown, retail trade workers and accommodation and food services workers in Illinois earned $17.43 per hour and

worked 35.5 hours per week in the 30 months prior to Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act and earned $19.64 per hour and worked 35.4

hours per week in the 30 months after (EPI, 2021). Wage growth for these workers in Illinois (+12.7 percent) has been slightly

faster than the rest of the United States’ but slower than Oregon’s. The change in hours for these Illinois workers (-0.3 percent)

also falls between the changes for Oregon for the rest of the United States.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

6

Six quarters (18 months) of data from the first quarter of 2017 through the second quarter of 2018 before

Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act are contrasted with six quarters (18 months) of data from the third quarter

of 2018 through the fourth quarter of 2019, which was during the phased implementation of Oregon’s

Fair Workweek Act.

2

At directly affected establishments in covered industries, Oregon has again fared better than their

competitors throughout the United States (Figure 4). The quarterly turnover rate of accommodation and

food services employees at large businesses increased by 0.4 percent in Oregon but rose by 1 percent in

similar establishments nationwide, a difference of -0.6 percent. For retail trade employees at

establishments with 500 or more workers, the worker turnover rate fell by 0.1 percent in Oregon but was

unchanged (0 percent) nationally, a difference of -0.1 percent. While the quarterly turnover rate did not

change significantly, the data indicate that the predictive scheduling law reduced worker turnover relative

to the national average.

The implementation of Oregon’s Fair Workweek Law also had no negative impact on employment for

directly affected businesses in covered industries (Figure 4). The number of stable jobs—or jobs held on

both the first and last day of the quarter with the same employer—increased by 6 percent at

accommodation and food services establishments with 500 or more employees in Oregon. By contrast,

they only increased by 2 percent for comparable large businesses nationwide, a difference of 4 percent.

Similarly, while stable jobs at large retailers decreased by 1 percent in Oregon during implementation of

the predictive scheduling law, they fell by nearly 2 percent nationwide, a difference of 1 percent.

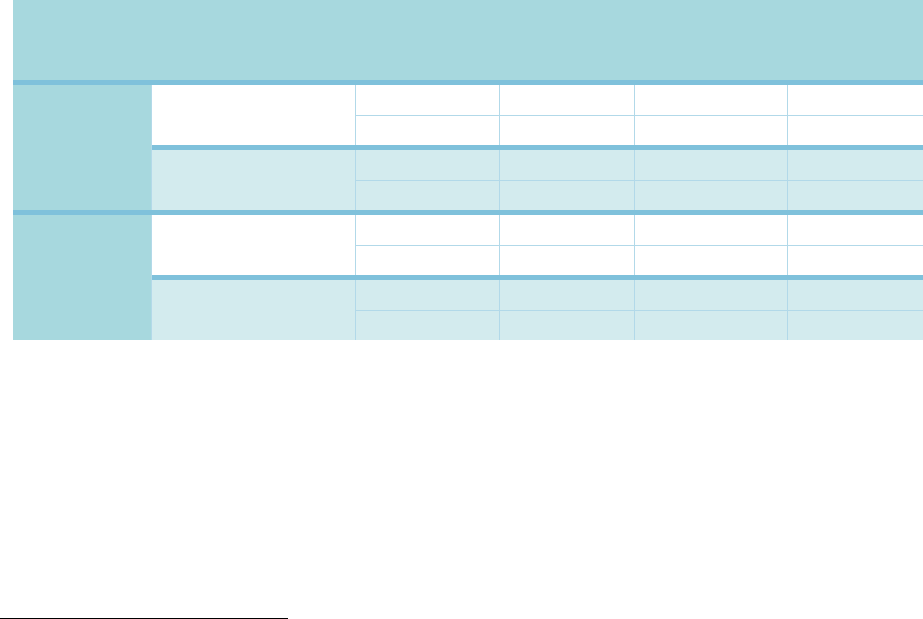

Figure 4: Worker Turnover Rates and Stable Employment in Large Establishments in Covered

Industries Before and After Oregon’s Fair Workweek Act

Large Establishments with

500 or More Employees

6-Quarter

Average

Pre-Policy

6-Quarter

Average

Post-Policy

Difference

Quarterly

Turnover

Rates

Accommodation

and Food Services

Oregon

14.6%

15.0%

+0.4%

United States

14.0%

15.0%

+1.0%

Retail Trade

Oregon

10.4%

10.4%

-0.0%

United States

10.9%

11.0%

+0.1%

Stable

Employment

Accommodation

and Food Services

Oregon

36,200

38,382

+6.0%

United States

4,144,744

4,213,402

+1.7%

Retail Trade

Oregon

106,215

105,182

-1.0%

United States

8,815,484

8,663,405

-1.7%

Source(s): Author’s analysis of 2017-2019 Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI) from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Longitudinal

Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD) program (LEHD, 2021). Note that percent values may not sum perfectly due to rounding.

The data suggest that the Fair Workweek Act has modestly improved labor market outcomes for workers

in Oregon without significantly affecting businesses in the state. The law expanded coverage to

approximately 172,000 workers who have reported improvements in rest times between shifts and

advanced notice of work schedules (Wolfe et al., 2018; Petrucci et al., 2021). At the same time, the weekly

earnings of affected workers have increased by 5 percent and underemployment has fallen by 0.6 percent

in Oregon relative to the rest of the United States. Finally, at directly affected employers with at least 500

employees, quarterly worker turnover has decreased by as much as 0.6 percent and stable employment

2

Note that 2020 was not included because data on turnover rates were not yet available during the time of the analysis.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

7

has increased by as much as 4 percent. Accordingly, while some business groups are opposed to fair

workweek legislation, there is no evidence that the policy has caused businesses to lay off workers in

Oregon (e.g., see Elejalde-Ruiz, 2019). Instead, the policy could be used by employers as a way to attract

workers back into industries hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic and retain those workers, reducing

turnover costs that negatively affect companies’ bottom lines (Boushey & Glynn, 2012).

A Fair Workweek Law Would Protect More than One Million Workers in Illinois

Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance is one of the most expansive ordinances to date, covering seven

different industries: building services, health care, hotels, manufacturing, restaurants, retail trade, and

warehouse services. Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance applies to hourly employees who earn less than

$26 per hour and salaried employees who earn less than $50,000 per year. Workers are covered if their

employer has at least 100 employees globally or at least 250 employees and 30 locations for certain

restaurants or at least 250 employees for nonprofit organizations.

Figure 5: Estimated Number of Workers Covered Under a Potential Fair Workweek Act in Illinois, 2019

Industry

Total Industry

Employment

Share of Workers

in Firms with

250+ Employees

Nonsupervisory

Share of

Employment

Total

Covered

Workers

Manufacturing

585,894

65.3%

69.9%

267,394

Retail Trade

587,163

68.2%

85.4%

341,646

Accommodation and

Food Services

528,446

43.0%

88.2%

200,680

Warehouse Services

(and Transportation)

281,410

71.2%

87.4%

175,047

Health Care (and

Social Assistance)

780,949

59.7%

88.3%

411,527

Building Services

(Administrative and

Waste Services)

438,704

66.3%

89.0%

259,043

Estimated Workers

Covered by Policy

1,655,337

Total Employees

in Illinois

5,995,905

Estimated Share

Covered by Policy

27.6%

Source(s): Authors’ analysis of 2019 Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI) data from the U.S. Census Bureau (Census, 2021), 2019

Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2021), and 2019 Current

Employment Statistics from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2021).

To calculate the number of workers who would be covered if Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance was

implemented statewide, total employment levels in manufacturing, retail trade, accommodations and

food services, warehouse services, health care and social assistance, and building services industries, as

reported in the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages for 2019, are multiplied by the share of each

industry’s workforce in firms with 250 or more employees nationwide from Quarterly Workforce

Indicators data for 2019. The resulting numbers for each industry are subsequently multiplied by the share

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

8

of workers in their respective sectors who are employed in nonsupervisory positions using 2019

information from the Current Employment Statistics dataset (Figure 5).

Estimates on the number of workers who would be protected by a fair workweek law in Illinois are

presented in Figure 5. Assuming that all nonsupervisory workers employed at establishments or franchises

with at least 250 employees would be covered regardless of income level, a statewide fair workweek law

would protect 1.6 million workers in Illinois, or 28 percent of the total workforce in Illinois. This includes

412,000 workers in health care, 342,000 workers in retail, 267,000 workers in manufacturing, 259,000

workers in building services, 201,000 hotel and restaurant workers, and 175,000 warehouse workers.

Figure 6: Demographic, Education, and Labor Market Data for Selected Workers in Illinois, 2019

Summary Statistics for Workers in

Illinois by Sector

Workers in the

Seven Covered

Industries

All Workers

in All

Industries

Difference

Demographics

Women

53.7%

47.3%

+6.4%

Men

46.3%

52.7%

-6.4%

White (non-Hispanic)

51.7%

62.9%

-11.2%

Black or African American

12.3%

11.3%

+1.1%

Hispanic or Latinx

30.0%

18.3%

+11.6%

All Other Races

6.0%

7.5%

-1.5%

Educational Attainment

Less than a High School Degree

15.4%

7.5%

+7.9%

High School Degree or Equivalent

33.1%

22.7%

+10.4%

Some College, No Degree

20.4%

17.0%

+3.3%

Associate Degree

11.4%

9.2%

+2.2%

Bachelor's Degree

15.9%

27.0%

-11.2%

Advanced Degree

3.9%

16.6%

-12.7%

No College Degree

68.8%

47.2%

+21.7%

College Degree

31.2%

52.8%

-21.7%

Labor Market Data

Average Wage Per Hour

$19.30

$29.01

-33.5%

Earns Less than $15 Per Hour

44.2%

23.8%

+20.4%

Earns Less than $26 Per Hour

79.8%

54.5%

+25.3%

Average Hours Worked Per Week

36.2

39.3

-7.8%

Full-Time Worker

71.7%

80.0%

-8.3%

Source(s): Author’s analysis of 2019 Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Groups (CPS-ORG) data from the U.S. Bureau

of Labor Statistics (EPI, 2021). Data are for all workers in Illinois who are paid by the hour and work for private or nonprofit

organizations in the seven industries that would be covered by a fair workweek law.

Figure 6 utilizes data from the Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Groups (CPS-ORG) to

understand the characteristics of workers who would be protected by a statewide fair workweek law (EPI,

2021). Demographic, educational attainment, and labor market data for workers in the seven industries

that would be covered by a statewide fair workweek law are compared with outcomes for all workers in

Illinois. The data reveal that the majority of workers who would be protected by the policy would be

women (54 percent) and White, non-Hispanic (52 percent). However, the workers who would be

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

9

protected by a fair workweek law would be disproportionately Hispanic or Latinx and Black or African

American. Of workers who would be covered by the law, 30 percent are of Hispanic or Latinx ethnicity

and 13 percent are Black or African American by racial background. By contrast, only 18 percent of the

total Illinois workforce is Hispanic or Latinx and just 12 percent are Black or African American (Figure 6).

Directly affected workers are also less likely to be college-educated and significantly more likely to earn

less than $15 per hour in Illinois (Figure 6). Fully 69 percent of workers who would be protected by the

policy do not have college degrees compared with 47 percent of all Illinois workers, a difference of 22

percent. Their average wage of about $19 per hour is 34 percent below the statewide average worker

hourly earnings of $29 per hour, and 44 percent earn less than $15 per hour—which is 20 percent higher

than the share earning less than $15 per hour throughout the Illinois economy (24 percent). The minimum

wage is currently $15 per hour in the City of Chicago and $12 per hour in Illinois, but will increase to $15

per hour in Illinois in January 2025 (BACP, 2021b; IDOL, 2021). It is also worth noting that 80 percent of

the directly affected workers earn less than $26 per hour. If a potential statewide law also uses this hourly

income threshold from the Chicago ordinance, then an estimated 1.3 million workers would be covered

(Figure 6).

Despite their precarious work schedules, directly affected workers would primarily be those who are

employed full-time (Figure 6). Workers in the industries that would be covered by a fair workweek law

average 36 hours per week. Fully 72 percent are employed full-time. However, the fair workweek law

would likely reduce the share of Illinois workers who are underemployed or involuntarily employed part-

time for economic reasons. A 2020 report from researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-

Champaign found that 65 percent of all Black and African American part-time workers and 70 percent of

all Hispanic and Latinx part-time workers in Illinois are underemployed and want more hours (Golden &

Dickson, 2020). Underemployment, the study found, is associated with problematic schedule practices.

Workers with the shortest advance notice of their schedules are the least satisfied with their work hours

and workers whose schedules are often changed exhibit higher rates of underemployment. The study also

found that irregular shift work and on-call work was highest in the industries covered by Chicago’s Fair

Workweek Ordinance (Golden & Dickson, 2020).

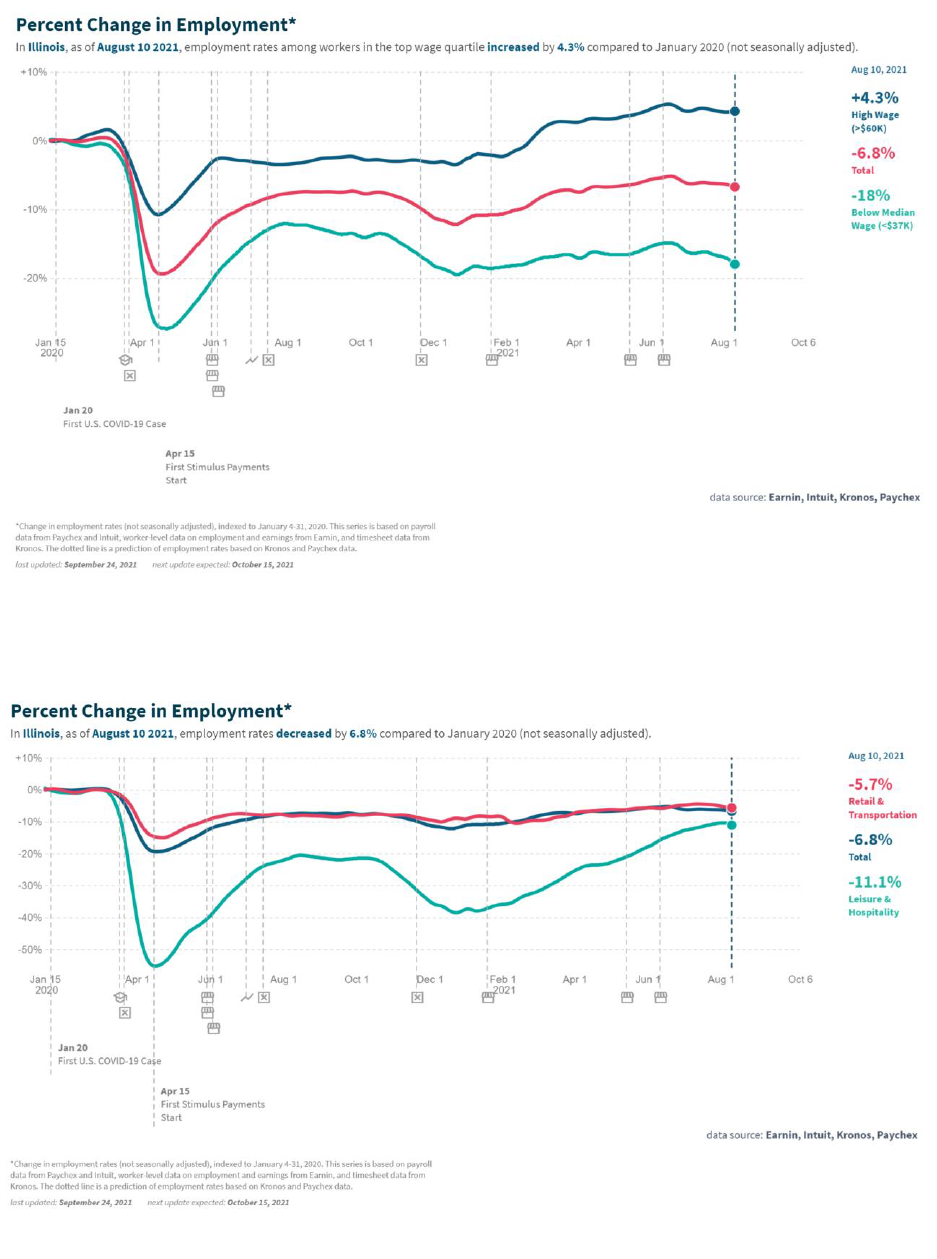

The 1.6 million Illinois residents who would benefit most from a statewide fair workweek law would be

disproportionately Women, Black, Hispanic, non-college-educated, and low-wage workers in essential and

frontline industries impacted most by the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, while high-wage Illinois

workers earning more than $60,000 per year have seen employment return and even exceed pre-

pandemic levels, job losses persist for low-wage workers (Figure 7). Jobs for low-wage Illinois workers

earning less than $37,000 per year remained 18 percent below their pre-pandemic level as of August 2021.

Similarly, Illinois’ aggregated leisure and hospitality industry still had 11 percent fewer jobs than before

the pandemic and the aggregated retail and transportation industry is 6 percent below pre-pandemic

levels.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

10

Figure 7: Change in Employment by Income Level in Illinois Since January 2020, As of August 2021

Source(s): Reproduction from “The Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker” reports produced by researchers at Harvard

University and Brown University (Chetty et al., 2021).

Figure 8: Change in Employment by Selected Industry in Illinois Since January 2020, As of August 2021

Source(s): Reproduction from “The Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker” reports produced by researchers at Harvard

University and Brown University (Chetty et al., 2021).

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

11

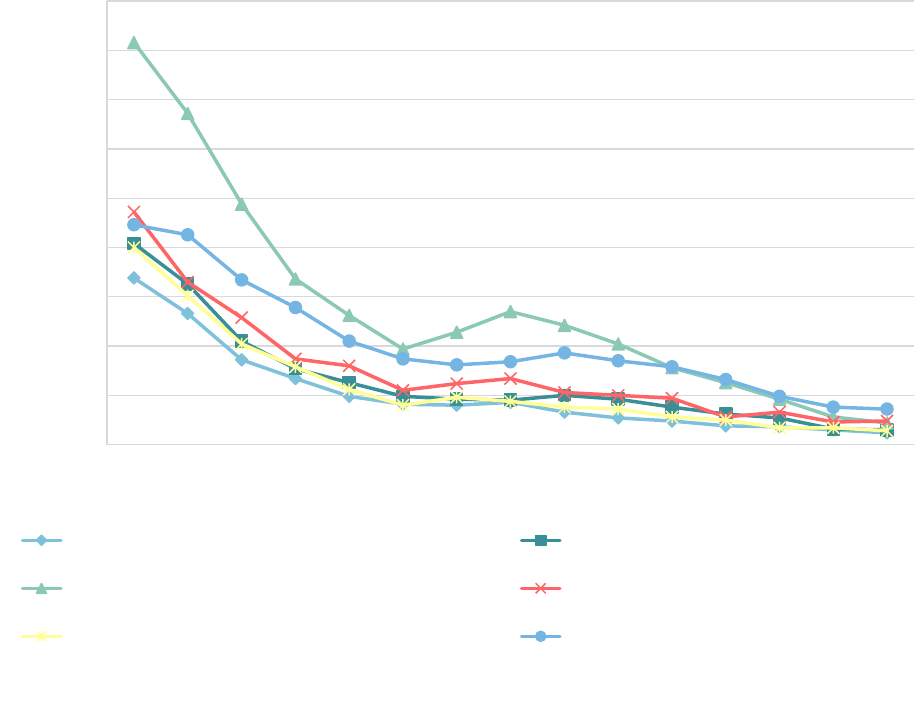

Finally, many of the workers who would be protected by a fair workweek law in Illinois have been unable

to work for extended periods of time due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 9). In May of 2020, 41 percent

of workers in the accommodation and food services industry were unable to work because their employer

closed or lost business due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 17 percent (manufacturing) and 24

percent (warehouse services) of workers in the other industries that would be covered by a statewide fair

workweek law were also unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to the virus.

Note that this is in addition to the workers who were unable to work for other COVID-19-related reasons,

such as a lack of child care and school closures. Well into the pandemic, between 1 percent

(manufacturing) and 4 percent (building services) of workers remained out of work because their

employer has closed or lost business (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Employed Persons Unable to Work at Some Point in the Last Four Weeks Because Their

Employer Closed or Lost Business Due to the Coronavirus Pandemic, May 2020 through July 2021

Source(s): Authors’ analysis of the Current Population Survey from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS, 2021).

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

May

'20

June

'20

July

'20

Aug.

'20

Sept.

'20

Oct.

'20

Nov.

'20

Dec.

'20

Jan.

'21

Feb.

'21

Mar.

'21

Apr.

'21

May

'21

June

'21

July

'21

SHARE OF WORKFORCE (%)

Manufacturing Retail Trade

Accomodation and Food Services Warehouse Services (and Transportation)

Healthcare (and Social Assistance) Building Services (Administrative and Waste Services)

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

12

Conclusion and Recommendations

Schedule instability is a problem that plagues workers in many industries and can lead to psychological

distress, poor sleep quality, work-family conflict, and unhappiness. Fair workweek laws have been

implemented in the State of Oregon and multiple municipalities, including the City of Chicago, to protect

workers from unstable scheduling practices. In Oregon, where the Fair Workweek Act covers as many as

172,000 workers, workers have experienced higher wages, less underemployment, more rest between

shifts, and improvements in advance notice of work schedules since enactment—all without negatively

impacting employment levels among directly affected businesses in covered industries.

The State of Illinois could follow Oregon and implement a law that would generally extend the Chicago

Fair Workweek Ordinance to all workers at large businesses across the state, protecting an estimated 1.6

million workers. If a potential statewide law used the same $26 per hour threshold as the Chicago

ordinance, then an estimated 1.3 million workers would be protected. The policy change would

disproportionately benefit women, Black, Hispanic, non-college-educated, and low-wage workers in

essential and frontline industries that have been impacted most by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the face

of growing concerns about labor shortages affecting both service industries and the goods-producing

manufacturing industry, a fair workweek law could help attract and retain workers in these hard-hit

sectors of the economy—providing both schedule security and predictability pay for workers and worker

stability and reduced turnover costs for employers (Davidson, 2021; Mutikani, 2021; Klein, 2021).

A fair workweek law in Illinois would produce positive societal impacts in Illinois. Research has found that

job satisfaction and overall well-being are higher among workers who work regular, predictable shifts and

who are content with their current hours. A fair workweek law would reduce irregular shift times and

increase the length of time for workers to receive advance notice of their work schedules, which would

improve health outcomes and worker life satisfaction. These improvements in worker well-being would

occur without negatively impacting employers in the state (Golden & Dickson, 2020).

Elected officials in Illinois should learn lessons from the experiences in Oregon and the City of Chicago in

any efforts to pass fair workweek legislation. First, there would be a need to educate and inform workers

of the new labor standards and their rights under the law. Studies from Oregon and Chicago have found

that employees were generally unaware of the fair workweek legislation (Loustaunau et al., 2020; Golden

& Dickson, 2020). Second, elected officials could consider policies to address standby lists and waivers

that can be abused by employers to avoid paying premium “Predictability Pay” when they change workers’

schedules on short notice. These exemptions significantly weaken Oregon’s fair workweek law (Petrucci

et al., 2021). Finally, while Chicago’s Fair Workweek Ordinance includes the important provision of

providing workers with more hours before hiring new workers, a statewide fair workweek law could also

provide workers with a minimum number of guaranteed hours to mitigate workers’ dependence on last-

minute shifts. With strong labor standards and a robust educational campaign, the implementation of a

fair workweek law would protect more than one million Illinois workers from unstable scheduling

practices.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

13

Sources

Bivens, Josh and Heidi Shierholz. (2021). “Restaurant Labor Shortages Show Little Sign of Going Economywide.”

Working Economics Blog. Economic Policy Institute.

Boushey, Heather and Sara Jane Glynn. (2012). There Are Significant Business Costs to Replacing Employees.

Center for American Progress.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2021). Databases, Tables & Calculators by Subject: Employment. U.S.

Department of Labor.

Business Affairs and Consumer Protection (BACP). (2021). (a). “Fair Workweek.” City of Chicago.

Business Affairs and Consumer Protection (BACP). (2021). (b). “Minimum Wage.” City of Chicago.

Census. (2021). “QWI Explorer.” U.S. Census Bureau.

Chetty, Raj; John Friedman; Nathaniel Hendren; Michael Stepner; and the Opportunity Insights Team. (2021).

“Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker.” The Economic Impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a New

Public Database Built Using Private Sector Data. Harvard University; Brown University; Bill & Melinda

Gates Foundation.

Davidson, Paul. (2021). “Breaking Down the Big US Labor Shortage: Crunch Could Partly Ease This Fall But Much

of It Could Take Years to Fix.” USA Today.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). (2021). Current Population Survey Extracts, Version 1.0.21.

Elejalde-Ruiz, Alexia. (2019). “Employers and Workers Battle Over Chicago’s Proposed Predictable Scheduling

Law.” Fair Workweek Initiative. Center for Popular Democracy.

Golden, Lonnie. (2015). Irregular Work Scheduling and Its Consequences. Economic Policy Institute.

Golden, Lonnie and Alison Dickson. (2020). Precarious Times at Work: Detrimental Hours and Scheduling in

Illinois and How Fair Workweek Policies Will Improve Workers’ Well-Being. University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign.

Golden, Lonnie and Jaeseung Kim. (2020). “Underemployment Just Isn’t Working for U.S. Part-Time Workers.”

The Center for Law and Social Policy.

Henly, Julia and Susan Lambert. (2014). “Unpredictable Work Timing in Retail Jobs: Implications for Employee

Work-Life Conflict.” ILR Review, 67(3): 986-1016.

Illinois Department of Labor (IDOL). (2021). “Hourly Minimum Wage Rates by Year: Pursuant to Public Act 101-

0001.” State of Illinois.

Klein, Matthew. (2021). “Where a Labor Shortage Is Most Acute: Manufacturing, Retail, and Transportation.”

Barron’s.

Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD). (2021). “LED Extraction Tool – Quarterly Workforce

Indicators.” U.S. Census Bureau.

Loustaunau, Lola; Larissa Petrucci; Ellen Scott; and Lina Stepick. (2020). Persistent Unpredictability: Assessing

the Impacts of Oregon's Employee Work Schedules Law. University of Oregon.

IMPLEMENTING A FAIR WORKWEEK LAW IN ILLINOIS

14

Manzo IV, Frank and Robert Bruno. (2020). The Effects of the Global Pandemic on Illinois Workers: An Analysis

of Essential, Face-to-Face, and Remote Workers During COVID-19. Illinois Economic Policy Institute;

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Mutikani, Lucia. (2021). “U.S. Service Sector Activity Inches Up in September; Shortages Persist – ISM Survey.”

Reuters.

Office of Senator Elizabeth Warren. (2019) Senator Warren and Representative Delauro announce

reintroduction of the schedules that work act: U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts [press

release].

Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries. (2021). Predictive scheduling. BOLI : Predictive scheduling : For Workers

: State of Oregon.

Petrucci, Larissa, Lola Loustaunau; Ellen Scott; and Lina Stepick. (2021). “Persistent Unpredictability: Analyzing

Experiences with the First Statewide Scheduling Legislation in Oregon.” ILR Review, 1-26.

Schneider, Daniel and Kristen Harknett. (2019). “Consequences of Routine Work-Schedule Instability for

Worker Health and Well-Being.” American Sociological Review, 84(1): 82-114.

Schneider, Daniel and Kristen Harknett. (2017). Income Volatility in the Service Sector: Contours, Causes, and

Consequences. The Aspen Institute; University of California, Berkeley; University of Pennsylvania.

State and Local Laws Advancing Fair Work Schedules. National Women's Law Center. (2019).

Taylor, S. (2021). What is fair workweek? TimeForge.

United States., & United States. (2011) The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, as amended. Washington, D.C.:

U.S. Dept. of Labor, Employment Standards Administration, Wage and Hour Division.

Wolfe, Julia; Janelle Jones; and David Cooper. (2018). ‘Fair Workweek’ Laws Help More than 1.8 Million

Workers: Laws Promote Workplace Flexibility and Protect Against Unfair Scheduling Practices.

Economic Policy Institute.

Cover Photo Credits

Blokhin, Andriy. (Accessed October 2021). “New York City, USA - October 30, 2017: Man chef cutting foccacia

bread pizza baked in oven in Rana restaurant kitchen in Chelsea Market (Stock Photo ID:

1065011039).” Shutterstock.com, downloaded with Shutterstock subscription.

Cervo, Diego. (Accessed October 2021). “Asian maid tidying up bed and cleaning luxury hotel room (Stock

Photo ID: 93542680).” Shutterstock.com, downloaded with Shutterstock subscription.

Wavebreakmedia. (Accessed October 2021). “Chef passing tray with french fries and burger to waitress in the

commercial kitchen (Stock Photo ID: 637820797).” Shutterstock.com, downloaded with Shutterstock

subscription.