Report of the Inter-Departmental

Group on National Coastal Change

Management Strategy

Prepared Jointly by the Department of

Housing, Local Government and Heritage

& the Office of Public Works

gov.ie

Table of Contents

Joint Ministerial Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 1

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 3

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3

Structure of Scoping report ................................................................................................................ 3

Chapter One - Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4

Chapter Two - Approaches to Coastal Change in other Jurisdictions ................................................. 4

Chapter Three - Current Irish Regulatory Context .............................................................................. 6

Chapter Four - Building the evidence base ......................................................................................... 6

Chapter Five - Key elements of an Irish Coastal Change Management Strategy ............................... 7

Strategic Pillar 1 – Enhancing Governance and Capacity Building ...................................................... 7

Strategic Pillar 2 - Understanding the Risk and Identifying Potential Technical Risk Management

Options ................................................................................................................................................ 8

Strategic Pillar 3 - Developing Management Responses to Coastal Change ...................................... 8

Summary of Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 10

Strategic Pillar ................................................................................................................................... 10

Recommendation .............................................................................................................................. 10

Strategic Pillar 1 ................................................................................................................................ 10

Strategic Pillar 2 ................................................................................................................................ 11

Strategic Pillar 3 ................................................................................................................................ 13

Glossary of Terms / Acronyms .......................................................................................................... 16

1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 21

2. Approaches to Coastal Change in Other Jurisdictions ...................................................................... 29

3. Current Irish Regulatory Context .................................................................................................. 35

4.0 Building the Evidence Base – Informing Strategic Coastal Management ................................. 43

5. Key elements of an Irish Coastal Change Strategy .......................................................................... 58

1

Joint Ministerial Foreword

It is clear that climate change is causing significant challenges for the entire planet. Many areas

around the world are already experiencing the impacts of climate change through more frequent

extreme weather events, changes in rainfall patterns and changes in temperature norms. Ireland is not

immune from these challenges and as temperatures are predicted to continue to rise due to the impact

of greenhouse gas emissions during this century the predictions for increases in sea levels will

exacerbate the problems that we will face, including in relation to our coastal areas.

Human activities are estimated to have already caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above

pre-industrial levels, and global mean sea level has risen about 20 cm since the beginning of the 20th

century, and is rising at approximately 3.5 cm per decade at present. The Intergovernmental Panel on

Climate Change has reported that for a 1.5°C rise in temperature, the global mean sea level could rise

by up to approximately 1m by 2100, and projections of more intense Atlantic storms could potentially

increase surge events and wave heights. This will further and significantly change our coastline and

could adversely impact on our coastal economy, society, heritage, culture and environment, if such

change is not managed appropriately.

In response to these challenges, the Government established the IDG Coastal Change to provide a

framework for key decisions to be taken on how Ireland can best manage its coast, being aware of the

future risks and the associated planning requirements. This report puts in place a road map for

responding to these challenges in a structured and planned way to provide the basis for a long-term

strategy for an integrated and co-ordinated approach to coastal change management.

Tackling coastal change management in response to climate change will be complex, multi-faceted

and dynamic demanding a range of research, policy and consequent management responses. This

report contains a range of recommendations, structured across three strategic pillars, for the

Government to consider. They are centred on developing management responses to coastal change

over the short, medium and longer terms and providing a comprehensive whole of Government

approach to the development of the range of policy responses that the challenge of coastal change

encompasses.

3

Executive Summary

Introduction

Ireland’s coastline is a valuable natural resource, which needs careful and sensitive management.

However, Ireland’s coast faces many challenges. The Climate Action Plan 2021 (DECC, 2021) identifies

that increases in sea levels and storm surge will result in increased frequency of coastal flooding and

erosion, with significant impacts for coastal and heritage sites situated in proximity to the coast and

on estuaries. The current evidence points to a gradual sea level rise of up to 1 metre to the year 2100

due to climate change. This will further and significantly change our coastline and could adversely

impact on our coastal economy, society, heritage, culture and environment, if such change is not

managed appropriately.

The Government has adopted a policy to assess and manage coastal flood risk with regard to both

existing risk and the potential impacts of climate change. However, managing Ireland’s coastal flood

risk addresses only part of the wider coastal change issues, and is not a strategy to manage all of

Ireland’s coastal hazards, nor does it provide a baseline assessment of the other hazards, including

from coastal erosion. This position is complicated by the fact that multiple investment projects along

the coast are typically planned and led by individual sectors and decisions are taken within Local

Authority (LA) boundaries.

Based on international best practice, ensuring best outcomes for the coastal area would be better

informed by an integrated coastal change management strategy. This would provide a framework to

determine the key decisions to be taken on how Ireland could best manage its coast, being aware of

the future risks and the associated planning requirements. An integrated coastal change management

strategy approach would also provide the framework to best inform both where and how decisions

regarding appropriate development/projects along the coast should be taken in the future, in

coordination with investment in flood risk management. The projected impact from climate change

reinforces the need to adopt such a strategic approach, with much more urgent attention required

with regards to coastal resilience (Climate Change Advisory Council, 2022).

In this context, an inter-departmental group was established by the Government to consider the

scoping of a National Coastal Change Management Strategy having regard to these issues. In so

doing it is recognised that there are current and urgent coastal change issues to be addressed in

parallel to the implementation of a medium to long-term framework. This group was tasked with

initially scoping out an approach for the development of an integrated, whole of Government,

strategy for managing our changing coast and to report back to Government with initial findings and

recommendations.

Structure of Scoping report

This scoping report is divided into five interrelated chapters:

Key elements

of an Irish

Coastal Change

Management

Strategy

Building the

evidence base

Current Irish

Regulatory

Context

Approaches to

Coastal Change

in other

Jurisdictions

Introduction

4

A summary of these chapters follows:-

Chapter One - Introduction

About 40% of people in Ireland live within 5km of the coast and about 40,000 live within 100 metres

of the coast (CSO, 2017). Ireland’s coastline is relatively long compared to other European countries

spanning approximately 5,800km.

Ireland’s coastal zone is characterised by considerable diversity, both in natural terms and in the range

and extent of human activity, including:

urban, rural and island coastal communities,

all of our major cities and the most densely populated parts of the country,

much of the country's industry is concentrated on or near the coast,

infrastructural and utility services including transport networks of road, rail, ports and

harbours; water supply and waste disposal; power, energy and communications; and

military infrastructures,

important economic resources for many sectors, e.g. the agricultural and tourism

sectors,

many areas of conservation value, due in part to the high ratio of coast to land area,

including designated areas of special conservation, geology and structures and sites

of cultural heritage significance,

access to a vast marine resource including fisheries, aquaculture and energy.

Coastal change management in the context of this report relates to the management of hazards and

risks at the coast associated with coastal erosion, accretion and the displacement of the inter-tidal

zone due to sea level rise, and in particular the potential increase in these hazards and risks

associated with the impacts of climate change. Existing arrangements are already in place with

regards to the risks of coastal flooding, and so this is not within the remit of the group or this

report.

Currently, there is no ongoing monitoring of Ireland’s changing coast that encompasses all of the

various risks. However, a range of work, already undertaken or ongoing, provides a certain level of

information and some indicators of the extent of the issue.

Tackling coastal change management in response to climate change will be complex, multi-faceted

and dynamic, demanding a range of policy and consequent operational responses.

A key objective of this report is to put in place a road map for responding to these challenges in a

structured and planned way to provide the basis for a long-term strategy for integrated coastal

change management.

Chapter Two - Approaches to Coastal Change in other Jurisdictions

An important task in preparing this report, was to consider lessons which could be learned from

other jurisdictions based on a range of EU and UK research projects. In addition, a desktop survey

was carried out to elicit policy development in a number of relevant European Countries with

geographic similarities, i.e. those European countries bordering the Atlantic seaboard and the North

Sea.

Since 1996, the European Commission has been working to identify and promote measures to

remedy the deterioration of Europe's coastal zones and to improve the overall situation. For over

two decades, the EU approach has promoted Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), at the

heart of which is coastal erosion management.

5

ICZM seeks to balance the various economic and social claims to the use of coastal areas (fishing,

shipping, port operation, industry and commerce, land-based transport infrastructure, agriculture

and forestry, wind energy, settlement development, tourism, etc.) with the objectives of coastal

zone protection (avoiding pollution, efficient use of the resource land, nature and cultural heritage

conservation, flood protection, etc.).

Similarly to Ireland, and influenced by broader EU developments in some cases, many countries are

developing marine spatial plans at national and regional level, with a varying degree of references to

coastal erosion and coastal change. There is a degree of evolution in these policies, and while there

are examples of good practice, there are other areas where the specific implementation issues are

less clear or well defined.

It is clear from the review of international practice, that while there are certain common themes,

often driven by EU Directives, there are varying models of coastal change management in other

jurisdictions reflective of their experience, legal and institutional culture.

There are a number of reasons why this is the case, such as the differing risks posed by coastal

change in each jurisdiction and the differing roles and responsibilities of various government

departments, agencies and local government bodies, etc. Consequently, there is no obvious single

model of best practice apparent for direct application in Ireland.

Drawing from the many examples of good practice in the management of coastal change evident in

the approach of other jurisdictions, there are a number of broad themes which should be considered

in any future policy being developed for Ireland, including:

Policy approach

o The need for coastal change management plans to be prepared to identify the

appropriate measures necessary to best manage the risks associated with

coastal change, in the short, medium and longer terms, with such plans

reviewed and updated at appropriate intervals.

o The consideration and application of high level risk management policy options

along the coastline or parts thereof. For example, no active intervention, hold

the line, managed realignment, managed retreat or advance the line, along each

reach of the coastline, as used in the UK Shoreline Management Plans.

o The use of a sediment management approach which can include various scales

of assessment based on sediment cells and sub-cells.

o The emphasis on sustainable management of the coastline as evident in the

approach in the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark.

Communications

o The importance of clearly communicating risks associated with coastal change to

coastal communities and including these communities in the decision making

process.

Data and Research

o The availability of high quality data to inform the decision making process. For

example, regular monitoring of coastal retreat and dunes (annually), monitoring

of dyke consolidation and monitoring of water levels and wave conditions as is

carried out in Denmark. Similarly, the National Network of Regional Coastal

Monitoring Programmes of England collect coastal monitoring data in a co-

ordinated and systematic manner to serve their coastal management needs.

6

o The importance of research to provide the up-to-date information required to

manage the risk from coastal change. In the UK, the Environment Agency

manages a Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management Research and

Development Programme which is a collaborative and academic led research

programme to provide information on the management of flood and coastal

erosion risk.

Chapter Three - Current Irish Regulatory Context

At the heart of the challenge of integrated coastal management is the issue of timescale. Regardless

of reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, sea levels will continue to rise for a significant length of

time, certainly much longer than ‘normal’ planning horizons.

While recognising that this is happening, there is a need to put in place responses that recognise the

long-term nature of the challenge. A key objective of this report is to put in place a road map for

responding to these challenges in a structured and planned way to provide the basis for a long-term

strategy for integrated coastal change management. Particularly important in this context is that

Ireland now has national planning frameworks in place for both the terrestrial area and the marine

area.

The legislative framework in the coastal zone is very complex and intricate, involving both EU and

national measures. In summary, the legislative measures serve one of three principal purposes - the

approval for future development, administration of activities or protection of the environment.

The regulatory framework relating to environmental considerations is complex and is heavily

informed by EU Directives. The embedding of environmental considerations into the regulatory

process is ongoing and is reflective of emerging case law and experience.

Measures to avoid further damage to the environment and where possible make improvements to it

will continue to be a feature of the regulatory environment. For the future, consideration needs to

be given to how best to integrate necessary responses to coastal change into an environmental

regulatory framework.

Chapter Four - Building the evidence base

Data and research are a critical underpinning to future policy evolution and implementation.

A Technical Working Group (TWG) was established to identify the current datasets and research

available across State organisations relevant to the monitoring of coastal change, with a brief to

recommend additional datasets and research considered necessary in the short, medium and longer

terms and identify the means and expected timeframe through which this should be captured.

A further objective of the TWG was to carry out an audit (by Local Authority area) of the indicative

critical infrastructure and assets at risk from coastal change, derived from currently available

information and data by reference to both the medium and high end sea level rise projections.

An extensive list of datasets at the national, regional and local scales relevant to the monitoring of

coastal change was collated. Each dataset has been classified as high, medium or low depending on

its relevance to the monitoring and/or analysis of coastal change hazard and risk. The data types

considered to be of most relevance are Aerial Imagery, Bathymetry Data, Coastal Features /

Infrastructure, Elevation Data, Erosion Data, Flood Data, Geological Data, Meteorological Data,

Oceanographic Data, Risk Receptors and Spatial Planning.

7

A gap analysis was also carried out on the existing data available in relation to monitoring coastal

change. This has identified gaps with regards to coastal monitoring and tidal zone data, and the critical

need for erosion hazard mapping and the collation of coastal defence asset data.

While there is significant data available with respect to coastal change in Ireland, there are gaps both

in the extent and type of data being gathered. There is a need for a co-ordinated approach to data

gathering in terms of its focus, effective resolution (spatial extent) and how often the data is

gathered.

The review of available research highlights that detailed consideration should be given to

implementing a coastal change research programme with the following objectives:

To coordinate, fund and manage coastal change research projects relevant to Ireland

To identify coastal change research priorities and opportunities for Ireland

To increase collaboration across State organisations and with the education sector

To provide scientific and technical advice, reports and guidance notes

A detailed review of the coastal research priorities will need to be carried out to inform any such

coastal change research programme.

Chapter Five - Key elements of an Irish Coastal Change Management Strategy

The range of integrated elements of a coastal change management strategy and the consequent

recommendations can be categorised under three overarching headings.

Strategic Pillar 1 – Enhancing Governance and Capacity Building

Responding to the impact of climate change on Ireland’s coast requires, broadly, a dual approach of

both mitigation (tackling the cause) and adaptation measures (reduce the impacts and adaptive

capacity and resilience). This report focuses on adaptation to coastal change.

Given the nature of the risks arising, the broad range of stakeholders with responsibilities to manage

these risks, and the complex legal and regulatory framework within which this must be achieved, there

is clearly a requirement for an integrated and co-ordinated response.

The recommended development of coastal change management plans, which may transcend Local

Authority areas, will require an appropriate policy framework to underpin and guide potential

management options. This will require the development and co-ordination of policy responses across

a range of Government Departments and Agencies.

Investment in capacity building across all key stakeholders is also necessary in order to ensure that

the requisite skills and knowledge are available as required.

Strategic pillar 1

• Enhancing

Governance and

Capacity Building

Strategic pillar 2

• Understanding the

Risk and Identifying

Potential Technical

Risk Management

Options

Strategic pillar 3

• Developing

Management

Responses to Coastal

Change

8

Strategic Pillar 2 - Understanding the Risk and Identifying Potential Technical Risk

Management Options

Scientific evidence and observations are clear that warming of the climate system is unequivocal and

points to the contribution of man-made (anthropogenic) greenhouse gas emissions increasing the

concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to levels not experienced in millennia.

Globally, scientific observations show an increase in global mean air and ocean temperatures and

widespread melting of snow and ice, leading to rising sea levels and an increase in the frequency,

intensity and duration of extreme weather events. The negative impacts of climate change are being

experienced in Ireland and will continue and intensify. This is particularly the case with respect to

rising sea levels, which, coupled with an increase in the frequency and duration of severe weather

events, will have long-term implications for the shape and location of our coastline.

At this point it is known that substantial property and infrastructure risks will arise from coastal

change. While there remains uncertainty over the rate of change and the degree of change at a given

point in time, this must not impede the assessment of the potential risks arising, and the consideration

of adaptive action that may be required to manage these risks.

A co-ordinated programme of monitoring and research, drawing from and contributing to EU and

international research, is required in order to ensure that the best available estimates of potential

coastal change and associated hazards and risks are identified, refined and updated on an ongoing

basis. Over the coming years, this expanding knowledge base will further inform the identification of

possible technical options to manage such risks.

Strategic Pillar 3 - Developing Management Responses to Coastal Change

At the heart of the challenge of coastal change risk management there is a need for a strategic coastal

change management framework. As previously outlined, this will be informed by an understanding of

hazards, risks and the identification of possible technical options. This understanding will be expanded

and refined over the coming years.

A range of approaches are possible, but these are commonly articulated in many jurisdictions, as listed

below. These can be applied individually or in combination at the local, regional and national levels.

Do nothing

No active intervention, allowing natural processes to take over with

areas of land being lost to the sea over time

Hold the line

Build or maintain coastal defences to protect a coastline against the

impacts of coastal change

Managed realignment

Landward realignment of existing coastal defences, or an existing

coastline, to a new, more sustainable alignment accounting for the

impacts of coastal change

Managed retreat

Co-ordinated movement of people and infrastructure away from risks

and allow the coastline to retreat

Advance the line

Defences are built out at sea e.g. tidal barrage, land reclamation

Such approaches must be underpinned by policy direction and supports, given the potentially

significant costs and impacts of possible approaches, and be informed by engagement with local

communities.

Whilst there is a requirement to identify and manage future risks arising from coastal change, there

are areas where coastal change is currently impacting communities and households across the State.

Developing longer-term management responses will be guided by the evolving approach to dealing

9

with extant risks. The recommendations outlined under this Pillar are centred on developing those

management responses over the short, medium and longer terms.

A summary of the recommendations made under each of these Pillars follows.

10

Summary of Recommendations

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

Strategic Pillar 1

Recommendation 1 - Governance

a) The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage be

designated the lead coordination role, to promote a joined-up,

whole of Government response to coastal change by all relevant

Departments / Agencies having regard to their existing policy

remits and to chair the Interdepartmental Steering Group outlined

below.

b) An Interdepartmental Steering Group on Coastal Change be

immediately established to identify possible approaches,

associated resource requirements, and to develop the range of

policy responses that the challenge of coastal change encompasses.

Additional resources should be provided to support the work of this

Group.

c) The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

should report on the work of the Interdepartmental Steering Group

to the Cabinet Sub-committee on Environment and Climate

Change, through the Senior Officials Group.

d) The Office of Public Works (OPW) be designated as the national

lead coordinating body for the assessment of coastal change

hazards and risks and the assessment of technical options and

constraints outlined in Recommendations 3 to 7 below. It is also

recommended that the OPW should be represented on the Senior

Officials Group.

e) An advisory group of national and international experts including

engineering, environmental, heritage and communications experts

be established by the Department of Housing, Local Government

and Heritage. It is suggested that this group be independently

chaired.

f) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should engage at an EU and

bilateral level with neighbouring jurisdictions to examine best

practice, lessons learned and to update knowledge.

g) Existing legislation should be reviewed to consider appropriate

amendments to align with these recommendations.

h) The Climate Action Regional Offices (CAROs), in conjunction with

relevant agencies, should establish a training and development

programme for local authority staff.

i) The CAROs should identify and scope, in conjunction with the

Interdepartmental Steering Group and the Local Government

Management Agency (LGMA), the requirement for additional

expert technical, environmental and administrative capacity at

local authority level.

Recommendation 2 – Capacity Development

a) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should undertake an

analysis at the local authority level and within relevant national-

level Departments / agencies of the relevant skills and resources

11

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

available and required to implement the adopted policies and

strategies for coastal change management.

b) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should develop, through

collaboration between relevant authorities and agencies, the

third-level institutions and other relevant stakeholders, the

programmes necessary to develop the required skill sets and

resources nationally for coastal change management in the long-

term.

Strategic Pillar 2

Recommendation 3 - Coastal Monitoring and Data Collection

a) The OPW be designated as the lead body for co-ordinating the

monitoring of physical coastal change, to include the gathering,

collation, mapping and analysis of geo-spatial and other relevant

datasets. The OPW, once suitably resourced with the relevant

suitably qualified staff, would be responsible for developing and

coordinating an ongoing national coastal change monitoring

programme to facilitate national scale assessments for the

identification of areas of risk to be monitored in detail, and then

for such areas:

Determining the level of monitoring required at each location

where detailed assessment should be undertaken, and

coordinating the required monitoring.

Specifying, collecting, storing and disseminating all data,

including aerial photography, oblique imagery, LiDAR, beach

topographic survey data, bathymetric data, wave data and

tidal data required to adequately monitor the coastline.

Undertaking, coordinating and promoting research in the area

of coastal change monitoring and implementation of

innovative monitoring methodologies.

This data collated should be stored centrally and be made

available where appropriate to stimulate new research and

innovation that may be possible based on the availability of this

essential coastal monitoring data.

B) Support the work of Met Éireann to produce a Coastal Flood

Forecast Service for Ireland that will aim to

produce authoritative tide tables

develop the best coastal flood forecast models for Ireland

expand the observation network in terms of tide gauges,

wave radars and near shore wave buoys/sensors.

Recommendation 4 – Coastal Defence Asset Database

a) The OPW to establish and maintain a National Coastal Defence

Asset Database of relevant regional and local coastal

infrastructure for the coast of Ireland. This database should be

sufficiently detailed to capture all coastal defences, both natural

and human-made, at a scale suitable for use in the assessment of

12

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

hazard and risk associated with coastal change, including their

location, purpose, physical dimensions and condition.

b) Coastal defence owners to plan and undertake a programme of

inspection to identify the condition of existing coastal defences

with a particular emphasis on those defences that are in public

ownership, located in settlements, or that are providing an

important coastal defence function.

c) Coastal defence owners to plan and prepare a programme of

necessary remediation / maintenance, where necessary, arising

from the prior inspection and condition surveys under the

programme of inspection.

Recommendation 5 – Coastal Change Research Programme

a) Development and implementation of a comprehensive coastal

change research programme by the OPW to meet the identified

range of objectives to support the assessment and management

of coastal change.

Recommendation 6 - National Assessment of Coastal Change Risk

a) The OPW to develop national-scale coastal erosion hazard

mapping and an associated risk assessment using the latest

available data and methodologies. This mapping should include an

assessment of the potential impact of a range of sea level rise

scenarios on coastal erosion rates to ensure areas at highest risk

of erosion due to climate change can be identified. To monitor

ongoing change and the associated risk from coastal erosion, and

to improve the assessment using the most up-to-date data,

knowledge and methodologies, this national scale assessment

should be reviewed at regular intervals, e.g. every six to twelve

years, and the erosion hazard mapping and risk assessment

updated if/as necessary.

b) The OPW to map the potential movement of the inter-tidal zone,

and assess the risks associated with such movement to

communities.

c) The OPW to undertake an assessment to identify the communities

and coastal areas at potentially significant risk from coastal

change, both now and in the future, making use of historic data,

predictive assessments and consultation with key stakeholders

such as the local authorities. This assessment should include the

identification of the habitats, cultural heritage and other sectoral

assets at risk from coastal change.

d) Each relevant sector and organisation shall identify infrastructure

and other assets at risk under future coastal change scenarios, as

part of the national assessment of coastal change risk, including

analysis of coastal archaeological sites and wrecks to assess the

likely effects of coastal change.

e) The OPW to undertake detailed risk analysis, at the scale of the

sediment cell and/or sediment sub-cell, for the locations identified

13

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

as being at potentially significant coastal change risk, with a

particular focus on affected urban settlements.

Recommendation 7 - Assessment of Technical Risk Management Options

a) The OPW to identify, assess and appraise technical options and

constraints, in consultation with local communities, to inform

decisions on the management of coastal change risks in relevant

areas and the long-term planning for the management of

potential future change.

b) The OPW to undertake a pilot project for such work to inform the

national implementation programme.

Strategic Pillar 3

Recommendation 8 – Short-term measures

a) In already identified vulnerable locations, local authorities and

State agencies should continue to engage with local communities

to help ascertain the most appropriate interventions. Policy issues

arising should be brought to the Interdepartmental Steering

Group for consideration and action.

b) Local authorities, in statutory plans, including the LA Climate

Action Plans required under the Climate Act, should continue to

identify potentially vulnerable locations that could be affected by

coastal change. It is recommended that statutory plans in such

cases put in place spatial policies to limit development in the

interests of not increasing the amount of development and

consequent population at risk from imminent coastal change.

c) The CAROs should continue to engage in skills training associated

with improving and deepening the local authority and State

agencies capability to respond to the effects of coastal change.

This training should include both the impact of coastal change on

coastal and underwater archaeology and the impact of coastal

defences and other measures on archaeological sites.

d) The CAROs should continue in association with State agencies,

particularly the OPW and Geological Survey Ireland (GSI), to carry

out appropriate research and evidence gathering to inform the

establishment of a long-term programme of response to coastal

change.

Recommendation 9 – Coastal Change Management Planning

a) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should initiate a pilot

programme to identify the most effective risk management

response option(s)/method(s) within a defined policy framework

and prepare a pilot coastal change management plan.

b) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should apply the defined

policy framework to potentially at-risk coastal cells and sub-cells

around the country and, in consultation with local communities

14

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

and other stakeholders, prepare a national set of coastal change

management plans.

c) Arising from suitable risk based analysis, each relevant sector and

organisation to identify appropriate measures to address the risk

e.g. structural or non-structural measures or relocation of existing

infrastructure to a less vulnerable location.

Recommendation 10 – Coastal Change Management Delivery

a) With regard to the implementation of capital works in the context

of the coastal change management plans, a programme of capital

measures should be prepared by the Interdepartmental Steering

Group, as determined appropriate through the joined-up, whole

of Government response for the management of potential future

coastal change.

i. The OPW should manage and coordinate the

implementation of any such programme of capital

measures to protect communities.

ii. Each sector to implement the capital and other technical

measures with regards to the management of risk to their

sectoral assets and objectives.

Recommendation 11 – Promotion of Nature-based Solutions

a) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should build a suitable

body of knowledge of the application of nature-based solutions as

a means for managing coastal change through assessments of

national and international work to date, research and pilot

studies, as necessary.

b) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should identify locations

around the coast of Ireland where nature-based solutions may

provide solutions and benefits in the areas of potentially

significant risk from coastal change.

c) The Interdepartmental Steering Group should promote a multi-

sectoral approach to the application of nature-based solutions in

the coastal environment to achieve multiple benefits in

conjunction with local communities.

Recommendation 12 – Planning Guidelines

a) The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

should prepare and publish spatial planning guidelines to give

policy direction in coastal areas that may be subject to coastal

change, taking account of environmental implications and, based

on the framework adopted for the Guidelines on the Planning

System and Flood Risk Management, seek to avoid inappropriate

new development in at risk coastal locations.

15

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

Recommendation 13 – Consider legislative options

a) Consideration should be given by the Department of Housing, Local

Government and Heritage as to how future beach nourishment and

re-nourishment projects involving the need to transfer large

volumes of sand, shingle or aggregate from offshore or nearshore

locations to either nearshore or upper foreshore can be more

effectively permitted or licenced under the relevant legislation. This

future need should balance the identified need for the coastal

project as a defence measure with other considerations such as

environmental impact.

b) Consideration should be given by the Interdepartmental Steering

Group to legislative changes that recognise the complex nature of

any programme or project necessary to mitigate or manage the

impacts of coastal change.

Recommendation 14 – Coastal State’s Maritime Area

The Department of Foreign Affairs, in consultation with the Department of

Housing, Local Government and Heritage as appropriate, should continue to

engage with the

United Nations International Law Commission to examine the international

law issues raised by the phenomenon of sea-level rise.

a) The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

should consider - in consultation with the Department of Foreign

Affairs – the impact, if any, of sea level rise on Ireland’s maritime

boundaries in future mapping exercises.

b) The Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

should engage with coastal

local authorities and the Chief Boundary Surveyor to agree a

process for updating each local

authority maritime boundary area as well as low and high water

marks, particularly in light

of their enhanced role in the maritime area under the Maritime

Area Planning Act 2021.

Recommendation 15 – Developing Managed Retreat Options

a) Consideration should be given by the Interdepartmental Steering

Group to identifying the most appropriate measures and

mechanisms required to support a managed retreat option for

communities and/or individual homes and properties at risk from

coastal change, including ensuring an adequate time period for

consideration and implementation, where appropriate, of

managed retreat and the timescale required for effective

movement of at risk communities, where deemed necessary.

b) A communications and consultation process should be put in place

with the affected communities, led by the local authority, over an

extended time period.

16

Strategic Pillar

Recommendation

c) Planning policy at a local level should reflect the risk and avoid

intensifying existing development uses or locating new

inappropriate development within the zone(s) most at risk from

coastal change and potential locations where managed retreat

may be feasible or necessary. Furthermore, planning policy should

be aligned, where necessary, to facilitate managed retreat

particularly with respect to the location of new replacement

dwellings / structures / development.

Glossary of Terms / Acronyms

Accretion

The accumulation of sediment, usually sand, which is evident by the seaward

advance of the shoreline.

AEP

Annual Exceedance Probability. This is the probability of an event occurring

or being exceeded in any one year. For example a 0.5% AEP event has a 0.5%

probability (or 1 in 200 chance) of occurring or being exceeded in any year.

AFA

Area for Further Assessment

Anthropogenic

Forcing

The change in the Earth's energy balance due to human economical activities.

Astronomical Tide

The rise and fall of water due solely to gravitational interactions between the

Earth, Moon, and Sun.

Bathymetry

The measure of the depth of water in oceans, seas or lakes.

Beach

Nourishment

The practice of adding large quantities of sand or sediment to beaches to

combat erosion and increase beach width.

BIM

Bord Iascaigh Mhara

BwN

Building with Nature

CARO

Climate Action Regional Office

CCMA

County and City Management Association

CCSAP

Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan

CERMS

Coastal Erosion Risk Management Study

CFRAM

Catchment Flood Risk Assessment and Management

17

CMSP

Coastal Monitoring Survey Programme

Coastal Resilience

The capacity of the socioeconomic and natural systems in the coastal

environment to cope with hazardous event, trends or disturbances, induced

by factors such as sea level rise, extreme events and human impacts, by

adapting whilst maintaining their essential functions.

CSO

Central Statistics Office

DAFM

Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine

DECC

Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications

DHLGH

Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

DHPLG

Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government

Dredging

Dredging is the removal of sediments and debris from the bottom of lakes,

rivers, harbours and other water bodies.

DSF

Document Stratégique de Façade

DSM

Digital Surface Model. A three-dimensional representation of the earth’s

natural and artificial features. It includes the tops of buildings, trees, power

lines and any other objects.

DTM

Digital Terrain Model. A three-dimensional representation of the earth's

surface, represented as an array of points with a defined height. The terrain

model contains information about the height without considering vegetation,

buildings, and other objects.

ECMWF

European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts

EEA

European Environment Agency

EGMS

European Ground Motion Service

EMODnet

European Marine Observation and Data Network

EO

Earth Observation

EPA

Environmental Protection Agency

Erosion

The wearing away of coastal land or beaches. Can result from a combination

of factors both natural and human induced.

ESA

European Space Agency

FHC

Fishery Harbour Centre

18

GMSL

Global mean sea level

GSI

Geological Survey Ireland

H++EFS

High++ End Future Scenario. A sea level rise scenario which represents an

increase in sea level of 2m.

H+EFS

High+ End Future Scenario. A sea level rise scenario which represents an

increase in sea level of 1.5m.

HAT

The maximum tide level possible given the harmonic constituents for that

particular location.

HEFS

High End Future Scenario. A sea level rise scenario which represents an

increase in sea level of 1m.

ICPSS

Irish Coastal Protection Strategy Study

ICWWS

Irish Coastal Wave and Water Level Modelling Study

ICZM

Integrated Coastal Zone Management

IDG

Inter-Departmental Group

IFSAR

Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar

IMDBON

Irish Marine Data Buoy Observation Network

INFOMAR

Integrated Mapping for the sustainable development of Ireland’s marine

resource

Inter-tidal Zone

The area where the ocean meets the land between high and low tides.

IPC

Integrated Pollution Control

IPCC

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

LA

Local Authority

LAT

The lowest tide level possible given the harmonic constituents for the

location.

LGMA

Local Government Management Agency

LiDAR

Light Detection and Ranging is a remote sensing technology. A LiDAR system

sends a light pulse to the ground. This pulse hits the ground and returns back

to a sensor on the system.

19

Littoral Drift

Littoral drift or longshore sediment transport is the term used for the

longshore transport of sediments (mainly sand), along the upper shoreline

due to the action of breaking and longshore currents.

MMO

Marine Management Organisation

MRFS

Mid-Range Future Scenario. A sea level rise scenario which represents an

increase in sea level of 0.5m.

MSFD

Marine Strategy Framework Directive

MSL

Mean Sea Level

NBAP

National Biodiversity Action Plan

NbS

Nature-based Solutions

NCCA

National Coastal Change Assessment

NDHM

National Digital Height Model

NHA

Natural Heritage Area

NMPF

National Marine Planning Framework

NPF

National Planning Framework

NSR

North Sea Region

Oblique Imagery

Oblique Imagery is aerial photography that is collected at an angle, usually

downward at a 40° to 50° angle to the ground.

OPW

Office of Public Works

Orthoimage

An orthoimage is an image that has been geometrically corrected

(orthorectified) to remove distortion caused by differences in elevation,

sensor tilt and optionally, by sensor optics.

OSi

Ordnance Survey Ireland

OSR

Ocean State Report

PFRA

Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment

Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry is the use of photography in surveying and mapping to

ascertain measurements between objects.

POC

Programas da Orla Costeira

POOC

Planos de Ordenamento da Orla Costeira

RNLI

Royal National Lifeboat Institution

20

SAC

Special Area of Conservation

Sediment Cell

In the context of a strategic approach to coastal management, a length of

coastline in which interruptions to the movement of sand or shingle along the

beaches or nearshore seabed do not significantly affect beaches in the

adjacent lengths of coastline (CIRIA, 2010).

Sediment Sub-cell

A subset of a sediment cell based on local sediment dynamics and

characteristics.

SMP

Shoreline Management Plan

SMR

Sites and Monuments Record

SPA

Special Protection Area

SSP

Shared Socioeconomic Pathway

TWG

Technical Working Group

WCRP

World Climate Research Programme

WIID

Wreck Inventory of Ireland Database

21

1. Introduction

1.1 The need for coastal change management policy and strategy

Ireland’s coastline is a valuable natural resource, which needs careful and sensitive management.

However, Ireland’s coast faces many challenges. The Climate Action Plan 2021 (DECC, 2021) identifies

that increases in sea levels and storm surge will result in increased frequency of coastal flooding and

erosion, with significant impacts for coastal and heritage sites situated in proximity to the coast and

on estuaries as one of the potential impacts of climate change on Ireland. The current evidence points

to a gradual sea level rise of up to 1 metre to the year 2100 due to climate change. This will further

and significantly change our coastline and could adversely impact on our coastal economy, society,

heritage, culture and environment, if such change is not managed appropriately.

The Government has adopted a policy to assess and manage coastal flood risk with regard to both

existing risk and the potential impacts of climate change. However, managing Ireland’s coastal flood

risk addresses only part of the wider coastal change issues, and is not a strategy to manage all of

Ireland’s coastal hazards nor does it provide a baseline assessment of the other hazards, including

from coastal erosion. This position is complicated by the fact that multiple investment projects along

the coast are typically planned and led by individual sectors and decisions are taken within local

authority boundaries.

Based on international best practice, investment in the coastal area would be better informed by an

Integrated Coastal Change Management Strategy. This would provide a framework to determine the

key decisions to be taken on how Ireland could best manage its coast, being aware of the future risks

and the associated planning requirements. An Integrated Coastal Change Management Strategy

approach provides the framework to best inform both where and how decisions regarding appropriate

projects along the coast should be taken in the future, in coordination with investment in flood risk

management. The projected impact from climate change reinforces the need to adopt such a strategic

approach, with much more urgent attention required with regards to coastal resilience (Climate

Change Advisory Council, 2022).

In this context, an inter-departmental group was established by the Government to consider the

scoping of a National Coastal Change Management Strategy having regard to these issues. In so doing

it is recognised that there are current and urgent coastal change issues to be addressed in parallel to

the implementation of a medium to long-term framework. This group was tasked with initially scoping

out an approach for the development of an integrated, whole of Government, strategy for managing

our changing coast and to report back to Government with initial findings and recommendations. This

is the subject of this report.

The Scope of Coastal Change

The focus of the inter-departmental group and of this report are the risks associated with coastal

erosion, accretion and the displacement of the inter-tidal zone. Existing arrangements are

already in place with regards to the risks of coastal flooding. Substantial work has previously

been undertaken to assess and set out measures to manage the risk of coastal flooding, such as

through the Catchment-based Flood Risk Assessment and Management (CFRAM) Programme,

the Irish Coastal Protection Strategy Study (ICPSS) (RPS Consulting Engineers, 2010, 2013 &

2014), the Irish Coastal Wave and Water Level Study (ICWWS) (RPS Consulting Engineers, 2020)

and the preparation of the Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan for Flood Risk Management

(OPW, 2019), and there is a significant programme of work also ongoing. The assessment and

management of coastal flooding is therefore not within the remit of the group or this report (see

Section 1.3.3).

22

1.2 The Irish Coastline

About 40% or about 2 million people in Ireland live within 5km of the coast and about 40,000 live

within 100 metres of the coast (CSO, 2017). Ireland’s coastline is relatively long compared to other

European countries spanning approximately 5,800 km of which:

56% is hard rock,

39% beaches,

3% artificial coast,

1% soft erodible rock, and

1% muddy coast.

Ireland’s coast is varied from high rocky cliffs that can resist Atlantic waves to sandy beaches that can

change with every tide. A large portion of the east and southeast coast is characterised by mobile

deposits.

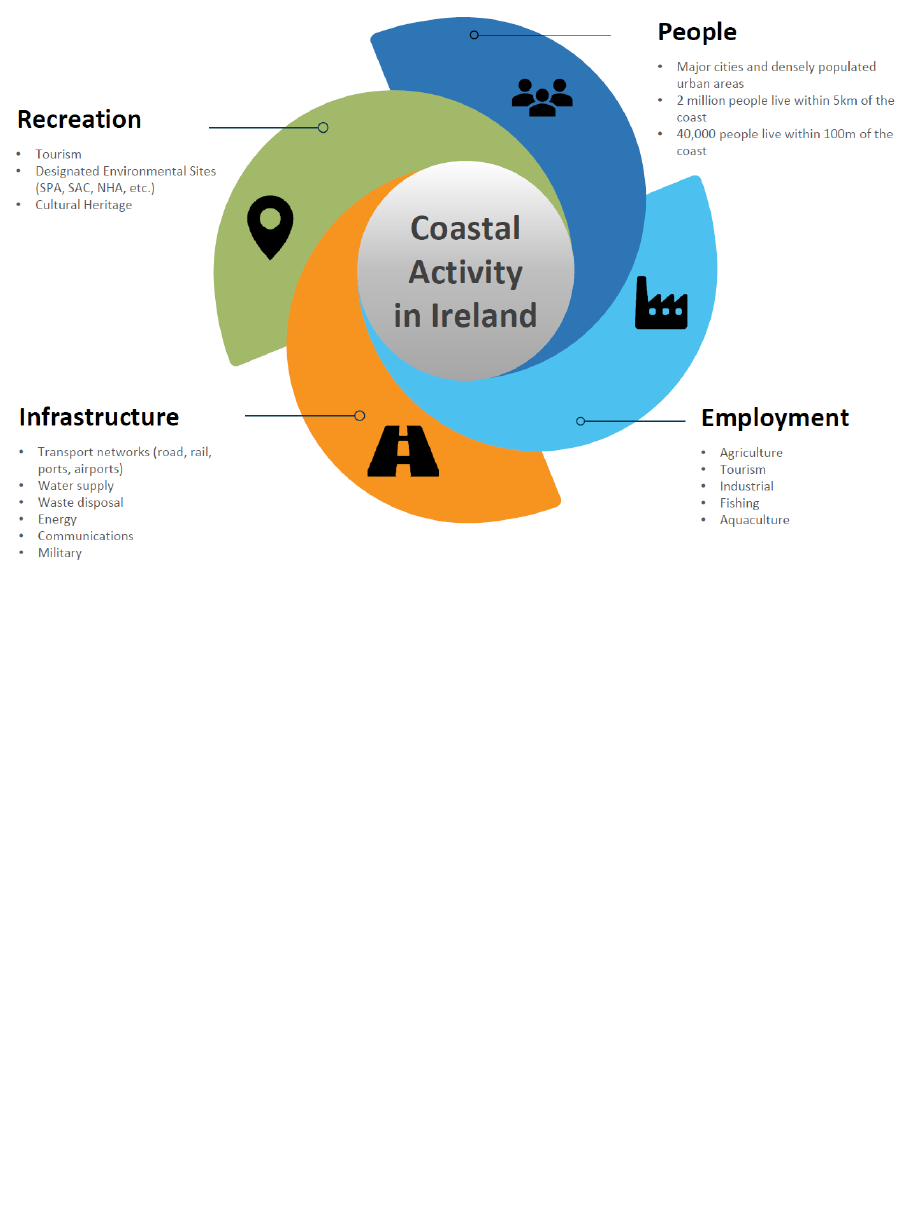

Ireland’s coastal zone is characterised by considerable diversity, both in natural terms and in the range

and extent of human activity, including:

urban, rural and island coastal communities,

all of our major cities and the most densely populated parts of the country,

much of the country's industry is concentrated on or near the coast,

infrastructural and utility services including transport networks of road, rail, ports and

harbours; water supply and waste disposal; power, energy and communications; and military

infrastructures,

important economic resources for many sectors, e.g. the agricultural and tourism sectors,

many areas of conservation value, due in part to the high ratio of coast to land area, including

designated areas of special conservation, geology and structures and sites of cultural heritage

significance,

access to a vast marine resource including fisheries, aquaculture and energy.

The variety and diversity of use of the coast of Ireland is summarised in Figure 1.1.

23

Figure 1.1: Variety and Diversity of Use of the Coast of Ireland

1.3 Understanding Coastal Change

Coastal change management in the context of this report relates to the management of hazards and

risks at the coast associated with coastal erosion, accretion and the displacement of the inter-tidal

zone due to sea level rise, and in particular the potential increase in these hazards and risks associated

with the impacts of climate change.

1.3.1 Natural Process of Coastal Erosion

Coastal erosion is the wearing away of coastal land or beaches and can result from a

combination of factors both natural and human induced.

As a natural process, coastal erosion continually reshapes shorelines through ocean currents,

tidal movements, littoral drift or sediment processes, as well as wind and wave action. It takes

place mainly during strong winds, high waves and storm sea conditions, and results in

coastline retreat and loss of land together with natural supply of sediment to adjacent coastal

areas.

1.3.2 Human Induced Coastal Erosion

Human activity landward of the coast and to seaward can also have an impact on the coast

and on erosion, including:

landward: dredging, land reclamation, vegetation clearing, mining and river damming,

and

seaward: building of hard defences such as ports, seawalls, or any other hard

structures as these may modify coastal sediment processes and transport.

24

It is now accepted that migration of people towards the coast, with the requisite growing

interference in the coastal zone, has resulted in coastal erosion risks being regarded as a

growing problem driven more by human activity than from the natural process.

1.3.3 Coastal Flooding

Coastal flooding is the inundation of land from estuaries and the open sea that can be caused

by a combination of extreme tidal levels, storm surge and waves. Coastal flooding is already a

significant risk for many areas around the coast, as demonstrated by the national Preliminary

Flood Risk Assessments

1

, the Catchment-based Flood Risk Assessment and Management

(CFRAM) Programme

2

and the National Coastal Flood Hazard Mapping

3

.

This risk is expected to increase significantly with the impacts of climate change, with the

mean sea level expected to rise by up to 1m and possibly more by the end of the century. For

example, with 1m of sea level rise the degree of damages that would be caused by an extreme

coastal flood on Limerick City are expected to increase more than ten-fold. Around the coast

what was a flood with only a 1% chance of being exceeded in any given year would be

expected to occur on an approximately annual basis by the end of the century.

The OPW is the lead agency for flood risk management in Ireland, including for coastal

flooding, and has in place a range of programmes for the assessment and management of

flood risk, including those required under the EU ‘Floods’ Directive

4

. The OPW also published

in 2019 the Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan for Flood Risk Management

5

that sets

out a series of actions to assess and manage the potential impacts of climate change on flood

risk. As there are existing arrangements in place with regards to coastal flooding, this aspect

of coastal change is outside the focus of this report. It should be noted however that coastal

flooding and coastal change are inter-linked and, subject to decisions made on future

arrangements, there will be a need for close coordination regarding the assessment and

management of risks arising.

1.3.4 Sea Level Rise and Change in the Inter-Tidal Zone

GMSL reconstructions based on tide gauge observations show a rise of 21cm from 1900-2020

at an average rate of 1.7 mm/year (Palmer et al., 2021 and Fox-Kemper et al., 2021 as cited

by the EEA, 2021). The rate of GMSL rise accelerated to 3.3 mm/year over the period 1993-

2018 and 3.7 mm/year over the period 2006-2018, more than twice as fast as during the 20th

century (Nerem et al., 2018 and Fox-Kemper et al., 2021 as cited by the EEA, 2021).

Since 1970, anthropogenic forcing has been the predominant cause of this accelerating sea

level rise both globally and in European regional seas. Thermal expansion of ocean water was

initially the main driver, but melting of glaciers and of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets

have exceeded the effects of thermal expansion since about 2000 (WCRP Global Sea Level

Budget Group, 2018, Oppenheimer et al., 2019 and Fox-Kemper et al, 2021 as cited by the

EEA, 2021).

Global climate models project that the rise in GMSL during the 21st century (i.e. in 2100,

relative to the period 1995-2014) will likely (66% confidence) be in the range of 0.28-0.55m

for a very low emissions scenario (SSP1-1.9), 0.44-0.76m for an intermediate emissions

1

https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/1c7d0a-preliminary-flood-risk-assessment-pfra/

2

https://www.floodinfo.ie/about_frm/

3

https://www.floodinfo.ie/publications/?t=48

4

https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/aba306-flood-risk-policy-and-co-ordination/#eu-floods-directive

5

https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/97984b-climate-change-and-sectoral-adaptation-plan/

25

scenario (SSP2-4.5) and 0.63-1.02m for a very high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5). Model

simulations that include the possibility of fast disintegration of the polar ice sheets, which is

assessed to have a low likelihood, project a GMSL rise of up to about 5m by 2150 under a very

high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5) (Fox-Kemper et al., 2021 as cited by the EEA, 2021).

The future behaviour of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets is still rather uncertain,

particularly under higher emissions scenarios. Studies considering processes that can lead to

a faster disintegration of the Antarctic ice sheet, including a potential collapse of marine-

based sectors, have estimated a GMSL rise of up to 2.3m by 2100 and up to 5.4m by 2150

(Bakker et al., 2017, Kopp et al., 2017, DeConto et al., 2021 and Fox-Kemper et al., 2021 as

cited by the EEA, 2021). The consideration of such high-end scenarios is important for long-

term coastal risk management, in particular in densely populated coastal zones (Mengel et al.,

2018 as cited by the EEA, 2021).

As sea levels rise around the coast of Ireland this will result in changes in the present extent

of the inter-tidal zone and upper foreshore. For example, at present the upper limit of the

inter-tidal zone at any location along the coast is defined by the present elevation of the

Highest Astronomical Tide (HAT) and the elevation of the coast or beach. Similarly, the lower

limit of the inter-tidal zone at any location along the coast is defined by the present elevation

of the Lowest Astronomical Tide (LAT) and the elevation of the foreshore or beach. As sea

levels continue to rise, so too will the astronomical tides, which will cause the landward

migration of the inter-tidal zone, resulting in low lying land or property currently located

immediately landward of the present HAT boundary or inter-tidal zone becoming submerged

on a very regular basis (daily in some cases) as part of the normal tidal processes.

1.3.5 Urban Development

Many of our towns and almost all of our major cities are located on the coast. Their location

has obvious vulnerabilities to sea level change, although the actual risk depends on a range of

factors not least of which is the topography of their location. Historically there have been a

range of flood defence and river channeling interventions, for example the quays in Dublin.

This reflects the long-term relationship our urban centres have had with the sea.

In the foreseeable future this will not change. Coastal locations will continue to be centres

for urban development, however they will have to adapt to the effects of coastal change. The

extent of adaptation is dependent on their location, the coastal conditions and the capability

for making appropriate, sustainable over time, interventions.

Considerable data is required to devise the appropriate range of initiatives needed to respond

to the long-term effects of coastal change. In the first instance further gathering of evidence

and modeling of coastal vulnerabilities needs to be undertaken in a systematic manner to

identify and prioritise interventions (physical, environmental or a mixture) and the future

location of strategic infrastructure. To assist in considering the future planning of our coastal

communities, there is a need for more developed and considered planning guidance, such as

currently exists for planning and flood risk management.

26

1.4 Scale of Impact from Coastal Change

Currently, there is no ongoing monitoring of Ireland’s changing coast that encompasses all of the

various risks. As previously outlined, there has been considerable work done and that is ongoing with

regards to coastal flooding. However, a range of other work, already undertaken or ongoing, provides

a certain level of information and some indicators of the extent of the issue. For example;

In 2013, the OPW completed the Irish Coastal Protection Strategy Study (ICPSS). This national

study provided strategic coastal erosion maps for the national coastline to the years 2030 and

2050 and to 2100 in respect of strategic coastal flood maps. The projected erosion assessment

was based on a ‘look back’ of changes to the coastline during the previous 30 years. While this

study excluded consideration of climate change with respect to erosion hazard, the OPW

provisionally estimated the impact to Ireland’s coast for a 1m sea level rise derived from the

ICPSS data.

The Local Government Management Agency (LGMA) and the County and City Management

Association (CCMA) Climate Change subcommittee carried out two national audits among

Irish coastal local authorities in 2016 to establish the extent of the coastal erosion at a national

scale and investigate practices and policies in place to deal with the issue in Ireland at the local

authority level. University College Cork was subsequently appointed by Fingal County Council

to prepare a report

6

in 2017 based on the findings of the two audits and to provide further

clarification on several issues.

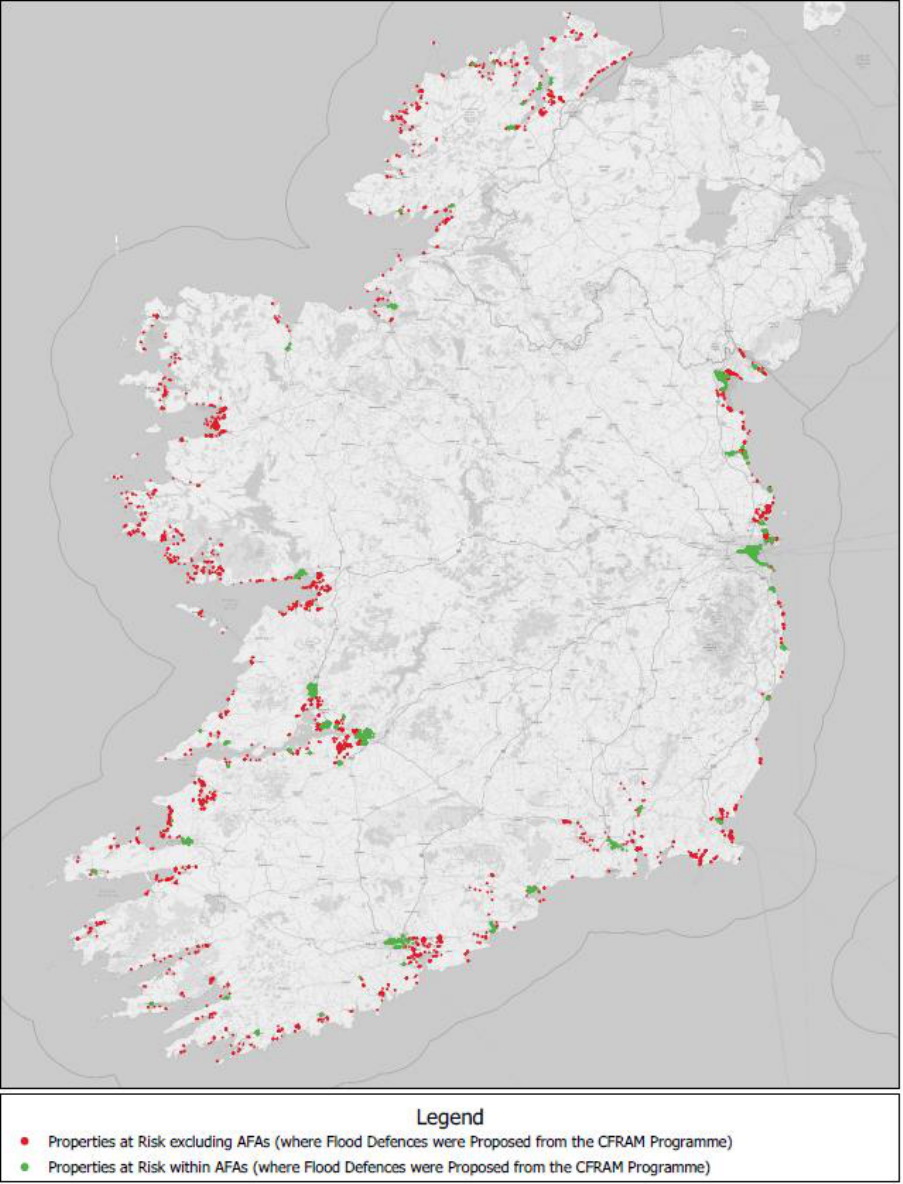

To inform the work of the inter-departmental group, the OPW further analysed and provisionally

projected information available to estimate the indicative scale of risk to Ireland’s coast from climate

change. As part of this process, the information from both the ICPSS and CFRAM studies were

combined. On the basis of this indicative and high level analysis, a number of issues were highlighted

that required immediate consideration and further actions or decisions to ensure effective and

sustainable management. These fell into issues related to coastal change and the separate issue of

coastal flooding. Substantial infrastructure and property was identified from this analysis to be at risk

from climate change including:

Public Utilities: Power Stations, Water Treatment Plants, Waste Water Treatment Plants, Gas

Assets and Telecommunication Exchanges,

Transport: Motorway, National, Regional and Local Roads, Ports, Airports, Railways

Social Services: Hospitals, Schools, Nursing / Residential Homes, Prisons, Caravan / Halting

Sites,

Public Infrastructure: Schools, Libraries, Community Centres, Local and Central Government

Offices (incl. Post Office), Emergency Services (Fire, Garda, Civil Defence, RNLI and Coast

Guard Stations), Health Centres, Churches, Parks and Public Gardens, Sports Facilities,

Playgrounds, heritage monuments and properties in public ownership,

Environmental: Natura 2000 sites (SACs, SPAs), Ramsar Sites, Annex IV (Habitats Directive)

species of flora and fauna, and their key habitats, Natural Heritage Areas, Nature Reserves,

Wildfowl Sanctuary, OSPAR

7

, National Parks,

Tourism and Cultural Heritage: Hotels, holiday homes, camping sites, beaches, cultural sites

and culturally significant environments may include submerged landscapes, shipwrecks,

archaeological objects, harbours, ports, jetties, piers, lighthouses, watchtowers, defences,

coastguard stations, cable stations, boathouses, follies, landing places, fish traps, kelp grids,

bridge sites, crannogs and tidal mills, and all sites included in the Sites and Monuments

Record,

6

Local Authority Coastal Erosion Policy and Practice Audit, Fingal County Council, 2017

7

www.ospar.org/about

27

Business: Industrial installations, urban waste water treatment plants, septic tanks, significant

slurry storage facilities, establishments defined under Directive 2012/18/EU

8

,

Agriculture: Agricultural lands and associated facilities,

Other: Private houses, sporting and community facilities.

Further national scale assessment has indicated that a range of infrastructure and assets could

become at risk within the inter-tidal zone in the future.

A related national scale assessment of risk due to coastal erosion has not yet been undertaken as there

are limited datasets available to inform such an assessment for the present day scenario and no

datasets available to inform such an assessment of the MRFS or HEFS.

1.5. Current Practice to Manage Coastal Change

Local authorities are responsible for the management of problems associated with coastal change and

erosion in their respective administrative areas. In undertaking this work, local authorities are

typically informed by the ICPSS and local knowledge. The Coast Protection Act, 1963 gave a legal basis

to support the request by the Local Authority for the OPW’s technical engineering expertise to inform

a decision to build any planned coastal protection structure.

Introduced in 2009, the OPW’s Minor Flood Mitigation Works and Coastal Protection Scheme is one

of the principal means of funding for local authorities to tackle the problems of coastal erosion within

their respective areas. The Scheme provides funding to local authorities to undertake minor flood

mitigation works or risk management studies, costing up to €0.75 million each, to address localised

flooding and coastal protection problems within their administrative areas.

Within this Scheme, the strategic decision to protect the coast rests with the local authority. The

OPW’s funding decision is based on technical aspects and costs assessed against benefits of current

assets, in a given location. No wider or longer-term planning decisions form part of this assessment.

The OPW does not provide for ongoing maintenance costs for such schemes and this is provided for

by local authorities from their own resources and from the block grant from the Department of

Housing, Local Government and Heritage.

Whilst coastal protection works may address coastal erosion problems locally they can also exacerbate

coastal erosion problems of coastline, intertidal and subtidal zones at other locations – up to tens of

kilometres away – or can generate other environmental problems, including unintended impact on

built and archaeological heritage. For this reason, the OPW generally requires such proposed works

or measures to be developed in conjunction with Coastal Erosion Risk Management Studies, which

significantly mitigate the potential for such adverse impacts. The State would only be aware of similar

studies underpinning private investment where the cumulative impact of environmental change is an

issue in a planning/foreshore consent.

The legislative framework for development in coastal areas is very complex, involving both EU and

national measures. These include the Planning and Development Acts, Foreshore Acts

9

, Harbours

Acts, Coast Protection Act, the European Union (Planning and Development) (Environmental Impact

8

https://eur-

lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2012:197:0001:0037:EN:PDF#:~:text=This%20Directive%20la

ys%20down%20rules,a%20consistent%20and%20effective%20manner.

9

A large part of the foreshore consent process will be overtaken by new arrangements being implemented

under the Maritime Area Planning Act, 2021.

28

Assessment) Regulations 2018, the EU Water Framework Directive, the Floods Directive, the Birds

Directive and the Habitats Directive.

At a national level, the agreement of the overarching National Marine Spatial Plan (NMPF) in 2021

provides a new way of looking at how Ireland uses the marine area and planning how best to use it

into the future. The NMPF seeks to balance the different demands for using the sea including the

need to protect the marine environment. It is about planning when and where human activities take

place at sea. There are also relevant policies in relation to seascape and landscape.

In addition, the National Planning Framework guides at a high-level strategic planning and

development for the country over the next 20+ years, so that as the population grows, that growth is

sustainable (in economic, social and environmental terms). It recognises that Ireland’s coastline is a

remarkable but a fragile resource that needs to be managed carefully to sustain its character and

attributes in physical, environmental quality and biodiversity terms.

At the European level, the European Commission has been working to identify and promote

measures in relation to Europe's coastal zones deterioration and to improve the overall situation,

which is largely based on an integrated approach to coastal zone management, and in later years the

focus is on marine spatial planning. In 2007, a three year EU CONSCIENCE project

10

was launched to

help inform how to improve sustainable management of coastal erosion across EU Member States.

1.6. Conclusion

It is clear that tackling coastal change management in response to climate change will be complex,

multi-faceted and dynamic demanding a range of research, policy and consequent management

responses. A key objective of this report is to put in place a road map for responding to these

challenges in a structured and planned way to provide the basis for a long-term strategy for

integrated coastal change management.

10

http://www.conscience-eu.net/

29

2. Approaches to Coastal Change in Other Jurisdictions

2.1 Introduction and Background

An important task of the IDG in preparing this scoping report, was to consider lessons which could

be learned from other jurisdictions based on a range of EU and UK research projects

11

. In addition, a

desktop survey was carried out to ellicit policy development in a number of relevant European

Countries with geographic similarities, i.e. those European countries bordering the Atlantic seaboard

and the North Sea. The content below is a synopsis and distillation of key elements of policy arising

in each jurisdiction.

2.2 EU Context

Since 1996, the European Commission has been working to identify and promote measures to

remedy the deterioration of Europe's coastal zones and to improve the overall situation. For over

two decades, the EU approach has promoted integrated coastal zone management,

12

at the heart of

which is coastal erosion management.

Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) seeks to balance the various economic and social

claims to the use of coastal areas (fishing, shipping, port operation, industry and commerce, land-

based transport infrastructure, agriculture and forestry, wind energy, settlement development,

tourism, etc.) with the objectives of coastal zone protection (avoiding pollution, efficient use of the

resource land, nature conservation, flood protection).

The key principles of ICZM include:

Thinking beyond traditional planning time frames, to plan for long-term issues such as

climate change,

Trying to see the bigger picture by taking both the land and marine dimensions of the coastal

zone into consideration in planning and management,

Working with nature rather than against it by recognising the limitations of the coastal

systems and the negative impacts of development and human activity, and

Using a combination of tools, such as awareness raising techniques, technology, legal and

policy instruments to achieve management objectives.

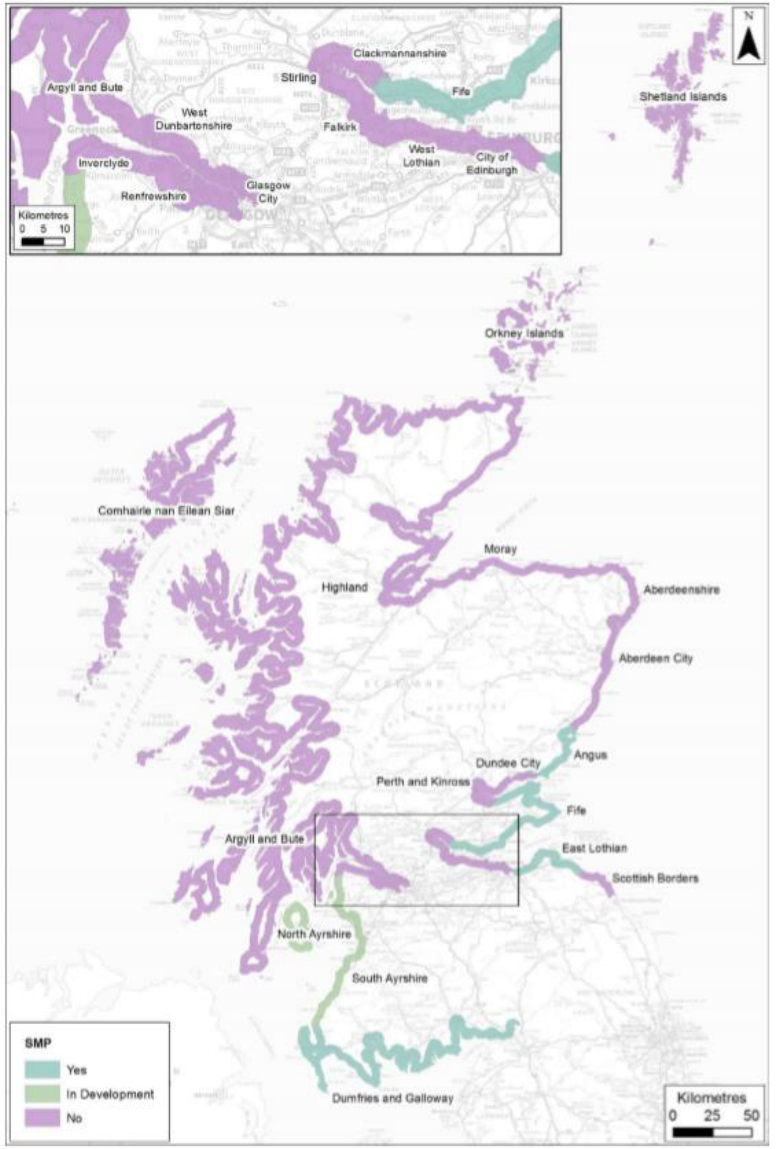

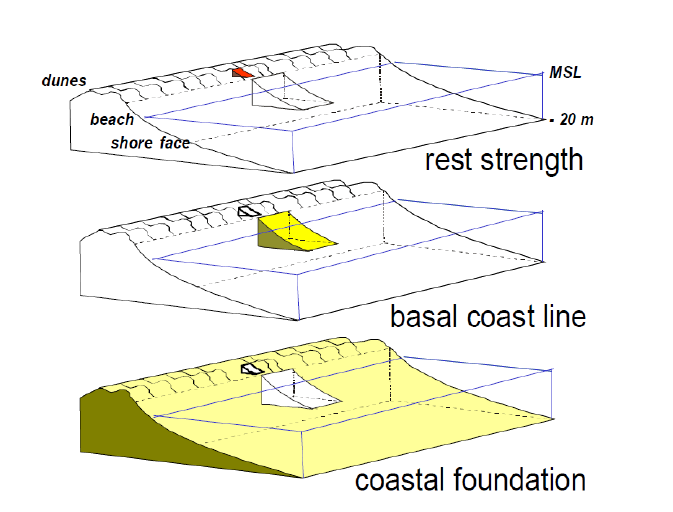

In 2007, a three year EU CONSCIENCE project was launched as part of the 6th Framework for