Climate Adaptation

Planning

Guidance for Emergency Managers

April 2024

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

This page intentionally left blank

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

i

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1

1.1. Purpose ............................................................................................................................ 1

1.2. Key Terms and Considerations for Climate Adaptation Planning ................................ 2

2. Climate Science for Emergency Managers ............................................................................... 5

2.1. Understanding Past and Potential Future Climate Conditions ..................................... 5

2.2. Climate Impacts Globally and in the United States ....................................................... 8

2.3. Regional Impacts .......................................................................................................... 10

2.4. Climate Impacts on People and the Economy ............................................................ 14

2.5. Climate Informed Decision-Making for Emergency Managers .................................. 18

2.6. Potential Tools for Climate Modeling .......................................................................... 19

2.7. Communicating Changes in Climate ........................................................................... 20

3. Climate Adaptation Planning: An Overview ............................................................................ 22

3.1. Principles of Climate Adaptation Planning.................................................................. 22

3.2. Climate Funding and Adaptation Solutions for Emergency Managers ..................... 25

3.3. Connecting Hazard Mitigation and Climate Adaptation Planning ............................. 29

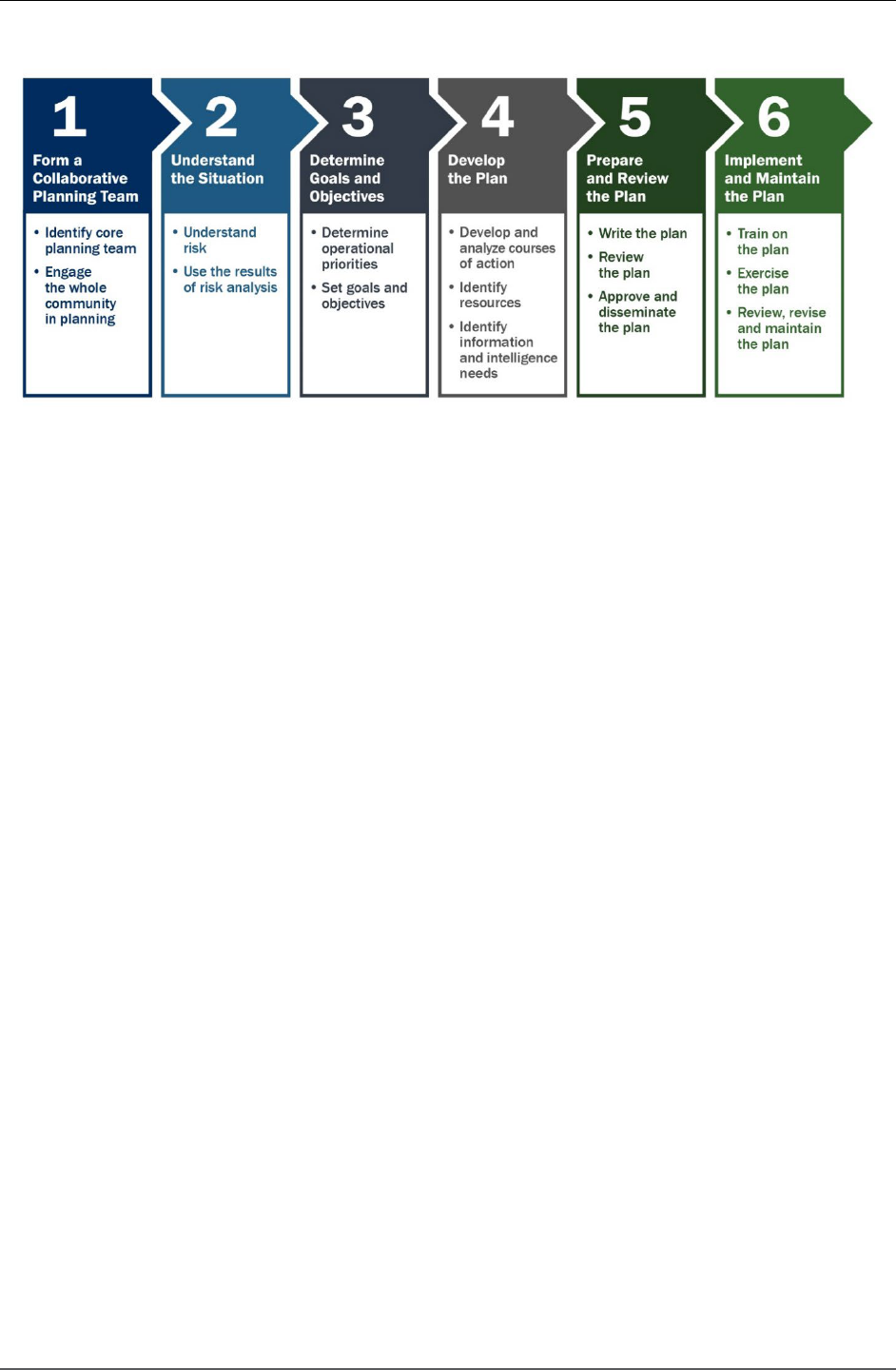

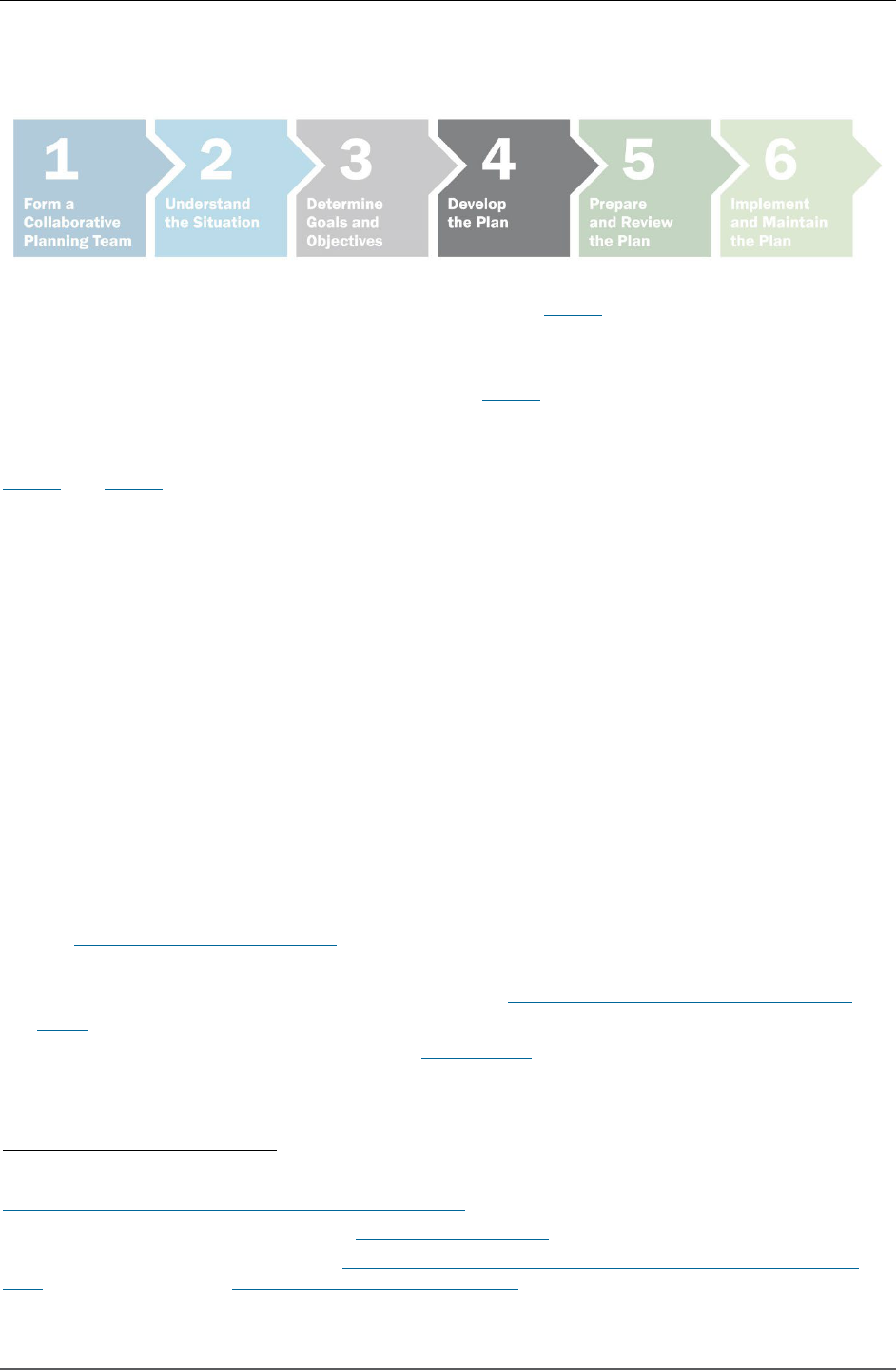

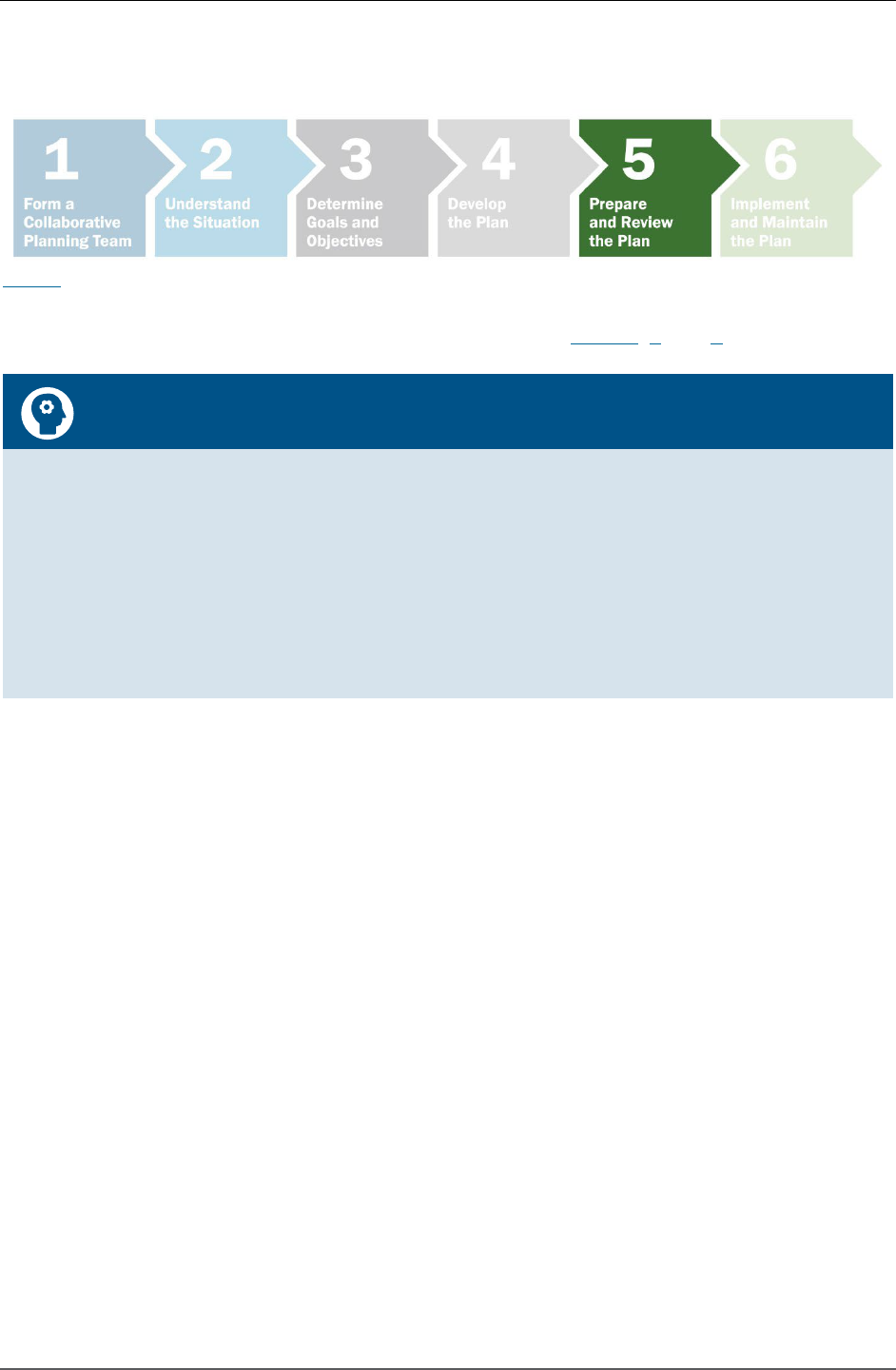

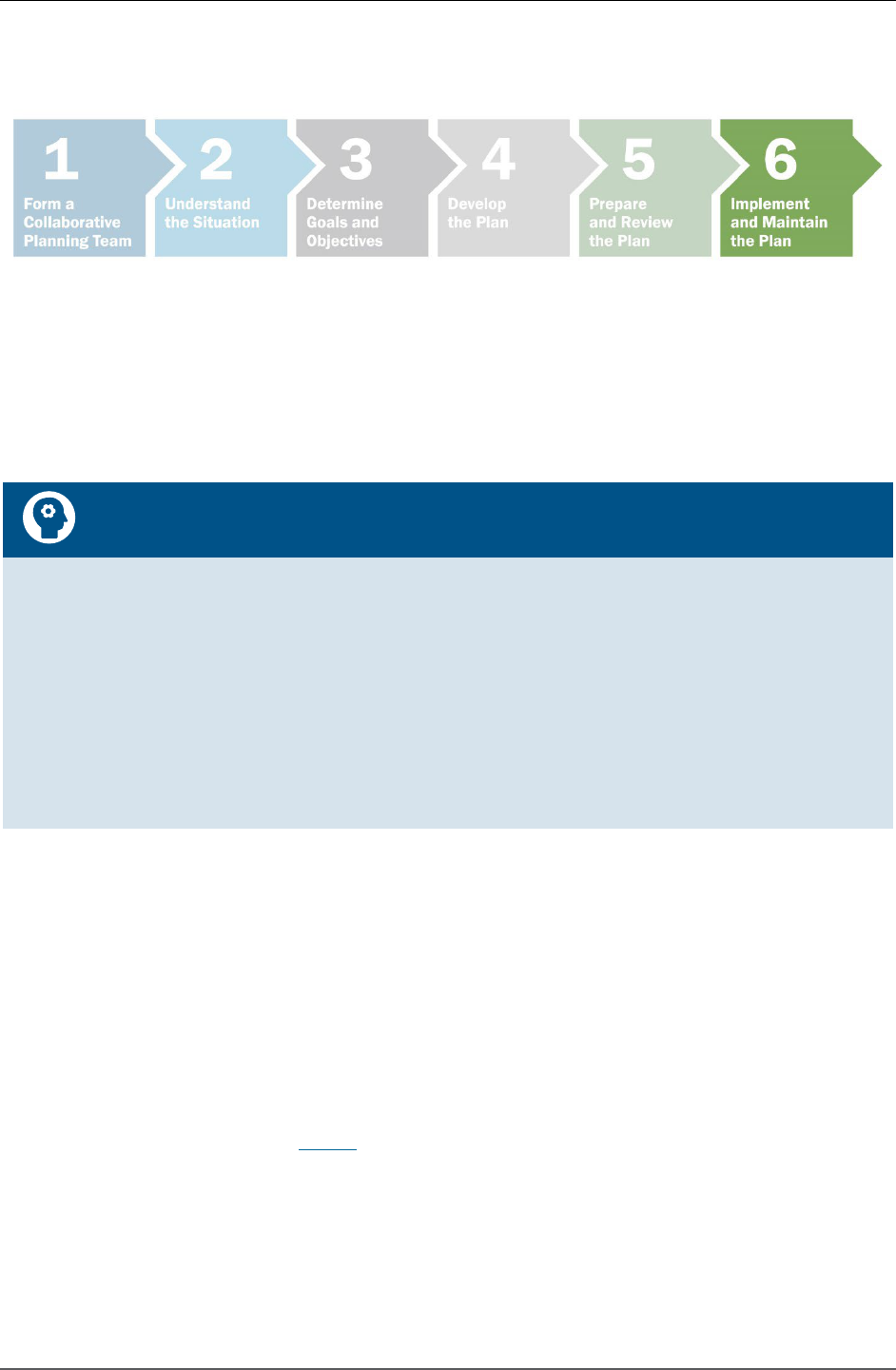

4. Climate Adaptation Planning: Six-Step Planning Process ...................................................... 32

4.1. Step 1: Form a Collaborative Planning Team ............................................................. 34

4.2. Step 2: Understand the Situation ................................................................................ 36

4.3. Step 3: Determine Goals and Objectives .................................................................... 41

4.4. Step 4: Develop the Plan ............................................................................................. 44

4.5. Step 5: Prepare and Review the Plan ......................................................................... 50

4.6. Step 6: Implement and Maintain the Plan .................................................................. 52

5. Conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 55

Appendix A: Climate Impacts on Emergency Response and Recovery Planning .......................... 56

Appendix B: Climate Data and Mapping Applications ................................................................... 62

Appendix C: Financing Climate Adaptation and Mitigation ........................................................... 64

Appendix D: Trainings and Additional Resources .......................................................................... 74

Appendix E: Glossary ...................................................................................................................... 77

Appendix F: Acronyms .................................................................................................................... 79

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

1

1. Introduction

Communities across the nation are experiencing changes in the natural hazards they face. Extreme

weather events such as extreme heat, floods, and wildfires are occurring more often or during

different times of the year. This makes it more difficult to plan for future incidents solely based on

what has happened in the past. The evolving hazard landscape means emergency managers need to

plan differently when assessing disaster risk and community resilience. To become more resilient,

communities should examine the changing environment, understand how future hazards could

unfold, and factor that information into their planning efforts.

1.1. Purpose

The Climate Adaption Planning: Guidance for

Emergency Managers (this guide) is intended

to help state, local, tribal, and territorial

(SLTT) emergency managers incorporate

climate adaptation into emergency

management planning efforts. It discusses

climate science in the context of disaster

preparedness and explains how emergency

managers can help communities develop

effective climate adaptation strategies.

Communities may use different terminology

around climate resilience and climate

adaptation efforts, but for the context of this

guide, the terminology will be subsequently

referred to as “climate adaptation planning.”

The introductory section provides an overview of this guide and definitions of key terms. Section 2

provides an overview of climate science, regional impacts, and potential tools for climate modeling.

Section 3 pr

esents an overview of climate adaptation planning before section 4 follows up with the

six step planning process based on Comprehensive Preparedness Guide (CPG) 101: Building and

Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans.

1

It also provides information and actions for each step.

Section 2 can be read as reference material, whereas Sections 3 and 4 provides case studies and

potential best practices emergency managers can take to plan for changes in climate. At the end of

each section and step are key takeaways for emergency managers. The Appendices provide

potential cascading impacts on response and recovery planning, more details on modeling tools,

resources for financing climate resilience, information on trainings, glossary, and acronym list.

1

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101: Developing and

Maintaining Emergency Operations Plans, Version 3.0. (2021).

https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_cpg-101-v3-developing-maintaining-eops.pdf

.

Climate Adaptation Planning

For the purpose of this guide, climate

adaptation planning is defined as a

systematic approach used to identify the

threats and hazards that might impact a

community given plausible future climatic

conditions. The process involves assessing

the risk posed by these threats or hazards

and positioning the community to avoid or

minimize the consequences of climate-

related disruptions.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

2

1.2. Key Terms and Considerations for Climate Adaptation Planning

Adaptation: Adjustment in natural or human systems to a new or changing environment that

exploits beneficial opportunities or moderates negative effects.

2

Climate mitigation (may also be called “mitigation” or “greenhouse gas [GHG] mitigation”):

Measures to reduce the amount and speed of future climate change by reducing emissions

of heat-trapping gases or removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

3

Hazard mitigation: Any sustained action taken to reduce or eliminate the long-term risk

to human life and property from hazards.

4

Nature-based solutions (NBS): The sustainable planning, design, environmental

management, and engineering practices that weave natural features and processes into the

built environment to promote adaptation and resilience.

5

Resilience: the ability to prepare for threats and hazards, adapt to changing conditions, and

withstand and recover rapidly from adverse conditions and disruptions.

6

Risk: Threats to life, health and safety, the environment, economic well-being, and other

things of value. Risks are often evaluated in terms of how likely they are to occur (probability)

and the damages that would result if they did happen (consequences).

7

Effective planning takes time and includes understanding potential future conditions, infrastructure,

and impacts, along with proactive integration with other plans. Too often, planning occurs in silos

which leads to conflicting community plans, especially in light of planning for the future with a

dynamic climate. An example of this would be an economic development plan that identifies a

waterfront district for expansion, which may conflict with a climate adaptation plan calling for

greenspace in the area due to an expected rise in the sea level. Through efforts such as hazard

mitigation and disaster recovery planning, emergency managers are in a key position to help bring

different parts of the community together to harmonize long-term strategies that address the

evolving climate as well as day-to-day planning challenges.

2

U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). Glossary: Adaptation. (2022).

https://downloads.globalchange.gov/strategic-plan/2022/USGCRP_2022-2031_Decadal_Strategic_Plan.pdf

.

3

USGCRP. Glossary: Mitigation. (2022). https://downloads.globalchange.gov/strategic-plan/2022/USGCRP_2022-

2031_Decadal_Strategic_Plan.pdf.

4

FEMA. 44 C.F.R. § 201.2: Definitions. (2023). https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-44/chapter-I/subchapter-D/part-

201/section-201.2.

5

FEMA. FEMA Resources for Climate Resilience. (2021).

https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_resources-climate-resilience.pdf

.

6

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment. (2023). https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/1#box-1_1.

7

USGCRP. Glossary: Risk. (2022). The U.S. Global Change Research Program 2022-2031 Strategic Plan.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

3

Hazard Mitigation versus Climate Mitigation for Emergency Managers

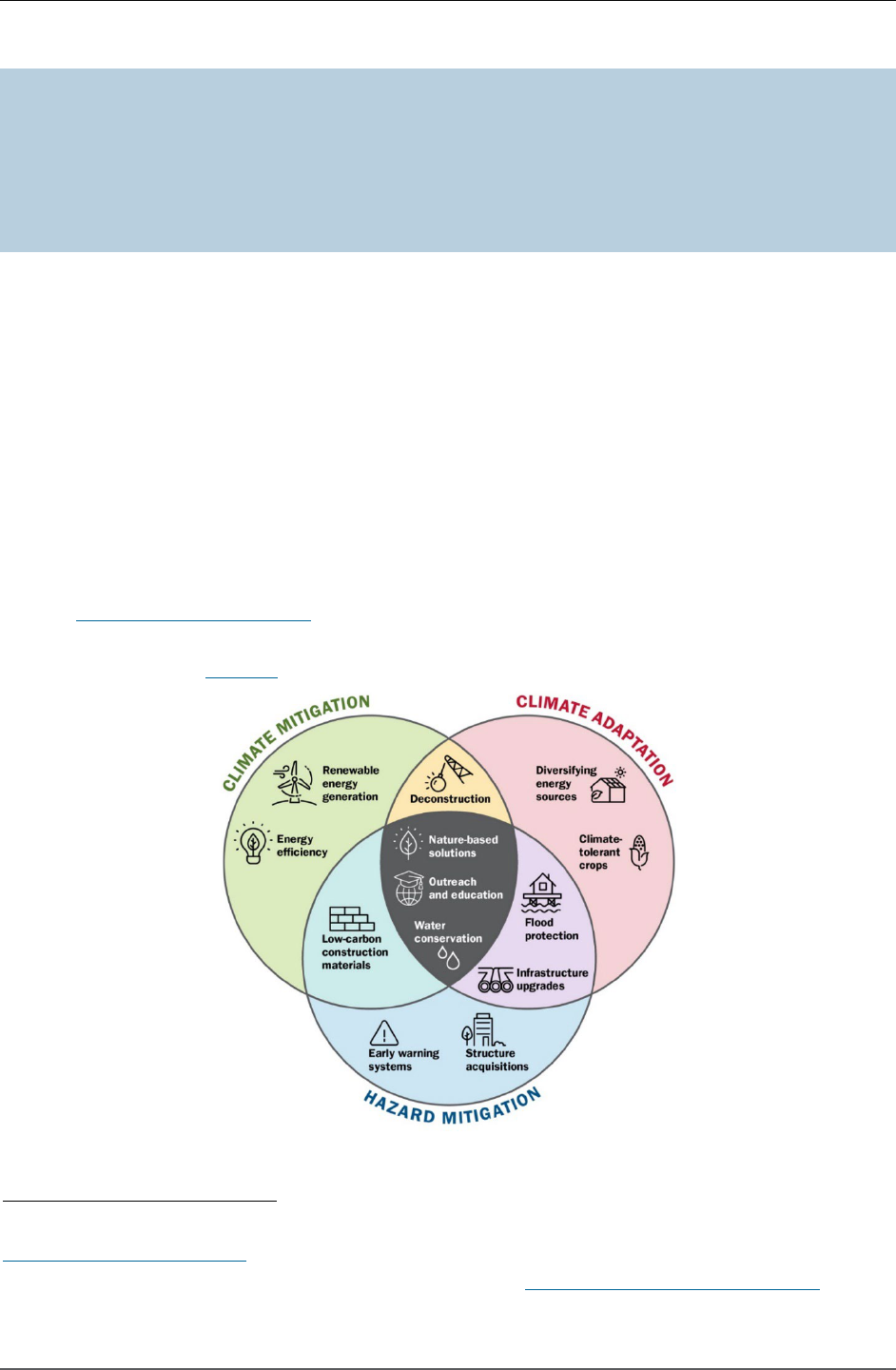

Emergency managers often shorten the phrase “hazard mitigation” to “mitigation,” however, in

the climate discipline, “mitigation” often refers to climate mitigation. Hazard mitigation is any

sustainable action to reduce or eliminate long-term risk. Climate mitigation is the reduction of

GHG emissions in the atmosphere to reduce the severity of human-caused climate changes.

Climate adaptation and hazard mitigation share a common goal of minimizing impacts from natural

hazards that are expected to increase in frequency and intensity due to climate change. Climate

adaptation is especially concerned with adjusting to future conditions and building resilience to

withstand those changes. As the future climate is variable and may present new challenges, climate

adaptation uses scenarios to help plan for uncertainty. Adaptation is also a process that continues

over time, responding to new information or climate conditions. Successful climate adaptation

solutions can vary depending on the scope of the action but often include changes in processes,

behaviors, and infrastructure. Adaptations can shorten recovery by building communities that are

more resilient for current and future hazards. Hazard mitigation and climate adaptation are essential

because the effects of climate change are happening now and are expected to worsen.

8

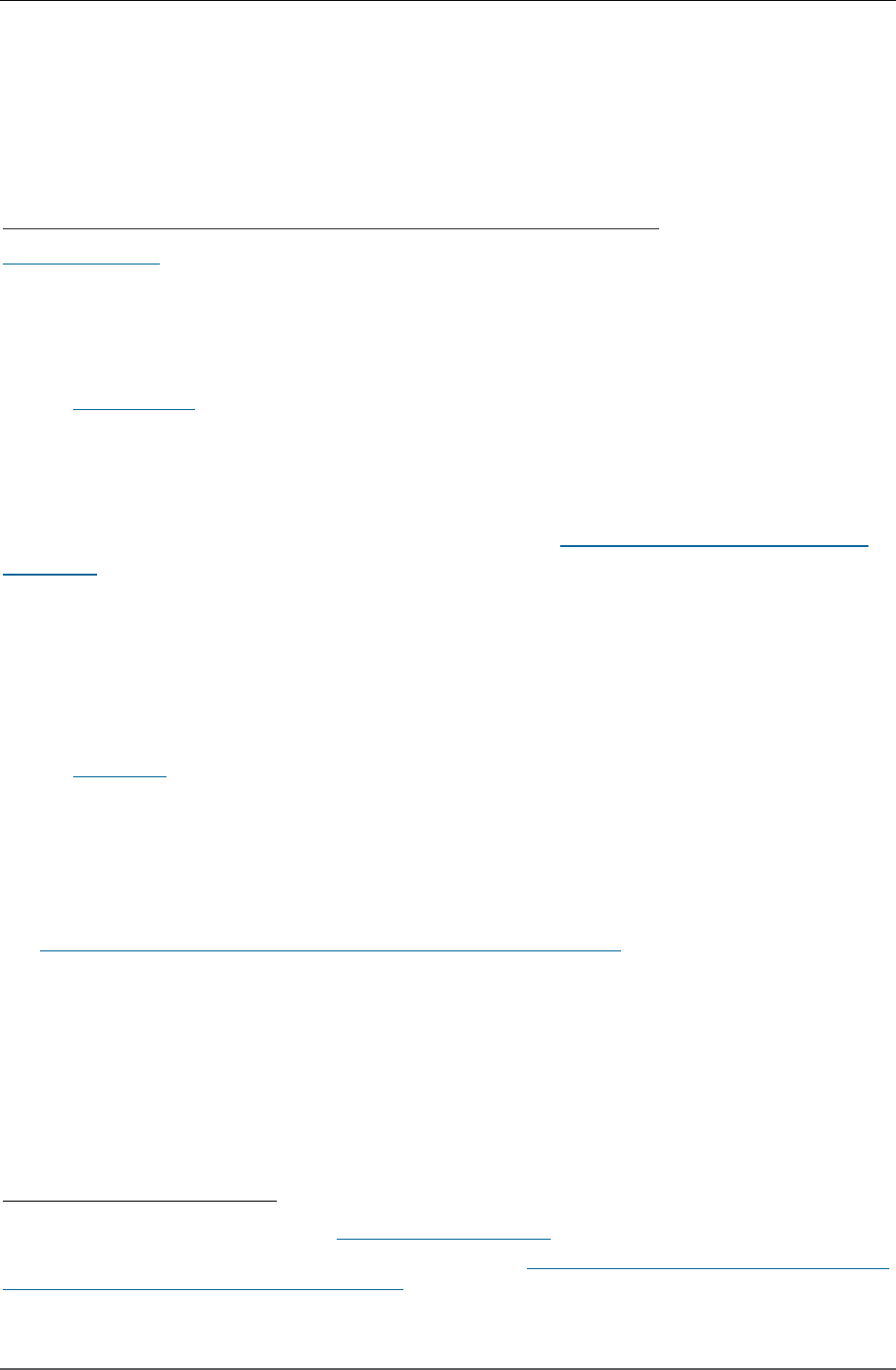

As all-hazards planners, emergency managers already consider the impacts of an evolving climate

through hazard mitigation planning.

9

By adding climate adaptation planning, emergency managers

can help promote climate resiliency across plans while supporting underserved populations and the

whole community (see

Figure 1 for examples).

Figure 1: Overlaps between Climate Mitigation, Hazard Mitigation, and Climate Adaptation

8

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Global Climate Change: The Effects of Climate Change. (2024).

https://climate.nasa.gov/effects/

.

9

For more information on hazard mitigation planning requirements, see https://www.fema.gov/hazard-mitigation.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

4

Key Takeaways for Emergency Managers: Introduction

Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and intense.

It is important to understand key terms commonly used in climate adaptation planning,

specifically the differences between hazard mitigation, climate mitigation, and climate

adaptation.

Climate adaptation planning seeks to assess climate-related hazards, develop courses of

action to mitigate risk, and devise strategies for responding to climate-related disruptions.

Emergency managers can help communities become more resilient by developing

effective hazard mitigation and adaptation strategies to lessen the impacts of an evolving

climate. They are in a key position to help bring different parts of the community together

to harmonize long term strategies that address climate adaptation as well as day-to-day

planning challenges in a comprehensive way.

10

10

This guide contains references to non-federal resources. Linking to such sources does not constitute an endorsement by

FEMA, the Department of Homeland Security, or any of its employees of the information or products presented.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

5

2. Climate Science for Emergency Managers

Climate science investigates the structure and dynamics of Earth’s climate system. It seeks to

understand global, regional, and local climate characteristics as well as the processes that influence

change over time. Climate science is similar to the academic discipline of emergency management

in that it draws on a number of scientific fields, including meteorology, oceanography, physics,

chemistry, environmental science, informatics, and computer science. Climate scientists are

increasingly working with engineers and social scientists across disciplines to understand and

explain how changing climatic conditions will impact individuals, communities, economies, and

infrastructure systems. This section describes the scientific underpinnings of the evolving climate

and its potential impacts, provides potential data tools for analyzing changes in the climate, and

introduces communication strategies needed to build climate-resilient communities.

2.1. Understanding Past and Potential Future Climate Conditions

Climate change is a broad term that can

cover changes in multiple parts of the

climate system, from temperature to

precipitation to wind patterns.

11

A region’s

climate provides the background

conditions that give rise to a location’s

weather events. Thus, climate can be

described as the “average weather” for an

area; it refers to the average of the

meteorological conditions and weather

patterns that occur over long time periods.

Through geologic time, Earth’s climate has

varied, reflecting the complex interactions

and dependencies of the solar, oceanic,

terrestrial, atmospheric, and living

components that make up Earth’s systems.

Earth experiences long cycles of warming

and cooling that span tens of thousands to

100,000 years in length. The cycles are

influenced by regular changes in Earth’s orbit that alter the intensity of the solar energy that the

planet receives, absorbs, and reflects. Earth’s climate has also been transformed over a long

timescale by changes in atmospheric chemistry and ocean circulation. It has also changed due to

sudden events, such as massive volcanic eruptions into the stratosphere.

11

For more information on Climate Essentials for Emergency Managers, see https://www.fema.gov/node/climate-

essentials-emergency-managers.

Climate versus Weather

Weather refers to short-term atmospheric

conditions while climate is the weather of a

specific region averaged over a long period of

time.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

6

The rate of change in the climate during the 20

th

century and early 21

st

century stands out in the

geological record as extremely rapid, especially relative to the last 10,000 years. Since the year

1900, global temperatures have risen by approximately 2°F, and climate scientists expect Earth’s

temperature will continue to rise at an increasing rate throughout the 21

st

century.

12

The key driver

of this growing rate has been attributed to the emission of gases that trap heat in the atmosphere,

commonly referred to as GHG.

13

Greenhouse Gases

GHG are gases that trap heat and solar radiation in Earth’s atmosphere rather than allowing it to

escape into space. This process of heating the atmosphere is known as the greenhouse effect.

GHG include carbon dioxide, methane, ozone, nitrous oxide, and industrial gases. Except for

industrial gases, all are naturally occurring and are important for regulating Earth’s temperature.

Human activities have increased the amounts of gases in the atmosphere, creating a disruption

in the complex system of feedback loops in Earth’s warming atmosphere and climate.

14

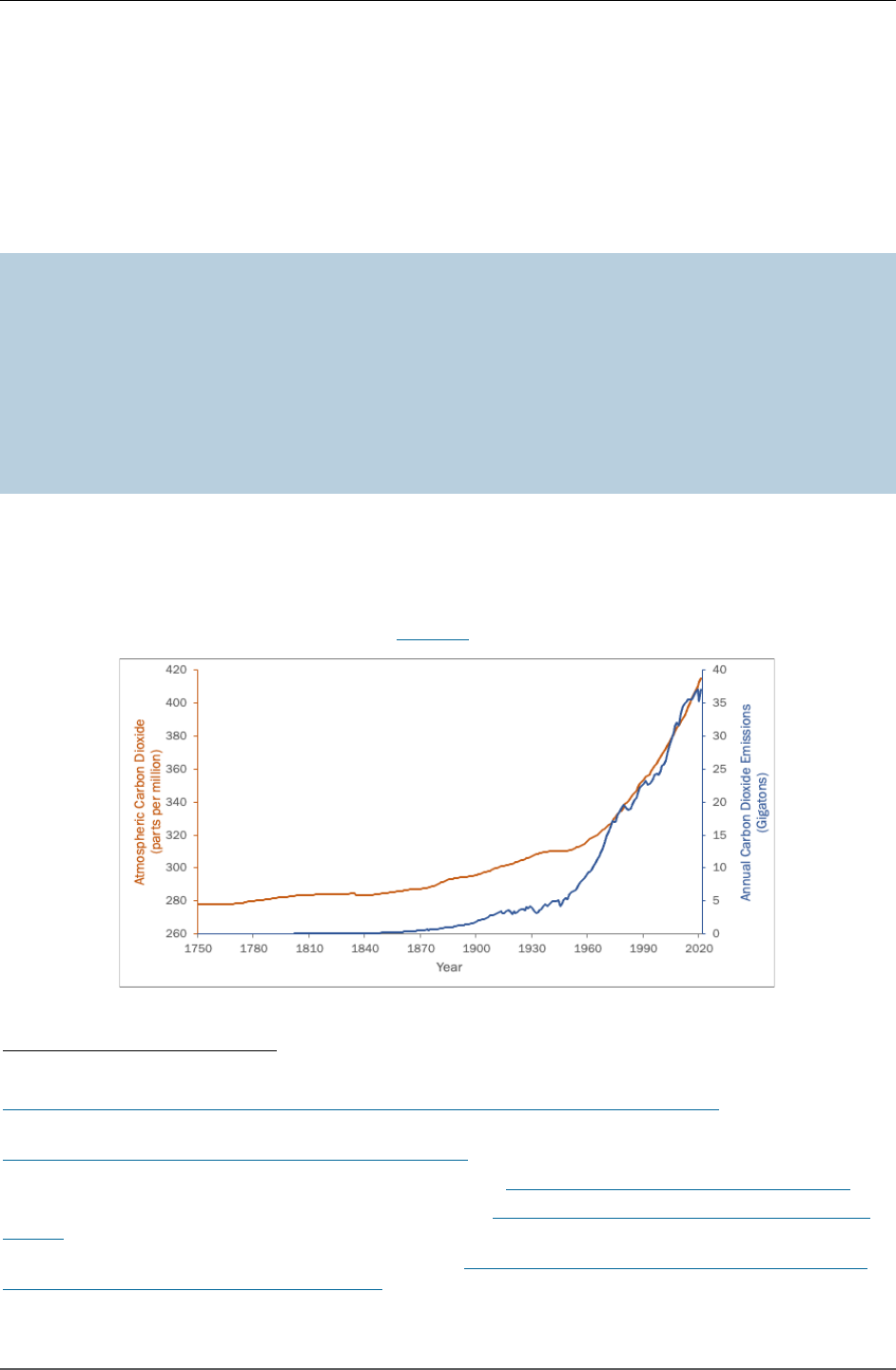

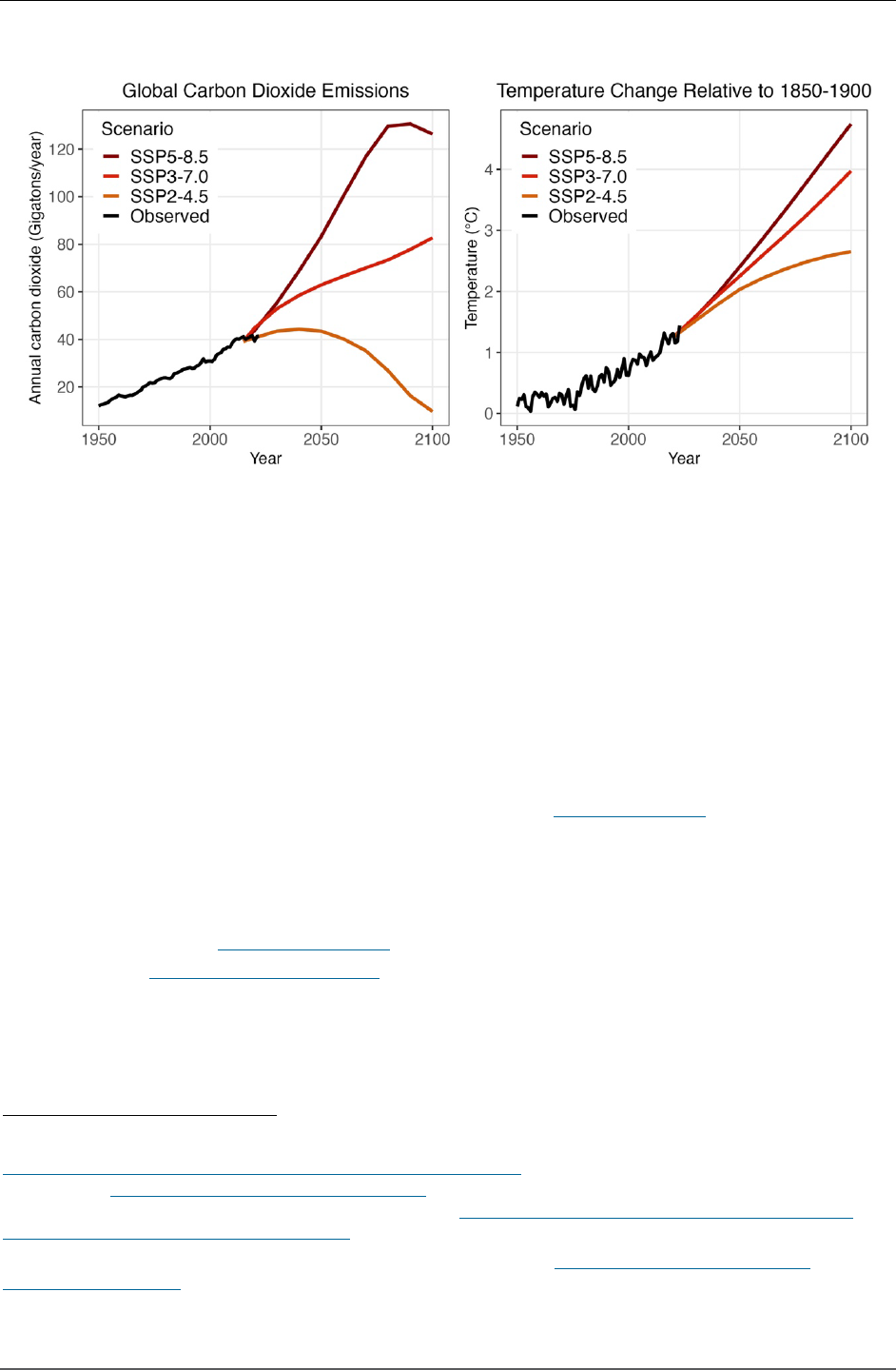

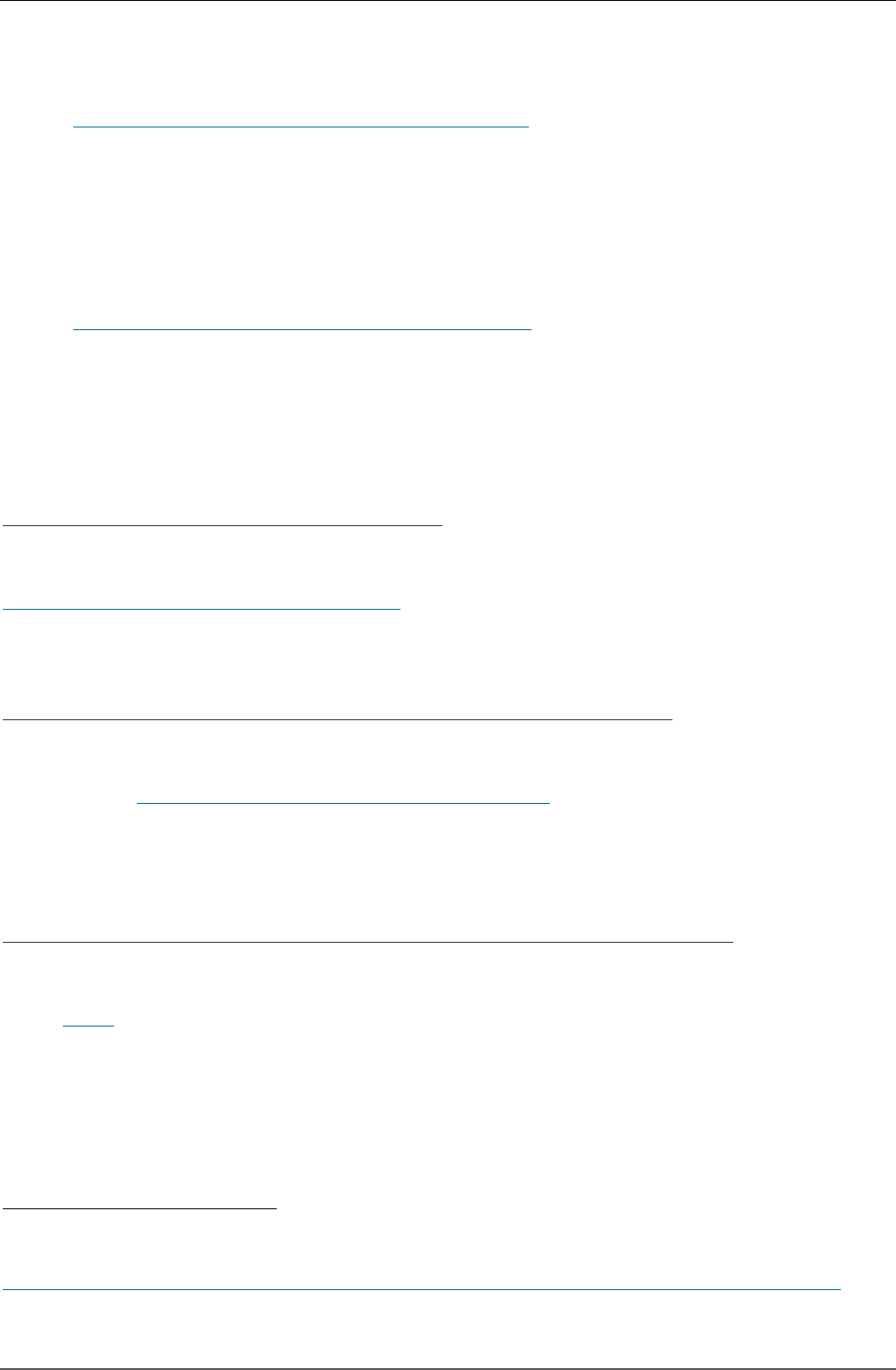

The types and severity of change in the climate depend on how much GHG have built up in the

Earth’s atmosphere. These gases have fluctuated over geologic time, yet human activities since the

pre-industrial era, most notably fossil fuel burning, have exponentially increased the release of

carbon dioxide emissions, resulting in a higher concentration of heat-trapping GHG and an increase

in Earth’s average surface temperature (see Figure 2).

15

Figure 2: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Amounts and Annual Emissions (1750 – 2021)

16

12

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Climate Change: Global Temperature. (2024).

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature

.

13

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Overview of Greenhouse Gases. (2024).

https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases

.

14

NASA Earth Observatory. Glossary: Greenhouse Gas Effect. (2024). https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/glossary/f/h.

15

NASA. Vital Signs of the Planet: What is Climate Change? (2024). https://climate.nasa.gov/global-warming-vs-climate-

change/.

16

NOAA. Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. (2023). https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-

climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

7

As it is not possible to determine exactly what future GHG emissions will be, climate scientists have

created scenarios to better understand how human behavior will shape the future climate. Recently,

these scenarios have been tied to societal narratives that describe potential challenges to climate

mitigation and adaptation; these narratives are called Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

17

uses SSPs for climate modeling scenarios

that reflect change since the pre-industrial era. Each SSP is based on different assumptions of

societal, demographic, and economic conditions that will either decrease, maintain, or increase

future GHG emissions. For example, SSP2-4.5 describes a middle of the road scenario where

significant action is taken to mitigate changes in the climate, yet emissions remain relatively high

until midcentury. SSP3-7.0 is a scenario with many challenges in reducing emissions, while SSP5-8.5

describes a world with very high levels of fossil-fuel development throughout the rest of the

century.

18

Table 1 and Figure 3

show the estimated impact of three scenarios on global temperature ranges.

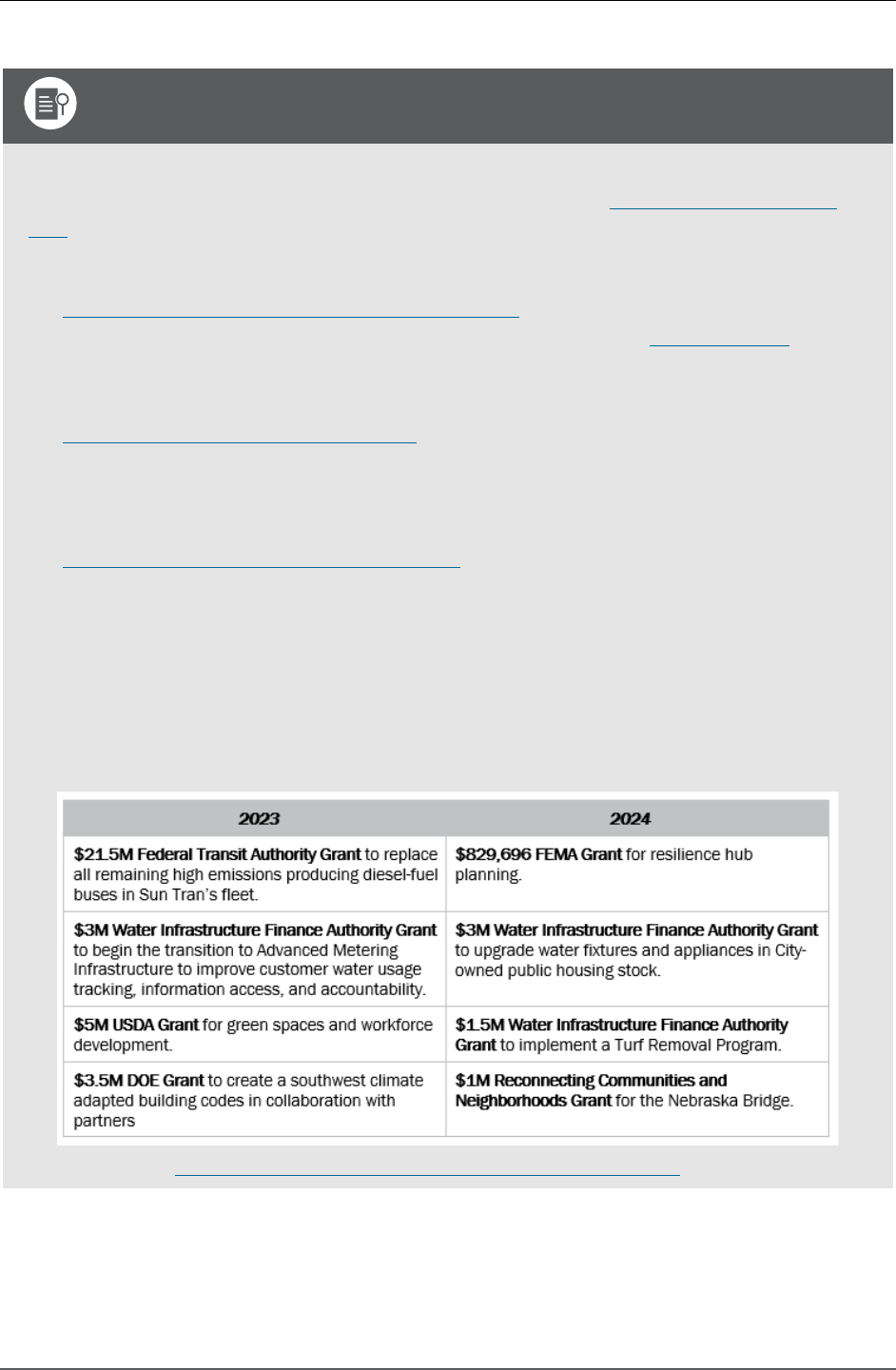

Table 1: Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) Impact on Global Temperature by 2100

SSP

Scenario

Global Mean Surface Temperature

Increase in 2081-2100 Relative to

1850-1900 Time Period

19

SSP2-4.5 Intermediate: Fossil fuel carbon emissions

peak mid-century, then decrease.

3.8°- 6.3°F (2.1 – 3.5° C)

SSP3-7.0 Higher: Assumes difficulty in reaching

emissions reductions with slow mitigation.

5.0°- 8.3°F (2.8 – 4.6° C)

SSP5-8.5 Highest: Fossil fuel carbon emissions continue

to increase throughout the century.

5.9°- 10.3°F (3.3 – 5.7° C)

17

The IPCC is an intergovernmental body of the United Nations responsible for advancing knowledge on climate change. It

provides objective and comprehensive scientific information on climate change. It undertakes a periodic, systematic review

of all relevant published literature and synthesizes the data and compiles key findings into "Assessment Reports."

18

The IPCC adopted SSPs as an update to Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) in its Sixth Assessment Report

(2023; https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

). Many publicly available climate data still use RCPs, including some of the

resources listed in this document. Fortunately, SSPs and RCPs share many similarities, with the second number in SSPs’

names matching several RCPs. For example, SSP5-8.5 is comparable to RCP8.5 and SSP2-4.5 to RCP4.5. Additional SSP

scenarios have been developed, including scenarios with GHG emissions trends substantially lower than SSP2-4.5;

however, we focus on the scenarios that most closely track with recent GHG emissions, ranging from intermediate to the

highest emissions scenario. See

USDA’s Climate Hubs for an explanation of SSPs and a comparison of RCPs and SSPs.

19

IPCC. Technical Summary: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. (2021).

https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_TS.pdf

.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

8

Figure 3: Carbon Emissions and Temperature Scenarios Based on SSPs

20

While the emission of GHG are currently the key driver of changes to the climate, other factors

influence both short- and long-term atmospheric patterns. For example, changes in land cover can

influence both weather and climate by altering the concentration of GHG and the exchange of energy

between land and the atmosphere. Furthermore, reforestation can provide localized cooling, even as

continued warming is expected for the planet as a whole and most regions on Earth.

Many factors will influence future GHG concentration including carbon capture and renewable energy

technology advancements, governmental and organizational policy decisions, consumer behavior,

and the pace of modernization in developing countries. Emergency managers are encouraged to

remain up to date with current science and undertake climate-informed risk analysis, especially as it

relates to climate impacts specific to a geographic region (see Regional Impacts

).

2.2. Climate Impacts Globally and in the United States

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors how global climate data

changes over time in its annual assessment. It al

so reports results through several Climate Change

Indicators on its Global Climate Dashboard.

21

On the next page are some of the NOAA Climate

Change Indicators:

20

Data compiled from these three sources: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. SSP Database. (2018).

https://tntcat.iiasa.ac.at/SspDb/dsd?Action=htmlpage&page=welcome. Copernicus Climate Change Service. ERA5 1940-

2023. (2023). https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/#!/home. Our World in Data. Annual total emissions of carbon dioxide

(CO

₂

), including land-use change, measured in tonnes. (2023). https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions#global-co2-

emissions-from-fossil-fuels-and-land-use-change.

21

For additional U.S.-based indicators, see the USGCRP Indicators Platform: https://www.globalchange.gov/our-

work/indicators?page=1

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

9

Annual Greenhouse Gas Index: Tracks the combined warming influence of the long-lived trace

gases in the atmosphere.

o The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen by 25 percent since 1958 and by

about 40 percent since the Industrial Revolution.

22

Global Surface Temperature: Tracks temperature measurements taken at locations around the

globe, which are converted from absolute temperature readings to temperature anomalies.

o Global temperatures rose approximately 2°F (~1°C) from 1900 to 2022.

23

Global Sea Level: Tracks sea level estimates provided through tide gauges and satellite

altimeters.

o Global sea level rise has accelerated from 1.7 mm per year throughout most of the 20

th

century to 3.2 mm per year since 1993.

24

In the United States (U.S)., emergency management response and recovery actions are being

impacted due changes in weather- and climate-related hazards. Changing weather patterns will

increase the severity, frequency, and impact of disasters. For example, the following list details

hazards that are common in emergency management plans and provides examples of associated

climate-related risk factors to consider:

Drought: As temperatures climb, evaporation rates increase. In drought conditions, high

evaporation rates will make droughts worse. Severe droughts can threaten drinking water

supplies and supply chains, reduce industrial output, and disrupt agriculture.

Extreme Heat: The annual number of very hot days is increasing. Extreme heat now regularly

affects all areas of the country. Furthermore, the “

urban heat island effect” can raise

temperatures by up to 10°F within urban environments.

25

,

26

Of all weather-related hazards,

extreme heat causes the highest number of deaths each year.

27

Coastal Flooding: Rising sea levels are contributing to more frequent and intense coastal floods

and storm surges, as well as recurring high tide flooding.

Inland Flooding: In many regions, more frequent and intense rains are leading to more severe

flooding, especially during the heaviest events. Heavy rain can also trigger flash flooding and

22

NOAA. Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. (2024). https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-

climate/climate-change-atmospheric-carbon-dioxide.

23

NOAA. Climate Change: Global Temperature. (2024). https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-

climate/climate-change-global-temperature.

24

NOAA. Climate Change: Global Sea Level. (2024) https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-

climate/climate-change-global-sea-level.

25

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 6: Land Cover And Land-Use Change. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/6/

.

26

For more information on the urban heat island effect, see https://www.heat.gov/pages/urban-heat-islands.

27

NWS/NOAA. Weather-related Fatality and Injury Statistics. (2022). https://www.weather.gov/hazstat/.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

10

cause rivers to overflow. As extreme flood events become more common, the risk of dam failure

is greater. Saturated soil also creates ideal conditions for landslides and mudslides.

Hurricanes: Warming ocean waters fuel larger and stronger tropical storm systems and weather

conditions and increase the likelihood of rapid intensification. The Caribbean, Gulf Coast,

Southeast, and Mid-Atlantic are seeing more destructive hurricanes.

Wildfires: Warmer temperatures are now more common, and intense droughts are creating the

conditions for larger wildfires. Wet growing seasons, paired with dry periods, can lead to high fuel

loads; warmer winter temperatures have allowed pests to decimate forest health, leading to

massive amounts of dead wood on forest lands. All these factors create conditions for larger and

more frequent wildfires and cascading smoke impacts.

This guide does not address all possible climate-related concerns and their potential impacts, as

climate science remains an evolving discipline.

28

For example, some climate research links extreme

cold events to Arctic warming due to its influence on the jet stream; however, this finding is not yet

well determined. Such cold air outbreaks significantly impacted people and infrastructure and should

still be factored into planning.

29

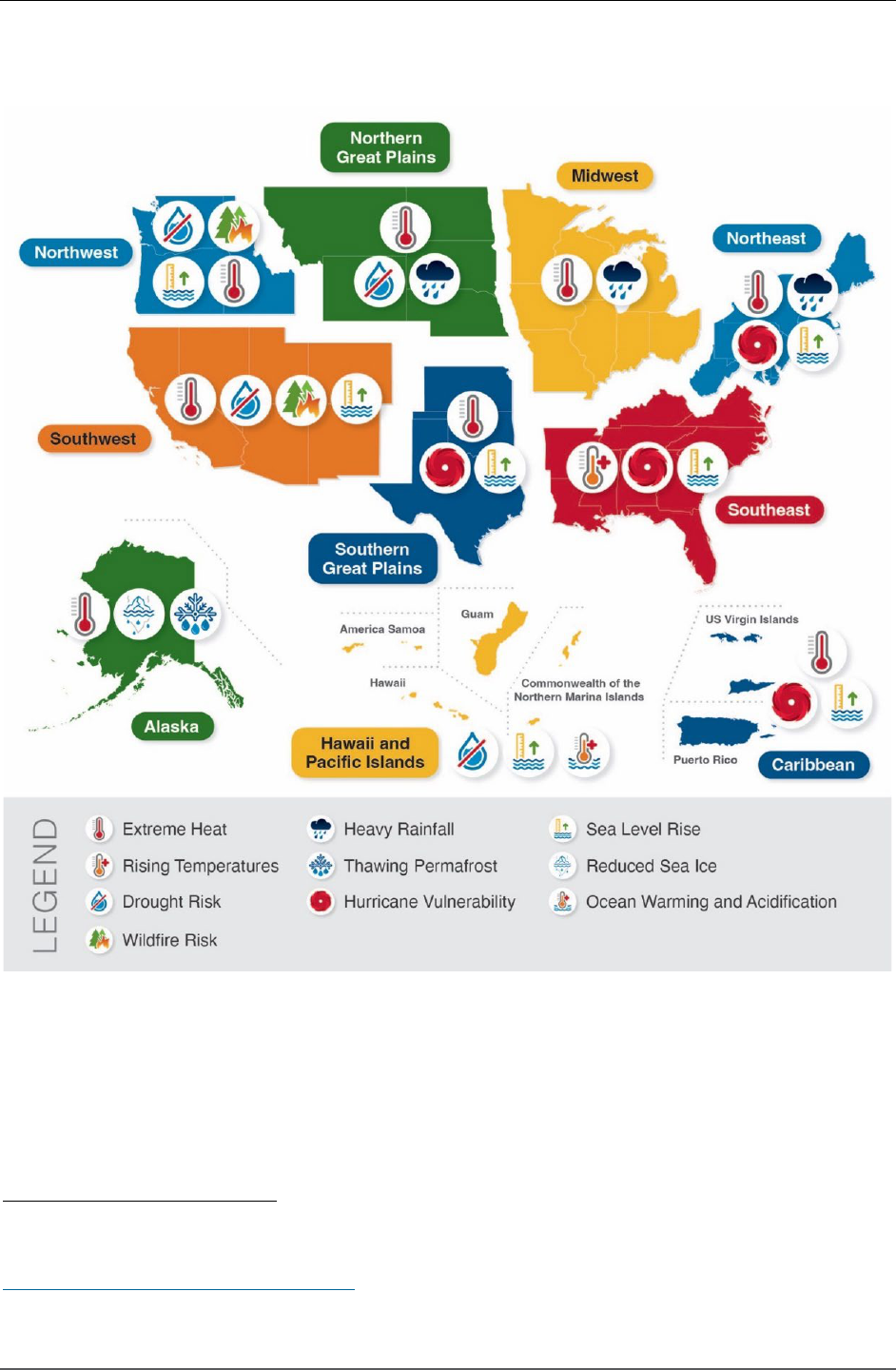

2.3. Regional Impacts

Changing hazards will impact communities and regions differently. The hazards that regions and

communities have been occasionally exposed to will become more frequent and severe. New areas

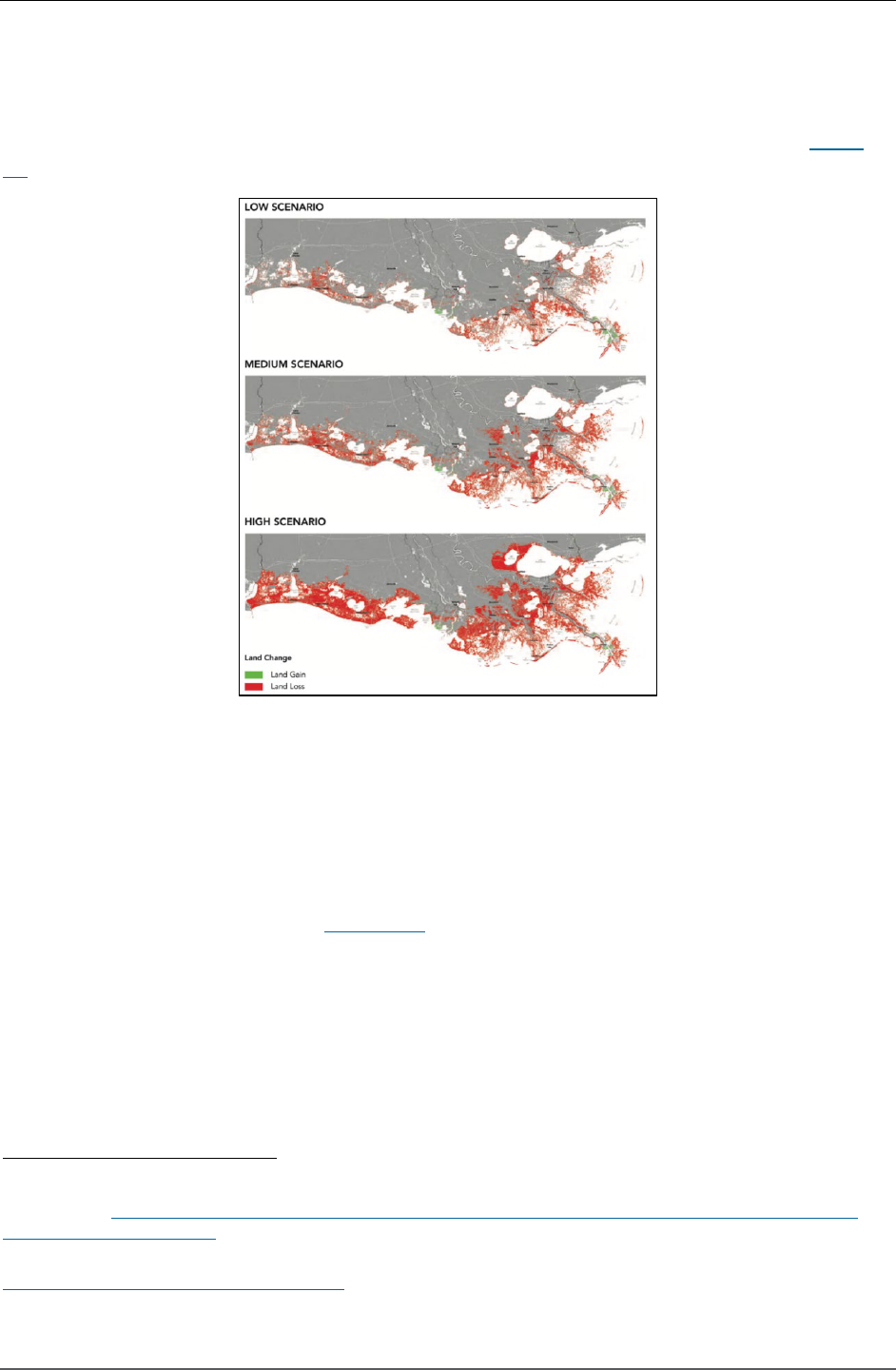

will also be affected. Figure 4 o

utlines the top climate-related hazards for each region in the U.S.

Note that this figure does not provide an exhaustive list of all climate-related hazards.

For a comprehensive summary of climate-r

elated risk for each region, see the regional chapters in

the Fifth National Climate Assessment and the 2022 State Climate Summaries.

30,31

The next section

provides a breakdown of potential climate-related impacts on communities by region.

28

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 3: Earth Systems Processes. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/3/.

29

For more information on FEMA’s Response and Recovery Climate Change Planning Guidance, see

https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_response-re

covery_climate-change-planning-

guidance_20230630.pdf.

30

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Regions. (2023). https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/regions/.

31

NOAA. State Climate Summaries. (2022). https://statesummaries.ncics.org/.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

11

2.3.1. POTENTIAL CLIMATE IMPACTS BY REGION

Figure 4. Regional Climate-Related Hazards

32

Northeast

33

The Northeast is experiencing warming temperatures and a large increase in the amount of

rainfall measured during heavy precipitation events.

32

Ibid. (Adapted figure).

33

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 21: Northeast. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/21/.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

12

Less distinct seasons, along with milder winters and earlier spring conditions, are already

altering environments in ways that adversely impact tourism, farming, and forestry. For example,

agriculture will likely face reduced yields as temperatures rise, potentially damaging livelihoods

and the regional economy.

More frequent heat waves in the Northeast are expected to increasingly threaten human health

through more heat stress and air pollution.

Sea level rise and more frequent heavy rains are expected to increase flooding and storm

surges, threatening infrastructure.

Southeast

34

Coastal communities in the Southeast are already experiencing warmer temperatures as well as

impacts from sea level rise, such as more frequent and more severe flooding.

Higher temperatures and greater demands for water will strain water resources.

Incidences of extreme weather, increased temperatures, and flooding will combine with high

rates of regional growth to have major impacts on human health, infrastructure, and agriculture.

Sea level rise is expected to contribute to increased storm surges, resulting in more damaging

hurricane and tropical storm events. Rising sea levels will increase the salinity of estuaries,

coastal wetlands, tidal rivers, and swamps, damaging habitats and degrading aquifers.

U.S Caribbean

35

Saltwater intrusion associated with sea level rise will reduce the quantity and quality of

freshwater in coastal aquifers.

Sea level rise, combined with stronger wave action and higher storm surges will worsen coastal

flooding and increase coastal erosion.

Projected increases in both average and extreme temperatures, resulting in higher levels of

noncommunicable diseases, behavioral health challenges, and excess mortality.

Midwest

36

Temperature increases in the Midwest have accelerated in recent decades, particularly

increases in nighttime and winter temperatures.

This region will likely experience warmer and wetter winters, springs with heavy precipitation, and

hotter summers with longer dry periods. Extremes may pose challenges for agriculture.

Risks to human health are expected to rise due to warming temperatures, reduced air quality,

and increased allergens.

Impacts to water quantity and quality are increasing the risks to ecosystem health, adequate

food production, surface water and groundwater uses, and recreation.

34

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 22: Southeast. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/22/.

35

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 23: U.S. Caribbean. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/23/.

36

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 24: Midwest. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/24/.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

13

Great Plains

37

,

38

Warmer winters are altering crop growth cycles and will require new agriculture and management

practices. Changes in water availability are likely to present challenges to agricultural irrigation

and threaten key wetland habitats.

Projected increases in temperature and drought frequency will further stress the High Plains

Aquifer, the primary water supply of the Great Plains.

Northwest

39

The Northwest is projected to face increased risks from extreme events, including flooding,

landslides, drought, wildfire, and heat waves.

The Northwest will likely be impacted by continued reductions in snowpack and lower summer

stream flows in the Northwest, worsening the existing competition for water resources. Larger

numbers of rain or snow events will also lead to additional flooding.

Higher temperatures, changing stream flows, and an increase in pests, diseases, and wildfires

will threaten forests, agriculture, and salmon populations.

Sea level rise is projected to increase the erosion of most coastlines, escalating infrastructure

and ecosystem risks.

Southwest

40

Observations of rapidly warming temperatures and reduced snowpack have been observed in

recent decades in the Southwest.

Increasing temperatures and more frequent and severe droughts are expected to heighten

competition for water for urban or residential use, agriculture, and energy production.

Indigenous populations are expected to experience difficulties associated with access to

freshwater, the sustaining of agricultural practices, and declines in cultural plant and animal

populations.

Drought, wildfire, invasive species, pests, and changes in species' geographic ranges will

increase threats to native forests and ecosystems.

Experiencing unprecedented extremes related to changes in climate, resulting in potential

droughts, larger and more frequent hailstorms, floods, and wildfires.

Older residents in rural areas and Indigenous communities are especially vulnerable to

increasingly severe and unpredictable climate impacts.

37

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 25: Northern Great Plains. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/25/.

38

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 26: Southern Great Plains. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/26/.

39

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 27: Northwest. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/27/.

40

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 28: Southwest. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/28/.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

14

Alaska

41

Extensive permafrost thaw is expected by the end of the 21st century, increasing the risk of

infrastructure damage.

Alaska is among the fastest warming regions on Earth, with temperatures warming twice as fast

as the global average since the middle of the 20th century.

Warming oceans will shift fisheries locations and impact productivity. Arctic sea ice is projected

to continue to decline, with nearly ice-free periods possible by mid-century.

Native Alaskans are expected to experience a declining availability of traditional foods and

reduced access to sea ice hunting grounds.

Hawaii and Pacific Islands

42

Dependable and safe water supplies for Pacific Island communities and ecosystems are

threatened by rising temperatures, changing rainfall patterns, sea level rise, and increased risk

of extreme drought and flooding.

Warmer and more acidic oceans are stressing coral reefs and fish habitats.

Sea level rise is expected to threaten biodiversity, ecosystems, and infrastructure of U.S. tropical

islands.

Changes in the climate are likely to affect the livelihoods of communities, tourism, and other

important economic sectors on tropical islands.

2.4. Climate Impacts on People and the Economy

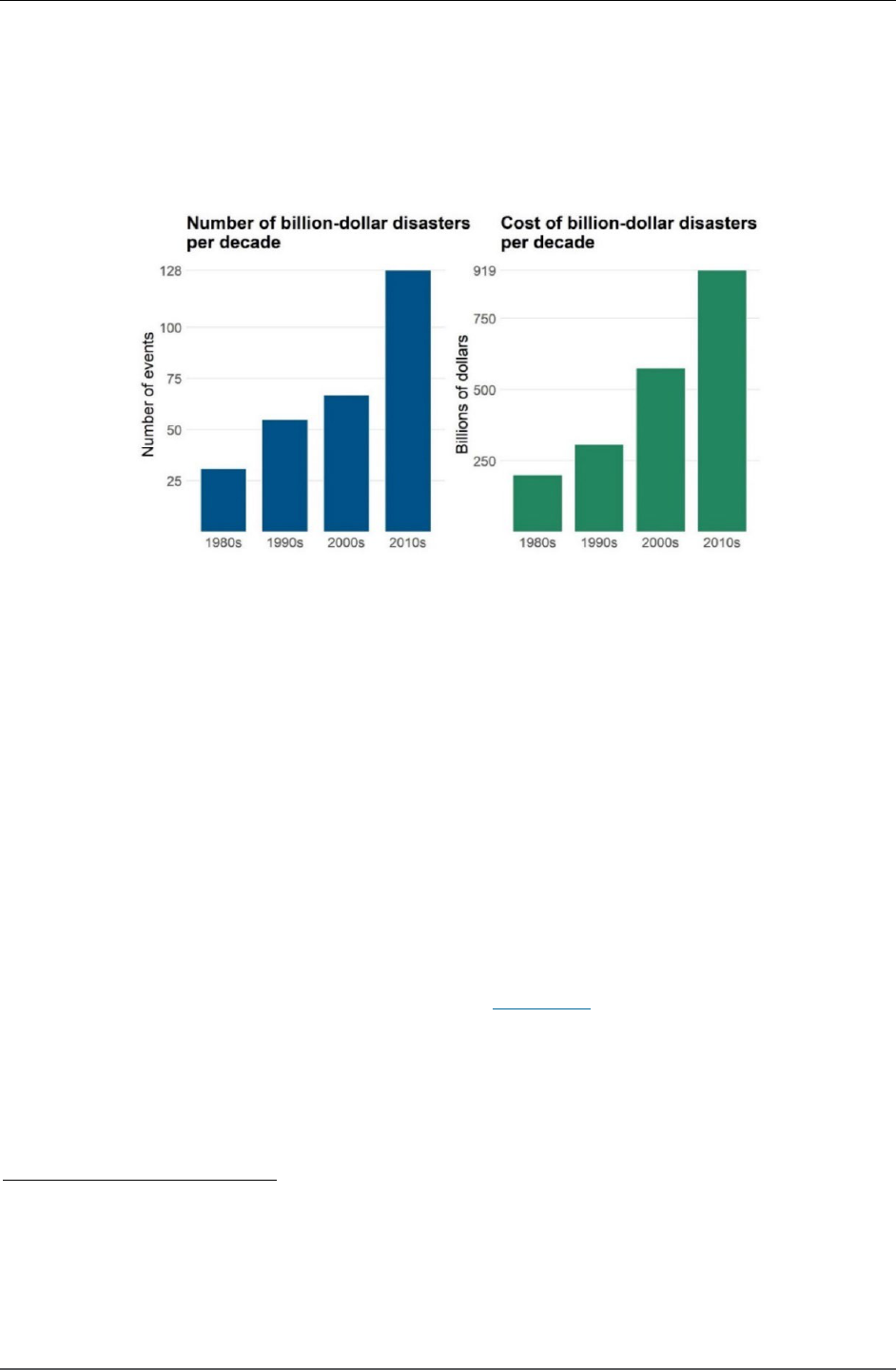

The frequency and complexity of disasters are increasing. According to NOAA, there were 28 climate -

driven disasters with losses exceeding $1 billion within the U.S. in 2023.

43

These events happened

across all parts of the country and included droughts, floods, severe storms, tropical cyclones,

wildfires, and winter storms that resulted in the deaths of 724 people. 2021 was the third-most

costly year for weather and climate-related disasters in the U.S., with only 2005 (Hurricane Katrina)

and 2017 (the California wildfires and hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria) causing more economic

impact. Since people live in high-risk areas, climate adaptation planning can play a key role in

reducing human vulnerability, risk to the built environment, and economic impacts.

While the frequency and severity of disasters over the coming century will continue to increase, such

changes are already being felt (see Figure 5

). For example, in the 1980s, a billion-dollar disaster

41

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 29: Alaska. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/29/.

42

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment: Chapter 30: Hawai’i and U.S.-Affiliated Pacific Islands. (2023).

https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/chapter/30/.

43

NOAA: National Centers for Environmental Information. U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters. (2024).

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

15

occurred approximately every four months on average.

44,45

Today, there is a billion-dollar disaster

occurring every three weeks, on average. The physical, economic, and social impacts from these

disasters are not distributed evenly. Disadvantaged populations are more likely to be exposed to the

worst disaster impacts and possess fewer resources to cope with the effects.

Figure 5: Trends in Billon-Dollar Disasters Events (Inflation-Adjusted)

Rising global temperatures are the most observable impact of a changing climate, resulting in

significant impacts on the frequency, severity, and geographical distribution of natural hazards. A

warmer atmosphere means more intense storms. The warmer atmosphere can hold more water

vapor, which results in increasing precipitation levels and higher risk of flooding. More heat in the

atmosphere and warmer ocean surface temperatures can lead to increased wind speeds in tropical

storms. Rising sea levels caused by melting glaciers and the thermal expansion of the ocean expose

coastlines to tidal flooding and greater storm surge. All these impacts lead to increased damages.

For example, shifting precipitation patterns can lead to more prolonged periods of drought while

greater evaporation rates dry out soils and reduce surface water. Reduced snowpack limits the

replenishment of reservoirs, creating water shortages and straining agriculture and livestock

production. These conditions can cascade to produce an environment conducive to the spread of

wildfire, with dry soil and vegetation as ample fuel for fires. For more in-depth examples of climate-

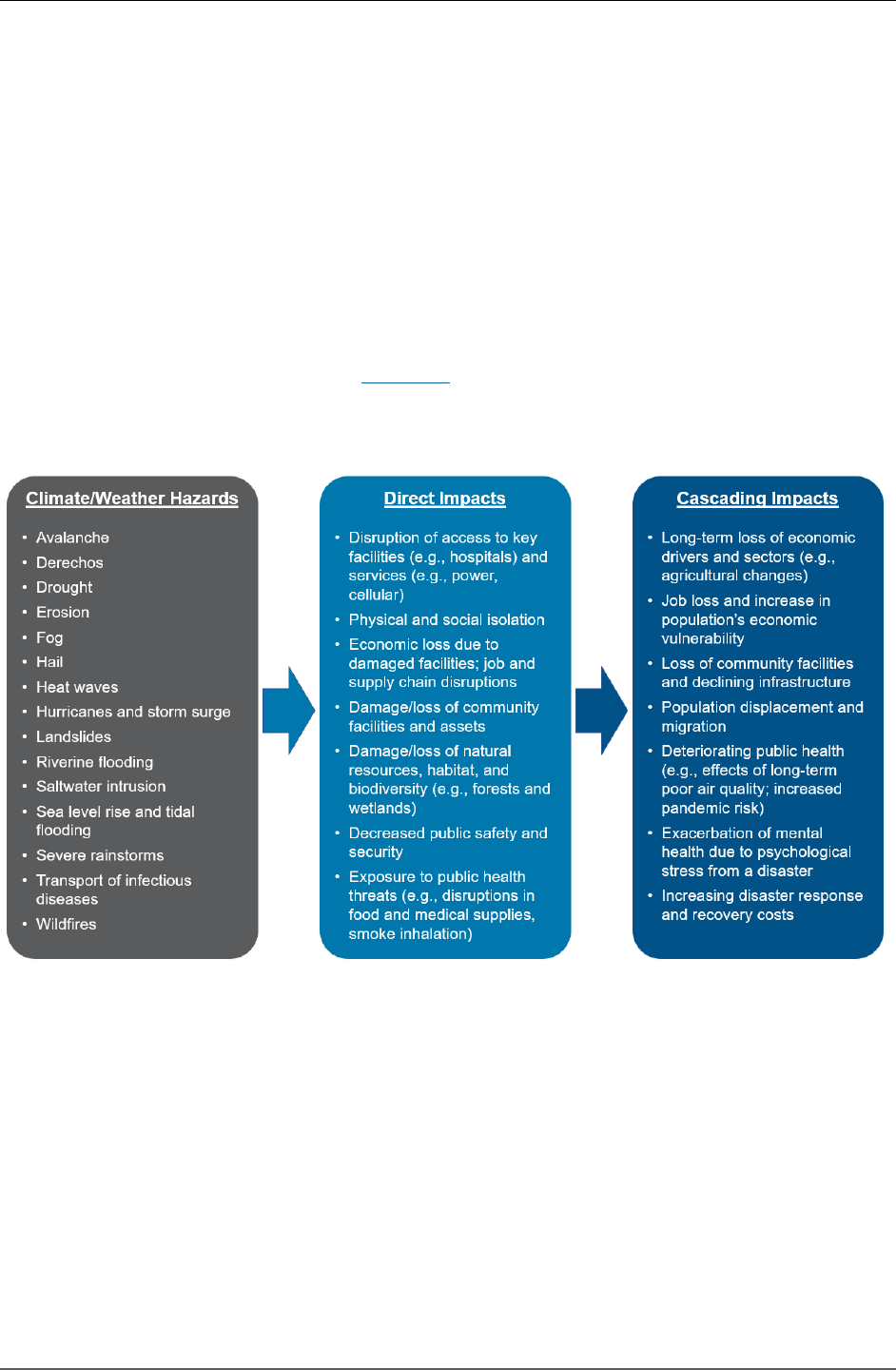

related hazards with direct and cascading impacts, see Appendix A

.

Climate-related risks can compound with other hazards to create new threats or exacerbate existing

ones. For example, long-term drought is accompanied by a greater risk of wildfire and wind erosion

(e.g., the 1930s Dust Bowl). Coastal areas afflicted by riverine flooding as a result of intense

44

Ibid.

45

Billion-dollar event measurements are adjusted by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI is a measure of the average

change overtime in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. The CPI is a

useful economic indicator, deflator of economic series, and a means to adjust dollar values.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

16

rainstorms upstream may simultaneously experience a severe hurricane. This, in turn, could double

the flooding impact and prolong the retreat of floodwater.

Extreme weather events, together with other natural and human-made health stressors, also

influence human health in numerous ways. Some existing health threats will intensify, and new

health threats may emerge. Not everyone is equally at risk due to social and economic inequities.

46

Potential health effects of physical, biological, and ecological disruptions include increased

respiratory and cardiovascular disease, injuries and premature deaths related to extreme weather

events, changes in the prevalence and geographical distribution of food- and water-borne illnesses

and other infectious diseases, and threats to mental health (see Figure 6).

47

Figure 6: Impact of Climate Change on Human Health

Climate threats may lead to other biological, technological, or economic threats. For example,

extreme heat can reduce outdoor labor activities or damage infrastructure exposed to conditions

beyond its design standards (e.g., melting roads, weakened bridges) or wildfire in one region can

affect air quality and human health in other regions, depending on where winds transport smoke.

Thus, different climate hazards can directly and indirectly affect a community or region’s economy,

creating new risks for agricultural or natural resource-dependent industries (e.g., skiing, fishing).

Individuals and businesses can also suffer from direct climate hazard impacts. This can include

damaged workplaces; lost income; reduced tax base; disrupted supply chains; destroyed

infrastructure, including power or internet; and inability to access a job site due to a damaged road.

46

USGCRP. Fifth National Climate Assessment. (2023). https://nca2023.globalchange.gov/.

47

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Climate Effects on Health. (2023).

https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm

.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

17

Climate and Equity: Keeping Equity at the Center of Climate Adaptation Planning

Underserved communities are disproportionately impacted by climate-driven hazards. For

example, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are more likely to reside in a highly

vulnerable flood zone due to years of discriminatory housing policy.

48

Lower income communities

are more likely to work jobs with direct exposure to climate hazards (e.g., workers in extreme

heat) and suffer greater harm from hazard-driven job disruptions or loss. Put simply, those with

the fewest resources to cope with climate change are often the most vulnerable to its impacts.

Keeping equity at the center of climate adaptation planning is key to ensuring the entire

community – not just a small subset – has access to the resources needed to adapt to climate

change. Importantly, it also means ensuring underserved communities can meaningfully

participate in decision-making, planning, and implementation of adaptation strategies. Action at

the local level is vital in this regard, as building resilience occurs within a local, site-specific

context. Emergency managers, elected and appointed officials, and other decision-makers are

responsible for addressing climate impacts and the distribution of adaptation benefits by viewing

the issue through an equity lens during every step of the planning process.

Climate impacts will affect many aspects of everyday life and may cause people and businesses to

relocate. This relocation process

will create both challenges and opportunities for communities, with

some areas losing population and others needing to accommodate an influx of new residents.

49,50

Emergency managers, with their expertise in hazard mitigation and adaptation, can help to improve

resilience for a community, and reduce involuntary relocation, through local climate adaptation

planning.

Environmental Justice

Environmental justice (EJ) is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people. The

goal will be achieved when everyone enjoys 1) the same degree of protection from

environmental and health hazards, and 2) equal access to the decision-making process to have

a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.

51

48

Fang, Clara et al. Equity in Climate Resilience Planning and Action: A Practitioner’s Guide. (2022).

https://doi.org/10.25923/765q-zp33

.

49

FEMA. FEMA Efforts Advancing Community-Driven Relocation. https://www.fema.gov/fact-sheet/fema-efforts-advancing-

community-driven-relocation.

50

de Sherbinin, Alex et al. Preparing for Resettlement Associated with Climate Change. Science 334(6055), 456-457.

(2011).http://www.jstor.org/stable/41351300

.

51

EPA. Environmental Justice. (2024). https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

18

2.5. Climate Informed Decision-Making for Emergency Managers

Emergency managers routinely influence and make decisions in highly uncertain situations. For

instance, emergency managers may be asked to recommend protective actions for a hurricane with

a 70 percent chance of landfall in their community in the next 72 hours, or for a chemical release

with wind conditions that may shift in the next 30 to 90 minutes. In responding to these scenarios,

emergency managers seek to minimize the risk while also arranging for the contingency that

conditions may change. As the situation evolves and new information becomes available, emergency

managers help leaders adjust risk management actions to cope with the evolving situation.

The decision-making approach used in planning, responding to, or recovering from disasters under

uncertain conditions is similar to that applied to climate adaptation planning, albeit with a much

longer timeline. Rather than operating over a period of hours or days, changes in the climate develop

over years, decades, and even centuries. Adaptation plans are often implemented over similar

timescales and usually reap rewards (e.g., risk reduction) over longer periods. Yet these plans also

need to be revised and updated regularly as new information is gathered (such as updated

projections of climate impacts). Climate adaptation planning should recognize that several potential

outcomes can occur, especially related to GHG emissions, but also that non-environmental factors

will influence the objectives and strategies of the plan.

Non-environmental factors that could impact jurisdictional climate adaptation planning include local

economic growth and demographic change, urban development patterns, and transportation needs.

Outside jurisdictional planning, individuals and businesses may contribute to adaptation. Examples

include individuals installing solar panels or businesses upgrading buildings to increase energy

efficiency in order to become more resilient to potential climate change impacts. By taking a broad

approach to planning for an uncertain future, emergency managers can help to ensure that climate

adaptation plans address a range of potential outcomes.

Emergency Management and Policy Change

Some emergency management policy changes come AFTER large disasters, such as after

Hurricane Katrina or Superstorm Sandy.

52

,

53

Yet, local emergency managers may be in a unique

position to address policy changes BEFORE disasters since they may be working with the elected

or appointed officials as well as the whole community.

54

A jurisdiction’s climate adaptation plan

may be used to support future policy changes that consider climate adaptation and resilience.

52

FEMA. Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006. (2006). https://www.congress.gov/bill/109th-

congress/house-bill/5441/text.

53

FEMA., Sandy Recovery Improvement Act of 2013. (2013). https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-

bill/152/text.

54

FEMA. Local Elected and Appointed Officials Guide. (2022).

https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_local-elected-officials-guide_2022.pdf

.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

19

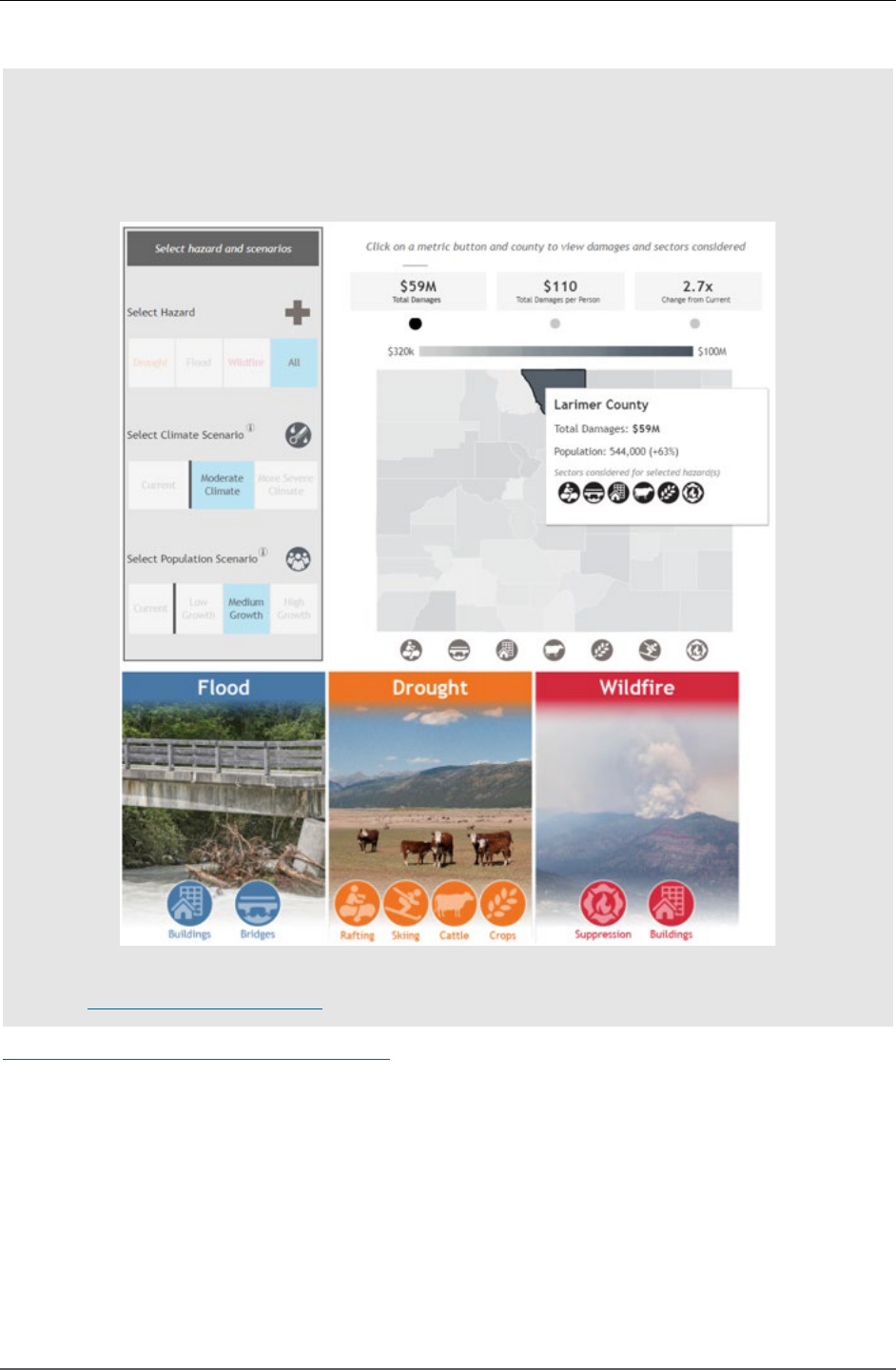

2.6. Potential Tools for Climate Modeling

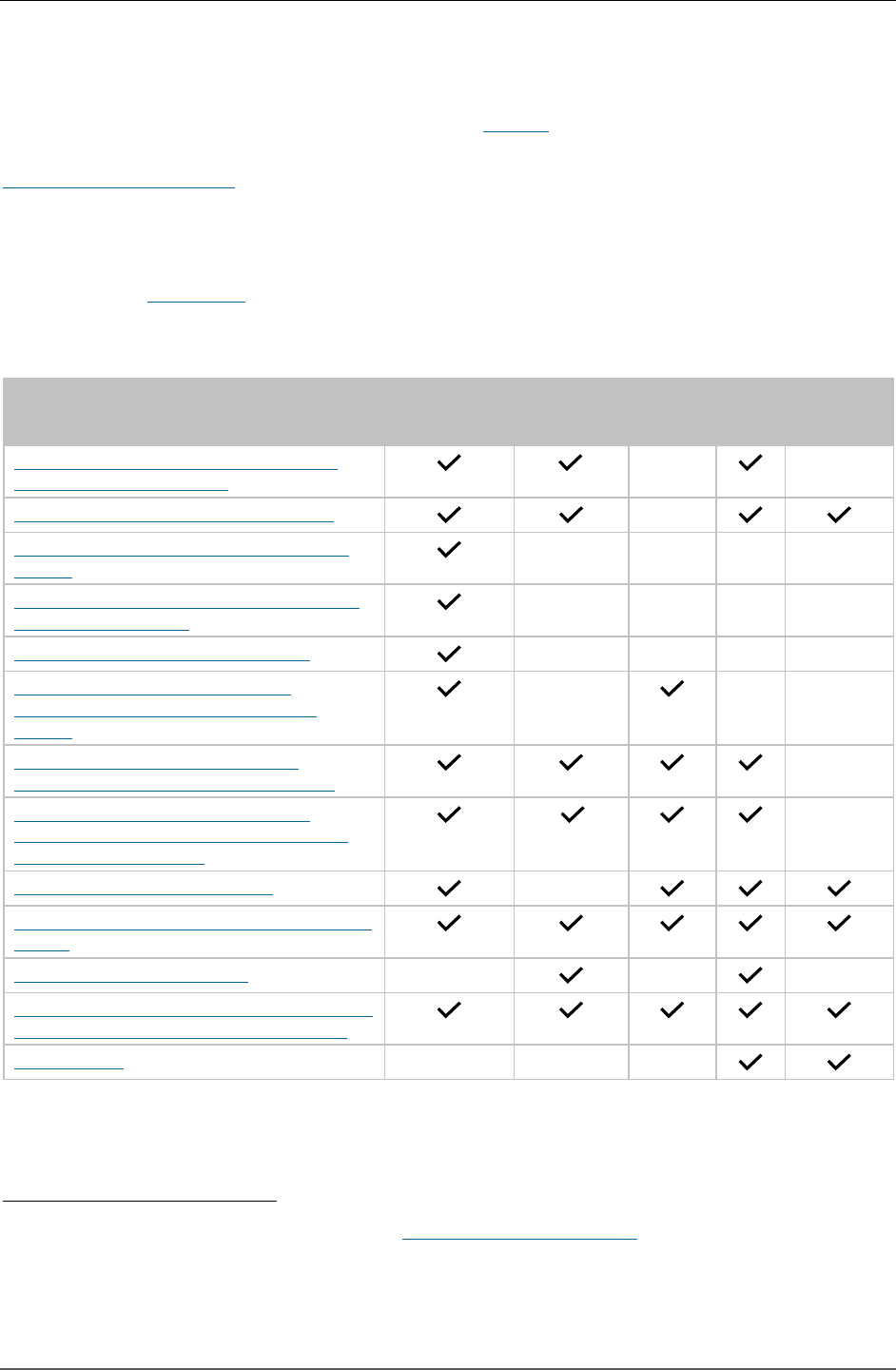

Many tools exist for potential climate modeling needs. Table 2 below provides information on tools’

applicability regarding social vulnerability, future conditions and some potential specific hazards. The

Climate Resilience Toolkit a

lso provides a website to start filtering for potential climate tools in

relation to specific regions, hazards, or community needs.

55

Using these tools, consistent with

applicable laws, emergency managers can further engage with the public and various planning

partners on potential decision-making for climate adaptation planning. For summaries on some of

these tools, see Appendix B

.

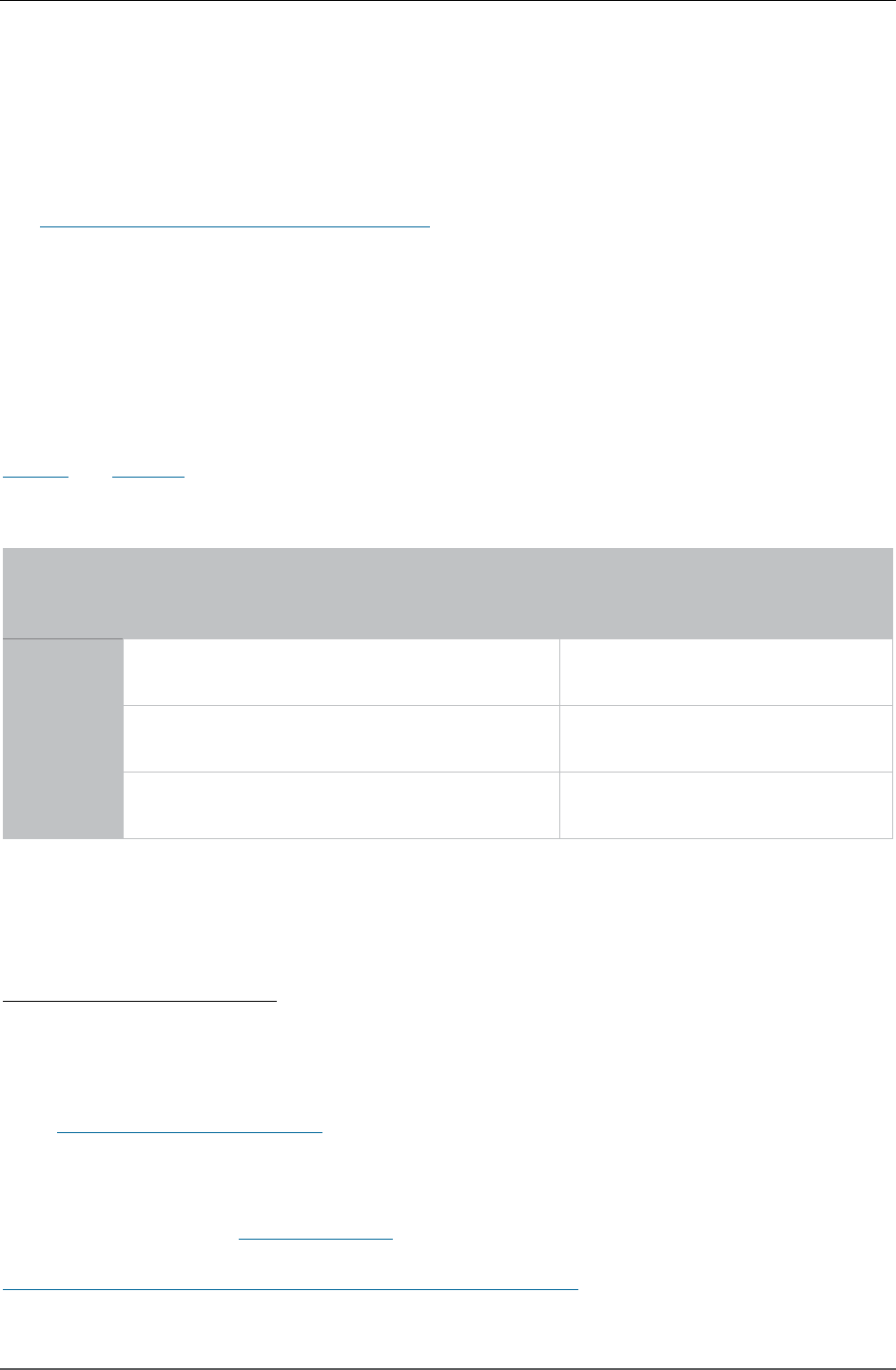

Table 2: Climate Resource Capability Inventory

56

Dataset / Application / Tool

Social

Vulnerability

Future

Conditions

Wildfire

Flood

Hurricane

Climate and Economic Justice Screening

Tool (CEJST) - White House

*

Coastal Flood Exposure Mapper – NOAA

Community Resilience Estimates - Census

Bureau

Low-Income Energy Affordability Data Tool -

Department of Energy

Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) – CDC

Wildfire Risk to Communities - U.S.

Department of Agriculture/U.S. Forest

Service

Climate Mapping for Resilience and

Adaptation (CMRA) - White House/NOAA

Environmental Justice Screening and

Mapping Tool (EJScreen) – Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA)

*

National Risk Index (NRI) - FEMA

Resilience Analysis and Planning Tool (RAPT)

- FEMA

Sea Level Rise Viewer - NOAA

Climate Risk and Resilience Portal (ClimRR) -

Argonne National Laboratory/AT&T/FEMA

Hazus - FEMA

*Denotes availability of climate data using SSPs (current as of April 2024).

55

NOAA, U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit: Tools. (2014). https://toolkit.climate.gov/tools.

56

This list is not all-inclusive and represents the most commonly available and used tools for emergency management.

Tools listed are often updated without notice. Capabilities identified are as of May 2023 by the FEMA Climate Team.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

20

2.7. Communicating Changes in Climate

Communicating the degree of uncertainty

associated with climate projections and

information about ongoing hazard events is a key

activity for emergency managers. They may think

of public information activities primarily in the

context of impending or ongoing disasters and

emergencies. However, risk communications and

public information can also include efforts to

build awareness about how one or more hazards

can affect a community. This includes

communicating changes in climate for different

contexts, such as ensuring that future flood risk

is considered during the zoning and building

permitting processes for new developments.

More broadly, public outreach efforts can help

community members understand that certain

hazards may become more frequent and severe, and that all members of the community can adopt

a solutions-based approach to these changing conditions.

Best Practices for Communicating Climate Change to Diverse Audiences

57

Use terms that resonate with the target audience and find common ground. “Future risk”

and “future conditions” may be good alternative terms to “climate change.”

Leverage the power of story, such as through video.

58

Data can be presented when woven

within the context of an engaging story. Without a locally relevant story, focusing too much

on the data may cause people to retreat from the conversation. Stories can make climate

change more relatable.

Focus on resiliency as well as climate change. Be sure to convey opportunities and a

positive outlook. Get the audience excited about a climate resilient nation and let them

know they have the power to be a changemaker.

Collaborate with partners who the audience trusts and can carry the message for you.

Avoid stereotypes. Members of the whole community, of all capacities, capabilities, and

beliefs, are taking action to address changes in climates.

57

NOAA, Isn't there a lot of disagreement among climate scientists about global warming? (2020). www.climate.gov/news-

features/climate-qa/isnt-there-lot-disagreement-among-climate-scientists-about-global-warming.

58

Climate stories NC, Click on individual stories at https://www.youtube.com/@climatestoriesnc6891/videos.

Scientific Consensus on Climate Change

The U.S.’s foremost scientific agencies and

organizations have recognized climate change

as a human-caused problem that should be

addressed. The USGCRP has published a

series of scientific reports documenting the

causes and impacts of global climate change.

NOAA, NASA, and the EPA have all published

reports and fact sheets stating that Earth is

warming mainly due to the increase in human-

produced heat-trapping gases.

Source: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/climate-

qa/isnt-there-lot-disagreement-among-climate-scientists-

about-global-warming

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

21

Climate can be a charged topic. Discussions around climate impacts can produce reactions ranging

from denial to anxiety or depression.

59

Therefore, it is important to ensure that information is

science- and evidence-based research from trusted sources and discussions emphasize concrete

actions to minimize climate impacts., Emergency managers can effectively communicate the

benefits of climate adaptation by framing the impacts of climate change as “future risks” or “future

impacts.” These terms highlight the frequency and severity of extreme weather events that may

increase, such as hurricanes, heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, floods, and precipitation.

60

The goal is

to encourage individuals and businesses to actively help decrease climate-related risk exposure.

Some public meetings may allow for two-way dialogues and public concerns furthering discussions of

potential adaptations that can lead to long-term community resilience and sustainability. For

example, there could be a discussion on how land use and zoning processes might mitigate climate

risks and provide additional social, economic and environmental benefits. Alternatively, local

meetings might provide opportunities to talk about how infrastructure and building projects, such as

using low-carbon materials, could be designed to address climate-related vulnerabilities.

Key Takeaways for Emergency Managers: Climate Science

The key factor currently driving changes in climate are the emission of gases that trap heat

in the atmosphere, commonly referred to as greenhouse gases (GHG). Since future GHG

emissions remain unclear, climate scientists created multiple potential futures; referred to

as Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs).

To be prepared for an uncertain future, emergency management planners should consider

a broad variety of scenarios and potential cascading disaster impacts on people and the

economy in their geographic region.

It is important to keep equity at the center of climate adaptation planning efforts as

underserved communities are disproportionately impacted by climate change and climate-

driven hazards.

Emergency managers can use a combination of climate modeling and social vulnerability

tools to support planning and decision-making in uncertain future climate conditions.

To communicate climate change threats to the public, emergency managers can focus on

terms such as “future risk” or “future conditions” to show how climate impacts may affect

individuals and the whole community.

59

Uppalapati, S., et al., The prevalence of Climate Change Psychological Distress among American adults. (2023).

60

NASA, Vital Signs of the Planet: What’s the Difference Between Climate Change and Global Warming? (2024).

https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/faq/whats-the-difference-between-climate-change-and-global-warming/

.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

22

3. Climate Adaptation Planning: An Overview

Climate adaptation planning requires planners to think in terms of decades rather than months or

years. While there is uncertainty regarding the severity of climate impacts, there is little doubt that

emergency managers can plan for more frequent and more severe climate-driven incidents.

Emergency managers will have a leading role in preparing communities for new risks that will be

driven by the evolving climate.

3.1. Principles of Climate Adaptation Planning

Climate adaptation planning starts with understanding the types of climate-related hazards and risks

a community will face. This begins with reviewing weather-related disasters that have occurred in the

past and then projecting how future climatic conditions may change traditional hazards and create

new climate-related risks. Consideration of future climate conditions can be integrated into existing

risk analysis and planning activities, such as the Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk

Assessment (THIRA), hazard mitigation plans, and the development of mitigation and recovery

strategies, plans, and exercise materials. Once a community has this information, they can identify

how they are likely to be affected by all-hazards. Specifically, they can estimate which geographic

areas, population groups, community services, and critical infrastructure elements are vulnerable.

In collaboration with a diverse set of community members, planners can then identify strategies and

actions for adapting to these new risks. An inclusive, community-wide approach is essential to

ensure that the planning process and the goals, objectives, and strategies are equitable. This means

identifying and prioritizing the needs of underserved groups and ensuring equal access to the

benefits of adaptation. A climate planning process that is both equity-focused and informed by

science will help produce a quality climate adaptation plan. Ultimately, climate adaptation principles

should be incorporated into all community planning processes.

Climate and Equity: Portrayal of Underserved Communities

The United Nations states “Poorer countries and underserved communities, including Indigenous

peoples who have protected the environment for generations, are often portrayed solely as

victims of climate change, rather than positive agents of change. The same is often the case for

women and girls. Make sure to highlight the voices, expertise, innovations, positive action, and

solutions by people from all walks of life and communities from all parts of the world.”

61

While climate adaptation planning is a heavily technical process due to its reliance on risk data and

climate models, it will be most successful when it is people-centered, collaborative, and equitable.

This includes building partnerships across the whole community, collectively proposing creative

strategies, and sharing decision-making responsibilities to reduce risk from climate change while

preserving what the community values most.

61

United Nations, Communicating on Climate Change. www.un.org/en/climatechange/communicating-climate-change.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

23

3.1.1. CLIMATE ADAPTATION PLANNING PRINCIPLES

Preparing for climate-related disruptions is a key part of creating climate-resilient communities;

however, climate adaptation planning goes beyond preparedness and disaster response. Adaptation

planning involves implementing policies, management strategies, and long-term investments as part

of a community-wide approach to reduce climate-related risk. The following four principles are

fundamental to climate adaptation planning:

Focus on the Future: Even though recent disasters have raised awareness of the impacts

of extreme weather, future climate conditions are likely to be different than what

communities have experienced in the past. Planning for climate resilience involves

planning periods of decades or longer. Planners should factor in how changing climate

conditions might interact with other aspects of a community. Some non-environmental

factors include development patterns, population demographics, and emerging

technologies (e.g., new methods of transportation). This inherent uncertainty is an

important aspect of climate adaptation planning.

Link to Community Planning Processes: Most communities have well-established planning

processes that provide the infrastructure, services, land use, economic development, and

public health foundations for a community to thrive and prosper over time. Effective

climate planning can be integrated into these planning efforts so that strategies are put

into place to adapt existing services, infrastructure, and capabilities to withstand future

climate-related challenges.

Leverage Partnerships and Relationships: Just as community planning processes strive to

be transparent and provide opportunities for public and stakeholder engagement, it is

particularly important for outreach and engagement to be part of climate adaptation

planning. Adapting to future climate stressors (e.g., long-term trends that increase

vulnerability) is a relatively new concept, and it is important to ensure community members

and key stakeholders are aware of the threats posed by a changing climate and the ways

in which these impacts could affect different parts of the community

Use a Multidisciplinary Approach: Climate adaptation planning involves the integration of

social, economic, and environmental considerations to promote innovative solutions that

are socially acceptable, viable, equitable, sustainable, and increase resiliency. Climate

adaptation planning is most effective when it incorporates multi-disciplinary strategies

based in natural science-, social science-, and engineering to increase the communities’

resilience to climate-related disruptions.

Examples include:

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

24

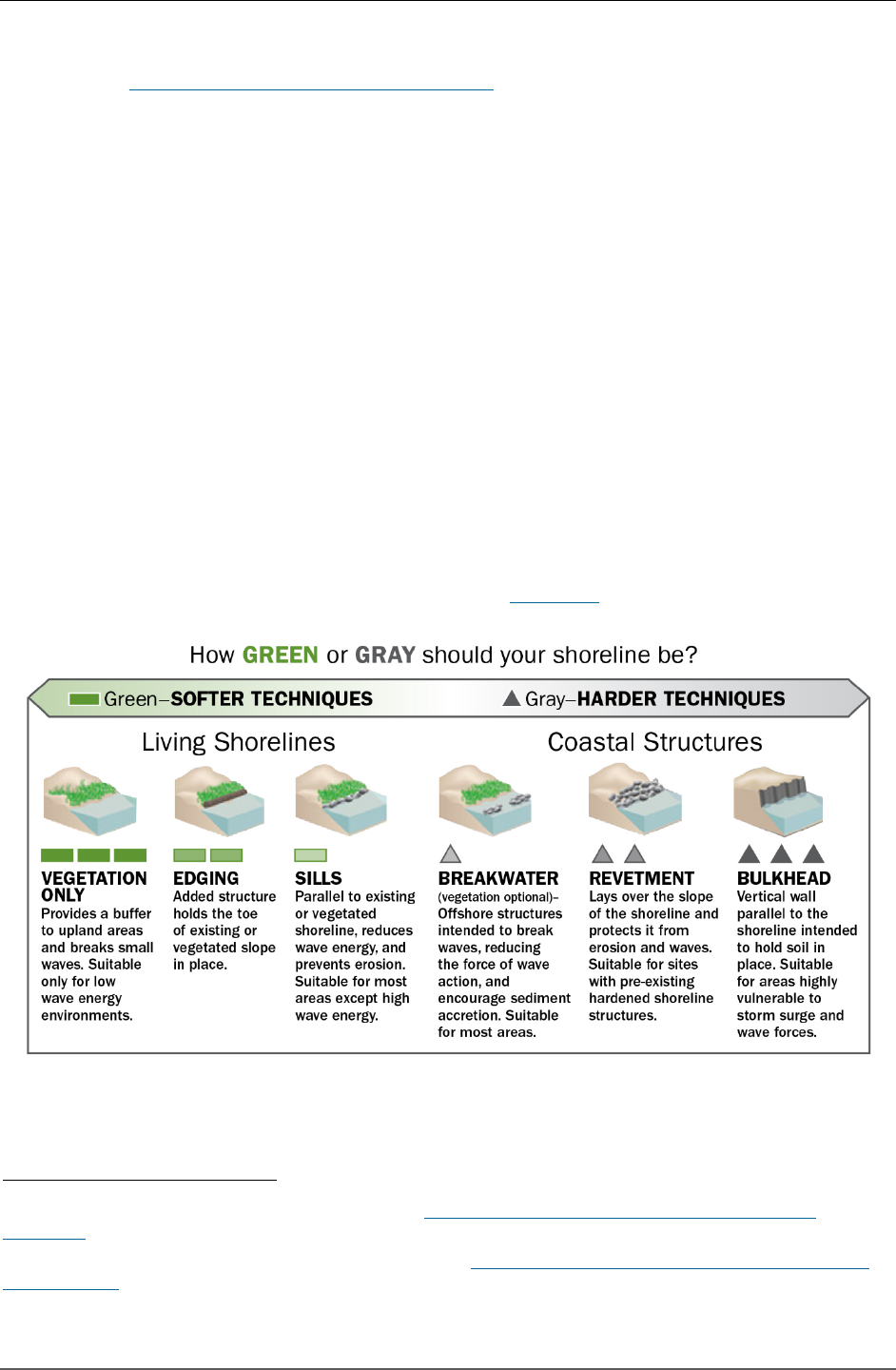

Natural sciences help in understanding the risks caused

by climate change, particularly those important to habitat

and biodiversity. This information can be used to mitigate

impacts on wildlife, such as fisheries. Nature-based

solutions (NBS) can also increase resilience through the

integration of natural features into the built environment,

helping to reduce flood risk, lower urban heat, and more.

Examples include

wetland restoration, permeable

pavement, green roofs, and living shorelines.

62

Social sciences provide important context for

understanding and responding to the public health,

economic, and equity impacts of climate change. Social

sciences can provide information about the impacts that

climate change will have on people and encourage

sustainable practices that best fit the needs and culture

of the community. An example is using local public health

data to inform improvement strategies that incorporate

future climate changes.

Engineering offers effective and innovative strategies for

adapting to the impacts of climate change and the

possibility of novel approaches in the future. For

example, there are opportunities to integrate the

engineering of stormwater infrastructure (e.g., flood

levees, drainage systems, rainwater retention measures)

and natural systems into a mutually reinforcing and cost-

effective approach for environmental management.

63

These approaches can also benefit climate mitigation,

such as by reducing building energy use.

Many communities also undertake pre-disaster recovery planning

64

that establishes strategies to

lessen disruptions following a disaster. These recovery strategies can be a useful foundation for

climate resilience in traditional planning. Aligning strategies and leveraging funding opportunities

can also contribute to a cohesive community climate adaptation strategy. These strategies can

include using traditional ecological knowledge.

62

For more information on NBS, see https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/nature-based-

solutions.

63

NOAA, Engineering With Nature: USACE, NOAA, and the Value of Partnership. (2022). Engineering with Nature: USACE,

NOAA, and the Value of Partnership - Podcast: Episode 55.

64

FEMA, Planning Guides: Pre-Disaster Recovery Plans for Tribal, Local, and State Governments. (2024).

https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/plan#pre-disaster

.

A field undergoing wetland restoration

Helping an elderly neighbor after

Hurricane Harvey (2017)

Combining solar panels with a green roof

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

25

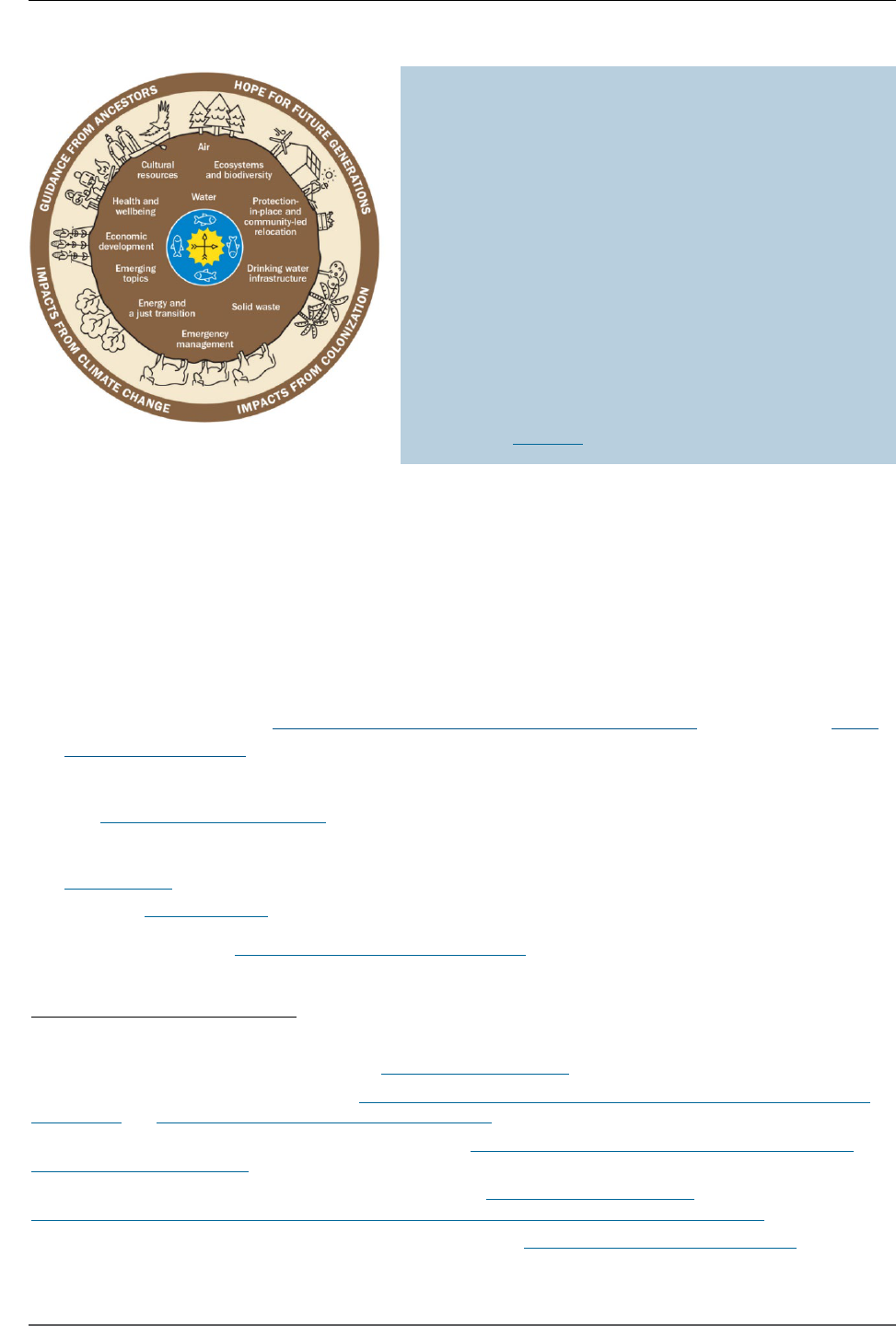

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Indigenous peoples maintain place-based knowledge

that holds thousands of years of natural resource

relationships and embodies multiple ways of

understanding resilient interactions between humans

and the ecosystem. Traditional cultural and ecological

knowledge is sound science and has been passed

down for generations through oral traditions. FEMA

acknowledges that Tribal Nations and Indigenous

peoples have performed resilience through traditional

ecological knowledge well before non-Indigenous

people came to North America or the U.S. became a

country (see Figure 7 at left).

65

3.2. Climate Funding and Adaptation Solutions for Emergency Managers

An important question to ask is, are established planning processes flexible enough to consider

adaptation and associated equity concerns, or do the processes need to change? Leveraging funding

opportunities through emergency management may provide potential solutions.

Before Disasters: Emergency managers work with—and invest funds in—communities to build a

nation able to withstand the climate hazards of today and those we can anticipate.

FEMA programs like the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) and the Flood

Mitigation Assistance (FMA) grant programs provide resources so communities are better

prepared before disasters or extreme weather events strike.

66

The National Exercise Program

provides support to federal and SLTT government partners to

assess and enhance response and recovery capacities.

67

FEMA grants

allow for investment in the infrastructure, including NBS and adoption of hazard-

resistant building codes, and response and recovery capabilities.

68

FEMA manages the National Flood Insurance Program which enables property owners to transfer

their financial risk through the purchase of flood insurance.

69

65

Figure adapted from: Status of Tribes and Climate Change Report, Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals,

Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ. (2021). http://nau.edu/stacc2021

.

66

For more information on BRIC and FMA, see https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/building-resilient-infrastructure-

communities and https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/floods.

67

For more information on the National Exercise Program, see https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-

preparedness/exercises/about.

68

For more information on FEMA grants and Building Codes, see https://www.fema.gov/grants and see

https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-management/building-science/building-codes-strategy.

69

For more information on the National Flood Insurance Program, see https://www.fema.gov/flood-insurance.

Figure 7: Indigenous Holistic Worldview

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

26

After Disasters: Emergency managers provide information and funding to help SLTT officials

strategically invest in building back to increase climate resilience.

FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP), including 406 Public Assistance Grants and

Post-Fire assistance, goes beyond just rebuilding; these grants fund efforts for building back

stronger and more resilient to future threats.

70

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

71

enables FEMA to fund costs associated with low-carbon

materials to help cut carbon pollution (GHG) to support climate resilience in communities.

72

Communities must have an approved hazard mitigation plan to apply for certain non-emergency

FEMA funding. More information can be found here.

73

Resources Available to Support Communities

FEMA Resources for Climate Resilience provides a comprehensive explanation of FEMA

programs planning for climate change.

74

Appendix C highlights other potential federal, state,

local, private, and philanthropic funding sources.

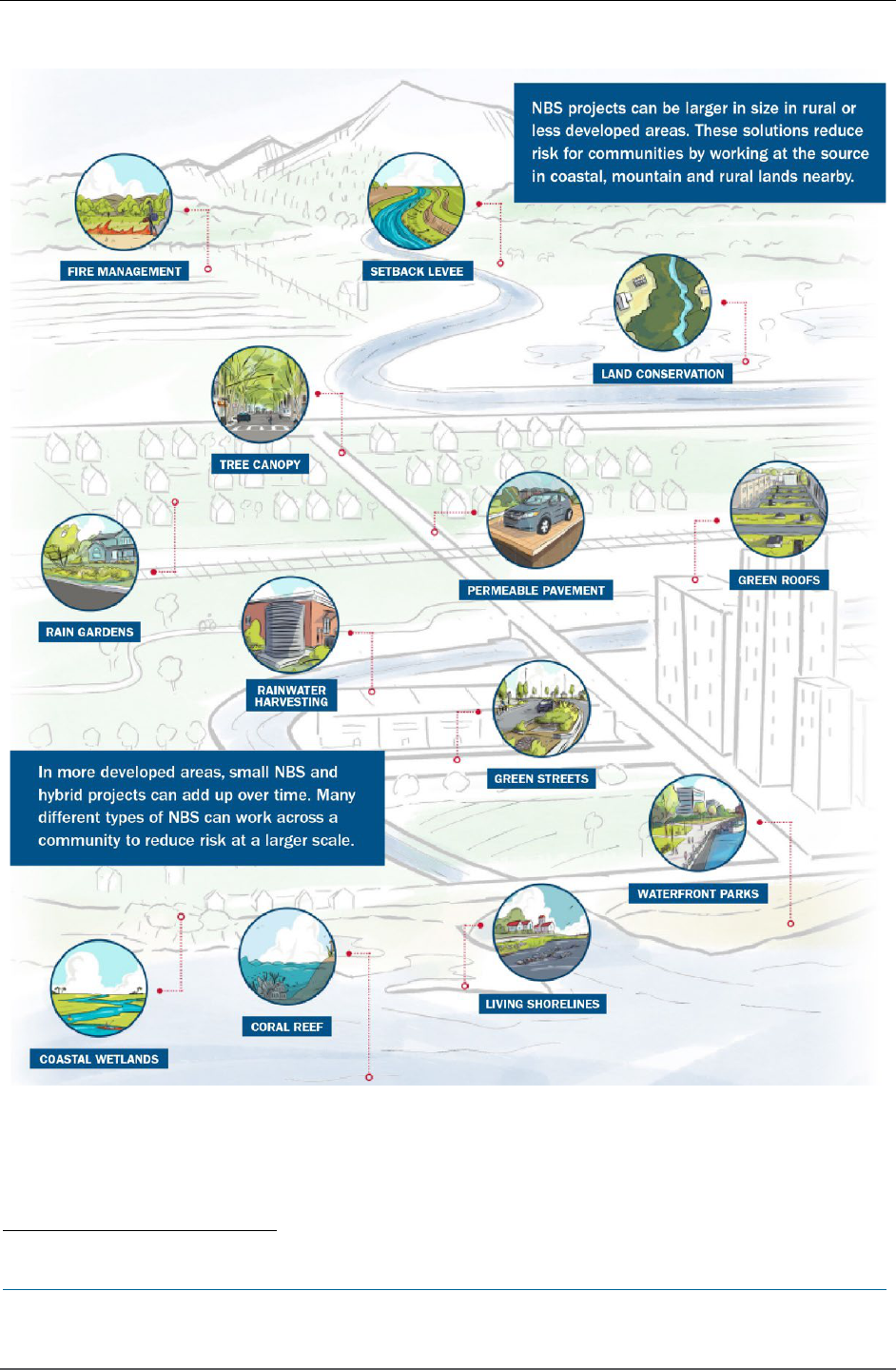

Climate adaptation strategies often have short- and long-term benefits beyond enhancing community

resilience. For example, using NBS to expand the flood water-carrying capacity of lands adjacent to a

river could provide recreational, aesthetic, biodiversity, and quality of life benefits to a community

(see Figure 8

). Benefits for other types of strategies might be linked to economic development,

public health, air and water quality, and improved housing. In some situations, climate adaptation

strategies could also contribute to reductions in GHG emissions.

Incorporating climate resilience principles throughout community planning can help reduce the

likelihood of engaging in maladaptation

. Examples of maladaptation include building seawalls that

then shift vulnerability to people elsewhere or eliminating floodplains, which in turn reduces the

nutrients in soils previously provided by flood water.

75

Officials who are often tasked with budgeting

for community services and capital investments should incorporate climate-related risk and

sustainability considerations into their decision-making processes.

70

For more information on FEMA’s HMGP and Post Fire Program, see https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/hazard-

mitigation and https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/post-fire.

71

For more information on the IRA, see https://www.whitehouse.gov/cleanenergy/inflation-reduction-act-guidebook/.

72

For more information on low-carbon goals, see https://www.fema.gov/grants/policy-guidance/low-carbon-goals.

73

For more information on mitigation planning grant requirements, see https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/risk-

management/hazard-mitigation-planning/requirements.

74

For more information on FEMA’s Resources for Climate Resilience, see

https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_resources-climate-resilience.pdf

.

75

Schipper, Lisa. Maladaptation: When Adaptation to Climate Change Goes Very Wrong. One Earth. (2020).

https://pubag.nal.usda.gov/catalog/7171690

.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

27

Figure 8: Examples of Nature-Based Solutions Across Landscapes

76

76

For more information on Building Community Resilience with Nature-Based Solutions, see

https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_nature-based-solutions-guide-2-strategies-success_2023.pdf

.

Climate Adaptation Planning: Guidance for Emergency Managers

28

Types of Adaptation

Low-Regrets: Low-regrets actions are cost-effective now and under a range of future climate

scenarios and do not involve hard trade-offs with other policy objectives. These actions are

relatively low cost and provide relatively large benefits under predicted future climates. They

contribute to adaptation while also having other social, economic, and environmental policy

benefits, including benefits related to mitigation. Examples include efforts to improve water

and energy efficiency; preserving landscapes in support of biodiversity; and land use

planning to minimize flood hazard exposure.

Incremental: This adaptation pathway involves discrete actions that minimize present-day

climate impacts. Typically, these actions follow a climate-related disruption and target

solutions to a specific event or vulnerability. Examples include increasing stormwater and

wastewater capacity; building flood protection; designing buildings to meet future climate

demands; and increasing water reservoirs.

Transformational: Transformative adaptation involves large-scale changes that contribute to

long-term societal resilience and sustainability. This can emerge from both individual and

collective action and takes a long-term perspective while recognizing diverse constituent

interests. Transformational adaptation may involve institutional reform, structural changes,

and coordination across multiple levels of governance. Examples include funding the

relocation of underserved communities; changing land use patterns to restrict use in high-

risk areas (e.g., wildland fires, flood-prone areas); and prioritizing protecting ecosystems.

Maladaptation: Maladaptive responses to climate-driven events are those that end up

increasing or shifting vulnerability and reducing community resilience. Such actions may

address short-term risks, but in the long run increase disaster exposure. Examples include

planting trees in wildfire-prone areas and neglecting underserved communities.

Climate adaptation strategies are also often more effective when implemented across many different

communities without pushing the impacts into other jurisdictions. Regional coordination can lead to:

Consensus on which future climate scenarios should be used in vulnerability analyses;