The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair

Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

By Evelin Caro Gutierrez, Elizabeth Allan and Megan Haberle

1

Introduction

PRRAC has previously raised the need for stronger civil rights guardrails in National Housing

Trust Fund,

2

but our concerns take on new urgency in 2021, as the program has recently more

than doubled in size,

3

and is projected to expand even further in future years.

4

This policy brief

assesses current federal and state guidelines for the Housing Trust Fund in several key areas of

fair housing policy, including site selection rules, local approval requirements, affirmative

marketing, tenant selection, and data transparency, along with specific policy recommendations

in each area. For reference, a fifty-state survey of National Housing Trust Fund policies is

included in an appendix.

I. Overview and History of the National Housing Trust Fund

The National Housing Trust Fund (NHTF) was established in 2008 as part of the Housing and

Economic Recovery Act of 2008.

5

NHTF aims to increase and preserve the national supply of

rental housing for extremely low-income (ELI) renter households

6

and very low-income renter

Policy Brief

April 2021

________________________________

1 Evelin Caro Gutierrez and Elizabeth Allan are students at the Yale Law School, classes of 2022 and 2021,

respectively. Megan Haberle is the former Deputy Director of PRRAC. This policy brief was developed for

PRRAC in 2020 under the auspices of the Community and Economic Development clinic, directed by Professor

Anika Singh Lemar and, from 2018-2020, Ludwig Fellow Emilee Gaebler. Paige Neville and Claire Hellweg,

summer interns in the clinic, provided research assistance, along with Caroline Doglio, a PRRAC Policy Intern.

2 The National Housing Trust Fund: Promoting Fair Housing in State Allocation Plans (PRRAC, May 2016),

https://www.prrac.org/pdf/Promoting_Fair_Housing_in_HTF_State_Allocation_Plans.pdf.

3 https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/HUD_No_21_053.

4 https://nlihc.org/resource/78-members-congress-send-dear-colleague-letter-biden-administration-support-

housed.

5 National Housing Trust Fund, 12 U.S.C. § 4568 (2008).

6 Defined as households with incomes that are 30% or less than the median income in the household’s area. 12

U.S.C. § 4568(f) (2008).

(VLI) households,

7

including the homeless. It also aims to increase homeownership among

these groups.

8

At the federal level, the program is administered by the Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD). Implementation, however, occurs at the state and local level. HUD

distributes NHTF funds to the states, in accordance with an allocation formula that weighs

state need and construction cost.

9

States are responsible for distributing the money to state

and sub-state level implementors who use NHTF funds to advance affordable housing through

the construction, rehabilitation and improvement of affordable housing units. States have

significant discretion with regard to how they will allocate NHTF funds, although the federal

statute and associated regulations impose certain restrictions.

10

For example, states can only

allocate a maximum of 10% of funds towards increasing homeownership, while there is no

restriction placed on the percent of funds allocated towards rental activity. If a state receives

less than $1 billion in a given year, it must allocate all funds towards ELI households (as

opposed to VLI households).

11

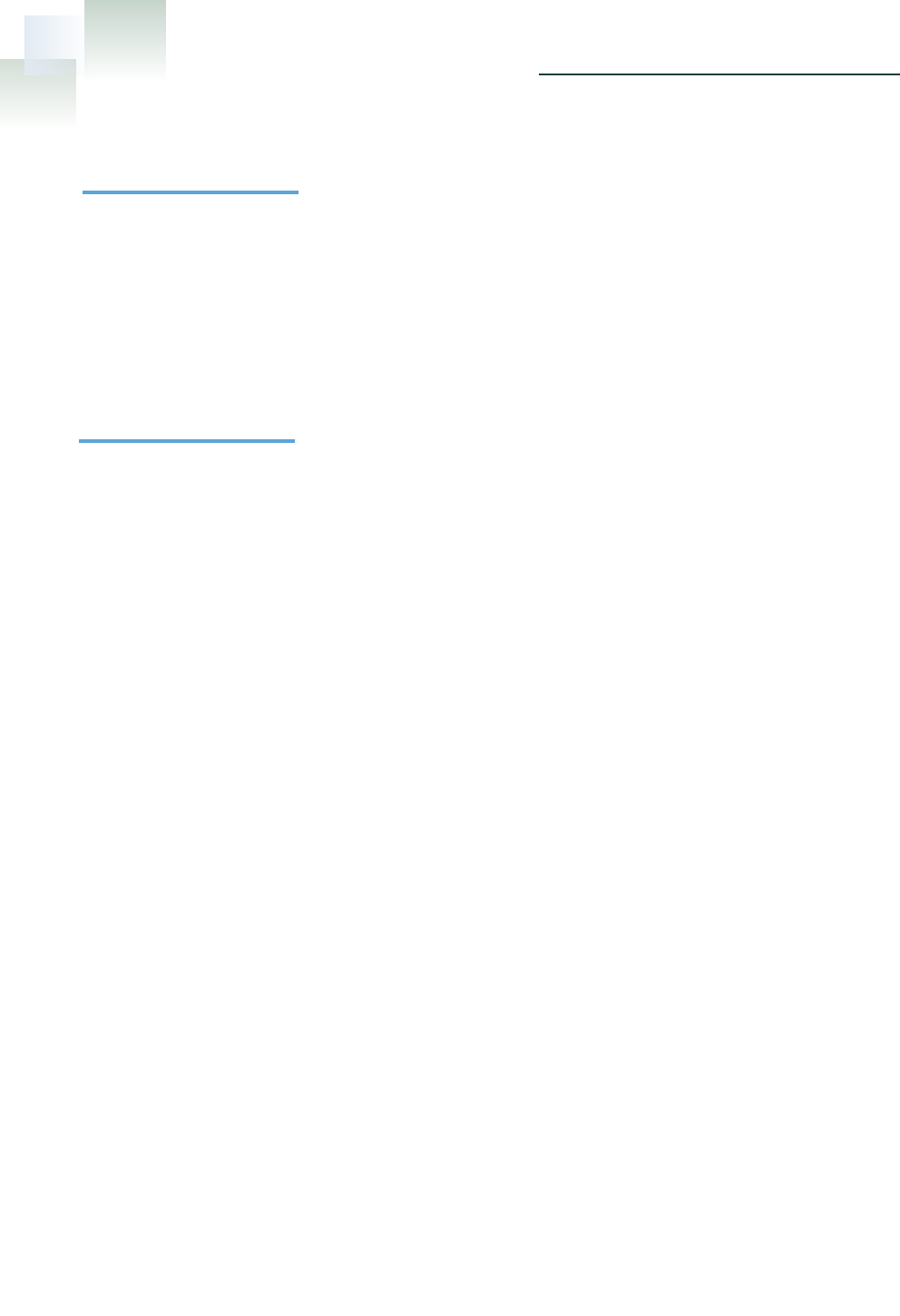

Between 2016-2019, the program distributed

almost $1 billion to the states. Before 2016, NHTF

did not make distributions. This delay was due to

NHTF’s unique financing mechanism. Along with

the Capital Magnet Fund, the NHTF is funded

through assessments on Freddie Mac and Fannie

Mae.

12

These assessments were paused during the

2008 financial crisis and did not resume until

2014.

13

The annual amounts allocated since 2016

are summarized in the table at right.

14

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

2

________________________________

7 Defined as households with incomes that are 30-50% or less than the median income the household’s area.

12 U.S.C. §4568 (f).

8 Id. §4568 (a).

9 Id. §4568 (c).

10 Federal regulations are found in the interim rule issued in 2015, at 24 C.F.R. § 93 and 24 C.F.R. §91.

11 24 C.F.R. §93.250.

12 Id. §93.1. See also The Housing Trust Fund: Background and Issues, Congressional Research Service (2016).

13 The Housing Trust Fund: Background and Issues, Congressional Research Service 1 (2016).

14 HTF Allocations, National Low Income Housing Coalition, https://nlihc.org/explore-issues/projects-

campaigns/national-housing-trust-fund/allocations.

15 Under the Budget Control Act, these allocated amounts are reduced slightly each year as part of a ten year

budget sequestration rule (which expires in 2022), intended to keep overall federal spending below a set

spending cap. For example, the amount actually available to states in 2021 will be $689.6 million, not $711

million.

Year Total Allocated

15

2021 $711M

2020 $326.4M

2019 $247.7M

2018 $266.8M

2017 $219.2M

2016 $173.6M

NHTF Annual Amounts Allocated

(2016 – 2021)

Since allocations began, there have been no major changes in regulation or implementation at

the federal level. The interim rule that HUD issued in 2015 continues to govern NHTF and there

are no outstanding requests for public comment.

16

Although the Trump administration

proposed eliminating funding for NHTF in several budget requests, Congress continued to

authorize NHTF allocations using the funds raised through the assessments on Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac.

17

There were several legislative proposals in the 116th Congress to increase

funding for NHTF, but these did not gain traction.

18

For additional details on federal regulations governing the National Housing Trust Fund, see

the attached appendix.

II. History of Segregation in Federal Housing Programs

Federal government housing programs have a long history of furthering and enabling racial

and economic segregation. Indeed, as described by Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law,

“[t]he purposeful use of public housing by federal and local governments to herd Africans

Americans into urban ghettos had as big an influence as any in the creation of our de jure

system of segregation.”

19

Until the 1960s, federal housing laws explicitly allowed the use of

federal funds to build segregated housing projects, a point explicitly re-affirmed in the 1949

Housing Act.

20

For example, the Techwood neighborhood in Atlanta, one of the first projects

of the New Deal Public Works Administration (PWA), intensified segregation by evicting

African American families from their homes. The new Techwood neighborhood, constructed

with federal funds, was open only to white tenants.

21

Similarly, the “redlining” of majority African American communities, which began with the

Federal Housing Act of 1934, resulted in explicit discrimination against minority communities.

Redlining arose from the practice of assigning neighborhoods risk-levels for mortgages or

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

3

________________________________

16 Housing Trust Fund 24 C.F.R. § 93.

17 See Kriston Capps, The Cruelest Cut in Trump’s Housing Budget, City Lab (May 2, 2017),

https://www.citylab.com/equity/2017/05/the-cruelest-cut-in-trumps-housing-budget/527730/; Donna Kimura,

What’s Eliminated in Trump’s 2020 Budget Plan, Affordable Housing Finance (March 22, 2019),

https://www.housingfinance.com/policy-legislation/whats-eliminated-in-trumps-2020-budget-plan_o.

18 See American Housing and Economic Mobility Act of 2019, S. 787, 116th Cong. (2019) (proposing $44.5

billion in federal appropriations for NHTF); Pathway to Stable and Affordable Housing for All Act, S.2946,

116th Cong. (2020) (proposing $40 billion in appropriations for NHTF) (both bills were introduced but did not

pass).

19 Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America 17

(2017).

20 Id. at 31.

21 Id. at 21.

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

4

housing loans.

22

Predominantly minority neighborhoods were “redlined” as high-risk, raising

the costs of homeownership. This discrimination resulted in white borrowers receiving 98% of

loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration between 1934 and 1962.

23

Redlining was

particularly harmful to middle class African Americans, who faced significantly greater levels of

difficulty in becoming homeowners than similarly situated white families.

24

Motivated by persistent segregation, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and urban

riots across the United States, the 1968 Fair Housing Act (FHA) banned explicit discrimination

in the sale, rental and financing of housing. The FHA also required federal housing agencies to

take affirmative steps to promote integration when implementing federal housing programs,

known as the affirmatively furthering fair housing (AFFH) requirement.

25

Unfortunately, the

AFFH provision was under-enforced and did little to actually promote housing integration.

Indeed, between 1972 and 2012, there are only two instances of HUD withholding money

based on a community’s failure to comply with the FHA. In a pointed indictment of the federal

government’s AFFH failure, the 2008 bipartisan National Commission on Fair Housing and

Equal Opportunity concluded:

The current federal system for ensuring fair housing compliance by state and local

recipients of housing assistance has failed. HUD only requires that communities

receiving federal funds “certify” to their funding agency fair housing. HUD requires no

evidence that anything is actually being done as a condition of funding and it does not

take adverse action if jurisdictions are directly involved in discriminatory actions or fail to

affirmatively further fair housing.

26

Patterns in the implementation of federal housing programs illustrate how these programs

often actively contribute to housing segregation despite the FHA’s mandate. Housing Choice

Vouchers, which create a portable housing benefit and theoretically should promote housing

mobility, are often concentrated in poor, low opportunity areas.

27

Similarly, the deference of

________________________________

22 Alexis C. Madrigal, The Racist Housing Policy that Made Your Neighborhood. The Atlantic (May 22, 2014),

https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/05/the-racist-housing-policy-that-made-your-

neighborhood/371439/.

23 Nikole Hannah-Jones, Living Apart: How the Government Betrayed a Landmark Civil Rights Law, ProPublica

(June 25, 2015), https://www.propublica.org/article/living-apart-how-the-government-betrayed-a-landmark-

civil-rights-law.

24 Rothstein, supra note 19 at 64.

25 The Fair Housing Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3608 (1968).

26 The Future of Fair Housing, The National Commission on Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity 44 (December

2008), https://www.prrac.org/projects/fair_housing_commission/The_Future_of_Fair_Housing.pdf. In 2015,

the Obama administration finally released a meaninful AFFH Rule (which was subsequently suspended by the

Trump administration in 2018).

27 Alicia Mazzara and Brian Knudsen, Where Families With Children Use Housing Vouchers: A Comparative Look

at the 50 Largest Metropolitan Areas (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and PRRAC, January 2019),

https://prrac.org/pdf/where_families_use_vouchers_2019.pdf.

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

5

the federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and the Home Investment

Partnership (HOME) programs to local preferences has often allowed for ongoing segregation

through discriminatory zoning practices and allocation criteria.

28

In addition, in some states

developments funded by the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) have been concentrated

in predominantly minority neighborhoods.

29

Patterns of segregation in LIHTC site selection

were at issue in the 2015 Supreme Court case, Texas Department of Housing and Community

Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, Inc (ICP). In Dallas, over 90 percent of LIHTC units were

located in census tracts with less than 50 percent white residents, perpetuating patterns of

racial segregation in the city.

30

The failure of federal policies to address economic and racial segregation is evident from the

persistent levels of segregation in America’s cities. Between 1993-2012, New York City

received around $4 billion in block grants from the federal government for housing programs;

yet, in 2012, the city was so segregated that 80 percent of African Americans would need to

move to create an integrated city.

31

Patterns of racial segregation often overlap with patterns

of economic segregation.

32

Today, young African Americans are ten times more likely to live in

poor neighborhoods as young white Americans.

33

By perpetuating neighborhood segregation, federal housing policies

contribute to disparate outcomes in health, education and income.

Geography determines residents’ access to schools, jobs,

infrastructure, transit, public safety, and a clean environment. When

federal housing resources are concentrated in low income, under-

resourced neighborhoods, low income families and children receive an

unequal share of public goods. For example, a recent study showed

that the four major federal housing programs systemically place

children in lower performing schools.

34

Conversely, childhood exposure

________________________________

28 The Future of Fair Housing, supra.

29 See, e.g., Phuong Tseng, Heather Bromfield, Samir Gambhir, & Stephen Menendian, Opportunity, Race, and

Low Income Housing Tax Credit Projects (Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California,

Berkeley, 2017); See also Jill Khadduri, Larry Buron, and Carissa Climaco, Are States Using the Low Income Tax

Credit to Enable Families with Children to Live in Low Poverty and Racially Integrated Neighborhoods? (PRRAC

and the National Fair Housing Alliance, 2007); Kirk McClure, Anne Williamson, Hye-Sung Han, “The LIHTC

Program, Racially/Ethnically Concentrated Areas of Poverty, and High Opportunity Neighborhoods,” 6 Texas

A&M Journal of Property Law 89 (December 2020).

30 Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project, 576 U.S. __, 3 (2015).

31 Hannah-Jones, supra note 23.

32 Jessica Trounstine, Race and Class Segregation and Local Public Policy. 70 Tax Law Review 513, 524 (2016-

2017).

33 Rothstein, supra note 19 at 185.

34 Ingrid Gould Ellen and Keren Horn, Housing and Educational Opportunity: Characteristics of Local Schools

Near Families with Federal Housing Assistance (PRRAC, July 2018),

https://www.prrac.org/pdf/HousingLocationSchools2018.pdf; See also Jennifer Jellison Holme, Erica

When federal housing

resources are concen-

trated in low income,

under-resourced neigh-

borhoods, low income

families and children

receive an unequal

share of public goods.

to a high opportunity neighborhood can have long term positive outcomes. In Raj Chetty’s well

known 2016 study, low income children who moved from high to low poverty neighborhoods

had objectively improved outcomes as young adults, including an increased likelihood of

college attendance, greater relationship stability, and higher

incomes.

35

Similarly, the test score gap between high and low-income

students is lower in integrated metro areas, suggesting that

integration supports more equitable access to schooling.

36

Fair Housing and Public Health

This policy brief is released in the middle of a national reckoning with

four centuries of racial injustice and oppression as well as the global

COVID-19 pandemic. It is clear that the virus has disproportionately

impacted low-income and minority neighborhoods, neighborhoods

that exist in their current form in large part as a result of government-

sponsored segregation.

37

Residents of segregated neighborhoods are disproportionately in

service jobs that cannot be conducted remotely and often must work in jobs that risk exposing

them to COVID-19 in order to pay daily costs. Public health officials have explained that the

death rate of African Americans from COVID-19 will be disproportionately high because low

access to health care and high levels of environmentally-driven pre-existing conditions. In

mapping the impact of the diseases, public health officials have seen spikes of COVID-19 in

the same neighborhoods that have known concentrations of other poor health outcomes,

such as lead poisoning and infant mortality.

38

Indeed, as one public health official said, “COVID

is unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustice and the

impact of residential segregation.”

39

Segregated housing has a history of driving disparate health outcomes. The pathways are

multiple, but key mechanisms include the following: (1) environmental quality and sanitation

tend to be lower in segregated communities, increasing the likelihood of environmental toxic

exposures through the air, ground and water, additionally rates of lead-poisoning and asthma

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

6

________________________________

Frankenberg, Joanna Sanchez, Kendra Taylor, Sarah De La Garza, Michelle Kennedy, “Subsidized Housing and

School Segregation: Examining the Relationship Between Federally Subsidized Affordable Housing and Racial

and Economic Isolation in Schools,” Education Policy Analysis Archives (November 2020).

35 R. Chetty, N. Hendren, and L. Katz, The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New

Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment, 106 AMERICAN ECONOMIC REVIEW 855-902 (2016)

(research uses neighborhood poverty as a proxy for opportunity).

36 Jonathan Rothwell, Housing Costs, Zoning and Access to High-Scoring Schools, Brookings 12-13 (April 2012),

https://www.brookings.edu/research/housing-costs-zoning-and-access-to-high-scoring-schools/.

37 Akilah Johnson and Talia Buford, Early Data Shows African Americans Have Contracted and Died of

Coronavirus at an Alarming Rate, ProPublica (April 2020), https://www.propublica.org/article/early-data-shows-

african-americans-have-contracted-and-died-of-coronavirus-at-an-alarming-rate.

38 Id.

39 Id.

Childhood exposure to a

high opportunity

neighborhood can have

long term positive

outcomes…including an

increased likelihood of

college attendance, greater

relationship stability, and

higher incomes.

tend to be higher; (2) safety tends to be lower in segregated areas, causing not only direct

harm but deterring social interaction and physical activity; (3) segregated neighborhoods tend

to have lower access to full-service supermarkets, reducing residents’ access to nutritious food

and increasing the likelihood of obesity; (4) proximity to high quality and affordable health care

tends to be lower in segregated neighborhoods.

40

Thus, integrating communities and helping

more low-income families of color obtain affordable housing in high opportunity

neighborhoods is critical from a public health perspective.

III. Fair Housing and the NHTF

Given the ongoing complicity of federal housing programs in perpetuating community

segregation and patterns of inequality, there is a significant risk that NHTF might also

contribute to housing segregation. Like many other federal programs, NHTF contains statutory

and regulatory provisions that incorporate fair housing principles. The federal rules governing

the NHTF require that funded programs comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

the Fair Housing Act, and promote “greater choice of housing opportunities.”

41

Additionally,

separate regulations require that all HUD programs affirmatively further fair housing.

42

Yet, as

the above history of federal housing programs suggests, these general mandates are often

ineffective at ensuring that federal housing programs actually contribute to fair housing goals.

This section conducts a detailed examination of six dimensions of the National Housing Trust

Fund: (1) Site Selection in High Opportunity Areas; (2) Local Approval and Opposition; (3)

Affirmative Marketing; (4) Tenant Selection; (5) Deciding Between Construction, Rehabilitation,

and Acquisition; (6) State Monitoring and Reporting. For each of these six issues, we describe

their connection to fair housing/ civil rights, including insights from other federal housing

programs; relevant existing laws, regulations, and policies at the

federal and state level (based on research conducted in spring of

2020); and priority areas for future policy change.

While state initiatives are important, it is essential that NHTF

shortcomings with regard to fair housing be addressed at the federal

level. As our analysis demonstrates, there is significant room for

additional fair housing protections at the federal level, while still giving states flexibility in

tailoring the program for state-specific contexts. When possible and practical, federal fair

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

7

________________________________

40 See Robert Hahn, Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation as a Root Social Determinant of Public Health and

Health Inequity: A Persistent Public Health Challenge in the United States, Poverty & Race Research Action

Council (June 2017), https://prrac.org/racial-and-ethnic-residential-segregation-as-a-root-social-determinant-

of-public-health-and-health-inequity-a-persistent-public-health-challenge-in-the-united-states-2/; Brian

Smedley and Philip Tegeler, Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing: A Platform for Public Health Advocates, 106

Am. J. Public Health (June 2016), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4880225/.

41 24 C.F.R. § 93.150(a).

42 24 C.F.R. Subpart A §§ 5.150 - 5.167-5.180.

While state initiatives are

important, it is essential

that NHTF shortcomings

with regard to fair housing

be addressed at the

federal level.

housing protections are preferable, as they do not depend on implementation by 50 different

state actors and can be more permanent. However, in the absence of federal regulations, state

policy can fill an important gap. For example, many states award NHTF funds through a

competitive process using a points system. State agencies implementing these systems could

incorporate the recommended fair housing principles into their selection criteria. Other fair

housing recommendations could be addressed by state legislatures, making them mandatory

in NHTF program administration.

1. Site Selection in High Opportunity Areas

A. Site Selection and Fair Housing

Site selection policies can have significant fair housing implications. If housing created or

preserved by the NHTF is concentrated in low-income or racially-concentrated areas, it can

perpetuate the segregation of low-income or minority communities.

Because racial and socioeconomic segregation is often associated with

fewer resources and lower opportunities, new affordable housing

projects should be located in racially and socioeconomically diverse

neighborhoods, those providing more resources.

As a result, site selection criteria should explicitly prioritize the creation

of affordable housing in high opportunity areas (from which it has historically been excluded).

High opportunity areas contain high-performing schools, health care, public amenities,

transportation, jobs and low crime rates, crucial ingredients for thriving families.

43

By way of

analogy, research on state-level preferences for high opportunity neighborhoods in the LIHTC

program suggests that explicit guidelines can be successful in creating affordable housing in

areas of high opportunity. A 2015 study demonstrated that states that incorporated siting

standards that encouraged the location of LIHTC credits in high opportunity neighborhoods

were successful in shifting more affordable housing to these neighborhoods.

44

The types of

criteria that advanced this goal included explicit preference for sites in “high opportunity

areas,” access to amenities, and the presence of meaningful community revitalization plans if

the project were to be located in lower opportunity neighborhoods.

45

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

8

________________________________

43 See R. Chetty supra 855-902 and Elizabeth Julian, Making the Case for Housing Mobility: the CMTO Study in

Seattle, Poverty & Race Research Action Council (Sep. 6, 2019), https://prrac.org/making-the-case-for-housing-

mobility-the-cmto-study-in-seattle-by-elizabeth-julian-may-august-2019-pr-issue/; Opportunity and Location in

Federally Subsidized Housing Programs: A New Look at HUD’s Site & Neighborhood Standard as Applied to

the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (PRRAC, Kirwan Institute & Opportunity Agenda, October 2011).

44 Ingrid Ellen, Keren Horn, Yiwen Kuai, Roman Pazuniak, and Michael Williams, Effect of QAP Incentives on the

Location of LIHTC Properties, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy

Development and Research 14-16 (April 2015),

https://www.novoco.com/sites/default/files/atoms/files/pdr_qap_incentive_location_lihtc_properties_050615.pdf.

45 Id. at 7-11. See also Sarah Oppenheimer et al, Building Opportunity II: Civil Rights Best Practices in the LIHTC

Program (PRRAC, July 2015), https://www.prrac.org/pdf/BuildingOpportunityII.pdf.

Site selection criteria

should explicitly prioritize

the creation of affordable

housing in high

opportunity areas.

Targeting high opportunity neighborhoods does not mean that resources should not be

directed towards disinvested, low-opportunity neighborhoods. However, in order to make a

genuinely positive impact on neighborhood opportunity, these resources should be

coordinated with other resources as part of a realistic neighborhood revitalization plan. For

example, LIHTC treasury regulations give preference to projects in low-income qualified census

tracks only if they are accompanied by a concerted community revitalization plan (CCRP).

46

Unfortunately, there have been significant shortcomings in the implementation of this

requirement, with few states adopting a robust definition of CCRPs.

47

As described in a 2017 PRRAC brief, CCRPs should include identified development partners, a

clear geography for revitalization, housing and non-housing developments, and

meaningful/achievable goals.

48

Additionally, CCRPs should include safeguards against

displacing existing residents and the preservation of affordable housing that serves existing

community members.

49

B. Federal NHTF Site Selection Criteria

The federal regulations for the HTF program do not provide sufficiently precise guidelines for

site selection, giving significant discretion to states. On a positive note, the NHTF regulation

does encourage site selection outside of segregated neighborhoods. Specifically, the regulation

attempts to limit the construction of new rental housing units in areas of concentrated

minority population, following the standard established in HUD’s project-based voucher (PBV)

program.

50

This regulation reads:

(2) The site must not be located in an area of minority concentration, except as

permitted under paragraph (e)(3) of this section, and must not be located in a racially

mixed area if the project will cause a significant increase in the proportion of minority to

non-minority residents in the area.

51

Federal regulations governing the PBV program (and NHTF by extension) define an area of

minority concentration as:

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

9

________________________________

46 Low-Income Housing Credit 26 U.S.C. § 42(m)(1)(B)(ii)(III); IRS Notice 2016-77, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-

drop/n-16-77.pdf

47 See Fair housing comments on Treasury Department Notice 2016-77, regarding the “Concerted Community

Revitalization Plan” requirement (PRRAC and coalition partners, February 2017),

https://prrac.org/pdf/Fair_housing_comments_on_LIHTC_CCRP_Notice_Feb_10_2017.pdf

48 Assessment Criteria For “Concerted Community Revitalization Plans”: A Recommended Framework (PRRAC,

March 2017), https://prrac.org/pdf/PRRAC_CCRP_recommendations_3_14_17.pdf

49 Id.

50 24 C.F.R § 93.150(b) (requiring that new rental construction projects comply with the site selection

requirements of Project-Based Voucher (PBV) Program 24 CFR § 983.57(e)(2)).

51 24 CFR § 983.57(e)(2).

7(i) the percentage of persons of a particular racial or ethnic minority within the area of the

site is at least 20 percentage points higher than the percentage of that minority group in the

housing market area as a whole or (ii) the total percentage of minority persons within the

area of the site is at least 20 points higher than the total percentage of minorities in the

housing market area.

52

The exceptions described in (e)(3) include:

(i) Sufficient, comparable opportunities exist for housing for minority families in the income

range to be served by the proposed project outside areas of minority concentration (see

paragraph (e)(3)(iii), (iv), and (v) of this section for further guidance on this criterion); or

(ii) The project is necessary to meet overriding housing needs that cannot be met in that

housing market area (see paragraph (e) (3)(vi)) of this section for further guidance on this

criterion).

[(iii-vi) provide definitions and clarifications of the above two provisions]

In other words, NHTF funds cannot be used to build new rental units in areas of minority

concentration unless either (a) sufficient housing opportunities, at similar levels of affordability, exist

for minority families outsides of the minority-concentrated neighborhood, i.e., there is a range of

sources of affordable housing for minority families in diverse neighborhoods; or (b) the proposed-

NHTF project is necessary for meeting an “overriding housing need” that cannot be met by a

project outside of the proposed site, e.g., the NHTF project is part of a

neighborhood revitalization strategy in that area. This requirement

should further fair housing goals by directing new housing

construction outside of areas of minority concentration, which can

often overlap with higher poverty/low opportunity areas, although the

exceptions to the rule are quite broad. Unfortunately, there is little

empirical evidence on the impact of the “minority concentration”

provisions on the location of PBV projects, making it difficult to

predict what impact this provision will have on NHTF site selection.

Importantly, the current federal regulation does not go so far as to

impose any requirement or even encouragement for NHTF project sites to be located in

neighborhoods of high opportunity or require the presence of CCRPs for construction in low-

income neighborhoods.

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

10

________________________________

52 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Office of Housing,

Notice H 2016-17, 25, (Nov. 10, 2016), https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/16-17HSGN_16-17PIHN.PDF (in

addition to defining areas of minority concentration, the regulation defines “area of the site” and “housing

market area.”).

Unfortunately, there is

little empirical evidence

on the impact of the

“minority concentration”

provisions on the location

of PBV projects, making

it difficult to predict

what impact this

provision will have on

NHTF site selection.

C. State NHTF Site Selection Criteria

There is a wide variety of criteria that states use for determining site selection. Some states

achieve geographic diversity by allocating funds by regions, others by distributing funds to

urban and rural communities, and others further this goal by prioritizing high opportunity

areas.

Several states, including Massachusetts, New Jersey, Georgia, Connecticut, Texas and

Delaware, prioritize high opportunity areas when evaluating projects for NHTF funds eligibility.

For example, Massachusetts encourages the creation of units for ELI individuals and families in

areas of opportunity, which it defines as “a neighborhood or community with a relatively low

concentration of poverty” or a “neighborhood or community that offers access to jobs, health

care, high performing school systems, higher education, retail and commercial enterprise, and

public amenities.”

53

Similarly, New Jersey prioritizes high opportunity areas which are

characterized by “low municipal poverty level, accessible public transportation within one mile,

and low municipal labor force unemployment rate.”

54

Georgia tackles geographic diversity by awarding points to properties not in food deserts,

defined as being more than 1 mile from a grocery store with meat, dairy and produce in an

urban area and more than 10 miles in rural areas.

55

Georgia also awards points to properties

near a traditional town square that is hub of commercial and community events or properties

near community or recreational centers relevant to tenant populations. Minnesota considers

each project’s proximity to certain community features that are priorities for Minnesota

Housing, such as economic integration areas, workforce housing communities, rural and tribal

areas, location efficiency (transit), access to higher performing schools, and community

revitalization areas.

56

Connecticut gives preference to projects in higher opportunity areas as demonstrated through

its official Opportunity Map,

57

while Texas awards NHTF applicants points based on an

Opportunity Index that also rewards projects located in high opportunity areas.

58

Delaware

encourages new development and preservation of affordable housing, especially affordable

rental housing, in areas of opportunity, while targeting community development investments,

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

11

________________________________

53 Massachusetts DRAFT 2019 Annual Action Plan, page 58 (2019).

54 New Jersey 2019 Annual Action Plan, page 47 (2019).

55 2017 State Of Georgia National Housing Trust Fund Allocation Plan, page 20 (2017).

56 Minnesota’s National Housing Trust Fund Allocation Plan, page 6. (2017).

57 State of Connecticut DRAFT 2019-2020 Action Plan for Housing and Community Development, page 16

(2019).

58 National Housing Trust Fund State of Texas 2017 Allocation Plan, page 62 (2017).

particularly sustainable homeownership, in areas of concentration of low-income and/or

minority households.

59

In a different vein, Washington D.C. encourages non-housing investments in poor

neighborhoods to increase the opportunities they provide to residents. In the D.C. 2017-21

Consolidated Plan, the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development includes a

commitment to “nonhousing investments that increase the desirability of distressed

neighborhoods through increasing community amenities, public investments, and economic

opportunities.”

60

Recognizing that such improvements might increase housing costs, D.C. also

includes provisions aimed at maintaining affordability through programs that allow tenants to

purchase in those communities.

61

Some states seek to make sure allocated funds are not concentrated in particular geographic

areas. Some of these approaches include distributing funds to rural and urban communities, or

by region. For example, Pennsylvania allocates 50% of NHTF resources to urban communities

and 50% to suburban/rural communities.

62

Similarly, California sets aside at least 20% of NHTF

funds for projects located in rural areas.

63

Alabama uses NHTF funds to expand the overall

rental housing supply located throughout the state in metropolitan and/or rural areas (or non-

metropolitan areas),

64

while Alaska emphasizes funding for rural community needs, especially

as they relate to low-and moderate-income (LMI) populations.

65

In Florida, program funding is

proportionally distributed across Large, Medium and Small counties and within these

groupings, they regularly use a “county award tally” to ensure that funding is further

distributed across as many counties as possible.

66

Tennessee similarly breaks the state into three

geographic divisions, East, Center and West, and awards funds to the highest scoring project

in each geographic division.

67

New York distributes funds considering whether the project

serves an area not awarded HTF funds before.

68

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

12

________________________________

59 Delaware Draft 2019 Annual Action Plan, page 29 (2019).

60 Washington D.C. Consolidated Plan (2017-21), page 161,

https://dhcd.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/dhcd/publication/attachments/FY2017-

2021%20DHCD%20final%20Consolidated%20Plan.pdf.

61 Id.

62 Pennsylvania 2018 Annual Action Plan, page 9 of Appendix F (2018).

63 California Draft 2019-20 Annual Action Plan, page 107 (2019).

64 Alabama Final 2020 AHFA HTF Allocation, page 3 (2020).

65 Alaska Final Annual Action Plan SFY 2020, page 39 (2020).

66 2017 National Housing Trust Fund Allocation Plan for Florida, page 8 (2017),

https://floridahousing.org/docs/default-source/programs/developers-multifamily-programs/competitive/final-

proposed-2017-florida-nhtf-plan-document.pdf?sfvrsn=2.

67 State of Tennessee fiscal Year 2019-20 Annual Action Plan for Housing And Community Development

Programs, page 65 (2019).

68 New York Draft 2019 Annual Action Plan, page 82 (2019).

Besides allocating a portion of the funds to rural areas, California also gives points to projects

based on “Need,” which includes consideration of the number of individuals experiencing

homelessness in the geographic jurisdiction.

69

This approach may be ineffective in furthering

fair housing as it could perpetuate segregation of low income communities. Other states such

as Arizona

70

and Colorado

71

prioritize projects that affirmatively further fair housing, but they

do not provide specific guidelines on how to achieve this goal.

D. Recommendations for Policy Change

Policymakers should consider developing stronger, more specific site selection criteria that

encourage the following: (1) racial and economic diversity in NHTF sites, while specifically

avoiding areas of high poverty and racial segregation; (2) site location in areas of high

opportunity, as measured by proximity to high-performing schools, overall neighborhood

safety, and the presence of beneficial neighborhood assets like grocery stores or community

centers, and accessible transit networks; and (3) a requirement for a meaningful CCRP if sites

are located in lower-income neighborhoods. The NHTF regulation has made an important first

step by limiting new rental construction in areas of “minority concentration,” and similar

guardrails should be put in place for other site selection criteria. At the federal level, these

criteria could be explicitly included in the project selection guidelines under 24 CFR §91.220.

In the absence of federal action, advocacy should focus on achieving stronger fair housing

siting guidelines at the state level. Although several states, as discussed

above, are prioritizing the distribution of NHTF to funds to projects in

areas of high opportunity, most states have failed to incorporate fair

housing principles into NHTF site selection criteria. States should

uniformly prioritize areas of high opportunity for NHTF grants. Criteria

based strictly on geography are insufficient.

To complement federal siting standards, other implementation details can be left to state’s

discretion. For example, allowing states to define the methodology for identifying high

opportunity areas would allow states to develop a definition that reflects the demographic,

geographical, and economic situation of the state. Connecticut has developed one such

approach, with a robust mapping of opportunity areas in the state in partnership with several

community organizations.

72

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

13

________________________________

69 California Draft, supra note 64.

70 Arizona 2018-2019 National Housing Trust Fund Annual Allocation Plan, page 2 (2018).

71 Colorado Draft Annual Action Plan 2019-2020, page 102 (2019).

72 Introduction to Opportunity Mapping, Open Communities Alliance,

https://www.ctoca.org/introduction_to_opportunity_mapping.

States should uniformly

prioritize areas of

high opportunity for

NHTF grants.

2. Local Approval and Opposition

A. Local Approval and Fair Housing

A requirement that local communities approve NHTF housing units

prior to construction or rehabilitation can have a negative impact on

fair housing objectives. As evidenced by other federal housing

programs, such as LIHTC, affluent or high opportunity neighborhoods

are more likely than lower opportunity neighborhoods to organize to

block the construction of affordable housing.

73

Given the difficulty of

obtaining local approval in more affluent areas, local approval criteria

can result in affordable housing units being concentrated in less affluent, and typically lower

opportunity, neighborhoods.

B. Federal NHTF Provisions on Local Approval

The federal NHTF statute contains no prohibition on local or neighborhood approval or

notification requirements. Prohibiting local approval requirements can facilitate fair housing

goals by lowering the barriers to locating NHTF projects in high opportunity areas.

Unfortunately, without federal regulation, states may feel empowered to require or incent local

approval as part of the state-level project selection criteria. By way of example, the federal

LIHTC regulations do not yet prohibit local approval even though 2016 guidance issued by the

Treasury Department clarified that states should not interpret LIHTC’s local “notification and

review” criteria as requiring or encouraging a local veto on proposed LIHTC projects,

74

and the

Department explicitly cited fair housing principles in issuing this ruling.

75

Despite this

requirement, many states continue to give localities a veto over proposed LIHTC projects.

76

States with stronger local approval requirements have a greater percentage of LIHTC units

located in high poverty areas.

77

Advocates have called on the federal government to add a

statutory prohibition on local vetoes to LIHTC developments to prevent state-level community

approval requirements.

78

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

14

________________________________

73 Ingrid Ellen, supra note 44 at 9-10.

74 I.R.S. Rev. Rul. 2016-29, 4-6, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rr-16-29.pdf.

75 Id. (Finding that local jurisdiction having “reasonable opportunity to comment” as laid out in Section

42(m)(1)(A)(ii) was misinterpreted by the allocating agency because its QAP provisions favored projects able to

show affirmative local support and rejected those which lacked it and since approval was more likely in high

minority communities it furthered residential segregation making it inconsistent with the Fair Housing Act).

76 Will Fischer, Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Could Do More to Expand Opportunity for Poor Families, Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities (Aug. 28, 2018), https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/low-income-housing-

tax-credit-could-do-more-to-expand-opportunity-for-poor-families.

77 Ingrid Ellen, supra note 44 at 15-16.

78 Will Fischer, supra note 76.

Allowing states to define

the methodology for

identifying high

opportunity areas would

allow states to develop

a definition that reflects

the demographic, geo-

graphical, and economic

situation of the state.

C. State NHTF Provisions on Local Approval

States approach local approval criteria in various ways. Some states including Alabama,

California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, North

Carolina do not include any discussion of local approval in their state Allocation Plans,

while others explicitly say the eligible project cannot require local approval to proceed.

Unfortunately, other states include some form of local approval criteria in which they

encourage and often require applicants to provide proof of local support for the eligible

project. For example, Alaska requires applicants for NHTF funding to show evidence

demonstrating the need for the subject development in the geographic area in which it is

proposed, which includes evidence of community support for the project as evidenced by at

least two written letters of support from the local government, community council(s), and non-

profit organizations located in the project area whose clients will likely benefit from the

project.

79

In Arkansas, qualified applicants must provide a letter of support from the chief

elected official or a majority of the members of the elected governing body of the jurisdiction

where the affordable housing is to be located.

80

Similarly, Washington awards points to

projects that show evidence of local priority and support from the jurisdiction in which the

project is located.

81

For instance, a project gets points if a letter of support from the local

public body (i.e., city or county) with jurisdiction over the project’s location is provided with the

application and if the applicant demonstrates the project meets a currently defined local

priority (e.g., consistent with the comprehensive plan, local resolution, ordinance, etc.).

Colorado includes “confirmed local political support and expected planning and zoning

approval within 90 days of State Housing Board approval” as two of the minimum application

threshold criteria for project readiness to proceed.

82

Other states require local approval for the purposes of zoning only. For example, in Arizona,

applicants must provide a letter from the unit of local government indicating whether the

property is appropriately zoned for the intended use.

83

Similar, Georgia requires applicants to

show evidence that the appropriate zoning is in place at the time of application submittal.

84

The letter from the authorized local government official must be included in the application

and it must confirm that the development site conforms to the site development plan. Texas

also requires applicants for funds to submit proof of zoning compliance in the form of a letter

from appropriate government official.

85

Similarly, in Michigan, applicants are required to

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

15

________________________________

79 Alaska Notice of Funding Availability The SFY 2020 Greater Opportunities For Affordable Living (GOAL)

Program, page 10 (2019).

80 Arkansas National Housing Trust Fund Program, page 7 (2019).

81 Washington State 2017 National Housing Trust Fund Allocation Plan, page 13 (2017).

82 Colorado Draft Annual Action Plan 2019-2020, page 156 (2019).

83 Arizona 2018-2019 National Housing Trust Fund Annual Allocation Plan, page 9 (2018).

84 2017 State of Georgia National Housing Trust Fund Allocation Plan, page 15 (2017).

85 National Housing Trust Fund State of Texas 2017 Allocation Plan, page 53 (2017).

provide documentation from the appropriate local official on official letterhead identifying the

address of the project, the property's current zoning designation and an explanation of

whether or not the project is permitted under the zoning ordinance.

86

While, as mentioned above, requiring or encouraging local approval is generally detrimental to

fair housing principles, at least one state uses the local approval process as a way to promote

fair housing in the projects they select. For example, Virginia requires local government review

of the site and neighborhood standards, but it does so to ensure the assisted projects are

“located where possible in areas that decrease the overall concentration of poverty and

minorities.”

87

The developer must demonstrate that the project is located on adequate and

accessible sites with access to services and facilities, that they comply with fair housing laws,

among other requirements.

D. Recommendations for Policy Change

Federal regulations do not mandate local approval or notification, and local approval or

notification requirements are also relatively rare at the state level. Nonetheless, the existence of

local approval requirements in these states is a barrier to fair housing

goals, as it empowers affluent communities to block affordable

housing developments in high opportunity areas. Ideally, federal

regulations would explicitly block local approval rather than being

silent on the issue.

States should also include flexibility for applicants facing community

opposition. For example, stringent zoning regulations are often used

as a pretext for blocking affordable housing in affluent housing, yet

most states explicitly require applicants for NHTF funds demonstrate

compliance with local zoning regulations. Fair housing goals would be better advanced if state

NHTF regulations allowed for flexibility in meeting local zoning requirements. Rather than

requiring strict adherence to local zoning laws, states could accept a project that seeks

variances or exceptions to local zoning regulations or one that reasonably pursued zoning

approval but has been unsuccessful due to community opposition to affordable, low-income

housing. In these latter cases, the state should help the applicant obtain the necessary

approvals, or grant extensions on HTF funding while the applicant appeals a restrictive zoning

ruling.

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

16

________________________________

86 Addendum V Application Exhibit Checklist For Multi-Family Housing-Housing Trust Fund Gap Financing

Program, page 5 (2019).

87 Virginia Affordable and Special Needs Housing – Consolidated Application Program Guidelines 2017-18,

page 13 (2017).

The existence of local

approval requirements in…

states is a barrier to fair

housing goals, as it

empowers affluent

communities to block

affordable housing

developments in high

opportunity areas.

3. Affirmative Marketing

A. Affirmative Marketing and Fair Housing

In the context of fair housing, affirmative marketing is a policy of intentionally designing

advertising, marketing and tenant outreach activities to reach tenants from traditionally

underserved communities.

88

One way to understand affirmative marketing strategies is that

they “level the information playing field” about access to affordable housing.

89

Another

framework views affirmative marketing as a necessary “nudge,” which encourages

marginalized groups to seek-out housing in areas that they may have believed to be out-of-

reach.

90

Empirical studies have found that affirmative marketing strategies are a significant

contributor in creating mixed-income and mixed-race neighborhoods.

91

Importantly, successful

affirmative marketing strategies often require innovative thinking. Traditional advertising

methods, such as “for rent” signs and newspaper ads are typically insufficient to attract low-

income tenants.

92

B. Federal NHTF Provisions on Affirmative Marketing

NHTF regulations explicitly require owners of NHTF-financed projects to adopt affirmative

marketing strategies.

93

In the NHTF regulation, affirmative marketing is defined as “actions to

provide information and otherwise attract eligible persons in the housing market area to the

available housing without regard to race, color, national origin, sex, religion, familial status, or

disability.”

94

The regulation states that affirmative marketing procedures must include the

following:

(i) Methods for informing the public, owners, and potential tenants about Federal fair

housing laws and the grantee's affirmative marketing policy (e.g., the use of the Equal

Housing Opportunity logotype or slogan in press releases and solicitations for owners,

and written communication to fair housing and other groups);

(ii) Requirements and practices the grantee and owner must adhere to in order to carry out

the grantee's affirmative marketing procedures and requirements (e.g., use of

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

17

________________________________

88 Megan Haberle, Ebony Gayles, and Philip Tegeler, Accessing Opportunity: Affirmative Marketing and Tenant

Selection in the LIHTC and Other Housing Programs, Poverty & Race Research Action Council 9-13 (Dec.

2012), https://www.prrac.org/pdf/affirmativemarketing.pdf.

89 Mark W. Zimmerman, Opening the Door to Race-Based Real Estate Marketing: South-Suburban Housing

Center v. Greater South Suburban Board of Realtors, 41 DEPAUL L. REV. 1271, 1316 (1992).

90 Haberle, supra note 88 at 10-11.

91 Id. See also Diane L. Houk, Erica Blake, and Fred Freiberg, Increasing Access to Low-Poverty Areas by Creating

Mixed-Income Housing, Fair Housing Justice Center (June 2007).

92 Haberle, supra note 88 at 12-13.

93 24 C.F.R. §93.350.

94 Id.

commercial media, use of community contacts, use of the Equal Housing Opportunity

logotype or slogan, and display of fair housing poster);

(iii) Procedures to be used by the grantee and owners to inform and solicit applications

from persons in the housing market area who are not likely to apply for the rental

housing or homeownership assistance program without special outreach (e.g., through

the use of community organizations, places of worship, employment centers, fair hous-

ing groups, or housing counseling agencies);

(iv) Records that will be kept describing actions taken by the grantee and owners to affir-

matively market rental housing units and homeownership assistance program and

records to assess the results of these actions; and

(v) A description of how the grantee will annually assess the success of affirmative market-

ing actions and what corrective actions will be taken where affirmative marketing

requirements are not met.

95

Additionally, NHTF is regulated by HUD’s affirmative marketing guidelines for HUD-

administered programs.

96

These regulations apply to NHTF-financed developments with five or

more units. HUD’s affirmative marketing regulations are extensive, and a 2012 PRRAC Policy

Brief contains fuller analysis of them.

97

C. State NHTF Provisions on Affirmative Marketing

States provide additional affirmative marketing guidance beyond the federal regulations to

NHTF projects in two ways. First, some states include affirmative marketing specification in

their NHTF allocation plans, either as a project requirement or as a selection criteria, as occurs

in the allocation plans of Florida, Missouri, Georgia, and Texas. For example, Florida requires

grantees to work with a Special Needs Household Referral Agency that will refer eligible

homeless, at-risk homeless or special needs households for residency in the NHTF-financed

units.

98

Missouri requires family developments proposed in opportunity areas to include an

affirmative marketing plan that proactively reaches out to families currently living in census

tracts where the poverty rate exceeds 40 percent.

99

The second, and more common, way that states address affirmative marketing is through non-

NHTF-specific affirmative marketing policies that apply to housing programs administered by

the state, including NHTF. For example, Connecticut has a statewide affirmative marketing

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

18

________________________________

95 Id.

96 Affirmative Fair Housing Marketing Regulations 24 C.F.R. §200.600 (1972) and Compliance Procedures for

Affirmative Fair Housing Marketing 24 C.F.R. §108 (1979). (Under 24 C.F.R. § 200.615, HUD’s affirmative

marketing guidelines apply to “applicants for participation in FHA subsidized and unsubsidized housing

programs” for multifamily projects of five or more units.)

97 Haberle, supra note 88.

98 Florida Allocation Plan, supra note 67.

99 Missouri 2019 National Housing Trust Fund Allocation Plan, 19 (2019).

plan.

100

The plan provides a precise definition of “least likely to apply” as those who do not live

in the development area because of “racial or ethnic patterns, perceived community attitudes,

price or other factors and need additional outreach to inform them of their opportunity to live

in the development.”

101

It also requires reporting on fair housing marketing efforts at least

three times prior to occupancy and annually thereafter. If Connecticut deems a developer’s

affirmative marketing strategies to be inadequate, it can require additional outreach,

potentially causing a delay in occupancy.

102

Similarly, New Jersey has independent regulations on affirmative marketing that apply to NHTF,

among other programs.

103

The New Jersey regulations include a definition of “least likely to

apply,” which takes a regional approach, not limiting potential tenants to those in the

immediately surrounding neighborhoods.

104

This is designed to attract people from all majority

and minority groups that are potentially eligible and in addition requires three broadcasting

methods, newspaper, radio and one medium selected by the developer like flyers or

advertising with community groups serving low-income populations.

105

Washington D.C. requires community-based partners, including NHTF grantees, to participate

in affirmative marketing training at least once per year.

106

The training is intended to educate

grantees on discriminatory practies and to build capacities that lead to more equitable service

delivery.

Other states with affirmative marketing policies for state-administered housing programs

include, but are not limited to, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, and New York.

D. Recommendations for Policy Change

At the federal level, NHTF-specific regulations and HUD affirmative marketing guidelines

provide a solid basis for successful affirmative marketing strategies. It is also encouraging that

many states have adopted their own affirmative marketing policies to govern state housing

programs. However, greater specificity is needed to ensure that affirmative marketing

strategies reach those most in need of affordable housing, who are often the most difficult to

reach through traditional marketing strategies. Policymakers should consider modifying federal

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

19

________________________________

100 Affirmative Furthering Fair Housing: A Guide for Housing Providers, Connecticut Fair Housing Center (2013)

https://www.ctfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/CFHC-AffirmFurthGuideProviders.pdf.

101 Id. at 24.

102 Id. at 11-12.

103 Uniform Housing Affordability Controls N.J.A.C.. 5:80-26.1 et seq. (2004),

https://www.state.nj.us/dca/divisions/lps/hss/admin_files/uhac/uhac.pdf.

104 Id. at 19.

105 Id. at 20-21.

106 Washington D.C. Consolidated Plan supra note 61 at 211.

and state affirmative marketing regulations to reflect research on the most effective affirmative

marketing strategies for reaching historically marginalized groups.

First, the federal regulation should mandate certain affirmative

marketing practices that positively contribute to diversity across

multiple contexts. These include mandating that marketing be open

for an extended period of time (e.g., six months) before a lease is

signed; giving developers sufficient time to identify applicants in the

“least likely to apply” category; and requiring that all affordable units

be placed on a central website, giving prospective tenants a one-stop-

shop for identifying affordable housing units.

107

Some states, such as

Massachusetts, already include these requirements, and these

practices should be explicitly incorporated in federal affirmative marketing requirements.

Second, greater specificity should be provided in defining those tenants “least likely to apply,”

and how to conduct targeted outreach. The absence of a definition of “least likely to apply” at

the federal level gives states too much flexibility. For example, if an analysis of those who are

least likely to who apply is limited to the immediate neighborhood of the project, it will fail to

target the true “least likely to apply” who likely live in segregated neighborhoods. Building on

this, marketing of fair housing opportunities should be conducted regionally, rather than

locally, to ensure that it reaches families living in segregated areas.

Finally, affirmative marketing strategies must include community engagement provisions.

Community-driven engagement is a demonstrated mechanism of increasing the applicant

pool.

108

These practices would include: (1) addressing residents’ concerns through specific

information; (2) sponsored community visits to discuss the housing program; (3) the

engagement of local groups; (4) recruiting applicants from public housing authority waitlists;

and (5) coordination among developers in the same area so that they jointly reach out to those

“least likely to apply,” giving potential tenants a streamlined source of information about

affordable housing.

109

States could require that developers provide evidence of pursuing each

of these four community engagement strategies as a program requirement.

4. Tenant Selection

A. Tenant Selection and Fair Housing

Tenant selection is closely related to affirmative marketing. Tenant selection procedures can

inadvertently reinforce patterns of segregation and discrimination. For example, screening

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

20

________________________________

107 Haberle, supra note 88 at 20-21.

108 Id. at 25-27.

109 Id. at 25-27.

Policymakers should

consider modifying federal

and state affirmative

marketing regulations to

reflect research on the most

effective affirmative

marketing strategies for

reaching historically

marginalized groups.

mechanisms, such as reliance on FICO scores and criminal background scores, can have a

disparate impact on traditionally disadvantaged groups, resulting in affordable housing not

going to those most in-need.

110

Similarly, local residency preferences too often reinforce

patterns of racial segregation since many neighborhoods are racially homogenous.

111

Tenant

selection policies should be designed to include those most in-need of affordable housing, and

practices known to disadvantage certain racial or socioeconomic groups should be prohibited.

B. Federal NHTF Provisions on Tenant Selection

The NHTF regulation contains specific prescriptions for tenant selection for rental housing,

although no analogous requirements are provided for homebuyers. First, landlords must

comply with the affirmative marketing requirements of the grantee (i.e., the state/ state

implementing agency). Second, the landlord must adopt and follow written tenant selection

criteria under §93.303 (d) that include the following:

(1) Limiting housing to income-eligible families

(2) Selection criteria reasonably related to the tenant’s ability to perform the obligations of the

lease (i.e., to pay the rent, not to damage the housing; not to interfere with the rights and

quiet enjoyment of other tenants)

(3) Limit eligibility or give preference to a particular segment of the population only if this is

done with written agreement of the grantee. This might include preferences for individuals

with disabilities, the homeless, veterans, etc. (There are several limitations to this allowance,

listed in §93.303 (d) (3)(i)-(ii))

(4) Cannot exclude tenants on the basis of holding Section 8 vouchers (under 24 CFR §982) or

being HOME rental assistance participants (under 24 CFR§92).

(5) Provide for the selection of tenants from a written waiting list in chronological order, insofar

as this is possible

(6) Give prompt written notification to any rejected applicant of the grounds for rejection

(7) Comply with the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), as detailed in §93.356.

Once again, the NHTF requirements are a good first step towards fair tenant selection

procedures, but lessons from other federal housing programs suggest that stronger guardrails

are needed to ensure that selection procedures do not result in discriminatory patterns of

tenant selection.

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

21

________________________________

110 Id. at 10.

111 Houk, supra note 91.

First, while it is fair to allow landlords to assess a tenant’s ability to fulfill lease obligations, the

regulation gives too much flexibility for landlords to adopt screening mechanisms that have a

demonstrated discriminatory effect. As noted above, FICO scores tend to disproportionately

disadvantage certain groups while not being strong predictors of future rent payments.

Indeed, HUD has issued guidance recommending the use of alternative credit assessments,

such as non-traditional credit reports, which rely on payment histories for rent utilities and

other specified items.

112

Criminal background is another commonly used screening tactic that

can have a discriminatory impact without necessarily being indicative of future tenant behavior.

HUD has similarly issued guidance on using criminal history in tenant selection and cautions

such information should be used in limited manners to ensure Fair Housing Act compliance.

113

As the NHTF regulation is currently written, it risks landlords defaulting to screening procedures

that will have a discriminatory impact.

Second, NHTF does not provide any guidance on residency preferences. In the implementation

of other federal housing programs, owners have often given preference to applicants from the

existing community or neighborhood.

114

Because of patterns of segregation, local residency

preferences have the potential to disproportionately exclude on the basis of race. Disallowing

local residency preferences would allow those “least likely to apply” to have increased access

to affordable housing in higher opportunity communities. Local residency requirements likely

violate existing NHTF requirements, which prohibit landlords from imposing selection criteria

that are not related to lease obligations. However, given the use of local residency as a

screening mechanism in other affordable housing programs, local residency preferences should

be explicitly banned in NHTF-funded developments.

Finally, the NHTF regulation does not require affirmative notification procedures for notifying

tenants on the waitlist. Given that the most disadvantaged tenants might be the most difficult

to reach (e.g., in homeless shelters or without reliable access to Internet), landlords should be

required to employ multiple means of notifying tenants on a waitlist and to provide several

days for a response before moving on to another tenant. Similarly, the NHTF regulation

recommends a chronological waitlist, but a better practice would be a lottery-based waitlist.

115

The first prospective tenants to file applications are often the most advantaged and tend to be

local residents. A randomized waitlist ensures that those who applied later, often the “least

likely to apply,” are given sufficiently opportunity to benefit from the housing.

Poverty & Race Research Action Council Policy Brief April 2021

22

________________________________

112 Haberle, supra note 88 at 40.

113 Office of General Counsel Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Act Standards to the Use of Criminal

Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate-Related Transactions. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development (Apr. 4, 2016), https://www.hud.gov/sites/documents/HUD_OGCGUIDAPPFHASTANDCR.PDF.

114 Haberle, supra note 88 at 38.

115 Id. at 39.

C. State NHTF Provisions on Tenant Selection

Most states do not address these fair housing issues in their NHTF allocation plans. Consistent

with the fair housing principles described above, a few states, such as Florida, Georgia, and

Ohio, discourage the use of potentially discriminatory tenant screening mechanisms, such as

FICO scores or criminal background. Our review of state allocation plans did not reveal any

states that regulated or provided recommendations for waitlist policies, such as local residency

preferences, or giving applicants sufficient time to respond to openings.

Many state allocation plans include tenant selection protocols that allow or instruct landlords

to give preferences to certain groups, as allowed under §93.303. Groups commonly given

preference as tenants under state allocation plans include veterans,

116

the homeless

117

, and

those with disabilities.

118

These group preferences might provide states with important means

to further state public policy goals or help particularly disadvantaged groups through the NHTF.

However, supporting these groups, in the absence of other policies, does not necessarily

further fair housing. These group preferences should be combined with tenant selection

procedures that address fair housing concerns, such as the avoidance of discriminatory

screening mechanisms and waitlist procedures discussed above. Tenant selection policies that

give group preferences but do not incorporate fair housing principles may result in housing

that serves the most advantaged members of these groups, rather than those most in-need of

housing. Combining fair housing regulations with group preferences would ensure that NHTF

funds are going to projects that serve most disadvantaged and contribute to the growth of

more integrated and thriving communities.

D. Recommendations for Policy Change

Policymakers should consider providing for stronger regulations and guidance related to

screening procedures, residency preferences, and waitlist policies. Given that few states have

tenant selection policies in place, federal action is particularly necessary to fill this gap and

states cannot be counted on to implement tenant selection policies consistent with fair

housing.

Specifically, federal requirements should be revised to advise against the use of screening

mechanisms with demonstrated discriminatory effects, such as FICO scores and criminal

The National Housing Trust Fund and Fair Housing: A Set of Policy Recommendations

23

________________________________

116 See e.g., NHTF Allocation Plans for for Alabama, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Michigan, Missouri, New

Jersey, New Mexico, Texas, Washington.

117 See e.g., NHTF Allocation Plans for Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida,

Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania,

Texas, Washington.

118 See e.g., NHTF Allocation Plans for Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Georgia, Missouri,

Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington.

background checks without the accompanying considerations of

mitigating circumstances. Instead, landlords should be encouraged to

use screening mechanisms that are more inclusionary, such as

accepting non-traditional credit scores, acknowledging some ELI

households will have no credit history, and allow the presentation of

mitigating circumstances for eviction history as well as criminal

records. Encouragingly, some states, such as Ohio, have adopted

these policies, and advocacy should focus on spreading such best

practices.

Second, federal rules or state requirements should prohibit

preferences for local residency. Third, federal and state tenant

selection requirements should include stronger waitlist notification

procedures to ensure that disadvantaged tenants are reached and given sufficient time to

respond. At the federal level, waitlist guidelines should also be changed to recommend a

randomized lottery for the waitlist rather than chronological order.

5. Deciding Between Construction, Rehabilitation, and Acquisition

A. Fair Housing Implications

NHTF is available for both construction and rehabilitation of housing. New construction

contributes to the goal of increasing the country’s overall housing stock, yet new construction

in areas of high poverty is likely to perpetuate patterns of segregation. We recommend that

projects in areas of high poverty should focus on acquisition or rehabilitation, rather than new

construction. To the extent there are necessary exceptions to this rule, new construction in

high poverty areas should be allowed only if accompanied by meaningful CCRPs (as discussed

in the site selection section). Projects in areas of opportunity can include construction,

rehabilitation, or acquisition.

B. Federal Provisions

Federal regulations do not provide guidance on the allocation of funds between construction,

rehabilitation or acquisition as long as the projects meet other NHTF requirements.