1

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

WORKING PAPER

DIIS WORKING PAPER

Decentralization and implementation of

climate change policy in Uganda

Esbern Friis-Hansen, Bernard Bashaasha and

Charles Aben

DIIS Working Paper 2013:17

2

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

© The authors and DIIS, Copenhagen 2013

Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS

Østbanegade 117, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark

Ph: +45 32 69 87 87

Fax: +45 32 69 87 00

E-mail: diis@diis.dk

Web: www.diis.dk

Cover Design: Carsten Schiøler

Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen

Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS

ISBN: 978-87-7605-625-4 (print)

ISBN: 978-87-7605-626-1 (pdf)

Price: DKK 25.00 (VAT included)

DIIS publications can be downloaded

free of charge from www.diis.dk

ESBERN FRIIS-HANSEN

PhD, Seniorforsker, DIIS

efh@diis.dk

BERNARD BASHAASHA

Dr., Principal at College of Agricultural and Environmental

Sciences, Makerere University, Uganda

CHARLES ABEN

PhD Candidate, Dept. of Extension & Innovation Study,

Makerere University, Uganda

DIIS Working Papers make available DIIS researchers’ and

DIIS project partners’ work in progress towards proper

publishing. They may include important documentation

which is not necessarily published elsewhere. DIIS Working

Papers are published under the responsibility of the author

alone. DIIS Working Papers should not be quoted without

the express permission of the author.

Climate Change and Rural Institutions is a four-year

collaborative research programme which explores the

role of district level institutions in providing an enabling

environment for climate change adaptation. The

programme is coordinated by DIIS in collaboration with

partners in Nepal, Uganda, Vietnam and Zambia. The

programme is funded by Danish Research Council for

Development Research, with additional support from the

Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security Programme

under the CGIAR Partnership.

For more information, please see www.diis.dk/ccri

3

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

CONTENTS

Preface 4

List of abbreviations 5

1. Introduction 7

1.1 Setting the scene 7

1.2 Study focus 8

1.3 Methodology 8

2. Genesis of climate change in Uganda 8

2.1 Geography of Uganda 8

2.2 Characteristics of climate change in East Africa 10

2.3 Gradual change in weather patterns in Uganda 11

2.4 Extreme climate events in Uganda 13

3. Recent economic, social and political change in Uganda 14

3.1 Economic development 14

3.2 Institutional change 15

3.3 Role of Eexternal Aactors/donors in development and

climate change 16

3.4 Evolution of the political character of the Ugandan state 16

4. Decentralization as unique feature of Uganda 18

4.1 Evolution of local government 18

4.2 Local government capacity to deliver services 18

5. National climate change policies and their implementation modalities 20

5.1 Emergency assistance policy OPM 20

5.2 NAPA 22

5.3 NCCP and implementation framework 23

6. Discussion 25

6.1 Compliance of climate change policy and Decentralization Act? 25

6.2 Political nature of Ugandan state and policy reform 26

6.3 Drivers of climate change policies 27

6.4 Implication of the gap between climate change policies

and decentralization 28

6.5 NCCP: bridging the gap between policy and practice? 29

6.6 Lack of understanding of climate change action by meso-level

institutions 30

7. Bibliography 31

Annex 1 and 2 33-34

4

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

PREFACE

This working paper is the rst of two working papers that presentings ndings

from the Climate Change and Rural Institutions (CCRI) research program on

how meso-level institutions in Uganda are responding to climate change and

extreme climate events. This working paper analyses national policies that to

support climate change mitigation and adaptation and their implementation

modalities. The second working paper focuses on the meso-level institutional

dynamics of how climate change action inside within as well as outside the

framework of climate change policies. For more information about CCRI,

see http://subweb.diis.dk/sw113176.asp

The CCRI research program undertakes empirical eldwork in Soroti, Amu-

ria and Katakwi districts located in of Teso region, Eeastern Uganda. The

research examines how extreme climate events such as the 2007 oods and

subsequent severe oods and droughts , as well as the gradual change in weath-

er patterns, are affecting meso-level institutions.

5

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CAADP Comprehensive Africa Agricultural Development

CAO Chief Administrative Ofcer

CCD Climate Change Department

CCRI Climate Change and Rural Institutions

CCU Climate Change Unit

CIF Climate Investment Fund

DANIDA Danish Agency for International Development

DDP District Development Plan

DFID Department for International Development

DNA Designated National Authority

DRR Disaster Risk Reduction

DSIP Development Strategy and Investment Plan

EAC East African Community

EC Electoral Commission

EU European Community

FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation

GoU Government of Uganda

GTZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit

ICEDA Integrated Community Education and Development

Association

IGG Inspectorate of Government

INC Initial National Communication

IPPC International Panel

KIDDP Karamoja Integrated Disarmament and Development

Programme

LGDP Local Government Development Plan

LGs Local Government

LRDP Luwero – Rwenzori Development Plan

MAAIF Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries

MDAs Ministries, Departments and Agencies

MEA Multilateral Environmental Agreements

MoH Ministry of Health

MOLG Ministry of Local Government

6

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

MoWE Ministry of Water and Environment

NAPA National Adaptation Plan of Action

NCCAC National Climate Change Advisory Committee

NCCF National Climate Change Focal point

NCCP National Climate Change Policy

NCCPC National Climate Change Policy Committee

NDP National Development Plan

NEPAD New Partnership for African Development

NGOs Non-Governmental Organisations

NUREP Northern Uganda Rehabilitation Programme

NUSAF Northern Uganda Social Action Fund

OPM Prime Minister’s Ofce

PRDP Peace Recovery and Development Plan

SLM sustainable land management

UHRC Uganda Human Rights Commission

UN United Nations

UNCBD Convention on Biological Diversity

UNCCD United Nations Convention to Combat Desertication

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNEP United Nations Environmental Programme

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

USAID United States Agency for International Development

USD US $

WB World Bank

WFP World Food Program

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

7

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Setting the scene

The focus of climate change policies and

action in Africa south of the Sahara differs

from the global agenda. While most debate

within the United Nations Framework Con-

vention on Climate Change relates to assess-

ing physical climate change and mechanisms

for mitigation, the main concern of most

African countries is how to adapt to the ef-

fects of climate change. A growing number

of projects addressing climate change adap-

tation and government are formulating new

policies that seek to provide a framework to

guide these activities. Yet, discussion of the

content of and driving forces behind climate

change adaptation in national policies has

been limited. Even less is known about how

such national climate change policies have

been implemented and their institutional set-

ting within the country. This working paper

explores the driving forces behind the formu-

lation of climate change policies in Uganda

and assesses its content and implementation

modalities. The working paper explores the

extent to which there is a gap between policy

and practice at the district and local levels.

Climate change in Uganda is very real factor

in people’s lives. Smallholder farming families

with little or no mechanization, irrigation or

use of seasonal chemical inputs are particu-

larly affected. While extreme climate change

events, such as oods and droughts, are not

a new phenomenon in Uganda, they have

become more frequent during the past dec-

ade. Meanwhile the long established weather

patterns around which farming systems have

evolved have gradually become more uncer-

tain. In combination, these expressions of

climate change are causing already vulnerable

rural people to become even more vulnera-

ble. While small-scale farmers have long ex-

perience in adapting to unpredictable weather

patterns, the type of uncertainty that is as-

sociated with climate change is beyond the

scope of rural people’s capacity to cope with.

They need help from outside the local com-

munity to adapt.

Such assistance has been guided by three

sets of policies that fall under the heading

of climate change. The policy that has been

around the longest is the policy of emergen-

cy assistance, reecting the fact that natural

hazards have existed for far longer than the

climate change agenda. Emergency assistance

policy is anchored in OPM. NAPA, which

came into force in 2008, was the rst policy

that directly addressed the challenges posed

by climate change and for the rst time set

priorities for supporting adaptation efforts.

NAPA is institutionally anchored across a

number of central ministries. The most recent

is the NCCP, which addresses climate change

in a comprehensive manner. The NCCP is in

the process of being accepted by government

and is led by a secretariate located within the

Ministry of Water and Environment.

Local government in Uganda is the gov-

ernance institution that is best suited to assist

farmers in adapting to climate change. Ugan-

da undertook a comprehensive decentraliza-

tion reform in 1993 and has since built up

government units at district and sub-county

level with elected councillors and technical

and administrative staff. In the decade follow-

ing decentralization reform the responsibility

for providing a wide range of services was

devolved from central ministries to the dis-

trict level, including education, health, roads

and agriculture. At the turn of the century

a second wave of reform took place aimed

at ‘deepening democracy’ and leading to the

establishment of new local institutions that

linked users at the primary service units to

local government institutions with the aim

8

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

of enhancing social accountability. However,

during the past decade the momentum of re-

form has run out of steam and the national

political agenda has shifted towards recentral-

ization and a return to neo-patrimonial gov-

ernance.

In spite of the fact that decentralised gov-

ernance structures would be the obvious

choice as an implementation mechanism for

creating an enabling environment supporting

rural people to adapt to climate change, until

now climate change policies have been imple-

mented through central ministries and NGOs

using project-based parallel structures.

1.2 Study focus

The working paper seeks to understand why

climate change policies have remained cen-

tralized till now by analysing the nature of the

state and government of Uganda. In particu-

lar, the paper examines the extent to which

climate change policies are being implement-

ed through decentralized political and admin-

istrative structures in Uganda and how. Ques-

tions asked in the two working papers include

the following:

• Are Uganda’s climate change policies con-

sistent with the Decentralization Act?

• Who is driving the formulation of climate

change policies, and how is this affecting

their implementation modalities?

• To what extent can the changing nature of

the Ugandan state explain a gap between

policy and practice?

• What is the implication of decoupling cli-

mate change policies and local government?

1.3 Methodology

Analysis of national decentralization and cli-

mate change policies is based on a literature

review combined with interviews of key in-

formants at the Climate Change Unit and

OPM. The geographical description and anal-

ysis of national trends in precipitation and

temperature are based on a literature review

of scientic reports and policy documents.

The analysis of climate change action at

the local government level is based on pri-

mary eldwork in Soroti, Amuria and Ka-

takwi districts, Teso region. The working

paper draws on information in unpublished

reports from three CCRI workshops with

local government politicians and technical

staff held in 2012 and 2013. Two workshops,

held in Soroti and Amuria districts, involved

25-30 participants representing politicians

(district councillors), chief administrative of-

cers (CAO) and technical staff from most

relevant departments. The third workshop

involved participants from nine districts in

Teso and Karamoja regions, including CAU,

the chairman of the district council (LC5

chair), district NAADS coordinators (DNC)

and district environmental ofcers (DEO).

In additional the section draws on thirty in-

depth interviews with key informants from

Soroti, Amuria and Katakwi districts.

Available studies from Teso compliment

the CCRI eldwork, including two recent cli-

mate change adaptation studies carried out by

students from Makerere University (Kizauzi

et al. 2012) and LIFE (Epilo, 2011).

2. GENESIS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

IN UGANDA

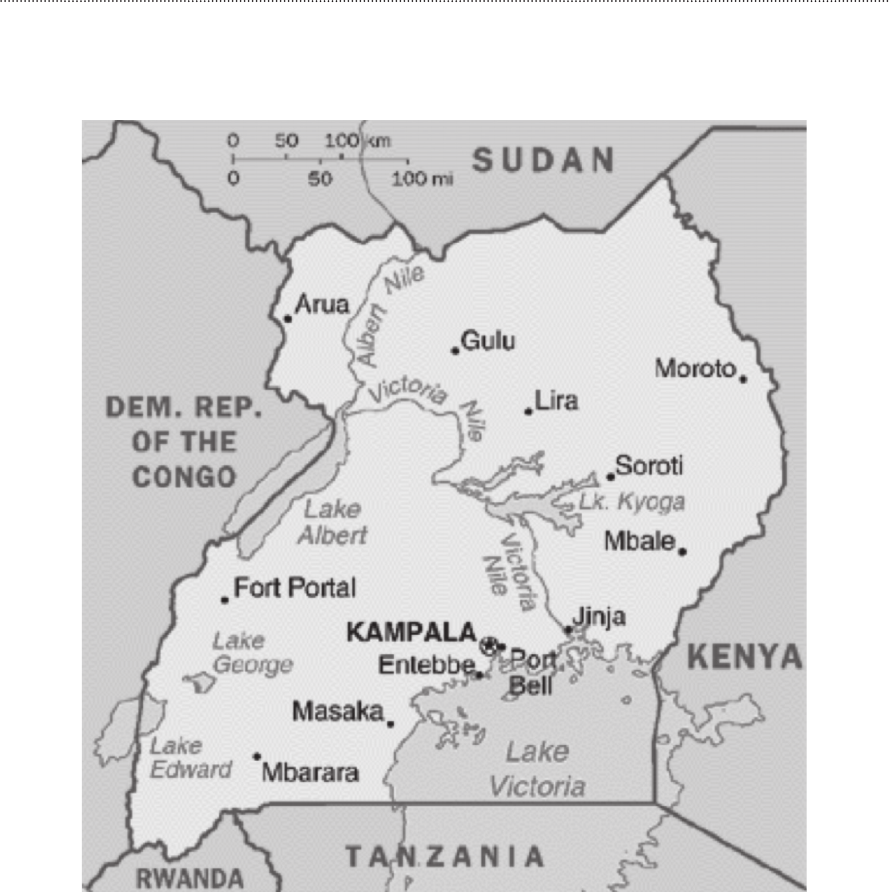

2.1 Geography of Uganda

Uganda lies across the equator and occupies

241,038 square kilometres, of which open

water and swamps constitute 43,941 square

kilometres or 18.2% of the total area. Most

9

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

parts of the country are at an average height

of 1,200 metres above sea level. The lowest

altitude is 620m (on the Albert Nile) and

the highest altitude (Mt Ruwenzori Peak) is

5,110m above sea level. The climate is equa-

torial, with moderate, humid and hot climatic

conditions throughout the year.

Uganda experiences a wet climate with two

distinct rainy seasons in a year in the south-

ern parts of the country, which merge into

one rainy season further north of the equa-

tor. The rainy period between October to De-

cember is described as the long period, and

the short period is between March and May

(McSweeney et al., 2008:1). The areas around

Lake Victoria are wetter than other areas of

the country and receive more than 2,100 mil-

limetres of rain annually, whereas the arid and

semi-arid north receives 500 millimetres per

year, thinning out to as low as 200 millime-

tres in the north-eastern corner (Encyclopaedia

of Earth). Average temperatures in the cool-

er regions of the southwest are below 20°C,

and reach 25°C in the northernmost parts

of the country, also considered the warmest

(McSweeney et al, 2008:1).

Figure 1. Map of Uganda

10

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

2.2 Characteristics of climate change

in East Africa

Climate change in East Africa manifests it-

self as two phenomena: (i) gradual change

of mean temperature, mean precipitation and

variation in precipitation; and (ii) increases in

the intensity and frequency of extreme cli-

mate events, such as droughts, oods, heat

waves and lightning (GoU NAPA, 2007:xiv;

GoU Climate Policy Paper, 2012:5). An analy-

sis of data from the International Emergency

Disaster Database by Shongwe et al. revealed

that there has also been an increase in the

number of reported hydro-meteorological

disasters in the East Africa region, from an

average of less than three events per year in

the 1980s, to over seven events per year in the

1990s, and almost ten events per year from

2000 to 2006, with a particular increase in

oods, from average of less than one event

per year in the 1980s to seven events per

year between 2000 and 2006 (Shongwe et al.

2010:3719).

Uganda has experienced an increase in the

frequency of droughts, with seven droughts

reported between 1991 and 2000. Also the

frequency of anomalously strong rainfall

causing oods has increased (Shongwe et al,

2010:3719). A total of 4.11 million people in

Uganda have been affected by climate-related

disasters of different kinds, such as oods,

disease outbreaks and droughts, since 1979

Table 1. Recent major climate hazards in Uganda

Source: Climate Policy Paper, 2012 and Climate Change Update 2013.

Drought

Landslide (Mass movement)

Drought

Flood

Drought

Drought

Drought

Drought

Epidemic

Flood

Drought

Drought

April-August

2013

March 2010

July 2008

August 2007

March 2005

June 2002

August 1999

January 1998

November 1997

November 1997

December 1987

1979

>500,000

338

1,100,000

718,045

600,000

655,000

700,000

126,000

100,000

153,500

600,000

500,000

Number of

People

Affected

Type of Disaster Date

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

11

(Heinrich Böller Foundation, 2010:22). In the

past, up to 34 per cent of crop damage in

Uganda has been caused by climate-induced

stimuli such as a lack of rainfall, crop diseases

and insect damage (Hisali et al., 2011:1245).

Hepworth and Goulden (2008) state that

oods in Uganda during 1961/62, 1997/98

and 2007 caused widespread infrastructural

damage, displacement and the destruction

of livelihood assets. Droughts have taken a

signicant toll with, for example, 1.8 million

people affected through increased malnutri-

tion, poverty, illness, asset loss and migra-

tion in the 1993/94 event (Hepworth and

Goulden, 2008:10).

2.3 Gradual change in weather

patterns in Uganda

The availability and accessibility of climate

data are major challenges in Uganda. Most

of the climate data produced in the country

does not meet the required standards due to

the irregular monitoring of collection equip-

ment, the few stations and poor station dis-

tribution. There is also a signicant lack of

historical meteorological data in Uganda. For

these reasons, as well as the limited modelling

work that has been done and the complex

interactions that exist between land cover,

oceanographic changes and climate, Uganda’s

climate projections are thus still very unrelia-

ble (GoU Climate Policy Paper, 2012:14-15).

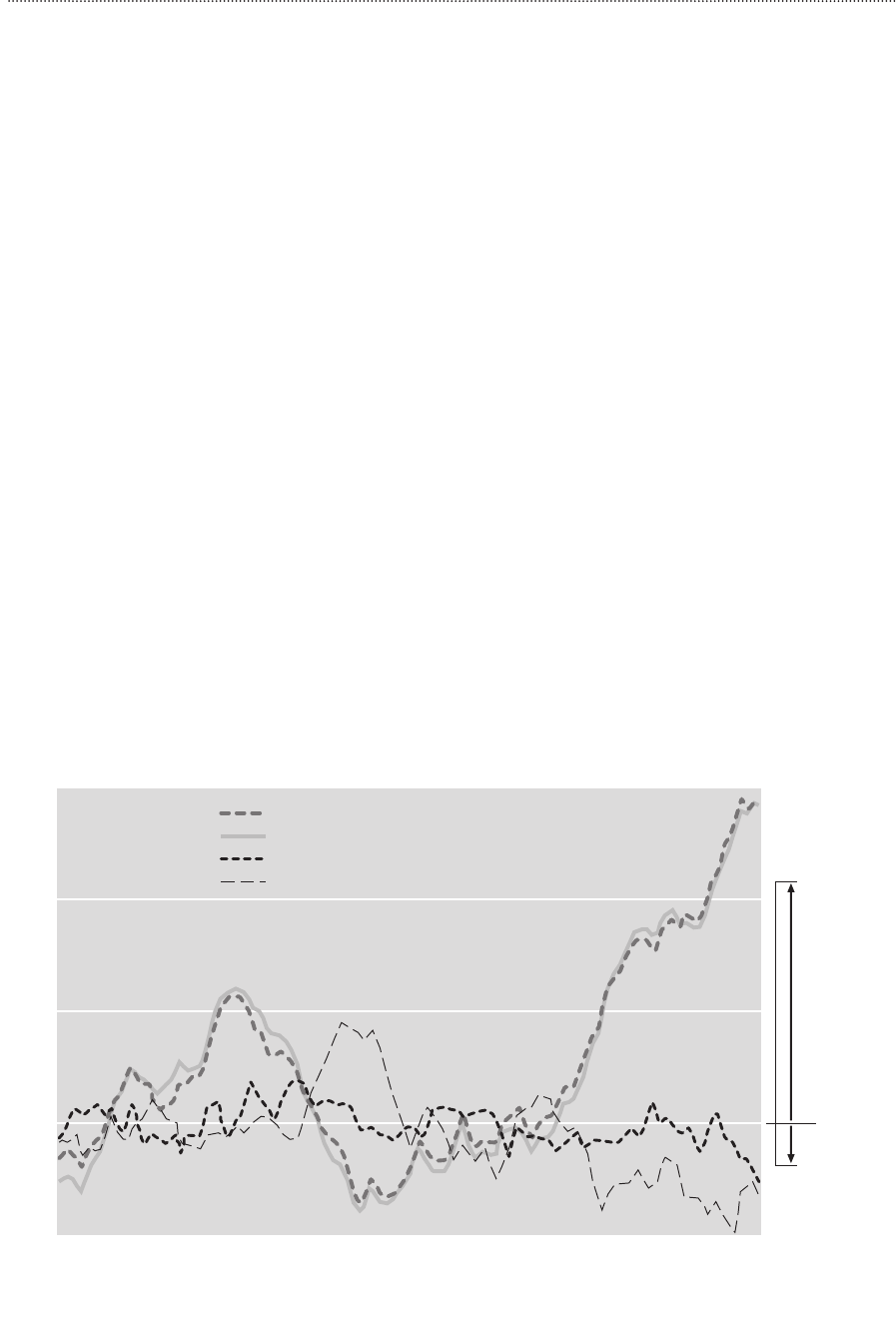

Figure 2 show time series of rainfall (ten-

year running mean) from 1900 to 2009. The

table indicates that “2000–2009 rainfall has

been, on average, about 8 per cent lower (-0.65

standard deviation) than rainfall between 1920

and 1969. Although the June–September rain-

fall appears to have been declining for a longer

period, the March–June decline has only oc-

curred recently.” (USGS 2012:2)

Figure 2. Trends in rainfall and temperature in Uganda

*

* Smoothed 1900-2009 March-June and June-September rainfall and air temperature time series for crop-growing

regions

+ 0.8

degrees

Celsius

- 8

percent

rainfall

Standard deviations

3

2

1

0

-1

1900

1955

2009

March-June temperature

June-September temperature

March-June rainfall

June-September rainfall

12

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

Lyon and DeWitt conclude that since 1999

the East Africa region has experienced a de-

cline in precipitation during the long rainy

season, which has continued since (Lyon and

DeWItt, 2012:4). Funk et al. (2008) state that

East Africa has seen precipitation decline

since 1979 (Funk et al., 2008:11082). Fur-

thermore, overall future climate projections

for East Africa show scientic disagreement

over total rainfall. Funk et al. (2008) suggest

that East Africa will expect a decline in total

rainfall, at least until 2030. The authors use

climate relationship data as opposed to raw

simulations (Funk et al., 2008:11083, 11085).

Conversely, the IPCC report Region Climate

Projections suggests that there is likely to be an

increase in annual mean rainfall in the future

(Christensen, 2007:850). There are, howev-

er, disagreements among scientists. Accord-

ing to McSweeney et al. (2008) observations

of rainfall over Uganda do show statistically

signicant decreasing trends in annual and

March to May rainfall (McSweeney et al.

2008:2).

According to a Climate Policy Paper

(2012), prepared by the Climate Change Unit

within the Ministry of Water and Environ-

ment in Uganda, changes have been observed

in rainfall patterns in Uganda. Rainfall has

become lower, more unreliable and uneven-

ly distributed, and where rain does fall, it is

heavier and more violent. In general, wet-

ter areas are tending to become wetter and

droughts more frequent. The main concern

is not the total amount of rain, but instead

its distribution, seasonality and intensity, the

policy paper concludes (GoU Climate Policy

Paper, 2012:5).

Trends in the variation in precipitation

based on daily rainfall data are, however,

mixed. McSweeney writes that there is no

signicant trend towards heavier and more

extreme rainfall events (McSweeney et al.

2008:2). Others report that rainfall in Ugan-

da has become more unreliable and uneven-

ly distributed (IGAD, 2010). An increase in

the intensities and frequency of heavy rains,

oods and landslides in highland areas, as

well as outbreaks of associated waterborne

diseases associated with the oods, were

also observed and conrmed by a Participa-

tory Rural Appraisal (NEMA, 2008). Recent

years have seen erratic onsets and ends to the

rainy seasons, and rainfall has been heavier

and more violent (GoU, 2007; MWE, 2010).

These are being followed by long droughts,

which are becoming more and more fre-

quent. El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO)

events have also been observed to be shorter

and more irregular (IGAD, 2010).

Shongwe et al. 2011 carried out a study

of possible changes in the intensity of mean

and extreme precipitation rates in East Afri-

ca. They state that ‘Evidence in support of

a future positive shift in the rainfall distri-

bution under global warming has been pre-

sented for most models, with only a single

model simulating a trend to less rain’. They

also conclude that ‘It is physically reasona-

ble, therefore, to conclude from this ocean–

atmosphere coupling pattern that global

warming could enhance the likelihood of

anomalously strong short rains’ (Shongwe et

al, 2010:3728f).

Since 2000, extreme rainfall conditions

have been regularly experienced in eastern

Uganda, where there has been an increase

of approximately 1500 mm in precipitation

in the December to January rainy season

(NEMA, 2008). Teso region has particular-

ly been affected by these trends. According

to the Uganda Department of Meteorology,

rainfall seasons have become more variable as

depicted by the analysis of cumulative average

ten-day totals. Although western, central and

northern Uganda experienced good rainfall,

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

13

the eastern region experienced dr-oaughts in

1997, showing the complexity of these var-

iations.

2.4 Extreme climate events in

Uganda

Recent droughts in Uganda. The western, north-

ern, and north-eastern regions have been ex-

periencing more frequent and longer-lasting

droughts than seen historically (GoU, 2007).

Between 1991 and 2000 there were seven

droughts in the Karamoja region, and the

years 2001, 2002, 2005 and 2008 also saw ma-

jor droughts (GoU, 2002; GoU, 2007; EM-

DAT, 2011). While there have always been

droughts in Uganda, evidence suggests they

are becoming more frequent and more severe

(IGAD, 2010). An example of such a severe

drought was the 2000 widespread drought in

the eastern and northern regions, with Arua

district being worst affected, although the

western region experienced good seasons.

The increased frequency and duration of

droughts is the most signicant climate-re-

lated change being experienced in Uganda

(GoU, 2007; MWE, 2010). See Figure 3.

Recent oods in Uganda. Uganda experienced

above normal rainfall in 1998 (an El Nino

year), resulting in oods that had serious neg-

ative impacts on several sectors, particularly

health and transport. The ooding of 1998

was followed by a severe drought in western

region, with Mbarara district being most af-

fected. From 2007 to date, the Teso sub-re-

gion in the north-eastern part of the country

has experienced major oods in November

that have continued to be intermittently fol-

lowed by long droughts and oods during

traditional planting seasons. This has virtually

derailed the planting strategies in the sub-re-

gion. These analyses show that the impact

of climate variability and climate change has

not been consistent across the whole country,

thereby posing serious implications for the

efciency of the national-level response. In

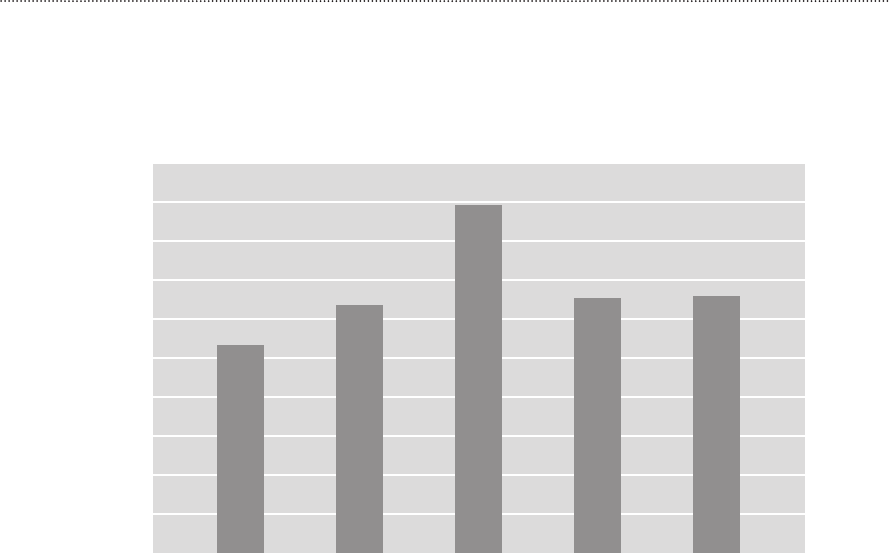

Figure 3. Drought occurrences in Uganda 1911-2000

Source: GoU 2007

Frequency of drought

Decades

1921-301911-20 1931-40 1941-50 1951-60 1961-70 1971-80 1981-90 1991-00

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Decade

1911-20

1921-30

1931-40

1941-50

1951-60

1961-70

1971-88

1981-90

1991-00

Frequency

of drought

1

1

1

0

1

0

3

2

7

14

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

September 2010, further ood disasters hit

the Teso region, leading to rotting cassava,

sweet potato tubers and groundnuts (GoU

Climate Policy Paper, 2012:13).

3. RECENT ECONOMIC, SOCIAL

AND POLITICAL CHANGE IN

UGANDA

3.1 Economic development

Uganda’s economy performed remarkably

well from independence to 1970, when the

country experienced relative political stability.

Ination was maintained at an average of 3

per cent per annum, real GDP grew by 5.2

per cent per annum, and scal decits rarely

exceeded 2.5 per cent of GDP. Real interest

rates were positive for most of the period,

the current account balance was in surplus,

and domestic savings averaged 15 per cent

of GDP. In the same period, the growth in

exports averaged 5 per cent per annum while

that of imports was 6.2 per cent.

From 1971 to 1979, Uganda’s economy

was seriously damaged by economic misman-

agement and civil conicts that negatively im-

pacted on the gains made during the previous

periods. The rate of ination averaged 30 per

cent per annum between 1970 and 1980, as

the government nanced public expenditure

through bank borrowing. During the same

period, GDP declined at 1.6 per cent per an-

num, exports by 8.5 per cent and imports by

9.8 per cent. This led to a decline in export

revenue, which subsequently impacted nega-

tively on the balance of payments and exter-

nal debt positions.

Growth in GDP was temporally restored

between 1981 and 1983, when an average

annual growth rate of 5.6 per cent was reg-

istered. Ination declined from 111 per cent

to 25 per cent. Overall budget decits were

reduced from 2.8 per cent of GDP in 1981 to

0.6 per cent in 1983 but rose to 11.9 per cent

of GDP in 1984. Thereafter, the civil strife

and political instability that ensued, especial-

ly in the central part of the country, negated

the achievements made. As a result, negative

GDP growth rates were recorded during the

period between 1984 and 1986.

In 1987, the government launched a

minimum Economic Recovery Programme

(ERP) followed by a series of other reforms

aimed at restoring macroeconomic stabili-

ty to provide a favourable environment for

economic growth and private-sector devel-

opment. The key reforms included a cur-

rency reform, changes in tax and scal pol-

icy geared towards improving revenues and

restraining expansion in Government ex-

penditures, while maintaining a strong focus

on economic recovery and growth. Between

1987 and 1996, GDP grew at an average an-

nual rate of 6.5 per cent, translating into 3.4

per cent growth in per capita terms. The de-

cline in monetary growth led to a substantial

reduction in ination.

Over the period 1997/1998 to 2000/2001,

GDP growth averaged 7.2 per cent per an-

num. Between 2000/01 and 2003/04 it aver-

aged 6.8 per cent and between 2004/05 and

2007/08, it was 8 per cent. As a result of

the global recession, which reduced the de-

mand for Uganda’s exports to Europe and

America, GDP growth declined slightly in

2008/09 to 6.2 per cent at basic prices but re-

covered in 2011/12. The scal decit stood

at 10.2 per cent and 7.9 per cent of GDP

on average during 2000/01 to 2003/04 and

2004/05 to 2007/2008respectively. Ination

was kept in single digits for most of these

periods, foreign reserves covered at least ve

months of imports, and exchange rates were

competitive.

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

15

There has been a signicant increase in both

foreign and local investment ows into the

economy. As a percentage of GDP, pri-

vate investment rose from 12.2 per cent in

2000/2001 to 20.6 per cent in 2006/2007.

Public investment averaged 5.1 per cent of

GDP over the same period but has been

more or less stagnant over the last decade.

Furthermore, the investment pattern of re-

cent years shows rising private construction,

especially of residential buildings, modest-

ly increasing investment in machinery and

equipment, and low levels of public con-

struction. This indicates issues with low

capital investment in industries, services and

labour productivity.

The global downturn has to some extent

negatively inuenced investments through

reduced private remittances, foreign direct

investment and loans, although recent global

economic trends, coupled with the resilience

of Uganda’s economy, have subdued the in-

itially perceived risks. Foreign Direct Invest-

ment (FDI) dropped from 5.3 per cent of

GDP in 2007/2008 to 4.6 per cent GDP in

2008/09 and was projected to remain slow in

2009/2010. However, the anticipated nega-

tive effects on aid were marginal, as most de-

velopment partners continued to meet their

obligations.

Uganda’s trade decit has been widening

despite improvements in the composition and

value of exports. The trade decit as a per-

centage of GDP declined from an annual av-

erage of 12.9 per cent for the period 2000/01

to 2003/2004 to 13.5 per cent for the period

2004/2005 to 2007/2008. The balance of

payments has also been unfavourable, with

a deteriorating trend in recent years. These

results could partly be due to lower demand

for Uganda’s exports in advanced economies,

although this is partly being compensated for

by increased regional exports.

3.2 Institutional change

Uganda has established a number of institu-

tions to enable effective public-sector man-

agement. These institutions are responsible

for policy formulation and implementation

and public service delivery. However, there

are opportunities to improve the structure

of the public sector, in particular with regard

to the allocation of roles and responsibilities

in service delivery. Most of the public insti-

tutions were formed in the early 1960s, be-

fore the liberalization policies of the 1990s.

The organization of some public institutions

is not suitable and impedes the delivery of

policy, regulation and public services. Oth-

er issues include overlaps and duplication

of mandates, weak oversight of institutions,

poor corporate governance and weak regula-

tory frameworks. The civil servants are still

poorly remunerated, and this limits their pro-

ductivity. Furthermore, the coordination of

public-sector institutions is still a challenge.

The progress made in both public admin-

istration and public-sector management is be-

ing hampered by corruption at various levels

of government. Government recognizes the

devastating socio–economic effects of cor-

ruption and is committed to taking corrective

and deterrent measures in order to fully real-

ize the potential for improving social and eco-

nomic conditions. Uganda ranks 130

th

out of

180 countries on Transparency Internation-

als’ 2009 Corruption Perception Index, while

many African countries rank better (Tanzania

126, Zambia 99, Swaziland 79, South Africa

56, and Botswana 37).

In order to enhance accountability in gov-

ernment, the accountability sector was estab-

lished in 2007 with the goal of promoting,

supervising and implementing accountability

systems. The sector comprises the Ministry

of Finance, Planning and Economic Devel-

opment, the Inspectorate of Government,

16

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

the Ofce of the Auditor General, the Di-

rectorate of Ethics and Integrity, the Ministry

of Public Service – Inspection, the Ministry

of Local Government, the Public Procure-

ment and Disposal of Public Assets Au-

thority, the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, the

Uganda Revenue Authority and development

partners. There is also a Stakeholders Forum

in which civil-society views are presented

and addressed. Civil society includes private

business, media, anti–corruption NGOs and

community groups, all of which play a vital

role in representing the views and experienc-

es of public service beneciaries and holding

public ofcials to account.

The legal, policy and regulatory framework

that guides the accountability sector includes

the Budget Act 2001, the Public Finance and

Accountability Act 2003, the National Audit

Act 2008 , the Leadership Code Act 2002, the

National Records and Archives Act 2001, the

Public Procurement and Disposal of Public

Assets Act 2003, and the Access to Informa-

tion Act 2005. Other laws pending legislation

include the Anti-Money Laundering Bill, the

Anti-Corruption Bill 2008, and the Whistle

Blowers’ Bill. A special court has also been

established to try corruption cases.

3.3 Role of external actors/donors in

development and climate change

The government of Uganda is still unable to

balance its budget and continues to depend

on external budget support, although the lev-

el of support is declining. Budget support in

the form of grants and concessionary loans

is projected to be US$ 281.3 million, equiva-

lent to Shs 734.1 billion, during FY 2012/13.

Budget support is projected to decrease mar-

ginally in US dollar terms in FY 2013/14 to

US$ 247.7 million or Shs 685 billion before

declining further over the remaining period

to about US $ 182.1 million or Sh 493.3 bil-

lion by 2012/17. The largest support received

under this mode of external nancing comes

from the World Bank Poverty Support Credit

(PRSC) of USD 100 million, followed by UK

and EU general budget support equivalent to

USD 30 million and USD 20 million respec-

tively.

At the same time, next year project support

disbursements are projected at US$ 745.7

million, equivalent to Shs 1,945.8 billion,

which will further rise to US$ 794.2 million

or Shs 2,196.9 billion during 2013/14. Project

support is projected to decline the follow-

ing three years and to be US$ 402.9 million,

or Shs 1,091 billion during the last year of

the Medium Term Expenditure Framework

(MTEF). The major benetting sectors are

works and transport, education, public man-

agement and health.

Meanwhile, amortization of external debt

is projected at US$ 96 million, equivalent to

Shs 250.4 billion in 2012/13. The level of ex-

ternal debt repayments is projected to remain

almost the same in US dollar terms over the

medium term. Net external debt repayments

are higher than the amortization schedules set

out above due to payments of arrears. Amor-

tization on domestic debt is projected at Shs

9.7 billion in each of the next ve years.

3.4 Evolution of the political

character of the Ugandan state

A number of democratic institutions have

been put in place in line with the 1995 con-

stitution. The three arms of government,

namely the legislature, the executive and the

judiciary, are now in place and functioning, al-

beit with varying degrees of respect for each

other’s constitutional mandates. Parliament

continues to exercise its constitutional man-

date and has strengthened a number of insti-

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

17

tutions for promoting democracy and good

governance including the Electoral Commis-

sion (EC), the Inspectorate of Government

(IGG), the Auditor General (with enhanced

powers) and the Uganda Human Rights

Commission (UHRC), among others.

However, the country’s culture of consti-

tutionalism is not improving fast, and many

of the institutions established in the legisla-

tive, executive and judicial branches of gov-

ernment are struggling to fully embrace the

ideals, principles and practices of democracy.

The media has been liberalized and is relative-

ly free, with both the print and electronic me-

dia providing citizens with ample opportuni-

ties to express their views on a wide range of

issues that affect their lives. At the same time,

Uganda has seen the dramatic emergence of

non-governmental and civil-society organiza-

tions willing and able to engage the arms of

government in policy debates and advocacy

of democracy and good political governance,

albeit with challenges in the policy and reg-

ulatory framework. However, in general the

citizen body is not yet empowered enough to

engage effectively in demanding their rights

and to insist that these institutions meet their

obligations.

The Ugandan state supported a series of

economic and governance reforms during

the 1990s carried out in close collaboration

with international aid agencies led by the

World Bank. A high level of commitment

by the president and the wider Ugandan po-

litical establishment, combined with donor

support, was crucial for the initial success of

these governance reforms. This combination

enabled the strengthening of ‘technocratic or

bureaucratic elites with some degree of in-

sulation from political and societal interests

through the creation of specialised, semi-au-

tonomous agencies responsible for reform

implementation’ (Robinson, 2006:13).

At the turn of the century, the reform pro-

cess in Uganda was viewed by World Bank

and international observers as one of the

most successful in Africa. However, over the

past decade the initial success in decentraliz-

ing and reforming the public sector has been

gradually undermined, leading to a reversal

of development and reform outcomes. While

national political commitment was an essen-

tial prerequisite for initiating reform, the ab-

sence of such political commitment became

a source of vulnerability for the reform in a

political culture with a powerful legacy of au-

thoritarianism and personal rule.

‘The principal explanation for stalled re-

form or reversals lies in the imperative of

preserving the institutional foundations of

neo-patrimonial politics’ (Robinson, 2006:13).

Over the past decade the politics of regime

maintenance in Uganda has prevailed over

development objectives and the strengthen-

ing of local government structures. As the

success of the reforms was increasingly at-

tributed to the semi-autonomous institutions

responsible for implementing governance

reforms (e.g. the NAADS secretariat) and

to local government structures, they became

susceptible to political manipulation from

central government. Over the past decade the

politics of regime maintenance has increas-

ingly become associated with neo-patrimoni-

al rule and re-centralization, challenging the

sustainability of successful decentralization

reforms.

The reversal of the decentralization reform

in Uganda has been explained by its reliance

on the personal commitment of President

Museveni over an extended time period and

the absence of a broader political constitu-

ency to ensure its sustainability (Robinson,

2006). A contributing factor to the erosion of

the commitment to the decentralized imple-

mentation of policy reform may be the shift

18

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

to multi-party elections in 2005. Increased

competition in multiparty elections in 2007

and 2011 has increased the importance of at-

tributing success for development outcomes.

This may ‘deepen rather than erode patrimo-

nial politics as newly mobilised constituencies

seek to access the benets that were formerly

the exclusive preserve of politicians and of-

cials associated with the NRM Movement’

(Robinson, 2006:12).

The political base of the NRM movement

has narrowed over the past decade, with

strong personal concentration power in the

hands of the President and a disproportion-

ate share of top political positions and civ-

il service appointments going to Ugandans

with strong kinship roots in the west of the

country (Robinson, 2006). Over the past dec-

ade Uganda has thus transformed itself from

one of countries in Africa that was most

closely associated with the type of structural

reforms supported by World Bank and inter-

national development agencies to a country

based on the type of neo-patrimonial poli-

tics commonly found in many other African

states (Hickey 2003).

4.

DECENTRALIZATION AS

UNIQUE FEATURE OF UGANDA

4.1 Evolution of local government

In 1993 in Uganda the Decentralization Act

was passed through parliament as an instru-

ment to deliver sub-national development

and to bring services closer to the people.

Decentralization envisioned good govern-

ance, democratic participation and control of

decision-making by local communities. Under

this policy, the following functions were de-

volved to local government: planning, budg-

ets, administration, scal management and

control, and administration of justice in local

council courts.

Local government functions through a

unied system of elected authorities at var-

ious levels, ranging from the village to the

city or district. The responsibility for local

planning, budgeting and implementation lies

primarily with the district/municipality and

sub-county/town council. The number of

districts with approved three-year develop-

ment plans increased from three in 1997 to

all the 80 districts that existed in 2009. This is

an indication that local government capacity

increased during this period. In connection

with national elections in 2011, the number

of districts was increased to 112. While creat-

ing new districts is popular among the people

living in the district and result in more votes

for the government, most technical observers

argue that it has resulted in increased expend-

iture on public administration (UNCDF).

4.2 Local government capacity to

deliver services

There has been progress in institutional and

human resource capacities in local govern-

ment. Under the LGDP, the government

designed and implemented a capacity-build-

ing programme for local government, which

has led to improvements in service delivery.

However, there are still gaps in stafng levels

(at 65 per cent), which affects service deliv-

ery. The most affected sectors include health,

agriculture and engineering, which have failed

to attract, deploy or retain skilled personnel.

In spite of the introduction of equalization

grants to bring disadvantaged local govern-

ment to the level of service delivery com-

parable to the rest of the country, regional

imbalances still exist. This is demonstrated

simply by disparities in poverty levels and so-

cial development indictors. While nationally

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

19

the proportion of the population below the

poverty line is 31 per cent, the incidence f

poverty is highest in the Northern region at

66 per cent, followed by the Eastern at 46.8

per cent, Western at 34.4 per cent and Central

at 27.2 per cent. The high incidence of pov-

erty in the north is attributed to the insurgen-

cy, which disrupted economic activities in the

northern and eastern parts of the country.

Gender inequalities are more pronounced

in the post-conict areas of the north than

in the rest of the country. Displacement and

resettlement have left many women with-

out any access to land. Conict has brought

about a breakdown in traditional household

roles whereby women have had to become

primary breadwinners, although they lack the

necessary skills. Many women and children

have been severely traumatized by the effects

of conict. Disruption of social services has

led to worse social outcomes, lower than na-

tional averages, in literacy, malnutrition, ma-

ternal mortality and fertility, among others.

Local government bodies (LGs) are funded

through central government grant transfers,

local revenue and borrowing. In addition,

many LGs access donations from devel-

opment partners. The Constitution of the

Republic of Uganda provides for three cat-

egories of grants, namely unconditional, con-

ditional and equalization. The Constitution

also gives powers to local government to col-

lect some tax and non-tax revenues. All these

sources are operations, although at different

levels of contribution to LG budgets. LGs

have powers to collect property taxes, but few

collect it effectively, and it is signicant only

in urban areas. Various local fees, licenses and

other minor revenues are collected.

The unconditional grants are at the dis-

cretion of LGs, but the largest percentage is

used to pay salaries. The conditional grants

are earmarked for specic development and

recurrent activities of national importance,

whereas the equalization grants are extended

to new LGs and those that are disadvantaged.

The multiplicity of fund transfer mecha-

nisms is a growing concern of local govern-

ment. Many of these mechanisms were not

well adapted to the decentralized framework,

which resulted in management and reporting

challenges. In addition, there were concerns

over the different designs and conditionalities

of the different grants.

To address these challenges, the govern-

ment introduced the Fiscal Decentralization

Strategy (FDS), which allows LGs some exi-

bility and/or discretion to reallocate resources

between and within sectors during planning

and budgetary processes. While a lot has been

achieved since the FDS was introduced, it has

not been fully embraced. Most LG budgets

still comprise of more than 80 per cent of

conditional grants.

To address regional and district imbalanc-

es, a number of afrmative action plans have

been implemented at sub-national levels with

some degree of success, including the North-

ern Uganda Rehabilitation Programmes

(NUREP) I & II and the Northern Uganda

Social Action Fund (NUSAF), the Karamoja

Integrated Disarmament and Development

Programme (KIDDP) and extensions of

equalization grants to address the imbalances

between districts. The government has devel-

oped and is implementing the Peace Recovery

ad Development Plan (PRDP) for northern

and eastern Uganda. The Luwero–Rwenzori

Development Plan (LRDP) is also being de-

veloped.

The PRDP will consolidate the achieve-

ments of previous afrmative action pro-

grammes in the region and enable the system-

atic rehabilitation and long-term recovery of

the post-conict north of the country. This

will reopen the area to meaningful produc-

20

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

tion, as well as reinstating democratic govern-

ance in the area.

Available evidence (Bashaasha et al. 2010)

so far suggests that devolution of responsi-

bility contributes to greater compliance with

some natural resource management (NRM)

requirements. In particular, the involvement

of locally accountable and representative

authorities in enacting and enforcing NRM

requirements appears critical for the legit-

imacy and success of such regulation. With

regard to forest conservation, comparison of

centralized and decentralized forms of for-

est management reveals ambiguous results.

There is evidence that forest conditions in

some areas have declined following decen-

tralization. The Bashaasha et al. estimates of

the cost of natural resource degradation in

Uganda are as high as 17 per cent of gross

national income (GNI) per year, of which 6

per cent consists of forest degradation and

11 per cent soil degradation.

5. NATIONAL CLIMATE CHANGE

POLICIES AND THEIR

IMPLEMENTATION MODALITIES

5.1 Emergency assistance policy

OPM

Disasters or emergencies refer to a series of

events that give rise to casualties, damage or

a loss of property, infrastructure, essential

services or means of livelihood on a scale

that is beyond the normal capacity of the

communities affected to cope with unaided.

According to the NDP, the most frequent

disasters in Uganda include displacement

of persons, famine, earthquakes, epidemics,

livestock and crop diseases, oods and land-

slides, and technological accidents, among

others. Many on the list can clearly be traced

back to climate change as either a direct or

indirect cause.

Disasters affect many people in Uganda,

and emergency assistance is therefore nat-

urally a highly sensitive political issue. The

NDP also reports that between 2000 and

2005, approximately 65.7 per cent of house-

holds in Uganda experienced at least one type

of disaster (UNHS 2005/06). The regional

distribution is shown in gure 4 below. The

tableshows that the Northern region was the

most severely affected because of the civil

strife. Here emergency assistance is associat-

ed with the temporary resettlement of affect-

ed people and refugees in camps, adding fur-

ther to the political sensitivity of emergency

assistance.

Uganda’s current disaster management

policy was formulated in the early 1990s. It

has three objectives: rst, to reduce the socio-

economic and environmental impacts of dis-

asters on people and the economy; secondly,

to address the causes of disasters. The emer-

gency policy distinguishes between ‘natural’

and human-induced causes of disaster; and

thirdly, to promote and uphold the rights of

refugees.

Because of the highly politically sensitive

nature of emergency assistance, the responsi-

bility for its coordination has been centralized

in OPM, represented by a junior minister.

The implementation of disaster management

policy has been devolved to seven regional

disaster coordination ofces that are linked

to disaster risk reduction committees (DRR)

at the district and sub-district levels. These in-

stitutions function in parallel with local gov-

ernment institutional structures and are not

integrated into the ongoing activities of local

government.

Qualitative interviews with local govern-

ment staff and other key informants in So-

roti, Amuria and Katakwi districts reveal that

21

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

the DDR institutions are dormant and are

only activated when there is an ofcially de-

clared emergency. Last time the DDRs were

activated in the three districts was during and

in the immediate aftermath of the 2007 ood

in Teso region. During this period the DDR

assisted by collecting information and mobi-

lizing local people for the emergency agencies

led by UNHCR and WFP.

As shown in table 1 (section 2) Teso has

experienced a series of oods and droughts

since 2007 that have been less severe in mag-

nitude and the number of people affected.

For this reason these extreme climate change

events were not ofcially declared emergen-

cies by OPM. As a consequence the UN

emergency agencies were active in these later

extreme events and the DDRs have remained

dormant.

Uganda’s emergency response has by and

large been one of response. The absence of

a credible early warning system has further

limited preventive activities prior to the oc-

currence of disasters. The UNDP is currently

working with the OPM on disaster risk reduc-

tion and management, as well as sponsoring

a 3.6M USD program on SLM. The UNEP

also is supporting the Ministry of Agriculture

to develop an early warning system and inte-

grate climate change into development pro-

grams.

During an interview in OPM it was made

clear that the Ugandan government has al-

located very limited resources to providing

relief and rehabilitation support in response

to emergencies. OPM therefore largely relies

on the UN emergency agencies, which only

mobilise their resources during major emer-

gencies. As a consequence communities that

are affected by extreme climate events that

are limited in scope and space and only affect

a more limited number of people fall below

the radar and remain without any govern-

ment support.

Figure 4. Percent of households that experienced more than one disaster

(2000-2005)

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Percent

Central Eastern Northern Western Uganda

Region

53.3

63.3

88.7

65.4 65.7

22

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

Local government is under a considerable

pressure to assist, but it does not receive

funding from central government for such

activities, and its assistance therefore often

remains symbolic.

The Government of Uganda has an-

nounced that it has initiated the formulation

of a new National Policy for Disaster Risk

Reduction and is also working on a program

of action to implement the policy. It is not

publicly known what the policy reform will

focus on or the extent to which it will ad-

dress the implementation challenges of the

current policy.

5.2 NAPA

National policies so far appear to have

been motivated by the need to ratify in-

ternational protocols. Uganda signed the

United Nations Framework Convention on

Climate Change (UNFCCC) on 13th June

1992 and ratied it on 8th September 1993.

Uganda has also ratied the Kyoto Proto-

col, which provides the basis for an interna-

tional response to the challenges of climate

change. In addition, Uganda is also a party

to a number of Multilateral Environmental

Agreements (MEAs) that have a strong link

with climate change, including the United

Nations Convention to Combat Deserti-

cation (UNCCD), the Ramsar Convention,

the Convention on Biological Diversity

(UNCBD) and the Montreal Protocol. In

response to commitments under Articles 4

and 12 of the UFCCC, Uganda developed

and submitted the Initial National Commu-

nication (INC) in 2002 and National Adap-

tation Programmes of Action (NAPA) in

2007, produced by the Department of Me-

teorology in the Ministry of Water, Lands

and Environment (MoWE) in its capacity

Table 2. Estimated Cost of NAPA Projects

Source: NAPA Uganda, 2007

Community Tree Growing Project

Land Degradation Management Project

Strengthening Meteorological Services

Community Water and Sanitation Project

Water for Production Project

Draught Adaptation Project

Vectors, Pests and Disease Control Project

Indigenous Knowledge and Natural Resource

Management Project

Climate Change and Development Planning

Project

Total

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

3.2

2.5

4.2

2.8

4.0

2.0

3.5

0.6

0.5

23.3

5.5

4.7

6.5

4.7

5.0

3.0

8.0

1.2

1.2

39.8

Limited

Area

Interventions

Country

Wide

Interventions

Project Title

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

23

as the National Climate Change Focal point

(NCCF) under the Convention.

The drawing up of NAPA was an exter-

nally driven policy process carried out by

a committee of representatives from the

relevant central ministries with the task of

making Uganda eligible to receive funding

from the Least Developed Country Fund

(LDCF). According to the GEF website,

a total of 49 NAPAs were formulated in

2005-2009, and the LDCF has had a total

of US$415 million available to fund them.

However, until now only US$177 million

has been approved for 47 projects, attract-

ing more than US$550 million in co-nanc-

ing in the process (http://www.thegef.org/

gef/ldcf ). Based on this, one can conclude

that less than one project has been funded

for each NAPA. Globally, the funding level

for NAPA has been signicantly lower than

expected. This is a direct consequence of

the political impasse and failure of United

Nations Framework Convention for Cli-

mate Change (UNFCCC) to reach an agree-

ment. The priorities of Uganda’s NAPAs

are shown in table 2 below. The extent to

which these projects have been funded is

not known.

According to UNFCCC guidelines, NA-

PAs should describe a country’s perception

of its most ‘urgent and immediate needs to

adapt to climate change’ (UNFCCC 2011:

p2). While the Uganda NAPA was formally

subject to a process of participatory consul-

tation, in reality the identication and prior-

itisation process was done by technical rep-

resentatives from central ministries. None of

the seventy participants in three CCRI work-

shops that were held in 2012 and 2013 who

represent nine local governments in TESO

and Karamoja regions knew about the NAPA

policy and priorities.

5.3 NCCP and implementation

framework

A draft Climate Change Policy was formulat-

ed during 2012 and will take effect subject to

approval by the Government. The process of

formulating a new national Climate Change

Policy has been driven by a newly established

Climate Change Unit (CCU) in the Depart-

ment of Meteorology in the Ministry of

Water and Environment (MoWE) that func-

tions as the National Focal Point for climate

change under the United Nations Framework

Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The Climate Change Policy Committee in the

Ministry of Water and Environment func-

tionally serves as a Steering Committee for all

climate change projects and provides advice

on climate change to the Minister of Wa-

ter and Environment. The Climate Change

Policy Committee currently consists of the

following members: Finance, Royal Danish

Embassy, OPM, MOH, MAAIF, Justice and

Constitutional Affairs, Energy and Mineral

Resources, Works and Transport, the Na-

tional Planning Authority and MoWE. Oth-

er organisations may be invited to CCPC

meetings. The policy formulation process has

been supported by international development

agencies, including the EU, DFID, DANI-

DA, World Bank and World Food Program

(WFP).

National Climate Change Policy places

a priority on adaptation, mitigation, and re-

search and observation. The policy priori-

tises climate change adaptation over climate

change mitigation. This is in harmony with

EAC regional climate change policy and log-

ic, given Uganda’s stage of development,

which is characterized by low levels of emis-

sion. Under adaptation, the policy recognizes

eleven sector-specic and two cross-cutting

priorities that fall under nine different line

ministries, as shown in annex 1. These line

24

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

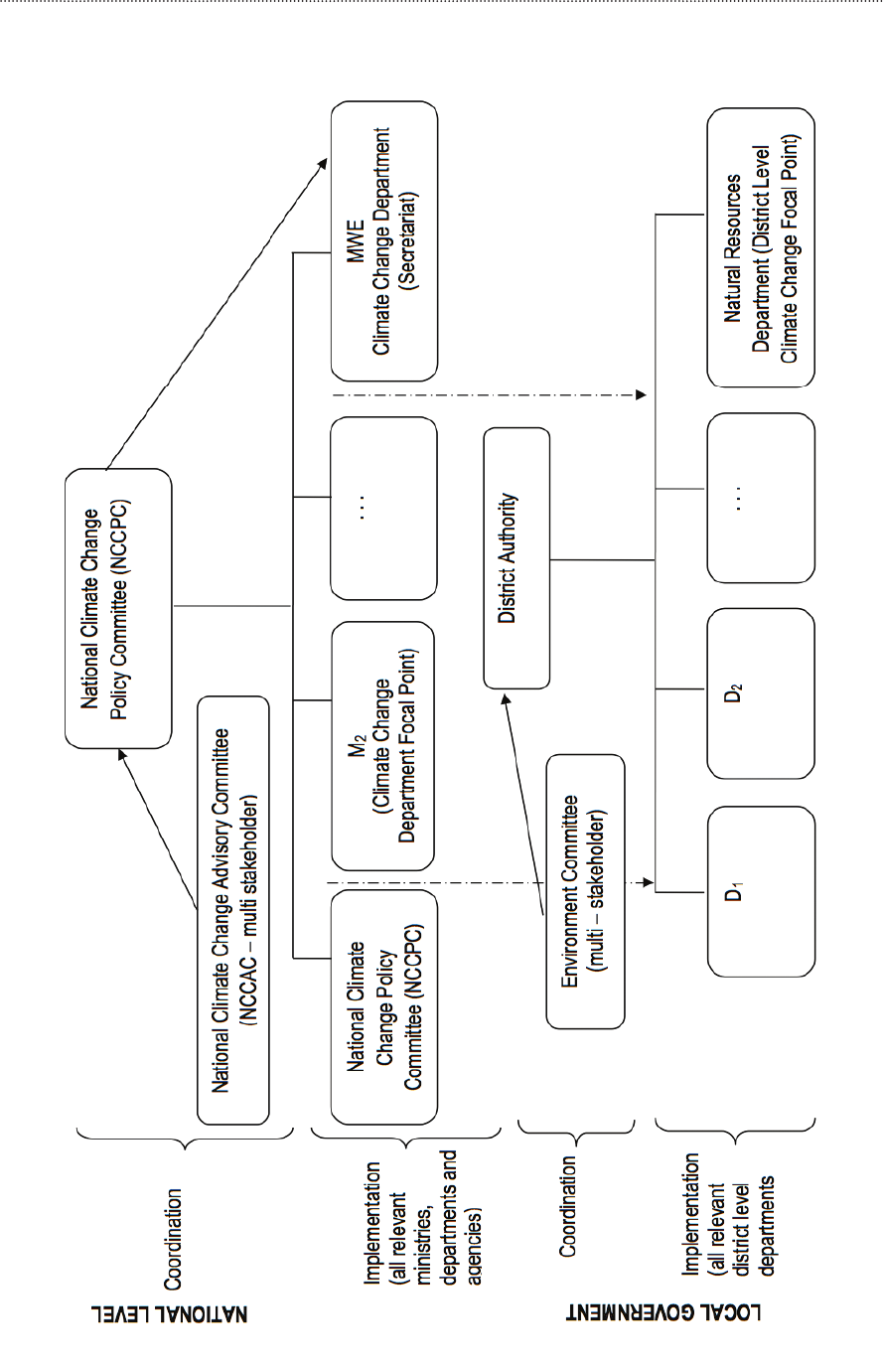

Figure 5. Institutional architecture for climate change action in Uganda

Source: Ministry of Water and Environment, National Climate Change Policy, 2012.

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

25

ministries are represented but not exactly rep-

licated at the local government and lower lev-

els, making coordination and implementation

at the lower levels of government questions

for research. Under mitigation, the policy rec-

ognizes ten sector-specic and two crosscut-

ting priorities that fall under six different line

ministries, as shown in annex 2.

The NCCP proposes to strengthen the

current climate change unit (CCU) and pro-

mote it to the level of a sectorial government

department named the Climate Change De-

partment (CCD) under the Ministry of Wa-

ter and Environment. This department is to

serve as the National Focal Climate Change

organ. The policy also proposes that the Nat-

ural Resources Department should serve as

the climate change focal point at the district

level, with all other departments ensuring that

climate change issues are integrated into the

district development plans. The policy prom-

ises to provide an implementation structure

to detail the accountabilities of the various

ministries, departments and agencies con-

cerned.

The NCCP emphasizes the multi-sectorial

nature of climate change and seeks to main-

stream climate change as cutting across other

development policies. At the national level it

is proposed to carry out such mainstreaming

through the establishment of a National Cli-

mate Change Policy Committee, with the task

of coordinating policy implementation and

of ensuring information ows on resource

allocations for the implementation of the

policy, as well as a National Climate Change

Advisory Committee to ensure working level

coordination and provide technical input to

the National Climate Change Policy Com-

mittee. The work of these two coordination

mechanisms has been guided by the Climate

Change Implementation Strategy, the ob-

jective of which is to enable more effective

planning and coordination of national-level

activities, including linkages with meso-level

institutions.

In addition to the CCD, three national

ministries or authorities (Finance, NPA and

MOLG) ensure policy implementation. Each

ministry, department and agency with a role

to play in the implementation of the policy

responses is expected to designate a depart-

mental focal point and is accountable for the

implementation of the prescribed policy re-

sponses that concern it. The Implementation

Strategy details the accountabilities of the

various ministries, departments and agencies

concerned around indicative climate change

programmes. They are expected to report

on their progress in the implementation of

their respective tasks and in the attainment of

their expected results. On the basis of these

reports, the CCD is tasked with preparing a

consolidated progress report on the overall

implementation of the climate change policy.

The proposed implementation structure

of climate change is summarized in Figure

5. As shown, the NCCP has nally embraced

the local government system as the key im-

plementation modality. At district level, the

policy provides for district-level focal points

with an environmental committee, and for

departments.

6. DISCUSSION

6.1 Compliance of climate change

policy and Decentralization Act?

The rst of the questions raised in the intro-

duction to the working paper was whether

Uganda’s climate change policies are compli-

ant with the Decentralization Act and current

local government institutional structures.

Up till now, the answer has been a clear no,

26

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

though when the new climate change poli-

cy takes effect, this is likely to change. The

working paper reveals that neither emergen-

cy policy nor NAPA uses local government

political and administrative institutions for

their implementation. The newly formulated

NCCP, which has not yet been approved by

the government, is compliant with the De-

centralization Act.

The fact that climate change policies have

been implemented in parallel with existing

local decentralization structures cannot be

justied with an argument that there is inade-

quate capacity in local government.

As discussed in section four, all districts

in Uganda had approved three-year District

Development Plans (DDP) by 2009. These

DDPs are decided by the district councils

consisting of councillors elected from each

of the sub-counties within the district. In a

well-established district the DDP is imple-

mented by 15-20 technical departments, cov-

ering a wide range of services. While local

government continues to be hampered by

various nancial, regulatory, capacity and ad-

ministrative constraints, these constraints are

not very different from those hampering the

central administration. While far from per-

fect, local government is well placed to sup-

port climate change adaptation.

6.2 Political nature of Ugandan state

and policy reform

In the introduction we set out to examine the

extent to which the nature of the state de-

termined whether or not climate change poli-

cies were compliant with the Decentralization

Act. In section 3.4 we analysed the changing

nature of the Ugandan state and described

how the commitment to reform and devo-

lution of power and responsibilities to local

government during the 1990s gradually erod-

ed during the 2000s. The section concluded

that the attribution of success for develop-

ment outcomes to central government during

the past decade has come to override reform-

and development-specic concerns.

Formulation of the comprehensive Decen-

tralization Act in 1993 and the subsequent

Table 3. Compliance of Climate Change Policies with Decentralization

Central government need to be

seen to act. Resettlement camps

highly politically sensitive.

Driver of reform was to

become eligible to receive UN

funding for climate change

projects.

Policy formulation process

guided by joint

government–multi-donor

committee. Policy reects

analysis rather than funding

availability.

No. Centralised coordination with concentrated local

institutions is not integrated into local government.

No. Implemented through projects managed by central

ministries in parallel with local government.

Yes. Implementation of policy fully integrated with local

government structures.

Emergency

response

NAPA

NCCP

Compliance with decentralization? Analysis whyPolicy

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

27

devolution of power, nancial resources and

responsibilities for service delivery are con-

sistent with our analysis of the nature of the

Ugandan state in the 1990s discussed in sec-

tion ve. As one of the most reform-compli-

ant countries in Africa during the 1990s, the

new local government institutions received

considerable capacity development support

from UNCDF, World Bank and other inter-

national donor organizations. However, this

does not explain why the government did not

allow the emergency policy formulated dur-

ing the same period to be compliant with the

Decentralization Act. As discussed earlier, all

decisions with regard to the coordination of

emergency assistance are centralized within

the OPM’s ofce, which is headed by its own

Minister. While the overall trend towards the

recentralization of power to central govern-

ment ts well with how NAPA was formu-

lated and implemented, the political analysis

is inconsistent with the fact that the NCCP

embrace the local government system and

in many ways resembles the types of reform

that Uganda was known for during the 1990s.

6.3 Drivers of climate change

policies

Our analysis of climate change policies in

section 5 revealed signicant differences in

the formulation process and drivers in this

process between the three policies. At the

same time we found a strong coherence be-

tween the interests of those driving the poli-

cy process and its implementation modalities.

Given the high political sensitivity of emer-

gency assistance, the formulation of emer-

gency policy during the early 1990s was close-

ly followed and guided by the government.

We argue that there are three sets of reasons

why the governance of emergency assis-

tance policy is centralized and non-compliant

with the Decentralization Act. First, it is po-

litically important to be seen to respond to

emergencies and to ensure that assistance is

seen to be attributed to central government.

Secondly, control over when and when not

to declare an emergency is important. His-

torically, emergencies in Uganda have been

closely linked to civil conicts. Thirdly, but

not least, the resettlement of displaced peo-

ple in camps as a consequence of emergen-

cies is politically highly sensitive because of

its security aspects.

NAPA is the rst national policy that is ful-

ly dedicated to adaptation to climate change.

As described in section ve, policy formu-

lation was driven by a need to be compliant

with the United Nations Framework Con-

vention for Climate Change requirements

in order to be eligible for funding from the

Least Developed Country Fund. Policy for-

mulation therefore became centralized, with

little more than token instrumental consul-

tation among so-called stakeholders outside

the central ministries and UN consultants.

As discussed in section 5, central ministerially

managed projects are the chosen implementa-

tion modality of NAPA, though it ignores the

Decentralization Act and local government

structures. Interviews with key informants in

the ministries suggest that, to the extent that

the NAPA priority projects were funded, a

larger proportion of the funding was used on

research or central ministry activities. Priori-

ties suggest that activities that reached local

farming communities were largely based on

transfers of technologies made to assist farm-

ers adapt to climate change, such as modern

drought-tolerant crop varieties.

As examined in section 5, the NCCP for-

mulation was guided by a Climate Change

Policy Committee that comprises represent-

atives from the OPM, Ministry of Finance,

six line ministries and a donor representative

28

DIIS WORKING PAPER 2013:17

(Danida). The policy formulation process was

supported by a group of international devel-

opment agencies, including the EU, DFID,

DANIDA, World Bank and World Food Pro-

gram (WFP).

Given this very high level of support for

policy development, it is not surprising that

the NCCP implementation framework is

compliant with the Decentralization Act. The

NCCP implementation framework fully em-

braces the decentralised governance struc-

tures, which will greatly enhance the chanc-

es to establish local forums for dialogue and

co-production of the ideas needed to address

rural people’s challenges in adapting to cli-

mate change.

6.4 Implication of the gap between

climate change policies and

decentralization

In the previous section we have tried to un-

derstand why a centralized mode of imple-

mentation was chosen for emergency assis-

tance and NAPA policies. In the following we

examine some of the negative impacts of this

choice.

The fact that the decentralised emergen-

cy assistance institutions are not integrated

with normal local government structures

clearly has a negative inuence on their ef-

ciency. Qualitative eldwork in Teso region

indicated that the DRR committees at the

district (LC5) and sub-country (LC3) levels

were dormant and were only reactivated as

a response to oods. The role of the RRD

has largely been to make assessments of the

current situation and to assist in mobilizing

people to receive assistance from internation-

al emergency NGOs. With no budget and