1

Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment:

Implementation in North Carolina

North Carolina Institute of Medicine

2013

The Medical Orders for Scope of Treatment (MOST) document is a standardized form that

patients can use to designate treatment preferences which can be used as medical orders across

healthcare facilities. The form must be completed by both the patient (or his or her authorized

representative) and the physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant. The MOST form

includes care preferences in regards to cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, antibiotics, intravenous

fluids, and feeding tubes, including scope of care (full care, limited care, comfort measures

only). These types of care preferences may be of particular use in nursing home settings. Studies

have shown that the patients’ preferences are more likely to be honored with use of similar

forms.

1,2

Despite generally high support of the MOST form by health professionals, there has

been some concern regarding time, complexity, literacy level, and need for annual update.

Nursing homes in NC are thought to have excellent compliance with documenting advanced care

directives, but the type of process used by most nursing homes in NC is widely varied. In

addition, we have no knowledge of the use of the MOST form in North Carolina, how it is

perceived by staff in health care settings, and whether there are barriers to its use. Also, while we

have some understanding of the use of advance care directives in nursing homes, less is known

about the role of the MOST form and other types of advanced directives in adult care homes and

assisted living facilities. Planning for advance care preferences often starts after a change in

health status concurrent with an acute care hospitalization, therefore understanding the role of

hospitals in advanced care planning and documentation is an important part of understanding the

use of the MOST form in NC.

In 2007, the NC General Assembly passed a bill regarding advanced directives, which, among

other things, authorized the creation of the MOST form for use across settings of care in North

Carolina. This legislation codified the requirements that must be followed in using the MOST

form, including when it will be used, what parties must sign the form, and how often it must be

updated. In addition, the legislation set forth that the North Carolina Institute of Medicine

(NCIOM) would study the process of end-of-life care in 2013.

3

Specifically, the NCIOM was

directed to:

“study issues related to the provision of end-of-life medical care in North

Carolina. As part of the study, the Division of Health Service Regulation,

Department of Health and Human Services, and the North Carolina Board of

Medicine shall provide to the Institute non-identifying information regarding

claims and complaints related to end-of-life medical treatment by health care

providers that was contrary to the express wishes of either the patient or a person

authorized by law to make treatment decisions on behalf of the patient. The

Institute may review any other data related to end-of-life medical care and

treatment the Institute determines is relevant.

2

The purpose of this study is to determine whether statutory changes related to

advance directives and health care powers of attorney impact the type and

quantity of end-of-life medical care provided to patients, whether the patient's or

patient representative's express wishes regarding the provision of treatment at the

end of life are being honored, and whether there is any change in the number of

persons who request continued treatment at the end of their lives, but do not

receive that treatment.”

The North Carolina Institute of Medicine took two approaches to study the use of the MOST

form in North Carolina. First, we conducted a series of interviews with key informants to better

understand how the MOST form was perceived and whether or not there were any formal

complaints about the use of the MOST form. The second part of the study was a web-based

survey of professionals involved in hospital discharge planning and ongoing care in a long-term

care facility (e.g. nursing home, assisted living, or adult care home to better understand their

advanced care planning process generally and their use of the MOST form more specifically.

Methods:

Key informant interviews

The key informant survey included discussions (face to face or by telephone) or email dialogues

with 20 stakeholders knowledgeable in end-of-life care and the delivery in NC. This included

directors or representatives of the NC Medical Board, the NC Medical Society, the Office of

Emergency Medical Services, the NC Bar Association, the NC Division on Aging, the NC

Health Care Facilities Association, hospice agencies, physicians (geriatric/palliative care),

attorneys, and ethicists. The interviews were framed around three issues: 1) perceptions around

the use of MOST forms, DNR forms, and health care power of attorney, 2) claims or complaints

that the MOST form was used contrary to the express wish of the patient regarding end-of-life

care, and 3) changes in end-of-life care related to the 2007 statute.

Web-based survey

To gather more broad-based input on the use of the MOST form in clinical settings, we

conducted a web-based survey of health professionals that are often involved in or supervising

advanced care planning. This was done using Qualtrics, a commercial platform for administering

web-based surveys.

Subjects

Representatives of four organizations agreed to send a link to a web-based survey: the NC Health

Care Facilities Association (representing nursing facilities in North Carolina), the NC

Association of Long Term Care Facilities (representing assisted living and adult care homes), the

NC Assisted Living Association (representing assisted living facilities), and the NC Chapter of

the American Case Management Association (representing hospital discharge planners). The lists

were not provided directly to the NCIOM. We included professionals from all four of these

organizations to gain a better understanding of the advance care planning across the spectrum of

long-term care facilities and from the perspective of the hospital-based discharge planning

professional.

3

Survey instrument

Staff from the NCIOM wrote the first draft of the survey instrument. The items were based on

the findings of a qualitative study of experience with the MOST form by nursing home

professionals.

4

Additional items were added to assure that we addressed the questions raised by

the North Carolina General Assembly in the authorizing statute. A draft survey was reviewed by

representatives of the participating organizations and by several members of the North Carolina

Partnership for Compassionate Care (a group of healthcare and community leaders dedicated to

improving communication and education about end-of-life care through local and statewide

initiatives). The survey was revised based on their feedback.

The survey included questions on the respondents’ familiarity with the MOST form, the types of

advanced care planning forms used by the institution, whether the MOST form is honored in the

institution, and any barriers or concerns about use of the MOST form. The survey specifically

asked respondents whether they had received complaints that treatment was provided in excess

of the wishes expressed by the patient on the MOST form, and if so, whether care was less

aggressive or more aggressive than wishes expressed on the MOST form. The study sent to

administrators of various ongoing care organizations was nearly identical. The survey of the

hospital-based care managers differed somewhat to capture the perspective of a patient upon

being discharged from the hospital, but included most of the same concepts regarding use of the

MOST form, barriers and complaints with the MOST form, and tools used for advance care

planning more generally.

Procedures:

A link to an online survey was sent to the four previously mentioned groups of professionals. If

they followed the link and agreed to the study conditions on the consent, they were directed to a

brief (<5 minutes) online survey. The survey was anonymous. After one week, the surveys were

re-sent to encourage participation. The study was approved by the UNC Committee on Human

Subject Research.

Results:

In the key informant interviews, stakeholder expressed varied perspectives on the uptake of

MOST forms. Generally, stakeholders felt that other forms were more common, including Don

Not Resuscitate (DNR) and 5 Wishes (a combined living will and healthcare power of attorney

that address comfort care and spirituality). Several informants mentioned that use of the forms

was dependent on the local physicians, most of whom were unfamiliar with the form or felt that

it was too cumbersome. When the form was being used, it was often due to local champions who

spread the use of the form in their communities. Several informants mentioned that the biggest

problem with the MOST, DNR, and other forms is when a family wants to override the wishes of

a critically ill loved one, creating conflict at the time of crisis. One respondent noted that at

his/her facility they did not accept the most form as an ‘order’ but stated that admitting

physicians generally reviewed the form and translated it into similar parameters available in the

institution’s computerized order entry system. Several informants commented that the law posed

challenges because it requires the use of original signed forms (e.g., copies are not valid). This

necessitated the patient to keep multiple originals at different locations. No stakeholder could

provide data on how often the forms were being used in their organization or facility.

4

The authorizing legislation required that the Division of Health Service Regulations, Department

of Health and Human Services, and the NC Medical Board provide the NCIOM with non-

identifying information regarding claims and complaints related to end-of-life medical treatment

by health care providers that was contrary to the express wishes of either the patient or a person

authorized by law to make treatment decisions on behalf of the patient. The NCIOM staff

interviewed the executive director of the NC Medical Board and the Director of Complaints for

the NC Medical Board. The Board receives approximately 1300 complaints per year, but the

complaints are not searchable in a way to conclusively examine the issues raised in the

authorizing legislation. However, the Director of Complaints has worked for the medical board

for 15 years, and reviews all complaints. She reported no increase in complaints regarding end-

of-life care since the authorizing legislation. She had vague recollection of one complaint in

which care exceeded that which was desired by the patient. She recalled that no action was taken

on this complaint, and could not recall whether or not this was related to any type of advanced

directive. The Executive Director and Director of Complaints reported that the Board gets

infrequent complaints about end-of-life care in which family members report that their wishes

are not met for end-of-life care when all family members are not in agreement or when there is a

disagreement between physician and family members. The Director of the Division of Health

Services Regulation and the Director of the Office of Emergency Medical Services reported that

they had not received specific complaints about the MOST form. They did report that they

maintained a record of the number of forms ordered and by which institutions, but they have no

way of knowing how many are completed. In a personal communication with the director of the

Office of Emergency Medical Services, she reported that 110,846 MOST forms were distributed

in 2012-2013 (compared to 185,829 DNR forms). The number of forms given to patients/clients

and the number of completed forms remain unknown. Though there is an option for keeping

DNR forms, living wills, and healthcare power of attorney forms online in a registry for a small

fee, there is no such registry option for MOST forms in NC.

The web-based survey yielded 242 responses. It is important to note that the number of potential

respondents is unknown and no response rate is reported. The respondents were well distributed

across the four organizations, representing responses from a spectrum of levels of care.

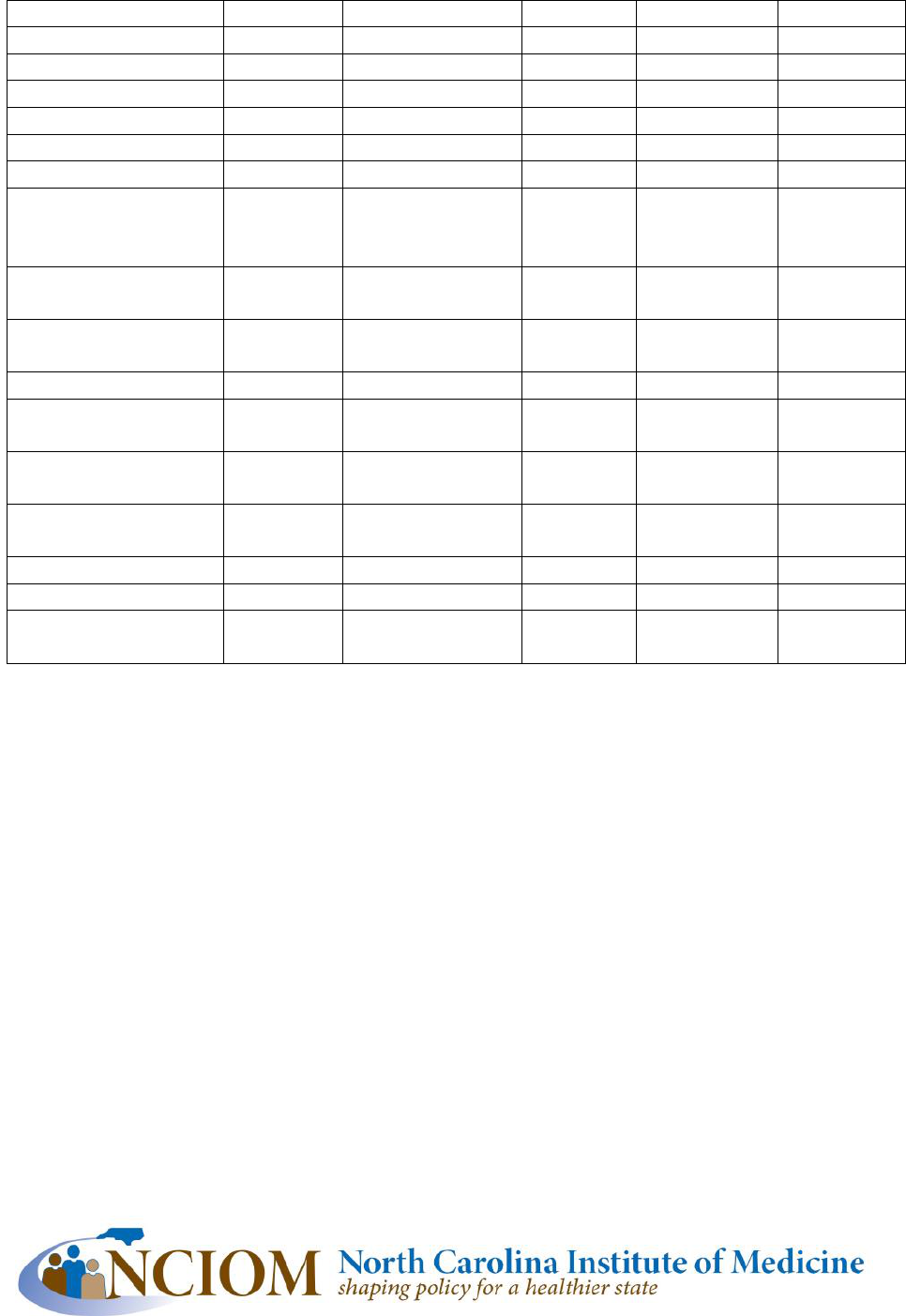

The general approach to advanced care planning and use of the MOST form is summarized in

Table 1. Advanced care planning is required or strongly recommended by the majority of

ongoing care organizations. DNR forms, living wills, and health care power of attorney forms

are more common than the MOST form. The majority of respondents have heard of the MOST

form, but the majority report that few residents or patients at their organization have a MOST

form. The overwhelming majority of organizations honor a MOST form completed elsewhere.

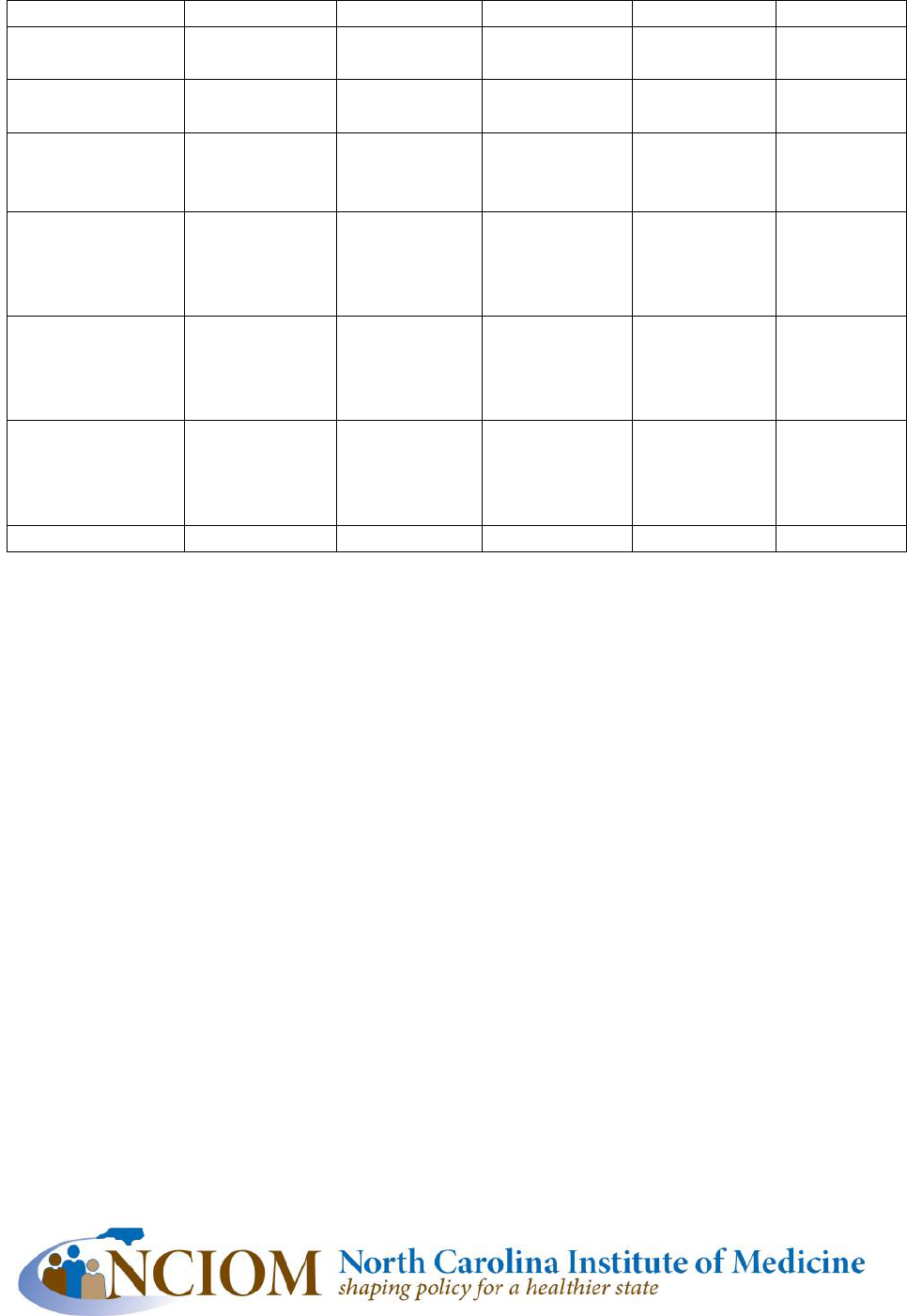

Respondents reported that they had heard few complaints with the MOST form, and the majority

of complaints were in regard to difficulty in understanding the form. Three respondents reported

that they had received complaints that more aggressive care was delivered in excess of care

wishes expressed on the MOST form. No respondents reported care that was less aggressive than

care wishes expressed on the MOST form, a finding consistent with previous research on the

POLST form.

2

(Reported complaints are summarized in Table 2.)

5

Table 1: Advanced Care Planning and Use of MOST Form

NCHCFA

1

NCALA

2

NCLTCF

3

NCCM

4

Total

Respondents (N)

76

41

61

64

242

Use MOST (%)

64

28

30

47

45

Use 5 Wishes (%)

5

3

3

6

5

Use DNR (%)

99

100

90

100

97

Use HCPOA (%)

66

95

77

94

81

Use Living Will (%)

65

87

60

87

74

Advanced Care

Planning required

(%)

33

23

15

NA

24

Strongly

recommended (%)

46

41

37

NA

42

Report >50% have

plan (%)

73

55

34

23

47

Heard of MOST (%)

97

76

63

94

84

Report >50% have

MOST (%)

17

6

6

4

9

26-50% Have MOST

(%)

9

3

0

12

7

1-25% Have MOST

(%)

54

76

51

48

55

None MOST (%)

13

14

43

36

27

Honors MOST (%)

80

100

91

86

88

Received complaints

about MOST (N)

1

6

2

5

14

1

NC Health Care Facilities Association

2

NC Assisted Living Association

3

NC Association of Long-Term Care Facilities

4

NC Chapter of the American Case Management Association

6

Table 2: Problems with MOST FORM (reported providers in an organization)

NCHCFA

1

NCALA

2

NCLTCF

3

NCCM

4

Total

Form difficult to

understand (N)

1

4

2

5

12

Scary to discuss

end of life(N)

-

1

-

2

3

Form too

comprehensive

(N)

1

2

1

1

5

Form too

specific/not

comprehensive

enough (N)

-

1

-

1

2

Care provided in

excess of wishes

on MOST form

(N)

-

2

-

1

3

Care less

aggressive than

wishes on

MOST form (N)

-

-

-

-

0

Other (N)

-

4

-

2

6

1

NC Health Care Facilities Association

2

NC Assisted Living Association

3

NC Association of Long-Term Care Facilities

4

NC Chapter of the American Case Management Association

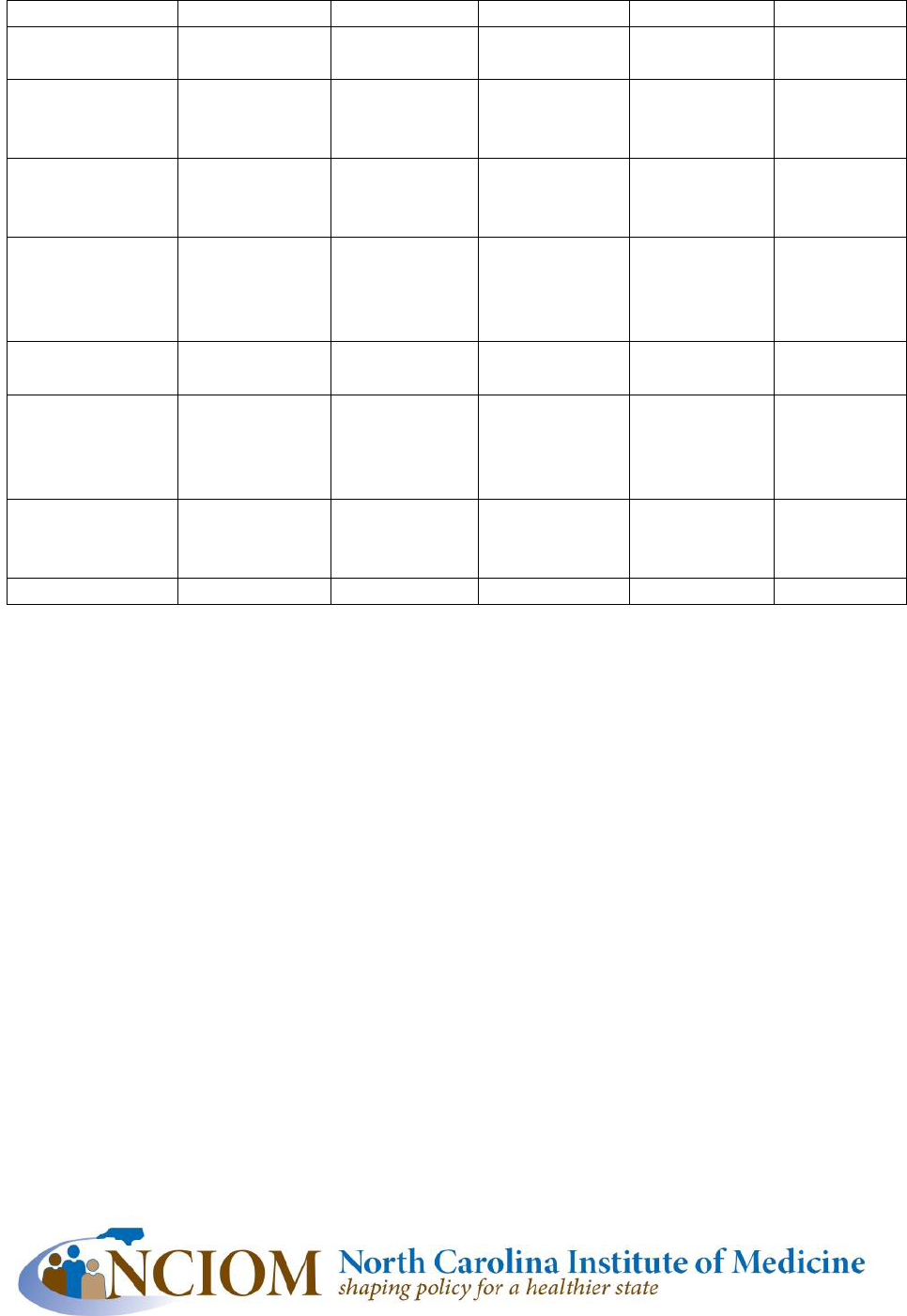

The perceived barriers to the use of the MOST form are summarized in Table 3. The common

concerns included: the form takes too much time, it is hard to match treatment goals to the form,

the review requirements are cumbersome, the form is difficult to understand, the form is

redundant of other paperwork, the form might be lost in transfer, and the form might not be

accepted upon transfer to other agencies. Closer look at the response by organization type reveal

some possible additional information. For example, time requirement is a much bigger problem

for hospital-based care managers than at ongoing care organizations. This may reflect the short

duration of relationship with patients and families in an acute care facility, the high acuity of

medical need, and the short duration of stays. Administrators at ongoing care facilities may feel

like admission to a long-term care facility is too late to start the discussion of advanced care

planning, but the feedback from care-managers may reflect the unique challenge of that

environment, indicating the need to start advanced care planning before acute illness or

decompensation of chronic disease. Concern that a form might be lost or not honored seems to

be a bigger problem for ongoing care organizations than for hospitals.

7

Table 3: Identified Barriers (reported by providers in an organization)

NCHCFA

1

NCALA

2

NCLTCF

3

NCCM

4

Total

Takes too much

time (%)

34

22

34

68

41

Hard to match

goals to

treatment (%)

13

30

29

42

28

Review

requirements

(%)

26

22

17

26

23

Difficult for

patients and

families to

understand (%)

33

48

40

32

37

Redundant

paperwork (%)

20

37

20

14

21

Concern form

would be lost

during transfer

(%)

38

37

20

8

25

Concern form

would not be

honored (%)

16

33

29

14

22

Other (%)

18

4

9

26

16

1

NC Health Care Facilities Association

2

NC Assisted Living Association

3

NC Association of Long-Term Care Facilities

4

NC Chapter of the American Case Management Association

Discussion:

This study of MOST implementation should serve two purposes. First, it provides assurance that

the authorizing statute requiring this study did not lead to large numbers of complaints about

ongoing care. There are no complaints that we could identify that the MOST form or its

authorizing legislation resulted in treatment being withheld at the end of life or treatment being

given in excess of that which was desired by the patient or his/her family. Likewise, concerns

about matching end-of-life treatment with wishes, and navigating family discord at the end of

life were not problems created by the MOST form nor will they be entirely solved by the MOST

form. Unfortunately, there was no baseline by which to examine a change in these problems over

time.

8

The second purpose of this study is to help providers of medical and long-term care in NC to

better understand the role, application, and limitations of the MOST form. The study points to a

number of possible program and policy changes that may improve the use and utility of the

MOST form. Similar barriers and challenges were identified after implementation of the POLST

form in California.

5

Universal acceptance of a MOST form upon transfer would be an important

solution to one perceived barrier. Also, efforts to simplify the form and processes may be

important solutions to improving utilization of the form. For example, if a copy of the form could

be honored, this would safeguard against losing the form. Another option would be the creation

of an electronic MOST form with accessibility between electronic health systems. In Oregon,

completed POLST (Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) health care providers who

complete a POLST form are required by law to enter the POLST form elements into a registry

which represents a valid order and is available 24 hours a day to emergency personnel and

hospitals unless a patient opts out.

6

This is quite different from the system in North Carolina,

where a MOST form can be sent to the Secretary of State by a patient, but the documents housed

in this registry do not represent valid orders as only the original documents can be used as valid

orders.

Perhaps the most important finding from this study is that advanced care planning is incorporated

at high rates at hospital discharge and admission to ongoing care facilities, at least those

represented by respondents to this study. Patients and providers at these facilities use a variety of

forms, incorporate advanced care planning into discharge and admission processes at high rates,

and report that high proportions of their clients have advanced care plans. Forms, processes and

regulations that facilitate discussion between family members, clients, and care providers will

help to maximize the chance that care preferences are honored at the end-of-life. The forms and

processes that encourage clients to consider a broader range of issues and options are likely to

lead to care that is more closely aligned with their wishes.

9

References

1. Hickman S, Tolle S, Brummel-Smith K, Carley M. Use of the physician orders for life-

sustaining treatment program in Oregon nursing facilities: Beyond resuscitation status. J Am

Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(9):1424-1429.

2. Hickman S, Nelson C, Perrin N, Moss A, Hammes B, Tolle S. A comparison of methods to

communicate treatment preferences in nursing facilities: Traditional practices versus the

physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(7):1241-1248.

3. General Assembly of North Carolina. Session law 2007-502 house bill 634 an act to clarify the

right to make advance directives and to designate health care agents; and to improve and

simplify the means of making these directives and designations. 502(2007).

4. Caprio A, Rollins V, Roberts E. Health care professionals’ perceptions and use of the medical

orders for scope of treatment (MOST) form in North Carolina nursing homes. Journal of the

American Medical Directors Association. 2012;13(2):162-168.

5. Wenger N, Citko J, O'Malley K, et al. Implementation of physician orders for life sustaining

treatment in nursing homes in California: Evaluation of a novel statewide dissemination

mechanism. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(1):51-57.

6. Fromme E, Zive D, Schmidt T, Olszewski E, Tolle S. POLST registry do-not-resuscitate

orders and other patient treatment preferences. JAMA. 2012;307(1):34-35.