De Souza 1

Michael De Souza

Professor Miller

African American Studies 202

15 May 2016

Economic Determinism and Ambition in the Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence

The Migration series by Jacob Lawrence is a sequence of sixty paintings (with

captions) portraying the mass movement of African Americans from the rural South to

cities in the North and West during the beginning of the twentieth century. The artist

was the child of African American migrants, and he grew up during the 1930s in

Harlem, where he took art classes. In planning the series, Lawrence did a lot of library

research on the history and causes of the migration. Reading the series from beginning

to end, the viewer can see that he puts the fruits of his learning into the scenes and

captions. This paper explores how the series represents the causes of the Great

Migration. I argue that Lawrence shows several economic factors, such as difficult

farming conditions in the South and greater job opportunities in the North, as providing

the basis for the mass movement, but I also think that he shows hope and ambition as

playing an important role.

First it might be helpful to discuss what historians say about the causes of the

Great Migration. Often they describe economic factors labeled “push” and “pull,” as

explained in an encyclopedia article: “The pull of labor shortages in northern industry

De Souza 2

and the lack of white male labor combined with the push of the devastation of the

cotton crops so many blacks labored on by flood and boll weevils to create conditions

for migration” (Adams 504). This is to say that migrants were pushed out of the South

and also pulled to the North and West by economic factors. The article goes on to

explain these factors more specifically. Migrants were influenced to migrate by labor

agents, who were paid to visit southern towns to recruit workers for northern industry;

by The Chicago Defender, a newspaper that was widely circulated throughout the South

and encouraged migration; and by kin networks, which sent word of opportunity in the

North and helped migrants make the journey and get settled. But it is perhaps insulting

to describe migrants only in terms of being pushed and pulled, since this description

makes them look desperate and incapable of acting for themselves. A historian named

James Grossman disagrees with limiting description to “push” and “pull” factors.

Discussing the views of American society during the migration, he says, “Public values

rested upon the assumption that blacks were by nature docile, dependent, and

unambitious” (38). But then he questions this view, saying that “the Great Migration

represented a refusal by one-half million black southerners to cooperate” with southern

leaders (38-39). While it seems clear that economic factors played an important role in

the migration, we can see that African Americans refused to sit still and instead acted on

their ambitions for a better life.

As I mentioned, Lawrence was the child of migrants and grew up in Harlem. He

De Souza 3

had never visited the South when he completed the Migration series in 1941, but he was

surrounded by migrants and heard their stories throughout his childhood (Turner,

Introduction). Lawrence’s mother raised him and his brother and sister alone (she

separated from Lawrence’s father when he was only seven years old [Phillips 161]). Like

many in Harlem during the Depression years, the family was poor. Despite poverty,

Lawrence found strength from the community of African Americans. Lawrence spoke

of the Harlem community, rather than a specific individual, as the inspiration for his

early artistic ambition: “I was inspired by teachers, by librarians—everybody in the

community, I guess, was a role model, really. I didn’t have a special person that I

thought of—I didn’t think in those terms. It was the community that was my role

model” (Interview). Though economic and social problems pushed and pulled migrants

from the South to Harlem, African Americans also found themselves set apart by racial

and economic divisions from the rest of New York City. In saying that the community

was his role model, Lawrence emphasizes that group ambition on behalf of its members

is inspirational. This message is central to the Migration series.

We should not forget that the Migration series made a big impact when it was

first exhibited in 1941. It was part of the first major exhibit of African American art in a

downtown New York gallery (Phillips 162). Part of his series was published in Fortune

magazine, and Lawrence sold the series in halves to two major museums before it went

on a national tour (163). Why was it so popular? One art historian writes, “The series

De Souza 4

appealed broadly to critics and viewers alike because it embodied American ideals

about individual good fortune” (Patton 156). That is, individual panels showed hopeful

actions by different African Americans. But it is interesting to notice that the series is

different from previous ones he painted, like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman,

which focused on a hero or heroine. Patricia Hills points this out, and she states that

“the people as a whole—acting with a collective will—take on a heroic dimension

beyond distinctions of class or gender” in the Migration series (146). There is possibly a

tension between these two views. Lawrence’s series draws out some opposing terms

defining African American life, such as rural/urban, North/South, and

individual/society. If we examine one opposition, individual/society, we can see how the

series works as a story connecting different paintings.

I think the beginning of the series helps us see how the opposition

individual/society shapes the story (Turner, Jacob Lawrence, panels 1-4). The first panel

shows a crowd of African Americans in a train station; gates list destinations as

Chicago, New York, and Saint Louis. The next panel portrays a white man operating

machinery, and the caption explains that there was a labor shortage in the North. The

third panel shows a group of African Americans carrying luggage and walking together.

The fourth panel shows a black man pounding a spike with a hammer, and its caption

says that African Americans were the remaining source of labor “after all others had

been exhausted.” So we can see a pattern: African American group, white individual,

De Souza 5

African American group, black individual (Hills also talks about this pattern [148]).

Although the pattern does not stay exactly this way throughout the series, the back-

and-forth between depictions of individuals and groups is pretty common. My point is

similar to this one in a scholarly article: “The narrative . . . is not linear, but alternates

between the insistent portrayal of the dominant event in the plot—the actual physical

displacement of the people—and paintings dealing with the main causes of this mass

migration” (Tribe 405). This quotation brings us back to the issue of causes, which I

think is related to the opposition individual/society. When Lawrence depicts the causes

pushing African Americans out of the South (like lynching, child labor, injustice, and

discrimination), he usually shows us only one person or a small group, like a family.

Some of the causes pulling migrants away from the South (labor agents, letters from

kin) also are shown having their effect on individuals or small groups. But when he

shows us scenes of actual migration, he paints groups walking, in train stations, or on

trains. So we can see how the opposition individual/society shapes the way he tells his

story.

There is evidence that the relationship between individual and society is

important to the development of Lawrence’s style. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., an important

scholar of African American culture, emphasizes the role of the individual in two

artistic movements:

Lawrence’s Migration series is an attempt to resolve the two central competing

De Souza 6

modes of representation in the African American tradition that clashed and

struggled for dominance in the 1920s and 1930s: a naturalism that sought to

reveal how individual “choice” was always shaped and curtailed by

environmental forces and a modernism that sought to chart the relation of the

individual will to the chaotic environment. (17)

It is interesting to think about what Gates says and compare it to the idea of the “push”

and “pull” causes for the migration. These causes can be seen as “environmental forces”

that make people do things (like migrate) even when they might think they are making

a choice. Gates also mentions the “individual will” that resists the environment. I think

what he is saying is that Lawrence shows a tension between economic determinism and

free will in his art, which would be like a mixture of naturalism and modernism. But I

think we could also say that determinism affects the individual and free will is an

expression of the group, at least if we follow the pattern of the opposition between

individual and society I talked about in the previous paragraph.

I do not want to neglect the importance of Lawrence’s choice of materials and

artistic process on his art. I mentioned that Lawrence was poor, so his choice of

materials was limited mostly by what he could afford. When he was a young art

student, Lawrence said, he chose poster paint and cheap brown paper for his art

supplies. He later spoke of the choice: “It was tough, strong, durable . . . and, eh, a jar of

color—red, yellow, blue, the primary colors—were, like, fifteen cents a jar at the five-

De Souza 7

and-dime, so I was dealing with very inexpensive material. And it suited me—it

benefited me” (Jacob Lawrence). Lawrence continued to use these cheap supplies even

after he became famous and probably could afford better ones. We might see the use of

cheap materials as a kind of economic determinism, forcing him to create with very

limited means.

For the Migration series, Lawrence first did library research so he could

understand his subject. He wrote the captions (which make up part of the story), and

then he outlined each panel with pencil (Steele 248). His compositions do not often use

traditional three-dimensional perspective. The style of the series exhibits what Ellen

Harkins Wheat calls “cubist angularity” (62). What is most interesting is the way he

painted the series (Steele 250). He started with black and painted the black parts in all of

the panels. He continued through the palette from the darkest to the lightest paints,

painting each color on every panel before moving on to the next color. Some see his

process as creating a unity among the individual panels. Jutta Lorensen, for example,

refers to his palette as the “migration colors,” and she explains its effect: “Lawrence’s

color code is a repetitive mode that accompanies the viewer/reader from the first panel

to the last, as the same shades of green, red, yellow, blue, brown, and an incisive use of

black are present throughout the entire series” (576). She shows how this works in her

interpretation of panel 6, which shows a train car filled with sleeping migrants: “each

bench unites two voyagers through the migration colors, thus reinforcing the

De Souza 8

resounding note of the communal, a prevalent theme in the Migration Series. The

composition of this ‘packed train’ with its appeal to collectivity nevertheless emphasizes

what is single and singular: a woman in a yellow dress nursing a child” (577). Lawrence

was forced by economic circumstances to use cheap materials and just a few colors. We

can see a parallel with the plight of African Americans, who were forced by poverty and

social conditions to a limited range of jobs. Lawrence seems to be saying that even when

faced with economic determinism, African Americans can find a way to express

personal hope and a collective spirit of ambition and resolve.

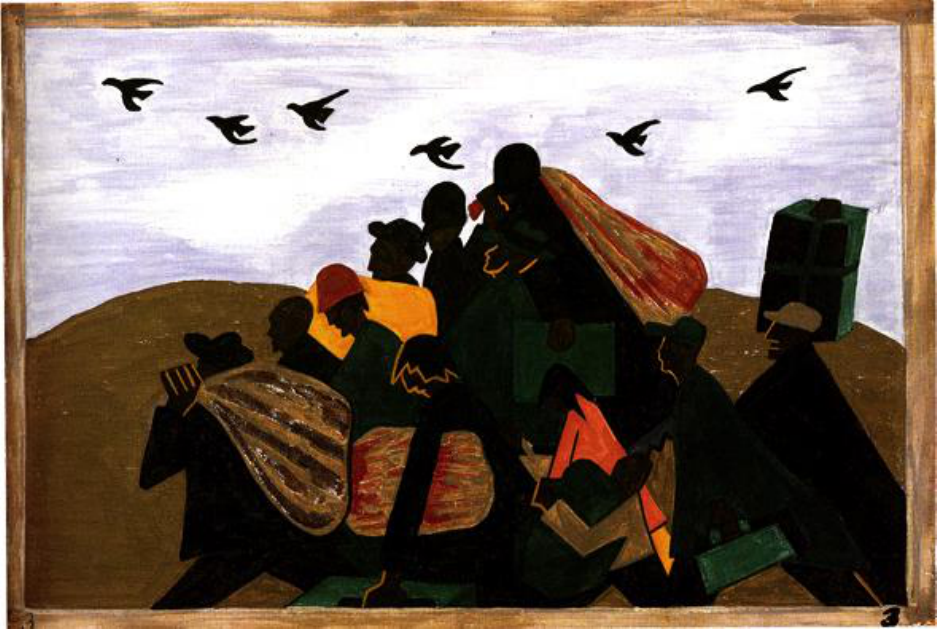

Fig. 1. A panel in the series showing a group of migrants walking together (Turner, Jacob

Lawrence, panel 3).

De Souza 9

I already discussed some panels that show causes of migration (usually

individuals), and I mentioned that the panels that depict migration usually show

groups. I want to say something more about how hope or ambition is represented in

some parts of the series. One of the best-known images in the series (see fig. 1) shows a

group of migrants with their luggage walking in profile from right to left; birds in the

sky are also shown in profile moving in the same direction, as if all were moving north

at the start of a hopeful spring. The viewer can see that some of the individuals in the

panels have their heads down, while others are looking forward or even up. Nearly

everyone has some luggage, but the burdens do not seem to be dragging them down.

The group has momentum. There is a bright yellow package toward the front of the

group, and a woman holding a baby is brightly clothed, symbolizing that hope for the

next generation is present. The landscape in the background is brown and bare, but the

birds are coming with the migrants. I think it is a hopeful panel that shows that

everyone in the group is strong and determined to “go North,” as the caption says. He

features children in other panels, like number 32, where a child in white and red clothes

sits on luggage facing the viewer and a crowd of black travelers waiting on benches

(Lawrence prepared a similar image as an illustration in a book of poems by Langston

Hughes [Lawrence, One-Way Ticket 63]). Then there is an image like panel 46, which

shows a staircase ascending from the viewer to an open doorway revealing sky and the

moon. The caption talks about unhygienic housing in the labor camps, but the image

De Souza 10

gives the sense that hope is on the other end of the stairs (at least we are looking up to

the outside, not down to the cellar). Stairways figure prominently in Lawrence’s art. As

one scholar has noted, “Lawrence’s use of steps is a visual Morse code tapping out a

message having to do with ascension and climbing” (Powell). As a contrast to panels

depicting economic or social forces pushing and pulling the migrants, Lawrence offers

many panels that show hope for those who are ambitious enough to make the journey.

In conclusion, I think that Jacob Lawrence understood the economic

circumstances that pushed African Americans from the South and pulled them to the

North, and he represented many of these factors in his Migration series. He understood

them in part because his family lived them, and he knew other African Americans with

similar experiences while he grew up in Harlem during the Depression years. He did

not see his community as total victims, however. He represents the Great Migration as a

hopeful expression of his group’s will for a better life. You can also see this belief in how

he handles his artistic process. Using inexpensive materials and only a few colors, he

painted a series that spoke to his community’s hopes and dreams and brought national

attention to his artistic achievement.

De Souza 11

Works Cited

Adams, Luther J. “Great Migration, Causes Of.” Encyclopedia of the Great Black Migration,

edited by Steven A. Reich, vol. 1, Greenwood Press, 2006, pp. 504-06.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. “New Negroes, Migration, and Cultural Exchange.” Turner, Jacob

Lawrence, pp. 17-21.

Grossman, James R. Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration. U of

Chicago P, 1989.

Hills, Patricia. “Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series: Weavings of Pictures and Texts.”

Turner, Jacob Lawrence, pp. 141-53.

Lawrence, Jacob. Interview. Jacob Lawrence: The Glory of Expression, directed by David

Irving, narrated by Ossie Davis, L & S Video, 1992.

---. “Jacob Lawrence Talks about Color.” Jacob Lawrence: Over the Line, Flash ed., Phillips

Collection, 2001, www.phillipscollection.org/sites/default/files/interactive/jacob-

lawrence-over-the-line/flash.html.

---, illustrator. One-Way Ticket. By Langston Hughes, Alfred A. Knopf, 1949.

Lorensen, Jutta. “Between Image and Word, Color and Time: Jacob Lawrence’s The

Migration Series.” African American Review, vol. 40, no. 3, 2006, pp. 571-86.

EbscoHost, connection.ebscohost.com/c/literary-criticism/24093790/between-

image-word-color-time-jacob-lawrences-migration-series.

Patton, Sharon F. African-American Art. Oxford UP, 1998.

De Souza 12

Phillips, Stephen Bennett. “Chronology: Jacob Lawrence and the Migration Series.”

Turner, Jacob Lawrence, pp. 161-64.

Powell, Richard J. Jacob Lawrence. Rizzoli International Publications, 1992.

Steele, Elizabeth. “The Materials and Techniques of Jacob Lawrence.” Over the Line: The

Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, edited by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, U

of Washington P, 2000, pp. 247-65.

Tribe, Tania Costa. “Visual Narrative and the Harlem Renaissance.” Word and Image, vol.

23, no. 4, 2007, pp. 391-413.

Turner, Elizabeth Hutton. Introduction. Turner, Jacob Lawrence, pp. 13-15.

---, editor. Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series. Rappahannock Press / Phillips

Collection, 1993.

Wheat, Ellen Harkins. Jacob Lawrence: American Painter. U of Washington P, 1986.