Minnesota Consumer

Debt Litigation

A STATEWIDE ACCESS

TO JUSTICE REPORT

2023

Minnesota State Bar Association Access to Justice Committee

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

2

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

2

Overview

Using state courts to collect debts has become extremely commonplace in the

U.S., and Minnesota is no exception. In 2019, more than half of the cases filed

in the state’s civil courts involved consumer debt. But court processes and

procedures in the state weren’t designed with unrepresented consumers in debt

litigation in mind, and they haven’t shifted to reflect the current reality. Minnesota

courts are seeing a high volume of debt cases being brought by businesses

against individual consumers who rarely have an attorney’s help.

To better understand the impact of Minnesota debt collection lawsuits, the

Minnesota State Bar Association Access to Justice Committee (ATJ) examined

bulk civil court data, analyzed policies, and conducted interviews in the state. The

Committee, which works to increase access to meaningful, effective assistance

for civil legal needs, was supported by Legal Services State Support, the

Minnesota State Bar Association (MSBA), Minnesota Judicial Branch, January

Advisors Data Science Consulting, and The Pew Charitable Trusts.

The Committee found that current practices—some unique to Minnesota, others

common across the country—have made it difficult for consumers without an

attorney to fully engage in debt litigation, or often to even know that there is a

case against them. On the other hand, the Committee found that the current

system is working well for businesses that turn to the courts to resolve debts.

Confusing and opaque processes, paired with minimal court oversight at key

points, mean that Minnesotans who want to engage in their case and use it as a

final opportunity to resolve their debts have no clear path for doing so.

Executive Summary

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

3

Key findings from this

analysis include:

The current debt litigation landscape has made

it difficult for Minnesota civil courts to realize

their stated vision that “the general public and

those who use the court system will refer to it as

accessible, fair, consistent, responsive, free of

discrimination, independent, and well-managed.”

1

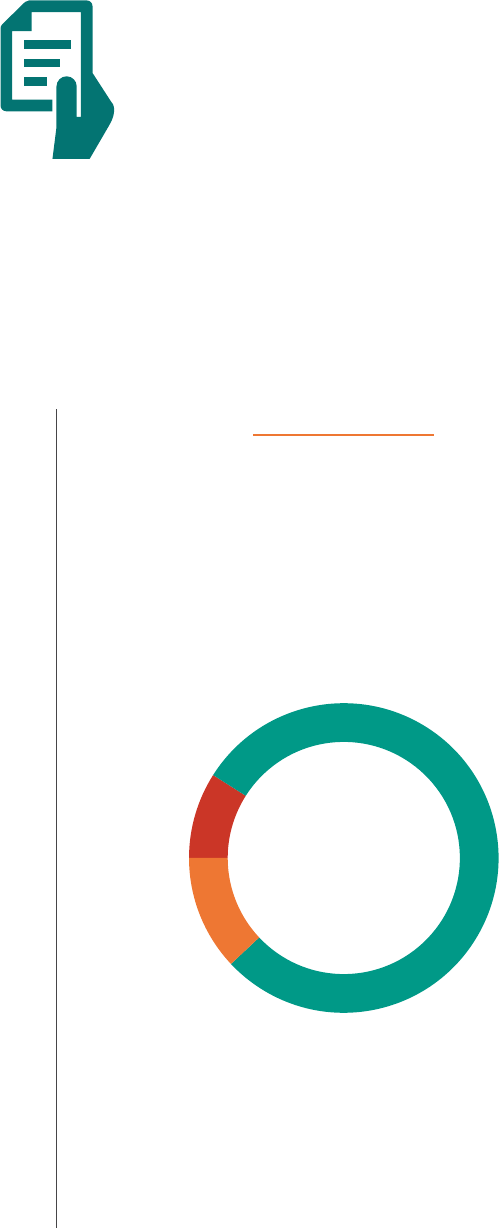

•• The overwhelming majority of debt cases in

Minnesota—82% of district court cases and 54% of

conciliation court cases —end in default judgment

in favor of the plaintiff.

•• Minnesota has fewer residents in debt than in

most places in the U.S., but more litigious plaintiffs,

with 1 in 8 debts in collections eventually filed as

civil court cases.

Executive Summary

Court processes and policies make it difficult

for Minnesota consumers to participate in and

resolve their cases.

•• More than half of debt cases filed in district court

involved less than $4,000, which means they are

eligible to be filed in conciliation court.

• More consumers engage in their lawsuit if

the case is brought in conciliation court than

in district court. Roughly 82% of consumer

debt cases in Minnesota district court end

in default (compared to 54% in conciliation

court), higher than in most states and above

national numbers.

•• Minnesota’s two-venue system for debt litigation

allows plaintiffs to choose whether to file in district

court or conciliation court for matters involving

$4,000 or less. This creates confusion and different

outcomes for consumers, almost none of whom are

represented by a lawyer.

• District court allows plaintiffs to serve

consumers notice of a lawsuit without filing

in court, creating confusion about the validity

of the matter.

•The official process for filing an answer in a

district court case is inconsistent with actual

practice; formal answers are expensive to

file, resulting in a practice whereby self-

represented consumers send informal

“answers” to plaintiffs attorneys, putting the

adverse party in the position of determining

whether the consumer has sufficiently

answered the claim.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

4

There are racial and income disparities in

who is being sued in Minnesota.

•• Overall, the rate of debt claims filed against Black

and Latino Minnesotans is more than twice that of

Non-Hispanic White Minnesotans.

•• The filing rate against consumers in

neighborhoods where the median household income

is $50,000 or less per year is 50% higher than

against those in neighborhoods where the median

household income is over $75,000 per year.

The services and protections available to debt

consumers are not reaching enough Minnesotans

or helping people avoid the worst consequences

of debt cases.

•• Most Minnesotans facing debt litigation represent

themselves. They often don’t make enough money to

hire a private attorney but make too much to qualify

for legal aid.

• An estimated 82% of cases are filed

against people who are above the legal aid

income threshold.

• Income requirements for legal aid

services, limited legal aid resources,

and competing priorities for in-demand

services across the legal spectrum meant

Minnesota legal aid served just 3,000 debt-

related cases between 2019 to 2021, out

of approximately 178,000 that were filed in

Minnesota courts during that time.

• The processes for enforcing a

judgment are largely handled by

plaintiffs, taking place outside of the

purview of the courts; as a result,

there is limited court data available

to understand the impact of post-

judgment activity on Minnesota

consumers.

Based on these findings,

the MSBA’s Access to Justice

Committee recommends

that policymakers and

civil justice leaders:

1

Develop specialized

procedural rules for debt

cases to better manage

consumer debt cases.

2

Create and improve

resources that empower

self-represented litigants to

participate in their cases.

3

Preserve economic stability

for debt-burdened Minnesotans,

so they can afford basic needs

while repaying their debts.

4

Expand services for

lower- and moderate-income

people who are struggling

with debt.

By making debt litigation

processes in Minnesota courts

less confusing and increasing

consumer protections and

resources, the state can cut costs

related to these cases, support

courts in their efforts to process

these matters more effectively,

and help consumers and creditors

reach resolution.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

5

Dori Rapaport, Chair

Executive Director, Legal Aid Service of Northeastern

Minnesota

Bridget Gernander

Legal Services Grant Manager & Minnesota IOLTA

Program Director, Minnesota Judicial Branch

Gregory Hanson

Associate Attorney, D.S. Erickson & Associates, PLLC

Bennett Hartz

Assistant Attorney General, Minnesota Attorney

General’s Office

Parker Maertz

Manager, Consumer Action Division, Minnesota

Attorney General’s Office

Lori Mittag

Conciliation Court Referee, Ramsey County

Workgroup Members

Katy Drahos

Access to Justice Director, Minnesota State Bar

Association / Hennepin County Bar Association /

Ramsey County Bar Association

Ron Elwood

Supervising Attorney, Legal Services Advocacy Project

Bridget Gernander

Legal Services Grant Manager & Minnesota IOLTA

Program Director, Minnesota Judicial Branch

Charles Nguyen

Hennepin County Senior Self-Help Center Specialist,

Minnesota Judicial Branch

Jena Reed

Self-Represented Litigant Program Manager,

Minnesota Judicial Branch

J. Singleton

Program Manager, Minnesota Legal Services State Support

Daniel Wassim

Associate Attorney, Dorsey & Whitney LLP

Jessica Whitney

Deputy Attorney General, Minnesota Attorney

General’s Office

Lindsay Ziezulewicz

Hennepin County Senior Self-Help Center Specialist,

Minnesota Judicial Branch

Access to Justice Committee Workgroup

Consumer Debt Litigation Project Leadership Team

Melissa Kantola

Deputy District Administrator, Minnesota Judicial Branch

Jena Reed

Self-Represented Litigant Program Manager,

Minnesota Judicial Branch

J. Singleton

Program Manager, Minnesota Legal Services State Support

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

6

Table of Contents

2 • EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

5 • WORKGROUP MEMBERS

6 • TABLE OF CONTENTS

7 • BACKGROUND

15 • RESEARCH FINDINGS

The characteristics of plaintiffs, debts, and consumers ����������������������������������� 15

How cases are processed in district and conciliation court ���������������������������� 23

What happens after court ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 31

35 • RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1: Develop specialized procedural rules to better

manage consumer debt cases ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 36

Recommendation 2: Expand resources to empower self-represented

litigants to participate in their cases ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 40

Recommendation 3: Preserve economic stability so Minnesotans can

afford basic needs while repaying their debts ����������������������������������������������������������� 42

Recommendation 4: Expand services for lower- and moderate-income

people who are struggling with debt ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 44

46 • ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

47 • METHODOLOGY

50 • APPENDIX

52 • ENDNOTES

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

7

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

7

Background

Minnesota has an active access to justice community and some good policies

on the books related to consumer debt lawsuits.

2

For example, the state is

ahead of other states in adopting documentation requirements for debt buyers

and prohibiting revival of debt after the statute of limitations has run. Minnesota

courts also have a strong operational infrastructure. Court staff’s commitment to

training, leveraging resources, and creating detailed process documents means

the day-to-day functions of the courts are well run. Nevertheless, Minnesotans

involved in debt litigation still experience challenges, and consumer debt cases

are flooding Minnesota civil courts.

Minnesota is unusual compared to other states in how little the judiciary

interacts with civil debt cases, and plaintiffs in Minnesota have an outsized role

in deciding where their matter is heard, when a case is formally filed, and how

money is collected if they receive a judgment in their favor. The research team

examined data provided by the courts to understand how the courts’ limited

involvement affects court users. The state’s two-venue system for civil matters

involving $4,000 or less, its rules allowing hip pocket

3

filing (the practice of

commencing a lawsuit upon serving the defendant with the summons, rather

than by filing a claim with the court), for district court matters, and the magnitude

of the plaintiffs’ role compared to that of the courts make Minnesota an outlier

among U.S. state civil courts.

In order to understand the scope and impact of debt collection lawsuits on

Minnesotan consumers, the MSBA Access to Justice Committee brought

together a diverse group of stakeholders with experience in Minnesota civil

courts and debt collection lawsuits to provide insight on data analyses and

identify data-informed recommendations to make the courts work better for all

parties involved. Among these stakeholders were judicial officers, legal services

attorneys, creditors attorneys, private consumer attorneys, consumer advocates

in the attorney general’s office, and service providers in the following areas:

financial counseling, mediation, court-based self-help, and lawyer referral.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

8

CONCILIATION COURT DISTRICT COURT

File first > then serve Serve first > then file

Answer not required.

Hearing automatically scheduled.

Answer generally required for a hearing.

No court-based mechanism to settle before filing. Some cases may be settled before filing.

Judicial officer enters default judgment if the

defendant does not show up to the hearing.

Plaintiff can file as a default judgment; it is

entered administratively by court administration.

Debt documentation requirements are the same

(only apply to debt buyers seeking default).

Debt documentation requirements are the same

(only apply to debt buyers seeking default).

Judgments must be docketed in

District Court to garnish.

Judgments are enforceable.

The fees associated with filing and responding to a case in conciliation court are lower than those in district court,

and debt defendants in conciliation court are significantly more likely to engage in their cases. While some of this

disparity in defendant participation may be attributed to district court settlements prior to judgment due to hip

pocket filing, it is unlikely that this practice accounts for the entirety of the differences in defendant participation.

Table 1

If the amount in controversy for a debt

case is $4,000 or less—something that

is true for the majority of debt cases filed

in Minnesota—the state allows plaintiffs to

select the venue for their complaint: either

conciliation court or district court. Plaintiffs

can file lower-dollar cases in district court

even if the amount in controversy makes

the case eligible for filing in conciliation

court. This can create two very different

experiences, and often different outcomes,

for consumers who owe similar amounts.

Typically, the unique features of district court

cases make them more complex and costly

for self-represented consumers to navigate.

Minnesota’s

Two-Venue

System for

Civil Matters

Differences between

conciliation court

and district court

Background

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

9

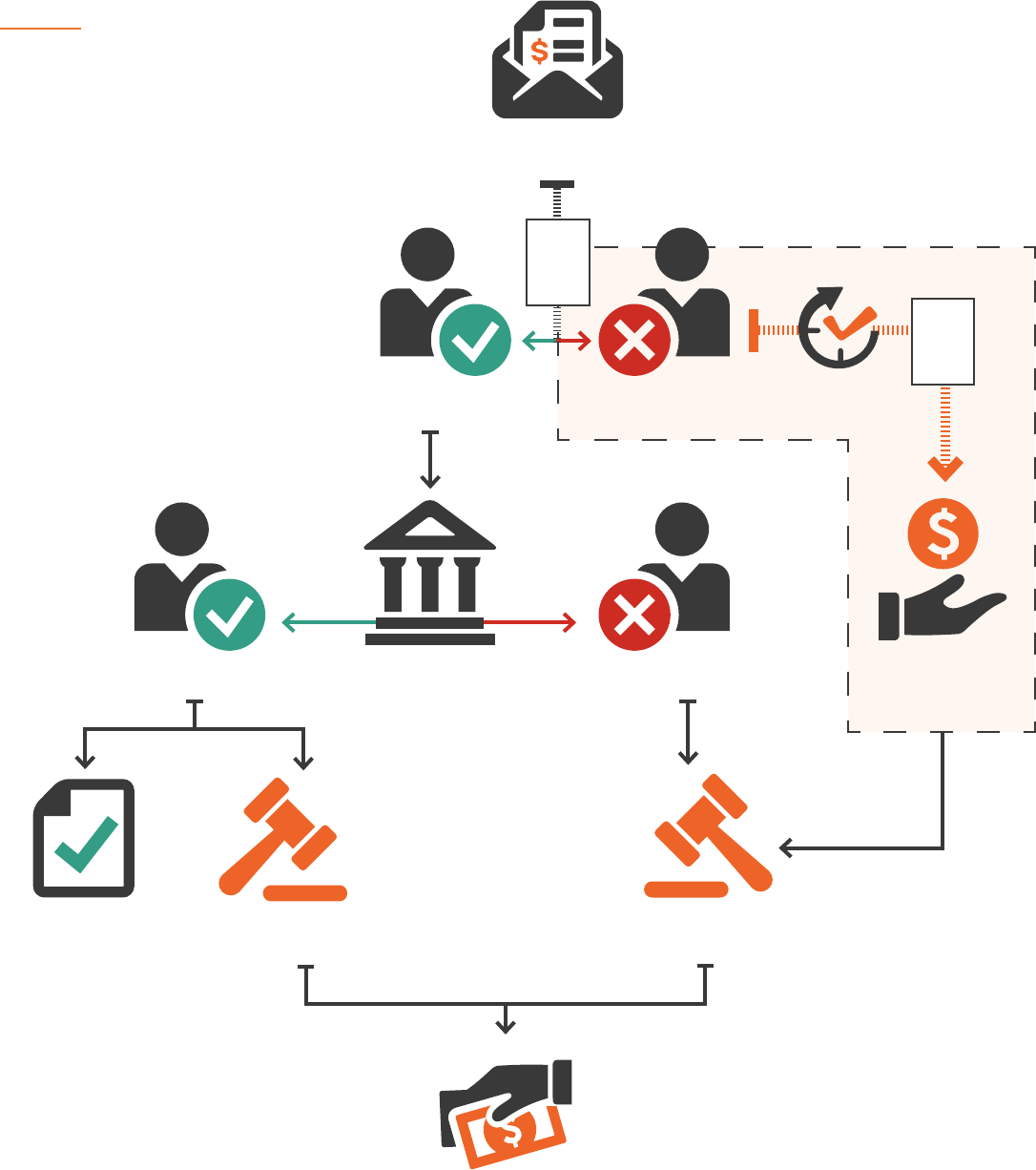

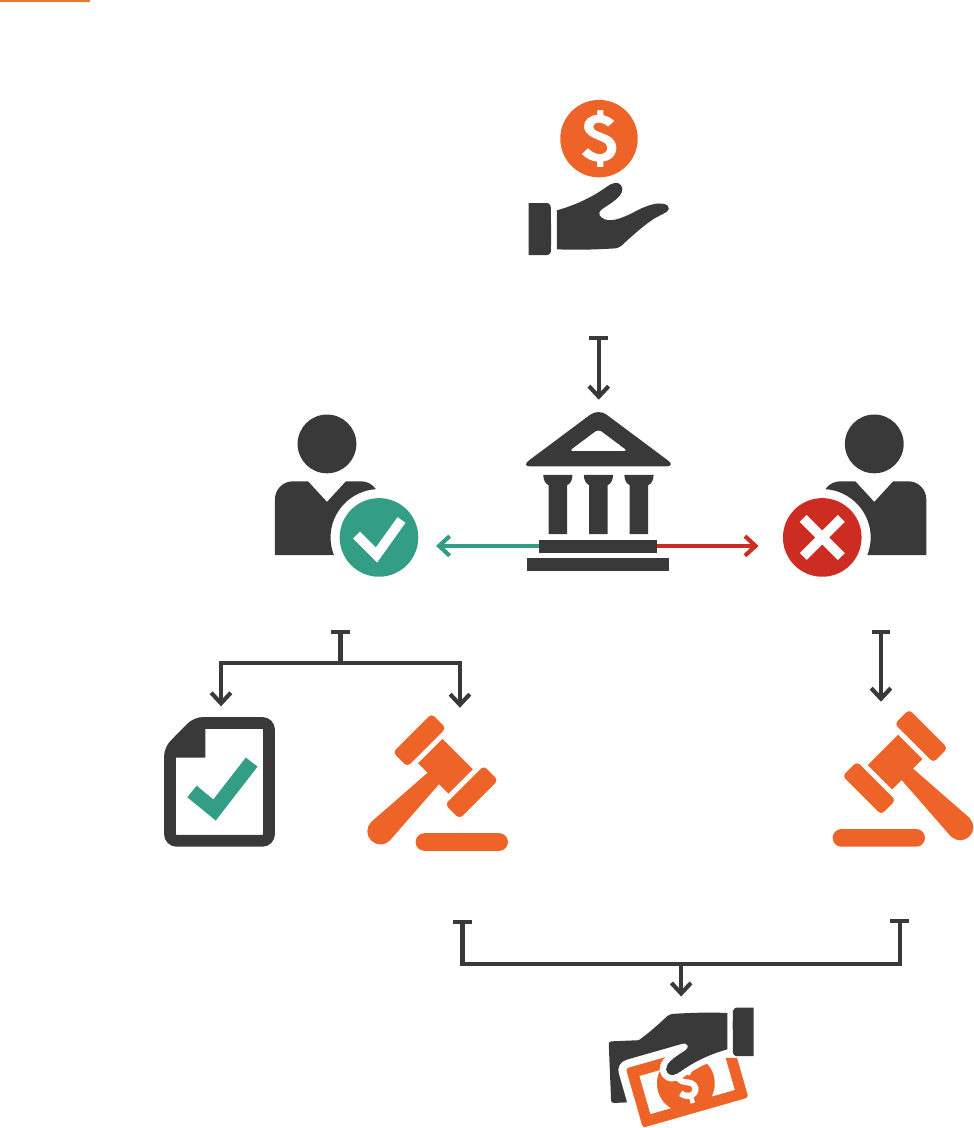

hearing

before judge

default

judgment

trial judgment

for plaintiff

plaintiff may begin

garnishment process

defendant

shows up

defendant

does not show

creditor / collector

can file claim for

default judgment

MINNESOTA DISTRICT COURT

defendant

does answer

defendant

does not answer

creditor / collector

serves defendant

POCKET FILING

within

21

days

within

1

year

dismissed

with/without prejudice

(court-ordered)

Figure 1:

District

Court

A lawsuit to collect on a

consumer debt in district

court follows the process

illustrated here.

Background

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

10

creditor / collector

files claim with court

hearing

default

judgment

trial judgment

for plaintiff

plaintiff can transcribe

judgment to district court

plaintiff may begin

garnishment process

dismissed

with/without prejudice

(court-ordered)

defendant

shows up

defendant

does not show

MINNESOTA CONCILIATION COURT

Figure 2:

Conciliation

Court

A lawsuit to collect on a

consumer debt in conciliation

court follows the process

illustrated here.

Background

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

11

Plaintiffs planning to file in district court are able to

serve consumers with a summons and complaint

before filing it with the court; they have up to

a year to file (and can also choose not to file).

Once consumers are served with a summons

and complaint, they have 21 days to respond to

the plaintiff. Consumers who don’t respond within

this window risk a default judgment—an automatic

decision in favor of the plaintiff when a consumer

doesn’t adequately respond to or participate in the

case against them. During this period, however, there

is no court-issued case number or requirement that

the plaintiff provide proof to the consumer that the

debt is valid. The courts do provide an answer form

(CIV302), but the Committee found that it is almost

never used by consumers being sued for debts. No

notice or official documents from the court are sent

to the consumer until after the judgment is entered,

at which point the court sends a notice of entry of

judgment.

This practice does not exist in conciliation court,

where plaintiffs must begin the litigation process by

filing their complaint with the court; consumers are

then served with a summons with a hearing date

and time.

4

Service and filing

requirements make

Minnesota an outlier

Background

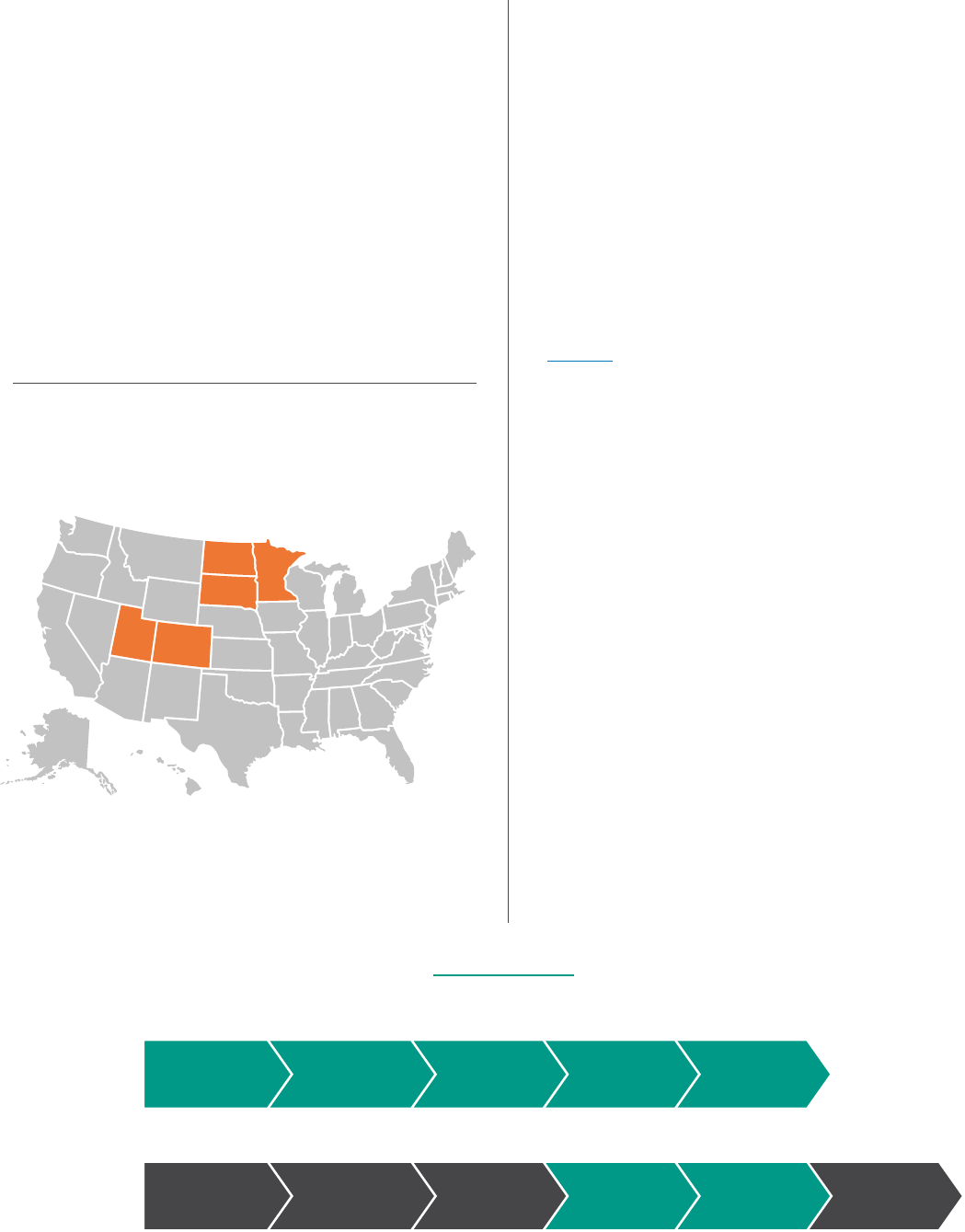

District court allows “hip pocket filing,” which

gives plaintiffs the leeway to serve consumers

notice of a debt lawsuit before filing that suit in

court. Minnesota is one of just a handful of states

(including Colorado, North Dakota, South Dakota,

and Utah) that employs this practice.

Figure 3: Stages of debt lawsuit with hip pocket filing

Map 1: Only 5 states employ hip pocket filing

Colorado, Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota,

and Utah permit some civil actions to commence at

service rather than filing.

Consumers who don’t respond within

21 days risk a default judgment—an

automatic decision in favor of the plaintiff

when a consumer doesn’t adequately

respond to or participate in the case

against them� During this period, however,

there is no court-issued case number or

requirement that the plaintiff provide proof

to the consumer that the debt is valid�

Notice and

Service

Suits Filed

with Court

Notice and

Service

Some Suits

Settled

Remaining

Suits Filed

with Court

Response

Response

Resolution

Resolution

Post-

Judgment

Post-

Judgment

Typical

state

n court involvement n out of court

Minnesota

hip pocket

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

12

In conciliation court, consumers are required to

participate in their hearings but are not required

to file an answer to the case unless entering

a counterclaim. In district court, not only are

consumers required to file an answer, but they

must pay a $285 filing fee (plus additional fees

depending on the judicial district) to do so. Few

state civil courts in the U.S. charge consumers to

answer, and no other state in the region has such a

high answer fee (see Fig. 14, p. 27). The consumer

can also respond by sending something in writing

directly to the plaintiff, but knowing how to compose

these informal responses can be confusing for self-

represented litigants, and they often don't know how

or where to send them, so the court generally has

no record of them.

Even compared to the handful of other states with

hip pocket filing practices, Minnesota district courts

allow plaintiffs one of the longest windows of time

between service and filing in the country, making it

an outlier among outliers. Most other states with hip

pocket filing, including Colorado, Utah, and North

Dakota, have hip pocket filing windows between 10

and 21 days, commensurate with the amount of time

defendants have to respond. Minnesota’s window

of 365 days for plaintiffs to file is far longer than the

window for consumers to respond.

Background

The lengthy filing time offers benefits and

drawbacks. A benefit of the longer filing time is

that it can allow plaintiffs and consumers time to

settle the matter before it reaches the court, without

incurring additional costs or creating a record. The

uneven timing requirements also have drawbacks:

because mandatory disclosures (including

documents in support of the plaintiff’s claim) are not

triggered unless the consumer responds, and debt

buyers are only required to provide documentation

14 days before applying for a default judgment,

consumers have less time to respond and attempt to

verify the claim than plaintiffs have to file.

5

According

to stakeholder interviews, service paperwork may be

discounted or viewed as a “scam” if there is nothing

about the case yet available through the courts. This

may impact a consumer’s likelihood of responding

to a case in time, or at all. Because the court is

not involved in the pre-filing process, there is no

data to indicate the number of cases settled out of

court. Altogether, these policies smooth the way for

plaintiffs to obtain default judgments.

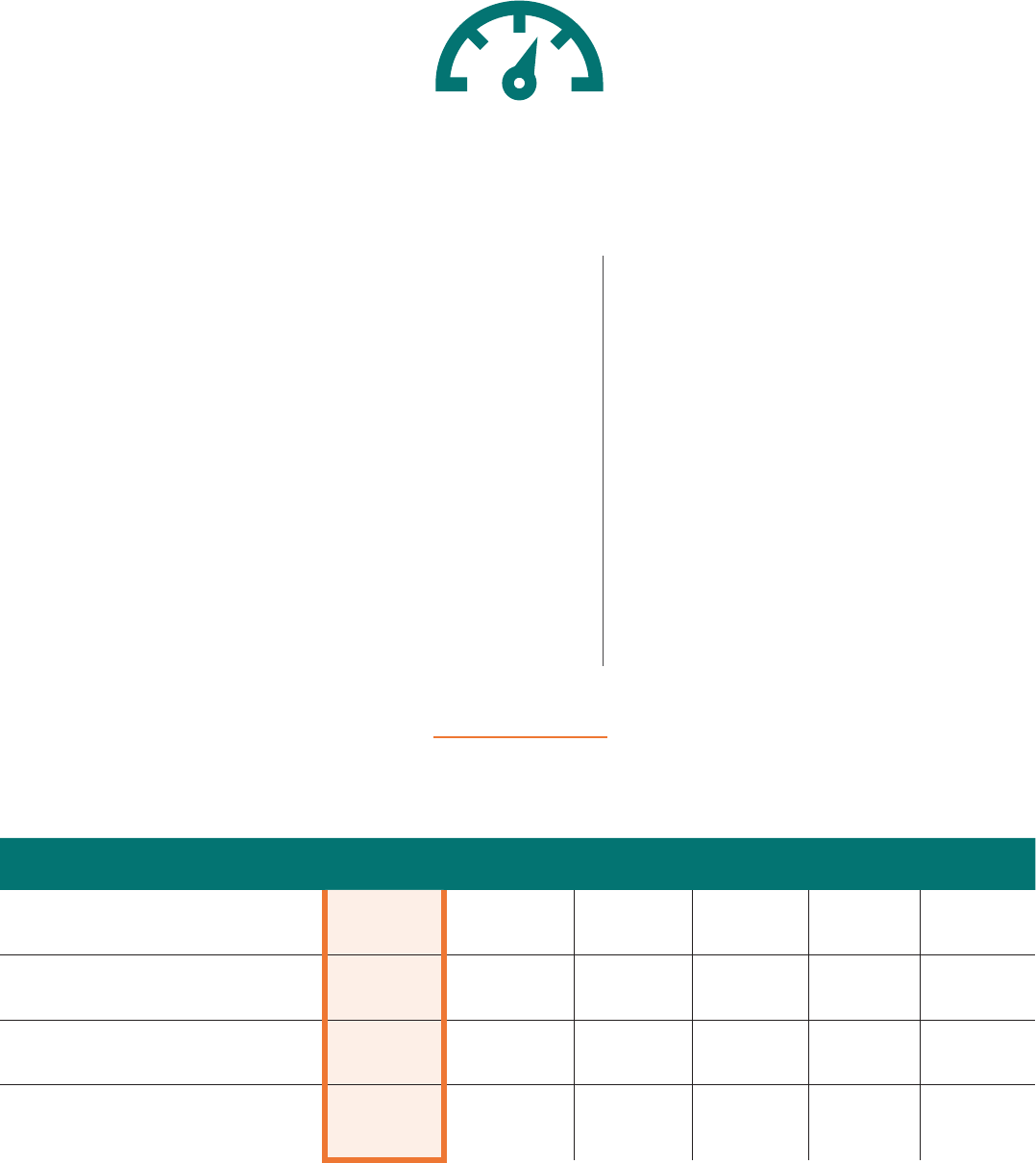

Table 2: States with hip pocket filing offer shorter windows

for plaintiff filing, defendant response than Minnesota

Comparison of “serve first" procedures in states where a civil

lawsuit may be commenced at service rather than filing.

STATE

Time between

service and filing

Time for defendant

to respond

SOUTH DAKOTA

“Forthwith upon service”

30 days

UTAH 10 days 21 days

COLORADO 14 days 21 days

NORTH DAKOTA 20 days 21 days

MINNESOTA 365 days 21 days

Source: N.D.R. Civ. P. Rule 3, Rule 5; S.D. Codified Laws § 15-2-30; CRCP 3(a); U.R.C.P. Rule 3, Rule 4; Minn. R. C. P. 3

According to stakeholder interviews, service

paperwork may be discounted or viewed as

a “scam” if there is nothing about the case

yet available through the courts�

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

13

Background

Courts Are

Hands-Off in

Post-Judgment

Matters

Minnesota courts have more limited involvement in

garnishment processes and other post-judgment

activities compared to other states. Plaintiffs and

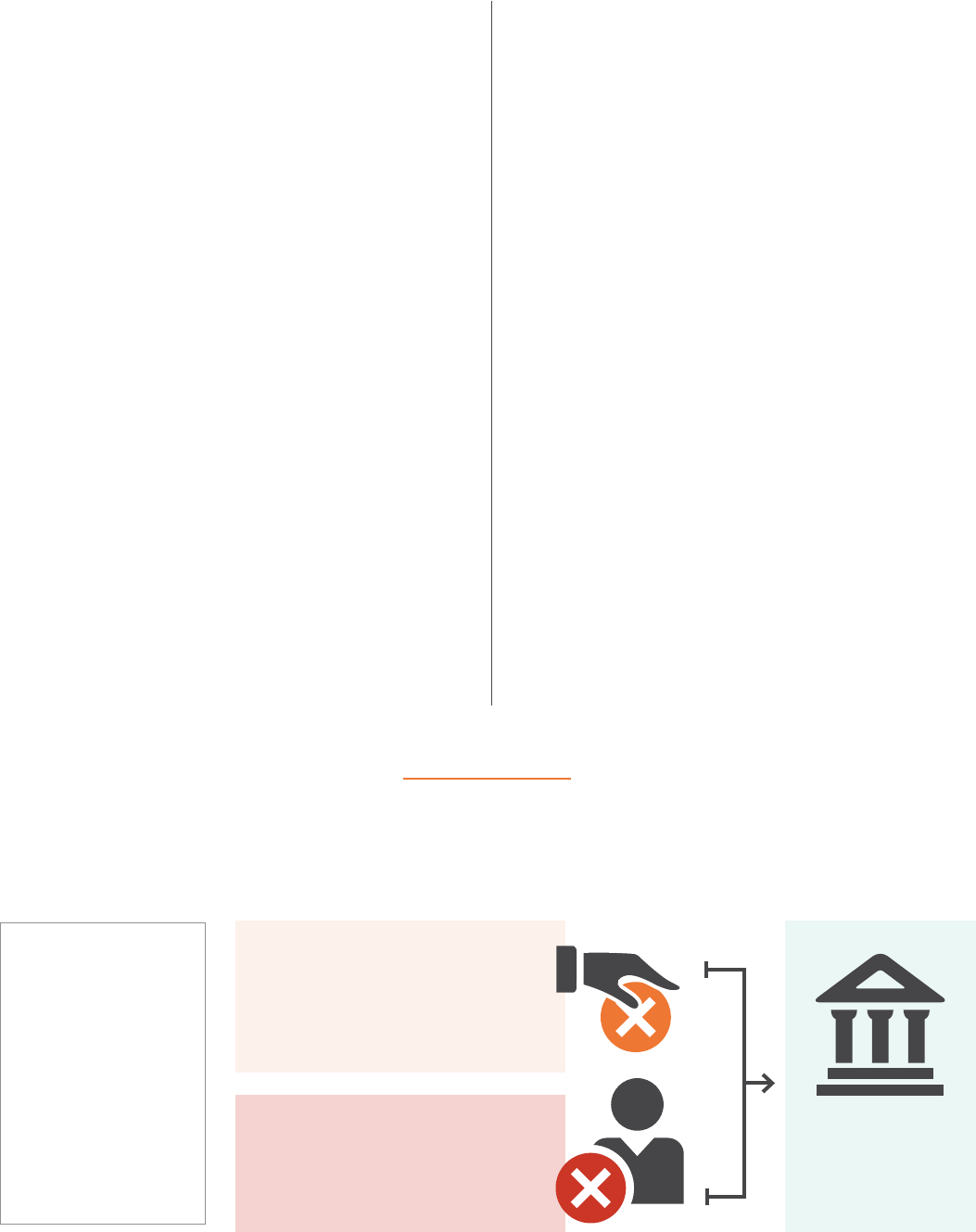

their attorneys usually directly communicate with

garnishees and self-represented defendants about

garnishment matters with little intervention from the

courts.

In most states, when plaintiffs want to collect

a judgment, the plaintiff must file for a writ of

garnishment (or execution) with the court, after

which the court issues a garnishment summons

that is served on both the consumer and their bank

or employer. The bank or employer then has to

answer to the court whether they have any of the

judgment debtor’s assets, so the court has a record

of how many garnishments were attempted and

whether there were assets subject to garnishment.

Additionally, in most states the consumer lets the

court know if they have assets that are protected

from garnishment or levy by filing an exemption form

with the court, meaning the court has some record

of and insight into how its judgments are enforced.

But Minnesota is not like most states. In Minnesota,

the plaintiff attorney, instead of the court, prepares

the garnishment summons that goes to the bank

or employer, as well as the notice that goes to the

consumer. The bank or employer answers directly

to the plaintiff to let them know whether there are

any assets subject to garnishment or levy. And if

the consumer wants to claim exemptions, instead

of filing a claim of exemptions with the court, the

consumer must communicate directly with the

plaintiff’s attorney. The court only gets involved in

exemptions if one of the parties objects and asks for

an exemption hearing, which may be burdensome

and/or confusing for self-represented consumers.

As a result of this hands-off process, the court

has incomplete knowledge of how plaintiffs are

using the power of the court to satisfy debts. Nor

do the courts have the opportunity for quality

control regarding whether consumers are able to

adequately assert their right to have exempt assets

protected from garnishment or levy. Lack of court

involvement also means that consumers have a

slower path to resolution when protected funds are

garnished.

In Minnesota, the judgment creditor doesn’t have to

apply for a writ until after the garnishment summons

has been served, the employer or bank has withheld

or frozen the funds, the exemption period has

passed, and the funds are released to them.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

14

Background

The Minnesota Attorney General’s Office

has collected stories of Minnesotans who

have experienced issues with the level of

the court’s involvement in post-judgment

activities� In 2016, Minnesotan “Jess Doe”

had a judgment entered against her for an

old debt; in 2023, she noticed a pending

transaction of over $13,000 in her bank

account by the collector� The next day, the

funds were released by Jess’s bank and

taken by the collector� Jess said that the

collector never sent a garnishment summons

or the two exemption forms that they are

required to send� Jess is on MinnesotaCare

and likely would have been eligible for the

exemption� She had to print the forms herself

and send them to the collector�

Although Minnesota has solid laws on the books

related to debt litigation, such as documentation

requirements for debt buyers and exemption policies

for consumers receiving public assistance, the

state’s challenge is making sure that the intentions

of those policies are being realized.

Methodology

The report used a mixed methods

approach to understand the landscape

of debt collection lawsuits in Minnesota.

This included conducting a policy

landscape analysis, process maps of

how a case moves through district and

conciliation court, stakeholder interviews,

and quantitative analysis of court data

from multiple sources (the Minnesota

Judicial Branch’s Civil Judgments Extract,

anonymized case intake data from

Minnesota-based legal aid organizations,

data from the 2015-2019 American

Community Survey, the Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau’s Consumer Complaint

Database, the 2017 Financial Well-Being

Survey, and a random sample of 1,000

cases filed between 2018 and 2021).

Unless otherwise noted, the findings in

this report generally concern cases filed

over the ten-year period between 2011-

2021. Also of note, because the courts

do not collect demographic information,

the researchers imputed demographic

information based on defendant names and

addresses.

The leadership team sought to interview

consumers with lived experience of civil

debt litigation in Minnesota. Interviewees

were identified through referrals from

LawHelpMN, the court’s Self-Help Center,

and Attorney General’s consumer hotline.

Several consumers scheduled interviews,

but ultimately only two consumers

participated. Additionally, the Attorney

General’s office provided three anonymized

accounts of consumers who had contacted

the consumer hotline for assistance with an

issue related to consumer debt litigation.

To conduct the analysis, the research

team consulted with the leadership team

to identify relevant research questions and

understand findings. For more information,

see the full methodological appendix.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

15

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

15

1. The majority of

Minnesota civil cases

are debt cases�

2. Debt collection lawsuits

are spread across the

state’s 10 judicial districts�

3. Most debt cases involve

$4,000 or less.

4. Debt buyers represent a

growing share of plaintiffs�

5. Minnesota has a

disproportionately high

debt case filing rate�

6. Black and Latino

Minnesotans at all income

levels are more likely than

White residents to have debt

suits filed against them�

7. Defendants rarely have legal

representation; plaintiffs

almost always do�

The characteristics of

plaintiffs, debts, and consumers

Research Findings

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

16

Research Findings The characteristics of plaintiffs, debts, and consumers

The majority of

Minnesota civil cases

are debt cases

Consumer debt cases are flooding Minnesota

civil courts. In 2019, debt collection lawsuits

were the most common civil case type in

Minnesota, making up 51% of the civil docket.

Minnesota courts see four times as many debt

cases as they do evictions, the next most

common case type.

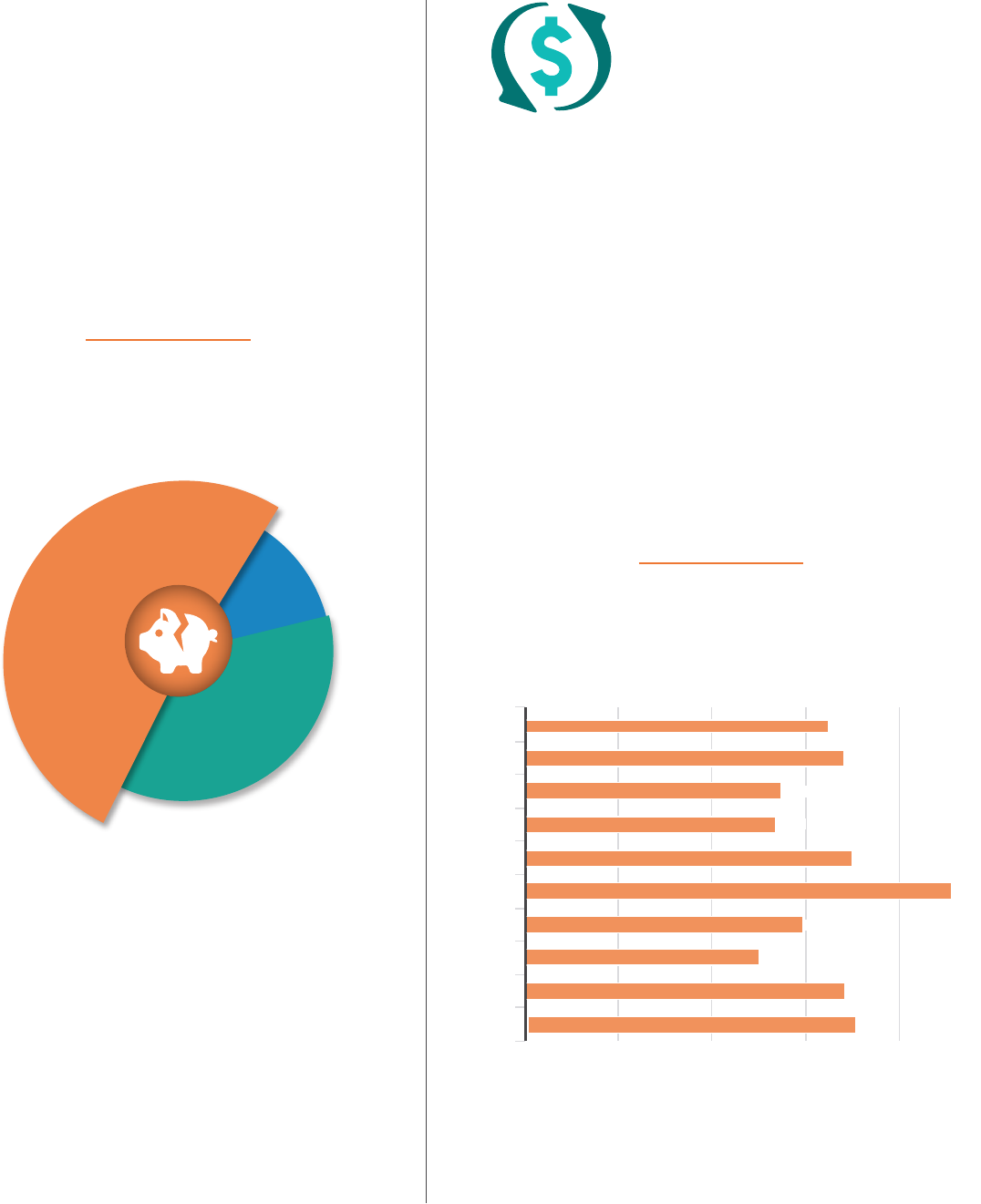

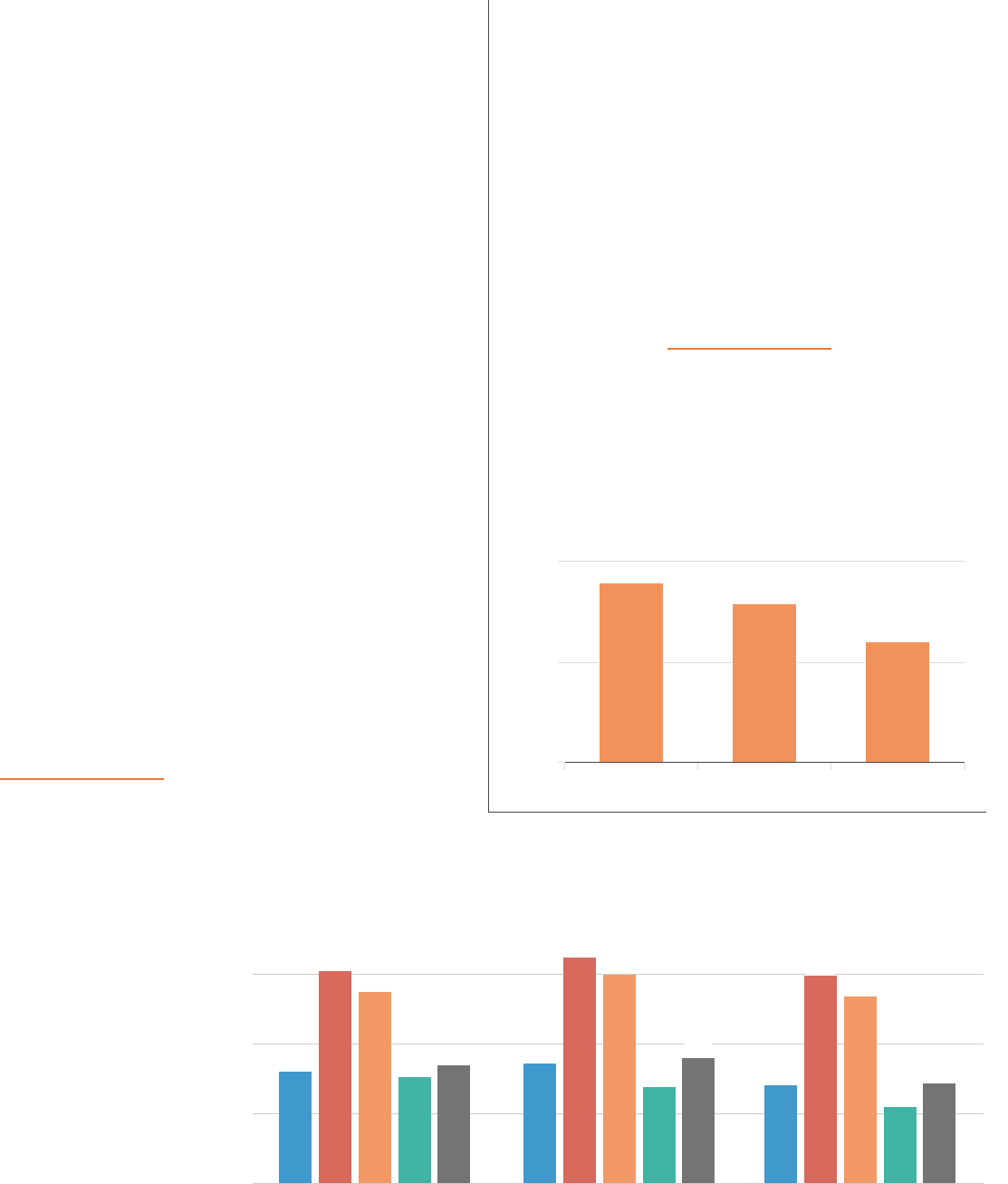

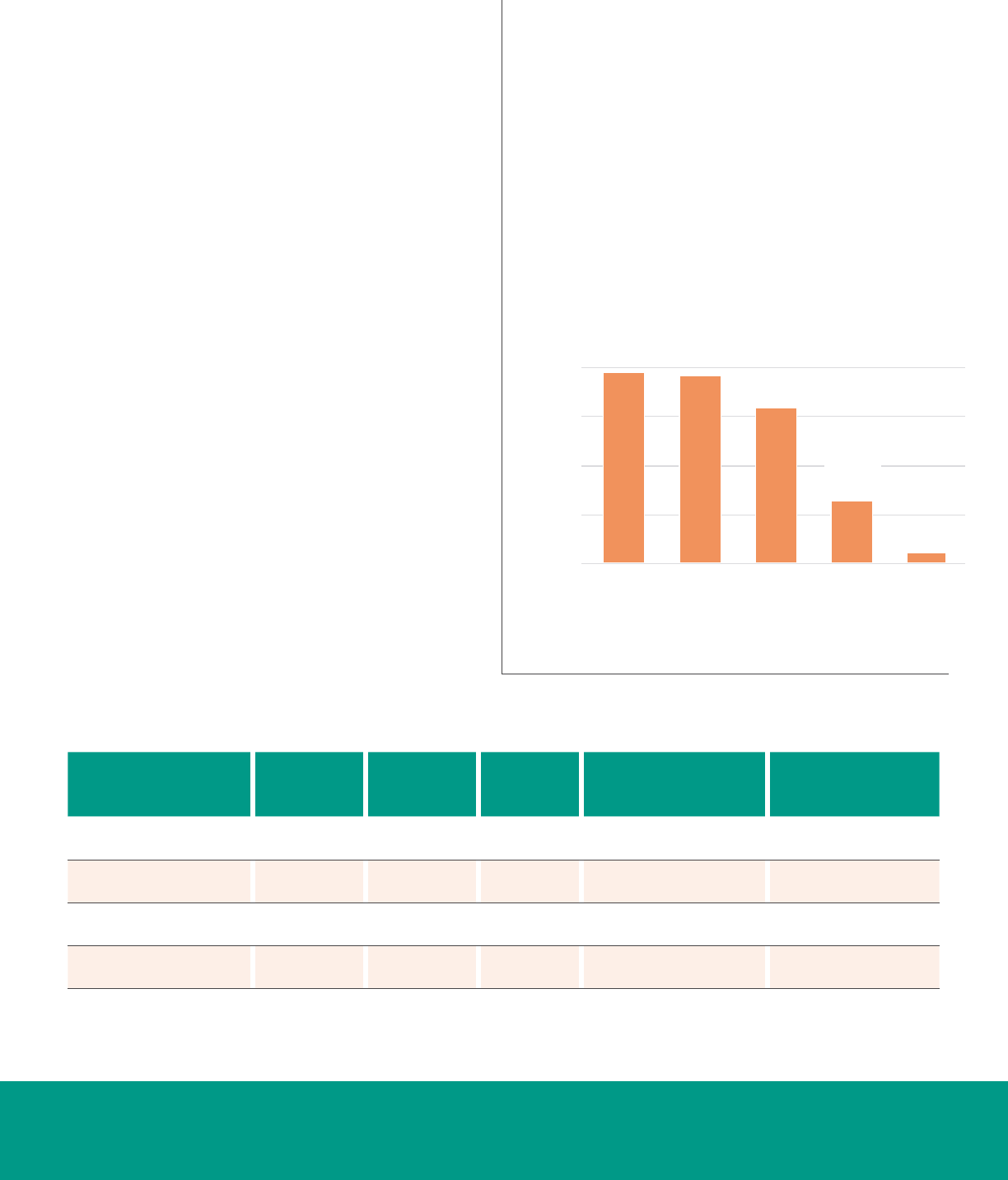

Figure 4: Consumer debt lawsuits

dominate the civil docket

Courts hear four times as many debt cases as

the next most-common case type.

Between 2011 and 2021, 664,000 debt

cases were filed in the two Minnesota venues

that hear such claims: district court and

conciliation court. Claims were distributed

almost evenly between the two courts during

that time span, with roughly 300,000 cases

filed in district court and 364,000 cases filed

in conciliation court.

Debt is everywhere

Consumer debt exists throughout Minnesota, from

Southern Minnesota to the Twin Cities, to the Iron

Range, and everywhere in between. Debt collection

lawsuits are filed all across the state and are not

confined to urban or rural areas.

Case filings are evenly spread across the state’s

10 judicial districts, for the most part. Residents in

judicial districts that include rural areas—such as the

Iron Range, which is included in the 6th District—

have a slightly higher rate of filings against them.

Urban residents, such as those in Minneapolis,

which falls under the 4th District, have a slightly

lower rate of filings against them.

Figure 5: Debt cases are spread across

all Minnesota judicial districts

Litigation is slightly more common in some areas,

but Minnesotans are affected statewide.

51%

consumer

debt

36%

other civil

12%

eviction

Number and share of civil cases filed by case type. Consumer debt cases

defined as cases filed in conciliation or district court (Default, Consumer

Credit, Confession of Judgment,) between a business (plaintiff) and

consumer (defendant). Transcript Judgments are removed from the total

count. Numbers do not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Sources: Minnesota Judicial Branch Civil Case Extract and District Court

Case Dashboard, 2019.

Judicial District

1

st

2

nd

3

rd

4

th

5

th

6

th

7

th

8

th

9

th

10

th

0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0

1.6

1.7

1.4

1.3

1.8

1.8

1.5

1.3

1.7

2.3

Debt collection filing rate

Average annual debt collection filing rate in Minnesota conciliation & district courts,

2017-2019. Filing rate calculated as number of cases filed per 100 residents.

Source: Minnesota Judicial Branch Civil Case Extract, 2017-2019;

American Community Survey

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

17

Minnesota has the lowest debt rate,

but it also has fewer adults with any

debts in collections�

In fact, there are more debt cases

filed in Minnesota as a share of

the population with any debt in

collections than other Great Lakes

states and Utah�

In other words, Minnesota has

fewer debtors but creditors and

debt buyers are more likely to

file lawsuits than in other states�

In terms of sheer numbers, Minnesota has fewer debt filings

than states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Utah,

and Texas. In 2019, there were 71,787 debt cases filed

in Minnesota, a rate of about 1.68 cases per 100 adults.

Minnesota also has a lower percentage of residents in debt

than in those states—just 13% of residents have a debt in

collections.

That low percentage of residents in debt would suggest that

creditors wouldn’t need to file lawsuits to recoup debt quite

as often as they do in other states. But, in fact, the litigation

rate for debt in the state is relatively high—nearly 1 in 8

people with debt in collections end up being sued—which

suggests creditors are actually more likely to file lawsuits in

Minnesota than in other states.

MINNESOTA MICHIGAN WISCONSIN INDIANA UTAH TEXAS

Debt Cases Filed (2019)

71,787

208,051 81,879 104,757 59,519 398,764

Debt Cases Per 100 Adults

1.68

2�64 1�8 2�03 2�6 1�86

% Residents with

Any Debt in Collections

13%

26% 20% 28% 19% 37%

Litigation rate:

Debt Cases per 100 Adults

with Any Debt in Collections

12.9

10�2 9�0 7�2 13�7 5

Figure 6: Minnesotans in debt are more likely to end up in court

Despite having fewer debt cases than in other states, consumers in Minnesota are sued more.

Source: January Advisors, Urban Institute

Minnesota has a high litigation rate

Minnesota has a relatively small number of residents in debt, but a high debt litigation rate.

Research Findings The characteristics of plaintiffs, debts, and consumers

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

18

Amounts in controversy

are too high for

consumers to pay,

but too low to justify

hiring an attorney

Most debt cases involve relatively

low amounts of money.

As is the case in other states, the majority of debt

collection lawsuits in Minnesota do not involve

large sums in the tens of thousands of dollars. The

median amount in controversy at the time of filing is

$1,211 in conciliation court and $3,411 in district

court. Just a quarter of consumers are sued for

$4,000 or more.

Although these amounts may seem low, plaintiffs

spend a considerable amount of time, money,

and effort trying to recoup these debts. And for

individual consumers who have had difficulty

paying back the debt they’ve accrued, the amounts

are significant. Litigating large numbers of these

small-dollar matters, which ostensibly could be

resolved outside of formal legal action, also places a

significant strain on court dockets.

The majority of plaintiffs

are debt buyers

Debt lawsuits in the state are largely

driven by a small number of high-volume

plaintiffs with expertise in filings such

claims and access to and mastery of

court tools, such as bulk filing, that allow

them to pursue and win large numbers

of cases�

6

In fact, just 10 firms were

responsible for filing two-thirds of debt

suits in the state in 2020 and 2021�

7

The majority of these cases involve credit card debt:

in district court, 95% of all lawsuits brought by debt

plaintiffs were over credit card debt, according to a

review of case documents among a random sample

of debt lawsuits filed between 2018 and 2021.

Three-quarters of debt cases filed in conciliation

court dealt with credit card debt.

The majority of plaintiffs are debt buyers--third-

party companies that purchase debts from original

creditors, often for pennies on the dollar, with the

intention of collecting the full amount owed.

8

Of the

top plaintiffs in Minnesota, debt buyers filed half of

all lawsuits from 2017 to 2019.

During that same time period, credit card companies

and banks filed 21% of lawsuits and medical

providers filed 12% of lawsuits. The remaining 18%

of debt cases were filed by smaller filers, such as

payday and other lenders.

Research Findings The characteristics of plaintiffs, debts, and consumers

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

19

Medical debt in Minnesota

In recent years, medical debt has

emerged as an area of concern for

policymakers� Medical debt and

other forms of debt, such as credit

card debt, are often intertwined and

interconnected� For example, patients

may resort to charging medical bills to

their credit cards, resulting in unpaid

credit card balances that actually stem

from medical expenses� Additionally,

some individuals may prioritize

paying their medical bills directly but

rely on credit cards to cover other

essential expenses like groceries

and transportation costs� Therefore,

while it is essential to recognize the

significance of medical debt as a

distinct issue, it is equally important to

acknowledge its interconnectedness

with credit card debt and the broader

financial challenges individuals face�

By adopting a holistic perspective,

policymakers can develop

Original Creditor Debt Buyer

Goods and Services 95%

Payday Loan/Fees 94%

Housing (Rent and HOA fees) 90%

Medical Services 72%

Auto Loan 69%

Utilities 46%

Credit Card/Bank Loan 30%

Other/Unknown 24%

Insurance-related payments 100%

Bail Bond 100%

Figure 7: Debt buyers and original creditors bring different types of debt to court

comprehensive strategies that address

both medical debt and the related

financial burdens faced by individuals�

The type of debt at issue in debt

collection cases in Minnesota is not

tracked by the courts� To identify

medical debt cases, researchers

reviewed court documents from a

subsample of cases and classified

debt as medical debt based on the

original creditor� Medical debt includes

debt accrued from hospitals, dentists,

outpatient clinics, and other medical

providers�

In Minnesota, medical debt accounts

for 17% of debt collection cases, with

a higher prevalence of such cases

in conciliation court (25%) compared

to district court (7%)� This amounts

to 0�28 cases per 100 adults in

Minnesota�

Whereas most debt litigation in

Minnesota is brought by debt buyers,

the majority of medical debt cases

(75%) are filed by original creditors;

for cases involving other types of

debt, such as credit card debt and

utilities, debt buyers predominate�

The prevalence of original creditors

filing medical debt cases highlights

the direct involvement of healthcare

providers and medical institutions

in pursuing legal action to collect

outstanding medical debts,

underscoring the unique dynamics

and characteristics of medical debt

within the debt collection landscape�

Source: Hand sample (N=1,001 cases) analysis of Minnesota consumer debt cases, 2018-2021.

Share of cases filed by original creditors and debt buyers by type of debt, 2019-2021.

5%

6%

10%

28%

31%

54%

70%

76%

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

20

Some of the top filers of medical

debt in the state are medical provid-

ers. Fairview Health Services is the

top filer Minnesota, accounting for

20% of all medical debt collection

filings. Other top medical providers

filing debt collection cases include

Center for Diagnostic Imaging

(10%), Healtheast Care System

(10%), and Mayo Health System

(4.6%). Debt buyers are also filing

medical debt cases in Minnesota,

including Accounts Receivable

Services (12%) and Accounts

Management Inc. (5%).

The amount of money involved in

medical debt cases taken to court

in Minnesota tends to be relatively

modest. The median amount in

controversy is $1,500, with the

interquartile range spanning from

$700 to $2,600. This is a lower

amount than in cases involving

credit card debt, auto loans, and

bail bonds. These figures suggest

that the medical debts subject to

legal action are more frequently

associated with patients who

struggle to meet their deductibles

rather than cases involving

astronomical hospital bills.

PLAINTIFF

Fairview Health Service 20%

Accounts Receivable

Services LLC

11.53%

Center For Diagnostic

Imaging

10%

Healtheast Care System 10%

Accounts Management Inc

5.38%

Mayo Clinic Health System 4.61%

Bradstreet Associates LLC

3.84%

Range Credit Bureau Inc

3.07%

Credit Service Intl Corp 1.53%

Winona Health 1.53%

Woodwinds Hospital 1.53%

Still, the total amount of money owed

in judgments for medical debts is

quite large. In 2019, an estimated $25

million in judgments was issued for

cases involving medical debt.

9

Looking

at case outcomes, most defendants

lose or settle their cases. But there are

important differences between cases in

conciliation and district courts. Medical

debt cases in conciliation court have

below-average default rates (40% vs

52% for all case types in conciliation)

and higher rates of settlement and

dismissals. In district court, medical

debts have a higher rate of default at

88%, which is similar to the average for

all case types in district court. These

differences may be partly due to the

amount of money owed in these cases:

the median medical debt in conciliation

court is $1,200 compared with $3,100

in district court.

Among conciliation court cases,

an estimated 70% of medical debt

cases that result in a judgment

are transcribed to district court,

according to an analysis of event

data from a subsample of cases.

That is slightly higher than the

average among all judgments in

conciliation court of 64%.

Table 3: Four plaintiffs account

for over 50% of medical debt

filings in Minnesota

Top filers 2018-2021, % of medical debt,

categorized by type of debt.

Figure 8: The median amount in controversy varies by type of debt

Median amount in controversy for district court cases by debt type, 2018-2021. Excludes transcript judgments.

0

2500

5000

7500

Auto Loan (1.7%)

Bail Bond (1.8%)

Credit Card/Bank Loan (64.1%)

Goods and Services (5.5%)

Housing (Rent and HOA fees) (2.6%)

Insurance-related payments (1.7%)

Medical Services (16.6%)

Other/Unknown (2.2%)

Payday Loan/Fees (2.3%)

Utilities (1.7%)

Source: random sample review of documents

Source: Hand sample (N=1,001 cases) analysis of Minnesota consumer debt cases, 2018-2021.

$7,688

$4,130

$2,031

$2,400

$1,785

$5,385

$1,507

$1,515

$430

$645

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

21

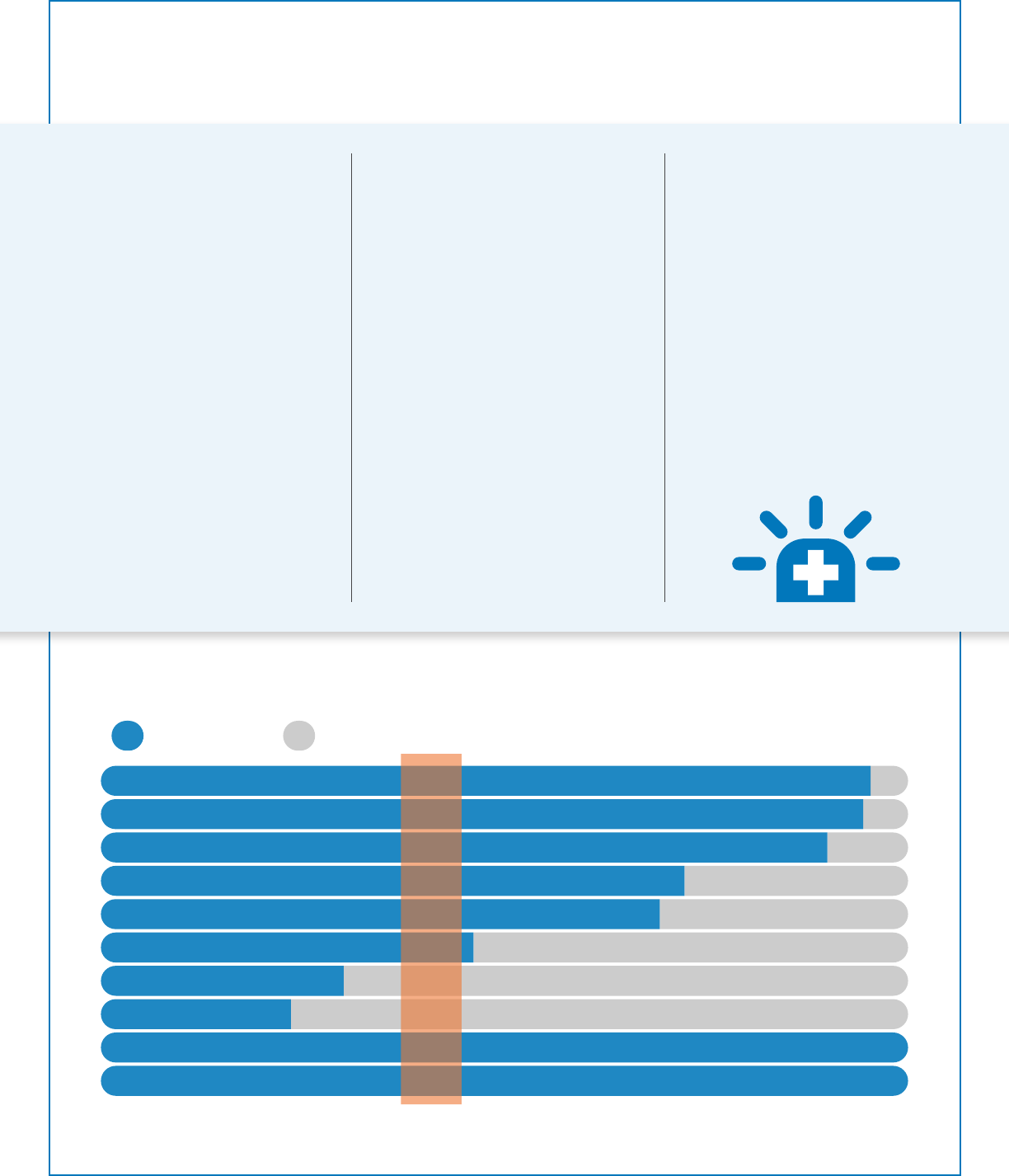

There are racial

disparities in who

is sued for debt

Black and Latino Minnesotans are

sued more often than White Minnesotans.

When creditors turn to the courts for help

collecting a debt, some Minnesotans are

disproportionately impacted.

Overall, the rate of debt claims filed against Black

and Latino Minnesotans is more than twice that of

Non-Hispanic White Minnesotans.

These racial gaps also exist in high-income

neighborhoods. While White Minnesotans in higher-

income neighborhoods tend to have lower rates

of debt claims filed against them than their White

counterparts in lower-income neighborhoods, the

same is not true of Black and Latino residents. In

both lower-income and high-income neighborhoods,

Black and Latino Minnesotans have a much

higher rate of debt claims filed against them than

their White neighbors. This pattern holds even in

Hennepin County, home to Minnesota’s largest

Black and Latino populations.

Figure 9:

Minnesotans of Color

of all income levels

face debt suits at

higher rates

Black and Latino

consumers are sued

two to three times as

often as Non-Hispanic

White consumers.

Number of debt lawsuits filed

per 100 adults by race-ethnicity of

defendant and neighborhood median

household income, 2017-2019.

Defendant’s race-ethnicity estimated

using first defendant’s surname and

race-ethnicity of census tract of

residence.

Figure 10: Minnesotans living in lower-income

areas are sued for debt in higher proportions

Debt litigation is brought more frequently against those

living in neighborhoods with a median household

income of $50,000 or less than those above $50,000.

Number of debt lawsuits filed per 100 adults by

neighborhood median household income, 2017-2019.

Only among non-Hispanic White residents are debt

caseloads highest among individuals in lower-income

neighborhoods, where the median household income

is less than $50,000, and lower among those in

higher-income neighborhoods, where the median

household income exceeds $75,000 a year.

This aligns with national data on borrowing.

Although higher-income households tend to borrow

more money through their credit cards than other

households, the amount of credit card debt that

lower-income households take on makes up a larger

percentage of their monthly income and liquid assets.

n Asian/AAPI n Black/African American n Hispanic/Latino n Non-Hispanic White n Other race-ethnicity

$50,000 or less $50,000 to $75,000 $75,000 or more

$50,000 or less $50,000 to $75,000 $75,000 or more

1.81.8

1.61.6

1.21.2

0

1

2

Debt filing rate (per 100 adults)

Research Findings The characteristics of plaintiffs, debts, and consumers

Source: Minnesota Judicial Branch Civil Case Extract, 2017-2019; American Community Survey

3

2

1

0

1.6

1.7

1.4

3.0

3.2

3.0

2.7

3.0

2.7

1.5

1.4

1.1

1.7

1.8

1.4

1.8

1.6

1.2

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

22

Legal representation

is uneven

Consumers rarely have legal representation;

plaintiffs almost always do.

Consumers have legal representation in only 3% of

district court cases and 0.2% of conciliation cases.

Plaintiffs, on the other hand, have representation in

98% of debt cases in district court; in conciliation

court, 69% of plaintiffs have an attorney.

Debt plaintiffs rely heavily on five specialized law

firms. Those five firms represented plaintiffs in nearly

60% of cases filed in 2018-2021.

There is a huge divide between plaintiffs and

defendants when it comes to their ability to navigate

civil court processes because so many cases are

litigated on the plaintiff side by law firms who are

skilled in these cases, and many of these firms work

on behalf of a handful of experienced companies

whose business is buying and collecting on unpaid

debts.

Conversely, many consumers involved in debt

litigation may fall into the “legal aid gap,” meaning

they do not have enough money to hire a private

attorney, but they earn too much to qualify for legal

aid services.

10

The income threshold for most legal aid eligibility

in Minnesota is 125% of the federal poverty line.

For a family of four, that’s less than $37,500 a

year. Statewide in 2019, only 8.4% of families in

Minnesota live below this threshold. Using census

tract information, the research team estimated

82% of all debt collection cases filed in Minnesota

from 2017 to 2019 were against consumers with

household incomes ineligible for legal aid.

Nearly two-thirds of cases were filed in

neighborhoods where fewer than 1 in 10 families

qualify for legal aid. The disconnect between people

needing free and affordable legal help and actually

being able to qualify for it, coupled with the fact

that Minnesota legal aid doesn’t have the resources

and attorneys to meet the demand for assistance,

meant legal aid programs were only able to serve

3,000 debt-related cases between 2019 to 2021.

Absent programs or legal resources for mid- or

moderate-income Minnesotans, a significant number

of defendants in consumer-facing debt lawsuits are

left to navigate the system on their own.

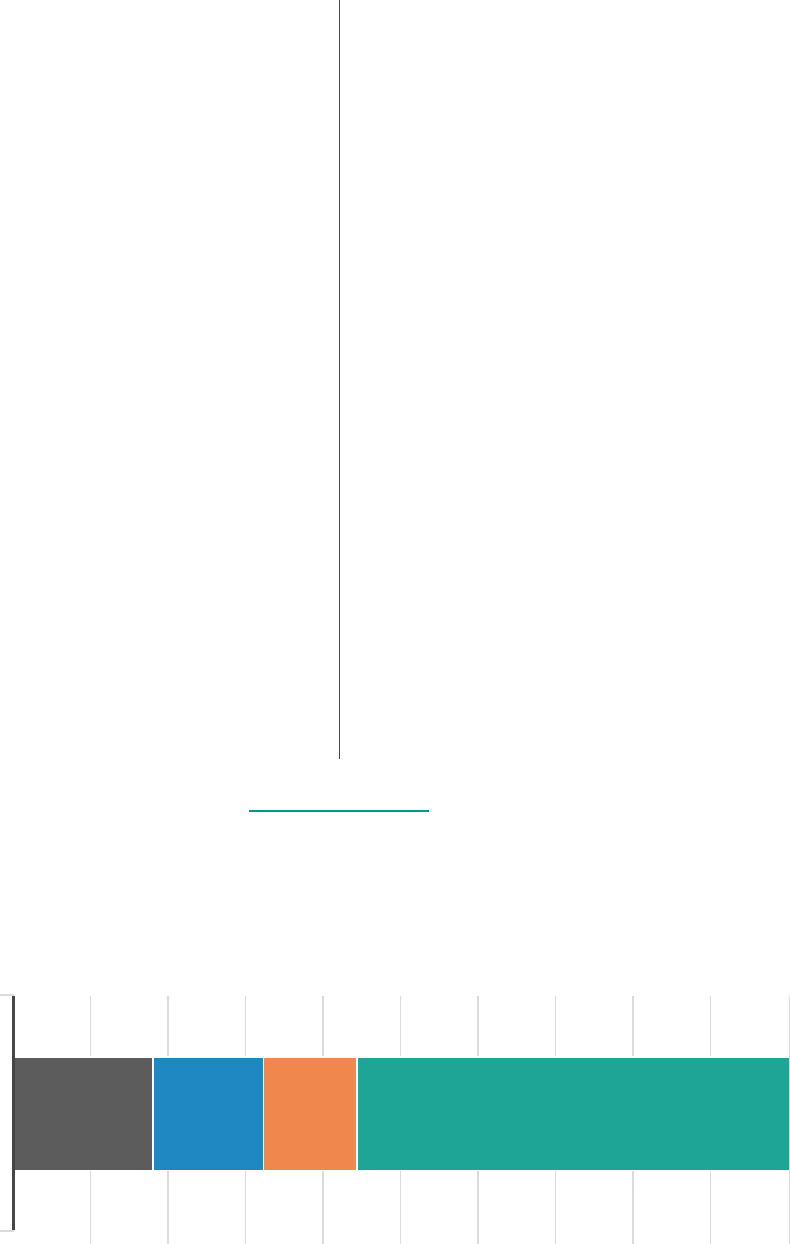

Figure 11: Consumers in debt span the income spectrum

More than half of suits are filed against Minnesotans earning less than $75,000 for a family of 3

(approximately 300% of the federal poverty line), but litigation affects all income groups.

n <125% FPL n 125%-199% FPL n 200%-299% FPL n 300%+ FPL

Research Findings The characteristics of plaintiffs, debts, and consumers

18�1% 14�2% 12�1% 55�6%

Estimate share

of debt collection

lawsuits filed

against adults

living above and

below the federal

poverty line,

2017-2019.

Source: Minnesota Judicial Branch Civil Case Extract, 2017-2019 American Community Survey

00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 0100 100

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

23

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

23

Research Findings

How cases are processed in

district and conciliation court

1. Debt cases in Minnesota

can be handled in one of

two venues, district court or

conciliation court, which have

very different processes and

requirements�

2. For cases involving $4,000

or less, plaintiffs can choose

the venue, leading to different

outcomes for consumers with

otherwise identical cases�

3. One in 10 district court

debt cases is filed eight

months after service, leading

to confusion when consumers

seek information about the

case from the courts�

4. The answer process in

district court is costly, unclear,

and inconsistent�

5. Debt litigation in district

court often ends in default

judgment�

6. Most plaintiffs submit at

least some of the required

documentation materials, but

many who don't still receive

default judgments in their favor�

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

24

Debt cases in Minnesota

are handled in one

of two venues

Consumer debt collection cases in Minnesota

are filed in one of two venues: district court or

conciliation court. Between 2017 and 2019,

approximately 57% of all debt collection lawsuits

were initiated in conciliation court; the remaining

43% were filed in district court.

Conciliation Court: 364,198

Transcript Judgment: 184,748

District Court: 485,401

Conciliation Appeal: 1,106

District Court Summons: 299,547

Defendant Responds: 66,238

Confession of Judgment: 11,986

Consumer Credit Contract: 54,252

No Response: 233,309

Default Judgment: 233,309

Settled/Dismissed/Not Transcribed: 178,344

District court provides plaintiffs with the opportunity

to seek judgments that enable them to collect

money from defendants through various means,

such as wage garnishment or seizing funds from

bank accounts. Conciliation court imposes a limit of

$4,000 on the maximum amount of money at stake

in a lawsuit. However, if a plaintiff in conciliation

court intends to use the garnishment process

to enforce a judgment, they can transcribe the

judgment into district court and then do so.

Of the cases filed in conciliation court between

2018 and 2021 that resulted in a judgment, more

than 60% were transcribed to district court for

further legal proceedings and enforcement actions.

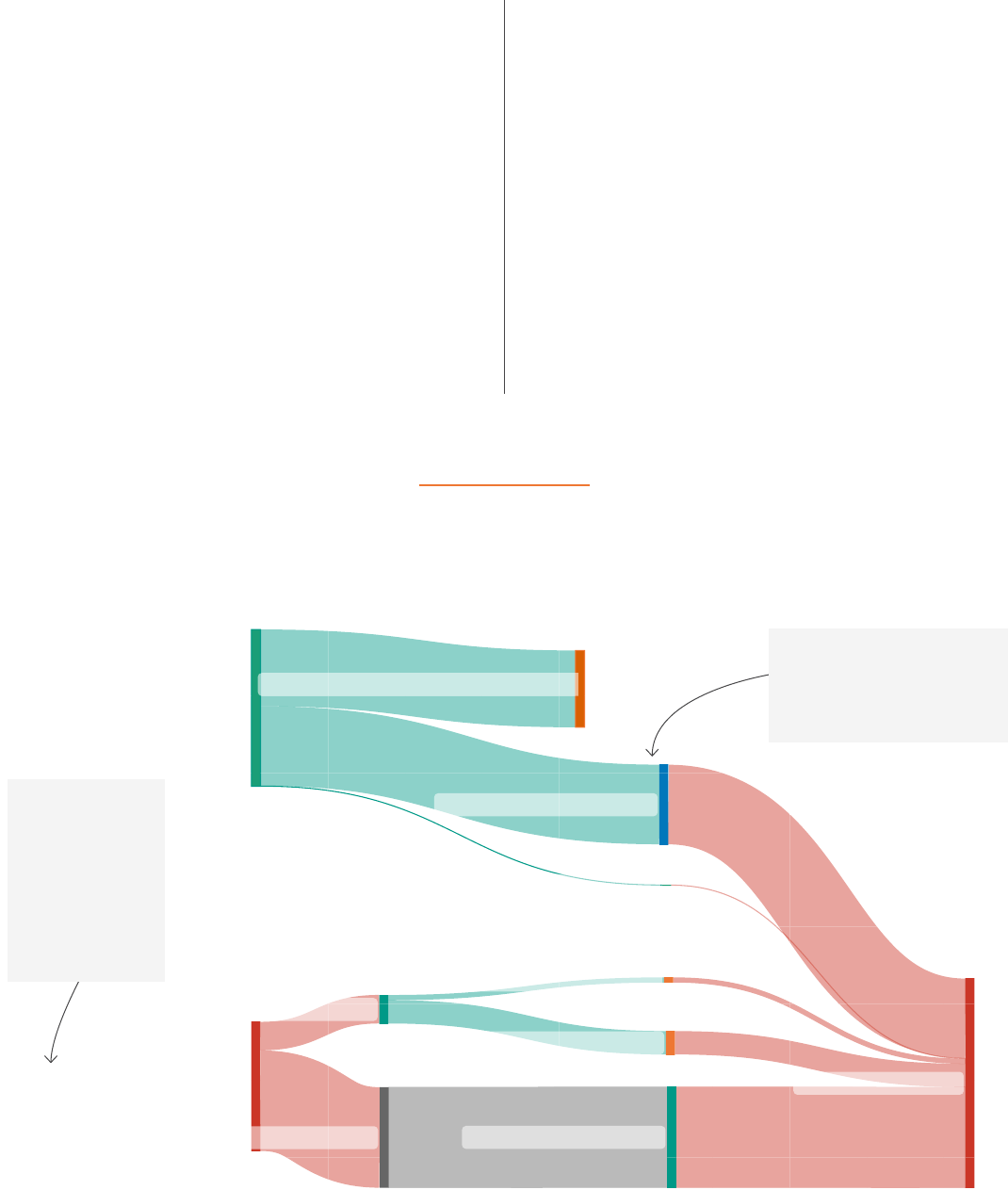

Figure 12: Volume of debt cases flowing through Minnesota’s civil courts

Conciliation and district courts both see a substantial volume of debt cases every year.

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

Source: January Advisors analysis of Minnesota Civil Judgment Extract

Transcript Judgmentsare not new

cases, but conciliation cases filed in

district court so that the judgment

can be enforced, e.g., through

garnishment.51%of conciliation court

cases are transcribed to district court.

Before district court

cases are filed,

defendants have 21 days

to respond to a properly

served summons. If they

do not respond, plaintiffs

can file the case as a

"Default Judgment."

How many outstanding

cases were never filed is

unknown.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

25

For cases involving

$4,000 or less, plaintiffs

choose the venue

Conciliation courts in Minnesota were designed

for the express purpose of creating a venue

“where people can have their cases heard without

complicated legal procedures.”

11

Sometimes

referred to as the “people’s court,” conciliation court

proceedings were designed to be easier to navigate

by non-attorneys.

Minnesota court rules allow plaintiffs to file

consumer debt claims involving less than $4,000

in either conciliation court or district court. Venue

choice varies from plaintiff to plaintiff. Some plaintiffs

prefer to file all of their cases in district court, some

file only in conciliation court, and others split cases

across venues.

Because conciliation court cases can be

transcribed to district court post-judgment,

the choice of venue doesn’t seem to make a

huge difference for plaintiffs, but does affect

consumers� One of the biggest impacts is

related to cost: when plaintiffs file cases

involving small amounts in district court, it’s

more costly for consumers, due to higher

filing fees and other costs that are ultimately

added to the judgment�

The difference between the judgment amount

and the original claim amount is greater in district

court ($360 in district court, compared to $80 in

conciliation court). District court cases involve

higher filing fees and court costs than conciliation

court cases.

Nearly six in 10 debt cases filed in district court

involve less than $4,000, and around half of the

cases in district court are for amounts under

$3,000. All of these cases are eligible to be filed in

conciliation court.

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

26

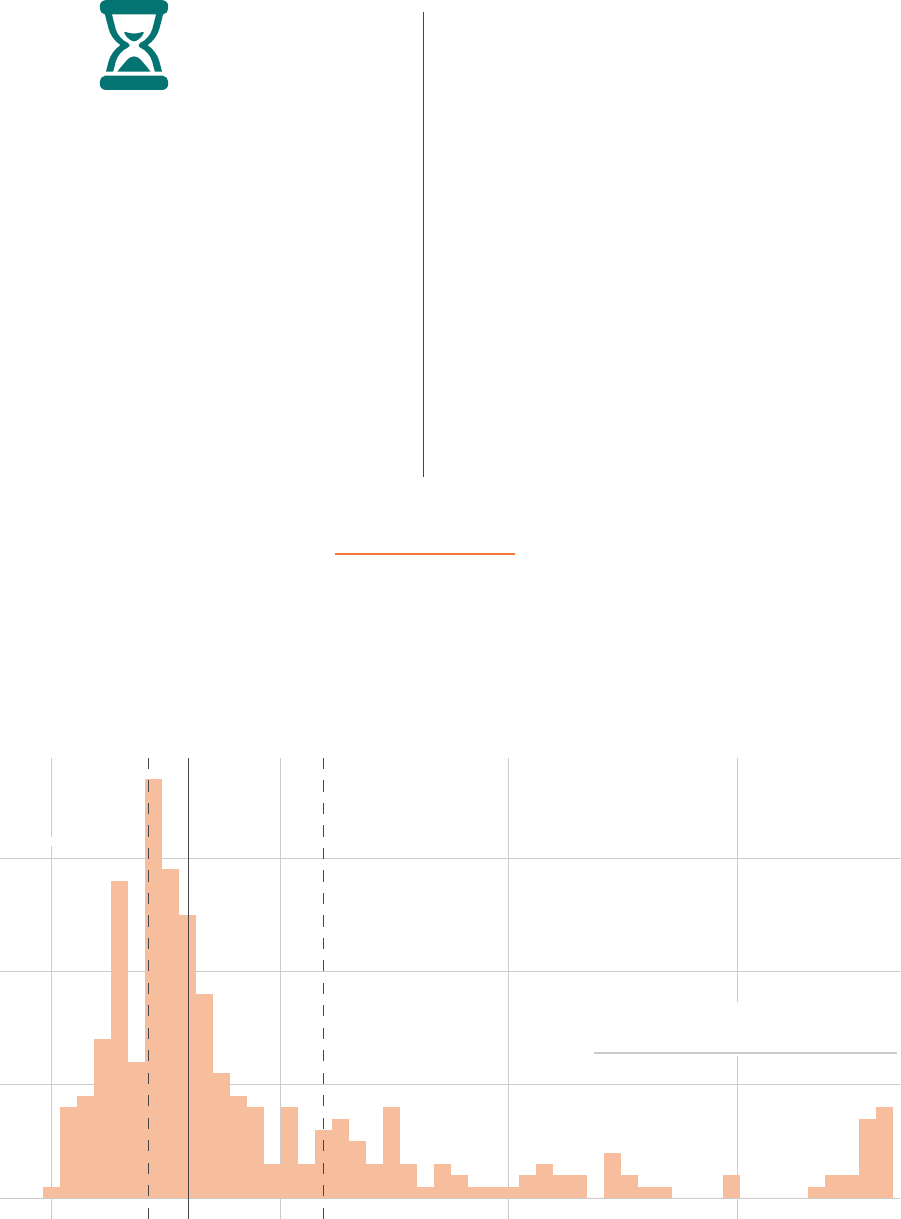

Figure 13: One in 10 district court cases are filed more than eight months after service

Most cases are filed within three months of service, but some

plaintiffs take advantage of Minnesota’s long window to file.

Distribution of district court cases (not including transcript judgments) by number of days between service and filings, 2018-2021.

One in 10 district court

debt cases filed more

than eight months after

the defendant is served

Most plaintiffs who filed a case in district court

did so within one to three months of serving a

defendant, but some took advantage of Minnesota’s

year-long grace period to file. One in 10 district

court cases are filed more than eight months after

the defendant is served.

Although fewer than 10% of cases are filed eight

months or more after service, that number still

reflects thousands of real Minnesotans facing the

uncertainty of debt litigation hanging over their

heads for months on end.

The yearlong grace period offers consumers and

debt plaintiffs a window of opportunity to settle a

case without filing.

It is impossible to know the number of cases that

are settled after the defendant has been served but

before the case is filed, since this process takes

place entirely outside of the court process. These

“ghost” cases are never known to the court because

the plaintiff doesn’t have to file them in court.

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

Source: Random sample (N= 1,001 cases) analysis of Minnesota consumer debt cases, 2018-2021

Number of cases

0 100 200 300

30

20

10

0

Number of days between service and filing

25th: 44 days 75th: 119 days

<10% of cases filed

8 months after service

Median:

60 days

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

27

The answer process in

district court is costly

and confusing

In district court, consumers are required to file a

formal answer to a case against them within 21

days, but doing so costs the consumer $285 or

more in “answer fees.” Defendants in conciliation

court, on the other hand, aren’t required to file a

written answer to either the plaintiff or the court

before scheduling a hearing; if they wish to file a

counterclaim, the cost is between $65 and $80.

Most neighboring states’ civil courts do not collect

answer fees in civil courts; those that do typically

have much lower fees than Minnesota.

In addition to the high cost associated with the

formal answer process, which may deter consumers

from responding, the answer process itself can

cause confusion, due to the lag time between

service and when a plaintiff files a case in district

court (because conciliation court does not allow hip

pocket filing, it eliminates the confusing process of

requiring defendants to respond to a case that has

not yet been filed in court).

Information gained through court data shows

that it is rare for a consumer to submit a formal

answer with the court. Stakeholders shared that

it is more common for defendants to submit some

sort of response directly to the plaintiff instead of

filing it with the court, and plaintiff attorneys we

spoke with mentioned they will accept any written

communication—it doesn’t have to be the court

answer form. Lack of information may be partly to

blame, but the courts have taken action to help

consumers better understand the cases against

them. In 2020, the district court summons (CIV802)

was revised, along with the complaint form, to be

more useful to self-represented litigants.

12

The

updated paperwork provides some information

for consumers who wish to contest a claim, but

summonses do not include details on how to settle

the case, agree to a payment

plan, or protect exempt

assets from garnishment. The

summons does, however, tell

the consumer that “If you

agree with the claims stated in

the Complaint, you don’t need

to respond. A default judgment

can then be entered against

you for what the Plaintiff asked

for in the Complaint.”

Similarly, although the

conciliation court process

is slightly less confusing

and involves fewer steps,

its summonses only provide

information about showing up

for a hearing and submitting

evidence, with no mention of

how to settle a case, agree

to a payment plan, or protect

wages from garnishment.

An examination of a sample of 106 cases filed in

district court since the revised form was adopted

found that none of the plaintiffs were using the new

form. Additionally, none of the forms the plaintiffs

prepared included plain language instructions and

links to the court’s help topic pages.

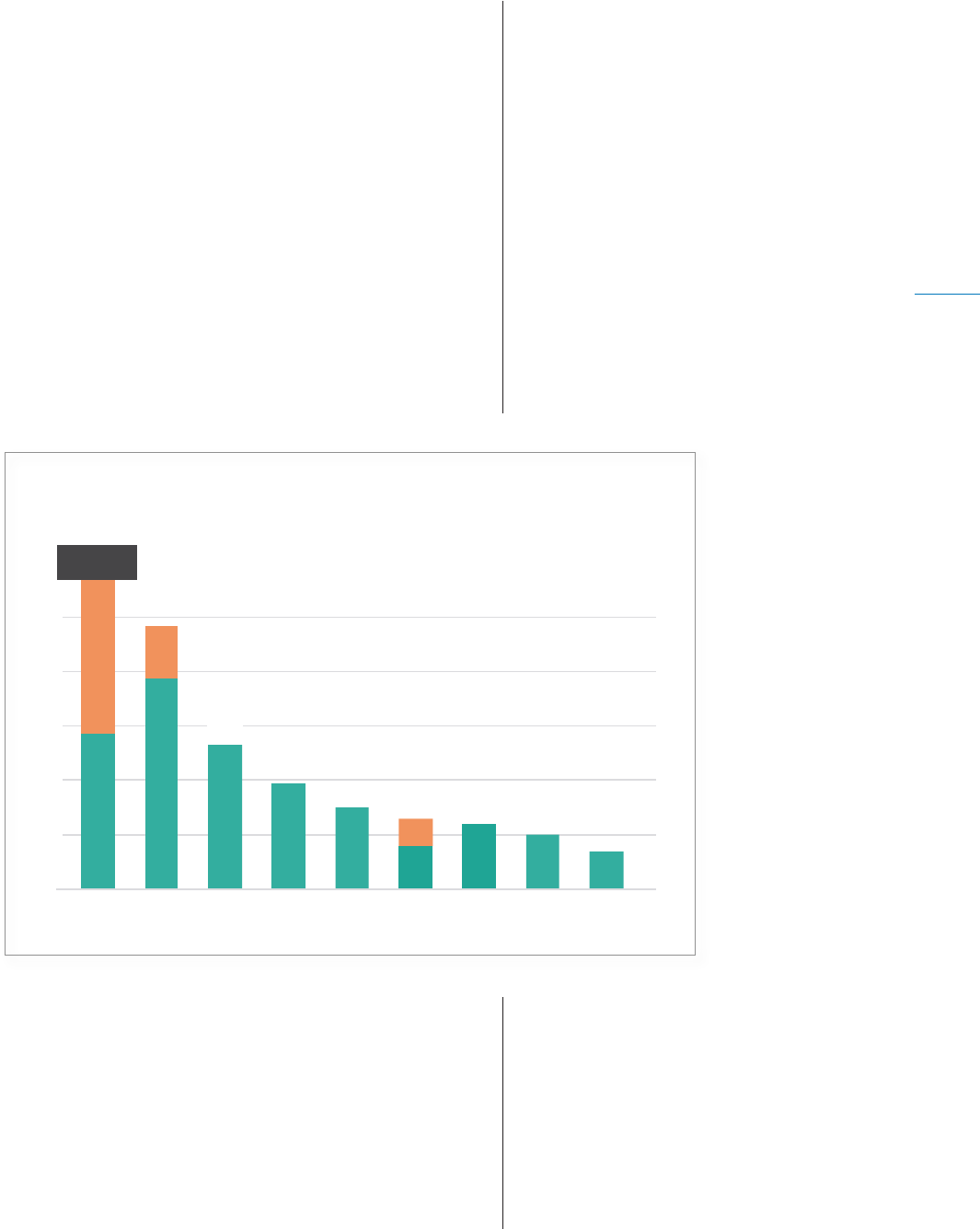

Figure 14: Comparison of filing and answer fees

Minnesota's costs to file make it an outlier among its neighbors.

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

n Filing Fee n Answer Fee

$500

$400

$300

$200

$100

$

570

$

484

$

266

$

195

$

150

$

130

$

120

$

100

$

70

MichiganWisconsinIllinois Iowa North

Dakota

Indiana South

Dakota

Ohio

Source: Pew analysis of selected civil court costs

Minnesota

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

28

Most debt cases in

Minnesota end in

default judgment

District Court

When a consumer fails to respond, or file an answer

to, a lawsuit, the matter ends in default judgment:

an automatic decision in favor of the plaintiff when

a defendant doesn’t adequately participate in the

case against them. Eighty-two percent of consumer

debt cases filed in district court end in default,

versus 54% in conciliation court. This rate may be

higher because other states do not allow hip pocket

service, which may indicate more cases being

resolved outside of court.

This district court default rate is higher than in most

states and above national numbers: in 2020, The

Pew Charitable Trusts reported that more than 70%

of debt collection lawsuits (in jurisdictions with

available data) ended in default judgments for the

plaintiff between 2010 and 2019.

Conciliation Court

For the 36,000 Minnesotans who are sued for debt

in conciliation court each year, there are fewer

barriers to participation. Conciliation court has no

answer requirement and when a plaintiff files a case,

the court automatically schedules a Zoom hearing.

Still, less than half of defendants show up to their

hearing in conciliation court. When they do, they

are often sent to breakout rooms with the creditors’

attorney to negotiate a payment plan, without a third-

party mediator and or any information about their

rights provided by the court. At the moment, there’s

no conciliation court form available for defendants

to deny or dispute the claim ahead of the hearing, or

to guide them through available defenses, such as

a debt being past the statute of limitations or having

been discharged by bankruptcy.

District court cases

add more costs for

consumers

In addition to a higher answer fee, district court

cases have other higher costs for consumers. Cases

that result in a judgment against the defendant

have a median final judgment amount that is

approximately $360 higher than the original amount,

compared to $80 higher than the original amount in

conciliation court cases.

Plaintiffs in district court also request post-judgment

interest more often than in conciliation court, which

can end up costing defendants $600 or more over

the original judgment amount.

$1,000 original claim

+ $167.00

pre-judgment interest and fees

+ $285.00

filing and service fee

+ $479.16

attorney fees (1/3 claim + interest + fee)

+ $96.56

5% post-judgment interest rate

+ $15.00

garnishment filing fee

$2,042.72

total judgment by end of year

Table 4: How costs add up for a consumer in a

typical debt lawsuit in district court

Minnesotans with debt cases face a host of costs and

fees in addition to the amount in controversy.

Because the typical debt lawsuit goes unanswered by the consumer, the $285 district

court answer fee is not included in this table.

Source: Minnesota Judicial Branch

13

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

29

When defendants in a district court debt case don’t

file an answer—likely due to confusing processes,

associated costs, or other factors—plaintiffs can

file for a default judgment. Minnesota, alongside

California, Arizona, Texas and North Carolina, was

a leader in requiring certain plaintiffs to prove the

legitimacy of their claim and that they are the proper

owner of the debt, even when the defendant does

not participate.

1. Copy of the written contract

2. Proof the defendant owns the debt

3. Last 4 of defendant’s SSN, if known

4. Proof of amount of debt

5. Name of original creditor

6. Breakdown of costs, fees, interest, as applicable

7. Valid and complete chain of title

8. Proof of service

9. Proof of 14 days’ notice of intent to apply for

default judgment.

Debt buyers are only required to file these

documents when seeking a default judgment, but

they do not have to include this information with the

initial complaint or to serve them on the consumer

with the notice of intent to seek default judgment.

This means consumers can still receive summonses

and complaints from a debt buyer they do not

recognize without any information on the original

creditor; in addition, they do not have access to

documents to validate the legitimacy of the claim,

the age of the debt, or the calculation of the amount,

unless they go through the process to request them.

Debt buyers applying for a default judgment are also

required by the statute to send an additional notice

to the consumer. Even then, there is no requirement

that the documentation proving the plaintiff’s claims

must be included in this notice.

Original creditors, such as credit card companies,

banks, payday lenders, or hospitals, are not required

to file any documentation proving the validity of

their claim. If the defendant fails to participate, the

creditor will get a default judgment without having to

show additional documentation.

Documentation of debt

Minnesota leads the region in requiring plaintiffs to file documentation, but requirements

only apply to debt buyers, and documents are not served to defendants.

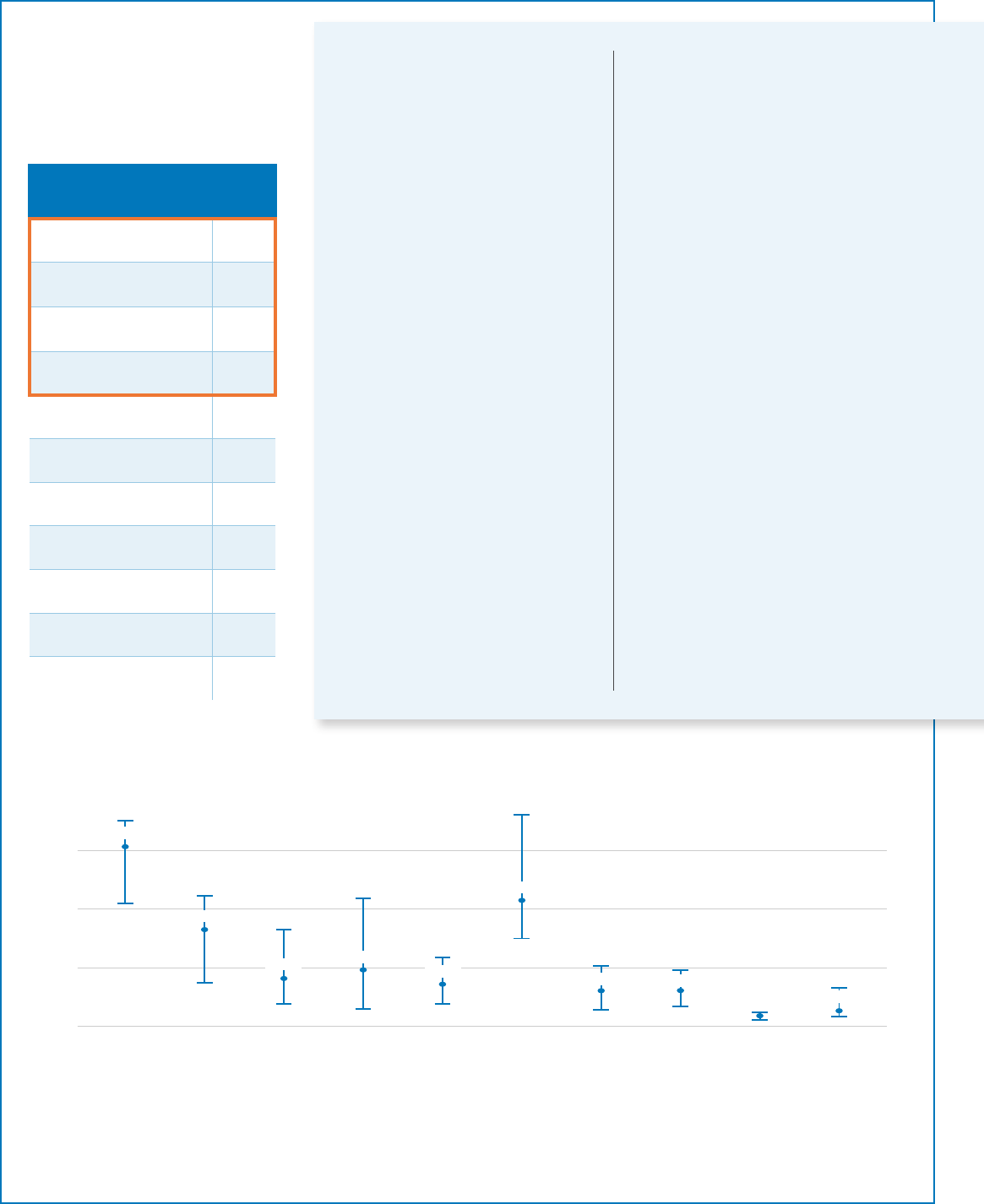

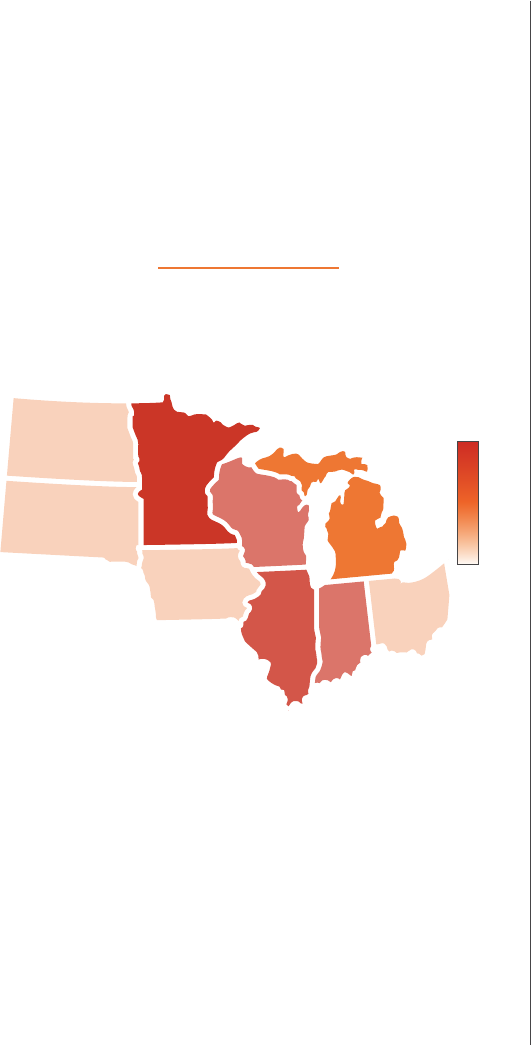

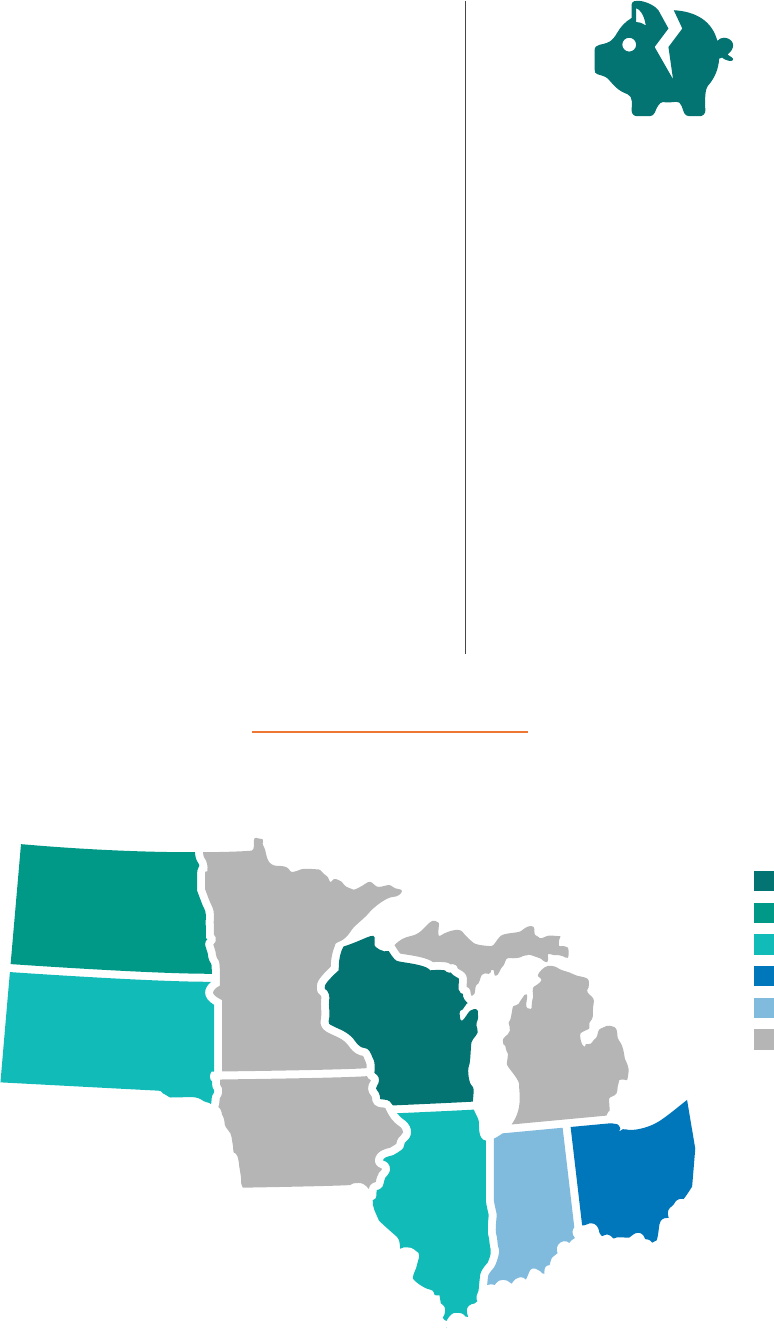

Figure 15: Minnesota has higher plaintiff burden

of proof than other Midwest states

The state leads region in requirements for debt buyers.

Plaintiff's

Burden of Proof:

The darker reds

indicate a relatively

higher burden of proof for plaintiffs in

consumer debt lawsuits; Minnesota is a

leader among its neighbors in requiring

debt buyers to fully substantiate their claims

before receiving a default judgment.

Minn. Stat. §548.101, enacted in 2013, requires

debt buyers who are seeking a default judgment to

file with the court proof of account, proof of amount,

and proof of ownership of the debt.

14

Before the

court may enter a default judgment, debt buyers

must submit the following documentation to the

court:

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

Source: Based on an analysis of court rules and state statutes that apply to debt

collection lawsuits in state civil courts.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

30

Although this documentation requirement was

implemented after a 2013 law change, to date, there

has been little data on compliance.

To determine whether debt buyers have

provided proper documentation in accordance

with regulations, researchers spot-checked a

representative sample of files for two of Minnesota’s

nine requirements. This analysis reviewed a

random sample of publicly available documents

in 1,000 cases filed in district court by debt

buyers between 2018-2021, looking for proof of

ownership and account. The analysis shows that

in an overwhelming majority of cases (79%), debt

buyers produced documents that met requirements.

In 12% of cases, the documents were sealed, and

in 9%, the debt buyer did not produce the required

documentation.

Despite the requirement that these documents be

filed before a default judgment is entered, almost

all cases lacking proper documentation still ended

in a default judgment (88% or 15 of the 17 cases

reviewed).

The data also showed that the large debt buying

companies that filed a high volume of cases each

year with the same few specialized law firms had

above average rates of documentation compliance.

Smaller debt buyers were much more likely to be

missing documentation.

Estimating documentation compliance

Most debt buyers submitted at least some of the required documentation materials,

but many who didn’t still received default judgments in their favor.

Figure 16: Most debt buyers present

required case documentation

Nearly 80% of debt buyer plaintiffs can show

documents proving their ownership and the

validity of the debt they are using the court to

collect, but it falls to the debtor to challenge the

veracity of those proofs.

9%

missing at least

one document

n 12% documents are sealed

n 79% has both documents

Research Findings How cases are processed in district and conciliation court

Compliance status with documentation requirements for debt buyer cases filed in

district court, 2018-2021.

Source: Hand sample (N=1,001 cases) analysis of Minnesota consumer debt cases,

2018-2021.

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

31

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

31

Research Findings

What happens after court

1. Minnesota courts have very little oversight of the

garnishment process�

2. Long-term consequences of debt judgments can

follow consumers for years�

3. Debt case outcomes harm defendants but don’t

make plaintiffs whole�

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

32

Enforcing a judgment

Minnesota courts have little oversight of the

garnishment process.

Garnishment is one of the few tools available to

plaintiffs to collect an outstanding debt. Because

garnishment is one of the most powerful tools the

court offers litigants, in most states courts remain

involved in this post-judgment process, usually

requiring plaintiffs to request a “writ of execution,”

which prompts the issuance of a garnishment

summons to the consumer’s employer and/or financial

institution to initiate the garnishment process.

In Minnesota, the process works differently, and most-

ly outside of the court’s oversight. Garnishment sum-

monses are prepared by the plaintiff’s attorney and

can be served to the consumer’s bank and employer

directly, without filing any record of it with the court.

As a result, debt plaintiffs in Minnesota can have funds

withheld from a consumer’s paycheck or can have

their bank accounts frozen without the court having

any knowledge of these transactions. If this happens,

the plaintiff can seek a writ of execution from the

courts, incurring a fee that is ultimately added to the

judgment amount, or the consumer can voluntarily

agree to have the funds released to the plaintiff by the

employer or bank.

15

This is different from most states,

where the plaintiff applies for a writ before they begin

the garnishment process and communications with

garnishees, and where the court issues the summons

for the garnishees and notice to the debtors or, in

cases like those in Illinois or Massachusetts, even

holds a garnishment review hearing.

The state’s garnishment exemption process also oper-

ates outside of the court: defendants who believe that

some or all of their wages or other assets are exempt

from garnishment send their exemption forms directly

to the plaintiff, rather than the court. In most states,

the exemptions are filed directly with the court and it

is up to the judge to review and approve them.

Minnesota has policies exempting anyone who re-

ceives means-tested public benefits from having their

wages garnished. However, these exemptions are not

self-executing, meaning the onus is on the consum-

er to assert that their wages are exempt to avoid the

disruption of post-judgment seizure. Without addi-

tional data, it is difficult to ascertain whether and to

what extent consumers are able to benefit from these

protections. Defendants get a notice 10 days before

their wages are withheld and have 10 days to claim

exemptions. After they claim exemptions, they have

to wait six more days for the creditor to object before

they can get their wages back.

Within 6 days of exemption notice

being filed (Creditor Objects!)

by filing a notice of objection with

the court and mailing a notice of

objection and notice of hearing

to bank and debtor.

(Debtor Objects!)

by filing a notice of objection

with the court and mailing a

notice of objection and notice

of hearing to bank and creditor.

Exemption Hearing

Hearing no sooner than

5, but no later than

7 days from filing.

Figure 17: Disputing exemptions

Aside from issuing a writ of execution upon plaintiff’s request, the court will generally not

get involved in the enforcement process unless one of the parties objects.

The creditor has six days

to object to the debtor’s

exemption notice.

The debtor can object if

they believe the creditor

is garnishing assets that

should be exempt.

If there is an objection,

the court will schedule an

exemption hearing.

These are rare.

Research Findings What happens after court

Source: Analysis of Minnesota policies, including Minn. Stat. §571.72

MINNESOTA CONSUMER DEBT LITIGATION |

33

Minnesota does not have a personal property exemption

protecting funds in a bank account. The only funds

exempt from seizure are federal and state means-tested

benefits. Federal benefits tend to be electronically tagged

so the bank can see that they are exempt assets, but state

benefits like the Minnesota Family Investment Program

(MFIP) are not, making it impossible for banks to discern

that these are public benefits that are exempt. Wages

deposited in a bank account are also exempt from seizure

for 20 days after deposit, though the burden is on the

consumer to show that they can be traced back to their

employment. In the case of bank accounts, consumers

don’t get notice until two days after the funds are frozen,

and then they have 14 days to claim that some of those

assets should be protected, such as public benefits or

wages. Creditors are given six days to object.

What this means for

consumers is that their

entire bank account,

including protected

assets, could be frozen

before they even get

notice, and that they

can stay frozen for a

week, with no access

to any money to cover

basic needs�

Minnesota is one of three

midwest states with no

bank account protections

for consumers

Research Findings What happens after court

Figure 18: Minnesota 1 of 3 Midwest states with no bank account protections for consumers