Patient Experience Journal Patient Experience Journal

Volume 6 Issue 3 Article 12

2019

Enhancing emergency care environments: Supporting suicidal Enhancing emergency care environments: Supporting suicidal

distress and self-harm presentations through environmental distress and self-harm presentations through environmental

safeguards and the built environment safeguards and the built environment

Stephanie Liddicoat

Swinburne University, Melbourne, Australia

Follow this and additional works at: https://pxjournal.org/journal

Part of the Environmental Design Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Interior

Architecture Commons, Other Architecture Commons, Other Mental and Social Health Commons, and the

Psychiatric and Mental Health Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Liddicoat S. Enhancing emergency care environments: Supporting suicidal distress and self-harm

presentations through environmental safeguards and the built environment.

Patient Experience Journal

.

2019; 6(3):91-104. doi: 10.35680/2372-0247.1361.

This Research is brought to you for free and open access by Patient Experience Journal. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Patient Experience Journal by an authorized editor of Patient Experience Journal.

Enhancing emergency care environments: Supporting suicidal distress and self-Enhancing emergency care environments: Supporting suicidal distress and self-

harm presentations through environmental safeguards and the built environment harm presentations through environmental safeguards and the built environment

Cover Page Footnote Cover Page Footnote

This article is associated with the Environment & Hospitality lens of The Beryl Institute Experience

Framework. (http://bit.ly/ExperienceFramework). You can access other resources related to this lens

including additional PXJ articles here: http://bit.ly/PX_EnvtHosp

This research is available in Patient Experience Journal: https://pxjournal.org/journal/vol6/iss3/12

Patient Experience Journal

Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019, pp. 91-104

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

© The Author(s), 2019. Published in association with The Beryl Institute

Downloaded from www.pxjournal.org 91

Research

Enhancing emergency care environments: Supporting suicidal distress and

self-harm presentations through environmental safeguards and the built

environment

Stephanie Liddicoat, Swinburne University, sliddicoat@swin.edu.au

Abstract

Self-harming and suicidal distress are prevalent, worldwide healthcare issues. Existing literature explains that both self-

harm and suicidal presentations at Emergency Departments are increasingly occurring, correlating to high costs in

healthcare service delivery. This scoping review aimed to (1) identify the current body of literature which examined the

relationship between design practice and service user experiences within Emergency Departments for self-harm and

suicidal distress presentations, and (2) identify the ways in which the built environment could increase the efficacy of

therapeutic efforts through improving service user outcomes and experiences. This scoping review established that there

was a paucity of research at the time of the review linking the design of the built environment with the provision of care

for self-harm and suicidal distress presentations specifically in Emergency Departments. This is despite the fact that

there is a significant body of literature pronouncing the links between good design practice and support of mental

wellbeing. However, this scoping review established the existence of a limited range of articles related to how design

practice can assist in addressing challenging behaviours, such as service user violence, and issues associated with triage of

clients with a mental illness. Design strategies from the literature are collated and discussed. Limitations of the field and

potential methodologies to address these limitations are also presented.

Keywords

Self-harm, suicidal distress, emergency department design, built environment, evidence-based design, environmental

safeguards

Introduction

In studies worldwide, it is cited that as many as 4% of

adults regularly self-harm, though this is likely not

representative of the full number of self-harming

individuals.

1

In the United States there are 650,000

presentations of self-harm per year,

2

and the strongest risk

factor predictive for suicide is previous self-harm.

3

It is

noted that at least 1% of patients who present to

emergency departments in the United Kingdom after self-

harm complete suicide within a year, and a further 3-5%

do so within the following 5-10 years.

4

Recent Australian

studies demonstrate that there were more than 26,000

hospitalisations for self-harm across Australia in 2010-

2011

5

and that this was a significantly rising trend over a

ten year period

5

. Presentations of self-harm and suicidal

distress are also often recurring; Lilley et al. note that 25%

of individuals presenting at hospital after self-injuring have

a history of self-harm,

6

and Owens and colleagues note

that 15-25% of individuals are likely to repeat within

twelve months.

7

The number of patients who have a mental illness

presenting to emergency departments (EDs) has been

consistently increasing. This has been attributed to the

mainstreaming of mental health services into general

services.

8

There is evidence suggesting that, in addition to

the increases in presentations by patients with a mental

illness, these patients are also presenting with increased

acuity.

9, 10

Morphet and colleagues suggest that 5-10% of

all presentations to Australian EDs are mental health

presentations.

11

Mental health patients present some of

the most challenging clinical situations to ED staff in

regards to their assessment and management

12-15

and are

commonly taxing to the ED due to long stays,

12

high

hospital admission rates

16, 17

and repeat use of the ED.

18

These issues are likely to increase with growth of

population and individuals experiencing mental

disorders.

19

Many service users present to the ED in an

acute crisis. Service users with challenging behaviours,

such as those who are acutely agitated, psychotic, or

aggressive, present ED staff with clinical situations that are

very demanding.

8

Presentation to EDs due to suicidal

distress and/or self-harm are frequent. Service users may

need urgent medical attention due to self-injury, and

community services may not be easily accessible.

8

Given

the interplay between architectural design and quality of

care, several researchers underscore the need for co-

operation among architects/designers and the service

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

92 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

users and staff who will experience the facilities they

create.

20, 21, 50

Built environment/architecture and mental wellbeing

There is a considerable body of literature affirming links

between mental wellbeing and good design practice.

Evaluations of specific design interventions have shown

that good design of a hospital’s environment leads to

better clinical outcomes and less stress for the users; both

patients and staff.

22-26

Research also links environmental

aspects, such as landscaping or natural elements, to the

reduction of stress and the promoting of recovery from

illness.

23, 27

Relative to psychiatric inpatient units, various dimension

of the built environment have shown to elicit supportive

therapeutic benefits for patients.

28

Multiple researchers

address the importance of a ‘deinstitutionalised’ and/or

‘homelike’ environment.

29-32

An orderly or organised

environment is also considered beneficial,

33, 34

as is an

environment that is well maintained.

35

Furnishings that

resist damage and are easily repaired or replaced are

considered a priority.

35, 36

Research has found that design

interventions which reduce incidences of aggression lead

to increased feelings of staff safety and security, and

reduced staff absences.

37

Design which encourages staff-

patient interactions is supported in the literature,

38

which

may include open nurse stations, among other design

features.

31, 35

Further, providing spaces for staff support

and respite is considered best practice.

39, 40

Multiple

researchers emphasise the need to provide spaces for

socialisation for both service users and staff, and the

development of a sense of community,

41-44

as well as

spaces which foster opportunities for autonomy.

45

Following a review of the literature, Karlin and Zeiss

concluded that within psychiatric settings, soft, indirect,

and pervasive or full-spectrum lighting are generally

recommended

46

Studies indicate that increased exposure

to daylight may reduce depressive symptoms

47

and reduce

agitation in patients.

30

Gutkowski and Gutman found that

well-lit spaces supported a therapeutic environment.

48

View to nature, natural landscapes and inclusion of nature

content within psychiatric settings is well discussed within

the literature.

49-51

A series of potential limitations are acknowledged within

the field linking environments with mental health

outcomes. These include:

• Difficulty in measuring of empirical evidence;

• Ill-defined, broad or generic nature of the research

terms and concepts;

• Lack of defined design initiatives.

There are some suggestions to mitigate these possible

limitations, which include the defining of specific user

groups, situations and contexts specific to the research

study, and the undertaking of post occupancy evaluations

which are closely related to defined users and research

terms. These suggestions are discussed below.

Difficulty in measuring empirical evidence and the ill-defined, broad

or generic nature of research terms and concepts

Existing literature acknowledges limitations regarding the

measuring and empirical evidence of the role of the built

environment in increased mental wellbeing.

52

This

limitation is attributed to both the generalised nature of

the research pertaining to mental health,

53

mental health

being a wide sphere

54

containing a multitude of mental

conditions, and also attributed to the definition of mental

health, which is commonly a fluid, ill-defined and

subjective concept and thus difficult to consistently

measure. Limitations are also acknowledged on the

definition of perceived value which design can add, and

the ability to measure such concepts or outcomes. How

the built environment could be broken down into

measurable components is a challenge in research in this

area. Again, this results in difficulty in empirical measuring

through the lack of defined concepts, terms and

interventions within the scope/aims of the research

project. Further, the literature acknowledges that the

analysis of environments and the identification of elements

which relate to various behavioural demands or mental

health symptoms is a neglected issue in psychology.

Importantly, it is acknowledged that the external “built

environment represents a modifiable feature to which

[patients] are exposed and is therefore important for

public health research,”

55

yet a need remains for research

identifying mechanisms by which the built environment

adversely and positively impacts health in order to develop

appropriate interventions.

53

Lack of defined design initiatives

Existing research in design and health seeks to mitigate the

limitations associated with the perceived and measurable

value of design initiatives and concepts through addressing

design for specifically defined user groups. It is made

apparent through existing literature that differing user

groups will respond to their environments in differing

ways, thus it is important to address any design initiatives

to the specific user group’s needs and experiences of space

in order to be effective.

56, 57

It is noted that more research

is needed to provide “more detailed, evidence-based

guidelines for designing optimal restorative environments

for different groups, contexts and activities.”

54

Predominant research methodologies, such as those

employed by Fornara and colleagues, are supportive of

defining specific user groups in order to tailor design

responses and mitigate this limitation of the lack of

empirical evidence. Defining user groups is a

methodology viewed as most reliably influential,

predictable and able to generate the outcomes of

bolstering mental wellbeing or clinical efficacy.

56, 58

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019 93

As acknowledged by Ke-Tsung and others, there is a gap

in the literature and more research is required in order to

test ways in which theories of restorative environments

and design supportive of mental wellbeing could be

manifest in design practice.

59

It is suggested by these

authors that defined research concepts and post

occupancy evaluation of designs are the means to address

this ambiguity of testing. It is recognised by Ulrich,

Parsons and Kaplan that much further research is required

in the areas relating to specific design outcomes. They

also note that further investigation is needed regarding the

validation of concepts used as guides to assess the

environmental aspects of a space conducive to supporting

mental wellbeing, for example the tangible valuation of the

aesthetic and psychological benefits of ‘attractive visual

landscapes.’

51

This ambiguity leads to difficulty in making

assessments and drawing research conclusions. Difficulty

also lies in defining the environments or modifications in

commensurate terms, which increases difficulty in

quantifying the effects of environments on individuals.

60

By defining research concepts clearly and in relation to a

specific user group and context/situation, the

quantification process and methodologies and design

suggestions can become more clear. Within studies, built

features or elements of the environment are often broadly

defined, examined variables including ‘territoriality’ for

example.

55

More broadly, the fluid definitions found of

‘mental health’ may be related to the paucity of definition

of spatial features or design guidelines. Researchers in this

area note that “the health measures… may have been too

global in content to reflect the influence of the more

specific design factors.”

61

Further, spatial and physical

features are not typically included in surveys examining

patient satisfaction or experience.

59, 62

The literature

reinforces the notions of user specific design and post

occupancy evaluation as potentially a core contributor to

the efficacy of design practice for improving mental

health.

In summary, although a considerable body of literature

exists affirming the links between good design practice and

the promoting of mental wellbeing, there are many

limitations of the research. These limitations include

definition of concepts within the studies, such as the value

of design initiatives, and actual testable design proposals or

suggestions to be employed in the built environment. The

existing body of literature aims to mitigate these

acknowledged limitations through research design

addressing a specific user group, with the purpose of

providing more measurable, defined outcomes. These

findings inform the scoping review focus discussed herein.

This scoping review aimed to (1) identify the current body

of literature which examined the relationship between

design practice and service user experiences within EDs

for self-harm and suicidal distress presentations, and (2)

identify the ways in which the built environment could

increase the efficacy of therapeutic efforts through

improving service user outcomes and experiences.

Methods

This scoping review assessed the existing literature in

relation to the below research question:

Does the design of Emergency Department built environments impact

the service user experience and mental health outcomes, specifically in

the case of self-harm and suicidal distress presentations?

This scoping review was undertaken by the author using

the methodology described by Arksey and O’Malley,

however it does not rule out the possibilities of relevant

existing studies that are subsumed under other conditions,

misnamed, or not correctly indexed by the databases

consulted.

63

Sources

Three reference databases were searched with no limits

applied to year of publication: Medline,

a

PsycINFO

b

and

the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals.

c

These three

databases ensure that a broad scope is achieved which

encapsulates literature containing primarily architecture-

focused articles and those drawing on medical and

psychological content.

These databases were explored for relevant publications

via a series of set keywords and topic areas.

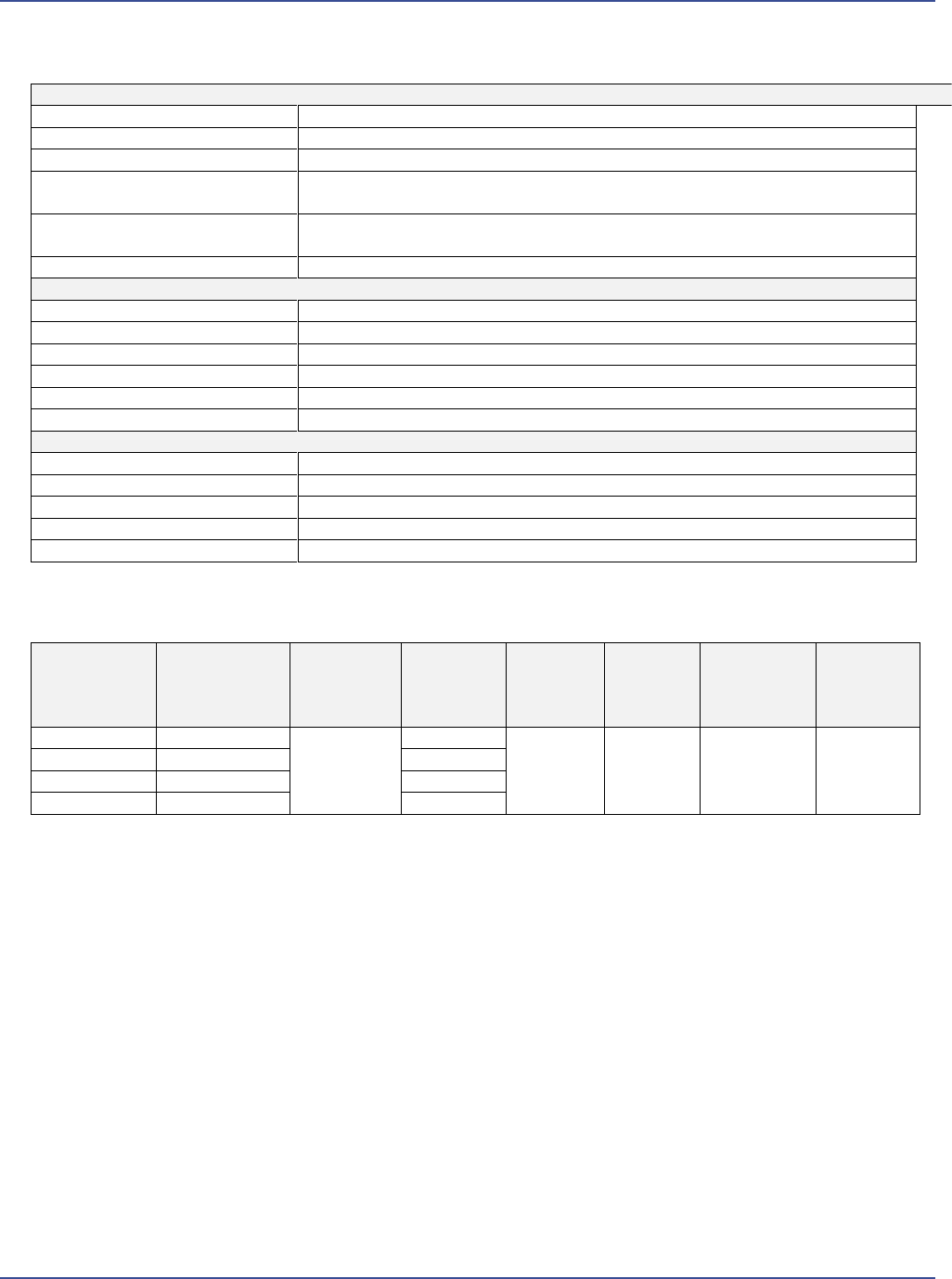

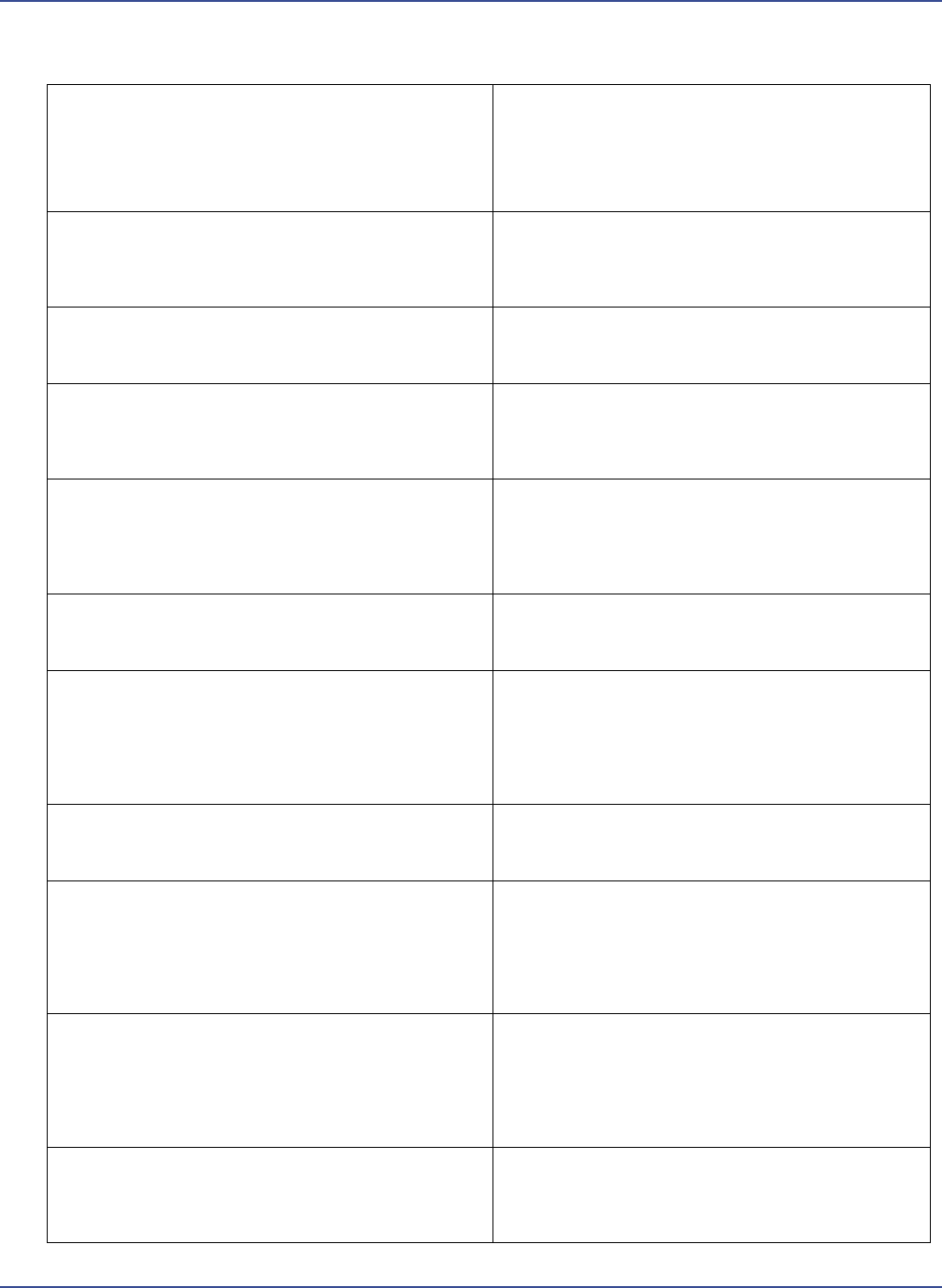

Search terms

Preliminary search terms were defined to reflect a number

of core concepts as defined by this scoping review (see

Table 1). These terms varied relative to the database being

searched and the appropriate subject indexing terms native

to that particular database. The record identification is

detailed in Table 2.

Article screening

Within the three databases searched, a review of all titles

was undertaken first, followed by a review of the abstracts

of publications whose title implied relevance or

titles where the relevance remained ambiguous. Articles

not written in the English language or with obviously

irrelevant titles were removed from the analysis. A

second screening process then took place, whereby the

abstract content was compared against the terms and

concepts of the review. Retrieval of the full text occurred

for the abstracts that suggested relevance as per the

research question and definitions, and also for those

abstracts which left further need for clarification of

relevance. A final selection of 29 articles were the subject

of review in full by the author. Where relevant, references

from articles were scanned to identify other papers that

may not have been identified through the initial database

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

94 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

search. A further 48 articles were identified from the

reference list of these articles for inclusion in the study. A

total of 77 articles were utilised in this scoping

review.

50

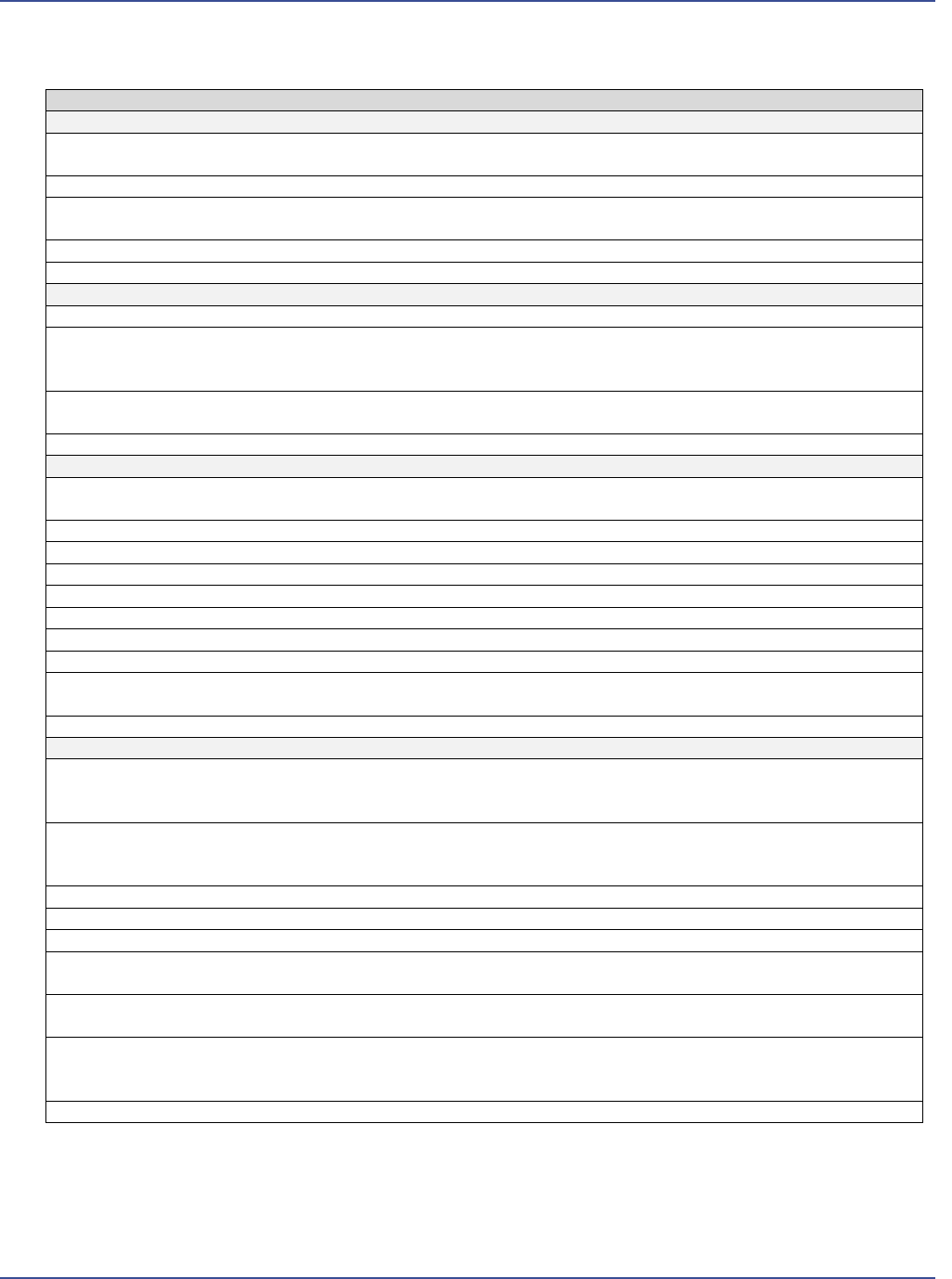

The twenty articles considered particularly

informative are presented in Table 3, alongside their main

contents.

A further step of the study reported herein included the

identification of design strategies contained in the

literature relative to providing environmental safeguards

and improving service user care specifically. This step

involved an identification of supplementary literature,

sourced from the articles’ reference lists, then reviewed in

order to supplement design guidance and compile a more

comprehensive list of design strategies.

Results

Summary findings from this scoping review are reported

across three areas: (1) built environment/architecture

relative to self-harm and suicidal distress; (2) emergency

department design and planning relative to self-harm and

suicidal distress presentations; and (3) design strategies.

Built environment/architecture relative to self-harm

and suicidal distress

After review of articles retained and relevant articles

identified through reference lists, this scoping review

confirmed a scarcity of research linking the treatment of

individuals who self-harm to the design of the built

environment specifically. Warzocha and colleagues

discussed the associations between deliberate self-harm

episodes and selected environmental factors; however, this

Table 1. Databases and Research Terms

Avery Index of Architectural Periodicals

Topic Area

Search Term(s) Used

Built Environment/Architecture

N/A

Self-Harm

“self-harm” OR “self-mutilation” OR “self-injurious behaviour”

Mental Health

“mental health” OR “mental health facilities” OR “psychiatric hospitals” OR

“environmental psychology”

Emergency department

“emergency department” OR “emergency room” OR “accident and emergency”

OR “accident & emergency” OR “a&e” OR “a & e”

Suicidal distress

“suicide” OR “suicidal distress” OR “suicidal ideation”

Medline

Topic Area

Search Term(s) Used

Built Environment/Architecture

“built environment” OR “environment design”

Self-Harm

“self-harm”

Suicidal distress

“suicide” OR “suicidal distress” OR “suicidal ideation”

Mental Health

“mental health”

Emergency department

“emergency department design” OR “emergency department design and planning”

PsycINFO

Topic Area

Search Term(s) Used

Built Environment/Architecture

“built environment” OR “architecture” OR “environmental effects”

Self-Harm

“self-injurious behaviour”

Suicidal distress

“suicide” OR “suicidal distress” OR “suicidal ideation”

Emergency department

“emergency department design” OR “emergency department design and planning”

Table 2. Records Identified

Database

Records

identified

from searches

Duplicates

Abstracts

reviewed

Full text

accessed

Excluded

Full text

accessed

and

included

Additional

records

sourced

Avery

49

11

49

96

67

29

48

Medline

295

78

PsycINFO

1145

87

Total

1489

214

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019 95

Table 3. Articles Considered Partially Informative

Bost, N., Johnston, A., Broadbent, M., & Crilly, J. (2018).

Clinian perspectives of a mental health consumer flow

strategy in an emergency department. Collegian 25, 415-

420.

Clinicians involved in the provision of care to consumers with a mental

illness who presented to the ED participated in this qualitative study;

themes explored include the built environment (although briefly

presented); findings discuss communication in the ED and strategies to

implement and sustain a new consumer flow in the ED

Broadbent, M., Moxham, L., & Dwyer, T. (2014).

Implications of the emergency department triage

environment on triage practice for clients with a mental

illness at triage in an Australian context. Australasian

Emergency Nursing Journal, 17, 23-29.

This paper details an observational ethnographic approach exploring

the implications of the emergency triage environment on the triage

practice of nurses who triage clients with a mental illness; this paper

confirms that the triage environment has a direct influences on the

nurses’ abilities to conduct an accurate and timely triage, particularly

for a client presenting with a mental illness; various dimensions of the

environment are discussed including security ,noise, visibility, among

others

Broadbent, M., Moxham, L., & Dwyer, T. (2010). Issues

associated with the triage of clients with a mental illness in

Australian emergency departments. Australasian Emergency

Nursing Journal, 13, 117-123.

This paper presents a summary of literature relative to the emergency

triage of clients with a mental illness; various dimensions of triage are

presented and analysed, including content covering waiting times,

models of care, and the values of recovery-oriented practice in this

context

Cardell, R., Bratcher, K. S., & Quinnett, P. (2009).

Revisiting 'suicide proofing' an inpatient unit through

environmental safeguards: A review. Perspectives in

Psychiatric Care, 45(36-44).

This paper identifies strategies in the literature to facilitate

environmental safeguards within psychiatric facilities to protect suicidal

individuals from harming themselves; strategies are presented across

several themes including bathrooms, bedrooms, the psychiatric unit, the

use of cameras, restriction of personal belongings, training of staff,

administrative responsibilities

Clark, D., Dusome, D., & Hughes, L. (2007). Emergency

department from the mental health client's perspective.

International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 16(2), 126-131.

Focus groups held with mental health patients and their families to

determine their level of satisfaction with care at regional EDs; results

indicate long waiting periods for these patients, impact of attitudes of

care providers, and cover family needs, diagnostic overshadowing, ‘no

where else to go’, and ‘what is missing’; emphasis on design strategies

to address perceived long waiting periods

Fay, L., Carll-White, A., & Harrell, J. (2017). Coming full

cycle: Linking POE findings to design application. Health

Environments Research & Design Journal, 10(3), 83-98.

This paper presents a full-cycle post occupancy evaluation and design

charrette for an emergency department; methods are detailed; findings

include the significance of workflow, communication, privacy and

confidentiality, safety and security; entry sequence redesign is presented

with associated design strategies/recommendations

Gharaveis, A., Hamilton, D. K., Pati, D., & Shepley, M.

M. (2017). Impact of visibility on teamwork, collaborative

communication, and security in emergency departments:

An exploratory study. Health Environments Research & Design

Journal. doi:1937586717735290

This study investigated the impact of visibility on teamwork,

collaborative communication and security issues in the ED; using

interview and on-site observation, this paper presents findings

pertaining to visibility and teamwork, patient assessment, comfort,

communication, security, and related design considerations; layouts,

workstation design, light and acoustics are among the environmental

aspects discussed

Guinther, L., Carll-White, A., & Real, K. (2014). One size

does not fit all: A diagnostic post-occupancy evaluation

model for an emergency department. Health Environments

Research & Design Journal, 7(3), 15-37.

This paper presents the detailed process and methods used in a post-

occupancy evaluation in an urban hospital emergency department; core

areas of evaluation are defined including environment, experience and

operations; connections made between privacy/confidentiality, noise,

occupancy levels and ED layout; a series of design suggestions provided

Huddy, J., & McKay, J. I. (1996). The top 25 problems to

avoid when planning your new emergency department.

Journal of Emergency Nursing, 22(4), 296-301.

Drawing on experience from work in an architectural firm, the

authors present 25 key themes for consideration when planning an

ED; related design dimensions are presented throughout

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

96 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

Table 3. Articles Considered Partially Informative (cont’d.)

Kaar, S. J., Walker, H., Sethi, F., & McIvor, R. (2017). The

function and design of seclusion rooms in clinical settings.

Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care, 13(81-91).

This paper provides a review of current literature on seclusion room

design; government and other guidance regarding architectural design

specifications is presented; related dimensions from environmental

psychology are discussed including light and nature, safety,

communication, location of seclusion, walls, ceilings and floors,

sanitation; detailed design guidance is provided

Lanza, M. L., Kayne, H. K., Hicks, C., & Milner, J. (1994).

Environmental characteristics related to patient assault. Issues in

Mental Health Nursing, 15(3), 319-335.

This study purpose was to examine the influence of environmental factors

on assault; three survey instruments are used to explore the links between

ward atmosphere and assault frequency; locations of highest assault

frequency are tabled; discussions presented relative to clinical implications,

including ward conditions and ward climate

Lenaghan, P. A., Cirrincione, N. M., & Henrich, S. (2018).

Preventing emergency department violence through design.

Journal of Emergency Nursing, 44(1), 7-12.

This paper provides a review of best design practice pertaining to preventing

ED violence; design strategies are tabled across several themes including

parking zone, entry zone, traffic management, care zones and room

clustering, specialised rooms

Marynowski-Traczyk, D., Moxham, L., & Broadbent, M. (2013).

A critical discussion of the concept of recovery for mental health

consumers in the emergency department. Australian Emergency

Nursing Journal, 16(3), 96-102.

This paper details Australian mental health reforms and their impact on

the ED; unique dimensions of care relative to mental health presentations

at the ED; the concept of recovery in the ED and related care initiatives

for optimal management of these service users, emphasis on best

understanding recovery-oriented approaches in order to inform care provision

Morphet, J., Innes, K., Munro, I., O/Brien, A., Gaskin, C., &

Reed, F. (2012). Managing people with mental health

presentations in emergency departments - A service exploration

of the issues surrounding responsiveness from a mental health

care consumer and carer perspective. Australian Emergency Nursing

Journal, 15(3), 148-155.

This paper presents a literature review, survey and focus group data

collection, analysing the issues associated with access to care in ED settings

for clients presenting with a mental illness; participants’ perspectives of the

ED are presented in key themes, including spatial requirements and how

the ED environment could be improved

Nayeri, N. D., & Aghajani, M. (2010). Patients' privacy and

satisfaction in the emergency department: A descriptive analytical

study. Nursing Ethics, 17(2), 167-177.

Questionnaires were administered in this study to examine the perceptions

of privacy and its relationships with patient satisfaction in three emergency

departments; types and frequency of privacy breaches are detailed;

implications for safety and perceptions of care are discussed

Pati, D., Harvey, T. E., Willis, D. A., & Pati, S. (2015).

Identifying elements of the health care environment that

contribute to wayfinding. Health Environments Research & Design

Journal, 8, 44-67.

This paper details a multi-method study designed to investigate the aspects

of the physical environment that contribute to wayfinding experiences in

hospital settings; physical design elements contributing to wayfinding

experiences include signs, architectural features, structural elements,

furniture, interior elements, among others; how such features contribute to

wayfinding is analysed; design strategies/information as relevant is

presented

Shafiei, T., Gaynor, N., & Farrell, G. (2011). The characteristics,

management and outcomes of people identified with mental

health issues in an emergency department. Journal of Psychiatric and

Mental Health Nursing, 18(1), 9-16.

This paper details a retrospective observational study of adults who attended

and ED and with an ED discharge diagnosis of a mental health disorder;

this study confirms that mental health clients had longer wait times in the

ED and many left before being assessed

Sheehan, B., Burton, E., Wood, S., Stride, C., Henderson, E., &

Wearn, E. (2013). Evaluating the built environment in inpatient

psychiatric wards. Psychiatric Services, 64(8), 789-795.

This study examined the relationships between staff satisfaction and design

features in psychiatric wards; using spatial observation (checklist of design

features) and multi-level modelling, the study confirms that objective

measurement of inpatient psychiatric facilities is feasible and can be used to

identify features which enhance service user satisfaction; non-corridor designs

and personal bathrooms had a strong positive association with staff ratings

of the built environment

Shepley, M. M., Watson, A., Pitts, F., Garrity, A., Spelman, E.,

Kelkar, J., & Fronsman, A. (2016). Mental and behavioural

health environments: Critical considerations for facility design.

General Hospital Psychiatry, 42, 15-21.

An extensive literature review and focus groups/interviews are reported in

this paper, with the aim of identifying the features in the physical

environment that are believed to positively impact staff and patients in

psychiatric environments; a table of design topics and references is provided;

key aspects of the physical environment are analysed in more detail and

with supporting data from the focus groups/interviews; design strategies are

presented

Zamani, Z. (2018). Effects of emergency department physical

design elements on security, wayfinding, visibility, privacy, and

efficiency and its implications on staff satisfaction and

performance. Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1-17.

doi:10.1177/193758618800482

This paper presents a mixed-method study exploring the connections

between ED physical design, attributes, performance and staff satisfaction;

a table of key descriptive statistics on staff satisfaction levels is provided;

themes include privacy, efficiency, security, visibility, wayfinding, which are

presented alongside design implications

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019 97

referred to the environment in terms of their exposure to

abuse and their family situation. The authors found that

past suicide attempt(s), alcohol issues within the family,

sustained physical and sexual abuse, and lack of family

support were significantly associated with undertaking self

harm.

64

The research identified linking the built

environment/architecture to suicide and self-harm was

focused predominantly on suicide or self-harm prevention

measures (simply inhibiting access to suicide

opportunities/means), rather than the ways in which the

built environment might provide a psychologically

nurturing or supportive environment for users who may

be in suicidal distress. This research acknowledges the role

of the built environment in mediating attempted and

completed suicides, and that service users are “very

knowledgeable about how to attempt suicide in hospital

settings, possibly more so than hospital staff.”

65

Interestingly however, service users were found to feel

reassured of their safety when hospitals took active

measures to ensure their safety.

65

Environmental safeguards are the structural features in

healthcare facilities which limit the means with which to

commit suicide. Whilst these safeguards cannot guarantee

suicide prevention, they have been shown to reduce the

incidence.

65

The function and design of seclusion rooms in

clinical settings is also discussed, relative to service users

who may be in suicidal distress or at risk of self-harming.

The literature supports the use of natural light and well-lit

environments as contributing to therapeutic settings

generally, however there is no literature relating light and

nature specifically to seclusion rooms.

66

This highlights a

need for research in this area, further supported by the

notion that user specific mental health design is important

to generate relative, effective and supportive design

interventions, as established in broader research.

Emergency department design and planning relative

to self-harm and suicidal distress presentations

The practice environment of the Emergency Department

(ED) refers to the people who inhabit this environment

and the physical space(s)/architecture in which the health

care is provided. As noted by Broadbent and colleagues,

“the triage environment does influence the ED triage and

assessment and the management of clients who present

seeking mental health care.”

67

A common feature in the

literature is that mental health presentations also spend

many hours within the ED.

8, 11, 50, 68

This paper presents

various design strategies/recommendations for ED design

and planning relative to mental health presentations.

Whilst these are not specific to suicidal distress and self-

harm presentations only, these design strategies may

provide a useful platform for future research to develop

design solutions specifically addressing suicidal distress

and self-harm presentations. The collected design aspects

and implications are presented in brief across five

headings: (1) privacy; (2) visibility; (3) entry sequence; (4)

flexibility and spatial layouts; and (5) wayfinding.

d

Privacy

A key goal of health services involves respecting privacy

and service users’ satisfaction. Intrusions of privacy, as

defined by Curtin,

69

may include: the physical presence of

unwanted persons; unwanted observation of or by a

person; dispersal of private, inaccurate, or misleading

information about a person; or encroachment on personal

decisions make in a person’s own sphere.

Installing privacy screens between registration stations is

suggested to ensure privacy and confidentiality, together

with ample circulation space and an area for queuing while

waiting to register.

70

Design attributes evidenced in the

literature which contribute to lowering noise levels and

increasing audial privacy include the use of single patient

rooms (which are also preferred by service users, as

detailed in Morphet and colleagues’ 2012 study), floor to

ceiling solid partitions, acoustical tiles/dividers, solid core

wood doors on most treatment rooms, provision of

private consultation rooms throughout the ED, curtain

partitioning in seated waiting areas which will house

multiple groups of waiting service users (and their

companions), and provision of secluded areas for cell

phone usage in close proximity to the waiting area

70, 71

It is

noted that provision of space for cell phone calls reduces

the overhearing of confidential information being

discussed, and thus minimises privacy and confidentiality

breaches, in addition to being a noise control measure

71

. It

is also important to provide spaces for staff to talk

confidentially to other staff members, which is noted as

lacking in EDs.

70

Further, provision of space for

ambulatory personnel or police to complete reports and

make telephone calls confidentially is necessary to

maintain privacy, and to reduce interference with the work

flow of the unit.

72

Privacy and security are implicated in the particular

challenges unique to management of triage and

management of clients with a mental illness in the ED.

Minimising public scrutiny of a person in mental distress is

considered imperative.

67

Research underscores the role of

environmental characteristics in affecting client behaviour

and outcomes, and emphasise the consideration of the

provision of a private, safe and quiet area to wait that is

visible from the ED triage area.

67

Vulnerable clients, who

are emotionally disturbed, possibly aggressive or agitated,

and “may be exhibiting bizarre behaviours often remain in

the waiting room in the absence of suitable alternative

areas.”

67

ED triage nurses have also identified the need for

a secure, private place for patients in mental distress,

whilst remaining visible by the ED triage nurse.

67

Mental

health clients, too, have reported that a separate space for

people with mental health illnesses would improve the ED

journey.

4,11

Further, consideration of privacy and how it is

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

98 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

afforded through design has implications for

communication between staff and clients regarding plans

of care.

11,50

Indeed, lack of privacy “has a negative

influence on the ability to garner accurate information

critical for ED triage decision-making and to provide

effective ongoing management of the client with a mental

illness.”

67

Visibility

Visibility in EDs linked to safety considerations and to

communication. Research highlights that architectural

design solutions should integrate principles of visibility and

surveillance which are critical to the ED triage process.

73

In Fay and colleagues’ study, nursing staff commented that

it was difficult for patients seated in the waiting area to

hear their name called, which could be attributed to limited

visibility into the waiting areas from the triage doors.

70

Open layouts are suggested as leading to increased face-to-

face communication. Research on nursing unit design

notes that enhanced visibility within centralised pods

promotes increased team interaction, communication, a

greater sense of cohesion and interdisciplinary

collaboration.

73-75

Further, location of the consultation

rooms is implicated in the staff’s ability to communicate

with service users, and the easy location of the registration

desk ensures ease of access to information about their visit

for both service users and visitors.

70

Staff workstations

should also be located to be within view of each other,

which is linked to reduced staff isolation, improved staff

morale, increased service user monitoring and improved

communication among caregivers.

50,76

Providing direct sight lines for security, registration and

nursing staff to treatment doors and waiting areas is

considered essential to maintain safety and security.

70

Clinicians who cannot see each other cannot help each

other if incidences of violence or aggression occur.

76

Eliminating columns or walls at check-in, waiting and pod

areas enhances visibility, as well as safety, communication

and delivery of care.

50,

73, 74

Physical security barriers may impact the provision of

visibility and have the potential to generate negative

feelings about a service user’s access to staff.

76

Appropriate

security features can be implemented discreetly, in a

manner that will not diminish the service user experience.

Further, spatial delineation can assist the facilitation of

safety in the ED. Clear distinction between waiting and

treatment areas can help define acceptable activities and

minimise risks of violence.

76

A safe room may also be

considered for integration into the ED. This room should

have capacity to be locked from the inside for staff, service

users and visitors to retreat, and equipped with a

telephone, duress alarm, reinforced door, a peephole and

external lock and key access.

76

Entry sequence

The entry sequence should be carefully considered in an

ED setting with respect to mental health presentations.

Huddy and colleagues suggest that “‘uncomfortable’ front

doors where ambulatory patients and family members

must enter at the same point with ambulance patients”

72

are problematic and should be avoided. Further, the

exterior of the ED needs to be designed simultaneously

with the interior to achieve appropriate patient flow. EDs

should have separate parking outside a walk-in entrance;

lighting and wayfinding from arriving vehicles is crucial to

facilitate a quick transfer to care.

76

Appropriately designed entries can also assist in the

management of ED violence and challenging behaviours.

It is suggested that all parking and ambulatory areas should

have security surveillance, and additional security support

should manage ED entries.

76

Further, entrances should be

positioned at an angle from driveways in order to prevent

intentional or accidental ramming or vehicular intrusion.

76

Weather cover for the ambulatory docking areas should be

considered as an important design issue.

72

Further, exhaust

fumes from ambulances queued in the ambulatory docking

configuration can infiltrate the ED and impair the ward

comfort and atmosphere. It is suggested that considered

placement of the vehicles, mechanical air pressure in

entrance vestibules, and exhaust openings in canopies can

deter exhaust fumes.

72

Placing security officers at the entrance gives patients and

others the psychological benefit of a visible security

presence, whilst allowing for active intervention when

needed.

77

As Lenaghan and colleagues note, “properly

placed, a security person can step in to restrict access when

necessary, manage high-risk situations, and communicate

and enforce hospital policies and curfews. Their

knowledge of the community can serve as a calming

presence, leading to early detection of threats and a greater

overall sense of control and security”

76

which is a useful

addition to the entry space.

50

Flexibility and spatial layouts

Flexibility of spatial usage is considered important in

maximising the effectiveness of the ED. It is suggested

that the design of the unit should not limit the types of

care that can be delivered in various treatment spaces; for

example, an examination room can be planned with air

change capacities to allow it to be used for an isolation

patient.

72

Further, provision of appropriate storage is

essential, and can also support flexibility of spatial use.

Where fast track components are included in EDs,

separation of the fast track and urgent/emergent care areas

of the ED can be accomplished in order to broaden the

functionality of both areas. If examination rooms are

placed between these functional areas, they may function

as fast track rooms or emergency care rooms, as needed,

accommodating patient overflow in each area.

72

Excessive

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019 99

distances between fast track and emergency care areas

should be minimised in the ED layout. Excessive distances

require additional support and storage spaces in both

areas, creating duplication of spaces which may be

managed by appropriate design planning.

72

A locked, roll-

down wall, locked cabinetry and gates, and impact resistant

laminate can be used to hide and store equipment and to

prevent patients from harming themselves.

76

Such

measures assist in the flexibility of spatial use and allow

equipment to be exchanged or replaced as required.

50

Wayfinding

Ineffective wayfinding and signage cause inefficiency and

workplace stress among healthcare providers. In the

absence of clear wayfinding strategies, patients may

wander, and may become abusive or aggressive to care

providers.

76

However, there is an acknowledged lack of

empirical research on the impact of navigation and

wayfinding in hospital-based ED facilities.

74

Including

waiting areas which are in direct line of sight from

registration spaces is recommended to promote intuitive

wayfinding and direct movement flows.

74

Meaningful spatial cues and design elements also

contribute to wayfinding. Pati and colleagues

78

identify

several aspects of the physical environment that contribute

to wayfinding, including maps, signs, logical clustering of

functions, furniture, logical pairing of interior architecture

elements, structural elements, architectural features, and

other elements such as artwork, maps and indoor plants.

They provide a series of tangible strategies for integrating

these features into positive wayfinding experiences. Whilst

not focused on ED environments specifically, these

strategies may provide useful in this context. Additionally,

it should be noted that mental health clients have

identified that replacing the term ‘mental health’ with

‘wellbeing’ in ED settings would improve their ED

experiences. This is due to a perception that stigma was

attached to the term ‘mental health.’

11

This should be

integrated into effective signage for the ED.

50

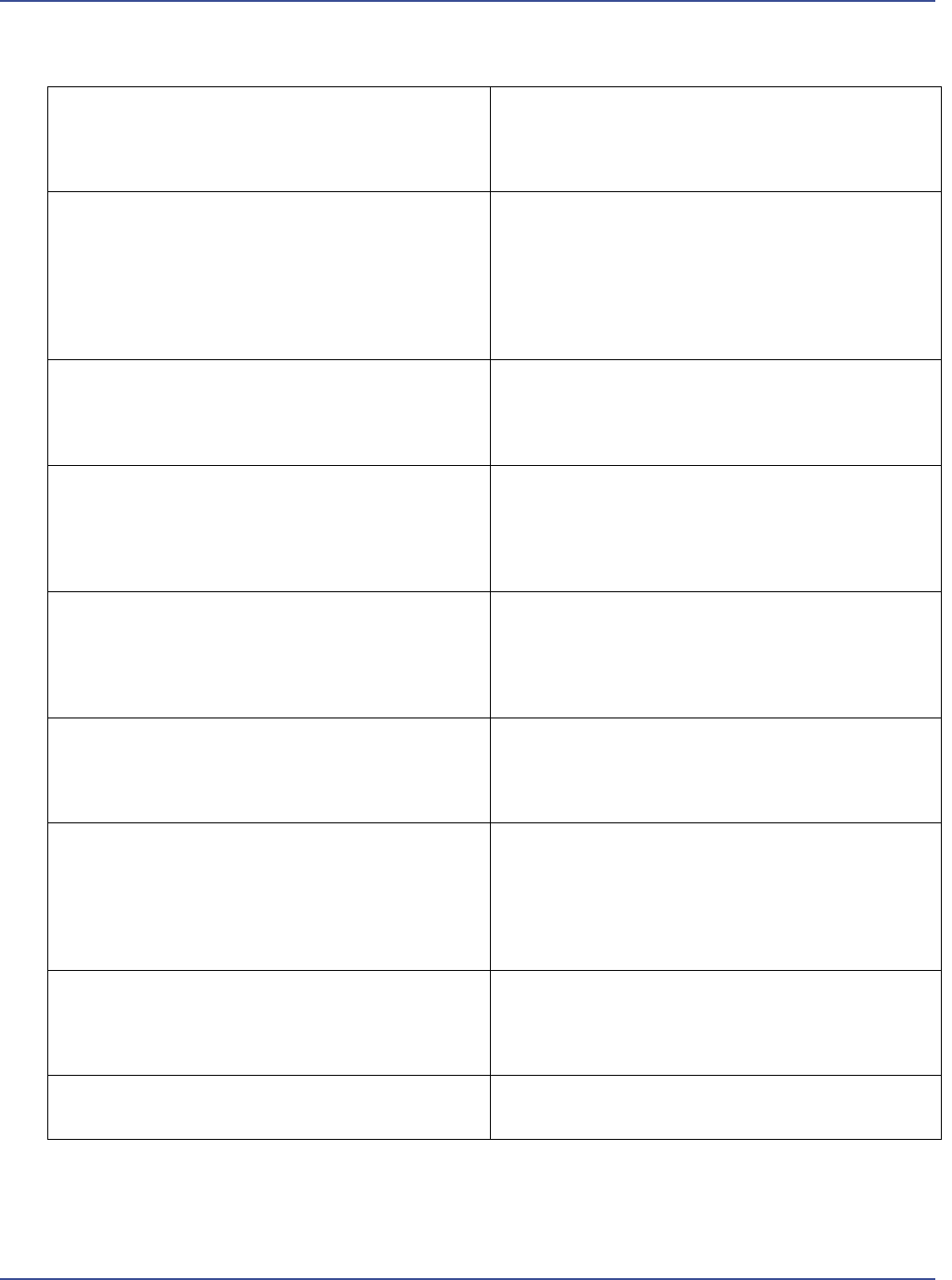

Design strategies

In addition to those strategies discussed in the previous

section, the research identified in this study also provides a

selection of tangible design strategies specifically to

facilitate environmental safeguards and improve service

user care across clinical settings. Supplementary literature,

sourced from the articles’ reference lists, were also

reviewed in order to compile a more comprehensive list of

design strategies (summarised in Table 4).

Discussion and summary

This paper affirms the existence of a body of literature

linking the environment with mental health outcomes,

there are many limitations within the research identified

and within the field as a whole. The limitations of the field

include:

• a difficulty in measuring of empirical evidence;

• the utilising of broad or generic research terms; and

• the lack of defined design initiatives.

Suggested methodologies to mitigate these limitations

include:

• designing for specific user groups; and

• the incorporation of defined research concepts and

terms;

• in conjunction with a specific user group and

context/situation.

Patient safety is acknowledged as an issue linked to the

built environment. The use of environmental psychology

and design theory related to aggression may be

hypothesised to have an effect on patient safety in terms

of reducing patient aggression and stress, and therefore

reducing measures such as restraint and incidences of self-

harm. Aspects of environmental psychology aimed at

reducing stress and aggression

30

may be useful to increase

service user safety within psychiatric settings. Most

existing literature related to safety concerns details aspects

of physical considerations, such as reducing ligature points

and fixtures which might be used as weapons.

79-81

This paper affirms the presence of a body of literature

linking good design practice with improved mental

wellbeing, yet highlights both the lack of design

implications contained in this research and the design

initiatives appropriate to varying mental health user

groups, including self-harm and suicidal distress

presentations specifically, particularly in EDs. This

scoping review confirmed a scarcity of research in the

databases searched linking ED design and planning with

supportive therapeutic effects for self-harm and suicidal

distress presentations specifically. Research identified

provided various design strategies/recommendations for

ED design and planning relative to mental health

presentations. Whilst these are not specific to suicidal

distress and self-harm presentations only, these design

strategies provide a useful platform for development of

possible design solutions for suicidal distress and self-harm

presentations through future research. This scoping review

thus verifies the need for further research studies in this

area.

The limitations of this scoping review are firstly associated

with the fact that findings are not a final output in their

own right, and a process of quality assessment was not

included in the present study. The results are further

constrained by the selection of search keywords and

criteria applied in the process, not least constrained by the

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

100 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

Table 4. Design suggestions for providing environmental safeguards and improving service user care

Providing environmental safeguards and improving service user care

Bathrooms

Shower heads should be flush or slanted so they will not support knotted clothing or sheets or other potential ligatures

that could be used in a hanging attempt.

Minimise breakaway shower heads, shower rods, clothes hooks, curtain rods and railings.

All fixtures should be considered as possible anchors for attempted hangings, including shelves, fire sprinklers, towel

racks and ceiling lights.

The provision of personal bathrooms tends to improve the dignity, privacy and safety of patients.

References:

65, 83-88

Bedrooms

Bedrails should be avoided where possible.

Minimise access to ligatures than patients may use to hang or asphyxiate themselves, such as belts, shoestrings,

bathrobe ties, telephone and receiver cords, ties, sheets that can be torn into strips, stockings, intravenous tubing or

other medical tubing.

Designs of beds that are free from multiple leverage points in order to minimise hangings are ideal, whilst also being

fireproof.

References:

65, 83-87

Within the ward

Non-protruding wing doorknobs are recommended.

Door hinges should be filed to a slant.

There should be no exposed pipes, sprinkler heads, light fixtures, vents, or ducts.

Ventilator grilles should have security screens with holes no more than 3/16 inches wide, or 16-mesh per square inch.

Plumbing should be concealed.

Non-breakable glass in windows and secure windows that do not open are recommended.

Doors should open outward or in both directions to prevent patients from barricading themselves into a room.

Limit access to roofs or high places, open stairwells, screen porches or elevator shafts.

If possible, there should be no electrical outlets in rooms.

Noncorridor designs, such as spoke designs and courtyard arrangements lend themselves to easier observation of

patients and, research shows, are preferred by patients and staff.

References:

65, 83-88

Seclusion Suites

High performance sound-absorbing ceiling and floor tiles are recommended to reduce the noise of the seclusion

environment. This is particularly important when designing seclusion environments providing care for multiple

patients simultaneously.

Features to reduce spatial disorientation are beneficial, and may include signage, environmental cues such as changes in

floor treatments, colour to denote different spaces and assist the patient to identify different functions of different

spaces.

Include views to nature where possible.

In the absence of views to nature, include nature art and prints on the walls.

White or grey should be avoided in seclusion rooms; in general, warm blue tones have a calming effect.

15m² should be considered as the minimum area required for the seclusion room and ensuite bathroom. A further

15m² should be provided for the staff observation area, giving a total of 30m².

Temperature control should be facilitated in order to ensure heating and cooling can be provided in a manner

responsive to patient needs without introducing undue noise.

Include a whiteboard or other display device that provides information to the patient. As suggested by Kaar and

colleagues, this information may include: “(1) orientation to time, place and person; (2) understanding of the treatment

they have been given; (3) knowledge of the team delivering care; and (4) expectations for decision making” (p. 89).

References:

46, 66, 89-93

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019 101

complexity of this multidisciplinary research and possible

omissions amongst the linked disciplines. Extension of the

searches conducted to grey literatures and other databases

may augment the records identified and may form the

subject of future reviews.

As noted by Broadbent and colleagues, “the triage, and

subsequent care, of clients with a mental illness in the ED

remains one of the biggest unresolved issues in

contemporary emergency care.”

82

By building creative and

innovative partnerships across clinical and design

disciplines, including service users, it is possible to develop

a more comprehensive understanding of the potential

support mechanisms the built environment may facilitate

in ED environments.

End Notes

a. Medline is the United States National Library of

Medicine’s database providing information from the

fields of Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Veterinary

Medicine, Allied Health and Pre-clinical Sciences. This

database contains research sourced from over 5,500

biomedical journals published in the United States and

internationally.

b. PsycINFO is the database of the American

Psychological Association and is the largest resource

devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioural

science and mental health.

c. The Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals covers

research within the architectural field, indexing over

700 international journals including scholarly literature

as well as publications of professional associations and

major international serials on architecture and design.

d. Further detail on specific design strategies can be

found in Reference 50.

References

1. Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate

self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and

psychological correlates. Am J Psychiatry.

2003;160:1501-8.

2. Wong N. Book review, sk goldsmith, tc pellmar, am

kleinman, we bunney jr (eds): Reducing suicide: A

national imperative. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1534-5.

3. Hawton K, Zahl D, Weatherall R. Suicide following

deliberate self harm: Long term follow up of patients

who presented to a general hospital. Br J Psychiatry.

2003;182:537-42.

4. Hawton K, Fagg J. Suicide and other causes of death,

following attempted suicide. Br J Psychiatry.

1988;152:359-66.

5. Pointer S. Trends in hospitalised injury, Australia.

Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare;

2013.

6. Lilley R, Owens D, Horrocks J, A H, Noble R, Bergen

H, et al. Hospital care and repetition following self-

harm: Multicentre comparison of self-poisoning and

self-injury. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;192:440-5.

7. Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non fatal

repetition of self-harm: At repeat episodes: Findings

from a multicentre cohort study. J Affect Disord.

2002;180:44-51.

8. Shafiei T, Gaynor N, Farrell G. The characteristics,

management and outcomes of people identified with

mental health issues in an emergency department. Int J

Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(1):9-16.

9. Wand T, Schaecken P. Consumer evaluation of a

mental health liason nurse service in the emergency

department. Contemp Nurse. 2006;21(1):14-21.

10. Marynowski-Traczyk D, Moxham L, Broadbent M. A

critical discussion of the concept of recovery for

mental health consumers in the emergency department.

Aust Emerg Nurs J. 2013;16(3):96-102.

11. Morphet J, Innes K, Munro I, O/Brien A, Gaskin C,

Reed F. Managing people with mental health

presentations in emergency departments - a service

exploration of the issues surrounding responsiveness

from a mental health care consumer and carer

perspective. Aust Emerg Nurs J. 2012;15(3):148-55.

12. Heslop L, Elson S, Parker N. Improving continuity of

care across psychiatric and emergency medicine

services: Combining patient data within a participatory

action research framework. J of Adv Nurs. 2000;31:135-

43.

13. Wand T, Happell B. The mental health nurse:

Contributing to improved outcomes for patients in the

emergency department. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2001;9:166-

76.

14. Happell B, Summers M, Pinikahana J. The triage of

psychiatric patients in the hospital emergency

department: A comparison between emergency

department nurses and psychiatric nurse consultants.

Accid Emerg Nurs. 2002;10:65-71.

15. Wynaden D, Chapman R, McGowan S, McDonough S,

Finn M, Hood S. Emergency department mental health

triage consultancy service: A qualitative evaluation.

Accid Emerg Nurs. 2003;11:158-65.

16. Hazlett SB, McCrthy ML, Londoner MS, Onyike CU.

Epidemiology of adult psychiatric visits to us

emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:193-

5.

17. Kunen S, Prejean C, Gladney B, Harper D, Mandry

CV. Deposition of emergency department patients

with psychiatric comorbidity: Results from the 2004

national hospital ambulatory medical care survey. Emerg

Med J. 2016;23:274-5.

18. Curran GM, Sullivan G, Williams K, Han X, Collins K,

Keys J, et al. Emergency department use of persons

with comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse

disorders. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:659-67.

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

102 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

19. Slade T, Johnston a, Teesson M, Whiteford H, Burgess

P, Pirkis J, et al. The mental health of Australians 2. Report

on the 2007 national survey of mental health and wellbeing.

Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2009.

20. Dvoskin JA, Radonski SJ, Bennett C, Olin JA, Hawkins

RL, Dotson LA, et al. Architectural design of a secure

forensic state psychiatic hospital. Behavioural Sciences &

the Law. 2002;20:481-93.

21. Howard T. Physical environment and use of space. In:

Campling P, Davies S, Farquharson G, editors. From

toxic institutions to therapeutic environments. London:

Gaskell; 2004. p. 69-78.

22. Ulrich RS. Essay evidence-based health-care

architecture. Medicine and Creativity.

2006;368(December):538-9.

23. Ulrich RS. Effects of interior design on wellness:

Theory and recent scientific research. J Health Care Inter

Des. 2001;3(1):97-109.

24. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Zhu X, DuBose J, Seo H, Choi

Y, et al. A review of the research literature on

evidence-based healthcare design (part i). HERD.

2008;1:61-125.

25. Marberry S, editor. Improving healthcare with better building

design. Chicago: Health Administration Press; 2006.

26. Berry LL, Parker D, Coile RC, Hamilton DK, O'Neill

DD, Sadler BL. The business case for better buildings.

Front Health Serv Manag. 2004;21:3-24.

27. Laumann K, Garling T, Morten Stormark K. Rating

scale measures of restorative components of

environments. J Environ Psychol. 2001;21:31-44.

28. Shepley MM, Watson A, Pitts F, Garrity A, Spelman E,

Kelkar J, et al. Mental and behavioural health

environments: Critical considerations for facility

design. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;42:15-21.

29. Tapak DM. Don't speak about us without us: Design

considerations and recommendations for inpatient

mental health environments for children and

adolescents. Winnipeg, Canada: University of

Manitoba; 2012.

30. Ulrich RS, Bogren I, Lundin S, editors. Towards a

design theory for reducing aggression in psychiatric

facilities. Arch 12; Architecture/Research/Care/Health

Conference; 2014; Gothenburg, Sweden: Chalmers

Institute of Technology.

31. Whitehead CC, Polsky RH, Crookshank L, Fik F.

Objective and subjective evaluation of psychiatric ward

design. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1984;141:639-44.

32. Wilson MR, Soth N, Robak R. Managing disturbed

behavior by architectural changes: Making spaces fit

the program. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth.

1992;10(2):63-74.

33. Eklund M, Harrison L. Ward atmosphere, client

satisfaction and client motivation in a psychiatric work

rehabilitation unit. Community Ment Health J.

2001;37(2):169-77.

34. Middelbow T, Schjodt T, Byrsting K, Gjerris A. Ward

atmosphere in acute psychiatric in-patient care:

Patients' perceptions, ideals and satisfaction. Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;103(3):212-9.

35. Christenfeld R, Wagner J, Patsva G, Acrish WP. How

physical settings affect chronic mental patients. Psychiatr

Q. 1989;60:253-64.

36. Liddicoat S. Perceptions of spatiality: Supramodal

meanings and metaphors in therapeutic environments.

Interiority. 2018.

37. Martin JH. Improving staff safety through an

aggression management program. Arch Psychiatr Nurs.

1995;9(4):211-5.

38. Tyson G, Lambert G, Beattie L. The impact of ward

design on the behaviour, occupational satisfaction and

well-being of psychiatric nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs.

2002;11:94-102.

39. Nejati A, Rodiek S, Shepley MM. Using visual

stimulation to evaluate restorative qualities of access to

nature in hospital staff break areas. Landsc Urban Plan.

2016;148:132-8.

40. Nejati A, Shepley MM, Rodiek S. A review of design

and policy interventions to promote nurses' restorative

breaks in healthcare workplaces. J Workplace Health Saf.

2016;64(2):70-7.

41. Davis C, Glick ID, Osow I. The architectural design of

a psychotherapeutic milieu. Hosp Community Psychiatry.

1979;30(7):453-60.

42. Gutkowski S, Ginath Y, Guttmann F. Improving

psychiatric environments through minimal architectural

change. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1992;43(9):920-3.

43. Sidman J, Moos RH. On the relation between

psychiatric ward atmosphere and helping behavior. J

Clin Psychology. 1973;29(1):74-8.

44. Turlington R. Creating a planetree inpatient psychiatric

unit. Health Facilities Managament Magazine.

2004;17(6):12-3.

45. Sorlie T, Parniakov A, Rezvy G, Ponomarev O.

Psychometric evaluation of the ward atmosphere scale

in a russian psychiatric hospital. Nordic J Psychiatry.

2010;64(6):377-83.

46. Karlin BE, Zeiss RA. Best practices: Environmental

and therapeutic issues in psychiatric hospital design:

Toward best practices. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1376-

8.

47. Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J

Urban Health. 2003;80(4):536-55.

48. Gutkowski S, Guttmann F. Program and process:

Designing the physical space of a day hospital. Isr J

Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1992;29(3):167-73.

49. Frumkin H. Beyond toxicity: Human health and the

natural environment. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(234-240).

50. Liddicoat S. Designing a supportive emergency

department environment for people with self harm and

suicidal ideation: A scoping review. Australas. Emeg.

Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.auec.2019.04.006

51. Ulrich RS. Human responses to vegetation and

landscapes. Landscape Urban Plan. 1986;13:29-44.

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019 103

52. Evans G, McCoy J. When buildings don't work: The

role of architecture in human health. J Environ Psychol.

1998;18:85-94.

53. Srinivasan S, O'Falton LR, Dearry A. Creating health

communities, healthy homes, healthy people: Initiating

a research agenda on the built environment and public

health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1446-50.

54. Joye Y, van den Berg AE. Restorative environments.

2012. In: Environmental Psychology: An introduction

[Internet]. New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; [57-66].

55. Messer LC, Maxson P, Miranda ML. The urban built

environment and associations with women's

psychosocial health. J Urban Health. 2012;90(5):857-71.

56. Fornara F, Bonaiuto M, Bonnes M. Percieved hospital

environment quality indicators: A study of orthopaedic

units. J Environ Psychol. 2006;26:321-34.

57. Gifford R. Environmental psychology: Principles and practice.

5 ed. Colville: Optimal Books; 2015.

58. Mourshed M, Zhao Y. Healthcare providers'

perception of design factors related to physical

environments in hospitals. J Environ Psychol.

2012;32:362-70.

59. Ke-Tsung H. A reliable and valid self-rating measure of

the restorative quality of natural environments.

Landscape Urban Plan. 2003;64:209-32.

60. Perkins DV, Perry J, C. Dimensional analysis of

behaviour setting demands in a community residence

for chronically mentally ill women. J Community Psychol.

1985;13:350-9.

61. Duffy M, Willson VL. The role of design factors of the

residential environment in the physical and mental

health of the elderly. J Housing Elderly. 1985;2(3):37-46.

62. Devlin AS, Arneill AB. Healthcare environments and

patient outcomes. Environ Behav. 2003;35:665-94.

63. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a

methodological framework. Int J Soc Res. 2005;8:19-32.

64. Warzocha D, Pawelczyk T, Gmitrowicz A.

Associations between deliberate self-harm episodes in

psychiatrically hospitalised youth and the type of

mental disorders and selected environmental factors.

Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2010;2(23-29).

65. Cardell R, Bratcher KS, Quinnett P. Revising 'suicide

proofing' an inpatient unit through environmental

safeguards: A review. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2009;45(36-

44).

66. Kaar SJ, Walker H, Sethi F, McIvor R. The function

and design of seclusion rooms in clinical settings.

Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care. 2017;13(81-91).

67. Broadbent M, Moxham L, Dwyer T. Implications of

the emergency department triage environment on

triage practice for clients with a mental illness at triage

in an australian context. Aust Emerg Nurs J. 2014;17:23-

9.

68. Clarke DE, Dusome D, Hughes L. Emergency

department from the mental health client's perspective.

Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2007;16:126-31.

69. Curtin LL. Patient privacy in a public institution. Nurs

Manag. 1993;24(6):26-7.

70. Fay L, Carll-White A, Harrell J. Coming full cycle:

Linkig poe findings to design application. HERD.

2017;10(3):83-98.

71. Guinther L, Carll-White A, Real K. One size does not

fit all; a diagnostic post-occupancy evaluation model

for an emergency department. HERD. 2014;7(3):15-37.

72. Huddy J, McKay JI. The top 25 problems to avoid

when planning your new emergency department. J

Emerg Nurs. 1996;22(4):296-301.

73. Gharaveis A, Hamilton DK, Pati D, Shepley MM.

Impact of visibility on teamwork, collaborative

communication, and security in emergency

departments: An exploratory study. HERD. 2017.

74. Zamani Z. Effects of emergency department physical

design elements on security, wayfinding, visibility,

privacy, and efficiency and its implications on staff

satisfaction and performance. HERD. 2018:1-17.

75. Bost N, Johnston A, Broadbent M, Crilly J. Clinian

perspectives of a mental health consumer flow strategy

in an emergency department. Collegian 25. 2018:415-20.

76. Lenaghan PA, Cirrincione NM, Henrich S. Preventing

emergency department violence through design. J

Emerg Nurs. 2018;44(1):7-12.

77. Lanza ML, Kayne HK, Hicks C, Milner J.

Environmental characteristics related to patient assault.

Iss Ment Health Nurs. 1994;15(3):319-35.

78. Pati D, Harvey TE, Willis DA, Pati S. Identifying

elements of the health care environment that

contribute to wayfinding. HERD. 2015;8:44-67.

79. Watts BV, Young-Xu Y, Mills P, DeRosier P, Kemp J,

Shiner B, et al. Examination of the effectiveness of the

mental health environment of care checklist in

reducing suicide on impatient mental health units. Arch

Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(6):588-92.

80. Geddes JR. Suicideand homicide in mentally ill

patients. BMJ. 1999;318(1225-1226).

81. Carr R. Psychiatric facility 2011. Available from:

http://www.wbdg.org/design.psychiatric.php.

82. Broadbent M, Moxham L, Dwyer T. Issues associated

with the triage of clients with a mental illness in

australian emergency departments. Aust Emerg Nurs J.

2010;13:117-23.

83. Joint Commission Resources. Suicide prevention: Toolkit

for implementing national patient safety goal 15a. Oakbrook

Terrace: Joint Commission Resources; 2007.

84. National Center on Institutions and Alternatives.

Suicide prevention and 'protrusion-free' design of

correctional facilities. Jail Suicide/Mental Health Update.

2003;12(1-20).

85. Sine DM, Hunt JM. Design guide for the built environment of

behavioural health facilities. 2 ed. Washington, DC:

National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems;

2007.

Enhancing emergency care environments, Liddicoat

104 Patient Experience Journal, Volume 6, Issue 3 – 2019

86. Taiminen TJ, Strandberg J, Kujari H. Inpatient suicide

on general hospital psychiatric ward. Arch Suicide Res.

1996;2(119-124).

87. Shepley MM, Pasha S. Design for mental and behavioural

health. London: Routledge; 2017.

88. Sheehan B, Burton E, Wood S, Stride C, henderson E,

Wearn E. Evaluating the built environment in inpatient

psychiatric wards. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(8):789-95.

89. Ulrich RS, Zimring C, Quan X, Joseph A. The role of

the physical environment in the hospital of the 21st

century. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Centre for

Health Design; 2004.

90. Carpman J, Grant M, Simmons D. No more mazes.

Research about design for wayfinding in hospitals. Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Hospitals, Patient and Visitor

Participation Project; 1984.

91. Ulrich RS. Effects of interior design on wellness:

Theory and recent scientific research. J Health Care Inter

Des. 1991;3(1):97-109.

92. Nanda U, Elsen S, Zadeh RS, Owen D. Effect of